Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Allelopathic Effects of Plant Fallen Leaves Extract on the Growth and Physiology of Thuidium kanedae

College of Forestry, Guizhou University, Guiyang, 550025, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiurong Wang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Metabolism Changes to Abiotic and Biotic Stresses: Plant Physiology and Biochemistry Responses and Possible Adaptations Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3667-3686. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.069653

Received 27 June 2025; Accepted 22 September 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Bryophytes play important ecological roles in terrestrial ecosystems, but their growth is often influenced by environmental factors and chemical interactions with surrounding vegetation. Fallen leaves are an important source of allelopathic substances, yet little is known about their impact on mosses. This study investigates the allelopathic effects of fallen leaves from Cinnamomum camphora, Pinus massoniana, and Bambusa emeiensis on the bryophyte Thuidium kanedae in Guiyang. The litter aqueous extract (0.0125 g/mL (T1), 0.025 g/mL (T2), 0.05 g/mL (T3), 0.1 g/mL (T4) and distilled water control (CK)) was used to regularly water and culture T. kanedae. During the 120-day test period, the physiological indexes such as new shoot length, branch length, branch number, coverage area, biomass, chlorophyll (Chl t), soluble protein (SP), soluble sugar (SS), malondialdehyde (MDA) content, peroxidase (POD), catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activities were measured regularly, and the Allelopathic effect response index (RI), the Synthetic allelopathic effect index (SE) and the Average synthetic allelopathic effect index (ASE) were calculated. The results indicated that the Allelopathic effect response index (RI) and the Synthetic allelopathic effect index (SE) of the three plant fallen leaf extracts on new main stem length, branch length, coverage area, and biomass of T. kanedae exhibit a “promotion at low concentrations and inhibition at high concentrations” trend. Specifically, at a concentration of T1, a promotive effect was observed, while concentrations greater than T1 generally began to show inhibitory effects, with the strongest inhibition occurring at T4. Correlation analysis showed that growth indicators were significantly negatively correlated with extract concentration, MDA content and SOD activity, while showing significant positive correlations with Chl t content, SS content and CAT activity. The ASE of the three plant species exhibited significant variation, ranging from inhibition to promotion, with the sequence being: C. camphora (−0.170) > B. emeiensis (−0.032) > P. massoniana (0.001). This indicates that the strength of allelopathic effects is influenced by the species of the donor plants. Overall, the allelopathic effects on T. kanedae are both concentration-dependent and species-specific.Keywords

Bryophytes are a major group in the plant kingdom, widely distributed across the world due to their strong adaptability [1]. They not only play crucial ecological roles in maintaining soil health [2], promoting nutrient cycling [3,4], regulating carbon balance [5], and enhancing ecosystem stability [6,7], but also possess unique ornamental value in landscape gardening [8]. The growth of mosses is closely correlated with environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, altitude [9,10], and vegetation type [11], and is also influenced by chemical interactions with other plants [12]. In urban green spaces, Cinnamomum camphora, Pinus massoniana, and Bambusa emeiensis are common tree species planted in patches [13], and their understory usually accumulates a large amount of litter, making vegetation renewal difficult. Research indicates that the physical barrier created by litterfall [14–16] and the chemicals it releases can inhibit seed germination and seedling growth [17]. It was found that T. kanedae is a widely distributed bryophyte that often appears in the understory of C. camphora, P. massoniana, and B. emeiensis, but its growth performance is significantly different, so it has become an ideal model for studying the ecological interaction between plants and mosses. In areas rich in litter, the distribution of short-ribbed plum moss is often uneven or even completely absent, which may be related to the physical shading of litter (such as affecting light and soil moisture) and its potential allelopathic effects, but the specific mechanism needs to be deeply verified. At present, most of the research on the allelopathy of plants focuses on vascular plants, while less attention is paid to the allelopathic effects of bryophytes. Existing studies on allelopathy in mosses mainly focus on the interspecific effects of mosses [12] and their effects on vascular plants [18–22], and there have been no systematic reports on the allelopathic effects of vascular plant litter on mosses. Therefore, this study aims to fill the research gap in this field by exploring the allelopathic potential of litter leaf extracts, improve the understanding of the mechanism of interspecific chemical interactions between forest surfaces, and provide a theoretical basis for the widespread application of bryophytes in understory ecological restoration and landscape construction.

Allelopathy is an important natural chemical regulatory mechanism in ecosystems [23]. By releasing chemical compounds into their surroundings, plants can promote or inhibit the growth and development of themselves and other species [24–26]. Fallen leaves are a primary means through which plants release allelopathic substances [27,28], as the chemicals generated during decomposition directly impact the soil and surrounding vegetation. Research has revealed that allelopathic substances released by fallen leaves from various tree species can influence the growth of neighboring plants. For example, when the content of C. camphora leaf litter was 10 g·kg−1, the plant heights of white Trifolium repens, Agrostis stolonifera, and Ophiopogon bodinieri decreased significantly by 16.20%, 16.26%, and 4.28%, respectively, compared to the control. Additionally, the leaf areas of white T. repens and A. stolonifera were significantly reduced by 15.31% and 12.68%, respectively, while the biomass of white T. repens and O. bodinieri decreased by 1.50% and 10.06% compared to the control [29]. The allelopathic effects of aqueous extracts from P. massoniana leaf litter varied among different recipient plants. At concentrations of 2.0%, 1.0%, 0.5%, 0.2%, and 0.1%, the aqueous extracts inhibited the growth of perennial ryegrass Lolium perenne L. and Macroptilium lathyroides, whereas Lupinus micranthus and Pennisetum americanum × P. purpureum exhibited low inhibition and high promotion at different concentrations [30]. Similarly, the leachate from Phyllostachys heterocycla cv. Pubescens leaf litter generally inhibited the seed germination of Cunninghamia lanceolata at concentrations of 1:25, 1:50, 1:100, and 1:200 (g/mL), except for a slight increase in germination rate at the 1:50 concentration compared to the control group [31]. Consequently, the allelopathic effects of fallen leaves on plant growth are influenced by plant species and leaf extracts concentration. Although extensive research exists on the allelopathic effects of fallen leaves from various tree species on the seed germination and seedling growth of trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants, studies on their impact on the reproductive growth of widely distributed understory bryophytes are scarce, and the mechanisms remain unclear.

Therefore, this study selects the widely distributed T. kanedae as the experimental material and conducts simulated laboratory experiments. It uses the leachate from fallen leaves of common urban green plants such as C. camphora, P. massoniana, and B. emeiensis to treat the short-ribbed feather moss, in order to explore its potential allelopathic effects and clarify the mechanisms of allelopathy of fallen leaves in the growth and physiology of moss plants. This not only provides a new theoretical basis for the influencing factors of bryophyte growth and distribution but also enriches the research field of allelopathy. At the same time, it also contributes to the scientific configuration and management of the plantation-bryophyte community landscape.

2.1 Plant Materials and Experimental Design

The experiment took place in a greenhouse at Guizhou University’ s experimental base in Huaxi, Guiyang, Guizhou Province. Located at 106°65′ E~107°17′ E and 26°45′ N~27°22′ N, the site lies within a mild, humid subtropical zone and exhibits distinct characteristics of a plateau monsoon climate. The area experiences a mean annual temperature of 15.3°C, an average relative humidity of 77%, and approximately 1148.3 h of sunshine per year [32].

Fallen leaves of C. camphora, P. massoniana, and B. emeiensis were collected from parks and similar-sized groves, with at least three plots per plant type. In each plot, 1 m × 1 m quadrats were set using the five-point method to collect freshly fallen leaves. The collected fallen leaves were rinsed with tap water, washed with distilled water, and air-dried. T. kanedae was collected from the forest floor, planted in 40 cm × 40 cm trays, and grown in the greenhouse for a month before the allelopathy test.

The air-dried fallen leaves were ground to a powder, sieved through a 40-mesh screen, and 15 g was placed in a 150 mL flask. Distilled water was added at a 1:10 ratio (1 g powder to 10 mL water) and shaken at 24°C for 24 h. The solution was filtered twice through 300-mesh gauze, yielding a stock solution (0.1 g/mL), which was stored at 4°C.

2.3.2 Bryophyte Cultivation and Allelopathy Experiment

Healthy T. kanedae, uniform in color and growth, were cleaned, cut into 1 cm pieces, and 10 g was evenly planted in 13 cm × 9 cm boxes lined with non-woven fabric. The stock solution was diluted and regularly applied to T. kanedae. Four treatments were set at concentrations of 0.0125 g/mL (T1), 0.025 g/mL (T2), 0.05 g/mL (T3), and 0.1 g/mL (T4), with distilled water (CK) as the control. The experiment lasted for 120 days, with 6 biological replicates for each treatment, all replicates performed simultaneously. With 30 boxes cultivated per donor plant, the three donor plants totaled 90 boxes. On the day of cultivation, 50 mL of each extract concentration was added to each box, with the control group receiving an equal volume of distilled water. Subsequently, the extracts were applied every 15 days until the end of the experiment at 120 days (for a total of 8 applications). During the cultivation period, tap water was supplied as needed based on drought conditions. On days 15, 30, 60, and 120, growth indicators (new main stem length, branch length, number of branches) were recorded, and final cover, biomass, and physiological indicators were measured on day 120.

2.4 Indicator Measurement and Methodology

2.4.1 Growth Indices Measurement

Measurements of growth indicators commenced on day 15 after irrigation. For each treatment, three replicates were randomly selected. Within each replicate, ten new shoots of T. kanedae were randomly chosen. The length of new main stem length, branch length, and number of branches were measured using a ruler and visual counting. The average values were calculated from ten shoots per replicate, with three replicates (totaling 30 shoots) measured per treatment. (Note: “New main stem length” refers to the length of newly developed primary branches, while “branch length” refers to the length of secondary lateral branches emerging from the primary branches. The length and number of branches were recorded once their growth commenced.). On the 120th day, the new shoot covered area was analyzed using ColorImpact software. After growth indices were measured, T. kanedae was harvested. For each treatment, three replicates were randomly selected, dried at 105°C for 30 min, and then at 65°C to a constant weight. Dry weight was measured using an electronic balance with 0.0001 g precision as the biomass index.

2.4.2 Physiological Indices Measurement

Chlorophyll content was determined using the ethanol extraction method, primarily based on the protocols described by Bao and Leng [33] and Shi et al. [32], and the total chlorophyll (Chl t) content was calculated according to the Arnon method. Soluble protein (SP) content was measured using the Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 method [34], and soluble sugar (SS) content using the Anthrone colorimetric method [34]. Malondialdehyde (MDA) and Peroxidase (POD) were measured using Suzhou Grace Biotechnology kits, while catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were measured using kits from Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.

The allelopathic effects of the leaf litter extracts of C. camphora, P. massoniana, and B. emeiensis on various growth parameters of T. kanedae were evaluated using the Allelopathic effect response index (RI) proposed by Williamson et al. The formula is as follows: RI = 1 − C/T (when T ≥ C); RI = T/C − 1 (when T < C), where C is the control value and T is the treatment value. An RI > 0 indicates a stimulatory effect, while RI < 0 indicates an inhibitory effect. The RI reflects the intensity and variation pattern of allelopathic effects on each individual growth parameter. The arithmetic mean of the RI for the growth indices of each treatment (T1, T2, T3, T4) indicates the Synthetic allelopathic effect index (SE), this method enabled a comparative assessment of allelopathic intensity and its variation across different concentrations (T1–T4), thereby revealing the concentration-dependent effects of allelopathy. Furthermore, the Average synthetic allelopathic effect index (ASE), calculated as the mean SE across all concentrations for each leaf litter extract, was used to evaluate the synthetical allelopathic strength of the three donor species, thus elucidating species-specific differences in allelopathic potential [35].

Data were organized and managed using Microsoft Excel 2021. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 27 software. A two-way ANOVA was employed to evaluate the effects of time (yr) and extract concentration (tr) on the new main stem length, branch length, and number of branches of T. kanedae, as well as to examine the influence of plant species (S) and extract concentration (tr) on its growth and physiological indicators. Multiple comparisons were carried out using Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance level of p < 0.05. Relationships between variables were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. All graphs were produced using Origin 2022.

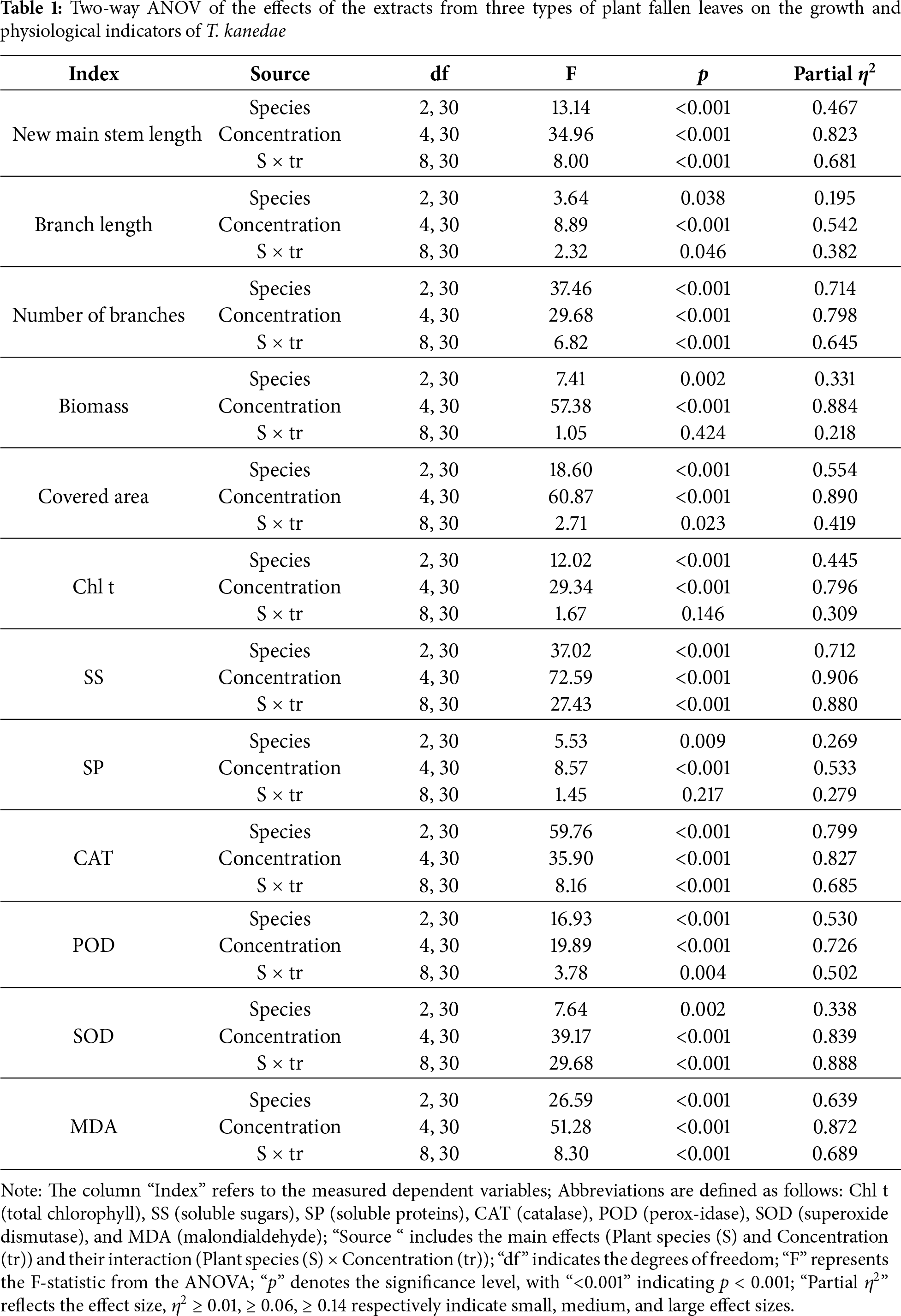

3.1 Two-Way ANOVA of the Effects of the Extracts from Three Types of Plant Fallen Leaves on the Growth and Physiological Indicators of T. kanedae.

The allelopathic effects of leaf litter extracts from three plant species—C. camphora, P. massoniana, and B. emeiensis—on the moss T. kanedae were investigated using two-way ANOVA (Table 1). The results indicated that the main effect of concentration had a highly significant influence on all measured indicators (*p* < 0.001), with very large effect sizes (according to Cohen’s criteria, partial η2 > 0.14 represents a large effect; all concentration effects in this study exceeded this threshold), demonstrating that extract concentration was the primary factor driving the responses of T. kanedae. The main effect of species was also highly significant (*p* < 0.001), indicating inherent differences in allelopathic potential among the three donor plant species. More importantly, the species × concentration interaction showed a significant or highly significant effect (*p* < 0.05) on most indicators (9/12), with particularly prominent effect sizes (e.g., partial η2 > 0.88 for soluble sugar and superoxide dismutase), confirming that the intensity and pattern of allelopathic effects depend on both the donor species and extract concentration, reflecting species specificity and concentration dependency. Given the significant interaction, simple effect analysis was further conducted with multiple comparisons of concentration levels within each tree species.

3.2 Effects of Various Treatments on Growth Indices of T. kanedae

The promoting or inhibiting effects of allelopathic stress environments on plant growth directly reflect the plant’s adaptive response. For bryophytes, growth indices such as new main stem length, branch length, number of branches, covered area, and biomass serve as indicators of their adaptation to allelopathic stress.

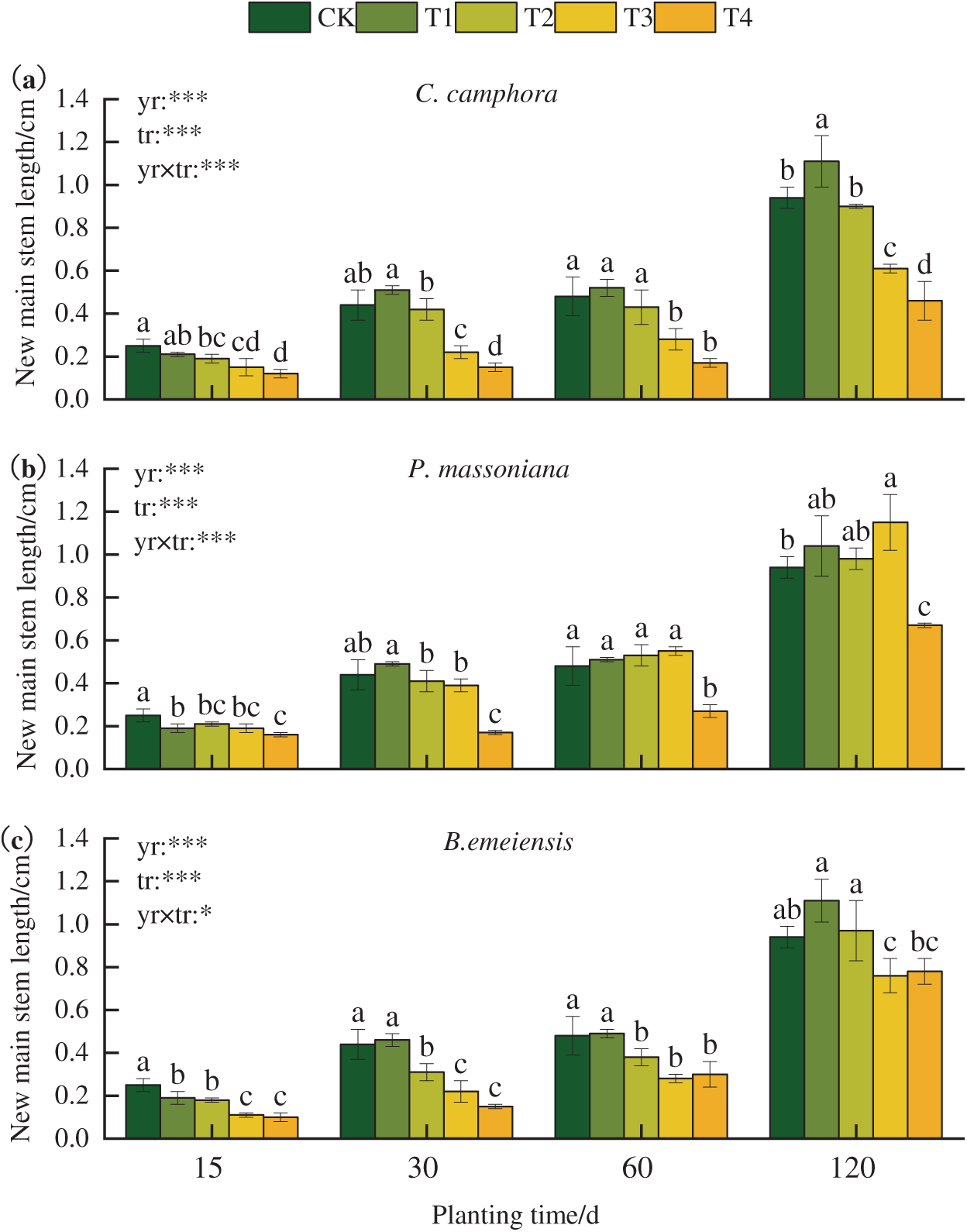

There were significant differences in the effects of different concentrations on the length of new main stem length of T. kanedae at each growth stage (Fig. 1). Compared to CK, all three leachates exhibited inhibitory effects during the initial stage (15 days). By 30 days, new main stem growth showed a clear concentration dependence: a slight but non-significant promotion under the T1 treatment, while the T2, T3, and T4 treatments generally exhibited significant inhibition. Over time, the inhibitory effects of some treatments weakened or even shifted to promotion. For instance, the T2 (mean difference = 0.050, 95% CI: −0.042 to 0.142, *p* = 0.277) and T3 (mean difference = 0.067, 95% CI: −0.026 to 0.159, *p* = 0.151) treatments on P. massoniana at 60 days, as well as the T1 treatment on B. emeiensis (mean difference = 0.023, 95% CI: −0.046 to 0.093, *p* = 0.500) at 30 days and the T2 treatment (mean difference = 0.027, 95% CI: −0.115 to 0.169, *p* = 0.704) at 120 days, resulted in a shift from inhibition to promotion in new main stem growth.

Figure 1: Effects of different fallen leaf extracts on the new main stem length of T. kanedae. Note: Different lowercase letters (a, b, c, etc.) indicate significant differences among treatments at each time point (p < 0.05). To clearly express the factors in the experimental design, yr was used to represent the time factor, tr to represent the concentration treatment, and yr × tr to indicate the interaction effect between time and concentration. A single asterisk (*) represents that the treatment shows a significant difference at the 0.05 level, and a triple asterisk (***) indicates a highly significant difference at the 0.001 level

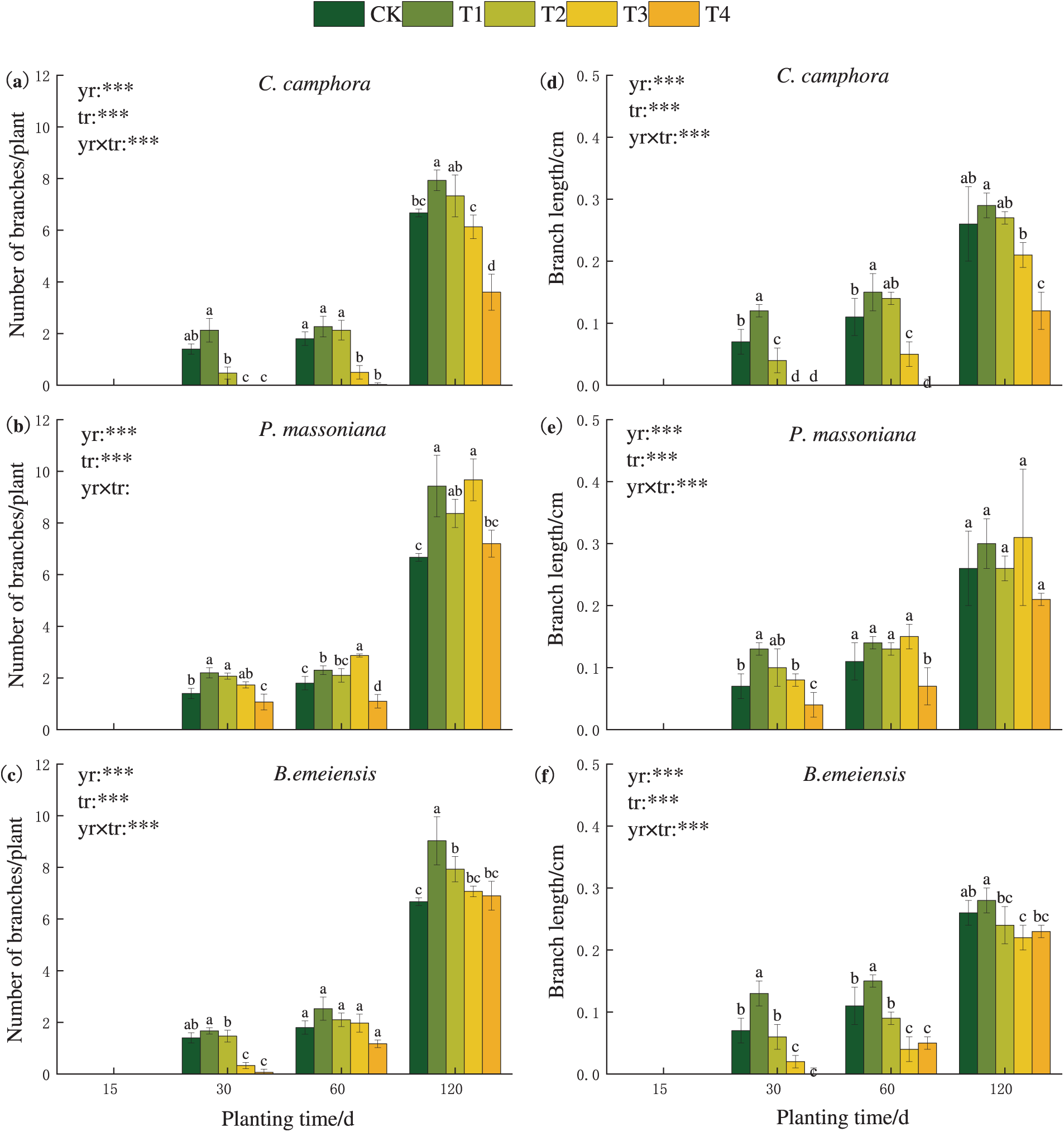

3.2.2 Branch Length and Number of Branches

From 30 days, T. kanedae begins to branch. During the observation period, T1 treatment generally promoted the increase of branch length and number, while T4 treatment showed inhibition in most cases except in some cases (e.g., P. massoniana and B. emeiensis had no significant effect on branch length at 120 days). It is noteworthy that some treatments exhibited an alleviation of inhibitory effects over time: the effect of T2 treatment on C. camphora at 60 days (mean difference = 0.333, 95% CI: −0.135 to 0.802, *p* = 0.156), T4 treatment on P. massoniana at 120 days (mean difference = 0.533, 95% CI: −0.495 to 1.562, *p* = 0.298), T3 treatment on B. emeiensis at 60 days (mean difference = 0.167, 95% CI: −0.302 to 0.635, *p* = 0.473), and T4 treatment on B. emeiensis at 120 days (mean difference = 0.233, 95% CI: −0.795 to 1.262, *p* = 0.647) on the number of branches shifted from inhibition to slight promotion. Similarly, the effect of T2 treatment on C. camphora at 60 days on branch length also turned to slight promotion (mean difference = 0.027, 95% CI: −0.003 to 0.057, *p* = 0.079), indicating that the allelopathic inhibitory effects weakened over time (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Effects of different fallen leaf extracts on number of branches (left) and branch length (right) of T. kanedae. Note: Different lowercase letters (a, b, c…) denote significant differences (p < 0.05) among treatments at each time point. In statistical models, ‘yr’ represents the time factor, ‘tr’ the concentration treatment, and ‘yr × tr’ their interaction. Significance levels are indicated as ***p < 0.001

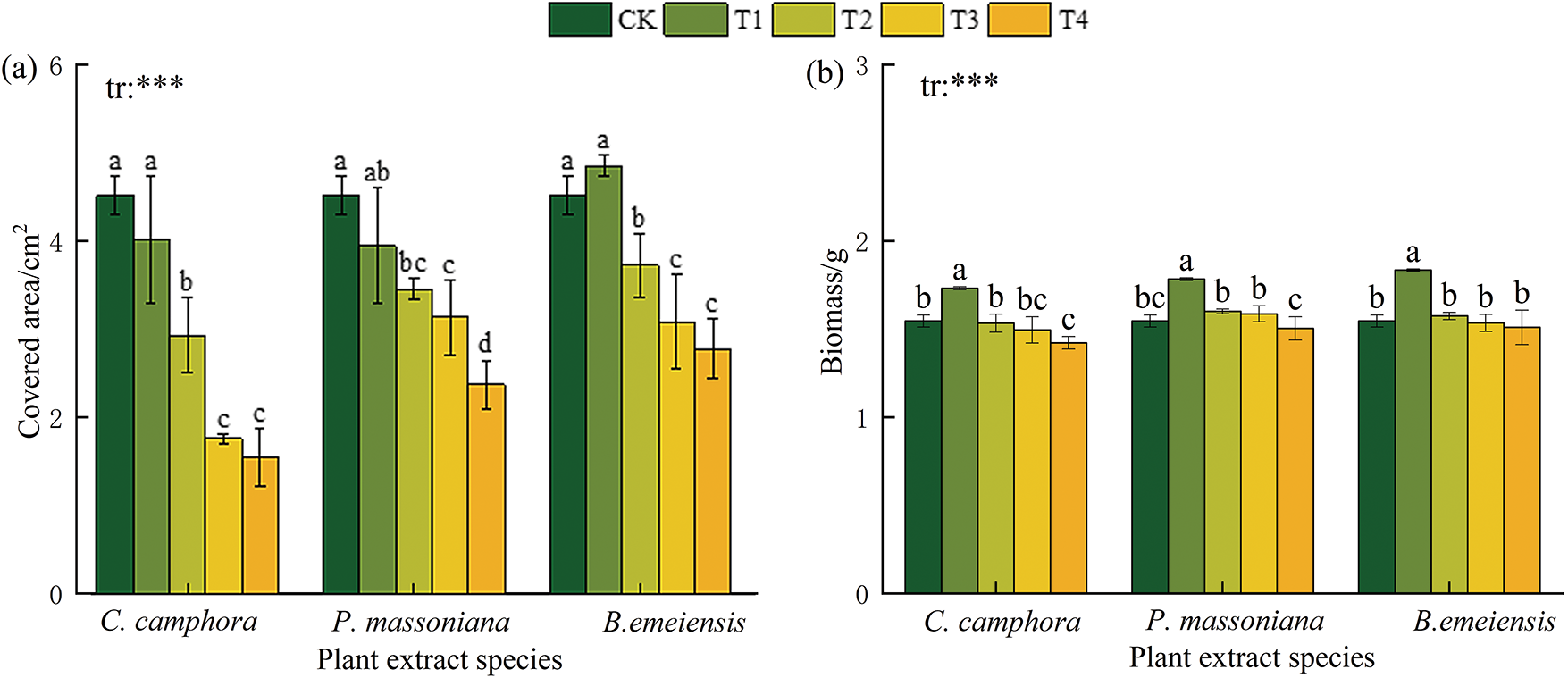

The coverage area of the T. kanedae decreased significantly with the increase of extract concentration. Except for the T1 treatment, all other concentrations inhibited the covered area, with the T4 treatment exhibiting the strongest inhibition. Compared to CK, C. camphora, P. massoniana, and B. emeiensis showed reductions of 65.61% (mean difference = −2.957, 95% CI: −3.589 to −2.235, *p* < 0.001), 47.49% (mean difference = −2.140, 95% CI: −2.772 to −1.508, *p* < 0.001), and 38.24% (mean difference = −1.732, 95% CI: −2.355 to −1.091, *p* < 0.001), respectively (Fig. 3a).

Figure 3: Effects of different fallen leaf extracts on the covered area (a) and biomass (b) of T. kanedae. Note: Lowercase letters (a, b, c) indicate inter-treatment differences (p < 0.05) per time point; factors are denoted as yr (time), tr (concentration), and yr × tr (interaction); asterisks signify within-treatment significance levels (***p < 0.001)

The T1 treatment significantly increased the biomass of T. kanedae, with the three plant species showing increases of 12.03% (mean difference = 0.186, 95% CI: 0.109 to 0.263, *p* < 0.001), 15.38% (mean difference = 0.238, 95% CI: 0.161 to 0.315, *p* < 0.001), and 18.70% (mean difference = 0.289, 95% CI: 0.212 to 0.366, *p* < 0.001) compared to CK, respectively. As the concentration increased, the biomass of T.kanedae generally exhibited a decreasing trend. Only the T4 treatment of C. camphora resulted in a significant reduction in biomass (mean difference = −0.123, 95% CI: −0.200 to −0.046, *p* = 0.003), while the other treatments showed no significant differences compared to CK (Fig. 3b).

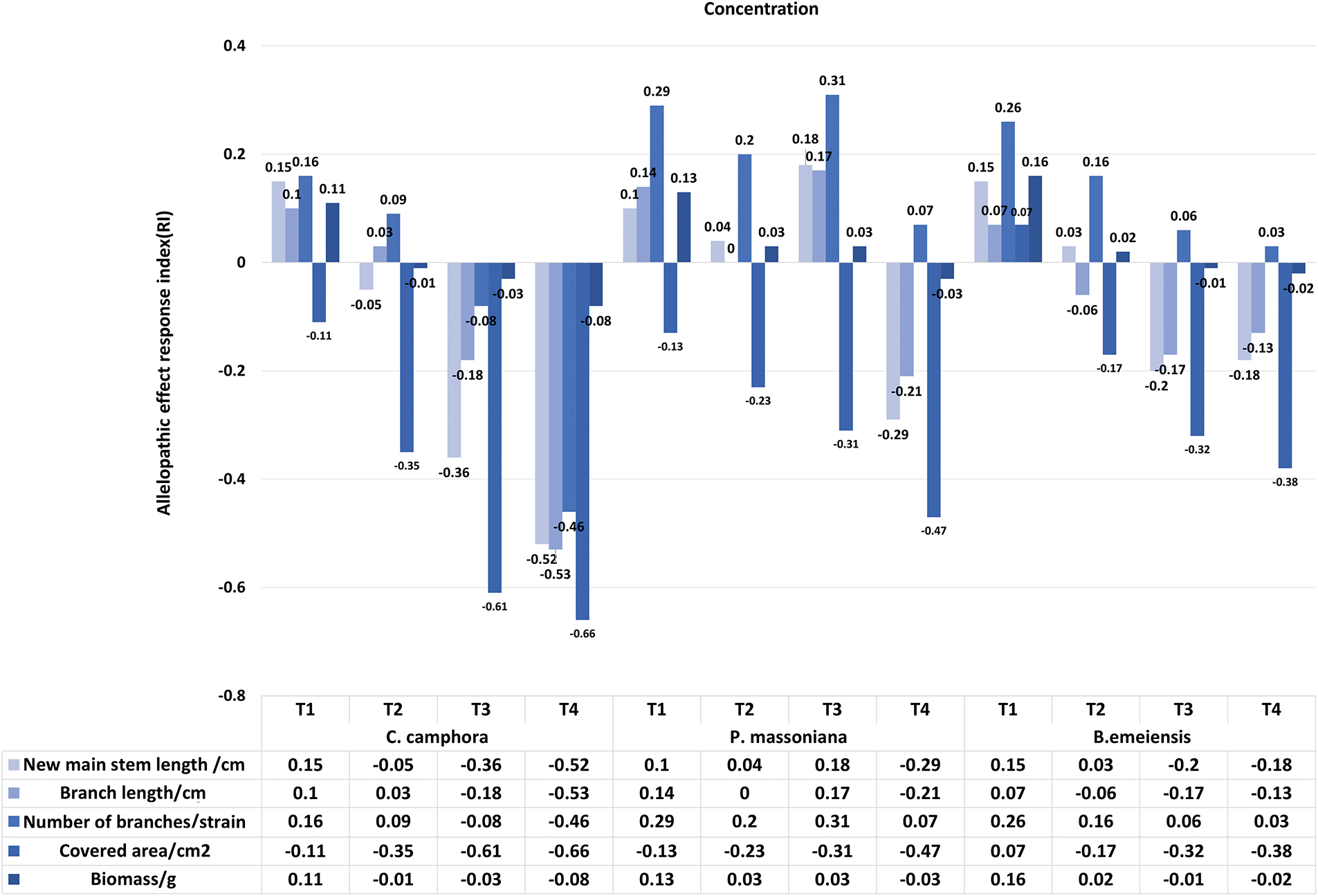

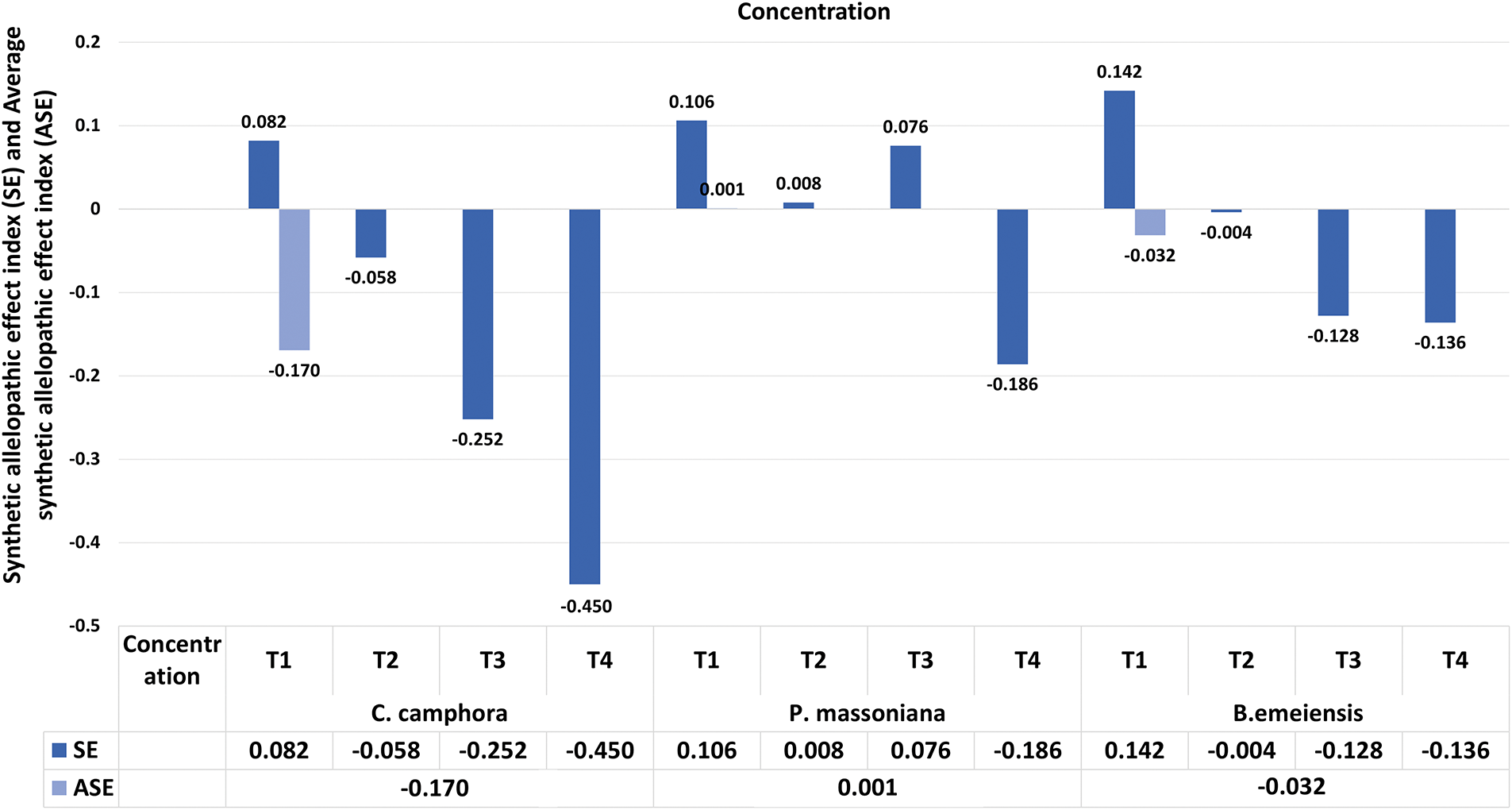

3.3 The Allelopathic Effects of Different Treatments on the Growth Parameters of T. kanedae

At 120 days, except for P. massoniana and B. emeiensis treatments, the RI of the other growth indexes (new main stem length, branch length, coverage area, biomass) showed concentration-dependent: T1 promoted and T4 inhibited. The SE showed that C. camphora and B. emeiensis were promoted at T1 and inhibited when the concentration increased. P. massoniana is inhibited only at T4. The ASE showed that C. camphora (−0.170) and B. emeiensis (−0.032) were inhibited overall, while P. massoniana (0.001) was slightly promoted (Figs. 4 and 5), reflecting clear species differences.

Figure 4: Effects of different fallen leaf extracts on the Allelopathic effect response index of T. kanedae

Figure 5: Effects of different fallen leaf extracts on the Synthetic allelopathic effect index and the Average synthetic allelopathic effect index of T. kanedae. Note: SE refers to synthetical effect of allelopathy index of growth indices, including new main stem length, branch length, number of branches, covered area, and biomass. ASE represents the average synthetical effect of allelopathy indices of the four concentrations

3.4 Effects of Fallen Leaves Extract on Physiological Indices of T. kanedae

Studying the physiological responses of plants to allelopathic stress helps elucidate the mechanisms by which plants adapt to allelopathic adversity. Photosynthesis (Chl t content), antioxidant enzyme activity (CAT, POD, SOD), cellular osmoregulatory substances (SS content, SP content), and membrane oxidation products (MDA content) are important indices reflecting plant responses to allelopathic stress [36–38].

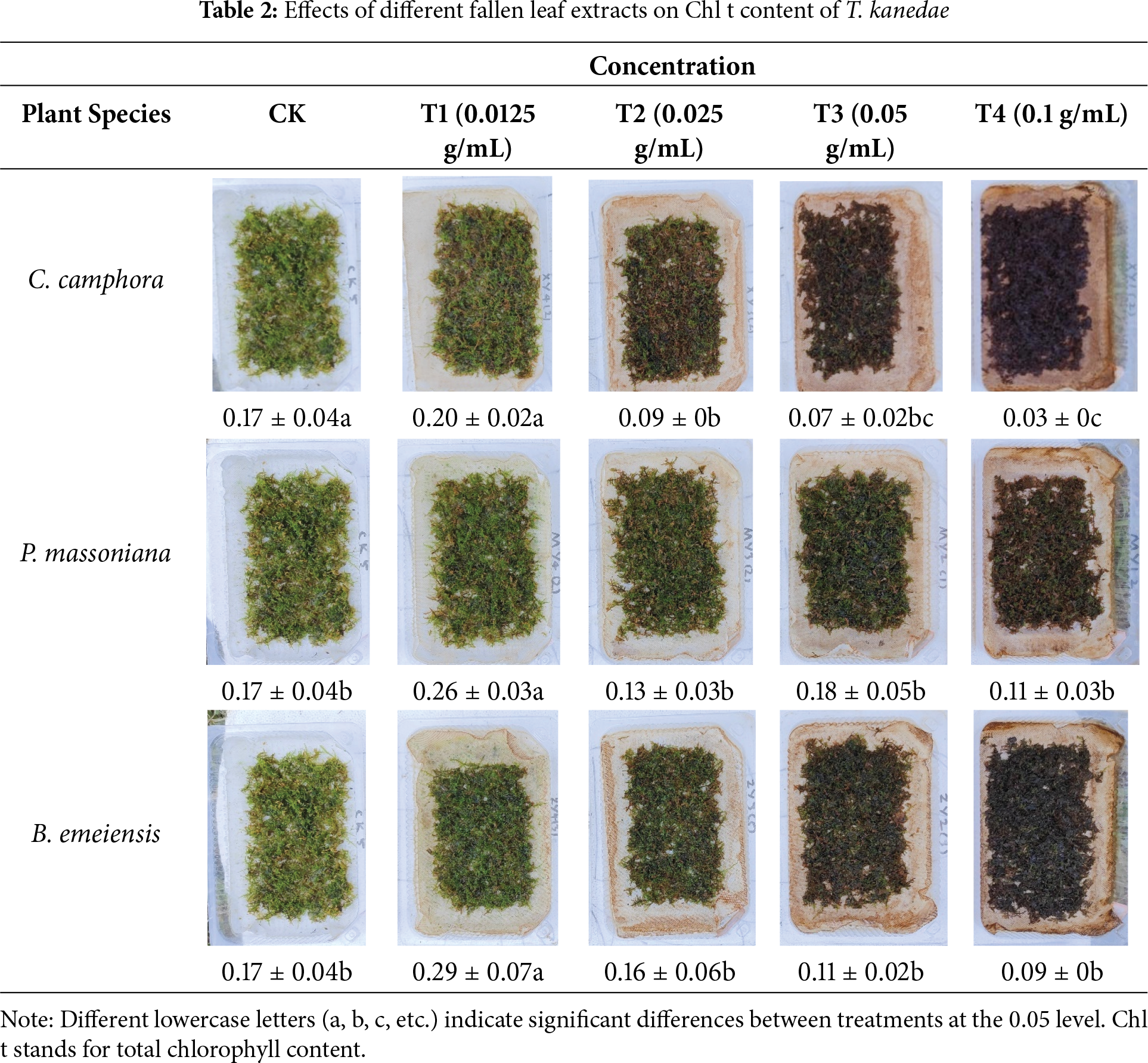

3.4.1 Impact on Chl t Content in T. kanedae

The T1 treatment of C. camphora, P. massoniana, and B. emeiensis extracts increased the Chl t of T. kanedae by 17.31% (mean difference = 0.030, 95% CI: −0.031 to 0.091, *p* = 0.326), 51.55% (mean difference = 0.089, 95% CI: 0.028 to 0.149, *p* = 0.006), and 69.48% (mean difference = 0.119, 95% CI: 0.059 to 0.180, *p* < 0.001), respectively, compared to CK. In contrast, the T2 to T4 treatments generally exhibited inhibitory effects, with the extent of inhibition increasing at higher concentrations. At the T4 concentration, Chl t decreased by 83.04% (mean difference = −0.143, 95% CI: −0.204 to −0.082, *p* < 0.001) for C. camphora, 33.97% (mean difference = −0.058, 95% CI: −0.119 to 0.002, *p* = 0.059) for P. massoniana, and 46.97% (mean difference = −0.081, 95% CI: −0.142 to −0.020, *p* = 0.011) for B. emeiensis (Table 2). These results indicate that low-concentration leachates promote chlorophyll synthesis, whereas high-concentration leachates inhibit it.

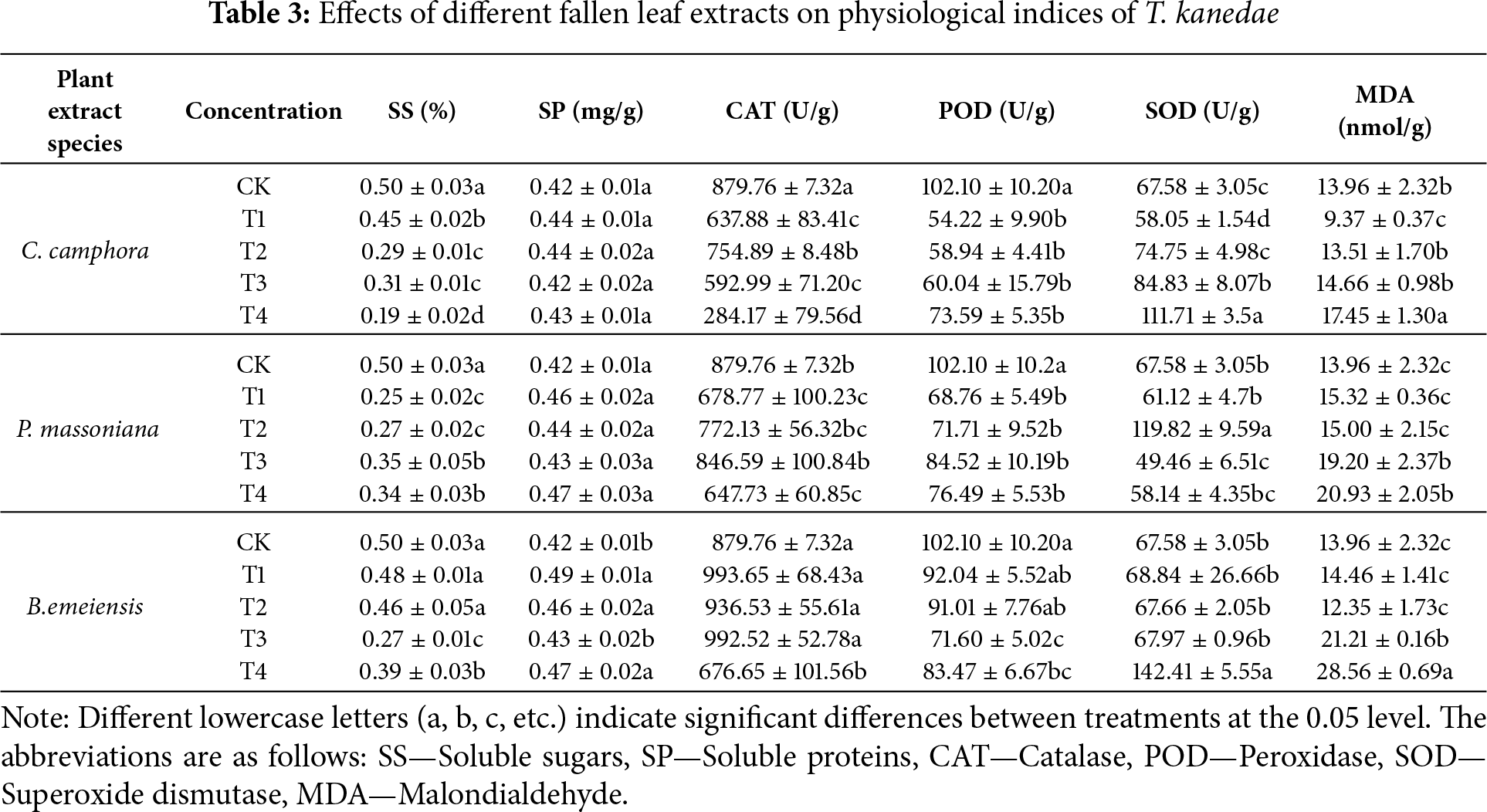

3.4.2 Impact on Osmoregulatory Substances in T. kanedae

The extracts of the three plant fallen leaves inhibited the SS content of T. kanedae while promoting its SP content. With increasing extract concentrations, SS content decreased in the C. camphora and B. emeiensis treatments, but increased in the P. massoniana treatment (Table 3). Among these, the T4 treatment of C. camphora, T1 treatment of P. massoniana, and T3 treatment of B. emeiensis exhibited the strongest inhibitory effects, showing reductions of 62.46% (mean difference = −0.313, 95% CI: −0.361 to −0.266, *p* < 0.001), 50.56% (mean difference = −0.254, 95% CI: −0.301 to −0.206, *p* < 0.001), and 45.91% (mean difference = −0.230, 95% CI: −0.278 to −0.183, *p* < 0.001) compared to CK, respectively. The B. emeiensis treatments—T1, T2, and T4—significantly increased the SP content of T. kanedae, with increases of 15.75% (mean difference = 0.067, 95% CI: 0.037 to 0.096, *p* < 0.001), 9.45% (mean difference = 0.040, 95% CI: 0.011 to 0.069, *p* = 0.009), and 10.24% (mean difference = 0.043, 95% CI: 0.014 to 0.073, *p* = 0.005) relative to CK. In contrast, the SP content in T. kanedae treated with C. camphora and P. massoniana leachates showed an increasing trend compared to CK, but the differences were not statistically significant.

3.4.3 Impact on T. kanedae’s Membrane Lipid Peroxidation Products and Antioxidant Enzyme Activity

As the concentration increased, MDA content—a marker of membrane lipid peroxidation—in T. kanedae increased, reaching its highest level under the T4 treatment for C. camphora, P. massoniana, and B. emeiensis (C. camphora: mean difference = 3.497, 95% CI: 0.711 to 6.284, *p* = 0.016; P. massoniana: mean difference = 6.969, 95% CI: 4.183 to 9.756, *p* < 0.001; B. emeiensis: mean difference = 14.605, 95% CI: 11.819 to 17.392, *p* < 0.001). Regarding antioxidant enzyme activities, CAT activity was significantly inhibited, showing an initial increase followed by a decline with rising concentration. The lowest CAT activity was observed under the T4 treatment for all three plants (C. camphora: mean difference = −595.591, 95% CI: −706.663 to −484.518, *p* < 0.001; P. massoniana: mean difference = −232.022, 95% CI: −343.095 to −120.949, *p* < 0.001; B. emeiensis: mean difference = −203.107, 95% CI: −314.180 to −92.035, *p* < 0.001). POD activity was also significantly suppressed, reaching its lowest levels under the T1 treatment for C. camphora (mean difference = −47.884, 95% CI: −62.312 to −33.456, *p* < 0.001) and P. massoniana (mean difference = −33.337, 95% CI: −47.766 to −18.909, *p* < 0.001), and under the T3 treatment for B. emeiensis (mean difference = −30.497, 95% CI: −44.926 to −16.069, *p* < 0.001). In contrast, SOD activity was markedly enhanced, peaking under the T4 treatment for C. camphora (mean difference = 44.123, 95% CI: 30.138 to 58.109, *p* < 0.001) and B. emeiensis (mean difference = 74.830, 95% CI: 60.844 to 88.815, *p* < 0.001), and under the T2 treatment for P. massoniana (mean difference = 52.242, 95% CI: 38.256 to 66.228, *p* < 0.001) (see Table 3). These results suggest that increasing concentrations of leaf litter leachates may induce membrane lipid peroxidation in T. kanedae, leading to elevated MDA levels and altered antioxidant enzyme activities, characterized by reduced CAT and POD activities but increased SOD activity.

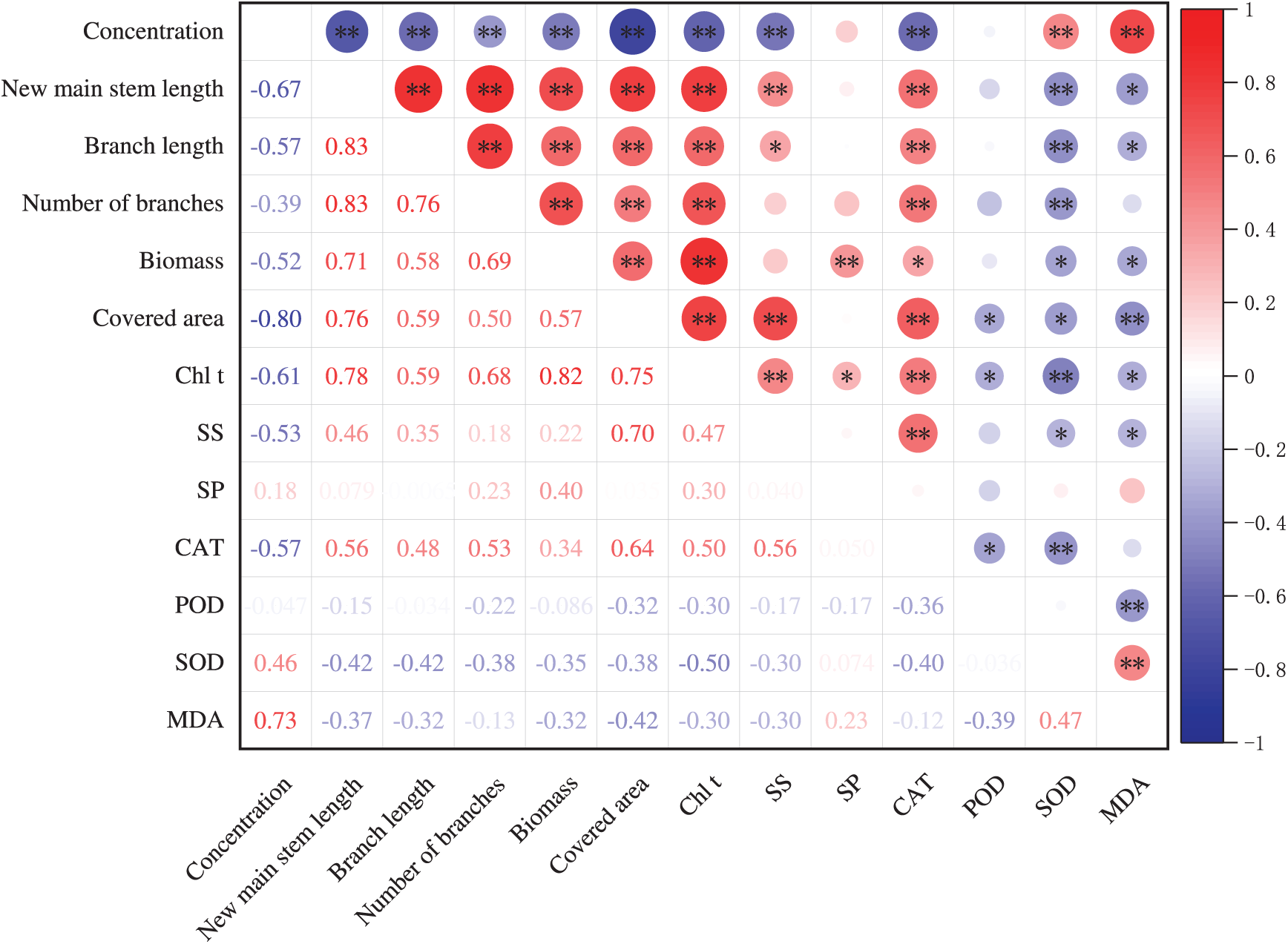

3.5 Correlation Analysis of Growth and Physiological Indicators of T. kanedae

As shown in Fig. 6, the lengths of new main stem length, branch lengths, number of branches, biomass, and coverage area of T. kanedae are significantly negatively correlated with the concentration of leaf litter leachate. Regarding osmotic adjustment substances, the SS content showed a significantly negative correlation with the concentration of leaf litter leachate, while the SP content was positively correlated with the concentration, though this correlation did not reach a significant level. It is noteworthy that both SS and SP contents are positively correlated with each growth index. The content of MDA, a product of membrane lipid peroxidation, is significantly positively correlated with the concentration of leaf litter leachate and negatively correlated with each growth index. In terms of antioxidant enzyme activity, the activity of CAT is significantly negatively correlated with the concentration and significantly positively correlated with each growth index. Conversely, the activity of SOD is significantly positively correlated with the concentration and significantly negatively correlated with each growth index. Overall, as the concentration of the leachate increases, the growth level of T. kanedae decreases, accompanied by a decrease in chlorophyll content, a reduction in SS, an increase in MDA content, a decrease in CAT activity, and an increase in SOD activity.

Figure 6: Correlation analysis of the growth and physiological indicators of T. kanedae treated with fallen leaf extracts from three plant species. Note: A single asterisk (*) represents that the treatment shows a significant difference at the 0.05 level, a double asterisk (**) indicates a highly significant difference at the 0.01 level. The abbreviations used are: total chlorophyll (Chl t), soluble sugars (SS), soluble proteins (SP), catalase (CAT), peroxidase (POD), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and malondialdehyde (MDA)

The strength of plant allelopathic effects is influenced by various factors such as the concentration of the aqueous extract, the types of allelochemicals, and the species of the recipient plants [33]. Allelochemicals typically exhibit a certain degree of selectivity, specificity, and a pronounced concentration effect. Among these factors, the concentration of allelochemicals is a key determinant of the intensity of their effects: when the concentration exceeds a certain threshold, it significantly inhibits seed germination or seedling growth of the recipient plants; whereas below this threshold, there may be no obvious inhibitory effect, and it might even promote growth [39]. Previous studies have demonstrated that allelochemicals often exhibit a dual effect on seed germination and plant growth, with low concentrations promoting and high concentrations inhibiting growth [40,41]. In the present study, similar “low-concentration promotion and high-concentration inhibition” patterns were observed in the RI and SE for new main stem length, branch length, coverage area, and biomass of T. kanedae, indicating that the growth of T. kanedae is affected by allelopathy in a concentration-dependent manner. Allelopathic effects may account for the uneven distribution of T. kanedae beneath forest litter, where a greater accumulation of leaf litter leads to higher concentrations of allelochemicals and stronger inhibitory effects, thereby suppressing T. kanedae growth. In contrast, when fallen leaves are sparse, the lower levels of allelochemicals may promote the growth of T. kanedae. The ASE further revealed species-specific differences in allelopathic intensity. Litter extracts from P. massoniana exhibited an overall promotive effect on the growth of T. kanedae, whereas extracts from C. camphora and B.emeiensis showed inhibitory effects, likely due to differences in their allelochemical composition. Moreover, Overtime, the allelopathic inhibitory effects on T. kanedae weakened, and in some treatments, even shifted to a promotive effect. For instance, by day 120, the P. massoniana T3 treatment significantly promoted new branch growth after initially inhibiting it. Similarly, the effects of C. camphora T2 (after day 60), P. massoniana T4 (day 120), B. emeiensis T3 (after day 60), and T4 (day 120) on number of branches shifted from inhibition to promotion. In addition, the branch length under the C. camphora T2 treatment also changed from inhibition to promotion after day 60. The research by Parmar et al. found that the allelochemicals in the fallen leaves of Melia dubia significantly inhibited the germination and early growth of peppers and eggplants in the early stages, but did not have a significant impact on later growth, biomass, and fruit yield in pot experiments, indicating that the allelopathic effects are stage-dependent and transient [42], this is similar to the findings of the present study. The mechanism of this late inhibition weakening or transformation into facilitation is not fully understood and may involve a variety of factors. For example, allelopathic substances may be degraded or transformed during culture, reducing their activity [43]; Another possible explanation is that the slow release of nutrients from litter may partially offset the earlier allelopathic inhibitory effects in the later stages, or that bryophytes developed some adaptation to allelopathic stress. However, these mechanisms need to be verified in the future by chemical analysis and time series decomposition experiments.

Allelochemicals affect the physiological and biochemical processes of plants, thereby promoting or inhibiting their growth and development [44,45]. Photosynthesis drives crop yield formation, with chlorophyll being the essential substance for photosynthesis, which greatly influences plant growth. This study revealed that the fallen leaf extracts from the three plants promoted Chl t content in T. kanedae at T1 concentration but inhibited it at T2 to T4 concentrations. Liu Yaoyao and colleagues [46] found that Phyllostachys edulis forest extracts promoted Chl t content in Cinnamomum septentrionale seedlings at low-concentrations but inhibited it at high-concentrations, which aligns with our results. This suggests that the allelochemicals in the fallen leaf extracts exert a dual effect on the Chl t content of T. kanedae. Correlation analysis revealed that Chl t content was negatively correlated with extract concentration but positively correlated with T. kanedae growth. This suggests that as extract concentration increased, Chl t content decreased, photosynthesis weakened, thus impeding growth.

When plants are subjected to external environmental stress, their internal osmoregulatory substances, such as SP and SS, participate in physiological recovery and repair processes. Yao Dandan and colleagues [47] found that coumarin solution treatment significantly increased the soluble protein and soluble sugar content in Lolium perenne under stress. This study observed that the fallen leaves extracts from the three plants raised the soluble protein content in T. kanedae while reducing its soluble sugar content. Soluble sugar content was significantly positively correlated with growth indicators. This might result from reduced soluble sugar content in T. kanedae, leading to osmotic imbalance and thus hindering normal plant development.

Allelopathy can enhance membrane lipid peroxidation, destabilize the membrane system, cause metabolic disorders, and inhibit plant growth and development [48,49]. MDA is a byproduct of membrane lipid peroxidation, and increased levels signify heightened cell membrane system damage [50,51]. Shao et al. [52] reported that extracts of Descurainia sophia, Galium tricorne, wild oat, and Vicia sativa all exhibited allelopathic inhibitory effects on wheat seed germination and seedling growth, and that the malondialdehyde (MDA) content in wheat leaves increased significantly, which aligns with our findings. We found that MDA content in T. kanedae was positively correlated with extract concentration and negatively correlated with growth indicators under treatment with fallen leaf extracts from the three plants. This indicates that as extract concentration increased, T. kanedae likely experienced membrane lipid peroxidation, resulting in higher MDA content, further damaging cell membranes and inhibiting growth.

SOD, CAT, and POD are three essential enzymes in the plant antioxidant system. SOD is the primary enzyme for scavenging oxygen free radicals [53], catalyzing their conversion to hydrogen peroxide and oxygen [54]; CAT further breaks down hydrogen peroxide, providing antioxidant defense [55]. POD is an important reactive oxygen species-scavenging enzyme that promotes the biosynthesis and accumulation of lignin and suberin in response to oxidative stress when plants are damaged [56,57]. After applying fallen leaf extracts to T. kanedae, CAT and POD activities were significantly inhibited, while SOD activity significantly increased. Furthermore, CAT activity was highly negatively correlated with concentration and positively correlated with growth indicators; SOD activity was highly positively correlated with concentration and significantly negatively correlated with growth indicators. This suggests that as extract concentration increased, SOD activity rose to counter oxidative stress, but it still exceeded its defensive capacity, leading to inhibited growth. Under the allelopathic stress of the extracts, CAT activity significantly decreased, reducing hydrogen peroxide removal capacity, causing oxidative damage to the plant, thereby inhibiting growth.

Overall, the leaf litter extract may affect the growth of T. kanedae through the following pathways: First, under high-concentration conditions, it may inhibit chlorophyll synthesis, potentially leading to reduced photosynthesis. Second, the decrease in SS content may indicate a decline in osmotic regulation capacity. Third, the increase in membrane lipid peroxidation levels and MDA accumulation may suggest impaired cell membrane stability. Finally, the rise in SOD activity coupled with the decrease in CAT activity may reflect a certain degree of imbalance in the antioxidant system. These changes collectively demonstrate a trend associated with the growth inhibition of T. kanedae, though the specific mechanisms require further experimental validation.

Plants influence the entire growth and development process of recipient plants by releasing allelochemicals. These secondary metabolites enter the environment through pathways such as rain and fog leaching, stem and leaf volatilization, root secretion, and decomposition of residual plant parts. They often first dissolve in rainwater, subsequently affecting seed germination and seedling growth to varying degrees. The collection of allelochemicals is commonly conducted using water as an extraction solvent at room temperature [58,59] to simulate their natural release forms, which helps in more accurately interpreting allelopathic phenomena. Therefore, the water extraction method can effectively reflect the actual process of plant allelochemicals entering the environment.

This study focuses on T. kanedae as the recipient plant to investigate the potential allelopathic effects of aqueous leaf litter extracts on its growth and physiological indicators. It should be noted that although the water extraction method is widely used in this field [60], it still has certain limitations. In addition to potential allelochemicals, aqueous extracts also contain soluble nutrients, osmotically active compounds, and possible microbial metabolites. Therefore, the observed physiological changes (e.g., reduction in chlorophyll content, accumulation of MDA, and alterations in antioxidant enzyme activity) may result from a combined action of allelochemicals, osmotic stress, and nutrient interference, rather than being solely attributable to allelochemical-specific effects. Future research should focus on the identification and chemical characterization of allelochemicals within aqueous extracts (e.g., quantitative detection of phenolics and terpenoids). Moreover, approaches such as osmotic calibration, sterile culture experiments, and systematic chemical profiling will be essential to distinguish the direct effects of allelochemicals from those of other abiotic and biotic factors. Such efforts will facilitate a more comprehensive and mechanistic understanding of allelopathic interactions between tree species and bryophytes, thereby elucidating the complexity of plant–plant chemical interactions with greater accuracy. In addition, the allelopathic effects observed from the litter of C. camphora, P. massoniana, and B. emeiensis may be closely related to their specific allelochemical compositions. Previous studies have shown that C. camphora litter is rich in terpenes, esters, alcohols, and ketones; P. massoniana litter contains abundant monoterpenes and volatile phenolic compounds; while bamboo litter is enriched with various phenolic acids and flavonoids. These allelochemicals may exert significant effects on plant growth and physiological processes. In line with these reports, the decline in chlorophyll content, elevated MDA levels, and decreased CAT activity observed in T. kanedae under high-concentration extracts suggest that such allelochemicals may, at least in part, contribute to the physiological stress and growth suppression in bryophytes. Finally, it should be emphasized that aqueous litter extracts, while a common proxy in allelopathy studies, cannot fully replicate natural ecological processes. In natural ecosystems, the release and action of allelochemicals are modulated by multiple factors, including soil physicochemical properties, microbial communities, rainfall, and temperature. These complex ecological interactions are difficult to simulate under experimental conditions. Hence, the findings of this study should be interpreted primarily as indirect evidence of potential allelopathic effects, rather than as a complete reproduction of natural ecological processes. Field-based controlled experiments in the future may provide further validation and deeper insights into the mechanisms governing litter–bryophyte interactions.

In conclusion, the extracts from the three plants significantly affected the growth and physiology of T. kanedae. The growth effects exhibited a concentration-dependent pattern characterized by “low promotion and high inhibition.” As the concentration increased, the inhibitory effect on growth intensified. Physiologically, Chl t content and soluble sugar content decreased, while malondialdehyde content increased. Catalase activity decreased, and superoxide dismutase activity increased. These changes may inhibit growth by suppressing photosynthesis, reducing osmoregulation, enhancing membrane peroxidation, and increasing antioxidant enzyme SOD activity while decreasing CAT activity. The ASE indicated that the leaf litter extract of P. massoniana promoted the growth of T. kanedae, whereas the extracts from C. camphora and B. emeiensis exhibited inhibitory effects. Based on the above results, timely cleaning of fallen leaves of C. camphora and B. emeiensis may help allelopathize their allelopathic inhibition against T. kanedae, but this suggestion is still in the preliminary inference stage, and its practical application effect needs to be verified by subsequent field experiments. These results provide strong evidence for understanding the chemosensory mechanisms of plant fallen leafextract on bryophytes and enrich the research field of allelopathy. Furthermore, these findings have important practical implications for the conservation and management of bryophytes.

Acknowledgement: I sincerely thank my advisor, Prof. Xiu-Rong Wang, my research group members Mu-Yan Xie, Li-Xin Duan, Mei-Xuan Xie, Bu-Fang Huang, Jun-Jie Shen, Jia-Qi Chen, Wei Tang, Yu Xie, Li-Zhen Chai, Bing-Yang Shi, Shuo-Yuan Yang, Hong-Mei Chen, as well as my classmate You-Sen Ao and all the laboratory teachers for their support and assistance.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, “Landscape Adaptation Evaluation of Bryophytes in Karst Areas and its Landscape Theory” (31960328), awarded to Xiurong Wang.

Author Contributions: Fang Liao designed and performed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. Muyan Xie and Lixin Duan experimented and recorded the data. Xiurong Wang supported this research and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All materials and data used or generated in this study can be made available upon request. For inquiries, please contact Fang Liao at fangliao92@gmail.com.

Ethics Approval: This study did not involve human participants, vertebrate animals, or endangered/protected species. Field sampling and the collection of non-protected plant material complied with institutional, national and international guidelines and legislation. Fallen leaves of Cinnamomum camphora, Pinus massoniana and Bambusa emeiensis were collected as naturally shed litter from municipal parks; no living trees were cut or injured. The recipient bryophyte Thuidium kanedae is a common, non-protected species in the study area. All necessary permissions for field sampling were obtained from the relevant management authorities prior to collection.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the content of this article.

References

1. Asakawa Y. Biologically active compounds from bryophytes. Pure Appl Chem. 2007;79(4):557–80. doi:10.1351/pac200779040557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Eldridge DJ, Guirado E, Reich PB, Ochoa-Hueso R, Berdugo M, Sáez-Sandino T, et al. The global contribution of soil mosses to ecosystem services. Nat Geosci. 2023;16(5):430–8. doi:10.1038/s41561-023-01170-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Rousk K, Michelsen A. The sensitivity of moss-associated nitrogen fixation towards repeated nitrogen input. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146655. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0146655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Oishi Y. Bryophytes enhance nitrogen content in decaying wood via biological interactions. Ecosphere. 2024;15(1):e4755. doi:10.1002/ecs2.4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Coe KK, Howard NB, Slate ML, Bowker MA, Mishler BD, Butler R, et al. Morphological and physiological traits in relation to carbon balance in a diverse clade of dryland mosses. Plant Cell Environ. 2019;42(11):3140–51. doi:10.1111/pce.13613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Turetsky MR, Bond-Lamberty B, Euskirchen E, Talbot J, Frolking S, McGuire AD, et al. The resilience and functional role of moss in boreal and arctic ecosystems. New Phytol. 2012;196(1):49–67. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04254.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yang T, Chen Q, Yang M, Wang G, Zheng C, Zhou J, et al. Soil microbial community under bryophytes in different substrates and its potential to degraded karst ecosystem restoration. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2022;175:105493. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2022.105493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Chen D, Wu W, Zhang C. Study on the application of bryophytes in landscaping. J Yangling Vocat Tech Coll. 2020;19(2):10–3. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

9. Ilić M, Igić R, Ćuk M, Veljić M, Radulović S, Orlović S, et al. Environmental drivers of ground-floor bryophytes diversity in temperate forests. Oecologia. 2023;202(2):275–85. doi:10.1007/s00442-023-05391-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. de Oliveira Marmo JJ, Silva MPP. Bryophytes of a Brazilian seasonally dry tropical forest: an overview of diversity and environmental drivers. Flora. 2025;330:152770. doi:10.1016/j.flora.2025.152770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Rola K, Plášek V, Rożek K, Zubek S. Effect of tree species identity and related habitat parameters on understorey bryophytes–interrelationships between bryophyte, soil and tree factors in a 50-year-old experimental forest. Plant Soil. 2021;466(1):613–30. doi:10.1007/s11104-021-05074-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu C, Bu ZJ, Mallik A, Rochefort L, Hu XF, Yu Z. Resource competition and allelopathy in two peat mosses: implication for niche differentiation. Plant Soil. 2020;446(1):229–42. doi:10.1007/s11104-019-04350-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Liu S. Landscape characteristics and database construction in urban public parks and road green space of Guiyang. Guiyang, China: Guizhou University; 2021. (In Chinese). doi:10.27047/d.cnki.ggudu.2021.001420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Möhler H, Diekötter T, Bauer GM, Donath TW. Conspecific and heterospecific grass litter effects on seedling emergence and growth in ragwort (Jacobaea vulgaris). PLoS One. 2021;16(2):e0246459. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0246459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. da Silva ER, da Silveira LHR, Overbeck GE, Soares GLG. Inhibitory effects of Eucalyptus saligna leaf litter on grassland species: physical versus chemical factors. Plant Ecol Divers. 2018;11(1):55–67. doi:10.1080/17550874.2018.1474393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Mingo A, Bonanomi G, Giannino F, Incerti G, Mazzoleni S. Dose-dependent positive-to-negative shift of litter effects on seedling growth: a modelling study on 35 plant litter types. Plant Ecol. 2023;224(6):563–78. doi:10.1007/s11258-023-01324-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhou YH, Guo CY, Luo SM, Tao XH, Zhou R, Liu SY, et al. Allelopathic effects of aqueous extracts from five economic tree species on seed germination of Turpinia arguta. South-Cent Agric Sci Technol. 2023;44(1):13–6. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

18. Whitehead J, Wittemann M, Cronberg N. Allelopathy in bryophytes—a review. Lindbergia. 2018;41(1):01097. doi:10.25227/linbg.01097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kato-Noguchi H. Allelopathic chemical interaction of bryophytes with vascular plants. Mini Rev Org Chem. 2017;13(6):422–9. doi:10.2174/1570193x13666161019122347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Michel P, Burritt DJ, Lee WG. Bryophytes display allelopathic interactions with tree species in native forest ecosystems. Oikos. 2011;120(8):1272–80. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2010.19148.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Matić NA, Ćosić MV, Božović DP, Poponessi S, Pavkov SD, Goga M, et al. Evidence of allelopathy among selected moss species with lettuce and radish. Agriculture. 2024;14(6):812. doi:10.3390/agriculture14060812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kato-Noguchi H, Seki T. Allelopathy of the moss Rhynchostegium pallidifolium and 3-hydroxy-β-ionone. Plant Signal Behav. 2010;5(6):702–4. doi:10.4161/psb.5.6.11642. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Li C, Yang X, Tian Y, Yu M, Shi S, Qiao B, et al. The effects of fig tree (Ficus carica L.) leaf aqueous extract on seed germination and seedling growth of three medicinal plants. Agronomy. 2021;11(12):2564. doi:10.3390/agronomy11122564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Macías FA, Mejías FJr, Molinillo JM. Recent advances in allelopathy for weed control: from knowledge to applications. Pest Manag Sci. 2019;75(9):2413–36. doi:10.1002/ps.5355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Bais HP, Vepachedu R, Gilroy S, Callaway RM, Vivanco JM. Allelopathy and exotic plant invasion: from molecules and genes to species interactions. Science. 2003;301(5638):1377–80. doi:10.1126/science.1083245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Xu Y, Chen X, Ding L, Kong CH. Allelopathy and allelochemicals in grasslands and forests. Forests. 2023;14(3):562. doi:10.3390/f14030562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Xu L, Yao L, Ai X, Guo Q, Wang S, Zhou D, et al. Litter autotoxicity limits natural regeneration of Metasequoia glyptostroboides. New For. 2023;54(5):897–919. doi:10.1007/s11056-022-09941-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Huang W, Reddy GVP, Shi P, Huang J, Hu H, Hu T. Allelopathic effects of Cinnamomum septentrionale leaf litter on Eucalyptus grandis saplings. Glob Ecol Conserv. 2020;21(10):e00872. doi:10.1016/j.gecco.2019.e00872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang SZ, Zhang F, Dong JF, Zhang K, Cui J, Wu XL. Allelopathic effects of decomposing Cinnamomum camphora leaf litter on three turfgrasses. Pratacultural Sci. 2018;35(9):2095–104. (In Chinese). doi:10.11829/j.issn.1001-0629.2017-0697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Jiang Y, Zhu X, Chen P. Allelopathic effects of aqueous extract of Pinus massoniana fallen leaves on four pasture species. J Anhui Agric Sci. 2018;46(25):96–100. (In Chinese). doi:10.13989/j.cnki.0517-6611.2018.25.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li XX, Lai JL, Yue JH, Rong JD, Chen LG, Chen LY, et al. Allelopathy of Phyllostachys pubescens extract on the seed germination of Chinese fir. Acta Ecol Sin. 2018;38(22):8149–57. (In Chinese). doi:10.5846/stxb201711061985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Shi B, Wang X, Chen H, Yang S. Growth and physiological responses of Plagiomnium acutum to different cultivation substrates. Acta Bot Boreali-Occident Sin. 2022;42(7):1208–18. (In Chinese). doi:10.7606/j.issn.1000-4025.2022.07.1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Bao W, Leng L. Determination of photosynthetic pigment content in bryophytes: a case study of Rhodobryum giganteum. Chin J Appl Environ Biol. 2005;11(2):235–7. (In Chinese). doi:10.3321/j.issn:1006-687X.2005.02.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang X, Huang J. Principles and techniques of plant physiology and biochemistry experiments. 3rd ed. Beijing, China: Higher Education Press; 2015. p. 171–3, 182–4. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

35. Xie M, Wang X. Allelopathic effects of Thuidium kanedae on four urban spontaneous plants. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):14794. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-65660-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Nasrollahi P, Razavi SM, Ghasemian A, Zahri S. Physiological and biochemical responses of lettuce to thymol, as allelochemical. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2018;65(4):598–603. doi:10.1134/s1021443718040167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Yang H, Song J, Yu X. Artemisia baimaensis allelopathy has a negative effect on the establishment of Elymus nutans artificial grassland in natural grassland. Plant Signal Behav. 2023;18(1):2163349. doi:10.1080/15592324.2022.2163349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang X, Wang S, Zhu J, Zuo L, Yang Z, Li L. Response mechanisms of sugarcane seedlings to the allelopathic effects of root aqueous extracts from sugarcane ratoons of different ages. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1020533. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1020533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhao J, Yang Z, Zou J, Li Q. Allelopathic effects of sesame extracts on seed germination of moso bamboo and identification of potential allelochemicals. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):6661. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-10695-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Perveen S, Mushtaq MN, Yousaf M, Sarwar N. Allelopathic hormesis and potent allelochemicals from multipurpose tree Moringa oleifera leaf extract. Plant Biosyst Int J Deal Aspects Plant Biol. 2021;155(1):154–8. doi:10.1080/11263504.2020.1727984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wang N, Tian Y, Chen H. Mutual allelopathic effect between invasive plant Aegilops tauschii and wheat. Int J Agric Biol. 2019;21(2):463–71. doi:10.17957/IJAB/15.0916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Parmar AG, Thakur NS, Gunaga RP. Melia dubia Cav. leaf litter allelochemicals have ephemeral allelopathic proclivity. Agrofor Syst. 2019;93(4):1347–60. doi:10.1007/s10457-018-0243-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Huang JB, Hu TX, Wu ZL, Hu HL, Chen H, Wang Q. Effects of decomposing leaf litter of Juglans regia on growth and physiological characteristics of Triticum aestivum. Acta Ecol Sin. 2014;34(23):6855–63. (In Chinese). doi:10.5846/stxb201303070363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Rice EL. Evidence for movement of allelopathic compounds from plants and absorption and translocation by other plants. In: Allelopathy. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1984. p. 309–19. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-092539-4.50016-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gharibvandi A, Karimmojeni H, Ehsanzadeh P, Rahimmalek M, Mastinu A. Weed management by allelopathic activity of Foeniculum vulgare essential oil. Plant Biosyst Int J Deal Aspects Plant Biol. 2022;156(6):1298–306. doi:10.1080/11263504.2022.2036848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Liu Y, Zhang R, Shen X, Wang S, Li W. Study on the effects of different extracts from Phyllostachys edulis forest on the growth of Phoebe chekiangensis seedlings. J West China For Sci. 2020;49(3):99–108. (In Chinese). doi:10.16473/j.cnki.xblykx1972.2020.03.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Yao DD, Wang JY, Zhou Q, Tang Q, Zhao GQ, Wu CX. Effect of coumarin on Italian ryegrass seed germination and seedling growth. Acta Prataculturae Sin. 2017;26(2):136–45. (In Chinese). doi:10.11686/cyxb2016303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Staszek P, Krasuska U, Ciacka K, Gniazdowska A. ROS metabolism perturbation as an element of mode of action of allelochemicals. Antioxidants. 2021;10(11):1648. doi:10.3390/antiox10111648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Morales M, Munné-Bosch S. Malondialdehyde: facts and artifacts. Plant Physiol. 2019;180(3):1246–50. doi:10.1104/pp.19.00405. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Ding J, Sun Y, Xiao CL, Shi K, Zhou YH, Yu JQ. Physiological basis of different allelopathic reactions of cucumber and figleaf gourd plants to cinnamic acid. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(13):3765–73. doi:10.1093/jxb/erm227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Lin CC, Kao CH. Effect of NaCl stress on H2O2 metabolism in rice leaves. Plant Growth Regul. 2000;30(2):151–5. doi:10.1023/A:1006345126589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Shao Q, Li W, Yan S, Zhang C, Huang S, Ren L. Allelopathic effects of different weed extracts on seed germination and seedling growth of wheat. Pak J Bot. 2019;51(6):2159–67. doi:10.30848/pjb2019-6(45). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Gill SS, Tuteja N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2010;48(12):909–30. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2010.08.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(9):405–10. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Foyer CH, Noctor G. Redox homeostasis and antioxidant signaling: a metabolic interface between stress perception and physiological responses. Plant Cell. 2005;17(7):1866–75. doi:10.1105/tpc.105.033589. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Almagro L, Gómez Ros LV, Belchi-Navarro S, Bru R, Ros Barceló A, Pedreño MA. Class III peroxidases in plant defence reactions. J Exp Bot. 2009;60(2):377–90. doi:10.1093/jxb/ern277. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Warinowski T, Koutaniemi S, Kärkönen A, Sundberg I, Toikka M, Simola LK, et al. Peroxidases bound to the growing lignin polymer produce natural like extracellular lignin in a cell culture of Norway spruce. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:1523. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.01523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Dai L, Wu L, Zhou X, Jian Z, Meng L, Xu G. Effects of water extracts of Flaveria bidentis on the seed germination and seedling growth of three plants. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):17700. doi:10.1038/s41598-022-22527-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Reigosa MJ, Pedrol N, González L, editors. Allelopathy: a physiological process with ecological implications. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

60. Motalebnejad M, Karimmojeni H, Majidi MM, Mastinu A. Allelopathic effect of aqueous extracts of grass genotypes on Eruca sativa L. Plants. 2023;12(19):3358. doi:10.3390/plants12193358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools