Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Rice Straw Fibers for Pulp Films Using DES and Streptomyces rochei Synergy

1 Institute of Agricultural Resources and Environment, Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Nanjing, 210014, China

2 Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Solid Organic Waste Resource Utilization, Nanjing, 225000, China

3 Key Laboratory of Saline-Alkali Soil Improvement and Utilization (Coastal Saline-Alkali Lands), Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Nanjing, 225000, China

4 College of Materials Science and Engineering, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, 210037, China

5 Key Laboratory of New Materials and Facilities for Rural Renewable Energy, MOA of China, Henan Agricultural University, Zhengzhou, 450002, China

* Corresponding Authors: Enhui Sun. Email: ; Mingjie Guan. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(9), 1803-1817. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0059

Received 14 March 2025; Accepted 18 July 2025; Issue published 22 September 2025

Abstract

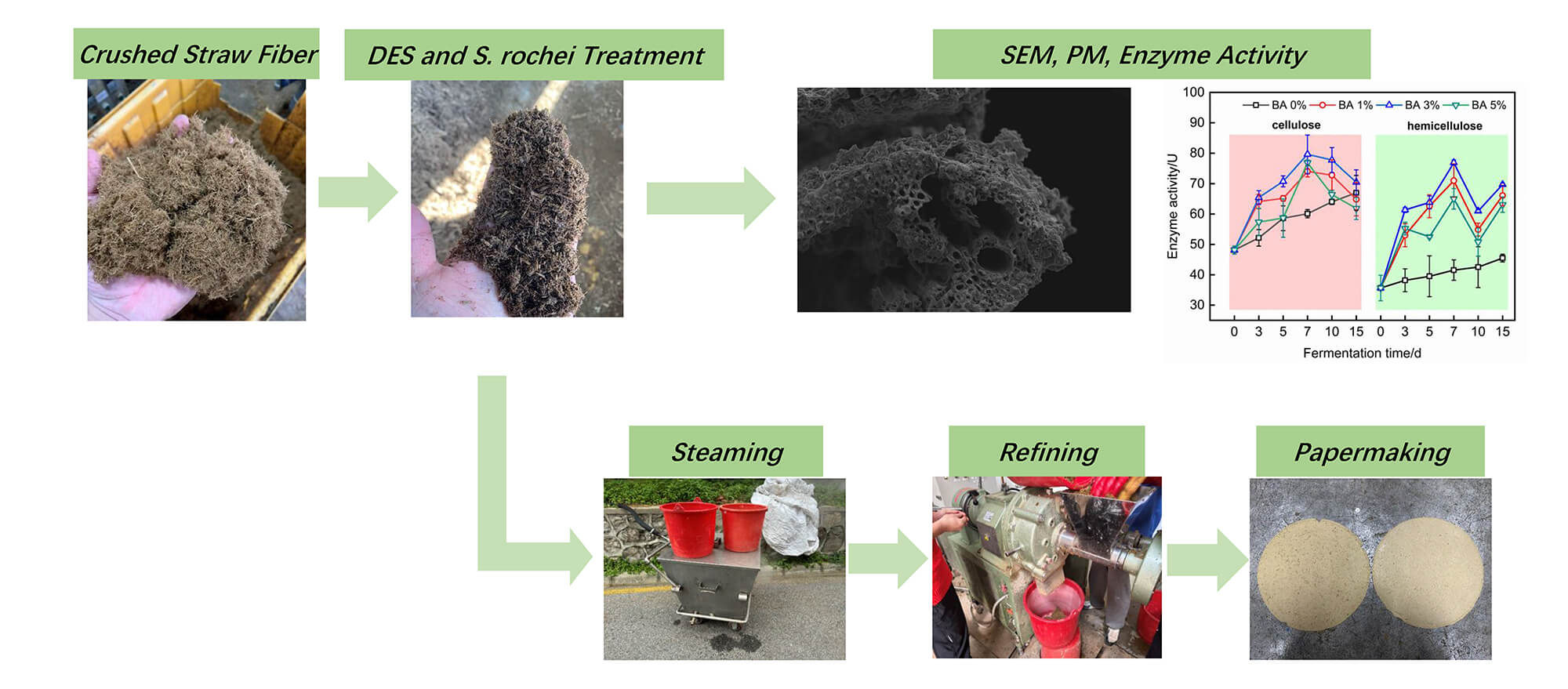

Long-time fermentation has always been one of the reasons restricting the development of straw biological pulping. This study aimed to develop a novel straw pulp film with shortened solid-state fermentation time with less than 20% mass loss rate by bio-pulping synergistic treatment of straw fibers with deep eutectic solvent (DES) and Streptomyces rochei (S. rochei). Results illustrated that at 3% S. rochei concentration with 7-day fermentation, both cellulose and hemicellulose enzyme activities of the treated rice straw fiber reached peak values with a fiber mass loss rate of 17.01%. Microstructural morphology revealed that S. rochei colonization initiated on straw surfaces and progressively penetrated internal structures, resulting in surface loosening and distinct disruption of cell wall tissues within vascular bundles in transverse sections. The treated rice straw strip indicated a maximum tensile strength of 46.22 MPa for (Bacteria) BA 3% at day 7, attributed to optimized synergistic effects of microfibril angle (MFA) and cellulose/hemicellulose relative content ratio. The modified straw pulp film exhibited significant enhancement in the tensile index (44.9% increase), burst index (10.3% increase), and tear index (60% increase) compared to untreated groups. This work demonstrated the important role of DES and S. rochei bio-pulping synergistic treatment in improving rice straw pulp performance, suggesting an eco-friendly, novel, and efficient biomass pretreatment technology for potential application prospects in sustainable agricultural mulching materials.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The demand for paper and paperboard in China has been continuously increasing in recent years, the shortage of raw materials particularly the insufficient capacity of wood pulp has led to large imports of raw materials [1–3]. However, approximately 1 billion tons of crop straw residues, dominated by cereal straws (75%), are discarded annually, causing severe environmental pollution through direct returning straw to the soil or throwing straw on the roadside [4–6]. However, the utilization of discarded straw for pulping can not only alleviate the pressure of the soil decomposition of straw but also solve the dilemma of the lack of appropriate straw application [7–9]. It is worth noting that straw itself is composed of various substances such as cellulose (30%–40%), hemicellulose (20%–30%), lignin (10%–20%) ash (5%–15%), pectin (1%–3%), etc [10]. Compared with traditional wood and bamboo pulp, straw pulp has low cellulose and lignin content, and high ash and pectin content, resulting in energy-intensive and low-efficient fiber separation, poor pulp strength, and elevated pollution through conventional chemi-mechanical pulp processes [11–13].

To reduce the conventional pulp-making energy consumption and environmental pollution, bio-pretreatment of plant fibers with enzymatic, fungi, or micro-organisms agents is investigated before conventional pulping processes. Enzymatic treatments degrade lignin or hemicellulose to enhance lignin dissolution, thereby facilitating fiber separation [14,15]. This approach reduces the refining energy consumption required for the fibrillation of separated fiber, decreases electrical power usage in refining stages, improves pulp yield, and minimizes chemical consumption in both cooking and bleaching stages, consequently reducing wastewater pollution [16,17]. Enzymatic processing remains underutilized in straw bio-pulping due to its inherently lower cellulose content compared to wood. In the pursuit of sustainable straw pulping, white rot fungi (Basidiomycota) have emerged as biochemical specialists. These organisms execute precision lignin removal with minimal cellulose disruption and preserve over 92% cellulose integrity in straw substrates. However, fungal treatment typically requires weeks to months and faces challenges in precise control of temperature, humidity, and pH conditions, hindering its industrial-scale implementation in bio-pulping [18–20]. Bacterial systems present a contrasting approach of 30%–50% lower lignin degradation efficiency than fungal counterparts, but display strategic advantages: (1) Fermentation timelines reduced by 60%–80%, (2) Operational tolerance to ±5°C temperature fluctuations, (3) 40% lower nutrient input requirements [21–23]. This may prompt an exploration of microbial alternatives with the capability of rapidly separating fiber to enhance bio-pulping industrial efficiency.

It is worth noting that not all straw pulping production necessitates rigorous lignin removal processes. Some low-grade paper products, such as agricultural mulching films, require higher retention of lignocellulosic components (cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin) to maximize the utilization of straw [24,25]. According to preliminary studies, Streptomyces rochei (S. rochei) (Actinobacteria) isolated from decomposing straw as a promising candidate bacterial, achieved a significant effect on fiber dissociation in 3–5 days at 60°C–70°C with high lignin retention [26,27]. The exposed hydroxyl groups on liberated fibers could form hydrogen bonding, resulting in low strength and non-adhesive inside straw-based products such as straw blankets [28], and seedling containers [29]. However, this method of preserving high lignin retention proved to be unsuitable for making straw-based papers requiring ≥2 refining cycles, as the amount of lignin softening at elevated refining temperatures and coating on fiber surfaces, impairing secondary refining performance and pulp forming [30]. Therefore, it is necessary to remove partly lignin of straw before making bio-pulp for low-grade straw paper such as agriculture mulch.

Deep eutectic solvents (DES) represent an emerging eco-friendly lignin separation method from plant raw materials. Compared to the alkaline pulping process (160°C–185°C), DES achieves lignin extraction at lower temperatures (80°C–160°C), yielding high-purity lignin fractions with enhanced reactivity, low molecular weight, and low condensation [31]. Some studies indicated that variations in DES hydrogen bond donor (HBD)/acceptor (HBA) ratios and temperatures critically influenced lignin removal efficiency from straw [32,33]. DES pretreatment disrupted the lignin-cellulosic matrix via impregnation, weakening lignin carbohydrate complexes (LCCs) to promote lignin dissolution. While choline chloride (ChCl) is commonly employed as HBA, the selection of HBD remains diverse [34]. DES has been demonstrated on obvious lignin removal efficacy but neglected its potential synergistic integration with microbial pretreatment. Nevertheless, the study on the compatibility of upstream DES formulations and downstream microbial treatments is deficient. Based on S. rochei propagation condition requirements and straw’s inherent carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio, urea, as a nitrogen-rich HBD, is hypothesized to synergistically enhance microbial pretreatment efficiency in straw bio-pulping.

This study innovatively employed a ChCl/urea DES system for rice straw impregnation pretreatment, followed by gradient fermentation with S. rochei under different concentrations. The treated straw fibers then were evaluated by microbial enzyme activity and chemical composition analysis, mass loss rate test, microstructure morphology characterization, and single fiber mechanical test. Subsequently, the tensile, tearing, and bursting index of the paper were measured after the treated straw fiber was pulped and made into the rice straw paper. The ultimate goal was to obtain straw pulp films through DES and S. rochei synergy for agriculture mulching with less mass loss ratio.

2.1 Materials and Instrumentation

The straw raw material came from the Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences (118.876° E, 32.034° N). After the mature rice grains were harvested, the integral straw above ground was cut into small pieces of 20–40 mm and stored after natural air drying. The microbial agents (Microbial Fertilizer (2014) Approval No. (1064)) used for biological pretreatment were purchased from Nanjing Ningliang Biotechnology Company, mainly composed of S. rochei. The chemicals used were choline chloride, acetic acid, acetone, 30% hydrogen peroxide, and epoxy resin obtained from Nanjing Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Nanjing, China). Urea was from Lingfeng Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China), and 100 μg/mL formaldehyde standard solution was from Beijing Coastal Hongmeng Standard Material Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China).

Several instrumentation were used consisting of a Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) EVO-LS10 (Jena, German), Sliding Slicer Yamato TU-213 (Tokyo, Japan), Polarization Microscope (PM) Olympus BX41 (Tokyo Japan), X-ray Diffraction (XRD) Bruker D8 (Billerica, German), Lab-scale Paper Making Machine PTI-95568 (Suzhou, China), High-Consistency Refiner ZGM (Nanjing, China), Paper Tensile Strength Tester SE062 (Shanxi, China), Paper Tearing Tester SE009 (Shanxi, China), Paper Bursting tester SE969920 (Shanxi, China).

2.2 DES and S. rochei Pretreatment of Rice Straw Fibers

2.2.1 DES Pretreatment of Rice Straw Fibers

ChCl and urea were mixed at a 1:2 molar ratio, stirred at 65°C for 1 h to form a transparent liquid. Crushed straw (1–5 cm) was adjusted to 65 ± 2% moisture content. DES liquid (3.5% of straw mass) was then sprayed onto the straw surfaces and homogenized, followed by 12-h pretreatment.

2.2.2 S. rochei Pretreatment of Rice Straw

Commercial S. rochei inoculant was activated on solid agar (30°C, 12 h), then propagated in liquid broth for 3–5 days to obtain a concentrated suspension. Residual DES was removed from pretreated straw via deionized water rinsing. The carbon-to-nitrogen (C/N) ratio of DES pretreated straw was 28 without nitrogen supplementation. After readjusting moisture to 65 ± 2%, straw was inoculated with bacterial suspension at 1%, 3%, and 5%, coded as BA 1%, BA 3%, and BA 5%, respectively, with a non-inoculated control (BA 0%). Fermentation proceeded at 65°C for 15 days in humidity-controlled chambers. Mass loss ratios were gravimetrically monitored on days 3, 5, 7, 10, and 15, with sterile water replenishment maintaining constant moisture [35].

Cellulose Enzyme [36]. Supernatants from centrifuged (4°C, 20 min) fermented straw were diluted and mixed with sodium acetate-acetic acid buffer (0.2 M, pH 4.8). After incubation (50°C, 60 min), the reaction was terminated with 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) reagent, boiled for 5 min, and centrifuged. Absorbance at 540 nm was measured via UV-vis spectrophotometer. Cellulose activity (units: μg glucose/min) was calculated by subtracting background reducing sugars and using a glucose standard curve (0–1 mg/mL). Triplicate measurements were performed for each sample.

Hemicellulose Enzyme [37]. Supernatants were diluted and mixed with citrate-phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 5.0) containing 1% (w/v) xylan. After incubation (50°C, 30 min), DNS reagent terminated the reaction. Absorbance at 540 nm was measured via UV-vis spectrophotometer. Hemicellulose enzyme activity (units: μg xylose equivalents/min) was quantified via a xylan standard curve (0–1 mg/mL). Triplicate measurements were performed for each sample.

Three experimental replicates were prepared for each sample. Each sample containing 0.3 g of oven-dried material was treated with 3 mL of 72% (w/w) sulfuric acid in a 30°C water bath for 1 h under constant agitation. The acid hydrolyzed mixture was then diluted to 4% (w/w) sulfuric acid concentration by adding deionized water and autoclaved at 121°C for 1 h. The hydrolysate was filtered through a glass microfiber filter to separate the supernatant from insoluble residue. For carbohydrate quantification, 1 mL of the filtered supernatant was neutralized with 40 μL of 50% NaOH and filtered through a 0.22 μm nylon filter. The neutralized solution was transferred to an HPLC vial and analyzed using high-performance liquid chromatography. Cellulose and hemicellulose contents were quantified via external calibration curves [38].

2.2.5 Microstructure Morphology

Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM). Straw segments from different fermentation times were sectioned into 60 μm transverse and longitudinal slices using a sliding microtome. The sliced specimens were freeze-dried at −55°C and 0.05 mbar for 24 h in a lyophilizer. The dried samples were then mounted on aluminum stubs and sputter coated with a 10 nm gold layer using an ion sputter coater for 60 s to enhance conductivity. The coated specimens were imaged using a SEM with an accelerating voltage of 25 kV to observe the microstructural morphology.

Polarizing Microscope (PM). The samples were trimmed into fine strips using a razor blade and thoroughly rinsed with distilled water. Gradient dehydration was performed by soaking samples into acetone at concentrations of 30%, 50%, 70%, 90%, and 100%, with each step lasting 20 min. Subsequently, the samples were infiltrated with epoxy resin using a graded series of acetone: epoxy resin mixtures at ratios of 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3, followed by pure epoxy resin, with each step maintained for 4 h. The infiltrated samples were then subjected to gradient curing in an oven at sequentially increasing temperatures (37°C, 45°C, and 60°C), with each temperature step held for 24 h. After curing, the samples were radially sectioned into 3 μm thin slices using an ultra-microtome. The slices were mounted on glass slides at a 5° tilt angle and observed under a polarized light microscope equipped with a rotating stage for birefringence analysis.

The straw samples were longitudinally split using a razor blade and flattened with three replicates. The prepared specimens were cut to dimensions of 100 μm (radial, R) × 5 mm (tangential, T) × 15 mm (longitudinal, L). The MFA was determined using a wide-angle X-ray diffractometer equipped with a Cu-Kα radiation source operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. The diffraction patterns were collected from the (002) lattice plane of cellulose, and the MFA was calculated using the 0.6 T method, where T represents the angular width at 60% of the maximum intensity of the (002) azimuthal scan.

2.2.7 Single Fiber Tensile Strength and Strip Tensile Strength

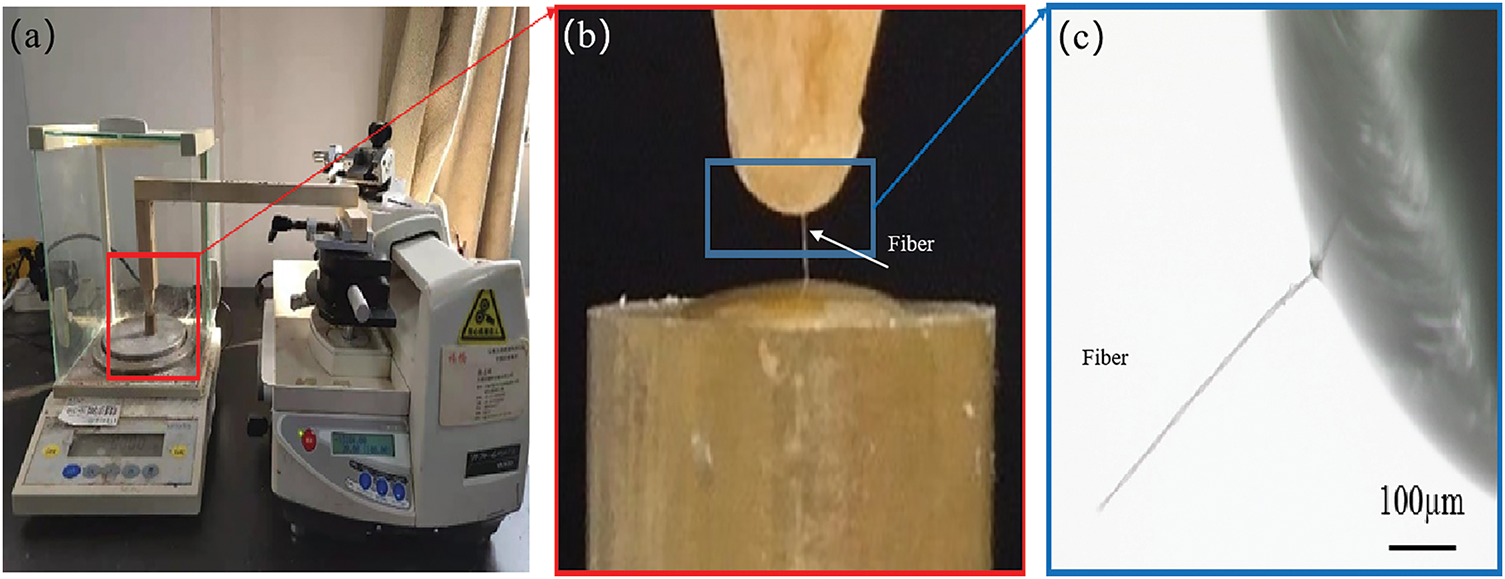

Single Fiber Tensile Strength. Straw strips were immersed in a maceration solution (glacial acetic acid: 30% hydrogen peroxide = 1:1, v/v) in test tubes and heated in a water bath at 70°C for 7 h until the samples turned white. The maceration solution was then decanted, and the samples were rinsed repeatedly with distilled water until a neutral pH was achieved. A small amount of distilled water was retained in the tubes, which were then vigorously shaken to disperse the straw into individual fibers. Single fibers were carefully extracted using fine-tipped tweezers under a stereo microscope. For tensile testing, a custom-built apparatus was employed, consisting of a semi-automatic microtome and a high precision electronic balance (0.001 g resolution), as illustrated in Fig. 1. The extracted single fiber was mounted by adhering their ends to a wooden beam support and a small copper block using UV-curable adhesive. The adhesive was cured under UV light (365 nm) for 60 s to ensure firm attachment.

Figure 1: Self-made single fiber tensile performance test instrument. (a) Single fiber tensile self-made test instrument; (b) UV adhesive bonding fiber and copper block; (c) Enlarged image of fiber breakage

Throughout the experiment, precise control of testing conditions was maintained, including consistent timing, temperature, and environmental parameters. During the tensile test, the microtome stage was gradually raised at a constant rate, simultaneously lifting the wooden beam support mounted on the stage. This motion applied a uniaxial tensile force to the single fiber until fracture occurred. At the moment of fiber fracture, two critical datasets were simultaneously recorded: The maximum load (breaking force) was measured using the high-precision electronic balance (0.001 g resolution). The displacement at fracture was determined from the microtome stage movement data. The breaking force and displacement values were used to calculate the tensile strength and strain of the single fiber, respectively. All tests were conducted under ambient laboratory conditions (23 ± 1°C, 50 ± 5% relative humidity) to ensure statistical reliability. The single fiber tensile strength was calculated using Eq. (1).

where σ = single fiber tensile strength (MPa), Pmax = breaking load (N), S = fiber cross section area (mm2), the average area of single fiber is 85.67 um2.

Strip tensile strength. Straw strips with a length of 4 cm were selected as the test specimens for evaluating the tensile properties of straw. The longitudinal tensile strength was measured using a universal mechanical testing machine with a crosshead speed of 10 mm/min. During the tensile tests, ensure that the specimens fractured at the middle position. The measurement was repeated three times with the same Eq. (1).

2.3.1 Preparation of Straw Pulp Film

Rice straw treated with DES and fermented with S. rochei was subjected to steam treatment in a pre-steaming chamber at 120°C for 30 min, followed by cooling to room temperature. The treated straw fibers were homogenized using a refiner at 600–900 rpm for four times. The resulting fibers were diluted to a 0.6% consistency and disintegrated in a laboratory pulper to obtain raw pulp material suitable for straw pulp film production. Straw pulp film was fabricated using a rapid Köthen sheet former with a target basis weight of 60 g/m2 (±2%). The formed pulp film was dried under vacuum (96 kPa) at 97°C for 3–5 min. After drying, the films were conditioned in a controlled environment (23 ± 1°C, 50 ± 2% relative humidity) for 24 h to equilibrium moisture content before further testing.

2.3.2 Mechanical Properties of Straw Pulp Films

The tensile index, bursting index, and tearing index of the rice straw pulp films were determined by the following international standards, ISO 1924-1 (tensile index,) ISO 2758 (bursting index), and ISO 1974 (tearing index). All tests were conducted under controlled environmental conditions (23 ± 1°C, 50 ± 2% relative humidity) after the pulp films were conditioned for 24 h. A minimum of 10 replicates were tested for each property, and the results were shown as mean and standard deviation.

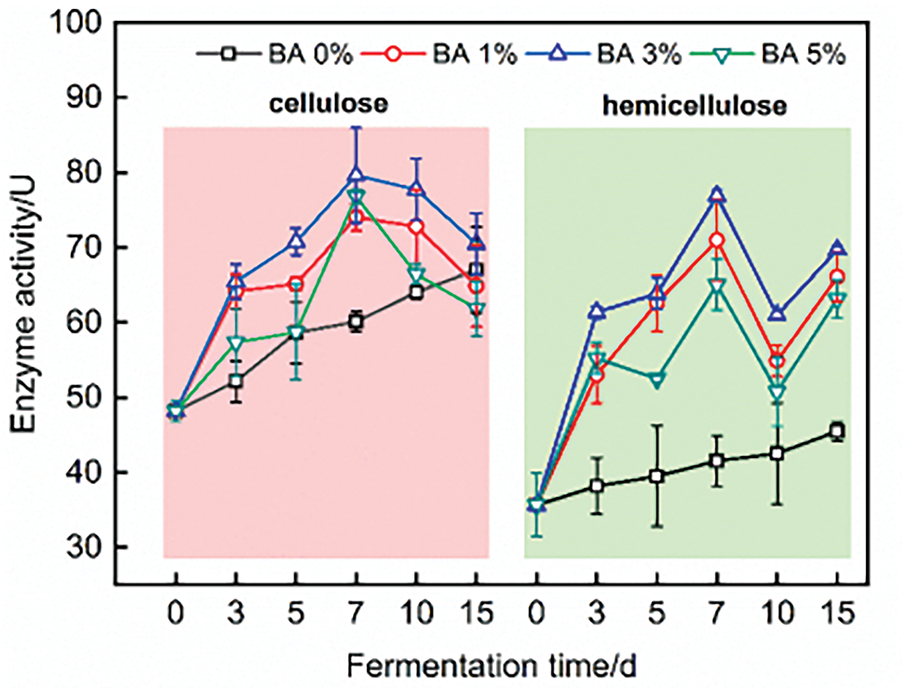

3.1 Enzyme Activity of Straw Fibers

As shown in Fig. 2, S. rochei may contribute to rapid proliferation during the initial fermentation stage by utilizing endogenous nutrients from straw, accompanied by accelerated increases in cellulose and hemicellulose enzyme activities that reached their peaks at day 7. BA 3% group obtained the maximum cellulose and hemicellulose enzyme activities (79.61/U and 76.89/U). This enzymatic enhancement was further promoted by nutrient release from straw itself decomposition, which might stimulate vigorous microbial metabolism [39]. Notably, the hemicellulose enzyme activity showed more pronounced improvement through S. rochei fermentation than cellulose enzyme activity.

Figure 2: Cellulose enzyme and hemicellulose enzyme of fermented straw fibers

Previous studies have demonstrated that S. rochei can decompose cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, though it exhibits significantly better decomposition efficiency on cellulose and hemicellulose compared to the relative recalcitrant lignin component [40,41]. The rice straw fibers, pretreated by DES, experienced cleavage of ester and ether bonds between carbohydrates and lignin at the p-coumaric acid and ferulic acid linkages, resulting in fiber structure relaxation and enhanced microbial fluid penetration [42,43].

When the inoculation level of S. rochei reached 3%, both cellulose and hemicellulose enzyme activities were significantly elevated compared to other concentration groups. This result may be attributed to three main factors: (a) Continuous microbial supplementation may accelerate the reproductive capacity, thereby improving enzymatic performance; (b) Excessive microbial proliferation leads to substrate nutrient depletion and insufficient oxygen supply, subsequently causing enzymatic decline [44]; (c) Rapid accumulation of metabolic byproducts (e.g., organic acids and ammonia) may exert inhibitory effects on microbial growth after 7 days. Both cellulose and hemicellulose enzyme activities exhibited varying degrees of reduction, indicating reaction system limitations including insufficient substrate nutrient availability and progressive enzyme inactivation during prolonged operational periods.

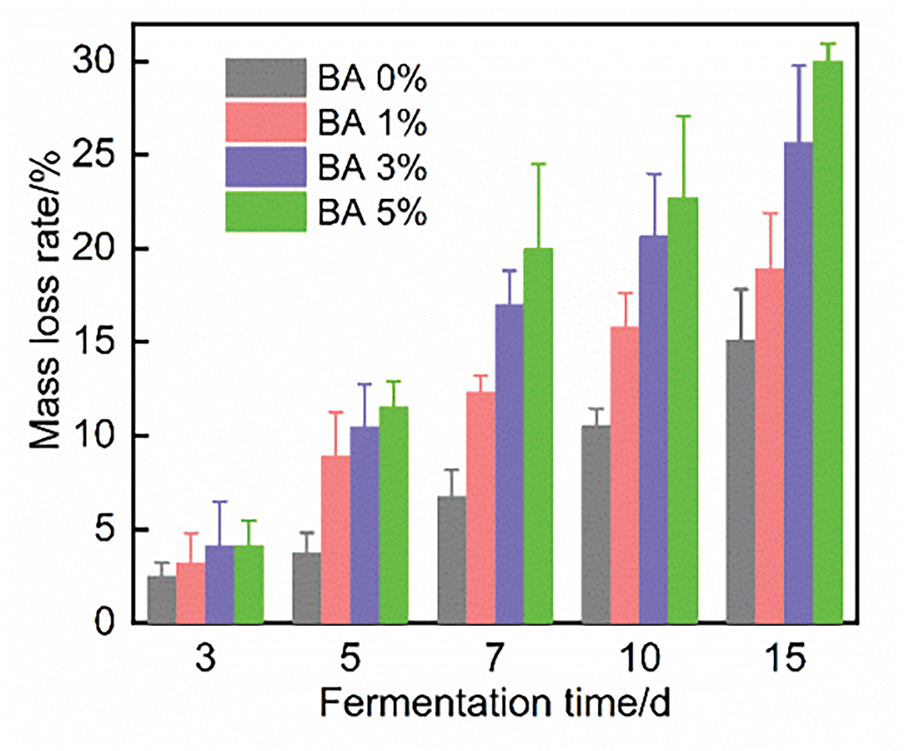

3.2 Mass Degradation and Cellulose/Hemicellulose Relative Content

As illustrated in Fig. 3, with the increase of fermentation days and concentration, the straw mass loss rate showed an upward trend. Taking the BA 3% group as an example, the mass loss rate was 4.16% on day 3, 17.01% on day 7, and 25.68% on day 15, indicating that the maximum degradation stage occurred near day 7. This pattern could be attributed to the initial compact straw structure, which gradually loosened as S. rochei fluids penetrated the fibers and accessed soluble nutrients. Enzyme activities were upregulated subsequently, leading to accelerated microbial proliferation and straw decomposition [39]. From the perspective of straw comprehensive utilization and economic feasibility, the mass loss rate during fermentation should suggestively not exceed 20%. Under the condition of maximum enzyme activity at day 7, the mass loss rate of 17.01% observed in the BA 3% group seems to be a suitable and compromising choice.

Figure 3: Mass loss rate of fermented straw fibers

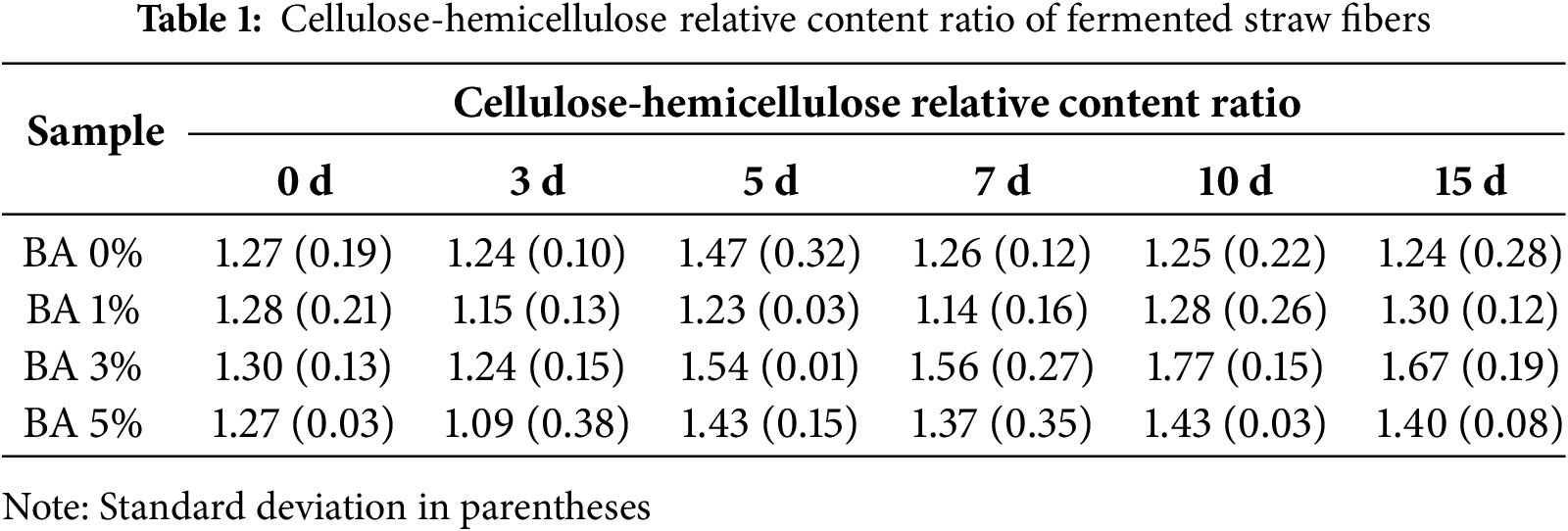

Table 1 reveals dynamic shifts of cellulose-hemicellulose relative content ratio during straw fermentation. In the early stage, hemicellulose (dominated by soluble xylans) should have exhibited a faster degradation rate than cellulose according to the previous enzyme results. However, all cellulose-hemicellulose relative content ratios showed a marked decrease by day 3, likely due to the initial degradation of cellulose-rich xylem tissues within epidermal cells outside and vascular bundles inside, which first came into contact with microbial fluid [45]. From day 5 onward, enhanced penetration of S. rochei fluids and elevated hemicellulose enzyme activity accelerated the hemicellulose degradation, leading to differential increases in the relative content ratios of cellulose and hemicellulose. Notably, the cellulose-hemicellulose relative content ratio peaked at 1.47 on day 5 in the BA 0% group, whereas the BA 3% group achieved a higher maximum ratio of 1.77 on day 10, confirming that S. rochei preferentially degrades hemicellulose more than cellulose significantly.

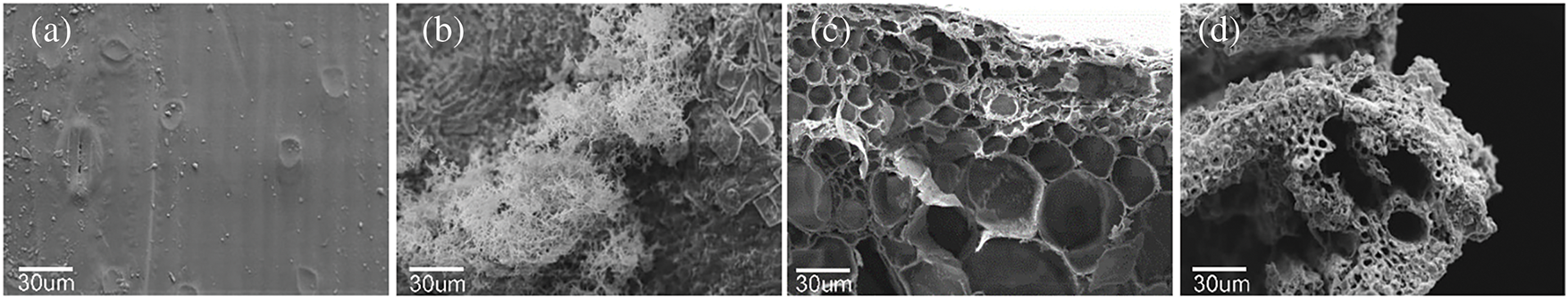

As shown in Fig. 4a,c, the longitudinal surface of raw rice straw exhibits a smooth and compact structure with a distinct waxy layer and epidermal stomata, while its cross-section displays well-organized cellular tissues, including intact parenchyma cell wall structures. In contrast, DES and S. rochei co-treated rice straw, depicted in Fig. 4b, demonstrates a gradual exposure of epidermal tissues beneath the waxy silicified layer, accompanied by degradation and detachment of external waxy and silicified cells. Extensive colonization of S. rochei on the surface facilitates microbial penetration into the straw interior, resulting in structural loosening. Cross-sectional observations reveal a significant disruption of cell wall tissues in vascular bundles, with relatively large vessels serving as preferential pathways for microbial infiltration. The originally ordered distribution of cellular structures becomes indistinct, attributed to the loss of xylan and fructan [46]. These key components play a role in binding and filling external waxy, silicified cells and internal vascular bundles. The loss of xylan and fructan leads to the stress released in highly lignified mechanical and epidermal tissues, coupled with collapsed parenchyma cells under compression, ultimately forming a densified structure as depicted in Fig. 4d.

Figure 4: Microstructure of rice straw. SEM image of (a) longitudinal section of untreated straw, (b) longitudinal section of straw with des and BA 5%, (c) horizontal section of untreated straw, (d) horizontal section of straw with des and BA 5%. Polarized image of (e) untreated straw, (f–h) straw with DES and BA 3% on 3th day, 7th day, 10th day

The mechanism of polarized light coloration illustrated in Fig. 4e,f arises from the differential refractive indices among cell wall layers, which induce perceptible variations in refractive brightness through visual observation. The cell wall exhibits a multilayered architecture with alternating thick and thin lamellae. The predominant thick layers demonstrate smaller MFAs relative to the cellular longitudinal axis, resulting in lower birefringence responses to polarized light. In contrast, the thin layers exhibit almost perpendicular to the cellular axis, displaying enhanced birefringence under polarized illumination and consequently manifesting brighter luminescence. The collective birefringent properties of these lamellar structures collectively constitute the phenomenon of alternating light and dark patterns observed in polarized light micrographs [47]. Crystalline cellulose domains exhibit strong birefringence due to their ordered structure, whereas amorphous regions demonstrate weaker optical responses. Hemicellulose displays diminished birefringence attributable to its lower crystallinity index, while lignin’s irregular arrangement renders it optically inactive. Consequently, the coloration patterns in straw specimens primarily originate from crystalline cellulose and partial hemicellulose components. Progressive fermentation time correlates with marked luminance reduction in regions far away from vessels, indicating preferential degradation in parenchyma cells. The initially intact circular cellular architecture undergoes structural collapse, manifesting as shriveled morphology with enhanced density. De-bonding between parenchyma and sclerenchyma cells occurs concomitantly with wall stress relaxation, generating birefringent bilayer visual effects adjacent to the vessel opening. At day 7 of fermentation, luminance attenuation extends to vessel regions, indicating an accelerated degradation of sclerenchyma cells. This phenomenon is correlated with S. rochei exhibiting progressive penetrating from exterior to interior cellular lumens. Ultimately, advanced degradation stages culminate in substantial disruption of cellulose crystalline domains, leading to progressive darkening of all structural components until complete optical extinction occurs [48].

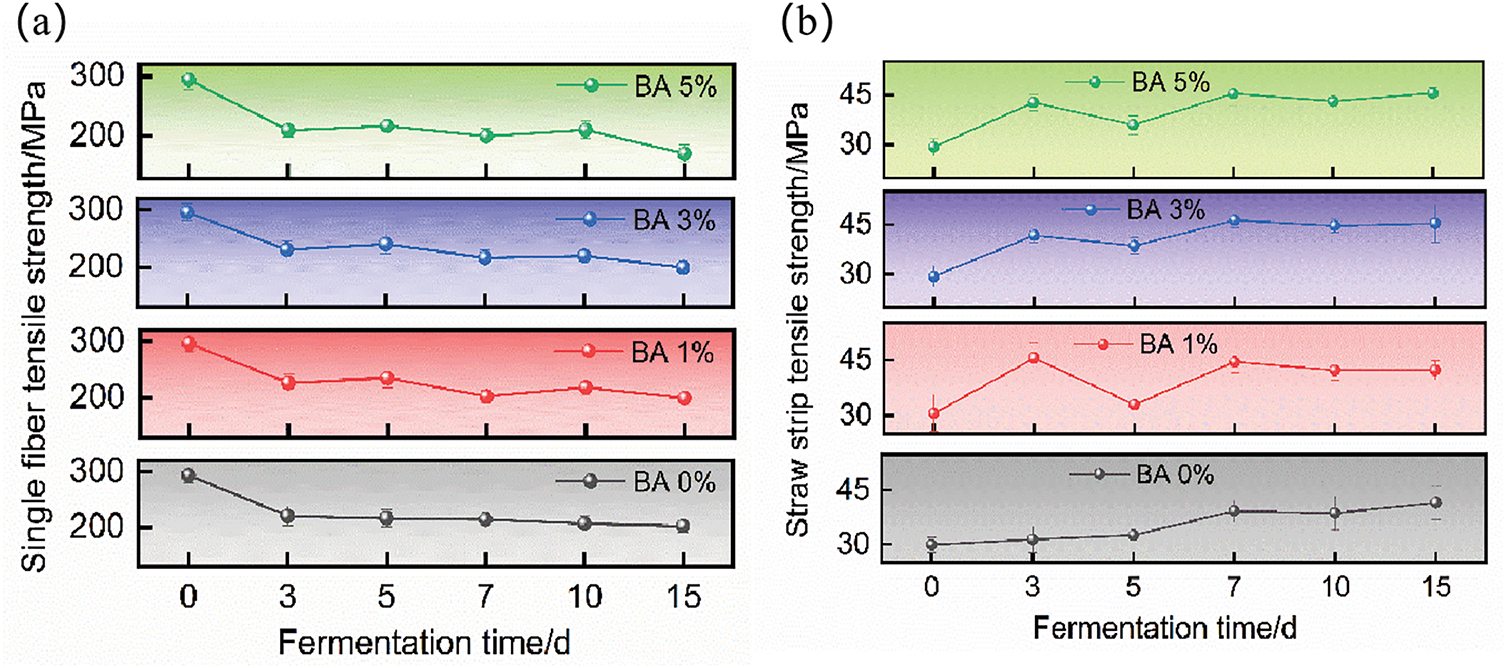

3.4 MFA, Mechanical Properties of Single Fibers and Straw Strips

In composite mechanics, the tensile strength of fiber-reinforced composites decreases as the angle between the off-axis tensile loading direction and the principal axis (termed the MFA) increases. Straw strips are typically composed of interlaced and overlapping fibers, where the interfiber bonding strength is significantly lower than the intrinsic strength of individual fibers. Under tensile loading, fracture initiation preferentially occurs at the weakest transverse bonding interfaces between fiber cells. The crack propagates longitudinally along fiber cells while circumventing thick-walled sclerenchyma fibers with higher mechanical resistance, progressively propagating through weaker transverse bonding regions. This failure mode ultimately culminates in rapid crack evolution and structural rupture [49]. An individual straw fiber is a hollow composite structure comprising hemicellulose and lignin as the matrix phase, reinforced by cellulose fibrils. Cellulose, organized as linear macromolecular chains aggregated into highly ordered microfibrils embedded within the cell wall, serves as the primary contributor to the mechanical strength of individual fibers. Hemicellulose permeates into the structural framework, functioning as an interfacial bonding agent between lignin and cellulose, thereby enhancing the integrated strength of individual fibers. Lignin, existing in an amorphous state, fills the primary architectural framework, imparting enhanced hardness and rigidity to individual fibers [50].

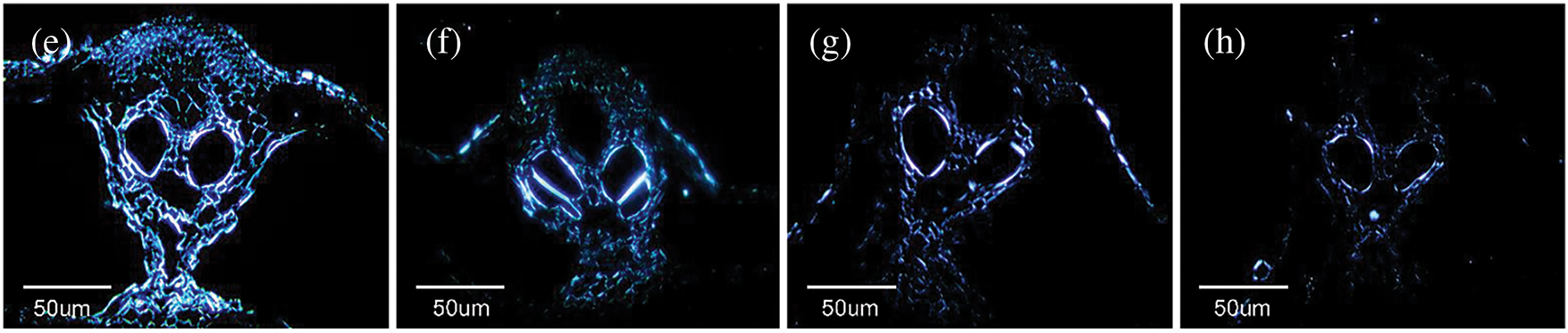

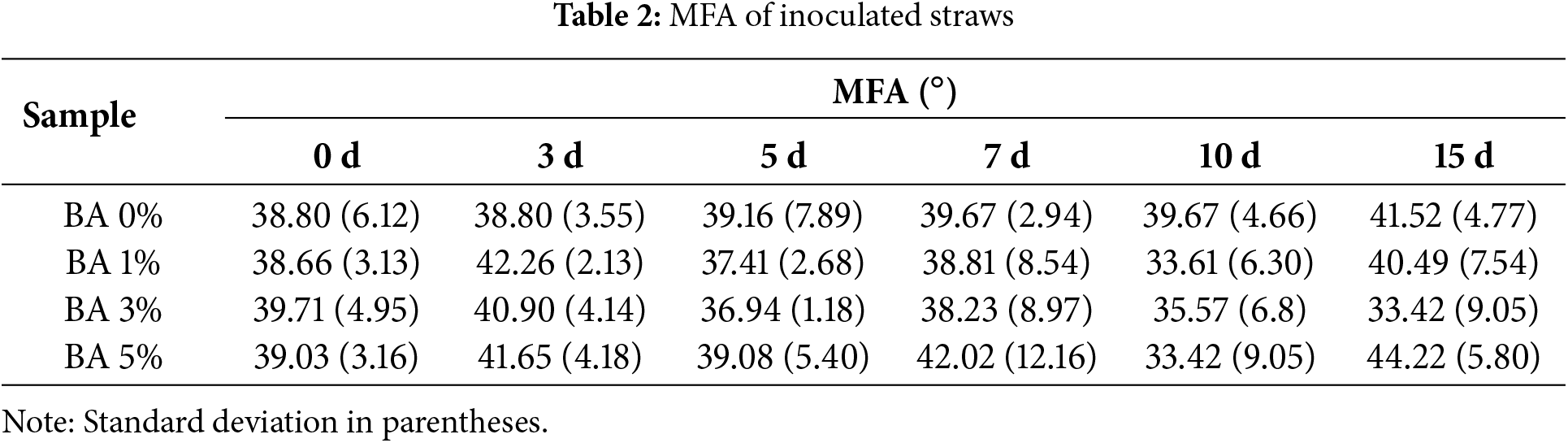

As shown in Table 2, the trend of MFAs in S. rochei treated straw consistently exhibited negative correlations with the relative content ratios of cellulose and hemicellulose during progressive fermentation days. The observed MFA increase on day 3 could be attributed to microbial penetration and hygroscopic swelling of microfibrils, which expanded interfibrillar spacing and induced disorganized microfibril alignment. Consequently, significant mechanical strength reduction of individual fibers is demonstrated in Fig. 5a. Meanwhile, DES caused the partial removal of low-strength components from lignin dissolution and epicuticular wax detachment. And, microbial secretion of viscous exopolymers (e.g., polysaccharides and proteins) during colonization filled internal voids and facilitated interfiber adhesion, thereby contributing to localized strength enhancement in straw segments as shown in Fig. 5b. The MFA reduction on day 5, combined with elevated Cellulose-hemicellulose relative content ratios, suggests that DES-induced lignin removal and microbial hemicellulose degradation disrupted microfibril anchoring structures, enabling microfibril reconfiguration. This mechanism resulted in variable strength increases in fibers, whereas straw strip strength decreased due to microbial degradation of middle lamellae and pit structures, which weakened interfiber cohesion. The MFA increase on day 7 likely originated from partial degradation of middle lamellae, which altered the straw’s architecture from matrix-mediated fiber connections to direct fiber-to-fiber interfacial contact. Enhanced interfacial contact areas promoted torsional realignment of microfibrils, while parenchyma cell compaction generated densified zones [51]. These structural modifications synergistically improved straw strip toughness, culminating in peak tensile strength at 46.22 MPa for BA 3%. The subsequent MFA decline on day 10 coincided with enzymatic cleavage of cell wall microfibrils, paralleled by marked reductions in cellulose and hemicellulose activities. During later fermentation stages, excessive microbial growth induced nutrient competition and oxygen depletion decelerated degradation kinetics, resulting in minimal mechanical property alterations in both individual fibers and straw strips [44]. Therefore, terminating fermentation at day 7 may not only optimize fiber surface modification but also maximally preserve structural integrity and mechanical performance.

Figure 5: Tensile properties of (a) single fiber and (b) straw strip under different days

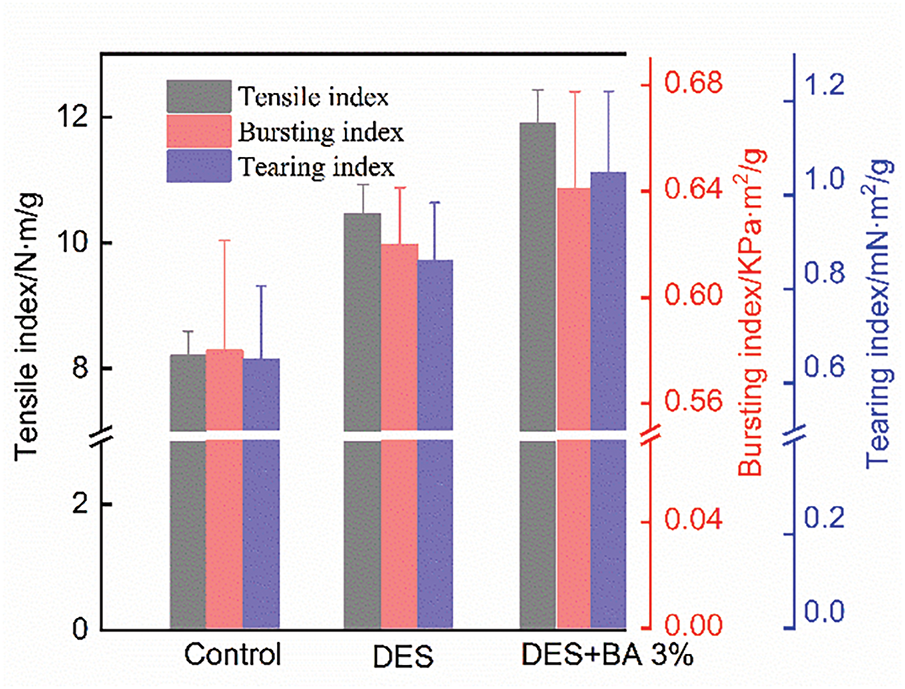

3.5 Mechanical Properties of Straw Pulp Films

Based on preliminary analysis, straw strips pretreated with 3% BA at day 7 were selected as the optimal formulation for film preparation, with comparisons of untreated samples and DES only treated counterparts, as illustrated in Fig. 6. Progressive pretreatment strategies significantly enhanced the mechanical properties of rice straw pulp films. The tensile index increased from 8.21 N·m/g for untreated films to 11.9 N·m/g for DES+BA 3% pretreated films (a 44.9% improvement), compared with a 14.1% enhancement over DES pretreated films. The bursting index rose from 0.58 kPa·m2/g for untreated films to 0.64 kPa·m2/g (a 10.3% increase) for DES+BA 3% pretreated films, representing a 5% improvement compared to DES pretreated films. The tearing index exhibited the most substantial enhancement, escalating from 0.65 to 1.04 mN·m2/g (60.0% increase) for DES+BA 3% pretreated films, with a 20.9% increment relative to DES-pretreated films. Notably, S. rochei inoculation contributed minimally to bursting resistance but substantially improved tensile and tear properties. This discrepancy arises because bursting performance depends not only on fiber intrinsic strength and hydrogen bonding but also on fiber length homogeneity caused by mechanical heterogeneity, which is a common deficiency of microbial treatments [52,53]. In conclusion, the DES and S. rochei bio-pretreatment collaborative strategy effectively enhanced film toughness, with optimal performance achieved under conditions of DES and 3% S. rochei inoculation, and 7-day treatment time.

Figure 6: Comparison of mechanical properties of straw pulp film

This study developed a ChCl/urea DES system for rice straw impregnation pretreatment, followed by gradient fermentation with S. rochei under 1%, 3%, and 5% concentration on rice straw fibers under varying fermentation days, along with evaluating the mechanical performance of straw-based pulp films. Results demonstrated that cellulose and hemicellulose enzyme activities peaked on day 7 of fermentation. BA 3% group obtained the maximum cellulose and hemicellulose enzyme activities (79.61/U and 76.89/U). A negative correlation was observed between the cellulose-hemicellulose relative content ratios and MFAs. At this stage, straw strips with 3% BA achieved a maximum tensile strength of 46.22 MPa, while individual fiber tensile strength exhibited an overall declining trend. Fermentation mass loss rate and microstructural morphology confirmed that 3% S. rochei with 7-day treatment yielded optimal performance. DES-BA 3% bio-pretreated pulp films revealed a 10.3% increment in bursting index, whereas tensile and tearing index showed significant increases of 44.9% and 60.0%, respectively. These findings collectively validate that the DES-BA 3% bio-pretreatment collaborative strategy effectively enhances the mechanical properties of straw pulp films.

Acknowledgement: We would like to acknowledge to Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Solid Organic Waste Resource Utilization; Key Laboratory of Saline-Alkali Soil Improvement and Utilization; Key Laboratory of New Materials and Facilities for Rural Renewable Energy; College of Materials Science and Engineering.

Funding Statement: This study was funded by the Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Fund of Jiangsu Province [Grant/Award Number: CX (24)1008], Key Research and Development Program Project of Henan Province (251111110100), and National State Science Foundation of China [Grant/Award Number: 21808093].

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Cheng Yong, Enhui Sun and Mingjie Guan; data collection: Xiaodong Fan, Jing Zhang and Ling Chen; analysis and interpretation of results: Cheng Yong, Zhiping Zhang, Ping Qu, Qiujun Wang, Hongying Huang and Hongmei Jin; draft manuscript preparation: Cheng Yong and Xiaodong Fan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Han QL, Zhao HL, Wei GX, Zhu YW, Li T, Xu M, et al. Sustainable papermaking in China: assessing provincial economic and environmental performance of pulping technologies. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2024;12(11):4517–29. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.3c07611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. He C, Shen J, Xu J, Sun F, Wang B. Quality evaluation of water disclosure of Chinese papermaking enterprises based on accelerated genetic algorithm. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):12225. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-39307-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Mboowa D. A review of the traditional pulping methods and the recent improvements in the pulping processes. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(1):1–12. doi:10.1007/s13399-020-01243-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ren J, Yu P, Xu X. Straw utilization in China—status and recommendations. Sustainability. 2019;11(6):1762. doi:10.3390/su11061762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Singh G, Gupta MK, Chaurasiya S, Sharma VS, Pimenov DY. Rice straw burning: a review on its global prevalence and the sustainable alternatives for its effective mitigation. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28(25):32125–55. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-14163-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Yang CW, Xing F, Zhu JC, Li RH, Zhang ZQ. Temporal and spatial distribution, utilization status, and carbon emission reduction potential of straw resources in China. Huan Jing Ke Xue. 2023;44(2):1149–62. doi:10.13227/j.hjkx.202201033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Nagpal R, Bhardwaj NK, Mishra OP, Mahajan R. Cleaner bio-pulping approach for the production of better strength rice straw paper. J Cleaner Prod. 2021;318(3–4):128539. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.128539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Varghese LM, Agrawal S, Nagpal R, Mishra OP, Bhardwaj NK, Mahajan R. Eco-friendly pulping of wheat straw using crude xylano-pectinolytic concoction for manufacturing good quality paper. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2020;27(27):34574–82. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-10119-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Chen H, Yang T, Wang J. Study on the application of Zizania latifolia straw in papermaking. BioResources. 2022;17(3):5106–15. doi:10.15376/biores.17.3.5106-5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Thomsen MH, Thygesen A, Thomsen AB. Hydrothermal treatment of wheat straw at pilot plant scale using a three-step reactor system aiming at high hemicellulose recovery, high cellulose digestibility and low lignin hydrolysis. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99(10):4221–8. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.08.054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang L, Larsson A, Moldin A, Edlund U. Comparison of lignin distribution, structure, and morphology in wheat straw and wood. Ind Crops Prod. 2022;187(3):115432. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Pang B, Zhou T, Cao XF, Zhao BC, Sun Z, Liu X, et al. Performance and environmental implication assessments of green bio-composite from rice straw and bamboo. J Cleaner Prod. 2022;375(6):134037. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.134037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Ma X, Zhai Y, Zhang R, Shen X, Zhang T, Ji C, et al. Energy and carbon coupled water footprint analysis for straw pulp paper production. J Cleaner Prod. 2019;233:23–32. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.06.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wei S, Liu K, Ji X, Wang T, Wang R. Application of enzyme technology in biopulping and biobleaching. Cellulose. 2021;28(16):10099–116. doi:10.1007/s10570-021-04182-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Gupta GK, Dixit M, Kapoor RK, Shukla P. Xylanolytic enzymes in pulp and paper industry: new technologies and perspectives. Mol Biotechnol. 2022;64(2):130–43. doi:10.1007/s12033-021-00396-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang H, Han L, Dong H. An insight to pretreatment, enzyme adsorption and enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass: experimental and modeling studies. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;140(8):110758. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.110758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Lecourt M, Sigoillot JC, Petit-Conil M. Cellulase-assisted refining of chemical pulps: impact of enzymatic charge and refining intensity on energy consumption and pulp quality. Process Biochem. 2010;45(8):1274–8. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2010.04.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Garg SK, Modi DR. Decolorization of pulp-paper mill effluents by white-rot fungi. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1999;19(2):85–112. doi:10.1080/0738-859991229206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Wu J, Xiao YZ, Yu HQ. Degradation of lignin in pulp mill wastewaters by white-rot fungi on biofilm. Bioresour Technol. 2005;96(12):1357–63. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2004.11.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Rodríguez-Couto S. Industrial and environmental applications of white-rot fungi. Mycosphere. 2017;8(3):456–66. doi:10.5943/mycosphere/8/3/7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Gauthier F, Archibald F. The ecology of fecal indicator bacteria commonly found in pulp and paper mill water systems. Water Res. 2001;35(9):2207–18. doi:10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00506-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Priyadarshinee R, Kumar A, Mandal T, Dasguptamandal D. Unleashing the potential of ligninolytic bacterial contributions towards pulp and paper industry: key challenges and new insights. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2016;23(23):23349–68. doi:10.1007/s11356-016-7633-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Chandra R, Raj A, Purohit HJ, Kapley A. Characterisation and optimisation of three potential aerobic bacterial strains for kraft lignin degradation from pulp paper waste. Chemosphere. 2007;67(4):839–46. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.10.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang X, You S, Tian Y, Li J. Comparison of plastic film, biodegradable paper and bio-based film mulching for summer tomato production: soil properties, plant growth, fruit yield and fruit quality. Sci Hortic. 2019;249(3):38–48. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.01.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Saglam M, Sintim HY, Bary AI, Miles CA, Ghimire S, Inglis DA, et al. Modeling the effect of biodegradable paper and plastic mulch on soil moisture dynamics. Agric Water Manage. 2017;193:240–50. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2017.08.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wu Z, Peng K, Zhang Y, Wang M, Yong C, Chen L, et al. Lignocellulose dissociation with biological pretreatment towards the biochemical platform: a review. Mater Today Bio. 2022;16(12):100445. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2022.100445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Wu Z, Peng K, Zhang Y, Wang M, Yong C, Chen L, et al. Advanced investigation of the interphase and degradation behavior of biocomposite pots prepared from straw fibers and the resin with enhanced degradability by keratin. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;203(2):117089. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Mamo M, Bubenzer GD. Decomposition parameters for straw erosion control blankets. Trans ASAE. 2004;47(3):721–5. doi:10.13031/2013.16104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Deng Z, Gao C, Song X. Research progress in low-carbon and environmentally friendly seedling containers. China Plast. 2022;36(12):108–20. (In Chinese). doi:10.19491/j.issn.1001-9278.2022.12.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Shao Z, Li K. The effect of fiber surface lignin on interfiber bonding. J Wood Chem Technol. 2006;26(3):231–44. doi:10.1080/02773810601023438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lim WL, Gunny AAN, Kasim FH, AlNashef IM, Arbain D. Alkaline deep eutectic solvent: a novel green solvent for lignocellulose pulping. Cellulose. 2019;26(6):4085–98. doi:10.1007/s10570-019-02346-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yao Z, Chong G, Guo H. Deep eutectic solvent pretreatment and green separation of lignocellulose. Appl Sci. 2024;14(17):7662. doi:10.3390/app14177662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Sumer Z, Van Lehn RC. Data-centric development of lignin structure-solubility relationships in deep eutectic solvents using molecular simulations. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2022;10(31):10144–56. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.2c01375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang CW, Xia SQ, Ma PS. Facile pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass using deep eutectic solvents. Bioresour Technol. 2016;219(3):1–5. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2016.07.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Du K, Guan M, Yong C, Sun E, Qu P, Huang H, et al. Enhanced interphase adhesion from bio-pretreated straw fiber in biodegradable composite pot: in-depth investigation of degradation interphase behavior. ACS Sustain Resour Manag. 2024;1(1):114–23. doi:10.1021/acssusresmgt.3c00055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chen K, Xu L, Bi Z, Fu Z. Kinetics analysis of the enzymatic hydrolysis of cellulose from straw stalk. Chin J Geochem. 2013;32(1):41–6. doi:10.1007/s11631-013-0605-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Özcan MM, Köse N. Monitoring of changes in physico-chemical properties, fatty acids and phenolic compounds of unroasted and roasted sunflower oils obtained by enzyme and ultrasonic extraction systems. J Food Meas Charac. 2023;17(1):849–62. doi:10.1007/s11694-022-01626-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Llano T, Quijorna N, Andrés A, Coz A. Sugar, acid and furfural quantification in a sulphite pulp mill: feedstock, product and hydrolysate analysis by HPLC/RID. Biotechnol Rep. 2017;15:75–83. doi:10.1016/j.btre.2017.06.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wei X, Li W, Song Z, Wang S, Geng S, Jiang H, et al. Straw incorporation with exogenous degrading bacteria (ZJW-6an integrated greener approach to enhance straw degradation and improve rice growth. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(14):7835. doi:10.3390/ijms25147835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Ji C, Wang J, Sun Y, Xu C, Zhou J, Zhong Y, et al. Wheat straw and microbial inoculants have an additive effect on no emissions by changing microbial functional groups. Eur J Soil Sci. 2024;75(3):e13494. doi:10.1111/ejss.13494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Fu B, Gao B, Zhang J, Huang H, Wei Z, Wang Q, et al. Increasing humification and reducing CH4 emission during rice straw fermentation: the role of Streptomyces rochei ZY-2. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2025;22(8):7025–36. doi:10.1007/s13762-024-06108-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Wang WY, Gao JH, Qin Z, Liu HM. Structural variation of lignin-carbohydrate complexes (LCC) in Chinese quince (Chaenomeles sinensis) fruit as it ripens. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;223:26–35. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.10.259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. He MK, He YL, Li ZQ, Zhao LN, Zhang SQ, Liu HM, et al. Structural characterization of lignin and lignin-carbohydrate complex (LCC) of sesame hull. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;209(2):258–67. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.04.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Daigger GT, Grady CPL. The dynamics of microbial growth on soluble substrates: a unifying theory. Water Res. 1982;16(4):365–82. doi:10.1016/0043-1354(82)90159-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Sarkar P, Bosneaga E, Auer M. Plant cell walls throughout evolution: towards a molecular understanding of their design principles. J Exp Bot. 2009;60(13):3615–35. doi:10.1093/jxb/erp245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Ward OP, Moo-Young M, Venkat K. Enzymatic degradation of cell wall and related plant polysaccharides. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 1989;8(4):237–74. doi:10.3109/07388558909148194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Mannan S, Zaffar M, Pradhan A, Basu S. Measurement of microfibril angles in bamboo using mueller matrix imaging. Appl Opt. 2016;55(32):8971–8. doi:10.1364/AO.55.008971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Chakraborty I, Rongpipi S, Govindaraju I. An insight into microscopy and analytical techniques for morphological, structural, chemical, and thermal characterization of cellulose. Microsc Res Tech. 2022;85(5):1990–2015. doi:10.1002/jemt.24057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Yu M, Cannayen I, Hendrickson J, Sanderson M, Liebig M. Mechanical shear and tensile properties of selected biomass stems. Trans ASABE. 2014;57(4):1231–42. doi:10.13031/trans.57.10131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Li Y, Zhu N, Chen J. Straw characteristics and mechanical straw building materials: a review. J Mater Sci. 2023;58(6):2361–80. doi:10.1007/s10853-023-08153-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Liu Z, Zhang Z, Ritchie RO. Structural orientation and anisotropy in biological materials: functional designs and mechanics. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30(10):1908121. doi:10.1002/adfm.201908121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Meijer HEH, Govaert LE. Mechanical performance of polymer systems: the relation between structure and properties. Prog Polym Sci. 2005;30(8):915–38. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2005.06.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Pothan LA, Oommen Z, Thomas S. Dynamic mechanical analysis of banana fiber reinforced polyester composites. Compos Sci Technol. 2003;63(2):283–93. doi:10.1016/S0266-3538(02)00254-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools