Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

A Comprehensive Analysis of the Mineral Profile of Three Wild Tulips in China

1 College of Agriculture and Animal Husbandry, Qinghai University, Xining, 810016, China

2 Key Laboratory of Qinghai Province for Landscape Plants Research, Xining, 810016, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiuting Ju. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Ethnobotany: Value and Conservation)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3527-3538. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.069643

Received 27 June 2025; Accepted 13 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Comprehensive evaluation based on mineral element content is one of the effective methods for the exploration and utilization of wild tulip germplasm resources. In this study, Tulipa iliensis, Tulipa tianschanica and Tulipa heterophylla distributed in China were used as the research objects. The contents of 10 mineral elements (N, K, P, S, Ca, Mg, Cu, Zn, Fe, Mn) in roots, bulbs and leaves were determined, and the three wild tulips were comprehensively evaluated by correlation analysis, principal component analysis and cluster analysis. The results showed distinct variations in mineral element content among different organs of T. iliensis, T. tianschanica and T. heterophylla, with T. heterophylla exhibiting significantly higher mineral content across all organs compared to the other two wild tulips. Correlation analysis revealed significant (p < 0.05) inter-element relationships in T. iliensis, T. tianschanica and T. heterophylla, with positive correlations between N and P, Ca and Zn in roots, P and Mg, P and Cu, Mg and Cu in bulbs, K and Mg, K and Fe, Zn and Mn, Mg and Fe in leaves, alongside a negative S and Fe correlation in leaves. The comprehensive evaluation identified N, S, Ca, and Zn as representative elements for assessing the three wild tulips, with their abundance ranking as follows: T. heterophylla > T. iliensis > T. tianschanica. The results of cluster analysis showed that T. heterophylla was clustered into one category in the roots because of the rich content of mineral elements. T. iliensis and T. tianschanica were clustered into one category in the bulbs because the accumulation of S element was higher than T. heterophylla. T. iliensis and T. heterophylla were clustered into one category in the leaves because of the rich content of mineral elements. The distribution of diverse mineral elements enables wild tulip germplasm resources to adapt to varied natural habitats, playing a decisive role in their response to specific environmental stresses. Studying mineral elements is an important way to gain an in-depth understanding of tulip germplasm resources. The results are of practical significance for conserving wild tulip resources and achieving sustainable utilization.Keywords

Tulipa gesneriana L. (Liliaceae) is globally recognized as one of the most significant ornamental plant species [1]. Tulipa not only has important economic, horticultural, aesthetic and ecological value, but also is a medicinal and edible plant, rich in a variety of natural mineral elements [2]. China serves as one of the natural distribution centers for the genus Tulipa, harboring abundant wild tulip resources that account for over 10% of the global total [3]. Notably, T. iliensis, T. tianschanica and T. heterophylla have attracted significant research attention due to their distinctive ecological adaptations and superior horticultural traits [4].

Mineral elements serve as material basis of plant growth and metabolism [5–7], playing pivotal roles not only throughout the plant life cycle but also in regulating critical physiological functions [8]. For example, N serves as a vital constituent of amino acids, proteins, nucleic acids, and chlorophyll, playing an indispensable role in plant growth, photosynthesis, and overall metabolic processes [9]. Mg constitutes the central component of chlorophyll, enabling plants to capture light energy during photosynthesis while additionally participating in enzyme activation and nucleic acid synthesis [10]. Zn can promote the growth of plants, while Ca serves not only as a messenger coupling extracellular signals with intracellular physiological responses, but also mediates environmental interactions. Crucially, Ca plays pivotal roles in transducing stress signals, protecting enzymatic activities, and regulating metabolite accumulation under abiotic stresses [11]. The mineral element content in plants not only reflects the nutritional status of their growth environment, but also exhibits close correlations with developmental processes, germplasm conservation, and potential utilization value [12,13]. Furthermore, these mineral elements, which are vital for plant physiology, also possess universal significance as indispensable nutrients for maintaining human and animal health. They are involved in key physiological processes such as metabolism and immune regulation in the human body. Currently, comprehensive evaluation based on mineral element content has been widely applied to ornamental plants such as Lilium spp. [14], Camellia petelotii [15], Astragalus sinicus L. [16], and Passiflora caerulea L. [17], serving as an effective methodology for identifying and utilizing elite germplasm resources [18].

This study investigated T. iliensis, T. tianschanica, and T. heterophylla by measuring 10 mineral elements in their roots, bulbs, and leaves. Integrating correlation analysis, principal component analysis, and cluster analysis, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of organ-specific mineral profiles to provide robust scientific support for the conservation and sustainable utilization of these wild tulip resources.

2.1 Collection and Pretreatment of Plant Materials

The study utilized T. iliensis, T. tianschanica and T. heterophylla as experimental materials. Plant materials were collected at the full flowering from Zhaosu County (81°0′11″ E, 42°49′31″ N) and Gongliu County (82°16′27″ E, 43°28′7″ N) in the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region of China. The sampling process ensures that the root, bulb and leaf organs are intact, and the growth and development status is normal (Fig. 1). For each wild tulip (T. iliensis, T. tianschanica, and T. heterophylla), fifteen individual plants were collected, and this constituted fifteen biological replicates each wild tulip. A total of 15 biological replicates were collected from 15 individuals of T. iliensis, T. tianschanica and T. heterophylla, respectively. The roots, bulbs, and leaves from the fifteen individuals of each species were separated and pooled by tissue type. The resulting pooled samples were then assigned the following codes (T. iliensis: YL; T. tianschanica: TS and T. heterophylla: YY). The numbered samples were placed in a constant temperature oven with a temperature of 36°C and a drying time of 48 h to ensure that the samples were completely dry. The dried samples were ground into powder and to be determined.

Figure 1: Plant morphology of T. iliensis, T. tianschanica, and T. heterophylla in their native habitats. (a) T. iliensis; (b) T. tianschanica; (c) T. heterophylla

2.2 Determination of Mineral Elements

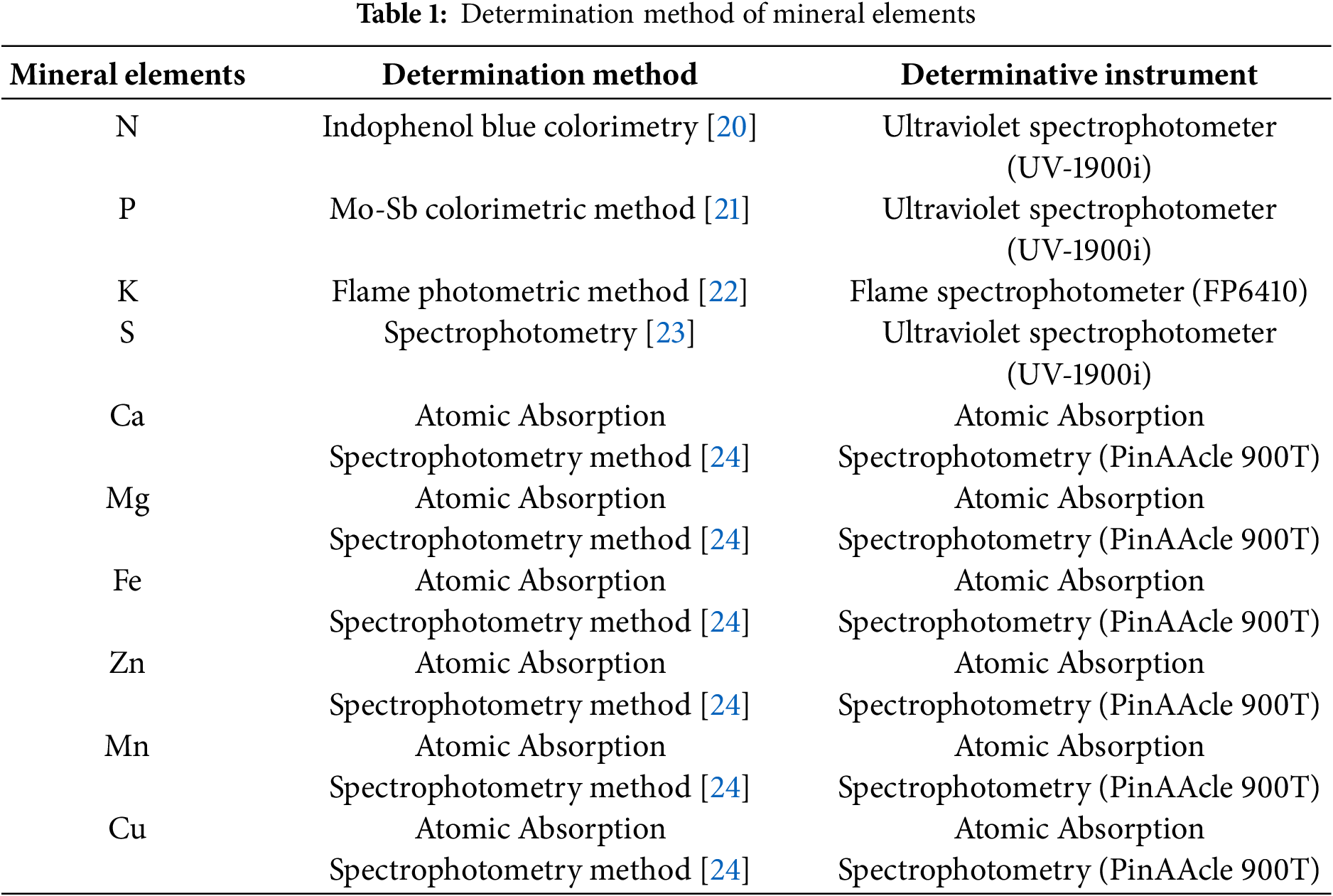

The sample treatment was carried out by nitric acid-perchloric acid digestion method [19]. Aliquots (0.25 g) of dried powder from different organs of T. iliensis, T. tianschanica, and T. heterophylla were separately weighed into digestion tubes, followed by sequential addition of 3 mL concentrated nitric acid, 1 mL perchloric acid, and 1 mL deionized water, with a 10 min standing period. The digestion protocol comprised four temperature stages: 30 min at 100°C, 30 min at 180°C, 30 min at 280°C, and 60 min at 380°C. Following complete digestion (evidenced by clear, transparent solutions in tubes), the samples were cooled to ambient temperature, diluted to 50 mL in volumetric flasks, filtered, and homogenized for subsequent analysis. Elemental analyses were performed using standardized methods (Table 1). Each determination of mineral element content was set up three repetitions.

2.3 Data Processing and Analysis

The mineral element content data across different organs of three wild tulips were systematically organized using Microsoft Excel 2021. One-way ANOVA analysis of variance and Duncan multiple comparison in SPSS 28.0 software were used to analyze the average content of mineral elements in roots, bulbs and leaves of three wild tulips at a 0.05 significant level. By calculating the Pearson correlation coefficient, the correlation analysis of mineral element contents in roots, bulbs and leaves of three wild tulips was carried out, and the correlation heat map was made by Origin 2021 software to visually display the correlation degree between mineral elements. SPSS 28.0 software was used to perform principal component analysis on the mineral element content of roots, bulbs and leaves of three wild tulips. The principal components were screened based on the principle of eigenvalue ≥1, and the component matrix was obtained by rotation. The comprehensive evaluation model was constructed according to the variance contribution rate. The hierarchical clustering analysis of mineral element contents in different organs of three wild tulips was carried out by the Ward clustering method using Origin 2021 software.

3.1 Analysis of Mineral Element Content Variations across Different Organs of Wild Tulips

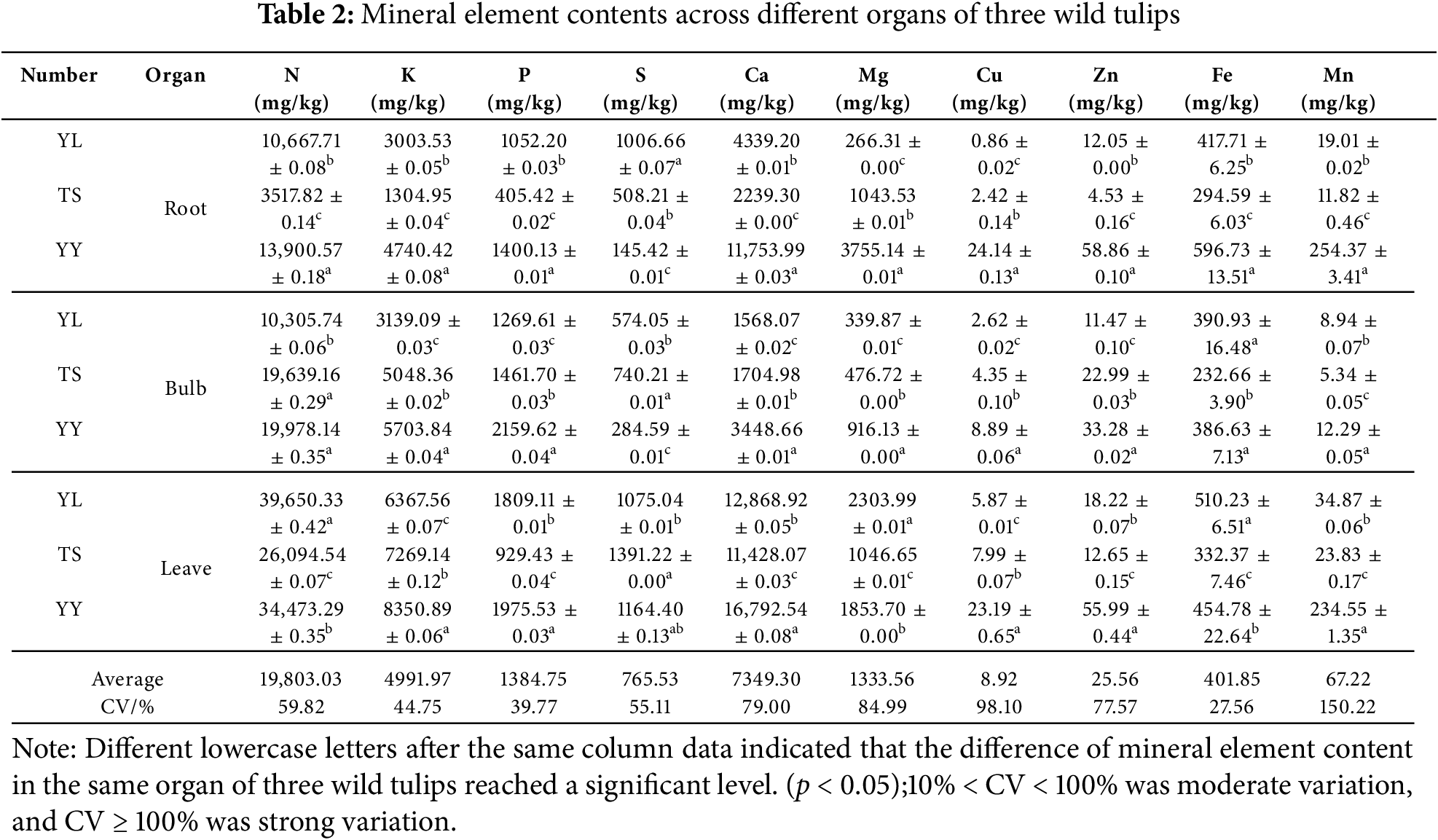

To elucidate the differential accumulation patterns of mineral elements across various organs, we quantified and analyzed 10 mineral elements in the roots, bulbs, and leaves of T. iliensis, T. tianschanica, and T. heterophylla (Table 2). Significant differences in mineral element contents were observed among the three wild tulips’ roots. T. heterophylla exhibited significantly higher concentrations of both macroelements (N, K, P, Ca, Mg) and microelements (Cu, Zn, Fe, Mn) compared to T. iliensis and T. tianschanica. Specifically, the N content in T. heterophylla reached 13,900.57 mg/kg, representing 1.30 times and 3.95 times higher concentrations compared to T. iliensis (10,667.71 mg/kg) and T. tianschanica (3517.82 mg/kg), respectively. The Ca content (11,753.99 mg/kg) in T. heterophylla was 2.71 times and 5.25 times higher than in T. iliensis (4339.20 mg/kg) and T. Tianschanica (2239.30 mg/kg), respectively. S element showed significant differences in the roots of three wild tulips, and the highest content in T. iliensis was 1006.66 mg/kg.

In bulbs, N content reached 19,639.16 mg/kg in T. tianschanica and 19,978.14 mg/kg in T. heterophylla, both significantly higher than in T. iliensis. The highest concentrations of P (2159.62 mg/kg), Ca (3448.66 mg/kg), Mg (916.13 mg/kg), Cu (8.89 mg/kg), Zn (33.28 mg/kg), and Mn (12.29 mg/kg) were all recorded in T. heterophylla. Fe content in T. iliensis (390.93 mg/kg) and T. heterophylla (386.63 mg/kg) showed no significant difference but were significantly higher than T. tianschanica (232.66 mg/kg). The highest content of S was 740.21 mg/kg in T. tianschanica.

In leaves, T. iliensis exhibited a characteristic mineral with elevated N (39,650.33 mg/kg), Mg (2303.99 mg/kg), and Fe (510.23 mg/kg) concentrations, all significantly higher than T. heterophylla and T. tianschanica. K (8350.89 mg/kg) and Ca (16,792.54 mg/kg) reached the highest value in T. heterophylla. In microelements, the contents of Cu (23.19 mg/kg), Zn (55.99 mg/kg) and Mn (234.55 mg/kg) in the leaves of T. heterophylla were significantly higher than those of T. iliensis and T. tianschanica. Through the analysis of the differences in mineral element content across various organs of three wild tulips, it was found that the mineral element content of various organs of T. heterophylla was richer than that of T. iliensis and T. tianschanica. Analysis of the coefficient of variation (CV) for 10 mineral elements in T. iliensis, T. tianschanica, and T. heterophylla revealed that Mn exhibited the strongest variability (CV = 150.22%), while the remaining 9 elements showed moderate variation intensity (CV range: 27.56%–98.10%), with Fe demonstrating the lowest variability (CV = 27.56%).

3.2 Correlation Analysis of Mineral Element Contents in Different Organs of Wild Tulips

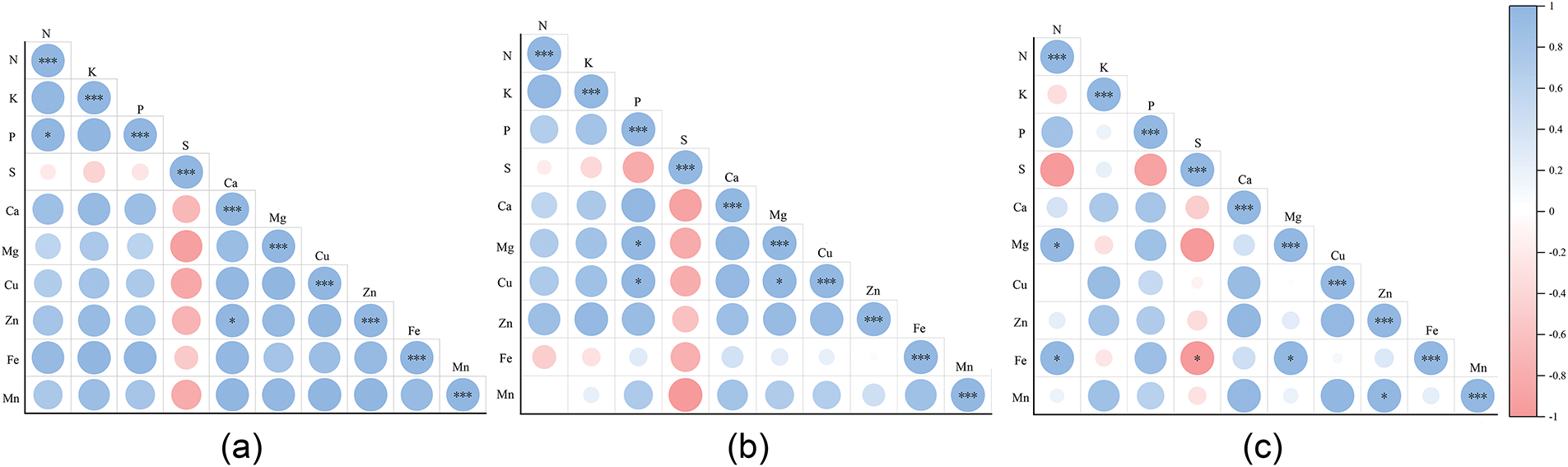

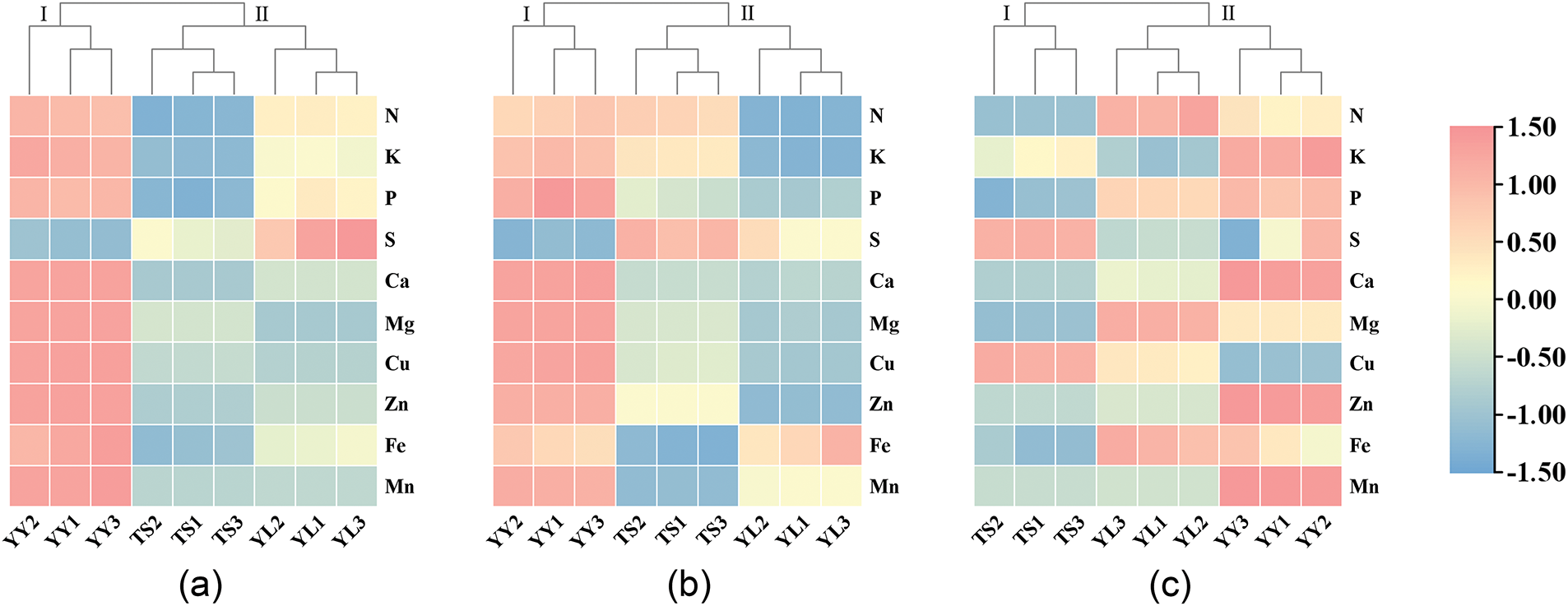

Correlation analysis was conducted to examine interrelationships among mineral elements across different organs of T. iliensis, T. tianschanica, and T. heterophylla (Fig. 2). Among the 10 mineral elements in roots of the three wild tulips (Fig. 2a), significant positive correlations (p < 0.05) were observed between N and P, as well as between Ca and Zn. In bulbs (Fig. 2b), significant positive correlations (p < 0.05) were detected between P and Mg, Mg and Cu, as well as P and Cu. In leaves (Fig. 2c), significant positive correlations (p < 0.05) existed among K and Mg, K and Fe, Zn and Mn, and Mg and Fe, whereas a significant negative correlation (p < 0.05) was observed between S and Fe.

Figure 2: Correlation analysis of mineral elements in different organs of three wild tulips. (a) roots; (b) bulbs; (c) leaves; *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001

3.3 Principal Component Analysis of Mineral Element Contents in Different Organs of Wild Tulips

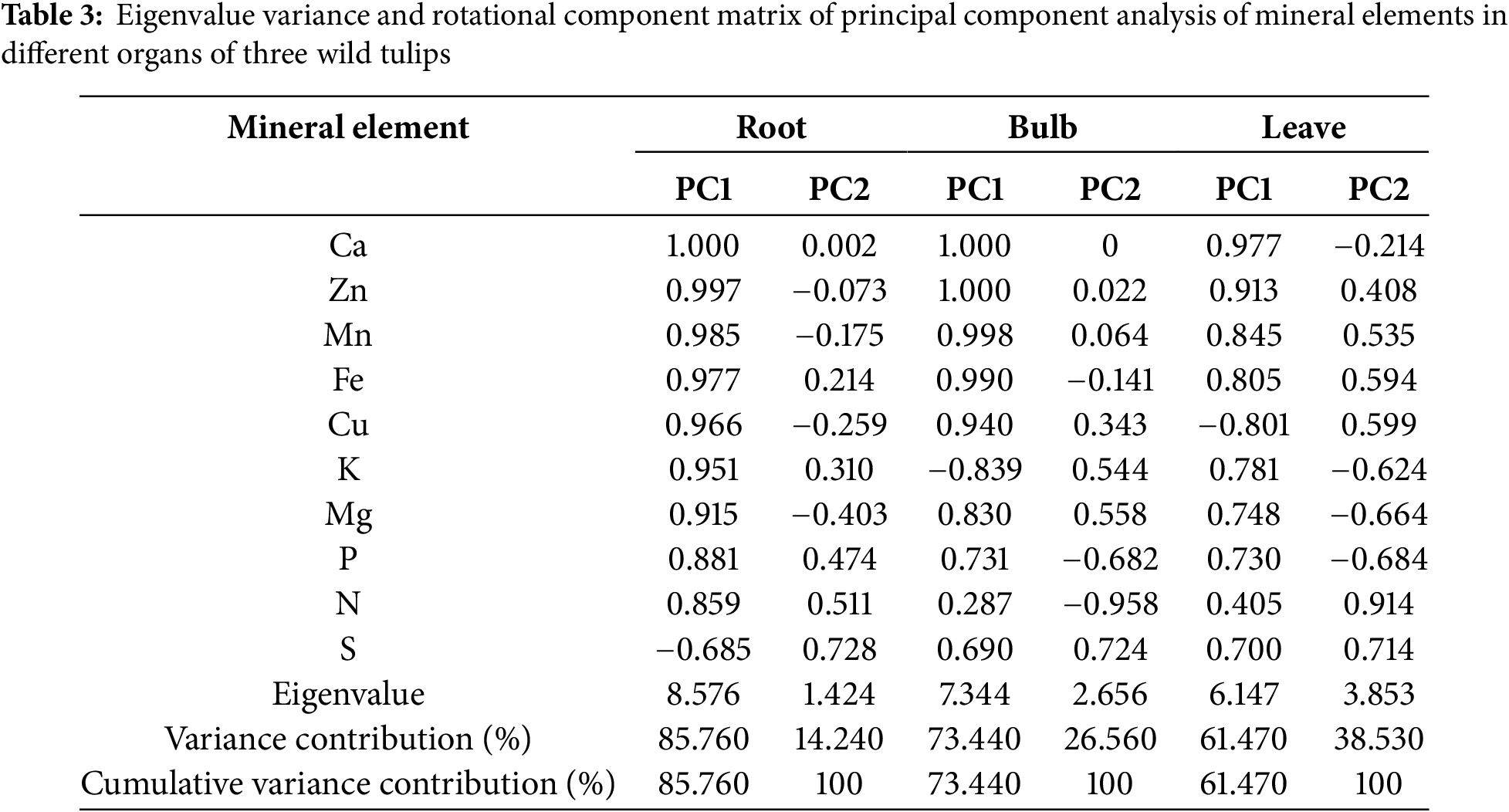

Principal component analysis was performed on 10 mineral elements across different organs (roots, bulbs, and leaves) of three wild tulips. Two principal components (PC1 and PC2) were extracted from each organ based on the criterion of eigenvalues ≥1 (Table 3). In roots, PC1 exhibited an eigenvalue of 8.576, while PC2 showed an eigenvalue of 1.424, representing 85.76% and 14.24% of the content of 10 mineral elements, respectively. The highest loading in PC1 was observed for Ca is 1.000, whereas S demonstrated the maximal loading in PC2 is 0.728. In bulbs, PC1 demonstrated an eigenvalue of 7.344 and PC2 exhibiting an eigenvalue of 2.656, representing 73.44% and 26.56% of the information of 10 mineral elements. The load values of Ca and Zn in PC1 were both 1.000, and the highest load value of S in PC2 is 0.724. In leaves, PC1 displayed an eigenvalue of 6.147 and PC2 exhibited an eigenvalue of 3.853, representing 61.47% and 38.53% of the information of 10 mineral elements. The highest loading in PC1 was observed for Ca is 0.977, while N showed the predominant loading in PC2 is 0.914. In summary, Ca, S, Zn and N are the representative mineral elements of T. iliensis, T. tianschanica, and T. heterophylla.

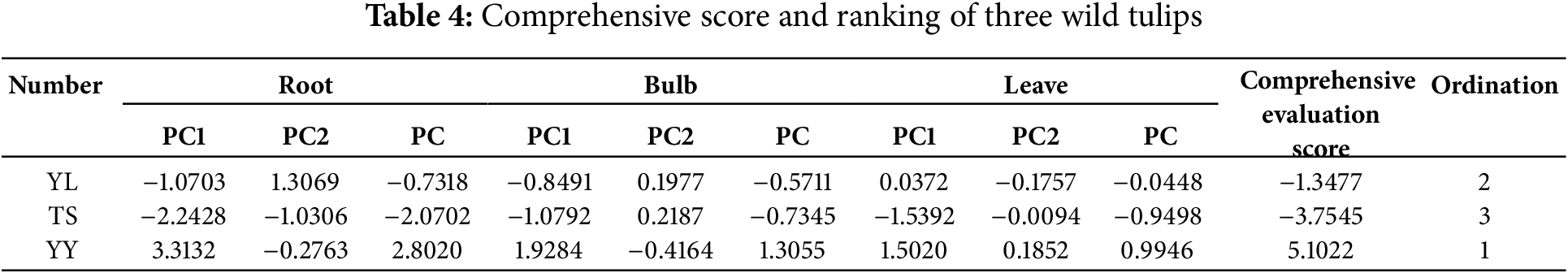

A comprehensive evaluation model was established with the cumulative variance contribution of the two principal components as the weight. The root: PC = 0.8576PC1 + 0.1424PC2; bulb: PC = 0.7344PC1 + 0.2656PC2; leave: PC = 0.6147PC1 + 0.3853PC2. The comprehensive evaluation results of three wild tulips were as follows: T. heterophylla (5.1022) > T. iliensis (−1.3477) > T. tianschanica (−3.7545) (Table 4).

3.5 Cluster Analysis of Mineral Element Contents in Different Organs of Wild Tulips

To systematically elucidate interspecific differences in mineral nutrient accumulation patterns among T. iliensis, T. tianschanica, and T. heterophylla, based on the contents of 10 mineral elements in roots, bulbs and leaves, the Ward clustering method was used to cluster the individuals with similar mineral element contents in different organs of three wild tulips (Fig. 3). Cluster analysis was performed on the mineral element content characteristics of the roots of three wild tulips (Fig. 3a). T. iliensis and T. tianschanica into one cluster due to their shared high S accumulation trait, while T. heterophylla formed a distinct separate cluster. Cluster analysis was carried out on the mineral element content characteristics of three wild tulip bulbs (Fig. 3b). T. iliensis and T. tianschanica together due to their higher S accumulation compared to T. heterophylla. Specifically, T. iliensis exhibited high accumulation of Mn and Fe, while T. tianschanica showed elevated levels of K and N, both with relatively low contents of Ca, Cu, and Mg. In contrast, T. heterophylla formed an independent cluster characterized by high accumulation of N, K, P, Ca, Mg, Cu, Zn, Fe, and Mn, but lower S content. The leaves clustering pattern (Fig. 3c) differed from roots and bulbs, with T. iliensis and T. heterophylla grouped together. Both species exhibited higher accumulation of N, P, Fe, and Mg, while T. heterophylla additionally showed superior accumulation of K, Ca, Cu, Zn, and Mn, though with consistently low S content. T. tianschanica formed a separate cluster due to its uniquely higher S accumulation compared to the other two wild tulips.

Figure 3: Cluster analysis of mineral elements content of three wild tulips. (a) roots; (b) bulbs; (c) leaves; YL1–YL3: three repeated samples of roots, stems and leaves of T. iliensis; TS1–TS3: three repeated samples of roots, stems and leaves of T. tianschanica; YY1–YY3: three repeated samples of roots, stems and leaves of T. heterophylla

4.1 Analysis of Mineral Element Content and Potential Value of Wild Tulips

Wild tulips, abundant in diverse mineral elements and bioactive compounds, possess significant medicinal value with promising applications in functional food development and traditional Chinese herbal medicine innovation [25]. Wild tulips contain colchicine, tuliposide and other alkaloids. Colchicine is an important bioactive compound in Chinese herbal medicine and has anti-inflammatory effect [26]. Tuliposide A, B, C have inhibitory effect on Bacillus subtilis [27]. Tulipa Systola, which grows between rocks in Iraqi Kurdistan, is popular as an anti-inflammatory and painkiller [28]. The total flavonoids extracted from tulips have good antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities [29]. The bulbs of wild tulips are rich in protein, starch, crude fiber, polysaccharide, vitamin C and calcium, its bulbs have the effects of clearing heat, detoxification, resolving masses and removing blood stasis, and can treat symptoms such as sore throat [30]. These further verify the edible and medicinal value of tulips.

Taking macronutrients as an example, the normal concentration of N content in plant dry matter is defined as being between 10,000 and 30,000 mg/kg [31]. In this study, the N content in the leaves of T. iliensis was determined to be 39,650.33 mg/kg, which exceeded the normal range. The normal concentration of K content in plant dry matter is defined as being between 2000 and 6000 mg/kg. In this study, the K content in the bulbs and roots of T. heterophylla was 5703.84 and 3139.09 mg/kg, respectively, both within the normal range. In contrast, the K content in the leaves was 8350.89 mg/kg, exceeding the normal range, indicating differential accumulation patterns of mineral elements across different organs of wild tulips. Among trace elements, the normal concentration of Fe in plant dry matter is defined as being between 50 and 250 mg/kg. In this study, the Fe content in the leaves of all three wild tulips exceeded the normal range, with values between 332.37 and 510.23 mg/kg, demonstrating a strong capacity for Fe enrichment in their leaves. The average Fe content was 74.3 times higher than that found in the leaves of Malva sylvestris [32]. The normal concentration of Zn content in plant dry matter is defined as being between 5 and 20 mg/kg. In this study, the Zn content in the bulbs of the three wild tulips ranged from 11.47 to 33.28 mg/kg, with an average concentration 61 times that of the zinc-rich fruit apple (Malus pumila Mill.) [33]. This finding further confirms that the mineral element content varies across different plant organs. Among the ten mineral elements analyzed, Mn was classified as highly variable, indicating substantial variation across different wild tulips and their organs. The remaining nine mineral elements exhibited moderate variability, with Fe, P, and K showing the lowest coefficients of variation, suggesting relative stability across the different wild tulips. The change of rich mineral elements is the material basis for wild tulips to complete their life cycle, which is involved in regulating its various biological activities, so that wild tulips have more potential value to be developed.

4.2 Correlation Analysis of Mineral Elements in Wild Tulip Organs

The correlation between the elements shows that the elements play an important role in maintaining the balance between the elements [34,35]. Significant positive correlations (p < 0.05) were observed between N and P, as well as Ca and Zn in roots of T. iliensis, T. tianschanica, and T. heterophylla. In bulbs, P and Mg, P and Cu, Mg and Cu showed pairwise positive correlations (p < 0.05), while leaves exhibited significant correlations between K and Mg, K and Fe, Zn and Mn, and Mg and Fe (p < 0.05) (Fig. 2). These findings suggest synergistic absorption mechanisms among these elements in roots, bulbs, and leaves of the three wild tulips. These findings are consistent with previous studies on mineral element correlations in Lilium spp. [36], Actinidia chinensis Planch. [37], and Ardisia elliptica Thunb. [15], demonstrating similar inter-element relationships across plant species. It is worth noting that S was significantly negatively correlated with Fe in the leaves of three wild tulips (p < 0.05), indicating that there is antagonism between S and Fe. This phenomenon may be attributed to distinct edaphic conditions and environmental factors, such as soil pH, redox potential in the habitats of T. iliensis, T. tianschanica and T. heterophylla, which collectively influence the bioavailability and plant uptake of S and Fe, ultimately resulting in their negative correlation [38]. Alternatively, the differential ion uptake in plants is mediated by specific transporter proteins [39], in the three wild tulips leaves, S and Fe may compete for shared transporters or transport channels. When the supply of S in the environment is sufficient, it will occupy more transport sites, thus inhibiting the absorption of Fe.

4.3 Comprehensive Evaluation of Wild Tulips Based on Mineral Element Content

While significant progress has been made in tulip research in recent years, particularly in areas such as flowering regulation [40] and flower senescence [41], it is crucial to note that mineral elements are vital components of enzymes, hormones, vitamins, and other active substances, playing an indispensable role in plant growth [42]. The content of mineral elements in plants has garnered widespread attention as a key indicator for assessing their development potential [43]. The rich mineral element content in Daphne altaica Pall. serves as a significant indicator for evaluating its medicinal value [44]. The mineral element content in Paeonia lactiflora Pall. can serve as an important indicator for evaluating its metabolic activity [45]. Evaluating wild tulips based on variations in their mineral element profiles holds potential significance for understanding individual survival and reproduction, as well as the distribution and adaptability within natural communities.

This study conducted a comprehensive evaluation of three wild tulips based on ten mineral elements (Table 4), revealing that T. heterophylla achieved the highest composite score, followed by T. iliensis, with T. tianschanica ranking the lowest. This reason may be attributed to their distinct distribution ranges. T. heterophylla are mostly distributed in the alpine zone between 2100–3100 m above sea level, T. iliensis are mainly distributed in the plain or the slope between 400–1400 m above sea level, and T. tianschanica are mainly distributed in the low mountain zone and grassland between 1000–1800 m above sea level [4]. Distinct geographical distributions result in significant variations in soil physicochemical properties, climatic conditions, and biotic factors within plant habitats, thereby influencing mineral element absorption, accumulation, and physiological metabolism in plants [46]. Additionally, interspecific competition and symbiotic relationships in different distribution ranges constitute critical factors affecting plant mineral uptake [47]. There may be a rhizosphere microbial community in the distribution area of T. heterophylla, which promotes the absorption of mineral elements. In the environment of T. iliensis and T. tianschanica, special niche competition or lack of effective colony symbiosis may reduce their absorption efficiency of mineral elements. At present, there are few studies on tulips. Based on the comprehensive evaluation of mineral element content, it is found that the comprehensive performance of tulips is better, which has great development potential and application value. In the future, it can be used as an excellent wild tulip germplasm resource for subsequent variety breeding and comprehensive utilization.

Acknowledgement: We are also grateful for the support from the Key Laboratory of Landscape Plants of Qinghai Province.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the “ Natural Science Foundation Project of Qinghai Province, China [2025-ZJ-950M]” and “ West Light Foundation. Chinese Academy of Science [1–7]”.

Author Contributions: Yue Ma: conceptualization, data curation, methodology, software, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Douwen Qin: investigation, methodology, software. Weiqiang Liu: methodology, software. Xiuting Ju: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, validition, writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Neriya Y, Morikawa T, Hamamoto K, Noguchi K, Kobayashi T, Suzuki T, et al. Characterization of tulip streak virus, a novel virus associated with the family Phenuiviridae. J Gen Virol. 2021;102(2):001525. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.001525. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Pourkhaloee A, Khosh-Khui M, Arens P, Salehi H, Razi H, Niazi A, et al. Molecular analysis of genetic diversity, population structure, and phylogeny of wild and cultivated tulips (Tulipa L.) by genic microsatellites. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2018;59(6):875–88. doi:10.1007/s13580-018-0055-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Cui Y, Xing G, Zhang Y, Tian H, Fu L, Qu L. Research progress on tulip germplasm resources and breeding in China. Hortic Seed. 2020;40(1):31–5. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

4. Xing G, Qu L, Zhang Y, Xue L, Su J, Lei J. Collection and evaluation of wild tulip (Tulipa spp.) resources in China. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2017;64(4):641–52. doi:10.1007/s10722-017-0488-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhao H, Yang Q. Study on influence factors and sources of mineral elements in peanut kernels for authenticity. Food Chem. 2022;382(2):132385. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Ibrahim YE, Ali Alshifaa M, Erama AK, Awadalla BO, Omer AOI. Proximate composition, mineral elements content and physicochemical characteristics of Adansonia digitata L. seed oil. Int J Pharma Bio Sci. 2019;10(4):119–26. doi:10.22376/ijpbs.2019.10.4.p119-126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Alonso-Esteban JI, Torija-Isasa ME, de Cortes Sánchez-Mata M. Mineral elements and related antinutrients, in whole and hulled hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) seeds. J Food Compos Anal. 2022;109(12):104516. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2022.104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Samantaray S, Rout GR, Das P. Role of chromium on plant growth and metabolism. Acta Physiol Plant. 1998;20(2):201–12. doi:10.1007/s11738-998-0015-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Cheal WF, Winsor GW. The effects of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium and magnesium on the growth of tulips during the second season of treatment and on the chemical composition of the bulbs. Ann Appl Biol. 1966;57(2):287–99. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1966.tb03823.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hänsch R, Mendel RR. Physiological functions of mineral micronutrients (Cu, Zn, Mn, Fe, Ni, Mo, B, Cl). Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2009;12(3):259–66. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2009.05.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Liang C, Zhang Y, Ren X. Calcium regulates antioxidative isozyme activity for enhancing rice adaption to acid rain stress. Plant Sci. 2021;306:110876. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.110876. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Tripathi R, Tewari R, Singh KP, Keswani C, Minkina T, Srivastava AK, et al. Plant mineral nutrition and disease resistance: a significant linkage for sustainable crop protection. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:883970. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.883970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Shrivastav P, Prasad M, Singh TB, Yadav A, Goyal D, Ali A, et al. Role of nutrients in plant growth and development. In: Contaminants in agriculture. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 43–59. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-41552-5_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Li Y, Guan Y, Guo S, Sun J, Xiang F, Mu L. Analysis and comprehensive evaluation of mineral elements in different organs of four wild lily varieties in Heilongjiang Province. J Northwest AF Univ. 2023;51(11):86–96. (In Chinese). doi:10.13207/j.cnki.jnwafu. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li G, Qi Y, Teng W, Huang X, Jiang C, Wei D, et al. Diversity analysis and evaluation of yellow camellia germplasm resources based on active ingredient and mineral element content. J Centr South Univ Fore Technol. 2025;45(5):9–18. doi:10.14067/j.cnki.1673-923x.2025.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Fang Y, Liu C, Ye L, He C, Zhang X, Wang M, et al. Analysis of mineral elements and vegetable nutritive value of shoots of Chinese Milk Vetch. Acta Agrestia Sinica. 2023;31(04):1099–105. (In Chinese). doi:10.11733/j.issn.1007-0435.2023.04.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Shi Q, Xie Z, Wang X, Xu J, Li J. Study on the optimum contents of mineral elements in the leaves of passion fruit (Passiflora edulis). J Fruit Sci. 2023;40(06):1190–201. (In Chinese). doi:10.13925/j.cnki.gsxb.20220579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liang F, Zhang C, Yang B, Wang L, Tang R, Huang S, et al. Quality identification and genetic diversity analysis of Brassica napus germplasm resources. Mol Plant Breed. 2022;20(12):4129–243. (In Chinese). doi:10.13271/j.mpb.020.004129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu LY, Wang P, Feng ML, Dong ZG, Li J. Study on determination of eight metal elements in Hainan arecanut leaf by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Spectrosc Spectr Anal. 2008;28(12):2989–92. [Google Scholar]

20. Huang C, Gao M, Luo H, Xu Y. Indophenol blue colorimetric method to determine grain protein content of cereal plants. Methods Mol Biol. 2024;2787:257–63. doi:10.1007/978-1-0716-3778-4_17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Lyu J, Yu C. Screening and identification of an efficient phosphate-solubilizing Burkholderia sp. and its growth-promoting effect on Pinus massoniana seedling. Chin J Appl Ecol. 2020;31(9):2923–34. doi:10.13287/j.1001-9332.202009.031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Xue GQ, Liu Q, Han YQ, Wei HG, Dong T. Determination of thirteen metal elements in the plant Foeniculum vulgare Mill. by flame atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Spectrosc Spectr Anal. 2006;26(10):1935–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

23. Andriushchenko AV, Kliachko IA. Determination of mineral elements in certain food products. I. The determination of trace elements by atomic absorption spectrophotometry. Vopr Pitan. 1973;32(1):80–3. (In Russian). [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Lee YJ, Sung JK, Lee SB, Lim JE, Song YS, Lee DB, et al. Plant analysis methods for evaluating mineral nutrient. Korean J Soil Sci Fert. 2017;50(2):93–9. doi:10.7745/kjssf.2017.50.2.093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ge L, Huang X, Zhang F, Zhou Q, Qian Y, Chen B, et al. Research progress on chemical constituents and pharmacological activities of tulips. Chin Wild Plant Res. 2019;38(05):79–83. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

26. Xu G, Xie Y, Mao Z. Investigation on colchicine of tulip plants in Xinjiang. Arid Zone Res. 1996;3:52–3. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

27. Cho JH, Joo YH, Shin EY, Park EJ, Kim MS. Anticancer effects of colchicine on hypopharyngeal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2017;37(11):6269–80. doi:10.21873/anticanres.12078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ibrahim MF, Hussain FHS, Zanoni G, Vidari G. The main constituents of Tulipa systola Stapf. roots and flowers; their antioxidant activities. Nat Prod Res. 2017;31(17):2001–7. doi:10.1080/14786419.2016.1272107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Ye J, Cao J, Chen X, Ma J, Li Y, Gao X, et al. Extraction optimisation and compositional characterisation of total flavonoids from the Chinese herb tulip: a natural source of antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents. Nat Prod Res. 2024;38(24):4332–9. doi:10.1080/14786419.2023.2281000. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhang Y, Xing G, Lu J, Zhang H, Wu T, Qu L. Analysis of the content of the nutritive components and active substances in the bulbs of Tulipa tianschanica. North Hortic. 2020;17:64–8. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

31. Mengel K, Kirkby EA, Kosegarten H, Appel T. Principles of plant nutrition. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2001. doi:10.1007/978-94-010-1009-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Guil Guerrero JL, Madrid PC, Torua Isasa ME. Mineral elements determination in wild edible plants. Ecol Food Nutr. 1999;38(3):209–22. doi:10.1080/03670244.1999.9991578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Kalkisim O, Ozdes D, Okcu Z, Karabulut B, Senturk HB. Determination of pomological and morphological characteristics and chemical compositions of local apple varieties grown in Gumushane, Turkey. Erwerbs Obstbau. 2016;58(1):41–8. doi:10.1007/s10341-015-0256-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Reddy AR, Munaswamy V, Reddy PVM, Reddy BR, Sudhakar P. Leaf nutrient status vis-à-vis fruit yield and quality of sweet orange (Citrus sinensis (L.) osbeck). Int J Plant Soil Sci. 2020;31(3):1–8. doi:10.9734/ijpss/2019/v31i330212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Yao SX, Xie J, Zeng KF. Comparative analysis of several mineral elements contents in vascular bundle of satsuma mandarin and ponkan mandarin fruit. Spectrosc Spectr Anal. 2017;37(4):1250–3. (In Chinese). doi:10.3964/j.issn.1000-0593(2017)04-1250-04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang L, Li Q, Wang L, Su Y, Li Y. Investigation on variation and relationship in mineral element content of different lilies in Yunnan. North Hortic. 2008;5:119–21. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

37. Peng T, Xie C, Miao S, Wang Z, Ma F, Wang N. Dynamic changes and correlations of mineral nutrients concentration in leaves of kiwifruit. South China Fruits. 2020;49(1):115–9. (In Chinese). doi:10.13938/j.issn.1007-1431.20190523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Saleem A, Zulfiqar A, Saleem MZ, Ali B, Saleem MH, Ali S, et al. Alkaline and acidic soil constraints on iron accumulation by rice cultivars in relation to several physio-biochemical parameters. BMC Plant Biol. 2023;23(1):397. doi:10.1186/s12870-023-04400-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Astolfi S, Celletti S, Vigani G, Mimmo T, Cesco S. Interaction between sulfur and iron in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:670308. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.670308. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Meng L, Yang H, La Y, Wu Y, Ye T, Wang Y, et al. Transcriptional modules and hormonal metabolic pathways reveal the critical role of TgHB12-like in the regulation of flower opening and petal senescence in Tulipa gesneriana. Hortic Adv. 2024;2(1):18. doi:10.1007/s44281-024-00031-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Meng L, Yang H, Xiang L, Wang Y, Chan Z. NAC transcription factor TgNAP promotes tulip petal senescence. Plant Physiol. 2022;190(3):1960–77. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiac351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Sareen A, Gupta RC, Bansal G, Singh V. Comparison of key mineral elements in wild edible fruits of Ziziphus mauritiana and Z. Nummularia using atomic absorption spectrophotometer (AAS) and flame photometer. Int J Fruit Sci. 2020;20(s2):S987–94. doi:10.1080/15538362.2020.1774468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Mohebi Z, Mojarrab M. The first comprehensive phytochemical study of Nectaroscordum tripedale (Trautv.) Grossh: composition of essential oil, antioxidant activity, total phenolic and flavonoid content and mineral elements. Pharm Chem J. 2022;55(10):1071–9. doi:10.1007/s11094-021-02539-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Li Y, He Q, Zhu X, Geng Z, Wang Y, Li J. A comparative study of the mineral elements in different medicinal plant parts of Daphne altaica Pall. J Wood Chem Technol. 2023;43(6):309–19. doi:10.1080/02773813.2023.2224303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Li Z, Liu D, Zhan L, Li L. Mineral elements and active ingredients in root of wild Paeonia lactiflora growing at Duolun County, Inner Mongolia. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2020;193(2):548–54. doi:10.1007/s12011-019-01725-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Zhang H, Wei F, Wang J, Long J, Wu N. Correlation analysis of mineral elements in yam tuber and in its environmental soil in Anshun of Guizhou province. J Southwest Univ Natl. 2017;39(05):31–6. doi:10.13718/j.cnki.xdzk.2017.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Tedersoo L, Bahram M. Mycorrhizal types differ in ecophysiology and alter plant nutrition and soil processes. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2019;94(5):1857–80. doi:10.1111/brv.12538. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools