Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

N6-Methyladenosine Promotes the Transcription of c-Src Kinase via IRF1 to Facilitate the Proliferation of Liver Cancer

1 School of Public Health, Xiangnan University, Chenzhou, 423000, China

2 Department of Basic Medicine, Xiangnan University, Chenzhou, 423000, China

3 Teaching and Research Section of Surgery, Xiangnan University Affiliated Hospital, Chenzhou, 423000, China

* Corresponding Author: Qun Xie. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Novel Targets and Biomarkers in Solid Tumors)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(7), 1679-1693. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.062747

Received 26 December 2024; Accepted 10 April 2025; Issue published 26 June 2025

Abstract

Background: Expression of mRNA is widely regulated by N6-methyladenosine (m6A). An increasing number of studies have shown that m6A methylation, facilitated by methyltransferase 3 (METTL3), is crucial in the progression of tumors. Previous reports have indicated the involvement of both METTL3 and c-Src kinase in the evolution of liver cancer. However, the potential connection between c-Src and the METTL3-mediated mechanism in liver cancer progression remains elusive. Methods: The correlation expression between c-Src and METTL3 between liver cancer patients and the control group was analyzed using the TCGA database, and was further demonstrated by Western blot and RT-qPCR. The functional roles of c-Src in METTL3-regulated liver cancer progression were investigated by cell proliferation assays and colony formation assays. The regulatory mechanism of METTL3 in c-Src expression was accessed by RNA-immunoprecipitation (RIP)-qPCR. Results: We demonstrated that c-Src kinase promoted liver cancer development, and the expression of SRC (encodes c-Src kinase) was positively correlated with METTL3 in liver cancer cases. We showed that SRC mRNA could be m6A-modified, and METTL3 regulated the transcription of SRC mRNA through interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF1). We revealed that IRF1, the expression of which was positively regulated by METTL3, was a novel transcription factor of c-Src. Lastly, The pro-proliferative effect of METTL3 on hepatocellular carcinoma was mechanistically linked to IRF1/c-Src axis activation, as evidenced by our experimental data. Conclusion: Results suggested that the METTL3/IRF1/c-Src axis played potential oncogenic roles in liver cancer development and the axis may be a promising therapeutic target in the disease.Keywords

Primary liver cancer ranks as the sixth most commonly diagnosed cancer, there were over three quarters of a million liver cancer deaths worldwide in 2022, positioning liver cancer as the third leading cause of cancer death after lung and colorectum, with an estimated 865,000 new cases and 757,948 deaths in 2022 [1]. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), as the most common histological subtype of primary liver cancer, constitutes 75% to 85% of all cases globally, making it the predominant form of hepatic malignancies [2]. With the reduction of hepatitis virus-induced liver cancer [3], nonviral risk factors [4] have increasingly garnered attention in liver cancer research [5]. Essentially, identifying novel targets that drive the progression of liver cancer is necessary for the development of targeted therapy against this deadly disease.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) represents the most prevalent internal modification in eukaryotic mRNAs [6]. m6A methylation is catalyzed by “writer” methyltransferases 3 (METTL3) and methyltransferase 14 (METTL14) and is demethylated by “eraser” demethylases AlkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and fat mass [7]. The coordinated interplay between m6A methyltransferases and demethylases orchestrates the spatiotemporal precision of RNA methylation homeostasis in mammalian cells, forming a dynamic reversible modification network critical for gene expression regulation. m6A modification functions as a crucial regulator of the mRNA life cycle, including pre-mRNA splicing [8], nucleo-cytoplasmic export [9], mRNA decay [10], and mRNA translation [11], and thereby regulating various cellular biological processes.

A growing body of work provides evidence that m6A promotes the development of cancers [12]. As the executor of m6A modification, METTL3 plays a crucial role in tumorigenesis. For instance, METTL3 is essential for the development and maintenance of myeloid leukemia in both mice and humans [13], modulates the Wnt/β-catenin-EMT axis in ESCC by stabilizing β-catenin/TCF4 transcriptional complexes to facilitate tumor invasion [14], and facilitates TGFβ signals to support tumor growth [15]. In HCC, METTL3-mediated m6A modification stabilizes ASPM mRNA via YTHDF1 recognition, thereby augmenting HCC cell proliferative capacityand metastatic potential [16]. Moreover, METTL3 is abnormally upregulated in HCC, and its expression has been shown to predict poor survival outcomes in HCC patients [17,18].

Classified as a non-receptor tyrosine kinase within the Src family kinases (SFKs), c-Src orchestrates key cellular dynamics including differentiation, motility, and intercellular adhesion through phosphorylation signaling [19]. C-Src kinase can be activated by diverse stimuli, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [20], P2RY2 (a purinergic GPCR receptor), reactive oxygen species (ROS) [21], high glucose [22], heterotrimeric G protein-coupled receptors [23], and PKA signaling [24]. Increasing evidence shows that c-Src is a critical factor in the development of a variety of human cancers [25], such as liver cancer [26–28]. However, it remains unclear if c-Src is associated with the METTL3-regulated mechanism in liver cancer.

In this study, we bridged the association between SRC and METTL3 according to publicly available liver cancer datasets with clinical data and functional analyses revealed that METTL3 modulates SRC mRNA expression through m6A-dependent mechanisms. We further provided evidence showing that IRF1 was a novel transcription factor of SRC, and the IRF1/c-Src axis participated in METTL3-promoted proliferation of liver cancer cells.

2.1 Cell Culture, Treatments, and Transfection

Liver cancer cell lines Huh7 and HepG2 were used for investigation in this study. Stably METTL3 silencing Huh7 and cells (sh-METTL3 Huh7), its control cells (sh-NC Huh7) were the gift from Prof. Hongsheng Wang (School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Sun Yat-Sen University). Use validated siRNA sequences for METTL3 (5′-GCCAAGGAACAATCCATTGTT-3′), silencing METTL3, transfected into HepG2 cells. IRF1 cDNA cloned into an expression vector (pcDNA3.1), transfected into sh-METTL3 Huh7 or siMETTL3 HepG2 cells. Use validated siRNA sequences for c-Src(5′-AAGUGCAAUGUGGACCGUAUC-3′) and IRF1(5′-CUGAAGAGCUUCAGCAUCA-3′), silencing either c-Src or IRF1, transfected into Huh7 or HepG2 cells. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco, 11965118, Carlsbad, CA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Gibco, 26140111, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 0.5 μg/mL Mycoplasma removal reagent (Beyotime, C0288S, Shanghai, China) at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator. For transfection, plasmids were transfected into cells using LipofectamineTM 3000 reagent (Invitrogen Life Technology, L3000001, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

The promoter region of SRC (encodes for c-Src kinase) was cloned into the pGL3 basic vector upstream of the F-Luc gene. Mammalian expression plasmids pcDNA3-METTL3 and pcDNA3-METTL3-D395A were gifts from Prof. Hongsheng Wang (School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China).

Cells were harvested and lysed in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 0.5 mM PMSF). Total proteins were extracted and quantified by BCA assay (Thermo, Prod# 23228), and 5× loading buffer was added to the proteins. A total of 30 μg of proteins from each sample were loaded and separated in 12% SDS-PAGE, then transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (ThermoFisher Scientific, LC2005, Waltham, MA, USA), and 5% defatted milk powder dissolved in TBST (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20) was used for blocking. PVDF membrane was incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. After three times TBST washing, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After washing with TBST, proteins in PVDF membrane bands were detected with luminol reagent (Santa Cruz, SC-2385, Dallas, TX, USA). GAPDH expression was used as the housekeeping protein. The primary antibodies used for immunoblotting included anti-c-Src (Abcam, ab109381, Cambridge, UK), anti-METTL3 (Abcam, ab195352, Cambridge, UK), anti-IRF1 (Abcam, ab245338, Cambridge, UK), and anti-GAPDH (Cell Signaling Technology, 5174S, Danvers, MA, USA) with 1:1000 dilution. The goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (Abcam, ab205718, Cambridge, UK) was used as secondary antibodies, with 1:5000 dilution. The immunoblotting results were representatives from at least three independent experiments. The band intensity of detected proteins was analyzed by ImageJ software (ImageJ 1.50i, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), and the presented values below each protein band were the mean from three independent experiments.

2.4 RNA Extraction and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from cells using Trizol reagent (TaKaRa, 9108Q, Beijing, China), and 1 μg total RNA was used as the template for cDNA synthesis in PrimeScript® First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (TaKaRa, D6110A, Beijing, China). qRT-PCR was performed in the SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM kit (TaKaRa, RR390A, Beijing, China) using specific primers. GAPDH was used as a control for normalization. The relation expression of tested genes was calculated by the cycle threshold values (Ct) as 2−ΔΔCt, where ΔCt = Gene Ct-Housekeeping gene Ct, ΔΔCt = ΔCt-Reference ΔCt, and Reference ΔCt = average of control group Ct. The primers of targeted human genes were as follows: SRC, forward 5′-AAGCCTGGCACGATGTCT-3′ and reverse 5′-CGATGTAAATGGGCTCCTCT-3′; pre-mRNA SRC, forward 5′-ATCTCATTGTGGTTTTGATT-3′ and reverse 5′-TGCGAGGATCACTTGAGCCC-3′; IRF1, forward 5′-AGAGAAAAGAAAGAAAGTCG-3′ and reverse 5′-TGGGCTGTCAATTTCTGGCT-3′; SRC promoter, forward 5′-TTCTTGTCAGTGCCTCAGTT-3′ and reverse 5′-CTTCTACGCCCCAGATCCGC-3′; GAPDH, forward 5′-GTCTCCTCTGACTTCAACAGCG-3′ and reverse 5′-ACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAGCCAA-3′; METTL3, forward 5′-CTATCTCCTGGCACTCGCAAGA-3′ and reverse 5′-GCTTGAACCGTGCAACCACATC-3′; FLUC, forward 5′-GGCCTGACAGAAACAACCAG-3′ and reverse 5′-AAGTCCACCACCTTAGCCTC-3′; RLUC, forward 5′-CGCTATTGTCGAGGGAGCTA-3′ and reverse 5′-GCTCCACGAAGCTCTTGATG-3′; HPRT1, forward 5′-TGACACTGGCAAAACAATGCA-3′ and reverse 5′-GGTCCTTTTCACCAGCAAGCT-3′; 18S, forward 5′-CGGACAGGATTGACAGATTGATAGC-3′ and reverse 5′-TGCCAGAGTCTCGTTCGTTATCG-3′.

2.5 m6A RNA-Immunoprecipitation (RIP) qPCR

The m6A-qRT-PCR was conducted according to published protocols [15]. A total of 200 µg total RNAs extracted by Trizol were used for immunoprecipitation by the m6A antibody (Abcam, ab286164, Cambridge, UK) or IgG (Abcam, ab172730, Cambridge, UK) in IP buffer (150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 100U RNase inhibitor). The m6A RNAs were immunoprecipitated by Dynabeads® Protein G (ThermoFisher Scientific, 10003D, Waltham, MA, USA) and eluted twice by elution buffer (5 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA pH 8.0, 0.05% SDS, 20 mg/mL Proteinase K). RNAs were then precipitated by ethanol and the RNA concentration was measured with a Qubit® RNA HS Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Q32852, Waltham, MA, USA). A total of 2 ng of total RNA (input) and m6A-IP RNA were used as the template for qRT-PCR. Hypoxanthine phosphoribosyl transferase 1 (HPRT1) was used as the internal control of the input samples.

Actinomycin D (Act-D; 5 μg/mL) (Sigma, SBR00013, Taufkirchen, Germany) was added to the serum-free culture medium for the indicated times. The cells were then washed by PBS and subjected to total RNA extraction by Trizol. RNA concentrations were quantified and qRT-PCR was performed. Detection of SRC mRNA levels represented the stability. 18S mRNA was used as the internal control.

Fractionation of the nuclear and cytoplasmic samples was performed using an NE-PER(R) nuclear and cytoplasmic extraction kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, 78833, Waltham, MA, USA). Total RNAs in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were extracted by Trizol. The nuclei–cytoplasm ratio was determined by the mRNA levels of targets in the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions, which were normalized to the levels of nuclear Metastasis Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1 (MALAT1) RNA and cytoplasmic 7SL RNA, respectively.

2.8 Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

The luciferase assay was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Beyotime Biotechnology, Beijing, China). Briefly, cells were co-transfected with pGL3–basic derived by SRC promoter and TK-R-luc reporter in a 6-well plate for 48 h. Cells were then analyzed with the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay system (Promega, E2920, Madison, WI, USA). Renilla luciferase (RLUC) was used to normalize firefly luciferase (FLUC) activity.

2.9 Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-qPCR

ChIP was performed using the Magna ChIP™ A/G Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Kit (Merck Millipore, 17-10085, Burlington, MA, USA) with an antibody specific for IRF1 (Abcam, ab243895, Cambridge, MA, USA; 2 µL for 107 cells) or normal rabbit IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-2357, Santa Cruz, CA, USA; 2 µL of 1:10 dilution). Following ChIP, quantitative PCR was utilized to amplify and quantify the immunoprecipitated DNA using primers specific for the IRF1 binding region on the SRC promoter. The IRF1 binding site within the SRC promoter region was obtained from the ENCODE Consortium. The ChIP-qPCR values were normalized to that of input control and represented as fold enrichment relative to the anti-normal rabbit IgG control group, using HPRT1 as internal control.

Cell proliferation was evaluated by CCK8 kit (Abcam, ab228554, Cambridge, UK) assay at indicated time points. 106 cells were seeded in 6-well plates one day before treatment. Cells were transfected with or without pcDNA3.1-SRC and control vectors. After transfection for 24 h, cells were trypsinized and seeded in 96-well plates (6 × 103 cells/well). CCK8 reagent was added in cells for a further 2 h incubation at 37°C. Subsequently, the OD values at 450 nm were recorded, and the cell proliferation diagram was plotted using the absorbance at each time point.

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates (1 × 103 cells/well) one day before treatment. The next day, cells were transfected with si-SRC, pcDNA3.1-SRC, or pcDNA3-METTL3 and control vectors as indicated. After transfection for 24 h, cells were trypsinized and re-suspended. A total of 1000 cells/well were seeded in 6-well plates, and cultured for 14 days. Cell colonies were gently washed by PBS, and then fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min. After PBS washing, cell colonies were incubated with crystal violet (1 mL crystal violet stock solution, add 9 mL PBS buffer solution) for 20 min. Photo recording was performed after PBS washing.

Expression levels of interested genes in tumor and normal tissues from liver cancer patients, survival analysis, and correlation analysis were performed using the online database Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2 (GEPIA2) http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index (accessed on 20 December 2024).

For the comparison of numerical variables between two groups, an unpaired t-test was used for normally distributed variables. For correlation analysis between two sets of numerical variables, Pearson correlation coefficient was used. Student’s t-test was used for the comparison of the mean equality of two independent samples, including the mRNA stability assay. One-way ANOVA analysis was used for the comparison of multiple groups. All analysis was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 9.0 (GraphPad Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and two-tailed p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3.1 Both SRC and METTL3 Are Associated with Worse Survival in Liver Cancer Patients

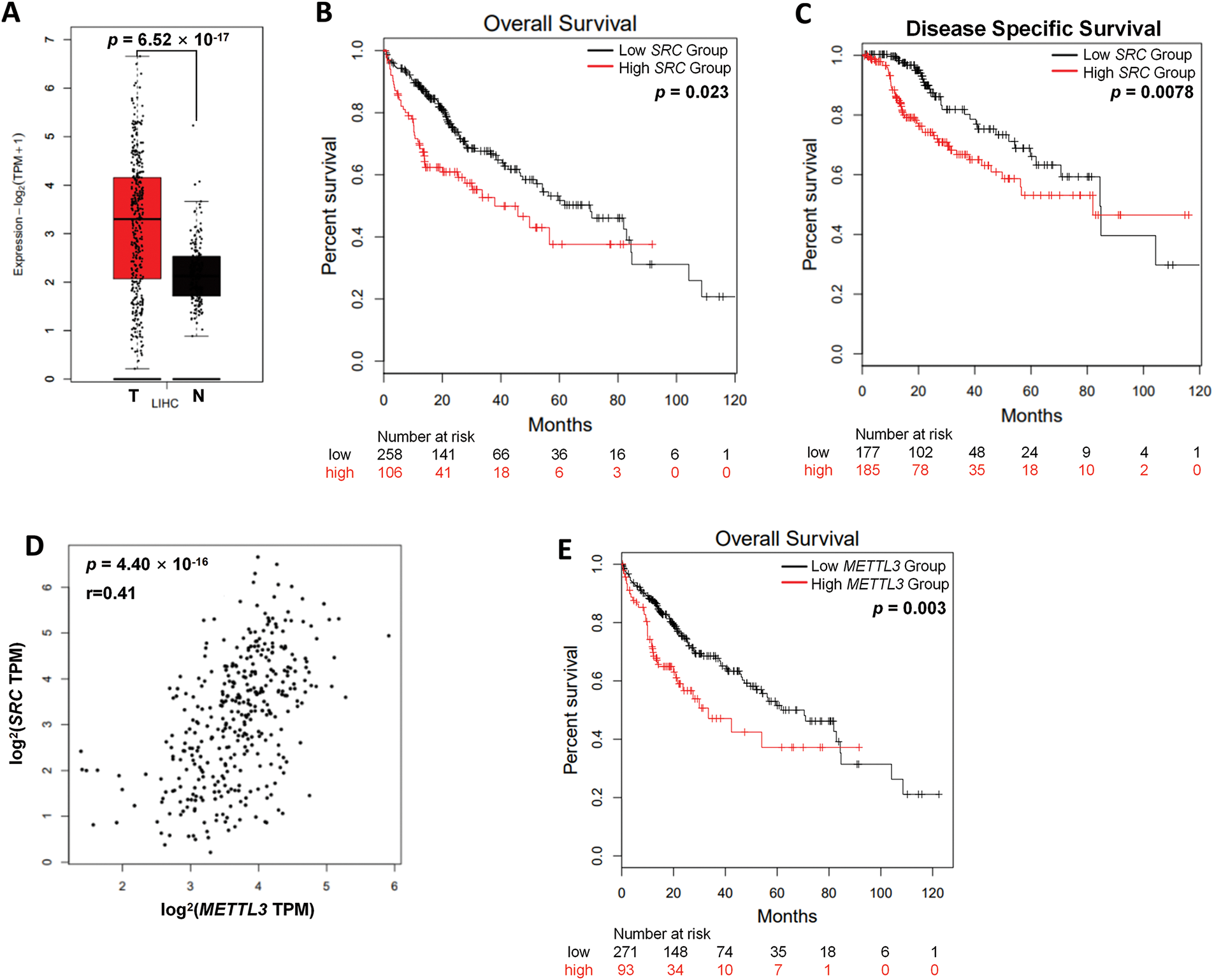

To analyze the potential role of c-Src in liver cancer, we first examined the SRC (code for c-Src) mRNA expression levels in the tumor and normal tissues from liver cancer patients of TCGA series of cases based on Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis 2 (GEPIA2) database [29]. Hepatocellular carcinoma samples displayed a dramatic surge in SRC expression compared with non-cancerous hepatic controls. (p = 6.52 × 10−17) (Fig. 1A). Kaplan-Meier analysis revealed that liver patients with increased SRC expression demonstrated significantly poorer overall survival (OS) (p = 0.023) (Fig. 1B) and disease-specific survival (p = 7.80 × 10−3) (Fig. 1C). Results confirmed the oncogenic role of c-Src in liver cancer.

Figure 1: Both SRC and METTL3 are associated with worse prognosis in liver cancer patients. (A) The relative mRNA expression of SRC in liver cancer patients (T, n = 369) compared with normal controls (N, n = 160) from TCGA datasets; (B, C) the Kaplan–Meier survival curves of overall survival (B) and disease-free survival (C) based on SRC expression in liver cancer patients; (D) association between SRC and METTL3 in liver cancer patients; (E) the Kaplan–Meier survival curves of overall survival based on METTL3 expression in liver cancer patients. The group cutoff for analysis in (B, C, E) was 50%

Next, the potential linkage between SRC and METTL3 in liver cancer was investigated. According to GEPIA2 analysis, there was a significant positive correlation between SRC and METTL3 expression in liver cancer tissues was observed (r = 0.41; p = 4.40 × 10−16) (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, liver cancer patients with higher METTL3 expression showed poorer OS (p = 3.00 × 10−3) (Fig. 1E). Together, results showed that both SRC and METTL3 were associated with worse survival of liver cancer patients.

3.2 METTL3 Regulates the Expression of c-Src in Liver Cancer Cells

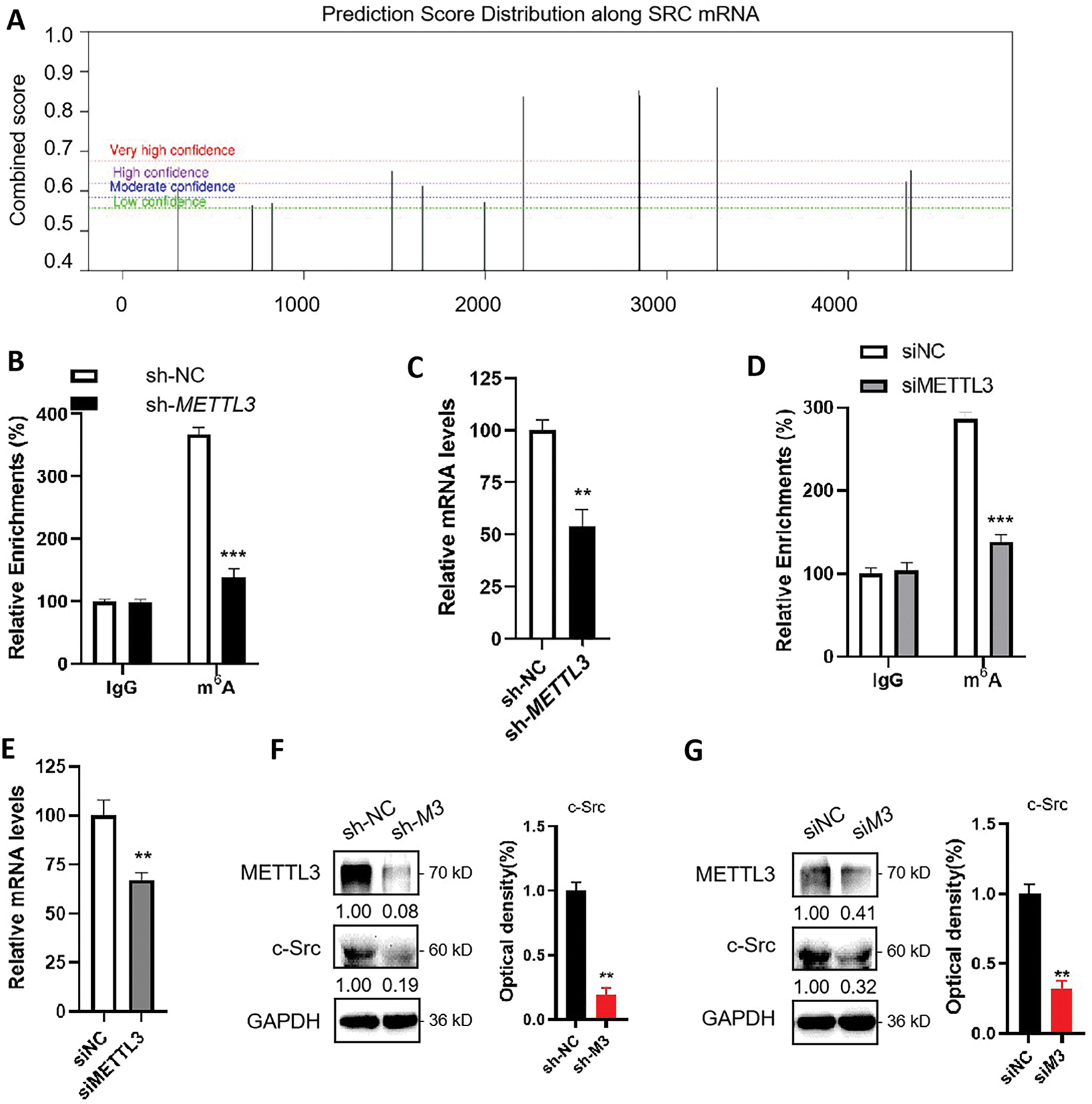

Since METTL3 is one of the key regulators of m6A, which commonly participates in the regulation of mRNA expression, results hinted that METTL3 may regulate the expression of SRC. We therefore hypothesized that SRC mRNA was a target of m6A modification. Firstly, we examined for possible m6A modification sites on SRC mRNA using the online tool SRAMP (http://www.cuilab.cn/sramp/, accessed on 20 December 2024). Results showed that there were three predicted m6A sites with very high confidence (Fig. 2A). Subsequently, we performed m6A-RIP-qPCR using control (sh-NC) Huh7 cells and METTL3 knockdown (sh-METTL3) Huh7 cells (Fig. 2B). RT-qPCR showed significant enrichment of SRC mRNA in the m6A-IP group in sh-NC Huh7 cells (Fig. 2C), indicating the presence of m6A modification on SRC mRNA. In sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells, SRC mRNA was no longer enriched in the m6A-IP group (Fig. 2B), suggesting the m6A modification on SRC mRNA was reversible. Similar observations were obtained when using HepG2 cells with siNC or siMETTL3 knockdown (Fig. 2D,E). Together, it suggested that SRC mRNA can be m6A modified reversely.

Figure 2: METTL3 regulates the expression of c-Src in liver cancer cells. (A) Prediction of m6A modifications on SRC mRNA; (B) m6A RIP-qPCR analysis of SRC mRNA in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells. Enrichment of SRC mRNA in m6A RIP samples was normalized to IgG and sample input; (C) Expression of SRC mRNA in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells; (D) m6A RIP-qPCR analysis of SRC mRNA in siNC and siMETTL3 HepG2 cells. Enrichment of SRC mRNA in m6A RIP samples was normalized to IgG and sample input; (E) Expression of SRC mRNA in siNC and siMETTL3 HepG2 cells; (F) Expression of METTL3 and c-Src in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 (sh-M3) in Huh7 cells; (G) Expression of METTL3 and c-Src in siNC and siMETTL3 (siM3) HepG2 cells. Data of (B–G) are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. Student’s t-test, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001.

In line with that mRNA expression is commonly regulated by m6A modifications, RT-qPCR results showed a significant reduction of SRC mRNA expression in sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells and siMETTL3 HepG2 cells (Fig. 2C,E). This result was consistent with the clinical data presented in Fig. 1E. Consistently, c-Src protein levels were significantly decreased in sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells and siMETTL3 HepG2 cells (Fig. 2F,G). Together, these data suggested that SRC mRNA can be m6A modified via METTL3, and METTL3 upregulated the expression of c-Src in liver cancer cells.

3.3 m6A Modulates the Transcription of SRC mRNA in Liver Cancer Cells

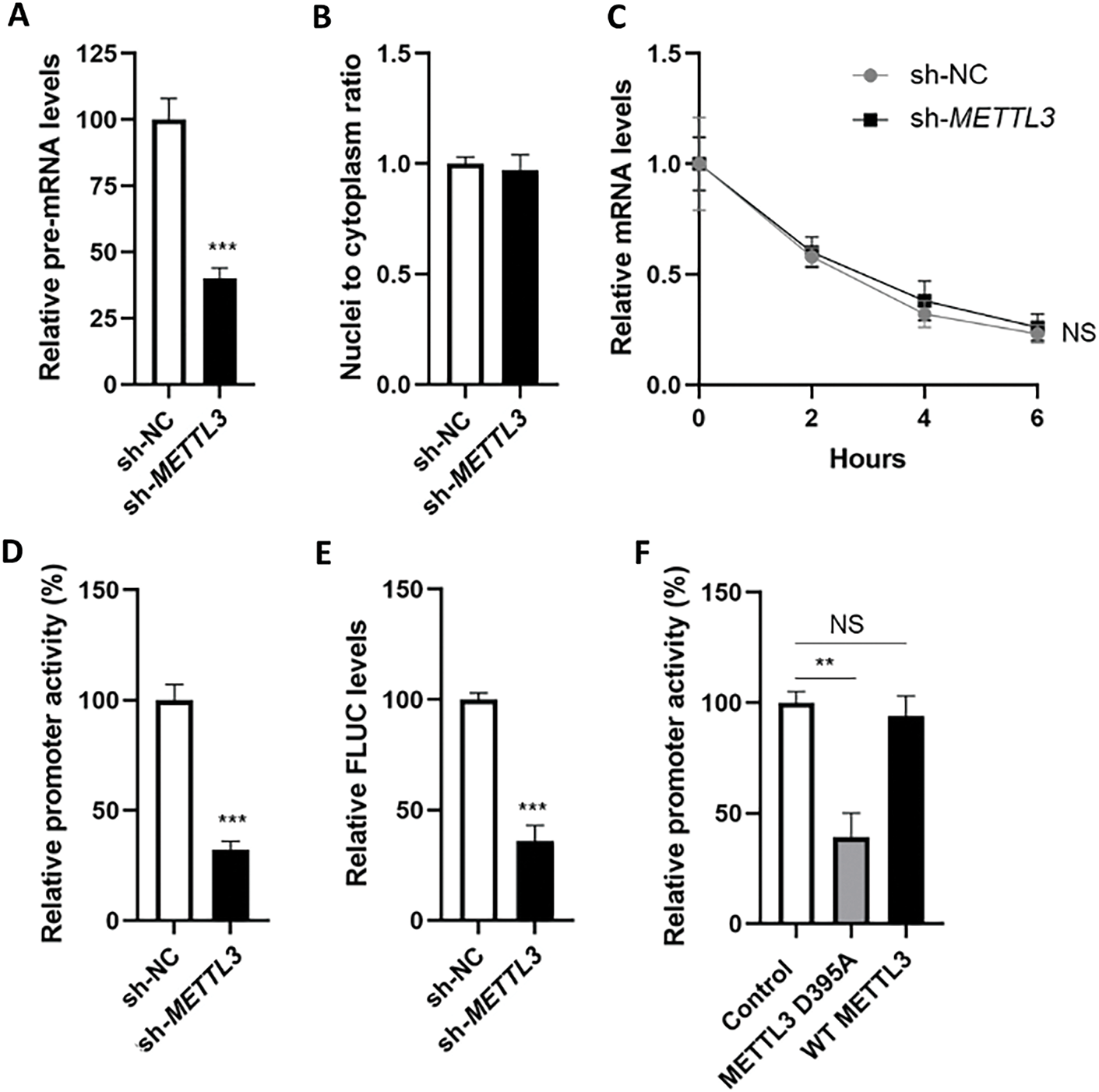

m6A modification is associated with almost all biological processes of mRNA, including transcription, nucleic-cytoplasm transport, and mRNA decay. RT-qPCR results showed that the pre-mRNA level of SRC was significantly decreased in sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells (Fig. 3A). However, neither the nuclear-to-cytoplasm ratio of SRC mRNA (Fig. 3B) nor the haft-life of SRC mRNA (Fig. 3C) showed a significant difference between sh-NC Huh7 and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells. Taken together, the results suggested that METTL3 may affect the pre-mRNA level of SRC.

Figure 3: m6A modulates the transcription of SRC mRNA in liver cancer cells. (A) Expression of SRC precursor mRNA in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells; (B) ratio of nuclei-to-cytoplasm SRC mRNA in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells; (C) half-lives of SRC mRNA in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells; (D) relative promoter activity of dual F-Luc reporter derived by SRC promoter in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells; (E) expression of FLUC mRNA from dual F-Luc reporter derived by SRC promoter in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells; (F) relative promoter activity of dual F-Luc reporter derived by SRC promoter in sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells overexpressing wild type METTL3 (WT METTL3) or catalytic mutant (METTL3 D395A). Data are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. Student’s t-test (A, B, D–F) or One-way ANOVA (C), **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 compared with control; ns no significance

To verify whether METTL3 regulated the transcription of SRC, we constructed a dual-luciferase reporter consisting of SRC promoter. Results from dual-luciferase assays showed that fluorescent signals (F-Luc) were suppressed in sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells (Fig. 3D). Consistently, the mRNA level of firefly luciferase (FLUC) was significantly decreased in sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells (Fig. 3E). After overexpressing wild-type or non-catalytic METTL3 in sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells, F-Luc products were recruited in cells overexpressing wild-type METTL3, but not the non-catalytic METTL3 (Fig. 3F). Together, results indicated that METTL3 modulated the transcription of SRC in liver cancer cells.

3.4 IRF1 Is a Novel Transcription Factor of c-Src That Is Regulated by METTL3

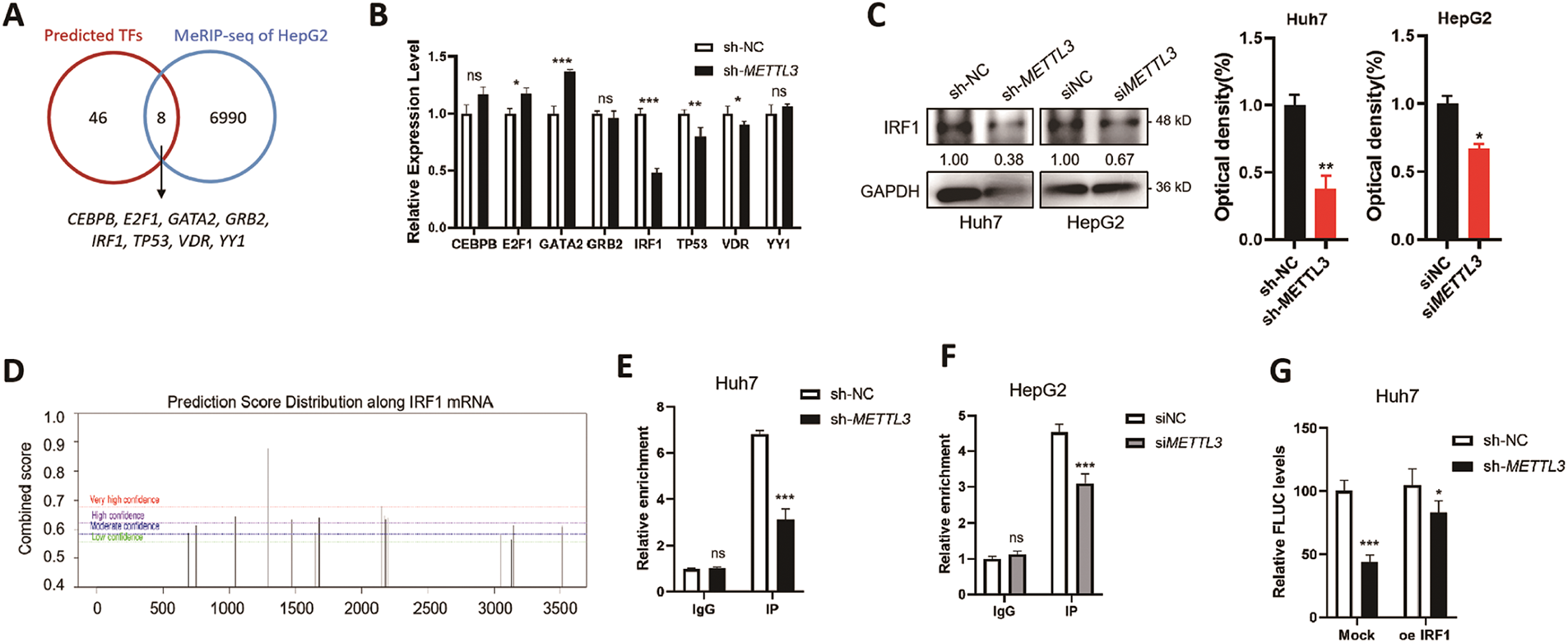

To explore how m6A regulates the transcription of c-Src, potential transcription factors (TFs) of c-Src were predicted via the JASPAR online tool (https://jaspar.elixir.no/, accessed on 20 December 2024). Results showed that there were 46 predicted TFs for c-Src, and 8 of them (CEBPB, E2F1, GATA2, GRB2, IRF1, TP53, VDR, and YY1) were identified as m6A targets (GSE37003; Fig. 4A). We assumed that the expressions of potential TFs for c-Src might be modulated by m6A and therefore affect the transcription of c-Src. RT-qPCR results of 8 TF candidates were examined in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells. Results showed that IRF1 mRNA was significantly downregulated in sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells (Fig. 4B). Similarly, Western blot analysis showed a decrease of IRF1 in sh-METTL3 Huh7 and si-METTL3 HepG2 cells (Fig. 4C). The reduction of IRF1 in METTL3 knockdown or silencing cells may be due to the positive regulation of m6A modification of IRF1 mRNA since there was one predicted m6A site with high confidence (Fig. 4D). However, the regulation of m6A of IRF1 mRNA expression remained to be explored. Together, results indicated that IRF1 might be a potential TF of SRC, which was associated with the m6A-regulated SRC transcription.

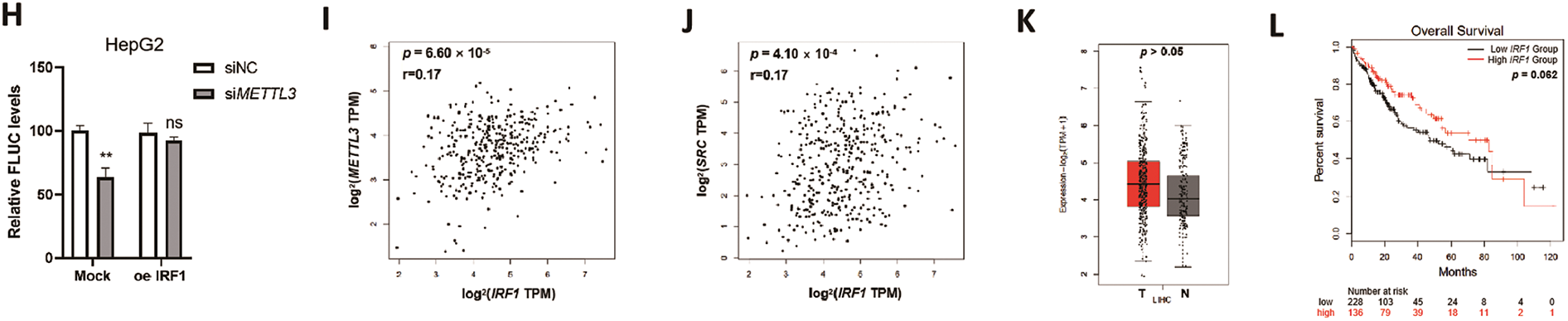

Figure 4: IRF1 is a novel transcription factor of c-Src that is regulated by METTL3. (A) Overlapping of online predicted TFs of SRC and the m6A-modified genes in HepG2 cells from MeRIP-sequencing dataset (GSE37003); (B) relative expression levels of m6A-modified predicted TFs of SRC in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells; (C) expression of IRF1 in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells, and siNC and siMETTL3 HepG2 cells; (D) prediction of m6A modifications on SRC mRNA; (E, F) m6A RIP-qPCR analysis of IRF1 mRNA in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells (E) and siNC and siMETTL3 HepG2 cells (F). Enrichment of IRF1 mRNA in m6A RIP samples was normalized to IgG and sample input; (G, H) expression of FLUC mRNA from dual F-Luc reporter derived by SRC promoter in sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells (G) and siNC and siMETTL3 HepG2 cells (H) with or without IRF1 overexpression; (I) correlation between METTL3 and IRF1 in liver cancer patients from TCGA datasets; (J) correlation between SRC and IRF1 in liver cancer patients from TCGA datasets; (K) the relative mRNA expression of IRF1 in liver cancer patients (T, n = 369) compared with normal controls (N, n = 160) from TCGA datasets; (L) the Kaplan-Meier survival curves of overall survival based on IRF1 expression in liver cancer patients. Data of (B, E–H) are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. Student’s t-test, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ns, no significant compared with controls

By using ChIP-qPCR, it was confirmed that IRF1 can bind to the promoter region of SRC in both Huh7 and HepG2 cells (Fig. 4E,F). In either sh-METTL3 Huh7 or siMETTL3 HepG2 cells, the binding affinity between IRF1 and SRC promoter region significantly decreased (Fig. 4E,F), suggesting that IRF1 may promote the transcription of SRC. To further verify the transcriptional regulation of IRF1 on SRC, dual-luciferase assays were performed in either sh-METTL3 Huh7 or siMETTL3 HepG2 cells overexpressing IRF1. Results showed that recruitment of IRF1 significantly enhanced the F-Luc levels (Fig. 4G,H). In addition, the expression of IRF1 was positively correlated to both SRC and METTL3 in liver cancer patients, p = 6.60 × 10−5 (Fig. 4I) and p = 4.10 × 10−4 (Fig. 4J), respectively. However, the expression of IRF1 showed a non-significant difference between liver cancer tissues compared to the control group (Fig. 4K). In addition, IRF1 level did not statistically affect the OS (p = 0.062) of liver cancer patients (Fig. 4L), which might be due to the comprehensive effects of IRF1 in cells. Together, results suggested that IRF1 is a novel TF of SRC that is regulated by METTL3.

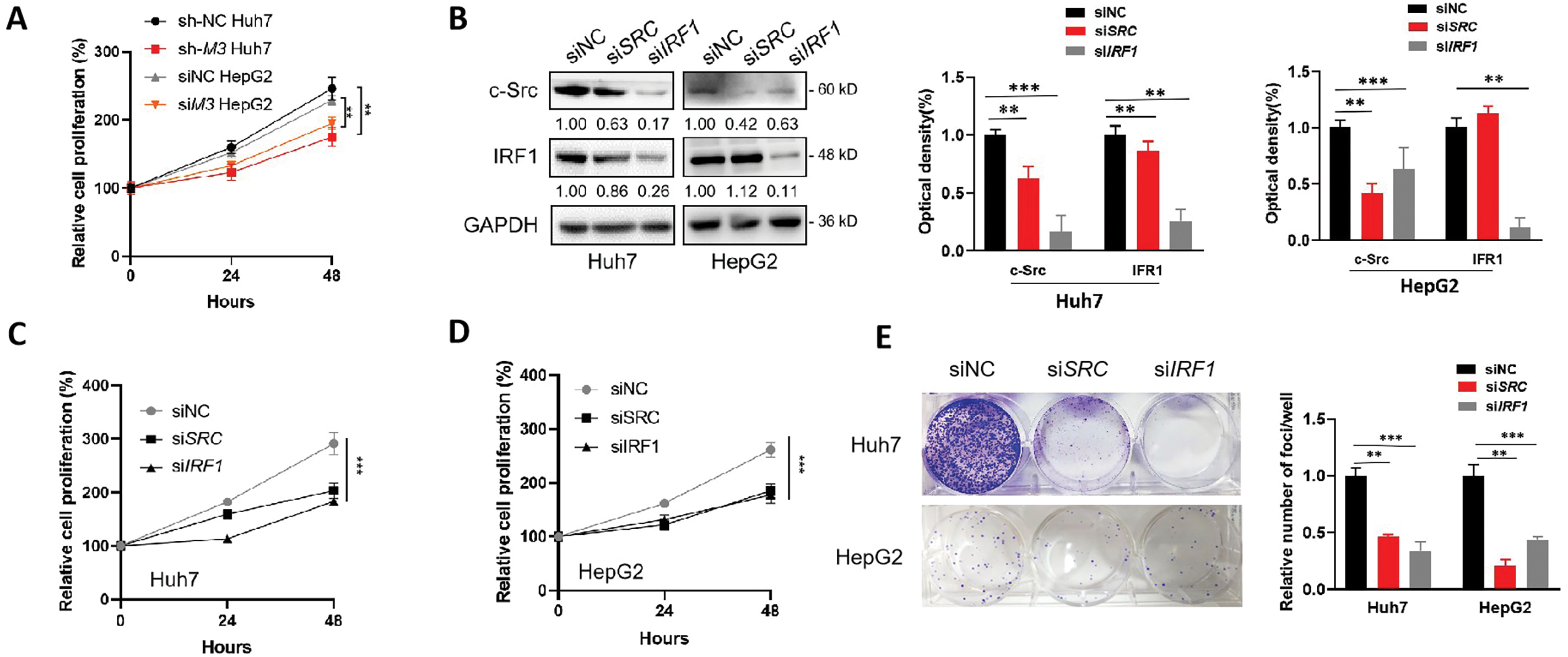

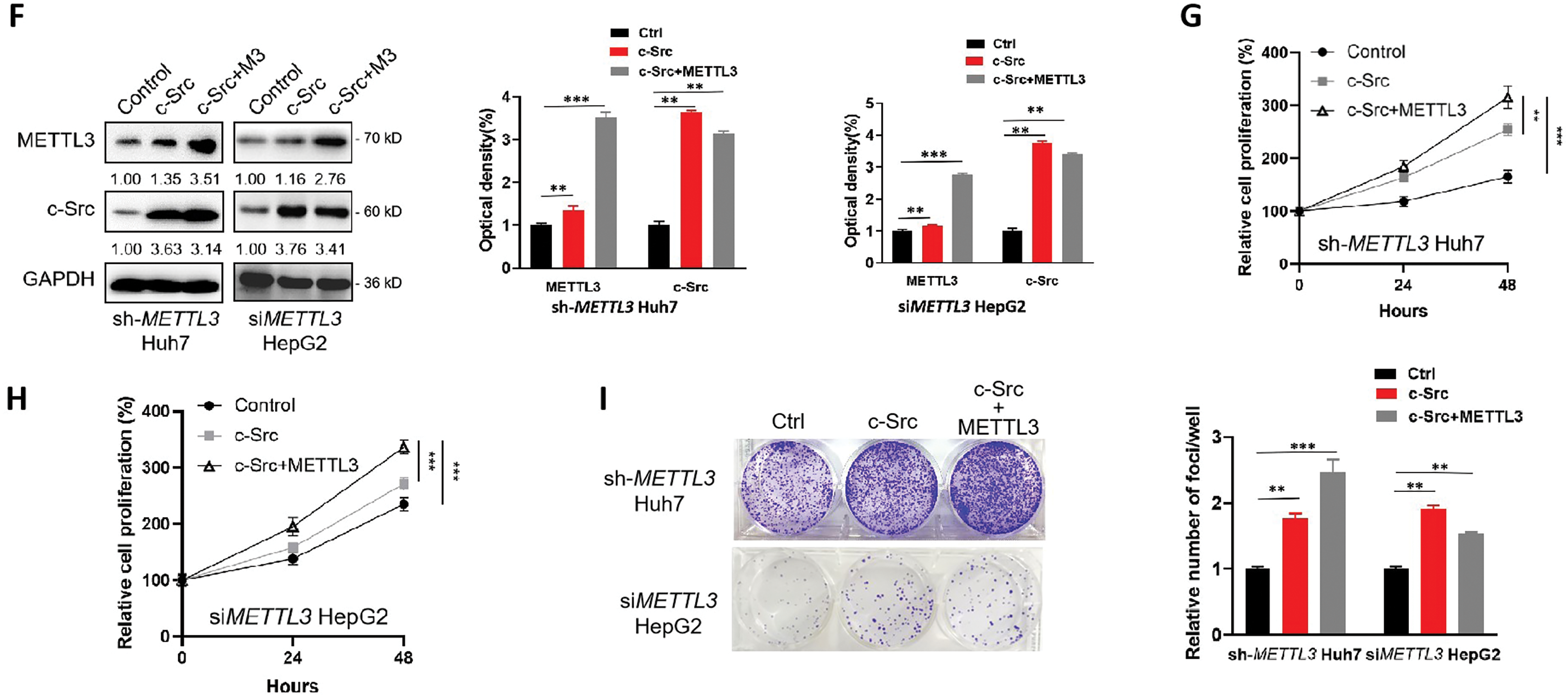

3.5 IRF1/c-Src Axis Is Associated with METTL3-Promoted Proliferation of Liver Cancer Cells

We hypothesized that the IRF1/c-Src axis was associated with the m6A-regulated development of liver cancer. In line with the oncogenic roles of METTL3, the knockdown of METTL3 in both Huh7 and HepG2 cells significantly suppressed their proliferation (Fig. 5A). When transiently silencing either c-Src or IRF1 expression (Fig. 5B), significant reductions in cell proliferation were observed (Fig. 5C,D). Notably, a more obvious reducing effect was obtained in cells silencing IRF1, which may be due to a more severe decrease of c-Src level (Fig. 5B) or other regulatory effects of IRF1. Consistently, similar results were obtained in colony formation assays using different liver cancer cells with silenced c-Src or IRF1 expression (Fig. 5E).

Figure 5: IRF1/c-Src is associated with the METTL3-promoted proliferation of liver cancer cells. (A) Relative cell proliferation of sh-NC and sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells, and siNC and siMETTL3 HepG2 cells; (B–E) expression of c-Src and IRF1 (B), relative cell proliferation (C, D) and colony formation (E) of Huh7 or HepG2 cells silencing c-Src or IRF1; (F–I) Expression of c-Src and METTL3 (F), relative cell proliferation (G, H) and colony formation (I) of sh-METTL3 Huh7 or si-METTL3 HepG2 cells overexpressing c-Src with or without METTL3. Data of (A, C, D, G, H) are presented as means ± SD from three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA, **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001 compared with controls

Since IRF1 unaffected the OS of liver cancer patients (Fig. 4L) and c-Src acts as an effector in the METTL3/IRF1/c-Src axis, we further overexpressed c-Src in sh-METTL3 Huh7 and siMETTL2 HepG2 cells, respectively, to confirm the oncogenic role of METTL3/IRF1/c-Src axis in liver cancer cell proliferation. After overexpressing c-Src, both proliferation and colony-forming capabilities of sh-METTL3 Huh7 cells and siMETTL2 HepG2 cells were partially restored (Fig. 5F–I). Together, our results showed a critical role of the IRF1/c-Src axis in the METTL3-promoted liver cancer progression.

Increasing evidence has shown that m6A methylation is associated with various biological functions and the onset of tumorigenesis [30,31]. Here, we reported that METTL3, acting as m6A methyltransferase, positively modulated the expression of c-Src kinase. In particular, METTL3 promoted the transcription of SRC via modulation of IRF1 expression, which was identified as a novel transfection factor of SRC. Last, we proved that the upregulation of IRF1/c-Src expression participated in the METTL3-promoted cell proliferation of liver cancer.

Our results indicated that METTL3 enhanced SRC transcription through a mechanism reliant on IRF1. The regulation of m6A on gene transcription is mediated by two major mechanisms: m6A directly regulation by affecting the chromatin accessibility and m6A mediates indirect regulation by altering the transcriptional activity of TFs linked to target genes. Recently, Liu et al. reported that knockout of METTL3 increased chromatin accessibility and activated transcription in a m6A-dependent manner [32]. Notably, regulation of m6A modifications on gene transcription is indirect as DNA does not contain m6A modification. For instance, the effects of m6A modifications stabilize chromosome-associated regulatory RNAs (carRNAs) and therefore suppress transcription [32]. Another mechanism for the m6A-regulated transcription process might be related to the expression changes of transcription factors. This is exemplified by reports that m6A can modulate the expression of bromodomain PHD finger transcription factor (BPTF), leading to the upregulation of SRC transcription [33]. Here, we reported that IRF1 was a novel TF of SRC, which can positively enhance the SRC transcription. Furthermore, we found that IRF1 was also a potential m6A target like SRC, which was confirmed by MeRIP-qPCR and online prediction. However, whether m6A affected the binding between IRF1 and SRC promoter, and how m6A regulated the expression of IRF1 remained further explored.

The relationship between m6A and c-Src appears to be m6A catalyst type-dependent and/or cancer type-dependent. For instance, the m6A methylase METTL14 was reported to negatively regulate the expression of SRC in renal cell carcinoma [33]. In contrast, the EGFR/SRC/ERK signaling pathway can phosphorylate and stabilize the m6A reader protein YTHDF2, which is necessary to sustain the invasive, proliferative, and tumorigenic properties of glioblastomas [34]. In liver cancer, the relationship between METTL3 and c-Src has seldom been reported. Our findings revealed that METTL3 upregulates SRC expression in hepatocellular carcinoma through IRF1-dependent regulation. Clinical data analysis showed a positive correlation between both METTL3/SRC and METTL3/IRF1, as well as the OS of liver cancer patients associated with METTL3/SRC expression. These data hinted at the potential roles of the METTL3/IRF1/c-Src axis in the development of liver cancer. Notably, the METTL3-regulated SRC expression might be cancer type-specific and the relationship between METTL3 and c-Src in other types of cancer remains an open question.

Modulating m6A modification has emerged as a pivotal focus in oncological therapeutic research over the past decade. One of the common strategies is inhibiting global m6A levels, such as the usage of small molecule inhibitors targeting METTL3 (i.e., STM2457). STM2457 has been identified and characterized where the inhibitor highly and selectively inhibited METTL3 activities [35]. More importantly, STM2457 attenuated the growth of leukemia cells and promoted their differentiation as well as apoptosis in vitro, and the METTL3 inhibitor prolonged the survival of leukemia mice models by impairing leukemia cell engraftment and suppressing leukemic stem cell subpopulations. However, the anti-tumor effect of targeting m6A is not efficient enough in the treatment of solid cancers. Therefore, discovering novel targets and combining m6A inhibition might be an emergent direction in enhancing m6A-dependent anti-cancer therapy [36,37]. Herein, we revealed that both IRF1 and c-Src showed promoted effects on the proliferation of liver cancer cells, hinting that either of them might be the potential target of liver cancer therapy. However, the combined inhibition effect between IRF1/c-Src and METTL3 required investigation.

We acknowledge the limitations of the study as follows: (1) Lack of in vivo data to validate our in vitro findings; (2) The regulation of m6A on IRF1 expression remained to be explored; (3) It is unlikely that c-Src kinase acted as the sole factor that participated in METTL3-regulated liver cancer cell proliferation, due to METTL3 has been reported to modulate multiple factors in cells through its m6A modification activities. For example, Snail (an EMT-inducing transcription factor) and the growth factor TGFβ1 were previously reported to be regulated by METTL3 required for the development of cancers [15].

In summary, we showed that METTL3/IRF1/c-Src axis played oncogenic roles in the development of liver cancer. Furthermore, we demonstrated that METTL3 positively regulated the transcription of c-Src kinase via IRF1, which was a novel TF of SRC. We further confirmed that the IRF1/c-Src axis promoted the METTL3-regulated proliferation of liver cancer cells. Detailed mechanisms on the METLL3/IRF1/c-Src axis in liver tumorigenesis and their effects in vivo warrant further investigations.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank staff of Department of Basic Medicine, Xiangnan University, and the Affiliated Hospital of Xiangnan University for their kind assistance. Thanks to the GEPIA2 technical team (Prof. Zemin Zhang, Peking University) for providing a powerful web server for clinical data analysis.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China (project No. 2022JJ40413), Outstanding Youth Project of Hunan Provincial Department of Education (project No. 22B0814), Regional Consolidated Foundation of Hunan Province of China (project No. 2023JJ50065), Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province of China (project No. 2023JJ50412).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Yanxi Peng, Qun Xie; draft manuscript preparation: Honggen Yuan, Kexin Yi, Xiaoqing Ou; review and editing: Zhanjie Jiang, Qian Zhang, Yanbin Meng; visualization: Yanxi Peng, Honggen Yuan; supervision: Qun Xie. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74(3):229–63. doi:10.3322/caac.21834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Yi J, Li B, Yin X, Liu L, Song C, Zhao Y, et al. CircMYBL2 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating E2F1 expression. Oncol Res. 2024;32(6):1129–39. doi:10.32604/or.2024.047524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Yang WS, Zeng XF, Liu ZN, Zhao QH, Tan YT, Gao J, et al. Diet and liver cancer risk: a narrative review of epidemiological evidence. Br J Nutr. 2020;124(3):330–40. doi:10.1017/S0007114520001208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Grisetti L, Garcia CJC, Saponaro AA, Tiribelli C, Pascut D. The role of Aurora kinase A in hepatocellular carcinoma: unveiling the intriguing functions of a key but still underexplored factor in liver cancer. Cell Prolif. 2024;57(8):e13641. doi:10.1111/cpr.13641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Yuan Z, Li B, Liao W, Kang D, Deng X, Tang H, et al. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis of YBX family reveals YBX2 as a potential biomarker in liver cancer. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1382520. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1382520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Dubin DT, Taylor RH. The methylation state of poly A-containing messenger RNA from cultured hamster cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1975;2(10):1653–68. doi:10.1093/nar/2.10.1653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang C, Wang S, Lu X, Zhong W, Tang Y, Huang W, et al. POP1 facilitates proliferation in triple-negative breast cancer via m6A-dependent degradation of CDKN1A mRNA. Res. 2024;7(1):0472. doi:10.34133/research.0472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Bartosovic M, Molares HC, Gregorova P, Hrossova D, Kudla G, Vanacova S. N6-methyladenosine demethylase FTO targets pre-mRNAs and regulates alternative splicing and 3′-end processing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(19):11356–70. doi:10.1093/nar/gkx778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, et al. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49(1):18–29. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Wang X, Zhao BS, Roundtree IA, Lu Z, Han D, Ma H, et al. N(6)-methyladenosine modulates messenger RNA translation efficiency. Cell. 2015;161(6):1388–99. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Choe J, Lin S, Zhang W, Liu Q, Wang L, Ramirez-Moya J, et al. mRNA circularization by METTL3-eIF3h enhances translation and promotes oncogenesis. Nature. 2018;561(7724):556–60. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0538-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zou Y, Zheng S, Xie X, Ye F, Hu X, Tian Z, et al. N6-methyladenosine regulated FGFR4 attenuates ferroptotic cell death in recalcitrant HER2-positive breast cancer. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):2672. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-30217-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Barbieri I, Tzelepis K, Pandolfini L, Shi J, Millan-Zambrano G, Robson SC, et al. Promoter-bound METTL3 maintains myeloid leukaemia by m6A-dependent translation control. Nature. 2017;552(7683):126–31. doi:10.1038/nature24678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang TT, Yi W, Dong DZ, Ren ZY, Zhang Y, Du F. METTL3-mediated upregulation of FAM135B promotes EMT of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via regulating the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2024;327(2):C329–40. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00529.2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Li J, Chen F, Peng Y, Lv Z, Lin X, Chen Z, et al. N6-methyladenosine regulates the expression and secretion of TGFbeta1 to affect the epithelial-mesenchymal transition of cancer cells. Cells. 2020;9(2):296. doi:10.3390/cells9020296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Wang A, Chen X, Li D, Yang L, Jiang J. METTL3-mediated m6A methylation of ASPM drives hepatocellular carcinoma cells growth and metastasis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35(9):e23931. doi:10.1002/jcla.23931. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Liu GM, Zeng HD, Zhang CY, Xu JW. Identification of METTL3 as an adverse prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(4):1110–26. doi:10.1007/s10620-020-06260-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Shen S, Yan J, Zhang Y, Dong Z, Xing J, He Y. N6-methyladenosine (m6A)-mediated messenger RNA signatures and the tumor immune microenvironment can predict the prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(1):59. doi:10.21037/atm-20-7396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Li X, Wang F, Ren M, Du M, Zhou J. The effects of c-Src kinase on EMT signaling pathway in human lens epithelial cells associated with lens diseases. BMC Ophthalmol. 2019;19(1):219. doi:10.1186/s12886-019-1229-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Singh S, Trevino J, Bora-Singhal N, Coppola D, Haura E, Altiok S, et al. EGFR/Src/Akt signaling modulates Sox2 expression and self-renewal of stem-like side-population cells in non-small cell lung cancer. Mol Cancer. 2012;11(1):73. doi:10.1186/1476-4598-11-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Giannoni E, Chiarugi P. Redox circuitries driving Src regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2014;20(13):2011–25. doi:10.1089/ars.2013.5525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Han ZH, Wang F, Wang FL, Liu Q, Zhou J. Regulation of transforming growth factor beta-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition of lens epithelial cells by c-Src kinase under high glucose conditions. Exp Ther Med. 2018;16(2):1520–8. doi:10.3892/etm.2018.634810.3892/etm.2018.6348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Malarkey K, Belham CM, Paul A, Graham A, McLees A, Scott PH, et al. The regulation of tyrosine kinase signalling pathways by growth factor and G-protein-coupled receptors. Biochem J. 1995;309(Pt 2):361–75. doi:10.1042/bj3090361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Beristain AG, Molyneux SD, Joshi PA, Pomroy NC, Di Grappa MA, Chang MC, et al. PKA signaling drives mammary tumorigenesis through Src. Oncogene. 2015;34(9):1160–73. doi:10.1038/onc.2014.41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Ishizawar R, Parsons SJ. c-Src and cooperating partners in human cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(3):209–14. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.09.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Yang J, Zhang X, Liu L, Yang X, Qian Q, Du B. c-Src promotes the growth and tumorigenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma via the Hippo signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2021;264(2):118711. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Song HE, Lee Y, Kim E, Cho CY, Jung O, Lee D, et al. N-terminus-independent activation of c-Src via binding to a tetraspan(in) TM4SF5 in hepatocellular carcinoma is abolished by the TM4SF5 C-terminal peptide application. Theranostics. 2021;11(16):8092–111. doi:10.7150/thno.58739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Hunter CA, Koc H, Koc EC. c-Src kinase impairs the expression of mitochondrial OXPHOS complexes in liver cancer. Cell Signal. 2020;72(48):109651. doi:10.1016/j.cellsig.2020.109651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W556–60. doi:10.1093/nar/gkz430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Huang H, Weng H, Chen J. m6A modification in coding and non-coding RNAs: roles and therapeutic implications in cancer. Cancer Cell. 2020;37(3):270–88. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2020.02.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. He LE, Li HY, Wu AQ, Peng YL, Shu G, Yin G. Functions of N6-methyladenosine and its role in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12943-019-1109-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Liu J, Dou X, Chen C, Chen C, Liu C, Xu MM, et al. N6-methyladenosine of chromosome-associated regulatory RNA regulates chromatin state and transcription. Sci. 2020;367(6477):580–6. doi:10.1126/science.aay6018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang C, Chen L, Liu Y, Huang J, Liu A, Xu Y, et al. Downregulated METTL14 accumulates BPTF that reinforces super-enhancers and distal lung metastasis via glycolytic reprogramming in renal cell carcinoma. Theranostics. 2021;11(8):3676–93. doi:10.7150/thno.55424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Fang R, Chen X, Zhang S, Shi H, Ye Y, Shi H, et al. EGFR/SRC/ERK-stabilized YTHDF2 promotes cholesterol dysregulation and invasive growth of glioblastoma. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):177. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20379-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Yankova E, Blackaby W, Albertella M, Rak J, De Braekeleer E, Tsagkogeorga G, et al. Small-molecule inhibition of METTL3 as a strategy against myeloid leukaemia. Nature. 2021;593(7860):597–601. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03536-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Moroz-Omori EV, Huang D, Kumar Bedi R, Cheriyamkunnel SJ, Bochenkova E, Dolbois A, et al. METTL3 inhibitors for epitranscriptomic modulation of cellular processes. ChemMedChem. 2021;16(19):3035–43. doi:10.1002/cmdc.202100291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Bedi RK, Huang D, Eberle SA, Wiedmer L, Sledz P, Caflisch A. Small-molecule inhibitors of METTL3, the major human epitranscriptomic writer. ChemMedChem. 2020;15(9):744–8. doi:10.1002/cmdc.202000011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools