Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Leaf Morphological Variation and Heterosis on Hybrid Progenies of Populus ussuriensis and P. simonii × P. nigra

1 State Key Laboratory of Tree Genetics and Breeding, School of Forestry, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, 150040, China

2 Institute of Fruits and Vegetables, Xinjiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Urumqi, 830091, China

3 Heilongjiang Academy of Forestry, Harbin, 150040, China

4 College of Life Science, Northeast Forestry University, Harbin, 150040, China

* Corresponding Author: Guanzheng Qu. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3205-3216. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.069994

Received 05 July 2025; Accepted 24 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Hybridization remains an important method for breeding new poplar varieties. It results in significant variation in leaf phenotype among parents and offspring, and among offspring themselves. This study aimed to investigate whether leaf shape variations were similar in offspring produced from reciprocal crosses. Specifically, two hybrid combinations were produced: the direct cross with Populus ussuriensis as the maternal parent and P. simonii × P. nigra as the paternal parent (HY53), and the reciprocal cross with P. simonii × P. nigra as the maternal parent and P. ussuriensis as the paternal parent (HY268). Using 3-month-old rooted cuttings from 40 clones (36 F1 hybrids and their parents) growing in a greenhouse, we measured and analyzed 14 leaf morphological traits to assess genetic variation and heterosis. The results showed HY53 clones generally exhibited greater average height than HY268 clones. Leaf phenotypes differed between the two hybrid combinations, with significant differences observed among parents and offspring for almost all traits, as revealed by analysis of variance (ANOVA). The phenotypic coefficient of variation was higher in HY268 clones. Additionally, leaf traits demonstrated high repeatability. Notably, some hybrid offspring exhibited positive or negative mid-parent heterosis, as well as over-parent heterosis for certain leaf phenotypes. The systematic cluster analysis further indicated distinct separation among HY268 clones. This research provides valuable materials for poplar breeding and offers insights into hybrid vigor in wood plants. The findings highlight the importance of reciprocal crossing in influencing leaf phenotype variation and heterosis, offering practical insights for future breeding strategies.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FilePoplar (Populus spp.) is an economically and ecologically valuable genus predominantly growing in temperate regions worldwide [1], covering over 31.4 million hectares globally, with approximately 8.25 million hectares in China [2]. As conventional crossbreeding remains a primary method for poplar improvement, exploiting heterosis (hybrid vigor) is crucial for breeding new poplar varieties [3]. In natural settings, the Aigeiros poplars and Tacamahaca poplars could undergo natural hybridization and exhibit significant hybrid vigor [4]. Previous studies had shown that the P. deltoides × P. trichocarpa hybrids were significantly more productive than the P. deltoides × P. nigra hybrids, irrespective of site [5]. Now, Populus simonii × P. nigra shows strong drought and salt tolerance, and it has been widely planted in the arid and cold regions of western Heilongjiang province [6]. Populus ussuriensis exhibited rapid growth and produced high-quality timber but had weak drought and salt-alkali resistance [7]. Therefore, leveraging the desirable traits of P. ussuriensis and P. simonii × P. nigra through intersectional hybridization and gene recombination is highly valuable. The objective was to create new variations and breed superior varieties. This approach held significant practical significance in the development of poplar varieties that could withstand diverse environmental challenges.

Leaf morphology, a highly heritable trait, has significant phenotypic diversity in different species or different parts of the same species, even in different environmental factors [8]. Leaf shape and size were closely related to overall growth and biomass yield [9]. It served as a key indicator for early growth selection and heterosis prediction [10]. Understanding the inheritance pattern of growth traits was fundamental for breeding programs [11]. Leaf traits were strongly genetically controlled, and interspecific or intraspecific hybridization often resulted in significant variation in offspring, and previous studies had demonstrated that hybrid poplars often exhibited enhanced leaf traits relative to their parents. For instance, hybrids of Populus trichocarpa × P. deltoides developed larger leaves than either parent, with the increased biomass attributed to inheritance of larger cell number from P. deltoides and larger cell size from P. trichocarpa [12]. Similarly, in P. deltoides × P. nigra hybrids, greater total leaf area resulted in higher biomass productivity [13]. Additionally, in triploid progenies, leaf size and shape more closely resembled the female parent P. trichocarpa than the male P. deltoides. Triploid hybrids inherited two alleles from the female parent and one from the male parent at each locus [14]. However, the extent to which direct and reciprocal crosses influence leaf phenotypic inheritance in poplar remains insufficiently explored.

In this study, 19 HY53 clones (the direct cross with P. ussuriensis as the female and P. simonii × P. nigra as the male) and 17 HY268 clones (the reciprocal cross with P. simonii × P. nigra as the female and P. ussuriensis as the male) and their parents (4 clones) were used to measure leaf morphological traits. The aim of the study was to determine whether direct and reciprocal hybrids exhibited consistent performance in leaf morphology. This study could provide useful insights into maternal genetic effects and growth variation, and provide excellent materials for breeding new poplar varieties.

Flower branches of P. ussuriensis female and male (clones Pus 5 and Pus 8, respectively) were collected from Weihe Forestry Bureau, Shangzhi City, Heilongjiang Province, and male and female flower branches (clones Psn 3 and Psn 26, respectively) of P. simonii × P. nigra were obtained from Northeast Forestry University. The hybrid combination with Pus 5 as the female and Psn 3 as the male was named HY53, while the hybrid combination with Psn 26 as the female and Pus 8 as the male was named HY268. The F1 progeny seedlings were obtained through hybridization in the spring of 2022. In March 2024, 19 vigorous and disease-free individuals from HY53 and 17 superior clones from HY268 were selected and clonally propagated via stem cutting. The cuttings were planted in pots measuring 14 cm in diameter and 12 cm in height, filled with a growth medium composed of black soil, turf soil, and vermiculite in a 10:1:1 ratio. Each clone was replicated with twelve plants. All seedlings were cultivated in a greenhouse under natural light conditions, with temperatures maintained between 10°C and 20°C, and watered once per day.

2.2 Leaf Morphology Measurements

In June 2024, the tree height (H) for seedlings (at 3 months of age) was measured using a tower ruler. For leaf trait measurements, three healthy, uniformly growing plants without pests and diseases were selected for each clone. For each plant, one leaf among the 8th to 10th positions from the apex was collected. The petiole was retained, and each sample was put into sealed plastic bags, numbered, labeled, and transported to the laboratory for phenotypic analysis. Leaf fresh weight (LFW) and Leaf dry weight (LDW) were measured using an electronic balance with 0.1 mg precision, and leaf water content (LWC) was calculated accordingly. Leaf length (LL), leaf width (LW), and petiole length (PL) were measured using a ruler. Leaf index (LI) was calculated as the ratio of leaf length to width. The leaf area (LA) was estimated using the grid method [15]. Specific leaf area (SLA) was calculated as the ratio of leaf area to dry mass, serving as a major indicator of plants’ relative growth rate [16]. Leaf tip angle (LTA) and leaf basal angle (LBA) were measured with a protractor. Meanwhile, the stomatal characteristics, including stomatal length (SL), stomatal width (SW), and stomatal density (SD), were examined under an optical microscope. For these measurements, three trees per clone were randomly selected, and one leaf from the 4th to 6th leaf below the apex was sampled from each tree. For each clone, 30 observations of stomatal lengths and stomatal widths were recorded. Stomatal density was assessed based on three replicate measurements per leaf.

Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 25.0 software. Analyses of variance (ANOVA) for different traits among clones were performed according to the following linear model, and F tests were performed to estimate the significance of ANOVA, and a 0.05 significance level was used to test the significance of the differences among clones [17]:

where Yij was the phenotypic value of the jth individual in clone i, μ was the overall mean, Ci was the effect of clone ith, and eij was the random error.

The coefficient of phenotypic variation (PCV) was calculated using the formula [18]:

where X and SD were respectively the phenotypic mean and standard deviation of the trait.

Repeatability (R) was estimated following Yin et al. [17] as follows:

where F value was from the analysis of variance.

The percentage of heterosis was estimated with two methods, the mid-parent heterosis (Hm) and the over-parent heterosis (Ho) [19]. Hm was calculated based on the mean value of both parents, while Ho was calculated based on the optimal phenotype value of both parents [20].

where F1 was the mean performance. P1 and P2 were the mean values of the two parents, respectively. PS was the value of the better parent.

Using raw data of different leaf traits without standardization, hierarchical clustering analysis was used to group different clones based on multiple leaf phenotypes [21].

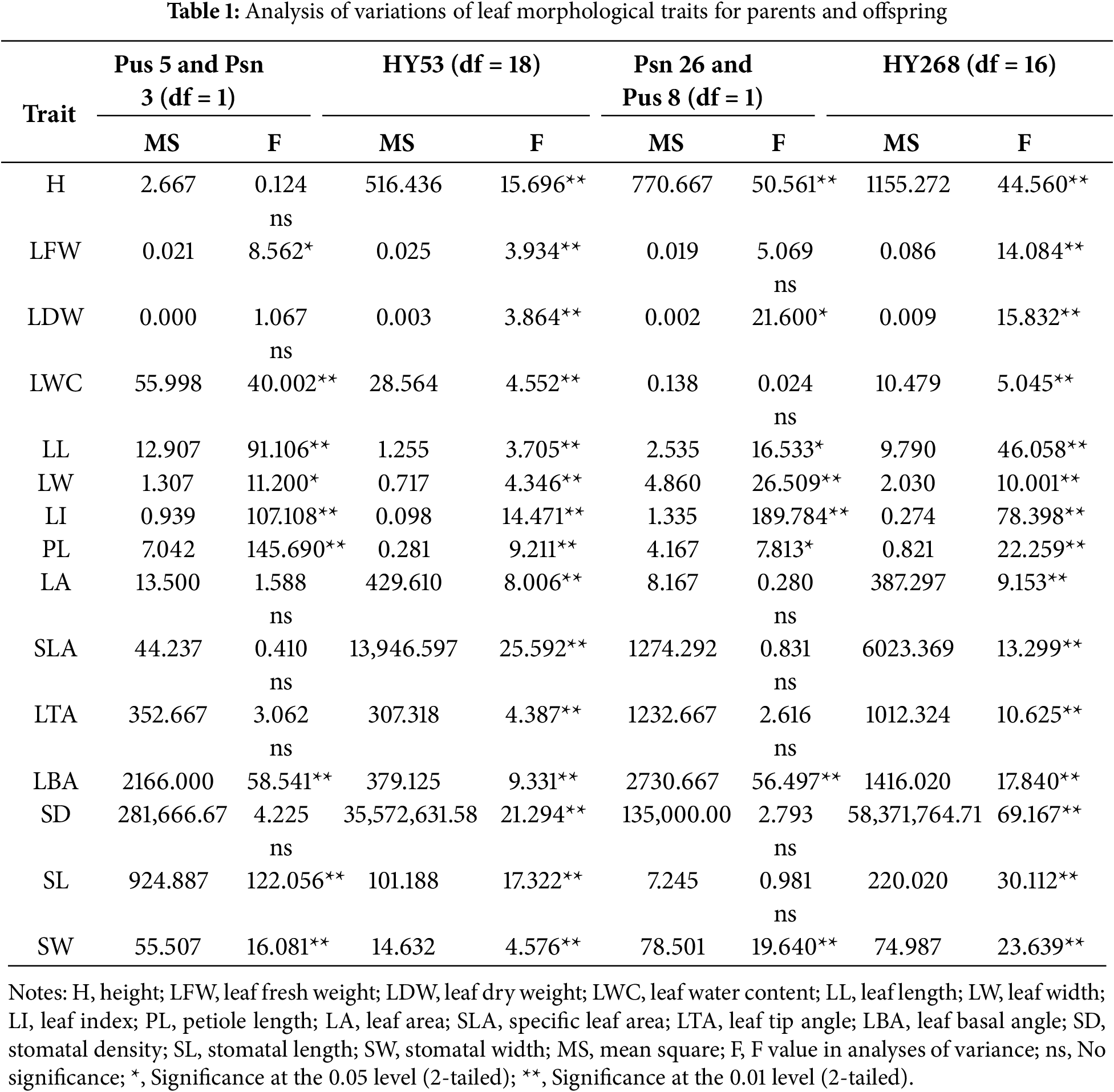

3.1 Traits Variations and Genetic Parameters

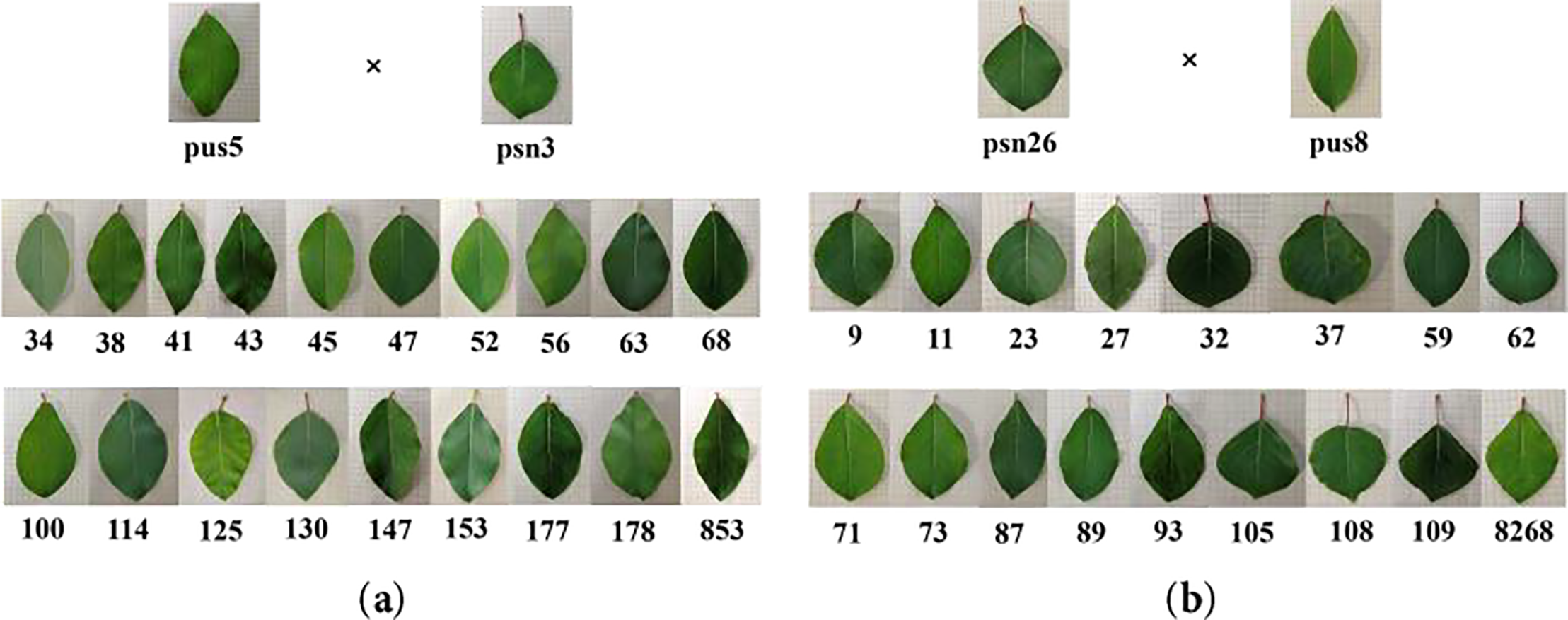

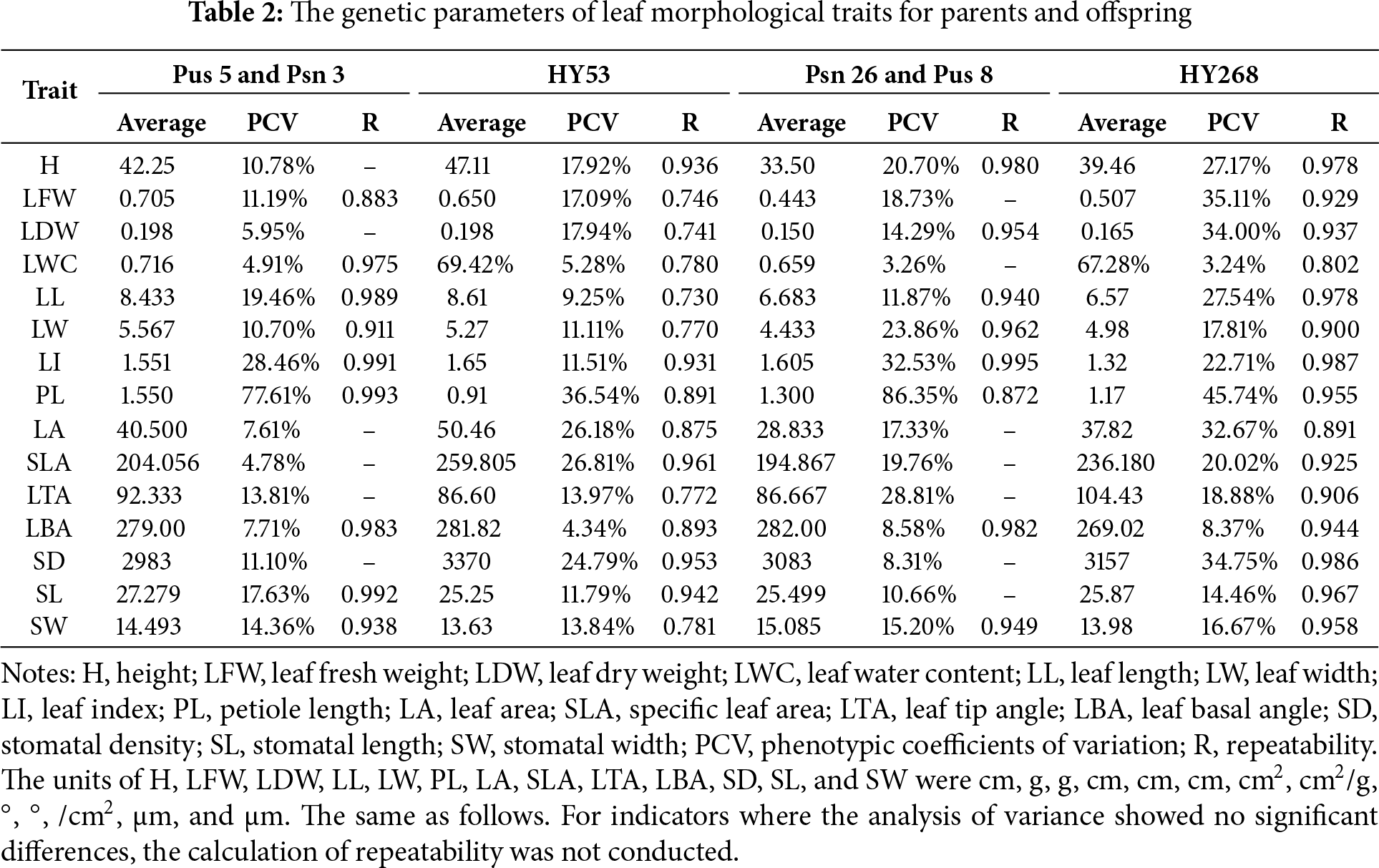

P. simonii × P. nigra leaves were diamond-shaped, while those of P. ussuriensis were oblong. The leaf phenotype of HY53 clones closely resembled that of P. ussuriensis, while HY268 clones showed greater morphological divergence from their parents (Fig. 1). Significant variations in leaf morphological traits were observed among offspring of both HY53 and HY268 clones (Table 1). No significant differences were detected in LDW, LA, SLA, LTA, and SD between the parents Pus 5 and Psn 3. Similarly, traits including LFW, LWC, LA, SLA, LTA, SD, and SL did not differ significantly between Psn 26 and Pus 8. The descriptive statistics, together with phenotypic coefficients of variation (PCV) and repeatability (R) were presented in Table 2. Among Pus 5 and Psn 3, the PCV value ranged from 4.78% (SLA) to 77.61% (PL), while for Psn 26 and Pus 8, they varied from 3.26% (LWC) to 86.35% (PL). For the offspring, PCV ranged from 4.34% (LBA) to 36.54% (PL) in HY53, and from 3.24% (LWC) to 45.74% (PL) in HY268. Compared to Pus 5 and Psn 3, Pus 8 and Psn 26 showed higher PCV value for most traits, except for LWC, LL, SD, and SL. Similarly, PCVs were generally higher among HY268 clones than HY53, except for LWC and SLA. Related to parents, offspring exhibited higher PCV in LFW, LDW, LA, SLA, and SD, but lower values in LI, PL, and LBA. The repeatability (R) was consistently high (R > 0.9) for all traits across both parental combinations. Among the offspring, all traits showed high repeatability (R > 0.730), with HY268 clones generally exhibiting higher repeatability values than HY53.

Figure 1: Leaf shape variation among parents and progeny of P. ussuriensis and P. simonii × P. nigra. (a): HY53. (b): HY268. Note: The solid line scale was 10 mm.

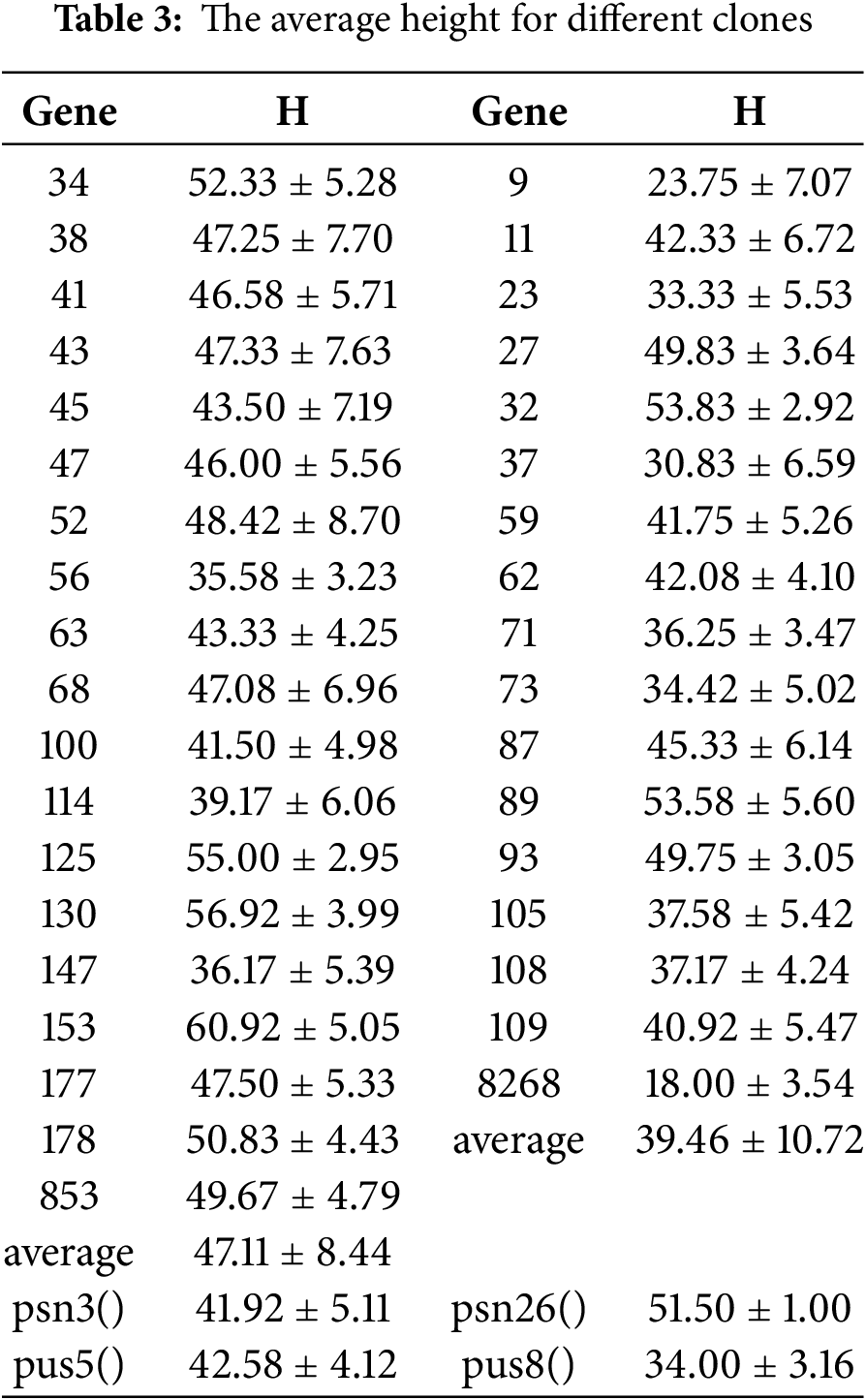

The average H for each clone was shown in Table 3. Among the HY53, Clone 153 exhibited the greatest height (60.92 cm), followed by Clone 130 and 125, whereas Clone 8268 showed the lowest H value. The average H of the parental clones Psn 3 and Pus 5 was 41.92 and 42.58 cm, respectively, and the total average H of HY53 clones was 47.11 cm. For the HY268 family, the parental clones Psn 26 and pus 8 had average heights of 51.50 and 34.00 cm, respectively, and the total average H of HY268 clones was 39.46 cm. Mean values for leaf traits across clones were provided in Supplementary Table S1 (HY53) and Table S2 (HY268). Among HY53 offspring, the female parent Pus 5 exhibited higher value in LWC, LL, LI, and LBA, but lower PL compared to its progeny. The male parent Psn 3 showed greater LW, PL, LTA, SL, and SW related to the offspring, though its LL and LI were lower. Mid-parent heterosis for leaf traits ranged from −41.29% (PL) to 27.32% (SLA). Six traits, including SLA, displayed positive mid-parent heterosis, while eight traits, including PL, showed negative values. Most traits exhibited negative over-parent heterosis, except for LA, SLA, and SD. In the HY268 population, the female parent Psn 26 had notably high petiole length, while Pus 8 showed higher LI and LBA, but lower LW, PL, and LTA. Among the offspring, Clone 93 displayed the highest values for LFW, LDW, LWC, LL, LW, LA, and LBA, whereas Clone 108 showed the lowest value across multiple traits, including LFW, LDW, LL, LW, LA, LTA, and LBA. Mid-parent heterosis in HY268 ranged from −17.76% (LI) to 31.16% (LA), with nine traits showing positive and five traits showing negative values. Positive over-parent heterosis was observed in LFW, LWC, LA, SLA, LTA, and SL, while the remaining traits exhibited negative value. Overall, hybrid progenies showed consistent heterotic patterns: LA, SLA, and SD displayed positive mid-parent heterosis, whereas PL and SW showed negative mid-parent heterosis. For over-parent heterosis, LA and SLA were positive over-parent heterosis, while LDW, LL, LW, LI, PL, LBA, and SW were negative over-parent heterosis.

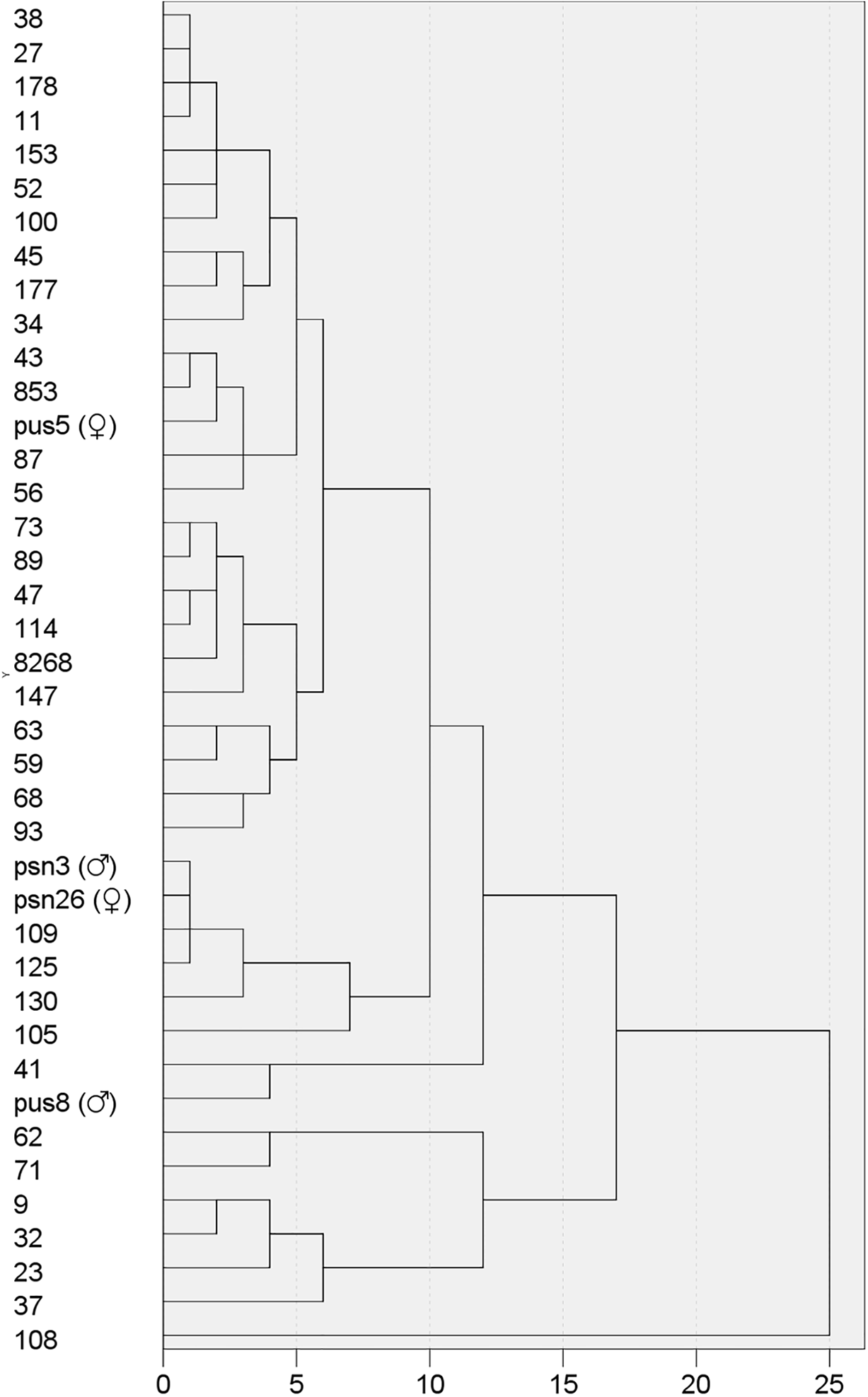

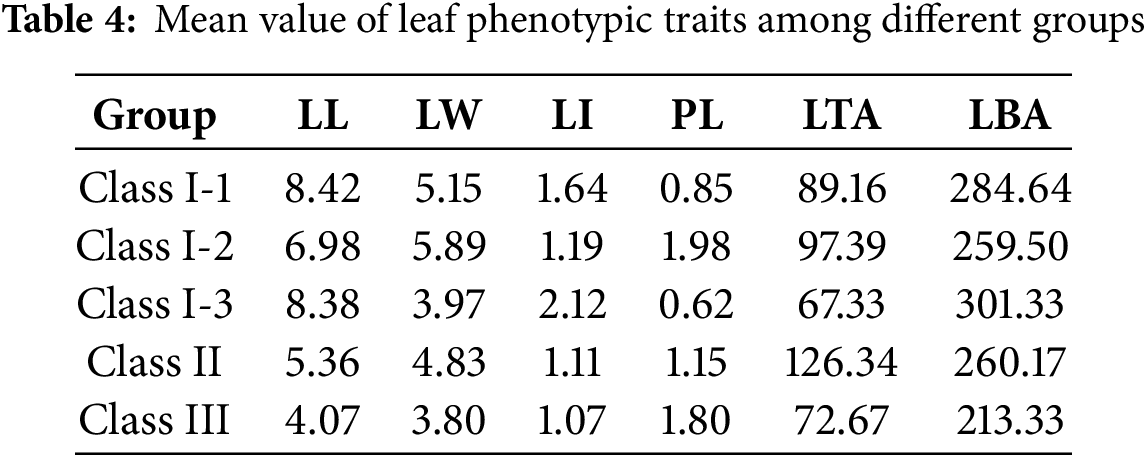

To investigate the leaf morphological variation among 36 hybrid offspring and their parents, hierarchical cluster analysis was performed. Initially, clustering analysis based on all traits revealed that extreme values—such as those of leaf fresh weight—caused certain clones with divergent leaf shapes to group together. Since the study focuses primarily on leaf shape variation, subsequent clustering incorporated the following morphological traits: leaf length, leaf width, leaf area index, petiole length, leaf tip angle, and leaf base angle. Using Euclidean distance, the hierarchical clustering result for 40 poplar clones was presented in Fig. 2. At a genetic distance of 15, the clones were grouped into three major categories: Class I comprised 33 clones, Class II contained 6 clones, and Class III consisted of a single clone (108). All 19 HY53 clones were classified into Class I, while all 6 clones in Class Ⅱ belonged to the HY268 family. HY53 offspring had leaf phenotypes more similar to the maternal parent (Pus 5). At a genetic distance of 10, Class I was further divided into three subgroups. Subclass I-1 included Pus 5 and 24 progeny clones. Subclass I-2 contained Clone 105, 109, 125, 130, along with parents Psn 3 and Psn 26. Subclass I-3 consisted of Clone 41 and Pus 8. The mean values of leaf phenotypic traits for each group and subclass were summarized in Table 4. The average leaf length in Class I was significantly greater than that of Class II and Class III. Clone 108 (Class III) exhibited the smallest leaf base angle (213.33°), which was significantly smaller than the overall mean (276.25°) and the average of both Class Ⅱ and Class Ⅲ. Further comparison among subclasses within Class I revealed that Subclass I-2 had smaller leaf length (6.98 cm) and leaf basal angle (259.50°), but greater petiole length (1.98 cm). In contrast, Subclass I-3 displayed smaller leaf width (3.97 cm), and larger leaf index (2.12) and leaf basal angle (301.33°).

Figure 2: Clustering analysis of F1 generation and their parents based on leaf phenotypic traits

4.1 Variation in Leaf Morphology for F1 Progenies and Parents

In China, the poplar varieties widely utilized in forestry production were predominantly developed through artificial cross-breeding. Since its initiation in the 1940s, cross-breeding programs have successfully selected and cultivated improved poplar varieties in major growing regions, yielding substantial economic and social benefits [22]. Cross-breeding not only enriched forest tree germplasm resources but also combined favorable traits from both parents, facilitating the development of novel superior varieties. Thus, it remained a vital strategy for poplar breeding both currently and in the foreseeable future. In this study, F1 hybrid progenies were generated through reciprocal crosses between P. ussuriensis and P. simonii × P. nigra, and their leaf traits were systematically measured and analyzed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) revealed significant differences in all leaf morphological traits among clones, indicating substantial phenotypic variation. The average tree height for HY53 progeny was higher than that of HY268, this result was similar to the findings of Liu et al. [23], who reported that over 17 years, the Populus deltoides × P. maximowiczii (D × M) population exhibited significantly larger diameter at breast height (DBH) and tree height than the reciprocal cross (M × D). The phenotypic coefficients of variation exceeding 20% were observed for traits including LFW, LDW, LL, LI, PL, LA, SLA, and SD, reflecting broad genetic variability in the F1 population. Such variations provided a promising basis for subsequent selective breeding of superior genotypes. Notably, HY268 clones exhibited higher PCV values for nearly all traits compared to HY53, except for LWC and SLA, suggesting greater segregation of characteristics within the HY268 group. additionally, the repeatability for leaf traits was high for both hybrid combinations, with all values exceeding 0.730—a pattern previously reported in hybrid progeny of Populus deltoides [24] and consistent with high repeatability [25]. The higher R values observed in HY268 clones further indicated that these traits were strongly genetically controlled and suitable for early selection [26].

4.2 Heterosis in Leaf Morphology for F1 Progenies

Hybridization can lead to heterosis (hybrid vigor), in which hybrids outperform their parents [27]. In trees, heterosis has been extensively studied in growth traits due to its economic importance [28]. Tree species are highly heterozygous, and F1 hybrid population typically exhibits significant segregation and variation in phenotypic traits [29]. Furthermore, the range of leaf shape variation in hybrid progeny was largely influenced by phenotypic divergence between the parents [14], highlighting its potential utility in breeding programs aimed at exploiting heterosis. In this study, the leaves of P. simonii × P. nigra were broad and short, while those of P. ussuriensis were narrow and long. Analysis of leaf morphological traits revealed that most traits exhibited negative over-parent heterosis (Ho), indicating that hybrid performance was lower than the superior parents for traits such as LDW, LL, LW, LI, PL, LBA, and SW. Similarly, negative mid-parent heterosis (Hm) reflected hybrid weakness [30]. For instance, Hm for LL and LW in HY53 clones was 2.07% and −5.30%, respectively, whereas in HY268 clones, it was −1.65% and 12.42%, respectively. These results suggested that leaf dimensions were strongly influenced by the maternal parent, consistent with findings in tea [31], underscoring the role of maternal inheritance or cytoplastic factors. Notably, LA and SLA displayed significant positive over-parent heterosis, indicating a potential morphological advantage inherited from parental lines. Similar parental leaf shape contrasts—e.g., small rhombic-ovate leaves in P. simonii and large triangular leaves in P. nigra [32]—had been reported, with hybrid leaf area often showing a paternal bias in frequency distribution [33]. Whether these morphological advantages translated into functional benefits, such as enhanced growth, remains unclear. Future studies should therefore integrate functional-morphological experiments, such as A–Ci curve analyses and resource-use efficiency assessments, to evaluate the physiological and ecological implications of these leaf traits. It should also be noted that heterosis expression was often context-dependent and influenced by environmental conditions [5]. This study was conducted under controlled greenhouse conditions with seedlings of a specific age, which might not fully represent trait expression under field environments or across development stages. Future validation using larger populations, multiple environments, and mature plants was warranted. Furthermore, future research should employ genomic approaches, such as quantitative trait locus (QTL) mapping or genome-wide association studies (GWAS) on this population, to identify the specific chromosomal regions and candidate genes controlling these leaf traits. Integrating genomic validation, field performance, and physiological assessments will be crucial for translating these findings into applied breeding strategies.

4.3 Cluster Analysis for Leaf Morphology for F1 Progenies and Parents

Cluster analysis divided the 36 progeny and their parents into three groups. Class Ⅲ contained only Clone 108, which was morphologically distinct due to its significantly smaller leaf basal angle and inverted triangular leaf shape. All 19 HY53 clones were clustered within Class I, whereas the 17 HY268 clones were distributed across groups, reflecting greater leaf shape variation within this cross. Previous studies had also reported that complementary inheritance of leaf traits occurred in poplar hybrids. For example, when hybridized with the same maternal parent (P. deltoides), progeny sired by P. trichocarpa displayed significant larger leaf area than either parent, whereas those sired by P. nigra exhibited intermediate leaf area [5]. Ridge et al. [12] similarly observed transgressive leaf area in P. trichocarpa × P. deltoides hybrids. Strong maternal effects had been reported in crosses between P. deltoides and P. simonii, where hybrid leaf morphology closely resembled the maternal parent, though leaf size showed paternal influence [34]. In contrast, no pronounced leaf morphology differences were detected between direct and reciprocal crosses of P. tremula and P. alba [35], suggesting genetic architecture of leaf traits was cross-specific. Although genome-wide association analysis (GWAS) had been applied to leaf shape traits in poplar [36], no significant SNPs were identified for leaf length, width, area, or aspect ratio, indicating these traits may be controlled by polygenic or non-genomic mechanisms.

In this study, the leaf phenotypic characters of 36 hybrid offspring and their parents were measured, which revealed significant genetic variation and heterosis. Reciprocal hybrids showed maternal influence and trait segregation, with several traits demonstrating positive or negative over-parent heterosis. These findings enhance our understanding of early-stage leaf morphology variation and heterosis in poplar, and also provide valuable genetic material for poplar breeding programs.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by “National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFD2200203)” and “the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. 2572022AW02 and No. 2572023CT19)”.

Author Contributions: Heng Zhang, Meng Wang, Dong Zeng, and Guanzheng Qu planned and designed the research. Heng Zhang, Meng Wang, Dong Zeng, Yunbo Xu, Dongyuan Guo, Xuanchen Liu, Zhanqi Ren, and Jinzi Zhang performed experiments and conducted fieldwork. Heng Zhang, Meng Wang, and Dong Zeng analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. Yuhang Liu, Qiuyu Wang, and Shuo Yu provided helpful comments on the draft and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.069994/s1.

References

1. Zhao XY, Li Y, Zheng M, Bian XY, Liu MR, Sun YS, et al. Comparative analysis of growth and photosynthetic characteristics of (Populus simonii × P. nigra) × (P. nigra × P. simonii) hybrid clones of different ploidides. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0119259. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0119259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Feng HL. Variation of methane flux in soil and stem of poplar plantation and its microbial mechanisms. [dissertation]. Nanjing, China: Nanjing Forestry University; 2022. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

3. Kondratovics T, Zeps M, Rupeika D, Zeltins P, Gailis A, Matisons R. Morphological and physiological responses of hybrid aspen (Populus tremuloides Michx. × Populus tremula L.) clones to light in vitro. Plants. 2022;11(20):2692. doi:10.3390/plants11202692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Wang TX, Ren JS, Huang QJ, Li JH. Genetic parameters of growth and leaf traits and genetic gains with MGIDI in three Populus simonii × P. nigra families at two spacings. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1483580. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1483580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Marron N, Dillen SY, Ceulemans R. Evaluation of leaf traits for indirect selection of high yielding poplar hybrids. Environ Exp Bot. 2007;61(2):103–16. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2007.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ahmed AKM, Fu ZX, Ding CJ, Jiang LP, Han XD, Yang AG, et al. Growth and wood properties of a 38-year-old Populus simonii × P. nigra plantation established with different densities in semi-arid areas of northeastern China. J For Res. 2020;31(2):497–506. doi:10.1007/s11676-019-00887-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wei M, Chen YX, Zhang MQ, Yang JL, Lu H, Zhang X, et al. Selection and validation of reference genes for the qRT-PCR assays of Populus ussuriensis gene expression under abiotic stresses and related ABA treatment. Forests. 2020;11(4):476. doi:10.3390/f11040476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Guet J, Fabbrini F, Fichot R, Sabatti M, Bastien C, Brignolas F. Genetic variation for leaf morphology, leaf structure and leaf carbon isotope discrimination in European populations of black poplar Populus nigra. Tree Physiol. 2015;35(8):850–63. doi:10.1093/treephys/tpv056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Gebauer R, Vanbeveren SPP, Volarik D, Plichta R, Ceulemans R. Petiole and leaf traits of poplar in relation to parentage and biomass yield. For Ecol and Manage. 2016;362:1–9. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2015.11.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Diao SF, Li FD, Duan W, Han WJ, Sun P, Fu JM. Genetic diversity of phenotypic traits of leaves in F1 progeny of persimmon. J China Agric Univ. 2017;22(2):32–44. doi:10.11841/j.issn.1007-4333.2017.02.04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Kamara MM, Safhi FA, Al Aboud NM, Aljabri M, Alharbi SA, Ghazzawy HS, et al. Genetic diversity and combining ability of developed maize lines to realize heterotic and high yielding hybrids for arid conditions. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2024;93(12):3465–85. doi:10.32604/phyton.2024.058628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ridge CR, Hinckley TM, Stettler RF, Van Volkenburgh E. Leaf growth characteristics of fast-growing poplar hybrids Populus trichocarpa × P. deltoides. Tree Physiol. 1986;1(2):209–16. doi:10.1093/treephys/1.2.209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Marron N, Ceulemans R. Genetic variation of leaf traits related to productivity in a Populus deltoides × Populus nigra family. Can J For Res. 2006;36(2):390–400. doi:10.1139/X05-245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Wu RL. Quantitative genetic variation of leaf size and shape in a mixed diploid and triploid population of Populus. Genet Res. 2000;75(2):215–22. doi:10.1017/S0016672399004279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao XY, Ma KF, Shen YB, Zhang M, Li KY, Wu RL, et al. Characteristic variation and selection of forepart hybrid clones of Sect. Populus J Beijing For Univ. 2012;34(2):45–51. doi:10.13332/j.1000-1522.2012.02.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Aihara T, Araki K, Sarmah R, Cai YH, Paing AMM, Goto S, et al. Climate-related variation in leaf size and phenology of Betula ermanii in multiple common gardens. J For Res. 2024;29(1):62–71. doi:10.1080/13416979.2023.2289731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Yin SP, Xiao ZH, Zhao GH, Zhao X, Sun XY, Zhang Y, et al. Variation analyses of growth and wood properties of Larix olgensis clones in China. J For Res. 2017;28(4):687–97. doi:10.1007/s11676-016-0359-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Hai PH, Jansson G, Harwood C, Hannrup B, Thinh HH. Genetic variation in growth, stem straightness and branch thickness in clonal trials of Acacia auriculiformis at three contrasting sites in Vietnam. For Ecol Manage. 2008;255(1):156–67. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2007.09.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu CT, Mao BG, Zhang YX, Tian L, Ma B, Chen Z, et al. The OsWRKY72-OsAAT30/OsGSTU26 module mediates reactive oxygen species scavenging to drive heterosis for salt tolerance in hybrid rice. J Integr Plant Biol. 2024;66(4):709–30. doi:10.1111/jipb.13640. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Kouago BA, Seka D, Brou KF, Bonny BS, Koffi KHJ, Adjoumani K, et al. Combining ability analysis of Cucurbita moschata D. in Cote d’Ivoire and classification of promising lines based on their gca effects. PLoS One. 2024;19(8):e0305798. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0305798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Fang SZ, Zhai XC, Wan J, Tang LZ. Clonal variation in growth, chemistry and calorific value of new poplar hybrids at nursery stage. Biomass Bioenerg. 2013;54(1):303–11. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2012.10.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen YN, Hu CJ, Zhuge Q, Hu JJ, Yin TM. Thirty years of Agrobacterium-mediated genetic transformation of Populus. Sci Silvae Sin. 2022;58(12):114–29. (In Chinese). doi:10.11707/i.1001-7488.20221211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Liu W, Liu CG, Zhang Y, Li JH, Ji JB, Qin XR, et al. Comparative study on growth characteristics and early selection efficiency of hybrid offspring of Populus deltoides ‘DD-109’ and P. maximowiczii in Liaoning. China Plants. 2025;14(1):111. doi:10.3390/plants14010111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Yan YB, Pan HX. Genetic variation and selection of seedling traits in hybrid progeny of Populus deltoides. J Zhejiang A&F Univ. 2021;38(6):1144–52. doi:10.11833/i.issn.2095-0756.20200803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Meena BL, Das SP, Meena SK, Kumari R, Devi AG, Devi HL. Assessment of GCV, PCV, heritability and genetic advance for yield and its components in field pea (Pisum sativum L.). Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2017;6(5):1025–33. doi:10.20546/ijcmas.2017.605.111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Alizadeh K, Fatholahi S, Teixeira da Silva JA. Variation in the fruit characteristics of local pear (Pyrus spp.) in the Northwest of Iran. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2015;62(5):635–41. doi:10.1007/s10722-015-0241-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Shi TL, Jia KH, Bao YT, Nie S, Tian XC, Yan XM, et al. High-quality genome assembly enables prediction of allele-specific gene expression in hybrid poplar. Plant Physiol. 2024;195(1):652–70. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiae078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Li BL, Howe GT, Wu RL. Developmental factors responsible for heterosis in aspen hybrids (Populus tremuloides × P. tremula). Tree Physiol. 1998;18(1):29–36. doi:10.1093/treephys/18.1.29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wan KH, Xu DZ, Bian LM, Zhang L, Chen ZQ. Analysis of F1 representative variation and heterosis of Chinese fir. J For Environ. 2024;44(5):476–83. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

30. Nadir S, Li W, Zhu Q, Khan S, Zhang XL, Zhang H, et al. A novel discovery of a long terminal repeat retrotransposon-induced hybrid weakness in rice. J Exp Bot. 2019;70(4):1197–207. doi:10.1093/jxb/ery442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Luo L, Huang YH, Zeng Z, Zhou MZ, Xie MW, Yan CY. Study on the genetic variation of leaf phenotype in F1 full-sib progeny of tea distant hybridization. J Tea Commun. 2020;47(4):568–75. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

32. Ren JS, Ji XY, Wang CH, Hu JJ, Nervo SE, Li JH. Variation and genetic parameters of leaf morphological traits of eight families from Populus simonii × P. nigra. Forests. 2020;11(12):1319. doi:10.3390/f11121319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Wang CH, Zhang XY, Li JH. Leaf morphological variation on progeny of Populus simonii × Populus nigra. For Res. 2020;33(3):132–8. doi:10.13275/i.cnki.lykxyj.2020.03.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Cheng XQ, Jia HX, Sun P, Zhang YH, Hu JJ. Genetic variation analysis of leaf morphological traits in Populus deltoides cl. ‘Danhong’ × P. simonii cl. ‘Tongliao1’ hybrid progenies. For Res. 2019;32(2):100–10. doi:10.13275/j.cnki.lykxyj.2019.02.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Grünhofer P, Herzig L, Schreiber L. Leaf morphology, wax composition, and residual (cuticular) transpiration of four poplar clones. Trees-Struct Funct. 2022;36(2):645–58. doi:10.1007/s00468-021-02236-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Yang WG, Yao D, Wu HM, Zhao W, Chen YH, Tong CF. Multivariate genome-wide association study of leaf shape in a Populus deltoides and P. simonii F1 pedigree. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0259278. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0259278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools