Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Melatonin Enhances Antioxidant Defense and Physiological Stability in Grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) Cultivars ‘Merlot’ and ‘Erciş’ under UV-B Stress

1 Department of Horticulture, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Van Yüzüncü Yıl University, Van, 65080, Türkiye

2 Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Van Yüzüncü Yıl University, Van, 65080, Türkiye

3 Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Ankara University, Ankara, 06110, Türkiye

4 Department of Plant Sciences, North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND 58102, USA

5Republic of Türkiye Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, General Directorate of Agricultural Research and Policies, Erzincan Horticultural Research Institute, Erzincan, 24060, Türkiye

* Corresponding Authors: Nurhan Keskin. Email: ; Ozkan Kaya. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Precision Fertilization and Nutrient Use Efficiency in Crops)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3471-3492. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073180

Received 12 September 2025; Accepted 10 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Climate change-driven environmental stresses, particularly ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation, pose severe threats to grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) productivity and physiological stability. This study investigated the protective role of melatonin in in vitro plantlets of two grapevine cultivars, ‘Merlot’ and ‘Erciş’, subjected to low (≈8.25 μW cm−2, 16 h) and high (≈33 μW cm−2, 4 h) UV-B exposure. Significant cultivar-specific responses were observed (p < 0.001). The ‘Erciş’ cultivar exhibited higher oxidative stress, with malondialdehyde (MDA) levels reaching 24.30 mmol g−1 FW in control plants compared with 14.91 ± 0.25 mmol g−1 FW in ‘Merlot’. Melatonin provided dose-dependent mitigation, reducing MDA to 12.68 in ‘Erciş’ and 8.52 ± 0.13 in ‘Merlot’ at 200 μmol L−1. Antioxidant enzyme activities increased significantly: superoxide dismutase rose from 0.02 ± 0.01 to 0.10 EU g−1 in ‘Erciş’ and to 0.13 EU g−1 in ‘Merlot’, catalase increased up to 0.08 in ‘Erciş’ and 0.16 in ‘Merlot’, while ascorbate peroxidase reached 1.06 ± 0.02 and 1.20 ± 0.03, respectively. Pigment traits also improved, with chlorophyll content increasing to 23.70 μg cm−2 in ‘Merlot’ and 22.66 μg cm−2 in ‘Erciş’, alongside enhanced nitrogen balance index values. Secondary metabolites were elevated, particularly total phenolic content (8.23 GAE 100 g−1 in ‘Erciş’ and 5.99 in ‘Merlot’) and antioxidant capacity (17.24 and 8.15 μmol TE g−1, respectively). Correlation analyses revealed strong positive associations between melatonin and antioxidant enzymes (r = 0.54–0.85), while principal component analysis explained 64.71% of total variance, separating cultivars and treatments clearly. Clustering patterns showed distinct grouping of enzymatic defenses, phenolic compounds, and pigments, reflecting coordinated protective mechanisms. Overall, melatonin application, especially at 200 μmol L−1, significantly enhanced enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defenses, stabilized photosynthetic pigments, and reduced oxidative damage, with stronger protective efficiency in ‘Merlot’. The research provided valuable insights for developing biotechnological approaches to enhance grape stress tolerance in the context of climate change challenges.Keywords

Light, serving as the fundamental physiological requirement for green plants, can influence plant growth and development in various ways through its physical and chemical effects, making this an important focus of modern agricultural research [1]. In this context, the depletion of the ozone layer caused by anthropogenic pollutants has led to an increase in ultraviolet-B (UV-B) radiation (280–315 nm) reaching the Earth’s surface, creating a significant abiotic stress factor for plants worldwide [2,3]. Although UV-B radiation constitutes only a small component (0.5%) of total solar radiation, its high energy content enables it to cause significant damage by interacting with critical biological molecules, including DNA, RNA, proteins, lipids, and plant hormones [4–6]. The projected annual increase of approximately 0.3–1% in UV-B radiation over the next 50 years [6] is expected to cause physiological disorders across a wide range of processes, from photosynthetic activity to growth and development mechanisms [2]. UV-B causes DNA damage, triggers the accumulation of reactive oxygen species, and impairs photosynthesis, making it one of the most concerning environmental stressors for plant production systems. Perennial fruit species such as grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.), which is widely cultivated both globally and in Türkiye, must cope with numerous biotic and abiotic stress conditions, including UV-B stress, due to their sessile nature in vineyard conditions. Ultraviolet (UV) radiation modulates secondary metabolism in the skin of Vitis vinifera L. berries, which affects the final composition of both grapes and wines [7]. UV radiation in grape berries regulates the expression of several phenylpropanoid biosynthesis related genes. Scientific research has demonstrated that UV-B radiation modulates secondary metabolism in grape leaves, regulates the expression of genes related to phenylpropanoid biosynthesis, and causes significant reductions in net photosynthesis, stomatal conductance, sub-stomatal CO2 concentration, and photosystem II efficiency following short-term UV-B exposure [8,9].

Flavonoids and stilbenes are secondary metabolites produced in plants that can play an important health-promoting role [10]. The biosynthesis of these compounds generally increases as a response to biotic or abiotic stress, with UV-B radiation causing up to 10-fold increases in flavonoid concentrations, representing one of the most important indicators of adaptive responses plants develop against this stress [11]. While light stress at low to moderate intensities can function as a eustress that stimulates beneficial adaptive responses, excessive or prolonged exposure can become problematic, leading to detrimental effects on plant physiology and metabolism. The ability of UV-B to trigger both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant responses, creating a eustress condition under optimal exposure levels, emphasizes the critical role of activating protective mechanisms in stress management. Among the defense mechanisms that plants develop against UV-B stress, activation of antioxidant systems, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and glutathione reductase (GR), and synthesis of protective compounds such as flavonoids, anthocyanins, and phenolic compounds stand out prominently. In this regard, recent research has revealed the critical role of melatonin (MEL; N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine) in plant stress physiology [12]. MEL is a multifunctional molecule that has been widely discovered in most plants. An increasing number of studies have shown that MEL plays essential roles in plant growth and stress tolerance. It has been extensively applied to alleviate the harmful effects of abiotic stresses. Phytomelatonin has been proven to function as a plant biostimulator, enhancing tolerance against various abiotic stresses, including extreme temperatures, drought, osmotic stress, heavy metals, and UV radiation [13]. MEL has been reported to delay and then increase the expression of Constitutively Photomorphogenic 1 (COP1), Elongated Hypocotyl 5 (HY5), HY5 Homolog (HYH), and Repressor of UV-B Photomorphogenesis 1/2 (RUP1/2), which act as central act-ants in the UV-B signaling pathway, thereby regulating their effects on antioxidant systems to protect plants from UV-B stress [14]. Furthermore, increased MEL levels in plant roots following UV-B exposure are considered an important indicator of this compound’s adaptive response in developing tolerance to adverse environmental conditions [15].

This indolamine compound, synthesized through tryptophan metabolism, performs multiple functions in plants, including regulation of circadian rhythm, control of growth and development processes, and enhancement of tolerance against environmental stress factors [16,17]. Research indicates that enhanced endogenous MEL levels through genetic modification or exogenous application may mitigate abiotic stress and enhance plant resilience. When a plant is exposed to abiotic stress, its endogenous MEL levels rise [18]. Comprehensive research has demonstrated that exogenous MEL treatments develop extraordinary resistance mechanisms, including regulation of plant growth through increases in endogenous MEL levels, direct inhibition of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species accumulation, and regulation of plant stress responses by indirectly affecting stress response pathways [19]. This indicates that endogenous MEL accumulation positively regulates UV-B signaling and UV-B stress tolerance, showing that this compound is critically important for limiting UV-B damage and promoting repair mechanisms [18]. In plants, it was observed that the concentration of endogenous MEL was increased after UV-B treatment for a short time, suggesting that endogenous MEL is involved in UV-B response [20]. Current literature indicates that in vitro conditions provide cost-effective and controlled methods for understanding stress tolerance in plants, with in vitro cultures being preferred as model systems in stress studies due to their numerous advantages [21–24]. However, the effectiveness of MEL under controlled in vitro conditions needs to be validated through in vivo and in situ studies to fully evaluate its responses under field conditions. Moreover, natural environments typically present multiple simultaneous stresses, such as combined drought, temperature extremes, and UV radiation, which can significantly alter plant responses compared to single stress effects observed under controlled conditions, necessitating comprehensive multi-stress evaluations for practical agricultural applications.

Given the increasing importance of developing sustainable strategies to mitigate UV-B stress effects in viticulture and the promising potential of MEL as a protective agent, this study comprehensively determines the effects of different concentrations of in vitro exogenous MEL applications on grapevine tolerance against UV-B stress. In this regard, the specific objectives of this research are: (i) to investigate the protective effects of exogenous MEL on grapevine plants under in vitro UV-B stress conditions, (ii) to evaluate the physiological and biochemical responses, including anti-oxidant activity and photosynthetic performance, and (iii) to assess the potential of MEL as a biostimulator for sustainable viticulture practices under climate change scenarios.

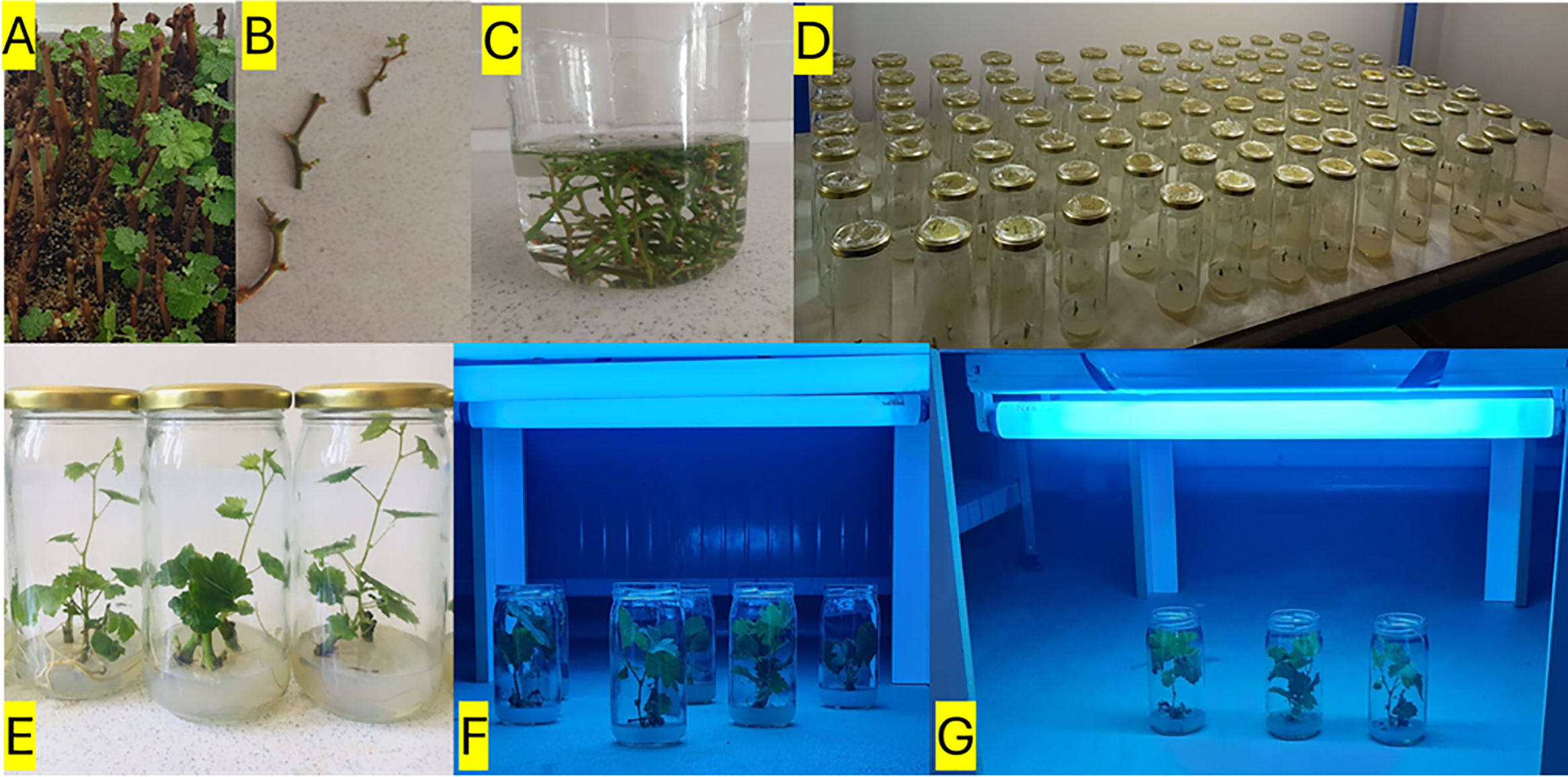

This study was conducted between 2021 and 2022 at Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Van Yuzuncu Yıl University, Van, Türkiye (38°34′05″ N, 43°16′50″ E). Plant materials were obtained from the Tekirdağ Viticulture Research Institute and the Erciş District Directorate of Agriculture and Forestry. The main materials of the study consisted of cuttings from ‘Merlot’ and ‘Erciş’ grape cultivars. ‘Merlot’ was selected as an internationally recognized cultivar widely used in viticulture research and commercial wine production, while ‘Erciş’ represents a local Turkish cultivar adapted to the regional environmental conditions of Eastern Anatolia, allowing for comparative assessment of UV-B stress responses between cosmopolitan and indigenous germplasm. Cuttings were collected during the winter dormancy period from healthy, mature, and well-lignified shoots without disease symptoms [25]. They were planted in pots containing a peat: perlite (1:1) mixture and grown under controlled conditions (8/16 h photoperiod, 24°C). Explants required for in vitro studies were obtained from the shoots developed from these cuttings (Fig. 1A).

Figure 1: Workflow of explant preparation, in vitro culture, UV-B irradiation, and biochemical analyses in grapevine. Dormant canes of Vitis vinifera L. cvs. ‘Merlot’ and ‘Erciş’ were collected during the winter season and prepared for rooting (A). Single-node explants were excised from developing shoots (B) and subjected to surface sterilization steps, including washing and pretreatment in sterile solutions (C). Explants were then cultured on semi-solid Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium supplemented with different concentrations of MEL (0, 100, 200 μM), and multiple jars were established under controlled conditions (D). In vitro plantlets developed from nodal explants are shown after establishment on culture medium (E). Plantlets with at least six fully expanded leaves were subsequently exposed to UV-B irradiation using fluorescent lamps (311 nm Philips TL 20W/01) at low and high doses, applied with multi-lamp (F) or single-lamp (G) configurations under sterile conditions

All glass, polypropylene, and metal materials were sterilized in an autoclave at 121°C for 1.5 h. In vivo-derived single-node microcuttings were used as the initial explants (Fig. 1B,C). For surface sterilization, a 15% sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) solution supplemented with a few drops of Tween 20 was used. Explants were first rinsed under running tap water, then treated with the disinfectant solution for 10 min on a magnetic stirrer. To remove the disinfectant, explants were rinsed three times with sterile distilled water (5 min each). For in vitro plantlet production, single-node cultures of ‘Merlot’ and ‘Erciş’ were established on semi-solid MS [26] medium supplemented with 0, 100, and 200 μmol L−1 MEL. The MEL concentrations were selected based on preliminary dose-response experiments and previous literature reporting effective ranges for enhancing abiotic stress tolerance in grapevine and other plant species under in vitro conditions [26]. Cultures were incubated at 25°C under a 16 h photoperiod. In vitro plantlets were propagated by continuing the subculturing process at 30-day intervals until a sufficient number of plants were obtained in the study.

According to Pontin et al. [27], in vitro plantlets (Fig. 1D,E) with at least six fully expanded leaves were exposed to low (311 nm Philips TL 20W/01, 16 h ≅ 8.25 μW cm−2) and high (311 nm Philips TL 20W/01, 4 h ≅ 33 μW cm−2) UV-B doses at a 40 cm distance under sterile conditions (Fig. 1F,G). After the treatments, leaf samples were stored at −80°C until extraction.

2.4 Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

One gram of leaf tissue was homogenized in 25 mL of methanol for 2 min using a homogenizer (IKA Ultra-Turrax T-25). The homogenate was kept at +4°C for 10 min, followed by centrifugation at 7000 rpm for 30 min (Beckman Coulter, Allegra X-300R, USA). The supernatant was stored at −20°C until analysis. Total phenolic content was determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method [28]. Absorbance was measured at 725 nm using a spectrophotometer (Genesys 10S UV-VIS, Thermo Scientific, USA), and results were expressed as gallic acid equivalents (GAE).

2.5 Determination of Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC)

Total antioxidant activity was measured using the Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) assay [29]. Absorbance was recorded at 593 nm, and results were expressed as Trolox equivalents (TE).

2.6 Antioxidative Enzyme Assays

For enzyme extraction, 1 g of leaf tissue was homogenized with 5 mL of cold extraction buffer containing 0.1 mM sodium phosphate, 0.5 mM Na-EDTA, and 1 mM ascorbic acid (pH 7.5). The homogenate was centrifuged at 18.000 rpm for 30 min at 4°C. The supernatant was immediately used to determine ascorbate peroxidase (APX) activity. For catalase (CAT) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) assays, 1 g of frozen leaf tissue was homogenized in 5 mL of 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer containing 0.5 mM Na-EDTA (pH 7.5) and centrifuged as above. CAT activity was assayed immediately, while SOD extracts were stored at −20°C until analysis [30].

2.6.1 Superoxide Dismutase (SOD)

SOD activity was determined by monitoring the inhibition of nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction at 560 nm. The reaction mixture contained 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 0.1 mM Na-EDTA, 33 μM NBT, 5 μM riboflavin, and 13 mM methionine (pH 7.0). Reactions were carried out at 25°C under 75 μmol m−2 s−1 light intensity for 10 min. Control samples were kept in the dark. One unit of SOD activity was defined as the amount of enzyme causing 50% inhibition of NBT reduction [31].

CAT activity was determined by monitoring the decomposition of H2O2 at 240 nm. The reaction mixture contained 0.05 M KH2PO4 buffer and 1.5 mM H2O2 (pH 7.0). Absorbance changes were recorded at 0 and 60 s, and activity was expressed based on the decrease in absorbance within one minute [30].

2.6.3 Ascorbate Peroxidase (APX)

APX activity was measured at 290 nm by following the ascorbate-dependent reduction of H2O2. The reaction mixture consisted of 50 mM KH2PO4 buffer, 0.5 mM ascorbic acid, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 1.5 mM H2O2 (pH 7.0). Absorbance was recorded at 0 and 60 s [32].

2.6.4 Lipid Peroxidation (MDA)

Malondialdehyde (MDA) as a Lipid Peroxidation and Stress Indicator Lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress damage were estimated by measuring malondialdehyde content. Half a gram of leaf tissue was homogenized in 10 mL of 0.1% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 5 min. One mL of the supernatant was mixed with 4 mL of 0.5% thiobarbituric acid (TBA) in 20% TCA. The mixture was incubated at 95°C for 30 min, cooled on ice, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. Absorbance of the supernatant was recorded at 532 and 600 nm, and MDA content was calculated [32,33].

Leaf nitrogen balance index (NBI), chlorophyll (Chl), anthocyanin (ANTH), and flavonol (FLAV) contents were measured using a portable leaf-clip device, DUALEX 4 Scientific (FORCE-A, Orsay, France).

2.8 Determination of Melatonin (MEL)

Leaf samples (100 mg) were ground in liquid nitrogen and extracted with 1 mL acetonitrile (ACN) for 12 h at 4°C in the dark. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min, the supernatant was evaporated under nitrogen. The residue was dissolved in 0.1 M HCl, extracted with diethyl ether, dried under nitrogen, and redissolved in H2O/MeOH (80/20, v/v). All steps were performed under dark conditions to prevent MEL degradation. MEL content was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) following Hidalgo-Ruiz et al. [34].

Descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± standard error (SE). A three-way factorial ANOVA was performed to evaluate the effects of cultivar (‘Erciş’, ‘Merlot’), UV-B dose (low, high), and treatment (control, 100 μmol L−1 MEL, 200 μmol L−1 MEL), along with their interactions, on the studied traits. Differences among group means were further examined using Duncan’s multiple range test at a significance threshold of p < 0.05. Analyses were carried out in IBM SPSS Statistics version 21.0. To explore interrelationships among the measured variables, principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted using GraphPad Prism version 9.3.1 (GraphPad Software, LLC, San Diego, CA, USA), and results were visualized in a biplot following the procedure of Evgenidis et al. [35]. In addition, hierarchical clustering combined with a heatmap was applied to illustrate the degree and structure of associations among traits, and this analysis was performed using the SRPLOT web-based platform (https://www.bioinformatics.com.cn/en, accessed on 27 August 2025).

3 Results, Discussion, and Conclusion

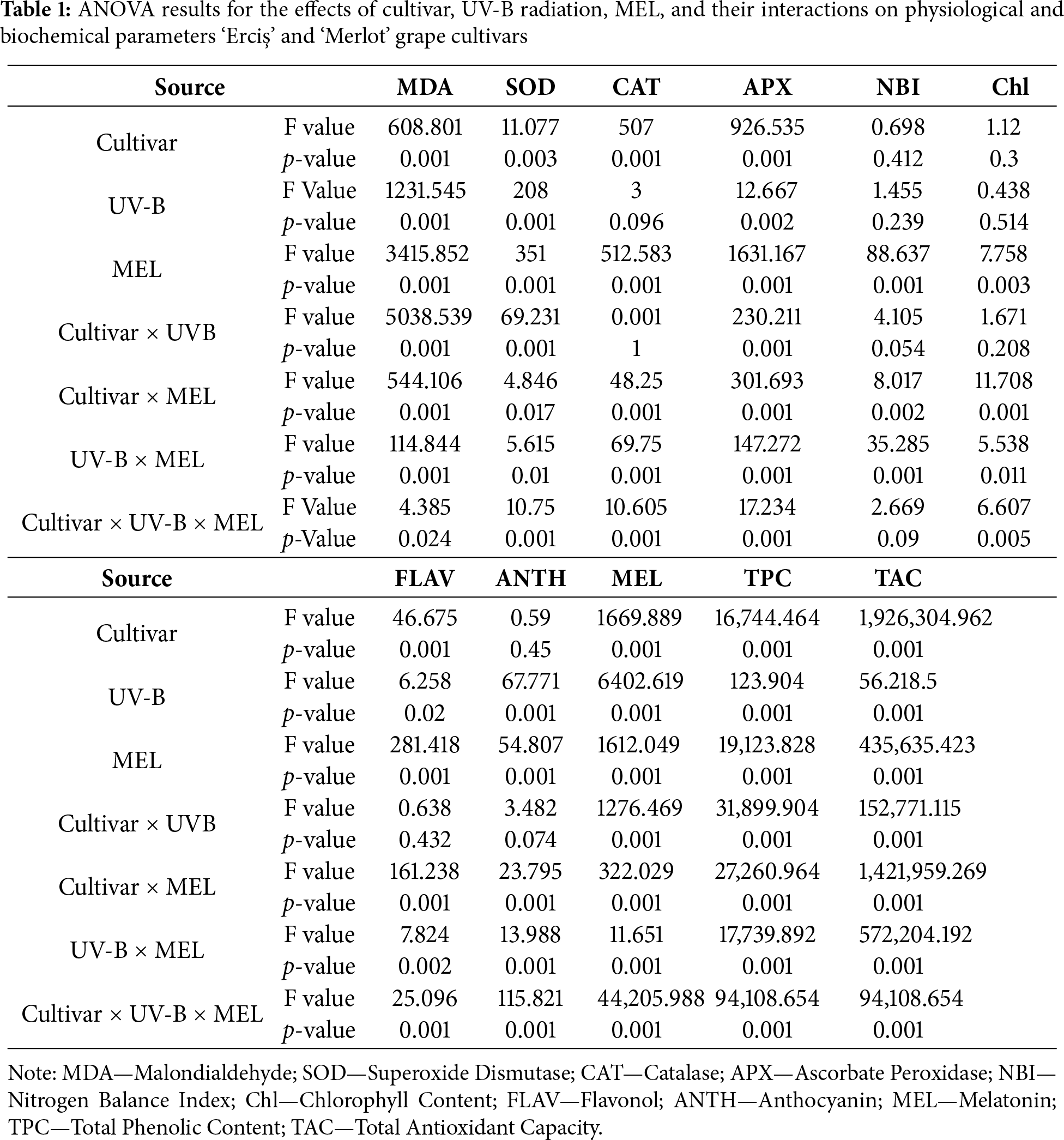

3.1.1 Enzymatic and Biochemical Parameters

The ANOVA results indicated that both cultivar, UV-B, and melatonin (MEL) treatments had significant effects on most of the evaluated parameters (Table 1). For MDA, highly significant effects (p < 0.001) were detected for cultivar (F = 608.801), UV-B (F = 1231.545), MEL (F = 3415.852), and their interactions. Similarly, SOD showed significant responses to cultivar (F = 11.077, p = 0.003), UV-B (F = 208.000, p < 0.001), MEL (F = 351.000, p < 0.001), and all interaction terms, including the three-way interaction (F = 10.750, p < 0.001). For CAT, cultivar (F = 507.000, p < 0.001) and MEL (F = 512.583, p < 0.001) effects were highly significant, while UV-B alone was not significant (F = 3.000, p = 0.096). Nevertheless, UV-B × MEL (F = 69.750, p < 0.001) and three-way interactions (F = 10.605, p < 0.001) were significant. APX activity was strongly affected by cultivar (F = 926.535, p < 0.001), UV-B (F = 12.667, p = 0.002), MEL (F = 1631.167, p < 0.001), and all interaction terms (p < 0.001). Regarding physiological traits, NBI showed significant variation only under MEL (F = 88.637, p < 0.001) and UV-B × MEL interaction (F = 35.285, p < 0.001), whereas cultivar (p = 0.412) and UV-B (p = 0.239) effects were not significant. Chlorophyll content was significantly affected by MEL (F = 7.758, p = 0.003), cultivar × MEL (F = 11.708, p < 0.001), and three-way interaction (F = 6.607, p = 0.005), while cultivar and UV-B effects were not significant. For secondary metabolites, Flavonol (FLAV) was significantly influenced by cultivar (F = 46.675, p < 0.001), UV-B (F = 6.258, p = 0.020), and MEL (F = 281.418, p < 0.001). Anthocyanin (ANTH) exhibited significant responses to UV-B (F = 67.771, p < 0.001), MEL (F = 54.807, p < 0.001), and all interaction terms except cultivar (p = 0.450). Melatonin (MEL) content was strongly affected by cultivar (F = 1669.889, p < 0.001), UV-B (F = 6402.619, p < 0.001), MEL treatments (F = 1612.049, p < 0.001), and their interactions (p < 0.001). Total Phenolic Content (TPC) also showed highly significant differences for all sources of variation, with the highest F value recorded for cultivar × MEL (F = 27,260.964, p < 0.001). Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) was the most sensitive trait, showing extremely high F values across all factors and interactions, including cultivar (F = 1,926,304.962, p < 0.001), MEL (F = 435,635.423, p < 0.001), and cultivar × MEL (F = 1,421,959.269, p < 0.001).

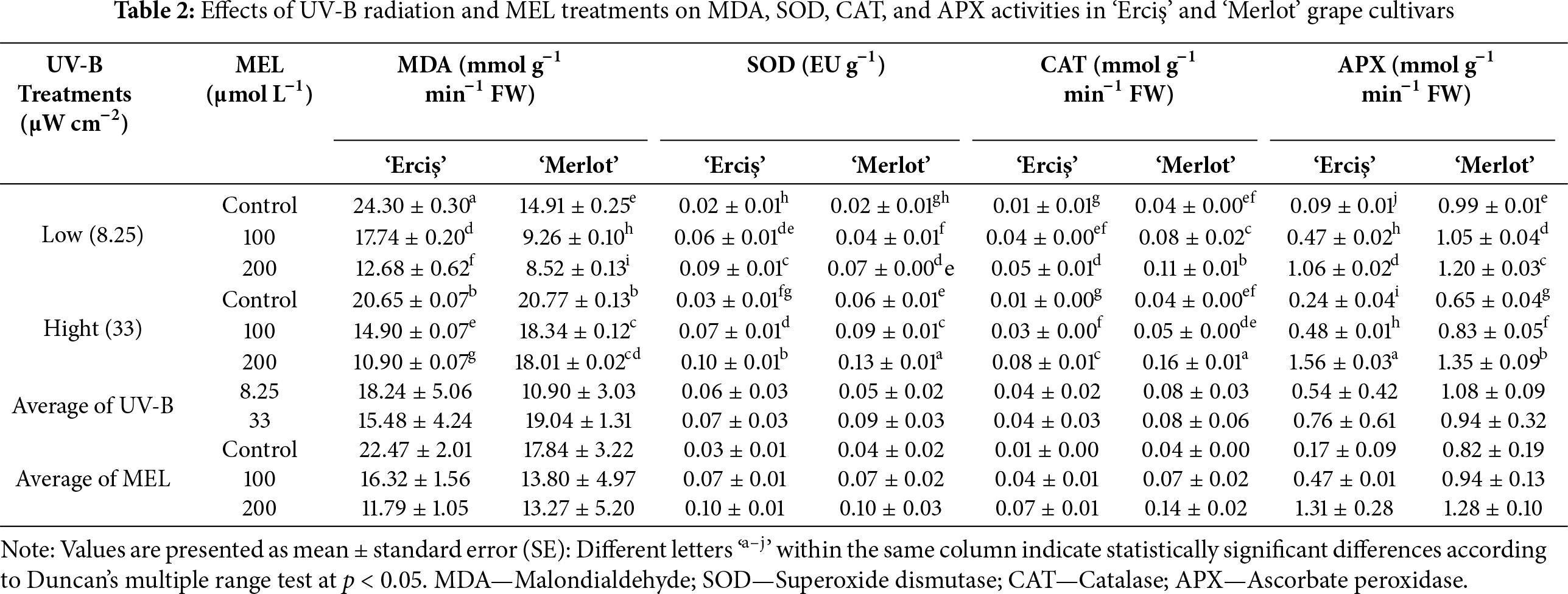

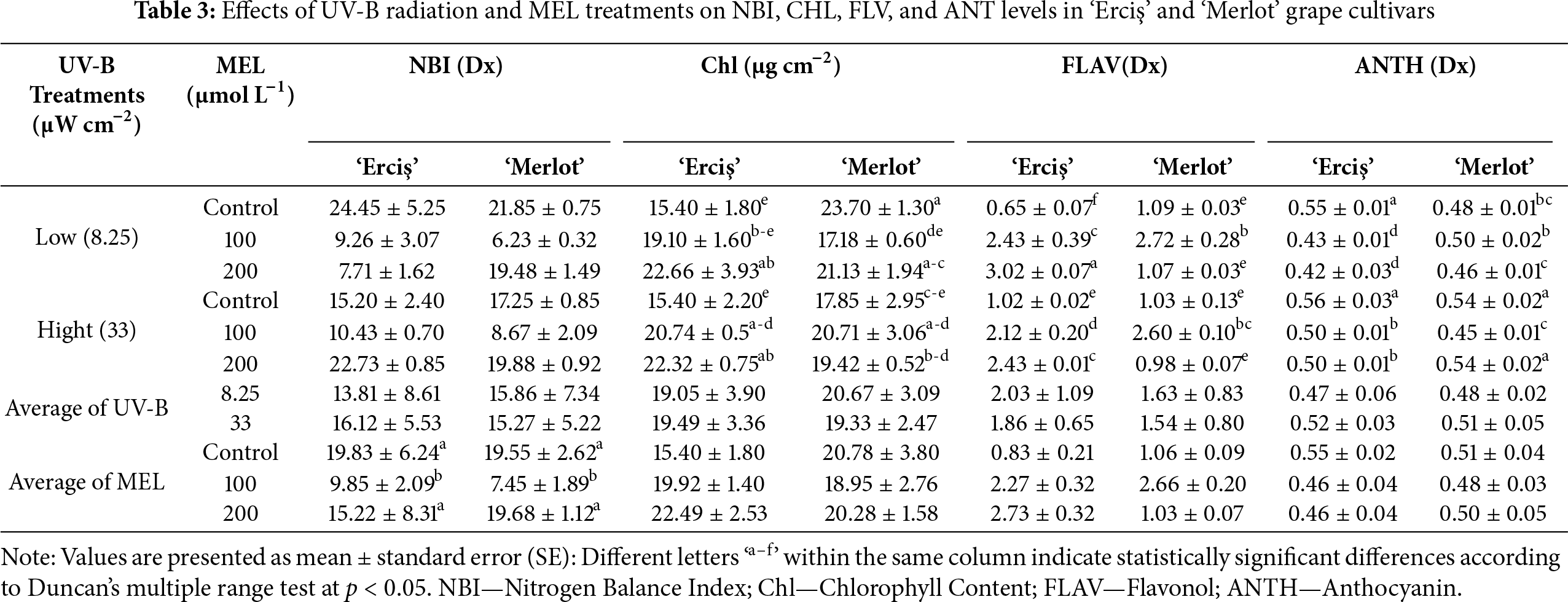

The effects of UV-B radiation and melatonin (MEL) treatments on MDA, SOD, CAT, and APX activities in ‘Erciş’ and ‘Merlot’ grapevine cultivars are shown in Table 2. For MDA, the highest value was recorded in the control of ‘Erciş’ under low UV-B (24.30 mmol g−1 FW), followed by the control of ‘Merlot’ under high UV-B (20.77). These were followed by the high UV-B control of ‘Erciş’ (20.65) and the control of ‘Merlot’ under low UV-B (14.91). MEL application markedly reduced MDA in a dose-dependent manner. At 200 μmol L−1 MEL, the lowest MDA values were observed, with 10.90 in ‘Erciş’ and 8.52 in ‘Merlot’ under low UV-B. Regarding SOD, the lowest activities were found in the controls of both cultivars under low UV-B (0.02 EU g−1). MEL treatments significantly increased activity, particularly at 200 μmol L−1, where values reached 0.10 in ‘Erciş’ and 0.13 in ‘Merlot’ under high UV-B. The second highest SOD activity was detected in ‘Erciş’ under low UV-B with 200 μmol L−1 MEL (0.09), followed by ‘Merlot’ at 100 μmol L−1 MEL (0.09). Considering CAT, control plants exhibited the lowest values, with 0.01 in ‘Erciş’ and 0.04 in ‘Merlot’ under low UV-B. MEL applications led to progressive increases, and the highest CAT activity was measured in ‘Merlot’ at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (0.16).

This was followed by ‘Erciş’ at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (0.08). For APX, the lowest value was recorded in the control of ‘Erciş’ under low UV-B (0.09), followed by the high UV-B control of the same cultivar (0.24). MEL applications significantly enhanced APX activity, with the highest value in ‘Erciş’ at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (1.56). This was followed by ‘Merlot’ at the same treatment (1.35), while intermediate values were observed at 100 μmol L−1 MEL (0.47–1.05). In general, melatonin applications consistently decreased lipid peroxidation (MDA) and increased antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, CAT, APX) across both cultivars. The protective effect was most pronounced at 200 μmol L−1 MEL, with ‘Merlot’ generally exhibiting higher enzymatic responses compared with ‘Erciş’.

3.1.2 Pigment, Phenolic, and Antioxidant Traits

The effects of UV-B radiation and melatonin (MEL) treatments on NBI, chlorophyll (Chl), flavonol (FLAV), and anthocyanin (ANTH) levels in ‘Erciş’ and ‘Merlot’ grape cultivars are presented in Table 3. In general, NBI was highest in control treatments, chlorophyll content was maximized by 200 μmol L−1 MEL, flavonol accumulation peaked in ‘Erciş’ with melatonin, and anthocyanin was most abundant in high UV-B controls. For NBI, the highest value was observed in ‘Erciş’ under low UV-B control (24.45), followed by ‘Merlot’ in the same treatment (21.85). The lowest NBI was found in ‘Merlot’ at 100 μmol L−1 MEL under low UV-B (6.23).

In our results, control treatments showed higher averages (19.83 in ‘Erciş’, 19.55 in ‘Merlot’), while the 100 μmol L−1 MEL treatment produced the lowest mean values in both cultivars. Regarding Chlorophyll content, the maximum value was recorded in ‘Merlot’ under low UV-B control (23.70), followed by ‘Erciş’ at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under low UV-B (22.66). The lowest chlorophyll was observed in ‘Erciş’ under low UV-B control (15.40). Across MEL averages, 200 μmol L−1 provided the highest chlorophyll levels in both cultivars, while controls exhibited the lowest values. Considering Flavonol, the highest accumulation occurred in ‘Erciş’ at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under low UV-B (3.02), followed by the same cultivar at 100 and 200 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (2.43 each). The lowest flavonol contents were detected in controls, particularly in ‘Erciş’ under low UV-B (0.65) and ‘Merlot’ under high UV-B (1.03). On average, MEL treatments at 200 μmol L−1 produced the highest flavonol values, whereas control treatments showed the lowest. For Anthocyanin, the highest level was measured in ‘Erciş’ under high UV-B control (0.56), closely followed by ‘Merlot’ at the same treatment (0.54). The lowest anthocyanin was observed in ‘Erciş’ at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under low UV-B (0.42). Across MEL averages, control plants had the highest anthocyanin contents (0.55 in ‘Erciş’, 0.51 in ‘Merlot’), while 100 and 200 μmol L−1 MEL treatments generally resulted in reduced values.

3.1.3 Melatonin, Total Phenolic Content, and Total Antioxidant Capacity

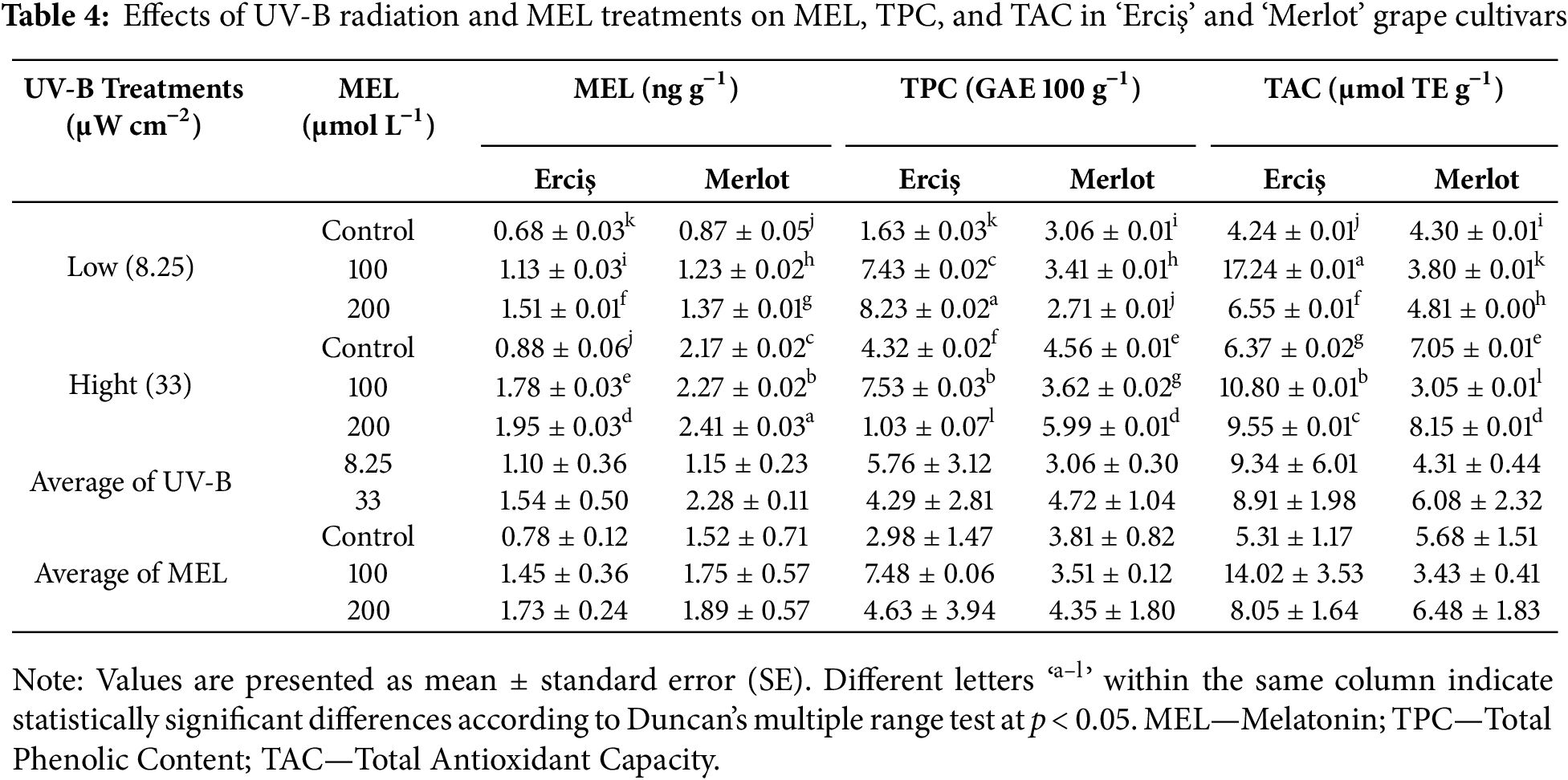

The effects of UV-B and melatonin (MEL) treatments on endogenous melatonin content, total phenolic content (TPC), and total antioxidant capacity (TAC) in ‘Erciş’ and ‘Merlot’ grape cultivars are shown in Table 4. For melatonin content, the highest value was measured in ‘Merlot’ at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (2.41 ng g−1), followed closely by the same cultivar at 100 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (2.27). In ‘Erciş’, the maximum melatonin level was 1.95 at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B. The lowest melatonin concentrations were recorded in the low UV-B controls, with 0.68 in ‘Erciş’ and 0.87 in ‘Merlot’.

Considering total phenolic content (TPC), the highest accumulation was observed in ‘Erciş’ at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under low UV-B (8.23), followed by the same cultivar at 100 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (7.53). In ‘Merlot’, the highest TPC was detected at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (5.99). The lowest phenolic levels occurred in ‘Erciş’ at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (1.03). Regarding total antioxidant capacity (TAC), the maximum value was recorded in ‘Erciş’ at 100 μmol L−1 MEL under low UV-B (17.24), followed by the same cultivar at 100 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (10.80). In ‘Merlot’, the highest TAC was found at 200 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (8.15). The lowest TAC values were observed in ‘Merlot’ at 100 μmol L−1 MEL under high UV-B (3.05) and in ‘Erciş’ under low UV-B control (4.24).

3.1.4 Correlation and Multivariate Analyses

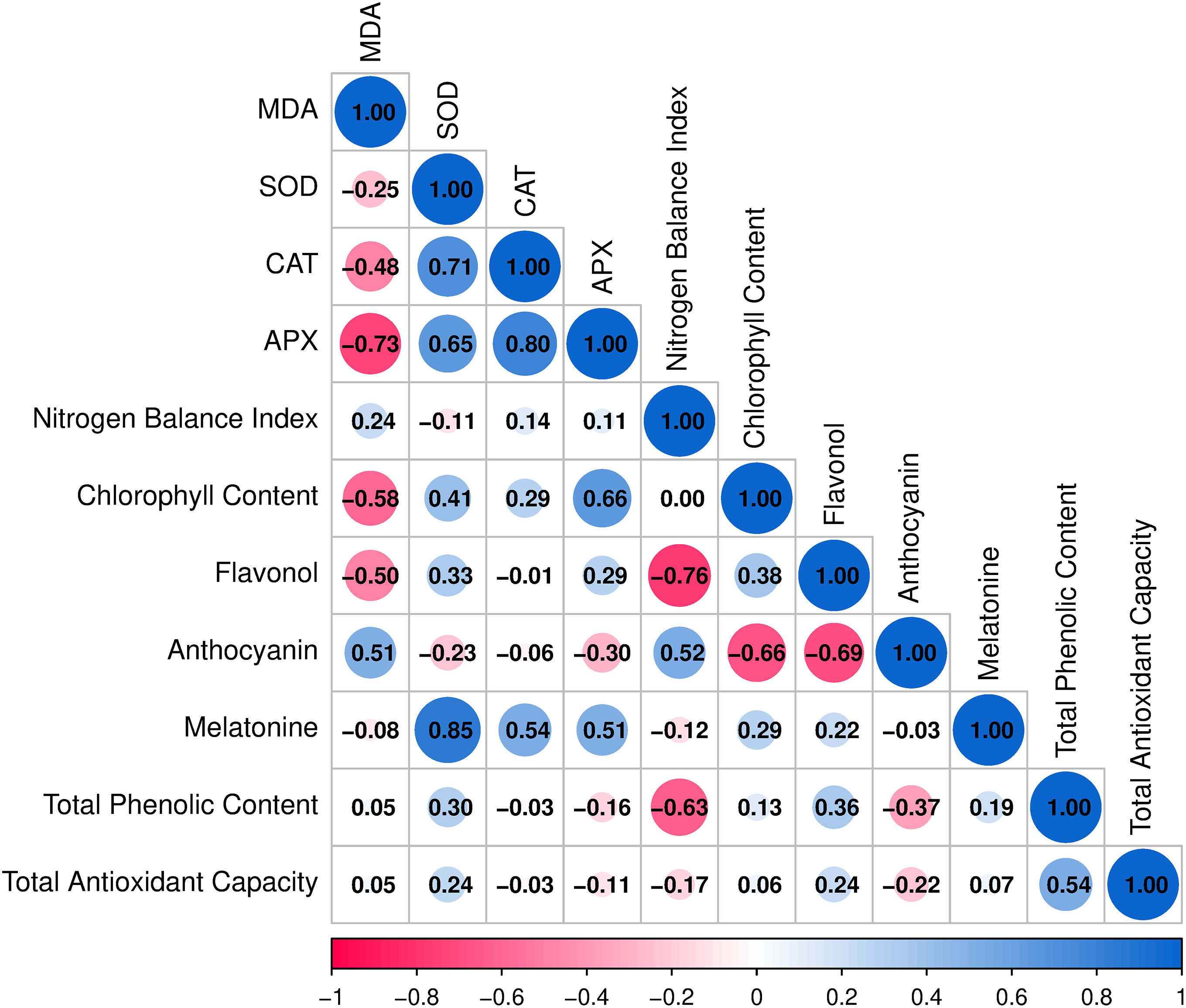

Results showed that MDA was negatively correlated with CAT (r = −0.48) and APX (r = −0.73), while it was positively correlated with anthocyanin (r = 0.51). SOD was positively correlated with CAT (r = 0.71), APX (r = 0.65), and MEL (r = 0.85). CAT displayed positive correlations with APX (r = 0.80) and MEL (r = 0.54), and APX was moderately and positively correlated with chlorophyll content (r = 0.66) and MEL (r = 0.51).

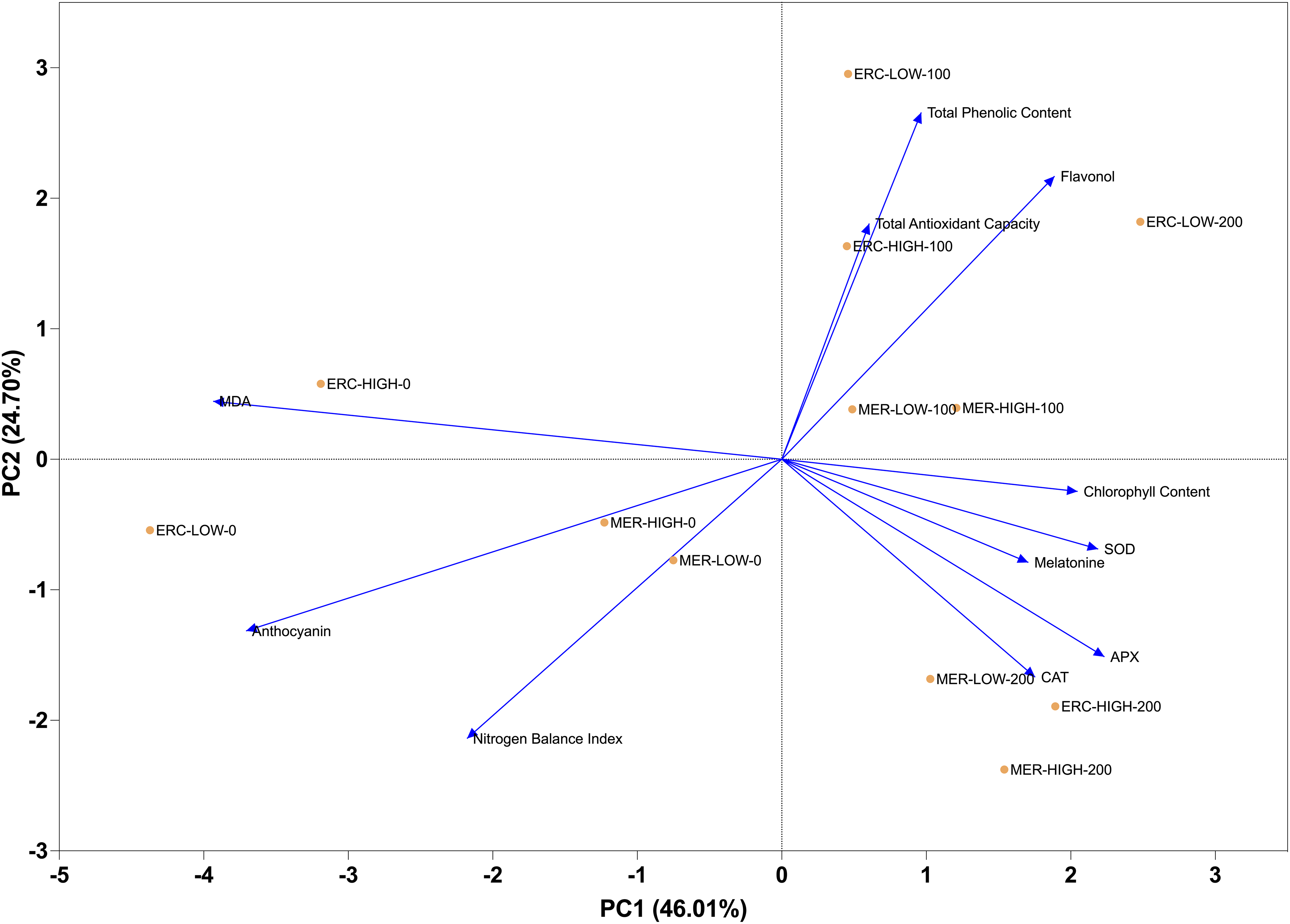

NBI exhibited weak associations with other parameters. Chlorophyll content showed a negative correlation with flavonol (r = −0.76) and a moderate positive correlation with anthocyanin (r = 0.52). Flavonol was negatively correlated with anthocyanin (r = −0.69), while anthocyanin was positively correlated with both MDA (r = 0.51) and chlorophyll content (r = 0.52). MEL was positively correlated with SOD (r = 0.85), CAT (r = 0.54), and APX (r = 0.51). Total phenolic content was moderately correlated with total antioxidant capacity (r = 0.54), and total antioxidant capacity showed weak to moderate associations with the remaining parameters (Fig. 2). Results showed that the first two principal components explained a large proportion (64.71%) of the total variance among the evaluated traits. Vectors of MDA, SOD, CAT, and APX are located closely, indicating strong contributions to the first principal component. Chlorophyll content and anthocyanin projected in the positive direction of the second component, while flavonol was located in the opposite direction, reflecting their contrasting associations. MEL, total phenolic content, and total antioxidant capacity were grouped together and oriented towards the positive side of the first principal component, highlighting their collective influence. The spatial distribution of the parameters demonstrated clear separation patterns, with antioxidant enzyme activities (SOD, CAT, APX) clustering distinctly from secondary metabolites (flavonol, anthocyanin, phenolics) (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Correlation matrix among physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant parameters in ‘Erciş’ and ‘Merlot’. Correlation coefficients (r) were calculated using Pearson’s correlation analysis. Positive values indicate direct relationships, while negative values indicate inverse relationships between traits. MDA—Malondialdehyde; SOD—Superoxide dismutase; CAT—Catalase; APX—Ascorbate peroxidase

Figure 3: Principal component analysis (PCA) of physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant parameters in ‘Erciş’ and ‘Merlot’ grape cultivars. Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to identify relationships and variance distribution among traits. The length and direction of vectors represent the contribution and association of each trait with the principal components. MDA—Malondialdehyde; SOD—Superoxide Dismutase; CAT—Catalase; APX—Ascorbate Peroxidase; NBI—Nitrogen Balance Index; Chl—Chlorophyll Content; FLAV—Flavonol; ANTH—Anthocyanin; MEL—Melatonin; TPC—Total Phenolic Content; TAC—Total Antioxidant Capacity

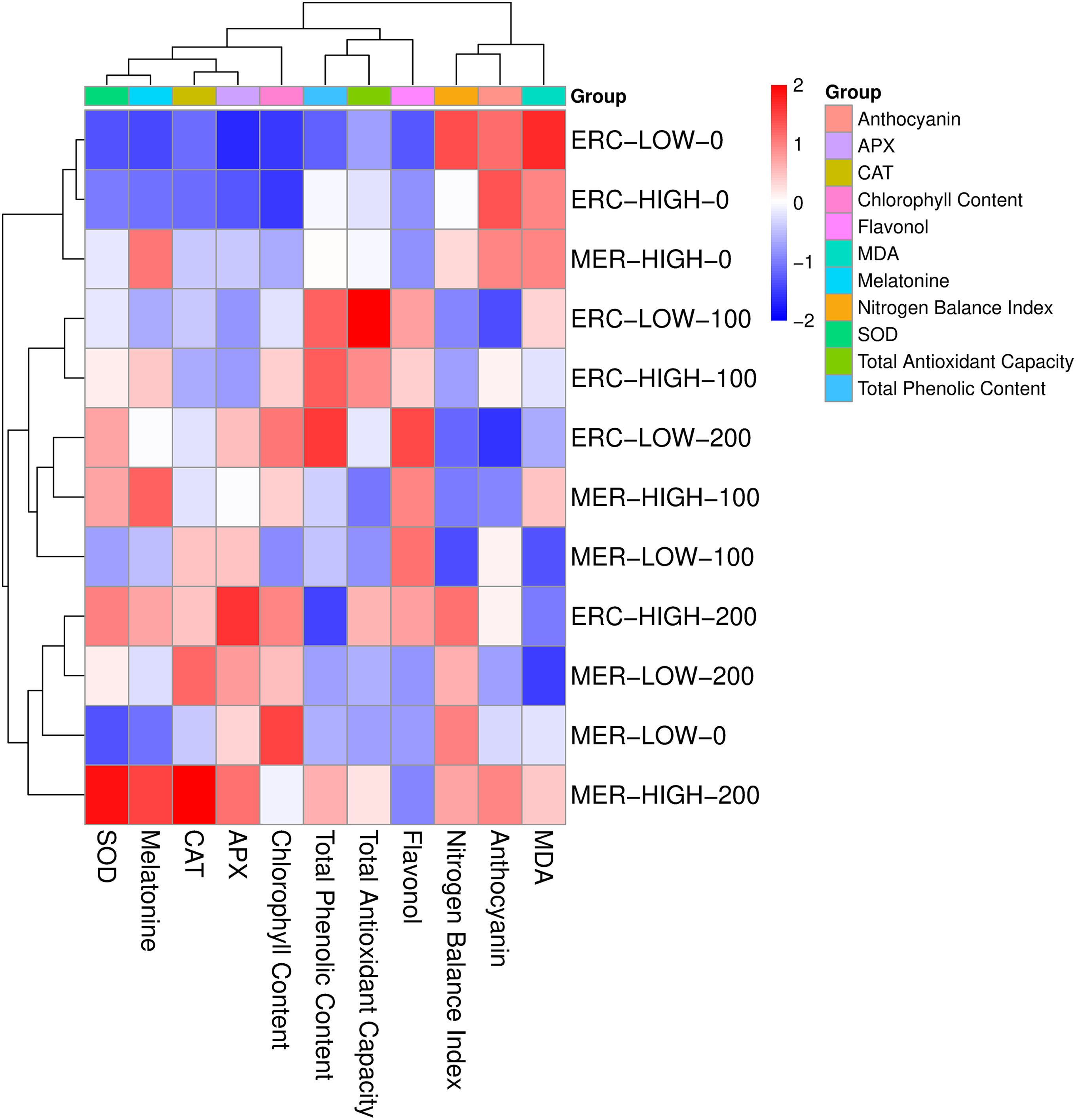

Clear clustering patterns formed between cultivars in response to UV-B doses and MEL treatments. Enzyme activities such as SOD, CAT, and APX were grouped closely together and exhibited strong positive associations with MEL. Total phenolic content and total antioxidant capacity clustered in the same group, reflecting their parallel behavior across treatments. Chl content and NBI are located in a separate cluster, showing distinct variation compared to other traits. FLAV and ANTH grouped independently, indicating different response patterns from antioxidant enzymes and phenolic compounds. At the treatment level, control groups (0 μmol L−1 MEL) were separated from 100 and 200 μmol L−1 MEL treatments, while high UV-B levels were clearly distinguished from low UV-B. The clustering pattern highlighted the separation between ‘Erciş’ and ‘Merlot’ cultivars, with cultivar-specific responses observed under combined UV-B and MEL treatments (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Heatmap clustering of physiological, biochemical, and antioxidant parameters under UV-B and MEL treatments in ‘Erciş’ and ‘Merlot’ grape cultivars. The heatmap was constructed based on hierarchical clustering using standardized values. Red indicates higher values, while blue indicates lower values of the measured traits. ERC—‘Erciş’; MER—‘Merlot’; MDA—Malondialdehyde; SOD—Superoxide Dismutase; CAT—Catalase; APX—Ascorbate Peroxidase; NBI—Nitrogen Balance Index; Chl—Chlorophyll Content; FLAV—Flavonol; ANTH—Anthocyanin; MEL—Melatonin; TPC—Total Phenolic Content; TAC—Total Antioxidant Capacity

3.2.1 Effects of Melatonin on Lipid Peroxidation and Antioxidant Enzyme Activities under UV-B Stress

The inter-cultivar differentiation in MDA accumulation, a primary indicator of lipid peroxidation, demonstrated that the ‘Erciş’ cultivar is more susceptible to oxidative damage than the ‘Merlot’ cultivar. This finding aligns with the genetic variation-dependent stress tolerance differences reported by Núñez-Olivera et al. [36] in different grape cultivars. The researchers emphasized that concentration differences of UV-absorbing compounds between cultivars determine the natural protection against photooxidative damage. The reduction in MDA levels caused by MEL treatments in both cultivars can be attributed to the direct ROS scavenging capacity of this indolamine molecule, as demonstrated by Zhang et al. [37]. MEL functions as a potent free radical scavenger through multiple mechanisms: it directly neutralizes hydroxyl radicals, superoxide anions, and singular oxygen through electron donation, while also stimulating the expression of antioxidant enzyme genes via activation of transcription factors such as heat shock factors (HSFs) and WRKY proteins, thereby establishing both immediate and long-term protective responses against oxidative stress [37–39]. The broad-spectrum antioxidant properties characterized by Reiter et al. [38] and Tan et al. [39] are clearly confirmed by the findings of the present study. MEL not only exhibits direct antioxidant effects but also induces cellular defense systems through upregulation of stress-responsive genes and modulation of phytohormone signaling pathways, as evidenced by the biochemical data obtained in this investigation.

The dose-dependent increase in SOD activity observed in the present study underscores the critical role of this enzyme in the dismutation of superoxide radicals to hydrogen peroxide and molecular oxygen. As stated by Van Breusegem et al. [40], the enhancement of antioxidant capacity by plants to minimize the effects of UV-B-induced reactive oxygen species is clearly manifested in the current findings. The mechanism underlying MEL-induced SOD enhancement involves transcriptional activation of SOD genes through MEL-responsive cis-acting elements and stabilization of SOD protein structure through post-translational modifications, preventing enzyme degradation under stress conditions. The inter-cultivar differences in SOD activity may be attributed to the genetic variation-dependent enzyme plasticity reported by Gregan et al. [41] in grapevines. The findings of the present study indicate that the MEL-induced increases in CAT and APX activities demonstrate the strengthening of cellular hydrogen peroxide detoxification through two distinct pathways. MEL enhances CAT activity by promoting enzyme oligomerization and protecting the heme prosthetic group from oxidative damage, while simultaneously upregulating APX through increased ascorbate availability and prevention of ascorbate oxidation, thus maintaining the ascorbate-glutathione cycle efficiency [42,43]. The inter-cultivar differences in APX activity point to cultivar-specific regulation of the ascorbate-glutathione cycle. This observation is consistent with the cultivar-specific antioxidant capacities reported by Berli et al. [42] and Alonso et al. [43] in grapevines. Furthermore, the coordinated upregulation of these enzymatic antioxidant systems represents an adaptive response to UV-B stress, where MEL potentially acts as a signaling molecule orchestrating cellular protective mechanisms through Ca2+-dependent signaling cascades and MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) pathway activation, leading to coordinated expression of multiple antioxidant genes [44]. The differential responses between cultivars may reflect inherent genetic differences in antioxidant enzyme gene expression patterns and their responsiveness to MEL modulation. The results suggest that this enzymatic cascade forms a comprehensive defense network, where each component contributes synergistically to maintain cellular redox homeostasis under oxidative stress conditions.

3.2.2 Melatonin-Mediated Regulation of Photosynthetic Pigments and Secondary Metabolite Accumulation

The results of the present study revealed alterations in photosynthetic pigments and secondary metabolites that demonstrate the multidimensional nature of plant defense against UV-B stress. The relative stability of Chl content in both cultivars is consistent with the photosynthetic pigment protection effect of MEL reported by Hardeland et al. [44] and Liang et al. [45] under various stress conditions. MEL protects chlorophyll through multiple mechanisms, including stabilization of thylakoid membrane structure, prevention of chlorophyllase activation, and maintenance of optimal pH in chloroplast stroma, thereby preserving photosynthetic efficiency under stress [44,45]. Indeed, the chlorophyll stabilization demonstrated by Wang et al. [46] in apple seedlings under drought stress supports the existence of similar protective mechanisms against UV-B stress. The improvement in NBI reflects the regulatory effect of MEL on nitrogen metabolism and protein synthesis, as emphasized by Li et al. [47]. This occurs through MEL-mediated enhancement of nitrate reductase activity and glutamine synthetase expression, facilitating efficient nitrogen assimilation and incorporation into amino acids and proteins. This finding suggests that MEL plays a role not only in antioxidant defense but also in the optimization of fundamental metabolic processes. The increase in nitrogen assimilation capacity represents an important indicator of the improvement in the plant’s overall physiological status. The changes in FLAV content constitute part of the plant response mechanism against stress factors characterized by Shomali et al. [48]. The data of the present study suggest that the increased flavonol accumulation in grapevines in response to UV-B stress reported by Liu et al. [49] supports the natural filtering role of these compounds against UV-B radiation. Flavonols accumulate preferentially in the leaf epidermis, where they function as a UV-screening shield by absorbing radiation in the 280–320 nm range, thereby preventing photodamage to underlying photosynthetic mesophyll cells. The biosynthesis of flavonols is upregulated through UV-B-induced expression of chalcone synthase (CHS), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), and flavonol synthase (FLS) genes via the UVR8-COP1-HY5 signaling pathway [48,49]. MEL further enhances this protective mechanism by promoting the expression of phenylpropanoid pathway genes and increasing the availability of precursor molecules such as phenylalanine and p-coumaric acid.

The findings in anthocyanin dynamics reflect the variable effect of UV-B on these pigments, as highlighted by Wilson et al. [50] and Wang et al. [51]. It is assumed that the increased anthocyanin content following MEL application against nickel stress in tomato reported by Jahan et al. [52] demonstrates that the biosynthesis of these pigments can be modulated by MEL under stress conditions. MEL stimulates anthocyanin biosynthesis through upregulation of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) and anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) genes, while also stabilizing MYB-bHLH-WD40 transcription factor complexes that control structural genes in the anthocyanin biosynthetic pathway [52]. The increase in total phenolic compound content is consistent with the view that these molecules enhance stress resistance as natural antioxidants, as emphasized by Fini et al. [53]. The accumulation of phenolic compounds on leaf surfaces as a protective mechanism against UV-B reported by Klein et al. [54], and Neugart and Schreiner [55] is confirmed by the results of this investigation. The upregulation of phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity and the consequent phenolic compound accumulation reported by Szafrańska et al. [56] in Vigna radiata emphasizes the regulatory role of MEL in the biosynthesis of these metabolites. MEL enhances PAL activity through post-translational modifications, including phosphorylation and prevention of proteolytic degradation, while also promoting PAL gene transcription via MEL-responsive elements in the promoter region. The changes in total antioxidant capacity (TAC) reveal the differences in intrinsic radical scavenging capacity between cultivars. The enhancement of total antioxidant capacity by exogenous MEL applications in apple seedlings exposed to UV-B stress reported by Wei et al. [57] shows parallelism with the findings of the present study. The increase in endogenous MEL concentrations is consistent with the endogenous MEL induction reported by Hardeland et al. [58] and Afreen et al. [15] in plants under high UV-B exposure. This endogenous biosynthesis occurs through enhanced expression of tryptophan decarboxylase (TDC), tryptamine 5-hydroxylase (T5H), serotonin N-acetyltransferase (SNAT), and N-acetylserotonin O-methyltransferase (ASMT) genes, representing a self-amplifying protective feedback mechanism [15].

3.2.3 Integrated Defense Networks: Correlation Patterns and Multivariate Response Strategies

The complex network of relationships revealed in the correlation analyses of the present study clearly demonstrates the coordinated working principle of antioxidant defense systems, which aligns with the integrated stress response mechanisms described by Mittler [59] and Suzuki et al. [60]. The negative correlations between MDA and antioxidant enzymes confirm that enzymatic defense effectively reduces oxidative damage, supporting the findings of Sharma et al. [61] regarding the protective role of antioxidant enzymes against lipid peroxidation. It is believed that the particularly strong negative correlation between MDA and APX emphasizes the critical role of ascorbate peroxidase in preventing lipid peroxidation, consistent with the studies of Foyer and Noctor [62] on ascorbate-glutathione cycle function. The strong positive correlations among antioxidant enzymes demonstrate that these enzymes form a synergistic defense system, as reported by Rao et al. [63] in their comprehensive review of reactive oxygen species networks. The findings of the present study suggest that the high correlation between SOD and CAT reflects the efficient detoxification of hydrogen peroxide by catalase, which is the dismutation product of superoxide, supporting the sequential enzymatic defense model proposed by Alscher et al. [64]. Similarly, it is considered that the positive relationship between CAT and APX reveals that hydrogen peroxide elimination occurs through two parallel pathways, as described by Mittler [65] in chloroplast and peroxisome compartmentalization studies. The strong positive correlations between MEL and antioxidant enzymes suggest that this hormone plays a central role in the transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation of enzymatic antioxidant systems, which is consistent with the regulatory functions of MEL reported by Arnao and Hernández-Ruiz [66] and Reiter et al. [67]. It is hypothesized that the very strong correlation between SOD and MEL supports the hypothesis that MEL may directly influence superoxide dismutase gene expression, as suggested by the molecular studies of Manchester et al. [68]. It is assumed that this situation strengthens the assumption that MEL activates transcription factors that modulate antioxidant gene expression at the molecular level, in line with the epigenetic regulation mechanisms proposed by Hardeland [69].

The relationships between chlorophyll content and secondary metabolites reflect the functional balance between photosynthetic pigments and protective metabolites, as described in the resource allocation studies of Herms and Mattson [70]. The results of the present study indicate that the negative correlation between chlorophyll and flavonol demonstrates that these two components specialize in different stress response strategies, supporting the growth-differentiation balance hypothesis of Loomis [71]. It is proposed that this inverse relationship between the UV-B protection function of flavonols and the role of chlorophylls in light-harvesting complexes reflects the plant’s optimization in resource allocation, consistent with the findings of Tattini et al. [72] on phenolic compounds and photosynthesis interactions. The strong contribution of antioxidant enzyme activities to the first principal component in the principal component analysis reveals that these enzymes play a dominant role in the general stress response, as demonstrated by the multivariate approaches used in stress physiology studies by Lawlor and Cornic [73]. It is believed that the formation of different clusters by enzyme activities and secondary metabolites indicates that these defense mechanisms are complementary yet independently functioning systems, supporting the multiple stress response pathway model described by Foyer et al. [74]. It appears that this situation suggests that the plant develops a multi-layered defense strategy and can activate different systems at different stress intensities, which aligns with the hierarchical stress response model proposed by Mittler and Blumwald [75]. The clustering patterns among cultivar, UV-B dose, and MEL applications emphasize the complexity of genotype × environment × application interactions, as highlighted in the genotype × environment interaction studies by Crossa et al. [76] and the stress interaction research of Sharma et al. [61]. These findings reveal the inadequacy of single-factor approaches in stress physiology and emphasize the importance of integrative analyses, supporting the systems biology approach advocated by Cramer et al. [77] in plant stress research. The differentiation patterns emerging in multivariate analyses demonstrate that each cultivar develops its own unique stress adaptation strategy and that MEL applications modify these strategies in a cultivar-specific manner, consistent with the genotype-specific stress responses reported by Des Marais et al. [78] and the cultivar-dependent MEL effects described by Arnao and Hernández-Ruiz [79].

This investigation demonstrated that melatonin (MEL) applications provided multifaceted protection against ultraviolet-B (UV-B) stress in grape cultivars through coordinated enhancement of enzymatic antioxidant systems, superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and non-enzymatic defense compounds. The study revealed cultivar-specific responses, with ‘Erciş’ showing higher oxidative damage, indicated by elevated malondialdehyde (MDA) levels compared to ‘Merlot’. The dose-dependent efficacy of MEL at 200 μmol L−1 concentration in reducing lipid peroxidation and enhancing antioxidant enzyme activities demonstrates its practical potential for viticulture applications. Addressing the research objectives, MEL functioned not merely as a direct antioxidant but as a regulatory molecule orchestrating cellular defense mechanisms through upregulation of stress-responsive genes and modulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging pathways. The preservation of photosynthetic pigments, chlorophyll (Chl) and nitrogen balance index (NBI), along with increased accumulation of flavonols (FLAV) and anthocyanins (ANTH), confirms MEL’s role in maintaining physiological integrity under UV-B stress. Enhanced total antioxidant capacity (TAC) measured through ferric reducing antioxidant power (FRAP) and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS) assays, combined with elevated endogenous MEL concentrations, validates the adaptive stress tolerance mechanisms in grapevines. The in vitro findings establish MEL as a promising biostimulator for sustainable viticulture under climate change scenarios. However, field validation studies incorporating multiple cultivars, varying environmental conditions, and diverse UV-B exposure regimes are essential before commercial implementation. Future research should determine optimal application protocols for vineyard management and investigate long-term effects on grape berry quality and vine productivity under natural field conditions where multiple abiotic stresses occur simultaneously.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Van Yüzüncü Yıl University Scientific Research Project Department (Project No. FYL-2021-9577). This study also constitutes a part of a master’s thesis (Sena Yıldız).

Author Contributions: Sena Yıldız, Nurhan Keskin, Birhan Kunter, Harlene Hatterman-Valenti and Ozkan Kaya: Collaborated on the study design, methodology, and execution. These individuals contributed to data visualization, statistical analysis, and manuscript preparation. Nurhan Keskin and Ozkan Kaya: Led the writing, editing, and revision process. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study are not publicly available as they were generated and analyzed specifically for the scope of this manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wu W, Chen L, Liang R, Huang S, Li X, Huang B, et al. The role of light in regulating plant growth, development and sugar metabolism: a review. Front Plant Sci. 2025;15:1507628. doi:10.3389/fpls.2024.1507628. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Liaqat W, Altaf MT, Barutçular C, Nawaz H, Ullah I, Basit A, et al. Ultraviolet-B radiation in relation to agriculture in the context of climate change: a review. Cereal Res Commun. 2024;52(1):1–24. doi:10.1007/s42976-023-00375-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Bernhard GH, Neale RE, Barnes PW, Neale PJ, Zepp RG, Wilson SR, et al. Environmental effects of stratospheric ozone depletion, UV radiation and interactions with climate change: UNEP environmental effects assessment panel, update 2019. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2020;19(5):542–84. doi:10.1039/d0pp90011g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Shi C, Liu H. How plants protect themselves from ultraviolet-B radiation stress. Plant Physiol. 2021;187(3):1096–103. doi:10.1093/plphys/kiab245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Mmbando GS, Ngongolo K. Environmental & health impacts of ultraviolet radiation: current trends and mitigation strategies. Discov Sustain. 2024;5(1):436. doi:10.1007/s42976-023-00375-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Nawkar GM, Maibam P, Park JH, Sahi VP, Lee SY, Kang CH. UV-induced cell death in plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(1):1608–28. doi:10.3390/ijms14011608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Keskin N, Kunter B. Stilbenes profile in various tissues of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. cv. ‘Ercis’). J Environ Prot Ecol. 2017;18(3):1259–67. [Google Scholar]

8. Alonso R, Berli FJ, Piccoli P, Bottini R. Ultraviolet-B radiation, water deficit and abscisic acid: a review of independent and interactive effects on grapevines. Theor Exp Plant Physiol. 2016;28(1):11–22. doi:10.1007/s40626-016-0053-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Gutiérrez-Gamboa G, Pszczólkowski P, Cañón P, Taquichiri M, Peñarrieta JM. UV-B radiation as a factor that deserves further research in Bolivian viticulture: a review. S Afr J Enol Vitic. 2021;42(2):201–12. doi:10.21548/42-2-4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kaya O. Unveiling the transformations in phytochemicals and grape features: a thorough examination of ‘Italia’ and ‘Bronx Seedless’ cultivars throughout multiple berry development stages. Eur Food Res Technol. 2024;250(8):2147–60. doi:10.1007/s00217-024-04527-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Gökçen İS, Keskin N. Physiological and biochemical response to ultraviolet stress in grapevine: in vitro modeling. Appl Fruit Sci. 2025;67(3):101. doi:10.1007/s10341-025-01320-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zengin R, Uğur Y, Levent Y, Erdoğan S, Hatterman-Valenti H, Kaya O. Sun-drying and melatonin treatment effects on apricot color, phytochemical, and antioxidant properties. Appl Sci. 2025;15(2):508. doi:10.3390/app15020508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Arnao MB, Cano A, Hernández-Ruiz J. Phytomelatonin: an unexpected molecule with amazing performances in plants. J Exp Bot. 2022;73(17):5779–800. doi:10.1093/jxb/erac253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yao JW, Ma Z, Ma YQ, Zhu Y, Lei MQ, Hao CY, et al. Role of melatonin in UV-B signaling pathway and UV-B stress resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Environ. 2021;44(1):114–29. doi:10.1111/pce.13882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Afreen F, Zobayed SMA, Kozai T. Melatonin in Glycyrrhiza uralensis: response of plant roots to spectral quality of light and UV-B radiation. J Pineal Res. 2006;41(2):108–15. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2006.00337.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Kaur H, Mukherjee S, Baluska F, Bhatla SC. Regulatory roles of serotonin and melatonin in abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2015;10(3):e1049788. doi:10.1080/15592324.2015.1049788. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Martinez V, Nieves-Cordones M, Lopez-Delacalle M, Rodenas R, Mestre TC, Garcia-Sanchez F, et al. Tolerance to stress combination in tomato plants: new insights in the protective role of melatonin. Molecules. 2018;23(3):535. doi:10.3390/molecules23030535. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Yıldız S, Gökçen İS, Kaya AÇ, Batuk M, Keskin N, Kunter B. Effect of in vitro melatonin applications on callus formation, antioxidant activity and total phenolic compound content in grapevine. Bahçe. 2023;52(Özel Sayı 1):67–71. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

19. Li C, Wang P, Wei Z, Liang D, Liu C, Yin L, et al. The mitigation effects of exogenous melatonin on salinity-induced stress in Malus hupehensis. J Pineal Res. 2012;53(3):298–306. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2012.00999.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Zeng W, Mostafa S, Lu Z, Jin B. Melatonin-mediated abiotic stress tolerance in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:847175. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.847175. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Keskin N, Kunter B. Induction of resveratrol production by UV radiation in callus cultures of Ercis grape cultivar. J Agric Sci. 2007;13(4):379–84. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

22. Nazir M, Asad Ullah M, Mumtaz S, Siddiquah A, Shah M, Drouet S, et al. Interactive effect of melatonin and UV-C on phenylpropanoid metabolite production and antioxidant potential in callus cultures of purple basil (Ocimum basilicum L. var. purpurascens). Molecules. 2020;25(5):1072. doi:10.3390/molecules25051072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Hasnain A, Naqvi SAH, Ayesha SI, Khalid F, Ellahi M, Iqbal S, et al. Plants in vitro propagation with its applications in food, pharmaceuticals and cosmetic industries; current scenario and future approaches. Front Plant Sci. 2022;13:1009395. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.1009395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Erland LAE, Saxena PK. Melatonin in plant morphogenesis. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol-Plant. 2018;54:3–24. doi:10.1007/s11627-017-9879-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Çelik H. Storage of grapevine cuttings and seedlings. TÜRKTOB Dergisi. 2019;28:4–9. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

26. Murashige T, Skoog F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol Plant. 1962;15(3):473–97. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1962.tb08052.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Pontin MA, Piccoli PN, Francisco R, Bottini R, Martinez-Zapater JM, Lijavetzky D. Transcriptome changes in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. Malbec leaves induced by ultraviolet-B radiation. BMC Plant Biol. 2010;10(1):224. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-10-224. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Swain T, Hillis WE. The phenolic constituents of Prunus domestica. I.—the quantitative analysis of phenolic constituents. J Sci Food Agric. 1959;10(1):63–8. doi:10.1002/jsfa.2740100110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Benzie IEF, Strain JJ. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of antioxidant power: the FRAP assay. Anal Biochem. 1996;239(1):70–6. doi:10.1006/abio.1996.0292. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Keskin N, Kaya O, Ates F, Turan M, Gutiérrez-Gamboa G. Drying grapes after the application of different dipping solutions: effects on hormones, minerals, vitamins, and antioxidant enzymes in Gök Üzüm (Vitis vinifera L.) raisins. Plants. 2022;11(4):529. doi:10.3390/plants11040529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Kaya O, Ates F, Kara Z, Turan M, Gutiérrez-Gamboa G. Study of primary and secondary metabolites of stenospermocarpic, parthenocarpic and seeded raisin varieties. Horticulturae. 2022;8(11):1030. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8111030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Keskin N, Bilir Ekbic H, Kaya O, Keskin S. Antioxidant activity and biochemical compounds of Vitis vinifera L. (cv. ‘Katıkara’) and Vitis labrusca L. (cv. ‘Isabella’) grown in black sea coast of Turkey. Erwerbs-Obstbau. 2021;63(Suppl 1):115–22. doi:10.1007/s10341-021-00588-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Heath RL, Packer L. Photoperoxidation in isolated chloroplast. I. Kinetics and stoichiometry of fatty acid peroxidation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1968;125(1):189–98. doi:10.1016/0003-9861(68)90654-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Hidalgo-Ruiz JL, Romero-González R, Vidal JLM, Frenich AG. A rapid method for the determination of mycotoxins in edible vegetable oils by ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Food Chem. 2019;288(2):22–8. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.03.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Evgenidis G, Traka-Mavrona E, Koutsika-Sotiriou M. Principal component and cluster analysis as a tool in the assessment of tomato hybrids and cultivars. Int J Agron. 2011;9(4):1–7. doi:10.1155/2011/697879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Núñez-Olivera E, Martínez-Abaigar J, Tomás R, Otero S, Arróniz-Crespo M. Physiological effects of solar ultraviolet-B exclusion on two cultivars of Vitis vinifera L. from La Rioja, Spain. Am J Enol Vitic. 2006;57(4):441–8. doi:10.5344/AJEV.2006.57.4.441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang N, Sun Q, Zhang H, Cao Y, Weeda S, Ren S, et al. Roles of melatonin in abiotic stress resistance in plants. J Exp Bot. 2015;66(3):647–56. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Manchester LC, Qi W. Biochemical reactivity of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2001;34(2):237–56. doi:10.1385/CBB:34:2:237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Tan DX, Manchester LC, Helton P, Reiter RJ. Phytoremediative capacity of plants enriched with melatonin. Plant Signal Behav. 2007;2(9):514–6. doi:10.4161/psb.2.6.4639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Van Breusegem F, Bailey-Serres J, Mittler R. Unraveling the tapestry of networks involving reactive oxygen species in plants. Plant Physiol. 2008;147(3):978–84. doi:10.1104/pp.108.122325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Gregan SM, Wargent JJ, Liu L, Shinkle J, Hofmann R, Winefield C, et al. Effects of solar ultraviolet radiation and canopy manipulation on the biochemical composition of Sauvignon Blanc grapes. Aust J Grape Wine Res. 2012;18(2):227–38. doi:10.1111/j.1755-0238.2012.00192.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Berli FJ, Alonso R, Beltrano J, Bottini R. High-altitude solar UV-B and abscisic acid sprays increase grape berry antioxidant capacity. Am J Enol Vitic. 2015;66(1):65–72. doi:10.5344/ajev.2014.14067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Alonso R, Berli FJ, Bottini R, Piccoli P. Acclimation mechanisms elicited by sprayed abscisic acid, solar UV-B and water deficit in leaf tissues of field-grown grapevines. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2015;91(3):56–60. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2015.03.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Hardeland R, Madrid JA, Tan DX, Reiter RJ. Melatonin, the circadian multioscillator system and health: the need for detailed analyses of peripheral melatonin signaling. J Pineal Res. 2012;52(2):139–66. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00934.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Liang C, Zheng G, Li W, Wang Y, Hu B, Wang H, et al. Melatonin delays leaf senescence and enhances salt stress tolerance in rice. J Pineal Res. 2015;59(1):91–101. doi:10.1111/jpi.12243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Wang P, Sun X, Li C, Wei ZW, Liang D, Ma FW. Long-term exogenous application of melatonin delays drought-induced leaf senescence in apple. J Pineal Res. 2013;54(3):292–302. doi:10.1111/jpi.12017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Li CC, Chen P, Lu GZ, Ma CY, Ma XX, Wang ST. The inversion of nitrogen balance index in typical growth period of soybean based on high definition digital image and hyperspectral data on unmanned aerial vehicles. J Appl Ecol. 2018;29(4):1225–32. (In Chinese). doi:10.13287/j.1001-9332.201804.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Shomali A, Das S, Arif N, Sarraf M, Zahra N, Yadav V, et al. Diverse physiological roles of flavonoids in plant environmental stress responses and tolerance. Plants. 2022;11(22):3158. doi:10.3390/plants11223158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Liu L, Gregan SM, Winefield C, Jordan B. Comparisons of controlled environment and vineyard experiments in Sauvignon Blanc grapes reveal similar UV-B signal transduction pathways for flavonol biosynthesis. Plant Sci. 2018;276:44–53. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2018.08.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Wilson A, Ferrandino A, Giacosa S, Novello V, Guidoni S. The effect of temperature and UV manipulation on anthocyanins, flavonols, and hydroxycinnamoyl-tartrates in cv Nebbiolo grapes (Vitis vinifera L.). Plants. 2024;13(22):3158. doi:10.3390/plants13223158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Wang H, Yang M, Martinez-Luscher J, Hilbert-Masson G, Gomès E, Pascual I, et al. Effects of elevated temperature and shaded UV-B radiation exclusion on berry biochemical composition in four grape (Vitis vinifera L.) cultivars with distinct anthocyanin profiles. Food Res Int. 2025;218(4):116823. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2025.116823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Jahan MS, Shu S, Wang Y, Chen Z, He M, Tao M, et al. Melatonin alleviates nickel stress by modulating antioxidant systems and secondary metabolism in tomato plants. BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:471. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110593. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Fini A, Guidi L, Ferrini F, Brunetti C, Di Ferdinando M, Biricolti S, et al. Drought stress has contrasting effects on antioxidant enzyme activity and phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in Fraxinus ornus leaves: an excess light stress affair? J Plant Physiol. 2012;169(10):929–39. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2012.02.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Klein FRS, Reis A, Kleinowski AM, Telles RT, Amarante LD, Peters JA, et al. UV-B radiation as an elicitor of secondary metabolite production in plants of the genus Alternanthera. Acta Bot Bras. 2018;32(4):615–23. doi:10.1590/0102-33062018abb0120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Neugart S, Schreiner M. UVB and UVA as eustressors in horticultural and agricultural crops. Sci Hortic. 2018;234:370–81. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2018.02.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Szafrańska K, Szewczyk R, Janas KM. Involvement of melatonin applied to Vigna radiata L. seeds in plant response to chilling stress. Cent Eur J Biol. 2014;9(11):1117–26. doi:10.2478/s11535-014-0330-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Wei Z, Li C, Gao T, Zhang Z, Liang B, Lv Z, et al. Melatonin increases the performance of Malus hupehensis after UV-B exposure. Plant Physiol Biochem. 2019;139:630–41. doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2019.04.026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Hardeland R, Pandi-Perumal SR, Cardinali DP. Melatonin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38(3):313–6. doi:10.1016/j.biocel.2005.08.020. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Mittler R. ROS are good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017;22(1):11–9. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2016.08.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Suzuki N, Rivero RM, Shulaev V, Blumwald E, Mittler R. Abiotic and biotic stress combinations. New Phytol. 2014;203(1):32–43. doi:10.1111/nph.12797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Sharma P, Jha AB, Dubey RS, Pessarakli M. Reactive oxygen species, oxidative damage, and antioxidative defense mechanism in plants under stressful conditions. J Bot. 2012;2012(1):1–26. doi:10.1155/2012/217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Foyer CH, Noctor G. Ascorbate and glutathione: the heart of the redox hub. Plant Physiol. 2011;155(1):2–18. doi:10.1104/pp.110.167569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Rao MJ, Duan M, Zhou C, Jiao J, Cheng P, Yang L, et al. Antioxidant defense system in plants: reactive oxygen species production, signaling, and scavenging during abiotic stress-induced oxidative damage. Horticulturae. 2025;11(5):477. doi:10.3390/horticulturae11050477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Alscher RG, Erturk N, Heath LS. Role of superoxide dismutases (SODs) in controlling oxidative stress in plants. J Exp Bot. 2002;53(372):1331–41. doi:10.1093/jexbot/53.372.1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Mittler R. Oxidative stress, antioxidants and stress tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2002;7(9):405–10. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02312-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Arnao MB, Hernández-Ruiz J. Melatonin and its relationship to plant hormones. Ann Bot. 2018;121(2):195–207. doi:10.1093/aob/mcx114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Zhou Z, Cruz MHC, Fuentes-Broto L, Galano A. Phytomelatonin: assisting plants to survive and thrive. Molecules. 2014;19(10):14396–421. doi:10.3390/molecules20047396. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Manchester LC, Coto-Montes A, Boga JA, Andersen LPH, Zhou Z, Galano A, et al. Melatonin: an ancient molecule that makes oxygen metabolically tolerable. J Pineal Res. 2015;59(4):403–19. doi:10.1111/jpi.12267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Hardeland R. Melatonin in plants—diversity of levels and multiplicity of functions. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7(815769):198. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.00198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Herms DA, Mattson WJ. The dilemma of plants: to grow or defend. Q Rev Biol. 1992;67(3):283–335. doi:10.1086/417659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Loomis RS. Growth-differentiation balance vs. carbohydrate-nitrogen ratio. Proc Am Soc Hortic Sci. 1932;29:240–5. [Google Scholar]

72. Tattini M, Galardi C, Pinelli P, Massai R, Remorini D, Agati G. Differential accumulation of flavonoids and hydroxycinnamates in leaves of Ligustrum vulgare under excess light and drought stress. New Phytol. 2004;163(3):547–61. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01126.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Lawlor DW, Cornic G. Photosynthetic carbon assimilation and associated metabolism in relation to water deficits in higher plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2002;25(2):275–94. doi:10.1046/j.0016-8025.2001.00814.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Foyer CH, Ruban AV, Noctor G. Viewing oxidative stress through the lens of oxidative signalling rather than damage. Biochem J. 2017;474(6):877–83. doi:10.1042/BCJ20160814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Mittler R, Blumwald E. Genetic engineering for modern agriculture: challenges and perspectives. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61(1):443–62. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Crossa J, Campos GDL, Pérez P, Gianola D, Burgueno J, Araus JL, et al. Prediction of genetic values of quantitative traits in plant breeding using pedigree and molecular markers. Genetics. 2010;186(2):713–24. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.118521. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Cramer GR, Urano K, Delrot S, Pezzotti M, Shinozaki K. Effect of abiotic stress on plants: a systems biology perspective. BMC Plant Biol. 2011;11(1):163. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-11-163. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Des Marais DL, Hernandez KM, Juenger TE. Genotype-by-environment interaction and plasticity: exploring genomic responses of plants to the abiotic environment. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2013;44(1):5–29. doi:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110512-135806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Arnao MB, Hernández-Ruiz J. Chemical stress by different agents affects the melatonin content of barley roots. J Pineal Res. 2009;46(3):295–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-079X.2008.00660.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools