Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Survey of Barley Sodium Transporter HvHKT1;1 Variants and Their Functional Analysis

1 Institute of Plant Science and Resources, Okayama University, 2 Chome-20-1 Central, Kurashiki, 710-0046, Japan

2 Department of Agronomy, Khulna Agricultural University, Khulna, 9100, Bangladesh

* Corresponding Author: Maki Katsuhara. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Responses to Biological and Abiotic Stresses)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(11), 3653-3665. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073959

Received 29 September 2025; Accepted 03 November 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) employs the Na+ transporter HvHKT1;1, which is an N+-selective transporter. This study characterized the full-length HvHKT1;1 (HvHKT1;1-FL) and three mRNA variants (HvHKT1;1-V1, -V2, and -V3), which encode polypeptides of 64.7, 54.0, 40.5, and 32.9 kDa, respectively. Tissue-specific expression profiling revealed that HvHKT1;1-FL is the most abundant transcript across leaf, sheath, and root tissues under normal conditions, with the highest expression in leaves. Under 150 mM NaCl stress, HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants showed a dynamic, time-dependent expression pattern, with peak leaf expression at 2 h, sheath expression at 12 h, and root expression at 2 h, suggesting their roles in early stress response. Functional analysis using two-electrode voltage-clamp measurements demonstrated that HvHKT1;1-FL is highly selective for Na+, with minimal conductance for K+, Li+, Rb+, or Cs+. It demonstrated high Na+ transport efficiency, characterized by higher Vmax and lower Km values, while the variants showed reduced Na+ currents, lower Vmax, and higher Km values, indicating decreased Na+ transport capacity. Reversal potential analyses further confirmed Na+ selectivity, with HvHKT1;1-FL displaying the strongest preference for Na+. Notably, while all variants retained Na+ selectivity, they showed reduced efficiency, as indicated by a more negative reversal potential in low Na+ conditions. These findings highlight the functional diversity among HvHKT1;1 variants, with HvHKT1;1-FL playing a dominant role in Na+ transport. The tissue-specific regulation of these variants under salinity stress underscores their importance in barley’s adaptive responses.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileSalinity, a major environmental factor affecting crop productivity worldwide, especially in drylands, where irrigation practices often contribute to soil salinization [1]. High salinity disrupts plant physiological processes by inducing osmotic stress, ion toxicity, and nutrient imbalance, leading to reduced seed germination, stunted growth, and lower yields [2]. Excessive sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) affect essential metabolic functions, impairing photosynthesis and enzymatic activities [3]. Barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) is an important cereal crop cultivated widely, serving as a staple food, feed, and key ingredient in brewing. Despite its adaptability to diverse climates, barley growth and productivity are significantly limited by soil salinity, a common abiotic stress that adversely affects plant water uptake, nutrient balance, and overall physiological functions [1]. Sodium toxicity is a primary factor in salinity stress, leading to ionic imbalances that disrupt cellular homeostasis and metabolic processes [3].

High-affinity potassium transporters (HKTs) are a category of important membrane proteins essential for maintaining potassium (K+) homeostasis in plants, especially under conditions of low soil K+ availability or salinity stress. These transporters mainly help the absorption and distribution of K+ and Na+, which are crucial for various physiological processes, including osmotic regulation, enzyme activation, and maintaining membrane potential [4]. HKTs are divided into two subclasses on the basis of their ion selectivity: Subclass I members primarily transport Na+, while Subclass II members are more selective for K+ [5]. The foremost HKT gene, HKT1, was recognized in wheat, where it arbitrates high-affinity K+ uptake and low-affinity Na+ transport [6]. Further research indicates that HKTs are widely existing across plant species such as Arabidopsis, rice, and barley, with their expression often regulated by environmental factors like salt stress, K+ deficiency, and osmotic stress [7,8]. In rice, OsHKT1;1 controls Na+ exclusion from shoots, enhancing salt tolerance by preserving a favorable Na+/K+ ratio [9]. Similarly, in wheat, the homolog TaHKT1;5-D is associated with improved Na+ elimination from leaves, aiding salinity tolerance in Triticum durum [10]. In maize, ZmHKT1;1 influences Na+ uptake and translocation, with its overexpression resulting in increased salt sensitivity [11]. The barley HKT1 gene was further identified as corresponding to HKT1;1 through phylogenetic analysis and encoded a transporter that is selective for Na+ [12]. Knockdown of HvHKT1;1 using barley BSMV-induced gene silencing enhanced sensitivity to salt and Na+ buildup in leaves and roots of barley lines, compared to controls, highlighting this gene’s crucial role in barley’s salt tolerance [12].

In nearly all previous cases, researchers have focused only on the full-length protein to measure transport activity. However, Imran et al. [13] reported the presence of several functional mRNA variants in rice OsHKT1;1. What about barley HvHKT1;1? In this study, we aimed to identify HvHKT1;1 mRNA variants in a barley cultivar, Haruna-nijo, and characterized their expression profiles and transport activities using qPCR analyses and two-electrode voltage-clamp (TEVC) experiments with Xenopus laevis (X. laevis) oocytes.

2.1 Plant Material and Growth Condition

Barley (Hordeum vulgare L., cv. Haruna-nijo) seeds were treated and grown. Briefly, seeds were sterilized with 10% H2O2 (10 min), germinated in aerated distilled water (1 day), and hydroponically cultured in 0.25 mM CaSO4 (2 d) followed by nutrient solutions (4 mM KNO3, 1 mM NaH2PO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mg liter–1 Fe-citrate and pH 5.5 with NaOH). A five-day-old plant was used to extract total RNA. After that, 17-day-old seedlings were treated with 150 mM NaCl for the gene expression investigation. Plants were sampled at 0 (as a control), 2, 6, 12, and 24 h following the start of treatment.

2.2 Extraction of DNA, RNA, and Synthesis of cDNA

Barley gDNA was isolated as described in the DNeasy Plant Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Total RNA was isolated as described in the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and then treated with DNase I (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) to remove gDNA contamination. Reverse transcription was performed according to the ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan).

2.3 Secondary Structure Analysis

The secondary structure was determined using the online software Protter Ver. 1.0 (http://wlab.ethz.ch/protter/start/, accessed on 02 March 2025) [14].

After preparing the total RNA, DNase treatment was performed to remove any contaminating gDNA. First-strand cDNA synthesis was conducted using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystem by Thermo Fisher Scientific). Once the cDNA was prepared, amplified HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants with specific primers (Supplementary Table S1). HvEF1α mRNA amplification served as internal control. Absolute quantification was conducted as mentioned previously [13], using the real-time PCR machine (model: 7300, Applied Biosystem, Foster City, CA, USA). Specific cDNAs served as standards to quantify every variant.

2.5 Preparation of cRNA for X. laevis oocytes Heterologous Expression

The cDNAs of HvHKT1;1 were subcloned into the vector pXβG as described [13,15]. Capped RNAs (cRNAs) were synthesized as mentioned previously [13]. The cRNAs at concentrations of 50 ng/50 nL or 50 nL of nuclease-free water for the control were injected into X. laevis oocytes. The oocytes after injection were kept at 18°C in MBS solution until electrophysiological measurements were performed [13].

Measurement of oocytes current using the TEVC technique was conducted 1 d after injection of cRNA as mentioned previously [13]. Biological replicates were generated from oocytes derived from different frogs and batches, with results representative of two or more independent batches unless otherwise specified.

Across the tested concentrations, conductance was assessed at membrane potentials from −75 to −120 mV. Ion permeability ratios were estimated from reversal potential shifts using a modified Goldman equation [16] that excluded Cl− permeability and accounted solely for monovalent cations such as Na+, K+, Rb+, Cs+, and Li+. The modified Goldman equation at the experimental temperature (20°C) is:

where Erev is the reversal potential (mV); α is (Px, the permeability for the ion X+)/(PNa, the permeability for Na+); [X+]out is the extracellular concentration of X+; [Na+]out is the extracellular concentration of Na+. The intracellular concentrations of ions were expected to be constant within a few minutes of the measurements.

Two reversal potentials, Erev(1) and Erev(2), were measured using two different external solutions with the concentrations of X+ and Na+ as follows: External solution (1); [X+]out(1) and [Na+]out(1) for Erev(1) ; External solution (2); [X+]out(2) and [Na+]out(2) for Erev(2). According to Erev described above,

Based on the values of Erev(1), Erev(2), [X+]out(1), [Na+]out(1), [X+]out(2), and [Na+]out(2), the ion permeability ratios α (PX/PNa) were calculated.

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25. Data were subjected to a one-way ANOVA. When more than two treatments were compared, Tukey’s post hoc test was applied. For comparisons involving only two treatments, post hoc tests were not applicable, and significance was based on the ANOVA p-value. In R 4.4.3, “ggplot2” and “minpack.lm” packages were used to analyze ionic conductance.

3.1 Identification of HvHKT1;1 Variants

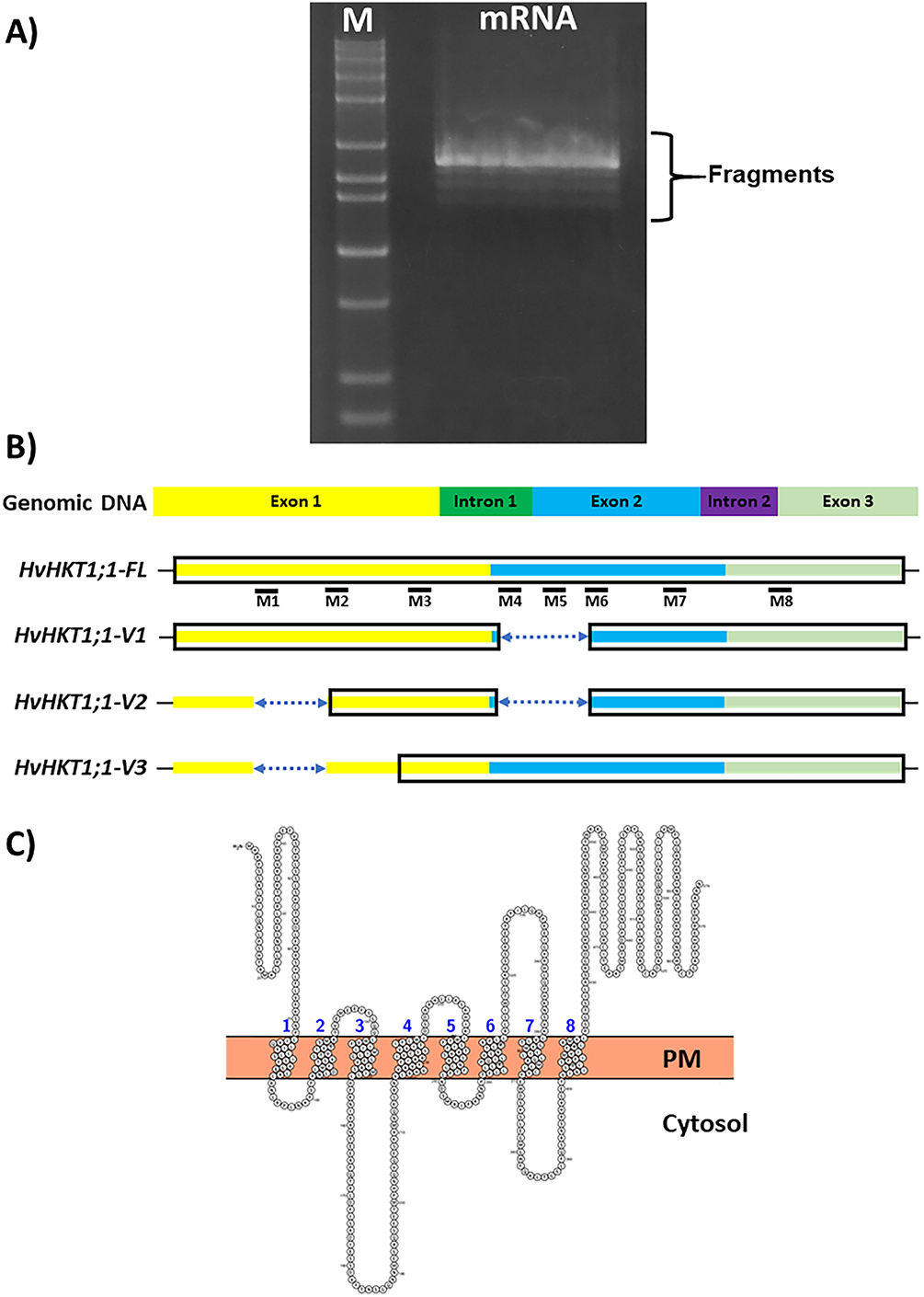

Amplified several fragments from cDNAs derived from the barley variety Haruna-nijo using full-length primers of HvHKT1;1 (Fig. 1A). This full-length HvHKT1;1 clone (HvHKT1;1-FL) encodes a 64.7 kDa polypeptide with 576 putative amino acids and consists of 1731 nucleotides (Figs. 1B and S1,S2). After sequencing, in addition to the full-length sequence, three splicing variants were identified. These variants, HvHKT1;1-V1, -V2, and -V3, have lengths of 1446, 1301, and 1586 nucleotides, respectively, and encode polypeptides of 54.0, 40.5, and 32.9 kDa, with 481, 362, and 294 deduced amino acids (Figs. 1B and S1,S2). Eight transmembrane domains (1–8) were projected using the online program Protter (http://wlab.ethz.ch/protter/start/), as shown in Fig. 1C.

Figure 1: HvHKT1;1 variants identified in barley cultivar Haruna-Nijo. (A) Gel picture of RT-PCR product that was amplified with primers for HvHKT1;1. (B) Diagrammatic representations of HvHKT1;1-FL and its splice variants. Black boxes designate amino acid regions identical to HvHKT1;1-FL; lines represent non-translated regions, and dotted lines show missing nucleotides (gaps) in comparison to the HvHKT1;1-FL sequence. (C) The transmembrane domain (M1M8) of HvHKT1;1-FL projected using Protter (http://wlab.ethz.ch/protter/start/, accessed on 02 November 2025) [14]

3.2 Expression Profiling of HvHKT1;1-FL and Its Variants

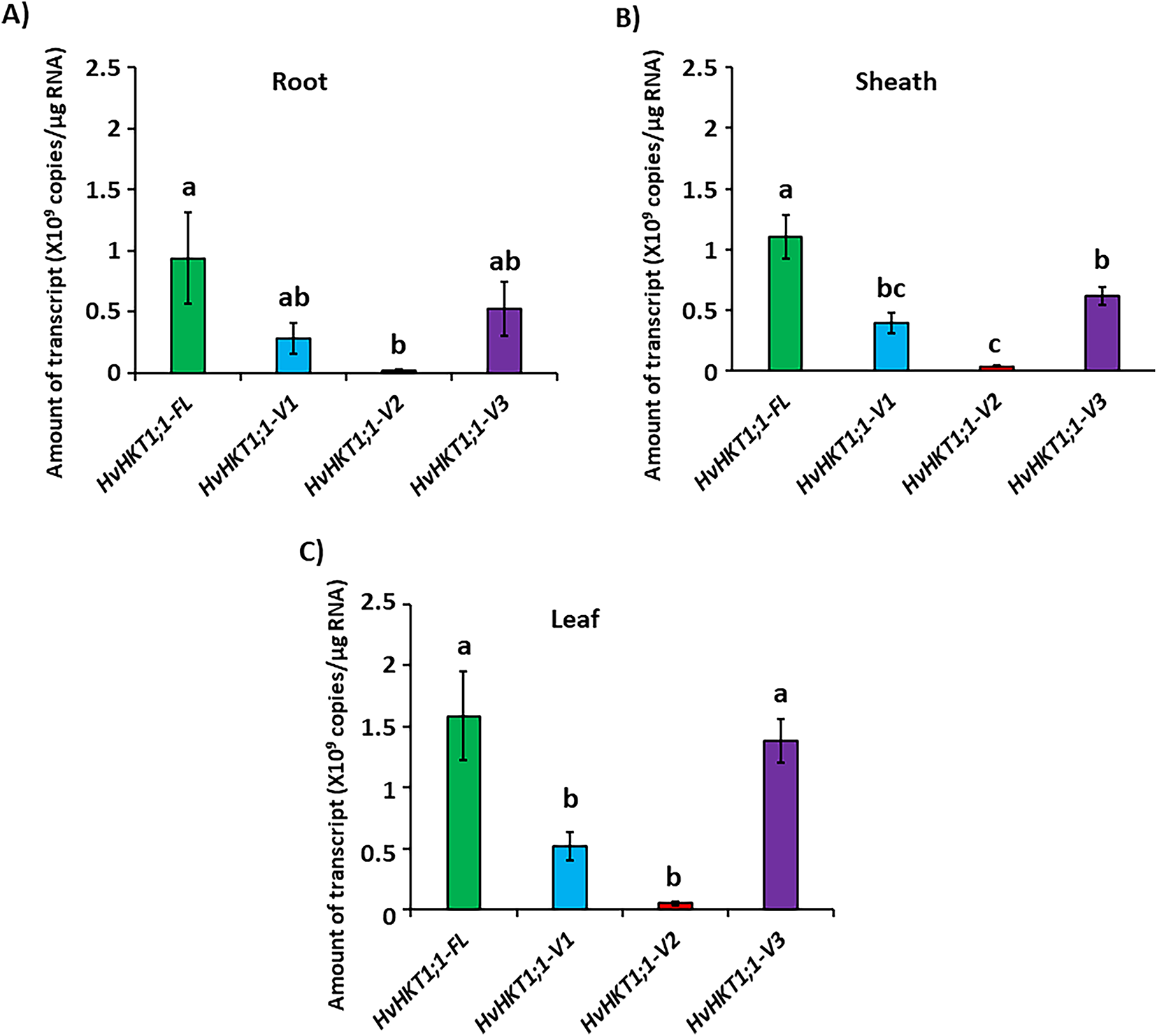

Barley plants at 17 days old were examined to evaluate the tissue-specific expression profile of HvHKT1;1 grown under normal conditions. The full-length HvHKT1;1-FL shows significantly highest expression in all tissues, especially in the leaf, followed by the sheath and root (Fig. 2A–C). However, HvHKT1;1-V1 shows moderate expression levels, mainly in the leaf and sheath, with minimal presence in the root, while HvHKT1;1-V2 exhibits relatively low expression across all tissues, with the lowest abundance among the variants (Fig. 2A–C). Interestingly, HvHKT1;1-V3 showed significantly high expression in the leaf, with a moderate level in the root and sheath, indicating its potential tissue preference distinct from the other variants (Fig. 2A–C).

Figure 2: qPCR analyses of HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants’ transcripts in the barley cultivar Haruna-Nijo grown under normal conditions. Expression of HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants in the roots (A), sheaths (B), and leaves (C) of 17-day-old plants was measured by absolute quantification. Data represent means of three samples ± SE (n = 3). Three separate experiments were conducted, yielding similar results. Different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05)

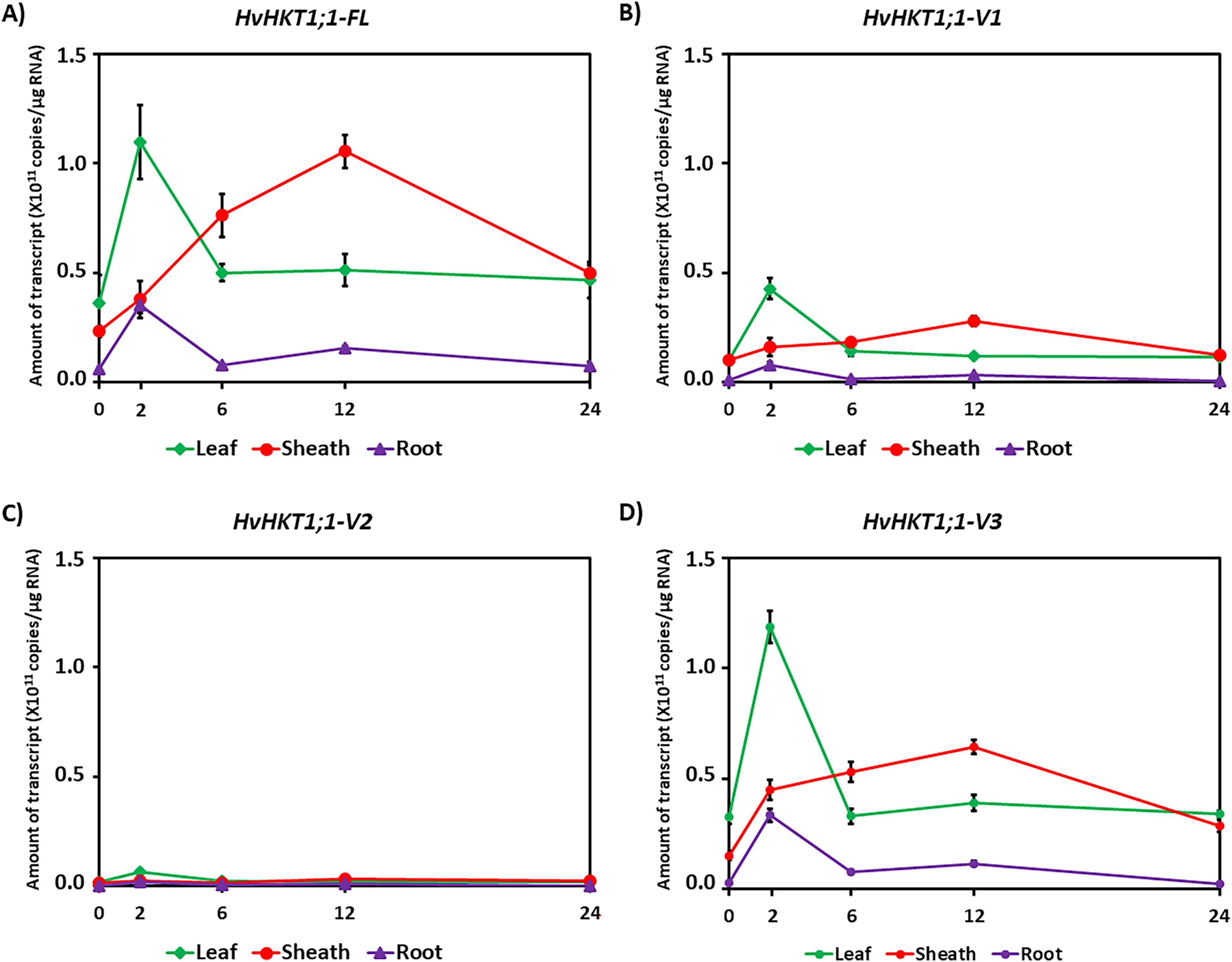

Next, we investigated the expression profiles of HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants in barley across different tissues—leaf, sheath, and root—under 150 mM salinity stress (Figs. 3 and S3). HvHKT1;1-FL reached peak expression at 2 h in the leaf, with maximum sheath expression at 12 h, while root expression peaked at 2 h and stayed low throughout the time course (Fig. 3A). However, HvHKT1;1-V1 also showed peak expression in the leaf at 2 h, and sheath at 12 h, although transcript levels were lower than FL, and root expression was minimal (Fig. 3B). In contrast, HvHKT1;1-V2 and HvHKT1;1-V3 exhibited a sharp peak in leaf expression at 2 h, followed by moderate sheath expression and minimal root expression (Fig. 3C,D). These findings suggest a coordinated, tissue-specific, and time-dependent regulation of HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants in response to salinity, with leaves and sheaths playing key roles in Na+ transport and homeostasis during early stress adaptation.

Figure 3: qPCR analysis of HvHKT1;1 transcripts in the barley cultivar Haruna-Nijo grown under saline conditions. Expression of HvHKT1;1-FL and every variant in root, sheath, and leaf was measured through absolute quantification. Seventeen-day-old Haruna-Nijo plants were grown with 150 mM NaCl solution for 0, 2, 6, 12, or 24 h before the extraction of total RNA. (A) HvHKT1;1-FL, (B) HvHKT1;1-V1, (C) HvHKT1;1-V2, and (D) HvHKT1;1-V3. Absolute transcript amounts (copies/μg RNA) are displayed. Data are means of three samples ± SE (n = 3). Three separate experiments were conducted, yielding similar results

3.3 Ion Transport Properties of HvHKT1;1-FL and Its Variants

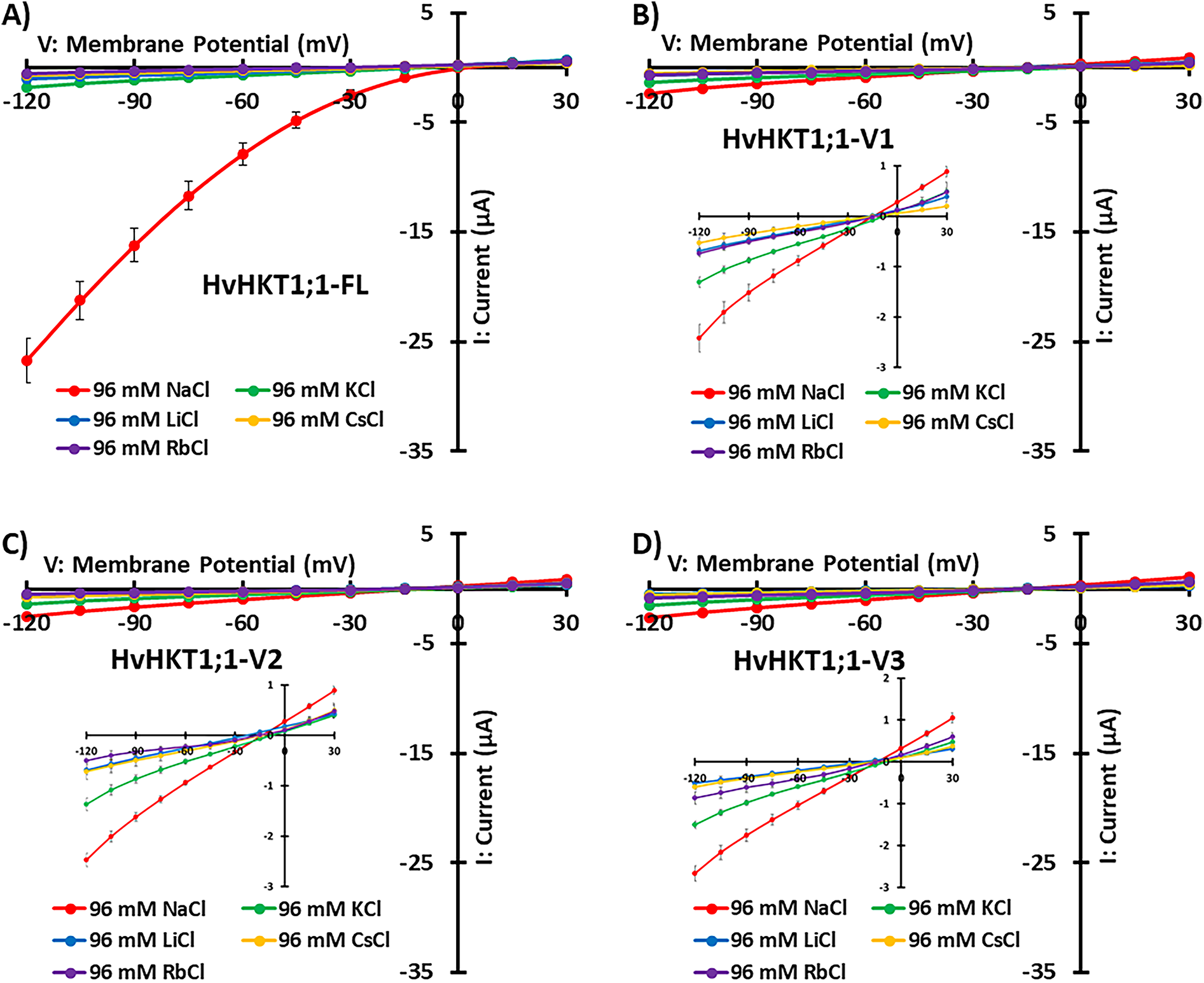

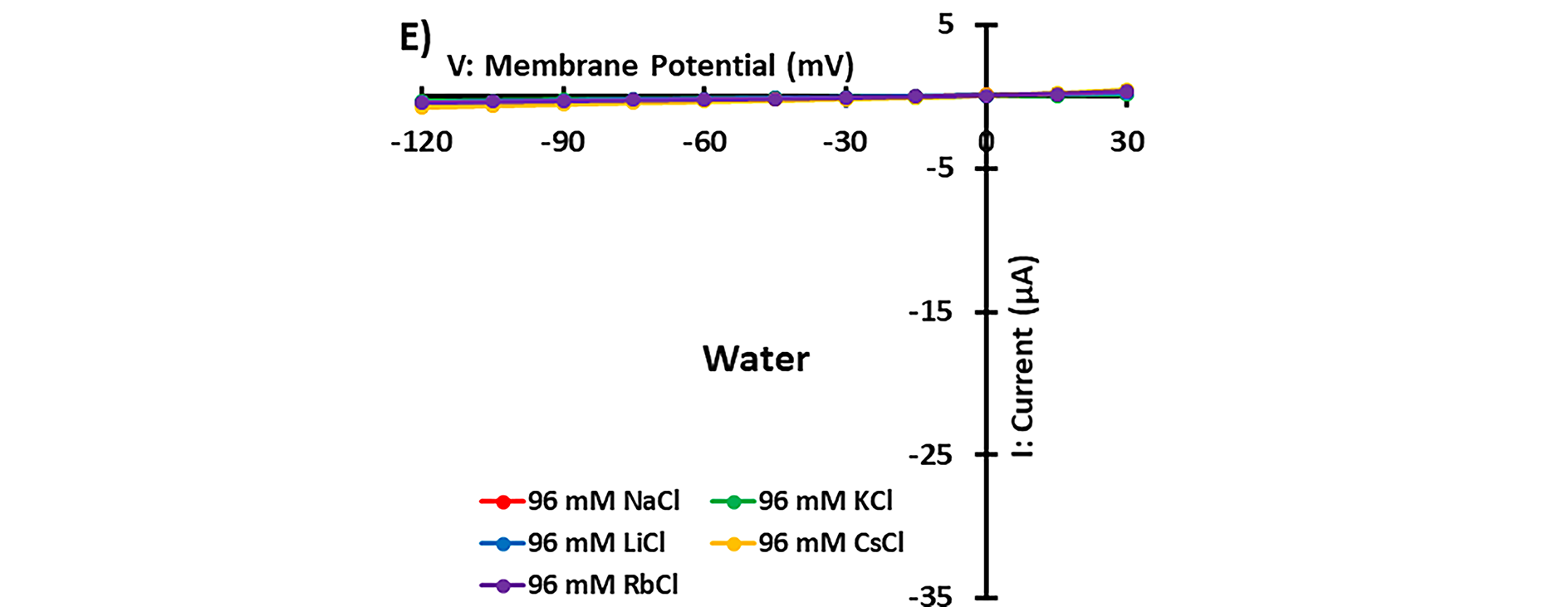

The figure presents TEVC measurements showing the ion transport properties of HvHKT1;1 and its splice variants from barley under different ionic conditions (96 mM NaCl, KCl, LiCl, CsCl, and RbCl) (Fig. 4). HvHKT1;1-FL (full-length) exhibited strong inward rectifying currents in a 96 mM Na+ bath solution while producing minimal currents akin to water-injected control oocytes in 96 mM K+, Li+, Rb+, and Cs+-containing bath solutions, indicating strong Na+ selectivity (Fig. 4A). In contrast, conductance analysis reveals a high Vmax (333 μS) and low Km (41 mM), indicating efficient Na+ transport with low affinity (Fig. S4A,B). On the other hand, HvHKT1;1-V1, -V2, and -V3 expression in oocytes showed reduced Na+ currents compared to the full-length, with minimal K+, Li+, Rb+, and Cs+ currents, demonstrating weaker transport capacity and decreased selectivity compared to HvHKT1;1-FL (Fig. 4B–D). Moreover, HvHKT1;1-V1, -V2, and -V3 showed progressively lower Vmax (46, 56, and 111 µS, respectively) and higher Km (89, 122, and 286 mM, respectively) values, suggesting reduced Na+ transport efficiency (Fig. S4C–H).

Figure 4: Monovalent alkaline cation selectivity of HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants. Current–voltage (I–V) curves from oocytes injected with 50 ng of HvHKT1;1-FL cRNA (A), HvHKT1;1-V1 cRNA (B), HvHKT1;1-V2 cRNA (C), HvHKT1;1-V3 cRNA (D), or 50 nL water (E) are present. External bath solutions comprised chloride salts of Na+, K+, Cs+, Rb+, or Li+ (each at 96 mM). The bath solution’s basic components included 1.8 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1.8 mM mannitol, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5 with Tris). Voltage steps ranged from −120 to +30 mV with 15 mV increments. Data are presented as mean ± SE (n = 5–14 for A–D and n = 5–10 for E). Insets display variants with low currents

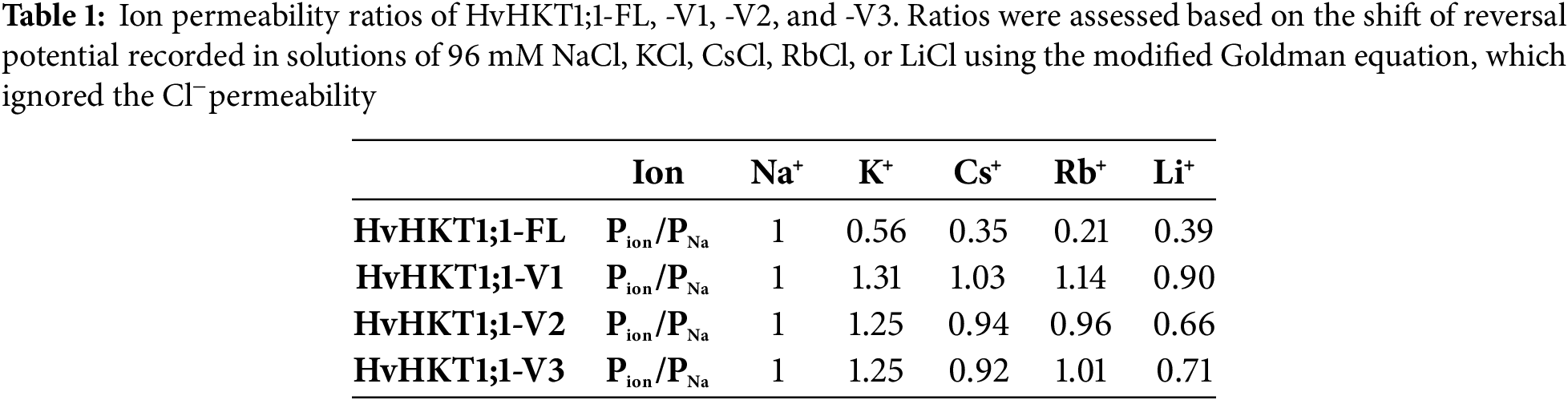

The reversal potential of HvHKT1;1-FL, -V1, -V2, and -V3-expressing oocytes in a 96 mM NaCl solution was approximately 4, −15, −14, and −14 mV, respectively (Fig. 4A–D). Their reversal potentials in a 96 mM KCl solution were −11, −8, −8, and −9 mV; in a 96 mM CsCl solution, −22, −14, −15, and −16 mV; in a 96 mM RbCl solution, −35, −12, −15, and −14 mV; and in a 96 mM LiCl solution, −20, −17, −24, and −23 mV, respectively (Fig. 4A–D). Based on these values, the ion permeability ratios of HvHKT1;1-FL, -V1, -V2, and -V3 were assessed using the modified Goldman equation as shown in Table 1. For HvHKT1;1-FL, the highest Pion/PNa ratio was obtained using Na+-derived data, while the lowest was for Rb+. Conversely, the Pion/PNa ratio is around 1 for all monovalent cations with a large variation in HvHKT1;1-V1, -V2, and -V3. The current in oocytes expressing these variants is also low. These results suggest that HvHKT1;1-V1, -V2, and -V3 have low selectivity for monovalent cations and exhibit weak transport activity (Table 1).

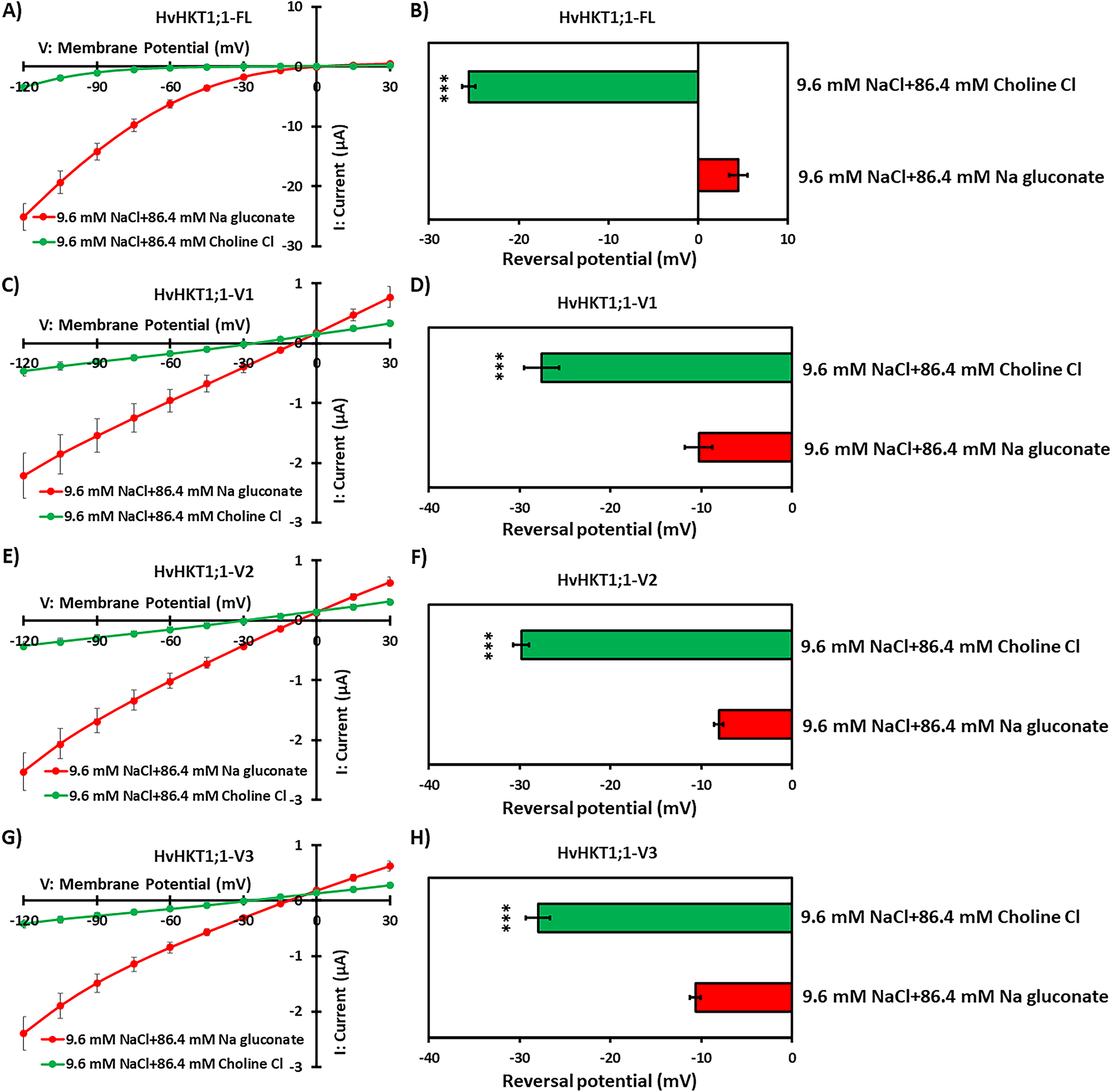

3.4 HvHKT1;1-FL and Its Variants Are Selective for Na+

To assess the affinity for Na+, the reversal potential shift of HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants (-V1, -V2, and -V3) was examined in response to decreasing extracellular Na+ concentration (Figs. 5 and S5). The current-voltage relationships indicated that HvHKT1;1-FL generated significantly larger currents in Na gluconate than in Choline-Cl, confirming HvHKT1;1-FL's strong preference for Na+ (Figs. 5A and S5A). Similarly, the variants (-V1, -V2, and -V3) also showed a preference for Na+ by producing larger currents in Na gluconate than in Choline-Cl (Figs. 5C,E,G and S5C,E,G). A decrease in extracellular Na+ concentration caused a more negative reversal potential, demonstrating that HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants efficiently transport Na+, while the more negative reversal potentials in Choline-Cl solutions indicated no permeability to Cl− (Figs. 5B,D,F,H and S5B,D,F,H). Collectively, these results confirm that HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants are Na+-selective transporters with similar ion selectivity profiles across different ionic conditions.

Figure 5: Na+ selectivity of HvHKT1;1-FL and its variants. Current–voltage (I–V) curves were recorded from oocytes injected with 50 ng of HvHKT1;1-FL cRNA (A), HvHKT1;1-V1 cRNA (C), HvHKT1;1-V2 cRNA (E), and HvHKT1;1-V3 cRNA (G). Reversal potential shifts were analyzed by changing the external Na+ concentration from 96 to 9.6 mM for HvHKT1;1-FL (B), HvHKT1;1-V1 (D), HvHKT1;1-V2 (F), and HvHKT1;1-V3 (H). External bath solutions contained 9.6 mM NaCl plus 86.4 mM Na gluconate or Choline-Cl. Basic elements in the bath solution included 1.8 mM MgCl2, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 1.8 mM mannitol, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5 with Tris). Voltage steps ranged from −120 to +30 mV with 15-mV increments. Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 6). Asterisks denote values significantly different from 9.6 mM NaCl + 86.4 mM Na gluconate as determined by one-way ANOVA (***p < 0.001). Post hoc tests were not applicable because only two groups were compared

The HKTs play a crucial role in salinity tolerance of plants by regulating the homeostasis of Na+ and K+, which is important for maintaining cellular functions in salty environments [4,8,17]. HKTs mainly facilitate Na+ and K+ selective transport across cell membranes, helping to reduce the toxic effects of excess Na+ in plant tissues [18]. Specifically, HKT1-type transporters, localized in the plasma membrane of root cells, help remove Na+ from the xylem sap, decreasing its movement to the shoots and protecting photosynthetic tissues from salt damage [4]. Additionally, HKTs contribute to osmotic adjustment and ion balance, which are essential for supporting growth and productivity during salt stress [17].

HKT subfamily 1 transporters play a key role in plant salinity tolerance by facilitating Na+ transport, preventing toxic ion buildup, and redistributing Na+ to vacuoles or less sensitive tissues [10]. A key function of these transporters is Na+ retrieval from the xylem, reducing its excessive accumulation in shoots and maintaining ionic balance [8]. AtHKT1;1, a passive Na+ transporter, is primarily expressed in xylem parenchyma, where it helps in Na+ unloading, thus enhancing salt tolerance [4,19]. Its presence in leaf phloem suggests an additional role in Na+ recirculation from shoots to roots [20]. In durum wheat, Na+ removal from leaves is a key function for salt stress adaptation, controlled by the loci Nax1 and Nax2, which encode Na+-selective transporters TmHKT1;4-A2 and TmHKT1;5 [10,21,22]. Similarly, OsHKT1;5 in rice regulates unloading Na+ from the xylem and phloem to protect young leaves under salt stress [9,23,24]. It has also reported that OsHKT1;1 is involved in Na+ exclusion from shoots and recirculation to roots [25,26]. In X. laevis oocytes, HvHKT1;1 exhibited Na+-selective transport, further confirming the specificity of HKT transporters in regulating Na+ homeostasis [12]. Previously, it has been reported that OsHKT1;1 produced several mRNA splicing variants [13]. However, only a few studies have reported on HvHKT1;1, and its detailed physiological functions and variants have not yet been studied. We assume that, like OsHKT1;1, other HKT1;1 may also produce variants. Based on this assumption, in this study, several variants of HvHKT1;1 (-V1, -V2, and -V3) were confirmed in addition to the HvHKT1;1 full-length (HvHKT1;1-FL) in a salt-tolerant barley cultivar, Haruna-nijo (Fig. 1).

In this study, HvHKT1;1-FL expressed in Xenopus oocytes exhibited higher inward rectifying currents in 96 mM Na+ (Fig. 4A), as previously mentioned [12], with little or no currents similar to the water-injected negative control in 96 mM K+, Li+, Cs+, or Rb+ solutions (Fig. 4A). Additionally, analysis of reversal potential, ion permeability ratio, and high Vmax, low Km values indicated efficient Na+ transport by HvHKT1;1-FL with low affinity (Table 1 and Fig. S4A,B). Moreover, reversal potential analysis confirmed the effective transport of Na+ by HvHKT1;1-FL, but not Cl− (Figs. 5A,B and S5A,B). In contrast, oocytes expressing HvHKT1;1-V1, -V2, and -V3 also showed notable Na+ currents, though with more moderate inward currents compared to HvHKT1;1-FL, and minimal transport of other ions (Fig. 4B–D). Additionally, the low Vmax and high Km values of these splice variants suggest reduced Na+ transport efficiency, implying alternative ion selectivity or decreased functionality relative to the full-length HvHKT1;1 (Fig. S4C–H). Furthermore, reversal potential analysis and ion permeability ratios indicated that HvHKT1;1 variants (-V1, -V2, -V3) functioned as Na+ channels (Table 1; Figs. 5C–H and S5C–H), but their selectivity was less than that of HvHKT1;1-FL.

It has been reported that AtHKT1;1 shows higher expression in roots than in shoots [27]. However, OsHKT1;1 is highly expressed after 12 h of salt stress treatment in shoots and shows no difference in expression in roots [25]. Additionally, Imran et al. [13] reported a gradual decline in OsHKT1;1 expression in shoots following salt stress exposure, with no clear pattern in roots. Moreover, Ali et al. [28] observed that EpHKT1;1 transcript upregulated more slowly in response to salt treatment. It has been demonstrated that CmHKT1;1 transcript level in roots exceeds that in the control, peaking at 6 h [29]. Moreover, LbHKT1;1 exhibited the greatest expression levels in both shoots and roots under salt stress conditions [30]. Similarly, in S. linearistipularis, exposure to NaCl increased the expression of SlHKT1.1 in both roots and shoots [31]. A previous study reported increased HvHKT1;1 expression in roots under salt stress conditions [12]. In this study, the HvHKT1;1-FL mRNA was the most abundant among the identified variants in roots, sheath, and leaves (Fig. 2). Furthermore, all variants, including the full-length, showed higher expression in the leaves of Haruna-nijo (Fig. 2). Under salt stress, HvHKT1;1-FL and HvHKT1;1-V3 display high transcript levels in leaves at 2 h and in sheaths at 12 h, with minimal root expression (Fig. 3A,D). HvHKT1;1-V1 follows a similar pattern but at lower levels (Fig. 3B). In contrast, HvHKT1;1-V2 shows the lowest expression across tissues (Fig. 3C). Though the variants are missing a partial or a full transmembrane domain, this missing domain does not affect the expression, as also reported in the case of OsHKT1;1 and OsHKT1;3 variants [13,15]. Overall, transcript levels are highest in sheaths over time, while root expression remains low across all variants, indicating tissue-specific and time-dependent regulation of HvHKT1;1 in barley. In conclusion, this study offers a comprehensive analysis of barley HvHKT1;1 and its splice variants, revealing distinct expression patterns and Na+ transport properties. HvHKT1;1-FL exhibits the highest expression and transport efficiency, whereas the variants display reduced Na+ transport, implying regulatory roles in sodium homeostasis. Expression profiling under salinity stress highlights tissue-specific and time-dependent regulation. Comparative studies among cereals reveal both conserved and divergent features of HKT1 transporters. In rice, OsHKT1;1 and OsHKT1;3 produce multiple splice variants that are stress-responsive and may fine-tune Na+ transport under salinity [13,15,25]. Some OsHKT1;1 variants are upregulated during early salt exposure and show reduced ion conductance, suggesting a potential role in Na+ uptake temporally rather than being non-functional by-products. Similarly, wheat transporters such as TaHKT1;5-D and TmHKT1;4-A2 are single full-length isoforms, but their alleles lead to differences in Na+ exclusion capabilities and salt tolerance levels [10,21,22]. In contrast, the barley HvHKT1;1 variants identified here appear to share Na+ selectivity with OsHKT1;1 variants but display distinct expression timing and tissue specificity, implying a species-specific regulatory mechanism. Their induction at early time points under salinity (especially in leaves) suggests possible adaptive modulation rather than transcriptional noise. However, functional attenuation (lower Vmax, higher Km) may also reflect partial loss of transport capacity, consistent with non-essential or regulatory variant roles. Therefore, the barley HvHKT1;1 variants may represent a combination of adaptive and functionally reduced forms, a pattern that aligns with OsHKT1;1’s stress-induced splicing diversity but diverges from the more stable single-gene expression observed in wheat HKT1;5. These findings enhance our understanding of Na+ transport in barley and offer insights for enhancing salinity tolerance in crops. Although our electrophysiological and expression data clarify variant-specific transport functions, we did not evaluate their effects on whole-plant Na+/K+ homeostasis or growth under salinity. However, previous studies have shown that HvHKT1;1 regulates tissue-level Na+ distribution and contributes to salt tolerance in barley [12]. But the previous report didn’t consider HvHKT1;1 variants, which were characterized in the present study, may differentially affect plant performance under saline conditions. Future research should investigate the physiological roles of these variants and their potential applications in crop breeding and genetic engineering to enhance stress resilience.

Acknowledgement: We thank Yoshiyuki Tsuchiya for his technical and experimental assistance.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP20K06708 to Maki Katsuhara, and an OU fellowship to Shahin Imran.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Shahin Imran and Maki Katsuhara; methodology, Maki Katsuhara; validation, Shahin Imran and Maki Katsuhara; formal analysis, Shahin Imran; investigation, Shahin Imran; writing—original draft preparation, Shahin Imran; writing—review and editing, Maki Katsuhara; visualization, Shahin Imran; supervision, Maki Katsuhara; project administration, Maki Katsuhara; funding acquisition, Maki Katsuhara. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data may be available after requesting to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.073959/s1.

References

1. Tarolli P, Luo J, Park E, Barcaccia G, Masin R. Soil salinization in agriculture: mitigation and adaptation strategies combining nature-based solutions and bioengineering. iScience. 2024;27(2):108830. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2024.108830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Pandit K, Chandni, Kaur S, Kumar M, Bhardwaj R, Kaur S. Salinity stress: impact on plant growth. Adv Food Secur Sustain. 2024;9(1):145–60. doi:10.1016/bs.af2s.2024.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhou H, Shi H, Yang Y, Feng X, Chen X, Xiao F, et al. Insights into plant salt stress signaling and tolerance. J Genet Genomics. 2024;51(1):16–34. doi:10.1016/j.jgg.2023.08.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Horie T, Hauser F, Schroeder JI. HKT transporter-mediated salinity resistance mechanisms in Arabidopsis and monocot crop plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2009;14(12):660–8. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2009.08.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Platten JD, Cotsaftis O, Berthomieu P, Bohnert H, Davenport RJ, Fairbairn DJ, et al. Nomenclature for HKT transporters, key determinants of plant salinity tolerance. Trends Plant Sci. 2006;11(8):372–4. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2006.06.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Schachtman DP, Schroeder JI. Structure and transport mechanism of a high-affinity potassium uptake transporter from higher plants. Nature. 1994;370(6491):655–8. doi:10.1038/370655a0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Garciadeblás B, Senn ME, Bañuelos MA, Rodríguez-Navarro A. Sodium transport and HKT transporters: the rice model. Plant J. 2003;34(6):788–801. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01764.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Hauser F, Horie T. A conserved primary salt tolerance mechanism mediated by HKT transporters: a mechanism for sodium exclusion and maintenance of high K+/Na+ ratio in leaves during salinity stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2010;33(4):552–65. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.02056.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ren ZH, Gao JP, Li LG, Cai XL, Huang W, Chao DY, et al. A rice quantitative trait locus for salt tolerance encodes a sodium transporter. Nat Genet. 2005;37(10):1141–6. doi:10.1038/ng1643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Munns R, James RA, Xu B, Athman A, Conn SJ, Jordans C, et al. Wheat grain yield on saline soils is improved by an ancestral Na+ transporter gene. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(4):360–4. doi:10.1038/nbt.2120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang M, Liang X, Wang L, Cao Y, Song W, Shi J, et al. A HAK family Na+ transporter confers natural variation of salt tolerance in maize. Nat Plants. 2019;5(12):1297–308. doi:10.1038/s41477-019-0565-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Han Y, Yin S, Huang L, Wu X, Zeng J, Liu X, et al. A sodium transporter HvHKT1;1 confers salt tolerance in barley via regulating tissue and cell ion homeostasis. Plant Cell Physiol. 2018;59(10):1976–89. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcy116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Imran S, Horie T, Katsuhara M. Expression and ion transport activity of rice OsHKT1;1 variants. Plants. 2020;9(1):16. doi:10.3390/plants9010016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wang Y, Kamau S, Song S, Zhang Y, Zhang X. Identification of high-affinity nicotinic acid transporter genes from Verticillium dahliae and functional analysis based on HIGS technology. J Cotton Res. 2025;8(1):20. doi:10.1186/s42397-025-00215-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Imran S, Tsuchiya Y, Tran STH, Katsuhara M. Identification and characterization of rice OsHKT1;3 variants. Plants. 2021;10(10):2006. doi:10.3390/plants10102006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Tran STH, Katsuhara M, Mito Y, Onishi A, Higa A, Ono S, et al. OsPIP2;4 aquaporin water channel primarily expressed in roots of rice mediates both water and nonselective Na+ and K+ conductance. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):12857. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-96259-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Almeida P, Katschnig D, de Boer AH. HKT transporters—state of the art. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14(10):20359–85. doi:10.3390/ijms141020359. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Riedelsberger J, Miller JK, Valdebenito-Maturana B, Piñeros MA, González W, Dreyer I. Plant HKT channels: an updated view on structure, function and gene regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(4):1892. doi:10.3390/ijms22041892. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Sunarpi, Horie T, Motoda J, Kubo M, Yang H, Yoda K, et al. Enhanced salt tolerance mediated by AtHKT1 transporter-induced Na unloading from xylem vessels to xylem parenchyma cells. Plant J. 2005;44(6):928–38. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02595.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Berthomieu P, Conéjéro G, Nublat A, Brackenbury WJ, Lambert C, Savio C, et al. Functional analysis of AtHKT1 in Arabidopsis shows that Na+ recirculation by the phloem is crucial for salt tolerance. EMBO J. 2003;22(9):2004–14. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Byrt CS, Xu B, Krishnan M, Lightfoot DJ, Athman A, Jacobs AK, et al. The Na+ transporter, TaHKT1;5-D, limits shoot Na+ accumulation in bread wheat. Plant J. 2014;80(3):516–26. doi:10.1111/tpj.12651. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Tounsi S, Ben Amar S, Masmoudi K, Sentenac H, Brini F, Véry AA. Characterization of two HKT1;4 transporters from Triticum monococcum to elucidate the determinants of the wheat salt tolerance Nax1 QTL. Plant Cell Physiol. 2016;57(10):2047–57. doi:10.1093/pcp/pcw123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Jabnoune M, Espeout S, Mieulet D, Fizames C, Verdeil JL, Conéjéro G, et al. Diversity in expression patterns and functional properties in the rice HKT transporter family. Plant Physiol. 2009;150(4):1955–71. doi:10.1104/pp.109.138008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Kobayashi NI, Yamaji N, Yamamoto H, Okubo K, Ueno H, Costa A, et al. OsHKT1;5 mediates Na+ exclusion in the vasculature to protect leaf blades and reproductive tissues from salt toxicity in rice. Plant J. 2017;91(4):657–70. doi:10.1111/tpj.13595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Wang R, Jing W, Xiao L, Jin Y, Shen L, Zhang W. The rice high-affinity potassium Transporter1;1 is involved in salt tolerance and regulated by an MYB-type transcription factor. Plant Physiol. 2015;168(3):1076–90. doi:10.1104/pp.15.00298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Campbell MT, Bandillo N, Al Shiblawi FRA, Sharma S, Liu K, Du Q, et al. Allelic variants of OsHKT1;1 underlie the divergence between indica and Japonica subspecies of rice (Oryza sativa) for root sodium content. PLoS Genet. 2017;13(6):e1006823. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Uozumi N, Kim EJ, Rubio F, Yamaguchi T, Muto S, Tsuboi A, et al. The Arabidopsis HKT1 gene homolog mediates inward Na+ currents in Xenopus laevis oocytes and Na+ uptake in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Plant Physiol. 2000;122(4):1249–59. doi:10.1104/pp.122.4.1249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ali A, Khan IU, Jan M, Khan HA, Hussain S, Nisar M, et al. The high-affinity potassium transporter EpHKT1;2 from the extremophile Eutrema parvula mediates salt tolerance. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:1108. doi:10.3389/fpls.2018.01108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Sun J, Cao H, Cheng J, He X, Sohail H, Niu M, et al. Pumpkin CmHKT1;1 controls shoot Na+ accumulation via limiting Na+ transport from rootstock to scion in grafted cucumber. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(9):2648. doi:10.3390/ijms19092648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Zhu Z, Liu X, Meng F, Jiang A, Zhou Y, Yuan F, et al. LbHKT1;1 negatively regulates salt tolerance of Limonium bicolor by decreasing salt secretion rate of salt glands. Plant Cell Environ. 2025;48(5):3544–58. doi:10.1111/pce.15375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Fu S, Chen X, Jiang Y, Dai S, Zhang H, Feng S, et al. Characterization of the Na+-preferential transporter HKT1.1 from halophyte shrub Salix linearistipularis. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2025;31(5):823–33. doi:10.1007/s12298-025-01605-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools