Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Ferroptosis: Mechanisms, Comparison with Cuproptosis and Emerging Horizons in Therapeutics

1 Department of Biopharmaceutics, Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Silkworm Bioreactor and Biomedicine, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hangzhou, 310018, China

2 Zhejiang Provincial Engineering Research Center of New Technologies and Applications for Targeted Therapy of Major Diseases, College of Life Sciences and Medicine, Zhejiang Sci-Tech University, Hangzhou, 310018, China

* Corresponding Author: Wen-Bin Ou. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: The Evolving Landscape of Cancer Treatment: Molecular Insights and Immunotherapeutic Breakthroughs)

Oncology Research 2026, 34(1), 8 https://doi.org/10.32604/or.2025.069049

Received 13 June 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

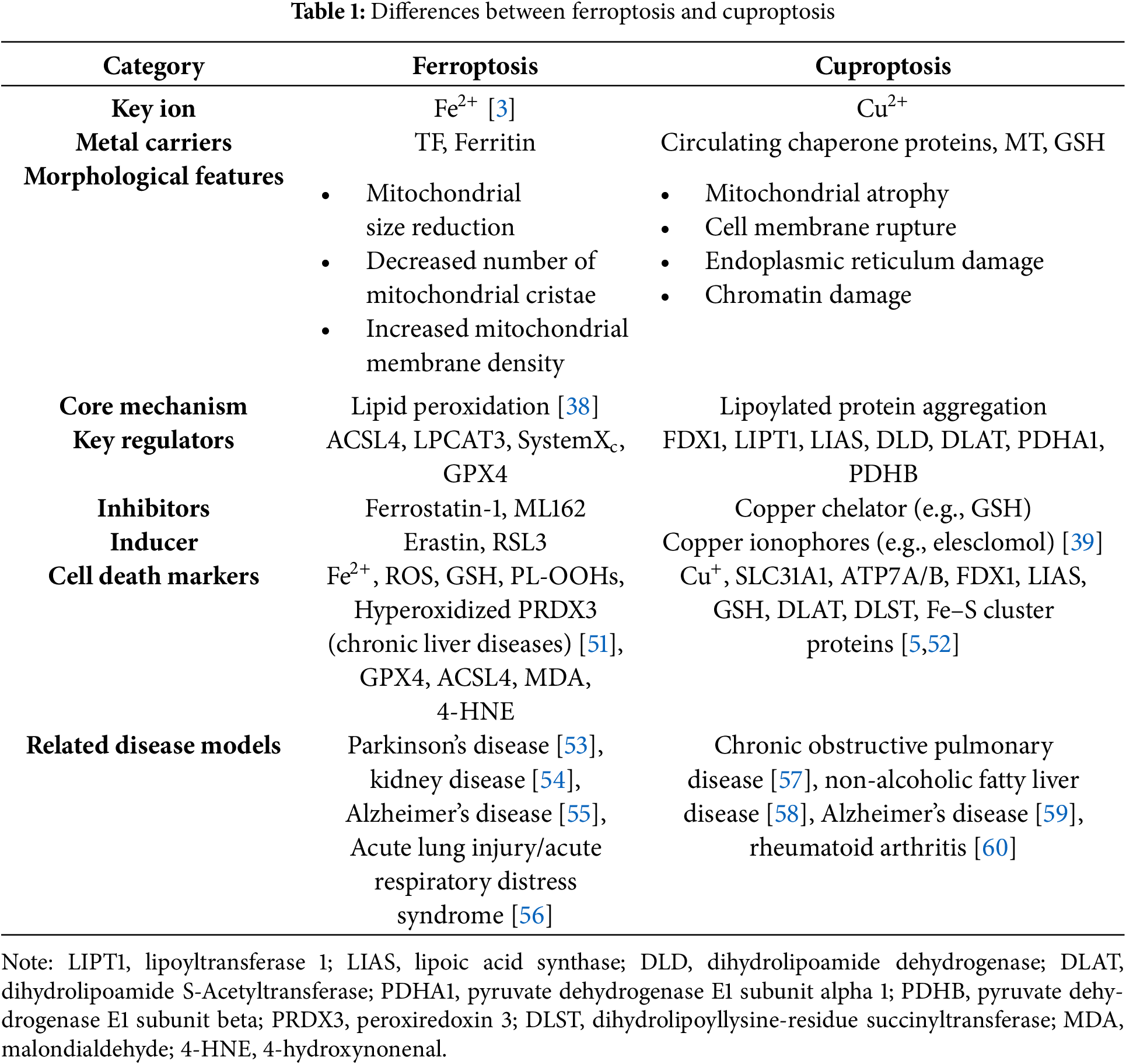

Ferroptosis is an iron-dependent, excessive lipid peroxidation-driven form of regulated cell death. The core mechanisms of ferroptosis include lipid peroxidation cascade, System Xc−-glutathioneglutathione peroxidase 4 axis, iron and lipid metabolism chaos, the NAD(P)Hferroptosis suppressor protein 1—ubiquinone axis, and GTP cyclohydrolase 1 tetrahydrobiopterin-dihydrofolate reductase axis. Cuproptosis is triggered by copper ions and involves ferredoxin 1-mediated aggregation of lipoylated proteins, differing fundamentally from ferroptosis. Both ferroptosis and cuproptosis exhibit dual roles (promote or inhibit) in cancers. And the sensitivity of different cancer types to ferroptosis varies, which may depend on special metabolic signatures (e.g., E-cadherin loss causes epithelial–mesenchymal transition, making tumors gain resistance to ferroptosis) and expression of antioxidant defense regulators (e.g., high expression of Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 and lncFASA make tumors easily sensitive). At present, traditional Chinese herbal medicine, combination therapy, and nano-delivery technology correlated with ferroptosis are being hotly studied by researchers in order to realize clinical translation of ferroptosis. In this review, we have summarized the core mechanisms of ferroptosis, ferroptosis differences from cuproptosis, its impact on cancers, and its translational implications in cancer therapy, helping readers quickly get the new information and horizons on them.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileCell death can be divided into accidental cell death (ACD) and regulated cell death (RCD) according to morphological, biochemical, and functional differences [1]. ACD happens instantaneously under extreme conditions, whereas RCD is regulated by a particular molecular mechanism regardless of extracellular perturbations. Hence, RCD plays an important role in organic homeostasis and development throughout our whole life and has practical application in the treatment of diseases such as cancer. Formerly, RCD covered ferroptosis, cuproptosis, apoptosis, necroptosis, pyroptosis, parthanatos, entosis, NETosis and so on [1,2].

Ferroptosis, a recently identified form of RCD, shows unique features [3]. During ferroptosis, cells display characteristic mitochondrial alterations, including shrinkage, increased electron density, cristae disappearance, and outer membrane rupture, distinguishing it from other death modalities [3]. The process is induced by intracellular microenvironment variation, chiefly associated with toxic lipid peroxide accumulation resulting from reactive oxygen species (ROS) overproduction and iron metabolism dysregulation [4]. Although both ferroptosis and cuproptosis depend on metal ions, their characteristics and underlying mechanisms are distinct. Cuproptosis is a new term and concept proposed in 2022, which is induced by copper-driven lipoylated protein aggregation [5]. Currently, promising cancer drugs based on ferroptosis and cuproptosis are constantly emerging. Diverse therapy (e.g., integrating with nanotechnology) and novel direction (e.g., bioactive compounds from Chinese herbs) bring more solutions to the issues of drug resistance and serious adverse events in existing medications. This review comprehensively outlines the core mechanisms of ferroptosis, its differences from cuproptosis, and its recent translational implications in cancer therapy.

2 Core Mechanisms in Ferroptosis

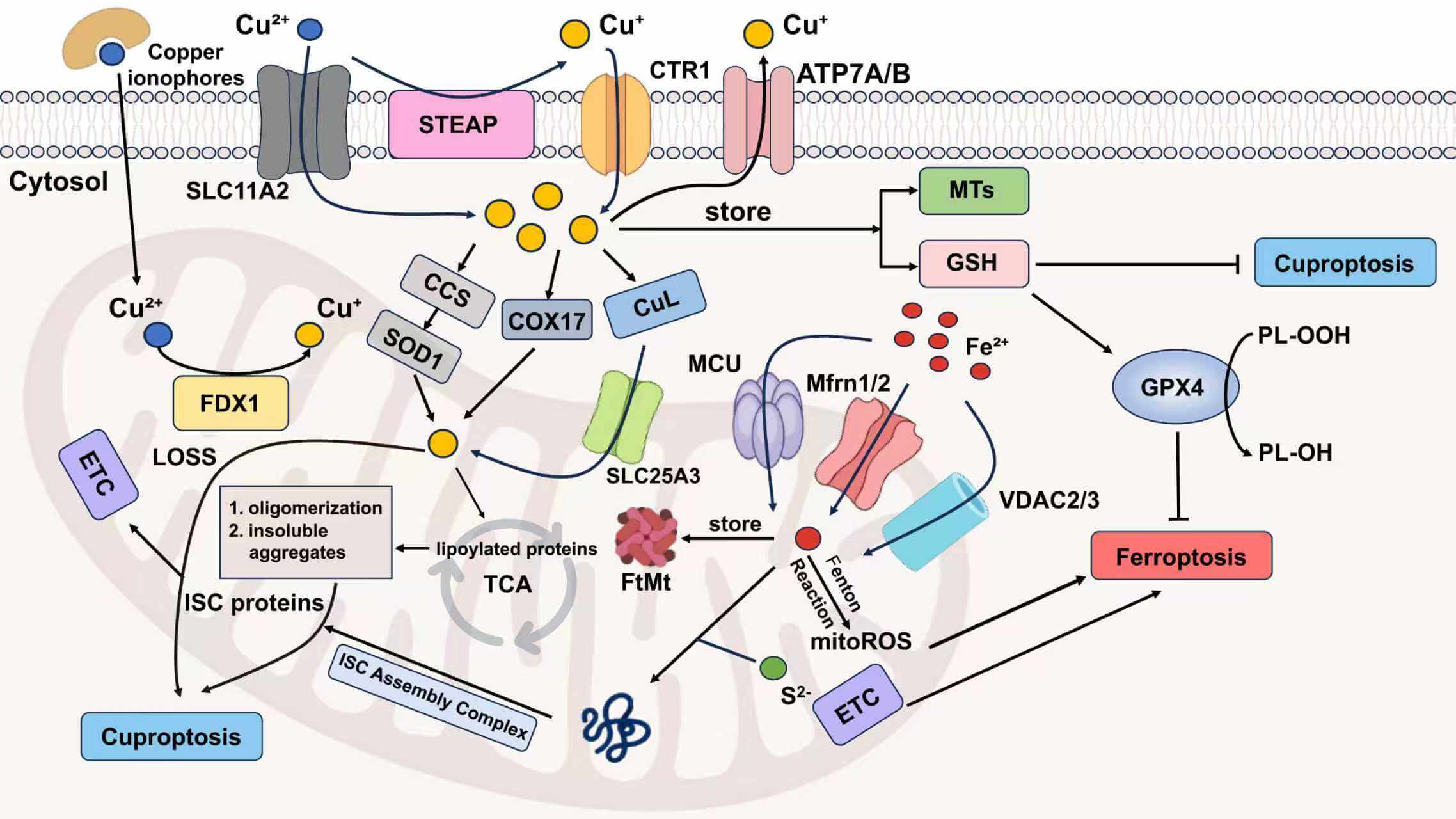

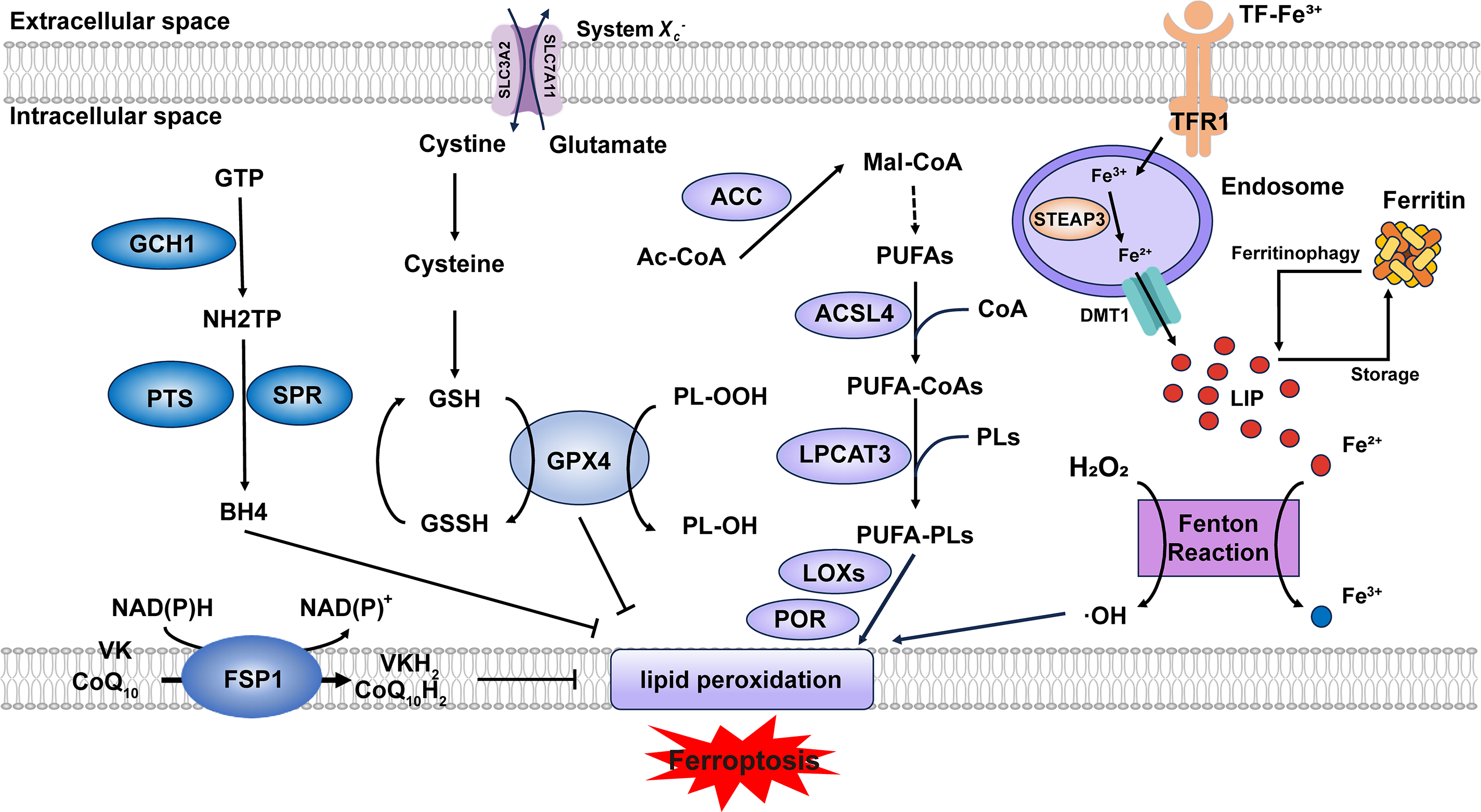

To date, the molecular mechanisms underlying ferroptosis have been progressively elucidated (Fig. 1). Beyond the well-established core machinery of ferroptosis, newly identified upstream regulators and cellular defense mechanisms are continuously expanding the ferroptosis regulatory network. Here, we briefly outline its core mechanisms and new ferroptosis-related relationships.

Figure 1: Core mechanisms of ferroptosis. Lipid peroxidation is driven by PUFA-PLs synthesis and excessive iron toxicity. The defense systems of ferroptosis mainly include System Xc−-GSH-GPX4 axis, NAD(P)H-FSP1-CoQ10 axis and GCH1-BH4-DHFR axis. When the activity of lipid peroxidation surpasses the detoxification capabilities provided by the defense systems, ferroptosis occurs. Abbreviation: GTP, guanosine triphosphate; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; Ac-CoA, acetyl-coenzyme A; Mal-CoA, malonyl-coenzyme A. Some of the materials in the picture are taken from the drawing software “Biorender”

2.1 The Lipid Peroxidation Cascade

Acyl-CoA synthetase long-chain family member 4 (ACSL4) and lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3 (LPCAT3) are two key enzymes in the biosynthesis of polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing phospholipids (PUFA-PLs). ACSL4 catalyzes the conjugation of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) with coenzyme A (CoA) to form PUFA-CoAs. Subsequently, LPCAT3 mediates the re-esterification of these PUFA-CoAs into phospholipids (PLs), generating PUFA-PLs [6]. Although PUFA-PLs contribute to membrane fluidity, their bis-allylic moieties render them susceptible to oxidation [7], which can be regarded as the foundation of lipid peroxidation. Current evidence indicates that the oxidation process primarily depends on two major pathways: (1) Free iron–induced fenton reaction (Fe2+ + H2O2 → Fe3+ + ·OH + OH−) produces excessive ROS [8]. (2) Enzyme-mediated reaction. Lipoxygenases (LOXs) and cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (POR) are capable of triggering lipid peroxidation through their catalytic dioxygenation of PUFAs by molecular oxygen [9]. Consequently, phospholipid hydroperoxides (PLOOHs) are produced, leading to the rupture of organelles and cell membranes.

System Xc−, a heterodimeric antiporter composed of solute carrier family 7 member 11 (SLC7A11) and solute carrier family 3 member 2 (SLC3A2) subunits, functions as a cystine/glutamate exchanger and plays a pivotal role in cellular antioxidant defense [10]. System Xc− transports cystine into the cell against glutamate at 1:1 stoichiometry [11]. Then cystine is reduced to cysteine to serve as a critical precursor for glutathione biosynthesis [12]. Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) utilizes reduced glutathione (GSH) as an essential cofactor to catalyze the reduction of cytotoxic lipid hydroperoxides to their corresponding non-toxic lipid alcohols, thereby preventing lethal lipid peroxidation in cells [13]. Consequently, pharmacological or genetic inhibition of either System Xc− or GPX4 represents approaches to induce ferroptosis. Ubiquitin-specific protease 8 (USP8) represents a novel regulatory mechanism of ferroptosis by modulating GPX4 stability, whose inhibition destabilizes GPX4 and expression stabilizes GPX4 [14]. Zinc finger DHHC-domain containing protein 8 (zDHHC8) palmitoylates GPX4 at Cys75, whose degradation attenuates GPX4 palmitoylation and enhancing ferroptosis sensitivity [15]. The long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) LncFASA binds to the Ahpc-TSA domain of peroxiredoxin1 (PRDX1), inhibiting its peroxidase activity by driving liquid-liquid phase separation, resulting in the accumulation of lipid peroxidation via the System Xc−-GPX4 axis [16] (Fig. S1).

Both the NAD(P)H-ferroptosis suppressor protein 1 (FSP1)—CoQ10 (ubiquinone) axis and the GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1)–tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4)–dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) axis are glutathione-independent mechanisms that act in parallel to GPX4 [17]. Myristoylated FSP1 predominantly localizes to the plasma membrane and functions as an NADH/NADPH-dependent oxidoreductase, converting CoQ10 (ubiquinone) to CoQ10H2 (ubiquinol) [18]. CoQ10H2, as a lipophilic antioxidant, reduces lipid peroxyl radicals to break the chain reaction of lipid peroxidation. In addition, CoQ10H2 can also indirectly regenerate α-tocopherol (vitamin E) through the CoQ10H2-mediated electron transport chain (ETC), and dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) can also reduce CoQ10 to CoQ10H2 [19], thus inhibiting ferroptosis. Recent studies suggest that FSP1 can function as a vitamin K reductase (VKR), consuming NAD(P)H to reduce vitamin K (VK) to VKH2, which acts as a radical-trapping antioxidant [20], but the complete inhibitory mechanism of VK on ferroptosis still requires further elucidation. GCH1 is responsible for catalyzing the initial and rate-limiting reaction in the biosynthesis of BH4, transforming GTP into 7,8-dihydroneopterin triphosphate (NH2TP), a key pterin phosphate intermediate. This product is then further metabolized by two additional enzymes, 6-pyruvoyltetrahydropterin synthase (PTS) and sepiapterin reductase (SPR), to ultimately yield BH4 [21]. Seminal work by Mariluz Soula et al. demonstrated that de novo BH4 biosynthesis constitutes an enzymatic antioxidant defense system through scavenging lipid peroxides. Mammalian cells employ two complementary mechanisms: the de novo pathway maintains basal BH4 levels, whereas the DHFR-mediated salvage pathway becomes essential during cellular BH4 deficiency [22]. Besides, in 2023, the SMURF2 (SMAD-specific E3 ubiquitin protein ligase 2)–GSTP1 (glutathione S-transferase pi 1) axis was found as a new ferroptosis defense way [23]. In summary, additional endogenous antioxidant molecules also exhibit anti-ferroptotic potential. Future research could characterize these molecules to complement the established ferroptosis defense systems.

The maintenance of iron homeostasis depends on precisely regulated iron uptake, storage, utilization, and export mechanisms [24]. Dietary iron is primarily present in the ferric (Fe3+) form, which undergoes reduction to the ferrous (Fe2+) state for cellular uptake. A coordinated action of intestinal reductases facilitates this critical conversion, most notably duodenal cytochrome B (DCYTB), coupled with subsequent transport via the divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) expressed on the apical membrane of duodenal enterocytes. Absorbed Fe2+ is exported across the basolateral membrane of enterocytes via ferroportin (FPN), where it undergoes oxidation to Fe3+, catalyzed by the multicopper oxidase hephaestin. The resulting Fe3+ is subsequently loaded onto transferrin (TF) for systemic delivery to peripheral tissues [25]. This circulating TF-Fe3+ is internalized via transferrin receptor 1 (TFR1) and reduced to Fe2+ by six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3 (STEAP3) in endosomes [26]. Divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) transports Fe2+ into the cytosol, where it enters the labile iron pool (LIP) (Fig. S2). This pool of redox-active iron plays critical roles in diverse biological processes [25]. Ferritin is a highly conserved iron-binding protein expressed in nearly all nucleated cells, where it functions as the primary intracellular iron storage complex to buffer iron fluctuations [25]. Ferritin can sequester excess iron. However, when its iron-binding capacity is saturated or elevated intracellular iron levels hinder the binding of ferritin heavy chain 1 (FTH1) to nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), which results in ferritinophagy [27,28], the labile iron pool (LIP) exceeds the physiological threshold. Under the condition that iron metabolism-related genes and proteins are dysregulated, iron overload occurs, triggering the fenton reaction.

The biosynthesis of PUFAs initiates with the conversion of acetyl-CoA to malonyl-CoA catalyzed by acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC). Malonyl-CoA serves as the essential two-carbon donor for the fatty acid synthase (FAS)-mediated elongation cycle, followed by desaturation via enzymes (e.g., FADS2 (fatty acid desaturase 2)) to generate PUFAs [6]. The quantity of PUFA-PLs determines the extent of lipid peroxidation and consequently modulates the sensitivity to ferroptosis. The expression levels of ACC, ACSL4, and LPCAT3 directly regulate the abundance of PUFA-PLs. By the way, in 2025, Zhang et al. demonstrated that in lenvatinib-induced ferroptosis of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells, deltex E3 ubiquitin ligase 2 (DTX2)-mediated degradation of hydroxysteroid (17β) dehydrogenase 4 (HSD17B4) reprograms lipid metabolism by suppressing docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) biosynthesis, thereby attenuating ferroptosis [29]. These findings suggest that HSD17B4 may serve as a novel regulator of lipid metabolism.

In conclusion, advances in ferroptosis mechanisms not only improve the safety evaluation of ferroptosis-targeted clinical translation but also expand the scope of drug discovery. What’s more, ferroptosis-iron overload-WNT/MYC-ornithine decarboxylase 1(ODC1)-polyamine-H2O2 axis is a positive feedback loop that amplifies ferroptosis and polyamine sensitizes cancer cells to ferroptosis in the way of extracellular vesicles and polyamine supplementation [30]. This discovery suggests a novel strategy to overcome tumor resistance to ferroptosis: using drug combinations to sensitize tumor cells to ferroptosis followed by ferroptosis-inducing therapy.

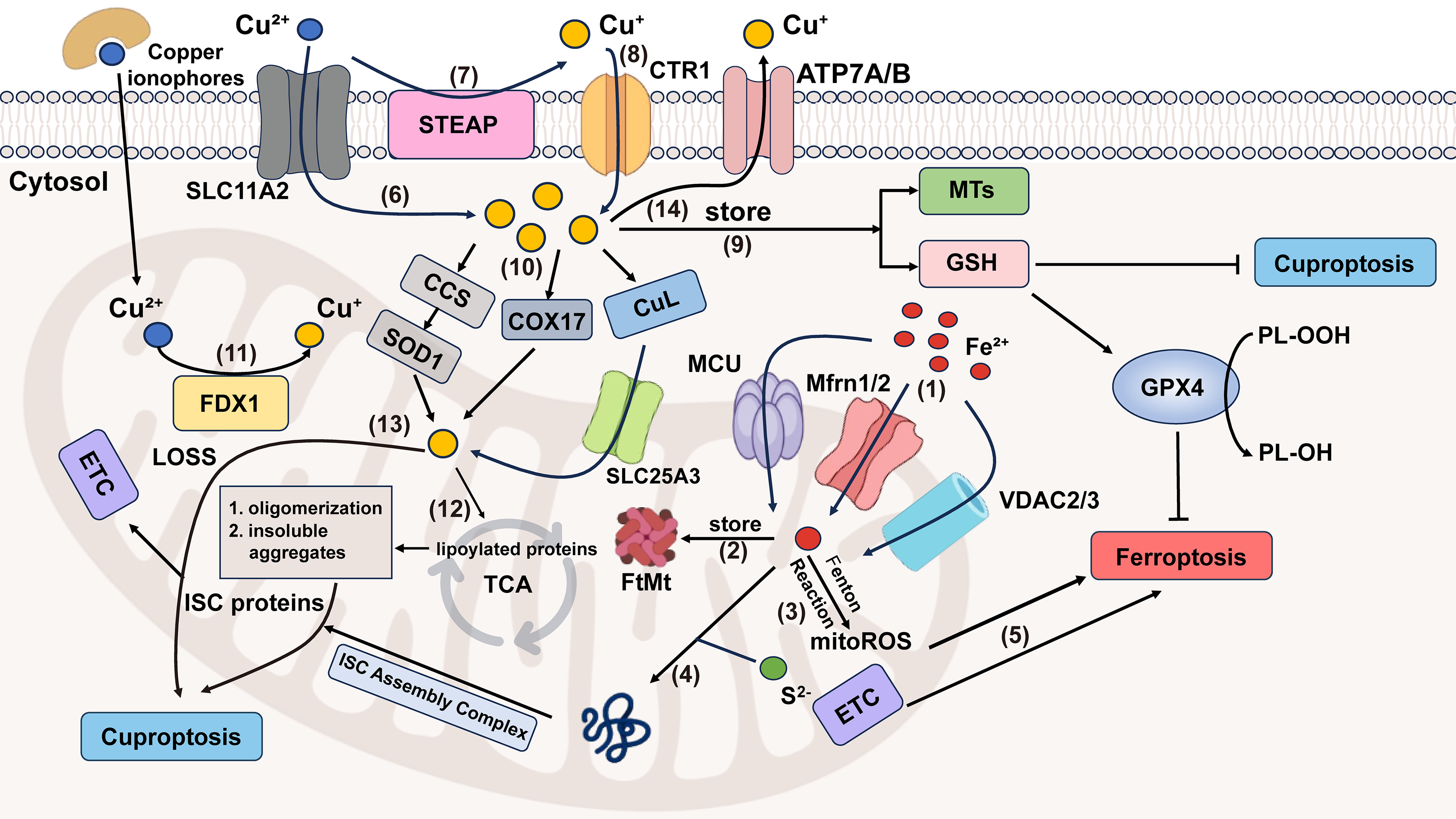

Copper is a crucial cofactor in biological systems, but becomes markedly cytotoxic when its concentration exceeds physiological thresholds. Cuproptosis is triggered by excessive copper ions (Cu2+) directly binding to lipoylated proteins in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, leading to aberrant oligomerization and subsequent formation of cytotoxic insoluble aggregates under prolonged copper stress, which gives rise to the loss of iron-sulfur cluster (ISC) protein, ultimately disrupting mitochondrial respiration chain and causing proteotoxic stress [31]. This does not involve lipid peroxidation and differs from the mechanism triggering ferroptosis.

Dietary copper initially exists in the digestive system as Cu2+. Cu2+ can be directly absorbed by DMT1 or is first reduced to Cu+ by the STEAP family and DCYTB, and then is uptaken by copper transporter 1/2 (CTR1/2) [32]. Due to the non-specific nature of DMT1, it is not suitable as a target for drug development. The absorption of dietary copper mainly relies on CTR1, while dietary iron is primarily absorbed through DMT1. In the intestinal epithelial cells, the copper chaperone antioxidant protein 1 (ATOX1) binds to Cu+ and transports Cu+ to the opposite side of the epithelial cell [33]. After that, copper-transporting P-type ATPases α (ATP7A) export Cu+ into blood circulation [34]. Iron is stored throughout the body cells, while copper is principally concentrated in the liver and eliminated through bile, so the metabolic imbalance of copper ions is closely related to liver and gallbladder diseases [35,36]. With the assistance of circulating chaperone proteins, copper is distributed to other tissues or organs, and then chiefly taken up by CTR1 [37].

In cells, copper is stored by metallothionein (MT) and other ligands [38]. GSH does act as one of the ligands, binding copper to control and regulate copper homeostasis. This mechanism establishes a shared molecular barrier and represents a critical molecular intersection between ferroptosis and cuproptosis. Buthionine sulfoximine (BSO), a specific inhibitor of GSH biosynthesis, has been proven to induce both ferroptosis and cuproptosis [39,40]. Copper chaperone for superoxide dismutase (CCS) can transport free copper to bind with superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), which is located between the cytosol and the mitochondrial intermembrane space (IMS) [41]. Cytochrome oxidase 17 (COX17) and copper ligands (CuL) can help copper enter the mitochondria [42,43].

Copper ionophores that can help increase intracellular copper levels are useful tools to study copper toxicity or induce cuproptosis [5]. Mitochondrial ferredoxin 1 (FDX1) and protein lipoylation are two important regulators of copper ionophore-induced cell death. FDX1 functions as a reductase that converts Cu2+ to its more toxic Cu+ form and causes the destabilization of Fe-S cluster proteins [44]. It can serve as a direct molecular target of elesclomol, which is also an upstream regulator of protein lipoylation [45]. Key genes regulating protein lipoylation comprise: (1) Lipoic acid biosynthesis components (LIAS (lipoyl synthase), LIPT1 (lipoyl amidotransferase), DLD (dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase)); (2) Lipoylated subunits of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex (DLAT (dihydrolipoyl transacetylase), PDHA1 (PDHα), PDHB (PDHβ)), as protein targets of lipoylation [46]. Similar to ferroptosis, dysregulation of copper metabolism also plays a dual role in cancer progression [32]. On the one hand, superfluous copper, as a cofactor for various enzymes, satisfies the conditions for the rapid proliferation of tumors [47,48]. On the other hand, copper suppresses cancer development by binding inappropriately with functional proteins [49,50] (Table 1).

Mitochondria play an important role in various physiological processes, like energy production [61]. Ferroptosis can occur either with or without the involvement of mitochondria, but cuproptosis must be mitochondria-dependent. When either of them occurs, the morphology of the mitochondria will change [5,62]. However, there are still differences between them. Mitochondria are the main source of ROS and major sites of iron utilization (containing up to 20%–50% within the cell) [63,64]. The entry of Fe2+ into mitochondria mainly depends on mitochondrial calcium uniporter (MCU), mitoferrin 1/2 (Mfrn1/2), and voltage-dependent anion-selective channel 2/3 (VDAC2/3). The way of generating mitochondrial reactive oxygen species(mitoROS) is similar to that of the cytoplasm. Namely, it also has ferritin (FtMt, an H-type ferritin) used in storage, and a free iron pool, which undergoes the Fenton reaction under abnormal conditions [65–67]. And another exclusive way is electron leakage of the ETC [64]. Fe-S cluster proteins are a significant component of ETC, and precisely need to undergo a mature process through the mitochondrial iron entering ISC assembly machinery [68]. Disruption of Fe-S clusters may cause electron leakage in the mitochondrial ETC, promoting ROS generation. In cuproptosis, it is excessive copper that leads to protein changes that damage the integrity of mitochondria, different from lipid peroxidation. Cu2+ enters mitochondria through copper ionophores, while Cu+ is transported via multiple specialized pathways, including the CCS-SOD1 chaperone system, COX17-mediated shuttling between the cytoplasm and mitochondria, and the CuL-Solute Carrier Family 25 Member 3 (SLC25A3) carrier complex in the mitochondrial inner membrane (Fig. 2). As previously mentioned, copper ions (Cu+/Cu2+) accumulation leads to the degradation of Fe-S cluster proteins. From the above, we can observe that Fe-S cluster proteins also seem to be the intersection point of ferroptosis and cuproptosis. So here comes the question: Can ferroptosis induced by iron overload occur simultaneously with cuproptosis? The answer is yes. Based on the above discussion, we can conclude that excessive copper that induces cuproptosis can first destroy Fe-S cluster proteins, thereby affecting the ETC, generating ROS, and promoting ferroptosis. Ferroptosis can help consume GSH and promote cuproptosis. Recent research also supplements and proves this point, which indicates that lactate metabolism plays a critical role in regulating both ferroptosis and cuproptosis [69]. Lactate accumulation induces intracellular acidification, creating a dual regulatory effect on metal metabolism. The resulting acidic environment directly promotes FTH1 dissociation to release stored iron, consequently elevating intracellular iron levels. Simultaneously, lactate-mediated suppression of glycolysis reduces cellular ATP availability, which functionally impairs the copper export activity of ATP7B (copper transporting ATPase 7β) and leads to progressive copper retention. This coordinated disruption of iron and copper homeostasis may synergistically potentiate metal-dependent cell death pathways. A mitochondria-targeted nano-heterojunction platform (MIL-Cu1.8S-TPP/FA) delivers copper and iron ions simultaneously, enhances ROS catalytic activity, disrupts mitochondrial iron-sulfur proteins, and synergistically induces ferroptosis and cuproptosis, achieving potent anti-tumor therapy combined with photothermal effects [70].

Figure 2: Crosstalk between ferroptosis and cuproptosis. (1) MCU, Mfrn1/2, VDAC2/3 transport Fe2+ into mitochondrial matrix. (2) FtMt stores Fe2+ in mitochondria. (3) Fe2+ in mitochondria can generate mitoROS through the Fenton reaction. (4) Mitochondrial Fe2+ and S2− enter the ISC assembly complex, responsible for the maturation of all ISC proteins, which is an important component of ETC. (5) ETC electron leakage and mitoROS participate in ferroptosis progression. (6) Cu2+ can enter cells either by forming lipid-soluble complexes with copper ionophores or through SLC11A2-mediated transport. (7) The STEAP family can reduce Cu2+ to Cu+. (8) Cu+ is specifically transported into cells by CTR1, a high-affinity copper importer. (9) In cells, Cu+ can be stored by MTs and GSH. (10) Mitochondria take up Cu+ through CCS-SOD1, COX17 (shuttling between the cytoplasm and the mitochondria) and CuL-SLC25A3 ways. (11) Cu2+ in mitochondria is reduced to the more toxic form (Cu+) by FDX1. (12) Excessive Cu+ induces lipoylated proteins’ oligomerization, and consequently, forms insoluble aggregates, ultimately causing cuproptosis. (13) Cu+ is also involved in cuproptosis by affecting the stability of ISC proteins. (14) Excess copper is exported extracellularly by ATP7A/B transporters. Abbreviation: SLC11A2, Solute Carrier Family 11 Member 2; ATP7A/B, ATPase copper transporter 7A and 7B. Some of the materials in the picture are taken from the drawing software “Biorender”

At present, there are not enough articles published regarding the specific concentration thresholds for iron and copper, nor has there been a comparison of the temporal kinetics of cuproptosis and ferroptosis. However, based on the mechanism and the available data, it can be inferred that the amount of iron required to cause ferroptosis is greater than that for cuproptosis and the time required to induce ferroptosis in the same type of cells may be longer than that for cuproptosis. Initially, ferroptosis is a process that requires gradual accumulation and collapse. But when copper levels are excessive, it causes direct damage to the mitochondria, bringing about cell death. Secondly, under most normal physiological conditions, the iron content in mammalian cells is significantly higher than the copper content [71,72]. Eventually, according to the data, for example, ferric ammonium citrate (FAC) exhibits cytotoxic effects on HT-1080 fibrosarcoma cells only at concentrations ≥5 mM in vitro [73], but in HEK293T cells overexpressing solute carrier family 31 member 1 (SLC31A1), a concentration of 10–20 μM was sufficient to induce cuproptosis in the majority of cells, with a significant decrease in viability approaching 0 [5]. But due to limited current clinical data and model complexity, the iron-copper concentration threshold awaits further verification in subsequent research.

In the first half of 2025, research and development of antitumor drugs based on cuproptosis primarily focused on nanotechnology. The developed tussah silk fibroin nanoparticles (TSF@ES-Cu NPs) effectively protect elesclomol (ES) and Cu2+, successfully addressing the short blood half-life issue of ES. The system innovatively utilizes the targeting function of natural RGD (Arginine-Glycine-Aspartic acid) peptides and the unique secondary structure characteristics of TSF, significantly enhancing drug-specific enrichment and controlled release in pancreatic tumor tissues, ultimately achieving remarkable improvement in therapeutic efficacy [74]. The constructed copper-based Prussian blue nanostructure (NCT-503@Cu-HMPB) selectively induces tumor cell cuproptosis by simultaneously inhibiting serine metabolism and enhancing copper ion toxicity, establishing a novel paradigm for cancer therapy based on cuproptosis and metabolic reprogramming [75]. Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) develops drug resistance by resisting cuproptosis through AKT1-mediated FDX1 phosphorylation [76]. The combination of AKT1 inhibitors with copper ionophores synergistically suppresses TNBC tumorigenesis, suggesting a potential novel therapeutic strategy for TNBC. A new ROS-responsive targeting cuproptosis nanomedicine (CuET@PHF) overcomes hypoxia via photothermal effects, upregulates FDX1, and triggers cuproptosis in TNBC stem cells (CSCs) for the first time, synergizing with immunogenic cell death to suppress tumor growth, recurrence, and metastasis [77]. In addition, the natural fungal-derived pochonin D (PoD) inhibits peroxiredoxin-1 (PRDX1) enzymatic activity by targeting Cys173, modulates cuproptosis, and serves as a novel copper ionophore and therapeutic strategy for TNBC [78].

4.1 The Roles of Ferroptosis in Cancer

Ferroptosis exerts bidirectional regulatory effects in oncogenesis, functioning as a tumor-suppressive mechanism in certain contexts while unexpectedly facilitating tumorigenesis in others. For instance, the combinatorial treatment of temsirolimus (mTOR inhibitor) and RSL3 (GPX4 inhibitor) synergistically induces ferroptosis, resulting in significant restraint of liver cancer progression [79]. Gambogenic acid inhibits the malignant progression of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) by inducing GCH1-regulated ferroptosis [80]. Metformin suppresses tumor growth by enhancing ferroptosis in ovarian cancer cells under energy stress conditions [81]. However, ferroptosis can also promote tumor progression under certain circumstances, which is related to the tumor microenvironment (TME) (triggering inflammation-related immunosuppression) and changes in key genes (e.g., p53). The inflammatory response associated with ferroptosis contributes to the formation of a tumor-promoting microenvironment through multiple mechanisms: stimulating cancer cell proliferation and migration, promoting angiogenesis, and suppressing adaptive immune function. Specifically, damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released during ferroptosis induce the secretion of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-8 (IL-8) as well as recruit and activate various immune cells (e,g., tumor-associated macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, regulatory T cells), directly promoting cancer cell proliferation, while upregulating pro-angiogenic factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) to accelerate tumor vascularization [82]. More importantly, the inflammatory microenvironment triggered by ferroptosis significantly inhibits T cell activation and proliferation, thereby compromising the clinical efficacy of immunotherapy [83]. When ROS levels are elevated, inflammatory cytokines and ROS upregulate the expression of ferroptosis-inducing enzymes (e.g., ACSL4), induce iron overload and membrane lipid peroxidation, thereby rendering cancer cells more susceptible to ferroptosis [84,85]. p53 is closely associated with the ferroptosis metabolic pathway and serves as its key regulatory factor [86]. When lipid peroxidation damage is mild and repairable, p53 helps cells resist ferroptosis by inhibiting dipeptidyl peptidase-4 (DPP4) activity or upregulating CDKN1A/p21 expression [87]. If the damage persists or becomes too severe, p53 induces ferroptosis by suppressing SLC7A11 expression or promoting spermidine/spermine N1-acetyltransferase 1 (SAT1) and glutaminase 2 (GLS2) expression, thereby eliminating damaged cells [88]. For example, ferroptotic cancer cell-derived 8-hydroxyguanosine (8-OHG) activates the stimulator of interferon genes (STING)-dependent DNA sensing pathway in tumor-associated macrophages, thereby fostering a pro-inflammatory TME that promotes pancreatic adenocarcinoma development [89,90]. Acidic nuclear phosphoprotein 32Et (ANP32Et) promotes esophageal cancer progression via p53/SLC7A11 axis-regulated ferroptosis [91]. This phenomenon may also be closely associated with intracellular ROS levels. Studies have shown that low ROS concentrations exert protective effects on normal cells, whereas moderate ROS levels, while detrimental to normal cells, may promote tumor cell proliferation. Nevertheless, excessively high ROS accumulation can ultimately induce tumor cell death [92,93]. For these cancer types where ferroptosis plays a promoting role, the use of ferroptosis inhibitors may provide certain alleviating effects. The combination of ferroptosis inhibitors with other antitumor drugs might achieve better therapeutic outcomes. However, specific treatment regimens should be tailored based on TME characteristics and tumor genetic mutation profiles. Regarding the carcinogenic effects and mechanisms of iron, the overall picture is inadequate, and more research is still needed.

Meanwhile, different types of cancer have varying sensitivities to ferroptosis, primarily determined by specific metabolic signatures and the integrity of antioxidant defense systems. It is reported that the glutamine-dependent breast cancer (BC) subgroup is sensitive to ferroptosis, and this sensitivity is associated with ACSL4 expression [94]. TNBC with high LncFASA expression exhibits enhanced susceptibility to ferroptosis [16]. While certain cancer types exhibit marked susceptibility to ferroptosis, others demonstrate intrinsic or acquired resistance mechanisms. In the lymphatic microenvironment, oleic acid protects melanoma cells from ferroptosis in an ACSL3-dependent manner, substantially enhancing their metastatic tumor-forming capacity. Compared to subcutaneously implanted melanoma, these lymph-colonizing cells exhibit superior ferroptosis resistance [95]. In lung cancer cells, GSH represents the most abundant antioxidant. The production of GSH is regulated not only by System Xc− but also involves the participation of glutamate transporters, particularly the excitatory amino acid transporter 3 (EAAT3). In 2025, Wen et al. reported that NF-κB drives EAAT3 expression, and knockdown of EAAT3 enhances the susceptibility of lung cancer cells to ferroptosis. Furthermore, upregulated EAAT3 in NSCLC tissues correlates with p65 protein levels, while smoking-induced inflammation promotes EAAT3 expression in lung cancer models [96]. Subsequent research could focus on targeting the NF-κB/EAAT3 axis in lung cancer to explore combined ferroptosis therapies. In 3D-cultured colorectal cancer models, the hybrid epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) phenotype confers robust ferroptosis resistance through integrin mechanotransduction and mitochondrial metabolic remodeling. Notably, this protective phenotype emerges as a delayed consequence of E-cadherin loss, rather than the anticipated ferroptosis sensitization [97]. Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) confer doxorubicin resistance to TNBC by augmenting zinc finger protein 64 (ZFP64)-mediated histone lactylation, thereby modulating ferroptosis sensitivity [98].

Emerging evidences reveal that ferroptosis induction may not only prove therapeutically ineffective in certain malignancies but could paradoxically promote tumor progression. Therefore, clinical application of ferroptosis inducers necessitates rigorous molecular classification and susceptibility assessment of the target cancer type.

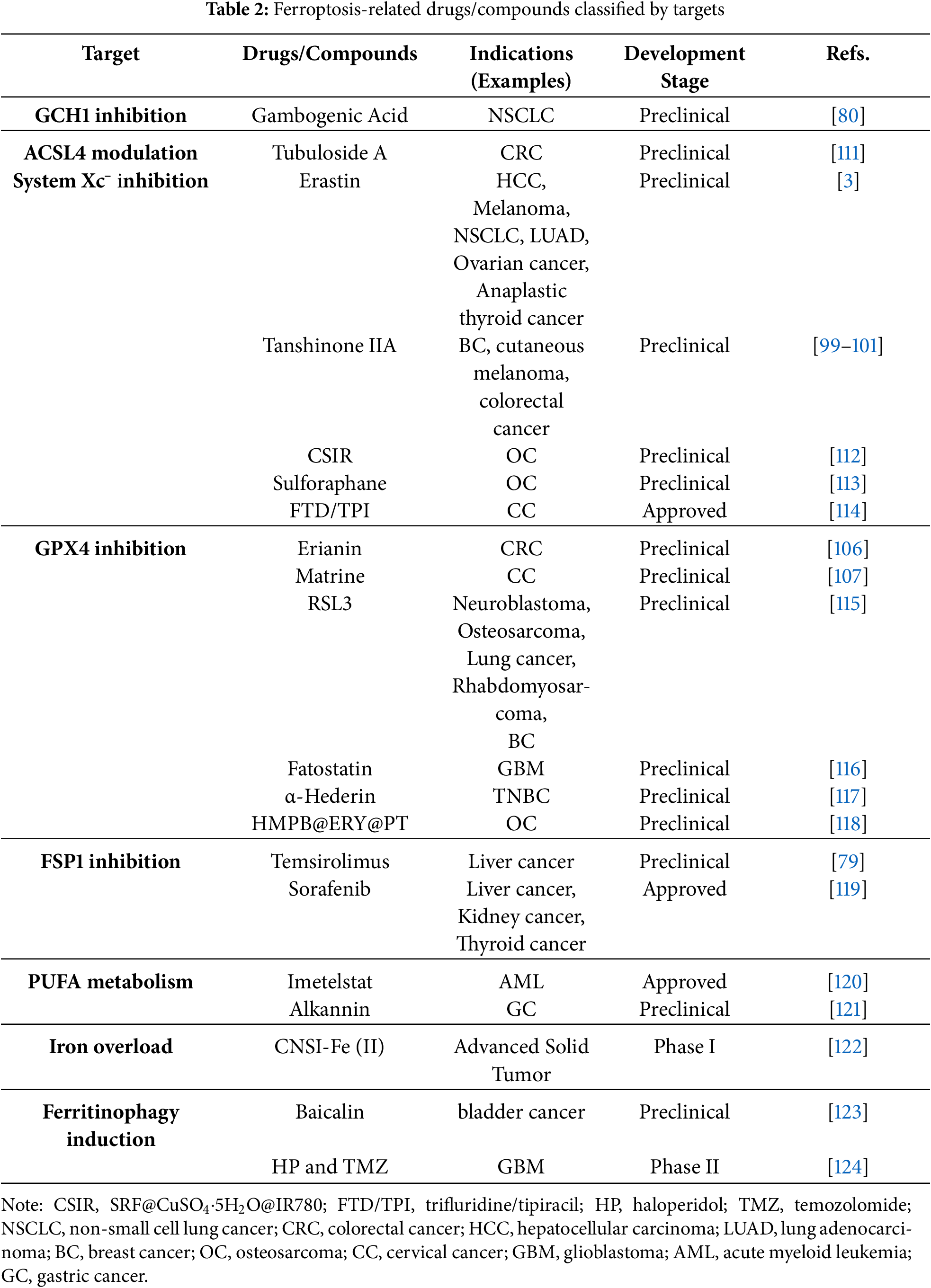

4.2 Targeting Ferroptosis in Cancer: Drug/Compounds and Therapy

Current research has found that certain active components in traditional Chinese herbal medicine can influence the initiation and progression of cancer by regulating the ferroptosis pathways. Tanshinone IIA (Tan IIA) induces ferroptosis in BC cells by modulating the lysine-specific demethylase 1 (KDM1A)-protein inhibitor of activated STAT 4 (PIAS4) axis to regulate SUMOylation-dependent destabilization of SLC7A11 [99]. In addition, Tanshinone IIA has been found to promote ferroptosis in cutaneous melanoma via STAT1-mediated upregulation of prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) expression [100] and in colorectal cancer (CRC) through the suppression of SLC7A11 expression via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway [101]. However, Li et al. reported that it inhibits hydrogen peroxide-induced ferroptosis in melanocytes by activating the nuclear erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway [102]. Nanoparticles related to Tanshinone IIA for anticancer applications will be discussed in the nanotechnology section. Although Tanshinone IIA has entered clinical trials for diseases such as left ventricular remodeling secondary to acute myocardial infarction [103], lipopolysaccharides (LPS)-induced mastitis [104], and cardiac function recovery, no cancer-related clinical trials have been identified to date [105]. Erianin inhibits CRC progression by inducing ferroptosis through promoting GPX4 ubiquitination and degradation [106]. Matrine induces ferroptosis in cervical cancer (CC) by activating the Piezo1 channel, which subsequently downregulates GPX4 expression [107] (Table 2). Similar to the clinical trial progress of Tanshinone IIA, matrine has been investigated in clinical trials for conditions such as perianal infection after chemotherapy for acute leukemia [108], chronic hepatitis B [109], and silicosis [110], but no cancer-related clinical trials have been identified to date. Future research may employ extraction, identification and chemical modification of bioactive compounds from Chinese herbs and other medicinal plants to screen for novel anticancer agents, whose mechanisms of action may involve but are not limited to the ferroptosis pathway. At present, there are very few traditional Chinese medicine components that have entered clinical trials. It is hoped that relevant clinical tests can be conducted in the future.

Imetelstat promotes the formation of PUFA-PLs, effectively ameliorating acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [120]. Researchers identified alkannin as a clinically promising natural product against gastric cancer (GC), and elucidated a previously unreported ferroptosis mechanism on lipid homeostasis regulation via the c-Fos/sterol regulatory element binding transcription factor 1 (SREBF1) axis [121]. Mechanistically, priming with oxidative stress-inducing chemotherapy potentiates the susceptibility of tumors to ferroptosis inducers, proposing a novel combinatorial therapeutic paradigm.

Exploring ferroptosis inducers can help establish an upstream and downstream relationship network. Nuclear accumulation of p53 and enhanced p62/SLC7A11 protein-protein interaction can downregulate SLC7A11, found through ferroptosis inducers (sulforaphane and Trifluridine/Tipiracil (FTD/TPI)) correlational studies [113,114]. In the experiment where Sorafenib induces ferroptosis, it is found that Sorafenib achieves this effect by promoting the ubiquitination and degradation of FSP1 mediated by tripartite motif containing 54 (TRIM54) [119]. Meanwhile, the finding of ferroptosis is beneficial in revealing the unknown mechanism of anti-cancer drugs. Originally, FTD/TPI just had promising anticancer activity, but its anticancer targets remained incompletely understood. Experimental data have manifested that it is associated with ferroptosis [114]. Mori Folium has anticancer activity, but its underlying mechanisms were unknown at first; it has now been revealed that it induces ferroptosis in GC cells by modulating the PI3K/AKT/GSK3β/NrF2 signaling pathway [125]. Besides, Alkannin [121], Tubuloside A (a proline 4-hydroxylase, alpha polypeptide III (P4HA3)) degrader, providing a potential strategy to overcome CRC resistant varieties) [111] are the same, elucidating the undefined mechanisms of action of anticancer agents.

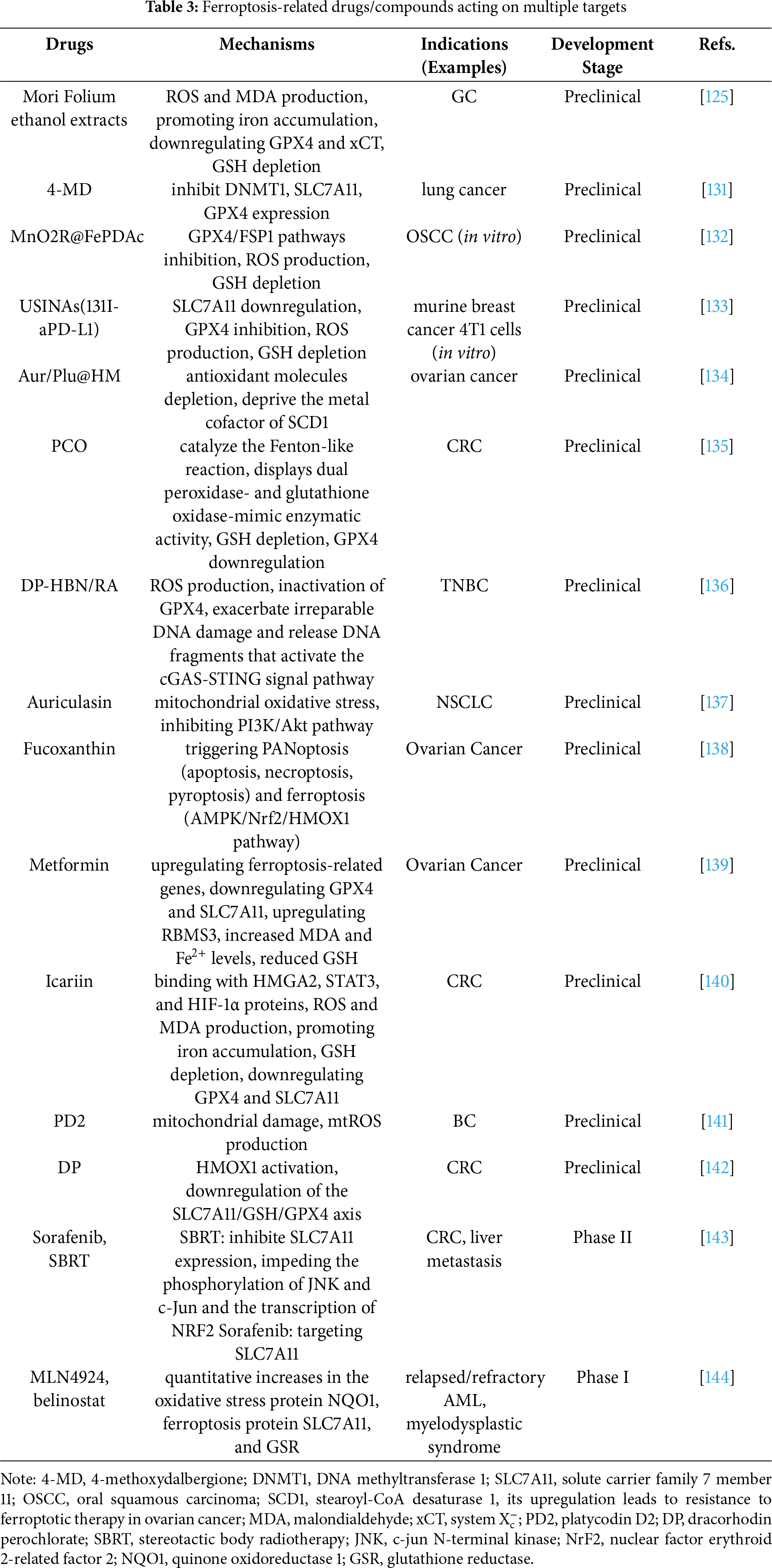

Combination therapy has shown remarkable advantages in the treatment of cancer. Many studies indicate that when ferroptosis inducers are combined with conventional anticancer drugs, they not only achieve multi-target synergistic effects, but existing experimental data also confirm that this combination strategy can significantly enhance antitumor efficacy. When Baicalin was combined with 5-Fu to combat GC, the expression levels of TFR1, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase 1 (NOX1), and COX2 were upregulated, whereas those of FTH1, ferritin light chain (FTL), and GPX4 were downregulated, leading to superior therapeutic efficacy [92]. Haloperidol (HP), as an effective adjunct therapy, reverses Temozolomide (TMZ) resistance and improves chemoradiotherapy efficacy in glioblastoma (GBM) [124]. Propranolol and capecitabine synergistically induce ferroptosis in CRC, although the original study demonstrated efficacy only in BRAF (V600E)-mutant HT-29 cells [126] (Table 3). Simultaneous induction of multiple RCD pathways, such as apoptosis and ferroptosis, represents a promising approach to augment anticancer efficacy and circumvent resistance mechanisms. With the discovery of ferroptosis regulatory factors in cancer and chemotherapy drug resistance targets, such as transmembrane protein 160 (TMEM160) [127], syntaxin 1A (STX1A) [128], vimentin-Interacting protein AS39 (VIPAS39) [129], and serine/threonine-protein kinase (SIK1) [130], the expansion of the target range has also broadened the application of combined treatment. Inhibit the known targets that confer resistance to ferroptosis for specific cancer types, and then induce ferroptosis, and so on. The mechanisms of action of drugs related to ferroptosis mainly focus on their core mechanisms, while the research on the development of drugs targeting these drug-resistant-related targets is relatively scarce.

In the development of ferroptosis-based cancer therapeutics, achieving selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells while sparing normal cells remains a central challenge. In recent years, nanomaterials with superior targeted delivery properties have been extensively investigated and applied due to their ability to enhance therapeutic specificity and safety significantly. Carbon nanoparticles-Fe (II) Complex (CNSI-Fe (II)) effectively delivers iron into tumor cells while exhibiting minimal systemic toxicity in tumor-bearing mice [122], having now advanced to Phase I clinical trials. Carbon nanosphere suspension injection (CNSI) is a commercially available and clinically applied carbon nanomaterial [145]. Animal studies and clinical observations indicate that CNSI exhibits minimal systemic toxicity [146] and contains abundant oxygen-containing functional groups capable of interacting with Fe2+. As a biocompatible carbon material, CNSI does not induce oxidative stress [147]. When administered via intratumoral injection, the limited quantity of TRF and other transport proteins restricts Fe2+ translocation into the cytoplasm. Consequently, neither CNSI nor iron alone demonstrates significant efficacy in tumor growth suppression. The potent antitumor effect of CNSI-Fe is attributed to the synergistic interaction between CNSI and Fe2+. Cellular uptake of CNSI particles via endocytosis facilitates Fe2+ delivery into the cytoplasm. Fe2+ exerts cytotoxicity by efficiently catalyzing H2O2 decomposition, while the elemental carbon further enhances the fenton reaction. Due to the blockage of the FPN pathway in tumor cells, Fe2+ cannot be effluxed, leading to its prolonged intracellular accumulation. Experimental studies confirm that the majority of CNSI and Fe remains localized within the tumor tissue post-injection. Since the tumor is surgically resected, long-term toxicity is unlikely to occur. From the perspective of targeted delivery mechanisms, CNSI-Fe(II) is particularly suitable for solid tumors. Eriodictyol-cisplatin nanomedicine synergistically induces ferroptosis and enhances chemosensitivity in osteosarcoma (OC) cells [118]. A carrier-free nanomedicine SRF@CuSO4·5H2O@IR780 (CSIR) synergistically enhances OC tumor eradication through GSH depletion, photodynamic therapy (PDT), and photothermal therapy (PTT), providing a multi-modal therapeutic approach [112]. The exploration of nanotechnology and related precision delivery approaches may expand the repertoire of applicable ferroptosis inducers or inhibitors for disease treatment. pH-responsive Tanshinone IIA-loaded calcium alginate nanoparticles overcome the poor aqueous solubility of Tanshinone IIA, thereby addressing its clinical application limitations [148]. Moreover, nanotechnology can also serve as a strategy for combination therapy. Arsenene-Vanadene nanodots (AsV) drug delivery system combines arsenic (As)-induced apoptosis with vanadium (V)-enhanced ferroptosis, opening new avenues for TNBC immunotherapy [149]. Redox-driven hybrid nanozyme (M@GOx/Fe-HMON) dynamically activates either ferroptosis or disulfidptosis in HCC by adapting to glucose heterogeneity [150]. Under high glucose, it triggers Gox glucose oxidase (Gox)-peroxidase (POD) cascade reactions to induce ferroptosis via ROS and GSH depletion, while under low glucose, it promotes disulfidptosis via NADPH exhaustion and cystine metabolism disruption, finally amplifying antitumor efficacy. A novel stimulus-responsive (pH/GSH-responsive) antitumor nanoplatform (ISL@RLP-Fe), based on polysaccharide-flavonoid-iron complexes, integrates the immunostimulatory activity of natural macromolecule Rosa laevigata polysaccharide (RLP), the chemotherapeutic potential of isoliquiritigenin (ISL), and the chemodynamic therapy (CDT) functionality of iron ions [151]. This system enables tumor microenvironment-specific disintegration and drug release, significantly reducing tumor mass and inhibiting cancer cell migration in preclinical models. The study demonstrates groundbreaking innovation by integrating traditional Chinese herbal medicine components with advanced nanotechnology, thereby establishing a novel methodology and conceptual framework for applying natural phytochemicals in anticancer therapeutics.

5 Conclusions and Future Prospects

Given the growing challenge of drug resistance to conventional therapies, ferroptosis induction has emerged as a promising novel approach and strategic alternative for clinical cancer treatment. Nonetheless, numerous compounds with clinical potential remain in the experimental stage, and their therapeutic applications require further validation. Ferroptosis-targeted anticancer therapies confront the same resistance challenges. The main directions that can be further expanded at present are as follows: (1) The crosstalk between ferroptosis and cuproptosis suggests potential for combinatorial targeting. Future therapeutic strategies could leverage this synergy by designing bifunctional agents that concurrently engage both mechanisms, thereby maximizing tumoricidal efficacy while minimizing off-target effects. (2) In comparative studies of ferroptosis and cuproptosis, the kinetic profiles (including initiation time and progression rate) and the minimum effective concentrations of copper/iron ions required to induce cell death still lack systematic quantitative analysis. (3) Multiple studies in 2025 have reported that traditional Chinese herbal medicines can inhibit cancer by regulating the ferroptosis pathway. These findings not only suggest the potential to extract, identify, and chemically modify their bioactive compounds, but also help elucidate the specific molecular mechanisms underlying their therapeutic effects. (4) Targeted drug delivery to tumor sites is essential to minimize damage to normal cells and expand therapeutic applications. Therefore, nanotechnology can be leveraged to develop more ferroptosis-inducing anticancer agents. (5) Combination therapeutic strategies still hold potential for further development, which may provide innovative solutions to address drug resistance challenges and reduce medication toxicity.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by National Natural Science Foundation (82272695), the Key Program of Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LZ23H160004), National Undergraduate Training Program for Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Zhejiang Xinmiao Talents Program, China.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Shujie Yin, Wen-Bin Ou; draft manuscript preparation: Shujie Yin; review and editing: Shujie Yin, Zong Li, Wen-Bin Ou; visualization: Shujie Yin, Zong Li; supervision: Wen-Bin Ou. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/or.2025.069049/s1.

References

1. Galluzzi L, Vitale I, Aaronson SA, Abrams JM, Adam D, Agostinis P, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cell death: recommendations of the nomenclature committee on cell death 2018. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25(3):486–541. doi:10.1038/s41418-025-01535-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Peng F, Liao M, Qin R, Zhu S, Peng C, Fu L, et al. Regulated cell death (RCD) in cancer: key pathways and targeted therapies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):286. doi:10.1038/s41392-022-01110-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Dixon SJ, Lemberg KM, Lamprecht MR, Skouta R, Zaitsev EM, Gleason CE, et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell. 2012;149(5):1060–72. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Zheng J, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: when metabolism meets cell death. Physiol Rev. 2025;105(2):651–706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Cobine PA, Brady DC. Cuproptosis: cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying copper-induced cell death. Mol Cell. 2022;82(10):1786–7. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2022.05.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Lei G, Zhuang L, Gan B. Targeting ferroptosis as a vulnerability in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(7):381–96. doi:10.1038/s41568-022-00459-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Lei G, Mao C, Yan Y, Zhuang L, Gan B. Ferroptosis, radiotherapy, and combination therapeutic strategies. Protein Cell. 2021;12(11):836–57. doi:10.1007/s13238-021-00841-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Tang D, Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res. 2021;31(2):107–25. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-00441-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Jiang X, Stockwell BR, Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22(4):266–82. doi:10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Li J, Jia YC, Ding YX, Bai J, Cao F, Li F. The crosstalk between ferroptosis and mitochondrial dynamic regulatory networks. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19(9):2756–71. doi:10.7150/ijbs.83348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Seibt TM, Proneth B, Conrad M. Role of GPX4 in ferroptosis and its pharmacological implication. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133(3):144–52. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Dixon SJ, Winter GE, Musavi LS, Lee ED, Snijder B, Rebsamen M, et al. Human haploid cell genetics reveals roles for lipid metabolism genes in nonapoptotic cell death. ACS Chem Biol. 2015;10(7):1604–9. doi:10.1021/acschembio.5b00245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Yang WS, Kim KJ, Gaschler MM, Patel M, Shchepinov MS, Stockwell BR. Peroxidation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by lipoxygenases drives ferroptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(34):E4966–75. doi:10.1073/pnas.1603244113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Li H, Sun Y, Yao Y, Ke S, Zhang N, Xiong W, et al. USP8-governed GPX4 homeostasis orchestrates ferroptosis and cancer immunotherapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2024;121(16):e2315541121. doi:10.1073/pnas.2409669121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhou L, Lian G, Zhou T, Cai Z, Yang S, Li W, et al. Palmitoylation of GPX4 via the targetable ZDHHC8 determines ferroptosis sensitivity and antitumor immunity. Nat Cancer. 2025;6(5):768–85. doi:10.1038/s43018-025-00937-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Fan X, Liu F, Wang X, Wang Y, Chen Y, Shi C, et al. LncFASA promotes cancer ferroptosis via modulating PRDX1 phase separation. Sci China Life Sci. 2024;67(3):488–503. doi:10.1007/s11427-023-2425-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Li W, Liang L, Liu S, Yi H, Zhou Y. FSP1: a key regulator of ferroptosis. Trends Mol Med. 2023;29(9):753–64. doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2023.05.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Doll S, Freitas FP, Shah R, Aldrovandi M, da Silva MC, Ingold I, et al. FSP1 is a glutathione-independent ferroptosis suppressor. Nature. 2019;575(7784):693–8. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1707-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Mao C, Liu X, Zhang Y, Lei G, Yan Y, Lee H, et al. DHODH-mediated ferroptosis defence is a targetable vulnerability in cancer. Nature. 2021;593(7860):586–90. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03539-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Hirschhorn T, Stockwell BR. Vitamin K: a new guardian against ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2022;82(20):3760–2. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2022.10.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Kojima S, Ona S, Iizuka I, Arai T, Mori H, Kubota K. Antioxidative activity of 5,6,7,8-tetrahydrobiopterin and its inhibitory effect on paraquat-induced cell toxicity in cultured rat hepatocytes. Free Radic Res. 1995;23(5):419–30. doi:10.3109/10715769509065263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Soula M, Weber RA, Zilka O, Alwaseem H, La K, Yen F, et al. Metabolic determinants of cancer cell sensitivity to canonical ferroptosis inducers. Nat Chem Biol. 2020;16(12):1351–60. doi:10.1038/s41589-020-0613-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang W, Dai J, Hou G, Liu H, Zheng S, Wang X, et al. SMURF2 predisposes cancer cell toward ferroptosis in GPX4-independent manners by promoting GSTP1 degradation. Mol Cell. 2023;83(23):4352–69.e8. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2023.10.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ru Q, Li Y, Chen L, Wu Y, Min J, Wang F. Iron homeostasis and ferroptosis in human diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):271. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01969-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Szymulewska-Konopko K, Reszeć-Giełażyn J, Małeczek M. Ferritin as an effective prognostic factor and potential cancer biomarker. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2025;47(1):60. doi:10.3390/cimb47010060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Chen X, Yu C, Kang R, Tang D. Iron metabolism in ferroptosis. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020;8:590226. doi:10.3389/fcell.2020.590226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Santana-Codina N, Gikandi A, Mancias JD. The role of NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy in ferroptosis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1301(Suppl):41–57. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-62026-4_4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Zhao H, Wang Z, Wang H. The role of NCOA4-mediated ferritinophagy in the ferroptosis of hepatocytes: a mechanistic viewpoint. Pathol Res Pract. 2025;270(6):155996. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2025.155996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang Z, Zhou Q, Li Z, Huang F, Mo K, Shen C, et al. DTX2 attenuates Lenvatinib-induced ferroptosis by suppressing docosahexaenoic acid biosynthesis through HSD17B4-dependent peroxisomal β-oxidation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Drug Resist Updat. 2025;81:101224. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2025.101224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Bi G, Liang J, Bian Y, Shan G, Huang Y, Lu T, et al. Polyamine-mediated ferroptosis amplification acts as a targetable vulnerability in cancer. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):2461. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-46776-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Wang Y, Zhang L, Zhou F. Cuproptosis: a new form of programmed cell death. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19(8):867–8. doi:10.1038/s41423-022-00866-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Guo Z, Chen D, Yao L, Sun Y, Li D, Le J, et al. The molecular mechanism and therapeutic landscape of copper and cuproptosis in cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):149. doi:10.1038/s41392-025-02192-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Tang D, Kroemer G, Kang R. Targeting cuproplasia and cuproptosis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2024;21(5):370–88. doi:10.1038/s41571-024-00876-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Lönnerdal B. Intestinal regulation of copper homeostasis: a developmental perspective. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88(3):846s–50s. doi:10.1093/ajcn/88.3.846s. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Xie J, Yang Y, Gao Y, He J. Cuproptosis: mechanisms and links with cancers. Mol Cancer. 2023;22(1):46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

36. Aggett PJ. An overview of the metabolism of copper. Eur J Med Res. 1999;4(6):214–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

37. La Fontaine S, Ackland ML, Mercer JF. Mammalian copper-transporting P-type ATPases, ATP7A and ATP7B: emerging roles. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42(2):206–9. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2009.11.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Wang Y, Tang C, Wang K, Zhang X, Zhang L, Xiao X, et al. The role of ferroptosis in breast cancer: tumor progression, immune microenvironment interactions and therapeutic interventions. Eur J Pharmacol. 2025;996(Suppl. 1):177561. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2025.177561. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Liu N, Chen M. Crosstalk between ferroptosis and cuproptosis: from mechanism to potential clinical application. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;171:116115. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.116115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Luo Y, Yan P, Li X, Hou J, Wang Y, Zhou S. pH-sensitive polymeric vesicles for GOx/BSO delivery and synergetic starvation-ferroptosis therapy of tumor. Biomacromolecules. 2021;22(10):4383–94. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.1c00960. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Robinson NJ, Winge DR. Copper metallochaperones. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79(1):537–62. doi:10.1146/annurev-biochem-030409-143539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Wang Y, Chen Y, Zhang J, Yang Y, Fleishman JS, Wang Y, et al. Cuproptosis: a novel therapeutic target for overcoming cancer drug resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 2024;72(1):101018. doi:10.1016/j.drup.2023.101018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Horng YC, Cobine PA, Maxfield AB, Carr HS, Winge DR. Specific copper transfer from the Cox17 metallochaperone to both Sco1 and Cox11 in the assembly of yeast cytochrome C oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(34):35334–40. doi:10.1074/jbc.m404747200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Tang D, Chen X, Kroemer G. Cuproptosis: a copper-triggered modality of mitochondrial cell death. Cell Res. 2022;32(5):417–8. doi:10.1038/s41422-022-00653-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Tsvetkov P, Detappe A, Cai K, Keys HR, Brune Z, Ying W, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism promotes adaptation to proteotoxic stress. Nat Chem Biol. 2019;15(7):681–9. doi:10.1038/s41589-019-0291-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Solmonson A, DeBerardinis RJ. Lipoic acid metabolism and mitochondrial redox regulation. J Biol Chem. 2018;293(20):7522–30. doi:10.1074/jbc.tm117.000259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Ge EJ, Bush AI, Casini A, Cobine PA, Cross JR, DeNicola GM, et al. Connecting copper and cancer: from transition metal signalling to metalloplasia. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022;22(2):102–13. doi:10.1038/s41568-021-00417-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kong R, Sun G. Targeting copper metabolism: a promising strategy for cancer treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1203447. doi:10.3389/fphar.2023.1203447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Xue Q, Kang R, Klionsky DJ, Tang D, Liu J, Chen X. Copper metabolism in cell death and autophagy. Autophagy. 2023;19(8):2175–95. doi:10.1080/15548627.2023.2200554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Jiang Y, Huo Z, Qi X, Zuo T, Wu Z. Copper-induced tumor cell death mechanisms and antitumor theragnostic applications of copper complexes. Nanomed. 2022;17(5):303–24. doi:10.2217/nnm-2021-0374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Cui S, Ghai A, Deng Y, Li S, Zhang R, Egbulefu C, et al. Identification of hyperoxidized PRDX3 as a ferroptosis marker reveals ferroptotic damage in chronic liver diseases. Mol Cell. 2023;83(21):3931–9.e5. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2023.09.025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Cong Y, Li N, Zhang Z, Shang Y, Zhao H. Cuproptosis: molecular mechanisms, cancer prognosis, and therapeutic applications. J Transl Med. 2025;23(1):104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

53. Mahoney-Sánchez L, Bouchaoui H, Ayton S, Devos D, Duce JA, Devedjian JC. Ferroptosis and its potential role in the physiopathology of Parkinson’s disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2021;196(Suppl 1):101890. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2020.101890. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Martin-Sanchez D, Fontecha-Barriuso M, Martinez-Moreno JM, Ramos AM, Sanchez-Niño MD, Guerrero-Hue M, et al. Ferroptosis and kidney disease. Nefrologia. 2020;40(4):384–94. doi:10.1016/j.nefro.2020.03.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Bao WD, Pang P, Zhou XT, Hu F, Xiong W, Chen K, et al. Loss of ferroportin induces memory impairment by promoting ferroptosis in Alzheimer’s disease. Cell Death Differ. 2021;28(5):1548–62. doi:10.1038/s41418-024-01290-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Ma A, Feng Z, Li Y, Wu Q, Xiong H, Dong M, et al. Ferroptosis-related signature and immune infiltration characterization in acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Respir Res. 2023;24(1):154. doi:10.1186/s12931-023-02429-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Qi W, Liu L, Zeng Q, Zhou Z, Chen D, He B, et al. Contribution of cuproptosis and Cu metabolism-associated genes to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2023;27(24):4034–44. doi:10.1111/jcmm.17985. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Liu C, Fang Z, Yang K, Ji Y, Yu X, Guo Z, et al. Identification and validation of cuproptosis-related molecular clusters in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28(3):e18091. doi:10.1111/jcmm.18091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Lai Y, Lin C, Lin X, Wu L, Zhao Y, Lin F. Identification and immunological characterization of cuproptosis-related molecular clusters in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:932676. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2022.932676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Jiang M, Liu K, Lu S, Qiu Y, Zou X, Zhang K, et al. Verification of cuproptosis-related diagnostic model associated with immune infiltration in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Endocrinol. 2023;14:1204926. doi:10.3389/fendo.2023.1204926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Nunnari J, Suomalainen A. Mitochondria: in sickness and in health. Cell. 2012;148(6):1145–59. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.02.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Wang H, Liu C, Zhao Y, Gao G. Mitochondria regulation in ferroptosis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2020;99(1):151058. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

63. Battaglia AM, Chirillo R, Aversa I, Sacco A, Costanzo F, Biamonte F. Ferroptosis and cancer: mitochondria meet “the iron maiden” cell death. Cells. 2020;9(6):1505. doi:10.3390/cells9061505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Gao M, Yi J, Zhu J, Minikes AM, Monian P, Thompson CB, et al. Role of mitochondria in ferroptosis. Mol Cell. 2019;73(2):354–63.e3. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Lv H, Shang P. The significance, trafficking and determination of labile iron in cytosol, mitochondria and lysosomes. Metallomics. 2018;10(7):899–916. doi:10.1039/c8mt00048d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiol Rev. 2014;94(3):909–50. doi:10.1152/physrev.00026.2013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Rauen U, Springer A, Weisheit D, Petrat F, Korth HG, de Groot H, et al. Assessment of chelatable mitochondrial iron by using mitochondrion-selective fluorescent iron indicators with different iron-binding affinities. Chembiochem. 2007;8(3):341–52. doi:10.1002/cbic.200600311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Stehling O, Lill R. The role of mitochondria in cellular iron-sulfur protein biogenesis: mechanisms, connected processes, and diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5(8):a011312. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a011312. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Zhi H, Yin W, Chen S, Zhang X, Yang Z, Man F, et al. Lactate metabolism regulating nanosystem synergizes cuproptosis and ferroptosis to enhance cancer immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 2026;325(5):123538. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2025.123538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Liu C, Guo L, Cheng Y, Gao J, Pan H, Zhu J, et al. A Mitochondria-targeted nanozyme platform for multi-pathway tumor therapy via ferroptosis and cuproptosis regulation. Adv Sci. 2025;12:e17616. doi:10.1002/advs.202417616. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Linder MC. Copper homeostasis in mammals, with emphasis on secretion and excretion. A Review Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(14):4932. doi:10.3390/ijms21144932. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Li HM, Long ZB, Han B. Iron homeostasis and iron-related disorders. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2018;39(9):790–2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

73. Lyamzaev KG, Huan H, Panteleeva AA, Simonyan RA, Avetisyan AV, Chernyak BV. Exogenous iron induces mitochondrial lipid peroxidation, lipofuscin accumulation, and ferroptosis in H9c2 cardiomyocytes. Biomolecules. 2024;14(6):730. doi:10.3390/biom14060730. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Gao S, Ge H, Gao L, Gao Y, Tang S, Li Y, et al. Silk fibroin nanoparticles for enhanced cuproptosis and immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer treatment. Adv Sci. 2025;12(18):e2417676. doi:10.1002/advs.202417676. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Ma Q, Gao S, Li C, Yao J, Xie Y, Jiang C, et al. Cuproptosis and serine metabolism blockade triggered by copper-based Prussian blue nanomedicine for enhanced tumor therapy. Small. 2025;21(5):e2406942. doi:10.1002/smll.202406942. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Sun Z, Xu H, Lu G, Yang C, Gao X, Zhang J, et al. AKT1 phosphorylates FDX1 to promote cuproptosis resistance in triple-negative breast cancer. Adv Sci. 2025;12(17):e2408106. doi:10.1002/advs.202408106. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Xiao C, Wang X, Li S, Zhang Z, Li J, Deng Q, et al. A cuproptosis-based nanomedicine suppresses triple negative breast cancers by regulating tumor microenvironment and eliminating cancer stem cells. Biomaterials. 2025;313:122763. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2024.122763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Feng L, Wu TZ, Guo XR, Wang YJ, Wang XJ, Liu SX, et al. Discovery of natural resorcylic acid lactones as novel potent copper ionophores covalently targeting PRDX1 to induce cuproptosis for triple-negative breast cancer therapy. ACS Cent Sci. 2025;11(2):357–70. doi:10.1021/acscentsci.4c02188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Tian RL, Wang TX, Huang ZX, Yang Z, Guan KL, Xiong Y, et al. Temsirolimus inhibits FSP1 enzyme activity to induce ferroptosis and restrain liver cancer progression. J Mol Cell Biol. 2025;16(8):mjae036. doi:10.1093/jmcb/mjae036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Wang M, Liu J, Yu W, Shao J, Bao Y, Jin M, et al. Gambogenic acid suppresses malignant progression of non-small cell lung cancer via GCH1-mediated ferroptosis. Pharmaceuticals. 2025;18(3):374. doi:10.3390/ph18030374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Wu Y, Zhang Z, Ren M, Chen Y, Zhang J, Li J, et al. Metformin induces apoptosis and ferroptosis of ovarian cancer cells under energy stress conditions. Cells. 2025;14(3):213. doi:10.3390/cells14030213. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Cang W, Wu A, Gu L, Wang W, Tian Q, Zheng Z, et al. Erastin enhances metastatic potential of ferroptosis-resistant ovarian cancer cells by M2 polarization through STAT3/IL-8 axis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;113(Pt B):109422. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.111651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Han C, Ge M, Xing P, Xia T, Zhang C, Ma K, et al. Cystine deprivation triggers CD36-mediated ferroptosis and dysfunction of tumor infiltrating CD8+ T cells. Cell Death Dis. 2024;15(2):145. doi:10.1038/s41419-024-06503-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Gao L, Zhang J, Yang T, Jiang L, Liu X, Wang S, et al. STING/ACSL4 axis-dependent ferroptosis and inflammation promote hypertension-associated chronic kidney disease. Mol Ther. 2023;31(10):3084–103. doi:10.1016/j.ymthe.2023.07.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Liu H, Xue H, Guo Q, Xue X, Yang L, Zhao K, et al. Ferroptosis meets inflammation: a new frontier in cancer therapy. Cancer Lett. 2025;620(3):217696. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2025.217696. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Liu Y, Su Z, Tavana O, Gu W. Understanding the complexity of p53 in a new era of tumor suppression. Cancer Cell. 2024;42(6):946–67. doi:10.1016/j.ccell.2024.04.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Xu R, Wang W, Zhang W. Ferroptosis and the bidirectional regulatory factor p53. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9(1):197. doi:10.1038/s41420-023-01517-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Kang R, Kroemer G, Tang D. The tumor suppressor protein p53 and the ferroptosis network. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133:162–8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

89. Chen X, Kang R, Kroemer G, Tang D. Broadening horizons: the role of ferroptosis in cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2021;18(5):280–96. doi:10.1038/s41571-020-00462-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Dai E, Han L, Liu J, Xie Y, Zeh HJ, Kang R, et al. Ferroptotic damage promotes pancreatic tumorigenesis through a TMEM173/STING-dependent DNA sensor pathway. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):6339. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20154-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Sun LY, Ke SB, Li BX, Chen FS, Huang ZQ, Li L, et al. ANP32E promotes esophageal cancer progression and paclitaxel resistance via P53/SLC7A11 axis-regulated ferroptosis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2025;144(3):113436. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2024.113436. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Yuan J, Khan SU, Yan J, Lu J, Yang C, Tong Q. Baicalin enhances the efficacy of 5-fluorouracil in gastric cancer by promoting ROS-mediated ferroptosis. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;164(3):114986. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114986. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Wang Y, Qi H, Liu Y, Duan C, Liu X, Xia T, et al. The double-edged roles of ROS in cancer prevention and therapy. Theranostics. 2021;11(10):4839–57. doi:10.7150/thno.56747. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Doll S, Proneth B, Tyurina YY, Panzilius E, Kobayashi S, Ingold I, et al. ACSL4 dictates ferroptosis sensitivity by shaping cellular lipid composition. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13(1):91–8. doi:10.1038/nchembio.2239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Ubellacker JM, Tasdogan A, Ramesh V, Shen B, Mitchell EC, Martin-Sandoval MS, et al. Lymph protects metastasizing melanoma cells from ferroptosis. Nature. 2020;585(7823):113–8. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2623-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Wen D, Li W, Song X, Hu M, Liao Y, Xu D, et al. NF-κB-mediated EAAT3 upregulation in antioxidant defense and ferroptosis sensitivity in lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16(1):124. doi:10.1038/s41419-025-07518-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Wei X, Ge Y, Zheng Y, Zhao S, Zhou Y, Chang Y, et al. Hybrid EMT phenotype and cell membrane tension promote colorectal cancer resistance to ferroptosis. Adv Sci. 2025;12(15):e2413882. [Google Scholar]

98. Zhang K, Guo L, Li X, Hu Y, Luo N. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote doxorubicin resistance in triple-negative breast cancer through enhancing ZFP64 histone lactylation to regulate ferroptosis. J Transl Med. 2025;23(1):247. doi:10.1186/s12967-025-06246-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Luo N, Zhang K, Li X, Hu Y, Guo L. Tanshinone IIA destabilizes SLC7A11 by regulating PIAS4-mediated SUMOylation of SLC7A11 through KDM1A, and promotes ferroptosis in breast cancer. J Adv Res. 2025;69(1):313–27. doi:10.1016/j.jare.2024.04.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Chen S, Li P, Shi K, Tang S, Zhang W, Peng C, et al. Tanshinone IIA promotes ferroptosis in cutaneous melanoma via STAT1-mediated upregulation of PTGS2 expression. Phytomedicine. 2025;141(5):156702. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Ge T, Li H, Xiang P, Yang D, Zhou J, Zhang Y. Tanshinone IIA induces ferroptosis in colorectal cancer cells through the suppression of SLC7A11 expression via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. Eur J Med Res. 2025;30(1):576. doi:10.1186/s40001-025-02842-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Li X, Tang S, Wang H, Li X. Tanshinone IIA inhibits hydrogen peroxide-induced ferroptosis in melanocytes through activating Nrf2 signaling pathway. Pharmacology. 2025;110(3):141–50. doi:10.1159/000541177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Mao S, Li X, Wang L, Yang PC, Zhang M. Rationale and design of sodium Tanshinone IIA sulfonate in left ventricular remodeling secondary to acute myocardial infarction (STAMP-REMODELING) trial: a randomized controlled study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2015;29(6):535–42. doi:10.1007/s10557-015-6625-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Yang L, Zhou G, Liu J, Song J, Zhang Z, Huang Q, et al. Tanshinone I and Tanshinone IIA/B attenuate LPS-induced mastitis via regulating the NF-κB. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;137(3):111353. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Zhang M, Liu Y, Sun X, Zhang X, Hua L. Salvia miltiorrhiza adjuvant therapy facilitates cardiac function recovery in patients with myocardial infarction. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2025;38(1):45–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

106. Zheng Y, Zheng Y, Chen H, Tan X, Zhang G, Kong M, et al. Erianin triggers ferroptosis in colorectal cancer cells by facilitating the ubiquitination and degradation of GPX4. Phytomedicine. 2025;139(1–2):156465. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156465. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Jin J, Fan Z, Long Y, Li Y, He Q, Yang Y, et al. Matrine induces ferroptosis in cervical cancer through activation of piezo1 channel. Phytomedicine. 2024;122:155165. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2023.155165. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Zhou Y, Gao H, Hua H, Zhu W, Wang Z, Zhang Y, et al. Clinical effectiveness of matrine sitz bath in treating perianal infection after chemotherapy for acute leukemia. Ann Palliat Med. 2020;9(3):1109–16. doi:10.21037/apm-20-912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Long Y, Lin XT, Zeng KL, Zhang L. Efficacy of intramuscular matrine in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2004;3(1):69–72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

110. Miao RM, Fang ZH, Yao Y. Therapeutic efficacy of tetrandrine tablets combined with matrine injection in treatment of silicosis. Zhonghua Lao Dong Wei Sheng Zhi Ye Bing Za Zhi. 2012;30(10):778–80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

111. Xu W, Deng K, Pei L. P4HA3 depletion induces ferroptosis and inhibits colorectal cancer growth by stabilizing ACSL4 mRNA. Biochem Pharmacol. 2025;233(6):116746. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2025.116746. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Xu T, Ma Q, Zhang C, He X, Wang Q, Wu Y, et al. A novel nanomedicine for osteosarcoma treatment: triggering ferroptosis through GSH depletion and inhibition for enhanced synergistic PDT/PTT therapy. J Nanobiotechnol. 2025;23(1):323. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-5440173/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

113. Zou Q, Zhou X, Lai J, Zhou H, Su J, Zhang Z, et al. Targeting p62 by sulforaphane promotes autolysosomal degradation of SLC7A11, inducing ferroptosis for osteosarcoma treatment. Redox Biol. 2025;79:103460. doi:10.1016/j.redox.2024.103460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

114. Huang M, Wu Y, Wei X, Cheng L, Fu L, Yan H, et al. Trifluridine/tipiracil induces ferroptosis by targeting p53 via the p53-SLC7A11 axis in colorectal cancer 3D organoids. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16(1):255. doi:10.1038/s41419-025-07541-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Pourhabib Mamaghani M, Mousavikia SN, Azimian H. Ferroptosis in cancer: mechanisms, therapeutic strategies, and clinical implications. Pathol Res Pract. 2025;269(6):155907. doi:10.1016/j.prp.2025.155907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Cai J, Ye Z, Hu Y, Ye L, Gao L, Wang Y, et al. Fatostatin induces ferroptosis through inhibition of the AKT/mTORC1/GPX4 signaling pathway in glioblastoma. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(3):211. doi:10.1038/s41419-023-05738-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Wu X, Jin L, Ren D, Huang S, Meng X, Wu Z, et al. α-Hederin causes ferroptosis in triple-negative breast cancer through modulating IRF1 to suppress GPX4. Phytomedicine. 2025;141(8):156611. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156611. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

118. Lin Z, Li Y, Wu Z, Liu Q, Li X, Luo W. Eriodictyol-cisplatin coated nanomedicine synergistically promote osteosarcoma cells ferroptosis and chemosensitivity. J Nanobiotechnol. 2025;23(1):109. doi:10.1186/s12951-025-03206-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Liu MR, Shi C, Song QY, Kang MJ, Jiang X, Liu H, et al. Sorafenib induces ferroptosis by promoting TRIM54-mediated FSP1 ubiquitination and degradation in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7(10):e0642. doi:10.1097/hc9.0000000000000246. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Bruedigam C, Porter AH, Song A, Vroeg in de Wei G, Stoll T, Straube J, et al. Imetelstat-mediated alterations in fatty acid metabolism to induce ferroptosis as a therapeutic strategy for acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Cancer. 2024;5(1):47–65. doi:10.1101/2023.04.25.538357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

121. Yu H, Kou Q, Yuan H, Qi Y, Li Q, Li L, et al. Alkannin triggered apoptosis and ferroptosis in gastric cancer by suppressing lipid metabolism mediated by the c-Fos/SREBF1 axis. Phytomedicine. 2025;140:156604. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Xie P, Yang ST, Huang Y, Zeng C, Xin Q, Zeng G, et al. Carbon nanoparticles-Fe(II) complex for efficient tumor inhibition with low toxicity by amplifying oxidative stress. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(26):29094–102. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c07617. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Kong N, Chen X, Feng J, Duan T, Liu S, Sun X, et al. Baicalin induces ferroptosis in bladder cancer cells by downregulating FTH1. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11(12):4045–54. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2021.03.036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

124. Shi L, Chen H, Chen K, Zhong C, Song C, Huang Y, et al. The DRD2 antagonist haloperidol mediates autophagy-induced ferroptosis to increase temozolomide sensitivity by promoting endoplasmic reticulum stress in glioblastoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2023;29(16):3172–88. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-22-3971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Hu X, Chang H, Guo Y, Yu L, Li J, Zhang B, et al. Mori Folium ethanol extracts induce ferroptosis and suppress gastric cancer progression by inhibiting the AKT/GSK3β/NRF2 axis. Phytomedicine. 2025;142:156789. doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2025.156789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

126. Alzahrani SM, Al Doghaither HA, Alkhatabi HA, Basabrain MA, Pushparaj PN. Propranolol and capecitabine synergy on inducing ferroptosis in human colorectal cancer cells: potential implications in cancer therapy. Cancers. 2025;17(9):1470. doi:10.3390/cancers17091470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

127. Huang C, Zeng Q, Chen J, Wen Q, Jin W, Dai X, et al. TMEM160 inhibits KEAP1 to suppress ferroptosis and induce chemoresistance in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2025;16(1):287. doi:10.1038/s41419-025-07621-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

128. Niu Y, Liu C, Jia L, Zhao F, Wang Y, Wang L, et al. STX1A regulates ferroptosis and chemoresistance in gastric cancer through mitochondrial function modulation. Hum Cell. 2025;38(3):66. doi:10.1007/s13577-025-01195-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

129. Jiang Y, Li J, Wang T, Gu X, Li X, Liu Z, et al. VIPAS39 confers ferroptosis resistance in epithelial ovarian cancer through exporting ACSL4. EBioMedicine. 2025;114(3):105646. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2025.105646. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

130. Zhang H, Ma T, Wen X, Jiang J, Chen J, Jiang J, et al. SIK1 promotes ferroptosis resistance in pancreatic cancer via HDAC5-STAT6-SLC7A11 axis. Cancer Lett. 2025;623:217726. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2025.217726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

131. Fan J, Lin H, Luo J, Chen L. 4-Methoxydalbergione inhibits the tumorigenesis and metastasis of lung cancer through promoting ferroptosis via the DNMT1/system Xc-/GPX4 pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2025;31(1):19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

132. Li C, Hua C, Chu C, Jiang M, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, et al. A photothermal-responsive multi-enzyme nanoprobe for ROS amplification and glutathione depletion to enhance ferroptosis. Biosens Bioelectron. 2025;278(29):117384. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2025.117384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

133. Shen J, Feng K, Yu J, Zhao Y, Chen R, Xiong H, et al. Responsive and traceless assembly of iron nanoparticles and (131)I labeled radiopharmaceuticals for ferroptosis enhanced radio-immunotherapy. Biomaterials. 2025;313(1):122795. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2024.122795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

134. Luo J, Shang Y, Zhao N, Lu X, Wang Z, Li X, et al. Hypoxia-responsive micelles deprive cofactor of stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 and sensitize ferroptotic ovarian cancer therapy. Biomaterials. 2025;314:122820. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2024.122820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

135. Li C, Luo Y, Huang L, Bin Y, Liang J, Zhao S. A hydrogen sulfide-activated Pd@Cu(2)O nanoprobe for NIR-II photoacoustic imaging of colon cancer and photothermal-enhanced ferroptosis therapy. Biosens Bioelectron. 2025;268(48):116906. doi:10.1016/j.bios.2024.116906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]