Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Advances in Tumor Microenvironment and Immunotherapeutic Strategies for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

1 Department of Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery, Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, 510120, China

2 Tianjin Key Laboratory of Acute Abdomen Disease Associated Organ Injury and ITCWM Repair, Institute of Integrative Medicine for Acute Abdominal Diseases, Tianjin Nankai Hospital, Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin, 300100, China

3 Department of Neurology, The Second Affiliated Hospital, University of South China, Hengyang, 421001, China

4 School of Pharmaceutical Science, Hengyang Medical School, University of South China, Hengyang, 421001, China

* Corresponding Authors: Liucui Chen. Email: ; Xinjun Lu. Email:

# These two authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Cancer Immunotherapy)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(9), 2309-2329. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.063719

Received 22 January 2025; Accepted 25 June 2025; Issue published 28 August 2025

Abstract

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a highly aggressive malignancy, largely driven by an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment (TME) that facilitates tumor growth, immune escape, and resistance to therapy. Although immunotherapy—particularly immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs)—has transformed the therapeutic landscape by restoring T cell-mediated anti-tumor responses, their clinical benefit as monotherapy remains suboptimal. This limitation is primarily attributed to immunosuppressive components within the TME, including tumor-associated macrophages, regulatory T cells (Tregs), and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs). To address these challenges, combination strategies have been explored, such as dual checkpoint blockade targeting programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1), programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), as well as synergistic use of ICIs with anti-angiogenic agents or TME-targeted interventions. These approaches have shown encouraging potential in enhancing immune efficacy. This review outlines the complex crosstalk between the TME and immunotherapeutic responses in HCC, emphasizing how combination regimens may overcome immune resistance. Furthermore, we discuss the remaining hurdles, including therapeutic resistance and immune-related adverse events, and propose future directions involving TME-associated biomarkers and individualized treatment strategies to improve patient outcomes.Keywords

As of 2020, liver cancer ranks as the sixth most frequently diagnosed malignancy and stands as the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide [1]. With an estimated 500,000 new cases reported annually, its global burden continues to rise alongside increasing death rates [2]. The introduction of the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging system has revealed that patients with untreated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have a median overall survival (mOS) of merely nine months [3]. Multiple risk factors contribute to HCC pathogenesis, including chronic infections with hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV), alcohol-induced cirrhosis, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, tobacco use, obesity, diabetes, and dietary exposures [4]. In early stages, curative interventions such as surgical resection, liver transplantation, or local ablation (e.g., radiofrequency ablation) can be effective [5]. However, recurrence remains a significant clinical challenge, with up to 70% of patients experiencing relapse within five years following curative treatment [6]. The tumor microenvironment (TME), composed of diverse non-malignant cell populations, actively contributes to HCC progression, including tumor proliferation, invasion, and metastasis. Its immunosuppressive nature not only facilitates disease progression but also impedes the success of immunotherapeutic approaches. Persistent inflammation driven by stromal and tumor-derived cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors leads to an immunosuppressive milieu, allowing tumor cells to evade immune surveillance. Complex interactions among immune cell subsets further exacerbate immune dysfunction and support carcinogenesis [7,8]. Despite the promise of systemic therapies, their effectiveness has been limited by an incomplete understanding of the TME’s regulatory mechanisms. Immunotherapy, particularly immune checkpoint blockade, offers a promising strategy by reactivating the host immune system or altering the TME. Notably, combinations such as atezolizumab plus bevacizumab (A + B) and durvalumab plus toripalimab (D + T) have shown encouraging results in clinical studies [9,10]. These regimens signify a shift toward multi-targeted strategies that simultaneously modulate different aspects of the TME, potentially enhancing treatment efficacy.

This study aims to elucidate the immunoregulatory role of the TME in HCC and to assess the therapeutic potential of combining immune checkpoint inhibitors with targeted agents. We hypothesize that mitigating immunosuppressive mechanisms within the TME through rational combination therapies can improve immune cell infiltration, reverse resistance, and enhance clinical outcomes in HCC. Ultimately, this review seeks to summarize current advancements in immunotherapy for HCC, emphasize the role of the TME in treatment response, and propose future directions for optimizing personalized therapeutic strategies.

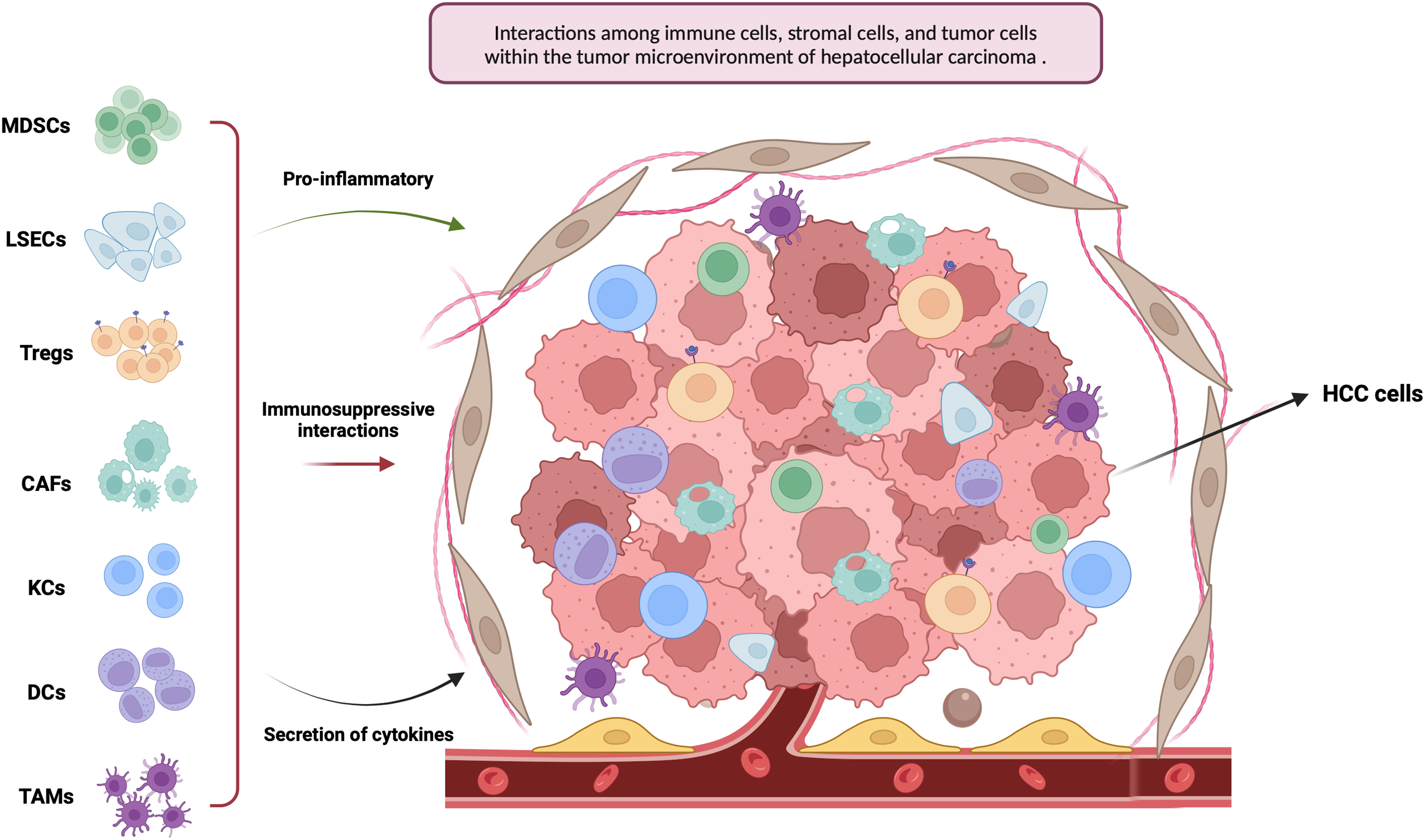

Emerging evidence highlights the crucial role of intercellular signaling between malignant hepatocytes and the surrounding hepatic microenvironment in driving the initiation and progression of HCC [11,12]. This complex regulatory landscape, known as the TME, influences multiple aspects of tumor biology. In HCC, the TME contributes to immune evasion by fostering immunosuppressive conditions and promoting immune tolerance, thereby facilitating tumor proliferation, invasion, and dissemination [12–14]. In this review, we examine the key elements within the TME that influence tumorigenesis, with a focus on the most relevant cellular and molecular components (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: This figure illustrates the tumor microenvironment of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with an emphasis on key immune and stromal cell populations, including tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), regulatory T cells (Tregs), dendritic cells (DCs), Kupffer cells (KCs), liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), and cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) (Created in https://BioRender.com)

2.1 Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs)

Macrophages, originating from bone marrow–derived circulating monocytes, display notable functional plasticity. They can polarize into two major subtypes with contrasting roles: pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages and anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, reflecting distinct activation states [15]. The M1 phenotype produces proinflammatory cytokines and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, contributing significantly to immune activation and the elimination of tumor cells [16]. Evidence suggests that the presence of M1 macrophages within tumors correlates with improved survival in cancer patients, underscoring their tumor-suppressive role [17]. In contrast, M2 macrophages contribute to immune regulation and tissue remodeling by dampening inflammatory responses. However, this phenotype also promotes tumor progression and immune escape, and is strongly linked to poor prognosis and metastasis in HCC [18]. For instance, through C-C motif chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) signaling, the M2 subtype can induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which facilitates tumor growth and invasion. This phenomenon significantly contributes to the unfavorable prognosis observed in individuals with the M2 subtype [19]. Tumor-derived Wnt ligands further promote M2 polarization, leading to immunosuppression. Therapeutic strategies targeting Wnt secretion in tumor cells or inhibiting Wnt/β-catenin signaling in TAMs have shown promise in preclinical models of liver cancer. Immunohistochemical markers such as CD86 (for M1) and CD163 or CD206 (for M2) are commonly used to differentiate macrophage subtypes in tumors. Sun et al. reported that low CD86+ M1 and high CD206+ M2 infiltration are associated with more aggressive HCC phenotypes, and the combined analysis of these markers may provide prognostic value [20]. The recent focus of research has been on populations of immunosuppressive TAMs. Specific cytokines released by HCC, such as interleukin-4 (IL-4), interleukin-13 (IL-13), colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1), CCL2, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 12 (CXCL12), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), are known to induce TAMs derived from other sources [21]. For instance, HCC can secrete CCL2 and recruit pro-inflammatory monocyte-derived macrophages expressing C-C motif chemokine receptor 2 (CCR2) through the signaling pathway of CCL2-CCR2. A study demonstrated that these macrophages could attract regulatory T cells by producing cytokines to suppress immune responses. Additionally, TAMs and myeloid-derived suppressor cells can enhance IL-10 production, thereby inhibiting the cytotoxicity of CD8+ T cells and natural killer (NK) cells. This effect can be partially blocked by using an anti-IL-10 antibody [22]. TAMs can secrete growth factors, such as vascular endothelial growth Factor (VEGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), which can stimulate endothelial cell migration and promote neovascularization. This process is known as angiogenesis and may contribute to cancer development [23]. Research shows sorafenib can increase macrophage recruitment and VEGF levels in HCC patients. Targeting receptors or signaling proteins is crucial to impede tumor progression and macrophage properties.

2.2 Myeloid-Derived Suppressed Cells (MDSCs)

The MDSCs encompass a heterogeneous population of immature myeloid cells, comprising granulocytic or polymorphonuclear MDSCs (PMN-MDSCs) and monocytic MDSCs (M-MDSCs). PMN-MDSCs exhibit morphological similarities to N2-polarized neutrophils, while M-MDSCs share a resemblance with M2-polarized macrophages [24]. In HCC, MDSCs are key mediators of immune tolerance, and their accumulation within tumor tissues is strongly correlated with poor prognosis [25]. Within the TME, MDSC expansion is driven by a variety of cytokines and chemokines. Tumor-derived factors such as granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) enhance MDSC recruitment. In addition, hepatic carcinoma-associated tumor-associated fibroblasts (TAFs) promote MDSC development via the IL-6/STAT3 signaling pathway [26]. By activating the EZH2/NF-κB signaling pathway, the cell cycle-related kinase (CCRK) protein found within hepatomas can cause an accumulation of MDSCs. The studies have demonstrated that MDSCs are attracted to VEGF and can enhance its availability through the production of MMP9. Additionally, MDSCs possess the ability to influence other cells via diverse mechanisms [27]. MDSCs suppress antitumor immunity by releasing immunoregulatory molecules such as arginase (ARG), inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), TGF-β, and IL-10. These factors impair T cell proliferation and diminish tumor-specific T cell activity. Additionally, like TAMs, MDSCs secrete galectin-9, which interacts with T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3 (TIM-3) on T cells, inducing apoptosis [28]. MDSCs inhibit the cytotoxicity and cytokine release of NK cells (e.g., interferon-γ (IFN-γ)), which is mediated by the NKp30 receptor [29]. MDSCs contribute to immunosuppression by facilitating the expansion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs. Additionally, in advanced HCC, MDSCs have been shown to interact with Kupffer cells, resulting in increased PD-L1 expression within the TME. The pivotal role of MDSCs has prompted researchers to explore targeted therapeutic strategies against these cells. Trabectedin, a novel chemotherapeutic agent, selectively targets tumor cells and induces apoptosis in bone marrow cells [30]. In a clinical study, it significantly reduced disease progression and mortality rates compared to best supportive care in patients with advanced malignancies [31]. Trabectedin has been shown to decrease intratumoral MDSC levels, potentially by downregulating MDSC-promoting factors like G-CSF secreted by TAFs [32]. In addition to reducing MDSC-promoting factors, Trabectedin can directly trigger MDSC apoptosis. By lowering MDSC abundance and modulating their suppressive activity, it enhances antitumor immune recognition and response [33]. Estrogen has been reported to impair the functional activity of myeloid cells in HCC [34]. Estrogen lowers the risk of liver cancer in female mice by suppressing Janus kinase activation and inhibiting the STAT6 signaling pathway in necrotic tumor cells. Epidemiological data also show that HCC incidence is generally higher in men than in women, particularly among older populations [35]. However, female HCC patients often have a better survival rate [36]. Estrogen can promote the activity of T cells and NK cells, and also enhance the immune recognition and elimination of tumor cells by modulating the function of DCs [37]. In female patients with HCC, estrogen may confer protection by promoting cellular immune activity and suppressing immune tolerance. Further studies are needed to clarify the regulatory mechanisms of MDSCs and their potential as therapeutic targets, which could provide new directions for liver cancer treatment strategies.

2.3 Regulatory T Cells (Tregs)

The TME in HCC is characterized by substantial lymphocytic infiltration, including B cells, tertiary lymphoid structures, and various T cell populations collectively known as tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). TILs modulate both innate and adaptive immune responses, thereby influencing tumor progression. Among these, multiple T cell subsets—such as αβ T cells, γδ T cells, CD4+ T cells, and CD8+ T cells—play central roles in orchestrating immune dynamics within the TME [38]. Evidence indicates that various T lymphocyte subsets fulfill distinct functions within the tumor microenvironment. Among them, CD4+ Tregs suppress antitumor immunity by inhibiting the activity of effector T cells. Tregs serve a dual role: they help maintain immune homeostasis and prevent autoimmunity, while also contributing to transplant tolerance. Although Treg accumulation in inflamed or tumor-infiltrated liver tissue may protect against collateral damage to normal hepatocytes, their immunosuppressive activity fosters immune tolerance toward tumor cells. This ultimately impairs the cytotoxic function of tumor-specific effector cells, such as CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), within the TME [39]. In HCC, the presence of Tregs within tumors and peripheral blood appears more influential than that of CD8+ T cells. Studies have reported a marked elevation in both the frequency and absolute number of CD4+CD25+ Tregs in the TME, along with higher peripheral Treg levels in HCC patients compared to individuals with HCV infection or healthy controls. Tregs mediate immunosuppression through multiple mechanisms, including the release of inhibitory cytokines, induction of cytolysis, metabolic disruption, and suppression of dendritic cell function via CTLA-4 and indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO). Notably, the secretion of TGF-β and IL-10 by Tregs within the TME impairs CD8+ T cell activity [40]. The collaboration between Tregs and Kupffer cells results in the release of IL-10, STAT3, and VEGF, which triggers Treg proliferation while inhibiting KCs from producing CD8+ T cells. It has been discovered that liver-specific chemokine receptor CCR6 draws Tregs into tumors where they are attracted by HCC cell-released CCL20. Additionally, various immune characteristics have been identified in Tregs including PD-1, CTLA-4, OX40, GITR, and TIM-3 [41]. These markers have been evaluated in both preclinical and clinical studies to assess their roles in chronic inflammation and tumor progression. Immunological analyses have revealed that Tregs can effectively suppress CD8+ T cell function. Spatial distribution studies indicate that Tregs are more concentrated in the tumor core, whereas CD8+ T cells are primarily localized at the tumor margins.

DCs, key antigen-presenting cells (APCs), are essential for antigen presentation, regulation of T cell differentiation, and modulation of T cell responses. In the human liver, DCs are primarily classified into plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) and classical DCs (cDCs). The pDCs, characterized by BDCA-2 and CD123 expression, respond to TLR7/8 ligands and contribute to antiviral defense through type I interferon secretion, though their capacity to activate T cells is limited. The cDCs, also known as myeloid DCs, are subdivided into CD141+/CD14− cDC1 and CD1c+/CD14+ cDC2 subsets. Both cDC1 and pDCs activate CD4+ T cells, while cDC1 and cDC2 facilitate MHC I–restricted activation of CD8+ T cells, supporting effector and memory T cell responses. Notably, cDC2 are abundant in the human liver but scarce in the spleen [42]. They contribute to antiviral immunity through type I interferon secretion but exhibit limited capacity to activate T cells [43]. Tumor cells promote the differentiation of DCs into an immature state by downregulating antigen presentation and adhesion molecules, while secreting immunosuppressive factors like IL-10 and VEGF. These immature DCs, in turn, activate Tregs, fostering immune tolerance and suppressing the activity of effector T cells [44]. Studies suggest a potential interaction between immunosuppressive Tregs and pDCs in HCC. DC vaccines are under investigation as a therapeutic approach, wherein patients are administered activated, mature DCs to elicit antitumor immune responses [45]. The study demonstrated favorable safety and tolerability profiles, suggesting that combining DC vaccines with immune checkpoint inhibitors could be a promising strategy for treating malignancies.

KCs, as a specialized subset of macrophages located within the hepatic sinusoids, constitute an integral component of the innate immune system. They originate from monocytes that adhere to the liver sinusoidal walls and undergo differentiation. Under specific physiological circumstances, phagocytosis serves as a rapid mechanism for eliminating exogenous particles or erythrocytes from the bloodstream [46]. In recent years, an increasing number of studies related to KCs have shown their significant impact on the early diagnosis and treatment of HCC [47]. KCs in the pathological state of TME can promote the activation of hepatic stellate cells, thereby promoting fibrosis of liver tissue, producing extracellular matrix (ECM), and triggering tumors. KCs are a key mediator for inflammatory reactions in liver tissue cells, and M2-type KCs express high levels of TGF-β1. Activate hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), which secrete ECM and promote liver fibrosis. When the body is in a normal state, there is always a dynamic balance between the production and degradation of ECM. During liver fibrosis, this balance is disrupted, causing ECM to accumulate and the liver to transform from normal to liver fibrosis or liver cancer. Meanwhile, the excessive accumulation of ECM may also cause local hypoxia, create an inflammatory microenvironment, and reduce the likelihood of the body effectively recognizing and killing liver cancer cells [48]. Additionally, Kupffer cells express α 1-Adrenergic Receptors (α 1-ARs) which can facilitate tumor initiation and metastasis through sympathetic nervous system modulation. Liver cancer is more prevalent in cases of liver cirrhosis following chronic inflammation, and in advanced stages of liver cirrhosis, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) exhibits abnormal hyperactivity, with SNS innervation playing a crucial role in HCC development. Studies have demonstrated that increased density of sympathetic nerve fibers and KCs α 1-ARs are associated with unfavorable prognosis in HCC; interventions such as sympathetic denervation or α 1-AR blockade have shown potential to reduce diethyl nitrosamine-induced liver cancer incidence and progression. Further investigations revealed that SNS activation via α 1-ARs promotes Kupffer cell activation, and sustains an inflammatory microenvironment, thereby facilitating HCC occurrence [49].

2.6 Liver Sinusoidal Endothelial Cells (LSECs)

LSECs are specialized endothelial cells that form the interface between circulating blood cells, hepatocytes, and hepatic stellate cells. Under physiological conditions, LSECs modulate hepatic vascular tone to maintain low portal pressure and stable blood flow. They also help preserve the quiescent state of hepatic stellate cells, thereby preventing intrahepatic vasoconstriction and fibrogenesis. Under pathological conditions, especially in HCC, LSECs significantly contribute to disease initiation and progression [50]. From a pathological perspective, it is believed that HCC progresses from precancerous lesions (low to high-grade developmental nodules) to early and late-stage HCC, originating from highly vascularized tumors. This process is closely linked to endothelial cell remodeling and contributes to both HCC development and metastasis. Tumor-driven capillarization of LSECs promotes HSC activation and fibrogenesis, whereas maintenance of the non-capillarized (fenestrated) phenotype helps inhibit HSC activation and protect against liver injury. Chemokines such as CXCL9 and CXCL16 regulate immune cell infiltration during liver disease progression, including in HCC. Furthermore, increased adhesion between circulating tumor cells and LSECs, along with LSEC-induced immune tolerance within the tumor microenvironment, facilitates metastatic dissemination of HCC cells [51]. As HCC progresses, LSECs in peritumoral regions undergo phenotypic alterations, including reduced expression of characteristic markers such as stabilin-2 and CD32b. In mouse xenograft models, peritumoral liver tissue exhibits increased microvascular density and elevated expression of proangiogenic genes, including IL-6 and IL-6R, compared to tumor core tissue [52]. Peritumoral endothelial cells isolated from HCC patients show greater proliferative capacity in response to IL-6 and soluble IL-6R stimulation compared to endothelial cells from tumor tissue. These findings highlight the active involvement of peritumoral endothelial cells in HCC progression and emphasize their relevance in exploring tumor–microenvironment interactions.

2.7 Hepatic Stellate Cells (HSCs)

HSCs, residing in the space of Disse, are pericyte-like cells that account for approximately 5%–10% of the total liver cell population [53,54]. HSCs participate in liver regeneration but exhibit inhibitory effects on liver cancer by secreting cytokines such as hepatocyte growth factor (HGF) and IL-6 [55]. Cirrhosis, as the main cause of HCC, is caused by long-term chronic inflammation leading to sustained activation of HSCs, ultimately leading to excessive scar formation in the liver, which in turn develops into fibrosis and cirrhosis, ultimately leading to HCC [56]. Several components of the TME, including TGF-β, platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), as well as vasoactive agents such as thrombin, angiotensin, and endothelin-1, contribute to the activation of HSCs [57]. The activation of HSCs also leads to changes in myofibroblast-like phenotype, production of ECM proteins, and infiltration of HCC. It can also lead to the activation of hematopoietic stem cells, promote the development of accumulated TME, and further maintain the stability of HCC cells [58]. In the process of HCC metastasis, the regulation of immune cells plays a crucial role in tumor immune evasion. The activation of HSCs can affect immune cells and promote their entry into an immunosuppressive state. Research has shown that the transdifferentiation of HSCs increases the production and content of extracellular vesicles (EVs). When modified EVs reach the macrophage membrane, they stimulate cytokine synthesis and release, as well as macrophage migration [59]. Filliol et al., demonstrated that in early disease stages, minimally activated or quiescent HSCs secrete hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which suppresses HCC progression. However, in more advanced stages, HSCs become fully activated and begin producing collagen I, thereby facilitating tumor growth [60]. The regulatory signals driving the functional heterogeneity of HSC subpopulations remain largely unexplored. Moreover, during fibrosis resolution, activated HSCs may either undergo apoptosis or transition into an inactivated state, which differs from their original quiescent form [61]. The involvement of HSCs in tumor metastasis is primarily mediated through their activation, which promotes EMT in HCC cells, facilitating metastatic spread. Elucidating how activated HSCs contribute at various stages of tumor development is essential for a deeper understanding of HCC pathogenesis.

2.8 Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs)

CAFs are integral components of the tumor stroma and modulate cancer progression through diverse mechanisms, including the secretion of growth factors, inflammatory mediators, exosomes, and the regulation of ECMn remodeling, angiogenesis, tumor biology, and therapeutic response [62,63]. Since most HCC arises in the context of liver cirrhosis, which involves fibroblast activation, proliferation, and accumulation, CAFs contribute to a microenvironment conducive to tumor initiation, progression, and metastasis [64]. During HCC development, tumor cells release various factors that recruit CAFs into TME. In turn, CAFs secrete a range of soluble molecules—including growth factors, inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and angiogenic factors—that promote tumor cell proliferation and dissemination [65]. Their crosstalk with cancer cells is mediated through a complex signal network that includes TGF-β, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), Wnt/β-signal pathways such as catenin, Janus kinase/signal transduction, and transcription activating factors (JAK/STATs), and epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) [66]. In recent studies on the role of CAFs in the progression of HCC, it was found that CAFs are involved in various chemokines in the TME endocrine system by activating Hedgehog or TGF-β pathways to promote the invasion and metastasis of HCC cells [67]. The TGF-β signaling pathway exhibits dual functionality—acting as a tumor suppressor in precancerous cells while promoting tumor progression in malignant cells. In the TME, TGF-β/Smad signaling facilitates EMT in tumor endothelial cells by upregulating Snail and Slug, thereby enhancing angiogenesis and the accumulation of myofibroblasts and CAFs. Emerging evidence also highlights the broad involvement of the JAK/STAT pathway, activated by CAFs, in regulating key oncogenic processes such as cellular plasticity, proliferation, migration, EMT, angiogenesis, and metastasis. In HCC, CAF-derived IL-6 triggers EMT in cancer cells via activation of the IL-6/JAK/STAT3 axis, which induces transglutaminase 2 (TG2) expression and promotes the mesenchymal phenotype [68]. Numerous studies emphasize the importance of interactions between HCC cells, CAFs, and other stromal components in driving tumor progression. While preclinical and clinical evidence has begun to uncover the involvement of CAFs in immune evasion and resistance to immunotherapy, further elucidation of their distinct roles in HCC could support the development of more effective molecularly targeted therapies.

CSCs represent a subpopulation within tumors that contribute to invasion, metastasis, recurrence, and resistance to therapy. They interact with various cytokines in TME, jointly promoting HCC progression. IL-6 secreted by TAMs in HCC activates STAT3 signaling, thereby enhancing the proliferation of CSCs. Additionally, IL-17E produced by non-CSCs promotes CSC proliferation and self-renewal through activation of the JAK/STAT3 and NF-κB signaling pathways in HCC [69]. Moreover, STAT3 enhances the expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2 and MMP-9), which contribute to ECM degradation and facilitate the upregulation of EMT-related transcription factors, such as Slug and Twist, ultimately promoting the invasive potential of CSCs in HCC [70]. CAFs secrete cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors to improve the self-renewal of CSCs. IL-6 and HGF produced by CAFs activate STAT3 signaling, leading to CSC activity [71]. The CSCs model for HCC suggests that tumor growth is driven by a subset of tumor stem cells in cancer. This model helps to explain several clinical features of HCC, such as the frequent recurrence following initially successful chemotherapy or radiotherapy, as well as tumor dormancy and resistance to treatment. Over the past two decades, growing research efforts have focused on the identification and characterization of liver CSCs, paving the way for the development of novel diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies for HCC [72].

3 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors (ICIs)

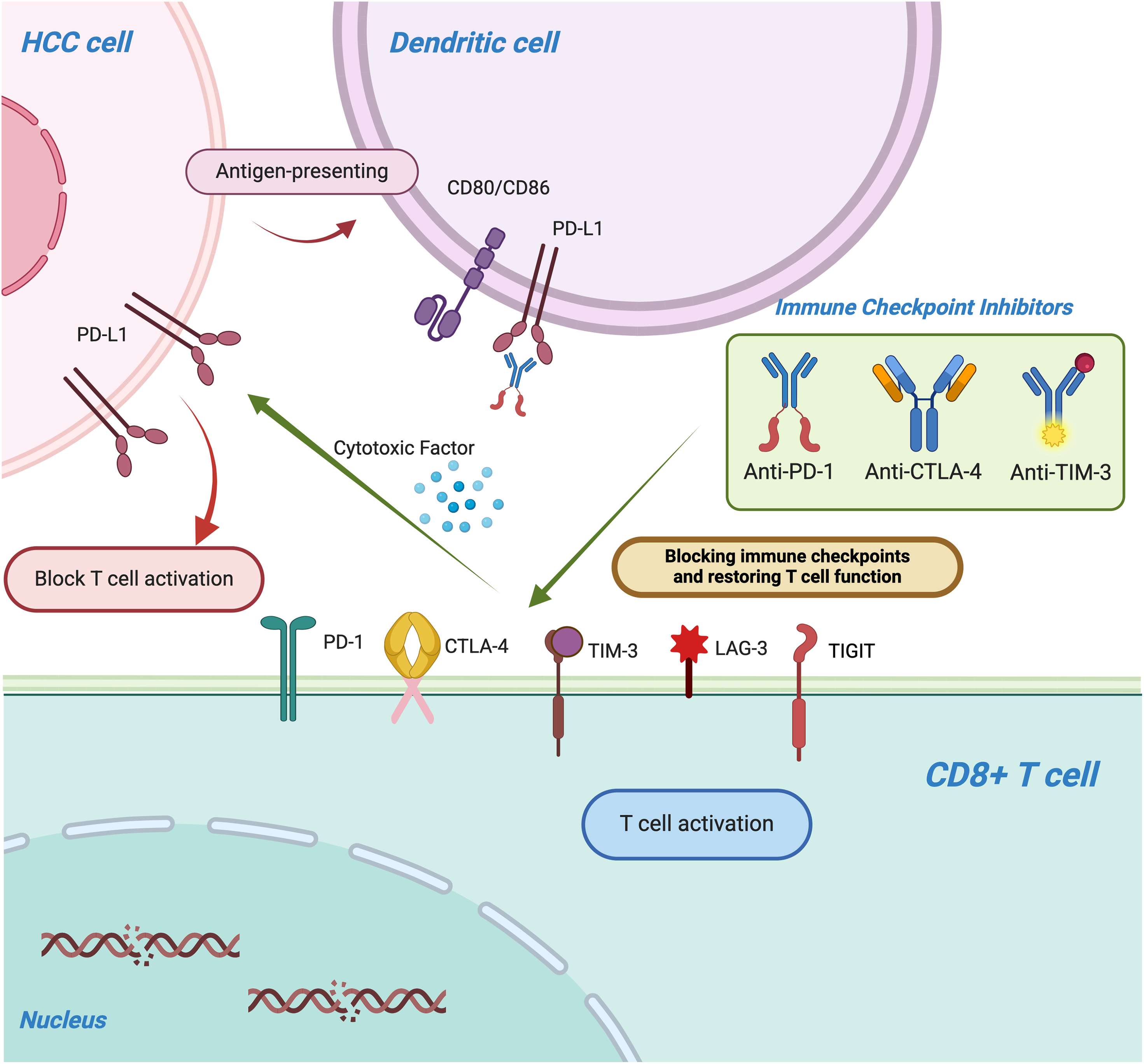

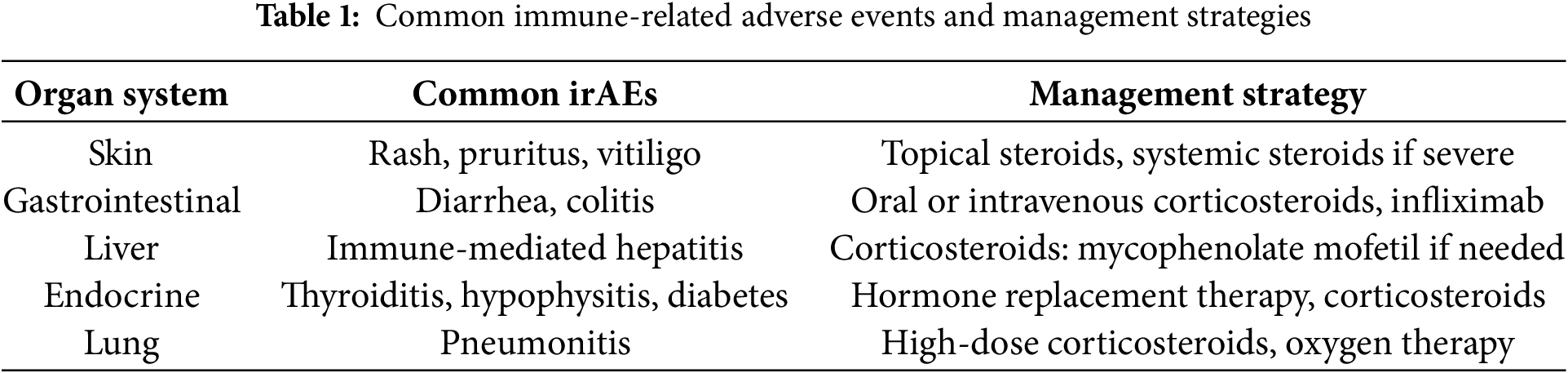

Immune checkpoints are a class of regulatory molecules within the immune system that modulate the activity of immune cells, maintaining the balance of immune responses and preventing excessive immune activation that could lead to autoimmune diseases or tissue damage [73]. These checkpoint molecules primarily function by interacting with receptors and ligands on immune cell surfaces, either inhibiting or promoting immune cell activation and function, thus enabling negative regulation of immune responses. For example, PD-1 (programmed cell death protein 1) and its ligand PD-L1 are widely studied immune checkpoints; their interaction inhibits T-cell function, aiding tumor cells in evading immune surveillance [74]. Similarly, CTLA-4 (cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4) inhibits T-cell activation by binding to CD80/CD86, thereby limiting the intensity and duration of immune responses [75]. Under normal physiological conditions, immune checkpoints play a crucial role in immune tolerance, preventing the immune system from attacking self-tissues. However, tumor cells often exploit these checkpoints by upregulating their expression to escape immune detection, promoting tumor growth and metastasis [76]. In recent years, immune checkpoint inhibitors (such as anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 antibodies) have emerged as a novel immunotherapeutic approach. By blocking these immune checkpoints, these inhibitors restore immune system function, reactivate T-cells and other immune cells, and enhance the immune system’s ability to recognize and eliminate tumors, representing a significant breakthrough in cancer therapy (Fig. 2). Immune checkpoint inhibitors can lead to a spectrum of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), most commonly affecting the skin, gastrointestinal tract, liver, and endocrine organs. Prompt recognition and appropriate management—often involving corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive agents—are critical to mitigate severity and prevent long-term complications (Table 1).

Figure 2: The figure illustrates the mechanism by which immune checkpoint molecules, including PD-1/PD-L1, CTLA-4, TIM-3, lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3), and T cell immunoreceptor with Ig and ITIM domains (TIGIT), suppress T-cell function and enable tumors to evade immune surveillance. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), such as anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti-CTLA-4 monoclonal antibodies, restore T-cell activity by blocking these inhibitory pathways

The protein PD-1 can be expressed by various types of cells, including active CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, B cells, Tregs, NKs, myeloid cells, monocytes, and DCs. During the effect phase of T cells, PD-1 primarily provides negative regulatory signals. The maintenance of immune tolerance and inhibition of cytotoxic T cells are of utmost importance [77]. PD-1 binds to either PD-L1 or PD-L2 to inhibit the immune system’s response against tumors [78]. PD-L1 is expressed in various non-immune cells as well as tumor cells, B cells, T cells, DCs, antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and MDSCs. In the TME of HCC, PD-L1 is predominantly found in tumor cells and some other APCs. On the other hand, PD-L2 expression is limited to APCs only, which may explain why anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies are effective while PD-L2 has minimal impact on antitumor immunity. In TME, multiple factors interact to affect the expression of PD-1 and PD-L1. For example, Y-box binding protein 1 (YBX1) and circRNA can regulate the expression of PD-L1 and inhibit the function of effector T cells [79,80]. In HCC cases, ICIs can prevent the interaction between PD-1 and PD-L1 from inducing immunosuppression. Patients with high levels of PD-1 or PD-L1 expression in HCC tend to have a poorer prognosis [81]. Among them, several classical drugs have been widely used in clinical practice, including nivolumab, pembrolizumab, durvalumab and atezolizumab.

Nivolumab is a monoclonal antibody that acts as a PD-1 inhibitor, which was approved by the US FDA in June 2015. By obstructing the interaction between PD-1 and its ligands, namely PD-L1 and PD-L2, Nivolumab enhances the activation of T cells to recognize cancer cells, thereby facilitating their elimination [82]. Durvalumab is currently the most frequently utilized FDA-approved PD-L1 monoclonal antibody, and it exhibits a superior safety and tolerability profile compared to conventional chemotherapy drugs. In ongoing clinical trials, it has demonstrated its ability to effectively impede the proliferation of HCC cells, reduce tumor volume, and prolong overall survival. The Phase 2 trial investigated the combination of durvalumab with tremelimumab or bevacizumab in patients diagnosed with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC) [83]. The co-inhibition of PD-L1 by bevacizumab and VEGF inhibition may exhibit an additive effect, enhancing clinical activity [84]. The introduction of atezolizumab has significantly advanced the treatment of advanced unresectable HCC. The FDA has approved the first-line treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (aHCC) to atezolizumab and bevacizumab, based on the findings from the IMbrave 150 study [85].

The CTLA-4 co-receptor functions as an inhibitor of immune responses and belongs to the CD28 co-receptor family. It is predominantly expressed in activated T cells, regulatory T cells, and naive T cells. In immature T cells, CTLA-4 resides intracellularly but translocates to the cell surface upon stimulation. In Tregs, it remains constitutively present and aids in suppressing immune responses. CTLA-4 competes with CD28 for binding to the costimulatory molecules CD80 (B7-1) and CD86 (B7-2) on antigen-presenting cells, such as DCs, with significantly higher affinity than CD28. While the interaction between B7-1 and CD28 promotes T cell activation, its engagement by CTLA-4 initiates inhibitory signaling pathways that suppress immune responses [86]. Monoclonal antibodies like ipilimumab and tremelimumab can block this negative regulatory response and are well tolerated. In 1996, Allison and his colleagues demonstrated through animal models that inhibitory antibodies that block CTLA-4 can boost the immune response against tumors, marking the first successful application of CTLA-4 in cancer treatment [87]. Tremelimumab is an inhibitor of CTLA-4 that belongs to the human IgG2 class. One of the earliest known practical immunotherapy experiments is to apply tremelimumab to patients with HCC and HCV-related cirrhosis who have progressed after treatment with sorafenib [88]. The utilization of these medications in isolation is infrequent, as they are commonly employed in conjunction with other therapies due to their distinctive mechanisms of action. The efficacy of tremelimumab, the anti-CTLA4, treatment in combination with durvalumab has been demonstrated in numerous phase I/II trials for advanced HCC.

TIM-3 (T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain containing-3) is an immune checkpoint molecule predominantly expressed on immune cells such as effector T cells (Teff), Tregs, NK cells, and DCs [89]. Through interactions with its ligands, including galectin-9, carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 1 (CEACAM1), and phosphatidylserine, TIM-3 inhibits T-cell function, promotes immune tolerance, and ultimately facilitates tumor immune evasion. In HCC, high TIM-3 expression is considered a critical marker of T-cell exhaustion, which directly impairs anti-tumor immune responses [90]. Studies have demonstrated that TIM-3 is highly expressed in CD8+ T cells and Tregs within tumor tissues and peripheral blood of HCC patients. This expression often correlates with increased tumor burden, enhanced invasiveness, higher recurrence rates, and is closely associated with disease progression and poor prognosis [91]. As an immune checkpoint molecule, TIM-3 can be targeted with inhibitors to restore T-cell function and enhance anti-tumor immunity [92]. Monoclonal antibodies targeting TIM-3, such as MBG453 and TSR-022, have entered preliminary stages of clinical application, with evidence suggesting their potential therapeutic efficacy against HCC. Furthermore, a synergistic relationship exists between TIM-3 and the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, with their co-expression often indicating a more profound state of T-cell exhaustion [93]. Preclinical and clinical studies in HCC have shown that dual blockade of TIM-3 and PD-1/PD-L1 enhances anti-tumor activity. This combination therapy improves the immunosuppressive TME and increases treatment response rates.

Lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) is a membrane protein predominantly expressed in immune cells such as CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, Tregs, and NK cells. LAG-3 interacts with major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) molecules to suppress T-cell proliferation, cytokine secretion, and cytotoxic function, thereby weakening anti-tumor immune responses [94]. It is frequently co-expressed with PD-1, collectively contributing to T-cell exhaustion. The high expression of LAG-3 on Tregs enhances their immunosuppressive capabilities, further promoting tumor immune evasion. LAG-3 inhibitors, such as Relatlimab, have demonstrated promising preclinical and clinical potential in various malignancies. Blocking LAG-3 restores T-cell function and bolsters anti-tumor immunity. In HCC, research is ongoing to evaluate the safety and efficacy of LAG-3 monoclonal antibodies. LAG-3 inhibitors have entered phase I/II clinical trials, including studies of Relatlimab in combination with Nivolumab for the treatment of HCC [95]. These trials aim to assess the safety, tolerability, and preliminary efficacy of the combination therapy. Early results indicate that dual blockade of LAG-3 and PD-1 exhibits significant anti-tumor activity with manageable toxicity profiles, highlighting its potential as a novel immunotherapy approach for HCC.

T-cell immunoglobulin and ITIM domain (TIGIT) is an immune checkpoint molecule whose expression is significantly upregulated in TME of HCC. TIGIT is primarily distributed on T cells, NK cells, and other immunosuppressive cell populations. By binding to its ligand CD155, TIGIT inhibits the activity of effector T cells and NK cells while enhancing the function of Tregs, thereby establishing an immunosuppressive TME [96]. This mechanism not only facilitates immune evasion by tumor cells but is also closely associated with HCC progression and poor prognosis. TIGIT monoclonal antibodies, as immune checkpoint inhibitors, have advanced to clinical trial stages. Blocking TIGIT alone or in combination with PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies can restore T-cell and NK cell function, strengthening anti-tumor immune responses. Furthermore, TIGIT inhibitors can be integrated with existing therapies such as targeted agents (e.g., sorafenib and lenvatinib) or locoregional treatments (e.g., ablation and embolization) to improve the TME and enhance therapeutic sensitivity [97]. For HCC patients, combination therapies may overcome the limitations of single-agent approaches, thereby improving overall treatment outcomes.

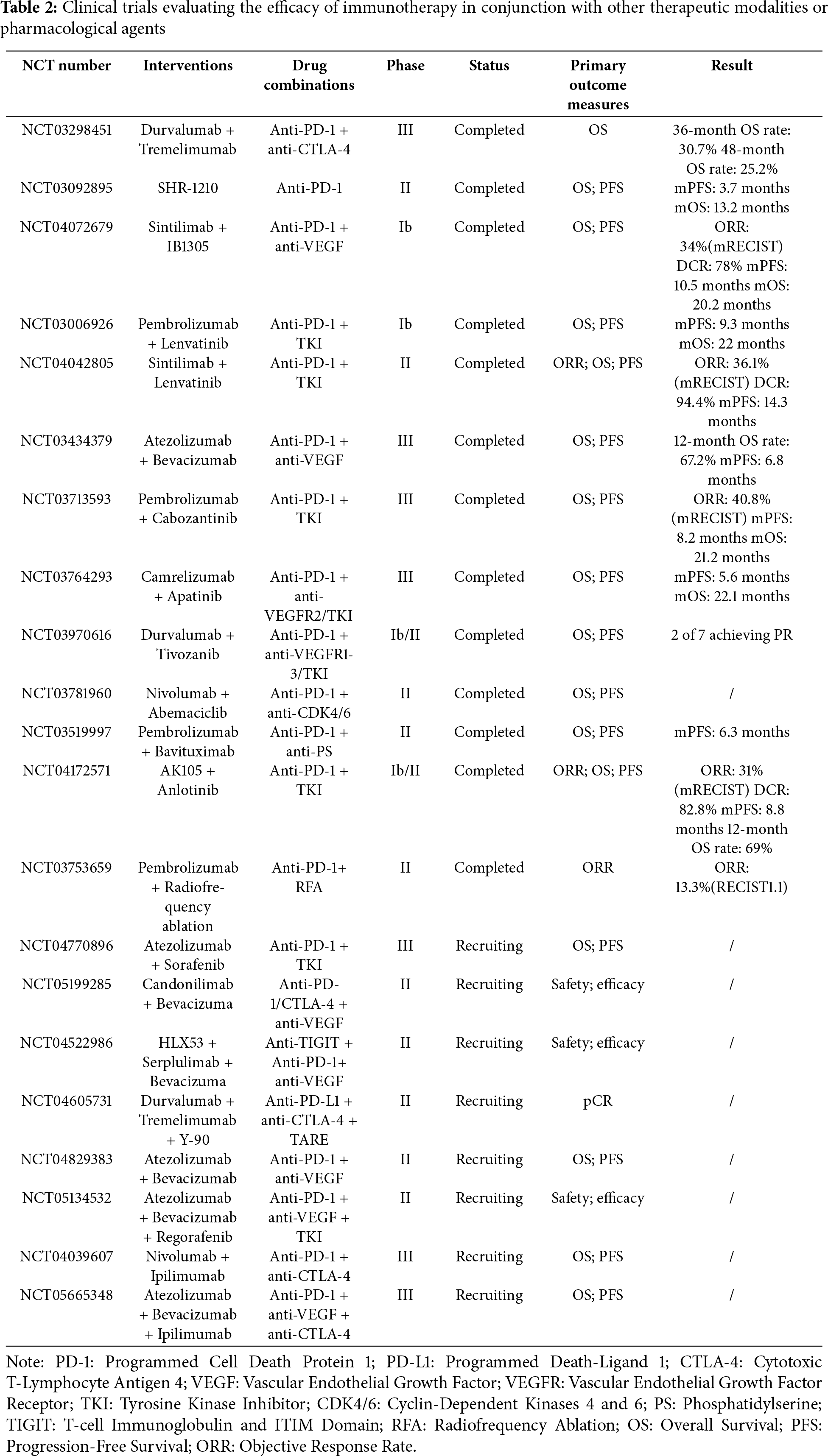

Given the heterogeneity of HCC and the complexity of the tumor microenvironment, a single therapeutic approach frequently falls short of addressing clinical requirements. Consequently, combination therapy strategies, such as the integration of ICI with immunotherapy, ICI with targeted therapies, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, have emerged as pivotal research directions in HCC treatment. The following highlights some of the most recent advancements in clinical research. In the table below, we present detailed information on clinical trials of ICI therapy that further substantiate the potential and efficacy of immunotherapy (Table 2).

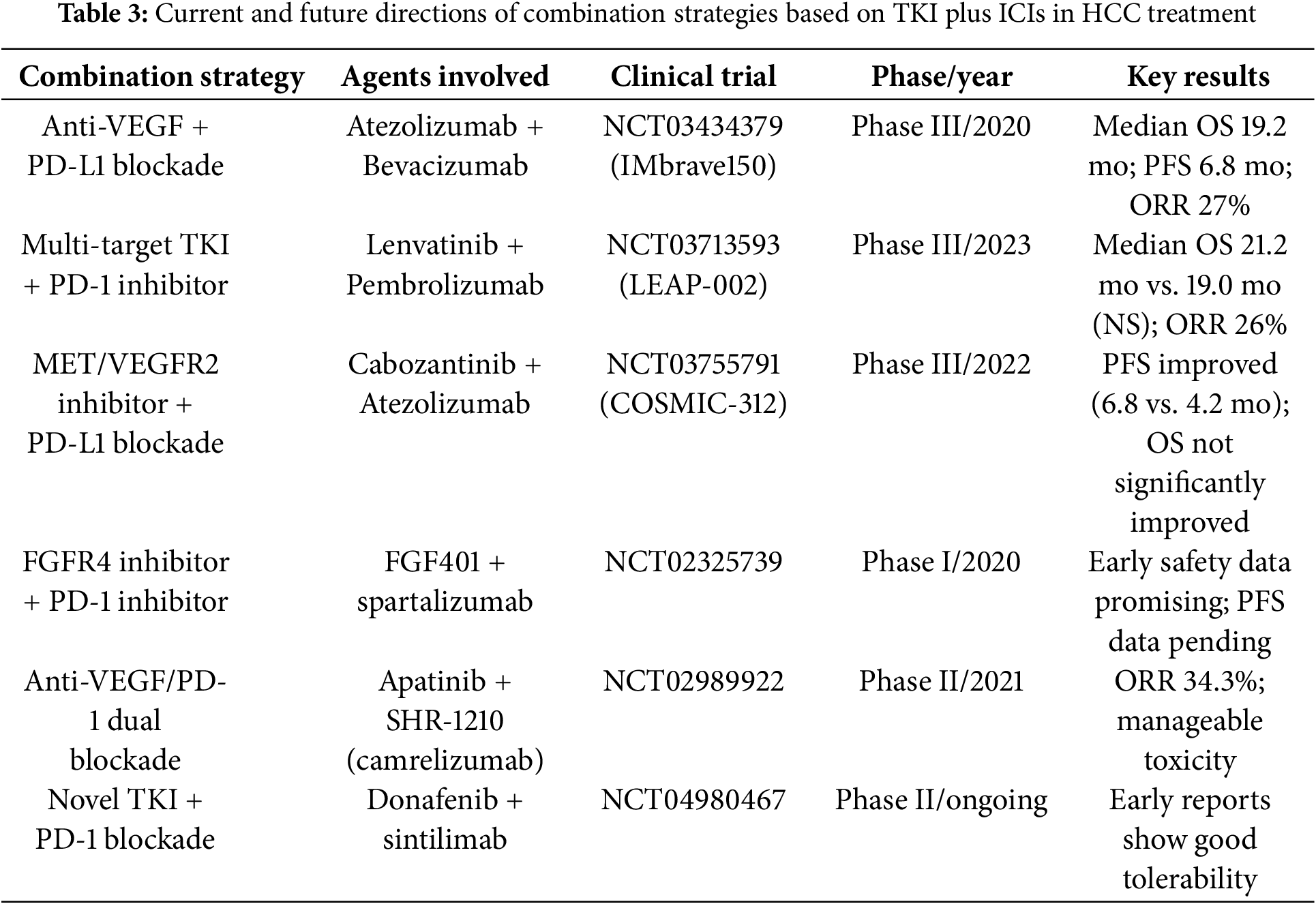

In patients with advanced HCC, the efficacy of single-agent ICIs is often limited. Combination ICI therapies have introduced new avenues for treatment. The concurrent use of PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors (e.g., nivolumab, pembrolizumab) and CTLA-4 inhibitors (e.g., ipilimumab) has demonstrated promising clinical outcomes across various tumor types. For HCC, studies indicate that combining PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors can significantly enhance T-cell activation and restore anti-tumor immune responses, particularly in patients who exhibit poor responses to monotherapy [77]. In the KEYNOTE-524 study, the combination of pembrolizumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and ipilimumab (CTLA-4 inhibitor) demonstrated superior efficacy compared to monotherapy [98]. Additionally, the combination of ICIs with immune stimulators, such as anti-CD40 or anti-OX40 antibodies, further amplifies the immune system’s ability to recognize and eliminate tumors [99]. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), as a key class of targeted therapies, play a pivotal role in the treatment of HCC by precisely disrupting aberrant signaling pathways involved in tumor growth and angiogenesis (Table 3). Combining ICIs with targeted therapies not only restores immune responses but also precisely inhibits tumor growth, emerging as a widely adopted and well-established clinical strategy. Common combinations include PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors with VEGF inhibitors or multi-targeted therapies. In the KORONA study, the combination of nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) and bevacizumab (VEGF inhibitor) demonstrated higher overall response rates and longer survival in patients with advanced HCC [100]. Similarly, recent studies have demonstrated that the combination of nivolumab and lenvatinib exhibits high clinical efficacy and tolerability, presenting a promising treatment option for advanced HCC [101]. Although chemotherapy has not shown strong advantages in HCC treatment strategies, its role has evolved with the advent of ICIs and interventional therapies. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy (HAIC) combined with ICIs has emerged as an effective neoadjuvant therapy for HCC [102]. Chemotherapy can reduce immunosuppressive cell populations within the tumor microenvironment (e.g., Tregs and MDSCs) and suppress immunoinhibitory signals, thereby creating a favorable condition for ICI therapy. Simultaneously, ICIs relieve T-cell immune suppression, and when combined with the direct cytotoxic effects of chemotherapy, they further enhance the immune system’s anti-tumor efficacy.

Bispecific antibodies (BsAbs) are engineered immunoglobulin constructs capable of simultaneously recognizing and binding to two distinct antigens or epitopes. Compared to conventional monospecific antibodies, BsAbs exhibit unique structural and functional advantages, enabling highly specific dual-targeted therapeutic strategies, particularly in oncology. The primary mechanism of action for BsAbs involves their ability to concurrently engage tumor-associated antigens (TAAs) and immune effector cells, effectively forming an immunological synapse that facilitates direct cytotoxic activity against tumor cells [103]. In HCC, BsAbs are designed to target overexpressed TAAs, such as Glypican-3 and alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), to achieve tumor-specific recognition [12]. Concurrently, they interact with immune effector cell receptors, including CD3 on T cells or CD16 on NK cells, promoting direct tumor-immune cell interactions and triggering robust anti-tumor immune responses. Additionally, BsAbs can simultaneously inhibit multiple oncogenic pathways. For example, VEGF/Ang-2 BsAbs effectively block key mediators of angiogenesis, thereby enhancing the efficacy of anti-angiogenic therapies in HCC [104]. Current investigations into Glypican-3, a highly specific antigen in HCC, have demonstrated that BsAbs targeting both Glypican-3 and CD3 can significantly enhance cytotoxic immune responses against tumor cells [105]. Advances in antibody engineering have driven the development of increasingly sophisticated BsAb platforms, including tri-specific antibodies and nanobody-based constructs, offering improved pharmacokinetics and tumor penetration. Looking forward, BsAbs are anticipated to play a pivotal role in the treatment of solid tumors, including HCC, and their integration with emerging immunotherapeutic modalities holds promise for overcoming therapeutic resistance and addressing the unmet clinical needs of patients with refractory or recurrent malignancies.

The TME plays a central role in the progression, immune evasion, and therapeutic resistance of HCC, making it both a major challenge and a promising target for treatment. Advances in immunotherapy, particularly ICIs, have offered a transformative approach to HCC management by reactivating anti-tumor immunity. However, the immunosuppressive components of the TME, including tumor-associated macrophages, Tregs, and MDSCs, limit the efficacy of ICIs when used alone. Combination therapies have emerged as a promising strategy to overcome these barriers. Dual checkpoint blockade, such as the combination of PD-1/PD-L1 and CTLA-4 inhibitors, has shown the potential to synergistically activate T cells and restore immune function. Additionally, integrating ICIs with anti-angiogenic agents, multi-kinase inhibitors, or TME-targeting approaches has demonstrated the ability to modulate the TME, enhance immune cell infiltration, and inhibit tumor progression. These approaches not only address the heterogeneity of HCC but also provide opportunities to reprogram the immune landscape of the tumor. Despite the encouraging progress, challenges such as immune-related toxicities, therapeutic resistance, and patient-specific variations in TME composition remain significant hurdles. Addressing these issues will require a deeper understanding of the molecular and cellular dynamics within the TME. Developing predictive biomarkers, tailoring combination regimens, and optimizing treatment sequencing are critical steps to refine these therapeutic strategies. In the future, leveraging insights into the TME to guide personalized immunotherapy approaches holds the potential to revolutionize HCC treatment. By targeting the complex interactions within the TME, combination therapies can achieve sustained anti-tumor responses, improve survival outcomes, and offer new hope for patients with this aggressive malignancy. As research continues to unravel the intricacies of the TME, immunotherapy will likely play an increasingly central role in transforming the landscape of HCC management.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the support provided by the Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (Grant No. 2024A1515012993) and the Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (Grant No. D202303078877). We also extend our appreciation to all the colleagues and institutions that contributed to the preparation of this manuscript. Their insights and assistance were invaluable to the successful completion of this work.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2024A1515012993) and the Project of Hunan Provincial Health Commission (No. D202303078877).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Jiahao Xue, Jingchang Zhang (Jiahao Xue and Jingchang Zhang contributed equally to this work); Draft manuscript preparation: Jingchang Zhang; Data acquisition and interpretation: Gang Chen; Review and editing: Jiahao Xue, Jingchang Zhang, Liucui Chen, Xinjun Lu; Visualization: Jingchang Zhang, Jiahao Xue; Supervision: Liucui Chen, Xinjun Lu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study did not involve human participants or animals and thus did not require ethics approval.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Rumgay H, Arnold M, Ferlay J, Lesi O, Cabasag CJ, Vignat J, et al. Global burden of primary liver cancer in 2020 and predictions to 2040. J Hepatol. 2022;77(6):1598–606. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2022.08.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. doi:10.3322/caac.21660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Fuster-Anglada C, Mauro E, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Caballol B, Sanduzzi-Zamparelli M, Bruix J, et al. Histological predictors of aggressive recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection. J Hepatol. 2024;81(6):995–1004. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2024.06.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Center MM, Jemal A. International trends in liver cancer incidence rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(11):2362–8. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.epi-11-0643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang CH, Cheng Y, Zhang S, Fan J, Gao Q. Changing epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. Liver Int. 2022;42(9):2029–41. doi:10.1111/liv.15251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69(1):182–236. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Shang R, Song X, Wang P, Zhou Y, Lu X, Wang J, et al. Cabozantinib-based combination therapy for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut. 2021;70(9):1746–57. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-320716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lu X, Zhang Y, Xue J, Evert M, Calvisi D, Chen X, et al. MAD2L1 supports MYC-driven liver carcinogenesis in mice and predicts poor prognosis in human hepatocarcinoma. Toxicol Sci. 2025;203(1):41–51. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfae126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Cappuyns S, Piqué-Gili M, Esteban-Fabró R, Philips G, Balaseviciute U, Pinyol R, et al. Single-cell RNA seq-derived signatures define response patterns to atezolizumab + bevacizumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2025;82(6):1036–49. doi:10.1016/s0168-8278(23)00513-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wang J, Li J, Tang G, Tian Y, Su S, Li Y. Clinical outcomes and influencing factors of PD-1/PD-L1 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Lett. 2021;21(4):279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

11. Lu X, Paliogiannis P, Calvisi DF, Chen X. Role of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway in liver cancer: from molecular genetics to targeted therapies. Hepatology. 2021;73(Suppl 1):49–61. doi:10.1002/hep.31310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Lu X, Deng S, Xu J, Green BL, Zhang H, Cui G, et al. Combination of AFP vaccine and immune checkpoint inhibitors slows hepatocellular carcinoma progression in preclinical models. J Clin Invest. 2023;133(11):e163291. doi:10.1172/jci163291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Shi X, Gao X, Liu W, Tang X, Liu J, Pan D, et al. Construction of the panoptosis-related gene model and characterization of tumor microenvironment infiltration in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Res. 2023;31(4):569–90. doi:10.32604/or.2023.028964. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Liang Y, Zhang R, Biswas S, Bu Q, Xu Z, Qiao L, et al. Integrated single-cell transcriptomics reveals the hypoxia-induced inflammation-cancer transformation in NASH-derived hepatocellular carcinoma. Cell Prolif. 2024;57(4):e13576. doi:10.1111/cpr.13576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wang H, Wang X, Zhang X, Xu W. The promising role of tumor-associated macrophages in the treatment of cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 2024;73(20):101041. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2023.101041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Aras S, Zaidi MR. TAMeless traitors: macrophages in cancer progression and metastasis. Br J Cancer. 2017;117(11):1583–91. doi:10.1038/bjc.2017.356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Narayanan S, Kawaguchi T, Peng X, Qi Q, Liu S, Yan L, et al. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes and macrophages improve survival in microsatellite unstable colorectal cancer. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):13455. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-49878-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Arvanitakis K, Koletsa T, Mitroulis I, Germanidis G. Tumor-associated macrophages in hepatocellular carcinoma pathogenesis, prognosis and therapy. Cancers. 2022;14(1):226. doi:10.3390/cancers14010226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Yeung OW, Lo CM, Ling CC, Qi X, Geng W, Li CX, et al. Alternatively activated (M2) macrophages promote tumour growth and invasiveness in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2015;62(3):607–16. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sun D, Luo T, Dong P, Zhang N, Chen J, Zhang S, et al. CD86+/CD206+ tumor-associated macrophages predict prognosis of patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. PeerJ. 2020;8(357):e8458. doi:10.7717/peerj.8458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Yu LX, Ling Y, Wang HY. Role of nonresolving inflammation in hepatocellular carcinoma development and progression. npj Precis Oncol. 2018;2(1):6. doi:10.1038/s41698-018-0048-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Wang J, Li D, Cang H, Guo B. Crosstalk between cancer and immune cells: role of tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Med. 2019;8(10):4709–21. doi:10.1002/cam4.2327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wan S, Kuo N, Kryczek I, Zou W, Welling TH. Myeloid cells in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;62(4):1304–12. doi:10.1002/hep.27867. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Veglia F, Perego M, Gabrilovich D. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells coming of age. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(2):108–19. doi:10.1038/s41590-017-0022-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Lu C, Rong D, Zhang B, Zheng W, Wang X, Chen Z, et al. Current perspectives on the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment in hepatocellular carcinoma: challenges and opportunities. Mol Cancer. 2019;18(1):130. doi:10.1186/s12943-019-1047-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Deng Y, Cheng J, Fu B, Liu W, Chen G, Zhang Q, et al. Hepatic carcinoma-associated fibroblasts enhance immune suppression by facilitating the generation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncogene. 2017;36(8):1090–101. doi:10.1038/onc.2016.273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zhou J, Liu M, Sun H, Feng Y, Xu L, Chan AWH, et al. Hepatoma-intrinsic CCRK inhibition diminishes myeloid-derived suppressor cell immunosuppression and enhances immune-checkpoint blockade efficacy. Gut. 2018;67(5):931–44. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2017-314032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Limagne E, Richard C, Thibaudin M, Fumet JD, Truntzer C, Lagrange A, et al. Tim-3/galectin-9 pathway and mMDSC control primary and secondary resistances to PD-1 blockade in lung cancer patients. Oncoimmunology. 2019;8(4):e1564505. doi:10.1080/2162402x.2018.1564505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Niu S, Xia C, Huang D, Wang L, Hu H, Yu S, et al. Requirements for human natural killer cells. Cell Prolif. 2024;57(5):e13588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

30. Denton NL, Chen CY, Hutzen B, Currier MA, Scott T, Nartker B, et al. Myelolytic treatments enhance oncolytic herpes virotherapy in models of ewing sarcoma by modulating the immune microenvironment. Mol Ther Oncolytics. 2018;11:62–74. doi:10.1016/j.omto.2018.10.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Gordon EM, Chawla SP, Tellez WA, Younesi E, Thomas S, Chua-Alcala VS, et al. SAINT: a phase I/expanded phase II study using safe amounts of ipilimumab, nivolumab and trabectedin as first-line treatment of advanced soft tissue sarcoma. Cancers. 2023;15(3):906. doi:10.3390/cancers15030906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wang J, Wang P, Zeng Z, Lin C, Lin Y, Cao D, et al. Trabectedin in cancers: mechanisms and clinical applications. Curr Pharm Des. 2022;28(24):1949–65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

33. Povo-Retana A, Landauro-Vera R, Alvarez-Lucena C, Cascante M, Boscá L. Trabectedin and lurbinectedin modulate the interplay between cells in the tumour microenvironment-progresses in their use in combined cancer therapy. Molecules. 2024;29(2):331. doi:10.3390/molecules30112472. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. He W, Wang M, Zhang X, Wang Y, Zhao D, Li W, et al. Estrogen induces LCAT to maintain cholesterol homeostasis and suppress hepatocellular carcinoma development. Cancer Res. 2024;84(15):2417–31. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-23-3966. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Hassan MM, Botrus G, Abdel-Wahab R, Wolff RA, Li D, Tweardy D, et al. Estrogen replacement reduces risk and increases survival times of women with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15(11):1791–9. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2017.05.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Sukocheva OA. Estrogen, estrogen receptors, and hepatocellular carcinoma: are we there yet? World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(1):1–4. doi:10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Chakraborty B, Byemerwa J, Krebs T, Lim F, Chang CY, McDonnell DP. Estrogen receptor signaling in the immune system. Endocr Rev. 2023;44(1):117–41. doi:10.1210/endrev/bnac017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Jiang H, Yang Z, Song Z, Green M, Song H, Shao Q. γδ T cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients present cytotoxic activity but are reduced in potency due to IL-2 and IL-21 pathways. Int Immunopharmacol. 2019;70:167–73. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2019.02.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Wolf D, Sopper S, Pircher A, Gastl G, Wolf AM. Treg(s) in cancer: friends or foe? J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(11):2598–605. doi:10.1002/jcp.25016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Lawal G, Xiao Y, Rahnemai-Azar AA, Tsilimigras DI, Kuang M, Bakopoulos A, et al. The immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. Vaccines. 2021;9(10):222–32. doi:10.3390/vaccines9101184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Zhao HQ, Li WM, Lu ZQ, Yao YM. Roles of tregs in development of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(24):7971–8. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i24.7971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Rahman AH, Aloman C. Dendritic cells and liver fibrosis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1832(7):998–1004. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.01.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Clemente-Casares X, Blanco J, Ambalavanan P, Yamanouchi J, Singha S, Fandos C, et al. Expanding antigen-specific regulatory networks to treat autoimmunity. Nature. 2016;530(7591):434–40. doi:10.1038/nature16962. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Lurje I, Hammerich L, Tacke F. Dendritic cell and T cell crosstalk in liver fibrogenesis and hepatocarcinogenesis: implications for prevention and therapy of liver cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(19):7378. doi:10.3390/ijms21197378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Fasano R, Shadbad MA, Brunetti O, Argentiero A, Calabrese A, Nardulli P, et al. Immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: new prospects for the cancer therapy. Life. 2021;11(12):1355. doi:10.3390/life11121355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Stahl EC, Haschak MJ, Popovic B, Brown BN. Macrophages in the aging liver and age-related liver disease. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2795. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Tacke F. Targeting hepatic macrophages to treat liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2017;66(6):1300–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

48. Chaulagain RP, Padder AM, Shrestha H, Gupta R, Bhandari R, Shrestha Y, et al. Deciphering the matrisome: extracellular matrix remodeling in liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Cureus. 2025;17(4):e82171. doi:10.7759/cureus.82171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Luo Q, Liu P, Dong Y, Qin T. The role of the hepatic autonomic nervous system. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2023;29(4):1052–5. doi:10.3350/cmh.2023.0244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Poisson J, Lemoinne S, Boulanger C, Durand F, Moreau R, Valla D, et al. Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells: physiology and role in liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2017;66(1):212–27. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.07.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Yang M, Zhang C. The role of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells in cancer liver metastasis. Am J Cancer Res. 2021;11(5):1845–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

52. Géraud C, Mogler C, Runge A, Evdokimov K, Lu S, Schledzewski K, et al. Endothelial transdifferentiation in hepatocellular carcinoma: loss of Stabilin-2 expression in peri-tumourous liver correlates with increased survival. Liver Int. 2013;33(9):1428–40. doi:10.1111/liv.12262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Yu Y, Li Y, Zhou L, Cheng X, Gong Z. Hepatic stellate cells promote hepatocellular carcinoma development by regulating histone lactylation: novel insights from single-cell RNA sequencing and spatial transcriptomics analyses. Cancer Lett. 2024;604(2):217243. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.217243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Chen N, Liu S, Qin D, Guan D, Chen Y, Hou C, et al. Fate tracking reveals differences between Reelin+ hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) and Desmin+ HSCs in activation, migration and proliferation. Cell Prolif. 2023;56(12):e13500. doi:10.1111/cpr.13500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Song Y, Kim SH, Kim KM, Choi EK, Kim J, Seo HR. Activated hepatic stellate cells play pivotal roles in hepatocellular carcinoma cell chemoresistance and migration in multicellular tumor spheroids. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):36750. doi:10.1038/srep36750. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Ruan Q, Wang H, Burke LJ, Bridle KR, Li X, Zhao CX, et al. Therapeutic modulators of hepatic stellate cells for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2020;147(6):1519–27. doi:10.1002/ijc.32899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Sällberg M, Pasetto A. Liver, tumor and viral hepatitis: key players in the complex balance between tolerance and immune activation. Front Immunol. 2020;11:552. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00552. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Hannivoort RA, Dunning S, Vander Borght S, Schroyen B, Woudenberg J, Oakley F, et al. Multidrug resistance-associated proteins are crucial for the viability of activated rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2008;48(2):624–34. doi:10.1002/hep.22346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Raposo G, Stoorvogel W. Extracellular vesicles: exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J Cell Biol. 2013;200(4):373–83. doi:10.1083/jcb.201211138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Filliol A, Saito Y, Nair A, Dapito DH, Yu LX, Ravichandra A, et al. Opposing roles of hepatic stellate cell subpopulations in hepatocarcinogenesis. Nature. 2022;610(7931):356–65. doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05289-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Kisseleva T, Brenner D. Molecular and cellular mechanisms of liver fibrosis and its regression. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;18(3):151–66. doi:10.1038/s41575-020-00372-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Sahai E, Astsaturov I, Cukierman E, DeNardo DG, Egeblad M, Evans RM, et al. A framework for advancing our understanding of cancer-associated fibroblasts. Nat Rev Cancer. 2020;20(3):174–86. doi:10.1038/s41568-019-0238-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Zhang X, Zhu R, Yu D, Wang J, Yan Y, Xu K. Single-cell RNA sequencing to explore cancer-associated fibroblasts heterogeneity: single vision for heterogeneous environment. Cell Prolif. 2024;57(5):e13592. doi:10.1111/cpr.13592. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Athavale D, Balch C, Zhang Y, Yao X, Song S. The role of Hippo/YAP1 in cancer-associated fibroblasts: literature review and future perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2024;604:217244. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.217244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Baglieri J, Brenner DA, Kisseleva T. The role of fibrosis and liver-associated fibroblasts in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(7):1723. doi:10.3390/ijms20071723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Chung JY, Chan MK, Li JS, Chan AS, Tang PC, Leung KT, et al. TGF-β signaling: from tissue fibrosis to tumor microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(14):7575. doi:10.3390/ijms22147575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Wu F, Yang J, Liu J, Wang Y, Mu J, Zeng Q, et al. Signaling pathways in cancer-associated fibroblasts and targeted therapy for cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):218. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00641-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Jia C, Wang G, Wang T, Fu B, Zhang Y, Huang L, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition via the transglutaminase 2-dependent IL-6/IL6R/STAT3 axis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(14):2542–58. doi:10.7150/ijbs.45446. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Wan S, Zhao E, Kryczek I, Vatan L, Sadovskaya A, Ludema G, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages produce interleukin 6 and signal via STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(6):1393–404. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2014.08.039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Zhang C, Guo F, Xu G, Ma J, Shao F. STAT3 cooperates with twist to mediate epithelial-mesenchymal transition in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Oncol Rep. 2015;33(4):1872–82. doi:10.3892/or.2015.3783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Li Y, Wang R, Xiong S, Wang X, Zhao Z, Bai S, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote the stemness of CD24+ liver cells via paracrine signaling. J Mol Med. 2019;97(2):243–55. doi:10.1007/s00109-018-1731-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Lee TK, Guan XY, Ma S. Cancer stem cells in hepatocellular carcinoma—from origin to clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;19(1):26–44. doi:10.1038/s41575-021-00508-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Tsai HF, Hsu PN. Cancer immunotherapy by targeting immune checkpoints: mechanism of T cell dysfunction in cancer immunity and new therapeutic targets. J Biomed Sci. 2017;24(1):35. doi:10.1186/s12929-017-0341-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Li B, Chan HL, Chen P. Immune checkpoint inhibitors: basics and challenges. Curr Med Chem. 2019;26(17):3009–25. doi:10.2174/0929867324666170804143706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Rui R, Zhou L, He S. Cancer immunotherapies: advances and bottlenecks. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1212476. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1212476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Topalian SL. Targeting immune checkpoints in cancer therapy. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1647–8. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.14155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Wang K, Coutifaris P, Brocks D, Wang G, Azar T, Solis S, et al. Combination anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapy generates waves of clonal responses that include progenitor-exhausted CD8+ T cells. Cancer Cell. 2024;42(9):1582–97.e10. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2024.08.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Lin X, Kang K, Chen P, Zeng Z, Li G, Xiong W, et al. Regulatory mechanisms of PD-1/PD-L1 in cancers. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

79. Yi J, Li B, Yin X, Liu L, Song C, Zhao Y, et al. CircMYBL2 facilitates hepatocellular carcinoma progression by regulating E2F1 expression. Oncol Res. 2024;32(6):1129–39. doi:10.32604/or.2024.047524. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Yuan Z, Li B, Liao W, Kang D, Deng X, Tang H, et al. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis of YBX family reveals YBX2 as a potential biomarker in liver cancer. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1382520. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1382520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Pang K, Shi ZD, Wei LY, Dong Y, Ma YY, Wang W, et al. Research progress of therapeutic effects and drug resistance of immunotherapy based on PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. Drug Resist Updat. 2023;66(5):100907. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2022.100907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Parvez A, Choudhary F, Mudgal P, Khan R, Qureshi KA, Farooqi H, et al. PD-1 and PD-L1: architects of immune symphony and immunotherapy breakthroughs in cancer treatment. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1296341. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1296341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Lim HY, Heo J, Kim T-Y, Tai WMD, Kang Y-K, Lau G, et al. Safety and efficacy of durvalumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: results from the phase 2 study 22 (NCT02519348). J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(4_suppl):436. [Google Scholar]

84. Kudo M. Scientific rationale for combined immunotherapy with PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies and VEGF inhibitors in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancers. 2020;12(5):1089. doi:10.3390/cancers12051089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894–905. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1915745. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Boutros C, Tarhini A, Routier E, Lambotte O, Ladurie FL, Carbonnel F, et al. Safety profiles of anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1 antibodies alone and in combination. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2016;13(8):473–86. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271(5256):1734–6. doi:10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Luo X, He X, Zhang X, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Shi Y, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: signaling pathways, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy. MedComm. 2024;5(2):e474. doi:10.1002/mco2.474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Zhang A, Fan T, Liu Y, Yu G, Li C, Jiang Z. Regulatory T cells in immune checkpoint blockade antitumor therapy. Mol Cancer. 2024;23(1):251. doi:10.1186/s12943-024-02156-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Dixon KO, Lahore GF, Kuchroo VK. Beyond T cell exhaustion: TIM-3 regulation of myeloid cells. Sci Immunol. 2024;9(93):eadf2223. doi:10.1126/sciimmunol.adf2223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Zhao L, Cheng S, Fan L, Zhang B, Xu S. TIM-3: an update on immunotherapy. Int Immunopharmacol. 2021;99:107933. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

92. Tsutsumi C, Ohuchida K, Tsutsumi H, Shimada Y, Yamada Y, Son K, et al. TIM3 on natural killer cells regulates antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in HER2-positive gastric cancer. Cancer Lett. 2024;611:217412. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.217412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Curigliano G, Curigliano H, Mach N, Doi T, Tai D, Forde PM, et al. Correction: phase I/Ib clinical trial of sabatolimab, an anti-TIM-3 antibody, alone and in combination with spartalizumab, an anti-PD-1 antibody, in advanced solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2024;30(17):3957. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-24-2131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Zhou X, Zhou F, Zhang L. Dual inhibition of PD-1 and LAG-3: uncovering mechanisms to reverse T cell exhaustion and enhance anti-tumor immunity. Sci Bull. 2024;70(5):624–6. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2024.11.029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Zhao Y, Hu Z, Bathena SP, Keidel S, Miller-Moslin K, Statkevich P, et al. Model-informed clinical pharmacology profile of a novel fixed-dose combination of nivolumab and relatlimab in adult and adolescent patients with solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2024;30(14):3050–8. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-23-2396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Guo Y, Yang X, Xia WL, Zhu WB, Li FT, Hu HT, et al. Relationship between TIGIT expression on T cells and the prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2024;24(1):1120. doi:10.1186/s12885-024-12876-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Assal RA, Elemam NM, Mekky RY, Attia AA, Soliman AH, Gomaa AI, et al. A novel epigenetic strategy to concurrently block immune checkpoints PD-1/PD-L1 and CD155/TIGIT in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Oncol. 2024;45(6):101961. doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2024.101961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Kudo M, Finn RS, Ikeda M, Sung MW, Baron AD, Okusaka T, et al. A phase 1b study of lenvatinib plus pembrolizumab in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: extended analysis of study 116. Liver Cancer. 2024;13(4):451–8. doi:10.1159/000535154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Diggs LP, Ruf B, Ma C, Heinrich B, Cui L, Zhang Q, et al. CD40-mediated immune cell activation enhances response to anti-PD-1 in murine intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2021;74(5):1145–54. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2020.11.037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Di Marco L, Pivetti A, Foschi FG, D.’Amico R, Schepis F, Caporali C, et al. Feasibility, safety, and outcome of second-line nivolumab/bevacizumab in liver transplant patients with recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2023;29(5):559–63. doi:10.1097/lvt.0000000000000087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Wu WC, Lin TY, Chen MH, Hung YP, Liu CA, Lee RC, et al. Lenvatinib combined with nivolumab in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma-real-world experience. Invest New Drugs. 2022;40(4):789–97. doi:10.1007/s10637-022-01248-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Jin ZC, Chen JJ, Zhu XL, Duan XH, Xin YJ, Zhong BY, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors and anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody/tyrosine kinase inhibitors with or without transarterial chemoembolization as first-line treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CHANCE2201a target trial emulation study. eClinicalMedicine. 2024;72:102622. doi:10.1016/j.annonc.2024.10.225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Ellerman DA. The evolving applications of bispecific antibodies: reaping the harvest of early sowing and planting new seeds. BioDrugs. 2024;39(1):75–102. doi:10.1007/s40259-024-00691-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Zeng W, Gouw AS, van den Heuvel MC, Zwiers PJ, Zondervan PE, Poppema S, et al. The angiogenic makeup of human hepatocellular carcinoma does not favor vascular endothelial growth factor/angiopoietin-driven sprouting neovascularization. Hepatology. 2008;48(5):1517–27. doi:10.1002/hep.22490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Zhu M, Wu Y, Zhu T, Chen J, Chen Z, Ding H, et al. Multifunctional bispecific nanovesicles targeting SLAMF7 trigger potent antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2024;12(8):1007–21. doi:10.1158/2326-6066.cir-23-1102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools