Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Key Plant Transcription Factors in Crop Tolerance to Abiotic Stresses

1 Laboratory of Scientific Innovation in Sustainability, Environment, Education, and Health, Era of Artificial Intelligence, High School Teachers-Training Institution, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdellah University, Fes, 30003, Morocco

2 Laboratory of Biotechnology & Sustainable, Development of Natural Resources, Polydisciplinary Faculty, Sultan Moulay Slimane University, Beni Mellal, 23000, Morocco

3 Centre of Agrobiotechnology and Bioengineering, Research Unit Labeled CNRST, Cadi Ayyad University, Marrakesh, 40000, Morocco

4 CAES, Agrobiosciences Program, Mohammed VI Polytechnic University, Ben Guerir, 43150, Morocco

5 Laboratory of Ecology and Environment, Faculty of Sciences Ben M’sick, Hassan II University of Casablanca, Casablanca, 20670, Morocco

* Corresponding Authors: Ahmed El Moukhtari. Email: ,

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Crop Plants: Physio-biochemical and Molecular Mechanisms)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3585-3610. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.072311

Received 24 August 2025; Accepted 22 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Abiotic stresses, such as drought, heavy metals, salinity, and extreme temperatures, are among the most common adverse threats that restrict the use of land for agriculture and limit crop growth and productivity. As sessile organisms, plants defend themselves from abiotic stresses by developing various tolerance mechanisms. These mechanisms are governed by several biochemical traits. The biochemical mechanisms are the products of key genes that express under specific conditions. Interestingly, the expression of these genes is regulated by specialized proteins known as transcription factors (TFs). Several TFs, including those from the bZIP, bHLH, MYB, HSF, WRKY, DREB, and DOF families, play critical roles in regulating plant growth, development, and responses to environmental changes. By binding to specific DNA sequences, TFs can act as molecular switches to repress or activate the transcription of targeted genes. Moreover, some TF genes have been engineered to strengthencrop resilience to multiple abiotic stresses. Identifying and manipulating TFs is an interesting research area that could aid in improving crop abiotic stress tolerance. This review describs the harmful effects of salinity, drought, temperature and heavy metals on plant growth and development. We also provide an updated discussion on how TFs regulate and activate the plant tolerance under different abiotic constraints. Our aim is to extend understanding of how abiotic stresses affect the physiological characteristics of plants and how TFs alleviate these deleterious effects on plant growth and productivity.Keywords

Plants are continuously exposed to several abiotic stresses that compromise their growth, development, and productivity [1]. Among these abiotic constraints, drought, heat, cold, freezing, salinity, and heavy metals are major factors limiting agricultural production worldwide [2–4]. Moreover, due to climate change, the effects of these stresses become more severe, restricting the use of land for agriculture and limiting crop growth and productivity [5]. Hence, as sessile organisms and to handle the different environmental constraints they face, plants developed multiple physiological, biochemical, cellular, and molecular tolerance mechanisms. In fact, the biochemical molecules that govern these responses are the products of crucial genes that are expressed only under certain conditions. Surprisingly, these divers’ reactions are intriguingly influenced by specialized proteins known as transcription factors (TFs), which govern downstream stress-induced genes and pathways.

TFs are regulatory proteins that control the transcriptional activity through binding to specific DNA sequences in the promoter regions of target genes, thus allowing fine-tuned activation or repression of these genes in response to environmental signals [6,7]. By coordinating the expression of multiple genes, TFs orchestrate effective cellular responses to abiotic stresses, ranging from the synthesis of osmoprotectants to the modulation of hormonal signaling or the activation of antioxidant systems [8,9]. TFs normally contain highly conserved DNA-binding domains (DBDs) that regulate the spatiotemporal expression of target genes involved in stress resistance mechanisms in plants [10].

Several TF families have been reported to be involved in abiotic stress tolerance [11–14]. Interestingly, each family is characterized by distinct DNA-binding domains and plays a specific role in the perception and transduction of stress signals [14–16]. Moreover, some of these families are acid abscisic (ABA)-dependent, while others participate in abscisic acid-independent response pathways, highlighting the complexity and functional redundancy of transcriptional regulatory networks [17,18].

The objective of the present review is to provide an integrated overview of the major TF families, including bZIP, bHLH, MYB, HSF, WRKY, DREB, and DOF, and their cross-stress regulatory roles in enhancing crop resilience to major abiotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, heavy metals, heat, and cold stress. Unlike previous published reviews that focus either on individual TF families or on single stresses, the present work emphasizes their overlapping functions, shared signaling pathways, and potential applications in crop improvement strategies. Furthermore, beyond outlining specific TF families, this review emphasizes how the main TF families interact during abiotic stress responses. Recent advances to exploit the key TF families in developing crops more resilient to climate change were discussed.

2 Effect of Abiotic Stress on Crop Growth and Development

In the context of climate change, water stress is one of the major challenges for agricultural production, particularly in arid and semi-arid regions characterized by little precipitation. Water deficit profoundly affects plants, disrupting physiological processes and altering growth and development [19]. It reduces cell turgor and relative water contents, which inhibit cell expansion, leading to stunted growth and reduced biomass [20]. Water deficit also triggers stomatal closure to minimize transpiration and water loss; however, this limits CO2 assimilation, reducing photosynthesis and causing energy imbalances. Besides, prolonged water deficit induces oxidative stress by inducing an overaccumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which damages cellular components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA [21]. Furthermore, water scarcity affects nutrient uptake and transport, exacerbating deficiencies that further compromise plant health and yield [22].

To alleviate the depressive effects of water deficit, plants activate a range of agro-morphological, physio-biochemical, and molecular responses. Morphologically, plants alter root architecture, extending root depth to access water reserves in deeper soil layers [23], and they reduce the leaf area and increase cuticle thickness to limit water loss. Optimal root system architecture plays an important role in enhancing plants’ capacity to effectively uptake water and nutrients, which therefore strengthens their resilience against water stress [24].

At the physio-biochemical level, plants exhibited many changes to overcome water deficit stress. The osmotic adjustment, achieved through the accumulation of compatible solutes like proline and soluble sugars, led to maintaining cell turgor and enzyme function under low water availability [5]. Upregulating antioxidant defense systems to neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) constitutes an important mechanism associated with water deficit tolerance in many species. Enzymes, such as catalase (CAT), superoxide dismutase (SOD), and peroxidase (POD), act synergistically with non-enzymatic antioxidants, like polyphenols, glutathione, and ascorbate to mitigate osmotic stress-induced oxidative damage [1]. Additionally, secondary metabolites, such as flavonoids and phenolics, not only scavenge ROS but also act as signaling molecules under drought stress [21]. The molecular responses focus on the signaling pathway, downregulation, and upregulation in gene expression. Hence, phytohormones such as ABA orchestrate water stress responses by inducing stomatal closure and regulating stress-related gene expression. Calcium (Ca) signaling acts as a secondary messenger in ABA-mediated pathways, amplifying stress signals and activating defense mechanisms. The regulation of aquaporin activity and gene expression is part of the adaptation mechanisms to water-deficient conditions, relying on complex processes and signaling pathways and complex transcriptional, translational, and post-transcriptional factors [25]. The aquaporin can play a key role in plant responses to water stress by maintaining water absorption and movement within the entire plant [26]. Molecular responses also include the activation of stress-responsive genes regulated by transcription factors, which modulate pathways involved in osmotic adjustment, antioxidant activity, and cell protection [27].

Salt stress was considered among the severe abiotic stresses that seriously affect the agricultural yield and ecological security worldwide. In fact, more than 900 million hectares of land are considered salt-affected, which is predicted to increase in the near future because of climate change [28]. Saline soils accumulate excessive soluble salts, which are detrimental to plants as they limit plant growth and productivity. In fact, many studies indicated that salinity constraint significantly affected plant growth at different growth stages, from seed germination to plant yield. Indeed, at seed germination, the exposition of the seed to salt stress induced hormonal imbalance, oxidative and osmotic stress, and disturbed seed reserve mobilization, as a key process of this stage [1]. For example, during seed germination of salt-stressed Medicago sativa [29] and Trigonella foenum-graecum [30], the authors showed that the mobilization of protein and sugar reserves, antioxidant activity, and embryo viability were negatively affected after the accumulation of Na+ in the embryo cells. Similarly, the other plant stages, including growth and yield productivity, were also destroyed after exposure to salinity stress [5]. Indeed, salt stress affects plant growth by two processes, namely, ionic toxicity and osmotic stress induction [31]. The high accumulation of salt ions, like Na+, in plant cells disturbs plant physiology significantly by deactivating antioxidant enzymes, inducing overaccumulation of ROS, and perturbating membrane cell stability [32]. Excessive Na+ ions in the soil could also mediate osmotic stress, as they reduce the water potential of the soil around the root surface, thereby limiting water availability for the plant and reducing plant water uptake [28]. In this way, salt stress leads to water deficit or osmotic stress in plants, which is one of the significant problems that plants grown in saline soils encounter. It also induces stomatal closure and disrupts photosynthetic pigments [32]. Salt-induced closure of stomata decreases the activity of CO2-fixing enzymes, thereby reducing the amount of CO2 available for fixation [3]. Additionally, due to the similarity between salt ions and essential nutrients for plant development, salt stress reduces the nutrient uptake, such as phosphorus (P), potassium (K), Ca, nitrogen (N), and iron (Fe) [5]. Altogether, salt stress reduces plant growth, reflected by the signification reduction in plant biomass in many plant species like Lavandula angustifolia [33], Nigella sativa [34], Oryza sativa [35], and Triticum aestivum [36]. In the same line, Lamsaadi et al. [37] correlated the significant reduction in plant growth and yield of T. foenum-graecum to the harmful effects of salt stress on water uptake, photosynthetic activity, antioxidant activity, and nutrient uptake.

2.3 Effect of Heavy Metals Stress

Environmental pollution by heavy metals has become a serious problem worldwide. In this context, extended human activities, in terms of urbanization and industrialization, have led to the wide distribution of pollutants and heavy metals in natural resources, like water, soil, and air. Various heavy metals are present in the environment in large amounts, like Nickel (Ni), Cobalt (Co), Cadmium (Cd), Mercury (Hg), and Arsenic (As), causing severe environmental problems [38]. Indeed, if they are present in the soil, they cause significant retardation in plant growth, decrease the nutritive value, reduce photosynthesis, and also pose harmful effects on human beings [2]. In addition, after their accumulation in plant cells, they cause numerous morphological, biochemical, and physiological alterations. In this context, many studies reported that plant exposure to heavy metals significantly inhibited seed germination, reduced root development, and limited the ability of the plant to uptake water and essential nutrients [21]. The negative effects of heavy metals on plant growth have been reported in several plant species, including Vigna radiata L. [39], Hordeum marinum Huds. [40], O. sativa L. [41] and H. vulgare L. [42]. Reduction in photosynthetic pigments, stomatal conductance, and gas exchange is also observed in plants exposed to heavy metal stress [43]. Moreover, another toxic effect of heavy metals on plant physiology is the high accumulation of ROS in plant cells, which induces oxidative stress leading to lipid and protein oxidation, and DNA damage, and eventually cell death [2]. Thus, heavy metals seriously affect many key physiological activities in plants, such as seed germination, photosynthesis, nutrient absorption, antioxidant activity, and cause significant reduction in plant growth and yield.

2.4 Effect of Extreme Temperatures Stress

One of the most harmful abiotic stresses for plants is the ongoing increase in surrounding temperature, which is exacerbated by climate change. Temperature rises severely disrupt the physiological functions of plants, reducing both growth and productivity [44]. Additionally, temperature drops, especially during freezing periods, pose significant challenges to plant survival by causing cellular damage and hindering development [45]. Both high and low temperatures can induce thermal stress, severely affecting plant growth and development, particularly germination, root development, and photosynthesis [4]. This stress often triggers excessive production of ROS, leading to cell membranes, DNA, and proteins damages, which disrupts fundamental physiological processes [46]. For example, when exposed to thermal stress at 30°C, Spinacia oleracea seeds show reduced germination rates and produce abnormal, less vigorous seedlings, a response associated with increased ROS production [47]. Hasanuzzaman et al. [48] demonstrated that high temperatures (around 33°C) in T. aestivum decreased cell viability and germination capacity. Moreover, under high temperatures (40°C), Sesamum indicum roots exhibit reduced growth due to oxidative damage and hormonal changes [46]. In Solanum lycopersicum L., the exposure of plants to a temperature of 42°C reduces root and shoot growth, disrupts sugar metabolism, and impairs photosynthesis, leading to decreased stomatal conductance and damage to photosynthetic enzymes [49]. At 40°C, T. foenum-graecum is adversely affected, with suppressed photosynthesis due to the downregulation of vital proteins, such as chlorophyll-binding proteins and ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase. Reduced dry weight, along with shorter roots and shoots, are additional consequences of this stress. The plant’s attempt to combat oxidative stress induced by high temperatures is observed as an adaptive response, marked by increased protein content and activation of antioxidant enzymes, including SOD, POD, and CAT [50].

Beyond the issues brought on by heat stress, crops are equally vulnerable to cold-induced thermal stress, which induces embryo dormancy, slows germination, and disrupts root growth, coleoptile length, and biomass production. For example, at 2°C, T. aestivum showed a significant reduction in germination and root growth [51]. However, prolonged exposure to −4°C can initially promote seed germination in Brassica rapa, though continued exposure reduces growth and biomass accumulation. Cold stress also disrupts membrane fluidity, affecting enzyme function and metabolic processes [52]. This response is not uniform across all plant species; some, such as Gossypium hirsutum, display variable responses. In fact, in G. hirsutum, cold-induced thermal stress leads to oxidative damage via ROS production, which activates antioxidant enzymes, disrupting membrane fluidity and hormonal regulation [52]. This stress is often mitigated by the production of protective proteins and soluble sugars, which help protect plants from oxidative damage [51]. Cold stress elicits diverse responses in plants, primarily through oxidative damage caused by overproduction of ROS, activation of antioxidant enzymes, and disruption of membrane integrity and hormonal balance [53]. Furthermore, exposure to low temperatures can cause tissue dehydration and water deficit by impairing water uptake, while leaf transpiration rates may remain unchanged, exacerbating the physiological stress [54].

3 Transcription Factors (TFs) and Plant Abiotic Stress Tolerance

3.1 Basic Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) TFs

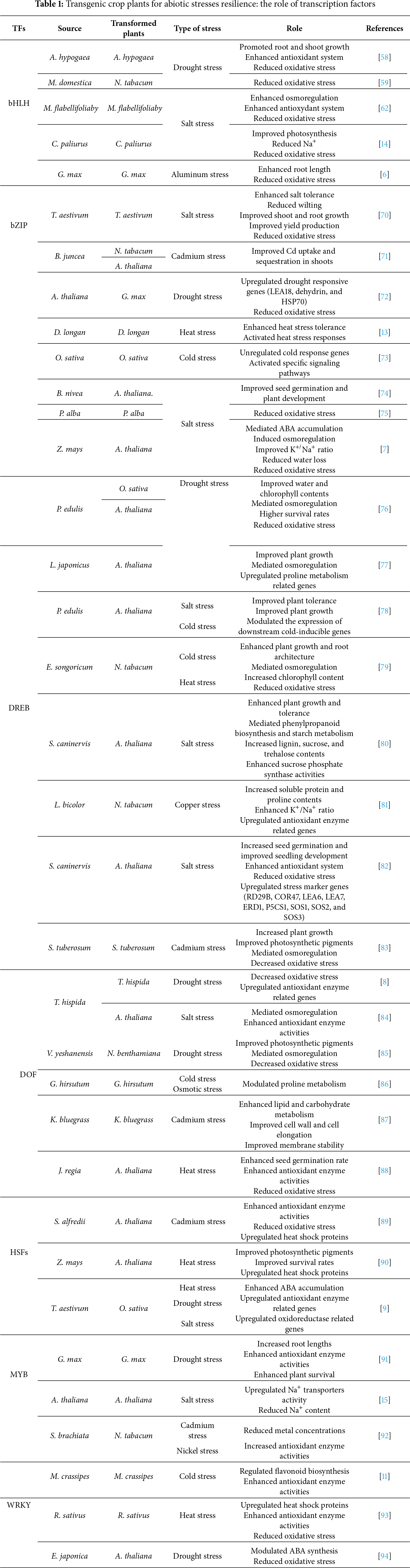

Basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) TFs are one of the most conversed TF families in plants, animals, and fungi [55]. It is among the key TFs that play many vital roles in plant development, and it includes 133 members [56]. Indeed, a defining feature of bHLH proteins is the conserved HER motif (His5-Glu9-Arg13), present in over 50% of plant bHLHs and essential for DNA binding [57]. In the same line, it was reported that bHLH TF is recognized for its significant involvement in plant responses to abiotic stresses, particularly under climate change constraints by regulating genes linked to stress tolerance mechanisms (Table 1). In fact, Li et al. [58] showed that the overexpression of AhbHLH112 improves drought tolerance in Arachis hypogaea plants through promoting root and shoot growth and activating the antioxidant system mechanism to reduce ROS production in plants. Similarly, the overexpression of MdbHLH130 enhances drought tolerance in Nicotiana tabacum by decreasing lipid peroxidation, as evidenced by lower electrolyte leakage level and malondialdehyde (MDA) content [59]. More than that, Liang et al. [60] evidenced that Trifoliate orange overexpressing PtrbHLH66 exhibited significantly enhanced drought resistance via ROS detoxification and regulation of ABA biosynthesis genes. Similarly, Zhai et al. [61] demonstrated that the overexpression of PlbHLH6, PlbHLH55, and PlbHLH64 could improve Pseudoroegneria seed germination under drought stress. In addition to water stress, bHLH also alleviates the harmful effect of salinity stress on plant growth and development (Table 1). In this context, Qiu et al. [62] indicated that the overexpression of MfbHLH38 significantly enhanced salt stress tolerance in Myrothamnus flabellifolia through increasing the antioxidant activity and the accumulation of the osmoprotectant compound, resulting in a reduction of ROS and MDA production in plant cells. The same results were recorded in other plants species, like Cyclocarya paliurus and Capsicum annuum, were the obtained findings revealed that when overexpressing CpbHLH36/68/146 and CabHLH035, respectively, an improved salt stress tolerance by enhancing photosynthetic performance, scavenging ROS and regulated the toxic level of salt ion like Na+ in plant cell was observed in transgenic plants compared to the wild types [14,63]. The beneficial effects of bHLH overexpression were also observed under other abiotic stresses, including heavy metal and extreme temperature constraints. For instance, in manganese-stressed Zea mays plants, the overexpression of ZmbHLH105 improved the stress tolerance by modulating antioxidant defenses and metal transporter expression [64]. Similarly, the overexpression of SlbHLH increases Cd stress tolerance in S. lycopersicum [65]. Likewise, in transgenic Glycine max that overexpresses GmbHLH30, increased root elongation and reduced ROS accumulation were observed under Al toxicity [6]. Moreover, the effect of bHLH TFs expression under extreme temperature stress is critically reported. In fact, Li et al. [66] showed that the overexpression of bHLH116 in M. sativa inactivates CBF genes at low temperatures, whereas A. thaliana expressed OrbHLH001 from Dongxiang Wild Rice showed high tolerance to freezing [67]. The same was shown for PavbHLH28 and IbbHLH79 TFs, where their overexpression significantly contributed to cold tolerance through CBF-independent ROS scavenging pathways and are promising candidates for molecular breeding in cold-sensitive crops such as sweet potato [68,69].

3.2 Basic Leucine Zipper (bZIP) TFs

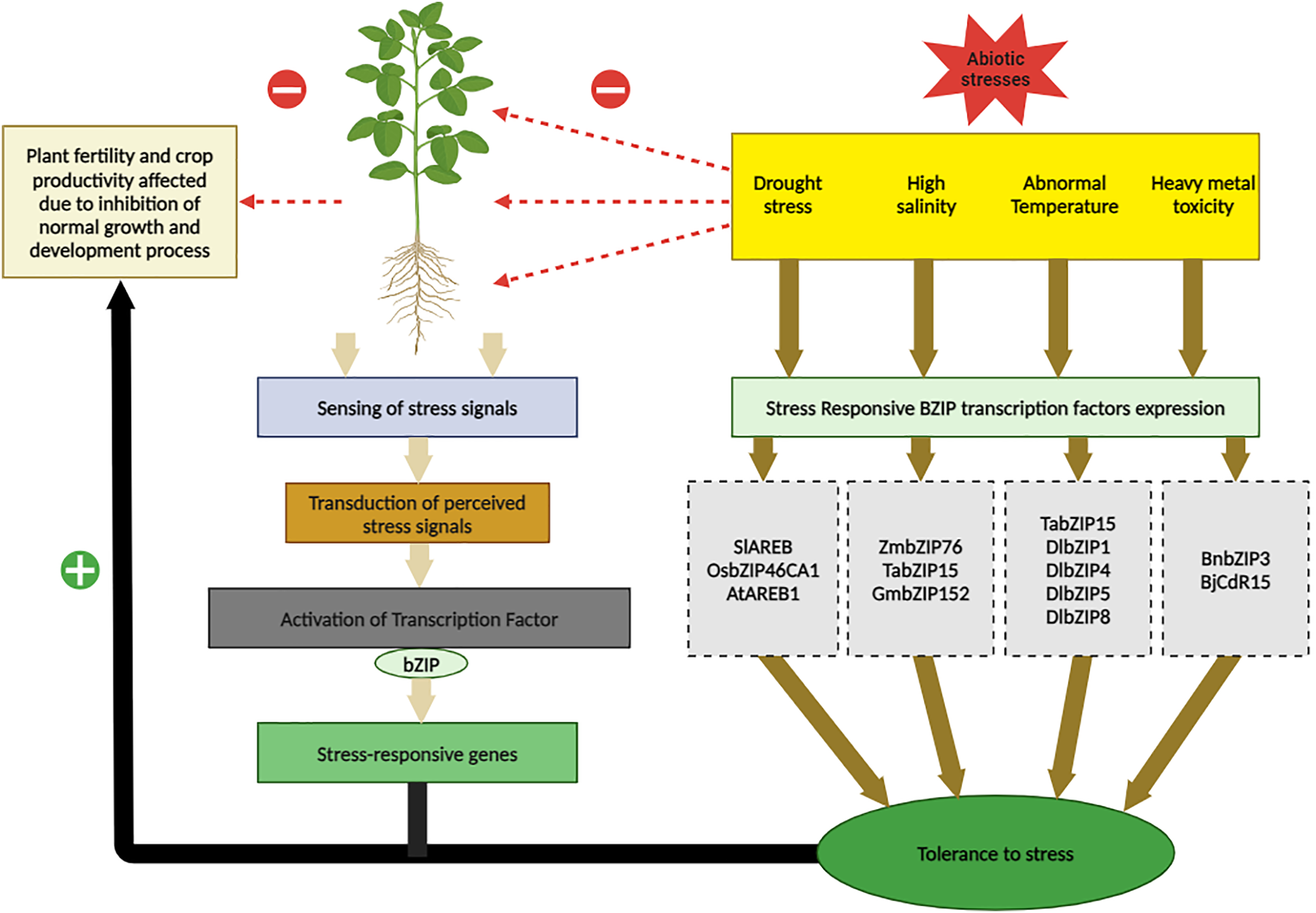

Plants are continuously subjected to fluctuating environmental conditions and are often challenged by diverse abiotic stresses, such as drought, high salinity, extreme temperatures, and heavy metal toxicity (Table 1; Fig. 1). These adverse factors severely disrupt physiological and metabolic processes, ultimately imposing significant constraints on crop yield and quality [95]. To survive and thrive under such unfavorable conditions, plants have evolved intricate adaptation mechanisms encompassing physiological, biochemical, and molecular responses [96]. Central to these responses are TFs, which regulate gene expression pathways to mediate stress tolerance.

Figure 1: The role of bZIP TFs in crop tolerance to abiotic stresses

Among the key TFs, the basic leucine zipper (bZIP) family represents a highly conserved and extensively studied group of transcriptional regulators in eukaryotes. These proteins play main roles in orchestrating gene expression in response to various environmental stimuli [97]. Structurally, bZIP TFs are defined by two key features: a basic region responsible for highly conserved, sequence-specific DNA binding and a less conserved leucine zipper motif essential for dimerization [96]. In plants, bZIPs preferentially bind cis-regulatory DNA elements with an ACGT core sequence, such as A-box (TACGTA), C-box (GACGTC), and G-box (CACGTG), although examples of non-palindromic binding sites also exist [98]. Functionally, bZIP TFs are pivotal in regulating stress-responsive gene networks under abiotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, and extreme cold. They also play essential roles in plant defense mechanisms, seed development, and various physiological and developmental processes. Upon activation by environmental or physiological signals, bZIP proteins bind to specific cis-regulatory elements within the promoter regions of target genes, thereby modulating transcription to drive adaptive and stress-mitigating responses [99].

In plant genetic engineering, bZIP TFs have emerged as crucial regulators that can be manipulated to enhance plant resistance to various stresses (Fig. 1). For example, overexpression of the T. aestivum TabZIP15gene under salt stress activates metabolic pathways and induces salt tolerance by interacting with TaENO-b, resulting in improved growth, reduced damage, and higher grain yield under saline conditions [70]. Similarly, in Z. mays, the ZmbZIP76 facilitates salt tolerance by interacting with TaENO-b in metabolic pathways [100]. Under salt and water deficit stress, Hsieh et al. [101] found that transgenic S. lycopersicum that overexpresses SlAREB was able to tolerate drought and salinity, as evidenced by better photosynthetic capacity and water content, upregulated stress-responsive genes, and enhanced overall stress resilience compared to wild-type plants. Under heavy metal stress, N. tabacum and Arabidopsis thaliana overexpressed BnbZIP3 TFs from B. junceashowed enhanced tolerance to heavy metals, drought, and salinity through the activation of the glutathione-dependent pathway [71]. Additionally, the overexpression of the B. napus BnbZIP3 in A. thaliana positively regulated tolerance to drought, salinity, and heavy metal stress, demonstrating its potential role in enhancing stress resilience [74]. Similarly, transferring and overexpressing GmbZIP152 from G. max in the model plants A. thaliana strengthened the tolerance of the transgenic plants to heavy metals [102]. Besides, Dimocarpus longan overexpressing DlbZIP1, DlbZIP4, DlbZIP5, and DlbZIP8 increased heat stress tolerance by initiating protective responses at 38°C [13]. Likewise, under drought stress, G. max overexpressing AtAREB1 from A. thaliana revealed increased drought tolerance mediated by regulating key drought-responsive genes through ABA-mediated signaling [72]. Similarly, O. sativa plants overexpressing the OsBZIP46CA1 were able to regulate the ABA signaling process and modulate physiological responses, such as stomatal closure and increased water uptake [103]. Moreover, in some aromatic and medicinal plants such as Allium sativum, the overexpression of AsbZIP26 enhanced alliin biosynthesis, helping the plant to cope with mechanical stress [104]. Taking all together, the studies above underscore the significant role of bZIPs in regulating stress adaptation mechanisms across different plant species.

3.3 Dehydration Responsive Element Binding (DREB) TFs

Dehydration-responsive element binding (DREB) TFs comprise one of two subfamilies of the APETALA2/Ethylene Responsive Element Binding Factor (AP2/ERF) family of TFs with a single AP2 domain. Most DREB TFs bind to the dehydration-responsive element (DRE), which was initially identified in the promoter of the drought-responsive RD29A gene [105]. DREB TFs were discovered by demonstration of the fact that Arabidopsis nuclear protein extracts contain at least one protein able to cause a mobility shift of oligo-nucleotides containing the DRE sequence (TACCGAC) in gel retardation studies [105]. Afterward, DREB TFs have subsequently been identified and characterized for a large number of plant species, such as Pennisetum glaucum [106], G. max [107], T. aestivum, and H. vulgare [108]. The DREB proteins found in Arabidopsis were divided into six subgroups, designated A-1 to A-6 [109]. A-1 and A-2 subgroups contain abiotic stress-responsive TFs. The third subgroup of Arabidopsis TFs contains ABSCISIC ACID INSENSITIVE 4 (ABI4), the fourth subgroup includes TINY-like proteins, and the fifth and sixth subgroups comprise RELATED TO APETALA 2 (RAP2) TFs [109]. Expression of most DREB genes is regulated by different environmental factors, and this induction may be either ABA-dependent or ABA-independent [17]. For example, according to a large number of observations made in multiple studies, DREB1 TFs are activated by four or fewer major abiotic stresses, including low and high temperatures, drought, and salinity.

Recently, a large number of DREB TFs have been isolated from both dicot and monocot plants, and introduced to other plant species to investigate their responsiveness to different abiotic stresses (Table 1). The obtained results indicated that the plant tolerance to drought, high salinity, cold/freezing, and heat stresses was significantly improved in transgenic plants overexpressing DREB TFs [110]. In their work, Wang et al. [77] documented that the overexpression of DREB TF, extracted from Lotus japonicas, in A. thaliana significantly improved plant growth, antioxidant activity, and proline content by increasing the expression level of related genes, such as AtP5CS1, AtP5CS2, AtRD29A, and AtRD29B genes. Hu et al. [78] reported the same results under salinity and cold stresses, where a significant improvement in plant height and root length and activation of the expression of downstream cold-inducible genes were observed after overexpression of DREB TF in transgenic Arabidopsis. Similarly, the overexpression of EsDREBTF in transgenic S. lycopersicum plants significantly enhanced plant growth, chlorophyll content, and proline accumulation with a significant reduction in oxidative stress markers, like MDA content under cold and heat stress conditions [79]. Furthermore, Li et al. [82] showed that the overexpression of ScDREB TF in transgenic A. thaliana alleviated the harmful effects of salinity constraints during seed germination and seedlings development by decreasing oxidative stress indicators, improving POD, CAT, and SOD activities, and increasing the transcriptional levels of stress marker genes and salt overly sensitive (SOS1, SOS2, and SOS3) genes. Under heavy metal constraints, the authors reported the same beneficial effect in many transgenic plants overexpressing DREB TFs (Table 1). For instance, Charfeddine et al. [83] indicated that the overexpression of StDREB TF in transgenic S. tuberosum significantly improved plant growth, photosynthetic pigment content, antioxidant activity, and proline content under Cd stress. In the same line, Ban et al. [81] reported that transferring and overexpressing LbDREB TF in N. tabacum importantly increased the contents of soluble protein and proline, elevated the K+/Na+ ratio, and up-regulated some stress-related genes, including SOD (Cu/Zn SOD) and POD under copper stress.

However, other experiments showed opposite effects, where the overexpression of this TF induced undesirable effects on plant growth, together with abiotic stress tolerance improvement. For instance, Josine et al. [111] reported that the overexpression of AtDREB2ACA led to the activation of stress-responsive genes and, consequently, to improvement of salt tolerance of transgenic Rosa chinensis plants, but this was accompanied by several undesirable phenotypic changes, including a reduction in leaf starch and chlorophyll content and changes in cuticle development. Similarly, the overexpression of the O. sativa OsDREB1A in transgenic A. thaliana plants led to severe growth retardation of transgenic plants compared with control plants, despite a clear improvement of freezing and dehydration tolerance of the transgenic lines [112]. Conversely, other research reported that the constitutive overexpression of DREB genes produced few or no negative changes in phenotypes of transgenic plants. In this line, Oh et al. [113] documented that the constitutive overexpression of a gene (AtDREB1A from Arabidopsis) similar to the O. sativa OsDREB1A, enhanced O. sativa tolerance to drought and high salinity without producing any negative phenotypic changes. Overexpression of the DREB-like transcription factor gene AhDREB1, originating from the halophyte Atriplex hortensis, in N. tabacum improved plant tolerance to high salt levels [114]. Overexpression of the O. sativa OsDREB2A did not cause any phenotypic changes in the transgenic A. thaliana [112], although overexpression of TaDREB1, TaDREB2, TaDREB3, and WDREB2 from T. aestivum and ZmDREB2A from Z. mays caused significant phenotypic changes and/or growth retardation of the transgenic A. thaliana, N. tabacum, and H. vulgare [108,114–116].

3.4 DNA Binding with One Finger (DOF) TFs

DOF is a plant-specific TF that belong to the member of the zinc finger family [10]. It consists mainly of 200–400 amino acid residues that are highly conserved. The DOF TFs hold two important domain structures. With 50–52 amino acid residues, the first domain is highly conserved and capable of forming a zinc finger [117]. It is known as the DNA-binding domain, which is located at the N-terminal region. The second domain is a less conserved transcriptional regulation domain located at the C-terminal region [10].

The DOF TFs family was discovered for the first time by Yanagisawa and Izui [118] in Z. mays plants. As an interesting TF family, other studies have been carried out earlier, which allow the characterization of 37 new DOF members in the model plant A. thaliana [119] and 30 DOF members in O. sativa [120]. Moreover, with the development of new tools, such as whole genome analysis, several DOF TFs have been identified with a species-dependent manner. For example, 35 DOF members were newly characterized in Setaria italica [121]. Another interesting study by Zhou et al. [122] evidenced the existence of 36 different DOF members in Citrullus lanatus. In 2021, other DOF members were identified, including 22 DOF in Spinacia oleracea [123], 24 DOF in R. chinensis [124], and 26 DOF in Betula platyphylla [125].

DOF TFs have been reported to play a central role in several biological processes, including the accumulation of seed reserve, dormancy and germination of seeds, photosynthesis, flowering, and other biological processes. For example, to elucidate the key role of ZmDOF36 and ZmDOF3 in starch accumulation during seed development, transgenic Z. mays were generated [126,127]. The authors demonstrated that the knockdown of the ZmDOF3 gene resulted in a decrease in starch biosynthesis, while the line overexpressing the ZmDOF36 gene was characterized by higher starch content. Additionally, in H. vulgare, the DOF proteins, such as HvDOF17 and HvDOF19, were shown to contribute to seed germination by regulating the expression of genes encoding aleurone hydrolase [128]. DOF TFs could also control plant growth and development. In A. thaliana, Wei et al. [129] evidenced that plants overexpressing the DOF TF COG1 exhibited larger rosettes and higher biomass, but the downregulation of the same TF dramatically reduced both rosette size and biomass.

Furthermore, DOF TFs have also been reported to play a key role in plant abiotic stress tolerance (Table 1). Thus, the overexpression of the Tamarix hispida DOF reduced the effect of drought-mediated ROS accumulation by modulating the expression of genes encoding antioxidant enzymes, including ThSOD, ThPOD, and ThGPX [8]. In the same way, transgenic N. benthamiana overexpressing VyDOF8 TF from Vitis yeshanensis showed improved tolerance to water stress, evidenced by higher chlorophyll and proline contents and lower MDA and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) contents [85]. Moreover, in G. hirsutum, Su et al. [86] showcased that the transgenic line overexpressing GhDOF1 exhibited higher tolerance to cold and osmotic stresses. Authors related the higher tolerance of transgenic plants to the ability of GhDOF1 to modulate the activity of proline metabolism enzymes, thereby increasing proline accumulation. More recently, Wang et al. [84] evidenced that A. thaliana overexpressing ThDOF8 TF, from the salt-tolerant Tamarix hispida, exhibited higher proline levels and enhanced SOD and POD activities, and ultimately salt-stress tolerance. Likewise, Xian et al. [87] revealed that DOF TF strengthens Kentucky bluegrass tolerance to Cd stress by orchestrating the expression of several genes associated with lipid, carbohydrate, cell wall, cell elongation, and membrane stability.

3.5 Heat Shock Factors (HSFs) TFs

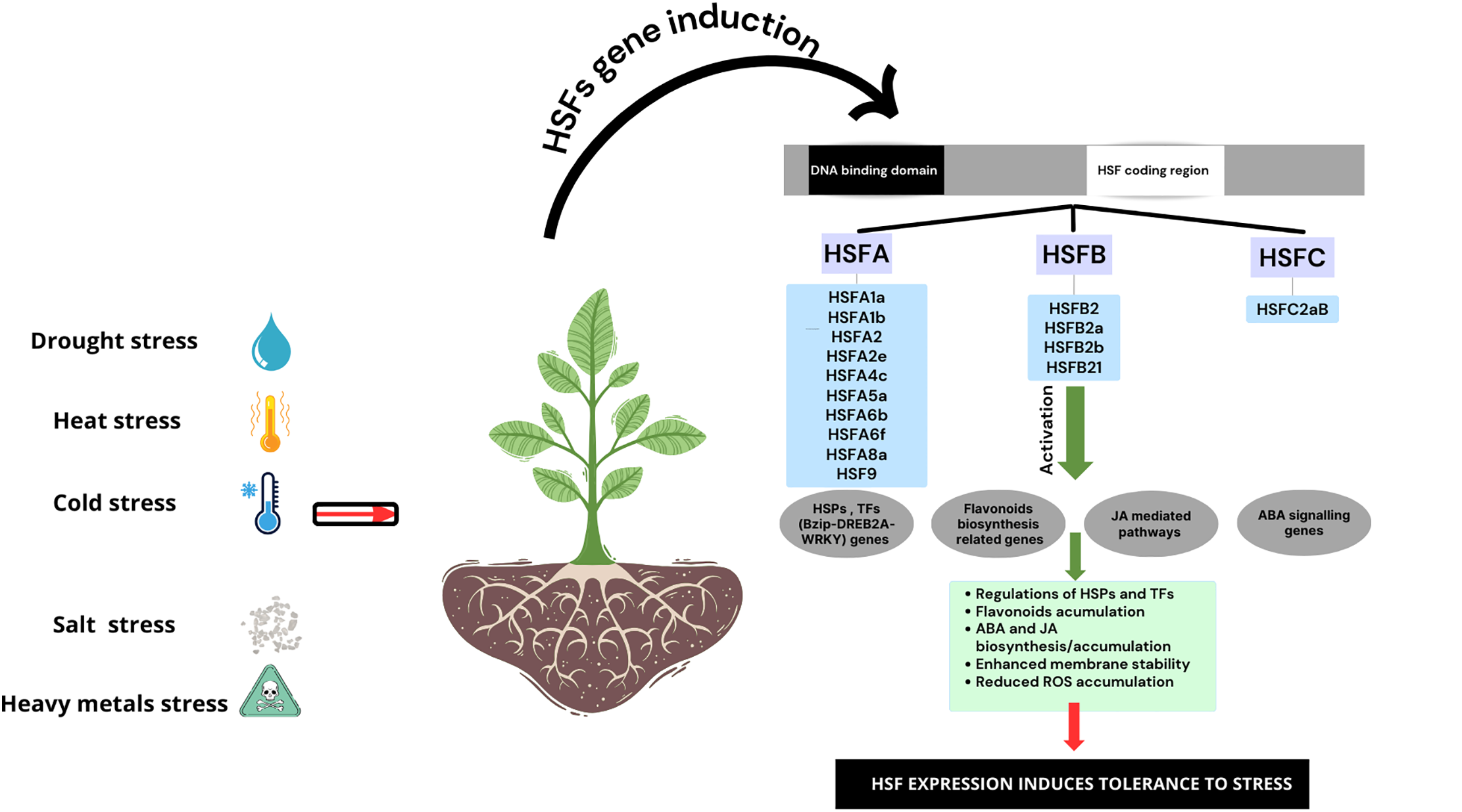

The Heat Shock Factors (HSFs) are one of the most identified TFs that play a vital role in regulating gene expression, which are involved in plant stress tolerance [9]. This TF is characterized by a modular structure that includes a DNA-binding domain (DBD) at the N-terminal responsible for recognizing heat shock elements (HSEs) and an oligomerization domain, required for the protein-protein interactions [130,131].

First, HSF TFs are recognized for their role in extreme temperature stress. Recently, they have also been identified as multifunctional regulators responding to various abiotic stresses, including salinity, drought, and toxic trace elements (Table 1; Fig. 2). HSFA1 acts as a principal regulator of the heat stress response. It regulates signaling events and interacts with HSFs A2 and B1 [130,131]. Overexpression of this TF has improved thermotolerance in many plant species. For example, in S. tuberosum, overexpression of StHSFA1 enhanced plant thermotolerance. This effect was linked to chromatin remodeling and activation of heat-responsive genes [132]. Similar findings were observed in H. vulgare [133], A. thaliana [134], and T. aestivum [135]. In these species, overexpression of TaHSFA6b, HSFA1b, and TaHSFC2a, respectively, improved ROS homeostasis, enhanced jasmonic acid-mediated heat responses, and increased HSP gene expression. This resulted in a significant increase in thermotolerance. Overexpression of AmHSF01 in Arabidopsis led to improved chlorophyll content and greater tolerance against heat stress [90]. TaHSFA6f improved tolerance to heat, drought, and salinity and modulated ABA sensitivity [9]. Similarly, Wang et al. [136] and Ma et al. [137] observed that overexpression of TaHSFA8a and TaHSFC3-4 in T. aestivum significantly enhanced drought tolerance. These changes increased flavonoid accumulation, scavenged ROS, and regulated the ABA signaling pathway to mediate drought resistance. Under the same stress, Wang et al. [136] showed that overexpression of MdHSFA8a in Malus domestica led to increased flavonoid and anthocyanin accumulation, and upregulated ABA signaling and antioxidant enzymes under drought stress. Similar protective effects were documented under cold stress (Fig. 2). For instance, Gao et al. [138] showed that overexpression of HSFB21 in Z. mays significantly promoted cold stress tolerance. It did so by modulating Bzip68 activity. Olate et al. [139] demonstrated that overexpression of HSFA1 enhances cold resistance in Arabidopsis, which is closely linked with salicylic acid receptors. Similarly, BnaHSFA2 overexpression improved ROS scavenging and reduced lipid peroxidation under freezing stress in transgenic B. napus [140].

Figure 2: The roles of Heat Shock Factors TFs in crop tolerance to abiotic stresses

In G. max and Populus alba, Bian et al. [141] and Song et al. [142] demonstrated that the overexpression of HSFB2b and HSFA5a significantly alleviated the negative effect of salt stress by increasing the biosynthesis and the accumulation of antioxidant molecules like flavonoid, and remarkably improved root development under saline conditions. Under heavy metal stress, the overexpression of HSF also presented the same beneficial effects on plant tolerance. In this context, overexpressing SaHSFA4c from Sedum alfredii in transgenic Arabidopsis lines resulted in enhanced Cd tolerance by reducing ROS accumulation and maintaining chlorophyll content [89]. Furthermore, expression analyses have shown that multiple HSF genes respond to combinations of stresses, indicating the presence of cross-tolerance mechanisms. For example, MsHSF genes in M. sativa are differentially regulated under various abiotic stresses conditions [143]. Moreover, H. vulgare overexpressing HvHSFA2e and S. tuberosum overexpressing SpHSFA4c evidenced improved heat and drought tolerance through increasing enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defense and osmotic adjustment [144,145].

3.6 The Myeloblastosis (MYB) TFs

The myeloblastosis (MYB) TFs are one of the most functionally diverse families of TFs in plants that play a vital role in regulating plant response to abiotic stresses, like salt stress, water deficit, cold, heat, and heavy metal toxicity [146,147]. This TF is discovered as an oncogene in the avian myeloblastosis virus, and it is defined by a conserved N-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD), and based on the number of MYB repeats, the MYB is categorized into four subgroups (1R, 2R, 3R, and 4R) [79]. In plants, the R2R3-MYB proteins, which are considered the largest MYB subfamily in plants, are particularly important in regulating the biosynthesis of secondary metabolism, the process of morphogenesis, and they are also important for plant tolerance to abiotic stress [148]. In fact, MYB TFs are frequently activated through ABA-dependent pathways, with specific members, such as MYB20, MYB15, and MYB41 [18]. In addition to ABA hormone, ethylene, jasmonic acid, auxin, gibberellin, cytokinin, and salicylic acid hormones could also modulate MYB-mediated stress responses [149].

Under stressed conditions, the MYB TFs have crucial roles in improving plant tolerance (Table 1). For example, MYBs TFs have numerous beneficial impacts in mediating the plant tolerance to heavy metal stress. For example, transgenic N. tabacum plants expressing SbMYB15 from Salicornia brachiata displayed increased tolerance to Cd and Ni evidenced by lower concentrations of Cd and Ni, and higher antioxidant enzyme activities as compared to the wild type [92]. Moreover, BnMYB2 from Boehmeria nivea has shown promise for phytoremediation regarding the elevated potential of the transgenic A. thaliana plants to accumulate Cd without any toxicity symptoms [150]. Likewise, Cd-stressed Daucus carota overexpressing DcMYB62 displayed increased levels of Cd tolerance due to the increase in carotenoids, ABA, and hydrogen sulfide, which are important for stress tolerance [151]. MYB TFs have been reported to improve plant tolerance to other abiotic stress, such as heat, as shown in A. thaliana overexpressing the TaMYB80 from T. aestivum [152]. Similar results were recorded under salt and drought-stressed conditions. In the study of Wang et al. [91], overexpressing GmMYB84 strengthened the tolerance of G. max to drought, evidenced by longer roots, higher antioxidant activity, and better survival. Similarly, transferring TaMYB30-B from T. aestivum to A. thaliana improved drought tolerance in transgenic plants [153]. Besides, under salt stress, overexpressing PfMYB44 in transgenic A. thaliana upregulates key genes, such as AtNHX1 and AtSOS1, which are important for ion homeostasis and stress response [15]. Additionally, by upregulating SOS2 and enabling Na+ efflux, MYB42 helps salt tolerance in A. thaliana [154].

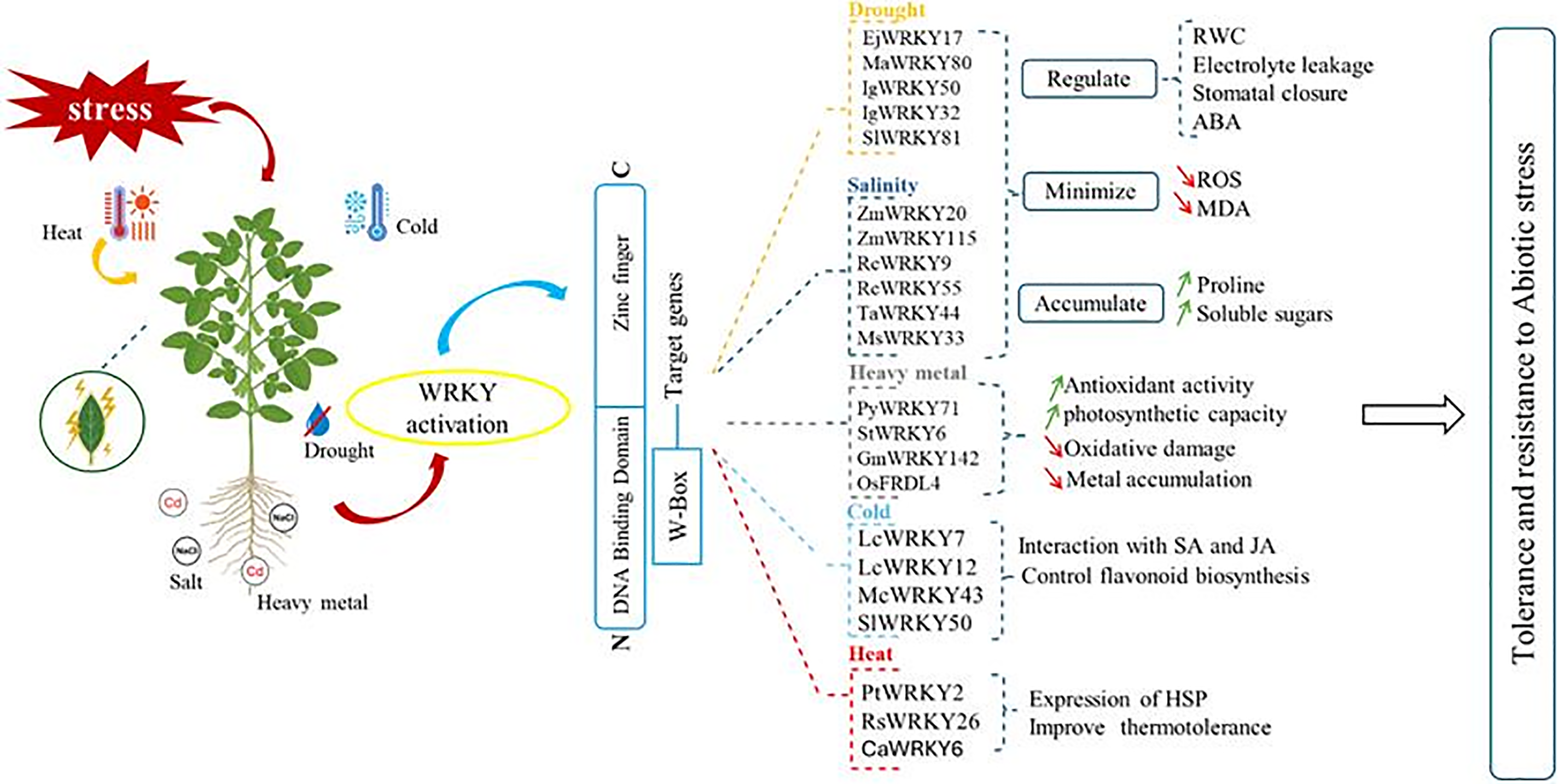

The WRKY gene family is a crucial group of plant-specific TFs that significantly enhance plant resilience to abiotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, heavy metals, cold, and heat through diverse molecular pathways (Table 1; Fig. 3). Since the discovery of the first member, SWEET POTATO FACTOR 1 (SPF1) from Ipomoea batatas [155], extensive genome sequencing has revealed numerous WRKY genes across many species, including Arabidopsis, chickpea, sorghum, cucumber, and Miscanthus [156,157]. WRKY proteins, typically characterized by a conserved ~60 amino acid DNA-binding domain with the WRKYGQK motif and a C2H2 or C2HC zinc finger motif, are categorized into three main groups (I, II, and III) and further subgroups based on structural features, allowing functional diversity and interaction with other proteins and transcription factors [158]. These TFs bind W-box elements in promoter regions to modulate stress-responsive gene expression, either activating or repressing pathways that control ROS detoxification, hormone signaling, and metabolic adjustments [159].

Figure 3: The roles of WRKY TFs in crop tolerance to abiotic stresses

In drought stress, WRKY genes, such as EjWRKY17 and MaWRKY80, modulate ABA synthesis and ROS scavenging, which reduce water loss and improve tolerance, while SlWRKY81 controls stomata behavior to mitigate dehydration [82,94,160]. WRKY TFs also regulate salt stress responses. For example, ZmWRKY20 and TaWRKY44 enhance ion homeostasis and antioxidant activity in Z. mays and T. aestivum, improving plant survival under saline conditions [161,162]. Heavy metal stress triggers WRKY activation via MAPK signaling, leading to enhanced expression of transporters, chelators, and antioxidant enzymes, with GmWRKY142 and StWRKY6 among those shown to increase Cd tolerance and accumulation capacity [163,164]. Furthermore, WRKYs contribute to Al tolerance by regulating citrate transporter expression, as seen in O. sativa Oswrky22 mutants [165].

These TFs engage extensively with phytohormone signaling pathways, including salicylic acid and jasmonic acid, modulating gene expression in response to cold and heat stresses [166]. Overexpression of WRKY genes, such as McWRKY43 and SlWRKY50, enhances flavonoid production and antioxidant defenses, conferring chilling tolerance [11,167]. WRKYs also regulate heat shock proteins and ROS detoxification pathways, exemplified by PtWRKY2 and RsWRKY26, which improved heat tolerance in A. thaliana and Raphanus sativus respectively [93,168]. Notably, WRKY proteins can form regulatory networks by interacting with each other. For example, Cai et al. [169] evidenced that CaWRKY6 activates CaWRKY40 which strengthened C. annuum tolerance to combined heat and humidity stress. Collectively, the broad functional versatility and evolutionary conservation of WRKY transcription factors underscore their vital role in plant abiotic stress adaptation (Table 1; Fig. 3) and provide promising targets for crop improvement strategies.

4 Crosstalk among Key TFs Families in Abiotic Stress Responses

In higher plants, each TF family plays a key role not only in plant development but also in their adaptation to abiotic stresses [8,9]. However, these regulators do not function independently, but interact in integrated networks, modulating each other to orchestrate coordinated responses [170]. These interactions enable fine-tuned regulation of defense genes and contribute to strengthening plant tolerance to adverse environmental conditions. For instance, in Chrysanthemum morifolium, the overexpression of CmDREB6 TF promoted the expression of CmHsfA4 and CmHSP90 TFs, which improve C. morifolium plant tolerance to heat stress, as reflected by a higher survival rate (85%) as compared to the wild-type (3.8%) [171]. Similarly, during heat stress conditions, A. thaliana plants lacking bZIP28 TF showed enhanced activation of APXs and HSPs-dependent pathways together with a significant accumulation of HsfA2 transcripts and H2O2 [172]. These findings suggest that HsfA2 TF may compensate for the deficiency in bZIP28 TF during heat stress. Moreover, in G. max submitted to osmotic stress, the GmWRKY27 TF was found to interact with GmMYB174 to bind to the W-boxes in the promoter of the GmNAC29, a negative factor of stress tolerance, which enhances salt and drought tolerance [170]. In another interesting study by Zhang et al. [173] on Poncirus polyandra, authors used protein-protein interaction prediction to showcase that PpWRKY regulates stomatal movement through MYB TF mediated ABA signaling process.

In summary, plant tolerance to abiotic stress results from a synergistic network between different TFs. Thus, understanding these interactions opens the way to more effective biotechnological and varietal improvement approaches, capable of exploiting the complementarity of these regulators to sustainably strengthen crop resilience.

Abiotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, extreme temperatures, and soil contamination with heavy metals, pose major threats to the growth, development, and productivity of crop plants. These environmental constraints strongly disrupt the major plant physiological and biochemical processes, including photosynthesis, nutrient uptake, water balance, and cellular integrity. Moreover, the severity of their effects in the context of climate change justifies the intensified research efforts that aim to develop more tolerant plant varieties capable of maintaining their yields under hostile conditions.

In this context, transcription factors (TFs) play a fundamental role in orchestrating plant adaptive responses to stress. These proteins act upstream of signaling cascades by activating or repressing the expression of some genes involved in cellular defense, osmoregulation, detoxification of reactive oxygen species, biosynthesis of protective compounds (such as osmoprotectants and heat shock proteins), and adjustment of energy metabolism.

Our review highlights seven major families of TFs-bZIP, bHLH, MYB, HSF, WRKY, DREB, and DOF—that have been genetically introduced or overexpressed in various transgenic plants to enhance their tolerance to specific stresses. Each factor has distinct, sometimes complementary, roles in activating target genes linked to stress signaling pathways, cellular protection, secondary metabolism, or osmoregulation, which contribute to strengthening the resilience of transgenic plants. Research on these factors has identified effective strategies for inducing specific or combined tolerance mechanisms, depending on the type of stress.

Besides their key fundamental roles in plant response to stressful conditions, the TFs also represent a good target for biotechnological applications. Progress in transgenic techniques, synthetic biology, and genome editing provides chances to fine-tune TF networks, allowing for the creation of crop variants with increased resistance to a variety of abiotic challenges. Moreover, to further understand TF interactions and find new regulatory hubs, integrated omics and systems biology techniques will be crucial. Subsequent investigations ought to concentrate on converting these understandings into practical uses, connecting lab findings with sustainable farming methods.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to all the partners involved in the RHIZOLEG Project in Morocco and Hungary. We thank the administrative and technical staff of the Polydisciplinary Faculty of Beni-Mellal, Sultan Moulay Slimane University and the staff of the MESRSI agency for their support.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the RHIZOLEG project, funded by the Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research, and Innovation of Morocco (MESRSI) under the Convention 2023 No. 6, as part of the Moroccan-Hungarian Cooperation for Scientific Research.

Author Contributions: Nadia Lamsaadi: conceptualization, investigation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Oumaima Maarouf: investigation, writing—original draft. Soukaina Lahmaoui: investigation, writing—original draft. Hamid Msaad: investigation, writing—original draft. Omar Farssi: investigation, writing—original draft. Chaima Hamim: investigation, writing—original draft. Mohamed Tamoudjout: investigation, writing—original draft. Hafsa Hirt: investigation, writing—original draft. Habiba Kamal: investigation, writing—original draft. Majida El Hassni: conceptualization, writing—review and editing. Cherki Ghoulam: conceptualization, writing—review and editing. Ahmed El Moukhtari: conceptualization, supervision, resources, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. Mohamed Farissi: conceptualization, supervision, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. El Moukhtari A, Lamsaadi N, Oubenali A, Mouradi M, Savoure A, Farissi M. Exogenous silicon application promotes tolerance of legumes and their N2 fixing symbiosis to salt stress. Silicon. 2022;14(12):6517–34. doi:10.1007/s12633-021-01466-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. El Rasafi T, Haouas A, Tallou A, Chakouri M, Aallam Y, El Moukhtari A, et al. Recent progress on emerging technologies for trace elements-contaminated soil remediation. Chemosphere. 2023;341(564):140121. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lamsaadi N, Farssi O, El Moukhtari A, Farissi M. Different approaches to improve the tolerance of aromatic and medicinal plants to salt stressed conditions. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants. 2024;39:100532. doi:10.1016/j.jarmap.2024.100532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Waqas MA, Wang X, Zafar SA, Ali Noor M, Hussain HA, Nawaz MA, et al. Thermal stresses in maize: effects and management strategies. Plants. 2021;10(2):293. doi:10.3390/plants10020293. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. El Moukhtari A, Lamsaadi N, Cabassa C, Farissi M, Savouré A. Molecular approaches to improve legume salt stress tolerance. Plant Mol Biol Report. 2024;42(3):469–82. doi:10.1007/s11105-024-01432-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Song Q, Qian SF, Chen XQ, Chen LM, Li KZ. Study on the function of transcription factor GmbHLH30 on aluminum tolerance preliminary in tampa black soybean. Life Sci Res. 2014;18(4):332–7. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

7. He L, Wu Z, Wang X, Zhao C, Cheng D, Du C, et al. A novel maize F-bZIP member, ZmbZIP76, functions as a positive regulator in ABA-mediated abiotic stress tolerance by binding to ACGT-containing elements. Plant Sci. 2024;341(1–2):111952. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2023.111952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Yang G, Yu L, Wang Y, Wang C, Gao C. The translation initiation factor 1A (TheIF1A) from Tamarix hispida is regulated by a dof transcription factor and increased abiotic stress tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8(837):513. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Bi H, Zhao Y, Li H, Liu W. Wheat heat shock factor TaHsfA6f increases ABA levels and enhances tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in transgenic plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(9):3121. doi:10.3390/ijms21093121. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Gupta S, Malviya N, Kushwaha H, Nasim J, Bisht NC, Singh VK, et al. Insights into structural and functional diversity of Dof (DNA binding with one finger) transcription factor. Planta. 2015;241(3):549–62. doi:10.1007/s00425-014-2239-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Yu Q, Liu C, Sun J, Ding M, Ding Y, Xu Y, et al. McWRKY43 confers cold stress tolerance in Michelia crassipes via regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(18):9843. doi:10.3390/ijms25189843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Wang Z, Peng Z, Khan S, Qayyum A, Rehman A, Du X. Unveiling the power of MYB transcription factors: master regulators of multi-stress responses and development in cotton. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;276(Pt 2):133885. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Zheng W, Xie T, Yu X, Chen N, Zhang Z. Characterization of bZIP transcription factors from Dimocarpus longan Lour. and analysis of their tissue-specific expression patterns and response to heat stress. J Genet. 2020;99(1):69. doi:10.1007/s12041-020-01229-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhang Z, Fang J, Zhang L, Jin H, Fang S. Genome-wide identification of bHLH transcription factors and their response to salt stress in Cyclocarya paliurus. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1117246. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1117246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Luo G, Cai W, Wang H, Liu W, Liu X, Shi S, et al. Overexpression of a ‘Paulownia fortunei’ MYB factor gene, PfMYB44, increases salt and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plants. 2024;13(16):2264. doi:10.3390/plants13162264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Zhang P, Wang R, Yang X, Ju Q, Li W, Lü S, et al. The R2R3-MYB transcription factor AtMYB49 modulates salt tolerance in Arabidopsis by modulating the cuticle formation and antioxidant defence. Plant Cell Environ. 2020;43(8):1925–43. doi:10.1111/pce.13784. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Agarwal PK, Jha B. Transcription factors in plants and ABA dependent and independent abiotic stress signalling. Biologia Plant. 2010;54(2):201–12. doi:10.1007/s10535-010-0038-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Gao L, Lv Q, Wang L, Han S, Wang J, Chen Y, et al. Abscisic acid-mediated autoregulation of the MYB41-BRAHMA module enhances drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2024;196(2):1608–26. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiae383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Oukaltouma K, El Moukhtari A, Lahrizi Y, Mouradi M, Farissi M, Willems A, et al. Phosphorus deficiency enhances water deficit impact on some morphological and physiological traits in four faba bean (Vicia faba L.) varieties. Ital J Agron. 2021;16(1):1662. doi:10.4081/ija.2020.1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Lahmaoui S, Hidri R, Msaad H, Farssi O, Lamsaadi N, El Moukhtari A, et al. Biostimulatory effects of foliar application of silicon and Sargassum muticum extracts on sesame under drought stress conditions. Plants. 2025;14(15):2358. doi:10.3390/plants14152358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. El Moukhtari A, Ksiaa M, Zorrig W, Cabassa C, Abdelly C, Farissi M, et al. How silicon alleviates the effect of abiotic stresses during seed germination: a review. J Plant Growth Regul. 2023;42(6):3323–41. doi:10.1007/s00344-022-10794-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Oukaltouma K, El Moukhtari A, Lahrizi Y, Makoudi B, Mouradi M, Farissi M, et al. Physiological, biochemical and morphological tolerance mechanisms of faba bean (Vicia fabaL.) to the combined stress of water deficit and phosphorus limitation. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2022;22(2):1632–46. doi:10.1007/s42729-022-00759-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Rabbi SMF, Warren CR, MacDonald C, Trethowan RM, Young IM. Soil-root interaction in the rhizosheath regulates the water uptake of wheat. Rhizosphere. 2022;21(11):100462. doi:10.1016/j.rhisph.2021.100462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang Y, Wu X, Wang X, Dai M, Peng Y. Crop root system architecture in drought response. J Genet Genomics. 2025;52(1):4–13. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2024.05.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Kapilan R, Vaziri M, Zwiazek JJ. Regulation of aquaporins in plants under stress. Biol Res. 2018;51(1):4. doi:10.1186/s40659-018-0152-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Maurel C, Boursiac Y, Luu DT, Santoni V, Shahzad Z, Verdoucq L. Aquaporins in plants. Physiol Rev. 2015;95(4):1321–58. doi:10.1152/physrev.00008.2015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Dorjee T, Cui Y, Zhang Y, Liu Q, Li X, Sumbur B, et al. Characterization of NAC gene family in Ammopiptanthus mongolicus and functional analysis of AmNAC24, an osmotic and cold-stress-induced NAC gene. Biomolecules. 2024;14(2):182. doi:10.3390/biom14020182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ahmad Saleem M, Khan A, Tu J, Huang W, Liu Y, Feng N, et al. Salinity stress in rice: multilayered approaches for sustainable tolerance. Int J Mol Sci. 2025;26(13):6025. doi:10.3390/ijms26136025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. El Moukhtari A, Lamsaadi N, Lebreton S, Mouradi M, Cabassa C, Carol P, et al. Silicon improves seed germination and seedling growth and alleviates salt stress in Medicago sativa L. by regulating seed reserve mobilization and antioxidant system defense. Biologia. 2023;78(8):1961–77. doi:10.1007/s11756-023-01316-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Lamsaadi N, El Moukhtari A, Oubenali A, Farissi M. Exogenous silicon improves salt tolerance of Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) during seed germination and early seedling stages. Biologia. 2022;77(8):2023–36. doi:10.1007/s11756-022-01035-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Lamsaadi N, Hidri R, Zorrig W, El Moukhtari A, Debez A, Savouré A, et al. Exogenous silicon alleviates salinity stress in fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) by enhancing photosystem activities, biological nitrogen fixation and antioxidant defence system. S Afr N J Bot. 2023;159(2):344–55. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2023.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. van Zelm E, Zhang Y, Testerink C. Salt tolerance mechanisms of plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2020;71(1):403–33. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050718-100005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Chrysargyris A, Michailidi E, Tzortzakis N. Physiological and biochemical responses of Lavandula angustifolia to salinity under mineral foliar application. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:489. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.00489. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Rashed NM, Shala AY, Mahmoud MA. Alleviation of salt stress in Nigella sativa L. by gibberellic acid and rhizobacteria. Alex Sci Exch J. 2017;38(6):785–99. doi:10.21608/asejaiqjsae.2017.4413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kim YH, Khan AL, Waqas M, Shim JK, Kim DH, Lee KY, et al. Silicon application to rice root zone influenced the phytohormonal and antioxidant responses under salinity stress. J Plant Growth Regul. 2014;33(2):137–49. doi:10.1007/s00344-013-9356-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hajiboland R, Cherghvareh L, Dashtebani F. Effects of silicon supplementation on wheat plants under salt stress. J Plant Process Funct. 2017;5(18):1–12. [Google Scholar]

37. Lamsaadi N, Ellouzi H, Zorrig W, El Moukhtari A, Abdelly C, Savouré A, et al. Enhancing fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.) productivity and seed quality through silicon-based seed priming under salt-stressed conditions. Russ J Plant Physiol. 2024;71(3):70. doi:10.1134/s1021443723602562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. El Moukhtari A, El Rasafi T, Lamsaadi N, El Bouhmadi K, Samir K, Haddioui A, et al. Bio-remediation of heavy metals: promising strategies for enhancing crop growth and productivity, Bio-organic amendments for heavy metal remediation. In: Husen A, Iqbal M, Ditta A, Mehmood S, Imtiaz M, Tu MS, editors. Bio-organic amendments for heavy metal remediation. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2024. p. 515–31. doi:10.1016/B978-0-443-21610-7.00031-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Madhogaria B, Banerjee S, Chakraborty S, Dhak P, Kundu A. Alleviation of heavy metals chromium, cadmium and lead and plant growth promotion in Vigna radiata L. plant using isolated Pseudomonas geniculata. Int Microbiol. 2025;28(Suppl 1):133–49. doi:10.1007/s10123-024-00546-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Rhimi N, Hajji M, Elkhouni A, Ksiaa M, Rabhi M, Lefi E, et al. Silicon reduces cadmium accumulation and improves growth and stomatal traits in sea barley (Hordeum marinum Huds.) exposed to cadmium stress. J Soil Sci Plant Nutr. 2024;24(2):2232–48. doi:10.1007/s42729-024-01689-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Hoang TTH, Truong TDH, Tran TD, Tran THS. Management of heavy metals in rice (Oryza sativa) soils by silicon rich biochar materials. Indian J Agri Sci. 2024;94(3):241–5. doi:10.56093/ijas.v94i3.142653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Khlifi N, Ghabriche R, Ayachi I, Zorrig W, Ghnaya T. How does silicon alleviate Cd-induced phytotoxicity in barley, Hordeum vulgare L.? Chemosphere. 2024;362:142739. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.142739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. da Cunha Neto AR, dos Santos Ambrósio A, Wolowski M, Westin TB, Govêa KP, Carvalho M, et al. Negative effects on photosynthesis and chloroplast pigments exposed to lead and aluminum: a meta-analysis. Cerne. 2020;26(2):232–7. doi:10.1590/01047760202026022711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Teskey R, Wertin T, Bauweraerts I, Ameye M, McGuire MA, Steppe K. Responses of tree species to heat waves and extreme heat events. Plant Cell Environ. 2015;38(9):1699–712. doi:10.1111/pce.12417. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Ortiz-Bobea A, Wang H, Carrillo CM, Ault TR. Unpacking the climatic drivers of US agricultural yields. Environ Res Lett. 2019;14(6):064003. doi:10.1088/1748-9326/ab1e75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Su X, Li C, Yu Y, Li L, Wang L, Lu D, et al. Comprehensive transcriptomic and physiological insights into the response of root growth dynamics during the germination of diverse sesame varieties to heat stress. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46(12):13311–27. doi:10.3390/cimb46120794. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. dos Anjos Neto AP, Oliveira GRF, da Costa Mello S, da Silva MS, Gomes-Junior FG, da Luz Coelho Novembre AD, et al. Seed priming with seaweed extract mitigate heat stress in spinach: effect on germination, seedling growth and antioxidant capacity. Bragantia. 2020;79(4):502–11. doi:10.1590/1678-4499.20200127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Hasanuzzaman M, Nahar K, Alam MM, Roychowdhury R, Fujita M. Physiological, biochemical, and molecular mechanisms of heat stress tolerance in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(5):9643–84. doi:10.3390/ijms14059643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Mishra S, Spaccarotella K, Gido J, Samanta I, Chowdhary G. Effects of heat stress on plant-nutrient relations: an update on nutrient uptake, transport, and assimilation. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(21):15670. doi:10.3390/ijms242115670. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Choudhary S, Bhat TM, Alwutayd KM, El-Moneim DA, Naaz N. Salicylic acid enhances thermotolerance and antioxidant defense in Trigonella foenum graecum L. under heat stress. Heliyon. 2024;10(6):e27227. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e27227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Zabihi-e-Mahmoodabad R, Jamaati-e-Somarin S, Khayatnezhad M, Gholamin R. Effect of cold stress on germination and growth of wheat cultivars. Adv Environ Biol. 2011;5(1):94–7. [Google Scholar]

52. Ilyas M, Khan WA, Ali T, Ahmad N, Khan Z, Fazal H, et al. Cold stress-induced seed germination and biosynthesis of polyphenolics content in medicinally important Brassica rapa. Phytomed Plus. 2022;2(1):100185. doi:10.1016/j.phyplu.2021.100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Ali Abro A, Qasim M, Abbas M, Muhammad N, Ali I, Khalid S, et al. Integrating physiological and molecular insights in cotton under cold stress conditions. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2025;72(3):2561–91. doi:10.1007/s10722-024-02143-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Bekele WA, Fiedler K, Shiringani A, Schnaubelt D, Windpassinger S, Uptmoor R, et al. Unravelling the genetic complexity of sorghum seedling development under low-temperature conditions. Plant Cell Environ. 2014;37(3):707–23. doi:10.1111/pce.12189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Carretero-Paulet L, Galstyan A, Roig-Villanova I, Martínez-García JF, Bilbao-Castro JR, Robertson DL. Genome-wide classification and evolutionary analysis of the bHLH family of transcription factors in Arabidopsis, poplar, rice, moss, and algae. Plant Physiol. 2010;153(3):1398–412. doi:10.1104/pp.110.153593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Heim MA, Jakoby M, Werber M, Martin C, Weisshaar B, Bailey PC. The basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor family in plants: a genome-wide study of protein structure and functional diversity. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20(5):735–47. doi:10.1093/molbev/msg088. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Toledo-Ortiz G, Huq E, Quail PH. The Arabidopsis basic/helix-loop-helix transcription factor family. Plant Cell. 2003;15(8):1749–70. doi:10.1105/tpc.013839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Li C, Yan C, Sun Q, Wang J, Yuan C, Mou Y, et al. The bHLH transcription factor AhbHLH112 improves the drought tolerance of peanut. BMC Plant Biol. 2021;21(1):540. doi:10.1186/s12870-021-03318-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Zhao Q, Fan Z, Qiu L, Che Q, Wang T, Li Y, et al. MdbHLH130, an apple bHLH transcription factor, confers water stress resistance by regulating stomatal closure and ROS homeostasis in transgenic tobacco. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:543696. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.543696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Liang B, Wan S, Ma Q, Yang L, Hu W, Kuang L, et al. A novel bHLH transcription factor PtrbHLH66 from trifoliate orange positively regulates plant drought tolerance by mediating root growth and ROS scavenging. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(23):15053. doi:10.3390/ijms232315053. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Zhai X, Wang X, Yang X, Huang Q, Wu D, Wang Y, et al. Genome-wide identification of bHLH transcription factors and expression analysis under drought stress in Pseudoroegneria libanotica at germination. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2024;30(3):467–81. doi:10.1007/s12298-024-01433-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Qiu JR, Huang Z, Xiang XY, Xu WX, Wang JT, Chen J, et al. MfbHLH38, a Myrothamnus flabellifolia bHLH transcription factor, confers tolerance to drought and salinity stresses in Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20(1):542. doi:10.1186/s12870-020-02732-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Zhang H, Guo J, Chen X, Zhou Y, Pei Y, Chen L, et al. Pepper bHLH transcription factor CabHLH035 contributes to salt tolerance by modulating ion homeostasis and proline biosynthesis. Hortic Res. 2022;9:uhac203. doi:10.1093/hr/uhac203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Sun K, Wang H, Xia Z. The maize bHLH transcription factor bHLH105 confers manganese tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Plant Sci. 2019;280(4):97–109. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.11.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Khan I, Asaf S, Jan R, Bilal S, Lubna, Khan AL, et al. Genome-wide annotation and expression analysis of WRKY and bHLH transcriptional factor families reveal their involvement under cadmium stress in toma to (Solanum lycopersicum L.). Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1100895. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1100895. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Li G, Jin L, Sheng S. Genome-wide identification of bHLH transcription factor in Medicago sativa in response to cold stress. Genes. 2022;13(12):2371. doi:10.3390/genes13122371. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Li F, Guo S, Zhao Y, Chen D, Chong K, Xu Y. Overexpression of a homopeptide repeat-containing bHLH protein gene (OrbHLH001) from Dongxiang Wild Rice confers freezing and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 2010;29(9):977–86. doi:10.1007/s00299-010-0883-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Cao X, Wen Z, Shen T, Cai X, Hou Q, Shang C, et al. Overexpression of PavbHLH28 from Prunus avium enhances tolerance to cold stress in transgenic Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2023;23(1):652. doi:10.1186/s12870-023-04666-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Jin R, Kim HS, Yu T, Zhang A, Yang Y, Liu M, et al. Identification and function analysis of bHLH genes in response to cold stress in sweetpotato. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2021;169:224–35. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2021.11.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Bi C, Yu Y, Dong C, Yang Y, Zhai Y, Du F, et al. The bZIP transcription factor TabZIP15 improves salt stress tolerance in wheat. Plant Biotechnol J. 2021;19(2):209–11. doi:10.1111/pbi.13453. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Farinati S, DalCorso G, Varotto S, Furini A. The Brassica juncea BjCdR15, an ortholog of Arabidopsis TGA3, is a regulator of cadmium uptake, transport and accumulation in shoots and confers cadmium tolerance in transgenic plants. New Phytol. 2010;185(4):964–78. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03132.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Fuhrmann-Aoyagi MB, de Fátima Ruas C, Barbosa EGG, Braga P, Moraes LAC, de Oliveira ACB, et al. Constitutive expression of Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor AREB1 activates cross-signaling responses in soybean under drought and flooding stresses. J Plant Physiol. 2021;257:153338. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2020.153338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Liu C, Wu Y, Wang X. bZIP transcription factor OsbZIP52/RISBZ5: a potential negative regulator of cold and drought stress response in rice. Planta. 2012;235(6):1157–69. doi:10.1007/s00425-011-1564-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Huang C, Zhou J, Jie Y, Xing H, Zhong Y, Yu W, et al. A ramie bZIP transcription factor BnbZIP2 is involved in drought, salt, and heavy metal stress response. DNA Cell Biol. 2016;35(12):776–86. doi:10.1089/dna.2016.3251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Hu J, Nan S, Zhou L, Yu C, Li Y, Zhao K, et al. PagbZIP75 decreases the ROS accumulation to enhance salt tolerance of poplar via the ABA signaling. Environ Exp Bot. 2024;228:106051. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2024.106051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Lan Y, Pan F, Zhang K, Wang L, Liu H, Jiang C, et al. PhebZIP47, a bZIP transcription factor from moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulispositively regulates the drought tolerance of transgenic plants. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;197(1):116538. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Wang D, Zeng Y, Yang X, Nie S. Characterization of DREB family genes in Lotus japonicus and LjDREB2B overexpression increased drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):497. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05225-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Hu X, Liang J, Wang W, Cai C, Ye S, Wang N, et al. Comprehensive genome-wide analysis of the DREB gene family in Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulisevidence for the role of PeDREB28 in plant abiotic stress response. Plant J. 2023;116(5):1248–70. doi:10.1111/tpj.16420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Li SL, Xia YZ, Liu J, Shi XD, Sun ZQ. Effects of cold-shock on tomato seedlings under high temperature stress. Chinese J Appl Ecol. 2014;25(10):2927. [Google Scholar]

80. Liang Y, Li X, Lei F, Yang R, Bai W, Yang Q, et al. Transcriptome profiles reveals ScDREB10 from Syntrichia caninervis regulated phenylpropanoid biosynthesis and starch/sucrose metabolism to enhance plant stress tolerance. Plants. 2024;13(2):205. doi:10.3390/plants13020205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Ban Q, Liu G, Wang Y. A DREB gene from Limonium bicolor mediates molecular and physiological responses to copper stress in transgenic tobacco. J Plant Physiol. 2011;168(5):449–58. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2010.08.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Li X, Zhang D, Gao B, Liang Y, Yang H, Wang Y, et al. Transcriptome-wide identification, classification, and characterization of AP2/ERF family genes in the desert moss Syntrichia caninervis. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8(47):262. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.00262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Charfeddine M, Charfeddine S, Bouaziz D, Ben Messaoud R, Bouzid RG. The effect of cadmium on transgenic potato (Solanum tuberosum) plants overexpressing the StDREB transcription factors. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult PCTOC. 2017;128(3):521–41. doi:10.1007/s11240-016-1130-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Wang P, Wang D, Li Y, Li J, Liu B, Wang Y, et al. The transcription factor ThDOF8 binds to a novel Cis-element and mediates molecular responses to salt stress in Tamarix hispida. J Exp Bot. 2024;75(10):3171–87. doi:10.1093/jxb/erae070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Li G, Xu W, Jing P, Hou X, Fan X. Overexpression of VyDOF8, a Chinese wild grapevine transcription factor gene, enhances drought tolerance in transgenic tobacco. Environ Exp Bot. 2021;190(25):104592. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2021.104592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Su Y, Liang W, Liu Z, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Ijaz B, et al. Overexpression of GhDof1 improved salt and cold tolerance and seed oil content in Gossypium hirsutum. J Plant Physiol. 2017;218:222–34. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2017.07.017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Xian J, Wang Y, Niu K, Ma H, Ma X. Transcriptional regulation and expression network responding to cadmium stress in a Cd-tolerant perennial grass Poa Pratensis. Chemosphere. 2020;250(4):126158. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.126158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Yang G, Gao X, Ma K, Li D, Jia C, Zhai M, et al. The walnut transcription factor JrGRAS2 contributes to high temperature stress tolerance involving in Dof transcriptional regulation and HSP protein expression. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18(1):367. doi:10.1186/s12870-018-1568-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Chen S, Yu M, Li H, Wang Y, Lu Z, Zhang Y, et al. SaHsfA4c from Sedum alfredii hance enhances cadmium tolerance by regulating ROS-scavenger activities and heat shock proteins expression. Front Plant Sci. 2020;11:142. doi:10.3389/fpls.2020.00142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Zhang H, Li G, Hu D, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Shao H, et al. Functional characterization of maize heat shock transcription factor gene ZmHsf01 in thermotolerance. PeerJ. 2020;8(2):e8926. doi:10.7717/peerj.8926. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Wang N, Zhang W, Qin M, Li S, Qiao M, Liu Z, et al. Drought tolerance conferred in soybean (Glycine max. L) by GmMYB84, a novel R2R3-MYB transcription factor. Plant Cell Physiol. 2017;58(10):1764–76. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcx111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Sapara KK, Khedia J, Agarwal P, Gangapur DR, Agarwal PK. SbMYB15 transcription factor mitigates cadmium and nickel stress in transgenic tobacco by limiting uptake and modulating antioxidative defence system. Funct Plant Biol. 2019;46(8):702–14. doi:10.1071/FP18234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. He Q, He M, Zhang X, Zhang X, Zhang W, Dong J, et al. RsVQ4-RsWRKY26 module positively regulates thermotolerance by activating RsHSP70-20 transcription in radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Environ Exp Bot. 2023;214:105467. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2023.105467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Wang D, Chen Q, Chen W, Liu X, Xia Y, Guo Q, et al. A WRKY transcription factor, EjWRKY17, from Eriobotrya japonica enhances drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(11):5593. doi:10.3390/ijms22115593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Ben Rejeb I, Pastor V, Mauch-Mani B. Plant responses to simultaneous biotic and abiotic stress: molecular mechanisms. Plants. 2014;3(4):458–75. doi:10.3390/plants3040458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

96. Jakoby M, Weisshaar B, Dröge-Laser W, Vicente-Carbajosa J, Tiedemann J, Kroj T, et al. bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(3):106–11. doi:10.1016/s1360-1385(01)02223-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Jin C, Li KQ, Xu XY, Zhang HP, Chen HX, Chen YH, et al. A novel NAC transcription factor, PbeNAC1, of Pyrus betulifolia confers cold and drought tolerance via interacting with PbeDREBs and activating the expression of stress-responsive genes. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:1049. doi:10.3389/fpls.2017.01049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Fukazawa J, Sakai T, Ishida S, Yamaguchi I, Kamiya Y, Takahashi Y. Repression of shoot growth, a bZIP transcriptional activator, regulates cell elongation by controlling the level of gibberellins. Plant Cell. 2000;12(6):901–15. doi:10.1105/tpc.12.6.901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

99. Lee GH, Min CW, Jang JW, Wang Y, Jeon JS, Gupta R, et al. Analysis of post-translational modification dynamics unveiled novel insights into Rice responses to MSP1. J Proteomics. 2023;287(3):104970. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2023.104970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Su H, Cao Y, Ku L, Yao W, Cao Y, Ren Z, et al. Dual functions of ZmNF-YA3 in photoperiod-dependent flowering and abiotic stress responses in maize. J Exp Bot. 2018;69(21):5177–89. doi:10.1093/jxb/ery299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

101. Hsieh TH, Li CW, Su RC, Cheng CP, Sanjaya, Tsai YC, et al. A tomato bZIP transcription factor, SlAREB, is involved in water deficit and salt stress response. Planta. 2010;231(6):1459–73. doi:10.1007/s00425-010-1147-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Chai M, Fan R, Huang Y, Jiang X, Wai MH, Yang Q, et al. GmbZIP152, a soybean bZIP transcription factor, confers multiple biotic and abiotic stress responses in plant. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(18):10935. doi:10.3390/ijms231810935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]