Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Mast Cells in the Solid Tumor Microenvironment: Multiple Roles and Targeted Therapeutic Potential

1 Department of Pathology, Hebei Key Laboratory of Molecular Oncology, The Cancer Institute, Tangshan People’s Hospital, Tangshan, 063001, China

2 Department of Oncology, State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China, Guangdong Provincial Clinical Research Center for Cancer, Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center, Guangzhou, 510060, China

3 Center for Global Health Research, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha Medical College and Hospitals, Saveetha University, Chennai, 600077, India

4 Research Institute of Oral Science, Nihon University School of Dentistry at Matsudo, Chiba, 271-8587, Japan

5 Department of Breast Surgery, The Sixth Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, South China University of Technology, Foshan, 528000, China

6 The First People’s Hospital of Foshan (The Affiliated Foshan Hospital of Southern University of Science and Technology), School of Medicine, Southern University of Science and Technology, Foshan, 528000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Pangzhou Chen. Email: ; Lewei Zhu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Novel Targets and Biomarkers in Solid Tumors)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(12), 3657-3678. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.069703

Received 28 June 2025; Accepted 17 September 2025; Issue published 27 November 2025

Abstract

The tumor microenvironment (TME) is a complex network composed of non-tumor cells, extracellular matrix, blood vessels, and various molecular signals that surround and profoundly influence tumor progression. As one of the key immune effector cells within the TME, mast cells (MCs) exhibit functional complexity, and their specific roles remain widely debated. Depending on the cancer type, spatial distribution, and interactions with other TME components, MCs can demonstrate dual regulatory capabilities—either promoting or inhibiting tumor growth. This characteristic has made them an important focus in current tumor immunology research. This review aims to systematically review the current understanding of MCs in the TME, with emphasis on their characteristics and functional differences across various tumor types, pathological status, and species. In recent years, advances in the understanding of MC markers, activation mechanisms, and biological functions have made targeting specific MC subsets an emerging therapeutic strategy. By comprehensively examining the origin, activation mechanisms, cellular interactions, and therapeutic regulation of MCs, this review provides new perspectives and a basis for future directions in tumor research and treatment.Keywords

The tumor microenvironment (TME), comprising tumor cells, non-tumor stromal cells, the extracellular matrix (ECM), vasculature, and diverse molecular signals, plays a crucial role in tumorigenesis and progression [1]. Tumors are frequently classified as “hot” or “cold” based on the extent of immune cell infiltration, a key determinant of anti-tumor immunity and therapeutic response. Mast cells (MCs), first described by Paul Ehrlich in 1879 [2], are key innate immune sentinels predominantly resident in barrier tissues like skin and mucosa, where they are vital mediators of allergic and inflammatory responses [3].

Interestingly, beyond their classical roles, MCs exhibit complex and multifaceted biological functions within TME [4]. Numerous studies have identified the pivotal role of MCs in the TME. MCs significantly influence tumor progression through diverse mechanisms, impacting tumor growth, angiogenesis, immune regulation, and even antigen presentation [5]. Recognized primarily for their role in hypersensitivity, MCs are now understood as critical modulators of the TME [6]. Their activity within the TME can exert either pro-tumorigenic or anti-tumorigenic effects, contingent upon the specific microenvironment and the profile of mediators they release.

Consequently, MCs contribute significantly to both innate and adaptive immune responses within the TME, facilitating antigen presentation and modulating T cell activity. Furthermore, the diverse array of bioactive molecules released by MCs are strongly implicated in tumor initiation and progression [7].

However, current research delineating MCs’ functions within the TME reveals considerable complexity and diversity, with recent studies highlighting divergent roles across different cancer types [8]. Comprehensive synthesis and critical examination of MCs’ contributions to the TME are therefore warranted. Given that immunotherapy, while promising, yields variable patient responses, targeting MCs emerges as a potential therapeutic strategy. Summarizing existing MC-targeting agents and clinical trials could inform future research directions. Understanding the specific functions of MCs within distinct tumor types is essential to rationally develop novel MC-targeted therapies that may enhance cancer treatment efficacy. Future research must prioritize elucidating the precise mechanisms of MCs’ action within the TME to translate these insights into effective therapeutic interventions.

MCs, as key components of the innate immune system, are distributed across various organs [9]. In adults, most hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) and MC progenitors originate from the bone marrow (BM).

Following their egress from the BM, these cells enter the bloodstream, migrating to tissues, where they undergo maturation into functional MCs under the influence of stem cell factor (SCF) [10]. In the BM, few HSCs differentiate into MCs because of the influence of cytokines. During embryonic and fetal development, mesenchymal stem cells from the yolk sac develop into pluripotent HSCs, which circulate and infiltrate organs, including the liver, BM, and skin [11].

The phenotypic traits of MC-committed progenitor cells in mice and humans include the expression of CD34, c-KIT (CD117), IL-3R, and CD13, typically accompanied by low FcεRI levels [12]. As MCs develop, their precursors lose CD34 and IL-3R alpha (CD123) expression while increasing FcεRI and c-KIT expression [13]. Notably, these progenitor cells possess adhesion molecules that enable migration to peripheral organs and tissues.

The activation or inhibition of MCs is modulated by a range of internal and external factors that interact with diverse receptors on the MC membrane. These receptors can be categorized based on the nature of their response to ligand–receptor binding: biphasic and monophasic reactive receptors [14,15].

3.1 Biphasic Reactive Receptors

Biphasic Reaction Process: Upon the binding of a biphasic reactive receptor to its specific ligand, a MCs initiate a biphasic reaction. The initial phase is characterized by rapid degranulation, during which MCs release pre-synthesized bioactive substances. In the subsequent phase, MCs engage in de novo synthesis and release of bioactive substances [14]. Fc epsilon RI (FcεRI) is a member of the multichain immune recognition receptor (MIRR) family and is a well-characterized example of a receptor that initiates biphasic reaction. On the surfaces of MCs, FcεRI exists as a tetrameric complex composed of an α subunit, a β subunit, and a dimer of γ subunits [16]. Upon cross-linking with the Fc region of immunoglobulin E (IgE), FcεRI initiates the activation of MCs through FcεRI-mediated pathways [17,18]. Antigen-specific binding induces the aggregation of IgE fragment–FcεRI complexes, leading to the rapid phosphorylation of the tyrosine kinase LYN. This event facilitates the phosphorylation of the immunoreceptor tyrosine activation motif (ITAM). Once phosphorylated, ITAM recruits the kinases, Src-like kinase (SLK, also called Fyn) and spleen tyrosine kinase (SYK), providing docking sites for SH2 domain–containing proteins and triggering a cascade of signaling events. This cascade ultimately results in calcium influx and alterations in gene transcription levels [19]. Ultimately, the aggregation of FcεRI culminates in the activation and degranulation of MCs, releasing bioactive substances, such as heparin and histamine [20].

In addition, the discovered biphasic reactive receptors also include neurokinin receptors, Mas-related G protein-coupled receptors, Endothelin (ET) receptors, Tropomyosin receptor kinase (Trk) receptors, opioid receptors, and platelet-activating factor [21].

3.2 Monophasic Reactive Receptors

Monophasic reactive receptors can be categorized into two distinct activation modes based on the response of MCs after following ligand–receptor interaction. The first activation mode involves MC degranulation exclusively induced by the binding of a specific ligand to a receptor, resulting in the release of preexisting inflammatory mediators. Research on this mode is currently limited, and the complement system has been the primary focus. Within this system, the components C3a and C5a can interact with their respective receptors, C3aR and C5aR, which are expressed on the MC membrane. This interaction facilitates the rapid degranulation of MCs and subsequent release of histamine [22].

Following ligand–receptor binding, the second mode of MC activation involves the synthesis and release of inflammatory factors de novo without degranulation. The prototypical receptor involved in this process is c-KIT. Previous studies have established that SCF is an activator of MCs, and its receptor, c-KIT is highly expressed on the surfaces of these cells. Upon binding to SCF, c-KIT undergoes autophosphorylation, initiating a cascade of downstream biological signaling events [23]. The activation of MCs mediated by the c-KIT receptor does not induce rapid degranulation. However, owing to the extensive integration of signaling pathways initiated by c-KIT and FcεRI, SCF binding to c-KIT can enhances the degranulation of MCs and FcεRI-induced release of cytokines simultaneously [24].

Apart from c-KIT, Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a considerable role in modulating the secondary activation pathway of MCs. Although most TLRs do not trigger MC degranulation, they can stimulate the secretion of various bioactive substances and modulate MC activation mediated by other receptors. Similarly, the activation of MCs by C-type lectin receptors [25] and nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptor 1 [26] does not result in degranulation but instead induces the release of cytokines and chemokines.

Chronic low-level inflammation is a key feature of tumors, indicating that MCs play a role in tumor biology [27]. Activated MCs release various bioactive substances, which are categorized into two types: pre-synthesized substances stored in basophilic granules, which constitute an intrinsic feature of MCs, and newly synthesized substances produced after transcriptional activation.

Histamine is a pre-synthesized bioactive compound predominantly derived from MCs. It serves as a critical mediator in allergic and inflammatory responses, facilitating vasodilation, bronchoconstriction, and mucus secretion [28]. In addition, it facilitates tumor proliferation by promoting angiogenesis [29]. In addition to histamine, MCs produce serine proteases, such as tryptase and chymase, which are involved in the proteolytic modification of high-density lipoproteins. Tryptase, released during MC activation, encompasses several isoforms, including tryptase α (encoded by TPSAB1), tryptase β (encoded by TPSAB1 and TPSB2), tryptase δ (encoded by TPSD1), tryptase γ (encoded by TPSG1), and tryptase ε (encoded by PRSS22). These isoforms facilitate angiogenesis, ECM degradation, and decrease adhesion among tumor cells [30,31]. Furthermore, the activation of MCs’ signaling pathways triggers the synthesis and secretion of novel bioactive substances, such as heparinase. Within the TME, MCs secrete heparinase, which interacts with breast cancer cells via the MUC1/estrogen receptor axis, contributing to the maintenance of cancer stem cell properties [32].

Notably, MCs migrating into an intratumoral region are activated in the inflammatory microenvironment and release vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), angiopoietin-1, and the chemokines CXCL1 and CXCL8 through degranulation. The receptors of these bioactive substances are distributed in the MCs’ membranes [33]. Therefore, MCs activated in TME further promote the recruitment of MCs by tumor cells through positive feedback [34,35].

5 Identification of MCs in the TME

In rodent tissues, MCs are categorized into connective tissue and mucosal MCs according to their anatomical location. Historically, most research on MCs has been conducted using rodent models. However, advancements in research techniques and methodologies have prompted a transition toward utilizing human systems [36]. Currently, the established gold standard for identifying human MCs involves the detection of metachromatic granules within the cytoplasm or the identification of c-KIT and tryptase via immunohistochemistry (IHC) [37]. Based on the type of serine protease they express, mature MCs can be classified into three distinct subsets: chymase-positive MCs (MCCs), tryptase-positive MCs (MCTs), and double protease (Tryptase and chymase)-positive MCs (MCTCs) [38]. Despite these advances, single-molecule detection technologies are limited in accurately determining the spatial localization of MCs and identifying degranulated MCs.

Advancements in sequencing technology have enabled researchers to utilize deconvolution algorithms, such as Cell-type Identification By Estimating Relative Subsets Of RNA Transcripts (CIBERSORT), to estimate the density of MCs within entire tissues [39,40]. Krishnan et al. [41] identified C1q tumor necrosis factor 8 as a characteristic protein of the MCTs subset in prostate cancer. Maimaitiyiming et al. [42] employed machine learning techniques to screen for MC-related genes signatures and were able to identify 13 marker genes across six prostate cancer datasets, collectively termed the MCs marker gene set. Xie et al. [43] applied single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to identify five characteristic MC-related genes (TPSAB1, TPSB2, CPA3, HPGDS, and MS4A2) in human colorectal cancer (CRC), which serve as reliable identifiers of MCs within the TME. Cai et al. [44] established a set of MC-related characteristic genes, including c-KIT, RAB32, CATSPER1, SMYD3, LINC00996, SOCS1, AP2M1, LAT, and HSP90B1. Additionally, Yang et al. [45] developed a predictive model incorporating four quiescent MC-related genes (MS4A2, GATA1, RGS13, and SLC18A2) for the TME of patients with non-small-cell lung cancer. Bao et al. [46] constructed novel molecular subtypes and a neural network prediction model based on an MCs-related gene signature in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD). This model accurately predicts immunotherapy response (98.7% accuracy) and reveals associations between the signature, TP53 mutation, and c-MYC pathway activation, offering novel strategies for immunotherapy and personalized treatment of early-stage LUAD.

Various marker genes for identifying MCs in the TME have been identified, but current techniques, such as single-molecule detection and bulk/single-cell RNA-seq, are limited in their ability to determine MCs’ spatial localization and interactions.

6.1 MCs in Spatial Transcriptomics

With the advent of spatial transcriptomics (ST), a technique that has gained substantial traction, the spatial distribution of MCs within the TME has garnered considerable interest. Unlike traditional sequencing technologies and IHC detection methods used in isolation, ST integrates spatial positioning data and is corroborated by multiplex IHC (mIHC). This integration facilitates a more comprehensive understanding of the localization and functional states of MCs within the TME. Current research on various tumor tissue types indicate a considerable increase in the number of MCs within tumor tissues and their adjacent counterparts [47].

Tumor cells release SCF, which recruits MCs to tumor sites by binding to c-KIT receptors [48]. Mao et al. [49] identified specific MCs in bladder Ewing sarcoma that interact with cancer cells through TNFSF12–TNFRSF12A. Another study [50] discovered that choroid plexus MCs, which rarely express FcεRIα unlike peripheral MCs, disrupt epithelial cells through degranulation, causing tumor-associated hydrocephalus and challenging the notion that the brain lacks immune cells. Xie et al. [43] demonstrated the colocalization of MCs with fibroblasts and endothelial cells. These cells may activate MCs through the KITLG–KIT axis, potentially suppressing tumor progression. Furthermore, Song et al. [51] observed elevated IL1B expression in macrophages within clear cell renal carcinoma samples, and ST analysis revealed the colocalization of VEGFA+ MCs with IL1B+ macrophages at the tumor–normal interface.

Recently, scRNA-seq has advanced the study of tumor cell composition and identification of malignant cells but struggles to reveal direct interactions and spatial relationships among cell subsets [52]. This limitation is partly due to the low infiltration of MCs in the TME, leading to their underrepresentation [53,54]. Additionally, the high cost and small sample sizes of ST analysis limit its use. ScRNA-seq, bulk RNA-seq, and ST each face challenges in distinguishing MCs in the TME when used alone. To better understand MCs’ roles, integrating IHC or mIHC techniques and using meta-chromatic particles, c-KIT, and tryptase, are recommended [55].

6.2 Different Functions of MCs in Different Areas

The infiltration location of MCs is linked to cancer progression. Xia et al. [56] reported that MCs predominantly localize around tumors and to a lesser extent at the invasion margin and within tumors. A method for visualizing TME, “Spatiopath,” shows MCs clustering near cancer cells [57]. In prostate cancer, elevated extratumoral MC density (MCD) correlates with increased recurrence post-surgery [58]. Intratumoral MCs inhibit angiogenesis and tumor growth, whereas peritumoral MCs promote tumor progression [59]. Similarly, in esophageal cancer, MCs at the tumor margin are linked to reduced survival and progression [60].

The role of MCs in breast cancer is debated. Sakalauskaitė et al. [61] found that MCs within tumors correlate with large tumor size and increased lymph node metastases, whereas MCs in the stroma are linked to favorable outcomes and increased lymphangiogenesis [62]. Conversely, a Malaysian study indicated that interstitial MCs have little impact on breast cancer progression [63]. This discrepancy may be attributed to breast cancer molecular types because MCD is notably lower in triple-negative breast cancer than in luminal A and B types [64,65].

6.3 Pro-Cancer Mechanisms of MCs

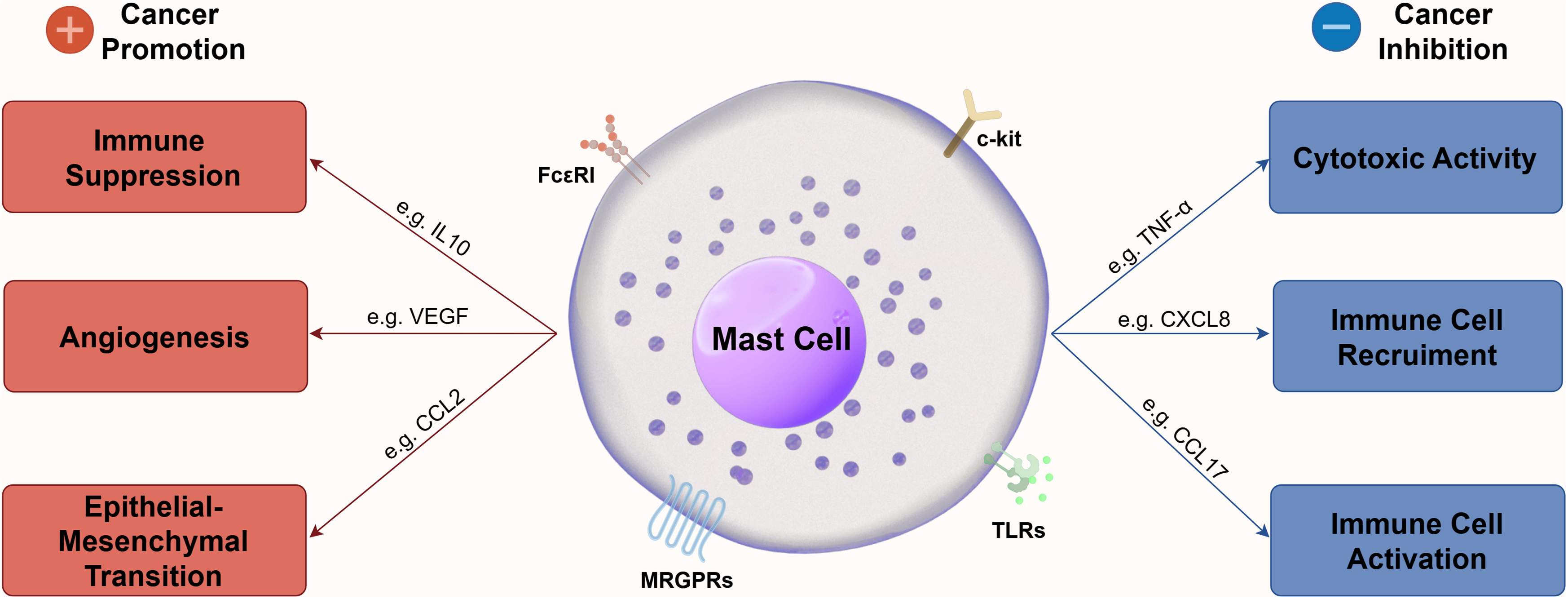

The mechanism by which MCs modulate the TME is highly complex (Fig. 1). The impact of MC infiltration on tumor progression and patient prognosis varies significantly across tumor types. Elevated MCs infiltration level is associated with tumor progression, recurrence and poorer prognosis, including lung adenocarcinoma [66], cervical cancer [67], bladder cancer [68], thyroid cancer [69,70], CRC [71,72], oral cancer [73], gastric cancer [74–76], pancreatic cancer [77–79], esophageal cancer [80], and breast cancer [32,81].

Figure 1: Mechanism of MCs to modulate TME. This figure was generated by Figdraw (ID: PRSIOcd47c)

Furthermore, MCs enhance interactions between estrogen receptors (ERs) and CCL2 within tumors, facilitating bladder cancer invasion through the MC–ER–CCL2 axis, which promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) activity [82]. Supporting a pro-tumorigenic role, Chang et al. [83] demonstrated suppressed pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) growth in MC-deficient mice; notably, tumor growth was restored when PDAC cells were transplanted into wild-type mice reconstituted with bone marrow (BM). Similarly, Varma et al. [84] observed increased MC infiltration in recurrent odontogenic keratocyst tissues, further suggesting a pro-invasive function for MCs.

6.4 Anti-Cancer Mechanisms of MCs

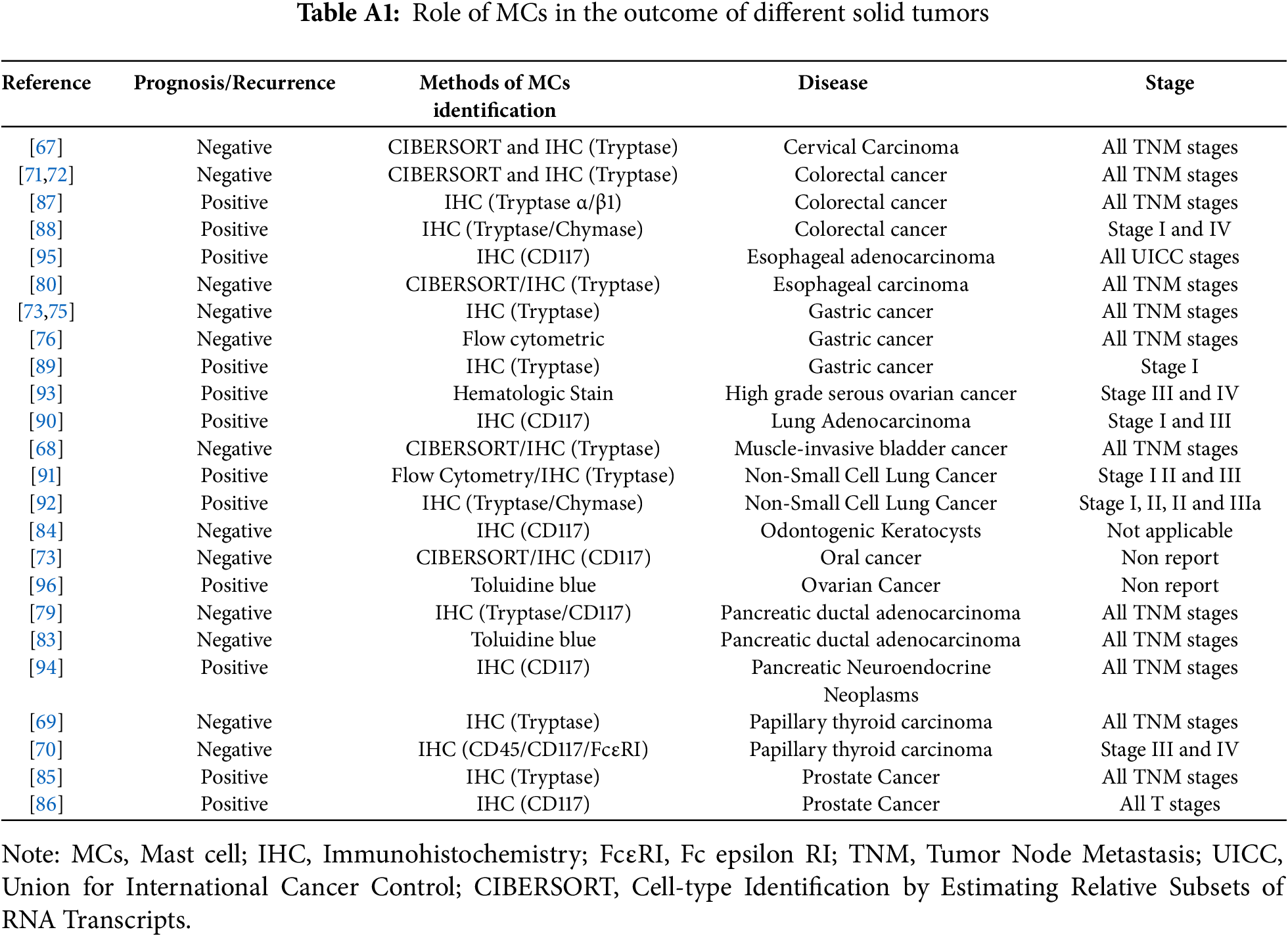

MCs perform functions beyond promoting cancer progression and thus linking them directly to cancer promoters is overly simplistic. Hempel et al. and Fleischmann et al. [85,86] found that MCs help to prevent the recurrence cases of prostate cancer. Several studies may explain why a higher intratumoral MC density correlates negatively with recurrence. MCs express MHC II for antigen presentation and the costimulatory molecule CD28 [86]. Similar findings were obtained in CRC [87,88], gastric cancer [89], and lung adenocarcinoma [90–92]. These contradictory findings need further investigation. In high-grade serous ovarian cancer, the deadliest gynecologic cancer, MCTCs levels rise after neoadjuvant therapy and serves as a positive prognostic factor [93].

As a component of the innate immune system, the tumor-suppressive effects of MCs are correlated with an increased presence of CD4+ T cells and CD15+ neutrophils [94]. In vitro and in vivo studies have demonstrated that MCs inhibit the proliferation of CRC cells and induce apoptosis through the release of various cytokines. This mechanism does not affect normal intestinal epithelial cells [87]. In the context of esophageal adenocarcinoma, the abundance of MCs is associated with low tumor stage and reduced frequency of lymph node metastasis, serving as a prognostic protective factor for patients with lymph node metastasis [95]. Furthermore, Meyer et al. [96] reported that MCs in rodent models exert an inhibitory effect on ovarian tumor growth, suggesting their potential as a novel therapeutic target for ovarian cancer. Given the functional complexity of MCs, research findings are extensive yet inconclusive. We summarize clinically relevant studies on MCs to elucidate the role of MC infiltration levels in solid tumors in Table A1.

6.5 Interaction of MCs with Main Components in the TME

6.5.1 Interaction among MCs, T Cells and NK Cells

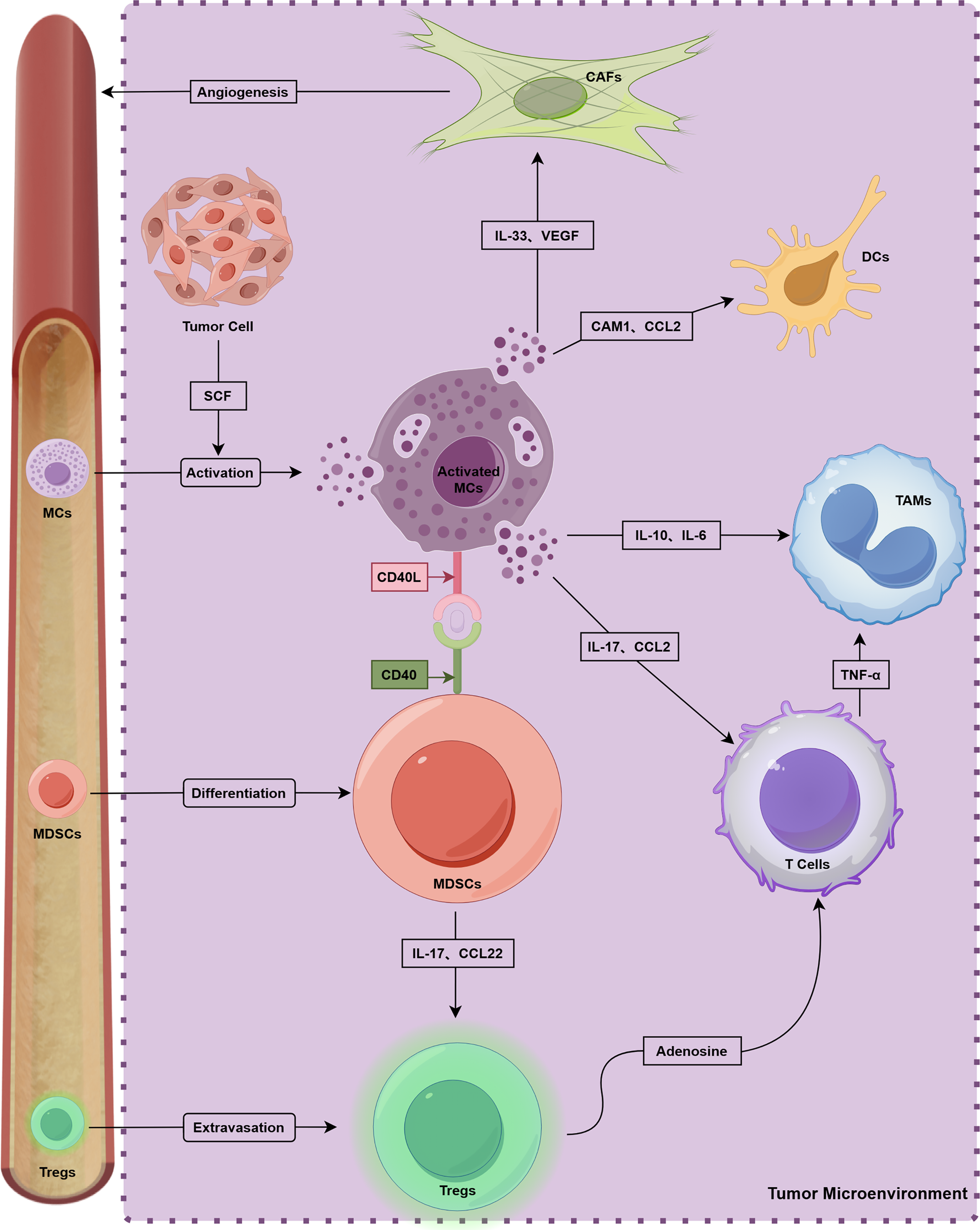

MCs play an important role in TME (Fig. 2). T cells and MCs constitute the innate immune system, and various T cell subtypes interact with MCs [29]. Tregs suppress immune response in different types of cancer, and MCs interact with Inducible T-cell co-stimulator (ICOS)+ Tregs through IL-33 and IL-2 and promote cancer progression. Additionally, activated MCs release IL-17 and adenosine, boosting Tregs’ proliferation [97]. In CRC, MCs prompt Tregs to enhance inflammation while maintaining their T cell suppression ability [98]. MCs-derived CXCL10 reversely promoted epithelial-mesenchymal transition and induced immunosuppressive TME of PDAC by recruiting CXCR3+ Tregs [99].

Figure 2: Crosstalk with multiple components and MCs in TME. This figure was generated by Figdraw (ID: ORUUIdd0d8)

Various studies on tumor immunotherapy highlight the immune system’s capability to combat cancer, with CD8+ T cells being crucial for antitumor immunity [100]. In esophageal cancer, IL17+ MCs attract CD8+ T cells and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) to inhibit cancer progression [101]. Similarly, in lung adenocarcinoma, certain MCs secrete CCL2 to recruit CCR2+ cytotoxic T cells, enhancing Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) treatment [102]. However, MCs can also suppress T cell antitumor activity. In pancreatic cancer, anti-OX40 treatment combined with MCs depletion increased CD8+ T cells infiltration [103]. MCs expressing galectin-9 inhibit CD8+ T cell immunity [70], and increased intratumoral MCs promote immune suppression and gastric cancer progression via the TNF-α-PD-L1 pathway [76]. In mice, MC deficiency inhibits CRC development while promoting CD8+ T cell infiltration [104].

The cross-talk between MCs and natural killer (NK) cells mainly acts on tumor surveillance and regression. NK cells rarely infiltrate tumors because of immunosuppressive microenvironments, although high-density MCs can release cytokines, such as CXCL8, CCL3, IFN, and histamine, which can recruit NK cells to suppress tumor progression [105].

6.5.2 Interaction between MCs and Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) play a crucial role in immunosuppression [106]. According to Jachetti et al. [107], MCs and MDSCs contribute to tumor pathogenesis through interactions involving the CD40L–CD40 axis, and MDSCs activate MCs by secreting TNF-α, IL-6, and other factors. Furthermore, IL17-positive MCs have the capacity to recruit MDSCs, thereby facilitating cancer progression [108]. Notably, a feedback loop appears to exist among MCs, MDSCs, and Tregs. This loop allows for the concurrent development of the TME and immunosuppression. MDSC-recruited MCs increase the levels of chemokines CCL17 and CCL22 through interactions with CCL2, which subsequently enhances the immunosuppressive function of Tregs [8].

6.5.3 Interaction between MCs and TAMs

Intercellular communication between MCs and TAMs constitutes an essential element in the regulation of tumor immunity. This interaction facilitates the development and progression of CRC [109]. Specifically, the activation of MCs via IL-33 enhances cancer progression and elevates microvessel density (MVD) by recruiting TAMs [110]. Liu et al. [111] demonstrated that MCs activate the IFN and NF-κB signaling pathways of bladder cancer cells within a co-culture system. This process increases the secretion of CCL2 and IL-13 by bladder cancer cells, thereby promoting the polarization of monocytes into TAMs.

6.5.4 Interaction between MCs, Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts, and Adipocytes

The dynamic interplay between tumor cells and their surrounding ECM is widely recognized as a crucial factor in the formation, progression, metastasis, and development of drug resistance in solid tumors. However, the relationship between the stroma and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes remains unclear. Nonetheless, substantial evidence indicates that the composition of the stroma considerably influences anti-tumor immunity and the responsiveness to immunotherapy [112].

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) play a crucial role in the TME, influencing ECM remodeling, tumor growth, drug resistance, and metastasis [113]. MCs regulate fibroblasts within the TME, promoting myofibroblast differentiation in breast cancer through tryptase activity [114]. SAMD14 acts as a tumor suppressor, and its overexpression modifies MCs, leading to increased CAF deposition in prostate cancer [115]. Additionally, exosome-associated IL33 activates MCs in pancreatic cancer, which then converts fibroblasts into inflammatory CAFs. However, this process can be inhibited by BAG6 overexpression [116].

Apart from CAFs, adipocytes are stromal cells too. Adipose tissue serves as a reservoir for MC progenitors, potentially recruiting MCs to the TME [117]. Additionally, MCs from adipose tissues can target and induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells [118].

6.5.5 MCs in Tumor Angiogenesis

Tumor angiogenesis, driven by endothelial cells, is crucial for tumor growth and spread by supplying oxygen and nutrients through new blood vessels [119]. A link between MCD and MVD in tumors has been established [120], and MCD had been positively correlated with MVD in oral squamous cell carcinoma [121], lung cancer [122], CRC [123], and gastric cancer [124,125]. Low proliferative activity and MVD were observed in melanoma cells inoculated in MCs-deficient mice but normalized after BM transplantation from normal mice. MCs enhance angiogenesis and tumor growth in cutaneous melanoma through the autocrine/paracrine signaling of SCF, CCL5, CCL11, and CCL18 [126–129].

Chymase and tryptase, which are key serine proteases from MCs, are closely linked to angiogenesis [130–132]. High tryptase levels correlate with increased MC infiltration and MVD [133]. Tumor-derived exosomes can deliver SCFs to MCs, influencing tryptase release and vascular endothelial growth [134]. Tryptase serves as a prognostic marker and is involved in angiogenesis across various types of cancer by regulating endothelial cell PAR-2 expression [89,135]. This evidence suggests that MCs play a role in promoting tumor angiogenesis and metastasis.

Some metabolites affect the function of MCs. For example, in cholangiocarcinoma, bile induces MCs to secrete platelet-derived growth factor B and angiopoietin 1/2, enhancing angiogenesis in cholangiocarcinoma [136].

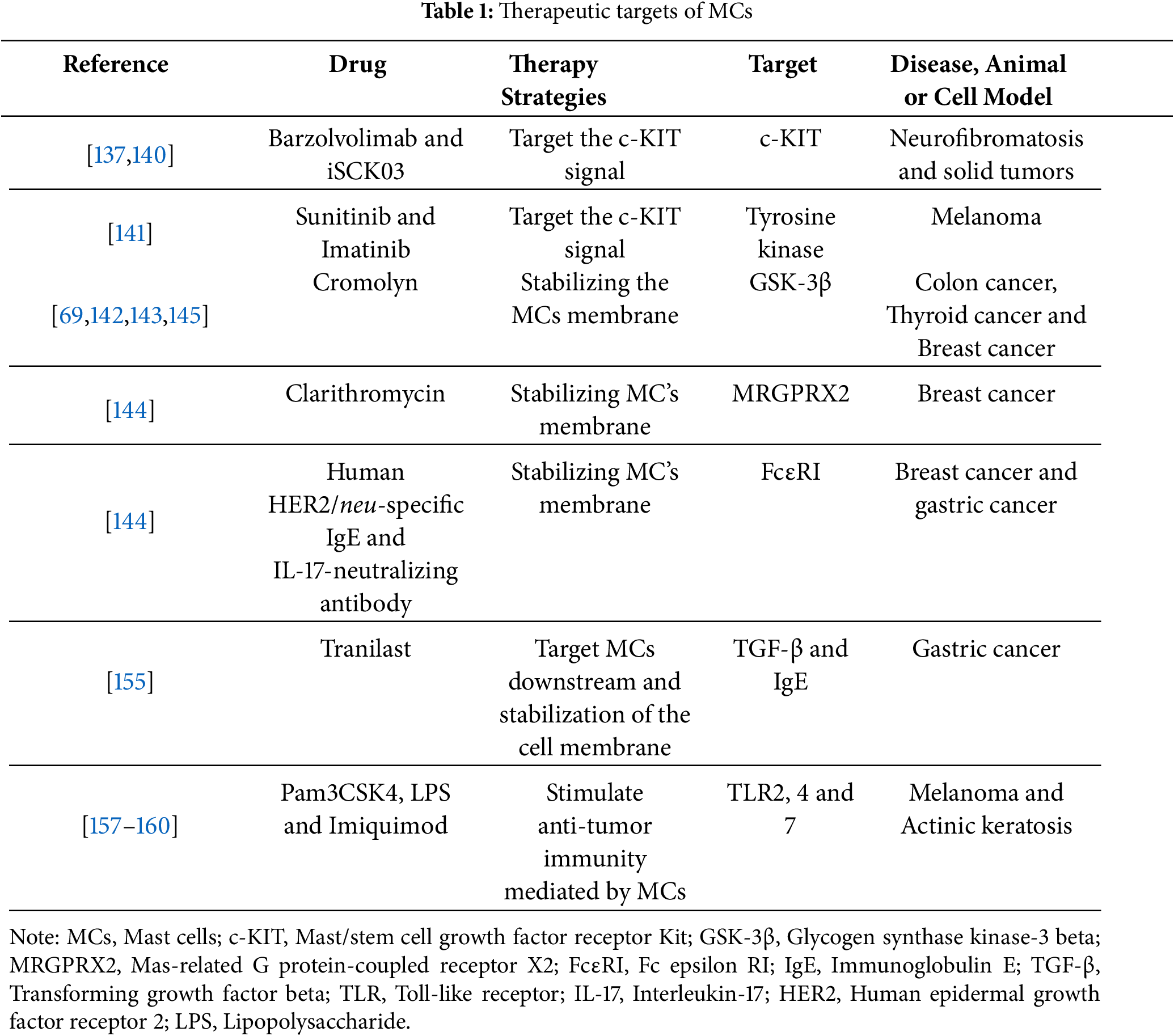

7 Targeted Therapy Strategies for MCs

There are many targeted therapy strategies for MC (Table 1), among which SCF/c-KIT is crucial for MC’s development and function, and TKIs, such as imatinib and nilotinib, can target MCs in some conditions, such as mastocytosis and allergies, by inhibiting the binding of SCF to c-KIT receptors [21]. Although pan-TKIs have been successfully used in cancer treatment, their ability to target MCs is limited because of off-target effects [6]. To address this limitation, barzolvolimab, which is a c-KIT-specific monoclonal antibody, has been developed. However, it has been tested only in neurofibromatosis and solid tumors (NCT02642016 and NCT02642016) [137–139]. Unfortunately, until now, all clinical trials of barzolvolimab for the treatment of solid tumors have not had published results.

In a preclinical study, Yang et al. [140] discovered that the c-KIT inhibitor iSCK03 boosts apoptosis signaling in breast cancer, enhancing antitumor effects. Additionally, combining anti-PD-1 therapy with sunitinib or imatinib leads to MC depletion and complete tumor regression [141].

Stabilizing MC membrane to inhibit MC activation and degranulation is a common therapeutic approach in allergy treatment. In this approach, clarithromycin, cromolyn, and ketotifen are commonly used [5], which have shown promise in preclinical cancer models. For example, the effectiveness of cromolyn in inhibiting tumor growth has been demonstrated in colon [142], thyroid [69], and breast cancer models [143–145]. In a phase II clinical trial (NCT05076682), cromolyn combined with anti-PD1 drugs demonstrated a synergistic effect in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) by targeting MCs, marking the only clinical trial focused on specific MC subset, antigen-presenting MCs (APMCs) [145]. This clinical trial demonstrated that combining cromolyn with anti-PD1 therapy in patients with metastatic TNBC refractory to prior immunotherapy achieved an objective response rate (ORR) of 50% with a favorable safety profile, offering a novel strategy for optimizing immunotherapy by targeting APMCs.

The application of IgE antibodies to enhance antitumor response has been proposed because they can inhibits MCs’ degranulation [146,147]. IgE is crucial for MCs activation, and monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), such as omalizumab, ligelizumab, quilizumab, and UB-221 block IgE from binding to FcεR, thus preventing MC activation [148]. In vitro, humanized monoclonal anti-HER-2/neu IgE and anti-CD20 IgE have been shown to inhibit MCs’ degranulation and tumor growth [149].

In addition to traditional mAbs, recombinant proteins, such as sdab-026, E2_79 and bi53_79, have been reported to have anti-IgE activity. Furthermore, Gunjigake et al. [150] reported that a recombinant IL-17-neutralizing antibody can inhibit MCs’ degranulation. These recombinant proteins are more productive and stable than mAbs. The route of administration is easier than that of mAbs and can be used through the mucous membranes.

Complement C3a-derived peptides, C3a7 and C3a9, may interact with the β chain of FcεR on the membranes of MCs, potentially decreasing the likelihood of IgE binding to FcεR and consequently influencing signal transduction [151–153]. However, this hypothesis has not been thoroughly investigated, and the precise function of these interactions remains unclear.

The direct regulation of bioactive substances secreted by MCs represents an effective strategy for modulating MCs activation [154]. Tryptase inhibitors, such as triniste, nafamostat mesylate, and gabexate mesylate has demonstrated antitumor efficacy in preclinical studies involving multibell solid tumors, either as monotherapies or in combination with other therapeutic agents [3]. Nakamura et al. [155] revealed that triniste inhibits the infiltration of MCs and TAMs within tumors while simultaneously enhancing infiltration by CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, Ma et al. [156] conducted an analysis of the three-dimensional structure of tryptase isoforms, leading to the identification and validation of the tryptase β-selective inhibitor compound 22978-61-6 (3,5-dichlorophenyl-1-carboxamide hydrochloride).

7.4 Stimulate Anti-Tumor Immunity Mediated by MCs

While substantial evidence supports the tumor-promoting roles of MCs, recent studies suggest that MCs, as integral components of the innate immune system, may also exhibit antitumor immune functions. Activation of MCs via TLRs leads to the secretion of cytokines with both direct and indirect antitumor activities. For example, in the B16.F10 murine melanoma model, TLR2 agonists stimulate the release of MC-derived interleukin-6 and CCL3, which directly inhibit tumor growth and indirectly facilitate the recruitment of natural killer cells (NKs) [157]. Although the potential for systemic toxicity necessitates thorough evaluation, these findings advocates for the investigation of TLR2 agonists as localized immunomodulators or in conjunction with NK cell-based therapies.

TLR4, the receptor specifically recognizing lipopolysaccharide (LPS), stimulates MCs to secrete CXCL10, thereby facilitating the recruitment of T cells in melanoma models. This position intratumoral LPS injection as a potential adjunctive strategy to enhance clinical anti-CTLA-4 therapy [158]. Despite its promise, successful clinical translation requires the development of safer synthetic TLR4 agonists tailored for human application, optimization of injection protocols, and validation of efficacy through clinical trials. Moreover, the pretreatment of MCs with the TLR7 agonist imiquimod has been shown to enhance the expression of co-stimulatory and activating molecules in dendritic cells (DCs), thereby improving the efficacy of targeting vaccines to DCs [159]. This approach presents a viable strategy for augmenting current DC vaccine. Additionally, imiquimod induces the release of CCL2 from MCs, facilitating the recruitment of plasmacytoid DCs to tumor sites and thereby promoting antitumor immunity [160]. Given imiquimod’s approval for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma and its established clinical efficacy, its repurposing, either as a monotherapy or in conjunction with DC vaccines, to activate MCs and modify TME holds considerable translational promise. However, the complexity of MC functions, alongside their potential protumorigenic effects, highlights the necessity for meticulous patient stratification and the identification of relevant biomarkers.

The diverse functions of MCs within the TME, along with recent studies investigating MCs as novel targets, have increasingly been discussed in the context of tumor immunotherapy. However, the overall potential of MC-targeted immunotherapy remains uncertain, which may be attributed to ambiguities in subset analysis of MCs and technical limitations in accurately identifying and characterizing these cells within the TME.

MCs play crucial roles in the TME, prompting the need to develop innovative approaches to differentiate MC subsets through the evaluation of new markers. Future research should emphasize the precise labeling of MC-specific subtypes, as certain subsets may represent promising targets for tumor immunotherapy. Nevertheless, extensive investigation is required before MC-targeted therapies can be effectively implemented. Additionally, therapeutic strategies designed to specifically modulate the functions of MC subsets must be carefully engineered to minimize off-target or contradictory effects.

The functional roles of MCs should also be explored in combination with other immunotherapeutic strategies to evaluate potential synergies between different treatment agents. While numerous in vivo and in vitro studies support this direction, comprehensive clinical trials focusing on MCs are essential to clearly establish the clinical relevance and therapeutic benefits of MC-targeted interventions in cancer patients.

It is important to note, however, that phenotypic and functional differences—including activation pathways—between murine and human MCs may hinder the translation of findings from animal models to clinical applications.

Acknowledgement: We acknowledge the support from the Department of Pathology (Tangshan People Hospital) and Department of Pathology (Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University). In addition, we would like to thank Prof. Ying Ma from Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital for her help in this review. We thank Figdraw (www.figdraw.com, accessed on 16 September 2025), for creating Figs. 1 and 2.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022A1515220184, Lewei Zhu) and Hebei Natural Science Foundation (H2024105019).

Author Contributions: Chenglu Lu and Huiting Zhang: Reviewing the literature and writing the original manuscript. Ujjal K. Bhawal: Collecting Paper. Lei Wang: Checking manuscript format. Jingwu Li: Polishing manuscript. Pangzhou Chen and Lewei Zhu: Revising and review original manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| BM | Bone Marrow |

| CAFs | Cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| CMA1 | Mast cell protease-1 |

| CTMCs | Connective tissue mast cells |

| CTRP8 | C1q tumor necrosis factor 8 |

| DCs | Dendritic cells |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| ERs | Estrogen receptors |

| ET | Endothelin |

| Trk | Tropomyosin receptor kinase |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| FcεRI | Fc epsilon RI |

| HNSCC | Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma |

| HSCs | Hematopoietic stem cells |

| IgE | Immunoglobulin E |

| ICAFs | Inflammatory cancer-associated fibroblasts |

| ICOS | Inducible T-cell co-stimulator |

| ITAM | Immunoreceptor tyrosine activation motif |

| LTB4 | Leukotriene B4 |

| LTs | Leukotrienes |

| mAbs | Monoclonal antibodies |

| MCC | Chymase-positive mast cell |

| MCD | Mast cell density |

| MCMGs | MCs marker gene sets |

| MCs | Mast cells |

| MCT | Tryptase-positive mast cell |

| mIHC | Multiplex immunohistochemistry |

| MIRR | Multi-chain immune recognition receptor |

| MMCs | Mucosal mast cells |

| MCTCs | (Tryptase and chymase)-positive mast cells |

| MRGPRs | Mas-related G protein-coupled receptors |

| MDSCs | Myeloid-derived suppressor cells |

| MVD | Microvessel density |

| NKRs | Neurokinins |

| NKs | Natural killer cells |

| NOD1 | Nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptor 1 |

| NSCLC | Non-small-cell lung carcinoma |

| OSCC | Oral squamous cell carcinoma |

| PAF | Platelet-activating factor |

| PDGF-B | Platelet-derived growth factor B |

| PGE2 | Prostaglandin E2 |

| PGs | Prostaglandins |

| RFS | Recurrence-free survival |

| SCF | Stem cell factor |

| SCGF | Stem cell growth factor receptor |

| ST | Spatial transcriptomics |

| SLK | Src-like kinase |

| SYK | Spleen tyrosine kinase |

| TAMs | Tumor-associated macrophages |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TLRs | Toll-like receptors |

| TME | Tumor microenvironment |

| TNBC | Triple-negative breast cancer |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor-α |

| TKIs | Tyrosine kinase inhibitors |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

1. Oya Y, Hayakawa Y, Koike K. Tumor microenvironment in gastric cancers. Cancer Sci. 2020;111(8):2696–707. doi:10.1111/cas.14521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Derakhshani A, Vahidian F, Alihasanzadeh M, Mokhtarzadeh A, Lotfi Nezhad P, Baradaran B. Mast cells: a double-edged sword in cancer. Immunol Lett. 2019;209:28–35. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2019.03.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Akin C, Siebenhaar F, Wechsler JB, Youngblood BA, Maurer M. Detecting changes in mast cell numbers versus activation in human disease: a roadblock for current biomarkers? J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2024;12(7):1727–37. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2024.03.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Dakal TC, George N, Xu C, Suravajhala P, Kumar A. Predictive and prognostic relevance of tumor-infiltrating immune cells: tailoring personalized treatments against different cancer types. Cancers. 2024;16(9):1626. doi:10.3390/cancers16091626. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Cao M, Gao Y. Mast cell stabilizers: from pathogenic roles to targeting therapies. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1418897. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1418897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Lichterman JN, Reddy SM. Mast cells: a new frontier for cancer immunotherapy. Cells. 2021;10(6):1270. doi:10.3390/cells10061270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. da Silva EZM, Jamur MC, Oliver C. Mast cell function: a new vision of an old cell. J Histochem Cytochem. 2014;62(10):698–738. doi:10.1369/0022155414545334. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhao J, Yang Z, Li D, Katirai F, et al. Mast cell: insight into remodeling a tumor microenvironment. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2011;30(2):177–84. doi:10.1007/s10555-011-9276-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Frossi B, Mion F, Tripodo C, Colombo MP, Pucillo CE. Rheostatic functions of mast cells in the control of innate and adaptive immune responses. Trends Immunol. 2017;38(9):648–56. doi:10.1016/j.it.2017.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Galli SJ, Tsai M, Wershil BK. The c-kit receptor, stem cell factor, and mast cells. What each is teaching us about the others. Am J Pathol. 1993;142(4):965–74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Putro E, Carnevale A, Marangio C, Fulci V, Paolini R, Molfetta R. New insight into intestinal mast cells revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(11):5594. doi:10.3390/ijms25115594. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Dahlin JS, Malinovschi A, Öhrvik H, Sandelin M, Janson C, Alving K, et al. Lin− CD34hi CD117int/hi FcεRI+ cells in human blood constitute a rare population of mast cell progenitors. Blood. 2016;127(4):383–91. doi:10.1182/blood-2015-06-650648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Valent P, Akin C, Hartmann K, Nilsson G, Reiter A, Hermine O, et al. Mast cells as a unique hematopoietic lineage and cell system: from Paul Ehrlich’s visions to precision medicine concepts. Theranostics. 2020;10(23):10743–68. doi:10.7150/thno.46719. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Bulfone-Paus S, Nilsson G, Draber P, Blank U, Levi-Schaffer F. Positive and negative signals in mast cell activation. Trends Immunol. 2017;38(9):657–67. doi:10.1016/j.it.2017.01.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Jiang YC, Ye F, Du Y, Tang ZX. Research progress of mast cell activation-related receptors and their functions. Acta Physiol Sin. 2019;71(4):645–56. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

16. Blank U, Ra C, Miller L, White K, Metzger H, Kinet JP. Complete structure and expression in transfected cells of high affinity IgE receptor. Nature. 1989;337(6203):187–9. doi:10.1038/337187a0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Matsuda K, Piliponsky AM, Iikura M, Nakae S, Wang EW, Dutta SM, et al. Monomeric IgE enhances human mast cell chemokine production: il-4 augments and dexamethasone suppresses the response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(6):1357–63. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Kawakami T, Kitaura J, Xiao W, Kawakami Y. IgE regulation of mast cell survival and function. In: Mast cells and basophils: development, activation and roles in allergic/autoimmune disease: novartis foundation symposium 271. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2005. p. 100–14. doi:10.1002/9780470033449.ch8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Draber P, Halova I, Polakovicova I, Kawakami T. Signal transduction and chemotaxis in mast cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2016;778:11–23. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2015.02.057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Saito H, Ishizaka T, Ishizaka K. Mast cells and IgE: from history to today. Allergol Int. 2013;62(1):3–12. doi:10.2332/allergolint.13-RAI-0537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Guo X, Sun M, Yang P, Meng X, Liu R. Role of mast cells activation in the tumor immune microenvironment and immunotherapy of cancers. Eur J Pharmacol. 2023;960:176103. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2023.176103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang X, Lan R, Liu Y, Pillarisetty VG, Li D, Zhao CL, et al. Complement activation in tumor microenvironment after neoadjuvant therapy and its impact on pancreatic cancer outcomes. npj Precis Oncol. 2025;9(1):58. doi:10.1038/s41698-025-00848-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. El-Agamy DS. Targeting c-kit in the therapy of mast cell disorders: current update. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;690(1–3):1–3. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.06.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Hundley TR, Gilfillan AM, Tkaczyk C, Andrade MV, Metcalfe DD, Beaven MA. Kit and FcεRI mediate unique and convergent signals for release of inflammatory mediators from human mast cells. Blood. 2004;104(8):2410–7. doi:10.1182/blood-2004-02-0631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kimura Y, Chihara K, Honjoh C, Takeuchi K, Yamauchi S, Yoshiki H, et al. Dectin-1-mediated signaling leads to characteristic gene expressions and cytokine secretion via spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) in rat mast cells. J Biol Chem. 2014;289(45):31565–75. doi:10.1074/jbc.M114.581322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Enoksson M, Ejendal KFK, McAlpine S, Nilsson G, Lunderius-Andersson C. Human cord blood-derived mast cells are activated by the Nod1 agonist M-TriDAP to release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines. J Innate Immun. 2011;3(2):142–9. doi:10.1159/000321933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Crusz SM, Balkwill FR. Inflammation and cancer: advances and new agents. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12(10):584–96. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2015.105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Alda S, Ceausu RA, Gaje PN, Raica M, Cosoroaba RM. Mast cell: a mysterious character in skin cancer. In Vivo. 2024;38(1):58–68. doi:10.21873/invivo.13410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Kannen V, Grant DM, Matthews J. The mast cell-T lymphocyte axis impacts cancer: friend or foe? Cancer Lett. 2024;588:216805. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Jiang Y, Wu Y, Hardie WJ, Zhou X. Mast cell chymase affects the proliferation and metastasis of lung carcinoma cells in vitro. Oncol Lett. 2017;14(3):3193–8. doi:10.3892/ol.2017.6487. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Ligan C, Ma XH, Zhao SL, Zhao W. The regulatory role and mechanism of mast cells in tumor microenvironment. Am J Cancer Res. 2024;14(1):1–15. doi:10.62347/EZST5505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Bongiorno R, Lecchi M, Botti L, Bosco O, Ratti C, Fontanella E, et al. Mast cell heparanase promotes breast cancer stem-like features via MUC1/estrogen receptor axis. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(9):709. doi:10.1038/s41419-024-07092-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Liu X, Li X, Wei H, Liu Y, Li N. Mast cells in colorectal cancer tumour progression, angiogenesis, and lymphangiogenesis. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1209056. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1209056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Park H, Kim D, Koh Y, Yoon SS. The upregulation of Pim kinases is essential in coordinating the survival, proliferation, and migration of KIT D816V-mutated neoplastic mast cells. Leuk Res. 2019;83:106166. doi:10.1016/j.leukres.2019.106166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Xie G, Wang F, Peng X, Liang Y, Yang H, Li L. Modulation of mast cell toll-like receptor 3 expression and cytokines release by histamine. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;46(6):2401–11. doi:10.1159/000489646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Levi-Schaffer F, Gibbs BF, Hallgren J, Pucillo C, Redegeld F, Siebenhaar F, et al. Selected recent advances in understanding the role of human mast cells in health and disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(6):1833–44. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2022.01.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Jain A, Jaiswal S, Vikey A, Bagulkar B, Bhat A, Shujalpurkar A. Quantification of mast cells in nonreactive and reactive lesions of gingiva: a comparative study using toluidine blue and immunohistochemical marker mast cell tryptase. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2021;25(3):550–1. doi:10.4103/jomfp.JOMFP_267_19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Pejler G, Rönnberg E, Waern I, Wernersson S. Mast cell proteases: multifaceted regulators of inflammatory disease. Blood. 2010;115(24):4981–90. doi:10.1182/blood-2010-01-257287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Danaher P, Warren S, Dennis L, D’Amico L, White A, Disis ML, et al. Gene expression markers of tumor infiltrating leukocytes. J Immunother Cancer. 2017;5:18. doi:10.1186/s40425-017-0215-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Newman AM, Liu CL, Green MR, Gentles AJ, Feng W, Xu Y, et al. Robust enumeration of cell subsets from tissue expression profiles. Nat Methods. 2015;12(5):453–7. doi:10.1038/nmeth.3337. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Krishnan SN, Thanasupawat T, Arreza L, Wong GW, Sfanos K, Trock B, et al. Human C1q Tumor Necrosis Factor 8 (CTRP8) defines a novel tryptase+ mast cell subpopulation in the prostate cancer microenvironment. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2023;1869(5):166681. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2023.166681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Maimaitiyiming A, An H, Xing C, Li X, Li Z, Bai J, et al. Machine learning-driven mast cell gene signatures for prognostic and therapeutic prediction in prostate cancer. Heliyon. 2024;10(15):e35157. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e35157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Xie Z, Niu L, Zheng G, Du K, Dai S, Li R, et al. Single-cell analysis unveils activation of mast cells in colorectal cancer microenvironment. Cell Biosci. 2023;13(1):217. doi:10.1186/s13578-023-01144-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Cai Z, Tang B, Chen L, Lei W. Mast cell marker gene signature in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):577. doi:10.1186/s12885-022-09673-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Yang Y, Qian W, Zhou J, Fan X. A mast cell-related prognostic model for non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis. 2023;15(4):1948–57. doi:10.21037/jtd-23-362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Bao X, Shi R, Zhao T, Wang Y. Mast cell-based molecular subtypes and signature associated with clinical outcome in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. Mol Oncol. 2020;14(5):917–32. doi:10.1002/1878-0261.12670. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Hempel Sullivan H, Maynard JP, Heaphy CM, Lu J, De Marzo AM, Lotan TL, et al. Differential mast cell phenotypes in benign versus cancer tissues and prostate cancer oncologic outcomes. J Pathol. 2021;253(4):415–26. doi:10.1002/path.5606. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Dahlin JS, Ekoff M, Grootens J, Löf L, Amini RM, Hagberg H, et al. KIT signaling is dispensable for human mast cell progenitor development. Blood. 2017;130(16):1785–94. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-03-773374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Mao W, Xu K, Wang K, Zhang H, Ji J, Geng J, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics of bladder Ewing sarcoma. iScience. 2024;27(10):110921. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.110921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Li Y, Di C, Song S, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Liao J, et al. Choroid plexus mast cells drive tumor-associated hydrocephalus. Cell. 2023;186(26):5719–38.e28. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Song X, Jiao J, Qin J, Zhang W, Qin W, Ma S. Single-cell transcriptomics reveals the heterogeneity and function of mast cells in human ccRCC. Front Immunol. 2025;15:1494025. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1494025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Stuart T, Satija R. Integrative single-cell analysis. Nat Rev Genet. 2019;20(5):257–72. doi:10.1038/s41576-019-0093-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Xie J, Yang A, Liu Q, Deng X, Lv G, Ou X, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing elucidated the landscape of breast cancer brain metastases and identified ILF2 as a potential therapeutic target. Cell Prolif. 2024;57(11):e13697. doi:10.1111/cpr.13697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Dwyer DF, Barrett NA, Austen KF. Immunological genome project consortium. Expression profiling of constitutive mast cells reveals a unique identity within the immune system. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(7):878–87. doi:10.1038/ni.3445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Komi DEA, Redegeld FA. Role of mast cells in shaping the tumor microenvironment. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2020;58(3):313–25. doi:10.1007/s12016-019-08753-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Xia Q, Ding Y, Wu XJ, Peng RQ, Zhou Q, Zeng J, et al. Mast cells in adjacent normal colon mucosa rather than those in invasive margin are related to progression of colon cancer. Chin J Cancer Res. 2011;23(4):276–82. doi:10.1007/s11670-011-0276-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Benimam MM, Meas-Yedid V, Mukherjee S, Frafjord A, Corthay A, Lagache T, et al. Statistical analysis of spatial patterns in tumor microenvironment images. Nat Commun. 2025;16(1):3090. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-57943-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Hempel Sullivan H, Heaphy CM, Kulac I, Cuka N, Lu J, Barber JR, et al. High extratumoral mast cell counts are associated with a higher risk of adverse prostate cancer outcomes. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(3):668–75. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-19-0962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Johansson A, Rudolfsson S, Hammarsten P, Halin S, Pietras K, Jones J, et al. Mast cells are novel independent prognostic markers in prostate cancer and represent a target for therapy. Am J Pathol. 2010;177(2):1031–41. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2010.100070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Fakhrjou A, Niroumand-Oscoei SM, Somi MH, Ghojazadeh M, Naghashi S, Samankan S. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating mast cells in outcome of patients with esophagus squamous cell carcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2014;45(1):48–53. doi:10.1007/s12029-013-9550-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Sakalauskaitė S, Riškevičienė V, Šengaut J, Juodžiukynienė N. Association of mast cell density, microvascular density and endothelial area with clinicopathological parameters and prognosis in canine mammary gland carcinomas. Acta Vet Scand. 2022;64(1):14. doi:10.1186/s13028-022-00633-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Rajput AB, Turbin DA, Cheang MC, Voduc DK, Leung S, Gelmon KA, et al. Stromal mast cells in invasive breast cancer are a marker of favourable prognosis: a study of 4, 444 cases. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;107(2):249–57. doi:10.1007/s10549-007-9546-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Awang Ahmad N, Lai SK, Suboh R, Hussin H. Comparison of mast cell density and prognostic factors in invasive breast carcinoma: a single-centre study in Malaysia. Malays J Med Sci. 2023;30(5):81–90. doi:10.21315/mjms2023.30.5.7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Keser SH, Kandemir NO, Ece D, Gecmen GG, Gul AE, Barisik NO, et al. Relationship of mast cell density with lymphangiogenesis and prognostic parameters in breast carcinoma. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2017;33(4):171–80. doi:10.1016/j.kjms.2017.01.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Sang J, Yi D, Tang X, Zhang Y, Huang T. The associations between mast cell infiltration, clinical features and molecular types of invasive breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7(49):81661–9. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.13163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Xiao H, Lässer C, Shelke GV, Wang J, Rådinger M, Lunavat TR, et al. Mast cell exosomes promote lung adenocarcinoma cell proliferation—role of KIT-stem cell factor signaling. Cell Commun Signal. 2014;12:64. doi:10.1186/s12964-014-0064-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Guo F, Kong WN, Li DW, Zhao G, Wu HL, Anwar M, et al. Low tumor infiltrating mast cell density reveals prognostic benefit in cervical carcinoma. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2022;21:15330338221106530. doi:10.1177/15330338221106530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Liu Z, Zhu Y, Xu L, Zhang J, Xie H, Fu H, et al. Tumor stroma-infiltrating mast cells predict prognosis and adjuvant chemotherapeutic benefits in patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7(9):e1474317. doi:10.1080/2162402X.2018.1474317. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Melillo RM, Guarino V, Avilla E, Galdiero MR, Liotti F, Prevete N, et al. Mast cells have a protumorigenic role in human thyroid cancer. Oncogene. 2010;29(47):6203–15. doi:10.1038/onc.2010.348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Hou Y, Wang Q, Su L, Zhu Y, Xiao Y, Feng F. Increased tumor-associated mast cells facilitate thyroid cancer progression by inhibiting CD8+ T cell function through galectin-9. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2023;56:e12370. doi:10.1590/1414-431X2023e12370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Mao Y, Feng Q, Zheng P, Yang L, Zhu D, Chang W, et al. Low tumor infiltrating mast cell density confers prognostic benefit and reflects immunoactivation in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2018;143(9):2271–80. doi:10.1002/ijc.31613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Malfettone A, Silvestris N, Saponaro C, Ranieri G, Russo A, Caruso S, et al. High density of tryptase-positive mast cells in human colorectal cancer: a poor prognostic factor related to protease-activated receptor 2 expression. J Cell Mol Med. 2013;17(8):1025–37. doi:10.1111/jcmm.12073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Cai XJ, Peng CR, Zhang JY, Li XF, Wang X, Han Y, et al. Mast cell infiltration and subtype promote malignant transformation of oral precancer and progression of oral cancer. Cancer Res Commun. 2024;4(8):2203–14. doi:10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-24-0169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Wang JT, Li H, Zhang H, Chen YF, Cao YF, Li RC, et al. Intratumoral IL17-producing cells infiltration correlate with antitumor immune contexture and improved response to adjuvant chemotherapy in gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(2):266–73. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdy505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Lv YP, Peng LS, Wang QH, Chen N, Teng YS, Wang TT, et al. Degranulation of mast cells induced by gastric cancer-derived adrenomedullin prompts gastric cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9(10):1034. doi:10.1038/s41419-018-1100-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Lv Y, Zhao Y, Wang X, Chen N, Mao F, Teng Y, et al. Increased intratumoral mast cells foster immune suppression and gastric cancer progression through TNF-α-PD-L1 pathway. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):54. doi:10.1186/s40425-019-0530-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Ma Y, Hwang RF, Logsdon CD, Ullrich SE. Dynamic mast cell-stromal cell interactions promote growth of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73(13):3927–37. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Vescio F, Ammendola M, Currò G, Curcio S. Close relationship between mediators of inflammation and pancreatic cancer: our experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30(23):2927–30. doi:10.3748/wjg.v30.i23.2927. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Karamitopoulou E, Shoni M, Theoharides TC. Increased number of non-degranulated mast cells in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma but not in acute pancreatitis. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2014;27(2):213–20. doi:10.1177/039463201402700208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Yin H, Wang X, Jin N, Ling X, Leng X, Wang Y, et al. Integrated analysis of immune infiltration in esophageal carcinoma as prognostic biomarkers. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(22):1697. doi:10.21037/atm-21-5881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Majorini MT, Cancila V, Rigoni A, Botti L, Dugo M, Triulzi T, et al. Infiltrating mast cell-mediated stimulation of estrogen receptor activity in breast cancer cells promotes the luminal phenotype. Cancer Res. 2020;80(11):2311–24. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-19-3596. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Choi HW, Naskar M, Seo HK, Lee HW. Tumor-associated mast cells in urothelial bladder cancer: optimizing immuno-oncology. Biomedicines. 2021;9(11):1500. doi:10.3390/biomedicines9111500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Chang DZ, Ma Y, Ji B, Wang H, Deng D, Liu Y, et al. Mast cells in tumor microenvironment promotes the in vivo growth of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(22):7015–23. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-11-0607. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Varma S, Pm S, Viswanathan Deepthi P, G I. Immunohistochemical analysis of CD117 in the mast cells of odontogenic keratocysts. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e67558. doi:10.7759/cureus.67558. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Hempel HA, Cuka NS, Kulac I, Barber JR, Cornish TC, Platz EA, et al. Low intratumoral mast cells are associated with a higher risk of prostate cancer recurrence. Prostate. 2017;77(4):412–24. doi:10.1002/pros.23280. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Fleischmann A, Schlomm T, Köllermann J, Sekulic N, Huland H, Mirlacher M, et al. Immunological microenvironment in prostate cancer: high mast cell densities are associated with favorable tumor characteristics and good prognosis. Prostate. 2009;69(9):976–81. doi:10.1002/pros.20948. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Song F, Zhang Y, Chen Q, Bi D, Yang M, Lu L, et al. Mast cells inhibit colorectal cancer development by inducing ER stress through secreting Cystatin C. Oncogene. 2023;42(3):209–23. doi:10.1038/s41388-022-02543-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Mehdawi L, Osman J, Topi G, Sjölander A. High tumor mast cell density is associated with longer survival of colon cancer patients. Acta Oncol. 2016;55(12):1434–42. doi:10.1080/0284186X.2016.1198493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Lin C, Liu H, Zhang H, Cao Y, Li R, Wu S, et al. Tryptase expression as a prognostic marker in patients with resected gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2017;104(8):1037–44. doi:10.1002/bjs.10546. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Kammer MN, Mori H, Rowe DJ, Chen SC, Vasiukov G, Atwater T, et al. Tumoral densities of T-cells and mast cells are associated with recurrence in early-stage lung adenocarcinoma. JTO Clin Res Rep. 2023;4(9):100504. doi:10.1016/j.jtocrr.2023.100504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Leveque E, Rouch A, Syrykh C, Mazières J, Brouchet L, Valitutti S, et al. Phenotypic and histological distribution analysis identify mast cell heterogeneity in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancers. 2022;14(6):1394. doi:10.3390/cancers14061394. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Shikotra A, Ohri CM, Green RH, Waller DA, Bradding P. Mast cell phenotype, TNFα expression and degranulation status in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38352. doi:10.1038/srep38352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. McAdams J, Ebott J, Jansen C, Kim C, Maiz D, Ou J, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy induces phenotypic mast cell changes in high grade serous ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res. 2024;17(1):192. doi:10.1186/s13048-024-01516-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Mo S, Zong L, Chen X, Chang X, Lu Z, Yu S, et al. High mast cell density predicts a favorable prognosis in patients with pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms. Neuroendocrinology. 2022;112(9):845–55. doi:10.1159/000521651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Dos Santos Cunha AC, Simon AG, Zander T, Buettner R, Bruns CJ, Schroeder W, et al. Dissecting the inflammatory tumor microenvironment of esophageal adenocarcinoma: mast cells and natural killer cells are favorable prognostic factors and associated with less extensive disease. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2023;149(10):6917–29. doi:10.1007/s00432-023-04650-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Meyer N, Hinz N, Schumacher A, Weißenborn C, Fink B, Bauer M, et al. Mast cells retard tumor growth in ovarian cancer: insights from a mouse model. Cancers. 2023;15(17):4278. doi:10.3390/cancers15174278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Huang B, Lei Z, Zhang GM, Li D, Song C, Li B, et al. SCF-mediated mast cell infiltration and activation exacerbate the inflammation and immunosuppression in tumor microenvironment. Blood. 2008;112(4):1269–79. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-03-147033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Blatner NR, Bonertz A, Beckhove P, Cheon EC, Krantz SB, Strouch M, et al. In colorectal cancer mast cells contribute to systemic regulatory T-cell dysfunction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(14):6430–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0913683107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Yin H, Chen Q, Gao S, Shoucair S, Xie Y, Habib JR, et al. The crosstalk with CXCL10-rich tumor-associated mast cells fuels pancreatic cancer progression and immune escape. Adv Sci. 2025;12(14):e2417724. doi:10.1002/advs.202417724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. St Paul M, Ohashi PS. The roles of CD8+ T cell subsets in antitumor immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 2020;30(9):695–704. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2020.06.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Wang B, Li L, Liao Y, Li J, Yu X, Zhang Y, et al. Mast cells expressing interleukin 17 in the muscularis propria predict a favorable prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(10):1575–85. doi:10.1007/s00262-013-1460-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Fan F, Gao J, Zhao Y, Wang J, Meng L, Ma J, et al. Elevated mast cell abundance is associated with enrichment of CCR2+ cytotoxic T cells and favorable prognosis in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 2023;83(16):2690–703. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-22-3140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Ma Y, Zhao X, Feng J, Qiu S, Ji B, Huang L, et al. Tumor-infiltrating mast cells confer resistance to immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer. iScience. 2024;27(11):111085. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.111085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Sakita JY, Elias-Oliveira J, Carlos D, de Souza Santos E, Almeida LY, Malta TM, et al. Mast cell-T cell axis alters development of colitis-dependent and colitis-independent colorectal tumours: potential for therapeutically targeting via mast cell inhibition. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10(10):e004653. doi:10.1136/jitc-2022-004653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Portales-Cervantes L, Dawod B, Marshall JS. Mast cells and natural killer cells-a potentially critical interaction. Viruses. 2019;11(6):E514. doi:10.3390/v11060514. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Xie J, Liu W, Deng X, Wang H, Ou X, An X, et al. Paracrine orchestration of tumor microenvironment remodeling induced by GLO1 potentiates lymph node metastasis in breast cancer. Adv Sci. 2025;12(32):e00722. doi:10.1002/advs.202500722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Jachetti E, Cancila V, Rigoni A, Bongiovanni L, Cappetti B, Belmonte B, et al. Cross-talk between myeloid-derived suppressor cells and mast cells mediates tumor-specific immunosuppression in prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2018;6(5):552–65. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-17-0385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Chen X, Churchill MJ, Nagar KK, Tailor YH, Chu T, Rush BS, et al. IL-17 producing mast cells promote the expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in a mouse allergy model of colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6(32):32966–79. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.5435. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Khan MW, Keshavarzian A, Gounaris E, Melson JE, Cheon EC, Blatner NR, et al. PI3K/AKT signaling is essential for communication between tissue-infiltrating mast cells, macrophages, and epithelial cells in colitis-induced cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(9):2342–54. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Eissmann MF, Dijkstra C, Jarnicki A, Phesse T, Brunnberg J, Poh AR, et al. IL-33-mediated mast cell activation promotes gastric cancer through macrophage mobilization. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2735. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-10676-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. Liu Z, Huang C, Mao X, Mi J, Zhang Q, Xie Y, et al. Single cell RNA-sequencing reveals mast cells enhance mononuclear phagocytes infiltration in bladder cancer microenvironment. J Cancer. 2024;15(17):5672–90. doi:10.7150/jca.99554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Turley SJ, Cremasco V, Astarita JL. Immunological hallmarks of stromal cells in the tumour microenvironment. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(11):669–82. doi:10.1038/nri3902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Xie J, Lin X, Deng X, Tang H, Zou Y, Chen W, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived extracellular vesicles: regulators and therapeutic targets in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Drug Resist. 2025;8:2. doi:10.20517/cdr.2024.152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Mangia A, Malfettone A, Rossi R, Paradiso A, Ranieri G, Simone G, et al. Tissue remodelling in breast cancer: human mast cell tryptase as an initiator of myofibroblast differentiation. Histopathology. 2011;58(7):1096–106. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.2011.03842.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Teng LKH, Pereira BA, Keerthikumar S, Huang C, Niranjan B, Lee SN, et al. Mast cell-derived SAMD14 is a novel regulator of the human prostate tumor microenvironment. Cancers. 2021;13(6):1237. doi:10.3390/cancers13061237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Alhamwe BA, Ponath V, Alhamdan F, Dörsam B, Landwehr C, Linder M, et al. BAG6 restricts pancreatic cancer progression by suppressing the release of IL33-presenting extracellular vesicles and the activation of mast cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2024;21(8):918–31. doi:10.1038/s41423-024-01195-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Poglio S, De Toni-Costes F, Arnaud E, Laharrague P, Espinosa E, Casteilla L, et al. Adipose tissue as a dedicated reservoir of functional mast cell progenitors. Stem Cells. 2010;28(11):2065–72. doi:10.1002/stem.523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Plotkin JD, Elias MG, Fereydouni M, Daniels-Wells TR, Dellinger AL, Penichet ML, et al. Human mast cells from adipose tissue target and induce apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Front Immunol. 2019;10:138. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Baldi S, Long N, Ma S, Liu L, Al-Danakh A, Yang Q, et al. Advancements in protein kinase inhibitors: from discovery to clinical applications. Research. 2025;8:0747. doi:10.34133/research.0747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Majorini MT, Colombo MP, Lecis D. Few, but efficient: the role of mast cells in breast cancer and other solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2022;82(8):1439–47. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-21-3424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Ansari FM, Asif M, Kiani MN, Ara N, Ishaque M, Khan R. Evaluation of mast cell density using CD117 antibody and microvessel density using CD34 antibody in different grades of oral squamous cell carcinoma. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2020;21(12):3533–8. doi:10.31557/APJCP.2020.21.12.3533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Longo V, Catino A, Montrone M, Galetta D, Ribatti D. Controversial role of mast cells in NSCLC tumor progression and angiogenesis. Thorac Cancer. 2022;13(21):2929–34. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.14654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Bolat Kucukzeybek B, Dere Y, Akder Sari A, Ocal I, Avcu E, Dere O, et al. The prognostic significance of CD117-positive mast cells and microvessel density in colorectal cancer. Medicine. 2024;103(29):e38997. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000038997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Micu GV, Stăniceanu F, Sticlaru LC, Popp CG, Bastian AE, Gramada E, et al. Correlations between the density of tryptase positive mast cells (DMCT) and that of new blood vessels (CD105+) in patients with gastric cancer. Rom J Intern Med. 2016;54(2):113–20. doi:10.1515/rjim-2016-0016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Ribatti D, Annese T, Tamma R. Adipocytes, mast cells and angiogenesis. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2020;61(4):1051–6. doi:10.47162/RJME.61.4.07. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Annese T, Tamma R, Bozza M, Zito A, Ribatti D. Autocrine/paracrine loop between SCF+/c-kit+ mast cells promotes cutaneous melanoma progression. Front Immunol. 2022;13:794974. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.794974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Ribatti D, Crivellato E, Candussio L, Nico B, Vacca A, Roncali L, et al. Mast cells and their secretory granules are angiogenic in the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31(4):602–8. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.00986.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Li MO, Wolf N, Raulet DH, Akkari L, Pittet MJ, Rodriguez PC, et al. Innate immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(6):725–9. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2021.05.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Shefler I, Salamon P, Zitman-Gal T, Mekori YA. Tumor-derived extracellular vesicles induce CCL18 production by mast cells: a possible link to angiogenesis. Cells. 2022;11(3):353. doi:10.3390/cells11030353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Ammendola M, Currò G, Laface C, Zuccalà V, Memeo R, Luposella F, et al. Mast cells positive for c-kit receptor and tryptase correlate with angiogenesis in cancerous and adjacent normal pancreatic tissue. Cells. 2021;10(2):444. doi:10.3390/cells10020444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Laface C, Laforgia M, Zito AF, Loisi D, Zizzo N, Tamma R, et al. Chymase-positive Mast cells correlate with tumor angiogenesis: first report in pancreatic cancer patients. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2021;25(22):6862–73. doi:10.26355/eurrev_202111_27234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

132. Kurihara-Shimomura M, Sasahira T, Shimomura H, Bosserhoff AK, Kirita T. Mast cell chymase promotes angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis mediated by activation of melanoma inhibitory activity gene family members in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2020;56(5):1093–100. doi:10.3892/ijo.2020.4996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Kaya Ş, Uçmak F, Bozdağ Z, Firat U. The relationship of mast cell density in pulmonary, gastric and ovarian malignant epithelial tumors with tumor necrosis and vascularization. Pol J Pathol. 2020;71(3):221–8. doi:10.5114/pjp.2020.99788. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

134. Xiao H, He M, Xie G, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Ye X, et al. The release of tryptase from mast cells promote tumor cell metastasis via exosomes. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):1015. doi:10.1186/s12885-019-6203-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

135. Marech I, Ammendola M, Leporini C, Patruno R, Luposella M, Zizzo N, et al. C-Kit receptor and tryptase expressing mast cells correlate with angiogenesis in breast cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2018;9(8):7918–27. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.23722. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

136. Shi A, Liu Z, Fan Z, Li K, Liu X, Tang Y, et al. Function of mast cell and bile-cholangiocarcinoma interplay in cholangiocarcinoma microenvironment. Gut. 2024;73(8):1350–63. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2023-331715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

137. Terhorst-Molawi D, Hawro T, Grekowitz E, Kiefer L, Merchant K, Alvarado D, et al. Anti-KIT antibody, barzolvolimab, reduces skin mast cells and disease activity in chronic inducible urticaria. Allergy. 2023;78(5):1269–79. doi:10.1111/all.15585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

138. Kolkhir P, Elieh-Ali-Komi D, Metz M, Siebenhaar F, Maurer M. Understanding human mast cells: lesson from therapies for allergic and non-allergic diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2022;22(5):294–308. doi:10.1038/s41577-021-00622-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

139. Liao CP, Booker RC, Brosseau JP, Chen Z, Mo J, Tchegnon E, et al. Contributions of inflammation and tumor microenvironment to neurofibroma tumorigenesis. J Clin Investig. 2018;128(7):2848–61. doi:10.1172/jci99424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

140. Yang Z, Chen H, Yin S, Mo H, Chai F, Luo P, et al. PGR-KITLG signaling drives a tumor-mast cell regulatory feedback to modulate apoptosis of breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2024;589:216795. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

141. Somasundaram R, Connelly T, Choi R, Choi H, Samarkina A, Li L, et al. Tumor-infiltrating mast cells are associated with resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):346. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20600-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

142. Aliabadi A, Haghshenas MR, Kiani R, Panjehshahin MR, Erfani N. Promising anticancer activity of cromolyn in colon cancer: in vitro and in vivo analysis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2024;150(4):207. doi:10.1007/s00432-024-05741-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

143. Samoszuk M, Corwin MA. Mast cell inhibitor cromolyn increases blood clotting and hypoxia in murine breast cancer. Int J Cancer. 2003;107(1):159–63. doi:10.1002/ijc.11340. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

144. Gao J, Su X, Zhang Y, Ma X, Ren B, Lei P, et al. Mast cell activation induced by tamoxifen citrate via MRGPRX2 plays a potential adverse role in breast cancer treatment. Biochem Pharmacol. 2025;233:116760. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2025.116760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

145. Wu SY, Jin X, Liu Y, Wang ZY, Zuo WJ, Ma D, et al. Mobilizing antigen-presenting mast cells in anti-PD-1-refractory triple-negative breast cancer: a phase 2 trial. Nat Med. 2025;31(7):2405–15. doi:10.1038/s41591-025-03776-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

146. Vogel M, Engeroff P. A comparison of natural and therapeutic anti-IgE antibodies. Antibodies. 2024;13(3):58. doi:10.3390/antib13030058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]