Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Flirting with Fertility: Cytokinin’s Expanding Role in Plant Reproduction

Center for Genomic Science Innovation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA

* Corresponding Author: Paige M. Henning. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Utilization of Biostimulants in Plant Growth and Health)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 2957-2983. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.068899

Received 10 June 2025; Accepted 18 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Cytokinins are ancient hormones present across all kingdoms of life except archaea, although functional biosynthesis pathways have yet to be identified in animalia. Known for their roles in cell division and proliferation, cytokinins are critical to plant life, as they regulate various aspects of vegetative growth, stress response, and reproduction. In this review, we summarize literature from 2020 to 2025 pertaining to the cytokinin functions in plant reproduction. While general aspects of cytokinin’s role in plant reproduction have been addressed, we particularly focus on the role of cytokinin in reproductive systems due to recent work identifying their role as sex-determining factors in dioecious species in Salicaceae and other families, their role in determining flower sex in monoecious species, and their involvement in self-incompatibility response and asexual reproduction.Keywords

Cytokinins (CK) were first identified in 1955 as the key factor responsible for cell division [1]. The first naturally occurring CK, and most abundant CK, trans-zeatin (tZ), was later isolated from Zea mays meristem [2]. In general, plant CKs are adenine derivatives, differing in their N6-isoprenoid side chain [3]; these different side chains determine the function of the specific CK [4]. In 1978, CK was formally recognized as hormones after demonstrating their ability to bind to tobacco cells [5]. In 1996, histidine kinases were the first hypothesized CK receptors [6] and empirically supported in 2001 [7]. Since their discovery, several natural and unnatural CK derivatives have been identified that have different roles [3,8–11].

CKs are an ancient phytohormone that play critical roles in plant development, including vegetative growth (reviewed in [12–15]), defense against biotic stress (reviewed in [16–19]), response to abiotic stress (reviewed in [20–23]), and reproduction. Unsurprisingly, these roles are accomplished through complex interactions between CK and other phytohormones, the most notable being auxin (reviewed in [24]). Given CK’s central role in positively regulating vegetative growth, reproduction, and biotic and abiotic stress response, CK-related gene families are of high agricultural interest, as manipulating CK levels may help negate the negative impact of climate change (reviewed in [25–28]) and increase crops’ economic value.

CK genes have been identified in bacteria, slime molds, fungi, and plants, but not in archaea, with functional biosynthesis pathways yet to be confirmed in animals [29]. While a functional biosynthesis pathway has not been identified in humans, recent research suggests that CK has the potential to be used in a medicinal setting. Preliminary work suggests CK may act as an effective cancer treatment [30,31], Parkinson’s therapeutic drug [32], skin health supplement [33], and has an assortment of other hypothetical medicinal uses (reviewed in [34]). Overall, this emphasizes the importance of CK not only to the plant community, but to the broader scientific community.

Here, we provide an updated review of our current understanding of the roles of CK in plant reproduction. We provide a brief historical overview of the major CK biosynthesis and signaling families, explore recent literature pertaining to their roles in reproduction, summarize recently identified key players in CK-mediated reproduction, and indirectly touch on crosstalk between CK and other phytohormones during reproduction.

2 A Brief Overview of Cytokinin Metabolism and Signaling

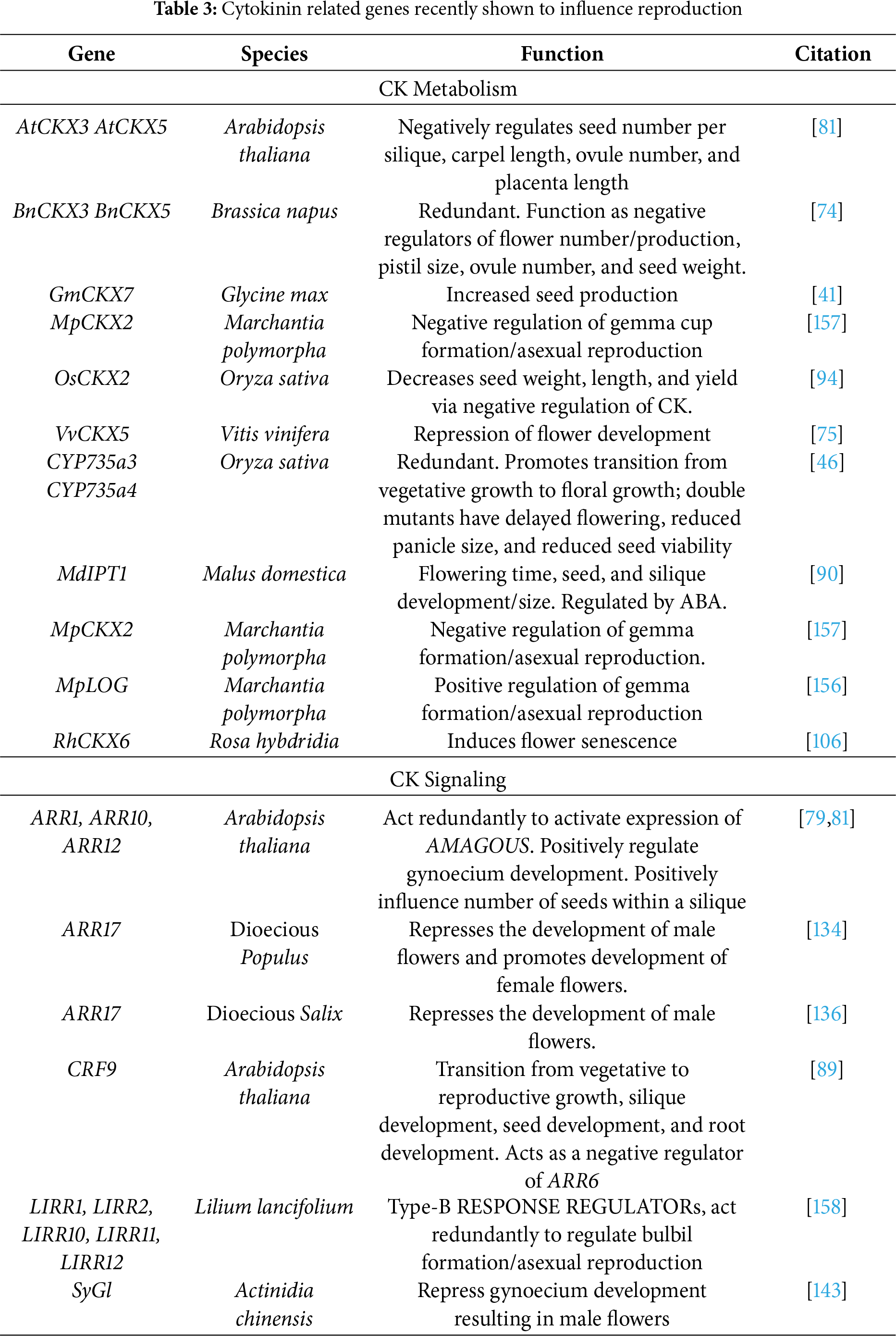

Cytokinin (CK) is primarily synthesized via the iPRMP-dependent pathway (Table 1). This is a multi-step pathway that begins with the synthesis of iP riboside 5′-monophosphate (iPRMP) from dimethylallyl diphosphate and ATP, ADP, or AMP by the ISOPENTENYLTRANSFERASE gene family [35,36]; the synthesis of iPRMP is the rate-limiting step of CK biosynthesis. Members of the CYP735A family hydrolyze iPRMP to tZ riboside 5′-monophosphate (tZRMP) [37]. Finally, members of the LONELY GUY family remove the riboside 5′-monophosphate from either iPRMP or tZRMP to produce isopentenyladenine (iP) or trans-Zeatin (tZ) respectively [38]. The CYTOKININ OXIDASE and UDP-glucosyl transferase 76C gene families regulate CK homeostasis either via irreversible oxidative cleavage or glucosylation, respectively [39,40].

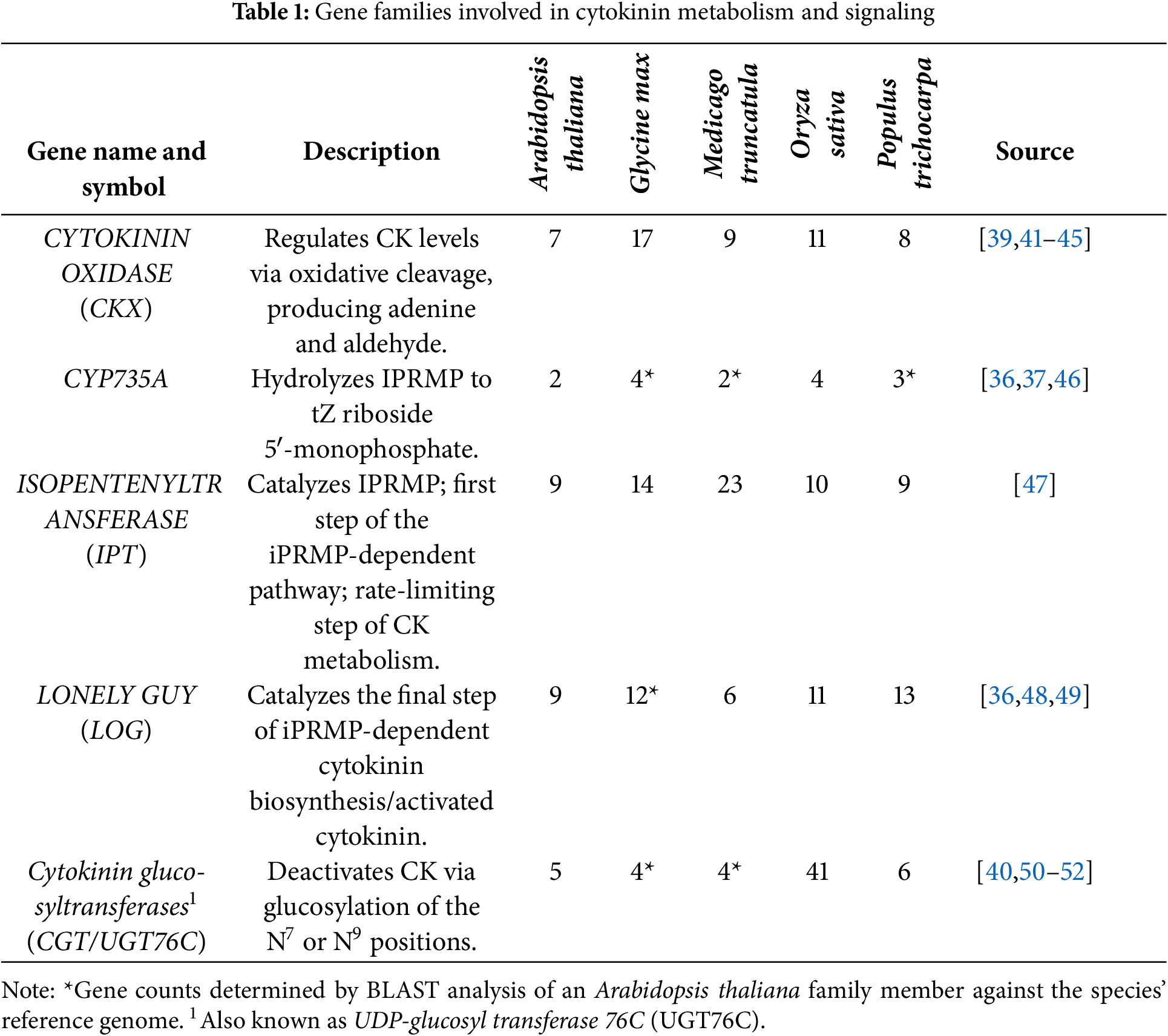

The primary receptor for CK is the ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE KINASE (AHK) family (Table 2).

AHK perceives extracellular CK and the CK produced in the ER, and in response phosphorylates ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE PHOSPHOTRANSFER PROTEIN (HPt) [65]. HPt transfers the phosphoryl group to an ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR (ARR) [57,66]. HPt also directly interacts with CYTOKININ RESPONSE FACTOR (CRF), but there is currently no evidence that it transfers the phosphoryl group to CRF.

Type-B ARR (ARR-B) acts as a positive regulator of CK response by upregulating CK responsive genes [67]. Type-A ARR (ARR-A) represses ARR-B activity as a means of negatively regulating CK response. The role of Type-C ARR (ARR-C) remains unclear as they lack a receiver domain [64], suggesting they may not be phosphorylated by AHPs. The expression patterns of ARR-C family members strongly correlate with the reproductive phase of Arabidopsis thaliana [64], suggesting that the subclade is primarily involved in CK signaling during reproduction.

The CRF family is a group of transcription factors that were originally identified as CK responsive, but in recent years, have been identified as responsive to a series of signals including environmental factors and abscisic acid (ABA) as reviewed in [68]. While there isn’t evidence that they receive a phosphoryl group from HPt, their C-terminal does contain a phosphorylation site that may be phosphorylated by MITOGEN-ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASES [59] in response to environmental cues or ABA. Further exploration of the family is required before strong statements can be made regarding the family.

In addition to the AHK family members that act as true CK receptors, there are AHK family members, referred to as CYTOKININ INDEPENDENT (CI), that have the ability to sense CK and trigger a feedback loop that mediates CK homeostasis [55]. It is unknown if they act as “true” receptors. A more detailed description of CK biosynthesis and signaling is reviewed in [69].

3 The Role of Cytokinin in Flower Development

3.1 General Flower Development

During floral development, CK levels are relatively high, often representing the most abundant hormone—but begin to decline at anthesis and continue to decrease throughout the remainder of the flower’s life in several species [70–73]. Elevated CK content has been correlated with an increase in flower number in a variety of species [71,74,75]. This trend aligns with changes in the expression of CK-related genes as several recent comparative transcriptomic studies have linked decreased CK content in the aging flower with altered expression of CK-related genes [72].

In Oryza sativa, increased CK levels are associated with decreased OIFC1, a regulator of axillary bud growth [76]. A reduction in CK biosynthesis activity leads to fewer spikelets per panicle likely due to reduced IPT, LOG, and CYP735A activity [77]. Overexpression of CYP735A3 or CYP735A4 resulted in an increase in tZ production and double knockouts (KO) resulted in a reduction in CK content and plants that lack panicles [46]. The CGT family in O. sativa is relatively large compared to dicots (Table 1), as the family is involved in degradation of CK, exploring the function of panicle expressed CGT family members in these backgrounds may provide additional insight into CK dynamics throughout panicle development as CK was not depleted entirely, suggesting some CK was produced and potentially marked for degradation by CGT.

Recent results suggest that the CKX family act as negative regulators of flowering and seed set. In Brassica napa, BnCKX3_A1, BnCKX3_A2, BnCKX3_C1, BnCKX3_C2, BnCKX5_A1, and BnCKX5_C1 act redundantly to maintain CK homeostasis [74]. Disruption of CK homeostasis in a sextuple KO line resulted in a significant increase in the number of flowers and seed pods [74]. Supporting the general importance of high CK concentrations during early flower development. The strong redundancy of the CKX family in B. napa’s flowers alludes to the importance of tight regulation of CK homeostasis. Emphasizing the importance of future work in the family, KO a single CKX may be of less biological relevance than multiple KOs.

Given CK’s role in cell proliferation, it is not surprising that high concentrations are critical for early flower development. Exploration of tissue-specific CK dynamics throughout bud development and senescence and the pathways associated with early CK concentrations may identify genes of horticultural and agricultural value. As highlighted by work in B. napa, manipulation of early CK content can lead to increased floral production—a trait of high horticultural value. Manipulation of pathways associated with CK’s decline throughout development may also identify genes associated with flower aging, as discussed in Section 5, which may be of interest to evolutionary studies in ephemeral plants.

CK was first described as the feminization hormone in 1984 [78], since then, it has been identified as a key regulator of feminization across a wide range of plant genera. Recent developments in Arabidopsis thaliana have expanded our understanding of CK’s role in promoting gynoecium development.

Type-B ARR—AtARR1, AtARR10, and AtARR12—have recently been identified as redundant key regulators of gynoecium development [79]. In a triple KO background, the MADS-BOX genes, AGAMOUS and AtSHP2, along with the transcription factor AtSPT, failed to reach wild type (WT) expression levels even after exogenous CK treatment [79]. These results suggest that AtARR1, AtARR10, and AtARR12 redundantly promote the transcription of these critical genes in response to CK.

AGAMOUS is involved in several aspects of floral development, including proper carpel formation. In agamous lines, stigmatic papillae and ovules do not develop properly unless treated with synthetic CK, BAP [79]. Similar to the triple atarr KO lines, the expression of AtSHP2, AtSPT, and AtCRC is significantly reduced in the agamous background despite CK treatment, indicating their expression is dependent on AGAMOUS [79]. As the expression of these genes significantly increased when the agamous line was treated with exogenous CK, though not to the same degree as the WT background, it’s likely other factors are also inducing expression in response to CK [79].

AtSPT is believed to activate the expression of three D3-type cyclins—CYCD3;1, CYCD3;2, and CYCD3;3—as it is capable of binding to their promoters [80]. In response to CK, these cyclins redundantly promote cell proliferation during gynoecium development. In triple cycd3;1, cycd3;2, cycd3;3 KO lines, gynoecium contain fewer, yet larger, cells [80].

Overall, these results from A. thaliana have identified a pathway critical for gynoecium development. Future microscopy work may provide insight into how the downstream effects of type-B ARR manipulation affect mitosis. It’s likely that microscopy work will reveal that overexpression ARR-B lines have more WT cells while KO arr-b lines have fewer cells that are longer than WT cells, similar to what was identified in the triple KO cycd3 lines. If longer cells are identified, it is likely that the cells have failed to complete mitosis and have entered into the endoreduplication cycle. Suggesting CK is acting as a negative regulator of endoreduplication during gynoecium development. Larger comparative—omic analyses of the arr-b vs. WT lines may provide additional insights into endoreduplication pathways that are being negatively regulated by CK.

Crosstalk between CK and other phytohormones is also likely crucial for successful female reproductive development. AtARR1 has been shown to physically interact with AtBZR1, a brassinosteroid (BR) responsive transcription factor, suggesting CK–BR crosstalk is involved in ovule development [81]. Additionally, a gibberellic acid (GA) receptor GID1 directly interacts with AtARR1, AtARR10, and AtARR12 and targets them for degradation in response to high GA and low CK levels [82]; suggesting that CK and GA act antagonistically during female germline development.

Comparative transcriptomic analysis of Prunus mume [83] and P. sibirica [84] identified auxin, CK, and GA as potential key regulators of pistil abortion. In P. mume, normal pistils exhibited significantly higher levels of auxin, CK, and ethylene compared to aborted pistils, while aborted pistils contained higher concentrations of GA and ABA compared to normal [83]. These findings suggest that GA and ABA promote abortion of the pistil, while auxin, CK and ethylene act to prevent it. Manipulation of these hormones through exogenous treatment of synthetic hormones or hormone inhibitors may shed some additional insight into how these hormones contribute or prevent pistil abortion.

Exploration of cell specific dynamics of these various phytohormones may provide additional insight into how they are contributing to carpel development. As AtARR1 participates in regulating genes important for CK response, comparing a atbzr1 background to the atarr1, atarr10, atarr12 may highlight the importance of BR in hypothetically negatively regulating the endoreduplication cycle while positively regulating mitosis. Given the role of GA in pistil abortion and GID1’s role in degrading ARR-Bs, it is possible that GID1 is a positive regulator of programmed cell death (PCD). Exploration of GID1 mutants may provide insight into GA’s role in PCD during reproduction.

Beyond CK’s role in influencing the development of staminate flowers in some genera—discussed later in this review—recent research into CK’s involvement in male reproduction has been limited. This may be due to the prominent role of auxin in male reproductive development and its antagonistic relationship with CK. Nonetheless, it is evident that CK homeostasis is still important to some extent in male reproduction. For instance, recent analyses have found that male sterile lines of Chinese cabbage have lower concentrations of tZ compared to fertile lines [85], suggesting that insufficient CK levels may lead to stamen abortion in this variety.

The negative effect of elevated CK levels on stamen development is further supported by recent comparative transcriptome analyses of stamen petaloid flowers of Alcea rosea, Clematis, and Eriobotrya japonica, which have suggested CK acts as a negative regulator of stamen development [86–88]. Petaloid stamen from E. japonica and Clematis have significantly higher CK concentrations relative to normal anthers [87,88]. As the normal petals of E. japonica also had higher CK concentrations relative to normal anthers, but to a lesser extent than the petaloid stamen [87], it is likely that regulation of CK levels is more critical for stamen development than petal formation.

These results generally support the hypothesis that CK primarily acts as a feminization hormone, likely due to its antagonistic relation with auxin. Future comparative work of CK and auxin dynamics, at the tissue and cellular level, and holistic-omics work of the gynoecium and stamen may provide better insight into how the hormones contribute to both organs. While there are several studies pertaining to the exploration of CK levels in auxin different backgrounds, especially pertaining to vegetative tissues, the work here supports the need for similar analyses in non-model organisms.

Additionally, CK’s hypothetical role in producing petaloid flowers is worth exploring, as incomplete flowers are of ornamental interest. If CK is regulating the production of petaloid stamen, then quantification of auxin and CK levels may be a quick approach for breeders interested in producing complete flowers. These results suggest GWAS studies of incomplete flowers may want to focus their attention on loci containing or near CK and auxin related genes.

4 Cytokinin Generally Acts as a Positive Regulator of Seed Development

Over the past five years, CK biosynthesis and homeostasis have been positively correlated with seed development and yield in Arabidopsis thaliana [62,89], Brassica rapa [54], Malus domestica [90], Poa pratensis [91], Cajanus cajan [92], Zea mays [93], Gylcine max [41,94], Oryza sativa [58,95], Vivia faba [96], Gossypium hirsutum [97], Vigna umbellata [98], and Solanum lycopersicum [99] Exploration of the hormone content of high seed set genotypes relative to low seed set genotypes of Glycine max revealed higher tZ contents in high seed set genotypes, while low seed set genotypes contained more CK precursors [41]. Suggesting, in G. max, high seed set genotypes are capable of processing CK precursors quicker than low seed set genotypes.

Many of the studies have indicated that the CKX family may be vital for seed set, as expression of CKX family members correlate with high seed set genotypes of Cajanus cajan [92] and G. max [41], but negatively correlated with seed set in Brassica napa, Oryza sativa, and Zea mays [93,94], highlighting the unique roles different CKX family members play in CK response.

GmCKX7, from G. max, is the highest expressed member of the CKX family in seed [41]. SNP analysis identified several alleles of GmCKX7 that correlate with the different seed set genotypes [41], while this suggests the alleles may determine seed set genotype, this hypothesis has yet to be explored. In O. sativa, CRISPR induced osckx2 loss-of-function mutants showed accumulation of CK in the flag leaf and panicle, and an increase in seed size and seed number [94]. Similarly, in B. napa, sextuple mutant ckx lines showed an increase in the number of seed pods and seed weight [74]; however, the mutant line also showed an increase in the number of aborted seeds, emphasizing the general importance of CK homeostasis in seed production. Double KO A. thaliana mutants of atckx3atckx5 showed a significant increase in the number of seeds per silique [81]. In Gossypium hirsutum, SEEDSTICK is a transcription factor that positively regulates CKX family members, though its role in G. hirsutum is unknown [97]. Exogenous expression of SEEDSTICK in A. thaliana resulted in upregulation of CKX3 and CKX5 and significantly reduced seed set [96].

It is likely that different members of the CKX family are acting as positive regulators while others are negative regulators of seed development. Phylogenetic exploration of the family across the genera is justified, as it may shed light onto why the family seems to possess conflicting roles in different genera—i.e., possible neofunctionalization of different subclades of the family. Alternatively, if it is found these seed related CKX family members are closely related, it may suggest that SNPs in GmCKX7 likely introduce structural changes in the protein resulting in a slight change in activity. If this is the case, exploration of the SNPs may identify portions of the protein that are important for CK inactivation.

5 The Complex Roles of Cytokinin in Fruit Development, Ripening, and Senescence

Early during fruit development, CK levels are high likely in correlation to rapid cell proliferation, but decline throughout fruit development [99]. This trend is associated with the onset of ripening and eventual senescence of the fruit [100,101].

Elevated CK levels are associated with increased fruit size. Prunus armeniaca produces significantly larger fruit than P. sibirica, primarily due to larger cell size [102]. Comparative transcriptomic analysis suggests CK metabolism is higher in P. armeniaca relative to P. sibirica, suggesting higher CK signaling promotes increased cell size and, consequently, larger fruit size. Similarly, girdled Solanum lycopersicum yield significantly larger fruits than their ungirdled counterpart, partly due to accumulation of CK in the fruit [103]. Ectopic expression of Arabidopsis thaliana AtCKX2 in S. lycopersicum significantly decreased CK levels, resulting in smaller fruit size and weight, and smaller seeds [98] supporting the role of high CK levels in fruit development. These trends suggest that treatment of crops with exogenous synthetic CKs may be an approach for increasing fruit weight and production. If this is the case, girdling crops may become obsolete as spraying crops with CK would be less time intensive. Additionally, as exogenous CPPU treatment of Litchi chinensis fruit showed delayed ripening and prevents overripening [100], general treatment of crops with synthetic CKs may not only increase fruit size, but also increase shelf life. Field analysis of the large scale application of synthetic CK during fruit development should be performed to determine the validity of this claim.

Several CK-related genes have been linked to fruit development in their native species. Exploration of the expression of CKX family members in four different genotypes of Vitis vinifera identified three members, VvCKX5, VvCKX7, and VvCKX9, that negatively correlated with berry size [75]. Ectopic expression of VvCKX5 in A. thaliana reduced flower number, flower size, and silique length [75]. Again, emphasizing the importance of high CK content during fruit development. In Malus domestica, overexpression of MdIPT1 increased callus growth on media without CK but supplemented with ATP, supporting its role as an ATP/ADP-IPT [90]. Ectopic expression of MdIPT1 in A. thaliana increased tZ content of the plant, promoted expression of flowering related genes, decreased leaf size, increased silique length, and seed number [90], suggesting MdIPT1 is likely promoting fruit development in M. domestica. This hypothesis should be supported through virus induced silencing of MdIPT1—a virus-based system would be a more effective approach given the relatively slow growth of M. domestica.

Results from the past five years regarding CK’s role in fruit development highlight the importance of CK during proper fruit development, but several questions remain unanswered. Exploration of the cellular dynamics of CK may provide further insight into its role in fruit development. For example, while it’s probable that increased fruit size is a result of increased mitosis, there is always the possibility that the increase in size is due to endoreduplication—a process that plants utilize to rapidly expand tissues. As CPPU treatment of L. chinensis fruit delayed ripening and prevented overripening, identification of CK-related pathways that negatively regulate fruit ripening may be of agricultural interest, especially for fruit that is difficult to transport due to issues pertaining to overripening. Prolonging the expression of genes that negatively regulate fruit ripening may be one approach to extending the shelf life of fruit—specifically through expression of CK biosynthesis genes on fruit specific promoters. Alternatively, profiling the expression of these proteins can allow for the development of an immunoassay for proteins of interest. This would allow farmers to begin harvesting fruit before they transition from fruit development to ripening. While exploring these hypotheses, taste should be taken into account, thus exogenous treatment with synthetic CKs may be of higher economic interest than genetic manipulation of CK-related pathways.

6 Cytokinin and Flower Senescence

Similar to its role in regulating leaf and fruit senescence, CK also plays a crucial role in regulating floral senescence, acting antagonistically to ethylene. A comparative transcriptomic analysis of the senescence of Dahlia florets identified ethylene as a potential positive regulator of senescence, while CK appeared to function as a negative regulator [104]. Treatment with ethylene inhibitors failed to consistently reduce senescence of Dahlia florets, whereas, application of BA consistently delayed senescence [104]. This pattern is further supported in several species of wild rose, where CK levels were significantly higher in unopened buds and gradually declined as flowers matured and senesced [105]. The decline is likely mediated by RhCKX6; knocking down expression of RhCKX6 delayed flower senescence in Rosa hybrida [106]. Although ethylene levels have not been directly quantified in rose flowers, monoterpene levels—known to correlate with ethylene biosynthesis—have been observed to increase gradually over time [105], suggesting a potential rise in ethylene production as the flower ages.

CK-ethylene crosstalk may be a potential target of interest when exploring avenues for prolonging flowering of ornamental plants. Comparative metabolomics throughout the flower’s life and senescence would support the antagonistic relationship between ethylene and CK in senescence and would provide insight into when the plant begins to transition from flowering to senescence. An accompanying proteomic analysis would help identify key players in CK and ethylene biosynthesis and homeostasis, which would identify targets for synthetic biology. While RhCKX6 is an obvious target for future analyses, due to the obvious redundancy of the CKX family, as discussed throughout this review, it is possible that a stronger phenotype would be observed in the rhckx6 background if additional CKX are KO’d. Delayed senescence is of general horticultural interest, as such, identification of these pathways in ornamental species such as roses and Dahlia will identify targets for similar studies in other ornamental species based on homology.

Beyond promoting floral longevity, disruption of CK homeostasis can trigger reproductive death. In Pyrus pyrifolia, withered flowers showed a higher concentration of CK and auxin compared to normal flowers. This observation was linked to differential methylation of CK and auxin related genes [107], implying altered epigenetic regulation that disrupts CK and auxin homeostasis. This unregulated homeostasis of CK and auxin likely halted normal bud development resulting in withered flowers. A similar pattern was observed in Hydrangea arborescens, where CK levels gradually declined throughout flowering; however, a significant spike in CK concentration occurred upon senescence, surpassing levels observed before flowering began [108]. This surge may reflect the breakdown of CK homeostasis that contributes to senescence rather than delaying it. Overall, these findings highlight the complex nature of CK signaling both prior to and during floral senescence.

7 Cytokinin as a Regulator Homomorphic Self-Incompatibility

There are two general forms of self-incompatibility (SI), homomorphic in which SI is not accompanied by morphological characteristics, and heteromorphic, in which SI is accompanied by the presence of two or more floral morphs [109]. To date, there is no evidence suggesting that CKs play a role in establishing heteromorphic SI; however, data from distant homomorphic SI members of Solanaceae indicate that manipulation of CK levels is required to trigger a SI response.

In Petunia hybrida, self-incompatibility response is triggered by programmed cell death (PCD) mediated through Caspase-Like Protease (CLP3) activity [110,111]. During SI crosses, CLP3 activation slows pollen tube elongation [111], marking the initiation of Petunia SI response. Suppressing CLP3 activity stops SI response during incompatible crosses [112], further supporting the role of CLP3 in initiating PCD. Treatment of P. hybrida with exogenous tZ results in a statically similar decline in growth [111], suggesting that CLP3 activity may be regulated by endogenous tZ.

The results from P. hybrida suggest further functional exploration of CLP3 may provide more insight into PCD. As repression of CLP3 activity through exogenous means removed SI barriers, KO CLP3 should produce similar results. If SI barriers are removed, phylogenetic analysis of the CLP family in Solanaceae should be performed across SI and self-compatible genera to explore the relationship of SI with CLP3.

CK involvement in RNA-based SI mechanisms appears to be conserved across distantly related members of Solanaceae [113]. In SC Solanum lycopersicum, pre-treatment of the stigma with tZ prior to selfing trigged an SI-like response, as indicated by a significant reduction in both pollen tube elongation and seed set [113]. The same treatment applied to SI S. chilense, S. pennellii, and S. habrochaites completely inhibited pollen tube growth. Additionally, tZ treatment of S. lycopersicum significantly increased CLP activity to a level statically comparable to selfed S. chilense, S. pennellii, S. habrochaites, and P. hybrida [113].

These results suggest that CK may be an important SI determinant factor in Solanaceae and justify further exploration of the role CK plays in SI in Solanaceae. Exploratory experiments utilizing CK repressors or exogenous CK treatments of other SI genera, as was previously done in Solanum, could rapidly expand our understanding of the relationship of CK and SI in Solanaceae. Understanding the role CK plays in SI is relatively important given the number of agriculturally important members of Solanaceae that are SI (i.e., tobacco, red pepper, potato, and tomato). Precise repression of CK signaling during the reproductive season of SI members of Solanaceae may be a lucrative method for increasing fruit yield by removing or reducing self-incompatibility barriers. Though it is important to acknowledge that current evidence for CK’s role in SI in Solanaceae is limited to two genera. Thus, this “coincidence” may be a result of convegent evolution and may not repersent a conserved approach to establishing SI in Solanaceae.

8 Cytokinin Plays a Critical Role in Monoecy

In monoecious species, individuals develop unisex flower types: staminate (male) flowers and pistillate (female) flowers. It has been proposed that evolution of monoecy must be reliant on a two gene system, a feminization and masculinization gene that are both related to phytohormones [114]. Given CK’s established role in gynoecium development, it is unsurprising that recent work has identified several genera that rely on altered CK for the development of pistillate flowers, overall, alluding to a role of the feminization gene in these genera in CK metabolism or signaling.

8.1 Cytokinin is Involved in Female Determination in Monoecious Malpighiales

In monoecious members of Malpighiales, which all produce significantly less pistillate flowers to staminate flowers, pistillate flower development is dependent on high CK levels relative to their male counterparts. Exogenous treatment of developing flowers with synthetic CK, 6-benzyladenine (BA), significantly increased pistillate-to-staminate ratio in Jatropha curcas [115], Manihot esculenta [116], Plukenetia volubilis [117], and Sapium sebiferum [118]. Complete feminization after BA treatment has been recorded in M. esculenta [119], and the development of hermaphrodites has been recorded in P. volubilis and J. curcas [117,120]. Overall, this suggests there is a threshold for CK content that must be met to prevent staminate flowers from developing.

Beyond floral changes, other observations have been made after BA treatment. Treatment of M. esculenta flowers increases female fertility but does not influence male fertility [121], while BA treatment of J. curcas staminate flowers causes sterility [122]. Treatment of Vernicia fordii flowers with BA induces expression of VfRR17 in pistillate flowers [123], implicating a role in pistillate flower development. Exogenous expression of VfRR17 in A. thaliana failed to produce a phenotype unless treated with BA, in which case, the transgenic lines suffered from reduced fertility and delayed flowering [123].

Transcriptomic analysis of J. curcas identified three phytohormone related genes—GIBBERELLIN 2-OXIDASE 8, IPT5, and JASMONIC ACID CARBOXYL METHYLTRANSFERASE—with expression patterns correlating with sex differentiation [115]. These findings suggest high CK is important for the development of pistillate buds, while high GA and jasmonic acid (JA) result in staminate bud development [115]. To explore the role of CK in pistillate flower development, A. thaliana AtIPT4 was exogenously expressed in J. curcas using a pistillate specific, JcTM6 promoter. Lines expressing AtIPT4 failed to produce pistillate flowers and had a significant reduction in staminate flowers, favoring the production of infertile bisexual flowers [120]. Beyond altered sex distribution, the expression of AtIPT4 in J. curcas resulted in larger flowers that lacked pollen, one line also had deformed ovules [120] overall, this suggests fine control over CK levels is likely required for the production of fertile plants. Though, as GA is likely a negative regulator of pistillate flower development [115] it is possible that disturbed CK/GA crosstalk resulted in some of the observed phenotypes.

In monoecious members of Malpighiales, it is evident that there is a strong correlation between CK and femaleness. While the discussed genera all belong to Euphorbiaceae, further exploration of the feminization effects of CK in monoecious species in other families, such as closely related Phyllanthaceae or Rafflesiaceae, which has an unknown relation to Euphorbiaceae, may reveal if this is a convergent trait or an ancestral trait. The exploration of exogenous treatment of CK on Rafflesiaceae may also provide some insight into the placement of the family, as phylogenetic analyses ignore the family due to its “problematic” nature.

Genetic exploration of the role of VfRR17 in a monoecious plant is also a strong research avenue. As V. fordii lacks a transformation system, viral induced silencing of VfRR17 would be an option for empirically supporting VfRR17 as a female determinant factor. Alternatively, as J. curcas has a transformation system [120], exogenous expression of VfRR17 in J. curcas has the possibility of empirically supporting its role in feminization. Though a better approach would be to identify its closest homolog of VfRR17 in J. curcas and silence its expression as this would aid in determining if Type-A ARRs are responsible for feminization across Euphorbiaceae.

8.2 Cytokinin and Other Monoecious Clades

While monoecious members of Malpighiales appear to rely heavily on CK for pistillate flower development, other clades exemplify the complex role of CK in sex determination.

In Cucurbita (Cucurbitales), CK regulates staminate flower development while ethylene is responsible for pistillate flower development. Transcriptomic analysis and a comparison of the phytohormone concentration of pistillate and staminate flowers of C. moschata suggest that auxin and CK regulate staminate flower development, while ethylene is responsible for pistillate flower development [124]. In further support of ethylene regulating the development of pistillate flowers, treatment of C. moschata flowers with ethephon, a synthetic ethylene, increased the number of pistillate flowers and decreased the CK content of the flowers [125]. Two androecious C. pepo mutants found to have point mutations in two ethylene receptors, ETR1A and ETR2B, thereby identifying potential candidates for femaleness [126]. Treatment of C. moschata flowers with ethephon had increased expression of ETR1A and ETR2b homologs, suggesting a conserved genetic basis for femaleness in Cucurbita [125]. To support ETR1A and ETR2B’s role in establishing femaleness, double KO lines of etr1a,etr2b, of C. pepo were generated. KO lines developed hermaphroditic and staminate flowers [127]. Hermaphrodites had much larger ovules than WT pistillate flowers and flowers did not open [127].

While genetic manipulation of etra1,etr2b have identified candidate feminization genes, the roles of CK and auxin in masculinization remain unclear. Exogenous CK and auxin treatment will aid in determining if one hormone plays a more critical role in masculinization, if both hormones are required for masculinization, or if neither hormone is important. Exploring CK content and other phytohormones across flower development may further determine the impact of CK and auxin on masculinization, especially if the study focuses on tissue specific content vs that of whole flower buds. If CK’s role in masculinization is supported, RNA-seq analysis throughout bud development in response to exogenous CK may help identify target candidates for genetic explorations.

In other clades that contain monoecious species, such as Fagales and Rosales, CK appears to act similarly to its role in Malpighiales, i.e., promotion of pistillate flower development. Transcriptomic work in Castanea henryi (Fagales) [128,129] and Morus indica (Rosales) [130] has also revealed a connection between CK and sex-determination. The metabolome of the pistillate flowers of M. indica contains significantly higher levels of metabolites used in the metabolism of zT relative to the staminate flower [130]. Forchlorfenuron (CPPU), a synthetic CK, induces feminization of C. henryi staminate flowers, empirically supporting CK’s potential role in establishing femaleness [128]. As the genetic basis of sex-determination has not been identified in either species, transcriptomic or proteomic analyses of the flowers throughout development and in response to exogenous CK treatment may provide more insight into the genetic basis of feminization in these species.

Overall, recent results push a narrative in which CK is the driving force of pistillate flowers in monoecious species, but in rare cases, can act as the driving force of staminate flowers. The results also exemplify monoecy’s reliance on phytohormone crosstalk, as most of the species discussed show different levels of phytohormones or have-omic data that suggest differential expression of phytohormone-related genes between the staminate and pistillate flowers. However, the results discussed in this review are constrained to very few orders, primarily falling into Malpighiale, due to a lack of recent publications pertaining to CK and monoecious species. Thus, it is difficult to fully conclude that CK is the general route to establishing femaleness in monoecious species. As such, additional work exploring how phytohormones contribute monoecy across a diverse set of lineages is required before confident generalizations can be made.

9 Cytokinin Plays a Critical Role in Dioecy

Dioecious plants have true sexes, with individuals producing either staminate or pistillate flowers. The sex determining region (SDR), which may reside on an autosome or sex chromosome, is responsible for establishing one of the sexes. It has been proposed that dioecy evolves from monoecy either through the gain of one or two genes [96], thus it would be assumed that phytohormones should also play some role in sex-determination. Recent advancements have identified several dioecious genera that rely on altered CK levels for sex-determination, including the model tree, Populus trichocarpa.

9.1 A Type-A ARR Contributes to Sex Determination in Malpighiales

Similar to the discussed monoecious members of Malpighiales, sex determination in Populus [131–135] and Salix [136,137] is regulated by CK. In both genera, ARR17, a cytokinin response regulator, acts as a negative regulator of maleness. Though manipulation of ARR17 differs depending on if the species relies on the XY or ZW sex-determination system.

In XY members of Populus, a partial duplication of ARR17 has occurred on the SDR of the Y-chromosome [134]. It is hypothesized that double stranded RNA (dsRNA) of the fragmented ARR17 is used as a guide for male-specific methylation of ARR17 [133], as supported by CRISPR ARR17 mutants of P. tremula. Silencing ARR17 resulted in females that produced functional stamen but failed to produce carpels and males that produced wildtype flowers [134]. In ZW members of Populus, ARR17 also drives sex determination; the genomic copy of ARR17 that establishes femaleness in the XY system is found in the SDR of ZW females [134,135]. Males completely lack a copy of ARR17, resulting in the production of male flowers. Overall, these results suggest that ARR17 is responsible for promoting femaleness and does not regulate maleness. Silencing of the partial duplication of ARR17 in male members of the XY system would further support this hypothesis, as silencing of the partially duplicated ARR17 should prevent methylation of ARR17 resulting in the production of female flowers.

In Salix, ARR17 exists in the SDR of the Z chromosome along with GATA15 [136]. In a rare monoecious individual of Salix purpurea, the Z chromosome lacks a copy of ARR17, but contains a copy of GATA15, suggesting ARR17 is only responsible for repressing “maleness”, while “femaleness” in S. purpurea is a result of GATA15 expression [136]. Empiricalwork focusing on silencing Overall, it appears that manipulation of ARR17 in general is a key feature of sex determination in all dioecious members of Salicaceae studied to date [138].

Despite the common reliance on CK for sex determination in the Salicaceae-Euphorbiaceae subclade of Malpighiales, there is currently no evidence that self-incompatibility in bisexual members of this subclade is reliant on CK [139]. There remains the potential that auxin-CK crosstalk may be important for establishing male mating-type in Turnera; auxin is responsible for establishing male mating-type in Turnera [140] and a member of the LOG family was previously found to be upregulated in the S-morph’s stamen [141]. Crosstalk between the hormones remains unexplored in the system. As the genetic basis of SI has not been explored in Passiflora, including the possible involvement of phytohormones, exploration of CK content, along with other hormones, may provide some insight into the basis of SI in Passiflora.

The implication that VfRR17 is the female determinant factor for V. fordii, correlates with the results from Populus and Salix. As the Partial clade and Euphorbioids share a common ancestor, there is the possibility that the last common ancestor of these basal clades was monoecious. Exploration of the evolution of the Type A ARR family may provide additional insight into if the manipulation of ARR17 is merely a convergent trait.

9.2 Cytokinin as a Positive Regulator of Femaleness

Aside from work in Malpighiales, recent work has failed to identify many examples of CK as a positive regulator of femaleness or negative regulator of maleness. All recent work linking CK to female bud development lacks any strong empirical evidence. The strongest example of CK’s role in femaleness is from Trachycarpus fortunei (Arecaceae), in which expression of CKX7 highly correlated with male flowers [142]. As the CKX family acts as negative regulators of CK levels, this result suggests lower levels of CK in male flowers. CK levels in the developing flowers of T. fortunei have not been quantified, thus it is unknown if CKX7 does reduce CK content in male buds. As a quick alternative to quantifying CK levels, exogenous treatment of male individuals with a synthetic CK may support the role of CK as a positive regulator of female development in T. fortunei.

CK also appears to contribute to sex determination in at least one dioecious gymnosperm. In Pinus tabuliformis (Pinaceae), comparative transcriptomic analysis of the ovules from sterile and fertile females found significant reduction in the expression of CK, auxin, and gibberellin related genes in sterile individuals [143]. Exploration of CK, auxin, and gibberellin levels in fertile and sterile females along with males would provide some empirical evidence for their importance.

Beyond conventional dioecy, CK is also implicated in establishing sexes in offshoots of dioecy. In functionally dioecious Elaeis guineensis (Arecaceae), CK levels were significantly higher in female flowers than in male flowers [144]. As auxin concentrations showed an opposite trend, being elevated in males, there is the possibility that cross-talk between CK and auxin is required for the establishment of sex [144]. Similarly, in androdioecious Punica granatum (Lythraceae), male flowers exhibited low levels of zeatin riboside relative to bisexual flowers, suggesting zeatin riboside is required for proper ovule development [145]. The identification of decreased levels of CK in both species suggest that transcriptomic or proteomic analysis of the developing buds may identify differentially expressed CK-related genes—thus identifying candidates for future genetic work.

9.3 Cytokinin as a Repressor of Femaleness

While there have been a limited number of recent cases of CK acting as the female sex-determinant hormone, there are several cases where CK establishes maleness. An interesting contrast to monoecious species, as CK typically appears to act as a feminization factor in monoecious genera, as discussed above. This discrepancy suggests that further exploration of both sytems across a diverse set of genera may provide some insight into how CK is affecting sex-determination.

In Actinidia chinensis (Actinidiaceae) sex is determined by two genes in the SDR of the Y-chromosome, FrBy and SyGI [146]; FrBY is a fasciclin-like protein that promotes maleness [146], while SyGI, a type-C CK response regulator, that repress gynoecium development preventing femaleness [147]. SyGI likely negatively impacts CK response, as treatment of male flowers with CK can partially save gynoecium development [148]. The role of SyGI supports the hypothetical function of type-C ARRs and sheds some insight into how they respond to CK.

In Carica papaya (Brassicales), CK levels negatively correlate with femaleness—aborted pistils from male flowers showed high expression CpLOG5 which was not expressed in female flowers [149]. Additionally, several other CK genes showed higher expression in the aborted pistil relative to the female flower [149]. In another study, CK-related genes were identified as overwhelming upregulated in the female flower relative to the male [150]. While exploring the methylome of the male vs. female flower, the only phytohormone related gene identified as differentially expressed and methylated was CpARR5 [151]. It is likely that crosstalk between CK and other hormones is occurring, as auxin [149], BR and JA [150] related genes were identified as upregulated in the female flower. Quantification of CK and other phytohormones in the male and female buds throughout development may provide some insight into the potential interplay of cross-talk in sex-determination—as CpLOG5 expression is male specific, one would expect higher levels of CK and related metabolites in male buds relative to female buds. Genetic manipulation of CpLOG5 and CpARR5 would also empirically support the importance of these genes in male-determination. If CpLOG5 is important for male-determination, then it would be anticipated that silencing would result in female flower development.

In Zanthoxylum armatum (Rutaceae), several CK response factors were identified as upregulated in the stamen along with pathways related to CK biosynthesis and signal transduction [152]. Z and tZ levels were also higher in male flowers [152], suggesting that CK establishes “maleness” in Z. armatum.

Vitis vinifera provides an unclear example of the role of CK in sex-determination. Sex is determined in V. vinifera ssp. Sylvestris (Vitales), wild grape, by an XY system with SDR consisting of several genes [153]. While APRT3y, a regulator of CK, is not located in the SDR, it is considered linked as recombination of APRT3y is repressed due to close proximity to the SDR [153]. As APRT3y is not expressed in hermaphrodites, it is believed that it represses gynoecium development and as a result, indirectly promotes maleness [154]. However, it is currently unknown if APRT3y is a negative or positive regulator of CK response. If it negatively regulates CK response, then this would suggest that CK is actually a positive regulator of femaleness. Further exploration of how APRT3y responds to CK is required before definitive statements can be made. A possible avenue for quickly exploring the role of APRT3y would be treatment of males with a CK repressor—if ARPT3y is a positive regulator of CK, repression of CK response should result in female flowers.

As previously stated, comparative studies across monoecious and dioecious species could clarify CK’s role in establishing femaleness and maleness. Expansion of work in a variety of monoecious and dioecious genera would rapidly expand our understanding of CK’s role in feminization. This is especially true of orders that contain both dioecious and monoecious species—especially if they are closely related, such as the Malpighiales. If dioecy is hypothesized to have evolved from monoecy in these subclades, then it would be expected that there are some similarities in how sex is determined. Such as the Malpighiales which seem to partially rely on manipulation of type-A ARRs for sex determination in both monoecious and dioecious species.

10 Cytokinin and Asexual Reproduction

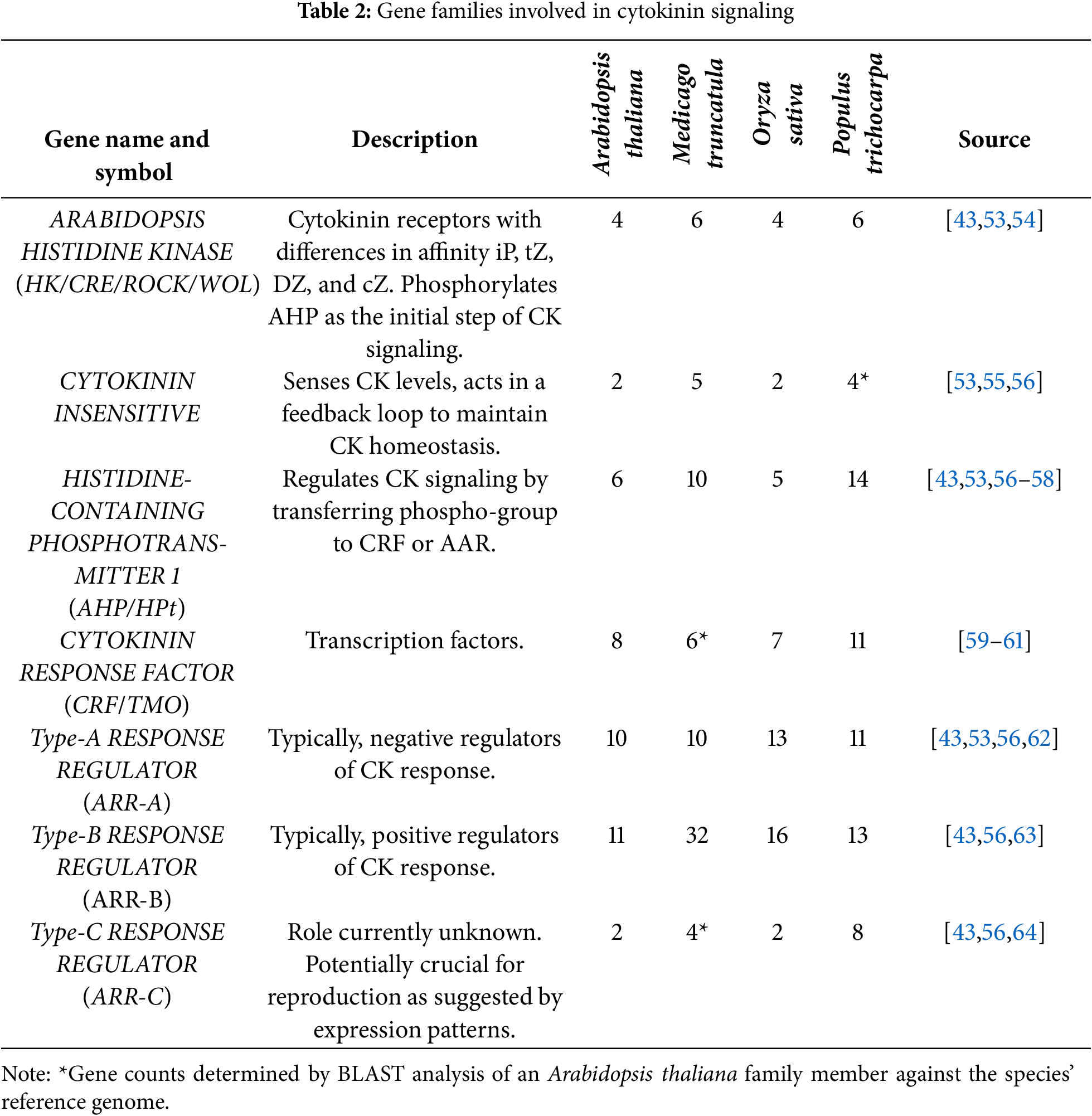

Due to CK’s important role in organogenesis and cell division, it is not surprising that it has recently been identified as a key regulator of asexual reproduction in several genera. One of the most well-supported examples is Marchantia polymorpha. In M. polymorpha, the transcription factor MpKAI2 initiates asexual reproduction by inducing gemma formation via manipulation of CK biosynthesis pathways [154–156]. KO mpkia2 lines do not express MpLOG, specifically in regions where gemma cup form, indicating that MpKAI2 regulates MpLOG expression [156]. The M. polymorpha genome contains a single LOG family member. mplog mutant lines are incapable of producing tZ, exhibit a significant reduction in gemma cups formation [140], and do not express MpGCAM1, a MYB transcription factor essential for gemma cup development [141]. Expression of MpGCAM1 is CK-dependent, as lines overexpressing MpCKX2 also have reduced MpGCAM1 expression and lack gemma cups [157].

In Lilium lancifolium, bulbil formation is initiated by five functionally redundant B-ARR—LIRR1, LIRR2, LIRR10, LIRR11 and LIRR12 [158]. With the exception of LIRR1, viral silencing of the genes failed to produce a phenotype, however, silencing all five resulted in a dramatic decrease in bulbil formation [158]. Emphasizing the importance of CK signaling in bulbil formation. Similarly, in Fortunella hindsii, the transcription factor FhRWP, which induces adventitious embryony [159], appears to regulate CK signaling [160]. Overexpression of FhRWP results in a significant increase in zeatin content and altered expression of CK-related genes [160]. The newly identified role of CK in asexual reproduction may be of great agricultural interest as vegeative propagation can allow breeders to rapidly reproduce individuals with traits of interest while skipping the seedling stage. Along with rapid reproduction, individuals produced through vegetative propogration have a tendacy to flower and fruit faster than individuals grown from seed, a train that is extremely important in slow growing fruit trees, such as F. hindsii. Beyond just genetic manipulation of CK regulated genes, these analyses suggest that spraying F. hindsii with synthetic CK may be a means to rapidly propograte individuals with traits of agricultural interest.

Although the role of CK in asexual reproduction has not been explored in Wolffia australiana, current data suggests CK may be potentially important for asexual reproduction. The genome of W. australiana lacks the CKX family [161], implying the species is incapable of regulating CK levels. Unregulated CK levels may explain the near absence of flowers in W. australiana and its heavy reliance on vegetative propagation [162] (see Table 3).

Further exploration of the role of CK in asexual reproduction may expand our general understanding of the evolution of the CK family. The complete absence of the CKX family in W. australiana poses several questions pertaining to CK homeostasis in the genus. Exploration of the CGT family and its function in W. australiana may provide insight into if the family is compensating for the lack of the CKX family. If this is the case, it furthers our understanding of the role of the CGT family and possible neofunctionalization of the family. Ectopic expression of CKX from closely related genera and exploration of how it affects CK cellular dynamics may provide more insight into if CK is unregulated and if this upregulation is preventing flowering and indirectly promoting asexual reproduction.

Unsurprisingly, CK continues to be recognized as a key player in plant reproduction. Given their fundamental roles in cell division and cell expansion and ancient nature, it is expected that CKs play critical roles in the development of reproductive organs, seeds, and fruits. As emphasized throughout this review, CK is not only capable of having positive effects on development but can also act as a negative regulator generally through unregulated CK homeostasis. Further exploration into the different roles CK homeostasis has on reproduction may identify additional pathways or genes that may be manipulated for agricultural applications, such as improving seed and fruit yield under stressful conditions or aiding in the process of vegetative propagation.

The emerging involvement of CKs in sex determination, both in monoecious plants and dioecious plants, while unexpected, aligns with the well-documented feminizing effects of CK during floral development. Furthermore, although the contributions of CKs to asexual reproduction and sexual barriers—i.e., self-incompatibility—are exciting, it is not surprising. Like other ancient hormones, there are likely several members of CK-related gene families that have undergone extensive neofunctionalization allowing CKs to undertake many general roles and several specialized roles. It is evident that CK is important for sex determination, incompatibility response, and asexual reproduction, as such, exploration of CK-regulated genes should be of consideration when exploring additional sexual systems in families that have empirical evidence supporting the role of CK in some genera’s sexual system, for example, SI response in Solanaceae.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by a National Science Foundation award to Henning PM (no. 2208975).

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| BA | 6-benzyladenine |

| BAP | 6-benzylaminopurine |

| ABA | Abscisic acid |

| AHK | ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE KINASE |

| HPt | ARABIDOPSIS HISTIDINE PHOSPHOTRANSFER PROTEIN |

| ARR | ARABIDOPSIS RESPONSE REGULATOR |

| BR | Brassinosteroid |

| CLP | Caspase-Like Protease |

| CRF | CYTOKININ RESPONSE FACTOR |

| CK | Cytokinins |

| dsRNA | double stranded RNA |

| CPPU | Forchlorfenuron |

| GA | Gibberellic acid |

| iPRMP | iP riboside 5′-monophosphate |

| iP | Isopentenyladenine |

| JA | Jasmonic Acid |

| KO | Knock out |

| PCD | Programmed cell death |

| SI | Self-incompatibility |

| SDR | Sex determining region |

| tZ | Trans-zeatin |

| ARR-A | Type-A ARR |

| ARR-B | Type-B ARR |

| ARR-C | Type-C ARR |

| tZRMP | tZ riboside 5′-monophosphate |

| WT | Wild Type |

References

1. Miller CO, Skoog F, Von Saltza MH, Strong FM. Kinetin, a cell division factor from deoxyribonucleic ACID1. J Am Chem Soc. 1955;77(5):1392. doi:10.1021/ja01610a105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Letham DS. Zeatin, a factor inducing cell division isolated from Zea mays. Life Sci. 1963;8(8):569–73. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(63)90108-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Nogué F, Gonneau M, Faure J-D. Cytokinins. In: Henry HL, Norman AW, editors. Encyclopedia of hormones. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2003. p. 371–8. doi:10.1016/B0-12-341103-3/00061-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Sakakibara H. Cytokinin biosynthesis and regulation. In: Litwack G, editor. Vitamins & hormones. Vol. 72. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2005. p. 271–87. doi:10.1016/S0083-6729(05)72008-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sussman MR, Kende H. In vitro cytokinin binding to a particulate fraction of tobacco cells. Planta. 1978;140(3):251–9. doi:10.1007/BF00390256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Kakimoto T. CKI1, a histidine kinase homolog implicated in cytokinin signal transduction. Science. 1996;274(5289):982–5. doi:10.1126/science.274.5289.982. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Inoue T, Higuchi M, Hashimoto Y, Seki M, Kobayashi M, Kato T, et al. Identification of CRE1 as a cytokinin receptor from Arabidopsis. Nature. 2001;409(6823):1060–3. doi:10.1038/35059117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Miller CO, Skoog F, Okumura FS, Von Saltza MH, Strong FM. Isolation, structure and synthesis of kinetin, a substance promoting cell Division1, 2. J Am Chem Soc. 1956;78(7):1375–80. doi:10.1021/ja01588a032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Okumura FS, Masumura M, Motoki T, Takahashi T, Kuraishi S. Syntheses of kinetin-analogs. I. Bull Chem Soc Jpn. 1957;30(2):194–5. doi:10.1246/bcsj.30.194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Klos D, Dušek M, Samol’ová E, Zatloukal M, Nožková V, Nesnas N, et al. New water-soluble cytokinin derivatives and their beneficial impact on barley yield and photosynthesis. J Agric Food Chem. 2022;70(23):7288–301. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.2c00981. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Matušková V, Zatloukal M, Pospíšil T, Voller J, Vylíčilová H, Doležal K, et al. From synthesis to the biological effect of isoprenoid 2′-deoxyriboside and 2′,3′-dideoxyriboside cytokinin analogues. Phytochemistry. 2023;205:113481. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2022.113481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Ma Y, Zhang Y, Xu J, Qi J, Liu X, Guo L, et al. Research on the mechanisms of phytohormone signaling in regulating root development. Plants. 2024;13(21):3051. doi:10.3390/plants13213051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Di X, Wang Q, Zhang F, Feng H, Wang X, Cai C. Advances in the modulation of potato tuber dormancy and sprouting. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(10):5078. doi:10.3390/ijms25105078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Sato H, Yamane H. Histone modifications affecting plant dormancy and dormancy release: common regulatory effects on hormone metabolism. J Exp Bot. 2024;75(19):6142–58. doi:10.1093/jxb/erae205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Choi HW. From the photosynthesis to hormone biosynthesis in plants. Plant Pathol J. 2024;40(2):99–105. doi:10.5423/PPJ.RW.01.2024.0006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Duhan L, Pasrija R. Unveiling exogenous potential of phytohormones as sustainable arsenals against plant pathogens: molecular signaling and crosstalk insights. Mol Biol Rep. 2025;52(1):98. doi:10.1007/s11033-024-10206-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Tian H, Xu L, Li X, Zhang Y. Salicylic acid: the roles in plant immunity and crosstalk with other hormones. J Integr Plant Biol. 2025;67(3):773–85. doi:10.1111/jipb.13820. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Zhang X, Gu D, Liu D, Ahmad Hassan M, Yu C, Wu X, et al. Recent advances in gene mining and hormonal mechanism for brown planthopper resistance in rice. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(23):12965. doi:10.3390/ijms252312965. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Singh A, Yajnik KN, Mogilicherla K, Singh IK. Deciphering the role of growth regulators in enhancing plant immunity against herbivory. Physiol Plant. 2024;176(6):e14604. doi:10.1111/ppl.14604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Jardim-Messeder D, de Souza-Vieira Y, Sachetto-Martins G. Dressed up to the nines: the interplay of phytohormones signaling and redox metabolism during plant response to drought. Plants. 2025;14(2):208. doi:10.3390/plants14020208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Nidhi, Iqbal N, Khan NA. Synergistic effects of phytohormones and membrane transporters in plant salt stress mitigation. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2025;221(5):109685. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2025.109685. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Dabravolski SA, Isayenkov SV. Exploring hormonal pathways and gene networks in crown root formation under stress conditions: an update. Plants. 2025;14(4):630. doi:10.3390/plants14040630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Joshi PS, Singla Pareek SL, Pareek A. Shaping resilience: the critical role of plant response regulators in salinity stress. Biochim Biophys Acta Gen Subj. 2025;1869(2):130749. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2024.130749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Hluska T, Hlusková L, Neil Emery RJ. The hulks and the deadpools of the cytokinin universe: a dual strategy for cytokinin production, translocation, and signal transduction. Biomolecules. 2021;11(2):209. doi:10.3390/biom11020209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Donyina GA, Szarvas A, Opoku VA, Miko E, Tar M, Czóbel S, et al. Enhancing sweet potato production: a comprehensive analysis of the role of auxins and cytokinins in micropropagation. Planta. 2025;261(4):74. doi:10.1007/s00425-025-04650-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Seerat A, Aslam MA, Rafique MT, Chen L, Zheng Y. Interplay between phytohormones and sugar metabolism in Dendrocalamus latiflorus. Plants. 2025;14(3):305. doi:10.3390/plants14030305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hussain S, Chang J, Li J, Chen L, Ahmad S, Song Z, et al. Multifunctional role of cytokinin in horticultural crops. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(3):1037. doi:10.3390/ijms26031037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Yin W, Dong N, Li X, Yang Y, Lu Z, Zhou W, et al. Understanding brassinosteroid-centric phytohormone interactions for crop improvement. J Integr Plant Biol. 2025;67(3):563–81. doi:10.1111/jipb.13849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Dabravolski SA, Isayenkov SV. Evolution of the cytokinin dehydrogenase (CKX) domain. J Mol Evol. 2021;89(9–10):665–77. doi:10.1007/s00239-021-10035-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Oshchepkov M, Kovalenko L, Kalistratova A, Sherstyanykh G, Gorbacheva E, Antonov A, et al. Anti-proliferative activity of ethylenediurea derivatives with alkyl and oxygen-containing groups as substituents. Biomedicines. 2025;13(2):316. doi:10.3390/biomedicines13020316. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Pagano C, Coppola L, Navarra G, Avilia G, Savarese B, Torelli G, et al. N6-isopentenyladenosine inhibits aerobic glycolysis in glioblastoma cells by targeting PKM2 expression and activity. FEBS Open Bio. 2024;14(5):843–54. doi:10.1002/2211-5463.13766. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Gan ZY, Komander D, Callegari S. Reassessing kinetin’s effect on PINK1 and mitophagy. Autophagy. 2024;20(11):2596–7. doi:10.1080/15548627.2024.2395144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Jabłońska-Trypuć A, Pankiewicz W, Wołejko E, Sokołowska G, Estévez J, Sogorb MA, et al. Human skin fibroblasts as an in vitro model illustrating changes in collagen levels and skin cell migration under the influence of selected plant hormones. Bioengineering. 2024;11(12):1188. doi:10.3390/bioengineering11121188. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Fathy M, Saad Eldin SM, Naseem M, Dandekar T, Othman EM. Cytokinins: wide-spread signaling hormones from plants to humans with high medical potential. Nutrients. 2022;14(7):1495. doi:10.3390/nu14071495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Sakakibara H. Five unaddressed questions about cytokinin biosynthesis. J Exp Bot. 2025;76(7):1941–9. doi:10.1093/jxb/erae348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Hirose N, Takei K, Kuroha T, Kamada-Nobusada T, Hayashi H, Sakakibara H. Regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis, compartmentalization and translocation. J Exp Bot. 2007;59(1):75–83. doi:10.1093/jxb/erm157. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Takei K, Yamaya T, Sakakibara H. Arabidopsis CYP735A1 and CYP735A2 encode cytokinin hydroxylases that catalyze the biosynthesis of trans-Zeatin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(40):41866–72. doi:10.1074/jbc.M406337200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Kurakawa T, Ueda N, Maekawa M, Kobayashi K, Kojima M, Nagato Y, et al. Direct control of shoot meristem activity by a cytokinin-activating enzyme. Nature. 2007;445(7128):652–5. doi:10.1038/nature05504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Kowalska M, Galuszka P, Frébortová J, Šebela M, Béres T, Hluska T, et al. Vacuolar and cytosolic cytokinin dehydrogenases of Arabidopsis thaliana: heterologous expression, purification and properties. Phytochemistry. 2010;71(17–18):1970–8. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.08.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Šmehilová M, Dobrůšková J, Novák O, Takáč T, Galuszka P. Cytokinin-specific glycosyltransferases possess different roles in cytokinin homeostasis maintenance. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7(8):1264. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.01264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Nguyen HN, Kambhampati S, Kisiala A, Seegobin M, Emery RJN. The soybean (Glycine max L.) cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase multigene family; identification of natural variations for altered cytokinin content and seed yield. Plant Direct. 2021;5(2):e00308. doi:10.1002/pld3.308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Ziegler P, Adelmann K, Zimmer S, Schmidt C, Appenroth KJ. Relative in vitro growth rates of duckweeds (Lemnaceae)—the most rapidly growing higher plants. Plant Biol. 2015;17(Suppl 1):33–41. doi:10.1111/plb.12184. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Brownlee BG, Hall RH, Whitty CD. 3-methyl-2-butenal: an enzymatic degradation product of the cytokinin, N-6-(delta-2 isopentenyl)adenine. Can J Biochem. 1975;53(1):37–41. doi:10.1139/o75-006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Immanen J, Nieminen K, Silva HD, Rojas FR, Meisel LA, Silva H, et al. Characterization of cytokinin signaling and homeostasis gene families in two hardwood tree species: Populus trichocarpa and Prunus persica. BMC Genomics. 2013;14(1):885. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-14-885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Wang C, Wang H, Zhu H, Ji W, Hou Y, Meng Y, et al. Genome-wide identification and characterization of cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase family genes in Medicago truncatula. J Plant Physiol. 2021;256(9):153308. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2020.153308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Kiba T, Mizutani K, Nakahara A, Takebayashi Y, Kojima M, Hobo T, et al. The trans-Zeatin-type side-chain modification of cytokinins controls rice growth. Plant Physiol. 2023;192(3):2457–74. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiad197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Rong C, Liu Y, Chang Z, Liu Z, Ding Y, Ding C. Cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase family genes exhibit functional divergence and overlap in rice growth and development, especially in control of tillering. J Exp Bot. 2022;73(11):3552–68. doi:10.1093/jxb/erac088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Wang X, Lin S, Liu D, Gan L, McAvoy R, Ding J, et al. Evolution and roles of cytokinin genes in angiosperms 1: do ancient IPTs play housekeeping while non-ancient IPTs play regulatory roles? Hortic Res. 2020;7(1):28. doi:10.1038/s41438-019-0211-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Zhao C, Yin H, Li Y, Zhou J, Bi S, Yan W, et al. Evolutionary analysis and catalytic function of LOG proteins in plants. Genes. 2024;15(11):1420. doi:10.3390/genes15111420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Mortier V, Wasson A, Jaworek P, De Keyser A, Decroos M, Holsters M, et al. Role of LONELY GUY genes in indeterminate nodulation on Medicago truncatula. New Phytol. 2014;202(2):582–93. doi:10.1111/nph.12681. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Liu L, Zhang F, Li G, Wang G. Qualitative and quantitative NAD+ metabolomics lead to discovery of multiple functional nicotinate N-glycosyltransferase in Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:1164. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.01164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Dauda WP, Shanmugam V, Tyagi A, Solanke AU, Kumar V, Krishnan SG, et al. Genome-wide identification and characterisation of cytokinin-O-glucosyltransferase (CGT) genes of rice specific to potential pathogens. Plants. 2022;11(7):917. doi:10.3390/plants11070917. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Rehman HM, Khan UM, Nawaz S, Saleem F, Ahmed N, Ahmad Rana I, et al. Genome wide analysis of family-1 UDP glycosyltransferases in Populus trichocarpa specifies abiotic stress responsive glycosylation mechanisms. Genes. 2022;13(9):1640. doi:10.3390/genes13091640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Tan S, Debellé F, Gamas P, Frugier F, Brault M. Diversification of cytokinin phosphotransfer signaling genes in Medicago truncatula and other legume genomes. BMC Genomics. 2019;20(1):373. doi:10.1186/s12864-019-5724-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Glover BJ, Torney K, Wilkins CG, Hanke DE. CYTOKININ INDEPENDENT-1 regulates levels of different forms of cytokinin in Arabidopsis and mediates response to nutrient stress. J Plant Physiol. 2008;165(3):251–61. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2007.01.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Burr CA, Sun J, Yamburenko MV, Willoughby A, Hodgens C, Boeshore SL, et al. Correction: the HK5 and HK6 cytokinin receptors mediate diverse developmental pathways in rice. Development. 2023;150(15):dev202221. doi:10.1242/dev.202221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Kim J. Phosphorylation of A-Type ARR to function as negative regulator of cytokinin signal transduction. Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3(5):348–50. doi:10.4161/psb.3.5.5375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Tsai YC, Weir NR, Hill K, Zhang W, Kim HJ, Shiu SH, et al. Characterization of genes involved in cytokinin signaling and metabolism from rice. Plant Physiol. 2012;158(4):1666–84. doi:10.1104/pp.111.192765. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Chen Y, Wu K, Zhang L, Wu F, Jiang C, An Y, et al. Comprehensive analysis of Cytokinin response factors revealed PagCRF8 regulates leaf development in Populus alba × P. Glandulosa. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;212(3):118361. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.118361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Hutchison CE, Li J, Argueso C, Gonzalez M, Lee E, Lewis MW, et al. The Arabidopsis histidine phosphotransfer proteins are redundant positive regulators of cytokinin signaling. Plant Cell. 2006;18(11):3073–87. doi:10.1105/tpc.106.045674. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Lei L, Ding G, Cao L, Zhou J, Luo Y, Bai L, et al. Genome-wide identification of CRF gene family members in four rice subspecies and expression analysis of OsCRF members in response to cold stress at seedling stage. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):28446. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-79950-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Rashotte AM, Goertzen LR. The CRF doma in defines cytokinin response factor proteins in plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10(1):74. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-10-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Mala KLN, Skalak J, Zemlyanskaya E, Dolgikh V, Jedlickova V, Robert HS, et al. Primary multistep phosphorelay activation comprises both cytokinin and abiotic stress responses: insights from comparative analysis of Brassica Type-A response regulators. J Exp Bot. 2024;75(20):6346–68. doi:10.1093/jxb/erae335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Gattolin S, Alandete-Saez M, Elliott K, Gonzalez-Carranza Z, Naomab E, Powell C, et al. Spatial and temporal expression of the response regulators ARR22 and ARR24 in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot. 2006;57(15):4225–33. doi:10.1093/jxb/erl205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Bauer J, Reiss K, Veerabagu M, Heunemann M, Harter K, Stehle T. Structure-function analysis of Arabidopsis thaliana histidine kinase AHK5 bound to its cognate phosphotransfer protein AHP1. Mol Plant. 2013;6(3):959–70. doi:10.1093/mp/sss126. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Suzuki T, Ishikawa K, Yamashino T, Mizuno T. An Arabidopsis histidine-containing phosphotransfer (HPt) factor implicated in phosphorelay signal transduction: overexpression of AHP2 in plants results in hypersensitiveness to cytokinin. Plant Cell Physiol. 2002;43(1):123–9. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcf007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Keshishian EA, Rashotte AM. Plant cytokinin signalling. Essays Biochem. 2015;58:13–27. doi:10.1042/bse0580013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Hallmark HT, Rashotte AM. Review—cytokinin response factors: responding to more than cytokinin. Plant Sci. 2019;289(9):110251. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Zhao J, Wang J, Liu J, Zhang P, Kudoyarova G, Liu CJ, et al. Spatially distributed cytokinins: metabolism, signaling, and transport. Plant Commun. 2024;5(7):100936. doi:10.1016/j.xplc.2024.100936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Zheng C, Liu C, Ren W, Li B, Lü Y, Pan Z, et al. Flower and pod development, grain-setting characteristics and grain yield in Chinese milk vetch (Astragalus sinicus L.) in response to pre-anthesis foliar application of paclobutrazol. PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0245554. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0245554. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Pérez-Rojas M, Díaz-Ramírez D, Ortíz-Ramírez CI, Galaz-Ávalos RM, Loyola-Vargas VM, Ferrándiz C, et al. The role of cytokinins during the development of strawberry flowers and receptacles. Plants. 2023;12(21):3672. doi:10.3390/plants12213672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Jing D, Chen W, Hu R, Zhang Y, Xia Y, Wang S, et al. An integrative analysis of transcriptome, proteome and hormones reveals key differentially expressed genes and metabolic pathways involved in flower development in loquat. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(14):5107. doi:10.3390/ijms21145107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Singh D, Sharma S, Jose-Santhi J, Kalia D, Singh RK. Hormones regulate the flowering process in saffron differently depending on the developmental stage. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1107172. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1107172. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Schwarz I, Scheirlinck MT, Otto E, Bartrina I, Schmidt RC, Schmülling T. Cytokinin regulates the activity of the inflorescence meristem and components of seed yield in oilseed rape. J Exp Bot. 2020;71(22):7146–59. doi:10.1093/jxb/eraa419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Moriyama A, Yamaguchi C, Enoki S, Aoki Y, Suzuki S. Crosstalk pathway between trehalose metabolism and cytokinin degradation for the determination of the number of berries per bunch in grapes. Cells. 2020;9(11):2378. doi:10.3390/cells9112378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Shibasaki K, Takebayashi A, Makita N, Kojima M, Takebayashi Y, Kawai M, et al. Nitrogen nutrition promotes rhizome bud outgrowth via regulation of cytokinin biosynthesis genes and an Oryza longistaminata ortholog of FINE CULM 1. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:670101. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.670101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Wu C, Cui K, Wang W, Li Q, Fahad S, Hu Q, et al. Heat-induced cytokinin transportation and degradation are associated with reduced panicle cytokinin expression and fewer spikelets per panicle in rice. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8(34978):371. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Delaigue M, Poulain T, Durand B. Phytohormone control of translatable RNA populations in sexual organogenesis of the dioecious plant Mercurialis annua L. (2n = 16). Plant Mol Biol. 1984;3(6):419–29. doi:10.1007/BF00033390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Gómez-Felipe A, Kierzkowski D, de Folter S. The relationship between AGAMOUS and cytokinin signaling in the establishment of carpeloid features. Plants. 2021;10(5):827. doi:10.3390/plants10050827. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Cerbantez-Bueno VE, Serwatowska J, Rodríguez-Ramos C, Cruz-Valderrama JE, de Folter S. The role of D3-type cyclins is related to cytokinin and the bHLH transcription factor SPATULA in Arabidopsis gynoecium development. Planta. 2024;260(2):48. doi:10.1007/s00425-024-04481-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Zu SH, Jiang YT, Chang JH, Zhang YJ, Xue HW, Lin WH. Interaction of brassinosteroid and cytokinin promotes ovule initiation and increases seed number per silique in Arabidopsis. J Integr Plant Biol. 2022;64(3):702–16. doi:10.1111/jipb.13197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Cai H, Liu K, Ma S, Su H, Yang J, Sun L, et al. Gibberellin and cytokinin signaling antagonistically control female-germline cell specification in Arabidopsis. Dev Cell. 2025;60(5):706–22.e7. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2024.11.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Shi T, Iqbal S, Ayaz A, Bai Y, Pan Z, Ni X, et al. Analyzing differentially expressed genes and pathways associated with pistil abortion in Japanese apricot via RNA-seq. Genes. 2020;11(9):1079. doi:10.3390/genes11091079. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Chen J, Zhang J, Liu Q, Wang X, Wen J, Sun Y, et al. Mining for genes related to pistil abortion in Prunus sibirica L. PeerJ. 2022;10(3):e14366. doi:10.7717/peerj.14366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Yang H, Chen M, Hu J, Lan M, He J. Lateral metabolome study reveals the molecular mechanism of cytoplasmic male sterility (CMS) in Chinese cabbage. BMC Plant Biol. 2023;23(1):128. doi:10.1186/s12870-023-04142-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Luo Y, Li Y, Yin X, Deng W, Liao J, Pan Y, et al. Transcriptomics analyses reveal the key genes involved in stamen petaloid formation in Alcea rosea L. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):551. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05263-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Jing D, Chen W, Xia Y, Shi M, Wang P, Wang S, et al. Homeotic transformation from stamen to petal in Eriobotrya japonica is associated with hormone signal transduction and reduction of the transcriptional activity of EjAG. Physiol Plant. 2020;168(4):893–908. doi:10.1111/ppl.13029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]