Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Transforming Sawdust Waste into Renewable Energy Resources: A Comprehensive Review on Sustainable Bio-Oil and Biochar Production via Thermochemical Processes

1 Department of Chemistry, Nile University of Nigeria, FCT, Abuja, 9000001, Nigeria

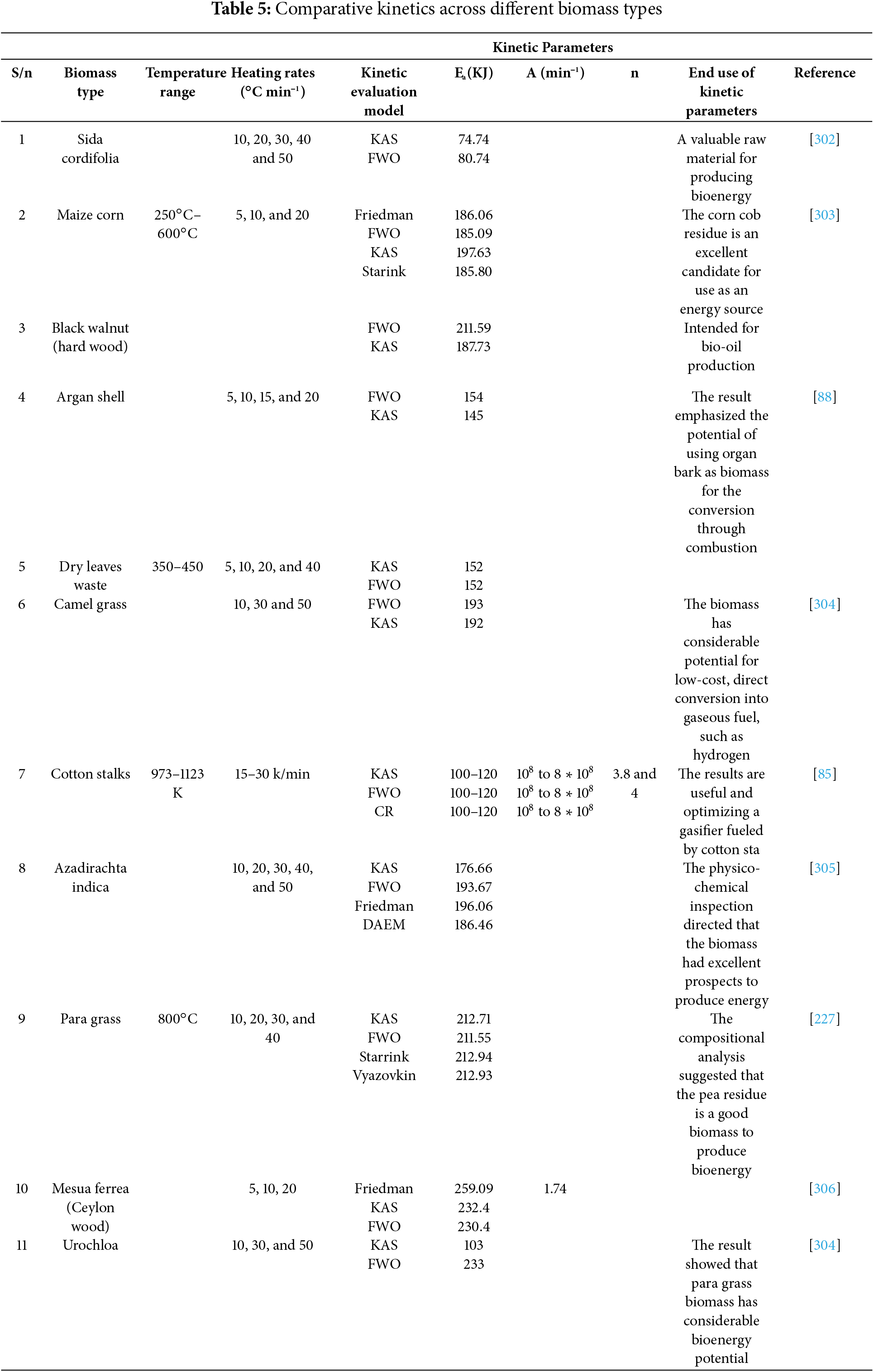

2 Waste to Wealth Research Group, Nile University of Nigeria, FCT, Abuja, 9000001, Nigeria

3 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Nile University of Nigeria, FCT, Abuja, 9000001, Nigeria

4 Department of Chemical Engineering, Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA 17837, USA

* Corresponding Author: Adekunle Adeleke. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(12), 2375-2430. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0109

Received 02 June 2025; Accepted 01 September 2025; Issue published 23 December 2025

Abstract

The increasing need for sustainable energy and the environmental impacts of reliance on fossil fuels have sparked greater interest in biomass as a renewable energy source. This review provides an in-depth assessment of bio-oil and biochar generation through the pyrolysis of sawdust, a significant variety of lignocellulosic biomass. The paper investigates different thermochemical conversion methods, including fast, slow, catalytic, flash, and co-pyrolysis, while emphasizing their operational parameters, reactor designs, and effects on product yields. The influence of temperature, heating rate, and catalysts on enhancing the quality and quantity of bio-oil and biochar is thoroughly analyzed. Additionally, the review examines advanced reactor technologies such as fluidized beds, fixed beds, auger reactors, and plasma pyrolysis systems. It also discusses recent progress in catalyst innovation and product enhancement techniques to overcome the challenges posed by bio-oil, including its high oxygen content and low stability. By synthesizing experimental results and conducting comparative analyses, the paper identifies existing research gaps and provides insights into future paths for effective biomass utilization, thereby aiding in the creation of economically viable and environmentally responsible bioenergy systems.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

1.1 Overview of Renewable Energy

Research into alternative energy sources has intensified due to the environmental impacts of fossil fuel use and increasing global commitment to sustainability. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), total energy consumption is projected to rise from 12,000 to 16,800 Mtoe between 2007 and 2030, with an annual growth rate of 1.5% [1]. However, fossil fuels such as coal and petroleum remain the dominant energy sources and account for approximately 56.6% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1]. To address this, the United Nations (UN) Climate Panel has proposed reducing GHG emissions by 50%–80% by 2050 [1]. Achieving these goals requires a significant transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources, which offer environmental benefits and long-term economic viability. Among renewable options, biomass has gained prominence due to its availability and environmental advantages. Biomass, primarily in the form of lignocellulosic material from forestry waste, aquatic plants, crop residues, and energy crops, is available in large quantities, estimated at around 220 billion tons annually [1]. These residues often require significant processing and disposal space; however, converting them into energy not only reduces environmental load but also generates economic value [2]. Recycling biomass waste into energy and fuel supports a bio-based economy, promotes resource efficiency, and contributes to job creation [3]. Biomass is chemically diverse, and its energy potential depends heavily on its composition. For instance, grain and animal waste are rich in starch, while plant-based residues contain varying proportions of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin [4]. These variations directly affect how biomass behaves under thermochemical conversion processes such as pyrolysis, gasification, combustion, and hydrothermal liquefaction. Among these, pyrolysis stands out for its ability to convert biomass into three valuable products bio-oil, biochar, and syngas within a short reaction time and under limited oxygen supply [5]. Pyrolysis has gained increasing attention for biofuel production due to its versatility, efficiency, and lower power requirements compared to other thermochemical methods. The liquid product, bio-oil, is considered one of the most promising carbon-neutral fuels for the future [6]. Its use significantly reduces emissions of sulfur dioxide and nitrogen oxides, and it can be easily stored and transported using existing infrastructure [7,8]. These features make bio-oil a more practical alternative to biogas or charcoal in many energy applications.

Various woody biomasses have been investigated for pyrolysis-based fuel production. For example, Siddiqi et al. [1] reported that the physicochemical characteristics of Shorea robusta biomass show strong potential for producing liquid fuel and biochar [9]. Similarly, Ameh et al. [10] studied Sal wood sawdust and found its derived fuel to be a promising substitute for fossil fuels. However, thermal pyrolysis often produces bio-oil with high viscosity, oxygen content, and acidity, limiting its direct application as a transportation fuel. These issues can be mitigated through catalytic pyrolysis, which enhances oil quality by promoting deoxygenation and reducing unwanted compounds. This review aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the pyrolysis of bio-oil and biochar derived from sawdust, with a focus on the influence of feedstock composition, pyrolysis conditions, and catalyst application. It critically evaluates recent advancements in characterization techniques, product optimization, and potential applications, while identifying research gaps and future prospects for sustainable bioenergy and biochar utilization.

1.2 The Role of Biomass in Addressing Environmental and Energy Issues

The globe is searching for renewable energy sources due to the depletion of fossil fuel reserves and rising expenses. To balance the production and consumption of energy resources, a variety of biomass sources including both lignocellulosic and non-lignocellulosic biomass are used. Woody biomass, agricultural residues, and plants that contain industrial byproducts like sewage sludge and animal dung, bones, microorganisms like algae, and various other sources are classified as non-lignocellulosic biomass that is used in catalysis, pollutant removal, and energy production. The main components of lignocellulosic biomass are cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, whereas the constituents of non-lignocellulosic biomass are proteins, carbohydrates, saccharides, and different inorganic substances [11].

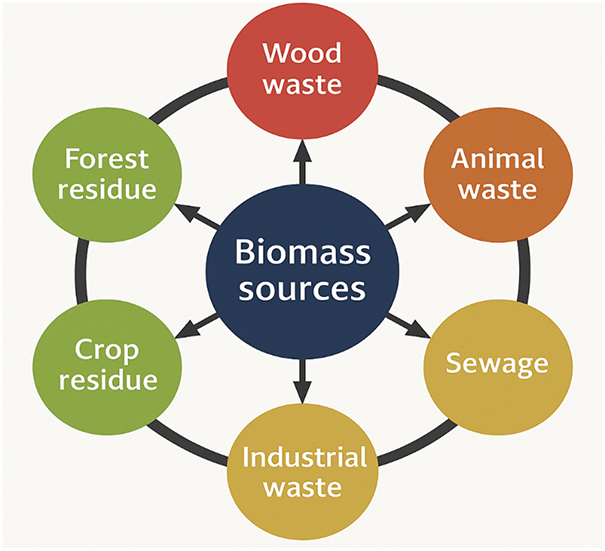

Researchers are interested in biomass as an alternative energy source since it is a renewable source of organic solid waste [12]. Because of a number of issues, such as excessive humidity, low density, and milling challenges, the original form of biomass is very challenging to use directly as fuel. Therefore, a variety of thermal techniques are used to transform the initial biomass samples into more workable material. Biomass undergoes chemical and physical changes during thermal degradation. When a material’s porosity increases, its physical and chemical properties alter as a result of thermal breakdown at various rates of temperature and variable product composition and characteristics [13]. Various sources of biomass waste are categorized based on origin and composition, as shown in Fig. 1. Through a variety of conversion pathways, lignocellulosic biomass, a renewable and carbon-neutral resource, can be transformed into biofuel and other intermediate compounds [14]. It is made up of biopolymers like cellulose (40%–60%), hemicellulose (20%–40%), and lignin (15%–30%) [15].

Figure 1: Various sources of bimass waste

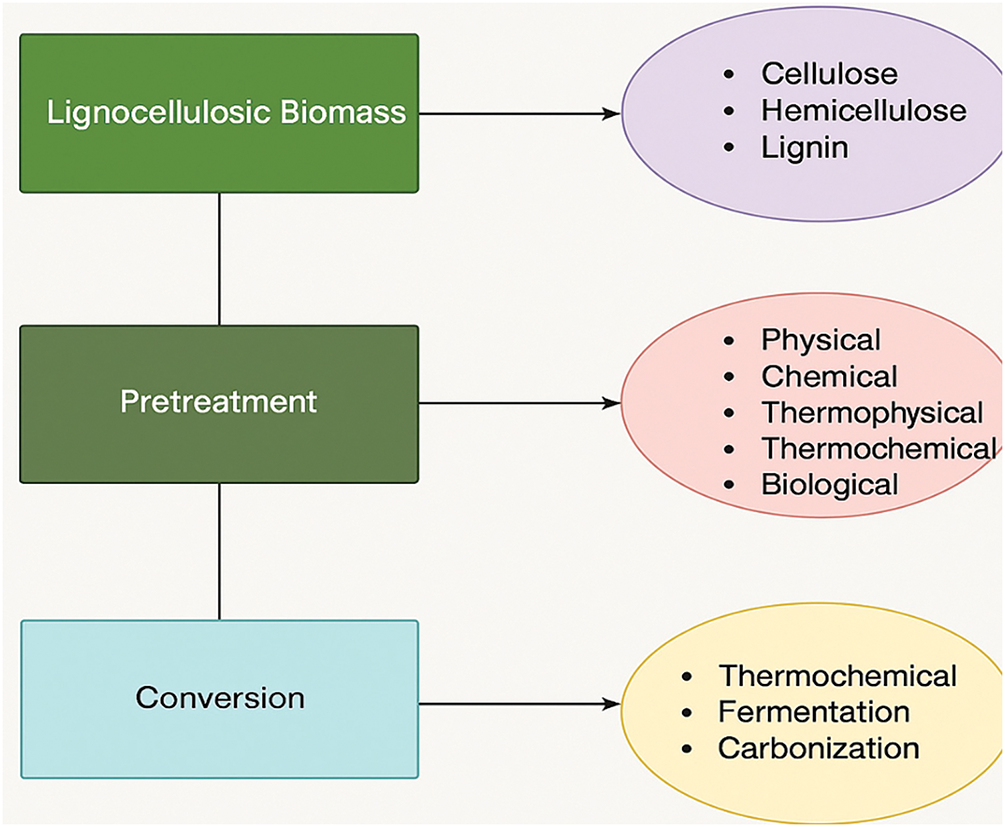

Cellulose, a crystalline polymer has the generic formula (C6H10O5) n and is made up of b-linked chains. Hydrogen bonds between the oxygen molecules in cellulose and the hydroxyl groups of glucose produce microfibrils that are joined in a carbohydrate matrix, giving a plant’s cell wall its strength and rigidity [16]. Compared to cellulose, hemicellulose is a complex amorphous polymer with a lower molecular mass and varied degree of branching. It shares structural and chemical similarities with cellulose. The kind and quantity of monosaccharides that make up its structure, which often consists of xylose (the most prevalent), galactose, glucose, arabinose, mannose, and sugar acids, set it apart from cellulose [17]. Hemicellulose should be eliminated during pretreatment because it binds to lignin, pectin, and cellulose micro-fibrils to form a cross-linked network that supports the structural integrity of cell walls [16]. Lignin, after cellulose and hemicellulose, is the most prevalent natural polymer on the planet [18]. This amorphous polymer matrix, which is the third major component of lignocellulosic biomass, is created by the random polymerization of three main phenylpropane monomers: coumaryl, coniferyl, and sinapyl alcohols [19]. According to their origin, these three lignin precursors cause the H (p-hydroxyphenyl), G (guaiacyl), and S (syringyl) to be acylated and exhibit varying abundances [20]. Determining the extent of lignin’s natural polymerization is challenging because it is always broken up during extraction and is made up of several substructures that repeat randomly together [21]. These three key components of lignocellulose material are arranged with acetyl groups, minerals, and phenolic substituents to form an extremely complicated structure [22]. Additionally, the components of lignocellulosic biomass determine its usage because cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin fractions interact differently in complex and wide-ranging molecular systems [22]. Pretreatment is required to dissolve the intricate bonds between these three main biomass constituents. The next step after pretreatment is to transform them into the desired chemical products. Fig. 2 displays the process’s schematic diagram.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram showing utilization of lignocellulose biomass

The main ways to characterize biomass are to examine its carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen contents to ascertain its elemental composition [23]. The primary reasons of the variation in the chemical composition and ash levels of biomass are the varying moisture concentrations, ash yields, and the presence of different kinds of inorganics in biomass. The elements that are most prevalent in biomass are Carbon (C), Hydrogen (H), Oxygen (O), Nitrogen (N), Calcium (Ca), Potassium (K), Silicon (Si), Magnesium (Mg), Aluminium (Al), Silicon (S), Iron (Fe), Phophorus (P), Chlorine (Cl), Sodium (Na), Manganese (Mn), and Titanium (Ti) [24]. The kinds of species found in biomass vary depending on whether it originates from agriculture, industrial waste, or waste from plants or animals [25]. Although in extremely little amounts, biomass also contains sulfur and nitrogen, indicating its amiable nature. Since the emission of Nitrogen oxides (NOx) and Sulfur oxides (SOx) is caused by the presence of nitrogen and sulfur, its low concentration is beneficial to the environment and does not harm it in any way [26]. According to literature, the most common components in biomasses are C, O, and H, with smaller amounts of K, P, and Si present in some of them [27]. The morphology and surface characteristics of biomass and biochar have been determined using a variety of characterization techniques in addition to elemental composition analysis, such as Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM), Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectrometer (EDX), and Surface Area Analyzer (SAA). According to the findings of these characterizations, lignocellulosic biomass has the potential to be used globally as a sustainable energy source [28–32]. Understanding the physicochemical characteristics of biomass, such as elemental composition and surface morphology, provides essential insights into its suitability for various thermochemical conversion technologies.

2 Thermochemical Biomass Conversion Pathways

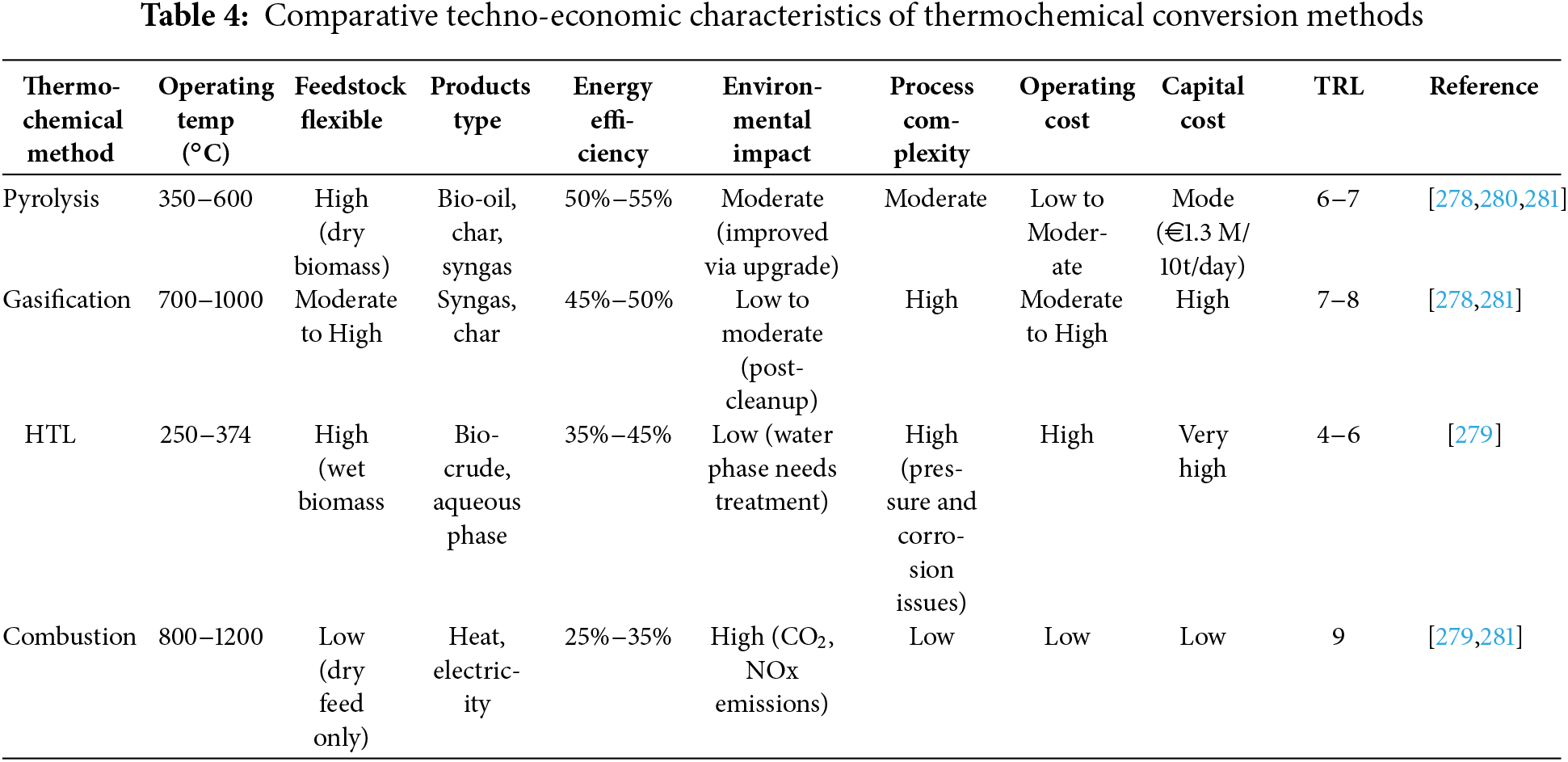

Building upon the feedstock properties discussed earlier, understanding the available thermochemical conversion routes is critical to selecting appropriate methods for transforming sawdust into valuable bio-products. Biomass can be transformed into a variety of beneficial products and energy sources, including heat, natural gas, biochar, bio-oil, and thermal and electrical energy, by employing a number of thermochemical processes [33,34]. Thermochemical conversion is essentially the thermal breakdown of organic biomass components to produce useful compounds. It is a successful alternative method of creating bioenergy that includes carefully regulated biomass oxidation or heating [32]. However, a variety of factors, including the type and quantity of biomass, its accessibility, the cost of the manufacturing process, options for the final products, and environmental concerns, influence the choice of conversion technique [33–35]. For example, the biomass feedstock should be low in moisture and in solid form. Likewise, using the wrong technology could lead to inefficiencies [36,37]. Common thermochemical technology categories often comprise combustion, hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL), torrefaction, gasification, and pyrolysis [32]. Among these, torrefaction and pyrolysis have received substantial attention due to their suitability for lignocellulosic feedstocks like sawdust. The next subsection explores torrefaction, particularly as a thermal pretreatment technique that enhances the efficiency of downstream processes such as pyrolysis.

Torrefaction serves as an essential first step in improving the thermal characteristics of biomass. It involves the drying of feedstock in an inert atmosphere, usually at temperatures between 200°C and 300°C. Torrefaction is characterized as light (200°C–235°C), mild (235°C–275°C), or severe (275°C–300°C) depending on the temperature range [34]. It may also be thought of as the gradual heating of biomass without the presence of oxygen. Hot vapors from the torrefaction process carry the volatile materials to the condenser for condensation. Torrefaction is a clean and promising thermochemical process frequently used as a thermal pretreatment for biomass resources [35]. Torrefaction has been shown to improve the efficiency of thermochemical conversion processes including gasification, liquefaction, and pyrolysis by eliminating moisture and partially breaking down the biomass [36]. Torrefaction has attracted significant attention because, in addition to the improved qualities of torrefied and densified biomass, the technologies associated with torrefaction are almost ready for commercialization. Compared to raw biomass, torrefied biomass exhibits several key advantages including enhanced hydrophobicity, improved grindability, increased higher heating value, reduced moisture content, and superior pelletizability stemming from structural changes like fiber degradation, reduced hemicellulose, and increased brittleness that facilitate densification and handling [37]. By increasing the proportion of carbon and lowering the oxygen level, torrefaction improves biomass’s heating value. Along with traces of aldehydes, ketones, ethers, esters, and alcohols, the condensed liquid product of torrefaction also contains water and carboxylic acids [38]. The non-condensable gases consist of Carbon Dioxide (CO2), Carbon Monoxide (CO), Methane (CH4) and traces of Hydrogen (H2). The torrefied solids left behind have properties similar to coal and hence can be used as green alternatives. One of the advantages of using torrefaction is that it does not emit any GHGs; instead, it fixes the carbon in the form of densified and dehydrated biomass for further thermochemical processing.

The torrefaction of biomass feedstocks, including cotton stalk, sugarcane bagasse, rice straw, rice husk, and oats, has been extensively studied by [39]. Under processing conditions involving temperatures of 250°C–300°C and residence times ranging from 15 to 60 min, significant changes in both the structural and chemical properties of the biomass were observed. Microwave drying, employed as a pretreatment, caused visible surface cracking in the biomass, facilitating the release of additional volatile compounds. This surface alteration also contributed to a reduction in crystallinity, enhancing the reactivity of the feedstocks. Such modifications are crucial for improving the efficiency of biomass utilization in thermochemical processes. The elemental analysis revealed that torrefied rice husk, sugarcane bagasse, and cotton stalk exhibited increased carbon content and heating values. These values were found to be comparable to those of bituminous coal, emphasizing the potential of these materials as high-energy-density fuels. In contrast, torrefied rice straw showed distinctive structural properties, with carbon exhibiting a high crystallinity of approximately 50%. Conversely, the carbon in rice husk and sugarcane bagasse predominantly displayed an amorphous structure. This variability in crystallinity across feedstocks indicates the influence of inherent material properties on the outcomes of torrefaction. These findings highlight the versatility and efficacy of torrefaction in enhancing biomass properties, making it a promising approach for converting agricultural residues into energy-dense, coal-like fuels.

Torrefied biomass is very compatible with dry pyrolysis, which prefers pre-dried feedstocks and usually takes place at 350°C–600°C in inert atmospheres. On the other hand, wet pyrolysis, also known as hydrothermal pyrolysis, processes biomass with a high moisture content without the requirement for drying because it works at pressures between 5 and 20 MPa and temperatures between 200°C and 350°C [40]. Torrefaction, a mild pyrolysis process for thermal pretreatment, aims to improve higher heating values and energy densities, reduce atomic O/C and H/C ratios, lower moisture content, enhance water resistance, increase grindability and reactivity, and achieve uniform properties. Dry torrefaction (DT) takes place between 200°C and 300°C in an oxygen-free atmosphere with low heating rates (usually less than 50°C/min). Often referred to as hydrothermal torre faction, wet torrefaction (WT) is a high-pressure (up to 4.6 MPa) thermal pretreatment procedure that is conducted in hot compressed water under inert circumstances, usually at temperatures between 180°C and 260°C [41]. WT has a number of benefits over DT. In order to achieve comparable solid yields, WT needs significantly lower temperatures and shorter holding times than DT. This leads to higher energy yields, a higher heating value and enhanced hydrophobicity. Consequently, when it comes to biomass energy densification and conservation, WT outperforms DT at this point. Furthermore, WT has a lot of promise as an affordable method of turning cheap, low-quality biomass materials into cleaner biomass fuels. WT can effectively process biomass materials with high moisture content, even when they are very wet, a condition that typically poses significant challenges for dry torrefaction. Overall, torrefaction enhances the fuel properties and thermal stability of biomass, making it an effective pretreatment that significantly improves the efficiency and product quality of subsequent pyrolysis processes.

Following torrefaction, gasification presents a more advanced thermochemical route, particularly for producing clean syngas from sawdust and other lignocellulosic feedstocks. The thermochemical process known as “gasification” has the capacity to convert any carbonaceous material into syngas [42]. Gasification offers the ability to produce char and gaseous products (such as H2, CO, CO2, and CH4) from a range of feedstocks. Energy can be produced from syngas in a variety of ways, including heat, electricity, biofuel, biomethane, chemicals, and hydrogen [43]. Hydrothermal gasification can function at relatively moderate temperatures (400°C–700°C), but thermal gasification of coal and complex biomass requires high temperatures (800°C–1200°C). The primary gaseous products of gasification are accompanied by condensable liquids that are high in biochemicals and water. The gas can be cleaned and recovered quite easily because of the limited tar development caused by the higher temperature [42]. Furthermore, high gasification temperatures promote endothermic reactions such as water-gas shift, methanation, and steam reforming, which result in a quicker reaction rate and almost total breakdown of biomass into gases. By using Fischer-Tropsch catalysis, the syngas can be transformed into clean fuels and goods with additional value [44]. In order to create syngas, hydrothermal gasification (HTG) uses subcritical or supercritical water as a reaction medium. Below the critical temperature of water (374°C) and above the critical pressure of water (22.1 MPa), respectively, subcritical and supercritical water exist. HTG’s primary advantage is its ability to effectively convert biomass with high moisture content, which would otherwise need expensive and energy-intensive drying processes prior to gasification [45]. On the other hand, because the heat of moisture evaporation typically exceeds the heat of biomass combustion, converting wet biomass through pyrolysis, liquefaction, and gasification is typically inefficient. Applications for the HTG product include chemical synthesis, electricity generation, and hydrogen-producing fuel cells. Recent studies have explored the gasification of agricultural waste biomass, such as cotton stalks, corn stalks, and rice straw, using various catalysts such as Marley clay, calcium hydroxide, dolomite, and cement kiln dust were evaluated in a bench-scale fixed-bed reactor operating at temperatures ranging from 700°C–800°C. Among these, calcium hydroxide and cement kiln dust were found to be particularly effective in increasing gas yields while significantly reducing tar and char formation [46]. While gasification is effective for generating gaseous fuels, it is less suitable for solid or liquid fuel production. The next section explores combustion a simpler, yet highly established thermochemical process widely used for direct heat and power generation.

In contrast to gasification, combustion relies on complete oxidation of biomass to generate thermal energy and is commonly employed for large-scale heating and electricity production. The combustion process consists of an exothermic series of processes. When chemical bonds break, the energy they contain is released. In the majority of industries and power plants, this energy is used to generate the steam required for turbines, which in turn generate heat and electricity. When it comes to alternative fuels like biomass, combustion is defined as the burning of organic materials. Wood is the most commonly used fuel for burning biomass [47]. Biomass combustion systems come in a variety of sizes, ranging from small domestic units of just a few kilowatts to large power plants with capacities up to hundreds of megawatts. These systems can provide heat and power with relatively high efficiency and at reasonable costs, with large-scale applications being particularly significant for the cost-effectiveness of steam plants [48]. Generally, there are two types of biomass combustion models: macroscopic and microscopic. The macroscopic characteristics of biomass specifically, its moisture content, heating value, density, particle size, and ash fusion temperature are given for macroscopic study. Among the characteristics that can be investigated under a microscope are thermal, chemical kinetics, and mineral data [49]. The interplay between fuel, energy, and ambient elements can be viewed as the three fundamental combustion operations. Biomass fuel burns in the boiler to produce flammable vapors that volatilize and burn like flames. With more air present, the residual material which is still a carbon char will subsequently catch fire. The heat produced during combustion can be utilized as a source for other conversion procedures that produce electrical energy, albeit this again depends on a number of other factors [50]. Although combustion is well established and cost-efficient, it is primarily limited to heat and power production. Hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) emerges as an alternative that offers the potential to produce liquid biofuels, particularly from wet biomass feedstocks.

2.4 Hydrothermal Liquefaction (HTL)

Following combustion, which mainly produces heat and electricity through complete oxidation, hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL) presents a more advanced approach for converting wet biomass into energy-dense liquid fuels. HTL thermochemically converts biomass into liquid biocrude using sub- or supercritical water under elevated temperature and pressure. Typical operating conditions range between 523 and 647 K and 4 to 22 MPa, depending on feedstock and reactor design [51]. This method enables any energy-intensive drying process to directly convert wet biomass material into liquid fuels [52]. Additionally, the resultant oil has a significant calorific value. Water serves as a solvent in this process and has several benefits, including improved biomass solubility, a low dielectric constant and viscosity, and support for acid-base reactions. Through decarboxylation and dehydration processes, some of the oxygen in biomass is eliminated. Carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, and water are the products of these reactions. To produce biofuels, biomass is subjected to a number of chemical reactions using hydrothermal processing technologies. These procedures include gasification, reforming, condensation, depolymerization, hydrolysis, and pyrolysis.

Sivabalan et al. [53] investigated the use of high moisture content waste from the tobacco processing sector for HTL in the manufacture of bio crude oil. The study investigated on optimized effects of operating circumstances to produce the most liquid bio crude oil possible. For HTL operating conditions, 280°C–340°C temperatures and 15–45 min residence times were considered, with a fixed biomass to deionized water ratio of 1:3. The yield of liquid bio crude oil at 310°C and 15 min was more than 52% w/w, which was the maximum. Additionally, the HTL of oak wood was investigated by [54] in order to create premium bio crude. They investigated the effects of using iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), and other metals as hydrogen generators and nickel (Ni) and cobalt (Co) as hydrodeoxygenation catalysts on the quality of bio crude. Supercritical water oxidizes Fe and Zn to produce active hydrogen. When Ni and Co are present, this hydrogen is subsequently used to power hydrodeoxygenation activities and stabilize biomass pieces during the process. The results show that bio crude yields are significantly impacted by the deployment of hydrogen generators. In summary, HTL offers a promising route for converting wet biomass into high-quality liquid bio-crude without the need for drying, making it energy-efficient for moisture-rich feedstocks. However, its reliance on high-pressure systems, complex reactor design, and catalyst requirements may limit its scalability and economic feasibility in certain contexts. The next section explores pyrolysis, a versatile thermochemical process that operates at atmospheric pressure and accommodates a wide variety of biomass types, making it more practical for scalable bio-oil and biochar production.

Among thermochemical conversion methods, pyrolysis stands out as a flexible and efficient process for converting lignocellulosic biomass into valuable energy products such as bio-oil, biochar, and syngas. It involves thermal decomposition of biomass in the absence or near absence of oxygen, offering significant potential for bioenergy and material applications. Pyrolysis is a process that converts biomass into energy by heating (not burning) at a high temperature and certain pressure with little or no oxygen. The most common byproduct of pyrolysis is charcoal, which is used extensively in metallurgical operations. Other by-products of pyrolysis include liquids (water, tar, and oil) and gases (methane, hydrogen, and carbon monoxide) [55]. Pyrolysis is a versatile and efficient process that turns solid biomass into a liquid that is easy to transport and store, enabling the efficient production of heat, power, and chemicals. But before pyrolysis, drying is essential for high moisture waste biomass, such as sludge and waste from meat production [56]. It is a complex process that pyrolyzes biomass using both sequential and simultaneous processes. When biomass is heated in an inert atmosphere, the components begin to thermally decompose at 350 to 550 degrees Celsius, which speeds up to 700°C–800°C when air is not present. Long chains of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen compounds break down into smaller molecules during pyrolysis as a result of the decomposition of biomass, producing gases and condensable vapors such as tars, oils, and solid charcoal. Depending on the pyrolysis process conditions, each of these components decomposes differently and to varying degrees [7]. Additionally, pyrolysis is further divided into many categories, including fast pyrolysis, catalytic pyrolysis, fast pyrolysis, and slow pyrolysis.

The low molecular weight lignin produced during pyrolysis exhibits significant physicochemical complexity, including high oxygen content, thermal instability, and molecular heterogeneity. As a result, detailed characterization of pyrolysis products has become a key focus to better understand and manage this complexity. The pyrolysis process occurs in two stages: primary pyrolysis, involving depolymerization, fragmentation, and char formation; and secondary pyrolysis, where further cracking and condensation reactions take place. Due to the poor physical and chemical properties of raw bio-oil such as acidity, viscosity, and low heating value upgrading is essential before it can be commercially utilized [57]. An immense diversity of pyrolysis processes, including flash pyrolysis, catalytic pyrolysis, slow pyrolysis, quick pyrolysis, can be employed depending on the operational parameters, each offering distinct product yields and characteristics. In summary, Pyrolysis is a key thermochemical pathway for converting biomass into bio-oil, biochar, and syngas. Its adaptability through fast, slow, flash, catalytic, or microwave-assisted modes allows for customized product yields. While raw bio-oil often needs upgrading due to its instability, advancements in catalysts and reactor design are enhancing its viability, making pyrolysis a leading option for sustainable biomass valorization.

Fast pyrolysis is the rapid heating of biomass at a high temperature in an oxygen-deficient atmosphere. When biomass undergoes thermal decomposition, it releases vapors, aerosols, and solid residues such as char. During the cooling and condensation stages, condensable vapors and aerosols form a dark brown bio-oil that typically has a high heating value due to its rich organic content. The char remains as a solid by-product. Depending on the feedstock and conditions, fast pyrolysis typically yields 60–70 wt % liquid products (bio-oil), 15–30 wt % solid products (biochar), and 10–20 wt % non-condensable gases [58]. Fast pyrolysis is an effective conversion technique because of four key features: it uses high heating rates, controlled temperature conditions (typically between 430°C and 500°C), a very short vapor residence time (less than 2 s), and rapid cooling of vapors and aerosols to produce bio-oil. In addition, this method uses less energy and is less costly than alternative approaches [59].

Other researches in the literature also address the integration of fast pyrolysis with other processes within the setting of a bio refinery. For example, to assess product yields and energy efficiency, Jafri et al. [58] examined six commercial methods for biofuel generation from forest leftovers. Most biofuel manufacturing paths involve integrating it with a pulp mill or a crude oil refinery. Thermochemical conversion processes included gasification, fast pyrolysis, and lignin depolymerization. According to Afraz et al. [60], they studied the fast pyrolysis of sugarcane bagasse and the upgrading of bio-oil using nickel-based catalysts (Nickel on Silica-Ni/SiO2 and Chromium doped Nickel on silica-Ni–Cr/SiO2). The upgraded bio-oil showed water and oxygen contents that were 63.3% and 43.3% lower, respectively, than those of the raw bio-oil, and its higher heating value (HHV) was 63% higher than that of the bagasse [60]. The upgraded bio-oil’s carbon recovery from sugarcane bagasse was 41.9% when using Ni/SiO2 and 32.5% when using Ni–Cr/SiO2. Additionally, a study by [61] conducted an experimental investigation on the quick pyrolysis of Miscanthus in a fluidized bed reactor, and then hydrolyzed the bio-oil that was produced over a Palladium on Carbon (Pd/C) catalyst in a fixed bed reactor. The phenol, ketone, aldehyde, alcohol, and acid components of the photolytic bio-oil were found to be transformed into over 41% of the alkanes in the upgraded fuel, according to the results [62].

The literature has a number of studies that concentrate on environmental assessments in addition to technical and economic ones. Shemfe et al. [63] for example, assessed the greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the quick pyrolysis and bio-oil upgrading of Miscanthus in the manufacture of bio-hydrocarbons. Similarly, Ref. [64] carried out a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) to assess the techno-economic and environmental aspects of producing renewable diesel through two methods: catalytic fast pyrolysis and fast pyrolysis followed by multiple catalytic hydro-treating and hydrocracking using U.S. forest residues [63]. A considerable amount of research has focused on the quick pyrolysis of biomass and upgrading of bio-oil to produce biofuel in recent years. This demonstrates the increasing attention and significance of this topic, given that the utilization of second-generation biofuels derived from lignocellulosic residues plays a major role in lowering greenhouse gas emissions and decarbonizing the transportation sector.

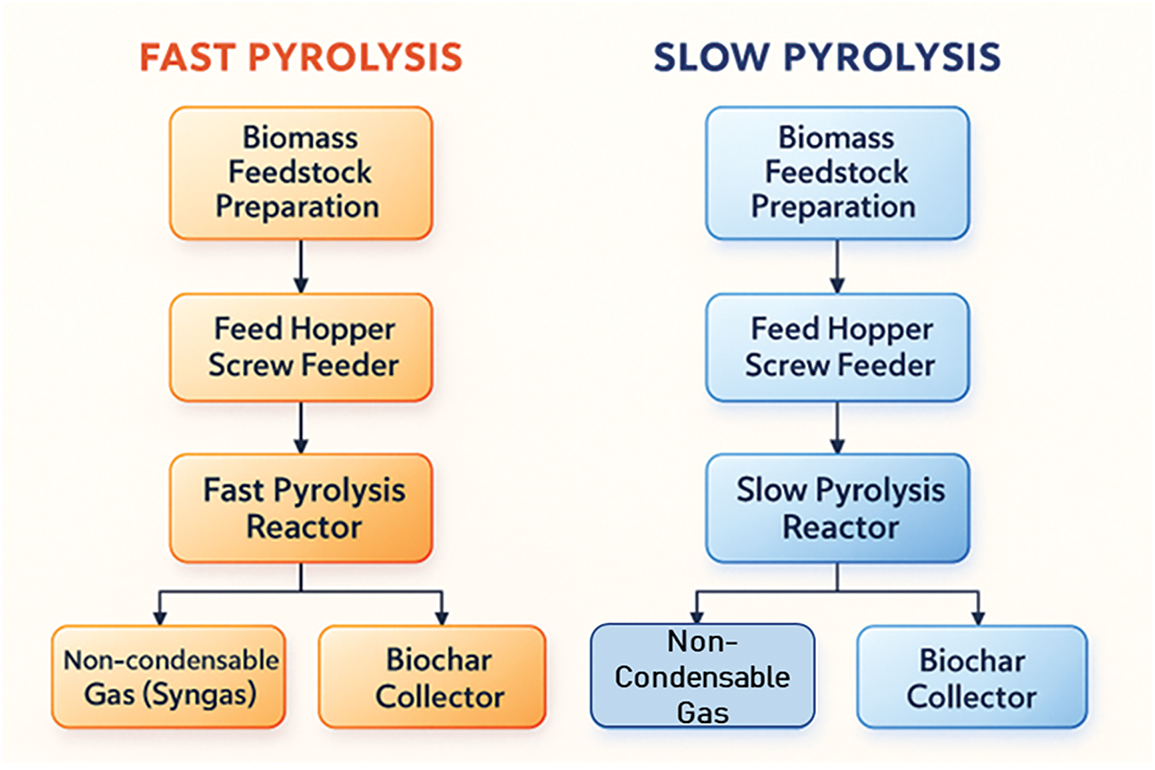

The method has been used for centuries, mostly in the manufacture of charcoal. As opposed to fast pyrolysis, slow conventional pyrolysis involves heating biomass to 500°C at a significantly slower rate, which allows the fumes produced to be continually removed [64]. As seen in Fig. 3, the production of char is particularly well-suited to the prolonged residence period and low temperature of slow pyrolysis. But because of its numerous drawbacks, this method is not suitable for producing high-quality bio-oil. Long-term residence times might cause original product fragmentation, which can negatively impact oil amount and quality. Additionally, the longer stay necessitates more energy [65]. A popular thermochemical method for turning lignocellulosic biomass into bio-oil is slow pyrolysis, which involves depolymerizing three-building biopolymers including cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin using heat and an inert atmosphere. Slow pyrolysis is a less energy-intensive method of producing bio oil than other thermal processes like hydrothermal liquefaction [66]. Furthermore, following catalytic upgrading, bio-oil from slow pyrolysis may be combined with other transportation fuels.

Figure 3: Fast and slow pyrolysis processes

The liquid bio-oil obtained from slow pyrolysis is dark brown in color and comprises several complex organic compounds such as alcohols, water, phenolics, ketones, esters, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids. Scholars have endeavored to synthesize pyrolysis bio-oil from diverse waste materials and assessed the properties of the bio-oil. About 42% bio-oil was created by the slow pyrolysis of linseed residue. This bio-oil was then analyzed using Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) methods, which mostly revealed the aliphatic and aromatic groups [67]. Similarly, 45% bio-oil was produced by slow pyrolysis of Prunus Armeniaca seed waste, and column chromatography mostly revealed the existence of polar and aliphatic chemicals, which are soluble in methanol and n-hexane, respectively [68]. Experimental pyrolysis of Pongamia pinnata (karanja) de-oiled seed cake yielded appreciable bio-oil, with Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS)/FTIR indicating mixtures of aliphatic and aromatic compounds alongside char and gas fractions [69]. The authors also looked into the slow pyrolysis of sawdust using a batch approach, and they found a bio-oil yield of roughly 45%. By using 1H and 13C NMR investigations, it was determined that the sawdust bio oil composition contained alkyl and aromatic groups [70]. Pyrolysis was carried out by Qing et al. [71] at different temperatures (400°C–700°C) on food waste that was collected from a food waste treatment factory in China. N-compounds contribute 40% (highest) of the total bio-oil at 500°C, according to the researchers’ GC-MS investigation, which showed that the production of bio-oil increases with temperature. A different study on food waste used leftover fruits and vegetables (banana, orange, onion, bell pepper peels, etc.) as feedstock for pyrolysis at different temperatures, times of reaction, and rates of heating in order to maximize the yield of biochar; the highest yields of biochar and bio-oil were found at 500°C and 300°C, respectively, and the bio-oil was enhanced with phenols, acids, and alcohols [72]. The comparison study conducted by Pascarella et al. [73] revealed that the middle level of bio-oil produced by slow pyrolysis of cherry seed biomass was 21 weight percent, whereas the high bio-oil yield of around 44% was obtained by fast pyrolysis of the same feedstock. It can be concluded from this that slow pyrolysis is essentially less effective than quick pyrolysis in terms of bio-oil yield and high levels of char generation. It follows that a change in the type of biomass or waste causes a noticeable variation in the composition of the bio-oil produced by slow pyrolysis.

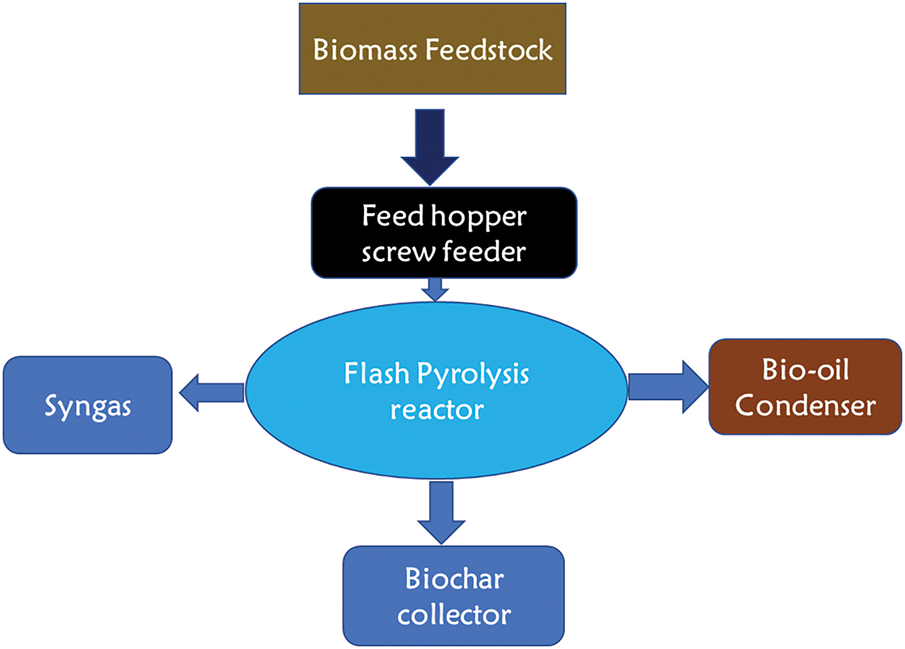

This method typically differs from traditional and rapid pyrolysis in that it uses big biomass pieces that have a temperature range of 1100°C–1300°C, a heating rate of more than 1000 Ks−1, and a relatively brief residence time, or 0.5–1 s. In comparison to quick pyrolysis, this method is better at producing high-quality goods [74]. The rapid heating rate is connected with high temperature and short residence time result in high bio-oil yield with little generation of char. As can be seen in the schematic in Fig. 4, the main issue with flash pyrolysis is that the liquid products contain biochar, which catalyzes the polymerization events inside the bio-oil and increases the viscosity of the oil. The minimum feedstock size is required for flash pyrolysis due to its fast reaction time and rapid heating [64]. Flash pyrolysis, however, has inadequate temperature stability. Additionally, the char has a catalytic action that produces more viscous oil with solid residue occasionally, rendering it economically unfeasible due to the additional costs associated with upgrading to improve the quality [75].

Figure 4: Flash pyrolysis process

The bio-oil derived via flash pyrolysis differs from traditional fossil oil derived from petroleum sources. In contrast to fossil fuel, bio-oil still has several drawbacks despite its many advantageous qualities. Because of its high concentration of oxygen-containing functional groups, the bio-oil has poor properties like high acidity and viscosity, non-volatility, thermal instability, lower energy density, and a tendency to polymerise in the presence of air. These characteristics depend on the raw material and the conditions of the pyrolysis process. Its heating value is about half that of conventional fossil fuel [76].

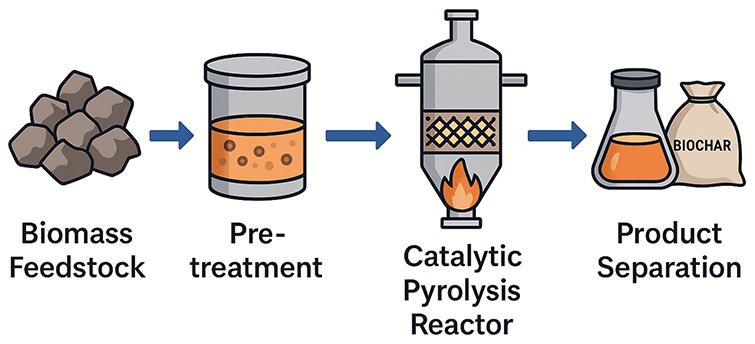

Catalytic pyrolysis is the most appropriate process for converting a variety of goods into premium liquid fuel since increased bio-oil quality and quantity are necessary for more effective fuel product utilization. The use of an effective catalyst is necessary to remove the reactive species because the liquid product created by fast py-rolysis contains more reactive oxygenated molecules. A catalyst added to rapid pyrolysis offers a greater chance of directly producing higher-quality hydrocarbons from biomass [77]. Fig. 5 shows the catalytic conversion of biomass feedstock exposed to pre-treatment process to ensure a separation between bio-oil and biochar. Numerous investigations have demonstrated that a synthetic catalyst may be used to effectively convert a variety of organic species into fuel-grade hydrocarbons. The unwanted characteristic of oxygenated molecules in bio-oil is their presence, which limits the applications of bio-oil. These must be removed in order to make the oil viable and economically appealing [78].

Figure 5: Catalytic pyrolysis process

Bio-oil frequently contains oxidized substances, such as lignin derivatives, which lower the fuel’s quality in a variety of ways. Its heating value can be lowered, stability can be increased, volatility can be decreased, and viscosity may be increased. The quality of the fuel would be increased by adding a catalyst to the biomass in the pyrolysis chamber prior to the start of the process. During catalytic pyrolysis, several reactions are coordinated, such as cracking, decarboxylation, aromatic side chain scission, dehydration, etc. Deoxygenation and the disintegration of bigger molecules into smaller ones are the outcomes of these processes. Changes in catalyst type, biomass type, processing parameters (e.g., temperature and time), and other variables can affect the resultant pyrolysates [79]. The amount of cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin in the biomass, together with some inorganic content, affect the characteristics of the bio-oil [80]. In addition to improving product quality, the catalyst lowers the activation energy and degradation temperature of the decomposition process. By efficiently lowering the oxygen concentration and raising the hydrogen to carbon ratio, catalysts improve the pyrolysis of biomass, which in turn raises the oil’s heating value and combustion efficiency. The principal factors influencing the quality and yield of pyrolysates are the biomass’s composition, reaction mechanism, and operating parameters, which include temperature, biomass particle size, type of catalyst, heating rate, and residence time [81].

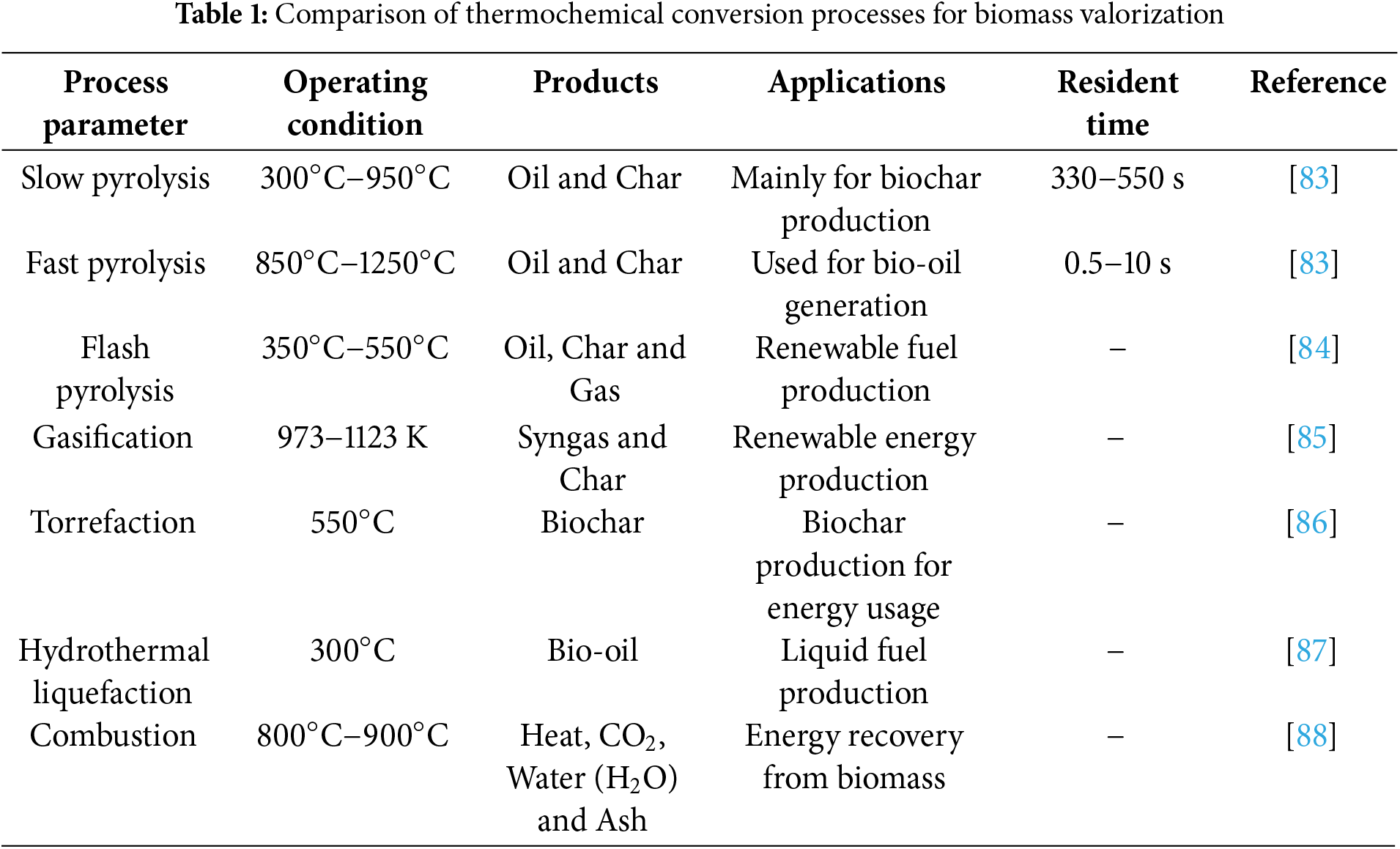

Numerous studies have been conducted on the catalytic hydro treatment of bio-oils to upgrade them, using different types of catalysts and reaction conditions. For instance, Oh et al. [82] used a variety of metal catalysts (Ni/C, Ni/mesoporous silica(SBA-15), Ni/alumimium-modified silica(Al-SBA-15), Ni-Manganese(Mn)/SBA-15, platinum(Pt)/C) to experimentally assess the catalytic hydrodeoxygenation of bio-oil generated from fast pyrolysis of woody biomass. The properties of hydro treated bio-oil, such as its miscibility in gasoline and diesel, were significantly improved by adding an emulsifier to each blend. The pyrolysis process and yields were significantly influenced by a number of parameters, such as temperature, heating rate, residence time, biomass particle size, catalyst presence, etc. Table 1 provides a comparative overview of key thermochemical conversion methods summarizing their typical operating conditions, product yields, and primary applications in bioenergy production.

3 Pyrolysis Reactors for Effective Biomass Conversion

The pyrolysis process relies heavily on reactors. Many different reactor layouts have been attempted in experimental settings in an effort to create reactors that may be used in commercial settings [89]. The most popular designs are those that can achieve large rates of heat and mass transfer, including circulation fluidized bed (CFB) and bubbling fluidized bed (BFB) reactors. Other types of reactors include plasma reactors, melting containers, and autoclaves [90], rotary kilns [91], cyclonic reactors [92], and reactors using an ablative process [93]. It is crucial to remember that the type of particle interaction depends on the reactor setup and increases the complexity of the pyrolysis process [94]. Regarding techno-economic criteria, each reactor architecture has pros and cons. Numerous research into the techno-economics of these reactors have been published in the literature [95–99]. Reactors for pyrolysis can be categorized according to a variety of factors, including the way the heat is supplied, how they operate, and how the particles travel within the reactor. Reactor design for the pyrolysis process involves a number of factors, including reaction temperature, inert gas flow rate, vapor residence time, heating rate, and heating type. For biomass to be converted into the intended product, each of these factors is crucial. For example, inert gas prevents the oxidation of organic materials by acting as a shield. Additionally, it assists the reactor’s temperature to be distributed evenly and releases the volatiles [99]. In general, pyrolysis reactors fall into one of two types: those with mechanical charge transport or those with a pneumatically displaced bed. For the former, there are fixed bed, fluidized bed, and circulating fluidized bed reactors; for the latter, there are rotating cone, ablative, auger, and stirred reactors.

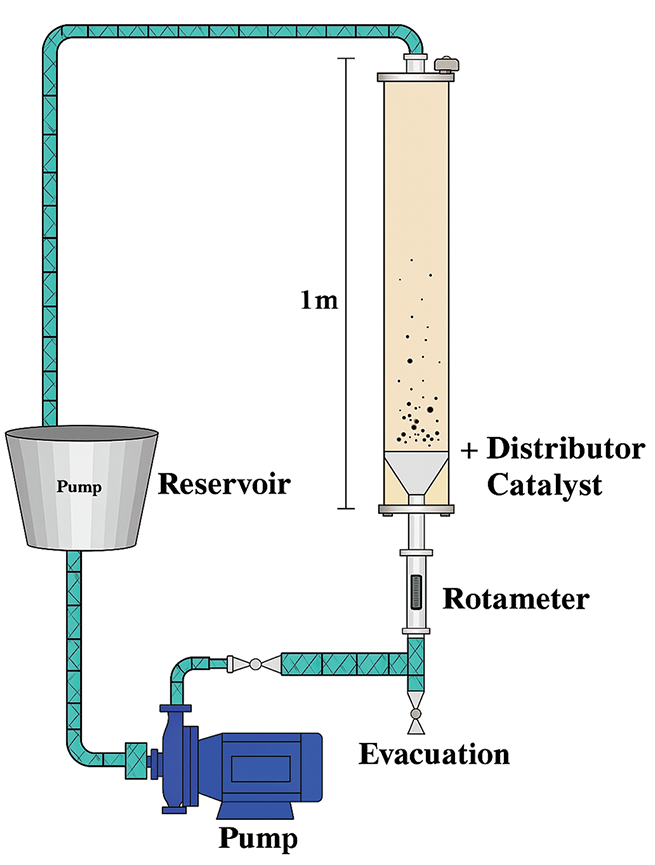

The most popular pyrolysis reactors are fluidized beds because of their many benefits, including superior temperature control, high heat transfer rates, ease of construction and operation, and the ability to scale up [100,101]. These reactors are typically used to investigate secondary tar cracking processes under long residence times and to analyze and comprehend the behavior of biomass during fast and flash pyrolysis [102]. These reactors are said to be suitable for pyrolyzing waste polymers [103], When considering other types of waste biomass, such as municipal solid waste (MSW), there are other challenges. First, the reactor’s feedstock needs to be easily fed in terms of size. Second, separating char from the bed material is very challenging [104]. Numerous researchers have tried to pyrolyze waste biomass, including lignocellulosic materials, both catalytically and non-catalytically using fluidized bed reactors [105–107], aquatic biomass [108,109], in addition to plastic garbage [110,111], tyre wastes [112,113] and MSW [114,115]. In most set ups, it requires the use of a rotameter and pump to ensure seamless movement of the biomass wastes (Fig. 6). Fluidized bed reactors are now the best choice for catalytic pyrolysis of waste biomass, according to data accessible in the literature. This is because the catalyst may be utilized again, whereas the cost of the catalyst could otherwise be a limiting factor [116].

Figure 6: Fluidized bed reactor. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [116] Copyright 2016, Elsevier

Furthermore, the reactor can be operated continuously, and circulating fluidized bed reactors are especially well-suited for large-scale operations from an economic standpoint. The pyrolysis of biomass and other wastes is commonly accomplished using two types of fluidized bed reactors: bubbling (BFB) and circulating (CFB) [95]. BFB are utilized for particles that are between 0.5 and 2 mm in size and yield a high liquid yield of 70 to 75 percent. However, fine char contamination of the liquid products can occur from this sort of reactor up to 15% of the weight, depending on the reactor’s design and the velocity of the fluidizing gas [117]. A significant distinction between BFB and CFB is the vapor residence time, which is normally 0.5–1 s for BFB and 2–3 s for CFB [118]. Fluidized-bed reactors are highly suitable for sawdust due to their excellent heat and mass transfer characteristics. They enable continuous operation, uniform temperature distribution, and higher bio-oil yields. Despite their complexity and need for more control systems, they are the most commercially viable for sawdust pyrolysis.

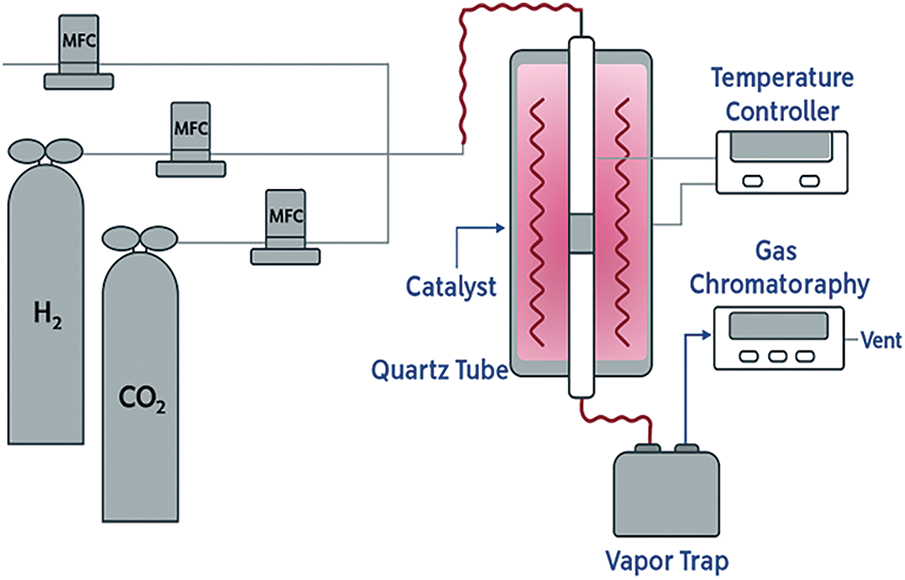

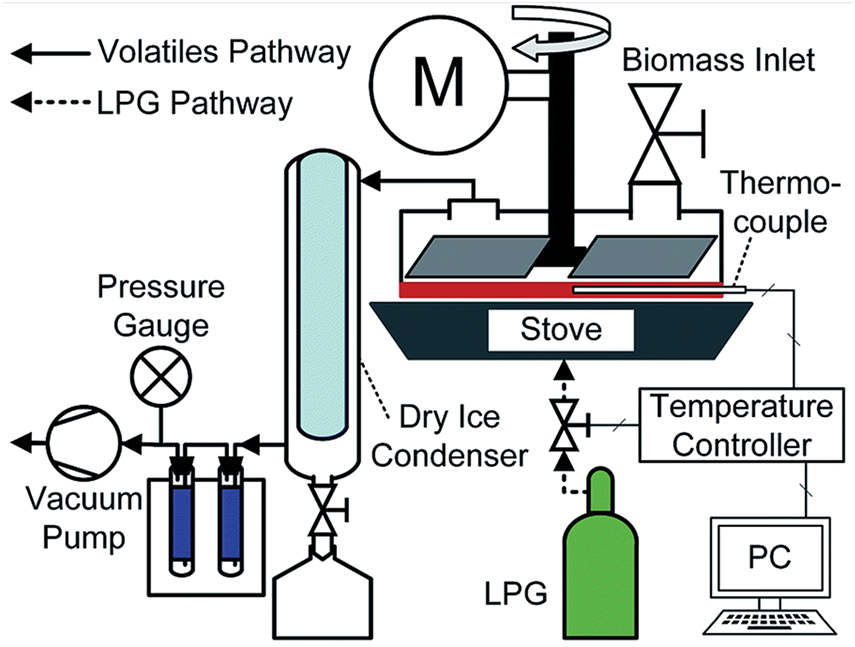

Fixed bed reactors are frequently chosen for lab-scale investigations due to their straightforward design and convenience of use. Large-scale fixed bed reactors haven’t yet shown their promise, while a lot of research is being done to find ways to distribute heat within the reactor uniformly [99,118]. Typically, a solid stationary bed is used for the reactions in a fixed bed reactor [119] and a thermocouple inside the bed regulates the amount of heat needed and at times a temperature controller is deployed (Fig. 7) for this purpose. This kind of reactor uses an inert gas to flush out the volatiles and keep the surroundings inert while receiving heat from an external source [110]. The fixed bed category has several variations, including two-stage fixed bed reactors, vertical fixed bed reactors, and horizontal fixed bed reactors [117,118]. Xiong et al. [120] investigated the formation of coke by pyrolyzing rice husks using a fixed bed system and varying the temperature between 300°C and 800°C. Despite their ease of design and operation, fixed bed reactors are known for their low heat transfer rate [121,122]. There are two ways to operate fixed bed reactors: batch mode and semi-batch mode. However, the results can vary greatly from batch to batch. These systems’ relatively low specific capacity restricts their use on a large scale, and they do not enable continuous operation [123]. Moreover, the need for a lengthy solid residency period and the challenges associated with eliminating char from the system can be considered additional significant drawbacks [122]. Fixed bed reactors can also be used as secondary pyrolysis reactors since they can readily receive the initial pyrolysis products, which typically consist of liquid and gaseous phases [124]. The fixed-bed reactor is easy to use, inexpensive, and ideal for sawdust pyrolysis on a modest scale. In contrast to more sophisticated designs, it has poor heat transfer and limited scalability, which lowers product yields. It is less suitable for continuous and effective bio-oil production due to its batch operation and uneven heating.

Figure 7: Fixed bed reactor. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [123] Copyright 2020, Elsevier

The “National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)” in Colorado, USA, invented the idea of ablative pyrolysis in the 1980s. Ablative pyrolysis operates on a very different principle than other pyrolysis methods. The process by which ablative technology works is comparable to that of melting butter on a hot skillet [95]. The biomass “melts” into leftover oil and evaporates when exposed to external pressure and heat from the reactor’s surface, creating pyrolytic vapors that can be collected via a cooling system (Fig. 8). The biomass’s surface exhibits a sharp temperature gradient, which causes a thin layer of reacting solids to form on the surface. Instead of occurring in the biomass itself, the reaction occurs at the surface layer in the ablative reactor, and heat transfer within the particle does not slow down the rate of reaction [125], however, the process is very dependent on the reactor’s surface temperature, the pressure that is delivered, and the contact between the biomass and the hot surface [126].

Figure 8: Ablative reactor. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [126]. Copyright, 2020 The Royal Society of Chemistry

Biomass is typically pyrolyzed in an ablative reactor using one of two fundamental methods: direct exposure to focused radiation (radiant ablative pyrolysis of biomass, or RAPB) or contact with a hot surface (contact ablative pyrolysis of biomass, or CAPB) [127]. The cost of producing bio-oil is further increased by the fact that all pyrolysis reactors currently on the market require energy-intensive grinding procedures to reduce the biomass feedstock to microscopic particle sizes, often less than 1 mm. For example, about 7%–9% of the total costs associated with producing bio-oil come from the expense of grinding wood into tiny particles [128]. Although ablative reactors might not seem appealing from an energy standpoint, they could be useful for transportable applications, which could be crucial to lowering the cost of bio-oil [129]. Ablation reactors frequently have low mechanical reliability and heat loss to the environment since the hot plate is exposed to the surrounding air. Furthermore, a post-treatment procedure is required since the intermediate liquid product becomes contaminated due to the char that forms on the hot plate’s surface [126]. Ablative reactors lower pre-processing expenses by doing away with the necessity for extremely tiny sawdust particles. High heat transfer rates are possible with them, but maintaining surface contact necessitates mechanical complexity. They are less popular for commercial sawdust pyrolysis due to their specialized uses and constrained scalability.

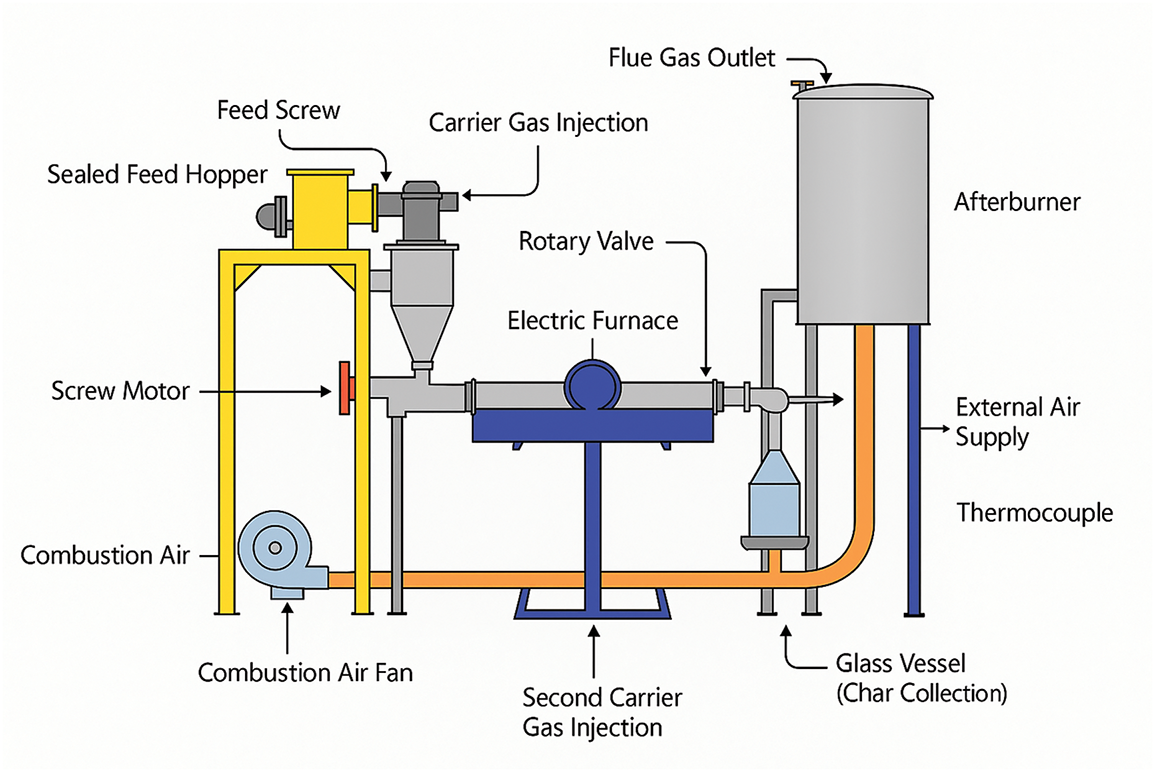

Pyrolysis in an auger (screw) reactor operates on a straightforward concept in contrast to many other methods. The biomass is forced to undergo pyrolysis in a heated tube. To maintain an inert atmosphere inside the reactor and supply the pressure needed for the pyrolysis vapors to be transferred, the tube is flushed with an inert gas [118]. In industry, solid biomass products are frequently transported and processed using augers. In addition to supplying the reactor with feedstock, the screw also extracts solid leftovers from the reactor. Furthermore, a reactor with the right design can enhance the heat transfer between heat carriers and biomass particles [130]. To transfer the energy needed for pyrolysis, the reactor wall is heated to a temperature higher than the pyrolysis temperature. To improve heat transfer from the wall to the biomass particles, the screw mixes the biomass feedstock as needed. Theoretically, the auger speed and inert gas flow rate regulate the residence duration of the solid and gaseous intermediate products once the biomass fed to the reactor has been fully volatilized [131]. Currently, auger reactors come in two different layouts depending on how many screws are used. These include pyrolizers with a single auger and those with two or three augers. A twin-auger system is far more effective at mixing biomass and granular heat carriers than a single-auger reactor. Furthermore, the twin-auger reactor can guarantee the full devolatilization of feedstock while reducing the power needed to operate the augers. Similar to BFB reactors, twin-auger pyrolyzers produce large quantities of liquid products [132,133]. Fig. 9 shows a schematic of a typical auger reactor with the feed screw, fuel gas outlet and the rotary valves quite evident. Note that the desired end-products determine the choice of technology and operational parameters. The heat needed for the pyrolysis can be provided directly through heat carriers or indirectly through the reactor walls. It is possible to use the first method for slow or intermediate pyrolysis and the second method for rapid pyrolysis. It is possible to use inert solid materials as heat carriers, including ceramic balls, silicon carbide, steel shot, sand, etc. [133,134]. Additionally, recycled char is employed as a heat carrier to promote higher gas fractions, improve secondary processes, and prevent the production of tar [135,136].

Figure 9: Auger’s reactor. Reprinted/adapted with permission from Reference [131]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier

Auger reactors are a viable option for dry sawdust because of their small size and controlled residence period. However, when feedstock is poorly prepared, they are prone to clogging and usually have lower heating rates. They are better suited for lab and pilot-scale settings due to their moderate performance.

In conclusion, fixed-bed and auger reactors, although simple and low-cost, suffer from limited heat transfer capacity and scaling challenges when processing fine biomass like sawdust, as seen in fixed-bed gasification of woody feedstocks [121] and auger reactor reviews [131]. Although they provide excellent heat transfer and lower grinding costs, ablative reactors are still less marketed and mechanically difficult. On the other hand, fluidized-bed reactors are the best choice for sawdust pyrolysis because they combine technical efficiency with commercial scalability. They do this by providing greater thermal performance, enhanced mixing, and continuous operation.

Several more established and planned reactor configurations have been extensively discussed in the literature in addition to the ones already mentioned. University of Twente created the rotating cone reactor (RCR) and Biomass Technology Group (BTG) later developed it [137] in the Netherlands in 1998. This reactor is relatively new and as efficient as a transport bed reactor, except instead of gas flow, centrifugal forces influence transport in a spinning cone. The main characteristics of the rotating cone reactor are (i) hot sand or other biomass and inert are forced up a rotating cone by centrifugation; (ii) char is gathered and burned in a fluidized bed to heat sand particles, which are then recalculated back into the reactor; and (iii) normally, 60%–70% of liquid yields on dry feed can be obtained. A more recent invention that works well for flash pyrolysis is the Pyros reactor. This technology can be used to turn wood biomass and biomass residues into high-quality, solid-free bio-oil [118]. This process is patented and involves pyrolysis in a cyclone where biomass is fed from the top and combined with a heated inert carrier, usually sand. The char is separated by centrifugal forces and gathered at the bottom of the cyclone, while the pyrolysis vapor is pulled off from the top.

Additionally, plasma-assisted pyrolysis is increasingly compelling because it delivers ultra-rapid heating rates and precise control over syngas composition. This results in cleaner gas with favorable heating value compared to conventional systems, which typically produce tar-laden syngas requiring downstream cleaning. Recent insights highlight plasma’s superior performance in achieving controlled syngas characteristics and reduced tar formation [138]. Utilizing a plasma reactor has the benefit of having a direct, independent heating source in the form of the plasma torch. This enables the use of various reactants and improves temperature control [139]. Furthermore, the high energy-density and temperature linked to thermal plasma and consequently fast reactions can overcome the possible issues with traditional pyrolysis. Combustible gases and manageable solid residues are produced by thermal plasma pyrolysis of waste biomass, including organic wastes [104]. According to a study on the plasma pyrolysis of polypropylene, the solid residue’s calorific value was nearly equal to that of elemental carbon, meaning that elemental carbon made up the majority of the residue. The authors also observed some unique carbon structures, which suggests the potential for the production of multiple high-value products [104]. The commercial growth of plasma technology has been hindered by technological challenges in many regions of the world. On the other hand, a recent review by Sikarwar et al. [140] highlighted the growing global popularity of plasma-assisted biomass treatment. The researchers attribute its increasing appeal to several advantages, including compact system design, versatility in processing various types of waste biomass, and its environmentally friendly nature.

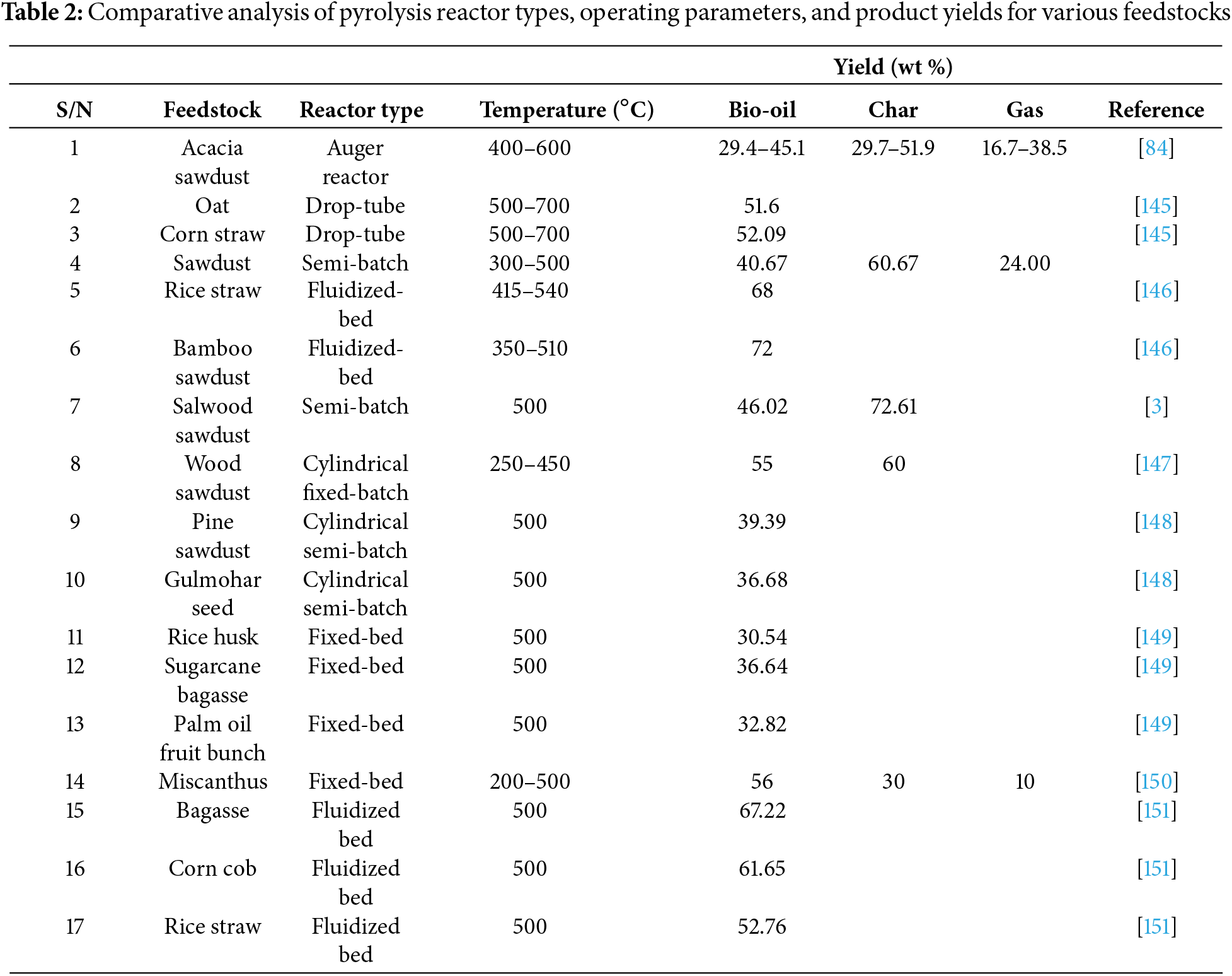

Zeng et al. [141] considered a solar irradiation-based pyrolysis reactor to process beech wood, which presented an intriguing solution to the heating of a pyrolysis reactor The technology of solar biomass pyrolysis is dominated by fixed bed reactors, however a variety of reactor layouts have been investigated for solar pyrolysis. Both vertical and horizontal orientations are possible for reactors used in solar pyrolysis [142]. It’s crucial to remember that the majority of the study in this field has only been done at the laboratory level. The largest technological obstacle to solar pyrolysis techniques is still reactor operation and scaling up. To achieve optimal conversion of the feedstock, a reactor with improved hydrodynamics for reactants moving through the focus zone is required [143]. In general, the unique circumstances involved in solar pyrolysis make the gas-solid reactor types that are frequently considered in chemical engineering unsuitable. Since solar pyrolysis reactors will probably differ significantly from conventional reactor designs in the future, new concepts must be developed [144]. To better illustrate the influence of reactor design on pyrolysis performance, a detailed comparison of commonly used reactor types is presented in Table 2.

Reaction Conditions in Other Thermochemical Processes

Although a lot of research has been done on the design of pyrolysis reactors, it is equally crucial to comprehend how operating conditions impact other thermochemical processes like gasification and hydrothermal liquefaction (HTL). In gasification, syngas composition and process efficiency are greatly impacted by operating factors like temperature, equivalency ratio (ER), and residence duration. An ER of 0.2 to 0.3 maximizes the yield of combustible gas and reduces the generation of tar, while raising the temperature from 400°C to 1000°C can increase biomass conversion from 46% to 82%, according to open-access studies. The choice of the gasifying agent (air, steam, or O2) further influences the syngas output; for example, mixes of oxygen and steam at about 800°C produce syngas with over 90% carbon conversion and H2 volume fractions above 43% [152]. Similarly, HTL uses sub- or supercritical water conditions to transform wet biomass into biocrude by using high temperature (250°C–374°C) and pressure (5–25 MPa). While working in this range improves hydrolysis and bio-crude yields, higher temperatures or pressures might cause secondary oil splitting into gas and char. Further studies indicate that prolonging residence time and keeping water and temperature constant maximizes the generation of biocrude, but too lengthy exposures or too high temperatures can reduce yield because of repolymerization [40]. These results collectively demonstrate that, similar to pyrolysis, precise control of temperature, pressure, ER, and residence time is essential for optimizing product quality, yield, and energy efficiency in gasification and HTL. Such information guarantees a thorough and impartial examination of all thermochemical pathways.

3.6 Advanced Pyrolysis Technologies

The goal of recent developments in pyrolysis technologies is to increase the yield, quality, and efficiency of pyrolysis products, supporting waste management and sustainable energy production. The most cutting-edge biomass pyrolysis technologies, such as co-pyrolysis, catalytic pyrolysis, microwave pyrolysis, hydrothermal pyrolysis, and plasma pyrolysis, are thoroughly examined in this section. Every technology is analyzed in terms of its workings, benefits, and possible uses.

Co-pyrolysis refers to the simultaneous pyrolysis of biomass with other feedstocks like plastics or coal. This process often enhances bio-oil yield and quality via synergistic thermal cracking and hydrogen transfer from co-reactants (e.g., plastics) that help suppress char formation and oxygenated byproducts [153]. This process improves the quantity and quality of the pyrolysis products without requiring the costly addition of catalyst, solvent, or significant hydrogen. For example, co-pyrolysis with polymers can boost liquid hydrocarbon output, increasing the process’s economic viability. Co-pyrolysis would make it possible to produce stable pyrolysis bio-oils from multiple feeds, something that is frequently impossible to accomplish independently. For instance, oils made from plastic fractions cannot be completely mixed with those made from biomass pyrolysis, which eventually results in the formation of several phases. Co-pyrolysis’s synergistic effects can result in better product dispersion and thermal degradation. According to studies, co-pyrolysis can greatly increase the bio-oil’s calorific value and lower its oxygen content, increasing its stability and energy density. Bio-oil’s high oxygen concentration makes it difficult to utilize as a fossil fuel substitute since it lowers its calorific value and increases instability and corrosion problems [154]. Co-pyrolysis requires intricate interactions between the co-reactant and the feedstock. For instance, the presence of plastics may contribute to the deoxygenation of bio-oil by supplying more hydrogen, increasing the hydrocarbon yields. The efficiency and product distribution of co-pyrolysis are greatly influenced by the process parameters, which include temperature, heating rate, and the ratio of biomass to co-reactant. Co-pyrolysis is also a cost-effective way to upgrade biomass pyrolysis systems because it can be readily implemented into already-existing pyrolysis units with little modification.

Catalysts are used in catalytic pyrolysis to increase the output and quality of bio-oil and gas. Biomass contains metallic minerals that can act as natural catalysts to change the pyrolysis products. Certain catalysts, like metal oxides, zeolites, and mesoporous materials, can be used to lower the amount of oxygen in bio-oil, producing fuel of higher quality. The selective synthesis of useful compounds is another benefit of this technique. Catalysts can improve the pyrolysis process’s deoxygenation, cracking, and reforming reactions, producing hydrocarbons and other useful compounds [155]. Both in situ and ex situ catalytic therapy are possible. There are various methods of implementation, even if we only consider the in situ alternative. In the reactor where the biomass is pyrolyzed, the catalyst can be added straight. This choice streamlines the catalytic pyrolysis procedure and may considerably lower the temperature at which the biomass components decompose [155]. The drawback is that it complicates the process of separating the catalyst from the leftover pyrolysis solid and, consequently, its subsequent reuse. Furthermore, the pyrolysis reactor’s operating parameters must fall halfway between those that are most appropriate for catalysis and pyrolysis.

In case the catalytic treatment is done online in a second stage [156], only the volatiles produced by the pyrolysis process would undergo treatment. As a result, the catalyst will be able to be used for longer. It is possible to pyrolyze several biomass batches while keeping the same catalytic bed. Furthermore, based on the kind of catalyst being used, the kind of solid that is wanted, the type of liquid, and the process’s target gas, the operating parameters for both pyrolysis and volatile treatment can be optimized independently. Actually, the yields and caliber of the pyrolysis products produced depend heavily on the catalyst and operation parameters used [157]. Catalytic pyrolysis has advanced recently, with an emphasis on creating new catalysts with excellent stability, selectivity, and activity. For example, the quantity and quality of bio-oil have been proven to be improved by modified natural zeolites. Acid and heat activation procedures can be used to increase these materials’ catalytic activity even more. Particularly, the acid’s strength, type, and number of sites all have a significant impact on the catalytic activity of acid catalysts [158]. ZSM-5 zeolite has been used extensively, either exactly as supplied or modified, to produce bio-oils that contain higher aromatic and olefin molecules [159,160].

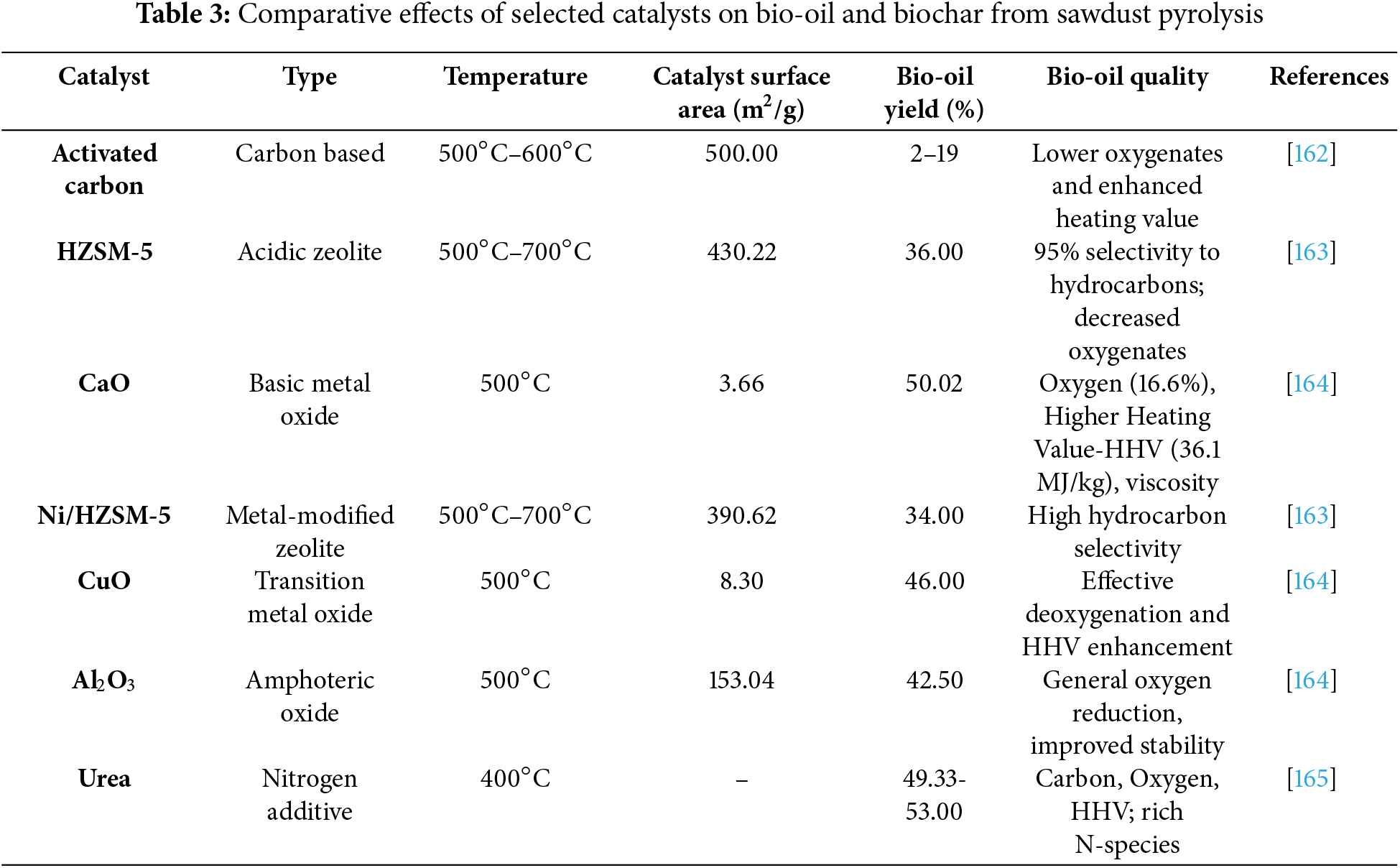

The quality of the bio-oil can be further improved by combining catalytic pyrolysis with other procedures, like hydrodeoxygenation (HDO), which qualifies it for use as a fuel for vehicles. High coke output, stability, catalyst deactivation, and regeneration are still major obstacles, though. The primary deactivation mechanism of zeolites that shortens their lifespan is coke formation. In the event that a fixed bed reactor the most straightforward and adaptable kind of catalytic reactor is employed, this coke may also raise the pressure drop across the bed [161]. These days, there are technical ways to counteract the quick deactivation caused by coke, like the ongoing regeneration of catalysts in the oil refining process known as Fluidized Catalytic Cracking (FCC). The production of coke, which quickly deactivates the catalyst, makes this regeneration a necessary step. However, these systems are expensive and complicated to build, operate, and maintain. Building on recent progress in catalyst design and performance evaluation, it is essential to compare how various catalyst types influence the yield, composition, and quality of bio-oil and biochar. Table 3 summarizes key findings from recent studies, focusing on catalysts commonly used in the catalytic pyrolysis of sawdust and other lignocellulosic feedstocks.

The comparison study shows that the kind of catalyst employed significantly affects the physicochemical characteristics of biochar as well as the yield and composition of bio-oil. CaO and other basic oxides greatly improve deoxygenation and raise the heating value of bio-oil. While metal-doped versions (like Fe/HZSM-5) enhance performance through synergistic effects, zeolitic catalysts like HZSM-5 encourage the synthesis of aromatic hydrocarbons with good selectivity. In particular, urea and other carbon-based and nitrogen-modified catalysts show great promise for enhancing the properties of biochar by providing functionalized surfaces and possible repurposing in energy storage or environmental remediation. Consequently, the catalyst selection should be in line with the intended result, be it optimizing fuel-grade bio-oil, improving biochar for cutting-edge uses, or striking a balance between the two under economical and environmentally friendly processing circumstances.

In microwave pyrolysis, the biomass is heated using microwave radiation. Numerous benefits of this approach include homogeneous temperature distribution, quick heating, and increased energy efficiency. Using less energy than traditional procedures, microwave pyrolysis can yield high-quality biochar and bio-oil. The biomass and microwave energy interact directly in the microwave heating mechanism, producing uniform and effective heating. There are two possible outcomes from microwave dielectric heating: thermal and non-thermal. Different temperature regimes produced by microwave heating are the cause of thermal effects. Situations when the outcome of a synthesis carried out under microwave settings deviates from the outcome of conventional heating at the same temperature are referred to as non-thermal effects (e.g., changes in reactivity and selectivity or acceleration). Nonetheless, the existence of certain (non-thermal) effects of microwaves is currently a contentious scientific topic [166,167]. When employing microwaves as a heating medium to pyrolyze biomass, the operating parameters are absolutely crucial. Both the nature of the biomass and the energy transfer that is accomplished will depend heavily on the size of the particles. There may need to be minimal moisture content because water is frequently the primary component of the biomass that absorbs microwaves. By introducing heating aids (microwave adsorbers), this deficiency in moisture can be addressed [168,169]. The lignocellulosic biomass components exhibit distinct breakdown under microwave-assisted heating and traditional electrical heating due to their disparate heating properties [170]. For example, inadequate absorption of microwave irradiation would limit microwave pyrolysis if microalgae biomass were utilized in place of cellulosic biomass [171]. In order to get around this restriction, researchers have combined algae with sorbents including coals, metal oxides, and activated carbons to produce high temperatures [172,173]. This technique has demonstrated the ability to scale up and integrate with other processes to improve the conversion of biomass.

Plasma pyrolysis efficiently converts biomass into syngas and charcoal by using plasma arcs to create extraordinarily high temperatures [174]. This process is quite effective and can process a variety of biomass feedstocks, even ones with a lot of moisture. Reactive species produced by the plasma arc speed up and complete the breakdown of biomass. High-purity syngas generation and waste-to-energy applications have both showed potential with plasma pyrolysis. Plasma pyrolysis works by creating a plasma arc, which raises the temperature to over 10,000°C and produces a highly reactive environment. Because of this high temperature, biomass can be completely broken down into its component parts, mainly carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and carbon monoxide [139,175]. Even with high moisture content, the plasma arc’s high energy density guarantees effective biomass conversion. Systems for plasma pyrolysis can be integrated with other waste treatment procedures and are generally small, which makes them appropriate for decentralized waste management.

4 Influence of Operating Conditions on Sawdust Pyrolysis

Temperature plays a crucial role in biomass pyrolysis by supplying the heat required to break the many different types of connections found in lignocellulosic biomass. Temperature is therefore one of the most crucial factors since it has a direct impact on the distribution of products, the extension of biomass decomposition, and calorific values [176]. Numerous published researches examining the impact of temperature on the ultimate yield of bio-oil have demonstrated that higher yields can only be achieved at temperatures between 450°C and 550°C. However, the feedstock and other operational conditions also have a significant impact on the ultimate bio-oil outputs [177–179]. Sohaib et al. [180] examined how temperature affected the rapid pyrolysis of sugarcane bagasse. At 500°C, the authors reported a bio-oil production of 60.4%, although modest outputs of gas and charcoal were attained, Lin and Chen found that when sugarcane bagasse was treated to pyrolysis at 500°C, identical bio-oil yields (55%) were obtained after 30 min of reaction time [181]. Furthermore, a study by [182] found that when rice husks were pyrolyzed at a temperature of 400°C to 500°C, the output of bio-oil increased from 11.3% to 35.9%.

Temperature affects not just the yield of bio-oil but also the distribution of the product overall. Excellent indicators for assessing the quality of the finished product are the levels of carbon and hydrogen. Therefore, the composition of high-quality bio-oil should be high in carbon and hydrogen, and as low in oxygen as feasible [182]. Additionally, according to [183,184] examined the effects of different pyrolysis temperatures on food waste and food waste solid digestate, finding that higher temperatures encourage the reduction of oxygen content while increasing carbon and hydrogen content. This is a significant finding because it appears that higher temperatures cause the hydrocarbons in the biomass to crack, which lowers the oxygen content in the bio-oil, which is expected and very desirable.

Another study that looked at the effect of temperature on the distribution of the final product was Alvarez et al. [185]. They found that when lignin broke down at 350°C, phenols (such as catechols, guaiacols, and alkyl-phenols) were produced when the temperature at which rice husks were pyrolyzed was raised. Temperatures above 600°C were also associated with a decrease in the concentration of ketones (including cyclopentenones and open-chain ketones) due to the condensation processes of the feedstock carbohydrates. Higher pyrolysis temperatures (>600°C) promote gasification reactions because they lead to the creation of lighter compounds, which in turn promotes cracking events. Interestingly, it appeared that temperature had no effect on the concentration of ethers, aldehydes, or water.

The heating rate is another important factor in biomass pyrolysis since it affects the kinds of breakdown products that are produced. Increased heating rates have the potential to quickly fracture biomass and encourage the production of volatiles [186]. The impact of varying heating rates on the ultimate yields of bio-oil has been extensively documented in scholarly works [182]. Furthermore, Sensöz et al. [187] used a fixed bed reactor to study various heating rates in the pyrolysis of olive bagasse. The scientists found that a paltry 8.4% increase in bio-oil yield resulted from raising the heating rate from 10 to 50 °C/min. Another study by the same team found that the heating rate had no effect on the bio-oil output from hornbeam shell pyrolysis [188]. It is important to note that raising the heating rates from 10 to 50 °C/min might not have a substantial enough effect on the yield of the finished product. It is therefore advised to use higher heating rate ranges, such as 10 to 100–300 °C/min, to get around any or both of the mass transfer and heat constraints. Raising the heating rates won’t produce any more gains in bio-oil yields when the mass transfer and heat constraints are overcome. For instance, Bhoi et al. [189] found increases in bio-oil yield when using a faster residence period (<2 s) and a greater heating rate (>1000 °C/s). Additionally, Xiong et al. [190] found that the final bio-oil yield from rice husk increased by 10% when heating at a high rate of 200 °C/s as opposed to medium (≉20 °C/s) and slow (≈0.33 °C/s) heating rates. It is important to note that the final bio-oil yields are impacted by a variety of factors, including temperature, reactor configuration, and biomass type, composition, and particle size, in addition to the combined effects of these variables. Furthermore, heating rates can affect the ideal temperature to optimize the yields of bio-oil in the end.