Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Cadmium Hyperaccumulation in Plants: Mechanistic Insights and Ecological Implications

1 School of Modern Industry for Selenium Science and Engineering, National R&D Center for Se-rich Agricultural Products Processing Technology, Wuhan Polytechnic University, Wuhan, 430023, China

2 College of Horticulture and Gardening, Yangtze University, Jingzhou, 434023, China

* Corresponding Authors: Shen Rao. Email: ; Shuiyuan Cheng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant and Environments)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3319-3348. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073602

Received 22 September 2025; Accepted 27 October 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Cadmium (Cd), a highly toxic heavy metal, represents a major global environmental threat due to its widespread dispersion through anthropogenic activities. Environmental Cd contamination poses significant risks to living organisms, including humans, animals, and plants. Certain plant species have evolved Cd hyperaccumulating capabilities to adapt to high-Cd habitats, playing critical roles in phytoremediation strategies. Here we review the biodiversity and biogeography of Cd hyperaccumulators, the underlying mechanisms of Cd uptake and accumulation, and the ecological impacts of hyperaccumulation. The major points are the following: twenty-four Cd hyperaccumulator species have been documented, with shoot Cd concentrations ranging from 170–9000 mg·kg−1; core mechanisms involve root uptake by metal transporters (e.g., heavy-metal ATPases, and natural resistance-associated macrophage proteins), ligand-facilitated translocation via organic acids and phytochelatins, and ABC transporter-mediated vacuolar sequestration. Cd hyperaccumulators exert complex effects on rhizosphere microbiota, herbivores, and neighboring plant communities. Future research priorities should focus on the functional characterization of Cd transporters and regulatory genes, and comprehensive assessments of the ecological consequences of Cd accumulation in plants.Keywords

Cd was first discovered in 1817 by Friedrich Stromeyer and Karl Hermann [1]. The environmental behavior and ecological risks of Cd depend largely on its chemical forms. These forms vary significantly across different environmental settings. In aquatic systems, Cd is mainly present as a divalent cation (Cd2+). It readily forms complexes with inorganic ligands—such as chloride [Cl−] and sulfate [SO42−]—as well as with organic ligands like humic acids [2]. Within lithospheric environments, Cd primarily occurs as sulfide minerals (e.g., greenockite, CdS), frequently associated with zinc, lead, and copper sulfide ore deposits [3]. The atmospheric Cd primarily originates from industrial stack emissions, fossil fuel combustion, and waste incineration. And the atmospheric Cd burden predominantly comprises particulate-phase species including Cd oxide (CdO), Cd sulfide (CdS), and Cd sulfate (CdSO4) [4]. In soil systems, Cd speciation is dominated by the bioavailable Cd2+ ion, though its environmental mobility and toxicity are modulated by complex interactions with soil constituents. To systematically resolve Cd partitioning in soils, Tessier et al. pioneered a five-step sequential extraction protocol (the Tessier method) that fractionates soil-bound Cd into operationally defined phases: (1) exchangeable (water/ion-soluble), (2) carbonate-bound (acid-soluble), (3) Fe/Mn oxide-bound (reducible), (4) organic matter/sulfide-bound (oxidizable), and (5) residual (crystalline lattice-bound) [5].

As a non-essential trace element with no known biological function, Cd exerts multisystem toxicity across plant and animal taxa. Human activities have significantly increased the release of Cd into the environment. Key sources include mining, industrial operations, phosphate fertilizers, and vehicle emissions. This elevated release has led to widespread contamination of agricultural systems and aquatic food chains [6]. Cd compounds are classified as Group 1 carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), with epidemiological studies linking chronic exposure to malignancies in lung, prostate, and renal tissues. The carcinogenic mechanisms involve both indirect epigenetic pathways (e.g., aberrant DNA methylation, histone modification, microRNA dysregulation) and direct genotoxic effects [7–9].

Phytotoxicity manifests through multiple physiological disruptions: root elongation inhibition, stomatal conductance reduction, chlorophyll degradation, and micronutrient homeostasis impairment. At the cellular level, Cd induces both damaging and repair processes in which the cellular redox status plays a crucial role. As a non-redox-active metal, Cd cannot directly generate reactive oxygen species (ROS). Nevertheless, it can indirectly stimulate the production of ROS as well as the activation of antioxidative defense systems (e.g., superoxide dismutase, catalase) [10]. This oxidative cascade damages lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, culminating in growth retardation, leaf necrotic lesions, and yield losses exceeding 30%–50% in sensitive crops [11,12]. Paradoxically, certain metallophytes have evolved sophisticated Cd detoxification mechanisms, including vacuolar sequestration, phytochelatin complexation, and selective ion transport regulation. These adaptive traits enable hyperaccumulator species to concentrate Cd in their aerial tissues at levels orders of magnitude above background concentrations. Relevant research highlights that using Cd hyperaccumulators to reduce soil Cd content is a promising solution for remediating contaminated soils [13]. This approach, which is of both ecological significance and phytoremediation potential, forms the focus of our subsequent discussion.

Hyperaccumulators, also known as metal-accumulating or super-accumulator plants, form a unique ecophysiological group. These plants can absorb heavy metals and transport them to their aboveground tissues. The metal concentrations in these tissues can be 10 to 100 times higher than those found in non-accumulator species. Remarkably, hyperaccumulators achieve this without showing symptoms of phytotoxicity [14]. The conceptual framework for hyperaccumulation was first established by Brooks et al. [15], who defined threshold criteria based on foliar metal concentrations. For Cd, the current consensus defines hyperaccumulators as plants achieving shoot concentrations >100 mg·kg−1 dry weight (DW) under natural soil conditions [16]. These plants possess unique adaptive traits. Key features include enhanced root uptake, efficient transport into the xylem via specific proteins (e.g., HMA3 and NRAMP transporters), and effective intracellular detoxification. These distinctive attributes have been refined through long-term evolution in metal-rich environments [17].

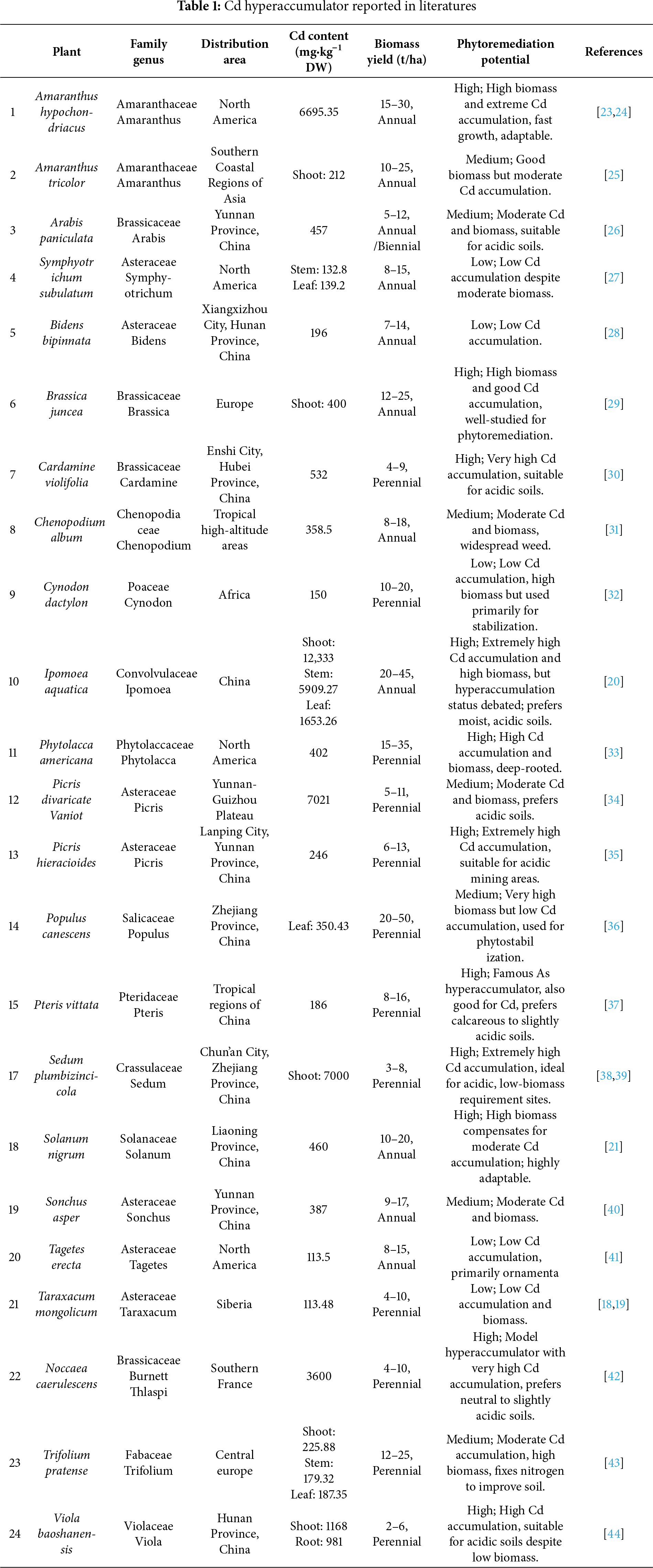

Our comprehensive literature review identifies 24 confirmed Cd hyperaccumulator species. These species belong to 11 angiosperm families and 19 genera (Table 1). Their tissue Cd concentrations vary widely, ranging from 113.48 mg·kg−1 dry weight in Taraxacum mongolicum [18,19] to 12,333 mg·kg−1 dry weight in the shoots of Ipomoea aquatica [20]. However, the hyperaccumulation status of Ipomoea aquatica remains debated, as its low root-to-shoot Cd ratio suggests an exclusion strategy rather than true hyperaccumulation [20]. This highlights the importance of considering not only absolute shoot concentrations but also allocation patterns and root-to-shoot ratios when defining hyperaccumulator species. While the shoot Cd concentration threshold of 100 mg·kg−1 DW is a practical operational criterion for identifying hyperaccumulators, it presents an oversimplified view. A more comprehensive definition must incorporate the efficiency of root-to-shoot translocation, typically quantified by the translocation factor (TF > 1). For instance, Ipomoea aquatica can accumulate extremely high Cd concentrations in its roots (up to 12,333 mg·kg−1), yet its low root-to-shoot Cd ratio suggests a strategy of exclusion and root sequestration rather than true hyperaccumulation, which is characterized by efficient aerial part translocation [20,21]. This distinction is critical for phytoremediation applications, where species with high TF and substantial biomass, like Solanum nigrum, are preferred for phytoextraction, despite potentially lower absolute tissue concentrations [21]. The over-reliance on a single concentration threshold may overlook key physiological mechanisms governing Cd distribution within the plant. Geospatial analysis shows a strong concentration of these plants in subtropical evergreen broad-leaved forests. This pattern is especially evident in post-mining areas of southern China. In these regions, high floristic diversity coexists with both natural Cd enrichment in soils and gradients of anthropogenic contamination. This biogeographic pattern suggests that hyperaccumulator evolution is driven by tripartite interactions between phylogenetic predisposition, persistent metal selection pressures, and ecological niche specialization [22].

Taxonomic analysis shows that Crassulaceae and Brassicaceae are the dominant families. This is exemplified by two pioneering species in phytoremediation research: Sedum alfredii, with a recorded shoot Cd concentration of 9000 mg·kg−1 dry weight, and Sedum plumbizincicola, with 7000 mg·kg−1 dry weight. These species were systematically characterized by Yu et al. [38] and Liu et al. [39], respectively. While Asteraceae exhibits the highest species richness (7 taxa), only Picris divaricata Vaniot demonstrates extreme Cd accumulation (7021 mg·kg−1 DW) [34], with most congeners accumulating moderate levels (132.8–387 mg·kg−1 DW). This intrafamilial disparity suggests divergent evolutionary trajectories in Cd tolerance mechanisms, possibly involving differential expression of metal transporters or chelators. Notable examples include the European Brassicaceae species Noccaea caerulescens, which can accumulate up to 3600 mg·kg−1 DW Cd in shoots [42], and the Chinese Violaceae species Viola baoshanensis (1168 mg·kg−1 DW) [44].

Geographic specialization is evident in East Asia’s karst regions, where four hyperaccumulators exceed 450 mg·kg−1 DW, likely reflecting adaptive responses to naturally elevated geochemical backgrounds (up to 50 mg·kg−1 soil Cd) and intensive historical mining. Contrastingly, North American species like Amaranthus hypochondriacus demonstrate balanced root-to-shoot allocation patterns, while African Cynodon dactylon maintains normal growth under 150 mg·kg−1 Cd stress through enhanced antioxidative metabolism [31]. Such biogeographic signatures imply region-specific genetic adaptations shaped by localized selection pressures. In practical phytoremediation, species such as Solanum nigrum are often prioritized. This plant shows a moderate Cd accumulation of 460 mg·kg−1 dry weight. However, its high biomass production compensates for this moderate accumulation level. This case illustrates the key trade-off in remediation design between metal concentration and harvestable yield [21].

2 Mechanism of Cd Accumulation in Plants

2.1 Absorption and Transport of Cd in Plants

Cd enters plant systems through two common pathways: (1) root absorption from soil or aquatic environments, and (2) foliar uptake from atmospheric deposition. Among these routes, root-mediated acquisition represents the principal mechanism of Cd accumulation in terrestrial plants (Fig. 1). The process of root Cd uptake occurs through both active transport and passive diffusion mechanisms. In soil environments, Cd predominantly exists as the divalent cation Cd2+, which shares physicochemical similarities with essential micronutrients including calcium (Ca2+), iron (Fe2+), and zinc (Zn2+). This ionic mimicry enables Cd2+ to exploit metal ion transporter systems designed for nutrient acquisition, facilitating its entry into root cells [45].

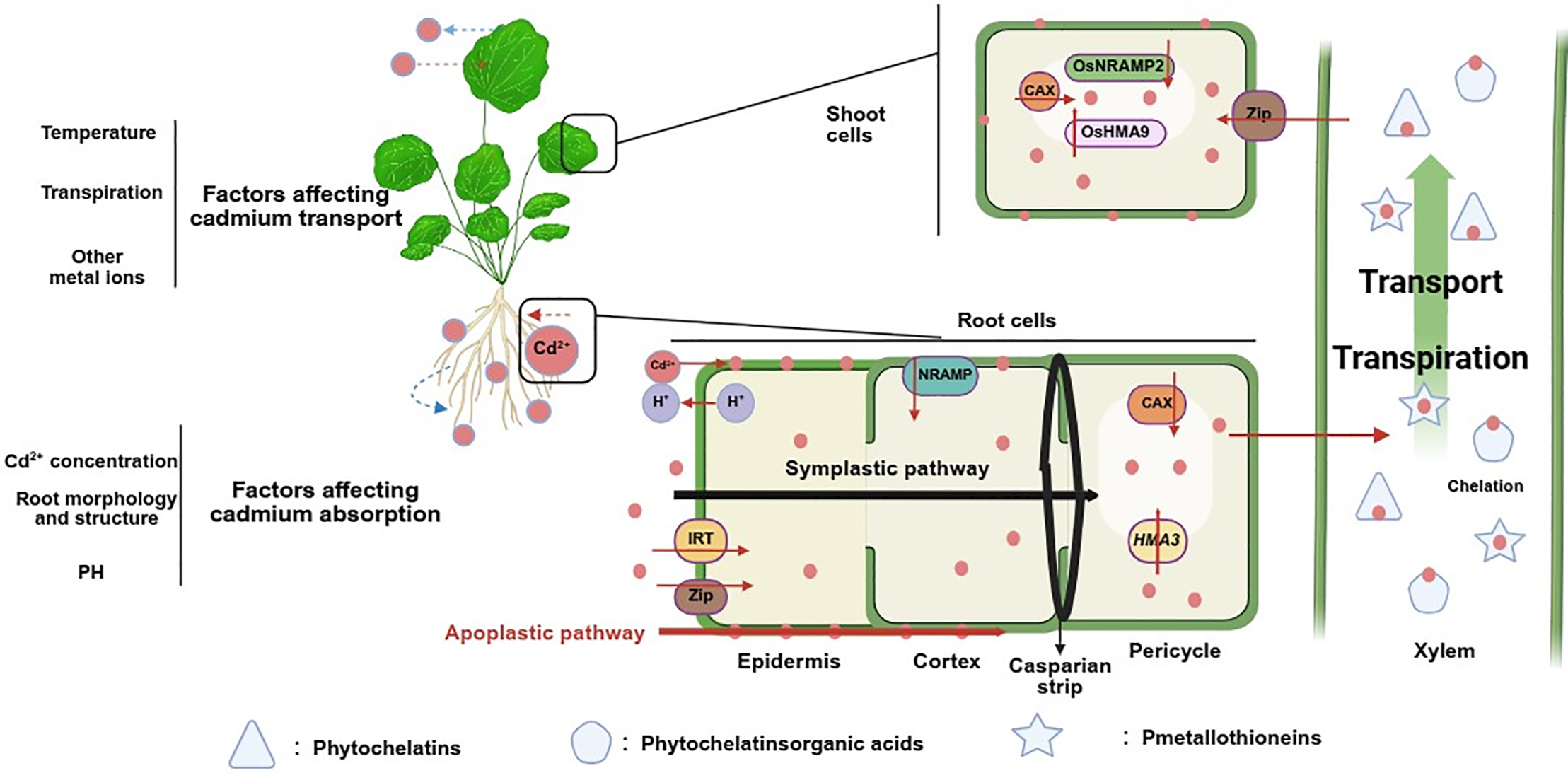

Figure 1: Mechanisms of Cd uptake and translocation in plants. Orange circles depict the pathways of Cd uptake, translocation, and accumulation in plants. Black arrows denote the symplastic pathway, in which Cd is transported between cells via plasmodesmata. Red arrows represent the apoplastic pathway, where Cd moves between cells through the cell wall [60]. ZIPs: the zinc-regulated transporters and iron-regulated transporter-like protein [70,71]; Nramp: the natural resistance-associated macrophage protein [72,73]; HMA: the heavy-metal ATPases [74,75]; CAX: the cation/H+ exchangers [76,77]

The soil solution maintains a dynamic equilibrium between freely hydrated Cd2+ ions and those adsorbed onto soil particulates. Plant roots actively modify their rhizosphere through proton excretion during respiration, promoting cation exchange where H+ ions displace Cd2+ from soil colloids. This desorption process enables Cd adsorption onto root epidermal surfaces through electrostatic interactions. Following surface adsorption, Cd2+ progresses through the root cortex primarily via the apoplastic pathway, where it interacts with cell wall components [46]. The cell wall matrix, comprising cellulose, lignin, hemicellulose, pectin, and structural proteins, provides abundant carboxyl groups that effectively chelate Cd ions [47]. This initial binding serves as a critical regulatory step in Cd entry into plant systems. The transmembrane Cd2+ concentration gradient between soil solution and root cytosol drives passive diffusion across plasma membranes. The Nernst equation tells us [48], for instance, that a membrane potential of −60 mV would be able to draw Cd2+ into the cell against an unfavorable gradient of 100:1. Moreover, since plant cells are often more negative than that, this electrochemical driving force is even stronger. Active transport mechanisms further enhance Cd accumulation through energy-dependent membrane transporters. The continuous depletion of soil solution Cd2+ at the root-soil interface establishes a concentration gradient that promotes Cd desorption from soil particles, thereby replenishing bioavailable Cd in the rhizosphere [49].

Multiple environmental and physiological factors modulate root Cd uptake efficiency, including soil Cd bioavailability, root system architecture, and soil pH conditions [50]. While soil Cd concentration generally correlates positively with plant Cd accumulation, this relationship exhibits nonlinear characteristics. At low to moderate soil Cd levels (<5 mg/kg), plants typically demonstrate concentration-dependent uptake patterns. However, beyond critical thresholds, Cd accumulation rates plateau due to saturation of transport mechanisms and potential phytotoxic effects that impair root function.

Root morphological features significantly influence Cd acquisition through two distinct mechanisms: (i) Apical dominance in Cd absorption: studies on the Cd hyperaccumulator Amaranthus hypochondriacus L. reveal that root tip regions within 100 μm of the apex exhibit 3–5 times greater Cd influx rates compared to mature root segments [51]. This spatial variation correlates with the developmental formation of endodermal barriers. Some roots have smaller apical surfaces and form Casparian strips earlier. These suberin-rich strips create a hydrophobic barrier in the cell walls. This barrier blocks the apoplastic flow of Cd into the stele. As a result, Cd must enter root cells through specific transporters via the symplastic pathway. This process ultimately reduces the root’s overall Cd uptake capacity [52]. (ii) Architectural modulation: Comparative analysis of rice genotypes demonstrates that low Cd-accumulating cultivars (e.g., ZH11) exhibit reduced root system biomass (23% smaller), shorter maximum root length (18% reduction), and higher aerenchyma porosity (34% increase) compared to high Cd-accumulating genotypes like GNZ [53]. These architectural adaptations likely restrict Cd absorption by limiting root-soil contact area and enhancing oxygen-mediated redox reactions that immobilize Cd.

Soil pH exerts profound control over Cd bioavailability through dissolution-precipitation equilibria. In alkaline environments (pH ≥ 8.5), Cd2+ forms insoluble hydroxides [Cd(OH)2] and carbonates [CdCO3], reducing soluble Cd concentrations by 80%–95%. Conversely, acidic soils (pH ≤ 4.0) promote Cd mobilization through competitive displacement by H+ ions, increasing soil solution Cd2+ concentrations by 3–5 fold compared to neutral pH conditions [54]. This pH-dependent solubility directly correlates with observed 2.7–4.1 times greater Cd accumulation in plants grown under acidic versus alkaline conditions.

Foliar Cd absorption represents a secondary uptake pathway that remains less characterized. Current evidence suggests two potential entry mechanisms: (1) passive influx through stomatal apertures during transpirational gas exchange, and (2) active transport via epidermal membrane proteins [55]. The transpiration-driven mass flow hypothesis suggests that atmospheric Cd particles can dissolve in moisture on leaf surfaces. These dissolved particles may then enter the stomatal chambers. However, this pathway still lacks sufficient experimental evidence. Emerging evidence from trichome-rich species indicates potential Cd sequestration in specialized epidermal structures, suggesting active transport involvement. However, the relative contributions of apoplastic versus symplastic foliar uptake pathways require systematic investigation. Elucidating these mechanisms represents a critical knowledge gap that warrants prioritized research attention, particularly given increasing atmospheric Cd deposition in industrial regions.

2.1.2 Upward Translocation of Cd

Cd absorbed from the soil solution initially accumulates in the root apoplast, an extracellular compartment that includes cell wall matrices and intercellular channels. Cd moves freely through the apoplastic pathway in this region. It is not blocked by membrane barriers. However, its movement can be impeded by the suberized Casparian strip and other hydrophobic cell wall segments. This process is energy-independent and represents passive diffusion [56]. However, Cd movement is regulated by the cation exchange capacity of the cell wall and exhibits pH dependence. As soil pH increases, progressive deprotonation occurs at carboxyl groups in root cell walls, enabling electrostatic interactions between positively charged Cd and negatively charged carboxylate moieties in the apoplastic domain [57,58]. At the endodermis, the Casparian strip blocks the apoplastic flow. This barrier forces Cd2+ ions to move through specific transport proteins, including NRAMPs, ZIPs, and HMAs. Consequently, the ions must first cross the plasma membrane into the cytoplasm before they can proceed toward the stele [59].

Cd translocation in plants occurs through both symplastic and apoplastic pathways. The symplastic pathway is primarily responsible for longitudinal transport, such as root-to-shoot translocation, while the apoplastic pathway facilitates transverse movement, such as intercellular transport within plant organs [60]. In the apoplastic route, Cd moves through cell walls between adjacent cells, whereas the symplastic route involves Cd movement through the symplast, a continuous network of cytoplasm interconnected by plasmodesmata. This process is characterized by significant resistance due to the selective permeability of the plasma membrane to solutes [61]. Following cytoplasmic entry in the pericycle, Cd is loaded into the xylem. Cd then moves upward over long distances primarily through xylem vessel lumina. These lumina are the hollow interiors of dead tracheary elements. They are part of the apoplast yet distinct from cell walls. This specialized pathway offers minimal resistance to the bulk flow of water and solutes driven by transpiration pull [62].

Once Cd enters the xylem, it forms complexes with ligands—molecules capable of binding to anchor proteins. These complexes, along with free ions, are transported to the aerial parts of the plant via the xylem, driven by transpiration [63]. During this process, Cd interacts with and partially transfers into the cell walls of xylem vessels. Under the pull of transpiration, Cd2+ further migrates through xylem cell walls into stem cell walls [62]. Within the stem, Cd is distributed in varying concentrations across intracellular compartments (e.g., cell walls, cytoplasm, vacuoles) and tissues (e.g., vascular tissues, parenchyma, epidermis) [64]. Cd enters the cytoplasm of leaf cells through metal transporters, while some free Cd ions and complexes are sequestered into organelles, particularly vacuoles, where they are stored as chelates [65]. A portion of the Cd accumulated in leaves can be redistributed to other organs through the phloem (Fig. 1). Phloem flow also facilitates Cd transport to reproductive organs, resulting in its accumulation in seeds [66]. Additionally, the phloem may contribute to Cd transport prior to its arrival in leaves, mediated by exchange between the xylem and phloem in the stem [66].

The translocation of Cd in plants is influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, transpiration, and interactions with other metal ions. Elevated temperatures enhance Cd uptake by increasing root activity and cell membrane permeability. For example, when temperatures are between 25°C–30°C, rice roots show increased expression of Cd transport genes such as OsNRAMP5 and OsHMA3. This elevated gene expression enhances the efficiency of Cd translocation to the plant’s aerial parts [67]. Furthermore, higher temperatures may increase Cd bioavailability by influencing soil pH and accelerating organic matter decomposition [68]. The movement of Cd in leaves is primarily driven by water flux from the vascular bundles, indicating that transpiration plays a critical role in Cd accumulation in foliar tissues. Higher transpiration rates correlate with faster Cd transport to stems and leaves [45]. Additionally, Cd transport is competitively inhibited by ions such as Ca2+, Mg2+, and Zn2+, while ions like K+ and Mn2+ show no significant inhibitory effects [69]. These interactions highlight the complex dynamics of Cd translocation in plants and underscore the need for further research to fully understand these mechanisms.

2.2 Distribution Patterns of Cd in Plants

Under normal conditions, Cd primarily accumulates in plant roots, with significantly lower concentrations in aerial tissues. This pattern is attributed to the roots’ efficient Cd retention mechanisms [78]. In roots, Cd predominantly localizes to the epidermal cell walls, root hair apoplasts, and vacuolar compartments of cortical cells. The pectic and hemicellulosic components of cell walls, which contain abundant carboxyl and hydroxyl functional groups, facilitate Cd immobilization through ion exchange and chelation [79]. The endodermal Casparian strip also serves as a hydrophobic barrier. This structure contains both lignin and suberin. It blocks the apoplastic movement of Cd into the vascular cylinder. As a result, Cd tends to accumulate in the outer tissues of the root [52,80]. In contrast, Cd in leaves primarily accumulates in the vacuoles of palisade and mesophyll cells [65]. Studies have reported that Cd is concentrated in the apoplastic regions of epidermal tissues, such as the bark and leaf epidermis in Gamblea innovans [79]. Studies using histochemical staining and confocal laser fluorescence microscopy have detected Cd in upper epidermal cells near stomatal margins. This cellular distribution likely results from the sequestration of Cd-ligand complexes within vacuoles [81]. Furthermore, energy dispersive X-ray fluorescence (ED-XRF) analysis revealed the presence of Cd in the necrotic tissues of the leaves [82].

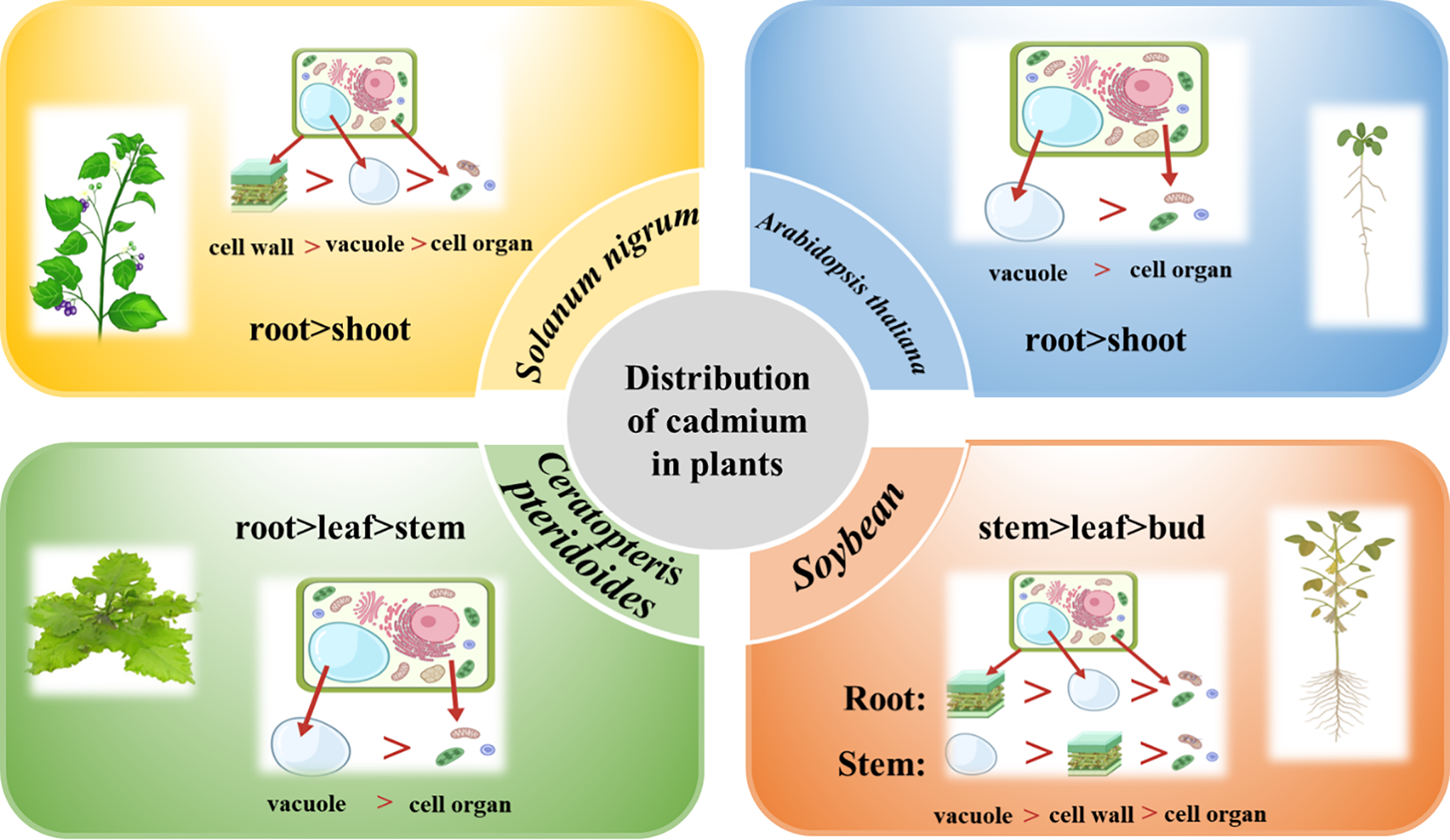

Cd distribution varies significantly among different plant species (Fig. 2). For example, in soybean, Cd accumulation follows the order stem > leaf > new shoot [83], while in tobacco, Cd levels in leaves are markedly higher than in roots and stems [84]. In contrast, Cd hyperaccumulators such as Microsorum pteropus exhibit an accumulation pattern of root > leaf > stem, consistent with observations in the fern Ceratopteris pteridoides [85]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, the accumulation level of Cd is root > shoot [86]. Subcellular distribution of Cd also shows interspecific differences. In Ceratopteris pteridoides, under Cd treatments of 10, 20, and 40 µM, Cd concentrations in the soluble fraction of leaves exceed those in organelles [87]. Similarly, in soybean roots exposed to Cd levels of 23 and 45 µM, the subcellular distribution follows the order cell wall > soluble fraction > organelles, while in stems, the order is soluble fraction > cell wall > organelles [88]. A comparable pattern is observed in the hyperaccumulator Solanum nigrum, where Cd distribution in roots is cell wall > soluble fraction > organelles [89].

Figure 2: Distribution of Cd in plants. The figure shows the distribution pattern of Cd in the tissues and subcellular regions of Solanum nigrum [89], Arabidopsis thaliana [86], Ceratopteris pteridoides [85,87] and soybean [83,88]

These distribution patterns highlight the heterogeneity of Cd accumulation across plant organs and subcellular compartments. However, the extent to which these patterns correlate with Cd accumulation and tolerance mechanisms remains unclear. Further research is needed to elucidate the physiological and molecular bases of Cd distribution in plants, particularly in relation to species-specific differences in Cd retention and translocation. Such insights could inform strategies to enhance Cd phytoremediation or reduce Cd accumulation in edible plant tissues.

2.3 Mechanism of Cd Accumulation and Tolerance in Plants

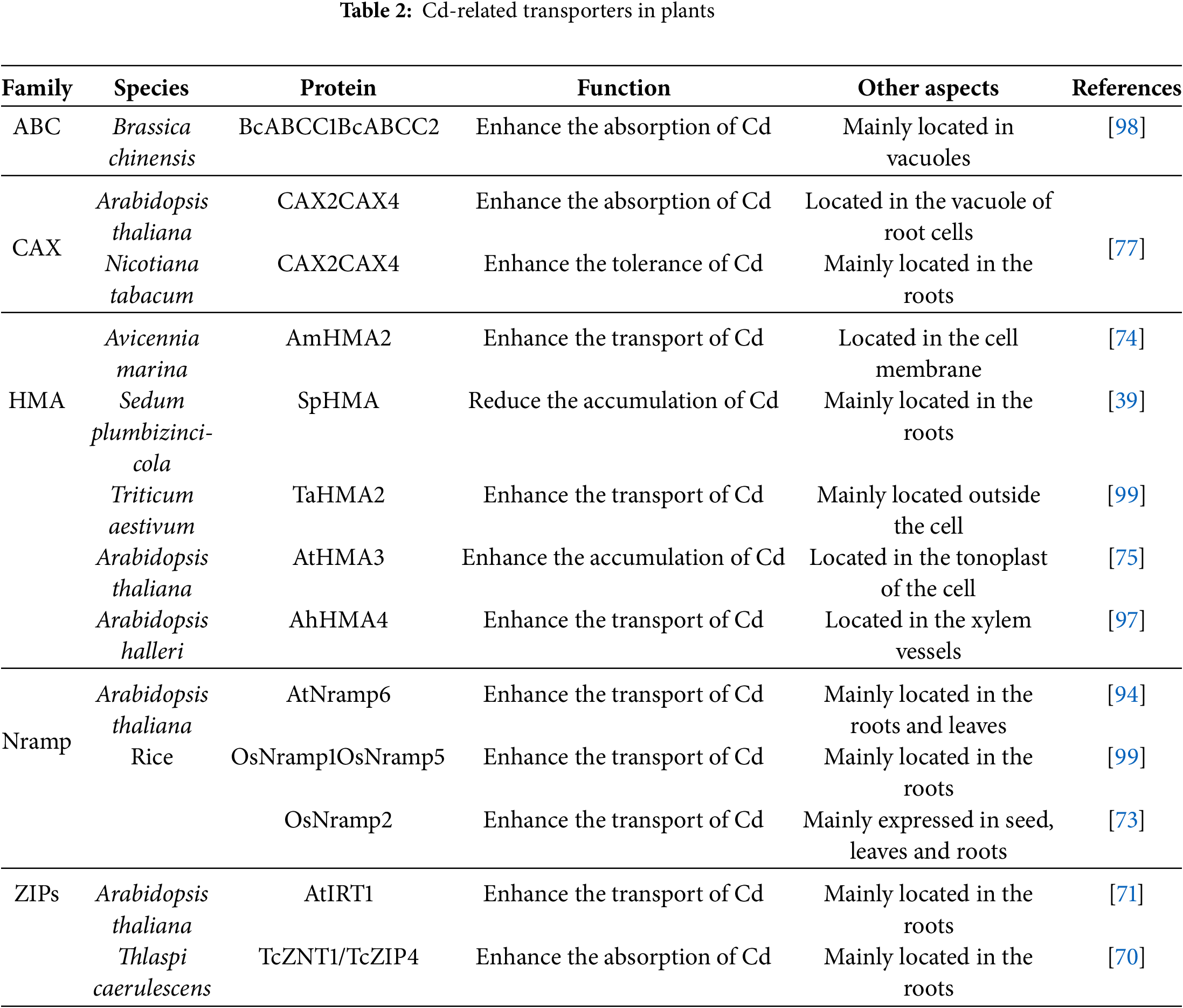

The translocation of Cd in plants is primarily mediated by several key transporter families (Table 2), including the zinc-regulated transporters and iron-regulated transporter-like proteins (ZIPs), the natural resistance-associated macrophage protein (Nramp), the cation/H+ exchangers (CAX), the heavy-metal ATPases (HMA), and ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC) [90].

The ZIP family plays a critical role in root metal uptake and intracellular transfer in plants [91]. For instance, in Thlaspi caerulescens, Cd is thought to enter root cells via TcZNT1/TcZIP4 [70]. Similarly, AtIRT1, the first identified ZIP family gene in Arabidopsis, is predominantly expressed in roots and is involved in the transport of divalent Cd²+ ions [71]. Knockout of AtIRT1 results in reduced Cd accumulation, underscoring its importance in Cd uptake [92].

Natural resistance-associated macrophage proteins (Nramps) are integral membrane transporters in plants responsible for the uptake, translocation, and detoxification of transition metals [93]. The Nramp family, identified in model plants such as Arabidopsis and rice, comprises seven members in rice and six in Arabidopsis. Several Nramp family transporters have been linked to Cd transport, including OsNRAMP1, OsNRAMP2, and OsNRAMP5 in rice, as well as AtNRAMP6 in Arabidopsis. In rice, OsNRAMP1 and OsNRAMP5 mediate Cd transport through a chelation mechanism [72], while OsNRAMP2 is predominantly expressed in seeds, roots, and leaves [73]. In Arabidopsis, AtNRAMP6 functions as an intracellular transporter involved in Cd mobilization [94].

Vacuolar sequestration of Cd in roots is another critical mechanism that reduces Cd translocation to aerial tissues. Transporters such as CAX2 and CAX4 play a pivotal role in mediating Cd chelation into vacuoles [76,77]. These transporters utilize the proton gradient across the vacuolar membrane to drive Cd uptake into vacuoles, thereby limiting Cd movement to shoots.

Heavy-metal ATPases (HMAs) are essential for Cd translocation from roots to shoots via transmembrane transport [95]. These transporters harness energy derived from ATP hydrolysis to drive Cd transport across membranes against electrochemical gradients. For example, HMA2, a member of the P-type ATPase superfamily, facilitates Cd efflux from the cytoplasm to the extracellular space, thereby maintaining cytoplasmic metal homeostasis [96]. Studies in wheat have implicated HMA2 in Cd transport to grains, while in Avicennia marina, the plasma membrane-localized transporter AmHMA2 mediates Cd transport [74]. Elevated expression and copy-number expansion of HMA4 are closely associated with efficient xylem loading and enhanced root-to-shoot Cd translocation in Brassicaceae hyperaccumulators. Research in Arabidopsis halleri using functional genomics and loss-of-function experiments has revealed a key mechanism. The AhHMA4 gene shows consistently high expression due to tandem gene duplications and cis-regulatory changes. This enhanced expression drives the efflux of metals from root pericycle and vascular cells into the xylem. This process is essential for the plant’s Cd hypertolerance and hyperaccumulation [97]. In contrast, HMA3 functions primarily as a tonoplast-localized transporter that mediates the vacuolar sequestration of Cd, thereby limiting the availability of Cd in the cytosol and reducing xylem loading. Studies of natural variation and mutants show that non-functional HMA3 alleles enhance Cd movement from roots to shoots. In contrast, functional HMA3 alleles sequester Cd in root vacuoles. This reduces Cd accumulation in shoots and grains. Researchers are now applying this mechanism to breed crop varieties with lower Cd content [75]. The functional specialization of HMA transporters is a cornerstone of Cd hyperaccumulation. While HMA3 facilitates vacuolar sequestration in roots, limiting Cd translocation, HMA4 plays the opposite and pivotal role in xylem loading. In hyperaccumulators like Noccaea caerulescens and Sedum plumbizincicola, the evolutionary adaptation of HMA4 is remarkable. Studies have demonstrated that these species possess multiple copies of the HMA4 gene due to tandem duplication, coupled with enhanced promoter activity, leading to constitutively high expression in root stele cells [39,97]. This genetic amplification enables sustained efflux of Cd²+ into the xylem sap against a concentration gradient, a process energetically driven by ATP hydrolysis. Consequently, Cd is efficiently translocated to shoots, defining the hyperaccumulation phenotype. In contrast, in non-hyperaccumulating plants, HMA4 expression is lower and more tightly regulated. In hyperaccumulators, knocking out the HMA4 gene greatly reduces Cd transport to the shoots. This result confirms the gene’s essential role. Conversely, overexpressing HMA4 in non-accumulator species can increase Cd accumulation in their shoots [39].

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters also play a significant role in Cd detoxification. For instance, in Brassica chinensis L., BcABCC1 and BcABCC2 utilize ATP hydrolysis to translocate Cd from the cytoplasm into vacuoles [98]. These transporters not only sequester Cd within vacuoles but also contribute to Cd tolerance by limiting its movement to sensitive cellular compartments.

Overall, the coordinated action of these transporters highlights the complexity of Cd translocation in plants and underscores the importance of understanding these mechanisms for developing strategies to mitigate Cd accumulation in crops.

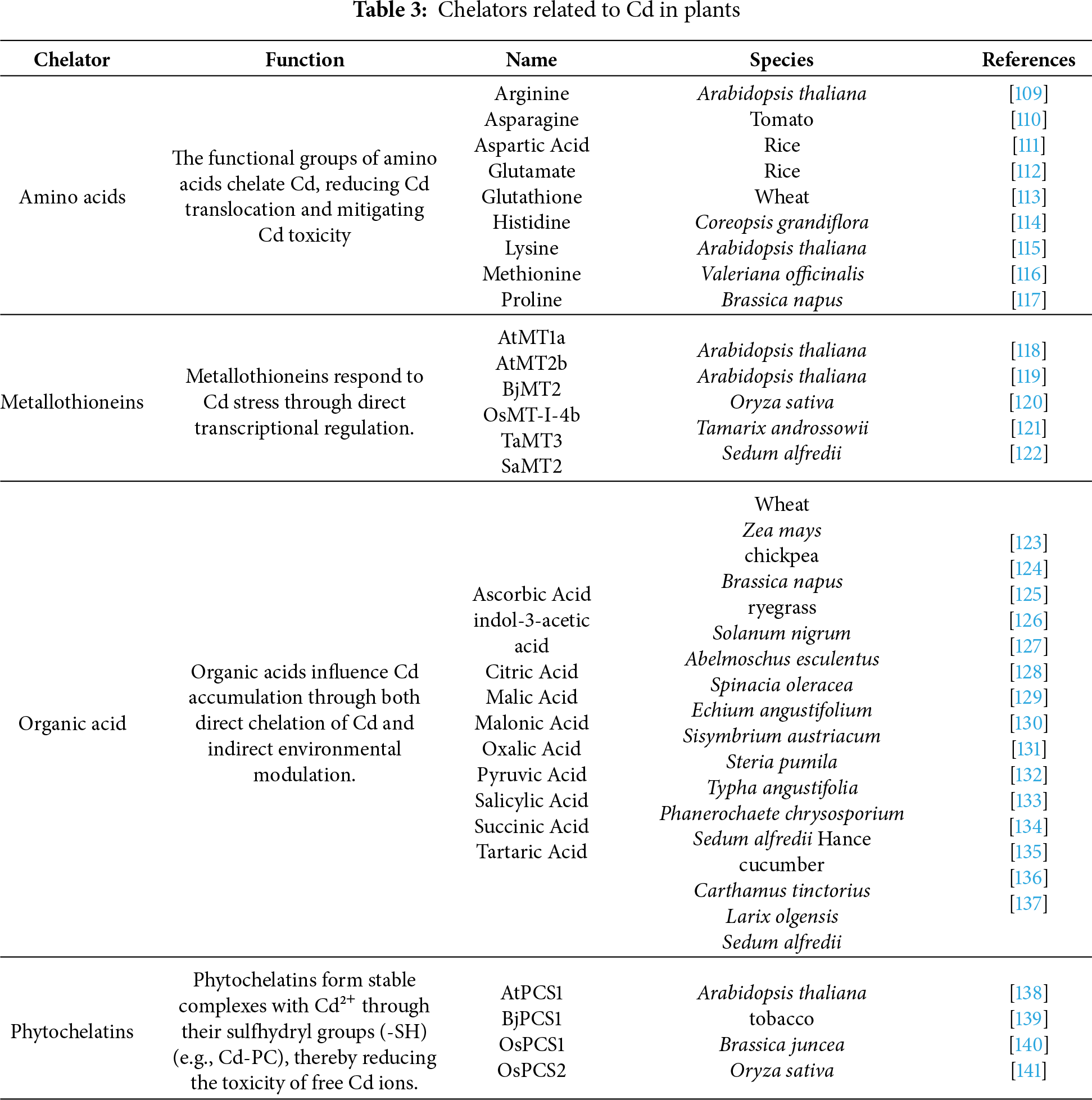

Heavy metal chelation plays a pivotal role in mediating tolerance and the accumulation of heavy metals in plants. Chelators mitigate the toxicity of Cd by forming stable complexes, thereby reducing its interaction with cellular organelles [100]. These chelators can be broadly categorized into four main groups: organic acids, phytochelatins (PCs), metallothioneins (MT), and amino acids (AA).

Organic acid chelation involves the formation of stable chemical complexes between organic acids and metal ions. In many plants, stress responses trigger the exudation of organic acids at the root-soil interface, enhancing mineral acquisition and tolerance to toxic metals [101]. Organic chelators are not only more efficient and environmentally sustainable but also biodegradable, improving the solubility, uptake, and stability of metals. Research on rice has demonstrated that oxalic acid and malic acid can chelate Cd, facilitating its detoxification [102]. Although Cd is typically adsorbed in soil and readily absorbed by plant roots, low-molecular-weight organic acids such as malic acid and oxalic acid can modify its chemical activity and bioavailability. For example, Hemarthria compressa alters the composition of its root exudates by secreting large amounts of organic acids (e.g., citric acid, fumaric acid, and malic acid), sugars (e.g., trehalose, maltose, and glucose), and fatty acids (e.g., citriconic acid). This modulation regulates rhizosphere soil pH and recruits beneficial microorganisms (e.g., Gp6, Sphingoaurantiacus, Devosia, and Neobacillus), thereby promoting plant growth and reducing Cd accumulation [103].

One of the most significant mechanisms for metal detoxification in plants involves the chelation of metals by low-molecular-weight proteins. Glutathione (GSH) serves as a key precursor for phytochelatin synthesis. It plays two vital roles: detoxifying metals and protecting plant cells from various environmental stresses. These stresses include oxidative stress [104]. PCs are small, cysteine-rich peptides that bind metal analogs through their -SH groups. Their biosynthesis is induced by various metals, which exhibit high affinity for phytochelatin ligands [105]. The role of PCs in Cd hyperaccumulators presents a fascinating paradox. While PCs are universally recognized for heavy metal detoxification in plants by forming non-toxic Cd-PC complexes destined for vacuolar sequestration, their role in some hyperaccumulators appears to be nuanced. In Sedum alfredii, a leading Cd hyperaccumulator, the PC-dependent detoxification pathway may be less dominant compared to non-accumulators. Instead, this species relies more heavily on vacuolar transporters like HMA3 and ligand-specific chelation with organic acids for detoxification [65,99]. This strategy may maintain a higher cytoplasmic Cd mobility, facilitating the efficient xylem loading required for hyperaccumulation. This mechanism differs from that in non-hyperaccumulators, which rely heavily on PCs for defense. It also contrasts with some hyperaccumulators where PCs remain important for tolerance. This difference indicates that hyperaccumulation may evolve by altering or bypassing standard detoxification pathways. The result is a shift from metal sequestration to enhanced translocation. Proteomic studies have confirmed the centrality of these classic detoxification pathways at a systemic level and revealed a more complex regulatory network. Under Cd stress, plants often increase production of key detoxification proteins. These include heat shock proteins, GSH S-transferases, and phytochelatin synthesis enzymes. Such proteins are frequently identified as differentially abundant proteins. Their upregulation represents a common defense strategy against Cd toxicity [106]. MT, low-molecular-weight proteins discovered in 1957, are cysteine-rich and may provide favorable binding sites for Cd chelation. While MT modulate the cellular toxicity of Cd, the mechanisms underlying this process remain largely unexplored [107].

AA also function as key metal chelators in plants. Proline, for example, plays several essential roles during Cd stress. It acts as an osmoprotectant to regulate cellular osmotic balance. When Cd stress raises external osmotic pressure, cells can lose water and become dehydrated. Proline accumulation counters this by increasing solute concentration inside cells. This process helps maintain water balance and prevents dehydration damage. In one study, treating maize seeds with proline before Cd exposure activated defense systems and reduced Cd toxicity, improving plant growth [108].

Table 3 summarizes current knowledge of Cd-binding chelators in plants. Research shows that organic acids and AA are well-studied in both diversity and function. In contrast, PCs and MT are less understood. Most studies on these compounds have used model organisms, and their detailed mechanisms remain unclear. Future work should focus on clarifying these processes and extending research to non-model plants. These steps will help improve phytoremediation methods and reduce Cd levels in crops.

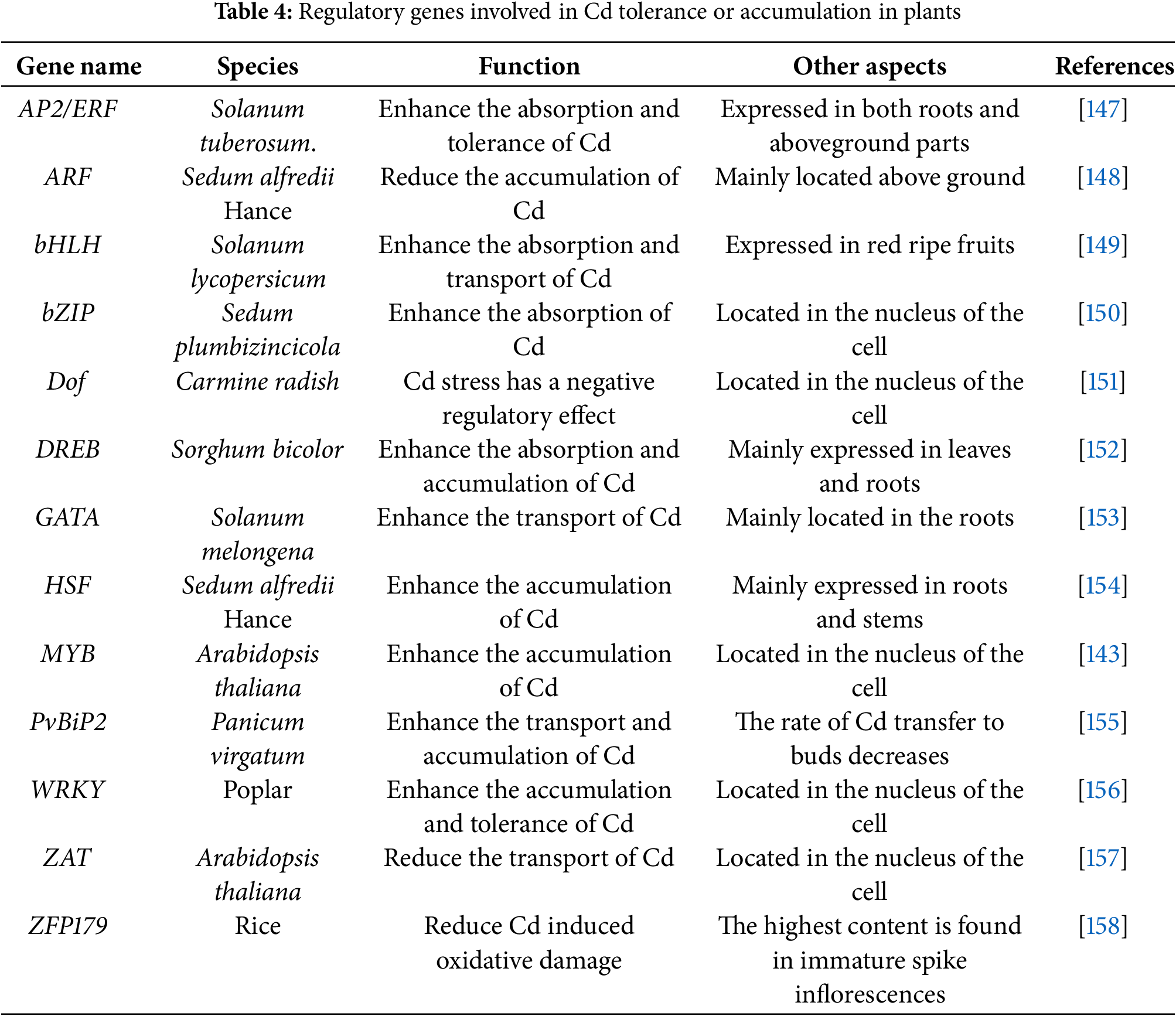

Gene regulation is critical for Cd accumulation in plants, with transcription factors (TFs) playing a central role in mediating plant responses to Cd stress. TFs such as WRKY, MYB, and bHLH have been reported to directly or indirectly regulate Cd tolerance or accumulation in plants [142,143]. These TFs exert their regulatory effects by controlling Cd-related genes, activating specific signaling pathways, or interacting with other proteins (Table 4).

Transcription factors orchestrate the plant’s response to Cd stress by forming intricate regulatory networks. The WRKY family exemplifies this complexity. In Arabidopsis, different WRKY members can exert opposing effects on Cd tolerance. For instance, WRKY12 acts as a negative regulator. It represses the expression of GSH1, limiting the production of GSH, a precursor for phytochelatin synthesis. This suppression sensitizes the plant to Cd toxicity [144]. In stark contrast, WRKY45 in the same species functions as a positive regulator by activating the expression of phytochelatin synthase genes (PCS1 and PCS2), thereby enhancing PC-based Cd sequestration and tolerance [145]. This juxtaposition within the same TF family illustrates the precise and multi-layered nature of the regulatory network, where the balance between positive and negative signals fine-tunes the metabolic investment in detoxification versus other physiological needs.

MYB TFs also play a significant role in Cd accumulation regulation. For example, in Arabidopsis thaliana, overexpression of MYB49 results in significantly increased Cd accumulation, whereas MYB49 knockout plants and plants expressing the chimeric repressor MYB49: SRDX (ERF-associated amphiphilic repression motif suppression domain) exhibit reduced Cd accumulation [143]. MYB49 directly binds to the promoters of bHLH38 and bHLH101, increasing their expression. This upregulation activates IRT1, a metal transporter gene that helps take up Cd. MYB49 also targets the promoters of HIPP22 and HIPP44, which are heavy metal-associated proteins. This binding boosts their expression and promotes Cd accumulation in cells. As a feedback mechanism controlling Cd uptake and accumulation in plant cells, Cd-induced abscisic acid (ABA) upregulates ABI5 expression. The ABI5 protein interacts with MYB49 and prevents its binding to downstream gene promoters, thereby reducing Cd accumulation [143]. Furthermore, in Arabidopsis thaliana, overexpression of AtbHLH38 and AtbHLH39 constitutively activates, either directly or indirectly, the expression of HMA3, MTP3, IREG2, and IRT2. The gene products of these loci enhance Cd sequestration in roots and reduce Cd translocation from roots to shoots [146].

Collectively, these TFs modulate plant sensitivity and tolerance to Cd by regulating downstream genes or signaling pathways. However, due to the vast number of TFs and the complexity of regulatory networks, only a limited number of Cd-related TFs have been characterized. Deciphering the functions and regulatory networks of Cd-related TFs remains a crucial objective, as it will provide foundational insights into the molecular mechanisms of Cd accumulation and tolerance in plants [143]. Future research should focus on expanding the characterization of Cd-related TFs to non-model plant species and elucidating the intricate regulatory networks that govern Cd responses. Such studies could pave the way for developing strategies to enhance Cd phytoremediation or reduce Cd accumulation in food crops.

2.3.4 Alleviation and Relief of Cd Toxicity

Plants employ several adaptive strategies to counteract and mitigate the toxic effects of Cd. The primary detoxification mechanisms can be categorized into three main aspects:

(i) Exclusion and compartmentalization of Cd: plants detoxify Cd by excluding it from sensitive tissues or compartmentalizing it within specific organelles. In roots, vacuoles serve as the primary detoxification organelles for Cd. Transporters mediate the chelation of Cd with GSH and transport it into vacuoles for storage, achieving intracellular compartmentalization. This process reduces cytoplasmic Cd content and limits its translocation to other tissues. For example, in rice (Oryza sativa), Cd efflux involves radial transport across root tissues and xylem loading, facilitating cellular export [159]. Similarly, Sedum alfredii Hance exhibits root Cd efflux, protecting root cells from Cd toxicity [160]. In Festuca arundinacea, Cd is excreted onto the leaf surface, enabling a phytoremediation strategy based on “root uptake-root-to-leaf translocation-leaf excretion” [161]. Additionally, gibberellins can be applied to enhance short-term Cd excretion from leaves, further supporting detoxification efforts [162].

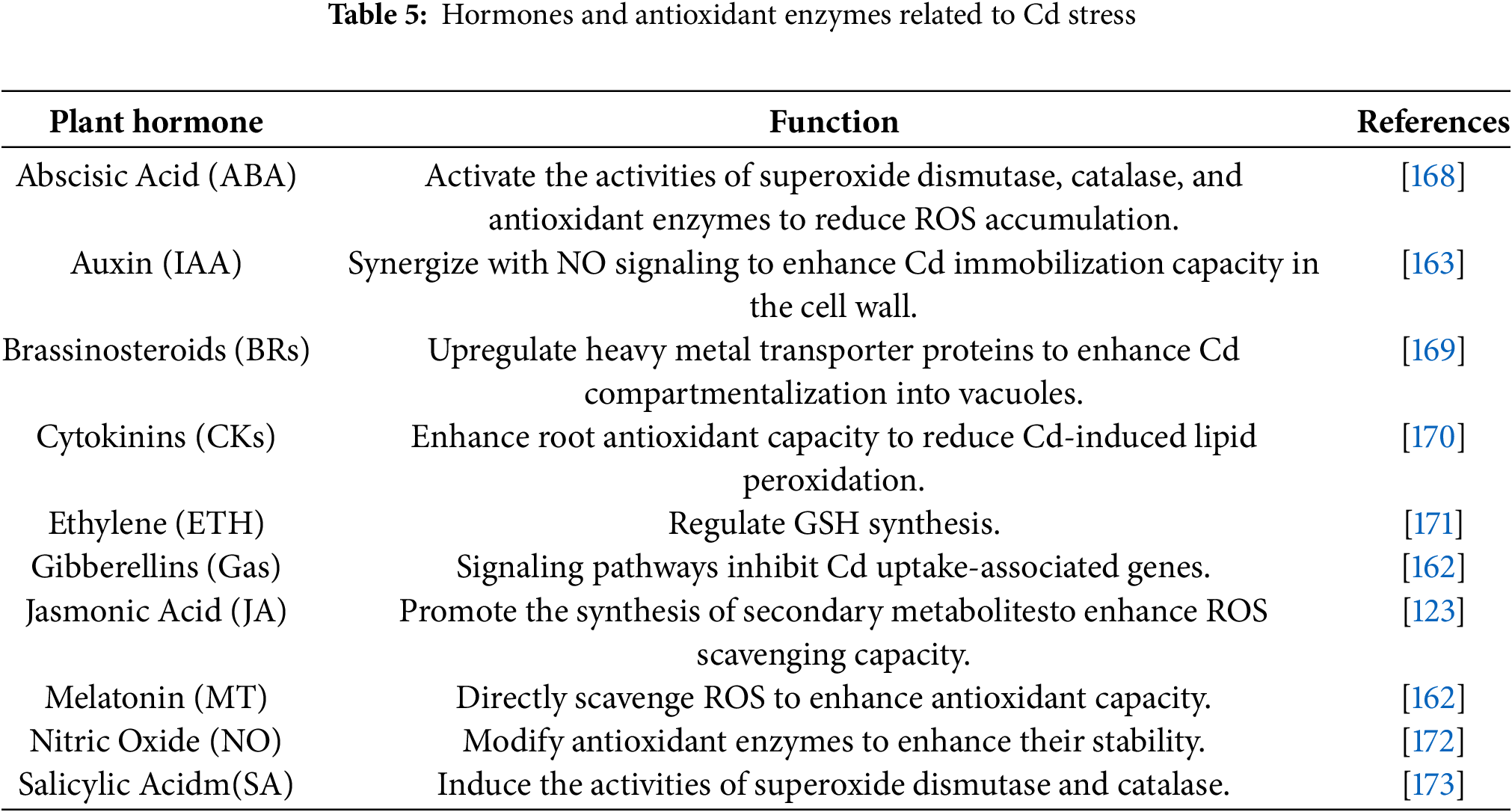

(ii) Synthesis of plant hormones and activation of antioxidant systems: plant hormones play a pivotal role in mediating responses to Cd stress (Table 5). For instance, in Cd-contaminated soil, exogenous auxin application enhances reactive oxygen species (ROS) scavenging in tomatoes, promotes root cell elongation and division, reduces root cell mortality, and improves plant survival under stress conditions [163]. Similarly, gibberellins stimulate cell division and elongation, increase plant biomass, and enhance Cd stress tolerance. In rice exposed to Cd stress, gibberellins improve Cd tolerance by regulating nitric oxide (NO) accumulation, thereby promoting growth [161].

The enzymatic antioxidant defense system is another critical component of Cd detoxification. Key enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) neutralize reactive oxygen species generated under Cd stress. SOD, as the first line of defense, catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide anion radicals into hydrogen peroxide and oxygen. Under Cd stress, SOD gene expression and enzymatic activity are typically upregulated in plants [164]. For example, in Cd-treated wheat seedlings, SOD gene transcription and enzyme activity are significantly enhanced, enabling more efficient scavenging of excess superoxide anion radicals and mitigating oxidative damage to cells [165].

(iii) Microbes in the rhizosphere help reduce Cd bioavailability in soils. They also support plant growth and lessen Cd toxicity. These microorganisms limit plant Cd uptake through several strategies. One method involves using carboxyl and amino groups on root cell walls to chelate Cd in the soil.

Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) form symbiotic partnerships with plant roots. This relationship improves plant stress tolerance. In Cd-polluted soils, AMF extend the root absorption area via their hyphal networks. This enhances the plant’s access to water and nutrients [166]. AMF also release glomalin, a glycoprotein that binds Cd ions. By immobilizing Cd, glomalin lowers its bioavailability.

For instance, Ligustrum lucidum inoculated with AMF shows much lower Cd levels in roots and shoots than non-inoculated plants in contaminated soil. The inoculated plants also grow better and produce more biomass [167].

Overall, these adaptive strategies highlight the multifaceted approaches plants use to detoxify Cd. Further research into these mechanisms could provide valuable insights for developing phytoremediation strategies and reducing Cd accumulation in agricultural crops.

3 Ecological Effects of Cd Accumulation in Plants

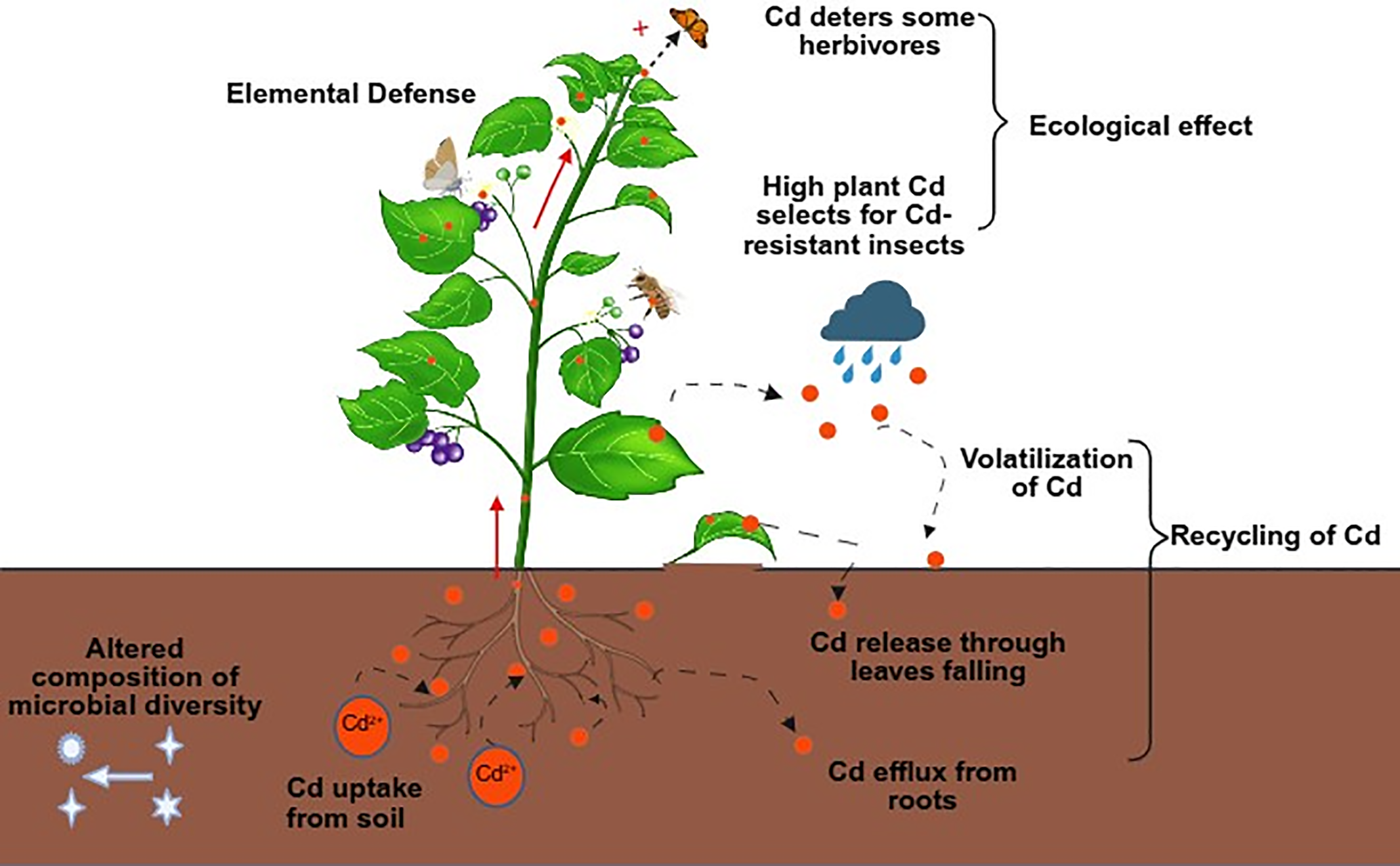

The natural cycle of Cd involves multiple phases, with Cd entering the environment primarily through volcanic activity, rock weathering, industrial emissions, and agricultural practices. While selenium can be volatilized from plants via foliar emission, it is hypothesized that Cd may also be eliminated through similar pathways. Hyperaccumulators may release Cd through root exudates, shed leaves, and foliar volatilization [174]. Subsequently, rainwater can leach Cd from plant residues, reintroducing it into soil or aquatic systems (Fig. 3). In bulk soil, much of the Cd may be bound to soil particles. This framework offers a novel perspective for investigating the Cd cycle and underscores the need to consider the ecological impacts of using hyperaccumulator plants for remediating Cd-contaminated soils, particularly on microorganisms, herbivores, and adjacent vegetation [175].

Figure 3: Ecological impacts of Cd accumulation in plants. Orange circles illustrate the translocation of Cd within plants and their cycling in the local ecosystem. In Cd-contaminated soil, the varying shapes represent alterations in biological communities [176,177]. Herbivores demonstrate elemental defense mechanisms [178,179], while elemental allelopathy exerts effects on neighboring plants [180,181]

Root-associated microorganisms, known as the root microbiota, form communities that live on rhizosphere soil particles. These microbes can grow and reproduce in this environment [182]. The rhizosphere microbiota consists mainly of bacteria, most of which are Gram-negative. Common bacterial genera include Pseudomonas, Xanthobacter, Alcaligenes, and Agrobacterium [182].

Root activities strongly influence these microbes. Some microbes use organic carbon released by plant roots. In return, they help plants take up more water and nutrients, supporting plant growth. However, other microorganisms are pathogenic and can harm plant health [183]. To defend themselves, plants release antimicrobial compounds or antibiotics. These substances limit the growth of harmful microbes.

Variation in Cd accumulation among plants can shift the composition of root-associated microbial communities. These changes often favor Cd-tolerant microorganisms over sensitive ones. For example, Sphingomonas bacteria can enlarge the root-soil interface and promote root organic acid release. This activity boosts Cd bioavailability and uptake in plants [176].

Cd accumulation strongly restructures rhizosphere microbial communities. It creates selective pressure that favors Cd-tolerant microbes over sensitive types. High Cd levels inhibit sensitive organisms through direct toxicity or by altering the rhizosphere environment. This results in lower microbial abundance and reduced functional activity.

Gram-positive bacteria are particularly vulnerable to Cd due to their thin cell walls and limited antioxidant defenses. In contrast, Cd-resistant microbes such as Sphingomonas and Pseudomonas gain a competitive edge under Cd stress. They often use strategies like metal chelation to survive [177].

The rhizosphere microbiome actively modulates Cd phytoavailability, creating a complex interplay between plants and microbes. Cd tolerant plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) can alter Cd solubility. For instance, some bacterial strains secrete siderophores and organic acids, which can acidify the rhizosphere and form complexes with Cd, potentially increasing its mobility for hyperaccumulators [176]. This aligns with findings that certain microbes can stimulate root organic acid secretion, enhancing Cd bioavailability. Conversely, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) often function as a biological filter. Their extensive extraradical mycelium can bind Cd ions through secretions like glomalin-related soil proteins, effectively immobilizing Cd in the rhizosphere and reducing its acquisition by the host plant, as observed in Ligustrum lucidum [167]. Therefore, hyperaccumulators may selectively enrich Cd-mobilizing bacteria to facilitate phytoextraction, while non-accumulators might associate with Cd immobilizing microbes like AMF for protection. This understanding highlights the potential of microbiome engineering to optimize phytoremediation strategies.

Cd accumulated in plant tissues exhibits toxicity to general herbivores, thereby inhibiting feeding by various herbivorous species. Cd hyperaccumulators, which predominantly occur in Cd-enriched soils, utilize Cd hyperaccumulation as a defense mechanism against herbivores and pathogens. This concept, termed the “elemental defense hypothesis,” has received substantial empirical support [184,185]. The “elemental defense” hypothesis is strongly supported by studies showing reduced herbivory on Cd-laden tissues [178]. However, the defense is multifaceted. Beyond direct toxicity, Cd exposure can systemically alter the plant’s phenotype. For example, in Yunnan Malania, Cd stress not only increases tissue Cd concentration but also modulates the emission of specific volatile organic compounds (VOCs). These induced VOCs act as an indirect defense by repelling ovipositing female insects, thereby reducing herbivore pressure beyond the direct effect of Cd toxicity [179]. This suggests a synergistic interaction between elemental and organic defenses.

Furthermore, this potent selection pressure inevitably drives the evolution of Cd-tolerant herbivore populations. These adapted insects can circumvent the elemental defense, potentially becoming specialized consumers on hyperaccumulator plants and creating a unique and complex trophic dynamic in metal-enriched environments. This underscores that the ecological outcome of hyperaccumulation is not a static deterrent but a dynamic, co-evolutionary arms race.

However, plant Cd accumulation on herbivores remains limited. Future studies could explore how Cd hyperaccumulating plants exert phytotoxic effects on Cd-sensitive plants while selecting Cd-tolerant herbivores as persistent consumers, thereby driving biological evolution. Such interactions may further influence Cd cycling throughout the food chain.

3.3 Impact on Neighboring Plants

In Cd-contaminated areas, hyperaccumulator plants can raise Cd levels in nearby plants [180]. The “elemental allelopathy hypothesis” proposes that hyperaccumulation offers a competitive edge by suppressing the growth of neighboring vegetation. Soil near hyperaccumulators contains more Cd than soil near non-accumulators [181]. This results from several release pathways: leaf litter deposition, root turnover, exudation, and possibly volatilization. Deep-rooted species bring up Cd from groundwater, while annual leaf litter returns Cd to topsoil. Although debated, foliar emission of methylated Cd may also contribute to airborne Cd. These mechanisms create localized Cd hotspots in soil. Such heterogeneity exerts distinct selective pressures on plant communities.

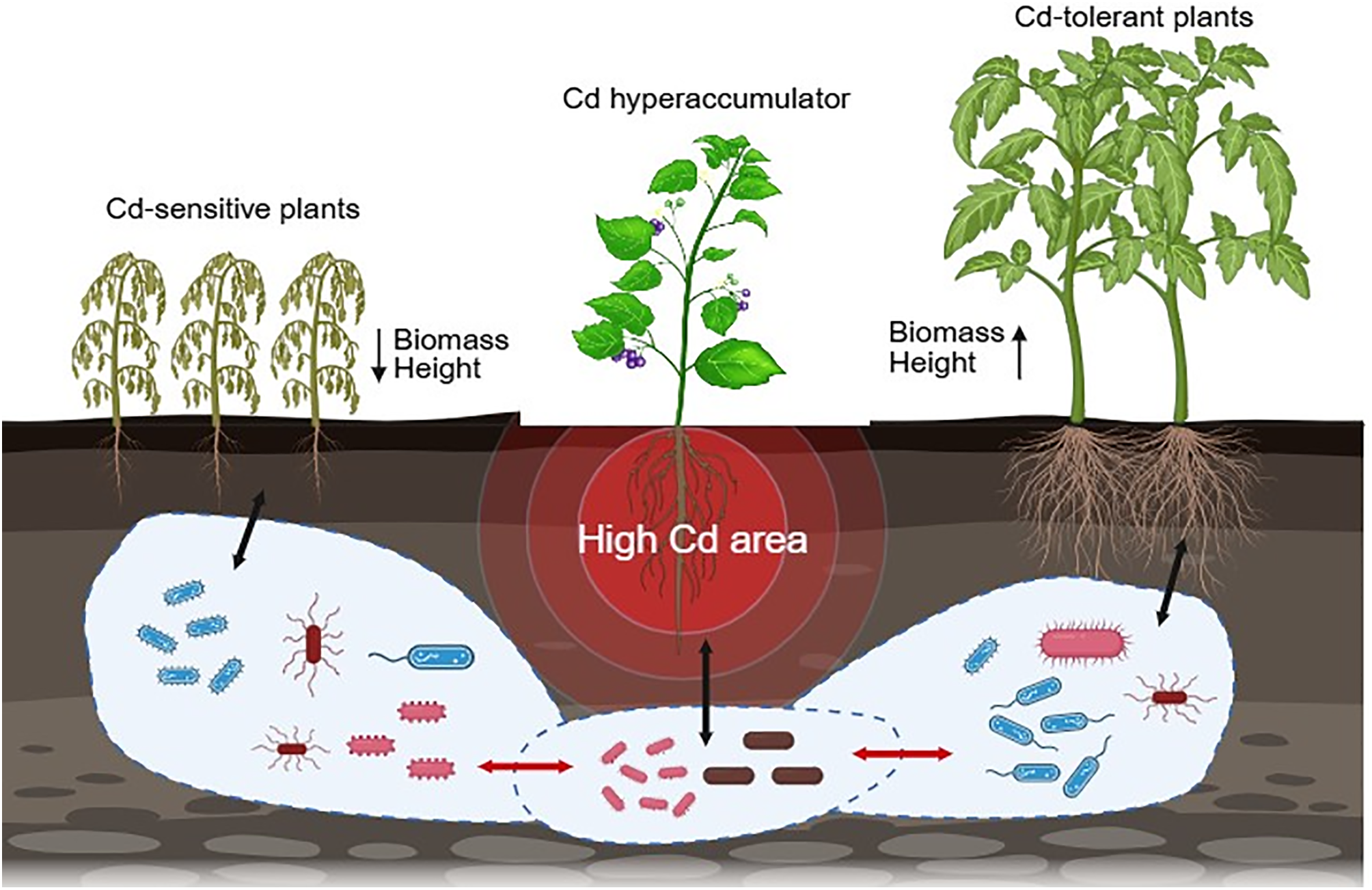

Hyperaccumulators affect neighboring plants differently, mainly depending on each plant’s Cd tolerance. Tolerant species may actually benefit from higher soil Cd. Elevated Cd can suppress herbivores and pathogens, thus reducing competition. Sensitive plants, however, suffer under increased Cd conditions. A plant’s response to Cd ultimately depends on exposure levels and inherent tolerance. Using Cd hyperaccumulators alongside conventional crops shows promise for managing Cd-rich soils. Co-cultivation or rotational planting could help reduce crop Cd content in contaminated areas. Yet intercropping may also lower yields due to competition for resources. A precision management approach may help balance these effects. For example, farmers might alternate between phytoremediation and crop production phases (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: The ecological impact of Cd in hyperaccumulated plants. The growth status of Cd-sensitive plants and Cd-tolerant plants in soil with high Cd pollution [180,181]. The changes of biological communities in different plant soils [176,177]

4 Synthesis and Future Perspective

This review summarizes Cd hyperaccumulators. It details their species, distribution, accumulation capacity, and biomass. It also explains the mechanisms of Cd uptake and transport. Furthermore, it explores the ecological effects on microbes, herbivores, and neighboring plants. The ultimate goal is to apply this knowledge for environmental cleanup and for reducing Cd in food crops. However, the utilization of Cd hyperaccumulators also presents potential ecological risks that warrant caution. These include the transfer of accumulated Cd into food webs through herbivores and the alteration of soil microbial communities and neighboring plant growth. Therefore, the large-scale deployment of phytoremediation requires careful risk-benefit assessment and long-term monitoring. To mitigate the ecological risks of Cd, integrated strategies are crucial. Implementing advanced wastewater treatment, such as adsorption and membrane filtration, can reduce Cd input at the source. Furthermore, ecological engineering solutions like constructed wetlands enhance natural Cd immobilization. Adopting a tiered management approach ensures environmental standards are met in critical zones, safeguarding aquatic ecosystems [186].

Cd accumulation in plants represents a dual-edged phenomenon with profound ecological implications. While hyperaccumulators offer a promising phytoremediation strategy for Cd-contaminated soils, their interactions with biotic and abiotic components unveil complex cascading effects. The restructuring of rhizosphere microbiomes under Cd stress favors metal-tolerant Proteobacteria, enhancing phytoextraction efficiency but compromising soil nutrient cycling. Herbivore deterrence through elemental defense and VOC-mediated signaling demonstrates evolutionary trade-offs, selecting for Cd-tolerant insect populations while disrupting trophic dynamics. Spatial redistribution of Cd via hyperaccumulator litterfall and root exudation creates ecological niches that favor metallophytes over sensitive species, reshaping plant community structures.

Important knowledge gaps remain in three key areas. First, we need to better characterize and quantify atmospheric Cd fluxes from leaf volatilization—especially methylated forms—across different ecosystems. Second, more study is needed on the long-term transfer of Cd through food webs at remediated sites, particularly via decomposer-predator pathways. Third, we must understand how hyperaccumulators, Cd-tolerant herbivores, and microbial communities evolve together under ongoing metal exposure.

Future research endeavors should employ multi-omics tools to elucidate the interactive mechanisms through which genes, microbiomes, and environmental factors collectively regulate cadmium (Cd) cycling. Field-based trials are warranted to evaluate rotational phytomanagement systems capable of sustaining both remediation efficacy and crop productivity. Such systems may encompass CRISPR-edited hyperaccumulators that sequester metals primarily in their root tissues. Concurrently, the development of crop cultivars with reduced Cd uptake capacity, coupled with the application of beneficial microbial inoculants, would mitigate ecological risks and enhance food safety. A comprehensive understanding of Cd dynamics, spanning from molecular transporters to landscape-scale metal migration, will facilitate the design of effective and sustainable remediation strategies. Notably, such strategies must safeguard ecosystem integrity while addressing human needs.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was funded by the Science and Technology Major Program of Hubei Province (2024BBA002), and the Key Research and Development Program of Hubei Province, China (No. 2023BBB065 and No. 2024EBA010).

Author Contributions: Mingwei Yue: Writing—original draft; Shen Rao: Funding acquisition, writing—review & editing; Xiaomeng Liu: Investigation, writing—review & editing; Wei Yang: Resources; Yuan Yuan: Software; Feng Xu: Funding acquisition, writing—review & editing; Shuiyuan Cheng: Project administration. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kragh H. Lost elements: the periodic table’s shadow side. Ambix. 2016;63(1):74–5. doi:10.1080/00026980.2016.1201303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Satarug S, Vesey DA, Gobe GC. Current health risk assessment practice for dietary cadmium: data from different countries. Food Chem Toxicol. 2017;106(Pt A):430–45. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2017.06.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Genchi G, Sinicropi MS, Lauria G, Carocci A, Catalano A. The effects of cadmium toxicity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):3782. doi:10.3390/ijerph17113782. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Satarug S, Garrett SH, Sens MA, Sens DA. Cadmium, environmental exposure, and health outcomes. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118(2):182–90. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901234. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Tessier A, Campbell PGC, Bisson M. Sequential extraction procedure for the speciation of particulate trace metals. Anal Chem. 1979;51(7):844–51. doi:10.1021/ac50043a017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Luo YH. Study on the repair of heavy metal contaminated soil. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2019;300(3):032076. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/300/3/032076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Waalkes MP. Cadmium carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 2003;533(1–2):107–20. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2003.07.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Ahmad P, Raja V, Ashraf M, Wijaya L, Bajguz A, Alyemeni MN. Jasmonic acid (JA) and gibberellic acid GA3 mitigated Cd-toxicity in chickpea plants through restricted cd uptake and oxidative stress management. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):19768. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-98753-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Da Silva J, Gonçalves RV, de Melo FCSA, Sarandy MM, da Matta SLP. Cadmium exposure and testis susceptibility: a systematic review in murine models. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2021;199(7):2663–76. doi:10.1007/s12011-020-02389-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Cuypers A, Plusquin M, Remans T, Jozefczak M, Keunen E, Gielen H, et al. Cadmium stress: an oxidative challenge. Biometals. 2010;23(5):927–40. doi:10.1007/s10534-010-9329-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ahsan AM, Safina N, Ravinder K, Hasan S, Azher NM, Awadhesh K, et al. Unraveling the mechanisms of cadmium toxicity in horticultural plants: implications for plant health. S Afr J Bot. 2023;163(4):433–42. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2023.10.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mzoughi Z, Souid G, Timoumi R, Cerf DL, Majdoub H. Partial characterization of the edible Spinacia oleracea polysaccharides: cytoprotective and antioxidant potentials against Cd induced toxicity in HCT116 and HEK293 cells. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;136(1–3):332–40. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.06.089. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Soubasakou G, Cavoura O, Damikouka I. Phytoremediation of cadmium-contaminated soils: a review of new cadmium hyperaccumulators and factors affecting their efficiency. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol. 2022;109(5):783–7. doi:10.1007/s00128-022-03604-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Reeves RD, Baker AJM, Jaffré T, Erskine PD, Echevarria G, Ent AVD. A global database for plants that hyperaccumulate metal and metalloid trace elements. New Phytol. 2017;218(2):432–4. doi:10.1111/nph.14907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Brooks RR, Lee J, Reeves RD, Jaffre T. Detection of nickeliferous rocks by analysis of herbarium specimens of indicator plants. J Geochem Explor. 1977;7:49–57. doi:10.1016/0375-6742(77)90074-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Das P, Samantaray S, Rout GR. Studies on cadmium toxicity in plants: a review. Environ Pollut. 1997;98(1):29–36. doi:10.1016/s0269-7491(97)00110-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Manara A, Fasani E, Furini A, DalCorso G. Evolution of the metal hyperaccumulation and hypertolerance traits. Plant Cell Environ. 2020;43(12):2969–86. doi:10.1111/pce.13821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wei SH, Wang SS, Zhou QX, Zhan J, Ma LH, Wu ZJ. Potential of Taraxacum mongolicum Hand-Mazz for accelerating phytoextraction of cadmium in combination with eco-friendly amendments. J Hazar Mater. 2010;181(1–3):480–4. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2010.05.038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Wei SH, Zhou QX, Mathews S. A newly found cadmium accumulator—Taraxacum mongolicum. J Hazard Mater. 2008;159(2–3):544–7. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2008.02.052. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Tanee T, Sudmoon R, Thamsenanupap P, Chaveerach A. Effect of cadmium on DNA changes in Ipomoea aquatica Forssk. Pol J Environ Stud. 2016;25(1):311–5. doi:10.15244/pjoes/60726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Dou XK, Dai HP, Skuza L, Wei SH. Cadmium removal potential of hyperaccumulator Solanum nigrum L. under two planting modes in three years continuous phytoremediation. Environ Pollut. 2022;307:119493. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2022.119493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao XF, Lei M, Chen TB. Species, habitat characteristics, and screening suggestions of cadmium hyperaccumulators in China. J Environ Sci. 2023;44(5):2786–98. (In Chinese). doi:10.13227/j.hjkx.202205305. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Lei L, Cui XY, Li C, Dong ML, Huang R, Li YX, et al. The cadmium decontamination and disposal of the harvested cadmium accumulator Amaranthus hypochondriacus L. Chemosphere. 2022;286(Pt 1):131684. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.131684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Liu JX, Chen WQ, Yang L, Li N, Wang YH, Kang YC. Effect of cadmium stress on phytochelatins in Amaranthus hypochondriacus L. during different growth periods. J Environ Sci. 2021;42(8):4053–60. (In Chinese). doi:10.13227/j.hjkx.202012024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Fan HL, Zhou W. Screening of amaranth cultivars (Amaranthus mangostanus L.) for cadmium hyperaccumulation. Agr Sci China. 2009;42(4):1316–24. doi:10.1016/S1671-2927(08)60218-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Tang YT, Qiu RL, Zeng XW, Ying RR, Yu FM, Zhou XY. Lead, zinc, cadmium hyperaccumulation and growth stimulation in Arabis paniculata Franch. Environ Exp Bot. 2008;66(1):126–34. doi:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2008.12.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Chen W, Jiang WY, Yang YX, Liao J, Wang HJ, Liang XL. A newly discovered camium hyperaccumulator—Astersubulatus Michx. Acta Ecol Sin. 2023;43(13):5592–9. (In Chinese). doi:10.5846/stxb202203160639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Peng KJ, Li XD, Luo CL, Shen ZG. Vegetation composition and heavy metal uptake by wild plants at six contaminated sites in Hunan Xiangxi area. China J Environ Sci Health. 2006;41(1):65–76. (In Chinese). doi:10.16258/j.cnki.1674-5906.2008.03.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Haag-Kerwer A, Schäfer HJ, Heiss S, Walter C, Rausch T. Cadmium exposure in Brassica juncea causes a decline in transpiration rate and leaf expansion without effect on photosynthesis. J Exp Bot. 1999;341(341):1827–35. doi:10.1093/jxb/50.341.1827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Huang DH, Mai SH, Chou S, Chen DQ. Effects of cadmium on growth and physiological characteristics of Cardamine violifolia. Hubei Agr Sci. 2022;61(5):87–90+97. (In Chinese). doi:10.14088/j.cnki.issn0439-8114.2022.05.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Dong FX, Tan SR, Yang YT, Chen B. Bermudagrass under water-flooding: physiological and biochemical response to cadmium stress. Chin Agr Sci Bull. 2017;33(33):120–6. (In Chinese). doi:10.11924/j.issn.1000-6850.casb17070119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Naz R, Khan MS, Hafeez A, Fazil M, Khan MN, Ali B. Assessment of phytoremediation potential of native plant species naturally growing in a heavy metal-polluted industrial soils. Braz J Biol. 2022;84:e264473. doi:10.1590/1519-6984.264473. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Peng KJ, Luo CL, You WX, Lian CL, Li XD, Shen ZG. Manganese uptake and interactions with cadmium in the hyperaccumulator—Phytolacca Americana L. J Hazard Mater. 2008;154(1–3):674–81. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2007.10.080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Tang YT, Qiu RL, Zeng XW, Fang XH, Yu FM, Zhou XY. Zn and Cd hyperaccumulating characteristics of Picris divaricata Vant. Int J Environ Pollut. 2009;1(2):26–38. doi:10.1504/IJEP.2009.02664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zu YQ, Li Y, Chen JJ, Qin L, Christian S. Hyperaccumulation of Pb, Zn and Cd in herbaceous grown on lead-zinc mining area in Yunnan, China. China Environ Int. 2005;31(5):755–62. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2005.02.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Li SC, Zhuo RY, Yu M, Lin XY, Xu J, Qiu WM, et al. A novel gene SpCTP3 from the hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola redistributes cadmium and increases its accumulation in transgenic Populus × canescens. Front Plant Sci. 2023;14:1111789. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1111789. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Xiao XY, Chen TB, An ZZ, Lei M, Huang ZC, Liao XY, et al. Potential of Pteris vittata L. for phytoremediation of sites co-contaminated with cadmium and arsenic: the tolerance and accumulation. J Environ Sci. 2008;20(1):62–7. doi:10.1016/s1001-0742(08)60009-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Yu G, Xiang JY, Liu J, Zhang XH, Lin H, Sunahara GI, et al. Single-cell atlases reveal leaf cell-type-specific regulation of metal transporters in the hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii under cadmium stress. J Hazard Mater. 2024;480(46):136185. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2024.136185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Liu H, Zhao HX, Wu LH, Liu AN, Zhao FJ, Xu WZ, et al. Heavy metal ATPase 3 (HMA3) confers cadmium hypertolerance on the cadmium/zinc hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola. New Phytol. 2017;215(2):687–98. doi:10.1111/nph.14622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Li Y, Fang QX, Zu YQ. Accumulation characteristics of two ecotypes Sonchus asper (L.) Hill. to Cd. Acta Agric Boreali-Occident Sin. 2008;6:1150–4. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

41. Meeinkuirt W, Phusantisampan T, Kubola J, Chumroenphat T, Pichtel J. Phytomanagement of cadmium using Tagetes erecta in greenhouse and field conditions. J Hazard Mater Adv. 2021;16(15):100481. doi:10.1016/j.hazadv.2024.100481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Morina F, Mijovilovich A, Mishra A, Brückner D, Vujić B, Bokhari SNH, et al. Cadmium and Zn hyperaccumulation provide efficient constitutive defense against Turnip yellow mosaic virus infection in Noccaea caerulescens. Plant Sci. 2023;336(16):111864. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2023.111864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Liu Y, Xie AN. Enrichment features of Trifolium pratense L. under cadmium stress. J Henan Agr Sci. 2011;40(1):82–4. (In Chinese). doi:10.15933/j.cnki.1004-3268.2011.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Liu W, Shu WS, Lan CY. Viola baoshanensis, a plant that hyperaccumulates cadmium. Sci Bull. 2004;01(1):29–32. doi:10.1007/BF02901739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Perfus-Barbeoch L, Leonhardt N, Vavasseur A, Forestier C. Heavy metal toxicity: cadmium permeates through calcium channels and disturbs the plant water status. Plant J. 2002;32(4):539–48. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01442.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Hart JJ, Welch RM, Norvell VA, Kochian LV. Transport interactions between cadmium and zinc in roots of bread and durum wheat seedlings. Physiol Plant. 2002;116(1):73–8. doi:10.1034/j.1399-3054.2002.1160109.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Xu J, Bao JQ. Adsorption and fixation mechanism of cadmium on celery (Apium graveolens L.) root cell wall and the analysis of FTIR spectra. Acta Sci Circumstantiae. 2015;5(8):2605–12. (In Chinese). doi:10.13671/j.hjkxxb.2014.0922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Brown AM. Flowcharts to aid student comprehension of Nernst equation calculations. Adv Physiol Educ. 2018;42(2):260–2. doi:10.1152/advan.00006.2018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Sterckeman T, Thomine S. Mechanisms of cadmium accumulation in plants. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2020;39(4):322–59. doi:10.1080/07352689.2020.1792179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Wei BL, Peng YC, Jeyakumar P, Lin LX, Zhang DL, Yang MY, et al. Soil pH restricts the ability of biochar to passivate cadmium: a meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2023;219(9):115110. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2022.115110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Han MX, Ullah H, Yang H, Yu G, You SH, Liu J, et al. Cadmium uptake and membrane transport in roots of hyperaccumulator Amaranthus hypochondriacus L. Environ Pollut. 2023;331(P1):121846. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2023.121846. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Barberon M. The endodermis as a checkpoint for nutrients. New Phytol. 2017;213(4):1604–10. doi:10.1111/nph.14140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Huang L, Li WC, Tam NFY, Ye ZH. Effects of root morphology and anatomy on cadmium uptake and translocation in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J Environ Sci. 2018;75(11):296–306. doi:10.1016/j.jes.2018.04.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Lian MH, Sun LN, Hu XM, Zeng XF, Guan X. Effect of pH on cadmium speciation in rhizosphere soil solutions of different cadmium accumulating plants. Chin J Ecol. 2015;34(1):130–7. (In Chinese). doi:10.13292/j.1000-4890.2015.0019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Zhu Z, Yang XD, Xu ZQ, Fei JC, Peng JW, Rong XM, et al. Foliar uptake, translocation and accumulation of heavy metals from atmospheric deposition in crops. J Plant Nutr Fert. 2021;27(2):332–45. (In Chinese). doi:10.11674/zwyf.20258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Zhang XT, Yang M, Yang H, Pian RQ, Wang JX, Wu AM. The uptake, transfer, and detoxification of cadmium in plants and its exogenous effects. Cells. 2024;13(11):907. doi:10.3390/cells13110907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Lukas H, Susan T, Rainer S, Bernd N. Column extraction of heavy metals from soils using the biodegradable chelating agent EDDS. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39(17):6819–24. doi:10.1021/es050143r. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Meychik NR, Nikolaeva YI, Yermakov IP. Ion-exchange properties of cell walls of Spinacia oleracea L. roots under different environmental salt conditions. Biochemistry. 2006;71(7):781–9. doi:10.1134/s000629790607011x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Yang GL, Zheng MM, Tian AJ, Liu YT, Feng D, Lv SM. Research on the mechanisms of plant enrichment and detoxification of cadmium. Biology. 2021;10(6):544–4. doi:10.3390/biology10060544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Qi XL, Tam NF, Li WC, Ye ZH. The role of root apoplastic barriers in cadmium translocation and accumulation in cultivars of rice (Oryza sativa L.) with different Cd-accumulating characteristics. Environ Pollut. 2020;264:114736. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.114736. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Yang JS, Ahmed RI, Liu H, Sheng S, Xiao W, Hu R, et al. Differential absorption of cadmium and zinc by tobacco plants: role of apoplastic pathway. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2024;37(1):101641. doi:10.1016/j.bbrep.2024.101641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Verbruggen N, Juraniec M, Baliardini C, Meyer CL. Tolerance to cadmium in plants: the special case of hyperaccumulators. Biometals. 2013;26(4):633–8. doi:10.1007/s10534-013-9659-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Liu HW, Wang HY, Ma YB, Wang HH, Shi Y. Role of transpiration and metabolism in translocation and accumulation of cadmium in tobacco plants (Nicotiana tabacum L.). Chemosphere. 2016;144(2):1960–5. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.10.093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Sari SHJ, Chien MF, Inoue C. Exploring Cd tolerance and detoxification strategies of Arabidopsis halleri ssp. gemmifera under high cadmium exposure. Int J Phytorem. 2025;29(7):1–7. doi:10.1080/15226514.2025.2456678. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Teng Y, Yu A, Tang YM, Jiang ZY, Guan WJ, Li ZS, et al. Visualization and quantification of cadmium accumulation, chelation and antioxidation during the process of vacuolar compartmentalization in the hyperaccumulator plant Solanum nigrum L. Plant Sci. 2021;310:110961. doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2021.110961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Hu Y, Tian SK, Foyer CH, Hou DD, Wang HX, Zhou WW, et al. Efficient phloem transport significantly remobilizes cadmium from old to young organs in a hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii. J Hazard Mater. 2019;365:421–9. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.11.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Shao JF, Che J, Yamaji N, Shen RF, Ma JF. Silicon reduces cadmium accumulation by suppressing expression of transporter genes involved in cadmium uptake and translocation in rice. J Exp Bot. 2017;68(20):5641–51. doi:10.1093/jxb/erx364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Zhang J, Wu S, Xu JL, Liang P, Wang MY, Naidu R, et al. Comparison of ashing and pyrolysis treatment on cadmium/zinc hyperaccumulator plant: effects on bioavailability and metal speciation in solid residues and risk assessment. Environ Pollut. 2020;272(5):116039. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116039. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Chao Y, Fu D. Kinetic study of the antiport mechanism of an Escherichia coli zinc transporter, ZitB. Biol Chem. 2004;279(13):12043–50. doi:10.1074/jbc.M313510200. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Plaza S, Tearall KL, Zhao FJ, Buchner P, McGrath SP, Hawkesford MJ. Expression and functional analysis of metal transporter genes in two contrasting ecotypes of the hyperaccumulator Thlaspi caerulescens. J Exp Bot. 2007;58(7):1717–28. doi:10.1093/jxb/erm025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Vert G, Barberon M, Zelazny E, Séguéla M, Briat JF, Curie C. Arabidopsis IRT2 cooperates with the high-affinity iron uptake system to maintain iron homeostasis in root epidermal cells. Planta. 2009;229(6):1171–9. doi:10.1007/s00425-009-0904-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Chang JD, Xie Y, Zhang HH, Zhang SR, Zhao FJ. The vacuolar transporter OsNRAMP2 mediates Fe remobilization during germination and affects Cd distribution to rice grain. Plant Soil. 2022;476(1–2):79–95. doi:10.1007/s11104-022-05323-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Yang W, Chen L, Ma YM, Hu R, Wang J, Li WH, et al. OsNRAMP2 facilitates Cd efflux from vacuoles and contributes to the difference in grain Cd accumulation between japonica and indica rice. Crop J. 2023;11(2):417–26. doi:10.1016/j.cj.2022.09.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Zhang LD, Song LY, Dai MJ, Liu JY, Li J, Xu CQ, et al. Inventory of cadmium-transporter genes in the root of mangrove plant Avicennia marina under cadmium stress. J Hazard Mater. 2023;459(3):132321. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2023.132321. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Chao DY, Silva A, Baxter I, Huang YS, Nordborg M, Danku J, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify heavy metal ATPase3 as the primary determinant of natural variation in leaf cadmium in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2012;8(9):e1002923. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002923. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Khanna K, Kohli SK, Ohri P, Bhardwaj R, Ahmad P. Agroecotoxicological aspect of Cd in soil-plant system: uptake, translocation and amelioration strategies. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2022;29(21):30908–34. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-18232-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Korenkov V, Hirschi K, Crutchfield JD, Wagner GJ. Enhancing tonoplast Cd/H antiport activity increases Cd, Zn, and Mn tolerance, and impacts root/shoot Cd partitioning in Nicotiana tabacum L. Planta. 2007;226(6):1379–87. doi:10.1007/s00425-007-0577-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Zhu TT, Li LY, Duan QX, Liu XL, Chen M. Progress in our understanding of plant responses to the stress of heavy metal cadmium. Plant Signaling Behav. 2021;16(1):1836884. doi:10.1080/15592324.2020.1836884. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Sakurai M, Tomioka R, Hokura A, Terada Y, Takenaka C. Distributions of cadmium, zinc, and polyphenols in Gamblea innovans. Int J Phytorem. 2019;21(3):217–23. doi:10.1080/15226514.2018.1524840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Kopittke PM, Punshon T, Paterson DJ, Tappero RV, Wang P, Blamey FPC, et al. Synchrotron-based X-ray fluorescence microscopy as a technique for imaging of elements in plants. Plant Physiol. 2018;178(2):507–23. doi:10.1104/pp.18.00759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Johnson CR, Hopf J, Shrout JD, Fein JB. Testing the component additivity approach to surface complexation modeling using a novel cadmium-specific fluorescent probe technique. J Colloid Interfac Sci. 2019;534:683–94. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2018.09.070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Pietrini F, Zacchini M, Iori V, Pietrosanti L, Ferretti M, Massacci A. Spatial distribution of cadmium in leaves and its impact on photosynthesis: examples of different strategies in willow and poplar clones. Plant Biol. 2010;12(2):355–63. doi:10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00258.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Xu K, Zheng LF, Chu KF, Xing CH, Shu JJ, Fang KM, et al. Soil application of graphitic carbon nitride nanosheets alleviate cadmium toxicity by altering subcellular distribution, chemical forms of cadmium and improving nitrogen availability in soybean (Glycine max L.). J Environ Manage. 2024;368:22204. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2024.122204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Jia HF, Yin ZR, Xuan DD, Lian WL, Han D, Zhu ZT, et al. Mutation of NtNRAMP3 improves cadmium tolerance and its accumulation in tobacco leaves by regulating the subcellular distribution of cadmium. J Hazard Mater. 2022;432(3):128701. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.128701. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

85. Bora MS, Gogoi N, Sarma KP. Tolerance mechanism of cadmium in Ceratopteris pteridoides: translocation and subcellular distribution. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;197:110599. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110599. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Wong CKE, Jarvis RS, Sherson SM, Cobbett CS. Functional analysis of the heavy metal binding domains of the Zn/Cd-transporting ATPase, HMA2, in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 2009;181(1):79–88. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02637.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Bora MS, Sarma KP. Anatomical and ultrastructural alterations in Ceratopteris pteridoides under cadmium stress: a mechanism of cadmium tolerance. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2021;218:112285. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Wang P, Deng XJ, Huang Y, Fang XL, Zhang J, Wan HB, et al. Comparison of subcellular distribution and chemical forms of cadmium among four soybean cultivars at young seedlings. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2015;22(24):19584–95. doi:10.1007/s11356-015-5126-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]