Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Adjuvant Chemotherapy Necessity in Stage I Ovarian Endometrioid Carcinoma: A SEER-Based Study Verified by Single-Center Data and Meta-Analysis

1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The First Clinical Medical College of Nanjing Medical University, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, 210029, China

2 Department of Gynecology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (Jiangsu Province Hospital), Nanjing, 210029, China

* Corresponding Author: Wenjun Cheng. Email:

# These two authors contributed equally to this work

Oncology Research 2025, 33(10), 3007-3022. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.065137

Received 04 March 2025; Accepted 18 June 2025; Issue published 26 September 2025

Abstract

Background: The benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage I ovarian endometrioid carcinoma (OEC) remains controversial. Hence, the study sought to explore its value in stage I OEC patients. Methods: Stage I OEC patients (1988–2018) were identified from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. Multivariate Cox analysis was used to control confounders. Logistic regression was used to explore factors associated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Cox regression analysis and Kaplan-Meier curves were used to assess the survival benefits. Single-center clinical data and meta-analysis following PRISMA guidelines provided external validation. Result: Adjuvant chemotherapy correlated with improved survival (Hazard Ratio (HR): 0.860, p = 0.011), as did lymphadenectomy (HR: 0.842, p < 0.001). Higher age, pathological stage, and tumor grade negatively affected survival. Chemotherapy administration associated with higher pathological stage (IB: Odds Ratio (OR) 1.565, p < 0.001; IC: OR 4.091, p < 0.001), higher grade (G2: OR 2.336, p < 0.001; G3: OR 4.563, p < 0.001), and lymphadenectomy (OR 1.148, p = 0.040). Stratification analysis showed adjuvant chemotherapy failed to improve prognosis in stage IA/IB patients regardless of grade or lymphadenectomy. For stage IC patients, chemotherapy benefited grade 1-2 or grade 3 patients without lymphadenectomy, and grade 3 patients with lymphadenectomy. Meta-analysis revealed reduced recurrence in stage IC patients (OR = 0.50, p = 0.035). Conclusion: Adjuvant chemotherapy confers survival benefits for stage IC patients, particularly those without lymphadenectomy.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileOvarian endometrioid carcinoma (OEC) is a rare subtype, accounting for about 10% of epithelial ovarian cancers [1]. It is often well differentiated, discovered early, associated with endometriosis, and has a favorable prognosis [2]. The current therapeutic paradigm consists of primary cytoreductive surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy, yet the indications for chemotherapy remain controversial across international guidelines. Current consensus recommends observation for stage IA, grade 1, and adjuvant chemotherapy for stage IC, grade 3. However, the benefits of chemotherapy for stage IA grade 2-3, stage IB grade 1-3, and stage IC grade 1-2 remain controversial (National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) [3,4]; International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) [5]; Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO) [6,7]; Korean Society of Gynecologic Oncology (KSGO) [8]; Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology (JSGO) [9]; Spanish Society for Medical Oncology (SEOM) [10]; European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) [11]). Clinical studies also offer conflicting views [12,13]. To resolve this ambiguity, the study conducted a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database analysis to evaluate the survival impact of chemotherapy in stage I OEC. Furthermore, the study integrated single-institution data with a systematic meta-analysis of prior studies to provide a comprehensive assessment, aiming to refine postoperative chemotherapy selection criteria for early-stage OEC and optimize patient outcomes.

2.1 Data Source and Collection in the SEER Database

The study population was derived from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database (SEER, November 2020 data submission). The target data were downloaded by using SEER*Stat 8.3.9.2 software. Patients diagnosed with OEC were defined by the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, third edition (ICD-O-3, https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/other-classifications/international-classification-of-diseases-for-oncology, accessed on 17 June 2025). The histology codes included: 8380/3, 8381/3, 8382/3 and 8383/3. The primary tumor site code was C56.9-Ovary. Yu Liang searched and collected data from the SEER database.

Those patients who met the following inclusion and exclusion criteria were enrolled. The inclusion criteria: (1) Patients were histologically diagnosed with OEC as the first primary tumor; (2) Patients were diagnosed between 1988 and 2018, at stage I; (3) Patients who had complete records of the following variables: (I) year of diagnosis; (II) age at diagnosis; (III) race/ethnicity; (IV) pathological stage; (V) tumor grade; (VI) surgery at primary site; (VII) chemotherapy; (VIII) survival data including survival time and vital status; (4) Patients who had at least one month of follow-up. The exclusion criteria: (1) Patients who did not undergo primary tumor-related surgery; (2) Patients with stage I not otherwise specified.

Data from the SEER is available for the public and the access license was obtained from the SEER (ID: 18177-Nov2020). Hence, institutional review board (IRB) approval was not required in this part.

2.2 Data Source and Collection in Our Single Center

We collected clinical data on more than 1000 ovarian cancer patients hospitalized at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University between 2010 and 2021. The inclusion criteria: (1) Patients were histologically diagnosed with OEC as the only primary tumor; (2) Patients were diagnosed between 2010 and 2021, at stage I; (3) Patients who had complete records of the following variables: (I) year of diagnosis; (II) age at diagnosis; (III) residential address and contact information; (IV) pathological stage; (V) tumor grade; (VI) surgery at primary site; (VII) chemotherapy; (VIII) survival data including survival time and vital status; (X) immunohistochemical parameters: WT-1(−), ER/PR(+), TP53wt, PAX8(+), Napsin A(−); (4) Patients who had at least one month of follow-up. Patients were followed up until May 2024. Zhao Mingrui searched and collected data on ovarian cancer patients from our single center. Whether survival analysis was performed depended on the sample size and survival data. If data were limited, descriptive analysis was performed. Our single-center retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (2020-MD-371).

2.3 Meta-Analysis for Verification

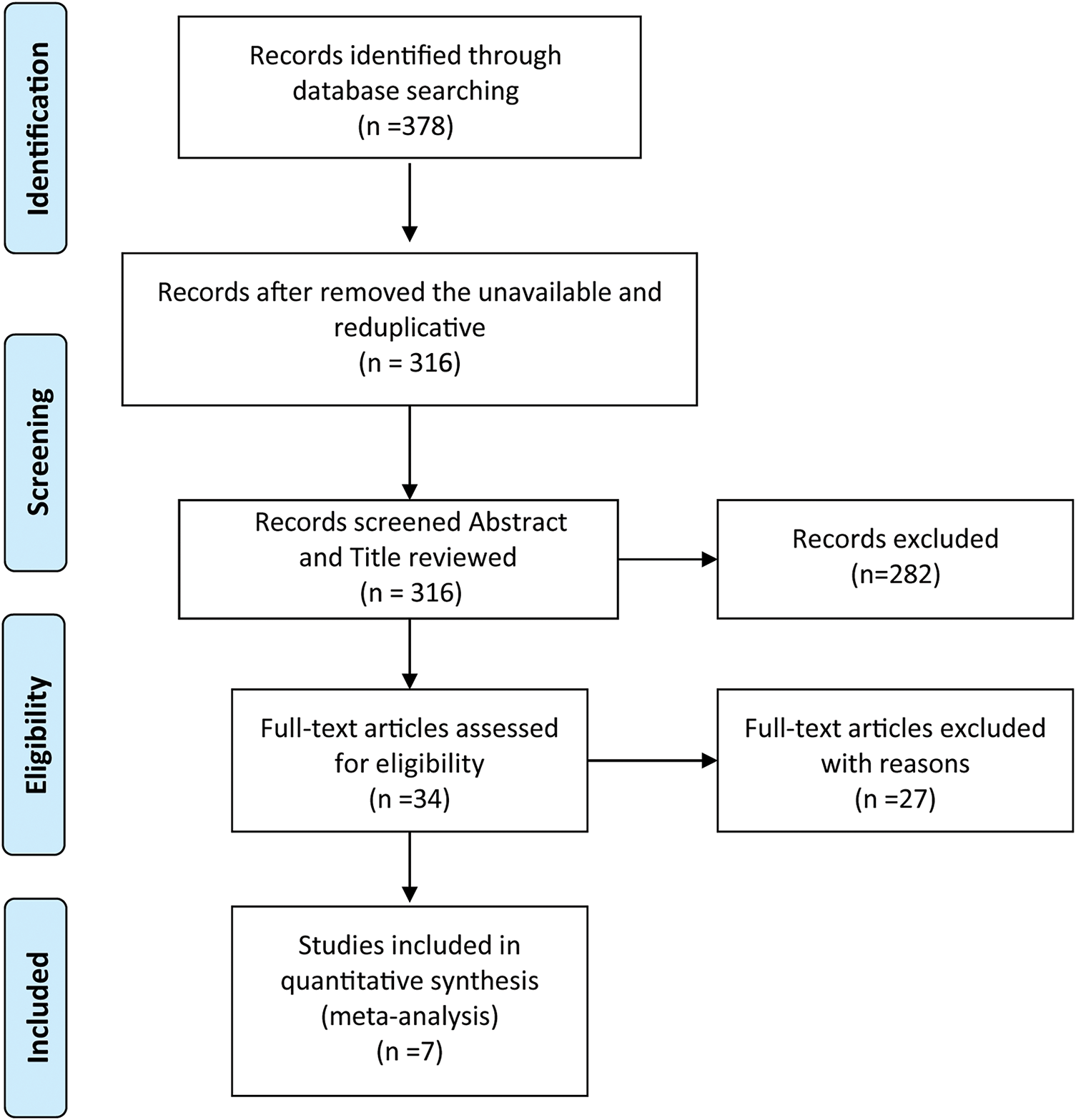

The part of the meta-analysis was based on the PRISMA guideline and undertaken to identify clinical trials or cohort studies concerning the effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on stage I OEC (The PRISMA checklist can be found in the supplementary files-PRISMA checklist). A literature search was performed in PubMed, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Google Scholar, Cochrane Library and CNKI, which included records up to December 2024. The keywords included “adjuvant chemotherapy”, “endometrioid ovarian cancer” and “stage I”. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and cohort studies; (2) patients exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy or no adjuvant chemotherapy; (3) the follow-up time was long enough to demonstrate a treatment difference. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Non-English or non-Chinese literature; (2) Repeated and inaccessible literature; (3) Literature with incomplete data. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the quality of the included studies. The main items include 3 parts: patient selection, intergroup comparability and outcome measurement. A total score of more than 6 was considered to be of satisfactory quality. Two independent researchers screened the literature, evaluated quality and extracted data independently. Any disagreements were discussed and solved by consensus or third-party arbitration. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was also not required in this part.

Pearson χ2 tests and Mann-Whitney U tests were used to evaluate the distributions of categorical and continuous variables between patients with or without adjuvant chemotherapy. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to control for potential confounders and identify independent prognostic factors associated with survival. The results were presented as hazard ratios (HR) with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). The binary logistic regression was performed to identify factors linked with the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy. The survival benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy was further assessed in stratified analyses using Kaplan-Meier survival analysis [14] and Cox regression analysis [15]. All statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS 26.0, X-tile 3.6 and R 4.3 software.

The meta-analysis was performed using STATA 12.0. The binary variables were evaluated by odds ratio (OR) and its 95% confidence interval (95% CI). According to the heterogeneity, the appropriate model (random or fixed) was then selected to merge the outcome indicators. All in all, p < 0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant result.

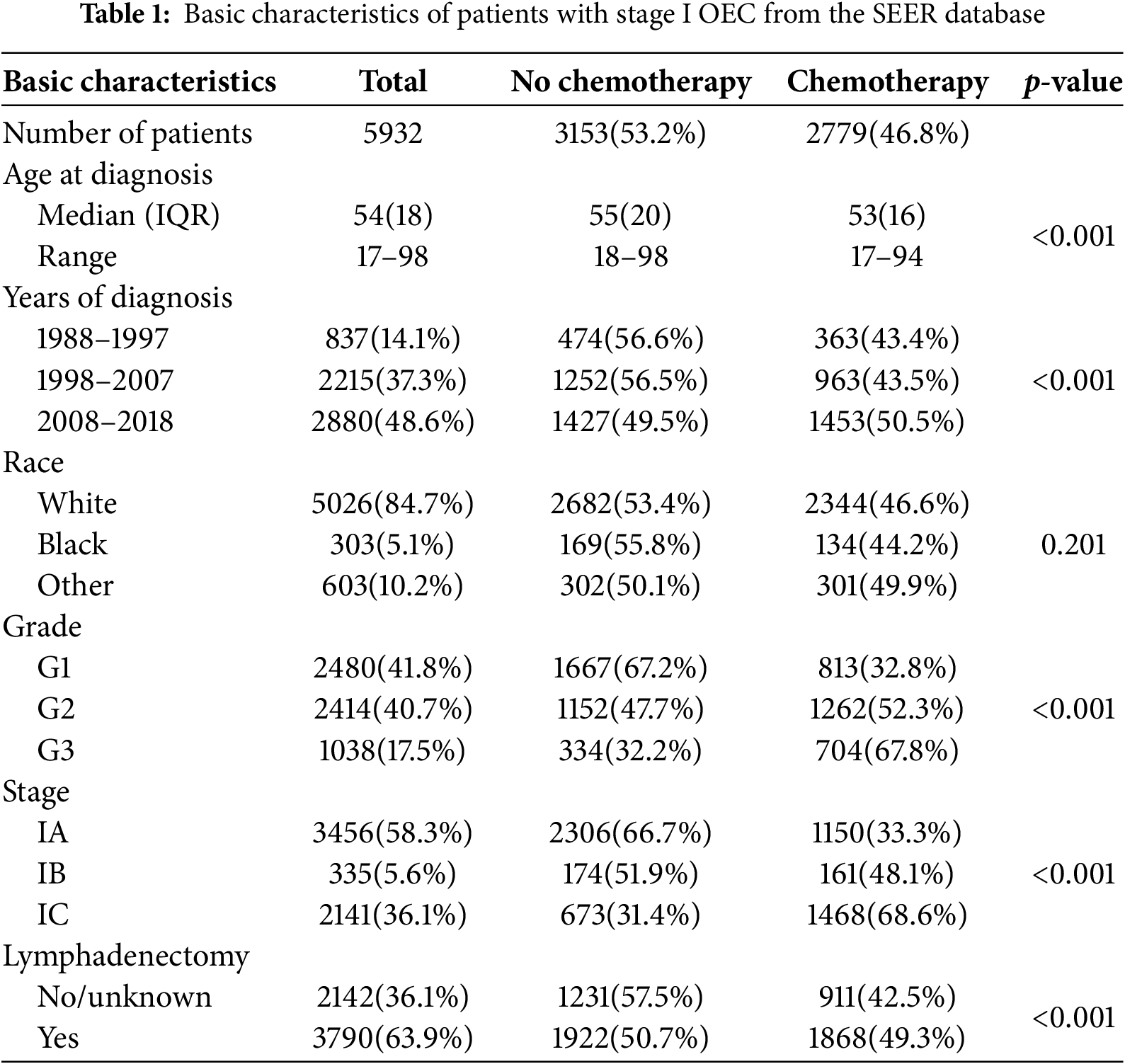

A total of 5932 eligible stage I early-onset ovarian cancer patients were identified. Follow-up duration ranged from 1 to 371 months, with a median of 101 months. Among these, 3456 patients were stage IA (58.3%), 335 were stage IB (5.6%), and 2141 were stage IC (36.1%). Most patients had grade 1 (n = 2480, 41.8%) or grade 2 (n = 2414, 40.7%) tumors, with only 1038 classified as grade 3 (17.5%). The median age was 54 years (interquartile range 18), predominantly White (84.7%), and 3790 patients (63.9%) underwent lymphadenectomy.

In total, 2779 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy, while 3153 did not. Those who received chemotherapy were younger (median age 53 vs. 55 years, p < 0.01). Chemotherapy use increased over time, with 43.4% and 43.5% of OEC patients receiving it during 1988–1997 and 1998–2007, respectively; this rate rose to 50.5% from 2008–2018. Furthermore, adjuvant chemotherapy use increased with tumor stage and grade: 33.3% in stage IA, 48.1% in stage IB, and 68.6% in stage IC (p < 0.01). The usage rate for grade 3 tumors was 67.8%, compared to 52.3% and 32.8% for grade 2 and grade 1, respectively (p < 0.01). Additionally, 49.3% of patients who underwent lymphadenectomy also received adjuvant chemotherapy. Demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

3.2 Prognostic Factors Associated with the Overall Survival of OEC

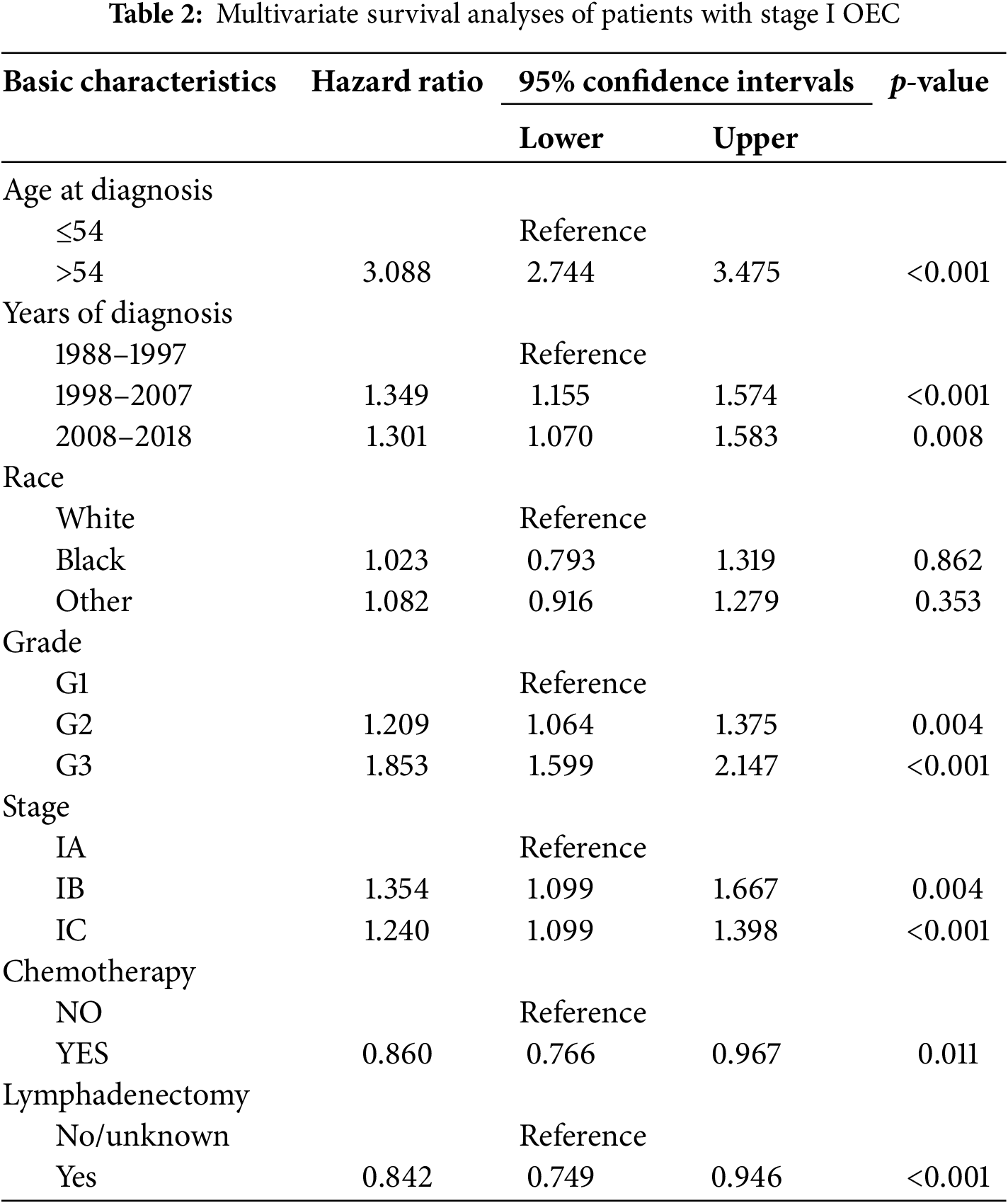

In this analysis, multivariate Cox regression was employed to control for confounding factors and identify independent prognostic factors in stage I early-onset ovarian cancer patients. Median age served as a distinguishing factor in the analysis. The results indicated that adjuvant chemotherapy (HR: 0.860, 95% CI: 0.766–0.967, p = 0.011) and lymphadenectomy (HR: 0.842, 95% CI: 0.749–0.946, p < 0.001) were protective prognostic factors. Conversely, older age, later diagnosis, higher pathological stage, and tumor grade were associated with poorer prognosis. Patients over 54 years had a significantly worse prognosis (HR: 3.088, 95% CI: 2.744–3.475, p < 0.001). Those diagnosed in 1998–2007 (HR: 1.349, 95% CI: 1.155–1.574, p < 0.001) and 2008–2018 (HR: 1.301, 95% CI: 1.070–1.583, p = 0.008) also showed worse outcomes compared to those diagnosed in 1988–1997. Higher tumor grades were linked to deteriorating prognosis: patients with grade 2 (HR: 1.209, 95% CI: 1.064–1.375, p = 0.004) and grade 3 tumors (HR: 1.853, 95% CI: 1.599–2.147, p < 0.001) had worse outcomes compared to grade 1. Furthermore, the risk of death increased with advancing pathological stage; patients with stage IB (HR: 1.354, 95% CI: 1.099–1.667, p = 0.004) and stage IC (HR: 1.240, 95% CI: 1.099–1.398, p < 0.001) had worse survival compared to stage IA patients. Notably, race showed no significant correlation with prognosis. These findings are detailed in Table 2.

3.3 Predictors Linked with the Receipt of Adjuvant Chemotherapy for OEC

To identify factors associated with adjuvant chemotherapy administration, the study conducted a binary logistic regression analysis, the results of which are presented in Table S1. Significant factors included years of diagnosis, age at diagnosis, tumor grade, pathological stage, and lymphadenectomy performance. Advancing pathological stage and tumor grade showed strong correlations; patients in stage IB (OR: 1.565, 95% CI: 1.236–1.981, p < 0.001) and stage IC (OR: 4.091, 95% CI: 3.629–4.612, p < 0.001) were more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy than those in stage IA. Similarly, patients with grade 2 (OR: 2.336, 95% CI: 2.062–2.647, p < 0.001) and grade 3 tumors (OR: 4.563, 95% CI: 3.860–5.393, p < 0.001) were more likely to receive chemotherapy compared to grade 1 patients. Performance of lymphadenectomy was also positively associated with adjuvant chemotherapy (OR: 1.148, 95% CI: 1.006–1.311, p = 0.040). Additionally, younger patients (OR: 0.785, 95% CI: 0.701–0.880, p < 0.001) and those newly diagnosed (OR: 1.201, 95% CI: 1.097–1.315, p < 0.001) were more likely to receive adjuvant chemotherapy.

3.4 Current Guideline Recommendations on the Administration of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Stage I OEC

The recommendations for adjuvant chemotherapy based on the following guidelines were summarized in Table S2. In conclusion, observation was commonly recommended in patients with stage IA grade 1 and adjuvant chemotherapy was necessary for patients with stage IC grade 3. This view was widely shared by current guidelines. However, whether adjuvant chemotherapy should be used in patients with stage IA grade 2-3, stage IB grade 1-3 and stage IC grade 1-2 was still controversial (NCCN [3,4]; FIGO [5]; CSCO [6,7]; KSGO [8]; JSGO [9]; SEOM [10]; ESMO [11]).

Stratification Survival Analysis Based on Predictors of Adjuvant Chemotherapy

To address the controversies in the current guidelines, the study performed a stratification analysis. Grade 1 and 2 patients were grouped according to multivariate Cox and binary logistic regression, and lymphadenectomy, tumor grade, and pathological stage were selected as stratification variables.

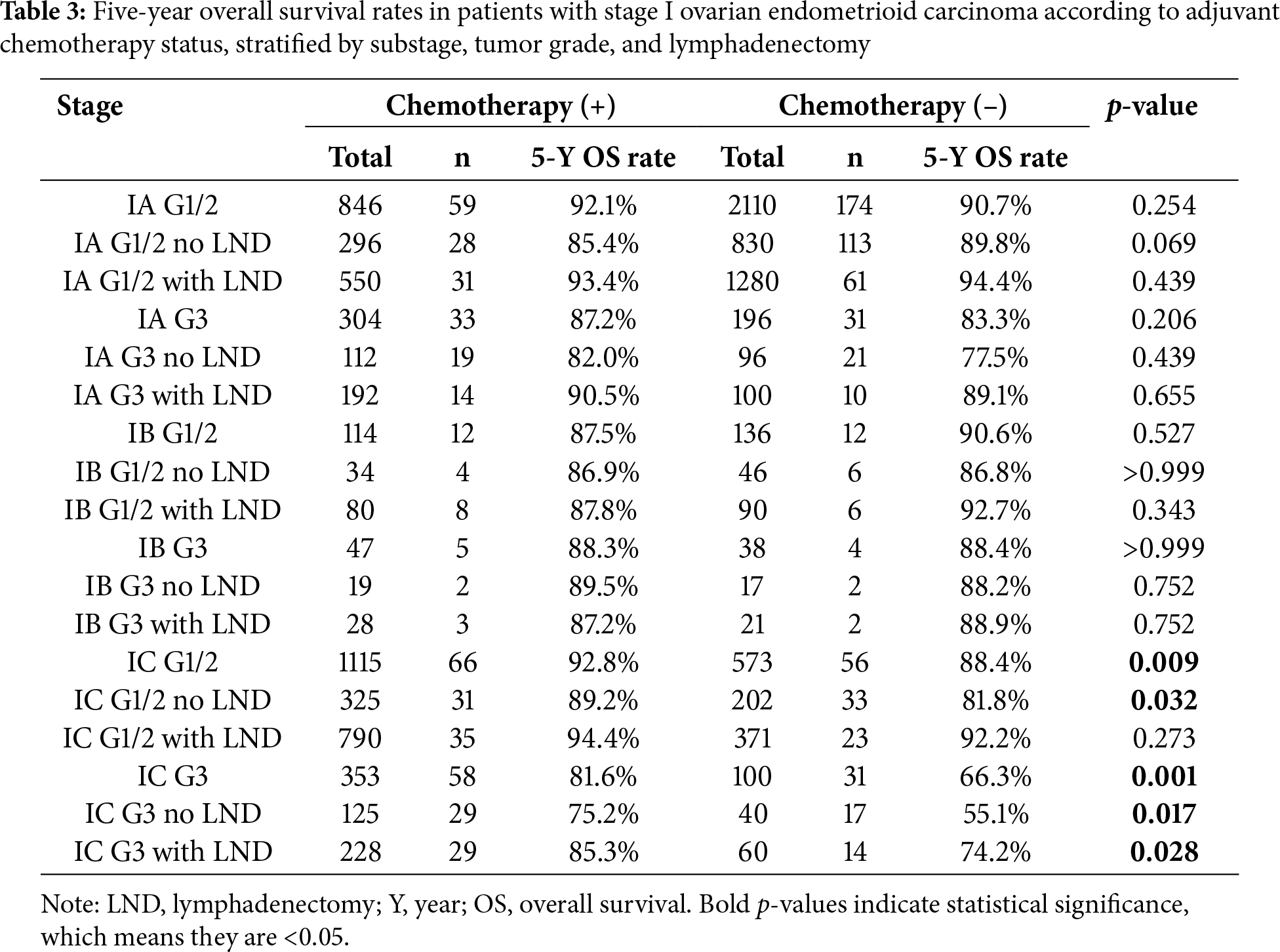

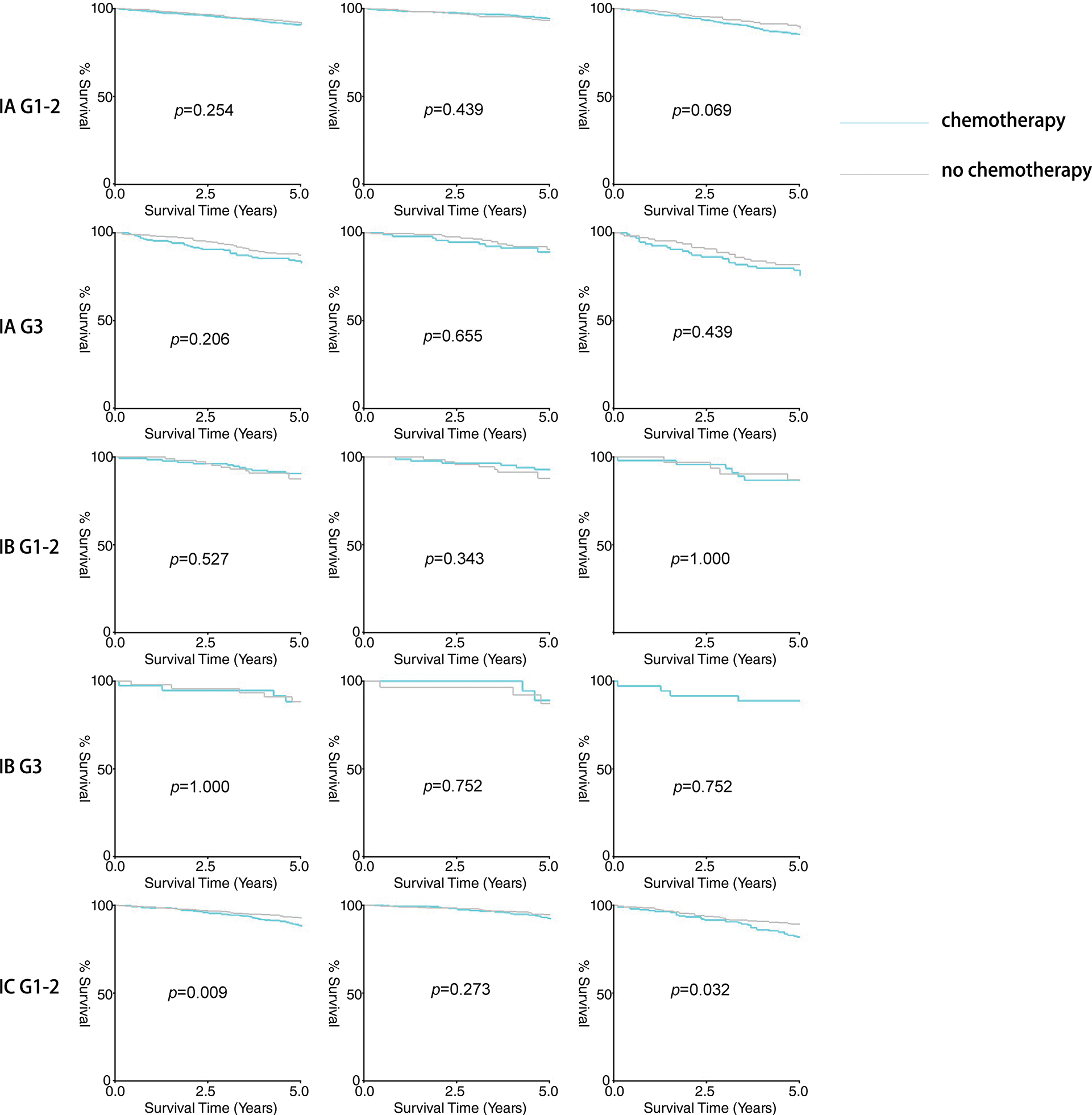

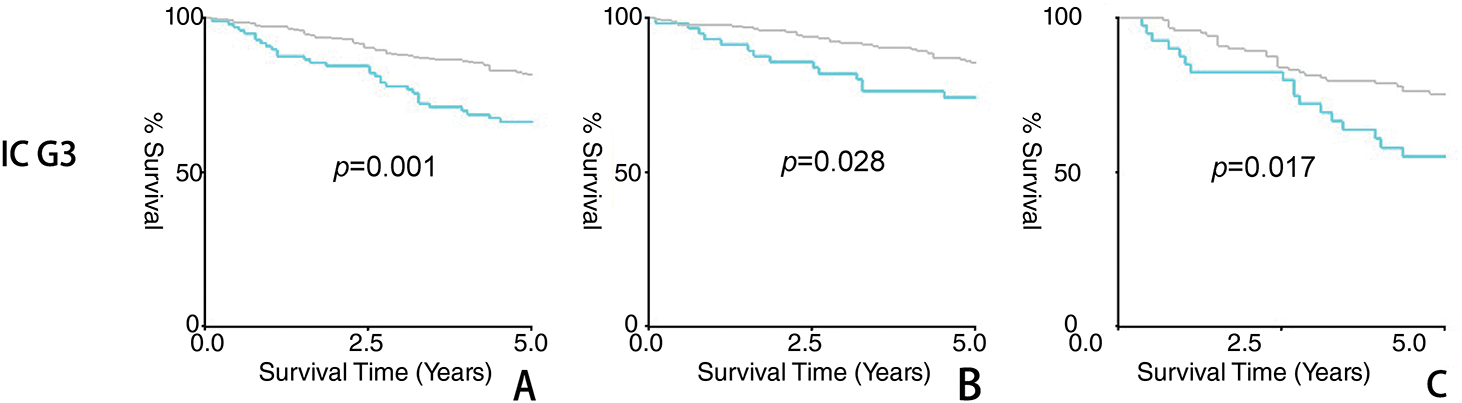

Firstly, the study compared the 5-year overall survival (OS) rates. As shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1, no significant differences were observed in stage IA/IB patients with tumor grades 1-2 or grade 3, regardless of lymphadenectomy. However, for stage IC grade 1-2 patients, the chemotherapy group had a higher 5-year OS rate (92.8% vs. 88.4%, p = 0.009), and for stage IC grade 3 patients, the rate was also higher (81.6% vs. 66.3%, p = 0.001). In subgroup analyses, adjuvant chemotherapy improved the 5-year survival for stage IC grade 1-2 (89.2% vs. 81.8%, p = 0.032) and grade 3 (75.2% vs. 55.1%, p = 0.017) patients without lymphadenectomy, and also for grade 3 patients with lymphadenectomy (85.3% vs. 74.2%, p = 0.028). However, no significant difference was noted for stage IC grade 1-2 patients with lymphadenectomy (94.4% vs. 92.2%, p = 0.273).

Figure 1: Result of five-year survival analysis between the adjuvant chemotherapy group and non-adjuvant chemotherapy group in patients with stage I OEC. (A): All patients; (B): Patients who received lymphadenectomy; (C): Patients who did not receive lymphadenectomy

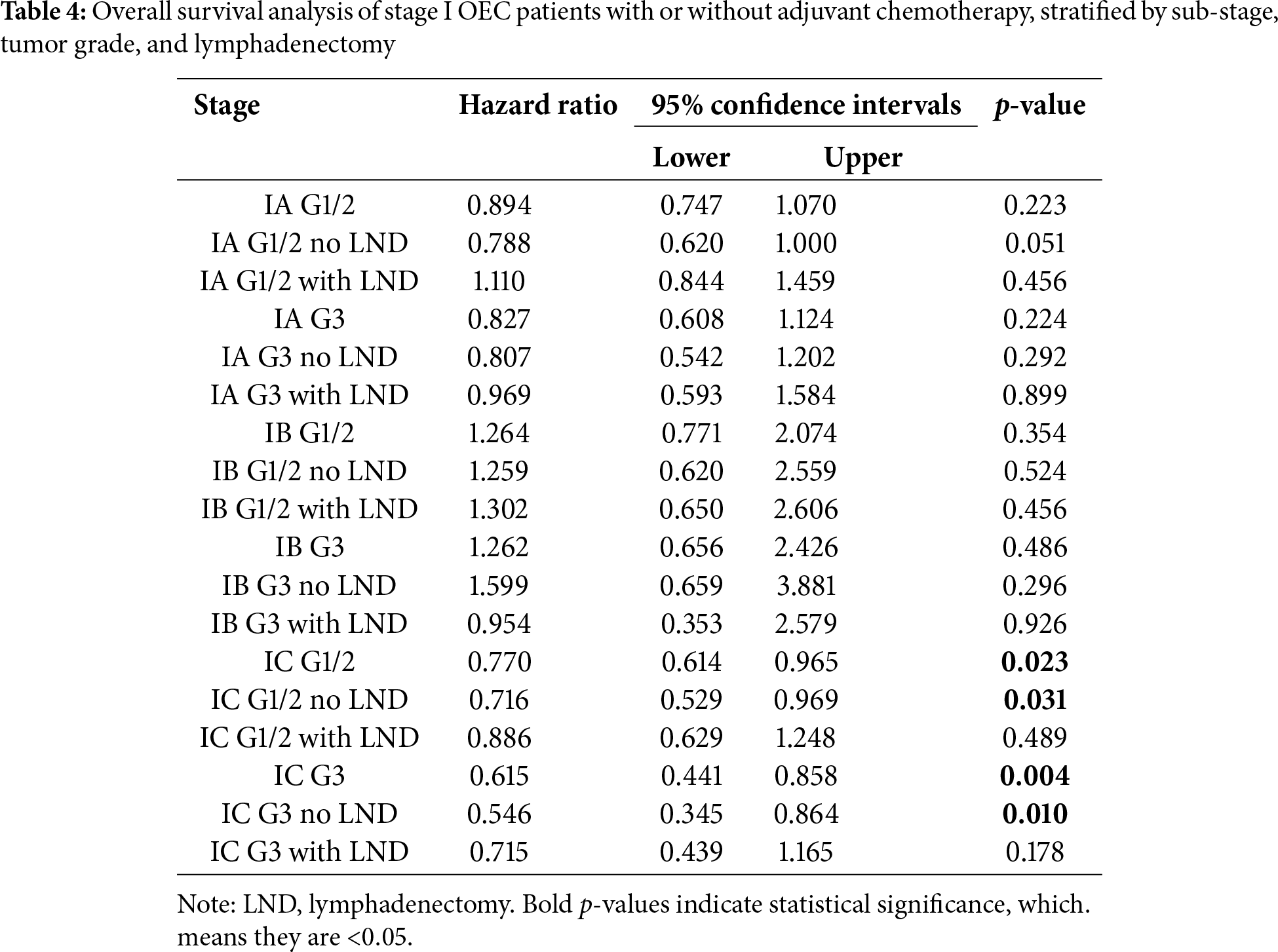

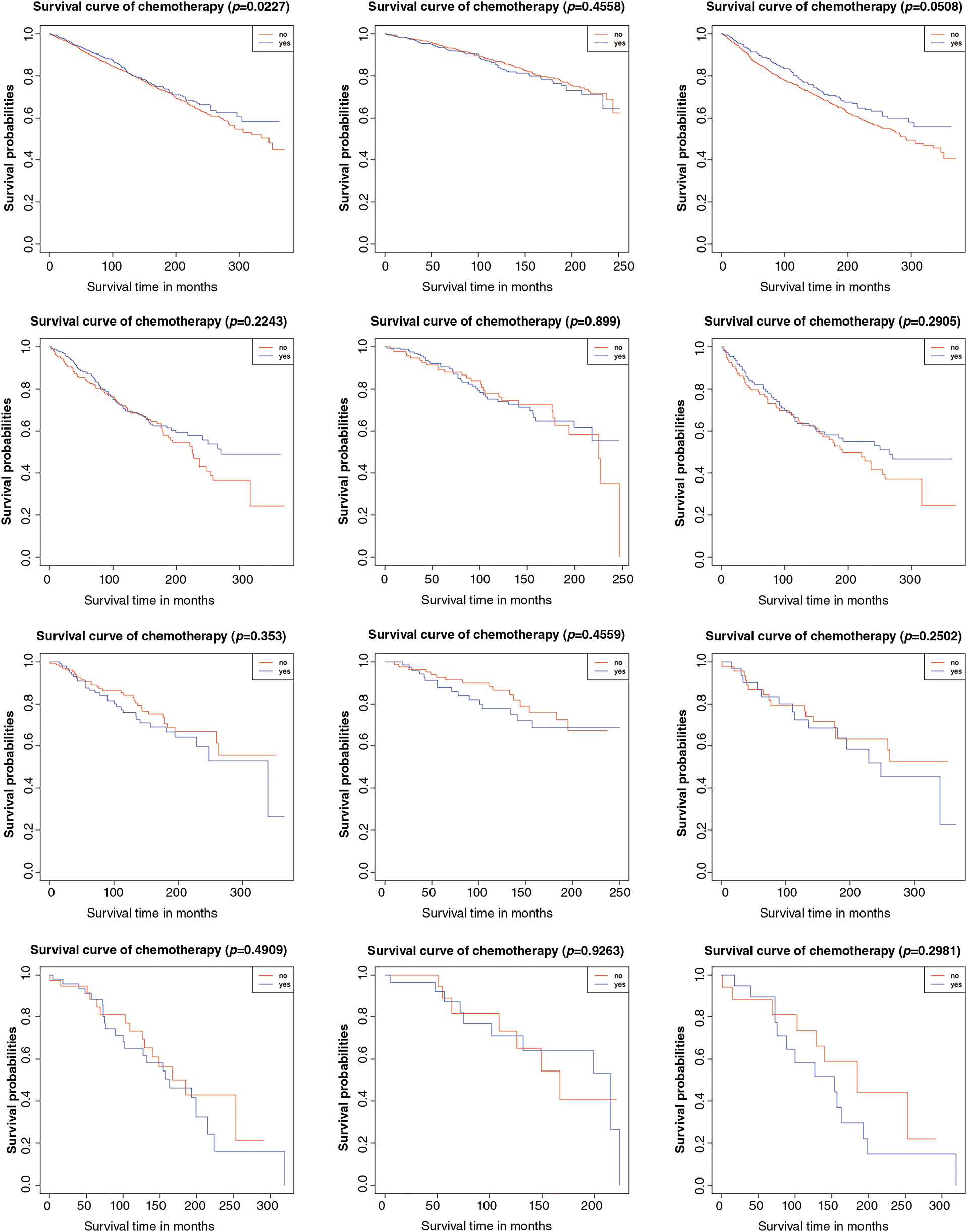

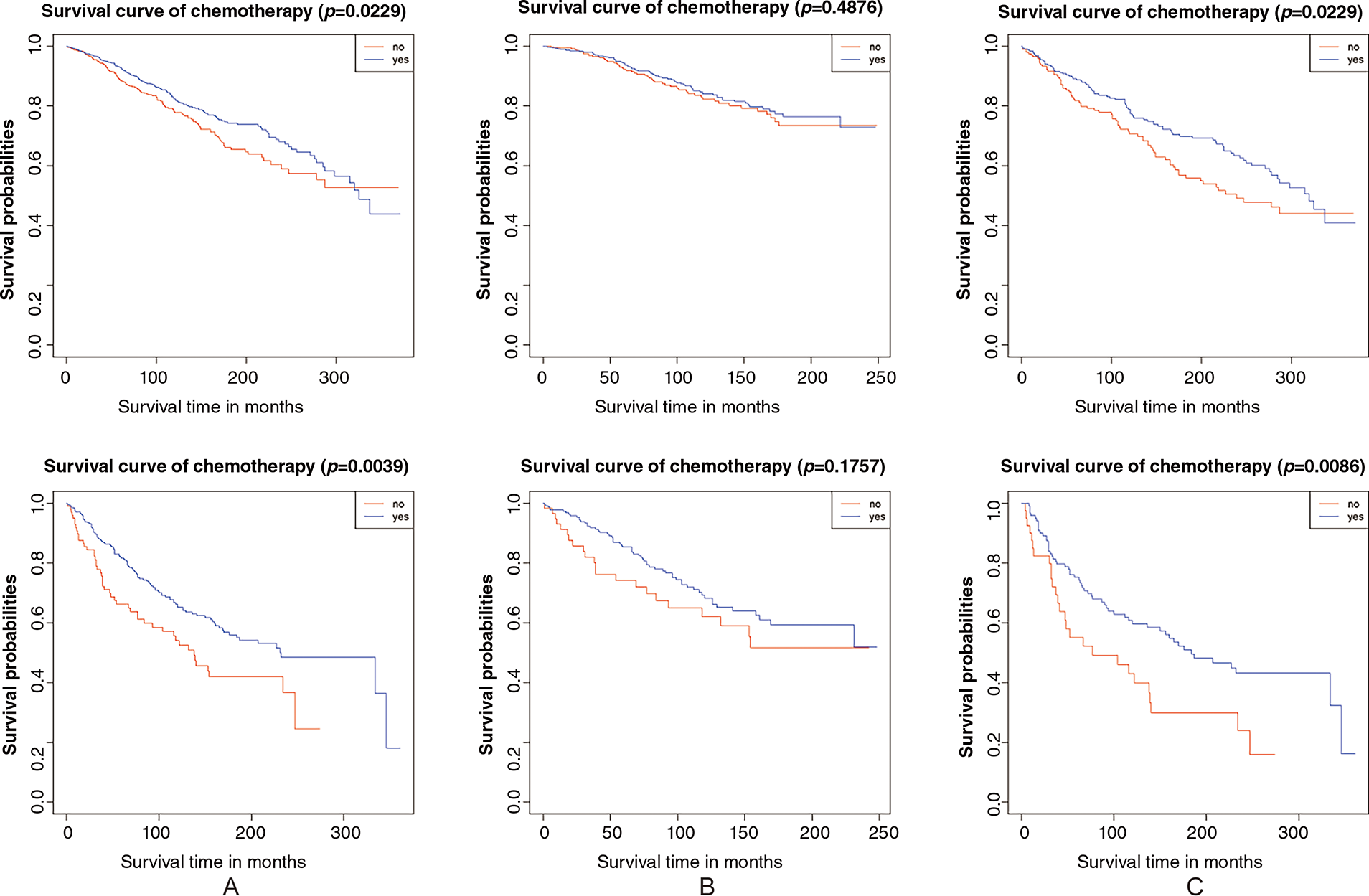

Secondly, we evaluated overall survival using hazard ratios, presented in Table 4, supported by Kaplan–Meier analysis. As previously noted, no significant differences were found in stage IA/IB patients with either tumor grade, irrespective of lymphadenectomy. In stage IC grade 1-2 (HR: 0.770, 95% CI: 0.641–0.965, p = 0.023) and grade 3 (HR: 0.615, 95% CI: 0.441–0.858, p = 0.004) subgroups, better prognoses were seen in the chemotherapy group. Further stratification indicated that chemotherapy improved prognosis for stage IC grade 1-2 (HR: 0.716, 95% CI: 0.529–0.969, p = 0.031) and grade 3 (HR: 0.546, 95% CI: 0.345–0.864, p = 0.010) patients without lymphadenectomy, but not for those with lymphadenectomy (grade 1-2 HR: 0.886, 95% CI: 0.629–1.248, p = 0.489; grade 3 HR: 0.715, 95% CI: 0.439–1.165, p = 0.178). Kaplan–Meier survival analysis results were presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Result of overall survival analysis between the adjuvant chemotherapy group and non-adjuvant chemotherapy group in patients with stage I OEC. (A): All patients; (B): Patients who received lymphadenectomy; (C): Patients who did not receive lymphadenectomy

3.5 Descriptive Analysis of Our Single-Center Data on the Administration of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Stage I OEC

A total of 40 patients with stage I OEC were initially reviewed, with seven excluded due to other OC subtypes or non-ovarian primary tumors. The remaining 33 patients were included for analysis, though the cohort size precluded formal survival analysis, limiting assessment to quantitative descriptive statistics. The median patient age was 49 years (interquartile range 11). All patients underwent comprehensive staging surgery, including lymphadenectomy: 9 had stage IA disease while 24 had stage IC. Histologically, 21 patients had grade 1-2 tumors, 7 had grade 3, and 5 had unspecified grade.

Adjuvant chemotherapy was administered to 23 patients, all receiving paclitaxel-platinum regimens (cisplatin or carboplatin). The chemotherapy group comprised 3 stage IA and 20 stage IC patients, while the non-chemotherapy group included 6 stage IA and 4 stage IC patients. As of May 2024, five deaths were recorded: two in stage IA (one treated with chemotherapy, one without) and three in stage IC (one treated, two untreated). Notably, all chemotherapy-naïve patients had grade 1-2 tumors. Based on these findings, our institutional practice favors adjuvant chemotherapy for grade 3 and stage IC patients.

3.6 Meta-Analysis on the Administration of Adjuvant Chemotherapy in Stage I OC

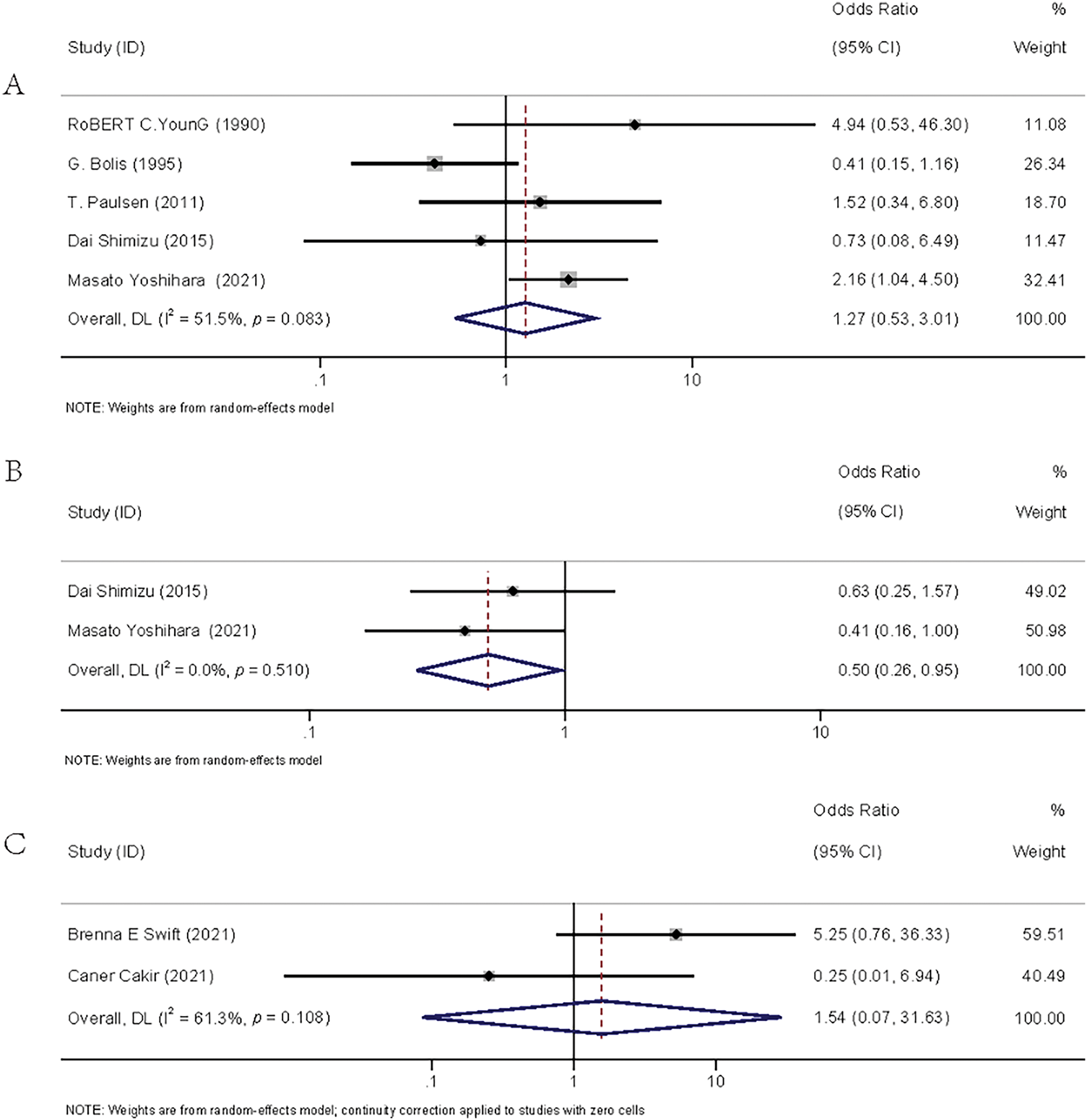

The flow diagram detailing the identification and inclusion process of targeted literature is shown in Fig. 3. Seven studies were included in the final meta-analysis, spanning three distinct time periods: two from 1990–2000 [16,17], two from 2010–2020 [18,19], and three from 2021–2025 [20–22]. The basic information of the included literature was presented in Table S3. Meta-analyses showed that adjuvant chemotherapy did not affect the recurrence of patients with stage IA/B OC (OR = 1.27, 95% CI: 0.53–3.01, p = 0.595, I2 = 51.50%) or stage IA/B OEC (OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 0.07–31.63, p = 0.780, I2 = 61.30%), but it could reduce the recurrence rate of patients with stage IC OC (OR = 0.50, 95% CI: 0.26–0.95, p = 0.035, I2 = 0.00%). The result is given in Fig. 4.

Figure 3: PRISMA flow chart

Figure 4: Forest plots of recurrence rates between the adjuvant chemotherapy group and the non-adjuvant chemotherapy group. (A): stage IA/B OC [16–19,22]; (B): stage IC OC [19,22]; (C): stage IA/B OEC [20–21]

Firstly, in the survival analysis of stage IA/IB patients, chemotherapy did not appear to provide survival benefits for those with grade 1-2, regardless of lymphadenectomy. Additionally, the meta-analysis showed no reduction in recurrence risk from chemotherapy for stage IA/IB OEC patients vs. observation.

Second, in stage IC grade 1-2 patients, chemotherapy significantly improved both 5-year and overall survival. Among those who did not undergo lymphadenectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated superior outcomes compared to observation. However, no survival benefit was observed in patients who received lymphadenectomy.

Third, for stage IC grade 3 patients, chemotherapy was associated with improved 5-year survival. Notably, patients without lymphadenectomy benefited in both 5-year and overall survival, whereas those who underwent lymphadenectomy only showed a 5-year survival advantage without significant overall survival improvement—a discrepancy potentially attributable to selection bias, given that half of the cases were derived from 2008-2018. Furthermore, our meta-analysis confirmed that chemotherapy significantly reduced recurrence rates in stage IC ovarian cancer patients.

This study’s first findings were consistent with those of some previous studies. Kumar et al., found no benefit in disease-free survival (DFS) for stage IA/IB OEC patients from adjuvant chemotherapy [23]. Cybulska et al., reported no progression-free survival (PFS) advantage [24], and Swift et al., also showed no survival improvement for grade 1-2 patients in stage IA/IB [20]. Our study, with a larger sample size compared to a SEER-based study, confirmed these findings [12]. A Cochrane meta-analysis on early-stage epithelial ovarian cancer also suggested withholding chemotherapy for stage IA/IB grade 1-2 patients [25]. However, some studies present opposing views. Chatterjee et al. found chemotherapy reduced mortality in stage IA/IB grade 2 patients but not in grade 1 [26]. Nasioudis et al. similarly indicated survival benefits for grade 2 patients, but none for grade 1 [13].

For grade 3 patients, no significant survival difference was observed between chemotherapy and observation, as supported by Nasioudis et al., [13] and Oseledchyk et al. [12]. However, Chatterjee et al. found chemotherapy reduced mortality in grade 3 patients [26]. The Cochrane meta-analysis also recommended chemotherapy for stage IA/IB grade 3 [25], noting that poorly differentiated tumors are more aggressive and tend to have worse prognoses [27,28].

Multiple studies supported our second result. ICON1’s extended follow-up suggested chemotherapy benefits for stage IC grade 2 [29], and Cybulska et al. found progression-free survival (PFS) benefits from chemotherapy in stage IC OEC [24]. Our results, based on a larger sample size, differ from Oseledchyk et al., who found no benefit from chemotherapy regardless of lymphadenectomy [12]. Nasioudis et al., however, reported chemotherapy benefits for stage IC grade 2 with lymphadenectomy, but not without it [13]. Nonetheless, we maintain our findings. Our conclusions align with long-term follow-up results from the ACTION trial, which suggested chemotherapy benefits in patients with non-optimal surgical staging, and with Kleppe et al., who noted no survival benefit from chemotherapy after lymph node dissection in early-stage ovarian cancer [30].

Oseledchyk et al. partially agreed with our third result, suggesting chemotherapy improves 5-year survival in those without lymphadenectomy, but no-lymphadenectomy itself may lead to occult metastasis [12]. Lymphadenectomy may reveal occult metastatic lesions and lead to a better prognosis for the patient [31]. A recent study further confirmed the necessity of chemotherapy for stage IC grade 3 patients after lymphadenectomy [32].

This retrospective study represents the largest SEER-based cohort investigating adjuvant chemotherapy in stage I OEC. A key strength lies in its alignment with current guidelines to address clinical controversies, supported by a robust sample size ensuring sufficient statistical power. We further enhanced validity through subgroup analyses and meta-analyses, incorporating our institutional experience.

However, limitations include potential selection bias from the lack of randomization, missing data on comorbidities, and unavailable disease-free, progression-free, disease-specific survival outcomes and not distinguishing between ‘none’ and ‘unknown’ lymphadenectomy status in SEER. Detailed chemotherapy regimen information was also lacking. Given the constraints of Kaplan-Meier analysis, future studies should incorporate additional covariates (e.g., chemotherapy cycles) and employ multifactorial Cox proportional hazards models for adjusted analyses. Furthermore, reliance on single-center data and limited comparable studies may restrict external validation and meta-analytic reliability. The studies included in the meta-analysis did not provide enough subtype-specific data for such comparisons, and we will take this as an important direction for future research.

Implications for Practice and Future Research

The study suggests that adjuvant chemotherapy improves prognosis in stage IC grade 3 patients and may be considered for stage IC grade 1-2, especially without lymphadenectomy. Observation is suitable for stage IA/IB grade 1-2. Although no survival difference was found in stage IA/IB grade 3, guidelines and our experience support chemotherapy in this group. These findings aid in developing postoperative treatment protocols for stage I OEC, potentially improving outcomes.

The postoperative observation seemed to be preferable for patients with stage IA/IB grade 1-2. For patients with stage IA/IB grade 3, adjuvant chemotherapy was acceptable to be chosen as postoperative management. Adjuvant chemotherapy could enhance the prognosis of patients with stage IC, especially those patients without lymphadenectomy.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the scientific research project of Jiangsu Province’s “333 Project” (BRA2019097); Jiangsu Provincial Key Medical Discipline of the 14th Five-Year Plan (ZDXK202210); Jiangsu Province Medicine Science and Technology Development Project (No. ZD202014).

Author Contributions:: Liang Yu, Mingrui Zhao and Jinhui Liu collected and collated the data from the SEER database. Liang Yu, Mingrui Zhao and Yuqin Yang performed the analysis. Liang Yu and Mingrui Zhao wrote the manuscript. Liang Yu and Jinhui Liu guided the statistical analysis. Lin Zhang polished the language of the article. Wenjun Cheng guided research directions. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Our single-center retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (2020-MD-371) and was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was waived by our Institutional Review Board due to the retrospective nature of our project. The SEER database analysis and meta-analysis components of this study did not require ethics approval, as they utilized publicly available de-identified data and previously published literature, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/or.2025.065137/s1.

References

1. Webb PM, Jordan SJ. Global epidemiology of epithelial ovarian cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024;21(5):389–400. doi:10.1038/s41571-024-00881-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Ye W, Wang Q, Lu Y. Construction and validation of prognostic nomogram and clinical characteristics for ovarian endometrioid carcinoma: an SEER-based cohort study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(15):13607–18. doi:10.1007/s00432-023-05172-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Armstrong DK, Alvarez RD, Bakkum-Gamez JN, Barroilhet L, Behbakht K, Berchuck A, et al. Ovarian cancer, version 2.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19(2):191–226. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2021.0007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Liu J, Berchuck A, Backes FJ, Cohen J, Grisham R, Leath CA, et al. NCCN guidelines® insights: ovarian cancer/fallopian tube cancer/primary peritoneal cancer, version 3.2024. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2024;22(8):512–9. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2024.0052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Berek JS, Renz M, Kehoe S, Kumar L, Friedlander M. Cancer of the ovary, fallopian tube, and peritoneum: 2021 update. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;155(Suppl 1):61–85. [Google Scholar]

6. Wu X, Zhang S. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of ovarian malignancies. China Oncology. 2021;31(6):490–500. [Google Scholar]

7. Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology Guidelines Working Committee. Chinese society of clinical oncology (CSCO) guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ovarian cancer (M). Beijing: People’s Health Publishing House; 2024. [Google Scholar]

8. Suh DH, Chang S-J, Song T, Lee S, Kang WD, Lee SJ, et al. Practice guidelines for management of ovarian cancer in Korea: a Korean society of gynecologic oncology consensus statement. J Gynecol Oncol. 2018;29(4):e56. doi:10.3802/jgo.2018.29.e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tokunaga H, Mikami M, Nagase S, Kobayashi Y, Tabata T, Kaneuchi M, et al. The 2020 Japan society of gynecologic oncology guidelines for the treatment of ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, and primary peritoneal cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2021;32(2):e49. doi:10.3802/jgo.2021.32.e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Redondo A, Guerra E, Manso L, Martin-Lorente C, Martinez-Garcia J, Perez-Fidalgo JA, et al. SEOM clinical guideline in ovarian cancer. 2020 Clin Transl Oncol. 2021;23(5):961–8. doi:10.1007/s12094-020-02545-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. González-Martín A, Harter P, Leary A, Lorusso D, Miller RE, Pothuri B, et al. Newly diagnosed and relapsed epithelial ovarian cancer: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2023;34(10):833–48. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2023.07.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Oseledchyk A, Leitao MMJr, Konner J, O’Cearbhaill RE, Zamarin D, Sonoda Y, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with stage I endometrioid or clear cell ovarian cancer in the platinum era: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Cohort Study, 2000–2013. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(12):2985–93. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Nasioudis D, Latif NA, Simpkins F, Cory L, Giuntoli RL2nd, Haggerty AF, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy for early stage endometrioid ovarian carcinoma: an analysis of the national cancer data base. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;156(2):315–9. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.11.125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Hess AS, Hess JR. Kaplan-Meier survival curves. Transfusion. 2020;60(4):670–2. [Google Scholar]

15. Koletsi D, Pandis N. Survival analysis, part 3: cox regression. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;152(5):722–3. doi:10.1016/j.ajodo.2017.07.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Young RC, Walton LA, Ellenberg SS, Homesley HD, Wilbanks GD, Decker DG, et al. Adjuvant therapy in stage I and stage II epithelial ovarian cancer. Results of two prospective randomized trials. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(15):1021–7. doi:10.1056/nejm199004123221501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bolis G, Colombo N, Pecorelli S, Torri V, Marsoni S, Bonazzi C, et al. Adjuvant treatment for early epithelial ovarian cancer: results of two randomised clinical trials comparing cisplatin to no further treatment or chromic phosphate (32p). Ann Oncol. 1995;6(9):887–93. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.annonc.a059355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Paulsen T, Kærn J, Tropé C. Improved 5-year disease-free survival for FIGO stage I epithelial ovarian cancer patients without tumor rupture during surgery. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;122(1):83–8. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.02.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shimizu D, Sato N, Sato T, Makino K, Kito M, Shirasawa H, et al. Impact of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage I ovarian carcinoma with intraoperative tumor capsule rupture. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2015;41(3):432–9. doi:10.1111/jog.12551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Swift BE, Covens A, Mintsopoulos V, Parra-Herran C, Bernardini MQ, Nofech-Mozes S, et al. The effect of complete surgical staging and adjuvant chemotherapy on survival in stage I, grade 1 and 2 endometrioid ovarian carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2022;32(4):525–31. doi:10.1136/ijgc-2021-003112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cakir C, Korkmaz V, Kimyon Comert G, Yuksel D, Kilic F, Kilic C, et al. Spotlight on oncologic outcomes and prognostic factors of pure endometrioid ovarian carcinoma. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2021;50(6):102105. doi:10.1016/j.jogoh.2021.102105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yoshihara M, Tamauchi S, Iyoshi S, Kitami K, Uno K, Mogi K, et al. Impact of incomplete surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy for the intraoperative rupture of capsulated stage I epithelial ovarian cancer: a multi-institutional study with an in-depth subgroup analysis. J Gynecol Oncol. 2021;32(5):e66. doi:10.3802/jgo.2021.32.e66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kumar A, Le N, Tinker AV, Santos JL, Parsons C, Hoskins PJ. Early-stage endometrioid ovarian carcinoma: population-based outcomes in British Columbia. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2014;24(8):1401–5. [Google Scholar]

24. Cybulska P, Tseng J, Zhou QC, Iasonos A, Delair DF, Mueller JJ, et al. Clinical outcomes of patients with endometrioid epithelial ovarian cancer following surgical treatment. J Surg Oncol. 2021;124(5):846–51. doi:10.1002/jso.26597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lawrie TA, Winter-Roach BA, Heus P, Kitchener HC. Adjuvant (post-surgery) chemotherapy for early stage epithelial ovarian cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015(12):Cd004706. [Google Scholar]

26. Chatterjee S, Chen L, Tergas AI, Burke WM, Hou JY, Hu JC, et al. Utilization and outcomes of chemotherapy in women with intermediate-risk, early-stage ovarian cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(6):992–1002. doi:10.1097/aog.0000000000001404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li M, Hong LI, Liao M, Guo G. Expression and clinical significance of focal adhesion kinase and adrenomedullin in epithelial ovarian cancer. Oncol Lett. 2015;10(2):1003–7. [Google Scholar]

28. Zhang Y, Shi X, Zhang J, Chen X, Zhang P, Liu A, et al. A comprehensive analysis of somatic alterations in Chinese ovarian cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):387. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79694-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Collinson F, Qian W, Fossati R, Lissoni A, Williams C, Parmar M, et al. Optimal treatment of early-stage ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(6):1165–71. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kleppe M, van der Aa MA, Van Gorp T, Slangen BF, Kruitwagen RF. The impact of lymph node dissection and adjuvant chemotherapy on survival: a nationwide cohort study of patients with clinical early-stage ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2016;66(12):83–90. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2016.07.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Bizzarri N, Imterat M, Fruscio R, Giannarelli D, Perrone AM, Mancari R, et al. Lymph node staging in grade 1–2 endometrioid ovarian carcinoma apparently confined to the ovary: is it worth?. Eur J Cancer. 2023;195(6):113398. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2023.113398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Gallotta V, Jeong SY, Conte C, Trozzi R, Cappuccio S, Moroni R, et al. Minimally invasive surgical staging for early stage ovarian cancer: a long-term follow up. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47(7):1698–704. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2021.01.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools