Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Phytochemicals, Antioxidation, and Heat Stability of Aqueous Extracts from Cherry (Prunus serrulata) Petals

Department of Food Nutrition and Safety, Sanda University, Shanghai, 201209, China

* Corresponding Author: Sy-Yu Shiau. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Ornamental Plants: Traits, Flowering, Aroma, Molecular Mechanisms, Postharvest Handling, and Application)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3047-3060. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070289

Received 12 July 2025; Accepted 03 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Consumers are increasingly demanding natural colorants that are safe and offer health benefits. In addition to their ornamental characteristics, Kanzan cherry (KC) blossoms present a promising source of red-hued natural colorants and functional bioactive substances. This research utilized distilled water to extract KC petals (KCP) and their ground powders (KCPP) under varying temperatures (30°C–90°C) and times (30–180 min). The total monomeric anthocyanins (TMAC) and total phenolics (TPC) in the extracts were evaluated via the pH differential and Folin–Ciocalteu methods. Antioxidant capacities were assessed by DPPH free radical scavenging ability and reducing power. Results indicated that the optimal extraction of TMAC and TPC from KCP occurred at 90°C for 30 min, and the resulting extracts exhibited the highest antioxidant activities among all tested temperatures and durations. Compared to different particle sizes, the finest KCPP generally produced extracts with the highest TMAC, TPC, and antioxidant activity, due to enhanced mass and heat transfer. When compared with the acidified alcohol method, hot water extraction resulted in 68.23% and 71.41% TMAC yields for petals and powders, respectively, while TPC levels were similar or higher. TMAC or TPC showed a significantly positive correlation (p < 0.01) with the antioxidant activities. These findings demonstrate that hot water extraction is a viable and environmentally friendly alternative for phytochemical recovery from KC. Additionally, elevated extraction temperature and pH accelerated anthocyanin degradation and shortened its half-life, while higher pH also lowered the activation energy, enthalpy, entropy, and Gibbs free energy. Thus, red–orange KC extracts with rich bioactivity may serve as promising ingredients for functional foods having acidic pH levels.Keywords

The flowering cherries or cherry blossoms (CB), scientifically known as Prunus spp. or Cerasus (subgenus) spp., belong to the Rosaceae family and is an ornamental plant widely cultivated in Japan, China, the USA, Canada, and other countries. Cherry flowers display a range of colors—including red, pink, greenish-yellow, and white—depending on the variety. Prunus serrulata ‘Kanzan’, commonly known as Kanzan cherry (KC), is a well-known cultivar of the Japanese late-blooming cherry. Renowned for its lush, double-petaled pink flowers, KC is a beloved ornamental variety commonly found in parks and gardens. Popular red—purple sweet cherries consumed as fruit generally come from Prunus avium or other related species [1].

Cherry flowers exhibit in vitro activities such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antiviral, α-glucosidase inhibitory, and anticancer effects, owing to their rich contents of bioactive compounds including anthocyanins, flavanols, polyphenols, and polysaccharides [2–5]. Total anthocyanin content as well as various anthocyanin species and amounts were the main factors determining the color difference of CB [6]. Red cherry flowers had higher flavonoids and polysaccharides and stronger α-glucosidase inhibition than white flowers [5]. Cherry flowers have long been used in food products such as sakura-cha (salted cherry blossom tea), cakes, and ice cream, serving both as natural pigments and sources of health-promoting compounds [7]. In 2022, China’s National Health Commission granted regulatory approval to KC as a novel food ingredient, authorizing its incorporation into common food products. This reclassification from ornamental plant to food-grade material spurred significant attention within the functional food sector.

Anthocyanins, natural pigments commonly found in flowers, are composed of anthocyanidins, sugars, and/or organic acids [8]. Cyanidin and petunidin were identified as the main anthocyanins in the petals of 11 cherry varieties, while peonidin and malvidin were also detected [6]. The chemical stability of these pigments is influenced by various conditions, including their molecular configuration, ambient temperature, pH, and water activity [9,10]. Blue anthocyanins (ternatins) found in butterfly pea flowers exhibited high stability at acidic and neutral pH levels due to acylation in their structure [8,11–13]. Anthocyanin extract from roselle calyces showed a higher degradation rate constant at elevated temperatures and pH levels [14]. The stability (half-life) of anthocyanins from saffron petals during storage was enhanced by microencapsulation with alginate and maltodextrin [15]. Acidic methanol or ethanol is a typical solvent for anthocyanin extraction [16,17]. However, water also serves as an effective and environmentally sustainable solvent for extracting anthocyanins from ornamental plants for food industry [10,18].

Research on cherry blossoms has largely focused on ornamental horticulture, including the effects of light irradiation on flower color and anthocyanin content of CB, and elucidating the biosynthetic mechanisms of anthocyanins [19,20]. Suo et al. [4] indicated dried CB petals produced by vacuum freeze-drying exhibited a superior appearance, higher contents of total anthocyanins, polyphenols, and flavonoids, as well as stronger antioxidant activity compared to those produced by the other six drying methods. Brozdowski et al. [2] reported that ground powders of black cherry flowers were extracted using three solvents: 60% methanol (ice-cooled ultrasonic bath for 45 min), 40% ethanol (room temperature for 5 days), and water (infusion with boiling water for 10 min). The results showed that 40% ethanol was most effective at extracting hydroxycinnamic acids, flavanols, and polyphenolic compounds, while water produced the lowest yields. Using an orthogonal design, the optimal extraction parameters for total flavonoids from KC were determined to be: 400 W of microwave power, 1:40 g/mL of material-to-liquid ratio, and 50% ethanol at 75°C [21]. Despite these efforts, comprehensive evaluations of post-harvest cherry blossoms—particularly regarding the aqueous extraction of phytochemicals and their antioxidant efficacy—remain sparse. We conducted studies on the water-based extraction of phytochemicals and their antioxidant activities from butterfly pea flowers, roselle, and grape skins under various temperatures and durations [22,23]. However, these studies did not include a detailed comparison of the effect of particle size on extraction efficiency, nor did they include an analysis of the relevant thermodynamic parameters related to thermal degradation of anthocyanins. In our previous work, the control extractions used 60% ethanol—rather than acidified ethanol—which was shown to be more effective in extracting anthocyanins. Therefore, the present study sought to examine how different extraction parameters, including temperature, duration, and particle size, affect total anthocyanin and polyphenol yields as well as antioxidation capacity in aqueous KC extracts. Furthermore, we compared the efficiency of extraction using water and acidic alcohol. Finally, the stability, and kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of anthocyanins from KC extract were evaluated under varying heat treatments (60°C–90°C), durations (0–5 h), and pH values (2.6–5.6).

Dried Kanzan cherry petals (KCP) with a moisture content of 9.949% and approximate dimensions of 18–20 mm in length × 14–15 mm in width were purchased from Yiduojia Food Co. (Sihong, Jiangsu). All reagents employed for food-related analytical procedures were of analytical grade quality.

2.2 Preparation of KC Petal Extracts

For this experiment, 1000 g of dried Kanzan cherry petals (KCP) were pulverized and separated through mesh sieves of 20, 40, and 60 mesh sizes. This process yielded KC petal powders (KCPP) with particle ranges of 0.85–0.42 mm, 0.42–0.25 mm, and less than 0.25 mm, respectively. The powders were stored in a desiccator to prevent moisture absorption before extraction. Both intact petals and their powdered forms were extracted using distilled water as the solvent. Aqueous extracts with a concentration of 2% (w/v) were prepared by combining 2 g of sample with 100 mL of distilled water. The mixtures were incubated in a water bath shaker at temperatures between 30°C and 90°C for durations of 30 to 120 min under agitation at 100 rpm. After extraction, the solution was filtered and rapidly cooled. As a comparative control, an ethanol-based extraction was conducted using 60% ethanol containing 1% HCl at 40°C for 30 min [16,24].

2.3 Total Monomeric Anthocyanin Content (TMAC)

The TMAC in KC extracts was analyzed using the pH differential method as described by Lee et al. [25]. In this procedure, 1 mL of the extract was separately mixed with 4 mL of two buffer systems: one at pH 1.0 containing 0.025 M potassium chloride (acidified with HCl) and the other at pH 4.5 composed of 0.4 M sodium acetate. The absorbance readings were recorded at wavelengths of 520 and 700 nm using a spectrophotometer. TMAC values for both KCPE and KCPPE were calculated according to the following formula:

where A = [(A520 nm−A700 nm)pH 1.0−(A520 nm−A700 nm)pH 4.5]; F = dilution factor; MW = 449.2 g/mol (molecular weight of cyanidin-3-glucoside); ε = 2690 L/mol mm (molar extinction coefficient of cyanidin-3-glucoside); and X = path distance (mm); V = volume of extract (mL); W = KCP or KCPP weight (g); DB = expressed on a dry weight basis.

According to the method [18], the TPCs of aqueous and ethanolic KC extracts were determined using the Folin–Ciocalteu reagent, employing gallic acid as the calibration standard. Results were reported as mg of gallic acid equivalents per kg of dry sample (mg GAE/kg).

The DPPH free radical scavenging activity of KC extracts was evaluated following the method of reference [26], using Trolox as the reference compound. The outcomes were presented as milligrams of Trolox equivalents per kilogram of dry sample (mg TE/kg). Furthermore, the reducing ability of these KC extracts was measured based on the procedure described by Oyaizu [27]. Specifically, 2.5 mL of extract was combined with 2.5 mL of 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.6) and 2.5 mL of 1% potassium ferricyanide solution. This mixture was incubated for 20 min at 50°C. Then add 2.5 mL of 10% trichloroacetic acid, and centrifuge the resulting mixture at 3000 rpm for 10 min. Subsequently, 2.5 mL of the supernatant was thoroughly mixed with 2 mL of distilled water and 0.5 mL of 0.1% ferric chloride solution, and the mixture was left at room temperature for 15 min. The absorbance was then read at 700 nm, and the reducing power was reported as mg TE per gram of dry sample.

2.6 Heat Stability of KC Anthocyanin

The heat stability of anthocyanins from KC was investigated under different conditions, including heating temperatures of 60°C, 70°C, 80°C, and 90°C, durations of 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 h, and pH levels of 2.6, 3.6, 4.6, and 5.6. In the experiment, 4 mL of KC extract was placed in a screw-capped glass test tube, and then 4 mL of a buffer solution (0.1 M citric acid and 0.2 M Na2HPO4) was added to adjust the pH to the targeted value (ranging from 2.6 to 5.6). The mixture was thoroughly blended and subsequently subjected to heating for different time periods at the designated temperatures.

The degradation kinetics of anthocyanins under thermal treatment was analyzed based on a first-order reaction model, as shown in Eq. (2):

where C0 represents initial TMAC, Ct denotes the concentration remaining after heating for t hours at a specific temperature and pH, k is the rate constant of the degradation reaction.

The half-life (t0.5), defined as the time required for the anthocyanin concentration to reduce by half, was determined using the following expression:

2.7 Experimental Design and Statistical Analysis

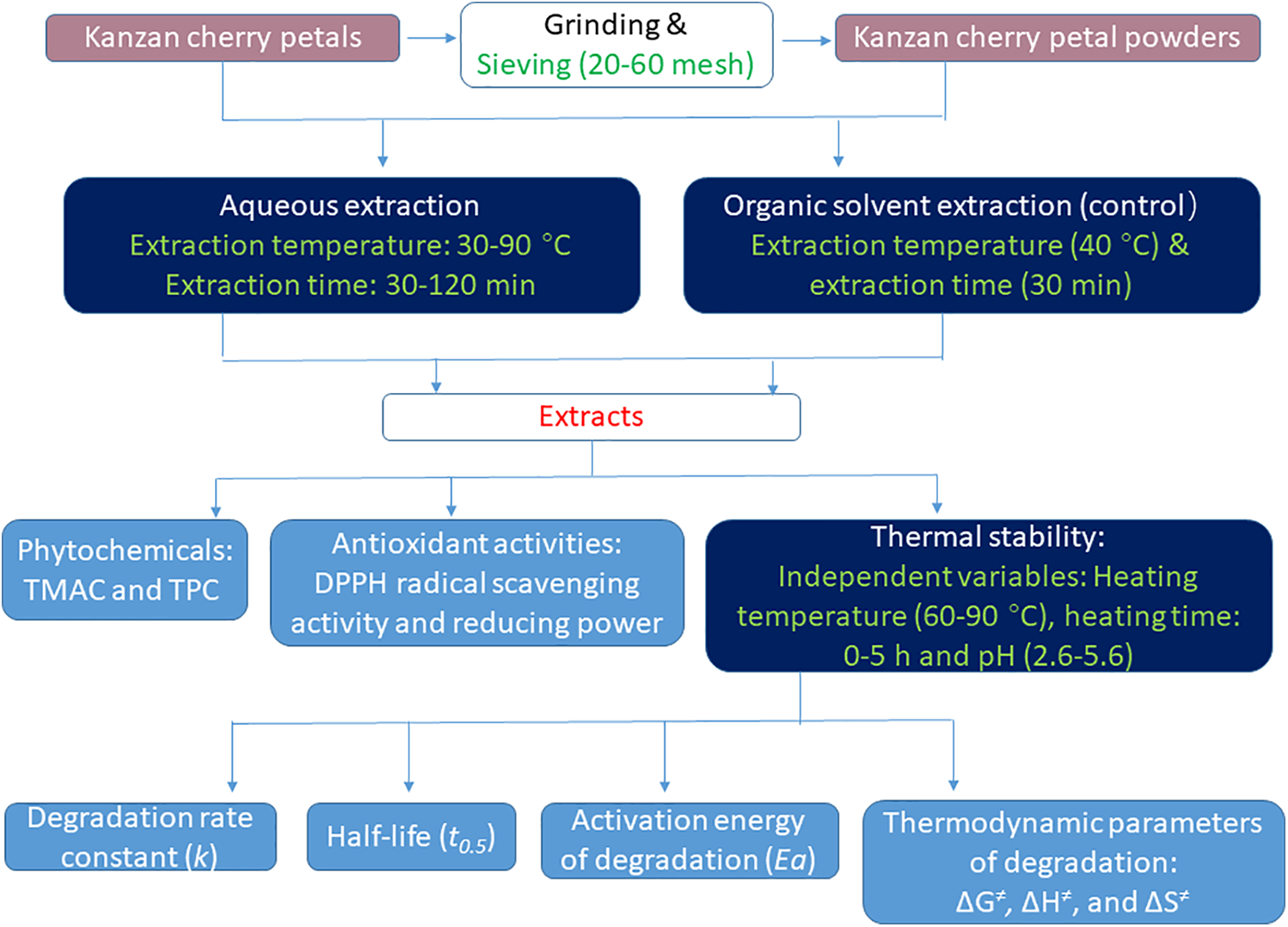

The experimental design and brief flowchart of this study are shown in Fig. 1. IBM SPSS Statistics 20 was used to analyze the data, which were obtained in triplicate for each treatment. One-way ANOVA, Duncan’s new multiple range test, and Pearson correlation analysis were performed to determine the statistical significance of differences among the values (p < 0.05).

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the experimental design and procedures

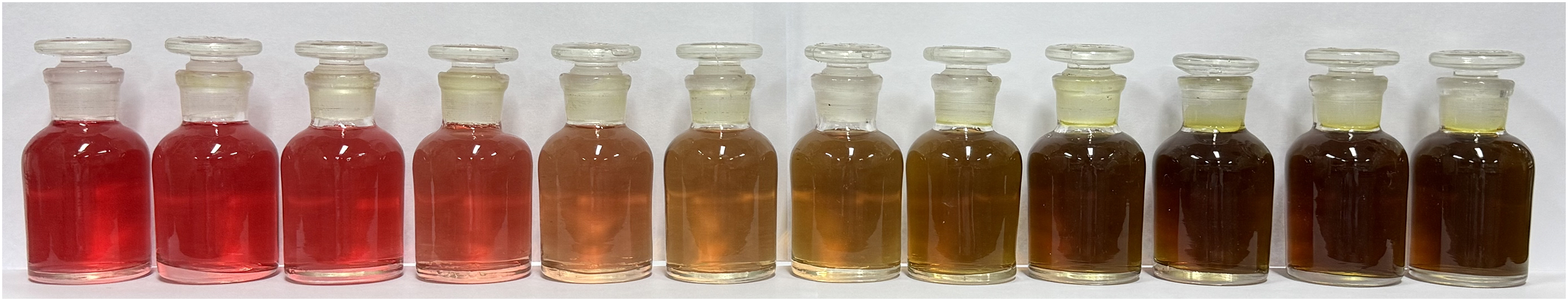

The pH values of KCPE prepared at extraction temperatures of 30°C–90°C (at 15°C intervals) for 30 min were 5.32, 5.19, 5.08, 5.08, and 4.93, respectively. This indicates that more acidic bioactive substances can be extracted at higher temperatures. The color changes of KCPE under different pH values are shown in Fig. 2. At pH 1–4, the extract exhibits a deep red to pink color, consistent with the typical color characteristics of anthocyanins in acidic environments. At pH 5–8, the color shifts to orange and yellow. When the pH is between 9 and 12, the yellow tone of the extract deepens and darkens, appearing as dark brown.

Figure 2: Color changes of KC extract at different pH levels (pH 1–12, from left to right)

3.2 Phytochemicals and Antioxidative Activities of KC Extracts

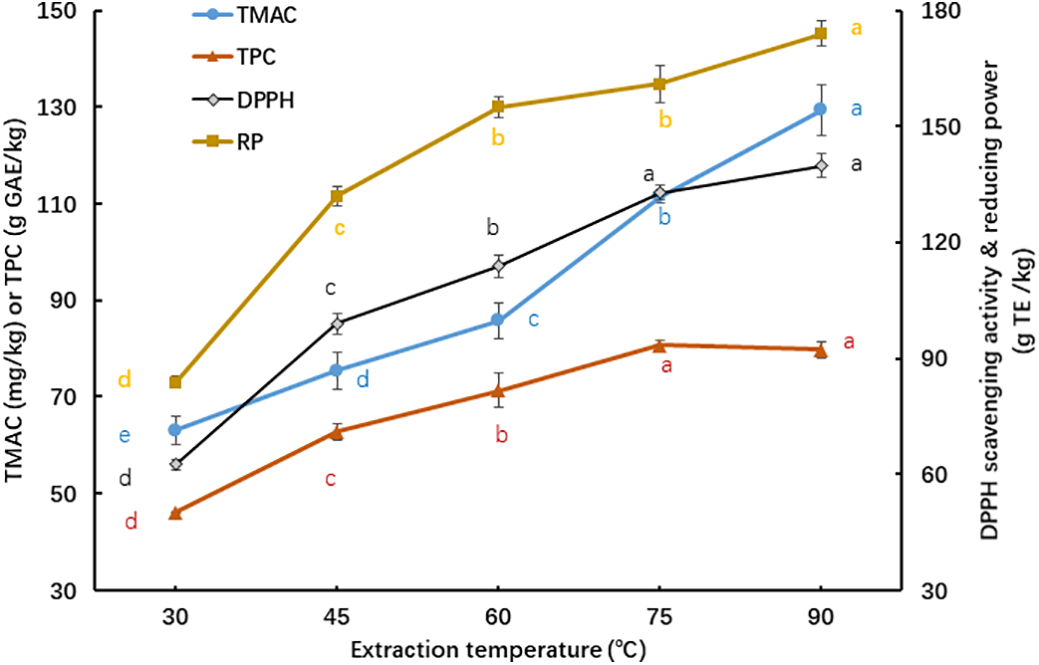

Fig. 3 depicts that the influence of different extraction temperatures (30°C–90°C) on the phytochemical contents and antioxidant activities of KCPE at a constant extraction duration of 30 min. A marked increase in TMAC and TPC of KCPE was observed as the extraction temperature increased from 30°C to 90°C. In the temperature range, the TMAC and TPC of KCPE were significantly (p < 0.05) increased by 105.2% and 72.8%, respectively. These enhancements were likely due to increased molecular internal energy and thermal disruption of plant cell membranes, which improved the release of bioactive compounds. Likewise, antioxidant properties, including DPPH radical scavenging ability and reducing power, were significantly (p < 0.05) enhanced at higher extraction temperatures—rising by 123.6% and 107.5%, respectively (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Influence of different extraction temperatures on the phytochemical contents and antioxidant activities of KCPE at a constant extraction duration of 30 min. Means with different letters ‘a–e’ in the same curve are significantly different (p < 0.05)

These results are consistent with the findings [22], in which butterfly pea flower and grape skin were used as raw materials and extracted for 30 min at temperatures between 30°C and 90°C. However, temperatures higher than 60°C were reported to be detrimental to the extraction efficiency of roselle calyx [22,28].

Extraction temperature and time are important factors affecting the yield of phytochemicals and their bioactivity. Generally, a longer extraction time can increase the extractability of heat-stable soluble substances. Based on the results in Fig. 3, KC petal extraction at 90°C appears to be a relatively optimal condition. KCP extracted at high temperatures is similar to preparing flower tea, where cherry blossoms are infused directly in 90°C hot water. Therefore, we selected 90°C at different extraction times to investigate their effects on bioactive characteristics.

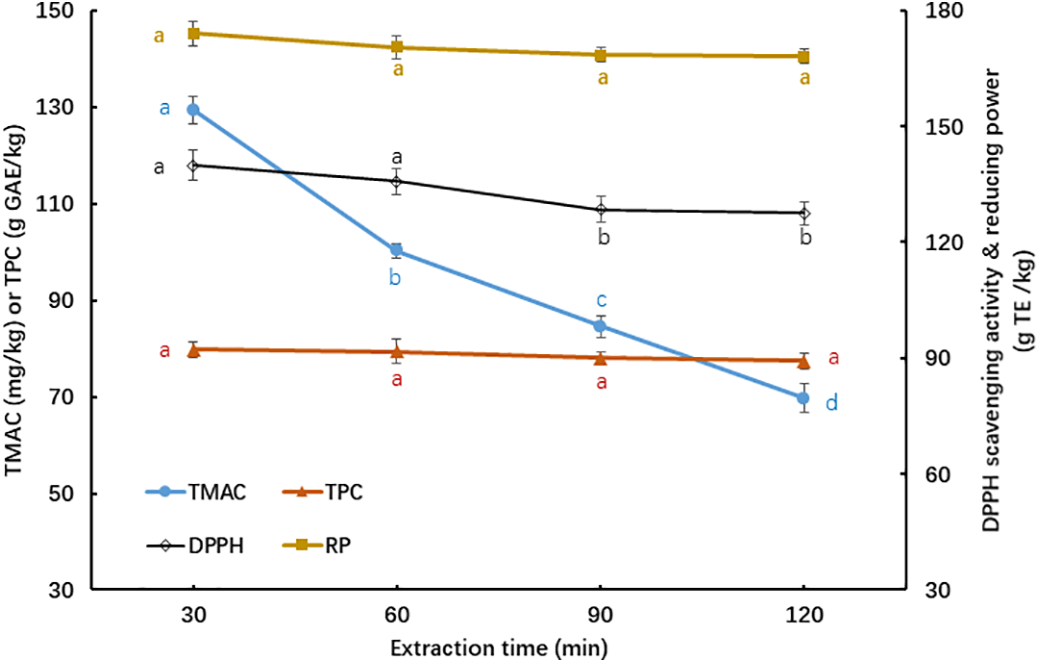

As shown in Fig. 4, extending the extraction time from 30 to 120 min at 90°C led to a gradual decline in the TMAC of KCPE, with the value at 120 min reduced to 53.83% of that measured at 30 min. However, TPC (ranging from 79.01–81.48 mg GAE/g) was insignificantly (p > 0.05) influenced by the extraction time. This suggests that anthocyanins in KC are unstable under prolonged extraction at high temperature (90°C), whereas polyphenols remain relatively stable. Yu et al. [22] reported that the TMAC and TPC of butterfly pea flower extracts obtained at 90°C remained relatively stable as the extraction duration extended from 30 to 90 or 120 min. In contrast, the anthocyanin content of roselle calyx extracted at 60°C steadily declined as the extraction time increased from 30 to 120 min. Since no literature was found on the influences of various extraction temperatures and durations on the bioactive compounds in cherry blossoms, it is not possible to compare or discuss the results of this study.

Figure 4: Influence of extraction time on phytochemicals and antioxidative activities of KCPE at 90°C of extraction temperature. Means with different letters ‘a–d’ in the same curve are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Regarding antioxidant activity, the DPPH radical scavenging ability of KCPE declined significantly (p < 0.05) by 8.80% after 120 min of extraction at 90°C. However, the reducing power remained relatively stable regardless of extraction duration, similar to the trend observed for TPC in Fig. 4. Based on the data presented in Figs. 3 and 4, the most favorable extraction conditions for obtaining total anthocyanins and phenolics from KCP were determined to be 90°C for 30 min.

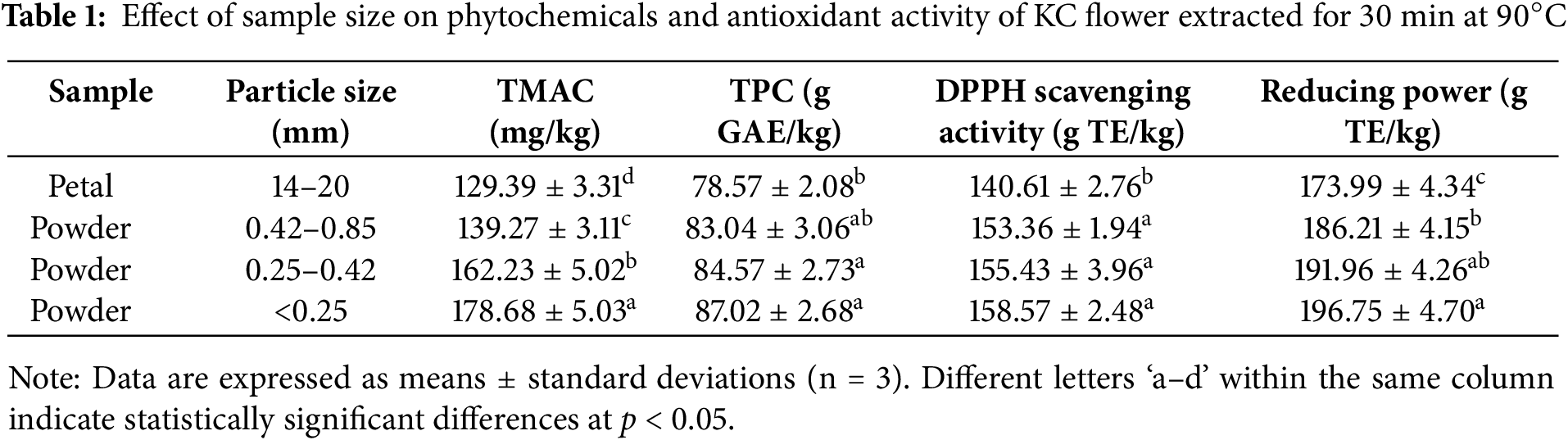

Table 1 presents the influences of varying sample sizes on the phytochemicals and antioxidant activity in KC extracts. As expected, KCP exhibited the lowest TMAC, TPC, DPPH scavenging activity, and reducing power among all the treatments tested, since the intact petals (18–20 mm in length × 14–15 mm in width) had a significantly larger size than their powdered forms. Grinding KC petals into powders (KCPPs) led to the breakdown of tissue and cellular structures. Generally, the finest KCPP facilitated better mass and heat transfer due to the largest surface area, resulting in its extract having the highest TMAC, TPC, and antioxidant activity. To the best of our knowledge, studies investigating the effects of different particle sizes on the extraction of anthocyanins and polyphenols from cherry blossoms are not found. The use of powdered Clitoria ternatea flower and Hibiscus sabdariffa calyx resulted in a shorter optimal extraction time for anthocyanins and polyphenols compared to the use of intact plant material [23,28].

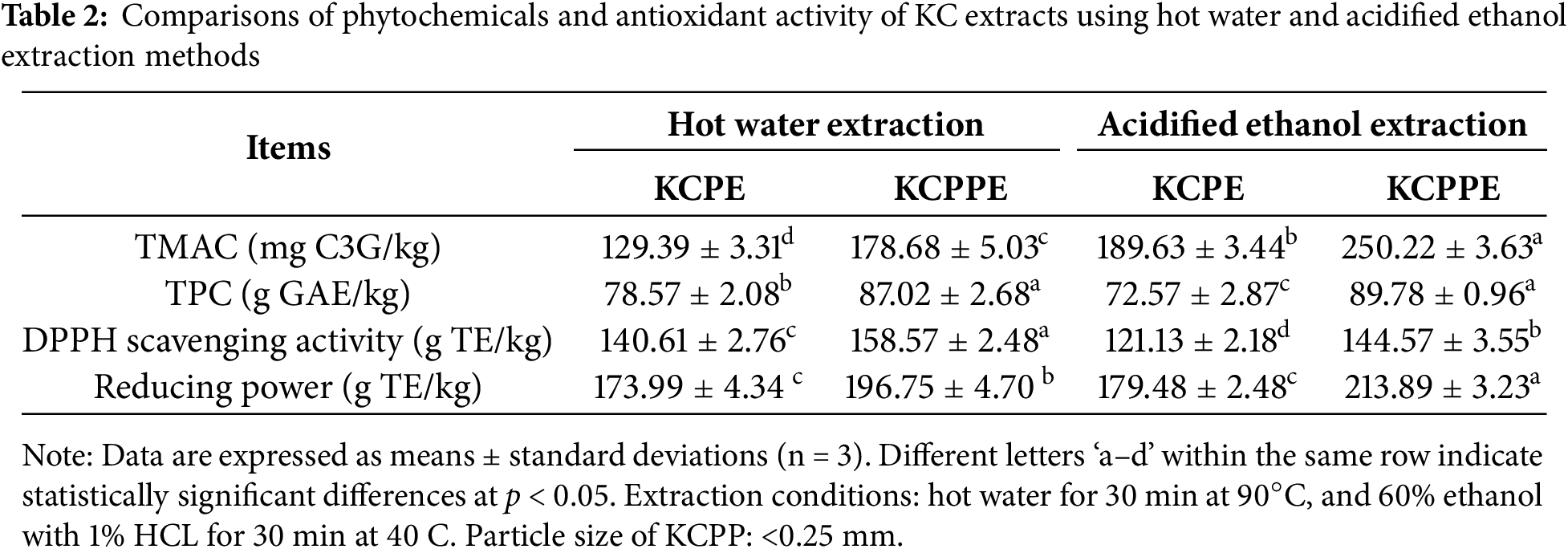

3.2.4 Comparison of Extraction Methods

Table 2 lists the comparisons of bioactive substances and their antioxidant activities from the petals and powders of KC extracted by the optimal hot water extraction (OHWE) for 30 min at 90°C and traditional acidic ethanol extraction (AEE). The extract from KCP powders using OHWE or AEE method had higher TMAC, TPC, DPPH scavenging activity and reducing power (by 13.08%–38.09%) than their petal forms, similar to the results in Table 1.

The TMAC values of both KCP and KCPP in the OHWE group were notably lower than those in the AEE group (p < 0.05), with ratios of 68.23% and 71.41%, respectively. Acidic ethanol extraction demonstrated significantly higher anthocyanin extraction efficiency, which may be attributed to the greater stability of anthocyanins under acidic and low-temperature (40°C) conditions, as well as the higher permeability of cell membrane caused by acidic alcohol, thereby enhancing anthocyanin solubility. However, the TPC of KC petals in the OHWE group was significantly more (by 8.27%) than that in the AEE group, while these two extraction methods had no significant effect on the TPC of KC powder. This indicates that most polyphenols in KC are heat stable during aqueous extraction at high temperature. The DPPH radical scavenging activities of both KCP and KCPP in the OHWE group were significantly greater than those observed in the AEE group, showing increases of 16.08% and 9.68%, respectively (p < 0.05). The AEE group of KCPP was significantly higher (by 8%) reducing power than the OHWE group, whereas no significant difference was observed between the two extraction methods for KCP.

Lee et al. [3] reported that CB of Prunus serrulata var. spontanea was extracted overnight at room temperature using different solvents (water, methanol, ethanol and acetone). The methanolic extracts of CB exhibited the highest TPC, free radical scavenging capacity, and reducing power. The ethanolic extracts had higher TPC and radical scavenging capacity than the aqueous extracts, though their reducing power was similar. Additionally, Park et al. [29] reported that ethanolic extracts of CB consistently indicated higher TPC and antioxidative capacity than water extracts across all plant parts tested (flower, branch, flesh, fruit, leaf, and seed).

Polyphenol-rich foods are generally associated with strong antioxidant properties. In the case of KC extracts, TMAC showed a significant positive correlation (p < 0.01) with both DPPH radical scavenging activity and reducing power, with correlation coefficients (r values) ranging from 0.756 to 0.814. Similarly, TPC exhibited a strong positive correlation with the two antioxidant assays, yielding an r value of 0.984 (p < 0.01). The contents of total phenols and total anthocyanins in CB petals were positively correlated with the antioxidant capacity indexes [6].

3.3 Heat Stability and Degradation Behavior of Anthocyanins from KCP Extracts

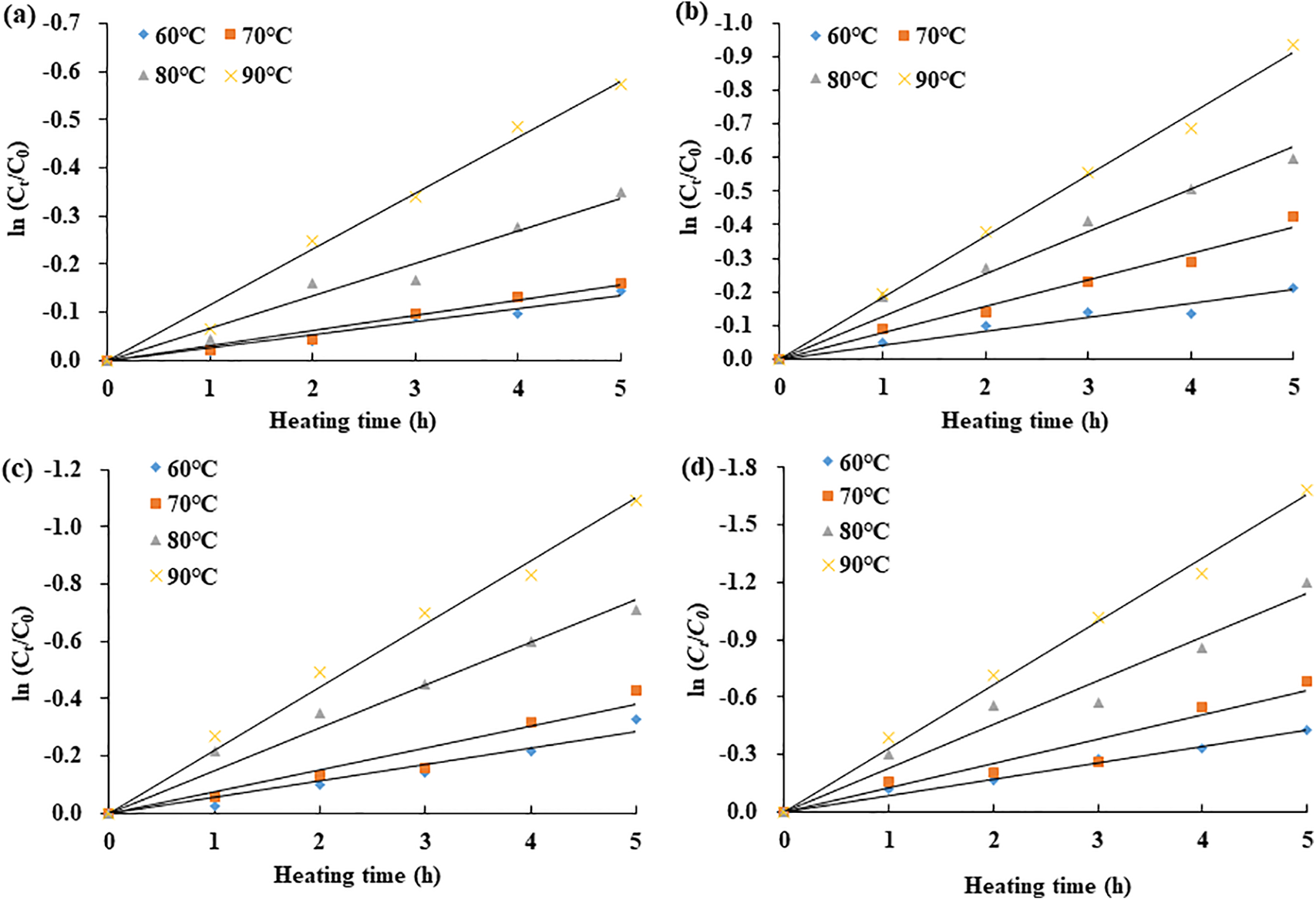

3.3.1 First-Order Model, Rate Constant and Half-Life of Degradation

Thermal degradation of aqueous anthocyanin extracts from KC petals was investigated under varying conditions, including temperatures ranging from 60°C to 90°C, durations from 0 to 5 h, and pH levels between 2.6 and 5.6. The results indicated that the degradation behavior of KC anthocyanins conformed well to a first-order kinetic model (Eq. (2)), with determination coefficients (R2) ranging from 0.93 to 0.99. Fig. 5 illustrates the thermal degradation patterns of anthocyanins from KC petal extracts across different pH values (2.6–5.6).

Figure 5: Thermal degradation profiles of anthocyanins from KC extracts subjected to heating at different pH levels: (a) pH 2.6, (b) pH 3.6, (c) pH 4.6, and (d) pH 5.6

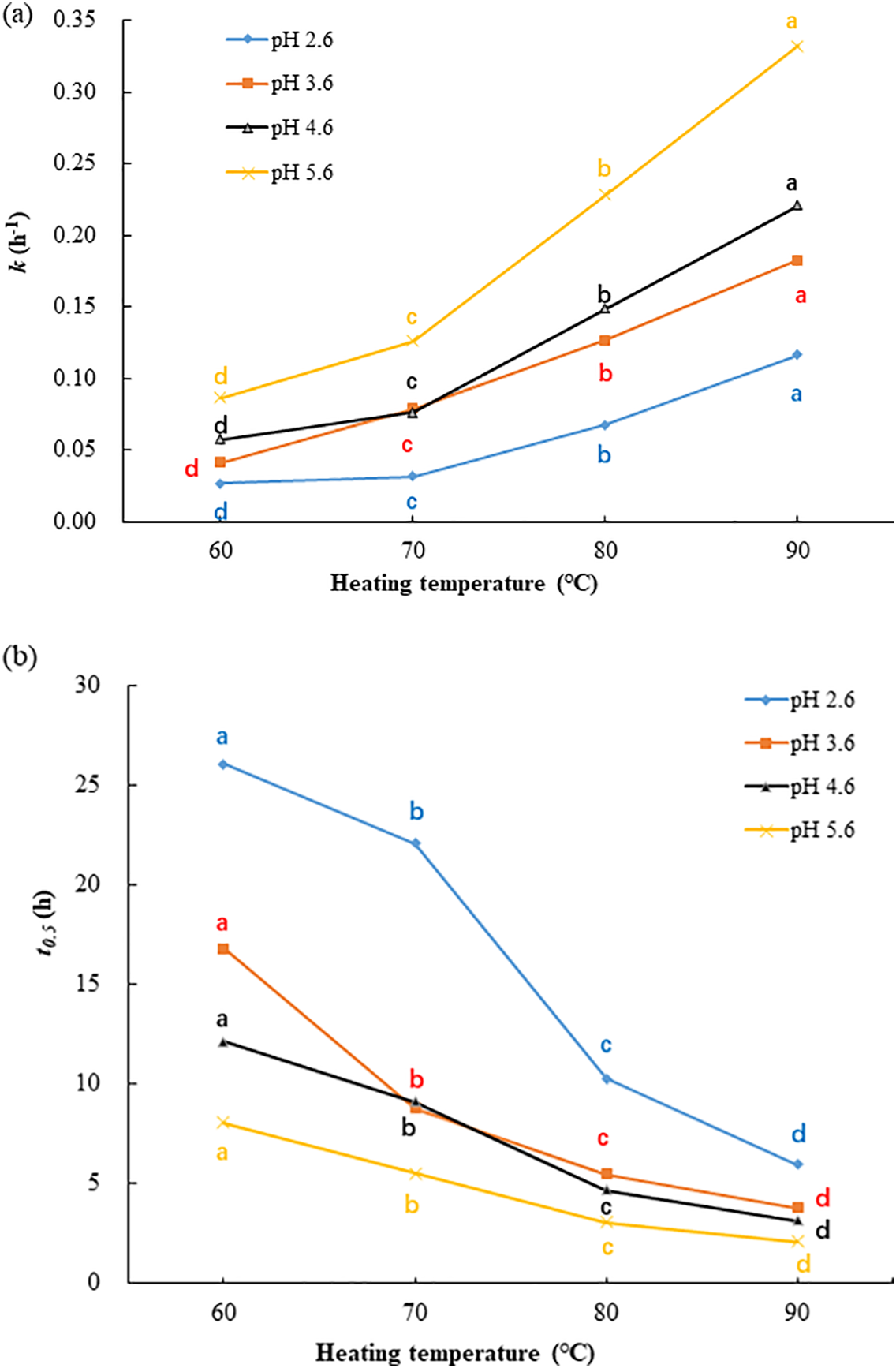

The kinetic parameters associated with the thermal degradation of KC anthocyanins under different heating temperatures and pH conditions are depicted in Fig. 6. The degradation rate constants (k) varied from 0.0266 to 0.3320 h−1. At a constant pH level (2.6–5.6), increasing the temperature from 60°C to 90°C led to a 3.86–4.43-fold rise in the k value. Likewise, at a fixed temperature (60°C–90°C), raising the pH from 2.6 to 5.6 resulted in a 2.85–4.22-fold increase in the k value. The highest degradation rate, 0.3320 h−1, was observed under the condition of 90°C and pH 5.6 (Fig. 6a). According to Eq. (2), after 2 h of heating at 90°C, the anthocyanin content would be expected to decrease to 21.68% of the original value. Therefore, the observed decrease (46.17%) in TMAC of KCP after extraction for 120 min at 90°C, as shown in Fig. 2, is reasonable. Fig. 6b shows that the half-life (t0.5) of KC anthocyanins decreased noticeably as both temperature and pH increased. Among all the experimental conditions, the longest half-life (26.06 h) occurred at 60°C and pH 2.6, while the shortest (2.09 h) was found at 90°C and pH 5.6.

Figure 6: Thermal degradation kinetics of anthocyanins from KC petals under various temperatures and pH levels: (a) degradation rate constants, (b) half-life values. Means with different letters ‘a–d’ in the same curve are significantly different (p < 0.05)

Under highly acidic conditions, anthocyanins predominantly exist in the form of a stable flavylium ion [9]. During storage at room temperature, the degradation rate constant of red onion anthocyanins increased by approximately 17 times as the pH level rose from 1.0 to 9.0 [16]. The primary anthocyanins in butterfly pea flowers are ternatins, which demonstrate good stability in both acidic and neutral conditions due to their polyacylated structure [11]. Furthermore, the pea flower anthocyanins exhibited a lower rate constant (0.0541 h−1) of thermal degradation at 90°C and pH 5.5 [22]. As far as we are aware, there have been no reports examining the thermal degradation kinetics of anthocyanins derived from cherry blossoms.

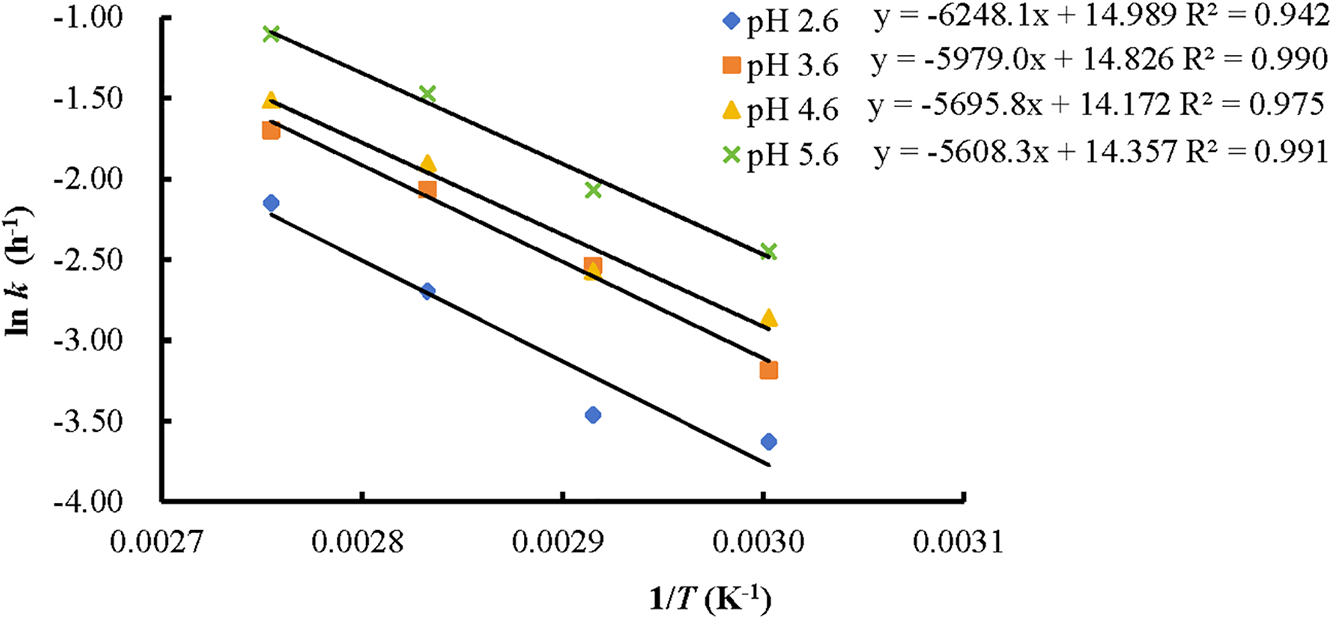

3.3.2 Arrhenius Model and Activation Energy

The temperature dependence of anthocyanin degradation kinetics can be described by the Arrhenius equation (Eq. (4)), which is commonly used to model chemical reaction rates:

In this equation, k represents the rate constant, k0 is the pre-exponential (frequency) factor, Ea denotes the activation energy (J/mol), R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol K), and T refers to the absolute temperature (K).

As shown in Fig. 7, the temperature dependence of the rate constants aligns with the Arrhenius equation, with R2 values ranging from 0.94 to 0.99. The calculated activation energies for anthocyanin degradation were 51.95, 49.70, 47.35, and 46.63 kJ/mol, respectively, and showed a decreasing trend as the pH increased from 2.6 to 5.6. This indicates that anthocyanins are more susceptible to temperature-induced degradation at lower pH (2.6) compared to higher pH levels. Similar trends were reported for Hibiscus sabdariffa extracts, where the activation energy dropped from 75.6 to 53.6 kJ/mol over a pH range of 2.0 to 5.0 [14]. Additionally, the activation energies for butterfly pea flower extracts (pH 7) and blackthorn extracts (unknown pH) were 83.21–101.15 kJ/mol and 53.96 kJ/mol, respectively [30,31].

Figure 7: Arrhenius equations of KC anthocyanins at different pH values

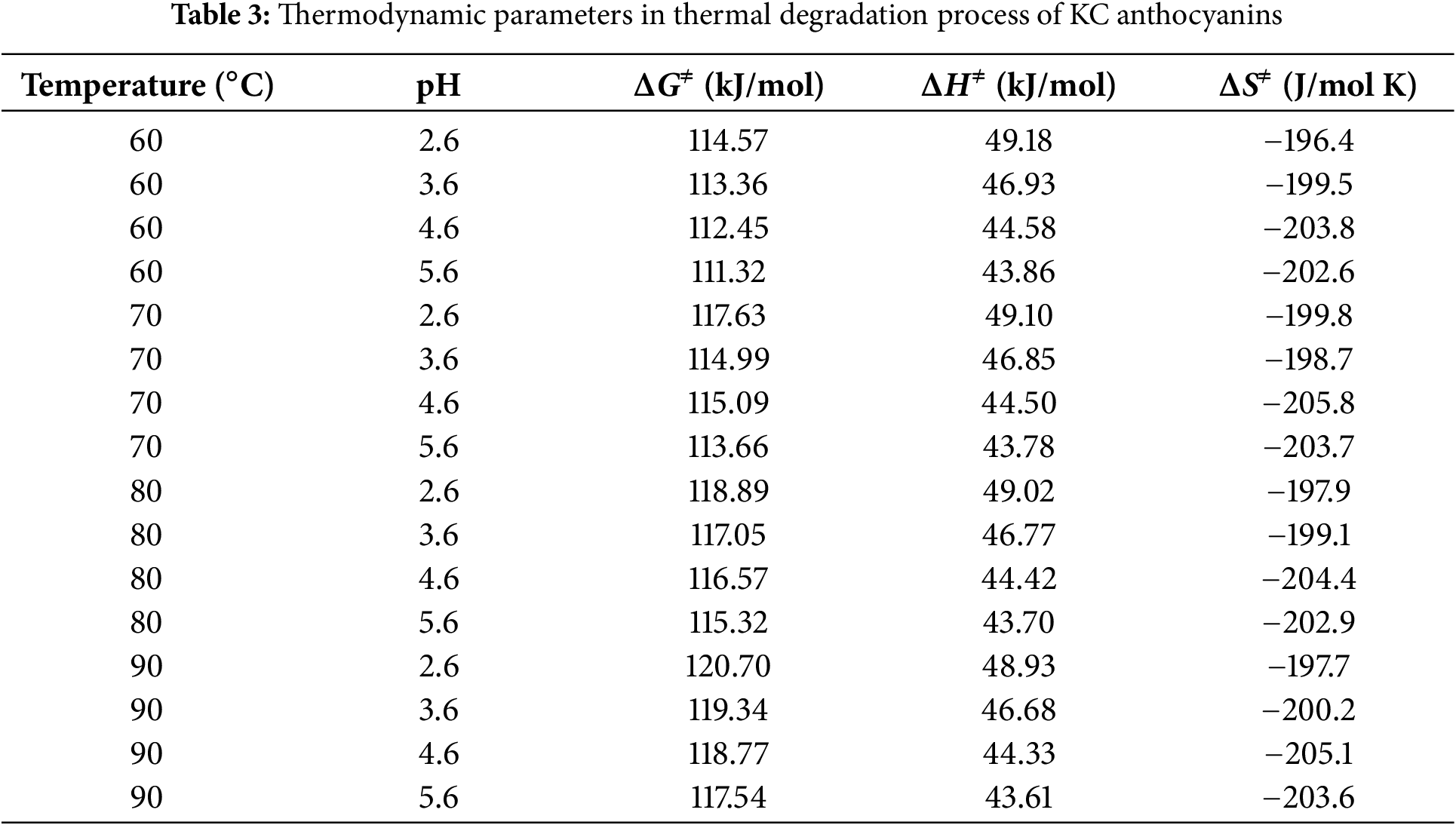

3.3.3 Thermodynamic Parameters

The thermodynamic parameters of anthocyanin degradation reactions were calculated by Eqs. (5)–(7) [32]:

where ΔG≠ represents the Gibbs free energy of activation (J/mol), R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol K), T denotes the absolute temperature (K), k is the reaction rate constant (s−1), h is Planck’s constant (6.6262 × 10−34 J s), kB is Boltzmann’s constant (1.3806 × 10−23 J/K), ΔH≠ stands for the activation enthalpy (J/mol), Ea is the activation energy (J/mol), and ΔS≠ refers to the activation entropy (J/mol K).

Table 3 lists the thermodynamic parameters for the thermal degradation process of KC anthocyanins at different temperatures and pH levels. The ΔG≠ values, ranging from 111.32 to 120.70 kJ/mol, increase with rising temperature and decreasing pH value. The positive ΔG≠ values indicate that the thermal degradation of KC anthocyanins proceeds through a non-spontaneous process. A higher ΔG≠ reflects greater difficulty in transitioning from reactants to the transition state. The positive enthalpy values in Table 3 show that the activation of anthocyanin degradation is endothermic. The relatively small ΔH≠ values (43.61 to 49.18 kJ/mol) suggest that the energy required to form the activated complex is minimal, indicating a favorable transition to the activated state. The results also show that pH has a greater influence on ΔH≠ values than temperature. The activation entropy values in this study ranged from −196.4 to −205.1 J/mol K, all of which were negative. As the pH value increases, the activation entropy becomes more negative. A negative ΔS≠ value reflects a decrease in molecular disorder during the formation of the transition state, implying that the thermal degradation of KC anthocyanins proceeds through a more ordered intermediate structure, potentially involving proton transfer or rearrangement of solvent molecules. For ethanolic anthocyanin extracts from blackthorn fruits, the activation parameters at 2°C–75°C were: ΔG≠ = 65.82–69.85 kJ/mol, ΔH≠ = 51.07–51.67 kJ/mol, and ΔS≠ = −51.45 to −55.65 J/(mol K) [31]. Both ohmic and traditional heating of anthocyanins in Barbados cherry pulp showed similar values for all thermodynamic parameters at 75°C–90°C: ΔG≠ (100.19–101.78 kJ/mol), ΔH≠ (71.79–71.94 kJ/mol), and ΔS≠ (−80.15 to −82.63 J/mol K) [32]. As far as we know, no literature has reported the thermodynamic parameter analysis of cherry blossom anthocyanins during thermal degradation.

Kanzan cherry blossoms serve as a promising source of natural pink to red pigments and are abundant in bioactive constituents. When the extraction duration was fixed at 30 min, increasing the temperature from 30°C to 90°C led to significant enhancements in TMAC, TPC, DPPH radical scavenging capacity, and reducing power of the KC petal extract. However, at 90°C, the TMAC and DPPH scavenging activity of KCPE gradually decreased as the extraction time increased from 30 to 120 min. In contrast, TPC and reducing power were not significantly affected by extraction time (p > 0.05). Particle size significantly influenced the yield of phytochemicals and the antioxidant properties in extracts from KC petals. In general, the finest KCPP resulted in extracts with the highest TMAC, TPC, and antioxidant activity, likely due to improved mass and heat transfer. A strong positive correlation (p < 0.01) was observed between TMAC, TPC, and the antioxidant activities. Acidic ethanol extraction exhibited significantly higher anthocyanin extraction efficiency. However, the TPC of KC petals and powders in the OHWE group was equal to or higher than that in the AEE group. Therefore, hot water extraction at 90°C for 30 min appears to be an effective and feasible method for extracting phytochemicals from KC petals and powders.

The thermal decomposition of anthocyanins in KC extracts conformed to a first-order kinetic model. As both heating temperature and pH increased, the degradation rate constants (k) also rose. The temperature dependence of the degradation rate was well characterized by the Arrhenius equation. The calculated activation energy (Ea) for anthocyanin degradation ranged between 46.63 and 51.95 kJ/mol, showing a decreasing trend with increasing pH. The associated thermodynamic parameters were as follows: ΔG≠ ranged from 111.32 to 120.70 kJ/mol, ΔH≠ from 43.61 to 49.18 kJ/mol, and ΔS≠ from −196.4 to −205.1 J/mol K. Therefore, the aqueous red extract derived from KC petals, being abundant in phytochemicals and exhibiting strong antioxidant activity, shows promise for application in acidic food systems and health-promoting products.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Research Fund (Project Number 2025YB12) and Innovation and Entrepreneurship Project (2024) of Shanghai Sanda University.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Sy-Yu Shiau; Methodology, Shuting Ni and Sy-Yu Shiau; Formal analysis, Shuting Ni and Sy-Yu Shiau; Investigation, Shuting Ni and Yanli Yu; Resources, Yanli Yu and Songling Cai; Data curation, Songling Cai and Wenbo Huang; Writing—original draft, Shuting Ni and Sy-Yu Shiau; Writing—review and editing, Yanli Yu and Sy-Yu Shiau; Supervision, Sy-Yu Shiau; Funding acquisition, Sy-Yu Shiau. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [Sy-Yu Shiau], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Liang D, Zhu T, Deng Q, Lin L, Tang Y, Wang J, et al. PacCOP1 negatively regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.). J Photochem Photobiol B. 2020;203(5):111779. doi:10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2020.111779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Brozdowski J, Waliszewska B, Gacnik S, Hudina M, Veberic R, Mikulic-Petkovsek M. Phenolic composition of leaf and flower extracts of black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.). Ann For Sci. 2021;78(3):66. doi:10.1007/s13595-021-01089-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Lee BB, Cha MR, Kim SY, Park E, Park HR, Lee SC. Antioxidative and anticancer activity of extracts of cherry (Prunus serrulata var. spontanea) blossoms. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2007;62(2):79–84. doi:10.1007/s11130-007-0045-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Suo K, Feng Y, Zhang Y, Yang Z, Zhou C, Chen W, et al. Comparative evaluation of quality attributes of the dried cherry blossom subjected to different drying techniques. Foods. 2023;13(1):104. doi:10.3390/foods13010104. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Wei Q, Liu RJ, Liu D, Wei CC. Compositions and their α-glycosidase inhibition activity of cerasua serrulata flowers. J Jinggangshan Univ. 2021;42(4):48–52. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

6. Ouyang SS, Cao SJ, Xiong Y, Wu SZ, Yu L, Bai WF, et al. Measurement of color values and active substances of different flowering cherry petals and analysis of antioxidant capacity. J Cent South Univ For Technol. 2024;44(2):166–73,183. doi:10.14067/j.cnki.1673-923x.2024.02.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Matsuura R, Moriyama H, Takeda N, Yamamoto K, Morita Y, Shimamura T, et al. Determination of antioxidant activity and characterization of antioxidant phenolics in the plum vinegar extract of cherry blossom (Prunus lannesiana). J Agric Food Chem. 2008;56(2):544–9. doi:10.1021/jf0717992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Jokioja J, Yang B, Linderborg KM. Acylated anthocyanins: a review on their bioavailability and effects on postprandial carbohydrate metabolism and inflammation. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2021;20(6):5570–615. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Enaru B, Dretcanu G, Pop TD, Stǎnilǎ A, Diaconeasa Z. Anthocyanins: factors affecting their stability and degradation. Antioxidants. 2021;10(12):1967. doi:10.3390/antiox10121967. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Vidana Gamage GC, Lim YY, Choo WS. Anthocyanins from Clitoria ternatea flower: biosynthesis, extraction, stability, antioxidant activity, and applications. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:792303. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.792303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Vuong TT, Hongsprabhas P. Influences of pH on binding mechanisms of anthocyanins from butterfly pea flower (Clitoria ternatea) with whey powder and whey protein isolate. Cogent Food Agric. 2021;7(1):1889098. doi:10.1080/23311932.2021.1889098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wallace TC, Giusti MM. Anthocyanins-nature’s bold, beautiful, and health-promoting colors. Foods. 2019;8(11):550. doi:10.3390/foods8110550. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Fu X, Wu Q, Wang J, Chen Y, Zhu G, Zhu Z. Spectral characteristic, storage stability and antioxidant properties of anthocyanin extracts from flowers of butterfly pea (Clitoria ternatea L.). Molecules. 2021;26(22):7000. doi:10.3390/molecules26227000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wu HY, Yang KM, Chiang PY. Roselle anthocyanins: antioxidant properties and stability to heat and pH. Molecules. 2018;23(6):1357. doi:10.3390/molecules23061357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Gull A, Masoodi FA, Gani A. Valorization of saffron petal waste anthocyanin extract, microencapsulation storage kinetic stability, and in vitro release behavior of anthocyanin microcapsules. Biomass Conv Bioref. 2025;15(4):5481–92. doi:10.1007/s13399-024-05599-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Oancea S, Drăghici O. pH and thermal stability of anthocyanin-based optimised extracts of Romanian red onion cultivars. Czech J Food Sci. 2013;31(3):283–91. doi:10.17221/302/2012-cjfs. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kucharska AZ, Oszmiański J. Anthocyanins in fruits of Prunus padus (bird cherry). J Sci Food Agric. 2002;82(13):1483–6. doi:10.1002/jsfa.1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Shiau SY, Yu Y, Li J, Huang W, Feng H. Phytochemical-rich colored noodles fortified with an aqueous extract of Clitoria ternatea flowers. Foods. 2023;12(8):1686. doi:10.3390/foods12081686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. An S, Arakawa O, Tanaka N, Zhang S, Kobayashi M. Effects of blue and red light irradiations on flower colouration in cherry blossom (Prunus × yedoensis ‘Somei-yoshino’). Sci Hortic. 2020;263(8):109093. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.109093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ye Q, Liu F, Feng K, Fu T, Li W, Zhang C, et al. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptome analysis of anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in Prunus serrulata. Plants. 2025;14(1):114. doi:10.3390/plants14010114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Li L, Yang B, Guo ZM, Chen JX, Ma S. Optimization of microwave extraction of total flavonoids from Kanzan flower and its antioxidant activity. China Food Addit. 2023;34(8):126–31. (In Chinese). doi:10.19804/j.issn1006-2513.2023.08.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Yu Y, Shiau S, Pan W, Yang Y. Extraction of bioactive phenolics from various anthocyanin-rich plant materials and comparison of their heat stability. Molecules. 2024;29(22):5256. doi:10.3390/molecules29225256. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Shiau SY, Wang Y, Yu Y, Cai S, Liu Q. Phytochemical, antioxidant activity, and thermal stability of Clitoria ternatea flower extracts. Czech J Food Sci. 2024;42(4):284–94. doi:10.17221/68/2024-cjfs. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Escher GB, Marques MB, do Carmo MAV, Azevedo L, Furtado MM, Sant’Ana AS, et al. Clitoria ternatea L. petal bioactive compounds display antioxidant, antihemolytic and antihypertensive effects, inhibit α-amylase and α-glucosidase activities and reduce human LDL cholesterol and DNA induced oxidation. Food Res Int. 2020;128(3):108763. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Lee J, Durst RW, Wrolstad RE. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: collaborative study. J AOAC Int. 2005;88(5):1269–78. doi:10.1093/jaoac/88.5.1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Liyana-Pathirana CM, Shahidi F. Antioxidant and free radical scavenging activities of whole wheat and milling fractions. Food Chem. 2007;101(3):1151–7. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.03.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Oyaizu M. Studies on products of browning reaction. Antioxidative activities of products of browning reaction prepared from glucosamine. Jpn J Nutr Diet. 1986;44(6):307–15. doi:10.5264/eiyogakuzashi.44.307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Cissé M, Bohuon P, Sambe F, Kane C, Sakho M, Dornier M. Aqueous extraction of anthocyanins from Hibiscus sabdariffa: experimental kinetics and modeling. J Food Eng. 2012;109(1):16–21. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2011.10.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Park JW, Yuk HG, Lee SC. Antioxidant and tyrosinase inhibitory activities of different parts of oriental cherry (Prunus serrulata var. spontanea). Food Sci Biotechnol. 2012;21(2):339–43. doi:10.1007/s10068-012-0045-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Muzi Marpaung A, Andarwulan N, Hariyadi P, Nur Faridah D. Thermal degradation of anthocyanins in butterfly pea (Clitoria ternatea L.) flower extract at pH 7. Am J Food Sci. 2017;5(5):199–203. doi:10.12691/ajfst-5-5-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Moldovan B, Ardelean A, David L. Degradation kinetics of anthocyanins during heat treatment of wild blackthorn (Prunus spinosa L.) fruits extract. Studia UBB Chemia. 2019;64(2):401–10. doi:10.24193/subbchem.2019.2.34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Mercali GD, Jaeschke DP, Tessaro IC, Marczak LDF. Degradation kinetics of anthocyanins in acerola pulp: comparison between ohmic and conventional heat treatment. Food Chem. 2013;136(2):853–7. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.08.024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools