Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Crude Extract of Ulva lactuca L., Spirulina platensis (Gomont) Geitler and Nostoc muscorum C. Agardh ex Bornet & Flahault for Mitigating Powdery Mildew and Improving Growth of Cucumber

1 Pests and Plant Diseases Unit, College of Agricultural and Food Sciences, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, 31982, Saudi Arabia

2 Vegetable Diseases Research Department, Plant Pathology Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center (ARC), Giza, 12619, Egypt

3 Department of Mycology Laboratories, Plant Pathology Research Institute, Agricultural Research Center (ARC), Giza, 12619, Egypt

4 Research and Training Station, King Faisal University King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, 31982, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plants Abiotic and Biotic Stresses: from Characterization to Development of Sustainable Control Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3023-3045. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067444

Received 04 May 2025; Accepted 02 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Powdery mildew of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) is a destructive disease caused by Podosphaera xanthii (Castagne) U.Braun & Shishkoff. This study aimed to investigate the antifungal effect of extracts of Ulva lactuca, Spirulina platensis, and Nostoc muscorum against P. xanthii and to improve the physiological and morphological traits of cucumber under commercial greenhouse conditions. The chemical composition of the individual extracts from U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum was analyzed utilizing High-performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography/Mass spectrometry (GC/MS). Cucumber plants were sprayed twice with 5% of the crude extracts of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum and their mixture (U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum). The fungicide Topas 100 EC (Syngenta) was applied at the recommended dose (0.250 mL/L) only for comparison. The HPLC analysis indicated that the U. lactuca extract was the richest in phenolic compounds (605.84 µg g−1 DW) compared to cyanobacterial extracts of S. platensis (214.77 µg g−1 DW) and N. muscorum (462.97 µg g−1 DW). The GC-MS spectrum analysis of methanolic extracts revealed 12 compounds in N. muscorum, 11 compounds in S. platensis and 22 compounds in U. lactuca extract. In the 1st experiment, among treatments, the combined mixture (U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum) and U. lactuca extract revealed the remarkable disease reduction attained 74.35% and 71.42%, respectively. However, the highest disease reduction was attributed to fungicide Topas 100 EC with value reached 85.28%. A similar pattern of results was also noted during the 2nd experiment. In both experiments, the extract of S. platensis had the lowest effectiveness in lowering the DS and AUDPC of powdery mildew disease. The combined mixture and U. lactuca extract resulted in a substantial (p < 0.05) increase in plant lengths, fresh and dry weights, leaves number, fruit number, and weight and yield/plant. Cucumber plants treated with either the extract of U. lactuca or the combined mixture exhibited the highest activity (0.084 and 0.088 U mL−1min−1) for peroxidase and (1.64 and 1.62 U mL−1min−1) for catalase, respectively, in the second experiment. The greatest increase in total phenolic content (7.97 mg g−1 FW) was noticed in plants following treatment with the combined mixture. The treatment with U. lactuca and S. platensis revealed a significant increase in carotenoids contents, reached up to 17.99 and 17.53 mg g−1 FW, respectively. We, therefore, support the need for considering sustainable management of powdery mildew of cucumber using the compounds derived from U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum and to improve cucumber growth.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileCucumber, classified under the Cucurbitaceae family as Cucumis sativus L., holds a prominent position among the most popular and important greenhouse vegetables worldwide. In Egypt, it is considered a key economic crop, both for domestic use and export markets [1]. Powdery mildews (phylum Ascomycota, order Erysiphales) are among the most frequently encountered plant pathogenic fungi, with over 900 species [2]. Cucurbit powdery mildew is caused by Podosphaera xanthii (Castagne) U. Braun & Shishkoff, formerly referred to Sphaerotheca fuliginea (Schltdl.). The disease presents with similar symptoms, including talcum-like, off-white, powdery fungal growths appearing on both sides of leaves, along with petioles, stems, and occasionally fruits [3,4]. However, these two species can be readily differentiated through light microscopy. The conidia of P. xanthii exhibit ovoid shape, germinate on the sides, and feature fibrosin bodies, which appear as refractive crystals. In contrast, the conidia of G. orontii exhibit barrel shape, germinate at the apex, and do not have fibrosin bodies [5]. Powdery mildew fungi have both sexual and asexual life cycles, but it is the asexual cycle that primarily contributes to most of the damage caused. Once a conidium contacts a vulnerable host, the asexual life cycle progresses through three distinct stages: (i) the initial formation of an appressorium and its penetration throughout the cuticle and cell wall, (ii) the development of the primary haustorium, and (iii) the formation of a hyphae mat (with creating secondary haustoria and appressoria), along with the conidiophores and conidia differentiation [4,6]. The disease may quickly progress under optimal conditions, spreading during a period of 3 to 7 days following initial infection, facilitated by the massive production and release of conidia [7]. In Egypt, P. xanthii is recognized as the pathogen responsible for causing powdery mildew in cucurbits [8]. Powdery mildew reduces photosynthesis, leading to the reduction of plant growth, early loss of foliage, and therefore substantial decreases in crop yield up to 30%–50% [9–11]. Chemical fungicides are frequently applied to control powdery mildew; however, the intensive reliance on fungicides is considered unfavorable owing to environmental pollution and the emergence of pathogen resistance [2,12].

Recently, there has been increased focus on decreasing the reliance on synthetic pesticides to support farming methods that are sustainable, environmentally conscious, and eco-friendly [13–15]. Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) are recognized as the most abundant, diverse, and extensively spread type of photosynthetic bacteria [16]. Their presence, along with eukaryotic algae, contributes significantly to the Earth’s biomass [17]. Nostoc species, which are significant cyanobacteria members of the Nostocaceae family, produce various bioactive components as polyunsaturated fatty acids, phycocyanin, phenolics, triterpenoids amino acids, sulphates polysaccharides and carotenoids [18–20]. Recently, Spirulina platensis has garnered substantial attention from researchers due to its rich micro and macronutrient contents. This ancient cyanobacterial food source has long been utilized and is now recognized as noteworthy in the scientific community [21]. Macroalgae, or seaweeds, are algae that grow quickly and require less freshwater to cultivate. Despite this, their cultivation costs are significantly lower than those of microalgae. Ulva lactuca, sometimes called “sea lettuce,” accounts for a common macroalgae that grows around the Mediterranean coast and is a member of the phylum Chlorophyta [22].

Biologically, cyanobacteria and algae are known as sources of naturally active substances like proteins, hormone-like substances, polysaccharides, and phenolic compounds [23,24]. These substances have many various biological effects, including antifungal, insecticidal, antiviral, antitumor, cytotoxic, antiproliferative, and phytotoxic [25,26]. Furthermore, compounds estimated at 40,000, produced by various macroalgae families like red, brown, and green algae, are crucial in safeguarding plants [27,28]. Cyanobacteria and algae had an inhibitory activity over a number of fungal pathogens through directly preventing pathogen growth and secondarily by enhancing plant defense responses [29–32]. Furthermore, the cyanobacteria extracts have been showed antagonistic activity against different plant pathogens, including Botrytis cinerea and Plasmopara viticola [33], Armillaria sp., Penicillium expansum, Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. melonis, Phytophthora cambivora, P. cinnamomi, Rosellinia, sp., Rhizoctonia solani, Sclerotinia sclerotium, and Verticillium albo-atrum [34], and Alternaria alternata, Botrytis cinerea, Phytophthora capsici and Rhizopus stolonifer [35]. They demonstrated also antifungal activity against powdery mildew causal agents; Sphareotheca fuliginea, Erysiphe necator, and Erysiphe polygoni [36]. Their antiviral properties also extended to viral agents, like tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), potato virus X (PVX), and plant pathogenic bacteria, comprising Xanthomonas, Pseudomonas, Agrobacterium, and Erwinia [37–41].

A multitude of research has shown the promising role of cyanobacteria as biofertilizers. For instance, Bibi et al. [42] and Shariatmadari et al. [43] explored the impact of water extracts from different strains of cyanobacteria on the growth of cucumbers, pumpkins, and tomatoes. They demonstrated that these extracts boosted the plant height, root length, and dry and wet biomasses, attributed to plant hormones like indole butyric acid (IBA) and indole acetic acid (IAA). Similar study by Haroun and Hussein [44] revealed that filtrates from the Anabaena oryzae and Cylindrospermum muscicola induced the Lupinus termis growth. This growth boost was attributed to higher chlorophyll-a and -b concentrations, enhanced photosynthetic efficiency, and increased nitrogen and carbon levels in the plant’s leaves. Furthermore, Mishra and Pabbi [45] reported a 19.48% increase in rice grain yield when the plants were co-cultured with cyanobacteria. Within hydroponic system, cyanobacteria colonize the rice roots, enhancing the function of defense and hydrolytic enzymes, inducing improved plant growth and higher yields [46]. In conclusion, cyanobacteria can boost plant growth through improving the performance, growth and yield [47]. Algae are also able to directly foster plants’ development and growth, by enhancing germination rates and improving plant traits [48–50]. These benefits stem from the action of metabolites, which stimulate many metabolic processes like photosynthesis, respiration, chlorophyll production, ion absorption, and nucleic acid production [51].

Despite the few numbers of scientific publications [36,52–55] investigated the antifungal activity against powdery mildew on cucurbits; cyanobacterial and algal species continue to be extremely valuable resources for the identification and commercialization of antimicrobial agents that are effective against powdery mildews and other plant pathogens. Within this context, our goals of this research were to: determine the natural active compounds in the U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum extracts; determine their antifungal activity against cucumber powdery mildew under greenhouse circumstances; investigate their extracts on physiological and morphological traits of cucumber; determine the natural compounds in the U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum extracts; and correlate the presence of these compounds under the mitigation of powdery mildew as well as enhanced growth parameters of cucumber.

2.1 Source of Cyanobacteria and Algae

The cyanobacteria Spirulina platensis (EGY-SP 2022) and Nostoc muscorum (EGY-NM 2022) were provided from the Soil Water and Environment Research Institute (Microbiology Department), Agricultural Research Center, Giza, Egypt. Green algae Ulva lactuca (EGY-UL 2022) was collected from exposed rocky sites along Port Said coast, Egypt.

2.2 Molecular Identification of Cyanobacteria and Algae

Total DNA was extracted from approximately 50 mg from algae and cyanobacteria using the Dellaporta protocol [56]. The16S and 18S rRNA genes were used for the identification of cyanobacteria and microalgae, respectively. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was accomplished on a 2720 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). PCR amplification and sequencing and of cyanobacterial 16S rRNA gene region was done using primer pairs cya106f and cya781r as outlined in Nübel et al. [57]. PCR amplification and sequencing of algal 18S rRNA gene region was accomplished utilizing the primer pairs NS1 and NS4 [58] as outlined in Lin et al. [59]. The PCR amplicons obtained were subjected to cleaning and both direction sequencing at the Macro-gene company located in Seoul, Korea. The software MEGA v.11 was used to correct sequences [60]. BLAST® was utilized to compare the sequence’s homology to the GenBank sequence database maintained by the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

2.3 Preparation of S. platensis, N. muscorum and U. lactuca Extracts

Algal and cyanobacterial biomass were subjected to extractions utilizing an modified version of the technique outlined in Safavi et al. [61]. Five grams of air-dried biomass of each of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum were soaked in 80% methanol (1:10 w/v) under agitation at 120 rpm at 28°C for 48 h. The extracts were sonicated utilizing an Ultrasonic processor VCX750 (Sonics & Materials, Inc., Newton, CT, USA), for 15 min at 30% amplitude, 5-s intervals, and 5-s pulses. Then, extracts underwent 10-min centrifugation at 3000× g, followed by filtration of the supernatant utilizing Whatman No. 4 filter paper. The resultant crude extract was utilized for screening its antifungal activity. The mixture was prepared by mixing the extracts of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum (1:1:1v%).

2.4 High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum Extracts

Phenolic acids were determined using HPLC analysis (Agilent 1260 series). The Zorbax Eclipse Plus C8 column (4.6 × mm 250 mm i.d., 5 μm) was employed in the separation process. The mobile phase, comprising water (A) and acetonitrile with 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid (B), was supplied at 0.9 mL/min flow rate. A sequential linear gradient was employed for the mobile phase as follows: 0 min (82% A); 0–1 min (82% A); 1–11 min (75% A); 11–18 min (60% A); 18–22 min (82% A); 22–24 min (82% A). The analysis was conducted at wavelength of 280 nm using a multi-wavelength detector. A 5 μL aliquot of sample solution was introduced to the column, while the temperature was controlled at 40°C.

2.5 Analysis of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum Extracts Using Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS)

To determine the chemical composition of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum extracts, Trace GC1310-ISQ mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific, Austin, TX, USA) was utilized with a TG–5MS direct capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm film thickness). The column oven temperature started at 35°C and gradually raised until it reached 200°C at a 3°C /min rate and stabilized for 3 mins. Then, the ultimate temperature was raised to 280°C by 3 °C/min and stabilized for 10 mins. The temperatures of the MS transfer line and injector were preserved at 260°C and 250°C, respectively. A constant flow rate (1 mL/min) of Helium gas was utilized as the carrier gas. A 3-min solvent delay was followed by an automated injection of diluted samples using the Autosampler AS1300 in split mode, with each injection containing 1 µL of the sample. EI mass spectra collection was conducted in full scan mode using an ionization energy of 70 eV on a range of m/z 40–1000. The ion source temperature was adjusted to 200°C. The components were determined through cross-referencing the mass spectra and retention times with the corresponding data in the NIST 11 and WILEY 09 mass spectral databases.

The antifungal effect of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum extracts and their mixture were investigated against powdery mildew of cucumber. Two experiments were conducted during season 2022/2023 under greenhouse conditions in two different geographical locations. The first experiment was conducted in Tukh (30°21′15.9″N 31°13′56.4″E), Kaliobyia, while the second experiment was conducted in El Haram (29°59′45.3″N 31°09′59.3″E), Giza, Egypt. The average daytime temperatures inside greenhouses fluctuated between 27°C and 35°C. The experiments were conducted on 45 days-old cucumber cv. Hisham which was naturally infected with P. xanthii. An experimental layout using a randomized complete block design (RCBD) was utilized. Each treatment included three replications, with each replication containing ten plants. Plants were grown on both sides of the ridge, maintaining a 50 cm distance between each plant within the row (10 m in length and 0.7 m width). Plants were sprayed with the crude extracts of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum and their mixture (U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum) at concentration of 5%. The fungicide Topas 100 EC (Syngenta) was used at the recommended dose (0.250 mL/L) only for comparison. Plants were sprayed twice at 14-day intervals. Control plants received spray treatments only with tap water. A drip irrigation system was used to implement a scheduled irrigation and fertilization program was applied for cucumber plant, following the recommendations of the Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture.

Disease severity (DS) was assessed at the initial time and through four time points with intervals of 7 days. The evaluation of the disease included visually estimation of powdery colonies of P. xanthii on fully developed leaves located in the central region of each plant. DS% was visually documented with a scale ranging from 0 to 4 as described by Morishita et al. [62], whereas: 0, no visual infection; 1 = less than 5% surface affected; 2 = 6%–25% surface affected; 3 = 26%–50% surface affected; and 4 = >50% of surface affected. DS percentage was computed from the following formula [63]:

In this formula, R denotes DS%; a represents the count of infected leaves appraised; b represents the numerical value associated with each grade; N represents the total count of inspected plants; and K represents the maximum infection level on the scale. AUDPC was estimated to compare disease severity across various treatments utilizing the Pandey equation [64].

2.7.2 Growth and Yield Parameters

At the age of 60 days, leaves number per plant, plant height (cm), and plant biomass (g) per plant were quantified. Ten plants were randomly selected to measure their growth and yield characteristics. An electronic balance was employed to promptly determine the fresh tissue weight (g), whereas the dry tissue weight (g) was calculated following biomass drying at 55°C for 72 h. During the harvest phase, count of fruits per plant, fresh fruit weight (g), and plant yield (kg) were also assessed.

2.8 Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

The antioxidant enzyme activity was determined in cucumber plants following 48 h of the second spray. To do this, a quantity of 1 gram of leaves was grinded using a sterile mortar in 100 mL of phosphate buffer solution, maintaining a 7.1 pH. The resulting liquid was then filtered using five layers of cheesecloth. Subsequently, the mix underwent 15-min of centrifuging at 3000× g. Clear supernatant served as a crude enzyme to determine the activity of the following enzymes. The enzymatic activity measurements were conducted at room temperature (25 ± 1°C) through estimating the absorbance increase at a specified wavelength every 10 sec for a 1-min duration using a Unico-2000 UV spectrophotometer (Unico Scientific, Hong Kong, China). Three replicate measurements were conducted; the average of these values was computed, and the activity was denoted in enzyme units (mg mL–1 min–1).

2.8.1 Polyphenol Oxidase (PPO)

The PPO activity was determined using the technique given by Matta and Dimond [65]. The reaction mixture comprised 1.0 mL of 0.03 M catechol, 0.2 mL enzyme extract, and 1.0 mL of 0.2 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The total volume attained 6.0 mL through adding distilled water. The mixture underwent incubation for 30 min at 30°C. PPO activity was assessed at wavelength of 420 nm.

The PO activity was assessed following Allam and Hollis [66] method; the cuvette used for the assay comprised 0.5 mL of 0.1 M potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 0.3 mL 0.05 M pyrogallol, 0.3 mL crude extract, and 0.1 mL of H2O2 (1.0%). Then, distilled water was introduced until the cuvette volume reached 3.0 mL. The mixture underwent incubation for 15 min at 25°C. Following the incubation, the reaction was stopped through introducing 0.5 mL of 5.0% (v/v) H2SO4 [67]. PO activity was determined by measuring the absorbance increase at wavelength of 425 nm.

The activity of CAT enzyme evaluation was conducted following the technique of Aebi [68]. In the cuvette with the specimen, 0.1 mL crude extract was combined with 0.5 mL 0.2 M. sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.6) and 0.3 mL H2O2 (0.5%). Then, distilled water was introduced until the cuvette volume reached 3.0 mL. The H2O2 degradation was monitored via absorbance quantification at wavelength 240 nm.

The β-GLU activity was assessed in accordance with the published methodology of Sun et al. [69]. 0.2 mL laminarin (0.2% w/v) was added to 0.1 mL of the enzyme solution, which had been dissolved in a 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). The mixture underwent 30-min of incubation at 30°C. To stop the reaction, the dinitrosalicylic acid solution was employed, followed by 5-min boiling. The β-1,3-glucanase activity was measured at wavelength 540 nm.

2.9.1 Chlorophyll (TC) and Carotenoids Contents (TCC)

The total amount of chlorophyll (T.Chl) was determined in cucumber leaves 48 h. post the second spray. Cucumber fresh leaves (1 g) were collected and cut into small fragments. The tissue was then homogenized in 80% acetone to extract the pigments, and the mixture was filtered to remove any solid particles, following the method outlined by Porra [70]. Crude extract was utilized to assess the chlorophyll level following the method of Arnon [71], Total chlorophyll calculation involved quantifying the optical density at 645 and 663 nm, followed by the application of Arnon [71]:

The same crude extract was used to determine carotenoid content at 480 nm following Kirk and Allen [72] using the following equation:

A = represents absorbance at the corresponding wavelength, FW = fresh weight.

2.9.2 Phenolic and Flavonoids Contents

The total phenolic content (TPC) was evaluated utilizing the Folin and Ciocalteu reagent, adhering to the technique of Snell and Snell [73]. At a wavelength of 520 nm, the phenolic content was determined calorimetrically as mg of gallic acid equivalents per gramme of FW. The aluminum chloride colorimetric method [74] was employed for the calorimetric determination of the flavonoid content at wavelength 420 nm, and values expressed as mg quercetin equivalent (QE) g−1 FW.

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare variances across the means of various groups using SPSS software v. 8.0. (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). In case of p < 0.05, differences among means were compared utilizing the least significant difference (LSD) test according to Snedecor [75].

Hierarchical Clustering Analysis (HCA) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) were carried out using a web-based platform MetaboAnalyst [76].

3.1 Molecular Characterization of Cyanobacteria and Algae

The PCR results revealed amplicons of the 16S rRNA of molecular weight of ~355 and 620 bp for N. muscorum and S. platensis, respectively. While the molecular weight of PCR amplicons of 18S rRNA was ~750 bp for U. lactuca. Based on a BLASTn search tool of NCBIs GenBank nucleotide database, the closets hit utilizing the 16S rRNA sequence of EGY-NM 2022 and EGY-SP 2022 had closest match 100% to N. muscorum (strain Meg1, GenBank KM596855) and S. platensis (strain CCC 478, GenBank JX014313), respectively. Whereas 18S rRNA sequence had 100% similarity to U. lactuca (strain C208, GenBank AB425960). The generated nucleotide sequences were submitted to the GenBank database, with these accession numbers; PP342551, PP342552 and PP339758 for N. muscorum and S. platensis and U. lactuca, respectively.

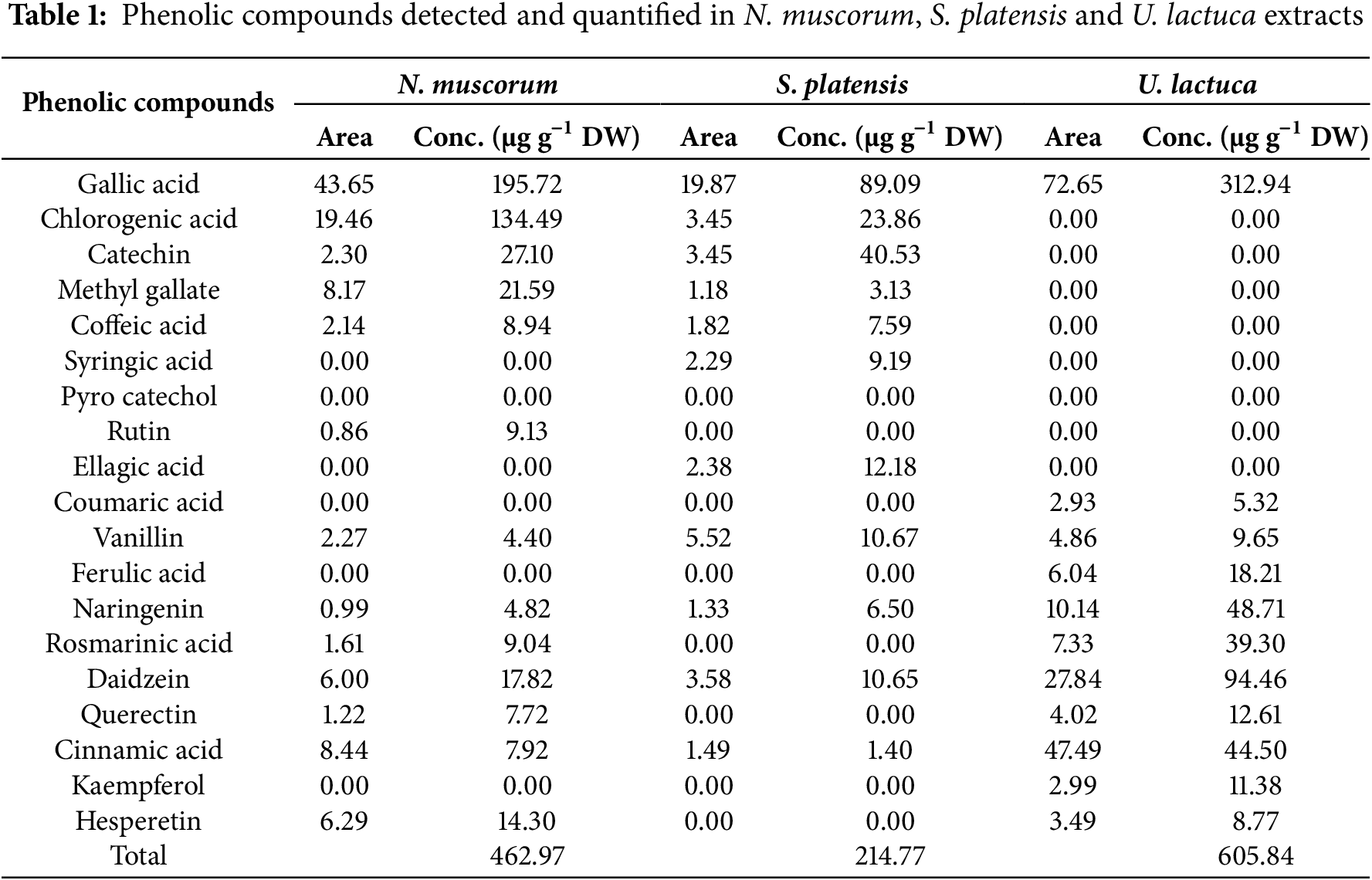

3.2 High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Analysis of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum Extracts

Phenolic components were characterized and measured utilizing HPLC analysis in the ethanolic extract of N. muscorum, S. platensis, and U. lactuca (Table 1). The gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, catechin, and methyl gallate were frequently detected in higher amounts than the other phenolic compounds. The U. lactuca extract was the richest in phenolic compounds (605.84 µg g−1 DW) compared to cyanobacterial extracts of S. platensis (214.77 µg g−1 DW) and N. muscorum (462.97 µg g−1 DW). The phenolic acids with the highest abundance in U. lactuca extract were gallic acid (312.94 µg g−1 DW). Alternatively, the extract of N. muscorum was richer than S. platensis in gallic acid (195.72 µg g−1 DW), methyl gallate (21.59 µg g−1DW), and chlorogenic acid (134.49 µg g−1 DW).

3.3 Gas Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) Analysis of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum Extracts

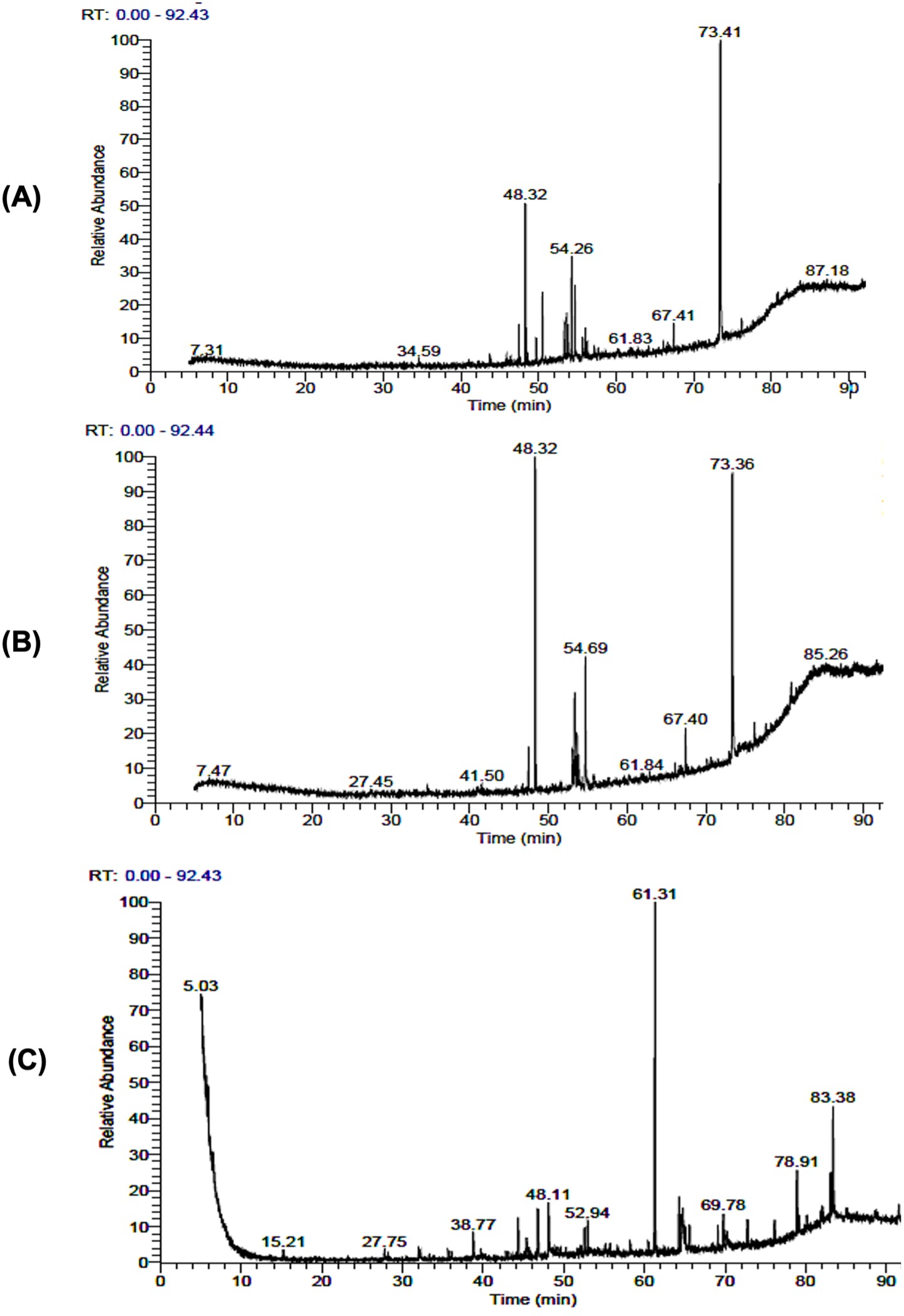

Fig. 1 depicts the occurrence of several components with distinct retention times, as verified by the GC-MS spectrum. The chemical analysis of methanolic extracts of N. muscorum using GC/MS led to the recognition of 12 compounds constituting 100% of the total detected compounds (Table S1). Fatty acids and their esters represented a significant portion, representing 89.97% of which erucylamide (36.48%), hexadecanoic acid, methyl ester (13.68%), cctadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester (7.54%), palmitic acid, ethyl ester (5.75%) was forming the bulk percentage. The chromatogram revealed that alcohols derived from phytol constituted 10.03% of the total peak areas observed. The extract of S. platensis consisted of 11 compounds, contributing 100% of the total detected compounds (Table S2). The chromatogram analysis showed that erucylamide, hexadecanoic acid methyl ester, and methyl stearate were the dominant compounds, together making up 67.79% of the total peak areas observed. The GC-MS profile revealed other fatty acids of hexadecenoic acid, linolenic acid, methyl ester, methyl 10-octadecenoate, 1,2-benzenedicarboxylic acid, cholesterinpalmitat, and cholest-5-en-3-ol, (3α) in small ratios. Remarkably, the GC/MS analysis of the U. lactuca extract facilitated the detection of 22 compounds, which constituted 100% of the total compounds (Table S3) (Fig. 1C). Phenol, 2,

Figure 1: GC–MS chromatographic profile of the recognized compounds in the extract of N. muscorum (A), S. platensis (B), and U. lactuca (C)

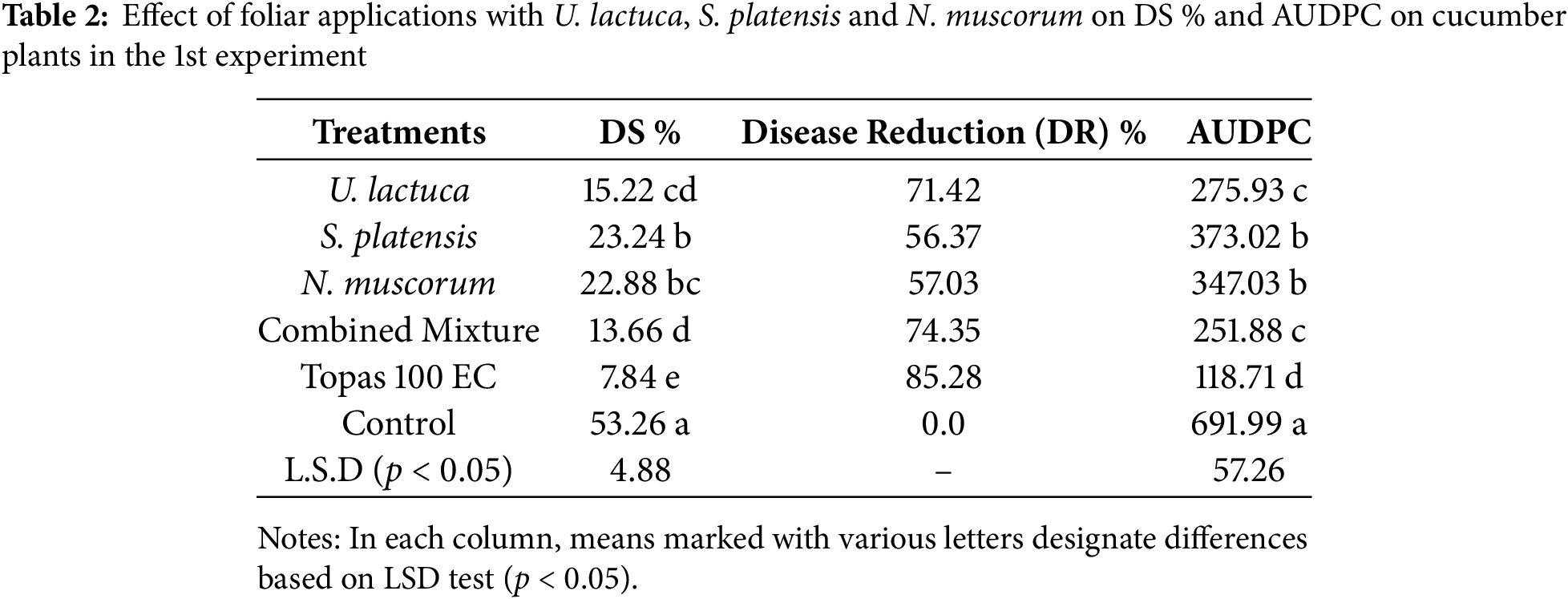

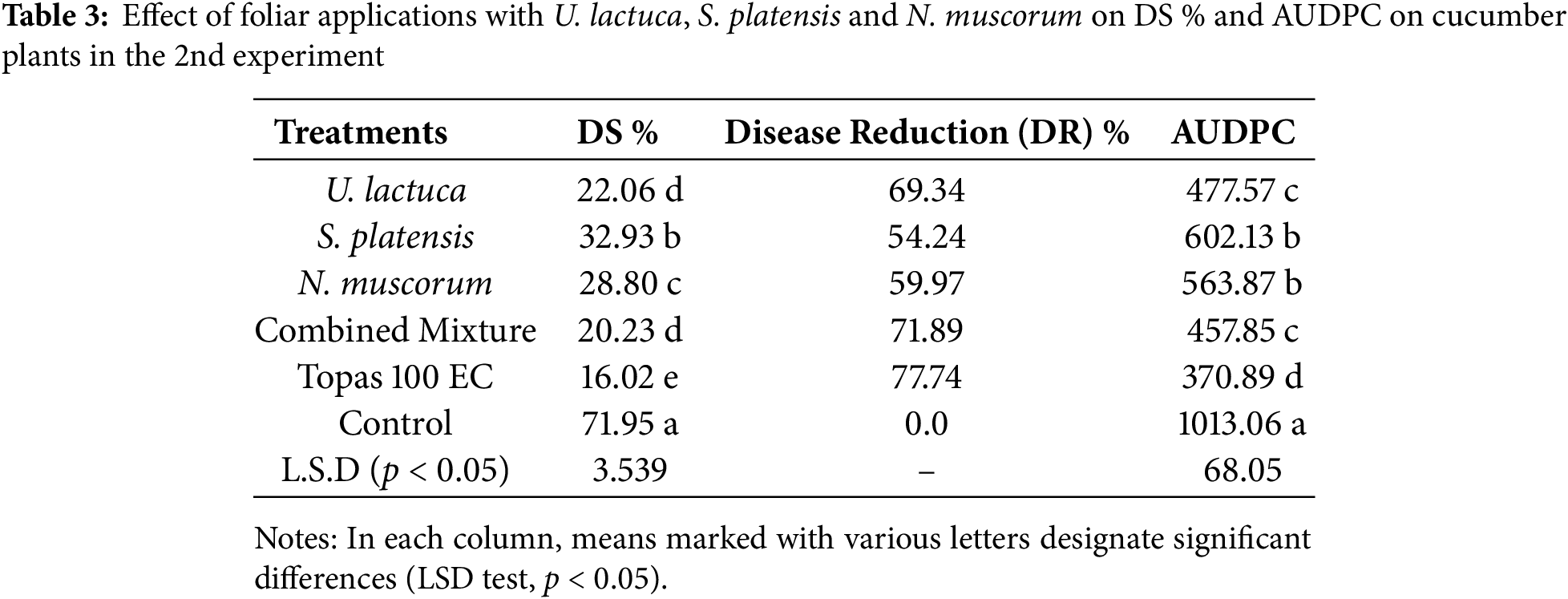

3.4 Antifungal Activity of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum Extracts against Powdery Mildew of Cucumber under Greenhouse Conditions

The inhibitory activity of the extract of U. lactuca, S. platensis, N. muscorum, and their mixture in comparison with fungicide on the severity of P. xanthii-induced powdery mildew under greenhouse conditions is shown in Tables 2 and 3. In the 1st experiment (Table 2), the combined mixture of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum was the most effective treatment reducing DS% to 13.66% and AUDPC to 251.88, with DR 73.35%. This was loosely followed by U. lactuca individual, which achieved 15.225% for DS and 275.93 for AUDPC with 71.42 DR. The lowest-performing treatment among the bioagents was S. platensis, which recorded 23.24% DS, 373.02 AUDPC, and 56.37% DR, indicating a weaker disease suppression effect compared to U. lactuca and N. muscorum. However, the synthetic fungicide Topas 100 EC showed superior performance with 7.84% for DS and 118.71 for AUDPC achieving the highest DR of 85.28%. A similar pattern of findings was also recognized with the same treatments in the 2nd experiment (Table 3). The combined mixture again outperformed individual algal and cyanobacterial treatments, recording 20.23% DS, 457.85 AUDPC, and 71.89% DR. U. lactuca followed closely with 22.06% DS and 477.57 AUDPC include the % DR. The lowest performing bioagent in this trial was S. platensis, with 32.93% DS, 602.13 AUDPC, and only 54.24% DR. Despite their effectiveness, both treatments were slightly less efficient than Topas 100 EC, which achieved 16.02% DS, 370.89 AUDPC, and 77.74% DR. The lowest performing was S. platensis, with 32.93% DS, 602.13 AUDPC, and 54.24% DR. Although Topas 100 EC maintained superior disease control (16.02% DS, 370.89 AUDPC, 77.74% DR). The control plots sprayed with water only revealed the maximum DS with values reached 53.26 and 71.95, and maximum AUDPC with values reached 691.99 and 1013.06 in both 1st and 2nd experiments, respectively. At the end, both of trials revealed that the tested cyanobacteria and algae showed promising results in controlling powdery mildew, they differed significantly from the effects seen in the controls and Topas fungicide.

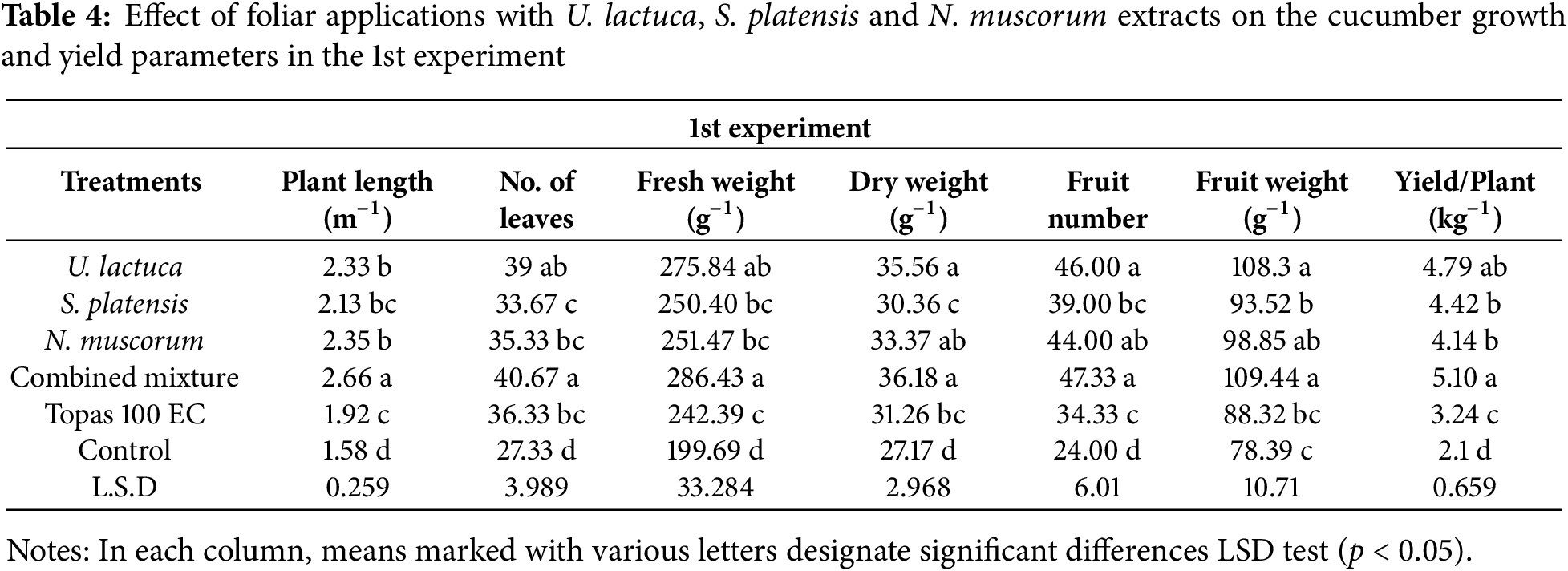

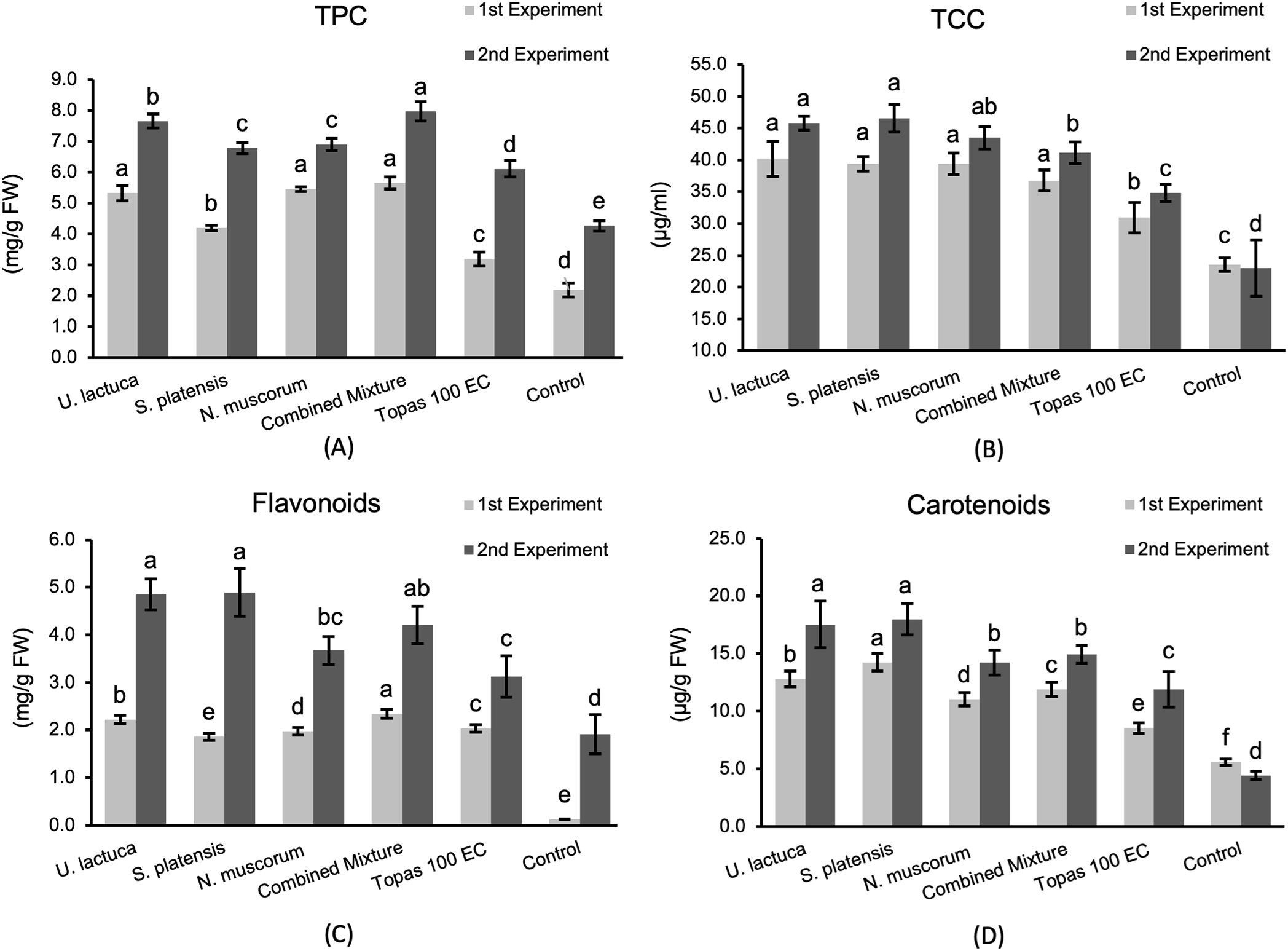

3.5 Growth and Yield Parameters of Cucumber Plants

Data in Tables 4 and 5 exhibited that all treatments improved the cucumber plants growth parameters relative to the control. In both experiments, treatment with the combined mixture and U. lactuca resulted in a substantial (p < 0.05) increase in plant lengths, fresh and dry weights, leaves number, fruit number, and weight and yield/plant in relative to other treatments as well as control plants. The remaining treatments showed no significant (p < 0.05) differences among each other but were still significantly different from control plants (Tables 4 and 5). Moreover, based on the LSD test, a significant variation was noted among plants treated with U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum extracts and fungicides in terms of measured parameters. However, as per the LSD test at (p < 0.05), this significant variation among treatments was not great.

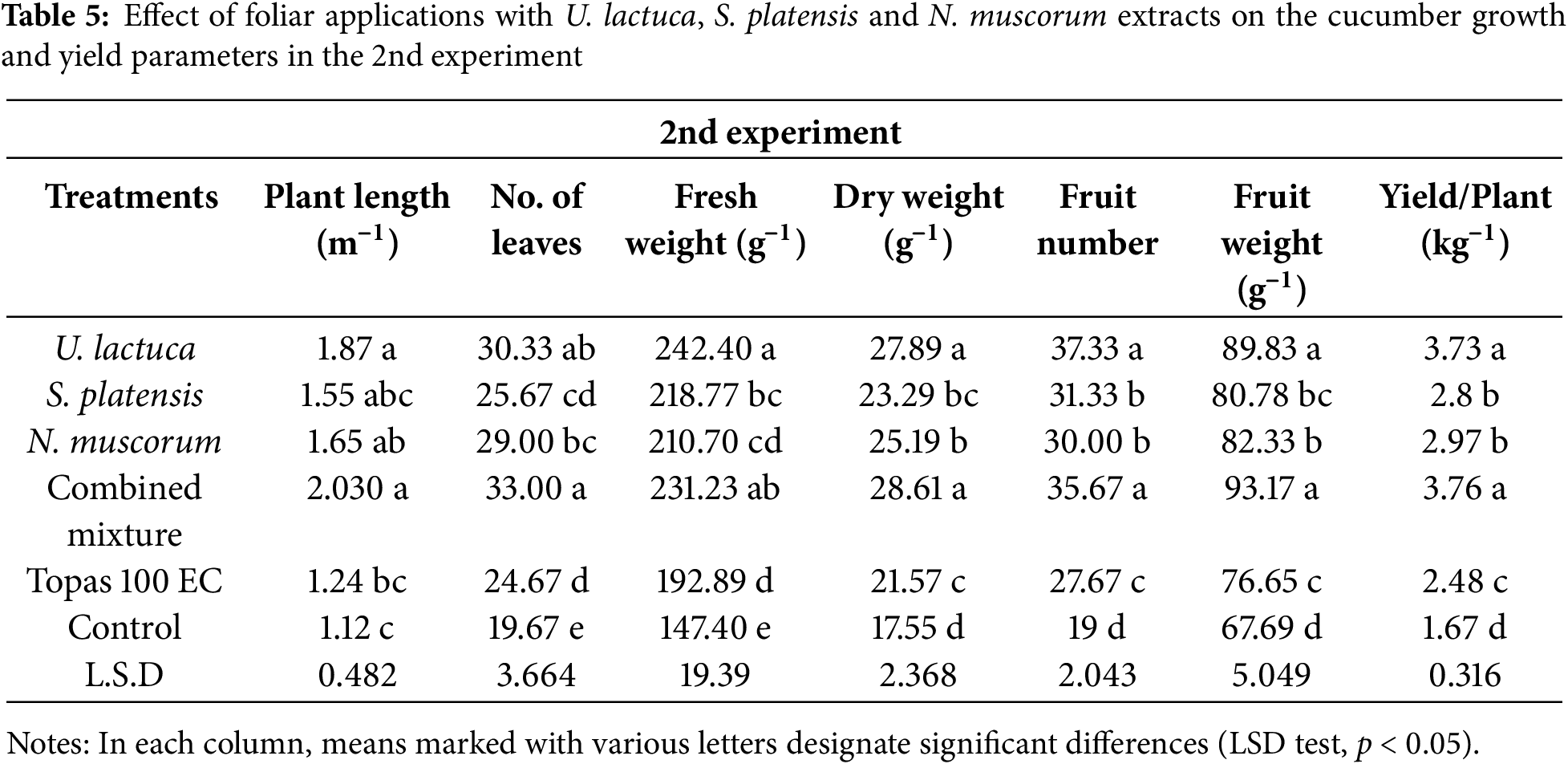

3.6 Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes

Results presented in Fig. 2 indicate that treatment with U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum and their combined mixture, along with fungicides, caused a statistically significant rise (p < 0.05) in the amount of PO, PPO, CAT, and β1,3 glucan enzymes in cucumber plants in the 1st and 2nd experiments when compared with untreated control. Generally, cucumber plants receiving treatment with either the extract of U. lactuca or the combined mixture exhibited the highest activity (0.084 and 0.088 U mL min−1) for PO and (1.64 and 1.62 U mL min−1) for CAT, respectively, in the 2nd experiment. The remaining treatments displayed moderate efficacy in increasing the activity of PO and CAT enzymes. Moreover, plants treated with U. lactuca also exhibited the highest PPO enzyme activity and recorded 0.138 U mL min−1. The other treatments exhibited moderate efficacy in increasing PPO activity and are still significantly higher than fungicide and control. Unlike, plants treated with Topas 100 EC displayed the lowest PO, PPO, CAT, and β1,3 glucan activity in the 1st and 2nd experiments relative to other treatments and control, which reached 0.58, 0.43, and 1.47 U mL min−1.

Figure 2: Activity of peroxidase (PO) (A), polyphenoloxidase (PPO) (B), catalase (CAT) (C), and β1, 3 glucan (D) enzymes assessed in infected cucumber leaves treated with U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum, and their mixture in relative to Topas 100 EC fungicide and control. The values expressed within columns represent the average of three repetitions ± standard deviation. According to the LSD test, bars designated by distinct letters varied significantly (p < 0.05)

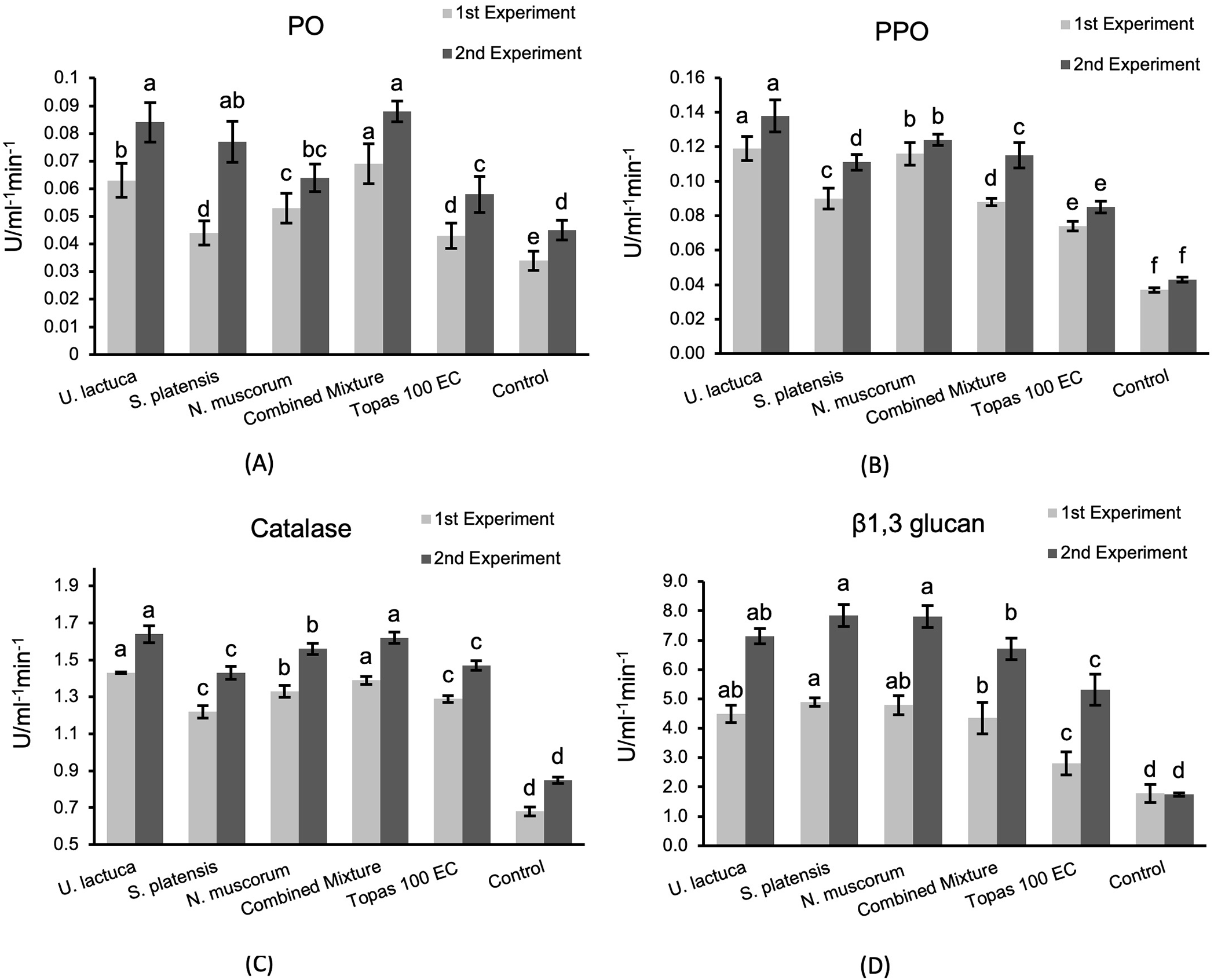

3.7 TCC, TPC, Flavonoids and Carotenoids Contents

Data shown in Fig. 3 reveal that the TPC, TCC, flavonoids, and carotenoids contents in cucumber plants, especially in the 2nd experiment, were extremely improved as a response for all treatments relative to the fungicide and control. No significant variation was noted among U. lactuca and S. platensis treatments in increasing TPC. The combined mixture was superior (7.97 mg g−1 FW). Moreover, all treatments triggered a substantial increase in TCC and flavonoids contents with no significant differences among them. Among the tested treatments, U. lactuca and S. platensis revealed a significant increase in carotenoids contents reached up to 17.99 and 17.53 mg g−1 FW, respectively.

Figure 3: The TPC (A), TCC (B), flavonoids (C), and carotenoids (D) in cucumber plants in response to treatments with U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum and their mixture in relative to Topas 100 EC fungicide and control. The values expressed within columns represent the average of three repetitions ± standard deviation. According to the LSD test, bars designated by distinct letters varied significantly (p < 0.05)

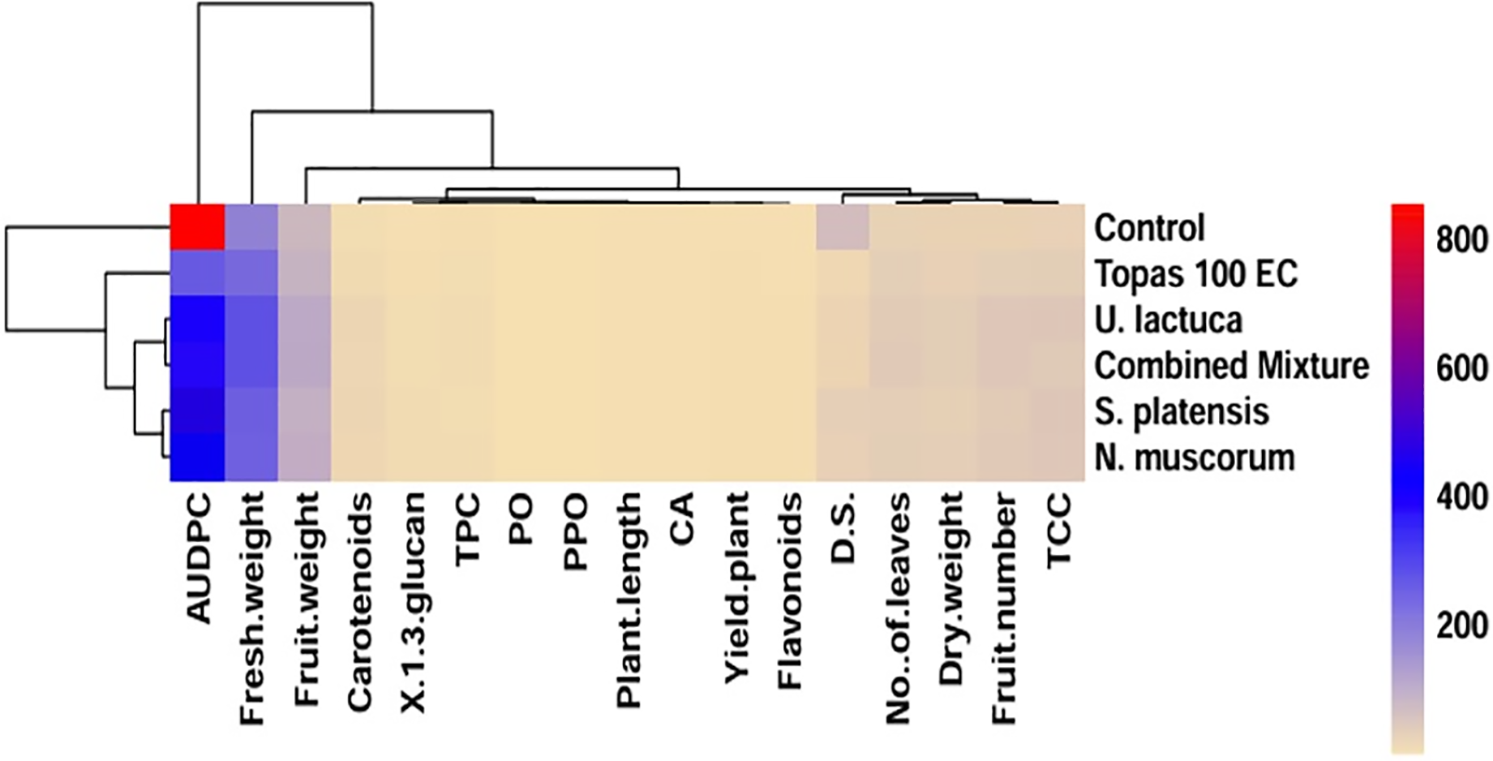

3.8 Hierarchical Clustering Analysis (HCA)

The relationships between the foliar applications of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum, as well as their mixture, in relation to the control and Topas 100 EC fungicide, are illustrated in a heatmap using the evaluated parameters (Fig. 4). The overall variations among all interventions were effectively identified through a heatmap analysis. Clearly, the application of the Tops fungicide resulted in the most pronounced inhibitory effect, as evidenced by the DS and AUDPC values being considerably reduced. In contrast, the evaluated U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum as well as their mixture exhibited encouraging DS and AUDPC values in relation to untreated control. The treatment involving the combined mixture and U. lactuca significantly enhanced plant lengths, fresh and dried weights, leaf number, fruit number, weight, and yield per plant compared to the control plants. The previously mentioned treatment demonstrated the greatest activity in PO and CAT enzymes. Nevertheless, the TPC only increased in response to foliar application of the combined mixture.

Figure 4: Heatmap correlation graph displaying the hierarchical clustering of the treatments and measured parameters, calculated as the average of two experiments. The treatments are denoted by rows, whereas the columns represent the distinct response variables. As indicated by the scale in the upper right corner of the heatmap, lower numerical values are denoted by green, while higher numerical values are represented by the color red. D.S = disease severity, AUDPC = the area under disease progress curve, TPC = total phenolic content, PO = peroxidase, PPO = polyphenol oxidase, and CAT = catalase

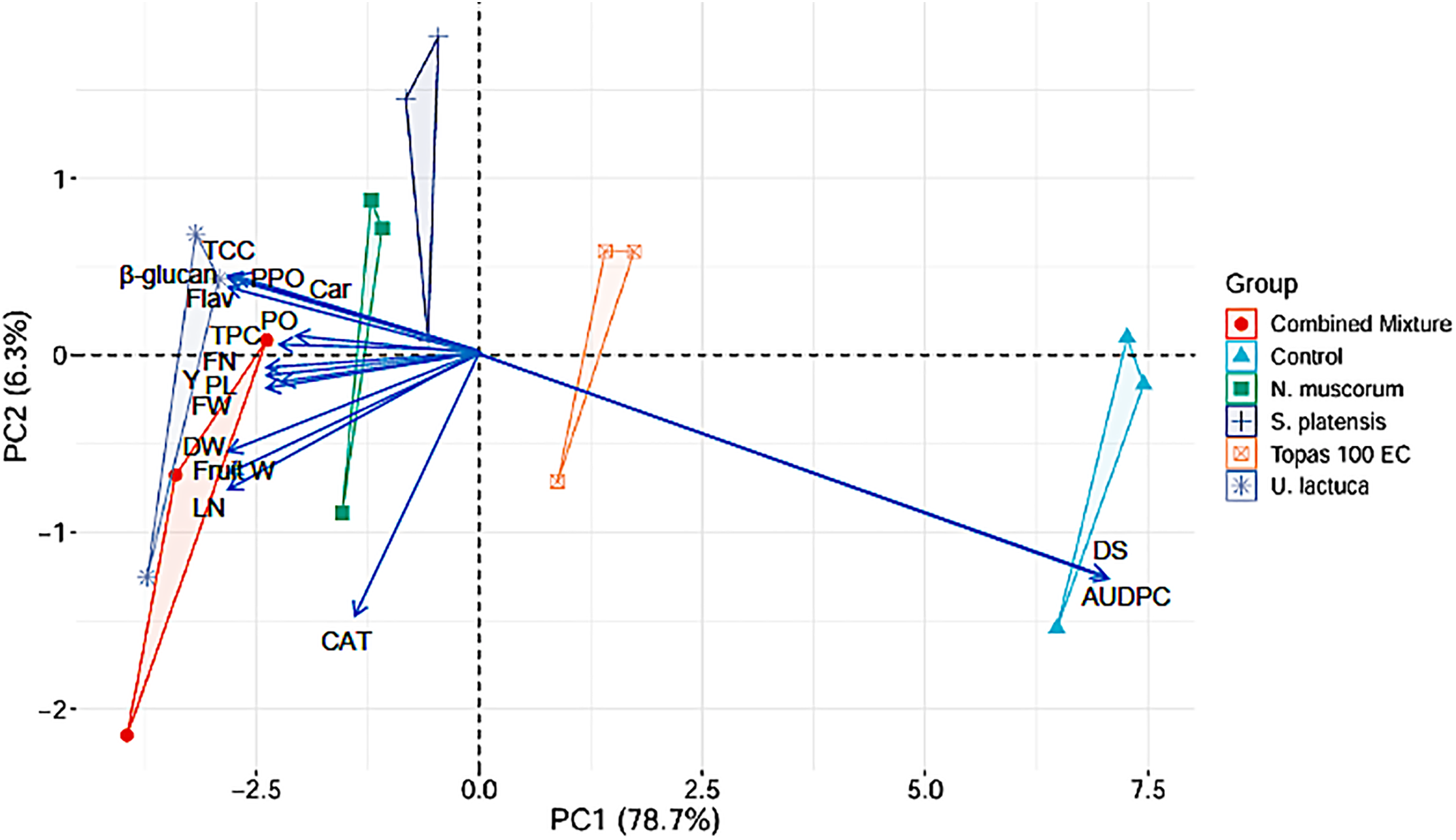

3.9 Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

To further comprehend treatment impact on the observed parameters, principal component analysis (PCA) was employed to determine the relation between evaluated parameters such as DS, AUDPC and yield, and morphology as well as physiochemical of cucumber plant (Fig. 5). For all parameters, two principal components (PC) are shown. PC1 and PC2 explained 85% of the difference between plants. The first component, PC1, explained 78.7% of the total variance, while the second component contributed 6.3%. Concerning the parameters in PC1, all had positive correlation except CAT, DS and AUDPC which showed negative contribution to DS and cucumber growth. Based on the treatments, the extracts of U. lactuca, N. muscorum and the mixture exhibited a positive correlation to cucumber growth parameters as wells powdery mildew disease parameters (DS and AUDPC).

Figure 5: Biplot of the first two principal components for DS, AUDPC, yield, morphological, and physiochemical parameters in cucumber plants. DS = disease severity, AUDPC = area under disease progress curve, TCC = total chlorophyll content, Car = carotenoids, Flav = flavonoids, TPC = total phenolic content, PO = peroxidase, PPO = polyphenol oxidase, and CAT = catalase, FN = fruit number, Y = yield/plant, PL = plant length, FW = fresh weight, DW = dry weight, Fruit W = fruit weight, LN = leaves number

The control of powdery mildew disease has been traditionally achieved using chemical fungicides. Nevertheless, there has been a growing call from both consumers and officials to decrease the utilization of chemical pesticides owing to environmental considerations, elevated purchasing expenses, and the continuous tightening of government regulations and restrictions [77]. The utilization of cyanobacteria and algae for managing bacterial and fungal diseases has been extensively investigated by several researchers, making it a pioneering concept in sustainable agriculture [31]. Contextually, the potential effect of specific cyanobacteria S. platensis and N. muscorum and the green algae U. lactuca was evaluated against P. xanthii over Topas 100 EC fungicide. Cyanobacteria and algae can produce different bioactive compounds with growth-promoting or antimicrobial characteristics [78,79]. Phenolic compounds are one of these chemicals that are found in the structure of microalgae and contribute to their antioxidant activity. Cyanobacteria and algae are well-known producers of phenolic compounds comprising catechin, protocatechuic, caffeic, gallic, vanillic, epicatechin, ferulicm, coumaric, and chlorogenic acids [21,24,80,81]. In this study, 19 phenolic compounds were detected and quantified. The produced amount varied, being U. lactuca was the richest with a value of 1523.13 µg g−1 DW. The dominant phenolic compounds were gallic and chlorogenic acids, with their greatest amounts found in the extracts of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum. Our findings concord well with those of Jerez-Martel et al. [80], who specified that gallic acid accounted for the dominant phenolic acid found in the crude extracts of microalgal and cyanobacterial strains. In general, it was noted that the U. lactuca exhibited an improved phenolic potential relative to the S. platensis and N. muscorum. Correspondingly, Klejdus et al. [82] indicated that microalgae contain higher levels of phenolic compounds than cyanobacteria species. The scarcity of phenolic compounds in cyanobacteria was attributed by the authors to the contrasting evolutionary stages of cyanobacteria and microalgae. They posited that microalgae, being more advanced organisms, have developed phenolic compounds as part of their stress adaptation mechanisms [82,83]. Unlike, Vega et al. [84] demonstrated that the extract of cyanobacterial Scytonema sp. exhibited higher content in phenolic compounds (22.5 mg g−1 DW) than red algal Porphyra umbilicalis (3 mg g−1 DW).

Profiling of metabolites has been determined as a method for investigating the complex chemical matrices of different compounds in the extract of studied algae and cyanobacteria. In our study, the GC-MS analysis demonstrated that U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum methanolic extracts consistently contained a variety of bioactive compounds. The composition ratios of the ingredients varied among the species analyzed. Nevertheless, certain fundamental compounds, including alcohols (like phytol), phenolic and fatty acids, sterols and hydrocarbons, were consistently found in high abundance across all species. These compounds have reported as anticancer, antioxidant, antibacterial and antifungal activity against several fungal and bacterial pathogens [85–89]. The mechanism of the identified fatty acids as antimicrobial agents against P. xanthii was not investigated in this study. However, their effects may result from the disruption of the cellular membrane, causing leakage, impaired nutrient uptake, and obstructing cellular respiration [90]. Furthermore, the diffusion of fatty acids into the microbial cell walls peptidoglycan meshwork may cause the damage and disintegration of the cellular membrane [41], resulting in peroxidative stress in the microbial cells [91]. Similarly, the antifungal compounds exert their activity by potentially modifying essential fungal cell components, resulting in impaired membrane integrity, hindering spore germination, and suppressing the synthesis of B-(1,3)-D-glucan [90]. Additionally, antifungal compounds have the potential to hinder lipid formation in the specific fungi by either inhibiting the biosynthesis of ergosterols or reducing the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids relative to saturated ones [92].

The greenhouse experimental findings indicated the antifungal potentiality of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum extracts against P. xanthii. According to statistical analysis, cucumber plants showed a significant variation in terms of DS and AUDPC following treatments with the extracts of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum. Substantial reductions in DS were noted following each application of the extracts and fungicide via foliar spray in both experiments. The application of U. lactuca extract exhibited the greatest inhibitory impact in reducing DS and AUDPC, followed by the treatment with N. muscorum extract. This finding was not surprising since the GC mas and HPLC profile of the U. lactuca extract was the richest in phenolic, fatty acids, alcohols, and hydrocarbon contents, which are likely the key contributors to the observed biological activity of U. lactuca. Consistent with our findings, the study of Jaulneau et al. [36] documented that the green algae Ulva armoricana extract guaranteed 90% protection against powdery mildew pathogens Erysiphe necator, E. polygoni, and Sphareotheca fuliginea. Nevertheless, Roberti et al. [53] indicated that the green algae Chlorella sp. and Ulva rigida, were unable to decrease the pathogen sporulation and the infected area significantly; however, they promoted the infected region, with Ulva rigida actually increasing pathogen sporulation. Additionally, Thankaraj et al. [93] evaluated different types of crude extract of red, brown, and green algae against powdery mildew on grapevine induced by Uncinula necator. The authors displayed the superior efficacy of the brown algae Dictyota dichotoma in reducing powdery mildew, with reduction values of 63.76% and 78.18% over control. Members of red algae, including Corallina sp. and Halopithys sp., have also demonstrated antifungal activity against P. xanthii on zucchini cotyledons [53]. The authors also found out that out of the tested brown algae, only the Sargassum sp. extract exhibited the capacity to alleviate symptoms of the disease and reduce sporulation.

Alternatively, cucumber plants receiving treatment with the extract of S. platensis and N. muscorum exhibited promising results in terms of DS and AUDPC when compared with the control in both experiments. Consistent with what we found, Ata et al. [94] found out that S. platensis and N. muscorum were more effective than Anabaena oryzae in reducing DS of Sugar Beet powdery mildew induced by Erysiphe betae under greenhouse and field conditions. By contrast, Roberti et al. [53] specified that the treatment of zucchini cotyledons with the Anabaena sp. extract exhibited the greatest reduction in the infected region and spore production of P. xanthii when compared with Spirulina sp. and other cyanobacteria. Earlier reports highlighted the antimicrobial activity of the N. muscorum extracellular products in combating pathogens affecting humans and plants [95–97]. The superior effect was obtained with the treatment of the combined mixture of the extracts of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum, which led to a significant decline in DS and AUDPC in both experiments. This can stem from the higher relative ratios of bioactive compounds like phenolic acids, fatty acids, and their esters along with other compounds. This suggests that the observed activity may be explained by the synergistic interaction of the ingredients present in each extract.

The variety of extracellular compounds produced by algae and cyanobacteria contribute significantly to boosting the growth of higher plants. Regarding the growth and yield parameters, the data evidently demonstrated that all tested extracts of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum and their mixture caused remarkable increases of all cucumber growth parameters over fungicide treatments and control in both experiments. In respect to their individual effect, the mixed extract ranked first in increasing growth and yield parameters during the two experiments, followed by treatment with U. lactuca extract. Several studies have documented the advantages of seaweed extracts in promoting the productivity and growth of various crops, including blackgram [98], soybean [99], tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) [100], wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) [101], rice (Oryza sativa L.) [102], maize (Zea mays) [103], and cucumber (Cucumis sativus) [55]. The measured parameters of plant growth and yield in our data align with the findings reported by previous researchers. In this perspective, Hassan et al. [55] showed that foliar treatment of a commercialized extract of three seaweed species, Jania rubens, Pterocladia capillacea, and U. lactuca, led to a rise in the fruit quality and yield components of cucumber. Moreover, Valencia et al. [104] found that foliar treatment of various algal extracts boosted the cucumber quality through attaining the maximum antioxidant capacity. The outcomes of our study were consistent with those of supporting similar beneficial effects of algal extracts [105]. According to Ata et al. [94], the treatment with the extract of S. platensis increased the fresh weight of 100 roots and root yield of sugar beet during two seasons, followed by N. muscorum. By contrast, no significant differences were noted among treatments with S. platensis and N. muscorum concerning fruit weight and yield/plant in both experiments.

Our study revealed a significant elevation in the levels of defense-linked enzymes PO, PPO, CAT, and β1,3 glucan was noticeably detected in plants that received treatment with methanolic extracts of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum along with their mixture relative to those untreated and fungicide-treated plants after the first and second spray. There was no significant (p < 0.05) difference among individual extracts as well as their combinations on the enzymatic activities. However, Ata et al. [94] indicated that the maximum increase in PO and PPO activities was distinguished in cucumber plants that received treatment with N. muscorum, followed by plants treated with S. platensis. Furthermore, plants treated with Tops fungicide exhibited a significant elevation in enzyme activities in comparison with control. This increase might be ascribed to the response of the infected plant defense system for limiting the disease spread. Interestingly, the inhibitory effect of methanolic extracts of U. lactuca, S. platensis, and N. muscorum might be linked to inducing plant defense-related enzymes and the chemical compounds of the tested extracts. Previous research studies [90,106] suggested that the antioxidant activity has been attributed to synergetic interaction among secondary metabolites, particularly polyunsaturated fatty acids, phenolic compounds, pigments, polysaccharides, and flavonoids. These findings could support our results that the increase in these enzymes’ activities could be a result of the synergistic effects among detected methanolic contents of fatty acids, phytol, alkaloids, phenolics, and hydrocarbons, particularly fatty acids. On the other hand, treatment with methanolic extracts of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum and their mixture revealed an increased accumulation of TPC, TCC, flavonoids and carotenoids contents in cucumber plants, especially after the second spray. Phenols, carotenoids, flavonoids and chlorophyll are of the secondary metabolites produced in seaweeds and microalgae [107,108]. These metabolites account for the main pigments produced by plants, macro and microalgae, that have been known for their antimicrobial effect in combating human and plant pathogens [108]. As previously noted, seaweed liquid extracts have the potential to raise chlorophyll level [109], raise the overall total yield [55] and stimulate growth and increase the productivity of cucumber [98,104]. We suggest that the higher antioxidant capacity of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum in this investigation may have been a result of presence and synergistic effects of chlorophyll, flavonoids, phenolics, and carotenoids.

Based on the findings from HPLC and GC-MS analyses, fatty acids and their esters were accountable for the antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of the investigated extracts. Additionally, notable proportions of bioactive compounds, such as organic alcohols (like phytol), phenolics, benzene derivatives, and hydrocarbons, were also identified. These compounds might act synergistically to exhibit the recorded activities. The findings of this study represent a significant advancement in the development of environmentally friendly control strategies utilizing a combination of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum to control powdery mildew, enhance cucumber growth and induce systemic resistance. The utilization of cyanobacterial and algal extracts, as they enhance growth and yield components, offers a promising alternative to reduce reliance on conventional fertilizers. These results, although preliminary, will serve as a basis for further field study. After finishing this study, subsequent research endeavors could concentrate on investigating the synergistic effects of U. lactuca, S. platensis and N. muscorum to develop bio-fertilizers and bio-fungicides for commercial purposes, thereby reducing reliance on mineral fertilizers as well as chemical fungicides to promote sustainable agriculture. However, various problems, bottlenecks, and application limits preventing their widespread use, as well as worries about their manufacturing costs, extraction, bioformulation, compatibility and product stability, and environmental safety, all stand in the way of fully realizing their promise.

Acknowledgement: Authors extend their gratefulness to the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this research through grant number KFU250394.

Funding Statement: The current research was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, through grant number KFU250394.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail and Eman Said Elshewy; methodology, Eman Said Elshewy; software, Ayman Y. Ahmed; validation, Eman Said Elshewy and Ayman Y. Ahmed; formal analysis, Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail and Eman Said Elshewy; investigation, Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail and Eman Said Elshewy; resources, Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail; data curation, Eman Said Elshewy; writing—original draft preparation, Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail; writing—review and editing, Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail and Hossam M. Darrag; visualization, Ayman Y. Ahmed and Hossam M. Darrag; supervision, Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail; project administration, Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail; funding acquisition, Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data collected or analyzed during this investigation are included in this study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.067444/s1.

References

1. Elagamey E, Abdellatef MAE, Haridy MSA, Abd El-aziz ESAE. Evaluation of natural products and chemical compounds to improve the control strategy against cucumber powdery mildew. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2023;165(2):385–400. doi:10.1007/s10658-022-02612-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Vielba-Fernández A, Polonio Á., Ruiz-Jiménez L, de Vicente A, Pérez-García A, Fernández-Ortuño D. Fungicide resistance in powdery mildew fungi. Microorganisms. 2020;8(9):1–34. doi:10.3390/microorganisms8091431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bakhat N, Vielba-Fernández A, Padilla-Roji I, Martínez-Cruz J, Polonio Á., Fernández-Ortuño D, et al. Suppression of chitin-triggered immunity by plant fungal pathogens: a case study of the cucurbit powdery mildew fungus Podosphaera xanthii. J Fungi. 2023;9(7):771. doi:10.3390/jof9070771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Pawełkowicz M, Głuchowska A, Mirzwa-Mróz E, Zieniuk B, Yin Z, Zamorski C, et al. Molecular insights into powdery mildew pathogenesis and resistance in cucurbitaceous crops. Agriculture. 2025;15(16):1743. doi:10.3390/agriculture15161743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Nayak AM, John P, Dhange PR. Identification and morph-metric characterization of powdery mildew infecting diverse host plants of southern gujarat, India. Int J Plant Soil Sci. 2023;35(20):153–66. doi:10.9734/ijpss/2023/v35i203795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Padilla-Roji I, Ruiz-Jiménez L, Bakhat N, Vielba-Fernández A, Pérez-García A, Fernández-Ortuño D. RNAi technology: a new path for the research and management of obligate biotrophic phytopathogenic fungi. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(10):9082. doi:10.3390/ijms24109082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. McGrath MT. Powdery mildew of cucurbits. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell Cooperative Extension; 2017. [Google Scholar]

8. Elgamal NG, Khalil MSA. First report of powdery mildew caused by Podosphaera xanthii on Luffa cylindrica in Egypt and its control. J Plant Prot Res. 2020;60(3):311–9. doi:10.24425/jppr.2020.133954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Tian M, Yu R, Yang W, Guo S, Liu S, Du H, et al. Effect of powdery mildew on the photosynthetic parameters and leaf microstructure of melon. Agriculture. 2024;14(6):886. doi:10.3390/agriculture14060886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Eldesoky AAI, Abd El-Nabi HM, Omran EE. Detecting mildew diseases in cucumber using image processing technique. Misr J Agric Eng. 2023;40(3):243–58. doi:10.21608/mjae.2023.201331.1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Elsisi AA. Evaluation of biological control agents for managing squash powdery mildew under greenhouse conditions. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2019;29(1):89. doi:10.1186/s41938-019-0194-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gan CM, Tang T, Zhang ZY, Li M, Zhao XQ, Li SY, et al. Unraveling the intricacies of powdery mildew: insights into colonization, plant defense mechanisms, and future strategies. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(8):3513. doi:10.3390/ijms26083513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ketta HA, Kamel SM, Ismail AM, Ibrahem ES. Control of downy mildew disease of cucumber using Bacillus chitinosporus. Egypt J Biol Pest Control. 2016;26(4):839–45. [Google Scholar]

14. Afifi MMI, Ismail AM, Kamel SM, Essa TA. Humic substances: a powerful tool for controlling fusarium wilt disease and improving the growth of cucumber plants. J Plant Pathol. 2017;99(1):61–7. [Google Scholar]

15. Zhang X, Huang Y, Chen WJ, Wu S, Lei Q, Zhou Z, et al. Environmental occurrence, toxicity concerns, and biodegradation of neonicotinoid insecticides. Environ Res. 2023;218(3):114953. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2022.114953. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Mikhailyuk T, Glaser K, Demchenko E, Hotter V, Pushkareva E, Karsten U. Diversity of algae and cyanobacteria from biological soil crusts in the high Arctic (Svalbard) along two different moisture gradients. Eur J Phycol. 2025;60(2):221–44. doi:10.1080/09670262.2025.2490372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Dudeja C, Masroor S, Mishra V, Kumar K, Sansar S, Yadav P, et al. Cyanobacteria-based bioremediation of environmental contaminants: advances and computational insights. Discov Agric. 2025;3(1):42. doi:10.1007/s44279-025-00193-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Nowruzi B, Haghighat S, Fahimi H, Mohammadi E. Nostoc cyanobacteria species: a new and rich source of novel bioactive compounds with pharmaceutical potential. J Pharm Heal Serv Res. 2018;9(1):5–12. doi:10.1111/jphs.12202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Perera RMTD, Herath KHINM, Sanjeewa KKA, Jayawardena TU. Recent reports on bioactive compounds from marine cyanobacteria in relation to human health applications. Life. 2023;13(6):1411. doi:10.3390/life13061411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Nowruzi B, Sarvari G, Blanco S. Applications of cyanobacteria in biomedicine. In: Handbook of algal science, technology and medicine. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2020. p. 441–53. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-818305-2.00028-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Uzlasir T, Selli S, Kelebek H. Effect of salt stress on the phenolic compounds, antioxidant capacity, microbial load, and in vitro bioaccessibility of two microalgae species (Phaeodactylum tricornutum and Spirulina platensis). Foods. 2023;12(17):3185. doi:10.3390/foods12173185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Khan N, Sudhakar K, Mamat R. Macroalgae farming for sustainable future: navigating opportunities and driving innovation. Heliyon. 2024;10(7):e28208. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e28208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Husain A, Nematullah M, Khan H, Shekher R, Farooqui A, Sahu A, et al. From pond scum to miracle molecules: cyanobacterial compounds new frontiers. Eur J Biol. 2024;83(1):94–105. doi:10.26650/EurJBiol.2024.1357041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lomartire S, Cotas J, Pacheco D, Marques JC, Pereira L, Gonçalves AMM. Environmental impact on seaweed phenolic production and activity: an important step for compound exploitation. Mar Drugs. 2021;19(5):245. doi:10.3390/md19050245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Demay J, Bernard C, Reinhardt A, Marie B. Natural products from cyanobacteria: focus on beneficial activities. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(6):320. doi:10.3390/md17060320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Rodrigues F, Reis M, Ferreira L, Grosso C, Ferraz R, Vieira M, et al. The neuroprotective role of cyanobacteria with focus on the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant potential: current status and perspectives. Molecules. 2024;29(20):4799. doi:10.3390/molecules29204799. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Raven PH, Evert RF, Eichhorn SE. Biology of plants. Washington, NJ, USA: Macmillan; 2005. [Google Scholar]

28. Saidani K, Bedjou F, Benabdesselam F, Touati N. Antifungal activity of methanolic extracts of four Algerian marine algae species. African J Biotechnol. 2012;11(39):9496–500. doi:10.5897/ajb11.1537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Righini H, Francioso O, Di Foggia M, Prodi A, Quintana AM, Roberti R. Tomato seed biopriming with water extracts from Anabaena minutissima, Ecklonia maxima and Jania adhaerens as a new agro-ecological option against Rhizoctonia solani. Sci Hortic. 2021;281:109921. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2021.109921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Berthon JY, Michel T, Wauquier A, Joly P, Gerbore J, Filaire E. Seaweed and microalgae as major actors of blue biotechnology to achieve plant stimulation and pest and pathogen biocontrol–a review of the latest advances and future prospects. J Agric Sci. 2021;159(7–8):523–34. doi:10.1017/S0021859621000885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Righini H, Francioso O, Quintana AM, Roberti R. Cyanobacteria: a natural source for controlling agricultural plant diseases caused by fungi and oomycetes and improving plant growth. Horticulturae. 2022;8(1):58. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8010058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lee SM, Ryu CM. Algae as new kids in the beneficial plant microbiome. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:599742. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.599742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Aziz A, Poinssot B, Daire X, Adrian M, Bézier A, Lambert B, et al. Laminarin elicits defense responses in grapevine and induces protection against Botrytis cinerea and Plasmopara viticola. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2003;16(12):1118–28. doi:10.1094/MPMI.2003.16.12.1118. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Biondi N, Piccardi R, Margheri MC, Rodolfi L, Smith GD, Tredici MR. Evaluation of Nostoc strain ATCC 53789 as a potential source of natural pesticides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70(6):3313–20. doi:10.1128/AEM.70.6.3313-3320.2004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Kim JD. Screening of cyanobacteria (Blue-Green algae) from rice paddy soil for antifungal activity against plant pathogenic fungi. Mycobiology. 2006;34(3):138. doi:10.4489/myco.2006.34.3.138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Jaulneau V, Lafitte C, Corio-Costet MF, Stadnik MJ, Salamagne S, Briand X, et al. An Ulva armoricana extract protects plants against three powdery mildew pathogens. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2011;131(3):393–401. doi:10.1007/s10658-011-9816-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Sano Y. Antiviral activity of alginate against infection by tobacco mosaic virus. Carbohydr Polym. 1999;38(2):183–6. doi:10.1016/S0144-8617(98)00119-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Pardee KI, Ellis P, Bouthillier M, Towers GHN, French CJ. Plant virus inhibitors from marine algae. Can J Bot. 2004;82(3):304–9. doi:10.1139/b04-002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Nagorskaya VP, Reunov AV, Lapshina LA, Ermak IM, Barabanova AO. Inhibitory effect of κ/β-carrageenan from red alga Tichocarpus crinitus on the development of a potato virus X infection in leaves of Datura stramonium L. Biol Bull. 2010;37(6):653–8. doi:10.1134/S1062359010060142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Esserti S, Smaili A, Rifai LA, Koussa T, Makroum K, Belfaiza M, et al. Protective effect of three brown seaweed extracts against fungal and bacterial diseases of tomato. J Appl Phycol. 2017;29(2):1081–93. doi:10.1007/s10811-016-0996-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Kumar V, Bhatnagar A, Srivastava J. Antibacterial activity of crude extracts of Spirulina platensis and its structural elucidation of bioactive compound. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5(32):7043–8. doi:10.5897/jmpr11.1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Bibi S, Saadaoui I, Bibi A, Al-Ghouti M, Abu-Dieyeh MH. Applications, advancements, and challenges of cyanobacteria-based biofertilizers for sustainable agro and ecosystems in arid climates. Bioresour Technol Reports. 2024;25(11):101789. doi:10.1016/j.biteb.2024.101789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Shariatmadari Z, Riahi H, Seyed Hashtroudi M, Ghassempour AR, Aghashariatmadary Z. Plant growth promoting cyanobacteria and their distribution in terrestrial habitats of Iran. Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2013;59(4):535–47. doi:10.1080/00380768.2013.782253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Haroun SA, Hussein MH. The promotive effect of algal biofertilizers on growth, protein pattern and some metabolic activities of Lupinus termis plants grown in siliceous soil. Asian J Plant Sci. 2003;2(13):944–51. doi:10.3923/ajps.2003.944.951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mishra U, Pabbi S. Cyanobacteria: a potential biofertilizer for rice. Resonance. 2004;9(6):6–10. doi:10.1007/bf02839213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Bidyarani N, Prasanna R, Chawla G, Babu S, Singh R. Deciphering the factors associated with the colonization of rice plants by cyanobacteria. J Basic Microbiol. 2015;55(4):407–19. doi:10.1002/jobm.201400591. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Kollmen J, Strieth D. The beneficial effects of cyanobacterial co-culture on plant growth. Life. 2022;12(2):223. doi:10.3390/life12020223. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Singh R, Parihar P, Singh M, Bajguz A, Kumar J, Singh S, et al. Uncovering potential applications of cyanobacteria and algal metabolites in biology, agriculture and medicine: current status and future prospects. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:515. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00515. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Han X, Zeng H, Bartocci P, Fantozzi F, Yan Y. Phytohormones and effects on growth and metabolites of microalgae: a review. Fermentation. 2018;4(2):25. doi:10.3390/fermentation4020025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Pan S, Jeevanandam J, Danquah MK. Benefits of algal extracts in sustainable agriculture. In: Grand challenges in biology and biotechnology. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 501–34. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-25233-5_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Górka B, Korzeniowska K, Lipok J, Wieczorek PP. The biomass of algae and algal extracts in agricultural production. In: Algae biomass: characteristics and applications. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 103–14. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-74703-3_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Roberti R, Galletti S, Burzi PL, Righini H, Cetrullo S, Perez C. Induction of defence responses in zucchini (Cucurbita pepo) by Anabaena sp. water extract. Biol Control. 2015;82(4):61–8. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2014.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Roberti R, Righini H, Reyes CP, Roberti R, Righini H, Reyes CP. Activity of seaweed and cyanobacteria water extracts against Podosphaera xanthii on zucchini. Ital J Mycol. 2016;45:66–77. doi:10.6092/issn.2531-7342/6425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Zhang S, Mersha Z, Vallad GE, Huang CH. Management of powdery mildew in squash by plant and alga extract biopesticides. Plant Pathol J. 2016;32(6):528–36. doi:10.5423/PPJ.OA.05.2016.0131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Hassan SM, Ashour M, Sakai N, Zhang L, Hassanien HA, Gaber A, et al. Impact of seaweed liquid extract biostimulant on growth, yield, and chemical composition of cucumber (Cucumis sativus). Agriculture. 2021;11(4):320. doi:10.3390/agriculture11040320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Dellaporta SL, Wood J, Hicks JB. A plant DNA minipreparation: version II. Plant Mol Biol Report. 1983;1(4):19–21. doi:10.1007/bf02712670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Nübel U, Garcia-Pichel F, Muyzer G. PCR primers to amplify 16S rRNA genes from cyanobacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63(8):3327–32. doi:10.1128/aem.63.8.3327-3332.1997. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc A Guid to Methods Appl. 1990;18(1):315–22. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Lin Z, Lin Z, Li H, Shen S. Sequences analysis of ITS region and 18S rDNA of ulva. ISRN Bot. 2012;2012(3):1–9. doi:10.5402/2012/468193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(7):3022–7. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Safavi M, Nowruzi B, Estalaki S, Shokri M. Biological activity of methanol extract from Nostoc sp. N42 and Fischerella sp. s29 isolated from aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems. Int J Algae. 2019;21(4):373–91. doi:10.1615/InterJAlgae.v21.i4.80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Morishita M, Sugiyama K, Saito T, Sakata Y. Powdery mildew resistance in cucumber. Japan Agric Res Q JARQ. 2003;37(1):7–14. [Google Scholar]

63. Descalzo RC, Rahe JE, Mauza B. Comparative efficacy of induced resistance for selected diseases of greenhouse cucumber. Can J Plant Pathol. 1990;12(1):16–24. doi:10.1080/07060669009501037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Pandey HN, Menon TCM, Rao MV. A simple formula for calculating area under disease progress curve. RACHIS. 1989;8(2):38–9. [Google Scholar]

65. Matta A, Dimond AE. Symptoms of Fusarium wilt in relation to quantity of fungus and enzyme activity in tomato stems. Phytopathology. 1963;53(5):574. [Google Scholar]

66. Allam AI, Hollis JP. Sulfide inhibition of oxidases in rice roots. Phytopathology. 1972;62(6):634–9. doi:10.1094/phyto-62-634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Kar M, Mishra D. Catalase, peroxidase, and polyphenoloxidase activities during rice leaf senescence. Plant Physiol. 1976;57(2):315–9. doi:10.1104/pp.57.2.315. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Aebi HE. Catalase in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1984;105:121–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

69. Sun MH, Gao L, Shi YX, Li BJ, Liu XZ. Fungi and actinomycetes associated with Meloidogyne spp. eggs and females in China and their biocontrol potential. J Invertebr Pathol. 2006;93(1):22–8. doi:10.1016/j.jip.2006.03.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Porra RJ. The chequered history of the development and use of simultaneous equations for the accurate determination of chlorophylls a and b. Discov Photosynth. 2005;20:633–40. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3324-9_56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Arnon DI. Copper enzymes in isolated chloroplasts. Polyphenoloxidase in Beta vulgaris. Plant Physiol. 1949;24(1):1–15. doi:10.1104/pp.24.1.1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Kirk JTO, Allen RL. Dependence of chloroplast pigment synthesis on protein synthesis: effect of actidione. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1965;21(6):523–30. doi:10.1016/0006-291x(65)90516-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Snell FD, Snell CT. Colorimetric methods. Vol. III. Princeton, Jersey, Toronto, New York and London: Van Nostrand Co., Inc.; 1953. 606 p. [Google Scholar]

74. Marinova D, Ribarova F, Atanassova M. Total phenolics and flavonoids in Bulgarian fruits and vegetables. J Univ Chem Technol Metall. 2005;40(3):255–60. [Google Scholar]

75. Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. 7th ed. Ames Iowa, IA, USA: Iowa State University Press; 1980. 507 p. [Google Scholar]

76. Xia J, Psychogios N, Young N, Wishart DS. MetaboAnalyst: a web server for metabolomic data analysis and interpretation. Nucl Acids Res. 2009;37:W652–60. doi:10.1093/nar/gkp356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Maloy OC. Plant disease control: principles and practice. 1993. 346 p. [Google Scholar]

78. Alsenani F, Tupally KR, Chua ET, Eltanahy E, Alsufyani H, Parekh HS, et al. Evaluation of microalgae and cyanobacteria as potential sources of antimicrobial compounds. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28(12):1834–41. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2020.11.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Cock IE, Cheesman MJ. A review of the antimicrobial properties of cyanobacterial natural products. Molecules. 2023;28(20):7127. doi:10.3390/molecules28207127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Jerez-Martel I, García-Poza S, Rodríguez-Martel G, Rico M, Afonso-Olivares C, Gómez-Pinchetti JL. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of crude extracts from microalgae and cyanobacteria strains. J Food Qual. 2017;2017(1):2924508. doi:10.37247/afs.1.2021.23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Seghiri R, Kharbach M, Essamri A. Functional composition, nutritional properties, and biological activities of moroccan spirulina microalga. J Food Qual. 2019;2019(3):1–11. doi:10.1155/2019/3707219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Klejdus B, Kopecký J, Benešová L, Vacek J. Solid-phase/supercritical-fluid extraction for liquid chromatography of phenolic compounds in freshwater microalgae and selected cyanobacterial species. J Chromatogr A. 2009;1216(5):763–71. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2008.11.096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Rico M, López A, Santana-Casiano JM, González AG, González-Dávila M. Variability of the phenolic profile in the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum growing under copper and iron stress. Limnol Oceanogr. 2013;58(1):144–52. doi:10.4319/lo.2013.58.1.0144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Vega J, Bonomi-Barufi J, Gómez-Pinchetti JL, Figueroa FL. Cyanobacteria and red macroalgae as potential sources of antioxidants and UV radiation-absorbing compounds for cosmeceutical applications. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(12):659. doi:10.3390/MD18120659. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Byju K, Anuradha V, Vasundhara G, Nair SM, Kumar NC. In vitro and in silico studies on the anticancer and apoptosis-inducing activities of the sterols identified from the soft coral, subergorgia reticulata. Pharmacogn Mag. 2014;10(37):S65–71. doi:10.4103/0973-1296.127345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. EL-Hefny M, Ali HM, Ashmawy NA, Salem MZM. Chemical composition and bioactivity of salvadora persica extracts against some potato bacterial pathogens. BioResources. 2017;12(1):1835–49. doi:10.15376/biores.12.1.1835-1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Kumar D, Karthik M, Rajakumar R. GC-MS analysis of bioactive compounds from ethanolic leaves extract of Eichhornia crassipes (Mart) Solms and their pharmacological activities. Pharma Innov J. 2018;7(8):459–62. [Google Scholar]

88. Al Bratty M, Makeen HA, Alhazmi HA, Alhazmi HA, Syame SM, Syame SM, et al. Phytochemical, cytotoxic, and antimicrobial evaluation of the fruits of miswak plant, Salvadora persica L. J Chem. 2020;2020(3):1–11. doi:10.1155/2020/4521951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Suleimen YM, Metwaly AM, Mostafa AE, Elkaeed EB, Liu HW, Basnet BB, et al. Isolation, crystal structure, and in silico aromatase inhibition activity of ergosta-5, 22-dien-3β-ol from the fungus Gyromitra esculenta. J Chem. 2021;2021(3):1–10. doi:10.1155/2021/5529786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Gheda SF, Ismail GA. Natural products from some soil cyanobacterial extracts with potent antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2020;92(2):1–18. doi:10.1590/0001-3765202020190934. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Desbois AP, Mearns-Spragg A, Smith VJ. A fatty acid from the diatom Phaeodactylum tricornutum is antibacterial against diverse bacteria including multi-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Mar Biotechnol. 2009;11(1):45–52. doi:10.1007/s10126-008-9118-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Gupta V, Ratha SK, Sood A, Chaudhary V, Prasanna R. New insights into the biodiversity and applications of cyanobacteria (blue-green algae)–prospects and challenges. Algal Res. 2013;2(2):79–97. doi:10.1016/j.algal.2013.01.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Thankaraj SR, Sekar V, Kumaradhass HG, Perumal N, Hudson AS. Exploring the antimicrobial properties of seaweeds against Plasmopara viticola (Berk. and M.A. Curtis) Berl. and De Toni and Uncinula necator (Schwein) Burrill causing downy mildew and powdery mildew of grapes. Indian Phytopathol. 2020;73:185–201. doi:10.1007/s42360-019-00137-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Ata A, Saleh R, Gad M, bakery El A, Omara R, Abou Zeid M. Management of powdery mildew caused by Erysiphe betae in sugar beet using algal products. Egypt J Phytopathol. 2023;51(2):1–13. doi:10.21608/ejp.2023.217725.1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Stephenson WM. The effect of hydrolysed seaweed on certain plant pests and diseases. In: Proceedings of the Fifth International Seaweed Symposium. Halifax, NS, Canada: Elsevier; 1966. p. 405–15. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-011841-3.50064-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. DeMule MCZ, De Caire GZ, Doallo S, De Halperin DR, DeHalperin L. Action of aqueous and ethereal algal extracts of Nostoc muscorum Ag.(No. 79a). II. Effect on the development of the fungus Cunninghamella blakesleeana in Mehlich’s medium. Bull Soc Argentina Bot. 1977;18:121–8. [Google Scholar]

97. De Caire GZ, De Cano MS, De Mule MCZ, De Halperin DR, Galvagno M. Action of cell-free extracts and extracellular products of Nostoc muscorum on growth of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Phyton (Buenos Aires). 1987;47(1–2):43–6. [Google Scholar]

98. Ahmed YM, Shalaby EA. Effect of different seaweed extracts and compost on vegetative growth, yield and fruit quality of cucumber. J Hortic Sci Ornam Plants. 2012;4(3):235–40. doi:10.5829/idosi.jhsop.2012.4.3.252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Rathore SS, Chaudhary DR, Boricha GN, Ghosh A, Bhatt BP, Zodape ST, et al. Effect of seaweed extract on the growth, yield and nutrient uptake of soybean (Glycine max) under rainfed conditions. South African J Bot. 2009;75(2):351–5. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2008.10.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Hernández-Herrera RM, Santacruz-Ruvalcaba F, Ruiz-López MA, Norrie J, Hernández-Carmona G. Effect of liquid seaweed extracts on growth of tomato seedlings (Solanum lycopersicum L.). J Appl Phycol. 2014;26(1):619–28. doi:10.1007/s10811-013-0078-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Shah MT, Zodape ST, Chaudhary DR, Eswaran K, Chikara J. Seaweed sap as an alternative liquid fertilizer for yield and quality improvement of wheat. J Plant Nutr. 2013;36(2):192–200. doi:10.1080/01904167.2012.737886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Layek J, Das A, Idapuganti RG, Sarkar D, Ghosh A, Zodape ST, et al. Seaweed extract as organic bio-stimulant improves productivity and quality of rice in eastern Himalayas. J Appl Phycol. 2018;30(1):547–58. doi:10.1007/s10811-017-1225-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Layek J, Das A, Ghosh A, Sarkar D, Idapuganti RG, Boragohain J, et al. Foliar application of seaweed sap enhances growth, yield and quality of maize in eastern himalayas. Proc Natl Acad Sci India Sect B–Biol Sci. 2019;89(1):221–9. doi:10.1007/s40011-017-0929-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Valencia RT, Acosta LS, Hernández MF, Rangel PP, Robles MÁG, del Cruz RCA, et al. Effect of seaweed aqueous extracts and compost on vegetative growth, yield, and nutraceutical quality of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) fruit. Agronomy. 2018;8(11):264. doi:10.3390/agronomy8110264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Hidangmayum A, Sharma R. Effect of different concentrations of commercial seaweed liquid extract of Ascophyllum nodosum as a plant bio stimulant on growth, yield and biochemical constituents of onion (Allium cepa L.). J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2017;6(4):658–63. [Google Scholar]

106. Abd El Sadek D, Hamouda R, Bassiouny K, Elharoun H. In vitro antioxidant and anticancer activity of cyanobacteria. Asian J Med Heal. 2017;6(3):1–9. doi:10.9734/ajmah/2017/34457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

107. Koizumi J, Takatani N, Kobayashi N, Mikami K, Miyashita K, Yamano Y, et al. Carotenoid profiling of a red seaweed pyropia yezoensis: insights into biosynthetic pathways in the order bangiales. Mar Drugs. 2018;16(11):426. doi:10.3390/md16110426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Gomes L, Monteiro P, Cotas J, Gonçalves AMM, Fernandes C, Gonçalves T, et al. Seaweeds’ pigments and phenolic compounds with antimicrobial potential. Biomol Concepts. 2022;13(1):89–102. doi:10.1515/bmc-2022-0003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Rouphael Y, De Micco V, Arena C, Raimondi G, Colla G, De Pascale S. Effect of Ecklonia maxima seaweed extract on yield, mineral composition, gas exchange, and leaf anatomy of zucchini squash grown under saline conditions. J Appl Phycol. 2017;29(1):459–70. doi:10.1007/s10811-016-0937-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.