Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Outcomes and Toxicity of Adult Medulloblastoma Treated with Pediatric Multimodal Protocols: A Single-Institution Experience

1 Pediatric Oncology Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, 00168, Italy

2 Department of Women and Child Health and Public Health, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, 00168, Italy

3 ARC Advanced Radiology Center (ARC), Department of Oncological Radiotherapy and Hematology, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, 00168, Italy

4 Pediatric Neurosurgery, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli, IRCCS, Rome, 00168, Italy

5 Department of Neuroscience, Section of Neurosurgery, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, 00168, Italy

6 Gemelli Advanced Radiotherapy, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario A. Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, 00168, Italy

7 Neurosurgery Unit, Department of Neurosciences, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, Rome, 00168, Italy

8 Neurosurgery Unit, Department of Neurosciences, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Rome, 00168, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Antonio Ruggiero. Email:

Oncology Research 2025, 33(12), 3855-3867. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.067948

Received 16 May 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

Background: Adult medulloblastoma (MB) represents less than 1% of central nervous system malignancies, lacking standardized therapeutic approaches due to its rarity. This retrospective single-center analysis aimed to assess survival outcomes and treatment-associated toxicities in adult MB patients managed with pediatric-derived protocols. Methods: Eighteen patients (≥18 years) with MB treated at Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS) (January 1997–January 2024) were analyzed. All received craniospinal radiotherapy with posterior fossa boost, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy utilizing pediatric regimens (PNET3, PNET4, PNET5, or high-risk protocols incorporating high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue). Primary outcomes included overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). Secondary analyses focused on comprehensive toxicity assessment. Results: The cohort included 11 males and 7 females (median age: 23 years). Metastatic disease was present in 6 patients (33%) at diagnosis. Histopathological distribution showed classic MB (55.5%), desmoplastic/nodular (39%), and large cell/anaplastic variants (5.5%). Molecular subgrouping (available in 6 patients) identified SHH subgroup in four cases and WNT subgroup in two. Three-year and five-year overall survival rates reached 94.5% and 88.8%, respectively. Treatment-related adverse events included grade 3–4 hematologic toxicities, clinically significant weight loss, and grade ≥3 neurological and ototoxic complications. These toxicities necessitated treatment modifications including dose adjustments, cycle delays, and occasional early discontinuation. Conclusions: Adult MB patients treated with pediatric-adapted protocols demonstrated excellent long-term survival outcomes, comparable to or surpassing historical data. Despite frequent toxicity requiring treatment modifications, these regimens proved feasible with acceptable risk-benefit profiles. These results support implementing modified pediatric protocols for adult MB management. Future multicenter investigations with larger cohorts are essential for refining risk stratification, optimizing treatment intensity, and evaluating long-term outcomes in this rare malignancy.Keywords

Medulloblastoma (MB), first characterized by Cushing and Bailey in 1925, is an aggressive grade IV embryonal tumor originating in the posterior cranial fossa [1]. MB shows a significant difference in frequency between age groups: it represents 15%–20% of all central nervous system (CNS) tumors in children aged 0–14 years, but occurs much less frequently in adults, accounting for less than 1% of CNS malignancies with an estimated incidence of only 0.6–1 case per million adults annually [2–4].

Treatment approaches for MB have evolved significantly since the 1950s, with particularly notable success in pediatric protocols. The integration of craniospinal radiotherapy with chemotherapy in the 1970s has revolutionized pediatric management, yielding current 5-year survival rates exceeding 80% for standard-risk cases and 60%–70% for high-risk pediatric patients [5,6]. Adult treatment has not consistently achieved comparable success rates, as patients frequently receive either modified pediatric regimens or adult-specific protocols that have not undergone the same rigorous multicenter validation process characteristic of pediatric trials. This disparity stems largely from biological differences in tumor behavior between age groups and the relative rarity of adult MB, which complicates the establishment of standardized treatment protocols [7].

Risk stratification in MB management has traditionally depended on a multifactorial assessment incorporating patient age at diagnosis, presence and extent of metastatic disease, degree of surgical resection achievable, and specific histological subtype characteristics, with these parameters serving as the cornerstone for treatment protocol selection and prognostic evaluation [8–10]. The Chang classification system (M0–M4) continues to guide metastatic staging despite its limitations in characterizing metastatic lesions beyond anatomical location. This classification creates particular challenges in risk assessment, as patients classified as M1 are now considered high-risk, despite ongoing debates regarding their prognosis compared to patients with solid metastases. The persistence of residual tumor exceeding 1.5 cm2 post-resection necessitates treatment intensification in established protocols, though recent clinical investigations challenge assumptions about subtotal resection inevitably yielding inferior outcomes compared to gross total resection, particularly when considering potential neurological morbidity associated with aggressive surgical approaches [9,10].

The identification of four molecular subgroups (WNT, SHH, Group 3, Group 4) defined by specific molecular alterations including pathway activations, chromosomal aberrations, and distinct mutational profiles has transformed MB classification with important age-related implications [5,11,12]. WNT tumors demonstrate excellent prognosis in children regardless of treatment intensity, while adult WNT tumors may exhibit less favorable outcomes [13]. SHH subgroup tumors predominate in both infants and adults but display markedly different genetic alterations and clinical behaviors between these age groups, necessitating different therapeutic approaches [14,15].

Adult MB demonstrates a different distribution of molecular subtypes compared to pediatric cases, with SHH subgroup tumors representing approximately 60% of adult cases vs. only 30% in children. Group 3 tumors, which carry the poorest prognosis in children, are exceedingly rare in adults, while Group 4 tumors occur in both populations but may exhibit different biological behavior across age groups [16].

Pediatric MB protocols have emerged from sequential multicenter trials, establishing well-defined regimens that balance efficacy against toxicity [17–19]. These typically incorporate risk-adapted craniospinal irradiation followed by intensive multiagent chemotherapy including cisplatin, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and etoposide [20,21]. Children generally demonstrate superior tolerance to these intensive regimens with appropriate supportive care [21–23]. In contrast, adult MB treatment lacks standardized protocols specifically designed for adult physiology and tumor biology. Many treatment centers apply modified pediatric regimens to adult patients, but these adaptations often result in increased toxicity leading to treatment interruptions, dose reductions, or premature termination of therapy. Hematological toxicity, neurotoxicity, and ototoxicity represent particularly challenging adverse effects in the adult population [24–26].

The integration of molecular profiling into clinical decision-making offers promising avenues for improving MB management across age groups. For pediatric patients, this approach has already enabled treatment de-escalation for favorable-risk groups (particularly WNT tumors) while maintaining excellent survival outcomes [11,14]. Similar molecular-guided treatment customization may benefit adult patients, though adult-specific prognostic markers require further validation through larger cohort studies.

Our institution has pioneered an approach applying pediatric treatment protocols to adult MB patients, with particular emphasis on understanding the role of adjuvant chemotherapy at initial diagnosis and assessing treatment tolerance. This strategy aims to overcome the historical disparities in outcomes between pediatric and adult populations by leveraging the extensively validated pediatric protocols with appropriate modifications for adult physiology. Our experience suggests that with careful management of toxicities and individualized supportive care, many adult patients can successfully complete modified pediatric regimens with improved outcomes compared to traditional adult approaches. This work contributes to addressing the significant gap in evidence-based treatment guidelines for adult MB. It provides valuable insights into the feasibility and efficacy of applying pediatric protocols across age groups for this rare but aggressive malignancy.

Management of MB in adult patients remains challenging due to the absence of universally accepted guidelines and conflicting evidence regarding treatment efficacy and tolerability. We performed a retrospective analysis of adult MB patients treated with pediatric protocols at our institution to evaluate long-term survival outcomes and comprehensively assess treatment-related toxicities, with particular focus on regimen adherence and completion rates.

2.2 Study Design and Patient Selection

This single-center retrospective study analyzed data from 18 consecutive adult patients with MB admitted to the Pediatric Oncology Unit, Fondazione Policlinico Universitario Agostino Gemelli IRCCS, between 01 January 1997 and 01 January 2024. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Università Cattolica Sacro Cuore-Policlinico Gemelli IRCCS (number DIPUSVSP-21-03-252). All patients provided written informed consent prior to enrolment.

The inclusion criteria for this study require participants to be at least 18 years of age at the time of their MB diagnosis. All participants must have a histopathologically confirmed diagnosis of MB. Additionally, participants must have received treatment using pediatric chemotherapy protocols rather than adult treatment regimens. Complete documentation of toxicity data throughout both the treatment period and subsequent follow-up care must be available for each participant included in the study.

The exclusion criteria eliminate participants who were younger than 18 years at diagnosis from the study population. Patients without a confirmed histological diagnosis of MB were also excluded, as were those with incomplete documentation of treatment-related toxicities during either the active treatment phase or follow-up period. Finally, patients who received treatment with chemotherapy regimens designed for adult populations rather than pediatric protocols were excluded from participation in this research.

The primary objective was to determine the overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) at 3- and 5-year. Secondary objectives included descriptive analysis of short-term and long-term toxicities associated with adjuvant chemotherapy in adult MB patients and characterization of the clinical features of adult MB.

Medical records were analyzed to extract the following information: age at diagnosis; sex; histological diagnosis and molecular subtyping (when available); primary tumor location; date of diagnosis; presence of metastatic disease at diagnosis; neurosurgical procedure details and timing; chemotherapeutic agents administered; radiotherapy characteristics (timing, dosage, target volumes); treatment modifications (dose reductions, delays, discontinuations); hematological toxicities; audiological toxicities; neurological toxicities; nutritional difficulties and weight loss; disease recurrence; minimum 12-month follow-up.

2.5 Disease Classification and Risk Stratification

Post-operative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed within 48 h of surgery and interpreted by a neuroradiologist to determine the extent of resection. When MRI was unavailable, the extent of resection was determined from the surgeon’s operative report. Patients in this study were categorized into distinct risk groups based on specific clinical and radiological characteristics. The standard-risk group included patients who showed no evidence of metastatic disease when evaluated through MRI or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis, and who had residual tumor measuring less than 1.5 cm2 following initial treatment. In contrast, patients were classified as high-risk if they demonstrated the presence of metastatic disease, defined as Chang stage M1 or higher, or if their residual tumor exceeded 1.5 cm2 in size. Molecular subtyping was performed when feasible using a combination of immunohistochemistry, DNA methylation arrays, next-generation sequencing, and targeted reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) for mRNA expression analysis.

All patients received craniospinal radiation therapy (RT) with a boost to the primary MB site. The total radiation dose varied according to treatment protocol. Patients received adjuvant chemotherapy with different pediatric regimens, including PNET3 (vincristine, etoposide, carboplatin, and cyclophosphamide), PNET4 (vincristine, cisplatin, and lomustine, and), PNET5 (vincristine, cisplatin, lomustine, and cyclophosphamide), and other combined regimens.

For patients treated with the PNET3 protocol, chemotherapy was administered after the completion of radiotherapy (35 Gy to the craniospinal axis with a boost to 54–58 Gy on the posterior cranial fossa), rather than before RT as specified in the original protocol. This modification was based on evidence from the German HIT91 study indicating that pre-RT chemotherapy was associated with myelotoxicity leading to RT delays or interruptions, and findings from the SIOPII trial demonstrating no benefit from pre-RT chemotherapy [17,18,20].

Treatment-related toxicities were classified according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5.0 (CTCAE) of the National Cancer Institute (NCI) (published 27 November 2017), with the exception of audiological toxicities, which were evaluated using the Brock criteria based on tonal audiometry assessment. Data collection focused on: (a) toxicities commonly observed in adults with MB treated with pediatric protocols: platinum-induced hearing loss; chemotherapy-associated neurological toxicity; nutritional difficulties and weight loss; (b) hematological toxicities frequently associated with treatment delays, modifications, or discontinuations

Continuous variables were expressed as median and standard deviation (SD). Categorical variables were presented as absolute frequencies and percentages and were compared using the Chi-squared test. Survival analyses were performed using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. XLSTAT software (ver. 2021.3.1, Addinsoft, Paris, France) was used for statistical analysis.

Overall survival (OS) is defined as the time from the start of treatment to the time of death from any cause and was censored at the date of last follow-up. Progression-free survival (PFS) is defined as the time from the start of treatment to either death, progression of disease, or development of a secondary tumor and was censored at the time of last follow-up.

During the study period, 18 adult patients with a presumptive diagnosis of MB were initially evaluated. One patient was excluded following histopathological re-evaluation, which revised the diagnosis to pineoblastoma. The final cohort consisted of 18 patients treated at our center between 01 January 1997 and 01 January 2024.

The cohort comprised 11 males (61%) and 7 females (39%), with a mean age at diagnosis of 25.5 years (SD 6.66) and a median age of 23 years. Disease staging was performed according to the Chang classification, with all patients undergoing pre-operative MRI, post-operative MRI within 48 h, and lumbar puncture for CSF cytological analysis [8].

Six patients (33%) presented with metastatic disease at diagnosis (2 were Chang M1 stage and 4 M3 stage), while 12 patients (67%) had localized disease confined to the posterior cranial fossa. All non-metastatic patients had post-surgical residual tumor absent or <1.5 cm2. No patients presented with or developed M4 disease during the course of illness or follow-up.

Histological analysis revealed classic MB in 10 patients (55.5%), desmoplastic/nodular MB (MB-DN) in 7 patients (39%), and large cell/anaplastic MB (LCA) in 1 patient (5.5%). No cases of MB with extensive nodularity (MB-MBEN) were observed. Molecular characterization was available for 6 patients (33.3%), with 4 classified as the SHH subgroup and 2 as the WNT subgroup, further limiting molecular subgroup analysis. No patients had comorbidities that would have contraindicated chemotherapy at diagnosis.

Among the 12 standard-risk patients, 6 (33%) received treatment according to the PNET3 protocol, 4 (22%) according to PNET4, and 2 (11%) according to PNET5. The evolution in treatment protocols reflected changes in institutional practice over the study period, with patients receiving the standard protocol that was active at the time of their diagnosis. Of the 6 high-risk patients, 4 (22%) received tandem thiotepa high-dose chemotherapy (HDCT) followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), and 2 (11%) received alternative high-risk MB chemotherapy regimens including thiotepa and carboplatin.

All patients received craniospinal radiotherapy with a boost to the posterior cranial fossa. The radiation dose varied according to risk classification and treatment protocol (23.4–36 Gy craniospinal irradiation, SD 8.9; 54–58 Gy posterior cranial fossa boost, SD 1.4). Radiotherapy was initiated within 40 days of surgery for all patients and completed within 50 days of initiation. Three patients (17%) required temporary interruption of radiotherapy due to hematological toxicities (neutropenia <500/mm3, thrombocytopenia <20,000/mm3).

All six high-risk patients received HDCT/ASCT with thiotepa-based conditioning regimens, although at different timepoints in their treatment course. Four patients received HDCT/ASCT as consolidation therapy, while two received mobilizing chemotherapy with carboplatin/etoposide followed by autologous transplantation with thiotepa conditioning as salvage therapy after disease relapse.

During treatment, patients received transfusion support according to institutional protocols: packed red blood cell transfusions for hemoglobin <7 g/dL, platelet transfusions for platelet counts <20,000/mm3, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor for persistent moderate/severe neutropenia or neutropenia requiring treatment interruption (neutrophil count <500/mm3 for >2 weeks).

Patients were followed for a median of 42 (range 12–264) months. All patients (n = 18) were alive at the 12-month follow-up post-diagnosis. At this time point, 17 patients (94.4%) exhibited disease remission, while one patient (5.6%) demonstrated disease progression at 9 months post-diagnosis. This non-responsive patient (with anaplastic features, and M3 stage) failed to respond to subsequent therapeutic interventions and succumbed to the disease at 35 months post-diagnosis.

One patient developed disease recurrence 34 months after initial diagnosis (20 months following the achievement of complete remission) and died 52 months from the time of original diagnosis. Another patient manifested multiple disease relapses and survived for 116 months after initial diagnosis before mortality occurred.

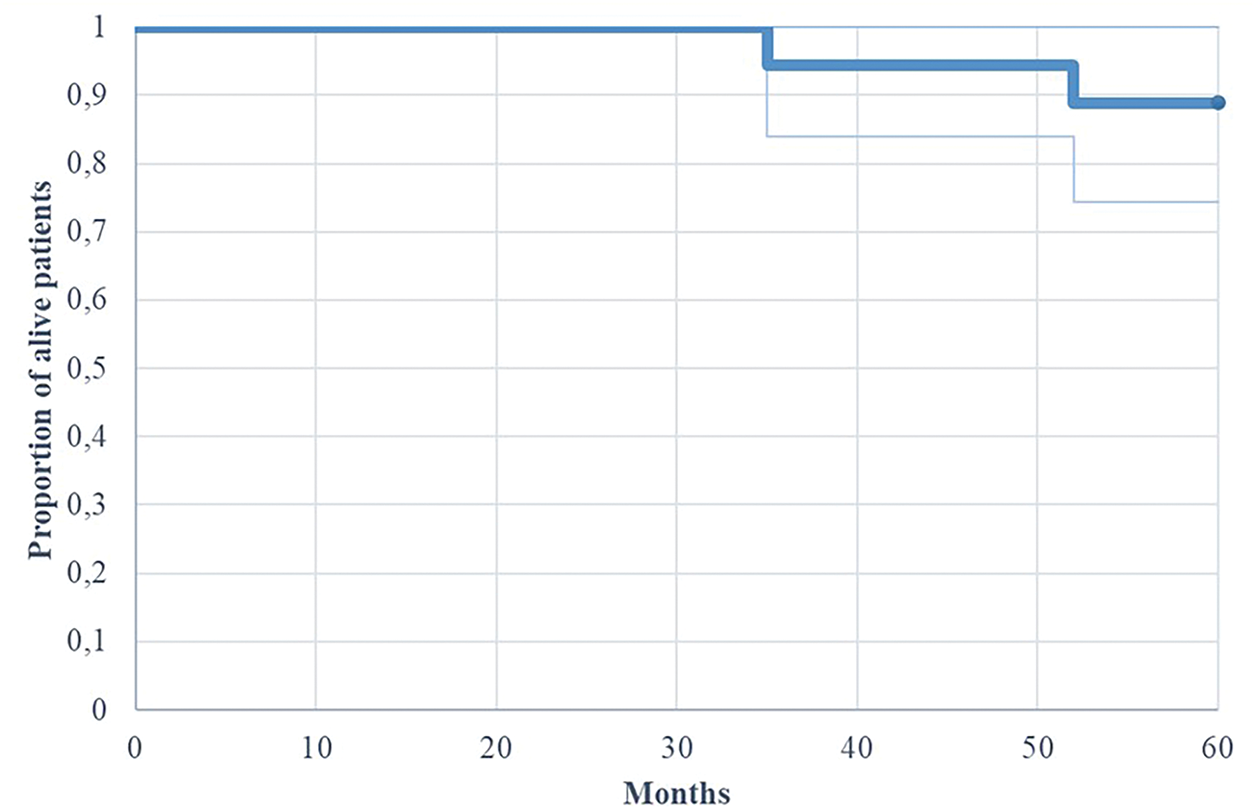

OS at 3 years and 5 years was 94.5% and 88.8%, respectively, for the entire cohort (Fig. 1 shows the Kaplan-Meier OS curve for the entire cohort). When stratified by risk classification, standard-risk patients demonstrated 3-year and 5-year OS rates of 100% and 91.6%, respectively, while high-risk patients exhibited rates of 83.3%, both at 3 and 5 years (p = 0.92 for 5-year OS comparison).

Figure 1: Kaplan-Meier of overall survival (OS) for patients with adult MB (n = 18)

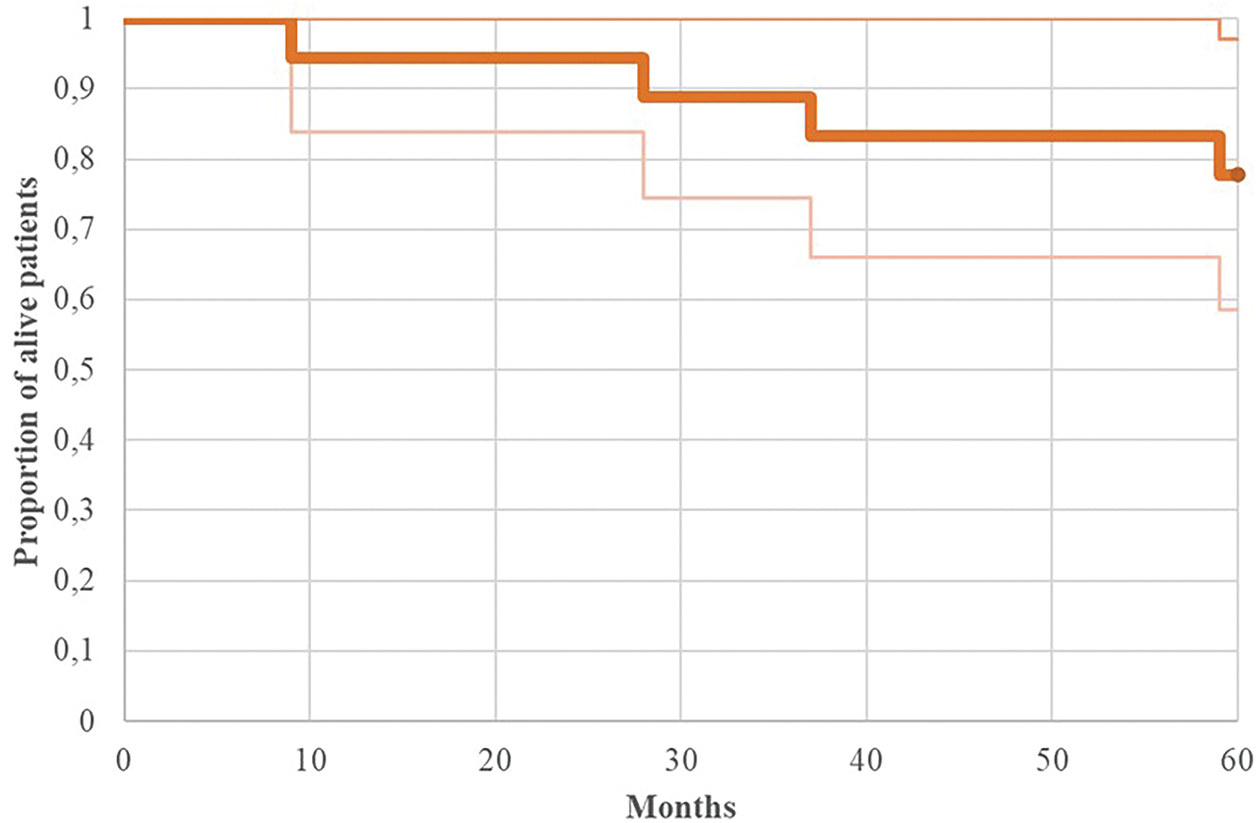

Regarding PFS, the entire cohort demonstrated 3-year and 5-year rates of 83.3% and 77.8%, respectively (Fig. 2 illustrates the Kaplan-Meier progression-free survival curve for all patients). Risk stratification revealed 3-year and 5-year PFS rates of 91.6% for standard-risk patients, compared to 66.6% and 50% for high-risk patients, respectively (p = 0.71 for 5-year PFS comparison).

Figure 2: Kaplan-Meier of progression-free survival (PFS) for patients with adult MB (n = 18)

3.4 Treatment-Related Toxicities

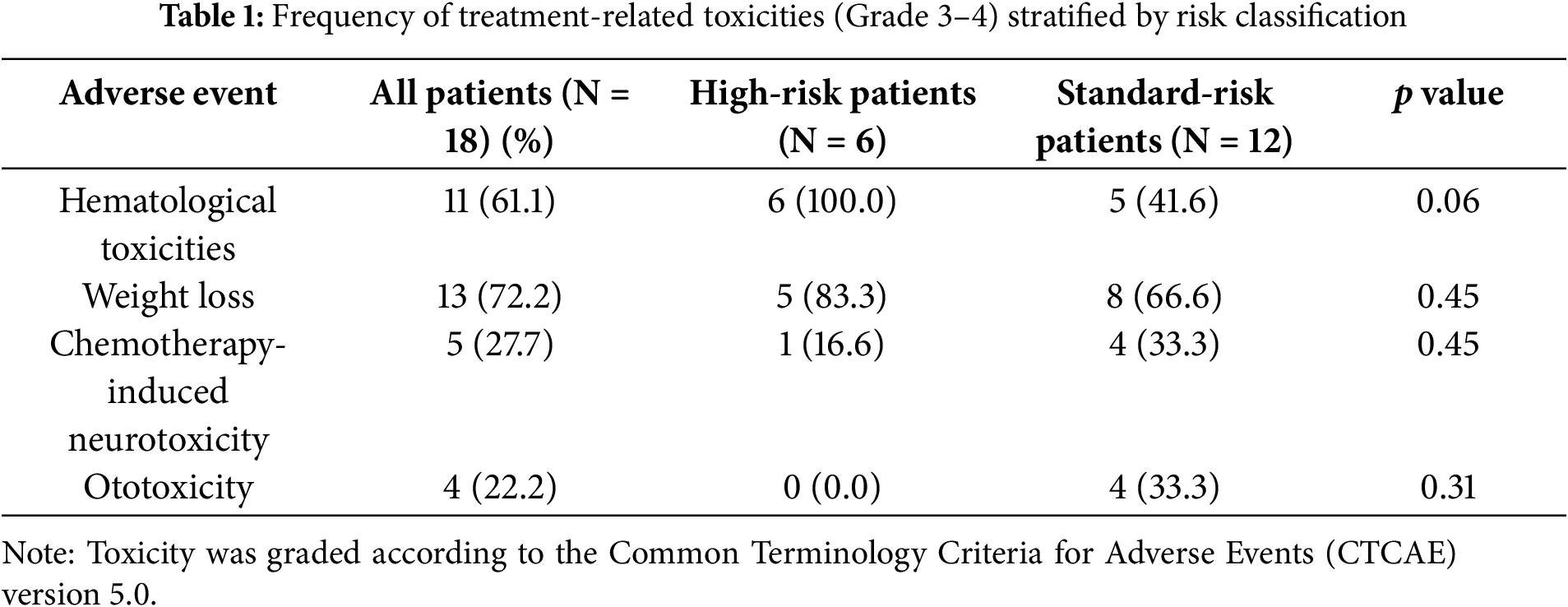

Among the observed adverse events, grade ≥3 hematological toxicities were predominant, occurring in 11 patients (61.1%). Chemotherapy-induced neurological complications were documented in 5 patients (27.7%), primarily manifesting as sensory-motor and autonomic neuropathies. Clinical presentations included decreased lower extremity strength, limb paresthesias, and constipation. Vincristine administration was identified as the principal causative agent, necessitating dose modifications in the majority of affected cases.

Severe ototoxicity (grade ≥3, characterized by hearing threshold exceeding 40 dB at frequencies of 4000 Hz and above) was observed in 4 patients (22.2%). Nutritional status deterioration was notable, with 13 patients (72.2%) exhibiting weight reduction exceeding 10% during the treatment course (Table 1 presents the detailed distribution of treatment-related adverse events by grade and frequency). This nutritional compromise was evident in both metastatic high-risk patients and those presenting with poor baseline performance status.

Treatment-related adverse events considerably influenced therapeutic protocol adherence. Chemotherapy cycle initiation delays were observed in 7 patients (38.8%), while dosage modifications of at least one chemotherapy agent were necessary in 10 patients (55.6%). Premature discontinuation or temporary suspension of chemotherapeutic intervention occurred in 8 patients (44.4%) due to treatment-emergent toxicities.

The survival outcomes observed in adult MB patients treated at our institution with pediatric-inspired chemotherapy protocols are encouraging and align with previously reported results for adult cohorts receiving combined chemoradiotherapy regimens [27–29]. Our patients achieved a 3-year OS of 94.5% and a 5-year OS of 88.8%, outcomes that compare favorably with the 5-year OS of 78% reported by Chen et al. (2022) for adults treated with chemoradiotherapy and with the 66% OS seen in patients receiving radiotherapy alone [30]. Similarly, Kocakaya et al. (2016) documented a 71% 9-year survival in comparable populations [31].

Contrary to the findings by Ma et al. (2020), who identified age as an independent prognostic factor (Hazard Ratio (HR) 1.01–1.02, p < 0.001), our data did not demonstrate a statistically significant association between age and survival (HR 0.824–1.220, p = 0.978) [7]. Moreover, treatment timing across our cohort remained within clinically acceptable limits, with no delays exceeding 30 days from surgery to chemotherapy initiation or 50 days from radiotherapy completion to subsequent chemotherapy commencement.

A major limitation of our study pertains to the availability of molecular profiling, which was completed in only six patients (four MB-SHH and two MB-WNT). This highlights an urgent need to implement routine molecular classification at diagnosis, in alignment with current World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations, to enhance risk stratification and guide treatment personalization in adult MB. However, although molecular subgrouping was available in only six patients, the prognostic implications of these classifications deserve consideration. WNT subgroup tumors are associated with the most favorable prognosis, with survival rates exceeding 90% in pediatric cohorts, while SHH tumors exhibit intermediate outcomes with constitutive activation of the SHH pathway through mutations in GLI1, GLI2, SUFU, and PTCH1 genes [32,33]. The two WNT patients in our series both achieved long-term survival, consistent with literature reports of excellent outcomes in this subgroup. Conversely, among the four SHH patients, survival outcomes varied, reflecting the known heterogeneity within this molecular classification. The lack of Group 3 and Group 4 patients in our molecularly characterized cohort limits comparative analysis, though Group 3 tumors typically demonstrate the worst survival outcomes with rates under 60% at 5 years. These findings underscore the critical importance of implementing routine molecular profiling at diagnosis to guide risk-adapted therapeutic strategies, particularly given the potential for treatment de-escalation in WNT patients and targeted approaches for SHH tumors.

While statistical comparisons with historical pediatric cohorts are constrained by our limited sample size, it is noteworthy that among six high-risk patients in our series, four who underwent tandem high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell rescue were alive at last follow-up (mean follow-up: ~4 years) [32]. Although maintenance therapy could not be completed in three patients due to persistent hematologic toxicity, these findings are consistent with outcomes in pediatric populations, where 5-year OS exceeds 80% in standard-risk and 60–70% in high-risk subgroups [33]. These preliminary results suggest that adult patients may benefit from intensified regimens analogous to those used in pediatric protocols.

Toxicity remains a significant concern when translating pediatric regimens to adult patients. Hematologic toxicity was frequent and often severe. Craniospinal irradiation is known to impair bone marrow function, contributing to treatment delays or dose modifications that may ultimately affect disease control [16,34–36]. In our cohort, grade ≥3 neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and/or anemia occurred in 61.1% of patients. This burden of toxicity led to chemotherapy discontinuation in 44.4%, dose delays in 38.8%, and dose reductions in 55.6% of cases. Although hematologic events were the primary driver of these modifications, the role of neurologic complications and nutritional decline warrants further investigation, particularly in assessing their potential impact on adherence and survival.

Audiologic toxicity, specifically cisplatin-induced hearing loss, was also notable. All patients who developed hearing impairment had received cisplatin-based regimens. In one case, early-onset ototoxicity prompted substitution of cisplatin with carboplatin, an agent with established efficacy and a more favorable auditory toxicity profile in MB [37–39]. These findings emphasize the necessity of routine audiometric monitoring during treatment to facilitate timely modifications. The multifactorial etiology of hearing loss—encompassing surgical trauma and cranial irradiation—also underscores the relevance of emerging strategies such as proton therapy, which may reduce ototoxic risk.

Neurologic toxicities, particularly vincristine-induced peripheral neuropathy, affected 27.7% of patients. Though generally reversible with dose adjustments or following treatment cessation, such toxicities may transiently impair functional status and quality of life. Vincristine-associated dysautonomia further contributed to gastrointestinal symptoms, including constipation, exacerbating nutritional challenges during therapy. Management of neurological toxicities was primarily reactive, with vincristine dose reductions or temporary discontinuation implemented upon symptom onset. Systematic monitoring included regular neurological assessments, though formal neuropathy grading scales were not consistently applied throughout the study period.

Nutritional compromise was prevalent, with 72.2% of patients experiencing >10% weight loss during chemoradiotherapy. This multifactorial complication—driven by mucositis-induced dysphagia, gastrointestinal toxicity, and overall treatment burden—significantly diminished patient well-being and autonomy. While all patients received symptomatic management and prophylactic antiemetics, enteral nutrition (via nasogastric or gastrostomy tubes) and total parenteral nutrition (TPN) were required in select high-risk patients, particularly during periods of severe mucositis or disease progression. While these measures were predominantly reactive rather than prophylactic, they proved effective in managing treatment-related complications and maintaining therapy feasibility.

The cumulative burden of toxicity translated into substantial treatment modification, highlighting the need for adult-specific dose-intensity optimization strategies. These modifications, while necessary for tolerability, may carry implications for treatment efficacy and long-term outcomes.

Due to the inherent rarity of adult MB and the resultant small sample size, this study is limited in its ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding prognostic factors or regimen-specific outcomes. The limited sample size of our cohort (n = 18) inherently restricts the generalizability of our findings and precludes robust statistical analysis of prognostic factors, particularly in subgroup comparisons between risk categories and molecular subtypes, which is a common limitation in studies of rare malignancies such as adult MB.

Nevertheless, our findings underscore the feasibility and potential efficacy of pediatric-inspired multimodal therapy in this population, while also illustrating the challenges posed by treatment-related toxicities. Collaborative multicenter studies with larger cohorts and systematic molecular profiling are essential to refine risk-adapted treatment strategies and improve outcomes for adults with MB.

The results obtained confirm that the use of adjuvant chemotherapy with schemes derived from pediatric protocols in adult patients with MB leads to a survival rate comparable to, and in some cases, even in the absence of statistical comparison, superior to available historical. Haematological, neurological, audiological toxicities, together with the nutritional difficulties observed, were relevant and led to interruptions, delays and reductions of chemotherapy dose in a significant percentage of patients. Nevertheless, the majority of the patients in study completed the treatment, and no death related to treatment or severe long-term sequelae were observed, indicating an overall acceptable survival and tolerability. Prospective studies evaluating the impact of more recent treatment protocols in terms of survival and long-term toxicities are necessary in order to identify the appropriate chemotherapy timing for different risk classes and the potential superiority of specific therapy regimens.

Adult MB still constitutes a field of exploration due to its rarity and due to its biological differences with pediatric MB. The rarity of the diseas determines several issues: some directly impact the single patient such as delay in diagnosis, receiving treatment within appropriate time frames, difficulties in finding specialists and referral centers specialized in the management of MB in adults; other issues impact indirectly on the prognosis of the adult patient with MB by hindering research, such as the difficulty in conducting clinical studies due to small sample sizes and the low interest of pharmaceutical companies in developing innovative therapeutic agents targeted for adults.

Being a “borderline” disease in terms of onset age and clinical characteristics, it is considered necessary for these patients to be treated by a multidisciplinary team that should include a neurosurgeon (with expertise in PCF and MB surgery), a pathologist (with possibility of centralized review and molecular analysis of the samples), a neuroradiologist, a pediatric oncologist (for the appropriate application and modulation of the chemotherapy regimen), a radiotherapist, a neurologist, a psychologist/therapist, and a palliative care specialized team. Collaboration between specialists is one essential criteria for the inclusion in the centre of the European Reference Network for the treatment of rare diseases (ERN, European Reference Network for rare diseases). The inclusion in an international reference network responsible for rare diseases is therefore a necessity for the management of adult MB patients, with predictable advantages for the patient in terms of faster access to experimental therapies, better management of chemo-radiotherapy in accordance with international protocols, resulting in benefits both from a medical, a social and a psychological perspective.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank “Fondazione per l’Oncologia Pediatrica” for their dedicated patient care and scientific support.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Antonio Ruggiero, Dario Talloa, and Alessio Albanese; methodology, Palma Maurizi and Stefano Mastrangelo; software, Alberto Romano; validation, Antonio Ruggiero, Tommaso Verdolotti, Gianpiero Tamburrini, and Silvia Chiesa; formal analysis, Dario Talloa; investigation, Giorgio Attinà and Rina di Bonaventura; resources, Antonio Ruggiero and Dario Talloa; data curation, Alberto Romano and Pier Paolo Mattogno; writing—original draft preparation, Dario Talloa; writing—review and editing, Antonio Ruggiero; visualization, Alessio Albanese, Alessandro Olivi, and Tommaso Verdolotti; supervision, Alessandro Olivi; project administration, Alberto Romano and Giorgio Attinà. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [Antonio Ruggiero], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore-Policlinico Gemelli IRCCS (number DIPUSVSP-21-03-252).

Informed Consent: All patients provided written informed consent prior to enrolment.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bailey P, Cushing H. Medulloblastoma cerebelli: a common type of midcerebellar glioma of childhood. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1925;14(2):192. doi:10.1001/archneurpsyc.1925.02200140055002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Louis DN, Perry A, Wesseling P, Brat DJ, Cree IA, Figarella-Branger D, et al. The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: a summary. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(8):1231–51. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noab106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Miller KD, Ostrom QT, Kruchko C, Patil N, Tihan T, Cioffi G, et al. Brain and other central nervous system tumor statistics 2021. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(5):381–406. doi:10.3322/caac.21693. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Price M, Neff C, Nagarajan N, Kruchko C, Waite KA, Cioffi G, et al. CBTRUS statistical report: american brain tumor association & NCI neuro-oncology branch adolescent and young adult primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2016–2020. Neuro Oncol. 2024;26(Supplement_3):iii1–53. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noae047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Otth M, Weiser A, Lee SY, von Rohr LR, Heesen P, Guerreiro Stucklin AS, et al. Treatment of medulloblastoma in the adolescent and young adult population: a systematic review. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2025;14(1):18–32. doi:10.1089/jayao.2024.0044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Cao L, Gu Z, Liu Z, Ding L. Causes of death among patients with primary malignant brain tumors in the US from 2000 to 2021. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2025;51(8):110223. doi:10.1016/j.ejso.2025.110223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ma AK, Freedman I, Lee JH, Miyagishima D, Ahmed O, Yeung J. Tumor location and treatment modality are associated with overall survival in adult medulloblastoma. Cureus. 2020;12(2):e7061. doi:10.7759/cureus.7061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Dufour C, Beaugrand A, Pizer B, Micheli J, Aubelle MS, Fourcade A, et al. Metastatic medulloblastoma in childhood: chang’s classification revisited. Int J Surg Oncol. 2012;2012(6):245385. doi:10.1155/2012/245385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Meyers SP, Wildenhain SL, Chang JK, Bourekas EC, Beattie PF, Korones DN, et al. Postoperative evaluation for disseminated medulloblastoma involving the spine: contrast-enhanced MR findings, CSF cytologic analysis, timing of disease occurrence, and patient outcomes. Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21(9):1757–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

10. Shi X, Sun X, Fan W, Dai X, Jiang M. Impact of radiation response on survival in pediatric medulloblastoma with residual or disseminated disease. Radiat Oncol. 2025;20(1):52. doi:10.1186/s13014-025-02632-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Goddard J, Castle J, Southworth E, Fletcher A, Crosier S, Martin-Guerrero I, et al. Molecular characterisation defines clinically-actionable heterogeneity within Group 4 medulloblastoma and improves disease risk-stratification. Acta Neuropathol. 2023;145(5):651–66. doi:10.1007/s00401-023-02566-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Kool M, Korshunov A, Remke M, Jones DTW, Schlanstein M, Northcott PA, et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: an international meta-analysis of transcriptome, genetic aberrations, and clinical data of WNT, SHH, Group 3, and Group 4 medulloblastomas. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(4):473–84. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-0958-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Srivastava S, Lingaiah R, Bhaisora K, Polavarapu NK, Pal L, Singh S, et al. Development and clinical validation of molecular subgrouping in medulloblastoma by targeted methylation sequencing. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2025;26(7):2569–75. doi:10.31557/APJCP.2025.26.7.2569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Taylor MD, Northcott PA, Korshunov A, Remke M, Cho YJ, Clifford SC, et al. Molecular subgroups of medulloblastoma: the current consensus. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(4):465–72. doi:10.1007/s00401-011-0922-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Robinson G, Parker M, Kranenburg TA, Lu C, Chen X, Ding L, et al. Novel mutations target distinct subgroups of medulloblastoma. Nature. 2012;488(7409):43–8. doi:10.1038/nature11213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Coltin H, Sundaresan L, Smith KS, Skowron P, Massimi L, Eberhart CG, et al. Subgroup and subtype-specific outcomes in adult medulloblastoma. Acta Neuropathol. 2021;142(5):859–71. doi:10.1007/s00401-021-02358-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Mushtaq N, Ain RU, Hamid SA, Bouffet E. Evolution of systemic therapy in medulloblastoma including irradiation-sparing approaches. Diagnostics. 2023;13(24):3680. doi:10.3390/diagnostics13243680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Edvardsson A, Lannering B, Gorgisyan J, Munck af Rosenschöld P, Björk-Eriksson T. A systematic review and meta-analysis with focus on radiotherapy of pediatric standard-risk medulloblastoma: new strategies are needed to improve survival and reduce side-effects. Radiother Oncol. 2025;211:111045. doi:10.1016/j.radonc.2025.111045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Packer RJ, Gajjar A, Vezina G, Rorke-Adams L, Burger PC, Robertson PL, et al. Phase III study of craniospinal radiation therapy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy for newly diagnosed average-risk medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(25):4202–8. doi:10.1200/JCO.2006.06.4980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Michalski JM, Janss AJ, Vezina LG, Smith KS, Billups CA, Burger PC, et al. Children’s oncology group phase III trial of reduced-dose and reduced-volume radiotherapy with chemotherapy for newly diagnosed average-risk medulloblastoma. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(24):2685–97. doi:10.1200/JCO.20.02730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Dufour C, Foulon S, Geoffray A, Masliah-Planchon J, Figarella-Branger D, Bernier-Chastagner V, et al. Prognostic relevance of clinical and molecular risk factors in children with high-risk medulloblastoma treated in the phase II trial PNET HR+5. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23(7):1163–72. doi:10.1093/neuonc/noaa301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. von Bueren AO, Kortmann RD, von Hoff K, Friedrich C, Mynarek M, Müller K, et al. Treatment of children and adolescents with metastatic medulloblastoma and prognostic relevance of clinical and biologic parameters. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(34):4151–60. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.67.2428. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Rutkowski S, Bode U, Deinlein F, Ottensmeier H, Warmuth-Metz M, Soerensen N, et al. Treatment of early childhood medulloblastoma by postoperative chemotherapy alone. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(10):978–86. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa042176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Singer R, Lorimer C, Welsh L, Carceller F, Vaidya S, Marshall LV, et al. Feasibility and outcomes of craniospinal irradiation and concurrent daily carboplatin in children and adults with high-risk central nervous system tumours. Clin Oncol. 2025;44(suppl 4):103866. doi:10.1016/j.clon.2025.103866. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Tabori U, Sung L, Hukin J, Laperriere N, Crooks B, Carret AS, et al. Medulloblastoma in the second decade of life: a specific group with respect to toxicity and management: a canadian pediatric brain tumor consortium study. Cancer. 2005;103(9):1874–80. doi:10.1002/cncr.21003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Beier D, Proescholdt M, Reinert C, Pietsch T, Jones DTW, Pfister SM, et al. Multicenter pilot study of radiochemotherapy as first-line treatment for adults with medulloblastoma (NOA-07). Neuro Oncol. 2018;20(3):400–10. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nox155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Friedrich C, von Bueren AO, von Hoff K, Kwiecien R, Pietsch T, Warmuth-Metz M, et al. Treatment of adult nonmetastatic medulloblastoma patients according to the paediatric HIT 2000 protocol: a prospective observational multicentre study. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(4):893–903. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2012.10.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Franceschi E, Minichillo S, Mura A, Tosoni A, Mascarin M, Tomasello C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in average-risk adult medulloblastoma patients improves survival: a long term study. BMC Cancer. 2020;20(1):755. doi:10.1186/s12885-020-07237-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Franceschi E, Hofer S, Brandes AA, Frappaz D, Kortmann RD, Bromberg J, et al. EANO-EURACAN clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment, and follow-up of post-pubertal and adult patients with medulloblastoma. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20(12):e715–28. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30669-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Chen B, Chen C, Zhao Y, Cui W, Xu J. The role of chemotherapy in the treatment of adult medulloblastoma. World Neurosurg. 2022;163:e435–49. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2022.04.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Kocakaya S, Beier CP, Beier D. Chemotherapy increases long-term survival in patients with adult medulloblastoma—a literature-based meta-analysis. Neuro Oncol. 2016;18(3):408–16. doi:10.1093/neuonc/nov185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Dufour C, Kieffer V, Varlet P, Raquin MA, Dhermain F, Puget S, et al. Tandem high-dose chemotherapy and autologous stem cell rescue in children with newly diagnosed high-risk medulloblastoma or supratentorial primitive neuro-ectodermic tumors. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(8):1398–402. doi:10.1002/pbc.25009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Lazow MA, Palmer JD, Fouladi M, Salloum R. Medulloblastoma in the modern era: review of contemporary trials, molecular advances, and updates in management. Neurother. 2022;19(6):1733–51. doi:10.1007/s13311-022-01273-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Korshunov A, Remke M, Werft W, Benner A, Ryzhova M, Witt H, et al. Adult and pediatric medulloblastomas are genetically distinct and require different algorithms for molecular risk stratification. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(18):3054–60. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Ruggiero A, Attinà G, Talloa D, Mastrangelo S, Romano A, Maurizi P, et al. Medulloblastoma in adolescents and young adults (AYAbridging pediatric paradigms and adult oncology practice. J Clin Med. 2025;14(13):4472. doi:10.3390/jcm14134472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Frappaz D, Faure-Conter C, Levard AB, Barritault M, Meyronet D, Sunyach MP. Medulloblastomas in adolescents and adults—can the pediatric experience be extrapolated? Neurochirurgie. 2021;67(1):76–82. doi:10.1016/j.neuchi.2018.10.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Spreafico F, Massimino M, Gandola L, Cefalo G, Mazza E, Landonio G, et al. Survival of adults treated for medulloblastoma using paediatric protocols. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(9):1304–10. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2005.02.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Fetoni AR, Ruggiero A, Lucidi D, De Corso E, Sergi B, Conti G, et al. Audiological monitoring in children treated with platinum chemotherapy. Audiol Neurootol. 2016;21(4):203–11. doi:10.1159/000442435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Rose O, Croonenberg T, Clemens S, Hinteregger T, Eppacher S, Huber-Cantonati P, et al. Cisplatin-induced hearing loss, oxidative stress, and antioxidants as a therapeutic strategy—a state-of-the-art review. Antioxidants. 2024;13(12):1578. doi:10.3390/antiox13121578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools