Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Innovative Bioplastics: Harnessing Microalgae and Low-Density Polyethylene for Sustainable Production

1 Water Pollution Research Department, National Research Center, Giza, P.O. Box 12622, Egypt

2 Institute of Textile Research and Technology, National Research Centre, Giza, P.O. Box 12622, Egypt

3 Packaging Materials Department, National Research Centre, Giza, P.O. Box 12622, Egypt

4 Chemical Engineering and Pilot Plant Department, National Research Centre, Giza, P.O. Box 12622, Egypt

5 Electronics Research Institute (ERI), Cairo, P.O. Box 12622, Egypt

* Corresponding Author: Sayeda M. Abdo. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(3), 599-616. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2024.057736

Received 26 August 2024; Accepted 18 November 2024; Issue published 20 March 2025

Abstract

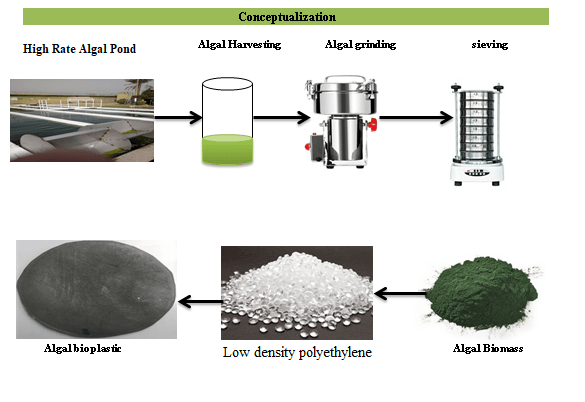

The accumulation of non-biodegradable plastic debris in the environment raises serious concerns about potential long-term effects on the environment, the economy, and waste management. To assess the feasibility of substituting commercial plastics for a biodegradable renewable polymer for many applications, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) was mixed with varying concentrations of algal biomass (AB). Algae are considered a clean, renewable energy source because they don’t harm the environment and can be used to create bioplastics. Algal biomass grown in a high rate algal pond (HRAP) used for wastewater treatment used at 12.5–50 weight percent. Mechanical, thermal, and morphological characteristics of the LDPE/AB mixes were studied. Improved compatibility and uniformity between the LDPE matrix and algal biomass phase were evident in the morphology of LDPE/AB blends. Tensile strength (TS) and elastic modulus (EM) of the prepared LDPE/AB blends significantly decreased to 4.63 and 255 MPa, respectively. Nevertheless, by increasing the concentration of AB up to 25% and 37.5%, the mechanical properties enhanced and raised to (TS = 6.75 MPa, EM = 426 MPa) and (TS = 7 MPa, EM = 494 MPa), respectively. Using 25% and 37.5% of AB significantly enhanced the miscibility and interaction between algal biomass and LDPE polymer. However, increasing the percentage of AB led to a reduction in the thermal stability of the LDPE/AB. In contrast, compatibilized blends demonstrated better thermal stability compared to un-compatibilized blends. These findings indicate that it is possible to develop a blend with improved structural, thermal, and mechanical properties by partially replacing LDPE with biodegradable algal biomass.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Plastic demand has expanded significantly every year since the discovery of polymers and the emergence of mass production [1]. These synthetic materials are characterized by their stability, transparency, lightweight nature, versatility, durability, affordability, and resistance to corrosion, along with high strength [2,3]. However, despite these significant advantages, the excessive use of fossil-based polymers leads to severe environmental consequences, including pollution, global warming, and depletion of fossil fuels. This is largely due to their hydrophobic properties and high resistance to biodegradation [4,5]. Furthermore, synthetic plastics are inherently persistent and can release toxic chemicals into the environment, particularly when improperly disposed of, which contaminates water bodies and negatively impacts ecosystems [6–8].

Conventional plastics are manufactured by mixing refined petroleum fuels with synthetic polymers made of carbon-carbon bonds. Covalent bonds connect this inert, hydrophobic, high molecular weight long chain of monomers, resulting in strong, durable, and elastic polymers [9]. Because conventional plastics are created from crude oil, they contribute to the depletion of natural resources as well as the generation of greenhouse gases, in addition to the environmental impact caused by conventional plastics’ non-biodegradability.

To address the challenges mentioned earlier, it is essential to develop plastics derived from natural renewable biomass sources. This shift is crucial for creating sustainable alternatives that can mitigate the environmental impact associated with conventional plastic production and disposal. By utilizing renewable resources, we can reduce reliance on fossil fuels and lower greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to a more sustainable future for materials science and environmental health [10]. The term “bioplastics” on the other hand refers to a broad category that encompasses “biodegradable,” “bio-based,” “renewable-based,” “compostable-based,” and “green bioplastics.” [11–13].

When it comes to sustainable development, bioplastics outperform synthetic plastics in several ways. They provide benefits such as utilizing bio-based materials instead of those derived from fossil fuels, and being environmentally friendly [14]. Additionally, they protect the environment by cutting back on greenhouse gas emissions. For instance, replacing PLA with PET (polyethylene terephthalate) results in a 60% reduction in emissions of greenhouse gas. Similar to that, replacing PE reduces harmful petrol emissions by 35% [15].

Nowadays, the creation of bioplastics frequently uses microorganisms and food crops including sugarcane, maize, potatoes, and wheat. The plants are utilized as a feedstock to extract starch, sugars, and enzymes that are then combined with plasticizers like sorbitol, and other chemicals to produce bioplastics [15]. Despite producing bioplastic with excellent chemical and mechanical qualities, plants pose a threat to the sustainability of the future because they increase competition for human consumption of feedstock. Additionally, the processes used to extract bioplastic from plants are difficult and have drawbacks such as low mechanical qualities and water resistance [16]. Recently, research has focused on developing methods to create bioplastic from algae [17,18].

In our ecosystem, microalgae are often numerous, and their polysaccharides can be processed and used to create biopolymers. Additionally, these species have a rapid rate of growth and are simple to cultivate in wastewater streams [1]. Algae is gaining attention as a possible source for the synthesis of biodegradable polymers since it is affordable, does not require the use of additional nutrients or bioreactor, unlike bacteria, produces a large amount of biomass, and is readily available all year round [18]. Algae also don’t compete with food sources, can withstand extreme conditions, can clean up wastewater, and can help remove carbon dioxide by using it as a source of nutrients for the formation of biomass [19].

Microalgae have shown promise as an effective approach for bio-valorization of wastewater treatment. This strategy promotes the cultivation of microalgae to produce products with added value, primarily proteins, carbohydrates, and lipids, while also enabling the production of bioplastics. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that microalgae may successfully remove a considerable amount of organic pollutants from wastewater before it is released into the environment. The new technology of cultivating microalgae in wastewater greatly reduced the cost of wastewater treatment when compared to the standard approach by producing microalgae biomass that can be utilized for bioplastic applications. This was accomplished by reducing carbon emissions, energy consumption, and chemical use [20].

Currently, there is still room for improvement in the technology and production efficiency of bioplastics, which is why algae-based plastics are not currently being manufactured on an industrial scale [21,22]. However, combining algal biomass with biopolymers or plastics leads to bioplastic production from algae. The most commonly used polymers employed as matrices in these composites at the moment are polyethylene and polypropylene [23].

Low-density polyethylene (LDPE) is an important thermoplastic for its advantageous mix of qualities, including flexibility, fluidity, transparency, and a glossy surface. In general, it is becoming more appealing to use lignocellulosic material to create plastic composites, especially for applications that require great volume and low cost [24]. LDPE is the most widely used material for packaging a variety of goods. These plastic materials are not easily degradable and have negative effects on the environment.

The production of bioplastics from microalgae holds great promise and is considered eco-friendly. However, several limitations hinder its commercialization, including: high production costs, technical challenges in extracting bioplastic from microalgae, limited market acceptance and biomass sources that may be more cost-effective or easier to process for bioplastic production.

This research aims to reduce dependency on fossil fuels to improve environmental sustainability. To evaluate the viability of replacing conventional nondegradable polymers with algal biomass, low-density polyethylene (LDPE) was mixed with varied volumes of dried algal biomass (12.5% to 50%). Additionally, the study focuses on using microalgal biomass grown in high-rate algal ponds (HRAP) used for wastewater treatment, which helps reduce costs by utilizing nutrient-rich wastewater for algal growth. Additionally, cost analysis is essential for successful commercialization compared to conventional plastic. This research presents a preliminary economic assessment to evaluate the proposed bioplastic production system.

2.1 Growing Algal Biomass Grown in HRAP

Microalgae were harvested from a high-rate algal pond specifically constructed for wastewater treatment. This pond is exposed to natural sunlight and experiences seasonal temperatures ranging from 15°C to 40°C, meanwhile, the temperature of the culture grown in the pond ranges between 23°C and 28°C. The pH level of the pond is between 8 and 9. The pilot facility occupies a land area of 90 m2 (17 m × 14 m).

2.2 Microalgal Community Structure

For the microscopic identification of microalgae, samples were placed in sterile glass containers and fixed with Legol’s solution. A volume of 0.2 mL of this solution was spread onto glass slides for examination. The dominant genera were identified by analyzing five slides per sample, with each slide being examined twice using an Olympus X3 microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan), in accordance with the key to freshwater algae [25,26].

2.3 Harvesting and Drying Algal Biomass

Algal biomass was collected and allowed to settle down in order to reduce water content. Water then was discarded. The algal biomass was spread out on Several trays inside the solar dryer constructed at the field where the temperature exceeded 40°C.

2.4 Grinding Dried Algal Biomass in a Planetary Ball Mill

A planetary ball mill (Retsch GmbH, Haan, Germany) equipped with a grinding jar and 1 mm beads made of yttrium-stabilized zirconium oxide was used to ground the algal biomass. The grinding process was interrupted every 10 min to allow the jar to cool to ensure optimal performance and prevent overheating. After grinding, the beads were removed from the algal biomass using a sieve. The aim of grinding algal biomass to fine powder was performed to increase the surface area, which can enhance the efficiency of subsequent processing steps.

2.5 Ecotoxicological Evaluation

The ecotoxicity of microalgal biomass was assessed using the Microtox analyzer 500 (Modern Water, USA), as previously described [27].

2.6 Particle Size Measurements

A particle size analyzer (Nano-ZS, Malvern Instruments Ltd., Great Malvern, UK) was used to determine the average diameter, size distribution, and zeta potential of the samples. Before the assessment, the sample was sonicated for 10–20 min to determine the size distribution and zeta potential.

2.7 Blending Algal Biomass with LDPE

To make algal biomass/LDPE films, a HAAkETM Rheomex TW100 Twin-Screw Extruder with 40 cm intermeshing screws was employed. Melt mixing at 220°C for 5 min was followed by sheet creation at 120 bar and 200°C utilizing two heated plates and a hydraulic press (Bucher plastics press KHL 100) [28].

The composition details of the bioplastic sheets for your convenience with details found in Table 1.

2.8 Characterization of Algal Bioplastic

2.8.1 FT-IR (Fourier Transforms Infrared) Spectroscopy

A Shimadzu 8400S FT-IR spectrophotometer was used to measure the FT-IR spectra of blends with various algal biomass ratios (0.0%, 12.5%, 25%, and 50%). Where the sample is introduced using a KBr disc, then placed in the sample holder and run a spectrum [29].

2.8.2 Diffraction of X-Rays (XRD)

The bioplastic films were evaluated using two different X-ray diffractometers. The first device was a Diano X-ray diffractometer with a CoK radiation source operating at 45 kV. Meanwhile, the second device was a Philips X-ray diffractometer with a Cu K source (45 kV, 40 mA, and = 0.15418 nm), a PW 1820 goniometer, and evaluated the samples throughout a 5 to 80° range. The device had a 0.02 step size and a 1 s step time [30].

2.8.3 SEM Stands for Scanning Electron Microscopy

A scanning electron microscope (JSM 6360LV, JEOL/Noran) with an accelerating voltage of 10–15 kV was used to analyze the morphology of the synthesized films. A thin layer of gold was placed on the surface at a low rate to prepare the samples for analysis. The collected photos were then analysed for further research [31].

2.8.4 Mechanical Characteristics of Bioplastic Films Manufactured

Tests were carried out in line with the ASTM standard D638-91 to evaluate the mechanical properties of our bioplastic films. LDPE/algal bomass films were kept in the conditioned room (temperature = 20°C) to evaluate the machine tests were performed at a controlled speed of 10 mm/min on an LK10k universal testing machine outfitted with a 5 KN load cell [28]. To accomplish more reliable results, three samples from each PU films sample were tested, and their average was measured as the test result.

The GBPI W303 (B) Water Vapour Permeability Analyzer was used to determine the rate of water vapour moving through a specified area with controlled humidity (4%–10%) and temperature (38°C). The water vapour transfer rate (WVTR) was calculated using the cup technique in accordance with JIS Z0208, 53,122-1, TAPPI T464, ASTM D1653, ISO 2528, and ASTM E96 standards. Furthermore, the rate of gas transfer (GTR) for oxygen was determined using a N530 B Gas Permeability Analyzer (China) in accordance with ASTM D1434-82 (2003) standard [28].

Soil burial test

Fabricated bioplastic films undergo soil burial tests. The bioplastic films were kept under soil for different time intervals of 7, 15, and 30 days to measure the weight loss [31]. To measure the weight loss of the samples the following equation was used:

where, W1 = weight of the bioplastic sample at the beginning of the experiment.

W2 = weight of the bioplastic sample at different time intervals.

3.1 Algal Dynamics and Predominance

Since 2019, our team has been researching microalgal-based bioplastics [32]. We identified several microalgal strains capable of producing polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), which we extracted from algal biomass. Microcystis sp. was the dominant species in the biomass collected from our high-rate algal ponds. We successfully incorporated this biomass into polyurethane, demonstrating its effectiveness [33]. Our current research focuses on using the entire microalgal biomass in bioplastic production, eliminating the need for organic solvent extraction. This approach aims to reduce environmental impact and expand the potential applications of our bioplastic films. Microcystis aeruginosa and Microcystis flos-aquae, both types of blue-green algae, were the dominant species in the algal biomass collected from the high-rate algal pond. The upper layer of the pond primarily consists of various Microcystis species, while a mix of green algae and diatom species can be found nearer the bottom. Among the detected species were Nitzschia linearis (from the diatom group) and Oscillatoria limnetica (a blue-green algae). Additionally, several green algae species were identified, including Scenedesmus quadricauda, Scenedesmus obliquus, Coelastrum microporum, Ankistrodesmus, Micractinium pusillum, and Selenastrum sp. As mentioned in previous work microalgal extract of microalgal biomass selected from HRAP with the same species was nontoxic and safe to be used [33]. Dominant microalgal species present in HRAP were similar to those found in the study of Park and Craggs 2010, where the species in their ponds included the green microalgae Scenedesmus sp., Pediastrum sp, Microactinium sp., and Ankistrodesmus sp. The majority of micro algae are unicellular and low intensity, ranging in size from 0.2 to 2 µm up to filamentous forms sizes 100 μm or higher.

Microalgae display a remarkable diversity of species, each with distinct biochemical compositions and growth traits, which are essential for bioplastic production. Key factors in selecting microalgal biomass include the levels of proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates; for instance, species like Scenedesmus and Chlorella are favored for their high carbohydrate content, which easily converts into biopolymers. Rapidly growing species, such as Microcystis and Chlorella, are preferred for their higher biomass yields. Additionally, specific environmental conditions can impact biomass yield and composition, making it essential to understand these requirements for optimal cultivation. Diverse algal communities can enhance the functional properties of bioplastics, improve metabolic pathways, and increase resilience to environmental changes. Utilizing a variety of species optimizes resource use and supports sustainable production processes. In summary, microalgal diversity is crucial for enhancing the quality and sustainability of bioplastic production, and ongoing research in this area will be vital for future advancements [10,29].

From the results obtained, it can be recognized that no bioluminescence inhibition of V. fischeri was recorded. The EC50 values for algal biomass after 5, 15, and 30 min of exposure were itemized in Table 2. The results showed that the EC50 values for algal biomass were higher than 100 after 5, 15, and 30 min. Furthermore, the EC50 values of algal biomass were almost similar to those observed in the control. It means that algal biomass is biocompatible and non-toxic. Therefore, it may be suitable for environmental applications [27].

After collecting microalgal biomass, it was dried and ground into small particles as shown in Fig. 1. After drying, the average particle size of algal biomass was assessed using dynamic light scattering. It was observed that microalgal biomass was prepared in small sizes attributable to the potential effect of the ball milling device. The majority of particle size is 107 nm with a polydispersity index (PdI: 0.2450) affirming the homogeneity of the ground powder. Wang in 2014 [34] showed that to prepare bioplastic films from spirulina sp. microalgae the samples were then milled into particles which had at least one dimension less than 850 μm.

Figure 1: Ground algal biomass

As mentioned before, 4 concentrations were used in addition to blank samples to evaluate bioplastic properties. Since microalgae have a high concentration of chlorophyll in their biomass, bioplastic films produced have a slightly green color according to algal biomass concentration in films. Fig. 2 shows the difference between a blank having a white color and a sample of bioplastic films containing algal biomass having green colored films.

Figure 2: (a) Blank biofilm of LDPE, (b) algal bioplastic film blended with LDPE

SEM analysis was used to evaluate the algal bioplastic films’ surface microstructure. The results in Fig. 3 revealed flaws and grooves in the bioplastic composite indicating sporadic character [33]. The properties of the bioplastic when it is pulled are influenced by the surface structure [35,36]. The surface has good interfacial attachment and is compatible except for having fewer cavities and cracks. The micrographs show some micropores, which could interact with soil-based microorganisms to speed up the biodegradation process [37]. However, it is obvious that algal biomass concentration in bioplastic films decreases voids and cracks in biofilms. The control film (Fig. 3A) shows no cracks. The addition of algal biomass created some cracks as seen in figure (Figs. 3B, 3C) using the orange arrow. However, increasing the algal biomass concentration decreases voids and cracks in biofilms (Figs. 3D, 3E). That is attributed to insufficient distribution of microalgal biomass at low concentrations, but raising the concentration enables the microalgal biomass to form more physical bonds, such as hydrogen bonds, with the film components, therefore improving their compatibility and homogeneity.

Figure 3: SEM photograph for bioplastic films (8000×); (A) LDPE, (B) LDPE/AB-12.5%, (C) LDPE/AB-25%, (D) LDPE/AB 37.5%, (E) LDPE/AB-50%

Thus, micropore occurrence can be an important factor both for biodegradation and for the mechanical strength of bioplastics. Micropores in bioplastics may offer an additional surface area to microbial colonization and, by supporting the penetration of enzymes and microorganisms responsible for degradation, promote material decomposition. The occurrence of micropores can increase the rate of biodegradation by facilitating easier access by microbes to the inner layers of the material. If micropores give rise to faster degradation of the bioplastic, then its environmental impact will be much lower than that of conventional plastics. On the other hand, micropores will initiate many weak points in the material, which could reduce the overall mechanical strength. The micropores would probably lower the tensile strength and impact resistance by making it more vulnerable to damage. Therefore, a compromise might be made between mechanical strength and biodegradability. Higher porosity has indeed shown an enhancement of degradability but compromises on the material’s structural integrity. Thus, while micropores may help improve the biodegradability of bioplastics by offering an entry for microorganisms, they shall also be weakening mechanical strength. Such are the trade-offs in the formulation of bioplastics for the balance between environmental concerns and structural properties.

3.4 X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis of Algal Biomass/LDPE Films

The XRD spectra of LDPE film and their blends with different concentrations of algal biomass (12.5%–50%) are shown in Fig. 4 to evaluate the algal biomass effect (AB) on the morphology and crystallinity of blended films. Pure LDPE exhibited two characteristic peaks at 2θ = 21.49° and 23.84° that attributed to (110) and (200) planes of crystal lattice orthorhombic. Blending algal biomass changed the peaks positions and intensity. Where, the peak at 2θ = 21.49° (in pure LDPE) shifted to higher 2 theta (21.73°, 21.84°, 22.3°, and 21.95° for LDPE/AB-12.5%, LDPE/AB-25%, LDPE/AB-37.5%, and LDPE/AB-50%, respectively). The peak intensity (2θ = 21.49°) decreased gradually with increased concentrations of algal biomass. Also, the peak at 2θ = 23.84° is completely disappeared in the blended films [38,39]. This revealed that the interaction and dispersion of AB with LDPE components caused a change in the morphological and crystalline structure of LDPE. Moreover, XRD spectra of blended films displayed other diffraction peaks appeared at 2θ = 14.4°, 17°, and 24°. The 14.4° and 17° related to (110) and (110) planes of the cellulosic parts that are present in algal biomass [40,41]. The 2θ = 24° is indicative of the scattering peak of TiO2 (101) that used as mentioned in Table 1.

Figure 4: X-ray diffraction pattern of LDPE, LDPE/AB-12.5%, LDPE/AB-25%, LDPE/AB 37.5%, LDPE/AB-50%

3.5 The Prepared Algal Biomass/LDPE Films’ FT-IR Spectroscopy

Fourier transform infrared spectra of an AB/LDPE blend with various ratios (0.0%, 12.5%, 25%, 37.5%, and 50%) were collected in the 500–3000 cm−1 range. This shows potential intermolecular bonds between ingredients in the bioplastic films. According to Fig. 5, the spectrum of the AB/LDPE films exposed no differences in the structure of the LDPE film or the created AB/LDPE blend. The identical spectra of all the samples show that the functional groups in them have comparable chemical structures.

Figure 5: FT-IR spectra of (A) LDPE, (B) LDPE/AB-12.5%, (C) LDPE/AB-25%, (D) LDPE/AB 37.5%, (E) LDPE/AB-50%

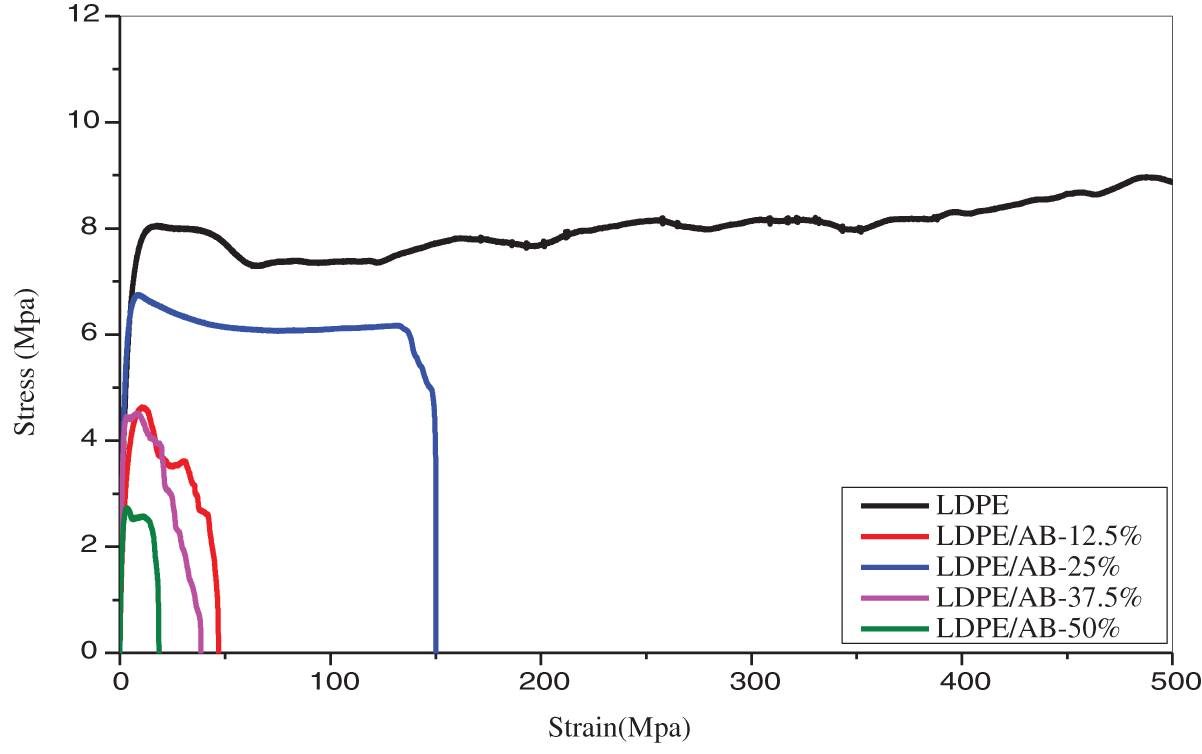

The films used as bioplastics should possess good mechanical properties, such as high strength, toughness, and durability. This is crucial because the films will be subjected to harsh environmental conditions. The mechanical properties of pure LDPE and their biocomposite films that arose from their blending with different concentrations of algal biomass (12.5%–50%) were evaluated through the determination of strength parameters such as tensile strength (TS) and elastic modulus (EM). The stress-strain curves of the films are illustrated in Fig. 6. It is clear from the stress-strain curve that the addition of algal biomass (AB) significantly re-rated the mechanical properties of the biocomposite films. Because the algal biomass has sporadic character and formed flaws and grooves on the surface of biocomposite films as seen in SEM images. Which causes the discontinuities and loss of cohesion of LDPE polymer. As shown, the pure LDPE film has a better tensile strength (15.5 MPa) and elastic modulus (304 MPa) compared to biocomposite films. When small amount of AB (12.5%) was added, the TS and EM significantly decreased to 4.63 and 255 MPa, respectively. That may be due to the bad distribution of AB between the chains of LDPE which restricted their ordering. However, by increasing the concentration of AB up to 25% and 37.5%, the mechanical properties enhanced and raised to (TS = 6.75 MPa, EM = 426 MPa) and (TS = 7 MPa, EM = 494 MPa), respectively. The 25% and 37.5% of AB were suitable for improving the miscibility and interaction between algal biomass and LDPE polymer. Finally, at a high concentration of AB (50%), the microalgal biomass particles aggregated, so retardation in tensile strength and young modulus was observed. These findings were convenient with SEM and TGA measurements. kinds of literature exhibited a similar trend. Where, Mohamed et al. [41] explained that the dispersion of CNTs or graphene to Polyethersulfone film reduces the rigidity and stiffness properties of the prepared nanocomposites. Also, thermoplastic corn starch films incorporating microalgae had lower mechanical properties as illustrated by Febra et al. [42]. Tensile strength increased with increasing algal biomass in the composite due to effective interfacial interaction between the algal biomass and LDPE, which improved the film’s compatibility and tensile strength.

Figure 6: Tensile properties of LDPE, LDPE/AB-12.5%, LDPE/AB-25%, LDPE/AB-37.5% and LDPE/AB-50%

Biomass from microalgae can be used to produce the blending materials, such as PLA, cellulose, starch, PHA, and protein. The creation of biocomposite using microalgal biomass left over from the biodiesel production process according to a study by Torres et al. [43], demonstrated the creation of biocomposites using microalgal biomass left over from the biodiesel production process. With the use of 20% leftover microalgae biomass and PBAT (poly (butyleneadipate-co-terephthalate)), plasticization in this study enhanced the tensile modulus, mechanical characteristics, and elongation of the biocomposites. The end products were proposed for use as agricultural films and will disintegrate in the soil [44].

With specific biomass concentrations, mechanical properties in bioplastics are enhanced; however, the optimal balance has to be realized to avoid mechanical performance compromise. This optimum would depend on many factors, including the application, processing considerations, and the desired properties of the final product. Testing and experimentation will be required to determine the ideal concentration of biomass that could result in optimum mechanical properties with the maintenance of biodegradability and other important features.

Studying the barrier properties of LDPE and algal biomass/LDPE films is considered to be very significant. Several parameters, such as filler dispersion, material crystallinity, and compatibility, may have an impact on barrier properties. The data in Table 3 reveal water vapour transmission rate (WVTR) values; the WVTR of LDPE was also 1.95 g/m2.day, and the WVTR values of algal biomass/LDPE films were 2.24, 4.85, 8.1, and 70.86 g/m2.day as the amount of raw algal biomass was increased. The values increased substantially, particularly in the case of algal biomass/LDPE films comprising 50% raw algal biomass. This rise was recognized as good miscibility (i.e., a smooth surface) and the blend’s high crystallinity, which resulted in an increase in tortuosity in the matrix, limiting water vapor movement. This discovery also demonstrates that algal biomass/LDPE films are extremely promising for packaging applications.

This would mean that the relative permeability of microalgae-based LDPE, in comparison with other bioplastics, must be equated with issues such as material composition and structure, processing methods, and the use of additives. Each feedstock material type-from corn to sugarcane and from cellulose to starch-has its particular properties, further affecting its permeability. Bioplastics from different feedstocks could have different gas permeability properties. PLA is one of the most well-known bioplastics and has relatively high gas permeability. Depending on the specific formulation and processing, microalgae-based LDPE may offer an improved gas or moisture barrier compared with a few other bioplastics sourced from different feedstocks. Because of renewable feedstock and possible biodegradability, microalgae-based LDPE and its some fellow bioplastics will be more compatible with ecological environments than regular plastics. Requirements for permeability differ according to the application. For some specific applications, either microalgae-based LDPE or some particular types of bioplastics will be quite useful with regard to their permeability characteristics. Furthermore, a variety of factors, such as material composition, processing method, and surrounding environmental considerations, goes to play a major role in the permeability characteristics of microalgae-based LDPE bioplastics when compared to other feedstocks. Every material class has its permeability properties with respective advantages and challenges, and their choice would depend upon application requirements and the environmental impact caused by an application. In fact, most materials used in a wide variety of applications require further research and development for the enhancement of permeability characteristics.

Any chemical or physical alteration to a substance brought on by biological activity is referred to as biodegradation. Biological agents frequently use organic polymers as a substrate for their energy and growth, with microbial biomass emerging as a byproduct of complete biodegradation [8]. The biodegradability of bioplastic films was done by burying films in the soil and measuring mass loss according to time (Fig. 7). The degradation of bioplastic films in the soil was measured at intervals. The results showed that the decomposition rate was somewhat weak, as the decomposition rate after a week ranged between 1%–2%. The degradation rate after one month reached 8%. This percentage is low, but compared to industrial plastics, these films are considered good, even if the degradation rate is weak. Some bioplastic examples have been created by the designers or researchers [16]. A bioplastic product created by Dutch designers Eric Klarenbeek and Maartje Dros made from algae may totally replace traditional plastics. They also set up the Algae Lab for algal cultivation and starch production as a source of raw materials for the bioplastic. A biodegradable product from algae was also developed [12,45], such as agar made from algae and coated calcium carbonate, to replace petroleum-based plastics. The products were strong light, durable, and long-lasting. To help keep the soil moist, the bioplastics can also be composted or utilized as fertilizer. Similarly, Ari J. combined water and red algae powder to make a substitute for the conventional plastic bottle [46]. In addition, Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE) is one of the most widely used packaging materials for a variety of products. However, the efficient disposal of LDPE poses significant challenges due to its resistance to degradation, which can have harmful effects on the environment. A viable solution is to degrade LDPE into simpler compounds that can be disposed of safely. Among the various degradation techniques available, biodegradation is increasingly favored as it is a more cost-effective method.

Figure 7: Biodegradation rate of LDPE films (Blank) and LDPE + Algal biomass at different concentrations

Biodegradation can be conducted in specially designed aqueous media that optimize the degradation process for maximum efficiency. This approach not only helps in breaking down LDPE but also minimizes the environmental impact associated with traditional disposal methods such as landfilling and incineration [47]. In summary, while LDPE is a prevalent packaging material, its disposal requires innovative solutions like biodegradation to mitigate environmental harm effectively.

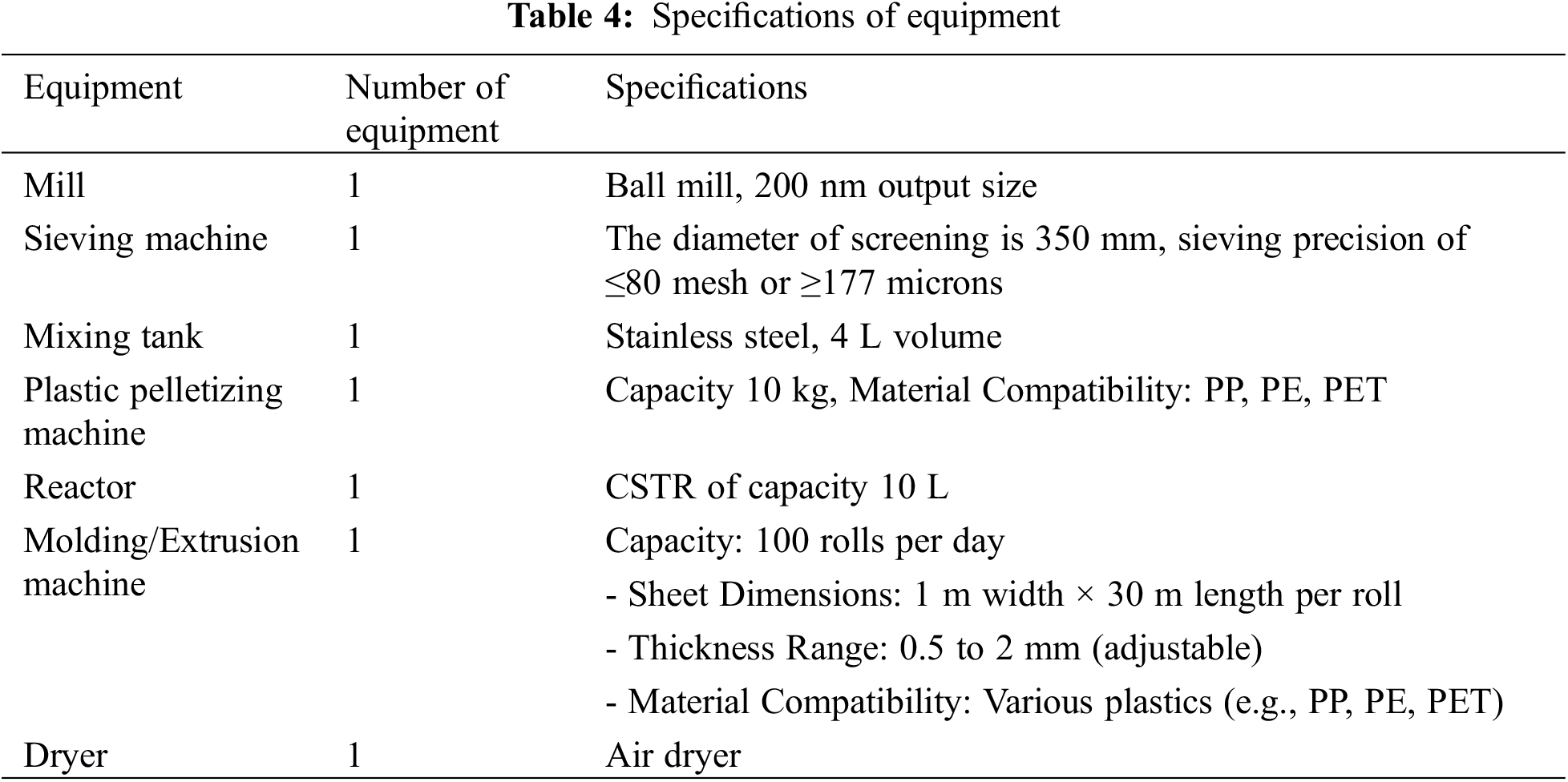

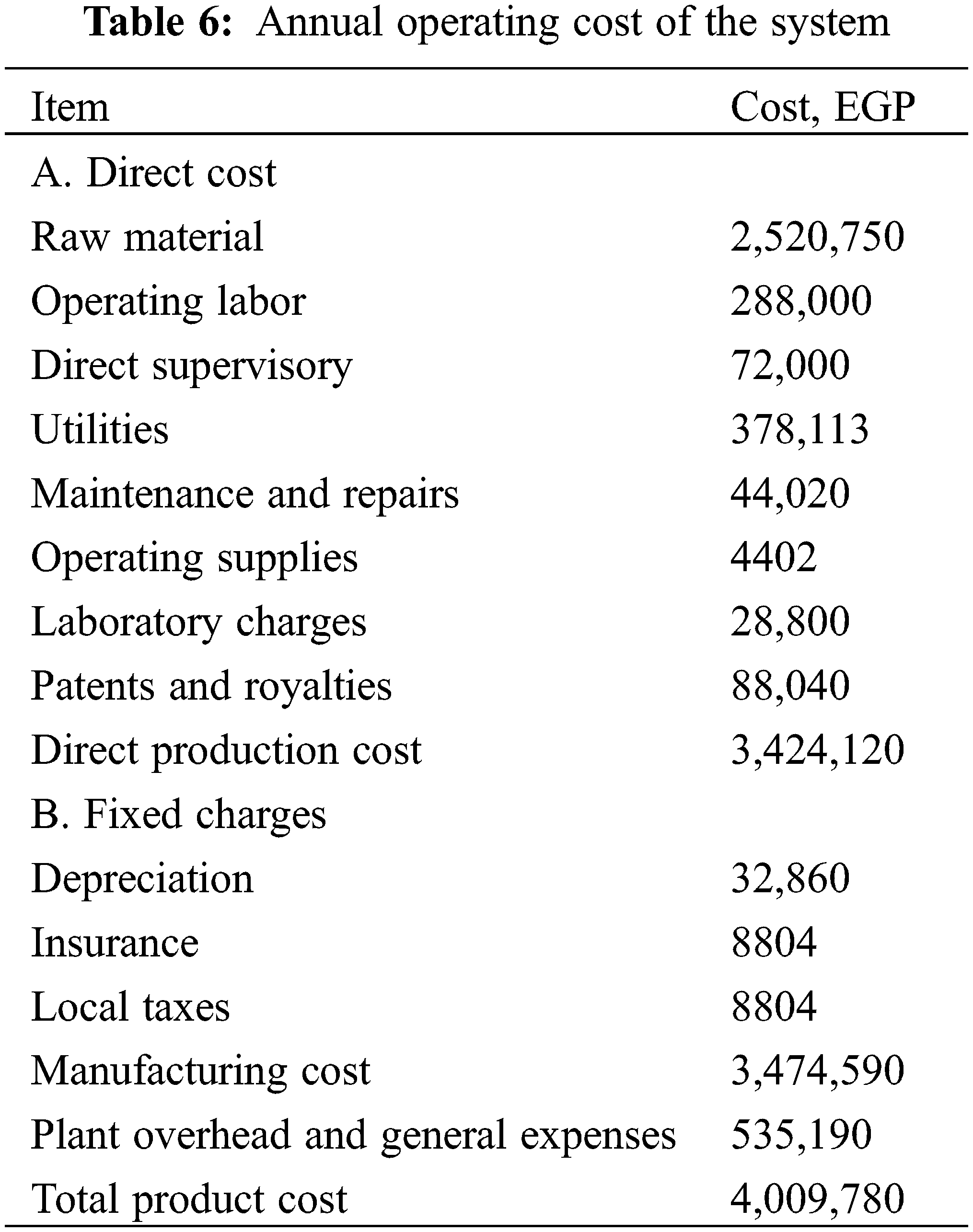

Bioplastics are an emerging trend, with global production capacity reaching 2.4 million tons (MT) in 2021 [48]. This figure is projected to increase to 7.5 MT by 2026 [49]. The economic assessment of the presented process is based on a daily production rate of 66 kg of bioplastic films. As detailed in Table 4, the equipment is designed for an annual production of 19.8 tons of bioplastic sheets, the facility operates 300 days per year and employs four laborers and a supervisor to process AB and LDPE as raw materials. Costs are calculated in Egyptian pounds EGP.

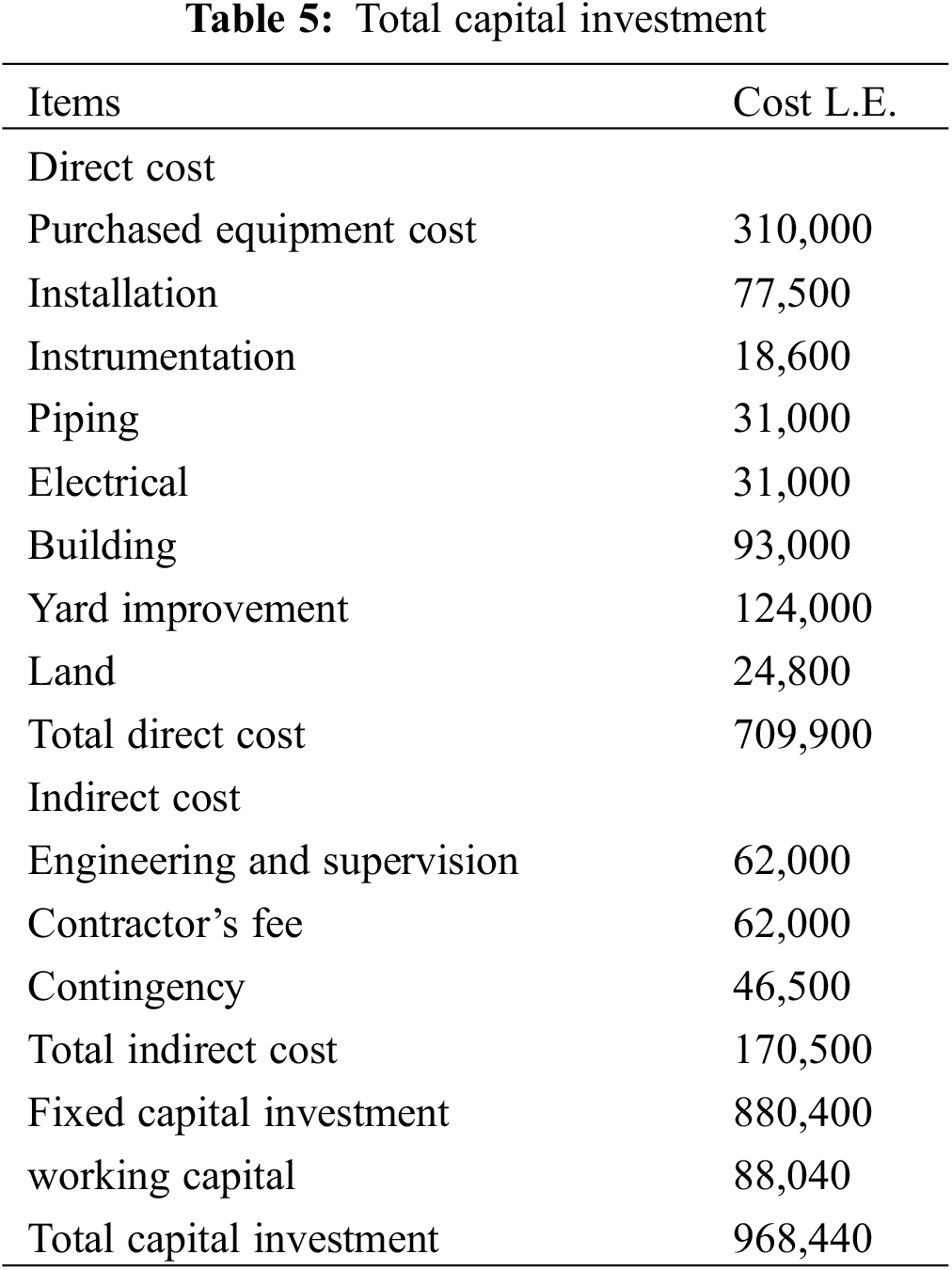

The capital investment required for the installed process equipment, along with all necessary auxiliaries for complete operation, is detailed in Table 5. The manufacturing cost encompasses direct production costs, fixed charges, and plant overhead costs. Direct production costs include expenses for raw materials, clerical and operating labor, maintenance, and utilities. Fixed charges account for equipment depreciation over 15 years and insurance costs. Plant overhead costs cover payroll overhead, storage facilities, packaging, and medical services. Administration costs which include executive salaries, legal fees, and communications represents the general expenses. The operating cost is calculated based on the following considerations; the utility charge constitutes 9.4% of the total product cost, laboratory charges are estimated as 10% of the labor cost, maintenance and repairs are considered as 5% of the fixed capital investment, operating suppliers are 10% of the maintenance cost, insurance is set at 0.5% of the fixed capital cost, and general expenses and plant overhead account for 13.3% of the total production cost. The operating expenses are summarized in Table 6.

The payout period is the shortest length of time required to recover the original capital investment through cash flow generated by the project [50,51]. The total annual income of this project is 4,455,000 EGP with an annual profit of 445,220 EGP. Based on Eq. (2), the payout period is estimated to be one year and ten months. The return on investment (ROI) of the project is 46.0%, as calculated in Eq. (3), indicating that this project is promising for investment.

The market price for bioplastics generally ranges from $2 to $7 per kg. Market commercialization relies heavily on public awareness of the benefits of bioplastic compared to petroleum-based plastics. A commitment to green thinking is essential for the sustainability and growth of this industry.

Mixing ground microalgal biomass with low-density polyethylene (LDPE) has proven to be effective in manufacturing bioplastic films. Utilizing microalgal biomass sourced from high-rate algal ponds has demonstrated its efficiency for bioplastic production. However, one of the challenges in commercializing bioplastics is the cultivation of microalgae. Growing microalgae on wastewater presents an economical solution, as they thrive on the nutrients found in such environments.

Mechanical property tests indicated that the tensile strength of the composite increased with higher amounts of microalgal biomass. This improvement is due to effective interfacial interaction between the microalgal biomass and LDPE, enhancing the compatibility and tensile strength of the films. Permeability results showed a significant increase in films containing 50% raw microalgal biomass, attributed to the blend’s excellent crystallinity and good miscibility, resulting in a smoother surface.

Despite the current impracticality of commercializing microalgae-based bioplastics on an industrial scale, advancements in technology and ongoing research and development in this field are crucial. With continued research, it is anticipated that a substantial number of bioplastics could be sustainably produced from microalgal biomass shortly, including investigations into the role of microalgae in the degradation of bioplastics.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: Open access funding is provided by the Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Author Contributions: Sayeda M. Abdo: investigation, conceptualization, methodology and writing the original draft. Youssef A. M.: conceptualization, data curation and methodology. Islam El Nagar: Methodology and data curation. Mehrez E. El-Naggar: conceptualization, writing original draft and data curation. Samar A. El-Mekkawi performed the process’ economic assessment and contributed in editing the final manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used to support the findings of this study is included in the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Arora Y, Sharma S, Sharma V. Microalgae in bioplastic production: a comprehensive review, institute for ionics. Arab J Sci Eng. 2023;48(6):7225–41. doi:10.1007/s13369-023-07871-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Devi RS, Kannan VR, Natarajan K, Nivas D, Kannan K, Chandru S, et al. The role of microbes in plastic degradation. In: Chandra R, editor. Environmental waste management. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2016. p. 341–70. [Google Scholar]

3. Sankhla IS, Sharma G, Tak A. Fungal degradation of bioplastics: an overview. In: New and future developments in microbial biotechnology and bioengineering. The Netherlands, Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2020. p. 35–47. [Google Scholar]

4. Gadhave RV, Das A, Mahanwar PA, Gadekar PT. Starch based bioplastics: the future of sustainable packaging. Open J Polym Chem. 2018;8:21–33. doi:10.4236/ojpchem.2018.82003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Peng Y, Wu P, Schartup AT, Zhang Y. Plastic waste release caused by COVID-19 and its fate in the global ocean. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021;118:e2111530118. doi:10.1073/pnas.2111530118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Sudhakar MP, Magesh PD, Dharani G. Studies on the development and characterization of bioplastic film from the red seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii). Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020;28:33899–913. [Google Scholar]

7. Sudhakar MP, Bargavi P. Fabrication and characterization of stimuli responsive scaffold/bio-membrane using novel carrageenan biopolymer for biomedical applications. Bioresour Technol Rep. 2023;21:101344. doi:10.1016/j.biteb.2023.101344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Sudhakar MP, Maurya R, Mehariya S, Karthikeyan OP, Dharani G, Arunkumar K, et al. Feasibility of bioplastic production using micro- and macroalgae a review. Environ Res. 2024;240:117465. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.117465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Cheah WY, Er AC, Aiyub K, Yasin NHM, Ngan SL, Chew KW, et al. Current status and perspectives of algae-based bioplastics: a reviewed potential for sustainability. Algal Res. 2023;71:103078. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2023.103078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Adetunji AI, Erasmus M. Green synthesis of bioplastics from microalgae: a state-of-the-art review. Polymers. 2024;16(10):1322. doi:10.3390/polym16101322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Acquavia MA, Pascale R, Martelli G, Bondoni M, Bianco G. Natural polymeric materials: a solution to plastic pollution from the agro-food sector 2021. Polymers. 2021;13(1):158. doi:10.3390/polym13010158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kakadellis S, Harris ZM. Don’t scrap the waste: the need for broader system boundaries in bioplastic food packaging life-cycle assessment–a critical review. J Clean Prod. 2020;274:122831. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zanchetta E, Damergi E, Patel B, Borgmeyer T, Pick H, Pulgarin A, et al. Algal cellulose, production and potential use in plastics: challenges and opportunities. Algal Res A. 2021;56:102288. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2021.102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Gill M. Bioplastic: a better alternative to plastics. Res Appl Nat Soc Sci. 2014;2:115–20. Available from: www.impactjournals.us. [Accessed 2024]. [Google Scholar]

15. Piemonte V. Bioplastic wastes: the best final disposition for energy saving. J Polym Environ. 2011;19(4):988–94. doi:10.1007/s10924-011-0343-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chia WY, Ying Tang DY, Khoo KS, Kay Lup AN, Chew KW. Nature’s fight against plastic pollution: algae for plastic biodegradation and bioplastics production. Environ Sci Ecotechnology. 2020;4:100065. doi:10.1016/j.ese.100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Cinar SO, Chong ZK, Kucuker MA, Wieczorek N, Cengiz U, Kuchta K. Bioplastic production from microalgae: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3842. doi:10.3390/ijerph17113842. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Priyadarshani I, Rath B. Commercial and industrial applications of micro algae a review. Algal Biomass Utilization. 2012;3(4):89–100. [Google Scholar]

19. Khoo KS, Chia WY, Tang DYY, Show PL, Chew KW, Chen WH. Nanomaterials utilization in biomass for biofuel and bioenergy production. Energies. 2020;13(4):892. doi:10.3390/en1304089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chong JWR, Khoo KS, Yew GY, Leong WH, Lim JW, Lam MK, et al. Advances in production of bioplastics by microalgae using food waste hydrolysate and wastewater: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2021;342:125947. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.125947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. López Pacheco IY, Rodas-Zuluaga LI, Cuellar-Bermudez SP, Hidalgo-Vázquez E, Molina-Vazquez A, Araújo RG, et al. Revalorization of microalgae biomass for synergistic interaction and sustainable applications: bioplastic generation. Mar Drugs. 2022;20(10):601. doi:10.3390/md20100601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Głowińska E, Gotkiewicz O, Kosmela P. Sustainable strategy for algae biomass waste management via development of novel bio-based thermoplastic polyurethane elastomers composites. Molecules. 2023;28(1):436. doi:10.3390/molecules28010436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Fabra MJ, Martínez-Sanz M, Gómez-Mascaraque LG, Coll-Marqués JM, Martínez JC, López-Rubio A. Development and characterization of hybrid corn starch-microalgae films: effect of ultrasound pre-treatment on structural, barrier and mechanical performance. Algal Res. 2017;28:80–7. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2017;10.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Salmah H, Romisuhani A, Akmal H. Properties of low-density polyethylene/palm kernel shell composites: effect of polyethylene co-acrylic acid. J Thermoplastic Compos Mater. 2013;26(1):3–15. doi:10.1177/0892705711417028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Streble H, Krauter B. Das leben in wassertropfen: mikroflora and microfauna des subasser: Ein bestimmungsbuch. Kosmos Verlag; 1978. [Google Scholar]

26. Shaheen MNF, Elmahdy EM, Rizk NM, Abdo SM, Hussein NA, Elshershaby A, et al. Evaluation of physical, chemical, and microbiological characteristics of waste stabilization ponds, Giza, Egypt. Environ Sci Eur. 2024;36(1):170. doi:10.1186/s12302-024-00965-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. El-Naggar ME, Abdelgawad AM, Abdel-Sattar R, Gibriel AA, Hemdan BA. Potential antimicrobial and antibiofilm efficacy of essential oil nanoemulsion loaded polycaprolactone nanofibrous dermal patches. Eur Polym J. 2023;184:111782. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2022.111782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Youssef AM, Abd El-Aziz ME, Morsi SMM. Development and evaluation of antimicrobial LDPE/TiO2 nanocomposites for food packaging applications. Polym Bull. 2023;80(5):5417–31. doi:10.1007/s00289-022-04346-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Youssef AM, Abou HY, El-Sayed SM, Kamel S. Mechanical and antibacterial properties of novel high performance chitosan/nanocomposite films. Int J Biol Macromol. 2015;76:25–32. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.02.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Abdo SM, Youssef AM, El-Liethy MA, Ali GH. Preparation of simple biodegradable, nontoxic, and antimicrobial PHB/PU/CuO bionanocomposites for safely use as bioplastic material packaging. Biomass Convers Bior. 2024;14(22):28673–83. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-03591-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Chowdhury MA, Badrudduza MD, Hossain N, Rana MM. Development and characterization of natural sourced bioplastic synthesized from tamarind seeds, berry seeds and licorice root. Appl Surf Sci Adv. 2022;11:100313. doi:10.1016/j.apsadv.2022.100313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Abdo SM, Ali GH. Analysis of polyhydroxybutrate and bioplastic production from microalgae. Bull National Res Centre. 2019;43(1):97. doi:10.1186/s42269-019-0135-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kowser MA, Hossain SMK, Amin MR, Chowdhury MA, Hossain N, Madkhali O, et al. Development and characterization of bioplastic synthesized from ginger and green tea for packaging applications. J Compos Sci. 2023;7(3):107. doi:10.3390/jcs7030107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang K. Bio-plastic potential of spirulina microalgae (Doctoral Dissertation). University of Georgia: Athens, GA, USA; 2014. [Google Scholar]

35. Amin MR, Chowdhury MA, Kowser MA. Characterization and performance analysis of composite bioplastics synthesized using titanium dioxide nanoparticles with corn starch. Heliyon. 2019;5(8):e02009. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Marichelvam MK, Manimaran P, Sanjay MR, Siengchin S, Geetha M, Kandakodeeswaran K, et al. Extraction and development of starch-based bioplastics from Prosopis Juliflora Plant: eco-friendly and sustainability aspects. Curr Res Green Sustain Chem. 2022;5(12):100296. doi:10.1016/j.crgsc.2022.100296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Boey JY, Lee CK, Tay GS. Factors affecting mechanical properties of reinforced bioplastics: a review. Polymers. 2022;14(18):3737. doi:10.3390/polym14183737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Bumbudsanpharoke N, Wongphan P, Promhuad K, Leelaphiwat P, Harnkarnsujarit N. Morphology and permeability of bio-based poly (butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBATpoly (butylene succinate) (PBS) and linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE) blend films control shelf-life of packaged bread. Food Control. 2022;132:108541. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Adelaja OA, Daramola. Preparation and characterization of low density polyethylene-chitosan nanoparticles biocomposite as a source of biodegradable plastics. Eur J Adv Chem Res. 2022;3:25–38. doi:10.24018/ejchem.2022.3.1.85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Shi B, Wideman G, Wang JH. A new approach of BioCO2 fixation by thermoplastic processing of microalgae. J Polym Environ. 2012;20(1):124–31. doi:10.1007/s10924-011-0329-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Mohamed A, Yousef S, Tonkonogovas A, Stankevičius A, Baltušnikas A. Fabrication of high-strength graphene oxide/carbon fiber nanocomposite membranes for hydrogen separation applications. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2023;172:941–9. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2023.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Fabra MJ, Martínez-Sanz M, Gómez-Mascaraque LG, Gavara R, López-Rubio A. Structural and physicochemical characterization of thermoplastic corn starch films containing microalgae. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;186:184–91. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.01.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Torres S, Navia R, Campbell Murdy R, Cooke P, Misra M, Mohanty AK. Green composites from residual microalgae biomass and poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalateprocessing and plasticization. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2015;3(4):614–24. doi:10.1021/sc500753h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Mogany T, Bhola V, Bux F. Algal-based bioplastics: global trends in applied research, technologies, and commercialization. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2024;1–23. [Google Scholar]

45. Paniz OG, Pereira CM, Pacheco BS, Wolke SI, Maron GK, Mansilla A, et al. Cellulosic material obtained from Antarctic algae biomass. Cellulose. 2020;27:113–26. doi:10.1007/s10570-019-02794-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Orendorz A, Brodyanski A, Lösch J, Bai LH, Chen ZH, Le Y, et al. Phase transformation and particle growth in nanocrystalline anatase TiO2 films analyzed by X-ray diffraction and raman spectroscopy. Surf Sci. 2007;601(18):4390–4. doi:10.1016/j.susc.2007.04.127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Veethahavya KS, Rajath BS, Noobia S, Kumar BM. Biodegradation of low density polyethylene in aqueous media. Procedia Environ Sci. 2016;35:709–13. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2016.07.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Ali SS, Elsamahy T, Abdelkarim EA, Al-Tohamy R, Kornaros M, Ruiz HA, et al. Biowastes for biodegradable bioplastics production and end-of-life scenarios in circular bioeconomy and biorefinery concept. Bioresour Technol. 2022;363:127869. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127869. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Abang S, Wong F, Sarbatly R, Sariau J, Baini R, Besar NA. Bioplastic classifications and innovations in antibacterial, antifungal, and antioxidant applications. J Bioresour Bioprod. 2023 Nov;8(4):361–87. doi:10.1016/j.jobab.2023.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Park H, Lee C. Theoretical calculations on the feasibility of microalgal biofuels: utilization of marine resources could help realizing the potential of microalgae. Biotechnol J. 2016;11(11):1461–70. doi:10.1002/biot.v11.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Peter M, Timmerhaus K. Solution manual to accompany Plant design and econ economics for chemical engineeringomics for chemical engineers. 4th edUSA: McGraw-Hill, Inc.; 1991. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools