Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Genetic Diversity of Tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa L.) Germplasm through Molecular Approaches to Obtain Desirable Plant Materials for Future Breeding Programs

1 Department of Floriculture, Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, Faculty of Horticulture, Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalya, Pundibari, Cooch Behar, 736165, West Bengal, India

2 Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Agriculture, Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalya, Pundibari, Cooch Behar, 736165, West Bengal, India

3 Department of Genetics and Plant Breeding, Faculty of Agriculture, Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalya, Pundibari, Cooch Behar, 736165, West Bengal, India

4 Department of Vegetable and Spice Crops, Faculty of Horticulture, Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalya, Pundibari, Cooch Behar, 736165, West Bengal, India

5 Department of Soil Science and Agricultural Chemistry, Faculty of Agriculture, Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalya, Pundibari, Cooch Behar, 736165, West Bengal, India

6 Department of Pomology and Post-Harvest Technology, Faculty of Horticulture, Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalya, Pundibari, Cooch Behar, 736165, West Bengal, India

7 Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, Taif, 21944, Saudi Arabia

8 Department of Biotechnology, College of Sciences, Taif University, P.O. Box 11099, Taif, 21944, Saudi Arabia

9 Soil Science Division, Bangladesh Wheat and Maize Research Institute, Dinajpur, 5200, Bangladesh

* Corresponding Authors: Soumen Maitra. Email: ; Akbar Hossain. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Plant Breeding and Genetic Improvement: Leveraging Molecular Markers and Novel Genetic Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3493-3508. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071450

Received 05 August 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

The present study investigated the genetic diversity of 24 germplasms of Polianthes tuberosa L. via 16 inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) marker techniques. The research findings revealed that the ISSR markers presented higher levels of band reproducibility and were more efficient at clustering germplasms. Among the 16 markers examined in this study, 12 had a complete polymorphism rate of 100%. The molecular analysis revealed a PIC ranging from 0.079 to 0.373, with a mean value of 0.30, whereas the range of the marker index was from 0.0001 to 0.409, with an average value of 0.03, and the primer resolving power ranged from 0.173 to 4.173, with a mean value of 2.02. The UPGMA clustering dendrogram indicated that all 24 germplasms were grouped into three main clusters. The study revealed a variable range of tree distances between 0.185 and 0.621, with the highest tree distance (0.621) detected between germplasms BR-24 and BR-1. Through these studies, the dissimilarity among the germplasms was evaluated, and diverse parents were identified for further crop improvement programs.Keywords

Tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa L.), an ornamental geophyte of the plant family Amaryllidaceae [1], known for its elegant cut flower- and sweet-scented aroma, inherited its generic name from the Greek word “Polios”, meaning white or shining and “Anthos”, meaning a flower [2]. It is of Mexican origin [3,4] and was distributed in various regions of the world throughout the 16th century as a cultivated plant, including India through Europe [5]. In India, tuberose is commonly known as Gulchari and Galshabbo in Hindi, Rajanigandha in Bengali and Nelasampangi in Telugu. The area under tuberose cultivation in India was 21,170 hectares, the production of loose flowers was 105.30 MT, and the production of cut flowers was 96.91 MT (Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers Welfare, Govt. of India, 2022–23). Long-distance shipment cannot attenuate the appearance of the inflorescence, for which it takes a front seat among the commercially valued ornamentals.

The genus Polianthes includes three types of inflorescences [6], i.e., single type having a single whorl of petals in florets mostly utilized in breeding programs as female parents [7], semidouble type having 2–5 whorls of petals in the florets and double type with >5 whorls of petals in the florets. It is diploid with a basic chromosome number of n = x = 30, of which 5 are large and the rest are small [8]. Assessing the genetic diversity of this commercial flowering ornamental is highly beneficial for studying the evolution of plants and their comparative genomics. This information can provide direction for sustaining the genetic integrity and diversity of tuberose germplasm collections from which breeders can develop new tuberose varieties with improved traits, such as enhanced fragrance, flower color, disease resistance or adaptability to different environments. To assess the genetic diversity for pre-determined breeding programmes, molecular marker-based approaches prove more authentic nowadays [9].

Molecular markers are specific nucleotide sequences that can be analysed by examining the variations in nucleotide sequences among different individuals [10,11]. For genetic diversity studies, different molecular methodologies are available, each of which differs in its informational content. ISSR involves the amplification of DNA segments located at a specific distance between 2 identical microsatellite repeat regions that are oriented in opposite directions [12]. The method employs microsatellites as primers in a single-primer PCR that amplifies numerous genomic loci, primarily focusing on simple sequence repeats of varying length. ISSRs possess the characteristic specificity of microsatellite markers but do not require any sequence information for the synthesis of primers, thereby benefiting from the advantage of being random markers [13]. ISSR markers can be used in genetic diversity analysis of tuberose because they do not need genome sequencing data, have high repeatability, and are fast, simple and inexpensive [14], which are capable of evaluating the genetic variability present either within a population or among potential parent plants. Breeders can ascertain the extent of genetic variation by examining the ISSR profiles of particular germplasms [15]. Keeping the above points in mind, this research investigation was carried out with the objective of performing a comprehensive evaluation to study the genetic diversity of tuberose through molecular markers and to select superior parents for hybridization among the twenty-four evaluated germplasms of tuberose.

The research investigation was conducted at the Instructional Farm, Department of Floriculture, Medicinal and Aromatic Plants, under the Faculty of Horticulture at Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Pundibari, Cooch Behar, West Bengal, India.

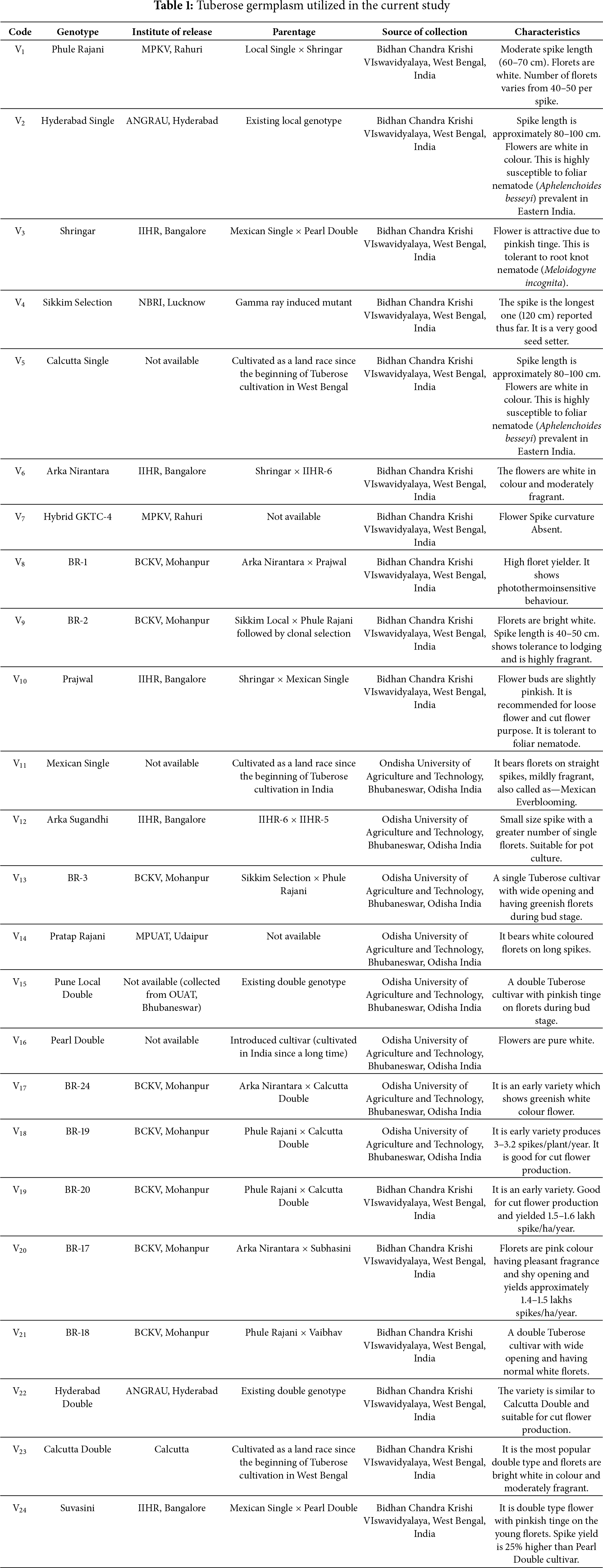

The germplasms used for evaluation are listed in Table 1. The geographical distribution of the selected germplasm are presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Germplasm and their geographical distribution used in the present study

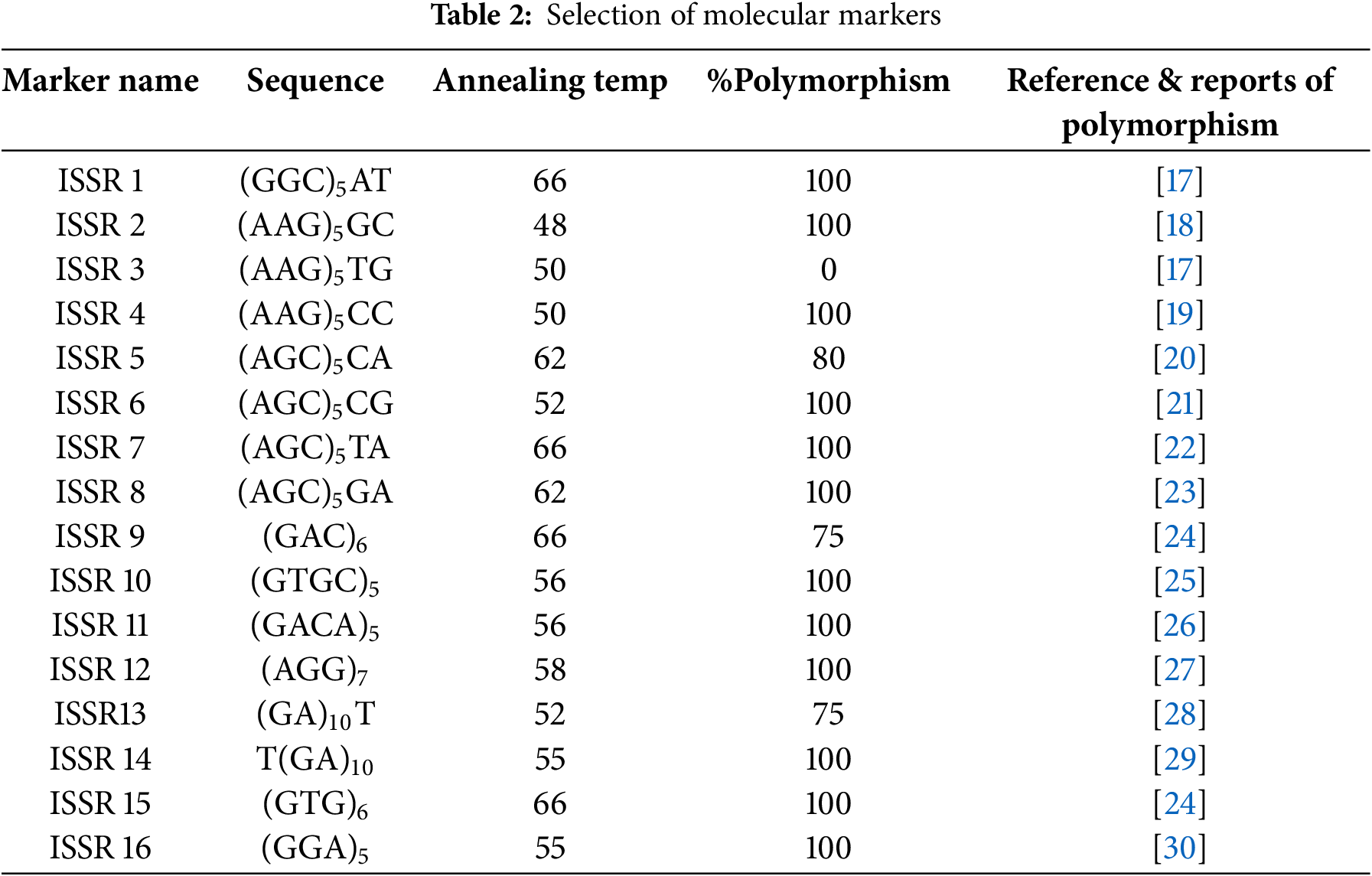

The molecular work was carried out at the Niche Area of Excellence Laboratory, UBKV. The total genomic DNA was extracted via a modified CTAB method [16]. The DNA concentration and purity were determined with a NanoDrop and UV-visible spectrophotometer at 260/280 nm (UV 1900i). The extracted DNA sample is known as a stock sample and was stored at −20°C. A total of 10 µL of stock sample and 90 µL of Milli-Q water were added, and the mixture was diluted to obtain a working sample. A total volume of 10 µL of PCR mixture (containing 5 µL of master mix, 1 µL of forward primer, 1 µL of reverse primer, 1 µL of genomic DNA and 2 µL of nuclease-free water) was prepared for PCR. After preparing for the reaction, the tubes were inserted into a thermal cycler (Veriti 96 Well Thermal-Applied Biosystems by Thermo Fischer Scientific Company). The DNA was amplified via polymerase chain reaction with 16 ISSR primer pairs (Table 2). For amplification of the DNA, initial denaturation at 94°C for 3 min, denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 45°C–60°C (35 cycles), extension at 72°C for 10 min and a final extension at 72°C for 4 min were performed. The electrophoretically amplified products were separated on 3% agarose. The gels were buffered with 1X TAE buffer at 75 volts for 45 min to one hour. The gel was subsequently observed via a gel documentation system with a UV transilluminator (iBright CL750 image system; Invitrogen, Thermo Fischer Scientific Company).

For each individual, the molecular identification profile was determined by assigning a score of 1 or 0 to indicate the presence or lack of the band, respectively. The simple matching coefficient (SM) was computed via the binary matrix. SM is determined via the following formula: SM = (a + d)/(a + b + c + d), where “a” represents the number of bands present in both individuals, “b” and “c” denote the count of bands present in just one individual, and “d” signifies the count of bands that are absent in both individuals. The evaluation of primer performance in distinguishing genotypes was conducted via several established metrics, including resolving power (RP), as proposed by [31]; the marker index (MI), as described by [32]; Shannon’s index (H’), as introduced by [33]; and the polymorphic information content, as defined by [34]. A cluster analysis utilizing the UPGMA method was performed to estimate the molecular dissimilarity and construct a dendrogram. The analysis was completed via a specific software package, DARwin 6.0.21, a software tool known for dissimilarity analysis and representation for Windows, which was developed by CIRAD [35]. The genotypes of Tuberose were clustered via the neighboring technique [35,36].

A total of 24 germplasms of tuberose were characterized via 16 ISSR markers. A list of different germplasms of tuberose and their characteristics is shown in Table 1. In the present study, 78 alleles were generated in total, of which 75 alleles were polymorphic [37] and three were monomorphic, thus generating 89.38% of the polymorphisms. A total of twelve primers were identified as 100% polymorphic among the 16 ISSR primers.

3.1 Band Size and Percentage of Polymorphic Alleles

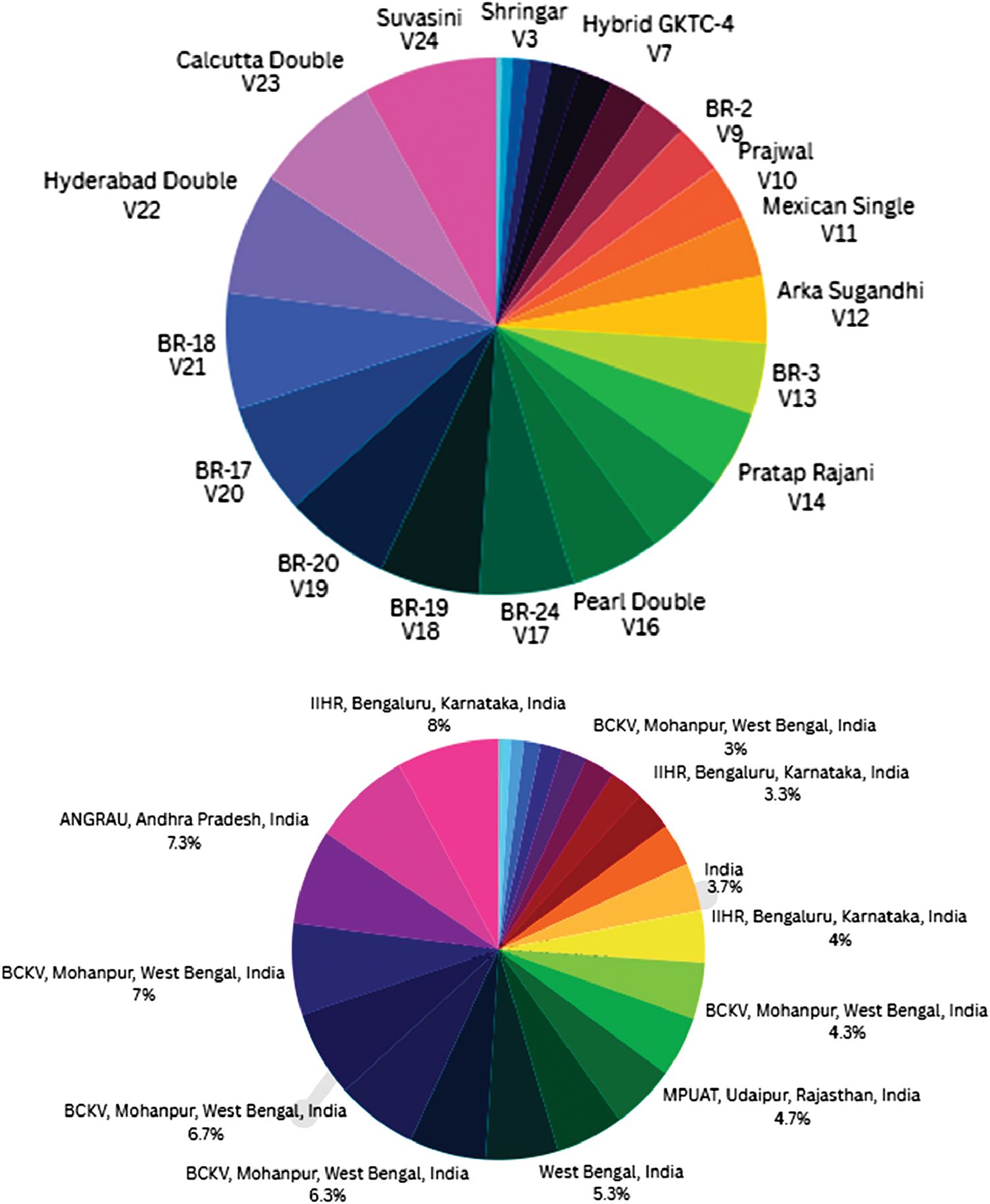

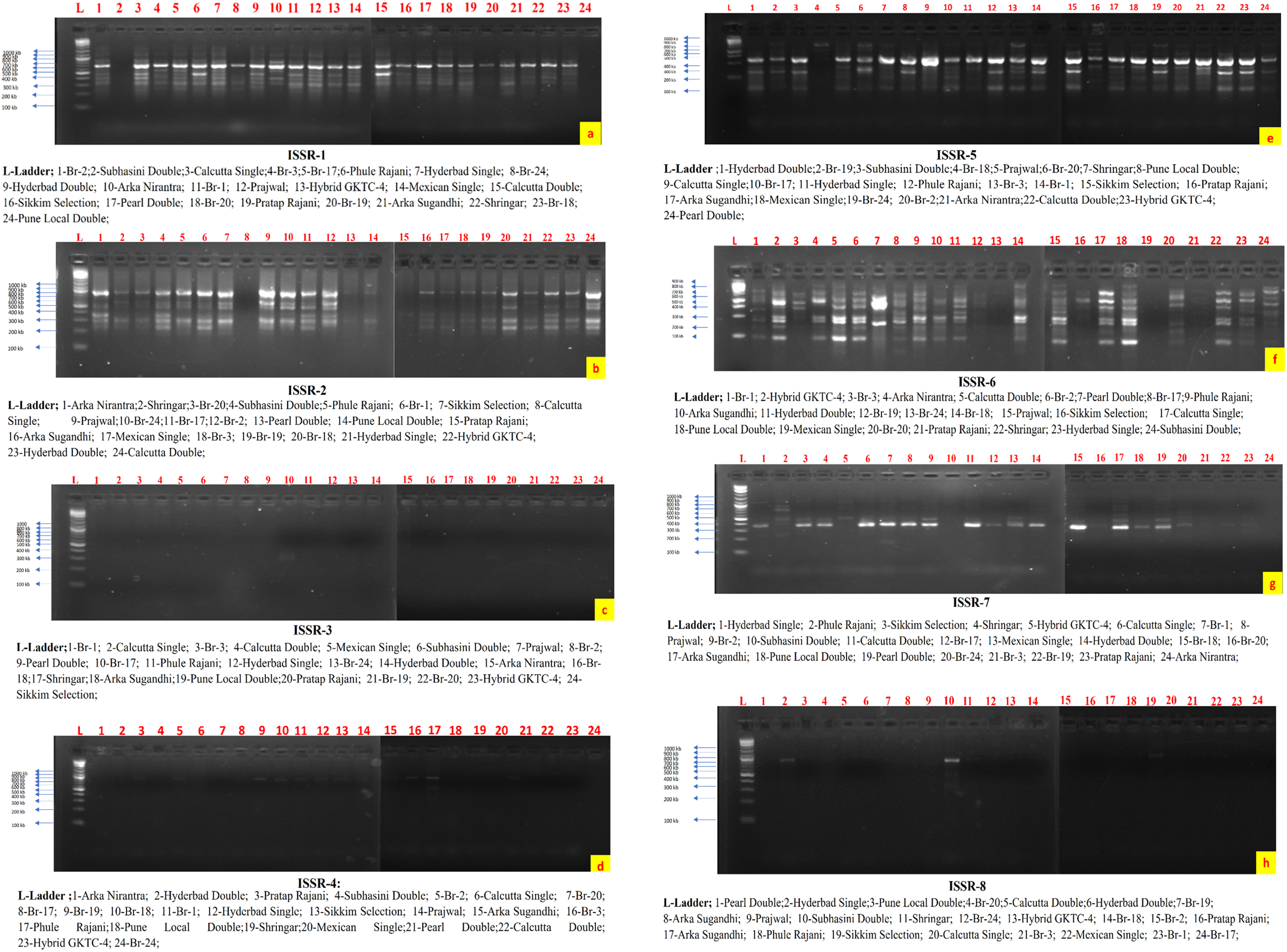

The observed band sizes in all 24 germplasms ranged from 150 to 1200 base pairs (bp). The number of amplified alleles produced by each individual ISSR varied between 3 and 9 bands, with an average of 4.69 alleles per primer [38]. The percentage of polymorphic alleles ranged from 75% to 100% (Figs. 2 and 3). In another study reported by [6] that assessed the genetic characteristics of seven tuberose germplasms, six ISSR primers were used, which revealed a polymorphism rate of 85.48%. Another similar study [39,40] used nine ISSR primers and reported a polymorphism rate of 92.50%, which aligns with the current research observations of a higher level of polymorphism when the ISSR marker system was used.

Figure 2: ISSR profiling of 24 germplasms of tuberose via a gel documentation system

Figure 3: ISSR profiling of 24 germplasms of tuberose via a gel documentation system

3.2 Amplification Details for ISSR Primers

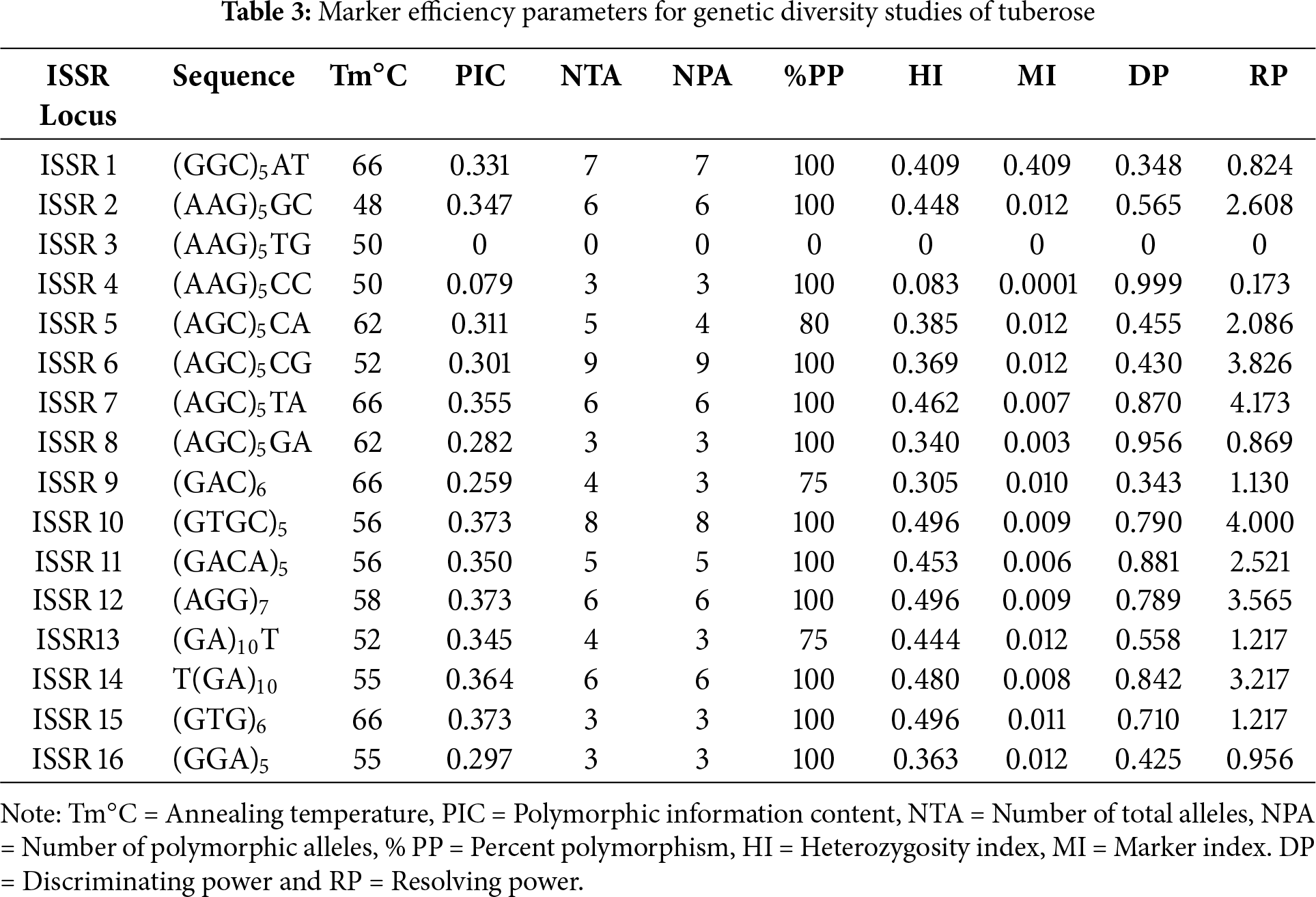

The amplification details for each ISSR primer are presented in Tables 2 and 3. The data generated via the use of 16 ISSR primers ranged from ISSR-1 to ISSR-16, with an average of 4.68 bands per primer.

3.3 Polymorphic Information Content (PIC)

The PIC ranged from 0.079 (ISSR 4) to 0.373 (ISSR 10, ISSR 12, ISSR 15), with an average value of 0.30 [41]. The PIC is employed to assess the discriminatory capacity of molecular markers and to estimate the genetic diversity of germplasms. The observed differences in polymorphic information content values across various tuberose germplasms can be attributed to both the genetic diversity inherent in the germplasms and the variability in the number of tested ISSR loci [31].

The resolving power demonstrated variability, ranging from 0.173 (ISSR 4) to 4.173 (ISSR 7), with an average value of 2.02 [42,43]. The obtained resolving power values indicate that the set of ISSR primers used in the study have the ability to differentiate between germplasms. Additionally, the efficiency of ISSR [30] markers within the range of RPs of 4.6 (ISSR 857) and 12.5 (ISSR 841) in the fingerprinting of potato cultivars has been reported.

Similarly, the marker index (MI) ranged from 0.0001 (ISSR 4) to 0.409 (ISSR 1), with a mean value of 0.03. In the present analysis, primers, namely, ISSR1, ISSR 2, ISSR 5, ISSR 6, ISSR 10, ISSR 12, and ISSR 14, which have above-average PICs, MIs and RPs, presented relatively high efficiency. Dinucleotide-based ISSR primers have been used to group germplasms of certain significant bulbous blooming plants and have demonstrated a good level of repeatability and an adequate degree of polymorphism [6]. Thus, the ISSR marker system. This type of marker was determined to be more productive in analysing diversity among closely related individuals because it targets different sites in the genome [12].

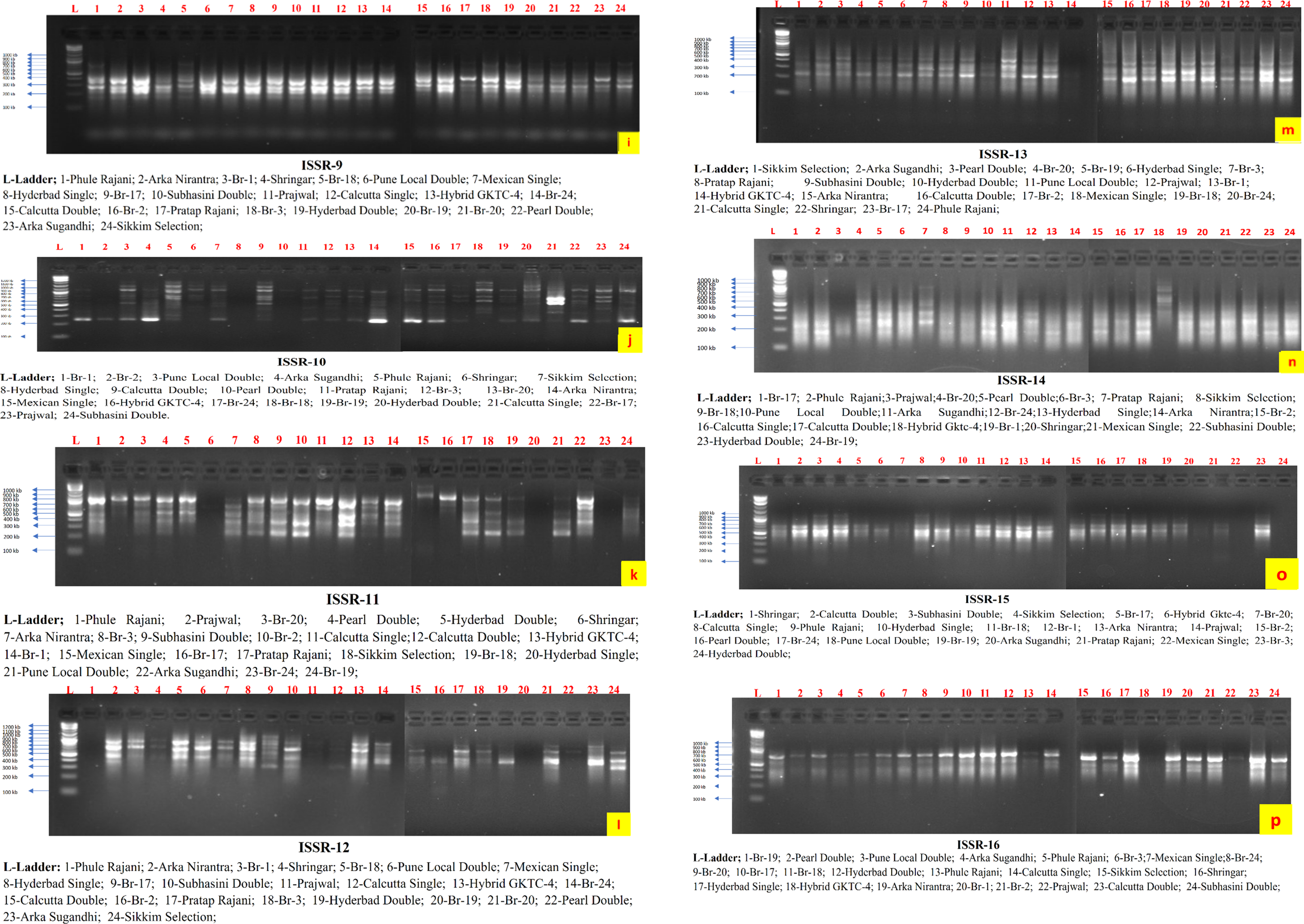

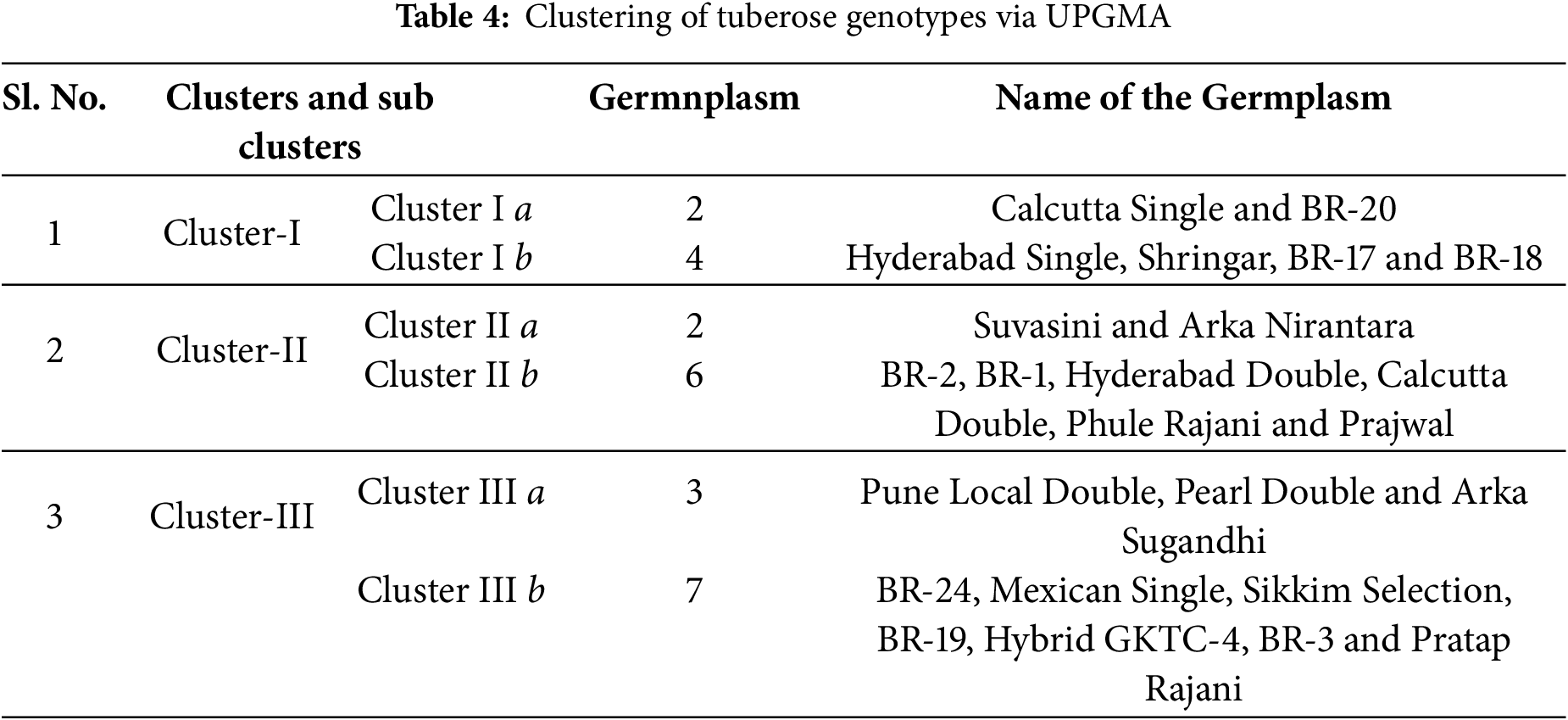

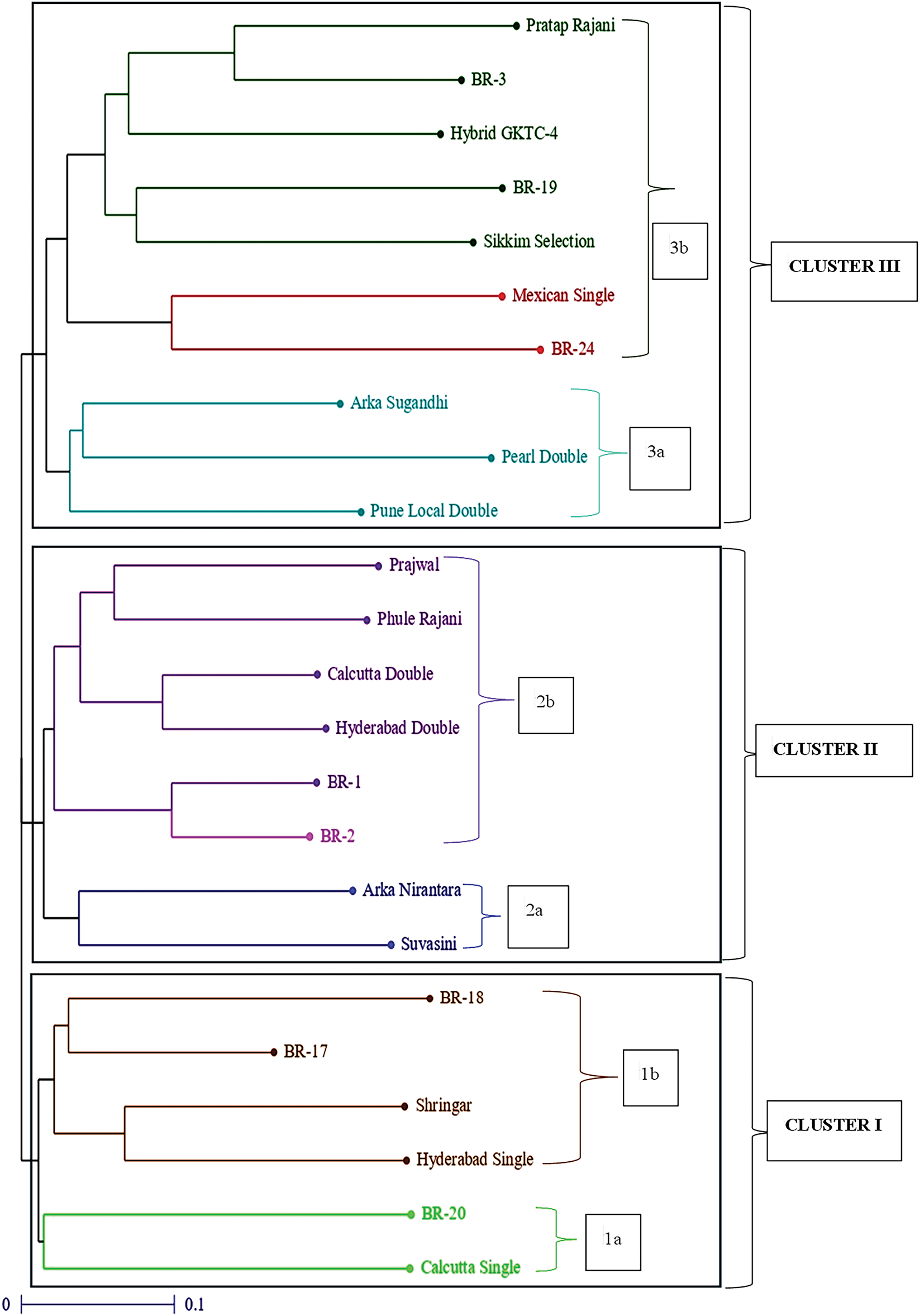

The 24 tuberose genotypes were clustered via the UPGMA method, resulting in the formation of three distinct clusters: Cluster I, Cluster II and Cluster III, which are listed in Table 4 and Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Dendrogram constructed via UPGMA for 24 tuberose genotypes [Colour lines representing number of germplasm in three cluster groups (from down to top), i.e., light green (1a), brown (1b), Royal blue (2a), Purple (2b), sea green (3a), Red, dark green (3b)]

Cluster-I comprises six cultivars, whereas cluster-II has eight germplasms with dissimilarities, and cluster-III comprises ten germplasms. Cluster I was separated into two subclusters, namely, I a and I b. Subcluster I a comprises two distinct germplasms, specifically Calcutta Single and BR-20. On the other hand, Subcluster I b was separated into subclusters consisting of the germplasms Hyderabad Single, Shringar, BR-17 and BR-18. Cluster II was subsequently separated into two subclusters, namely, IIa and IIb. Subcluster IIa was composed of two germplasms, namely, Suvasini and Arka Nirantara. Subcluster IIb was further subdivided into subclusters, comprising the germplasms BR-2, BR-1, Hyderabad Double, Calcutta Double, Phule Rajani and Prajwal. Cluster III was subdivided into 2 subclusters, namely, IIIa and IIIb. Subcluster IIIa was then subdivided into subclusters, encompassing the germplasms Pune Local Double, Pearl Double and Arka Sugandhi. Subcluster III b was further subdivided into subclusters, consisting of the germplasms BR-24, Mexican Single, Sikkim Selection, BR-19, Hybrid GKTC-4, BR-3 and Pratap Rajani.

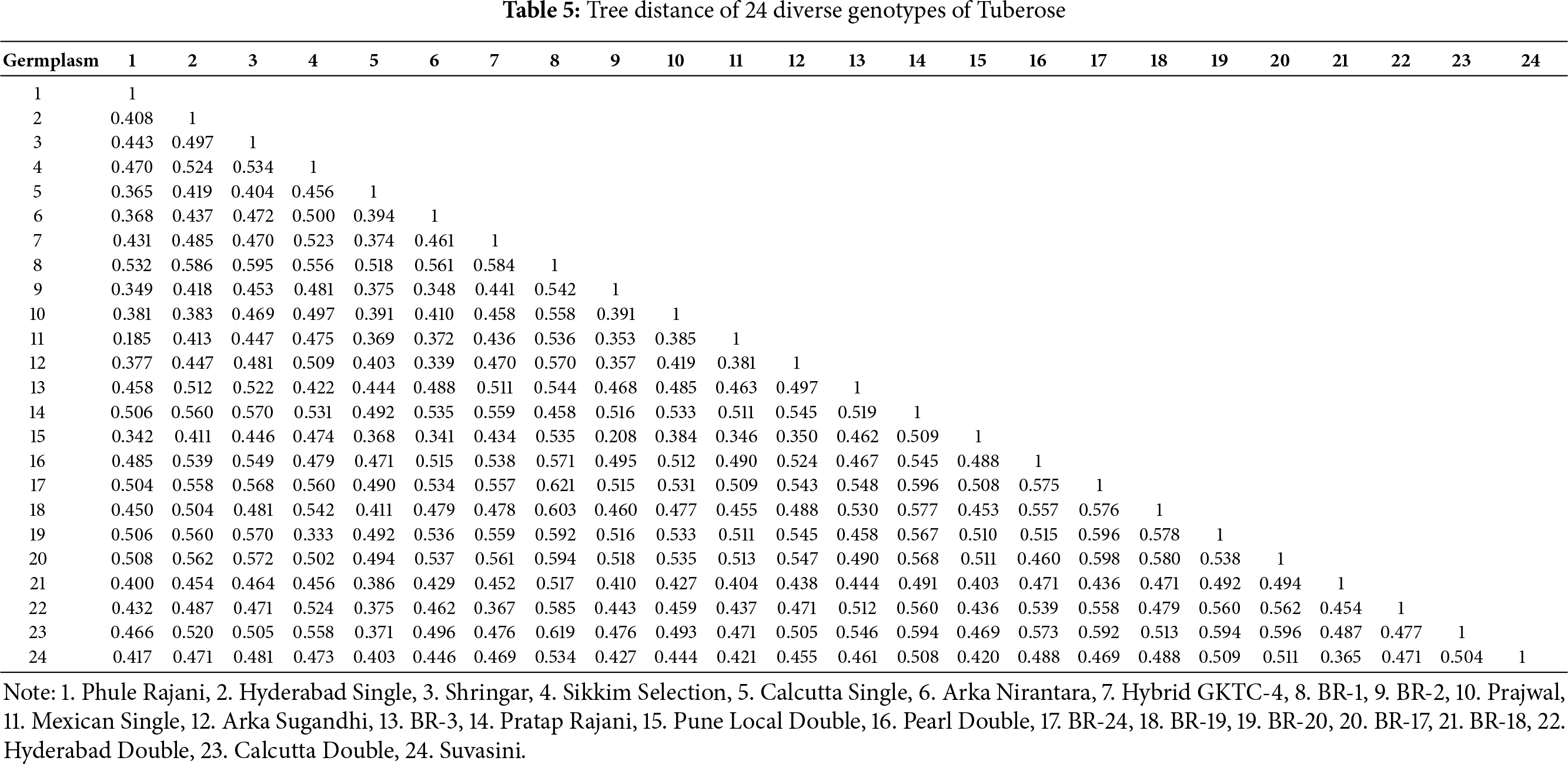

The concept of tree distance is utilized to measure the genetic variation between different germplasms quantitatively (Table 4). The range of tree distance, which helps in investigating the spatial distribution and patterns of genetic diversity within the population or group of tuberose germplasms, varied between 0.185 and 0.621, and the obtained results are comparable to the information generated in tuberose [44] and in Gladiolus [45]. The greatest tree distance (0.621) was detected between germplasms BR-24 and BR-1, followed by BR-18 and BR-24, with a tree distance of 0.598, whereas the lowest tree distance (0.185) was 0.185 between germplasms Mexican Single and Phule Rajani, indicating an extensive range of germplasms within the study area (Table 5).

Among the examined markers, ISSR 6 [NTA-9, NPA-9 and 100% polymorphism] presented the highest level of polymorphism in comparison with the other markers. The ISSR, i.e., ISSR 10, ISSR 12 and ISSR 15, had a maximum PIC value of 0.374. Among the 16 markers examined in the present investigation, 12 had a complete polymorphism rate of 100%. The UPGMA dendrogram yielded three primary clusters, each of which was subsequently subdivided into subclusters. The germplasms BR-1 and BR-24 presented a significant level of diversity, as indicated by a tree distance of 0.621 in the dendrogram analysis. These findings indicate that these two germplasms possess an extensive range of genetic variations that render them distinct and make them suitable for inclusion in a productive tuberose breeding programme. In the present study, ISSR marker-related observations supported the genetic diversity of the tuberose germplasms studied.

Acknowledgement: The authors are thankful to Bidhan Chandra Krishi Viswavidyalaya and Odisha University of Agriculture and Technology for providing the germplasm of Tuberose and to the Niche Area of Excellence Laboratory, Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, for extending the facilities to conduct the research trial. The authors also extend their appreciation to Taif University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work through project number (TU-DSPP-2025-30).

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Uttar Banga Krishi Viswavidyalaya, India; Bangladesh Wheat and Maize Research Institute, Dinajpur 5200, Bangladesh. The study was also funded by Taif University, Saudi Arabia, Project No. (TU-DSPP-2025-30).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Soumen Maitra, Vardhelli Soukya, and Saikat Das and Nandita Sahana; Methodology: Vardhelli Soukya, Soumen Maitra, Saikat Das, Nandita Sahana, Rupsanatan Mandal, Arindam Das, Ashok Choudhury and Prodyut Kumar Paul; Data curation: Vardhelli Soukya, Soumen Maitra, Nandita Sahana, Rupsanatan Mandal, Ahmed Gaber, Mohammed M. Althaqafi and Akbar Hossain; Visualization and validation: Vardhelli Soukya, Soumen Maitra, Saikat Das, Nandita Sahana, Arpita Mandal Khan, Arindam Das and Rupsanatan Mandal; Formal analysis: Vardhelli Soukya, Soumen Maitra, Nandita Sahana, Rupsanatan Mandal, Arindam Das, Arpita Mandal Khan, Ahmed Gaber, Mohammed M. Althaqafi and Akbar Hossain; Writing—original draft preparation: Vardhelli Soukya, Soumen Maitra, Saikat Das, Nandita Sahana, Rupsanatan Mandal, Arindam Das, Akbar Hossain, Ashok Choudhury and Prodyut Kumar Paul; Review and editing: Soumen Maitra, Ahmed Gaber, Mohammed M. Althaqafi and Akbar Hossain; Supervision: Soumen Maitra, Ahmed Gaber, Mohammed M. Althaqafi and Akbar Hossain. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data may be available upon request to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Baker JG. Handbook of the Amaryllideae, including the Alstroemerieae and Agaveae. London, UK: George Bell and Sons; 1888. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.15516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Safeena SA, Thangam M, Desai AR, Singh NP. Ready reckoner on cultivation of tuberose. Tech Bull. 2015;50:1–33. [Google Scholar]

3. Trueblood EWE. Omixochitl—the tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa). Econ Bot. 1973;27(2):157–73. doi:10.1007/bf02872987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Waithaka K, Reid M, Dodge L. Cold storage and flower keeping quality of cut tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa L.). J Hortic Sci. 2001;76(3):271–5. doi:10.1080/14620316.2001.11511362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Yadav LP, Maity RG. Tuberose. In: Bose TK, Yadav LP, editors. Commercial flowers. Calcutta, India: Calcutta Publication; 1989. p. 518–44. [Google Scholar]

6. Kameswari PL, Girwani A, Rani RK. Genetic diversity in tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa L.) using morphological and ISSR markers. Electron J Plant Breed. 2014;59(1):52–7. doi:10.23880/oajar-16000294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Naik BC, Kamble BS, Tirakannanavar S, Parit S. Evaluation of different genotypes of tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa L.) for yield and quality. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2018;7(8):53–60. doi:10.20546/ijcmas.2018.708.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Whitaker TW. Tuberose. J Arnold Arbor. 1934;15:133–4. [Google Scholar]

9. Borah R, Bhattacharjee A, Rao SR, Kumar V, Sharma P, Upadhaya K, et al. Genetic diversity and population structure assessment using molecular markers and SPAR approach in Illicium griffithii, a medicinally important endangered species of Northeast India. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2021;19(1):118. doi:10.1186/s43141-021-00211-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Nadeem MA, Nawaz MA, Shahid MQ, Doğan Y, Comertpay G, Yıldız M, et al. DNA molecular markers in plant breeding: current status and recent advancements in genomic selection and genome editing. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2018;32(2):261–85. doi:10.1080/13102818.2017.1400401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Nagy S, Poczai P, Cernák I, Gorji AM, Hegedűs G, Taller J. PICcalc: an online program to calculate polymorphic information content for molecular genetic studies. Biochem Genet. 2012;50(9–10):670–2. doi:10.1007/s10528-012-9509-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Gupta M, Chyi YS, Romero-Severson J, Owen JL. Amplification of DNA markers from evolutionarily diverse genomes using single primers of simple-sequence repeats. Theor Appl Genet. 1994;89(7):998–1006. doi:10.1007/BF00224530. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Joshi SP, Gupta VS, Aggarwal RK, Ranjekar PK, Brar DS. Genetic diversity and phylogenetic relationship as revealed by inter simple sequence repeat (ISSR) polymorphism in the genus Oryza. Theor Appl Genet. 2000;100(8):1311–20. doi:10.1007/s001220051440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Kao CN, Huang WL, Lin WC, Miyajima I, Huang KL. DNA molecular markers for genetic identification of tuberose. J Fac Agric Kyushu Univ. 2022;67(2):133–9. doi:10.5109/4797819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhao KG, Zhou MQ, Chen LQ, Zhang D, Robert GW. Genetic diversity and discrimination of Chimonanthus praecox (L.) link germplasm using ISSR and RAPD markers. HortScience. 2007;42(5):1144–8. doi:10.21273/hortsci.42.5.1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Doyle JJ. Isolation of plant DNA from fresh tissue. Focus. 1990;12:13–5. [Google Scholar]

17. Mondal D, Kantamraju P, Jha S, Sundarrao GS, Bhowmik A, Chakdar H, et al. Evaluation of indigenous aromatic rice cultivars from sub-Himalayan Terai region of India for nutritional attributes and blast resistance. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):4786. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-83921-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Taghipour S, Ehtesham Nia A, Khodayari H, Mumivand H, Shafiei MR. Morphological and genetic variation of thirty Iranian Dendranthema (Dendranthema grandiflorum) cultivars using multivariate analysis. Hortic Environ Biotechnol. 2021;62(3):461–76. doi:10.1007/s13580-021-00342-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Hota T, Pradhan C, Ranjan Rout G. Agromorphological and molecular characterization of Sesamum indicum L.—an oil seed crop. Am J Plant Sci. 2016;7(17):2399–411. doi:10.4236/ajps.2016.717210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nath A, Maloo SR, Meena BL, Gangarani Devi A, Tak S. Assessment of genetic diversity using ISSR markers in green gram [Vigna radiata (L.) Wilczek]. Int J Curr Microbiol App Sci. 2017;6(5):1150–8. doi:10.20546/ijcmas.2017.605.125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Lenka D, Tripathy SK, Kumar R, Behera M, Ranjan R. Assessment of genetic diversity in quality protein maize (QPM) inbreds using ISSR markers. J Environ Biol. 2015;36(4):985–92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Kahodariya J, Sabara P, Vakharia D. Assessment of genetic diversity in old world and new world cotton cultivars using RAPD and ISSR markers. IJBT. 2015;14:511–7. [Google Scholar]

23. Baliyan D, Sirohi A, Kumar M, Kumar V, Malik S, Sharma S, et al. Comparative genetic diversity analysis in chrysanthemum: a pilot study based on morpho-agronomic traits and ISSR markers. Sci Hortic. 2014;167:164–8. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2013.12.029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Cichorz S, Gośka M, Litwiniec A. Miscanthus: genetic diversity and genotype identification using ISSR and RAPD markers. Mol Biotechnol. 2014;56(10):911–24. doi:10.1007/s12033-014-9770-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Sagwal V, Sihag P, Singh Y, Mehla S, Kapoor P, Balyan P, et al. Development and characterization of nitrogen and phosphorus use efficiency responsive genic and miRNA derived SSR markers in wheat. Heredity. 2022;128(6):391–401. doi:10.1038/s41437-022-00506-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Escandón A, Pérez de la Torre M, García M, Heinz R. Analysis of genetic variability by ISSR markers in Calibrachoa caesia. Electron J Biotechnol. 2012;15(5):8. doi:10.2225/vol15-issue5-fulltext-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Kpatènon MJ, Salako KV, Santoni S, Zekraoui L, Latreille M, Tollon-Cordet C, et al. Transferability, development of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers and application to the analysis of genetic diversity and population structure of the African fan palm (Borassus aethiopum Mart.) in Benin. BMC Genet. 2020;21(1):145. doi:10.1186/s12863-020-00955-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Jessica I, Torre MCP, Coviella MA, Aguirre EDV, Elechosa MA, Baren VCM, et al. In vitro propagation of Lippia integrifolia (Griseb.) Hier. and detection of genetic instability through ISSR markers of in vitro-cultured plants. Rev Fac Agron. 2016;115(1):67–76. [Google Scholar]

29. Liu HB, Liu J, Wang Z, Ma LY, Wang SQ, Lin XG, et al. Development and characterization of microsatellite markers in Prunus sibirica (Rosaceae). Appl Plant Sci. 2013;1(3):1200074. doi:10.3732/apps.1200074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Kashyap PL, Kumar S, Kumar RS, Tripathi R, Sharma P, Sharma A, et al. Identification of novel microsatellite markers to assess the population structure and genetic differentiation of Ustilago hordei causing covered smut of barley. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2929. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.02929. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Prevost A, Wilkinson MJ. A new system of comparing PCR primers applied to ISSR fingerprinting of potato cultivars. Theor Appl Genet. 1999;98(1):107–12. doi:10.1007/s001220051046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Powell W, Morgante M, Andre C, Hanafey M, Vogel J, Tingey S, et al. The comparison of RFLP, RAPD, AFLP and SSR (microsatellite) markers for germplasm analysis. Mol Breed. 1996;2(3):225–38. doi:10.1007/BF00564200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shannon CE, Weaver W. The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana, IL, USA: University of Illinois Press; 1949. [Google Scholar]

34. Weising K, Nybom H, Pfenninger M, Wolff K, Kahl G. DNA fingerprinting in plants: principles, methods, and applications. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

35. Perrier X, Collet JP. DARwin software: dissimilarity analysis and representation for windows. [cited 2025 Oct 18]. Available from: https://darwin.cirad.fr/. [Google Scholar]

36. Kumar Yadav DR, Ercal G. A comparative analysis of progressive multiple sequence alignment approaches using UPGMA and neighbor join based guide trees. IJCSEIT. 2015;3(4):1–9. doi:10.5121/ijcseit.2015.5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Venkatesan J, Ramu V, Sethuraman T, Sivagnanam C, Doss G. Molecular marker for characterization of traditional and hybrid derivatives of Eleusine coracana (L.) using ISSR marker. J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2021;19(1):178. doi:10.1186/s43141-021-00277-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Ghonaim MM, Habeb MM, Mansour MTM, Mohamed HI, Omran AAA. Investigation of genetic diversity using molecular and biochemical markers associated with powdery mildew resistance in different flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) genotypes. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):412. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05113-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Bharti H, Singh KP, Singh R, Kumar R, Singh MC. Genetic diversity and relationship study of single and double petal tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa L.) cultivars based on RAPD and ISSR markers. Ind J Hort. 2016;73(2):238. doi:10.5958/0974-0112.2016.00054.2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Tran DH, Dao TH, Ngo XB, Nguyen VH, Dao TV, Nguyen TD. Genetic diversity of peach (Prunus persica) accessions collected in northern Vietnam using ISSR markers. Diversity. 2025;17(3):151. doi:10.3390/d17030151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Degu HD, Tehelku TF, Kalousova M, Sato K. Genetic diversity and population structure of barley landraces from Southern Ethiopia’s Gumer district: utilization for breeding and conservation. PLoS One. 2023;18(1):e0279737. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0279737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Lavudya S, Thiyagarajan K, Ramasamy S, Sankarasubramanian H, Muniyandi S, Bellie A, et al. Assessing population structure and morpho-molecular characterization of sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) for elite germplasm identification. PeerJ. 2024;12(4):e18205. doi:10.7717/peerj.18205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Abd-Dada H, Bouda S, Khachtib Y, Bella YA, Haddioui A. Use of ISSR markers to assess the genetic diversity of an endemic plant of Morocco (Euphorbia resinifera O. Berg). J Genet Eng Biotechnol. 2023;21(1):91. doi:10.1186/s43141-023-00543-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Khandagale K, Padmakar B, Lakshmana Reddy DC, Sane A, Aswath C. Genetic diversity analysis and barcoding in tuberose (Polianthes tuberosa L.) cultivars using RAPD and ISSR markers. J Hortic Sci. 2014;9(1):5–11. doi:10.24154/jhs.v9i1.209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Chaudhary V, Kumar M, Sharma S, Kumar N, Kumar V, Yadav HK, et al. Assessment of genetic diversity and population structure in gladiolus (Gladiolus hybridus Hort.) by ISSR markers. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2018;24(3):493–501. doi:10.1007/s12298-018-0519-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools