Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Genome-Wide Scanning Analysis for MYB and MADS in Hydrangea macrophylla and the Inflorescence Type Related Candidate Genes Expression Analysis

1 Department of Landscape Architecture, School of Design, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, 200240, China

2 School of Agriculture and Biology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, 200240, China

3 Shanghai Chenshan Botanical Garden, Shanghai, 201602, China

4 Shanghai Engineering Research Center of Urban Tree Ecology and Applications, Shanghai, 200020, China

5 Hangzhou Landscaping Incorporated Company, Hangzhou, 310020, China

* Corresponding Author: Jun Qin. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Nutrient Dynamics in Improving Plant Productivity and Ecosystem Functioning: Adaptation and Resource Conservation)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3539-3562. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.071989

Received 17 August 2025; Accepted 20 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Hydrangea macrophylla is a popular ornamental shrub with a lot of economic and aesthetic value. It is known for its different flower shapes (lacecap and mophead) and the way its flowers change color depending on the pH of the soil. Even though it is important for gardening, we still don’t know much about the molecular processes that lead to flower growth. The purpose of this study was to find and study SNP-related genes and transcription factors that are connected to the growth of H. macrophylla flowers. Genome-wide SNP analysis identified 11 SNPs associated with MYB transcription factors and 10 SNPs linked to a MADS-box SEP1 gene, highlighting their potential role in inflorescence-type regulation. These SNPs provide genomic resources for functional validation and marker-assisted breeding in Hydrangea macrophylla. We found the MYB and MADS-box gene families, which are important for pigmentation and flower organ identity, through an analysis of the transcriptome and gene expression. The MYB family has 73 1R-MYBs, 105 R2R3-MYBs, and 4 3R-MYBs. The MADS-box family had 42 Type I (M-type) members and 36 Type II (MIKC-type) members. Motif and phylogenetic analysis showed that certain domains were preserved. For example, R2R3-MYBs and MIKC-type MADS genes are grouped with Arabidopsis orthologs, which suggests that their functions are also preserved. There was a clear link between the greatest expression of MADS-box genes and the distinct phases of floral bud differentiation. Some MYB genes, on the other hand, showed alternative expression patterns that may help petals or sepals develop. qRT-PCR validation of representative MYB and MADS-box genes corroborated the transcriptome-based expression profiles, supporting their role in flower development and inflorescence-type regulation.Keywords

Hydrangea macrophylla is a widely cultivated deciduous shrub that originates from the regions of Japan and China, related to the genus Hydrangea and the Saxifragaceae family, with enriched historical and horticultural value in the East, South, Southwest, and Central parts of China [1]. As a significant center for Hydrangea germplasm, China is currently harboring 73 species as an important center for the germplasm of Hydrangea, of which 27 species and 11 varieties fall into the endemic category [2]. Over centuries, particularly since the Tang Dynasty, Hydrangeas have been used as ornamental species in Chinese gardens [3]. In recent times, nearly 1000 cultivars are existing around the globe. Hydrangeas are mostly cherished for their beautiful, substantial inflorescences, vibrant and showy flowers, and prolonged flowering periods. This long-standing appeal has resulted in the plant’s widespread use in various horticultural forms, including fresh-cut flowers, potted plants, and specialty garden designs [4].

The H. macrophylla has two primary inflorescence forms: Mophead and Lacecap, with breeding efforts increasingly focused on maximizing ornamental flowers [5].

The lacecap hydrangea has a flat or slightly domed corymb-like arrangement of flowers. In the middle is a cluster of many small, nondecorative florets that are usually less noticeable since their petals are smaller and their hue is greenish or pale. There is a single outer ring, or perhaps a few dispersed individuals, of larger, showy, sterile florets with enlarged, petaloid sepals that are mostly there to lure pollinators. The way the space is set up makes it easy to see the nondecorative florets from above.

Mophead Hydrangea: This type of flower cluster is round or half-spherical and mostly made up of sterile florets with big, colorful sepals. The decorative florets are so tightly packed and so many that they completely cover any nondecorative florets that might be there. Because of this, the reproductive parts are hidden from view, and the display is mostly for decoration and to attract pollinators.

Studies reveal that Hydrangea flower types may follow Mendelian inheritance patterns, though some complex traits, such as double-petaled flowers or inflorescence homogeneity, are governed by recessive genes and complex genetic interactions [6].

Plant inflorescences play a critical role in reproduction, evolving from vegetative meristem to inflorescence meristem and finally to flower meristem. Inflorescence formation is complex, involving numerous genes and pathways [5]. In maize, for instance, traits related to ear formation are polygenic, with studies using genome-wide association analysis to map key trait loci [7]. Similarly, Brassica napus and bamboo inflorescences have been studied using resequencing and genetic mapping to elucidate inflorescence development mechanisms [8,9].

The molecular basis of Hydrangea flower development has also been explored extensively, particularly through MADS-box, MYB, and bHLH transcription factors [10]. The MADS-box gene group is integral to floral organ development and has been found to regulate inflorescence structures in species like Arabidopsis [11] and Phyllostachys edulis [12]. MYB and bHLH transcription factors further contribute to color formation and flower opening processes, forming regulatory complexes that impact various aspects of growth and flowering [13]. For example, Ref. [14] demonstrated the practical application of SNP assays for marker-assisted selection, developing a diagnostic SNP marker for Rhizoctonia resistance in sugar beet. Beyond natural allelic variation, SNP-based breeding can also benefit from promoter engineering strategies. showed that manipulation of a conserved BnFUSCA3 promoter enhanced seed oil content in rapeseed, highlighting the potential of combining SNP-based selection with promoter-level modifications for trait improvement.

This broad spectrum of research underscores the potential for further advances in Hydrangea breeding and genetic analysis, with SNP markers, genetic mapping, and the study of key transcription factors offering insights into complex trait inheritance and adaptation. The MADS-box and MYB gene families are notably highlighted as they serve as key regulators of floral organ identity, inflorescence structure, and pigmentation [15]. Other transcription factors, like bHLH and WRKY, serve supportive or downstream functions; yet, MYB and MADS typically demonstrate the most direct and significant influence on floral shape across various plant systems [16,17]. The focus of this paper is to recognize and describe the genetic mechanisms underlying flower morphology in Hydrangeas. Despite prior research, the specific genes and molecular pathways that govern Hydrangea flower shape remain largely undefined. This research aims to pinpoint candidate genes potentially involved in flower morphology by examining SNP loci on the scaffolds MADS and MYB2. Through functional annotation, four genes were preliminarily identified as possible regulators of Hydrangea flower form. Additionally, this study identifies members of the MYB and MADS-box gene families, both integral to flower development, and investigates their evolutionary relationships to aid predictive analysis of their influence on Hydrangea flower morphology.

2 Experimental Material and Methods

This study intended to examine the spatial and temporal expression patterns of genes related to single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers associated with inflorescence morphology in H. macrophylla, concentrating on the Lacecap and Mophead flower cultivars.

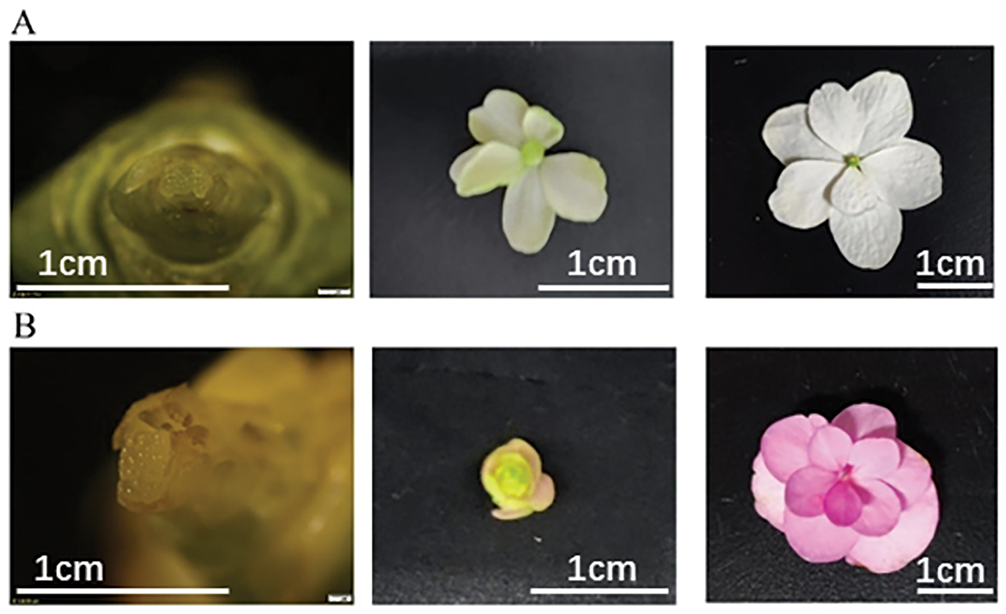

Samples for spatial expression analysis were obtained in October 2022 from two typical cultivars: ‘White Angel’ (Lacecap) and ‘Kahou’ (Mophead). Samples such as stems, leaves, and decorative floral organs were collected at various developmental phases (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Stage of flower bud differentiation and sepals of different Hydrangea cultivars in October. (A): ‘White Angel’ flower buds, bud stage decorative flowers, full flower stage decorative flowers; (B): ‘Kahou’ flower bud, bud stage decorative flowers, full flower stage decorative flowers

For the examination of temporal expression, flower buds were harvested from hybrid progeny resulting from the crossbreeding of ‘Tivoli’ and ‘Tabi’. Buds were collected during critical floral differentiation phases in October, November, and January. All samples were promptly frozen in liquid nitrogen and preserved at −80°C for subsequent examination.

Inflorescence type was classified based on floral morphology, where ‘Lacecap’ cultivars displayed marginal showy florets with central fertile florets, while ‘Mophead’ cultivars exhibited fully showy florets. Developmental stages of floral buds were defined by bud size and morphology (early bud initiation, semi-open, and fully open stages), following visual inspection under a stereomicroscope. For each trait and stage, three biological replicates were collected from independent plants, and each replicate comprised pooled tissues to minimize individual variation. Variables such as floral organ type (sepal, petal, stamen, pistil) and tissue type (leaf, stem, bud) were explicitly recorded during sampling to allow comparison across spatial and temporal datasets.

2.2 Characterization of MYB and MADS Genes in H. macrophylla

To identify members of the MYB and MADS-box transcription factor families in H. macrophylla, the FASTA file of the Hydrangea genome and protein sequences (version HMA_r1.2_1) was downloaded from the published reference genome of the cultivar ‘Aozora’ (https://plantgarden.jp/en/list/t23110, accessed on 19 October 2025).

Two complementary approaches were used for gene identification. Initially, Hidden Markov Model (HMM) profiles corresponding to MYB and MADS domains were obtained from the Pfam database (http://pfam.xfam.org/) and utilized with HMMER software to perform domain-specific searches within the Hydrangea protein dataset. Subsequently, a homology-based approach was implemented by employing 168 MYB protein sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana, along with 70 M-type and 76 MIKC-type MADS-box protein sequences, all sourced from the Plant Transcription Factor Database (http://planttfdb.gao-lab.org/index.php, accessed on 19 October 2025).

These sequences were aligned to the Hydrangea protein database using local BLAST, with an E-value threshold set at 1 × 10−10. Outputs from both the HMM and homology-based methods were merged for further analysis. To confirm the presence of conserved domains in the candidate MYB and MADS proteins, validation was conducted using both the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (NCBI-CDD; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi, accessed on 19 October 2025), and Pfam.

Furthermore, the isoelectric points (pI) and molecular weights (Mw) of the predicted transcription factors were calculated using the ExPASy ProtParam tool (http://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 19 October 2025), and their likely subcellular localization was assessed using the WoLF PSORT prediction tool (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/).

2.3 Analysis of Conserved Domains and Motifs in Hydrangea MYB and MADS Genes

Conserved domain prediction and classification of MYB and MADS-box transcription factor families in H. macrophylla were conducted using the Pfam database and the InterProScan tool (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/, accessed on 19 October 2025). Several order alignments of the MYB and MADS family proteins were performed using MAFFT software. Phylogenetic trees were subsequently created in MEGA 11 using the neighbor-joining method with appropriate parameters.

To further characterize the structural features of these transcription factors, conserved motifs were identified using the MEME Suite (http://meme-suite.org/index.html, accessed on 19 October 2025). The settings were configured to detect up to 10 distinct motifs, with motif lengths ranging from 6 to 50 amino acids. TBtools software was employed to visualize domain structures, motif arrangements, and phylogenetic associations.

2.4 Phylogenetic Analysis of Hydrangea MYB and MADS Genes

Protein sequences of the MYB and MADS-box gene families identified in H. macrophylla were aligned alongside 168 MYB and 146 MADS-box protein sequences from Arabidopsis thaliana using the MAFFT alignment tool. Following the sequence alignment, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 11 software, applying the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) method with 1000 bootstrap replications and default configuration parameters. This comparative analysis provided insights into the evolutionary relationships between the gene families of Hydrangea and Arabidopsis.

2.5 RNA Extraction and Reverse Transcription

The Hydrangea genomic RNA was isolated with an Invitrogen PureLink RNA Mini Kit, and reverse transcription into cDNA was conducted using a cDNA synthesis kit. For each sample, three specimens from the same plant were combined to extract a singular RNA sample, whereas distinct plants of the same floral type served as biological duplicates.

A cDNA reaction system was prepared using 1500 ng of total RNA at the corresponding concentration. A total of 1 μL of random primer p(dN)6 (100 pmol), 1 μL of dNTP mix (final concentration 0.5 mM), and RNase-free ddH2O were combined to reach a final volume of 14.5 μL. The mixture was moderately vortexed, briefly centrifuged (3–5 s), and incubated at 65°C for 5 min in a water bath, followed by immediate cooling on ice for 2 min. After another brief spin (3–5 s), additional components were introduced: 4 μL of 5× RT buffer, 0.5 μL of RiboLock RNase Inhibitor (20 U; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Pudong District, Shanghai, China.), and 1 μL of Maxima Reverse Transcriptase (200 U). The complete reaction mix was gently mixed, quickly centrifuged, and then subjected to a reverse transcription cycle using a PCR system. The synthesized cDNA was stored at −20°C until further use.

2.6 Quantitative Fluorescent PCR

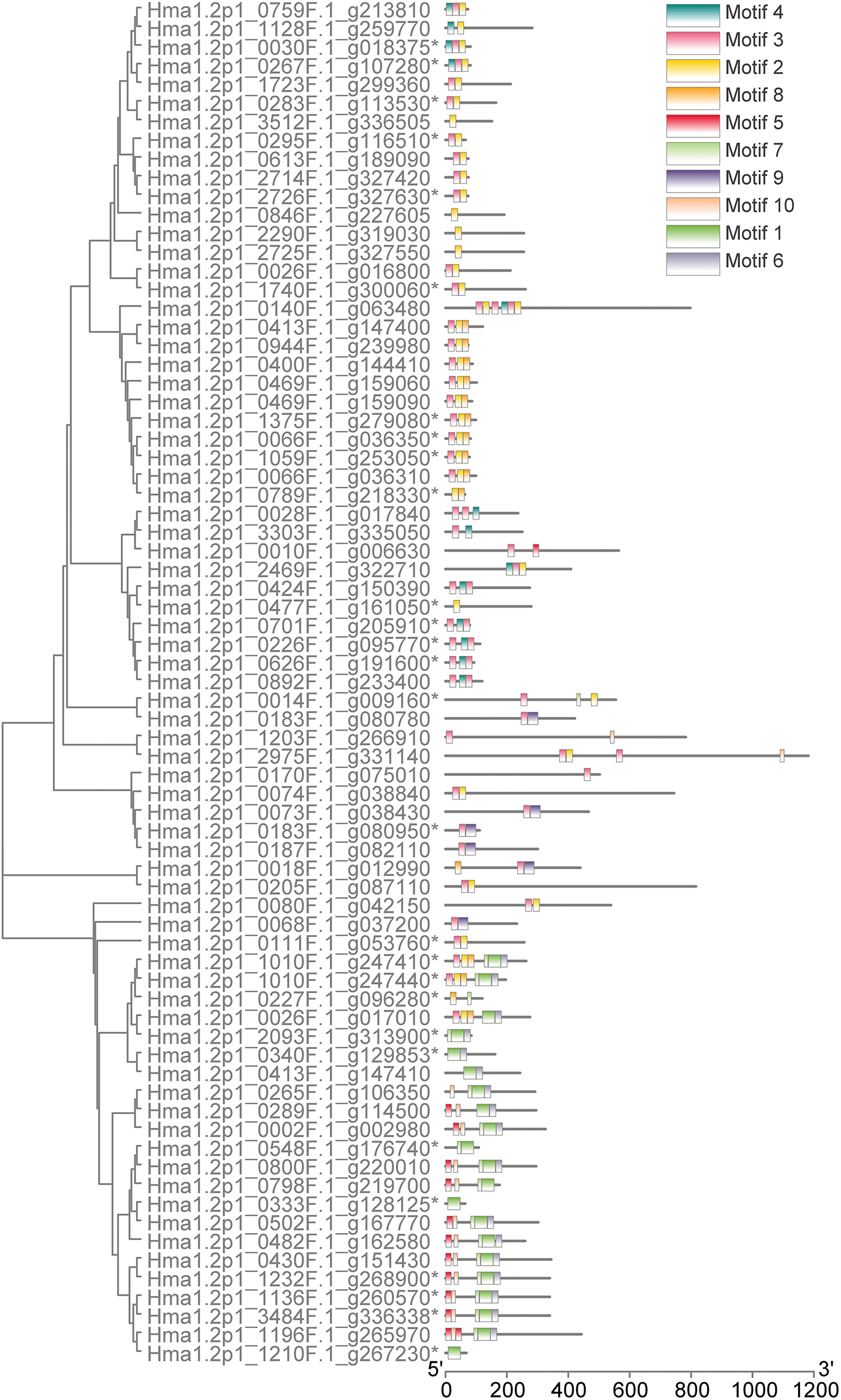

Drawing upon findings from our previous genome-wide association study [18], the SNPs closely related to inflorescence morphology in H. macrophylla clustered in the scaffolds Hma1.2p1_0653F.1, Hma1.2p1_0669F.1 and Hma1.2p1_0060F.1. HmMYB1 (Hma1.2p1_0653F.1_g196210), HmMYB2 (Hma1.2p1_0669F.1_g200310), and HmMADS1 (Hma1.2p1_0060F.1_g032780) were identified in the scaffolds as potential regulators of inflorescence type and flower development. These genes, belonging to the MYB and MADS-box transcription factor families, were selected for spatiotemporal expression profiles.

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was conducted. The actin gene, characterized by high and stable expression across different Hydrangea tissues, was selected as the internal reference. Coding sequences (CDS) from the reference genome were used to design gene-specific primers using Primer 5.0 software. Table 1 contains the sequences of the primers used in this study. The qRT-PCR assay was performed in a 20 μL reaction mixture comprising 10 μL of 2× ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Nanjing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China), 1 μL of synthesized cDNA, 0.4 μL each of forward and reverse primers, and RNase-free double-distilled water to adjust the final volume.

The amplification process was executed on an ABI QuantStudio platform with the following thermal protocol: an initial denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 10 s, and a combined annealing and extension step at 60°C for 30 s. To confirm the specificity of the amplification, a melting curve analysis was conducted post-PCR. All reactions were carried out in three technical replicates to ensure consistency and reliability. Negative control reactions, containing ddH2O instead of cDNA, were included to check for any potential contamination. Gene expression levels were quantified using the 2–ΔCT method, and the data were processed with Microsoft Excel.

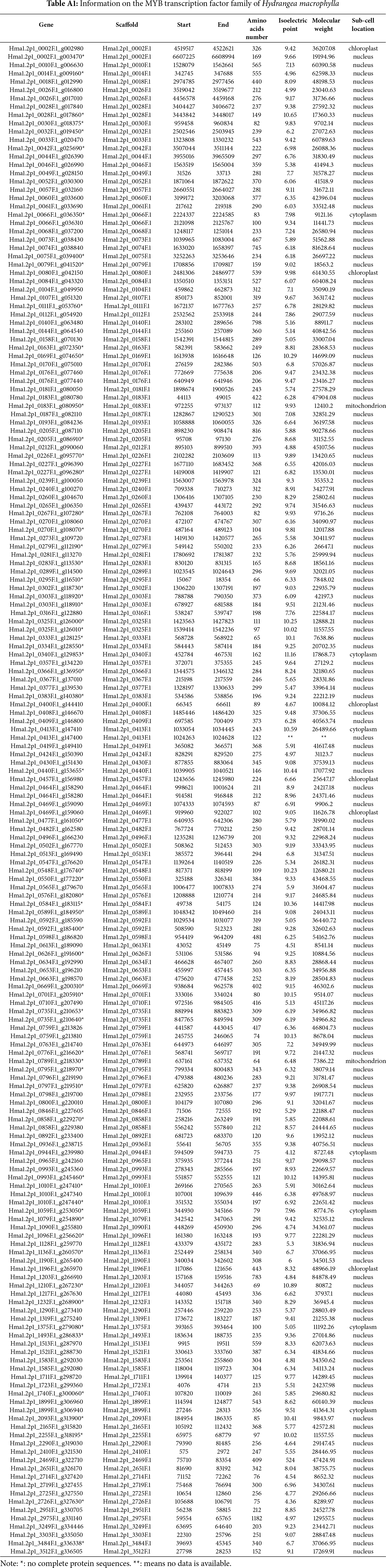

3.1 Identification of MYB Gene Families in the Hydrangea Genome

Using the PFAM MYB domain model (PF00249) and HMMER, 69 MYB sequences were initially obtained in the Hydrangea genome. Subsequent BLAST searches against Arabidopsis MYB proteins yielded 205 candidates in the Hydrangea genome, of which 182 non-redundant HmMYB proteins were retained after domain validation. Of these HmMYBs, 81 members have a pI below 7 and 101 have a pI higher than 7, indicating a prevalence of basic proteins. By subcellular localization predictions, it showed that most of HmMYBs localize in the nuclear, with fewer in the chloroplast, mitochondria, or cytosol (Appendix A).

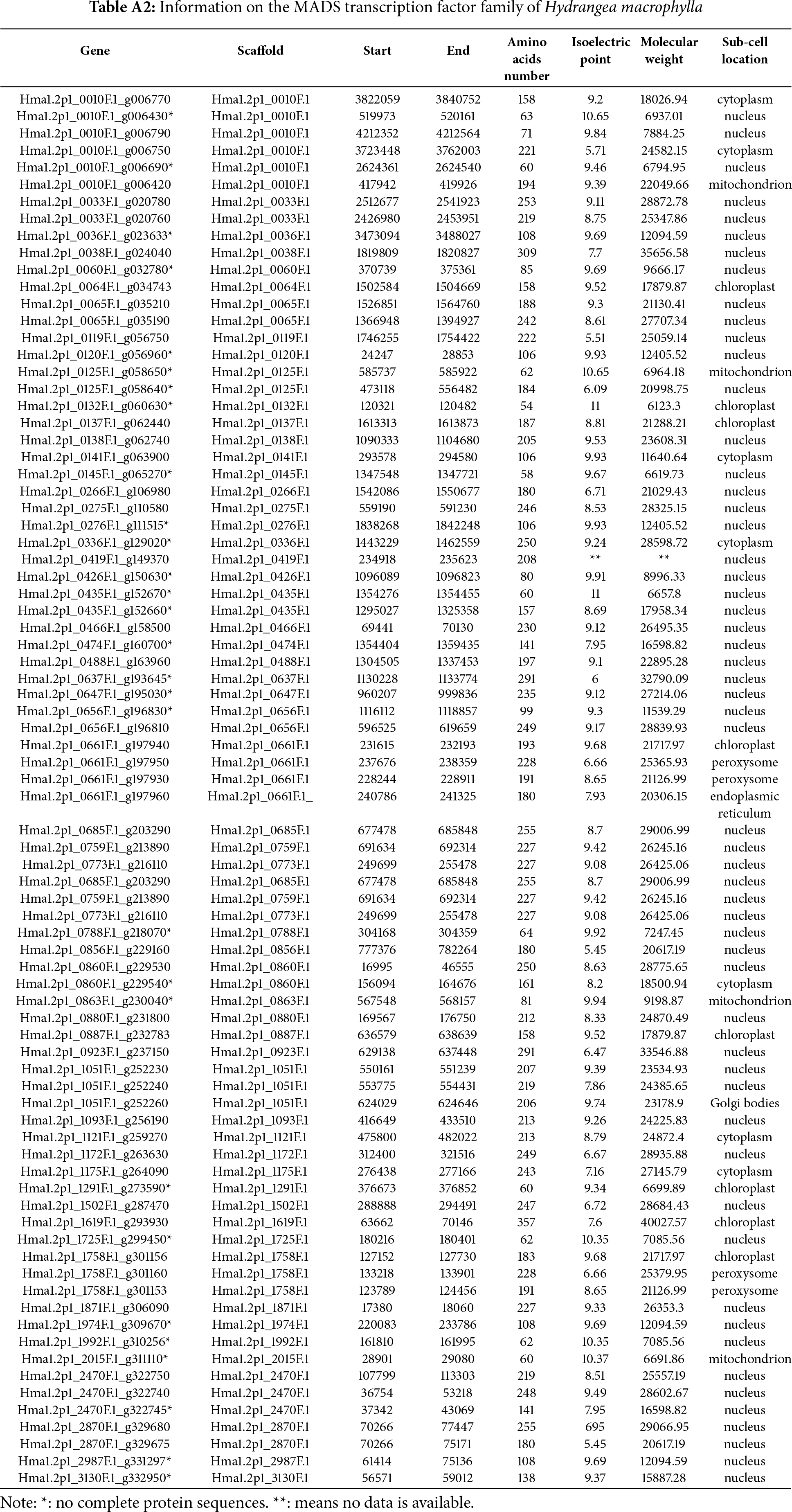

3.2 Identification of MADS Gene Families in the Hydrangea Genome

The conserved MADS domain model (PF00319) was used to identify 25 sequences using HMMER. A complementary BLAST search with Arabidopsis MADS proteins yielded 84 preliminary hits. After redundancy removal and domain verification, 78 unique MADS-box genes were confirmed. Of these HmMADSs, 64 were basic proteins (pI > 7). Subcellular predictions revealed nuclear localization for 53 proteins, with others in chloroplasts, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi body, and peroxisomes (Appendix B). Notably, a gene cluster on scaffold Hma1.2p1_0010F.1 includes five tandemly arranged MADS-box genes.

3.3 Conserved Domain and Motif Analysis of MYB Gene Family

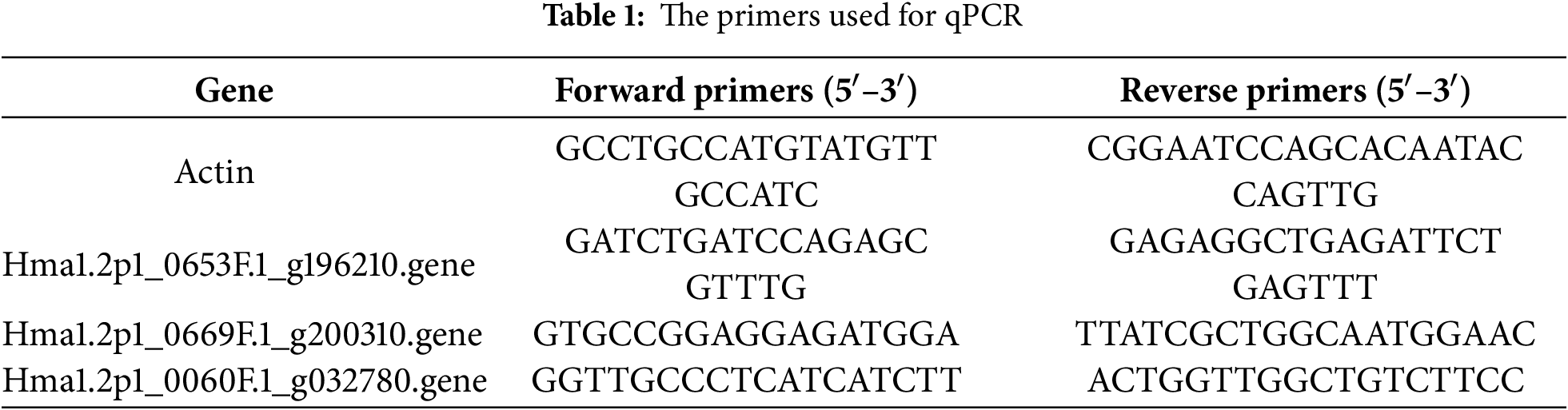

The HmMYB genes were classified into 3 groups, 1R-MYB, 1R-MYB, and R2R3-MYB, based on the number of DNA-binding domains. 73 HmMYBs belong to 1R-MYB, 105 HmMYBs to R2R3-MYB, and 4 to 3R-MYB. Due to sequence incompleteness, motif analysis focused on 1R- and R2R3-MYB subgroups.

For 1R-MYB, 73 members were identified, but 28 lacked full sequences. Motif analysis (MEME) identified 10 conserved motifs, with Motif2 and Motif3 most frequent, followed by Motif1 and Motif5 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Prediction of motif of 1R-MYB in Hydrangea macrophylla

There were 10 conserved motifs identified in R2R3-MYBs, with Motif1 and Motif3 present in all R2R3-MYBs genes except 35 incomplete R2R3-MYBs. All the members in this group existed 3 conserved motifs at least, a maximum of 8 motifs (Fig. 3). Phylogenetic clustering aligned with motif conservation, suggesting structural-functional relationships.

Figure 3: Prediction of conserved motif of R2R3-MYB in Hydrangea macrophylla

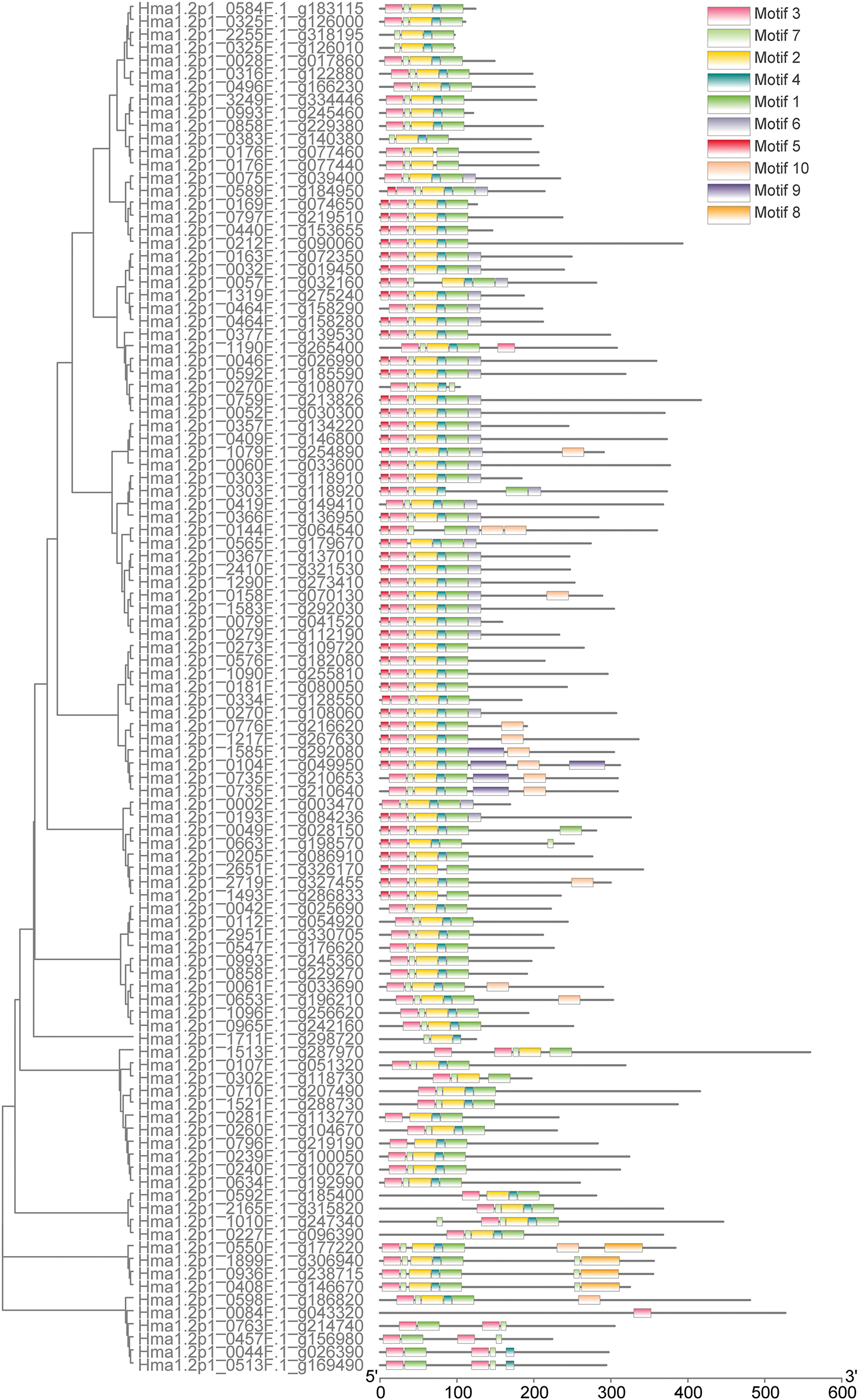

3.4 Conserved Domain and Motif Analysis of MADS Gene Family

Among the 78 MADS genes, 42 were classified as Type I (M-type), and 36 as Type II (MIKC-type). Type I genes contained Motif1 and close to the 5′ end, in some cases, Motif 2, 4, and 5 (Fig. 4). Most Type II genes had complete K domains and 2–8 motifs, commonly Motif 1, 2, 3, and 5 (Fig. 5), reflecting higher structural complexity and potential functional diversity.

Figure 4: Prediction of conserved motif of Tyepe I (M-type) MADS in Hydrangea macrophylla

Figure 5: Prediction of conserved motif of type II (MIKC-type) MADS in Hydrangea macrophylla

3.5 Evolutionary Analysis of MYB and MADS Gene Families

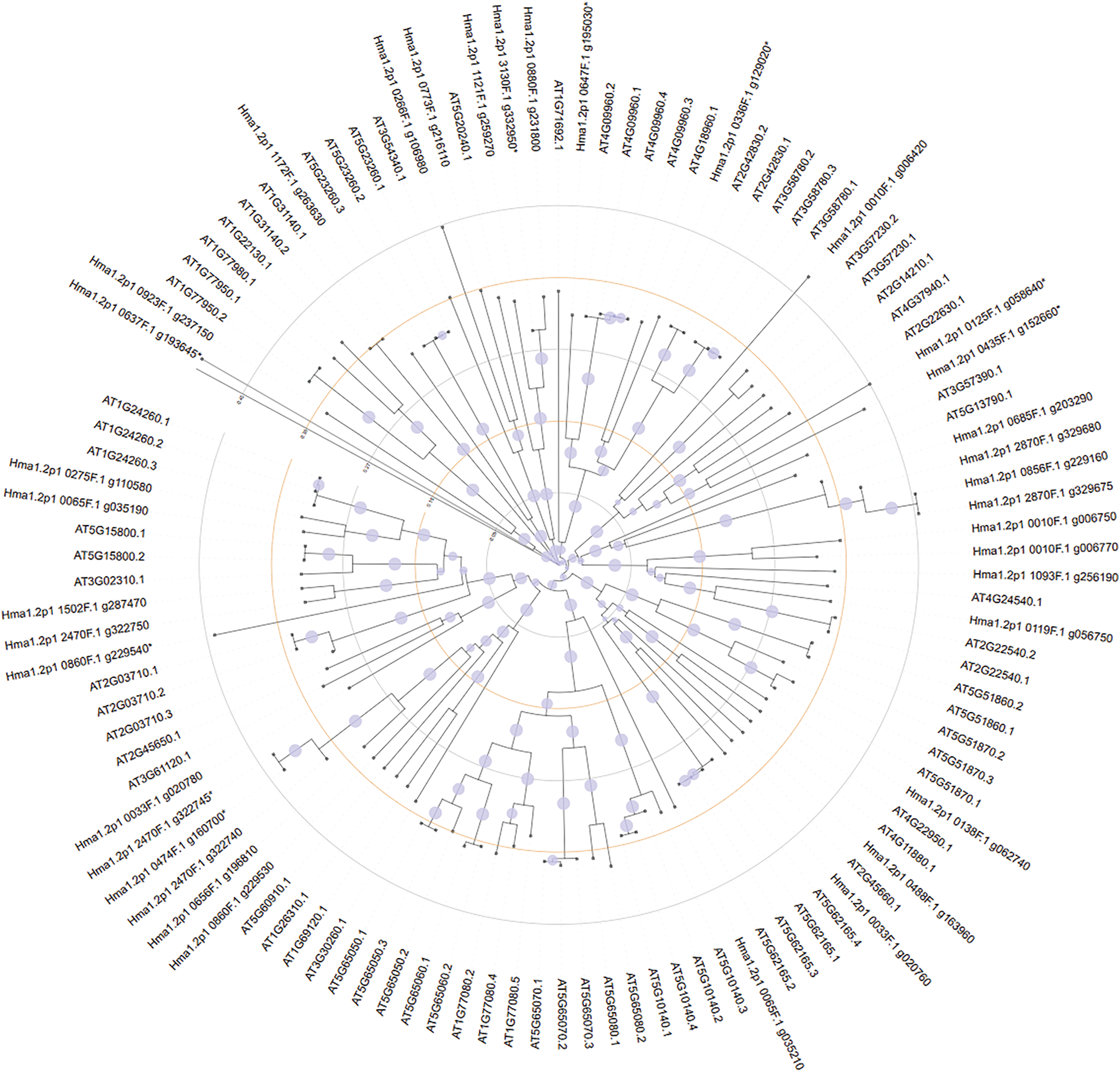

Multiple sequence alignment of 182 Hydrangea MYB genes and 168 Arabidopsis MYBs revealed 29 incomplete Hydrangea sequences. Phylogenetic analysis indicated gene clustering between species, suggesting conserved functions (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Phylogenetic relationship of MYB genes between Hydrangea macrophylla and Arabidopsis thaliana

For MADS-box genes, separate trees were constructed for M-type (Fig. 7) and MIKC-type genes (Fig. 8). M-type genes showed limited interspecies clustering, suggesting divergent evolution. In contrast, MIKC-type MADS genes from both species formed conserved clades, indicating shared evolutionary trajectories.

Figure 7: M-type MADS gene phylogenetic relationship between Hydrangea macrophylla and Arabidopsis thaliana

Figure 8: MIKC-type gene phylogenetic relationship between Hydrangea macrophylla and Arabidopsis thaliana

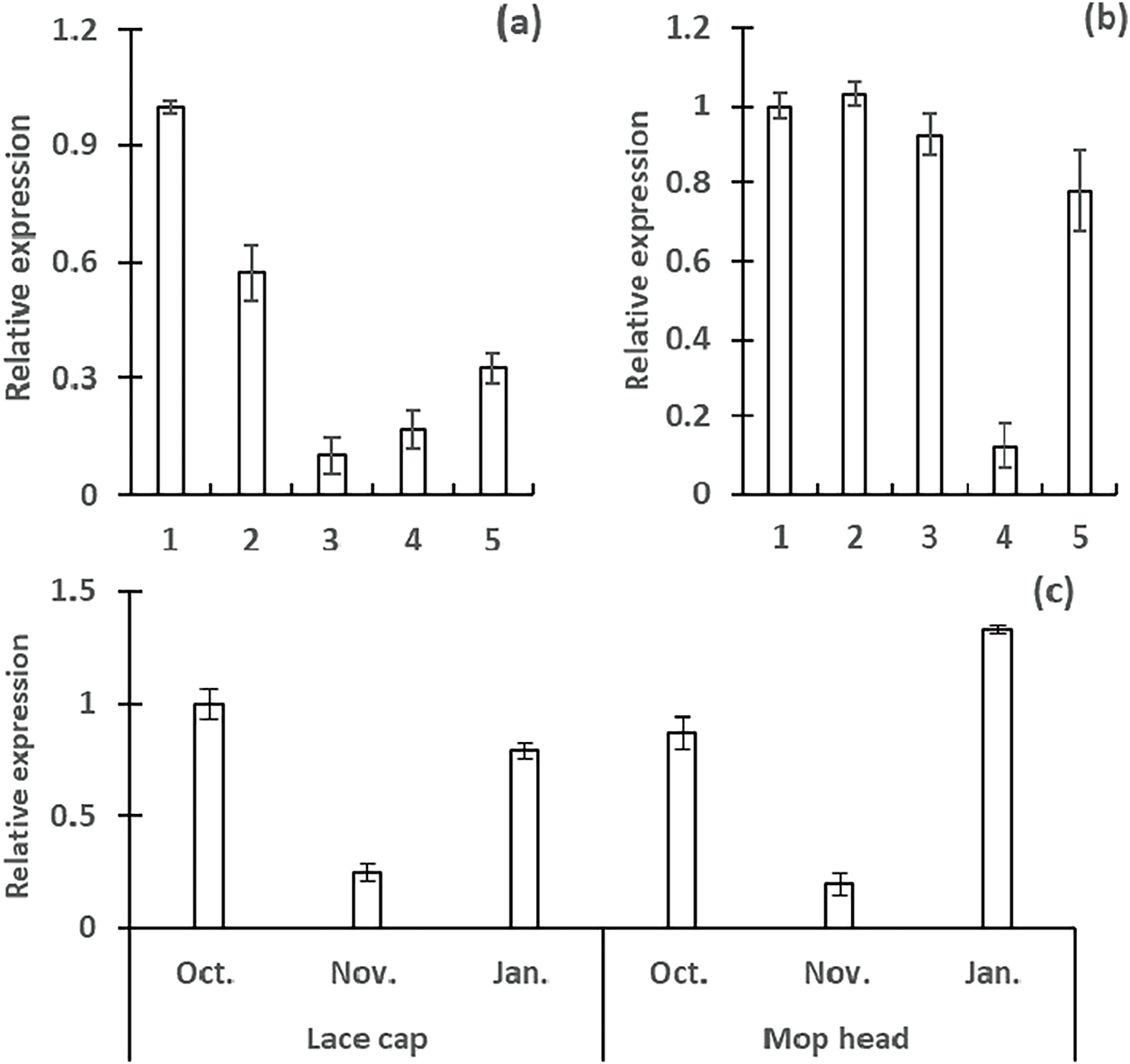

3.6 Spatiotemporal Expression Profiles of MYB Transcription Factors

Expression analysis of HmMYB1 (Hma1.2p1_0653F.1_g196210) revealed cultivar-specific dynamics. In the lacecap cultivar ‘White Angel’, transcript levels peaked in stems (~10-fold higher than in flower buds) and increased progressively in floral tissues during bud development (Fig. 9a). The mophead cultivar’ Kahou’ similarly exhibited stem-predominant expression but with reduced organ-to-organ variation (Fig. 9b).

Figure 9: Expression analysis of HmMYB1 gene (Hma1.2p1_0653F.1_g196210) in different developmental stages and tissues of Hydrangea. 1: branch, 2: leave, 3: inflorescence bud, 4: semi open sepal, 5: full open sepal. (a): ‘White angel’, (b): ‘Kahou’, (c): developmental stages of inflorescence buds

Among F1 hybrids, expression fluctuated during bud development, reaching minimal levels in November for both inflorescence types. By January, HmMYB1 abundance was markedly higher in mophead inflorescence buds than in lacecap buds. These results implicate HmMYB1 in stem function and inflorescence bud differentiation (Fig. 9c).

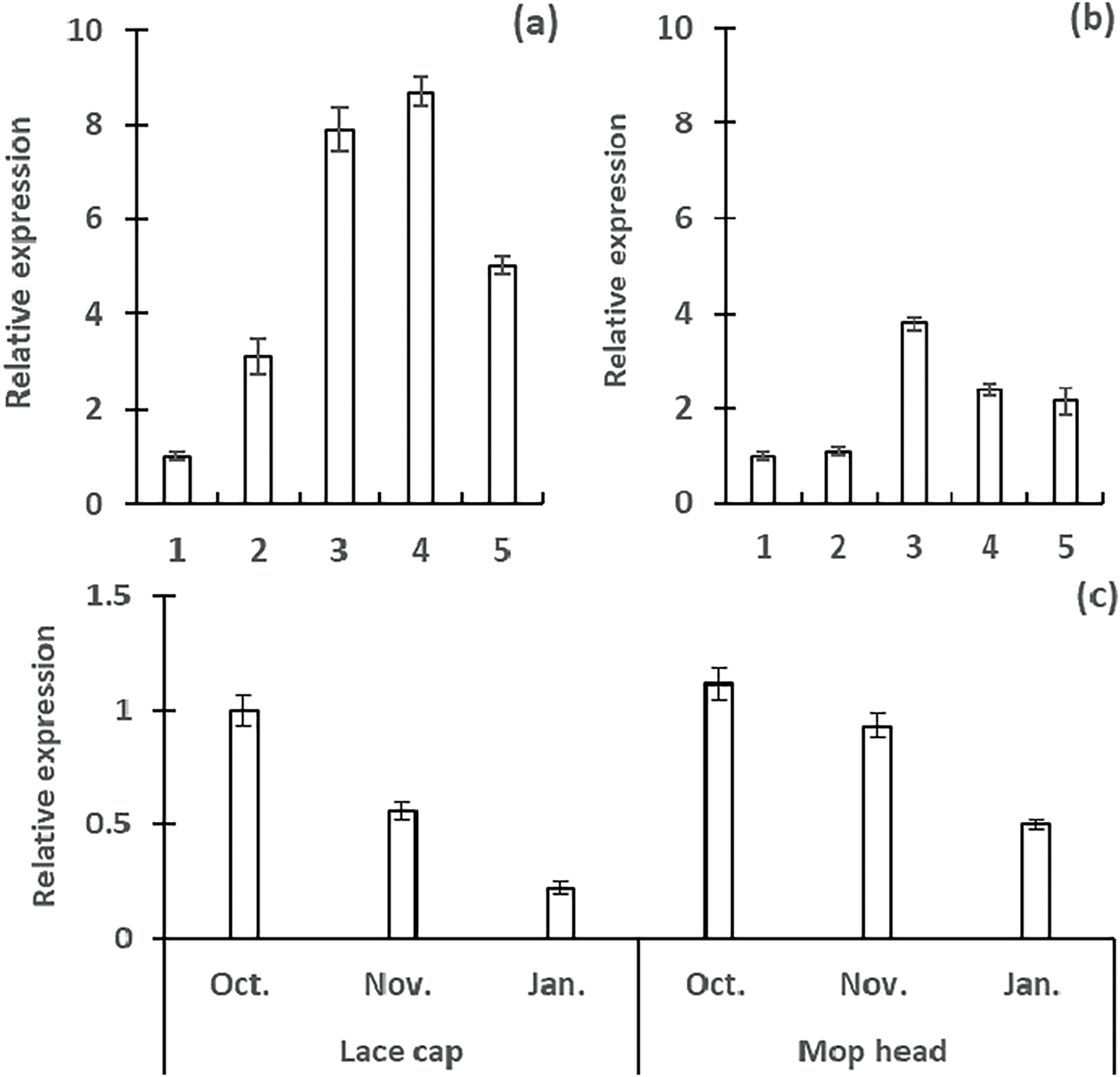

HmMYB2 exhibited spatiotemporal dynamics across cultivars. In ‘White Angel’ (lacecap), expression peaked in inflorescence buds and bud-stage decorative flowers (stages 3–4), with moderate persistence in mature flowers (stage 5) (Fig. 10a). ‘Kahou’ (mophead) showed similar bud-stage peaks (stage 3) but significantly attenuated expression in decorative flowers (stages 4–5) (Fig. 10b).

Figure 10: Expression analysis of HmMYB2 gene (Hma1.2p1_0669F.1_g200310) in different developmental stages and tissues of Hydrangea. 1: branch, 2: leave, 3: inflorescence bud, 4: semi open sepal, 5: full open sepal. (a): ‘White angel’, (b): ‘Kahou’, (c): developmental stages of inflorescence buds

F1 hybrids displayed a temporal decline from October to January in both inflorescence types, with mophead exhibiting the steepest reduction. These results position HmMYB2 as a key regulator of early floral differentiation and a determinant of inflorescence architecture (Fig. 10c).

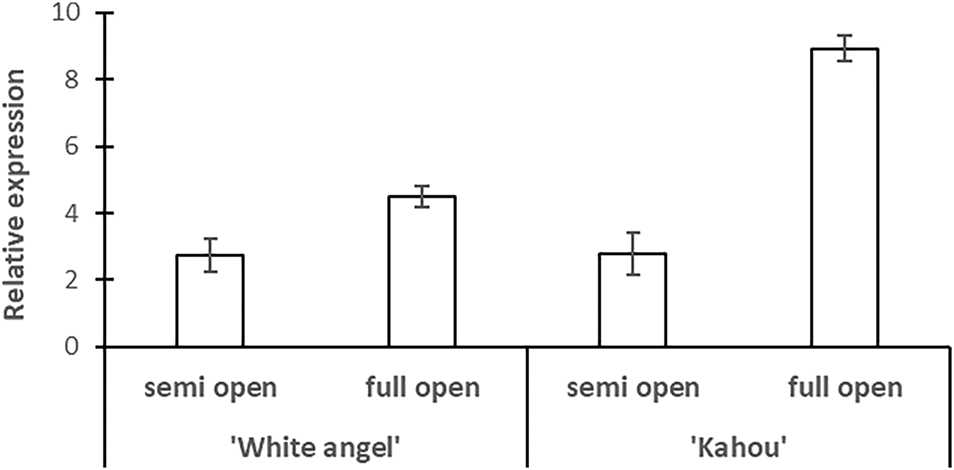

3.7 Spatiotemporal Expression of MADS Transcription Factors

HmMADS1 (Hma1.2p1_0060F.1_g032780) exhibited a distinct expression pattern that depends on both developmental stage and cultivar (Fig. 11). In both ‘White Angel’ and ‘Kahou’, transcript abundance was greater in completely open ornamental flowers than in semi-open flowers. For ‘White Angel’, expression rose moderately from the semi-open to the completely open stage, indicating a function in the progression toward full floral development. Conversely, ‘Kahou’ demonstrated a significant elevation in HmMADS1 expression during full bloom, with transcript levels over thrice more than those in semi-open flowers, indicating the greatest expression across all evaluated circumstances.

Figure 11: Expression analysis of HmMADS1 gene (Hma1.2p1_0060F.1_g032780) during florets development of Hydrangea

The significant increase in ‘Kahou’, along with the constant trend observed in both cultivars, suggests that HmMADS1 may serve as a crucial regulator in the terminal phases of floral organ development, potentially affecting petal growth, pigmentation, or the differentiation of reproductive organs. The cultivar-specific level of expression indicates potential genetic variations in the regulatory pathways governing HmMADS1 activity, which may influence differences in ornamental flower form and blooming timing.

MYB and MADS Transcription factors are involved in a number of biological pathways that are concerned with the flower formation, color, shape, and fragrance of flowers, along with inflorescence type and formation in many plant species. MYB TFs contain a repetitive MYB domain as a characteristic feature and are counted for the sepal formation, differentiation of cells, and pigment synthesis. In ornamental plants, also in Hydrangeas, anthocyanins production is related to MYBs, which contribute to flower coloration [19].

In the development of pollen, MYB genes have a special part for instance, in Arabidopsis thaliana, the fertility of pollens is modulated by the MYB gene family [20]. Floral bud formation is also accomplished by the involvement of these genes [21], as evidenced by studies in Dendrobium officinalis, epidermal morphology of cells can be altered through silencing of the DhMYB1 gene, which leads to changes in the shape of petals to a flattened form from a conical one [22]. In addition, the production of anthocyanin and floral fragrance is also associated with the MYB family in a number of species, which include orchids and Hydrangea as well [23,24].

In floral parts development, such as petals, sepals, carpel, and stamens the MADS box gene family has a pivotal involvement, which confers structural and functional diversification to flowers [25]. Moreover, TFs such as MYC2, belong to the bHLH family of genes, are proven to indulge in the promotion of Arabidopsis thaliana flowering through blockage of JA dependent flowering pathway and also regulates the development of the calyx [26]. When bHLH proteins interact with other MYB proteins, they generate complicated complexes that are involved in numerous processes of floral development. Prior research studies have proven the contribution of the MAD box family in the determination of flowering induction period, floral organogenesis, and epigenetic regulations of flower formation. MYB and MADS box TFs together, depicted a massive correlation in the production of flowers by plants [27]. In the case of Hydrangea, alterations in the phenotype of flowers can be created by the induction of mutations and changes in the expression levels of MADS genes [28]. This approach supports targeted screening of gene family members that influence specific inflorescence characteristics in Hydrangeas.

The spatiotemporal expression analysis of four candidate genes (bHLH, MYB2, MADS, and MYB1) linked to Hydrangea inflorescence types MYB2 encodes an MYB transcription factor, MADS encodes a MADS-box transcription factor, and bHLH encodes a bHLH transcription factor. According to literature, MYB, MAD box, and bHLH genes control sepal, flower, and inflorescence formation and its type in various plants such as tomato, chickpea, and some others [5,29]. Selected genes exhibited expression in sepals during both bud differentiation and flowering stages, with noted differences between spherical and Lacecap Hydrangea types. These genes also displayed high expression in stems and leaves, indicating a potential role in response mechanisms outside floral tissues and in developmental processes specific to Hydrangea formation.

The primary morphological distinction between spherical and Lacecap Hydrangea inflorescences lies in sepal development. In the case of spherical type inflorescence, small sepals that surround the inflorescence get enlarged and create a thickened circular structure, affected by the elongation of the internodes of the axis on which the inflorescence resides. Conversely, in other cultivars that comprises a flat top head, ornamental sepals are developed only by nonornamental flowers that are present in the middle. It was observed that these differences extend beyond sepal size to encompass inflorescence structure and axial internode length, attributes that the conventional ABC model does not fully explain for ornamental flower formation. Yet, Hydrangea follows a mechanism that is more complex that the ABCDE flowering pattern for the formation of ornamental and non-ornamental structures of flowers.

In conclusion, the present findings underscore the intricate genetic regulation underlying Hydrangea inflorescence morphology, implicating MYB, MADS, and bHLH genes as contributors to a complex trait shaped by multiple genetic and environmental factors. This study contributes to the foundation for further molecular analysis of inflorescence traits in Hydrangeas, offering insights that may facilitate molecular-assisted breeding and the targeted manipulation of ornamental characteristics.

This paper offers critical perceptions into the genetic regulation of Hydrangea flower morphology by investigating the spatiotemporal expression of key transcription factor genes, including MYB, MADS, and bHLH, linked to flower development and type differentiation. The findings highlight significant gene expression differences between spherical and Lacecap Hydrangea types, suggesting a genetic basis for morphological variation. Notably, the MADS gene, with its specific expression in flower buds and sepals, confers a major contribution in the ABCDE model to study developmental stages of flowers, and also to the structural formation of Hydrangea flowers.

Furthermore, the comprehensive identification and classification of 182 MYB genes and 78 MADS genes within the Hydrangea genome, along with the analysis of their molecular characteristics and conserved motifs, provides a foundational understanding of the functional properties of these gene families. The phylogenetic analysis, comparing Hydrangea genes to those in Arabidopsis, elucidates the evolutionary relationships that have shaped the diversification of gene families involved in flower development, offering a comparative framework for understanding morphological traits in Hydrangeas.

These findings significantly advance our understanding of the genetic mechanisms underlying Hydrangea flower morphology, with implications for breeding programs focused on improving ornamental qualities and creating new cultivars with desired flower shapes. This research lays the groundwork for upcoming revisions on the functional validation of key genes and molecular-assisted breeding strategies, ultimately contributing to the enhancement of Hydrangea cultivation.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This project was funded by Science and Technology Research Project of Shanghai Greening and City Appearance Administration in 2023 (G232406).

Author Contributions: Qunlu Liu conducted the literature review and drafted the manuscript. Fiza Liaquat, Qiqi Tang, and Amber Malik contributed to data analysis and manuscript revision. Jun Yang, Kang Ye, and Jun Qin provided methodological guidance. Shuai Qiu and Kai Gao assisted with image preparation, language polishing, and formatting. Jun Qin supervised the overall progress of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Appendix A

Appendix B

References

1. Wang Y, Song F, Zhu J, Zhang S, Yang Y, Chen T, et al. GSA: genome sequence archive. Genom Proteom Bioinform. 2017;15(1):14–8. doi:10.1016/j.gpb.2017.01.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Cheng Z, Ge W, Li L, Hou D, Ma Y, Liu J, et al. Analysis of MADS-box gene family reveals conservation in floral organ ABCDE model of moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:656. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Chen D, Burley JB, Machemer T, Schutzki R. Ordination of selected traditional Japanese gardens, traditional Chinese gardens, and modern Chinese gardens. Int J Cult Hist. 2021;8(1):14. doi:10.5296/ijch.v8i1.18250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Meng D, Cao Y, Chen T, Abdullah M, Jin Q, Fan H, et al. Evolution and functional divergence of MADS-box genes in Pyrus. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1266. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-37897-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Shinozaki Y, Hao S, Kojima M, Sakakibara H, Ozeki-Iida Y, Zheng Y, et al. Ethylene suppresses toma to (Solanum lycopersicum) fruit set through modification of gibberellin metabolism. Plant J. 2015;83(2):237–51. doi:10.1111/tpj.12882. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Li M, Cao Y, Debnath B, Yang H, Kui X, Qiu D. Cloning and expression analysis of flavonoid 3′, 5′-hydroxylase gene from Brunfelsia acuminata. Genes. 2021;12(7):1086. doi:10.3390/genes12071086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Wen J, Li J, Wu K, Zeng J, Li L, Fang L, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals PpMYB1 and PpbHLH1 promote anthocyanin accumulation in Phalaenopsis pulcherrima flowers. Biomolecules. 2025;15(7):906. doi:10.3390/biom15070906. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Li B, Gao C, Zhang Y, Wang D, Xu Y. Evolution and expression analysis reveal the potential role of the MADS-box gene family in regulating the development of floral organs and stress responses in Iris. BMC Genom. 2022;23(1):25. [Google Scholar]

9. Dutta S, Biswas P, Chakraborty S, Mitra D, Pal A, Das M. Identification, characterization and gene expression analyses of important flowering genes related to photoperiodic pathway in bamboo. BMC Genom. 2018;19(1):190. doi:10.1186/s12864-018-4571-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Soneson C, Love MI, Robinson MD. Differential analyses for RNA-seq: transcript-level estimates improve gene-level inferences. F1000Research. 2015;4:1521. doi:10.12688/f1000research.7563.2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Guan H, Wang H, Huang J, Liu M, Chen T, Shan X, et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of MADS-box family genes in Litchi (Litchi chinensis Sonn.) and their involvement in floral sex determination. Plants. 2021;10(10):2142. doi:10.3390/plants10102142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hsu CC, Chen YY, Tsai WC, Chen WH, Chen HH. Three R2R3-MYB transcription factors regulate distinct floral pigmentation patterning in Phalaenopsis spp. Plant Physiol. 2015;168(1):175–91. doi:10.1104/pp.114.254599. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ravi S, Hassani M, Heidari B, Deb S, Orsini E, Li J, et al. Development of an SNP assay for marker-assisted selection of soil-borne Rhizoctonia solani AG-2-2-IIIB resistance in sugar beet. Biology. 2021;11(1):49. doi:10.3390/biology11010049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Khojayori FN, Ponraj U, Buch K, Zhao Y, Herrera-Ubaldo H, Glover BJ. Evolution and development of complex floral displays. Development. 2024;151(21):dev203027. doi:10.1242/dev.203027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Li J, Chen Y, Zhang R, Wang R, Wu B, Zhang H, et al. OsWRKY70 plays opposite roles in blast resistance and cold stress tolerance in rice. Rice. 2024;17(1):61. doi:10.1186/s12284-024-00741-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Tang QQ, Li JS, Qiu S, Zhang XQ, Gao K, Qin J, et al. Genome-wide association study of Hydrangea macrophylla inflorescence type. J Plant Genet Resour. 2023;24(4):1174–85. (In Chinese). doi:10.13430/j.cnki.jpgr.20230208004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang W, Wu Y, Schnable JC, Zeng Z, Freeling M, Crawford GE, et al. High-resolution mapping of open chromatin in the rice genome. Genome Res. 2012;22(1):151–62. doi:10.1101/gr.131342.111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Battat M, Eitan A, Rogachev I, Hanhineva K, Fernie A, Tohge T, et al. A MYB triad controls primary and phenylpropanoid metabolites for pollen coat patterning. Plant Physiol. 2019;180(1):87–108. doi:10.1104/pp.19.00009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Ma Z, Hu L, Zhong Y. Structure, evolution, and roles of MYB transcription factors proteins in secondary metabolite biosynthetic pathways and abiotic stresses responses in plants: a comprehensive review. Front Plant Sci. 2025;16:1626844. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1626844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Schwinn KE, Boase MR, Bradley JM, Lewis DH, Deroles SC, Martin CR, et al. MYB and bHLH transcription factor transgenes increase anthocyanin pigmentation in Petunia and Lisianthus plants, and the Petunia phenotypes are strongly enhanced under field conditions. Front Plant Sci. 2014;5(58):603. doi:10.3389/fpls.2014.00603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wang B, Wen X, Fu B, Wei Y, Song X, Li S, et al. Genome-wide analysis of MYB gene family in Chrysanthemum × morifolium provides insights into flower color regulation. Plants. 2024;13(9):1221. doi:10.3390/plants13091221. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Anuar MAK. Investigation into the role of R2R3-MYB transcription factors related to flower shape and colour in Dendrobium orchids [master’s thesis]. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: University of Malaya; 2023. [Google Scholar]

23. Shang Y, Ma Y, Zhou Y, Zhang H, Duan L, Chen H, et al. Biosynthesis, regulation, and domestication of bitterness in cucumber. Science. 2014;346(6213):1084–8. doi:10.1126/science.1259215. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Dombrecht B, Xue GP, Sprague SJ, Kirkegaard JA, Ross JJ, Reid JB, et al. MYC2 differentially modulates diverse jasmonate-dependent functions in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2007;19(7):2225–45. doi:10.1105/tpc.106.048017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Chen Q, Li J, Yang F. Genome-wide analysis of the mads-box transcription factor family in Solanum melongena. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(1):826. doi:10.3390/ijms24010826. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Wei B, Zhang RZ, Guo JJ, Liu DM, Li AL, Fan RC, et al. Genome-wide analysis of the MADS-box gene family in Brachypodium distachyon. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84781. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Lin Y, Li W, Chen Q, Lin Y, Ye W, Wu H, et al. Evolution and expression of MYB genes in Chinese bayberry (Morella rubra) based on transcriptome analysis. PeerJ. 2020;8:e9585. [Google Scholar]

28. Mao X, Cai T, Olyarchuk JG, Wei L. Automated genome annotation and pathway identification using the KEGG Orthology (KO) as a controlled vocabulary. Bioinformatics. 2005;21(19):3787–93. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/bti430. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Caballo C, Berbel A, Ortega R, Gil J, Millán T, Rubio J, et al. The SINGLE FLOWER (SFL) gene encodes a MYB transcription factor that regulates the number of flowers produced by the inflorescence of chickpea. New Phytol. 2022;234(3):827–36. doi:10.1111/nph.18019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools