Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Recent Advances in Hydrothermal Carbonization of Biomass: The Role of Process Parameters and the Applications of Hydrochar

School of Life Science and Food Engineering, Huaiyin Institute of Technology, Huai’an, 223003, China

* Corresponding Author: Hongzhen Luo. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Process and Engineering of Lignocellulose Utilization)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2026, 14(1), 4 https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0157

Received 06 August 2025; Accepted 11 October 2025; Issue published 23 January 2026

Abstract

Biomass is a resource whose organic carbon is formed from atmospheric carbon dioxide. It has numerous characteristics such as low carbon emissions, renewability, and environmental friendliness. The efficient utilization of biomass plays a significant role in promoting the development of clean energy, alleviating environmental pressures, and achieving carbon neutrality goals. Among the numerous processing technologies of biomass, hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) is a promising thermochemical process that can decompose and convert biomass into hydrochar under relatively mild conditions of approximately 180°C–300°C, thereby enabling its efficient resource utilization. In addition, HTC can directly process feedstocks with high moisture content without the need for high-temperature drying, resulting in lower energy consumption. Based on a systematic analysis of the critical articles mainly published in 2011–2025 related to biomass, HTC, and hydrochar applications, in this review, the category of biomass was first classified and the chemical compositions were summarized. Then, the main chemical reaction pathways involved in biomass decomposition and transformation during the HTC process were introduced. Meanwhile, the roles of key process parameters, including reaction temperature, residence time, pH, feedstock type, pressure, mass ratio of biomass to water, and the use of catalysts on HTC, were carefully discussed. Finally, the applications of hydrochar in energy utilization, environmental remediation, soil improvement, adsorbent, microbial fermentation, and phosphorus recovery fields were highlighted. The future directions of the HTC process were also provided, which would respond to climate change by promoting the development of the sustainable carbon materials field.Keywords

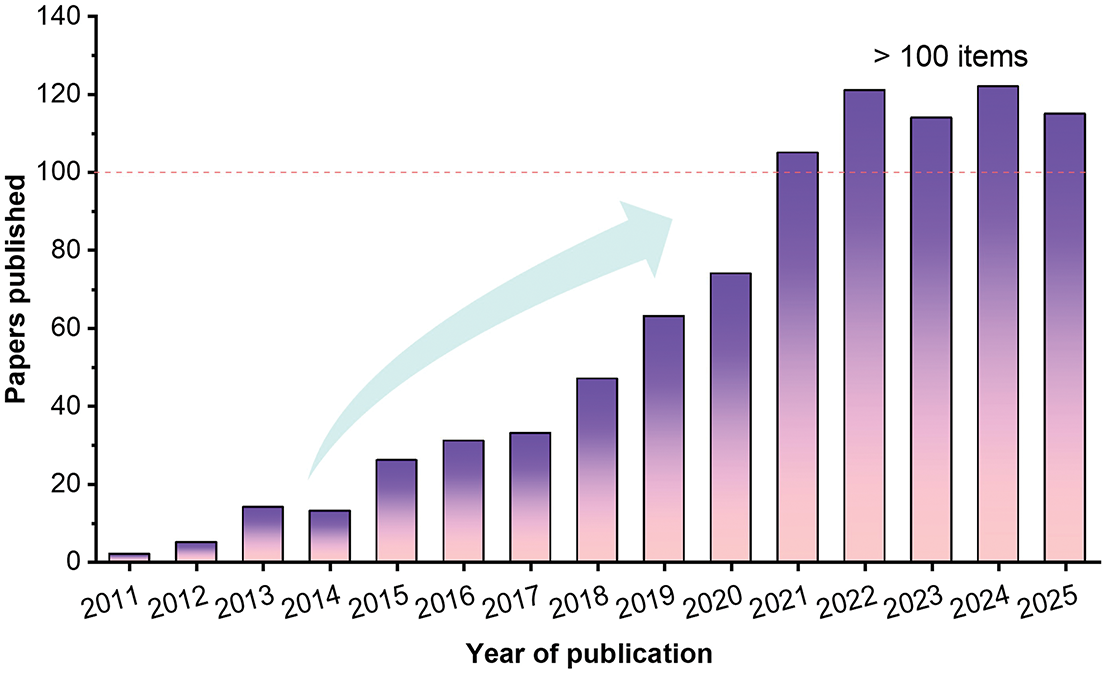

Due to the rapidly growing energy demand and the severe challenges posed by global climate change, the establishment of a low-carbon, sustainable energy production system is regarded as an urgent priority. Biomass energy has been recognized as one of the major research hotspots worldwide because of its advantages of renewability, wide availability, and relatively low cost [1]. Among various resources, lignocellulosic biomass is the most abundant renewable carbon resource on Earth, primarily derived from agricultural and forestry residues. It has been estimated that approximately 200 billion tons of lignocellulosic biomass are fixed globally each year, while in China alone, the annual generation of agricultural straw biomass was estimated at around two billion tons [2]. However, in practice, a significant proportion of biomass resources is directly discarded or openly burned; the direct combustion of biomass is often accompanied by the generation of substantial smoke, leading to reduced visibility and deterioration of air quality [3], while incomplete combustion results in the release of large amounts of persistent organic pollutants [4]. Nowadays, pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) are the most dominant approaches for synthesizing carbon materials derived from solid waste and lignocellulosic biomass. Compared with the conventional pyrolysis route, HTC generally offers higher energy efficiency due to the simple procedure without drying pretreatment for natural biomass. In addition, HTC is conducted under mild hydrothermal conditions, whereby high-temperature oxidative reactions are effectively avoided and emissions of smoke and persistent pollutants are markedly reduced. Meanwhile, biomass is stably converted into energy-dense hydrochar, enabling a cleaner utilization pathway and contributing to climate change mitigation. Consequently, HTC is widely regarded as an environmentally friendly biomass conversion technology with significant low-carbon potential [5]. Fig. 1 presents the distribution of publications retrieved from the Scopus database during the past 15 years (2011–2025) using “biomass” and “hydrothermal carbonization” as the search keywords. It is clearly found that the published papers related to the topics were above 100 items per year after 2020. Based on the above analysis, the development of efficient biomass conversion technologies such as HTC is essential for the realization of the “peak carbon dioxide emissions and carbon neutrality” targets proposed by the Chinese government. To provide valuable guidance for biomass conversion and HTC, in this review, the state-of-the-art advances in HTC of biomass were carefully summarized, especially focusing on the effects of key parameters on HTC and the wide applications of biomass-derived hydrochar.

Figure 1: Annual number of publications related to biomass and hydrothermal carbonization in the past 15 years (2011–2025). The figure was based on the search results from the Scopus database

At present, over 20 billion tons of carbon dioxide have been steadily released into the atmosphere as a consequence of anthropogenic actions, and such massive and continuous emissions are being recognized as intensifying global climate change [6]. However, due to its carbon-neutral characteristics, biomass energy is considered to contribute significantly less to the accumulation of carbon dioxide compared to fossil fuels, thereby enabling effective reductions in carbon dioxide emissions. In addition, biomass utilization for energy production is a simple approach, and infertile soils unsuitable for conventional agriculture, as well as degraded or contaminated lands, have been restored through the cultivation of biomass energy crops. It is noteworthy that non-food biomass, including crop residues, biomass wastes, and various discarded materials, has also been shown to be efficiently converted and utilized, thereby allowing the tremendous potential of biomass resources within a circular economy framework to be fully demonstrated.

Biomass is generally defined as organic matter derived from living organisms, in which the content of inorganic components, such as ash and minerals, is relatively low. Based on its origin, it is categorized into woody biomass, herbaceous biomass, aquatic biomass, and biomass derived from municipal solid waste. In China, the annual production of biomass resources was approximately 3.5 billion tons in 2020, which is equivalent to ~0.50 billion tons of standard coal. In addition, the substantial variations in the ash and carbon contents among different biomass feedstocks have been observed, and these compositional differences exert significant impacts on both the yield and physicochemical properties of hydrochar produced by HTC [7].

Woody biomass is a key global renewable resource and the most abundant organic source of energy. It has been reported that in 2010, approximately 30 EJ of energy was consumed from woody biomass, representing approximately 9% of total global primary energy use and 65% of renewable primary energy utilization [8]. Woody biomass, such as poplar, willow, pine, and eucalyptus, is characterized by a high lignin content, dense structure, and relatively high calorific value, with cellulose and lignin contents generally exceeding those of herbaceous biomass. Moreover, the elemental compositions of woody biomass exhibit lower variability with significant uniformity, and it is regarded as advantageous for large-scale processing and high-value utilization.

Herbaceous biomass is defined as organic resources that are derived from non-woody stems or seasonal herbaceous plants. According to their growth cycles, herbaceous biomass can be classified into two categories of annual and perennial plants. Annual herbaceous plants complete their life cycle within a single season, whereas perennial plants can provide biomass across multiple growing seasons. Typical herbaceous biomass examples encompass agricultural residues like wheat straw, rice straw, and corn stalks [9]. Due to their high yield and easy accessibility, they have been regarded as one of the important renewable biomass resources. It should be noted that woody and herbaceous biomass are generally named as lignocellulosic biomass.

Aquatic biomass is defined as organic matter derived from organisms that are grown in aquatic environments, including various aquatic plants, algae, and certain aquatic microorganisms. Although its carbon content is considered to be lower than that of lignocellulosic biomass, several distinctive advantages are attributed to aquatic biomass, such as its short growth cycle and relatively high nitrogen and sulfur contents. In addition, the volatile substances and fixed carbon in aquatic biomass are typically found to be of comparable levels, which is regarded as beneficial for maintaining stable reaction behavior during thermochemical conversion processes.

Urban solid waste is composed of diverse biogenic organic fractions, such as food waste, discarded paper, and natural fiber textiles. Due to the heterogeneous sources and complex composition of municipal solid waste, significant variability in its chemical constituents has been observed, which is typically characterized by relatively high carbon content and low oxygen content.

2.3 Major Components of Biomass

High-molecular-weight polysaccharides are regarded as the primary constituents of lignocellulosic biomass, among which cellulose and hemicellulose account for as comprising 60% to 80% of lignocellulosic materials and, together with lignin, are involved in forming the structural framework of plant cell walls. Cellulose is recognized as the primary constituent of green plant cell walls, with its average content in plant biomass being estimated at approximately 33% [10]. The high content of cellulose highlights its significant potential as a renewable carbon feedstock for HTC. As the most widespread organic biopolymer found in nature, cellulose is composed of β-D-glucose units linked by β-1,4-glycosidic bonds, forming a linear high-molecular-weight structure [11]. It can be extracted from a broad spectrum of biomass feedstocks and has been regarded as possessing significant renewable potential, being considered one of the most important sources for sustainable biofuel production in the future.

Hemicellulose is classified as another type of natural polysaccharide found in the cellular walls of plants and is considered the second most abundant renewable component in lignocellulosic biomass. Its structure is more complex than that of cellulose, being composed of various heteropolysaccharides, mainly including xylan, glucuronoxylan, mannan, and glucomannan. In comparison with cellulose, hemicellulose exhibits a reduced polymerization level and often presents short-chain or branched structures. As a result, its thermal and chemical stability is relatively poor, and it is typically the first component to be decomposed during thermochemical conversion processes.

Lignin is defined as an aromatic polymer with a three-dimensional network structure, which is embedded within the plant cell wall composed of cellulose and hemicellulose, collectively forming the structural framework of plant cell walls. It is primarily formed through oxidative radical coupling of three monolignol units of p-coumaryl alcohol, coniferyl alcohol, and sinapyl alcohol [12]. The lignin content typically accounts for 15%–30% of lignocellulosic biomass, with the exact proportion varying depending on plant species, growth conditions, and soil characteristics.

3 Fundamental Principles of HTC

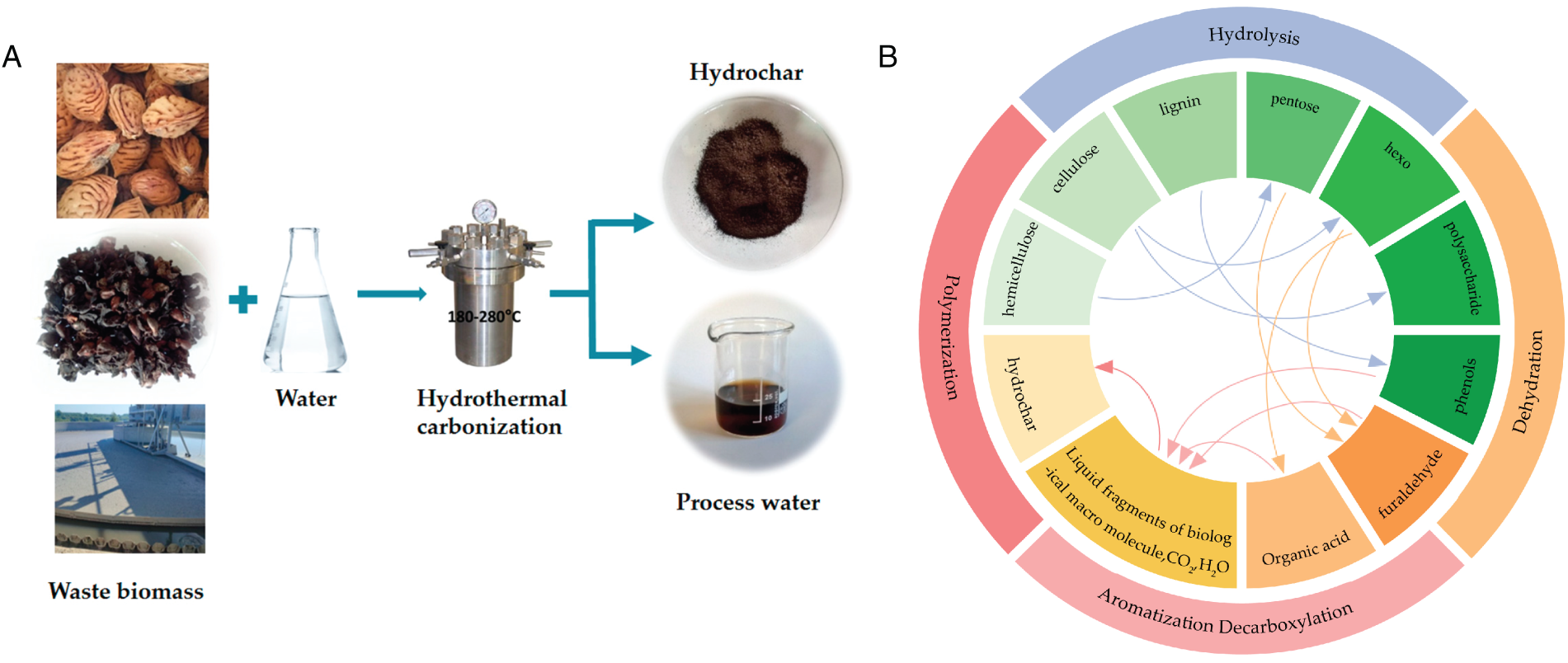

HTC is a sustainable thermochemical process, whereby biomass is decomposed and converted into carbon-rich solid products under elevated temperatures and pressures in an aqueous environment [13]. Fig. 2A illustrates the general process flow of a typical HTC reaction. The process is generally performed at temperatures between 180°C and 300°C. Under these conditions, adequate thermal input breaks macromolecular linkages and promotes interactions between water and structural polymers such as cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin. As a result, the macromolecular structures are decomposed into smaller units, which facilitates hydrolytic processes and subsequent chemical transformations. Concurrently, pressures ranging from 2 to 25 MPa preserve water in its subcritical form. It enhances water’s dual role as a reaction medium and active reactant, improving reaction efficiency. Under these conditions, water exhibits a higher ionic product, lower viscosity, and enhanced solvating ability, which improves reactant diffusion and overall reaction efficiency. In addition to serving as a reaction medium, water participates directly in bond cleavage, molecular rearrangement, and transformation reactions, thereby influencing the decomposition of biomass and the composition and distribution of products. Under elevated temperature/pressure conditions, and in an oxygen-deficient environment, macromolecular constituents, including cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin, are subjected to a sequence of recombination reactions, resulting in the formation of hydrochar characterized by high carbon content and enhanced structural stability [14].

Figure 2: The schematic representation and the reaction pathways of HTC. (A) Process flow diagram of HTC [5]. (B) Proposed reaction pathways of HTC [16]

The main reaction pathways taking place during HTC comprise hydrolysis, dehydration, decarboxylation, and aromatization [15]. In addition, the fundamental process of HTC is depicted in Fig. 2B [16]. Under conditions of 180°C–260°C, significant dehydration and decarboxylation reactions are induced, resulting in a pronounced reduction of oxygen-containing functional groups [17]. Concurrently, the formation of fused aromatic ring structures is promoted, thereby increasing the carbon content and markedly enhancing the calorific value of hydrochar. For example, Koprivica et al. used Paulownia leaves as feedstock to produce hydrochar as a potential energy source by HTC technology, and the results indicate that the hydrochars produced at higher temperatures have superior combustion properties, high energy content, stronger thermal stability, and long-time heat with higher ignition temperature [17]. Hydrolysis reaction occurred under moderate conditions of 180°C–250°C, and cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin are broken down into sugars and other low-molecular-weight compounds [18]. Within this temperature range, the reaction rate is enhanced, thereby improving the conversion efficiency of biomass and the overall product yield [19]. As the temperature is increased to 250°C–300°C, dehydration and decarboxylation reactions are intensified, resulting in the formation of organic compounds in the liquid phase. The hydrolysis products subsequently undergo dehydration reactions, during which important intermediates such as furfural and organic acids are generated, accompanied by the shortening of molecular chain segments. This process plays a crucial role in carbon framework formation and provides radical locations for follow-up aromatization reactions [20]. Aromatization and decarboxylation are considered key secondary transformation steps during HTC. Aromatization involves the rearrangement of carbon atoms in dehydration-derived intermediates to create highly stable aromatic structures. This transformation primarily occurs among furfural, organic acids, and phenolic compounds derived from hydrolysis. Through these reactions, large aromatic macromolecular fragments, CO2, and water are generated, thereby increasing the stability and carbon richness of the resulting carbonaceous products [21]. At elevated temperatures, organic molecules undergo condensation and polymerization reactions to form larger and more stable molecular structures. These structures constitute a significant portion of hydrochar and contribute to its high carbon content and heat resistance [22]. Through a series of physicochemical transformations, biomass is ultimately converted into hydrochar with unique structural and functional properties. Hydrochar is typically characterized by an elevated specific surface area (SSA) and a porous architecture, and robust physicochemical stability.

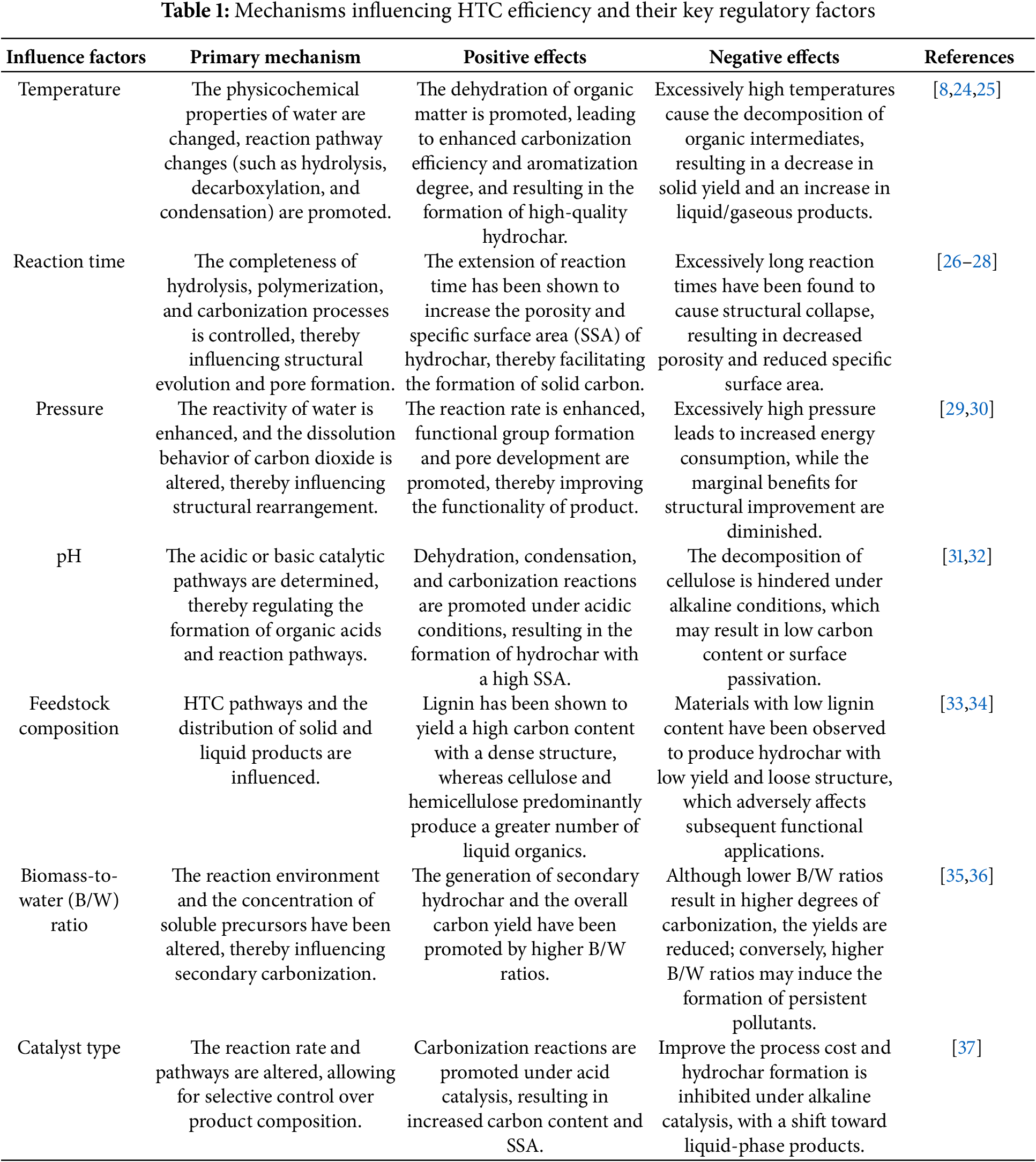

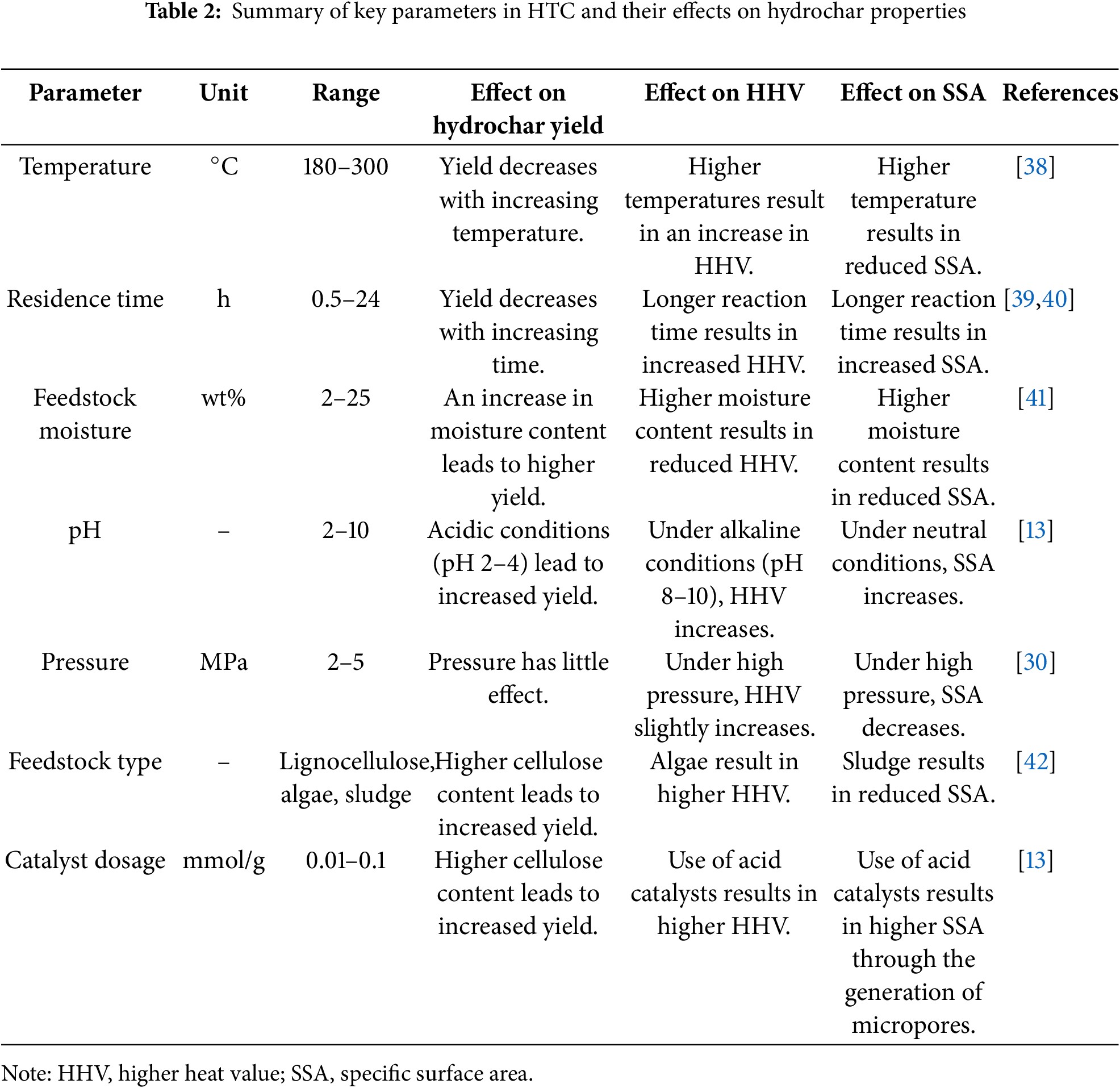

4 Characteristics of the Hydrothermal Carbonization: The Role of Process Parameters

Throughout the HTC process, the allocation and ultimate characteristics of the resulting products are governed by the combined influence of various process parameters. Among them, reaction temperature, time, pressure, pH, catalyst type, feedstock characteristics, and the biomass-to-water mass (B/W) ratio have been identified as the key factors affecting conversion efficiency and product performance. A systematic summary of the major parameters influencing the HTC process and their corresponding effects is presented in Table 1. In addition, the effects of key operation parameters on the hydrocarbon yield and its physicochemical properties are presented in Table 2. Based on the recent studies, the key roles of process parameters on HTC performance were discussed in the following sections.

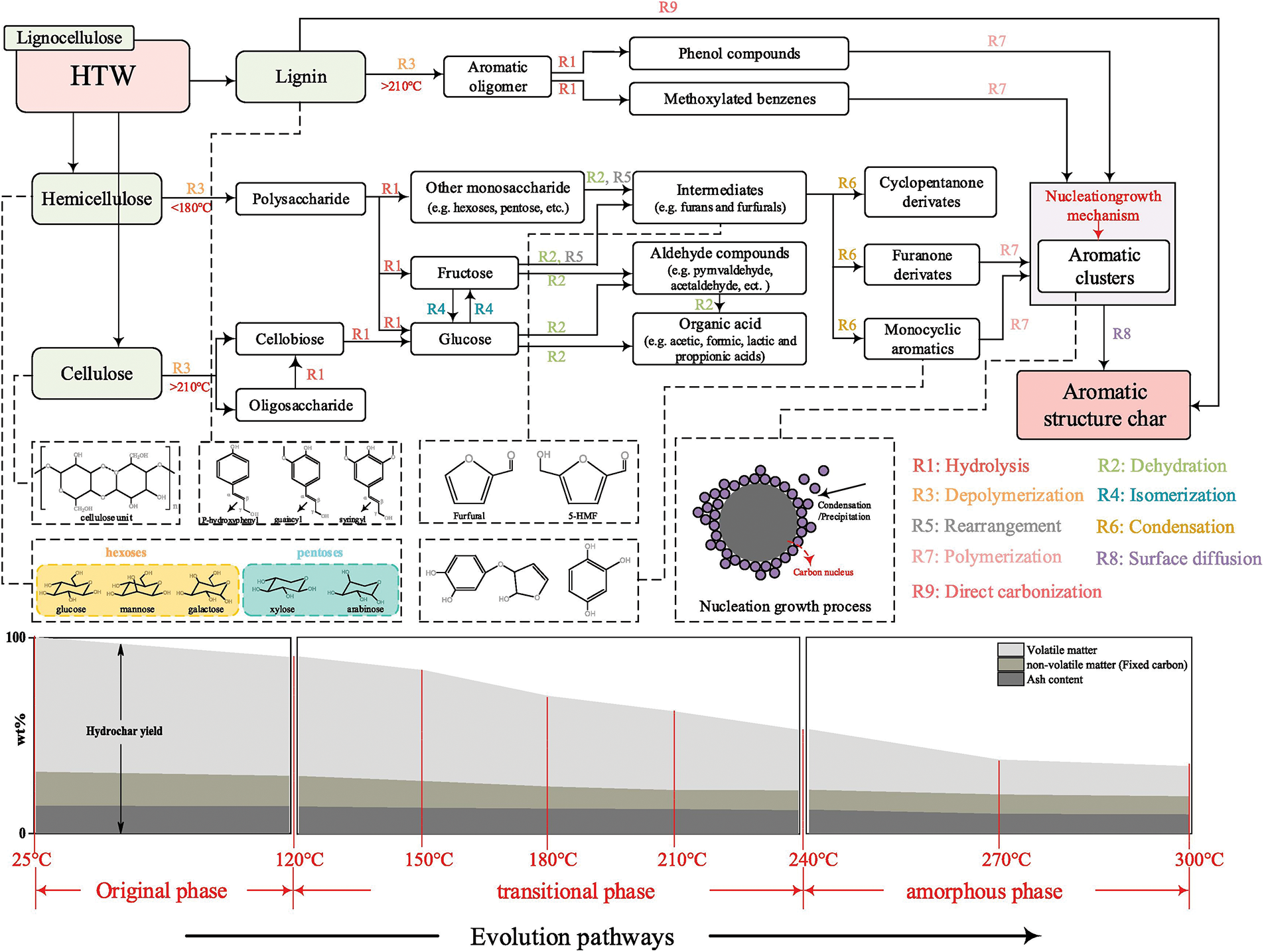

Temperature is one of the most critical parameters in the HTC process. Fig. 3 illustrates the main transformation pathways of lignocellulosic biowaste during HTC, together with the temperature-dependent variation in hydrochar yields [23]. The effect of temperature on hydrothermal reactions is essentially considered to result from the combined influence of changes in the properties of the aqueous environment and alterations within the reaction system itself (Table 1). Its primary role lies in providing sufficient thermal energy to break the chemical bonds within biomass, thereby facilitating thermolytic reactions. As the reaction temperature increases, the conversion efficiency of biomass is generally enhanced; however, it also significantly influences the composition and distribution of the resulting products [24]. The main products of the HTC process include solid, liquid, and gaseous fractions. At relatively low temperatures (180°C–200°C), solid products dominate. Under these conditions, hydrolysis and condensation reactions are favored, promoting the formation of carbon-rich hydrochar. When the temperature is increased to 250°C–300°C, dehydration and decarboxylation reactions are intensified, favoring the production of liquid-phase organics. Moderate temperature elevation has been found to enhance the carbonization and aromatization of hydrochar, thereby improving its functional properties. However, excessive temperatures may cause over-cracking or volatilization of valuable intermediates, resulting in a reduction in overall solid yield [25]. Therefore, temperature regulation in the HTC process not only directly determines the type and distribution of products but also significantly affects the quality and final application potential of the resulting hydrochar.

Figure 3: The evolution pathways of lignocellulosic biomass during the HTC process. Reprinted with permission from reference [23]. Copyright © 2019, Elsevier

4.2 Influence of Reaction Time

The reaction time has been found to significantly influence hydrolysis only within a certain range, beyond which its effects on reaction progression and product properties tend to plateau. Zhang et al. further observed that prolonged residence times favor the formation of solid and gaseous products, whereas the yield of liquid products exhibits an inverse trend [26]. Additionally, as reaction time increases, the porosity and SSA of the resulting hydrochar have been shown to increase. However, insufficient reaction times may lead to incomplete HTC of biomass, resulting in reduced hydrochar yield and diminished structural stability. Conversely, excessively long reaction times can cause over-carbonization, leading to structural collapse of the carbon material, decreased porosity, and reduced SSA (Table 2). These changes adversely affect the adsorption capacity of hydrochar, ultimately impacting product quality and application [27,28].

Pressure is also a crucial parameter in the HTC process, significantly influencing reaction rates, product structure, and functional performance (Tables 1 and 2). In batch HTC systems, reaction pressure is inherently generated and primarily determined by the reaction temperature, water filling ratio, and feedstock composition, rather than by external gas injection [30]. As pressure increases, both the physical and chemical properties of water are altered, enhancing its reactivity and solvation capability, which in turn accelerates biomass conversion [29]. Maintaining the system pressure within appropriate ranges allows better control over biomass decomposition and hydrolysis behaviors, supporting efficient hydrothermal reactions. Furthermore, the solubility of carbon dioxide is significantly increased under high-pressure conditions, which not only facilitates the regulation of oxygen-containing functional groups on the hydrochar surface but also promotes the development of porous structures, thereby improving SSA and adsorption performance [43]. Therefore, proper regulation of reaction pressure is beneficial for enhancing the energy efficiency and conversion efficiency of the HTC process, while also providing an effective strategy for tuning the structure and optimizing the functionality of hydrochar materials.

As one of the key parameters influencing the HTC process, the acid-base environment of the reaction system is not only reflected by the pH value but is also recognized to play a pivotal role in governing the reaction pathways, conversion efficiencies, and the resultant physicochemical characteristics of the hydrochar product. It has been demonstrated by previous studies that during the HTC process, a gradual decrease in system pH is typically observed as the reaction progresses. This decline is primarily attributed to the continuous generation of organic acids, including acetic acid, formic acid, lactic acid, and levulinic acid. These organic acids are not only produced as intermediate reaction products but are also regarded as essential regulators by which the reaction pathways and final product properties are influenced [44]. At reaction conditions near 180°C, the formation of organic acids is observed to be most pronounced, culminating in the system pH reaching its minimum value. However, with a further increase in temperature, these organic acids are prone to undergo condensation and repolymerization reactions, which result in a significant diminution of acidic species concentration, thereby causing the pH to elevate and gradually approach a neutral level [32]. It is noteworthy that despite the initial pH varying between 2 and 12, the pH of the reaction liquid at the end of the HTC process is consistently maintained within the range of 2.8 to 4.2, indicating that the system exhibits a certain degree of intrinsic buffering capacity [31]. The reaction is significantly catalyzed under acidic conditions—typically within the range of pH 2.5–4.0, where the hydrolysis, dehydration, and condensation of biomass macromolecules are effectively promoted, thereby accelerating the carbonization process and enhancing both the carbon content and structural density of the solid products [45,46]. For example, the carbonization degree was significantly enhanced in a baked pine system upon the addition of acetic acid [47]. Furthermore, in a study where poplar was treated with acidic process water at pH 3.5, it was demonstrated that the acidic environment effectively catalyzed the dehydration reactions [48]. However, the effects of acidic conditions on decarboxylation reactions, monomer repolymerization, and other reaction mechanisms remain insufficiently understood and warrant further investigation. Related studies have also revealed that hydrochars produced under acidic conditions typically exhibit larger SSA and pore volumes, along with smaller pore sizes, thereby demonstrating enhanced adsorption performance [49]. For instance, hydrochars produced via HCl treatment have been shown to possess significantly higher adsorption capacities compared to those obtained through deionized water or NaOH treatments [50]. Conversely, under alkaline conditions, acid-catalyzed hydrolysis reactions are suppressed, thereby hindering the depolymerization of cellulose and hemicellulose. However, the conversion efficiency of lignin is observed to increase in alkaline environments. Studies have indicated that alkaline conditions inhibit the formation of organic acids and sugars, while facilitating the production of lignin-derived monomers such as catechol and guaiacol [49]. Moreover, under high pH conditions, a reduction in both the higher heating value (HHV) and carbon content of hydrochar may be observed, accompanied by potential surface passivation phenomena, which could adversely affect its subsequent application performance. Elevated alkalinity has also been associated with an increase in the H/C ratio of the product, thereby reducing its overall energy density [51]. Overall, pH not only influences the yield and carbon content of hydrochar but also determines its pore structure and surface properties (Table 2). By optimizing the acid/base conditions of the reaction system, the reaction pathways can be more effectively directed, enabling synergistic improvements in both carbonization efficiency and the functional performance of the resulting hydrochar.

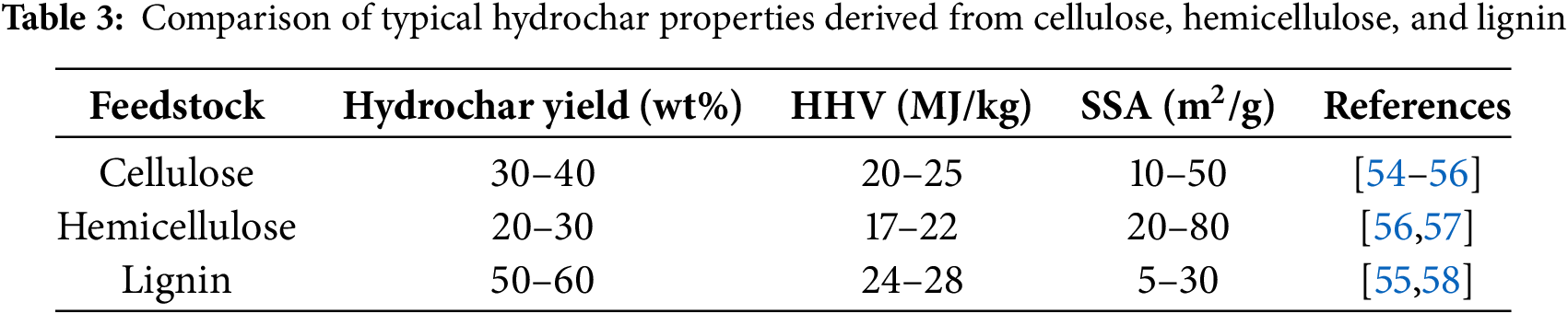

4.5 Influence of Feedstock Properties

Biomass feedstocks exhibit significant variations in their structural and chemical compositions due to differences in growth environments and growth cycles. These variations have been found to influence the reaction behavior during hydrothermal conversion and the types and distribution of HTC products. The primary components of biomass—cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—have been shown to possess distinct thermal reactivities and decomposition pathways under HTC conditions. Feedstocks rich in cellulose and hemicellulose tend to favor the formation of liquid products such as sugars, intermediate esters, and organic acids, whereas those with higher lignin content are more prone to producing hydrochar [34]. The influence of lignin content on bio-oil yield was investigated by Zhong and Wei using five typical lignocellulosic biomasses: Chinese fir, ash, Masson pine, poplar, and silver poplar [33]. It was observed that bio-oil yields gradually decreased with increasing lignin content, while hydrochar production significantly increased. This phenomenon was mainly attributed to the propensity of lignin-derived intermediates to undergo condensation and cyclization reactions, which reduce the stability and yield of liquid-phase products [52,53]. Furthermore, feedstock composition has been found to determine hydrochar yield, structural features, the pore size distribution, SSA, and related physicochemical properties. The regulatory effect of lignin and cellulose content on hydrochar porosity has been widely confirmed, demonstrating significant value in the development of hydrochar-based functional materials. Typical results in product yield, HHV, and SSA of cellulose-, hemicellulose-, and lignin-derived hydrochar are summarized in Table 3.

4.6 Mass Ratio of Biomass to Water

It has been reported that lower B/W ratios typically result in reduced hydrochar yields, while a higher degree of carbonization is achieved (Tables 1 and 2). For example, during the HTC of softwood, increasing the water dosage while keeping the biomass loading constant promoted a greater extent of carbonization [36]. In contrast, higher B/W ratios have typically resulted in increased hydrochar yields, albeit with a lower degree of carbonization [35,36]. For primary hydrochar, its formation is mainly attributed to solid–solid reactions, the equilibrium of which is not significantly affected by solid concentration. As a result, the yield of primary hydrochar remains relatively constant across different biomass-to-water (B/W) ratios. In contrast, the formation of secondary hydrochar is more sensitive to the concentration of liquid-phase precursors. Under higher B/W ratios, elevated concentrations of soluble organic intermediates in the reaction medium increase the probability of polymerization, thereby promoting the formation of secondary hydrochar and contributing to an overall increase in yield [59,60]. In addition, the B/W ratio is shown to potentially influence the environmental behavior of hydrochar. Gao et al. evaluated the effect of B/W ratio on the formation of persistent free radicals (PFRs)—a class of potentially hazardous contaminants to human health—in hydrochar derived from rice straw [61]. The range of B/W ratios investigated in the experiments was from 1:2.5 to 1:20. It was found that under a higher B/W ratio of 1:2.5, the formation of PFRs was markedly increased, whereas under more diluted conditions (B/W ratio of 1:20), PFR formation was significantly decreased [61]. Consequently, a lower B/W ratio was recommended by the authors during hydrochar preparation to enhance its environmental safety. Overall, systematic studies on the impact of B/W ratio on the physicochemical properties and environmental behavior of hydrochar remain limited, highlighting the need for further in-depth investigation into its underlying mechanisms and regulatory strategies.

Catalysts are playing a significant regulatory role in the HTC process, where the reaction rate, pathway selection, and the composition and quality of the final products are markedly influenced, thereby fulfilling the comprehensive requirements for reaction efficiency and product selectivity [62]. Different types of catalysts exhibit distinct catalytic effects depending on the hydrolysis mechanisms involved. Typically, acidic catalysts effectively promote the hydrolysis of macromolecular polysaccharides such as cellulose and hemicellulose, accelerating the HTC process, whereas alkaline catalysts tend to inhibit char formation and favor the production of liquid-phase products (Table 1). An ideal catalyst is expected to possess high thermal stability, strong catalytic activity, economic viability, and good selectivity toward target products [37]. For instance, when dilute HCl or H2SO4 was introduced (pH 2–3), the SSA of hydrochar was increased from approximately 15 m2/g to around 100 m2/g, while the carbon yield was also improved by ~10%–15% compared to non-catalyzed conditions [63]. Conversely, alkaline catalysts such as Na2CO3 and KOH tend to reduce solid yields by approximately 15%–20% but promote higher production of soluble organics, shifting selectivity toward liquid products [64]. In the HTC system, catalysts could facilitate organic matter conversion by modulating reaction rates. The physical and chemical properties of catalysts also directly influence the structure and performance of hydrochar. Effective diffusion of catalytic particles into biomass enhances the decomposition of complex organic constituents such as lignin and cellulose, thereby promoting hydrochar formation. Additionally, in practical deployment, attention is required with regard to catalyst recyclability and detoxification, as residual acidic/alkaline catalysts in process water may pose environmental risks and therefore must be recovered and neutralized before disposal or reuse.

The valorization of waste biomass for renewable energy and biofuel production has become a key development goal in many developed and developing countries, promoting the bioeconomy concept. Raw biomass is generally regarded as a low-quality fuel source due to its low energy density and relatively high ash and moisture content [53,65]. In contrast, hydrochar produced via HTC exhibits significant advantages in fuel properties, including higher carbon content, increased energy density, reduced ash and volatile matter, as well as enhanced material stability and dehydration characteristics [5]. Hydrochar has been reported to possess HHV ranging from 25.15 to 29.01 MJ/kg, and the HHV of lignite is ~25 MJ/kg [66]. Additionally, its ash content was found to be 6.7%–7.7%, which falls within the typical range for lignite ash [67]. Therefore, the overall performance of hydrochar can be comparable to that of lignite and even some commercial coals. A key advantage of the HTC process lies in its ability to transfer inorganic elements from the feedstock into the liquid phase, thereby reducing the ash content in hydrochar [68]. Low ash content is a highly desirable attribute for solid fuels, since elevated levels of specific inorganic elements in fuels and biomass can cause increased emissions, corrosion, fouling, clogging, and slagging during direct combustion [69,70].

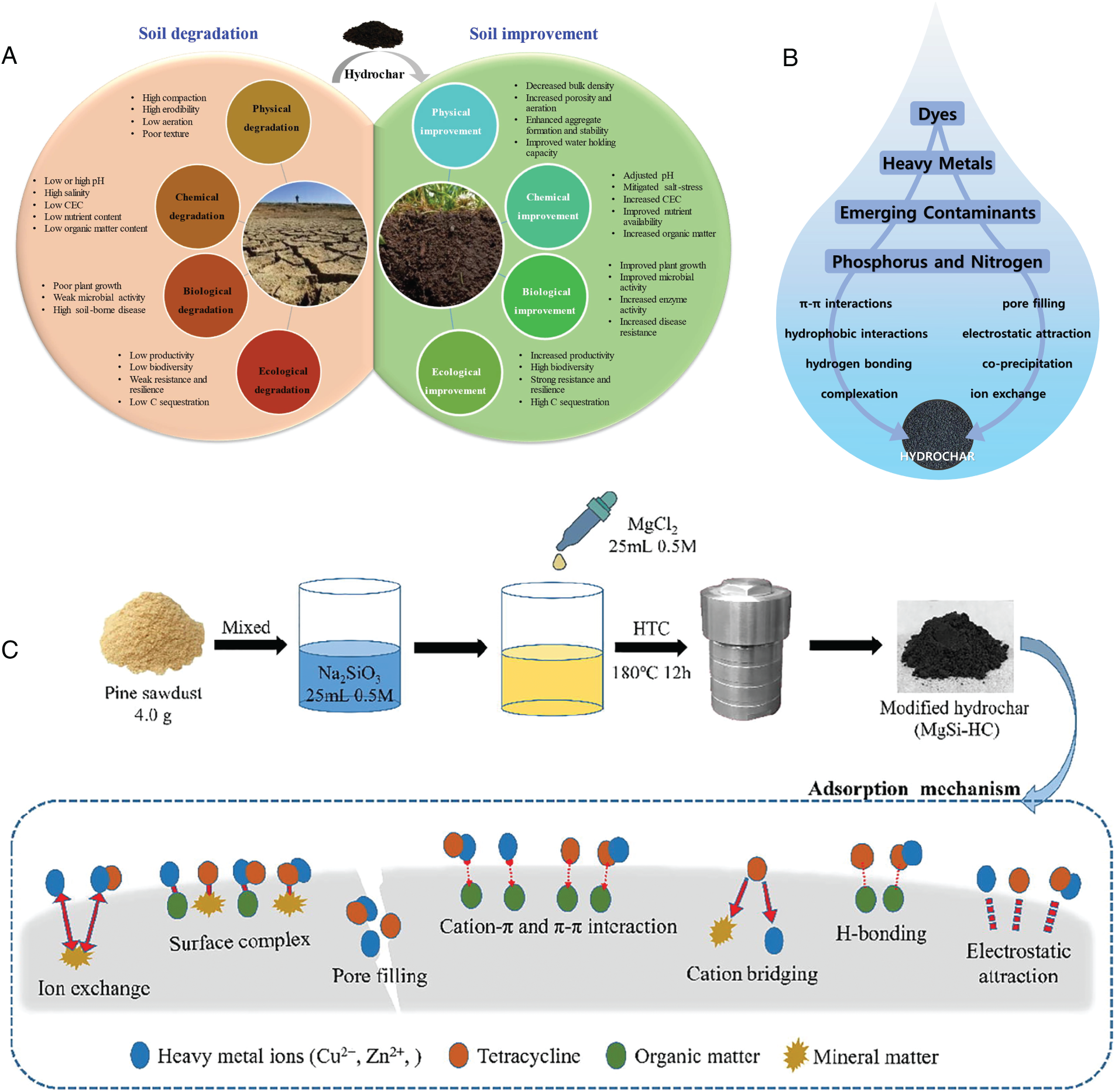

The quality of soil has been continuously deteriorating due to the influence of multiple natural factors, particularly intensified by anthropogenic activities. This degradation is manifested through a series of adverse phenomena such as soil desertification, acidification, and alkalization, ultimately resulting in the overall decline of soil environmental conditions [71]. Such soil degradation has been recognized not only as a serious threat to agricultural productivity but also as a critical challenge to the sustainability of ecosystems and the stability of the global climate [72]. Fig. 4A shows the improvement effect exerted on degraded soil by HTC carbon materials. Degraded soils are typically characterized by low porosity and high bulk density, which may result in increased compaction, poor water retention capacity, and heightened susceptibility to erosion [73]. Owing to their porous architecture and low specific weight, adding hydrochar with the loads of 2.5–6.0 wt% has demonstrated the potential to improve soil porosity by 6.3%–11.5% and reduce bulk density by 8.2%–18.9%, thereby enhancing the structural stability of soils [73,74]. Studies have shown that hydrochar possesses the ability to adsorb and retain pesticides within agricultural systems, which helps optimize pesticide utilization and reduce the potential risk of groundwater contamination [75,76]. However, a portion of the carbon components in hydrochar can undergo rapid mineralization upon soil application, with carbon content potentially decreasing by 30%–40% within the first 12 to 19 months [77,78]. Additionally, certain organic compounds present in hydrochar may exhibit toxicity toward soil microorganisms or plants, representing a potential limitation for its application in soils. Hydrochar produced at 260°C has been reported to reduce wheat growth by 20%–30% due to its toxic effects. In contrast, hydrochar generated at lower HTC temperatures (<200°C) did not exert significant effects under nutrient-rich soil conditions [79]. However, under nutrient-deficient soils, hydrochar derived from 170°C–200°C processing was found to decrease wheat growth by up to 50%, a phenomenon described as “apparent phytotoxicity,” which was attributed to nutrient scarcity exacerbated by microbial immobilization [79]. To mitigate this issue, simple washing, aerobic treatment, or low-temperature processing have been demonstrated as effective approaches to reduce toxic constituents in raw hydrochar, thereby enhancing its environmental compatibility [80,81]. The labile fraction of hydrochar can stimulate soil microbial activity, whereas the capacity of its recalcitrant fraction for long-term carbon sequestration remains a subject of debate [82]. The carbon sequestration benefits of hydrochar application in soil depend on its long-term stability over timescales ranging from decades to millennia. Its high carbon content, thermal stability, and recalcitrance are considered key attributes enabling efficient carbon sequestration in soils [83,84].

Figure 4: The application of hydrochar and its possible adsorption mechanisms. (A) The improvement effect exerted on degraded soil by hydrochar. Reprinted with permission from reference [94]. Copyright © 2022, Elsevier. (B) The possible adsorption mechanisms of water pollutants by biomass-derived hydrochar. Reprinted with permission from reference [85]. Copyright © 2023, Elsevier. (C) The synthesis procedure of hydrochar and the adsorption mechanisms of heavy metals and organic contaminants. Reprinted with permission from reference [92]. Copyright © 2020, Elsevier

Among various pollution control strategies, adsorption has been regarded as an efficient, cost-effective, and environmentally friendly approach for the removal of organic pollutants. Hydrochar is widely used as a low-cost and efficient adsorbent for aqueous pollutants due to its excellent adsorption properties [50]. Fig. 4B presents the various mechanisms that may be involved in the adsorption of aqueous pollutants by hydrochar [85]. It has been demonstrated in numerous studies that hydrochar can effectively remove typical organic pollutants such as dyes, pharmaceuticals, and pesticides. Organic pollutants are generally classified into natural and anthropogenic categories. These contaminants are widely distributed across environmental media such as water, air, and soil. Some of them can be degraded under microbial action, and even structurally stable compounds such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are degradable by specific soil microorganisms under certain conditions [86]. However, certain organic pollutants with complex structures or high stability are poorly biodegradable in natural environments and exhibit long-term persistence, as well as teratogenic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic properties, posing serious threats to ecosystem stability and human health. The raw hydrochar typically exhibits limited adsorption capacity and generally requires physical/chemical activation to enhance its performance. Current studies have identified hydrochar as an ideal precursor for activation, with superior properties compared to untreated raw biomass [87]. In addition to alkali activation, modification with metal salts is an effective strategy for improving the adsorption performance of hydrochar. Regarding adsorption mechanisms, the interactions between organic pollutants and hydrochar primarily involve pore filling, surface complexation, ion exchange, cation bridging, π–π interactions, and electrostatic adsorption [88,89]. Under alkaline conditions, the increased negative surface charge density of HTC-derived materials strengthens electrostatic interactions with positively charged dye molecules. Moreover, the marginal effect of adsorption could decrease within a pH range of 9–11, indicating that intrinsic mechanisms such as complexation and ion exchange are also involved. Compared to heavy metal ions, organic pollutants may form more stable associations with the hydrochar surface through hydrogen bonding, thereby enhancing both adsorption efficiency and selectivity.

Unlike most organic pollutants, heavy metals cannot be naturally eliminated via biodegradation processes, and their bioaccumulation through the food chain can be progressively amplified, eventually leading to toxic concentrations in the human body and causing health issues. Stable complexes between heavy metal ions and proteins/enzymes within organisms have been formed, which interfere with normal physiological functions and result in enzyme activity inhibition, metabolic disorders, and chronic toxicity. Therefore, the efficient removal of heavy metals from environmental media by adsorption technology is a key strategy to reduce their bioavailability and curb ecological risk propagation. Hydrochar has been shown to exhibit outstanding heavy metal ion adsorption capacity owing to its tunable pore structure, high SSA, and abundant oxygen-containing functional groups on the surface [90]. For example, hydrochars derived from wheat straw, corn stalk, and sawdust activated by potassium hydroxide have been confirmed to effectively remove cadmium from water [46]. Simić et al. investigated the effectiveness of lead ion removal by corncob-derived hydro-pyrochar, which was prepared via a two-step process involving HTC followed by pyrolysis in a MgCl2 medium, and the maximum Pb adsorption capacity reached up to 87.08 mg/g [91]. Additionally, alkaline-modified hydrochars have also demonstrated favorable performance in the removal of lead (Pb) and cadmium. These studies have shown that, through appropriate modification, hydrochar has been prepared as a novel, highly efficient adsorbent with tunable structure and superior performance for the removal of various pollutants. Fig. 4C illustrates the synthesis of HTC-derived carbon materials and the mechanisms by which heavy metal and organic pollutants are removed through adsorption [92]. Recently, the overall adsorption performances of lignocellulose-derived hydrochar on heavy metals, organic dyes, and hormones have been reviewed, which focused on the adsorption capacity (qmax) and adsorption isotherm models (Langmuir, Freundlich, Redlich-Peterson model) [93]. In summary, hydrochar has demonstrated multiple adsorption mechanisms and highly tunable structures in the removal of both organic and heavy metal pollutants, indicating strong potential as an efficient and environmentally friendly adsorbent. The efforts should be directed toward further elucidating its interfacial interaction mechanisms and developing functionalization methods to enable effective removal of complex contaminants from the environment.

Significant effects of hydrochar on the regulation of archaeal microbial community structures have been demonstrated, particularly in promoting the growth of methanogenic microorganisms. Using 10 g/L hydrochar prepared from digestate at 200°C for 6 h was reported to enhance anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and sewage sludge [95]. In this case, the cumulative methane production was improved by 27% and the microbes relevant to methane synthesis (e.g., Methanosaeta and Syntrophomonas) were largely enriched. Furthermore, it has been reported that the total methanogen abundance in the hydrochar-treated group was nearly doubled relative to the control, accompanied by a similar shift in the dominant methanogenic genus from Methanobacterium to Methanosarcina [96]. Notably, under conditions with inhibitory factors present, the enrichment of methanogens was still promoted by hydrochar addition. For example, in an 8 g/L ammonia environment, the relative abundance of Methanosarcina decreased to 0.6%–12.9%, whereas after hydrochar addition, its abundance was maintained at a higher level of 18.2%–22.1% [97]. At ammonia concentrations of 0.5 and 4 g/L, methane yield increased by approximately 10% with the addition of 10 g/L hydrochar, which was produced from poplar wood at 300°C for 1 h. Furthermore, under a high ammonia concentration of 8 g/L, the addition of 10 g/L hydrochar resulted in a maximum methane yield enhancement of up to 220% [98]. Given the close association between methanogens and methane production [96], the promotion of methanogen enrichment by hydrochar highlights its significant potential for application in microbial fermentation processes.

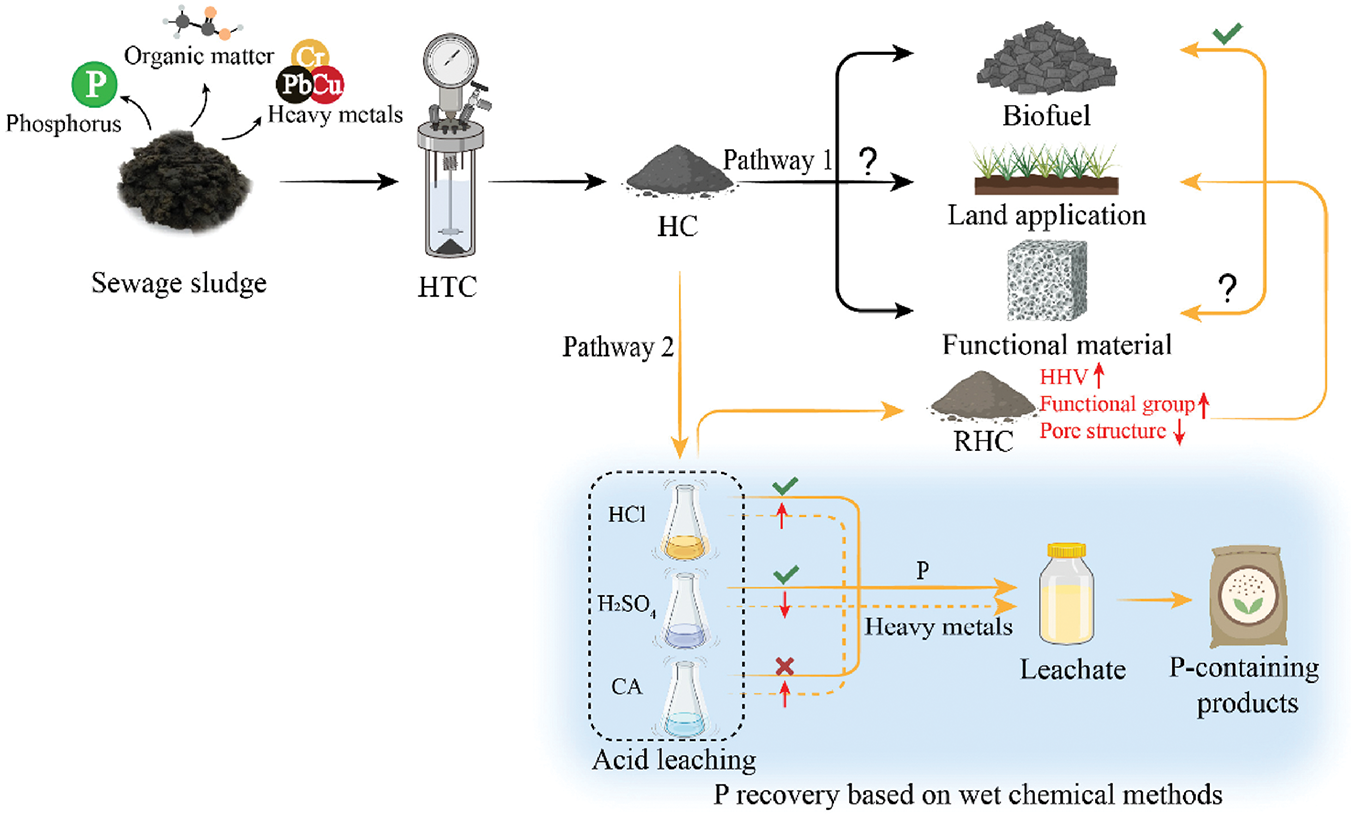

Waste biomass contains substantial amounts of phosphorus, an element of strategic importance due to the limited natural phosphate rock reserves predominantly located in Morocco, the United States, and China. Consequently, relevant European legislation actively promotes and funds phosphorus recovery from waste streams [99]. Studies have demonstrated that up to 95% of the total phosphorus content can be recovered through the HTC of waste biomass [99–102]. During the HTC process, phosphorus is primarily partitioned into the solid phase. Subsequent acid leaching of the recovered hydrochar facilitates phosphorus removal into the aqueous phase. Finally, phosphorus can be precipitated from the alkaline-treated solution, enabling its recovery. Fig. 5 illustrates the conceptual utilization pathways of HTC-derived products by balancing phosphorus recovery, heavy metal concomitant leaching, and residual hydrochar utilization [103]. Pathway I involves the direct use of hydrochar (HC) obtained from HTC, with current applications primarily including biofuels, land applications (e.g., fertilizers and soil conditioners), and functional materials (such as adsorbents and electrode materials). Pathway II entails the recovery of phosphorus through wet chemical methods, followed by the subsequent utilization of the resulting recovered hydrochar (RHC). The results indicate that when using HCl and H2SO4 as extractants for a 1 h reaction, the maximum phosphorus leaching yields reached up to 79.8% (HCl) and 82.0% (H2SO4) [103]. Compared to the HTC process without phosphorus recovery, the integrated process could additionally yield phosphorus-containing products, which would have significant potential in the situation of the global shortage of phosphate fertilizers.

Figure 5: Comparison of the overall benefits between HTC (pathway I) and HTC combined with phosphorus recovery (pathway II). Reprinted with permission from reference [103]. Copyright © 2025, Elsevier

Biomass primarily comprises woody plants, herbaceous plants, aquatic plants, and municipal solid waste, and is recognized as a renewable resource. Its main constituents—cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin—are high-molecular-weight organics with favorable carbon-neutral characteristics, playing a vital role in mitigating the escalating greenhouse gas emissions. HTC is an efficient and environmentally friendly thermochemical conversion technology that transforms various biomass types into hydrochar with enhanced carbon content and energy density under relatively mild reaction conditions, thereby improving its value for resource utilization. The HTC process is influenced by multiple factors, among which reaction temperature is the primary factor influencing reaction pathways. Feedstock type significantly affects reaction behavior and the final properties of hydrochar, while reaction time, pressure, and catalyst selection further regulate hydrochar yield and physicochemical characteristics. In terms of practical applications, hydrochar shows broad prospects. As a solid fuel, hydrochar exhibits high calorific value and low ash content, with combustion performance comparable to or even surpassing certain commercial coals. When applied as a soil amendment, hydrochar improves soil structure, enhances nutrient retention, and possesses potential for carbon sequestration, contributing to sustainable agriculture; however, its environmental effects require further evaluation and management. Hydrochar also demonstrates excellent adsorption capacities and, after physical or chemical modification, shows strong removal efficiencies for various organic pollutants and heavy metals, indicating its potential as a novel low-cost material for environmental remediation. In summary, HTC provides a practical pathway for the valorization and energy recovery of waste biomass. Future research should focus on in-depth elucidation of reaction mechanisms, the design of functional composite materials, and systematic evaluation of environmental behaviors and long-term benefits, aiming to facilitate the large-scale application of hydrochar in various fields.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (22578155, 22478147), and the Natural Science Foundation of Huaian City (HAB2024051).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Cheng Zhang: Investigation, methodology, resources, writing—original draft; Rui Zhang: investigation; Yu Shao: investigation; Jiabin Wang: investigation, writing—original draft; Qianyue Yang: methodology; Fang Xie: investigation, methodology; Rongling Yang: investigation; Hongzhen Luo: conceptualization, project administration, resources, supervision, writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: This article does not involve data availability.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Li N, Yan K, Rukkijakan T, Liang J, Liu Y, Wang Z, et al. Selective lignin arylation for biomass fractionation and benign bisphenols. Nature. 2024;630:381–6. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07446-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Ryan AJ, Rothman RH. Engineering chemistry to meet COP26 targets. Nat Rev Chem. 2022;6(1):1–3. doi:10.1038/s41570-021-00346-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Wang J, Wang G, Wu C, Li J, Cao C, Li J, et al. Enhanced aqueous-phase formation of secondary organic aerosols due to the regional biomass burning over North China Plain. Environ Pollut. 2020;256:113401. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. de Oliveira Galvão MF, Sadiktsis I, Batistuzzo de Medeiros SR, Dreij K. Genotoxicity and DNA damage signaling in response to complex mixtures of PAHs in biomass burning particulate matter from cashew nut roasting. Environ Pollut. 2020;256:113381. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Petrović J, Ercegović M, Simić M, Koprivica M, Dimitrijević J, Jovanović A, et al. Hydrothermal carbonization of waste biomass: a review of hydrochar preparation and environmental application. Processes. 2024;12(1):207. doi:10.3390/pr12010207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xu H, Gao Y, Wang C, Guo Z, Liu W, Zhang D. Exploring the nexuses between carbon dioxide emissions, material footprints and human development: an empirical study of 151 countries. Ecol Indic. 2024;166:112229. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2024.112229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Shafizadeh A, Shahbeik H, Rafiee S, Moradi A, Shahbaz M, Madadi M, et al. Machine learning-based characterization of hydrochar from biomass: implications for sustainable energy and material production. Fuel. 2023;347:128467. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.128467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Nizamuddin S, Baloch HA, Griffin GJ, Mubarak NM, Bhutto AW, Abro R, et al. An overview of effect of process parameters on hydrothermal carbonization of biomass. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2017;73:1289–99. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2016.12.122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yu S, He J, Zhang Z, Sun Z, Xie M, Xu Y, et al. Towards negative emissions: hydrothermal carbonization of biomass for sustainable carbon materials. Adv Mater. 2024;36:2307412. doi:10.1002/adma.202307412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Etale A, Onyianta AJ, Turner SR, Eichhorn SJ. Cellulose: a review of water interactions, applications in composites, and water treatment. Chem Rev. 2023;123:2016–48. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zhu J, Shao C, Hao S, Zhang J, Ren W, Wang B, et al. Recent progress on the dissolution of cellulose in deep eutectic solvents. Ind Crops Prod. 2025;228:120844. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2025.120844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shorey R, Salaghi A, Fatehi P, Mekonnen TH. Valorization of lignin for advanced material applications: a review. RSC Sustainability. 2024;2:804–31. doi:10.1039/D3SU00401E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Xie S, Zhang T, You S, Mukherjee S, Pu M, Chen Q, et al. Applied machine learning for predicting the properties and carbon and phosphorus fate of pristine and engineered hydrochar. Biochar. 2025;7(1):19. doi:10.1007/s42773-024-00404-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shen Q, Zhu X, Peng Y, Xu M, Huang Y, Xia A, et al. Structure evolution characteristic of hydrochar and nitrogen transformation mechanism during co-hydrothermal carbonization process of microalgae and biomass. Energy. 2024;295(3):131028. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.131028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Madusari S, Jamari SS, Nordin NIAA, Bindar Y, Prakoso T, Restiawaty E, et al. Hybrid hydrothermal carbonization and ultrasound technology on oil palm biomass for hydrochar production. ChemBioEng Rev. 2023;10(1):37–54. doi:10.1002/cben.202200014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Liu G, Zhang T. Advances in hydrothermal carbonization for biomass wastewater valorization: optimizing nitrogen and phosphorus nutrient management to enhance agricultural and ecological outcomes. Water. 2025;17:800. doi:10.3390/w17060800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Koprivica M, Petrović J, Ercegović M, Simić M, Milojković J, Šoštarić T, et al. Improvement of combustible characteristics of Paulownia leaves via hydrothermal carbonization. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2024;14:3975–85. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-02619-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu X, Chen Y, Wang H, Yuan S, Dai X. Obtain high quality hydrochar from waste activated sludge with low nitrogen content using acids and alkali pretreatment by enhancing hydrolysis and catalyzation. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2024;177:106315. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2023.106315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hong J, Bao J, Liu Y. Removal of methylene blue from simulated wastewater based upon hydrothermal carbon activated by phosphoric acid. Water. 2025;17:733. doi:10.3390/w17050733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. He X, Zhang T, Xue Q, Zhou Y, Wang H, Bolan NS, et al. Enhanced adsorption of Cu(II) and Zn(II) from aqueous solution by polyethyleneimine modified straw hydrochar. Sci Total Environ. 2021;778:146116. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Liu G, Xu Q, Abou-Elwafa SF, Alshehri MA, Zhang T. Hydrothermal carbonization technology for wastewater treatment under the Dual Carbon goals: current status, trends, and challenges. Water. 2024;16:1749. doi:10.3390/w16121749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sudibyo H, Budhijanto B, Marbelia L, Güleç F, Budiman A. Kinetic and thermodynamic evidences of the Diels-Alder cycloaddition and Pechmann condensation as key mechanisms of hydrochar formation during hydrothermal conversion of Lignin-Cellulose. Chem Eng J. 2024;480:148116. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.148116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhuang X, Zhan H, Song Y, He C, Huang Y, Yin X, et al. Insights into the evolution of chemical structures in lignocellulose and non-lignocellulose biowastes during hydrothermal carbonization (HTC). Fuel. 2019;236(1):960–74. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2018.09.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Akhtar J, Saidina Amin N. A review on operating parameters for optimum liquid oil yield in biomass pyrolysis. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2012;16:5101–9. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2012.05.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Deepak KR, Mohan S, Dinesha P, Balasubramanian R. CO2 uptake by activated hydrochar derived from orange peel (Citrus reticulatainfluence of carbonization temperature. J Environ Manag. 2023;342:118350. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.118350. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang B, von Keitz M, Valentas K. Thermochemical liquefaction of high-diversity grassland perennials. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2009;84(1):18–24. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2008.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Atallah E, Kwapinski W, Ahmad MN, Leahy JJ, Zeaiter J. Effect of water-sludge ratio and reaction time on the hydrothermal carbonization of olive oil mill wastewater treatment: hydrochar characterization. J Water Process Eng. 2019;31(1):100813. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2019.100813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu X, Fan Y, Zhai Y, Liu X, Wang Z, Zhu Y, et al. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of rape straw and microalgae: pH-enhanced carbonization process to obtain clean hydrochar. Energy. 2022;257:124733. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.124733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Lachos-Perez D, César Torres-Mayanga P, Abaide ER, Zabot GL, De Castilhos F. Hydrothermal carbonization and Liquefaction: differences, progress, challenges, and opportunities. Bioresour Technol. 2022;343:126084. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Heidari M, Dutta A, Acharya B, Mahmud S. A review of the current knowledge and challenges of hydrothermal carbonization for biomass conversion. J Energ Inst. 2019;92:1779–99. doi:10.1016/j.joei.2018.12.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Yang W, Shimanouchi T, Kimura Y. Characterization of the residue and liquid products produced from husks of nuts from carya cathayensis sarg by hydrothermal carbonization. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2015;3:591–8. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b00103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lucian M, Volpe M, Gao L, Piro G, Goldfarb JL, Fiori L. Impact of hydrothermal carbonization conditions on the formation of hydrochars and secondary chars from the organic fraction of municipal solid waste. Fuel. 2018;233:257–68. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2018.06.060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhong C, Wei X. A comparative experimental study on the liquefaction of wood. Energy. 2004;29:1731–41. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2004.03.096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Peterson AA, Vogel F, Lachance RP, Fröling M, Antal MJJr, Tester JW. Thermochemical biofuel production in hydrothermal media: a review of sub-and supercritical water technologies. Ener Environ Sci. 2008;1(1):32–65. doi:10.1039/B810100K. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kambo HS, Dutta A. Comparative evaluation of torrefaction and hydrothermal carbonization of lignocellulosic biomass for the production of solid biofuel. Energy Convers Manag. 2015;105:746–55. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2015.08.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Pauline AL, Joseph K. Hydrothermal carbonization of organic wastes to carbonaceous solid fuel—A review of mechanisms and process parameters. Fuel. 2020;279:118472. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Westermann P, Jørgensen B, Lange L, Ahring BK, Christensen CH. Maximizing renewable hydrogen production from biomass in a bio/catalytic refinery. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2007;32(17):4135–41. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2007.06.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Samaksaman U, Pattaraprakorn W, Neramittagapong A, Kanchanatip E. Solid fuel production from macadamia nut shell: effect of hydrothermal carbonization conditions on fuel characteristics. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2023;13:2225–32. doi:10.1007/s13399-021-01330-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Canencio KNP, Montaño MEA, Giona RM, Bail A. Impact of key parameters on the hydrothermal carbonization process of sewage sludge: a systematic review. Environ Eng Res. 2025;30(1):240247. doi:10.4491/eer.2024.247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Ndoun MC, Darko SA. Characterization and evaluation of carbonaceous materials from the hydrothermal carbonization of waste pharmaceuticals. arXiv:2302.06020. 2023. doi:10.48550/arxiv.2302.06020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Khan MA, Hameed BH, Siddiqui MR, Alothman ZA, Alsohaimi IH. Hydrothermal conversion of food waste to carbonaceous solid fuel—a review of recent developments. Foods. 2022;11:4036. doi:10.3390/foods11244036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ischia G, Berge ND, Bae S, Marzban N, Román S, Farru G, et al. Advances in research and technology of hydrothermal carbonization: achievements and future directions. Agronomy. 2024;14:955. doi:10.3390/agronomy14050955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Gallego-Mena L, Campana R, Villardon A, Dorado F, Sánchez-Silva L. Optimisation of hydrothermal carbonisation of olive stones for enhanced CO2 capture: impact of zinc chloride activation. J Environ Chem Eng. 2025;13:117321. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2025.117321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Watanabe M, Sato T, Inomata H, Smith RLJr, Arai KJr, Kruse A, et al. Chemical reactions of C1 compounds in near-critical and supercritical water. Chem Rev. 2004;104:5803–22. doi:10.1021/cr020415y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Möller M, Nilges P, Harnisch F, Schröder U. Subcritical water as reaction environment: fundamentals of hydrothermal biomass transformation. ChemSusChem. 2011;4:566–79. doi:10.1002/cssc.201000341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Fuertes A, Arbestain MC, Sevilla M, Maciá-Agulló JA, Fiol S, López R, et al. Chemical and structural properties of carbonaceous products obtained by pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonisation of corn stover. Soil Res. 2010;48(7):618–26. doi:10.1071/SR10010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Lynam JG, Coronella CJ, Yan W, Reza MT, Vasquez VR. Acetic acid and lithium chloride effects on hydrothermal carbonization of lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresour Technol. 2011;102:6192–9. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2011.02.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Stemann J, Putschew A, Ziegler F. Hydrothermal carbonization: process water characterization and effects of water recirculation. Bioresour Technol. 2013;143:139–46. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.05.098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Reza MT, Rottler E, Herklotz L, Wirth B. Hydrothermal carbonization (HTC) of wheat straw: influence of feedwater pH prepared by acetic acid and potassium hydroxide. Bioresour Technol. 2015;182(1):336–44. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2015.02.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Flora JFR, Lu X, Li L, Flora JRV, Berge ND. The effects of alkalinity and acidity of process water and hydrochar washing on the adsorption of atrazine on hydrothermally produced hydrochar. Chemosphere. 2013;93:1989–96. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.07.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Liang J, Liu Y, Zhang J. Effect of solution pH on the carbon microsphere synthesized by hydrothermal carbonization. Procedia Environ Sci. 2011;11:1322–7. doi:10.1016/j.proenv.2011.12.198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Demirbaş A. Effect of lignin content on aqueous liquefaction products of biomass. Energy Convers Manag. 2000;41:1601–7. doi:10.1016/S0196-8904(00)00013-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Pan YG, Velo E, Roca X, Manyà JJ, Puigjaner L. Fluidized-bed co-gasification of residual biomass/poor coal blends for fuel gas production. Fuel. 2000;79:1317–26. doi:10.1016/S0016-2361(99)00258-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Paksung N, Pfersich J, Arauzo PJ, Jung D, Kruse A. Structural effects of cellulose on hydrolysis and carbonization behavior during hydrothermal treatment. ACS Omega. 2020;5:12210–23. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c00737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Bevan E, Santori G, Luberti M. Kinetic modelling of the hydrothermal carbonisation of the macromolecular components in lignocellulosic biomass. Bioresou Technol Rep. 2023;24:101643. doi:10.1016/j.biteb.2023.101643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Kozyatnyk I, Benavente V, Weidemann E, Gentili FG, Jansson S. Influence of hydrothermal carbonization conditions on the porosity, functionality, and sorption properties of microalgae hydrochars. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):8562. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-35331-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Jia J, Wang R, Chen H, Liu H, Xue Q, Yin Q, et al. Interaction mechanism between cellulose and hemicellulose during the hydrothermal carbonization of lignocellulosic biomass. Ener Sci Eng. 2022;10:2076–87. doi:10.1002/ese3.1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Sun W, Bai L, Chi M, Xu X, Chen Z, Yu K. Study on the evolution pattern of the aromatics of lignin during hydrothermal carbonization. Energies. 2023;16(3):1089. doi:10.3390/en16031089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Favas G, Jackson WR. Hydrothermal dewatering of lower rank coals. 1. Effects of process conditions on the properties of dried product. Fuel. 2003;82(1):53–7. doi:10.1016/S0016-2361(02)00192-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Racovalis L, Hobday MD, Hodges S. Effect of processing conditions on organics in wastewater from hydrothermal dewatering of low-rank coal. Fuel. 2002;81:1369–78. doi:10.1016/S0016-2361(02)00024-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Gao P, Yao D, Qian Y, Zhong S, Zhang L, Xue G, et al. Factors controlling the formation of persistent free radicals in hydrochar during hydrothermal conversion of rice straw. Environ Chem Lett. 2018;16:1463–8. doi:10.1007/s10311-018-0757-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Wang Q, Wu S, Cui D, Zhou H, Wu D, Pan S, et al. Co-hydrothermal carbonization of organic solid wastes to hydrochar as potential fuel: a review. Sci Total Environ. 2022;850:158034. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Sugie S, Maeda H. Conversion of rice husks into carbonaceous materials with porous structures via hydrothermal process. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2024;31:45711–7. doi:10.1007/s11356-024-34217-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Hammerton JM, Ross AB. Inorganic salt catalysed hydrothermal carbonisation (HTC) of cellulose. Catalysts. 2022;12(5):492. doi:10.3390/catal12050492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Pinto F, André RN, Carolino C, Miranda M, Abelha P, Direito D, et al. Gasification improvement of a poor quality solid recovered fuel (SRF). Effect of using natural minerals and biomass wastes blends. Fuel. 2014;117:1034–44. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2013.10.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Yao Y, Xia P, Zhao L, Yang C, Huang R, Wang K. Effects of temperature and duration on the combustion characteristics of hydrochar prepared from traditional Chinese medicine residues using hydrothermal carbonization process. Int J Energy Res. 2024;2024(1):3595643. doi:10.1155/er/3595643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Aliyu M, Iwabuchi K, Itoh T. Upgrading the fuel properties of hydrochar by co-hydrothermal carbonisation of dairy manure and Japanese larch (Larix kaempferiproduct characterisation, thermal behaviour, kinetics and thermodynamic properties. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2023;13:11917–32. doi:10.1007/s13399-021-02045-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Lang Q, Guo X, Wang C, Li L, Li Y, Xu J, et al. Characteristics and phytotoxicity of hydrochar-derived dissolved organic matter: effects of feedstock type and hydrothermal temperature. J Environ Sci. 2025;149:139–48. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2023.10.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Jain A, Balasubramanian R, Srinivasan MP. Tuning hydrochar properties for enhanced mesopore development in activated carbon by hydrothermal carbonization. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2015;203:178–85. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2014.10.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Petrović J, Simić M, Mihajlović M, Koprivica M, Kojić M, Nuić I. Upgrading fuel potentials of waste biomass via hydrothermal carbonization. Hemijska Industrija. 2021;75:297–305. doi:10.2298/HEMIND210507025P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Lal R. Soil degradation by erosion. Land Degrad Develop. 2001;12:519–39. doi:10.1002/ldr.472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Heikkinen J, Keskinen R, Soinne H, Hyväluoma J, Nikama J, Wikberg H, et al. Possibilities to improve soil aggregate stability using biochars derived from various biomasses through slow pyrolysis, hydrothermal carbonization, or torrefaction. Geoderma. 2019;344:40–9. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2019.02.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Abel S, Peters A, Trinks S, Schonsky H, Facklam M, Wessolek G. Impact of biochar and hydrochar addition on water retention and water repellency of sandy soil. Geoderma. 2013;202–203:183–91. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2013.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Liu Y, Liu X, Ren N, Feng Y, Xue L, Yang L. Effect of pyrochar and hydrochar on water evaporation in clayey soil under greenhouse cultivation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:2580. doi:10.3390/ijerph16142580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Eibisch N, Schroll R, Fuß R. Effect of pyrochar and hydrochar amendments on the mineralization of the herbicide isoproturon in an agricultural soil. Chemosphere. 2015;134:528–35. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.11.074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Eibisch N, Schroll R, Fuß R, Mikutta R, Helfrich M, Flessa H. Pyrochars and hydrochars differently alter the sorption of the herbicide isoproturon in an agricultural soil. Chemosphere. 2015;119:155–62. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.05.059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. de Jager M, Röhrdanz M, Giani L. The influence of hydrochar from biogas digestate on soil improvement and plant growth aspects. Biochar. 2020;2:177–94. doi:10.1007/s42773-020-00054-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Malghani S, Jüschke E, Baumert J, Thuille A, Antonietti M, Trumbore S, et al. Carbon sequestration potential of hydrothermal carbonization char (hydrochar) in two contrasting soils; results of a 1-year field study. Biol Fertil Soils. 2015;51:123–34. doi:10.1007/s00374-014-0980-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Luutu H. Phytotoxicity and Ecotoxicology of Hydrothermal carbonisation-treated wastes [Ph.D. thesis]. Lismore, NSW, Australia: Southern Cross University; 2023. [Google Scholar]

80. Busch D, Stark A, Kammann CI, Glaser B. Genotoxic and phytotoxic risk assessment of fresh and treated hydrochar from hydrothermal carbonization compared to biochar from pyrolysis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2013;97(6):59–66. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2013.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Hitzl M, Mendez A, Owsianiak M, Renz M. Making hydrochar suitable for agricultural soil: a thermal treatment to remove organic phytotoxic compounds. J Environ Chem Eng. 2018;6:7029–34. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2018.10.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Dang CH, Cappai G, Chung J-W, Jeong C, Kulli B, Marchelli F, et al. Research needs and pathways to advance hydrothermal carbonization technology. Agronomy. 2024;14(2):247. doi:10.3390/agronomy14020247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Li S, Chan CY. Will biochar suppress or stimulate greenhouse gas emissions in agricultural fields? Unveiling the dice game through data syntheses. Soil Systems. 2022;6(4):73. doi:10.3390/soilsystems6040073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Elkhlifi Z, Iftikhar J, Sarraf M, Ali B, Saleem MH, Ibranshahib I, et al. Potential role of biochar on capturing soil nutrients, carbon sequestration and managing environmental challenges: a review. Sustainability. 2023;15(3):2527. doi:10.3390/su15032527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Cavali M, Libardi Junior N, de Sena JD, Woiciechowski AL, Soccol CR, Belli Filho P, et al. A review on hydrothermal carbonization of potential biomass wastes, characterization and environmental applications of hydrochar, and biorefinery perspectives of the process. Sci Total Environ. 2023;857:159627. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Ghanbari F, Moradi M. Application of peroxymonosulfate and its activation methods for degradation of environmental organic pollutants: review. Chem Eng J. 2017;310:41–62. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2016.10.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Ferrentino R, Ceccato R, Marchetti V, Andreottola G, Fiori L. Sewage sludge hydrochar: an option for removal of methylene blue from wastewater. Appl Sci. 2020;10(10):3445. doi:10.3390/app10103445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Qian W-C, Luo X-P, Wang X, Guo M, Li B. Removal of methylene blue from aqueous solution by modified bamboo hydrochar. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2018;157:300–6. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.03.088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Zhang X, Zhang Y, Ngo HH, Guo W, Wen H, Zhang D, et al. Characterization and sulfonamide antibiotics adsorption capacity of spent coffee grounds based biochar and hydrochar. Sci Total Environ. 2020;716:137015. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Zhang Z, Zhu Z, Shen B, Liu L. Insights into biochar and hydrochar production and applications: a review. Energy. 2019;171:581–98. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2019.01.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Simić M, Petrović J, Koprivica M, Ercegović M, Dimitrijević J, Vuković NS, et al. Efficient adsorption of lead on hydro-pyrochar synthesized by two-step conversion of corn cob in magnesium chloride medium. Toxics. 2025;13(6):459. doi:10.3390/toxics13060459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Deng J, Li X, Wei X, Liu Y, Liang J, Song B, et al. Hybrid silicate-hydrochar composite for highly efficient removal of heavy metal and antibiotics: coadsorption and mechanism. Chem Eng J. 2020;387:124097. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.124097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Wang C, Zhang W, Qiu X, Xu C. Hydrothermal treatment of lignocellulosic biomass towards low-carbon development: production of high-value-added bioproducts. EnergyChem. 2024;6:100133. doi:10.1016/j.enchem.2024.100133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Khosravi A, Zheng H, Liu Q, Hashemi M, Tang Y, Xing B. Production and characterization of hydrochars and their application in soil improvement and environmental remediation. Chem Eng J. 2022;430:133142. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.133142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Xu Q, Luo L, Li D, Johnravindar D, Varjani S, Wong JWC, et al. Hydrochar prepared from digestate improves anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and sewage sludge: performance, mechanisms, and implication. Bioresour Technol. 2022;362:127765. doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2022.127765. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Shi Z, Usman M, He J, Chen H, Zhang S, Luo G. Combined microbial transcript and metabolic analysis reveals the different roles of hydrochar and biochar in promoting anaerobic digestion of waste activated sludge. Water Res. 2021;205:117679. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2021.117679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Xu Q, Yang G, Liu X, Wong JWC, Zhao J. Hydrochar mediated anaerobic digestion of bio-wastes: advances, mechanisms and perspectives. Sci Total Environ. 2023;884:163829. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.163829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Usman M, Shi Z, Ji M, Ren S, Luo G, Zhang S. Microbial insights towards understanding the role of hydrochar in alleviating ammonia inhibition during anaerobic digestion. Chem Eng J. 2021;419:129541. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.129541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Marin-Batista JD, Mohedano AF, Rodríguez JJ, de la Rubia MA. Energy and phosphorous recovery through hydrothermal carbonization of digested sewage sludge. Waste Manag. 2020;105:566–74. doi:10.1016/j.wasman.2020.03.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Bhatt D, Shrestha A, Dahal RK, Acharya B, Basu P, MacEwen R. Hydrothermal carbonization of biosolids from waste water treatment plant. Energies. 2018;11(9):2286. doi:10.3390/en11092286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Becker GC, Wüst D, Köhler H, Lautenbach A, Kruse A. Novel approach of phosphate-reclamation as struvite from sewage sludge by utilising hydrothermal carbonization. J Environ Manag. 2019;238:119–25. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.02.121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Merzari F, Goldfarb J, Andreottola G, Mimmo T, Volpe M, Fiori L. Hydrothermal carbonization as a strategy for sewage sludge management: influence of process withdrawal point on hydrochar properties. Energies. 2020;13(11):2890. doi:10.3390/en13112890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Wang C, Zhou H, Wu C, Sun W, Sun X, He C. Phosphorus recovery from sewage sludge-derived hydrochar: balancing phosphorus recovery, heavy metal concomitant leaching and residual hydrochar utilization. J Clean Prod. 2025;491:144756. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2025.144756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools