Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

ICAT mediates the inhibition of stemness and tumorigenesis in acute myeloid leukemia cells induced by 1,25-(OH)2D3

1 Graduate School, Zhuhai Campus of Zunyi Medical University, Zhuhai, 519041, China

2 Department of Advanced Diagnostic and Clinical Medicine, Zhongshan People’s Hospital, Zhongshan, 528403, China

3 Graduate School, Guangdong Medical University, Zhanjiang, 524023, China

* Corresponding Authors: MING HONG. Email: ; WEIJIA WANG. Email:

Oncology Research 2025, 33(3), 695-708. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2024.051746

Received 14 March 2024; Accepted 06 June 2024; Issue published 28 February 2025

Abstract

Background: The role of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 (1,25-(OH)2D3) in cancer prevention and treatment is an emerging topic of interest. However, its effects on the stemness of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells are poorly understood. Methods: The proliferation and differentiation of AML cells (HL60 and NB4) were investigated by the CCK-8 assay, immunocytochemical staining, and flow cytometry. The abilities of HL60 and NB4 cells to form spheres were examined by the cell sphere formation assay. In addition, the levels of stemness-associated markers (SOX2, Nanog, OCT4, and c-Myc) in HL60 and NB4 cells were measured by western blotting and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction. Moreover, we obtained β-catenin-interacting protein 1 (ICAT)-knockout and ICAT-overexpressing HL-60 cells using gene editing and lentiviral infection techniques and investigated the role of ICAT in modulating the stemness-inhibiting effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 using the aforementioned experimental methods. Finally, we validated our findings in vivo using NOD/SCID mice. Results: 1,25-(OH)2D3 inhibited the proliferation and stemness of AML cells (HL60 and NB4) and induced their differentiation into monocytes. Additionally, the knockdown of ICAT in HL60 cells attenuated the inhibitory effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on proliferation and stemness and suppressed the expression of stemness markers. Conversely, overexpression of ICAT enhanced the aforementioned inhibitory effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3. Consistently, in NOD/SCID mice, 1,25-(OH)2D3 suppressed tumor formation by HL-60 cells, and the effects of ICAT knockdown or overexpression on 1,25-(OH)2D3 aligned with the in vitro findings. Conclusion: 1,25-(OH)2D3 inhibits AML cell stemness, possibly through modulation of the ICAT-mediated Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.Keywords

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a type of blood and bone marrow cancer characterized by the rapid accumulation of abnormal white blood cells, known as myeloblasts. These cells interfere with the production of normal blood cells, leading to symptoms such as fatigue, infections, and easy bruising or bleeding. AML can affect people of all ages but is more common in older adults [1]. AML comprises a complex group of diseases. The WHO has proposed a classification of acute leukemia that incorporates genetic, epidemiological, and immunologic factors in addition to morphological factors. The latest classification also includes molecular analyses [2]. Current therapeutic strategies for AML include chemotherapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and immunotherapy [3]. However, conventional chemotherapy often fails to achieve long-term remission, and disease relapse is frequent [4]. Studies have illustrated that stemness, the ability of leukemia cells to self-renew and resist differentiation, is a major driver of primary drug resistance in AML [5]. Addressing both stemness and specific high-risk co-mutations could potentially circumvent resistance and enhance survival outcomes for individuals diagnosed with AML [5]. Therefore, targeting the stemness of leukemia cells is particularly crucial in the context of treatment resistance, prognosis, and relapse in AML.

1,25-(OH)2D3, also known as 1α,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3, is a multifunctional hormone and a key controller of human genetic activity. It influences the characteristics and functions of different types of cells by regulating the activity of numerous genes in a specific manner depending on the tissue and cell type [6]. Prior studies indicated that 1,25-(OH)2D3 can regulate innate and adaptive immunity as well as calcium and bone homeostasis [7–9]. Studies also reported that 1,25-(OH)2D3 can inhibit the stemness of cancer cells. Specifically, 1,25-(OH)2D3 has inhibitory effects on tumor cell proliferation and promotive effects on the differentiation of tumor cells, including colorectal cancer, melanoma, and leukemia cells [10–12]. In addition, 1,25-(OH)2D3 has been demonstrated to attenuate the stemness of tumor cells, including ovarian cancer cells, pancreatic cancer cells, breast cancer cells, and glioblastoma stem-like cells [13–17]. 1,25-(OH)2D3 exerts anticancer effects by modulating multiple signaling pathways to inhibit tumor cell stemness. Previous research highlighted the pivotal role of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling in mediating the suppressive effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on the stemness of breast cancer and ovarian cancer cells [18,19]. In previous research studying the effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in AML differentiation, 1,25-(OH)2D3 was found to inhibit the entry of β-catenin protein into the nucleus by upregulating β-catenin–interacting protein 1 (ICAT) and then suppressing the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, inducing the differentiation of acute promyelocytic leukemia cells into a mononuclear line, with ICAT playing a pivotal role in this process [20]. Earlier investigations revealed that ICAT inhibits glioblastoma proliferation and suppresses colorectal cancer progression by targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling [21,22]. Nevertheless, the precise mechanism by which 1,25-(OH)2D3 and ICAT affect AML cell stemness remains largely unknown.

In this study, HL-60 and NB4 cells underwent treatment with 1,25(OH)2D3 to assess its impact on cell proliferation, differentiation, and the expression of markers associated with stemness. The investigation aimed to uncover how 1,25(OH)2D3 influences the stem cell characteristics of AML cells. Our data demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D3 inhibited the stemness of HL-60 and NB4 cells, providing evidence supporting the use of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in leukemia treatment. Additionally, the experimental data from prior investigations revealed that ICAT protein expression was increased in HL-60 cells following exposure to 1,25(OH)2D3. Leveraging CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing technology alongside lentivirus transfection, we successfully engineered HL-60 cell models featuring ICAT knockout or overexpression. Subsequently, we demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D3 suppresses stemness through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling via a mechanism mediated by ICAT. This provides novel insights into the potential mechanisms of current antitumor therapy in leukemia.

NB4 cells were purchased from Wuxi Newgain Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Wuxi, China), and HL-60 cells were procured from the Chinese Academy of Sciences. HL60 cells were cultured in IMDM medium (SH30228.01, Cytiva, CO, USA), with 20% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, USA). NB4 cells were cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (CGM112.05, Cellmax, Guangzhou, China) with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Grand Island, USA) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, Grand Island, USA). All cells were maintained in a 37°C, 5% CO2 cell culture incubator. 1,25-(OH)2D3 (D1530, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in absolute ethyl alcohol and stored at −20°C at a concentration of 1 × 10−3 M/L. The concentration of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in the drug medium was 1 × 10−7 M/L.

Cells were seeded at a density of 104 cells in 96-well plates. Cells in the drug group were incubated with 1 × 10−7 M 1,25-(OH)2D3, and cells in the control group were untreated. All other conditions were identical between the groups. Twenty microliters of CCK-8 reagent (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) were added to each well at the specified time point (0, 1 day, 2 day, and 3 day), followed by incubation for 2.5 h, and the absorbance at 450 nm was measured in a spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) to calculate the relative growth rate of the cells.

Cells from both the control and experimental groups were collected at 72 h for Wright–Giemsa staining (BioVision, Guangzhou, China). Esterase staining was performed using the Acid α-Naphthyl Acetate Esterase Staining Kit (G2390, Solarbio, Guangzhou, China) [23], and NaF inhibition assays were conducted to observe cellular morphology using a BX-63 upright microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

CD14 detection by flow cytometry

Approximately 2 × 105/mL cells were exposed to 1,25-(OH)2D3 (10−7 M, as a positive control) for 72 h. Cells were washed for twice by pre-cold 1× PBS. Then, incubated with anti-CD14 antibody (Becton Dickinson, NJ, USA) in the dark. After 30 min, cells were washed by pre-cold PBS and detected with flow cytometry (CytoFLEX S, Beckman-Coulter, CA, USA) [24].

First, 0.5 × 103 cells were seeded into ultra-low attachment 24-well plates. Starting from day 0, 200 µL of sphere-specific culture medium was added, and 200 µl of sphere-specific culture medium was added again on days 3, 6, 9, and 12. Photographic documentation and quantification of tumor spheres (diameter > 30 μm) were conducted on days 9, 12, and 15 [25].

Total proteins was extracted using RIPA lysis buffer (C1053, Applygen, Beijing, China) containing protease inhibitors (4693132001, Roche, Basel, Switzerland), and the protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid assay (BIV-K812-1000, BioVision). Proteins (30 µg/well) were separated by 12% SDS-PAGE and then transferred to a PVDF membrane (ISEQ00010, Millipore, Danvers, MA, USA). Membranes were sealed with 5% skim milk for 0.5 h and incubated with the following primary antibodies at 4°C overnight: anti-β-tubulin (AF1216, 1:5000, Beyotime), anti-SOX2 (ab97959, 1:2000, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-OCT4 (ab179800, 1:2000, Abcam), anti-Nanog (4903S, 1:2000, CST, Danvers, MA, USA), and anti-c-Myc (GTX10825, 1:1000, GeneTex, SoCal, UK). Subsequently, the membranes were incubated for 1.5 h at 24°C with Alexa Fluor 488B-labeled anti-rabbit IgG (ab6721, 1:5000, Abcam). Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (WBKLS0500, Millipore, MA, USA) was used to detect the blots using a chemiluminescence imager (Fusion SoloS. EDGE, VILBER, Paris, France). The intensity was analyzed using Image Lab™ software (Bio-Rad).

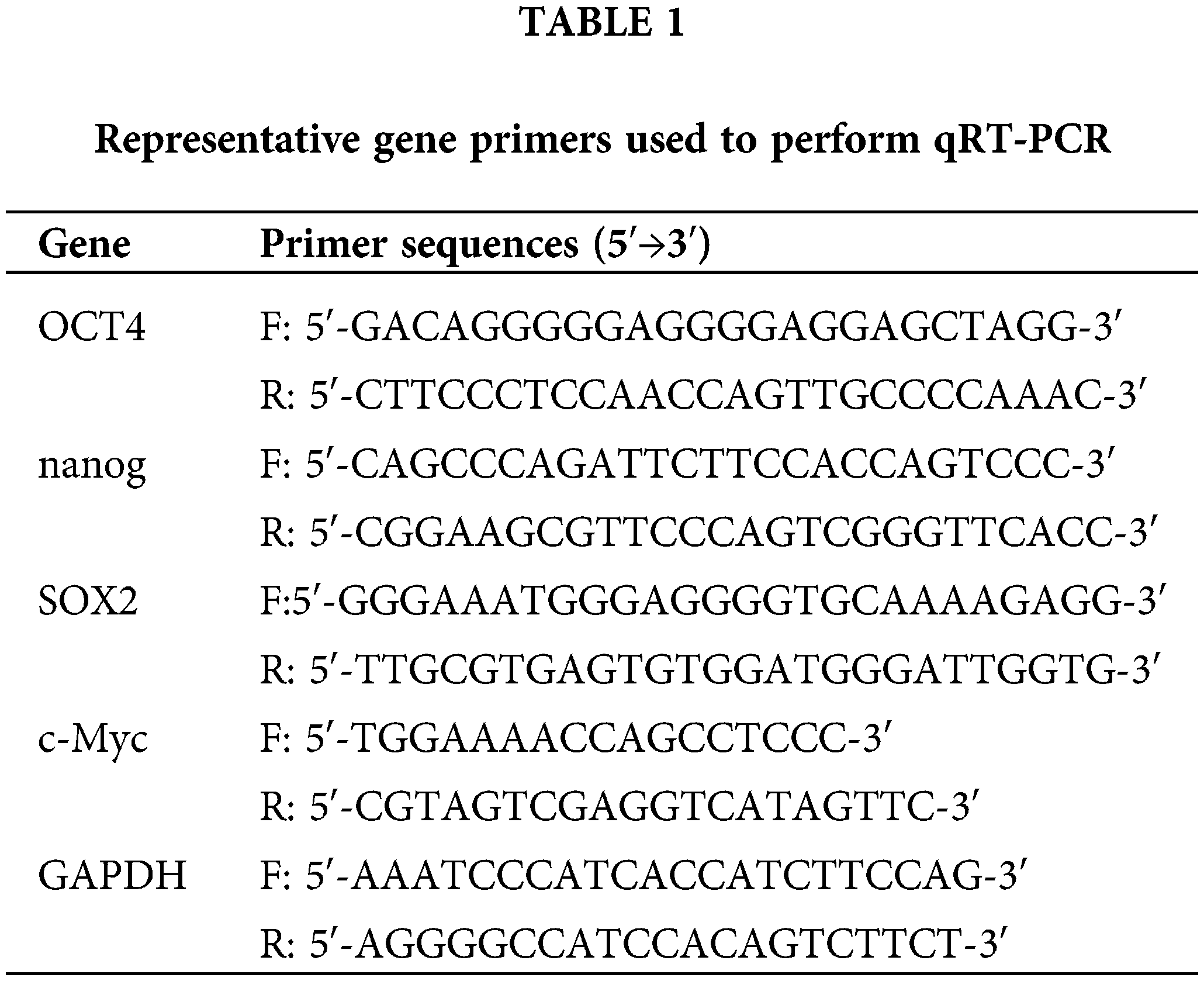

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

The experimental and control groups of cells were subjected to total RNA extraction with TRIzol reagent (15596026, Life Technologies, South San Francisco, CA, USA). Subsequently, cDNA synthesis was performed following the manufacturer’s instructions using the HiScript® III RT SuperMix for qPCR (+gDNA wiper) kit (R223-01, Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The sequences of primers are shown in Table 1. qRT-PCR was conducted using PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix (A25742, Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) and the ABI PCR System (Applied Biosystems). The thermocycling parameters were as follows: 50°C for 120 s; 95°C for 120 s; and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 s and 60°C for 60 s. The dissolution curve protocol was 95°C for 15 s, 60°C for 60 s, and 95°C for 15 s. Relative gene expression levels were calculated by the 2−ΔΔCq method [26]. GAPDH was applied as a normalization control.

CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing and lentivirus infection techniques

The human CTNNBIP1 (ICAT) gene was knocked out in HL-60 cells using CRISPR/Cas9 [27]. Homozygous ICAT gene knockout (Sh-HL-60) was confirmed by PCR and by sequencing electroporated single clones. The lentiviral vector LVEFS>KozakHumanCTNNBIP1CDS[NM_020248.3]CMV>EGFP/T2A/Puro was constructed, validated by PCR, and sequenced. 293T cells were infected with ICAT lentivirus, a control vector, and a helper plasmid for lentivirus packaging. The ICAT overexpression virus and control virus were then used to infect HL-60 cells, resulting in stably transfected ICAT-overexpressing cells (Gh-HL-60) and empty vector cells (EV-HL-60), as determined by screening with puromycin. Harvested cells were used for subsequent experiments.

The animal experiments in the current study were approved and supervised by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhongshan People’s Hospital (No. K-2023-214). 54 (eighteen in each group) nude mice (6-week-old male NOD/SCID), which were purchased from GemPharmatech Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China, were maintained in pathogen-free facilities. All the animals were weighed and randomly into groups according to their weight using StudyDirector™ (3.1.399.19, Studylog System, Inc., S. San Francisco, CA, USA) Select the Matched distribution method for grouping. Approximately 106 Sh-HL60, Gh-HL60, and HL60 cells were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of mice (eighteen mice in each group) for tumorigenesis. When the average tumor volume reached 100 mm3, mice were randomly assigned to two groups with 3 mice per group: the treatment (1,25-(OH)2D3) and control (PBS) groups. Mice in the treatment group received 0.5 μg/kg 1,25-(OH)2D3 intraperitoneally twice a day for 2 weeks. Tumor size was measured twice a week. Tumour volumes were calculated according to the formula (width2 × length)/2. The mice were humanely killed, and the weight of the excised tumor was measured.

All data in this study were generated from three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were conducted with the GraphPad Prism 7.0 software. Differences between the two groups were assessed by the two-tailed Student’s t-test. Differences between before and after treatment were assessed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). p < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

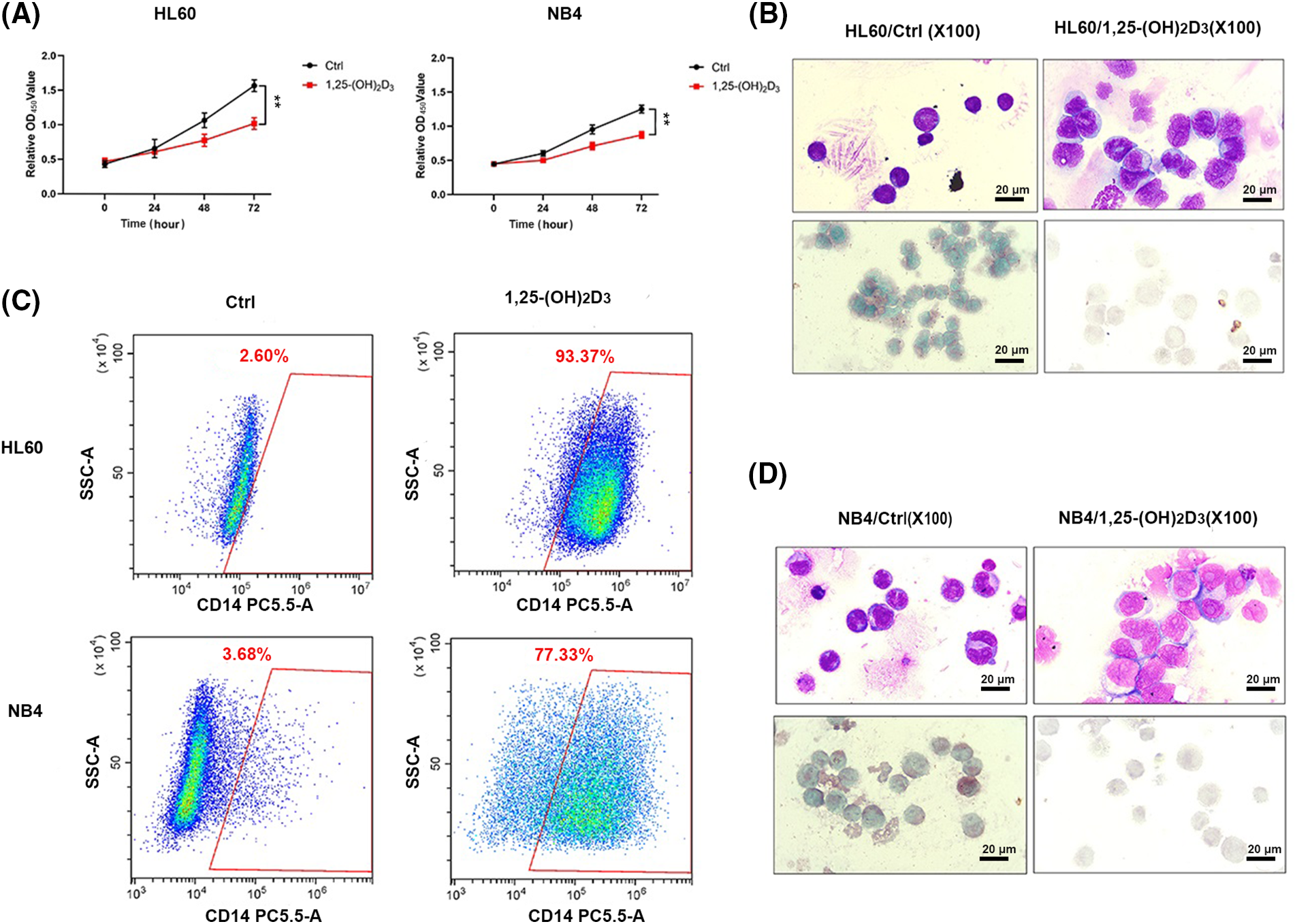

Antiproliferative and monocytic differentiation-inducing effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 I AML cells

We used the CCK-8 assay to validate the suppressive effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on the proliferation of HL-60 and NB4 cells (Fig. 1A). We also employed an immunohistochemical assay to elucidate the monocytic lineage differentiation induced by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in NB4 and HL-60 cells (Fig. 1B,D). The expression of the monocytic differentiation marker CD14 was remarkably upregulated after treatment (Fig. 1C). The results indicated that 1,25-(OH)2D3 significantly inhibits cell proliferation in HL-60 and NB4 cells while inducing their differentiation toward the monocytic lineage.

Figure 1: Antiproliferative and monocytic differentiation-inducing effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on AML cells. (A) The proliferation of HL-60 and NB4 cells following 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment for 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. The results are presented as the mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. **p < 0.01. (B) Representative images of Wright–Giemsa staining, esterase staining, and NaF inhibition experiments in untreated and drug-treated HL-60 cells. (C) Representative flow cytometry data depicting the percentage of cells that were positive for the surface antigen CD14 in untreated and drug-treated HL-60 and NB4 cells. (D) Representative images of Wright–Giemsa staining, esterase staining, and NaF inhibition experiments in untreated and drug-treated NB4 cells.

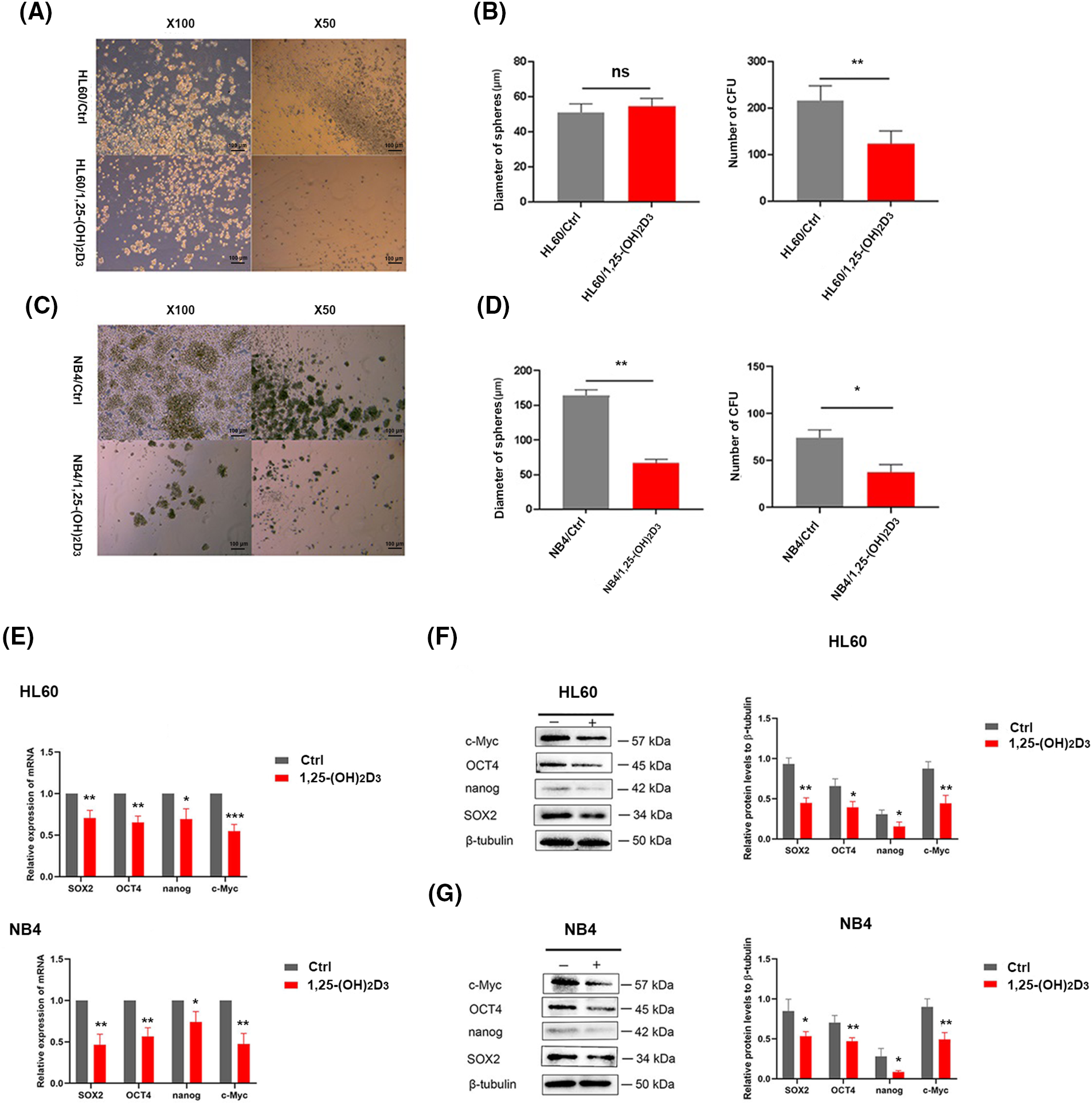

Inhibition of stemness by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in AML cells

We also conducted a cell sphere formation assay to further determine the effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on the stemness of HL-60 and NB4 cells. 1,25-(OH)2D3 suppressed sphere formation by these cells, as evidenced by reductions in the number (Fig. 2A,B) and diameter of spheres (Fig. 2C,D). Regarding stemness marker gene expression, the expression of OCT4, Nanog, SOX2, and c-Myc was inhibited by 1,25-(OH)2D3 at the protein (Fig. 2E) and mRNA levels (Fig. 2F,G). These results indicated that 1,25-(OH)2D3 significantly decreased the stemness of HL-60 and NB4 leukemia cells.

Figure 2: Inhibition of stemness by 1,25-(OH)2D3 in AML cells. (A) Stemness of HL-60 cells treated with or without 1,25-(OH)2D3 (Ctrl) was analyzed by the sphere formation assay (×50 and ×100 magnification). (B) Quantification and statistical analysis of the data in A. (C) Stemness of NB4 cells treated with or without 1,25-(OH)2D3 (Ctrl) was analyzed by the sphere formation assay (×50 and ×100 magnification). (D) Quantification and statistical analysis of the data in C. (E) qRT-PCR of SOX2, OCT4, Nanog, and c-Myc expression. (F) Protein expression of SOX2, OCT4, Nanog, and c-Myc after treatment with or without 1,25-(OH)2D3 for 72 h in HL-60 cells was analyzed by western blotting. (G) Protein expression of OCT4, SOX2, c-Myc, and Nanog after treatment with or without 1,25-(OH)2D3 for 72 h in NB4 cells was verified by western blot. nsp > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

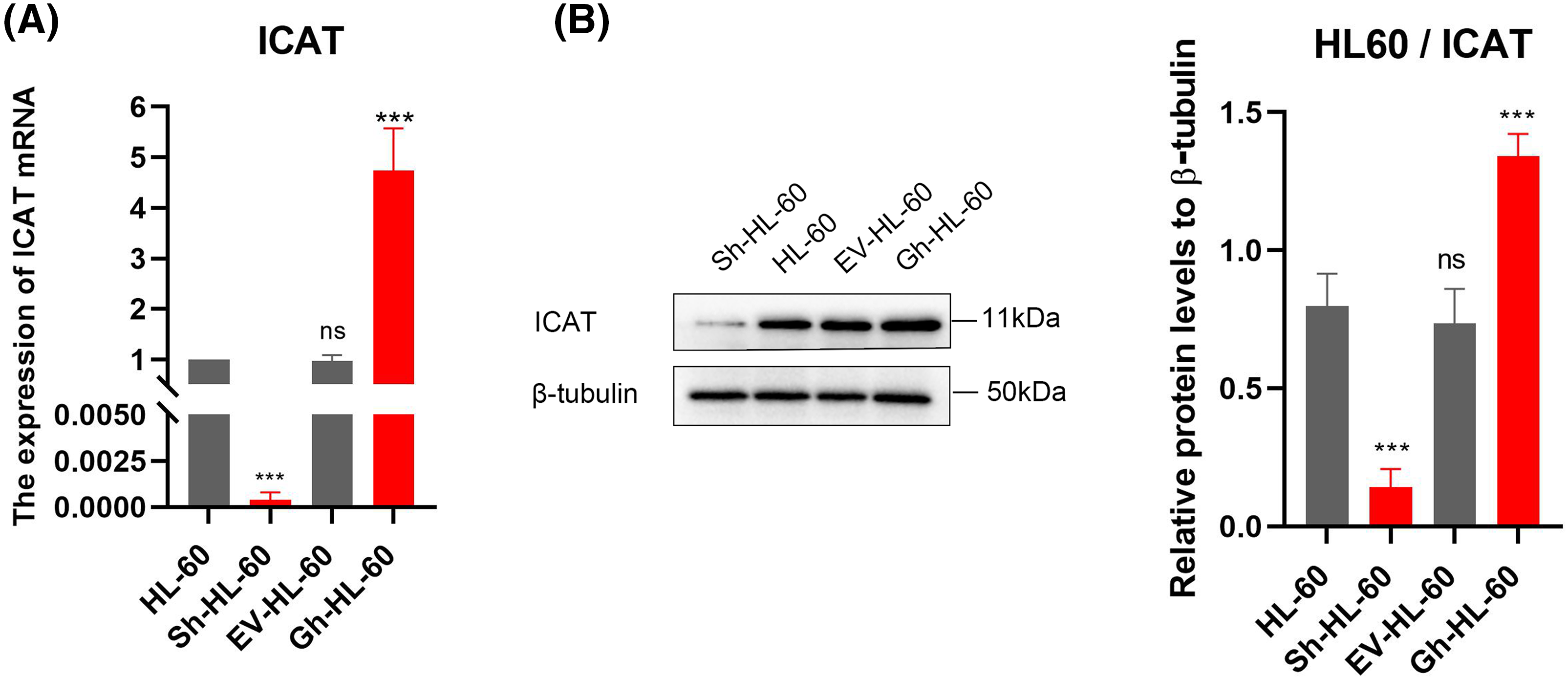

Validation of stable HL-60 strains with ICAT gene knockout or overexpression

HL-60 cells stably transfected with ICAT gene knockout and ICAT gene overexpression constructs were successfully generated and verified by qRT-PCR and western blotting, as presented in Fig. 3A,B. The sequencing results of ICAT gene knockout and overexpression vector construction are provided in the Appendix A (Fig. A1 and Table A1).

Figure 3: Stable HL-60 cells were identified with both ICAT gene knockout and overexpression. (A) Quantitative real-time PCR was conducted to assess ICAT expression in these stable HL-60 transfectants. (B) Western blotting analysis was performed to examine ICAT expression in the stable HL-60 cells. Results represent the mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. nsp > 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

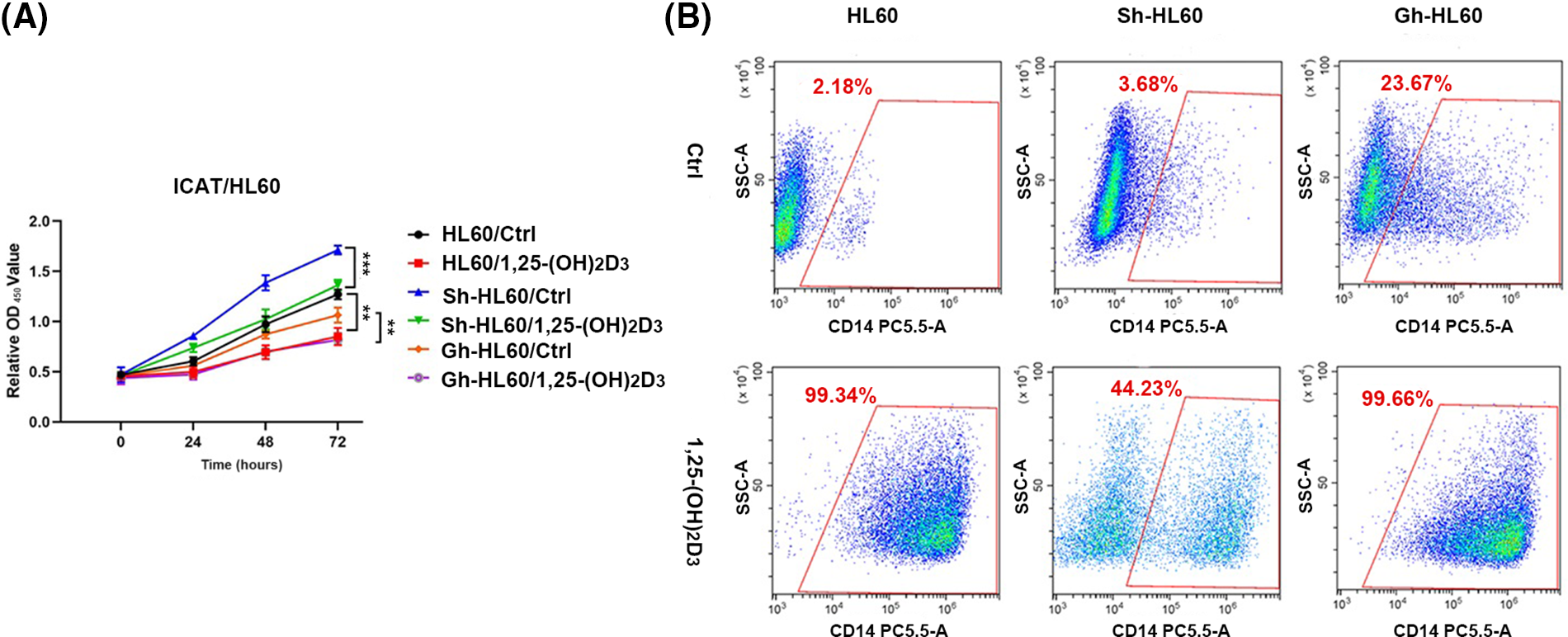

Role of ICAT in the 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated inhibition of AML cells proliferation and induction of monocytic differentiation

The results of the CCK-8 assay indicated 1,25-(OH)2D3 inhibited the proliferation of HL-60 cells, and this effect was lessened by ICAT knockout (Fig. 4A). Flow cytometry revealed 1,25-(OH)2D3 induced mononuclear differentiation, and this effect was weakened by ICAT knockout and increased by more than 20% by ICAT overexpression (Fig. 4B). These findings indicate that 1,25-(OH)2D3 may influence HL-60 cell differentiation through ICAT expression.

Figure 4: ICAT expression’s involvement in the inhibition of AML cell proliferation and the promotion of monocytic differentiation by 1,25-(OH)2D3 was investigated. (A) HL-60, Sh-HL-60, and Gh-HL-60 cell proliferation was monitored at 0, 24, 48, and 72 h post 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment. Data represent the mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (B) Flow cytometry analysis demonstrated the percentage of CD14-positive cells among treated and untreated HL-60, Sh-HL-60, and Gh-HL-60 cells.

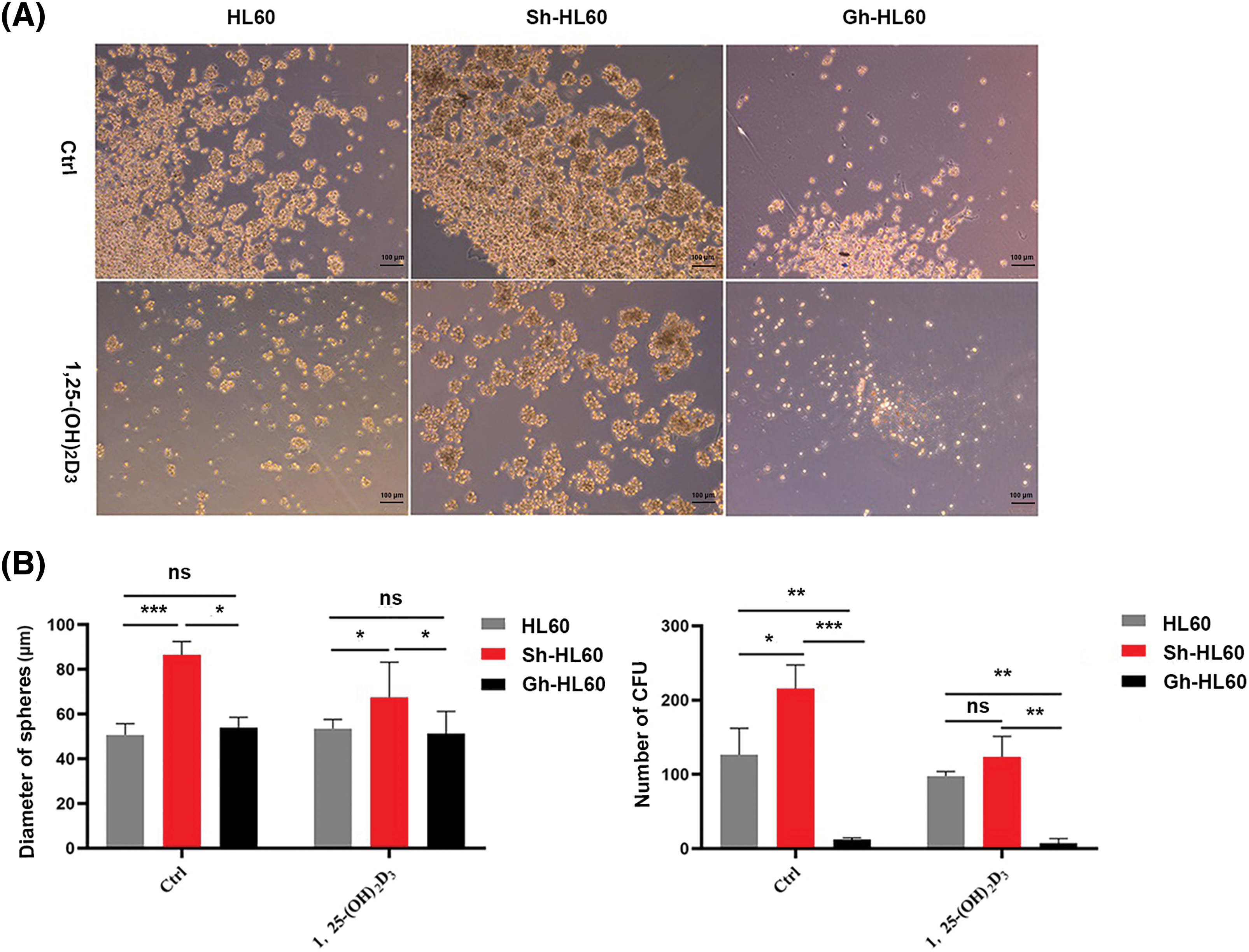

Enhancement of the 1,25-(OH)2D3-induced inhibition of AML cells sphere formation by ICAT expression

We performed cell sphere formation experiments to examine the role of ICAT expression in the inhibition of HL-60 cell sphere formation by 1,25-(OH)2D3. Our results indicated that, in untreated control cells, knockdown of ICAT alone enhanced sphere formation by HL-60 cells, whereas overexpression of ICAT alone inhibited their spheroidization. Meanwhile, in cells incubated with 1,25-(OH)2D3, ICAT overexpression enhanced its inhibitory effect, whereas 1,25-(OH)2D3 could not effectively inhibit the spheroidization of HL-60 cells after ICAT knockout, as evidenced by the changes in the number and diameter of spheroids (Fig. 5A,B).

Figure 5: ICAT expression enhanced the inhibitory effect of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on AML cell sphere formation. (A) Stemness of HL-60, Sh-HL-60, and Gh-HL-60 cells treated with or without 1,25-(OH)2D3 (Ctrl) was analyzed by the sphere formation assay (×100 magnification). (B) Quantification and statistical analysis of the data in A. Results represent the mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. nsp > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

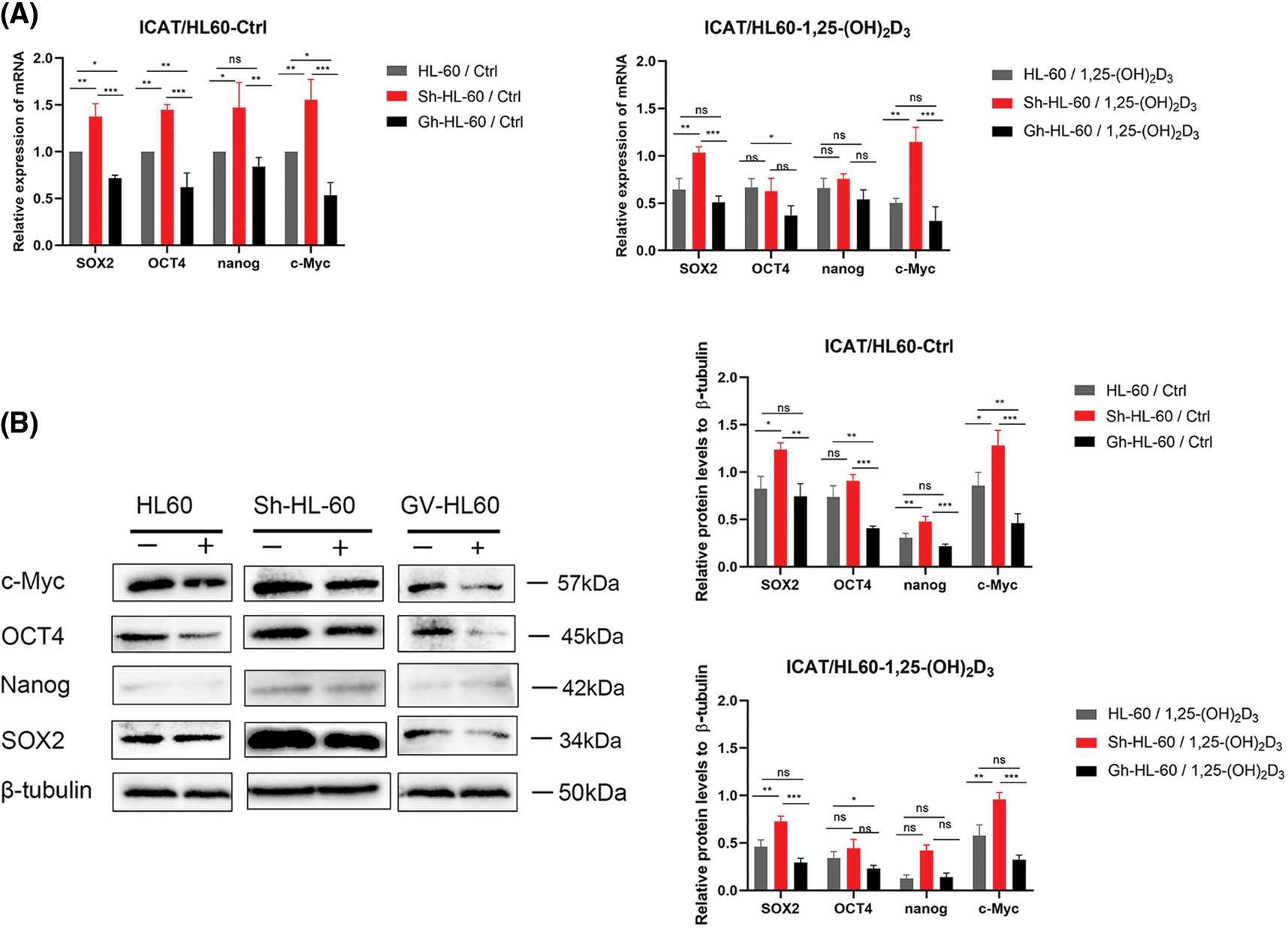

Downregulation of stemness markers by 1,25-(OH)2D3 through ICAT expression in AML cells

We assessed stemness-related gene expression (SOX2, Nanog, OCT4, c-Myc) in AML cells using qRT-PCR. ICAT knockout lessened the inhibitory effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on SOX2 and c-Myc expression, whereas these effects were enhanced by ICAT overexpression. In addition, ICAT overexpression enhanced the effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on OCT4 expression (Fig. 6A). The results of western blotting aligned with those of qRT-PCR (Fig. 6B), indicating that ICAT promoted the downregulation of stemness markers in AML cells treated with 1,25-(OH)2D3. This suggests that 1,25-(OH)2D3 inhibits AML cell stemness by modulating ICAT, and ICAT alone can suppress stemness characteristics.

Figure 6: Downregulation of stem cell markers by 1,25-(OH)2D3 through ICAT expression in AML cells. (A) qRT-PCR of SOX2, OCT4, Nanog, and c-Myc expression in HL-60, Sh-HL-60, and Gh-HL-60 cells after treatment with or without 1,25-(OH)2D3 for 72 h. (B) Protein expression of SOX2, OCT4, Nanog, and c-Myc after treatment with or without 1,25-(OH)2D3 for 72 h in HL-60, Sh-HL-60, and Gh-HL-60 cells was analyzed by western blotting. Results represent the mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. nsp > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

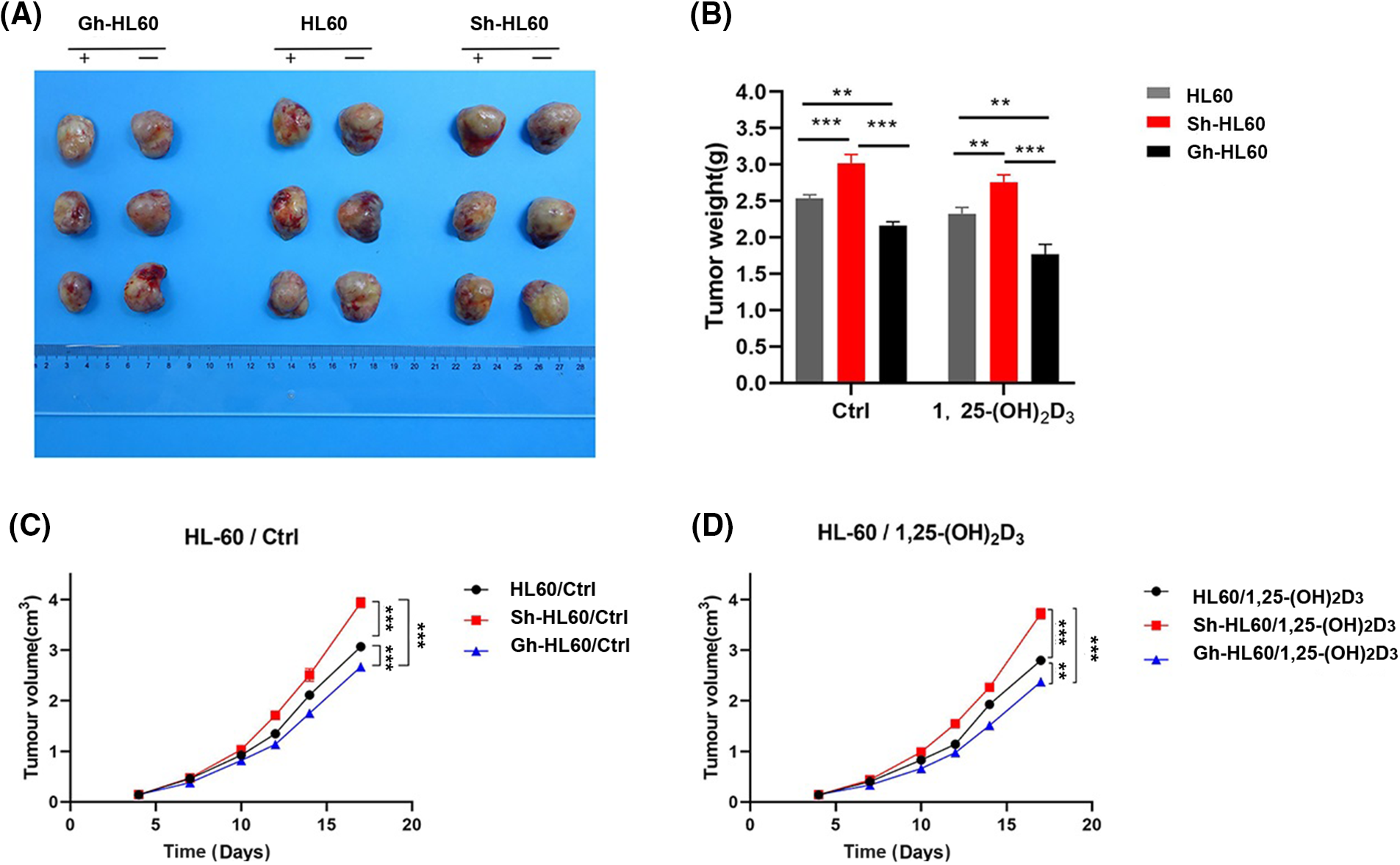

Inhibition of xenograft growth by 1,25-(OH)2D3 and ICAT expression in vivo

We conducted an in vivo tumor growth study using HL-60, Sh-HL-60, and Gh-HL-60 xenograft mouse models. 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment significantly reduced tumor size and weight in mice. In the untreated control group, overexpression of ICAT reduced the volume and weight of xenograft tumors in the HL-60 model, whereas knockdown of ICAT increased tumor volume and weight (Fig. 7A–C). In the 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment group, overexpression of ICAT enhanced the tumor-suppressing effect of 1,25-(OH)2D3, whereas this effect was attenuated by ICAT knockout (Fig. 7B,D).

Figure 7: Inhibition of xenograft tumor by 1,25-(OH)2D3 and ICAT expression in vivo. (A) Photographs of tumors xenografts. (B) The effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 and ICAT expression on tumor weight. (C) The corresponding tumor volumes in the untreated group at the indicated times are presented. (D) The corresponding tumor volumes after 1,25-(OH)2D3 injection on the indicated days. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Cell stemness is defined by its quiescent state, pluripotent nature, and ability for long-term self-renewal [22]. It plays critical roles in leukemia initiation, progression, and relapse [28], but the key determinants of leukemia cell stemness are poorly understood [29]. Therefore, targeting leukemia cell stemness could be a promising strategy for improving the efficacy of leukemia treatment [30]. 1,25-(OH)2D3 is the most biologically active vitamin D metabolite [31]. Upon binding with its receptor, it initiates the translocation of the receptor complex to the nucleus, where it interacts with the genome, regulating the expression of over 1200 genes [32]. Studies have illustrated that immune cells, such as monocytes, dendritic cells, lymphocytes, and macrophages, express the vitamin D receptor. 1,25-(OH)2D3 can activate immune cells, such as T and B cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells, to regulate immunity and increase the production of antimicrobial peptides and neutralizing antibodies [33–35]. In addition, studies have revealed that 1,25-(OH)2D3 acts as an efficient anticancer agent through several signaling pathways [36–40]. Recent data suggest that 1,25-(OH)2D3 plays a regulatory function in both normal and cancerous stem cells, exerting an inhibitory effect on stem-like properties across diverse tumor types including hepatocellular carcinoma, breast, colorectal, prostate, and gastric cancer cells [36,41–45]. However, the effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on the stemness of AML cells has not been well studied. In this study, we investigated the effects of 1,25-(OH)2D3 on the stemness of AML cells. The experimental results provided evidence that 1,25-(OH)2D3 may directly inhibit the stemness of AML cells, and the compound suppressed the proliferation of NB4 and HL-60 cells and induced their differentiation into monocytes. This is consistent with previous studies suggesting that 1,25-(OH)2D3 can stimulate myeloid stem cells to preferentially differentiate into monocytes and macrophages [46]. In addition, the present results revealed that 1,25-(OH)2D3 can also suppress sphere formation by HL-60 and NB4 cells and suppress the expression of the stemness markers SOX2, Nanog, OCT4, and c-Myc in HL-60 and NB4 cells. The results indicated that 1,25-(OH)2D3 can inhibit the stemness of AML cells, as previously observed in breast cancer, colorectal cancer, and other tumors.

In our previous studies examining the role of ICAT in AML differentiation, we found that the entry of β-catenin protein into the nucleus was inhibited by upregulating ICAT expression, and then inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway induced the differentiation of HL-60 acute promyelocytic leukemia cells into a mononuclear line [20]. ICAT is a 9-kDa polypeptide that plays a negative role in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling by inhibiting β-catenin nuclear signaling via binding to β-catenin and competing with the transcription factor T cell factor [47,48]. ICAT is a key protein in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling that negatively modulates β-catenin co-transcriptional activity [48,49]. As an important molecule of the Wnt signaling pathway, ICAT sustains stemness by maintaining multipotency in certain cell types [50]. Activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling is one of the important mechanisms of tumorigenesis [51]. To further elucidate the function of ICAT in the 1,25-(OH)2D3-mediated inhibition of AML cell stemness, we knocked out and overexpressed the ICAT gene in HL-60 cells and analyzed its role by western blotting, qRT-PCR, and cell sphere formation assays. In untreated cells, knockout of ICAT alone enhanced the stemness of HL-60 cells, while upregulation of ICAT inhibited the stemness of these cells. In the 1,25-(OH)2D3 treatment group, ICAT overexpression enhanced the stemness-inhibiting effect of 1,25-(OH)2D3 in AML cells, whereas ICAT knockout weakened this inhibitory effect. These results suggested that 1,25-(OH)2D3 suppresses stemness through the Wnt/β-catenin signaling through a mechanism mediated by ICAT protein. Moreover, we validated these results in vivo in NOD/SCID mice. Previous studies illustrated that 1,25-(OH)2D3 suppresses cancer cells proliferation and promotes their differentiation, primarily by antagonizing TGF-β, Wnt/β-catenin, and EGF signaling pathways [6]. However, 1,25-(OH)2D3 interacts with the vitamin D receptor which binds to specific DNA sequences known as vitamin D response elements, thereby controlling the expression of interconnected downstream genes [52].

Recent research has shown that decreased ICAT expression correlates with unfavorable disease-free and overall survival outcomes in AML, indicating that ICAT is closely involved in AML progression [50]. In the current study, our initial focus was on understanding the role of ICAT in the suppression of AML cell stemness by 1,25-(OH)2D3. Our findings revealed that 1,25-(OH)2D3 reduces AML cell stemness by targeting the Wnt/β-catenin signaling, a process facilitated by ICAT protein. Nevertheless, there were certain limitations in our research. Notably, while the dosage of 1,25-(OH)2D3 administered to nude mice was based on existing literature, the delay in tumor extraction resulted in larger tumor sizes.

In summary, our study revealed that 1,25-(OH)2D3 suppresses the stem-like properties of AML cells, likely by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling via ICAT. These findings offer fresh insights into how 1,25-(OH)2D3 may exert its anti-leukemic effects. Additionally, our observations suggest that ICAT plays a role in curtailing the stemness of AML cells, with its expression tightly linked to this characteristic. Therefore, further studies on the role and regulation of ICAT might reveal a novel therapeutic target for overcoming treatment resistance, improving prognosis, and preventing relapse in patients with AML.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The study was financial supported by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022B1515230007).

Author Contributions: Literature search, experimental, and wrote the manuscript: Yulian Wang; analysis and interpretation of results: Lianli Zhu; participated in some experiments: Ronghao Zeng; participated in some experiments: Yunping Pu; participated in some experiments: Baijian Chen; participated in some experiments: Yuwei Tan; provided advice during the study and manuscript: Weijia Wang; draft manuscript amend and preparation: Ming Hong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The original data in this study can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics Approval: The research was approved and supervised by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Zhongshan People’s Hospital (No. K-2023-214).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Thomas GE, Egan G, García-Prat L, Botham A, Voisin V, Patel PS, et al. The metabolic enzyme hexokinase 2 localizes to the nucleus in AML and normal haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells to maintain stemness. Nat Cell Biol. 2022;24(6):872–84. doi:10.1038/s41556-022-00925-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Arber DA, Orazi A, Hasserjian R, Thiele J, Borowitz MJ, Le Beau MM, et al. The 2016 revision to the World Health Organization classification of myeloid neoplasms and acute leukemia. Blood. 2016;127(20):2391–405. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-03-643544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Thol F, Ganser A. Treatment of relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2020;21(8):66–76. doi:10.1007/s11864-020-00765-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Mattes K, Gerritsen M, Folkerts H, Geugien M, van den Heuvel FA, Svendsen AF, et al. CD34+ acute myeloid leukemia cells with low levels of reactive oxygen species show increased expression of stemness genes and can be targeted by the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax. Haematologica. 2020;105(8):e399–e403. doi:10.3324/haematol.2019.229997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Wang F, Morita K, DiNardo CD, Furudate K, Tanaka T, Yan Y, et al. Leukemia stemness and co-occurring mutations drive resistance to IDH inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):2607. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22874-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Fernández-Barral A, Bustamante-Madrid P, Ferrer-Mayorga G, Barbáchano A, Larriba MJ, Muñoz A. Vitamin D effects on cell differentiation and stemness in cancer. Cancers. 2020;12(9):2413–31. doi:10.3390/cancers12092413. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Bikle DD. Vitamin D regulation of immune function. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2022;20(3):186–93. doi:10.1007/s11914-022-00732-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Sîrbe C, Rednic S, Grama A, Pop TL. An update on the effects of vitamin D on the immune system and autoimmune diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(17):9784–812. doi:10.3390/ijms23179784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wimalawansa SJ. Infections and autoimmunity-the immune system and vitamin D: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2023;15(17):3842–74. doi:10.3390/nu15173842. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Slominski AT, Brożyna AA, Skobowiat C, Zmijewski MA, Kim TK, Janjetovic Z, et al. On the role of classical and novel forms of vitamin D in melanoma progression and management. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2018;177:159–70. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.06.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Supnick HT, Bunaciu RP, Yen A. The c-Raf modulator RRD-251 enhances nuclear c-Raf/GSK-3/VDR axis signaling and augments 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-induced differentiation of HL-60 myeloblastic leukemia cells. Oncotarget. 2018;9(11):9808–24. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.24275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Gleba JJ, Kłopotowska D, Banach J, Turlej E, Mielko KA, Gębura K, et al. Polymorphism of VDR gene and the sensitivity of human leukemia and lymphoma cells to active forms of vitamin D. Cancers. 2022;14(2):387–405. doi:10.3390/cancers14020387. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li Z, Jia Z, Gao Y, Xie D, Wei D, Cui J, et al. Activation of vitamin D receptor signaling downregulates the expression of nuclear FOXM1 protein and suppresses pancreatic cancer cell stemness. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(4):844–53. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2437. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Shan NL, Wahler J, Lee HJ, Bak MJ, Gupta SD, Maehr H, et al. Vitamin D compounds inhibit cancer stem-like cells and induce differentiation in triple negative breast cancer. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;173:122–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.12.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ji M, Liu L, Hou Y, Li B. 1α,25‐Dihydroxyvitamin D3 restrains stem cell‐like properties of ovarian cancer cells by enhancing vitamin D receptor and suppressing CD44. Oncol Rep. 2019;41(6):3393–403. doi:10.3892/or.2019.7116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Attia YM, El-Kersh DM, Ammar RA, Adel A, Khalil A, Walid H, et al. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase-1 and p-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance by curcumin and vitamin D3 increases sensitivity to paclitaxel in breast cancer. Chem Biol Interact. 2020;315(1–2):108865–900. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2019.108865. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Jia Z, Wang K, Duan Y, Hu K, Zhang Y, Wang M, et al. Claudin1 decrease induced by 1,25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3 potentiates gefitinib resistance therapy through inhibiting AKT activation-mediated cancer stem-like properties in NSCLC cells. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):122–35. doi:10.1038/s41420-022-00918-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Jeong Y, Swami S, Krishnan AV, Williams JD, Martin S, Horst RL, et al. Inhibition of mouse breast tumor-initiating cells by calcitriol and dietary vitamin D. Mol Cancer Ther. 2015;14(8):1951–61. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-15-0066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Srivastava AK, Rizvi A, Cui T, Han C, Banerjee A, Naseem I, et al. Depleting ovarian cancer stem cells with calcitriol. Oncotarget. 2018;9(18):14481–91. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.24520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Geng YY, Xie JY, Wang WJ. The role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway regulated by ICAT in monocytic differentiation of AML HL-60 cells with 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 treatment. Chin J Clin Sci. 2020;3(38):218–22 (In Chinese). doi:10.13602/j.cnki.jcls.2020.03.15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang K, Zhu S, Liu Y, Dong X, Shi Z, Zhang A, et al. ICAT inhibits glioblastoma cell proliferation by suppressing Wnt/β-catenin activity. Cancer Lett. 2015;357(1):404–11. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2014.11.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Hu J, Wang Z, Chen J, Yu Z, Zhang J, Li W, et al. Overexpression of ICAT inhibits the progression of colorectal cancer by binding with β-Catenin in the cytoplasm. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2021;20(11):15330338211041253. doi:10.1177/15330338211041253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Huang Q, Wang L, Ran Q, Wang J, Wang C, He H, et al. Notopterol-induced apoptosis and differentiation in human acute myeloid leukemia HL-60 cells. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2019;13:1927–40. doi:10.2147/dddt.S189969. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Xu Y, Chen X. MicroRNA (let-7b-5p)-targeted DARS2 regulates lung adenocarcinoma growth by PI3K/AKT signaling pathway. Oncol Res. 2024;32(3):517–28. doi:10.32604/or.2023.030293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Xu Y, Mou J, Wang Y, Zhou W, Rao Q, Xing H, et al. Regulatory T cells promote the stemness of leukemia stem cells through IL10 cytokine-related signaling pathway. Leukemia. 2022;36(2):403–15. doi:10.1038/s41375-021-01375-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–8. doi:10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Janik E, Niemcewicz M, Ceremuga M, Krzowski L, Saluk-Bijak J, Bijak M. Various aspects of a gene editing system-CRISPR-Cas9. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24):9604–23. doi:10.3390/ijms21249604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Wang J, Wang P, Zhang T, Gao Z, Wang J, Feng M, et al. Molecular mechanisms for stemness maintenance of acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Blood Sci. 2019;1(1):77–83. doi:10.1097/BS9.0000000000000020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zhu H, Zhang L, Wu Y, Dong B, Guo W, Wang M, et al. T-ALL leukemia stem cell ‘stemness’ is epigenetically controlled by the master regulator SPI1. eLife. 2018;7:38314–41. doi:10.7554/eLife.38314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Lim INX, Nagree MS, Xie SZ. Lipids and the cancer stemness regulatory system in acute myeloid leukemia. Essays Biochem. 2022;66(4):333–44. doi:10.1042/EBC20220028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Bertoli S, Tavitian S, Bories P, Luquet I, Delabesse E, Comont T, et al. Outcome of patients aged 60-75 years with newly diagnosed secondary acute myeloid leukemia: a single-institution experience. Cancer Med. 2019;8(8):3846–54. doi:10.1002/cam4.2020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Hanel A, Bendik I, Carlberg C. Transcriptome-wide profile of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D3 in primary immune cells from human peripheral blood. Nutrients. 2021;13(11):4100–13. doi:10.3390/nu13114100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Aygun H. Vitamin D can prevent COVID-19 infection-induced multiple organ damage. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2020;393(7):1157–60. doi:10.1007/s00210-020-01911-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. McGregor R, Chauss D, Freiwald T, Yan B, Wang L, Nova-Lamperti E, et al. An autocrine vitamin D-driven Th1 shutdown program can be exploited for COVID-19. bioRxiv. 2020;18:210161. doi:10.1101/2020.07.18.210161. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chauss D, Freiwald T, McGregor R, Yan B, Wang L, Nova-Lamperti E, et al. Autocrine vitamin D signaling switches off pro-inflammatory programs of TH1 cells. Nat Immunol. 2022;23(1):62–74. doi:10.1038/s41590-021-01080-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Abu El Maaty MA, Dabiri Y, Almouhanna F, Blagojevic B, Theobald J, Büttner M, et al. Activation of pro-survival metabolic networks by 1,25(OH)2D3 does not hamper the sensitivity of breast cancer cells to chemotherapeutics. Cancer Metab. 2018;6(1):11–28. doi:10.1186/s40170-018-0183-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Zheng W, Cao L, Ouyang L, Zhang Q, Duan B, Zhou W, et al. Anticancer activity of 1,25-(OH)2D3 against human breast cancer cell lines by targeting Ras/MEK/ERK pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:721–32. doi:10.2147/ott.S190432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Han N, Jeschke U, Kuhn C, Hester A, Czogalla B, Mahner S, et al. H3K4me3 is a potential mediator for antiproliferative effects of calcitriol (1α,25(OH)2D3) in ovarian cancer biology. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(6):2151–66. doi:10.3390/ijms21062151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Ji MT, Nie J, Nie XF, Hu WT, Pei HL, Wan JM, et al. 1α,25(OH)2D3 radiosensitizes cancer cells by activating the NADPH/ROS pathway. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:945–56. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.00945. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Olszewska AM, Nowak JI, Myszczynski K, Słominski A, Żmijewski MA. Dissection of an impact of VDR and RXRA on the genomic activity of 1,25(OH)2D3 in A431 squamous cell carcinoma. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2023;582:112–24. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4474791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Leyssens C, Verlinden L, Verstuyf A. Antineoplastic effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 and its analogs in breast, prostate and colorectal cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2013;20(2):31–47. doi:10.1530/ERC-12-0381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Huang J, Yang G, Huang Y, Zhang S. Inhibitory effects of 1,25(OH)2D3 on the proliferation of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through the downregulation of HDAC2. Oncol Rep. 2017;38(3):1845–50. doi:10.3892/or.2017.5848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Li M, Li L, Zhang L, Hu W, Shen J, Xiao Z, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D(3) suppresses gastric cancer cell growth through VDR- and mutant p53-mediated induction of p21. Life Sci. 2017;179:88–97. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2017.04.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Ferrer-Mayorga G, Niell N, Cantero R, González-Sancho JM, Del PL, Muñoz A, et al. Vitamin D and Wnt3A have additive and partially overlapping modulatory effects on gene expression and phenotype in human colon fibroblasts. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):8085–97. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44574-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang Y, Li Y, Wei Y, Cong L. Molecular mechanism of vitamin D receptor modulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in gastric cancer. J Cancer. 2023;14(17):3285–94. doi:10.7150/jca.81034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Gocek E, Marchwicka A, Baurska H, Chrobak A, Marcinkowska E. Opposite regulation of vitamin D receptor by ATRA in AML cells susceptible and resistant to vitamin D-induced differentiation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;132(3–5):220–6. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2012.07.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Gottardi CJ, Gumbiner BM. Role for ICAT in beta-catenin-dependent nuclear signaling and cadherin functions. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;286(4):747–56. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00433.2003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Domingues MJ, Martinez-Sanz J, Papon L, Larue L, Mouawad L, Bonaventure J. Structure-based mutational analysis of ICAT residues mediating negative regulation of β-catenin co-transcriptional activity. PLoS One. 2017;12(3):e0172603. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0172603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Han H, Zhu B, Xie J, Huang Y, Geng Y, Chen K, et al. Expression level and prognostic potential of beta-catenin-interacting protein in acute myeloid leukemia. Medicine. 2022;101(33):30022–28. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000030022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Song JH, Park E, Kim MS, Cho KM, Park SH, Lee A, et al. l-Asparaginase-mediated downregulation of c-Myc promotes 1,25(OH)2D3-induced myeloid differentiation in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(10):2364–74. doi:10.1002/ijc.30662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Tian M, Wang X, Sun J, Lin W, Chen L, Liu S, et al. IRF3 prevents colorectal tumorigenesis via inhibiting the nuclear translocation of β-catenin. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):5762–76. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19627-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Zhou Q, Qin S, Zhang J, Zhon L, Pen Z. Xing T. 1,25(OH)2D3 induces regulatory T cell differentiation by influencing the VDR/PLC-γ1/TGF-β1/pathway. Mol Immunol. 2017;91:156–64. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2017.09.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Figure A1: IACT knockout monoclonal sequencing results. IACT knockout HL-60 cells monoclonal sequencing results.

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools