Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Different Irrigation Regimes and Biochar Applications on Pollen and Anther Development in Capsicum annuum Plant

Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Bursa Uludag, Görükle Campus, Bursa, 16059, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Sevinç Başay. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Emerging Strategies in Sustainable Vegetable Cultivation and Protection)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3217-3229. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071755

Received 11 August 2025; Accepted 24 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

Water scarcity is an escalating global challenge that severely threatens productivity and reproductive success in crops, particularly in drought-sensitive species such as Capsicum annuum L. Although deficit irrigation strategies are widely recommended to enhance water use efficiency, knowledge remains limited regarding their interactions with soil amendments such as biochar and the consequent impacts on reproductive traits. This study aimed to evaluate the combined effects of deficit irrigation strategies and biochar application on pollen viability and morphology in Capsicum annuum. The experiment was conducted under full, partial, and deficit irrigation regimes with and without biochar treatment, following a randomized block design. The primary parameters examined were pollen viability (viable, semi-viable, and non-viable rates), anther width and length, and pollen width and length. Microscopic measurements and statistical analyses (p ≤ 0.05) revealed significant effects of both irrigation regimes and biochar applications. Under deficit irrigation, viable, semi-viable, and non-viable pollen rates were 29.84%, 32.95%, and 37.21%, respectively, whereas the highest viable pollen rate was observed under full irrigation. In partial irrigation, viable pollen accounted for 31.67%, semi-viable for 38.81%, and non-viable for 29.49%. In plots treated with biochar under partial irrigation, anther width (1700.89 μm), anther length (3805.34 μm), pollen width (26.93 μm), and pollen length (37.42 μm) reached the highest values, while the lowest values were recorded in deficit irrigation plots without biochar. These findings emphasize the importance of integrating biochar into irrigation management to mitigate the adverse effects of water stress on pollen development. Nevertheless, further research is needed to clarify the long-term implications of these practices for reproductive success and agricultural sustainability.Keywords

Abiotic stresses such as drought are among the main causes of yield losses in crop production [1]. Drought, as one of the most critical environmental stress factors, limits plant growth and productivity by disrupting physiological and biochemical processes such as photosynthesis, respiration, nutrient transport, and hormone balance [2,3]. Globally, only about 15% of agricultural land is irrigated, yet this area accounts for nearly 50% of food production; therefore, water scarcity is regarded as one of the greatest threats of the 21st century [4]. Alongside salinity, drought is the most dominant abiotic factor affecting plant development and yield, exacerbated further by global warming [5]. Vegetables are particularly sensitive to extreme environmental conditions [6], and in peppers, drought can reduce yield and quality by up to 70%, with the most critical stress stages being seedling establishment and the pre-flowering phase [4].

Biochar is a carbon-rich, porous material produced through the pyrolysis of organic residues under limited or absent oxygen conditions. Owing to its high surface area and structural stability, biochar enhances soil water and nutrient retention, supports microbial activity, and contributes to pH regulation, thereby improving soil fertility. These properties highlight its role as a sustainable soil amendment in agricultural production [7–10].

Pollen viability is a critical determinant of plant reproductive success and is directly influenced by environmental stresses, particularly water stress. Elevated temperature and humidity levels have been reported to reduce pollen viability, thereby disrupting reproductive systems in certain plant species [11]. Drought and heat stress impair carbohydrate and energy metabolism within the anther during pollen development, leading to a marked reduction in viable pollen [12]. Studies have further demonstrated that drought not only decreases pollen viability but also restricts anther growth, potentially resulting in sterility within the reproductive cycle of flowering plants [13,14]. Moreover, when drought and high temperature stress occur simultaneously, sucrose metabolism, specifically sucrose synthase activity, is suppressed, causing severe declines in pollen viability [12]. Consequently, pollen viability and anther development represent some of the most sensitive stages under water stress, posing a direct threat to yield and seed production [15].

The goal of this study was to analyze pollen viability under field conditions. The Capsicum annuum ‘Postal’ variety was used in this research. Pollen viability was assessed using in vitro pollen germination, a widely accepted and efficient method for field applications. Clearly identifying the tolerance and sensitivity levels of Capsicum annuum L.cv. Postal variety under drought conditions is essential for initiating future breeding programs focused on improving drought resistance in pepper plants.

Capsicum annuum L. (sweet pepper) is one of the most economically important vegetable crops worldwide and is widely cultivated in both open-field and greenhouse systems due to its nutritional value, consumer demand, and high market potential. In Turkey, pepper is a major horticultural product with significant regional and export value, particularly in the Mediterranean and Marmara regions. However, pepper is highly sensitive to abiotic stress factors, especially drought, which affects critical stages such as flowering, fruit set, and seed development [3,16]. Despite the global and regional importance of pepper, relatively few studies have focused on the combined effects of deficit irrigation and biochar application on its reproductive development, particularly pollen viability and anther morphology. Most previous research has prioritized vegetative growth or yield parameters, leaving a knowledge gap regarding the underlying physiological and anatomical responses of reproductive organs under stress conditions. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate how irrigation regimes and biochar affect key reproductive traits in Capsicum annuum L., with particular emphasis on the role of biochar as a soil amendment that enhances water retention and mitigates the adverse effects of drought, offering important insights into strategies for maintaining productivity under water-limited conditions.

2.1.1 Experimental Site and Plant Material

The experiment was conducted at Bursa Uludağ University, Faculty of Agriculture, Research and Experiment Field, Turkey (40°13′08.0364″ N; 28°52′12.0036″ E). The soil at the experimental site was classified as clayey, with organic matter contents of 1.51% and 0.18%, pH values of 6.50 and 7.84, and salt contents of 0.045% and 0.017%, respectively. The plant material consisted of Capsicum annuum L. cv. Postal seedlings, which were raised in a substrate mixture of organic peat and farmyard manure.

2.1.2 Biochar Characteristics and Application

The biochar used in this study was produced from agricultural pruning residues through slow pyrolysis at approximately 500°C under limited oxygen conditions. Following production, the biochar was ground and sieved to a particle size smaller than 2 mm. It was characterized by a pH of about 9.0, an organic carbon content of 60%, and a cation exchange capacity of nearly 65 cmol(+) kg−1, reflecting typical properties of wood-based biochar with the potential to improve soil structure, water retention, and nutrient availability [17,18]. Biochar was applied to the experimental plots at a rate of 1 t per decare. After soil preparation, the material was uniformly broadcast over the soil surface and incorporated into the root zone with a rotary tiller to ensure homogeneous distribution.

2.2.1 Seedling Production and Transplanting

Seeds of the Postal cultivar were sown on 12 March 2024, and seedlings were raised under controlled conditions in low plastic tunnels. A hardening treatment was applied before field transplantation to increase seedling tolerance to environmental stresses. Transplantation was performed on 13 May 2024, when seedlings had developed two to four true leaves and well-formed root systems. Plants were placed at a depth of approximately 3–5 cm up to the collar level, following a randomized plot design as described by [19].

2.2.2 Irrigation Treatments and System

The amount of irrigation water to be applied in each treatment was calculated using the following equation:

where

The crop coefficient was obtained daily from TAGEM-SUET software from the first irrigation to the last irrigation [20]. Crop coefficients varied in the range of 0.48–1.00 during the growing season. In this study, the Penman-Monteith (FAO56-PM) method was used to estimate daily ET0 [21]. The FAO Penman-Monteith method uses meteorological data such as average maximum and minimum temperature, relative air humidity, wind speed, and solar radiation. Daily meteorological data were obtained from an automatic meteorological station approximately 500 m from the experiment field for this study.

Three irrigation treatments were established as follows: (1) full irrigation (FI), 100% of water requirement (ETc) calculated according to the Penman-Monteith equation and the Kc coefficient; (2) partial irrigation (DI75), 75% of ETc; (3) deficit irrigation (DI50), 50% of ETc.

In this study, a drip irrigation system was used for irrigation plots. The drip irrigation system was composed of a main pipeline, a manifold, and laterals. The distance between main plots was 2 m. Each plot consists of 4 lateral lines. The lateral line spacing was 0.4 m. The discharge rate of the drippers was 4 L/h, and the drippers were spaced 25 cm apart within lateral lines. According to previous pepper studies, irrigation was applied at 4 or 6-day intervals [22,23]. Irrigation was uniformly applied to all treatments at the beginning of planting based on 100% replacement of ET losses for plants to be well established.

Thereafter, deficit irrigation treatments were started on 21 May 2024. The amount of irrigation water applied in different irrigation treatments was measured through water meters.

2.2.3 Anther and Pollen Measurements

In the balloon stage, flowers of Capsicum annuum grown under biochar-amended and non-amended conditions with full irrigation, partial irrigation, and deficit irrigation treatments, 30 anthers and pollen grains were collected to measure their longitudinal length (µm) and transverse width (µm) (Fig. 1). For this purpose, anthers and pollen grains were placed on a microscope slide, and a drop of glycerin was added before covering with a coverslip. Another measurements were performed using a stereo microscope, while pollen dimensions were measured under a light microscope equipped with a DP-20 digital system.

Figure 1: Anther (A) and pollen (B) appearance measured under a microscope in capia pepper ‘Postal’ cultivar. l = length, w = width

Pollen viability was determined using a 1% 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) solution. Pollen grains were obtained from unruptured anthers of balloon-stage pepper flowers by placing them on a slide, adding one or two drops of TTC solution, and crushing them with a glass rod. The slides were then covered with a coverslip to prevent air exposure and left at room temperature for three hours. This procedure was conducted in three replicates for each treatment, and the number and percentage of viable, semi-viable, and non-viable pollen grains were recorded. Viable pollen stained red, semi-viable pollen appeared light red to pink, and non-viable pollen remained unstained (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Views of viable, semi-viable and dead pollen grains in capia pepper ‘Postal’ cultivar

The statistical analysis of pollen viability, anther, and pollen morphology data was performed using the JMP statistical software. All analyses were conducted in three replicates, and mean values were used for evaluation. Differences among means were compared using the least significant difference (LSD) test at a significance level of p < 0.05.

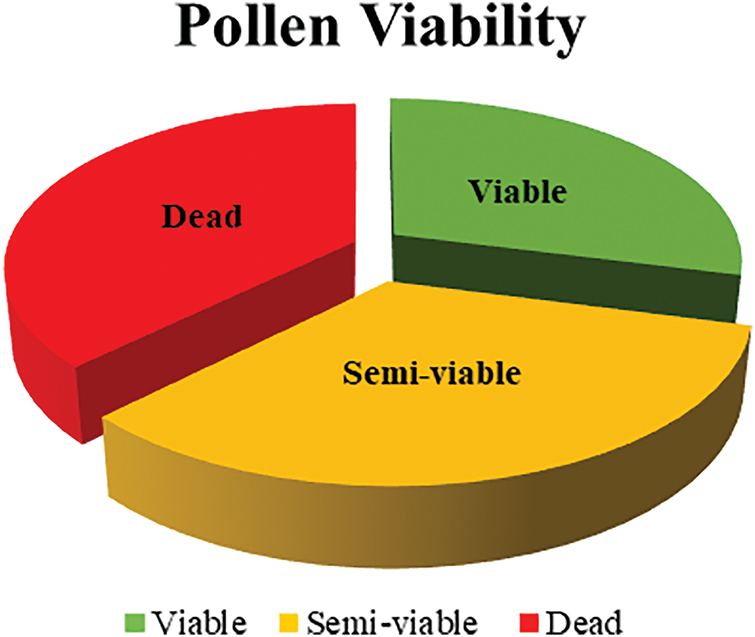

No statistically significant differences were observed between treatments and irrigation levels in biochar-amended and non-amended plots (p > 0.05); however, differences in pollen viability rates were found to be statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) (Fig. 3). The findings indicated that the highest proportion was recorded in non-viable pollen at 37.00 percent, followed by semi-viable pollen at 34.00 percent and fully viable pollen at 29.00 percent. These results suggest that different irrigation regimes have a significant impact on pollen viability and that drought stress may have substantial consequences on pollen physiology.

Figure 3: Pollen viability rates in Capsicum annuum under different irrigation regimes in biochar-amended and non-amended plots (%)

A study examining the effects of drought stress on Capsicum annuum pollen physiology and fertility reported that drought conditions significantly reduced water use efficiency and pollen quality [24]. Furthermore, a study investigating the differential expression of genes associated with pollen viability in Capsicum annuum under drought stress revealed that while certain genes support pollen development under drought conditions, water stress generally leads to a decline in pollen fertility [25].

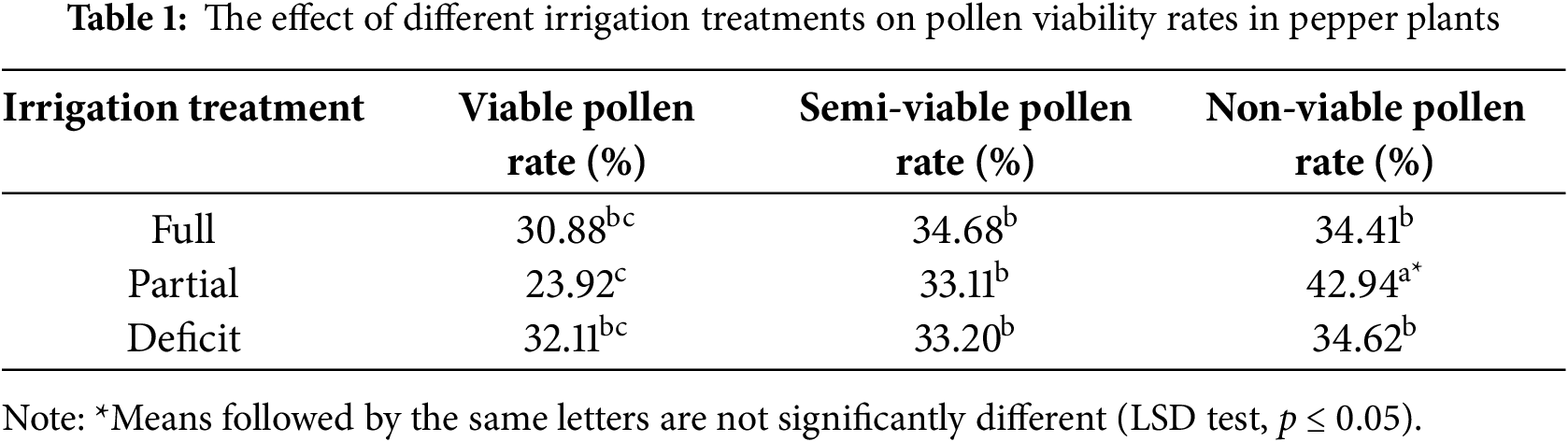

Statistically significant differences in pollen viability rates were observed among different irrigation regimes applied in the experimental plots (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 1). Pollen viability rates varied between 23.92 percent and 42.94 percent depending on the irrigation treatments. The highest percentage of non-viable pollen, 42.94 percent, was recorded under partial irrigation conditions, while the lowest percentage of viable pollen, 23.92 percent, was also observed under the same treatment. Under deficit irrigation, the viable pollen rate was 32.11 percent, the semi-viable pollen rate was 33.20 percent, and the non-viable pollen rate was 34.62 percent. In full irrigation conditions, the viable pollen rate was recorded as 30.88 percent, the semi-viable pollen rate as 34.68 percent, and the non-viable pollen rate as 34.41 percent. Water deficiency can significantly impact pollen viability in plants. A study conducted by Almeida et al. (2021) [26] investigated the effects of different irrigation methods on water use efficiency and yield in Capsicum annuum, revealing a direct correlation between irrigation practices and pollen development. Similarly, Richard et al. (2015) [27] examined the effects of different irrigation levels on pepper yield and water use efficiency under shaded and open-field conditions. Their findings confirmed the negative effects of water limitation on both pollen viability and crop productivity. Mild water stress may activate various adaptive mechanisms in plants that help sustain pollen viability. For instance, enhanced activities of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, CAT, POD, etc.) and the accumulation of osmoprotectants (proline, soluble sugars) can preserve cell membrane integrity, thereby supporting the proper development of pollen. In contrast, full irrigation may induce excessive soil moisture, leading to oxygen deficiency in the root zone, which can impair metabolic processes and reduce pollen viability. Furthermore, the pepper genotype employed in this study may have developed tolerance mechanisms to moderate stress, potentially contributing to the observed outcome. Consistently, previous studies, including Zhang et al. (2023) [28] and Arathi and Smith (2023) [29], have reported that mild water stress can, under certain conditions, enhance pollen viability and reproductive success.

These results indicate that irrigation regimes have a significant impact on pollen viability. The highest proportion of non-viable pollen and the lowest percentage of viable pollen recorded under partial irrigation highlight the adverse effects of water restriction on pollen physiology. The findings underscore the necessity of optimizing irrigation strategies to mitigate the detrimental impacts of water stress on reproductive development in Capsicum annuum.

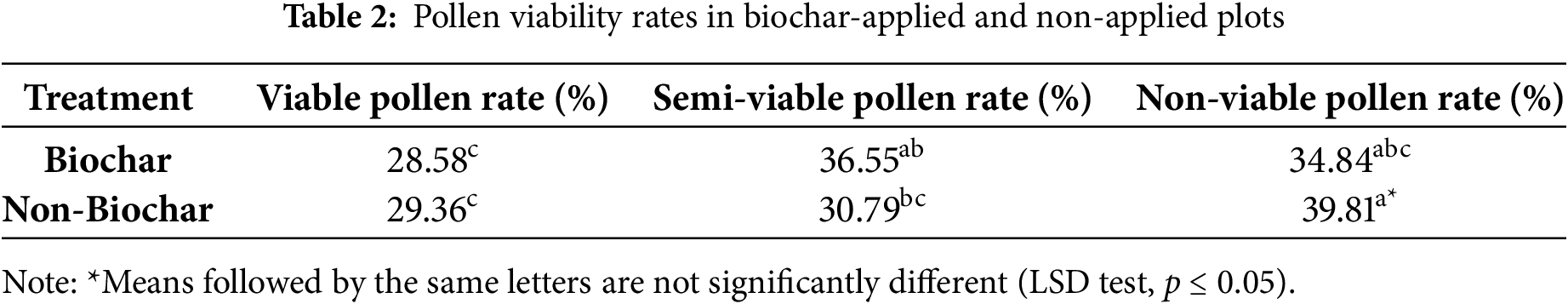

The differences of biochar and non-biochar treatments were found to be statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 2). Pollen viability rates varied between 28.58 percent and 39.81 percent across different treatments. The highest proportion of non-viable pollen, 39.81 percent, was recorded in non-biochar plots, while the highest proportion of semi-viable pollen, 36.55 percent, was observed in biochar-amended plots. In both cases, the lowest rates were recorded in the viable pollen category, suggesting that biochar application did not make a significant contribution to the formation of fully viable pollen.

The findings indicate that biochar application has a significant effect on pollen viability, particularly in reducing the proportion of non-viable pollen. However, despite the observed increase in semi-viable pollen rates, biochar did not lead to a statistically significant improvement in fully viable pollen rates. These results align with findings from previous studies in the literature. A study conducted by Fathi et al. (2022) [30] demonstrated that sago husk biochar applications enhanced growth and yield in pepper plants but did not directly improve pollen viability. Similarly, Wisnubroto et al. (2017) [31] reported that biochar applications contribute to long-term soil fertility and plant growth, yet have no direct impact on pollen physiology.

The potential effects of biochar on pollen viability may be linked to its ability to enhance water management and stress tolerance in plants. Gaber et al. (2024) [32] found that biochar supports plant growth and yield by promoting root development under water stress conditions.

The present findings suggest that while biochar application positively influences pollen viability by reducing the proportion of non-viable pollen, it does not lead to a statistically significant enhancement in fully viable pollen rates. This indicates that despite its beneficial effects on soil fertility and water management, biochar does not provide a distinct advantage in terms of pollen physiology. Indeed, Zhang et al. (2016) [33] reported that excessive application of biochar could inhibit seed germination and seedling growth, revealing its potential phytotoxic effects. Recent studies corroborate this caution: Kataya et al. (2024) [34] found that certain biochar types, particularly at higher doses or lower pyrolysis temperatures, led to inhibition of wheat seed germination and early shoot elongation in germination-assay tests. Similarly, Zabaleta et al. (2024) [35] observed that biochar extracts derived from agro-industrial wastes had species-specific phytotoxic effects on seed germination, root and shoot growth, especially in highly sensitive plant species. These findings suggest that while biochar is overall beneficial, its dosage, feedstock type, production conditions, and the sensitivity of plant species must be carefully considered to avoid adverse effects on reproductive and early developmental stages.

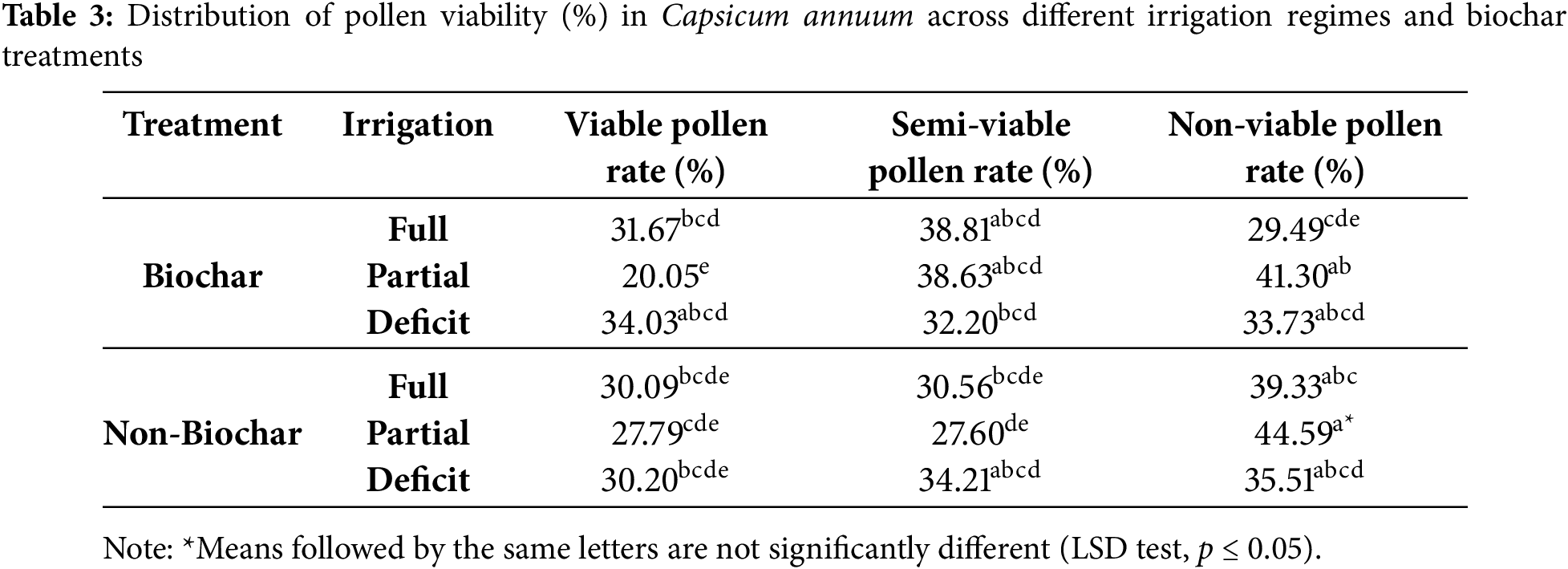

The application × irrigation interaction showed statistically significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) in the viable, semi-viable, and non-viable pollen rates of Capsicum annuum plants (Table 3). In biochar-amended plots, the highest viable pollen rate, 31.67 percent, was recorded under full irrigation, followed by 38.81 percent semi-viable pollen and 29.49 percent non-viable pollen. Under partial irrigation, the viable pollen rate dropped significantly to 20.05 percent, while the non-viable pollen rate peaked at 41.30 percent. In deficit irrigation conditions, the viable pollen rate increased to 34.03 percent, while the semi-viable and non-viable pollen rates were recorded at 32.20 percent and 33.73 percent, respectively.

Biochar application has been shown to enhance growth and yield in Capsicum annuum. A study using sago husk biochar reported that biochar application increased flower bud formation and stem height [26]. This aligns with the findings in Table 3, where pollen viability rates were relatively higher in biochar-treated plots. Arnaoudova and Arnaoudov (2020) [16] found that water stress negatively affects Capsicum annuum pollen fertility, reducing pollen viability by an average of 37.4 percent. This supports the results observed in biochar-free plots, where partial irrigation led to an increase in non-viable pollen rates.

Similar trends were observed in non-biochar plots. Under full irrigation, the viable pollen rate was recorded at 30.09 percent. However, in partial irrigation conditions, this rate dropped to 27.79 percent, while the non-viable pollen rate increased to 44.59 percent. In deficit irrigation, the viable pollen rate in non-biochar plots rose to 30.20 percent, while the non-viable pollen rate was recorded at 35.51 percent. Chakhchar et al. (2024) [36] reported that water-saving irrigation strategies, such as Partial Root Drying and Regulated Deficit Irrigation, improve physiological parameters in pepper plants. Since deficit irrigation was found to increase viable pollen rates under certain conditions (Table 3), these irrigation techniques may provide beneficial effects under specific circumstances. These findings support the results presented in Table 3 and suggest that biochar amendments and optimized irrigation strategies can positively impact pollen viability and overall plant health in Capsicum annuum.

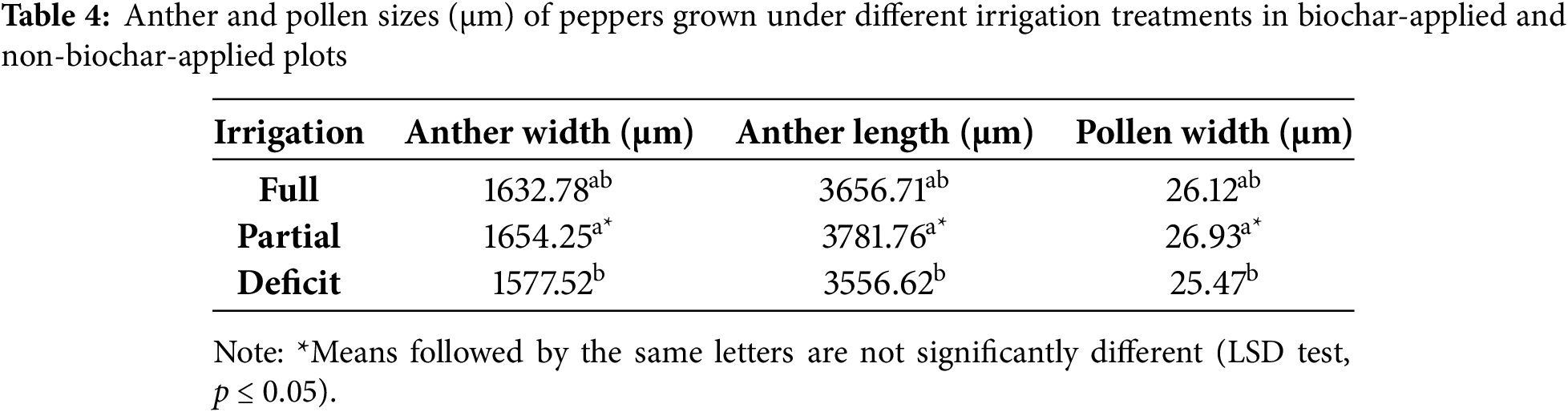

Statistically significant differences were observed among irrigation regimes in terms of anther width, anther length, and pollen width (p ≤ 0.05) (Table 4), whereas pollen length did not show a statistically significant change depending on irrigation levels (p > 0.05). The partial irrigation treatment resulted in the highest values for anther width 1654.25 µm, anther length 3781.76 µm, and pollen width 26.93 µm, indicating that this irrigation strategy provided the most favorable conditions for the morphology of reproductive organs. In contrast, deficit irrigation negatively affected anther and pollen size, leading to the lowest values for anther width 1577.52 µm, anther length 3556.62 µm, and pollen width 25.47 µm. Although full irrigation had a supportive effect on anther and pollen development, partial irrigation produced higher values for all measured parameters. These findings align with previous studies in the literature. Zamljen et al. (2020) [37] reported that different irrigation treatments altered metabolite accumulation in pepper plants and that water deficiency exerted a suppressive effect on flower development and pollen production. This observation is consistent with the reduction in pollen and anther size observed under deficit irrigation in the present study. Additionally, Wang et al. (2020) [38] identified the CaMF5 gene as being associated with anther development in pepper plants, with different environmental factors influencing its expression levels. The varied effects of irrigation regimes on anther and pollen development observed in this study support the hypothesis that irrigation levels may influence gene expression patterns related to reproductive organ formation. Furthermore, Guo et al. (2018) [13] demonstrated that the Aborted Microspores (AMS)-Like gene plays a crucial role in anther and microspore development in pepper plants. The reduced anther and pollen size under deficit irrigation observed in this study may be explained by these genetic mechanisms. Overall, this study highlights that irrigation regimes are a key factor in determining pollen and anther development, with partial irrigation emerging as the most effective strategy. Deficit irrigation resulted in reduced anther and pollen size, while full irrigation supported reproductive organ development but was not as effective as partial irrigation. The findings are further supported by literature, suggesting that partial irrigation provides optimal conditions for pollen development, minimizes the adverse effects of water stress on pollen physiology, and contributes to an efficient fertilization process.

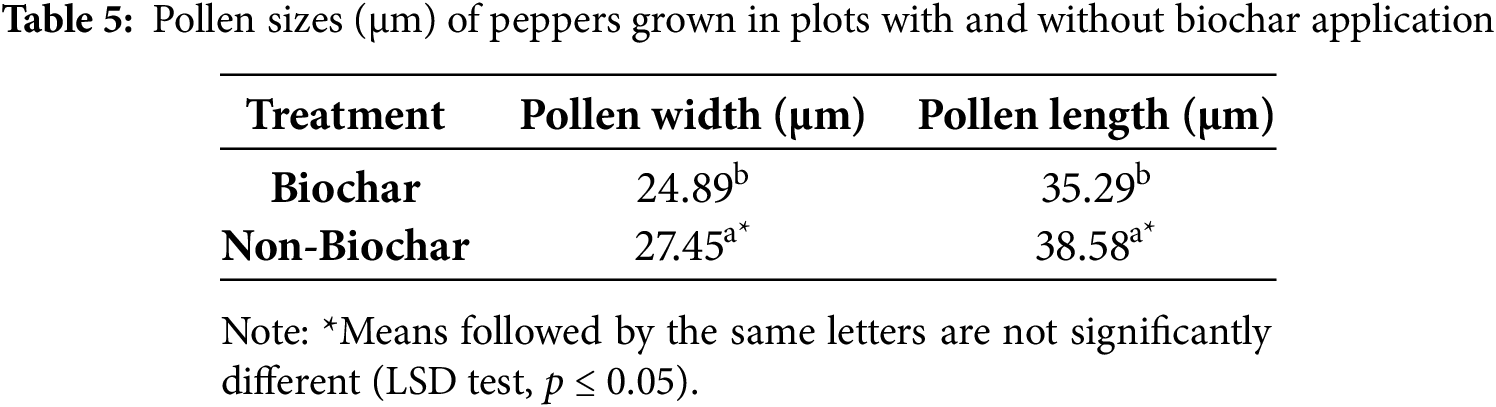

The application of biochar in pepper cultivation was found to have a statistically significant effect on pollen morphology at the p ≤ 0.05 level. Pollen width and pollen length were found to be higher in peppers grown in non-biochar plots compared to those in biochar-amended plots (Table 5). The average pollen width was measured as 27.45 µm in non-biochar plots, whereas in biochar-amended plots, it was recorded as 24.89 µm. Similarly, pollen length was found to be 38.58 µm in non-biochar plots and 35.29 µm in biochar-amended plots. These differences were statistically significant at the p ≤ 0.05 level, indicating that biochar application does not contribute to an increase in pollen dimensions. Statistical analyses revealed that pollen width and pollen length were significantly higher in non-biochar plots. Conversely, a significant reduction in pollen size was observed in biochar-amended plots. The variations in pollen morphology may be associated with how biochar affects soil structure and plant development processes. Biochar is known to enhance soil water retention capacity, thereby supporting plant growth. However, the observed effects on pollen development may be linked to biochar’s interactions with micronutrient uptake and water balance. Several studies in the literature have reported varying effects of biochar on reproductive physiology. A study conducted by Kumar et al. (2018) [39] found that biochar application promoted overall growth and increased disease resistance in pepper plants. However, further research is needed to fully understand its direct effects on plant reproductive physiology. Similarly, a study by Macias-Bobadilla et al. (2020) [24] emphasized the negative impacts of water stress on pollen development, noting that drought conditions could lead to a reduction in pollen size. The observation of smaller pollen sizes in biochar-amended plots may be related to changes in water balance and micronutrient uptake in these plots, as well as genetic and physiological modifications occurring during pollen development.

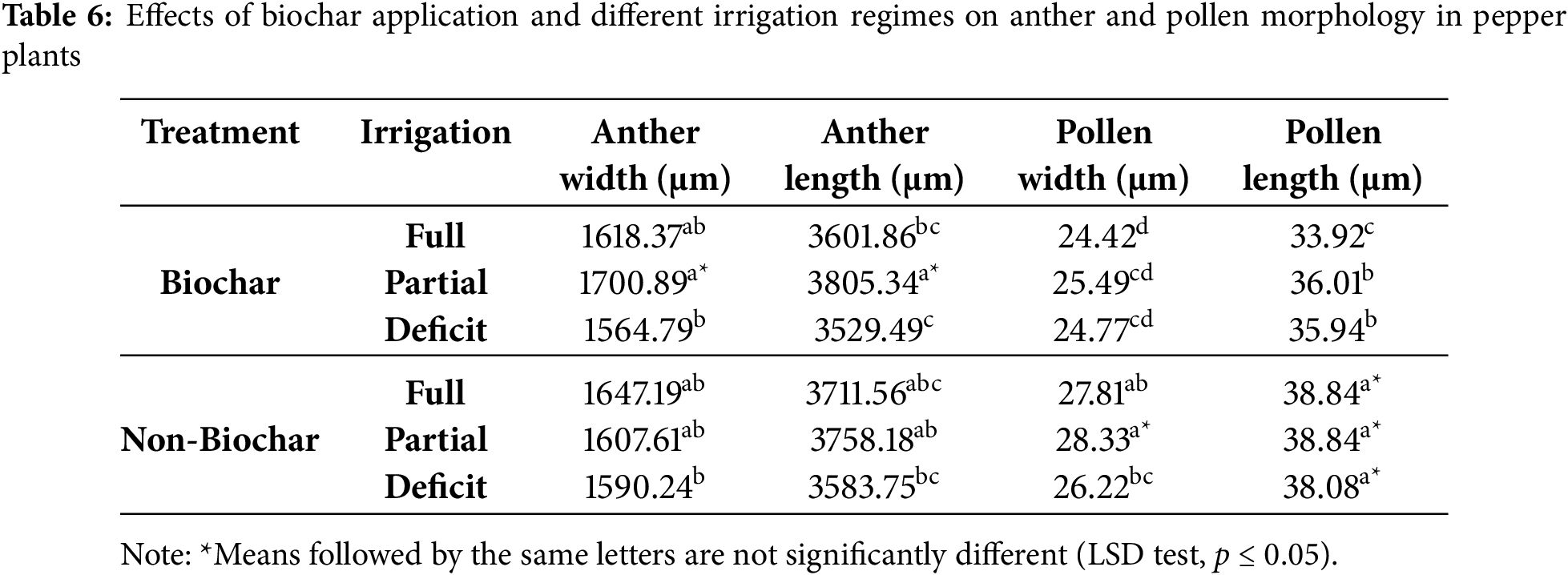

The application × irrigation interaction was found to be statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) for anther width (μm), anther length (μm), pollen width (μm), and pollen length (μm) (Table 6). Comparisons between biochar-amended and non-amended plots showed that the largest anther width and length were obtained under partial irrigation in biochar treated plots. In biochar-amended plots, anther width ranged from 1564.79 to 1700.89 μm, while anther length varied between 3529.49 and 3805.34 μm. In non-biochar plots, anther width ranged from 1590.24 to 1647.19 μm, and anther length varied between 3583.75 and 3758.18 μm. The largest anther dimensions were observed under partial irrigation in bio-char-amended plots, whereas the smallest anther dimensions were recorded under deficit irrigation in non-biochar plots. It is suggested that biochar may positively influence anther development by enhancing soil water retention capacity and optimizing nutrient availability.

Biochar is considered to have a positive effect on anther development by increasing water retention capacity and optimizing soil nutrient availability. Similarly, a study conducted by Fahad et al. (2015) [40]. Demonstrated that high-temperature stress significantly reduces pollen fertility, anther dehiscence, and pollen germination in rice plants. However, it was observed that these adverse effects were substantially mitigated in plants treated with biochar and phosphorus fertilization. The study reported that rice plants subjected to biochar application exhibited higher pollen fertility, improved anther dehiscence, and increased pollen germination rates.

In terms of anther development, a study by Rodríguez-Peña and Wolfe (2023) [41] found that anther dehiscence duration and morphology are significantly influenced by climatic factors. The study determined that larger anther openings prolonged the duration of pollen release. Additionally, high humidity and low-temperature conditions were found to extend anther dehiscence time, thereby delaying pollen dispersion. These findings support the hypothesis that biochar may enhance anther development by improving water retention and stabilizing microclimatic conditions.

Regarding pollen morphology, in non-biochar-treated plots, pollen width ranged from 26.22 to 28.33 μm, while pollen length varied between 38.08 and 38.84 μm. The highest pollen length was recorded under full irrigation conditions in biochar-free plots. Conversely, in biochar-treated plots, pollen width ranged from 24.42 to 25.49 μm, and pollen length varied between 33.92 and 36.01 μm. These findings indicate that pollen dimensions were generally smaller in biochar-treated plots.

In this context, Fatmi et al. (2020) [42] conducted a study highlighting that pollen morphology is subject to variations based on climatic conditions. Their research examined the pollen morphology of Atriplex halimus L., a species found in arid and hyper-arid regions, under different ecological conditions. The findings revealed that pollen shape varied according to climatic zones and that water availability played a crucial role in pollen development. The most common pollen types were more prevalent in arid regions, while distinct pollen morphologies were identified across different bioclimatic zones. Consequently, it is hypothesized that biochar may influence pollen development by increasing water retention and altering pollen size.

These results indicate that the effects of biochar on pollen and anther development are closely associated with irrigation regimes. Specifically, under partial irrigation conditions, biochar appears to enhance anther size. However, from a pollen morphology perspective, biochar application has been found to reduce both pollen width and length. This suggests that biochar may alter the mechanisms of water and nutrient uptake during pollen development, thereby exerting distinct physiological effects on pollen formation. Further research is required to assess the long-term impacts of biochar on anther and pollen morphology under varying soil and climatic conditions.

The findings indicate that irrigation regimes play a crucial role in pollen viability. Under deficit irrigation conditions, the proportion of non-viable pollen increased, whereas full irrigation was associated with higher viable pollen rates. Partial irrigation exhibited a more balanced distribution of pollen viability. In terms of anther and pollen morphology, the highest anther width and length values were recorded under partial irrigation in biochar-amended plots, while biochar application was found to reduce pollen width and pollen length. These results suggest that biochar and irrigation regimes directly influence pollen development and anther morphology, highlighting their strong connection with water management strategies. Particularly, partial irrigation had a positive effect on anther development, while it caused a slight reduction in pollen size. Future studies should focus on the long-term effects of biochar and its interaction with different irrigation regimes to comprehensively analyze its impact on reproductive physiology and underlying mechanisms.

Acknowledgement: We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Prof. Dr. Hayrettin Kuşçu and Dr. Bilge Arslan for their valuable contributions to the design and implementation of the irrigation program.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The planning, establishment of the experiment, and execution of cultural practices were carried out by Başak Müftüoğlu. Measurements of anther and pollen dimensions, as well as pollen viability assays, were performed by Sevinç Başay. Statistical analyses and manuscript preparation were jointly conducted by both authors. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yaban İ, Kabay T. Kuraklik stresinin urfa biberinde iyon klorofil ve enzim içerikleri üzerine etkisi. Toprak Su Derg. 2019;8(1):11–7. doi:10.21657/topraksu.544650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Söylemez S. The impact of waterpad and different irrigation levels on the yield, plant development and some quality features of the pepper. Fresenius Environ Bull. 2021;30(4):3134–40. [Google Scholar]

3. Kuşvuran Ş, Uslu Kiran S, Altuntaş Ö. The morphological, physiological and biochemical effects of drought in different pepper genotypes. TURJAF. 2020;8(6):1359–68. doi:10.24925/turjaf.v8i6.1359-1368.3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Penella C, Calatayud A. Pepper crop under climate change: grafting as an environmental friendly strategy. Climate resilient agriculture: strategies and perspectives. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2018. p. 129–55. doi:10.5772/intechopen.72361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Molla A, Andualem AM, Ayana MT, Zeru MA. Effects of drought stress on growth, physiological andbiochemical parameters of two Ethiopian red pepper (Capsicum annum L.) cultivars. J Appl Hortic. 2023;25(1):32–8. doi:10.37855/jah.2023.v25i01.05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Prasad BVG, Chakravorty S. Effects of climate change on vegetable cultivation. Nat Environ Pollut Technol. 2015;14(4):923–29. [Google Scholar]

7. Sarkar D, Panicker TF, Mishra RK, Kini MS. A comprehensive review of production and characterization of biochar for removal of organic pollutants from water and wastewater. Water-Energy Nexus. 2024;7:243–65. doi:10.1016/j.wen.2024.11.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Edeh IG, Mašek O, Buss W. A meta-analysis on biochar’s effects on soil water properties—new insights and future research challenges. Sci Total Environ. 2020;714:136857. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136857. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Hoque MM, Saha BK, Scopa A, Drosos M. Biochar in agriculture: a review on sources, production, and composites related to soil fertility, crop productivity, and environmental sustainability. C. 2025;11:50. doi:10.3390/c11030050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Khan S, Irshad S, Mehmood K, Hasnain Z, Nawaz M, Rais A, et al. Biochar production and characteristics, its impacts on soil health, crop production, and yield enhancement. Plants. 2024;13:166. doi:10.3390/plants13020166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Aronne G, Iovane M, Strumia S. Temperature and humidity affect pollen viability and may trigger distyly disruption in threatened species. Ann Di Bot. 2021;11:77–82. doi:10.13133/2239-3129/17157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li H, Tiwari M, Tang Y, Wang L, Yang S, Long H, et al. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses reveal that sucrose synthase regulates maize pollen viability under heat and drought stress. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2022;246:114191. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.114191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Guo J, Liu Y, Wu T, Zhang X. The Aborted Microspores (AMS)-like gene is required for anther and microspore devel-opment in Capsicum annuum L. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2018;132:326–34. doi:10.3390/ijms19051341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Razzaq MK, Rauf S, Khurshid M, Iqbal S, Bhat JA, Farzand A, et al. Pollen viability an index of abiotic stresses tolerance and methods for the improved pollen viability. Pak J Agri Res. 2019;32(4):609–24. doi:10.17582/journal.pjar/2019/32.4.609.624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang J, Loka D, Wang J, Ran Y, Shao C, Tuersun G, et al. Co-occurring elevated temperature and drought stress inhibit cotton pollen fertility by disturbing anther carbohydrate and energy metabolism. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;208:117894. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Arnaoudova Y, Arnaoudov B. Screening Capsicum genotypes for increased drought tolerance by in vitro pollen germina-tion and pollen tube length. Bulg J Vet. 2020;23(1):52–8. [Google Scholar]

17. IBI. International biochar initiative, standardized product definition and product testing guidelines for biochar that is used in soil (Version 2.1). 2025 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://biochar-international.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/IBI_Biochar_Standards_V2.1_Final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

18. Lehmann J, Joseph S. Biochar for environmental management: science and technology and implementation. 2nd ed. London, UK: Routledge; 2012. doi:10.4324/9780203762264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Acar M. Tarimsal Deneme Teknikleri. Karadeniz Tarimsal Araştirma Enstitüsü., Samsun, Eğitim Döküman-lari. 2020 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://arastirma.tarimorman.gov.tr/ktae/Belgeler/Uzaktangitim/Deneme%20Teknikleri/ARA%C5%9ETIRMA%20AMA%C3%87LI%20DNEME%20TEKN%C4%B0KLER%C4%B0%20mustafa%20acar.pdf. [Google Scholar]

20. Tagem Suet. Computer Software Web Page. Turkish General Directorate of Agricultural Research & Policies. 2024 [cited 2025 Sep 23]. Available from: https://tagemsuet.tarimorman.gov.tr. [Google Scholar]

21. Allen RG, Pereira LS, Raes D, Smith M. Crop evapotranspiration—guidelines for computing crop water require-ments—FAO Irrigation and drainage paper 56. Rome, Italy: FAO; 1998. [Google Scholar]

22. Sezen SM, Yazar A, Eker S. Effect of drip irrigation regimes on yield and quality of field grown bell pepper. Agric Water Manage. 2006;81(1–2):115–31. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2005.04.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kuşçu H, Turhan A, Özmen N, Aydinol P, Demir AO. Response of red pepper to deficit irrigation and nitrogen fertiga-tion. Arch Agron Soil Sci. 2016;62(10):1396–410. doi:10.1080/03650340.2016.1149818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Macias-Bobadilla I, Vargas-Hernandez M, Guevara-González R, Rico-García E, Ocampo-Velázquez R, Torres-Pacheco I. Differential response to water deficit in chili pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) growing in two types of soil under different irrigation regimes. Agriculturae. 2020;10(9):381. doi:10.3390/agriculture10090381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Borràs D, Barchi L, Schulz K, Moglia A, Acquadro A, Kamranfar I, et al. Transcriptome-based identification and functional characterization of nac transcription factors responsive to drought stress in Capsicum annuum L. Front Genet. 2021;12:743902. doi:10.3389/fgene.2021.743902. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Almeida CDGCD, Gordin LC, Almeida ACDS, Santos Júnior JA, Almeida BGD, Provenzano G. Assessing yield and water use efficiency of Capsicum annuum L. cultivated in a greenhouse under different irrigation strategies. In: Proceedings of the vEGU21, the 23rd EGU General Assembly; 2021 Apr 19–30. Online. doi:10.5194/egusphere-egu21-8349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Richard A, Jerson V, Alexandre S, Cicero U, Roxanna R, Juan C. Supplemental irrigation levels in bell pepper un-der shade mesh and in open-field: crop coefficient, yield, fruit quality and water productivity. Afr J Agric Res. 2015;10(44):4117–25. doi:10.5897/AJAR2015.10341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang J, Cheng M, Cao N, Li Y, Wang S, Zhou Z, et al. Drought stress and high temperature affect the antioxidant metabolism of cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) anthers and reduce pollen fertility. Agronomy. 2023;13(10):2550. doi:10.3390/agronomy13102550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Arathi HS, Smith TJ. Drought and temperature stresses impact pollen production and autonomous selfing in a California wildflower, Collinsia heterophylla. Ecol Evol. 2023;13:e10324. doi:10.1002/ece3.10324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Fathi NKM, Bukhori MFM, Abdullah SMAA, Wahi R, Zailani M, Gopal MMR. Effect of sago bark biochar application on Capsicum annuum L. var. Kulai growth and fruit yield. Malays Appl Biol. 2022;51(3):127–35. doi:10.55230/mabjournal.v51i3.2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Wisnubroto E, Utomo W, Indrayatie E. Residual effect of biochar on growth and yield of red chili (Capsicum annuum L.). J Agric Technol. 2017;4(1):28–31. doi:10.18178/joaat.4.1.28-31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Gaber M, Nasser GA, Hussein A. Positive effects of biochar on pepper growth, yield, and root distribution under water stress conditions. AJSWS. 2024;8(2):57–74. doi:10.21608/AJSWS.2024.256889.1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang P, Zhang R, Fang X, Song T, Cai X, Liu H, et al. Toxic effects of graphene on the growth and nutritional levels of wheat (Triticum aestivum L.short- and long-term exposure studies. J Hazard Mater. 2016;317:543–51. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.06.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Kataya G, El Charif Z, Badran A, Cornu D, Bechelany M, Hijazi A, et al. Evaluating the impact of different biochar types on wheat germination. Sci Rep. 2024;14:28663. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-76765-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Zabaleta R, Sánchez E, Navas AL, Fernández V, Fernandez A, Zalazar-García D, et al. Phytotoxicity assessment of agro-industrial waste and its biochar: germination bioassay in four horticultural species. Agronomy. 2024;14:2573. doi:10.3390/agronomy14112573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chakhchar A, Dakir S, Echchiguer H, Choukri A, Filali-Maltouf A, El Modafar C. Enhancing growth and tolerance traits in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) through water-saving irrigation practices. Not Sci Biol. 2024;16(3):1–13. doi:10.55779/nsb16312040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zamljen T, Zupanc V, Pintar M, Šircelj H. Influence of irrigation on yield and primary and secondary metabolites of bell pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Agric Water Manage. 2020;234:106264. doi:10.1016/j.agwat.2020.106104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang P, Chen L, Gao S, Xie Y. Identification and characterization of a LEA-like gene CaMF5 involved in anther de-velopment in Capsicum annuum. Hortic Plant J. 2020;71(5):1445–57. doi:10.1016/j.hpj.2019.07.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kumar P, Elad Y, Shtienberg D, Meller-Harel Y. Biochar potential in intensive cultivation of Capsicum annuum L. Sci Hortic. 2018;232:65–72. [Google Scholar]

40. Fahad S, Hussain S, Saud S, Tanveer M, Bajwa A, Hassan S, et al. A biochar application protects rice pollen from high-temperature stress. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2015;96:281–7. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.08.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Rodríguez-Peña RA, Wolfe AD. Effect of climate, anther morphology and pollination syndrome on pollen availability in Penstemon. J Pollinat Ecol. 2023;35:296–311. doi:10.26786/1920-7603(2023)703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Fatmi H, Maalem S, Harsa B, Dekak A, Chenchouni H. Pollen morphological variability correlates with a large-scale gradient of aridity. Web Ecol. 2020;20:19–32. doi:10.5194/we-20-19-2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools