Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Early Chemodiversity of Alkaloids in Seedlings Annona Species

Laboratorio de Fisiología y Química Vegetal, Instituto de Ciencias Biológicas, Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, 29039, Chiapas, México

* Corresponding Author: Alma Rosa González-Esquinca. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Secondary Metabolism and Functional Biology Volume II)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3509-3526. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.072586

Received 30 August 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

The seedling phase represents an initial and critical stage for the establishment of individuals in the ecosystem. During this stage, specialized metabolites contribute to survival; however, studies analyzing the presence of these molecules and the reasons for their production and accumulation are still scarce. Annonaceae is a botanical family recognized for the chemodiversity of its secondary metabolites; nearly 1000 alkaloids have been reported in approximately 150 adult specimens. The aim of this study was to determine whether alkaloid biosynthesis in Annonaceae is expressed from early stages. For this purpose, Annona macroprophyllata, Annona muricata, Annona purpurea, and Annona reticulata seedlings, tropical Annonaceae with a history of alkaloids in adult stages, were studied. Alkaloids were extracted using the selective acid-base method from roots, stems, and leaves of seedlings with one to two pairs of leaves. The chemical composition analysis was performed using gas chromatography coupled to a mass spectrum. The identity of molecules was confirmed with standards and bibliographical references. Alkaloids were detected in the tissues of all species, and 28 of these metabolites were identified, 92% with a benzylisoquinoline structure. Many of them have reports of various biological activities. These alkaloids are not derived from the mother plant, as no alkaloids were found in the seeds. Nine, nine, eight, and twenty alkaloids were detected in seedlings of A. macroprophyllata, A. muricata, A. reticulata, and A. purpurea, respectively. The roots of all species are the organs with the most alkaloids (both in abundance and chemical richness). In conclusion, alkaloid metabolism is expressed during the early development stages in Annonaceae and could be associated with the chemical defense theory. These findings enhance our understanding of how seedlings use chemical strategies to adapt to their environment. They also demonstrate that seedlings can produce active compounds, even when grown under controlled conditions.Keywords

The seedling stage is one of the most critical phases in the life cycle of a plant. Seedling survival is relevant to the size and genetic variability of populations and to the species composition of plant communities [1]. Seedling development has been widely studied regarding its genetic, physiological, metabolic, and ecological aspects [1–3]. However, one of the metabolic processes that has received less attention is the presence of molecules associated with secondary metabolism.

Secondary metabolites during early seedling development could come from seeds or be the product of de novo biosynthesis [4]. In both cases, the biosynthesis and accumulation of these specialized molecules provide better survival attributes since their biological activities and ecological functions would be crucial for the successful establishment of seedlings in the environment in which they will grow [4,5].

The secondary metabolism of the Annonaceae family gives origin to about 2600 molecules [6–9]. Alkaloids with almost 1000 molecules are the most numerous class in these plants and, of them, those with benzylisioquinoline structure are the predominant ones, although azafluorenones, azanthranquinones, benzoquinazolines, caulindoles, indole-sesquiterpene, and pyrrolidines have also been reported [6,10–12].

Annona is one of the three genera of Annonaceae with the most reported alkaloids [6]. For example, about 22 alkaloids are reported in Annona muricata [13–18]; in Annona purpurea, almost 50 of these nitrogenous metabolites [19–21], and in Annona reticulata, at least 15 are reported [22–24]. This alkaloidal metabolism diversity has been reported almost exclusively in adult individuals [6,25], with few organ-specific studies carried out by our working group in young plants such as Annona emarginata [26], A. muricata [27], A. purpurea [28], and A. reticulata [23], and during germination and early seedling growth phases of Annona cacans [29], Annona macroprophyllata [30], and A. muricata [27].

In particular, the presence of alkaloids during germination, the seedling stage, and juvenile stages of some Annonaceae has been documented. For example, in the monitoring of the alkaloid liriodenine during seedling germination and establishment [31], the relevance of this alkaloid as part of the response to water stress is known, to such an extent that it is postulated as an osmolyte in A. reticulata [23,32]. Likewise, its participation as a possible defense molecules against phytopathogens has also been pointed out [27,28,30,33]. Therefore, the early development is a study model that makes it possible to provide data on the “reason to be” of these molecules, by analyzing their presence, chemical diversity, location, and biosynthesis.

In the search to characterize this metabolic event and to point out the importance of secondary metabolism in early plant development, the presence, diversity, and location of alkaloids during the seedling phase of some species of the genus Annona, with the presence of alkaloids in the adult, stage were investigated. This study shows the diversity of alkaloids in leaves, stems, and roots of Annona macroprophyllata, Annona purpurea, Annona muricata, and Annona reticulata seedlings.

This research will deepen our understanding of how seedlings allocate energy resources to produce defense molecules. Initially, seedlings rely on energy reserves from the seed itself, and later they use energy gathered through photosynthesis. This ability could enable the production of active compounds without needing to harvest mature plants. As a result, we could accelerate the production process and improve yields by cultivating seedlings under optimal, controlled conditions.

For the study, the seedling phase was considered as the one that had developed between one and two pairs of leaves with the presence of cotyledons (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Seedling phase with one and two pairs of leaves with the presence of cotyledons

Approximately 1000 A. macroprophyllata, A. muricata, A. purpurea, and A. reticulata seeds were collected in the municipality of San Lucas, Chiapas, Mexico, during the years 2023–2024. After three to six months of storage, seeds were sterilized by soaking in a commercial sodium hypochlorite solution (3.5%) for two minutes, followed by three rinses with sterile distilled water; and germinated on moist paper rolls in a germination chamber under controlled conditions of 25°C ± 1°C, 65%–75% relative humidity, and photoperiod of 12 h light (at intensity of 500 μM m−2 s−1) and 12 h darkness. Each germinated seed was transplanted into 1-L containers with substrate consisting of soil from the region with agrolite (8:2) and placed in a bioclimatic chamber under the same conditions as the seeds during germination. Seedlings were watered with 50 mL of distilled water every 72 h until they reached the development of two to four leaves, which was achieved in a period of 1 to 2 months from the beginning of germination.

2.2 Alkaloids Extraction Preparation

The chemical profile of alkaloids was determined in seeds, root barks, stem barks, and leaves using five to ten grams of plant material, which in some cases involved the use of up to 10 seedlings per experimental unit, with n = 10 per tissue per species.

Alkaloid extracts were obtained using the acid-base technique [31]. Plant tissues were dehydrated at room temperature and reduced to a fine powder. This plant powder was degreased with hexane at a ratio of 1 to 10 in a water bath at 55°C for eight hours, three times. The resulting botanical material was moistened at a ratio of 1:5 with aqueous Na2CO3 solution and dried at room temperature for 48 to 72 h. Samples were then extracted with CHCl3 for 2 h and filtered by gravity. The chloroform extract was submitted to liquid-liquid extraction with aqueous 1N HCl solution. The acid phase was alkalinized to pH 9 with Na2CO3, and alkaloids were obtained from this aqueous phase with CHCl3. Possible water residues were removed with anhydrous Na2SO4.

The total alkaloid content was determined by spectrophotometry at 254 nm, using alkaloid liriodenine, to elaborate the standard curve (y = 0.0881× − 0.0112, R2 = 0.9949), since it is a major alkaloid in Annonaceae. The concentration of alkaloidal extracts of each tissue was analyzed by gas chromatography coupled to a mass spectrometer (GC/MS).

2.3 Chemical Composition Analysis by Gas Chromatography Coupled to Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS)

The alkaloidal extracts of roots, stems, and leaves (n = 10) were analyzed in a Claurus 600 chromatograph coupled to SQ 8T mass spectrum (Perkin Elmer®), under conditions established by De-la-Cruz et al. [25]. The analysis was performed with 1 μL extract aliquots dissolved in methanol at 5 mg·mL−1. Perkin Elmer® Elite-1 capillary column (32 m × 0.32 mm and 0.25 mm film thickness) was used as the stationary phase and helium as carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.2 mL min−1. The temperature program used started at 150°C for 1 min, with an increase of 10°C min−1 up to 280°C, being maintained for 16 min. Mass acquisition in the spectrometer was performed at 70 eV with 2.89 scans and detection of fragments from 50 to 500 Da, and the ion source temperature was maintained at 250°C. The quadrupole temperature was 250°C.

The identity of compounds was realized by the concordance of the mass spectra with those in the NIST/EPA/NIH database version 2.2 [34] and, whenever possible, values were compared with authentic standards (annomontine, liriodenine and oxopurpureine) available in the authors’ laboratory [21,25,31] or were donated by Professor Dr. Diego Cortes of the University of Valencia, Spain (asimilobine and isoboldine). In addition, the mass spectra correspondence (M/Z) reported in other articles and in the Pubchem database of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI), a component of the National Library of Medicine of the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH), was used. Chromatograms were processed using the Turbo-Mass software (PerkinElmer®, version 6.1.0).

The presence of total alkaloids was included in the statistical analyses only if they were detected in at least ten replicates. Total alkaloid content (μg g−1 dry weight) was calculated for roots, stems, and leaves of each species. Prior to parametric tests, data were checked for normality (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test). A Kruskal–Wallis (K–W) test was performed to compare the total alkaloid content among species for each organ independently (roots, stems, and leaves). In addition, within each species, the K-W test was used to compare total alkaloid content between roots, stems, and leaves, followed by Mann-Whitney post hoc tests to identify significant pairwise differences (p < 0.05).

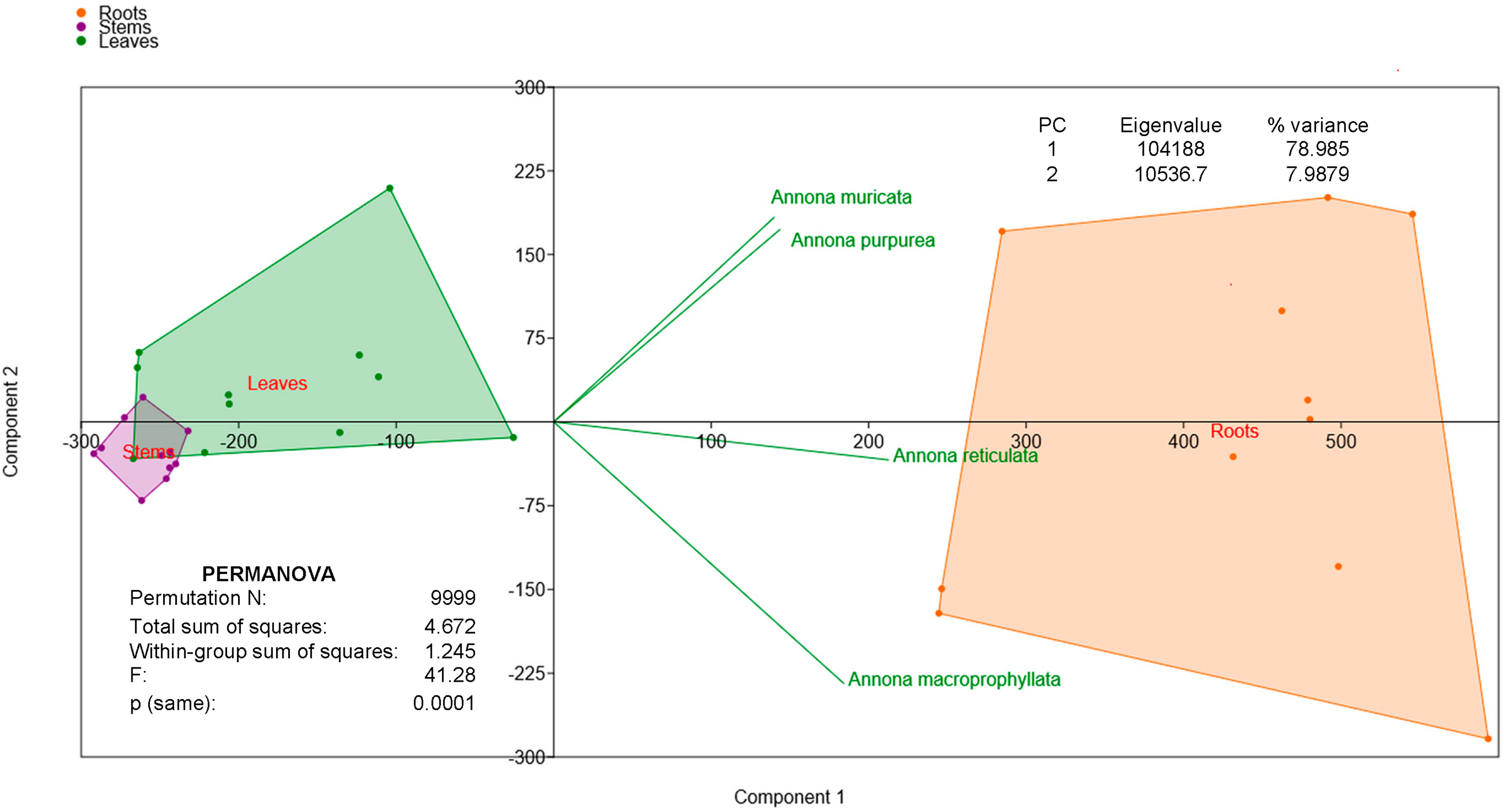

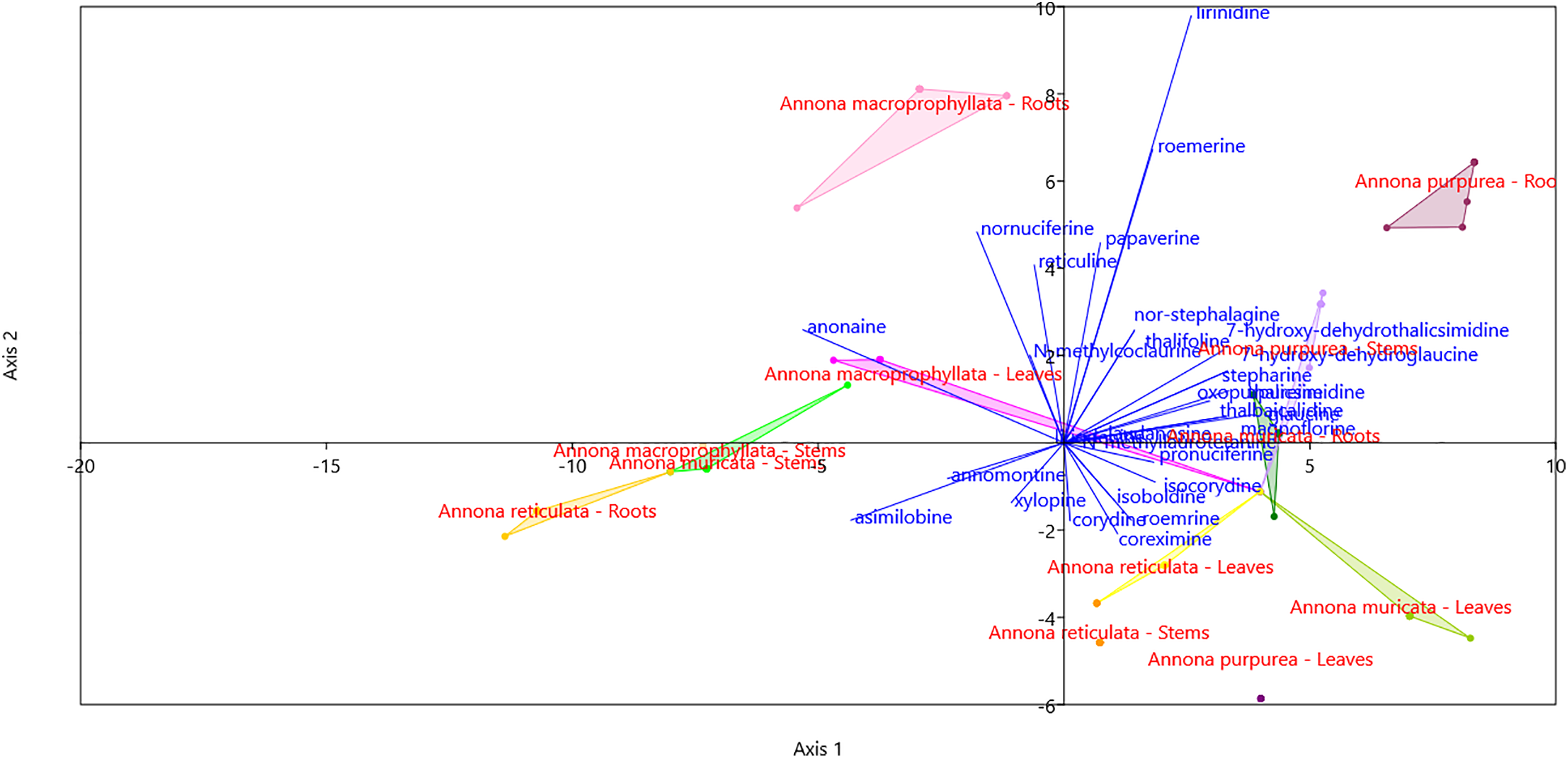

To explore patterns in the quantitative alkaloid data, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted using standardized concentrations for all detected compounds across the three plant organs in all species. Component loadings were examined to identify the alkaloids that contributed most to the separation among species and organs in the ordination space, and a PERMANOVA test was conducted to identify significant differences (p < 0.05).

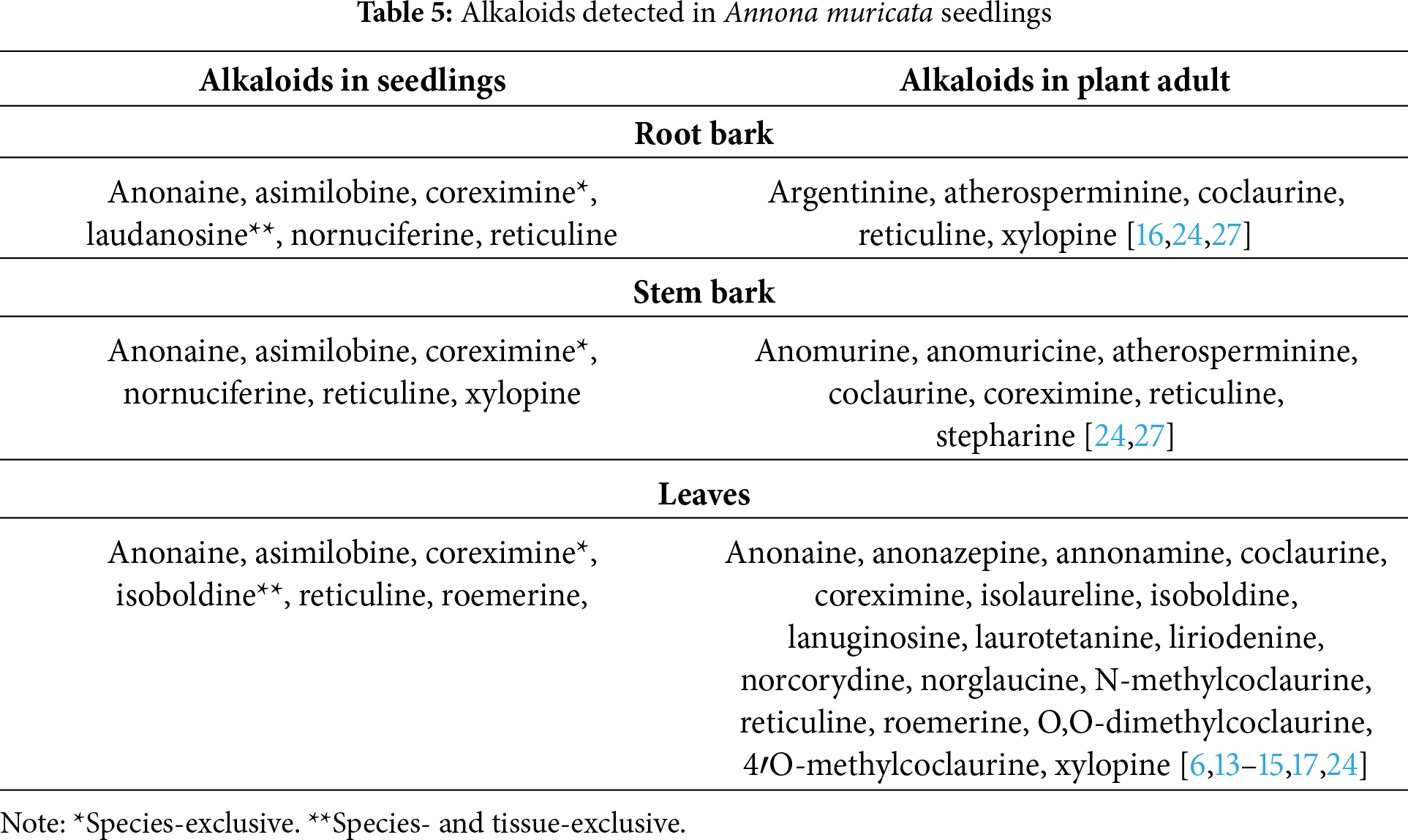

For qualitative analysis of alkaloid profiles, a presence/absence and frequency data matrix was compiled for each compound detected in roots, stems, and leaves of all species by seedling. Similarity among profiles was evaluated using the Jaccard index, which considers the number of shared presences over the total number of presences in both samples. A similarity value of 1.0 indicates identical profiles, whereas 0 indicates no compounds in common. The frequency dataset was transformed prior to analysis to improve normality and homoscedasticity, and subsequently subjected to Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) to assess and visualize chemical affinities among species and organs.

All statistical analyses were performed using PAST software version 5.2.2 [35].

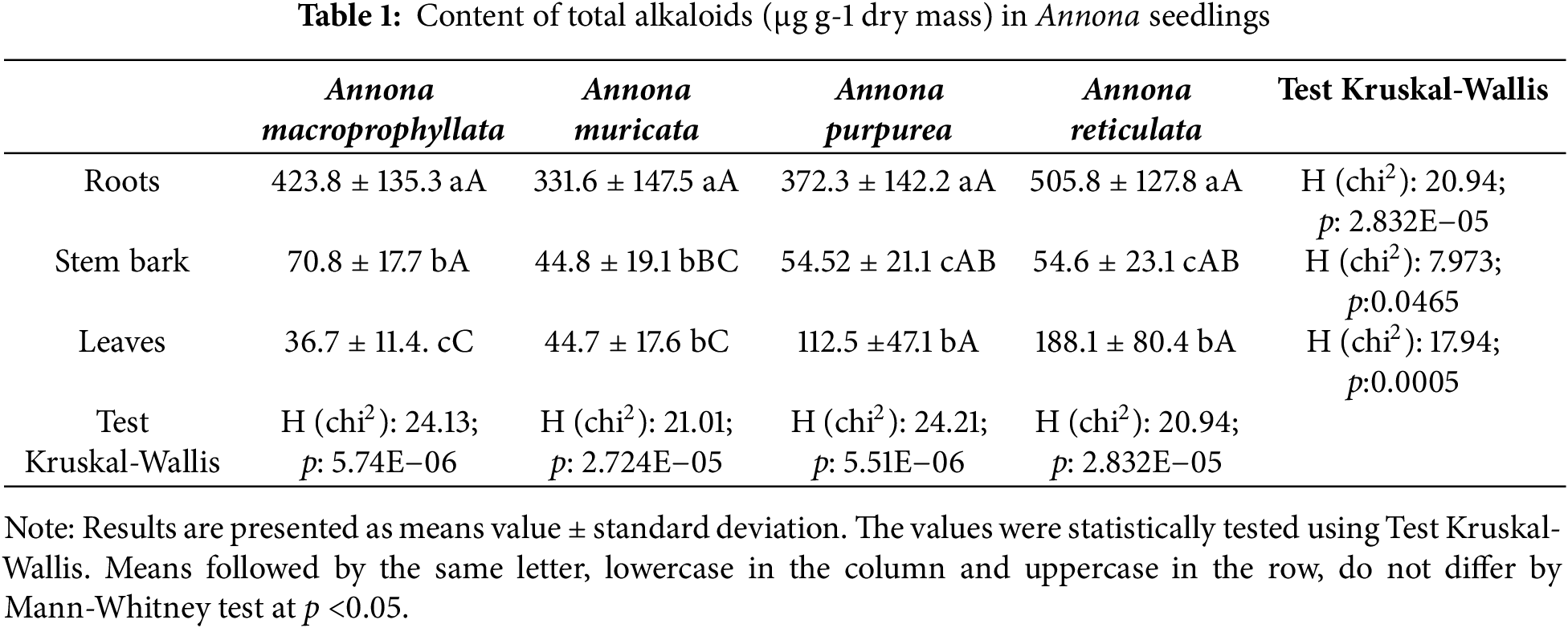

3.1 Total Alkaloids Content in the Seedlings of Annona

Both similar trends and significant differences in alkaloid yields were observed among species and tissues. In A. macroprophyllata, the roots accumulated up to eleven times more alkaloids than the stems and leaves. In contrast, A. muricata exhibited a slightly lower accumulation, with roots having seven times more alkaloids than both tissues. For A. purpurea and A. reticulata, the roots contained nine and seven times more alkaloids than the stems, respectively, and three times more than the leaves.

Differences between the leaves and stems varied among species. Annona reticulata and A. purpurea stored more alkaloids in their leaves than in the stems, while in A. macroprophyllata, this pattern was reversed. In A. muricata, the levels in both tissues were similar (Table 1).

No significant differences in alkaloid content were found among the species in the stems; however, the leaves showed noteworthy variations. Annona reticulata and A. purpurea accumulated nearly three times as many alkaloids (188 and 113 μg g−1, respectively) compared to A. macroprophyllata and A. muricata, which had lower levels (37 and 45 μg g−1, respectively).

In summary, roots showed the highest abundance of alkaloids among seedlings, ranging from three to eleven times higher than in other tissues, a trend that was supported by the principal component analysis (PCA, Fig. 2), which explained 87% of the variance (Permanova p = 0.001). Although A. muricata had an average of 331.6 μg of alkaloids per gram of roots, and A. reticulata had 505.8 μg g−1, no significant differences were detected between the four species.

Figure 2: Principal component analysis (PCA) of alkaloids total content of seedlings Annona. Component 1 and 2 accounts for 87% of the variance. PERMANOVA indicates statistical significance (F: 41.28; p: 0.0001)

3.2 Alkaloids Identified in the Seedlings of Annona

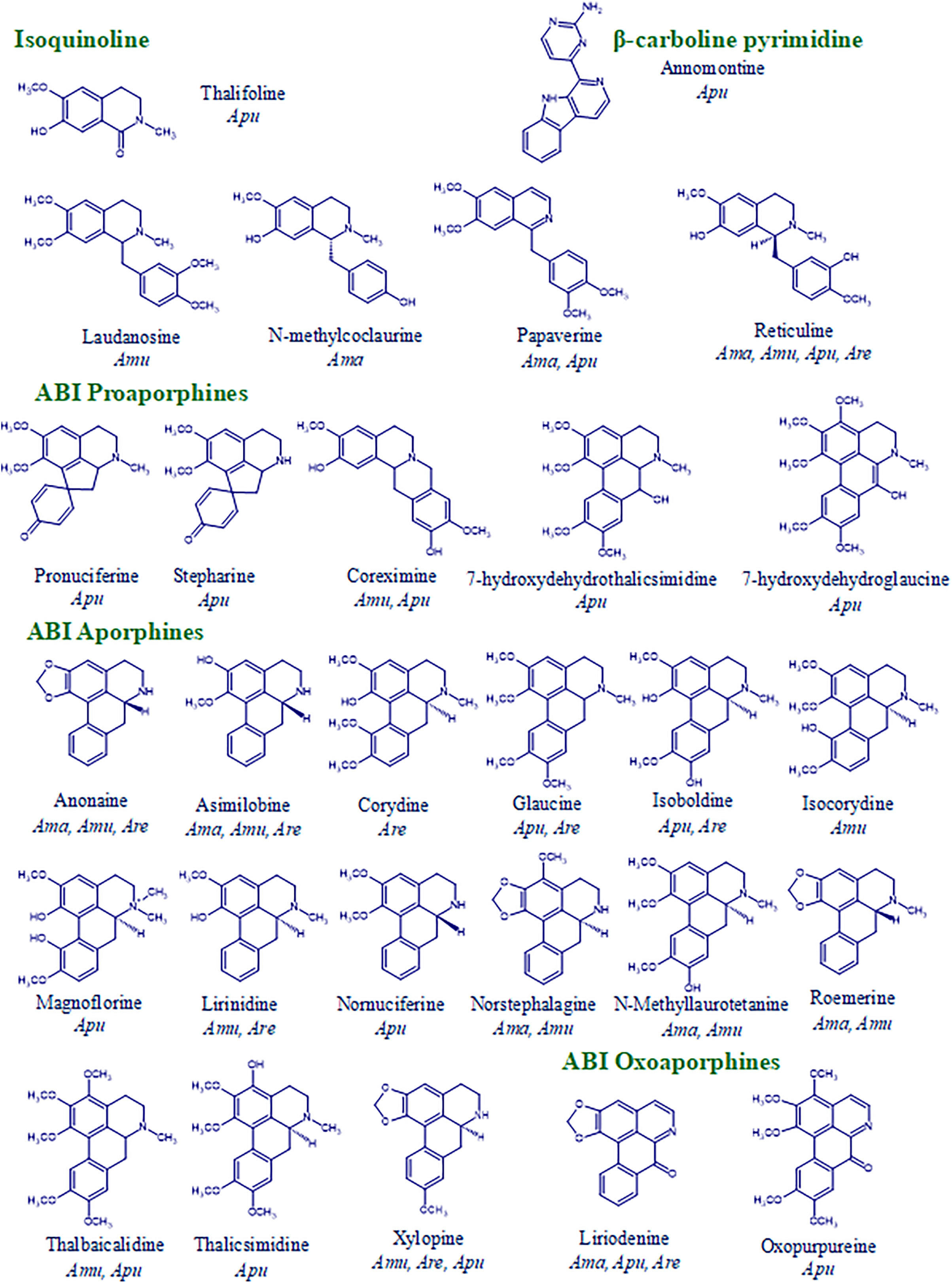

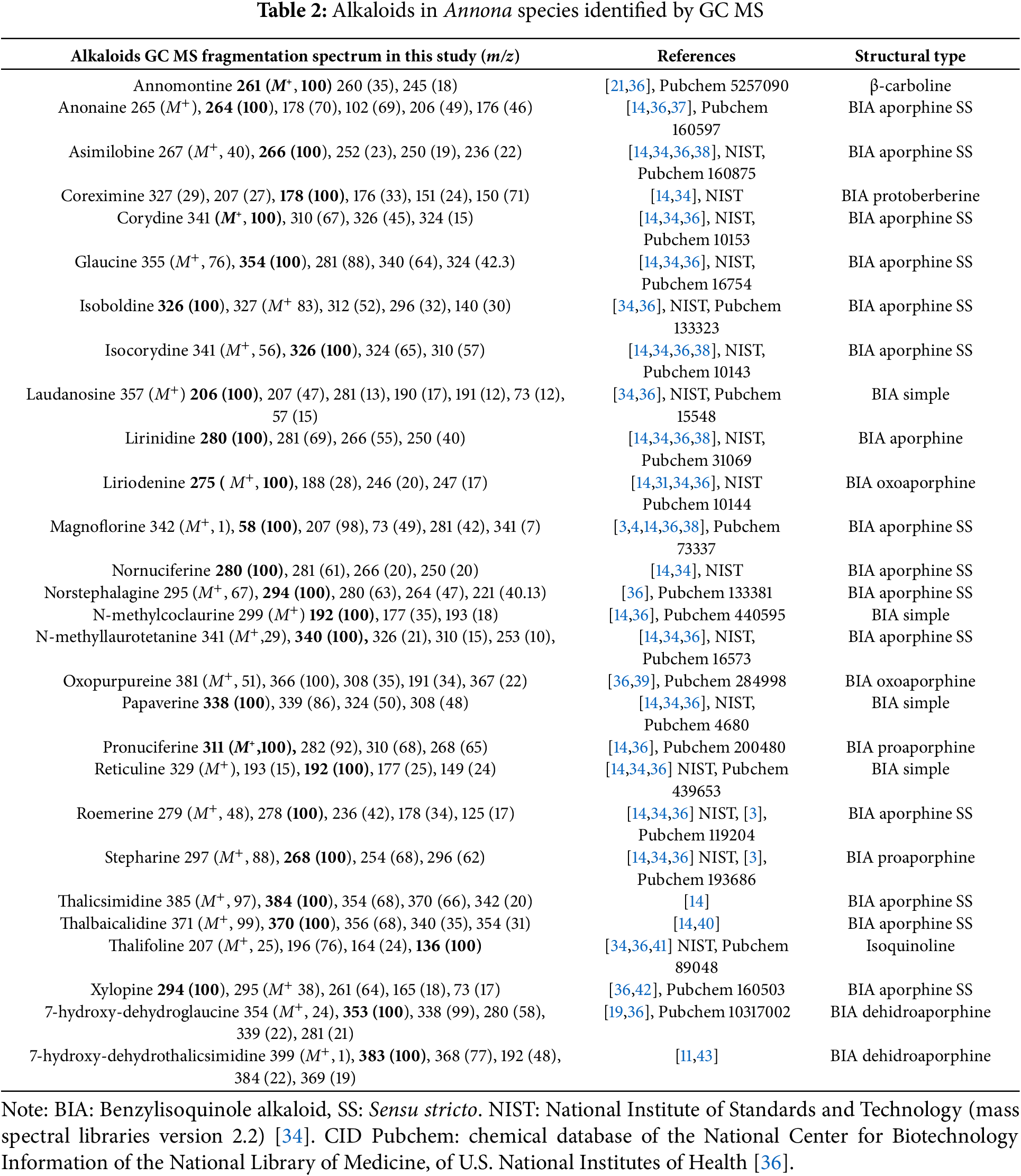

Twenty-eight alkaloids were identified, 26 benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIA), one isoquinoline alkaloid, and one with a pyrimidine-β-carboline structure (Table 2).

BIA includes a structural diversity of six types: four simple benzylisoquinolines (among them, reticuline); two aproaporphines (pronuciferine and stepharine), fifteen sensu stricto aporphines (such as anonaine), two oxoaporphines (such as oxopurpureine); two dehydroaporphines such as, dehydrothalicmisidine, and one tetrahydroprotoberberine (coreximine) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Alkaloid diversity of Annona seedlings. Are: A. reticulata; Ama: A. macroprophyllata; Amu: A. muricata; Apu: A. purpurea

There are 11 alkaloids common to Annona species; reticuline is the only one present in all species; five alkaloids were detected in three species, and another five in two species. However, 17 alkaloids are exclusive to one species, including annomontine, N-methylcoclaurine, laudanosine, coreximine, magnoflorine, stheparine, oxopurpureine, and 7-hydroxydehydroglaucine.

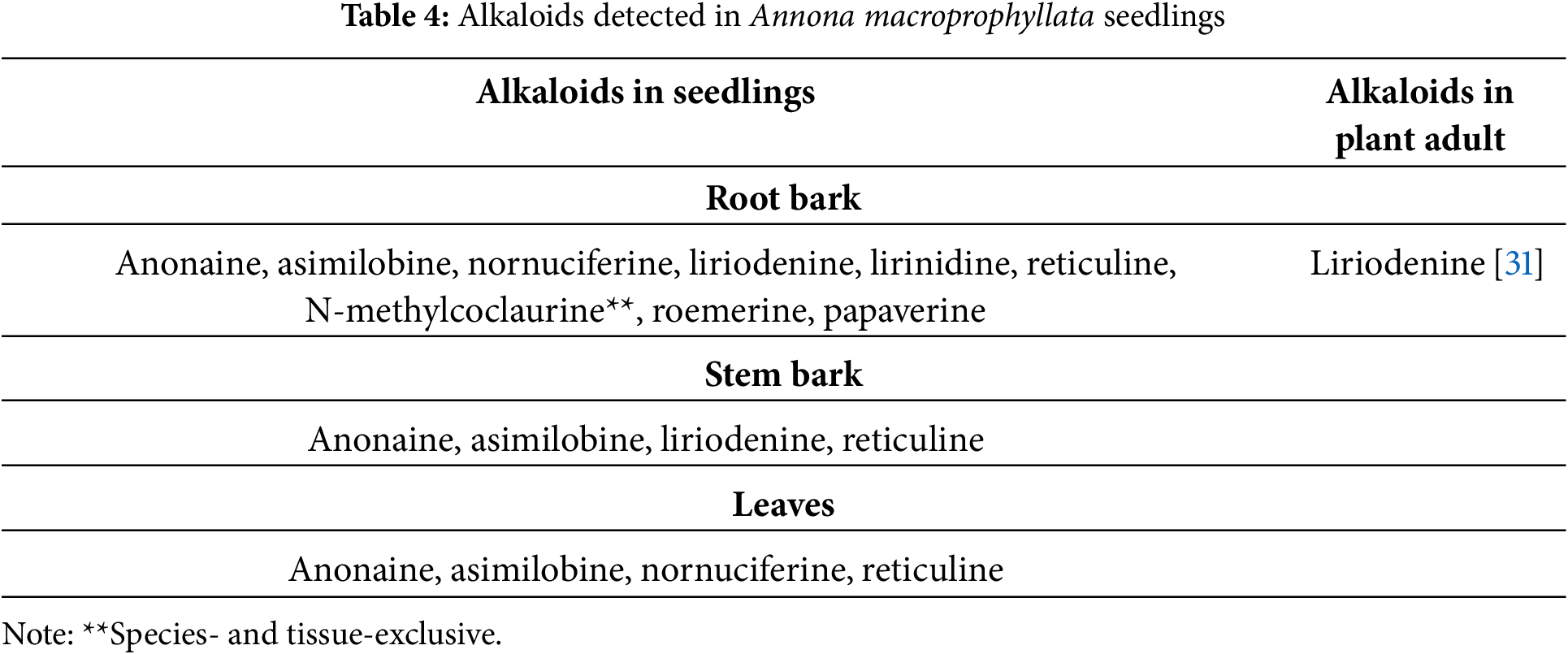

Under the extraction and analysis conditions of this study, no alkaloids were detected in the seeds of any of the species. In addition, to facilitate comparison, the alkaloids present in adult plants of each species are included. This demonstrates that, regardless of the stage of development, phenological phase, or growth conditions, the biosynthetic pathways responsible for producing these nitrogenous metabolites remain active at both stages.

3.3 Chemiodiversity of Alkaloids in Annona seedlings

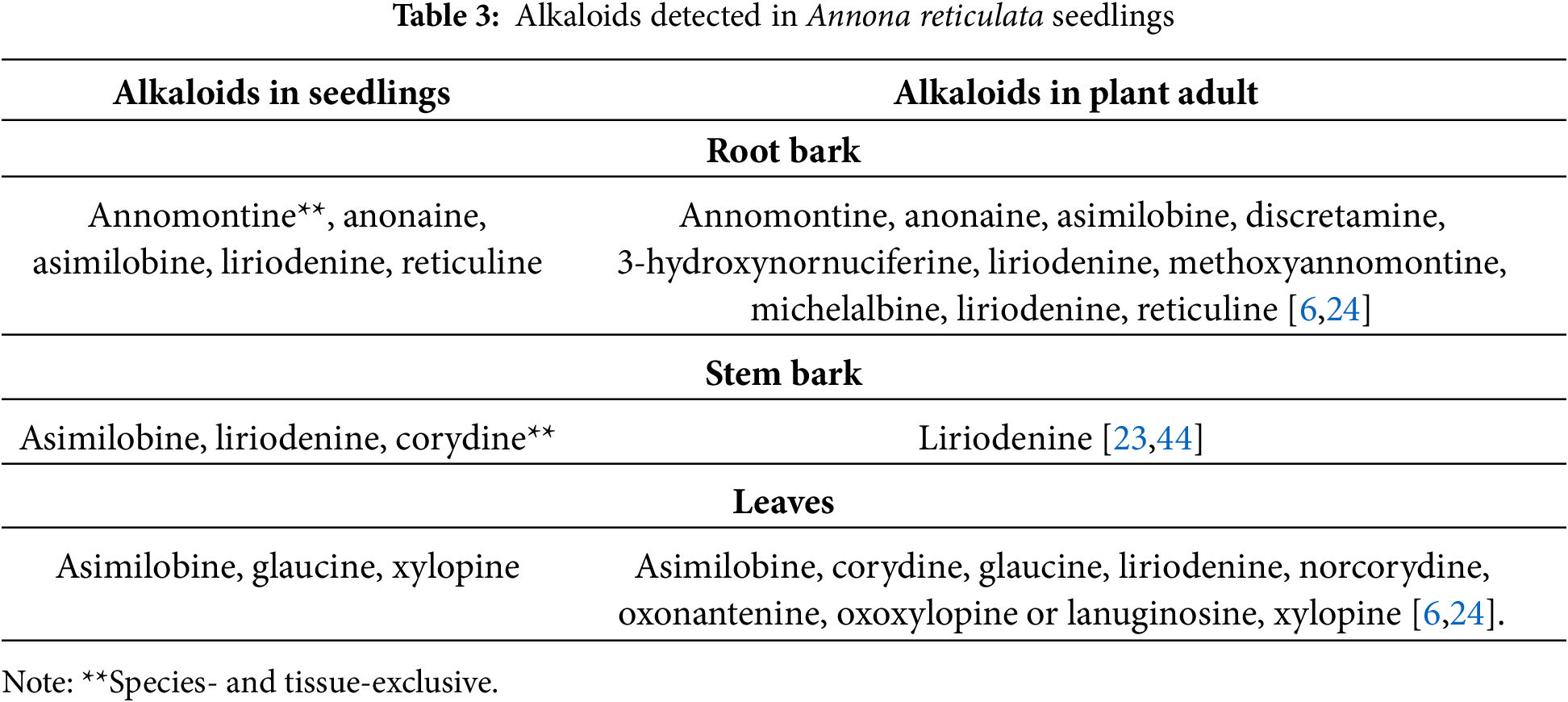

Annona reticulata seedlings are capable of producing at least eight alkaloids, the highest number being detected in roots: including annomontine, whose accumulation was exclusive to this tissue and to this species. In stems, aporphine corydine was identified, which was only found in the tissue of this species. Asimilobine was common to the three tissues (Table 3). The eight alkaloids have already been reported in adult plants.

In A. macroprophyllata seedlings, nine alkaloids were identified in roots, anonaine, asimilobine, and reticuline in stems and leaves; liriodenine is common in stems and roots, and nornuciferine in roots and leaves. Only N-methylcoclaurine is exclusive to the roots of this species. To date, only liriodenine has been reported in adult individuals (Table 4).

Nine alkaloids were detected in A. muricata seedlings, six in each tissue, four common to all tissues (anonaine, asimilobine, coreximine, and reticuline), nornuciferine in stems and roots, xylopine was only found in stems, and roemerine only in leaves. Laudanosine is exclusive to the roots of this species, and isoboldine to leaves. Six of these nine alkaloids have already been reported in adult plants, but not asimilobine, nornuciferine, and laudanosine (Table 5).

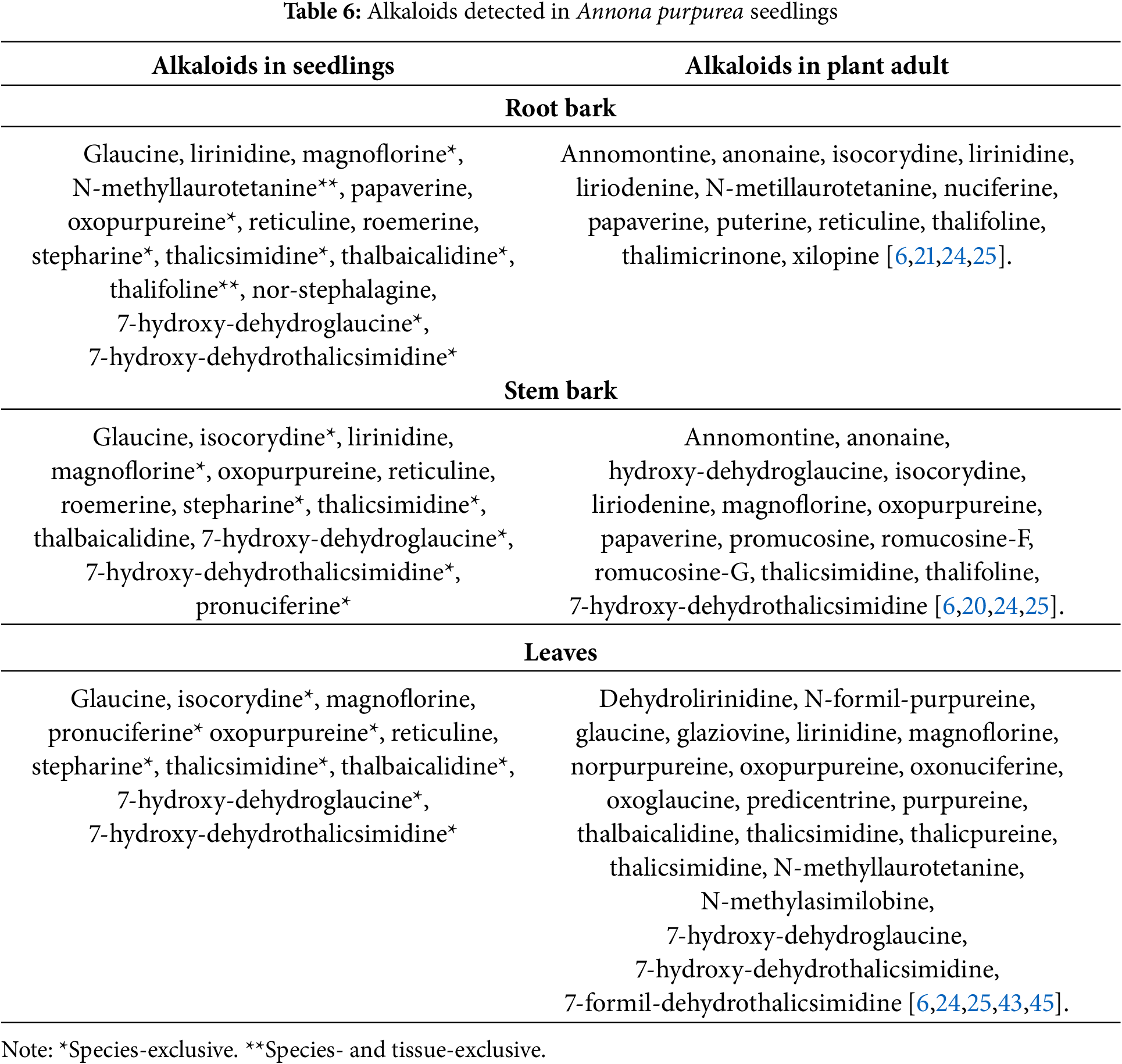

In A. purpurea seedlings, 20 alkaloids were detected, of which 15 were in roots, 13 in stems and 11 in leaves. Of these, eight are common to all tissues (glaucine, magnoflorine, oxopurpureine, stheparine, thalicisimidine); lirinidine is found in stems, and roots, and pronuciferine in stems and leaves. Seven alkaloids were only detected in this species, including oxopurpureine. Thalifoline and n-methyllaurotetanine are exclusive to the roots of this species. Of these 20 alkaloids, nine have been reported in adults, but not n-stheporalagine and roemerine (Table 6).

In the roots of A. macroprophyllata, A. purpurea, and A. reticulata, a higher alkaloid richness was observed (9, 5, and 13 alkaloids, respectively). In comparison, the leaves (4, 3, and 13) and the stems (4, 3, and 11, respectively) had fewer alkaloids. In contrast, A. muricata exhibited a nearly equivalent number of alkaloids across all tissues, with 6 in the roots, 6 in the stems, and 5 in the leaves.

There are no similar profiles that clearly group the species or tissues of the studied seedlings; each tissue has a distinctive chemodiversity (Fig. 4). For instance, while roots had a higher richness of alkaloids, their composition did not show similarity, as indicated by the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) results. The only notable grouping was found in the stems of A. muricata and A. macroprophyllata, which shared three common alkaloids—anonaine, asimilobine, and reticuline—accounting for at least 50% of their alkaloid profile.

Figure 4: Linear discriminant analysis (LDA) of alkaloids identified in roots, stems and leaves of Annona seedlings

The seedling stage is critical for plant survival, due to environmental fluctuations in the habitat in which it attempts to establish itself, competition for resources such as light and nutrients with other plants, and the common presence of natural enemies [1]. When the seedling emerges from the soil, it begins photomorphogenesis, a sequence of light-induced growth and development events that lead to the formation of functional leaves [46]. Such development is supported by the energy reserves of seeds until reaching photosynthetic capacity.

To understand the presence of secondary metabolites (SM) in seedlings, one might first consider the conceptual frameworks on chemical defense, which are summarized under the assumption that plants have the dilemma of allocating resources to grow and/or defend themselves [47–51].

In this conceptual framework, several types of secondary metabolites are considered part of the defense strategy, and their production implies that seedlings invest costly resources in chemical defense along with their growth and development processes. For example, the growth-differentiation balance hypothesis assumes that SM are produced within physiological restrictions, so that seedlings would prioritize cell and tissue growth and differentiation processes over the production of secondary metabolites [49,52]. While the hypothesis of optimal defense suggests that young tissues are vulnerable and better chemically protected than old or senescent tissues [48], SM production should be preferentially assigned to tissues of interest to consumers and therefore at risk of attack by natural enemies [51,53,54].

The allocation of resources of Annonaceae seedlings for the production of alkaloids, documented here, assumes that these molecules must play an important role in their development or survival, since, along with the energy reserves for biomass production, resources are allocated for the biosynthesis of secondary molecules. Since alkaloids are nitrogenous molecules, Annonaceae seedlings must “carefully manage” the carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) availability to optimize their growth and metabolism, because the relative C/N proportion is critical for both growth and chemical defense, and that under C/N proportion certains, it seems that the synthesis of nitrogenous compounds such as alkaloids is favored [51,55,56].

The knowledge of these hypotheses may facilitate the understanding of the reason for the presence of SM in early stages of the plant, stages that have not yet been incorporated into the conceptual framework of the defense theory [4,51,57].

The alkaloid diversity of Annona seedlings documented here, is an early expression character that is conserved throughout the life cycle of the species, since at least 70% of documented alkaloids have been reported in juveniles or adults of the four species [6,23–25,27], which maybe show that these species use these defensive molecules in different phenophases of their life cycle.

There are some alkaloids, such as asimilobine, laudanosine, and nornuciferine, that have not been reported so far in adult A. muricata individuals [6,16,24]; there are metabolites found in adults that are not found in seedlings, for example, 3-hydroxynornuciferine, methoxyannomontine, and michelalbine in A. reticulata leaves, which raises the possibility of a phenophase-specific biosynthesis. In A. macroprophyllata, only liriodenine has been reported [31]; however, preliminary data of this species have shown that the early alkaloid profile is included in the profile of adult stages.

The presence of secondary metabolites from other species in early phenophases of plant development has been poorly documented [4]; in particular, the biosynthesis of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids has been studied in eight-day-old Papaver seedlings [58]. In Annonaceae, it has been observed that alkaloid biosynthesis occurs in the first days of germination of A. cacans, A. macroprophyllata, and A muricata [27,29,31].

In general, it has been observed that the structural diversity of alkaloids found in the adult phase is represented in seedlings, that is, the biosynthesis pathways of isoquinoline, indole and benzylisoquinoline alkaloids from amino acids phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan are active at these state of development; in particular, the diversification pathways of benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIA), which is characteristic in Annonaceae [6,10,11].

The similarities in alkaloid diversity of species under study indicate that there are common alkaloid biosynthetic pathways among them, for example, reticuline, asimilobine, anonaine, and liriodenine have been reported in about 40, 50, 60, and 100 species, respectively, and are perhaps the most widely distributed secondary metabolites in the family [6,10]. While the 15 alkaloids exclusive to seedlings of this study, such as laudanosine, coreximine, magnoflorine, thalicsiminidine, and thalifoline, are alkaloids of limited distribution; in particular, annomontine, a β-carboline pyrimidine, has only been reported in four species of the genus Annona [6,21] and for the first time in seedlings. This does not mean that they are exclusive to the species, some have been reported in adults of other species, for example, corydine is produced by Annona squamosa and Annona atemoya [6,24,59], and even by other genera such as Guatteria, Uvaria, and Popovia [6].

Alkaloids are distributed in all seedling organs, although with a higher proportion in roots, tissues frequently reported in the isolation of these molecules in adult individuals [6]. It may be the site of biosynthesis or accumulation as a form of protection against soil pathogens. Within the species, the alkaloid profiles are similar, which means that the biosynthetic routes can occur in several tissues or that molecules are produced in one site and then shared with the other organs. The biosynthetic pathways of only a few alkaloids in the Annonaceae family are known, although they have been studied in other plant families, indicating an area for further research, for example, in Berberidaceae and Papaveraceae. The biosynthesis of BIAs, including magnoflorine and papaverine, has been studied [60,61], which are detected in A. purpurea and A. macroprophyllata seedlings.

Several alkaloids found in seedlings have biological activities that suggest their role in chemical defense mechanisms. For example, liriodenine is an oxoaporphine capable of inhibiting about 25 phytopathogenic microorganisms [25,30]. This alkaloid is produced in early stages in amounts similar to those of adult specimens [31] and in proportions in which they can inhibit the infestation of phytopathogenic fungi [30]. Anonaine, isoboldine, magnoflorine, papaverine, reticuline, and roemerine are also alkaloids present in seedlings with strong antibacterial and antifungal activity [6,24,62]. Some other alkaloids have been reported with antiparasitic (liriodenine, nornuciferine, xylopine), cytotoxic (roemerine), and central nervous system (annomontine, papaverine) activities [6,21,24]. This suggests that the investment of resources for the production of these molecules would have a relevance in the survival of the species.

The presence of these alkaloids is constitutive, that is, it is inherent to the species. However, it has been documented that seedlings or young Annonaceae plants increase the proportion of alkaloids when attacked by phytopathogenic fungi [28,33], water stress [23,32], or the exogenous application of phytoregulators [26,29]. In other words, it is also a sensitive metabolism that responds to several external factors.

The presence of alkaloids in the tissues of seedlings raises two possibilities; the first of which is that they could be contributions from the mother plant, for which secondary molecules should be located in the tissues of seeds. In Annonaceae, seeds contain a tiny embryo of a few millimeters wrapped in an endosperm that occupies more than 95% of the seminal volume. However, although phytochemical studies have been carried out on seeds, alkaloids have only been reported in Annona cherimola [63], A. atemoya [59], and Annona senegalensis [64,65], in contrast to the omnipresence of acetogenins. This inference indicates that most alkaloids is biosynthesized de novo, so that biosynthesis is supported by the reserves deposited in the endosperm, which remains in the seedling stage, or by the photosynthesis of the first leaves. In this study, no alkaloids were detected in the seeds, indicating that they are biosynthesized de novo.

Alkaloids come mainly from amino acids, in particular, 26 of the 28 alkaloids identified are BIA, each molecule of which must be biosynthesized from two tyrosine molecules [65]. In turn, annomontine and thalifoline, according to their structure, should come from the amino acids tryptophan and phenylalanine. The origin of such precursors could be the reserve proteins of seeds. Subsequently, the photosynthetic activity must provide amino acids from the primary metabolism.

This panorama indicates that Annonaceae seedlings are devoting carbon skeletons both for the development of new tissues and for nitrogenous molecules that will allow them to establish themselves in the environment.

In conclusion, secondary metabolism enables the presence of molecules with biological activities in early plant development. Alkaloid biosynthesis is expressed from the first stages of life of A. macroprophyllata, A. muricata, A. purpurea, and A. reticulata. This expression is conserved until the adult stage of the species, being the same metabolic pathways that promote high diversity of alkaloids. The presence of these nitrogenous molecules with various biological activities of ecological relevance is an advantage for the establishment of seedlings in the ecosystem; therefore, they are part of the chemical defense strategy, and can be associated with the defense theory. Further studies could clarify the reason for the organ-specific distribution of these alkaloids, and in particular their abundance and richness in the roots.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge a grant from Secretaria de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (SECIHTI) from Mexican Govern.

Funding Statement: The authors gratefully acknowledge a grant the call of “Ciencia de Frontera” (CF 2023-1-2756; Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencias y Tecnologías).

Author Contributions: Iván De-la-Cruz-Chacón and Alma Rosa González-Esquinca conceived and designed the study. Data collection and analysis was performed by Iván De-la-Cruz-Chacón, Christian Anabí Riley-Saldaña, Marisol Castro-Moreno and Claudia Azucena Durán-Ruiz. The manuscript was written by Iván De-la-Cruz-Chacón and Alma Rosa González-Esquinca. The manuscript was revised by Christian Anabí Riley-Saldaña, Marisol Castro-Moreno and Claudia Azucena Durán-Ruiz. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hanley ME, Fenner M, Whibley H, Darvill B. Early plant growth: identifying the end point of the seedling phase. New Phytol. 2004;163(1):61–6. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01094.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Weitbrecht K, Müller K, Leubner-Metzger G. First off the mark: early seed germination. J Exp Bot. 2011;62(10):3289–309. doi:10.1093/jxb/err030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bewley JD, Bradford KJ, Hilhorst HWM, Nonogaki H. Germination. In: Seeds. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2012. p. 133–81. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-4693-4_4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. De-la-Cruz Chacón I, Riley-Saldaña CA, González-Esquinca AR. Secondary metabolites during early development in plants. Phytochem Rev. 2013;12(1):47–64. doi:10.1007/s11101-012-9250-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hartmann T. The lost origin of chemical ecology in the late 19th century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(12):4541–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0709231105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Lúcio ASSC, da Silva Almeida JRG, Da-Cunha EVL, Tavares JF, Barbosa Filho JM. Alkaloids of the Annonaceae: occurrence and a compilation of their biological activities. In: The alkaloids: chemistry and biology. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press; 2015. p. 233–409. doi:10.1016/bs.alkal.2014.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Coelho Kaplan MA, Figueiredo MR, Rocha MEdN, Marques AM, dSantos PRD. In: Panorama Quimiossistematico Em Annonaceae Annonaceae: Tópicos Selecionados. Curitiba, Brazil: Editora CRV; 2015. p. 117–38. [Google Scholar]

8. Neske A, Ruiz Hidalgo J, Cabedo N, Cortes D. Acetogenins from Annonaceae family. Their potential biological applications. Phytochemistry. 2020;174(Pt 1):112332. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2020.112332. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Menezes R, Sessions Z, Muratov E, Scotti L, Scotti M. Secondary metabolites extracted from Annonaceae and chemotaxonomy study of terpenoids. J Braz Chem Soc. 2021;32:2061–70. doi:10.21577/0103-5053.20210097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Leboeuf M, Cavé A, Bhaumik PK, Mukherjee B, Mukherjee R. The phytochemistry of the Annonaceae. Phytochemistry. 1980;21(12):2783–813. doi:10.1016/0031-9422(80)85046-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cavé A, Leboeuf M, Waterman PG. The aporphinoid alkaloids of the Annonaceae. In: Alkaloids: chemical and biological perspectives 5. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. p. 133–270. [Google Scholar]

12. Yoshida NC, Siqueira JMD, Rodrigues RP, Correia RP, Garcez WS. An azafluorenone alkaloid and a megastigmane from Unonopsis Lindmanii(Annonaceae). J Braz Chem Soc. 2013;24(4):529–33. doi:10.5935/0103-5053.20130090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Matsushige A, Kotake Y, Matsunami K, Otsuka H, Ohta S, Takeda Y. Annonamine, a new aporphine alkaloid from the leaves of Annona muricata. Chem Pharm Bull. 2012;60(2):257–9. doi:10.1248/cpb.60.257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Fofana S, Ziyaev R, Abdusamatov A, Zakirov SK. Alkaloids from Annona muricata leaves. Chem Nat Compd. 2011;47(2):321. doi:10.1007/s10600-011-9921-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Fofana S, Keita A, Balde S, Ziyaev R, Aripova SF. Alkaloids from leaves of Annona muricata. Chem Nat Compd. 2012;48(4):714. doi:10.1007/s10600-012-0363-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Nugraha AS, Haritakun R, Lambert JM, Dillon CT, Keller PA. Alkaloids from the root of Indonesian Annona muricata L. Nat Prod Res. 2021;35(3):481–9. doi:10.1080/14786419.2019.1638380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Huynh NV, Nguyen Huu DM, Huynh NT, Chau DH, Nguyen CD, Nguyen Truong QD, et al. Anonazepine, a new alkaloid from the leaves of Annona muricata (Annonaceae). Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2022;78(5–6):247–51. doi:10.1515/znc-2022-0136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Leboeuf M, Legueut C, Cavé A, Desconclois J, Forgacs P, Jacquemin H. Alcaloïdes des annonacées XXIX: alcaloïdes de l’Annona muricata L. Planta Med. 1981;42(5):37–44. doi:10.1055/s-2007-971543. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Chang FR, Wei JL, Teng CM, Wu YC. Antiplatelet aggregation constituents from Annona purpurea. J Nat Prod. 1998;61(12):1457–61. doi:10.1021/np9800046. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Chang FR, Chen CY, Wu PH, Kuo RY, Chang YC, Wu YC. New alkaloids from Annona purpurea. J Nat Prod. 2000;63(6):746–8. doi:10.1021/np990548n. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Del Carmen Rejón-Orantes J, González-Esquinca AR, de la Mora MP, Roldan Roldan G, Cortes D. Annomontine, an alkaloid isolated from Annona purpurea, has anxiolytic-like effects in the elevated plus-maze. Planta Med. 2011;77(4):322–7. doi:10.1055/s-0030-1250406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Suresh HM, Shivakumar B, Shivakumar SI. Phytochemical potential of Annona reticulata roots for antiproliferative activity on human cancer cell lines. Adv Life Sci. 2012;2(2):1–4. doi:10.5923/j.als.20120202.01. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Castro-Moreno M, Tinoco-Ojangurén CL, Del Rocío Cruz-Ortega M, González-Esquinca AR. Influence of seasonal variation on the phenology and liriodenine content of Annona lutescens (Annonaceae). J Plant Res. 2013;126(4):529–37. doi:10.1007/s10265-013-0550-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Nugraha AS, Damayanti YD, Wangchuk P, Keller PA. Anti-infective and anti-cancer properties of the Annona species: their ethnomedicinal uses, alkaloid diversity, and pharmacological activities. Molecules. 2019;24(23):4419. doi:10.3390/molecules24234419. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. De-la-Cruz-Chacón I, Riley-Saldaña CA, Arrollo-Gómez S, Sancristóbal-Domínguez TJ, Castro-Moreno M, González-Esquinca AR. Spatio-temporal variation of alkaloids in Annona purpurea and the associated influence on their antifungal activity. Chem Biodivers. 2019;16(2):e1800284. doi:10.1002/cbdv.201800284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Sousa MC, De-la-Cruz-Chacón I, Campos FG, Vieira MAR, Corrêa PLC, Marques MOM, et al. Plant growth regulators induce differential responses on primary and specialized metabolism of Annona emarginata (Annonaceae). Ind Crops Prod. 2022;189:115789. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Riley-Saldaña CA, Del Rocío Cruz-Ortega M, Martínez Vázquez M, De-la-Cruz-Chacón I, Castro-Moreno M, González-Esquinca AR. Acetogenins and alkaloids during the initial development of Annona muricataL. (Annonaceae). Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2017;72(11–12):497–506. doi:10.1515/znc-2017-0060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Toledo-González KA, Riley-Saldaña CA, Salas-Lizana R, De-la-Cruz-Chacón I, González-Esquinca AR. Alkaloidal variation in seedlings of Annona purpurea Moc. & Sessé ex Dunal infected with Colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Penz.) Penz. and Sacc. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2023;107(1):104611. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2023.104611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Sousa MC, Bronzatto AC, González-Esquinca AR, Campos FG, Dalanhol SJ, Boaro CSF, et al. The production of alkaloids in Annona cacans seedlings is affected by the application of GA4+7+6-Benzyladenine. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2019;84:47–51. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2019.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. De la Cruz-Chacón I, González-Esquinca AR, Guevara Fefer P, Jímenez Garcia LF. Liriodenine, early antimicrobial defence in Annona diversifolia. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2011;66(7–8):377–84. doi:10.1515/znc-2011-7-809. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. de la Cruz Chacón I, González-Esquinca AR. Liriodenine alkaloid in Annona diversifolia during early development. Nat Prod Res. 2012;26(1):42–9. doi:10.1080/14786419.2010.533373. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Cisneros-Andrés A, Cruz-Ortega R, Castro-Moreno M, González-Esquinca AR. Liriodenine and its probable role as an osmolyte during water stress in Annona lutescens (Annonaceae). Int J Plant Biol. 2024;15(2):429–41. doi:10.3390/ijpb15020033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Riley-Saldaña CA, de-la-Cruz-Chacón I, Del Rocío Cruz-Ortega M, Castro-Moreno M, González-Esquinca AR. Do Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and Rhizopus stolonifer induce alkaloidal and antifungal responses in Annona muricata seedlings? Z Naturforsch C J Biosci. 2022;78(1–2):57–63. doi:10.1515/znc-2021-0297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. National Institute of Standards and Technology. The NIST mass spectral search program for the NIST/EPA/NIH mass spectra library version 2.2 [software]. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2014. [Google Scholar]

35. Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD. PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electron. 2001;4(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

36. Kim S, Chen J, Cheng T, Gindulyte A, He J, He S, et al. PubChem 2023 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(D1):D1373–80. doi:10.1093/nar/gkac956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Azimova SS, Yunusov MS. Natural compounds: alkaloids, plant sources, structure and properties. New York, NY, USA: Springer; 2013. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-0560-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Guinaudeau H, Leboeuf M, Cavé A. Aporphine alkaloids. Lloydia. 1975;38(4):275–338. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

39. Guinaudeau H, Lebœuf M, Cavé A. Aporphinoid alkaloids, V. J Nat Prod. 1994;57(8):1033–135. doi:10.1021/np50110a001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Guinaudeau H, Leboeuf M, Cavé A. Aporphinoid alkaloids, IV. J Nat Prod. 1988;51(3):389–474. doi:10.1021/np50057a001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Georghiou PE, Wang YC. An efficient synthesis of thalifoline. Synthesis. 2002;(15):2187–90. doi:10.1055/s-2002-34844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Egydio APM, Valvassoura TA, Santos DYAC. Geographical variation of isoquinoline alkaloids of Annona crassiflora Mart. from cerrado. Brazil Biochem Syst Ecol. 2013;46:145–51. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2012.08.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Chang FR, Wei JL, Teng CM, Wu YC. Two new 7-dehydroaporphine alkaloids and antiplatelet action aporphines from the leaves of Annona purpurea. Phytochemistry. 1998;49(7):2015–8. doi:10.1016/s0031-9422(98)00376-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Saad JM, Hui YH, Rupprecht JK, Anderson JE, Kozlowski JF, Zhao GX, et al. Reticulatacin: a new bioactive acetogenin from Annona reticulata (Annonaceae). Tetrahedron. 1991;47(16–17):2751–6. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)87082-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Sánchez G, Estrada O, Acha G, Cardozo A, Peña F, Ruiz MC, et al. The norpurpureine alkaloid from Annona purpurea inhibits human platelet activation in vitro. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2018;23(1):15. doi:10.1186/s11658-018-0082-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Samiei S, Rasti P, Ly Vu J, Buitink J, Rousseau D. Deep learning-based detection of seedling development. Plant Methods. 2020;16(1):103. doi:10.1186/s13007-020-00647-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Bryant JP, Chapin FS, Klein DR. Carbon/nutrient balance of boreal plants in relation to vertebrate herbivory. Oikos. 1983;40(3):357–68. doi:10.2307/3544308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. McKey D. Adaptive patterns in alkaloid physiology. Am Nat. 1974;108(961):305–20. doi:10.1086/282909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Herms DA, Mattson WJ. The dilemma of plants: to grow or defend. Q Rev Biol. 1992;67(3):283–335. doi:10.1086/417659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Berenbaum MR. The chemistry of defense: theory and practice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(1):2–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.1.2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Stamp N. Out of the quagmire of plant defense hypotheses. Q Rev Biol. 2003;78(1):23–55. doi:10.1086/367580. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Herms DA. Effects of fertilization on insect resistance of woody ornamental plants: reassessing an entrenched paradigm: fig. 1. Environ Entomol. 2002;31(6):923–33. doi:10.1603/0046-225x-31.6.923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Feeny P. Plant apparency and chemical defense. In: Biochemical interaction between plants and insects. Boston, MA, USA: Springer; 1976. p. 1–40. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-2646-5_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. McKey D. Distribution of secondary compounds within plants. In: Herbivores: their interaction with secondary plant metabolites. New York, NY, USA: Academic Press; 1979. p. 55–134. [Google Scholar]

55. Royer M, Larbat R, Le Bot J, Adamowicz S, Robin C. Is the C: n ratio a reliable indicator of C allocation to primary and defence-related metabolisms in tomato? Phytochemistry. 2013;88:25–33. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.12.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

56. Qi Y, Gao P, Yang S, Li L, Ke Y, Zhao Y, et al. Unveiling the impact of nitrogen deficiency on alkaloid synthesis in konjac corms (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume). BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):923. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-05642-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Erb M, Kliebenstein DJ. Plant secondary metabolites as defenses, regulators, and primary metabolites: the blurred functional trichotomy. Plant Physiol. 2020;184(1):39–52. doi:10.1104/pp.20.00433. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Han X, Lamshöft M, Grobe N, Ren X, Fist AJ, Kutchan TM, et al. The biosynthesis of papaverine proceeds via (S)-reticuline. Phytochemistry. 2010;71(11–12):1305–12. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.04.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Al Kazman BSM, Harnett JE, Hanrahan JR. Identification of annonaceous acetogenins and alkaloids from the leaves, pulp, and seeds of Annona atemoya. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(3):2294. doi:10.3390/ijms24032294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Facchini PJ. Alkaloid biosynthesis in plants: biochemistry, cell biology, molecular regulation, and metabolic engineering applications. Annu Rev Plant Physiol Plant Mol Biol. 2001;52(1):29–66. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.52.1.29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Samanani N, Park SU, Facchini PJ. Cell type-specific localization of transcripts encoding nine consecutive enzymes involved in protoberberine alkaloid biosynthesis. Plant Cell. 2005;17(3):915–26. doi:10.1105/tpc.104.028654. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Li HT, Wu HM, Chen HL, Liu CM, Chen CY. The pharmacological activities of (–)-anonaine. Molecules. 2013;18(7):8257–63. doi:10.3390/molecules18078257. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Del Fresno AV, Rios Canavate JL. Alkaloids from Annona cherimolia seed. J Nat Prod. 1983;46(3):438–38. doi:10.1021/np50027a029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Tamfu AN, Tagatsing Fotsing M, Talla E, Jabeen A, Mbafor Tanyi J, Shaheen F. Bioactive constituents from seeds of Annona senegalensis Persoon (Annonaceae). Nat Prod Res. 2021;35(10):1746–51. doi:10.1080/14786419.2019.1634713. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Beaudoin GAW, Facchini PJ. Benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in opium poppy. Planta. 2014;240(1):19–32. doi:10.1007/s00425-014-2056-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools