Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Boosting Structural and Dielectric Properties of Polyvinyl Alcohol/Starch/Carboxymethyl Cellulose Films with Iron-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots for Advanced Applications

1 Department of Chemistry, College of Education for Pure Sciences (Ibn Al-Haitham), University of Baghdad, Baghdad, 10053, Iraq

2 Chemistry Department, Faculty of Science, King Khalid University, Abha, 61421, Saudi Arabia

3 Egyptian Drug Authority (EDA) formerly National Organization for Drug Control and Research (NODCAR), Giza, 29, Egypt

4 Cellulose and Paper Department, National Research Centre, Dokki, Giza, 12622, Egypt

5 Photochemistry Department, National Research Centre, Dokki, Giza, 12622, Egypt

* Corresponding Author: Ahmed M. Khalil. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Recent Advances on Renewable Materials)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(7), 1459-1473. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0046

Received 25 February 2025; Accepted 18 April 2025; Issue published 22 July 2025

Abstract

In this study, the casting process is used to fabricate modified polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), starch (S), and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) polymer blend films (PVA/S/CMC) loaded with various concentrations of iron-doped carbon quantum dots (Fe-CQDs) and denoted as (PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs). A one-step microwave strategy was employed as a facile method to prepare Fe-CQDs. Through a series of characterization techniques, fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, x-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis, and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) have been used to show the successful integration of Fe-CQDs into the PVA/S/CMC matrix. Loading the synthesized Fe-CQDs to the polymeric matrix significantly enhanced the mechanical properties of the films represented in the tensile strength, Young’s modulus, and hardness. However, the elongation decreased noticeably upon increasing the iron-doped carbon dots. The surface wettability was also studied by measuring the contact angle of the prepared films. The findings showed a noticeable elevation in these measurements by increasing the Fe-CQDs content, declaring the role of a hydrophobic character in these nanoparticles when introduced into a hydrophilic polymeric system. The dielectric characteristics of the reinforced polymer composite films were evaluated. These results revealed that the ac-conductivity of the investigated films was boosted with increasing Fe-CQDs’ ratio and frequency. The PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs films possess substantial potential for efficient energy storage applications.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Polymers, in their various forms, are not just materials we encounter daily. They are the building blocks of innovation in engineering and technology. Integrating various polymers or inorganic materials with polymers is an effective approach for boosting a material’s performance and enabling the development of innovative composites that improve the characteristics of the original blend [1]. One of these famous polymers is polyvinyl alcohol (PVA). It is a versatile polymer with a wide range of industrial uses. It may be a biodegradable synthetic polymer with a backbone primarily made up of C–C linkages [2]. In addition to its exceptional film formation ability, good chain segmental dynamics, superior solid solvent for a variety of metal salts, good charge storage devices, and high dielectric strength, the water-soluble PVA polymer is hydrophilic and biodegradable [3]. The hydroxyl (–OH) group in the PVA material’s chemical composition and low melting point temperature are responsible for these admirable qualities. Due to these advantageous characteristics, PVA has been the subject of meticulous consideration in creating of polymer nanocomposites for optoelectronic and nanodielectric applications [4], as well as in manufacturing a series of solid polymer electrolytes [5]. However, PVA’s semicrystalline structure limits ion mobility and presents some challenges, including low mechanical and thermal stabilities, which must be improved through polymer mixing to expand its vast technological potential [6,7].

On the other hand, the most important category of polysaccharides is the nontoxic-biodegradable cellulose ethers. It comprises carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), possessing exceptional film-forming capabilities, high viscosity, transparency, and mechanical strength. In addition, due to its amorphous nature, CMC facilitates faster ionic mobility.

A carboxylate group in the structure allows for the formation of a wide range of complexes with other polymers and additives [8]. Another interesting water-soluble natural polymer is the starch. Higher plants create starch to store energy. In most plants, starch is a semicrystalline polymer kept in reserve as granules. The repeating 1,4-α-D glucopyranosyl units amylose and amylopectin make up this compound. Amylose, with its nearly linear structure and repeating units connected by α (1–4) connections, amylopectin has approximately 5% of α (1–6)-linked branches and α (1–4)-linked backbone. Amylose and amylopectin levels vary depending on the plant source [9].

CMC can enhance the mechanical and barrier qualities of starch-based films. Furthermore, the brittleness of starch formulations can be addressed by adding plasticizers such as sorbitol, glycerol, and maltitol. Plasticizers such as glycerol lower the glass transition temperature and raise permeability by reducing intermolecular tensions and increasing polymer chain mobility [10]. These encouraging qualities supported the PVA/starch/CMC blend as a polar electro-active and exceptional thermophysical material for creating multifunctional composites that will find extensive usage in biomedical and pharmaceutical applications as well as the creation of future cutting-edge electronics [11]. Recent research found that the inclusion of nanomaterials into the matrix of blend polymers is capable of changing the physical, mechanical, and electrical properties of the nanocomposite. The effect of sodium montmorillonite clay on the physical properties and enzymatic hydrolysis polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), starch (S), and carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) polymer blend films (PVA/S/CMC) nanocomposites using enzyme a-amylase was studied by Taghizadeh et al. [2]. Various polymers including, PVA and cellulosic derivatives, have been reported as composites doped with different fillers, showing promising findings. Methyl cellulose was loaded with sodium iodide (NaI) to be directed for energy storage electrochemical double-layer capacitor application [12]. Moreover, the ionic conductivity of poly-electrolytic PVA films has been enhanced upon being doped with NaI [13]. The electrical conductivity of PVA/CMC was boosted after doping with zinc oxide (ZnO) and hematite (Fe2O3) nanoparticles [14].

Quantum dots (QDs) are recognized as significant zero-dimensional materials owing to their notable physical properties [15]. Carbon quantum dots (CQDs) have been predicted to surpass more established pioneers in several fields due to their intriguing electronic character [16], high surface area, adaptable surface modification [17], and advantageous optical stability [18]. In addition, CQDs inherited the benefits of carbon materials [19], including their high electrical conductivity, robust adsorption capacity, non-toxicity, and innocuousness [20]. Functionalizing [21] or doping [22] CQDs has become a popular and fascinating issue in CQD frontier studies to achieve novel chemical or physical properties. Metal dopants have long been regarded as one of the most effective methods for altering the electrical, magnetic, and optical characteristics of nanoparticulate hosts [23–25]. Arsalan et al. reported that Fe-doped CQDs can effectively detect various concentrations of diclofenac sodium in the range of 5–300 μM [26]. Tammina et al. reported that combining CQDs with Ag+ and dopamine quenched their PL intensity of CQDs due to the electron transport between the CQDs and their surrounding materials [27]. Recently, CQDs have gained prominence as electrode materials in supercapacitor design, largely due to their high electronic conductivity and tunable optoelectronic properties. These properties, which are the foundation of their advantages, instill confidence in their performance. Moreover, the low toxicity and cost-effective precursor of CQDs have significantly enhanced their popularity over inorganic QDs as electrode materials. CQDs can be used individually or as part of a composite in a supercapacitor. They have been employed as negative or positive electrodes in symmetric and asymmetric supercapacitors [28]. Fe-CQDs/polypyrrole composite-based supercapacitor retained ~94% of its capacitance after 2000 cycles, while the supercapacitor-based pure polypyrrole retained ~79.4% of its capacitance, indicating the CQDs’ importance in the stability of the supercapacitor [29,30]. Microwave irradiation can be employed as an efficient processing tool for polymers. Microwaves, with their uniform energy, have become a staple in synthesizing CQDs, thanks to their remarkable speed, high efficiency, and user-friendly nature. In 2009, Zhu and his team achieved a significant milestone by creating fluorescent CQDs with a restricted size distribution for the first time, using a high-frequency microwave to pyrolyze polyethylene glycol and saccharide [31]. A leap forward was made in 2017 when Choi et al. achieved a 23.3% quantum yield by pyrolyzing AB2-type lysine using microwave-induced thermal polyamidation and carbonization, which can be completed in just 5 min [32]. This microwave-assisted approach has not only become one of the most popular and essential techniques for CQD synthesis. It is also a relief for researchers, as it operates in controlled conditions and eliminates the need for complicated equipment, simplifying the process.

Consequently, in this work, we aim to describe a straightforward, affordable, and quick synthesis method that uses casting process to create PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs environmental-acceptability nanocomposite films. Fe-CQDs were synthesized by a microwave assisted process. The structural, mechanical, and electrical properties of PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs nanocomposite films were examined in detail and found to be tunable by changing the concentration of Fe-CQDs.

Graphite powder (99.9%) was obtained from Fisher Scientific, Loughbrough, UK. Ferrous Chloride (FeCl2) was purchased from Fluka, Gothenburg, Sweden. Sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) medium viscosity, 98.5% with DS = 0.70–0.85, was purchased from Nilkanth Organics, Mumbai, India. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) and starch (soluble) were acquired from Sigma Aldrich, Burlington, MA, USA. Glycerol and citric acid were purchased from El-Nasr Co., Giza, Egypt. The chemicals were utilized without being treated.

2.2.1 Preparation of Fe-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots (Fe-CQDs)

Iron-doped carbon quantum dots (Fe-CQDs) were prepared via a microwave-assisted process using the hydrothermal treatment of graphite/iron mixture. First, a definite weight of a graphite and FeCl2 with weight ratios of 3:1 was mixed in a mortar. The resulting precursor was dispersed in distilled water and microwaved in a domestic microwave at 700 W for 7 min. The obtained suspension was centrifuged, washed, and dried in an oven, yielding Fe-CQDs.

2.2.2 Preparation of Composite Film (PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs)

The films were synthesized through the casting method, and the component ratios were selected according to Gulati et al. [33]. The PVA/S/CMC film was fabricated by separately dissolving 0.2 g CMC/10 mL H2O, 2 g PVA/starch (4:1 wt/wt)/10 mL H2O, and 0.1 citric acid/5 mL H2O. The CMC solution was added to the PVA/starch solution with stirring, followed by the citric acid solution and 0.5 mL glycerol as a plasticizer. For (PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs) nanocomposite films, Fe-CQDs were sonicated in H2O for 5 min using an ultrasonic dropper. They were added dropwise to the above mixture under mechanical stirring and stirred for 30 min with different Fe-CQDs ratios. The solution was poured into the Petri dish and evaporated at 60°C. Then, the obtained films were labeled S1, S2, S3, S4 and S5. They correspond to 0, 0.02, 0.06, 0.1 and 0.2 g of Fe-CQDs, respectively. The thickness of the films was investigated using the digital caliper with an accuracy of 0.001.

2.3.1 Fourier Transforms Infrared Spectroscopy–Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR–ATR)

The infrared spectra of the prepared films were measured using the attenuated total reflectance technique (ATR-FTIR) with a Perkin Elmer Spectrum 100 T FT-IR spectrometer (Waltham, MA, USA), equipped with a DTSG detector and a universal ATR accessory featuring a diamond/ZnSe crystal. FTIR spectra were obtained at a resolution of 4 cm−1 and an average of 4 scans per spectrum, covering the 400–4000 cm−1 range.

2.3.2 X-Ray Diffraction Analysis (XRD)

To obtain the films’ X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns, a Philips X-ray diffractometer utilizing a Cu-Kα radiation source (λ = 0.15418 nm), along with a PW 1930 generator and a PW 1820 goniometer, was utilized.

To examine the size and shape of the Fe-CQDs, a transmission electron microscope (TEM) (FEI TECNAI G2 F20-ST) running at 200 kV was employed. Fe-CQDs were dispersed in water and then drop-cast onto a copper grid coated with carbon to create the sample. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to examine the surface morphology of the fabricated film (Tescan Vega 3 SBU) Brno-Kohoutovice, Czech Republic. An accelerating voltage of 10–15 kV captured the imaging. The non-destructive energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) equipment attached to scanning electron microscopy was used to study the elemental distribution.

2.3.4 Contact Angle Measurements

The water-contact angles of the fabricated films were measured according to the ASTM (D-7334) standard test using the GA-1102 Optical Contact Angle instrument from Hunan Gonoava Instrument Co., Ltd. (Changsha, China). Each sample was tested 3 times to obtain the plotted results.

2.3.5 Mechanical Investigations

The mechanical properties of fabricated films, such as tensile strength (MPa), elongation (%), and Young’s modulus (MPa) were checked according to the TAPPI T494–06 standard method using a universal testing machine (LR10K; Lloyd Instruments, Fareham, UK) with a 100-N load cell at a constant crosshead speed of 2.5 cm/min. 5 dumbbell-shaped specimens were cut out of standard 4 mm width and 50 mm length to plot their average values. Hardness measurements were carried out using a Shore D durometer, DIN 53505, ASTM 2240.

The processed samples’ relative complex permittivity and conductivity were calculated using a Hioki 50-3532 LCR Hi Tester with a frequency range of 42 to 5 MHz. A great way to describe the electrical characteristics of polymeric materials is to use a dielectric measurement. It measures how a composite material reacts to an applied field. By using dielectric relaxation spectroscopy, it is possible to investigate how capacitance (C) and conductance (G) change with temperature and frequency. The following equation provides the value for the complex dielectric permittivity:

Dielectric constant (ε′) = dC/εoA

Dielectric loss factor (ε″) = Gd/εoAω

where A is the electrodes’ surface area, d is the sample’s thickness, εo is the space’s permittivity, and ω is the angular frequency. The specimens were cut to have length × width of 1 cm × 1 cm. The thickness was measured individually according to that of each sample.

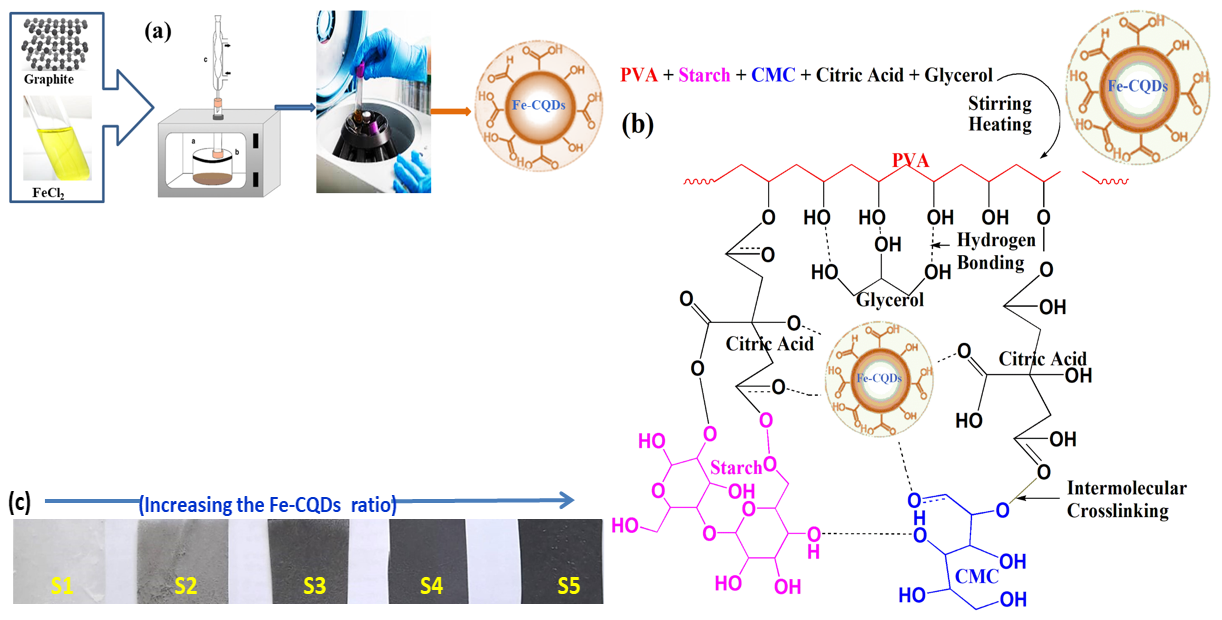

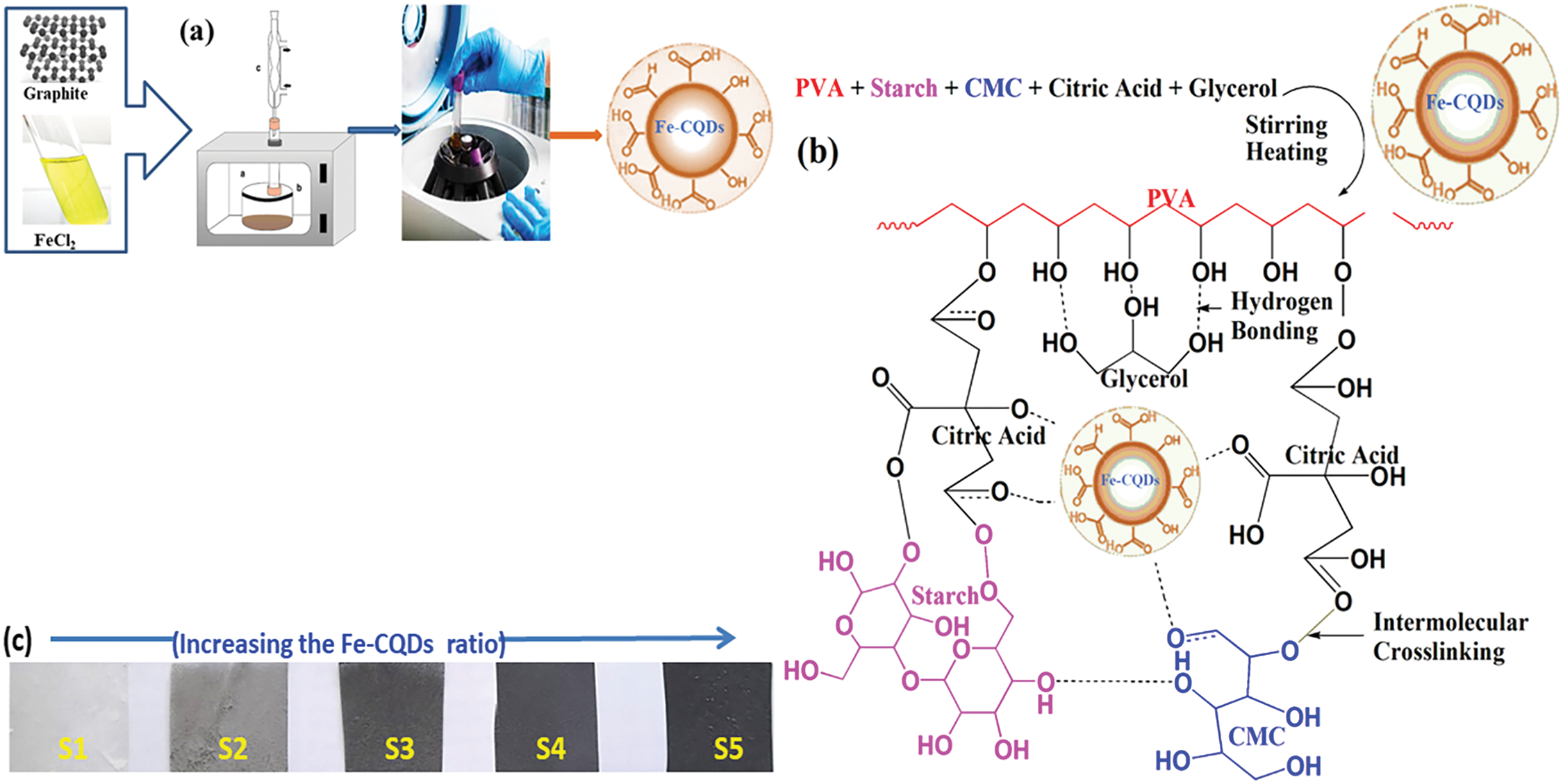

3.1 An Overview for the Synthesis of Fe-CQDs and Film Formation

This work focuses on preparing eco-friendly films with good mechanical and promising electrical properties. Consequently, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), sodium carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC), and starch were selected as biodegradable and polar polymers. Moreover, citric acid is a low-cost organic acid that contains three carboxylic groups that can react with the –OH groups of PVA, CMC, or starch, and form esters was selected as a crosslinker. While glycerol has three –OH groups, it is chosen as a plasticizer. When PVA, starch, and CMC are blended, strong hydrogen bonds between molecules are frequently formed by OH groups, which improves system integrity and synergistic stability [34,35]. Fig. 1 shows the formation of PVA/S/CMC blended film. It is anticipated that hydrogen bonding with an intramolecular, electrostatic, and chemical interaction will result from the interaction of the Fe-CQDs nanoparticles with the PVA/S/CMC blend matrix. This interaction improves the physical characteristics of these composite materials, particularly their mechanical and electrical properties. Moreover, digital photos are present in this figure, indicating the gradual change in the color of the prepared films as they become darker upon increasing the content of Fe-CQDS in the polymeric films.

Figure 1: (a) A schematic diagram for microwave assisted of Fe-CQDs synthesis, (b) PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs film structure and (c) Digital images for the prepared films

3.2 Characterization of Fe-CQDs

The FTIR spectrum of Fe-CQDs is shown in Fig. 2a. It represents a characteristic peak at 2116 cm−1 for C–O stretching vibration. Another peak is displayed at 1631 cm−1 pointing to the prepared carbon quantum dots that show sp2 hybridization from the carbon chain. Moreover, Fe-CQDs show significant peaks at 468 and 556 cm−1. They may be identified with the vibration mode of the iron-oxygen bond in the formed iron quantum dots. The vibrational Fe-O peaks are identified in the crystal lattice of the investigated Fe-CQDs. Fig. 2b illustrates the XRD pattern of the synthesized Fe-CQDs. The determined peak at 2θ = 9.7° is characteristic of the iron atom. A diffraction peak is noticed at 2θ = 16°. It refers to the graphitic feature of the carbon quantum dots at (002) with the amorphous entity of this graphitic allotrope. In addition, distinctive peaks are shown at 2θ = 26.3°, 35.1°, 43.6° and 54.3°. They refer to (220), (311), (400) and (511) respectively. The morphology of Fe-CQDs is displayed in the TEM image of Fig. 2c. It shows the spherical form of these quantum dots. Iron nanoparticles unite with carbon quantum dots to compose the desired iron-doped carbon quantum dots. It is elucidated that during the preparation through microwave processing, carbon nanoparticles are linked together forming agglomerated particles [36]. Fig. 2d demonstrates the particle size distribution of the fabricated quantum dots with an average diameter size of 8 nm.

Figure 2: (a) FTIR (b) XRD (c) TEM (d) Diameter distribution of Fe-CQDs

3.3 Characterization of the Prepared Films

3.3.1 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy–Attenuated Total Reflection (ATR–FTIR)

At ambient temperature, IR spectroscopy was employed to investigate the interaction of PCMC and PVA with the Fe-CQDs. Fig. 3 displays the ATR spectrum of PVA/S/CMC and PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs. Firstly, the characteristic band of PVA/S/CMC film is symmetrical stretching of O–H groups at 3278 cm−1. For CMC and starch an asymmetrical stretching of the C–H bonds of groups (R-CH2OH) group appears at 2921 cm−1 with asymmetrical and symmetrical stretching of the COO− group at 1587 and 1418 cm−1, respectively. Such bands may be due to the formed acetal group between CMC, starch, and PVA [37]. The main functional group of PVA reveals the vibration of the carbon skeleton in the range of 1375 to 1028 cm−1, correlating to intramolecular forces of OH and COO− groups. A stretching of C–O–C at 1016 cm−1 can be referred to as the existence of oxygen permitting the intermolecular hydrogen bonding in CMC, starch, and PVA. A stretching for the C=O bond in the acetyl group of PVA arises at 1731 cm−1. Secondly, in the PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDS film, the previously discussed bands for the investigated polymeric substrates appear in addition to new ones denoting the loaded iron quantum dots. Two notable peaks are located at 465 and 557 cm−1, referring to the vibration of bonding between iron and oxygen.

Figure 3: FTIR of PVA/S/CMC and PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs films

The XRD pattern of PVA/S/CMC is displayed in Fig. 4. It ranges from pure PVA at ambient room temperature from 3° to 80°. PVA and starch possess a sharp diffraction peak at 18.8°. It corresponds to (110) reflection denoting an orthorhombic lattice, as shown in Fig. 4a. CMC reveals a change of its amorphous structure to a crystalline upon being blended with PVA. CMC shows a less intense to relatively broad diffraction peak at 39.7°. These polymers indicated effective compatibility concerning broadening the peak intensity after being blended. In addition, they exhibit a semi-crystalline formation as they come into view at crystalline and amorphous domains. The XRD pattern of PVA/S/CMC nanocomposite loaded with Fe-CQDs displayed the diffraction peaks of these doped quantum dots that cope with the discussed results of Fig. 2b. Fe-CQDs show a peak at 26.3°. Moreover, characteristic peaks arise at 39.7° and 54.3°, confirming the presence of doped iron in the carbon quantum dots as displayed in Fig. 4b. Additionally, the existence of iron as magnetite in the prepared quantum dots is inset in Fig. 4c representing the peaks with card number 96-900-2333 for iron.

Figure 4: XRD of (a) PVA/S/CMC, (b) PVA/S/CMC/Fe-CQDs films and (c) Fe-CQDs

3.3.3 Surface Morphology and EDX Analyses

Fig. 5 investigates the morphological features of the PVA/S/CMC and PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs films. The SEM micrograph of the polymeric blend shows a homogenous interaction between the existing polymeric components. It refers to an ongoing amorphous microstructure of the blend system without phase separation. Few pores emerge in the polymeric network resulting from physical or chemical crosslinks between the macromolecular chains. PVA, starch, and CMC originate free radicals. Subsequently, they link together to produce a crosslinked network structure. Hence, this polymeric substrate possesses an acceptable miscibility due to the generated hydrogen bonding between the present polymers. Notably, the EDX peaks for PVA, starch, and CMC are represented in their major C and O elements at 0.28 and 0.5 keV, respectively. Another peak appears at 2.1 keV, referring to gold as a coating layer for the investigated samples. The SEM image of PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs nanocomposite shows a homogenous structure with white spots referring to the introduced Fe-CQDs. Few cracks appear due to the restricted motion of CMC chains inside the PVA grid. The EDX spectrum shows the same characteristic peaks represented for the PVA/S/CMC blend in addition to new ones. These peaks are apparent at 0.7, 6.4, and 8.9 which refer to an iron element of the Fe-CQDs in the tested film.

Figure 5: SEM of PVA/S/CMC and EDX of PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs

3.3.4 Contact Angle Measurements

Surface wettability is an essential feature in determining the changes in the affinity of the samples toward water. Fig. 6 shows the contact angle measurements of water droplets with digital photos for each investigated sample. This test has been carried out to track the hydrophilic and hydrophobic characteristics of PVA, starch, and CMC before and after introducing Fe-CQDs. Commonly, the contact angles of the PVA/S/CMC showed a decrement in their values upon increasing the content of Fe-CQDs to them. PVA, starch (water-soluble), and CMC are hydrophilic organic polymers. They show a contact angle value of 28° with the highest wettability. The hydroxyl group is the major functional one in the PVA and starch chains. Hence, these polymers can compose hydrogen bonds with water. Moreover, CMC possesses hydrophilic carboxylic groups that bond powerfully with water. Upon inserting the modified carbon quantum dots into the PVA, starch, and CMC matrix, the contact angle values elevated steadily upon raising the quantum dots’ concentration. This observation points to the hydrophobic nature of the used Fe-CQDs which decreases the wettability of the explored polymer-based nanocomposites. The structure, surface roughness, and chemical composition of the composite films affect the wettability to a large extent. The concentration of ions affects the formation of the polymeric network structure. Various metal ions have different capabilities [38] to set bonds with the COO− or OH groups of the polymeric chains.

Figure 6: Contact angle measurements of PVA/S/CMC and PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs films

PVA, CMC, and starch are polar polymers. Thus a composite comprising these polymers is likely to produce films with excellent mechanical properties. The mechanical properties of polymeric substrates depict various experimental parameters. Among these characters, tensile strength reveals the opposition to the breaking process upon applying a certain load on the polymer. Elongation at break % shows the maximum length to which the polymer can be stretched under constant force. Moreover, Young’s modulus demonstrates the stress and strain relationship of the polymer. In Fig. 7, the mechanical properties of PVA/S/CMC films in the absence and presence of Fe-CQDs are shown. The tensile strength (TS) of the prepared films showed increasing values ranging from 16.3 to 29.4 MPa, as displayed in Fig. 7a. This change in TS values may be correlated to the interface between PVA, starch, and CMC during the blending process. It impacts the orientation of the polymeric chains. Sometimes, this transformation can promote the sliding or fracture of these polymers during the stretching process. Hence, it can be noticed that the loading of Fe-CQDs decreased the flexibility by diminishing the elongation at break % values (Fig. 7b) with some changes in the structure and mechanical characteristics. For the same reason, elevated tensile strength and Young’s modulus (Fig. 7c) values can be monitored. In addition, using glycerol in these composites contributes in enhancing the mechanical properties. The PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs nanocomposite films revealed a higher Young’s modulus. This finding denotes adequate strength in conserving the properties of these films. The improvement in the mechanical properties of these films may be attributed to the existence of Fe-CQDs. These quantum dots showed the capability of their interaction with the polymeric matrix via van der Waals forces or ionic linkages without diminishing the polymeric structure.

Figure 7: (a) Tensile strength; (b) Elongation %; (c) Young’s modulus of PVA/S/CMC and PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs films

Various applications can be monitored via mechanical properties such as hardness. The latter properties rely on many factors, such as chain stiffness and intermolecular forces of the contributing polymers. From the results, it can be noticed that PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs nanocomposite films expressed higher hardness values than that of PVA/S/CMC film, as shown in Fig. 8. Hardness increases with increasing the content of nanofiller in the investigated films. It resisted the resistance of the cracking force in the polymer. This augmentation may be correlated to the spread of the used quantum dots, limiting the mobility of polymer chains. In this case, the matrix can avoid deformation. Consequently, the filler content enhanced the performance of the prepared composites.

Figure 8: Hardness of PVA/S/CMC and PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs films

3.3.6 Dielectric and Ac-Conductivity Investigations

The dielectric and conductivity of the prepared compositions were studied on about eight frequency decades ranging from 0.1 Hz to 10 MHz. Fig. 9 illustrates the frequency dependence of the dielectric constant, ε′, on frequency. The higher frequency range starting from 10 kHz reduces the composition and frequency effect on the dielectric constant (ε′). This behavior reflects the lag of fluctuation of all kinds of polarizations behind the alteration of the applied electric field.

Figure 9: Dielectric constant against frequency (log-log scale) of PVA/S/CMC and PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs films at ambient temperature

The lower frequency range, starting from 10 kHz and going down to 0.1 Hz, shows two trends in this behavior. The first trend goes down to 10 Hz, showing a linear increase in the dielectric constant with decreasing frequency. It reflects the combination of conductivity and polarization dynamics affected by metallic moieties [39,40]. The range from 10 Hz down to 0.1 Hz shows a clear decrease in the rate of change. The raised questionhere is: Does this anomalous behavior reflect the contribution of electrode polarization? To clarify such point, the ac-conductivity is presented against frequency in Fig. 10. The higher frequency shows the frequency dependence on the conductivity. It follows the well-known power law (PL) down to a characteristic frequency hopping (fh), which characterizes the hopping time of the free charge carriers. In other words, the higher the hopping frequency, the shorter the hopping time, hence the higher the dc-conductivity.

Figure 10: Ac-conductivity against frequency (log-log scale) of PVA/S/CMC and PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs films at ambient temperature

The conductivity in the less dependent range characterizes the dc-conductivity of the investigated samples. It varied between 0.261 and 0.723 µS/cm (at spot frequency point 1 kHz) as Fe-CQDs increased. As the frequency decreases from 10 Hz, the conductivity shows a remarkable decrease. This phenomenon is due to the buildup of the double layers at the electrodes, or what is usually called electrode polarization (EP). This feature reflects the ability of the investigated samples’ ability to be applied in the electrical energy storage application. Introducing Fe-CQDs into PVA/S/CMC contributed to elevating the electric conductivity values for this blend due to the existence of iron. The hydroxyl groups in these polymers assisted in delocalizing p electrons. Thus, donating electrons may take place by lowering the electron density. The present matrix forms a donor-acceptor system as Fe-CQDs are loaded. Hence, charge carriers may be initiated with enhanced energy levels due to the presence of these quantum dots, which have an important influence in promoting electron transfer. The growth in the mobility of charge carriers can contribute to improve the conductivity [41,42]. In this manner, further work should be carried out considering the compositions and measuring temperatures to enhance the ability of the materials to store electrical energy.

The casting method was effectively used in this work to produce nanocomposite (PVA/S/CMC@Fe-CQDs) films. The morphological, mechanical, and electrical behaviors were studied. The SEM/EDX examination demonstrated the adhesion and dispersion of Fe-CQDs in the PVA/S/CMC matrix. The mechanical behavior of films was significantly enhanced by the incorporation of Fe-CQDs into the PVA/S/CMC matrix. Because of the increased density of crosslinking behavior, Young’s modulus and strength at break rose dramatically as the concentration of Fe-CQDs inside the nanocomposite increased. The contact angle steadily increased as the number of Fe-CQDs increased because of the network structure that formed between the PVA/S/CMC chains and the Fe-CQDs particles. Furthermore, a thorough analysis of the nanocomposite film’s electrical behavior revealed that the concentration of Fe-CQDs adjusted it. The design of electronic devices is one possible use for the PVA/S/CMC/Fe-GQDs nanocomposite films.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the National Research Centre (NRC), Egypt for the support in performing this research activity.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Ahmed M. Khalil and Samir Kamel have the same contribution in conceptualization, draft preparation, investigations, writing, and editing. Lekaa K. Abdul Karem, Badriah Saad Al-Farhan, Ghada M. G. Eldin contributed in data collection, investigations, writing, and revising. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mahmood RS, Salman SA, Ali Bakr N. The electrical and mechanical properties of Cadmium chloride reinforced PVA: PVP blend films. Pap Phys. 2020;12:120006. doi:10.4279/pip.120006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Taghizadeh MT, Sabouri N, Ghanbarzadeh B. Polyvinyl alcohol: starch: carboxymethyl cellulose containing sodium montmorillonite clay blends; mechanical properties and biodegradation behavior. SpringerPlus. 2013;2(1):376. doi:10.1186/2193-1801-2-376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Al-Muntaser AA, Pashameah RA, Sharma K, Alzahrani E, Hameed ST, Morsi MA. Boosting of structural, optical, and dielectric properties of PVA/CMC polymer blend using SrTiO3 perovskite nanoparticles for advanced optoelectronic applications. Opt Mater. 2022;132(49):112799. doi:10.1016/j.optmat.2022.112799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hussien HAJ, Hashim A. Synthesis and exploring the structural, electrical and optical characteristics of PVA/TiN/SiO2 hybrid nanosystem for photonics and electronics nanodevices. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. 2023;33(8):2331–45. doi:10.1007/s10904-023-02688-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Dennis JO, Shukur MF, Aldaghri OA, Ibnaouf KH, Adam AA, Usman F, et al. A review of current trends on polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based solid polymer electrolytes. Molecules. 2023;28(4):1781. doi:10.3390/molecules28041781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Waly AL, Abdelghany AM, Tarabiah AE. Study the structure of selenium modified polyethylene oxide/polyvinyl alcohol (PEO/PVA) polymer blend. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;14(5):2962–9. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.08.078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Abdelghany AM, Ayaad DM, Mahmoud SM. Antibacterial and energy gap correlation of PVA/SA biofilms doped with selenium nanoparticles. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2020;10(5):6236–44. doi:10.33263/BRIAC105.62366244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Turky G, Moussa MA, Hasanin M, El-Sayed NS, Kamel S. Carboxymethyl cellulose-based hydrogel: dielectric study, antimicrobial activity and biocompatibility. Arab J Sci Eng. 2021;46(1):17–30. doi:10.1007/s13369-020-04655-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang L, Zhao J, Li F, Jiao X, Yang B, Li Q. Effects of amylose and amylopectin fine structure on the thermal, mechanical and hydrophobic properties of starch films. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;282(3):137018. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.137018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Avérous L. Biodegradable multiphase systems based on plasticized starch: a review. J Macromol Sci Part C Polym Rev. 2004;44(3):231–74. doi:10.1081/MC-200029326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Asnag GM, Awwad NS, Ibrahium HA, Moustapha ME, Alqahtani MS, Menazea AA. One-pot pulsed laser ablation route assisted Molybdenum trioxide nano-belts doped in PVA/CMC blend for the optical and electrical properties enhancement. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater. 2022;32(6):2056–64. doi:10.1007/s10904-022-02257-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Aziz SB, Brevik I, Hamsan MH, Brza MA, Nofal MM, Abdullah AM, et al. Compatible solid polymer electrolyte based on methyl cellulose for energy storage application: structural, electrical, and electrochemical properties. Polymers. 2020;12(10):2257. doi:10.3390/polym12102257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Cyriac V, Ismayil, Noor IM, Mishra K, Chavan C, Bhajantri RF, et al. Ionic conductivity enhancement of PVA: carboxymethyl cellulose poly-blend electrolyte films through the doping of NaI salt. Cellulose. 2022;29(6):3271–91. doi:10.1007/s10570-022-04483-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Alshammari FH. Electrical conductivity of polyvinyl alcohol/carboxymethyl cellulose doped by zinc oxide and hematite nanoparticles for optoelectronics devices. Inorg Chem Commun. 2024;168(8):112855. doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Fan X, Zhang G, Li J, Shang Z, Zhang H, Gao Q, et al. Study on foamability and electromagnetic interference shielding effectiveness of supercritical CO2 foaming epoxy/rubber/MWCNTs composite. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2019;121:64–73. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2019.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sher F, Ziani I, Smith M, Chugreeva G, Hashimzada SZ, Prola LDT, et al. Carbon quantum dots conjugated with metal hybrid nanoparticles as advanced electrocatalyst for energy applications—a review. Coord Chem Rev. 2024;500(4):215499. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Emam HE. Carbon quantum dots derived from polysaccharides: chemistry and potential applications. Carbohydr Polym. 2024;324(70):121503. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Latif Z, Shahid K, Anwer H, Shahid R, Ali M, Lee KH, et al. Carbon quantum dots (CQDs)-modified polymers: a review of non-optical applications. Nanoscale. 2024;16(5):2265–88. doi:10.1039/D3NR04997C. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. El-Shal MA, Hendawy HAMH, Eldin GMG, El-Sherif ZA. Application of nano graphene-modified electrode as an electrochemical sensor for determination of tapentadol in the presence of paracetamol. J Iran Chem Soc. 2019;16(5):1123–30. doi:10.1007/s13738-018-01585-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Si QS, Guo WQ, Wang HZ, Liu BH, Ren NQ. Carbon quantum dots-based semiconductor preparation methods, applications and mechanisms in environmental contamination. Chin Chem Lett. 2020;31(10):2556–66. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2020.08.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhu P, Liu Y, Tang Y, Zhu S, Liu X, Yin L, et al. Bi-doped carbon quantum dots functionalized liposomes with fluorescence visualization imaging for tumor diagnosis and treatment. Chin Chem Lett. 2024;35(4):414–9. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2023.108689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Salman BI, Hassan AI, Al-Harrasi A, Ibrahim AE, Saraya RE. Copper and nitrogen-doped carbon quantum dots as green nano-probes for fluorimetric determination of delafloxacin; characterization and applications. Anal Chim Acta. 2024;1327:343175. doi:10.1016/j.aca.2024.343175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Mahdi SH, Karem LKA. Synthesis, characterization, anticancer and antimicrobial studies of metal nanoparticles derived from Schiff base complexes. Inorg Chem Commun. 2024;165(4):112524. doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2024.112524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Benjamin I, Ekpong BO, Abdullah HY, Agwamba EC, Anyambula IA, Adedapo SA, et al. Surface modification of transition metals (TM: Mn, Fe, Co) decorated Pt-doped carbon quantum dots (Pt@CQDs) nanostructure as nonenzymatic sensors for nitrotyrosine (a biomarker for Alzheimerperspective from density functional theory. Mater Sci Semicond Process. 2024;174(3):108245. doi:10.1016/j.mssp.2024.108245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Abdalsahib NM, Karem LKA. Preparation, characterization, antioxidant and antibacterial studies of new metal (II) complexes with Schiff base for 3-amino-1-phenyl-2-pyrazoline-5-one. Int J Drug Deliv Technol. 2023;13(1):290–6. doi:10.25258/ijddt.13.1.47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Arsalan G, Mohsen J, Hamid E. Synthesis of carbon quantum dots and Fe-doped carbon quantum dots as fluorescent probes via one-step microwave process for rapid and accurate detection of diclofenac sodium. J Clust Sci. 2023;35(1):237–51. doi:10.1007/s10876-023-02480-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Tammina SK, Yang D, Koppala S, Cheng C, Yang Y. Highly photoluminescent N, P doped carbon quantum dots as a fluorescent sensor for the detection of dopamine and temperature. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2019;194:61–70. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2019.01.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Elugoke SE, Uwaya GE, Quadri TW, Ebenso EE. Carbon quantum dots: basics, properties, and fundamentals. In: Berdimurodov E, Verma DK, Guo L, editors. Carbon dots: recent developments and future perspectives. Washington, DC, USA: ACS Publications; 2024. p. 3–42. [Google Scholar]

29. Lv L, Fan Y, Chen Q, Zhao Y, Hu Y, Zhang Z, et al. Three-dimensional multichannel aerogel of carbon quantum dots for high-performance supercapacitors. Nanotechnol. 2014;25(23):235401. doi:10.1088/0957-4484/25/23/235401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen G, Wu S, Hui L, Zhao Y, Ye J, Tan Z, et al. Assembling carbon quantum dots to a layered carbon for high-density supercapacitor electrodes. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):19028. doi:10.1038/srep19028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Zhu H, Wang X, Li Y, Wang Z, Yang F, Yang X. Microwave synthesis of fluorescent carbon nanoparticles with electrochemiluminescence properties. Chem Commun. 2009;7(34):5118–20. doi:10.1039/b907612c. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Choi Y, Thongsai N, Chae A, Jo S, Kang EB, Paoprasert P, et al. Microwave-assisted synthesis of luminescent and biocompatible lysine-based carbon quantum dots. J Ind Eng Chem. 2017;47:329–35. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2016.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Gulati K, Lal S, Arora S. Synthesis and characterization of PVA/Starch/CMC composite films reinforced with walnut (Juglans regia L.) shell flour. SN Appl Sci. 2019;1(11):1416. doi:10.1007/s42452-019-1462-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Bella GR, Jeba JRS, Avila TBS. Polyvinyl alcohol/starch/carboxymethyl cellulose ternary polymer blends: synthesis, characterization and thermal properties. Int J Curr Res Chem Pharm Sci. 2016;3(6):43–50. [Google Scholar]

35. Khalil AM, Kamel S. Microwave-assisted acetylated lignin loaded into cellulose acetate for efficient UV-shielding films. J Renew Mater. 2025;13(2):401–12. doi:10.32604/jrm.2024.057419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Schwenke AM, Hoeppener S, Schubert US. Synthesis and modification of carbon nanomaterials utilizing microwave heating. Adv Mater. 2015;27(28):4113–41. doi:10.1002/adma.201500472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Mansur HS, Sadahira CM, Souza AN, Mansur AAP. FTIR spectroscopy characterization of poly (vinyl alcohol) hydrogel with different hydrolysis degree and chemically crosslinked with glutaraldehyde. Mater Sci Eng C. 2008;28(4):539–48. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2007.10.088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Abdel-Rahman LH, Basha MT, Al-Farhan BS, Shehata MR, Abdalla EM. Synthesis, characterization, potential antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticancer, DNA binding, and molecular docking activities and DFT on novel Co(IINi(IIVO(IICr(IIIand La(III) Schiff base complexes. Appl Organomet Chem. 2022;36(1):e6484. doi:10.1002/aoc.6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Al-Farhan BS, Gouda GA, Farghaly OA, EL Khalafawy A. Potentiometeric study of new Schiff base complexes bearing morpholine in ethanol-water medium with some metal ions. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2019;14(4):3350–62. doi:10.20964/2019.04.38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Aml MA, Mona AM, Ghada MGE, Rupesh KM, Abdelhamid E. Self-assembled ruthenium decorated electrochemical platform for sensitive and selective determination of amisulpride in presence of co-administered drugs using safran in as a mediator. Microchem J. 2021;164:106061. doi:10.1016/j.microc.2021.106061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Sood Y, Singh K, Mudila H, Lokhande PE, Singh L, Kumar D, et al. Insights into properties, synthesis and emerging applications of polypyrrole-based composites, and future prospective: a review. Heliyon. 2024;10(13):e33643. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e33643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Sood Y, Mudila H, Katoch A, Lokhande PE, Kumar D, Sharma A, et al. Eminence of oxidants on structural-electrical property of polypyrrole. J Mater Sci Mater Electron. 2023;34(18):1401. doi:10.1007/s10854-023-10834-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools