Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Plant-Based Cellulose Nanopapers with Applications for Packaging, Protective Films and Energy Devices

Instituto de Investigaciones en Ciencia y Tecnología de Materiales (INTEMA), Facultad de Ingeniería, Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata-CONICET, Mar del Plata, 7600, Argentina

* Corresponding Author: Mirta I. Aranguren. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(8), 1491-1519. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0079

Received 28 December 2024; Accepted 23 June 2025; Issue published 22 August 2025

Abstract

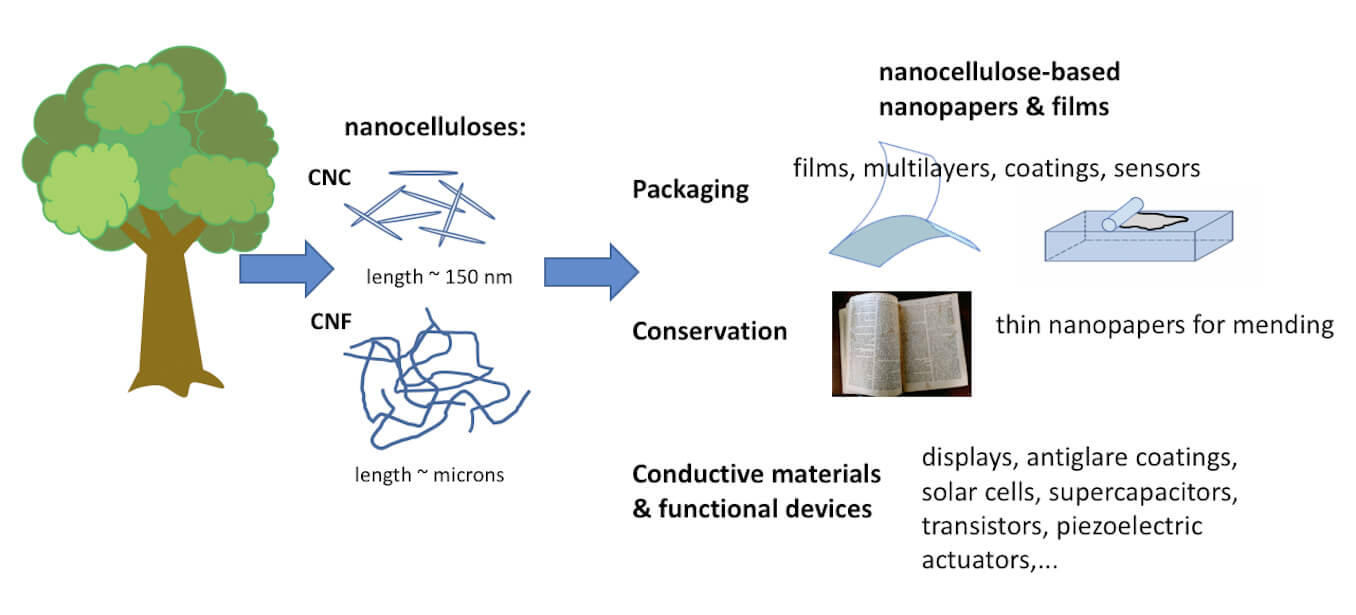

Interest in the use of cellulose nanomaterial’s continues to grow, both in research and industry, not only due to the abundance of raw materials, low toxicity and sustainability, but also due to the attractive physical and chemical properties that make nanocelluloses useful for a wide range of end-use applications. Among the large number of potential uses, and nanocelluloses modification and processing strategies, the chosen topic of this review focuses exclusively on plant-derived cellulose microfibers/nanofibers (CNF) and cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) processed into 2D structures—nanopapers and nanofilms—fabricated as self-standing films or applied as coatings. The end uses considered are: combination with standard papers and cardboards for packaging, mending material for the conservation and protection of cellulosic heritage artifacts, and component-parts of complex designs of functional devices for energy harvesting and storage. In these contexts, nanocelluloses provide high mechanical and ecofriendly properties, transparency and tunable haze, as well as flexibility/bendability in the resulting films. All these characteristics make them extremely attractive to a market seeking for sustainable, light weight and low cost raw materials for the production of goods. General perspectives on the current advantages and disadvantages of using CNF and CNC in the selected areas are also reviewed.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileCellulose-based applications have accompanied human development for centuries, with writing paper being among the most significant. On the other hand, the study of the particular properties of nanomaterials obtained from vegetable structures is much more recent, experiencing a slow increase during the 90 s and showing a steep growth since the beginning of this century [1]. The wide variety of potential sources ensures the global availability of raw materials, and the potential production volume is enormous (a figure of 1.5 × 1012 t/year is frequently reported) [2,3].

Although nanocelluloses can be derived from various sources—plants, algae, animals, or bacteria—this review focuses exclusively on those obtained from higher plants. Briefly, plant-derived nanocelluloses are classified by size into micro/nanofibrillar cellulose and cellulose nanocrystals (CNC). Cellulose-based nanofibers (CNF) are prepared from cellulose fibers using mechanical energy input, which may be accompanied by chemical or enzymatic treatments [4]. CNFs can present a large variation in thickness (generally 5 to 50 nm) and lengths in the order of microns, leading to some ambiguity in terminology throughout the literature. CNCs are typically slightly thinner (~3 to 20 nm) but shorter (~100–200 nm), and are obtained through oxidation or acid hydrolysis, often followed by additional energy-intensive mechanical treatments [5]. In both cases, micro/nanofibers and nanocrystals are low density materials (~1.5 g/cm3) with excellent mechanical properties (tensile modulus~6–30 GPa) and low thermal expansion coefficient, CTE (~2–25 ppm/K) [6], in addition to the relative ease of chemical modification and biodegradability. Because of these good properties, films prepared from nanocelluloses have attracted attention in the areas of packaging, special papers, protective films, flexible substrates or supports for sensors, electronics and energy storage and harvesting, etc. [1,6,7].

The largest envisioned application for nanocelluloses lies in the pulp and paper industry where they can be used as additives, resulting in lighter and stronger papers and cardboards, and also reducing production costs [1]. Being highly compatible with regular paper, easily printable, biodegradable and of low toxicity, nanocelluloses have been identified as useful materials for improving the quality of papers intended for packaging (including food packaging) and as protective coatings for valuable and old documents [8–10]. They have also been used in the papermaking process [11] as reinforcing additives to enhance the mechanical and barrier properties of paper and/or to improve its brightness and printability [12]. The addition of nanocelluloses to pulps has a similar effect to that of refining, with nanocelluloses playing the dual role of “fines” and process additives. The large surface area generated in this way and the H-bonds formed with the cellulose-pulp reduce the water-fibers interactions. Optical properties are also affected, with the papers becoming denser and less opaque. Furthermore, the deposition of nanocelluloses as coating films on conventional papers has been shown to have beneficial effects, such as increasing the surface density of the paper, decreasing the water absorption and reducing the permeability due to the reduced porosity, which also improves the surface properties [13], to the extent of serving as barrier in grease-proof papers [14]. Huang et al. [15] provided an illustrative comparison of the properties of a conventional paper and a nanopaper. In particular, transparency of the nanopaper is similar to that of traditional plastic films (~90% transparency at 550 nm, compared to ~20% for a conventional paper), and the mechanical properties and coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) largely exceed those of plastic films (ultimate stress = 200–400 and 50 MPa; CTE = 12–28.5, and 20–100 ppm/K for nanopaper and plastic, respectively), with the additional advantage of nanocelluloses being biodegradable and having low toxicity.

A less usual field of application of nanopapers is as new components in the manufacture of functional devices. Our current lifestyle involves the use of a huge number of electronic devices that, once discarded, are mostly neither biodegradable nor recyclable, so replacing some of their components with biodegradable cellulosic materials is highly desirable. In some cases, chemical modifications are performed in order to reduce the hygroscopicity of cellulose, while still taking advantage of its other valuable characteristics [3,16].

In the present review, only the preparation of films/nanopapers from plant-derived nanocelluloses will be considered, with focus on their applications as coatings and transparent films for stronger packaging papers, as protective barriers or mending materials for old documents and artifacts, and as flexible films for the production of electronic, harvesting and storage energy devices.

The function of food packaging is to protect products during transportation, storage and marketing by delaying spoilage, blocking the entrance of oxygen, and extending the shelf life of the food, while also providing product information to consumers. However, food packaging, especially single-use packaging, is a major ecological concern worldwide due to the large environmental pollution caused by its use. For this reason, the industrial and scientific sectors have become very interested in the development of new materials that could be used for food packaging and that would simultaneously reduce pollution [17,18]. To date, the vast majority of food containers are made from petroleum derived raw materials, resulting in a high dependence on a non-renewable, polluting and expensive resource. Due to this and the aforementioned ecological concerns, renewable raw materials started to be studied and used for the production of food packaging, for example starch [19], polylactic acid (PLA) [20], polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB), [21], gluten [22] and cellulose [23] among others. However, while their use meets the biodegradability requirement [24], the challenge of increasing competitiveness in terms of properties and cost remains. Thus, a usual strategy has been to incorporate biodegradable renewable materials as coatings or as layers in multilayer packaging films (e.g., to improve the oxygen barrier performance [25]) or to add inorganic oxides to biobased formulations [26]. Another complementary approach is to use cellulose based materials (including nanocelluloses) that are intrinsically biodegradable and can be applied as coatings and be used in multilayer films. Thus, paper, being abundant, renewable, and having low cost, is one of the preferred materials as wrapping papers and flexible and rigid materials for primary and secondary packaging [17,18]. In recent years, there has been a significant surge in the use of CNF in packaging applications to replace standard cellulose fibers of larger dimensions (micron-size). Good barrier properties, processability, stability and high transparency are just some of the desired properties for the most widely used packaging materials.

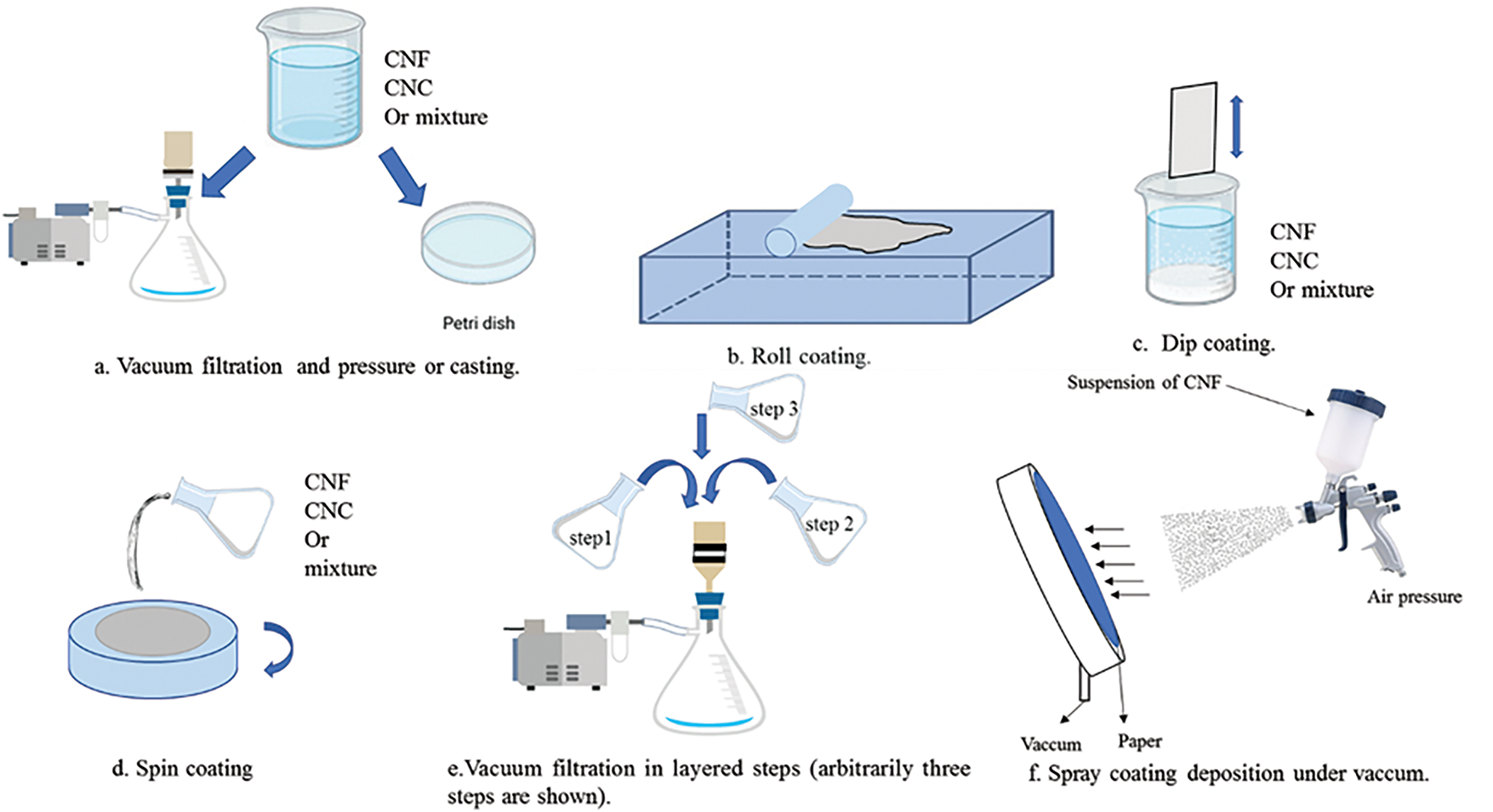

Modified regular papers and nanopapers, being made from naturally occurring cellulosic fibers, can be prepared from processes that already exist in the pulp and paper industry. The usual methods to produce papers or to modify them at laboratory scale include vacuum filtration, rod/roll coating, dip coating, spin coating, sputtering and spraying [3] among several others (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Schematic drawing showing some of the processing methods frequently mentioned in the literature to fabricate nanocellulose films

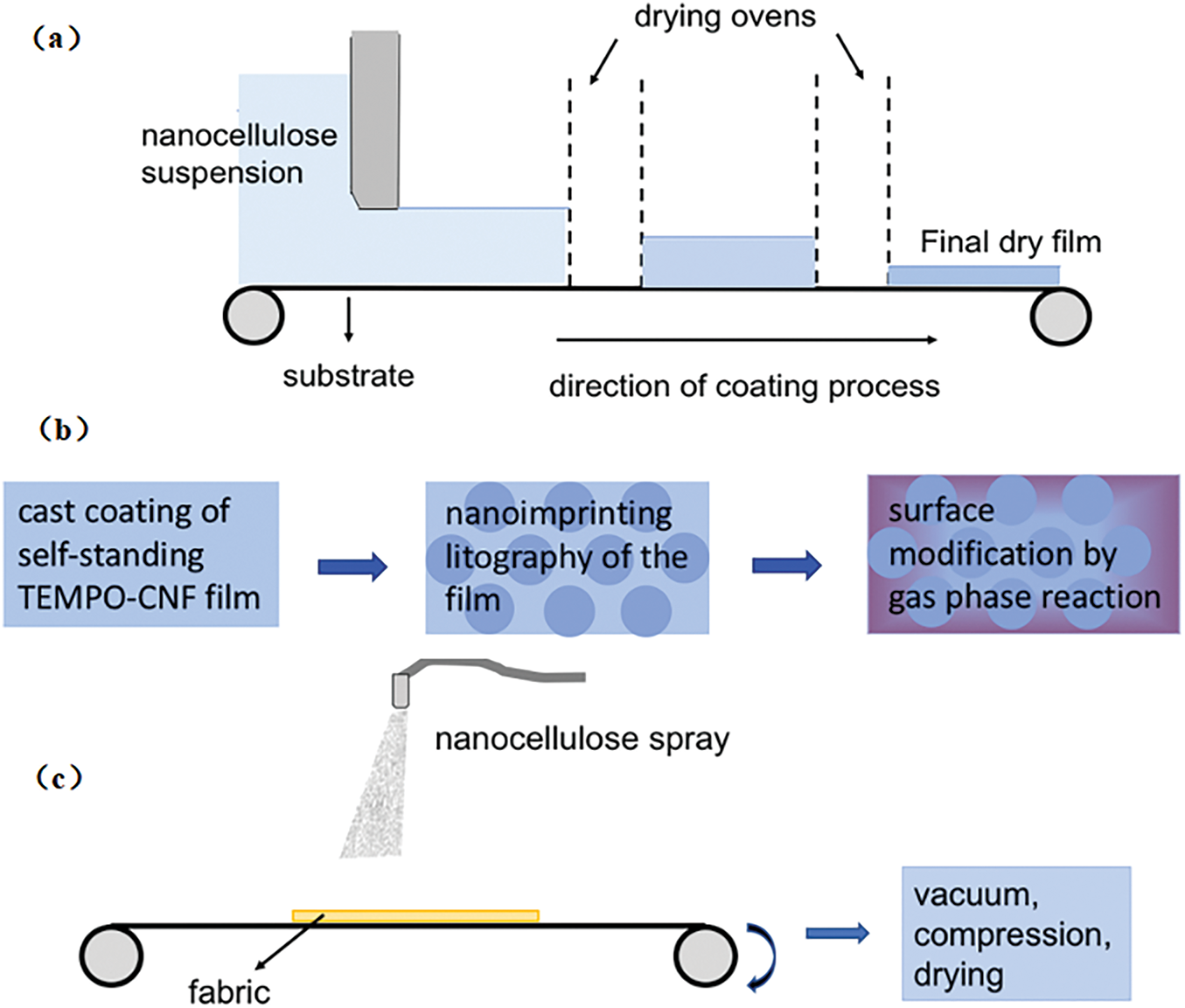

While most of the publications show preparation methods fitted to the laboratory work, some groups have also considered pilot plant production (Fig. 2). Generally, the processes reported are scaled-up from laboratory methods, such as casting, coating and spraying. For example, Claro et al. [27] presented comparative results from CNF and CNC films prepared using a coating equipment for continuous casting with a production of 6 m/h of the nanocellulosic films (Fig. 2a). Another example of the scaling-up process, is the semi-industrial roll-to-roll pilot scale equipment used by the VTT group (Finland) to produce a multilayer film made from PET/TEMPO-CNF/LDPE to reach the requirements of the modified atmosphere needed in food packaging [28]. The CNF layer played the role of oxygen barrier and the authors proposed the use of the layered film in the case of dried or low-moisture-content foods, such as snacks, nuts and other dry fruits, spices, etc. The Finnish institute also prepared a self-standing CNF film making use of a continuous cast-coating of a TEMPO-CNF on a supporting plastic at a semi-pilot scale commercial unit. The CNF suspension was prepared using 30% of sorbitol as plasticizer and 10% polyvinylalcohol (dry basis) to obtain flexible and less brittle films of about 20–25 μm of thickness. The process also contemplated roll-to roll nanoimpresion and surface plasma modification [29] (Fig. 2b). Still, other authors used the coating of a hydrophilic nylon fabric onto which CNF was sprayed. To accelerate the dewatering, vacuum was applied (filtration step) followed by compression and drying [30] (Fig. 2c).

Figure 2: Continuous processes reported for the production of cellulose nanopapers: (a) continuous coating (based on [27]); (b) continuous cast coating (based on [29]); (c) continuous spraying coating (based on [30,31])

It is noteworthy that the publications show a preference for the use of CNF over CNC due to the cohesion of the nanopapers produced from the CNF compared to that of CNC. Additionally, it is worth noting that casting methods are based on the deposition of the nanocellulose suspension on a non-absorbing substrate, so that a self-standing nanopaper can subsequently be obtained. The disadvantage lies in the high humidity of the casted material and the relatively long drying time and/or the energy consumption needed to accelerate this step. On the other hand, coating is done onto a permeable substrate so that a nanocellulose top layer is formed, which modifies the properties of the composite film [30,31].

2.2 Humidity Effect and “Crosslinking” of the Nanocelluloses

Regardless of the scale of the process selected, a fairly general and non-trivial problem is the negative effect of humidity and hydration of the nanopapers, which affect the cohesion and performance under humid conditions, particularly when considering industrial scale processing and commercialization.

The interactions of water molecules with the hydroxyl groups of the cellulose reduce the interfibrillar hydrogen bonds and can lead to a reduction in the final properties of the films. Although this effect is widely recognized, the detailed interactions of water with nanocellulose are not fully identified, as they depend largely on the source of the nanocelluloses, the production process and their overall history [32]. In general, the hydrophilicity of cellulosic coatings makes them ineffective as humidity barriers and thus, the addition of inorganic particles (to increase the tortuous path of the diffusing molecules) or crosslinking of the cellulose have been considered. For example, while drying and heating usually lead to hornification in the case of the CNC, the TEMPO oxidized CNF behaves differently because of its higher charge density. TEMPO-CNF is not readily crosslinked by this method, and consequently, CNF derived nanopapers subjected to this consolidation method are more sensitive to humidity and water than CNC nanopapers [32].

To reduce the effect of moisture on nanopapers, some authors have worked on fixing the cellulosic nanostructures using different types of crosslinking. For example, Toivonen et al. [33] prepared transparent nanopapers (~70–90% transparency in the 400–800 nm range) and physically crosslinked them with chitosan (75–80% deacetylation degree). In particular, the mixtures CNF/chitosan at 80/20 w/w (dry basis) showed the best mechanical properties in the water soaked state (ultimate strength of 100 MPa at maximum strain of 28%). Homogeneous mixtures of both polyelectrolytes were only possible in a narrow pH range, around 3.4. The authors also observed that by using the sediment formed in the CNF production step instead of the supernatant, the films were more opaque because of the thicker and longer fibers that formed the sediment and the resulting higher porosity of the films. Using an analogous approach, a cationic CNC suspension was prepared using aminoguanidine hydrochloride and then mixed in different proportions with TEMPO-CNF [34]. The homogenized mixture was vacuum filtered to form the nanopapers. The draining time (filtration step) was shorter with cationic-CNC: TEMPO-CNF = 40:60, and this film also showed improved mechanical properties, even when wet.

Van Nguyen and Lee [35] prepared films of CNF with up to 5 wt.% of glycerol and used hot pressing to fix the film structure. Contrary to what could be expected from adding hydrophilic glycerol, the structural stability was increased due to hydrogen bonds developed between the CNF and the glycerol that resulted in reduced interactions with water and thus, a marked reduction in water sorption.

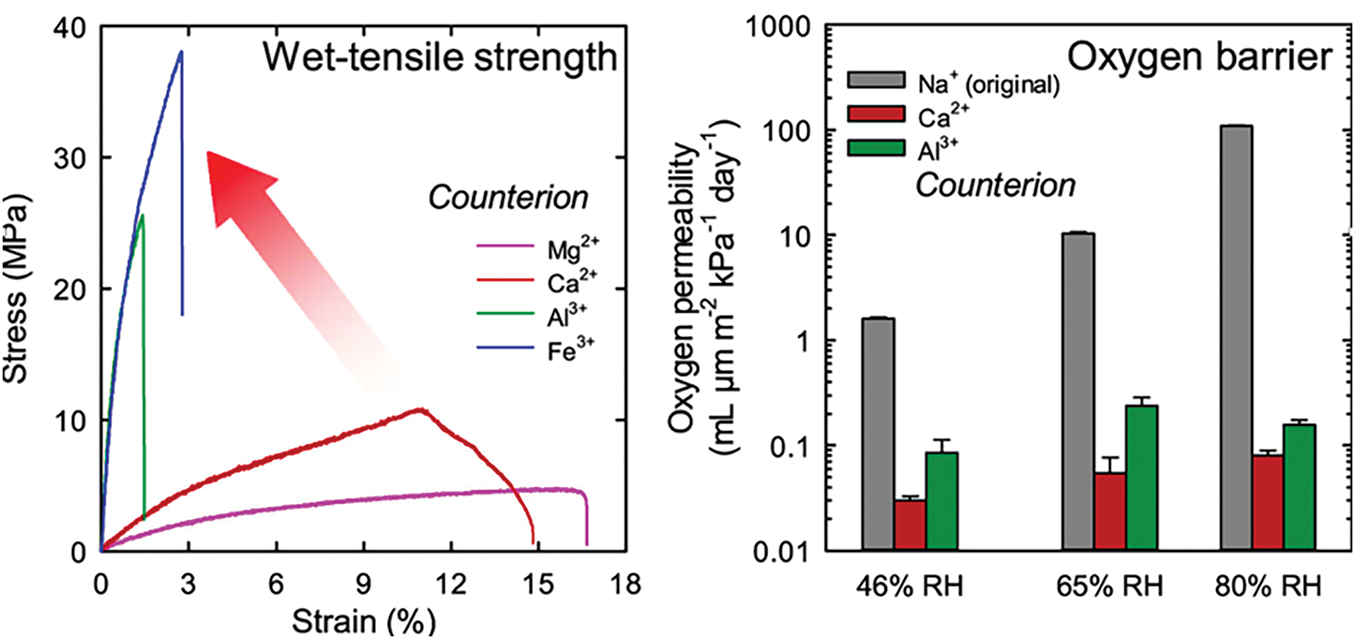

Shimizu et al. [36] reported an interesting approach of physically crosslinking TEMPO-CNF (Na+ as counterion) by exchange of the monovalent cation with bi and trivalent cations. Particularly, Al+3-crosslinked films showed good mechanical properties even at high water contents (Young’s modulus of ~3 GPa at 470% water content). Ca+2 and Al+3 carboxylate films exhibited very low oxygen permeability even at 80% relative humidity (0.08 and 0.15 mL µm m2 day−1 kPa−1, respectively). The improvements were related to the interfibrillar crosslinking via multivalent cations (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Effect of physical crosslinking of TEMPO-CNF nanopapers [Reproduced with permission from Ref. [36]. Copyright © 2015 Elsevier B.V.]

Chemical crosslinking of nanocelluloses with glutaraldehyde has also been considered [37], although in that case, the film was applied as support for circuits. Likewise, the complexation of phosphorylated CNF with chitosan nanocrystals was considered for the stabilization of supporting films, which will be addressed in another section [38].

2.3 Lignin Containing Nanocelluloses

The reason behind the use of plant nanocelluloses not completely separated from lignin is based on the cost of the bleaching process and its polluting effect on the environment. Therefore, it seems most reasonable to investigate the performance of lignin containing nanopapers. Some authors have considered the preparation of nanocelluloses with different contents of lignin and found that their content had detrimental effects on the water vapor transmission rate, being higher at higher lignin concentration. Derived nanopapers showed longer and connected pores in presence of lignin, which explains the higher water mobility in the material [13]. On the contrary, Farooq et al. [39] reported positive activity of lignin as waterproofing, antioxidant, and UV-shield agent in strong and ductile CNF films using an optimal concentration of 10 wt.% colloidal lignin particles. The authors also discussed the importance of drying conditions and lignin morphology.

Hu et al. [40] also considered the incorporation of lignin nanoparticles onto the surface of nanopapers prepared with incompletely separated lignin-CNF. The authors highlighted the possibility of adjusting properties of interest in food packaging, such as hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity, thermal stability, UV blocking capability, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities.

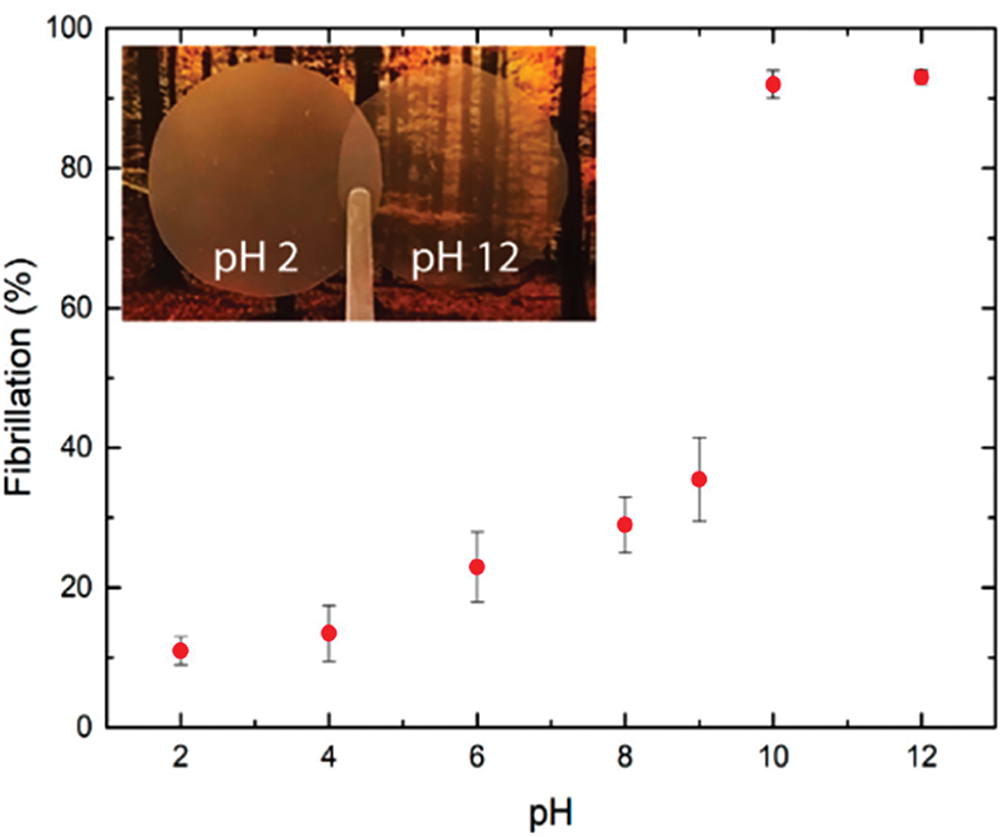

For some packaging applications, transparency is a key issue and thus, different approaches have been developed to improve this property, which will be further discussed in the context of other nanopaper applications. To this end, a transparent paper was prepared at laboratory scale from TEMPO-oxidized cellulose fibers using the simple filtration method, performed using a Buchner funnel and a membrane of polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) [41]. Gorur et al. [42] considered such a method, using a vacuum filtration setup equipped with a standard sheet-former wire. The authors included an additional step to increase the transparency of the papers, consisting of a pH-induced auto-fibrillation. The initial paper was immersed in a NaOH solution at pH 12, obtaining a wet paper that was subsequently dried at high temperature and reduced pressure. The effect of improving transparency with pH can be seen in Fig. 4. According to the authors, this was a fast process that did not differ much from the conventional papermaking and allowed to obtain competitive properties.

Figure 4: Example of the effect of the pH on the fibrillation of cellulose fibers. The inset shows digital photos of the films taken at a height of 10 mm above the image. Adapted with permission from Ref. [42]

Claro et al. [27] presented comparative results from films made from CNF, CNC and their mixtures. The objective was to improve the optical and mechanical properties of the neat CNF films, and compare the performance with different CNF/CNC ratios. Additionally, the authors compared the films made from the nanocelluloses of eucalyptus and of curaua. While the density of the original cellulose sheets ranged from 0.22 to 0.26 g/cm3, those of the CNF and CNC films were 0.46–0.51 g/cm3 and 1.21–1.3 g/cm3, respectively. Accordingly, the density of the CNF/CNC films increased with the CNC content in the mixtures, which also led to films with more homogeneous and smoother surfaces as well as higher transparency. Greater fibrillation was achieved in the eucalyptus fibers compared to the curaua fibers, leading to higher mechanical resistance in the first case. The reduced porosity of the films (observed at high CNC contents and leading to higher density) resulted in greater transparency and gloss.

To improve the overall performance of packaging films, a frequent and highly effective strategy is to use nanocellulose as one of the layers, in a layer-by-layer formulation, e.g., as a coating layer to improve barrier properties, printability and/or mechanical properties in paper packaging [43]. The application of CNF as coating to improve the barrier properties to gases (mainly oxygen) in conventional paper packaging can also be done by spraying, press coating and roll or bar spreading, for example. The importance of reducing oxygen permeability in food packaging is recognized as a fundamental requirement, since high oxygen concentrations in food can trigger oxidative reactions in lipids and proteins, ultimately resulting in food decomposition and, furthermore, in the growth of microorganisms that might be originally present in the food [44]. Coating leads to the increase of the paper thickness reducing its bendability and so, in some cases thinner substrates have been used, with concurrent reduction of the thickness of the synthetic layers present [11].

With the goal of reducing oxygen transport through the film, Kato et al. [45] used microcrystalline cellulose to produce a mixture of cellulose I and II, which was treated by TEMPO oxidation to obtain a mixture of soluble celluronic acid and crystalline cellulose I to be applied as a film-forming coating improving the oxygen barrier properties of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) films. Air permeability was reduced in the work of Ozcan et al. [10] by using CNF/TEMPO-oxidized CNF to improve the surface of a core board paper replacing petroleum-based derivatives. The improved performance was explained by the filling of the porous surface of the board with CNF. Furthermore, the treated papers showed smoother surfaces and higher gloss than the original board, leading to better printability with less ink [10].

Different nanocelluloses have also been used to prepare multilayer films with improved properties. de Oliveira et al. [46] investigated the effect of using spray coating to apply layers of neat CNF and a mixture CNF/nanoclay as coating for Kraft paper. Overall, the addition of layers resulted in improved barrier properties due to a reduction in porosity. The mechanical properties also showed some improvement, but the addition of a high number of layers (4–5 layers) was detrimental, probably due to the cellulose hornification resulting from the wetting-drying cycles applied to form the multilayered papers.

On the other hand, hydrophobic layers have frequently been added on cellulosic layers to reduce their water sorption capacity [32,47]. In those cases, layers of thermoplastics are used to protect the nanocellulose layers from humidity. Layers can also be compounded with nanoparticles as barrier components, such as nanoclays [47].

When multilayer films are used, it is critical to determine the adhesion between the layers. For example, Li et al. [48] reported that good adhesion was developed between CNC and PET and oriented polyamide, leading to high transparency (~90%) and low haze, with potential applications for their antifog properties and good performance as oxygen barrier. In the case of Mirmehdi et al. [49], they used a corona discharge process as a strategy to increase the surface energy of a commercial paper substrate, which increased the adhesion of a sprayed coating prepared from a suspension mixture of CNF/nanoclay (0–5 wt.%) [49]. Their results indicate that the corona discharge had a positive effect on tensile strength when neat CNF was used, but the opposite occcurred when the CNF/nanoclay mixture was sprayed. On the other hand, composite spraying had a positive effect on the oxygen permeability: reductions in oxygen permeation of ~90% and in water vapor transmission of ~86% were achieved using the corona discharge treatment and a 5% nanoclay suspension mixture with a spraying time of 50 s.

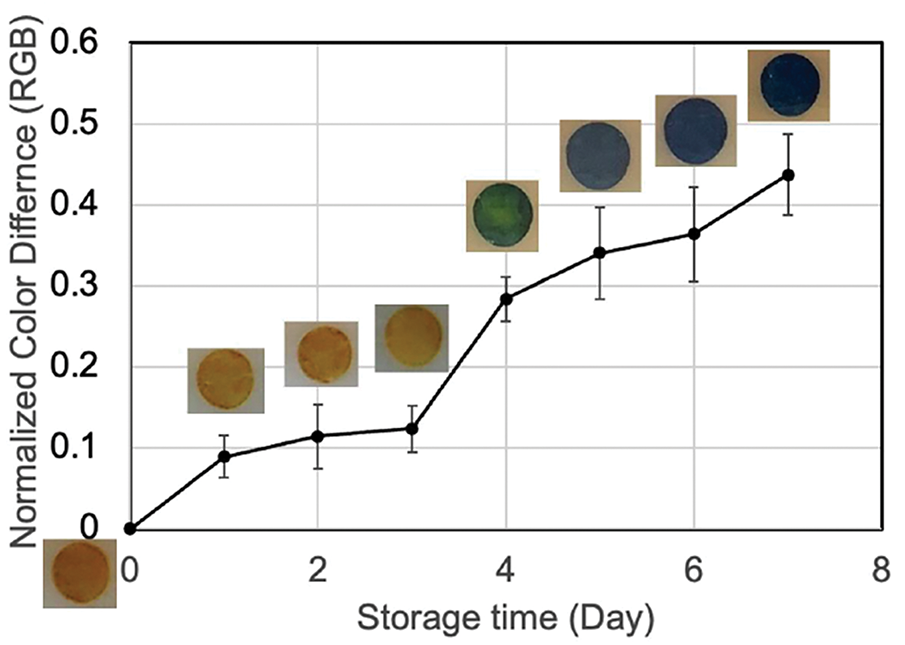

Cellulose nanopapers can also be prepared/modified to perform as food quality sensors during storage. Al Tamini et al. [50] used TEMPO-CNF to prepare a nanopaper by the vacuum filtration/high pressure compression method, followed by adsorption of a pH-sensitive dye (1% ethanol solution of bromocresol green) and subsequent drying. The sensor was used to detect spoilage in chicken breast stored at 20°C. After three days, a very clear color change of the sensing nanopaper from yellow to blue was observed, supporting its use as pH-sensor in food applications (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Color differences (normalized based on day 1) showing the changes observed in the nanopapers used as pH sensors, to detect chicken breast spoilage. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [50]

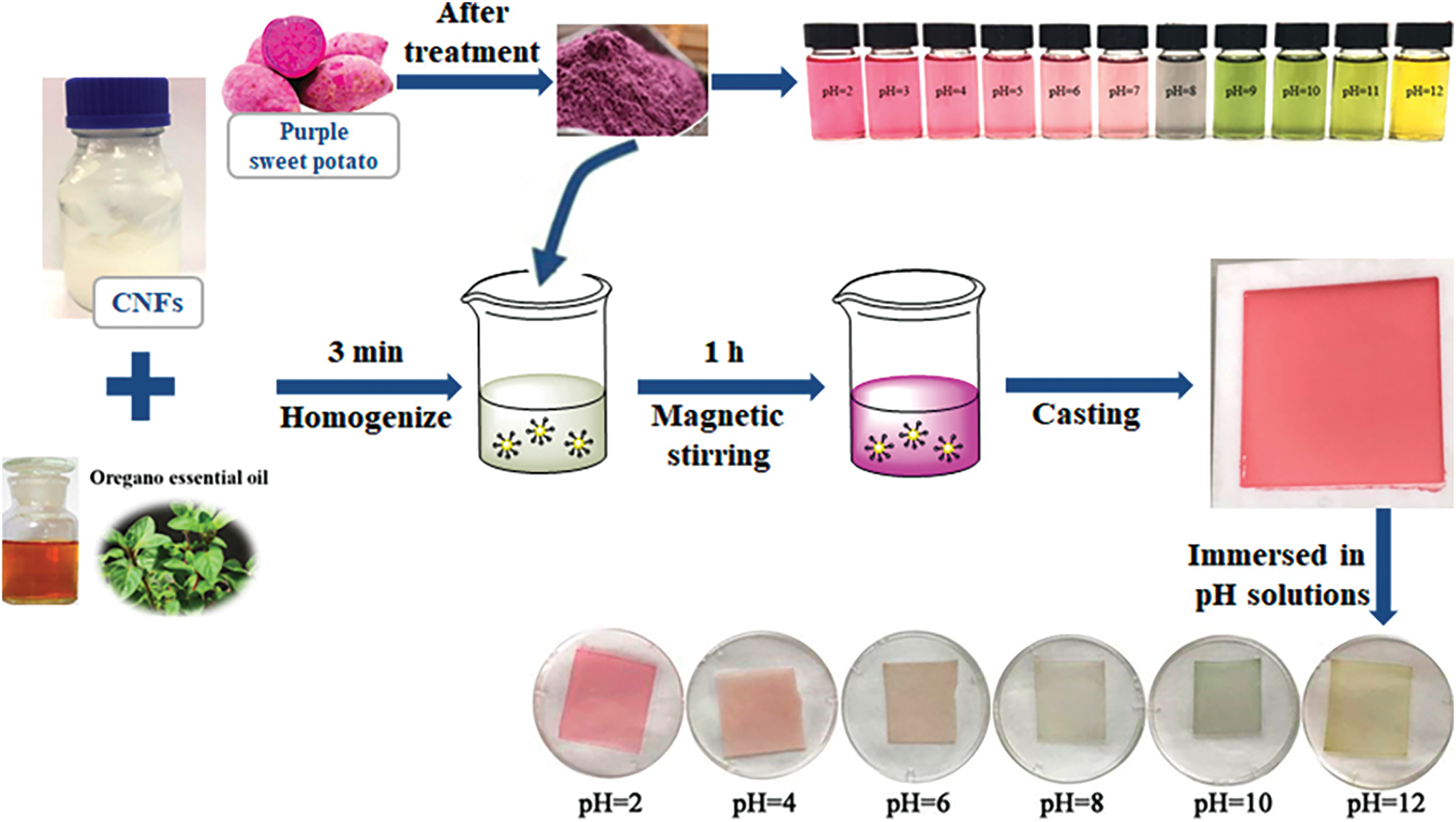

Analogously, Chen et al. [51] prepared CNF from pulp bagasse to produce films that served as pH indicators and also exhibited antibacterial properties. The authors incorporated sweet potato anthocyanins, causing the films to change from red at pH = 2 to yellow at pH = 12 (Fig. 6). Oregano essential oil was added to the films to incorporate biocide activity against E. Coli and Listeria Monocytogenes. This type of antibacterial activity was also developed in films made from polyethyleneimine (PEI) grafted to CNF via a Schiff base. At low pH, protonation of PEI led to biocide activity [52].

Figure 6: CNF nanopapers as pH indicators and with antibacterial activity [Reproduced with permission from Ref. [51]. Copyright © 2020 Elsevier B.V.]

In summary, in packaging applications, there is a preference for the use of CNF over CNC due to the shape stability and flexibility of the nanopapers. However, the addition of CNC is common to tune mechanical properties, transparency, porosity and printability. In general, increasing the content of CNC improves all these properties. The reduction of porosity is related to the increased density of the nanopaper and to smoother surfaces, resulting in more transparent and glossy films.

The nanopapers production tends to be simple and inspired in the paper production processes at the laboratory and pilot plant scales. The unavoidable negative effect of the humidity on hydrophilic nanocelluloses has been addressed through complexation with metal cations, hornification (mainly of CNC), chemical crosslinking or encapsulation of a cellulosic layer in the case of multilayer-films. Table S1 (Supplementary Materials) shows a brief summary of the results used in this work.

3 Nanopapers and Nanocellulose Coatings for the Conservation of Works of Art and Heritage Objects

An emerging yet valuable application of nanopapers is their use as protective coatings and mending materials for old printings, wooden artifacts, and canvases in the conservation of cellulose-based cultural heritage objects [53–55].

Old cellulose-based papers that exhibit age-degradation frequently require deacidification, but also consolidation, for which nanocellulose is well-suited due to its intrinsic compatibility with the original substrate. Traditionally, paper repair is performed using Japanese paper, which is strong and thin (several thicknesses are available) and produces a relatively low visual impact. Recently, the use of nanocellulose films and coatings has shown excellent results in the repair and protection of cellulosic artifacts (made of wood, paper and textiles), including mending of transparent papers. In the case of written pieces, treated documents have also shown improved readability [56,57]. Xu et al. [58] grafted CNC with oleic acid in addition to Ca2+ nanoparticles and dispersed the mixture in ethanol. Artificially aged papers were treated with neat CNC and combined dispersions, which resulted in an increase of the weight of the paper of about 10%, corresponding to a surface coverage of 7.5 g/m2. The process using the neat grafted CNC dispersion without cationic nanoparticles led to an almost complete recovery of the paper’s ultimate tensile strength. In contrast, when the combined dispersion was applied, the acidification of the paper was reduced, but at the cost of lower mechanical recovery and in both cases without visual changes with respect to the original paper. Operamolla et al. [59] also considered the use of CNC dispersions for consolidation and protection of old paper books. The best results were obtained by using HCl in the acidolysis step to produce CNC, followed by dialysis until pH neutrality was reached. A sonicated CNC suspension (1.5 wt.%) was applied by soft brush, obtaining an outstanding transparency. The authors emphasized the reversibility of the process—CNC could be removed using a cleaning hydrogel— which is essential in restoration practices.

Camargos et al. [54] used composite coatings of CNF, CNC and lignin nanoparticles as protective coatings of cellulosic substrates (wood, paper, fabrics). The aqueous dispersions used showed positive effect on the protection against moisture, heat and UV radiation (accelerated aging). Layers of water-based carnauba wax nanoparticles were also applied to reduce water sorption. The layers could be removed using a cleaning hydrogel.

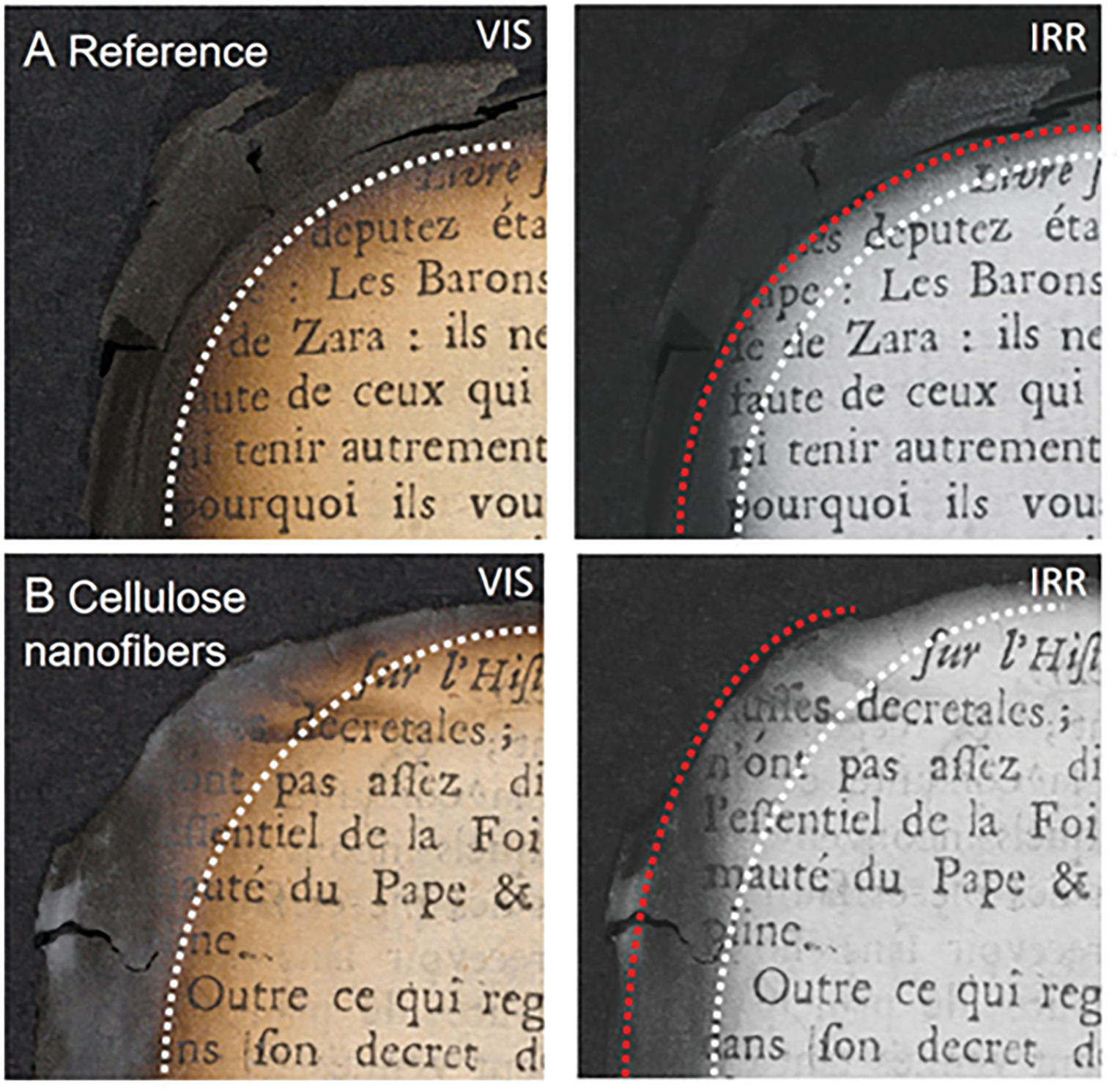

Fire damage of historical documents leaves fragile, partially charred samples, and their handling requires previous mechanical stabilization [60] (Fig. 7). Commercial CNF dispersions were successfully tested in the stabilization of heavily damaged samples. Readability was not compromised under conventional light (due to the low haze of the coating) or using infrared reflectology (IRR), a technique frequently used to examine layers and underdrawings in works of art. The use of CNF gave better results than the thinnest Japanese paper. The same group used CNF for mechanical stabilization with an additional chemical treatment to counteract the acidic effect of ancient iron gall ink [61].

Figure 7: Example of mending fire-damaged historical papers with CNF and Japanese paper for comparison. The dotted lines show the limit of readability. VIS: conventional light (left); IRR: infrared reflectology (right). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [60]

CNC nanopapers have also been used as “patches” for the conservation of historical wooden artifacts that had been subjected to outdoor conditions [62]. Silane- and glycerol-modified CNC patches were applied to fill cracks and voids because they were transparent and able to be colored. However, further studies were recommended to reduce the sensitivity to moisture and microorganisms infestation.

Other valuable cellulose-based heritage artifacts include canvases. In uncontrolled environments, canvas-supported paintings can undergo hydrolytic degradation as a result of thermal and humidity variations. Bridarolli et al. [53] compared the protection of canvas by applying a CNF coating or a sililated composite of CNC, showing better performance of the latter because of its reduced sensitivity to humidity changes.

Because of the high transparency of the nanopapers, they have also been used in the conservation of torn old cinematographic slides (originally made in 1849–1880) as part of a museum conservation project [55]. The original slides were made from very thin papers (polyorama panoptique slides) and adhesives and different Japanese papers were used to repair them. However, these papers were not thin enough to hide the mending zone. Instead, a CNF nanopaper offered the best result, with virtually no visual effect on the original images and thus, it was the material selected for the conservation of the slides.

As a general overview, in mending and protecting cellulosic historical artifacts, transparency is of the utmost importance and therefore, nanocelluloses, particularly CNC, are ideally suited for the task. An exception may be the mending of transparent slides, which also require flexibility. The additivation with other chemicals to reduce the acidity in old written papers is essential to protect the documents from further aging-deterioration. The mending of wooden artifacts benefits from the easy coloring of the cellulosic nanomaterials, which are used to coat and fill aged and damaged surfaces.

4 Nanopapers/Nanocellulose Films for Conductive Materials and Electronic Devices

Devices such as conductors, supercapacitors, sensors, solar cells, and transistors, require conductive layers and/or printed circuits, and in all those cases a substrate is required on which the devices/components are fabricated. Other functional films are used to formulate antiglare surfaces and light diffusers, and in each case, flexibility, transparency, light scattering (to varying degrees), low weight, printability, and compatibility with conductive materials and nanoparticles are key parameters for this type of applications [15].

In fact, over the past decades, a large interest has been growing in flexible supports, because glass, which has been frequently used as substrate, results in rigid films not fitted for use in foldable displays, flexible electronics and energy related devices. Currently, there is a trend toward the use of large screen displays in electronic devices, which must also be lightweight and foldable for easy transport [63]. Thus, synthetic polymeric materials, such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) or polyethylene naphthalate (PEN), have been proposed instead of glass [64]. However, many polymers do not exhibit good volume thermal stability or cannot be easily chemically modified, and most of them are not ecofriendly [65]. In contrast, nanocellulosic materials present good mechanical properties while maintaining flexibility (a property achieved mostly by using micro/nanofibrillar cellulose), transparency and low CTE, intrinsic ecofriendliness, a large number of reactive sites that can easily participate in chemical reactions, and an easy-to-print surface [4,66]. In fact, all these characteristics are required to achieve a superior alternative to the use of traditional polymers or glass.

As it will be obvious in the following sections the vast majority of the nanocelluloses used in electronic devices have been CNF and not CNC, the reason being the need for flexible and consolidated substrates, [66] which can be more easily manufactured from the flexible and comparatively longer CNF than from the stiffer and shorter CNC.

4.1 Flexible Electroconductive Cellulose Nanopapers

While cellulose is not intrinsically conductive, it can be doped or combined with conductive polymers, metallic particles and/or conductive carbonic materials to introduce conductivity at a useful level. The resulting nanocomposites often combine characteristic advantages of both nanocelluloses and conductive materials [2,67,68].

Various strategies have been used to combine nanocelluloses with the active/conductive components of functional devices: mixing, grafting, coating. For the last method, different techniques can also be applied: rod coating, dip coating, spin coating, sputtering, spraying, layered filtration, etc. in much the same way to that previously explained for the processing of nanopapers in packaging applications [69].

Regarding the combination with conductive polymers: polyaniline, polypyrrole and polythiophene have been used to take advantage of the conductivity of the polymers and the flexibility, cohesion, light weight, mechanical properties and biodegradability of the nanocelluloses. Vacuum assisted filtration was the method selected by Liang et al. [70] to produce a cellulose nanopaper infused/coated with polyaniline (PANI): poly (sodium 4-styrene sulfonate), which exhibited high specific capacitance and 85% retention after 8000 cycles. Similarly, Liu et al. [71] used a related preparation method to obtain a 58 μm-thick CNF nanopaper with poly (3,4-ethylenedioxy thiophene): polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT: PSS), with PSS as the counterion. The full film CNF/PEDOT: PSS/(Ti3C2Tx), showed improved tensile strength and fracture strain with the use of the CNF layer (from 8.9 to 60 MPa and from 0.87% to 4.60%, respectively). The film displayed a high electromagnetic shielding efficiency because of the very high conductivity achieved.

Polythiophene was also used to graft CNF films by in-situ polymerization, resulting in changes in the conductivity from 9.4 × 10−3 μS/cm for the neat CNF film to 133 μS/cm for the nanopaper with the longest grafting step (24 h) used in the study, thus transforming the nanopaper from an insulator to a semiconductor. The conductivity was an order of magnitude higher than that of silicon semiconductors, according to the authors [72].

An in-situ polymerization process was also used by Gopakumar et al. [73] working with a CNF nanopaper, but in this case using polyaniline that formed H-bonds with the CNF and achieving a strong interface between the polymer and the nanocellulose. The hybrid nanopaper was effective in attenuating electromagnetic radiation in the 8.2–12.4 GHz band used in radar applications. A 1 mm-thick nanopaper showed a shielding effectivity larger than 99% attenuation at 8.2 GHz, which was considered useful for the telecommunications sector.

As already mentioned, CNC has not been used as widely as CNF in the production of nanopapers; however, Liu et al. [74] prepared films from CNC modified by the in-situ polymerization of aniline, obtaining flexible and conductive films. The authors observed a jump in the electrical conductivity from 10−6 to 10−2 S/cm when the percentage of PANI increased from 10 to 20 wt.%.

Different carbon nanomaterials have also been combined with nanocelluloses to produce conductive flexible films: carbon nanotubes (CNT), graphene oxide (GO), reduced graphene oxide (RGO) and graphite nanoplatelets [4,75,76]. Another example is the obtention of ~3.4 nm thick graphene layers, prepared by mechanical in-situ exfoliation of graphite in a nanocellulose dispersion, from which films were produced by vacuum filtration (Fig. 8) [77]. Agglomeration of graphene was prevented by the interaction with the nanocellulose. Subsequent immersion of the films in a solution containing metal cations allowed for cation-π interactions between metal graphene and the cellulose. These interactions resulted in improved mechanical properties, electrical conductivity and electromagnetic shielding effectiveness.

Figure 8: (Top) Schematic of the production of films from CNF and exfoliated graphene. (Bottom) (a) TEM image of the exfoliated graphene; (b–d) results of the size of the platelets and their thicknesses [Adapted with permission from Ref. [77]. Copyright © 2023 Elsevier Ltd.]

In other cases, additional benefits to that of increased conductivity were obtained, such as the much improved dispersion of carbon nanotubes (single walled carbon nanotubes, SWNTs) in the presence of CNCs in aqueous media leading to transparent conductive films. For example, Olivier et al. prepared hybrid films assembled with a layer by layer technique deposited on a glass substrate [78]. The film was prepared by immersion in poly(allylamine hydrochloride) used as polycationic layer followed by water rinsing, drying and subsequent immersion in the CNC/SWCNT dispersion followed by rinsing and drying. Thus, a bilayer is obtained and this process can be repeated to obtain an n-bilayer assembly, which was reported to generate uniform films with the thickness growing in direct proportion to the number of bilayers. Then, the authors added the electrodes by gold sputtering and measured electrical conductivity values from 6.10−4 (Ω·m)−1 to 15 (Ω·m)−1 by varying the SWCNT concentration from 1 to 12 wt.%.

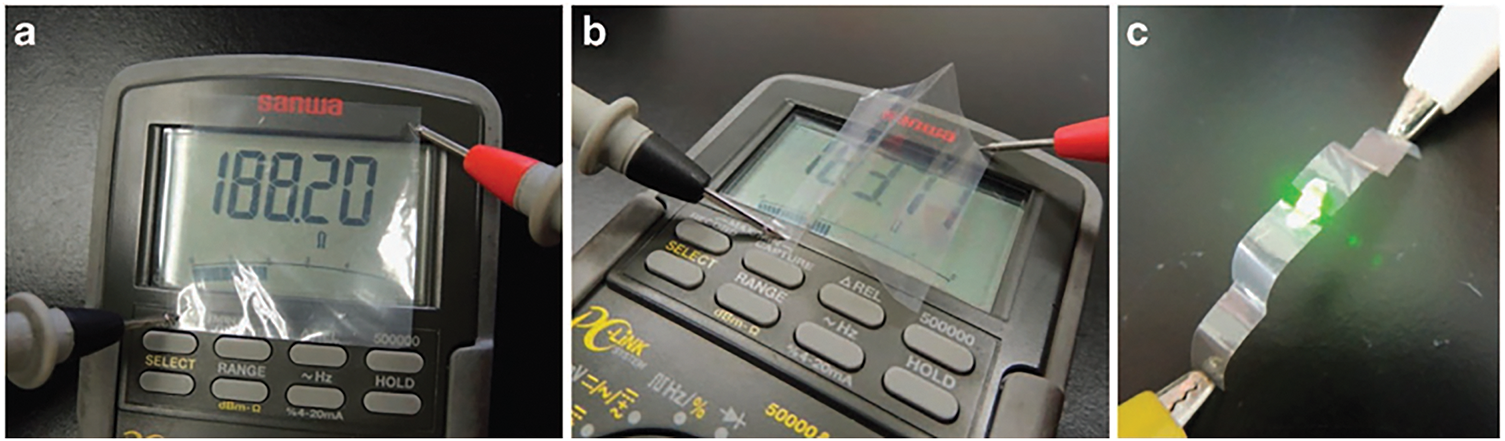

Nanocellulose-based conductive films have been prepared by different methods such as printing the circuits on the nanopapers [79], coating via metal sputtering, ink printing or transfer of the already preformed circuits onto CNF substrates [16], mixing of the metallic particles with the nanocelluloses. Adding filtration steps in the manufacture of the nanopapers that include the active components in the suspension/solution can easily lead to functional nanopapers. Koga et al. [80] used the last method by post-filtration of aqueous dispersions of silver nanowires or carbon nanotubes through the nanopaper that acted as substrate Figs. 9 and 10. The nanopaper containing Ag nanowires showed a transparency of 88% and a sheet resistance of 12 Ω/square, which was reported to be 75 times lower than that of a PET film. The transparent conductive nanopapers were foldable with minimum changes in the measured conductivity (Figs. 10 and 11).

Figure 9: Added filtration step in the manufacture of functional films (PET and CNF nanopaper). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [80]

Figure 10: (a) Detail of the filtration procedure used to prepare the CNF nanopapers. (b) The image below shows three nanopapers: neat CNF nanopaper (left), CNT/CNF nanopaper (middle) and Ag nanowires/CNF nanopaper (right). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [80]

Figure 11: Resistance values of the Ag nanowires/CNF nanopaper before (a) and after (b) folding (188 Ω and 184 Ω, respectively). Lighting of a green LED on an Ag nanowires/CNF nanopaper (c). Adapted from Ref. [80]

When circuits are defined via ink printing, there is an advantage in using nanopapers over conventional papers because the first ones contain smaller pores, which lead to improved sharpness of the printed tracks and increases the connection between adjacent metallic particles. As it was discussed for conventional printing on paper packaging, the printability of conductive inks is also improved thanks to the reduction of pore size. For example, a conductivity of 500 S/cm was achieved in a CNF paper “crosslinked” (consolidated) with hydroxypropylmethyl cellulose and combined with silver nanowires [81]. The use of CNF nanopapers as suitable substrates for Ag and CNT printed electronics has resulted in printed tracks with lower electrical resistance (even when the film was bent) than those printed on plastics like polyimides or PEN [82]. Other applications have been envisioned for these types of films, such as radio frequency antennas printed with Ag inks on glutaraldehyde crosslinked CNF films. These films exhibited much enhanced dimensional stability in contact with water as compared to uncrosslinked nanopapers, which led to significantly better results when using aqueous inks [37].

In general, when using nanopapers in electronics, their sensitivity to water should be particularly considered. Lakovaara et al. [83] used hydrophobized cellulose nanomaterial as coatings for CNF films to enhance their water resistance, and as a result, ink removal from coated films was partially or completely inhibited.

Zhang et al. [38] formulated more stable films by complexation of phosphorylated CNF with chitosan nanocrystals. The films reached a wet tensile strength of ~18 MPa, with good thermal stability and self-extinguishing behavior. The stabilization in wet environments and the achieved properties were considered promising for use in optoelectronics.

4.2 Importance of Transparency and Haze for Functional Applications

Not only the flexibility of the CNF nanopapers, but also their transparency are key properties for several applications. While nanopapers show in general high transparency, they can exhibit different degrees of haze, which is defined as the percentage of the incident light that is scattered by a surface in more than 2.5°. This property is responsible for the effect of milkiness or frosting of an otherwise transparent film and can be adjusted to obtain surfaces ranging from highly reflective to anti-glare [84,85]. This effect can be used for aesthetic reasons, as anti-glare protective coatings/films, or as panels to diffuse light evenly and consequently, it is a useful optical property for diverse functional applications.

4.2.1 High Transparency and Low Haze: Displays

High optical transmittance and conductivity are requirements for the preparation of optoelectronic devices. Indium-tin oxide (ITO) is generally used, as it has a transmittance above 75% and a conductivity in the order of 104 S/cm depending on, among other factors, the layer thickness. However, it presents clear disadvantages, such as lack of sustainability, high cost and brittleness.

As in other applications, transparent, flexible, sustainable and inexpensive nanopapers are becoming an alternative worth pursuing. In particular, nanopapers to be used in displays and touchscreens require high transparency with concurrent low haze [86]. For example, Song et al. prepared transparent conductive nanopapers using hemp and bamboo CNF mixed with Ag-nanowires, which showed a sheet resistance of 1.9 Ω/square with a transmittance of 86% at a wavelength of 550 nm [81]. The sheet resistance remained almost constant for up to1000 cycles of bending-unbending at 135°. The conductivity was demonstrated by the capacity for lighting two light emitting diode (LED, 3 V). In fact, Yagyu et al. prepared light emitting diodes by silver printing on CNF substrates of low carboxylate content (a feature that was considered to achieve higher thermal resistance) with high optical transparency, low haze and low CTE [87]. There was an increase in yellowness of the nanopapers when heated, but the variation in color was negligible when the heating was applied for 10 min at 140°C in air, which was a much better response than that obtained with several polymer films. The change was more clearly visible when heating at higher temperatures or using a CNF with higher carboxylate content.

Zhu et al. [65] worked on the preparation of transparent films to be used as flexible displays and demonstrated that by tailoring the packing of the cellulose in the films, it was possible to maintain high transparency while varying the haze of the films, thus widening the number of possible applications. In particular, they prepared clear films with more than 90% of total transmittance and haze lower than 1% by using TEMPO-microfibers to obtain flexible nanofibers with thickness of about 10–20 nm and lengths of about 500 nm. The process included partial dissolution of the CNF in an ionic liquid and further pressing to obtain the clear paper. The authors made a prototype of a display after deposition of graphene on the nanocellulose substrate, with the composite flexible film ultimately showing an effective touchscreen response.

Kwon et al. [88] protected Ag-nanowire networks in flexible transparent electrodes by using layer-by-layer assembly of chitin and CNF, taking advantage of the opposite charges in the two biopolymers. The protected electrode showed enhanced stability under UV/O3, thermal and chemical treatments and cyclic bending tests. As proof of concept, the flexible electrodes were arranged to perform as transparent heaters and pressure sensors.

4.2.2 Transparent but Hazy Nanopapers

The use/combination of cellulose micro/nanofibers and CNC has been a strategy for producing transparent nanopapers with different degrees of haze. Larger nanoelements increase the scattering of incident light and, therefore, increase the haze. Consequently, CNC nanopapers show high transparency with lower haze than nanopapers from CNF or microfibrillated cellulose, whereas conventional paper is essentially opaque, unless a very thin paper is produced. Usually, transparent nanopapers with different degrees of haze are considered for the fabrication of energy harvesting and storage devices, in which the scatter of light renders a matte surface that reduces light reflection and better distributes the incident light, a behavior of interest in photovoltaic applications. Moreover, the mesoporous structures that scatter light also provide a large surface area, which is beneficial for the construction of charge collectors and storage devices [86]. In fact, cellulose nanopapers (mainly made from CNF) are frequently reported to feature high transparency and high haze, low density, low cost, in addition to being relatively easy to prepare, biodegradable and of low toxicity. As in other applications, the flexibility of nanocellulose-based films has been an asset when used as separators and solid electrolytes for energy harvesting and storage applications [3,16]. Humidity, on the other hand, would require control, and hydrophobic layers could be used to protect the cellulosic nanopaper [84].

4.3 Anti-Glare Coatings and Solar Cells

Anti-glare coatings/films, as well as solar cells substrates, must exhibit high transparency, but with high optical haze, so that light scattering reduces reflection and improves absorption in the case of the active materials in the solar cells [86]. As further discussed, this behavior is also favorable in the preparation of energy storage devices such as batteries, supercapacitors and transistors. For example, a highly transparent yet hazy paper was prepared similarly to an ordinary paper using pulp microfibers partially dissolved in an ionic liquid [65]. The result was a strong paper containing mesopores responsible for the observed light dispersion. The film was applied as coating on a digital display (organic light-emitting diode, OLED) to suppress glare with high efficiency.

The large surface area provided by the mesoporous structure of these films ensures good charge transport for photons, which can be absorbed and converted into electrical energy [89]. Thus, the tailoring of surface rugosity in transparent papers has been studied. For example, Wu et al. prepared films by mixing micron- and nanosized fibers that led to differences in diffusive light transmission (haze as high as 78%) [90]. The papers had a transparency ~90% and were prepared as coatings on thin silicon wafers to improve the capacity of the thin films to absorb light energy and thus, to be used in solar cell fabrication. The authors also proved that when a green OLED supported on glass was modified by deposition of a nanocellulose film on the back surface of the glass, the current density-voltage was unchanged due to the added layer, but the light output power was increased about 15%.

In particular, solar cells require layers with different characteristics: light must enter, and absorption should happen in the layers where energy is collected. The total cell thickness should be low to achieve highly efficient lightweight cells. Among the requirements, an antireflective coating layer is needed, so that light enters with minimal reflection. Because cellulose is an intrinsically insulating material, the most common use of nanopapers in solar cells is as substrate of high transparency and haze.

Ha et al. [41] used nanocellulose papers to reduce reflection and improve the performance of a GaAs solar cell. Actually, the application of the anti-reflection coating was very effective, as the surface texture of the cellulose layer led to a response essentially independent of the wavelength of the incident light. The authors prepared the nanopaper with TEMPO-microfibers, obtaining highly transparent yet hazy films, particularly valuable in the case of thin films. They soaked the cellulose paper with PVA as adhesive and used it to coat a GaAs solar cell that originally reflected 35%–45% of the incident light. However, with the addition of the cellulose paper, this value was reduced to 25%–35%. As a result, the overall power conversion efficiency (ratio of incident power in the form of light to the output electrical power, PCE) increased from 13.56% to 16.79%.

Nogi et al. [63] worked with nanopapers prepared from a 0.7 wt.% suspension of CNF (~15 nm thick and 15–20 μm in length) to produce flexible solar cells. Even though the use of polymer substrates allowed them to obtain flexible films (an improvement compared to ITO solar cells), these same authors demonstrated the advantage of using a cellulose nanopaper as the substrate for Ag nanowires instead of using PET or polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) films. The authors proposed a simple preparation process in which the Ag nanowires suspension is deposited on a silicon wafer and, after drying, the CNF suspension is dropped onto the previous layer and dried to obtain a transparent paper by peeling it off the wafer. The resulting composite nanopaper had a sheet resistance of 148 Ω/square with a transmittance of 95% and a PCE of 3.2%. Comparatively, a similar film prepared with PVA instead of CNF had a sheet resistance of 297 Ω/square. Furthermore, the electrical resistance of films made from PVA or from PET increased exponentially after 3–5 folding cycles, whereas that of the nanopaper remained virtually constant for at least 20 folding cycles.

Jung et al. [91] prepared flexible solar cells using a combination of a TEMPO-CNF nanopaper (transparency and haze of 90% and 80%, respectively) with perovskite as substrate and light absorber. The nanopaper was silane-treated to reduce the adverse effect of humidity. The perovskite was mixed with halides to vary the color of the solar cell, and the electrode layer was made by sputtering three layers of Ti oxide, Ag and Ti oxide (dielectric–metal–dielectric, DMD). In this case, a PCE of 6.37% was achieved, and the authors considered that there was room for improvement by enhancing the conductivity and transmittance of the substrate.

Analogously, Valdez García et al. [84] also worked with nanocelluloses for use in organic and perovskite solar cells. They prepared encapsulated cells that required low temperature processing. By using this method, the problem of moisture sensitivity of the nanocelluloses is reduced or eliminated, which also reduces premature biodegradation. Costa et al. prepared solar cells using CNC and CNF as alternative substrates and compared their performance with respect to that of glass [92]. The PCE of the cells showed variations depending on the used substrate, being 3.0%, 1.4% and 0.5% for the glass, CNC and CNF. In the case of the latter two, the performance can be traced to the roughness of the nanopapers, which was 8.3 and 10.9 nm (CNC and CNF nanopaper, respectively), measured over an area of 10 × 10 μm.

Some authors have suggested that high roughness and porosity in nanopaper substrates can result in low PCE and that the problem is exacerbated if CNF with very high surface roughness (surface height variation of ~40 nm) are used [6]. For this reason, Zhou et al. [6] chose to fabricate solar cells on CNC substrates, achieving a power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 2.7%, and end-of-life recyclability by separating the original main components.

In order to simultaneously achieve high transmittance and high haze characteristics, cellulose micro/nanofibers of different sizes have been deliberately combined. Thus, Fang et al. [86] prepared nanopapers with ∼96% of transparency and ∼60% optical haze from TEMPO-microfibers and highlighted the presence of fines that reduced the volume of pores in the final paper, thus increasing its transparency. The paper was used to coat a solar cell (as it was also done by Ha et al. [41]), resulting in a PCE increase from 5.34% to 5.88%. The use of microfibers instead of nanofibers accelerated the drying step, which was considered a potential advantage for the process.

The tribological effect, consisting of the electric charge transfer between two sliding objects, was also considered for energy harvesting based on an amine- crosslinked-modified TEMPO-CNF nanopaper. The proof of concept was the energy output provided by stepping on a modified active board, which enabled the lighting of a string of LEDs [93].

Because of their folding capability, the nanocelluloses have been combined with conductive materials to prepare flexible electrodes for batteries [94]. Electrodes prepared from CNF and graphite showed a conductivity of 0.3 S/cm, measured after wrapping them around hoses of different diameters (0.6–6.4 cm) [95]. CNF nanopaper has also been used as separator in Li-ion batteries, as in the case of Chun et al. [96], who prepared a separator of ~19 μm and found advantages over a 20 μm-separator made from PP/PE/PP, in particular due to the nanopaper’s much lower thermal shrinkage (negligible) compared to that of the plastic separator (36%). The nanopaper was obtained from CNF dispersed in a mixture of water/isopropyl alcohol. Interestingly, the porosity of the paper was controlled by varying the solvents ratio. The lowest porosity was obtained with pure water, while a porosity close to that of the synthetic PP/PE/PP separator was measured when the isopropanol/water ratio was in the range of 100/0 to 95/5. Porosity played an important role because large pores (common when using standard paper separators) can lead to internal short circuits. The authors compared the performance of the CNF and synthetic separators. For the nanopaper prepared with 95/5 isopropanol/water, they found an ionic conductivity of 0.75 mS/cm, a tensile modulus of 4767 MPa, and a tensile strength of 42 MPa, while the corresponding values for the synthetic separator were 0.73 mS/cm, 678 MPa and 180 MPa. Although less flexible, the authors considered that there was room for improvement for the CNF nanopapers. Furthermore, when measuring self-discharge and discharge capacity retention after 100 cycles (charge-discharge), very little difference was found between the performances of the batteries prepared with both types of separators. Apparently, the tuned nanoporous structure was the main variable that enabled similar performance. There was also an additional advantage of the CNF separator when using high polarity electrolytes, as it was wetted much more efficiently than the synthetic one, thus increasing the range of polar electrolytes that could be used in battery preparation.

Leijonmarck et al. [97] prepared a Li-ion battery using three layers based on CNF as binder material and using a water paper making procedure of vacuum filtering in steps as schematized in Fig. 1e. The negative electrode was formed from a dispersion of CNF, graphite and SuperP carbon (a conductive additive). The separator was prepared from a dispersion 1:1 (dry weight) of CNF and SiO2. The positive electrode contained CNF, LiFePO4 and SuperP carbon. The overall structure was 250 μm thick, with a strength at break of 5.6 MPa when soaked in electrolyte.

Other efficient energy storage devices are supercapacitors, consisting mainly of two electrodes separated by a dielectric barrier, which can store large amounts of energy with rapid charging/discharging rates, low maintenance costs, high power density and usually long life properties that are well suited for use in electric and electronic applications [98,99]. As in the case of other energy applications, cellulose nanopapers facilitate charge storage in supercapacitors due to the large surface area that can be tailored based on the particular size of the chosen nanocellulose and the process and solvent selected to produce the nanomaterial [100]. The mesoporous structure can also serve as electrolyte reservoir, facilitating the transfer of charges and/or ions for capacitors and pseudocapacitors. An example was given by Wang et al. [101], who proposed the preparation of supercapacitors from transparent and flexible CNF substrates using a layer by layer deposition of PANI followed by that of PEDOT: PSS or reduced graphene oxide (rGO). The characterization of multilayer structures showed improved capacitance for the rGO structures although with lower optical transmittance due to the color given by the rGO.

Flexible transistors (devices based on semiconductor materials that are used to amplify or switch electrical signals) have been developed to act in different types of electronic devices and displays. For example, Seo et al. [102] prepared an active silicon membrane that was transferred onto a CNF substrate using an adhesive. Photoresist patterning and etching were then performed to obtain a transistor that operated in the microwave range both in the flat and bent states. Other authors [15] prepared transistors using a CNF substrate coated with a layer of CNT. The authors highlighted the benefits of using CNF because of the excellent bonding to the CNT, avoiding electrical short circuits thanks to the reduction of CNT protruding from the film. CNF transparent nanopaper was also used by Fujisaki et al. [103] as both a substrate and a dielectric layer to prepare an organic thin film transistor (OTFT). They used spin coating of the CNF to achieve low surface roughness and low current leakage in the array, leading to a performance similar to that of transistors based on plastic substrates.

To prepare a flexible transistor, Gaspar et al. [104] used a CNF nanopaper based on cotton cellulose as both a substrate and a dielectric layer. The semiconductor oxide was sputtered onto one side of the nanocellulose, and the array exhibited an on/off intensity modulation above 105, surpassing the performance of thin film transistors produced with conventional paper.

Hybrid micro/nanopapers were studied for their high transparency with tailored haze [105]. The films were produced from a mixture of TEMPO microfiber suspension of southern yellow pine bleached pulp and CNF incorporated in different proportions. All hybrid papers had transparency above 90% but haze ranging from 18% to 60%, and the authors selected the nanopaper made from 100% CNF to fabricate a transistor with an Ion/Ioff ratio ~1 · 105.

Piezoelectric harvesting devices based on nanocelluloses have also been investigated. Piezoelectric properties (derived from the ability of certain materials to produce electricity as a result of applied stress) were discovered in wood in 1950 by Bazhenov. As it happens with other crystals without a center of symmetry, cellulose crystals are responsible for this property in woods [16]. A permanent electric “giant” dipole has been measured in cellulose nanocrystals, but even CNF films with non-aligned crystalline regions can exhibit piezoelectric behavior [106–110]. Tuukkanen and Rajala [111] compared the efficacy of using CNC and CNF films and found a 2 to 4-fold higher sensitivity when using the former, which essentially contains the crystalline blocks of the nanocellulose, instead of the CNF, which also has a large contribution from the amorphous blocks.

In general, integrated modified cellulose nanopapers that exploit movement and pressure changes for energy harvesting have been prepared as lightweight structures that integrate sensors and actuators for microelectromechanical systems, robotics, speakers, micropumps and others [112]. Thin CNC films have been shown to achieve a piezoelectric performance comparable to that of a reference ZnO film [113,114].

Piezoelectric response has been used in the production of soft electroactuators from cationically modified CNF doped with ionic liquids and Li salts (different anions were used and efficiency compared) [115]. In general, humidity affects the performance of piezoelectric nanopapers by softening the actuators so that anions can move more easily. This effect can also be produced by increasing the voltage [116].

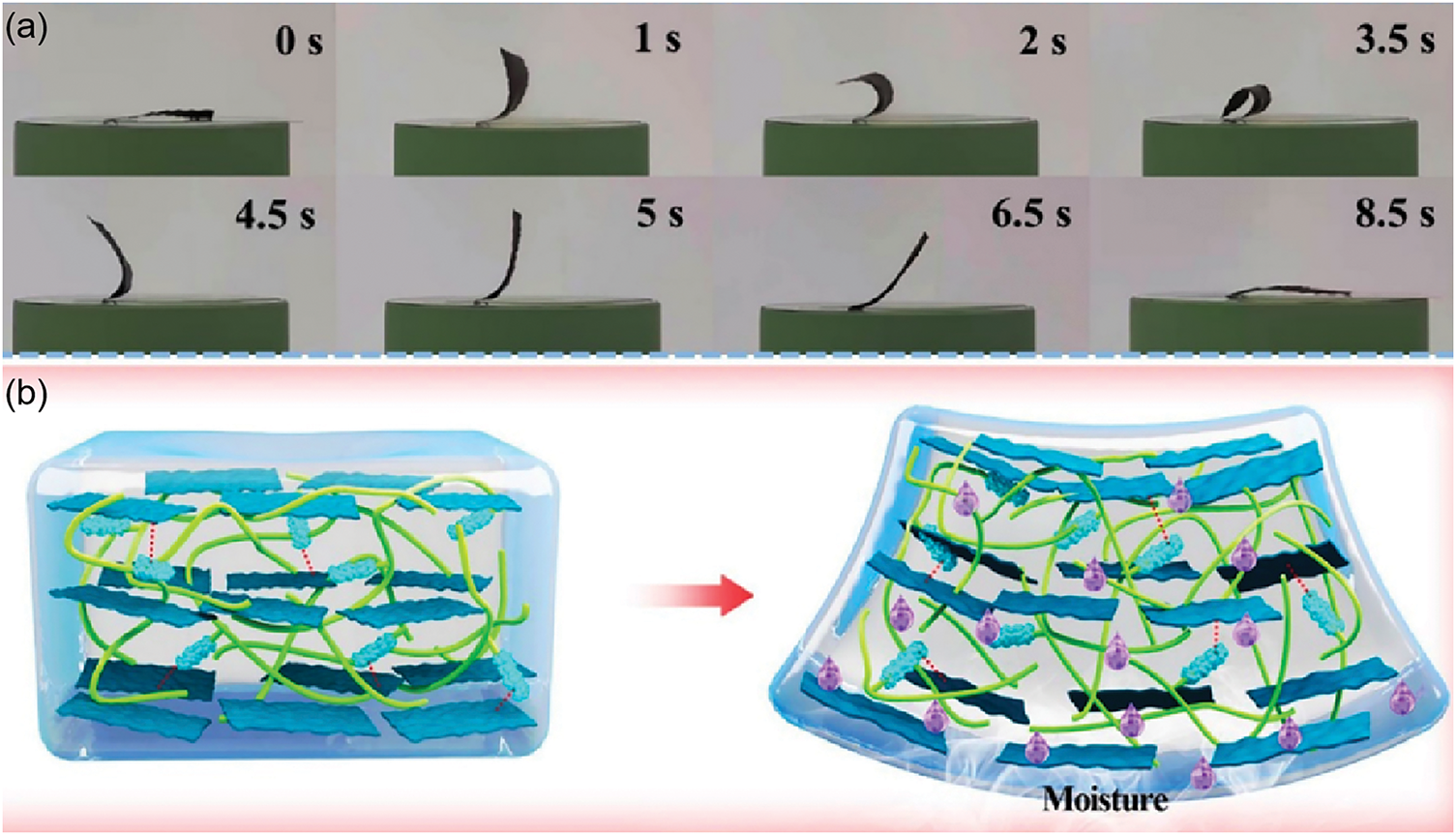

Humidity sensing films were prepared from gallic acid-modified CNF with up to 20 wt.% Ti3C2 powder (one of the 2D inorganic compounds known as MXenes) using vacuum filtration [117]. Alternating humidity conditions imposed on a CNF-Ga/MXene composite film induced an output of alternating voltage. It was suggested that the sensitivity and correlation between humidity and voltage (and also deformation) would allow for its use as actuator. Fig. 12 illustrates this behavior: a 35 μm thick film is shown, which by applying an ad-hoc humidity gradient, suffers bending (154.7° within 3 s). After removing the gradient, the film returned to its original shape in ~9 s.

Figure 12: Example of the sensitivity to a humidity gradient of a CNF-nanocomposite film (CNF-Ga/MXene). Response of the film upon exposure to humidity gradient, 0–3 s (first row) and after its removal, 3–8.5 s (second row). Graphical illustration of the effect of humidity entering from the down-face of film (bottom). Adapted from Ref. [117]

In summary, as with nanopapers used in packaging, a common requirement for those used in electronics is flexibility and very often, transparency. The degree of haze varies depending on the specific application: low for displays, higher for energy harvesting and storage applications. Tunability of the properties through CNF and CNC mixing is a clear advantage, as is their easy printability and combination with conductive polymers, nanoparticles such as CNT and graphenes, as well as different metals and inorganic oxides.

For these types of applications, the process is still limited to laboratory scale, and better control of the porosity and surface roughness of the films is required if larger volume processes are to be considered. Low surface roughness is essential for printed circuits.

Hydrophobicity remains an issue, while biodegradability represents a clear advantage over plastic films.

During the last two decades, global interest in the use of biobased sources, in particular cellulose, for the production of materials has steadily increased. The utilization of nanocelluloses as nanopapers covers a wide range of applications and these 2D structures, considered as self-standing films or as coatings on synthetic or natural supports (including conventional papers and boards), were the focus of this review.

A widely shared opinion is that the consolidation of widespread commercial adoption of nanocelluloses depends on ensuring consistency in their characteristics across different sources and production batches. Although currently there are several producers of different types of nanocelluloses from vegetable sources, each product may differ from other commercially available products. Consequently, at the other end of the production process—the manufacturing of final products and functional devices—the use of nanocelluloses as raw material is finding resistance from the potential users because the material cannot yet offer constant characteristics, such as size and size distribution, surface charge, etc. However, significant efforts are currently being devoted to standardize processes, while simultaneously reducing energy and production costs.

On the other hand, the potential application of known processes (such as those based on papermaking technologies) or relatively simple modifications thereof appear to be the most promising routes for the preparation of nanopapers on a large scale. In this regard, the examples presented as continuous processes are appealing proposals to reduce the time and costs of manufacture. However, further development is required because, due to the large water content, long drying times are usually required. Furthermore, while high-performance processes would be desirable for photovoltaic applications, they require very smooth surfaces, which are not typically achieved with CNF films. On the other hand, CNC films or CNF-CNC hybrid films might be more suitable for these processes and applications.

In the production of some devices, transparency and bendability are fundamental requirements. In these cases, nanocelluloses (particularly CNF for bendable nanopapers and CNC or their mixtures for highly transparent films) are very promising materials thanks to their tunable optical properties, tunable surfaces (which are also easily printable), low CTE (lower than that of many synthetic polymers), and their biodegradable nature. The enforcement of legislation dedicated to the preservation and care of the environment is a key factor in the development and use of ecofriendly materials in general, and nanocelluloses in particular, for these applications.

The literature reviewed demonstrates the widespread preference for CNF over CNC, due to the aforementioned advantages of greater film cohesion and improved flexibility. Another advantage of using CNF is its lower production cost compared to that of CNC. Besides, the additional steps required to obtain CNC, which include the use of strong acids followed by several washing steps, result in a less environmentally-friendly process. However, CNC has proven to be invaluable when high transparency is the primary goal (for example in the conservation of heritage cellulosic artifacts or the preparation of transparent displays) and for tuning porosity, transparency and haze for harvesting light/energy devices. Moreover, nanocelluloses have been favorably compared to carbon nanotubes (CNT) because of the large availability of raw materials for nanocellulose production, their relatively lower price and lower toxicity. The use of nanocelluloses with incompletely separated lignin could be advantageous in applications where some coloration is not an issue. In addition to the lower preparation cost, lignin’s UV and biocidal properties may be a desirable addition to the films.

The use of nanocelluloses in the development of stimuli-responsive smart materials can also be identified as a promising area of application due to their intrinsic (or chemically added) sensitivity to water, pH, ions and vapors, particularly in bioapplications due to their low toxicity.

Another challenge to surmount is the negative effect of humidity and hydration on the nanopapers and their overall cohesion and performance under these conditions, particularly when considering industrial scale processing and commercialization. Methods proposed to improve the cohesion and stability of the nanopapers include the diverse approaches to crosslinking reported. The use of chemical and/or physical agents of crosslinking requires further development. Some of the simpler techniques that could be coupled/implemented in continuous processes would be preferred.

The efforts invested in the development of nanocelluloses, and cellulose nanopapers in particular, are well spent: nanocelluloses are materials with attractive properties, reactive sites amenable to reaction, easy to be combined/compounded with other active chemicals and/or nanoparticles, and processable by relatively simple methods to produce materials with tunable properties, all of which allows to foresee the development of useful and effective applications in the near future.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank Prof. J.F. González and Dr. J.M. González for the helpful revision of the final version of the manuscript.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET, Argentina), grant number PIP 0991 and by Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata (UNMdP, Argentina), grant number 15/G686-ING690/23.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm that Mirta I. Aranguren and Verónica L. Mucci contributed equally in conceptualization, writing (original draft), review and editing, supervision and funding acquisition for the realization of this review work. The authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Given the nature of this work (review) this statement is not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0079/s1.

References

1. Eichhorn SJ, Dufresne A, Aranguren MI, Marcovich NE, Capadona JR, Rowan SJ, et al. Review: current interna-tional research into cellulose nanofibres and nanocomposites. J Mats Sci. 2010;45(1):1–33. doi:10.1007/s10853-009-3874-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Hassan SH, Voon LH, Velayutham TS, Zhai L, Kim HC, Kim J. Review of cellulose smart material: biomass conversion process and progress on cellulose-based electroactive paper. J Renew Mater. 2018;6(1):1–25. doi:10.7569/JRM.2017.634173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Dufresne A. Nanocellulose processing properties and potential applications. Curr For Rep. 2019;5(2):76–89. doi:10.1007/s40725-019-00088-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Wang J, Han X, Zhang C, Liu K, Duan G. Source of nanocellulose and its application in nanocomposite packaging material: a review. Nanomater. 2022;12(18):3158. doi:10.3390/nano12183158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Casado U, Mucci VL, Aranguren MI. Cellulose nanocrystals suspensions: liquid crystal anisotropy, rheology and films iridescence. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;261(10):117848. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2021.117848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zhou Y, Fuentes-Hernandez C, Khan TM, Liu J-C, Hsu J, Shim JW, et al. Recyclable organic solar cells on cellulose nanocrystal substrates. Sci Rep. 2013;3(1):1536. doi:10.1038/srep01536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Tafete GA, Abera MK, Thothadri G. Review on nanocellulose-based materials for supercapacitors applications. JEnergy Storage. 2022;48(14):103938. doi:10.1016/j.est.2021.103938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Leppänen I, Hokkanen A, Österberg M, Vähä-Nissi M, Harlin A, Orelma H. Hybrid films from cellulose nanomaterials—properties and defined optical patterns. Cellulose. 2022;29(16):8551–67. doi:10.1007/s10570-022-04795-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Asghari-Varzaneh E, Shekarchizadeh H. Fascinating properties and applications of nanocellulose in the food industry. In: Md Newaz Kazi S, Huang J, editors. Nanocellulose—Sources, preparations, and applications. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2024. doi:10.5772/intechopen.114085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ozcan A, Tozluoglu A, Kandirmaz EA, Tutus A, Fidan H. Printability of variative nanocellulose derived papers. Cellulose. 2021;28(8):5019–31. doi:10.1007/s10570-021-03861-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hashemzehi M, Mesic B, Sjöstrand B, Navqvi MA. Comprehensive review of nanocellulose modification and applications in papermaking and packaging: challenges, technical solutions, and perspectives. BioResources. 2022;17(2):3718–80. doi:10.15376/biores.17.2.Hashemzehi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tajik M, Torshizi HJ, Resalati H, Hamzeh Y. Effects of cationic starch in the presence of cellulose nanofibrils on structural, optical and strength properties of paper from soda bagasse pulp. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;194(2):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.04.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Lengowski EC, Bonfatti EA, Kumode MMN, Carneiro ME, Satyanarayana KG. Nanocellulose in the paper making. In: Inamuddin Thomas S, Kumar Mishra R, Asiri A, editors. Sustainable polymer composites and nanocomposites. Cham, Swizerland: Springer; 2019. p. 1027–66. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-05399-4_36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Klemm D, Kramer F, Moritz S, Lindström T, Ankerfors M, Gray D, et al. Nanocelluloses: a new family of nature-based materials. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50(24):5438–66. doi:10.1002/anie.201001273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Huang J, Zhu H, Chen Y, Preston C, Rohrbach K, Cumings J, et al. Highly transparent and flexible nanopaper transistors. ACS Nano. 2013;7(3):2106–13. doi:10.1021/nn304407r. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Sabo R, Yermakov A, Law CT, Elhajjar R. Nanocellulose-enabled electronics, energy harvesting devices, smart materials and sensors: a review. J Renew Mater. 2016;4(5):297–312. doi:10.7569/JRM.2016.634114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lavoine N, Desloges I, Khelifi B, Bras J. Impact of different coating processes of microfibrillated cellulose on the mechanical and barrier properties of paper. J Mater Sci. 2014;49(7):2879–93. doi:10.1007/s10853-013-7995-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Otto S, Strenger M, Maier-Nöth A, Schmid M. Food packaging and sustainability—consumer perception vs. correlated scientific facts: a review. J Clean Prod. 2021;298(3):126733. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ochoa-Yepes O, Di Giogio L, Goyanes S, Mauri A, Famá L. Influence of process (extrusion/thermo-compression, casting) and lentil protein content on physicochemical properties of starch films. Carbohyd Polym. 2019;208(5–6):221–31. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.12.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Iglesias Montes ML, D’Amico DA, Manfredi LB, Cyras VP. Effect of natural glyceryl tributyrate as plasticizer and compatibilizer on the performance of bio-based polylactic acid/poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) blends. J Polym Environ. 2019;27(7):1429–38. doi:10.1007/s10924-019-01425-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Iglesias-Montes ML, Soccio M, Siracusa V, Gazzano M, Lotti N, Cyras VP, et al. Chitin nanocomposite based on plasticized poly (lactic acid)/poly (3-hydroxybutyrate) (PLA/PHB) blends. Polymers. 2022;14(15):3177. doi:10.3390/polym14153177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Montaño-Leyva B, Ghizzi D, da Silva G, Gastaldi E, Torres-Chávez P, Gontard N, et al. Biocomposites from wheat proteins and fibers: structure/mechanical properties relationships. Ind Crops Prod. 2013;43(1):545–55. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.07.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Gao Y, Huang C, Ge D, Liao Y, Chen Y, Li S, et al. Highly efficient dissolution and reinforcement mechanism of robust and transparent cellulose films for smart packaging. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;254(3):128046. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.128046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Langhe D, Ponting M. Manufacturing and novel applications of multilayer polymer films. 1st ed. Norwich, NY, USA: William Andrew; 2016. doi:10.1016/C2014-0-02177-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Farris S, Introzzi L, Piergiovanni L. Evaluation of a biocoating as a solution to improve barrier, friction and optical properties of plastic films. Packag Technol Sci. 2009;22(2):69–83. doi:10.1002/pts.826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Priolo MA, Gamboa D, Holder KM, Grunlan JC. Super gas barrier of transparent polymer-clay multilayer ultrathin films. Nano Lett. 2010;10(12):4970–4. doi:10.1021/nl103047k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Claro P, de Campos A, Corrêa A, Rodrigues V, Luchesi B, Silva L, et al. Curaua and eucalyptus nanofiber films by continuous casting: mixture of cellulose nanocrystals and nanofibrils. Cellulose. 2019;26(4):2453–70. doi:10.1007/s10570-019-02280-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Vartiainen J, Kaljunen T, Nykanen H, Malm T, Tammelin T. Improving multilayer packaging performance with nanocellulose barrier layer. In: Proceedings of the TAPPI Place Conference; 2014 May 13–15; Ponte Vedra, FL, USA. [cited 2025 Jun 22]. Available from: https://cris.vtt.fi/en/publications/improving-multilayer-packaging-performance-with-nanocellulose-bar. [Google Scholar]

29. Khakalo A, Mäkelä T, Johansson L-S, Orelma H, Tammelin T. High-throughput tailoring of nanocellulose films: from complex bio-based materials to defined multifunctional architectures. ACS Appl Bio Mater. 2020;3(11):7428–38. doi:10.1021/acsabm.0c00576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]