Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Antioxidant and Antiproliferative Potential of Nutrient—Rich Tragopogon dubius Stem and Leaves

1 Department of Botanical and Environmental Sciences, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, 143005, Punjab, India

2 Department of Zoology, College of Science, King Saud University, P.O. Box 22452, Riyadh, 11495, Saudi Arabia

3 Central Research Laboratory, Department of Medical Research on Experimental Animals, King Saud University, P.O. Box 22452, Riyadh, 11495, Saudi Arabia

4 Department of Biosciences, University Centre for Research and Development, Chandigarh University, Mohali, 140413, Punjab, India

* Corresponding Author: Satwinderjeet Kaur. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: Linking the Gap Between Properties, Compounds and Cropping Strategy)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3401-3426. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.067984

Received 18 May 2025; Accepted 23 September 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

The Tragopogon dubius is traditionally used to treat many ailments, consumed as a vegetable, and utilized as fodder for livestock. Tragopogon dubius, found in the Kashmir Himalayas, is the least explored for its bioactivity properties and has a unique geographical location. This study is the first attempt to investigate the antioxidant, anticancer, and genoprotective properties of the aqueous extracts from the leaves (AQ-TrDL) and stems (AQ-TrDS) of this plant. AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS demonstrated significant amounts of phenolic and flavonoid contents. GC-HRMS identified various phytochemicals belonging to different classes, like carboxylic acids, fatty acid derivatives, phenols, and triterpenoids. DPPH, Superoxide, FRAP, and ABTS antioxidant assays showed that AQ-TrDS exhibited stronger radical scavenging activities than AQ-TrDL, with IC50 values ranging from 40.31 to 73.58 μg/mL. Cytotoxicity tests revealed that AQ-TrDS significantly inhibited the growth of cancer cells in MCF-7, HCT-116, HeLa, and A-549 cell lines, with over 50% inhibition observed at concentrations ranging from 56.62 to 98.32 μg/mL. Importantly, minimal effects were seen in normal fibroblast L-929 cells, with GI50 values over 434 μg/mL. Additionally, genoprotective tests showed that AQ-TrDS effectively reduced “H2O2”-induced DNA damage in lymphocytes, decreasing damage by up to 61.18% at a concentration of 320 μg/mL. HPLC analysis of amino acids identified 10 amino acids in T. dubius leaves and 14 in stems, showing its nutritional value. Overall, these findings highlight the biomedical potential of T. dubius aqueous extracts for developing new pharmaceutical agents.Keywords

The vast diversity of plant species is an important resource for the food, pharmaceutical, and cosmetic industries [1]. Botanical components, including herbs, roots, flowers, fruits, leaves, seeds, decoctions, herbal teas, and prepared extracts, have been extensively utilized in traditional and folk medicine for centuries. These botanical ingredients are trusted for the treatment of a wide range of ailments, including dermatological conditions, digestive disorders, respiratory issues, cardiovascular health, immune modulation, pain management, and detoxification [2,3]. A significant number of pharmacologically active drugs have been developed from medicinal plants, displaying substantial clinical efficacy against conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and inflammation. Many of these drugs were isolated based on indigenous knowledge systems [4].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), a large proportion of rural and urban populations in Africa, India, and other developing nations continue to rely on traditional medicine for primary healthcare [5]. Traditional herbal remedies are considered safer, more affordable, with fewer adverse side effects, and reliance upon natural plant products is globally increasing [6]. The evaluation of plant extracts against cancer cell lines is well documented in the literature, serving as a model to assess the anticancer potential of various phytochemicals [7]. Compounds such as polyphenols, flavonoids, terpenoids, glycosides, diterpenes, carboxylic acids, and tannins play crucial roles in cancer prevention by disrupting key signalling pathways. These phytochemicals exhibit antiproliferative, antimetastatic, antiestrogenic, and proapoptotic properties [8–10]. The emergence of new diseases and the increasing resistance to conventional treatments have emphasized the urgent need for natural remedies capable of enhancing the body’s resistance to various pathologies [11,12].

Plants are rich sources of antioxidants either in the form of raw extracts or as isolated compounds. They play a pivotal role in stabilizing and deactivating free radicals before they can damage cellular structures [13,14]. The balance between antioxidants and free radicals is imperative in maintaining and achieving optimal physiological functioning and must coexist in balance. Consequently, the incorporation from external sources of antioxidants can effectively keep the regulation of oxidative damage in control. Scientifically validated investigations have indicated that synthetic antioxidants hydroxyanisole and butylated hydroxytoluene, have detrimental effects. This has ignited the shift towards the quest for safe natural plant constituents with antioxidant activity like polyphenols, catechins, lignans, flavonoids, triterpenoids, etc. [15]. Additionally, plant-derived elements are essential for maintaining human health, as they provide critical nutrients and amino acids necessary for optimal physiological function and growth [16,17].

Tragopogon dubius, commonly referred to as yellow salsify or ‘goats’ beard, is a perennial herbaceous plant belonging to the Asteraceae family. Traditionally, T. dubius has been consumed for its edible roots, which can be cooked, roasted, or added to soups and stews [18,19]. In traditional medicine, this plant has been used to support digestive health, provide mild laxative effects, alleviate diarrhea, and act as a diuretic [20]. Infusions and decoctions prepared from T. dubius are employed as remedies for ailments such as coughs, colds, and minor infections. Topically, it is applied to soothe skin irritations and reduce cutaneous swelling [21]. In indigenous communities in Jammu and Kashmir, India, T. dubius is particularly prized for its wound-healing properties. Extracts derived from different parts of the plant, including water, methanol, and ethyl acetate extracts, have demonstrated significant antioxidant, antibacterial, anticancer, and antifungal activities [15,22,23]. However, the full therapeutic potential of T. dubius remains underexplored. This study aims to investigate the antioxidant, anticancer, and genoprotective potentials of aqueous extracts derived from the leaves and stems of T. dubius, while also unraveling its nutritional significance, including the amino acid and elemental profiles. This research contributes to the understanding of T. dubius as a multifaceted plant with potential applications in the food, pharmaceutical, and nutraceutical industries, aligning with several of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The plant Tragopogon dubius was harvested at morning time during June from the elevated mountainous region of the village Lajoora from the Pulwama district, Jammu & Kashmir, India (33°52′21.13″ N, 74°53′34.27″ E, and an altitude of 1669.0 m above sea level). Mr. Akhtar Malik performed taxonomical identification at the University of Kashmir. A voucher specimen (No.: 2940-(KASH)) was preserved at the Centre of Taxonomy and Biodiversity, University of Kashmir, Hazratbal, Srinagar, India. Fresh leaves and stems were dried at 40°C for 12 h in an oven, then finely powdered and stored in airtight glass containers for subsequent analysis.

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, ≥99.9%), ethidium bromide (EtBr, ≥95%), sodium carbonate (99.5%), Folin–Ciocalteu reagent (98%), aluminium chloride (99.5%), nicotine amide adenine dinucleotide (NADH, 98%), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2, 97%), sodium hydroxide (97%), nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT, 95%), phenazine methosulfate (PMS, 95%), low melting point agarose (LMPA, 98%), nicotine amide adenine dinucleotide (NADH, 98%), normal melting point agarose (NMPA, 98%), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT, 98%), were purchased from HiMedia laboratories Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India. Gallic acid (99%), HPLC-grade methanol (99%), DPPH (98%), and rutin (99%) were procured from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA). RPMI-1640 (99%) and DMEM (99%) media were obtained from Merck Sigma Aldrich. All bioassays were conducted using analytical grade reagents.

2.3 Preparation of Aqueous Extract of Leaves and Stem

One hundred grams of the finely powdered leaves and stems of Tragopogon dubius were each placed into separate conical flasks and extracted with 500 mL of double-distilled autoclaved water at room temperature for 24 h under continuous stirring using a magnetic stirrer. The resulting solutions were filtered through Whatman filter paper, producing black-colored filtrates. To ensure that no residue passed through, the filtrates were centrifuged at 3000× g. The clear solutions were then concentrated to near dryness using a rotary evaporator. The semi-solid extracts were air-dried at 40°C for 5 days to eliminate residual moisture, yielding 1.4 g of AQ-TrDL (leaf extract) and 2.5 g of AQ-TrDS (stem extract). The extracts were stored at 4°C for further analysis. The extraction method followed that of [24], with slight modifications.

2.4 Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents

The Folin-Ciocalteu method for total phenolic content (TPC) determination and aluminium chloride method for total flavonoid content (TFC) were employed for the AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS extracts, following the protocol adopted by Chandni et al. with slight modifications [25]. Gallic acid and rutin served as the standard compounds, with TPC expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry extract weight (mg GAE/g DW) and TFC as milligrams of rutin equivalents per gram of dry extract weight (mg RE/g DW). The chemicals and reagents required encompass folin-Ciocalteu reagent, sodium carbonate, aluminium chloride, sodium nitrite, sodium hydroxide, double-distilled water, and methanol.

2.5 Antioxidant Activity Assays

2.5.1 DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) Assay

The DPPH assay was performed using a modified method [26] to evaluate the free radical scavenging ability of AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS. Six different concentrations of the extracts (25, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/mL) were prepared. A stock solution of 4 mg DPPH in 100 mL methanol (HPLC grade) was prepared. Two milliliters of the DPPH stock solution were mixed with 0.3 mL of the extract solution, and the reaction mixtures were incubated in darkness for 30 min at room temperature. A blank containing DPPH and methanol (without extract) was also prepared. After incubation, 300 μL of the reaction mixture from each concentration in triplicate were placed in 96-well plates, and the absorbance was measured at 517 nm. Rutin was used as the standard antioxidant. The percentage of radical scavenging activity was calculated using the formula:

where Ac is the absorbance of the control and As is the absorbance of the sample.

2.5.2 Superoxide Radical Scavenging Assay

The superoxide radical scavenging capacity of AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS was evaluated according to the method of [27]. The reaction mixture consisted of 1 mL of NBT solution (1.56 mM in phosphate buffer, pH 8), 1 mL of NADH solution (468 μM in phosphate buffer, pH 8), 1 mL of the extracts (25 to 800 μg/mL concentrations), and 0.5 mL of PMS solution (60 μM in phosphate buffer, pH 8). After a 5-min incubation at 25°C, the absorbance was measured at 560 nm. The percentage inhibition of superoxide radicals was calculated using the formula:

where Ac is the absorbance of the control reaction (without the sample) and As is the absorbance of the reaction with the sample at different concentrations.

2.5.3 FRAP (Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power) Assay

The FRAP assay was performed as described by [28]. The reaction mixture consisted of 200 μL of extract using different concentrations ranging from 25 μg/mL to 800 μg/mL) and 3 mL of FRAP reagent (composed of sodium acetate buffer, TPTZ, and FeCl3·6H2O in a 10:1:1 ratio). After incubation at 37°C for 30 min, the absorbance was measured at 593 nm. The percentage of inhibition was calculated using the formula:

where A593 sample is the absorbance of aqueous extracts with different concentrations at 593 nm wavelengths in absorbance mode and A593 control is absorbance of FRAP solution at 593 nm wavelength without sample.

2.5.4 ABTS (2,2-Azino-bis (3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonate))

The ABTS assay was performed with minor modifications, based on the method described by [29]. The ABTS radical cation (ABTS•+) was generated by mixing 7.0 mM ABTS solution with 2.45 mM potassium persulfate and incubating in the dark for 16 h. The resulting solution was diluted with ethanol to achieve an absorbance of 0.70–0.75 at 734 nm. In the assay, 100 μL of extract (concentrations ranging from 25 to 800 μg/mL) was mixed with 2.9 mL of ABTS solution. The reaction mixture was incubated in the dark for 6 min, and the absorbance was measured at 734 nm. Rutin was used as the standard. The percentage of ABTS inhibition was calculated as follows:

where AC is the absorbance of untreated control cells, and AS is the absorbance of treated cells at various extract concentrations.

2.6 MTT (3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) Assay

The cytotoxic efficacy of crude aqueous leaf and stem extracts from Tragopogon dubius were assessed against several human cancer cell lines, including MCF-7 (breast), HCT-116 (colon), HeLa (cervical), and A549 (lung), as well as a normal mouse fibroblast cell line (L-929), utilizing the MTT assay as per standard protocols [30]. All cell lines were procured from NCCS Pune, India, and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 20% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), 100 μg/mL penicillin, and 100 μg/mL streptomycin. Cultures were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator under controlled conditions. Cell line selection was based on initial screening for extract sensitivity, specificity, and selective cytotoxicity, which supported the in vivo extrapolation of the in vitro results. Cancer cells were seeded at a density of 8 × 103 cells per well in 96-well plates and allowed to adhere for 24 h. Cells were subsequently exposed to varying concentrations (15.125–500 μg/mL) of the AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS extracts for an additional 24 h. Following treatment, cells were incubated with 20 μL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL) for 3 h, facilitating the formation of formazan crystals. These were then dissolved by adding 100 μL of DMSO, after which absorbance was recorded at 570 nm. Each concentration was tested in triplicate for each cell line studied, to ensure reliability, reproducibility, and for the calculation of standard deviation and statistical significance. The GI50 values, representing the concentration of extracts required to inhibit 50% cell growth, were calculated using the following formula:

where A0 is the absorbance of untreated control cells, and A1 is the absorbance of treated cells at various extract concentrations.

Based on cytotoxicity results, the AQ-TrDS extract was found to exhibit superior anticancer activity against MCF-7, HCT-116, HeLa, and A549 cell lines. The apoptotic effects of AQ-TrDS on these cancer cells were further investigated using fluorescence microscopy, with a focus on mitochondrial and nuclear alterations.

DAPI and Rhodamine Staining

Cancer cells were seeded into 24-well plates at an optimal density of approximately 1 × 105 cells/well and incubated overnight to facilitate adhesion and proliferation, as previously described by [25]. Each well was then exposed to a GI50 concentration of the AQ-TrDS extract for 24 h. After the completion of the treatment period, the media containing unattached dead cells and AQ-TrDS was removed. The treatment period, the media containing unattached dead cells and AQ-TrDS was removed, and each well was washed with 1× PBS (Phosphate-Buffered Saline). After washing, 0.490 μL of 1× PBS was added again to each well, where 10 μL of DAPI (Stock solution, 1 μg/mL) and 10 μL of Rhodamine 123 (stock solution, 1 μg/mL) were mixed. The mixture was then allowed to incubate in the dark for 30 min inside a CO2 incubator. After incubation with respective dyes, the excess dyes were removed by washing gently twice with 1× PBS, followed by visualizing through a fluorescence microscope (Nikon Eclipse T2, Japan) to observe nuclear alterations and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential.

2.8 Genotoxicity via Alkaline Comet Assay

The alkaline comet assay, based on the protocol by [31] was used to evaluate the genotoxic potential of AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS extracts. Briefly, 1 × 104 cells were exposed to various concentrations (40, 80, 160, and 320 μg/mL) of the extracts for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. H2O2 (5 μg/mL) was employed as a positive control to induce oxidative DNA damage. To assess the genoprotective capacity, extracts were co-incubated with H2O2. Following treatment, cells were embedded in 0.5% low-melting-point agarose (LMPA) on slides pre-coated with 1% normal-melting-point agarose, solidified at 4°C, and later immersed in lysis buffer (pH 10) for 4 h at 4°C. DNA migration was induced by electrophoresis at 25 V and 300 mA for 30 min. After neutralization and staining with ethidium bromide, comets were visualized under a Nikon Eclipse Ts2 fluorescence microscope (Japan). DNA damage was quantified using Comet Assay Software Project (Casp lab).

Amino acid composition was analysed utilizing an Agilent 1260 series High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) system (Agilent Technologies, Waldbronn, Germany) equipped with a diode array detector, as per the standardized Agilent protocol. The system incorporated an Agilent Advance Bio AAA column (4.6 × 100 mm) housed within a thermostatically controlled column compartment maintained at 40°C. Sample preparation was conducted through a standardized protocol involving 24 h hydrolysis at 110°C using 6 M hydrochloric acid (HCl) to yield protein hydrolysates. The amino acids were separated and quantified via pre-column derivatization, utilizing FMOC (fluorenyl methoxycarbonyl) chloride for primary amino acids and OPA (o-phthaldialdehyde) for proline. Calibration was performed using a standard amino acid mixture (0.5 μM/mL for each amino acid). The mobile phase consisted of 40 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) as phase A, and a mixture of acetonitrile, methanol, and water (45:45:10 v/v) as phase B. A 2.5 μL sample injection was employed, with separation achieved at a flow rate of 2 mL/min. The gradient program began with a 0% phase B for 1.9 min, followed by an increase to 53% phase B over 16.3 min. A washing step at 100% phase B and re-equilibration at 0% phase B concluded the run, with a total analysis time of 26 min. Each sample was analysed in triplicate [32–34].

2.10 Sample Preparation for Mineral Constituent Estimation

Mineral content in the leaves and stems of T. dubius was determined using the acid digestion method. One gram of dried, ground seed sample was placed in a 250 mL conical flask, followed by the addition of 20–30 mL of a tri-acid mixture (HNO3:H2SO4:HClO4 = 10:1:4). The contents were gently stirred to ensure thorough moistening of the sample, then heated on an electric hot plate at 180–200°C until white fumes appeared, and the solution became colorless. Upon partial drying or yellowing of the solution, an additional 5 mL of the tri-acid mixture was added. Once digestion was completed, the flask was removed from the heat and allowed to cool. Subsequently, 20–30 mL of distilled water was added, and the contents were thoroughly mixed. The solution was then filtered using Whatman No. 1 filter paper into a 100 mL volumetric flask, with repeated washing of the conical flask to ensure complete transfer of minerals [35].

Elemental Analysis via Microwave Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (MP-AES)

Elemental analysis was conducted using an Agilent 4210 Microwave Plasma Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (MP-AES) system (Agilent Technology Company), equipped with a standard MP-AES torch, concentric nebulizer, and glass cyclonic spray chamber. The nebulizer flow rate ranged from 0.45 to 0.95 L/min, with an uptake time of 70 s at 80 rpm. Measurements were taken in triplicate, with a stabilization time of 5 s.

2.11 Gas Chromatography-High Resolution Mass Spectrometry (GC-HRMS) Analysis

The aqueous extracts of T. dubius AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS were analysed using gas chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry (GC-HRMS). An Agilent 7890 Gas Chromatograph, coupled with a JEOL AccuTOF GCV JMS-T100GCV Mass Spectrometer, was utilized. Helium served as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. Separation was achieved using an HP-5 capillary column (30 m μm film thickness). Samples diluted in acetone at a 1:100 v/v ratio, were injected with a split ratio of 1:10 for 1 min, maintaining the injector temperature at 250°C. The column temperature was initially set at 60°C for 2 min, followed by a rise to 250°C, then increased to 280°C at a rate of 30°C/min and held for 10 min. Mass spectra were recorded within a mass range of 45–650 amu at energy of 70 eV. Identification of the constituents was based on the obtained mass of peaks with library matches.

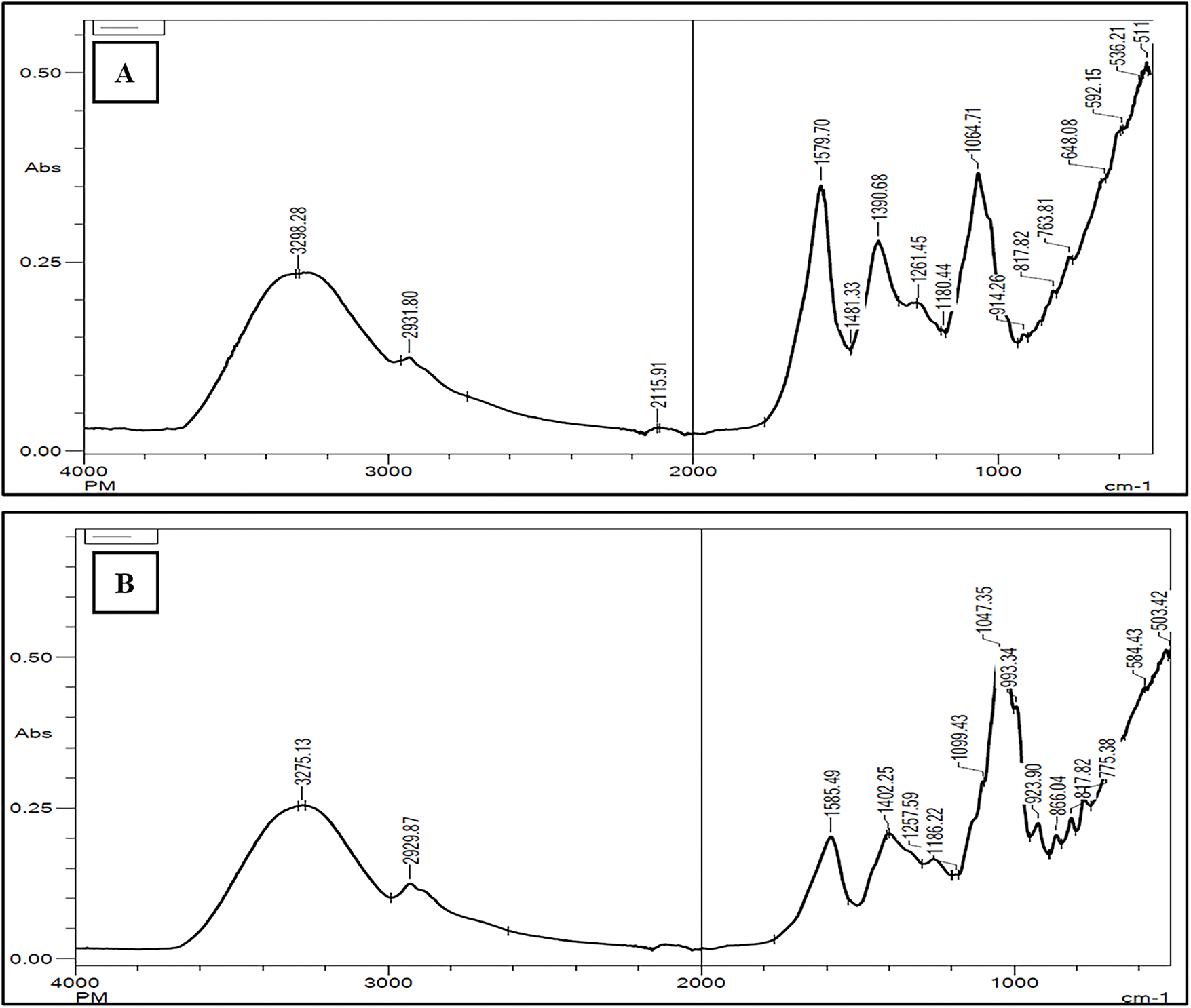

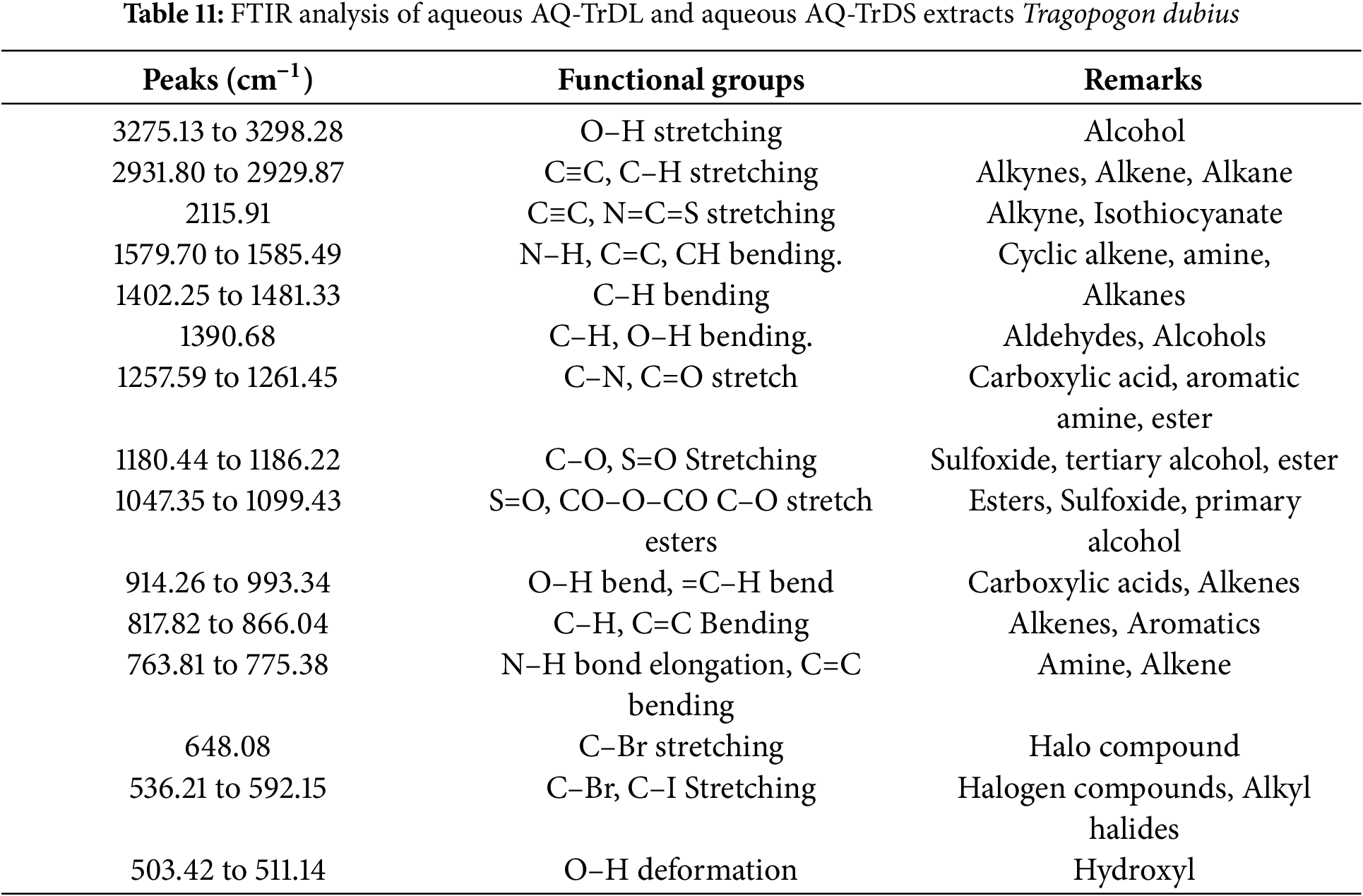

2.12 Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy was employed to analyse the AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS aqueous extracts. Spectra were recorded in absorbance mode using a Shimadzu FTIR spectrometer (Model IR Tracer-100), covering a frequency range of 400–4000 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1. FTIR analysis provided detailed insights into the functional groups present in the aqueous extracts by analysing distinct absorption bands, facilitating a comprehensive characterization of their chemical composition [36].

Statistical Analysis

Experiments were carried out in triplicate, and for statistical analysis, data were presented as the Mean ± standard deviation. One-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) with a significance level set at p ≤ 0.05 was used to calculate significant differences among the data variables. Tukey’s HSD (Honestly Significant Difference) test, conducted through post hoc comparisons, was used to assess and compare the means. The standard curve parameters were used to calculate GI50 and IC50 values using Excel software (2019) by comparing data variables in triplicate.

3.1 Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content

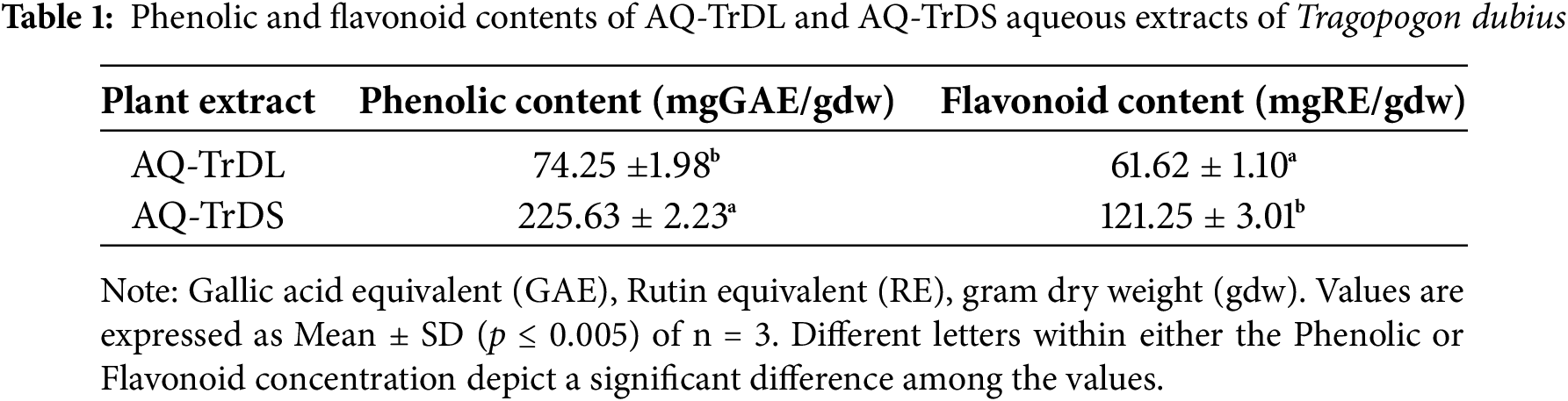

In the present investigation, the phenolic and flavonoid concentrations in the aqueous extracts AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS of T. dubius were analysed and are presented in Table 1. The AQ-TrDS extract exhibited a significantly higher phenolic content of 225.63 ± 2.23 mg GAE/g extract, compared to the AQ-TrDL extract, which recorded 74.25 ± 1.98 mg GAE/g extract. Similarly, the total flavonoid content was more abundant in AQ-TrDS, with a conentration of 121.25 ± 3.01 mg RE/g extract, while AQ-TrDL showed a lower flavonoid content of 61.62 ± 1.10 mg RE/g extract. The significant levels of phenolic and flavonoid content underscore the extract’s promise as a natural source of bioactive compounds for pharmaceutical or nutraceutical applications.

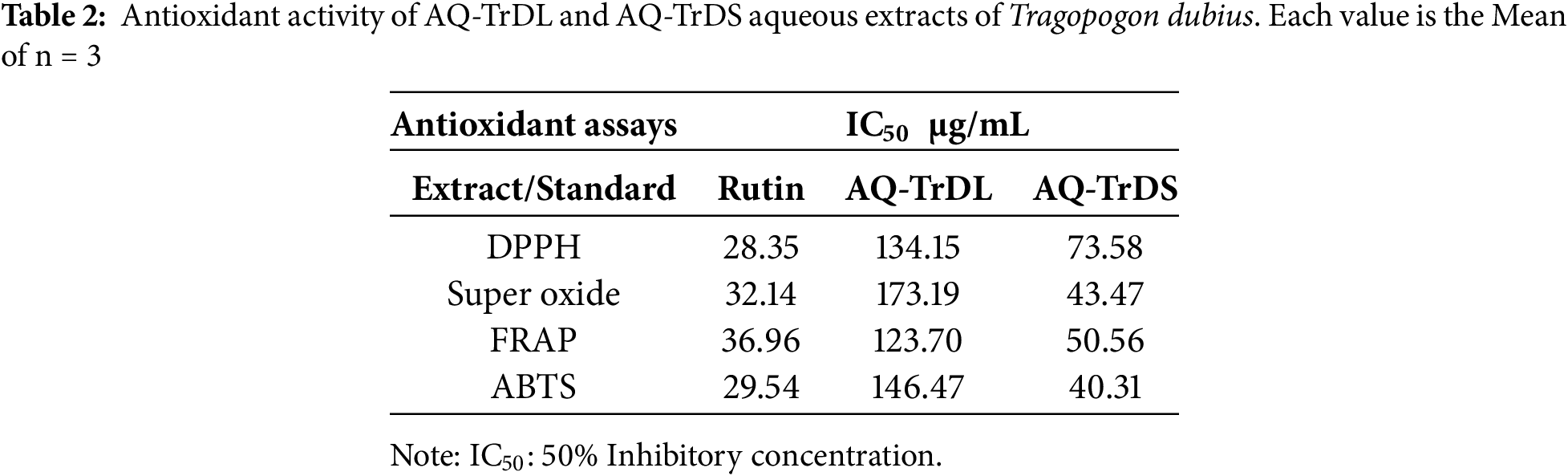

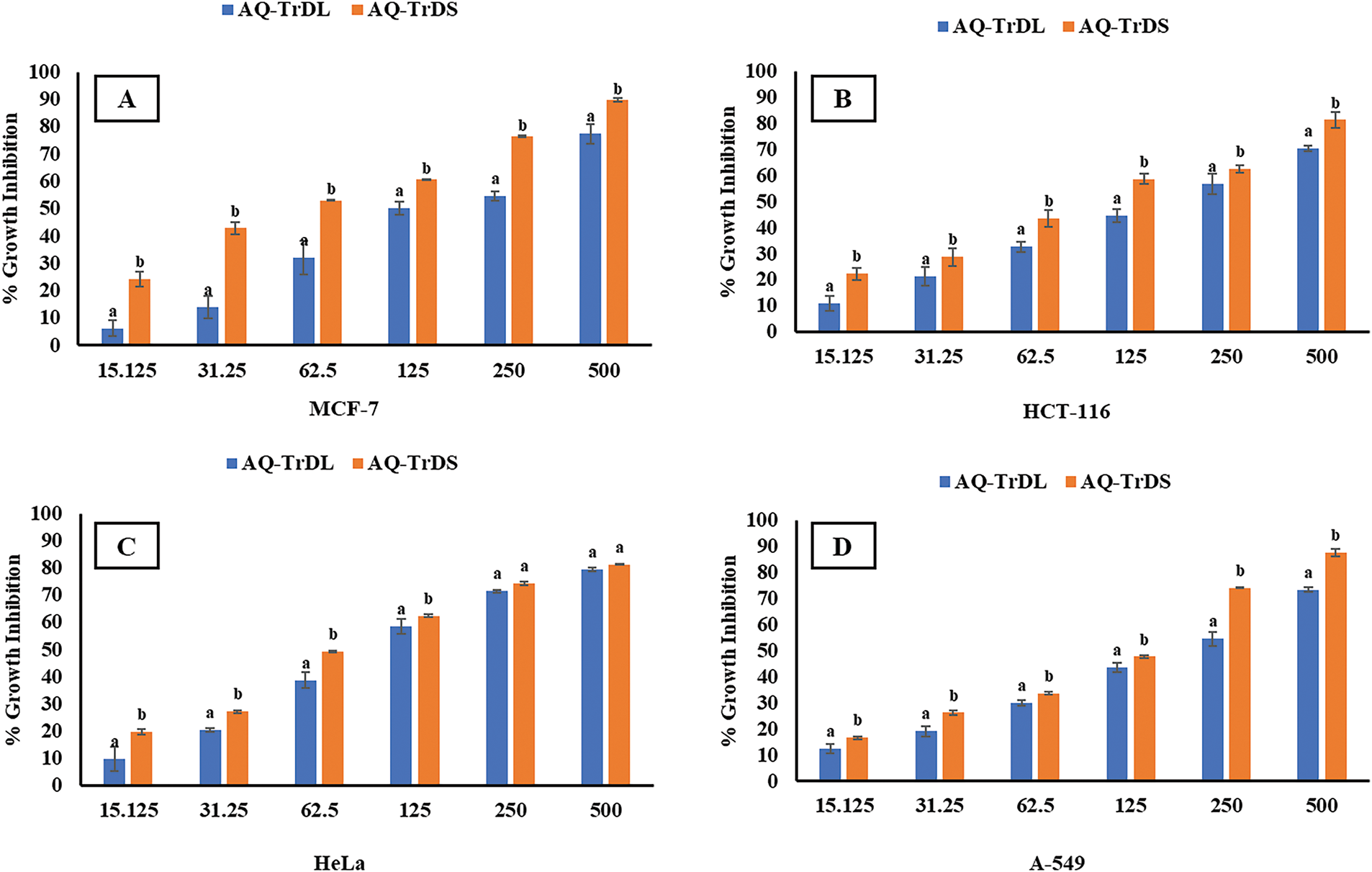

In this study, the antioxidant potential of the AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS aqueous extracts of T. dubius were evaluated using DPPH, superoxide, FRAP, and ABTS radical scavenging assays. The IC50 values and inhibition percentages for these assays are summarized in Table 2. The results revealed concentration-dependent antioxidant potential at concentrations ranging from 25 to 800 μg/mL, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The AQ-TrDS extract consistently exhibited the and most potent antioxidant activity across all assays, with IC50 values of 73.58 μg/mL (DPPH), 43.47 μg/mL (superoxide), 50.56 μg/mL (FRAP), and 40.31 μg/mL (ABTS), and corresponding inhibition percentages of 87.53%, 92.05%, 86.65%, and 92.61%, respectively. In contrast, the AQ-TrDL extract an IC50 value of 173.19 μg/mL. The reference standard, rutin, demonstrated IC50 values of 28.35, 32.14, 36.96, and 29.54 μg/mL in the DPPH, superoxide, FRAP, and ABTS assays, respectively. The potent antioxidant activity observed in AQ-TrDS supports the extract’s potential as a natural therapeutic source against oxidative stress-related conditions.

Figure 1: Antioxidant activity of aqueous extracts AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS fractions. (A) DPPH radical scavenging assay (B) Super oxide radical scavenging assay (C) FRAP antioxidant assay and (D) ABTS radical scavenging assay. Each histogram is the mean ± SD of n = 3. Different letters (a, b) denote significant difference (p < 0.05) between AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS at different concentrations

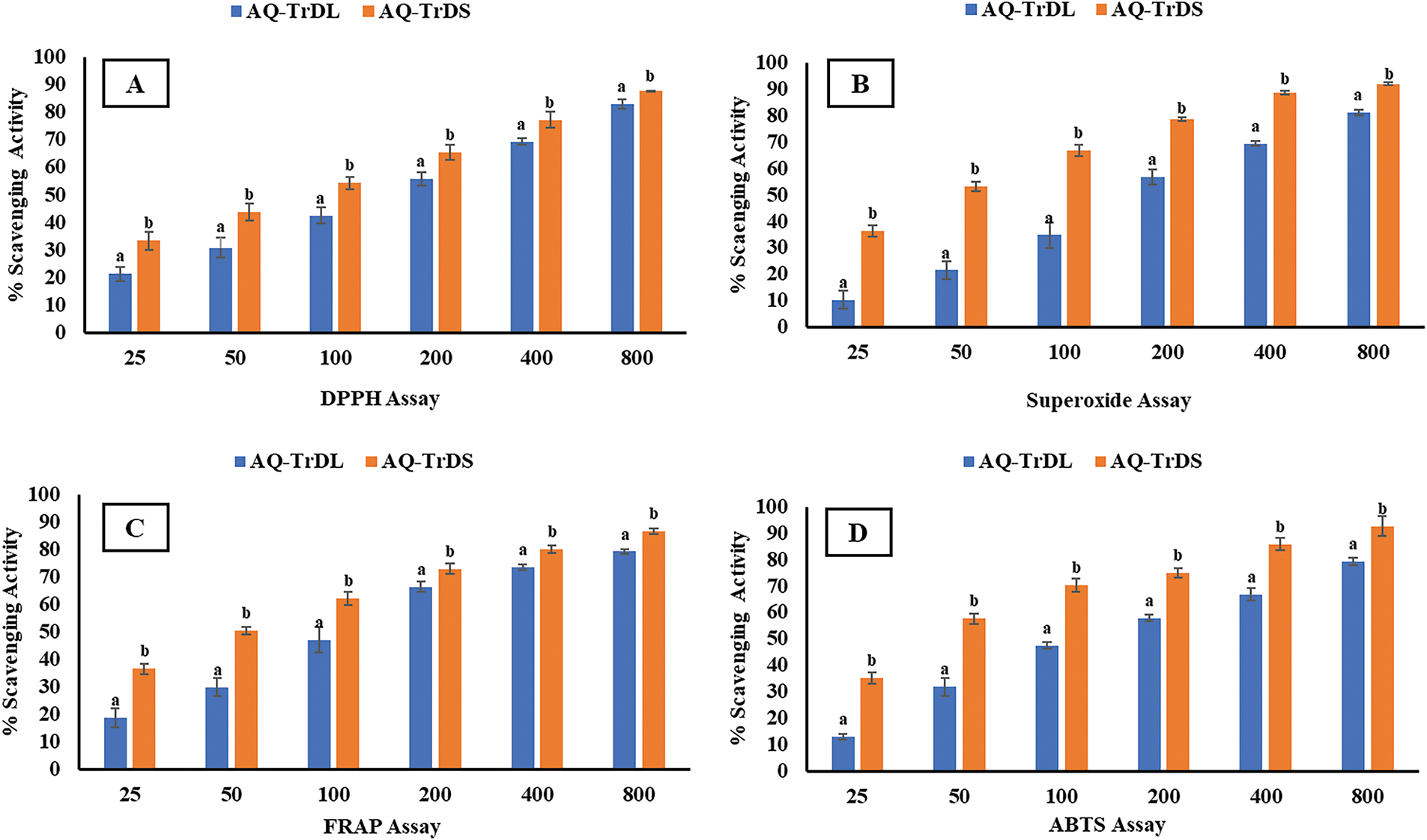

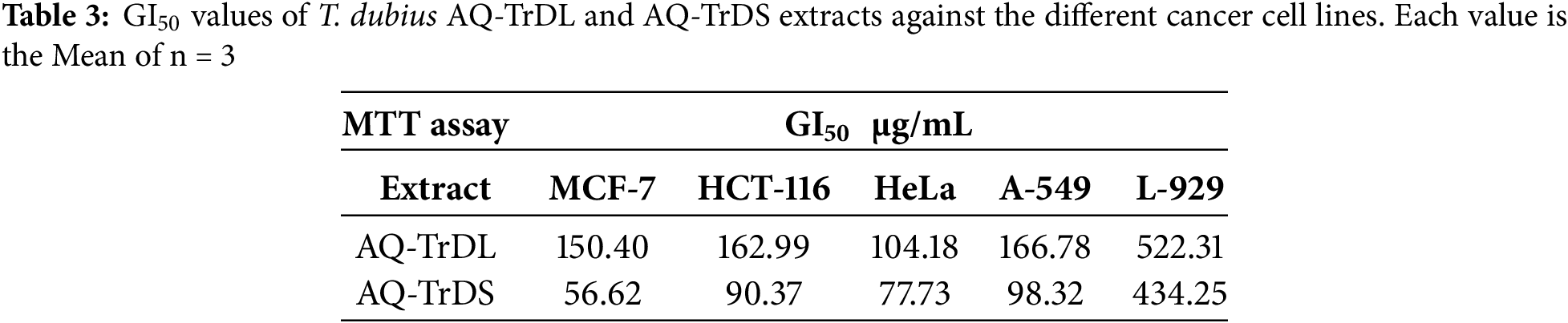

The anticancer efficacy of AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS extracts was evaluated against MCF-7 (breast cancer), HCT-116 (colon cancer), HeLa (cervical cancer), and A-549 (lung cancer) cell lines, as well as the normal fibroblast L-929 cell line, using the MTT assay in vitro. Among the tested extracts, AQ-TrDS demonstrated the highest cytotoxicity, inhibiting more than 50% of cell proliferation in MCF-7, HCT-116, HeLa, and A-549 cell lines at concentrations of 56.62, 90.37, 77.73, and 98.32 μg/mL, respectively. The inhibitory effects of AQ-TrDS on cancer cell viability were observed to be concentration-dependent (Fig. 2), with maximum growth inhibition rates of 89.81%, 81.35%, 81.33%, and 87.78% at the highest tested concentration of 500 μg/mL in the respective cancer cell lines. In contrast, AQ-TrDL exhibited comparatively lower cytotoxic activity, with a GI50 value of up to 166.78 μg/mL in the A-549 cell line. The GI50 values for all tested cell lines are presented in Table 3. Significant variations in cytotoxicity were observed between AQ-TrDS and AQ-TrDL, suggesting differential efficacy against the selected cancer cell lines. Notably, both extracts exhibited minimal toxicity towards the normal fibroblast L-929 cell line, with GI50 values of 522.31 μg/mL and 434.25 μg/mL for AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS, respectively. The potent antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects of the extract depict its valuable bioactive constituents and underscore its potential for developing plant-based natural chemotherapeutic agents.

Figure 2: Cytotoxic potential of T. dubius AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS against (A) MCF-7 (B) HCT-116 (C) HeLa and (D) A-549 cancer cell lines after 24 h treatment. Values are represented as mean ± SD of n = 3. Data labels with different letters (a, b) represents significant difference among the values at different concentrations of AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS extracts with respect to each cell line

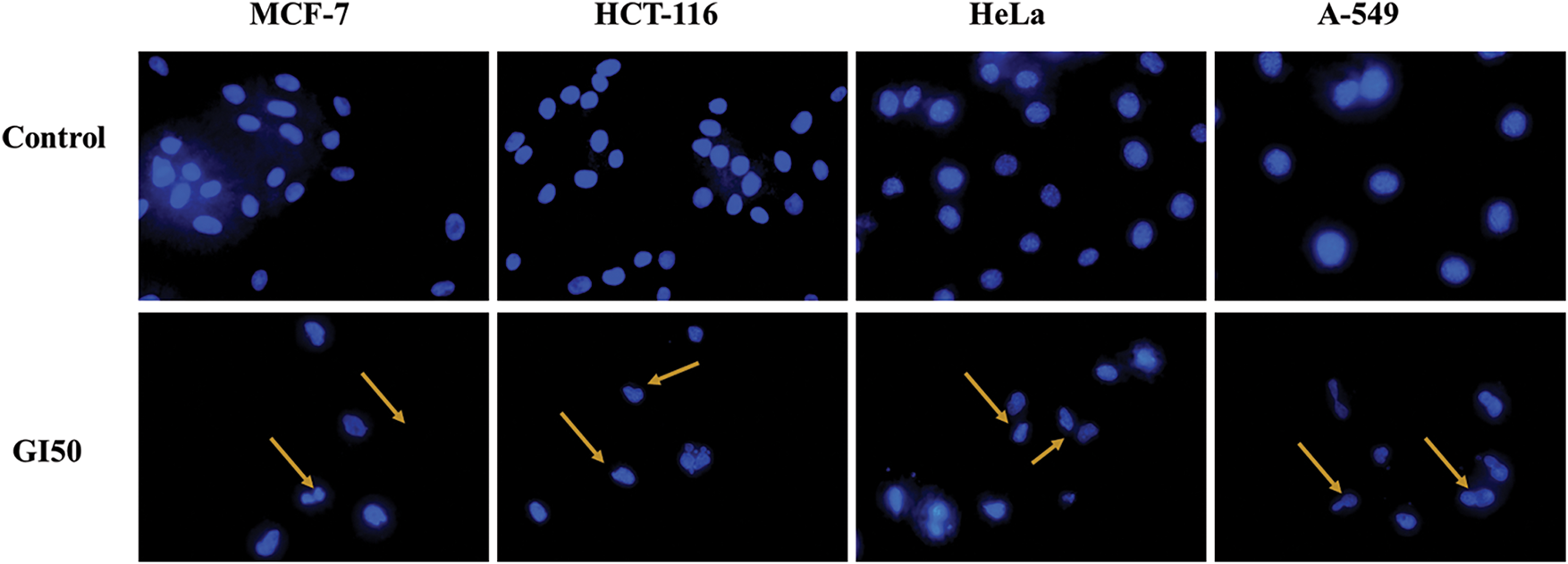

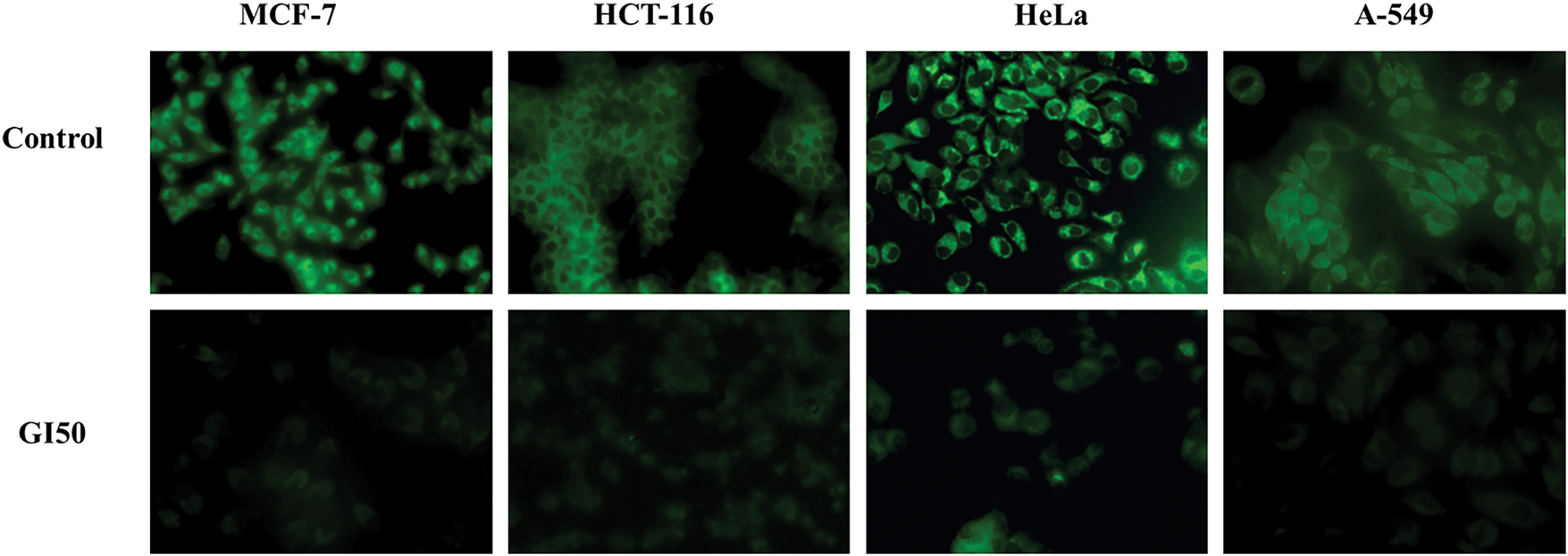

3.4 Fluorescence Microscopy for Assessing the Apoptotic Effect of AQ-TrDS Extract

Given that the aqueous extract of Tragopogon dubius (AQ-TrDS) demonstrated superior antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects on the aforementioned cancer cell lines, fluorescence microscopy was employed to further assess apoptotic induction. DAPI staining was utilized to visualize alterations in nuclear morphology as depicted in Fshow. In contrast, Rhodamine 123 staining was applied to monitor mitochondrial membrane potential at given in Fig. 3. In contrast, Rhodamine 123 staining was applied to monitor mitochondrial membrane potential as shown in Fig. 4 at the GI50 concentration of the extract. The findings revealed that treatment with AQ-TrDS extract induced significant nuclear alterations, including membrane blebbing, shrinkage, and fragmentation—hallmarks of apoptotic processes within cancer cells. Furthermore, the analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential showed a marked disruption following exposure to the extract, evidenced by a substantial reduction in fluorescence intensity compared to untreated control cells. These morphological aberrations and the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential corroborate the hypothesis that AQ-TrDS extract contains bioactive phytochemicals capable of inducing apoptosis. Thus, these results advocate for the further isolation and characterization of Tragopogon dubius phytochemicals for potential therapeutic applications in cancer treatment.

Figure 3: DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining of cancer different cells, depicting nuclear damage upon treatment with GI50 of AQ-TrDS. Arrows indicate apoptotic and damaged nuclei

Figure 4: Rhodamine 123 staining, confirming loss of mitochondrial membrane potential when treated with GI50 concentration of AQ-TrDS extract for 24 h. The treated cells can be visualized as having lost fluorescence compared to the untreated control

3.5 Genotoxic and Genoprotective Evaluation

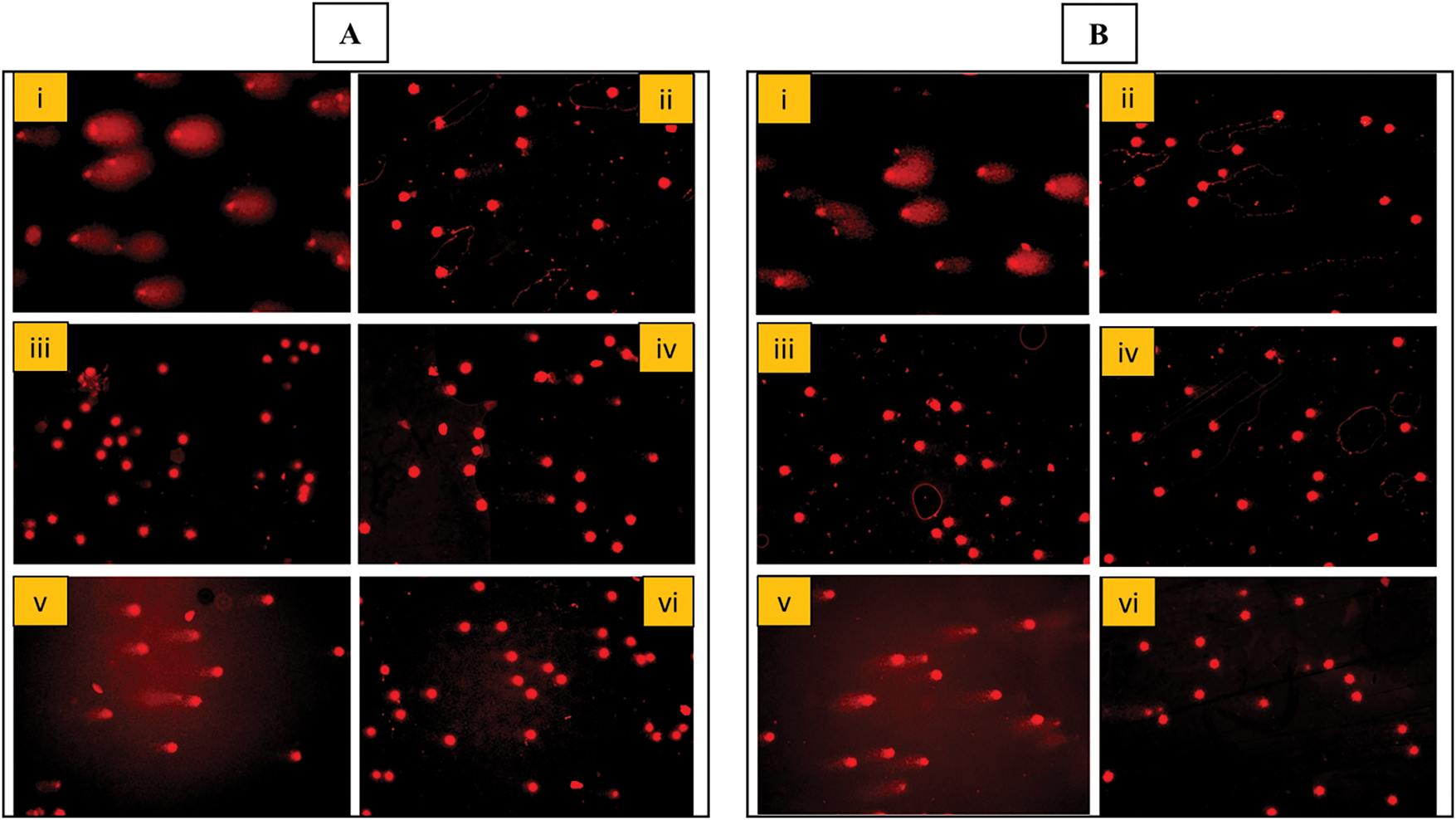

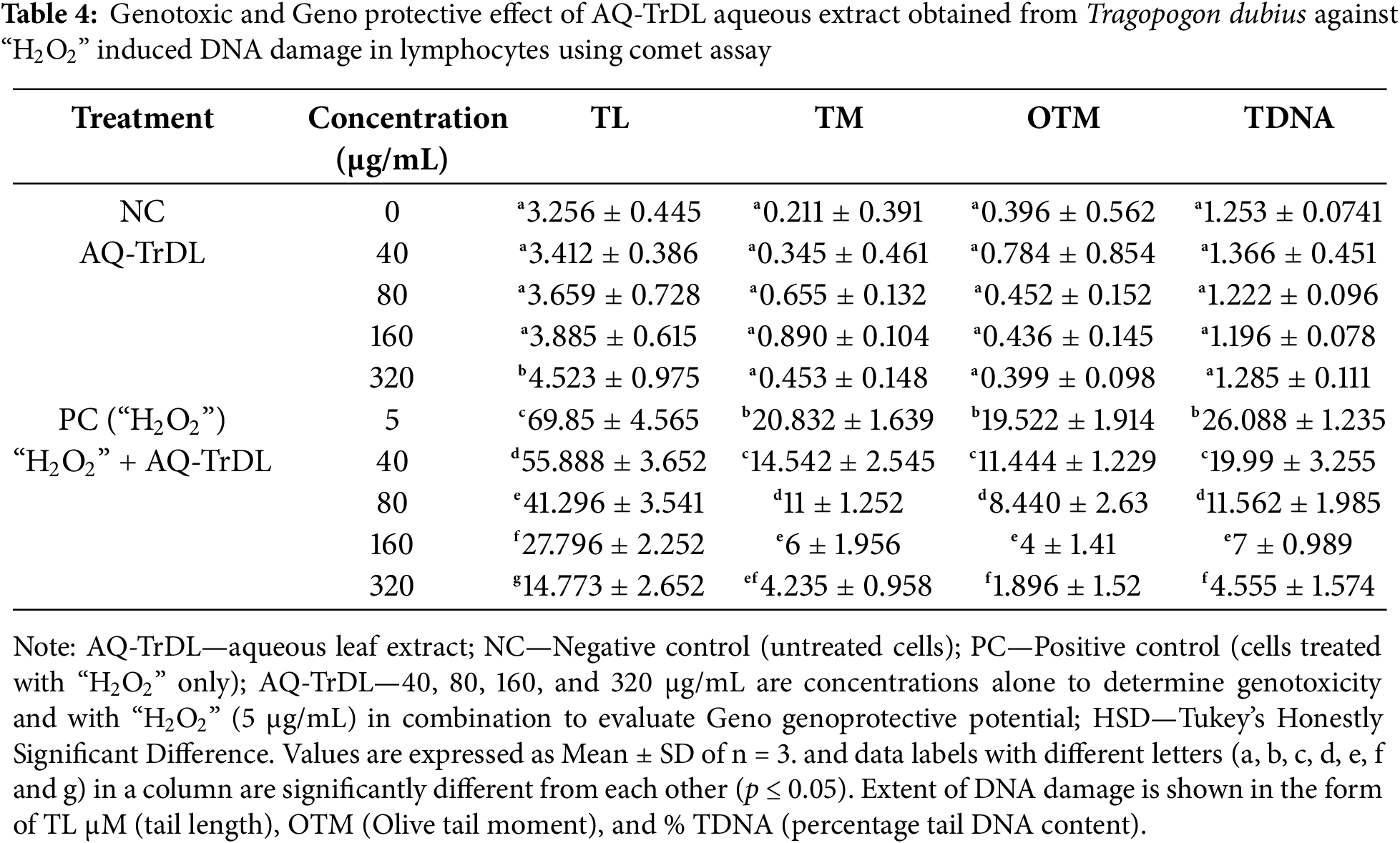

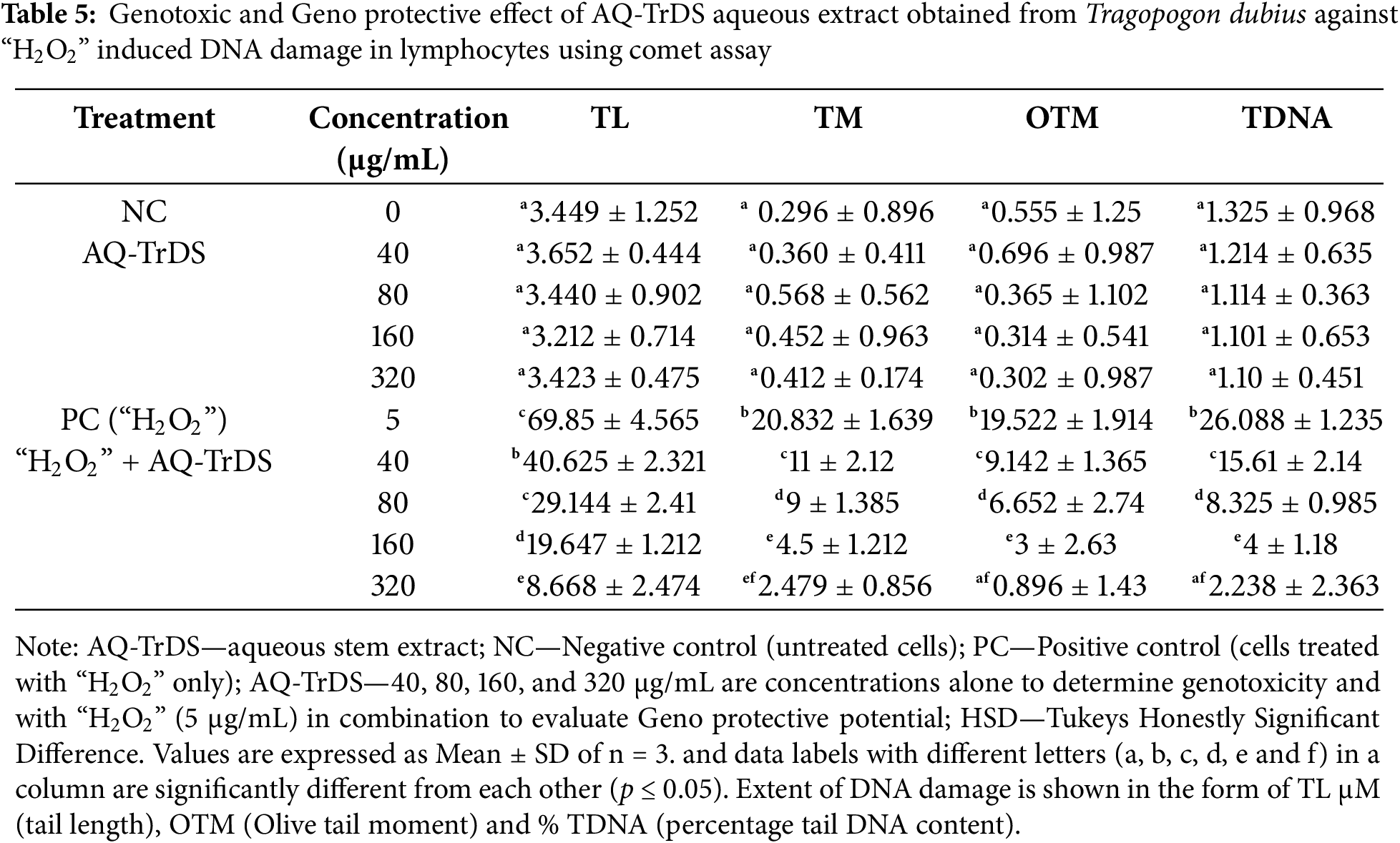

The genotoxicity and genoprotective potential of AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS aqueous extracts were assessed using the alkaline comet assay on human blood lymphocytes at concentrations of 40, 80, 160, and 320 μg/mL. This assay aimed to evaluate the extent of DNA damage. Our results revealed that none of the tested concentrations of AQ-TrDL or AQ-TrDS induced significant DNA fragmentation or comet formation in human lymphocytes, indicating the absence of genotoxic properties in these extracts. The morphology of the treated lymphocytes remained essentially spherical, consistent with the negative control group, thereby substantiating the lack of notable genotoxic effects (Fig. 5). Hydrogen peroxide (“H2O2”) was used as the positive control, effectively inducing DNA damage in blood lymphocytes, as demonstrated in Fig. 5Ai, Bi. The treated lymphocytes were analysed for tail length (TL), olive tail movement (OTM), and percentage tail DNA content (% TDNA). No statistically significant alterations were observed in these parameters when compared to the control group, as presented in Tables 4 and 5. However, both AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS extracts exhibited a substantial protective effect against “H2O2”—induced DNA damage in lymphocytes, with AQ-TrDS demonstrating a more pronounced effect even at the lowest tested concentration (40 μg/mL). This enhanced protective activity may be attributed to the presence of bioactive phytochemicals in the extract. The extent of DNA damage induced by “H2O2” initially recorded at 69.85% was progressively reduced to 40.625%, 29.144%, 19.647%, and 8.668% by AQ-TrDS at concentrations of 40, 80, 160, and 320 μg/mL, respectively. The non-genotoxic and strong genoprotective profile of AQ-TrDS supports its relevance for developing safe pharmaceutical and nutraceutical formulations, but much in-depth toxicological investigations through animal models are necessary to validate the extract’s biosafety potential.

Figure 5: Ethidium bromide-stained DNA of blood lymphocytes. (A,B): (i) Positive control cells showing DNA damage (DNA tail) treated with “H2O2” (5 μg/mL) (ii) Negative control untreated cells (iii,iv) Cells treated with 40 and 320 μg/mL concentration each of AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS extract showing no DNA damage or genotoxicity. B (v,vi) Cells treated with Tragopogon dubius AQ-TrDL) and AQ-TrDS aqueous extracts with 40 and 320 μg/mL concentration depicting protective effect (Comet tail shortened) at higher concentration

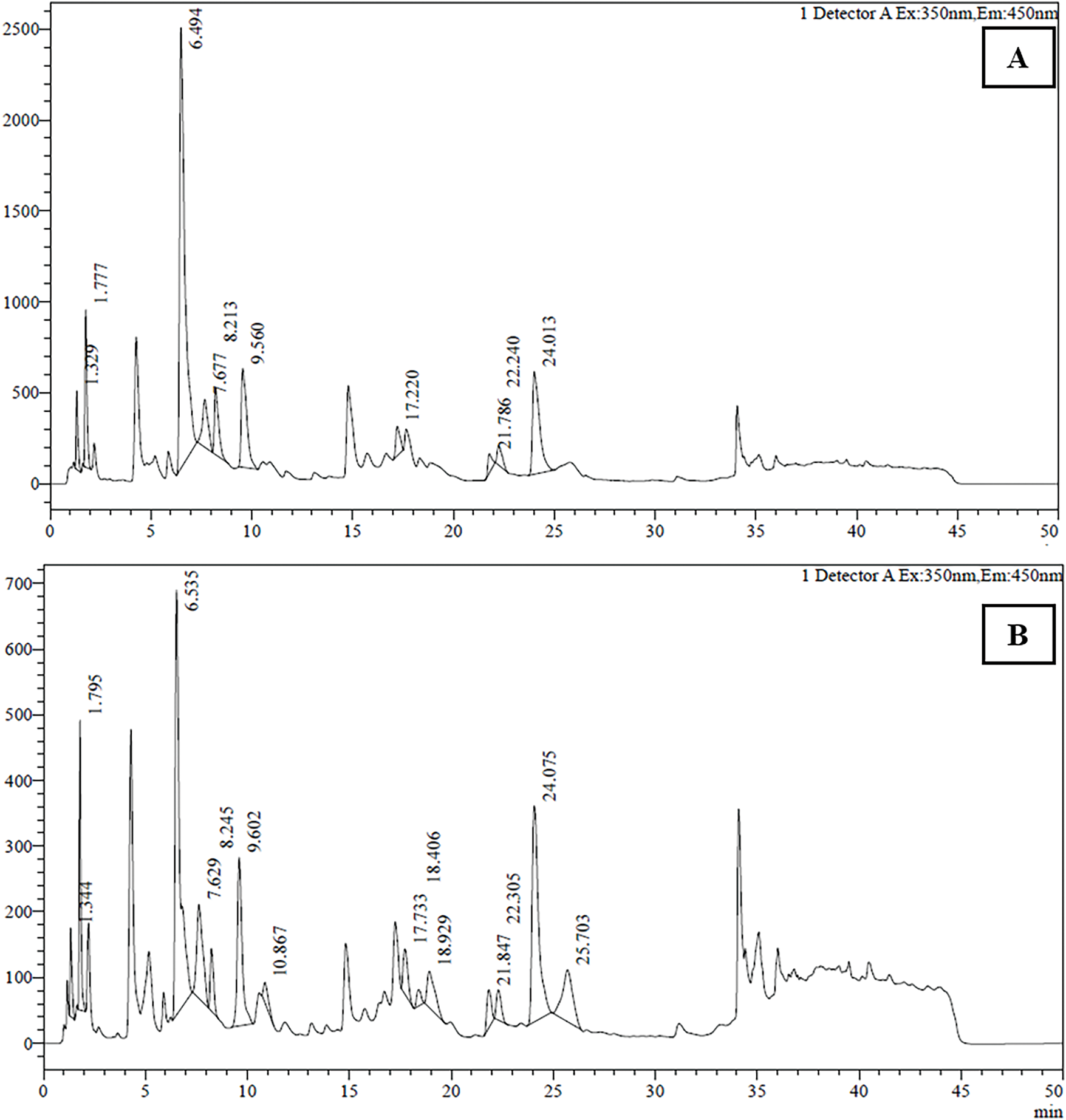

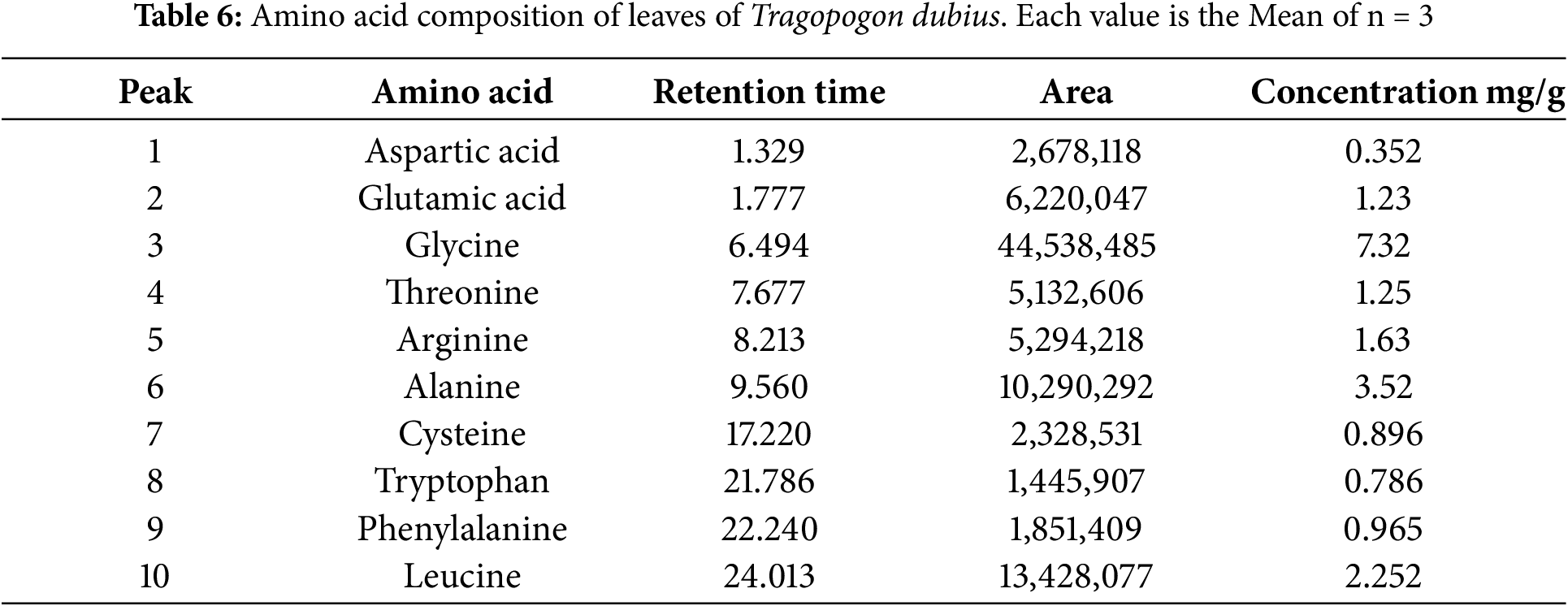

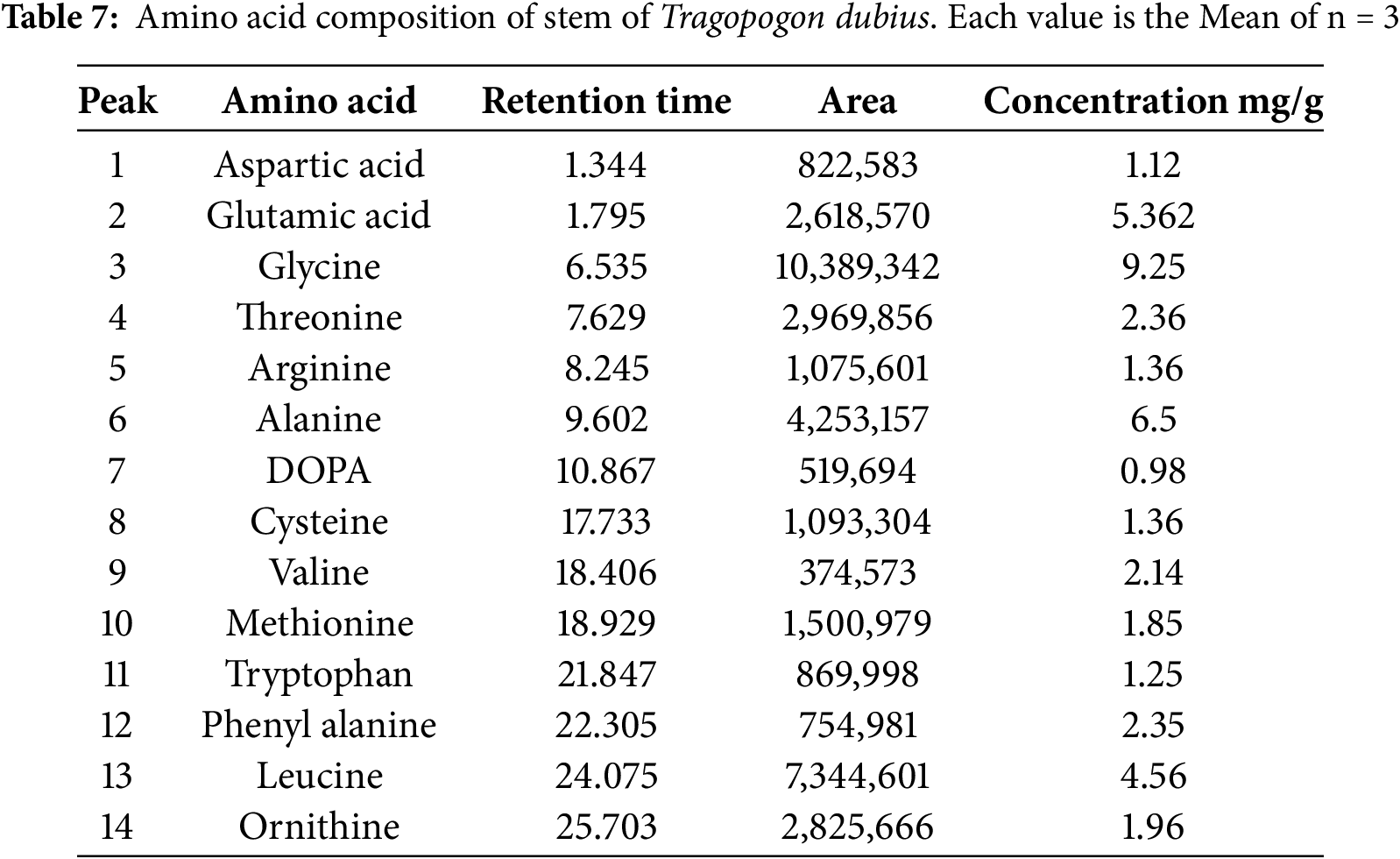

The amino acid profile of T. dubius leaves and stems was meticulously analysed, revealing the presence of several key amino acids: aspartic acid, glutamic acid, glycine, threonine, arginine, alanine, tyrosine, cystine, valine, tryptophan, phenylalanine, and leucine. These amino acids were precisely identified and quantified using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), with concentrations reported as milligrams per gram of protein. Chromatograms are shown in micrograms per gram of protein. Chromatograms are shown in micrograms per gram of protein. The chromatograms are shown in Fig. 6. The detailed results, including peak number, area, retention time, and amino acid concentration for both leaf and stem samples, are provided in Tables 6 and 7. In total, 10 amino acids were identified in the leaf samples, while 14 were detected in the stem samples of T. dubius.

Figure 6: Amino acid chromatograms of (A) Leaf and (B) Stem of Tragopogon dubius

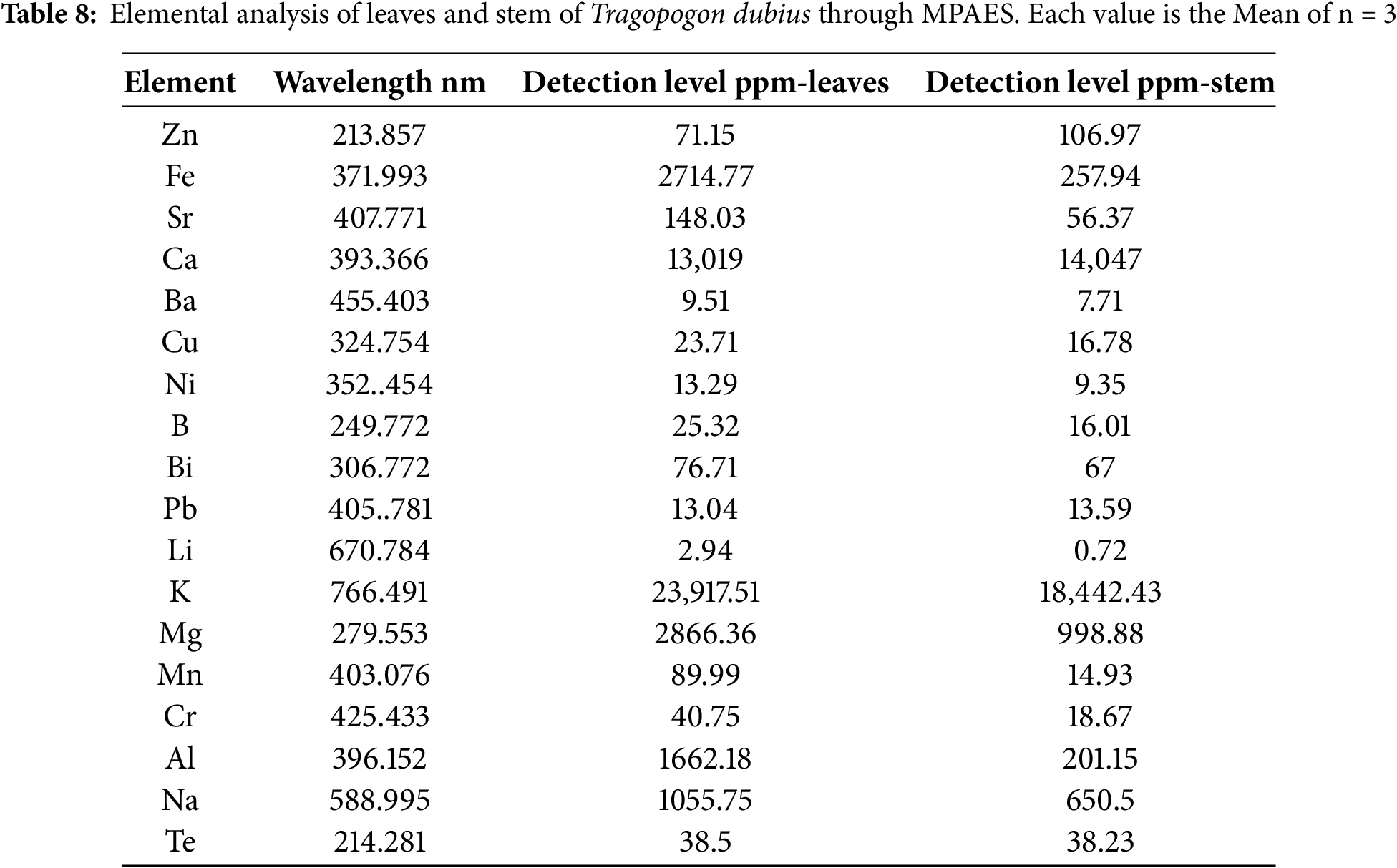

The elemental composition of Tragopogon dubius leaves and stems was analysed using Microwave Plasma-Atomic Emission Spectroscopy (MPAES), with the results summarized in Table 8. The analysis reveals the presence of several major elements, including sodium (Na), potassium (K), magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), bismuth (Bi), aluminium (Al), and iron (Fe). Trace elements such as manganese (Mn), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), lithium (Li), and nickel (Ni) were also detected. Furthermore, the presence of potentially toxic heavy metals, such as lead (Pb) and chromium (Cr), was noted; however, their concentrations were minimal and remained within the permissible limits established by the FAO/WHO guidelines. Notably, the elemental concentrations varied between the leaf and stem tissues [37]. The leaves exhibited elevated levels of iron, calcium, potassium, magnesium, aluminium, and sodium. In contrast, the stems showed high concentrations of only calcium, potassium, and magnesium. The detection of vital elements enhances the dietary value of Tragopogon dubius and can be added in developing plant-based mineral-enriched supplements and herbal formulations.

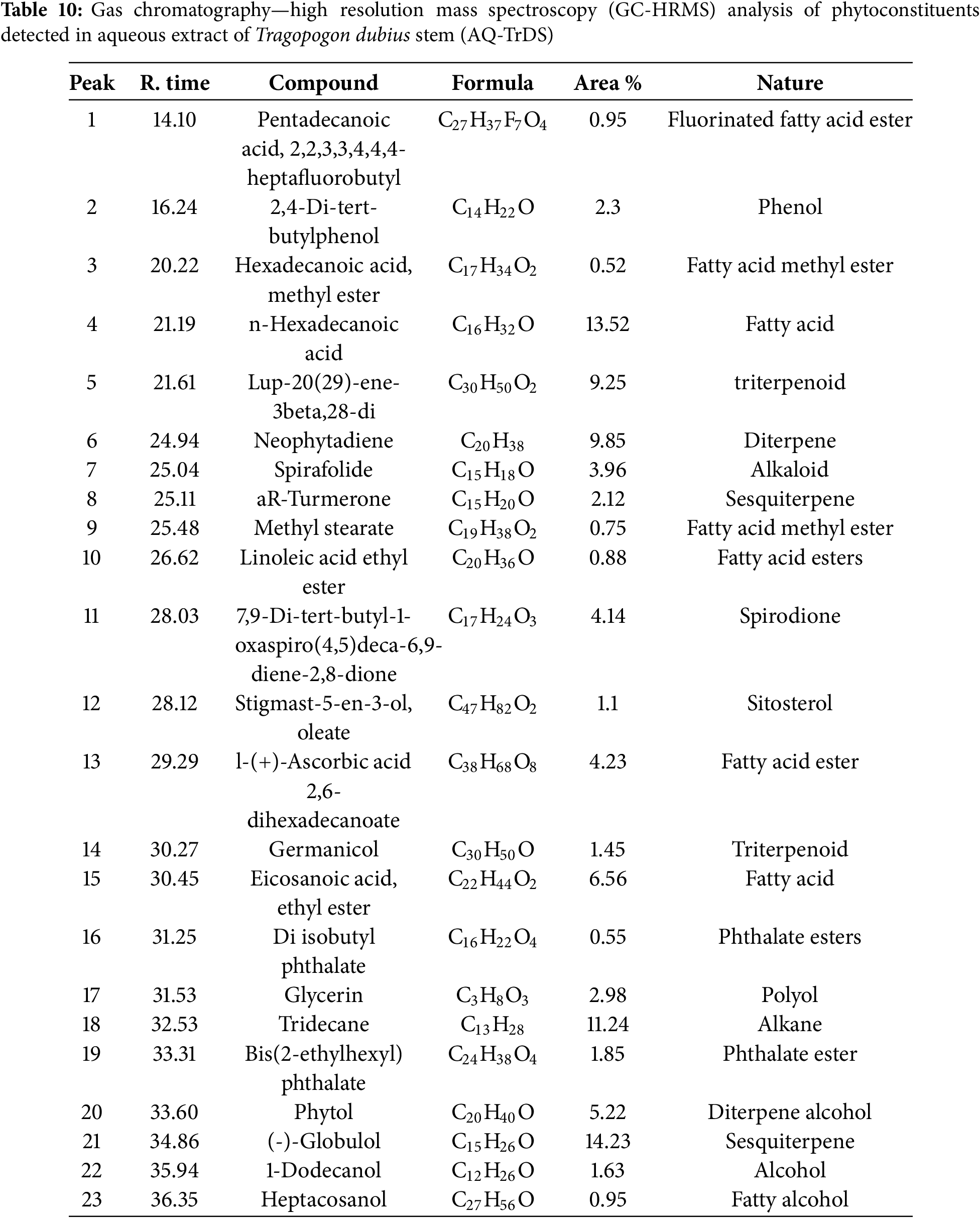

3.8 GC-HRMS Analysis of AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS Extract

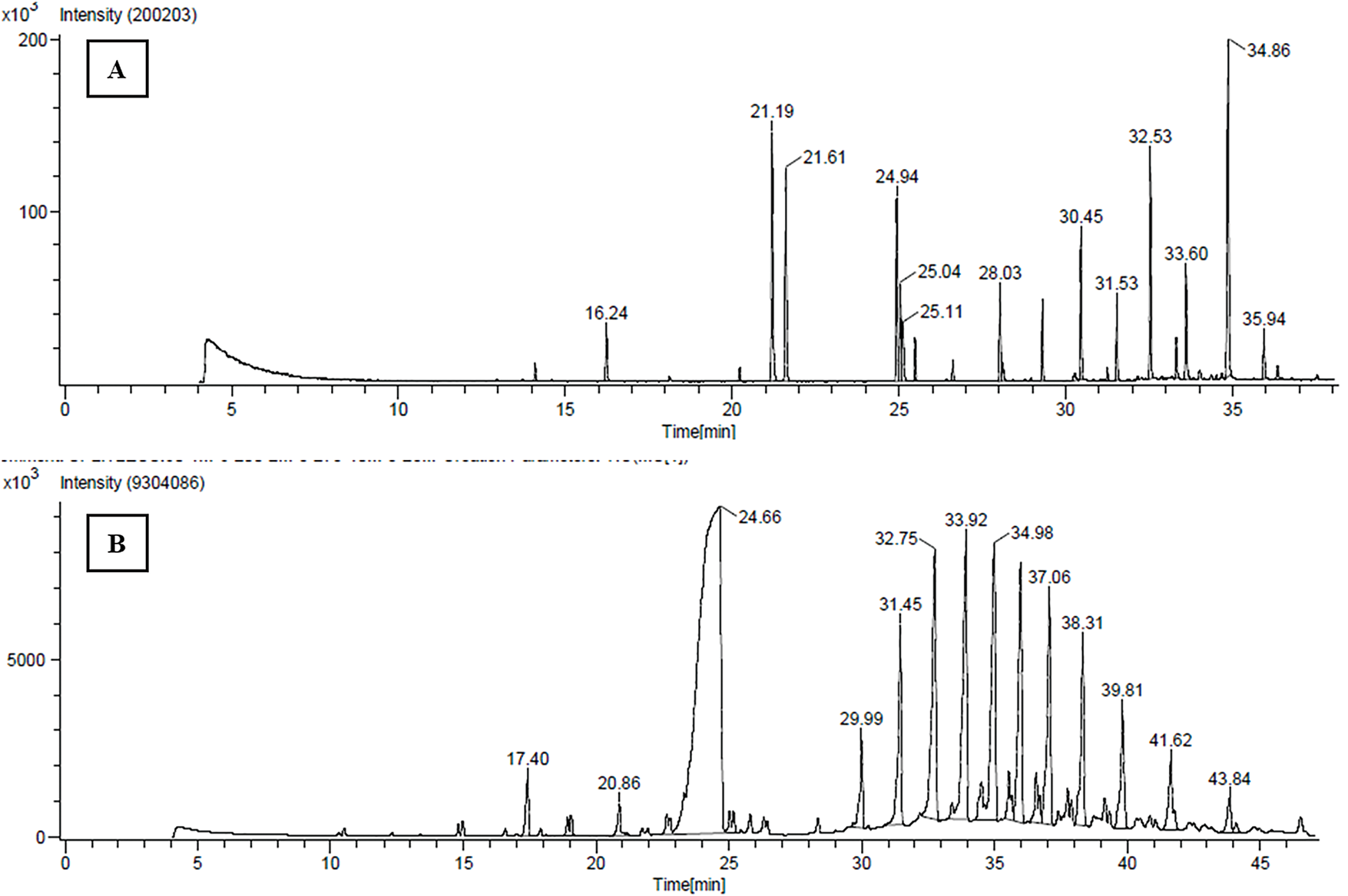

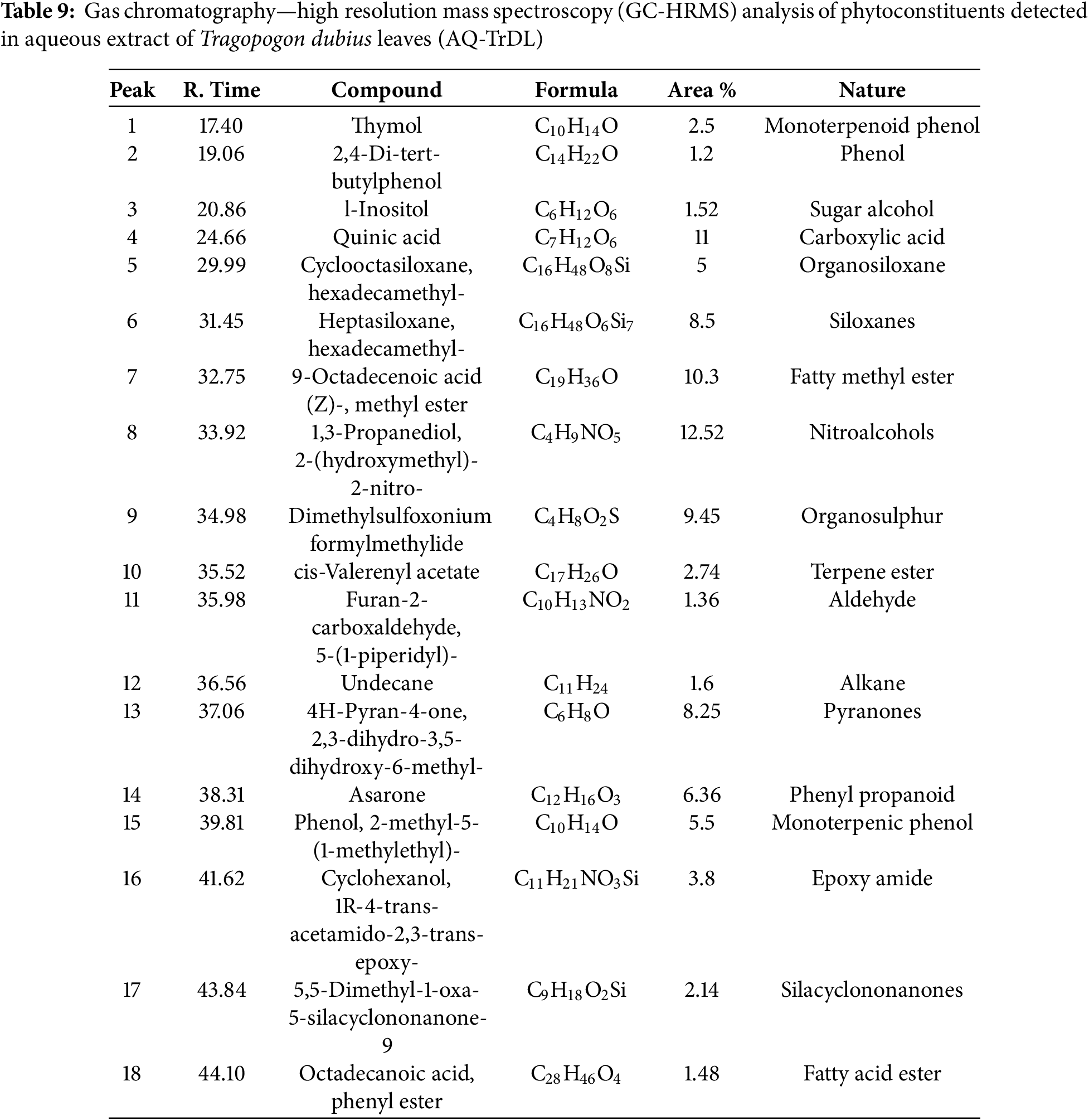

The GC-HRMS analysis revealed a diverse array of phytochemicals in the aqueous extracts of Tragopogon dubius AQ-TrDL and AQ-TrDS). Distinct chromatographic peaks in the aqueous extracts corresponded to various phytoconstituents. Specifically, the AQ-TrDL extract was found to contain 18 phytochemical constituents, while the AQ-TrDS extract harbored 23 distinct constituents; their respective chromatograms are presented in Fig. 7. Prominent phytochemicals identified in the AQ-TrDL extract include quinic acid (11%), 1,3-propanediol, 2-(hydroxymethyl)-2-nitro (12.52%), and 9-Octadecenoic acid (Z)-, methyl ester (10.3%). Conversely, the AQ-TrDS extract was dominated by (-)-Globulol (14%), Tridecane (11.24%), and n-Hexadecenoic acid (13.52%). Collectively, these extracts encompass a broad spectrum of chemical classes, including triterpenoids, fatty acids, carboxylic acids, diterpenes, alcohols, and esters. Comprehensive details regarding the active principles, including their retention times (RT), molecular formulas, molecular weights, and concentrations (expressed as peak area %), are provided in Tables 9 and 10. The rich diversity of phytochemicals validate that Tragopogon dubius leaves and stems as valuable sources for pharmaceutical and nutraceutical applications.

Figure 7: GCHRMS chromatograms (A) AQ-TrDL extract of Tragopogon dubius (B) AQ-TrDS of Tragopogon dubius

The infrared (IR) absorption spectra of the aqueous extracts from the leaves and stems of T. dubius are depicted in Fig. 8. The major peaks observed in the FTIR spectra correspond to various functional groups, including alcohols, alkanes, alkenes, alkynes, aldehydes, amines, carboxylic acids, esters, sulfoxides, hydroxyl groups, and alkyl halides. Table 11 summarizes the functional groups linked to these peaks in the FTIR spectra of the leaf and stem extracts, which align with the phytoconstituents identified through GC-HRMS analysis.

Figure 8: (A) FTIR analysis of aqueous leaf (AQ-TrDL) and (B) aqueous stem (AQ-TrDS) extracts Tragopogon dubius

Phenolic and flavonoid constituents are renowned for their extensive physiological properties, including antiallergenic, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, cardioprotective, and vasodilatory effects [38–40]. Uysal previously reported the total phenolic content (TPC) and total flavonoid content (TFC) of T. dubius leaves collected from Turkey, using water (TPC: 22.48 ± 0.49; TFC: 14.34 ± 0.38), ethyl acetate (TPC: 25.90 ± 1.57; TFC: 26.98 ± 0.26), and methanol (TPC: 37.19 ± 0.91; TFC: 58.49 ± 0.51) as solvents (Uysal et al., 2019). These values were notably lower than those observed in our study, as detailed in Table 1. The AQ-TrDS extract exhibited elevated levels of phenolic and flavonoid content. These results aligns with numerous studies that have reported an increase in antioxidant activity concomitant with higher polyphenol and flavonoid levels [41].

Free radicals are highly reactive molecules with unpaired electrons, which contribute to oxidative damage in cells and tissues through interactions with various biomolecules [42]. Plant extracts or phytochemicals have redox properties that allow them to act as reducing agents, hydrogen donors, and singlet oxygen quenchers, thus neutralizing harmful reactive oxygen and nitrogen species [43–45]. Various studies have reported significant antioxidant potential in aqueous and other solvent extracts of Tragopogon species, such as Tragopogon grammnifolius and Tragopogon porrifolius [46–49]. Uysal evaluated the antioxidant potential of water, methanol, and ethyl acetate extracts of T. dubius and found that the ethyl acetate extract exhibited strong antioxidant activity. This highlights the importance of methodological variations and geographical factors in affecting the concentrations of phenolic, flavonoid, triterpenoid, glycoside, and other phytochemicals. These variations, in turn, influence the antioxidant and therapeutic properties of plants [22,50,51]. Our previous study on methanolic extracts of T. dubius roots revealed moderate antioxidant activity and lower phenolic and flavonoid content compared to aqueous extracts of leaves and stems [15].

The antitumor potential of Tragopogon species such as T. porrifolius, T. pratensis, and T. malicus has been documented against various cancer lines, including breast (MDA-MB-231), colorectal (Caco-2), osteosarcoma (KHOS and HOS), human acute T leukemia (J-45.01), and human hepatocellular carcinoma (HepG2), demonstrating apoptosis-inducing potential [48,49,52–54]. To the best of our knowledge, Tragopogon dubius has not been extensively explored for its anticancer potential. This is the first report on the cytotoxic potential of aqueous leaf and stem extracts, assessing their anticancer potential. Our recent publications indicated that isolated fractions from methanolic root extract, ethyl acetate extract of stem and leaves, methanolic extract, and its synthesized silver nanoparticles were potent inhibitors of glioblastoma (LN-18), lung (A-549), breast (MCF-7) and, cervix (HeLa) cancer cells, underscoring the medicinal value of T. dubius in cancer research [15].

Members of the Asteraceae family, including T. dubius, have extensive therapeutic applications and a long history of use in traditional medicine [23,55]. This study represents the first examination of the genotoxic effects of T. dubius, consumed as food in various countries. Remarkably, our findings showed that aqueous extracts of T. dubius leaves and stems induce no visible damage to human lymphocytes and exhibit protective effects against “H2O2”-induced damage. Similar results have been reported for aqueous extracts from Lamiaceae species, Cornus mas, Scoparia dulcis, and Vernonia cinerea, as well as vegetables from the Asteraceae family, which demonstrate genoprotective potential largely attributed to their antioxidant activity [56–58].

Amino acids are fundamental components of proteins and are essential for nearly all biological processes. They play roles in metabolic functions as precursors to critical compounds such as hormones, neurotransmitters, and other bioactive molecules [59]. Tragopogon dubius is thus noteworthy for its rich reservoir of essential amino acids, potentially making it a valuable choice of diverse diets, especially for those seeking plant-based protein sources.

The elemental composition of plants is crucial for understanding their nutritional profiles, evaluating product quality, and ensuring food safety, as some plants may accumulate toxic elements such as lead, arsenic, or cadmium from the environment [60,61]. Analysing these elements ensures that the plant as a food is safe to consume and does not pose health risks [62]. Our elemental analysis of T. dubius reveals its richness in essential elements, including calcium, magnesium, potassium, and iron, suggesting its potential as a functional food.

Gas chromatography high resolution mass spectrometry (GC-HRMS) separates individual compounds based on their retention time (R.T) and further analyzes them at the molecular level using mass spectrometry (MS) [63,64]. The AQ-TrDS extract, exhibiting superior antioxidant and anticancer activities, contains compounds such as n-hexadecenoic acid, neophytadiene, 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol, and (-)-globulol, known for their antioxidant and anticancer properties [65–69]. Phytol, a diterpenoid alcohol, is also reported for its anti-inflammatory potential, with anticancer and antidiuretic activities as documented by previous studies [70,71]. The detected compounds in AQ-TrDS like spirafolide, germanicol, lup-20(29)-ene-3beta,28-di, aR-Turmerone, linoleic acid ethyl ester are known to possess potent neuroprotective, genoprotective, anticancerous, and antioxidant effects that support the observed effect of AQ-TrDS extract [72–76]. The presence of diverse functional groups indicates a complex mixture of bioactive compounds, which may contribute to various pharmacological activities. For instance, hydroxyl groups from phenolic compounds may offer antioxidant benefits, while carboxylic acids and aldehydes could contribute to antimicrobial properties [77,78]. The findings could facilitate the development of natural product-based therapies or dietary supplements derived from T. dubius. Future perspectives of this work should focus on isolating individual bioactive compounds from the AQ-TrDS extract to elucidate their specific roles in antioxidant and anticancer activities. For apoptosis confirmation, nuclear fragmentation and mitochondrial membrane potential disruption are primary evidence, so further validation through apoptotic markers needs to be conducted for future studies.

In conclusion, this study presents a comprehensive investigation of the phytochemical and biomedical properties of aqueous extracts from the leaves and stems of Tragopogon dubius. The AQ-TrDS demonstrated superior efficacy in both antioxidant and anticancer activities. AQ-TrDS extract showed apoptosis inducing potential as confirmed through nuclear and mitochondrial disruptions. Additionally, AQ-TrDS demonstrated strong genoprotective effects against “H2O2”-induced DNA damage, further enhancing its therapeutic potential. The presence of key micronutrients, amino acids, detection of diverse bioactive phytochemicals, and safe levels of heavy metals, adding a wide range of applications for T. dubius in nutraceuticals, pharmaceuticals, and other industries.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge IIT Bombay, Emerging Life Sciences, Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar (India) for providing necessary facilities.

Funding Statement: This paper was supported by Research institute/Center Supporting Program (RICSP-25-3), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualisation: Sheikh Showkat Ahmad; methodology: Sheikh Showkat Ahmad; validation: Sheikh Showkat Ahmad, Satwinderjeet Kaur; writing—original draft preparation: Sheikh Showkat Ahmad, Chandni Garg; writing—review and editing: Sheikh Showkat Ahmad, Chandni Garg, Dalia Fouad, Islam Abdulrahim Alredah, Sandeep Kaur, Satwinderjeet Kaur; supervision: Satwinderjeet Kaur. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lubbe A, Verpoorte R. Cultivation of medicinal and aromatic plants for specialty industrial materials. Ind Crops Prod. 2011;34(1):785–801. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2011.01.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chandrasekara A, Shahidi F. Herbal beverages: bioactive compounds and their role in disease risk reduction—a review. J Tradit Complement Med. 2018;8(4):451–8. doi:10.1016/j.jtcme.2017.08.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Michalak M. Plant extracts as skin care and therapeutic agents. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(20):15444. doi:10.3390/ijms242015444. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Prasathkumar M, Anisha S, Dhrisya C, Becky R, Sadhasivam S. Therapeutic and pharmacological efficacy of selective Indian medicinal plants—a review. Phytomed Plus. 2021;1(2):100029. doi:10.1016/j.phyplu.2021.100029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Oyebode O, Kandala NB, Chilton PJ, Lilford RJ. Use of traditional medicine in middle-income countries: a WHO-SAGE study. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(8):984–91. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. World Health Organization. WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine 2019. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2019. [Google Scholar]

7. Khan T, Ali M, Khan A, Nisar P, Ahmad Jan S, Afridi S, et al. Anticancer plants: a review of the active phytochemicals, applications in animal models, and regulatory aspects. Biomolecules. 2019;10(1):47. doi:10.3390/biom10010047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Rudzińska A, Juchaniuk P, Oberda J, Wiśniewska J, Wojdan W, Szklener K, et al. Phytochemicals in cancer treatment and cancer prevention—review on epidemiological data and clinical trials. Nutrients. 2023;15(8):1896. doi:10.3390/nu15081896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. George BP, Chandran R, Abrahamse H. Role of phytochemicals in cancer chemoprevention: insights. Antioxidants. 2021;10(9):1455. doi:10.3390/antiox10091455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Unnisa A, Chettupalli AK. Promising role of phytochemicals in the prevention and treatment of cancer. Anti Cancer Agents Med Chem. 2022;22(20):3382–400. doi:10.2174/1871520622666220425133936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Snowden FM. Emerging and reemerging diseases: a historical perspective. Immunol Rev. 2008;225(1):9–26. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00677.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Roth J, Szulc AL, Danoff A. Energy, evolution, and human diseases: an overview. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(4):875S–83. doi:10.3945/ajcn.110.001909. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Akbari B, Baghaei-Yazdi N, Bahmaie M, Mahdavi Abhari F. The role of plant-derived natural antioxidants in reduction of oxidative stress. Biofactors. 2022;48(3):611–33. doi:10.1002/biof.1831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Brewer MS. Natural antioxidants: sources, compounds, mechanisms of action, and potential applications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2011;10(4):221–47. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00156.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ahmad SS, Garg C, Kour R, Bhat AH, Raja V, Gandhi SG, et al. Metabolomic insights and bioactive efficacies of Tragopogon dubius root fractions: antioxidant and antiproliferative assessments. Heliyon. 2024;10(16):e34746. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e34746. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Samtiya M, Aluko RE, Dhewa T, Moreno-Rojas JM. Potential health benefits of plant food-derived bioactive components: an overview. Foods. 2021;10(4):839. doi:10.3390/foods10040839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Grusak MA, DellaPenna D. Improving the nutrient composition of plants to enhance human nutrition and health. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 1999;50(1):133–61. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Moromete C, Arcus M, Bucur L, Rosoiu N. General data regarding Tragopogon dubius scop. species-pharmacognostic analysis. Stud Univ Vasile Goldiş Ser Ştiinţele Vieţii. 2014;24(4):399–405. [Google Scholar]

19. Wright C. Mediterranean vegetables: a cook’s compendium of all the vegetables from the world’s healthiest cuisine, with more than 200 recipes. Boston, MA, USA: Harvard Common Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

20. Hosler DMEG. Studies of medicinal plant use by residents of Catron County, New Mexico [master’s thesis]. Denver, CO, USA: University of Colorado at Denve; 1989. [Google Scholar]

21. Layeghi-Ghalehsoukhteh S, Jalaei J, Fazeli M, Memarian P, Shekarforoush SS. Evaluation of ‘green’ synthesis and biological activity of gold nanoparticles using Tragopogon dubius leaf extract as an antibacterial agent. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2018;12(8):1118–24. doi:10.1049/iet-nbt.2018.5073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Uysal S, Senkardes I, Mollica A, Zengin G, Bulut G, Dogan A, et al. Biologically active compounds from two members of the Asteraceae family: Tragopogon dubius Scop. and Tussilago farfara L. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2019;37(12):3269–81. doi:10.1080/07391102.2018.1506361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Ali Abdalla M, Zidorn C. The genus Tragopogon (Asteraceaea review of its traditional uses, phytochemistry, and pharmacological properties. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;250(3):112466. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2019.112466. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Li HB, Jiang Y, Wong CC, Cheng KW, Chen F. Evaluation of two methods for the extraction of antioxidants from medicinal plants. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2007;388(2):483–8. doi:10.1007/s00216-007-1235-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Chandni, Ahmad SS, Saloni A, Bhagat G, Ahmad S, Kaur S, et al. Phytochemical characterization and biomedical potential of Iris kashmiriana flower extracts: a promising source of natural antioxidants and cytotoxic agents. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):24785. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-58362-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Blois MS. Antioxidant determinations by the use of a stable free radical. Nature. 1958;181(4617):1199–200. doi:10.1038/1811199a0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Nishikimi M, Appaji N, Yagi K. The occurrence of superoxide anion in the reaction of reduced phenazine methosulfate and molecular oxygen. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1972;46(2):849–54. doi:10.1016/s0006-291x(72)80218-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Benzie IF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239(1):70–6. doi:10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(9–10):1231–7. doi:10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00315-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kumar P, Nagarajan A, Uchil PD. Analysis of cell viability by the MTT assay. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2018;2018(6). doi:10.1101/pdb.prot095505. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Singh NP, McCoy MT, Tice RR, Schneider EL. A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp Cell Res. 1988;175(1):184–91. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(88)90265-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Mateen A, Singh G. Evaluating the potential of millets as blend components with soy protein isolate in a high moisture extrusion system for improved texture, structure, and colour properties of meat analogues. Food Res Int. 2023;173(Pt 2):113395. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2023.113395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Mengerink Y, Kutlán D, Tóth F, Csámpai A, Molnár-Perl I. Advances in the evaluation of the stability and characteristics of the amino acid and amine derivatives obtained with the o-phthaldialdehyde/3-mercaptopropionic acid and o-phthaldialdehyde/N-acetyl-L-cysteine reagents. High-performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry study. J Chromatogr A. 2002;949(1–2):99–124. doi:10.1016/s0021-9673(01)01282-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Consultation FE. Dietary protein quality evaluation in human nutrition. FAO Food Nutr Pap. 2011;92:1–66. [Google Scholar]

35. Bankaji I, Kouki R, Dridi N, Ferreira R, Hidouri S, Duarte B, et al. Comparison of digestion methods using atomic absorption spectrometry for the determination of metal levels in plants. Separations. 2023;10(1):40. doi:10.3390/separations10010040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Nataraj N, Hussain M, Ibrahim M, Hausmann AE, Rao S, Kaur S, et al. Effect of altitude on volatile organic and phenolic compounds of Artemisia brevifolia wall ex dc. from the western Himalayas. Front Ecol Evol. 2022;10:864728. doi:10.3389/fevo.2022.864728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Mensah E, Kyei-Baffour N, Ofori E, Obeng G. Influence of human activities and land use on heavy metal concentrations in irrigated vegetables in Ghana and their health implications. In: Appropriate technologies for environmental protection in the developing world. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2009. p. 9–14. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-9139-1_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Tungmunnithum D, Thongboonyou A, Pholboon A, Yangsabai A. Flavonoids and other phenolic compounds from medicinal plants for pharmaceutical and medical aspects: an overview. Medicines. 2018;5(3):93. doi:10.3390/medicines5030093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Sun W, Shahrajabian MH. Therapeutic potential of phenolic compounds in medicinal plants-natural health products for human health. Molecules. 2023;28(4):1845. doi:10.3390/molecules28041845. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Roy A, Khan A, Ahmad I, Alghamdi S, Rajab BS, Babalghith AO, et al. Flavonoids a bioactive compound from medicinal plants and its therapeutic applications. BioMed Res Int. 2022;2022:5445291. doi:10.1155/2022/5445291. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Saeed N, Khan MR, Shabbir M. Antioxidant activity, total phenolic and total flavonoid contents of whole plant extracts Torilis leptophylla L. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2012;12(1):221. doi:10.1186/1472-6882-12-221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Phaniendra A, Jestadi DB, Periyasamy L. Free radicals: properties, sources, targets, and their implication in various diseases. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2015;30(1):11–26. doi:10.1007/s12291-014-0446-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Kasote DM, Katyare SS, Hegde MV, Bae H. Significance of antioxidant potential of plants and its relevance to therapeutic applications. Int J Biol Sci. 2015;11(8):982–91. doi:10.7150/ijbs.12096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Bibi Sadeer N, Montesano D, Albrizio S, Zengin G, Mahomoodally MF. The versatility of antioxidant assays in food science and safety-chemistry, applications, strengths, and limitations. Antioxidants. 2020;9(8):709. doi:10.3390/antiox9080709. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Asif M. Chemistry and antioxidant activity of plants containing some phenolic compounds. Chem Int. 2015;1(1):35–52. [Google Scholar]

46. Farzaei MH, Khanavi M, Moghaddam G, Dolatshahi F, Rahimi R, Shams-Ardekani MR, et al. Standardization of Tragopogon graminifolius DC. extract based on phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity. J Chem. 2014;2014(1):425965. doi:10.1155/2014/425965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Farzaei MH, Rahimi R, Attar F, Siavoshi F, Saniee P, Hajimahmoodi M, et al. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of essential oil and extracts of Tragopogon graminifolius, a medicinal herb from Iran. Nat Prod Commun. 2014;9(1):121–4. doi:10.1177/1934578x1400900134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Tenkerian CA. Anticancer and antioxidant effects of Tragopogon porrifolius extract [dissertation]. Beyrouth, Lebanon: Lebanese American University; 2011. doi:10.26756/th.2011.40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Al-Rimawi F, Rishmawi S, Ariqat SH, Khalid MF, Warad I, Salah Z. Anticancer activity, antioxidant activity, and phenolic and flavonoids content of wild Tragopogon porrifolius plant extracts. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016(1):9612490. doi:10.1155/2016/9612490. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Vilkickyte G, Raudone L. Phenological and geographical effects on phenolic and triterpenoid content in Vaccinium vitis-idaea L. leaves. Plants. 2021;10(10):1986. doi:10.3390/plants10101986. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Čulina P, Cvitković D, Pfeifer D, Zorić Z, Repajić M, Elez Garofulić I, et al. Phenolic profile and antioxidant capacity of selected medicinal and aromatic plants: diversity upon plant species and extraction technique. Processes. 2021;9(12):2207. doi:10.3390/pr9122207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Tenkerian C, El-Sibai M, Daher CF, Mroueh M. Hepatoprotective, antioxidant, and anticancer effects of the Tragopogon porrifolius methanolic extract. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2015;2015(1):161720. doi:10.1155/2015/161720. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Kucekova Z, Mlcek J, Humpolicek P, Rop O, Valasek P, Saha P. Phenolic compounds from Allium schoenoprasum, Tragopogon pratensis and Rumex acetosa and their antiproliferative effects. Molecules. 2011;16(11):9207–17. doi:10.3390/molecules16119207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Sasmakov SA, Putieva ZM, Azimova SS, Lindequist U. In vitro screening of the cytotoxic, antibacterial and antioxidant activities of some Uzbek plants used in folk medicine. Asian J Trad Med. 2012;7(2):73–80. [Google Scholar]

55. Rolnik A, Olas B. The plants of the Asteraceae family as agents in the protection of human health. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):3009. doi:10.3390/ijms22063009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Oalđe Pavlović M, Kolarević S, Đorđević J, Jovanović Marić J, Lunić T, Mandić M, et al. A study of phytochemistry, genoprotective activity, and antitumor effects of extracts of the selected Lamiaceae species. Plants. 2021;10(11):2306. doi:10.3390/plants10112306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Szczepaniak O, Ligaj M, Stuper-Szablewska K, Kobus-Cisowska J. Genoprotective effect of cornelian cherry (Cornus mas L.) phytochemicals, electrochemical and ab initio interaction study. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;152(3):113216. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113216. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Johnson J, Varghese L. Genoprotective potentials of two traditional medicinal plants Scoparia dulcis L. and Vernonia cinerea (L.) Less. J App Biol Biotech. 2024;2024:1–6. doi:10.7324/jabb.2024.142447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Kolukisaoglu Ü. D-amino acids in plants: sources, metabolism, and functions. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(15):5421. doi:10.3390/ijms21155421. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Rawat H, Ahmad Bhat S, Dhanjal DS, Singh R, Gandhi Y, Mishra SK, et al. Emerging techniques for the trace elemental analysis of plants and food-based extracts: a comprehensive review. Talanta Open. 2024;10(26):100341. doi:10.1016/j.talo.2024.100341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Okereafor U, Makhatha M, Mekuto L, Uche-Okereafor N, Sebola T, Mavumengwana V. Toxic metal implications on agricultural soils, plants, animals, aquatic life and human health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(7):2204. doi:10.3390/ijerph17072204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Gallo M, Ferrara L, Calogero A, Montesano D, Naviglio D. Relationships between food and diseases: what to know to ensure food safety. Food Res Int. 2020;137(3):109414. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Nugraha A, Nandiyanto ABD. How to read and interpret GC/MS spectra. Indonesian J Multidic Res. 2021;1(2):171–206. doi:10.17509/ijomr.v1i2.35191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Thodi RC, Sukumaran ST. Metabolic profiling through GC-HRMS analysis of ethnomedicinal species Pittosporum dasycaulon MIQ. (Pittosporaceae). Int J Bot Stud. 2021;6(4):19–27. [Google Scholar]

65. Bharath B, Perinbam K, Devanesan S, AlSalhi MS, Saravanan M. Evaluation of the anticancer potential of Hexadecanoic acid from brown algae Turbinaria ornata on HT-29 colon cancer cells. J Mol Struct. 2021;1235(2):130229. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.130229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Nair RVR, Jayasree DV, Biju PG, Baby S. Anti-inflammatory and anticancer activities of erythrodiol-3-acetate and 2,4-di-tert-butylphenol isolated from Humboldtia unijuga. Nat Prod Res. 2020;34(16):2319–22. doi:10.1080/14786419.2018.1531406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Nouir S, Dbeibia A, Bouhajeb R, Haddad H, Khélifa A, Achour L, et al. Phytochemical analysis and evaluation of the antioxidant, antiproliferative, antibacterial, and antibiofilm effects of Globularia alypum (L.) leaves. Molecules. 2023;28(10):4019. doi:10.3390/molecules28104019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Rodriguez S, Sueiro RA, Murray AP, Leiro JM. Essential oil. Proceedings. 2019;3:1–15. [Google Scholar]

69. Selmy AH, Hegazy MM, El-Hela AA, Saleh AM, El-Hamouly MM. In Vitroand in silico studies of neophytadiene; A diterpene isolated from Aeschynomene elaphroxylon (Guill. & Perr.) Taub. as apoptotic inducer. Egypt J of Chem. 2023;66(10):149–61. [Google Scholar]

70. Kiruthiga C, Jaya Balan D, Jafni S, Anandan DP, Devi KP. Phytol and (-)-α-bisabolol Synergistically trigger intrinsic apoptosis through redox and Ca2+ imbalance in non-small cell lung cancer. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2024;56(2):103005. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2023.103005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Vats S, Gupta T. Evaluation of bioactive compounds and antioxidant potential of hydroethanolic extract of Moringa oleifera Lam. from Rajasthan, India. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2017;23(1):239–48. doi:10.1007/s12298-016-0407-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Ham A, Kim B, Koo U, Nam KW, Lee SJ, Kim KH, et al. Spirafolide from bay leaf (Laurus nobilis) prevents dopamine-induced apoptosis by decreasing reactive oxygen species production in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2010;33(12):1953–8. doi:10.1007/s12272-010-1210-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Hu YL, Wang XB, Chen DD, Guo XJ, Yang QJ, Dong LH, et al. Germanicol induces selective growth inhibitory effects in human colon HCT-116 and HT29 cancer cells through induction of apoptosis, cell cycle arrest and inhibition of cell migration. J BUON. 2016;21(3):626–32. doi:10.2147/ijn.s24160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Liu K, Zhang X, Xie L, Deng M, Chen H, Song J, et al. Lupeol and its derivatives as anticancer and anti-inflammatory agents: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic efficacy. Pharmacol Res. 2021;164(2):105373. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Yusuf M, Pal S, Shahid M, Asif M, Khan SA, Tyagi R. Docking and ADMET study of arturmerone: emerging scaffold for acetylcholine esterase inhibition and antidiabetic target. J Appl Organometallic Chem. 2023;3(1):1. [Google Scholar]

76. Szczepańska P, Rychlicka M, Groborz S, Kruszyńska A, Ledesma-Amaro R, Rapak A, et al. Studies on the anticancer and antioxidant activities of resveratrol and long-chain fatty acid esters. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(8):7167. doi:10.3390/ijms24087167. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Orlo E, Russo C, Nugnes R, Lavorgna M, Isidori M. Natural methoxyphenol compounds: antimicrobial activity against foodborne pathogens and food spoilage bacteria, and role in antioxidant processes. Foods. 2021;10(8):1807. doi:10.3390/foods10081807. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Thummajitsakul S, Samaikam S, Tacha S, Silprasit K. Study on FTIR spectroscopy, total phenolic content, antioxidant activity and anti-amylase activity of extracts and different tea forms of Garcinia schomburgkiana leaves. LWT. 2020;134(1):110005. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools