Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

The Reductive Amination of Biomass-Based Aldehydes and Alcohols towards 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan: Progress, Challenges and Prospects

1 Key Laboratory of Green Chemistry and Technology of Ministry of Education, College of Chemistry, Sichuan University, Chengdu, 610064, China

2 Sichuan Research Institute of Chemical Quality and Safety Testing, Chengdu, 610031, China

3 Sichuan Institute of Product Quality Supervision and Inspection, Chengdu, 610100, China

* Corresponding Authors: Ruixiang Li. Email: ; Jiaqi Xu. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(9), 1683-1706. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0043

Received 21 February 2025; Accepted 07 May 2025; Issue published 22 September 2025

Abstract

Primary diamines play an important role in the chemical industry, where they are widely used as raw materials for the manufacture of pharmaceuticals and polymers. Currently, primary diamines are mainly derived from petroleum, while harsh or toxic conditions are often needed. Biomass is abundant and renewable , which serves as a promising alternative raw material to produce primary diamines. This review primarily focuses on the synthesis of 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan (BAMF), a bio-based diamine with potential as a biomonomer for polyamides and polyureas. Specifically, this review emphasizes the synthesis of BAMF from three biomass-derived alcohols and aldehydes, namely 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan (BHMF), and 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF). These are the key substrates to get BAMF and could be readily obtained from carbohydrates. Even though great effort has been put into the synthesis of BAMF, it remains a tough problem to obtain BAMF with a high yield at a low cost due to the inevitable side reactions, such as unwanted hydrogenation reactions and condensation reactions. Many strategies have been proposed to solve this problem, such as the hydrogen-borrowing strategy and stepwise reductive amination strategy. Herein, we will summarize the key advancements in this area, and discuss the challenges that need to be responded in the future, hoping to provide an insight into the design and development of a more efficient system for the production of biomass-derived diamines.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

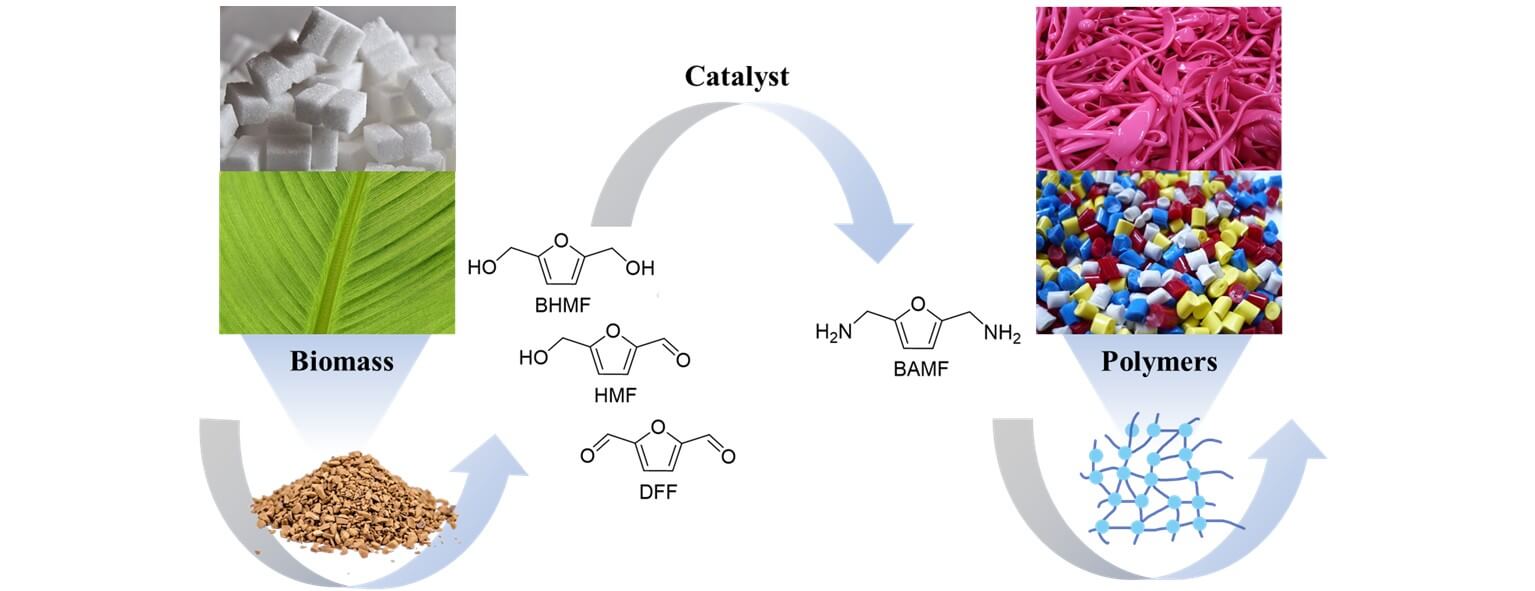

Primary diamines are important feedstocks for the chemical industry, which have been widely used as solvents, key intermediates for pharmaceuticals, the building blocks for polyamides and polyureas, etc. [1–3]. Furthermore, their potential for more diverse and functional applications is increasingly being recognized. Currently, primary diamines are mainly derived from petroleum, and harsh or toxic conditions are needed [4–6]. Given the importance and huge demand for primary diamines, it is necessary to find a greener and more sustainable way to synthesize primary diamines [7–9]. Biomass emerges as a promising alternative for feedstocks, which is abundant and renewable [10–13]. In this review, we mainly focus on the synthesis of a potential bio-based diamine, 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan (BAMF), which is a useful bio-monomer for the production of polymers, hardeners, and elastomers (Fig. 1) [14–16].

Figure 1: Schematic diagram for the conversion of biomass-derived alcohols and aldehydes into primary diamines

BAMF consists of a furan ring substituted at the 2 and 5 positions with aminomethyl groups, resulting in a rigid and planar molecular geometry. The primary amine groups enable BAMF to participate effectively in polymerization reactions, while the aromatic furan ring enhances the thermal stability of polymers, making them suitable for high-temperature applications. Polymers incorporating BAMF may also exhibit increased rigidity and mechanical strength due to the planar structure of furan ring. Additionally, the electron-rich nature of the furan ring can influence the reactivity of the amine groups, potentially affecting the final properties of the polymer. Furthermore, as a biomass-derived compound, BAMF contributes to sustainability by reducing reliance on fossil fuels. As a result, these properties position BAMF as a promising substitute for traditional diamines.

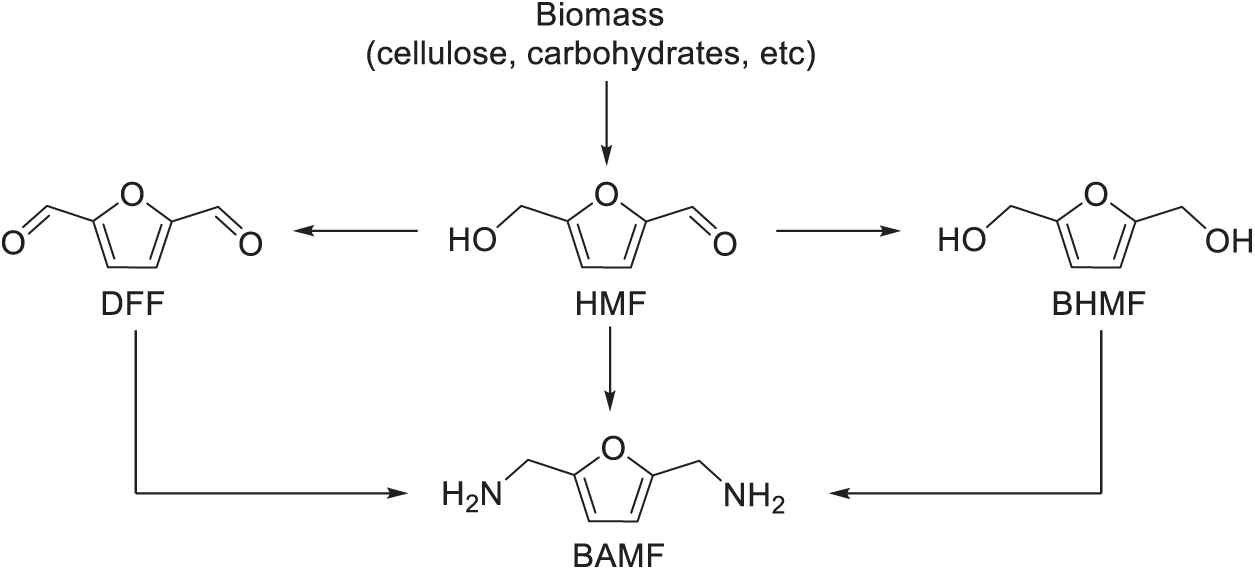

Biomass-derived aldehydes and alcohols are the main sources for the production of BAMF. Sugars, including sucrose, are industrially produced by extracting them from sources such as sugarcane or sugar beet. Subsequently, sucrose can be hydrolyzed to yield glucose and fructose. Under appropriate conditions, these monosaccharides can be converted into raw materials for BAMF production. In this context, we will mainly focus on the synthesis of BAMF from 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan (BHMF), and 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF), which are the platform molecules and can be readily obtained by sugars (Scheme 1) [17–19]. There are a lot of side reactions during the reductive amination of the biomass-derived substrates (e.g., HMF, BHMF and DFF) into BAMF. In order to obtain BAMF with a high yield, several strategies have been proposed to date, such as the stepwise reductive amination strategy and the hydrogen-borrowing strategy [17,18,20]. Concurrently, many advanced heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysts have been developed at the same time [21,22]. Even though great effort has been put into the synthesis of BAMF, it remains a significant challenge to produce BAMF selectively at a low cost that meets the industrial requirements. In this review, we will discuss the progress, challenges, and prospects in the production of 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan (BAMF), and provide insight into designing and developing a more efficient system for the fabrication of biomass-derived diamines.

Scheme 1: Overview of the synthesis of biomass-derived 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan (BAMF)

2 Synthesis of 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan from Biomass-Derived Aldehydes and Alcohols

2.1 Synthesis of 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan from 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural

5-Hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) is recognized as a valuable platform chemical that can be conveniently obtained from sugars like fructose or glucose (Scheme 2) [20,23–25]. HMF can be selectively transformed into 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan (BHMF), or 2,5-diformylfuran (DFF) by the tailoring of its active aldehyde group (C=O) and its alcoholic hydroxyl group (C-OH) (Scheme 1). Both BHMF and DFF could undergo amination reaction to form BAMF, which is to be discussed in the subsequent 2.2, 2.3 parts of this review. In this part, we will focus on the formation of BAMF via the direct di-amination of 5-HMF.

Scheme 2: The synthesis of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (5-HMF) from a monosaccharide [20,23,24]

Many efforts have been devoted into the transformation of HMF into BAMF. Komanoya et al. constructed an efficient system using a combination of Ru/Nb2O5 heterogeneous catalyst and [Ru(CO)ClH(PPh3)3]/Xantphos homogeneous catalyst (Scheme 3), which successfully converted HMF into BAMF with high selectivity [26]. As revealed in Scheme 3,5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfurylamine (HMFA) can be obtained in 96% isolated yield in Step 1. Then, the further reductive amination of HMFA yields BAMF with a 93% gas chromatography (GC) yield in the Step 2 by the [Ru(CO)ClH(PPh3)3]/Xantphos (Xantphos = 4,5-bis-(diphenylphosphino)-9,9-dimethylxanthene) system.

Scheme 3: The two-step strategy for the synthesis of BAMF from HMF. Adapted with permission from Ref. [26], Copyright © 2017, American Chemical Society

For Step 1, Komanoya et al. screened a wide range of supported metal catalysts (designated as M/support, where M = Ru, Rh, Pd, Ni, Cu, Ag, or Pt, and support = Nb2O5, SiO2, TiO2, C, Al2O3, ZrO2, and MgO). Among these catalysts, Ru/Nb2O5 (Scheme 3, Fig. 2) exhibited superior activity, selectivity, and stability in catalyzing the reductive amination of HMF to form HMFA, with an isolated yield of 96%. They proposed that the exceptional catalytic performance of Ru/Nb2O5 may be attributed to the reduced electron density of Ru species on the Nb2O5 surface.

Figure 2: SEM images of (a) Nb2O5 and (b) Ru/Nb2O5. Adapted with permission from Ref. [26], Copyright © 2017, American Chemical Society

Noteworthily, it is a tough task to selectively convert aldehyde into primary amine. Taking the monoaldehyde furfural (1a) as an example, numerous potential side products can emerge during the reductive amination processes (Scheme 4). Undesirable side products may arise from the hydrogenation reactions (such as 1a to 6a, and 2a to 5a) and condensation reactions (e.g., 8a to 4a, and 2a to 7a), leading to the formation of primary alcohol (6a), dimeric or trimeric side products ((3a,7a and 4a). Therefore, it is vital to construct a suitable catalyst in order to obtain target primary amine with high selectivity.

Scheme 4: Proposed reaction pathways and possible products for the reductive amination of 1a. Adapted with permission from Ref. [26], Copyright © 2017, American Chemical Society

Control experiments showed that dimeric imine 3a could be transformed to produce target 2a in 98% yield over Ru/Nb2O5. However, the dimeric amine 7a and trimeric imidazoline 4a were unsuccessful in producing 2a (Scheme 5). Based on these results, Komanoya et al. proposed a plausible underlying mechanism for the conversion of 1a to 2a (Scheme 4). First, 1a will react with excess NH3 to generate furfurylimine (8a) intermediate. 8a will be converted to stable 4a without catalyst, which does not produce 2a. Catalyzed by Ru/Nb2O5, 8a intermediate is hydrogenated to yield the target amine product 2a. Then, 2a undergoes a reversible reaction with the raw material 1a, which contributes to the formation of 3a. 2a is obtained from 3a, rather than the formation of hydrogenated product 7a. Thus, Ru/Nb2O5 served as an important part in promoting the formation of 2a while inhibiting unwanted side reactions. This ability to convert dimeric imine intermediate into target primary amine also contributed to the ultrahigh selectivity towards HMFA over Ru/Nb2O5.

Scheme 5: Control experiment to show the possibility of converting 3a, 4a, and 7a into target 2a. Adapted with permission from Ref. [26], Copyright © 2017, American Chemical Society

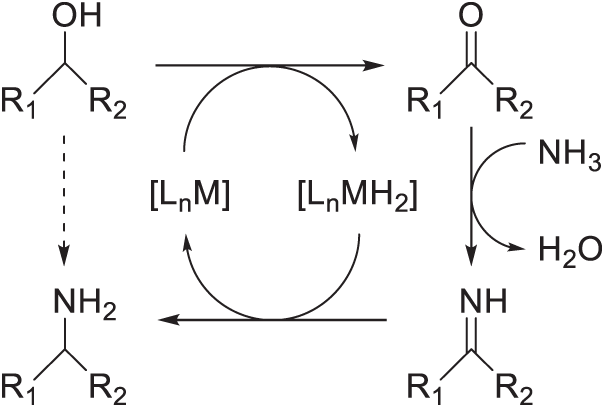

In Step 2, it was achieved by the [Ru(CO)ClH(PPh3)3]/Xantphos to selectively catalyze the isolated HMFA into BAMF with a 93% GC yield. The further reductive amination of HMFA by Ru-complex was believed to follow a strategy often referred to as “Hydrogen Shuttling” or “Borrowing Hydrogen” strategy (Scheme 6) [27–30]. That is to say, the alcohol might undergo dehydrogenation processes with the help of Ru-complex to form ketone or aldehyde along with the concurrent in-situ formation of a Ru-H complex; then NH3 will react with newly formed ketone or aldehyde to form imine in-situ; the Ru-H complex could turn the imine into amine and revert to the original Ru complex. Utilizing this strategy, HMFA could be efficiently converted into BAMF with high selectivity. Komanoya et al.’s work manifested that merging the heterogeneous amination system and homogeneous amination system provided an efficient pathway to synthesize BAMF from the direct amination of HMF.

Scheme 6: “Hydrogen shuttling strategy” or “hydrogenation borrowing strategy” for direct amination of alcohols with ammonia. R1, R2: substitutional group, M: transition metal; Ln: ligand [27,28]

Ni-based amination systems also demonstrate the potential to transform HMF into BAMF [31–35]. It is reported by Zhou et al. that a high yield (60.7%) of BAMF could be achieved over Raney Ni (Table 1), whereas other catalysts, such as Raney Co, and Pt/C, exhibited very poor activity. The presence of the C=O group in HMF is suspected to undergo polymerization reaction with BAMF, which might be a key reason for the unsatisfactory selectivity. Along with the detected side-products, Zhou et al. proposed that the C=O group of HMF would be converted into CH-NH2 firstly, followed by the dehydrogenation of the C-OH group to form a C=O group. Subsequently, the newly formed C=O undergoes repeated reductive amination to yield BAMF (Scheme 7). Alongside, several by-products, such as 2,5-furandimethonal and 5-hydroxymethyltetrahydrofuranamine were generated by the over-hydrogenation reactions. Unluckily, the stability of Raney Ni was poor, and the yield of BAMF shows a notable decrease at the fourth time. Zhou et al. attributed the instability of the Raney Ni to the generation of Ni3N during cycle tests.

Scheme 7: The proposed underlying pathway for reductive amination of HMF into BAMF over Raney Ni [31]

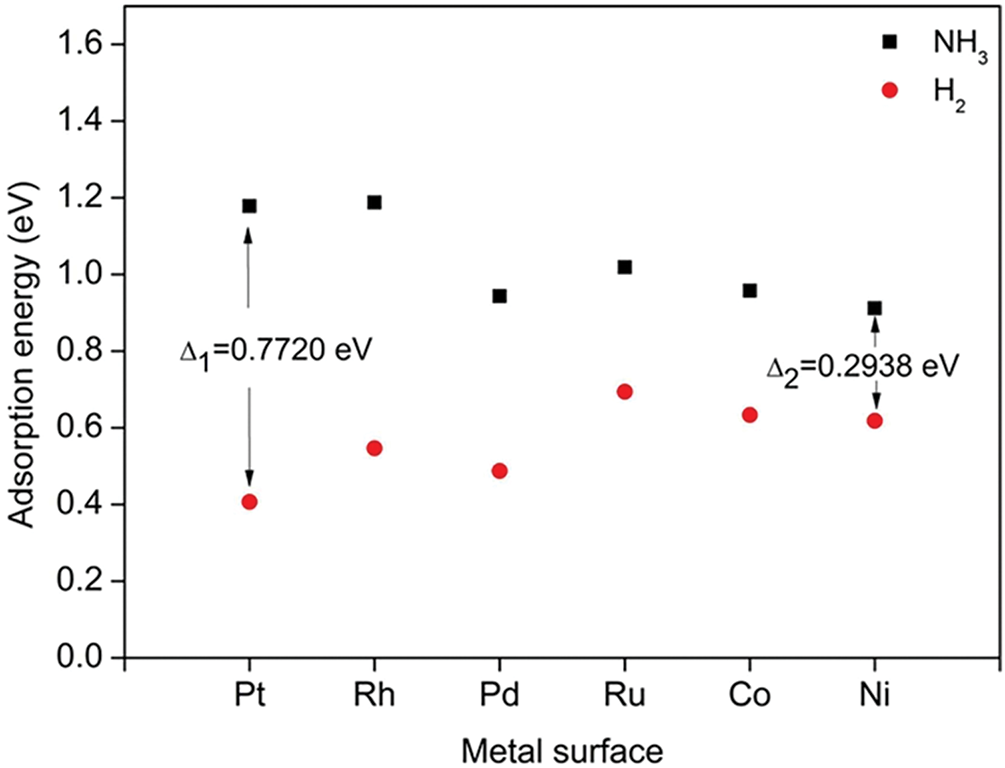

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations represent a robust computational technique grounded in quantum mechanics, extensively utilized to analyze the electronic structures of atoms, molecules, and various materials. DFT calculation is widely applied in physics, chemistry, and materials science. The results from DFT calculation revealed that differences in the absorption energy over catalysts, such as Raney Ni and Pt/C, between NH3 and H2 played an important role in their reductive amination activity (Fig. 3). The reductive amination of a C-OH group involves a multi-step process: first, the C-OH group undergoes dehydrogenation; this is followed by imine formation through imidization of a carbonyl (C=O) group, and finally, the resulting C=NH intermediate is hydrogenated to produce the corresponding amine. Given that NH3 and H2 will competitively adsorb on the catalyst surface, the poor reductive amination activity of noble metal for -OH might be due to their large adsorption energy differences between NH3 and H2. Due to the stronger interactions with NH3 than H2, it impairs the dehydrogenation steps. As a result, Pd/C, Raney Co, Ru/C and Pt/C showed poor activity for the reductive amination of C-OH, and their main product was 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfurylamine (HMFA) instead of BAMF. Notably, Ni showed the smallest adsorption energy difference between NH3 and H2 at 0.29 eV, indicating that it offers a higher proportion of active sites favorable for H2 desorption. Consequently, HMFA can undergo further dehydrogenation on the Ni surface, leading to a relatively high yield of the desired primary diamine.

Figure 3: Calculated adsorption energy of H2 and NH3 on different metal active sites based on DFT calculations. Adapted with permission from Ref. [31], Copyright © 2019, Wiley-VCH

HMF contains both aldehyde group (C=O) and hydroxyl group (C-OH) [36,37]. Considering the activity of C-OH is poorer than that of C=O, it is also possible to increase the yield of BAMF by stepwise hetero-catalyst systems. In 2021, Wei et al. proposed a stepwise reductive amination system to convert HMF, and a high yield of 88.3% for BAMF could be obtained over Raney Co and Raney Ni (Scheme 8c) [32] Raney Co could not cause the amination of C-OH group, but can efficiently convert the C=O into primary amine. In this stepwise reductive amination system, the reaction was firstly performed at a lower temperature (120°C) over Raney Co, in which HMFA could be obtained with a 99.5% yield. After the reaction, Raney Co was filtrated. Then Raney Ni was added and the reaction continued at a higher temperature (160°C) for another 10 h for the amination of C-OH, considering the amination of C-OH is much more difficult. Under the optimum condition, a high yield of 88.3% for BAMF was obtained by this stepwise reduction amination system.

Scheme 8: Different reaction methods to obtain BAMF from HMF [32]

Wei et al. also tried one-step amination of HMF by Raney Ni under 160°C for 12 h, and 82.3% yield of BAMF was achieved. Given that elevated temperature might not be beneficial for the initial amination of the C=O group, the reaction was initiated at a milder temperature of 120°C for 2 h, followed by a higher temperature of 160°C for an additional 10 h. Under these conditions, a BAMF yield of 86.5% was obtained (Scheme 8b), which, while improved, remained slightly lower than that achieved via the two-step amination approach.

Wei et al. reported that Raney Ni could be reused up to four times for the amination of HMF to BAMF under 0.2 MPa NH3, after which a gradual decline in catalytic activity was observed. However, when the NH3 pressure was increased to 0.35 MPa, the catalyst maintained its performance for only one to two cycles. Characterization of the spent Raney Ni using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (Fig. 4) suggested that catalyst deactivation was likely due to the formation of Ni3N and the surface adsorption of alkyl amines. In order to utilize in the industry, it is urgent to find a way to prolong the lifetime of the catalyst.

Figure 4: The characterizations of reused Raney Ni: (a) XRD pattern, (b, c) XPS spectra of Ni 2p and N 1s. Adapted with permission from Ref. [32], Copyright © 2021, Wiley-VCH

Apart from Raney Ni, other Ni-based catalysts also showed the potential in facilitating the formation of BAMF with a relatively high yield. Zhou et al. fabricated a series of NixAl-CT catalysts derived from Ni-Al hydrotalcite-like precursors, where ‘x’ denoted the molar ratio of Ni/Al (ranging from 0.5–4) and CT represented the calcination temperature of the precursor (400–800°C) [34]. NixAl-CT catalysts were applied in the direct reductive amination of HMFA into BAMF in the absence of H2 through the hydrogen borrowing strategy (Scheme 9). Prior to the amination reactions, the NixAl-CT catalysts were calcinated in 10 % H2/Ar flow at 500°C. The highest yield of BAMF could be achieved by Ni2Al-600 with a yield of 70.5%. Unfortunately, the NixAl-CT catalysts were still not stable enough, which was easy to deactivate due to the presence of NH3.

Scheme 9: Direct amination of HMFA into BAMF over Ni2Al-600 in the absence of H2 through the hydrogen borrowing strategy. NixAl-CT catalysts based on Ni-Al hydrotalcite-like precursors, where x denoted the molar ratio of Ni/Al and CT represented the calcination temperature of the precursor [34]

The catalytic supports along with the cooperation with secondary metals might also have a vital impact on the reduction amination of HMF to BAMF. Wei et al. prepared a series of supported Ni-based catalysts by screening 6 supports and 14 bimetallic catalysts [33]. For the support, they found that γ-Al2O3 was the best candidate. According to the calculation results of the Cambridge Sequential Total Energy Package (CASTEP) in Material Studio, the γ-Al2O3 benefited the adsorption of HMF and weakened the O-H bond of HMF, which might be the reason why γ-Al2O3 promoted the reductive amination of -OH group. Regarding the incorporation of secondary metals, most did not exhibit a significant synergistic effect. Specifically: (1) when Cr, Mo, or Ce was introduced, neither BAMF nor HMFA was detected; (2) the use of V, Zr, or Au resulted primarily in high yields of HMFA; and (3) for other secondary metals, a mixture of BAMF and HMFA was formed, accompanied by only minor amounts of by-products. Under the optimized conditions, 10Ni/γ-Al2O3 and 10NiMn(4:1)/γ-Al2O3 could achieve comparable performance with Raney Ni with the BAMF yields of 86.3% and 82.1%, respectively. Notably, 10NiMn(4:1)/γ-Al2O3 showed better reusability than that 10Ni/γ-Al2O3. The 10Ni/γ-Al2O3 could be reused about 3 times without an obvious decrease in performance. In comparison, the 10NiMn(4:1)/γ-Al2O3 could still get above 70% BAMF yield after 5 cycles. The incorporation of Mn contributed to the formation of uniformly dispersed Ni particles and enhanced the structural stability of the γ-Al2O3 support, which might contribute to the slightly improved stability of Ni-based catalysts.

2.2 Synthesis of 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan from 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan

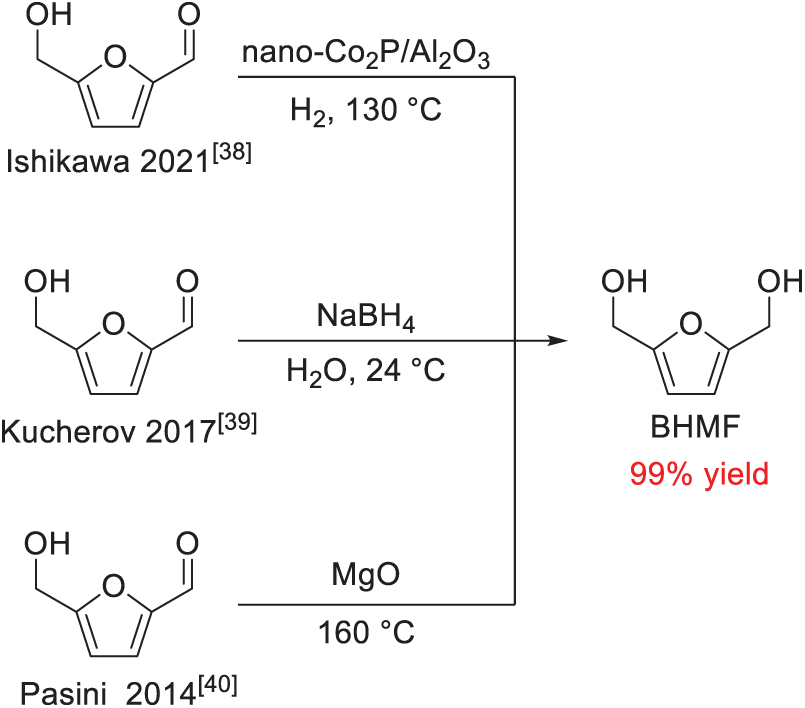

2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan (BHMF) is a biomass-derived primary diol, which could be readily obtained by the reduction of HMF with a high yield of up to 99% (Scheme 10) [38–41]. Therefore, synthesizing BAMF via the direct amination of BHMF presents a practical and cost-effective approach, owing to the easy accessibility of BHMF and the affordability of ammonia. Various systems have been explored for the conversion of primary diols into primary diamines, and the amination of BHMF has been reported in several recent patent filings. Nevertheless, the inherently poor leaving-group ability of the –OH moiety poses a significant challenge for the direct amination of alcohols with NH3 in amine synthesis. As a result, current pathways to BAMF derived from BHMF remain limited or inefficient.

Scheme 10: Several representative works for the synthesis of BHMF [38–40]

Pingen et al. investigated a series of ruthenium complexes as potential catalysts for the direct amination of diols with ammonia (Scheme 11) [28]. The amination of diols catalyzed by Ru complexes is likely to proceed via the “Hydrogen Shuttling” or “Borrowing Hydrogen” mechanism (Scheme 6), which has already been discussed in Section 2.1 [42–45].

Scheme 11: The amination procedures of BHMF towards BAMF by different Ru catalysts. Adapted with permission from Ref. [28], Copyright © 2018, Wiley-VCH

Pingen et al. found that Ru complex C1 reported by Milstein showed the best performance. In the course of the reaction, an amino alcohol intermediate is initially formed, serving as a crucial transitional species. This intermediate is then gradually transformed into the target diamine (Fig. 5). Noteworthily, a substantial excess of NH3 was essential to suppress the formation of undesired by-products, such as secondary amines or oligomers. However, there were still a certain amount of higher molecular weight side products even with the addition of excess NH3, which could not be detected by GC analysis. In their work, Gas chromatography (GC) analysis indicated a product purity ranging from 90% to 100% under optimized conditions. In contrast, proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectroscopy revealed a lower purity of approximately 85%, suggesting the presence of side products with higher molecular weight.

Figure 5: Reaction profile of the direct amination of 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan (BHMF) with NH3 with catalyst C1. Adapted with permission from Ref. [28], Copyright © 2018, Wiley-VCH

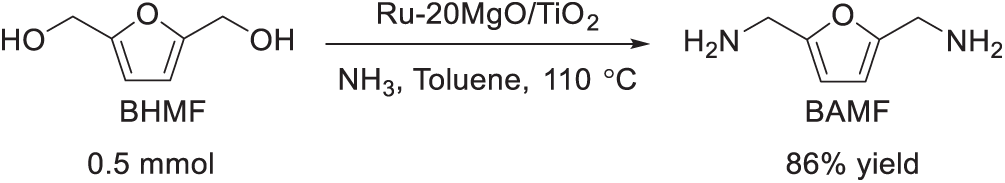

Compared with homogeneous catalysts, heterogeneous catalysts are more liable to be separated and recycled. In 2020, Kita et al. successfully demonstrated the direct amination of BHMF to BAMF using heterogeneous catalysts, employing the hydrogen borrowing strategy [18]. They prepared and screened the supported Ru–xM catalysts (x = M loading (wt%) that Ru and alkaline earth metal (Mg, Ca, Sr, and Ba) were co-deposited on metal oxide supports (TiO2, SiO2, Al2O3, ZrO2 and Nb2O5). They found that Ru-20MgO/TiO2 (Fig. 6) exhibited high catalytic activity and reusability (Scheme 12). Following NaOH treatment and subsequent hydrogen reduction, Ru–20MgO/TiO2 demonstrated excellent reusability, maintaining a high BAMF yield of 86% over three consecutive cycles without significant loss in catalytic activity. CO-adsorption infrared (IR) spectroscopy revealed that the Ru species in Ru–20MgO/TiO2 exhibited a greater electron-donating capacity compared to those in Ru/TiO2. This suggests that Ru interacts directly with MgO rather than TiO2, as electron transfer from MgO to Ru enhances Ru’s electron-donating properties. Control experiments further confirmed that a physical mixture of Ru/TiO2 and MgO performed similarly to Ru/TiO2 alone, underscoring the importance of direct contact between Ru and MgO for improved catalytic activity.

Figure 6: (a) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image and (b–d) the corresponding EDS analysis of Ru–20MgO/TiO2. Ru–xM/support: x = M loading (wt%). Adapted with permission from Ref. [18], Copyright © 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry

Scheme 12: The synthesis of BAMF from BHMF by hydrogenation borrowing strategy [18]

The Ru–20MgO/TiO2 catalytic system could afford BAMF with 86% yield by the direct amination of BHMF with NH3 (Scheme 12), which is a relatively high result compared with the reported method. Therefore, Kita et al. work provides an efficient heterocatalyst system to selective amination of BHMF by NH3 towards BAMF.

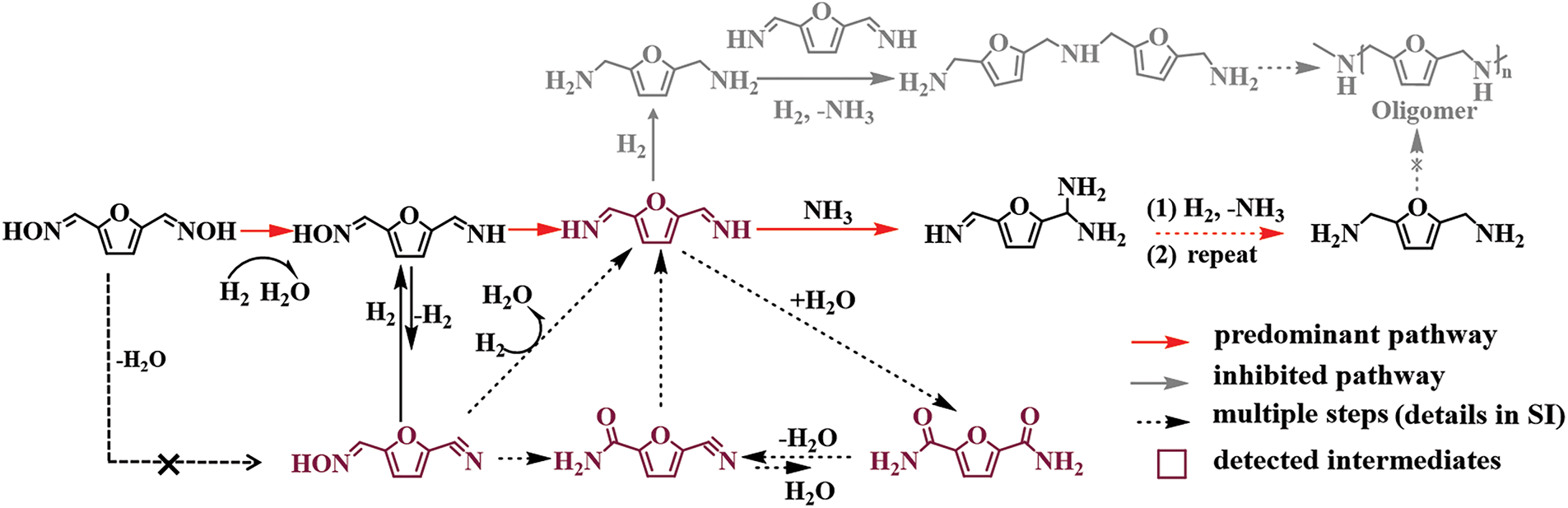

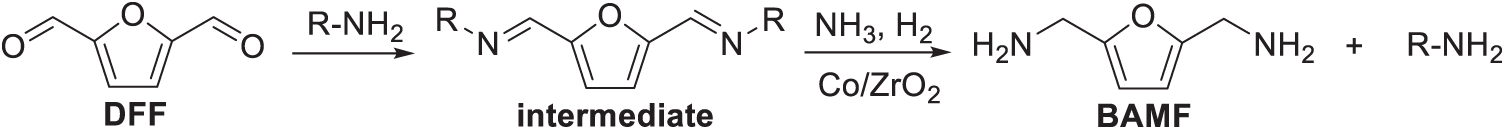

2.3 The Synthesis of 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan from 2,5-diformylfuran

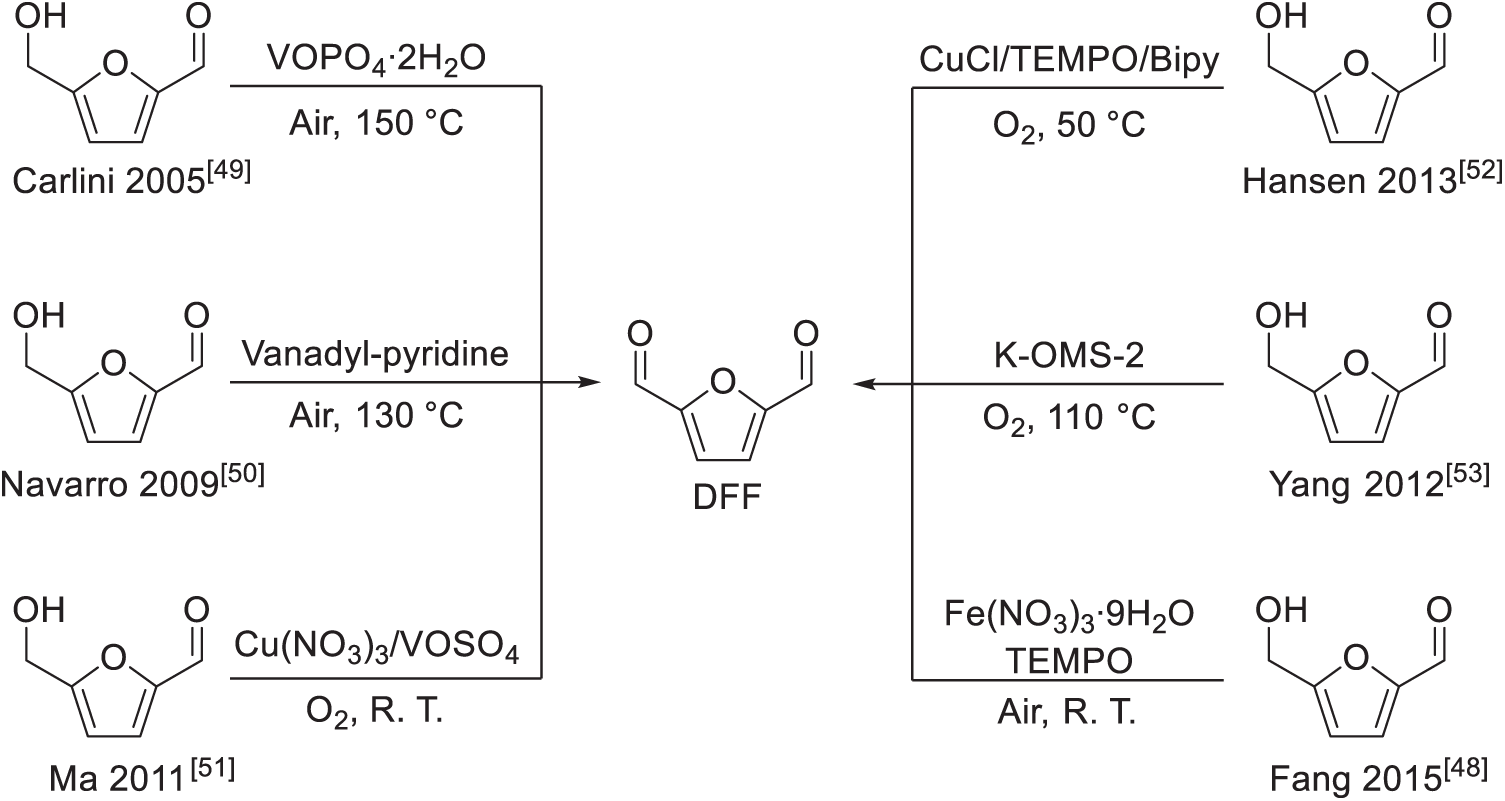

2,5-diformylfuran (DFF) is a valuable biomass-derived dialdehyde, which can be readily obtained from carbohydrate (Scheme 13) or 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) (Scheme 14) [46–48,54–56]. Forming BAMF from DFF through reductive amination is straightforward. Initially, the aldehyde functionality of DFF readily reacts with ammonia, generating a diimine intermediate, subsequently converted into BAMF via hydrogenation. Unfortunately, the BAMF produced tends to further react with residual DFF, leading to imine formation. This imine intermediate undergoes irreversible condensation reactions, ultimately producing undesired oligomeric side-products (Scheme 15) [17]. Consequently, the direct reductive amination of DFF typically results in BAMF yields that are significantly lower than desired.

Scheme 13: The synthesis of DFF from fructose. (a) Fructose (2 mmol), catalyst (25 mg of Sg-CN), KBr 5.0 mg, and water 2 mL, 100°C, 30 min. Sg-CN: sulfonated graphitic carbon nitride [46] (b) catalyst (La(OTf)3, 2.5 mol%), fructose (1 mmol), S (6 mmol), solvent (2 mL), 150°C, 18 h. DFF yield was quantified by the use of high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with an external standard [47]

Scheme 14: Several representative works for the synthesis of DFF from HMF [48–53]. In many cases, the yield of DFF from HMF was more than 90%. Adapted with permission from Ref. [48], Copyright © 2015, Elsevier

Scheme 15: The challenge in the one-step reductive amination of DFF to BAMF

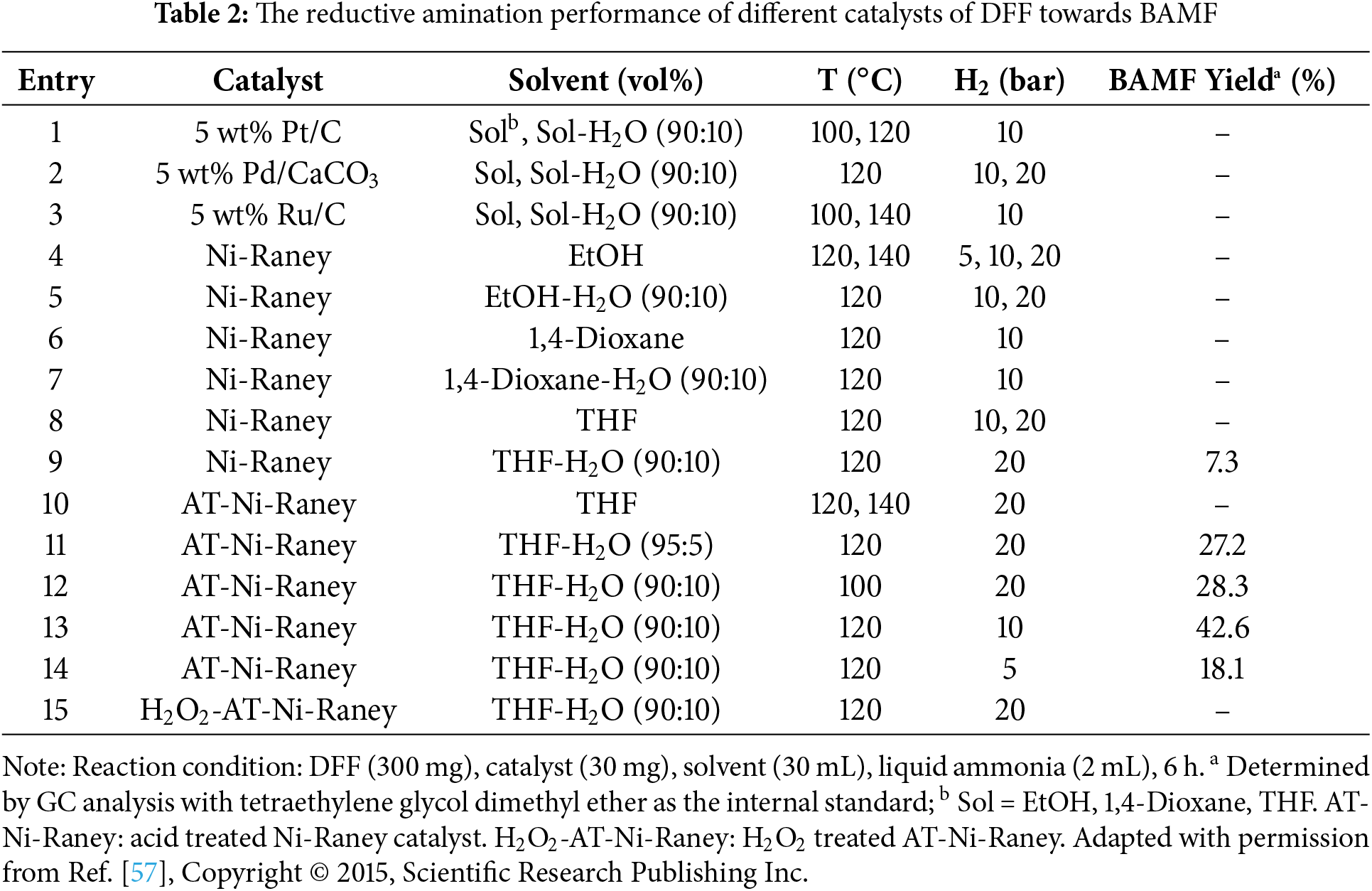

For instance, Kim et al. explored the direct reductive amination of DFF using various amination catalysts, including Ni-Raney, Pt/C, and others, to evaluate their effectiveness in promoting the desired transformation [57]. Complete conversion of DFF was achieved with all tested catalysts, attributed to the rapid and efficient reaction between DFF and ammonia. However, no BAMF was detected when Ru/C, Pt/C or Pd/CaCO3 was used (Table 2, Entries 1–3). When Ni-Raney catalysts were employed in a THF–water mixed solvent, only a modest amount of BAMF was obtained, with the highest yield reaching just 42.6%. This was accompanied by the formation of significant amounts of oligomeric by-products. Therefore, despite the ease of obtaining DFF from biomass, its selective reductive amination to BAMF remains a substantial challenge. This highlights the urgent need for the development of more effective strategies to achieve high selectivity and yield in the conversion of DFF to BAMF.

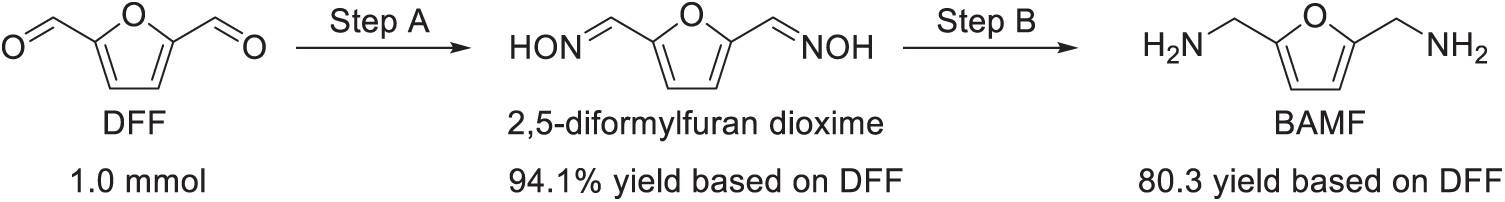

Recently, a few strategies were proposed to solve this problem [17,20]. Xu et al. put forward a two-step procedure to efficiently synthesize BAMF from biomass-derived DFF for the first time (Scheme 16) [17]. Initially, DFF underwent an oximation reaction, successfully yielding 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime with a yield of 94.1%. Subsequently, this intermediate was converted to BAMF, achieving an 80.3% overall yield relative to the starting material (DFF), and importantly, no significant oligomeric side-products were observed.

Scheme 16: Synthesis of BAMF using DFF as the starting material. In Step A, DFF reacts with hydroxylamine hydrochloride (NH2OH·HCl) to form 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime. Subsequently, in Step B, the resulting dioxime is converted into BAMF using Rh/HZSM-5 as the catalyst in the presence of aqueous ammonia and hydrogen gas. Adapted with permission from Ref. [17], Copyright © 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry

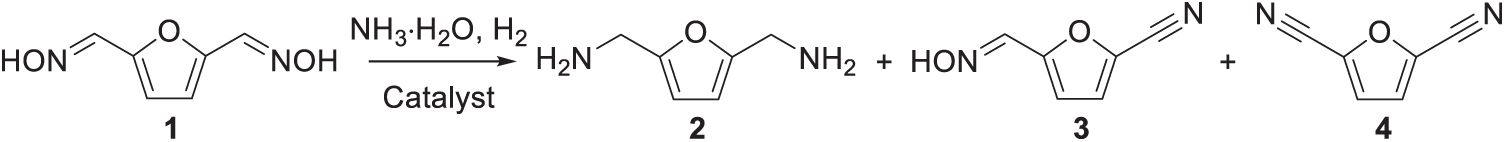

The first step, the oximation of DFF, is easy to operate with a high isolated yield [58]. For the second step, multiple reaction pathways could exist, so it is necessary to construct highly selective catalyst in the conversion of 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime (1) to a primary diamine (Scheme 17). For example, when conventional hydrogenation catalysts such as Raney Ni, Ru/C, or Rh/C were employed, BAMF formation was not observed. Similarly, catalysts utilizing Rh supported on materials like MCM-41, NaY, and aluminum oxide also resulted in unsatisfactory yields, accompanied by oligomeric by-products containing amide and substituted amine groups. To address this challenge, Xu et al. propose a dehydration-hydrogenation strategy to improve the selectivity of 1 towards BAMF (Scheme 18). The critical aspect of this approach involves crafting catalysts with strong acidic sites to facilitate aldoxime dehydration into nitrile intermediates, coupled with catalytic active sites capable of effectively hydrogenating the resulting nitrile groups in situ.

Scheme 17: Catalytic conversion of 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime over different catalysts. Adapted with permission from Ref. [17], Copyright © 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry

Scheme 18: The conversion of 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime to BAMF. Adapted with permission from Ref. [17], Copyright © 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry

Xu et al. found that Rh nanoparticles dispersed on HZSM-5 were an excellent catalyst for the conversion of 1 towards BAMF. The acidic nature of HZSM-5 facilitated the dehydration reaction converting compound 1 into the corresponding nitrile, with catalytic activity improving as the support acidity increased. Nevertheless, the acidity level of HZSM-5 also impacted the distribution and dispersion of Rh nanoparticles (Fig. 7), a factor crucially linked to their performance in nitrile hydrogenation. As the ratio of SiO2/Al2O3 rose, Rh nanoparticles exhibited greater aggregation, leading to poorer dispersion. Such microstructural changes significantly influenced the catalytic activity for hydrogenating nitriles into the primary diamine product. Consequently, as Rh nanoparticle sizes increased, their hydrogenation catalytic activity notably decreased, although no significant change was observed regarding the selectivity towards BAMF. Catalytic hydrogenation activity also played a crucial role in determining reaction outcomes. For example, using Ru/HZSM-5 catalyst led exclusively to the dehydration product (yielding 58.5%), indicating that Ru/HZSM-5 was ineffective at converting the dehydration intermediates to BAMF. Additionally, the absence of 28% aqueous ammonia resulted in no detectable BAMF formation, demonstrating that excess ammonia is essential for BAMF production. As illustrated in Scheme 19, the initially formed amines may react with imine intermediates, producing undesired oligomeric by-products. However, in the presence of excess NH3, the primary imine intermediate preferentially forms gem-diamine intermediates, which subsequently undergo hydrogenolysis to yield the primary amine, thereby suppressing oligomer formation [59]. The outstanding catalytic performance of Rh/HZSM-5 can be attributed to its superior activity in both dehydration and hydrogenation reactions. Consequently, Rh/HZSM-5 achieved the highest BAMF yield of 94.1% under optimized reaction conditions, without significant by-product formation. Given the straightforward preparation of 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime, this approach represents an efficient and practical route to synthesize BAMF starting from DFF.

Figure 7: TEM images of Rh/HZSM-5 catalysts. Adapted with permission from Ref. [17], Copyright © 2018, Royal Society of Chemistry

Scheme 19: Mechanism for the formation of secondary and tertiary amines via gem-diamines

Subsequently, Xu et al. introduced a sequential three-step route for converting fructose directly into BAMF (Scheme 20) [60]. In the first step, fructose is transformed into DFF with an outstanding 94% yield. Next, DFF reacts with NH2OH·HCl to form 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime, achieving a 96% yield. Finally, the carbon-shell-confined Co nanoparticles (Co@CNT-700) catalyst is employed to convert 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime into BAMF. Overall, this streamlined process enables the direct conversion of biomass into BAMF with an approximate 87% yield.

Scheme 20: A sequential three-step strategy to obtain BAMF from biomass. Reaction conditions: step 1: 200 mg fructose, 50 mg Al(NO3)3, CuBr2 (5 mol%) , 30 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), 140°C, 24 h. Step 2: 1.2 g DFF, 2.1 g hydroxylamine hydrochloride, 2.4 g NaAc, 50 mL H2O, 110°C, 6 h. Step 3: 1.0 mmol 1a, 0.5 MPa NH3, 4 MPa H2, 0.1 g Co@CNT-700, 15 mL EtOH, 90°C, 2 h. Adapted with permission from Ref. [60], Copyright © 2025, American Chemical Society

It is worth noting that, besides producing the target BAMF, the intermediate 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime is susceptible to side reactions such as dehydration, self-condensation, or isomerization under the reaction conditions, which can yield nitriles or amides (3a–6a as shown in Scheme 20), thereby adding complexity to the reaction. Fortunately, maintaining an NH3-rich atmosphere effectively inhibits these condensation pathways, and the side products (nitriles and amides) are gradually redirected through alternative routes into the desired BAMF, resulting in excellent overall selectivity (Scheme 21).

Scheme 21: The proposed reaction pathways for the formation of BAMF over Co@CNT-700 catalyst. Adapted with permission from Ref. [60], Copyright © 2025, American Chemical Society

Zhang et al. put forward a new strategy to synthesize BAMF from DFF with an ultra-high selectivity up to 95% (Scheme 22) [20]. The core elements of their strategy relied on the reversible nature of the transimination reaction and the higher nucleophilicity of alkylamines compared to ammonia. A more nucleophilic alkylamine was employed to react with the highly reactive dialdehyde, forming secondary di-imines. This approach effectively helped suppress undesired polymerization side reactions. Due to reversibility of transimination reaction, NH3 could competitively react with secondary di-imines to form primary di-imines. Subsequently, supported metal catalysts were introduced to fine-tune the transimination and hydrogenation activities, enabling the efficient production of BAMF with high yield.

Scheme 22: In Zhang’s work, a more nucleophilic alkylamine, such as n-propylamine, was utilized to scavenge the dialdehyde. Then, Co/ZrO2 catalyst was employed to control both the transimination and hydrogenation steps, achieving high selectivity in the formation of BAMF [20]

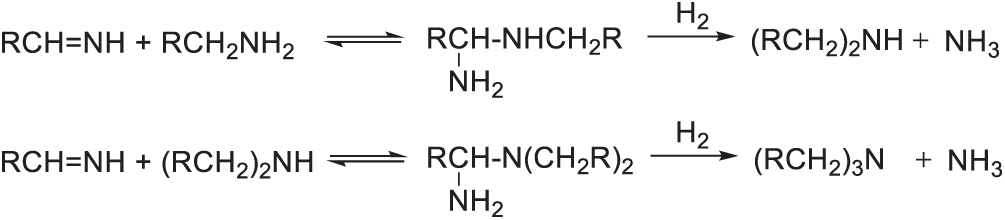

Short-chain aliphatic amines possess greater nucleophilicity than ammonia. For instance, n-butylamine readily reacts with DFF to form secondary di-imines (6a), which serve as key intermediates in the reductive amination process—even in the absence of a catalyst. When an excess of n-butylamine is used, it effectively suppresses undesired side reactions of DFF, such as condensation. Fortunately, this imination reaction is reversible, allowing NH3 to competitively react with 6a via transimination, leading to the formation of primary di-imines (8a) (Scheme 23). However, secondary di-imine 6a is more stable than 8a, the formation of 8a would be very slow. Both 6a and 8a di-imines could undergo subsequent hydrogenation reaction to form secondary di-amine (4a) and primary di-amine (2a). Thus, it is very important to find the suitable catalysts to regulate the competitive transimination and hydrogenation reactions to obtain BAMF with high selectivity.

Scheme 23: Taking n-butylamine as an example, the transimination reaction is reversible. N-butylamine could react with DFF to form 6a as the key intermediate. Then, NH3 will react with 6a through transimination reaction to form primary di-imine (8a). Finally, the BAMF could be obtained by the hydrogenation of 8a [20]

Zhang et al. reported that Co and Ni catalysts exhibited notable activity and selectivity for the production of BAMF (Table 3). Among them, Co/ZrO2 delivered the highest BAMF yield of 95%. Interestingly, the choice of support appeared to have a limited effect on catalytic performance, as evidenced by similar results across different supports (Table 3, entries 1–4). In contrast, Cu showed no catalytic activity, and most noble metal catalysts, with the exception of Ru, were ineffective in producing BAMF (Table 3, entries 8–11). When Pd, Pt, and Ir catalysts were used, the main product was 4a, whereas Rh primarily yielded 5a. These findings suggest that the excessive hydrogenation capacity of noble metals leads to the over-reduction of the secondary di-imine intermediate, preventing effective transimination with NH3. The optimal adsorption characteristics of the Co/ZrO2 catalyst for NH3 and H2 likely play a critical role in fine-tuning both the transimination and hydrogenation steps, which may explain its superior selectivity toward BAMF. Leveraging this well-designed strategy, high-yield synthesis of BAMF from the reductive amination of DFF was successfully achieved.

3 Conclusions, Challenges and Future Perspectives

3.1 Summary of Key Advancements in 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan Synthesis

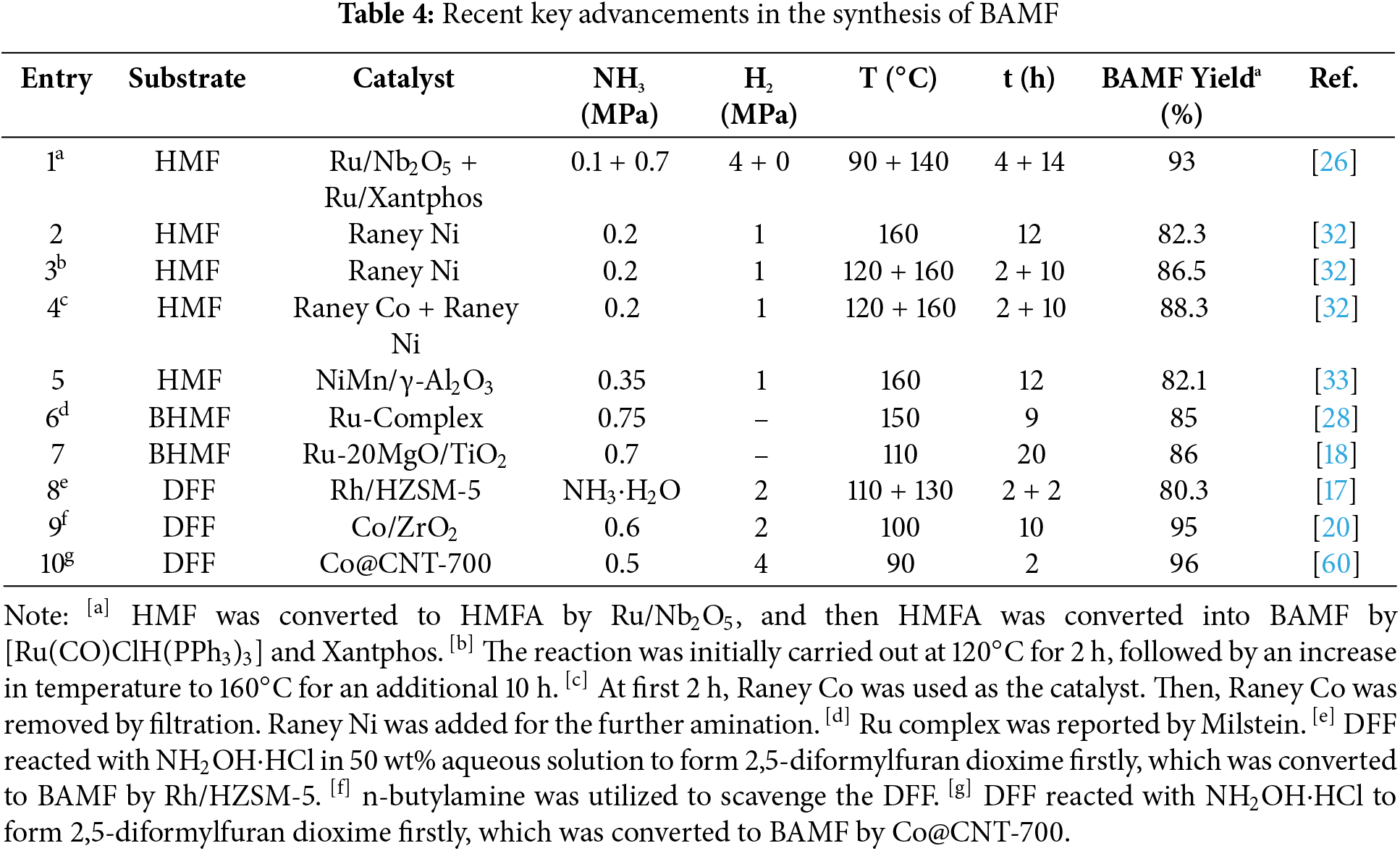

Given the significance of biomass-derived primary diamines, substantial research efforts have been dedicated to the synthesis of BAMF. The primary substrates for the synthesis of BAMF are biomass-based alcohols and aldehydes, such as HMF, BHMF, and DFF. For example, DFF can be readily obtained from fructose, an important type of biomass. Based on those substrates, several heterogeneous and homogeneous catalytic systems were developed, and a relatively high selectivity towards BAMF could be obtained now (Table 4).

Nickel-based catalysts have proven to be effective candidates when using HMF as the substrate, which contains both hydroxyl (C-OH) and carbonyl (C=O) functional groups. Among these, the reductive amination of the C-OH group is notably more challenging than that of the C=O group. Ni-based catalysts are capable of efficiently facilitating the reductive amination of C-OH, leading to relatively high BAMF yields ranging from 82% to 88% (Table 4, entries 2–5). A further enhancement in yield, reaching 93%, can be achieved through a two-step reductive amination approach (Table 4, entry 1). This strategy combines the use of a heterogeneous Ru/Nb2O5 catalyst with a homogeneous [Ru(CO)ClH(PPh3)3]/Xantphos system. In the first step, HMF is transformed to 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfurylamine with a 96% isolated yield using Ru/Nb2O5. Subsequently, the second step employs [Ru(CO)ClH(PPh3)3]/Xantphos to carry out the reductive amination of HMFA, achieving a 93% BAMF yield as determined by GC analysis.

The reductive amination of BHMF towards BAMF mainly follows the so-called “Hydrogen borrowing” or “Hydrogen shuttling” strategy. In this strategy, the C-OH group will undergo dehydrogenation processes with the help of metal catalysts to form C=O. This is accompanied by the concurrent formation of metal-H species in-situ; then NH3 will react with formed C=O to form C=NH; the metal-H species could turn the C=NH into C-NH2 and revert to the original metal catalysts. Both homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts showed the potential in the direct amination of BHMF through a hydrogen borrowing strategy. For example, a Ru-complex catalyst developed by Milstein delivered an 85% yield of BAMF (Table 4, entry 6), while the Ru–MgO/TiO2 catalyst also demonstrated excellent performance, achieving a BAMF yield of 86% (Table 4, entry 7).

DFF only contains C=O group, making it relatively easy to undergo amination process and form BAMF. However, DFF would easily react with BAMF to form abundant oligomer by-products. Thus, the yield of BAMF is still not satisfactory by the one-step direct reductive amination of DFF. A more viable way is to scavenge the highly active dialdehyde to avoid the side reactions. For instance, DFF could efficiently react with NH2OH to form 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime as the intermediate. This intermediate can then be selectively converted into BAMF with an 80.3% yield based on DFF over Rh/HZSM-5. Using a more nucleophilic alkylamine, such as n-butylamine, to scavenge DFF has also proven to be an effective strategy. Due to the reversibility of transimination reaction, NH3 could competitively react with secondary di-imine intermediates to form primary di-imine, and a high yield of 95% for BAMF could be obtained by Co/ZrO2.

3.2 Challenges, Limitations and Prospects

Despite significant advancements in the synthesis of biomass-derived primary diamines, several challenges remain that must be overcome before these processes can be translated into industrial-scale applications. Biomass-derived alcohols and aldehydes are the main substrates for the synthesis of BAMF. Taking HMF as an example, even though HMF could be readily obtained from biomass, its production often demands an excessive amount of additives to ensure optimal yield. In one case, 5 g [EMIM]Cl was needed in order to convert 500 mg glucose into HMF. Even though ionic liquids, such as [EMIM]Cl, can be reused, their efficiency gradually decreases due to the accumulation of impurities, such as water and catalytic residues, over multiple cycles, which reduces their performance. Ionic liquid degradation can also occur when exposed to high temperatures or oxygen, further limiting the number of effective recycling cycles. Additionally, fructose emerges as the preferred source to produce furan-based alcohols and aldehydes due to its structure advantages, while the yields of substrates from other biomass sources, such as glucose, are still not desirable. The future progress in the production of substrates will absolutely contribute to their downstream applications, which in turn boosts the large-scale synthesis of biomass-derived primary diamines.

With the more accessible of the substrates, how to get a higher yield of BAMF is another challenge. There are a lot of side reactions during the reductive amination of the biomass-derived substrates (HMF, BHMF, and DFF). Among them, the condensation reactions between C=O and C-NH2 group and the unwanted hydrogenation reactions are two main kinds of side reactions. And it is possible to further increase the yield of target primary diamines by (1) the deeper understanding of the underlying mechanism and (2) the precise control of the catalysts and reaction conditions. For example, HMF possesses both hydroxyl (C-OH) and carbonyl (C=O) functional groups, with the reductive amination of the C-OH group being notably more difficult than that of the C=O group. Thus the C=O group would prefer to transform into C-NH2 to get 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfurylamine (HMFA) as an intermediate firstly. Then a dehydrogenation catalyst would be required to convert C-OH to the corresponding C=O group, which will undergo reductive amination to get BAMF. As a result, a stepwise amination strategy often obtains a higher yield of BAMF than that of the one-step direct process. If the catalyst structure could be precisely controlled to incorporate two kinds of active sites, it is possible to realize the stepwise strategy by a single catalyst. Moreover, the surface of catalyst needs to be carefully manipulated to achieve a balance adsorption of the substrates, NH3, and H2. For instance, if the interaction between NH3 and the catalyst was too strong, it will inevitably interfere with the adsorption of substrates and H2, which is harmful for the dehydrogenation/hydrogenation of the substrates and leads to the low yield of target primary diamines. Compared with BHMF, both HMF and DFF are more promising starting materials for commercial-scale production of BAMF. This is because HMF and DFF can be directly derived from sugars, whereas BHMF requires an additional conversion step from HMF, incurring extra costs. HMF and DFF each have distinct advantages: HMF is more readily obtained from biomass, while DFF exhibits higher reactivity toward BAMF synthesis. However, the high reactivity of DFF can also be a double-edged sword, necessitating more precise catalyst design and advanced methodologies to fully exploit its potential.

The reaction conditions also play an important role in promoting the formation of BAMF. For instance, the higher NH3 pressure often benefits the inhibition of the condensation and unwanted hydrogenation side reactions. However, the higher NH3 pressure also leads to the severe absorption of NH3, which is harmful to the dehydrogenation/hydrogenation processes. This dilemma is difficult to solve, thus the reaction conditions need to be carefully optimized in order to get a high product yield. The low concentration of substrates is also beneficial to obtain a high yield of BAMF, because it is difficult to avoid the condensation side reaction between the highly active C=O groups and C-NH2 groups. But this is not favorable for the large-scale production of BAMF. Another powerful way to avoid the condensation side reaction is to scavenge the highly active C=O by NH2OH or a more nucleophilic alkylamine. The yield of BAMF could be significantly improved especially for the DFF substrate. But the NH2OH·HCl is not recyclable, which will severely reduce the economy. Alkylamine is somehow recyclable, but the additional recycling procedure also increases the cost. It is urgent to develop an efficient and more cost-efficient way to avoid the condensation reaction.

Lastly, the stability of the catalyst remains a significant bottleneck. For instance, Raney Ni is a potential candidate for the amination of HMF to BAMF, however it can be reused only for several cycles (<5), and the activity will dramatically decrease due to the NH3 corrosion. Therefore, the upgrading of catalysts to meet the challenge of reusability is also vital for the practical applications in the future.

Acknowledgement: We acknowledge support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Comprehensive Training Platform of the Specialized Laboratory at the College of Chemistry.

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported by China Scholarship Council, Science and Technology Project of the State Administration for Market Regulation (2022MK111), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

Author Contributions: Li Ji, Jiawei Mao, Jiaqi Xu and Ruixiang Li conceived the idea and co-wrote the paper. Jiaqi Xu, and Ruixiang Li supervised this project. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| BAMF | 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan |

| HMF | 5-hydroxymethylfurfural |

| BHMF | 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan |

| DFF | 2,5-diformylfuran |

| HMFA | 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furfurylamine |

References

1. Gupta NK, Reif P, Palenicek P, Rose M. Toward renewable amines: recent advances in the catalytic amination of biomass-derived oxygenates. ACS Catal. 2022;12:10400–40. doi:10.1021/acscatal.2c01717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Foubelo F, Nájera C, Retamosa MG, Sansano JM, Yus M. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of 1,2-diamines. Chem Soc Rev. 2024;53:7983–8085. doi:10.1039/D3CS00379E. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lozano-Pérez AS, Kulyabin P, Kumar A. Rising opportunities in catalytic dehydrogenative polymerization. ACS Catal. 2025;15:3619–35. doi:10.1021/acscatal.4c08091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Bini L, Müller C, Wilting J, von Chrzanowski L, Spek AL, Vogt D. Highly selective hydrocyanation of butadiene toward 3-pentenenitrile. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:12622–3. doi:10.1021/ja074922e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Froidevaux V, Negrell C, Caillol S, Pascault J-P, Boutevin B. Biobased amines: from synthesis to polymers; present and future. Chem Rev. 2016;116:14181–224. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Pelckmans M, Renders T, Van de Vyver S, Sels B. Bio-based amines through sustainable heterogeneous catalysis. Green Chem. 2017;19:5303–31. doi:10.1039/C7GC02299A. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang X, Gao S, Wang J, Xu S, Li H, Chen K, et al. The production of biobased diamines from renewable carbon sources: current advances and perspectives. Chin J Chem Eng. 2021;30:4–13. doi:10.1016/j.cjche.2020.12.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Stuyck W, Janssens K, Denayer M, de Schouwer F, Coeck R, Bernaerts KV, et al. A sustainable way of recycling polyamides: dissolution and ammonolysis of polyamides to diamines and diamides using ammonia and biosourced glycerol. Green Chem. 2022;24:6923–30. doi:10.1039/D2GC02233H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yang B, Yu A, Wang Y. Recent advances in the catalytic synthesis of 1,3-diamines. ChemCatChem. 2023;15:e202300141. doi:10.1002/cctc.202300141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Asghar A, Sairash S, Hussain N, Baqar Z, Sumrin A, Bilal M. Current challenges of biomass refinery and prospects of emerging technologies for sustainable bioproducts and bioeconomy. Biofuels Bioprod Bioref. 2022;16:1478–94. doi:10.1002/bbb.2403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Okolie JA, Mukherjee A, Nanda S, Dalai AK, Kozinski JA. Next-generation biofuels and platform biochemicals from lignocellulosic biomass. Int J Energy Res. 2021;45:14145–69. doi:10.1002/er.6697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sun S, Liu Z, Xu ZJ, Wu T. Opportunities and challenges in biomass electrocatalysis and valorization. Appl Catal B Environ Energy. 2024;358:124404. doi:10.1016/j.apcatb.2024.124404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jaswal A, Singh PP, Mondal T. Furfural–a versatile, biomass-derived platform chemical for the production of renewable chemicals. Green Chem. 2022;24:510–51. doi:10.1039/D1GC03278J. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Delidovich I, Hausoul PJ, Deng L, Pfützenreuter R, Rose M, Palkovits R. Alternative monomers based on lignocellulose and their use for polymer production. Chem Rev. 2016;116:1540–99. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang S, Ding X, Wang Y. A new method for green production of 2-aminomethylpiperidine from bio-renewable 2, 5-bis(aminomethyl)furan. Green Chem. 2024;26:2067–77. doi:10.1039/D3GC03082B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li X, Zhao J, Sun B, Wang C, Zhang X, Mu X. Preparation of furanyl primary amines from biobased furanyl derivatives over heterogeneous catalysts. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2023;11:17951–78. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c04593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xu Y, Jia X, Ma J, Gao J, Xia F, Li X, et al. Selective synthesis of 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan via enhancing the catalytic dehydration-hydrogenation of 2,5-diformylfuran dioxime. Green Chem. 2018;20:2697–701. doi:10.1039/C8GC00947C. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kita Y, Kuwabara M, Yamadera S, Kamata K, Hara M. Effects of ruthenium hydride species on primary amine synthesis by direct amination of alcohols over a heterogeneous Ru catalyst. Chem Sci. 2020;11:9884–90. doi:10.1039/D0SC03858J. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. You H, Dong B, Liang J, Guo L, Shi Q, Li F. Reductive amination of 2,5-furandicarbaldehyde to N, N’-Disubstituted 2, 5-bis (aminomethyl) furan under atmospheric pressure of hydrogen gas catalyzed by a metal-ligand bifunctional iridium catalyst. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2024;13:725–30. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.4c08606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Qi H, Liu F, Zhang L, Li L, Su Y, Yang J, et al. Modulating trans-imination and hydrogenation towards the highly selective production of primary diamines from dialdehydes. Green Chem. 2020;22:6897–901. doi:10.1039/D0GC02280B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Truong CC, Mishra DK, Suh YW. Recent catalytic advances on the sustainable production of primary furanic amines from the one-pot reductive amination of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. ChemSusChem. 2023;16:e202201846. doi:10.1002/cssc.202201846. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Sun T, Yang S, Liu Y, Li X, Liao W, Wei S, et al. A novel approach for the preparation of furandiamines utilizing biomass platform chemicals as substrates via Gabriel synthesis. Mol Catal. 2025;570:114679. doi:10.1016/j.mcat.2024.114679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Xiao Y, Song Y-F. Efficient catalytic conversion of the fructose into 5-hydroxymethylfurfural by heteropolyacids in the ionic liquid of 1-butyl-3-methyl imidazolium chloride. Appl Catal A Gen. 2014;484:74–8. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2014.07.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Atanda L, Shrotri A, Mukundan S, Ma Q, Konarova M, Beltramini J. Direct production of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural via catalytic conversion of simple and complex sugars over Phosphated TiO2. ChemSusChem. 2015;8:2907–16. doi:10.1002/cssc.201500395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang J, Jia W, Sun Y, Yang S, Tang X, Zeng X, et al. An efficient approach to synthesizing 2, 5-bis(N-methyl-aminomethyl)furan from 5-hydroxymethylfurfural via 2, 5-bis(N-methyl-iminomethyl)furan using a two-step reaction in one pot. Green Chem. 2021;23:5656–64. doi:10.1039/D1GC01635K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Komanoya T, Kinemura T, Kita Y, Kamata K, Hara M. Electronic effect of ruthenium nanoparticles on efficient reductive amination of carbonyl compounds. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:11493–99. doi:10.1021/jacs.7b04481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Pingen D, Müller C, Vogt D. Direct amination of secondary alcohols using ammonia. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:8130–3. doi:10.1002/anie.201002583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Pingen D, Schwaderer JB, Walter J, Wen J, Murray G, Vogt D, et al. Diamines for polymer materials via direct amination of Lipid- and Lignocellulose-based alcohols with NH3. ChemCatChem. 2018;10:3027–33. doi:10.1002/cctc.201800365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Nallagangula M, Subaramanian M, Kumar R, Balaraman E. Transition metal-catalysis in interrupted borrowing hydrogen strategy. Chem Commun. 2023;59:7847–62. doi:10.1039/D3CC01517C. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhao L, Chen Y, Zhang C, Chen H, Zheng X, Xue W, et al. Ru-CNP complex-catalyzed hydrogen transfer/Annulation reaction of 2-Nitrobenzylalcohol via an outer-sphere mechanism. J Org Chem. 2025;90:4959–72. doi:10.1021/acs.jojkc.5c00157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhou K, Liu H, Shu H, Xiao S, Guo D, Liu Y, et al. A comprehensive study on the reductive amination of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-bisaminomethylfuran over Raney Ni through DFT calculations. ChemCatChem. 2019;11:2649–56. doi:10.1002/cctc.201900304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wei Z, Cheng Y, Zhou K, Zeng Y, Yao E, Li Q, et al. One-step reductive amination of 5-Hydroxymethylfurfural into 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan over Raney Ni. ChemSusChem. 2021;14:2308–12. doi:10.1002/cssc.202100564. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wei Z, Cheng Y, Huang H, Ma Z, Zhou K, Liu Y. Reductive amination of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan over alumina-supported Ni-based catalytic systems. ChemSusChem. 2022;15:e202200233. doi:10.1002/cssc.202200233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Zhou K, Xie R, Xiao M, Guo D, Cai Z, Kang S, et al. Direct amination of biomass-based furfuryl alcohol and 5-(aminomethyl)-2-furanmethanol with NH3 over hydrotalcite-derived Nickel catalysts via the hydrogen-borrowing strategy. ChemCatChem. 2021;13:2074–85. doi:10.1002/cctc.202001922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Yuan H, Kusema BT, Yan Z, Streiff S, Shi F. Highly selective synthesis of 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan via catalytic amination of 5-(hydroxymethyl) furfural with NH3 over a bifunctional catalyst. RSC Adv. 2019;9:38877–81. doi:10.1039/C9RA08560B. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Liu P, Li X, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Zhao J. One-step reductive amination of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-bis(aminomethyl)furan over a core-shell structured catalyst. J Catal. 2024;429:115291. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2024.115291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Li Y, Huang H, Jiang M, Xi W, Duan J, Ratova M, et al. Advancements in transition bimetal catalysts for electrochemical 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) oxidation. J Energy Chem. 2024;98:24–46. doi:10.1016/j.jechem.2024.06.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ishikawa H, Sheng M, Nakata A, Nakajima K, Yamazoe S, Yamasaki J, et al. Air-stable and reusable cobalt phosphide nanoalloy catalyst for selective hydrogenation of furfural derivatives. ACS Catal. 2021;11:750–7. doi:10.1021/acscatal.0c03300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kucherov F, Galkin K, Gordeev E, Ananikov V. Efficient route for the construction of polycyclic systems from bioderived HMF. Green Chem. 2017;19:4858–64. doi:10.1039/C7GC02211E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Pasini T, Lolli A, Albonetti S, Cavani F, Mella M. Methanol as a clean and efficient H-transfer reactant for carbonyl reduction: scope, limitations, and reaction mechanism. J Catal. 2014;317:206–19. doi:10.1016/j.jcat.2014.06.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Vikanova K, Redina E, Kapustin G, Chernova M, Tkachenko O, Nissenbaum V, et al. Advanced room-temperature synthesis of 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan—a monomer for biopolymers—from 5-hydroxymethylfurfural. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2021;9:1161–71. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.0c06560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Liu H, Zhang R, Zheng X, Xie J, Tang B, Li Z, et al. Hydrogen-donating behavior and hydrogen-shuttling mechanism of liquefaction solvents under Fe- and Ni-based catalysts. Fuel. 2024;368:131586. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2024.131586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Karanwal N, Kurniawan RG, Kwak SK, Kim J. Rhenium-promoter-free ruthenium-zirconia catalyst for high-yield direct conversion of succinic acid to 1,4-butanediol in water. Chem Eng J. 2024;498:155603. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.155603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Cui T, Gong H, Ji L, Mao J, Xue W, Zheng X, et al. Efficient co-upcycling of glycerol and CO2 into valuable products enabled by a bifunctional Ru-complex catalyst. Chem Commun. 2024;60:12221–4. doi:10.1039/D4CC02436B. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zheng Y, Long Y, Gong H, Xu J, Zhang C, Fu H, et al. Ruthenium-catalyzed divergent acceptorless dehydrogenative coupling of 1,3-diols with arylhydrazines: synthesis of pyrazoles and 2-pyrazolines. Org Lett. 2022;24:3878–83. doi:10.1021/acs.orglett.2c01497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Verma S, Baig RN, Nadagouda MN, Len C, Varma RS. Sustainable pathway to furanics from biomass via heterogeneous organo-catalysis. Green Chem. 2017;19:164–8. doi:10.1039/C6GC02551J. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Nguyen QNB, Le HAN, Ly PD, Phan HB, Tran PH. One-step synthesis of 2,5-diformylfuran from monosaccharides by using lanthanum (iii) triflate, sulfur, and DMSO. Chem Commun. 2020;56:13005–8. doi:10.1039/D0CC05582D. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Fang C, Dai J-J, Xu H-J, Guo Q-X, Fu Y. Iron-catalyzed selective oxidation of 5-hydroxylmethylfurfural in air: a facile synthesis of 2,5-diformylfuran at room temperature. Chin Chem Lett. 2015;26:1265–8. doi:10.1016/j.cclet.2015.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Carlini C, Patrono P, Galletti AMR, Sbrana G, Zima V. Selective oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde to furan-2,5-dicarboxaldehyde by catalytic systems based on vanadyl phosphate. Appl Catal A Gen. 2005;289:197–204. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2005.05.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Navarro OC, Canos AC, Chornet SI. Chemicals from biomass: aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furaldehyde into diformylfurane catalyzed by immobilized vanadyl-pyridine complexes on polymeric and organofunctionalized mesoporous supports. Top Catal. 2009;52:304–14. doi:10.1007/s11244-008-9153-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Ma J, Du Z, Xu J, Chu Q, Pang Y. Efficient aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran, and synthesis of a fluorescent material. ChemSusChem. 2011;4:51–4. doi:10.1002/cssc.201000273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Hansen TS, Sádaba I, García-Suárez EJ, Riisager A. Cu catalyzed oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-diformylfuran and 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid under benign reaction conditions. Appl Catal A Gen. 2013;456:44–50. doi:10.1016/j.apcata.2013.01.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Yang Z-Z, Deng J, Pan T, Guo Q-X, Fu Y. A one-pot approach for conversion of fructose to 2,5-diformylfuran by combination of Fe3O4-SBA-SO3H and K-OMS-2. Green Chem. 2012;14:2986–9. doi:10.1039/c2gc35947b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Wang Q, Li Y, Guan H, Yu H, Wang X. Hydroxyapatite-supported polyoxometalates for the highly selective aerobic oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural or glucose to 2,5-diformylfuran under atmospheric pressure. ChemPlusChem. 2021;86:997–1005. doi:10.1002/cplu.202100199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Li G, Sun Z, Yan Y, Zhang Y, Tang Y. Direct transformation of HMF into 2,5-diformylfuran and 2,5-dihydroxymethylfuran without an external oxidant or reductant. ChemSusChem. 2017;10:494–8. doi:10.1002/cssc.201601322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Lv G, Wang H, Yang Y, Deng T, Chen C, Zhu Y, et al. Direct synthesis of 2,5-diformylfuran from fructose with graphene oxide as a bifunctional and metal-free catalyst. Green Chem. 2016;18:2302–7. doi:10.1039/C5GC02794B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Le N-T, Byun A, Han Y, Lee K-I, Kim H. Preparation of 2,5-bis (aminomethyl) furan by direct reductive amination of 2,5-diformylfuran over nickel-raney catalysts. Green Sust Chem. 2015;5:115. doi:10.4236/gsc.2015.53015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Xu Y, Jia X, Ma J, Gao J, Xia F, Li X, et al. Efficient synthesis of 2,5-dicyanofuran from biomass-derived 2,5-diformylfuran via an oximation-dehydration strategy. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2018;6:2888–92. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b03913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Gomez S, Peters JA, Maschmeyer T. The reductive amination of aldehydes and ketones and the hydrogenation of nitriles: mechanistic aspects and selectivity control. Adv Synth Catal. 2002;344:1037–57. doi:10.1002/1615-4169(200212)344:10<1037::AID-ADSC1037>3.0.CO;2-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Chen Y, Yang S, Wang J, Ji L, Cui T, Dai C, et al. Targeted conversion of biomass into primary diamines via carbon shell-confined cobalt nanoparticles. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2025;17:9231–42. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c17669. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools