Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Lactylation in Cancer: Unlocking the Key to Drug Resistance and Therapeutic Breakthroughs

1 Clinical School of Medicine, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, 230022, China

2 Department of Gastrointestinal Surgery, The Second People’s Hospital of Wuhu, Wuhu, 241000, China

* Corresponding Author: Guangyao Li. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: New Insights in Drug Resistance of Cancer Therapy: A New Wine in an Old Bottle)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(11), 3327-3346. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.067343

Received 30 April 2025; Accepted 27 June 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

Lactylation, a post-translational modification process that adds lactate groups to lysine residues, plays a crucial role in cancer biology, especially in drug resistance. However, the specific molecular mechanisms of lactylation in cancer progression and drug resistance are still unclear, and therapeutic strategies targeting the lactylation pathway are expected to overcome metabolic reprogramming and immune evasion. Therefore, this article provides a comprehensive description and summary of lactylation modification and tumor drug resistance. Numerous studies have shown that, due to the Warburg effect, there is an abnormally high level of lactate in tumor cells. Elevated levels of lactate promote metabolic reprogramming and alter key cellular processes, including gene expression, DNA repair, and immune regulation. These cellular processes are precisely the key factors for tumor cells to develop drug resistance. Lactylation also affects the tumor microenvironment, promoting immune evasion and resistance to immunotherapy in tumor cells. This modification affects proteins involved in metabolic pathways, glycolysis, and mitochondrial function, further supporting tumor growth and metastasis. Therefore, this article provides a comprehensive description and summary of lactylation modification and tumor drug resistance to clarify the specific mechanisms between the two and provide references and directions for future research on tumor drug resistance.Keywords

Cancer is a major global health concern, with increasing morbidity and mortality rates worldwide [1]. As an age-related disease, cancer poses a particular threat to China, which has the world’s largest elderly population (≥60 years) and is experiencing an unprecedented population ageing [2]. As a result, cancer has become one of the most common causes of death in China [2,3]. At present, the main treatments for cancer include surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), which is the third leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide, and there is still no effective treatment for it [1,4,5]. In Asia, radical treatments such as surgery and liver transplantation are available for early-stage liver cancer, but the 5-year recurrence rate of HCC after hepatectomy is as high as 70%, even in patients with a single tumor ≤ 2 cm [6]. The 5-year recurrence rate after liver transplantation is only 10%–15%, but the extreme scarcity of liver sources cannot make liver transplantation the primary treatment method [6]. In addition, most patients with HCC are usually diagnosed at an advanced stage and are no longer eligible for curative treatment, and most patients can only be treated with drugs [7]. First-line drugs for advanced liver cancer, such as Sorafenib, Apatinib, and Bevacizumab, can significantly improve patient prognosis. Unfortunately, patients easily develop resistance to these drugs, which has a significant adverse effect on treatment [8–10]. This phenomenon also occurs in a variety of cancers, such as breast cancer [11], non-small cell lung cancer [12], and pancreatic cancer (PC) [13], so addressing tumor resistance is critical to the treatment and prognosis of cancer patients.

After searching for the keywords “tumor” and “drug resistance” on the PubMed website and reading a large number of related literature on tumor drug resistance, this review found that the emergence of tumor drug resistance is closely related to lactic acid modification. Recent studies have shown that histone lactylation alters chromatin structure and transcription, driving cancer progression and leading to drug resistance [14]. In addition, lactylation regulates immune cell function and promotes immunosuppression and tumor immune escape, which further complicates treatment. Therefore, we have integrated recent articles on tumor drug resistance and lactylation modification in the hope of elucidating the specific mechanisms between the two.

2 Biological Basis of Lactylation Modification

2.1 Discovery and Significance

Since its discovery in 1780, lactic acid has often been mistakenly thought to be a metabolic waste product under low-oxygen conditions and has a variety of harmful effects [15]. Later, the lactate shuttle hypothesis proved that lactate could be used both as an energy source and as a signaling molecule [16]. In the 1920s, Otto Warburg made the groundbreaking observation that tumors consume more glucose than surrounding normal tissue. This led him to come up with the concept of aerobic glycolysis, the process by which glucose is fermented into lactic acid instead of carbon dioxide in an oxygen-rich environment. This mechanism is currently referred to as the Warburg effect [17].

Lactylation was first described in 2019, when researchers discovered that histone proteins can be modified by emulsion groups under conditions of high glycolytic activity [18]. This modification has attracted great attention in epigenetics and cellular metabolism studies due to its role in cellular metabolism and its involvement in the regulation of various biological processes, especially in cancer cells [19–21]. Influencing protein function through lactylation is essential for cells to adapt to metabolic changes, especially in rapidly proliferating tumor cells exhibiting the Warburg effect (where aerobic glycolysis predominates). This discovery establishes a direct link between metabolism and epigenetic regulation, highlighting lactylation as a novel mechanism of cellular response to metabolic changes [19]. Unlike other Protein Post-translational Modifications (PTMs), such as acetylation or methylation, which rely on intermediates such as acetyl-CoA or S-adenosylmethionine, lactylation is uniquely tied to lactate metabolism, further reinforcing its role in linking energy production to cellular function [20]. Lactylation is now recognized as a significant regulatory mechanism with significant implications for gene expression, immune response, cell differentiation, and various disease pathologies.

2.2.1 Lactate Source and Donor Role

The basis of lactate modification is the production of lactic acid and its role as an acyl donor:

(1) Lactate production by glycolysis pathway: In the process of cell metabolism, especially under anaerobic or high sugar conditions, glucose is converted into pyruvate through the glycolytic pathway, and then reduced to lactate under the action of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) [22]. (2) Intracellular accumulation of lactic acid: Lactic acid can enter cells through monocarboxylic acid transporters (MCTs) or be directly produced by intracellular metabolism, and the level of lactate is significantly increased in the tumor microenvironment, inflammation, and hypoxia, providing sufficient substrates for lactylation modification [19]. (3) Formation of lactyl-CoA: Lactate can form Lactyl-CoA under the mediation of Coenzyme A (CoA), which is similar to the formation of acetyl coenzyme A (Acetyl-CoA) and provides an acyl donor for the lactylation of lysine residues [23].

2.2.2 Catalytic Mechanism of Lactylation Modification

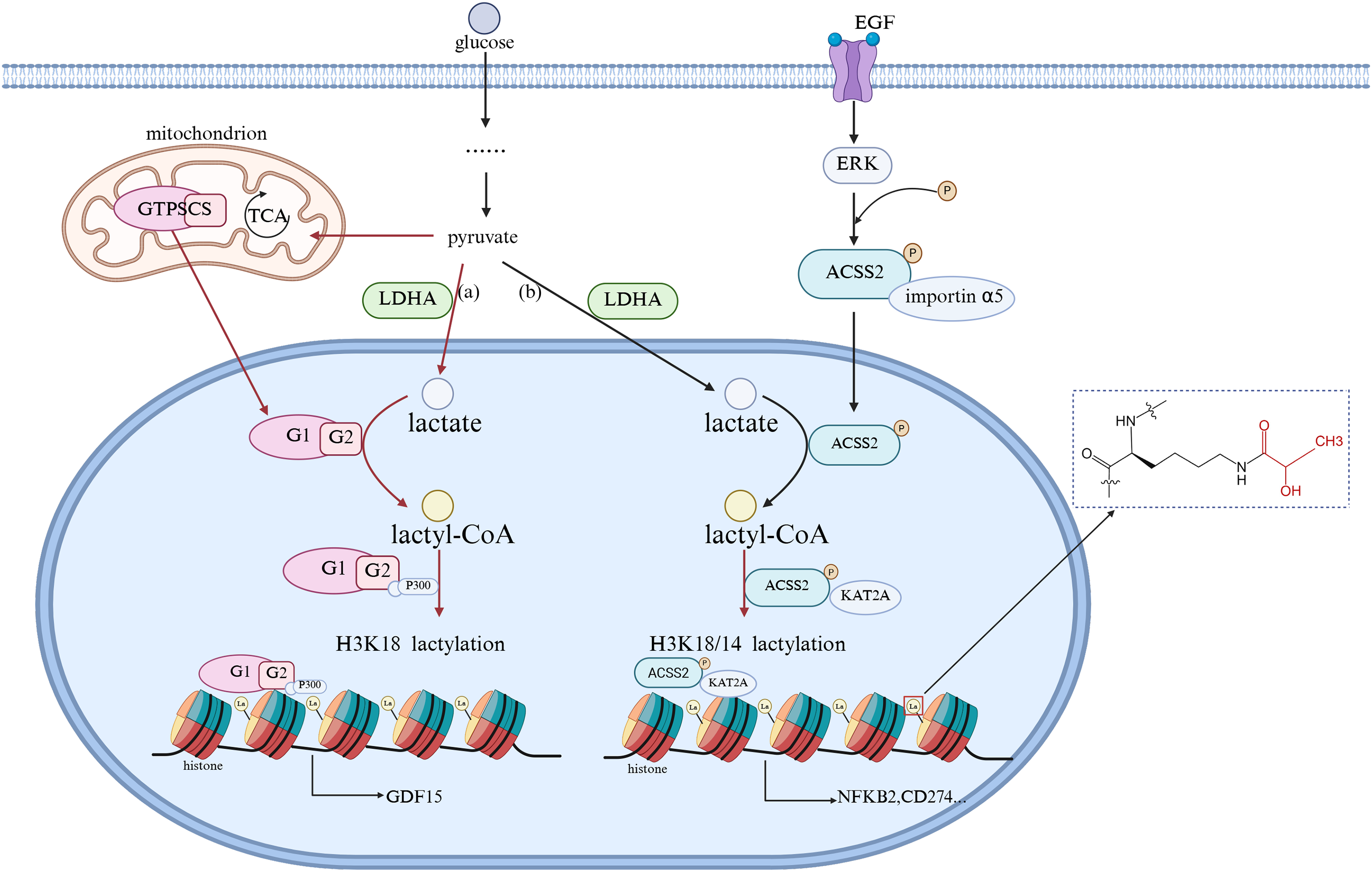

Lactylation modification usually occurs on lysine (Lys) residues, and lactylation occurs when lactic acid groups covalently attach to the lysine residues of proteins, similar to acetylation, affecting protein function and interactions [19]. This process is often driven by an increase in intracellular lactate levels, which are often in response to hypoxia or enhanced glycolytic activity. Current research suggests that lactylation modification may be a spontaneous chemical reaction, but it may also be catalyzed by specific acyltransferases. For example, Fig. 1a: GTP-dependent succinyl-CoA synthetase in mammalian mitochondria (GTPSCS) can enter the cell nucleus through the nuclear localization signal of its G1 subunit, promote the synthesis of lactyl-CoA in the cell nucleus with lactate as a substrate, and enhance the interaction with the acyltransferase P300 (which transfers acetyl groups to histone lysine tails) through the acetylation modification at the K73 site of the G2 subunit, cooperatively regulating the level of histone H3 lysine 18 lactylation (H3K18la), upregulating the expression of the pro-cancer protein GDF15 [24]. Fig. 1b: After being activated by binding with epidermal growth factor (EGF), the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) induces the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) to promote the phosphorylation of Acetyl-CoA synthetase 2 (ACSS2). Once phosphorylated, ACSS2 binds with importin α5 and undergoes nuclear translocation, entering the cell nucleus. Using lactate as a substrate, it enhances the production of lactyl-CoA within the nucleus. Additionally, it binds with lysine acetyltransferase 2A (KAT2A) to acetylate histone tyrosine, regulating the H3K18/14la levels and promoting the expression of NFKB2 and CD274 [25].

Figure 1: Molecular Link between Intracellular Lactate and Lactylation. EGF, epidermal growth factor; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; LDHA, lactate dehydrogenase A; ACSS2, Acetyl-CoA synthetase 2; GTPSCS, GTP-dependent succinyl-CoA synthetase in mammalian mitochondria. (The figure was made using Biorender)

2.2.3 Removal Mechanism of Lactylation Modifications

The reversibility of lactylation modifications is still being explored, and no specific delactylase has been identified. Studies have shown that some deacetylases (e.g., SIRT family) may have delactylation functions, such as SIRT3 and SIRT6, which play a role in the removal of histones and acylation modifications of metabolic enzymes, but the specific role of lactylation has not been fully understood [26–28]. The discovery of specific delactylating enzymes in the future will further reveal the modularity of lactylation modifications and their dynamic changes in cellular homeostasis.

2.3 Functional Role of Lactylation

2.3.1 Gene Regulation and Epigenetic Control

One of the most important discoveries about lactylation is its role in gene expression. Histone lactylation has been shown to activate gene transcription by altering chromatin structure [18,29,30]. Unlike acetylation, which enhances gene activation primarily by neutralizing histone charge, lactylation is associated with persistent transcriptional activation of genes involved in immune response and metabolic adaptation. For example, it was demonstrated that lactylation could drive the switch of macrophages from a pro-inflammatory (M1) to an anti-inflammatory (M2) state [31,32]. This shift is essential for tissue repair and immune resolution, highlighting the role of lactylation in immune regulation. The ability of lactylation to modulate long-term gene expression patterns suggests that it may be involved in Immune memory (Immune memory—comprising T cells, B cells, and plasma cells and their secreted antibodies—is crucial for human survival. It enables the rapid and effective clearance of a pathogen after re-exposure, to minimize damage to the host) [33] and cellular adaptations to metabolic changes.

2.3.2 Cell Differentiation and Development

In addition to its effects on gene transcription, lactylation is also involved in the process of cell differentiation. Studies have shown that stem cells use lactylation to regulate gene expression programs in specific lineages [34]. For example, in embryonic and hematopoietic stem cells, lactylation affects the differentiation pathway and determines cell fate decisions, which are essential for tissue development and homeostasis [34–36]. The role of lactylation in neural differentiation has also been explored, and studies have found that lactate-mediated alterations affect neurodevelopmental genetic programming [37]. Given the brain’s high metabolic demands and reliance on lactate produced by glycolysis, lactylation may be a key regulatory mechanism in neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity [38]. In addition, lactylation plays a crucial role in regulating the transcriptional programs required for tissue repair and homeostasis in muscle regeneration.

2.3.3 Effects on Metabolic Pathways

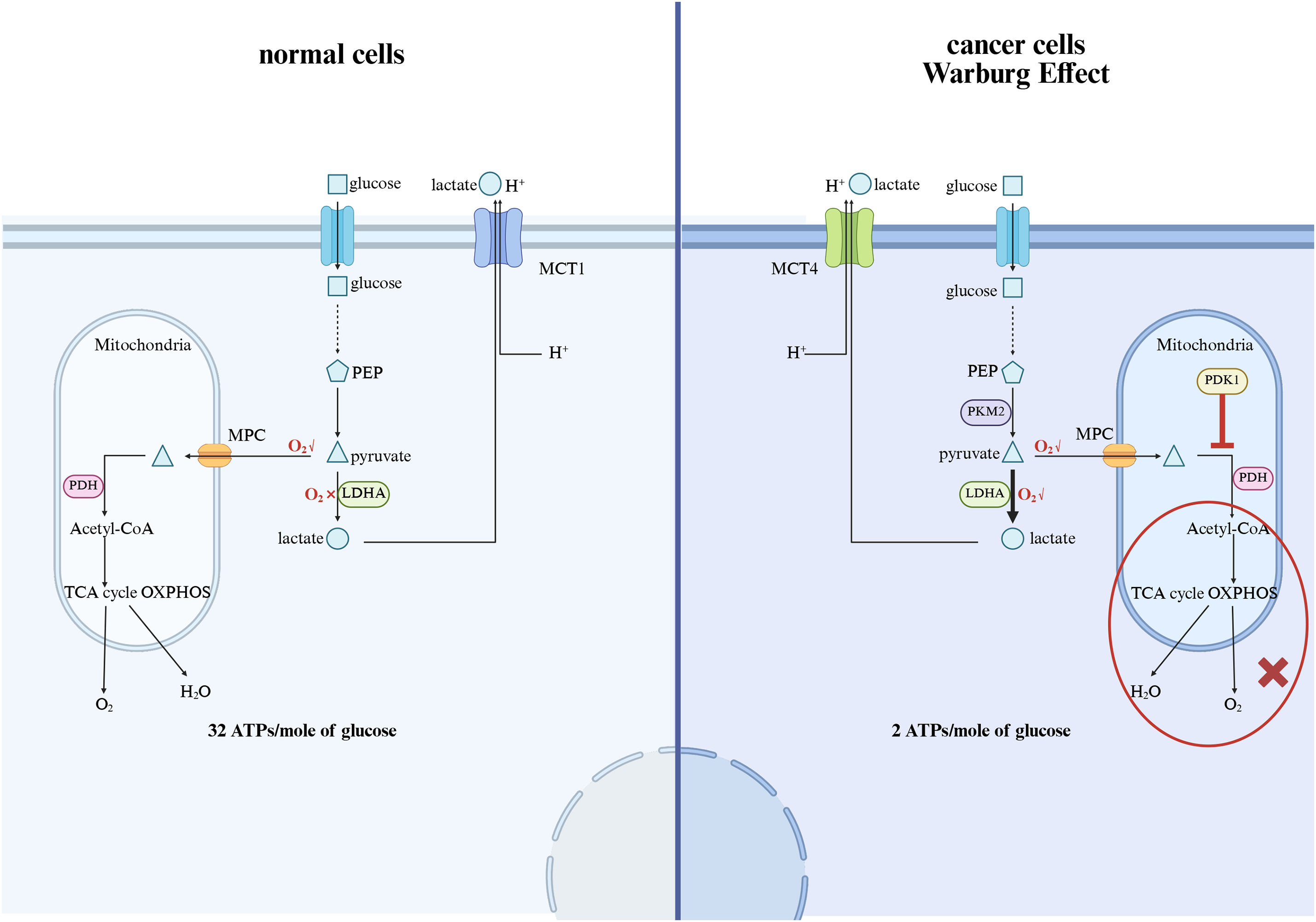

Because lactylation is intrinsically related to lactate metabolism, its role in metabolic regulation is of particular interest. Studies have shown that lactylation may affect metabolic enzyme activity, thereby regulating key pathways such as glycolysis, oxidative phosphorylation, and fatty acid metabolism [39]. By altering the function of metabolic enzymes, lactate fermentation may provide a mechanism for cells to fine-tune energy production in response to changes in environmental conditions. The Warburg effect in cancer metabolism manifests as cancer cells preferentially consuming glucose and relying on glycolysis rather than oxidative phosphorylation to generate ATP, even under aerobic conditions. The metabolic changes resulting from the Warburg effect are as follows [17,40]: Due to the expression of proto-oncogenes and the suppression of tumor suppressor genes in cancer cells, the transcription of low-activity pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2), mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1), monocarboxylate transporter 4 (MCT4), etc., is activated. The expression of PKM2 limits the conversion of phosphoenolpyruvate to pyruvate, leading to an increase in the backup of glucose carbons, i.e., intermediates, above pyruvate kinase, which are shunted into various pathways for material synthesis, allowing continuous proliferation and development of tumor cells; PDK1 expression inactivates pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), and the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation are inhibited, causing cancer cells to primarily undergo glycolysis even under aerobic conditions, i.e., aerobic glycolysis, and the excessive expression of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) in cancer cells leads to the accumulation of lactate, which is transported outside the cell via MCT4 to participate in the formation of the tumor microenvironment, aiding in immune evasion; finally, since the rate of cytoplasmic ATP generation is approximately 100 times that of mitochondria, even though aerobic glycolysis yields only 2 moles of ATP per glucose molecule, as long as there is sufficient extracellular glucose supply, the ATP supply per unit time is higher than that of oxidative glucose metabolism, providing ample energy supply for cancer cells, and the significant increase in the demand for ATP in cancer cells also accelerates aerobic glycolysis (Fig. 2). At present, strategies to reduce lactate levels, inhibit lactate production, or regulate lactate-dependent gene expression are being explored as possible interventions for malignancies characterized by metabolic dysregulation [41].

Figure 2: The mechanism of the Warburg effect and the impact on cancer. MCT1, Monocarboxylate Transporter 1; PEP, Phosphoenolpyruvate; MPC, Mitochondrial Pyruvate Carrier; PDH, Pyruvate Dehydrogenase; LDHA, Lactate Dehydrogenase A; PKM2, Pyruvate kinase M2; PDK1, Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle; OXPHOS: Oxidative phosphorylation (The figure was made using Biorender)

2.4 Relationship between Lactylation and Disease

Lactylation is biologically significant in a variety of disease settings, particularly in cancer and immune diseases [42]. In cancer cells, increased glycolytic flux leads to increased lactate production, which in turn enhances histone lactylation and regulates gene expression patterns favorable to tumor progression. This metabolic-epigenetic interaction has been observed in various malignancies, including breast, colorectal, and glioma [43]. Excess lactate can enter the nucleus and induce histone lactylation, and this modification is catalyzed by the p300 enzyme, altering gene expression to promote tumor growth, for example, elevated histone H3 lysine 18 lactylation (H3K18la) levels in bladder cancer cells promote the expression of key transcription factors YY1 and YBX1, in which YBX1 plays a role in promoting DNA repair; YY1 can upregulate DNA repair genes (such as PTEN and Rad51), multidrug resistance genes (MDR1/ABCB1), and others, together leading to the chemotherapy resistance of tumor cells [44]. In addition, lactate also affects immune cells, especially macrophages, inducing their transformation into M2-type tumor-associated macrophage (TAM) phenotypes, thereby promoting immunosuppression and helping tumors escape immune surveillance [45].

3 Mechanisms of Tumor Drug Resistance

Cancer drug resistance is a major obstacle to effective cancer treatment, and its resistance mechanism can be broadly divided into intrinsic resistance and acquired resistance [46]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that both inherent and acquired tumor resistance significantly undermine the effectiveness of treatment [47]. To date, a variety of tumor resistance mechanisms have been studied and confirmed.

3.1 Tumor Cell Drug Target Mutations

The development of drug resistance, driven by mutations in drug targets, is one of the most daunting challenges in cancer treatment. Many targeted therapies work by binding to specific proteins whose activity drives tumor progression, and mutations within these target proteins can alter drug binding affinity, rendering the drug ineffective. One of the most well-documented examples is the emergence of secondary mutations in the BCR-ABL fusion protein in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), which confers resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as imatinib. Mutations such as T315I, Y253H, and E255K within the kinase domain reduce the binding capacity of imatinib, perpetuating BCR-ABL signaling [48]. Similarly, resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is often caused by an EGFR T790M mutation that restores ATP affinity and reduces drug binding. These mutations are not random, but are often positively selected under drug stress, highlighting the dynamic evolutionary processes within the tumor during treatment [49]. In addition to kinases, resistance mutations in hormone receptors, such as ESR1 in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer, have also been widely documented. Mutations in ESR1, especially in the ligand-binding domain, can lead to constitutive receptor activation even in the absence of estrogen, thereby undermining the efficacy of endocrine therapy [11]. These target mutations not only disrupt drug-target interactions but also alter downstream signaling, often reconnecting the signaling network to maintain oncogenic programs, illustrating the profound impact of drug-target mutations on treatment failure.

3.2 Inhibition of the Apoptotic Pathway

Inhibition of the apoptotic pathway involves complex interactions of molecular mechanisms, including regulation of Bcl-2 family proteins, inhibition of caspase activity, and activation of survival pathways such as PI3K/AKT signaling [50]. Among these mechanisms, overexpression of anti-apoptotic proteins such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL plays a key role in promoting cell survival by preventing extramitochondrial mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) and cytochrome c release. Activation of the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, which promotes cell survival and growth by phosphorylating downstream targets such as Bad and caspase-9, is common in malignancies, thereby preventing the initiation of apoptosis. In addition, inhibition of initiator and executioner caspases, such as caspase-8 and caspase-3, is a hallmark of apoptotic resistance in cancer cells. This resistance not only promotes tumor progression but also confers resistance to chemotherapeutic agents that target the apoptotic pathway.

Autophagy is a catabolic process responsible for the degradation of cellular components and plays a dual role in cell survival and cell death. Inhibition of autophagy is achieved by inhibition of key autophagy-related genes (ATGs) and the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway, a central regulator of cell growth and autophagy [51]. The mTOR complex, especially Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 (mTORC1), is a key regulator of autophagy inhibition. Activation of mTORC1 inhibits the UNC-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) complex, which is essential for autophagosome formation. This inhibition is commonly observed in cancer cells, where overactive mTOR signaling inhibits autophagy and enhances cell proliferation. In addition, Beclin-1 protein is a key regulator of autophagy initiation and is negatively regulated by Bcl-2, linking autophagy inhibition to apoptosis resistance [52].

3.4 Tumor Microenvironment (TME)

The TME is a complex and dynamic ecosystem that plays a vital role in tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and response to treatment. It is made up not only of cancer cells but also of various stromal cells, including fibroblasts, endothelial cells, pericytes, immune cells, and an abundance of extracellular matrix (ECM), all of which are embedded in the evolving biochemical environment [53]. The cellular composition and biochemical properties of TME vary depending on tumor type and stage, but certain hallmarks, such as hypoxia, low pH, and immunosuppression, are common to many malignancies. For example, cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) can modulate tumor behavior by secreting cytokines, remodeling the ECM, and directly interacting with tumor cells to enhance invasion and resistance to treatment [54]. TME also promotes angiogenesis, allowing tumors to establish their blood supply, which further supports their metabolic needs and dissemination potential. Importantly, interactions between immune cells, including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), regulatory T cells (Tregs), and bone marrow-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), generate an immunosuppressive niche that protects tumors from immune surveillance and promotes immune evasion [55]. This intricate network of cellular crosstalk, biochemical gradients, and mechanical forces forms a permissive and protective environment that sustains cancer progression and severely limits treatment efficacy.

A growing body of evidence suggests that epigenetic modifications can alter gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. These modifications are particularly important in the setting of resistance to chemotherapy and targeted therapy. One of the most studied mechanisms is methylation of CpG islands, which can lead to tumor suppressor gene silencing or oncogene activation, leading to cancer development and treatment failure [56,57]. Aberrant DNA methylation can affect multiple pathways involved in cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, and DNA repair, allowing cancer cells to survive therapeutic stress. In addition to DNA methylation, histone modifications, such as acetylation and methylation, also play a crucial role in regulating chromatin structure and accessibility. Epigenetic alterations not only contribute to the acquisition of drug resistance but also mediate the survival of cancer stem cells (CSCs) [58]. CSCs are subsets of cells within tumors that can self-renew and differentiate into different cell types, and they are generally more resistant to conventional therapies than bulk tumor cells; therefore, CSCs are considered to be the root cause of tumor recurrence and metastasis.

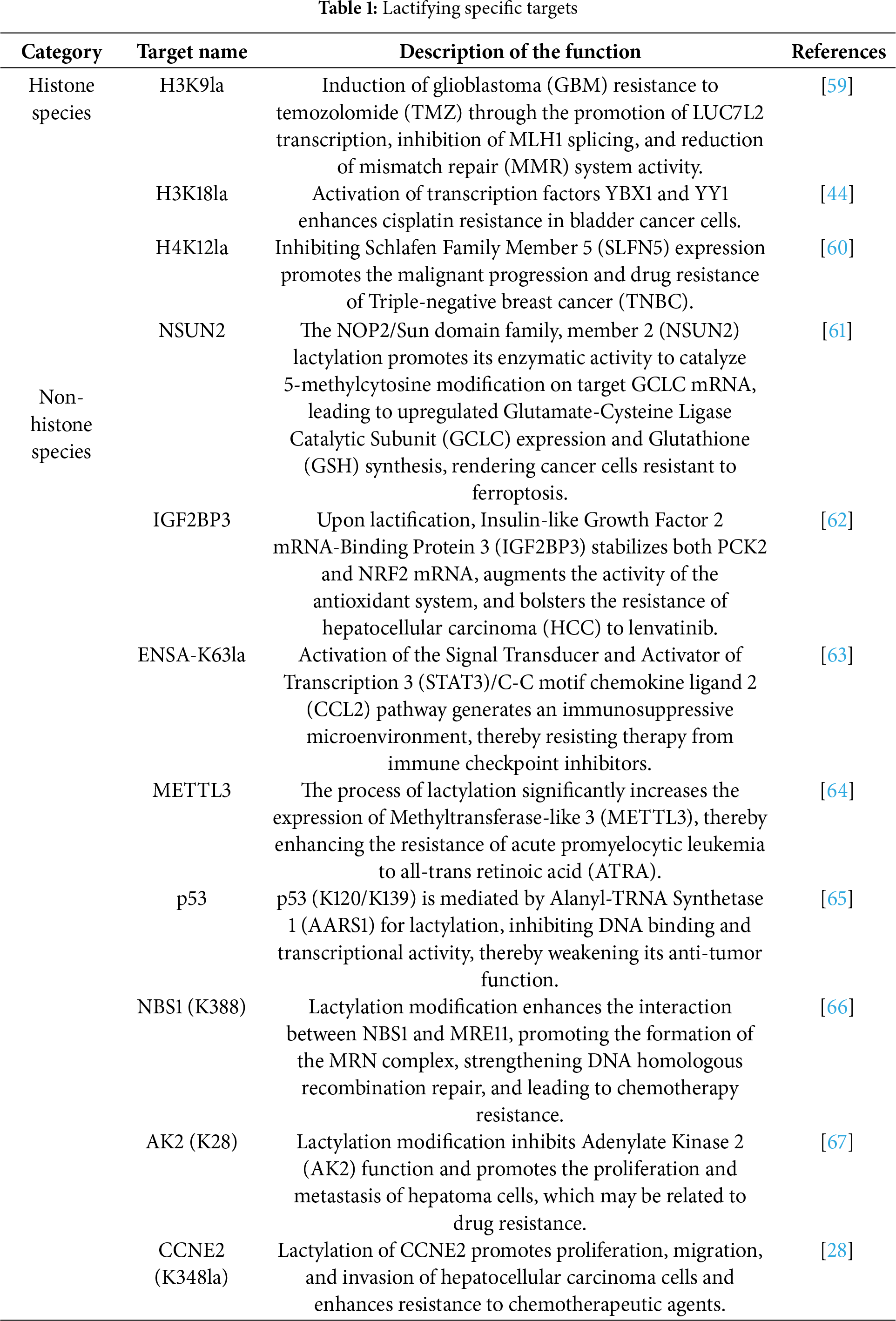

4 The Relationship between Lactylation and Tumor Drug Resistance

A large number of studies have demonstrated that lactylation is one of the core mechanisms driving cancer drug resistance. It promotes metabolic reprogramming, enhances DNA repair, regulates the immune microenvironment, and modulates autophagy by lactifying specific targets of histones and non-histones (Table 1). Due to the Warburg effect, tumor cells preferentially produce energy through anaerobic glycolysis, even in the presence of oxygen, resulting in the accumulation of lactic acid in tumor cells as a by-product of glycolysis. The accumulation of lactate in the tumor microenvironment plays a key role in driving the lactylation process, which in turn drives these resistance mechanisms.

4.1 Lactylation Modification Promotes Metabolic Reprogramming

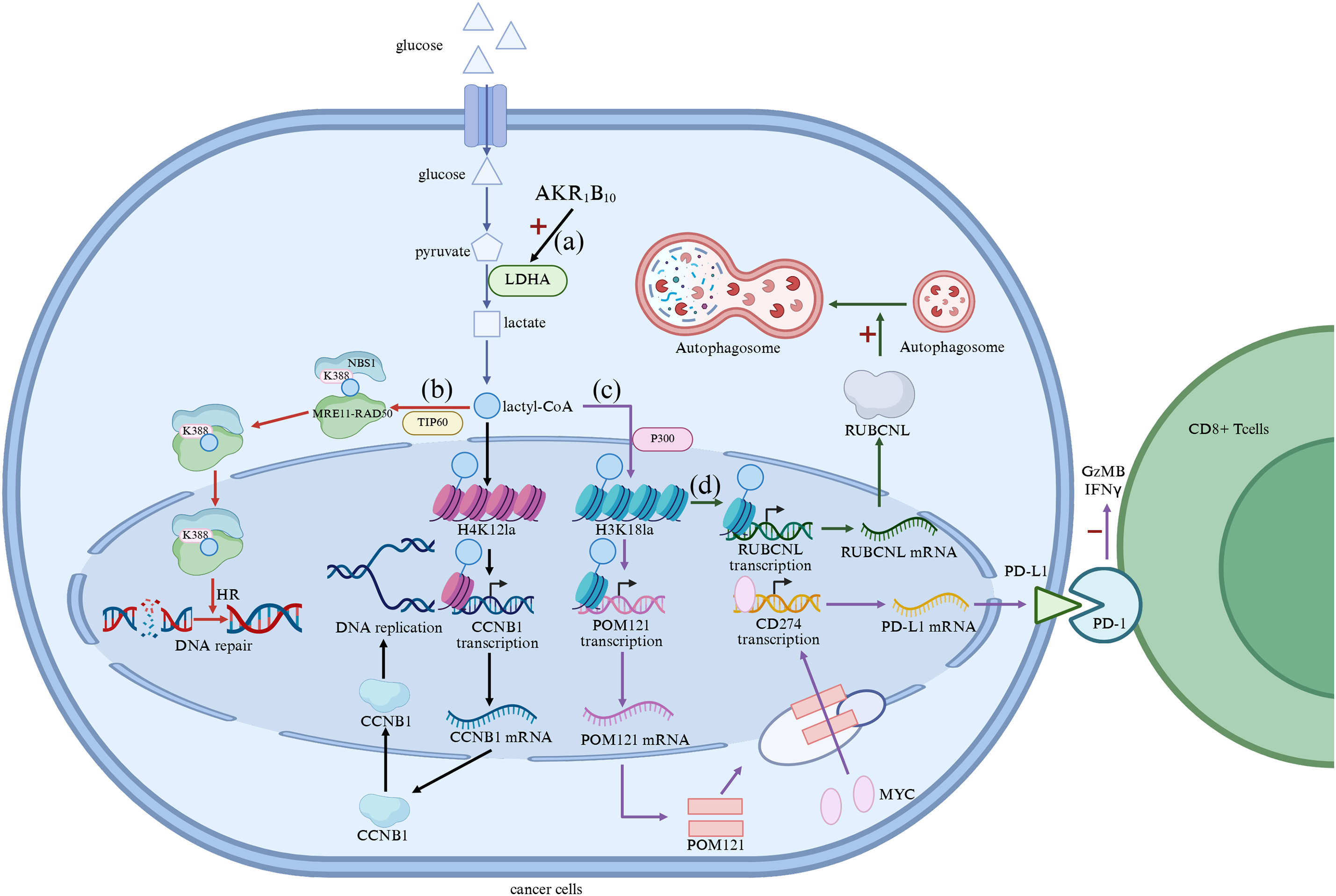

One of the main contributions of lactylation to drug resistance is through enhanced glycolysis, a key metabolic pathway that provides energy to tumor cells under stressful conditions. Metabolic reprogramming characterized by increased glycolysis is a hallmark of tumorigenesis and resistance in various cancers. For example, cancer stem cells (CSCs) are a small subpopulation within tumors that have the ability to self-renew and generate new tumor cells. These cells are generally more resistant to conventional therapies and contribute to tumor recurrence. Lactylation plays a key role in maintaining the metabolic state of CSCs, which are highly dependent on glycolysis and rely on lactate for energy production. By promoting the expression of glycolytic enzymes and cell cycle regulators through histone lactylation, lactate supports the survival of CSCs under stressful conditions, including those triggered by chemotherapy [68,69]. In addition, aldehyde ketone reductase family 1 B10 (AKR1B10) has been shown to promote the Warburg effect in brain metastases of lung cancer, resulting in acquired resistance to the chemotherapeutic agent pemetrexed (PEM), which crosses the blood-brain barrier [70]. AKR1B10 enhanced glycolysis by upregulating LDHA, which converted pyruvate into lactate, leading to increased lactate production. This accumulation of lactate served as a precursor for histone lactylation, particularly H4 lysine 12 lactylation (H4K12la), which facilitated the activation of cell-cycle genes such as CCNB1, ultimately enhancing DNA replication and cell-cycle progression (Fig. 3a). This upregulation of glycolysis and histone lactylation driven by AKR1B10 was a key determinant in resistance to PEM, further exemplifying the central role that lactylation plays in metabolic reprogramming and drug resistance.

Figure 3: (a) Lactate Facilitates Metabolic Rewiring; (b) Lactylation promotes DNA repair; (c) Modulation of immune microenvironment by lactylation; (d) Regulation of autophagy by lactylation modification. AKR1B10, Aldehyde Ketone Reductase Family 1 B10; LDHA, Lactate Dehydrogenase A; CCNB1, cyclin B1; POM121, Pore Membrane Protein 121; PD-L1, Programmed cell Death 1-ligand 1; PD-l, Programmed Death-1 (The figure was made using Biorender)

4.2 Lactated Modification Promotes DNA Repair

Lactylation also affects DNA repair mechanisms, which are essential for the survival of cancer cells under therapeutic stress. In many cancers, the DNA damage response (DDR) pathway is upregulated to repair DNA lesions induced by chemotherapy and radiation. Lactate-induced lactylation has been shown to enhance the repair of DNA double-strand breaks by promoting the activity of DNA repair proteins. For example, in gastric cancer cells, the lactylation of NBS1 K388 is catalyzed by TIP60 on lactyl-CoA, promoting the formation of the NBS1-MRE11-RAD50 trimeric MRN complex and the accumulation of HR repair proteins at DNA double-strand break sites. Through the MRN complex sensing DNA double-strand breaks (DSB), activating DNA repair pathways, and the function of HR repair proteins, DNA repair in cancer cells is enhanced, producing drug resistance [66] (Fig. 3b). In glioblastoma, lactylation of the X-ray Repair Cross Complementing 1 (XRCC1) protein, a key player in DNA repair, enhances its ability to repair DNA damage, thereby contributing to the development of resistance to chemoradiotherapy. This enhanced DNA repair capacity allows cancer cells to develop resistance to the genotoxic effects of the chemotherapy drug temozolomide (TMZ) [71]. Enzymes that inhibit lactate production or involve lactylation may provide a novel strategy to sensitize tumors to DNA-damaging agents, especially in cancers where lactylation plays a key role in maintaining genomic stability.

4.3 Lactylation Modification Regulates the Immune Microenvironment

In addition to promoting metabolic reprogramming and enhancing DNA repair, lactylation also regulates the immune microenvironment, aiding in immune evasion and resistance to immunotherapy. Tumors often reprogram the immune microenvironment to evade immune surveillance, in which lactate plays a key role [20]. In the tumor microenvironment (TME), high levels of lactate suppress the function of immune cells, particularly cytotoxic T cells, and promote the polarization of immunosuppressive cells such as Tregs and M2 macrophages [31,32]. Lactylation further contributes to immune evasion by stabilizing immune checkpoint proteins and promoting the accumulation of Tregs in the TME. For example, in NSCLC, histone lactylation (3HK18la) activates the transcription of pore membrane protein 121 (POM121), which enhances the MYC nuclear translocator. The elevated levels of nuclear MYC bind directly to the CD274 promoter, inducing PD-L1 expression, significantly inhibiting Granzyme B (GzMB) and Interferon-γ (IFNγ) levels in cocultured Cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), attenuating the cytotoxicity of CTLs, and contributing to the immune escape of NSCLC cells [72,73] (Fig. 3c). This lactate-induced immunosuppression is a major obstacle to the effectiveness of immune checkpoint inhibitors, and targeting the lactylation pathway may help overcome resistance to immunotherapy by restoring immune function and promoting anti-tumor immunity.

4.4 Lactylation Modification Regulates Autophagy

Autophagy is a cellular mechanism that maintains homeostasis by degrading damaged organelles and proteins [74]. In cancer cells, autophagy is often upregulated in response to therapeutic stress, allowing the cells to survive harsh conditions. Lactate-induced lactylation has been shown to promote the expression of autophagy-related genes, which helps cancer cells adapt to nutrient deprivation and survive chemotherapy. For example, in metastatic colorectal cancers (CRC), histone H3 lysine 18 lactylation (H3K18la) promotes the transcription of RUBCNL genes, enhancing autophagy through autophagosome maturation and contributing to CRC progression [75] (Fig. 3d).

5 Clinical Significance of Lactylation and Tumor Drug Resistance

5.1 Reveal the Mechanism of Drug Resistance and Provide New Ideas for Drug Resistance Reversal

Lactylation contributes to drug resistance by modifying both histone and non-histone proteins, thereby regulating gene expression and activating key signaling pathways associated with chemoresistance, immunosuppression, and metabolic adaptation. Notably, studies in hepatocellular carcinoma, prostate cancer, melanoma, and lung cancer have demonstrated how lactylation drives specific resistance phenotypes, such as stabilizing Insulin-like Growth Factor 2 mRNA-Binding Protein 3 (IGF2BP3), promoting Wnt/β-catenin signaling, or expanding Tregs [62,73,76,77].

These examples collectively illustrate how lactylation-driven mechanisms operate across different tumor types, often converging on shared pathways such as metabolic rewiring, immune evasion, and enhanced survival signaling. By mapping these mechanisms, this review highlights lactylation as a core hub linking metabolic stress to therapeutic resistance. This understanding provides a theoretical foundation for developing rational combination therapies aimed at reversing resistance and improving treatment efficacy across multiple cancers.

5.2 It has Become an Important Biomarker for the Prediction and Stratification of Tumor Treatment Effects

The level of lactylation modification is closely related to the response of tumor cells to chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. Some studies have found that elevated lactylation levels are closely related to poor prognosis in patients, especially in immune checkpoint inhibitor treatment populations, and the high expression of lactylation-modifying proteins in tumor tissues may indicate the formation of an immunosuppressive microenvironment, which in turn affects treatment response [78,79]. Therefore, lactylation-related molecules such as histone H3 lysine 18 lactylation (H3K18la) [76], IGF2BP3 [62], and NSUN2 [80] are expected to be used as predictors of efficacy or patient typing tools to assist in precision treatment.

5.3 Provide New Targets and Combination Therapy Strategies for Anti-Drug Resistance Therapy

The formation of lactylation modification depends on the high lactate state in tumor cells, and targeting lactate production and lactylation-related enzymes (such as LDHA, p300, etc.) becomes an important strategy to reverse drug resistance. Studies have shown that LDH inhibitors such as FX11 can reduce lactate levels, reduce lactylation modifications, and restore chemotherapy sensitivity [81]; At the same time, the combination of metabolic modulators and existing chemotherapy/targeted drugs has demonstrated synergistic anti-tumor effects in a variety of tumor models [82]. In response to the immunosuppressive effect driven by lactylation modification, it can also form synergies with programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1)/ programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitors to enhance anti-tumor immune response and overcome immunotherapy resistance [73,83,84]. In addition, the role of lactylation in regulating angiogenesis and metastasis is a key process that supports tumor growth and metastasis. Lactylation has been shown to regulate the expression of angiogenic factors such as fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2) through lactated transcription factors such as YY1 [85]. This lactylation enhanced the transcriptional activity of YY1, which led to increased FGF2 expression and might be one of the mechanisms underlying its promotion of tumor angiogenesis. In addition, lactylation affects the metastatic potential of tumor cells by regulating the expression of proteins involved in cell migration and invasion. Therefore, targeted therapies targeting the lactylation pathway that regulates angiogenesis and metastasis may provide a novel strategy to inhibit tumor growth and prevent cancer from spreading to other organs. This approach may be particularly beneficial in cancers known to have positive metastatic behavior, such as breast [86], prostate [87], and lung [88] cancers.

5.4 Promote the Development of Individualized Treatment Strategies

Lactylation modification has certain plasticity and dynamics, which are regulated by multiple factors such as metabolic state, acidity of microenvironment, and partial pressure of oxygen. Therefore, the development of a strategy of “dynamic monitoring + precise intervention” based on lactylation modification-related markers will help to achieve individualized anti-drug resistance therapy in the true sense. For example, through the dynamic monitoring of lactylation modification profile, the patient’s response to a treatment strategy can be assessed in real time, and the treatment plan can be adjusted in time to improve the efficacy and avoid unnecessary toxic side effects.

6 Limitations and Challenges of Current Research

Although lactylation has attracted considerable attention as a post-translational modification affecting cancer biology, there are still some challenges that hinder its comprehensive understanding and clinical application in cancer drug resistance. One of the main limitations is the lack of precise and standardized techniques to measure lactylation in biological samples. In contrast to more established PTMs such as acetylation or phosphorylation, lactylation is still in the exploratory stage, and the tools for detecting and quantifying this modification have not been fully developed. Current methods, such as western blotting and mass spectrometry, still need to be further optimized to reliably measure lactylation in a variety of tissue types, especially clinical samples. In addition, the lack of universal antibodies against lactylated proteins complicates the study of this modification in different cancers, limiting its application in clinical settings.

Another challenge is the complexity of explaining the biological significance of lactylation. Although lactylation has been shown to play a role in cancer progression and drug resistance, its exact mechanism remains unclear. The dual role of lactylation as both a metabolic signal and an epigenetic regulator makes it difficult to determine whether it is primarily involved in tumorigenesis, progression, or resistance. For example, studies have shown that lactylation of histones can regulate gene transcription and promote tumor survival, but it remains uncertain whether lactylation is a major driver of these processes or simply reflects secondary metabolic changes [21]. More comprehensive functional studies are needed to determine the exact role of lactylation in various cellular pathways and to assess its impact on chemoresistance.

The lack of established biomarkers of lactylation-related modifications is also an obstacle to its clinical application. While certain lactylation-related features, such as those found in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [89,90] and pancreatic adenocarcinoma [91,92], show potential to predict patient outcomes, but they are still in their early stages. For example, the lactylation-related gene signatures identified for TNBC, while promising, have not been validated in larger clinical cohorts or applied to treatment decisions. In addition, lactylation-related features often overlap with other molecular features, such as glycolysis and hypoxic pathways, which makes it difficult to attribute changes in drug resistance specifically to lactylation without further unraveling these interrelated mechanisms.

As the understanding of the role of lactylation in cancer drug resistance continues to advance, the review has identified three promising future research directions.

First, develop reliable, standardized methods to quantify lactylation in a clinical setting. Advancing the sensitivity and specificity of these assays is critical to translating lactylation studies into therapeutic contexts. More accurate quantification of lactylation modifications, especially in tumor samples, will help better understand and target lactylation pathways in cancer.

Second, further research is needed on the molecular mechanisms by which lactylation affects cancer progression and drug resistance. While lactylation has been shown to modulate key proteins involved in DNA repair and immune regulation, its full role in different cancer types remains unclear. For example, how lactylation interacts with other post-translational modifications, such as acetylation and methylation, to drive tumorigenesis remains to be fully elucidated. Understanding these interactions is critical to determining the precise role of lactylation in the molecular network that regulates cancer cell survival and drug resistance. In addition, the potential of lactylation in modulating tumor cell plasticity and metastasis needs to be explored further, as these processes are central to treatment failure.

Finally, since lactylation is associated with metabolic reprogramming, targeting lactate metabolism provides a new therapeutic strategy to overcome drug resistance. Recent studies have shown that targeting lactate production and lactylation offers the potential to sensitize tumor cells to chemotherapy and immunotherapy [93,94]. Combining lactate metabolism inhibitors, such as LDHA inhibitors, with traditional cancer treatments may enhance treatment effectiveness and reduce the development of resistance [94]. In addition, understanding how lactylation affects immune cell function opens up new avenues for immunotherapy, as lactate-mediated lactylation in immune cells may promote immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Targeting these metabolic and epigenetic pathways represents a promising strategy to improve cancer treatment outcomes and address the challenge of drug resistance.

In conclusion, lactylation provides a novel and promising target for cancer therapy, especially in the context of drug resistance. Further study of the molecular mechanisms of lactylation, its role in various cellular processes, and its potential as a therapeutic target will provide valuable insights into overcoming cancer treatment resistance. Combining strategies that target lactylation with existing treatments can significantly improve treatment outcomes and provide new avenues for personalized cancer care.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Anhui Provincial Health Commission Provincial Financial Support for Youth Programs (No. AHWJ2023A30159) and Wuhu Science and Technology Program Project (No. 2024kj072).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Guangyao Li; draft manuscript preparation: Xiangnan Feng and Dayong Li; visualization: Pingyu Wang and Xinyu Li; supervision: Guangyao Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| HCC | Hepatocellular carcinoma |

| PC | Pancreatic cancer |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| PTMs | Protein post-translational modifications |

| LDH | Lactate dehydrogenase |

| LDHA | Lactate dehydrogenase A |

| MCTs | Monocarboxylic acid transporters |

| CoA | Coenzyme A |

| PKM2 | Pyruvate kinase M2 |

| PDK1 | Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 |

| MCT4 | Monocarboxylate transporter 4 |

| PDH | Pyruvate dehydrogenase |

| H3K18la | Histone H3 lysine 18 lactylation |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| CML | Chronic myeloid leukemia |

| TKIs | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

| MOMP | Mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization |

| ATGs | Autophagy-related genes |

| TME | The tumor microenvironment |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| CAFs | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| MDSCs | Marrow-derived suppressor cells |

| CSCs | Cancer stem cells |

| AKR1B10 | Aldehyde ketone reductase family 1 B10 |

| H4K12la | H4 lysine 12 lactylation |

| DDR | DNA damage response |

| DSB | DNA double-strand breaks |

| TMZ | Temozolomide |

| Tregs | T cells |

| POM121 | Pore membrane protein 121 |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| APOC2 | Apolipoprotein C-II |

| FGF2 | Fibroblast growth factor 2 |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

References

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. doi:10.3322/caac.21660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen X, Giles J, Yao Y, Yip W, Meng Q, Berkman L, et al. The path to healthy ageing in China: a Peking University-lancet commission. Lancet. 2022 Dec 3;400(10367):1967–2006. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(22)01546-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, Chen R, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2016. J Natl Cancer Cent. 2022;2(1):1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jncc.2022.02.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Hwang SY, Danpanichkul P, Agopian V, Mehta N, Parikh ND, Abou-Alfa GK, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: updates on epidemiology, surveillance, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2025;31:S228–54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Jokhadze N, Das A, Dizon DS. Global cancer statistics: a healthy population relies on population health. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):224–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

6. Torimura T, Iwamoto H. Treatment and the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. Liver Int. 2022;42(9):2042–54. doi:10.1111/liv.15130. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ducreux M, Abou-Alfa GK, Bekaii-Saab T, Berlin J, Cervantes A, de Baere T, et al. The management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Current expert opinion and recommendations derived from the 24th ESMO/World Congress on Gastrointestinal Cancer, Barcelona, 2022. ESMO Open. 2023;8(3):101567. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

8. Tang W, Chen Z, Zhang W, Cheng Y, Zhang B, Wu F, et al. The mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: theoretical basis and therapeutic aspects. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):87. doi:10.1038/s41392-020-0187-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. He K, An S, Liu F, Chen Y, Xiang G, Wang H. Integrative analysis of multi-omics data reveals inhibition of RB1 signaling promotes apatinib resistance of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(14):4511–24. doi:10.7150/ijbs.83862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Zhu AX, Abbas AR, de Galarreta MR, Guan Y, Lu S, Koeppen H, et al. Molecular correlates of clinical response and resistance to atezolizumab in combination with bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Med. 2022;28(8):1599–611. doi:10.1038/s41591-022-01868-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Will M, Liang J, Metcalfe C, Chandarlapaty S. Therapeutic resistance to anti-oestrogen therapy in breast cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2023;23(10):673–85. doi:10.1038/s41568-023-00604-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Eichner LJ, Curtis SD, Brun SN, McGuire CK, Gushterova I, Baumgart JT, et al. HDAC3 is critical in tumor development and therapeutic resistance in Kras-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Adv. 2023;9(11):eadd3243. doi:10.1126/sciadv.add3243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zeng S, Pöttler M, Lan B, Grützmann R, Pilarsky C, Yang H. Chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18):4504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Zhu Z, Zheng X, Zhao P, Chen C, Xu G, Ke X. Potential of lactylation as a therapeutic target in cancer treatment (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2025;31(4):91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Ferguson BS, Rogatzki MJ, Goodwin ML, Kane DA, Rightmire Z, Gladden LB. Lactate metabolism: historical context, prior misinterpretations, and current understanding. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118(4):691–728. doi:10.1007/s00421-017-3795-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Brooks GA. Lactate shuttles in nature. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30(2):258–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Liberti MV, Locasale JW. The warburg effect: how does it benefit cancer cells? Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41(3):211–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

18. Zhang D, Tang Z, Huang H, Zhou G, Cui C, Weng Y, et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature. 2019;574(7779):575–80. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1678-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Yu X, Yang J, Xu J, Pan H, Wang W, Yu X, et al. Histone lactylation: from tumor lactate metabolism to epigenetic regulation. Int J Biol Sci. 2024;20(5):1833–54. doi:10.7150/ijbs.91492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Yang Z, Zheng Y, Gao Q. Lysine lactylation in the regulation of tumor biology. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2024;35(8):720–31. doi:10.1016/j.tem.2024.01.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Li H, Sun L, Gao P, Hu H. Lactylation in cancer: current understanding and challenges. Cancer Cell. 2024;42(11):1803–7. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2024.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Chen J, Huang Z, Chen Y, Tian H, Chai P, Shen Y, et al. Lactate and lactylation in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):38. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-02082-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Iozzo M, Pardella E, Giannoni E, Chiarugi P. The role of protein lactylation: a kaleidoscopic post-translational modification in cancer. Mol Cell. 2025;85(7):1263–79. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2025.02.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Liu R, Ren X, Park YE, Feng H, Sheng X, Song X, et al. Nuclear GTPSCS functions as a lactyl-CoA synthetase to promote histone lactylation and gliomagenesis. Cell Metab. 2025;37(2):377–94.e9. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2024.11.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Zhu R, Ye X, Lu X, Xiao L, Yuan M, Zhao H, et al. ACSS2 acts as a lactyl-CoA synthetase and couples KAT2A to function as a lactyltransferase for histone lactylation and tumor immune evasion. Cell Metab. 2025;37(2):361–76.e7. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2024.10.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zhang XW, Li L, Liao M, Liu D, Rehman A, Liu Y, et al. Thermal proteome profiling strategy identifies CNPY3 as a cellular target of gambogic acid for inducing prostate cancer pyroptosis. J Med Chem. 2024;67(12):10005–11. doi:10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c00140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Fan Z, Liu Z, Zhang N, Wei W, Cheng K, Sun H, et al. Identification of SIRT3 as an eraser of H4K16la. iScience. 2023;26(10):107757. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2023.107757. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Jin J, Bai L, Wang D, Ding W, Cao Z, Yan P, et al. SIRT3-dependent delactylation of cyclin E2 prevents hepatocellular carcinoma growth. EMBO Rep. 2023;24(5):e56052. doi:10.15252/embr.202256052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wang N, Wang W, Wang X, Mang G, Chen J, Yan X, et al. Histone lactylation boosts reparative gene activation post-myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2022;131(11):893–908. doi:10.1161/circresaha.122.320488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Agbleke AA, Amitai A, Buenrostro JD, Chakrabarti A, Chu L, Hansen AS, et al. Advances in chromatin and chromosome research: perspectives from multiple fields. Mol Cell. 2020;79(6):881–901. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2020.07.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ma W, Ao S, Zhou J, Li J, Liang X, Yang X, et al. Methylsulfonylmethane protects against lethal dose MRSA-induced sepsis through promoting M2 macrophage polarization. Mol Immunol. 2022;146(10):69–77. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2022.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hayes C, Donohoe CL, Davern M, Donlon NE. The oncogenic and clinical implications of lactate induced immunosuppression in the tumour microenvironment. Cancer Lett. 2021;500(5):75–86. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2020.12.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Lam N, Lee Y, Farber DL. A guide to adaptive immune memory. Nat Rev Immunol. 2024;24(11):810–29. doi:10.1038/s41577-024-01040-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Li Y, Li Q, Zhang K, Wu Y, Nuerlan G, Wang X, et al. Metabolic rewiring and post-translational modifications: unlocking the mechanisms of bone turnover in osteoporosis. Aging Dis. 2026;17(2):1–28. doi:10.14336/AD.2025.0123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Merkuri F, Rothstein M, Simoes-Costa M. Histone lactylation couples cellular metabolism with developmental gene regulatory networks. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):90. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-44121-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Dong Q, Zhang Q, Yang X, Nai S, Du X, Chen L. Glycolysis-stimulated esrrb lactylation promotes the self-renewal and extraembryonic endoderm stem cell differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(5):2692. doi:10.3390/ijms25052692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Gong H, Zhong H, Cheng L, Li LP, Zhang DK. Post-translational protein lactylation modification in health and diseases: a double-edged sword. J Transl Med. 2024;22(1):41. doi:10.1186/s12967-023-04842-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Sun S, Xu Z, He L, Shen Y, Yan Y, Lv X, et al. Metabolic regulation of cytoskeleton functions by HDAC6-catalyzed α-tubulin lactylation. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):8377. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-3917945/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Li F, Si W, Xia L, Yin D, Wei T, Tao M, et al. Positive feedback regulation between glycolysis and histone lactylation drives oncogenesis in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):90. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-02008-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Vaupel P, Multhoff G. Revisiting the Warburg effect: historical dogma versus current understanding. J Physiol. 2021;599(6):1745–57. doi:10.1113/jp278810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Fan H, Yang F, Xiao Z, Luo H, Chen H, Chen Z, et al. Lactylation: novel epigenetic regulatory and therapeutic opportunities. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metab. 2023;324(4):E330–8. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00159.2022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Li X, Yang Y, Zhang B, Lin X, Fu X, An Y, et al. Lactate metabolism in human health and disease. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):305. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01206-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Wang J, Wang Z, Wang Q, Li X, Guo Y. Ubiquitous protein lactylation in health and diseases. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2024;29(1):23. doi:10.1186/s11658-024-00541-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Li F, Zhang H, Huang Y, Li D, Zheng Z, Xie K, et al. Single-cell transcriptome analysis reveals the association between histone lactylation and cisplatin resistance in bladder cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 2024;73(45):101059. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2024.101059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Kzhyshkowska J, Shen J, Larionova I. Targeting of TAMs: can we be more clever than cancer cells? Cell Mol Immunol. 2024;21(12):1376–409. doi:10.1038/s41423-024-01232-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Kopecka J, Salaroglio IC, Perez-Ruiz E, Sarmento-Ribeiro AB, Saponara S, De Las Rivas J, et al. Hypoxia as a driver of resistance to immunotherapy. Drug Resist Updat. 2021;59(S2):100787. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2021.100787. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Gonçalves AC, Richiardone E, Jorge J, Polónia B, Xavier CPR, Salaroglio IC, et al. Impact of cancer metabolism on therapy resistance—clinical implications. Drug Resist Updat. 2021;59(2020):100797. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2021.100797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Braun TP, Eide CA, Druker BJ. Response and resistance to BCR-ABL1-targeted therapies. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(4):530–42. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2020.03.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Cooper AJ, Sequist LV, Lin JJ. Third-generation EGFR and ALK inhibitors: mechanisms of resistance and management. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2022;19(8):499–514. doi:10.1038/s41571-022-00639-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Carneiro BA, El-Deiry WS. Targeting apoptosis in cancer therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2020;17(7):395–417. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-0341-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Niu X, You Q, Hou K, Tian Y, Wei P, Zhu Y, et al. Autophagy in cancer development, immune evasion, and drug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2025;78(3):101170. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2024.101170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Maiuri MC, Le Toumelin G, Criollo A, Rain JC, Gautier F, Juin P, et al. Functional and physical interaction between Bcl-X(L) and a BH3-like domain in Beclin-1. EMBO J. 2007;26(10):2527–39. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7601689. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Ma L, Hernandez MO, Zhao Y, Mehta M, Tran B, Kelly M, et al. Tumor cell biodiversity drives microenvironmental reprogramming in liver cancer. Cancer Cell. 2019;36(4):418–30.e6. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2019.08.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Zhang H, Yue X, Chen Z, Liu C, Wu W, Zhang N, et al. Define cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in the tumor microenvironment: new opportunities in cancer immunotherapy and advances in clinical trials. Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):159. doi:10.1186/s12943-023-01860-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Kundu M, Butti R, Panda VK, Malhotra D, Das S, Mitra T, et al. Modulation of the tumor microenvironment and mechanism of immunotherapy-based drug resistance in breast cancer. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):92. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-01990-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Arechederra M, Bazai SK, Abdouni A, Sequera C, Mead TJ, Richelme S, et al. ADAMTSL5 is an epigenetically activated gene underlying tumorigenesis and drug resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2021;74(4):893–906. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2020.11.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Wang X, Wang Y, Xie M, Ma S, Zhang Y, Wang L, et al. Hypermethylation of CDKN2A CpG island drives resistance to PRC2 inhibitors in SWI/SNF loss-of-function tumors. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(11):794. doi:10.1038/s41419-024-07109-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Huang T, Song X, Xu D, Tiek D, Goenka A, Wu B, et al. Stem cell programs in cancer initiation, progression, and therapy resistance. Theranostics. 2020;10(19):8721–43. doi:10.7150/thno.41648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Yue Q, Wang Z, Shen Y, Lan Y, Zhong X, Luo X, et al. Histone H3K9 lactylation confers temozolomide resistance in glioblastoma via LUC7L2-mediated MLH1 intron retention. Adv Sci. 2024;11(19):2309290. doi:10.1002/advs.202309290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Li J, Chen Z, Jin M, Gu X, Wang Y, Huang G, et al. Histone H4K12 lactylation promotes malignancy progression in triple-negative breast cancer through SLFN5 downregulation. Cell Signal. 2024;124(3):111468. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2024.111468. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Niu K, Chen Z, Li M, Ma G, Deng Y, Zhang J, et al. NSUN2 lactylation drives cancer cell resistance to ferroptosis through enhancing GCLC-dependent glutathione synthesis. Redox Biol. 2025;79:103479. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2024.103479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Lu Y, Zhu J, Zhang Y, Li W, Xiong Y, Fan Y, et al. Lactylation-driven IGF2BP3-mediated serine metabolism reprogramming and RNA m6A-modification promotes lenvatinib resistance in HCC. Adv Sci. 2024;11(46):e2401399. doi:10.1002/advs.202401399. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Sun K, Zhang X, Shi J, Huang J, Wang S, Li X, et al. Elevated protein lactylation promotes immunosuppressive microenvironment and therapeutic resistance in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2025;135(7):e187024. doi:10.1172/jci187024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Cheng S, Chen L, Ying J, Wang Y, Jiang W, Zhang Q, et al. 20(S)-ginsenoside Rh2 ameliorates ATRA resistance in APL by modulating lactylation-driven METTL3. J Ginseng Res. 2024;48(3):298–309. doi:10.1016/j.jgr.2023.12.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Zong Z, Xie F, Wang S, Wu X, Zhang Z, Yang B, et al. Alanyl-tRNA synthetase, AARS1, is a lactate sensor and lactyltransferase that lactylates p53 and contributes to tumorigenesis. Cell. 2024;187(10):2375–92.e33. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.04.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Chen H, Li Y, Li H, Chen X, Fu H, Mao D, et al. NBS1 lactylation is required for efficient DNA repair and chemotherapy resistance. Nature. 2024;631(8021):663–9. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07620-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Yang Z, Yan C, Ma J, Peng P, Ren X, Cai S, et al. Lactylome analysis suggests lactylation-dependent mechanisms of metabolic adaptation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Metab. 2023;5(1):61–79. doi:10.1038/s42255-022-00710-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Deng J, Li Y, Yin L, Liu S, Li Y, Liao W, et al. Histone lactylation enhances GCLC expression and thus promotes chemoresistance of colorectal cancer stem cells through inhibiting ferroptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16(1):193. doi:10.1038/s41419-025-07498-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Shi L, Li B, Tan J, Zhu L, Zhang S, Zhang Y, et al. Exosomal lncRNA Mir100hg from lung cancer stem cells activates H3K14 lactylation to enhance metastatic activity in non-stem lung cancer cells. J Nanobiotechnology. 2025;23(1):156. doi:10.1186/s12951-025-03198-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Duan W, Liu W, Xia S, Zhou Y, Tang M, Xu M, et al. Warburg effect enhanced by AKR1B10 promotes acquired resistance to pemetrexed in lung cancer-derived brain metastasis. J Transl Med. 2023;21(1):547. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-2331831/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Li G, Wang D, Zhai Y, Pan C, Zhang J, Wang C, et al. Glycometabolic reprogramming-induced XRCC1 lactylation confers therapeutic resistance in ALDH1A3-overexpressing glioblastoma. Cell Metab. 2024;36(8):1696–710.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2024.07.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Zhang C, Zhou L, Zhang M, Du Y, Li C, Ren H, et al. H3K18 lactylation potentiates immune escape of non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res. 2024;84(21):3589–601. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-23-3513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Chen J, Zhao D, Wang Y, Liu M, Zhang Y, Feng T, et al. Lactylated apolipoprotein C-II induces immunotherapy resistance by promoting extracellular lipolysis. Adv Sci. 2024;11(38):e2406333. doi:10.1002/advs.202470226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Levine B, Kroemer G. Biological functions of autophagy genes: a disease perspective. Cell. 2019;176(1–2):11–42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

75. Li W, Zhou C, Yu L, Hou Z, Liu H, Kong L, et al. Tumor-derived lactate promotes resistance to bevacizumab treatment by facilitating autophagy enhancer protein RUBCNL expression through histone H3 lysine 18 lactylation (H3K18la) in colorectal cancer. Autophagy. 2024;20(1):114–30. doi:10.1080/15548627.2023.2249762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Chaudagar K, Hieromnimon HM, Kelley A, Labadie B, Shafran J, Rameshbabu S, et al. Suppression of tumor cell lactate-generating signaling pathways eradicates murine PTEN/p53-deficient aggressive-variant prostate cancer via macrophage phagocytosis. Clinical Cancer Research. 2023;29(23):4930–40. doi:10.1101/2023.05.23.540590. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Chaudagar K, Hieromnimon HM, Khurana R, Labadie B, Hirz T, Mei S, et al. Reversal of lactate and PD-1-mediated macrophage immunosuppression controls growth of PTEN/p53-deficient prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(10):1952–68. doi:10.1136/jitc-2022-sitc2022.0879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Yang H, Zou X, Yang S, Zhang A, Li N, Ma Z. Identification of lactylation related model to predict prognostic, tumor infiltrating immunocytes and response of immunotherapy in gastric cancer. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1149989. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1149989. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Cheng Z, Huang H, Li M, Liang X, Tan Y, Chen Y. Lactylation-related gene signature effectively predicts prognosis and treatment responsiveness in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pharmaceuticals. 2023;16(5):644. doi:10.3390/ph16050644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Wang K, Kong F, Han X, Zhi Y, Wang H, Ren C, et al. Integrative multi-omics reveal NSUN2 facilitates glycolysis and histone lactylation-driven immune evasion in renal carcinoma. Genes Immun. 2025;13:286. doi:10.1038/s41435-025-00336-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. He Y, Chen X, Yu Y, Li J, Hu Q, Xue C, et al. LDHA is a direct target of miR-30d-5p and contributes to aggressive progression of gallbladder carcinoma. Mol Carcinog. 2018;57(6):772–83. doi:10.1002/mc.22799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Lee B, Park OK, Pan L, Kim K, Kang T, Kim H, et al. Co-delivery of metabolic modulators leads to simultaneous lactate metabolism inhibition and intracellular acidification for synergistic cancer therapy. Adv Mater. 2023;35(46):e2305512. doi:10.1002/adma.202305512. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Cai J, Song L, Zhang F, Wu S, Zhu G, Zhang P, et al. Targeting SRSF10 might inhibit M2 macrophage polarization and potentiate anti-PD-1 therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Commun. 2024;44(11):1231–60. doi:10.1002/cac2.12607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Huang ZW, Zhang XN, Zhang L, Liu LL, Zhang JW, Sun YX, et al. STAT5 promotes PD-L1 expression by facilitating histone lactylation to drive immunosuppression in acute myeloid leukemia. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):391. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01605-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Wang X, Fan W, Li N, Ma Y, Yao M, Wang G, et al. YY1 lactylation in microglia promotes angiogenesis through transcription activation-mediated upregulation of FGF2. Genome Biol. 2023;24(1):87. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-910016/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Hou X, Ouyang J, Tang L, Wu P, Deng X, Yan Q, et al. KCNK1 promotes proliferation and metastasis of breast cancer cells by activating lactate dehydrogenase A (LDHA) and up-regulating H3K18 lactylation. PLoS Biol. 2024;22(6):e3002666. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.3002666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Luo Y, Yang Z, Yu Y, Zhang P. HIF1α lactylation enhances KIAA1199 transcription to promote angiogenesis and vasculogenic mimicry in prostate cancer. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;222(Pt B):2225–43. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.10.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Yan F, Teng Y, Li X, Zhong Y, Li C, Yan F, et al. Hypoxia promotes non-small cell lung cancer cell stemness, migration, and invasion via promoting glycolysis by lactylation of SOX9. Cancer Biol Ther. 2024;25(1):2304161. doi:10.1080/15384047.2024.2304161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Cui Z, Li Y, Lin Y, Zheng C, Luo L, Hu D, et al. Lactylproteome analysis indicates histone H4K12 lactylation as a novel biomarker in triple-negative breast cancer. Front Endocrinol. 2024;15:1328679. doi:10.3389/fendo.2024.1328679. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Zhu Y, Fu Y, Liu F, Yan S, Yu R. Appraising histone H4 lysine 5 lactylation as a novel biomarker in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):8205. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-92666-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Zheng Y, Yang Y, Xiong Q, Ma Y, Zhu Q. Establishment and verification of a novel gene signature connecting hypoxia and lactylation for predicting prognosis and immunotherapy of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma patients by integrating multi-machine learning and single-cell analysis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(20):11143. doi:10.3390/ijms252011143. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Peng T, Sun F, Yang JC, Cai MH, Huai MX, Pan JX, et al. Novel lactylation-related signature to predict prognosis for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30(19):2575–602. doi:10.3748/wjg.v30.i19.2575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Lin J, Liu G, Chen L, Kwok HF, Lin Y. Targeting lactate-related cell cycle activities for cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022;86(Pt 3):1231–43. doi:10.1016/j.semcancer.2022.10.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Qu J, Li P, Sun Z. Histone lactylation regulates cancer progression by reshaping the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1284344. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1284344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools