Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Zinc Oxide Nanoparticle Alleviates the Inhibition of Dendrobium huoshanense Photosynthesis by Cadmium through Enhancing Antioxidant Enzyme System

1 College of Biological and Pharmaceutical Engineering, Anhui Engineering Research Center for Eco-Agriculture of Traditional Chinese Medicine, West Anhui University, Luan, 237012, China

2 Department of Plant Science, School of Agriculture and Biology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, 201109, China

3 Low Dimensional Materials Research Center, Khazar University, Baku, AZ1096, Azerbaijan

4 Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Sakarya University of Applied Sciences, Arifiye, 54580, Türkiye

5 National Key Laboratory for Tropical Crop Breeding, School of Breeding and Multiplication (Sanya Institute of Breeding and Multiplication), Hainan University, Sanya, 572025, China

* Corresponding Authors: Cheng Song. Email: ; Muhammad Aamir Manzoor. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Application of Nanomaterials in Plants)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3427-3451. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.070778

Received 23 July 2025; Accepted 11 September 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

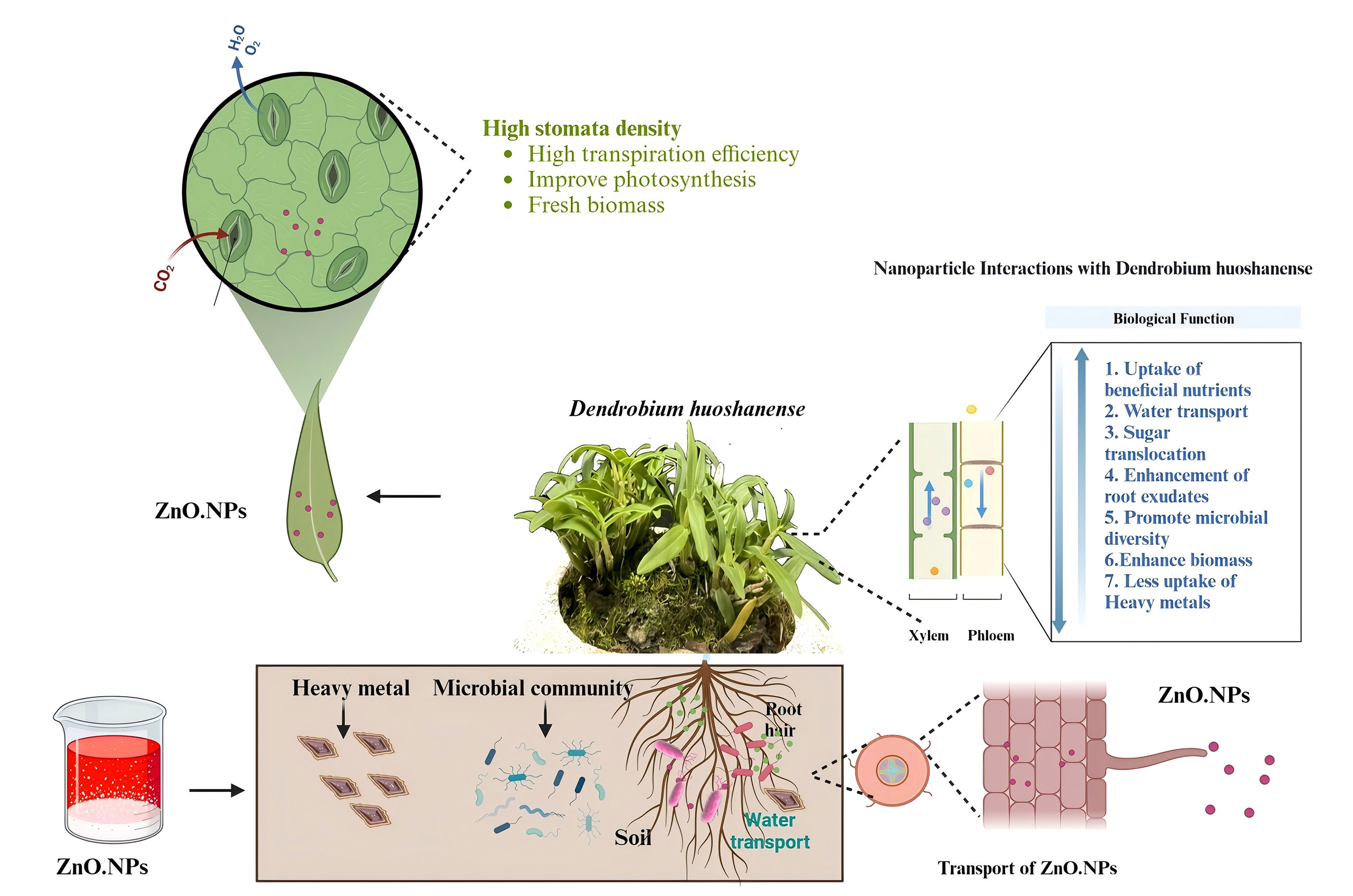

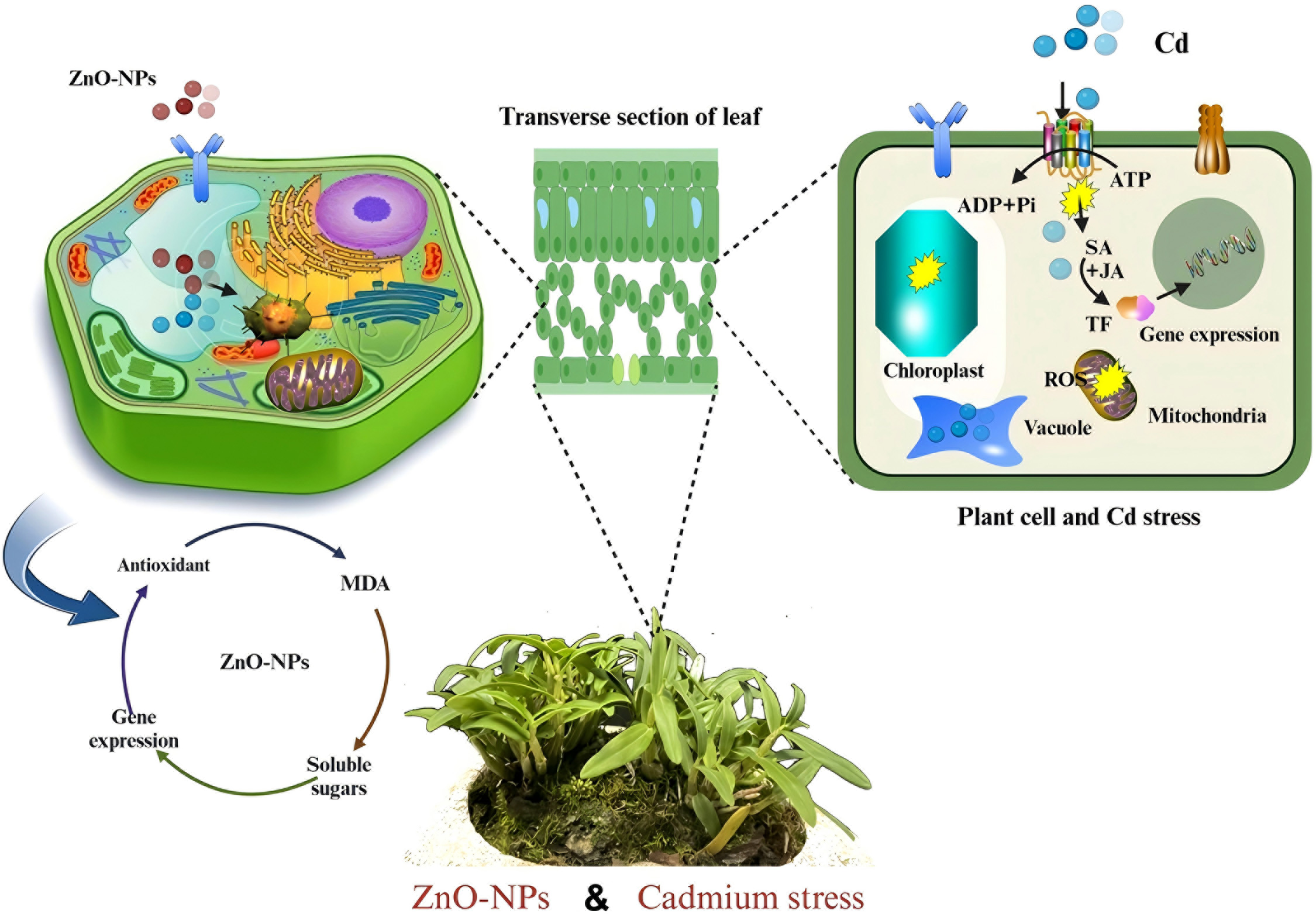

Heavy metal pollution has become a pervasive environmental issue affecting numerous regions worldwide. Recently, there has been significant attention given to the application of nano-enabled technologies with the purpose of enhancing plant development and alleviating heavy metal stress. This study aimed to illustrate the potential of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) to enhance the morphological traits of D. huoshenense exposed to cadmium (Cd) stress. The chemical structure and elemental composition of the ZnO-NPs were characterised by a series of analytical methods, including X-ray diffraction, UV-Vis spectrometry, XPS, and TEM. Plant samples used were collected at 0, 5, and 15 days in order to assess physiological and biochemical parameters under different Cd treatments. ZnO-NPs administered in pot experiments have been shown to enhance plant proliferation through the modulation of Cd enrichment levels. The results revealed that ZnO-NPs enhanced plant growth by increasing soluble sugars and proline levels, enhancing activities of antioxidant enzymes (SOD, POD, CAT, APX) and reducing electrolyte leakage (EL) and malondialdehyde (MDA) content. Furthermore, ZnO-NPs enhanced the net photosynthetic rate, transpiration, stomatal conductance, and chlorophyll content in leaves subjected to Cd stress at the 10-day sampling stage. Exogenous ZnO-NPs significantly elevated the expression of genes associated with flavonoid biosynthesis, potentially facilitating the accumulation of medicinal compounds to mitigate Cd stress. Taken together, these findings provide a novel perspective on the strategies employed by medicinal plants in response to Cd.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileHeavy metals are present in over 5 million contaminated sites worldwide. This global issue has received much attention because of the recent rapid industrialization and urbanization, widespread mining, frequent use of agrochemicals, and inadequate or nonexistent waste management [1,2]. The Ministry of Environmental Protection in China has reported that heavy metal contamination affects over 19% of agricultural soil reports, indicating an ongoing increase in heavy metal contamination of farmland soil in both China and India [3]. Heavy metals have gained public attention in recent years due to their frequent presence in food and human blood at elevated concentrations. Abiotic and biotic processes both mobilize heavy metals in soils. Plant growth is significantly impacted by heavy metal stress, which in turn has a direct and indirect effect on human health through the food chain [4]. Various plant species have varying responses to heavy metal stress. Despite the fact that most agricultural plants eliminate heavy metals from their systems or limit their movement to parts that aren’t meant for human consumption, rice is an exception because its grains absorb high concentrations of these metals [5]. D. huoshanense contains very little heavy metal pollution in its natural habitat. Currently, most D. huoshanense plants are cultivated under forests or artificially. Some varieties cultivated in mining areas (Jinzhai county) have excessive levels of Pb or Cd, which has brought unprecedented disaster to the local ecological environment and the industry. The excessive heavy metals primarily detected in D. huoshanense are cadmium and lead. These heavy metals pose a serious threat to the quality and safety of traditional Chinese medicines due to the polluted environment in which they grow, including contaminated stones and other substrates. ZnO reduces Cd accumulation by enhancing the antioxidant capacity, mitigating Cd damage to cells, and promoting the binding of Cd to pectin in the cell wall, which enhances fixation and reduces transport to the aerial parts. Additionally, it inhibits the activity of genes that transport Cd by regulating the expression of metal-binding proteins and antioxidant enzyme genes [6]. Study has shown that applying a zinc and selenium mixture to the leaves of rice can increase the binding efficiency of Cd to pectin and promote Cd fixation in flag leaf cell walls. This process enhances cadmium fixation in leaves and reduces Cd content in rice grains. Additionally, these mixtures can upregulate genes related to metal-binding proteins and antioxidant enzymes while downregulating the metal transport genes [7]. Furthermore, ZnO-NPs significantly enhanced photosynthesis, osmotic regulation, and antioxidant levels in Hibiscus syriacus, reducing root cell damage. Electron microscopy observation revealed that cadmium primarily accumulated in the root epidermis and cortex, with localized accumulation in the xylem. Treatment with ZnO-NPs significantly reduced the extent of Cd-induced ultrastructural damage in the roots [8]. These results suggest that ZnO significantly reduces Cd transport in the xylem.

The quality of medicinal plants is impacted by heavy metal stress, which rare earth elements can successfully mitigate. One of the most prevalent and dangerous environmental issues with soil pollution nowadays is heavy metal pollution [9]. After entering the soil, pollutants make it difficult for soil microorganisms to break down. As a result, they can easily build up in the soil and be absorbed by crops, which can put people’s health at risk due to the rise in issues with agricultural product safety and quality [10]. Elevated toxicity levels of cadmium (Cd) and lead (Pb) hinder plant growth and cause necrosis. Cd toxicity disrupts plants by hindering carbon fixation and lowering chlorophyll content, which reduces photosynthetic efficiency. Exposure to Cd and Pb in soil causes osmotic stress in plants by decreasing leaf relative water content, stomatal conductance, and transpiration, ultimately resulting in physiological harm to the plants [11–13]. In the last few decades, nanoparticles have attained more attention in various human endeavors, including agriculture, food production, and medicine. In agriculture, Cu, Fe, Si, and Zn metal nanoparticles have been used in fertilizers, growth enhancers, pesticide formulations, and nanocarriers to see how they affect crop growth and make plants more resistant to heavy metals [14,15]. ZnO-NPs stand out among applied nanoparticles due to their unique characteristics and modes of action [16]. Renowned for its exceptional solubility, zinc oxide (ZnO) releases zinc ions, which are critical for mitigating heavy metal stress’s effects. This is explained by zinc’s crucial function in metabolic pathways that affect how plants react to stress [17,18]. Zinc is a crucial trace element for plant growth and development, and it significantly affects a wide range of plant physiological processes [19,20]. It affects auxin levels, vegetative and reproductive organs, and the rate at which seeds germinate. In addition, zinc has a positive effect on potassium concentration, growth parameters, antioxidant activity, and the concentrations of sodium and phosphorus in plants. Zinc’s effect on tryptophan synthase activity is linked to how it controls auxin levels [21]. Zinc also affects sugar transport and photosynthesis in plants, which controls the metabolism of carbohydrates. Carbonic anhydrase is a zinc metalloenzyme essential to photosynthesis, which shows a positive relationship between plant zinc levels and its activity. Zinc’s role in starch metabolism also impacts plant sugar transportation. Zinc deficiency has been shown to increase sugar content while decreasing starch metabolism in broad beans. Sustaining an ideal zinc concentration can promote plant development and increase resilience to adversity [22].

Dendrobium species is a highly esteemed traditional Chinese medicine with an extensive history of medicinal use [23,24]. However, the genus contains a number of species with widely differing qualities. D. huoshanense is a distinguished endemic epiphytic orchid species acknowledged as a national geographical indication product in China. This plant is mainly found in the Dabie Mountains and their environs, especially in Huoshan County in Anhui, China [25]. The main ingredients in D. huoshanense are polysaccharides, alkaloids, flavonoids, bibenzyl, phenanthrene, and other substances. Different types of ingredients have different regulatory and pharmacological activities [26,27]. Many studies have shown that it has many benefits, such as protecting the liver, reducing inflammation, fighting free radicals, preventing cataracts and glycation, slowing down the aging process, fighting tumors and rheumatoid arthritis, and preventing atherosclerosis [28,29]. The healing properties of D. huoshanense come from its active ingredients, which are flavonoids, sesquiterpenes, and polysaccharides. This is an important way to judge the quality of the plant. Its diverse chemical composition and wide-ranging pharmacological effects have attracted much attention, but they also pose difficulties for future study [2,30]. Heavy metal stress may affect the synthesis and accumulation of active components such as polysaccharides, alkaloids, and phenolic compounds in Dendrobium plants. For example, cadmium and lead may influence the molecular structure, content, and biological activity of polysaccharides by inducing oxidative stress, interfering with enzyme activity, or altering secondary metabolic pathways [31,32]. Studies have shown that heavy metal stress may lead to enhanced activity of antioxidant enzymes in plants to counteract oxidative stress, which may indirectly affect the pharmacological activity of polysaccharides or alkaloids [33,34]. Additionally, heavy metal stress typically triggers oxidative stress, and plants may respond by increasing antioxidant substances (such as polysaccharides and phenolic compounds) or enzyme activity. However, high-concentration heavy metal stress may disrupt the antioxidant system, reducing the plant’s antioxidant capacity and thereby affecting its medicinal value. Heavy metal cadmium may interfere with the immune-modulating function of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides by activating pro-inflammatory pathways or inducing apoptosis [35]. Studies indicate that under heavy metal stress, the molecular weight and glycosylation composition of polysaccharides in plants may change, leading to reduced activation capacity in immune cells and thereby affecting anti-inflammatory effects [36]. Additionally, D. huoshanense may exhibit growth inhibition under heavy metal stress. Chloroplast genome studies indicate that photosynthesis-related genes may be affected by heavy metals, leading to reduced photosynthetic efficiency and consequently decreased accumulation of secondary metabolites [6]. Although a sizable amount of literature has been written summarizing the Dendrobium genus, a dearth of thorough literature specifically addresses heavy metal stress on D. huoshanense [6,37]. The foliar application of ZnO-NPs under heavy metal stress in D. huoshanense has not been fully explored. Therefore, it is crucial to decrease the amount of metal stress (Cd and Pb) that D. huoshanense absorbs from the soil when under metal stress, as this issue is likely to worsen in the future. This experiment aims to find out how well foliar-applied ZnO-NPs affect the uptake of Cd from the soil into the shoots of plants. It was thought that applying ZnO-NP from outside the plant would increase the efficiency of photosynthetic processes and lower the buildup of Cd and Pb in plants that were stressed, which would lead to better growth.

2.1 Preparation and Characterization of the ZnO-NPs

Previous study have been employed to use the high-purity anhydrous ZnCl2 powder as a precursor to produce ZnO through synthesis. The ZnCl2 was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Lot No.: 429430, Purity ≥ 99.995%), a reputable provider of chemicals for the purposes. KOH, a necessary reagent in the synthesis process, was obtained from Taian Luchen Chemical Co., Ltd. (Lot No.: P431767, Purity ≥ 99.95%). Both reagents were utilised in their original form, without undergoing any additional purification or alteration. The synthesis and all associated procedures were conducted using deionised water, guaranteeing the removal of any contaminants that could potentially impact the quality of the final ZnO product. The production of ZnO was carried out utilizing a hydrothermal process, a widely recognized methodology for creating nanostructured materials. The procedure commenced by accurately measuring the quantities of ZnCl2 and KOH, which were subsequently dissolved in 70 mL of deionized water. The solution was meticulously blended to guarantee the full dispersion of the reagents and to create a homogeneous reaction environment. The dispersion method is achieved by uniformly stirring with a homogenizer. After the solution was created, it was moved into a 100 mL stainless-steel autoclave. The autoclave, specifically engineered to endure elevated pressures and temperatures, was subsequently hermetically sealed and heated to a precise temperature of 190°C. The reaction was sustained at this temperature for a period of 6 h, facilitating the interaction between ZnCl2 and KOH to produce ZnO. Once the reaction was finished, the autoclave was left to cool down to the temperature of the surrounding environment. The resultant solid, identified as ZnO, was subsequently gathered and underwent a sequence of rinses using deionized water. The washing process was repeated iteratively to guarantee the elimination of any remaining reactants or by-products, effectively neutralizing the precipitate. After the washing operation, the ZnO precipitate was subjected to drying in an oven at a temperature of 80°C for a duration of 24 h. The drying process was essential in eliminating any residual moisture from the sample. After being dried, the ZnO was pulverized using a mortar and pestle for a duration of 20 min to provide a fine and uniform powder that is appropriate for subsequent characterization and analysis.

The synthesized ZnO powder was subjected to various characterization procedures to assess its structural, optical, and morphological properties. In a 100-mL flask, the required amount of ZnO-NPs was diluted in 10 mL of ddH2O to make a stock solution with a concentration of 100 mg/L. The ddH2O was subsequently added to the flask until it reached a total volume of 100 mL. The previously outlined process involved preparing the additional concentrations of 10 and 50 mg/L by diluting the stock solution [38]. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis was utilized to determine the crystal structure of ZnO. The measurements were conducted utilizing a D8 Advance Da Vinci X-ray diffractometer, which was equipped with monochromatic CuKα radiation, with λ = 1.5406 Å [39,40]. XRD patterns were employed to confirm the absence of impurities in the ZnO material and to determine the size of the crystalline particles and the parameters of the crystal lattice. Bragg’s Law determines the relationship between the 2-theta values and the corresponding Miller indices (hkl), represented as nλ = 2dsin θ. In this equation, λ represents the wavelength of the X-rays and represents the interplanar spacing, θ represents the diffraction angle (half of the 2-theta value), and it represents the order of diffraction. The d-spacing for each peak was determined by utilizing Bragg’s Law, which involves calculating the 2-theta values and applying the formula d = λ/2sin θ. The optical properties of ZnO were examined using a Lambda 750S UV-Vis spectrometer [38,41]. The UV-Vis absorption spectra were recorded across a suitable wavelength range to analyze the optical absorption of ZnO-NPs. The Kubelka-Munk method was used to find band gap energy of ZnO. This is a well-known way to estimate the band gap using data on diffuse reflectance. XPS was employed to examine the elemental composition and chemical state of the ZnO. This approach yielded comprehensive data on the surface chemistry of ZnO, encompassing the precise oxidation states of zinc and oxygen within the material. The morphology and particle size of the ZnO were examined through transmission electron microscopy (TEM). The TEM test was analyzed with a Hitachi JEM microscope, which produced high-resolution ZnO-NPs with their sizes, shapes, and locations [42,43]. These characterization methods fully understood the structural, optical, and chemical properties of the synthesized ZnO, proving its suitability for a wide range of potential applications [44].

2.2 Plant Material, Growth and Experimental Design

D. huoshanense materials were purchased from Douhuzhilu Technology Co., Ltd. (Taipingfan County, Huoshan, China) in October 2023. Two-year-old D. huoshanense plants were selected as experimental material. The experiment was conducted at Shanghai Jiaotong University, with a temperature of 20 ± 5.0°C and a humidity of 70% RH ± 10%. The D. huoshanense stems utilized in this study were kept in a growth chamber. The plants were subsequently cultivated at a temperature of 25°C ± 2°C with a photoperiod of 12/12 h (day/night, 30 μmol⋅m−2·S−1). Uniformly grown seedlings of D. huoshanense were placed in white polyethylene pots measuring 12 cm in height and 13 cm in diameter. The cultivation took place in a natural setting, with above-ground spraying for stress and regulation and to ensure ventilation with the outside world. Before treatment, the plants were given a week to get used to their new surroundings. Plants in different groups were sprayed above ground during the experiment every day between nine and ten in the morning. Four plants with three replications for each gradient were placed in a big tray and four concentration gradients of ZnO-NPs (0, 20, 40, 50, and 100 mg/L) were used in this experiment to observe the potential impacts of NPs. Best concentration of ZnO-NPs was selected on the basis of preliminary experiments. ZnO-NPs at concentration of 50 mg/L were used to uncover the potential impacts of NPs. To evaluate pertinent indices, samples were taken 0, 10 and 15 days after Cd treatment. The MDA, polysaccharide content, and physiological characteristics were monitored to determine the appropriate heavy metal concentration. The plants were sprayed with 50 mg/L ZnO-NPs after a 10-day treatment with 200 mg/L Cd under normal growth conditions. First, ten and fifteen days after spraying, relevant indices were sampled, measured, and the average values were recorded [9].

2.3 Determination of Pigment Content and Photosynthetic Parameters

The methods outlined in the previous study were slightly modified to measure the amounts of carotenoids and chlorophylls [45]. The upper leaves of D. huoshanense were chosen, the edges and midribs were cut off, the leaves were dried with gauze, and then rinsed with distilled water. The leaves were diced into 0.5 * 0.5 cm pieces, and 0.1 g of evenly distributed sample leaves were weighed. Five milliliters of 80% acetone were added to a large test tube sealed with tape containing the weighed sample leaves. The extract was put into a 25 mL brown volumetric flask following a 24-h extraction period in the dark. The extraction process was carried out four times until the leaves turned white, adding 5 mL of acetone (80%) to the test tube each time. A 25 mL final volume adjustment was made. A spectrophotometer measured the optical density of 80% acetone at 663 and 645 nm as a blank control. The measurements were then used to calculate the leaves’ chlorophyll content. The calculation formula of chlorophyll content was obtained by the 80% acetone method as follows. Chla, Chlb, TotalChl and Car are chlorophyll a, chlorophyll b, total chlorophyll and carotenoids, respectively.

The gas exchange parameters were determined following the established method with minor modifications. The German WALZ MINI-PAM-II Photosynthesis Yield Analyzer (Effeltrich, Germany) was used to measure various leaf fluorescence parameters. A pot of D. huoshanense was moved from the greenhouse to indoor conditions, and another pot of plants subjected to different treatments (Cd, ZnO-NP, Cd+ZnO-NP) was selected. Leaf clips were attached in similar positions, and the samples were dark-adapted for 20 min. Subsequently, the leaf fluorescence parameters were measured with the chlorophyll fluorescence meter set to the FW/Fm configuration. The net photosynthetic rate (Pn), stomatal conductance (Gs), internal CO2 concentration (Ci), and transpiration rate (Tr) were measured from the fourth mature leaf.

2.4 Proline and Soluble Sugar Contents Estimation

The proline contents were measured according to the well-established protocol with minor changes. For this analysis, 80% ethanol was used to create fresh leaves (0.5 g), which were then incubated for one hour at 80°C in a water bath. Following centrifugation, the solution was put in an incubator; after removing the supernatant, 5% phenol and 0.5 mL of distilled water were added. After an hour of incubation, 2.5 mL of sulfuric acid was added, and the absorbance at 490 nm was measured with a spectrophotometer. The content of soluble sugars was assessed using the phenol-sulfuric acid method.

2.5 Determination of Lipid Peroxidation and Electrolyte Leakage

To determine the malondialdehyde (MDA) concentration in D. huoshanense, 0.5 g of plant tissue was subjected to centrifugation at 8000–13,000× g and 4°C following homogenization in phosphate buffer at a pH of 7.8. Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) and 5% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) were added to an MDA reaction solution. After adding 2.5 mL of the reaction mixture to 1.5 mL of enzyme extract, an aliquot was prepared and promptly transferred from the water bath to an ice bath after 15 min at 95°C. After a 10-min centrifugation at 4800× g, the sample’s absorbance was assessed at two wavelengths: 532 and 600 nm [46]. Different treatment of D. huoshanense leaves were soaked in deionized water for 1 h, and the initial conductivity value was recorded. The samples were then stirred and measured every two hours for a total of 24 h. Finally, the samples were boiled for 15 min, and the maximum conductivity was measured after cooling, allowing for the calculation of electrolyte leakage from the leaves.

2.6 Antioxidant Enzymatic Activity Assays

To test the antioxidant enzymes, 0.5 g of leaf tissue was mixed together in a 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) solution with 1% polyvinylpyrrolidone. The mixtures were centrifuged at 15,000× g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was collected to test the activities of enzymes including ascorbate peroxidase (APX), superoxide dismutase (SOD), peroxidase (POD), and catalase (CAT). A detailed procedure is provided elsewhere [47].

The total RNA was extracted using a QIAGEN kit (QIAGEN, Germany). Gel electrophoresis and a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were used to assess the quality of the RNA samples. The PrimeScript™ II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) was used to perform RT-PCR. Actin was used as an internal control gene. The qRT-PCR primers were designed using Primer Premier 5.0 and are presented in Table S1. The expression levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method [48].

One-way ANOVA and t-tests were performed using SPSS software (version 25.0) to determine the significance differences between each two groups. For all phenotypic and gene expression analyses, the significance level was obtained by comparing the Cd-treated group with the other groups. The asterisks indicate a significant difference between the two sample groups (p-value < 0.001).

3 Characterization of ZnO-NPs Property

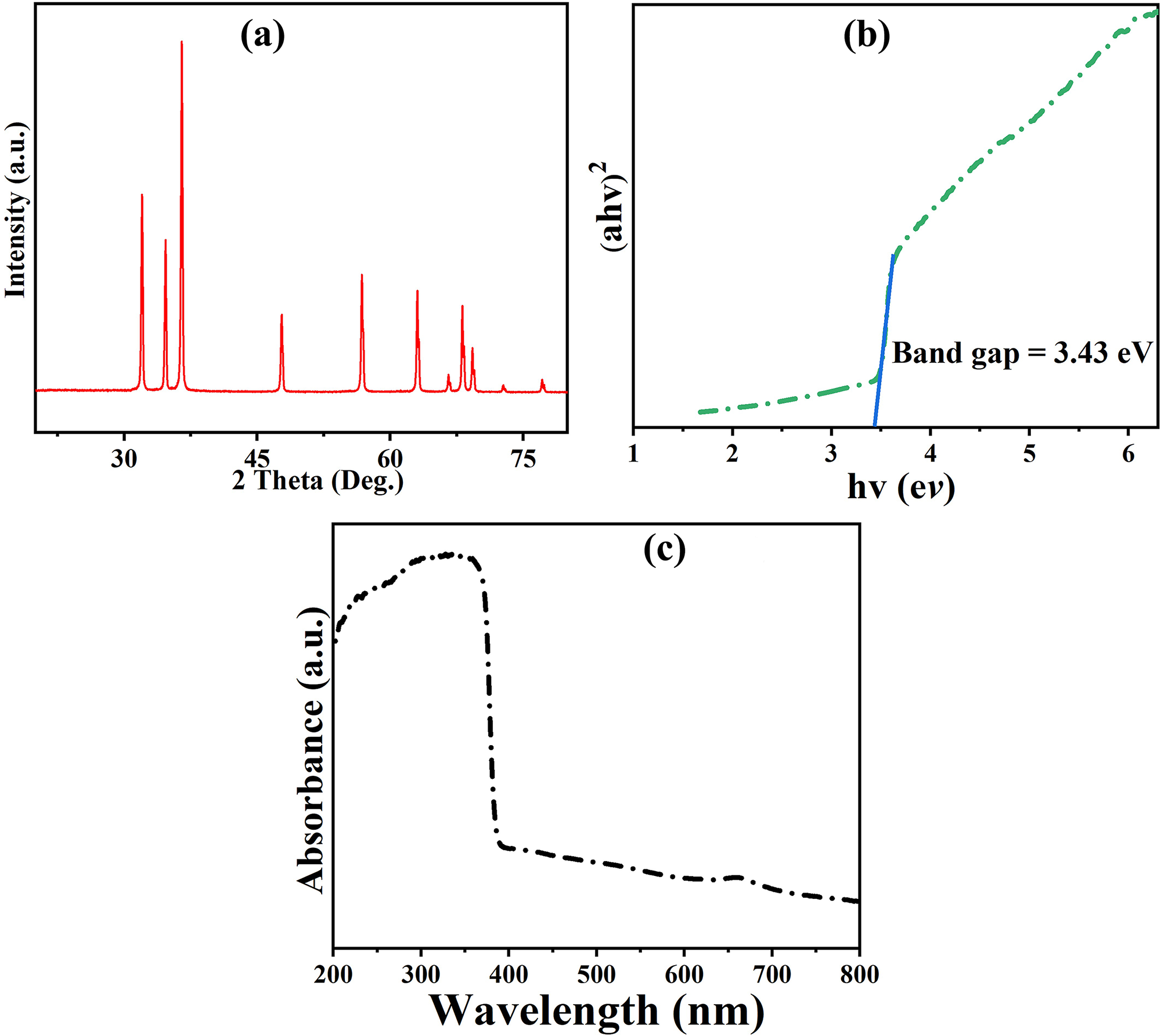

The XRD analysis of ZnO confirmed that it has a hexagonal wurtzite structure (Fig. 1). The crystallographic identification of ZnO was confirmed by correlating the diffraction peaks with the powder diffraction file #36-1451. The Miller indices (hkl) measured for ZnO are (100), (002), (101), (102), (110), (103), (200), (112), (201), (202), and (003). These indices correspond to particular diffraction angles of 31.99°, 34.63°, 36.40°, 47.70°, 56.80°, 62.99°, 66.58°, 68.14°, 69.28°, 72.70°, and 77.10°, respectively. The lattice parameters for ZnO in the hexagonal wurtzite structure are roughly 3.249 Å for the a-axis, which is the length of the hexagonal base, and around 5.206 Å for the c-axis, which is the height of the hexagonal prism. The c/a ratio, which is about 1.597, denotes the proportional dimensions of the unit cell and impacts the material’s physical characteristics [49,50]. The determined volume of the unit cell (V) is approximately 8.51 Å. The bulk density of ZnO is approximately 5.606 g/cm3, accounting for any holes or pores within the material. It indicates the mass of the substance per unit volume. Theoretical density, in the absence of any porosity, is roughly 5.606 g/cm3, calculated based on the crystal structure and lattice characteristics (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1: Spectral and structural analysis of ZnO-NPs: (a) Xrd spectra; (b) Tauc’s plots of ZnO NPs Tauc’s plots; (c) UV-Vis spectra of ZnO NPs

The spectrum shows that ZnO-NPs strongly absorb light in the ultraviolet (UV) range (Fig. 1c). This is a unique property of ZnO because it has a large energy gap. The absorption diminishes significantly when the wavelength extends beyond the UV zone, signifying a reduction in absorption as the light shifts into the visible spectrum. The optical band gap energy of the ZnO NPs was determined. The band gap energy of ZnO-NPs was calculated using the Tauc plot, based on UV-Vis absorption data, and found to be approximately 3.43 eV, which is theoretically expressed by Eq. (5):

The constant values A, h, n, α, and Eg represent Plank’s constant, light frequency, absorption coefficient, and band gap energy, respectively. The Tauc plot was created by graphing the quantity vs. the photon energy hv (Fig. 1b). The value of Eg is obtained from the intersection point. The band gap energy of the ZnO-NPs was determined to be approximately 3.43 eV using this study. The observed band gap of 3.43 eV is slightly higher than that of bulk ZnO (3.2–3.37 eV), which is consistent with quantum confinement effects reported in nanoscale ZnO [51,52]. ZnO-NPs exhibit a wide optical band gap of 3.43 eV, making them ideal for optoelectronic applications like UV light emitters and photodetectors [52].

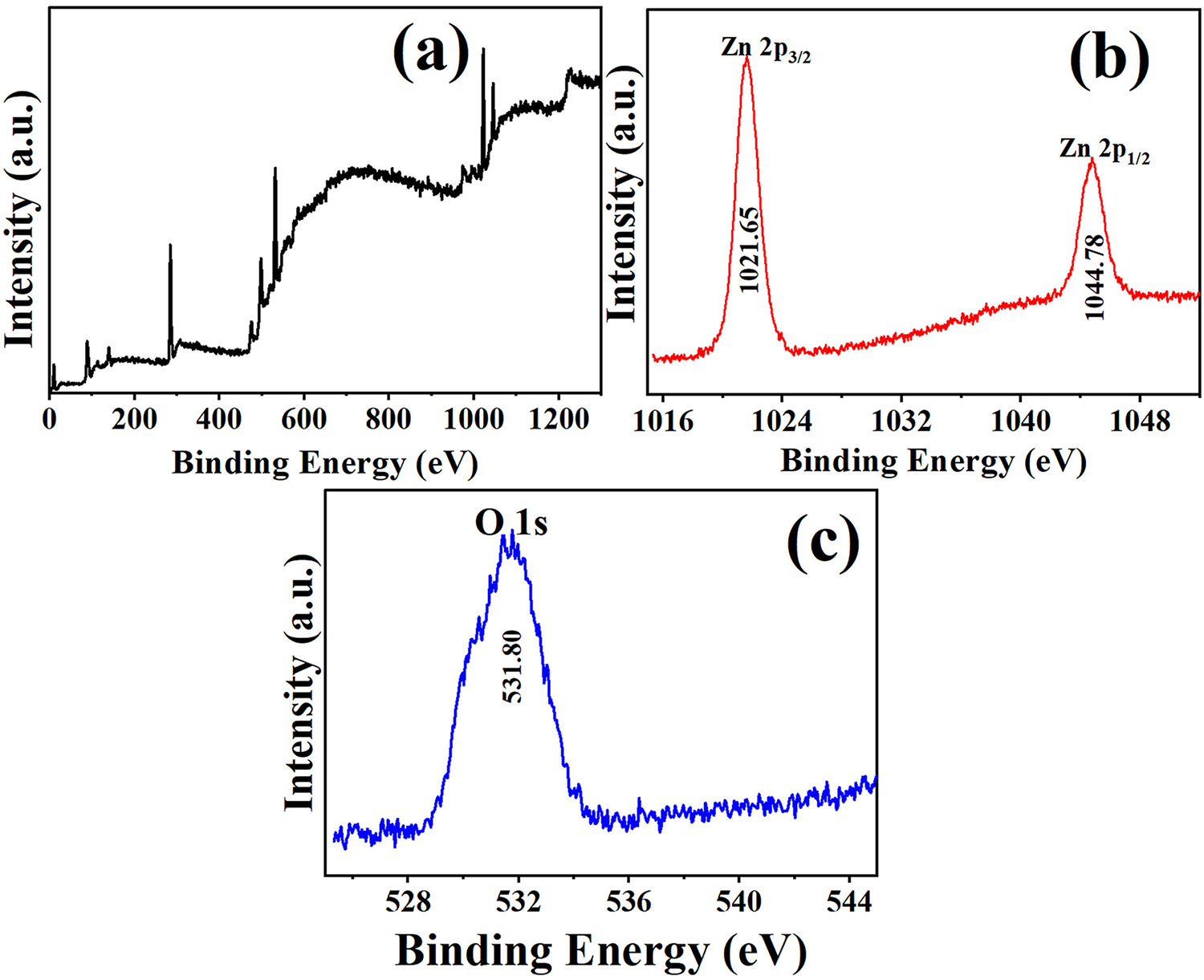

The XPS was conducted to investigate the elemental composition and chemical state of the synthesized ZnO-NPs (Fig. 2). The survey scan of ZnO NPs indicated the presence of Zn and O as the main components, indicating the successful production of ZnO (Fig. 2a). The oxidation states of these components display the high-resolution XPS spectrum for the Zn 2p region (Fig. 2b). The spectrum plays a crucial role in determining the chemical state of zinc in the ZnO-NPs. The Zn 2p spectrum usually exhibits two separate peaks that correspond to the spin-orbit doublet of Zn 2p electrons: Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p1/2. The initial maximum, corresponding to the Zn 2p3/2 level, is detected with a binding energy of around 1021.65 eV. The presence of this peak in the ZnO lattice is indicative of the presence of zinc in the divalent state (Zn2+). The second peak, which corresponds to the Zn 2p1/2 level, is located at a binding energy of around 1044.78 eV, with a 23.13 eV separation, confirming the Zn2+ oxidation state. The disparity in energy between the Zn 2p3/2 and Zn 2p1/2 peaks aligns with the established values for ZnO, providing more evidence that zinc mostly resides as Zn2+ within the nanoparticle structure.

Figure 2: Elemental composition and chemical state of ZnO-NPs. (a) XPS survey spectra; (b) high-resolution spectra of Zn 2p and (c) O1s

The high-resolution O1s XPS spectrum was analyzed to examine the chemical states of oxygen in the ZnO-NPs. The deconvoluted O1s spectrum was displayed (Fig. 2c). The O1s spectrum commonly displays several peaks due to the diverse chemical surroundings of oxygen atoms in the sample. The peak at 531.80 eV can be attributed to the oxygen atoms in areas of the ZnO lattice that lack sufficient oxygen or to the hydroxyl group often present on the surface of ZnO-NPs. These surface species reflect the inherent surface reactivity of ZnO, which is particularly significant for applications in photocatalysis and biomedical systems [53–55].

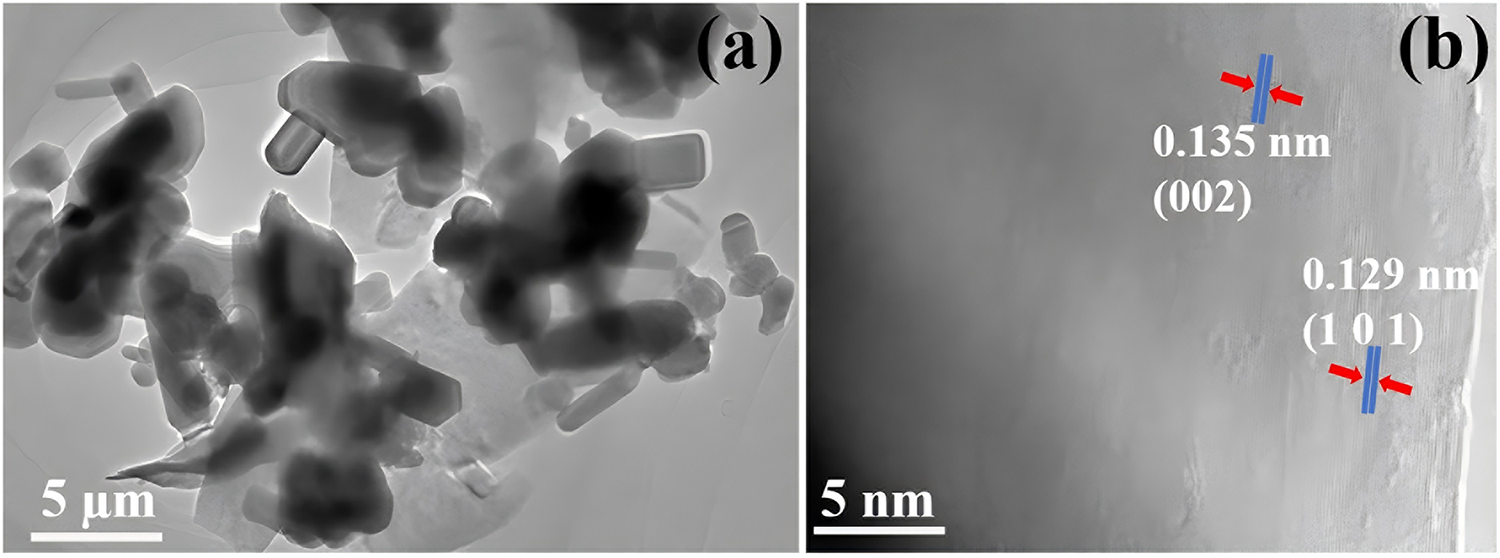

The results showed that the ZnO-NPs have diameters that range from 30 to 200 nm, showing a broad size dispersion of the particles (Fig. 3a). The ZnO-NPs displayed many morphologies, such as hexagonal prisms, slender rods, almost spherical shapes, and irregular forms. A more comprehensive structural examination of the ZnO-NPs was carried out utilizing high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM). The HR-TEM image, which specifically targeted solitary ZnO NPs, yielded essential information regarding the crystalline structure of the particles. The HR-TEM investigation identified distinct lattice spacings of 0.135 and 0.129 nm in the ZnO-NPs. The values mentioned represent the crystallographic planes (002) and (101) of the hexagonal wurtzite structure of ZnO (Fig. 3b). The remarkable feature is the detection of elongated particles with a significant ratio between length and width, which are aligned parallel to the c-axis. This discovery indicates that the formation of crystals in these ZnO-NPs primarily happens along the c-axis. The parallel alignment of the (002) and (101) planes with the c-axis provides additional evidence of the directional growth of the ZnO nanorods [56].

Figure 3: TEM analysis of ZnO-NPs. (a) TEM image and (b) HR-TEM analysis of ZnO NPs

3.1 Effect of ZnO-NPs on Physiological Attributes

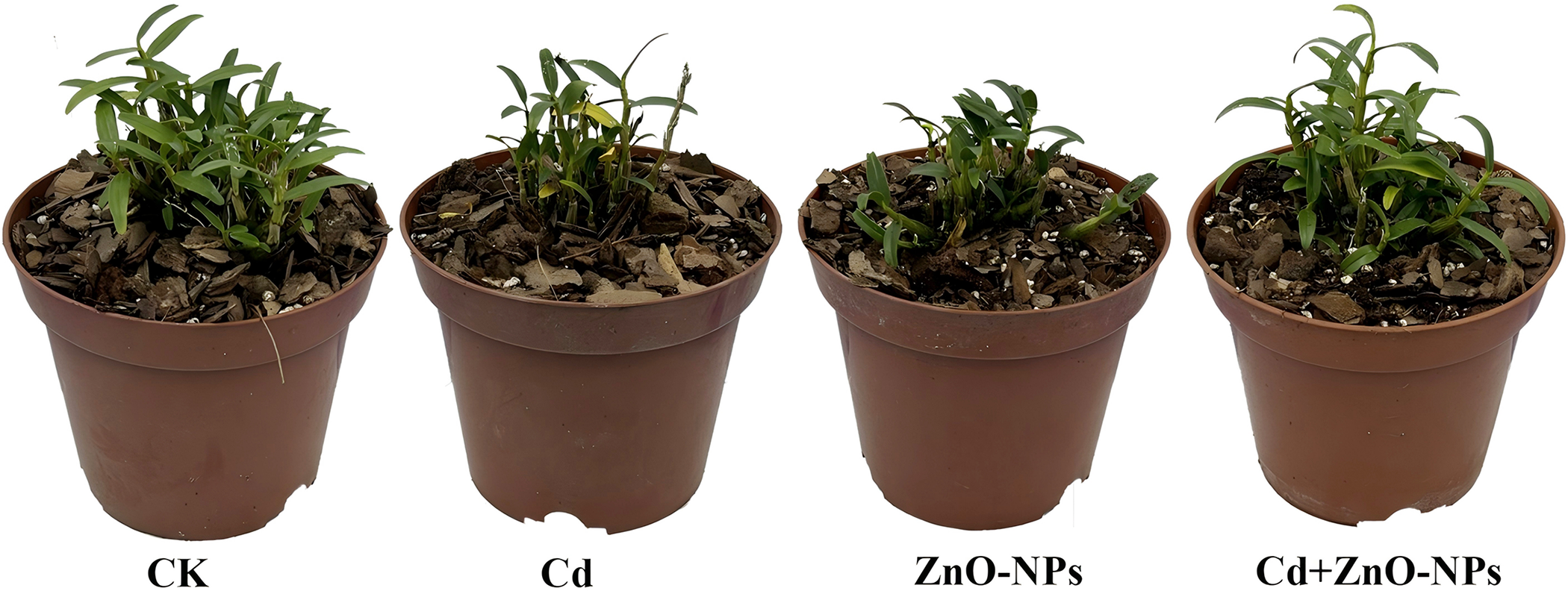

Heavy metal stress resulted in a significant reduction in plant growth and development. In this study, the hexagonal ZnO-NPs were used to facilitate D. huoshanense seedlings grow when they were under heavy metal stress. Compared to non-treated plants, excessive Cd stress had a negative impact on the seedlings, as shown by decreased vitality, lower biomass, leaf browning, and premature aging. Under Cd stress, D. huoshanense seedlings significantly reduced their fresh weight and dry weight shoots. The application of ZnO-NPs alone and in conjunction with Cd stress led to a significant increase in fresh and dry weights and shoot and root lengths under both natural and Cd stress conditions. Compared to the control group, Cd treatment inhibited the growth of D. huoshanense to some extent, with the average number of roots and fresh weight of stem segments reduced by 20% and 45%, respectively. However, after the application of ZnO-NP, the growth conditions of D. huoshanense significantly improved, nearly matching the growth level of the control (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Impact of ZnO-NPs on D. huoshenense development under cadmium stress. CK: group treated with water, Cd: group treated with 200 mg/L Cd, ZnO-NPs: group treated with 50 mg/L ZnO-NPs, Cd+ZnO-NPs: group treated with 200 mg/L Cd and 50 mg/L ZnO-NPs

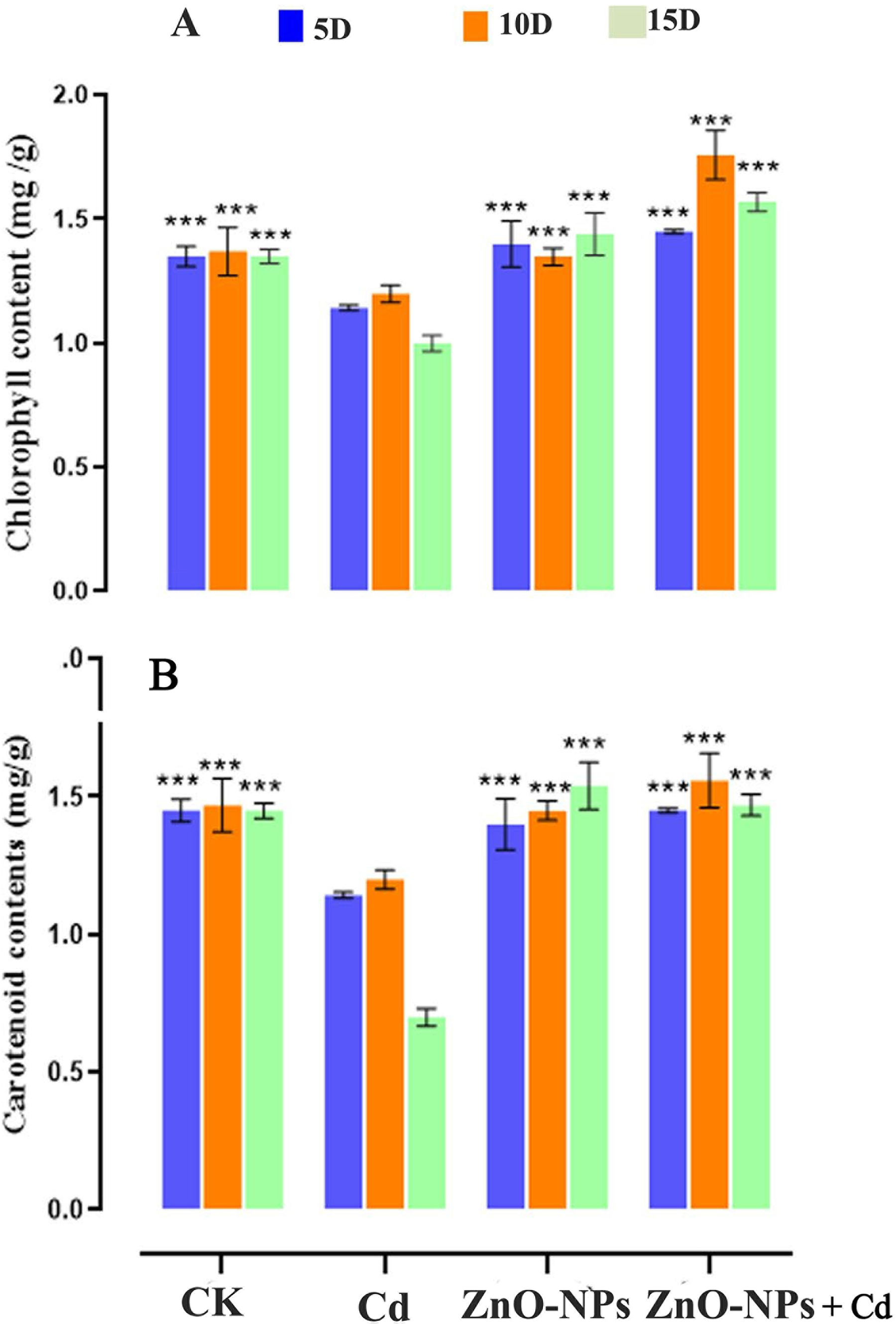

3.2 Effect of ZnO-NPs on Chlorophyll Contents under Cd Stress

Cd stress at a 200 mg/L concentration individually decreased the chlorophyll content in plants relative to the control group (Fig. 5A). ZnO-NPs influenced the concentrations of both chlorophyll. The Chl content peaked on the seventh day after the 100 mg/L NPs treatment, and it was considerably different from the CK and control values (p < 0.05). At the same time, the concentration of Chl peaked at 0.41 mg/g, which means that it increased 1.41 times over CK. Heavy metal stress significantly decreased the carotenoid contents compared with the control. When ZnO-NPs were added to D. huoshanense, the amount of carotenoids increased compared to the CK group that was no treatment (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5: Impact of ZnO-NPs on chlorophyll pigments under Cd stress. (A) Chlorophyll contents; (B) Carotenoid contents. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (Student’s t-test ***p < 0.001) between the treated and control group with three replicates (n = 3)

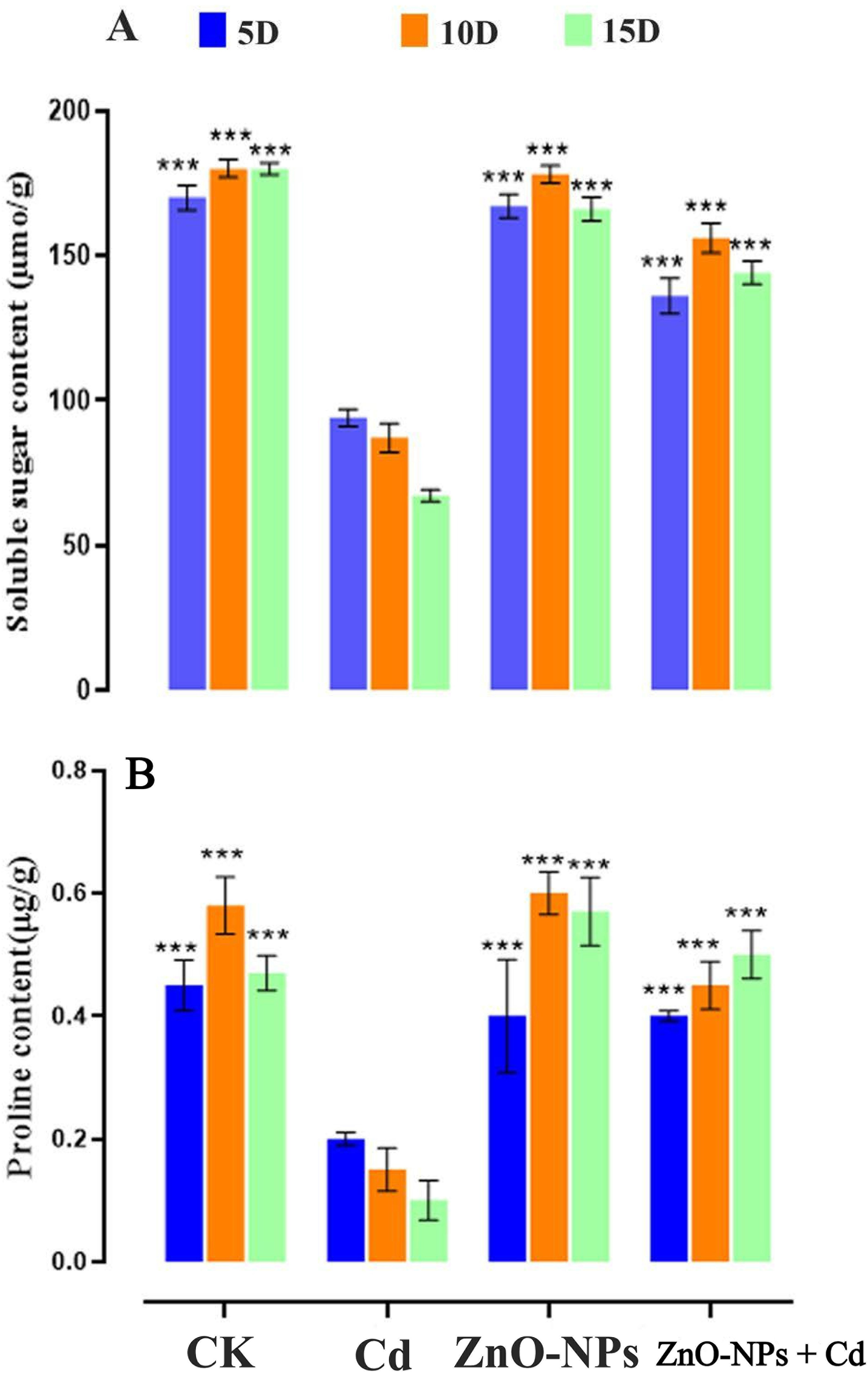

3.3 Effect on Proline and Soluble Sugar Contents under Cd Stress

Under heavy metal stress, D. huoshanense leaves showed a significant rise in proline content as the Cd concentration rose (Fig. 6). As the heavy metal level increased to 200 mg/L, the proline level in D. huoshanense leaves exhibited a significant decrease compared to the CK group (p < 0.01). When compared to single heavy metal treatments, the proline content in D. huoshanense leaves rose significantly (p < 0.05) during ZnO-NPs treatments at 5 days, 10 days, and 15 days. Pro content in D. huoshanense leaves was marginally elevated compared to the control, only at a concentration of 50 mg/L and a treatment duration of 15 days for ZnO-NPs. The results demonstrated that the presence of ZnO-NPs resulted in a 17% increase in proline content compared to control plants. The concentration of ZnO-NPs caused the soluble sugar content to peak (Fig. 6A). It was demonstrated that zinc could induce the production of soluble sugars, even at low concentrations. The evidence indicated that zinc exposure manifested a cumulative effect, characterised by an enhancement in its impact on soluble sugar production over time. The levels of soluble sugar exhibited variation during the initial 15-day period of zinc treatment across all experimental groups (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6: Impacts of ZnO-NPs on osmotic substances under Cd stress in D. huoshanense. (A) Soluble sugar contents; (B) Proline contents. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (Student’s t-test ***p < 0.001) between the treated and control group with three replicates (n = 3)

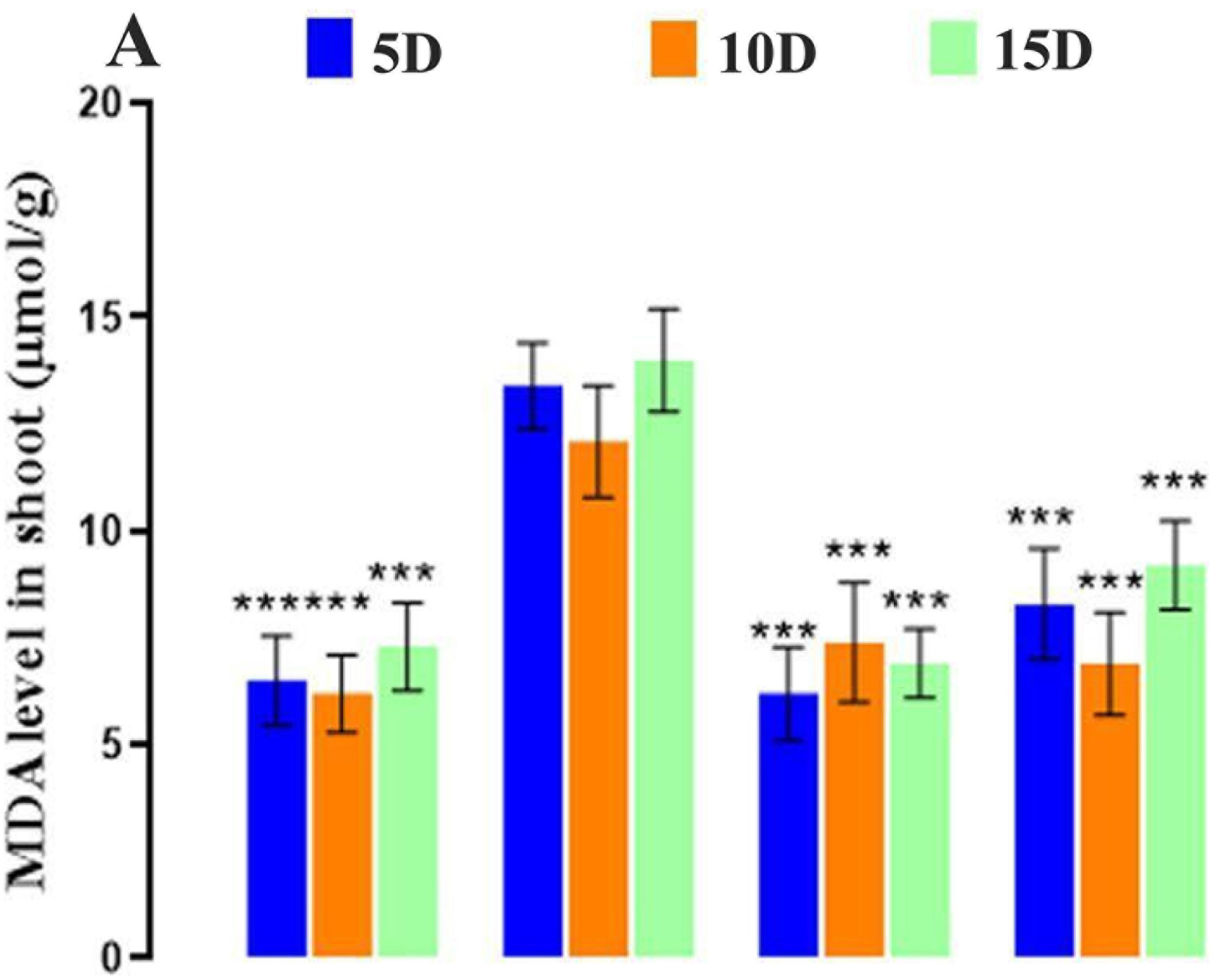

3.4 Effects of ZnO-NPs on H2O2 and MDA Level under Cd Stress

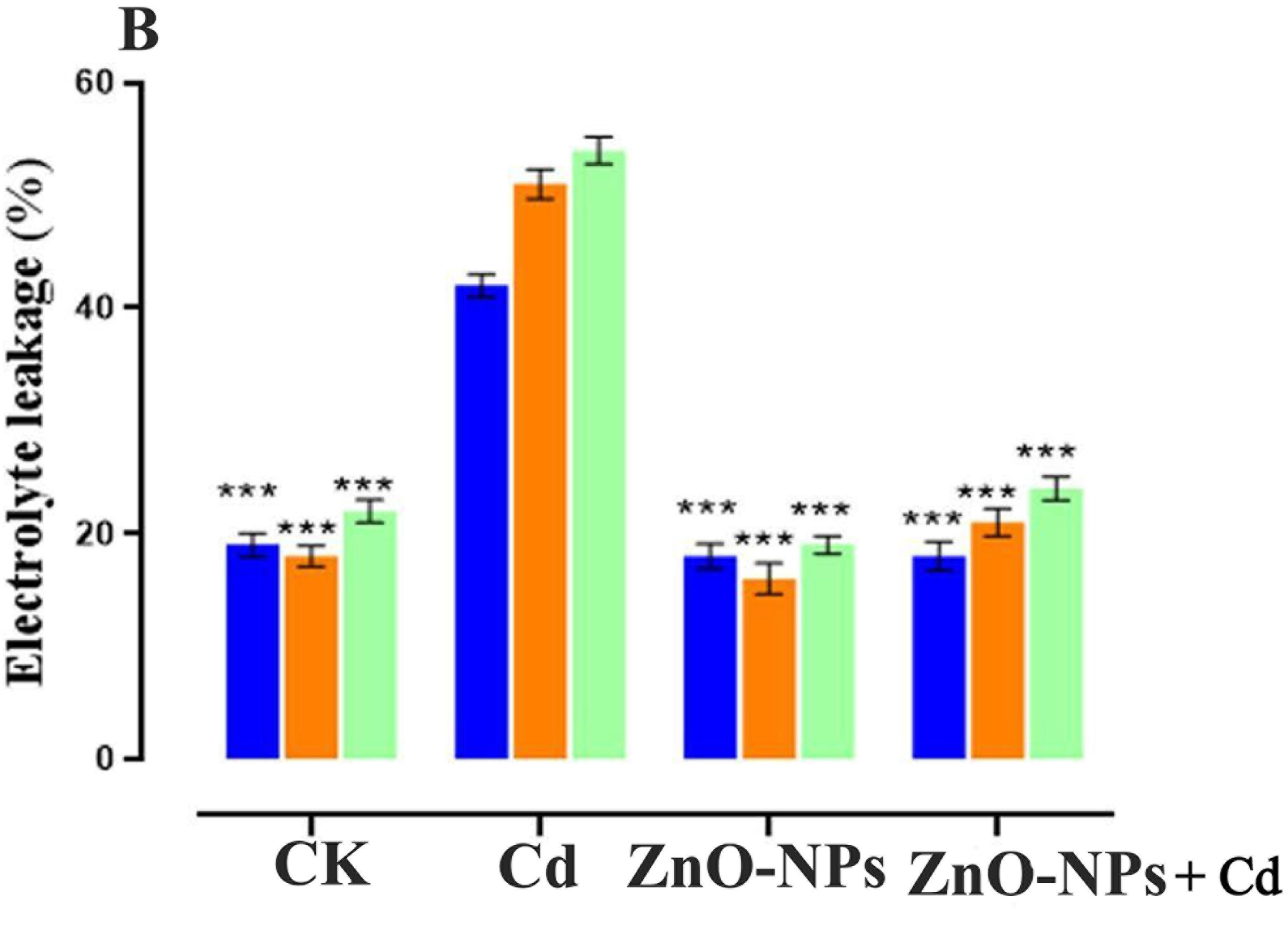

The MDA content in shoots was quantified to examine the damage inflicted by oxidative stress on cell membranes. In our current findings, the MDA contents considerably increased when Cd was applied to D. huoshanense (Fig. 7A). Conversely, the amended ZnO NPs decreased the MDA content. The MDA content was at its lowest during the ZnO-NPs treatment. Zinc significantly impacted its MDA content. On day 5, the MDA content decreased in the treatment of ZnO-NP compared to the control group. Meanwhile, the MDA content on days 5–15 was identical under 200 mg/L Cd stress. In the last step, ZnO-NPs with metal stress were added to a slowly changing MDA content. This shows that high metal stress doses greatly increase MDA production. Thus, Cd stress had a negative impact on D. huoshanense. However, from day 5 to day 15, there was a trend toward a decrease in MDA in relation to the ZnO-NPs concentration. When applied with 200 mg/L of Cd concentration, the leaves of D. huoshanense had a much higher MDA content than the CK group. These differences were statistically significant (p < 0.05). Under extreme stress, the MDA content in D. huoshanense leaves gradually dropped as the concentration of ZnO-NPs treatment increased, reaching its lowest value (p < 0.05) after 5, 10, and 15 days, respectively. Cd stress increased the amount of electrolyte leakage (EL) in D. huoshanense compared to the control group (Fig. 7B). The results indicated that an extended duration of Cd treatment corresponded to an increased stimulatory effect on D. huoshanense and enhanced EL. On day 5, the H2O2 concentration in D. huoshanense gradually escalated with prolonged metal exposure, peaking on day 15, surpassing the levels observed in the control group. On day 15, the EL level under heavy metal stress attained a maximum value exceeding that of the control group. Nonetheless, the EL level content markedly diminishes under metal stress following ZnO-NPs treatment compared to CK treatment.

Figure 7: Effect of ZnO-NPs on MDA level and electrolyte leakage. (A) MDA; (B) Electrolyte leakage. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (Student’s t-test ***p < 0.001) between the treated and control group with three replicates (n = 3)

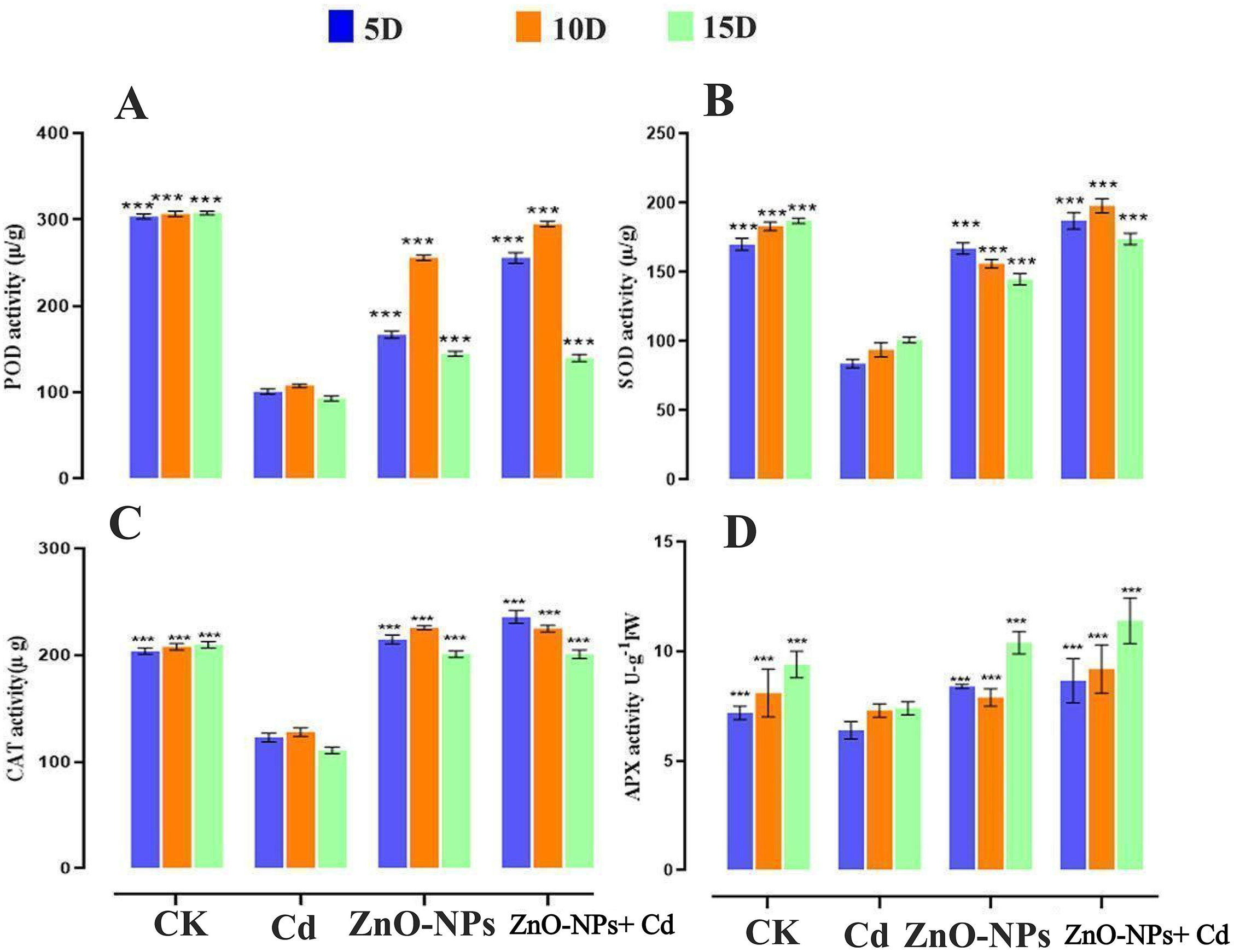

3.5 Impact of ZnO-NPs on the Activity of Antioxidant Enzymes

To investigate how ZnO-NPs amendment impacts Cd-induced toxicity, the antioxidant enzymatic defense system SOD, POD, CAT, and APX were measured. In the current study, the antioxidant enzymes were stimulated by Cd stress, compared to ZnO-NPs alone and the untreated control treatment (Fig. 8). The SOD content decreased at the start of the Cd stress time interval and began to increase after 10 days. The results demonstrate that heavy metals first activate antioxidant enzymes to cope with abiotic stress tolerance. The amount of SOD in D. huoshanense leaves gradually went up over the course of 5 to 15 days of ZnO-NPs treatment. The trend in the SOD activity of leaves from days 10 to 15 was comparable to that of the treated control at a 200 mg/L heavy metal concentration and the ZnO-NPs alone (Fig. 8A). Consequently, the application of ZnO-NPs concentrations to D. huoshanense may enhance the production of SOD, which can neutralize the free radicals generated by Cd stress. The elevated concentrations of Cd resulted in the absence of antioxidant enzyme production, which consequently led to the accumulation of free radicals. The activity of SOD in D. huoshanense leaves exposed to a concentration of 200 mg/L of metal stress was significantly reduced in comparison to the control group (p < 0.05). The activity of SOD under heavy metal treatment exhibited an initial increase followed by a subsequent decrease over time. After 10 and 15 days of treatment, the highest levels of SOD, POD, and CAT activities were seen at a concentration of 50 mg/L ZnO-NPs under heavy metal stress. These levels were significantly different (p < 0.05) from other treatments and the control group (Fig. 8B). The antioxidant enzymes drastically varied with amended ZnO-NPs under Cd stress.

Figure 8: Effect of ZnO-NPs on antioxidant enzymatic activities. (A) SOD, (B) POD, (C) CAT, (D) APX. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (Student’s t-test ***p < 0.001) between the treated and control group with three replicates (n = 3)

As the duration of ZnO-NP treatment increased, POD and CAT activities trended upward. Interestingly, compared to the control group, the treatment groups’ CAT activities were noticeably higher (Fig. 8B,C). On day 5, the ZnO-NPs treatment groups had significantly higher CAT activities, which peaked in the final condition and did better than both treated and untreated CK. POD activities also showed notable shifts on days 10 and 15, consistent with the patterns seen in other antioxidant enzymes (Fig. 8B). Consequently, the modified ZnO-NPs treatment substantially enhanced CAT and POD levels in D. huoshanense. Significant differences (p < 0.05) were found between the CAT activity of D. huoshanense leaves that were treated with a single Cd and the control (Fig. 8C). The CAT activity of D. huoshanense leaves exhibited an increasing trend with elevated concentrations of ZnO-NPs under Cd conditions. After being treated with ZnO-NPs for 5 and 10 days, the activities of antioxidant enzymes peaked (p < 0.05) at a ZnO-NPs concentration of 50 mg/L, compared to Cd treatment alone and the CK group. Furthermore, the APX was examined to assess oxidative damage in D. huoshanense. APX was not significantly different between the CK and zinc treatment groups on day 5 (Fig. 8D). On day 14, extended treatment and concentrations exceeding 100 μmol/L resulted in an elevation of APX content relative to the control group (p < 0.05). The peak concentration was 3.39 times greater than the value documented in CK group. The APX levels were markedly elevated following treatment with ZnO-NPs at 15 days compared to the control group. The results indicate that applying ZnO-NPs under Cd stress enhanced the activity of all antioxidant enzymes.

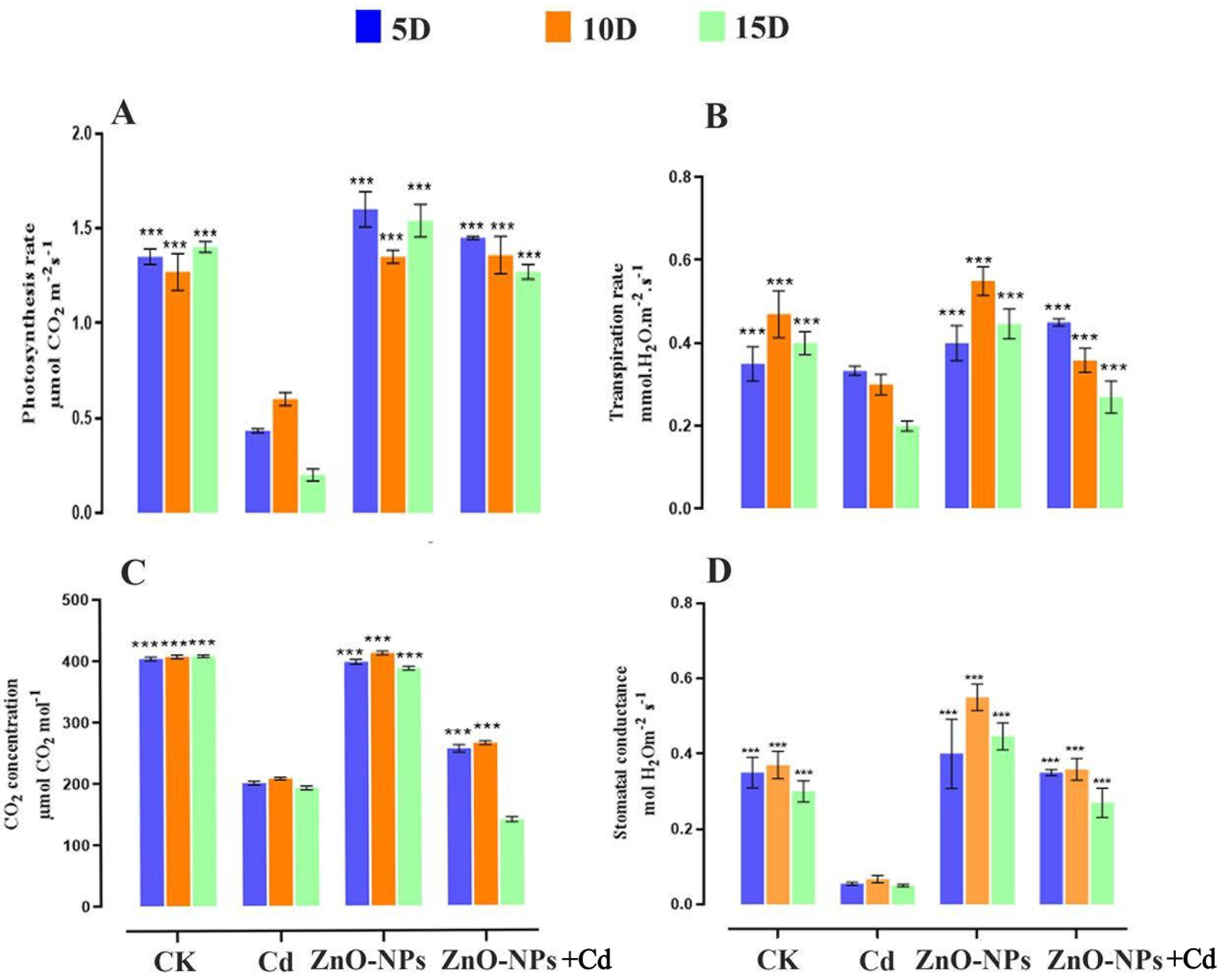

3.6 Impact of ZnO-NPs on the D. huoshanense Photosynthesis

Cd stress significantly reduced chlorophyll contents. ZnO-NPs supplemented with metal improved the photosynthetic pigments and strengthened the defense system. Based on remarkable findings, we investigated the ZnO-NPs amended with heavy metal stress on the net photosynthesis rate. Current results revealed that exposure to heavy metal stress significantly decreased the net photosynthesis rate. ZnO-NPs alone and applied with Cd enhanced Pn, Gs, Tr, and Ci compared to treated and CK group (Fig. 9). Compared to the control, ZnO-NPs amended with metal treatment showed a significant increase in photosynthetic efficiency. Over a treatment period of 5–15 days, the net Pn gradually increased (Fig. 9A). A single 200 mg/L heavy metal application significantly damaged the photosystem. ZNO-NPs increased the net photosynthesis rate, suggesting that zinc may have a dose-dependent impact on the photosystem mechanism. The study examined the highest recorded value of Pn when ZnO-NPs were applied under conditions of Cd stress. Being a key component of chloroplasts, Zn promotes the production of chlorophyll, which is positively associated with photosynthesis rate. Similarly, the application of ZnO-NPs under Cd stress significantly increased Tr and Gs compared to both the treated control and the ZnO-NPs alone application (Fig. 9B,C). In comparison with untreated control and alone ZnO-NPs treatments, the activity of Tr and Gs was found to be significantly reduced at the first treatment time at day 5. At 10 and 15 days, both values tend to be increased, respectively, except Ci (p < 0.05). D. huoshanense exposed to Cd stress significantly reduce Ci (Fig. 9D). The Ci level at first increased and decreased with treatment time compared to all other groups under supplementation of ZnO-NPs amended heavy metal stress.

Figure 9: Effects of ZnO-NPs on net photosynthesis index in D. huoshanense under Cd stress. (A) Photosynthesis rate; (B) Transpiration rate; (C) CO2 intake; (D) Stomata conductance. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (Student’s t-test ***p < 0.001) between the treated and control group with three replicates (n = 3)

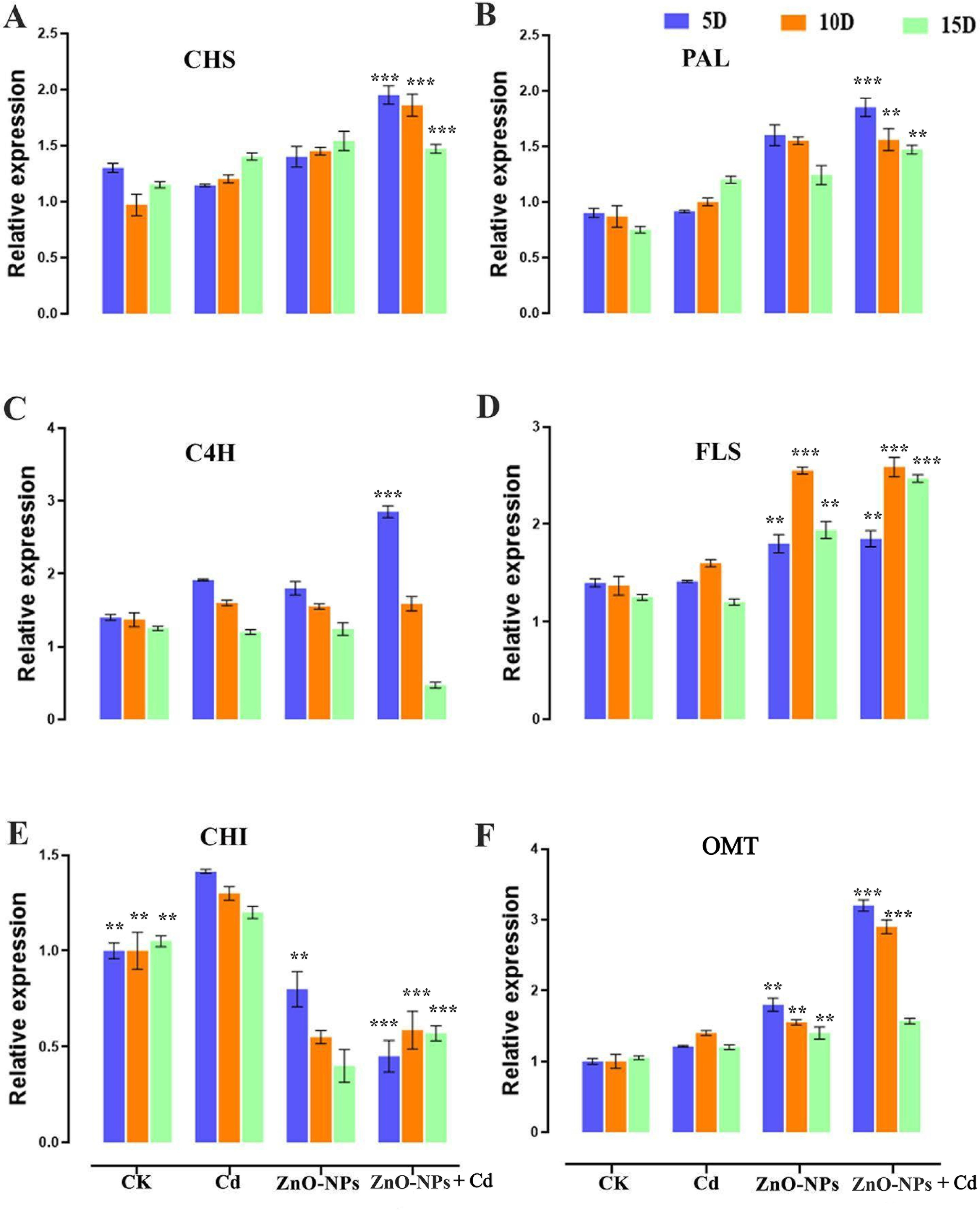

3.7 Effects of ZnO-NPs on the Expression of Stress-Related Genes

The leaves of D. huoshanense contain structure-rich flavonoids, an important secondary metabolite. The expression of genes associated with flavonoid biosynthesis in D. huoshanense stems at various growth stages has been further investigated (Fig. 10). Most genes encoding PAL, OMT, C4H, CHS, and CHI were upregulated in the upstream following the combined application of Cd and ZnO-NPs from one and two years grown D. huoshanense. Compared with Cd alone, Cd treatment combined with ZnO-NPs induced the expression of CHS, PAL, and OMT genes more effectively (Fig. 10A,B,F). This combined treatment increased the expression of C4H at an early stage (5 days) but inhibited its expression at a later stage (15 days) (Fig. 10C). FLS facilitates the hydroxylation of flavonoids, producing dihydrokaempferol. In the two-year-old samples subjected to heavy Cd stress, the expression of FLS-encoding genes was diminished compared to ZnO-NPs (Fig. 10D). Cd treatment significantly stimulated the expression of CHI gene, which was significantly reduced by the addition of ZnO-NPs at a later stage (Fig. 10E). The results indicated that six flavonoid synthesis-related genes exhibited specific expression patterns. The expression levels of the PAL, CHS, FLS and OMT genes were found to be elevated 2.0-fold, 1.8-fold, 1.8-fold and 3.2-fold, respectively, in the ZnO-NP group in comparison with the control group. However, the expression of the C4H gene exhibited a marked increase of approximately 2-fold on the 5 day, subsequently decreasing to 0.5-fold on the 15 day. In contrast, Cd treatment significantly increased the expression level of the CHI gene, while the ZnO-NP alone and Cd+ZnO-NP combined treatments reduced it by 50%, respectively. This indicates that cadmium and zinc oxide particles activate most genes of the flavonoid synthesis pathway, which may enhance the antioxidant effects of flavonoids.

Figure 10: Effect of ZnO-NPs on the expression pattern of stress-related genes involved in flavonoid biosynthesis pathway. (A) CHS, (B) PAL, (C) C4H, (D) FLS, (E) CHI, (F) OMT. The data represent the mean ± standard deviation (Student’s t-test ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01) between the treated and control group with three replicates (n = 3)

The field of agriculture has witnessed an increased focus on nanotechnology, driven by its remarkable characteristics, including its ability to facilitate heavy metal tolerance in various agricultural crops [3,57,58]. Due to their nanoscale size and greater efficiency compared to the bulk form of Zn, ZnO-NPs have emerged as potential micronutrients that can regulate plant growth and development under severe stress conditions [59]. Zinc plays a vital role in maintaining the stability of biological membranes by interacting with phospholipids and sulfhydryl groups, especially under stress conditions. In addition, the presence of heavy metals can adversely affect various functions of plants, including physiological, biochemical and metabolic activities [60]. The objective of this study is to elucidate the tolerance mechanism of heavy metal stress in D. huoshanense through foliar application. The physiological attributes of the plant biomass were reduced by Cd [61,62]. The accumulation of heavy metals disrupts the water balance, depriving plants of water and significantly reducing their growth [63]. Furthermore, accumulation of heavy metal result in nutritional imbalances and disturbances in physiological processes. The effects of Cd in various crops have been shown to result in a decrease in biomass and inhibition of root growth in different plants [64,65]. The concentration of ZnO-NPs is subject to variation depending on the administered dose [66–68]. This study demonstrates that ZnO-NPs significantly mitigates the Cd toxicity issue and results in enhanced plant growth. Chlorophyll content analysis is a valuable method for determining the impact of stress on various physiological processes, including photosynthesis, plant growth, and biochemical processes [69,70]. In this study, the addition of ZnO-NPs to Cd-treated D. huoshanense plants resulted in an increase in the levels of chlorophyll and carotenoids. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies, which demonstrated that heavy metals significantly inhibit photosynthesis and chlorophyll content. It has been demonstrated that increased exposure to Cd results in the induction of oxidative stress through the enhancement of ROS production. Nevertheless, ZnO-NPs have been demonstrated to enhance the pigments utilised by plants for photosynthesis by mitigating the deleterious effects of Cd stress [71–73].

It has been demonstrated that elevated levels of heavy metal stress result in a reduction of total soluble sugars, proteins, osmolytes, and proline levels. Our results indicated that ZnO-NPs have the capacity to enhance the levels of sugars and proline concentrations. This phenomenon can be elucidated by the observation that photosynthetic activity reached its zenith at a concentration of 100 mg/L, resulting in excessive accumulation of soluble sugar as a carbon source. The incorporation of ZnO-NPs has been observed to facilitate enhanced control of osmotic pressure in the presence of cadmium, thereby resulting in elevated levels of soluble sugars. This pattern was consistent with previous findings [22,59]. Soluble sugars are essential osmoregulatory substances that control cytoplasmic osmotic pressure to protect protein molecules, enzymes, and biofilms. In our study, we found that the soluble sugars content gradually increased in response to an increase in ZnO-NPs concentration. Plant cells have been observed to actively sequester soluble substances such as proteins and sugars in order to mitigate the effects of heavy metal stress. This process has been shown to reduce the intracellular osmotic potential, thereby ensuring adequate hydration and facilitating normal cellular physiological functions [74]. Abiotic stresses, including heavy metal stress, are closely linked to the boosting of ROS. The initial indicators of heavy metal accumulation in plants are increased production of ROS and oxidative damage. These ROS can induce cellular damage by degrading proteins, altering genetic material, and causing membrane lipid peroxidation [75,76]. Zinc, an essential component of antioxidant enzymes, plays a critical role in the scavenging of H2O2 [77]. Our findings demonstrated that heavy metal alone elevated the MDA content and H2O2 level, indicating that membrane damage peaked during heavy metal stress. However, supplementation with ZnO-NPs led to a significant decrease in the MDA content and H2O2 level [78–80]. Plants have developed defense mechanisms against ROS, with antioxidants playing a crucial role in this process (Fig. 11). The activation of antioxidants is intricately associated with defense mechanisms against abiotic stressors. Ascorbic acid, catalase, peroxidases, superoxide dismutase, and numerous other antioxidants are essential for the detoxification of ROS [81,82].

Figure 11: Impact of ZnO-NPs and gene expression analysis under Cd stress. Plant hormones that control the expression of downstream proteins, such as JA, and SA, improve the detoxification capacity of plants against cadmium stress. The regulation methods have been reported thus far, as indicated by the arrows with solid lines; the regulation methods are still unclear, as indicated by the arrows with dotted lines. Polyline arrows indicate exogenous additions

Plants mitigate damage from reactive oxygen species by enhancing the activity of antioxidant enzymes and elevating the levels of antioxidant compounds. The exogenous application of ZnO-NP led to a significant alteration in the expression levels of relevant antioxidant enzymes within D. huoshanense, notably at elevated concentrations. This phenomenon manifested as a gradual rise in H2O2 and superoxide radical production within the plant’s leaves, corresponding to heightened zinc levels. Under Cd stress, SOD and CAT, two common antioxidant enzymes, scavenge free radicals and reactive oxygen species from plants. SOD is a crucial enzyme that actively scavenges ROS in plants, primarily converting O2 to H2O2. CAT primarily prevents the accumulation of H2O2 [83]. It was demonstrated that D. huoshanense exhibits a capacity for self-regulation in response to external stress, with this ability being dose-dependent. Our results indicated that there was an initial rise in SOD activity with the elevation of ZnO-NPs. In addition, zinc has been shown utilized in plants to enhance SOD activity, thereby enhancing their resilience to environmental stress. Increases in zinc content were accompanied by concomitant rises in CAT activity. This finding suggested that the primary function of SOD and CAT was to remove ROS [9]. The process of chelation of Mg ions caused by heavy metal toxicity impede photosynthesis and chlorophyll production. Increased anthocyanin production result in apparent chlorosis, diminished growth, necrosis, and leaf reddening, which are indicators of subsequent chlorophyll breakdown [75,84].

The application of ZnO-NPs on D. huoshanense improved photosynthesis. Zinc is imperative for plant photosynthesis, as it constitutes structural components and functions as an enzyme activator [19,70]. The application of 50 mg/L of external ZnO-NPs supplemented with heavy metal stress, demonstrated the highest Pn and Tr. Any fluctuation in zinc concentration, whether an increase or a decrease, resulted in a progressive decline in net Pn and Tr. As a result, the optimal concentration of ZnO-NPs was beneficial for improving transpiration and photosynthesis of D. huoshanense. The elevated levels of heavy metal stress have the capacity to enhance oxidative damage and inhibit the photosystem. However, zinc treatment has been shown to have a significant impact on the photosynthesis process, whilst simultaneously reducing oxidative damage [85–87]. The intercellular CO2 concentration in D. huoshanense leaves reduced under low ZnO-NPs treatment but rose with elevated zinc concentrations. This suggests that elevated zinc levels may impact the CO2 utilization, while optimal concentrations of ZnO-NPs facilitate CO2 utilization. This observation is consistent with previous studies [22,88]. As a result, there was a clear correlation between the net Pn and Gs but a negative correlation between the intercellular CO2 concentrations in D. huoshanense. Flavonoids possess the capacity to enhance the tolerance of heavy metal stress. Flavonoids are also one of the key active compounds in D. huoshanense and possess strong antioxidant properties. Previous studies have shown that ZnO treatment alleviated the inhibitory effects of Cd to some extent [89]. Therefore, in our analysis of stress-related genes, we focused specifically on the expression of key genes in the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway. The results showed that compared with the CK and Cd groups, the combined treatment of Cd+ZnO-NP could significantly induce the expression of flavonoid biosynthesis pathway genes. The majority of the enzyme genes implicated have been cloned and their functions validated in various model plants [90]. The expression patterns of the CHS, DFR, FLS, and F3H genes contribute to the process of synthesizing flavonoids, which in turn protect plants from chromium stress [91]. One of the key components of the flavonoid biosynthesis pathway is flavonol biosynthesis. FLS is an essential gene in the biosynthesis of flavonol. It facilitates the hydroxylation of the C-3 position in the flavonoid structure, synthesizing various flavonols. FLS is extensively conserved in plants and connects the flavonoid synthesis pathway and the catechin synthesis pathway [92,93]. This study showed that the application of ZnO-NPs to the leaves of D. huoshanense resulted in enhanced development, increased the production of photosynthetic pigments, regulated osmotic stress, and facilitated the elimination of heavy metals. In addition, ZnO-NPs changed a number of biochemical pathways and the antioxidant system, which helped reduce the effects of other metal stresses.

Although ZnO-NPs have shown promise in agriculture as nanofertilizers, their long-term effects on plant health are complex, with both beneficial and potentially adverse outcomes depending on factors like concentration, application method, plant species, and environmental conditions. High doses of ZnO-NPs can induce oxidative stress, reduce growth, and cause cellular damage [94,95]. ZnO-NPs can alter soil microbial communities, which may indirectly affect plant health. A field study indicated that ZnO-NPs had a promotional effect on soil bacteria, unlike Fe3O4-NPs, but long-term accumulation could disrupt soil ecosystems [96]. Foliar application of ZnO-NPs is a promising strategy for delivering zinc to plants, but its scalability in field conditions faces several challenges and opportunities. Foliar application allows direct nutrient delivery to leaves, bypassing soil-related limitations like low solubility or fixation [97]. Field trials indicate that low to moderate doses (e.g., 50–100 mg/L) are effective without toxicity, making foliar application cost-effective. However, optimal doses vary by crop and environmental conditions. In addition, repeated foliar applications may lead to NP deposition in soil or water, potentially affecting non-target organisms. Comprehensive field studies are needed to assess long-term environmental and health impacts.

ZnO-NPs play an impressive role in promoting plant growth and ameliorating Cd stress in D. huoshanense. In this study, 50 mg/L of ZnO-NPs helped plants grow by improving their physiological traits and net photosynthesis rate and protecting them from oxidative damage caused by Cd stress. ZnO-NPs increased soluble sugars, proline levels, and activities of SOD, POD, CAT, and APX while decreasing electrolyte leakage and MDA content. They also enhanced the net photosynthetic rate, transpiration rate, stomatal conductance, and chlorophyll A and B levels in leaves exposed to Cd stress. Exogenous ZnO-NPs also increased the expression of genes related to flavonoid biosynthesis, potentially aiding in the accumulation of medicinal compounds in D. huoshanense. This study provides a scientific reference for the application of ZnO-NPs in the cultivation of Dendrobium species and the detoxification of heavy metals.

Acknowledgement: Thank you Professor Han Bangxing of West Anhui University for his support.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Open Fund of Anhui Engineering Research Center for Eco-agriculture of Traditional Chinese Medicine (WXZR202318), High-level Talents Research Initiation Fund of West Anhui University (WGKQ2022025) and Quality Engineering Project of West Anhui University (wxxy2024011), Quality Engineering Project of Anhui Province (2024zybj032), Development of Big Data Integration and Analysis Platform for Traditional Chinese Medicine Genomics (0045025050) and Anhui Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students (S202510376030).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Cheng Song; methodology, Cheng Song, Muhammad Aamir Manzoor; software, Cheng Song, Iftikhar Hussein Shah; validation, Cheng Song, Iftikhar Hussein Shah; formal analysis, Cheng Song, Iftikhar Hussein Shah; investigation, Cheng Song, Iftikhar Hussein Shah; resources, Cheng Song; data curation, Cheng Song, Muhammad Aamir Manzoor; writing—original draft preparation, Cheng Song, Iftikhar Hussein Shah, Ghulam Abbas Ashraf; writing—review and editing, Cheng Song, Muhammad Aamir Manzoor, Muhammad Arif; visualization, Cheng Song, Iftikhar Hussein Shah; supervision, Muhammad Aamir Manzoor; project administration, Cheng Song; funding acquisition, Cheng Song. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.070778/s1. Table S1: Primers for RT-PCR analysis of genes related to flavonoid biosynthesis.

References

1. Khalid S, Shahid M, Niazi NK, Murtaza B, Bibi I, Dumat C. A comparison of technologies for remediation of heavy metal contaminated soils. J Geochem Explor. 2017;182:247–68. doi:10.1016/j.gexplo.2016.11.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhou P, Pu T, Gui C, Zhang X, Gong L. Transcriptome analysis reveals biosynthesis of important bioactive constituents and mechanism of stem formation of Dendrobium huoshanense. Sci Rep. 2020;10:2857. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-59737-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Zhou P, Adeel M, Shakoor N, Guo M, Hao Y, Azeem I, et al. Application of nanoparticles alleviates heavy metals stress and promotes plant growth: an overview. Nanomaterials. 2020;11:26. doi:10.3390/nano11010026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Maglovski M, Rybanský Ľ., Bujdoš M, Adamec L, Bardáčová M, Blehová A, et al. Nitrogenous nutrition affects uptake of arsenicand defense enzyme responses in wheat. Pol J Environ Stud. 2021;30:2213–31. doi:10.15244/pjoes/127912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Xue T, Liao X, Wang L, Gong X, Zhao F, Ai J, et al. Effects of adding selenium on different remediation measures of paddy fields with slight-moderate cadmium contamination. Environ Geochem Health. 2020;42:377–88. doi:10.1007/s10653-019-00365-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Song C, Dai J, Ren Y, Manzoor MA, Zhang Y. Underlying mechanism of Dendrobium huoshanense resistance to lead stress using the quantitative proteomics method. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24:748. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05476-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Zheng S, Xu C, Zhu H, Huang D, Wang H, Zhang Q, et al. Foliar application of zinc and selenium regulates cell wall fixation, physiological and gene expression to reduce cadmium accumulation in rice grains. J Hazard Mater. 2024;480:136302. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.136302. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang X, Zhao Y, Huang L, Luo X, Zhang C, Mao Z, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles alleviated Cd toxicity in Hibiscus syriacus L. by reducing Cd translocation and improving plant growth and root cellular ultrastructure. J Hazard Mater. 2025;491:137920. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2025.137920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Li X, Fan Y, Ma J, Gao X, Wang G, Wu S, et al. Cerium improves the physiology and medicinal components of Dendrobium nobile Lindl. under copper stress. J Plant Physiol. 2023;280:153896. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2022.153896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Huang Y, Wang L, Wang W, Li T, He Z, Yang X. Current status of agricultural soil pollution by heavy metals in China: a meta-analysis. Sci Total Environ. 2019;651(Pt 2):3034–42. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Rizwan M, Ali S, Abbas T, Zia-Ur-Rehman M, Hannan F, Keller C, et al. Cadmium minimization in wheat: a critical review. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2016;130:43–53. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.04.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Sabouri Z, Kazemi Oskuee R, Sabouri S, Tabrizi Hafez Moghaddas SS, Samarghandian S, Sajid Abdulabbas H, et al. Phytoextract-mediated synthesis of Ag-doped ZnO–MgO–CaO nanocomposite using Ocimum basilicum L seeds extract as a highly efficient photocatalyst and evaluation of their biological effects. Ceram Int. 2023;49:20989–97. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.03.234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sabouri Z, Sabouri M, Moghaddas SSTH, Mostafapour A, Samarghandian S, Darroudi M. Plant-mediated synthesis of Ag and Se dual-doped ZnO-CaO-CuO nanocomposite using Nymphaea alba L. extract: assessment of their photocatalytic and biological properties. Biomass Conv Bioref. 2024;14:32121–31. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-04984-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Shah IH, Sabir IA, Rehman A, Hameed MK, Albashar G, Manzoor MA, et al. Co-application of copper oxide nanoparticles and Trichoderma harzianum with physiological, enzymatic and ultrastructural responses for the mitigation of salt stress. Chemosphere. 2023;336:139230. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.139230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao L, Lu L, Wang A, Zhang H, Huang M, Wu H, et al. Nano-biotechnology in agriculture: use of nanomaterials to promote plant growth and stress tolerance. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68:1935–47. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.9b06615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Alkasir M, Samadi N, Sabouri Z, Mardani Z, Khatami M, Darroudi M. Evaluation cytotoxicity effects of biosynthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles using aqueous Linum usitatissimum extract and investigation of their photocatalytic activityackn. Inorg Chem Commun. 2020;119:108066. doi:10.1016/j.inoche.2020.108066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Faizan M, Hayat S, Pichtel J. Effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles on crop plants: a perspective analysis. In: Hayat S, Pichtel J, Faizan M, Fariduddin Q, editors. Sustainable agriculture reviews. Vol. 41. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2020. p. 83–99. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-33996-8_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Manzoor MA, Xu Y, Lv Z, Xu J, Wang Y, Sun W, et al. Nanotechnology-based approaches for promoting horticulture crop growth, antioxidant response and abiotic stresses tolerance. Plant Stress. 2024;11:100337. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2023.100337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Manzoor MA, Shah IH, Ali Sabir I, Ahmad A, Albasher G, Dar AA, et al. Environmental sustainable: biogenic copper oxide nanoparticles as nano-pesticides for investigating bioactivities against phytopathogens. Environ Res. 2023;231:115941. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2023.115941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang Y, Wang Y, Ding Z, Wang H, Song L, Jia S, et al. Zinc stress affects ionome and metabolome in tea plants. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2017;111:318–28. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2016.12.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Akladious SA, Mohamed HI. Physiological role of exogenous nitric oxide in improving performance, yield and some biochemical aspects of sunflower plant under zinc stress. Acta Biol Hung. 2017;68:101–14. doi:10.1556/018.68.2017.1.9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Fan Y, Jiang T, Chun Z, Wang G, Yang K, Tan X, et al. Zinc affects the physiology and medicinal components of Dendrobium nobile Lindl. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;162:656–66. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.03.040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Dai J, Wei P, Wang Y. Highly efficient N-doped carbon quantum dots for detection of Hg2+ and Cd2+ ions in Dendrobium huoshanense. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2021;16:210716. doi:10.20964/2021.07.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Deng Y, Chen L-X, Han B-X, Wu D-T, Cheong K-L, Chen N-F, et al. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of specific polysaccharides in Dendrobium huoshanense by using saccharide mapping and chromatographic methods. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2016;129:163–71. doi:10.1016/j.jpba.2016.06.051. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Chen S, Dai J, Song X, Jiang X, Zhao Q, Sun C, et al. Endophytic microbiota comparison of Dendrobium huoshanense root and stem in different growth years. Planta Med. 2020;86:967–75. doi:10.1055/a-1046-1022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Song C, Ma J, Li G, Pan H, Zhu Y, Jin Q, et al. Natural composition and biosynthetic pathways of alkaloids in medicinal Dendrobium species. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:850949. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.850949. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang Y, Zhang W, Manzoor MA, Sabir IA, Zhang P, Cao Y, et al. Differential involvement of WRKY genes in abiotic stress tolerance of Dendrobium huoshanense. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;204:117295. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Hao J-W, Chen Y, Chen N-D, Qin C-F. Rapid detection of adulteration in Dendrobium huoshanense using NIR spectroscopy coupled with chemometric methods. J AOAC Int. 2021;104:854–9. doi:10.1093/jaoacint/qsaa138. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wang Y, Dai J, Chen R, Song C, Wei P, Wang Y, et al. Long noncoding RNA-based drought regulation in the important medicinal plant Dendrobium huoshanense. Acta Physiol Plant. 2021;43:144. doi:10.1007/s11738-021-03314-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yuan Y, Yu M, Jia Z, Song X, Liang Y, Zhang J. Analysis of Dendrobium huoshanense transcriptome unveils putative genes associated with active ingredients synthesis. BMC Genom. 2018;19:978. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-5305-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Cuypers A, Vanbuel I, Iven V, Kunnen K, Vandionant S, Huybrechts M, et al. Cadmium-induced oxidative stress responses and acclimation in plants require fine-tuning of redox biology at subcellular level. Free Radic Biol Med. 2023;199:81–96. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2023.02.010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Yu Y, Alseekh S, Zhu Z, Zhou K, Fernie AR. Multiomics and biotechnologies for understanding and influencing cadmium accumulation and stress response in plants. Plant Biotechnol J. 2024;22:2641–59. doi:10.1111/pbi.14379. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Maleki M, Ghorbanpour M, Kariman K. Physiological and antioxidative responses of medicinal plants exposed to heavy metals stress. Plant Gene. 2017;11:247–54. doi:10.1016/j.plgene.2017.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Umar AW, Naeem M, Hussain H, Ahmad N, Xu M. Starvation from within: how heavy metals compete with essential nutrients, disrupt metabolism, and impair plant growth. Plant Sci. 2025;353:112412. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2025.112412. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Popov Aleksandrov A, Mirkov I, Tucovic D, Kulas J, Zeljkovic M, Popovic D, et al. Immunomodulation by heavy metals as a contributing factor to inflammatory diseases and autoimmune reactions: cadmium as an example. Immunol Lett. 2021;240:106–22. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2021.10.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Kosakivska IV, Babenko LM, Romanenko KO, Korotka IY, Potters G. Molecular mechanisms of plant adaptive responses to heavy metals stress. Cell Biol Int. 2021;45:258–72. doi:10.1002/cbin.11503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Dai J, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Ding X, Song C. Data notes on the proteomics of Dendrobium huoshanense under pb treatment. BMC Genom Data. 2024;25:22. doi:10.1186/s12863-024-01205-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Shah IH, Sabir IA, Ashraf M, Rehman A, Ahmad Z, Azam M, et al. Phyto-fabrication of copper oxide nanoparticles (NPs) utilizing the green approach exhibits antioxidant, antimicrobial, and antifungal activity in Diospyros kaki fruit. Fruit Res. 2024;4(1):e022. doi:10.48130/frures-0024-0015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kumar L, Kumar P, Narayan A, Kar M. Rietveld analysis of XRD patterns of different sizes of nanocrystalline cobalt ferrite. Int Nano Lett. 2013;3:8. doi:10.1186/2228-5326-3-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Uvarov V, Popov I. Metrological characterization of X-ray diffraction methods at different acquisition geometries for determination of crystallite size in nano-scale materials. Mater Charact. 2013;85:111–23. doi:10.1016/j.matchar.2013.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Agarwal S, Jangir LK, Rathore KS, Kumar M, Awasthi K. Morphology-dependent structural and optical properties of ZnO nanostructures. Appl Phys A. 2019;125:553. doi:10.1007/s00339-019-2852-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Alves TEP, Kolodziej C, Burda C, Franco A. Effect of particle shape and size on the morphology and optical properties of zinc oxide synthesized by the polyol method. Mater Des. 2018;146:125–33. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2018.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Kim K-M, Choi M-H, Lee J-K, Jeong J, Kim Y-R, Kim M-K, et al. Physicochemical properties of surface charge-modified ZnO nanoparticles with different particle sizes. Int J Nanomed. 2014;9 Suppl 2:41–56. doi:10.2147/IJN.S57923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Shah IH, Ashraf M, Khan AR, Manzoor MA, Hayat K, Arif S, et al. Controllable synthesis and stabilization of Tamarix aphylla-mediated copper oxide nanoparticles for the management of Fusarium wilt on musk melon. 3 Biotech. 2022;12:128. doi:10.1007/s13205-022-03189-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Rehman A, Weng J, Li P, Shah IH, Rahman SU, Khalid M, et al. Green synthesized zinc oxide nanoparticles confer drought tolerance in melon (Cucumis melo L.). Environ Exp Bot. 2023;212:105384. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2023.105384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Buege JA, Aust SD. [30] Microsomal lipid peroxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1978;52:302–10. doi:10.1016/S0076-6879(78)52032-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Faizan M, Bhat JA, Chen C, Alyemeni MN, Wijaya L, Ahmad P, et al. Zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO-NPs) induce salt tolerance by improving the antioxidant system and photosynthetic machinery in tomato. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;161:122–30. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.02.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Lopez-Zaplana A, Nicolas-Espinosa J, Carvajal M, Bárzana G. Genome-wide analysis of the aquaporin genes in melon (Cucumis melo L.). Sci Rep. 2020;10:22240. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79250-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Özgür Ü., Alivov YI, Liu C, Teke A, Reshchikov MA, Doğan S, et al. A comprehensive review of ZnO materials and devices. J Appl Phys. 2005;98:041301. doi:10.1063/1.1992666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Pearton SJ, Norton DP, Ip K, Heo YW, Steiner T. Recent progress in processing and properties of ZnO. Superlattices Microstruct. 2003;34:3–32. doi:10.1016/S0749-6036(03)00093-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Rouchdi M, Salmani E, Fares B, Hassanain N, Mzerd A. Synthesis and characteristics of Mg doped ZnO thin films: experimental and ab-initio study. Results Phys. 2017;7:620–7. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2017.01.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Goktas S, Goktas A. A comparative study on recent progress in efficient ZnO based nanocomposite and heterojunction photocatalysts: a review. J Alloys Compd. 2021;863:158734. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.158734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Levtushenko A, Khyzhun O, Shtepliuk I, Bykov O, Jakieła R, Tkach S, et al. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy study of highly-doped ZnO: Al, N films grown at O-rich conditions. J Alloys Compd. 2017;722(3):683–9. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2017.06.169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Al-Gaashani R, Radiman S, Daud AR, Tabet N, Al-Douri Y. XPS and optical studies of different morphologies of ZnO nanostructures prepared by microwave methods. Ceram Int. 2013;39:2283–92. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2012.08.075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Areeshi MY. A review on biological synthesis of ZnO nanostructures and its application in photocatalysis mediated dye degradation: an overview. Luminescence. 2023;38:1111–22. doi:10.1002/bio.4432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Onyszko M, Zywicka A, Wenelska K, Mijowska E. Revealing the influence of the shape, size, and aspect ratio of ZnO nanoparticles on antibacterial and mechanical performance of cellulose fibers based paper. Part Part Syst Charact. 2022;39:2200014. doi:10.1002/ppsc.202200014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Faizan M, Bhat JA, Hessini K, Yu F, Ahmad P. Zinc oxide nanoparticles alleviates the adverse effects of cadmium stress on Oryza sativa via modulation of the photosynthesis and antioxidant defense system. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;220:112401. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Konate A, He X, Zhang Z, Ma Y, Zhang P, Alugongo G, et al. Magnetic (Fe3O4) nanoparticles reduce heavy metals uptake and mitigate their toxicity in wheat seedling. Sustainability. 2017;9:790. doi:10.3390/su9050790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Paramo LA, Feregrino-Pérez AA, Guevara R, Mendoza S, Esquivel K. Nanoparticles in agroindustry: applications, toxicity, challenges, and trends. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:1654. doi:10.3390/nano10091654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Hafeez B, Khanif YM, Saleem M. Role of zinc in plant nutrition—a review. Am J Exp Agric. 2013. doi:10.5281/ZENODO.8225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Azhar M, Zia Ur Rehman M, Ali S, Qayyum MF, Naeem A, Ayub MA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of different biochars and conventional organic materials on growth, photosynthesis and cadmium accumulation in cereals. Chemosphere. 2019;227:72–81. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.04.041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Qayyum MF, Rehman MZU, Ali S, Rizwan M, Naeem A, Maqsood MA, et al. Residual effects of monoammonium phosphate, gypsum and elemental sulfur on cadmium phytoavailability and translocation from soil to wheat in an effluent irrigated field. Chemosphere. 2017;174:515–23. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.02.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Chen F, Li Y, Zia-Ur-Rehman M, Hussain SM, Qayyum MF, Rizwan M, et al. Combined effects of zinc oxide nanoparticles and melatonin on wheat growth, chlorophyll contents, cadmium (Cd) and zinc uptake under Cd stress. Sci Total Environ. 2023;864:161061. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.161061. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Ghouri F, Shahid MJ, Liu J, Lai M, Sun L, Wu J, et al. Polyploidy and zinc oxide nanoparticles alleviated Cd toxicity in rice by modulating oxidative stress and expression levels of sucrose and metal-transporter genes. J Hazard Mater. 2023;448:130991. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.130991. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Ronzan M, Piacentini D, Fattorini L, Della Rovere F, Eiche E, Riemann M, et al. Cadmium and arsenic affect root development in Oryza sativa L. negatively interacting with auxin. Environ Exp Bot. 2018;151:64–75. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2018.04.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Ali S, Rizwan M, Noureen S, Anwar S, Ali B, Naveed M, et al. Combined use of biochar and zinc oxide nanoparticle foliar spray improved the plant growth and decreased the cadmium accumulation in rice (Oryza sativa L.) plant. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2019;26:11288–99. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-04554-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Seleiman MF, Alotaibi MA, Alhammad BA, Alharbi BM, Refay Y, Badawy SA. Effects of ZnO nanoparticles and biochar of rice straw and cow manure on characteristics of contaminated soil and sunflower productivity, oil quality, and heavy metals uptake. Agronomy. 2020;10:790. doi:10.3390/agronomy10060790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Wang X, Sun W, Zhang S, Sharifan H, Ma X. Elucidating the effects of cerium oxide nanoparticles and zinc oxide nanoparticles on arsenic uptake and speciation in rice (Oryza sativa) in a hydroponic system. Environ Sci Technol. 2018;52:10040–7. doi:10.1021/acs.est.8b01664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Rehman A, Khalid M, Weng J, Li P, Rahman SU, Shah IH, et al. Exploring drought tolerance in melon germplasm through physiochemical and photosynthetic traits. Plant Growth Regul. 2024;102:603–18. doi:10.1007/s10725-023-01080-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Sperdouli I, Adamakis I-DS, Dobrikova A, Apostolova E, Hanć A, Moustakas M. Excess zinc supply reduces cadmium uptake and mitigates cadmium toxicity effects on chloroplast structure, oxidative stress, and photosystem II photochemical efficiency in salvia sclarea plants. Toxics. 2022;10:36. doi:10.3390/toxics10010036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]