Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Stepwise Pretreatment of Pulsed Electric Fields and Solid Substrate Fermentation Using Pleurotus ostreatus on Coconut Dregs

1 Agro-Industrial Technology, Faculty of Agricultural Technology, University of Brawijaya, Malang, 65145, Indonesia

2 Agro-Industrial Technology, Faculty of Agricultural Technology, University of Andalas, Padang, 25163, Indonesia

3 Agricultural and Biosystem Engineering, Faculty of Agricultural Technology, University of Brawijaya, Malang, 65145, Indonesia

* Corresponding Authors: Wenny Surya Murtius. Email: ; Bambang Dwi Argo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Special issue from 1st International Conference of Natural Fiber and Biocomposite (1st ICONFIB) 2024 )

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(5), 997-1020. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0004

Received 01 October 2024; Accepted 18 December 2024; Issue published 20 May 2025

Abstract

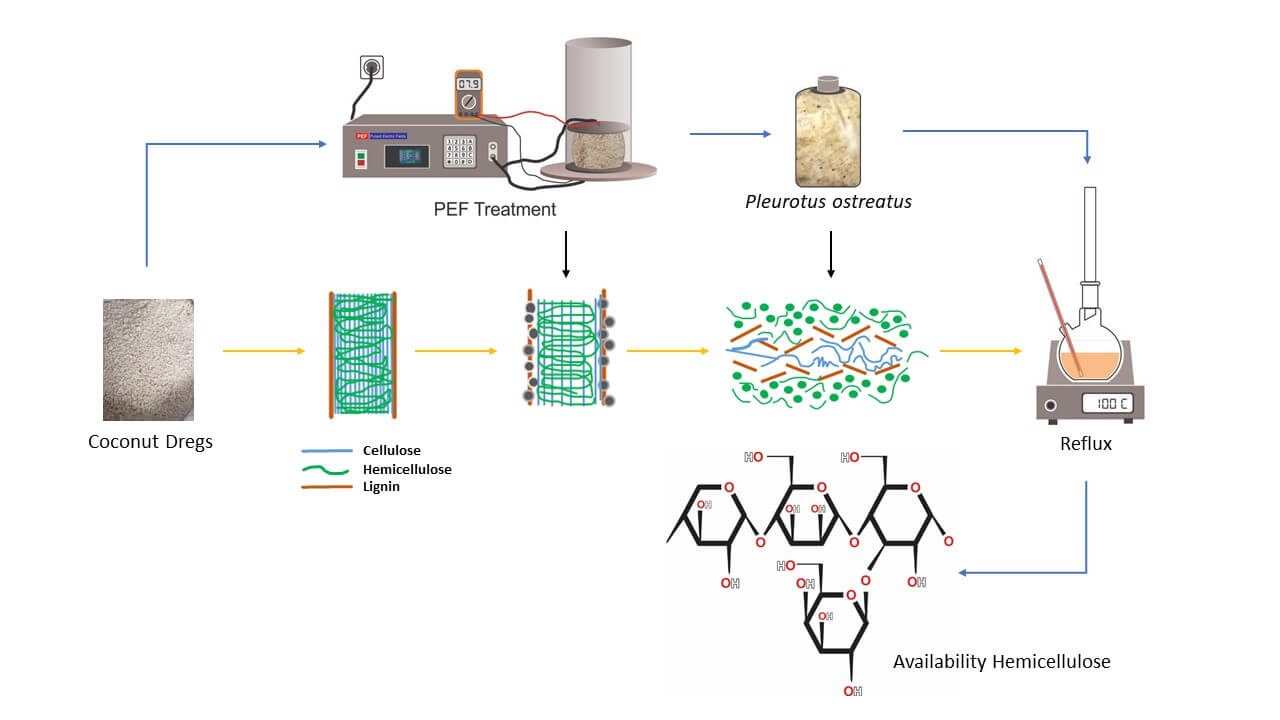

A stepwise pretreatment process for coconut dregs (CD) has been investigated to enhance availability of hemicellulose. Recently, lignocellulose-rich agricultural waste such as CD has garnered substantial attention as a sustainable raw material for producing value-added bio-products. To optimize the process variables within the stepwise pretreatment using Pulsed Electric Field (PEF) and Solid-State Fermentation (SSF), Response Surface Methodology (RSM) based on Central Composite Design (CCD) was employed. PEF, a non-thermal physical treatment, offers advantages such as low energy consumption and reduced processing times, while SSF utilizes Pleurotus ostreatus to promote biodegradation. A statistical model was constructed using a three-factor CCD that included five center points and axial points, with variables including PEF treatment duration (30, 60, and 90 s), substrate particle size (20, 40, and 60 mesh), and incubation time (10, 20, and 30 days). Changes in lignocellulose composition were analyzed to evaluate their effects on the process. The optimal parameters identified were a particle size of 40 mesh, a PEF treatment duration of 61 s, and an incubation period of 12.5 days. Under these conditions, the process yielded an impressive increase in hemicellulose availability by 106.53%, a minimization of cellulose loss to 6.28%, and a successful delignification resulting in a 21.78% removal of lignin.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Hemicellulose is a heterogeneous and branched polysaccharide that envelops cellulose, forming a crucial link between cellulose and lignin. It consists of a complex mixture of D-glucose, D-galactose, D-mannose, D-xylose, L-arabinose, glucuronic acid, and 4-O-methyl-glucuronic acid [1] including polymers such as arabans, xylans, and galactans [2]. The presence of substantial substitutions with acetic acid endows hemicellulose with an amorphous and flexible structure, significantly contributing to cell wall stability through its interaction with cellulose [1]. Although hemicellulose is insoluble in water, it readily dissolves in weak acids, bases, and enzymatic solutions. Its comparatively lower mechanical strength relative to cellulose renders it more amenable to chemical treatments, facilitating its conversion into biofuels, bioethanol, biochar, fermentable sugars, and other valuable products [2].

Coconut dregs (CD) are a lignocellulosic biomass characterized by a composition of cellulose (47.18%), hemicellulose (12.10%), and lignin (10.58%) [3]. Numerous studies have explored the potential of CD as a raw material for the production of second-and third-generation bioethanol [4]. Pretreatment methods have been shown to enhance its lignocellulosic content to 14.8% cellulose, 27.7% hemicellulose, and 12.4% lignin. Research indicates that hydrothermal pretreatment combined with acid hydrolysis can significantly reduce the lignocellulose composition of CD to 3.32% cellulose, 1.50% hemicellulose, and 1.73% lignin [5]. Due to its lignocellulosic content, CD holds considerable promise as a feed-stock for generating valuable bio-based products [4,6].

The rigid structure of lignocellulose contributes to biomass recalcitrance, complicating its direct conversion into bio-products [7]. Lignin strong association with cellulose and hemicellulose further enhance the biomass’s resilience against degradation [8]. To overcome this challenge, pretreatment is essential for disrupting the lignocellulosic matrix and improving enzyme accessibility [6,9]. The synergy of various pretreatment methods has shown significant potential for enhancing hemicellulose availability [4], thus enabling the hydrolysis of hemicellulose into monosaccharides for subsequent conversion [1,10].

Effective pretreatment is paramount in processing lignocellulosic biomass, as it facilitates hydrolysis [11]. A combinatorial approach utilizing different pretreatment methods often yields better results compared to a singular approach, given that biomass types possess distinct physicochemical characteristics that influence treatment outcomes. Stepwise pretreatment methods have proven to be particularly effective in breaking down lignocellulosic biomass [12].

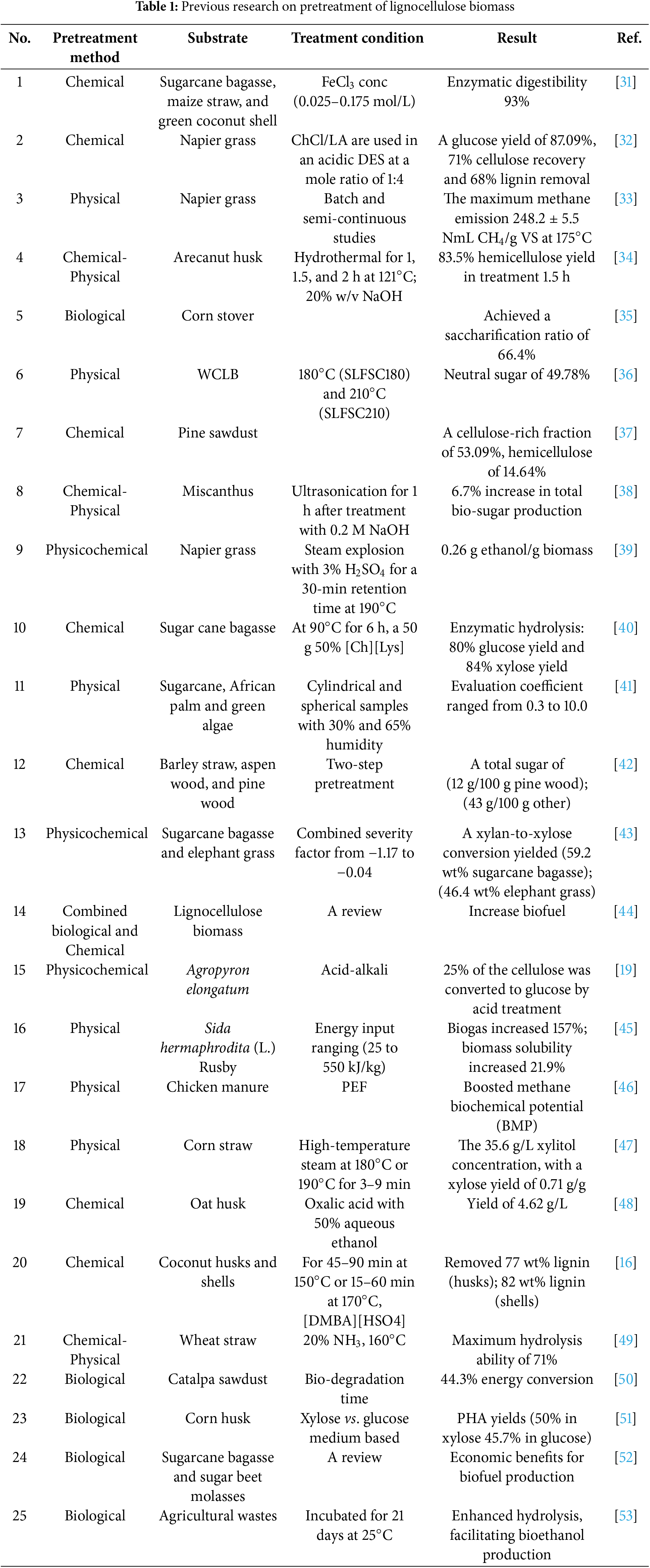

Chemical pretreatments, particularly acid and alkali treatments, are known for their efficiency in disrupting lignocellulose structures [13,14]. Alkali treatment, for instance, enhances biomass porosity, thereby improving enzymatic hydrolysis yields [15]. Physical methods, such as microwaves treatment, serve to reduce crystallinity and augment enzyme accessibility, leading to increased sugar yields [16,17]. Ultrasonic cavitation represents another technique capable of dismantling complex biomass structures [18]. A summary of related studies can be found in Table 1. While existing methods demonstrate efficiency, further innovation is required to develop pretreatments that effectively balance low energy consumption, cost-effectiveness, and environmental sustainability, thereby facilitating greater hemicellulose availability. One promising physical pretreatment technique is the pulsed electric field (PEF) method.

PEF is characterized as non-thermal pretreatment that employs low energy while applying an electric field for a brief duration [19]. This method promotes the formation of pores in cell membranes, thus increasing porosity and surface area, which subsequently enhances biomass processing efficiency [19,20]. Observations using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) have shown that PEF treatment significantly improves pore uniformity and abundance in CD, facilitating structural breakdown [21]. Lignin’s complex structure and water-insolubility pose challenges for subsequent processing [22]. However, physical pretreatments are advantageous, yielding increased surface area, diminished cellulose crystallinity, straighforward operation, and minimal environmental impact [8]. These methods are foundational for enzymatic saccharification and fermentation, crucial steps in converting biomass into biofuels [23]. Synergistic approaches that physically disrupt biomass structures serve to complement enzymatic activity, resulting in enhanced delignification rates and improved sugar yields [24,25].

This study integrates PEF with solid-state fermentation (SSF) utilizing Pleurotus ostreatus [6,26]. Fungi such as P. ostreatus produce lignin-degrading enzymes, including lignin peroxidase (LiP), manganese peroxidase (MnP), and laccase, which enhance hemicellulose accessibility [27]. Biological treatments using fungi are both energy-efficient and environmentally friendly [28]. It is crucial to develop pretreatment methods that are both cost-effective and sustainable for effective biomass processing. The utilization of agro-industrial waste, such as CD, as feedstock aligns with ecological goals while simultaneously creating adding value [29,30]. This study aims to evaluate the effect of a stepwise pretreatment approach using P. ostreatus focusing on enhancing hemicellulose availability in CD.

The primary resources used in this investigation used CD obtained from extraction of coconut milk at pressing kiosks located in Padang, West Sumatra-Indonesia alongside pure culture of P. ostreatus. The principle equipment necessary for this research was the pulsed electric field (PEF) system.

Pretreatment of the combination of PEF and SSF using P. ostreatus, using response surface methodology (RSM) experimental design with central composite design (CCD). CCD is a fractional factorial design equipped with a center point and a group of axial points. In this study, three independent variables (X) were considered: Substrate size (CD particle size) with options 20, 40 and 60 mesh, PEF contact duration define as the length of time the CD is exposed to the electric field, with durations of 60, 90 and 120 s, and incubation time, set at 10, 20 and 30 days. The response variables (Y) consisted of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin content. Tests were conducted based on the recommendation generated by the CCD variables with three replications for each variable.

CD was dried in a cabinet dryer until the maximum moisture content of 12%. Following this, the CD was resized to the specific particle size 20, 40 and 60 mesh.

The PEF treatment chamber was constructed from acrylic, with a separation distance of 10 cm between the positive and negative electrodes within the chamber. High-voltage pulses are generated by several circuits in the PEF generator. The control panel is equipped with a timer (OMRON type H5CX-AN), an input voltage regulator, a high voltage activation button, a power button, and a speed control button.

The CD, which had been reduced by treatment, was put into PP placed in PEF voltage was set to produce an electric field strength with frequency of 7.9 kV, pulse width of 27 and pretreatment time was added into 30, 60, 90 s.

2.6 Inoculum Development of Pleurotus ostreatus

P. ostreatus culture obtained from white oyster mushroom farmers in Malang City, Indonesia, was rejuvenated on CD media at 30°C for 72 h.

10% P. ostreatus culture was inoculated into 30 g of CD medium, which had been supplemented with bran, lime and sterile molasses. The moisture content of the medium was maintained at 70%, followed by incubation according to the specified treatment conditions. The process was subsequently terminated by drying the CD medium in a cabinet dryer until the moisture content was reduced to a maximum of 12%.

2.8 Stages of Response Analysis

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted in R studio to examine the response variable (Y) that was acquired. Following data processing, a linear model was generated, which was then evaluated for significance using the p-value and for the adequacy of the regression model by evaluating the lack of fit. The model demonstrated a good to the data, as the anticipated lack of fit in this instance was minimal.

Data analysis was executed by multiple regression analysis to obtain an optimization model represented by the formula:

Y as estimated response, β0 as constant, β1, β2 and β3 linear parameters, β11, β22 and β33 as quadratic variable parameters, β123 as interaction and ε as random error. The stationary point is the optimum response surface, and the contour and surface plots display the optimum response value, which is shown in a 3D graphic.

2.10 Lignocellulose Content Test with Chesson Method

One gram of dried CD (value “a”) was combined with 150 mL of water. To ensure thorough mixing of the raw material with the water, the mixture was refluxed in a water bath maintained at 100°C for one hour. Following the reflux process, the mixture was filtered using distilled water to wash the residue until the pH was neutral. Subsequently, the residue was dried in an oven at 105°C until a constant weight was achieved, which was referred to as value “b.” The Hot Water Soluble (HWS) content was the calculated using Eq. (1), which quantity the amount of starch that dissolves in hot distilled water [26].

2.10.1 Calculation of Hemicellulose Content

After being treated with 1 N H2SO4, the residue was refluxed for one hour at 100°C in a water bath. Following reflux, the mixture was filtered and thoroughly washed until the pH reached neutral. Subsequently, the residue was dried in an oven at 105°C until a constant weight was achieved, refer to as value “c.” The results were calculated using Eq. (2).

2.10.2 Calculation of Cellulose Content

Ten milliliters of 72% H2SO4 were applied to the residue, and it was left to soak for four hours at room temperature. After adding 150 mL of 1 N H2SO4, the liquid was refluxed for an hour with reverse cooling in a water bath. The residue was refluxed, filtered, and then rinsed with water until the pH was neutral. After that, it was oven-dried for an hour at 105°C until its weight remained constant, which was noted as value “d.” Eq. (3) is used in the computation.

2.10.3 Calculation of Lignin Content

The material was placed in an electric furnace and heated to 500°C for two hours to facilitate ignition. After allowing it to cool slightly, the material was transferred to a desiccator for half an hour, or until the weight stays constant. This weight was recorded as “e.” Eq. (4) was emplyed to calculate the lignin content, while Eq. (5) was utilized to determine the extent of lignin removal.

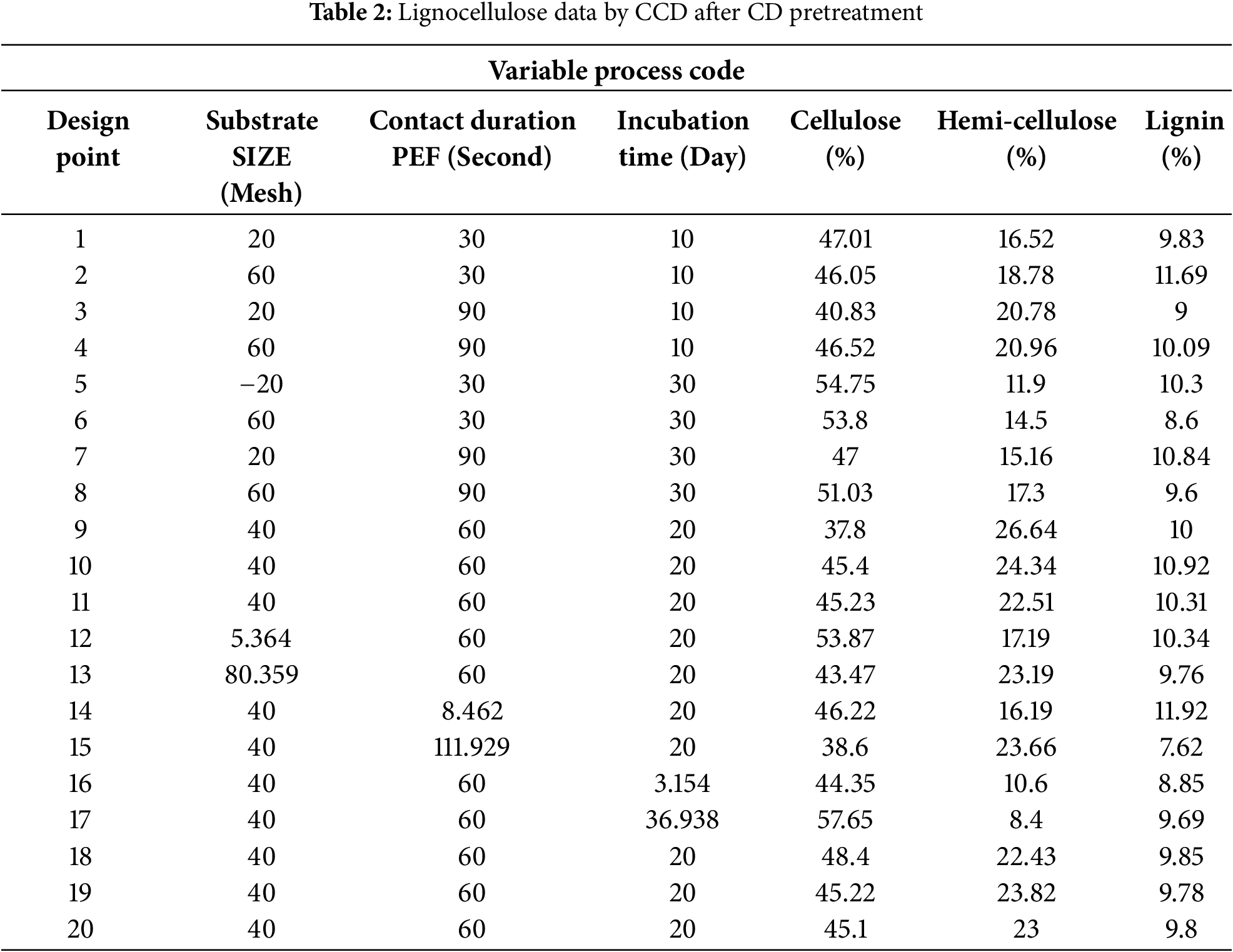

One of the pivotal steps in converting lignocellulosic biomass into high-value products is the pretreatment process. Effective pretreatment is essential to break down the compact and resilient structure of lignocellulosic biomass, ensuring high digestion yields in subsequent processing stages [7,54,55]. Table 2 presents a central composite design (CCD) for post-pretreatment lignocellulosic CD, with treatment ranges determined by preliminary studies on incubation times and previous research concerning substrate size and pulsed electric field (PEF) contact duration.

Lignocellulose exhibits unique structural changes during pretreatment, with fibers approximately 5 µm in diameter [56]. Studies show that the crystallinity index of lignocellulosic components is affected by the duration of PEF interaction. For untreated CD biomass, the crystallinity index measures 68.97%. PEF treatment progressively reduces this index with increasing contact time: 64.57% after 30 s, 61.15% after 60 s, and 55.77% after 90 s [21]. Similar findings have been observed in studies of brown rice starch, where PEF treatment reduces crystallinity via electroporation, likely due to pore formation that alters the permeability of the biomass’s cell membranes [57]. The reduction in biomass crystallinity can be attributed to the formation of mesopores within the cell walls [58]. Statistical analysis reveals a significant variation in porosity with respect to PEF contact duration (p < 0.001), demonstrating a linear relationship between contact time and increase in porosity [21].

Additionally, PEF pretreatment impacts the functional groups within lignocellulosic compounds of CD, particularly within the crystalline structure of cellulose [21]. Spectroscopic analysis shows structural changes evidenced by peak shifts in the 700–1500 cm−1 range, indicating modifications to the crystalline regions of lignocellulose [59]. The PEF treatment weakens these crystalline regions, significantly affecting both intermolecular and intramolecular bonds within lignocellulosic compounds [56].

The condition of CD cells post PEF treatment, particularly with extended contact times, significantly improved their accessibility to enzymes produced by P. ostreatus during the SSF pretreatment stage. Notably, the mycelial growth of P. ostreatus was both faster and more extensive on CD treated with a PEF contact duration of 90 s, which nearly covering the biomass entirely. In contrast, with a shorter PEF contact time of 30 s, mycelial coverage was uneven, and the biomass was not fully colonized, particularly at the bottom. Previous research highlights that P. ostreatus hyphae are partitioned by septa, each containing multiple nuclei within a shared cytoplasm. The branching hyphae in the mycelial network, some specialized in nutrient absorption, further contribute to fungal colonization. The rapid mycelial growth observed on CD treated for 90 s suggests that this optimal contact period optimizes the capacity of P. ostreatus to penetrate the biomass and extract nutrients [60].

Furthermore, the ability of P. ostreatus to produce lignocellulolytic enzymes, specifically targeting and degrading lignocellulosic cell walls, bolsters its effectiveness as a biological pretreatment agent [61]. These enzymes include manganese peroxidase (MnP), versatile peroxidase (VP), and laccase, which form a highly efficient ligninolytic system. Genome sequencing of P. ostreatus reveals its ability to adapt this enzymatic system to various substrates [27]. The ligninolytic activity of these enzymes facilitates the breakdown of both phenolic and non-phenolic forms of lignin, facilitating the conversion of lignin and cellulose into simple sugars and other micromolecules that serve as carbon sources for fungal growth [62,63].

Additionally, studies highlighting the fermentation of lignocellulosic substrates, such as cocoa husks and wheat straw, demonstrate that the enzymatic degradation of lignin by P. ostreatus increases the availability of fermentable sugars. This process improves the digestibility of both hemicellulose and cellulose [64,65]. Pretreatment with P. ostreatus has been shown to improve the susceptibility of lignocellulosic substrates to enzymatic hydrolysis by partially degrading lignin, which in turn increasing the cell surface area. Moreover, P. ostreatus produces hydrolytic enzymes such as cellulase, xylanase, and pectinase, which work synergistically with its ligninolytic enzymes to achieve more effective biomass degradation and maximize sugar release [66,67].

3.1 Central Composite Designs (CCD) Respone Data on Cellulose, Hemicellulose and Lignin

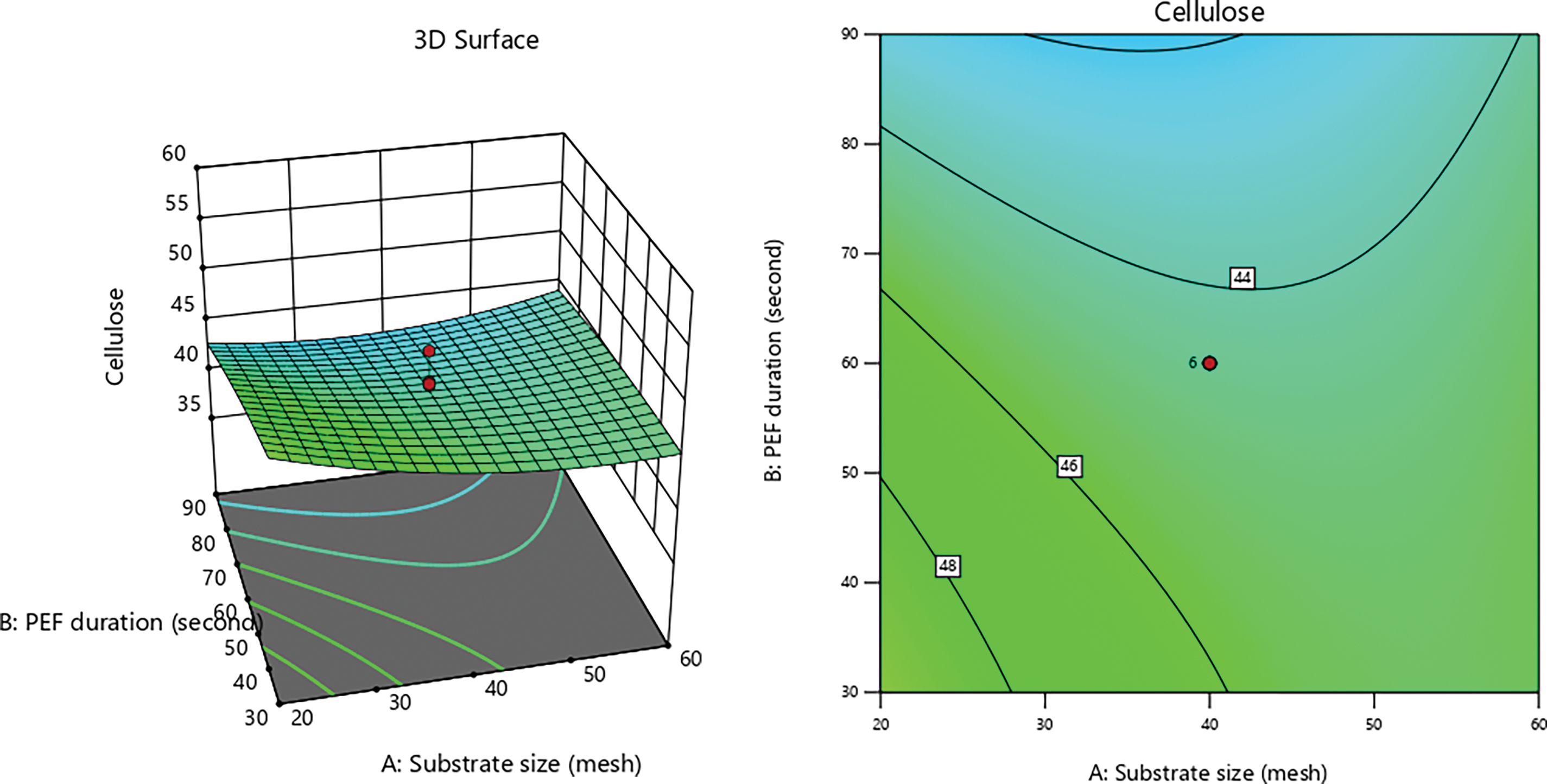

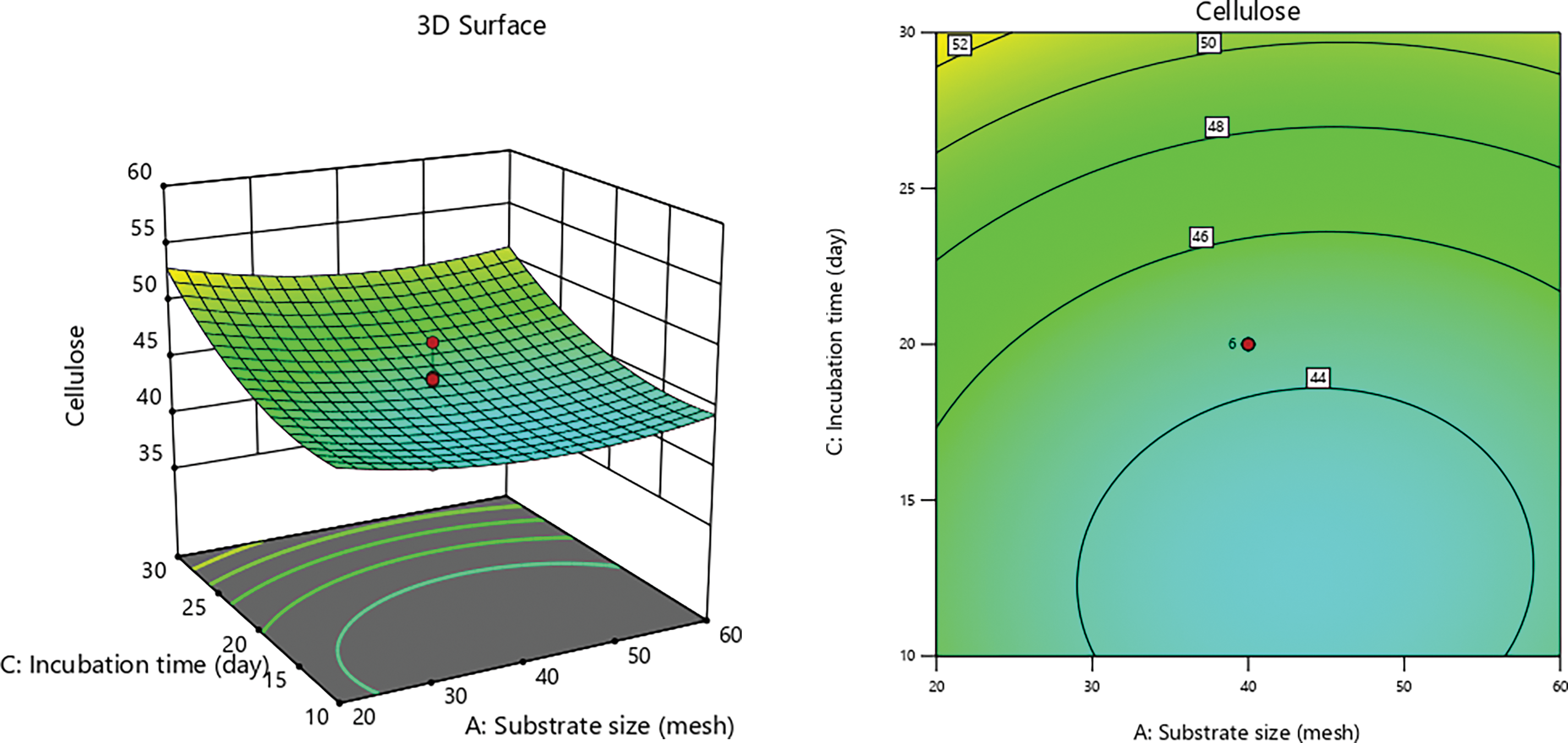

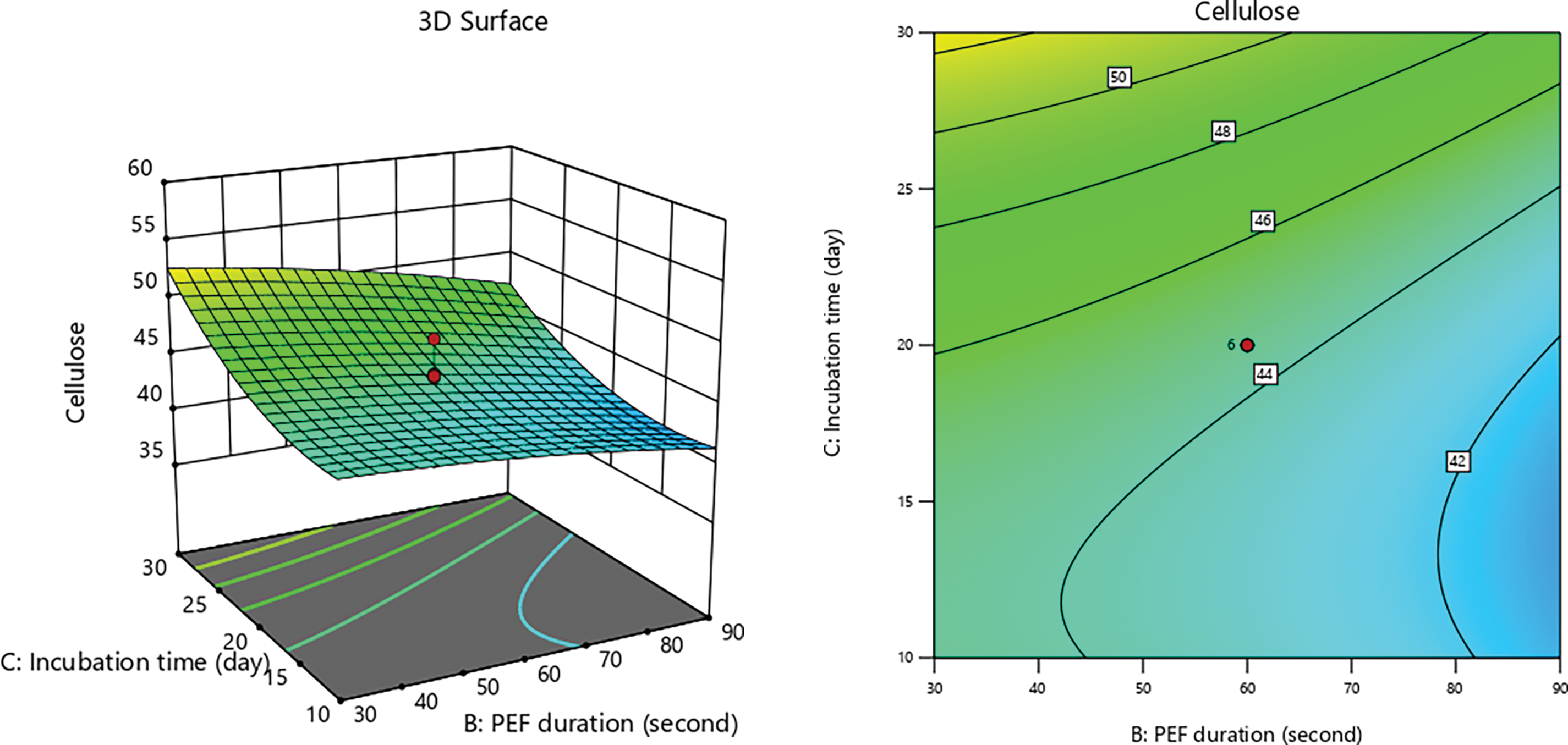

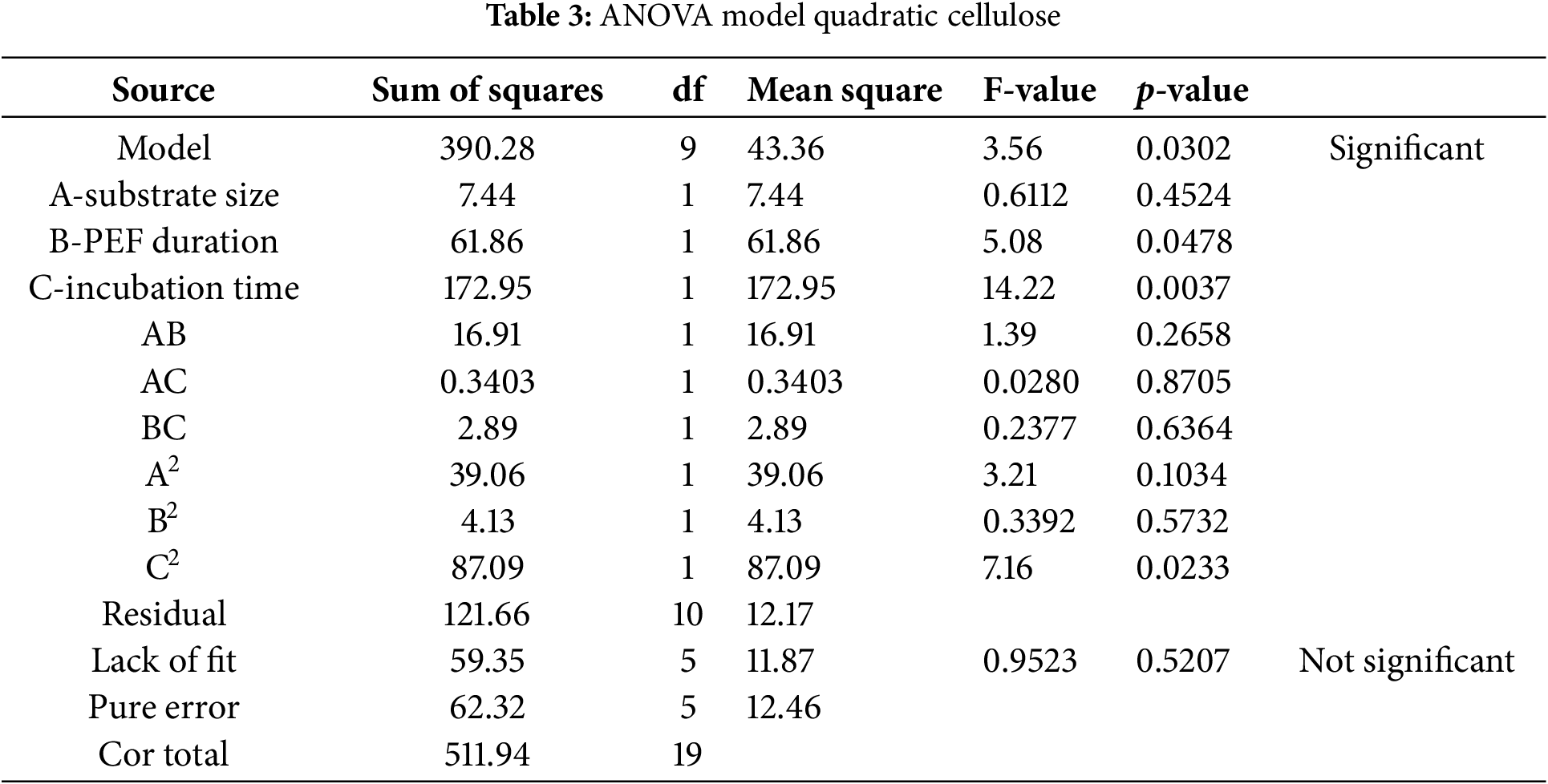

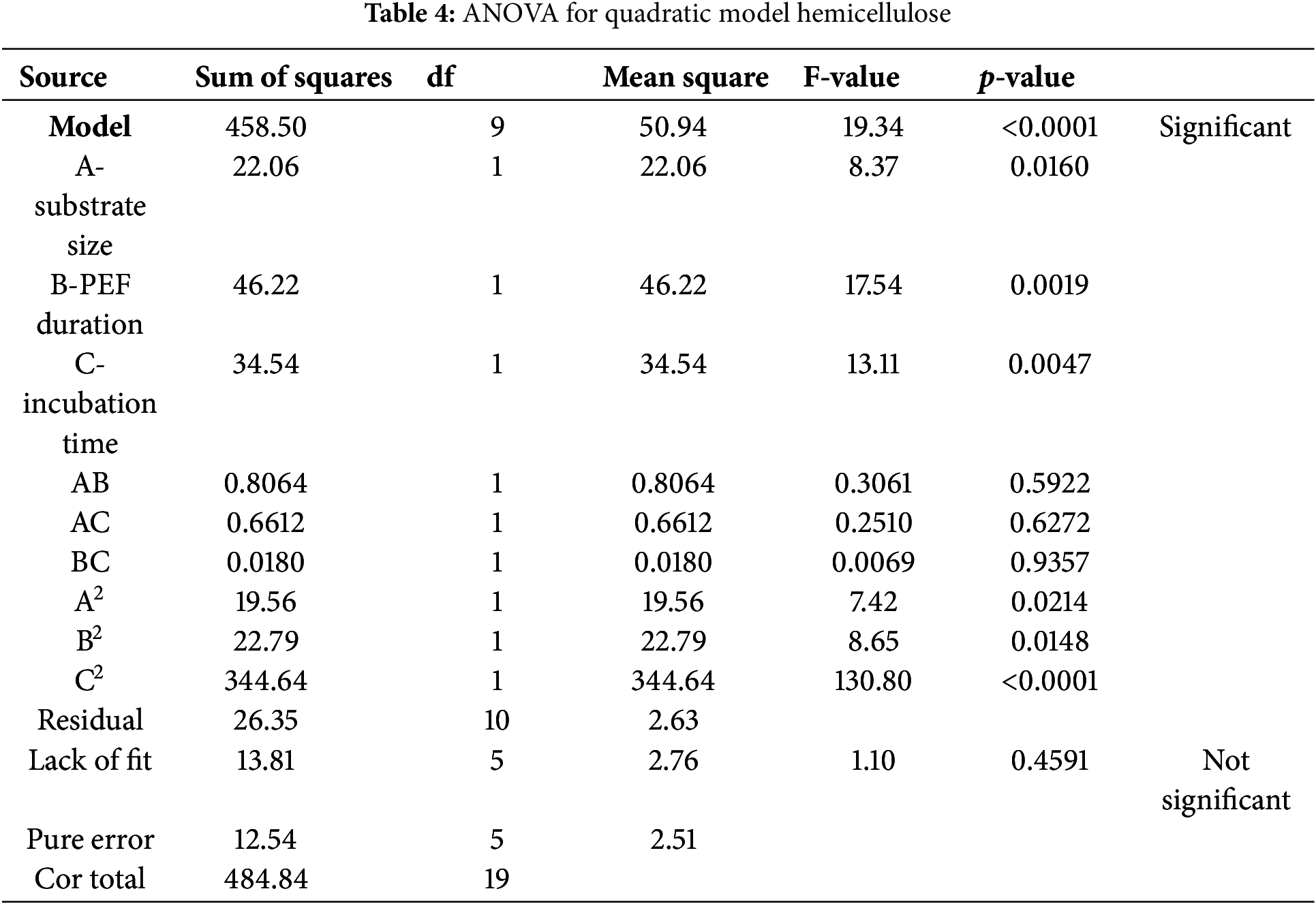

The reduction in cellulose content during pretreatment is attributed to the disruption of the lignocellulose cell wall, which enhances the accessibility of cellulose and hemicellulose for subsequent release [68]. In this study, the stepwise pretreatment utilizing PEF and SSF effectively decompose the lignocellulosic structure of CD (Figs. 1–3). Among the lignocellulosic components, cellulose is particularly susceptible to microbial degradation [69]. Table 3 for ANOVA model resulting:

Figure 1: 3D graphs of the effect of PEF duration with substrate size on cellulose content

Figure 2: 3D graphs of the effect of incubation time with substrate size on cellulose content

Figure 3: 3D graphs of the effect of incubation time with PEF duration on cellulose content

P. ostreatus produces various cellulolytic enzymes, including endoglucanase, exoglucanase, and cellobiohydrolase, each of which targets cellulose in distinct ways. Endoglucanase hydrolyzes the amorphous regions of cellulose randomly, generating new chain ends and oligosaccharides of varying lengths. Conversely, exoglucanase acts on both the reducing and non-reducing ends of the cellulose polysaccharide chain, releasing glucose through its glucanohydrolase activity or producing cellobiose through cellobiohydrolase activity [60]. Statistical analysis process yielded the following Eq. (6) was obtained:

The enzymatic degradation of lignocellulose by P. ostreatus initiates with the breakdown of lignin, reaching its peak around the 15th day of incubation. This initial lignin degradation enhances access to cellulose and hemicellulose, rendering these components more susceptible to further enzymatic action [22,68,70]. Following the lignin breakdown, P. ostreatus synthesize cellulase enzymes targeting cellulose, with this activity typically peaking around the 30th day of incubation [71,72]. Research by [70] corroborates these findings, indicating that laccase activity, crucial for lignin degradation, also peaks on the 15th day of incubation. On the same day, both cellulase and xylanase activities commence gradually intensifying to reach their maximum levels around day 30. Interestingly, cellulase activity surpasses xylanase activity at this stage, indicating a stronger enzymatic affinity for cellulose degradation. This sequence of enzymatic activity highlights the efficiency of P. ostreatus in decomposing lignocellulosic biomass.

This study demonstrates a slightly accelerated degradation pattern due to variations in PEF (pulsed electric field) contact duration during pretreatment. The substrate is more accessible after PEF contact, which enhances the electroporation effect on the lignocellulosic biomass. PEF pretreatment involves applying high-voltage electric pulses to biological materials, including cell membrane materials of lignocellulosic biomass, to induce electroporation [19,56,59]. When subjected to high-voltage PEF, electroporation enhances membranes permeability, allowing normally impermeable molecules to penetrate [21,56,57,73]. High-voltage pulses must be applied to biomass to effectively disrupt cell membranes and enhance access to the internal components [74].

The electroporation mechanism in lignocellulosic biomass, upon exposure to high voltage PEF, elevates the transmembrane potential and generates pores in the cell membrane [19,75]. These pores facilitate the breakdown of cell walls and the extraction of cellular components by allowing air molecules and other substances to enter the cell [76]. Furthermore, electroporation promotes the breakdown and conversion of lignocellulosic biomass by altering cellular structure and increasing membrane permeability [77,78]. Substrate size also directly influences the reaction process by affecting surface area, which is crucial for reaction kinetics and mass transfer rates in applied systems [79]. In this case, substrate size affects the porosity produced by different PEF contact times, thereby improving the effectiveness of electroporation and pretreatment.

The complicated structure of lignocellulose breaks down during pretreatment, greatly facilitating the release of hemicellulose [39]. To further investigate this effect, these results were applied to a second-order quadratic model of coded units (Table 4), and a statistical analysis process yielded the following Eq. (7).

PEF pretreatment enhances the permeability of the CD cell membrane, thereby increasing the availability of hemicellulose through several mechanisms: enzymes produced by P. ostreatus can more readily penetrate biomass cells and access hemicellulose that is tethered to cellulose and obstructed by lignin may be liberated as a result of changes in membrane permeability; and dissolved hemicellulose can diffuse more easily owing to cell wall rupture induced by PEF [19,29,79].

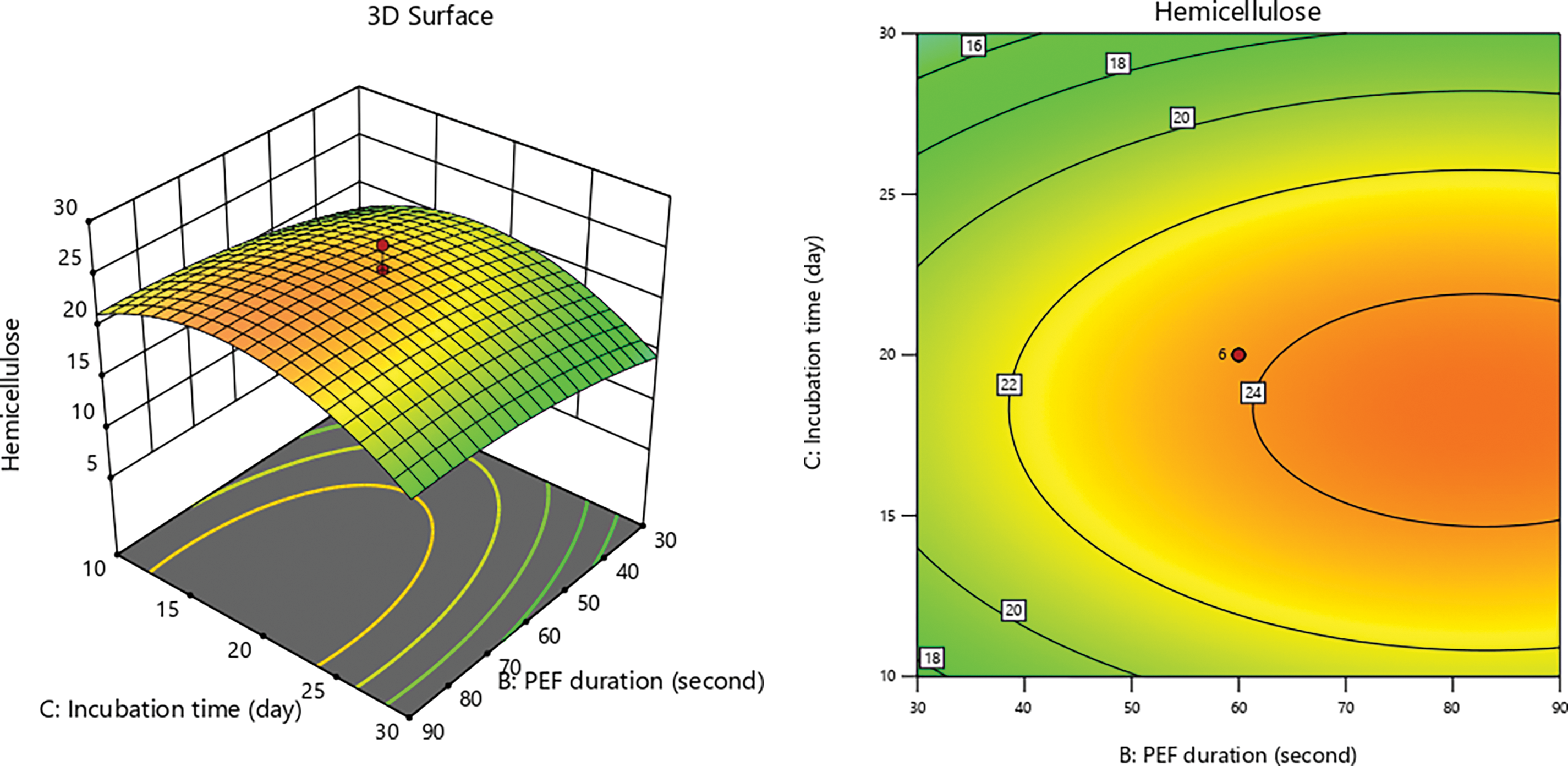

Electroporation induced by PEF occurs when biomass is subjected to high-voltage pulses, resulting in an increase in transmembrane potential that leads to the formation of pores in the cell membrane [19,75]. These pores facilitate the entry of molecules into the cell, facilitating the disintegration of cell wall and extraction of cellular components [76]. Additionally, electroporation can alter cellular structure and enhance membrane permeability, which supports the breakdown and conversion of lignocellulosic biomass [77,78]. Fig. 4 illustrates that the PEF contact time and substrate size exhibits a direct proportionality in their effects until optimal conditions are achieved. The test results indicate a consistent trend corresponding to the hemicellulose content produced.

Figure 4: 3D graphs of hemicellulose content due to PEF duration with substrate size

SSF, serving a secondary pretreatment step following PEF, employs P. ostreatus, which effectively disrupts the lignin-hemicellulose matrix through its lignin-degrading activity. Enzymes such as LiP and MnP produced by P. ostreatus generate reactive free radicals that contribute to the degradation of lignin’s structure. These lignin bonds, both aryl and aliphatic, are further cleaved into simpler molecules, such as phenols and organic acids, by LiP and laccase, produced by P. ostreatus, thereby enhancing hemicellulose accessibility [27,63,80].

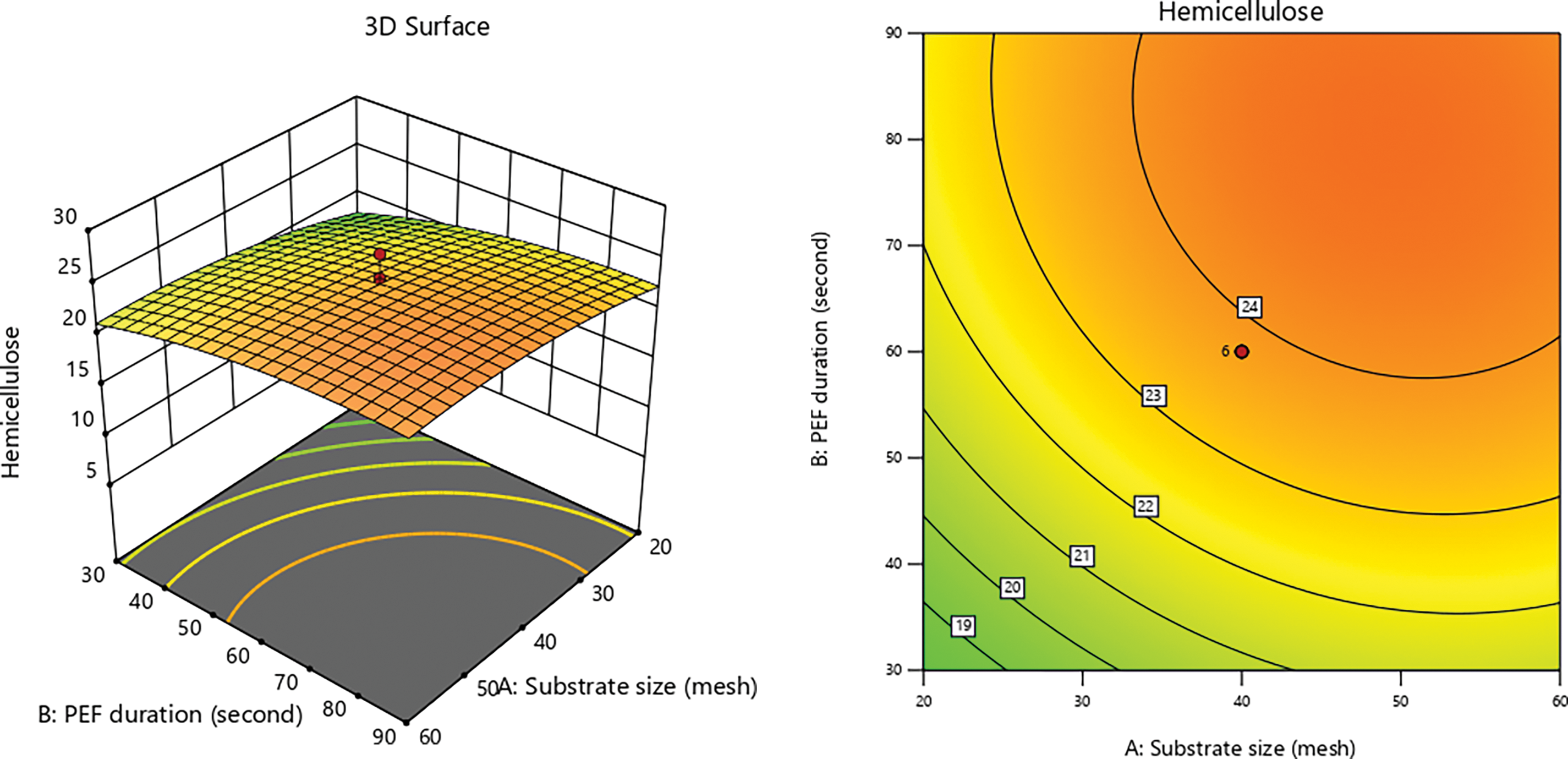

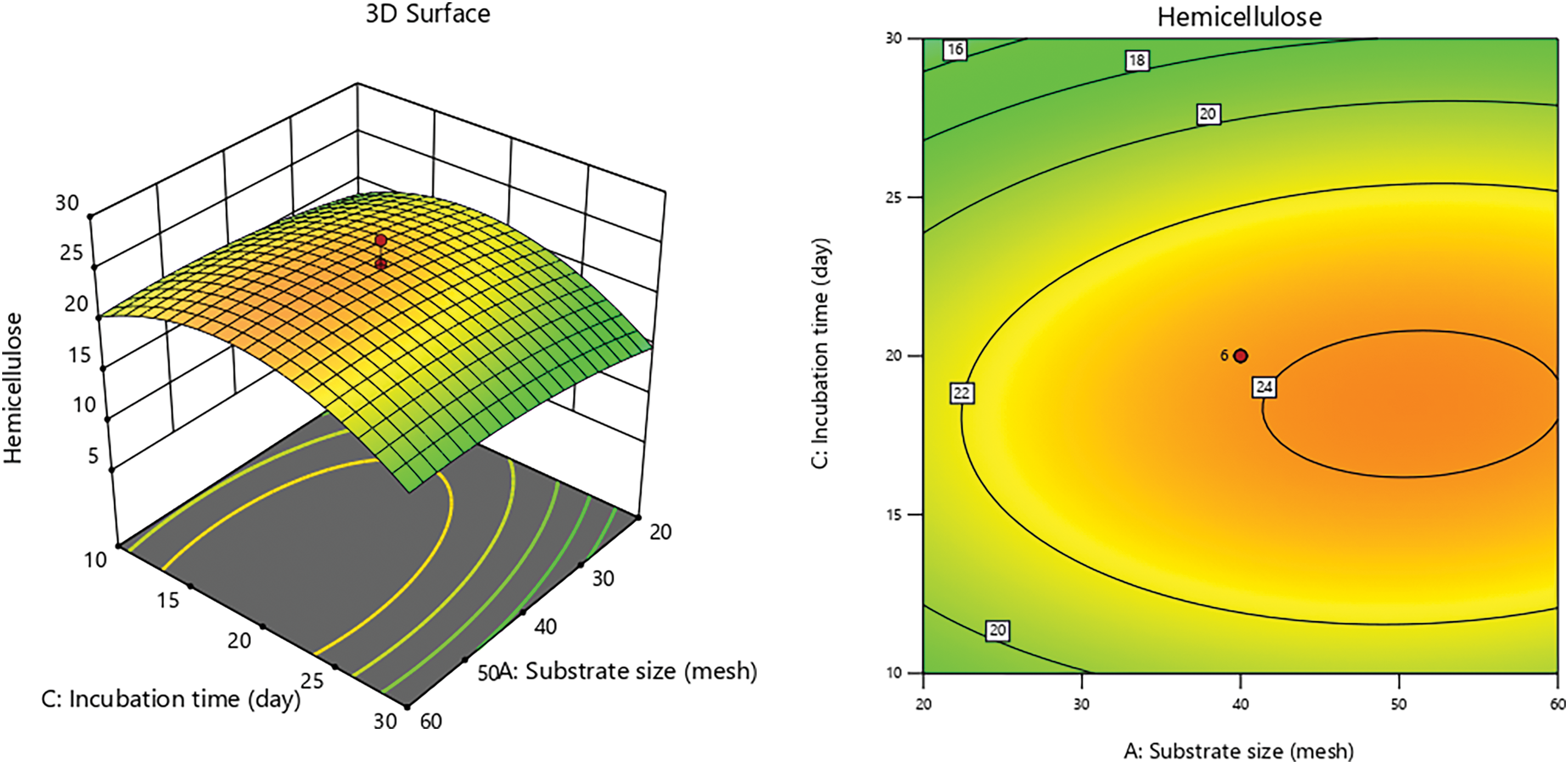

Figs. 5 and 6 reveal a fluctuating pattern of hemicellulose content, with decreases observed over ptolonged incubation periods. As incubation progresses, the metabolic activity of P. ostreatus increases, elevating its carbon demand. Sugars like glucose and xylose become essential carbon sources for the growth of P. ostreatus. Research by [81] highlights that P. ostreatus naturally synthesizes enzymes that decompose lignin and cellulose. Reference [70] added that the laccase activity from P. ostreatus transforms lignocellulosic components into low molecular weight, soluble molecules, which are then utilized for cell growth and the formation of fruiting bodies.

Figure 5: 3D graph of hemicellulose content due to incubation time with PEF duration

Figure 6: 3D graph of hemicellulose content due to incubation time with substrate size

Research reported by [82], describes lignin degradation process in P. ostreatus as occurring in three phases: the transfer of lignin fragments into hyphal cells, subsequent metabolism for ATP synthesis, and depolymerization facilitated by extracellular enzymes. Additionally, reference [70] states that P. ostreatus extensively utilizes xylose as a growth substrate.

Aligning with these findings, the increase in hemicellulose content during the vegetative phase reflects the fungus’s minimal utilization of carbon from hemicellulose at this stage. As reported by [70] xylanase activity remains low or is suppressed due to elevated laccase activity during the early vegetative phase. Reference [83] further explains that day 15 of incubation marks a peak in nutrient absorption, at which point xylanase activity experiences an increases.

Lignin, an integral component plant cell walls, is highly robust and resistant to both biotic and abiotic degradation. It provides structural support and protection to cellulose and hemicellulose. Within lignocellulosic compounds, lignin acts as a binding matrix that unites cellulose and hemicellulose into a cohesive unit, contributing to strength of plant cell walls [70]. Structurally, lignin is a branched polymer composed of monomers, dimeric, and alkyl-aryl ether-bonded oligomeric phenylpropane units [68,84]. It include various functional groups, including methoxy, hydroxyl, carbonyl, and carboxyl, comprising approximately 15%–40% of the dry biomass weight in plant cell walls [54].

By generating ligninolytic enzymes, P. ostreatus demonstrates an effective capacity to eliminate aromatic chemicals and break down both organic and inorganic pollutants. Several key enzymes are involved in lignin breakdown within lignocellulosic substrates [83]. Following pretreatment with PEF, the increased porosity in cell membranes of CD enhance the accessibility of extracellular ligninolytic enzymes produced by P. ostreatus, thus facilitating lignin degradation [85]. The enzyme-mediated degradation occurs in several steps: (1) LiP modifies chemical bonds in lignin alongside oxygen molecules, oxidizing functional groups on lignin’s side chains to disrupt complex bonds; (2) MnP acts synergistically with LiP to oxidize phenolic compounds, accelerating degradation by reducing free radicals generated during the process; (3) laccase oxidazes both phenolic and non-phenolic lignin compounds by producing free radicals, which aid in breaking down the complex lignin linkages [22,68,85]. Notably, laccase enzymes, primarily produced by fungi such as P. ostreatus, are pivotal for lignin degradation and precede the hydrolysis of cellulose and hemicellulose [70].

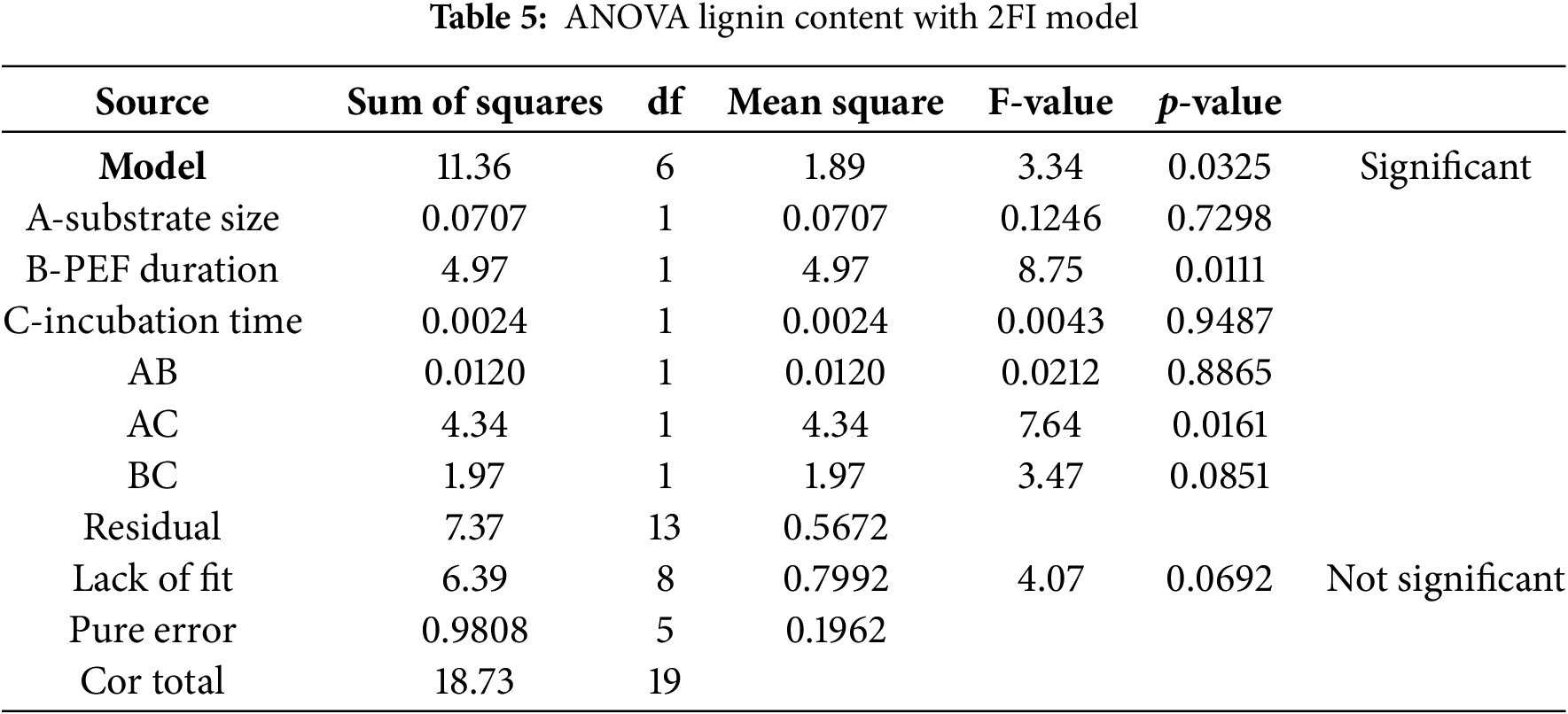

The degradation of lignin occurs in two distinct phases: (I) non-specific extracellular depolymerization into aryl and bi-aryl compounds, and (II) mineralization by specific catabolic enzymes. Aerobic Basidiomycota fungi, including P. ostreatus, can fully mineralize lignin into CO2 and H2O [68,85]. P. ostreatus strains demonstrate efficient lignin degradation, with significant activity observed by the 15th days of incubation [85]. The pretreatment method employed in this study effectively reduced lignin content, asconfirmed by statistical analysis and Eq. (8), with ANOVA 2FI model (Table 5).

This indicates a successful delignification process, facilitating the release of hemicellulose and cellulose from CD. Due to their robust hydrolytic and oxidative enzyme systems, white-rot fungi such as P. ostreatus are well-known for their effective lignin breakdown, making them highly valuable for biorefinery applications [86]. Key enzymes driving this process include LiP, MnP, versatile peroxidase (VP), and laccase. These enzymes become most active during the vegetative phase, initiating the initial steps of lignin degradation [26].

The LiP enzyme also oxidizes non-phenolic aromatic compounds, while VPs, a hybrid of LiP and MnP oxidizes both non-phenolic and phenolic substances [60]. These oxidative enzymes generally exhibit peak effectiveness after 10th days of incubation, aligning with the vegetative phase preceding fruiting body formation. In studies using sawdust without PEF pretreatment, P. ostreatus maintains laccase activity for up to 35th days post-incubation [70] MnP oxidizes Mn2+ to Mn3+ using H2O2, while laccase, a copper-containing polyphenol oxidase, catalyzes the transformation of phenolic substrates into phenoxy radicals. In addition, to producing extracellular lignocellulolytic enzymes, P. ostreatus also generates enzymes that produce H2O2, including glyoxal oxidase, and phenol oxidase [60].

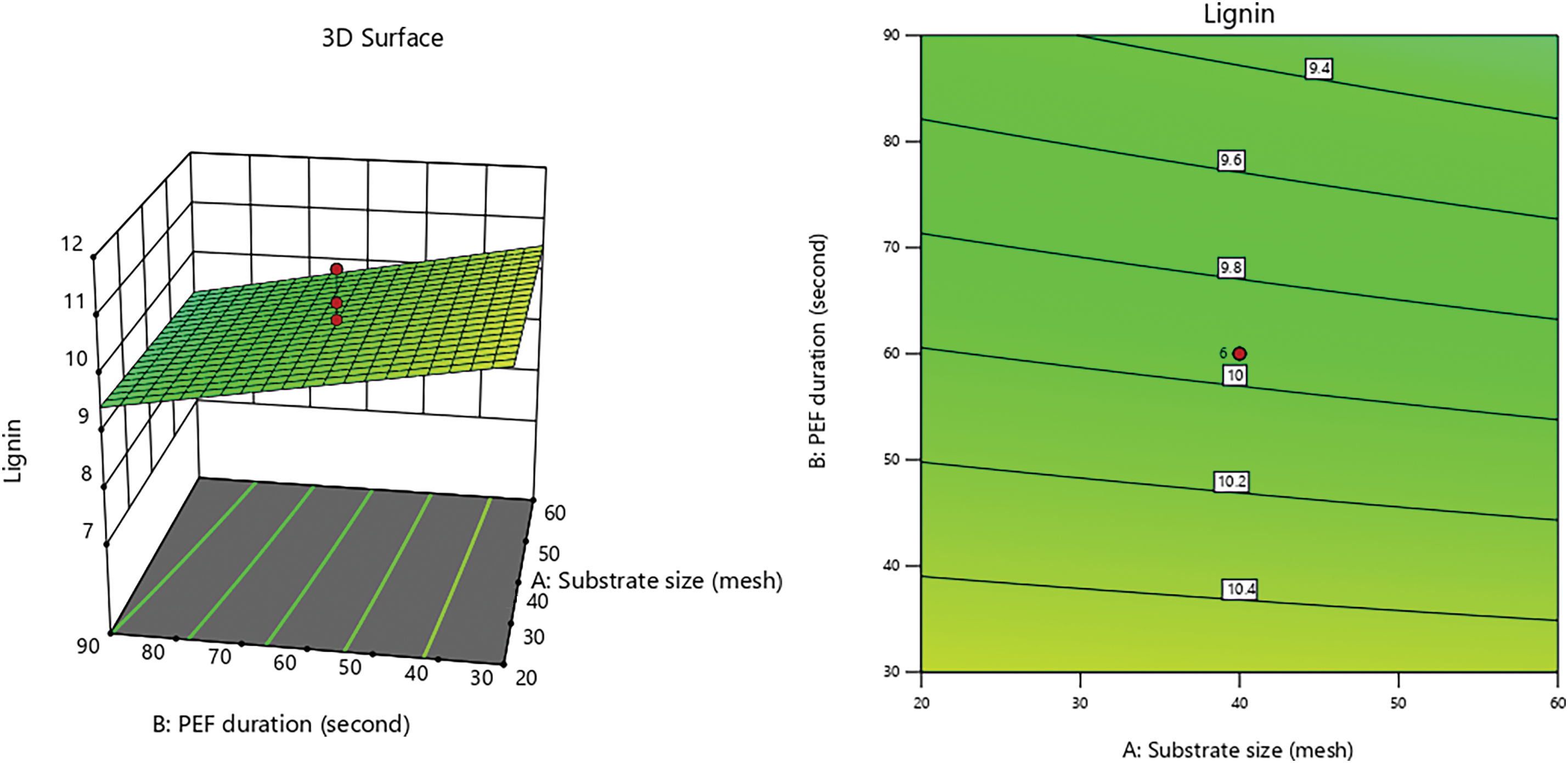

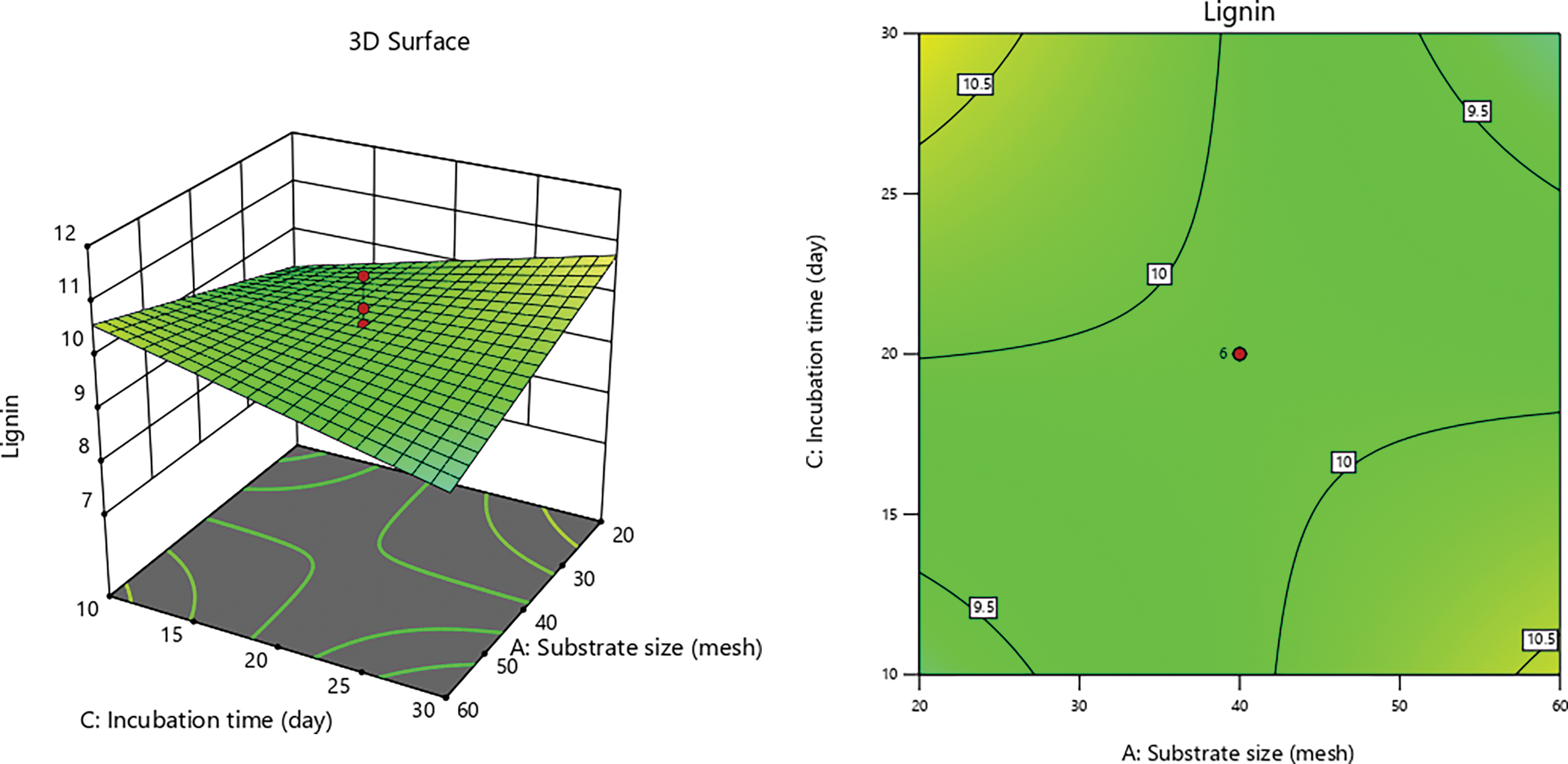

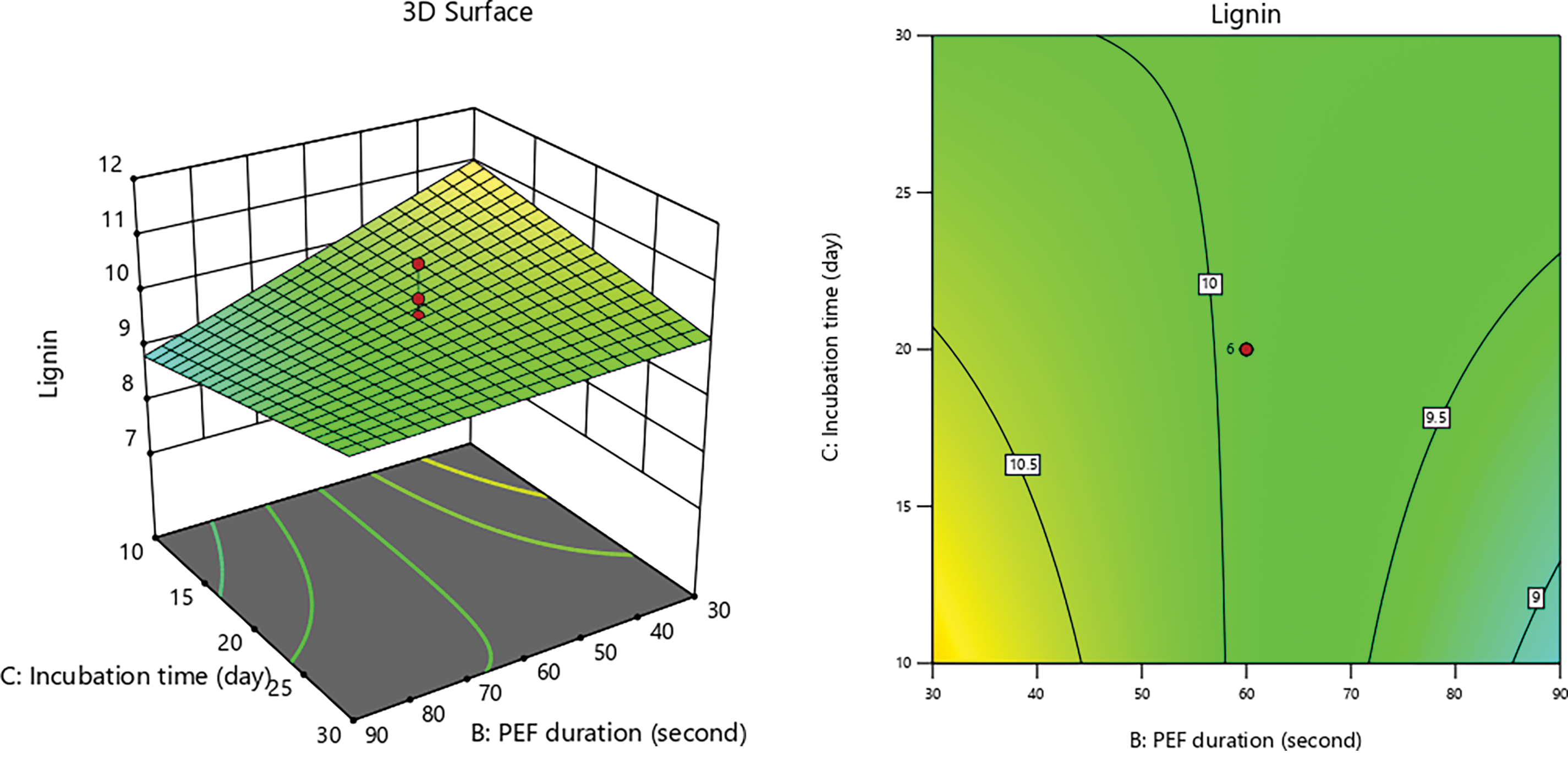

Figs. 7–9 illustrate interaction graphs of incubation time with substrate size and PEF contact time, demonstrate a significant effect in reducing lignin content. Smaller CD substrate sizes lead to increased pore formation due to the impact PEF’s, as smaller particles with larger surface areas are more susceptible to electroporation effects [79]. This enables even distribution of electrical energy applied to the CD, creating uniform pores and enhancing delignification by white-rot fungi [87,88].

Figure 7: 3D graph of lignin content influenced by PEF duration with substrate size

Figure 8: 3D graph of lignin content influenced by incubation time with substrate size

Figure 9: 3D graph of lignin content influenced by incubation time with PEF duration

Extended incubation further amplifies lignin reduction, studies on corn stalk degradation by white-rot fungi indicate a continuous decrease in lignin content up to 30 days of incubation, coresponding with high production of ligninolytic enzyme (laccase, MnP, and LiP) during the vegetative phase (13). In this study, the expansion and lignin-degrading activity of P. ostreatus in CD medium were also augmented by prolonged PEF contact duration.

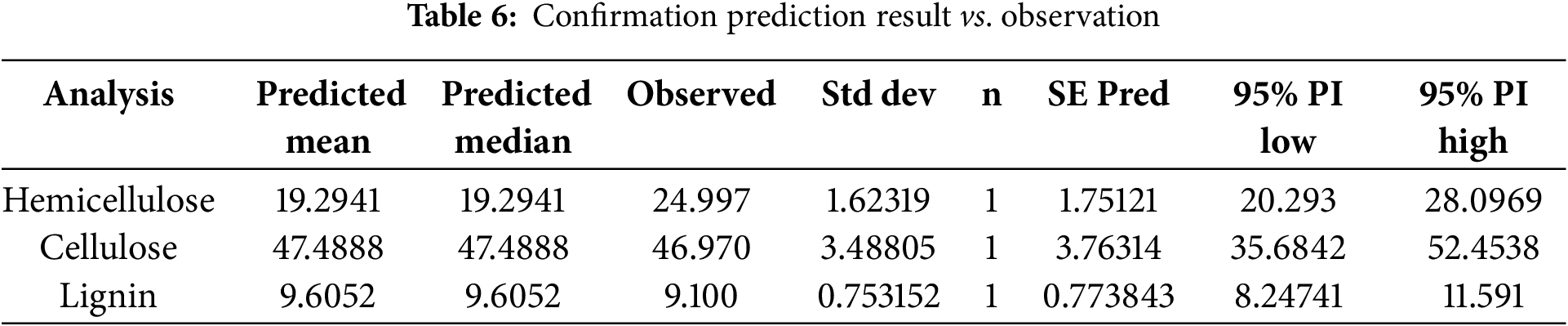

3.2 Confirmation of Recommendation Results

For CD pretreatment, the Response Surface Methodology (RSM) suggests that the substrate size be 45.20 mesh (around 40 mesh), the PEF contact time be 60.90 s, and the incubation period be 12.5 days. Under these recommended conditions, experiments yielded a hemicellulose content of 24.997%, cellulose content of 46.970%, and lignin content of 9.100%, presented in Table 6.

The decrease in lignin concentration indicates that pretreatment process successfully achieved delignification, which in turn allowed for rupture of lignin walls and a reduction in cellulose crystallinity, thereby enhancing the accessibility of hemicellulose. Delignification disrupts the ester bonds between lignin and hemicellulose due to ligninolytic enzymes produced by P. ostreatus [89]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that this process modifies the chemical structure of hemicellulose by removing acetyl groups, further improving the availability of the hemicellulose fraction [90,91].

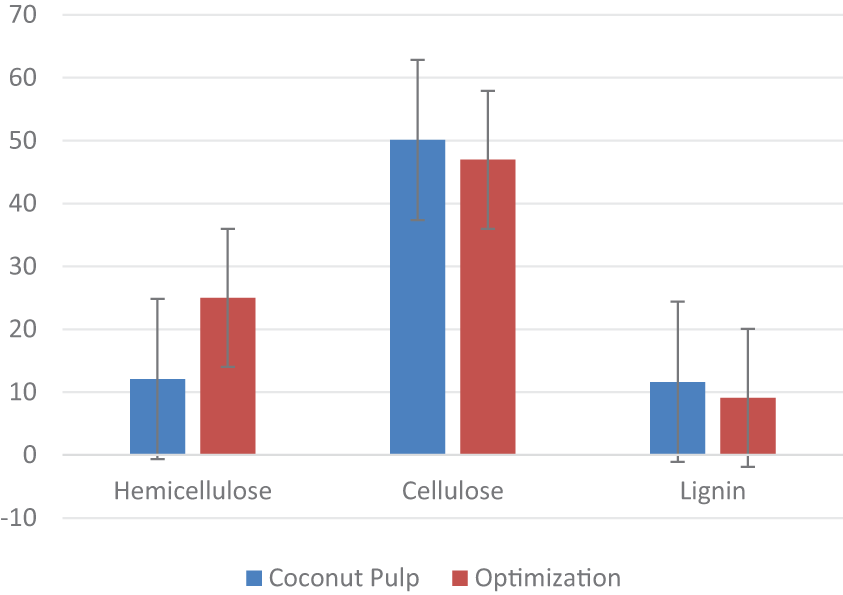

As previously discussed, the reduction in the size of CD particles utilized in this study significantly influences the formation of pores, particularly with extended PEF contact time. The electroporation effect is more pronounced when a larger cell surface area is achieved through a smaller biomass particles size [79]. Reduced particles sizes allow for a more uniform distribution of the applied electrical energy, leading to more homogeneous pore formation. Consequently, decreasing particle size increase the surface area of the cells, which facilitates the enzymatic process and the subsequent release of hemicellulose [92]. Describing the application of physical pretreatment methods, such as mechanical size reduction through ball milling, has proven efficient in enhancing the hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass. In this context, coupling the conditions of CD with bio-delignification using P. ostreatus improves the efficiency of ligninolytic enzymes activity in remodeling the lignin structure within CD [87,88]. These optimal conditions demonstrate effective degradation of lignocellulose component, resulting in increased availability of hemicellulose, which can subsequently be hydrolyzed to produce fermentable sugars for conversion into products such as biofuels. A comparison of lignocellulosic content in CD before and after initial treatment is illustrated in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Optimized levels of lignocellulose components in CDR vs. after pretreatment

The combined pretreatment of PEF and SSF using P. ostreatus on CD has led to a significant enhancement in hemicellulose solubility, with an increase of 106.53%. Furthermore, this method resulted in a 6.28% reduction in cellulose content and achieved a 21.78% lignin removal through delignification. These results indicate strong potential for converting hemicellulose and its derivative sugars into high-value products, particularly those resulting from sugar hydrolysis. The factors optimized through RSM, specifically a PEF contact time of 61 s, a substrate size of 45 mesh, and an incubation period of 12.5 days—have demonstrated their efficacy in these applications.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to coconut milk entrepreneurs in the city of Padang, West Sumatra, Indonesia, who contributed to the availability of coconut dregs raw materials. And thanks also to white oyster mushroom farmers in Malang City, East Java, Indonesia for cooperation in mushroom cultivation.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by BIMA from Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology, grant number 045/E5/PG.02.00.PL/2024, with derivative contracts 00309.54/UN10.A0501/BT.01.03.2/2024.

Author Contributions: Wenny Surya Murtius: data collection; Wenny Surya Murtius, Bambang Dwi Argo, Irnia Nurika, Sukardi: analysis and interpretation of results; Wenny Surya Murtius, Bambang Dwi Argo, Irnia Nurika, Sukardi: draft manuscript preparation. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Upon request, the corresponding author will make the datasets created during the current study available.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| RSM | Response surface methodology |

| CCD | Central composite design |

| PEF | Pulsed electric fields |

| SSF | Solid substrate fermentation |

| CD | Coconut dregs |

| LiP | Lignin peroxidase |

| MnP | Mangan peroxidase |

| VP | Versatile peroxidase |

| Mn | Mangan |

References

1. Machado G, Leon S, Santos F, Lourega R, Dullius J, Mollmann ME, et al. Literature review on furfural production from lignocellulosic biomass. Nat Resour. 2016;7(3):115–29. doi:10.4236/nr.2016.73012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Awogbemi O, Kallon. Valorization of agricultural wastes for biofuel applications. Heliyon. 2022 Oct;8(10):e11117. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e11117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Murtius WS, Argo BD, Nurika I, Sukardi. Identification of availability and lignocellulosic properties in coconut dregs waste. J Appl Agric Sci Technol. 2024;8(1):92–105. doi:10.55043/jaast.v8i1.248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Leesing R, Somdee T, Siwina S, Ngernyen Y, Fiala K. Production of 2G and 3G biodiesel, yeast oil, and sulfonated carbon catalyst from waste coconut meal: an integrated cascade biorefinery approach. Renew Energy. 2022 Nov 1;199:1093–104. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.09.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mariano APB, Unpaprom Y, Ramaraj R. Hydrothermal pretreatment and acid hydrolysis of coconut pulp residue for fermentable sugar production. Food Bioprod Process. 2020 Jul 1;122:31–40. doi:10.1016/j.fbp.2020.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Gonçalves FA, Ruiz HA, Silvino dos Santos E, Teixeira JA, de Macedo GR. Bioethanol production by Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia stipitis and Zymomonas mobilis from delignified coconut fibre mature and lignin extraction according to biorefinery concept. Renew Energy. 2016 Aug 1;94:353–65. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2016.03.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Bhandari PS, Makwana BP, Gogate PR. Microwave and ultrasound assisted dual oxidant based degradation of sodium dodecyl sulfate: efficacy of irradiation approaches and oxidants. J Water Process Eng. 2020;36:101316. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Huang C, Liu J, Geng W, Tang W, Yong Q. A review of lignocellulosic biomass pretreatment technologies. Paper Biomater. 2021;6(3):61–76. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.136815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Lee T. Using CO2 as an oxidant in the catalytic pyrolysis of peat moss from the north polar region. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54(10):6329–43. doi:10.1021/acs.est.0c01862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Świątek K, Gaag S, Klier A, Kruse A, Sauer J, Steinbach D. Acid hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass: sugars and furfurals formation. Catalysts. 2020;10(4). doi:10.3390/catal10040437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gu H, An R, Bao J. Pretreatment refining leads to constant particle size distribution of lignocellulose biomass in enzymatic hydrolysis. Chem Eng J. 2018 Nov 15;352:198–205. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2018.06.145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Jamaldheen SB, Kurade MB, Basak B, Yoo CG, Oh KK, Jeon BH, et al. A review on physico-chemical delignification as a pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for enhanced bioconversion. Bioresour Technol. 2022 Feb 1;346:126591. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Kucharska K, Rybarczyk P, Hołowacz I, Łukajtis R. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic materials as substrates for fermentation processes. Molecules. 2018 Nov 10;23(11):2937. doi:10.3390/molecules23112937. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Xie X, Chen M, Tong W, Song K, Wang J, Wu S, et al. Comparative study of acid- and alkali-catalyzed 1,4-butanediol pretreatment for co-production of fermentable sugars and value-added lignin compounds. Biotechnol Biofuels Bioprod. 2023 Mar 28;16(1):52. doi:10.1186/s13068-023-02303-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Jing DR, Feng ZD, Jie YD, Qing QX. pH-responsive lignin-based magnetic nanoparticles for recovery of cellulase. Bioresour Technol. 2019 Dec 1;294:126591. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ovejero-Pérez A, Ayuso M, Rigual V, Domínguez JC, García J, Alonso MV, et al. Technoeconomic assessment of a biomass pretreatment + ionic liquid recovery process with aprotic and choline derived Ionic liquids. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2021 Jun 28;9(25):8467–76. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c01361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Jablonowski ND, Pauly M, Dama M. Microwave assisted pretreatment of Szarvasi (Agropyron elongatum) biomass to enhance enzymatic saccharification and direct glucose production. Front Plant Sci. 2022;12:1–12. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.767254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Bratishko V, Shulga S, Tigunova O, Achkevych O. Ultrasonic cavitation of lignocellulosic raw materials as effective method of preparation for butanol production. In: 22nd International Scientific Conference Engineering for Rural Development Proceedings; 2023; Latvia University of Life Sciences and Technologies, Faculty of Engineering. doi:10.22616/ERDev.2023.22.TF053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Sukardi S, Pranowo D, Safitri P. Modelling of pulsed electric field (PEF) pretreatment on fresh Moringa oleifera leaves extraction using response surface methodology (RSM). Industria: Jurnal Teknologi Dan Manajemen Agroindustri. 2022;11(2):101–6. doi:10.21776/ub.industria.2022.011.02.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Suryanto H, Fikri AA, Permanasari AA, Yanuhar U, Sukardi S. Pulsed electric field assisted extraction of cellulose from mendong fiber (Fimbristylis globulosa) and its characterization. J Nat Fibers. 2018 May 4;15(3):406–15. doi:10.1080/15440478.2017.1330722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Murtius WS, Argo BD, Nurika I, Sukardi. A study of porosity, crystallinity index, and functional group of coconut dreg by pulsed electric fields duration of contact effect. Kexue Tongbao/Chin Sci Bul. 2024;69(2):1127–39. doi:10.1016/j.idairyj.2010.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Nakazawa T. A molecular genetics approach to elucidating the mechanisms underlying lignin degradation by white-rot fungi. Lignin. 2023 Aug 1;4(0):1–9. doi:10.62840/lignin.4.0_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mutrakulcharoen P, Pornwongthong P, Anne Sahithi ST, Phusantisampan T, Tawai A, Sriariyanun M. Improvement of potassium permanganate pretreatment by enzymatic saccharification of rice straw for production of biofuels. E3S Web Conf. 2021 Sep 10;302:02013. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202130202013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wagner AO, Lackner N, Mutschlechner M, Prem EM, Markt R, Illmer P. Biological pretreatment strategies for second-generation lignocellulosic resources to enhance biogas production. Energies. 2018 Jul 9;11(7):1797. doi:10.3390/en11071797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Baruah J, Nath BK, Sharma R, Kumar S, Deka RC, Baruah DC, et al. Recent trends in the pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for value-added products. Front Energy Res. 2018 Dec 18;6:141. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2018.00141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Nurika I, Shabrina EN, Azizah N, Suhartini S, Bugg TDHH, Barker GC. Application of ligninolytic bacteria to the enhancement of lignocellulose breakdown and methane production from oil palm empty fruit bunches (OPEFB). Bioresour Technol. 2022 Feb 1;17:100951. doi:10.1016/j.biteb.2022.100951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Sekan AS, Myronycheva OS, Karlsson O, Gryganskyi AP, Blume YB. Green potential of Pleurotus spp. in biotechnology. PeerJ. 2019 Mar 29;7:e6664. doi:10.7717/peerj.6664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wu Z, Peng K, Zhang Y, Wang M, Yong C, Chen L, et al. Lignocellulose dissociation with biological pretreatment towards the biochemical platform: a review. Mater Today Bio. 2022 Dec;16:100445. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Sharma S, Tsai ML, Sharma V, Sun PP, Nargotra P, Bajaj BK, et al. Environment friendly pretreatment approaches for the bioconversion of lignocellulosic biomass into biofuels and value-added products. Environments. 2023 Jan 1;10(1):6. doi:10.3390/environments10010006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Vu VNH, Kohári-Farkas C, Filep R, Laszlovszky G, Ban MT, Bujna E, et al. Design and construction of artificial microbial consortia to enhance lignocellulosic biomass degradation. Biofuel Res J. 2023 Sep 1;10(3):1890–900. doi:10.18331/BRJ2023.10.3.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Santana JC, Silva ACM, Abud AKS. Pretreatment and enzymatic saccharification of water hyacinth, sugarcane bagasse, maize straw, and green coconut shell using an organosolv method with glycerol. J Braz Chem Soc. 2022;33(9):1117–33. doi:10.21577/0103-5053.20220032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Panakkal EJ, Cheenkachorn K, Chuetor S, Tantayotai P, Raina N, Cheng YS, et al. Optimization of deep eutectic solvent pretreatment for bioethanol production from Napier grass. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2022;54:102856. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2022.102856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Phuttaro C. Anaerobic digestion of hydrothermally-pretreated lignocellulosic biomass: influence of pretreatment temperatures, inhibitors and soluble organics on methane yield. Bioresour Technol. 2019;284:128–38. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2019.03.114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Singh RD, Bhuyan K, Banerjee J, Muir J, Arora A. Hydrothermal and microwave assisted alkali pretreatment for fractionation of arecanut husk. Ind Crops Prod. 2017;102:65–74. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.03.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Xu C, Ma F, Zhang X, Chen S. Biological pretreatment of corn stover by irpex lacteus for enzymatic hydrolysis. J Agric Food Chem. 2010 Oct 27;58(20):10893–8. doi:10.1021/jf1021187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Kamdem I, Jacquet N, Tiappi FM, Hiligsmann S, Vanderghem C, Richel A, et al. Comparative biochemical analysis after steam pretreatment of lignocellulosic agricultural waste biomass from Williams Cavendish banana plant (Triploid Musa AAA group). Waste Manage Res. 2015;33:1022–32. doi:10.1177/0734242X15597998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Yang X, Zheng A, Zhao Z, Wang Q, Wang C, Liu S, et al. External fields enhanced glycerol pretreatment of forestry waste for producing value-added pyrolytic chemicals. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;168:113603. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Byun J, Cha YL, Park SM, Kim KS, Lee JE, Kang YG. Lignocellulose pretreatment combining continuous alkaline single-screw extrusion and ultrasonication to enhance biosugar production. Energies. 2020 Oct 28;13(21):5636. doi:10.3390/en13215636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ismail KSK, Matano Y, Sakihama Y, Inokuma K, Nambu Y, Hasunuma T, et al. Pretreatment of extruded Napier grass by hydrothermal process with dilute sulfuric acid and fermentation using a cellulose-hydrolyzing and xylose-assimilating yeast for ethanol production. Bioresour Technol. 2022 Jan 1;343. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Hou XD, Li N, Zong MH. Facile and simple pretreatment of sugar cane bagasse without size reduction using renewable ionic liquidswater mixtures. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2013 May 6;1(5):519–26. doi:10.1021/sc300172v. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Shangdiar S, Lin YC, Ponnusamy VK, Wu TY, Fia AZ, Amorim J, et al. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass from sugar bagasse under microwave assisted dilute acid hydrolysis for biobutanol production. Bioresour Technol. 2023;361(23):101146. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Sjulander N, Kikas T. Two-step pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass for high-sugar recovery from the structural plant polymers cellulose and hemicellulose. Energies. 2022;15(23):8898. doi:10.3390/en15238898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Toscan A, Morais ARC, Paixão SM, Alves L, Andreaus J, Camassola M, et al. High-pressure carbon dioxide/water pre-treatment of sugarcane bagasse and elephant grass: assessment of the effect of biomass composition on process efficiency. Bioresour Technol. 2017 Jan 1;224:639–47. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2016.11.101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Meenakshisundaram S, Fayeulle A, Léonard E, Ceballos C, Liu X, Pauss A. Combined biological and chemical/physicochemical pretreatment methods of lignocellulosic biomass for bioethanol and biomethane energy production—a review. Appl Microbiol. 2022 Sep 30;2(4):716–34. doi:10.3390/applmicrobiol2040055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Kisielewska M, Rusanowska P, Dudek M, Nowicka A, Krzywik A, Dębowski M, et al. Evaluation of ultrasound pretreatment for enhanced anaerobic digestion of Sida hermaphrodita. Bioenergy Res. 2020 Sep 1;13(3):824–32. doi:10.1007/s12155-020-10108-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Szwarc D, Nowicka A, Zieliński M. Comparison of the effects of pulsed electric field disintegration and ultrasound treatment on the efficiency of biogas production from chicken manure. Appl Sci. 2023 Jul 1;13(14):8154. doi:10.3390/app13148154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wang W, Ling H, Zhao H. Steam explosion pretreatment of corn straw on xylose recovery and xylitol production using hydrolysate without detoxification. Process Biochem. 2015 Oct 1;50(10):1623–8. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2015.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Sar T, Arifa VH, Hilmy MR, Ferreira JA, Wikandari R, Millati R, et al. Organosolv pretreatment of oat husk using oxalic acid as an alternative organic acid and its potential applications in biorefinery. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2022;1–10. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-02408-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Sipponen MH, Österberg M. Aqueous ammonia pre-treatment of wheat straw: process optimization and broad spectrum dye adsorption on nitrogen-containing lignin. Front Chem. 2019 Aug 2;7:545. doi:10.3389/fchem.2019.00545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Ali SS, Mustafa AM, Kornaros M, Manni A, Sun J, Khalil MA. Construction of novel microbial consortia CS-5 and BC-4 valued for the degradation of catalpa sawdust and chlorophenols simultaneously with enhancing methane production. Bioresour Technol. 2020;301:122720. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2019.122720. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. de Souza L, Manasa Y, Shivakumar S. Bioconversion of lignocellulosic substrates for the production of polyhydroxyalkanoates. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020 Sep 1;28:101754. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Mustafa G, Arshad M, Bano I, Abbas M. Biotechnological applications of sugarcane bagasse and sugar beet molasses. In: Biomass conversion and biorefinery. Springer Science and Business Media Deutschland GmbH; 2023. Vol. 13, p. 1489–501. doi:10.1007/s13399-020-01141-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Ahmed El-Imam A, Akoh P, Saliman S, Ighalo E. Mushroom-mediated delignification of agricultural wastes for bio-ethanol production. Niger J Biotechnol. 2021 Jul 28;38(1):137–45. doi:10.4314/njb.v38i1.16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Siddique M, Soomro SA, Aziz S. Characterization and optimization of lignin extraction from lignocellulosic biomass via green nanocatalyst. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2022;1–9. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-03598-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Murtius WS, Argo BD, Nurika I, Sukardi. Pretreatment; langkah penting peningkatan efisiensi konversi lignoselulosa. 1st ed. HeiPublishing; 2024 (In Indonesian) [cited 2024 Nov 20]. Available from: https://heipublishing.id/product/pretreatment-langkahpenting-peningkatan-efisiensi-konversi-biomasa-lignoselulosa. [Google Scholar]

56. Jang SK, Jeong H, Choi IG. The effect of cellulose crystalline structure modification on glucose production from chemical-composition-controlled biomass. Sustainability. 2023 Apr 1;15(7):5869. doi:10.3390/su15075869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Almeida RLJ, Santos NC, Muniz CES, da Silva Eduardo R, de Almeida Silva R, Ribeiro CAC, et al. Red rice starch modification-combination of the non-thermal method with a pulsed electric field (PEF) and enzymatic method using α-amylase. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253:127030. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Sun K, Changyu L, Jiang J, Bu Q, Lin G, Lu X, et al. Microporous activated carbons from coconut shells produced by self-activation using the pyrolysis gases produced from them, that have an excellent electric double layer performance. New Carbon Mater. 2017 Oct;32(5):451–9. doi:10.1016/S1872-5805(17)60134-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Vydrina I, Malkov A, Vashukova K, Tyshkunova I, Mayer L, Faleva A, et al. A new method for determination of lignocellulose crystallinity from XRD data using NMR calibration. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2023 Jun 1;5:100305. doi:10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Li M, Marek SM, Peng J, Liu Z, Wilkins MR. Effect of moisture content and inoculum size on cell wall composition and ethanol yield from switchgrass after solid-state Pleurotus ostreatus treatment. Trans ASABE. 2018;61(6):1997–2006. doi:10.13031/trans.12981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Suhartini S, Rohma NA, Mardawati E, Kasbawati, Hidayat. Biorefining of oil palm empty fruit bunches for bioethanol and xylitol production in Indonesia: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2022;154:111817. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.111817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Xiao Q, Ma F, Li Y, Yu H, Li C, Zhang X. Differential proteomic profiles of Pleurotus ostreatus in response to lignocellulosic components provide insights into divergent adaptive mechanisms. Front Microbiol. 2017 Mar 23;8:480. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Xiao Q, Yu H, Zhang J, Li F, Li C, Zhang X, et al. The potential of cottonseed hull as biorefinery substrate after biopretreatment by Pleurotus ostreatus and the mechanism analysis based on comparative proteomics. Ind Crops Prod. 2019;130:151–61. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.12.057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Sufyan A, Ahmad N, Shahzad F, Embaby MG, AbuGhazaleh A, Khan NA. Improving the nutritional value and digestibility of wheat straw, rice straw, and corn cob through solid state fermentation using different Pleurotus species. J Sci Food Agric. 2022 Apr 26;102(6):2445–53. doi:10.1002/jsfa.11584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Nur YS, Djulardi A, Nuraini N. Response of laying quail to a diet enriched with cocoa pods fermented by Pleurotus ostreatus. J Worlds Poult Res. 2020 Mar 25;10(1):96–101. doi:10.36380/jwpr.2020.13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Waghmare PR, Khandare RV, Jeon BH, Govindwar SP. Enzymatic hydrolysis of biologically pretreated sorghum husk for bioethanol production. Biofuel Res J. 2018 Sep 1;5(3):846–53. doi:10.18331/BRJ2018.5.3.4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Halis R, Tan HR, Ashaari Z, Mohamed R. Biomodification of kenaf using white rot fungi. Bioresources. 2012 Jan 18;7(1):984–96. doi:10.15376/BIORES.7.1.0984-0996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Stefanović S, Maksimović JD, Maksimović V, Bartolić D, Djikanović D, Radosavljević JS, et al. Functional differentiation of two autochthonous cohabiting strains of Pleurotus ostreatus and Cyclocybe aegerita from Serbia in lignin compound degradation. Bot Serb. 2023;47(1):135–43. doi:10.2298/BOTSERB2301135S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Siddique M, Nawaz Mengal A, Khan S, Ali Khan L, Khan Kakar E. Pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass conversion into biofuel and biochemical: a comprehensive review. MOJ Biol Med. 2023;8(1):39–43. doi:10.15406/mojbm.2023.08.00181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Saskiawan I, Widhyastuti N, Kasirah, Sutardi. Pola aktivitas enzim lakase, selulase, dan xilanase pada masa pertumbuhan budidaya jamur tiram putih [Pleurotus ostreatus (Jacq.) P. Kumm.]. J Biologi Indones. 2021;17(2):145–51 (In Indonesian). doi:10.47349/jbi/17022021/145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Limbongan LY. The effect of reeds and washed rice water on the growth and production of white oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus). J World Sci. 2023 May 29;2(5):622–31. doi:10.58344/jws.v2i5.288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Hodijat A, Nurlina E. Optimal conditioning of growth media white oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) to increase productivity. R J Appl Res. 2023 Jun 22;9(6). doi:10.47191/rajar/v9i6.04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Pirah S, Wang X, Javed M, Simair K, Wang B, Sui X, et al. Lignocellulose extraction from sisal fiber and its use in green emulsions: a novel method. Polymers. 2022 Jun 1;14(11):2299. doi:10.3390/polym14112299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Bonakdar M, Graybill PM, Davalos RV. A microfluidic model of the blood-brain barrier to study permeabilization by pulsed electric fields. RSC Adv. 2017;7(68):42811–8. doi:10.1039/C7RA07603G. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Suchanek M, Olejniczak Z. Low field MRI study of the potato cell membrane electroporation by pulsed electric field. J Food Eng. 2018;231:54–60. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Zhang R, Gu X, Xu G, Fu X. Improving the lipid extraction yield from Chlorella based on the controllable electroporation of cell membrane by pulsed electric field. Bioresour Technol. 2021;330:124933. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.124933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Levkov K, Linzon Y, Mercadal B, Ivorra A, González CA, Golberg A. High-voltage pulsed electric field laboratory device with asymmetric voltage multiplier for marine macroalgae electroporation. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2020 Mar 1;60:102288. doi:10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Golberg A, Levkov K. System-based protection method for high-voltage pulse generator switching units in biomass electroporation. Open Res Eur. 2023 Oct 12;3:171. doi:10.12688/openreseurope.16465.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Moreno-Chocontá LN, Lozano-Pérez AS, Guerrero-Fajardo CA. Evaluation of the effect of particle size and biomass-to-water ratio on the hydrothermal carbonization of sugarcane bagasse. ChemEngineering. 2024 Apr 1;8(2):43. doi:10.20944/preprints202402.1121.v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Saha BC, Qureshi N, Kennedy GJ, Cotta MA. Biological pretreatment of corn stover with white-rot fungus for improved enzymatic hydrolysis. Int Biodeterior Biodegradation. 2016 Apr;109:29–35. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2015.12.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Dimawarnita F, Perwitasari U, Marsudi S, Faramitha. The utilization of oil palm empty fruit bunches for growth of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) and biodelignification process during planting cycle. Agrivita. 2022;44(1):165–77. doi:10.17503/agrivita.v44i1.2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Nakazawa T, Yamaguchi I, Zhang Y, Saka C, Wu H, Kayama K, et al. Experimental evidence that lignin-modifying enzymes are essential for degrading plant cell wall lignin by Pleurotus ostreatus using CRISPR/Cas9. Environ Microbiol. 2023 Oct 1;25(10):1909–24. doi:10.1111/1462-2920.16427. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Fiana RM, Murtius WS, Syukri D, Saskiawan I. Azo congo red dye decolorization by oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) F209. Asian J Plant Sci. 2023;22(3):452–7. doi:10.3923/ajps.2023.452.457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Pollegioni L, Tonin F, Rosini E. Lignin-degrading enzymes. FEBS J. 2015 Apr 1;282(7):1190–213. doi:10.1111/febs.13224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Li G, Wang Y, Zhu P, Zhao G, Liu C, Zhao H. Functional characterization of laccase isozyme (PoLcc1) from the edible mushroom Pleurotus ostreatus involved in lignin degradation in cotton straw. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Nov 1;23(21):13545. doi:10.3390/ijms232113545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Dashora K, Gattupalli M, Tripathi GD, Javed Z, Singh S, Tuohy M, et al. Fungal assisted valorization of polymeric lignin: mechanism, enzymes and perspectives. Catalysts. 2023;13(1):149. doi:10.3390/catal13010149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Hoang PH, Dat HT, Cuong TD. Pretreatment of coir lignocellulose for preparation of a porous coir-polyurethane composite with high oil adsorption capacity. RSC Adv. 2022;12(24):14976–85. doi:10.1039/D2RA01349E. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Zahra A, Lim SK, Shin SJ. Characterization of lignocellulose nanofibril from desilicated rice hull with carboxymethylation pretreatment. Polysaccharides. 2024 Mar 1;5(1):16–27. doi:10.3390/polysaccharides5010002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Sun SC, Sun D, Cao XF. Effect of integrated treatment on enhancing the enzymatic hydrolysis of cocksfoot grass and the structural characteristics of co-produced hemicelluloses. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2021 Dec 7;14(1):88. doi:10.1186/s13068-021-01944-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Megersa S, Feleke S. Enzymatic hydrolysis of two-way pretreated sawdust of Eucalyptus globulus and Cupressus lusitanica. Eur J Sustain Dev Res. 2019 Dec 7;4(1):em0110. doi:10.29333/ejosdr/6343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Trevorah RM, Othman MZ. Alkali pretreatment and enzymatic hydrolysis of Australian timber mill sawdust for biofuel production. J Renew Energy. 2015;2015:1–9. doi:10.1155/2015/284250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Zhang H, Zhang W, Wang S, Zhu Z, Dong H. Microbial composition play the leading role in volatile fatty acid production in the fermentation of different scale of corn stover with rumen fluid. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024 Jan 4;11:1275454. doi:10.3389/fbioe.2023.1275454. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools