Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

UHMK1 Promotes Prostate Cancer Progression through a Positive Feedback Loop with MTHFD2

1 Department of Urology, The Third Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, 510630, China

2 Department of Ultrasound, Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, 510120, China

* Corresponding Authors: Hengjun Xiao. Email: ; Hua Wang. Email:

# These two authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Novel Biomarkers and Treatment Strategies in Solid Tumor Diagnosis, Progression, and Prognosis)

Oncology Research 2025, 33(9), 2331-2351. https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.065119

Received 04 March 2025; Accepted 09 July 2025; Issue published 28 August 2025

Abstract

Background: U2AF homology motif kinase 1 (UHMK1) has been associated with RNA processing and protein phosphorylation, thereby influencing tumor progression. The study aimed to explore its regulatory mechanisms and biological functions in human prostate cancer (PCa). Methods: In this study, we systematically evaluated the expression and prognostic significance of UHMK1 in public databases, followed by validation through immunohistochemistry (IHC) in PCa specimens. Both gain-of-function and loss-of-function experiments were conducted to elucidate the role of UHMK1 in vitro and in vivo. Additionally, a series of molecular and biochemical assays were performed to investigate the regulatory mechanisms underlying UHMK1 activity. Results: Our findings revealed that UHMK1 expression was significantly upregulated in PCa tissues and correlated with poor patient prognosis, as demonstrated by analysis of public datasets and confirmed by immunohistochemical staining. Functional studies showed that UHMK1 depletion suppressed tumor cell proliferation and metastasis, while its overexpression promoted these processes. Mechanistically, we identified that UHMK1 phosphorylates nuclear receptor coactivator 3 (NCOA3), which subsequently activates activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) to upregulate methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2 (MTHFD2) transcription. Interestingly, MTHFD2 was found to reciprocally enhance UHMK1 expression, establishing a positive feedback loop. Conclusions: In conclusion, our data suggest that the UHMK1-MTHFD2 axis forms a positive feedback loop that drives PCa progression. Targeting this loop represents a promising therapeutic strategy for restraining prostate cancer development and progression.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileProstate cancer (PCa) is one of the most prevalent cancers among men worldwide [1]. Approximately one-third of patients are diagnosed with advanced PCa at their first visit, rendering them ineligible for radical therapy [2–4]. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) remains the cornerstone of treatment at this stage [5]. While initially effective, ADT often becomes ineffective once PCa progresses to castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) [6]. Currently, limited effectiveness poses a significant clinical challenge in treating CRPC. Further research into PCa pathogenesis and molecular mechanisms may help aid in identifying novel treatment strategies for managing advanced PCa in the future.

U2AF homology motif kinase 1 (UHMK1) is a distinctive serine/threonine kinase initially identified as a regulator of the cell cycle [7,8]. UHMK1 has been shown to interact with various proteins, including splicing factor 1 (SF1) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA), suggesting roles in pre-mRNA splicing and other biological processes [9–11]. For example, elevated UHMK1 expression correlates with poor prognosis, while silencing UHMK1 inhibits tumor proliferation and xenograft growth in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma [12]. Moreover, in melanoma, UHMK1 inhibits tumor cell death by reprogramming mitochondrial metabolism [13]. However, the expression of UHMK1 in PCa is not clear, let alone its biological functions.

Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase 2 (MTHFD2) is widely recognized as a key enzyme involved in mitochondrial folate one-carbon metabolism [14]. MTHFD2 is considered bifunctional due to both its metabolic roles and nonenzymatic activities [15]. It has been shown to contribute to cancer proliferation and is thought to play a significant role in tumor development and progression [16–18]. By analyzing next-generation sequencing (NGS) data, we identified MTHFD2 as a potential downstream target of UHMK1. However, it remains to be tested whether MTHFD2 plays a specific role in the progression of PCa.

In this study, our aim was to investigate the expression of UHMK1 in prostate cancer, as well as its biological functions and regulatory mechanisms during prostate progression. Additionally, we further explored the interaction mechanism between UHMK1 and MTHFD2.

2.1 Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) and the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) Data Acquisition

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) data and associated clinical information for normal prostate and prostate cancer (PCa) tissues were sourced from the GTEx and TCGA databases (https://gtexportal.org/home/; https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov) (accessed on 8 July 2025). Patients with incomplete clinical data or unavailable survival data were excluded from this analysis. Samples were stratified according to their Gleason scores (GS) and N stages [19] for subsequent analysis.

2.2 Clinical Specimens and Survival Data

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) specimens (n = 6), PCa tissues (n = 112) and matched adjacent non-tumor normal tissues (GS < 7, n = 6; GS = 7, n = 6; GS > 7, n = 6) were obtained from patients treated at the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University between 2016 and 2020. Clinicopathological data and postoperative follow-up information were collected from 112 patients with prostate cancer. The experimental protocols involving human specimens in this study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Medical Ethics Board of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (II2023-059-01), and written informed consent was obtained from each subject.

2.3 Immunohistochemical (IHC) Staining

BPH and PCa specimens underwent fixation and processing for IHC following established protocols [20]. Sections were incubated with UHMK1 polyclonal primary antibody (1:100; Proteintech, 11624-1-AP, Chicago, IL, USA). Imaging was utilized with an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Staining intensity was graded: 0 (negative), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), 3 (strong). The percentage of stained cells was categorized: 0 (0%), 1 (<10%), 2 (11%–50%), 3 (51%–80%), 4 (>80%). The immunoreactive score (IRS) was calculated as the product of intensity and percentage scores (intensity grade × percentage score).

Proteins were extracted from tissues or whole cells using a Whole Cell Lysis Assay (KeyGenBioTECH, KGP250, Nanjing, China). Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were isolated with a Nuclear/Cytoplasmic Protein Extraction Kit (KeyGenBioTECH, KGP150), adhering to the supplier’s guidelines. Western blot analysis was performed using established methods [21]. Primary antibody specifics are listed in Table S1. Enhanced Chemiluminescence (ECL; Affinity, KF8005, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) enabled band detection, and ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, MD, USA) was utilized for density quantification.

2.5 Reverse Transcription Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from tissues or whole cells using the HP Total RNA Kit (Omega, R6812-02, Norcross, GA, USA) and reverse-transcribed with the PrimeScript RT Master Mix (Takara, RR036A, Otsu-shi, Japan). RT-qPCR was performed on a LightCycler 480 system (Roche, Indianapolis, IN, USA) using a TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (TliRNase HPlus) kit (Takara, RR820A, Otsu-shi, Japan). Relative mRNA expression was calculated via the 2−ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as the internal control. Primer sequences are listed in Table S2.

2.6 Cell Culture and Drug Treatments

RWPE-1, LNCaP, 22RV1, DU145, PC3, and HEK-293T cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). All the cell lines were subjected to Short Tandem Repeat (STR) authentication and confirmed to be mycoplasma-free. RWPE-1 cells were cultured in keratinocyte-serum-free medium (SFM; Gibco, 17005042, Grand Island, NY, USA), while LNCaP, 22RV1, and PC3 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco, 11875093) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, C0232). DU145 and HEK-293T cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Gibco, 11965092) with 10% FBS. All cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2. The small-molecule inhibitor DS18561882 was purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE, Monmouth Junction, NJ, USA) and was used in subsequent cell experiments at a final concentration of 50 μM. The phosphatase PP2A was purchased from MyBioSource (MBS1042952, San Diego, CA, USA) and was used in subsequent cell experiments at a final concentration of 10 μg/mL [22].

2.7 Sirna, Plasmid, and Lentivirus Transfection

siRNAs targeting UHMK1, MTHFD2, ATF4, NCOA3, and a negative control were synthesized by RiboBio (Guangzhou, China). Plasmids for UHMK1 overexpression and controls were produced by GeneChem (Shanghai, China). Transfections were conducted using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (Invitrogen, 11668-019, Carlsbad, CA, USA) as per the manufacturer’s instructions, with knockdown (in PC3 and DU145)/overexpression (in 22RV1) efficiency assessed by Western blotting 48 h post-transfection. Target sequences for siRNAs are provided in Table S3. For stable knockdown, lentiviruses carrying shRNA targeting UHMK1 (GV344hU6-MCS-Ubiquitin-firefly_Luciferase-IRES-puromycin) and a control vector were constructed by GeneChem. Following transfection into PC3 cells and selection with puromycin (2 μg/mL) for two weeks, stable lines were confirmed by Western blotting, using the target sequence 5′-GCCTATCACCTAAGAGACCTT-3′.

Cell viability was evaluated using Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK8; CK04, Dojindo, Kumamoto, Japan). PC3 (5 × 102 cells/well), DU145 (2 × 103 cells/well) and 22RV1 (1 × 103 cells/well) cells were seeded in 96-well plates and cultured for 1–5 days. At specified intervals, the medium was replaced with fresh culture medium containing 10 μL of CCK8 solution, followed by incubation for one hour at 37°C. Absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a microplate reader (Tecan, SPARK®10M, Männedorf, Switzerland).

Cells were seeded in 6-well plates (PC3, 1 × 105 cells/well; DU145 and 22RV1, 2 × 105 cells/well) and grown until 100% confluence, after which a scratch was created in the monolayer using a pipette tip. The medium was replaced with serum-free medium, and images were captured immediately and at 24 h (PC3) or 48 h (DU145 and 22RV1) post-scratch to assess wound closure, using an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

Cell invasion was assessed using 24-well BioCoat Matrigel Invasion Chambers (8 µm pore size, Corning, NY, USA). PC3 (3 × 104 cells/well), DU145 (8 × 104 cells/well) and 22RV1 (5 × 104 cells/well) cells were seeded in the top chamber with serum-free medium, while complete medium was added to the bottom chamber. After 24 h, invaded cells on the lower membrane surface were fixed, stained with 0.1% crystal violet, and counted under an Olympus IX71 inverted microscope (Tokyo, Japan).

2.11 Orthotopic Prostate Tumor Formation Assay

Four to six-week-old BALB/c nude male mice were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of Sun Yat-sen University. Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment (24 ± 2°C, 50 ± 5% humidity, 12-h light/dark cycle) with ad libitum access to food and water. Mice were randomly divided into two groups (six per group) by using a random number table. Under isoflurane (induction, 5%; maintenance 2%) inhalation anesthesia, the bilateral testes of the mice were removed, and then stable luciferase-expressing PC3 cells (UHMK1-silenced or control cells, 1 × 106 cells/mouse) were injected into the bilateral anterior prostate lobes using a syringe with a 31-gauge needle. After four weeks, bioluminescent signals were induced by intraperitoneal injection of D-luciferin (150 mg/kg) and imaged using an IVIS Spectrum System (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Mice were then humanely euthanized by carbon dioxide asphyxiation, and tumors were harvested for further analysis. All animal procedures complied with the ARRIVE guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sun Yat-sen University (SYSU-IACUC-2021-000777).

2.12 Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) Assay

ChIP was performed in PC3 and DU145 cells using the ChIP Assay Kit (Beyotime Biotechnology, P2078, Beijing, China) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Cross-linked chromatin was sonicated into 200- to 1000-bp fragments and immunoprecipitated with ATF4 antibody (1:200; Cell Signaling Technology, 11815, Danvers, MA, USA) or normal rabbit IgG antibody (1:200; Proteintech, B900610). Following purification, the immunoprecipitated DNA was amplified by PCR and analyzed via agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR primers for MTHFD2 included: upstream primer: 5′-GTCAAGGTGTTGACAGGATTGGT-3′ and downstream primer: 5′-TCAAAGTATCTCTCCCGCAAGGA-3′.

2.13 Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay

A dual-luciferase reporter assay was conducted in HEK-293T cells. Firefly promoter–luciferase reporter constructs (0.5 µg, MTHFD2-WT or MTHFD2-mutant promoter) were co-transfected with ATF4 plasmids (0.5 µg) using Lipofectamine 2000 Reagent (11668-019, Invitrogen). Renilla luciferase reporter (0.5 µg) served as an internal control. Luciferase activity was measured using a Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (E1910, Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The ATF4 plasmids, firefly promoter–luciferase reporters and renilla luciferase reporter used above were constructed by GeneChem.

2.14 Coimmunoprecipitation (CO-IP) Assay

Briefly, PC3 or DU145 cells were lysed using a Whole Cell Lysis Assay (KeyGenBioTECH, KGP250) and the lysates were incubated with NCOA3 antibody (1:50; Abcam, ab2831, Cambridge, MA, USA) or normal rabbit IgG antibody (1:50; Proteintech, B900610) overnight at 4°C. Then the complexes were immunoprecipitated using 20 µL Protein A+G Agarose (P2055, Beyotime Biotechnology) for three hours at 4°C. Following washes, samples were eluted with SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer (2×, pH = 6.8; P0015A, Beyotime Biotechnology) and boiled before Western blot analysis.

Metabolism-related gene sets were obtained from the GSEA Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB, https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb/index.jsp) (accessed on 8 July 2025). The raw sequencing expression matrices were converted by FPKM, and then each gene was Z-score normalized in the row direction to achieve comparability of expression levels among different genes. Finally, heatmaps were plotted using the pheatmap package in R (version 4.2.2, R Foundation, Vienna, Austria) to visualize the average expression levels of metabolism-related genes after UHMK1 knockdown. For heatmap visualization, sample R1802792 represents the negative control group (si-Con), and R1802791 represents the UHMK1 knockdown group (si-UHMK1). The potential binding sites of ATF4 in the promoter region of MTHFD2 were predicted using the JASPAR database (https://jaspar.genereg.net/) (accessed on 8 July 2025).

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 23.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). All in vitro experiments were performed in triplicate, with all data presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Differences between two groups were assessed using Student’s t-test, while one-way ANOVA followed by a Student–Newman–Keuls post hoc test was employed for multiple comparisons. The association between UHMK1 expression and clinicopathological characteristics was analyzed using the Chi-square test. Survival analysis was performed using the log-rank test based on Kaplan–Meier methods. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

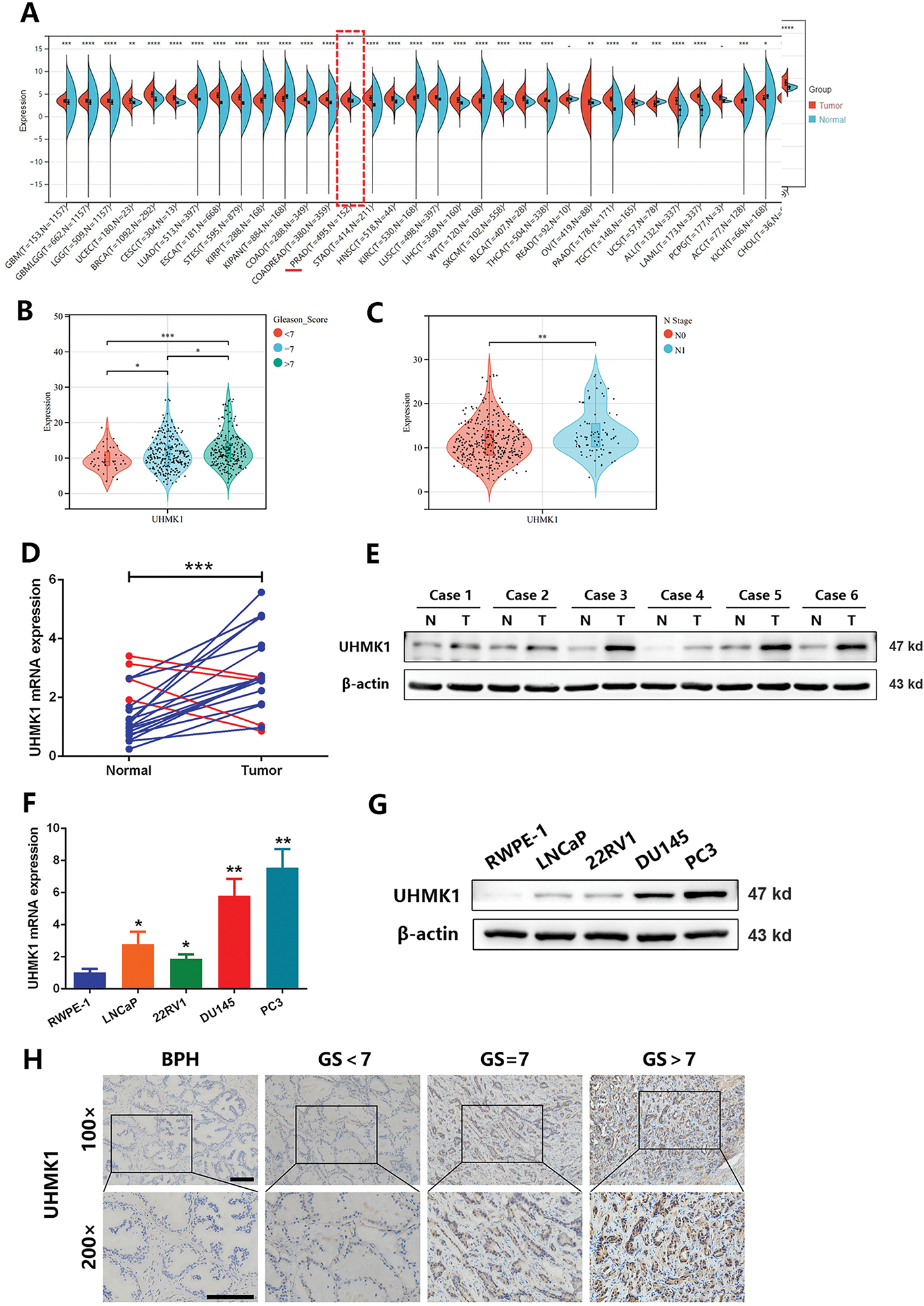

3.1 Elevated UHMK1 Expression in PCa Positively Correlates with Tumor Malignancy

Based on both TCGA and GTex public datasets, UHMK1 expression levels were significantly higher in PCa samples compared to normal samples. Increased UHMK1 expression was observed in patients with high Gleason scores and lymph node metastasis (Fig. 1A–C). RT-qPCR and Western blotting analyses of UHMK1 expression in PCa tissues and adjacent normal tissues showed that both mRNA and protein levels of UHMK1 were significantly elevated in PCa tissues compared to paracancerous tissues (Fig. 1D,E). In vitro, evaluations across PCa cell lines (LNCaP, 22RV1, DU145, PC3) compared to normal prostatic epithelial cells (RWPE-1) also displayed significantly heightened UHMK1 expression at both transcript and protein levels (Fig. 1F,G). IHC further validated UHMK1 upregulation in PCa compared to BPH tissues. Crucially, UHMK1 expression was strongly associated with Gleason score, tumor stage, and lymph node metastasis status, but not patient age (Figs. 1H,I and Table S4). Moreover, Kaplan–Meier analysis of our single-center cohort study involving 112 patients indicated that PCa patients with higher levels of UHMK1 had poorer biochemical recurrence (BCR)-free survival (Fig. 1J). Collectively, these findings establish UHMK1 overexpression in PCa as a feature linked to tumor malignancy.

Figure 1: U2AF Homology Motif Kinase 1 (UHMK1) is highly expressed in prostate cancer (PCa) and positively correlates with tumor malignancy. (A) UHMK1 mRNA expression levels across various cancers from the TCGA and GTEx datasets. (B) UHMK1 mRNA expression levels in PCa tissues with different Gleason scores from the TCGA database. (C) UHMK1 mRNA expression levels in stage N0-N1 PCa tissues from the TCGA database. (D) RT-qPCR analysis of UHMK1 mRNA expression in 20 pairs of PCa tumor tissues and adjacent normal tissues. Blue lines indicate an increased UHMK1 expression in tumors, whereas red lines indicate a decreased UHMK1 expression in tumors. (E) Western blot analysis of UHMK1 protein expression in pairs of matched PCa (T) and adjacent normal tissues (N). (F) RT-qPCR analysis of UHMK1 mRNA expression in different PCa cell lines. (G) Western blot analysis of UHMK1 protein expression in different PCa cell lines. (H, I) Representative IHC staining of UHMK1 in BPH and PCa tissues with different Gleason scores (GS) (scale bar = 100 μm; n = 6 per group). (J) Kaplan-Meier analysis of BCR-free survival for PCa patients with differential expression of UHMK1. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001

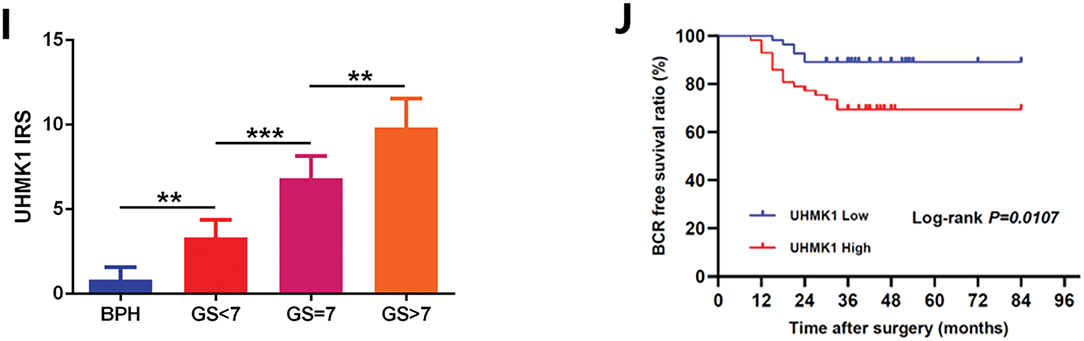

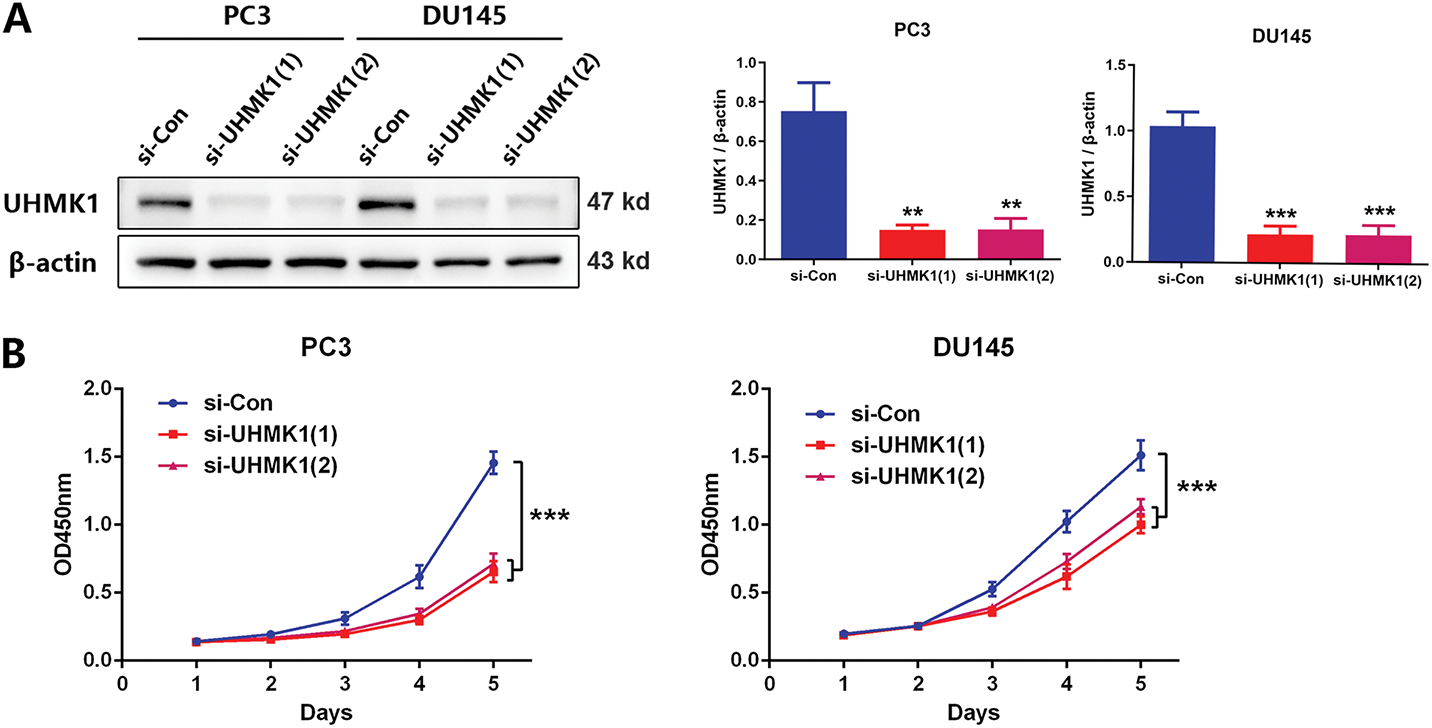

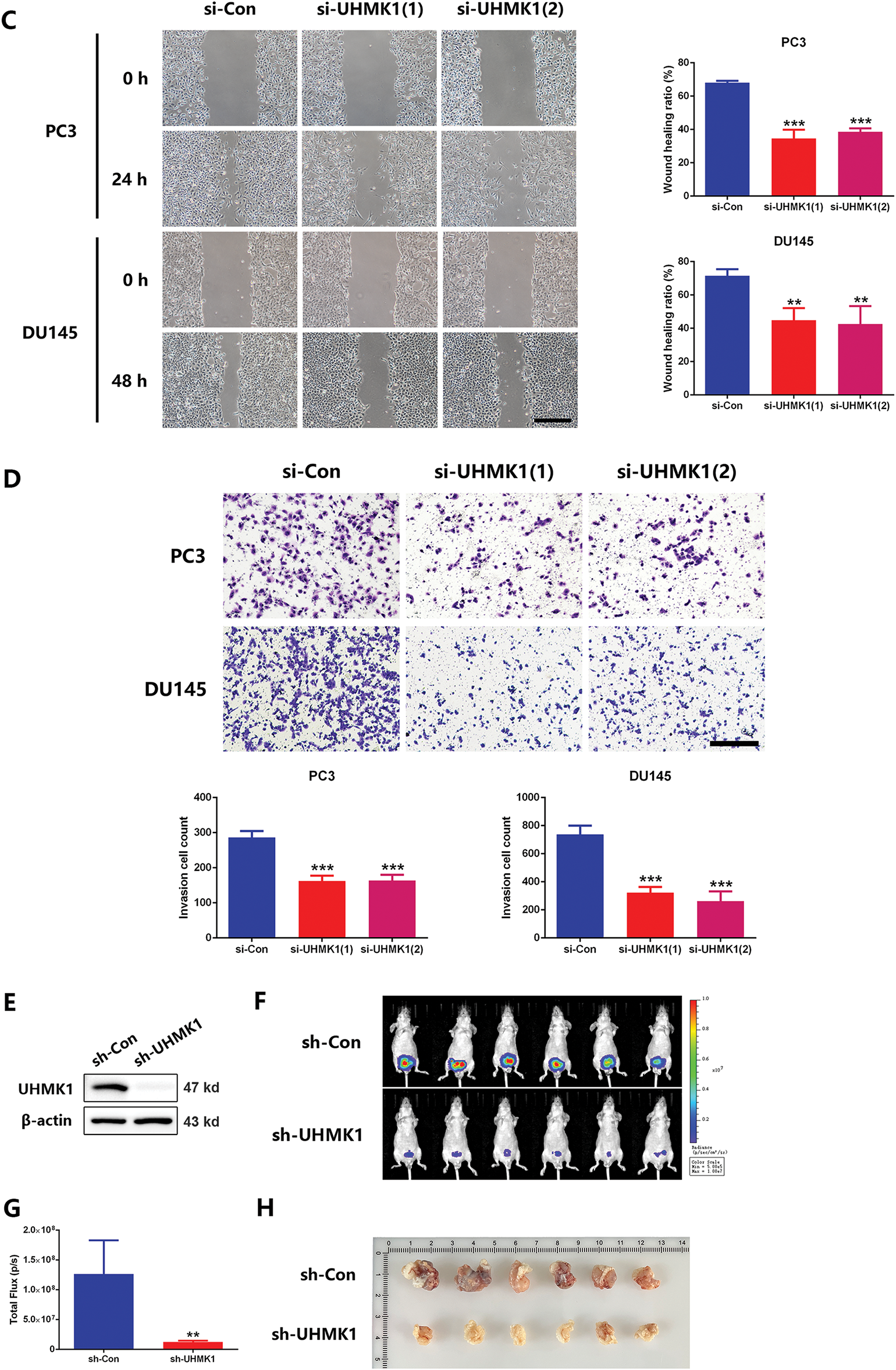

3.2 UHMK1 Promotes PCa Cell Proliferation and Invasion In Vitro and In Vivo

To delineate UHMK1’s functional role in PCa, we knocked down UHMK1 expression in PC3 and DU145 cells and overexpressed UHMK1 in 22RV1 cells (Fig. 2A; Fig. S1A). Western blot analysis showed that the knockdown efficiency of the two siRNA copies against UHMK1 was 80.2% and 79.8% in PC3 cells and 79.0% and 79.0% in DU145 cells, respectively. Depletion of UHMK1 significantly impaired the proliferation of PC3 and DU145 cells, whereas its overexpression enhanced proliferation in 22RV1 cells (Fig. 2B; Fig. S1B). Similarly, wound healing and cell invasion assays demonstrated that the migration and invasion abilities were decreased in PC3 and DU145 cells after UHMK1 knockdown but increased in 22RV1 cells after UHMK1 overexpression (Fig. 2C,D; Fig. S1C,D). To further evaluate the effect of UHMK1 on PCa tumorigenicity in vivo, we established an orthotopic human prostate tumor model by injecting stably silenced UHMK1 and control PC3 cells. UHMK1-silenced PC3 cells exhibited reduced tumorigenicity and formed smaller tumors compared to the control cells (Figs. 2E–H). Taken together, these data suggest that UHMK1 promotes PCa progression in vitro and vivo.

Figure 2: UHMK1 promotes PCa cell proliferation and invasion in vitro and in vivo. (A) Western blot analysis demonstrating the efficiency of UHMK1 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells. (B) CCK8 assay to assess the proliferation ability of PC3 and DU145 cells following UHMK1 knockdown. (C) Wound healing assay to assess the migratory capacity of PC3 and DU145 cells following UHMK1 knockdown (scale bar = 400 μm). (D) Cell invasion assay to assess the invasive capacity of PC3 and DU145 cells following UHMK1 knockdown (scale bar = 200 μm). (E) Western blot analysis demonstrating the efficiency of UHMK1 silencing in PC3 cells. (F, G) Bioluminescent images of tumor formation following xenografting of PC3 cells with UHMK1 silencing (n = 6 per group). (H) Gross images of tumors extracted from xenograft mice. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

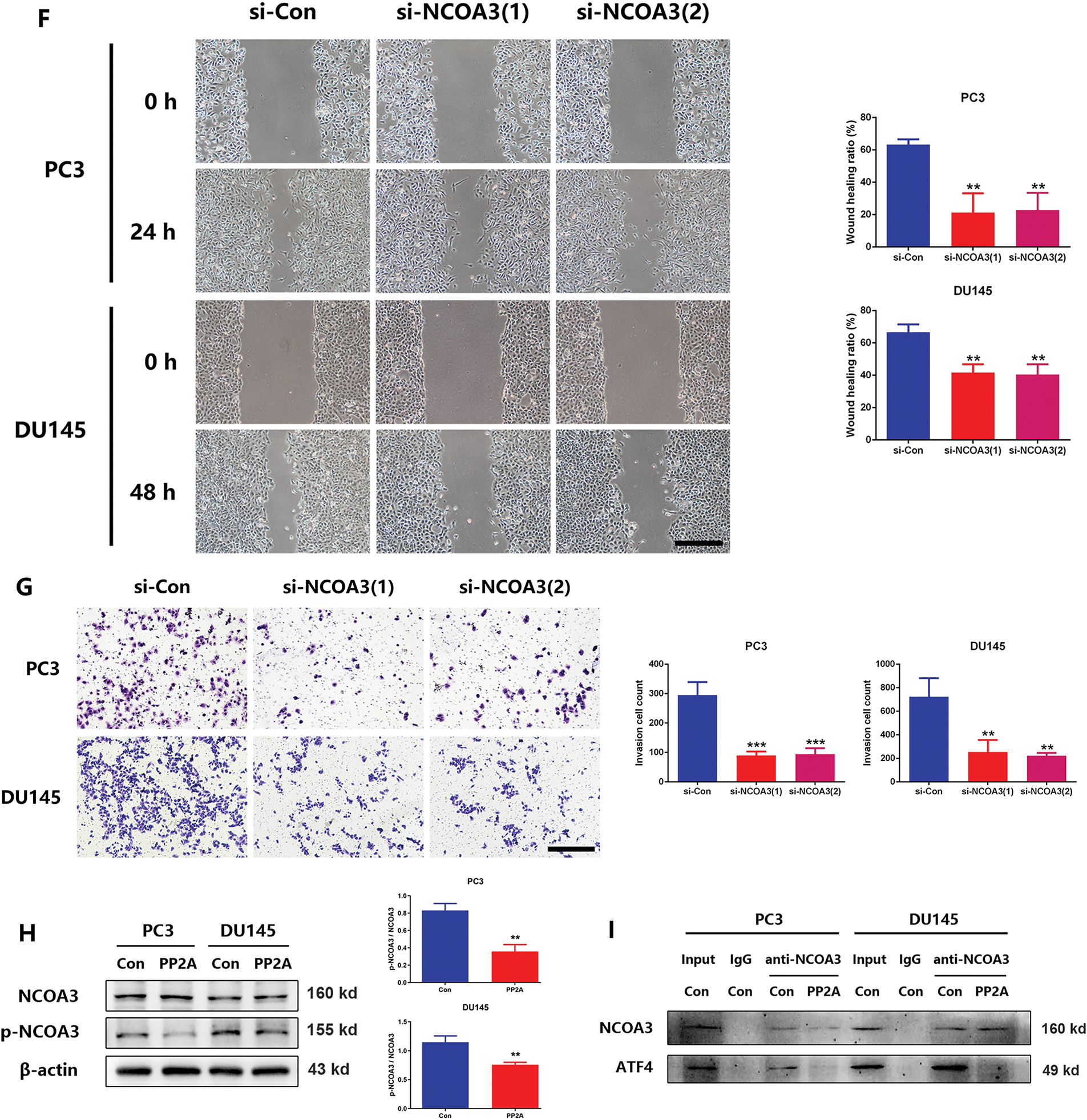

3.3 MTHFD2 Mediates the Role of UHMK1 in Promoting PCa Progression

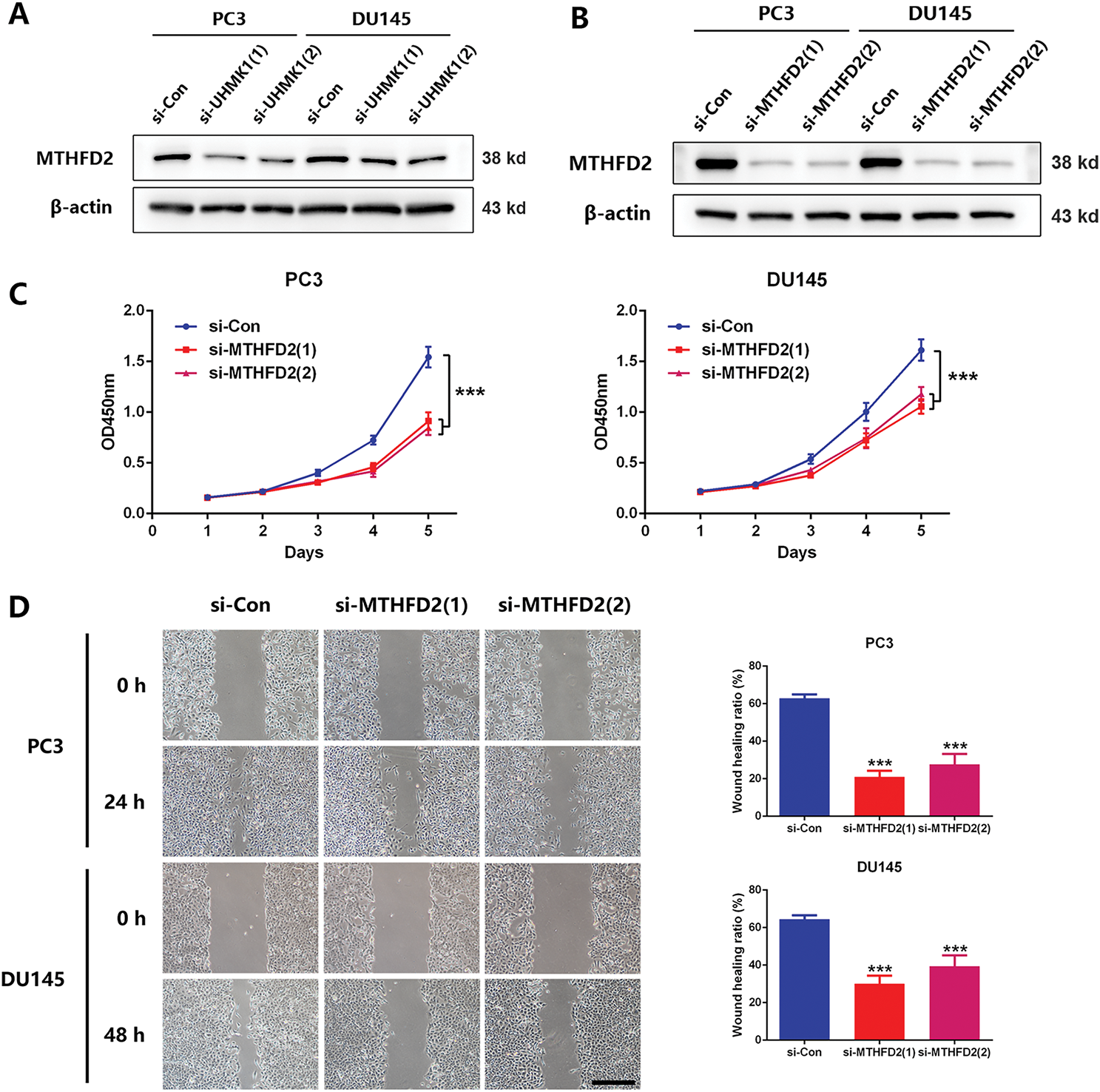

Based on NGS data, we identified a panel of nucleotide metabolism-related genes that may be regulated by UHMK1 (Fig. S2A). Subsequent RT-qPCR validation in UHMK1-knockdown PC3 and DU145 cells confirmed downregulation of PHGDH, PSAT1, PSPH, MTHFD2, DHFR, PPAT, and TYMS (Fig. S2B). Western blot assays showed that MTHFD2 expression was reduced after UHMK1 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells (Fig. 3A,B). Further in vitro experiments revealed that MTHFD2 knockdown inhibited the proliferation, migration and invasion of PC3 and DU145 cells (Fig. 3C–E). Moreover, DS18561882, a highly potent isozyme-selective inhibitor of MTHFD2, was capable of abrogating the aggressive behavior induced by UHMK1 overexpression in 22RV1 cells (Fig. S2C-F). All of the above results suggest that MTHFD2 is a downstream regulatory target of UHMK1 and mediates the role of UHMK1 in promoting PCa progression.

Figure 3: Methylenetetrahydrofolate Dehydrogenase (MTHFD2) mediates the role of UHMK1 in promoting PCa progression. (A) Western blot analysis of the protein levels of MTHFD2 following UHMK1 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells. (B) The confirmation of MTHFD2 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells by Western blot. (C) CCK8 assay to measure the proliferation ability of PC3 and DU145 cells following MTHFD2 knockdown. (D) Wound healing assay to measure the migratory capacity of PC3 and DU145 cells following MTHFD2 knockdown (scale bar = 400 μm). (E) Cell invasion assay to determine the invasive potential of PC3 and DU145 cells following MTHFD2 knockdown (scale bar = 200 μm). **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

3.4 UHMK1 Mediates MTHFD2 Expression via Activating ATF4

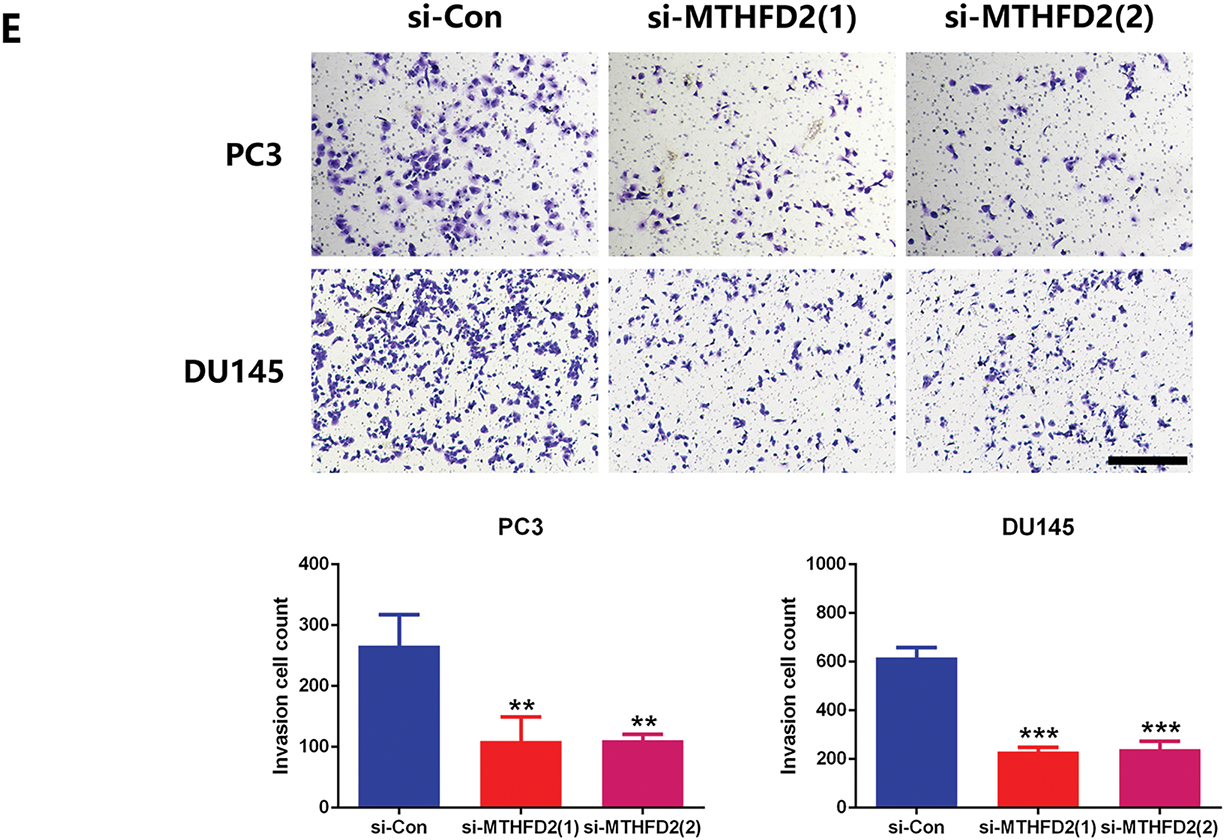

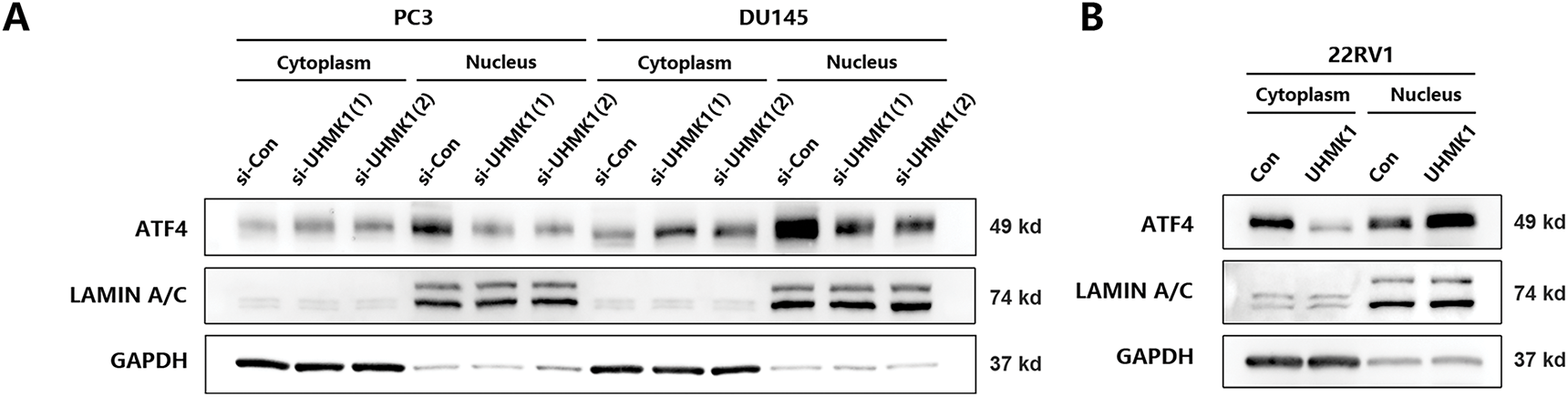

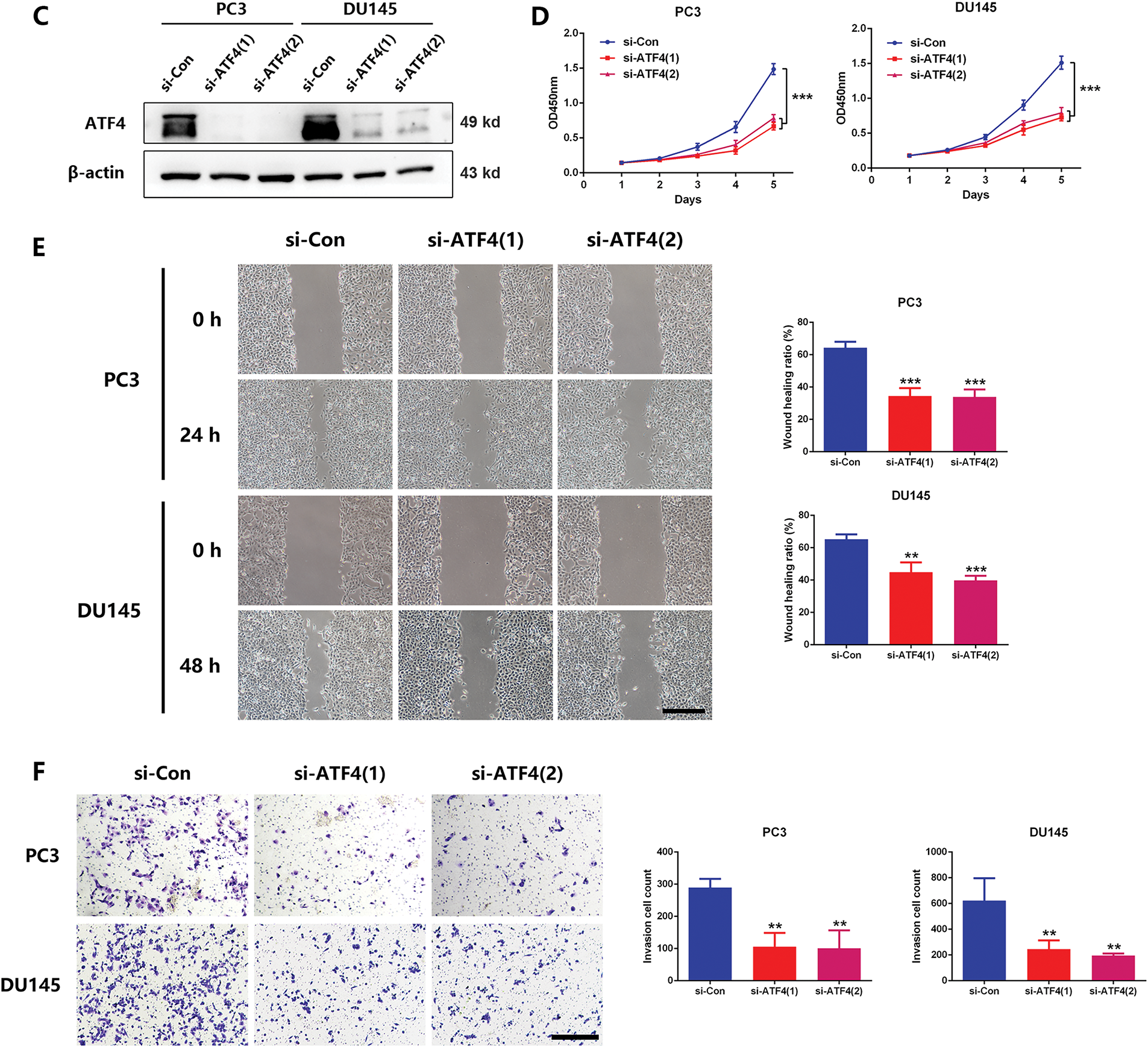

It has been reported that the expression of MTHFD2 was dependent on the stimulation of ATF4, a transcription factor whose nuclear translocation is essential for its transcriptional activity [23]. Therefore, we speculate whether ATF4 is involved in the regulation of MTHFD2 by UHMK1. Western blot analyses revealed that the nuclear protein level of ATF4 was reduced after UHMK1 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells, whereas the nuclear protein level of ATF4 was increased after UHMK1 overexpression in 22RV1 cells, indicating that UHMK1 influences the nuclear translocation of ATF4 (Fig. 4A,B). Additionally, knockdown of ATF4 significantly decreased the proliferation, migration, and invasion of PCa cells (Fig. 4C–F).

Figure 4: UHMK1 promotes the activation of Activating Transcription Factor 4(ATF4) to initiate MTHFD2 expression. (A) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear protein levels of ATF4 following UHMK1 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells. (B) Western blot analysis of cytoplasmic and nuclear protein levels of ATF4 following UHMK1 overexpression in 22RV1 cells. (C) Confirmation of ATF4 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells by Western blotting. (D) CCK8 assay to assess the proliferation ability of PC3 and DU145 cells following ATF4 knockdown. (E) Wound healing assay to assess the migratory ability of PC3 and DU145 cells following ATF4 knockdown (scale bar = 40 μm). (F) Cell invasion assay to assess the invasive ability of PC3 and DU145 cells following ATF4 knockdown (scale bar =200 μm). **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

To investigate whether ATF4 can transcriptionally activate MTHFD2 in PC3 cells, we first performed RT–qPCR and Western blot assays, which revealed that MTHFD2 mRNA and protein levels were decreased following ATF4 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells (Fig. S3A,B). Using the JASPAR database, then, we identified two potential ATF4 binding sites in the MTHFD2 promoter region (Fig. S3C). Mutation of these sites led to a significant reduction in MTHFD2-luciferase reporter activity, suggesting that ATF4 can transcriptionally activate the MTHFD2 promoter through these binding sites (Fig. S3D). Furthermore, ChIP assays confirmed that the ATF4 directly interacts with the MTHFD2 promoter (Fig. S3E). These findings indicate that UHMK1 enhances ATF4 activation, thereby initiating MTHFD2 expression in prostate cancer cells.

3.5 UHMK1-Induced Phosphorylation of NCOA3 Is Responsible for the Activation of ATF4

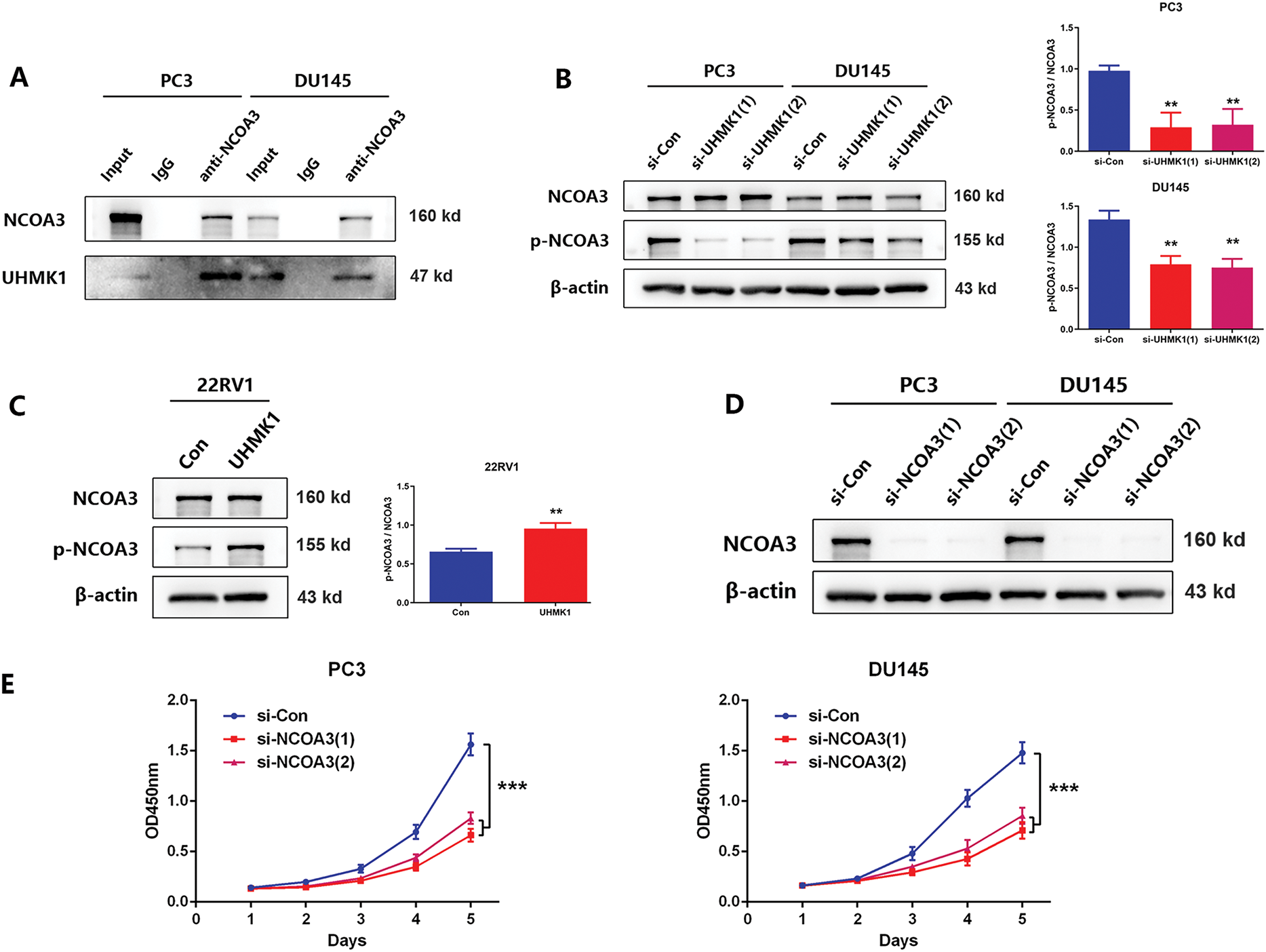

To explore the mechanism by which UHMK1 promotes the nuclear translocation of ATF4, we focused on NCOA3, a well-established coactivator of ATF4. CO-IP assays revealed an interaction between endogenous NCOA3 and UHMK1 in PCa cells (Fig. 5A). Western blot results demonstrated that phosphorylation levels of NCOA3 at serine 857 decreased following UHMK1 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells, whereas these levels increased following UHMK1 overexpression in 22RV1 cells, indicating that UHMK1 regulates NCOA3 phosphorylation at serine 857 (Fig. 5B,C). Furthermore, NCOA3 knockdown in PCa cells resulted in inhibition of cell proliferation, migration and invasion (Figs. 5D–G). These findings suggest that NCOA3 may be involved in UHMK1-mediated cancer progression.

Figure 5: UHMK1-induced phosphorylation of Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 3(NCOA3) was responsible for the activation of ATF4. (A) A Coimmunoprecipitation (CO-IP) assay revealed an interaction between endogenously expressed NCOA3 and UHMK1 in PC3 and DU145 cells. (B, C) Western blotting analyses were performed to evaluate NCOA3 and serine 857-phosphorylated NCOA3 protein expression following UHMK1 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells, and UHMK1 overexpression in 22RV1 cells. (D) Confirmation of NCOA3 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells by Western blot. (E) CCK8 assay to assess the proliferation ability of PC3 and DU145 cells following NCOA3 knockdown. (F) Wound healing assay to assess the migratory ability of PC3 and DU145 cells following NCOA3 knockdown (scale bar = 400 μm). (G) Cell invasion assay to evaluate the invasive ability of PC3 and DU145 cells following NCOA3 knockdown (scale bar = 200 μm). (H) Western blotting analyses were performed to evaluate NCOA3 and phosphorylated NCOA3 protein expression following PP2A treatment in PC3 and DU145 cells. (I) CO-IP assay to evaluate the binding of NCOA3 to ATF4 and the effect of PP2A on this binding. (J) Western blotting analyses were performed to assess cytoplasmic and nuclear ATF4 protein expression following NCOA3 knockdown or PP2A treatment in PC3 and DU145 cells. **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Recent studies have shown that phosphorylated NCOA3 is recruited by ATF4 to form transcriptional complexes, initiating nuclear translocation and regulating downstream gene expression [24]. To verify that phosphorylated NCOA3 binds to ATF4, PP2A (a phosphatase that inhibits NCOA3 phosphorylation) was used to pretreat PCa cells [25]. Following PP2A treatment, NCOA3 phosphorylation at serine 857 was significantly reduced in PC3 and DU145 cells (Fig. 5H). CO-IP assays revealed that NCOA3 directly binds to ATF4, and this interaction was inhibited by PP2A (Fig. 5I). Subsequently, we focused on whether phosphorylated NCOA3 induces nuclear translocation of ATF4 and used PP2A to inhibit this process in vitro. Western blot analyses further confirmed that the nuclear translocation of ATF4 was significantly blocked following PP2A treatment, which inhibited NCOA3 phosphorylation (Fig. 5J). These results suggested that UHMK1-dependent phosphorylation of NCOA3 at serine 857 may be responsible for initiating ATF4 activation.

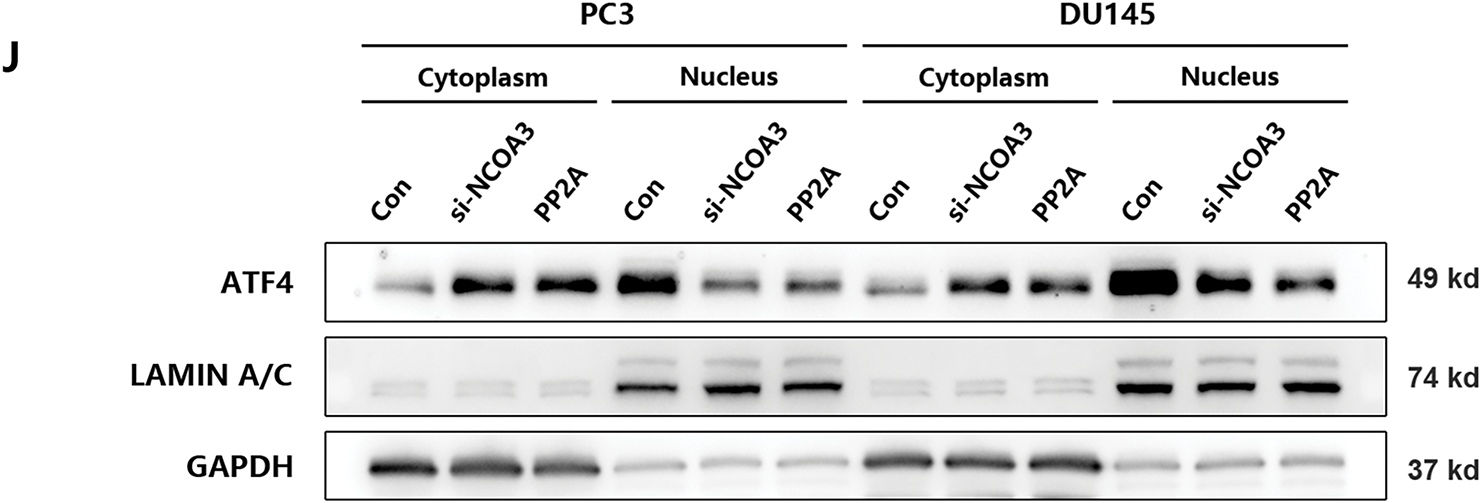

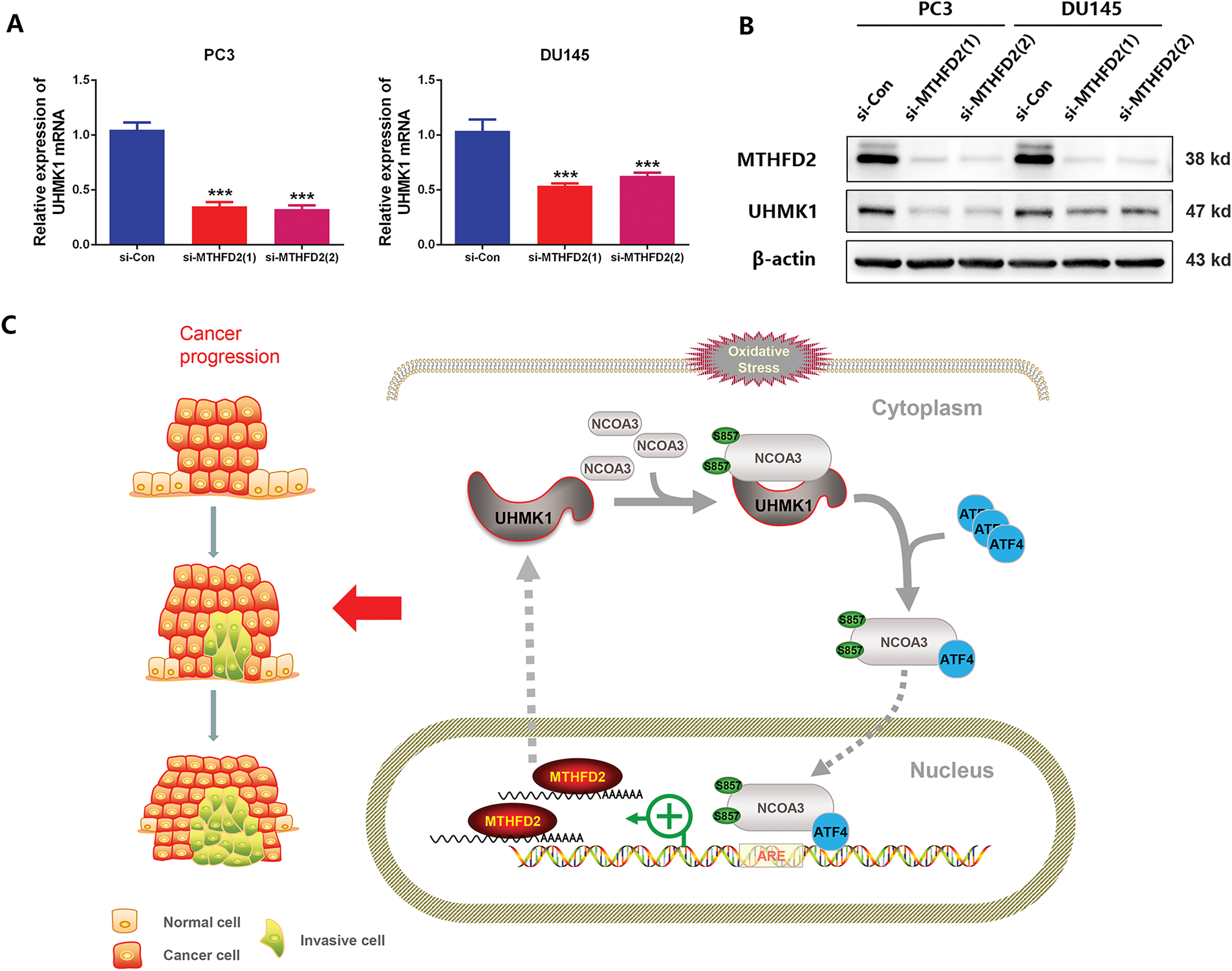

3.6 A Positive Feedback Loop Exists between UHMK1 and MTHFD2

Previously, we demonstrated that UHMK1 enhances MTHFD2 expression by promoting NCOA3 phosphorylation and ATF4 nuclear translocation. Interestingly, we also observed that silencing MTHFD2 in PC3 and DU145 cells led to significant reductions in both the mRNA and protein levels of UHMK1 (Fig. 6A,B). These findings suggest that MTHFD2 regulates UHMK1 expression. Collectively, our results indicate the existence of a positive feedback loop between UHMK1 and MTHFD2, sustaining continuous activation of this signaling pathway and facilitating tumor progression (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6: A positive feedback loop exists between UHMK1 and MTHFD2. (A) RT-qPCR was performed to assess the mRNA level of UHMK1 following MTHFD2 knockdown in PC3 and DU145 cells. (B) Western blotting was performed to evaluate UHMK1 protein expression under the same conditions. (C) A schematic illustrating the role of the UHMK1/MTHFD2 positive feedback loop in PCa progression (created using ScienceSlides-PowerPoint (PPT) software). ***p < 0.001

UHMK1 dysregulation or mutation represents a high-penetrance factor implicated in diverse cancers [26–28]. In colorectal cancer, hyperactivating UHMK1/STAT3 positive feedback loop contributes to colorectal cancer cell proliferation and chemoresistance. Additionally, EBLN3P overexpression enhances tumorigenesis by attenuating miR-323a-3p-mediated suppression of UHMK1 [29,30]. Studies investigating the role of Ser/Thr kinase in the progression of PCa have gained increasing attention in recent years [31–33]. However, the biological function of UHMK1, a Ser/Thr kinase, in the development of PCa remains unclear. In our study, we observed that UHMK1 was aberrantly overexpressed in PCa, a finding further confirmed by public TCGA and GTEx datasets. Analysis of our 7-year follow-up data revealed that higher UHMK1 expression was significantly correlated with poorer BCR-free survival. Furthermore, we demonstrated that UHMK1 upregulation in PCa significantly enhanced tumor growth and dissemination. Collectively, these findings suggest that UHMK1 functions as an oncogene and is associated with poor prognosis.

As mentioned earlier, UHMK1 has been recognized as a critical downstream effector of many signaling pathways that drive cancer proliferation and invasion [34–36]. We suggest that the unidentified downstream signaling cascade of UHMK1 is essential for regulating the aforementioned processes. Recently, Feng et al. found that UHMK1 enhances gastric cancer progression by increasing de novo purine synthesis, indicating metabolic reprogrammed as a key factor in cancer progression [37]. In this study, we identified several potential downstream targets of UHMK1 in PCa related to serine, purine, and amino acid metabolism and one-carbon metabolism through transcriptome sequencing. These pathways are essential for nucleotide synthesis, suggesting that UHMK1 may also be involved in nucleotide metabolic reprogramming in PCa. Given that serine, purine and amino acid metabolism supply precursors for one-carbon metabolism, we hypothesize that targeting one-carbon metabolism could effectively suppress tumor growth [38]. Therefore, we focused on MTHFD2, a key regulator in the mitochondrial one-carbon pathway, which is overexpressed in various tumors [39–41]. In lung cancer, MTHFD2 is activated by ATF4 to maintain redox homeostasis and contributes to cancer progression by regulating AKT/GSK-3β/β-catenin signaling [42,43]. In PCa, we found that MTHFD2 knockdown significantly inhibited cell aggression, likely due to its roles in nucleotide synthesis, S-adenosyl methionine biosynthesis and redox homeostasis. Moreover, MTHFD2 inhibition reversed UHMK1-induced PCa aggressiveness, suggesting that MTHFD2 is critical for UHMK1-mediated behaviors. Interestingly, we also discovered that MTHFD2 could regulate UHMK1 expression. Possibly through specific transcription factors, warranting further investigation. This study is the first to propose a UHMK1/MTHFD2 positive feedback loop in PCa progression, potentially involving nucleotide metabolism reprogramming.

Mechanistically, we identified ATF4 as a downstream effector of UHMK1. Tameire et al. showed that c-myc drives ATF4 nuclear enrichment to meet bioenergetic demands during tumor progression [44]. In this study, UHMK1 knockdown enhanced ATF4 nuclear translocation without affecting its mRNA levels, suggesting that UHMK1 is crucial for ATF4 activation. Moreover, Ben-Sahra et al. revealed that ATF4 stimulates MTHFD2 to enhance de novo purine synthesis in several cancers [45]. Here, we found that ATF4 knockdown inhibited MTHFD2 expression and restrained PCa cell growth and dissemination. Promoter sequence analysis revealed two potential ATF4 binding sites in the MTHFD2 promoter, and dual-luciferase reporter and ChIP assays confirmed direct interaction between ATF4 and the MTHFD2 promoter. These data strongly suggest that ATF4 is a key signal transducer in the UHMK1/MTHFD2 positive feedback loop.

NCOA3 is a coactivator that collaborates with transcription factors in tumorigenesis [46]. Gupta et al. suggested that NCOA3 is the key effector in activating the PERK-ATF4 pathway in breast cancer [24]. Our data concluded that NCOA3 binds to ATF4, forming a protein complex that acts as a direct coactivator for ATF4 activation. Given that hyperactivation of NCOA3 is common in many tumors, its posttranslational modification, particularly phosphorylation, has recently gained increasing attention [47–49]. It has been noted that phosphorylation of NCOA3 is required for the regulation of its transcriptional activity, which is closely correlated with protein stability, flexibility and subcellular localization [50,51]. In a previous report, phosphorylated NCOA3 at serine 857 has been shown to enhance ATF4 transcriptional activity [23,52]. Our findings demonstrate that phosphorylation of NCOA3 at serine 857 plays a role in UHMK1-mediated ATF4 transcriptional activity in PCa. However, additional experimental studies are required to confirm whether phosphorylation at this specific site is essential for ATF4 activation.

This study has certain limitations. We identified a positive feedback loop between UHMK1 and MTHFD2 and confirmed that UHMK1 enhances MTHFD2 expression by promoting NCOA3 phosphorylation and ATF4 nuclear translocation. However, the specific mechanism by which MTHFD2 reciprocally regulates UHMK1 expression remains unclear, particularly given that MTHFD2 is primarily localized to the mitochondria, whereas UHMK1 is in the nucleus and cytoplasm. Additionally, the exact phosphorylation site of NCOA3 induced by UHMK1 requires further investigation. Furthermore, although we explored the role of UHMK1, an oncoprotein, in PCa as a potential therapeutic target, the literature on specific chemical inhibitors targeting UHMK1 is limited. Based on current research, certain known compounds may offer valuable insights for future research. For instance, Le et al. reported that trastuzumab can concentration-dependently inhibit UHMK1 expression in breast cancer [53]. Additionally, FMF-06-098-1, a multitargeted inhibitor, promotes the degradation of UHMK1 via a kinase degradation pathway [54]. All these compounds’ clinical efficacy requires further validation. These issues represent critical directions for our future research.

This study provides strong evidence that UHMK1 contributes to PCa progression through a UHMK1/MTHFD2 positive feedback loop, suggesting that UHMK1 might be a potential biomarker and attractive therapeutic target for advanced PCa.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81902617 and 82100816), Guangdong Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 2021A1515012322), and Guangzhou Basic and Applied Basic Research Subject-Young Doctor’s “Sailing” Project (Grant No. 2024A04J4702).

Author Contributions: Chi Zhang: Writing—original draft, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation. Xi Huang: Validation, Investigation, Data curation. Cheng Hu: Formal analysis, Data curation. Bowen Tang: Visualization, Validation. Jianjie Wu, Weian Zhu: Formal analysis, Data curation. Zhuolun Sun: Visualization, Validation. Xiangfu Zhou: Writing—review & editing. Hengjun Xiao: Writing—review & editing, Supervision, Investigation, Conceptualization. Hua Wang: Writing—original draft, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The experimental protocols involving human specimens in this study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Medical Ethics Board of the Third Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University (II2023-059-01), and written informed consent was obtained from each subject. All animal procedures complied with the ARRIVE guidelines and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Sun Yat-sen University (SYSU-IACUC-2021-000777).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/or.2025.065119/s1.

Abbreviations

| UHMK1 | U2AF Homology Motif Kinase 1 |

| NCOA3 | Nuclear Receptor Coactivator 3 |

| MTHFD2 | Methylenetetrahydrofolate Dehydrogenase 2 |

| SF1 | Splicing Factor 1 |

| AMPA | α-Amino-3-Hydroxy-5-Methyl-4-Isoxazolepropionic Acid |

| ATF4 | Activating Transcription Factor 4 |

| PCa | Prostate Cancer |

| IHC | Immunohistochemistry |

| ADT | Androgen Deprivation Therapy |

| CRPC | Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer |

| NGS | Next-Generation Sequencing |

| BPH | Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia |

| IRS | Immunoreactive Score |

| ECL | Enhanced Chemiluminescence |

| ATCC | American Type Culture Collection |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| SPF | Specific Pathogen-Free |

| Chip | Chromatin Immunoprecipitation |

| CO-IP | Coimmunoprecipitation |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| BCR | Biochemical Recurrence |

References

1. Siegel RL, Kratzer TB, Giaquinto AN, Sung H, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. 2025 CA Cancer J Clin. 2025;75(1):10–45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

2. Daher M, Telvizian T, Dagher C, Abdul-Sater Z, Massih SA, Chediak AE, et al. High rates of advanced prostate cancer in the Middle East: analysis from a tertiary care center. Urology Annals. 2021;13(4):418–23. doi:10.4103/ua.ua_47_20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Pauchard F, Kramer F, Kirmayr M, Escobar M. Stage at diagnosis of prostate cancer in an institutional hospital. Review and comparison of national and international data. Rev Med Chil. 2023;151(6):711–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

4. Sekhoacha M, Riet K, Motloung P, Gumenku L, Adegoke A, Mashele S. Prostate cancer review: genetics. Diagnosis Treatment Options, and Alternative Approaches. Molecules. 2022;27(17):5730. doi:10.3390/molecules27175730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Desai MH, Parsi M, Potdar RR. Triple-arm androgen blockade for advanced prostate cancer: a review. Med Oncol. 2021;38(7):75. doi:10.1007/s12032-021-01520-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Schaeffer EM, Srinivas S, Adra N, An Y, Barocas D, Bitting R, et al. Prostate cancer, version 4.2023, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21(10):1067–96. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2010.0010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Boehm M, Yoshimoto T, Crook MF, Nallamshetty S, True A, Nabel GJ, et al. A growth factor-dependent nuclear kinase phosphorylates p27(Kip1) and regulates cell cycle progression. EMBO J. 2002;21(13):3390–401. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdf343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Arfelli VC, Chang YC, Bagnoli JW, Kerbs P, Ciamponi FE, Paz L, et al. UHMK1 is a novel splicing regulatory kinase. J Biol Chem. 2023;299(4):103041. doi:10.1101/2022.05.21.492919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Manceau V, Kielkopf CL, Sobel A, Maucuer A. Different requirements of the kinase and UHM domains of KIS for its nuclear localization and binding to splicing factors. J Mol Biol. 2008;381(3):748–62. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2008.06.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Pedraza N, Ortiz R, Cornado A, Llobet A, Aldea M, Gallego C. KIS, a kinase associated with microtubule regulators, enhances translation of AMPA receptors and stimulates dendritic spine remodeling. J Neurosci. 2014;34(42):13988–97. doi:10.1523/jneurosci.1573-14.2014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Manceau V, Swenson M, Le Caer JP, Sobel A, Kielkopf CL, Maucuer A. Major phosphorylation of SF1 on adjacent Ser-Pro motifs enhances interaction with U2AF65. FEBS J. 2006;273(3):577–87. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05091.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Luo Y, Han S, Yan B, Ji H, Zhao L, Gladkich J, et al. UHMK1 is a novel marker for personalized prediction of pancreatic cancer prognosis. Front Oncol. 2022;12:834647. doi:10.3389/fonc.2022.834647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Smith LK, Parmenter T, Kleinschmidt M, Kusnadi EP, Kang J, Martin CA, et al. Adaptive translational reprogramming of metabolism limits the response to targeted therapy in BRAF(V600) melanoma. Nat Commun. 2022;13(1):1100. doi:10.1101/626952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ramos L, Henriksson M, Helleday T, Green AC. Targeting MTHFD2 to exploit cancer-specific metabolism and the DNA damage response. Cancer Res. 2024;84(1):9–16. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-23-1290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhu Z, Leung G. More than a metabolic enzyme: mTHFD2 as a novel target for anticancer therapy? Front Oncol. 2020;10:658. doi:10.3389/fonc.2020.00658. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Shang M, Yang H, Yang R, Chen T, Fu Y, Li Y, et al. The folate cycle enzyme MTHFD2 induces cancer immune evasion through PD-L1 up-regulation. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):1940. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-22173-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Liu X, Liu S, Piao C, Zhang Z, Zhang X, Jiang Y, et al. Non-metabolic function of MTHFD2 activates CDK2 in bladder cancer. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(12):4909–19. doi:10.1111/cas.15159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhu L, Liu X, Zhang W, Hu H, Wang Q, Xu K. MTHFD2 is a potential oncogene for its strong association with poor prognosis and high level of immune infiltrates in urothelial carcinomas of bladder. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):556. doi:10.1186/s12885-022-09606-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Cornford P, van den Bergh RCN, Briers E, Van den Broeck T, Brunckhorst O, Darraugh J, et al. EAU-EANM-ESTRO-ESUR-ISUP-SIOG guidelines on prostate cancer-2024 update. Part I: screening, diagnosis, and local treatment with curative intent. Eur Urol. 2024;86(2):148–63. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2025.02.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sun Z, Mao Y, Zhang X, Lu S, Wang H, Zhang C, et al. Identification of ARHGEF38, NETO2, GOLM1, and SAPCD2 associated with prostate cancer progression by bioinformatic analysis and experimental validation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:718638. doi:10.3389/fcell.2021.718638. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Huang Y, Su M, Zhang C, Zhan H, Yang F, Gao Z, et al. Activation of translocator protein alleviates mechanical allodynia and bladder dysfunction in cyclophosphamide-induced cystitis through repression of BDNF-mediated neuroinflammation. Eur J Pain. 2022;26(6):1234–44. doi:10.1002/ejp.1942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Yang J, Fan GH, Wadzinski BE, Sakurai H, Richmond A. Protein phosphatase 2A interacts with and directly dephosphorylates RelA. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(51):47828–33. doi:10.1074/jbc.m106103200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Dasgupta S, Rajapakshe K, Zhu B, Nikolai B, Yi P, Putluri N, et al. Metabolic enzyme PFKFB4 activates transcriptional coactivator SRC-3 to drive breast cancer. Nature. 2018;556(7700):249–54. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0018-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Gupta A, Hossain MM, Miller N, Kerin M, Callagy G, Gupta S. NCOA3 coactivator is a transcriptional target of XBP1 and regulates PERK-eIF2α-ATF4 signalling in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2016;35(45):5860–71. doi:10.1038/onc.2016.121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Amsailale R, Beyaert M, Smal C, Janssens V, Van Den Neste E, Bontemps F. Protein phosphatase 2A regulates deoxycytidine kinase activity via Ser-74 dephosphorylation. FEBS Lett. 2014;588(5):727–32. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.01.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li Y, Wang S, Jin K, Jin W, Si L, Zhang H, et al. UHMK1 promotes lung adenocarcinoma oncogenesis by regulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Thoracic Cancer. 2023;14(12):1077–88. doi:10.1111/1759-7714.14850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang X, Feng Y, Gao F, Li T, Guo Y, Ge S, et al. Expression and clinical significance of U2AF homology motif kinase 1 in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Surg, Oral Med, Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2024;138(5):626–34. doi:10.1016/j.oooo.2024.07.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Niu H, Zhao M, Huang J, Wang J, Si Y, Cheng S, et al. UHMK1-dependent phosphorylation of Cajal body protein coilin alters 5-FU sensitivity in colon cancer cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2022;20(1):18. doi:10.1186/s12964-022-00820-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Xu XH, Song W, Li JH, Huang ZQ, Liu YF, Bao Q, et al. Long Non-coding RNA EBLN3P Regulates UHMK1 Expression by Sponging miR-323a-3p and promotes colorectal cancer progression. Front Med. 2021;8:651600. doi:10.3389/fmed.2021.651600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Gao X, Bao W, Bai J, Fan K, Li L, Li Y. UHMK1 aids colorectal cancer cell proliferation and chemoresistance through augmenting IL-6/STAT3 signaling. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(5):424. doi:10.1038/s41419-022-04877-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Chen H, Dong K, Ding J, Xia J, Qu F, Lan F, et al. CRISPR genome-wide screening identifies PAK1 as a critical driver of ARSI cross-resistance in prostate cancer progression. Cancer Lett. 2024;587:216725. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Ma J, Li L, Ma B, Liu T, Wang Z, Ye Q, et al. MYC induces CDK4/6 inhibitors resistance by promoting pRB1 degradation. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):1871. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-45796-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. He T, Li NX, Pan ZJ, Zou ZH, Chen JC, Yu SZ, et al. Serine/threonine kinase 36 induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition promotes docetaxel resistance in prostate cancer. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):729. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-51360-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Wu ZZ, Xu Q. Bladder cancer-associated transcript 1 promotes melanoma cell proliferation and invasion via the miR-374b-5p/U2-associated factor homology motif kinase 1 axis. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2022;38(2):97–107. doi:10.1002/kjm2.12463. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Wei T, Weiler SME, Toth M, Sticht C, Lutz T, Thomann S, et al. YAP-dependent induction of UHMK1 supports nuclear enrichment of the oncogene MYBL2 and proliferation in liver cancer cells. Oncogene. 2019;38(27):5541–50. doi:10.1038/s41388-019-0801-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Barbutti I, Machado-Neto JA, Arfelli VC, de Melo Campos P, Traina F, Saad STO, et al. The U2AF homology motif kinase 1 (UHMK1) is upregulated upon hematopoietic cell differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2018;1864(3):959–66. doi:10.1101/187385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Feng X, Ma D, Zhao J, Song Y, Zhu Y, Zhou Q, et al. UHMK1 promotes gastric cancer progression through reprogramming nucleotide metabolism. EMBO J. 2020;39(5):e102541. doi:10.15252/embj.2019102541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Labuschagne CF, van den Broek NJ, Mackay GM, Vousden KH, Maddocks OD. Serine, but not glycine, supports one-carbon metabolism and proliferation of cancer cells. Cell Rep. 2014;7(4):1248–58. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhu Z, Kiang K, Li N, Liu J, Zhang P, Jin L, et al. Folate enzyme MTHFD2 links one-carbon metabolism to unfolded protein response in glioblastoma. Cancer Lett. 2022;549(4):215903. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2022.215903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Mo J, Gao Z, Zheng L, Yan M, Xue M, Xu J, et al. Targeting mitochondrial one-carbon enzyme MTHFD2 together with pemetrexed confers therapeutic advantages in lung adenocarcinoma. Cell Death Discov. 2022;8(1):307. doi:10.1038/s41420-022-01098-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Liu J, Huang G, Lin H, Yang R, Zhan W, Luo C, et al. MTHFD2 enhances cMYC O-GlcNAcylation to promote sunitinib resistance in renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2025;85(6):1113–29. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-24-0050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Shi Y, Xu Y, Yao J, Yan C, Su H, Zhang X, et al. MTHFD2 promotes tumorigenesis and metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma by regulating AKT/GSK-3β/β-catenin signalling. J Cell Mol Med. 2021;25(14):7013–27. doi:10.1111/jcmm.16715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Gao Y, Feng L, Zhang L, Geng J, Zhang E. ATF4/MYC regulates MTHFD2 to promote NSCLC progression by mediating redox homeostasis. Dis Markers. 2022;2022(2):7527996. doi:10.1155/2022/7527996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Tameire F, Verginadis I, Leli N, Polte C, Conn C, Ojha R, et al. ATF4 couples MYC-dependent translational activity to bioenergetic demands during tumour progression. Nat Cell Biol. 2019;21(7):889–99. doi:10.1038/s41556-019-0347-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Ben-Sahra I, Hoxhaj G, Ricoult S, Asara J, Manning B. mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science. 2016;351(6274):728–33. doi:10.1126/science.aad0489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Li L, Deng C, Chen Q. SRC-3, a steroid receptor coactivator: implication in cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(9):4760. doi:10.3390/ijms22094760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Ma G, Ren Y, Wang K, He J. SRC-3 has a role in cancer other than as a nuclear receptor coactivator. Int J Biol Sci. 2011;7(5):664–72. doi:10.7150/ijbs.7.664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kiliti AJ, Sharif GM, Martin MB, Wellstein A, Riegel AT. AIB1/SRC-3/NCOA3 function in estrogen receptor alpha positive breast cancer. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1250218. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1250218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Bezrookove V, Kashani-Sabet M. NCOA3, a new player in melanoma susceptibility and a therapeutic target. Cancer Gene Ther. 2022;29(5):399–401. doi:10.1038/s41417-022-00449-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Wu RC, Smith CL, O’Malley BW. Transcriptional regulation by steroid receptor coactivator phosphorylation. Endocr Rev. 2005;26(3):393–9. doi:10.1210/er.2004-0018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Fang Z, Zhao G, Zhao S, Yu X, Feng R, Zhang YE, et al. GTF2H4 regulates partial EndMT via NF-kappaB activation through NCOA3 phosphorylation in ischemic diseases. Innovation. 2024;5(2):100565. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2024.100565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Ma F, Zhu Y, Liu X, Zhou Q, Hong X, Qu C, et al. Dual-specificity tyrosine phosphorylation-regulated kinase 3 loss activates purine metabolism and promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Hepatology. 2019;70(5):1785–803. doi:10.1002/hep.30703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Le XF, Pruefer F, Bast RCJr. HER2-targeting antibodies modulate the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27Kip1 via multiple signaling pathways. Cell Cycle. 2005;4(1):87–95. doi:10.4161/cc.4.1.1360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. WIPO | PCT. Bifunctional compounds for targeted protein degradation of kinases: world intellectual property organization. WO2022093742. [cited 2025 Jun 11]. Available from: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2022093742A1/en?oq=WO2022093742. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools