Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Colored Tubes and Chlorella Vulgaris Bioinput Improve Growth and Quality of Hancornia speciosa Seedlings

1 Agronomy Department, Mato Grosso do Sul State University, Cassilândia, 79543-899, MS, Brazil

2 Agronomy Department, Federal University of Grande Dourados, Dourados, 79804-970, MS, Brazil

* Corresponding Author: Edilson Costa. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant and Environments)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3109-3123. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070221

Received 10 July 2025; Accepted 15 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Hancornia speciosa ‘Gomes’, commonly known as mangabeira, is a fruit-bearing tree native to Brazil that plays a crucial role in sustaining its native biome, restoring degraded areas, and improving the socio-environmental conditions of these regions. The use of colored materials and bioinputs can help improve the quality of seedling production of Hancornia speciosa. This study aimed to evaluate the use of colored seedling tubes and a Chlorella vulgaris-based bioinput in developing Hancornia speciosa seedlings. The experiment was conducted at the Mato Grosso do Sul State University (UEMS), in Cassilândia, MS, using a completely randomized design in a 5 × 2 factorial arrangement. Treatments included colored reflective tubes (blue, white, red, yellow, and black) and bioinput application (absence or presence). The Hancornia speciosa seeds were collected near the Cassilândia campus and the Chlorella vulgaris-based bioinput was produced at the Microalgae and Biotechnology Laboratory of the Centro de Desenvolvimento Sustentável do Bolsão Sul-Mato-Grossense (CEDESU). The bioinput was applied at sowing and after 30, 60 and 90 days after emergence (DAE), totalizing three applications. An increase in plant height, number of leaves, chlorophyll a and total, CO2 assimilation rate, water use efficiency was observed. The combination of tube color and the presence of the Chlorella vulgaris bioinput significantly improved biometric traits, seedling quality index, chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll content, and CO2 concentration, thus enhancing the seedling quality and potentially increasing field establishment and survival rates.Keywords

Hancornia speciosa ‘Gomes’ (Mangabeira) belongs to the Apocynaceae family and is a fruit-bearing plant native to Cerrado biome, with broad geographic distribution across Brazil’s Central-West, North, Northeast, and Southeast regions. It is a medium-sized tree, typically ranging from 2 to 10 m in height, and is characterized by its twisted and rough trunk [1].

It is generally propagated sexually and produces recalcitrant seeds with pulp containing inhibitory substances that impair germination, resulting in low germination rates and slow, irregular seedling growth. These factors make propagation challenging for producing Hancornia speciosa seedlings [2].

However, the production of Hancornia speciosa seedlings can contribute to environmental conservation and species preservation, as this plant plays a crucial role in sustaining its native biome and can be used in the restoration of degraded areas, improving the socio-environmental conditions of these regions [3].

The restoration of degraded areas is a challenge that requires innovative strategies. In this context, the use of microalgae-based bioinputs presents a promising alternative for plant production, as they possess biostimulant and biofertilizer properties that enhance plant growth, increase resistance to stress, and promote overall development [4]. These bioinputs contain significant amounts of polyamines, antioxidant compounds, vitamins, polysaccharides, amino acids, and phytohormones such as indole-3-acetic acid, abscisic acid, cytokinins, ethylene, and gibberellins, which have a synergistic influence on the overall metabolism of plants [5].

Another important factor for plant growth is an optimal light environment, that can significantly influence plant growth, photosynthetic rate, transpiration rate, and stomatal conductance and is considered a limiting factor for plant development [6]. The light energy that plants receive is utilized according to its wavelength, intensity, and direction, and it is perceived by photoreceptors, which in turn trigger important physiological responses to these stimuli [7].

The use of tubes or benches with reflective materials aims to redirect part of the photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), which would otherwise be lost, back to the plants. This redirection allows shaded areas of the plants to also receive light. The additional exposure to PAR can influence various physiological aspects, such as the production of photosynthetic pigments and chlorophyll activity, leading to morphological changes, including variations in plant growth, height, and stem diameter [6].

Alternatives such as using reflective materials have been adopted to increase photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in cultivation environments, as these materials aim to maximize the use of solar radiation and improve seedling quality [8]. Using reflective materials is an effective and low-cost method that enhances PAR in production areas and can promotes vigorous plant growth [9].

Given the environmental and socioeconomic importance of Hancornia speciosa, it is essential to develop techniques to improve the production of high-quality seedlings and contribute to species preservation. The combined use of microalgae-based bioinputs and reflective materials may provide a synergistic effect, contributing to more uniform and vigorous seedling growth, and thus represents a sustainable approach to improving seedling production systems. The hypothesis was that the use of colored tubes to modify light quality, combined with the application of microalgae, promotes significant improvements in seedling growth and vigor. Thus, this study aimed to evaluate the use of colored seedling tubes and Chlorella vulgaris bioinput in the formation of Hancornia speciosa seedlings.

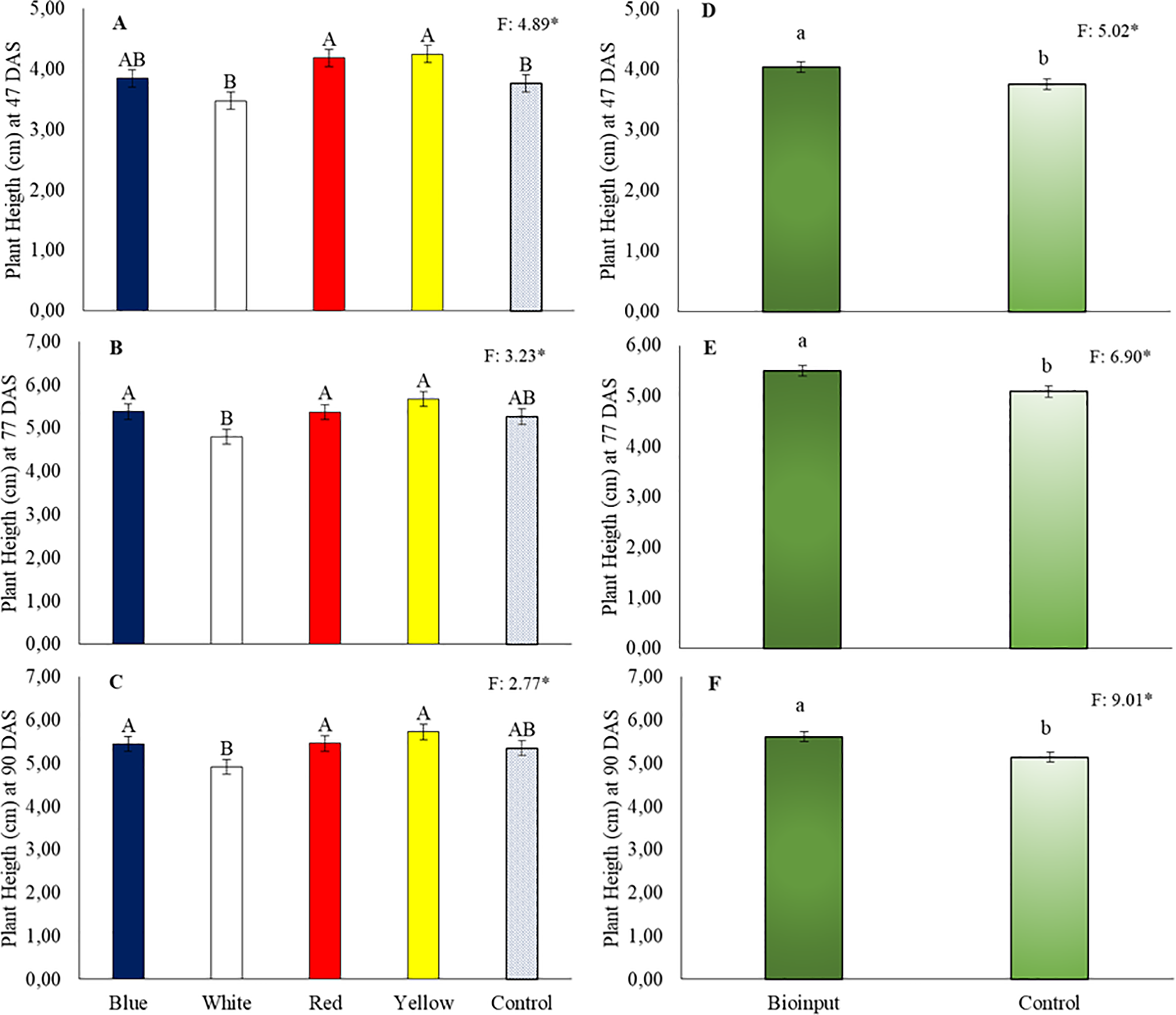

At 47 DAS, plants grown in red and yellow tubes, which did not differ from those grown in blue tubes, showed greater height than those grown in white and control (black) tubes (Fig. 1A). At 77 DAS (Fig. 1B) and 90 DAS (Fig. 1C), plant height in blue, red, and yellow tubes was similar to that in the control treatment but remained lower than that of plants grown in white tubes. In all height measurements, the application of Chlorella vulgaris microalgae had a positive influence, promoting taller plants. The microalgae application led to height increases of 7.6% (Fig. 1D), 8.1% (Fig. 1E), and 9.1% (Fig. 1F) in Hancornia speciosa seedlings at 47, 77, and 90 DAS, respectively.

Figure 1: Height of Hancornia speciosa seedlings at 47 (A,D), 77 (B,E), and 90 (C,F) days after sowing (DAS), grown in different colored seedling tubes with or without the application of a Chlorella vulgaris-based microalgae bioinput. Means followed by the same uppercase letters ‘A–B’ (tube colors) and lowercase letters ‘a–b’ (bioinput application) do not differ significantly according to the LSD test (p < 0.05). Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05

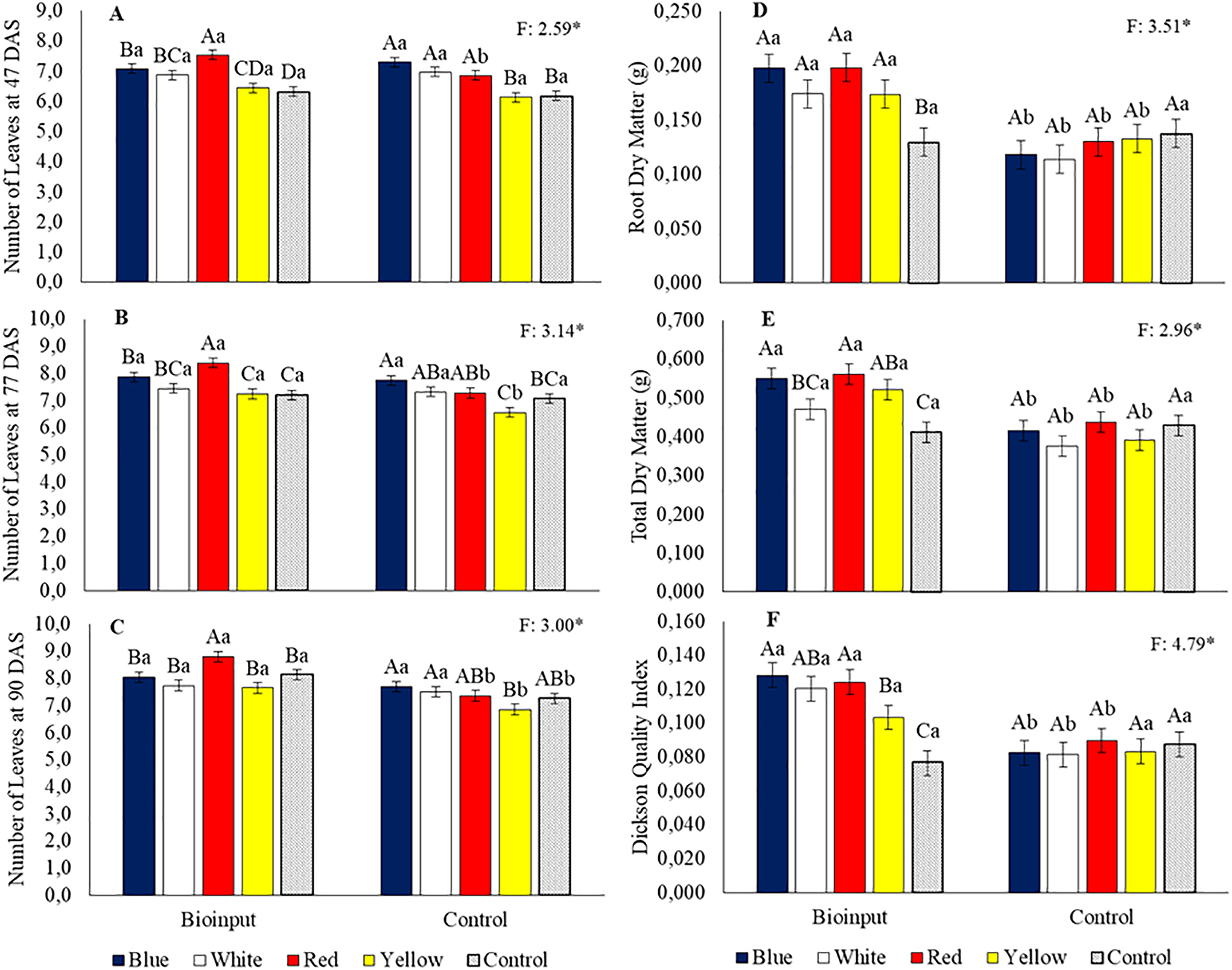

With the application of Chlorella vulgaris at 47 (Fig. 2A), 77 (Fig. 2B), and 90 DAS (Fig. 2C), plants grown in red tubes showed a greater number of leaves compared to those grown in tubes of other colors and the control. At 47 DAS, the number of leaves in seedlings from red, blue, and white tubes was 19.1%, 11.9%, and 8.5% higher than the control (Fig. 2A). At 77 DAS, seedlings in red and blue tubes had 16.5% and 9.1% more leaves than the control (Fig. 2B). At 90 DAS, the number of leaves in seedlings from red tubes was 8.3% higher than the control (Fig. 2C).

Figure 2: Number of leaves at 47 (A), 77 (B), and 90 (C) days after sowing (DAS); root dry mass (D); total dry mass (E); and Dickson Quality Index (F) of Hancornia speciosa seedlings grown in different colored seedling tubes with or without the application of a Chlorella vulgaris-based microalgae bioinput. Means followed by the same uppercase letters ‘A–C’ (tube colors) and lowercase letters ‘a–b’ (bioinput application) do not differ significantly according to the LSD test (p < 0.05). Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05

Without the application of microalgae, at 47 DAS, plants grown in blue, white, and red tubes had a higher number of leaves than those in yellow and control tubes, with increases of 18.1%, 12.8%, and 10.8% over the control, respectively (Fig. 2A). At 77 DAS, plants in blue tubes had more leaves than those in yellow and control tubes, with increases of 17.9% and 9.5%, respectively (Fig. 2B). At 90 DAS, plants in blue and white tubes showed more leaves than those in yellow tubes, with increases of 12.4% and 9.5%, respectively (Fig. 2B).

The number of leaves in red tubes at 47 DAS was 9.9% higher with microalgae application than the untreated control (Fig. 2A). The number of leaves in red and yellow tubes at 77 DAS was 15.4% and 10.3% higher, respectively, with microalgae application than in the control treatment (Fig. 2B). The number of leaves in red, yellow, and control tubes at 90 DAS was 19.64%, 11.6%, and 12.0% higher, respectively, with microalgae application compared to no application (Fig. 2C).

With the application of Chlorella vulgaris, plants grown in colored tubes showed greater root dry mass than those in the control tube, whereas, without application, treatments did not differ significantly (Fig. 2D). The root dry mass of plants in red, blue, white, and yellow tubes was 53.2%, 52.8%, 34.5%, and 34.2% higher than that of plants in the control tray (Fig. 2D). For blue, white, red, and yellow tubes, applying Chlorella vulgaris led to increases in root dry mass of 67.4%, 52.9%, 52.7%, and 30.5%, respectively, compared to treatments without the application (Fig. 2D).

With the application of the microalgae bioinput, plants grown in blue, red, and yellow tubes showed greater total dry mass than those in the control tube, while treatments without application showed no significant differences (Fig. 2E). The total dry mass of plants in blue, red, and yellow tubes was 33.9%, 36.7%, and 27% higher than that of plants in the control tube (Fig. 2E). For blue, white, red, and yellow tubes, applying Chlorella vulgaris led to increases in total dry mass of 32.6%, 25.4%, 28.1%, and 33.0%, respectively, compared to treatments without application (Fig. 2E).

With the application of Chlorella vulgaris, plants grown in colored tubes showed a higher Dickson Quality Index (DQI) than those grown in the control tube, while treatments without application showed no significant differences (Fig. 2F). The DQI of plants grown in red, blue, white, and yellow tubes was 67.4%, 57.2%, 62.2%, and 35.0% higher than that of plants in the control tube (Fig. 2F). For blue, white, red, and yellow tubes, applying Chlorella vulgaris led to increases in root dry mass of 55.2%, 47.5%, 38.4%, and 24.1%, respectively, compared to treatments without application (Fig. 2F).

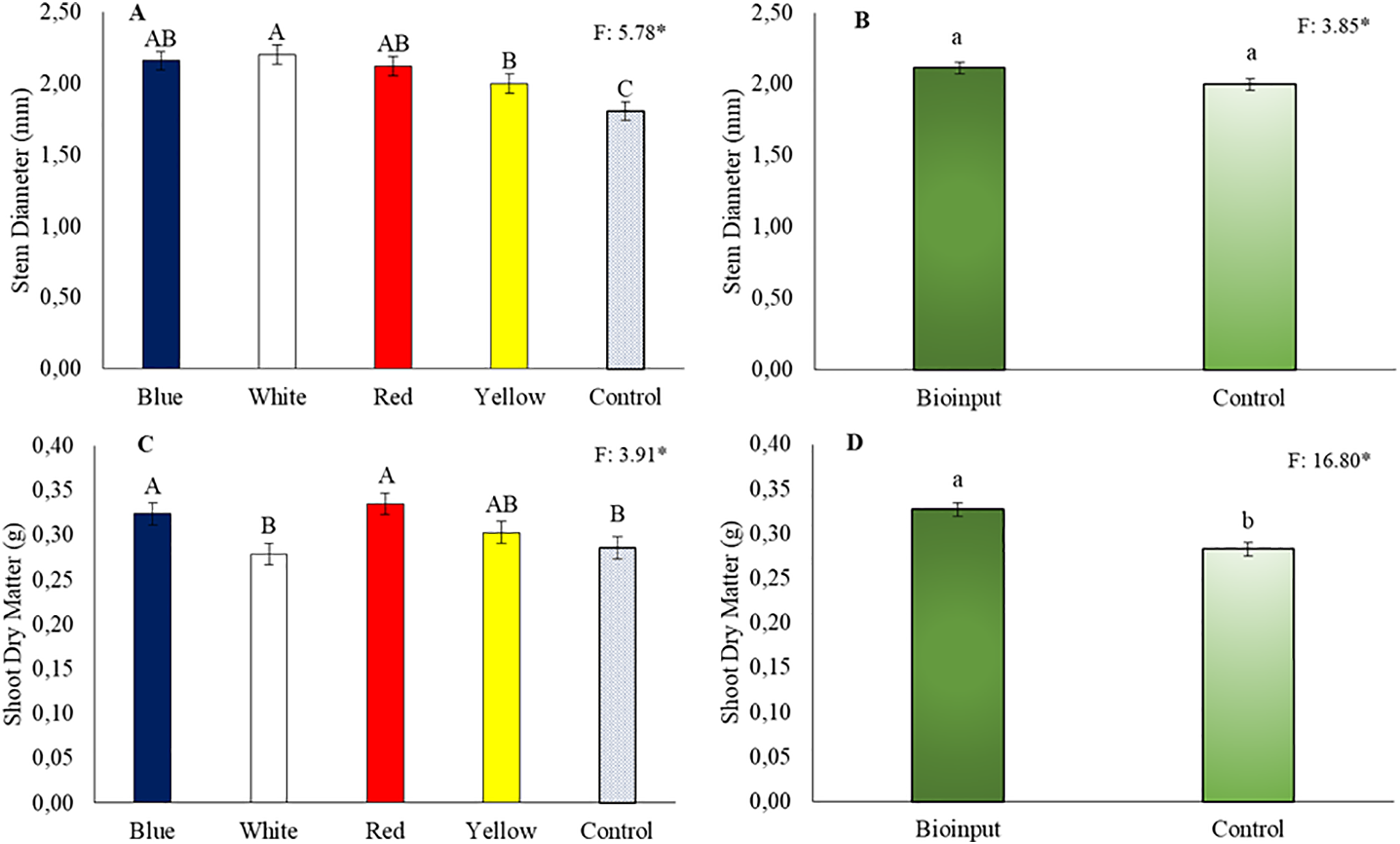

Plants grown in all colored tubes showed greater stem diameter than those in the control treatment (Fig. 3A), and the application of microalgae did not increase seedling stem diameter (Fig. 3B). The shoot dry mass of plants in red, blue, white, and yellow tubes was 19.6%, 22.0%, 17.5%, and 10.9% higher than that of plants in the control tube (Fig. 3C). Applying Chlorella vulgaris increased shoot dry mass in Hancornia speciosa seedlings by 15.8% (Fig. 3D).

Figure 3: Stem diameter (A,C) and shoot dry mass (B,D) of Hancornia speciosa seedlings grown in different colored seedling tubes with or without the application of a Chlorella vulgaris-based microalgae bioinput. Means followed by the same uppercase letters ‘A–C’ (tube colors) and lowercase letters ‘a–b’ (bioinput application) do not differ significantly according to the LSD test (p < 0.05). Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05

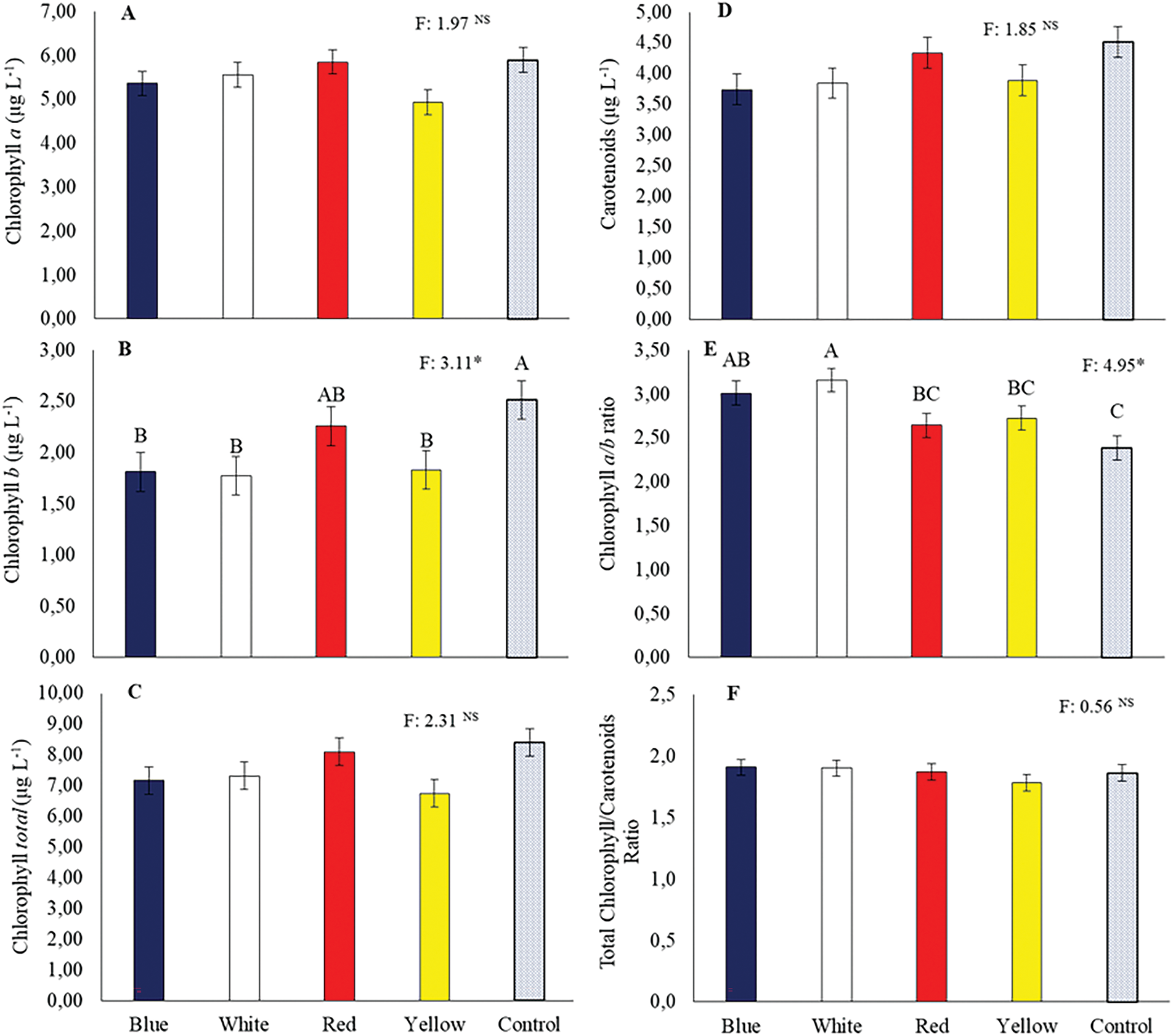

Overall, tube color did not enhance chlorophyll or carotenoid contents compared to the control. However, among the colored tubes, the red tube increased chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, and total chlorophyll contents (Fig. 4A–C). The highest chlorophyll a/b ratio was observed in the white tube (Fig. 4E). Nevertheless, no significant differences were found between colors and the control for the total chlorophyll/carotenoid ratio.

Figure 4: Chlorophyll a (A), chlorophyll b (B), total chlorophyll (C), and carotenoids (D) concentrations, chlorophyll a/b ratio (E), and total chlorophyll/carotenoid ratio (F) in Hancornia speciosa seedlings grown in different colored seedling tubes. Means followed by the same uppercase letters ‘A–C’ do not differ significantly according to the LSD test (p < 0.05). Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05. NS, not significant.

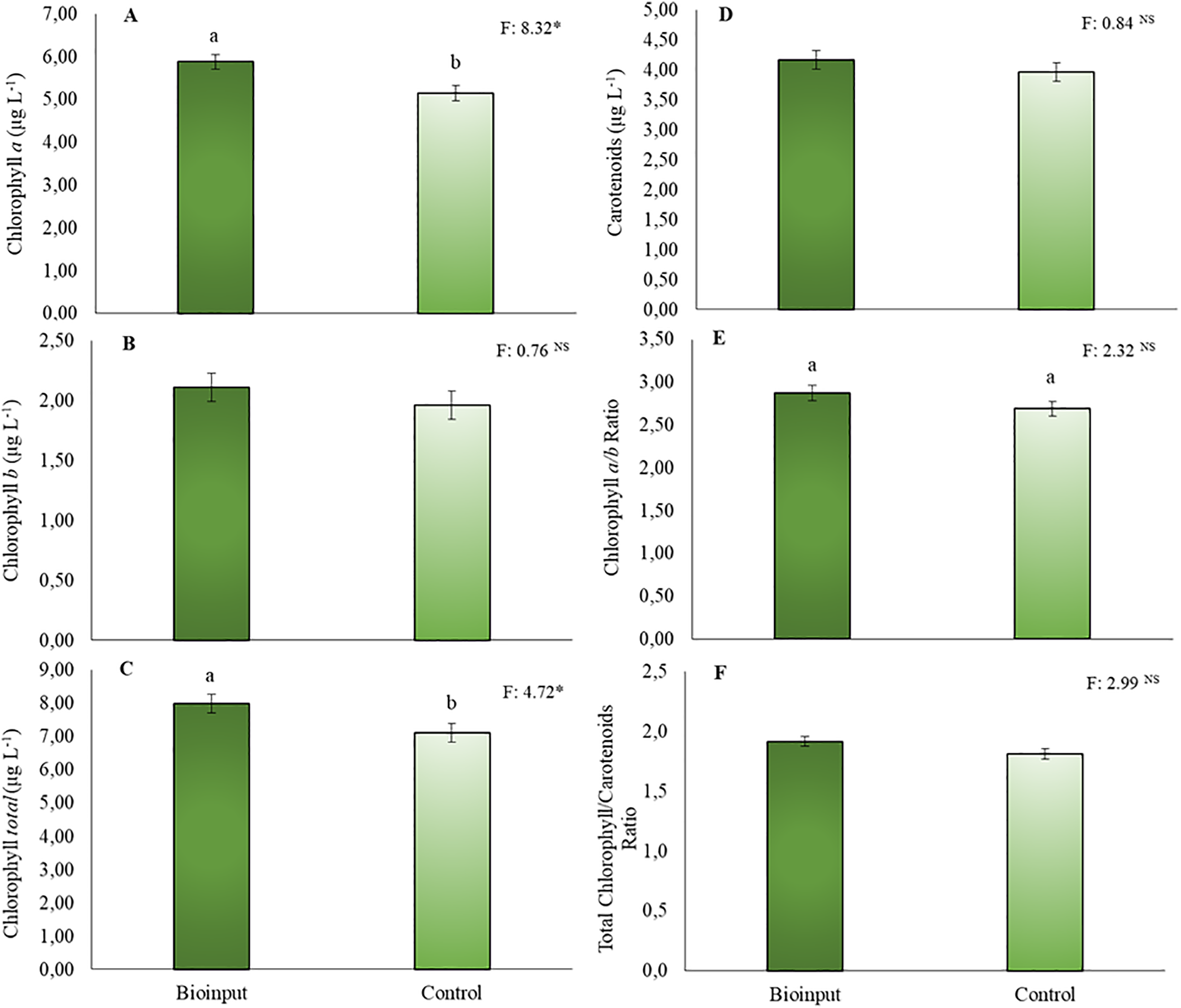

The application of Chlorella vulgaris resulted in significant increases only in chlorophyll a (Fig. 5A) and total chlorophyll (Fig. 5C) contents. No significant differences were observed for the other pigment parameters compared to the treatment without microalgae application (Fig. 5B–E).

Figure 5: Chlorophyll a (A), chlorophyll b (B), total chlorophyll (C), and carotenoids (D) concentrations, chlorophyll a/b ratio (E), and total chlorophyll/carotenoid ratio (F) in Hancornia speciosa seedlings grown with or without the application of a Chlorella vulgaris-based microalgae bioinput. Means followed by the same lowercase letters ‘a–b’ do not differ significantly according to the LSD test (p < 0.05). Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05. NS, not significant

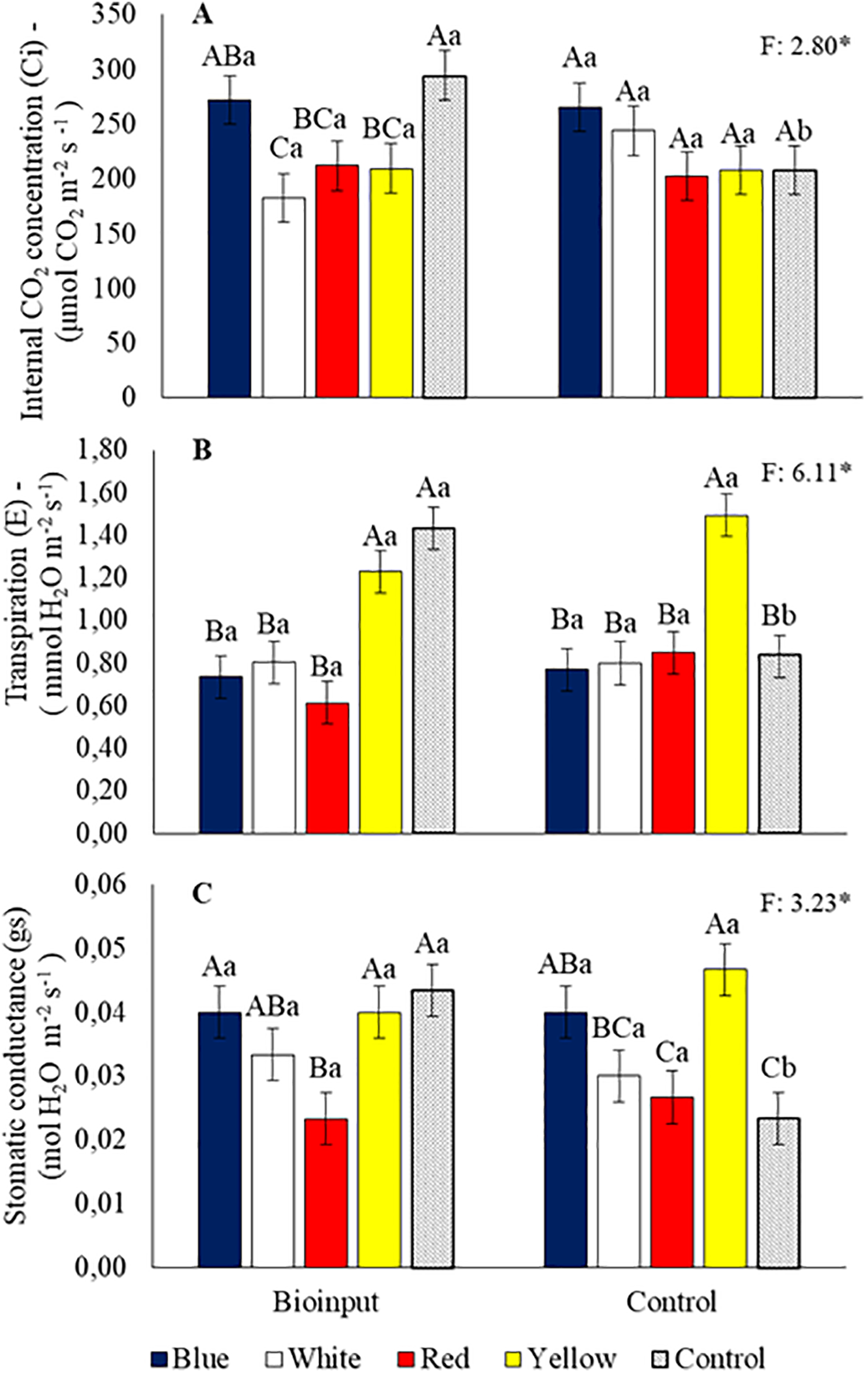

The internal CO2 concentration in plants grown with microalgae application was highest in the control tube; among the colored tubes, the highest concentration was observed in the blue tube. Without microalgae application, no significant differences existed between the colored tubes and the control (Fig. 6A). The highest transpiration rate with microalgae application was observed in the control and yellow tubes, while without application, the yellow tube showed the highest transpiration (Fig. 6B). Stomatic conductance in plants grown with microalgae application was greater in the blue, white, yellow, and control tubes. The highest values in plants grown without microalgae application were found in the yellow and blue tubes (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6: Internal CO2 concentration (A), transpiration rate (B), and stomatic conductance (C) in Hancornia speciosa seedlings grown in different colored seedling tubes with or without the application of a Chlorella vulgaris-based microalgae bioinput. Means followed by the same uppercase letter ‘A–C’ (for comparisons among tube colors within each bioinput application) and lowercase letter ‘a–b’ (for comparisons between bioinput applications within each tube color) do not differ significantly according to the LSD test (p < 0.05). Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05

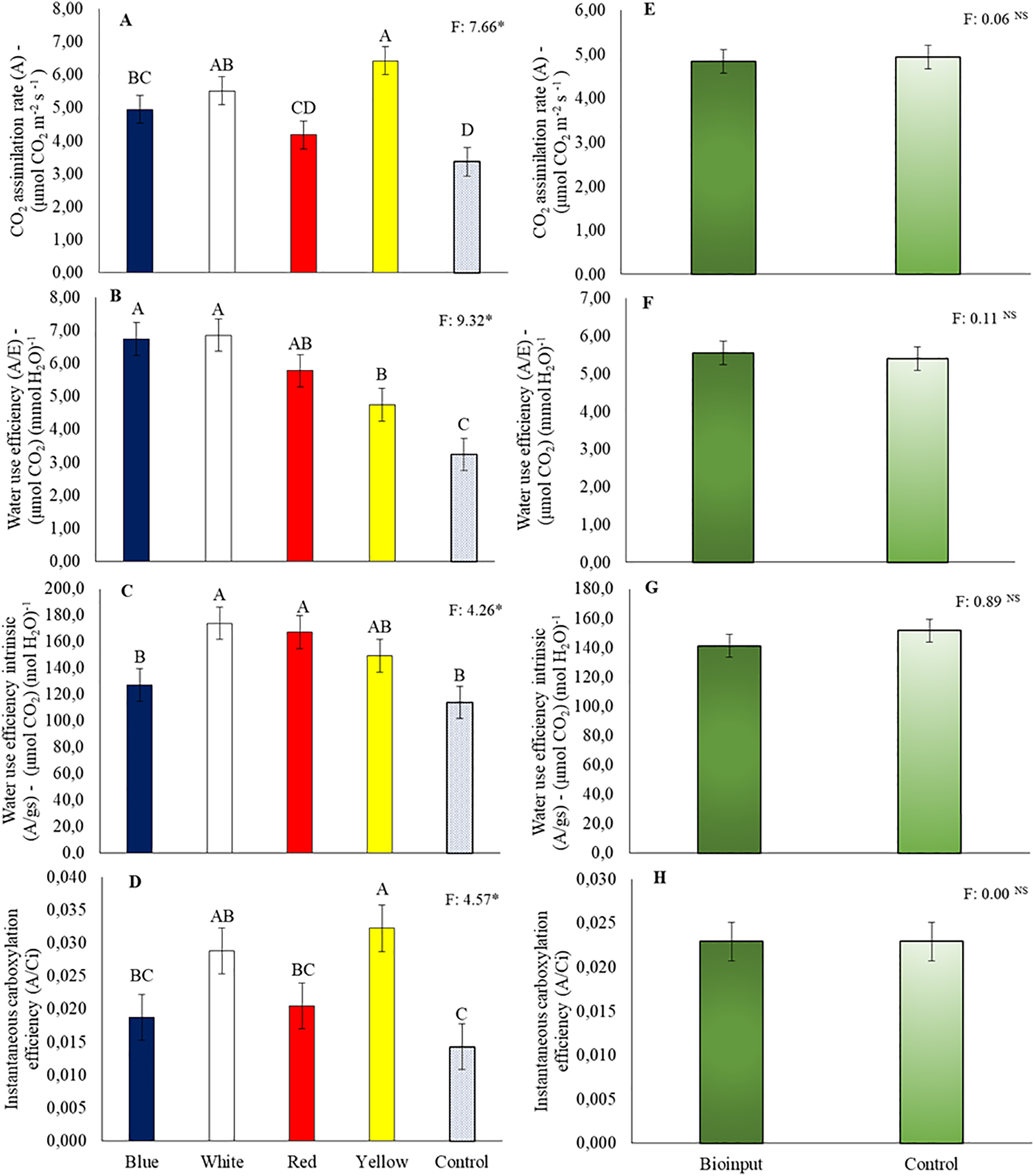

The highest CO2 assimilation rate in the seedlings was observed in the yellow tube, which was greater than in those grown in the blue, red, and control tubes (Fig. 7A). Water use efficiency of plants grown in blue and white tubes was higher than in yellow and control tubes (Fig. 7B). The instantaneous carboxylation efficiency of seedlings in the yellow tube was higher than those grown in blue, red, and control tubes (Fig. 7C). Intrinsic water use efficiency was higher in plants grown in white and red tubes than in blue and control tubes (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7: Net photosynthesis rate (A,E), water use efficiency (B,F), intrinsic water use efficiency (C,G), and instantaneous carboxylation efficiency (D,H) of Hancornia speciosa seedlings grown in different colored seedling tubes with or without the application of a Chlorella vulgaris-based microalgae bioinput. Means followed by the same uppercase letters ‘A–D’ (tube colors) do not differ significantly according to the LSD test (p < 0.05). Vertical bars represent the standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05. NS, not significant

Applying Chlorella vulgaris microalgae did not increase CO2 assimilation rate, water use efficiency, intrinsic water use efficiency, and instantaneous carboxylation efficiency in Hancornia speciosa plants (Fig. 7E–H).

Plant photosynthesis is influenced by light intensity, wavelength, and duration of sunlight exposure, which regulate seedling development through photoreceptors [10]. Alternatives, such as using reflective materials [9], or shading materials [8], have been adopted to increase photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) in cultivation environments, aiming to maximize the use of solar radiation and improve seedling quality [8].

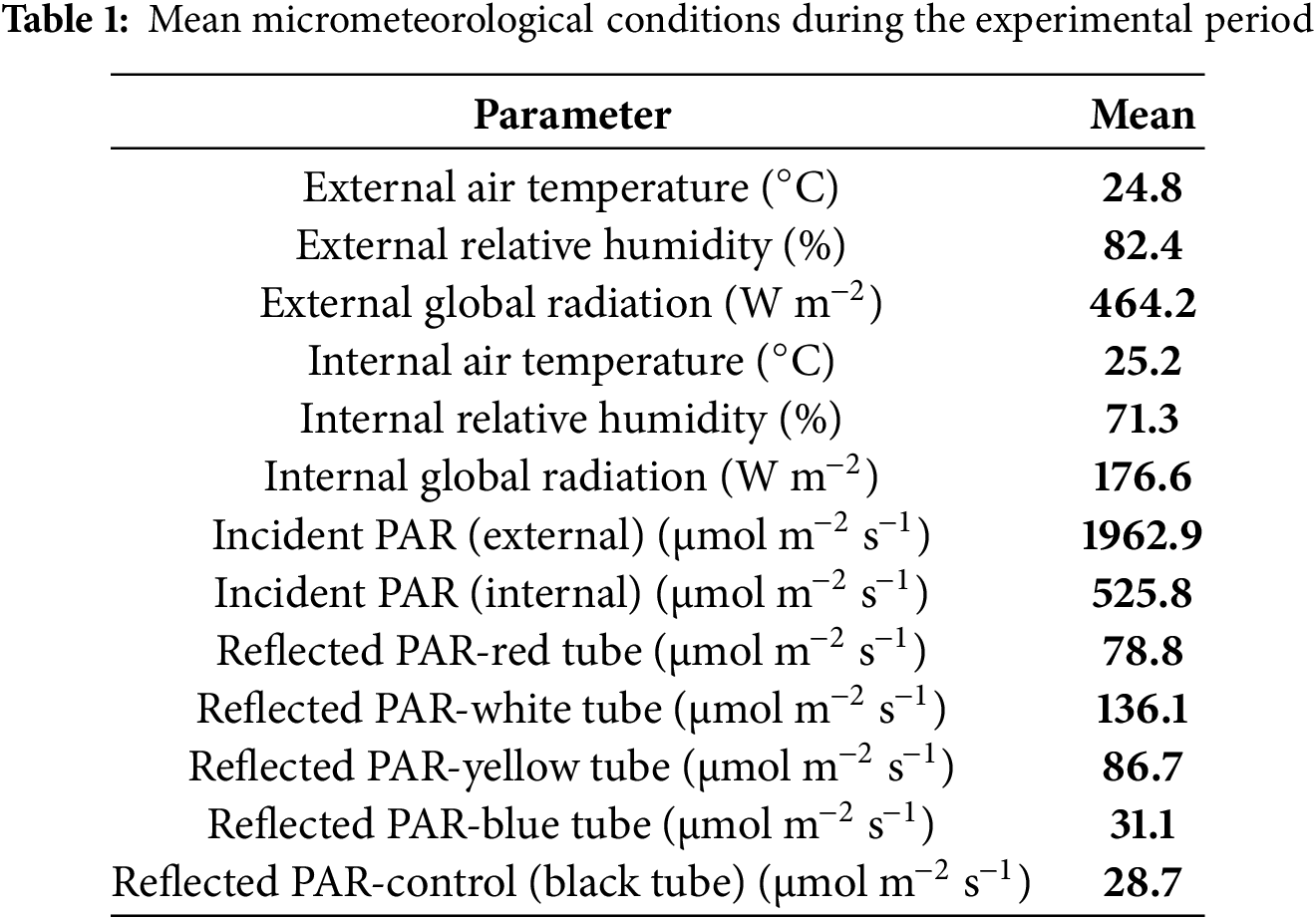

Growing Hancornia speciosa seedlings in colored tubes increased light reflectance, improving the availability of PAR (Table 1) and influenced growth parameters and gas exchange. Colored tubes, especially red and blue, enhanced plant height, number of leaves, stem diameter, and dry mass accumulation. These tube colors, associated with photoreceptors such as cryptochromes and phytochromes [9], contributed to increased growth and other key physiological processes that improve the overall quality of Hancornia speciosa seedlings.

PAR reflectance from blue wavelength, is known to favors photosynthesis, highlighting the importance of light quality within this spectrum region [11]. Using colored reflective materials has a positive effect by improving the distribution of photosynthetically active radiation across the plant leaf area [9], thereby increasing leaf number. Using colored reflective materials can enhance the reflection of radiation utilized in plant metabolic processes, which may lead to greater biomass accumulation [6].

The use of colored reflective materials resulted in seedlings with a higher Dickson Quality Index, which is a strong indicator of seedling quality, as it accounts for structural robustness and the balance among height, stem diameter, and dry mass distribution in quality assessments. Studies using colored reflective cultivation benches have shown that red wavelength [11–14], as well as blue wavelength [11,12], demonstrate the strong influence of light quality and quantity on enhancing plant quality [11]. Similar growth results were observed for Rosa acicularis [11], Capsicum annuum L. [12], Carica papaya L. [13], and Capsicum chinense [9].

Applying microalgae improved plant growth, leaf number, and dry biomass in Hancornia speciosa seedlings [15], contributing to producing high-quality seedlings. Microalgae-based bioinputs contain significant amounts of phytohormones, along with various nutrients such as potassium, calcium, magnesium, carbohydrates, proteins, and vitamins [16], which exert a synergistic influence on the overall metabolism of plants [5].

The bioinput improved seedling quality by increasing shoot and root dry biomass and leaf production [16–18], it contains important components that enhance resistance to abiotic stress [19,20]. Similar results were observed in Lepidium sativum [21]. Using bioinputs and colored tubes can promote improvements in plant morphological traits [22]. Although stem diameter was positively influenced by tube color, the application of microalgae had no significant effect, this suggests that the response to light intensity from tube color and the effects of Chlorella vulgaris may occur through distinct physiological pathways, light intensity directly influencing stem diameter, while Chlorella vulgaris primarily affects other biometric traits.

The application of Chlorella vulgaris increased chlorophyll a and total chlorophyll contents, as microalgae possess biostimulant properties and contain bioactive compounds, including photosynthetic pigments, proteins, polyamines, carbohydrates, amino acids, and vitamins [5]. All of these components influence overall plant metabolism, the synthesis of photosynthetic pigments, and enzymatic activity, ultimately leading to improved plant growth and yield. Similar results were observed in strawberry seedlings [22].

Using colored tubes combined with Chlorella vulgaris application increased the number of leaves, plant height, photosynthesis, water use efficiency, instantaneous carboxylation efficiency, and intrinsic water use efficiency in plants grown in colored tubes. Using colored tubes and microalgae application represents a promising alternative for producing high-quality seedlings.

The experiment was conducted at Mato Grosso do Sul State University (UEMS), Cassilândia Campus, located in the municipality of Cassilândia. The site is situated at a latitude of −19.1225° (19°07′21″ S), a longitude of −51.7208° (51°43′15″ W), and an altitude of 516 m.

The experiment was conducted in an agricultural greenhouse measuring 18.0 m in length, 8.0 m in width, and 4.0 m in height at the gutter. The structure was arched and covered with a 150-micron low-density polyethylene film featuring light diffusion and anti-drip properties. Beneath the low-density polyethylene film, a thermoreflective aluminized screen with 42%–50% shading was installed. The zenithal opening was sealed with a white 30% shade screen, and the sides and front were covered with a 30% monofilament shading screen (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: Overview of the agricultural greenhouse used in the experiment

Sexual propagation was used, with seeds collected near the Cassilândia campus during the fruit maturation in November 2023. Two seeds were sown per tube, and thinning was performed later, leaving only one seedling per tube. Twenty five tubes were planted, serving as replicates.

The experiment followed a completely randomized design in a 5 × 2 factorial arrangement, with treatments consisting of reflective seedling tubes in five colors (blue, white, red, yellow, and a commercial black control) and the application of a microalgae-based bioinput derived from Chlorella vulgaris (absence or presence). Four replications with five plants per plot were used for biometric evaluations, and three replications were used for pigment content and gas exchange measurements.

The colored reflective trays/tubes were prepared by applying two layers of sealant to the plastic surface of the trays and tubes, followed by two layers of matte white paint, two layers of metallic reflective colored paint, and a final coating of clear varnish (Fig. 9), with the reflectance values presented in Table 1.

Figure 9: Colored trays/tubes

The Chlorella vulgaris microalgae bioinput (0.7 g per liter of dry biomass) was produced at the Microalgae and Biotechnology Laboratory of the Centro de Desenvolvimento Sustentável do Bolsão Sul-Mato-Grossense (CEDESU) using a glass column tubular reactor with a flow diameter-to-height ratio of 1:7, in an open system. The bioinput exhibited the following physicochemical characteristics: pH 5.5; oxidation–reduction potential of 320 mV; total dissolved solids (TDS) of 600 ppm; electrical conductivity of 1200 μS cm−1; nitrate nitrogen (NO3−-N) at 157 mg L−1; ammonium (NH4+) at 15 mg L−1; and phosphate (P2O5) at 25 mg L−1.

The tubes (115 mL), arranged in 96-cell trays, were filled with the commercial substrate Carolina Soil®, and sowing occurred on 30 November 2023. Carolina Soil® is composed of sphagnum peat, vermiculite, and agro-industrial organic residues. Seedling emergence was observed 17 days after sowing (DAS).

Three Chlorella vulgaris microalgae bioinput applications were performed using a manual sprinkler, with 20 mL applied per tube in each application. The first application was performed at the time of sowing, directly onto the substrate. The second and third applications were also substrate-applied at 30 and 60 days after emergence (DAE), corresponding to 47 and 77 days after sowing (DAS).

Reflected photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) (μmol m−2 s−1) from the treatments (trays/tubes) was monitored daily using a portable digital pyranometer (Apogee®) at 9:30 a.m. (local time, GMT-4) on clear-sky days without clouds or haze. Air temperature (°C), relative humidity (%), and external and internal global radiation (W m−2) were recorded using an Irriplus® automatic weather station, model E4000, positioned both at the center of the greenhouse and outside. Readings were taken every 60 min (Table 1), and global radiation (W m−2) was monitored between 10:00 a.m. and 4:00 p.m.

The biometric parameters evaluated were plant height (PH), number of leaves (NL), stem diameter (SD), shoot dry mass (SDM), root dry mass (RDM), total dry mass (TDM), and Dickson quality index [23]. Plant height and number of leaves were evaluated at 47, 77, and 90 days after sowing (DAS). Seedling height was measured using a millimeter-graded ruler from the base of the stem to the apical meristem. Leaf count was performed on the same dates as the height assessments. At 90 DAS, measurements were taken for stem diameter (SD), shoot dry mass (SDM), root dry mass (RDM), total dry mass (TDM), and Dickson quality index. Shoot and root dry masses were determined after drying the plant material in a forced-air circulation oven at 65°C for three days, then weighing on an analytical balance. Total dry mass was calculated as the sum of shoot and root dry masses.

The pigments evaluated included chlorophyll a (CLA), chlorophyll b (CLB), total chlorophyll (CLT), and carotenoids (Car), with subsequent determination of the CLA/CLB and CLT/Car ratios. Chlorophyll (a and b) and carotenoid extractions were performed following the methodology of Lichtenthaler [24]. A total of 0.5 g of fresh plant material was weighed and mixed with 5 mL of 80% acetone, then stored in 14 mL test tubes for 48 h at 25°C under refrigeration. After this period, the samples were centrifuged for 15 min at 4000 rpm, and the supernatant was diluted at a ratio of 0.5 mL extract to 1.5 mL of 80% acetone. Absorbance readings were taken using a spectrophotometer at wavelengths of 470, 647, 653, 663, and 665 nm.

The gas exchange parameters evaluated were internal CO2 concentration (Ci), transpiration rate (E), stomatal conductance (gs), and net photosynthesis (A). From these, the following physiological efficiencies were calculated: water use efficiency (WUE = A/E), instantaneous carboxylation efficiency (EiCi = A/Ci), and intrinsic water use efficiency (A/gs). Gas exchange measurements were taken at 9:00 a.m. on leaves from the middle third of the plant, with three readings per replicate, using a portable infrared gas exchange analyzer (LCi, ADC Bioscientific, Hertfordshire, United Kingdom).

Data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA), and treatment means were compared using LSD test at a 5% significance level. All statistical analyses were performed using SISVAR software [25]. Significant results for the main factors are presented when no interaction was observed, and for the interaction, when it was significant.

Colored seedling tubes, particularly red and blue, positively influenced the growth and quality of Hancornia speciosa seedlings, especially when combined with the application of a microalgae-based bioinput derived from Chlorella vulgaris. The bioinput significantly improved key morphological parameters and the seedling quality index.

These results demonstrate the potential of combining colored containers and biotechnological inputs as an effective, low-cost strategy to improve seedling production. Furthermore, this approach may contribute to better establishment and higher survival rates in the field, offering practical applications for both restoration initiatives and commercial cultivation of Hancornia speciosa. Future studies should focus on field validation of these findings, and potential applicability to other native species.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel (CAPES, Brazil) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil).

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Giovana Pinheiro Viana da Silva, Edilson Costa; methodology, Edilson Costa; formal analysis, Giovana Pinheiro Viana da Silva, Paulo Henrique Rosa Melo, Fernanda Pacheco de Almeida Prado Bortolheiro, Thaise Dantas; investigation, Giovana Pinheiro Viana da Silva, Paulo Henrique Rosa Melo, Fernanda Pacheco de Almeida Prado Bortolheiro, Thaise Dantas; data curation, Giovana Pinheiro Viana da Silva, Edilson Costa, Flávio Ferreira da Silva Binotti; writing—original draft preparation, Giovana Pinheiro Viana da Silva, Carlos Eduardo da Silva Oliveira, Abimael Gomes da Silva; writing—review and editing, Edilson Costa, Carlos Eduardo da Silva Oliveira, Abimael Gomes da Silva, Fernanda Pacheco de Almeida Prado Bortolheiro, Flávio Ferreira da Silva Binotti; supervision, Edilson Costa; project administration, Edilson Costa. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author, [E.C.], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Silva EF, Silva Júnior JF, Nascimento WF, Silva ACBL. Genetic resources of mangabeira (Hancoria speciosa ‘Gomes’) in protected areas in Brazil. Rev Bras Frutic. 2022;44(1):e-834. doi:10.1590/0100-29452022834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Soares ANR, Silva AVC, Muniz EN, Melo MFV, Santos PS, Ledo AS. Biometry, emergence and initial growth of accessions and mangaba progenies. J Agric Sci. 2019;11(4):436–48. doi:10.5539/JAS.V11N4P436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rachmat HH, Ginoga KL, Lisnawati Y, Hidayat A, Imanuddin R, Fambayun RA, et al. Generating multifunctional landscape through reforestation with native trees in the tropical region: a case study of Gunung Dahu Research Forest, Bogor, Indonesia. Sustainability. 2021;13(21):11950. doi:10.3390/su132111950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ronga D, Biazzi E, Parati K, Carminati D, Carminati E, Tava A. Microalgal biostimulants and biofertilisers in crop productions. Agronomy. 2019;9(4):192. doi:10.3390/agronomy9040192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Kapoore RV, Wood EE, Llewwellyn CA. Algae biostimulants: a critical analysis of biostimulants for sustainable agricultural practices. Biotechnol Adv. 2021;49:107754. doi:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2021.107754. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Taiz L, Zeiger E. Fisiologia vegetal. Porto Alegre, Brazil: Artmed; 2017. p. 918. [Google Scholar]

7. Lazzarini LES, Pacheco FV, Silva ST, Coelho AD, Medeiros APR, Bertolucci SKV, et al. Use of light-emitting diode (LED) in the physiology of cultivated plants—review. Scia Agrar Parana. 2017;16(2):137–44. [Google Scholar]

8. Ili’c ZS, Milenkovi’c L, Šuni’c L, Fallik E. Shading net and grafting reduce losses by environmental stresses during vegetables production and storage. Biol Life Sci. 2022;16:27. doi:10.3390/IECHo2022-12506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Bortolheiro FPAP, Silva KGP, Silva GPV, Martins MB, Costa E, Vendruscolo EP, et al. Photosynthetic pigments and growth of Guaraci Cumari do Pará Pepper (Capsicum chinense Jacq.) seedlings on growth benches with different color wavelengths. Int J Horticul Sci Technol. 2025;12(3):365–74. [Google Scholar]

10. Bilodeau SE, Wu BS, Rufyikiri AS, Macpherson S, Lefsrud M. An update on plant photobiology and implications for cannabis production. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:296. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00296. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Davarzani M, Aliniaeifard S, Mehrjerdi MZ, Roozban MR, Saeedi AS, Gruda NS. Optimizing supplemental light spectrum improves growth and yield of cut roses. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):21381. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-48266-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Adibian M, Yosef H, Sasan A. Effect of supplemental light quality and season on growth and photosynthesis of two cultivars of greenhouse sweet pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Int J Hortic Sci Technol. 2023;10(Special Issues):51–66. doi:10.22059/ijhst.2023.353706.609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Cabral RDC, Vendruscolo EP, Martins MB, Zoz T, Costa E, Silva AGD. Material reflectante en bancos de cultivo y paja de arroz sobre el sustrato en la producción de plántulas de papaya. Rev Mex Ciênc Agríc. 2020;11(8):1713–23. doi:10.29312/remexca.v11i8.2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Cavalcante DF, Garcia AA, Vendrucolo EP, Seron CC, Costa E, Bastos FEA, et al. Reflector materials on benches act as supplementary sources of light in rucola cultivation. Comunic Sci. 2024;15:e4046. doi:10.14295/cs.v15.4046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Suchithra MR, Muniswami DM, Sri MS, Usha R, Rasheeq AA, Preethi BA, et al. Effectiveness of green microalgae as biostimulants and biofertilizer through foliar spray and soil drench method for tomato cultivation. S Afr J Bot. 2022;146:740–50. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2021.12.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Prisa D. Chlorella vulgaris improves growth of Abrometiella scapigera, Abrometiella brevifolia and Abrometiella chloranta and reduces root attack by nematodes. GSC Advan Res Rev. 2024;19(01):170–7. doi:10.30574/gscarr.2024.19.1.0155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Gitau MM, Farkas A, Balla B, Ordog V, Futó Z, Maróti G. Strain-specific biostimulant effects of Chlorella and Chlamydomonas green microalgae on Medicago truncatula. Plants. 2021;10(6):1060. doi:10.3390/plants10061060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Vildanova GI, Allaguvatova RZ, Kunsbaeva DF, Sukhanova NV, Gaysina LA. Application of Chlorella vulgaris Beijerinck as a biostimulant for growing cucumber seedlings in hydroponics. BioTech. 2023;12(2):42. doi:10.3390/biotech12020042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Feitosa PM, Santos CC, Ribeiro LM, Dias JRPC, Proence VS. Potencial do uso de extratos de algas na agricultura sustentável. Ed Científica. 2024;2:78–98. doi:10.37885/240616886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Turhan A, Şensoy S. Utilization of microalgae [Chlorella vulgaris Beyerinck (Beijerinck)] on plant growth and nutrient uptake of garden cress (Lepidium sativum L.) grown in different fertilizer applications. Int J Agric Environ Food Sci. 2022;6(2):240–5. doi:10.31015/jaefs.2022.2.6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Collado C, Hernández R. Efeitos da intensidade da luz, composição espectral e paclobutrazol na morfologia, fisiologia e crescimento de transplantes ornamentais de petúnia, gerânio, amor-perfeito e dianthus. J Plant Growth Regu. 2021;41:461–78. doi:10.1007/s00344-021-10306-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kim YN, Choi JH, Kim SY, Yoon YE, Choe H, Lee KA, et al. Biostimulatory effects of Chlorella fusca CHK0059 on plant growth and fruit quality of strawberry. Plants. 2023;12(24):4132. doi:10.3390/plants12244132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Dickson A, Leaf AL, Hosner JF. Quality appraisal of white spruce and white pine seedling stock in nurseries. For Chron Mattawa. 1960;36:10–3. doi:10.5558/tfc36010-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Lichtenthaler HK. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzymol. 1987;148:350–82. doi:10.1016/0076-6879(87)48036-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ferreira DF. Sisvar: a computer analysis system to fixed effects split plot type designs. Rev Bras Biometr. 2019;37(4):529–35. doi:10.28951/rbb.v37i4.450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools