Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia, a case report and review of the literature

1 Hematology Department, La Princesa University Hospital, Madrid, 28006, Spain

2 Hematology/Oncology, Mercy Clinic Oncology and Hematology–Joplin, Misouri, MO 64804, USA

* Corresponding Authors: LUIS MIGUEL JUáREZ-SALCEDO. Email: ; SAMIR DALIA. Email:

Oncology Research 2025, 33(3), 505-517. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.058175

Received 06 September 2024; Accepted 20 December 2024; Issue published 28 February 2025

Abstract

T-prolymphocytic leukemia is a rare and aggressive hematological malignancy characterized by the clonal proliferation of mature lymphoid T-cells. The pathogenesis of T-PLL is closely linked to specific chromosomal abnormalities, primarily involving the proto-oncogene T-cell leukemia/lymphoma 1 gene family. Recent advancements in molecular profiling have identified additional genomic aberrations, including those affecting the Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT) signaling pathway. This case report presents a patient with T-prolymphocytic leukemia whose cytogenetic and molecular analysis revealed a t(X;14)(q28;q11.2) translocation and a STAT5B mutation. Here, we aim to review the genetic and molecular underpinnings of T-prolymphocytic leukemia, as well as current treatment options, with a focus on the anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab and JAK inhibitors. While alemtuzumab followed by allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation remains the standard of care for eligible patients, its efficacy is limited and many patients are ineligible. Emerging therapeutic approaches, such as JAK/STAT inhibitors, offer promising potential for improving patient outcomes.Keywords

Prolymphocytic leukemia is a hematological malignancy characterized by the proliferation of mature lymphoid cells and can derive from either B-lymphocytes (B-PLL) or T-lymphocytes [1]. This rare disease accounts for ~2% of mature lymphoid cell neoplasms, with T-lymphoid leukemia being more common than B-lymphoid leukemia [2]. The disease primarily affects older adults, with a median age of diagnosis >60 years in different series. While research on its incidence and other demographics is limited, data extracted from the National Cancer Database and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database have revealed an increase in its incidence in recent years, likely due to improved recognition and diagnostic criteria, with greater prevalence in males and individuals with a history of other neoplasms [3]. T-prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) is an aggressive neoplasm characterized by lymphocytosis, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hepatosplenomegaly [4]. The diagnosis, staging, and assessment of response to treatment of this pathology are established according to the working consensus of the T-PLL International Study Group (T-PLL-ISG), with the aim of harmonizing research efforts and supporting clinical decision-making [4].

The pathogenesis of T-PLL is primarily driven by overexpression of the oncogene T-cell leukemia/lymphoma 1 (TCL1). Inactivation of the ataxia-telangiectasia mutated (ATM) gene and chromosomal abnormalities of chromosome 8 are also common [5]. Moreover, recent studies have revealed a complex mutational landscape, identifying recurrent mutations in genes not previously associated with T-PLL. These mutations often affect epigenetic regulators, DNA repair proteins, and the JAK/STAT pathway [6].

Standard first-line treatment for T-PLL typically involves the humanized anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab. However, randomized studies specifically evaluating the use of alemtuzumab for T-PLL are lacking, and the therapeutic benefit has been extrapolated from small prospective and retrospective series, which suggest response rates of 92%. Unfortunately, responses to alemtuzumab are often transient and disease progression is inevitable. Without consolidation therapy such as allogenic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT), disease-free survival (DFS) typically does not exceed one year [4]. Allo-HSCT is considered the only curative treatment option and would be considered for patients who achieve complete remission (CR). However, only 30%–50% of patients with T-PLL are eligible for allo-HSCT due to reduced performance status, other comorbidities, and age [7]. While current treatment options for relapsed T-PLL are limited and lack strong evidence supporting their use, new therapeutic approaches targeting specific molecular alterations are under investigation. In the present clinical case report, we identified the presence of a STAT5B mutation through next-generation sequencing (NGS). Given this finding, we focused our review of novel therapeutic options on strategies targeting the JAK/STAT pathway and STAT5B, a potential avenue for improving outcomes in patients with this challenging disease.

A systematic literature search based on a clinical case was performed using PubMed and EMBASE databases to identify articles and studies that assessed the genetic and molecular landscape of T-PLL, current treatment options in patients with T-prolymphocytic leukemia, and emerging therapeutic approaches, such as JAK/STAT inhibitors. The search was restricted to articles and studies published in English and Spanish.

Our case was a 64-year-old woman with no relevant medical history or prior infections. She was independent in her daily activities. She reported being completely asymptomatic from a general point of view, with no associated secondary symptoms. At the time of admission to the hematology department, she had recently been diagnosed with right lobar pneumonia. Despite experiencing mild respiratory symptoms and fever, she remained in generally good health.

Laboratory findings demonstrated progressive leukocytosis with lymphocytosis over the past 6 months; specifically, a leukocyte count of 71.47 × 109/L and lymphocytosis of 62.01 × 109/L. Physical examination was unremarkable, with no masses or palpable lymph nodes and no skin lesions. The remaining laboratory parameters were normal (hemoglobin 11.8 g/dL, platelets 149,000/mm3, neutrophils 6.76 × 109/L), with normal coagulation and biochemical parameters (normal renal and hepatic profile, ions in range, corrected calcium 9.2 mg/dL, lactate dehydrogenase 303 U/L). Serology for hepatotropic viruses, HIV and HLTV-1 were negative, but positive IgG antibodies to cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex, and varicella zoster were detected.

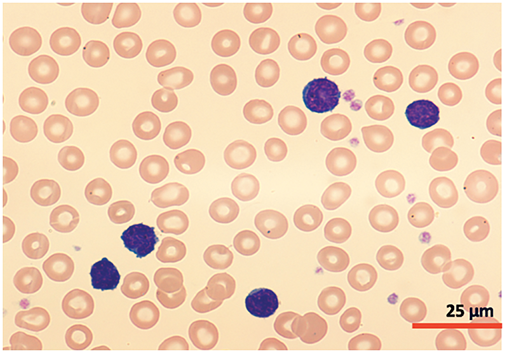

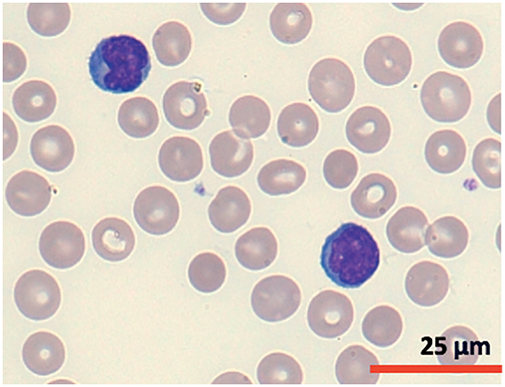

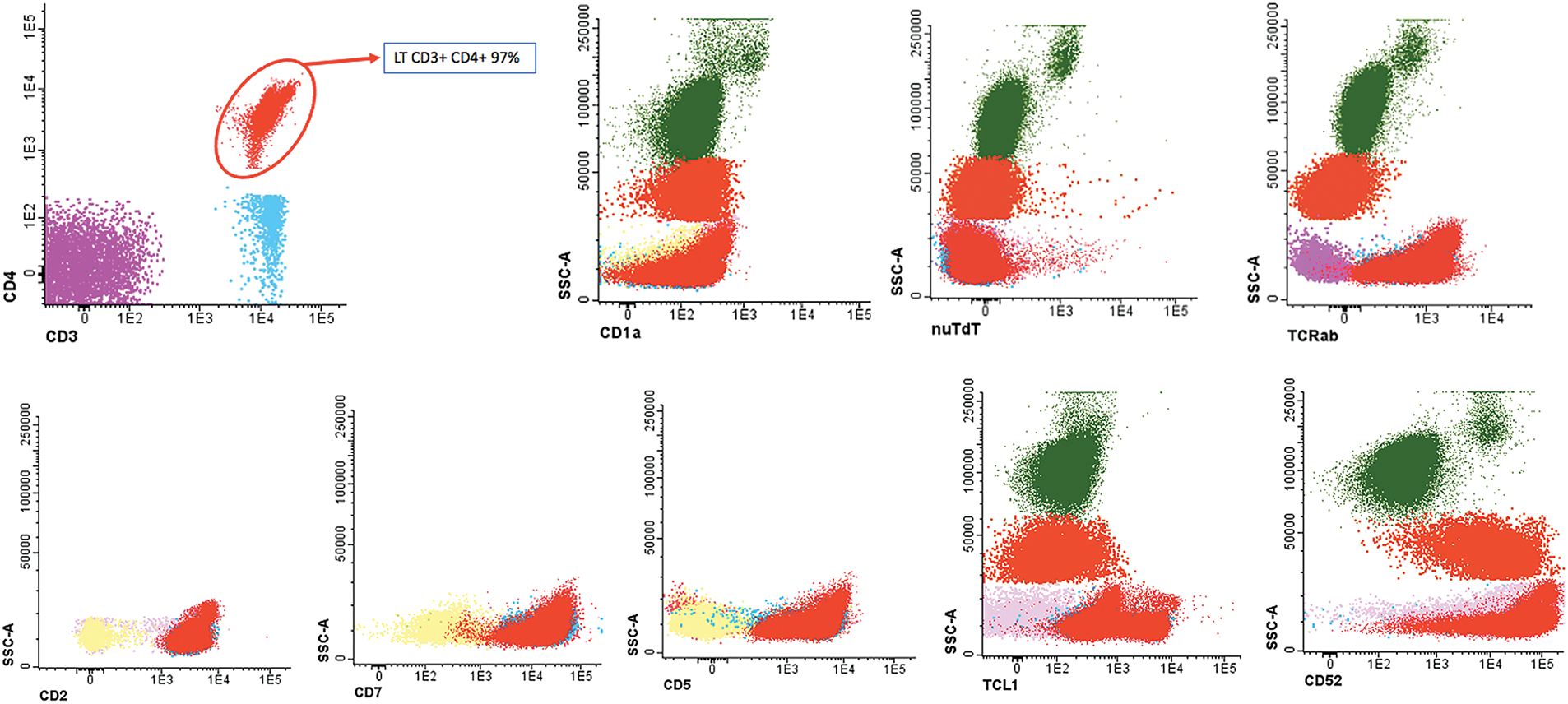

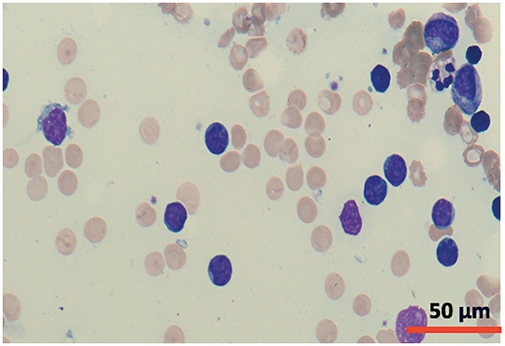

A cytomorphological and immunophenotypic study was performed on peripheral blood. Peripheral blood smears (Figs. 1 and 2) confirmed marked lymphocytosis with the presence of small atypical lymphocytes, with condensed chromatin, irregularly shaped nuclei, absence of nucleoli, scant basophilic cytoplasm, and occasional “blebs”. Flow cytometry analysis (Fig. 3) revealed that 78% of lymphocytes were mature T-lymphocytes with a CD4+ immunophenotype, positive for pan-T markers, CD52++, CD26+, TCL1, and exhibiting a T-cell receptor (TCR) rearrangement. These findings are consistent with a diagnosis of T-PLL.

Figure 1: Cytomorphology of leukemic cells from peripheral blood smear. May-Grümwald-Giemsa staining. 40×.

Figure 2: Cytomorphology of leukemic cells from peripheral blood smear. May-Grümwald-Giemsa staining. 100×.

Figure 3: Flow cytometry peripheral blood sample demonstrated an aberrant T-cell population. CD4+ T lymphocytes: 97% of the lymphocyte population (78% of total cellularity) with pathological phenotype: TCRab+, CD34−, CD117, nuTdT−, CD3+, CD4+, CD8−, CD5+, CD45+, CD45RA−, CD7+, CD2+, CD28+, CD26+ and CD27+, CD57−, cyCD30−, CD279+, heterogeneous TCL1 (20%++), CD52++, CD56−, CD1a−, CD10− and CD99−.

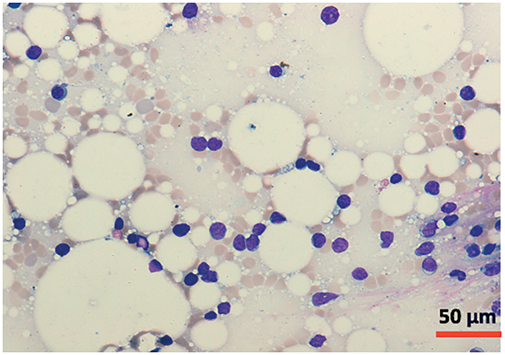

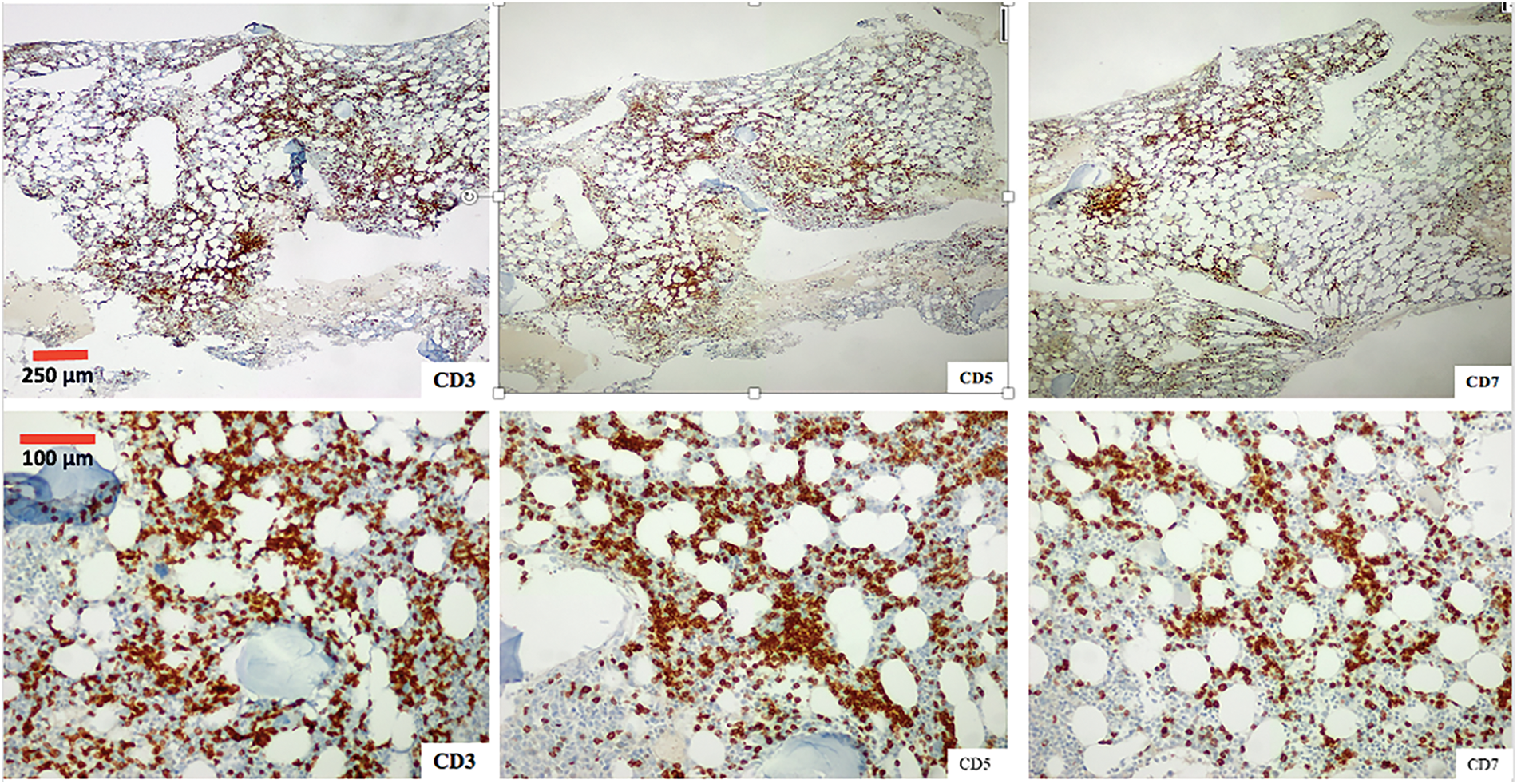

A bone marrow aspirate and biopsy were performed, revealing significant lymphocyte infiltration (50%–60% infiltration; Figs. 4 and 5) with characteristics similar to those described in peripheral blood. The biopsy demonstrated nodular and interstitial lymphocyte accumulations, confirmed by immunohistochemistry as T-cells (positive for CD3, CD5, and CD7) (Fig. 6).

Figure 4: Cytomorphology of leukemic cells from marrow aspirate. May-Grümwald-Giemsa staining. 20×.

Figure 5: Cytomorphology of leukemic cells from marrow aspirate. May-Grümwald-Giemsa staining. 40×.

Figure 6: Photomicrograph of the one marrow biopsy, Immunohistochemical staining ×4 (first row) and ×10 (second row) for T-cell markers CD3, CD5 and CD7.

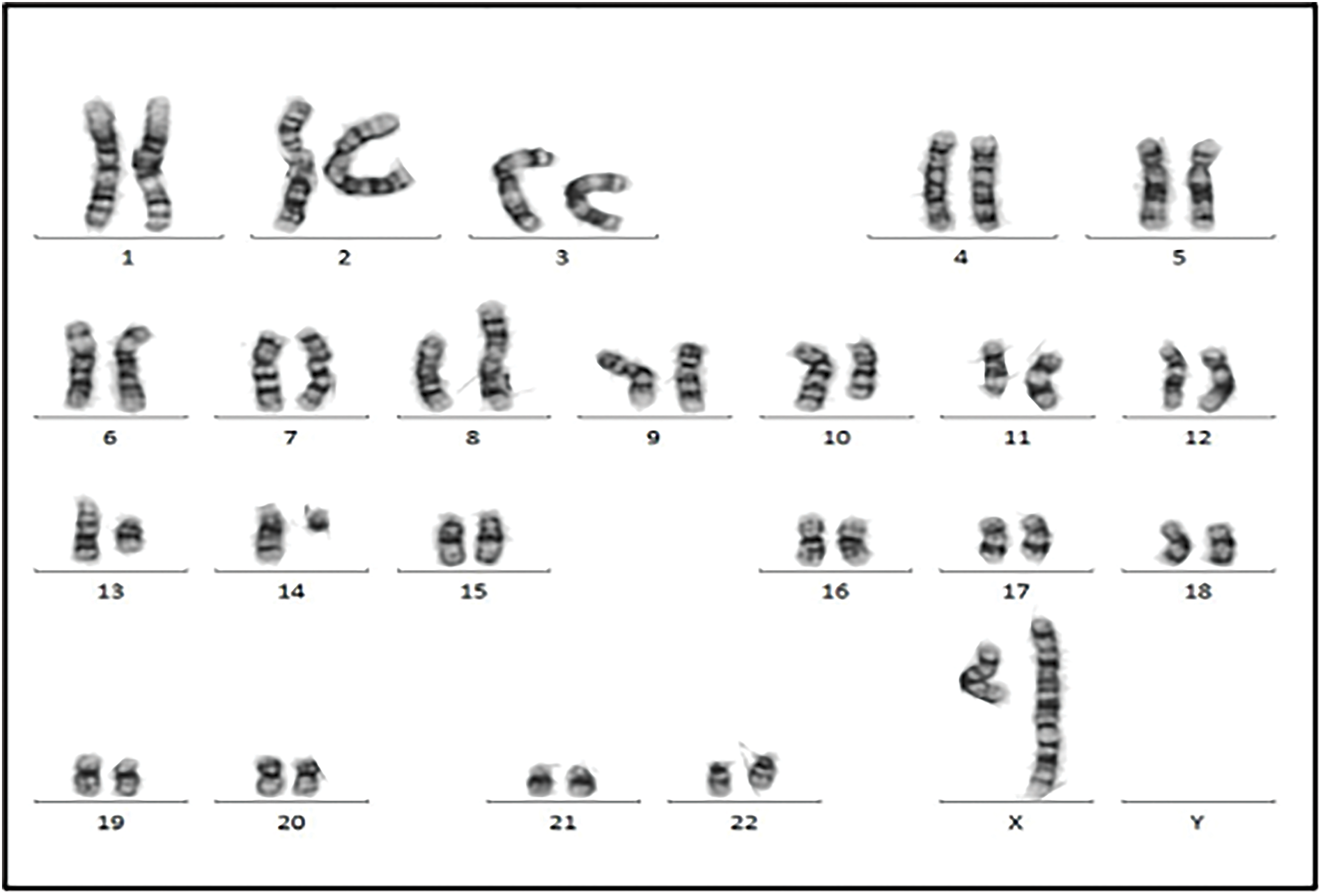

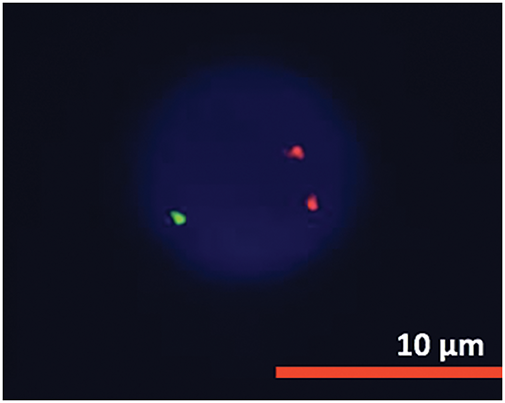

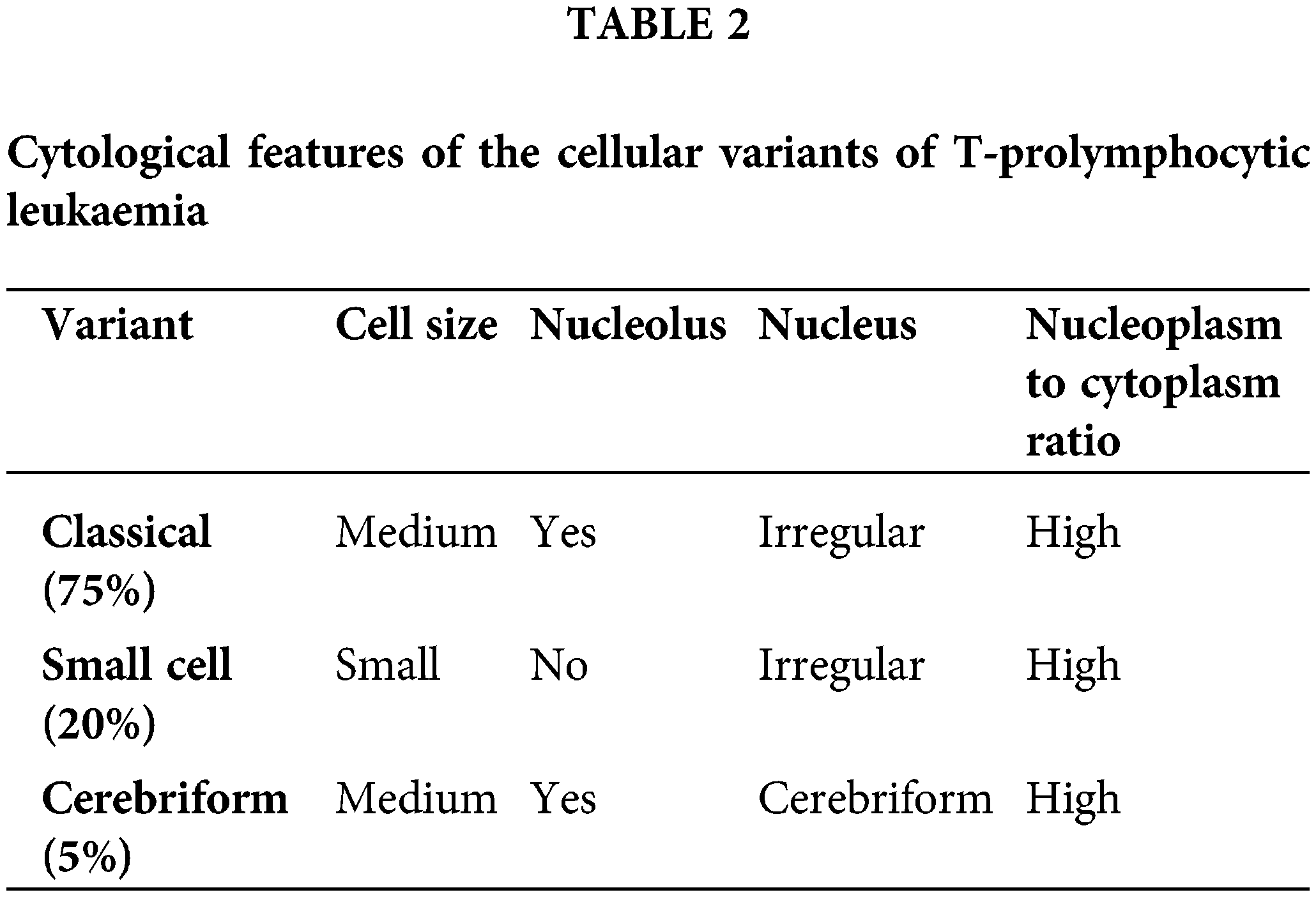

Cytogenetic analysis (Fig. 7) revealed a complex karyotype with a translocation t(X;14)(q28;q11.2) and a derivative X chromosome, der(X)t(X;14)dup(X)(q26). This chromosomal aberration is associated with disruption of MTCP1, a hallmark of T-PLL. Additionally, abnormalities involving chromosome 11 (including the ATM gene locus), isochromosome 8, and deletions on chromosome 13 were observed. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis detected T-cell receptor α/δ (TCRA/D) rearrangement and confirmed the deletion of ATM and the 13q14.2 region (Figs. 8 and 9). TCL1a gene rearrangement was not detected. Due to the unavailability of an MTCP1-specific probe, direct confirmation of the MTCP1 rearrangement by FISH was not possible. NGS of a bone marrow aspirate identified a gain-of-function (GOF) mutation in the STAT5B gene (Q706L) with a variant allele frequency (VAF) of 4.9%, considered a pathogenic variant in T-PLL. Furthermore, NGS confirmed the presence of mutations in ATM, with a VAF of 51.5%, consistent with a germline origin. Additional mutations were identified in TYK2 (VAF 39.2%) and PLCG1 (VAF 1.8%), while no mutations in p53 were detected. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of peripheral blood detected clonal TCR gene rearrangements.

Figure 7: Chromosomal analysis showed the neoplastic cells with a complex karyotype with 46,X, t(X;14)(q28;q11.2),der(X)t(X;14)dup(X)(q26), i(8)(q10), del(10)(q23q34), del(11)(p14p15), del(11)(q14), −13, +mar [10]/46, XX [10].

Figure 8: FISH analysis detected ATM deletion.

Figure 9: FISH analysis detected 13 deletion.

A total body computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a normal-sized liver and spleen but identified numerous lymphadenopathies in the cervical, mediastinal, hilar and retroperitoneal regions. While the number of these enlarged lymph nodes was significant, most were not significantly large in size. These findings are consistent with a lymphoproliferative disorder.

Integrating this information with other clinical findings, a diagnosis of T-PLL was established, fulfilling diagnostic criteria. The disease was likely in an indolent phase.

The patient required hospitalization for treatment of the previously described respiratory infection. Despite intravenous antibiotics, her condition deteriorated, leading to sepsis and intensive care unit admission. She developed respiratory failure requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation. Vasoactive support with low-dose noradrenaline was initiated. No specific pathogen was identified.

Given the significant lymphocytosis, nearing 100,000 × 109/L, and the aggressive nature of T-PLL immediate disease burden reduction was necessary. However, due to an ongoing infection, initiating treatment with alemtuzumab was delayed to avoid potential exacerbation. Instead, a pre-phase treatment with corticosteroids and cytoreduction with cyclophosphamide (200 mg/m2 for 5 days) was initiated. Despite prophylactic measures with hydration and allopurinol, tumor lysis syndrome developed, necessitating rasburicase administration.

Considering the potential for infectious complications related to alemtuzumab and the temporary control of the disease, we elected to delay the initiation of outpatient treatment until the infection had fully resolved.

No alemtuzumab-related infusion reactions occurred. The patient tolerated the maximum treatment dose well during the first week of administration. Pre-medication with dexchlorpheniramine, paracetamol, and urban was given for all treatment doses. Periodic CMV monitoring by quantitative PCR detected CMV reactivation in blood two days after initiating alemtuzumab treatment, although the patient remained asymptomatic. A peak CMV viral load of 1870 IU/mL was reached five days after treatment initiation. Preventive valganciclovir treatment (900 mg every 12 h for 14 days) was initiated. Alemtuzumab treatment was not interrupted. CMV viral load dropped below 500 IU/mL four days after starting valganciclovir and was undetectable after completing the 14-day course.

The patient tolerated alemtuzumab treatment well, with no significant cytopenias or need for transfusions or G-CSF. As a single infectious complication, the patient developed a new episode of bilateral pneumonia, without microbiological isolation, in the seventh week of alemtuzumab treatment, which resolved after alemtuzumab was temporarily discontinued.

After completing eight weeks of therapy, a CR was confirmed by peripheral blood counts and bone marrow examination. Flow cytometry detected negative minimal residual disease (MRD) in bone marrow. Additional diagnostic tests such as TCR rearrangement and FISH were not performed. A full-body CT scan showed a significant reduction in the lymphadenopathy existing at diagnosis. Given the achieved CR, the patient was considered a suitable candidate for allo-HSCT to consolidate the response.

T-PLL is typically an aggressive hematological malignancy. Most patients present with a rapidly progressive clinical course characterized by splenomegaly (around 80% of cases, being the most common finding), often massive, secondary symptoms (65%), and lymphadenopathy (50%–60%), usually small in size. Peripheral blood lymphocytosis is usually marked, typically greater than 100,000 × 109/L [2]. T-PLL is also distinguished by the presence of extramedullary involvement. Cutaneous involvement is common (25%) in the form of rash, erythroderma, or nodular lesions, as well as peripheral edema and pleuroperitoneal effusions (15%). Involvement of other extranodal sites such as the lung, kidney, or central nervous system is rare. Hematological cytopenias, particularly anemia, and thrombopenia, are common [2,4].

Approximately one-third of T-PLL cases are initially diagnosed as isolated stable lymphocytosis, a condition characterized by a subtle increase in lymphocyte count without overt symptoms [4]. This form of presentation may lead to misdiagnosis due to similarities with other lymphoproliferative disorders typically associated with stable lymphocyte counts and lack of symptoms, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). All patients diagnosed in this indolent phase will eventually progress to the characteristic aggressive form of the disease.

Notably, there are no discernable clinical, laboratory, demographic, morphological, or immunophenotypic features between the indolent and aggressive forms of the disease at diagnosis. Similarly, there are no clinical or laboratory distinctions between the presentation of secondary progression and initially active forms. T-PLL appears to be a biphasic disease, with the initial indolent phase likely being underdiagnosed.

Awareness of the two disease presentations is essential for optimal therapeutic management. Active disease is indicated by the presence of symptomatic hepatosplenomegaly or lymphadenopathy, secondary symptoms, organ involvement (skin, lung, pleural/peritoneal effusions), or cytopenias, and necessitates immediate treatment. For asymptomatic disease, regular monitoring is crucial to identify the onset of disease-related signs and symptoms, assess changes in blood cell counts, particularly lymphocytosis and cytopenias, and recognize rapid increases in lymphocyte count, similar to B-CLL. A doubling of the lymphocyte count within 6 months, or a 50% increase within 2 months, should prompt treatment consideration [4].

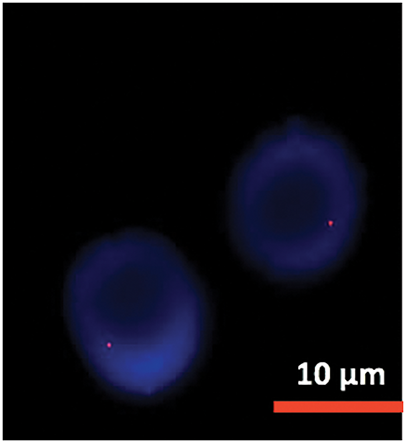

A diagnosis of T-PLL can typically be established through the analysis of peripheral blood samples, integrating morphological and immunophenotypic findings. However, molecular and genetic information, including FISH and chromosome banding analysis, is now essential for definitive diagnosis, particularly in light of recent diagnostic criteria [4]. While NGS is not mandatory, it can provide valuable supplementary information when available. Table 1 outlines the diagnostic criteria for T-PLL. A diagnosis of T-PLL requires the demonstration of the first three major diagnostic criteria. The initial two major criteria are considered defining characteristics of the disease. While the third major criterion, involving alterations in TCL1a or MTCP1, is prevalent in most T-PLL cases, it is not universally present [4].

The incorporation of molecular and genetic features into diagnostic criteria has advanced the classification of T-cell neoplasms with leukemic features, which often exhibit overlapping clinical and phenotypic characteristics. Patients presenting with mature T-cell leukemias who do not meet the established diagnostic criteria for any of these entities, by definition should be classified as having peripheral T-cell lymphoma, not otherwise specified (PTCL-NOS) [1,8]. Differentiating between T-PLL-TCL1-negative cases and PCLT-NOS with leukemic involvement can be complex. In such cases, the presence of extranodal involvement characteristic of T-PLL and other T-PLL-related genetic alterations can guide the diagnosis. For a definitive diagnosis of T-PLL/TCL1-negative cases, the presence of one of these minor diagnostic criteria is necessary [4].

While evaluation of bone marrow infiltration is standard practice in the initial assessment of lymphoproliferative processes, it is not necessary to definitively diagnose T-lymphoproliferative leukemia. However, it remains important for evaluating treatment response. To differentiate between T-lymphoproliferative leukemia and adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma (A-TLL), serological testing or negative PCR for human T-lymphotropic virus 1 (HTLV-1) is required.

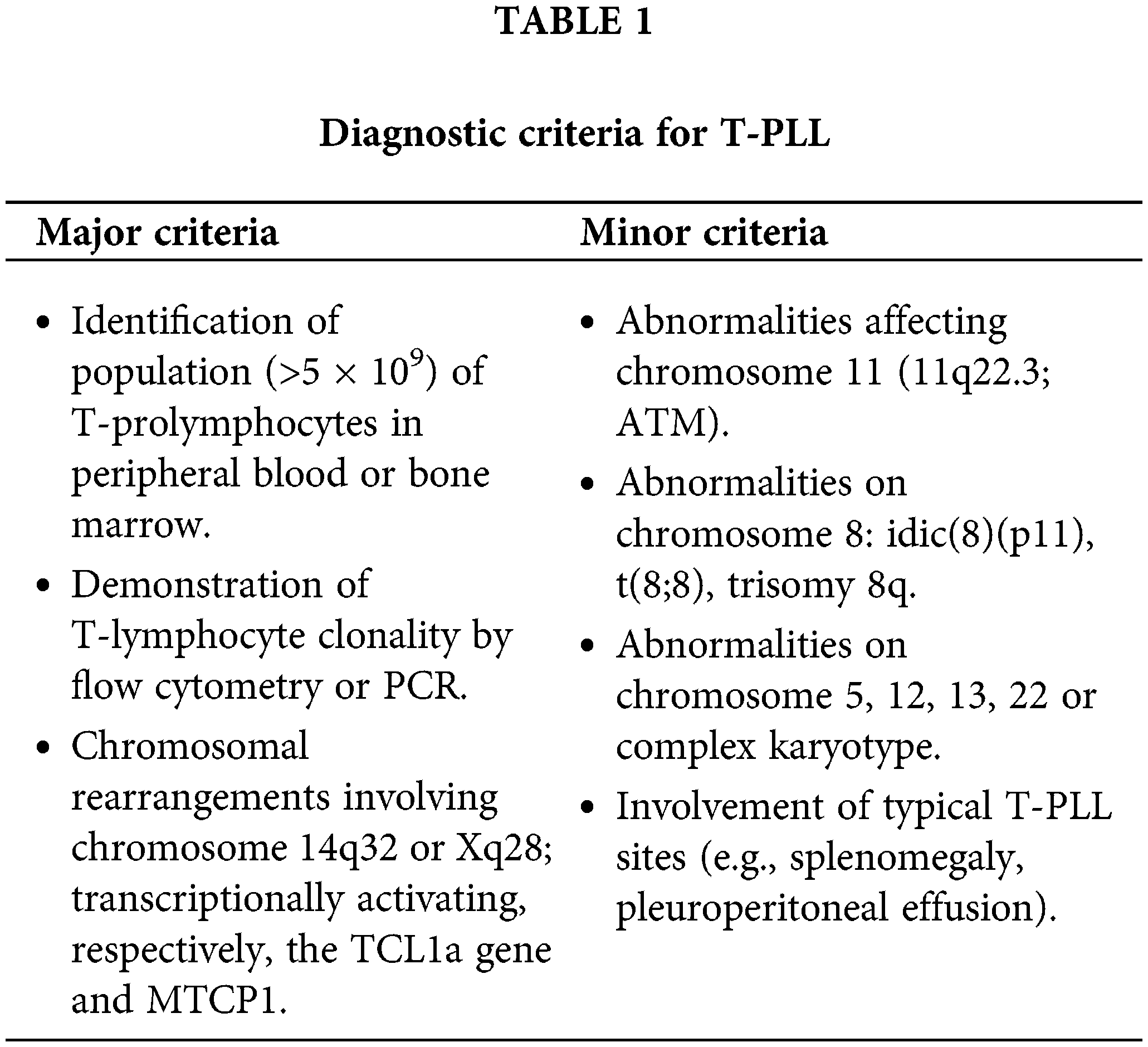

Three different morphological variants of neoplastic cells have been described in T-PLL, the characteristics of each of these forms are presented in Table 2 [2].

Typical prolymphocytes in T-PLL are medium-sized cells characterized by a condensed nuclear chromatin pattern, a prominent nucleolus, a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and a basophilic, non-granular cytoplasm with occasional small cytoplasmic protrusions or blebs [2].

Flow Cytometric Immunophenotype

Prolymphocytes characteristic of T-PLL have a distinctive immunophenotype typical of a post-thymic mature T-cell neoplasm, lacking TdT and CD1a expression while exhibiting positivity for CD3. The majority of T-PLL cells display a CD4+ CD8− phenotype, with less frequent CD4+ CD8+ co-expression and rare other CD4/CD8 combinations. Pan-T markers, including CD2, CD5, and CD7, are typically expressed. CD26 is positive, and CD25 is present in ~25% of cases. A defining feature of T-PLL is the universal expression of CD52, which serves as the therapeutic target of the monoclonal antibody alemtuzumab. There is an absence of natural killer (NK) cell markers. The definitive diagnosis of T-PLL is confirmed by the detection of TCL1 [9,10]. While the anti-human TCL1 monoclonal antibody (BD Pharmigen Alexa Fluor) employed in our panel detects TCL1, it cannot differentiate between TCL1a and MTCP1, likely due to their structural homology.

Genetics and Molecular Profile

T-PLL is usually associated with complex karyotypes (70%–80% of cases). The most common and specific cytogenetic abnormality is the rearrangement of the TCL1 gene (more than 90% of cases), which is considered the primary event in T-PLL pathogenesis. The TCL1 gene family of proto-oncogenes consists of 5 isoforms, with TCL1a and MTCP1 (mature T-cell proliferation) being the more relevant for T-PLL. These isoforms are located on chromosome 14q32.1 and Xq28.1, respectively. In most cases, inv(14)(q11.2q32) or t(14;14) (q11.2;q32), juxtapose TCL1a with the TCR A/D locus, leading to overexpression of TCL1a through positive regulation by TCR enhancing elements. Rarely, as in the case we report, t(X;14)(q28;q11.2) juxtaposes the TRA/D locus at 14q11.2 with MTCP1 at Xq28, resulting in overexpression of the MTCP1 oncoprotein [5]. To date, only 15 isolated cases of T-PLL with t(X;14)(q28;q11.2) have been described [11]. The clinicopathological features and molecular profile of patients with t(X;14)(q28;q11.2) T-PLL are not well characterized. It remains unclear whether they share similar characteristics with classical T-PLL with 14q32/TCL1a gene rearrangement. TCL1 and MTCP1 proteins present similarity in a large part of the amino acid sequence [5].

TCL1 acts as a cofactor for Akt kinase. TCL1 is involved in lymphopoiesis and is normally expressed only in immature lymphoid cells. Overexpression in mature lymphoid cells is abnormal [5].

Inactivation of the ATM gene is found in more than 80% of cases, and germline mutations in ATM increase the risk of developing T-PLL. ATM is a tumor suppressor, and changes in its expression disrupt DNA repair [5]. While deletions or mutations in p53 are not highly prevalent, a functional alteration in p53 often occurs due to the loss of ATM [7]. These findings may contribute to the chemorefractory nature of T-PLL.

Other recurrent genetic changes include abnormalities on chromosomes 8, 5, 12, 13, 22 [5]. No individual cytogenetic abnormality has prognostic implications, but complex karyotypes are associated with worse outcome [12].

While the previously described alterations in TCL1 are not sufficient to induce leukemogenesis, a second mutational impact model has been proposed for clonal evolution in T-PLL [13]. Recent studies have expanded our understanding of the mutational landscape beyond previously identified lesions. A meta-analysis of 10 published studies (n = 275) revealed constitutive hyperactivation of STAT5B in all analyzed samples. In 90% of these cases, a known genomic alteration could explain this hyperactivation, suggesting the identification of a new molecular signature. Furthermore, 62.1% of the cases harbored somatic mutations related to GOF, most frequently in JAK3 (36.4%), STAT5B (18.8%), and JAK1 (6.3%), often as a subclonal event. More than two-thirds of the other cases without JAK/STAT mutations showed alterations in negative regulators, which could also explain the overactivation [14]. These findings align with previously published series [6,15,16]. Other common genetic lesions include EZH2 (epigenetic regulators), and CHEK2 (DNA repair/checkpoint) [6].

Based on these findings, a model of constitutive activation of the JAK/STAT pathway in the pathogenesis of T-PLL has been proposed. The JAK/STAT pathway is involved in lymphopoiesis, participating in the proliferation, differentiation, and migration of T-cells.

In the previously mentioned series of 15 T-PLL/MCTP1 patients, all patients with available NGS molecular studies had mutations in the JAK/STAT pathway, with JAK3 mutations being the most common [11].

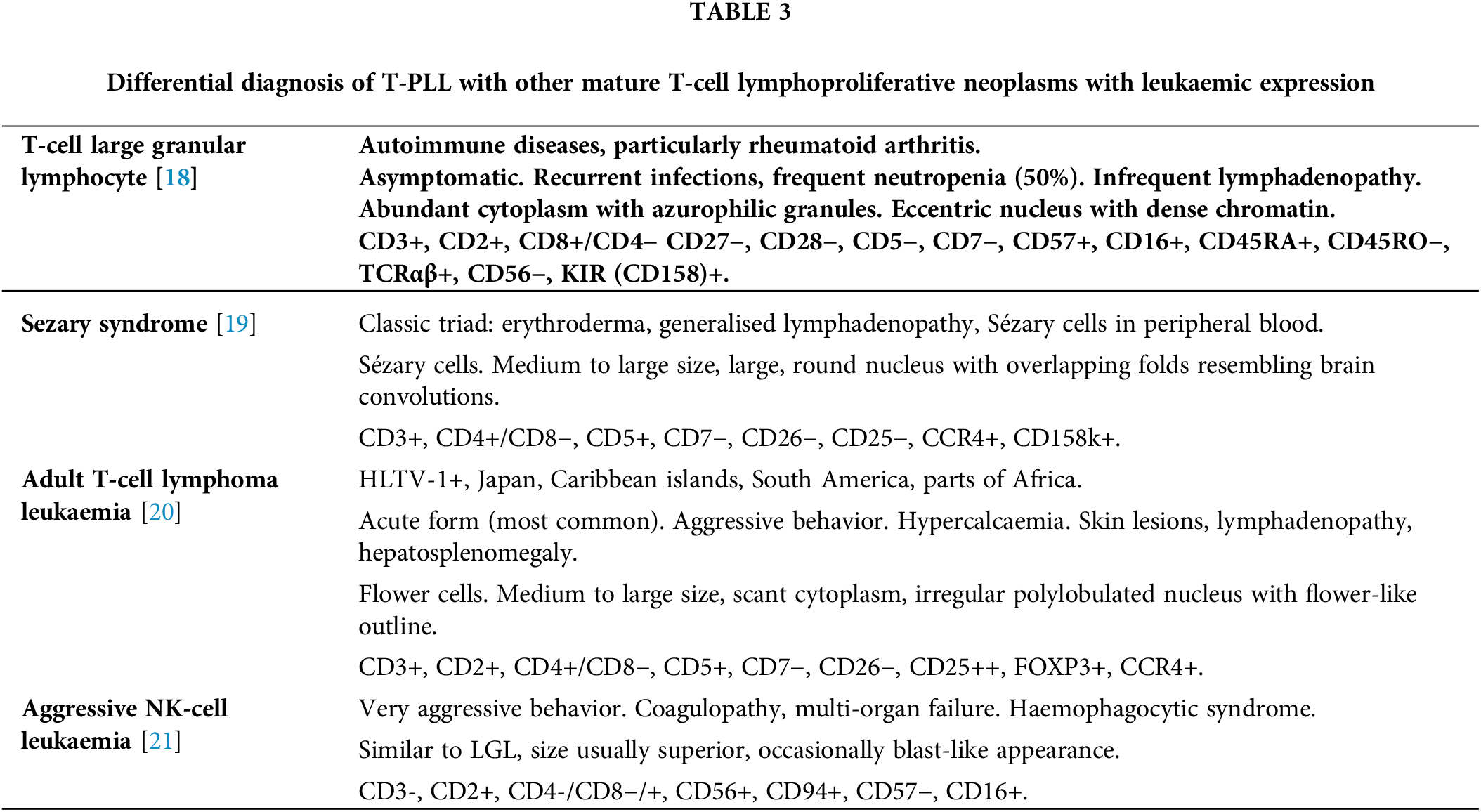

T-PLL must be distinguished from other mature T-cell lymphoproliferative neoplasms that can manifest in the peripheral blood, including large granular lymphocyte (LGL) leukemia, Sézary syndrome (SS), A-TLL, and aggressive NK-cell leukemia. The integration of clinical, cytomorphological, immunophenotypic, and genetic information is crucial for a correct diagnosis [10,17]. Table 3 provides a summary of the main differential characteristics.

A diagnosis of A-TLL requires a positive HTLV-1 serology. While these T-cell neoplasms share some clinical features, certain characteristics can help distinguish them. The presence of hepatosplenomegaly at diagnosis is more common in A-TLL and LGL leukemia, while palpable lymphadenopathy is typical in SS. Skin lesions are common across all entities, although the presence of generalized erythroderma is characteristic of SS. T-PLL often presents with a rapid increase in lymphocyte count. Eosinophilia is common in SS, while neutropenia is characteristic of LGL leukemia. Autoimmune phenomena are frequent in LGL leukemia [8]. Among T-cell neoplasms with peripheral blood expression, T-PLL is the only entity with a uniformly defined molecular abnormality used for diagnostic purposes.

Patients with indolent forms of disease, irrespective of treatment, inevitably progress to aggressive disease over time. No statistically significant difference in the rate of this progression has been observed between treated and untreated patients. Therefore, there is currently no evidence to support the immediate initiation of treatment for indolent disease. The decision to start treatment is typically based on the presence of active disease [4].

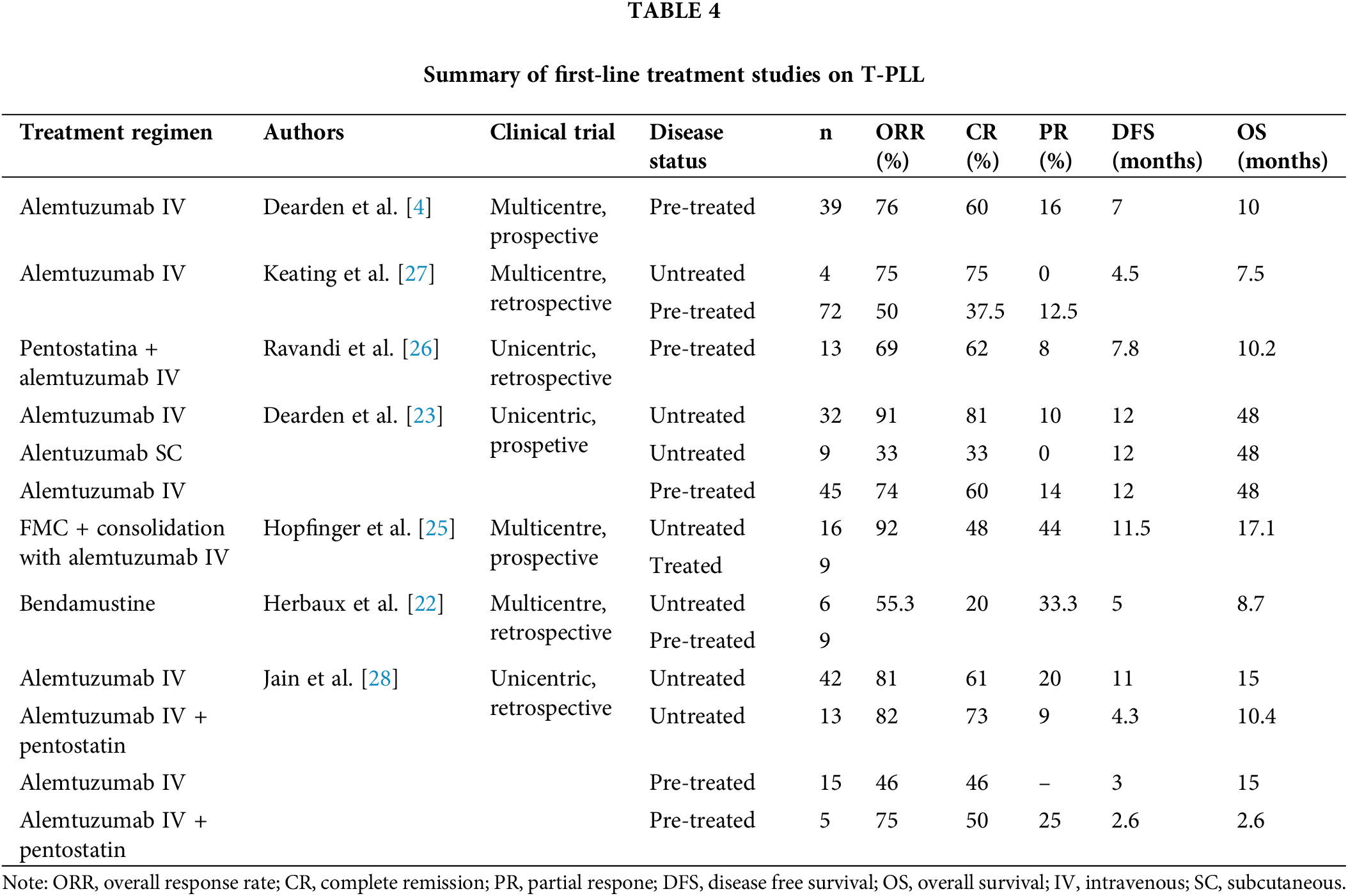

Conventional chemotherapy has proven ineffective in treating T-PLL. CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) based and related regimens have been disappointing [4]. Alternative regimens have also been tested in T-PLL. For instance, intravenous pentostatin monotherapy achieved medinan DFS of only 6 months [4]. While intravenous bendamustine monotherapy showed some promise, with a 55.3% PR rate and improved DFS and overall survival (OS) for responders, the median OS for all patients remained below 9 months [22]. Given these underwhelming outcomes, chemotherapy is not considered a first-line treatment for T-PLL [2].

Intravenous alemtuzumab is the most effective treatment for patients with T-PLL. Dearden et al. described CR rates of up to 81% with alemtuzumab monotherapy in previously untreated patients, with a 12-month DFS of 67 [23]. Unlike chronic lymphoid processes, subcutaneous administration of alemtuzumab was considerably less effective than intravenous administration, even compared with relapsed/refractory patients treated with intravenous alemtuzumab beyond the first-line setting [23]. In contrast to chronic lymphoid processes where polychemotherapy regimens such as fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone can enhance treatment outcomes, using this regimen before alemtuzumab did not improve the overall response rate (ORR) or DFS [24], and could even increase toxicity, potentially hindering the completion of full intravenous alemtuzumab treatment [25].

While the combination of alemtuzumab with pentostatin yielded superior results to those obtained with pentostatin alone, as expected from the data presented above, it did not demonstrate statistically significant improvements in depth or duration of response (CR: 62%, DFS: 7.8 months in pre-treated patients) [26] compared with intravenous alemtuzumab monotherapy, as reported by Deaden et al. [23]. However, the combination did outperform the regimen used by Keating et al. [27] in pre-treated patients with manageable toxicity. Intravenous alemtuzumab monotherapy regimens showed significantly higher DFS and OS than combination regimens with pentostatin, both in untreated and pre-treated patients [28]. No prospective studies have directly compared alemtuzumab in monotherapy with its combination with pentostatin. Additionally, there is no evidence supporting the benefit of alemtuzumab maintenance therapy, hence it is not recommended [4]. Table 4 summarizes the results of the above-mentioned studies.

A. Highlights of treatment with alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab, a humanized IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody targeting the CD52 antigen, has been used to treat B-CLL. Indeed, most of the safety and adverse event data for alemtuzumab come from studies on patients with CLL. CD52 is a cell surface glycoprotein highly expressed on the surface of various immune cells, including normal and neoplastic lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and eosinophils. It is absent on hematopoietic precursors, red blood cells, and platelets [2]. Alemtuzumab binds to CD52, triggering cell lysis through complement-dependent cytotoxicity and antibody-dependent cytotoxicity, leading to lymphodepletion.

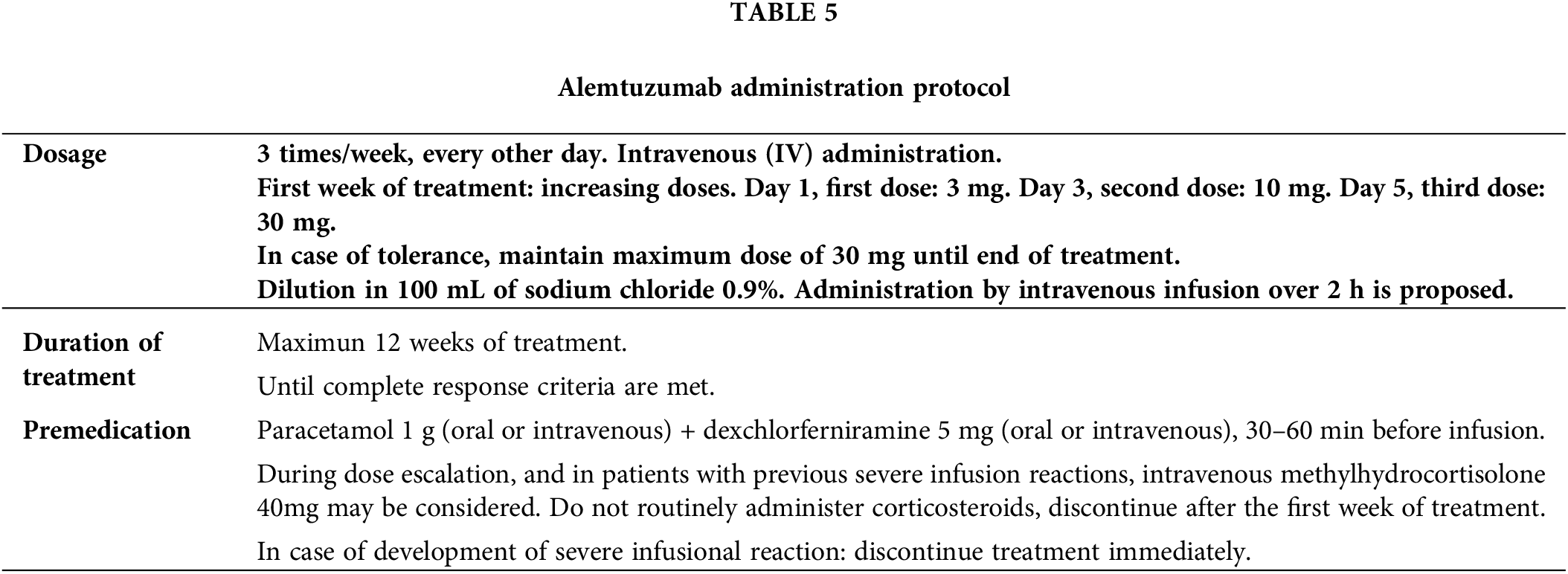

The dosing and duration of alemtuzumab treatment are outlined in Table 5 [2]. Peak drug doses are usually achieved within the first week of treatment. Infusion-related adverse reactions during early treatment might necessitate slower dose escalation. If treatment is interrupted for more than one week, the dose should be gradually increased upon restarting therapy.

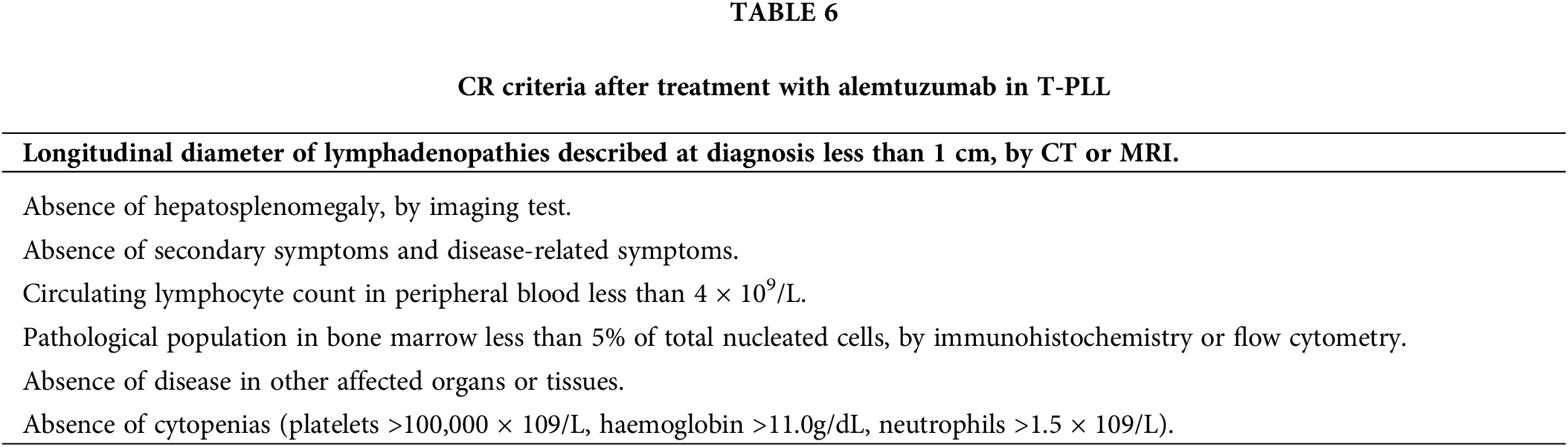

The duration of alemtuzumab treatment is determined by the patient’s response. If disease progression or lack of response occurs during treatment, discontinuation should be considered. Consensus guidelines recommend a bone marrow evaluation to confirm CR [4]. Alemtuzumab treatment should continue until the bone marrow is disease-free. Once CR is achieved in the peripheral blood and in affected nodal and extranodal sites, a bone marrow aspirate and biopsy should be considered.

The criteria for CR are outlined in Table 6, requiring the fulfillment of all specified parameters [4]. While there are no specific criteria for assessing remission of nodal involvement in T-PLL, the RECIL criteria [29] are proposed due to their adequate correlation in response assessment between unidimensional and bidirectional measurement. Alternatively, the Lugano [30] and iwCLL [31] criteria can be considered [4].

Currently, CR assessment does not require the use of MRD assays. Despite the genetic nature of T-PLL, molecular biology and genetics do not play a significant role in routine response assessment. The clinical relevance of MRD assessment in T-PLL remains undefined. However, in parallel with standardized flow cytometry, techniques such as TCR rearrangement analysis and FISH could be applied to assess the absence of diagnostic genetic alterations, providing insights into treatment response depth, particularly in clinical trial settings.

B. Infectious risk

Alemtuzumab significantly weakens the immune system, posing a serious risk of opportunistic infections in patients already immunocompromised due to their underlying condition. Prevention and proper management of infectious complications are thus crucial.

Prophylactic measures with co-trimoxazole and acyclovir are recommended [2]. Importantly, the recovery of CD4+ cell counts may be delayed for several months after the last dose of alemtuzumab. Additionally, there might be a prolonged period of immunodeficiency even after normal lymphocyte counts return. Therefore, a conservative approach suggests continuing both prophylaxes for six months post-treatment or until CD4+ cell counts are above 250,000/μL. Antifungal and antibacterial prophylaxis is not recommended [2].

Bacterial infections occur predominantly at the beginning of alemtuzumab treatment. Viral infections tend to start around three weeks into treatment, and fungal infections become more frequent after one month of treatment.

Immunocompromised patients are at increased risk of CMV infection. Indeed, CMV reactivation is considered the most common opportunistic infection associated with alemtuzumab therapy in this patient group. While preemptive therapy significantly reduces the risk of developing CMV disease, it is not entirely eliminated. A retrospective Spanish study on patients with T-PLL reported an incidence of CMV reactivation of 38.9% and CMV disease of 4.9% [32]. Early studies likely underestimated these figures due to limited CMV monitoring capabilities. By contrast, recent studies, that incorporate periodic CMV viral load monitoring and proactive preventive measures, report lower rates of symptomatic infections.

CMV reactivation does not occur after the completion of alemtuzumab therapy. Patients receiving concurrent steroid therapy were found to be at a heightened risk of CMV reactivation [32].

A CMV serological test is crucial before initiating treatment. While specific CMV prophylactic treatment can prevent symptomatic reactivation, it is not routinely recommended. However, it may be considered for high-risk patients at the discretion of the healthcare provider. Regular monitoring of CMV viral load through quantitative PCR is advised. Asymptomatic patients with positive CMV viremia should receive preemptive treatment but can continue alemtuzumab therapy. Discontinuation of alemtuzumab should be considered in patients experiencing CMV symptoms or diagnosed with CMV disease [33].

Patients treated with alemtuzumab are susceptible to a wide range of infections. It is imperative to assess the patient’s serological status and history of previous infectious processes to enable effective surveillance and prevention of reactivation of latent infections.

Role of Allogeneic Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in T-PLL

Allo-HSCT is currently the only potentially curative therapy and should be considered in eligible patients after achieving a response to cytoreductive therapy [34]. However, it has been published that in the majority of patients who achieved complete remission, this procedure was not associated with increased progression-free survival or overall survival [28]. A multi-institutional retrospective case series of 27 T-PLL patients, reported on behalf of the French Society for Stem Cell Transplantation (SFGM-TC), showed 3-year DFS and OS after allo-HSCT of 26% and 36%, respectively [35]. Another study evaluating data from CIBMTR (Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research) reported 4-year rates of OS and DFS of 30% and 25.7% with allo-HSCT [36]. A retrospective study from the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) in 41 patients who received allo-HSCT reported a 3-year relapse-free mortality (NRM) of 41%, DFS 19%, and OS 21% [37]. Allo-HSCT has been reported to yeld durable remissions, especially if offered after achieving a CR [38].

Disease relapse is the most frequent cause of death (about 50% of cases) in these patients [28]. In some cases, if allogeneic transplantation is not possible, autologous transplantation may be considered.

New Therapies in the Treatment of T-PLL

A deeper understanding of T-PLL pathogenesis has opened the door to novel therapeutic strategies targeting specific molecular pathways. Some of these approaches are currently being investigated in clinical trials [39].

Approaches include MDM2 inhibition to restore p53 activity in T-PLL cells and induce apoptosis; PARP inhibition to promote apoptosis by impairing DNA repair mechanisms; and BH3 mimetics to target the Bcl-2 family of proteins and induce apoptosis. Another approach is epigenetic therapy such as hypomethylating agents and HDAC inhibitors to exploit the high frequency of epigenetic alterations. Because positive regulation by TCR enhancer elements is involved in the pathogenesis of T-PLL, TCR kinase inhibition (ITK inhibitors) as well as AKT/PI3H inhibitors would block TCR signaling pathways [10,17]. Furthermore, the development of novel antibodies with reduced immunosuppressive effects is a priority. CCR7, a prognostic biomarker for OS in T-PLL, is a promising target [40]. While chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy offers potential, the identification of specific antigens on malignant T-cells remains a significant challenge, limiting its current application in T-PLL.

GOF mutations involving JAK/STAT family members, recurrent in T-PLL, together with the successful use of JAK/STAT inhibitors in myeloproliferative neoplasms and graft-versus-host disease, suggest that JAK inhibition may offer new therapeutic avenues for T-PLL [41].

Ex vivo drug screening has revealed the sensitivity of neoplastic T-PLL cells to JAK inhibitors, even in cases where this sensitivity is not directly predicted by the specific mutational status of JAK/STAT [16]. While JAK3 mutations have been linked to lower rates of OS, neither STAT5B mutations nor other mutations in GOF genes appear to have prognostic implications [16,42]. The STAT5B N642H, a highly activating mutation of the pathway, appears to confer resistance to ruxolitinib [16].

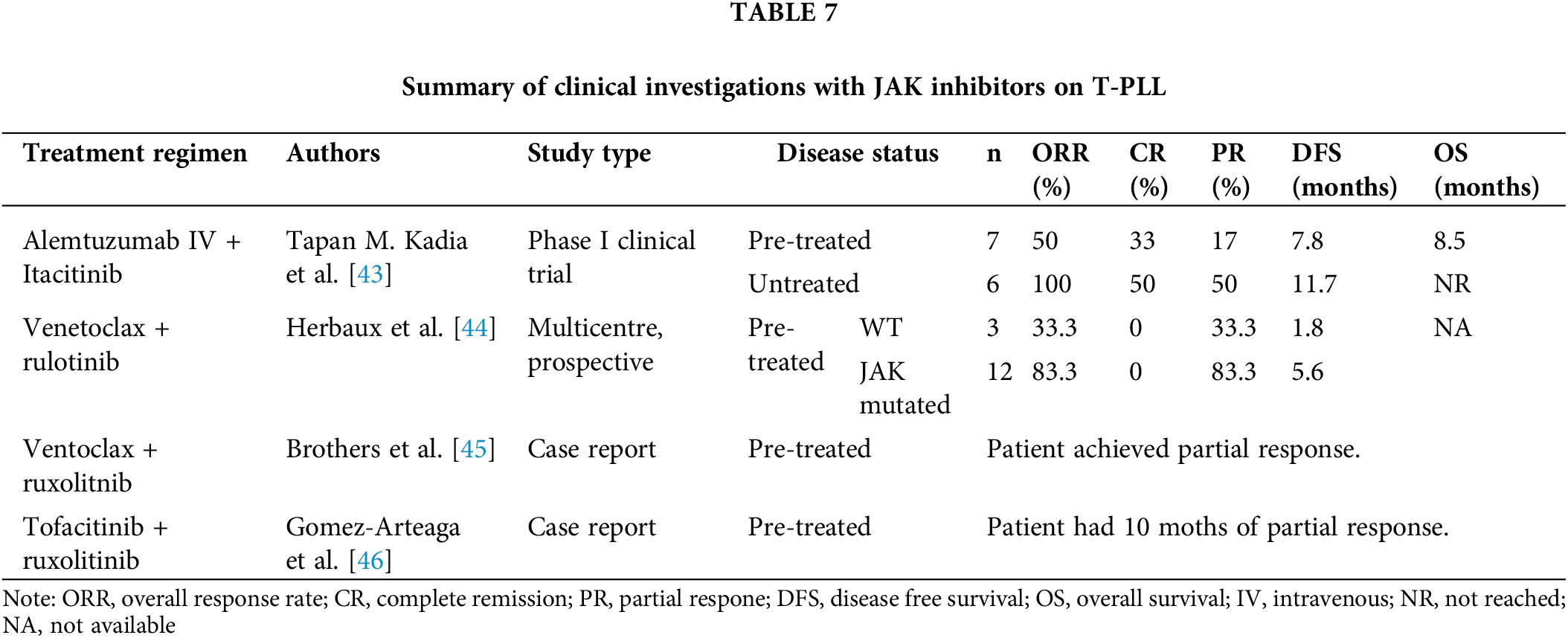

A few isolated studies have explored the use of JAK inhibitors in patients with T-PLL. The results of these studies are summarized in Table 7.

A phase I clinical trial (NCT03989466) assessed the combination of alemtuzumab with itacitinib (JAK1 inhibitor). This trial, the largest to date utilizing JAK inhibitors in T-PLL, demonstrated promising results. In pre-treated patients, the ORR was 50%. When used as a front-line treatment, all patients achieved at least a PR. Moreover, the CR rate was 30% in pre-treated patients and 50% in untreated patients. These CRs were associated with deep remissions, with negative MRD by flow cytometry. The median first-line DFS was 11.7 months, and the median OS had not been reached at 16 months (with OS exceeding 70% at six months). The addition of the JAK inhibitor did not increase toxicity [43].

Inhibition of the JAK/STAT pathway with ruxolitinib increases the dependence of neoplastic cell survival on the Bcl-2 protein [47], thereby sensitizing T-PLL cells to venetoclax. This suggests that the combination of these two agents could yield improved outcomes. A retrospective multicenter study involving 15 patients with refractory/relapsed disease evaluated the combination of ruxolitinib and venetoclax. The ORR was 73.3%, with only PRs observed. Analysis of the molecular status revealed better outcomes in patients with JAK mutations, as the median progression-free survival was significantly shorter in the wild-type group (5.6 months vs. 1.8 months) [44].

A preclinical study using a combination of ruxolitinib and tofacitinib demonstrated an additive effect ex vivo [46]. Additionally, a clinical case report described a patient with refractory T-PLL treated with this combination who achieved a PR that was sustained for ten months [46]. Finally, the selective STAT-5 inhibitor pimozide has proven effective in cultured T-cells [6].

The present case report highlights a rare cytogenetic anomaly in T-PLL, with isolated cases described in the literature [11]. Cytogenetic findings revealed the rearrangement of Xq28 (where MTCP1 is located) juxtaposed with the TCR A/D locus on chromosome 14. Unlike most cases of T-PLL, TCL1a is not rearranged (by FISH). TCL1 overexpression is detected by flow cytometry, and may occur in both MTCP1/T-PLL and TCL1a/T-PLL due to the high structural homology between these proteins of the same proto-oncogene family. The clinical, pathological, immunophenotypic, and genetic profiles of patients with t(X;14)(q28;q11.2) are not well characterized due to the rarity of the disease and the lack of overlap data with TCL1a/T-PLL [11]. The low incidence of cases limits progress, necessitating further data collection.

As in other hematological diseases, cytogenetic and molecular knowledge plays a crucial role and is already integrated into new T-PLL definitions [4]. While FISH and chromosome banding analysis are essential, NGS, though not currently required for diagnosis, provides valuable additional information. As molecularly defined prognostic subgroups and targeted therapies emerge, NGS may soon influence treatment decisions.

Alemtuzumab, an anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody, is the best available first-line therapeutic option. Its long history of use has led to the development of well-established treatment protocols to manage associated complications. However, the responses are temporary, and early relapse is common, posing a significant challenge. Cures are primarily achieved through allo-HSCT, but this is not always feasible for all patients. Given the poor prognosis and the lack of approved drugs, there is an urgent need for novel therapies, especially in relapsed/refractory disease. Recent advancements in understanding the molecular basis of T-PLL [6] and the identification of new target molecules [7,10,16] offer hope for future treatments. Clinical trial development is hindered by the low incidence of the disease, emphasizing the importance of case reporting.

In our case, NGS upon diagnosis identified a STAT5B mutation, aligning with the JAK/STAT pathway and the mutational profile of T-PLL observed in recent studies [6,11,14,15,42]. Given this specific molecular target, we focused our attention on potential therapeutic options targeting this pathway. Available studies cannot be directly compared limited by factors such as population design and sample size, but it suggests that adding JAK inhibitors to alemtuzumab may not significantly improve response rates compared with monotherapy, they may offer potential benefits in terms of DFS and OS, which is valuable. However, randomized controlled trials are necessary to definitively establish the efficacy of this combination therapy, so in the case reported we use alemtuzumab as monotherapy in the frontline. Considering the limited treatment options for relapsed T-PLL and the need to improve first-line outcomes, we propose to continue investigating the addition of a JAK inhibitor as a potential therapeutic strategy. For our patient in the event of relapse, guided by the molecular insights gained from NGS testing, we propose its use.

We need institutions to share data to help better figure out if JAK inhibitors would be useful in the upfront treatment of T-PLL patients with JAK/STAT pathway mutations in conjunction with alemtuzumab. If this can occur, we would propose a clinical trial randomizing patients to alemtuzumab vs. the combination with a JAK inhibitor. This may improve outcomes and even limit bone marrow transplant needs in this poorly understood and deadly disease.

T-PLL is a rare disease with limited treatment options and a low success rate. Alemtuzumab is currently the treatment with the most promising outcomes. However, new therapies are needed that offer better response rates and fewer side effects. A deeper understanding of the pathogenesis of this disease has identified potential new therapeutic targets, which are now being investigated in various clinical trials. While the initial results of these trials are encouraging, further research is necessary to confirm their efficacy.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding or this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows. Study conception and design: Luis Manuel González-Rodríguez, Luis Miguel Juárez-Salcedo, Eva Arranz; analysis and interpretation of results: Luis Manuel González-Rodríguez, Luis Miguel Juárez-Salcedo, Samir Dalia, Maria José López de la Osa; data collection: Luis Manuel González-Rodríguez, Javier Loscertales, Jimena Cannata-Ortiz, Javier Ortiz; draftt manucript preparation: Luis Manuel González-Rodríguez, Eva Arranz, Adrián Alegre. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethic Approval: This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at La Princesa University Hospital (approval number: 5828) and was in compliance with what is established regarding ethical principles for medical research with human participants in Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent is available.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Alaggio R, Amador C, Anagnostopoulos I, Attygalle AD, Araujo IBO, Berti E, et al. The 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: lymphoid neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36(7):1720–48. doi:10.1038/s41375-022-01620-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Cross M, Dearden C. B and T cell prolymphocytic leukaemia. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2019;32(3):217–28. doi:10.1016/j.beha.2019.06.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Vardell VA, Ermann DA, Fitzgerald L, Shah H, Hu B, Stephens D, et al. T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia: epidemiology and survival trends in the era of novel treatments. Am J Hematol. 2024;99(3):494–6. doi:10.1002/ajh.27205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Staber PB, Herling M, Bellido M, Jacobsen ED, Davids MS, Kadia TM, et al. Consensus criteria for diagnosis, staging, and treatment response assessment of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2019;134(14):1132–43. doi:10.1182/blood.2019000402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Sun S, Fang W. Current understandings on T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia and its association with TCL1 proto-oncogene. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;126(1):110107. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Kiel MJ, Velusamy T, Rolland D, Sahasrabuddhe AA, Chung F, Bailey GN, et al. Integrated genomic sequencing reveals mutational landscape of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2014;124(9):1460–72. doi:10.1182/blood-2014-03-559542. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Braun T, Von Jan J, Wahnschaffe L, Herling M. Advances and perspectives in the treatment of T-PLL. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2020;15(2):113–24. doi:10.1007/s11899-020-00566-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. El-Sharkawi D, Attygalle A, Dearden C. Mature T-cell leukemias: challenges in diagnosis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:777066. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.777066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Muñoz Calleja C, Minguela Puras A. Diagnosis and immunophenotypic monitoring of leukocyte neoplasms. Barcelona: Elsevier; 2018. [Google Scholar]

10. Gutierrez M, Bladek P, Goksu B, Murga-Zamalloa C, Bixby D, Wilcox R, et al. T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia: diagnosis, pathogenesis, and treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(15):12106. doi:10.3390/ijms241512106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Hu Z, Medeiros LJ, Xu M, Yuan J, Peker D, Shao L, et al. T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia with t(X;14)(q28;q11.2a clinicopathologic study of 15 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2023;159(4):325–36. doi:10.1093/ajcp/aqac166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hu Z, Medeiros LJ, Fang L, Sun Y, Tang Z, Tang G, et al. Prognostic significance of cytogenetic abnormalities in T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Am J Hematol. 2017;92:441–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

13. Rashidi A, Fisher SI. T-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small-cell variant of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia: a historical perspective and search for consensus. Eur J Haematol. 2015;95:199–210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Wahnschaffe L, Braun T, Timonen S, Giri AK, Schrader A, Wagle P, et al. JAK/STAT-activating genomic alterations are a hallmark of T-PLL. Cancers. 2019;11:1833. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

15. Bellanger D, Jacquemin V, Chopin M, Pierron G, Bernard OA, Ghysdael J, et al. Recurrent JAK1 and JAK3 somatic mutations in T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia. 2014;28:417–9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

16. Andersson EI, Pützer S, Yadav B, Dufva O, Khan S, He L, et al. Discovery of novel drug sensitivities in T-PLL by high-throughput ex vivo drug testing and mutation profiling. Leukemia. 2018;32:774–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

17. Braun T, Dechow A, Friedrich G, Seifert M, Stachelscheid J, Herlingl M. Advanced pathogenetic concepts in T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia and their translational impact. Front Oncol. 2021;11:775363. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.775363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Park SH, Lee YJ, Kim Y, Kim HK, Lim JH, Jo JC. T-large granular lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Res. 2023;58(S1):S52–S57. doi:10.5045/br.2023.2023037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Lee H. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Blood Res. 2023;58(S1):S66–S82. doi:10.5045/br.2023.2023023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Rodríguez-Zúñiga MJM, Cortez-Franco F, Qujiano-Gomero E. Adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma. Review of scientific literatura. Dermo-Syphiliographic Record. 2018;109:399–407. [Google Scholar]

21. Ousset L, Carré L, Protin C, Gadaud N, Evrard S, Rieu JB. Aggressive NK-cell leukaemia: diverse morphology, distinct clinical features. Br J Haemol. 2024;206(2):410–1. [Google Scholar]

22. Herbaux C, Genet P, Bouabdallah K, Pignon JM, Debarri H, Guidez S, et al. Bendamustine is effective in T-cell prolymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2015;168(6):916–9. doi:10.1111/bjh.13175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Dearden CE, Khot A, Else M, Hamblin M, Grand E, Roy A, et al. Alemtuzumab therapy in T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia: comparing efficacy in a series treated intravenously and a study piloting the subcutaneous route. Blood. 2011;118(22):5799–802. doi:10.1182/blood-2011-08-372854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Pflug N, Cramer P, Robrecht S, Bahlo J, Westermann J, Fink A, et al. New lessons learned in T-PLL: results from a prospective phase-II trial with fludarabine-mitoxantrone–cyclophosphamide-alemtuzumab induction followed by alemtuzumab maintenance. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(3):649–57. doi:10.1080/10428194.2018.1488253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Hopfinger G, Busch R, Pflug N, Weit N, Westermann A, Kinf A, et al. Sequential chemoimmunotherapy of fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and cyclophosphamide induction followed by alemtuzumab consolidation is effective in T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia: FMC plus alemtuzumab in T-PLL. Cancer. 2013;119(12):2258–67. doi:10.1002/cncr.27972. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Ravandi F, Aribi A, O’Brien S, Faderl S, Jones D, Ferrajoli A, et al. Phase II study of alemtuzumab in combination with pentostatin in patients with T-cell neoplasms. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(32):5425–30. doi:10.1200/JCO.2009.22.6688. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Keating MJ, Cazin B, Coutré S, Birhiray R, Kovacsovics T, Langer W, et al. Campath-1H treatment of T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia in patients for whom at least one prior chemotherapy regimen has failed. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(1):205–13. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Jain P, Aoki E, Keating M, Wierda WG, O’Brien S, Gonzalez GN, et al. Characteristics, outcomes, prognostic factors and treatment of patients with T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL). Ann Oncol. 2017;28(7):1554–9. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdx163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Younes A, Hilden P, Coiffier B, Hagenbeek A, Salles G, Wilson W, et al. International working group consensus response evaluation criteria in lymphoma (RECIL 2017). Ann Oncol. 2017;28:1436–47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

30. Cheson BD, Ansell S, Schwartz L, Gordon LI, Advani R, Jacene AH, et al. Refinement of the Lugano classification lymphoma response criteria in the era of immunomodulatory therapy. Blood. 2016;128(21):2489–96. doi:10.1182/blood-2016-05-718528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Döhner H, et al. iwCLL guidelines for diagnosis, indications for treatment, response assessment, and supportive management of CLL. Blood. 2018;131(25):2745–60. doi:10.1182/blood-2017-09-806398. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Vallejo C, Ríos E, de la Serna J, Jarque I, Ferrá C, Sánchez-Godoy P, et al. Incidence of cytomegalovirus infection and disease in patients with lymphoproliferative disorders treated with alemtuzumab. Expert Rev Hematol. 2011;4(1):9–16. doi:10.1586/ehm.10.77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Ljungman P, de la C, Robin C, Crocchiolo RR, Einsele H, Hill JA, et al. Guidelines for the management of cytomegalovirus infection in patients with haematological malignancies and after stemm cell transplantation from the 2017 European conference on infections in Leukemia (ECIL 7). Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(8):e260–72. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30107-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Varadarajan I, Ballen K. Advances in cellular therapy for T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Front Oncol. 2022;12:781479. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.781479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Guillaume T, Beguin Y, Tabrizi R, Nguyen S, Blaise D, Deconinck E, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for T-prolymphocytic leukemia: a report from the French society for stem cell transplantation (SFGM-TC). Eur J Haematol. 2015;94(3):265–9. doi:10.1111/ejh.12430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Murphy HS, Ahn KW, Estrada-Merly N, Alkhateeb HB, Bal S, Kharfan-Dabaja MA, et al. Outomes of allogenic hematopoietic cell transplantation in T cell prolymphocytic leukemia: a contemporany analysis from the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Transplant Cell Ther. 2022;28:187–7. [Google Scholar]

37. Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W, Dearden C, de Wreede L, van Biezen A, Brinch L, Leblond V, et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in T-prolymphocytic leukemia: a retrospective study from the European group for blood and marrow transplantation and the royal marsden consortium. Leukemia. 2012;26(5):972–6. doi:10.1038/leu.2011.304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Dholaria BR, Ayala E, Sokol L, Nishihori T, Chavez JC, Hussaini M, et al. Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. A single-center experience. Lenk Res. 2018;67:1–5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

39. Colon Ramos A, Tarekegn K, Aujla A, Garcia De De Jesus K, Gupta S. T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia: an overview of current and future approaches. Cureus. 2021;13(2):e13237. doi:10.7759/cureus.13237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Cuesta-Mateos C, Fuentes P, Schrader A, Juárez-Sánchez R, Loscertales J, Mateu-Albero T, et al. CCR7 as a novel therapeutic target in T-cell PROLYMPHOCYTIC leukemia. Biomark Res. 2020;8(1):54. doi:10.1186/s40364-020-00234-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Schrader A, Crispatzu G, Oberbeck S, Mayer P, Pützer S, Von Jan J, et al. Actionable perturbations of damage responses by TCL1/ATM and epigenetic lesions form the basis of T-PLL. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):697. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-02688-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Stengel A, Kern W, Zenger M, Perglerová K, Schnittger S, Haferlach T, et al. Genetic characterization of T-PLL reveals two major biologic subgroups and JAK3 mutations as prognostic marker. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2016;55(1):82–94. doi:10.1002/gcc.22313. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Kadia TM, Ravandi F, Borthakur G, Yilmaz N, Montalban-Bravo G, Adewale L, et al. A phase Ib pilot study of itacitinib combined with alemtuzumab in patients with T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL). Blood. 2021;138(Supplement 1):1375–5. doi:10.1182/blood-2021-153691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Herbaux C, Poulain S, Ross-Weil D, Bay JO, Guillermin Y, Lemonnier F, et al. Preliminary study of ruxolitinib and venetoclax for treatment of patients with T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia refractory to, or ineligible for alemtuzumab. Blood. 2021;138(Supplement 1):1201–1. doi:10.1182/blood-2021-149228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Brothers J, Castillo DR, Jeon WJ, Joung B, Linhares Y. Partial response to venetoclax and ruxolitinib combination in a case of refractory T-prolymphocytic leukemia. Hematology. 2023;28(1):2237342. doi:10.1080/16078454.2023.2237342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Gomez-Arteaga A, Margolskee E, Wei MT, van Besien K, Inghirami G, Horwitx S. Combined use of tofacitinib (pan-JAK inhibitor) and ruxolitinib (a JAK1/2 inhibitor) for refractory T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia (T-PLL) with a JAK3 mutation. Leuk Lymphoma. 2019;60(7):1626–31. doi:10.1080/10428194.2019.1594220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Herbaux C, Kornauth C, Poulain S, Chong SJF, Collins MC, Valentin R, et al. BH3 profiling identifies ruxolitinib as a promising partner for venetoclax to treat T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2021;137(25):3495–3506. doi:10.1182/blood.2020007303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools