Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

An Investigation into the Cationic Dye Adsorption Capacity of Prickly Pear Cactus-Derived Cellulose

Laboratory of Materials and Environment for Sustainable Development, LR18ES10, University of Tunis El Manar, 9, Avenue Dr. Zoheir Safi, Tunis, 1006, Tunisia

* Corresponding Author: Rached Ben Hassen. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Biobased Materials for Advanced Applications )

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(7), 1389-1411. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0022

Received 29 January 2025; Accepted 07 May 2025; Issue published 22 July 2025

Abstract

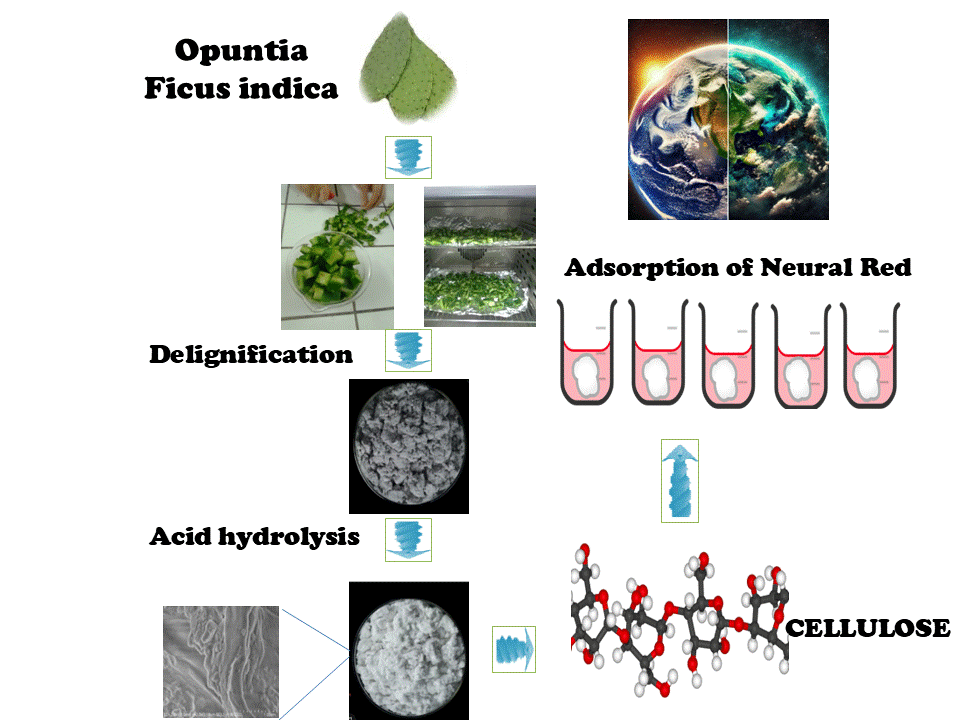

This research aims to investigate the potential of a plant cellulose developed from Opuntia ficus-indica (OFI) cladode as a sustainable and renewable adsorbent for the removal of neutral red (NR), a cationic dye pollutant, from aqueous environments. Analysis of raw and treated OFI using X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) demonstrated the successful extraction of type cellulose. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) analysis of the nitrogen adsorption-desorption isotherm revealed an improved specific surface area of 12.4 m2/g after treatment. A systematic study of key parameters in batch adsorption experiments revealed removal rates greater than 90% at pH = 3, an adsorbent dosage of 3 g/L and an initial dye concentration of 100 mg/L with equilibrium achieved within 2 h. The high correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.98) obtained with the Langmuir isotherm model suggests that the adsorption behavior is consistent with monolayer surface adsorption. A maximum adsorption capacity (Qm) of 357.1 mg/g for neutral red dye was achieved, demonstrating a significant adsorption capacity relative to other materials such as chitosan-modified activated carbon and halloysite nanotubes. The pseudo-second-order model effectively described the kinetics of the adsorption phenomena. Thermodynamic analysis revealed an exothermic and spontaneous adsorption process, with an enthalpy change (ΔH) of −24.886 kJ/mol, indicative of predominantly physisorption-driven interactions. Moreover, the regenerated cellulose exhibited a retention of over 70% efficiency after multiple adsorption-desorption cycles, highlighting its potential as an excellent reusable adsorbent. The outcomes of this research present an environmentally conscious alternative to synthetic adsorbents, facilitating the effective NR dye removal through renewable and sustainable means.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The rapid pace of industrialization and population growth has exacerbated water pollution, particularly in textile, food processing, cosmetics, printing, and paper manufacturing [1,2]. In developing countries, where persistent organic pollutants (POPs) with synthetic dyes a particularly prevalent and hazardous class of contaminants [3,4] pose a major challenge in wastewater treatment [5]. Their extensive use, coupled with their high stability due to complex aromatic structures, renders them resistant to degradation by light, heat, and conventional oxidants, leading to their accumulation in aquatic ecosystems. This persistence poses significant risks to human health, as exposure to organic dyes has been linked to immunotoxicity, carcinogenicity, and chronic diseases. Therefore, for environmental protection, it is paramount to develop effective techniques for pre-discharge dye removal from wastewater [6]. Several techniques have been investigated for dye removal, including coagulation-flocculation [7], adsorption, ion exchange, oxidation and advanced oxidation [8], phytoremediation [9] as well as electrochemical [10] and photochemical degradation [11] and a variety of biological treatment methods, such as biodegradation [12], constructed wetlands, and aerobic/anaerobic processes [13]. Among these, adsorption [14–18] has become a prominent technique for water purification, especially in resource-constrained environments, owing to its operational simplicity, economic feasibility, and demonstrated high removal efficiencies for various contaminants [19,20]. The efficacy of adsorption hinges significantly on the physicochemical properties of the chosen adsorbent. Numerous materials have been investigated, including activated carbon [21], zeolites [22], carbon nanotubes [23], and cellulose-based materials [24]. Among these, Cellulose-based adsorbents, in particular, have gained significant attention due to their high surface area, hydroxyl groups containing, biodegradability, and modifiability, which allow for enhanced selectivity and adsorption capacity in wastewater treatment applications [25,26]. Optimizing an adsorption process requires not only selecting of an effective adsorbent but also ensuring a consistent and sustainable supply of the material. In response to the escalating environmental burden of dye pollution, research has intensified towards developing cost-effective and environmentally benign adsorbents derived from abundant agricultural waste streams, such as fruit tree pruning residue [27,28], sawdust [29], and cactus [30]. These readily available and inexpensive materials have exhibited promising adsorption performance in laboratory-scale studies for the remediation of colored effluents. In this context, the present study explores the development of sustainable adsorbents by investigating the activation of Opuntia ficus-indica (OFI) cladode powder. Various treatment methods, including acid activation as previously demonstrated by Djobbi et al. [31], were applied to enhance the adsorption performance of the material while simultaneously facilitating the extraction of plant-derived cellulose. The obtained results highlight the potential-added value of the use of OFI, an abundant agricultural byproduct. Due to its biodegradability, low extraction cost, and environmentally friendly properties, OFI-based adsorbents represent a promising alternative for sustainable water treatment, with potential applications across environmental remediation and biotechnological fields [32–34].

This study aims to generate and optimize a plant cellulose extracted from Opuntia ficus-indica cladode powder (TCP) as a sustainable and efficient adsorbent for the removal of the cationic dye Neutral Red (NR) from aqueous solutions. While NR has been extensively studied using various adsorbents, its removal using cellulose-based materials remains largely unexplored, making this work a novel contribution to the field of dye adsorption. To achieve this, work TCP was synthesized through a simple chemical treatment process. Comprehensive physicochemical characterization of the material was conducted before and after treatment using X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) to assess structural and morphological modifications. A systematic study was conducted to evaluate the adsorption performance of TCP by investigating the influence of several key operational parameters, namely pH solution, adsorbent dosage, initial dye concentration, contact time, and temperature. Furthermore, adsorption kinetics, isotherm models, and thermodynamic parameters were analysed to elucidate the underlying adsorption mechanisms governing NR uptake.

Prickly pear cladodes, serving as the primary raw material, were sourced from Kasserine from the northeastern region of Tunisia. Chemical reagents utilized in the preparation and modification processes included: sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99% purity) for alkaline treatment; sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH) for bleaching; and hydrochloric acid (HCl, 37%) for acidic hydrolysis. The target adsorbate, Neutral Red dye (C.I. 50,040), was also employed. All chemicals were procured from reputable suppliers, System ChemAR and Sigma-Aldrich, and used as received without further purification.

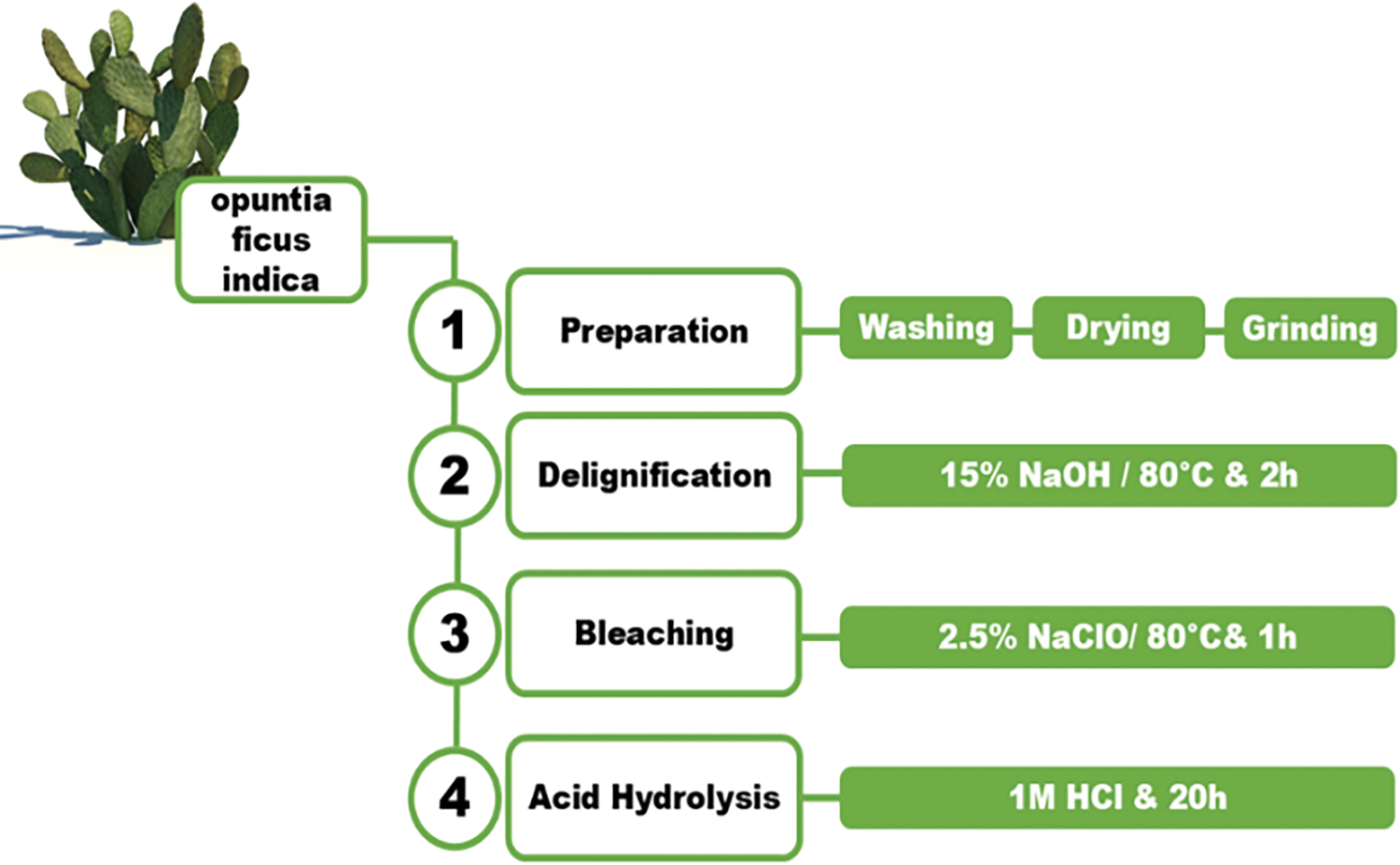

Prickly pear cladodes were harvested in June from northeastern Tunisia. To ensure the removal of any residual impurities, the cladodes were thoroughly washed with distilled water before being cut into 5 cm pieces. Subsequent low temperatures drying for 48 h prevented degradation and facilitated grinding to yielding the raw cladode powder (RCP) suitable for further processing. To obtain the bio-adsorbent, the raw material underwent three sequential processing steps following the protocol established by Mohamed et al. [35] with slight modifications (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: A simplified process flow diagram illustrating the isolation of TCP from OFI cladodes

To remove lignin, a complex polymer that hinders cellulose extraction, the raw cladode powder underwent alkaline treatment with 15% sodium hydroxide solution at 80°C for 2 h. To remove any residual chemicals and ensure neutrality, the mixture was filtered, and the residue was thoroughly washed with distilled water until the washings exhibited a neutral pH.

Following delignification, the residue was treated with 2.5% sodium hypochlorite solution and heated at 80°C for 1 h to further remove residual lignin and other impurities. Subsequent filtration and washing with distilled water ensured the removal of any remaining chemicals, preparing the sample for the next stage.

The bleached residue was treated with 1M hydrochloric acid solution for 20 h. This step primarily serves to dissolve whewellite, a (calcium oxalate crystal) commonly found in prickly pear cactus, which is soluble in acidic conditions. Following acid treatment, the mixture was filtered and washed to remove the HCl excess. The adsorbent, cellulose extract from Opuntia ficus-indica, was then dried, ground, and stored in a sealed container for further use with the name treated cladode powder (TCP).

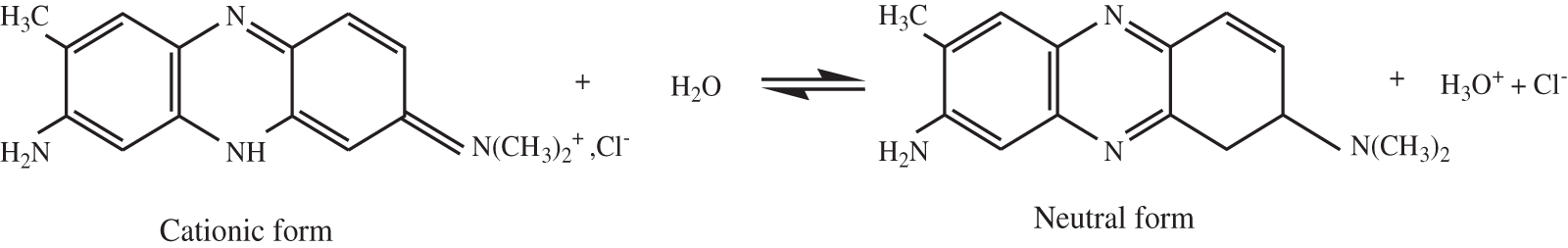

Neutral Red (C.I. 50,040), dye powder obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, was dissolved in deionized water to prepare a 1 g/L stock aqueous solution. To achieve the required concentrations for experiments, the stock solution was diluted appropriately using deionized water. Fig. 2 illustrates the dissociation equilibrium between the cationic and neutral forms of Neutral Red in aqueous solution.

Figure 2: Dissociation equilibrium between the cationic and neutral forms of neutral red in aqueous solution

2.4 Adsorbent Characterization

The crystalline characteristics of RCP and TCP were analyzed from X-ray patterns captured using X-ray Diffractometer PANalytical X’Pert Pro powder with Cu Kα radiation at 450 kV and 40 mA. XRD data were collected with a continuous scan mode over a 2θ range of 5–80° with a 0.028° step size and a 40-s step time. The crystallinity index (C.I.) was calculated based on the method described by Segal et al. [36] using the reflected intensity data, as shown in Eq. (1):

where:

• I002 is the peak intensity corresponding to the crystalline domain (2θ = 22.6°).

• Iam is the peak intensity corresponding to the amorphous domain (2θ = 19.0°).

Fourier Transform Infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to characterize the functional groups present in RCP and TCP samples. FTIR spectra were acquired using a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrometer (Billerica, MA, USA) in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 with a spectral resolution of 4.0 cm−1.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs of RCP and TCP were obtained using a Hitachi S-3400N SEM (UTT) operating at 30 kV under vacuum conditions. Prior to analysis, samples were mounted on metal stubs and sputter-coated with gold for 2 min using a Bio-Rad coater to enhance conductivity.

The specific surface area of the materials was analyzed using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method, employing nitrogen (N2) adsorption at 77 K. These measurements were conducted with a Micromeritics ASAP 2020 sorptometer (USA).

Using laser Doppler electrophoresis (Malvern NanoZetasizer ZS) at 25°C, the zeta potential of 0.1% (w/v) aqueous sample of TCP was measured. Triplicate measurements were taken, and the average zeta potential is presented.

For the adsorption studies, 50 mL aliquots of the dye solution were placed in 150 mL Erlenmeyer flasks for batch experiments. To study the effect of adsorbent dose, the mass of TCP was varied while keeping the initial NR concentration constant at 100 mg/L and adjusting the pH as needed. The influence of initial dye concentration was determined by varying the initial NR concentration from 20 to 300 mg/L and maintaining a fixed TCP mass. Kinetic studies were carried out over a contact time range of 0 to 240 min. Thermodynamic studies were performed at temperatures ranging from 25 to 80°C. At specified durations, the mixture was centrifuged, then, the residual dye (NR) excess was quantified using a spectrophotometric method. All experiments were carried out in duplicate to enhance the reliability and reproducibility of the experimental data.

A calibration curve was constructed by measuring the absorbance of known NR concentrations at λmax (540 nm) with a Shimadzu UV-Vis spectrophotometer. The equilibrium dye uptake, qeq (mg·g−1) was calculated using Eq. (2):

in which C0 and Ce are the initial concentration and equilibrium concentration of the NR (mg·L−1), respectively, V is the volume of the dye solution (L) and m is the mass of TCP.

The removal efficiency adsorption of NR dye was determined using the Eq. (3) below:

in which C0 (mg·L−1) is the initial concentration of solutions and Ce (mg·L−1) is the final concentration after the corresponding reaction time.

2.6 Recyclability of Adsorbent and Desorption Studies

The reusability of the TCP adsorbent was evaluated through five consecutive cycles of dye (NR, 100 mg·L−¹) adsorption and desorption under optimized conditions. Following the procedure of Batool et al. [37], the adsorbent sample was filtered and cleaned with a 0.1 M HCl eluent for desorption after reaching adsorption equilibrium. After acid treatment, the adsorbent was thoroughly washed with deionized water (DI) to eliminate any residual acid before being directly reused in subsequent adsorption experiments. The residual dye concentration was determined after each adsorption step and the desorption efficiency was calculated using the Eq. (4):

in which Cad (mg·L−1) represents the dye concentration at time t during desorption, C0 (mg·L−1) is the initial dye concentration and Ce (mg·L−1) is the equilibrium dye concentration during adsorption.

3.1 Adsorbent Characterization

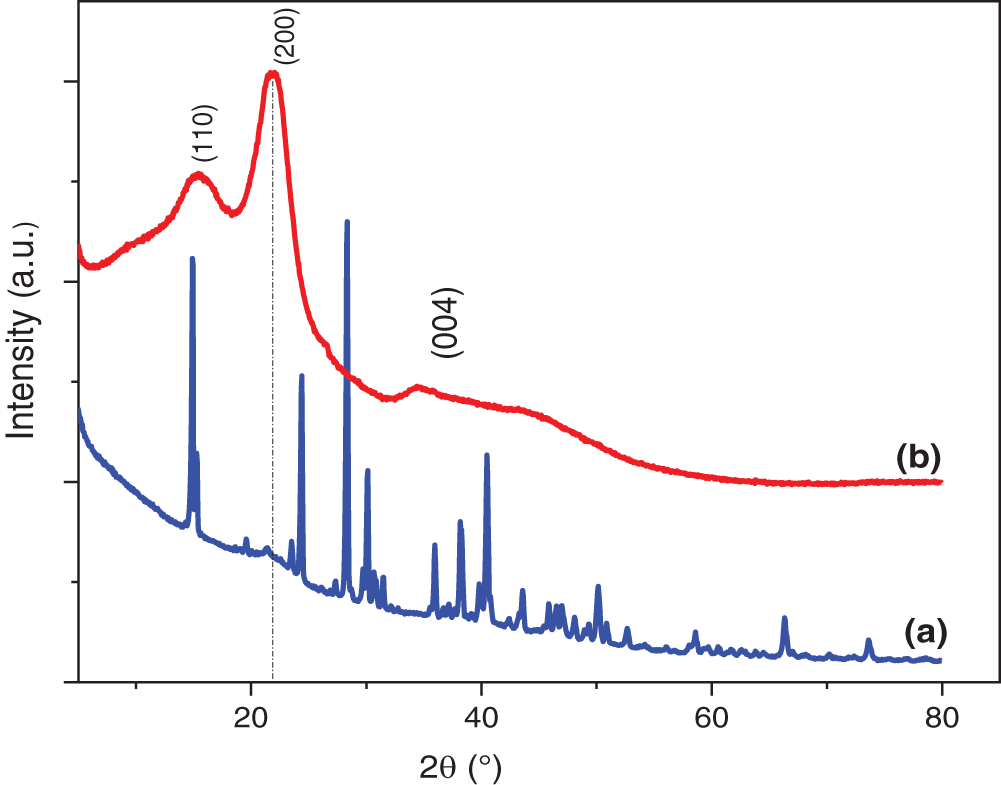

XRD analysis was performed on RCP and TCP before and after treatment to determine their crystalline structure. The results shown in Fig. 3 revealed the presence of cellulose

Figure 3: XRD curves of (a) RCP and (b) TCP

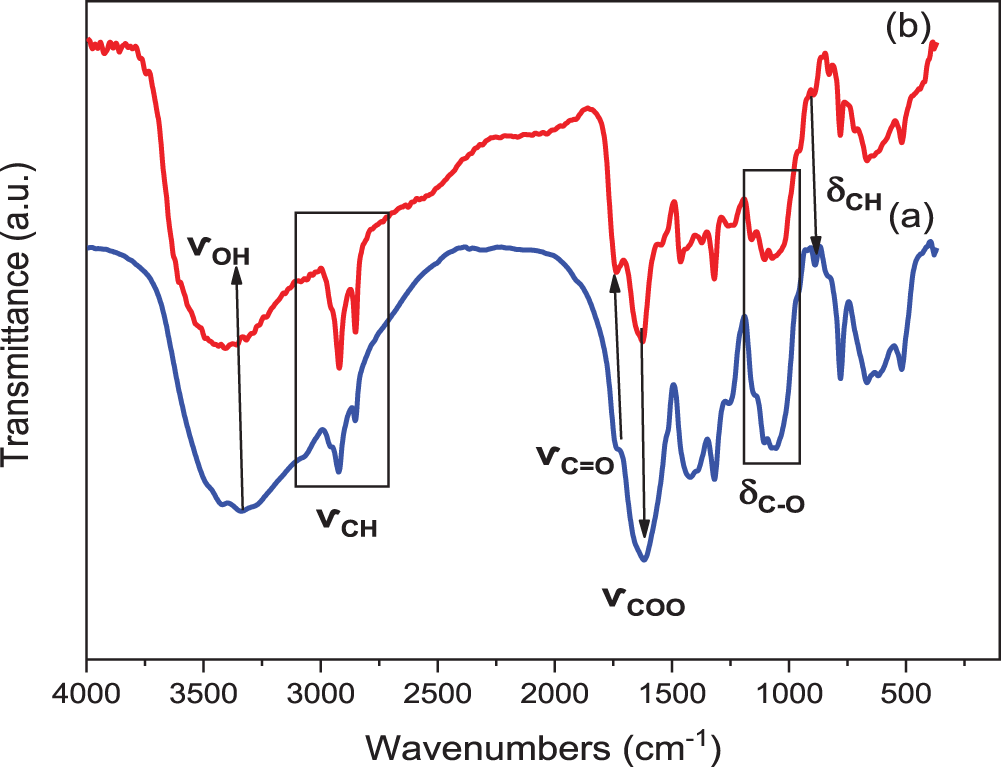

The FTIR spectra of both RCP and TCP samples, illustrated in Fig. 4, reveal strong similarities, suggesting comparable chemical compositions, enabling the identification of their characteristic functional groups. A broad absorption band at 3000–3500 cm−1, attributed to -OH stretching vibrations, suggests hydrogen bonding within the cellulose matrix [42]. Additionally, the characteristic -CH stretching vibration of cellulose, appearing around 2935 cm−1, was present in both spectra. Further structural insights were gained through the identification of absorption bands associated with cellulose. An absorption band observed at 1724 cm−1 is characteristic of the C = O bending vibration, whereas the band appearing in the 1610–1620 cm−1 range is attributed to the stretching vibrations of the carboxyl (COOH) group [43,44]. The 1000–1100 cm−1 band corresponds to both symmetric and asymmetric deformations of C-O bonds [45]. Moreover, the absorption band appearing at 883 cm−1 is characteristic of the glycosidic C-H rocking vibration and O-H bending, which are indicative of β-glycosidic linkages between anhydroglucose units [46]. These absorption bands are hallmarks of native Cellulose I, confirming that the chemical structure of cellulose remained intact throughout the treatment process. However, key differences between RCP and TCP spectra highlight the effects of the applied treatments. The absorption bands at 1251 cm−1, associated with acetyl groups in the xylan component and acyl oxygen (C = O) in hemicelluloses, was detected in RCP but absent in TCP. Similarly, the absorption band at 1422 cm−1, associated with lignin, was also missing from the TCP spectrum [47]. This indicates the effective removal of hemicellulose and lignin during alkaline delignification and acid hydrolysis [48]. Another notable distinction was the presence of an absorption bands at 1325 cm−1 in the RCP spectrum, attributed to the characteristic carboxylate stretching vibrations of calcium oxalate crystals, a common inorganic component in cactus plants [49]. The absence of this absorption band in TCP suggests that the treatment significantly reduced calcium oxalate content, a finding further corroborated by XRD analysis.

Figure 4: FTIR of (a) RCP and (b) TCP

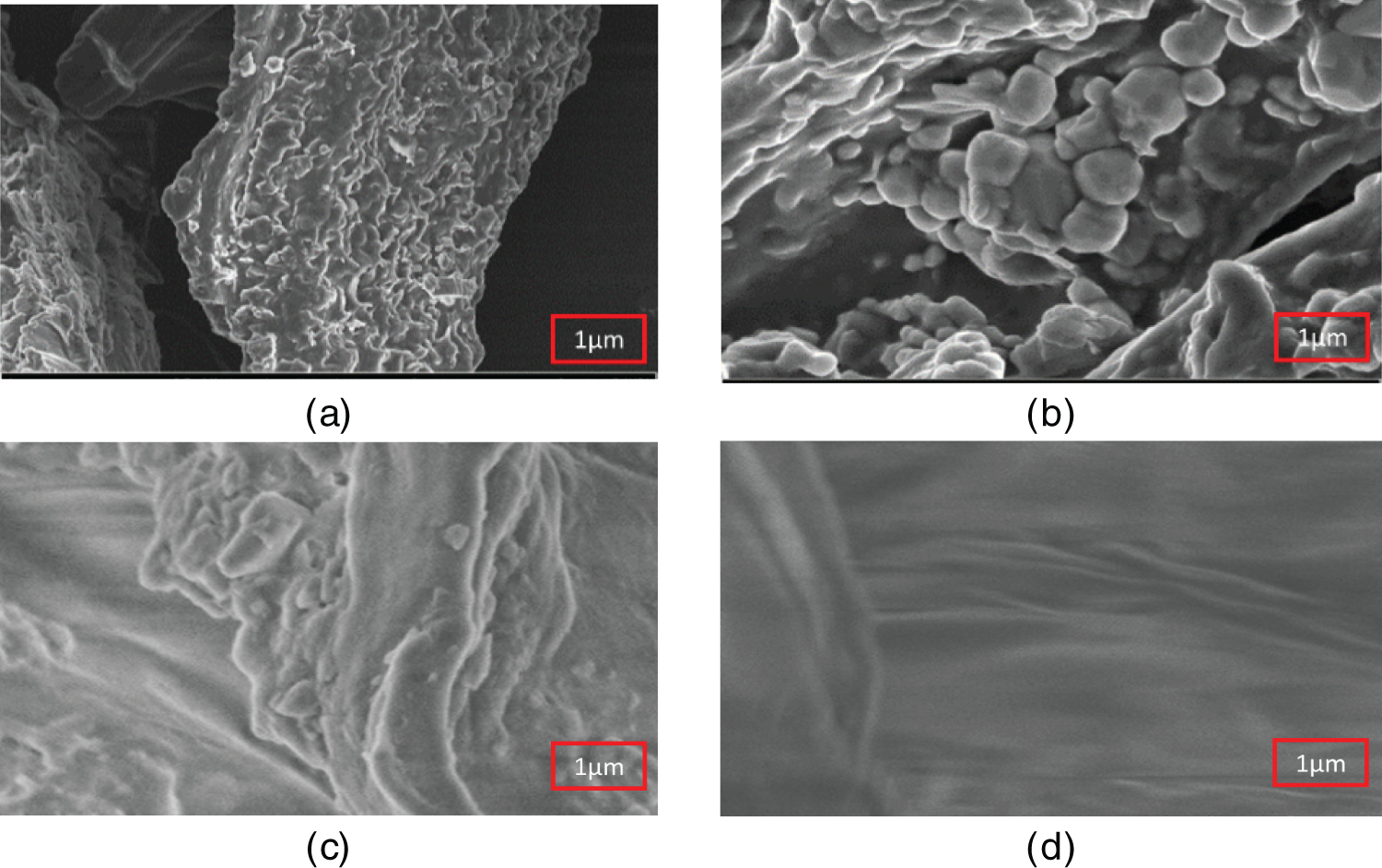

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to comprehensively examine the surface morphology of both raw and treated materials. High-magnification microscopic observations (Fig. 5a,b) unveiled that raw biomass fibers possess a rough, uneven surface distinguished by prominent undulations [50]. Scattered throughout this topography, clusters of promin crystalline structures, identified as calcium oxalate, were evident. These crystals exhibited a distinctive parallelepiped shape, resembling miniature, three-dimensional boxes. Following the treatment process (Fig. 5c,d), a substantial transformation in the fiber morphology became apparent. The previously rugged surface appeared smoother, with a significant reduction in the pronounced undulations. Raw cactus underwent defibrillation, resulting in the removal of non-cellulosic components and the isolation of individual microfibers [51]. Simultaneously, a noticeable decrease in the density and visibility of the calcium oxalate crystals was observed, suggesting that the acid treatment had effectively dissolved it.

The BET method was employed to measure the specific surface area of RCP and TCP adsorbents. The RCP displayed a notably low specific surface area, mirroring observations reported by Tejada-Tovar et al. [52] for the Opuntia ficus indica biosorbent. The inherent non-porous structure, and the presence of aggregated minerals such as calcium carbonate (CaCO3) and calcium oxalate monohydrate (CaC2O4·H2O) on its surface, as evidenced by SEM (Fig. 5), are likely the cause of this restricted surface area. Following treatment to produce TCP, a significant increase in specific surface area was observed, rising from 1.6 m2/g for RCP to 12.4 m2/g for TCP. Concurrently, the pore volume experienced a substantial augmentation. The increased surface area is a result of the treatment’s effective removal of impurities, such as whewellite and carbonates, which also induces a structural change in the cellulosic fibers. These findings validate the successful synthesis of TCP, which exhibits a considerably enhanced specific surface area compared to the untreated RCP.

Figure 5: SEM of RCP (a,b) and TCP (c,d)

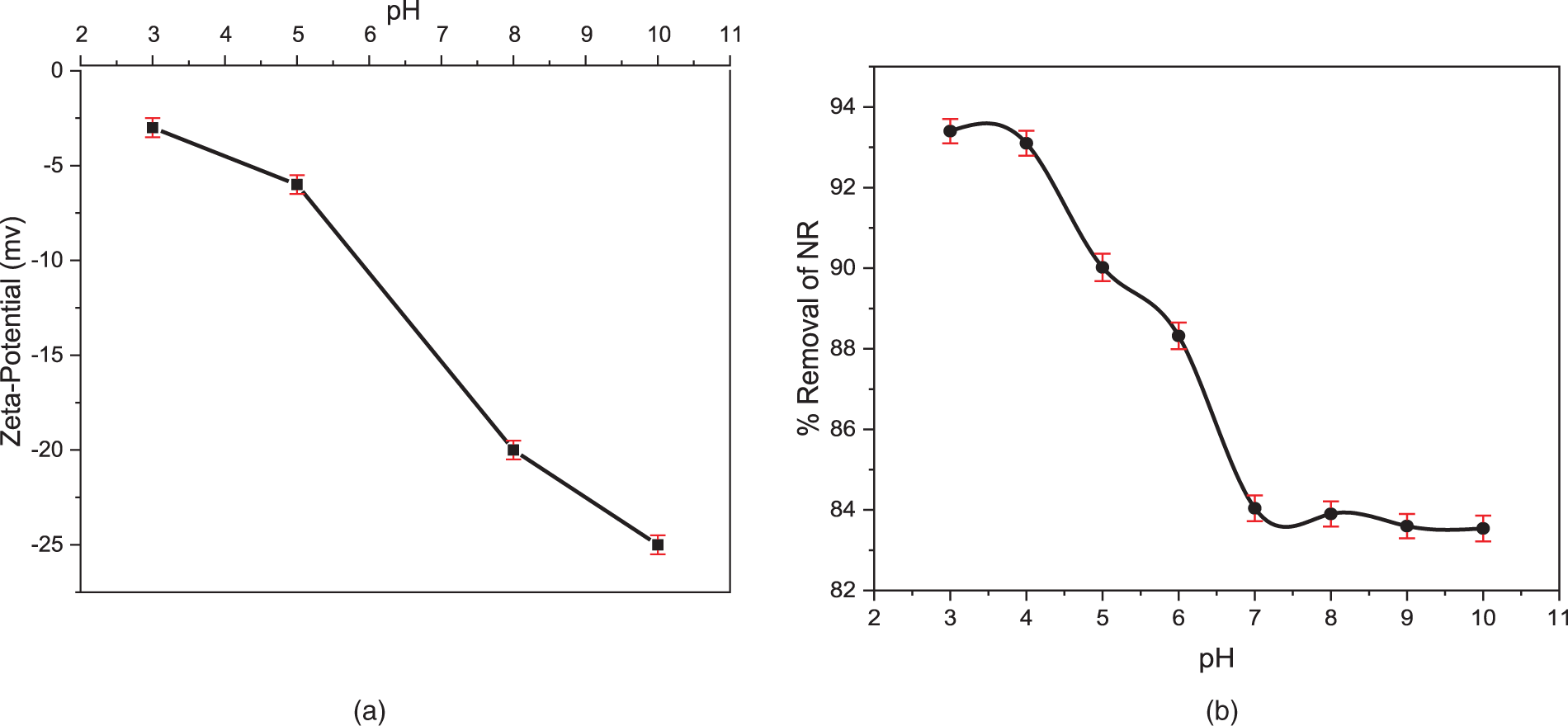

As shown in Fig. 6a, the TCP exhibits a negative zeta potential across all pH values, a characteristic of cellulose due to its abundant hydroxyl groups that maintains the surface electrokinetics of cellulose anionic on all the pH range [53–55]. This negative charge promotes the adsorption of positively charged dye molecules through electrostatic interactions [56,57]. Due to its persistent negative surface charge across different pH values, TCP exhibits a strong affinity for cationic dyes such as neutral red. This electrostatic interaction, along with ionic adsorption, governed the uptake of neutral red on TCP across all tested pH levels, consistently yielding an adsorption capacity greater than 84% (Fig. 6b). As the solution pH decreases towards acidic medium, the concentration of H+ increases and the dissociation equilibrium of NR in water (Fig. 2) evolves in the direction of increasing the cationic form, which leads to a higher adsorption of the cationic dye (NR) onto the TCP reaching a removel of 93%.

Figure 6: Zeta-Potential vs. pH for the TCP (a) The effect of solution pH on the adsorption of NR onto TCP was investigated, using an initial dye concentration of 100 mg/L, a TCP mass of 150 mg, and a contact time of 2 h (b)

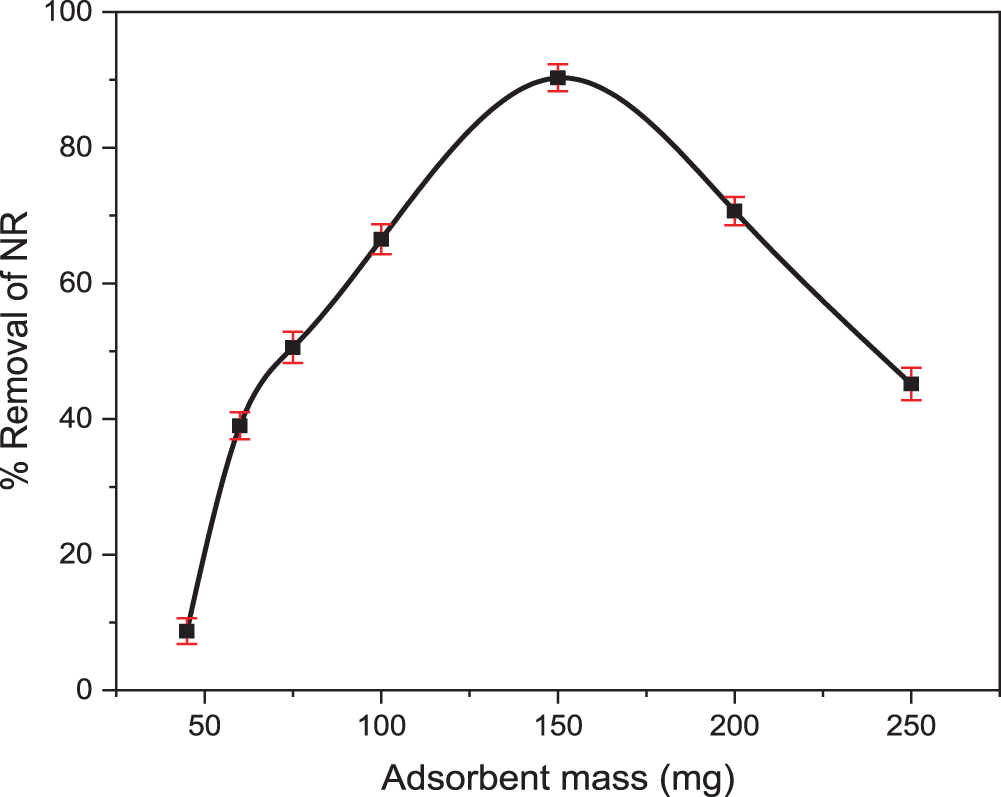

Fig. 7 illustrates a positive correlation between TCP dosage and NR removal, increasing from 8.71% to 90.3% with dosages up to 150 mg. Beyond a certain point, further increases in TCP dosage resulted in diminishing returns in terms of adsorption capacity, suggesting that the adsorption sites had likely become saturated on the adsorbent surface. This phenomenon suggests that increasing the adsorbent dosage enhances treatment efficiency, enabling the purification of larger effluent volumes while maintaining a constant TCP concentration [58]. The TCP dosage resulting in the highest adsorption capacity was determined to be 3 g/L, and this value was subsequently used for all further experiments. TCP showed superior cationic dye adsorption compared to Tuntun et al. [59] which examined nanocrystallite cellulose, with higher efficiency and faster equilibrium. This is likely due to TCP’s more accessible adsorption sites and stronger affinity for NR molecules, stemming from its structural and chemical properties.

Figure 7: The effect of adsorbent mass (TCP) on the adsorption of NR was investigated, using an initial dye concentration of 100 mg/L, own original pH, and a contact time of 2 h

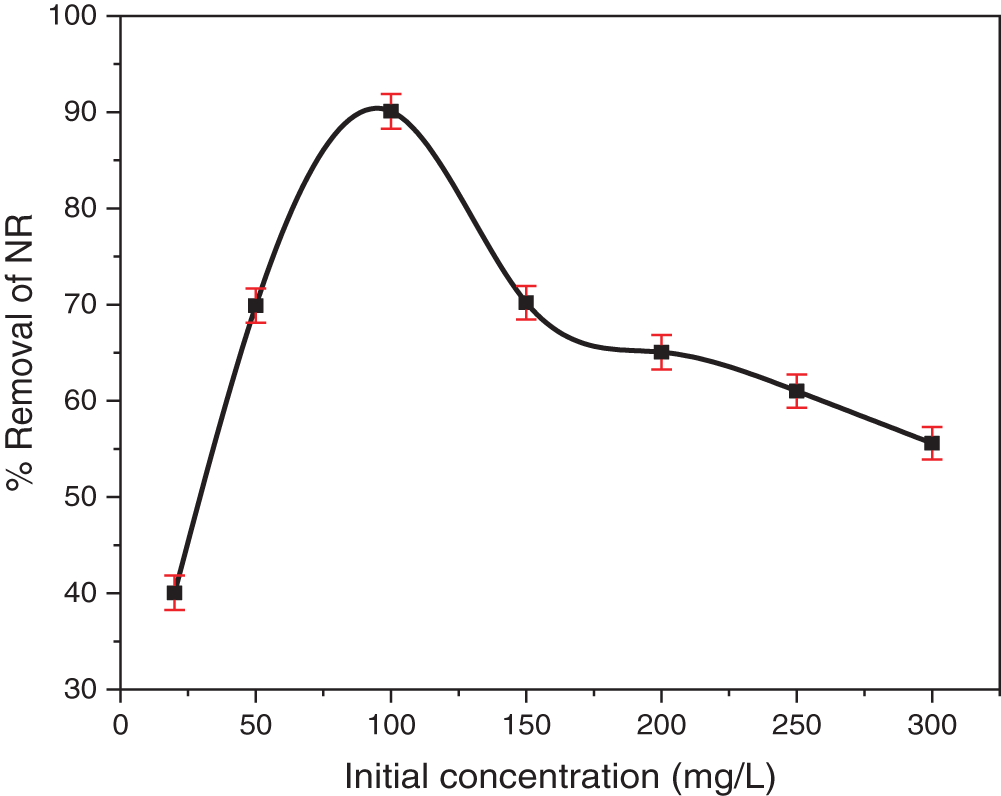

3.4 Effect of Initial Dye Concentration

The initial dye concentration exerts a strong influence on adsorption, primarily due to competition for available adsorption sites [60]. Fig. 8 depicts the adsorption behavior as a function of initial dye concentration, which was varied from 20 to 300 mg/L. An increase in initial NR concentration led to higher removal efficiency, peaking at 100 mg/L, beyond which efficiency decreased. The enhanced removal at lower concentrations is attributed to the greater concentration gradient, which drives dye molecule diffusion towards the TCP surface, overcoming mass transfer limitations and fostering stronger dye-TCP interactions [61]. The optimal initial NR concentration for the given TCP amount was found to be 100 mg/L, resulting in the highest NR removal efficiency of 90.1%.

Figure 8: The effect of initial NR concentration on adsorption was investigated within a range of 20–300 mg/L, using a fixed TCP mass of 150 mg, own original pH, and a contact time of 2 h

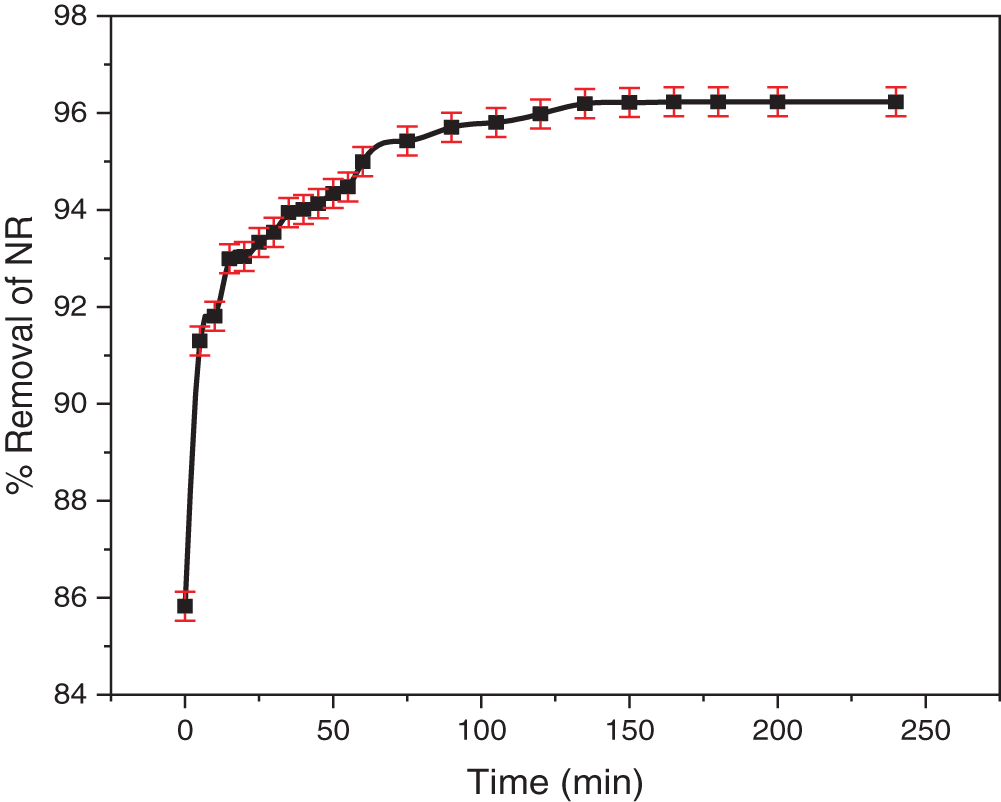

The kinetics of NR adsorption were evaluated by monitoring the removal of NR from the solution over time (Fig. 9). A rapid initial uptake indicated rapid occupation of surface sites. Equilibrium was achieved within approximately 120 min, suggesting a gradual diffusion of NR into the TCP structure. Following the initial rapid phase, adsorption slowed, likely due to site saturation and repulsive interactions among adsorbed dye molecules. A slight increase in removal was observed up to 135 min, but the negligible change (0.21%) suggests that equilibrium was effectively reached at 120 min. This minimal increase may be attributed to dye aggregation, hindering diffusion into deeper, higher-energy sites within the adsorbent. As micropores become filled, diffusion of aggregated molecules is restricted, minimizing any further adsorption [62]. These findings led us to conclude that 120 min is the optimal contact time for this study.

Figure 9: The effect of contact time on the adsorption of NR onto TCP was investigated, using an initial dye concentration of 100 mg/L, a TCP mass of 150 mg, own original pH, and varying contact times

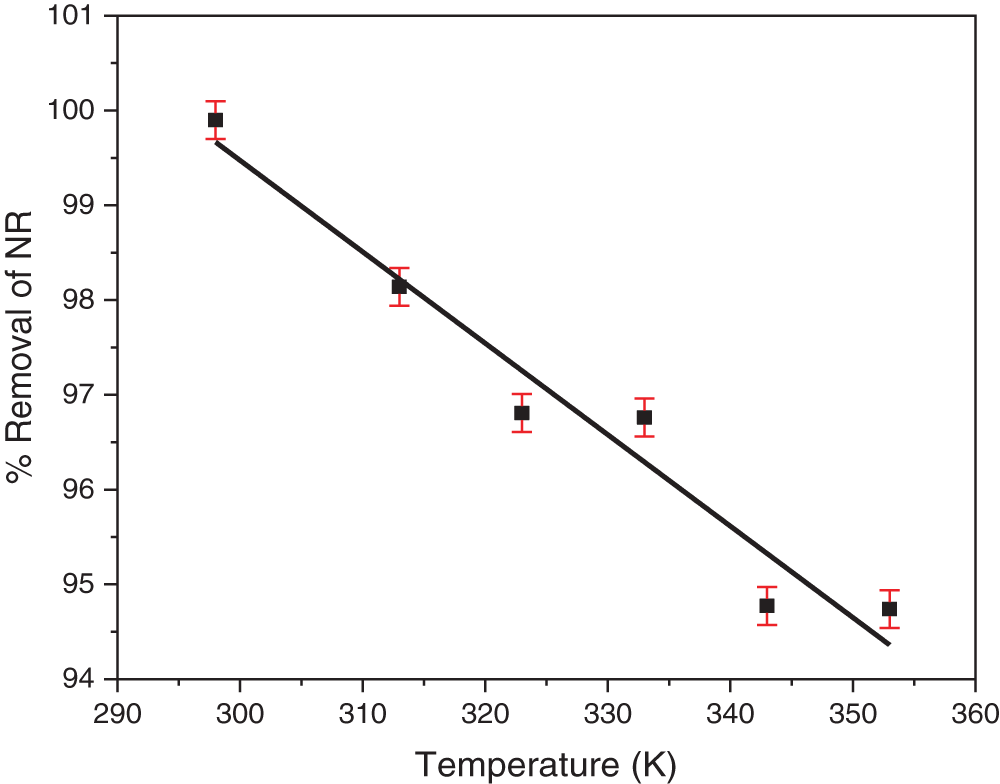

The effect of temperature on NR adsorption onto TCP was investigated within a range of 25 to 80°C. Maximum NR removal (99.89%) was observed at 25°C. As temperature increased, NR removal gradually decreased, reaching 94.71% at 80°C (Fig. 10). This trend suggests that the adsorption of NR onto TCP is an exothermic process, likely driven by the formation of weak bonds between the dye and the adsorbent surface [63]. Elevated temperatures may weaken these interactions, resulting in reduced adsorption [64].

Figure 10: The effect of temperature on NR removal by TCP was investigated using an initial dye concentration of 100 mg/L, a TCP mass of 150 mg, own original pH, and a contact time of 2 h

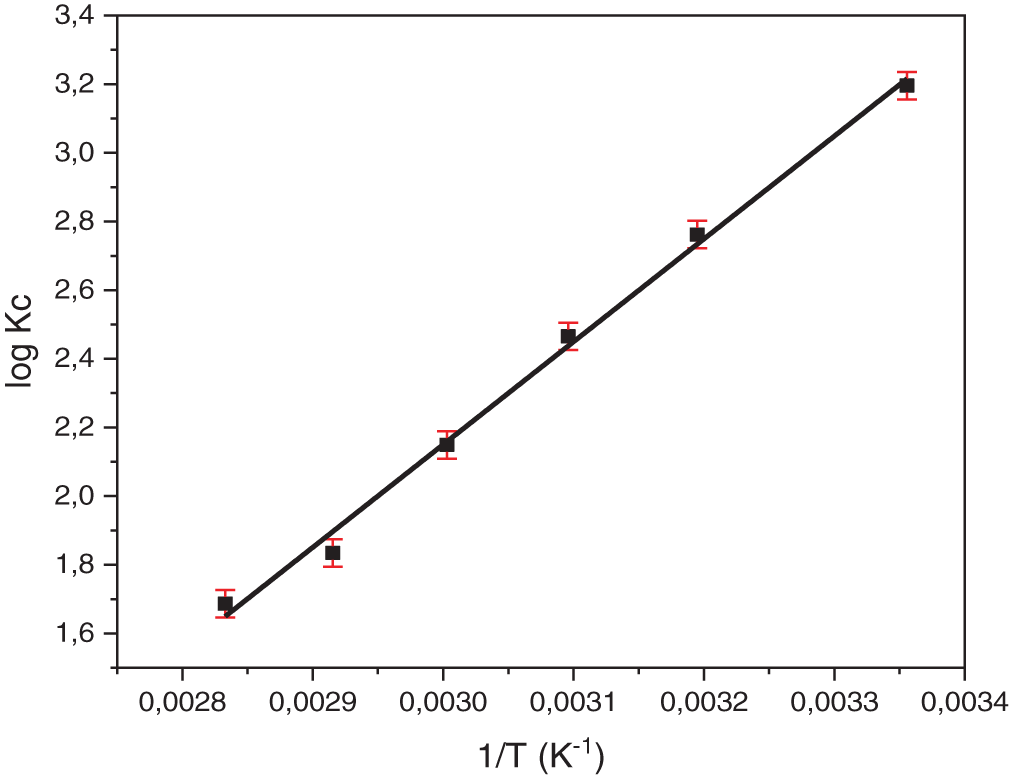

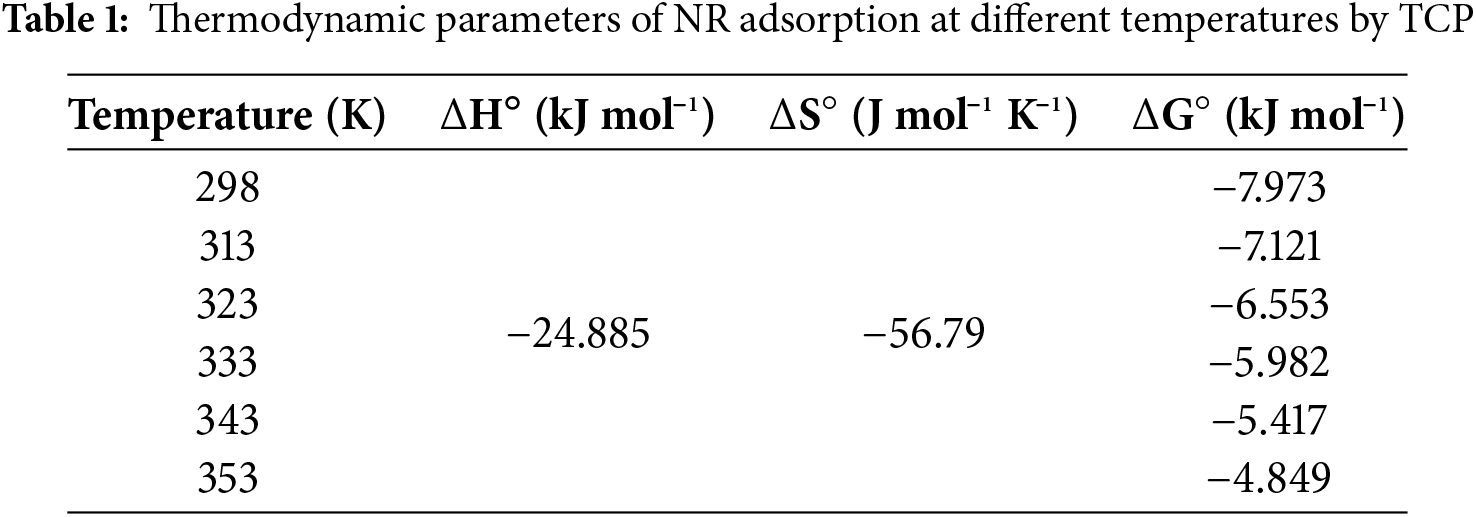

Thermodynamic parameters, including Gibbs free energy (ΔG°), enthalpy (ΔH°) and entropy (ΔS°) associated with adsorption, can be determined using the following Eqs. (5)–(7):

where Kc is the equilibrium constant, Ce is the equilibrium concentration in solution (mg/L) and qe is the amount of NR adsorbed on the adsorbent per liter of solution at equilibrium (mg/L). ΔG°, ΔH° and ΔS° are changes in Gibbs free energy (kJ/mol), enthalpy (kJ/mol) and entropy (J/mol/K), respectively. R is the gas constant (8.314 J·mol−1·K−1), T is the absolute temperature (K).

The plot of Ln Kc vs. 1/T (Fig. 11) was used to calculate ΔH° from the slope and ΔS° from the intercept, according to the Van’t Hoff equation (Eq. (8)). ΔG° values were subsequently calculated using the relationship ΔG° = ΔH° − TΔS°.

Figure 11: The Van’t Hoff plot for the adsorption of NR onto TCP

As shown in Fig. 11, the decreasing of NR adsorption with increasing temperature (298–353 K) strongly suggests that the adsorption process releases heat and is therefore exothermic. Table 1 presents a summary of the calculated thermodynamic parameters. The negative ΔG° values is a strong indicator of a spontaneous and thermodynamically favorable adsorption process [65]. The negative ΔH° values strongly indicate that the adsorption process is exothermic [66]. This finding is consistent with the theoretically predicted exothermic adsorption of AC3N4 nanosheets, as demonstrated by DFT calculations in Khajavian et al. [67]. The negative entropy change (ΔS) observed during dye adsorption reflects the immobilization of dye molecules on the biomass surface [68]. This transition from a state of high mobility in solution to a more restricted state at the interface leads to a decrease in system randomness and contributes to the overall thermodynamic driving force for the adsorption process [69]. The |ΔH| value of 24.89 kJ·mol−1 is significantly lower than the 40 kJ·mol−1 threshold, further supporting the physisorption nature of the adsorption process. This suggests that NR adsorption onto TCP occurs primarily through weak intermolecular interactions rather than chemical bonding. The adsorption mechanism involves multiple forces, with electrostatic interactions playing a key role by attracting the cationic dye to negatively charged sites, such as carboxyl (-COOH) groups, on the TCP surface [70]. Additionally, hydrogen bonding between cellulose hydroxyl (-OH) groups and the dye’s amino (-NH2) and oxygen (O) groups enhances adsorption, while van der Waals forces further contribute to dye retention [61]. These combined interactions facilitate the overall adsorption process, reinforcing its physical rather than chemical nature. Our findings are further supported by the work of Hegazy et al. [71], who investigated the interaction between cellulose derived from sawdust and Methylene Blue using Density Functional Theory (DFT). Their study highlights similar adsorption mechanisms, emphasizing the role of electrostatic interactions and hydrogen bonding in the adsorption of cationic dyes onto cellulose-based materials.

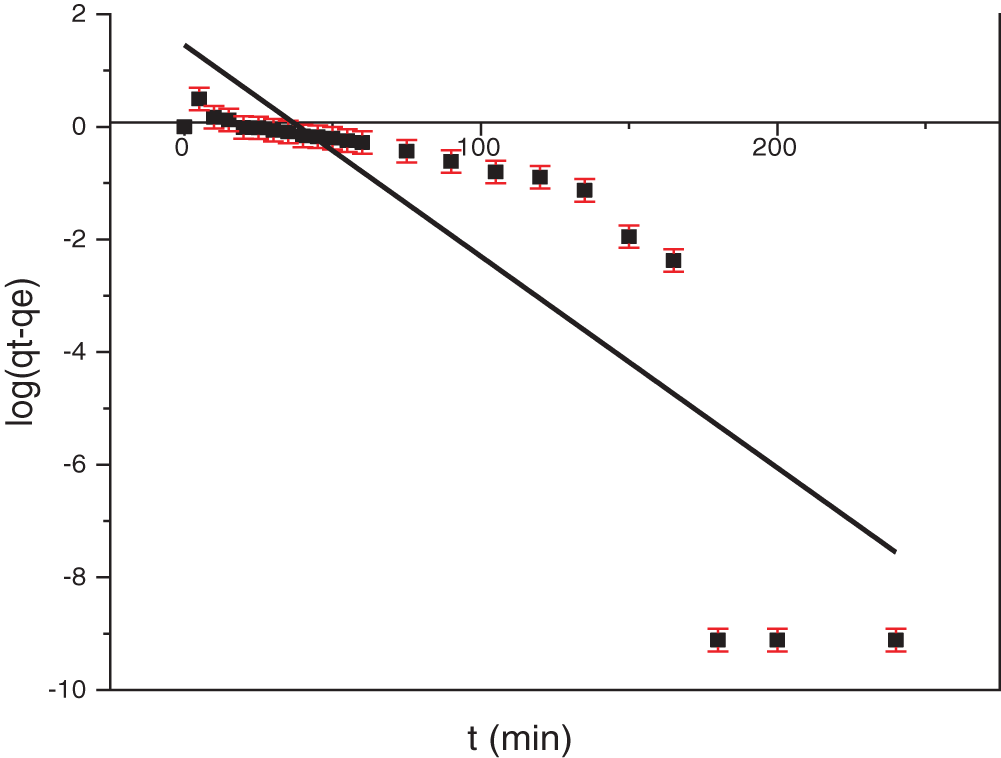

3.7 Adsorption Equilibrium Study

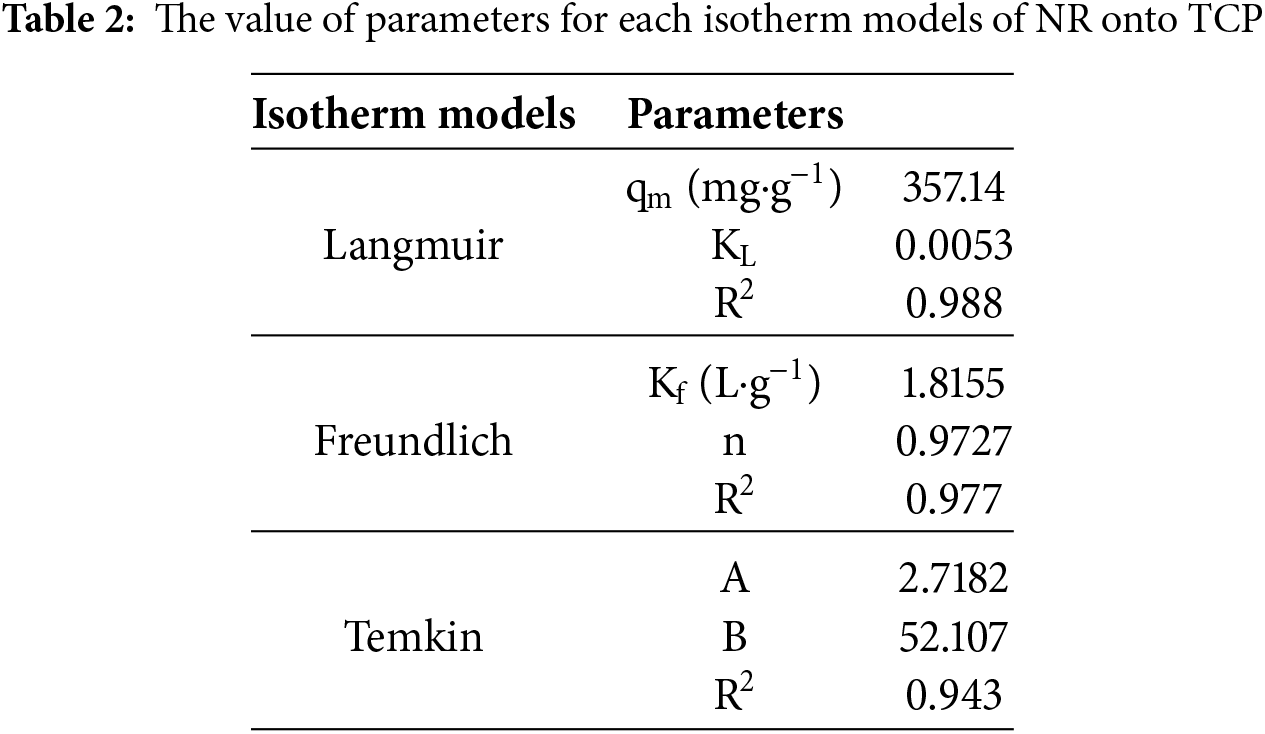

The adsorption isotherm capacity is paramount in assessing the maximum adsorption capacity of the system, which is critical for evaluating system performance. It provides a concise overview of the system’s behavior, revealing the adsorbent’s efficiency and enabling an economic assessment of its commercial applications for the specific solute [72]. To accurately model the observed experimental data for the considered system, the Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin isotherm equations were evaluated.

The Langmuir model for dye-biomass systems assumes monolayer adsorption on a homogeneous surface with no dye-dye interactions and constant adsorption energy. This simplified model provides a theoretical basis for understanding dye removal by biomass, though real systems may exhibit more complex behavior [73].

The non-linear Langmuir isotherm equation can be rearranged into a linear form (Eq. (9)):

where qe represents the amount of adsorbate adsorbed per mass unit of adsorbent at equilibrium (mg/g), Ce is the equilibrium concentration of the adsorbate in solution (mg/L), qm and KL are the Langmuir constants, representing the maximum adsorption capacity for the solid phase loading and the energy constant related to the heat of adsorption, respectively.

Eq. (9) is transformable into the linear form of Eq. (10):

The Freundlich isotherm, an empirical model, is widely utilized to describe adsorption phenomena on surfaces exhibiting heterogeneity in terms of adsorption energies [74], which vary across different sites. It assumes that adsorption energy decreases as more adsorbate molecules occupy the surface. Mathematically, it’s represented as (Eq. (11)):

Ce is the equilibrium concentration, Kf is the Freundlich constant, and n is the heterogeneity factor. While the Freundlich isotherm is an empirical model often employed to describe adsorption on surfaces exhibiting a wide range of adsorption site energies, it may not accurately represent the adsorption behavior in all systems.

Eq. (11) can be linearized to yield Eq. (12):

The Temkin isotherm model accounts for the heterogeneous nature of the adsorption process. It assumes a linear decline in the heat of adsorption as surface coverage increases, reflecting the varying binding energies of adsorption sites across the adsorbent surface. Unlike the Freundlich isotherm, which assumes a logarithmic decrease in adsorption heat, the Temkin isotherm posits a linear decline. It is commonly expressed as (Eq. (13)) [75]:

where A and B are Temkin isotherm constants.

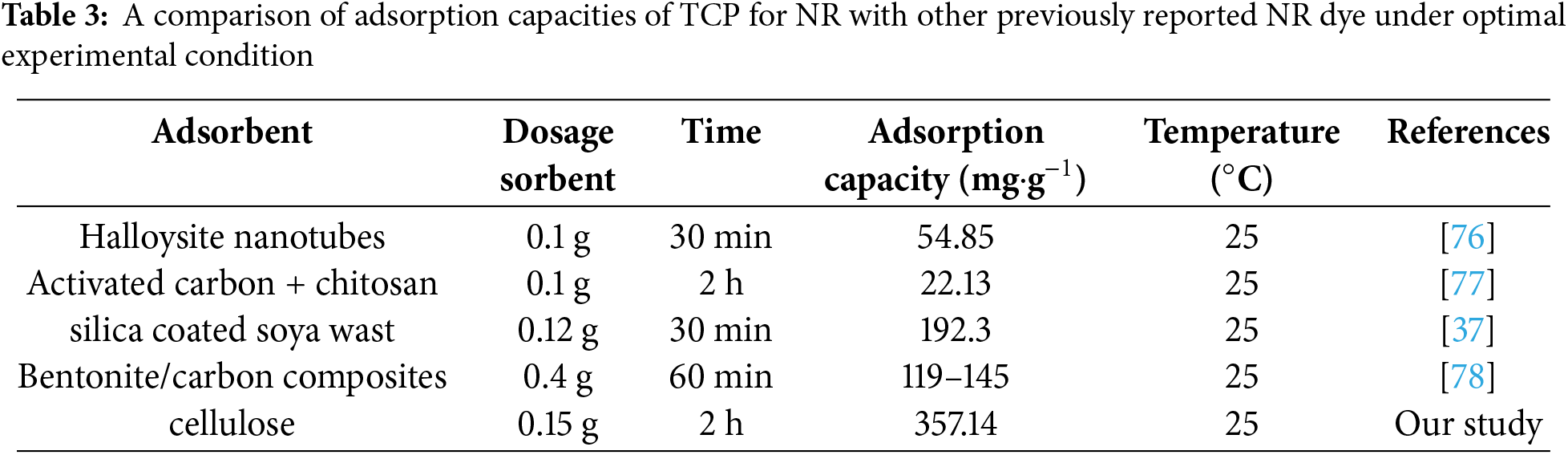

The adsorption of NR dye onto TCP was best represented by the Langmuir isotherm model, achieving a maximum adsorption capacity (Qm) of 357.14 mg/g (Table 2), as evidenced by the highest R2 value among tested models (Langmuir, Freundlich, and Temkin), which are graphically represented in Fig. 12. Notably, this Qm value is superior to other adsorbents (Table 3), highlighting TCP’s potential for efficient NR removal. This enhanced performance is likely due to its high surface area, porous structure, and abundant hydroxyl and carboxyl functional groups, facilitating dye interaction through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic forces. Despite requiring a 2 h equilibrium time, TCP’s high adsorption capacity makes it a promising, eco-friendly option for wastewater treatment.

Figure 12: Adsorption isotherm of (a) Langmuir, (b) Freundlich and (c) Temkin of NR onto TCP (T = 25°C, own original pH, 150 mg adsorbent dosage and a contact time of 2 h)

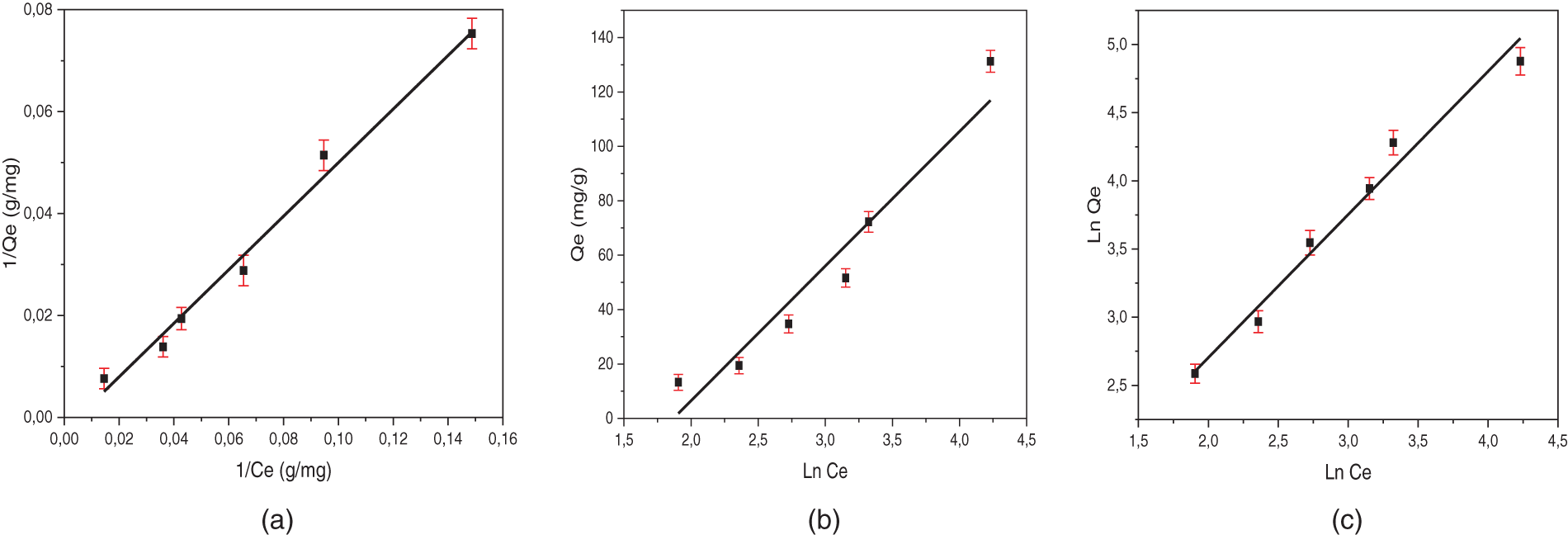

Kinetic models are employed to elucidate the underlying mechanisms of adsorption processes, including mass transfer and chemical reactions. The pseudo-first-order kinetic model, originally proposed by Lagergren et al. [79], is frequently used to describe adsorption phenomena in solid-liquid systems.

The pseudo-first-order kinetic model is expressed as (Eq. (14)):

after integration by applying the initial conditions qt = 0 at t = 0 parameters, including pH solution, adsorbent dosage, initial and qt = qt at t = t, Eq. (15) becomes:

Eq. (15) can be transformed into a linear equation:

where qt is the adsorption capacity at time t (mg/g) and Kad (min−1) is the pseudo-first-order rate constant, was applied to the present study of NR dye adsorption.

Linear plots of log(qe − qt) vs. time (Fig. 13) were used to determine the rate constant (kad) and calculate the correlation coefficients, these values are presented in Table 4. However, the pseudo-first-order model exhibited poor fit to the experimental data, as evidenced by low correlation coefficients. Moreover, a significant disparity was observed between the experimentally determined (qe) and the values predicted by the model. These findings indicate that the pseudo-first-order model may have limitations in describing the adsorption kinetics of NR dye onto the adsorbent.

Figure 13: Pseudo-first-order kinetic fit for adsorption of NR onto TCP at 25°C

To further analyze the kinetic data, the pseudo-second-order model developed by Ho et al. [80] was employed.

This model can be expressed as (Eq. (17)):

Eq. (17) can be transformed into a linear equation:

where k is the pseudo-second-order rate constant.

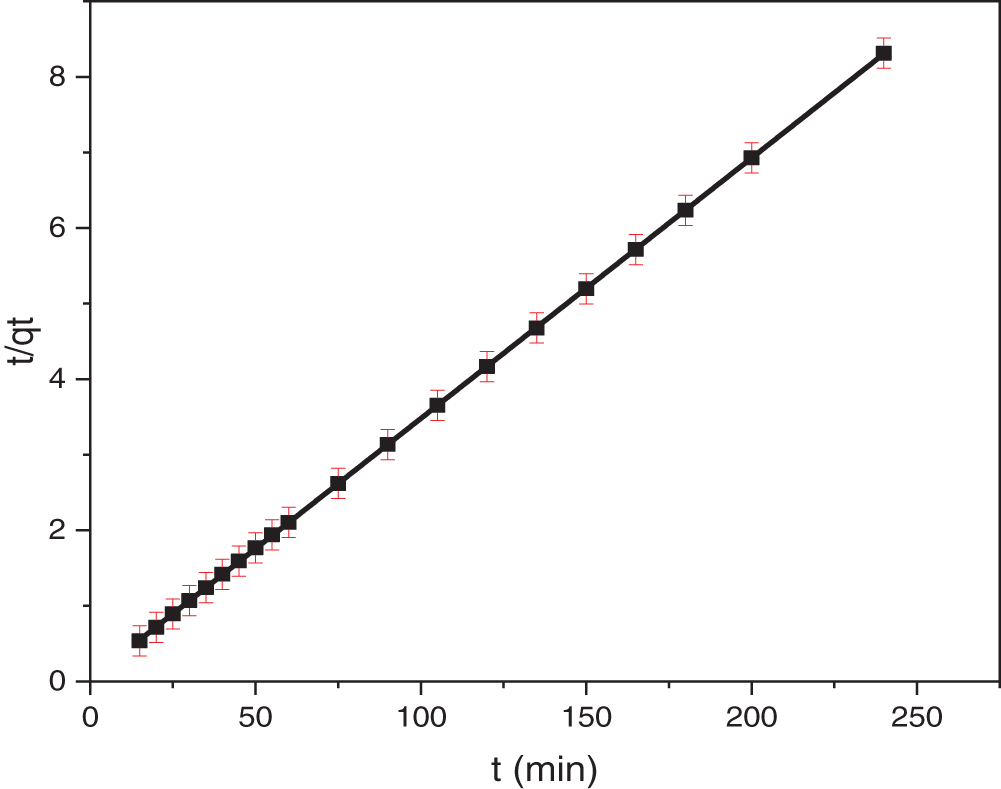

To assess the applicability of the pseudo-second-order kinetic model, a plot of t/qt vs. t (Fig. 14) was constructed. A linear relationship in this plot is indicative of pseudo-second-order kinetics. The slope and intercept of this linear plot can be used to determine the key kinetic parameters: qe (the equilibrium adsorption capacity), k (the rate constant), and h (the initial adsorption rate), which are summarized in Table 4. In our study, we obtained an excellent linear fit with a strong correlation coefficient (R2 = 0.999). Furthermore, the qe values estimated by the pseudo-second-order model showed excellent agreement with the experimentally determined values. These results strongly suggest that NR adsorption onto TCP follows a pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Villabona-Ortíz et al. [81] reported comparable results for the adsorption of anionic dyes onto modified cellulose derived from wheat residues.

Figure 14: Pseudo-second-order kinetic fit for adsorption of NR onto TCP at 25°C

4 Regeneration Efficiency and Reuse Potential

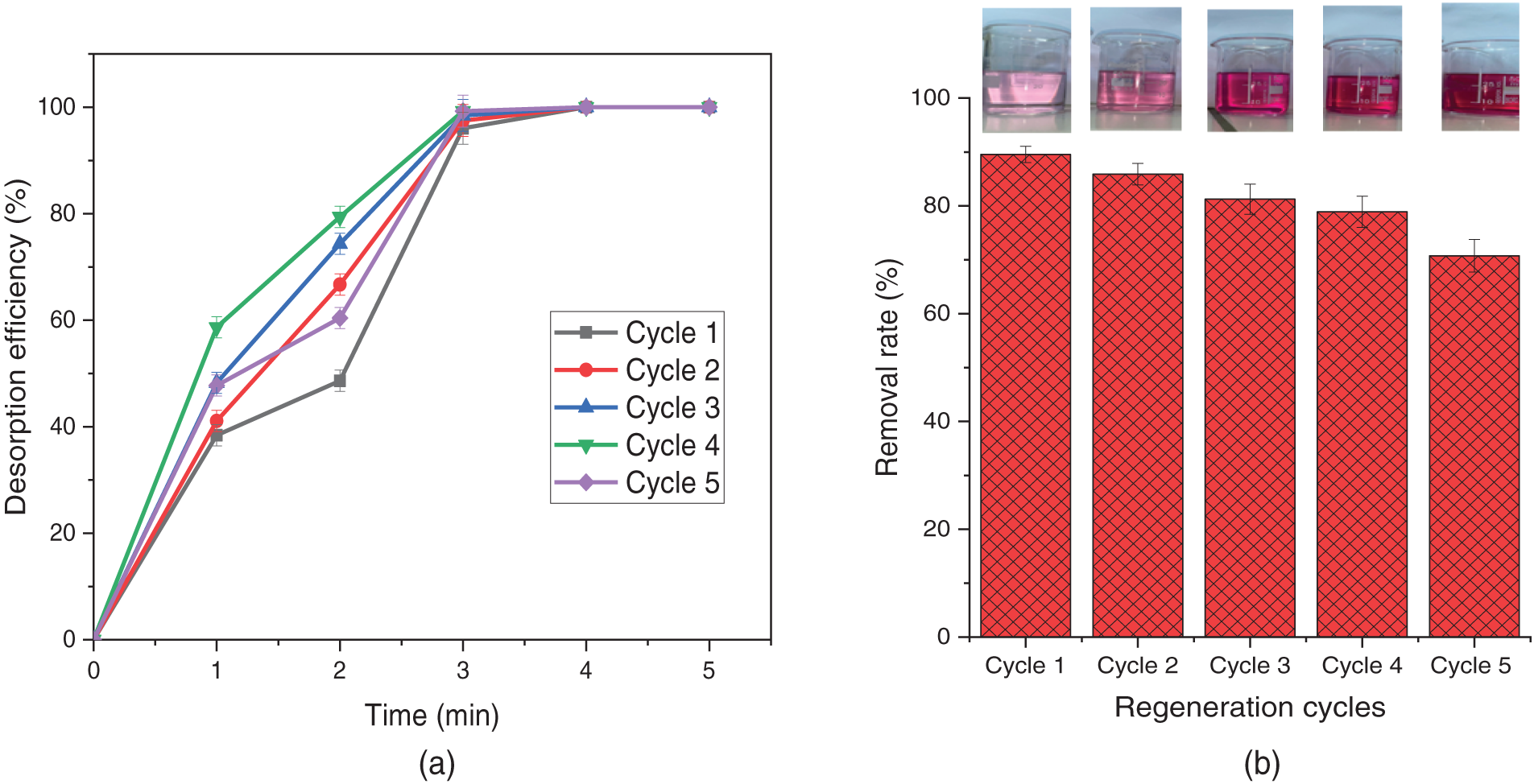

Although TCP is a renewable adsorbent, its effectiveness extends beyond single-use applications, as it can be regenerated and reused for repeated pollutant adsorption [25]. The desorption of NR dye from the TCP surface was simple and fast, requiring only a rinse with 0.1 M HCl at room temperature followed by deionized water, achieving maximum release within 4–5 min per cycle, as depicted in Fig. 15a. Notably, TCP demonstrated excellent reusability, retaining over 70% adsorption efficiency after five cycles under optimal conditions (150 mg/45 mL adsorbent, pH ~3.0, T ~298 K, and a contact time of 2 h), confirming its excellent reusability as an adsorbent (Fig. 15b). Furthermore, TCP’s large particle size allowed for easy recovery via rapid filtration, eliminating the need for drying and enabling immediate reuse. Throughout the regeneration process, TCP maintained good dispersion and rapid dye adsorption, demonstrating its potential for sustainable and cost-effective wastewater treatment.

Figure 15: (a) Desorption efficiency of NR dye as a function of the time and (b) NR removal rate (%R) after repeated adsorption-desorption cycles

In this study we successfully isolated and characterized Treated Cladode Powder (TCP) from OFI pads. XRD analysis unequivocally confirmed the presence of the crystalline Iβ cellulose polymorph within the isolated TCP, a significant achievement following the effective acid treatment of the OFI cladode powder. FTIR and SEM provided compelling evidence for the successful removal of non-cellulosic impurities, resulting in a relatively pure cellulose fraction. Subsequently, the isolated TCP was evaluated as an adsorbent for the removal of NR dye from aqueous solutions. Through a comprehensive investigation of adsorption parameters, this study revealed that removal rates of over 90% could be achieved at a pH of 3, an adsorbent dosage of 3 g/L, and an initial dye concentration of 100 mg/L, with equilibrium achieved within 2 h. Experimental adsorption data were effectively described by the Langmuir isotherm model (R2 = 0.98), strongly suggesting a monolayer adsorption mechanism for NR dye onto the TCP surface. Kinetic analysis demonstrated that the pseudo-second-order model offered a superior fit compared to the pseudo-first-order model. Thermodynamic studies revealed that the adsorption of NR dye onto TCP is a spontaneous and exothermic process, suggesting that the dye-TCP interactions are energetically favorable. The negative values of ΔG° and ΔH° (ΔH = −24.886 kJ/mol) further support the predominant involvement of physisorption interactions, primarily driven by van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonding between the dye molecules and the hydroxyl groups on the TCP surface. A maximum adsorption capacity (Qm) of 357.1 mg/g for NR dye was achieved, demonstrating a significant adsorption capacity relative to other materials. Moreover, the regenerated cellulose exhibited a retention of over 70% efficiency after five adsorption-desorption cycles, highlighting its potential as an excellent reusable adsorbent. In this research work we successfully demonstrated the feasibility of producing a high-quality cellulose adsorbent from OFI. The prepared adsorbent exhibited exceptional performance in removing the textile dye, red neutral, from aqueous solutions. These findings underline the potential of cellulose-based materials derived from agricultural waste as sustainable and cost-effective adsorbents for water treatment.

Acknowledgement: The authors are deeply grateful to Professor Sami Boufi for the Zeta potential measurements and to Professor Nejib Mekni for his kind assistance in refining the English of this manuscript. Financial support from the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research of Tunisia is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The synthesis, structural characterisation by powder XRD, FTIR, MEB and adsorption measurements by UV spectroscopy: Alma Jandoubi, Mehrzia Krimi and Rached Ben Hassen. Draft manuscript preparation: Alma Jandoubi, Mehrzia Krimi and Rached Ben Hassen. Writing—review and editing: Alma Jandoubi, Mehrzia Krimi and Rached Ben Hassen. Supervision: Mehrzia Krimi and Rached Ben Hassen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, RBH, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| NR | Neutral Red |

| RCP | Raw Cladode Powder |

| TCP | Treated Cladode Powder |

| OFI | Opuntia fiicus-indica |

References

1. Markandeya, Mohan D, Shukla SP. Hazardous consequences of textile mill effluents on soil and their remediation approaches. Clean Eng Technol. 2022;7:100434. doi:10.1016/j.clet.2022.100434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Salahshoori I, Namayandeh Jorabchi M, Ghasemi S, Golriz M, Wohlrab S, Ali Khonakdar H. Advancements in wastewater treatment: a computational analysis of adsorption characteristics of cationic dyes pollutants on amide functionalized-MOF nanostructure MIL-53 (Al) surfaces. Sep Purif Technol. 2023;319:124081. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2023.124081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Marghade D, Shelare S, Prakash C, Soudagar MEM, Yunus Khan TM, Kalam MA. Innovations in metal-organic frameworks (MOFspioneering adsorption approaches for persistent organic pollutant (POP) removal. Environ Res. 2024;258:119404. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2024.119404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Luong HVT, Le TP, Le TLT, Dang HG, Tran TBQ. A graphene oxide based composite granule for methylene blue separation from aqueous solution: adsorption, kinetics and thermodynamic studies. Heliyon. 2024;10(7):e28648. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Al-Tohamy R, Ali SS, Li F, Okasha KM, Mahmoud YA, Elsamahy T, et al. A critical review on the treatment of dye-containing wastewater: ecotoxicological and health concerns of textile dyes and possible remediation approaches for environmental safety. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;231:113160. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.113160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Negash A, Tibebe D, Mulugeta M, Kassa Y. A study of basic and reactive dyes removal from synthetic and industrial wastewater by electrocoagulation process. S Afr N J Chem Eng. 2023;46:122–31. doi:10.1016/j.sajce.2023.07.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Marques DG, de Melo Franco Domingos J, Nolasco MA, Campos V. Textile effluent treatment using coagulation-flocculation and a hydrodynamic cavitation reactor associated with ozonation. Chem Eng Sci. 2025;304:121094. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2024.121094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Heryanto H, Tahir D. Trends, mechanisms, and the role of advanced oxidation processes in mitigating azo, triarylmethane, and anthraquinone dye pollution: a bibliometric analysis. Inorg Chem Commun. 2025;175:114104. doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2025.114104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Aryal M. Phytoremediation strategies for mitigating environmental toxicants. Heliyon. 2024;10(19):e38683. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Salman AB, Al-khateeb RT, Abdulqahar SN. Electrochemical removal of crystal violet dye from simulated wastewater by stainless steel rotating cylinder anode: cod reduction and decolorization. Desalin Water Treat. 2024;320:100787. doi:10.1016/j.dwt.2024.100787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hemmatzadeh E, Bahram M, Dadashi R. Photochemical modification of tea waste by tungsten oxide nanoparticle as a novel, low-cost and green photocatalyst for degradation of dye pollutant. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2024;313:124104. doi:10.1016/j.saa.2024.124104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Gurav R, Bhatia SK, Choi TR, Choi YK, Kim HJ, Song HS, et al. Application of macroalgal biomass derived biochar and bioelectrochemical system with Shewanella for the adsorptive removal and biodegradation of toxic azo dye. Chemosphere. 2021;264(Pt 2):128539. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.128539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Condrachi L, Barbu M. Anaerobic digestion processes controller tuning using fictitious reference iterative method. IFAC-PapersOnLine. 2022;55(7):453–8. doi:10.1016/j.ifacol.2022.07.485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Khalfaoui A, Laggoun Z, Derbal K, Benalia A, Ghomrani AF, Pizzi A. Experimental study of selective batch bio-adsorption for the removal of dyes in industrial textile effluents. J Renew Mater. 2025;13(1):127–46. doi:10.32604/jrm.2024.056970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ahmed HM, Kebede WL, Yaebyo AB, Digisu AW, Tadesse SF. Adsorptive removal of methylene blue dye by a ternary magnetic rGO/AK/Fe3O4 nanocomposite: studying adsorption isotherms, kinetics, and thermodynamics. Chem Phys Impact. 2025;10:100800. doi:10.1016/j.chphi.2024.100800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Tang L, Liu C, Liu X, Zhang L, Fan B, Wang B, et al. Efficient adsorption of crystal violet by different temperature pyrolyzed biochar-based sodium alginate microspheres: a green solution for food industry dye removal. Food Chem X. 2025;26(1):102311. doi:10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Mushahary N, Sarkar A, Das B, Rokhum SL, Basumatary S. A facile and green synthesis of corn cob-based graphene oxide and its modification with corn cob-K2CO3 for efficient removal of methylene blue dye: adsorption mechanism, isotherm, and kinetic studies. J Indian Chem Soc. 2024;101(11):101409. doi:10.1016/j.jics.2024.101409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Saheed IO, Zairuddin NI, Nizar SA, Ahmad Kamal Megat Hanafiah M, Latip AFA, Suah FBM. Adsorption potential of CuO-embedded chitosan bead for the removal of acid blue 25 dye. Ain Shams Eng J. 2024;15(12):103125. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2024.103125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Loebsack G, Yeung KKC, Berruti F, Klinghoffer NB. Impact of biochar physical properties on adsorption mechanisms for removal of aromatic aqueous contaminants in water. Biomass Bioenergy. 2025;194:107617. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2025.107617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Molina GA, Trejo-Caballero ME, Elizalde-Mata A, Silva R, Estevez M. An eco-friendly strategy for emerging contaminants removal in water: study of the adsorption properties and kinetics of self-polymerized PHEMA in green solvents. J Water Process Eng. 2024;67:106261. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Anuse DD, Patil SA, Chorumale AA, Kolekar AG, Bote PP, Walekar LS, et al. Activated carbon from pencil peel waste for effective removal of cationic crystal violet dye from aqueous solutions. Results Chem. 2025;13:101949. doi:10.1016/j.rechem.2024.101949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Jia X, Kanbaiguli M, Zhang B, Huang Y, Peydayesh M, Huang Q. Anisotropic Chitosan-nanocellulose/Zeolite imidazolate frameworks-8 aerogel for sustainable dye removal. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2024;676:298–309. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2024.07.130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Loura N, Rathee K, Dhull R, Singh M, Dhull V. Carbon nanotubes for dye removal: a comprehensive study of batch and fixed-bed adsorption, toxicity, and functionalization approaches. J Water Process Eng. 2024;67:106193. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2024.106193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kausar A, Zohra ST, Ijaz S, Iqbal M, Iqbal J, Bibi I, et al. Cellulose-based materials and their adsorptive removal efficiency for dyes: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;224:1337–55. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.10.220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Ali Aslam A, Hassan SU, Saeed MH, Kokab O, Ali Z, Nazir MS, et al. Cellulose-based adsorbent materials for water remediation: harnessing their potential in heavy metals and dyes removal. J Clean Prod. 2023;421:138555. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2023.138555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Garba ZN, Lawan I, Zhou W, Zhang M, Wang L, Yuan Z. Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) based materials as emerging adsorbents for the removal of dyes and heavy metals—a review. Sci Total Environ. 2020;717:135070. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.135070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Ahmad MA, Eusoff MA, Oladoye PO, Adegoke KA, Bello OS. Optimization and batch studies on adsorption of Methylene blue dye using pomegranate fruit peel based adsorbent. Chem Data Collect. 2021;32:100676. doi:10.1016/j.cdc.2021.100676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Munir G, Mohamed HEA, Hkiri K, Ghotekar S, Maaza M. Phyto-mediated fabrication of Mn2O3 nanoparticles using Hyphaene thebaica fruit extract as a promising photocatalyst for MB dye degradation. Inorg Chem Commun. 2024;167:112695. doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Meas A, Wi E, Chang M, Hwang HS. Carboxylmethyl cellulose produced from wood sawdust for improving properties of sodium alginate hydrogel in dye adsorption. Sep Purif Technol. 2024;341:126906. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2024.126906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Worku GD, Abate SN. Efficiency comparison of natural coagulants (Cactus pads and Moringa seeds) for treating textile wastewater (in the case of Kombolcha textile industry). Heliyon. 2025;11(4):e42379. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2025.e42379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Djobbi B, Miled GLB, Raddadi H, Hassen RB. Efficient removal of aqueous manganese (II) cations by activated Opuntia ficus-indica powder: adsorption performance and mechanism. Acta Chim Slov. 2021;68(3):548–61. doi:10.17344/acsi.2020.6248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Al-Msiedeen AM, Jamhour RMAQ, Al-Soud AS, Al-Zeidaneen FK, Alnaanah SA, Alrawashdeh AI, et al. Powdered Opuntia ficus-indica as an effective adsorbent for the removal of phenol and 2-nitrophenol from wastewater: experimental and theoretical studies. Desalin Water Treat. 2024;320:100859. doi:10.1016/j.dwt.2024.100859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Volpe M, Adair JL, Gao L, Fiori L, Goldfarb JL. Sustainable treatment of naturally occurring heavy metals in Sicilian water via hydrothermal carbonization, secondary biofuel extraction, and activation of Opuntia ficus-indica. Chem Eng J. 2025;505:159030. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.159030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Ifguis O, Ziat Y, Belkhanchi H, Ammou F, Moutcine A, Laghlimi C. Adsorption mechanism of Methylene Blue from polluted water by Opuntia ficus-indica of Beni Mellal and Sidi Bou Othmane areas: a comparative study. Chem Phys Impact. 2023;6:100235. doi:10.1016/j.chphi.2023.100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Malainine ME, Dufresne A, Dupeyre D, Mahrouz M, Vuong R, Vignon MR. Structure and morphology of cladodes and spines of Opuntia ficus-indica. Cellulose extraction and characterisation. Carbohydr Polym. 2003;51(1):77–83. doi:10.1016/S0144-8617(02)00157-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Segal L, Creely JJ, Martin AEJr, Conrad CM. An empirical method for estimating the degree of crystallinity of native cellulose using the X-ray diffractometer. Text Res J. 1959;29(10):786–94. doi:10.1177/004051755902901003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Batool A, Valiyaveettil S. Chemical transformation of soya waste into stable adsorbent for enhanced removal of methylene blue and neutral red from water. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9(1):104902. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2020.104902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Contreras-Padilla M, Rivera-Muñoz EM, Gutiérrez-Cortez E, del López AR, Rodríguez-García ME. Characterization of crystalline structures in Opuntia ficus-indica. J Biol Phys. 2015;41(1):99–112. doi:10.1007/s10867-014-9368-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. El Azizi C, Hammi H, Chaouch MA, Majdoub H, Mnif A. Use of Tunisian Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes as a low cost renewable admixture in cement mortar preparations. Chem Afr. 2019;2(1):135–42. doi:10.1007/s42250-019-00040-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Judith RD, Pámanes-Carrasco GA, Delgado E, Rodríguez-Rosales MDJ, Medrano-Roldán H, Reyes-Jáquez D. Extraction optimization and molecular dynamic simulation of cellulose nanocrystals obtained from bean forage. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2022;43:102443. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2022.102443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Kallel F, Bettaieb F, Khiari R, García A, Bras J, Chaabouni SE. Isolation and structural characterization of cellulose nanocrystals extracted from garlic straw residues. Ind Crops Prod. 2016;87:287–96. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.04.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Maceda A, Soto-Hernández M, Peña-Valdivia CB, Trejo C, Terrazas T. Characterization of lignocellulose of Opuntia (Cactaceae) species using FTIR spectroscopy: possible candidates for renewable raw material. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2022;12(11):5165–74. doi:10.1007/s13399-020-00948-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Tinh NT, Phuong NT, Nghiem DG, Dan DK, Khang PT, Dat NM, et al. Green synthesis of sulfonated graphene oxide-like catalyst from corncob for conversion of hemicellulose into furfural. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(10):11011–22. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-03136-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ouhammou M, Jaouad A, Bouchdoug M, Mahrouz M. Extraction and isolation of cellulose from cladodes of Cactus Opuntia ficus-indica. J Biomed Res Environ Sci. 2022;3(9):1108–11. doi:10.37871/jbres1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Medina OJ, Patarroyo W, Moreno LM. Current trends in cacti drying processes and their effects on cellulose and mucilage from two Colombian Cactus species. Heliyon. 2022;8(12):e12618. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Vieyra H, Figueroa-López U, Guevara-Morales A, Vergara-Porras B, San Martín-Martínez E, Aguilar-Mendez MÁ. Optimized monitoring of production of cellulose nanowhiskers from Opuntia ficus-indica (Nopal Cactus). Int J Polym Sci. 2015;2015:871345. doi:10.1155/2015/871345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Latham KG, Matsakas L, Figueira J, Rova U, Christakopoulos P, Jansson S. Examination of how variations in lignin properties from Kraft and organosolv extraction influence the physicochemical characteristics of hydrothermal carbon. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2021;155:105095. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2021.105095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Kassab Z, Abdellaoui Y, Salim MH, Bouhfid R, Qaiss AEK, El Achaby M. Micro- and nano-celluloses derived from hemp stalks and their effect as polymer reinforcing materials. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;245:116506. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Benhamou A, Boussetta A, Grimi N, El Idrissi M, Nadifiyine M, Barba FJ, et al. Characteristics of cellulose fibers from Opuntia ficus-indica cladodes and its use as reinforcement for PET based composites. J Nat Fibres. 2022;19(13):6148–64. doi:10.1080/15440478.2021.1904484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Ferfari O, Belaadi A, Bedjaoui A, Alshahrani H, Khan MKA. Characterization of a new cellulose fiber extracted from Syagrus Romanzoffiana rachis as a potential reinforcement in biocomposites materials. Mater Today Commun. 2023;36:106576. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.106576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Kassab Z, Syafri E, Tamraoui Y, Hannache H, Qaiss AEK, El Achaby M. Characteristics of sulfated and carboxylated cellulose nanocrystals extracted from Juncus plant stems. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;154:1419–25. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Tejada-Tovar C, de Cartagena U, Bonilla-Mancilla H, Villabona-Ortíz A, Ortega-Toro R, Licares-Eguavil J. Effect of the adsorbent dose and initial contaminant concentration on the removal of Pb(II) in a solution using Opuntia ficus-indica shell. Rev Mex De Ingeniería Química. 2021;20(2):555–68. doi:10.24275/rmiq/ia2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Jing K, Liu X, Liu T, Wang Z, Liu H. Facile and green construction of carboxymethyl cellulose-based aerogel to efficiently and selectively adsorb cationic dyes. J Water Process Eng. 2023;56:104386. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2023.104386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Yuan HB, Tang RC, Yu CB. Microcrystalline cellulose modified by phytic acid and condensed tannins exhibits excellent flame retardant and cationic dye adsorption properties. Ind Crops Prod. 2022;184:115035. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Mahouche-Chergui S, Grohens Y, Balnois E, Lebeau B, Scudeller Y. Adhesion of silica particles on thin polymer films model of flax cell wall. Mater Sci Appl. 2014;5(13):953–65. doi:10.4236/msa.2014.513097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Tan KB, Reza AK, Abdullah AZ, Amini Horri B, Salamatinia B. Development of self-assembled nanocrystalline cellulose as a promising practical adsorbent for methylene blue removal. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;199:92–101. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.07.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Prathapan R, Thapa R, Garnier G, Tabor RF. Modulating the zeta potential of cellulose nanocrystals using salts and surfactants. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Aspects. 2016;509:11–8. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.08.075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Benhalima T, Ferfera-Harrar H. Eco-friendly porous carboxymethyl cellulose/dextran sulfate composite beads as reusable and efficient adsorbents of cationic dye methylene blue. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;132:126–41. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.03.164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Tuntun SM, Sahadat Hossain M, Akter S, Bahadur NM, Alam MS, Ahmed S. Synthesis of nano crystallite cellulose and chitosan from waste natural source for the adsorption of cationic and anionic dyes in aqueous medium. Hybrid Adv. 2024;6:100270. doi:10.1016/j.hybadv.2024.100270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Altwala A, Jabli M. Extraction of cellulose from Forsskaolea tenacissima L. through alkalization and bleaching processes: characterization, and application to the adsorption of hazardous cationic dyes from water. Results Chem. 2025;13:102010. doi:10.1016/j.rechem.2024.102010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Skwierawska AM, Bliźniewska M, Muza K, Nowak A, Nowacka D, Zehra Syeda SE, et al. Cellulose and its derivatives, coffee grounds, and cross-linked, β-cyclodextrin in the race for the highest sorption capacity of cationic dyes in accordance with the principles of sustainable development. J Hazard Mater. 2022;439:129588. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Nannu Shankar S, Dinakaran DR, Chandran DK, Mantha G, Srinivasan B, Nyayiru Kannaian UP. Adsorption kinetics, equilibrium and thermodynamics of a textile dye V5BN by a natural nano complex material: clinoptilolite. Energy Nexus. 2023;10:100197. doi:10.1016/j.nexus.2023.100197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Islam MR, Mostafa MG. Adsorption kinetics, isotherms and thermodynamic studies of methyl blue in textile dye effluent on natural clay adsorbent. Sustain Water Resour Manag. 2022;8(2):52. doi:10.1007/s40899-022-00640-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Lombardo S, Thielemans W. Thermodynamics of adsorption on nanocellulose surfaces. Cellulose. 2019;26(1):249–79. doi:10.1007/s10570-018-02239-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Le TP, Luong HVT, Nguyen HN, Pham TKT, Trinh Le TL, Tran TBQ, et al. Insight into adsorption-desorption of methylene blue in water using zeolite NaY: kinetic, isotherm and thermodynamic approaches. Results Surf Interfaces. 2024;16:100281. doi:10.1016/j.rsurfi.2024.100281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Zhu HY, Fu YQ, Jiang R, Jiang JH, Xiao L, Zeng GM, et al. Adsorption removal of Congo red onto magnetic cellulose/Fe3O4/activated carbon composite: equilibrium, kinetic and thermodynamic studies. Chem Eng J. 2011;173(2):494–502. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2011.08.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Khajavian M, Kaviani S, Piyanzina I, Tayurskii DA, Nedopekin OV, Haseli A. Amide-functionalized g-C3N4 nanosheet for the adsorption of arsenite (As3+process optimization, experimental, and density functional theory insight. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Aspects. 2024;690:133803. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2024.133803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Türk FN, Eren MŞA, Arslanoğlu H. Adsorption of Reactive Black 5 dye from aqueous solutions with a clay halloysite having a nanotubular structure: interpretation of mechanism, kinetics, isotherm and thermodynamic parameters. Inorg Chem Commun. 2025;171:113600. doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2024.113600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Wang Y, Zhao L, Hou J, Peng H, Wu J, Liu Z, et al. Kinetic, isotherm, and thermodynamic studies of the adsorption of dyes from aqueous solution by cellulose-based adsorbents. Water Sci Technol. 2018;77(11–12):2699–708. doi:10.2166/wst.2018.229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. El-Shafey S, Salama A, Abouzeid R. Nanocomposite of cellulose nanofibers/alumina for effective adsorption of brilliant blue and ethyl orange dyes: equilibrium, kinetic and mechanism studies. Desalin Water Treat. 2025;321:100875. doi:10.1016/j.dwt.2024.100875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Hegazy S, Ibrahim HH, Weckman T, Hu T, Tuomikoski S, Lassi U, et al. Synergistic pyrolysis of cellulose/Fe-MOF composite: a combined experimental and DFT study on dye removal. Chem Eng J. 2025;504:158654. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.158654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Ayawei N, Ebelegi AN, Wankasi D. Modelling and interpretation of adsorption isotherms. J Chem. 2017;2017:3039817. doi:10.1155/2017/3039817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Tiab D, Donaldson EC. Shale-gas reservoirs. In: Petrophysics. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2016. p. 719–74. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-803188-9.00012-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Freundlich H. Über die Adsorption in Lösungen. Z Für Phys Chem. 1907;57U(1):385–470. (In German). doi:10.1515/zpch-1907-5723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Ohale PE, Onu CE, Ohale NJ, Oba SN. Adsorptive kinetics, isotherm and thermodynamic analysis of fishpond effluent coagulation using chitin derived coagulant from waste Brachyura shell. Chem Eng J Adv. 2020;4:100036. doi:10.1016/j.ceja.2020.100036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Luo P, Zhao Y, Zhang B, Liu J, Yang Y, Liu J. Study on the adsorption of Neutral Red from aqueous solution onto halloysite nanotubes. Water Res. 2010;44(5):1489–97. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2009.10.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. de Freitas FP, Carvalho AMML, Carneiro ACO, de Magalhães MA, Xisto MF, Canal WD. Adsorption of neutral red dye by chitosan and activated carbon composite films. Heliyon. 2021;7(7):e07629. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Fathy N, El-Khouly S, Ahmed S, El-Nabarawy T, Tao Y. Superior adsorption of cationic dye on novel bentonite/carbon composites. Asia-Pacific J Chem Eng. 2021;16(1):e2586. doi:10.1002/apj.2586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Lagergren S, Svenska B. On the theory of so-called adsorption of materials, Royal Swed. Kungliga Svenska Vetenskapsakademiens Handlingar. 1898;24:1–13. [Google Scholar]

80. Ho YS, McKay G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 1999;34(5):451–65. doi:10.1016/S0032-9592(98)00112-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Villabona-Ortíz Á, Figueroa-Lopez KJ, Ortega-Toro R. Kinetics and adsorption equilibrium in the removal of azo-anionic dyes by modified cellulose. Sustainability. 2022;14(6):3640. doi:10.3390/su14063640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools