Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Integration of Biopolyesters and Natural Fibers in Structural Composites: An Innovative Approach for Sustainable Materials

1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Mataram, Mataram, 83125, Indonesia

2 Department Research Center for Biomass and Bioproducts, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Jl. Raya Bogor Km 46, Cibinong, Bogor, 16911, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Nasmi Herlina Sari. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Valorization of Lignocellulosic Biomass for Functional Materials)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(8), 1521-1546. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0058

Received 13 December 2024; Accepted 25 February 2025; Issue published 22 August 2025

Abstract

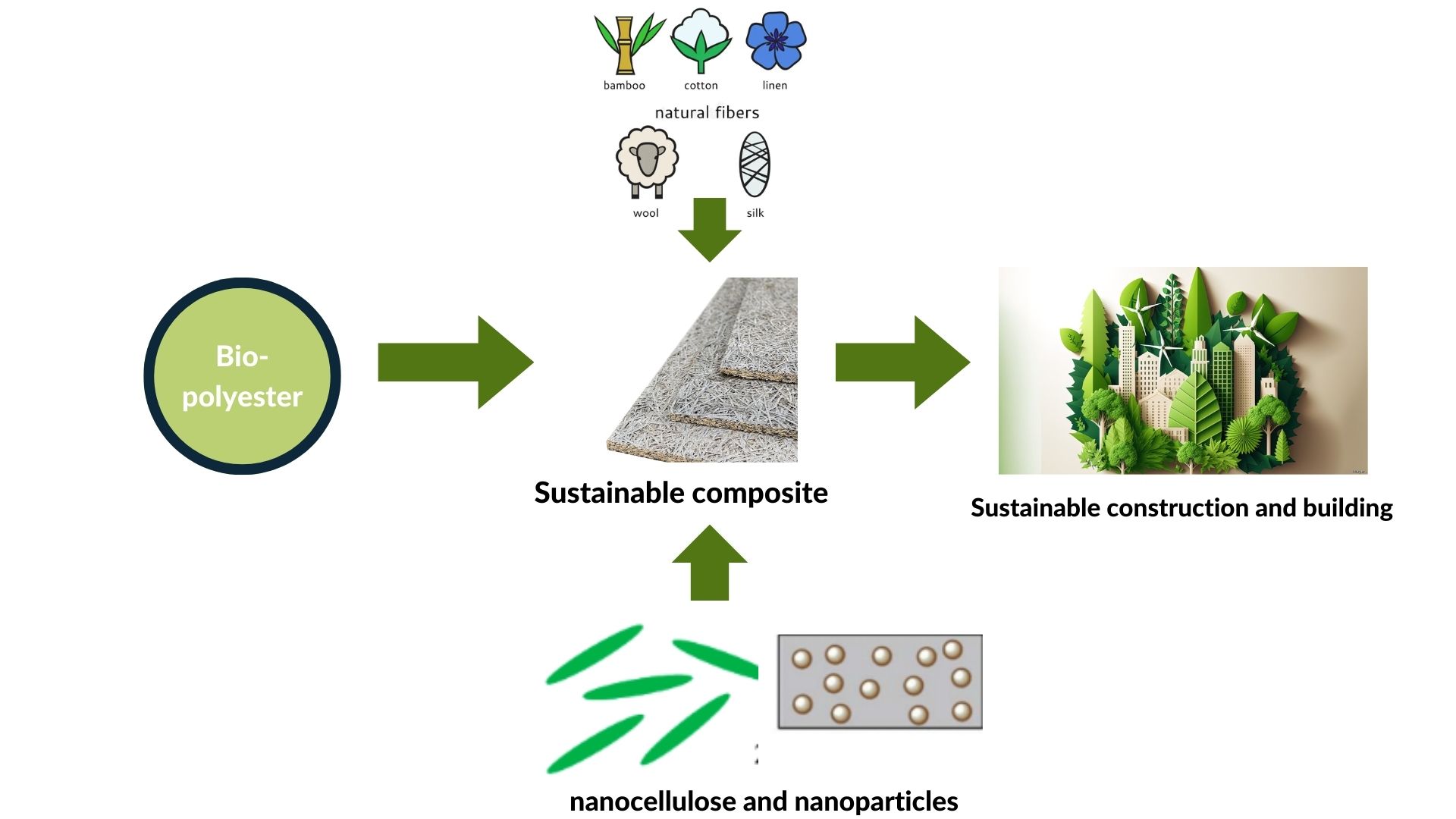

Composites made from biopolymers and natural fibers are gaining popularity as alternative sustainable structural materials. Biopolyesters including polylactic acid (PLA), polybutylene succinate (PBS), and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA), when mixed with natural fibers such as kenaf, hemp, and jute, provide an environmentally acceptable alternative to traditional fossil-based materials. This article examines current research on developments in the integration of biopolymers with natural fibers, with a focus on enhancing mechanical, thermal, and sustainability. Innovative approaches to surface treatment of natural fibers, such as biological and chemical treatments, have demonstrated enhanced adhesion with biopolymer matrices, increasing attributes such as tensile strength and rigidity. Furthermore, nano filling technologies such as nanocellulose and nanoparticles have improved the attributes of multifunctional composites, including heat conductivity and moisture resistance. According to performance analysis, biopolymer-natural fiber-based composites may compete with synthetic composites in construction applications, particularly in lightweight buildings and automobiles. However, significant issues such as degradation in humid settings and long-term endurance must be solved. To support a circular economy, solutions involve the development of moisture-resistant polymers and composite recycling technology. This article examines current advancements and identifies problems and opportunities to provide insight into the future direction of more inventive and sustainable biocomposites, and also the dangers they pose to green technology and industrial materials. These findings are significant in terms of the development of building materials which are not only competitive but also contribute to global sustainability.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The worldwide environmental crisis, which is defined by climate change, plastic waste, and limited resources, has fueled the demand for sustainable materials. Fossil-based products, such as traditional plastics, contribute to non-biodegradable trash and increase carbon footprint [1–4]. In response, biopolymers and natural fibers have emerged as promising options for creating ecologically friendly composites that may be used in a variety of structural applications [5,6]. Biopolymers like polylactic acid (PLA), polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA), and polybutylene succinate (PBS) have competitive mechanical properties and are biodegradable in the environment, making them ideal candidates for promoting a circular economy [7–10]. Furthermore, these biopolymers have gained popularity because of their potential to be manufactured from renewable biomass and exceptional biodegradability. Biopolymers, as a matrix in composites, have good compatibility with fibers from plants, making them great candidates for replacing synthetic materials in construction and vehicles [11]. Natural fibers such as kenaf, ramie, and Ficus macrocarpa have advantages in the form of abundant availability, thin, and good mechanical durability [12,13], so combining them with biopolymers can produce composites that are not only biodegradable but additionally have superior structural performance and extend the material’s service life in certain applications.

Previous research has demonstrated that biopolymer-based composites and natural fibers have a high potential to replace synthetic materials in a variety of industries, including automotive, construction, and household appliances [11,14,15]. This is primarily owing to these materials’ ability to form composites with high mechanical strength (tensile and flexural strength) and good thermal qualities (controlled thermal conductivity and thermal stability). For example, Ochi [16] discovered that incorporating kenaf fiber into a PLA matrix resulted in a composite with a tensile strength improvement of up to 30% above pure PLA, but hemp fibers improve rigidity in other biopolymer matrices [17,18]. Furthermore, the lightweight, cheap, and renewable character of the fibers, and also the biodegradability of biopolymers, make these materials suitable for use in promoting a circular economy and preserving the environment [11,18]. Despite their numerous advantages, significant technological hurdles continue to impede the mainstream implementation of these materials. The primary difficulty is poor adhesion between a biopolymer matrix and natural fibers, that is frequently caused by variations in chemical characteristics and surface energy. Poor adhesion can impair load transfer efficiency between composite components, lowering overall mechanical performance. In addition, the hydrophobic nature of biopolymers frequently contrasts with the hydrophilic makeup of natural fibers, resulting in increased moisture absorption and mechanical property loss under humid conditions [19,20]. To circumvent these limits, modification strategies such as the use of nanoparticles as extra fillers, silanization of fiber surfaces, and the addition of compatibilization agents have shown promising results [21–23]. For example, plasma or nano-coating modification of fiber surfaces has been shown to increase fiber-matrix interactions, leading to composites with better moisture resistance and mechanical qualities [24,25]. As a result, developing these creative procedures is vital to ensuring the materials’ long-term performance. In addition to technological hurdles, manufacturing process optimization is a primary priority for biopolymer-natural fiber-based composites at the industrial scale [26]. Further research is required to better understand the link between material composition, manufacturing characteristics, and composite performance. This may include research on manufacturing procedures like injection molding and compression molding, that can alter fiber distribution and interfacial strength. At the same time, these materials’ multifunctional features, which include biodegradability and thermal resistance, make them suitable for a broader range of applications, such as the green energy and electronics industries. A strategic move that not only provides technical answers but also supports international sustainability programs is the creation of composite materials based on biopolymers and natural fibers. Effective biopolymer and natural fiber integration are anticipated to lessen adverse environmental effects while promoting the industrial shift to green technology.

Furthermore, Rzhepakovsky et al. [27] discussed the construction of a biocompatible scaffold made of bacterial cellulose and gelatin composites for tissue engineering. This work emphasizes the significance of biopolymer materials in biomedical applications, particularly scaffolding that promotes tissue growth and regeneration. Although this study concentrated on bacterial cellulose and gelatin, the data support using polymers like PLA, PHA, and PBS in your research. This is due to the fact that all three polymers have similar biocompatible and biodegradable qualities, making them great candidates for use in tissue engineering and sustainable material development. Thus, incorporating PLA, PHA, and PBS into this work is consistent with the current trend in the creation of biopolymer scaffolds for biological applications and sustainable materials.

As a result, the purpose of this literature review is to look at the most recent advances in the combination of biopolyesters and natural fibers, such as fiber chemical modification, the growth of biopolyesters that are more robust to harsh circumstances, and enhanced production processes. Furthermore, an evaluation of the mechanical and thermal characteristics of these biopolyesters will be performed to identify the key problems that must be overcome, as well as to provide in-depth insights into the potential of these renewable composites in modern structural applications.

2 Biopolymers in Structural Composites

2.1 Types of Biopolyesters Used

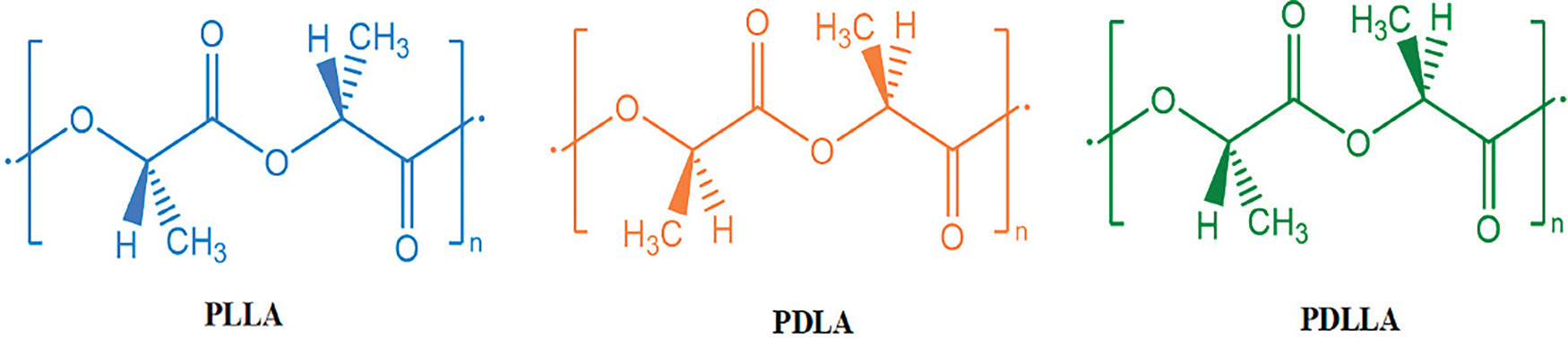

The biodegradable characteristics of PLA and its derivation from renewable resources including corn starch, sugarcane, cassava, and sugar beet make it a popular biopolymer in the creation of sustainable structural composites. According to Wu et al. [7], PLA is typically produced using the lactide ring-opening polymerization (ROP) technique, which yields three primary stereo configurations (Fig. 1): racemic polylactic acid (PDLLA), right-handed polylactic acid (PDLA), and left-handed polylactic acid (PLLA). Significant variations exist between these stereo arrangements in terms of crystallinity, thermal performance, and particular applications. Because of its more uniform deterioration, PDLA is frequently utilized in medical applications, whereas PLLA, which has a high crystallinity, is appropriate for structural applications that call for stiffness. Applications requiring high flexibility typically use PDLLA, which is amorphous [28].

Figure 1: Three-dimensional configuration of PLA [7]

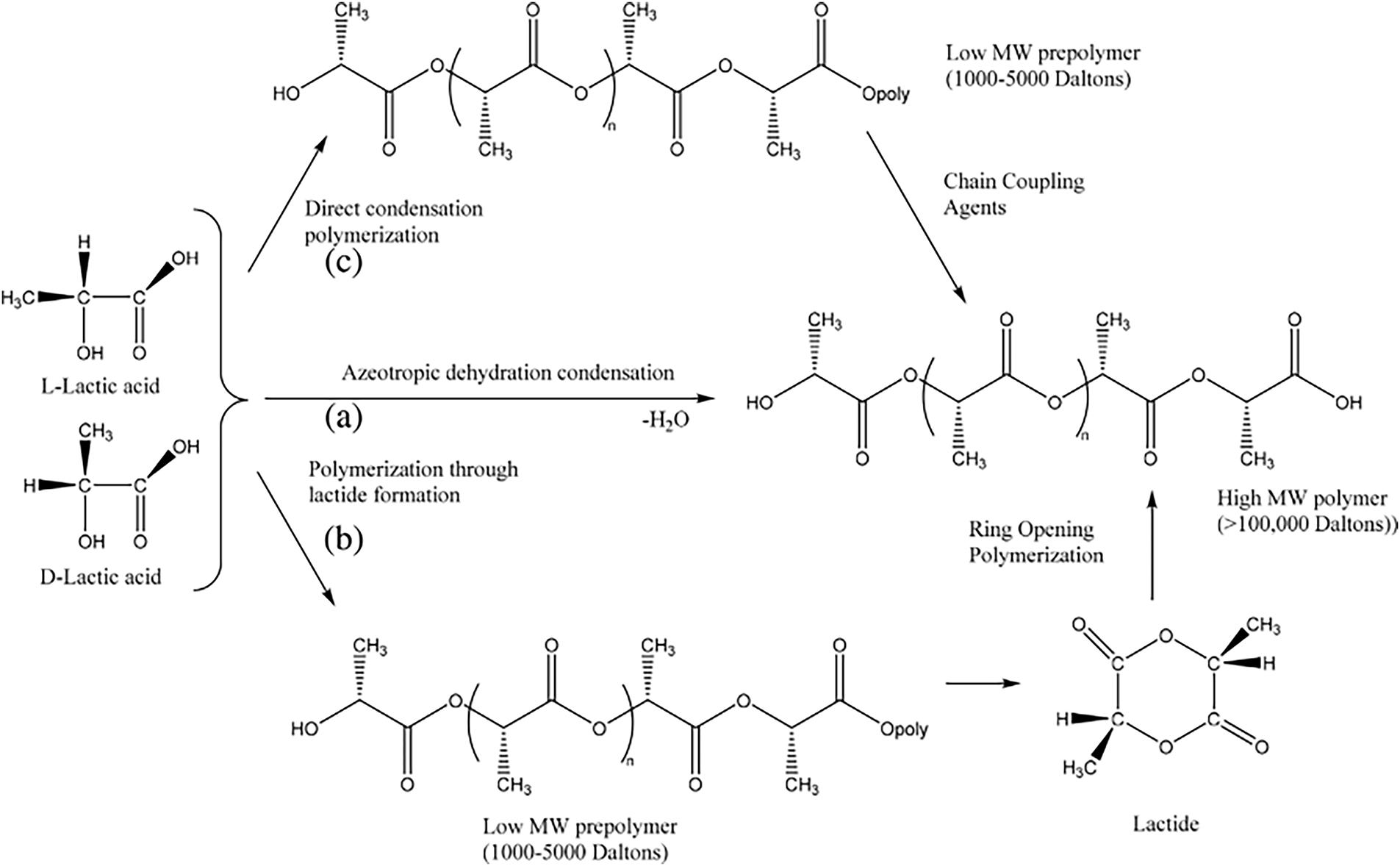

Polylactic acid (PLA) is a thermoplastic aliphatic polyester derived from renewable sources such as corn, cassava, sugarcane, and sugar beet starch. The production process is divided into three stages: saccharification, fermentation, and ring-opening polymerization [26]. This approach enables the manufacture of PLA with a high molecular weight and narrow molecular weight distribution while also facilitating the elimination of byproducts such as water [29]. When compared to other biopolymers, PLA has better mechanical and thermal performance due to these features. However, the PLA synthesis process is more difficult and requires high-quality raw ingredients, contributing to PLA’s high production costs and market pricing [28]. To improve manufacturing efficiency, several PLA synthesis methods have been developed, such as direct condensation polymerization and lactide ring-opening polymerization (ROP). The immediate condensation polymerization method is a simpler approach for producing PLA, however it generally results in low molecular weight. In contrast, the ROP approach employs lactone monomers as precursors, giving PLA a high molecular weight and more consistent characteristics, but it necessitates tighter reaction control and higher initial material costs [30]. Furthermore, the ROP approach is thought to be preferable since it reduces the generation of byproducts that can degrade PLA purity. Fig. 2 depicts a detailed comparison of multiple PLA synthesis methods, including the main process routes and each method’s pros and limitations. The process begins with L-lactic acid and D-lactate as monomers and proceeds through three major pathways: azeotropic dehydration condensation, which produces low-molecular-weight (1000–5000 Dalton) prepolymers (Fig. 2a), lactide formation via cyclization (Fig. 2b), or direct polymerization via condensation. Chain-linking agents can be used to extend low-molecular-weight prepolymers into high-molecular-weight (>100,000 Dalton) polymers. Alternatively, the generated lactide can be polymerized by ring-opening to generate high-molecular-weight PLA. This procedure exhibits the versatility in manufacturing PLA with desired properties using several synthesis strategies.

Figure 2: Polylactide (PLA) is synthesized from lactic acid in three steps: (a) azeotropic dehydration condensation to produce low molecular weight prepolymer, (b) lactide formation followed by ring-opening polymerization to produce high molecular weight PLA, and (c) direct condensation polymerization [7,29]

In addition to being less harmful to the environment, PLA is produced using 25% to 55% less fossil fuel than polymers derived from petroleum. Because PLA is transparent, highly biocompatible, low toxicity, and amenable to standard processing techniques like extrusion and injection molding, it is the preferred material for non-construction applications like consumer goods, medical devices, and packaging. PLA has good mechanical qualities, including a tensile strength of 50–70 MPa, an elongation at break of approximately 4%, an impact strength of about 2.5 kJ/m2, and a Young’s modulus of about 4 GPa at ambient temperature. Methyl groups (CH3) give it hydrophobic qualities, which also contribute to its quite high-water resistance. However, PLA’s use in a variety of applications is limited. Pure PLA has poor melt strength, a low melting point, and is brittle. Pure PLA has a very high air flammability and the potential to create flammable liquids because to its low oxygen index of 18% [30–32]. The sluggish rate of crystallization in PLA-based composites poses a significant problem in their manufacture, which might have a negative impact on their mechanical and thermal properties. To remedy this, researchers have investigated a variety of ways, including combining PLA with other polymers, integrating nanoparticles, and reinforcing it with natural fibers. These techniques improve interfacial bonding, crystallization behavior, heat stability, and mechanical strength, making the composites more appropriate for demanding structural applications [30,31]. These developments increase PLA’s utilization of green technology and more intricate multipurpose materials while also enhancing its performance in structural applications.

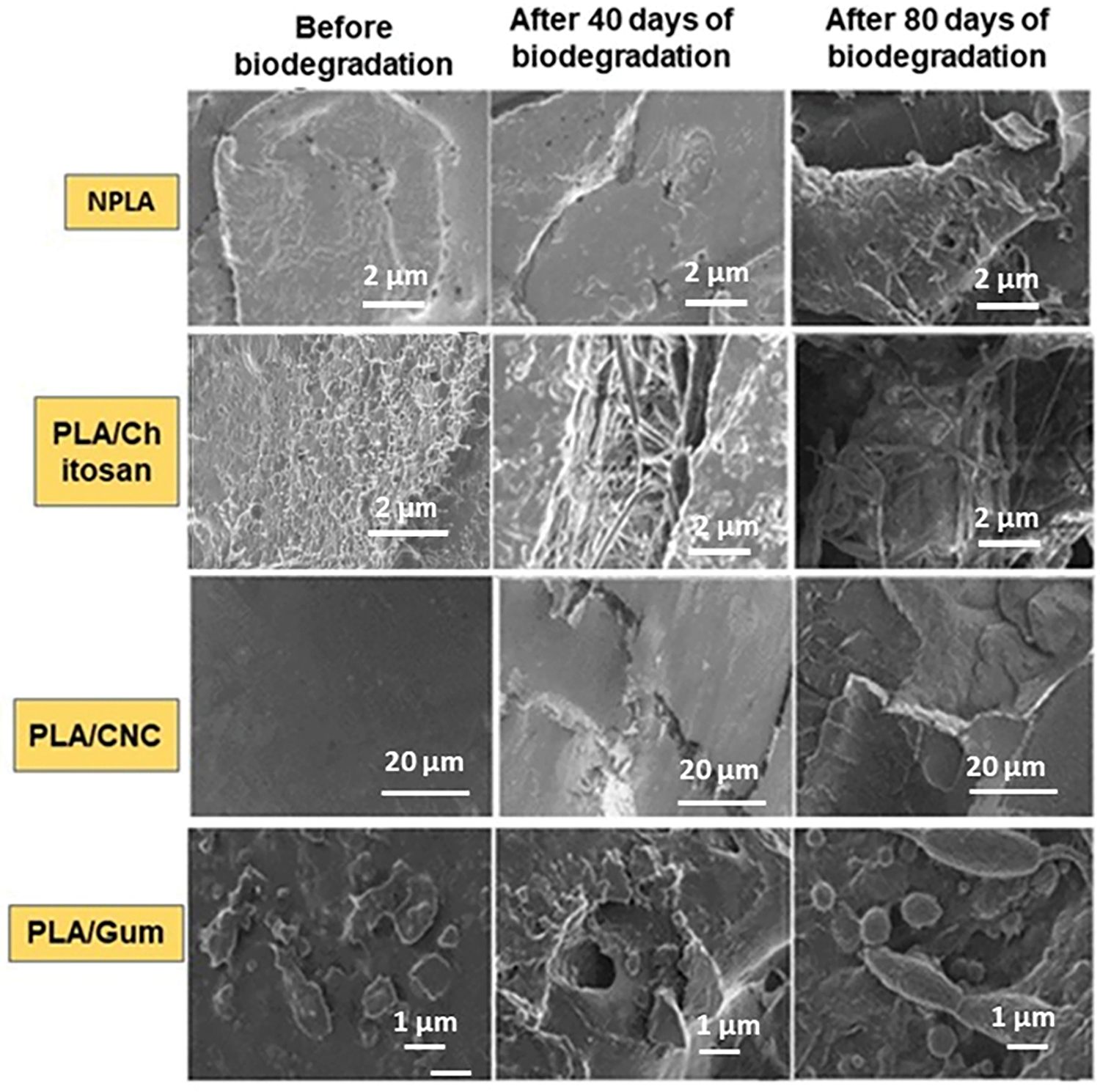

PLA is frequently used as a matrix for natural fibers in structural composites because of the fiber’s ability to improve mechanical performance while using fewer petroleum-based ingredients. However, PLA has several limits that must be addressed, particularly its resilience to high temperatures and humidity, which can impact its mechanical and thermal properties [28]. To address these issues, several experiments have been done to improve the durability of PLA through chemical modification or inclusion with fillers or other reinforcing elements, such as nanoparticles or natural fibers. For example, Fig. 3 shows an example of deterioration on the outside of a PLA-based green biocomposite. These morphological alterations were noticed between the 40th and 80th days of the compost process. During the biodegradation process, intermediates were formed as a result of microbial absorption in the amorphous zone and hydrolysis. This resulted in the formation of large holes and cracks on the polymer surface and a cross-section during the biodegradation process, which is connected with microbial action or creation of biofilm on the polymer surface and cell diffusion to the polymers core, causing surface erosion and leaving voids in the PLA. This displacement of the films during biodegradation also shows that microorganisms first ingest small chains, and subsequently target long crystal chains via chain scission processes [33]. These morphological changes also demonstrate that this new type of PLA-based composite is biodegradable in controlled composting settings.

Figure 3: Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) images of the different test samples before and after biodegradation under composting conditions [33]

The coupling of PLA with natural fibers like kenaf, hemp, and jute has been proven to improve composite tensile strength and resistance to thermal deformation [12]. Despite significant limitations, PLA remains the primary choice for developing more environmentally acceptable biopolymer-based structural composites [34].

2.1.2 Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA)

PHAs are a class of biopolymers created organically by microorganisms through the fermentation from renewable organic resources. They have good biodegradability qualities and have the potential to be used in structural composites. When compared to other biopolymers such as polylactic acid (PLA), PHAs such as polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) and polyhydroxyvalerate (PHV) have advantages in terms of mechanical strength, agility, and moisture resistance [8,23]. PHAs are particularly appealing for structural applications because of their capacity to biodegrade in the environment, offering them a greener option to petrochemical-based synthetics. A number of studies have shown that PHAs can replace traditional plastics in a variety of applications, including packaging, medical products, and renewable fiber-based composites [35].

Although PHA has several advantages, one disadvantage is that it is more expensive to produce than other biopolymers like PLA. As a result, recent research has focused on the development of superior fermentation techniques as well as the identification of less expensive renewable raw material sources. PHA is commonly utilized as a matrix for natural fibers in composites due to its ability to promote flexibility and resilience to deterioration [36]. Kumar Sachan et al. [8] discovered that composites made with PHA/natural fibers, like kenaf or jute fibers, have higher mechanical strength and function better in humid environments than PLA-based composites. Although production costs are a key impediment, PHA’s potential as a base material to promote sustainable structural composites remains enormous, particularly with advancements in production technology and material formulation optimization.

2.1.3 Polybutylene Succinate (PBS)

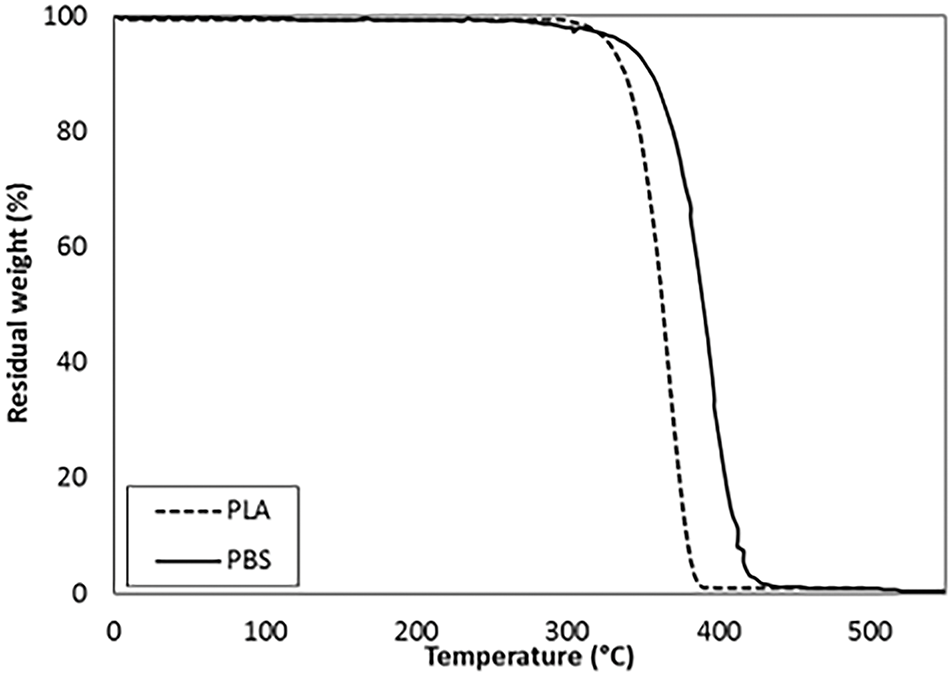

PBS is an aliphatic biopolymer made by polymerizing succinic acid with 1,4-butanediol. It has outstanding mechanical qualities and is very biodegradable. PBS has more flexibility and high-temperature tolerance than other biopolymers that includes PLA, making it an appealing candidate for construction composite applications [37]. One of the most significant advantages of PBS is its ability to maintain strong mechanical qualities even in humid settings, which other biopolymers struggle with. Furthermore, PBS has a low melting point, making standard processing techniques like as injection and extrusion easier and more efficient. PBS is more thermally stable than PLA, with beginning thermal breakdown temperatures of around 340°C and 328°C, respectively. Fig. 4 displays the results of the thermogravimetric analysis of PLA and PBS.

Figure 4: Thermal stabilities of PLA and PBS [37]

PBS is frequently mixed with natural fibers in structural composites to enhance material performance and reduce reliance on petroleum-based polymers. Song et al. [26] discovered that PBS-based composites reinforced with kenaf or hemp fibers have greater tensile strength and elastic modulus than PLA or PHA-based composites. Furthermore, natural fibers improve thermal and mechanical deformation resistance in PBS composites, which makes them more competitive for long-term structural applications. The primary problem, however, is achieving effective integration among the PBS matrix and natural fibers, that frequently necessitates fiber surface modification or the application of binding agents to promote material adhesion. Further research in this field focuses on improving performance and establishing more efficient and environmentally friendly PBS manufacturing processes, hence increasing the material’s potential in long-term structural composite applications.

Besides from PLA, PHA, and PBS, numerous other biopolyesters have considerable potential in sustainable structural composite applications [26,38]. One of them is poly trimethylene terephthalate (PTT), a terephthalic acid and 1,3-propanediol-based biopolymer with outstanding mechanical properties, extreme temperature resistance, and water resistance. PTT’s greater melting point than PLA and PBS allow it to be used in buildings that require stronger heat resistance. Furthermore, PTT is resistant to oxidation and degradation, which increases the longevity of biopolymer-based composites in a broader variety of applications such as automotive and construction. Other biopolyesters, like bio-based polyamides (bio-PA), are garnering interest in sustainable structural composites, according to recent research. Bio-PA, which is made from renewable raw materials including castor oil, offers comparable mechanical strength, high temperatures resistance, and durability to synthetic polyamides. Composites of bio-PA and natural fibers, including kenaf and sisal fibers, have been proven to improve mechanical performance while also providing a solution to minimize reliance on petrochemical-based polymers. Despite other biopolyesters are still in the research and development stage, the increasing trend shows that the utilization of biopolyesters in structural composites offers a promising alternative to sustainable materials with properties nearly equivalent to conventional petroleum-based materials, while also making a significant contribution to reducing the industry’s carbon footprint [39,40].

2.2 Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Biopolymers

2.2.1 Tensile Strength, Elastic Modulus, and Thermal Resistance

The mechanical properties of biopolymers, particularly tensile strength and elastic modulus, play a critical role in determining their performance in structural composites. Biopolymers such as PLA and PHA exhibit relatively high tensile strengths compared to conventional synthetic plastics but have lower elastic moduli, which limits their use in applications requiring high rigidity [35,36,40]. For instance, PLA’s tensile strength can reach 50–70 MPa, while its elastic modulus ranges from 2–4 GPa. To overcome these limitations, reinforcing PLA with natural fibers like kenaf or hemp has proven effective in enhancing both tensile strength and elastic behavior, with composites showing significantly better performance than pure PLA [15,41]. Thermal stability is another critical factor, particularly for applications requiring resistance to elevated temperatures. PLA’s operating temperature limit of 60°C–70°C restricts its use in high-temperature environments. However, alternatives such as PBS and PTT demonstrate improved thermal resistance, with PBS exhibiting a melting point of approximately 115°C. PBS-natural fiber composites have shown the ability to retain structural integrity under high temperatures, making them suitable for construction and automotive applications that endure harsh conditions [11]. Surface modification of natural fibers further enhances the integration of fibers with biopolymer matrices, improving both mechanical and thermal properties. Techniques such as silane treatments or resin plating strengthen adhesion, resulting in composites with up to 30%–40% greater tensile strength compared to unmodified counterparts [38,42,43]. Combining such surface modification approaches with tailored matrix formulations optimizes the performance of biopolymer composites, enabling their use in diverse structural applications.

2.2.2 Comparison with Conventional Synthetic Polymers

The mechanical and thermal properties of biopolymers differ greatly from those of synthetic polymers such as polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and polystyrene. While PE and PP have tensile strengths of 30–40 MPa and elastic moduli of 1–2 GPa, biopolymers like PLA and PHA have comparable tensile strengths but lower elastic moduli, which restricts their use in rigid structural applications [10,44]. Furthermore, PLA’s low heat resistance limits its applicability in high-temperature applications.

However, biopolymers provide different advantages in terms of sustainability and environmental effect. Natural fiber reinforcement improves mechanical performance significantly, closing the gap between biopolymers and artificial polymers. PLA-based composites reinforced with kenaf or hemp fibers, for example, show up to a 50% increase in tensile strength, making them suitable for lightweight, environmentally friendly applications [10]. Further advances, such as increased crystallinity, crosslinking, and chemical changes, have helped to improve biopolymer mechanical and heat resistance. These tactics not only improve performance, but also encourage the use of petrochemical-based materials in applications like lightweight building and transportation, reducing dependency on nonrenewable resources [35,43,45,46].

2.3 Biopolymer Modification for Performance Improvement

2.3.1 Reinforcement with Nanoparticles and Bio Additives

Biopolymer reinforcement with nanoparticles and bio-additives has emerged as a viable strategy for improving the mechanical and thermal properties of biopolymer-based composites. Metal nanoparticles (e.g., silver and copper nanoparticles), carbon nanoparticles (e.g., graphene and carbon nanotubes), and silica-based nanoparticles have all been shown to significantly improve the tensile strength, thermal resistance, and deformation resistance of biopolymers like PLA and PHA [10]. For example, adding graphene nanoparticles to a PLA matrix can boost the composite’s tensile strength by up to 40% and elastic modulus by 50%. These nanoparticles improve the composite’s microstructure, stress distribution, and tolerance to high temperatures [47,48]. This reinforcement is critical for applications that demand materials with excellent performance, like automotive components or construction projects that must withstand intense loads and temperatures.

In addition to nanoparticles, bio-additives are increasingly being employed to enhance the functionality of biopolymers in structural composites. Bioadditives including cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) fibers, the tannins, and natural plant polymers can boost the mechanical strength and thermal endurance of biopolymers [49,50]. For example, adding CNCs to the PLA matrix greatly boosted tensile strength and thermal stability due to the interaction among nanostructured fibers and the polymer matrix, resulting in stronger connections [51,52]. The use of bio-additives not only increases composite performance but also strengthens the material’s sustainability, as these additives are produced from renewable, biodegradable sources. Overall, the reinforcement strategy using nanoparticles and bioadditives offers a solution for increasing the value of biopolymers in high-performance structural composite applications while adhering to sustainability and environmental principles.

2.3.2 Copolymerization or Blending Techniques

Copolymerization and blending procedures have been shown to improve biopolymers’ mechanical and thermal properties. Composites with greater tensile strength, temperature resistance, and flexibility can be created by combining biopolymers such as PLA with PHA, starch, or even synthetic polymers like PP. PLA-PHA mixes, for example, have better deformation resistance and temperature endurance than pure PLA, outperforming it in structural applications [10]. Copolymerization not only blends monomers, but also inserts functional groups that improve stability and thermal resistance. Copolymerizing PLA with lactic acid, for example, produces materials with increased heat tolerance, which is critical for applications that require strong thermal performance. These methodologies allow for the production of biopolymers customized to specific uses, such as automotive and construction, while reducing reliance on petroleum-based resources and promoting sustainability.

3 Natural Fibers as Reinforcements in Structural Composites

3.1 Types of Natural Fibers Used

3.1.1 Kenaf, Jute, Hemp, Sisal, and Nanocellulose

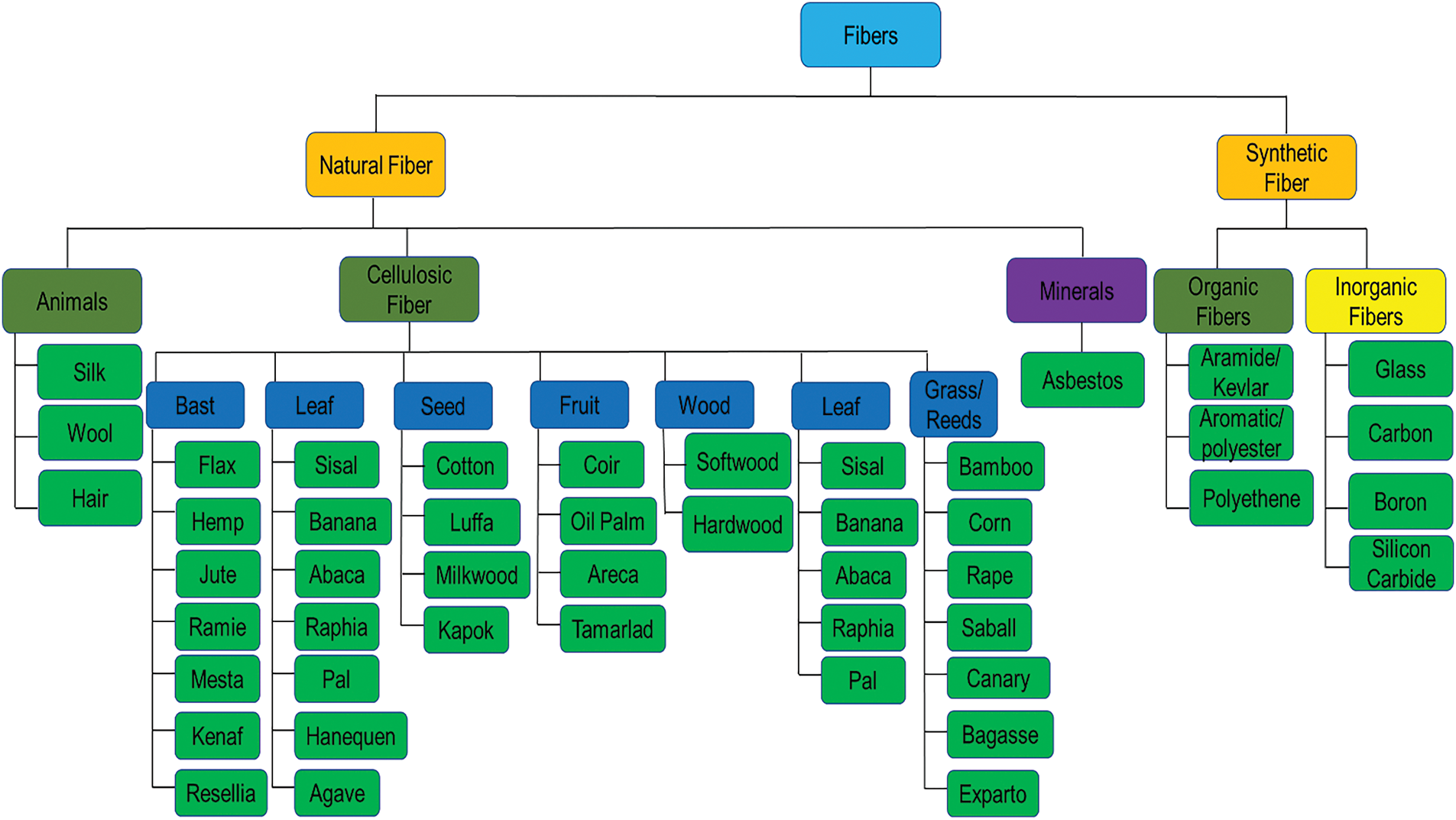

Because they are lightweight, sustainable as a renewable resource, and have strong mechanical qualities, natural fibers like kenaf, jute, ramie, and sisal have drawn a lot of interest in the production of structural composites, in detail presented in Fig. 5. For instance, kenaf has a high tensile strength and may be applied to construction and automotive settings. Kenaf fiber composites offer better elastic modulus and tensile strength than other natural fiber composites, making them an excellent alternative for structural applications. The production of composite panels has also made extensive use of jute and ramie fibers, which are known for their inexpensive manufacture. Composites made of these fibers have better load-bearing resistance and higher compressive strength than those made of other natural fibers. Because of its exceptional resilience to extreme weather, sisal is also becoming more and more popular. This makes it a perfect material for structural applications in the automotive and construction industries [53,54].

Figure 5: Types of natural fiber and synthetic fibers [55]

To enhance mechanical and thermal qualities, nanocellulose is being utilized more and more in structural composites in addition to traditional natural fibers. Plant fibers are hydrolyzed to produce nanocellulose, which has a very strong and light microstructure and modifiable functional qualities that enhance composite performance [49,55]. The addition of nanocellulose to biopolymer matrices like as PLA or PHA has been proven to considerably boost their tensile strength and temperature tolerance while being sustainable [10]. Furthermore, nanocellulose can be used as a reinforcing in natural fiber-based composite matrices, improving the interaction among the fibers and the polymer matrix, thus improving the composite’s overall performance. Overall, the utilization of natural fibers in structural composites, that include kenaf, jute, ramie, sisal, and nanocellulose, has significant potential for generating sustainable materials with excellent properties, appropriate for applications requiring high mechanical strength and endurance.

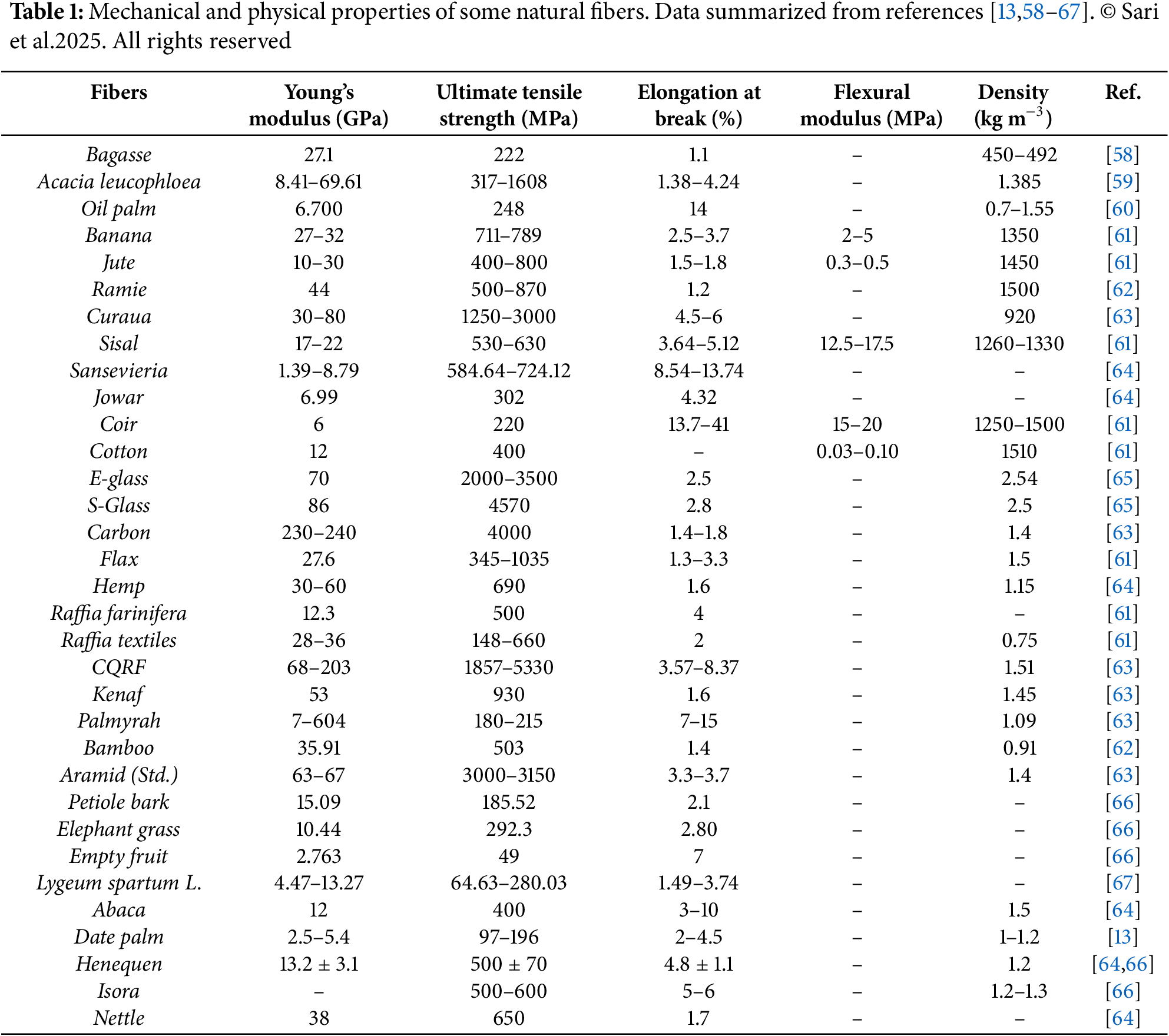

3.1.2 Comparison of Mechanical Properties of Different Natural Fibers

The mechanical properties of several natural fibers must be compared before choosing the best materials for structural composite applications. Natural fibers have varying tensile strengths, elasticity moduli, and load resistance, all of which influence the performance of composites, whose details are shown in Table 1. Kenaf, jute, and sisal fibers all have relatively high tensile strengths, although kenaf performs better in particular applications, such as automotive and building. Kenaf-based composites outperformed jute and sisal fibers in terms of tensile strength and elastic modulus [56,57]. This makes kenaf a preferable alternative for applications requiring higher mechanical strength, however, jute and sisal can still be used for smaller loads. In addition, Ramie fiber is also noted for its great mechanical strength, with multiple tests indicating that it is more load resistant than jute and sisal fibers, but slightly lower than kenaf. Composites using hemp fibers has been known have higher tensile strength and resistance to repeated stresses than jute and sisal-based composites. However, because of its brittleness, hemp is harder to process, making it less suitable for structural composite applications. Thus, the selection of natural fiber types is heavily influenced by the specific application needs and operational circumstances, with fibers such as kenaf and hemp being more suitable for applications that require higher mechanical strength, and jute and sisal being more suitable for inexpensive and light-load applications.

3.2 Surface Modification of Natural Fibers

3.2.1 Chemical Treatment (Alkalization, Silanization)

Chemical treatments on natural fiber surfaces, such as alkalization and silanization, are beneficial in enhancing the binding strength between cellulose fibers and polymer matrixes in structural composites. Table 2 provides a detailed comparison of the chemical compositions of natural fibers. Alkalization, which involves treating fibers with an alkaline solution that includes sodium hydroxide (NaOH), aims to eliminate hemicellulose and lignin while increasing fiber surface, hence improving fiber adherence to the polymer matrix [21,68–70]. Alkalizing kenaf fibers boosted the tensile strength of the resultant composites by increasing the density and homogeneity of the fiber surface, enabling greater contact with the polymer matrix. Furthermore, alkalization reduced the non-uniformity of fiber shape, which has the potential to enhance the composites’ mechanical and thermal properties [21,71–73]. The reaction in fiber during alkali treatment based on:

(Fiber – OH + NaOH) → (Fiber – O–Na+ + H2O)

Silanization, on the other hand, is the process of applying silane chemicals to natural fiber surfaces to generate a thin layer. Silanes can form covalent bonds with the fiber surface and give more reactive functional groups, improving compatibility with the polymer matrix. Zhang et al. [74] discovered that silanizing hemp fibers resulted in considerable gains in the tensile strength and waterproofing of PLA composites. This silane compound was also demonstrated to lessen reliance on environmental humidity, which is a common issue for natural fibers. Natural fiber-based composites were more resistant to environmental conditions including dampness and high temperatures after this treatment [56,68]. Overall, chemical treatments like alkalization and silanization are excellent options for improving the performance of natural fiber-based structural composites, resulting in higher strength, water resistance, and resistance to environmental impacts.

3.2.2 Physical Treatment (Plasma, Nano Coating)

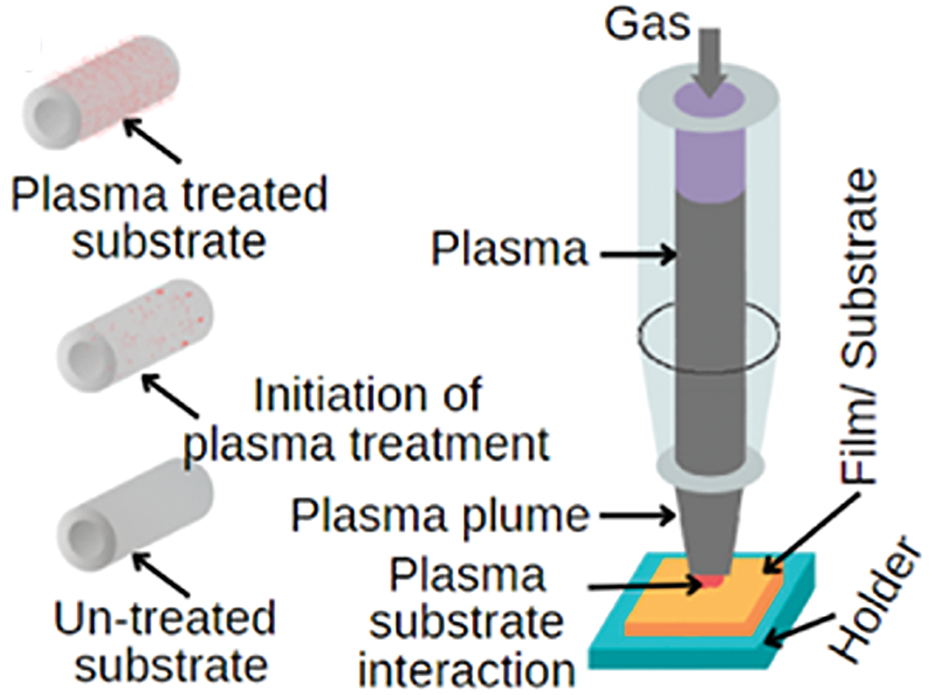

Physical treatments on natural fiber surfaces, including plasma treatment and nano-coating, have emerged as potential strategies for improving the mechanical characteristics and adhesion of natural fibers to polymer matrices in structural composites. Plasma treatment (Fig. 6), which uses ionized gas to change the fiber surface, can increase surface roughness and introduce more polar functional groups into the fibers. Kenaf fibers treated with oxygen plasma were shown to have increased adhesion to PLA-based polymer matrices, leading in increased composite tensile strength and water resistance [24,25,79]. Plasma treatment may decrease dependency on chemical processes, provide a more ecologically friendly alternative, and alter the surface features of fibers without affecting the underlying fiber structure.

Figure 6: Physical treatments for fiber modification with plasma treatment [80]

In spite of plasma treatment, nano-coating on the exterior of natural fibers has been proposed as a means of improving composite performance. Nano-coating is a technique that uses a thin layer of substances that consist of metal, carbon, or tiny particles of silica to boost environmental resistance and mechanical strength in composites. Hemp fibers coated with titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticles have been demonstrated to improve thermal resistance, ultraviolet (UV) radiation resistance, and tensile strength in biopolymer composites [81,82]. Nano-coating may additionally boost waterproofing and mechanical wear resistance, both of which are significant difficulties in outdoor applications. Therefore, physical treatments like plasma and nanocoating provide efficient ways to enhance the natural fibers’ mechanical qualities and resilience to environmental influences in structural composites.

3.3 Matrix-Fiber Adhesion: Challenges and Solutions

3.3.1 Effect of Surface Modification on Adhesion

Surface modification of natural fibers improves the adhesion between the fibers and the polymer matrix, and this is a significant aspect of assessing the performance of biopolymer-based structural composites. Recent research has demonstrated that both physical and chemical treatments on the fiber surface may enhance interphase interactions, boost adhesion, and lower the likelihood of failure at the fiber-matrix interface. According to Kumar et al. [69], alkalization of kenaf fibers can improve bonding among the fibers and the PLA matrix by introducing hydroxyl groups on the outside of the fiber, increasing polarity and affinity to the polymer matrix. This increases the composite’s tensile strength and resists deformation. Silanization of jute fibers has been found to improve adhesion to polyamide matrices, resulting in considerable improvements in composite mechanical properties and stability [83]. Furthermore, physical surface changes like plasma treatment and nanocoating have also been demonstrated to improve matrix-fiber adhesion. Jute fibers treated with oxygen plasma have been discovered to have increased surface roughness, which enhances physical adhesion with bioplastic-based polymer matrices [24]. Nano-coating, such as silica nanoparticles on fibers, enhances adhesion by altering the interfacial layer and improving adhesive strength. Furthermore, physical treatments can improve the composite’s durability to environmental conditions such as humidity and high temperatures, which commonly decrease the durability of natural fiber-based composites. As a result, an appropriate surface modification strategy is required to improve fiber-matrix adhesion in structural composites, making it a successful option for improving the performance and durability of sustainable composites.

3.3.2 Increasing Cohesion between Composite Components

For composites made of natural fiber and biopolymers to perform at their best, component cohesion must be increased. Increased mechanical strength and improved resilience to harsh loads and environmental conditions are made possible by the composite’s strong matrix and natural fiber cohesion. The use of chemically altering natural fibers, such as silanization or alkalization, to increase the cohesiveness among the fiber and the matrix is one strategy that has been extensively researched. Alkalizing kenaf fibers removes lignin and hemicellulose from the fiber the outside, enabling for improved contact between the fibers and the polymer matrix, boosting composite cohesiveness and lowering the danger of phase separation [54,84]. Silanization of jute fibers is known to cause cross-linking between the outer section of the fibers and the PLA-based polymer matrix, resulting in a significant increase in cohesiveness and resistance to environmental stress [21,29]. Aside from chemical alteration, modern methods of manufacture like nanomaterial-based composites are a viable way to improve cohesiveness. The use of silica nanoparticles into PLA matrices has been found to improve composite component compactness, with the nanoparticles acting as extra reinforcements to promote chemical and physical interactions with natural fibers [42,84]. Furthermore, processing techniques like as 3D printing can be employed to create more integrated structures with more equal fiber distribution in the polymer matrix, hence minimizing flaws and boosting component cohesion. As a result, a combination of fiber surface modification, nanomaterial use, and innovative processes can provide a successful way for enhancing cohesion in biopolymer and natural fiber-based composites, increasing their competitiveness in sustainable structural applications [79,85].

4 Performance of Biopolymer-Natural Fiber Composites

4.1 Mechanical Properties of Composites

4.1.1 Tensile Strength, Flexural Strength, Stiffness, and Impact Resistance

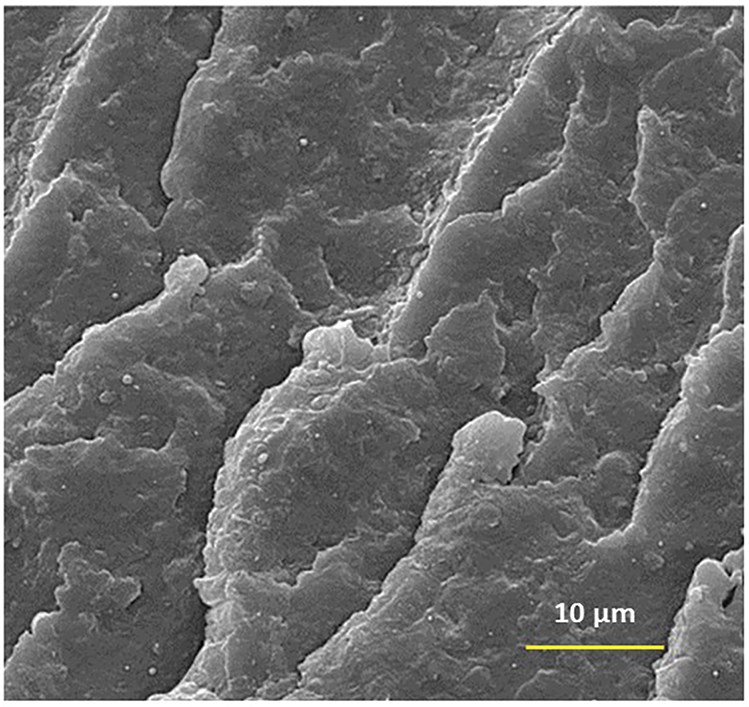

Tensile and flexural strength are key indicators of the mechanical performance of biopolymer-natural fiber composites. Studies have demonstrated that incorporating natural fibers such as kenaf, jute, or ramie into biopolymers like PLA and PBS significantly enhances these properties. For example, alkalized PLA-kenaf fiber composites show a 30% improvement in tensile strength compared to pure PLA, while PBS-hemp fiber composites with surface-modified fibers exhibit superior flexural strength due to enhanced fiber-matrix adhesion [2,31,37,86–88]. Fig. 7 depicts the microstructure of an optimal biopolymer composite formulation by Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of a 50:50 blend of PLA and PBS polymers. This microstructure demonstrates the uniform distribution of the polymer matrix as well as the potential for inter-component interactions, both of which are critical for boosting the composite’s mechanical performance. The combination of these two biopolymers, along with natural fiber reinforcing, results in a material with superior mechanical qualities suitable for a variety of applications, including construction and automotive.

Figure 7: SEM micrographs of biopolymer blend of PLA:PBS (50:50 w:w) [38]

Stiffness and impact resistance are important properties for structural applications in addition to tensile and bending strength. While biopolymer-natural fiber composites have lesser stiffness than synthetic polymer-based composites, it can be overcome through targeted changes. Nanocellulose, also known reinforcement in PLA composites boosted rigidity by up to 40% while retaining optimum flexibility. Similarly, combining biopolymers including PLA with polycaprolactone (PCL) increases impact resistance by 20%, resulting in a balanced improvement in mechanical properties [89,90]. Biopolymer composites can obtain mechanical qualities that match the requirements of structural applications while being sustainable through the combination of fiber surface treatments, nanotechnology reinforcement, and polymer blending.

4.1.2 Comparison with Synthetic Fiber-Based Composites

Due to mechanical performance differences, biopolymer-natural fiber composites are frequently compared to synthetic fiber-based composites like glass or carbon fibers. Natural fiber composites often have lower tensile strength and stiffness than synthetic fiber-based composites. PLA and kenaf fiber-based composites, on the other hand, can attain tensile strengths that are up to 70% greater than glass fiber-PLA composites, indicating competitive potential in some applications. Although natural fiber-based composites have lower flexural strength, fiber surface modification, including alkalinization or silanization, may enhance fiber-matrix adhesion [32,91].

Because natural fibers are more flexible than synthetic fiber composites, biopolymer-natural fiber composites have an advantage in terms of impact resistance. Composites made of PHA and hemp fiber are up to 25% more impact resistant than composites made of glass fiber. Natural fibers have a better energy absorption capability, which accounts for this. Composites made from synthetic fibers, on the other hand, outperform in terms of heat stability and rigidity. Nanocellulose or nanoparticle reinforcing in composites has been shown to be comparable in stiffness to synthetic fiber composites [46]. As a result, incorporating natural fibers into biopolymer composites provides an economical and sustainable solution in structural applications, particularly in terms of sustainability and reduced production costs.

4.2 Thermal Properties and Environmental Resistance

4.2.1 Thermal Stability, Thermal Conductivity, and Moisture Resistance

Biopolymer-natural fiber composites face thermal stability issues due to the natural characteristics of biopolymers and fibers, which breakdown at high temperatures. PLA reinforced with hemp fiber has a thermal stability range of 150°C–180°C, which is lower than that of other synthetic fiber composites like glass fiber. Thermal stability, however, can be increased by changing the fiber surface and employing thermal additives like carbon nanoparticles. The inclusion of graphene oxide nanoparticles to hemp fiber-PLA composites increased thermal stability by up to 20%, demonstrating that technical advancements can address this issue [48].

Biopolymer-natural fiber composites often have lower thermal conductivity than fiberglass composites, making them better suited for thermal insulation applications [87,92]. PBS-based composites reinforced with kenaf fibers have a thermal conductivity of around 0.25 W/mK, which is significantly lower than carbon fiber-based composites. Furthermore, moisture resistance is difficult to achieve since natural fibers absorb water. Fiber alkalization can reduce water intake by up to 30%, while hydrophobic coatings can significantly improve moisture resistance. As a result, with the right modifications, biopolymer-natural fiber composites may offer equivalent thermal performance and environmental resilience [85].

4.2.2 Degradation Studies Under Extreme Environmental Conditions

One of the biggest obstacles in using biopolymer-natural fiber composites for building use is material deterioration in extreme environmental conditions, such as high humidity, extreme temperatures, or alkali and acidic surroundings [37]. In humid and hot conditions, biopolymers like PLA and PHA undergo considerable hydrolysis and thermal degradation. PLA-jute fiber composites have known decreased up to 40% of their tensile strength after 30 days of exposure to 90% relative humidity at 60°C. This emphasizes the importance of heat stability and moisture resistance via biopolymer modification or the inclusion of stabilizing chemicals. Surface treatment of natural fibers with hydrophobic coatings or nanoparticles has been shown to boost degradation resistance [56] In their investigation, nanocellulose coating on kenaf fibers in PBS composites significantly improved degradation resistance in acidic and alkaline environments. Furthermore, the combination of copolymerization and additives, including natural antioxidants, can reduce the oxidative degradation process, reducing breakdown rates by up to 25% when compared to traditional composites [93]. These findings demonstrate that changes in composite formulation can greatly improve the resistance of biopolymer-natural fiber composites to harsh conditions, broadening their potential uses in difficult situations.

4.3 Multifunction of Bio Composites

4.3.1 Electrical/Thermal Conductivity and Biodegradability

The goal of creating biopolymer-natural fiber composites is becoming more and more concentrated on obtaining multifunctional qualities, such as thermal or electrical conductivity that can be coupled with biodegradability. Conductive nanoparticles like graphene or carbon nanotubes (CNTs) can be added to biopolymers with low thermal conductivity, including PLA and PHA [8,47]. When 1 weight percent CNTs were added to PLA-kenaf fiber composites, the thermal conductivity rose by 30% but the fibers remained biodegradable, as reported by Zhang et al. [47]. This work demonstrates that natural fibers serve as a medium to enhance the dispersion of nanomaterials in the biopolymer matrix, which enhances thermal properties, in addition to their mechanical reinforcement role.

Biodegradability is still a significant benefit of biocomposites over composites made of synthetic polymers, in addition to conductivity. PLA-jute fiber composites that have been treated with silver nanoparticles exhibit high biological degradation in nature within 120 days while also having antibacterial capabilities [86]. This implies that adding functional additives does not always affect the composite’s capacity to decompose naturally. Additionally, the integration of PBS-based biopolymers with nanocellulose fibers can create composites with moderate heat conductivity that continue to decompose in industrial composting settings [38], thereby increasing the range of applications in the sustainable electronics sector. The combination of these multifunctional qualities’ points to the enormous potential of biocomposites in a range of structural applications requiring for a blend of environmental sustainability and thermal or electrical performance.

4.3.2 Applications for Green Technology and Sustainability

Biopolymer and natural fiber-based composites have gained popularity as material solutions to support green technologies, particularly due to their ability to meet sustainability standards while also providing acceptable mechanical functions. Biocomposites are utilized to lower carbon footprints and substitute difficult-to-decompose synthetic materials in applications such as automotive and construction. PLA composites with sisal fibers have been found to be used in vehicle interiors, saving up to 15% of weight compared to normal petrochemical-based polymers while maintaining mechanical strength [56]. Furthermore, these composites are biodegradable, allowing for natural recycling and promoting the concept of the circular economy.

Biocomposites have been used to make miniature solar panels, wind turbines, and thermal insulation products for sustainable energy. Composites consisting of PHA and nanocellulose have been found to be effective insulators in solar cells, with a low temperature conductivity and strong moisture resistance [35]. This application not only improves energy consumption but also reduces post-use waste because these composites are biodegradable under normal settings. Furthermore, Biopolymer composites, such as PLA-based composites and carbon nanoparticles, have been used to create ecologically friendly flexible electronic devices [4]. This demonstrates that biocomposites are not only consistent with green technology requirements, but they have also emerged as a key driver in achieving worldwide sustainability.

5 Applications of Biopolymer and Natural Fiber-Based Composites

Biopolymer and natural fiber-based composites have showed considerable promise in the construction industry, particularly for the production of wall panels, structural beams, and other constructional components. Several studies have demonstrated that these composites can be a lighter, more sustainable, and ecologically friendly alternative to traditional construction materials like concrete and steel. Using PLA reinforced with jute fiber as a wall panel delivers appropriate mechanical strength for low structural applications while also increasing thermal efficiency due to the thermal insulation capabilities of natural fibers [86]. These composite-based wall panels are also moisture resistant, making them perfect for usage in high-humidity conditions. Structural beams made of PBS-based composites reinforced with kenaf fiber have been shown to be rigid enough for non-load-bearing construction applications such as wall panels [37]. These beams have a lower density than oak but have comparable tensile strength, making them appropriate for modular building systems. Another study discovered that biopolymer and nanocellulose fiber-based building elements have regulated biodegradation capabilities, allowing construction waste to disintegrate naturally after the material’s useful life has passed, supporting sustainable building design principles [34]. Overall, the use of biopolymers and natural fibers in construction provides numerous potentials to reduce environmental effect while maintaining appropriate structural performance.

Biopolymer-based composites and natural fibers are becoming more used in the automobile sector, particularly for car body frames, interior components, and acoustic insulation. PLA reinforced with hemp fiber for vehicle body components can reduce vehicle weight by up to 30% when compared to standard metal materials [81]. This weight decrease considerably increases fuel efficiency while retaining structural strength. PLA-hemp fiber is also resistant to corrosion and environmental degradation, making it a more sustainable solution. This advancement is extremely significant to the automotive trend of lightweight and ecologically efficient vehicles. Dashboards, door trims, and seats, for example, have all used biopolymer-natural fiber composites. PBS combined with sisal fiber has been shown to produce composites with good flexural strength and regulated biodegradability [42]. In the meantime, PHA-based composites including kenaf fiber have been shown to have superior sound absorption capacity for soundproofing [17,28]. This allows the composite to effectively reduce vehicle cabin noise. This composite not only promotes sustainability by lowering carbon footprints, but it also increases user comfort through increased sound insulation and heat regulation.

6 Development Challenges and Opportunities

6.1.1 Degradation in Humid and Extreme Temperature Environments

One of the most difficult difficulties in the research and development of biopolymer and renewable fiber-based composites is deterioration in humid environments and at severe temperatures. Biopolymers like PLA and PHA absorb water, reducing mechanical strength and causing delamination in composites [10]. Natural fibers, including kenaf and jute or bamboo have a high affinity for water, which speeds up the deterioration of composite structures when employed in high humidity settings. Furthermore, high temperatures can expedite biopolymer hydrolysis, resulting in a loss in its elastic modulus and tensile strength, limiting the use of these composites in harsh environments such as exterior construction or the automobile sector [86,87].

Several efforts have been undertaken to increase the stability of biocomposites in harsh weather. One method is to apply chemical treatments to fibers, such as alkalization and the silanization, which have been demonstrated to lower water absorption and enhance matrix-fiber adhesion [81,91]. Furthermore, adding nanoparticles to biopolymers, such as nano silica or clay, can improve heat resistance and slow thermal deterioration. While, Adding nanoparticles to PLA-hemp fiber composites has been shown to increase heat stability by up to 20% and reduce water absorption by up to 30% [81]. Although these findings are encouraging, manufacturing expenses and technological effectiveness remain hurdles to wider industrial-scale uses.

6.1.2 Limitations of Fiber-Matrix Adhesion and Production Costs

The limited adhesion between the fibers and the biopolymer matrix is a major challenge in the development of biopolymer and natural fiber-based composites. Biopolymers such as PLA and PBS are hydrophobic, but natural fibers have rough and polar surfaces [28,42]. This incompatibility reduces the effectiveness of load transfer among the fiber and the matrix, which lowers the composite’s tensile strength and elastic modulus. Various fiber surface modification techniques, including alkalization, silanization, and plasma treatment, have been used to improve fiber-matrix adhesion Alkalization can improve interfacial interactions and increase composite tensile strength by up to 25% [91].

In addition to adhesion issues, production costs constitute a hurdle to the use of biocomposites in larger structural applications. The production of biopolymers, such as PLA and PHA, as well as the fiber modification process, are more expensive than traditional synthetic polymers like PP or polyethylene terephthalate. Biopolymer production costs are still 30%–50% higher than synthetic polymers, owing to the greater cost of renewable raw ingredients and inefficient production procedures [18,94]. However, multiple studies have found that expanding production size and optimizing manufacturing technologies can dramatically cut production costs. Furthermore, combining low-cost bio-based additives with natural fiber waste recycling has the potential to cut costs without losing composite mechanical performance.

6.2 The Future of Bio Composites

6.2.1 Integration into the Circular Economy and Recycling Potential

Biopolymer and renewable fiber-based composites have the opportunity to be integrated into the circular economy as an idea, which involves producing, using, and recycling materials while decreasing waste and resource consumption. One of the primary benefits of biocomposites is that they degrade naturally, which allows for lower environmental consequences when the material’s useful life has ended. Reducing dependency on new raw materials and improving sustainability can be achieved by recycling PLA or natural fiber-based biocomposites into new products through appropriate recycling procedures [91,95]. The integration of biocomposites in the circular economy has the potential to reduce plastic and conventional material waste while also supporting a more ecologically friendly sector. Developing technologies for the chemical and mechanical disintegration of biocomposites is crucial to extending material life cycles and minimizing plastic pollution [96]. However, technical and economic hurdles must be addressed before recycling may be fully realized and integrated into the circular economy. According to Kumar et al. [69], despite the fact that biocomposites offer numerous benefits, their recycling technique is still more difficult than that of traditional plastics due to the strong connection between the biopolymer matrix and cellulose fibers. Technology improvement is required to more efficiently disrupt the matrix-fiber connections, either through chemical or mechanical techniques. However, advancements in recycling processes and production growth can cut costs while increasing biocomposites’ sustainability. Integration into the circular economy can also provide fresh prospects for biopolymer-based composites and organic fibers in industries such as automotive, building, and packaging, where waste disposal and recycling are major concerns.

6.2.2 Prospects of Nano-Bio Composite Technology in the Structural Industry

Nano-bio composites are one of the most prospective new paths for increasing the stability of biopolymer and renewable fiber-based composites. This method makes use of nanoparticles that include cellulose nanoparticles, nano-clay, and carbon nanotubes to enhance the mechanical, thermal, and functional characteristics of biocomposites [31,97]. Nanoparticles incorporated into a biopolymer matrix, such as PLA, could enhance tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, and resistance to moisture and high temperatures [10,42]. This nano-bio nanocomposite technology has the potential to overcome some of the disadvantages of traditional biocomposites, such as limited mechanical deformation resistance and thermal stability [98]. Furthermore, nano-bio composites can help to produce lighter, more powerful, and more durable materials, all of which are in high demand in structural industries like building and automotive. Despite the immense promise of nano-bio composite technology, production costs and application volume remain significant difficulties. To be used on an industrial scale, the production of nano-bio composites—which combine natural fibers and nanoparticles—requires technological advancements and is still fairly costly [51,95,99,100]. This also affects how competitive it is with traditional plastic fibers and composites made of polymers. Regardless, with advancements in nanotechnology and composite manufacturing, particularly in sustainable nanoparticle processing and inclusion, the possibilities for nano-bio composites are extremely promising. The use of such technology in the structural sector has the potential to result in the production of more sustainable, efficient, and high-performing materials, as well as a reduction in reliance on conventional, non-environmental raw material sources.

Incorporating polyesters and natural fibers into structural composites is a game-changing strategy for developing sustainable materials with wide-ranging applications. Biopolyesters like PLA, PHA, and PBS provide benefits such as biodegradability, sustainability, and compatibility with natural fibers, while reinforcements such as kenaf, jute, and nanocellulose improve the mechanical, thermal, and structural performance of these composites. The synergistic coupling of biopolymers and natural fibers not only increases the environmental friendliness of the materials, but it also delivers lightweight and high-strength alternatives ideal for demanding applications. Fiber surface treatments and copolymerization are two key breakthroughs in the synthesis and modification of biocomposites that have proven helpful in overcoming obstacles such as poor fiber-matrix adhesion and limited durability under humid or severe temperature conditions. Furthermore, using reinforcing agents such as nanoparticles has shown promise in improving the characteristics of biocomposites. Efforts to optimize manufacturing processes, such as the implementation of energy-efficient and scalable green technology, are critical for lowering production costs and enhancing economic viability. Future research should focus on the development of biocomposites with improved environmental resilience, particularly long-term performance under hard conditions, in order to expand their application in industries like construction, automotive, and packaging. Furthermore, researching innovative synthesis processes and recycling procedures can help biocomposites play a larger part in the circular economy, assuring their long-term viability and industrial significance.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude to University of Mataram for providing the facilities and resources necessary to conduct this research. Special thanks are extended to colleagues and collaborators who offered invaluable feedback and support during the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding Statement: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. All costs associated with the study, including materials, equipment, and publication, were covered solely by the authors.

Author Contributions: Nasmi Herlina Sari: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Methodology, Conceptualization. Suteja: Writing—review & editing, Writing—original draft, Methodology. Widya Fatriasari: Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors do not have permission to share data.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Holmberg K, Tilsted JP, Bauer F, Stripple J. Expanding European fossil-based plastic production in a time of socio-ecological crisis: a neo-Gramscian perspective. Energy Res Soc Sci. 2024;118(7):103759. doi:10.1016/j.erss.2024.103759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Elfaleh I, Abbassi F, Habibi M, Ahmad F, Guedri M, Nasri M, et al. A comprehensive review of natural fibers and their composites: an eco-friendly alternative to conventional materials. Results Eng. 2023;19(3):101271. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ihlenfeldt S, Schillberg S, Herrmann C, Vogel S, Arafat R, Harst S. Mycelium-based-composites—vision for substitution of fossil-based materials. Procedia CIRP. 2024;125:78–83. doi:10.1016/j.procir.2024.08.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Reppas-Chrysovitsinos E, Svanström M, Peters G. Estimating fossil carbon contributions from chemicals and microplastics in Sweden’s urban wastewater systems: a model-based approach. Heliyon. 2024;10(18):e37665. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37665. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Sahraeian S, Abdollahi B, Rashidinejad A. Biopolymer-polyphenol conjugates: novel multifunctional materials for active packaging. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;280:135714. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yao Y, Zhao Q, Tao Y, Liu K, Cao T, Chen Z, et al. Different charged biopolymers induce α-synuclein to form fibrils with distinct structures. J Biol Chem. 2024;300(11):107862. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2024.107862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wu Y, Gao X, Wu J, Zhou T, Nguyen TT, Wang Y. Biodegradable polylactic acid and its composites: characteristics, processing, and sustainable applications in sports. Polymers. 2023;15(14):3096. doi:10.3390/polym15143096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Kumar Sachan RS, Devgon I, Mohammad Said Al-Tawaha AR, Karnwal A. Optimizing Polyhydroxyalkanoate production using a novel Bacillus paranthracis isolate: a response surface methodology approach. Heliyon. 2024;10(15):e35398. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Turco R, Mallardo S, Zannini D, Moeini A, Serio M, Tesser R, et al. Dual role of epoxidized soybean oil (ESO) as plasticizer and chain extender for biodegradable polybutylene succinate (PBS) formulations. Giant. 2024;20:100328. doi:10.1016/j.giant.2024.100328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ilyas RA, Sapuan SM, Kadier A, Kalil MS, Ibrahim R, Atikah MSN, et al. Properties and characterization of PLA, PHA, and other types of biopolymer composites. In: Advanced processing, properties, and applications of starch and other bio-based polymers. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020. p. 111–38. [Google Scholar]

11. Poorna Chandrika KV, Prasad RD, Lakshmi Prasanna S, Shrey B, Kavya M. Impact of biopolymer-based Trichoderma harzianum seed coating on disease incidence and yield in oilseed crops. Heliyon. 2024;10(19):e38816. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38816. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Faruk O, Bledzki AK, Fink HP, Sain M. Progress report on natural fiber reinforced composites. Macromol Mater Eng. 2014;299(1):9–26. doi:10.1002/mame.201300008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tengsuthiwat J, Vinod A, Vijay R, Rangappa SM, Siengchin S. Characterization of novel natural cellulose fiber from Ficus Macrocarpa bark for lightweight structural composite application and its effect on chemical treatment. Heliyon. 2024;10(9):e30442. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e30442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Tauseef M, Azam F, Iqbal Y, Ahmad S, Ahmad F, Masood R, et al. Development and evaluation of silver-infused Biopolymer coated cotton wound dressings as possible wound healing material. Heliyon. 2024;10(19):e38407. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Miao BH, Headrick RJ, Li Z, Spanu L, Loftus DJ, Lepech MD. Development of biopolymer composites using lignin: a sustainable technology for fostering a green transition in the construction sector. Clean Mater. 2024;14(8):100279. doi:10.1016/j.clema.2024.100279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ochi S. Mechanical properties of kenaf fibers and kenaf/PLA composites. Mech Mater. 2008;40(4–5):446–52. doi:10.1016/j.mechmat.2007.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang D, Zhou X, Gao Y, Lyu L. Structural characteristics and sound absorption properties of waste hemp fiber. Coatings. 2022;12(12):1907. doi:10.3390/coatings12121907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zou CY, Han C, Xing F, Jiang YL, Xiong M, Li LJ, et al. Smart design in biopolymer-based hemostatic sponges: from hemostasis to multiple functions. Bioact Mater. 2025;45:459–78. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.11.034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ren Z, Wang C, Zuo Q, Yousfani SHS, Anuar N, Zakaria S, et al. Effect of alkali treatment on interfacial and mechanical properties of kenaf fibre reinforced epoxy unidirectional composites. Sains Malays. 2019;48(1):173–81. doi:10.17576/jsm-2019-4801-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Djalal M, Nafissa M, Mansour R, Jawaid M, Hocine M, Lamia B. Effect of alkali treatment on new lignocellulosic fibres from the stem of the Aster squamatus plant. J Mater Res Technol. 2024;32(1):2882–90. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2024.08.104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Barczewski M, Matykiewicz D, Szostak M. The effect of two-step surface treatment by hydrogen peroxide and silanization of flax/cotton fabrics on epoxy-based laminates thermomechanical properties and structure. J Mater Res Technol. 2020;9(6):13813–24. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.09.120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Khan A, Vijay R, Lenin Singaravelu D, Arpitha GR, Sanjay MR, Siengchin S, et al. Extraction and characterization of vetiver grass (Chrysopogon zizanioides) and kenaf fiber (Hibiscus cannabinus) as reinforcement materials for epoxy based composite structures. J Mater Res Technol. 2020;9(1):773–8. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.11.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Day R, Adhikari S, Peng Y. Properties of polylactic acid and biochar-based composites for environment-friendly plant containers. Clean Eng Technol. 2024;23:100850. doi:10.1016/j.clet.2024.100850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Jabbar A, Bryant M, Armitage J, Tausif M. Oxygen plasma treatment to mitigate the shedding of fragmented fibres (microplastics) from polyester textiles. Clean Eng Technol. 2024;23:100851. doi:10.1016/j.clet.2024.100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lopresti F, Campora S, Tirri G, Capuana E, Carfì Pavia F, Brucato V, et al. Core-shell PLA/Kef hybrid scaffolds for skin tissue engineering applications prepared by direct kefiran coating on PLA electrospun fibers optimized via air-plasma treatment. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2021;127:112248. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2021.112248. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Song J, Zhang R, Li S, Wei Z, Li X. Properties of phosphorus-containing polybutylene succinate/polylactic acid composite film material and degradation process effects on physiological indexes of lettuce cultivation. Polym Test. 2023;119:107921. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2023.107921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Rzhepakovsky I, Piskov S, Avanesyan S, Sizonenko M, Timchenko L, Anfinogenova O, et al. Composite of bacterial cellulose and gelatin: a versatile biocompatible scaffold for tissue engineering. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;256(Pt 1):128369. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128369. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Li X, Lin Y, Liu M, Meng L, Li C. A review of research and application of polylactic acid composites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2023;140(7):e53477. doi:10.1002/app.53477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhou L, Ke K, Yang MB, Yang W. Recent progress on chemical modification of cellulose for high mechanical-performance Poly(lactic acid)/Cellulose composite: a review. Compos Commun. 2021;23:100548. doi:10.1016/j.coco.2020.100548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Rosli NA, Ahmad I, Anuar FH, Abdullah I. The contribution of eco-friendly bio-based blends on enhancing the thermal stability and biodegradability of Poly(lactic acid). J Clean Prod. 2018;198:987–95. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.07.119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Trivedi AK, Gupta MK, Singh H. PLA based biocomposites for sustainable products: a review. Adv Ind Eng Polym Res. 2023;6(4):382–95. doi:10.1016/j.aiepr.2023.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Singhvi MS, Zinjarde SS, Gokhale DV. Polylactic acid: synthesis and biomedical applications. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;127(6):1612–26. doi:10.1111/jam.14290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Kalita NK, Sarmah A, Bhasney SM, Kalamdhad A, Katiyar V. Demonstrating an ideal compostable plastic using biodegradability kinetics of poly(lactic acid) (PLA) based green biocomposite films under aerobic composting conditions. Environ Chall. 2021;3:100030. doi:10.1016/j.envc.2021.100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Santos NS, Silva MR, Alves JL. Reinforcement of a biopolymer matrix by lignocellulosic agro-waste. Procedia Eng. 2017;200(2):422–7. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2017.07.059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Huang XY, Qi ZD, Dao JW, Wei DX. Current situation and challenges of polyhydroxyalkanoates-derived nanocarriers for cancer therapy. Smart Mater Med. 2024;5(4):529–41. doi:10.1016/j.smaim.2024.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Guo R, Cen X, Ni BJ, Zheng M. Bioplastic polyhydroxyalkanoate conversion in waste activated sludge. J Environ Manag. 2024;370(11):122866. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Lyyra I, Sandberg N, Parihar VS, Hannula M, Huhtala H, Hyttinen J, et al. Hydrolytic degradation of polylactide/polybutylene succinate blends with bioactive glass. Mater Today Commun. 2023;37(12):107242. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Abdollahi Moghaddam MR, Ali Hesarinejad M, Javidi F. Characterization and optimization of polylactic acid and polybutylene succinate blend/starch/wheat straw biocomposite by optimal custom mixture design. Polym Test. 2023;121(1):108000. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2023.108000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wang ZY, Zhang XW, Ding YW, Ren ZW, Wei DX. Natural biopolyester microspheres with diverse structures and surface topologies as micro-devices for biomedical applications. Smart Mater Med. 2023;4(1):15–36. doi:10.1016/j.smaim.2022.07.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Dedieu I, Peyron S, Gontard N, Aouf C. The thermo-mechanical recyclability potential of biodegradable biopolyesters: perspectives and limits for food packaging application. Polym Test. 2022;111(12):107620. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2022.107620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Feng D, Liang B, Wan Y, Yi F, Liu L, Zhang Y, et al. Mechanical and water stability properties of biopolymer-treated silty sand. J Rock Mech Geotech Eng. 2024. doi:10.1201/9781315364230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Freire NF, Cordani M, Aparicio-Blanco J, Fraguas Sanchez AI, Dutra L, Pinto MCC, et al. Preparation and characterization of PBS (Polybutylene Succinate) nanoparticles containing cannabidiol (CBD) for anticancer application. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol. 2024;97:105833. doi:10.1016/j.jddst.2024.105833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Rajan KP, Thomas SP, Gopanna A, Al-Ghamdi A, Chavali M. Polyblends and composites of poly (lactic acid) (PLAa review on the state of the art. J Polym Sci Eng. 2018;1(3):10–24. doi:10.24294/jpse.v1i1.723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Glaser TK, Plohl O, Vesel A, Ajdnik U, Ulrih NP, Hrnčič MK, et al. Functionalization of polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) material using chitosan nanoparticles with incorporated resveratrol as potential active packaging. Materials. 2019;12(13):2118. doi:10.3390/ma12132118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Ilyas RA, Sapuan SM, Harussani MM, Hakimi MY, Haziq MM, Atikah MN, et al. Polylactic acid (PLA) biocomposite: processing, additive manufacturing and advanced applications. Polymers. 2021;13(8):1326. doi:10.3390/polym13081326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Tian J, Zhang R, Wu Y, Xue P. Additive manufacturing of wood flour/polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) fully bio-based composites based on micro-screw extrusion system. Mater Des. 2021;199(n.d.):109418. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2020.109418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Balaji KV, Shirvanimoghaddam K, Naebe M. Multifunctional basalt fiber polymer composites enabled by carbon nanotubes and graphene. Compos Part B Eng. 2024;268(10):111070. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.111070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hassin MS, Faruk MO, Ali MI, Begum S. Evaluation of physical and mechanical properties of graphene oxide reinforced epoxy/Kevlar hybrid composites. Hybrid Adv. 2024;6(1):100217. doi:10.1016/j.hybadv.2024.100217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Harini K, Chandra Mohan C. Isolation and characterization of micro and nanocrystalline cellulose fibers from the walnut shell, corncob and sugarcane bagasse. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;163:1375–83. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Syafri E, Jamaluddin, Sari NH, Mahardika M, Amanda P, Ilyas RA. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanofibers from Agave gigantea by chemical-mechanical treatment. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;200:25–33. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.12.111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Hassan MM, Rahman MM, Ghos BC, Hossain MI, Al Amin M, Al Zuhanee MK. Extraction, and characterization of CNC from waste sugarcane leaf sheath as a reinforcement of multifunctional bio-nanocomposite material: a waste to wealth approach. Carbon Trends. 2024;17(2):100400. doi:10.1016/j.cartre.2024.100400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Sharma A, Thakur M, Bhattacharya M, Mandal T, Goswami S. Commercial application of cellulose nano-composites—a review. Biotechnol Rep (AMST). 2019;21(1):e00316. doi:10.1016/j.btre.2019.e00316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Loganathan TM, Hameed Sultan MT, Ahsan Q, Jawaid M, Naveen J, Md Shah AU, et al. Characterization of alkali treated new cellulosic fibre from Cyrtostachys renda. J Mater Res Technol. 2020;9(3):3537–46. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.01.091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Herlina Sari N, Wardana ING, Irawan YS, Siswanto E. Characterization of the chemical, physical, and mechanical properties of NaOH-treated natural cellulosic fibers from corn husks. J Nat Fibres. 2018;15(4):545–58. doi:10.1080/15440478.2017.1349707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Karthik K, Rajamanikkam RK, Venkatesan EP, Bishwakarma S, Krishnaiah R, Saleel CA, et al. State of the Art: natural fibre-reinforced composites in advanced development and their physical/chemical/mechanical properties. Chin J Anal Chem. 2024;52(7):100415. doi:10.1016/j.cjac.2024.100415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Karim FE, Islam MR, Ahmed R, Siddique AB, Begum HA. Extraction and characterization of a newly developed cellulose enriched sustainable natural fiber from the epidermis of Mikania micrantha. Heliyon. 2023;9(9):e19360. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e19360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Srisuwan S, Prasoetsopha N, Suppakarn N, Chumsamrong P. The effects of alkalized and silanized woven sisal fibers on mechanical properties of natural rubber modified epoxy resin. Energy Proc. 2014;56:19–25. doi:10.1016/j.egypro.2014.07.127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Cottrell JA, Ali M, Tatari A, Martinson DB. Effects of fibre moisture content on the mechanical properties of jute reinforced compressed earth composites. Constr Build Mater. 2023;373(4):130848. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2023.130848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Satyanarayana KG, Guimarães JL, Wypych F. Studies on lignocellulosic fibers of Brazil. Part I: source, production, morphology, properties and applications. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2007;38(7):1694–709. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2007.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Arthanarieswaran VP, Kumaravel A, Kathirselvam M, Saravanakumar SS. Mechanical and thermal properties of Acacia leucophloea fiber/epoxy composites: influence of fiber loading and alkali treatment. Int J Polym Anal Charact. 2016;21(7):571–83. doi:10.1080/1023666x.2016.1183279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Li X, Tabil L, Panigrahi S. Chemical treatments of natural fiber for use in natural fiber-reinforced composites: a review. J Polym Environ. 2018;15(1):25–33. doi:10.1007/S10924-006-0042-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]