Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

β-Aminobutyric Acid Promotes Germination of Aged Triticale Seeds and Alleviates Oxidative Stress

1 Yuriev Plant Production Institute, National Academy of Agrarian Sciences of Ukraine, Kharkiv, 61060, Ukraine

2 Department of Agriculture and Herbology, State Biotechnological University, Kharkiv, 61002, Ukraine

3 Czech Agrifood Research Center, Prague, 16100, Czech Republic

4 Department of Plant Protection, Poltava State Agrarian University, Poltava, 36003, Ukraine

* Corresponding Author: Yuriy E. Kolupaev. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Stress Metabolites of Plants: Protective and Regulatory Functions)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(10), 3125-3143. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071822

Received 12 August 2025; Accepted 09 September 2025; Issue published 29 October 2025

Abstract

β-Aminobutyric acid (BABA) is a physiologically active plant compound that has not been extensively studied. It has been shown to increase resistance to biotic and abiotic stress factors and enhance seed germination in certain plant species. However, its effects on cereal grains with low germination rates have not yet been studied. This study investigated the effects of BABA on the germination of aged triticale seeds, the metabolite content of seedlings, and the state of their antioxidant systems. The study found that a three-hour treatment of seeds in BABA solutions at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 mM increased germination energy and germination (by 10%–14%) and enhanced the accumulation of shoot and root biomass (by 17%–26%). Additionally, amylase activity increased in the grains, and the accumulation of osmolytes (sugars and proline) increased in the shoots. The content of anthocyanins in shoots increased by almost twofold, and the activity of antioxidant enzymes (superoxide dismutase, catalase, and guaiacol peroxidase) increased by approximately 20%–30%. Simultaneously, BABA seed priming caused a noticeable decrease in the levels of hydrogen peroxide and lipid peroxidation products in the shoots of seedlings. The conclusion was made that the use of BABA as a bioregulator has the potential to enhance the germination of seeds with low sowing qualities. This is due to the ability of BABA to activate the metabolism of reserve substances in the grain and prevent the development of oxidative stress.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Over the past two decades, information on the functions of non-proteinogenic amino acids in plants has rapidly accumulated [1–3]. Plants are known to synthesize over 250 amino acids that do not participate in protein synthesis but perform essential functions for growth, development, and responses to stress factors [4]. Some of these amino acids serve as precursors for many primary and secondary metabolites in plants and other organisms [5]. Important non-proteinogenic amino acids synthesized by plants include α-, β-, and γ-isomers of aminobutyric acid [3]. The role of endogenous α-aminobutyric acid remains largely unknown. However, two other aminobutyric acid isomers are being investigated as important participants in plant adaptive responses [6]. Researchers have paid the most attention to the physiological role of γ-aminobutyric acid [7], which is probably due to its high content in plants and well-known synthesis and catabolism pathways [8]. Meanwhile, β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) is present in plant cells at levels approximately 1200 times lower than those of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [9]. Nevertheless, the ability of a number of higher plants to synthesize BABA has now been proven. Its concentration increases in response to various biotic and abiotic stressors [9,10] and during plant senescence [11].

Different isomers of aminobutyric acid may play a role in plant seed germination. For example, a positive correlation has long been established between the amount of endogenous GABA in wheat grains and their germination capacity [12]. Treatment with GABA has been shown to prevent a decrease in the content of unsaturated and polyunsaturated fatty acids and contribute to the preservation of viability in pumpkin seeds (Cucurbita pepo subsp. pepo) subjected to artificial aging [13]. Several studies have demonstrated that the positive impact of priming various crop plant seeds with aminobutyric acid isomers on germination under adverse conditions [3]. Until recently, research on seed and plant priming has focused on the more common GABA [14]. However, in recent years, several studies have demonstrated that BABA can enhance seed germination, particularly under adverse conditions [15–17].

It is well known that germination energy is one of the main indicators of seed quality and plays a key role in ensuring optimal germination and yield [18]. Of the various agronomic strategies developed to enhance germination energy, priming is recognized as an effective method for inducing the necessary physiological processes for germination [19–21]. The term ‘seed priming’ usually refers to soaking seeds in a specific solution that provides partial hydration but not germination, followed by re-drying to the original moisture content [22]. Cells perceive the priming procedure as an external signal, primarily about a change in moisture content, which leads to the activation of a signaling network [23]. Development of innovative priming methods, especially those involving nanoparticles and new groups of compounds with hormonal activity, opens up new opportunities for economical and environmentally safe influence on seed germination under optimal and stressful conditions and subsequent plant development [24–26].

Several processes occurring during priming have been described at the cellular scale. These processes include cell cycle activation and the mobilization of reserve polymers, such as proteins and starch [25]. Seed germination processes are accompanied by an increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are involved in the formation of redox signals necessary for seedling growth [27]. However, to control the amount of ROS during seed germination, the antioxidant system must also be activated [28]. In this regard, it is proposed that both plant hormones, which activate the signaling network and thereby the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes, and metabolites that may have direct or indirect antioxidant effects, be used as priming agents for seed treatment [29]. BABA belongs to a group of compounds that activate the antioxidant system [30,31].

It should be noted that increased ROS formation in seeds may be one of the main causes of seed aging [32]. Improper seed storage, which causes accelerated aging, leads to the formation of ROS, which activates lipid peroxidation (LPO), ultimately resulting in membrane damage [33]. Oxidative stress also causes protein carbonylation, which is characteristic of aging seeds [34], and, in some cases, DNA damage [33,35]. In this regard, the use of classic antioxidants, in particular glutathione and ascorbic acid, as priming agents may be effective in improving the germination of aged seeds or seeds with deteriorated sowing quality due to improper storage [36]. Recently, however, the effects of compounds that can exert both direct (i.e., binding ROS) and indirect (i.e., activating the expression of target genes of the antioxidant system) protective effects have been investigated. Such compounds include melatonin and GABA, which are widespread in plant cells [37,38]. The similar effects of BABA have not yet been sufficiently studied, although experimental data have been obtained on BABA’s ability to increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes and enhance the accumulation of low-molecular-weight antioxidants in plants under various stressors [3].

Seeds of triticale, a hybrid species obtained by crossing wheat and rye, are characterized by a fairly rapid decline in germination during storage under suboptimal conditions [39]. Aging triticale seeds have proven to be a convenient model for studying the effects of new priming agents, particularly melatonin and GABA [39,40]. However, the effect of BABA on triticale seed germination has not yet been specifically studied.

This study aimed to investigate the effect of BABA on the germination of aged triticale seeds in connection with the possible activation of the antioxidant system and the accumulation of multifunctional stress metabolites in seedlings.

2.1 Plant Material and Experimental Design

The study used winter triticale (× Triticosecale) seeds of the Raritet cultivar (originator: Yuriev Plant Production Institute of the National Academy of Agrarian Sciences of Ukraine), from the 2021 generation. The seeds were stored indoors for three years under uncontrolled conditions. During the summer months, the temperature periodically exceeded 30°C, while in the winter, it dropped to −8°C. The relative humidity exhibited fluctuations between 25%–30% and 80%–85% during storage. Previous studies have shown that these conditions significantly reduce the germination energy and rate of triticale seeds, causing accelerated aging similar to natural aging [39].

The seeds were disinfected with a 5% sodium hypochlorite solution for 15 min and then washed eight times with sterile distilled water. Further experimental procedures are schematically represented in Fig. 1. Some of the seeds were placed in glasses with distilled water for three hours (hydropriming). As previously demonstrated, this procedure alone increases seed germination by approximately 10% [39]. In this regard, the control group consisted of the variants with hydropriming. The seeds of the experimental variants were treated with BABA solutions (“TCI America”, Tokyo, Japan) at final concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.5 mM (with a seed-to-solution ratio for priming of 1:3). After priming, the seeds of all variants were dried in a thermostat at 24°C with 40% humidity for 24 h (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Scheme of the experiment on the effects of β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) on germination of triticale grains

Seventy-five approximately identical triticale grains were placed on double filter paper moistened with 8 mL of distilled water within Petri dishes. The seeds were then placed in a dark thermostat at 24°C and left to germinate for three days. Germination energy and rate were assessed after two and three days, respectively (Fig. 1). Seeds with shoots equal to or longer than the grain size were considered germinated. After three days of germination, the biomass of the roots and shoots was evaluated. Biochemical indicators (except amylase activity) were determined in the shoots of three-day-old seedlings. Amylase activity was estimated in the grains 48 h after germination began (Fig. 1).

2.2 Analysis of Amylase Activity

Total amylase activity was determined in seeds using starch-containing agar plates and ImageJ software [41]. The grains were cut with a sharp lancet. The halves of the grains without embryos were placed cut side down in Petri dishes on plates containing 1% agar and 0.2% starch. The samples were then incubated in a thermostat at 24°C for three hours. Then, the gels were poured with 10 mL of diluted Lugol’s solution (0.04% I2 in 0.1% KI). After five minutes, the excess solution was removed with an autopipette, and the image was photographed with a Samsung SM-N9750 camera on glass covered with paper and lit from below. The photographs were analyzed using ImageJ software (version 1.54 g). Color images were converted to single-channel halftones to remove variability caused by color information and analyze differences in color intensity. Masks of illuminated halos around the grains were created on the pre-processed images using ImageJ selection tools, excluding the cut areas of the grains themselves [41]. The pixel area of the selected areas was measured using ImageJ tools. The results were converted to mm2. Enzyme activity was expressed in conventional units (mm2/h). To determine the proportion of β-amylase in the total enzyme activity, a separate analysis was conducted in which 2 mM EDTA, which inhibits α-amylase, was added to the starch-containing agar [42].

2.3 Determination of Sugar Content

The total soluble carbohydrate content of the seedlings’ shoots was determined using the modified Roe method [43,44]. The plant material was homogenized in distilled water and boiled in a water bath for 10 min. Equal volumes of 30% ZnSO4 and 15% K4[Fe(CN)6] were then added to precipitate proteins. The samples were stirred, filtered through paper filters, and diluted with distilled water as needed. Then, 1 mL of the diluted extract was mixed with 3 mL of anthrone reagent. The comparison solution had 1 mL of purified water instead of the extract. The samples were boiled in a water bath for seven minutes, cooled, and the absorption was determined at 610 nm using a UV-1280 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). D-glucose was used as a standard.

2.4 Determination of Proline Content

Proline content was determined using the method described by Bates et al. [45], with minor modifications. The shoot samples were homogenized in distilled water. Then, the homogenate was boiled for 10 min in a water bath. The samples were then cooled and filtered through paper filters. In reaction tubes, 1 mL of extract, glacial acetic acid, and ninhydrin reagent were mixed. The tubes were covered with foil caps and heated in a boiling water bath for one hour. Absorption was determined at a wavelength of 520 nm. L-proline served as the standard.

2.5 Determination of Secondary Metabolite Content

To determine the total content of phenolic compounds and anthocyanins, the shoots were homogenized in 10 mL of 80% ethanol, extracted for 20 min at room temperature, and then subjected to centrifugation in an MPW 350R centrifuge (MPW MedInstruments, Poland) at 8000 g for 15 min. To analyze the phenolic compound content, 0.5 mL of the supernatant was added to reaction tubes along with 8 mL of distilled water and 0.5 mL of Folin’s reagent. The tubes were mixed and, after 3 min, 1 mL of 10% sodium carbonate was added. One hour later, the absorption of the reaction mixture was measured at 725 nm [46]. The phenolic compound content was expressed in micromoles of gallic acid per gram of fresh weight.

Before determining the anthocyanin content, the supernatant was acidified with HCl to a final concentration of 1% [47]. Absorption was measured at 530 nm. The results were expressed as the absorption index per gram of fresh weight in conventional units.

2.6 Determination of Antioxidant Enzymes’ Activity

To analyze the activity of antioxidant enzymes, shoot samples were homogenized on ice in 0.15 M K, Na-phosphate buffer (pH 7.6) containing 0.1 mM EDTA and 1 mM dithiothreitol [48]. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min at a temperature not exceeding 4°C.

Superoxide dismutase (SOD) total activity was determined at a pH of 7.6 in the reaction mixture using a method based on the enzyme’s ability to compete with nitroblue tetrazolium for superoxide anion radicals formed by an aerobic interaction of NADH and phenazine methosulfate. Catalase (CAT) activity was determined by the amount of H2O2 decomposed per unit time at the reaction mixture pH of 7.0. Guaiacol peroxidase (GPX) activity was analyzed using guaiacol as the hydrogen donor and H2O2 as the substrate. Prior to analysis, the pH of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 6.2 using a K, Na-phosphate buffer. Then, the absorbance of tetraguaiacol (TG, E = 26.6 mM−1 cm−1), formed in the reaction mixture, was measured at 470 nm.

2.7 Determination of Hydrogen Peroxide Content

To determine the hydrogen peroxide content, shoot samples were homogenized in a 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) solution on ice. The samples were then centrifuged at 8000 g for 10 min at a temperature not exceeding 4°C. The amount of H2O2 was subsequently estimated in the supernatant using the ferricyanide method [49]. It is based on the oxidation of Fe2+ to Fe3+ by H2O2 in an acidic medium, followed by the formation of a colored complex of Fe3+ with SCN– ions. Hydrogen peroxide solutions were used as standards.

2.8 Determination of Lipid Peroxidation Products

To analyze the content of lipid peroxidation (LPO) products, mainly malondialdehyde (MDA), plant material samples were homogenized in a solution of 0.25% thiobarbituric acid in 10% TCA (experimental sample) or only 10% TCA (control sample). The mixtures were boiled in foil-covered test tubes in a water bath for 30 min. The tubes were then cooled and centrifuged for 15 min at 10,000 g, after which the absorption of the supernatant was measured at wavelengths of 532 nm (the main signal) and 600 nm (non-specific light absorption, which was subtracted from the main result, A532) [50]. The MDA content was calculated based on the molar extinction coefficient (E = 1.55 × 105 M−1 cm−1).

2.9 Repetition of Experiments and Statistical Processing of Results

The effect of BABA treatment on seed germination and biomass of seedling organs was determined by conducting at least three repetitions of each experiment, with each repetition consisting of 75 grains or seedlings. For biochemical analyses (except amylase activity determination), each sample consisted of at least 12 shoots, and the analyses were performed in triplicate. Amylase activity was determined in five replicates, and data for each replicate were obtained in separate Petri dishes containing all experimental variants, with each variant represented by four grains.

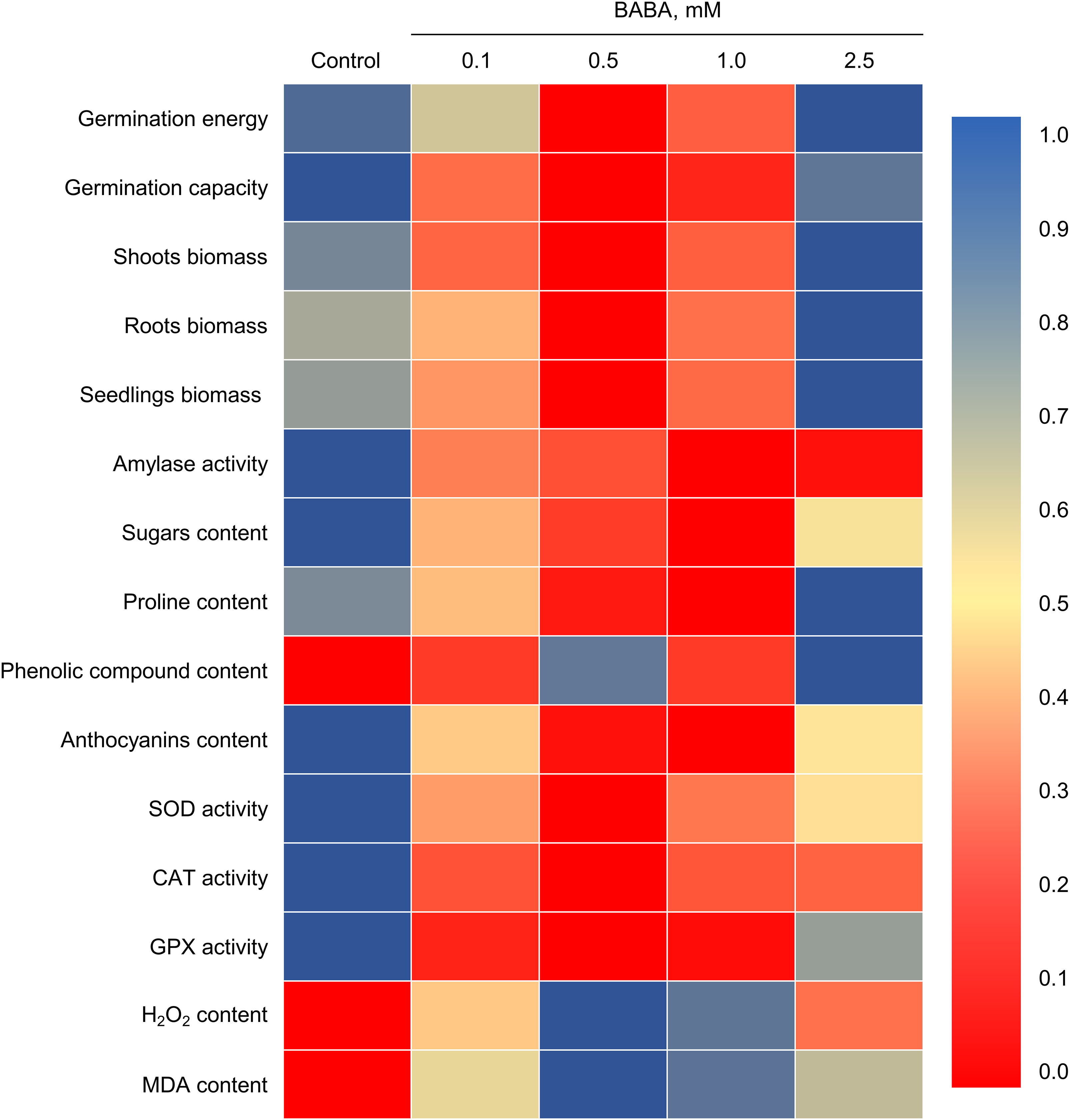

For the determination of the significance of differences between variants according to the studied indicators, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, and a Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple comparisons. In the analysis of seedling biomass, a separate one-way ANOVA was performed for shoot, root, and whole seedling weight indices at different BABA concentrations. Figures and tables display the mean values from three biological replicates and their respective standard errors. Different letters indicate significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 by Fisher’s LSD test. When constructing the heat map, we normalized all parameters to the range of 0 to 1 (min-max). Pearson’s correlation coefficients and their significance were calculated using MS Excel.

3.1 Seed Germination and Seedling Biomass

The germination energy and rate of triticale seeds that underwent natural aging were low (Fig. 2A). Priming the seeds with BABA at concentrations of 0.1, 0.5, and 1 mM increased their germination energy and rate. Exposure to higher concentrations of BABA did not positively affect grain germination.

Figure 2: Effect of β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) on × Triticosecale grain germination (A) and seedling growth (B), and the average germinated seedlings’ phenotype (C). Different letters ‘a–c’ denote values with significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 by Fisher’s LSD test within an individual indicator (organ)

Treatment of seeds with BABA at the same concentrations, ranging from 0.1 to 1 mM, increased the shoot and root biomass of seedlings (Fig. 2B). The most effective concentration was 0.5 mM. Meanwhile, exposure to 2.5 mM BABA did not affect shoot biomass but slightly reduced root biomass and consequently the total mass of seedlings. The seedlings in this variant were almost identical to those in the control (Fig. 2C).

3.2 Amylase Activity in Grains

Total amylase activity in triticale grains after 48 h of germination increased with BABA priming across the studied concentration range (0.1–2.5 mM; Fig. 3). It should be noted that the presence of an α-amylase inhibitor (2 mM EDTA) was found to result in β-amylase activity identified in wheat grain being no more than 10%–12% of the total amylase activity. Therefore, the quantitative measurement of β-amylase was not performed because of the assumption that α-amylase activity primarily contributes to the total enzyme activity in grains.

Figure 3: Effect of β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) on amylase activity in triticale grains (A) and typical view of the measurement result (B). Different letters ‘a–b’ denote values with significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 by Fisher’s LSD test

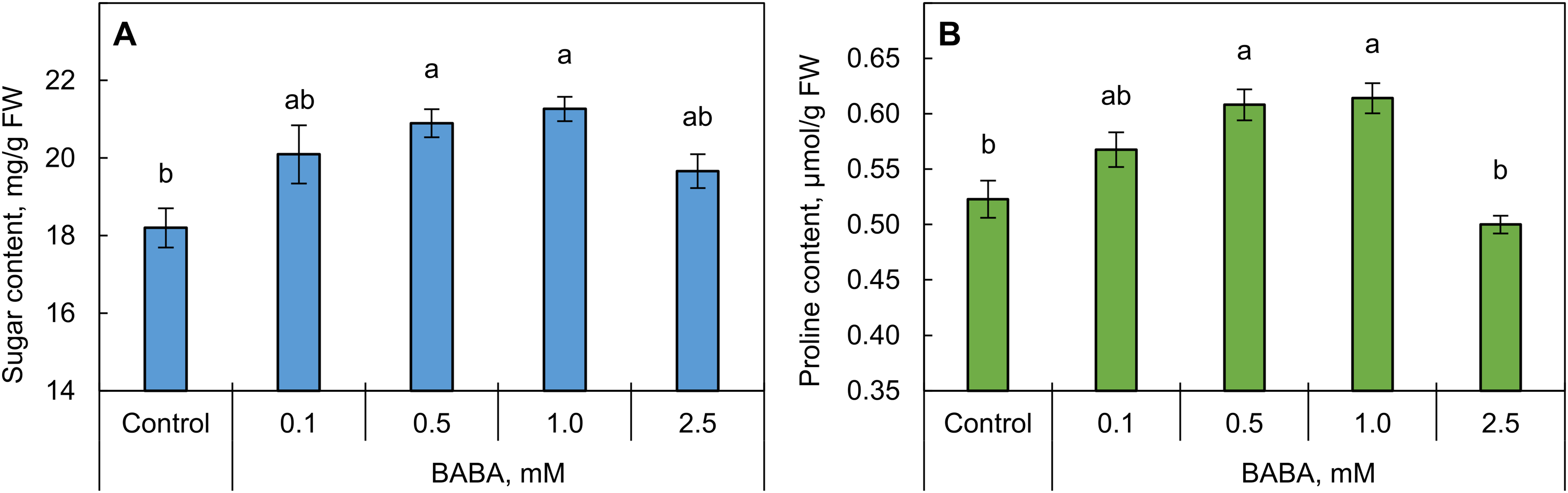

3.3 Content of Sugars, Proline, and Secondary Metabolites in Seedling Shoots

Treatment of triticale grains with BABA at concentrations 0.5 and 1 mM caused a significant (p ≤ 0.05) increase in sugar content in the shoots (Fig. 4A). Within this same concentration range, BABA caused an increase in free proline content in triticale shoots (Fig. 4B). A higher concentration of BABA (2.5 mM) did not significantly affect the osmolyte content in shoots (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Effect of β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) on sugar (A) and proline (B) content in triticale shoots. Different letters ‘a–b’ denote values with significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 by Fisher’s LSD test

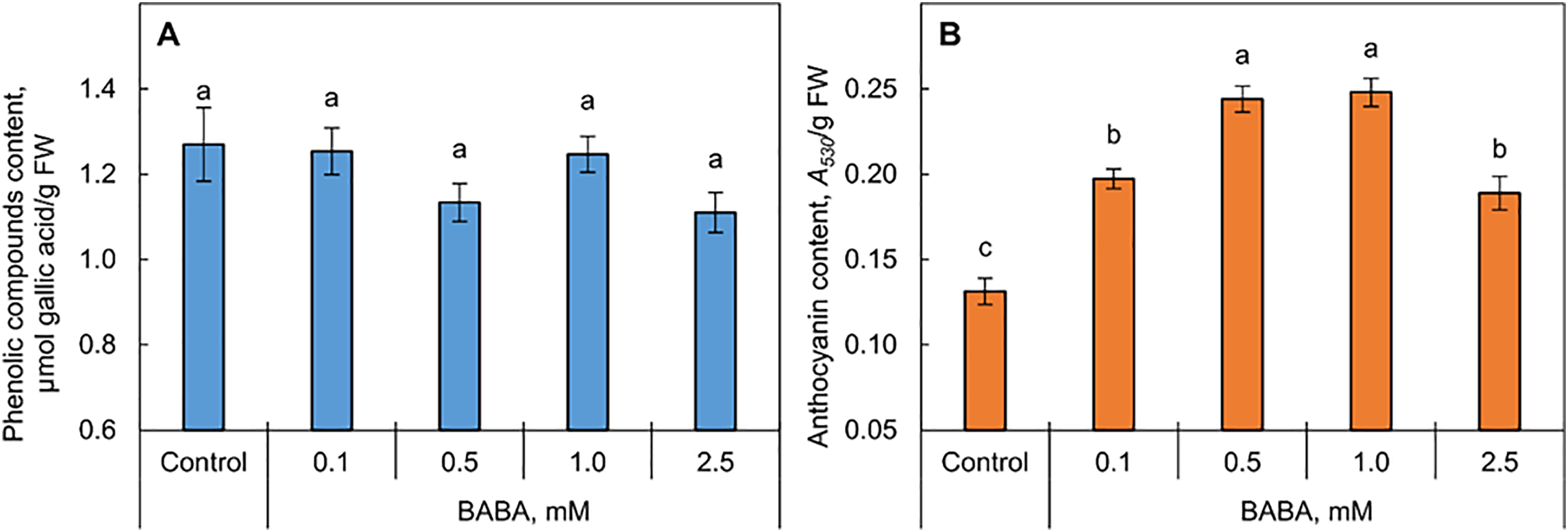

The total content of phenolic compounds in shoots of seedlings from seeds primed with BABA did not differ from the control (Fig. 5A). At the same time, treatment of seeds with BABA in the entire concentration range caused a significant increase in the content of anthocyanins in shoots (Fig. 5B). In the 0.5- and 1.0-mM BABA variants, it was almost two fold.

Figure 5: Effect of β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) on the total content of phenolic compounds (A) and anthocyanins (B) in triticale seedling shoots. Different letters ‘a–c’ denote values with significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 by Fisher’s LSD test

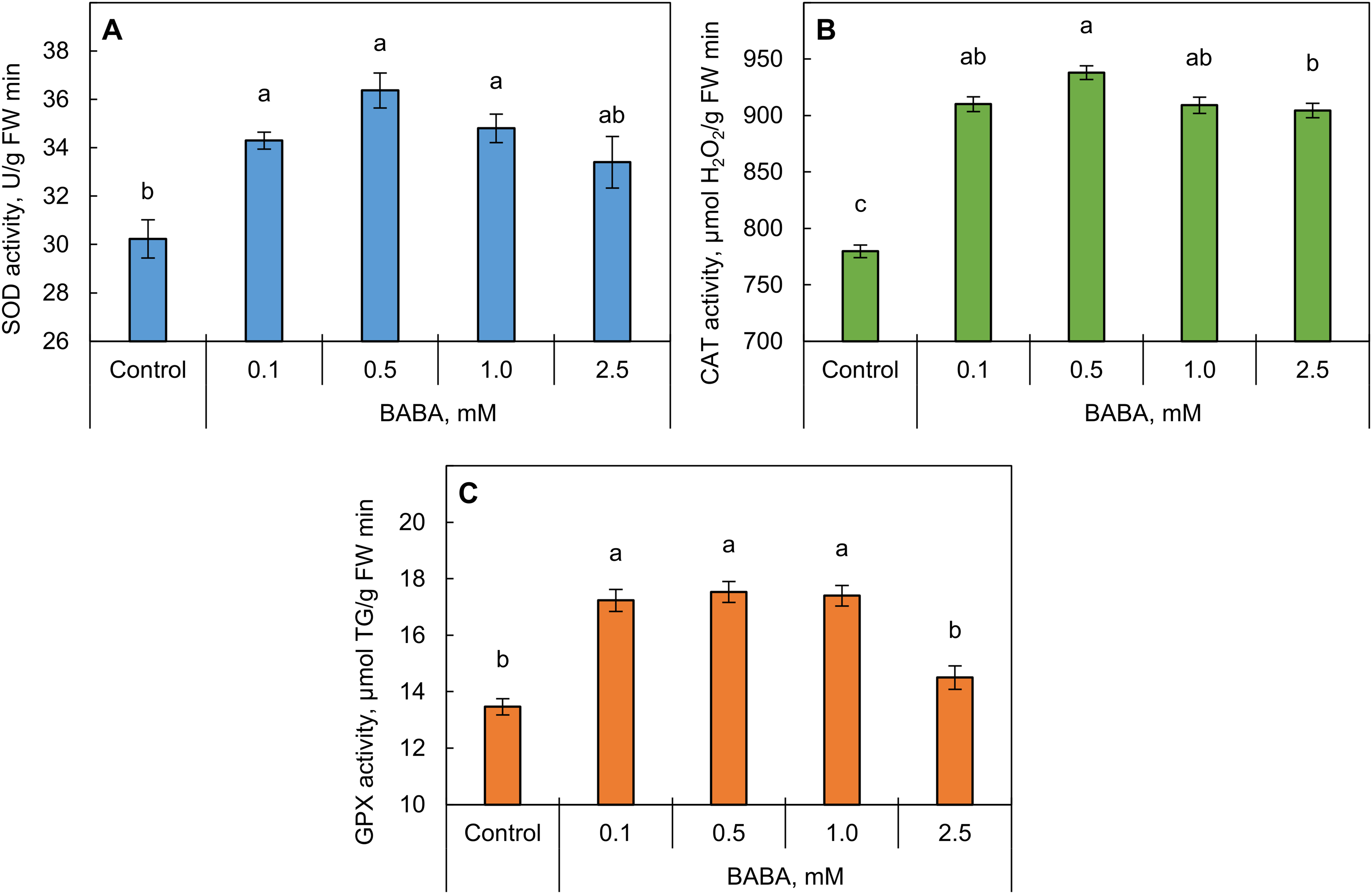

3.4 Antioxidant Enzymes’ Activity in Seedling Shoots

Priming triticale seeds with BABA at all concentrations led to an increase in SOD activity (14%–21% relative to the control) (Fig. 6A). Additionally, an increase in CAT activity (16%–20% relative to the control) was observed in the seedlings obtained from all primed seeds (Fig. 6B). A significant increase of approximately 30% in GPX activity was observed in the shoots of seedlings obtained from seeds primed with BABA at concentrations of 0.1–1.0 mM (Fig. 6C). However, the higher concentration of BABA (2.5 mM) did not significantly increase GPX activity (p ≤ 0.05).

Figure 6: Effect of β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) on the activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD, A), catalase (CAT, B), and guaiacol peroxidase (GPX, C) in triticale seedlings. Different letters ‘a–c’ denote values with significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 by Fisher’s LSD test

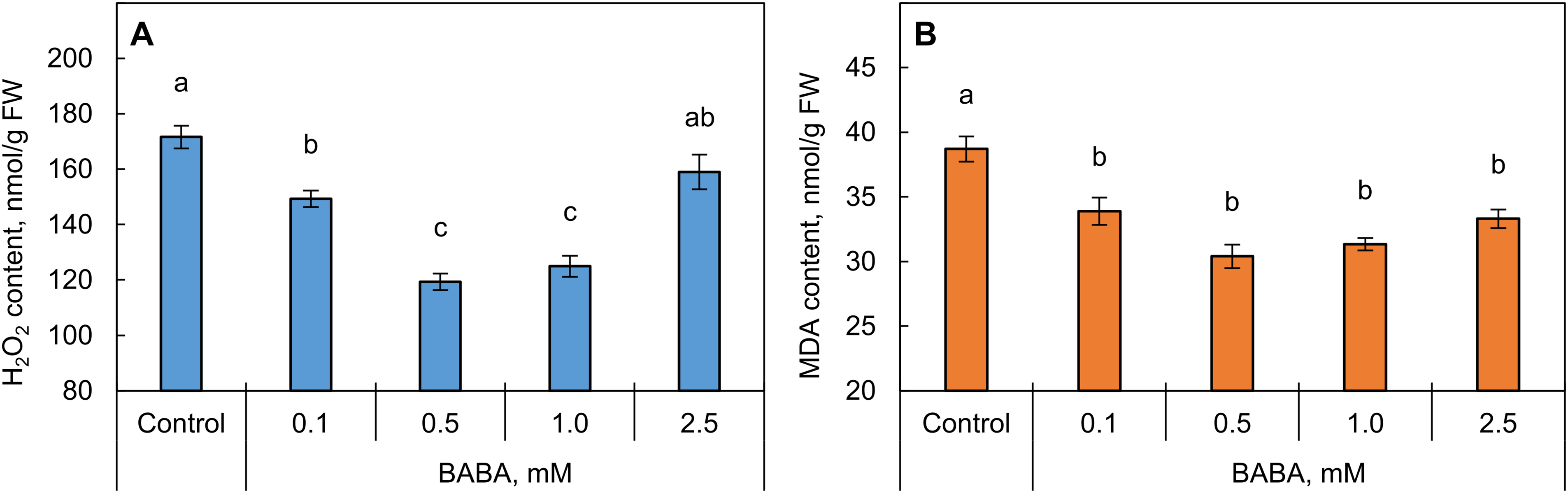

3.5 Hydrogen Peroxide and MDA Content in Seedling Shoots

Treating seeds with BABA at concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 mM decreased the hydrogen peroxide content in the shoots of seedlings (Fig. 7A). The most significant decrease in H2O2 content occurred with BABA concentrations of 0.5 and 1.0 mM. Meanwhile, priming BABA seeds at a concentration of 2.5 mM did not significantly alter hydrogen peroxide content.

Figure 7: Effect of β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) on hydrogen peroxide (A) and malondialdehyde (MDA, (B) content in triticale shoots. Different letters ‘a–c’ denote values with significant differences at p ≤ 0.05 by Fisher’s LSD test

Under BABA seed priming conditions, a decrease in final LPO product MDA content was observed across the entire concentration range (Fig. 7B). This effect was most pronounced at 0.5 and 1 mM.

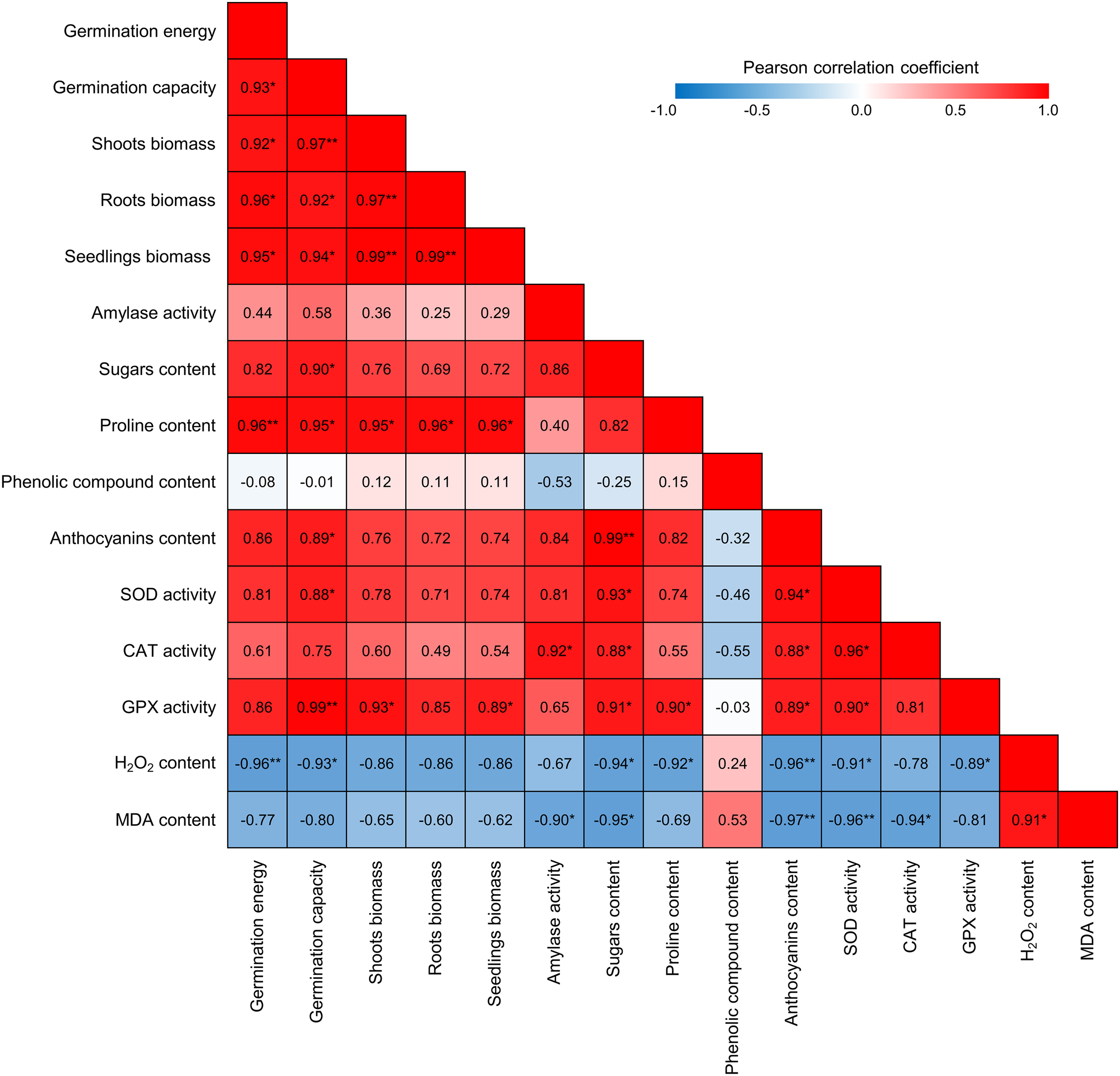

3.6 Correlation between Physiological and Biochemical Indicators of Seed Germination

The calculations showed a close positive correlation between the seed germination and seedling growth and the content of multifunctional metabolites, such as sugars and proline, in shoots (Fig. 8). Thus, the correlation between seed germination and sugar content (r = 0.90) was significant at p ≤ 0.05. A fairly strong correlation (r = 0.82, significant at p ≤ 0.1) was also found between the seed germination energy and the sugar content in shoots. Additionally, a fairly high level of correlation was found between the sugar content in shoots and the amylase activity in grains (r = 0.86, significant at p ≤ 0.1). This may indicate that the hydrolysis of reserve starch in grains contributes to the accumulation of sugars in shoots. An even closer relationship was found between the seed germination, seedling growth, and proline content in the shoots; in this case, all r-values were between 0.95 and 0.96 (Fig. 8). Anthocyanin content in the shoots also positively correlated with the seed germination (r = 0.86, significant at p ≤ 0.1).

Figure 8: Pearson correlation between growth indices and biochemical parameters during triticale seed germination after priming with β-aminobutyric acid. *Correlation is significant at p ≤ 0.05, **Correlation is significant at p ≤ 0.01. See the text for other explanations

Seed germination was also closely correlated with the activity of two antioxidant enzymes, SOD and GPX (Fig. 8). Moreover, the activity of GPX was closely correlated with the shoot and seedling biomass (r = 0.93 and 0.89, respectively).

At the same time, a strong inverse correlation was found between the hydrogen peroxide content and all indicators of seed germination and seedling growth (r values ranged from −0.86 to −0.96). A fairly high negative correlation was also observed between growth indicators and the MDA content. For instance, the correlation between the seed germination and the MDA content in shoots was −0.80, which is significant at p ≤ 0.1.

Some biochemical indicators were closely correlated with each other. Thus, nearly all of the studied indicators that characterize the state of the enzymatic antioxidant system (SOD, CAT, and GPX activity) were closely inversely correlated with markers of oxidative stress, such as hydrogen peroxide and the LPO product MDA (Fig. 8). An even closer inverse correlation was found between these markers and anthocyanin content (significant at p ≤ 0.01). Additionally, a significant inverse correlation was observed between sugar content and H2O2 and MDA levels in the shoots of seedlings (r = −0.94 and −0.95, respectively, p ≤ 0.05). Finally, a very strong direct correlation (r = 0.99, p ≤ 0.01) between the content of sugars and anthocyanins in shoots indicates the presence of functional relationships between them. Furthermore, the content of both sugars and anthocyanins was significantly (p ≤ 0.05) positively correlated with the activity of all studied antioxidant enzymes (Fig. 8).

Our work demonstrates, for the first time, that BABA increases the germination energy and germination of aged triticale seeds (Figs. 2 and 9). Additionally, using triticale as an experimental model, we demonstrated BABA’s ability to enhance seedling biomass accumulation for the first time. Concurrently, literature exists on enhancing the root and shoot growth of Triticum aestivum seedlings from seeds treated with BABA [51]. Increasing seed germination and enhancing seedling growth by treating seeds with BABA has also been demonstrated in several other plant species [16,52–54]. However, the effects of BABA have mainly been studied in the context of adverse effects, particularly osmotic or salt stress. The effects of BABA on seeds with reduced germination due to aging have not yet been investigated. Our study demonstrates the effectiveness of short-term priming of BABA seeds within 3 h, whereas most studies use significantly longer soaking times (6–12 h or more) [17,30]. Prolonged priming followed by drying may be ineffective because of the transition of seeds to the radicle emergence stage and their decreased resistance to drying [55]. In this regard, the effectiveness of short-term priming shown in our study may be of practical importance.

Figure 9: Heat map of changes in growth parameters and the biochemical indicators of triticale seedlings under the influence of β-aminobutyric acid (BABA). All values are normalized from 0 to 1

One reason for the enhanced germination of triticale seeds in our experiments under the influence of BABA may be the activation of amylase (Figs. 3 and 9). There is little literature on the effects of BABA on amylase gene activity and/or expression in plants. However, an increase in the number of α-amylase transcripts has been demonstrated in corn plants primed with BABA [56]. The method we used to determine amylase activity did not involve a differentiated analysis of individual amylase forms [41]. Nevertheless, as previously mentioned, a specific analysis of amylase activity using starch-containing agar with EDTA added, which inhibits α-amylase [42], revealed minimal residual amylase activity in both the control and BABA-primed grains. Therefore, the observed increase in amylase activity under the influence of BABA can be primarily attributed to an increase in α-amylase activity.

Seed priming triggers a variety of metabolic events. Among these events, the synthesis of amylase de novo and an increase in its activity are key factors that determine an increase in soluble carbohydrate content and the mobilization of hydrolyzable products from storage tissues to the embryo [25,29,57]. This process is particularly important for enhancing the germination of aged seeds, in which amylase activity is typically lower. For instance, osmopriming has been shown to cause a greater increase in amylase activity in aged rice seeds than in normal seeds with higher initial amylase activity [58].

Apparently, increased amylase activity is one of the main reasons for the increase in sugar content in seedling shoots under the influence of BABA seed priming (Figs. 4A and 9). A close correlation was found between these two factors (r = 0.86, Fig. 8). In general, the relationship between amylase activity and the mobilization of reserve carbohydrates for the development of seedling organs has been demonstrated in various cereal species [28,55,56]. The effect of increasing sugar content due to increased amylase activity in germinating cereal seeds can be achieved by treating them with certain stress metabolites, such as spermidine [59] or signal molecule donors, in particular the H2S donor sodium hydrosulfide [50]. There is little data in the literature regarding the effect of BABA seed priming on sugar accumulation in seedlings. Treatment of Vigna unguiculata (L.) seeds with 1.5 mM BABA has been shown to increase sugar content in seedlings under normal moisture conditions and osmotic stress [54]. Regarding cereals, evidence shows increased sugar accumulation in rice shoots from seeds primed with BABA [52]. This effect was observed during seed germination under both normal conditions and osmotic stress. The ability of exogenous BABA to increase amylase activity and sugar accumulation during the germination of aged cereal seeds has been reported by us for the first time. Our experiments revealed a high correlation (r = 0.90) between seed germination and sugar content in shoots, suggesting a significant role for carbohydrate metabolism in seedling development (Fig. 8).

Priming triticale seeds with BABA increased the shoot content of free proline (Fig. 3B), a multifunctional metabolite that plays a substantial role in osmoregulation [60,61] and in antioxidant defense [62,63]. A number of studies have found that different seed priming methods, including hydropriming, can promote proline accumulation, which may have a positive effect on seed germination and seedling growth [25,29]. Our experiments revealed a significant positive correlation between proline content and all parameters characterizing seed germination and shoot biomass accumulation in triticale (Fig. 8). The ability of BABA to enhance proline accumulation in tissues has also been demonstrated using a number of objects, and in some studies, this effect of BABA was observed in the absence of stress, which is consistent with the results of the present study. For instance, priming rice seeds increased proline accumulation in shoots during grain germination, both under salt stress [64] and under normal water conditions [52]. Treating Vigna unguiculata seeds with BABA increased proline content in seedlings under normal moisture conditions and osmotic stress induced by PEG 6000 [54]. Spraying sunflower plants with BABA increased proline content in leaves [65]. However, treatment of Brassica napus L. seedlings with BABA did not affect proline content under physiologically normal conditions but promoted its accumulation under salt stress [53]. A similar effect of BABA treatment was observed in Calendula officinalis L. plants under salt stress [30]. BABA treatment of Tagetes erecta L. plants promoted proline accumulation under salt stress [66]. On the other hand, foliar treatment of corn plants with BABA has been shown to decrease proline accumulation under drought conditions [67]. Treating beans (Vicia faba L.) with BABA by adding it to the nutrient solution in hydroponic culture increased proline content under osmotic stress. However, this increase was small and occurred only when a single concentration of BABA (1 mM) was used [68].

The differences in the effect of BABA on proline accumulation reported in different studies are difficult to interpret, since they were obtained not only on plants of different species, but also under completely different experimental conditions. In general, it can be said that exogenous BABA is capable of modulating the accumulation of important osmolytes, such as proline and sugars, in plants. In the context of seed germination, this modulation may be important for osmoregulation and metabolite supply to etiolated shoots. Additionally, proline and sugars may contribute to the antioxidant defense of seedling cells [69].

In addition to sugars and proline, important multifunctional stress-protective compounds include secondary metabolites [70,71]. Priming of triticale seeds with BABA did not affect the total content of phenolic compounds, but it caused a strong increase in the content of anthocyanins (important flavonoid pigments) in the shoots (Fig. 5). The literature reports that BABA can induce the accumulation of phenolic compounds, anthocyanins, and phytoalexins in plants [72]. For example, treatment of Medicago intertexta L. seeds with BABA enhanced seedling growth under optimal conditions and led to an increased accumulation of phenolic compounds and flavonoids [73]. In another legume species (Vigna unguiculata), an increase in phenolic compound content was also found due to BABA seed priming [54,74]. These effects were observed under both normal and osmotic stress conditions. BABA priming of Calendula officinalis seeds also increased the content of phenolic compounds, especially flavonoids, in seedlings under normal conditions and stabilized these indicators under salt stress [30]. Generally, the induction of seed germination by various priming agents is often accompanied by increased secondary metabolite synthesis, particularly flavonoids with high antioxidant activity [29,31]. However, it remains unclear how specific BABA’s ability to enhance the accumulation of secondary metabolites in plants is. Nevertheless, this effect may be significant for seed germination and seedling development in triticale, as a strong positive correlation was observed between germination rates and anthocyanin content in our experiments (Fig. 8).

When analyzing the results obtained, attention should also be paid to the close relationship between the increase in anthocyanin and sugar content in seedling shoots induced by BABA. As previously mentioned, the correlation coefficient between these two indicators was 0.99. Molecular genetic methods have shown that an increase in sucrose content in Arabidopsis plants can activate the expression of genes that encode the key enzyme in secondary metabolite synthesis, phenylalanine ammonia-lyase, as well as genes that encode subsequent enzymes involved in anthocyanin synthesis [75]. In this regard, it should be noted that it is currently believed that disaccharides and fructans, along with polyphenolic compounds and classic antioxidants (ascorbate and glutathione), form a cytoplasmic antioxidant network [76].

An important aspect of BABA’s positive effect on triticale seed germination is the activation of the enzymatic component of the antioxidant system (Fig. 9). This is indicated by the high direct correlation between GPX activity and all the studied indicators of seed germination and seedling growth, as well as the significant correlation between SOD activity and seed germination (Fig. 8). Regarding GPX, it is important to note that this enzyme is multifunctional and involved in the transformation of secondary metabolites, which are crucial for developing plant resistance [77]. Our study revealed a strong direct correlation between anthocyanin content and GPX activity, as well as strong inverse correlations between these indicators and hydrogen peroxide content (Fig. 7). These results align with the idea that the oxidation of anthocyanins by class III peroxidases, to which GPX belongs, contributes significantly to the detoxification of hydrogen peroxide [78].

In general, under the conditions of our experiments, oxidative stress markers (H2O2 and MDA content) were closely inversely correlated with the activity of all three antioxidant enzymes studied: SOD, CAT, and GPX. The literature contains data on the increased activity of antioxidant enzymes and enhanced gene expression in plants of various taxonomic groups when they are exposed to BABA. These effects are mainly associated with BABA’s induction of plant resistance to stress factors. For instance, BABA-induced drought resistance in beans was accompanied by increased SOD, CAT, GPX, and ascorbate peroxidase activities, as well as increased levels of their transcripts [68]. Treatment of Vigna radiata seeds with BABA led to increased seedling resistance to osmotic and salt stresses and increased the activity of SOD and GPX [79]. BABA treatment increased the drought tolerance of rapeseed plants and caused an increase in the activity of SOD, GPX, and ascorbate peroxidase [80]. Treating corn plants with BABA increased their drought tolerance and was accompanied by increased glutathione reductase gene activity and expression, ensuring a high pool of GSH [67]. Priming citrine seeds with BABA increased salt tolerance and caused an increase in the levels of proteins involved in redox regulation, particularly glutathione-S-transferase, dehydroascorbate reductase, SOD, and glutathione peroxidase, in the roots and cotyledons [15]. In general, there is reason to believe that the use of BABA will expand the possibilities for managing seed germination, including seeds with reduced sowing qualities, as well as the subsequent resistance of plants grown from primed seeds to either abiotic stress factors or pathogens, since BABA has elicitor properties [25,81].

Our study is the first to establish the positive effect of BABA priming on the germination of aged triticale seeds. Treating seeds with BABA also enhanced seedling growth, with the greatest positive effects observed at concentrations of 0.5 and 1 mM. It was found that important components of the positive effect of BABA on the germination of triticale seeds are the effects of increasing amylase activity in grains and the accumulation of sugars and proline in shoots. BABA also significantly increased the accumulation of anthocyanins, which have potent antioxidant properties, in the shoots. These indicators were in close direct correlation with the growth effects. Additionally, treating seeds with BABA increased the activity of enzymatic antioxidants. The activity of the multifunctional enzyme GPX was particularly closely related to the growth effects. The results obtained from this study suggest the potential of BABA as another tool for regulating growth processes and stress-protective systems in plants.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The study was carried out with partial support from the project of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine 2-24-26 BO Development of Measures to Ensure Sustainable Productivity of Agrophytocenoses under the Influence of Abiotic and Biotic Stress Factors, state registration No. 0124U000457.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Yuriy E. Kolupaev and Mykola V. Shevchenko; methodology, Tetiana O. Yastreb and Alexander I. Oboznyi; investigation, Tetiana O. Yastreb, Alexander I. Oboznyi and Yuriy E. Kolupaev; data curation, Tetiana O. Yastreb, Mykola V. Shevchenko and Liubov N. Kobyzeva; writing—original draft preparation, Yuriy E. Kolupaev and Tetiana O. Yastreb; writing—review and editing, Tetiana O. Yastreb; supervision, Yuriy E. Kolupaev and Liubov N. Kobyzeva. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Cai J, Aharoni A. Amino acids and their derivatives mediating defense priming and growth tradeoff. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2022;69:102288. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2022.102288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Jin Y, Zhi L, Tang X, Chen Y, Hancock JT, Hu X. The function of GABA in plant cell growth, development and stress response. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2023;92(8):2211–25. doi:10.32604/phyton.2023.026595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Decsi K, Ahmed M, Rizk R, Abdul-Hamid D, Kovács GP, Tóth Z. Emerging trends in non-protein amino acids as potential priming agents: implications for stress management strategies and unveiling their regulatory functions. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(11):6203. doi:10.3390/ijms25116203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Nehela Y, Mazrou YSA, El_Gammal NA, Atallah O, Xuan TD, Elzaawely AA, et al. Non-proteinogenic amino acids mitigate oxidative stress and enhance the resistance of common bean plants against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Front Plant Sci. 2024;15:1385785. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1385785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Trovato M, Funck D, Forlani G, Okumoto S, Amir R. Editorial: amino acids in plants: regulation and functions in development and stress defense. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:772810. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.772810. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Tarkowski Ł.P, Signorelli S, Höfte M. γ-Aminobutyric acid and related amino acids in plant immune responses: emerging mechanisms of action. Plant Cell Env. 2020;43(5):1103–16. doi:10.1111/pce.13734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ramesh SA, Tyerman SD, Gilliham M, Xu B. γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) signalling in plants. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2017;74(9):1577–603. doi:10.1007/s00018-016-2415-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ansari MI, Jalil SU, Ansari SA, Hasanuzzaman M. GABA shunt: a key-player in mitigation of ROS during stress. Plant Growth Regul. 2021;94(2):131–49. doi:10.1007/s10725-021-00710-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Thevenet D, Pastor V, Baccelli I, Balmer A, Vallat A, Neier R, et al. The priming molecule β-aminobutyric acid is naturally present in plants and is induced by stress. New Phytol. 2017;213(2):552–9. doi:10.1111/nph.14298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Kolupaev YE, Shevchenko MV, Shkliarevskyi MA, Dmitriev AP. Cellular mechanisms of inducing plant resistance to stressors by β-aminobutyric acid. Cytol Genet. 2025;59(4):369–87. doi:10.3103/S009545272504005X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Balmer A, Glauser G, Mauch-Mani B, Baccelli I. Accumulation patterns of endogenous β-aminobutyric acid during plant development and defence in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Biol. 2019;21(2):318–25. doi:10.1111/plb.12940. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Galleschi L, Floris C. Metabolism of ageing seed: glutamic acid decarboxylase and succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase activity of aged wheat embryos. Biochem Und Physiol Der Pflanz. 1978;173(2):160–6. doi:10.1016/S0015-3796(17)30473-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Afshari RT, Seyyedi SM. Exogenous γ-aminobutyric acid can alleviate the adverse effects of seed aging on fatty acids composition and heterotrophic seedling growth in medicinal pumpkin. Ind Crops Prod. 2020;153:112605. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Vijayakumari K, Jisha KC, Puthur JT. GABA/BABA priming: a means for enhancing abiotic stress tolerance potential of plants with less energy investments on defence cache. Acta Physiol Plant. 2016;38(9):230. doi:10.1007/s11738-016-2254-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ziogas V, Tanou G, Belghazi M, Diamantidis G, Molassiotis A. Characterization of β-amino- and γ-amino butyric acid-induced citrus seeds germination under salinity using nanoLC-MS/MS analysis. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36(5):787–9. doi:10.1007/s00299-016-2063-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Elradi S, Suliman M, Zhou G, Nimir E, Nimir N, Zhu G, et al. Seeds priming with ß-aminobutyric acid alleviated salinity stress of chickpea at germination and early seedling growth. Chil J Agric Res. 2022;82(3):426–36. doi:10.4067/S0718-58392022000300426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Abdulbaki AS, Alsamadany H, Alzahrani Y, Alharby HF, Olayinka BU. Seed priming of pepper (Capsicum annuum L.) with β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) alleviates drought stress. Pak J Bot. 2024;56(2):419–26. doi:10.30848/PJB2024-2(31). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Elias SG. The importance of using high quality seeds in agriculture systems. Agric Res Technol. 2018;4:555961. doi:10.19080/ARTOAJ.2018.15.555961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Matkowski H, Daszkowska-Golec A. Wisdom comes after facts—an update on plants priming using phytohormones. J Plant Physiol. 2025;305:154414. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2024.154414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Sariñana-Aldaco O, Ayala-Contreras CA, González-Morales S, Cadenas-Pliego G, Pérez-Alvarez M, Berenice Morales-Díaz A, et al. Effects of seed priming and foliar application of selenite, nanoselenium, and microselenium on growth, biomolecules, and nutrients in cucumber seedlings. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2025;94(7):2131–53. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.067577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhu L, Tang G, An X, Li H, Chen Q. Melatonin priming increases the tolerance of tartary buckwheat seeds to abiotic stress. Agronomy. 2025;15(7):1606. doi:10.3390/agronomy15071606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Dawood MG. Stimulating plant tolerance against abiotic stress through seed priming. In: Rakshit A, Singh H, editor. Advances in seed priming. Singapore: Springer; 2018. p. 147–83. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-0032-5_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Paparella S, Araújo SS, Rossi G, Wijayasinghe M, Carbonera D, Balestrazzi A. Seed priming: state of the art and new perspectives. Plant Cell Rep. 2015;34(8):1281–93. doi:10.1007/s00299-015-1784-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Rhaman MS, Tania SS, Imran S, Rauf F, Kibria MG, Ye W, et al. Seed priming with nanoparticles: an emerging technique for improving plant growth, development, and abiotic stress tolerance. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2022;22(4):4047–62. doi:10.1007/s42729-022-01007-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Rhaman MS. Seed priming before the sprout: revisiting an established technique for stress-resilient germination. Seeds. 2025;4(3):29. doi:10.3390/seeds4030029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Jawaid MZ, Khalid MF, Elezz AA, Ahmed T. Seed priming mitigates the salt stress in eggplant (Solanum melongena) by activating antioxidative defense mechanisms. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2025;94(8):2423. doi:10.32604/phyton.2025.068303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kranner I, Minibayeva FV, Beckett RP, Seal CE. What is stress? Concepts, definitions and applications in seed science. New Phytol. 2010;188(3):655–73. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03461.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Aswathi KPR, Kalaji HM, Puthur JT. Seed priming of plants aiding in drought stress tolerance and faster recovery: a review. Plant Growth Regul. 2022;97(2):235–53. doi:10.1007/s10725-021-00755-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Jatana BS, Grover S, Ram H, Baath GS. Seed priming: molecular and physiological mechanisms underlying biotic and abiotic stress tolerance. Agronomy. 2024;14(12):2901. doi:10.3390/agronomy14122901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Ali EF, Hassan FAS. β-Aminobutyric acid raises salt tolerance and reorganises some physiological characters in Calendula officinalis L. plant. Ann Res Rev Biol. 2018;30(5):1–16. doi:10.9734/arrb/2018/v30i530027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Cañizares E, Giovannini L, Gumus BO, Fotopoulos V, Balestrini R, González-Guzmán M, et al. Seeds of change: exploring the transformative effects of seed priming in sustainable agriculture. Physiol Plant. 2025;177(3):e70226. doi:10.1111/ppl.70226. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang K, Zhang Y, Sun J, Meng J, Tao J. Deterioration of orthodox seeds during ageing: influencing factors, physiological alterations and the role of reactive oxygen species. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;158:475–85. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.11.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Kurek K, Plitta-Michalak B, Ratajczak E. Reactive oxygen species as potential drivers of the seed aging process. Plants. 2019;8(6):174. doi:10.3390/plants8060174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Rajjou L, Lovigny Y, Groot SPC, Belghaz M, Job C, Job D. Proteome-wide characterization of seed aging in Arabidopsis: a comparison between artificial and natural aging protocols. Plant Physiol. 2008;148(1):620–41. doi:10.1104/pp.108.123141. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Afzal I. Seed priming: what’s next? Seed Sci Technol. 2023;51(3):379–405. doi:10.15258/sst.2023.51.3.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Xia F, Cheng H, Chen L, Zhu H, Mao P, Wang M. Influence of exogenous ascorbic acid and glutathione priming on mitochondrial structural and functional systems to alleviate aging damage in oat seeds. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):104. doi:10.1186/s12870-020-2321-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Shehu AA, Alsamadany H, Alzahrani Y. β-Aminobutyric acid (BABA) priming and abiotic stresses: a review. Int J Biosci. 2019;14(5):450–9. doi:10.12692/ijb/14.5.450-459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Kolupaev YE, Kokorev OI, Shevchenko MV, Marenych MM, Kolomatska VP. Participation of γ-aminobutyric acid in cell signaling processes and plant adaptation to abiotic stressors. Stud Biol. 2024;18(1):125–54. doi:10.30970/sbi.1801.752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kolupaev YE, Taraban DA, Kokorev AI, Yastreb TO, Pysarenko VM, Sherstiuk E, et al. Effect of melatonin and hydropriming on germination of aged triticale and rye seeds. Botanica. 2024;30(1):1–13. doi:10.35513/Botlit.2024.1.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Shakhov IV, Kokorev AI, Yastreb TO, Dmitriev AP, Kolupaev YE. Increasing germination and antioxidant activity of aged wheat and triticale grains by priming with gamma-aminobutyric acid. Ukr Bot J. 2024;81(4):290–304. (In Ukrainian). doi:10.15407/ukrbotj81.04.290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Yastreb TO, Shkliarevskyi MA, Kolupaev YE. Quantitative determination of amylase activity in germinating cereal grains using agar plates and ImageJ software. Botanica. 2025;31(2):54–63. doi:10.35513/Botlit.2025.2.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Zhang H, Dou W, Jiang CX, Wei ZJ, Liu J, Jones RL. Hydrogen sulfide stimulates β-amylase activity during early stages of wheat grain germination. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5(8):1031–3. doi:10.4161/psb.5.8.12297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Roe JH. The determination of dextran in blood and urine with anthrone reagent. J Biol Chem. 1954;208(2):889–96. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)65614-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kolupaev YE, Yastreb TO, Salii AM, Kokorev AI, Ryabchun NI, Zmiievska OA, et al. State of antioxidant and osmoprotective systems in etiolated winter wheat seedlings of different cultivars due to their drought tolerance. Zemdirb-Agric. 2022;109(4):313–22. doi:10.13080/z-a.2022.109.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Bates LS, Walden RP, Tear GD. Rapid determination of free proline for water stress studies. Plant Soil. 1973;39(1):205–7. doi:10.1007/BF00018060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Bobo-García G, Davidov-Pardo G, Arroqui C, Vírseda P, Marín-Arroyo MR, Navarro M. Intra-laboratory validation of microplate methods for total phenolic content and antioxidant activity on polyphenolic extracts, and comparison with conventional spectrophotometric methods. J Sci Food Agric. 2015;95(1):204–9. doi:10.1002/jsfa.6706. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Nogués S, Baker NR. Effects of drought on photosynthesis in mediterranean plants grown under enhanced UV-B radiation. J Exp Bot. 2000;51(348):1309–17. doi:10.1093/jxb/51.348.1309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kolupaev YE, Horielova EI, Yastreb TO, Ryabchun NI, Kirichenko VV. Stress-protective responses of wheat and rye seedlings whose chilling resistance was induced with a donor of hydrogen sulfide. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2019;66(4):540–7. doi:10.1134/S1021443719040058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Sagisaka S. The occurrence of peroxide in a perennial plant, Populus gelrica. Plant Physiol. 1976;57(2):308–9. doi:10.1104/pp.57.2.308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Yastreb TO, Kokorev AI, Dyachenko AI, Shevchenko MV, Marenych MM, Kolupaev YE. Indices of carbohydrate metabolism and antioxidant system state during germination of aged wheat and triticale seeds treated with H2S donor. Ukr Biochem J. 2024;96(5):79–95. doi:10.15407/ubj96.05.079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Ozkurt N, Bektaş Y. Chemical priming with β-aminobutyric acid (BABA) for seedling vigor in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). J Inst Sci Technol. 2022;12(1):104–14. [Google Scholar]

52. Jisha KC, Puthur JT. Seed priming with beta-amino butyric acid improves abiotic stress tolerance in rice seedlings. Rice Sci. 2016;23(5):242–54. doi:10.1016/j.rsci.2016.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Mahmud JA, Hasanuzzaman M, Khan MIR, Nahar K, Fujita M. β-Aminobutyric acid pretreatment confers salt stress tolerance in Brassica napus L. by modulating reactive oxygen species metabolism and methylglyoxal detoxification. Plants. 2020;9(2):241. doi:10.3390/plants9020241. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Aswathi KPR, Sen A, Puthur JT. Comparative study of cis- and trans-priming effect of PEG and BABA in cowpea seedlings on exposure to PEG-induced osmotic stress. Seeds. 2023;2(1):85–100. doi:10.3390/seeds2010007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Liu C, Liu J, Huang M, Sun J, Liu C. Study on re-germination and storage ability on dehydration wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seeds after germination. Bot Res. 2018;7(3):294–304. doi:10.12677/br.2018.73038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Shaw AK, Bhardwaj PK, Ghosh S, Azahar I, Adhikari S, Adhikari A, et al. Profiling of BABA-induced differentially expressed genes of Zea mays using suppression subtractive hybridization. RSC Adv. 2017;7(69):43849–65. doi:10.1039/c7ra06220f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Bose B, Kumar M, Singhal RK, Mondal S. Impact of seed priming on the modulation of physico-chemical and molecular processes during germination, growth, and development of crops. In: Rakshit A, Singh H, editor. Advances in seed priming. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2018. p. 23–40. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-0032-5_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Lee SS, Kim JH. Total sugars, alpha-amylase activity, and germination after priming of normal and aged rice seeds. Korean J Crop Sci. 2000;45(2):108–11. [Google Scholar]

59. Hussain S, Zheng M, Khan F, Khaliq A, Fahad S, Peng S, et al. Benefits of rice seed priming are offset permanently by prolonged storage and the storage conditions. Sci Rep. 2015;5(1):8101. doi:10.1038/srep08101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Forlani G, Trovato M, Funck D, Signorelli S. Regulation of proline accumulation and its molecular and physiological functions in stress defence. In: Hossain MA, Kumar V, Burritt DJ, Fujita M, Mäkelä PSA, editors. Osmoprotectant-mediated abiotic stress tolerance in plants: recent advances and future perspectives. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2019. p. 73–97. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-27423-8_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Mansour MMF, Salama KHA. Proline and abiotic stresses: responses and adaptation. In: Hasanuzzaman M, editors. Plant ecophysiology and adaptation under climate change: mechanisms and perspectives. II: mechanisms of adaptation and stress amelioration. Singapore: Springer Nature; 2020. p. 357–97. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-2172-0_12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Ghosh UK, Islam MN, Siddiqui MN, Cao X, Khan MAR. Proline, a multifaceted signalling molecule in plant responses to abiotic stress: understanding the physiological mechanisms. Plant Biol. 2022;24(2):227–39. doi:10.1111/plb.13363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Raza A, Charagh S, Abbas S, Hassan MU, Saeed F, Haider S, et al. Assessment of proline function in higher plants under extreme temperatures. Plant Biol. 2023;25(3):379–95. doi:10.1111/plb.13510. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Kappen LJ, Thomas D, Prameela P. Chemical seed priming to improve salinity tolerance in rice. J Ind Soc Coast Agric Res. 2022;40(1):13–22. doi:10.54894/JISCAR.40.1.2022.116327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Wasaya A, Yaqoob S, Ditta A, Yasir TA, Sarwar N, Javaid MM, et al. Exogenous application of β-aminobutyric acid improved water relations, membrane stability index, and achene yield in sunflower hybrids under terminal drought stress. Pol J Env Stud. 2024;33(4):5367–479. doi:10.15244/pjoes/177182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Hussein RM, Mohammadi M, Eghlima G, Ranjbar ME. Zulfiqar F. β-aminobutyric acid enhances salt tolerance of African marigold by increasing accumulation rate of salicylic acid, γ-aminobutyric acid and proline. Sci Hortic. 2024;327(5):112828. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2023.112828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Shaw AK, Bhardwaj PK, Ghosh S, Roy S, Saha S, Sherpa AR, et al. β-Aminobutyric acid mediated drought stress alleviation in maize (Zea mays L.). Env Sci Pollut Res Int. 2016;23(3):2437–53. doi:10.1007/s11356-015-5445-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Abid G, Ouertani RN, Jebara SH, Boubakri H, Muhovski Y, Ghouili E, et al. Alleviation of drought stress in faba bean (Vicia faba L.) by exogenous application of β-aminobutyric acid (BABA). Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2020;26(6):1173–86. doi:10.1007/s12298-020-00796-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Kolupaev YE, Relina LI, Oboznyi AI, Ryabchun NI, Vasko NI, Kolomatska VP, et al. Stress metabolites in wheat: role in adaptation to drought. Ukr Biochem J. 2025;97(3):13–41. doi:10.15407/ubj97.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Khlestkina E. The adaptive role of flavonoids: emphasis on cereals. Cereal Res Commun. 2013;41(2):185–98. doi:10.1556/crc.2013.0004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Qaderi MM, Martel AB, Strugnell CA. Environmental factors regulate plant secondary metabolites. Plants. 2023;12(3):447. doi:10.3390/plants12030447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Choudhary A, Kumar A, Kaur H, Balamurugan A, Padhy AK, Mehta S. Plant performance and defensive role of β-amino butyric acid under environmental stress. In: Husen A, editor. Plant performance under environmental stress. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 249–75. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-78521-5_10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Selim S, Akhtar N, El Azab E, Warrad M, Alhassan HH, Abdel-Mawgoud M, et al. Innovating the synergistic assets of β-amino butyric acid (BABA) and selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) in improving the growth, nitrogen metabolism, biological activities, and nutritive value of Medicago interexta sprouts. Plants. 2022;11(3):306. doi:10.3390/plants11030306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Aswathi KPR, Puthur JT. Enhancement in major metabolites content of cowpea seeds induced by β-amino butyric acid (BABA). In: Abdussalam AK, Shackira AM, editors. Plant functional biology. Kannur, India: Sir Syed College; 2021. p. 125–9. [Google Scholar]

75. Solfanelli C, Poggi A, Loreti E, Alpi A, Perata P. Sucrosespecific induction of the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2006;140(2):637–46. doi:10.1104/pp.105.072579. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Bolouri-Moghaddam MR, Le Roy K, Xiang L, Rolland F, Van den Ende W. Sugar signaling and antioxidant network connections in plant cells. FEBS J. 2010;277(9):2022–37. doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07633.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Freitas CD, Costa JH, Germano TA, Rocha RDO, Ramos MV, Bezerra LP. Class III plant peroxidases: from classification to physiological functions. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;263((Pt 1)):130306. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Zhao YW, Wang CK, Huang XY, Hu DG. Anthocyanin stability and degradation in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2021;16(12):1987767. doi:10.1080/15592324.2021.1987767. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Jisha KC, Puthur JT. Seed priming with BABA (β-amino butyric acida cost-effective method of abiotic stress tolerance in Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek. Protoplasma. 2016;253(2):277–89. doi:10.1007/s00709-015-0804-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Rajaei P, Mohamadi N. Effect of beta-aminobutyric acid (BABA) on enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidants of Brassica napus L. under drought stress. Int J Biosci. 2013;11(3):41–7. doi:10.12692/ijb/3.11.41-47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Sanchez-Lucas R, Bosanquet JL, Henderson J, Catoni M, Pastor V, Luna E. Elicitor specific mechanisms of defence priming in oak seedlings against powdery mildew. Plant Cell Env. 2025;48(6):4455–74. doi:10.1111/pce.15419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools