Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Traditional Uses, Polysaccharide Pharmacology, and Active Components Biosynthesis Regulation of Dendrobium officinale: A Review

1 Institute of Chinese Materia Medica, China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences, State Key Laboratory for Quality Ensurance and Sustainable Use of Dao-di Herbs, Beijing, 100700, China

2 Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin, 301617, China

3 Zhangzhou Pien Tze Huang Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Zhangzhou, 363099, China

4 Zhejiang Provincial Station of Cultivated Land Quality and Fertilizer Management, Hangzhou, 310000, China

5 Yueqing Municipal Bureau of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Yueqing, 325600, China

* Corresponding Authors: Guozhuang Zhang. Email: ; Linlin Dong. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3721-3748. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.072062

Received 18 August 2025; Accepted 15 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Dendrobium officinale (DO) is a well-recognized medicinal and edible plant with a long history of application in traditional medicinal practices across China and Southeast Asia. Recent studies have demonstrated that DO is abundant in diverse bioactive compounds, including polysaccharides (DOP), flavonoids, alkaloids, and bibenzyls thought to exert a range of pharmacological effects, such as anti-tumor and immunomodulatory effects. However, our comprehensive understanding of two key aspects—pharmacological functions and biosynthetic mechanisms—of DO’s major constituents remains limited, especially when considered within the clinical contexts of traditional use. To address this gap, this study reviews DO’s historical applications, clinical effects, and related formulations through an analysis of ancient texts spanning nearly two millennia—with special attention to region-specific traditional medical texts. This provides a historical and empirical foundation for further exploration of its modern pharmacological potential. Given the central role of DOP in DO’s biological activities, this paper further summarizes its therapeutic applications across various diseases and the underlying mechanisms, with special emphasis on structure–activity relationships. This focus is particularly important because the structural characteristics of DOP are highly dependent on extraction and analytical methods, which have contributed to inconsistencies in pharmacological findings over the past two decades. Finally, the review highlights recent advances in the understanding of the in vivo biosynthesis and regulatory mechanisms of the major bioactive components in DO, with a particular focus on molecular regulation and responses to agricultural interventions. These factors are critical for the production of high-quality DO. Overall, this study develops a comprehensive knowledge framework that connects DO’s traditional applications of DO to its two key research areas: pharmacological functions and quality formation. We anticipate this framework will offer clear guidance for future research from a clinical perspective.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileDendrobium officinale (Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo) is a perennial epiphytic Orchidaceae species, whose stems are widely utilized in traditional medicinal practices and functional food products. Over the past few decades, the cultivation scale of Dendrobium officinale (hereinafter referred to as DO) in East Asia has expanded significantly, with the Chinese mainland emerging as the primary production region. Existing studies and GMPGIS predictions show that DO is most suitable for cultivation in southeastern China, especially in provinces such as Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, and Guizhou (Fig. 1a, Table S1). These predicted results are largely consistent with the actual situation. For example, Wenzhou in Zhejiang Province and Yueqing (a city adjacent to Wenzhou) are renowned as the “Hometown of Dendrobium officinale”; Zhangzhou in Fujian Province is also a major production area of DO in the province. In addition, other provinces including Guangdong, Guangxi, and Guizhou are also key production regions of DO in China. Modern DO cultivation methods are diverse, including greenhouse cultivation, epiphytic cultivation (growing on trees), and lithophytic cultivation (growing on rocks and cliff walls). DO grown via these distinct techniques exhibits notable differences in morphological traits (Fig. 1b,c). O has a long history as a source of traditional medicine. Although some researchers have sorted out the traditional pharmacological effects of DO based on mainstream ancient books and classics, such as Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing, Ming Yi Bie Lu, and Ben Cao Gang Mu [1], some other relatively less mainstream ancient books have not been counted in detail and systematically, which may miss some potential efficacy of DO. Furthermore, the current traditional applications of DO are mainly based on the plant itself, and there is no summary and induction of the processed products of DO or the prescriptions with DO as the main component. A systematic and comprehensive summary of the traditional efficacy of DO and the prescriptions with DO as the main component will help us have a clearer understanding of such a medicine-food homologous plant with a long history as DO.

Figure 1: Predicted suitable cultivation areas for DO and the morphology of DO under different cultivation patterns. (a), GMPGIS-predicted cities in China suitable for cultivating DO. (b), Different cultivation patterns of DO. ①–⑥ correspond to greenhouse cultivation, epiphytic log cultivation, horizontal log cultivation, living tree (date palm) cultivation, rock cultivation, and cliff cultivation, respectively. (c), Whole-plant and aboveground morphology of DO under different cultivation conditions. (d), Annual number of publications and annual citations of DO

Over the past two decades, the excellent therapeutic efficacy of DO has spurred a significant increase in related research. As shown in Fig. 1d, the number of publications on DO has generally trended upward, while the annual citation count has not kept pace. These studies on DO mainly focus on three key areas: pharmacological effects, medicinal chemistry, and improvement of medicinal material quality. Modern pharmacological studies based on in vitro and in vivo models have confirmed that DO possesses a wide range of pharmacological activities. Phytochemical research on DO has isolated and identified approximately 240 compounds from its stems, leaves, flowers, and other tissues—primarily including polysaccharides, bibenzyls, phenanthrenes, flavonoids, and phenolic acids. This has laid the foundation for establishing the correlation between compounds and biological activities [2]. A thorough understanding of the endogenous and exogenous factors that affect the synthesis and accumulation of active components in DO is key to improving its medicinal quality and promoting the sustainable development of the DO industry. This has also become a research focus for pharmacognosists, with continuous in-depth studies aided by advances in multi-omics tools. For example, high-quality genomic data of DO has been obtained through high-throughput sequencing, which is of great significance for revealing its genetic information and functional genes [3]. Transcriptomics and metabolomics analyses can be used to explore differential metabolites under different conditions or developmental stages and identify genes involved in metabolic changes [4]. Despite significant progress in DO research, there are still many challenges, mainly reflected in two key aspects: First, the structure-activity relationship of DO polysaccharides (DOP) remains unclear, which may be related to the diversity of DOP extraction and characterization methods, as well as the lack of unified standards and classifications. Second, the exogenous factors (such as temperature, light, etc.) that affect the accumulation of active components in DO, as well as the endogenous molecular regulatory mechanisms, still need to be systematically summarized. A systematic summary of integrated omics technology and molecular biology studies related to the biosynthetic control of key active components in DO will help construct molecular regulatory networks, thereby accelerating the breeding of new DO varieties.

Starting from the traditional efficacy of DO, this paper comprehensively reviews and sorts out ancient books that record the traditional uses of DO and prescriptions containing DO as a key component. It summarizes the main effects of DO itself and the prescriptions where it serves as a primary ingredient. Additionally, the paper systematically reviews the pharmacological activities of DO, with a particular focus on DO polysaccharides (DOP) and their structure-activity relationship. Furthermore, it outlines the endogenous regulatory mechanisms for the biosynthesis of active components and the exogenous factors that promote the modulation of active components, laying a foundation for future research related to DO.

The Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection, which includes international core journals selected via strict peer review [5], enables systematic integration of high-quality global research on Dendrobium officinale (e.g., cultivation techniques, bioactive components, pharmacological mechanisms) while avoiding interference from non-core/low-relevance literature. So all literature in this study was retrieved from the WoS Core Collection, with indexing dates limited to 01 January 2002–31 December 2024, and search topic set to “*Dendrobium officinale*”—initially identifying 822 documents. Book-type publications were excluded here: only two such works were retrieved, namely Dendrobranchiata (2014) and Microsatellite Markers: Potential and Opportunities in Medicinal Plants (2010). Their content was overly complex and had low relevance to DO research, justifying their removal. To improve accuracy, document types were further restricted to “Article” or “Review,” excluding 10 early access publications, 10 meeting abstracts, 8 corrections, 8 editorial materials, 7 news items, 7 proceeding papers, 1 letter, and 1 reprint. The final dataset comprised 40 Reviews and 739 Articles, totaling 779 documents.

3 Traditional Applications of Dendrobium officinale

Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo, a precious traditional Chinese medicinal herb, has a long history of use in traditional Chinese medicine. Endowed with diverse therapeutic effects, it has been highly valued by medical practitioners across dynasties (Table 1). As early as the Don Han Dynasty, Shen Nong Ben Cao Jing recorded that this herb mainly addresses bodily injuries, relieves impediment, regulates Qi downward, replenishes deficiencies and emaciation of the five internal organs, and enhances Yin essence. Long-term consumption can strengthen the gastrointestinal tract, reduce body weight, and extend lifespan—a sign that people of that era had recognized its key role in replenishing deficiencies and regulating internal organs.

In the Wei-Jin Dynasties, Ming Yi Bie Lu further noted that this herb is non-toxic; it primarily enriches essence, supplements internal insufficiencies, regulates stomach Qi, increases muscle mass, expels pathogenic heat and miliaria from the skin, and eases cold-induced arthralgia and weakness in the knees and feet. From these descriptions, it is evident that DO not only nourishes essence and Qi but also treats disorders related to the digestive system, muscles, and skin.

As time progressed, DO was increasingly used in medical works and prescriptions of subsequent dynasties. In the Tang Dynasty’s Bei Ji Qian Jin Yao Fang, there were various prescriptions centered on this herb: for example, Shi Hu Di Huang Jian was used to treat gynecological deficiencies, shortness of breath, and chest tightness; Huai Nan Ba Gong Shi Hu Wan Bing San addressed rheumatic pain and limited mobility in the lower back and feet; and Shi Hu Jiu could alleviate conditions such as Qi stagnation due to wind-deficiency, pain with contracture in the knees and feet, and walking impairment caused by weakness. These prescriptions fully demonstrate the therapeutic benefits of DO in addressing gynecological and rheumatic diseases.

In Song Dynasty medical works, the utilization of DO became more detailed. Shi Hu Jiu (recorded in Tai Ping Sheng Hui Fang) mainly replenishes deficient fatigue, boosts Qi and physical strength, relieves arthralgia and weakness in the lower back and feet, improves joint mobility, and strengthens muscles and bones. In Ji Feng Pu Ji Fang, prescriptions such as Shi Hu Wan and Shi Hu San targeted symptoms including deficient fatigue, flaccidity with arthralgia, limb spasms, bodily emaciation, and hand-foot pain—reflecting the great value of DO in replenishing deficiencies and fortifying muscles and bones.

During the Ming and Qing Dynasties, understanding and application of DO deepened further. Ben Cao Gang Mu recorded that it could treat spontaneous sweating caused by fever and internal obstruction of carbuncle suppuration, while Ben Cao Bei Yao mentioned that it gently nourishes the liver and kidney, clears deficiency-heat, astringes primordial Qi, enriches essence, and strengthens Yin.

Drawing on these traditional therapeutic benefits and theories of traditional Chinese medicine, the Chinese Pharmacopoeia (2020 Edition) concludes that Dendrobium officinale has a sweet taste and slightly cold nature, acting on the stomach and kidney meridians. It nourishes the stomach to promote fluid production and replenishes Yin to clear heat, and is used to treat symptoms such as fluid depletion from febrile diseases, dry mouth and polydipsia, stomach Yin insufficiency (accompanied by anorexia, nausea, and retching), lingering fever after illness, Yin deficiency with excessive fire, bone-steaming fever, blurred vision, and muscle-bone flaccidity..

From ancient medical works and prescriptions, it can be seen that in traditional applications, DO was mainly used for tonifying deficiency-fatigue, strengthening muscles and bones, benefiting essence and Qi, regulating the spleen and stomach, treating rheumatic arthralgia, and some skin diseases. Based on the traditional curative effects in ancient times and the theories of traditional Chinese medicine, the China Pharmacopoeia Committee concludes that DO is sweet in flavor and slightly cold in nature5. It acts on the meridians of the stomach and the kidney. It can benefit the stomach and promote the production of body fluids, nourish Yin and clear heat. It is used to treat symptoms such as body fluid depletion due to febrile diseases, dry mouth and polydipsia, insufficiency of stomach Yin, anorexia accompanied by nausea and retching, lingering fever after illness, Yin deficiency with effulgent fire, steaming bone-fever, blurred vision, and flaccidity of muscles and bones

4 Pharmacological Effects of Polysaccharides in Dendrobium officinale

With the advancement of technology, research on traditional Chinese medicines no longer focuses solely on their basic therapeutic effects. Instead, it aims to identify the main active compounds responsible for their efficacy and the underlying mechanisms of action. Recent studies indicate that nearly 250 chemical constituents have been isolated from DO [2]. These include polysaccharides, bibenzyls, phenanthrenes, flavonoids, phenolic acids, alkaloids, and others. Among these, polysaccharides are the most abundant and are currently regarded as the most important active components of DO.

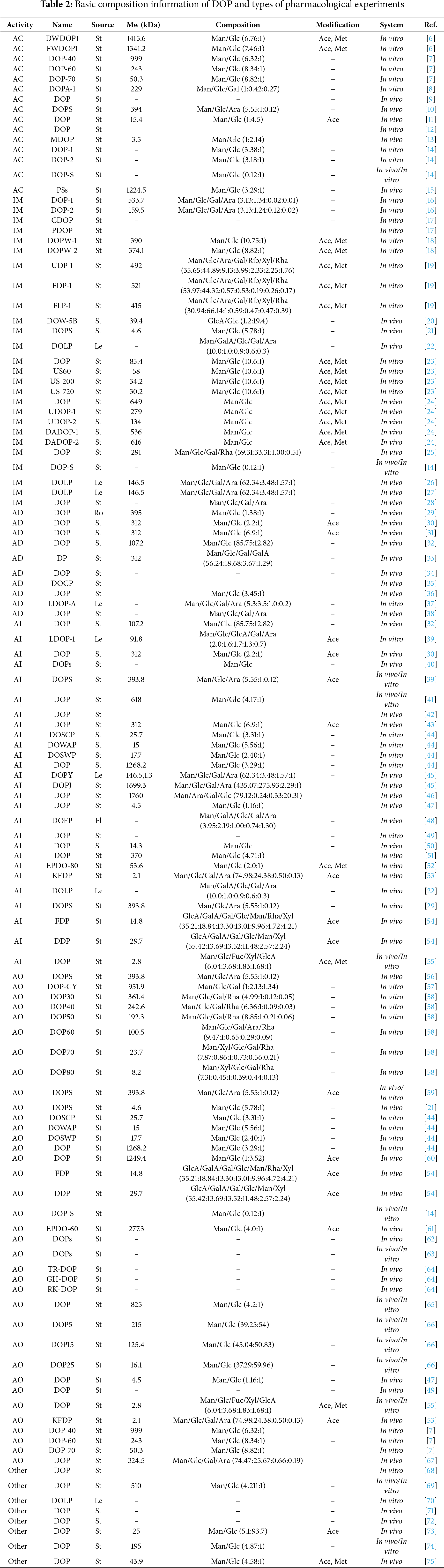

The bioactivity of polysaccharides is closely associated with their chemical features, such as molecular weight, structural traits, and functional group modifications. Polysaccharide products can vary significantly due to differences in extraction and isolation methods, and these variations undermine the reproducibility of pharmacological studies. A systematic analysis of the reported characteristics, pharmacological effects, and mechanisms of action can help elucidate the structure-activity relationships of DOP and promote research standardization. To this end, the following sections provide a comprehensive review of the pharmacological research on Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides (DOP), organized by their six main categories of bioactivity: anti-cancer, immunomodulatory, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and others (Fig. 2). Building on this, we systematically summarize in detail the chemical structural features (molecular weight, monosaccharide composition, and functional group modifications) associated with these polysaccharides exhibiting different pharmacological activities (Table 2). By summarizing the source parts, molecular weights, monosaccharide components, pathological models, effects and their mechanisms in the research on the pharmacodynamic effects of polysaccharides (Table S2), we found that there is significant variation in the biological activities of polysaccharides, which is closely related to their chemical characteristics (molecular weight, structural features, and functional group modification). This work aims to lay a foundation for elucidating the structure-activity relationships of polysaccharides with different structures as much as possible.

Figure 2: Key pharmacological activities of DOP and their regulatory genes or pathways. Red indicates promotion, blue indicates inhibition, and blac-k indicates regulation

All anti-tumor studies used polysaccharides extracted from the stems of DO, with molecular weights ranging from 3.5 to 1224.5 kDa and a predominant composition of glucose and mannose (Table 2). In vitro experiments employed various cancer cell lines, including Hela, HepG2, THP-1, HGC27, AGS, and H22 cells. These studies showed that DOP mainly exerts anti-cancer activity by inducing tumor cell apoptosis, achieved through regulating several signaling pathways such as p38/MAPK, Bcl-2/Bax, STAT6/PPAR-γ, and JAGGED1/NOTCH1 [6,7,12] (Fig. 2). In vivo studies further revealed that DOP can: inhibit gastric precancerous lesions in rats by modulating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [9]; suppress tumor growth in tumor-bearing mice by directly targeting Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2) on tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) and inducing their M1 polarization [11]; improve clinical symptoms of chronic colitis in colorectal cancer mice [10]; and significantly reduce the growth of transplanted S180 sarcoma in mice [13].

In studies exploring the immunomodulatory activity of DOP, polysaccharides from both DO stems (DOP) and leaves (DOLP) have been tested via in vitro and in vivo experiments. For in vitro studies, only stem-derived polysaccharides were used, with primary cell models including macrophage RAW264.7 cells, splenocytes, and NK cells (Table S2). In RAW264.7 cells, DOP has been shown to enhance phagocytic activity, boost NO release, and stimulate cell proliferation [6,76]. It also raises both the secretion levels and mRNA expression of macrophage cytokines (IL-6, IL-10, TNF-α). Notably, while TNF-α and IL-6 act as pro-inflammatory factors, IL-10 has anti-inflammatory properties—indicating DOP has dual immunomodulatory effects, with both pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory actions [23]. Other studies have found that DOP can either bind to the surface of RAW264.7 cells or be internalized [18], offering key insights into its regulatory mechanisms. For splenocytes and NK cells, DOP promotes splenocyte proliferation and strengthens NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity [16]. In vivo models have used both immunosuppressed and normal mice (Table S2). In immunosuppressed mice, both DOP and DOLP protect immune organs, reduce immune damage, adjust gut microbiota composition, and enhance immunity [9,12]. In normal mice, DOP significantly increases gut microbiota diversity, boosts beneficial bacteria while lowering harmful bacteria, improves colonic health, and strengthens immune responses [20]. Current research into the mechanisms behind DOP’s immunomodulatory activity is still relatively limited. For gut microbiota-mediated immunomodulation, potential mechanisms may include producing butyrate to affect gut microbiota and inhibiting CD4+ Th cell proliferation to modulate microbial composition [10,11] At the genetic and signaling pathway level (Fig. 2), DOLP upregulates the expression of Cd19, Cr2, and Il7r genes while downregulating Dntt gene expression—thus promoting hematopoietic function to enhance immune cell proliferation and differentiation [27]. Meanwhile, DOP suppresses overexpression of proteins in the TLR4 signaling pathway, which significantly alleviates cyclophosphamide-induced immunosuppression [28].

Polysaccharides from all three parts of DO—roots, stems, and leaves—have demonstrated therapeutic effects on diabetes, with research primarily based on in vivo experiments using T2D rat/mouse models (Table S2). Only one in vitro study has been reported, which uses NCI-H716 cells as the experimental model. DOP can alleviate diabetes through multiple strategies, including modulating various metabolic pathways (glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, amino acid metabolism) and adjusting gut microbiota [29,31,35]. For glucose metabolism, DOP corrects glucose metabolism disorders by promoting glycogen synthesis and regulating the activity of glucose-metabolizing enzymes [29]; For lipid metabolism, it rectifies abnormal ectopic lipid deposition and lowers serum levels of total cholesterol, triglycerides, and LDL-C [35]; For amino acid metabolism, it adjusts the upregulated BCAA metabolism caused by gut microbiota dysbiosis [31]. The mechanisms by which DOP regulates diabetes are shown in Fig. 2 and detailed as follows: DOP effectively rectifies glucose metabolism disorders by regulating PI3K/Akt signaling pathway-mediated glycogen synthesis and glucose metabolism [29]; it mitigates type 2 diabetes by upregulating mRNA expression of tight junction proteins Claudin-1, Occludin, and ZO-1, while reducing intestinal inflammation and oxidative stress damage via the LPS/TLR4/TRIF/NF-κB pathway [32]; it modulates TET2 by enhancing AMPK phosphorylation and improving mitochondrial function to prevent diabetes-induced neuronal apoptosis [33]; it achieves significant hypoglycemic and lipid-regulating effects by upregulating expression of genes including Glut2, Gck, Pklr, Insr, Pdx-1, and Ins1, while downregulating the apoptosis-related gene Caspase-3 [35]; it adjusts gut microbiota composition, reduces endotoxin levels, and inhibits TLR4 expression—thereby alleviating inflammatory responses and improving insulin resistance, as well as promoting expression of short-chain fatty acid receptors FFAR2/FFAR3 and increasing secretion of gut hormones GLP-1 and PYY to repair islet damage, suppress appetite, and enhance insulin sensitivity [36]; it improves obesity-induced insulin resistance by regulating the JAK/STAT/SOCS3 signaling pathway, downregulating SOCS3 expression, and upregulating IRS-1 [38].

4.4 Anti-Inflammation Activity

DOP extracted from stems, leaves, and flowers all show anti-inflammatory activity. Related pharmacological studies have primarily used in vivo experiments using various inflammatory rat or mouse models (Table S2), with in vitro models including GES-1 cells, RAW264. 7 cells, and LPS/IL-22-induced inflamed HaCaT keratinocyte cells. In vivo studies have shown that DOP possesses broad therapeutic efficacy against multiple inflammation-related diseases, including colitis, airway inflammation, pharyngitis, alcoholic liver injury, gastric ulcers, neuritis, atopic dermatitis, and inflammation-induced Sjögren’s syndrome [40,42,46,48,50,51,53,56] (detailed in Table S2). In vitro cellular experiments revealed: (1) leaf-derived DOP (LDOP-1) effectively prevented LPS-induced damage to GES-1 cells [39]; (2) three yeast-fermented DOP (DOSCP, DOWAP, DOSWP) and non-fermented DOP all reduced LPS-induced inflammatory responses in RAW264.7 macrophages [44]; and (3) a stem-derived DOP inhibited IL-22-induced hyperproliferation of keratinocytes without affecting normal keratinocyte growth [49]. Current research on DOP’s anti-inflammatory mechanisms is relatively comprehensive (Fig. 2). Specific findings include: (1) DOP ameliorates intestinal inflammation via the LPS/TLR4/TRIF/NF-κB pathway [32]; (2) DOP (LDOP-1) prevents LPS-induced GES-1 cell damage by regulating TLR4/NF-κB signaling to inhibit inflammatory factor release [39]; (3) potential benefits in reducing smoking-related pulmonary oxidative stress and inflammation through MAPK and NF-κB pathway inhibition [40]; (4) DOP (DOPS) significantly alleviates inflammatory responses and oxidative stress by suppressing TLR4 signaling while activating Nrf2 pathway, thereby mitigating colitis-associated lung injury [59]; (5) therapeutic effects on ESS mice through BAFF/BAFFR and Fas/Fas-L pathway inhibition to reduce inflammation and apoptosis [42]; (6) improvement of DNFB-induced atopic dermatitis in mice via MAPK/NF-κB/STAT3 pathway suppression [46]; (7) amelioration of chronic pharyngitis in rats by modulating TLR4/NF-κB pathway [48]; and (8) attenuation of oxidative stress and neuroinflammation through Nrf2/HO-1 pathway activation [56].

Studies on the antioxidant activity of DOP have predominantly utilized stem-derived polysaccharides, with investigations covering both in vivo and in vitro settings. While conventional rodent models have been used for in vivo studies, the experimental design has been extended to include Caenorhabditis elegans models. In vitro investigations have included not only cellular experiments but also chemical assays such as DPPH, ABTS, and hydroxyl radical scavenging assays, thereby enabling comprehensive evaluation of DOP’s antioxidant properties through multiple indicators. In vivo research has demonstrated that DOP’s antioxidant effects manifest through enhanced activities of antioxidant enzymes including SOD and GSH-Px, along with reduced MDA levels [60]. These antioxidant properties further contribute to therapeutic benefits for specific organ systems and pathological conditions: improved outcomes for oxidative stress-associated learning and memory dysfunction [56], significant suppression of glial cell overactivation in aging mice [60], mitigation of testicular oxidative damage [62], effectively lowering oxidative stress levels in nematodes (a change that extends lifespan) [63], strengthened protection against skin photoaging [55], and aiding in the amelioration of type 2 diabetes through antioxidant mechanisms [35]. In vitro experiments have confirmed DOP’s capacity for DPPH, ABTS, and hydroxyl radical scavenging [58]. Additionally, DOP exhibits protective effects against H2O2-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyocytes [57], and and mitigates photoaging in HaCaT cells [55], with further details provided in Table S2. Current research has identified the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway as the key mechanism underlying DOP’s antioxidant activity. Upregulation of this pathway has been shown to suppress oxidative stress in ovariectomy- and D-galactose-induced cognitive decline models [56]. Furthermore, experimental evidence confirms that DOP can ameliorate H2O2-induced H9c2 cardiomyocyte apoptosis through modulation of PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways [57], as illustrated in Fig. 2

In addition to the primary pharmacological activities of DOP discussed above, recent studies have identified several other therapeutic effects associated with polysaccharides isolated from DO stems and leaves (most evidence comes from in vivo investigations, Table 2). In vivo studies have demonstrated that DOP can significantly inhibit dexamethasone-induced osteoporosis in both zebrafish and mouse models [69], markedly mitigate testosterone-induced hair follicle miniaturization and alopecia symptoms, and ameliorate cognitive dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease mice [75]. In vitro experiments have revealed DOP’s ability to promote osteogenic differentiation of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells under DEX exposure [69]. Together, in vivo and in vitro studies collectively suggest that DOP provides certain beneficial effects for improving liver fibrosis [74].

4.7 Summary of the Structure-Activity Relationship of DOP

In summary, DOP exhibits diverse biological activities, yet investigating the factors influencing its biological activities is equally important. The antitumor activity of DOP is correlated with its molecular weight, with smaller molecular weights associated with more potent antitumor effects. For instance, Yu et al. (2018) found that crude polysaccharide FWDOP (undegraded, 1341.0 kDa) exerted no significant activity against HeLa cells, whereas the degraded polysaccharides F1–F6 (all with molecular weights below 100 kDa) demonstrated notable antiproliferative activity [6]. Similarly, Xing et al. (2018) isolated four DOP fractions with different molecular weights via ethanol fractional precipitation, among which the smallest fraction, DOP-70 (50.3 kDa), exhibited the strongest antitumor activity [7]. Furthermore, the antitumor activity of DOP may stem from its core chemical structure. Wan et al. (2024) used β-mannanase to degrade DOP (1224.54 kDa) into oligosaccharides-1, and this oligosaccharide retained antitumor activity in mice with colon cancer, thus confirming that this structural feature is central to the anti-CAC (colitis-associated cancer) effect of polysaccharides [15]. The immunomodulatory activity of DOP is primarily influenced by purification level, degree of acetylation (DA), monosaccharide composition, and molecular weight. Tao et al. (2019) observed that purified DOP fractions more effectively promoted the proliferation of macrophages and lymphocytes, and their immunomodulatory activity was notably stronger than that of crude polysaccharides [18]. Both in vitro and in vivo studies have shown that DOP with higher DA exhibits stronger bioactivity, a property that weakens as acetylation levels decline, highlighting that an optimal acetylation level is crucial for DOP’s immunomodulatory effects [23,24]. In vitro experiments revealed that alterations in monosaccharide composition and molecular weight of DOP following fermentation with Bacillus sp. DU-106 significantly stimulated the proliferation of RAW 264.7 cells and the production of nitric oxide and IL-1β [19]. Additionally, both in vitro and in vivo studies showed that moderate reduction in molecular weight achieved through ultrasonication significantly boosts DOP’s immunomodulatory effects, though overly low molecular weights can diminish this activity [23,24]. Studies on factors affecting DOP’s antidiabetic activity remain limited. Existing studies suggest that DOP extracted from fresh DO has greater anti-inflammatory activity compared to DOP extracted from dried samples [54]. Moreover, incorporating DOP into emulsions strengthens its anti-inflammatory effects, improving skin conditions in photoaged mice, offering insights for optimizing DOP’s efficacy through different delivery matrices [55]. The molecular weight of DOP has been associated with its antioxidant activity in several studies, with medium and small molecular weight fractions potentially providing more effective antioxidant effects [7,66]. Pectin-based DOP from fresh DO exhibit better antioxidant properties than those extracted from dried samples [54]. Additionally, differences in antioxidant capacity have been noted between DOP extracted from DO grown under different cultivation substrates [64]. Furthermore, developing DOP into multilayer emulsions can enhance its stability and skin absorption efficiency, thus boosting its antioxidant performance [55].

5 Regulation of Bioactive Compound Biosynthesis

The accumulation of bioactive compounds in medicinal plants is influenced by complex interactions between genetic factors and abiotic/biotic environmental conditions. Elucidating the biosynthetic regulatory mechanisms of these active components can provide critical targets for breeding new medicinal plant varieties, developing ecological cultivation methods, and achieving cost-effective synthesis of bioactive compounds. Although molecular biology and multi-omics technologies have significantly advanced our understanding of regulatory networks governing the biosynthesis of critical compounds in medicinal plants, research on most bioactive components in DO remains in its early stages. This review synthesizes current knowledge on biosynthetic mechanisms and multidimensional factors regulating compound accumulation, with the goal of offering a foundational reference for further investigations into the biosynthesis (original: aiming to provide a fundamental atlas for further research into the biological synthesis control, optimized for vocabulary diversity and reduced term repetition) of bioactive compounds in DO.

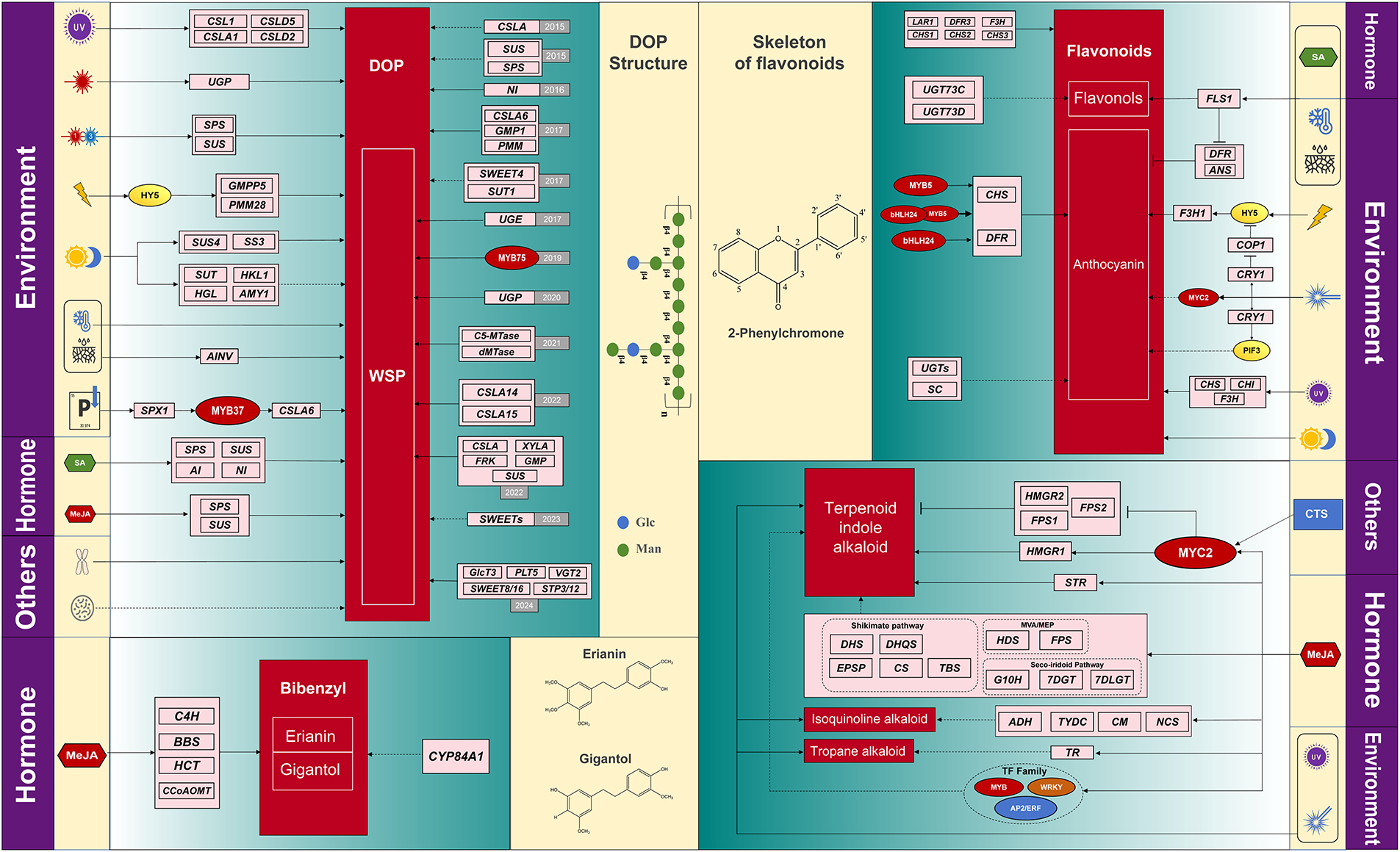

5.1 Dendrobium officinale Polysaccharides

Numerous genes involved in regulating DOP biosynthesis and accumulation have been identified. In 2015, He et al. discovered eight CSLA genes through transcriptome analysis, demonstrating their involvement in bioactive mannan biosynthesis in DO [77]; in the same year Yan et al. completed the first whole-genome sequencing of DO and analyzed biosynthetic pathways of medicinal components, revealing extensive duplication of SPS and SUS genes associated with polysaccharide production [78]. In 2016, Gao et al. functionally validated an NI gene through molecular cloning, confirming its correlation with DOP accumulation [79]. Concurrently, the second version of DO genome was released, which identified genes involved in glucomannan and galactoglucomannan biosynthesis [80]. Zhang et al. further compared juvenile and adult plant transcriptomes, identifying 37 differentially expressed cellulose synthase-related genes and 627 transcription factor genes—thereby providing key insights into elucidating polysaccharide biosynthesis mechanisms [81]. In 2017, He et al. conducted follow-up studies that employed Arabidopsis transgenic lines (35S: CSLA6, 35S: GMP1, 35S: PMM) to functionally validate the roles of CSLA6, GMP1, and PMM in DOP biosynthesis [82–84]. Their additional research revealed twice higher polysaccharide content in stems than leaves, with differential expression of sugar transporter genes SWEET4 and SUT1 potentially mediating phloem loading [85]. Yu et al.’s cloning and analysis of UGE gene demonstrated its critical function in water-soluble polysaccharide (WSP) accumulation [86]. The year 2019 marked the first experimental verification of transcriptional regulation in DOP biosynthesis, with He et al. confirming MYB75’s role in WSP accumulation [87]. Chen et al. (2020) showed that UGP expression enhanced both WSP content and stress resistance [88]. Yu et al. revealed C5-MTase and dMTase’s dual functions in WSP accumulation and stress response [89]. Recent advances include Si et al.’s 2022 study identifying five candidate WSP biosynthesis genes (SUS, XYLA, FRK, GMP, CSLA5) through harvest-time comparisons [90], and Wang et al.’s discovery of two CSLA genes essential for mannan synthesis [91]. Hao et al. (2023) screened 25 SWEET sugar transporters potentially may be critical for polysaccharide accumulation [92], while Fan et al.’s 2024 work characterized seven sugar transporter genes (SWEET8/16, STP3/12, VGT2, PLT5, pGlcT3) from MST, SUT and SWEET families as potential contributors to polysaccharide biosynthesis [93].

Abiotic factors significantly influence the synthesis and accumulation of DOP, including hormones, light quality, minerals, and environmental stressors, as illustrated in the upper left of Fig. 3. Hormones play a crucial role in DOP accumulation. Yuan et al. (2014) found that salicylic acid (SA) enhances polysaccharide content by altering the activity of sucrose-metabolizing enzymes [94]. Another study (2017) demonstrated that exogenous application of low-concentration methyl jasmonate (MeJA) promotes DOP production, whereas high concentrations inhibit it by upregulating the activity of sucrose-metabolizing enzymes and the expression of sucrose biosynthesis genes, thereby affecting polysaccharide biosynthesis [95]. Numerous studies highlight the importance of light quality in DOP synthesis. Wang et al. (2024) reported that red light significantly upregulates the UGP gene in DO compared to blue and yellow light, thereby promoting DOP biosynthesis [96]. Conversely, Lei et al. found that a red-to-blue light ratio of 1: 3 (R:B 1: 3) enhances polysaccharide accumulation in protocorms by increasing the activity of SPS and SUS [97]. Li et al. (2021) revealed that strong light highly induces HY5 expression, which directly binds to the promoters of GMPP2 and PMT28 (genes involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis), activating their expression and promoting polysaccharide accumulation in DO [98]. Additionally, Chen et al. (2020) discovered that UV-B radiation also induces polysaccharide accumulation [99]. Mineral elements, particularly phosphorus, play a vital regulatory function in DOP biosynthesis. Feng et al. (2024) elucidated the SPX1-MYB37-CSLA6 signaling pathway, providing a theoretical basis for phosphorus deficiency-induced polysaccharide accumulation in DO [100]. Yu et al. (2018) observed increased polysaccharide content in Dendrobium stems under low-temperature storage [101], while Liu et al. (2024) reported that AINV gene expression under dehydration and cold stress leads to elevated soluble sugar content [102]. Furthermore, Chen et al. (2024) found that diurnal temperature variations enhance polysaccharide levels in PLBs, with genes such as SUS, SUT, HKL1, HGL, AMY1, and SS3 identified as associated with polysaccharide synthesis [103]. Beyond abiotic factors, certain biotic factors also influence DOP biosynthesis. For instance, rhizospheric bacteria like Pandoraea spp. may have potential in promoting DOP production [104]. Additionally, Pham et al. (2019) suggested that chromosome doubling could be a viable strategy to increase DO biomass and polysaccharide yield [105].

Figure 3: Biosynthesis and regulation of major bioactive compounds in DO. This figure was created using Adobe Illustrator

Regulatory genes related to DOP synthesis: CSLA: cellulose synthase like A; SPS: sucrose-phosphate synthase; SUS: sucrose synthase; NI: neutral invertase; GMP: GDP-mannose pyrophosphorylase; PMM: phosphomannomutase; SWEET: sugars will eventually be exported transporters; SUT: sucrose transporter; UGE: UDP glucose 4-epimerase; UGP: uridine diphosphate glucose pyrophosphorylase; C5-MTase: cytosine-5 DNA methyltransferase; dMTase: DNA demethylase; XYLA: xylose isomerase; FRK: fructokinase; GlcT: glucose transporter 1 isoform X1; PLT: polyol transporter 5-like; STP: sugar transport protein MST6-like; VGT: D-xylose-proton symporter-like 3; AI: alkaline invertase; CSL1: cellulose synthase-like 1; CSLD: cellulose synthase-like D; HKL: hexokinase-like; AMY: alpha-amylase-like; HGL: heteroglycan glucosidase; SS: starch synthase; AINV: acid invertases; SPX: SPX domain-containing proteins.

Regulatory genes related to Bibenzyl synthesis: BBS: bibenzyl synthase (or bibenzyl synthase-like); C4H: trans-cinnamate 4-monooxygenase; CCoAOMT: Caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase. HCT: HydroxycinnamoylCoA shikimate/quinate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase.

Regulatory genes related to Flavonoid synthesis: UGT: UDP-glycosyltransferase; SC: serine carboxypeptidase; F3H: Flavanone-3-hydroxylase; DFR: Dihydroflavonol reductase; CHS: Chalcone synthase; LAR: leucoanthocyanidin reductase. FLS: flavonol synthase; ANS: anthocyanidin synthase. PIF: phytochrome-interacting factors; CRY: cryptochrome; COP: constitutively photomorphogenic; CHI: chalcone isomerase.

Regulatory genes related to Alkaloid synthesis: STR: strictosidine synthase; HMGR: 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase; FPS: Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase; DHS: 3-Dehydroshikimate synthase; DHQS: 3-Dehydroquinate synthase; EPSP: 5-Enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase; CS: Chorismate synthase; TBS: Tryptophan biosynthesis synthase; ADH: Aromatic aldehyde dehydrogenase; CM: Coclaurine methyltransferase; TYDC: Tyrosine decarboxylase; NCS: Norcoclaurine synthase; TR: Tropinone reductase; G10H: Geraniol-10-hydroxylase; 7DGT: 7-Deoxyloganetic acid glucosyltransferase; 7DLGT: 7-Deoxyloganetin glucosyltransferase; HDS: Hydroxymethylbutenyl Diphosphate Synthase.

DOP structure of DOP refers to the article by Wong et al. [76].

DO harbors a diverse array of bioactive components. However, current targeted research on the regulation of these bioactive components has been limited to bibenzyls, flavonoids, and alkaloids. Moreover, such research is relatively less extensive compared to that on polysaccharides. Therefore, we have organized these components into a single section to provide an overview of the research progress pertaining to their biogenic synthesis modulation in DO.

Current research on the biosynthesis and regulation of bibenzyl compounds in DO remains limited (Ju et al., 2021). They further conducted transcriptome analysis to identify key genes involved in bibenzyl biosynthesis, with erianin and gigantol serving as representative compounds of this class. Their study revealed that exogenous application of MeJA promotes bibenzyl biosynthesis, alongside increased expression levels of the C4H, BBS, HCT, and CCoAOMT genes—findings that indicate their potential role as key regulators in MeJA-driven bibenzyl biosynthesis. CYP84A1 was also identified as a potential contributor to bibenzyl production [106], as illustrated in the lower left of Fig. 3.

The regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis in DO is illustrated in the upper right of Fig. 3. For genes involved in flavonoid production, Ren et al. (2020) integrated transcriptomic and LC-MS network analysis and found that anthocyanins in DO may be linked to genes encoding UGTs and SC [107]. Yuan et al. (2020) used tissue-specific transcriptomics to identify genes active in flavonoid biosynthesis, and outlined the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway while verifying the role of key genes such as LAR1, DFR3, F3H, CHS1, CHS2, and CHS3 [108]. Yang et al. (2023) identified and cloned two transcription factors, MYB5 and bHLH24, which both directly bind to the promoter regions of CHS and DFR in DO, thus modulating their activity. Co-transfection of these two factors significantly boosted the expression of CHS and DFR. Notably, MYB5 and bHLH24 may form heterodimers to strengthen their regulatory effects [109]. Current research shows that hormones and external environmental factors (temperature, drought, and light) affect flavonoid production in DO. Yu et al. (2021) found that FLS1 expression correlates significantly with flavonol levels in both juvenile and mature DO plants. FLS1 downregulates DFR and ANS, reducing anthocyanin content while increasing flavonol accumulation. Moreover, FLS1 expression increases markedly under cold, drought, or salicylic acid treatment [110]. Under high-intensity light, HY5 is strongly induced and directly binds to F3H1, playing a role in anthocyanin biosynthesis [98]. Blue laser light significantly promotes total flavonoid accumulation: since COP1 suppresses HY5, blue laser-activated CRY1 inhibits COP1, thereby preventing COP1-mediated degradation of HY5. Additionally, increased expression of MYC2 and PIF3 may also contribute to anthocyanin accumulation [111]. UV-B radiation enhances flavonoid production, likely by regulating the expression of CHS, CHI, and F3H [99].

Regulation of alkaloid biosynthesis in DO is illustrated in the lower right section of Fig. 3. As early as 2013, Guo et al. identified potential alkaloid biosynthesis genes through transcriptome analysis, suggesting that cytochrome P450s, aminotransferases, methyltransferases, multidrug resistance protein transporters, and certain transcription factors in DO might be involved in alkaloid synthesis [112]. Subsequently, Zhu et al. (2017) discovered and cloned a novel MYC gene from DO, which can be induced by both MeJA and chitosan (CTS). Overexpression of MYC2 reduced the relative transcript levels of HMGR2, FPS1, and FPS2 while enhancing HMGR1 expression. Thus, MYC2 may participate in TIA synthesis by regulating key enzymes in the mevalonate (MVA) pathway [113]. In Jiao et al. (2018)’s study, high-alkaloid-producing PLBs were obtained by optimizing treatments with tryptophan, secologanin, and MeJA, accompanied by STR activity [114]. Chen et al. (2019) conducted comparative transcriptome analysis and revealed that MeJA induces P450 family genes, aminotransferase genes, and methyltransferase genes, providing important candidate genes for further elucidating the sesquiterpene alkaloid biosynthesis pathway in DO [115]. Jiao et al. (2022) treated DO PLBs with TIA precursors (tryptophan and secologanin) and MeJA, measuring alkaloid content in different treatment groups. The study found that both TIA precursors and MeJA promoted alkaloid accumulation. Transcriptome analysis showed significant upregulation of genes in the MVA/MEP pathway (e.g., HDS, FPS), the secologanin pathway (e.g., G10H, 7DGT, 7DLGT), and the shikimate pathway (e.g., DHS, DHQS, EPSP, CS, AS, TBS), as well as key enzyme-encoding genes like STR. Similar upregulation was observed in genes involved in isoquinoline alkaloid (e.g., ADH, CM, TYDC, NCS) and tropane alkaloid biosynthesis (e.g., TR). Additionally, 13 transcription factors were predicted, primarily from the AP2/ERF, WRKY, and MYB families, which may regulate alkaloid biosynthesis [116]. Different light conditions also affect alkaloid synthesis in DO. Chen et al. (2020) found that UV-B radiation promotes alkaloid production [99], while Li et al. reported that blue laser irradiation enhances alkaloid accumulation [111].

5.3 Summary of the Regulatory Mechanisms of Bioactive Compounds

The biosynthesis governance of bioactive compounds in DO relies on the interaction of genetic factors and abiotic/biotic environments, with research showing uneven progress—DOP are the most thoroughly studied, while other compounds lag behind, and overall research suffers from insufficient comprehensive analysis. Across different bioactive components, three core regulatory consensuses have emerged: first, jasmonic acid (JA) signaling acts as a universal regulator, with low-concentration methyl jasmonate (MeJA) promoting polysaccharide accumulation via upregulating SPS/SUS [94], inducing bibenzyl biosynthesis by activating C4H/BBS/HCT [105], and stimulating alkaloid production through regulating P450s and STR [114,115]; second, MYB and HY5 transcription factors play conserved cross-component roles, such as MYB75 promoting water-soluble polysaccharide (WSP) accumulation [86], MYB5 forming heterodimers with bHLH24 to regulate flavonoid genes [108], and HY5 mediating both polysaccharide (via GMPP2/PMT28) and anthocyanin (via F3H1) synthesis under light [97,110]; third, abiotic stress (UV-B, low temperature, phosphorus deficiency) consistently enhances metabolites, including UV-B upregulating polysaccharides/flavonoids/alkaloids [98] and phosphorus deficiency triggering the SPX1-MYB37-CSLA6 pathway for polysaccharides [99]. Despite these patterns, several critical discrepancies exist: in light quality regulation of polysaccharides, red light alone (Wang et al. [95]) vs. R:B 1:3 ratio (Lei et al. [96]) was found optimal, likely due to different experimental materials (intact plants vs. protocorms) and unregulated photon flux density; MeJA showed concentration-dependent dual effects on polysaccharides (promotion at low concentration, inhibition at high [94]) but only promotion on bibenzyls/alkaloids [105,115], possibly because polysaccharide synthesis is more sensitive to JA-induced feedback inhibition; and MYC2’s role in alkaloid synthesis remains ambiguous—Guo et al. [112] found it differentially regulates MVA pathway enzymes (upregulating HMGR1, downregulating HMGR2/FPS1) but did not quantify its net effect on terpenoid indole alkaloid (TIA) accumulation, with subsequent studies failing to resolve this gap.

6 Conclusions and Perspectives

Similar to other traditional Chinese medicines, Dendrobium officinale possesses extensive traditional and modern applications, which are closely associated with its bioactive components. In this study, the traditional applications of D. officinale were summarized by reviewing ancient medical texts; meanwhile, relevant literatures were consulted to generalize the pharmacological effects of D. officinale polysaccharides and the synthetic regulation of the main bioactive components of D. officinale. Additionally, this study identified the limitations of research related to the structure-activity relationship of D. officinale polysaccharides and the synthetic regulation of its main bioactive components. Among these limitations, the structure-activity relationship of polysaccharides constitutes a major challenge: polysaccharides with different chemical structures (e.g., molecular weight, monosaccharide composition, and acetylation level) exhibit differences in their pharmacological effects, while current pharmacological studies in this field lack standardization. Furthermore, research on the synthetic regulation of polysaccharides (the primary bioactive component of D. officinale) remains insufficient, and studies on other bioactive components (such as flavonoids, alkaloids, and bibenzyls) are even more inadequate—no comprehensive synthetic regulatory network has been established for these components.

Moving forward, standardized DOP extraction and isolation protocols should be prioritized to reduce structural heterogeneity, with the following specific methodological standardization directions to supplement: For extraction technology, it is necessary to optimize key parameters of different methods (e.g., ultrasonic power, enzymolysis temperature/time, water bath extraction ratio) and establish unified efficiency indicators (e.g., polysaccharide yield, active structural unit retention rate) to avoid structural differences caused by inconsistent conditions; in the purification process, clarify the selection criteria of purification materials (e.g., macroporous resin model, gel column filler type) and standardize operation steps (e.g., eluent concentration gradient, flow rate control) to ensure the consistency of polysaccharide purity and structural integrity across different studies; regarding structural characterization, build a unified technical system—including standard detection methods for molecular weight distribution (using gel permeation chromatography with calibrated standards), monosaccharide composition (using high-performance liquid chromatography with pre-column derivatization), and glycosidic bond configuration (using nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy with unified spectral parameters)—and construct a shared DOP structural database to realize the comparability of structural data; for activity evaluation, develop standardized in vitro and in vivo activity evaluation systems (such as unified cell models like specific immune cell lines for immunomodulatory activity, unified animal models like standardized tumor-bearing mouse models for antitumor activity, and consistent detection indicators and methods like unified kits and detection wavelengths for cytokine determination) to avoid deviations in structure-activity relationship analysis caused by different activity evaluation conditions. Prior to conducting pharmacological experiments, clarify the structural characteristics of polysaccharides via the above standardized methods to facilitate in-depth research into their structure-activity relationships. As for the synthesis and regulation of active components, many identified functional genes still lack concrete validation, and the construction of transcription factor regulatory networks remains insufficient. Future efforts should focus on molecular-level validation of these functional genes, identifying key transcription factors that regulate active components, and exploring the molecular mechanisms by which multiple transcription factors coordinately regulate synthase genes. This will provide a theoretical foundation for precision breeding.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the Scientific and technological innovation project of China Academy of Chinese Medical Sciences (CI2023E002, CI2024E003), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82304663), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Public Welfare Research Institutes (ZZ16-XRZ-072, ZZ17-YQ-025, ZXKT22052, and ZXKT22060), and the National Key Research and Development Program (2022YFC3501803).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception: Ruikang Ma, Guozhuang Zhang, Linlin Dong; data collection: Ziying Huang; data visualization: Ruikang Ma; analysis and interpretation of results: Zexiu Zhang, Ruohui Lu, Zhiyi Luo, Mengni Li, Pengyue Zhang, Xiaohong Lin (provided funding support and sample resources); draft manuscript preparation: Ruikang Ma, Ziying Huang, Menghan Li; manuscript revision: Guozhuang Zhang, Linlin Dong; review of manuscript: Ruikang Ma, Guozhuang Zhang, Linlin Dong; funding support: Zexiu Zhang, Ruohui Lu, Zhiyi Luo, Mengni Li, Pengyue Zhang, Xiaohong Lin, Guozhuang Zhang, Linlin Dong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.072062/s1.

References

1. Chen W, Lu J, Zhang J, Wu J, Yu L, Qin L, et al. Traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacology, and quality control of Dendrobium officinale kimura et. migo. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:726528. doi:10.3389/fphar.2021.726528. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Li Y, Chang QX, Xia PG, Liang ZS. The different parts of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo: traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, and product development status and potential. Phytochem Rev. 2025;24(1):985–1026. doi:10.1007/s11101-024-09973-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Niu Z, Zhu F, Fan Y, Li C, Zhang B, Zhu S, et al. The chromosome-level reference genome assembly for Dendrobium officinale and its utility of functional genomics research and molecular breeding study. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2021;11(7):2080–92. doi:10.1016/j.apsb.2021.01.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Liu S, Zhang H, Yuan Y. A comparison of the flavonoid biosynthesis mechanisms of Dendrobium Species by analyzing the transcriptome and metabolome. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(19):11980. doi:10.3390/ijms231911980. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Merigó JM, Yang JB. A bibliometric analysis of operations research and management science. Omega. 2017;73(1):37–48. doi:10.1016/j.omega.2016.12.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yu W, Ren Z, Zhang X, Xing S, Tao S, Liu C, et al. Structural characterization of polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale and their effects on apoptosis of HeLa cell line. Molecules. 2018;23(10):2484. doi:10.3390/molecules23102484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Xing S, Zhang X, Ke H, Lin J, Huang Y, Wei G. Physicochemical properties of polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale by fractional precipitation and their preliminary antioxidant and anti-HepG2 cells activities in vitro. Chem Cent J. 2018;12(1):100. doi:10.1186/s13065-018-0468-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Wei Y, Wang L, Wang D, Wang D, Wen C, Han B, et al. Characterization and anti-tumor activity of a polysaccharide isolated from Dendrobium officinale grown in the Huoshan County. Chin Med. 2018;13(1):47. doi:10.1186/s13020-018-0205-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Zhao Y, Li B, Wang G, Ge S, Lan X, Xu G, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides inhibit 1-methyl-2-nitro-1-nitrosoguanidine induced precancerous lesions of gastric cancer in rats through regulating Wnt/β-catenin pathway and altering serum endogenous metabolites. Molecules. 2019;24(14):2660. doi:10.3390/molecules24142660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liang J, Li H, Chen J, He L, Du X, Zhou L, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides alleviate colon tumorigenesis via restoring intestinal barrier function and enhancing anti-tumor immune response. Pharmacol Res. 2019;148:104417. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Wang HY, Ge JC, Zhang FY, Zha XQ, Liu J, Li QM, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide promotes M1 polarization of TAMs to inhibit tumor growth by targeting TLR2. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;292:119683. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Zhao Y, Lu X, Huang H, Yao Y, Liu H, Sun Y. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide converts M2 into M1 subtype macrophage polarization via the STAT6/PPAR-r and JAGGED1/NOTCH1 signaling pathways to inhibit gastric cancer. Molecules. 2023;28(20):7062. doi:10.3390/molecules28207062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. He Y, Jiang P, Bian M, Xu G, Huang S, Sun C. Structural characteristics and anti-tumor effect of low molecular weight Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides by reconstructing tumor microenvironment. J Funct Foods. 2024;119(1):106314. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2024.106314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yu J, Long Y, Chi J, Dai K, Jia X, Ji H. Effects of ethanol concentrations on primary structural and bioactive characteristics of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides. Nutrients. 2024;16(6):897. doi:10.3390/nu16060897. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Wan Z, Zheng G, Zhang Z, Ruan Q, Wu B, Wei G. Material basis and core chemical structure of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides against colitis-associated cancer based on anti-inflammatory activity. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;262(Pt 2):130056. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Xia L, Liu X, Guo H, Zhang H, Zhu J, Ren F. Partial characterization and immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides from the stem of Dendrobium officinale (Tiepishihu) in vitro. J Funct Foods. 2012;4(1):294–301. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2011.12.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Cai HL, Huang XJ, Nie SP, Xie MY, Phillips GO, Cui SW. Study on Dendrobium officinale O-acetyl-glucomannan (Dendronan®part III-Immunomodulatory activity in vitro. Bioact Carbohydr Diet Fibre. 2015;5(2):99–105. doi:10.1016/j.bcdf.2014.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tao S, Lei Z, Huang K, Li Y, Ren Z, Zhang X, et al. Structural characterization and immunomodulatory activity of two novel polysaccharides derived from the stem of Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo. J Funct Foods. 2019;57:121–34. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2019.04.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tian W, Dai L, Lu S, Luo Z, Qiu Z, Li J, et al. Effect of Bacillus sp. DU-106 fermentation on Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide: structure and immunoregulatory activities. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;135(4):1034–42. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Li M, Yue H, Wang Y, Guo C, Du Z, Jin C, et al. Intestinal microbes derived butyrate is related to the immunomodulatory activities of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;149(3):717–23. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Sun SJ, Deng P, Peng CE, Ji HY, Mao LF, Peng LZ. Extraction, structure and immunoregulatory activity of low molecular weight polysaccharide from Dendrobium officinale. Polymers. 2022;14(14):2899. doi:10.3390/polym14142899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Xie H, Fang J, Farag MA, Li Z, Sun P, Shao P. Dendrobium officinale leaf polysaccharides regulation of immune response and gut microbiota composition in cyclophosphamide-treated mice. Food Chem X. 2022;13(6):100235. doi:10.1016/j.fochx.2022.100235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Guo X, Yang M, Wang C, Nie S, Cui SW, Guo Q. Acetyl-glucomannan from Dendrobium officinale: structural modification and immunomodulatory activities. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1016961. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.1016961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Shan Z, Wang Y, Jin Z, Liu J, Wang N, Guo X, et al. Insight into the structural and immunomodulatory relationships of polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale-an in vivo study. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;139:108560. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhou W, Tao W, Wang M, Liu W, Xing J, Yang Y. Dendrobium officinale Xianhu 2 polysaccharide helps forming a healthy gut microbiota and improving host immune system: an in vitro and in vivo study. Food Chem. 2023;401(5):134211. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Li J, Tao W, Zhou W, Xing J, Luo M, Lu S, et al. Dendrobium officinale leaf polysaccharide has a dual effect of alleviating the syndromes of immunosuppressed mice and modulating immune system of normal mice. J Funct Foods. 2024;113(5):105974. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2023.105974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Li J, Tao W, Zhou W, Xing J, Luo M, Yang Y. The comprehensive analysis of gut microbiome and spleen transcriptome revealed the immunomodulatory mechanism of Dendrobium officinale leaf polysaccharide on immunosuppressed mice. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;278(Pt 4):134975. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Yang C, Li J, Luo M, Zhou W, Xing J, Yang Y, et al. Unveiling the molecular mechanisms of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides on intestinal immunity: an integrated study of network pharmacology, molecular dynamics and in vivo experiments. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;276(Pt 2):133859. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133859. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Wang K, Wang H, Liu Y, Shui W, Wang J, Cao P, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide attenuates type 2 diabetes mellitus via the regulation of PI3K/Akt-mediated glycogen synthesis and glucose metabolism. J Funct Foods. 2018;40:261–71. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2017.11.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yang J, Chen H, Nie Q, Huang X, Nie S. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide ameliorates the liver metabolism disorders of type II diabetic rats. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;164(1):1939–48. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.08.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Chen H, Nie Q, Hu J, Huang X, Yin J, Nie S. Multiomics approach to explore the amelioration mechanisms of glucomannans on the metabolic disorder of type 2 diabetic rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(8):2632–45. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.0c07871. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Chen X, Chen C, Fu X. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide alleviates type 2 diabetes mellitus by restoring gut microbiota and repairing intestinal barrier via the LPS/TLR4/TRIF/NF-kB axis. J Agric Food Chem. 2023;71(31):11929–40. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.3c02429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chen L, He X, Wang H, Fang J, Zhang Z, Zhu X, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide prevents neuronal apoptosis via TET2-dependent DNA demethylation in high-fat diet-induced diabetic mice. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;233(8):123288. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123288. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Huang C, Yu J, Da J, Dong R, Dai L, Yang Y, et al. Dendrobium officinale Kimura & Migo polysaccharide inhibits hyperglycaemia-induced kidney fibrosis via the miRNA-34a-5p/SIRT1 signalling pathway. J Ethnopharmacol. 2023;313:116601. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2023.116601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Li C, Wang Y, Huang Z, Zhang Y, Li J, Zhang Q, et al. Hypoglycemic effect of polysaccharides of Dendrobium officinale compound on type 2 diabetic mice. J Funct Foods. 2023;106(4):105579. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2023.105579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Liu H, Xing Y, Wang Y, Ren X, Zhang D, Dai J, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide prevents diabetes via the regulation of gut microbiota in prediabetic mice. Foods. 2023;12(12):2310. doi:10.3390/foods12122310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Xiong J, Fang J, Chen D, Xu H. Physicochemical property changes of Dendrobium officinale leaf polysaccharide LDOP-A and it promotes GLP-1 secretion in NCI-H716 cells by simulated saliva-gastrointestinal digestion. Food Sci Nutr. 2023;11(6):2686–96. doi:10.1002/fsn3.3341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Jiang W, Tan J, Zhang J, Deng X, He X, Zhang J, et al. Polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale improve obesity-induced insulin resistance through the gut microbiota and the SOCS3-mediated insulin receptor substrate-1 signaling pathway. J Sci Food Agric. 2024;104(6):3437–47. doi:10.1002/jsfa.13229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Yang K, Lu T, Zhan L, Zhou C, Zhang N, Lei S, et al. Physicochemical characterization of polysaccharide from the leaf of Dendrobium officinale and effect on LPS induced damage in GES-1 cell. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;149(4):320–30. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Liang Y, Du R, Chen R, Chu PH, Ip MSM, Zhang KYB, et al. Therapeutic potential and mechanism of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides on cigarette smoke-induced airway inflammation in rat. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;143(5):112101. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Liu H, Liang J, Zhong Y, Xiao G, Efferth T, Georgiev MI, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide alleviates intestinal inflammation by promoting small extracellular vesicle packaging of miR-433-3p. J Agric Food Chem. 2021;69(45):13510–23. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.1c05134. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Zhu P, Ou G, Zhou T, Zhu W, Sun W, Wei X, et al. The polysaccharide from Dendrobium officinale can improve mice with sjögren’s syndrome by regulating BAFF and fas expressions. J Food Biochem. 2023;2023:4733651. doi:10.1155/2023/4733651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Fan S, Zhang Z, Zhong Y, Li C, Huang X, Geng F, et al. Microbiota-related effects of prebiotic fibres in lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxemic mice: short chain fatty acid production and gut commensal translocation. Food Funct. 2021;12(16):7343–57. doi:10.1039/d1fo00410g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Chen H, Shi X, Cen L, Zhang L, Dai Y, Qiu S, et al. Effect of yeast fermentation on the physicochemical properties and bioactivities of polysaccharides of Dendrobium officinale. Foods. 2022;12(1):150. doi:10.3390/foods12010150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Li J, Tao W, Zhou W, Xing J, Luo M, Lu S, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides alleviated DSS-induced ulcerative colitis in mice through remolding gut microbiota to regulate purine metabolism. J Funct Foods. 2024;119(2):106336. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2024.106336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Liao J, Zhao W, Zhang Y, Zou Z, Zhang Q, Chen D, et al. Dendrobium officinale Kimura et Migo polysaccharide ameliorated DNFB-induced atopic dermatitis in mice associated with suppressing MAPK/NF-κB/STAT3 signaling pathways. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;335(4):118677. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2024.118677. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Qi J, Zhou S, Wang G, Hua R, Wang X, He J, et al. The antioxidant Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide modulates host metabolism and gut microbiota to alleviate high-fat diet-induced atherosclerosis in ApoE (-/-) mice. Antioxidants. 2024;13(5):599. doi:10.3390/antiox13050599. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Yan M, Tian Y, Fu M, Zhou H, Yu J, Su J, et al. Polysaccharides, the active component of Dendrobiumofficinale flower, ameliorates chronic pharyngitis in rats via TLR4/NF-κb pathway regulation. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;335(4):118620. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2024.118620. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Zeng B, Yan Y, Zhang Y, Wang C, Huang W, Zhong X, et al. Dendrobium officinale Polysaccharide (DOP) inhibits cell hyperproliferation, inflammation and oxidative stress to improve keratinocyte psoriasis-like state. Adv Med Sci. 2024;69(1):167–75. doi:10.1016/j.advms.2024.03.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Zeng X, Tang S, Dong X, Dong M, Shao R, Liu R, et al. Analysis of metagenome and metabolome disclosed the mechanisms of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide on DSS-induced ulcerative colitis-affected mice. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;277:134229. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134229. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang M, Xu L, Chen L, Wu H, Jia L, Zhu H. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides as a natural functional component for acetic-acid-induced gastric ulcers in rats. Molecules. 2024;29(4):880. doi:10.3390/molecules29040880. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Zhu H, Xu L, Chen P, Li Z, Yu W, Sun P, et al. Structure characteristics, protective effect and mechanisms of ethanol-fractional polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale on acute ethanol-induced gastritis. Food Funct. 2024;15(8):4079–94. doi:10.1039/d3fo05540j. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Ma JJ, Wu WY, Liao J, Liu L, Wang Q, Xiao GS, et al. Preparation of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide by lactic acid bacterium fermentation and its protective mechanism against alcoholic liver damage in mice. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72(31):17633–48. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.4c03652. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Hui A, Xu W, Wang J, Liu J, Deng S, Xiong B, et al. A comparative study of pectic polysaccharides from fresh and dried Dendrobium officinale based on their structural properties and hepatoprotection in alcoholic liver damaged mice. Food Funct. 2023;14(9):4267–79. doi:10.1039/d3fo00182b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Guo L, Yang Y, Pu Y, Mao S, Nie Y, Liu Y, et al. Dendrobium officinale Kimura & Migo polysaccharide and its multilayer emulsion protect skin photoaging. J Ethnopharmacol. 2024;318(Pt B):116974. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2023.116974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Liang J, Wu Y, Yuan H, Yang Y, Xiong Q, Liang C, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides attenuate learning and memory disabilities via anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory actions. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;126:414–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.12.230. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Zhang JY, Guo Y, Si JP, Sun XB, Sun GB, Liu JJ. A polysaccharide of Dendrobium officinale ameliorates H2O2-induced apoptosis in H9c2 cardiomyocytes via PI3K/AKT and MAPK pathways. Int J Biol Macromol. 2017;104(Pt A):1–10. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Fan H, Meng Q, Xiao T, Zhang L. Partial characterization and antioxidant activities of polysaccharides sequentially extracted from Dendrobium officinale. J Food Meas Charact. 2018;12(2):1054–64. doi:10.1007/s11694-018-9721-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Wen Y, Xiao H, Liu Y, Yang Y, Wang Y, Xu S, et al. Polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale ameliorate colitis-induced lung injury via inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress. Chem Biol Interact. 2021;347(5):109615. doi:10.1016/j.cbi.2021.109615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Xu L, Zeng X, Liu Y, Wu Z, Zheng X, Zhang X. Inhibitory effect of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide on oxidative damage of glial cells in aging mice by regulating gut microbiota. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;247:125787. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.125787. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Cai M, Zhu H, Xu L, Wang J, Xu J, Li Z, et al. Structure, anti-fatigue activity and regulation on gut microflora in vivo of ethanol-fractional polysaccharides from Dendrobium officinale. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;234(2):123572. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Mu Y, Che B, Tang K, Zhang W, Xu S, Li W, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides improved reproductive oxidative stress injury in male mice treated with cyclophosphamide. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2023;30(48):106431–41. doi:10.1007/s11356-023-29874-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Tang Y, Zhang X, Lin Y, Sun J, Chen S, Wang W, et al. Insights into the oxidative stress alleviation potential of enzymatically prepared Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides. Molecules. 2023;28(7):3071. doi:10.3390/molecules28073071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Okoro NO, Odiba AS, Yu Q, He B, Liao G, Jin C, et al. Polysaccharides extracted from Dendrobium officinale grown in different environments elicit varying health benefits in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nutrients. 2023;15(12):2641. doi:10.3390/nu15122641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Jing Y, Hu J, Zhang Y, Sun J, Guo J, Zheng Y, et al. Structural characterization and preventive effect on alcoholic gastric mucosa and liver injury of a novel polysaccharide from Dendrobium officinale. Nat Prod Res. 2024;38(7):1140–7. doi:10.1080/14786419.2022.2134363. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Pang X, Wang H, Guan C, Chen Q, Cui X, Zhang X. Impact of molecular weight variations in Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides on antioxidant activity and anti-obesity in Caenorhabditis elegans. Foods. 2024;13(7):1040. doi:10.3390/foods13071040. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Duan H, Yu Q, Ni Y, Li J, Yu L, Yan X, et al. Dose-dependent effect of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide on anti-aging in Caenorhabditis elegans: a metabolomics analysis focused on lipid and nucleotide metabolism regulation. Food Biosci. 2024;61(1):104615. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2024.104615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Sun Y, Zhang S, He H, Chen H, Nie Q, Li S, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of the prebiotic properties of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides, β-glucan, and inulin during in vitro fermentation via multi-omics analysis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253(Pt 7):127326. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Wang Y, Jiang Z, Deng L, Zhang G, Xu X, Alonge E, et al. Dendrobium offificinale polysaccharides prevents glucocorticoids-induced osteoporosis by destabilizing KEAP1-NRF2 interaction. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;253(Pt 1):126600. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.126600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Yang Y, Tao W, Zhou W, Li J, Xing J, Luo M, et al. The short-term and long-term effects of Dendrobium officinale leaves polysaccharides on the gut microbiota differ. J Funct Foods. 2023;110(1):105807. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2023.105807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Zhang Y, Li Y, Tang Q, Wang H, Peng Y, Luo M, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide (DOP) promotes hair regrowth in testosterone-induced bald mice. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2023;47(2):833–41. doi:10.1007/s00266-022-03144-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Duan H, Yu Q, Ni Y, Li J, Yu L, Yan X, et al. Synergistic anti-aging effect of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide and spermidine: a metabolomics analysis focusing on the regulation of lipid, nucleotide and energy metabolism. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;278(Pt 4):135098. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135098. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Šutovská M, Mažerik J, Kocmálová M, Uhliariková I, Matulová M, Capek P. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides-chemical properties and pharmacodynamic effects on the airways in experimental conditions. Arch Pharm. 2024;357(3):e2300537. doi:10.1002/ardp.202300537. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Yang X, Ji W, Zhou Z, Wang J, Cui Z, Pan X, et al. Dendrobium officinale polysaccharide regulated hepatic stellate cells activation and liver fibrosis by inhibiting the SMO/Gli 1 pathway. J Funct Foods. 2024;112(3):105960. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2023.105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Fu J, Liang Z, Chen Z, Zhou Y, Xiong F, Liang Q, et al. Deciphering the therapeutic efficacy and underlying mechanisms of Dendrobium officinale polysaccharides in the intervention of Alzheimer’s disease mice: insights from metabolomics and microbiome. J Agric Food Chem. 2025;73(9):5635–48. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.4c07913. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Wong TL, Li LF, Zhang JX, Zhang QW, Zhang XT, Zhou LS, et al. Oligosaccharide analysis of the backbone structure of the characteristic polysaccharide of Dendrobium officinale. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;134(11):108038. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.108038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. He C, Zhang J, Liu X, Zeng S, Wu K, Yu Z, et al. Identification of genes involved in biosynthesis of mannan polysaccharides in Dendrobium officinale by RNA-seq analysis. Plant Mol Biol. 2015;88(3):219–31. doi:10.1007/s11103-015-0316-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Yan L, Wang X, Liu H, Tian Y, Lian J, Yang R, et al. The genome of Dendrobium officinale illuminates the biology of the important traditional Chinese orchid herb. Mol Plant. 2015;8(6):922–34. doi:10.1016/j.molp.2014.12.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Gao F, Cao XF, Si JP, Chen ZY, Duan CL. Characterization of the alkaline/neutral invertase gene in Dendrobium officinale and its relationship with polysaccharide accumulation. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15(2). doi:10.4238/gmr.15027647. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Zhang GQ, Xu Q, Bian C, Tsai WC, Yeh CM, Liu KW, et al. The Dendrobium catenatum Lindl. genome sequence provides insights into polysaccharide synthase, floral development and adaptive evolution. Sci Rep. 2016;6(1):19029. doi:10.1038/srep19029. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Zhang J, He C, Wu K, Teixeira da Silva JA, Zeng S, Zhang X, et al. Transcriptome analysis of Dendrobium officinale and its application to the identification of genes associated with polysaccharide synthesis. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:5. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.00005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. He C, Zeng S, Teixeira da Silva JA, Yu Z, Tan J, Duan J. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of the phosphomannomutase (PMM) gene from Dendrobium officinale and evidence for the involvement of an abiotic stress response during germination. Protoplasma. 2017;254(4):1693–704. doi:10.1007/s00709-016-1044-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. He C, Yu Z, Teixeira da Silva JA, Zhang J, Liu X, Wang X, et al. DoGMP1 from Dendrobium officinale contributes to mannose content of water-soluble polysaccharides and plays a role in salt stress response. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):41010. doi:10.1038/srep41010. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. He C, Wu K, Zhang J, Liu X, Zeng S, Yu Z, et al. Cytochemical localization of polysaccharides in Dendrobium officinale and the involvement of DoCSLA6 in the synthesis of mannan polysaccharides. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8(1599):173. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. He L, Fu S, Xu Z, Yan J, Xu J, Zhou H, et al. Hybrid sequencing of full-length cDNA transcripts of stems and leaves in Dendrobium officinale. Genes. 2017;8(10):257. doi:10.3390/genes8100257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]