Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Identifying the Causative Pathogen of Rosa roxburghii Tratt. Fruit Rot and Laboratory Screening for Control Agents

1 Guizhou Institute of Mountain Resources, Guiyang, 550001, China

2 Pubei County Bureau of Industry and Information Technology, Qinzhou, 535300, China

* Corresponding Author: Wenwen Su. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plant Protection and Pest Management)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 4079-4090. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.072856

Received 05 September 2025; Accepted 25 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

To identify the pathogen responsible for fruit rot disease in Rosa roxburghii Tratt. from Guiding County, Guizhou Province, China, diseased fruit samples were collected. The pathogen was isolated, purified, and identified through morphological, molecular, and pathogenic analyses. Subsequently, its biological characteristics were evaluated. Furthermore, to determine the agent with the strongest toxicity against the identified pathogen, the antifungal activity of six chemical and biological agents was evaluated through indoor toxicity assays. Finally, Neopestalotiopsis clavispora was identified as the pathogen responsible for fruit rot disease in R. roxburghii Tratt. The diameter of the pathogen grown under different carbon and nitrogen sources, temperatures, and pH values was measured using the crossintersection method. The optimal carbon and nitrogen sources were soluble starch and peptone, respectively. The optimal growth temperature ranged from 25°C to 30°C, and the optimal growth pH ranged from 4 to 8. The antifungal effects of six agents, including carvacrol 5% aqueous solution and trifloxystrobin–tebuconazole 75% water-dispersible granules, on the mycelial growth rate of N. clavispora were evaluated. All six agents inhibited N. clavispora, with thiophanate–methyl 70% wettable powder showing the strongest antifungal effect and effectively inhibiting mycelial growth even at the lowest concentration. This was followed by difenoconazole–azoxystrobin 48% suspension concentrate, ethylicin 80% emulsifiable concentrate, and trifloxystrobin–tebuconazole 75% WG, with half-maximal effective concentrations of 0.0105, 0.0272, and 0.0368 mg/L, respectively. These findings provide a scientific basis for the application of pesticides in the field-based, environmentally friendly control of fruit rot disease in R. roxburghii Tratt.Keywords

Rosa roxburghii Tratt., a perennial deciduous shrub of the Rosaceae family, is widely distributed across Guizhou, Yunnan, Sichuan, and other regions in China [1,2]. In Guizhou, the cultivation area of R. roxburghii Tratt. is approximately 133,333 ha, making it the largest production region in China. The fruits of R. roxburghii Tratt. have a unique flavour and are rich in vitamin C, vitamin P, and bioactive compounds [3,4,5,6,7,8], including superoxide dismutase, organic acids, amino acids, and various beneficial trace elements essential for human health. Furthermore, its fruits exhibit antioxidant and anti-ageing effects that help prevent hypertension and reduce blood sugar and lipid levels [9,10]. In the food industry, R. roxburghii Tratt. has been increasingly used in the production of beverages, desserts, yogurt, and beer. As a plant with medicinal and nutritional properties as well as other distinctive characteristics, R. roxburghii Tratt. has a broad application potential [11,12,13]. Guiding County is one of the major production and processing regions of R. roxburghii Tratt. in Guizhou. However, in recent years, because of the expansion of planting areas and factors such as unscientific management and irrational pesticide use, diseases affecting R. roxburghii Tratt. have become increasingly prevalent.

The main diseases affecting R. roxburghii Tratt. include powdery mildew, stem rot, viral diseases, black spot disease, brown spot disease and sooty mould disease [14,15]. Most studies on R. roxburghii Tratt. diseases have primarily investigated the incidence patterns; prevention and control of powdery mildew [16]; as well as the identification, prevention and control of the causative pathogens of top rot [17]. Other diseases have been mentioned only in investigational reports, with no further in-depth research conducted. In this study, we conducted a disease survey in 30 prickly-ash orchards across Guiding County from 2024 to 2025. The average incidence of prickly-ash fruit rot exceeded 20%, substantially affecting local fresh fruit production and quality. Therefore, this study identified the specific causative pathogen and effective, environmentally friendly control agents. Pathogen isolation and identification were performed using samples collected from diseased fruits, followed by pathogenicity testing and screening of suitable control agents in the laboratory. The findings of this study provide a scientific basis for the prevention and control of fruit rot disease in R. roxburghii Tratt.

The pathogen was isolated and purified from diseased R. roxburghii Tratt. [18]. Thirty diseased fruits collected from the field were selected for tissue separation, and small pieces of diseased tissue (3 mm × 3 mm) were excised from the junction of diseased and healthy areas of the fruits. First, these tissue samples were immersed in 75% alcohol solution for 45–60 s for disinfection. The samples were rinsed three times with sterile water, with each rinse lasting 30–45 s. Next, the samples were transferred onto sterilised filter paper to absorb excess water and air-dried. Subsequently, the tissue samples were inoculated onto PDA medium in Petri dishes in a triangular arrangement. The dishes were then incubated in a constant temperature incubator at 28°C for 3–5 days. For purification, a small portion of newly grown mycelium was collected from the edge of the pathogenic colonies. This purification step was repeated 2–3 times until a pure culture was successfully obtained. Pure cultures were stored briefly at 4°C until use.

2.2 Morphological Identification of Pathogen

Purified pathogenic fungi were inoculated onto fresh culture media and cultured at 28°C. After 7 days of inoculation, the characteristics of the pathogenic fungi colonies as well as the morphological characteristics and colour of the mycelia were recorded. Subsequently, a small portion of mycelium was placed on a glass slide and covered with distilled water. The characteristics of the mycelium and conidia were observed under a high-quality interference microscope. Pathogenic fungal species were preliminarily identified using traditional fungal classification methods.

2.3 Molecular Identification of Pathogen

The genomic DNA of the purified pathogenic fungi was extracted using a fungal genomic DNA extraction kit (Wuxi Bio TeKe Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Wuxi, China), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Gene fragments were amplified using the universal fungal primers ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′) as well as EF1-728F (5′-CATCGAGAAGTTCGAGAAGG-3′) and EF1-986R (5′-TACTTGAAGGAACCCTTACC-3′). The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification system used a total sample volume of 25 μL containing 1 μL each of the forward and reverse primers, 1 μL DNA extract, 12.5 μL of 2× PCR Master Mix and 9.5 μL ddH2O. The PCR cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 58°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 80 s. A final extension was performed at 72°C for 10 min, after which the products were maintained at 4°C. The PCR products were analysed by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Subsequently, the PCR products were sent to Sangon Biotech (Shanghai Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) for sequencing. The obtained sequences were subjected to a homology search in the National Center for Biotechnology Information database, and sequences with high similarity were retrieved. Using Fusarium sp. KU556588.1 as the out-group, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbour-joining method with 1000 bootstrap replicates using MEGA 11.0 software. The taxonomic position of the strain was ultimately determined by integrating these results with morphological identification.

The pathogenicity of the isolated strains was evaluated according to Koch’s postulates. Healthy fruits were first surface-disinfected with 75% ethanol, rinsed thoroughly with sterile water and air-dried naturally on a laminar-flow workbench.

Wound inoculation: A wound inoculation assay was performed to assess pathogenicity. Two incisions were made at the centre of each fruit using a sterile scalpel. A PDA plug of approximately 5 mm containing an actively growing fungal strain was placed into each wound. Wound-free inoculation: A 5-mm diameter fungal plug was placed on a healthy R. roxburghii Tratt. without any wounds. The control was inoculated with a sterile PDA plug. Three fruits were inoculated for each treatment group, and the entire experiment was replicated three times. The fruits for the different treatment groups were placed in storage boxes. Sterile water was added to the bottom of each box, and a layer of sterile filter paper was placed on top. Then, the boxes were covered and incubated at 28°C with 85% relative humidity under a 12-h light/dark cycle. The fruits were visually monitored regularly, and digital photographs were taken to document the development of symptoms. The size of the disease lesions was carefully measured and recorded. After the disease symptoms appeared on the fruits, the same isolation protocol as described earlier was used to re-isolate and purify the pathogens from the diseased tissues. The morphological and cultural characteristics of the re-isolated strains were compared with those of the originally inoculated pathogens to confirm their identity.

2.5 Determination of Control Agent Toxicity

Mycelial growth rate was measured to evaluate the inhibitory effects of six chemical pesticides on the pathogen causing R. roxburghii Tratt. fruit rot. All pesticides were diluted in a concentration gradient according to their optimal spraying concentrations to prepare pesticide-incorporated culture media with varying concentrations. Five concentration gradients were established for each pesticide (Table 1). Each gradient was replicated three times. Mycelial discs, 5 mm in diameter, were obtained with a punch and placed onto the medicated Petri dishes. PDA medium without pesticide was used as the control. The inoculated culture media were incubated at 25°C. After 7 days of incubation, the colony diameters were measured using the crossintersection method. The inhibitory effects of each pesticide on pathogen mycelial growth were calculated accordingly. Bactericidal rate (%) = (Cultivation diameter of control group − Cultivation diameter of treated group)/(Cultivation diameter of control group − Cake diameter) × 100. Significance tests for differences among treatments were conducted using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Relevant statistical analyses were performed using DPS7.05 software, with the logarithm of drug concentration plotted on the abscissa and the inhibition rate converted to a probability value on ordinate. The correlation coefficient (r) and the toxicity regression equation were calculated to determine the inhibitory concentrations of the various test agents on the pathogenic fungi.

Table 1: Concentration gradients for the control agents analysed.

| Experimental Pesticide | Concentration Gradient (mg/L) |

|---|---|

| Carvacrol 5% AS | 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 |

| Tetramycin 0.3% AS | 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8 and 1.6 |

| Ethylicin 80% EC | 0.01, 0.02, 0.04, 0.08, 0.16 and 0.32 |

| Difenoconazole–azoxystrobin 48% SC | 0.0125, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.20 |

| Trifloxystrobin–tebuconazole 75% WG | 0.015, 0.045, 0.135, 0.405 and 1.215 |

| Thiophanate–methyl 70% WP | 0.0125, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1 and 0.20 |

2.6 Biological Characteristics of the Pathogen

2.6.1 Effect of Different Carbon and Nitrogen Sources on the Pathogen

Using Czapek’s medium as the basal medium, an equivalent amount (3.0 g) of glucose, D-sorbitol, D-galactose or soluble starch was individually used to replace the sucrose in the medium. Similarly, an equivalent amount (2.0 g) of ammonium chloride, glycine, urea and peptone were respectively used to replace NaNO3 in the medium. Thus, media with different carbon and nitrogen sources were prepared. After inoculation, the media were incubated at 25°C in a constant temperature incubator under dark conditions with 40% relative humidity. Each medium type was prepared in triplicate. Pathogen growth was observed and recorded after 7 days.

2.6.2 Effect of pH on the Pathogen

The pH of the prepared PDA medium was adjusted to 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, 5.0, 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, 10.0 and 11.0 using 1 mol/mL HCl and NaOH. Then, Petri dishes were filled with the PDA media at different pH values and inoculated with the pathogen. The dishes were incubated at 25°C in a constant temperature incubator under dark conditions with 40% relative humidity. Each pH treatment was replicated three times. After 7 days, pathogen growth was observed and recorded.

2.6.3 Effect of Temperature on the Pathogen

The pathogen-inoculated media were incubated at 5°C, 10°C, 15°C, 20°C, 25°C, 30°C and 35°C under dark conditions. Each temperature treatment was replicated three times. After 7 days, pathogen growth was observed and recorded.

3.1 Symptoms of R. roxburghii Tratt. Fruit Rot

Field investigations and observations of diseased fruits revealed that R. roxburghii Tratt. fruit rot predominantly occurs during the maturation stage, causing substantial damage. Symptoms were primarily observed in the central section of the fruits. At the early stage of the disease, red spots appear on the fruit surface. As the disease progressed to the middle and late stages, the affected areas developed into reddish-brown depressions, with the lesion margins exhibiting ulcer-like characteristics (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Symptoms of fruit rot disease in Rosa roxburghii Tratt.

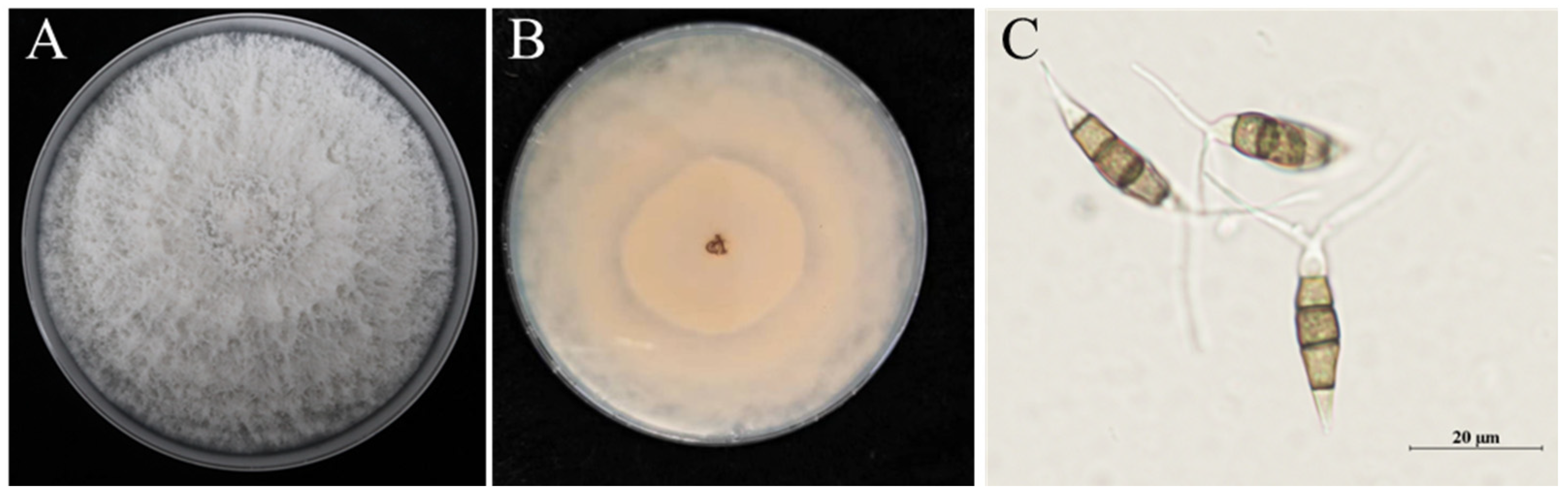

3.2 Isolation and Morphological Observation of the Pathogen

Following the identification of pathogens, the strains were isolated, purified and cultured on PDA medium at 25°C for 7 days. The pathogen colonies exhibited white, flocculent concentric rings. The aerial mycelium was dense, and the reverse side of the culture medium exhibited a pale beige colour (Fig. 2B). The conidia were solitary, yellow–brown and fusiform. The conidia contained four septa, dividing each into five cells. Most apical and basal cells were transparent, whereas the three central cells were darker, predominantly yellow–brown. Two colourless and transparent appendages were present at the apex of each conidium, and a short appendage was present at the base (Fig. 2C). Based on these morphological characteristics, the pathogen was preliminarily identified as a fungus of the genus Neopestalotiopsis.

Figure 2: Morphological identification of the causative pathogen of Rosa roxburghii Tratt. fruit rot. (A), Top view of Petri dish containing the pathogen colony cultured on potato dextrose agar medium; (B), Bottom view of the Petri dish culture; (C), Conidia.

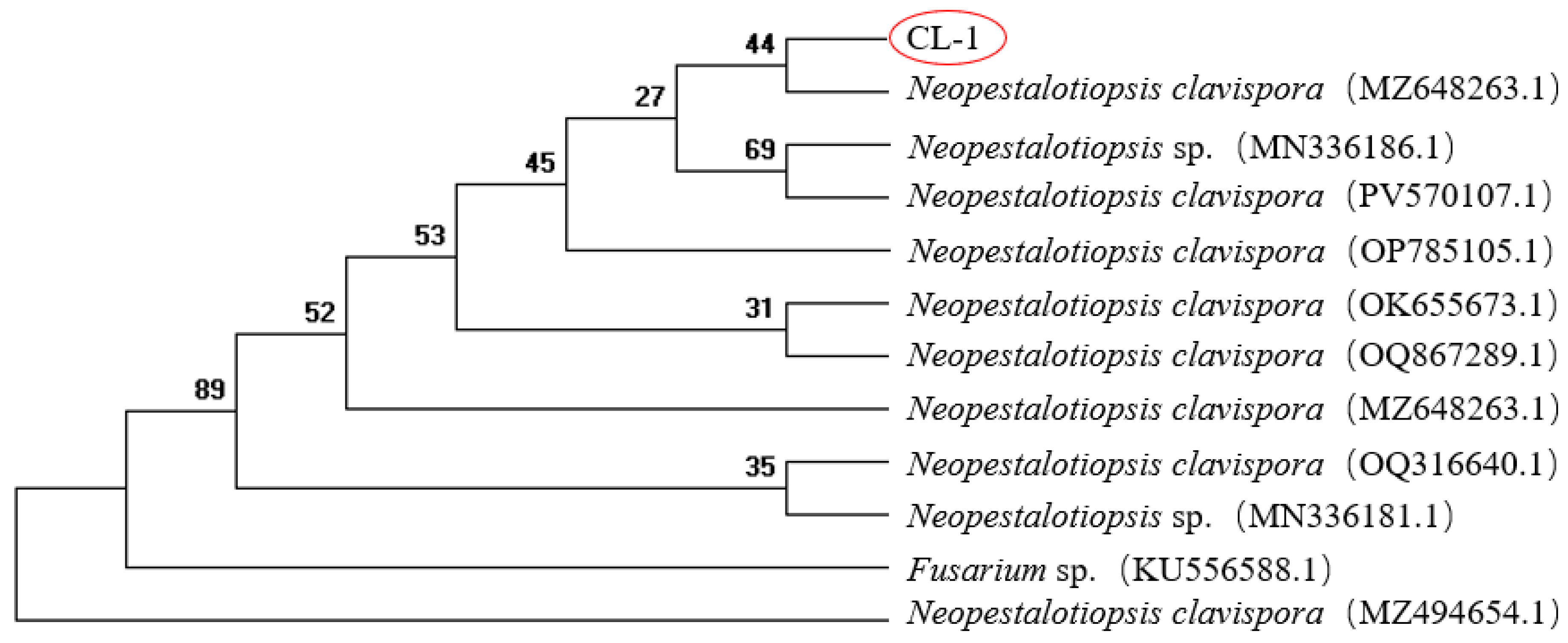

3.3 Molecular Identification and Phylogenetic Tree Analysis of the Pathogen

The internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the isolated pathogen was amplified. The sequencing results obtained after amplification were submitted to the GenBank database for BLAST homology alignment. Sequences with high similarity were retrieved and downloaded. Subsequently, sequence alignment was performed using MEGA11 software, and a phylogenetic tree was constructed. Online BLAST alignment revealed that the ITS sequence of the pathogen shared over 99% similarity with multiple strains of Neopestalotiopsis spp. Clustering results (Fig. 3) demonstrated that the ITS sequence of the pathogen grouped within the same clade as Neopestalotiopsis clavispora, indicating that the isolate CL-1 has the closest genetic relationship with N. clavispora. Combined with the morphological identification results, the pathogen responsible for R. roxburghii Tratt. fruit rot was conclusively identified as N. clavispora.

Figure 3: Phylogenetic tree of pathogenic fungi based on ITS and TEF1 multi-gene sequences.

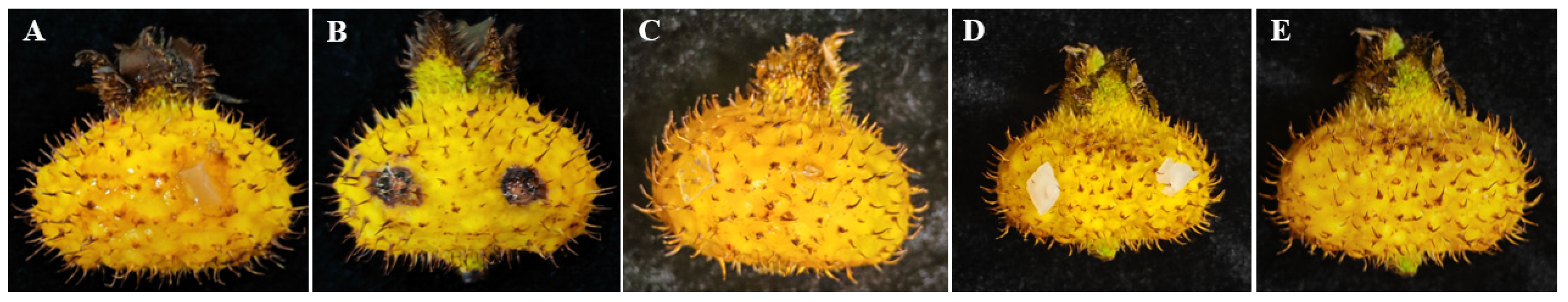

A re-inoculation experiment was conducted using the isolated strains. Sterile medium blocks served as the control, whereas inoculations were performed with culture medium containing mycelial blocks under both wounded and non-wounded conditions. Five fruits were inoculated per condition, with two inoculation points on each fruit. The experiment was repeated three times for biological replicates. After 7 days of inoculation, no lesions were observed at sites inoculated with sterile medium blocks (Fig. 4A). In contrast, sites inoculated with pathogen mycelial blocks developed dark-brown lesions with pustular substances at the margins (Fig. 4B). After 7 days of non-wounded inoculation, neither fruits treated with PDA culture blocks nor those treated with pathogen mycelial blocks showed any infection (Fig. 4C,D), and no lesions or pus-like substances were observed on the fruit surface after removing the mycelial blocks (Fig. 4E). The pathogen was successfully re-isolated from the infected fruits following wounded inoculation. These findings confirm that N. clavispora is the causative agent of R. roxburghii Tratt. fruit rot.

Figure 4: Pathogenicity assessment of the fruit rot pathogen in Rosa roxburghii Tratt. Note: (A), Inoculate PDA after wound treatment, (B), Inoculate the mycelial blocks after wound treatment, (C), Inoculate PDA after non-wound treatment, (D), Inoculate the mycelial block after non-wound treatment, (E), The fruit after removing mycelial blocks following non-wound inoculation.

3.5 Screening of Chemical Agents for Controlling N. clavispora

All six chemical agents inhibited the mycelial growth of N. clavispora. However, significant variations in the antifungal efficacies were observed among the different agents (Table 2). Analysis of the EC50 values of each agent revealed that thiophanate–methyl 70% WP exhibited the strongest antifungal activity. Difenoconazole–azoxystrobin 48% SC, ethylicin 80% EC and trifloxystrobin–tebuconazole 75% WG also showed notable inhibitory effects, with EC50 values of 0.0105, 0.0272 and 0.0368 mg/L, respectively. A 0.3% tetramycin AS exhibited moderate antifungal activity, with an EC50 of 0.1225 mg/L. In contrast, carvacrol 5% AS exhibited relatively weak activity, with an EC50 of 0.2288 mg/L.

Table 2: Toxicity analysis of six control agents on the mycelial growth of Neopestalotiopsis clavispora.

| Experimental Pesticide | Virulence Regression Equation | Coefficient of Relationship (r) | EC50 (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carvacrol 5% AS | Y1 = 1.1008X1 + 5.7052 | 0.9871 | 0.2288 |

| Tetramycin 0.3% AS | Y2 = 1.3694X2 + 6.2485 | 0.9466 | 0.1225 |

| Ethylicin 80% EC | Y3 = 3.208X3 + 10.0236 | 0.8712 | 0.0272 |

| Difenoconazole–azoxystrobin 48% SC | Y4 = 1.1287X4 + 7.2319 | 0.9771 | 0.0105 |

| Trifloxystrobin–tebuconazole 75% WG | Y5 = 0.9613X5 + 6.3782 | 0.9761 | 0.0368 |

| Thiophanate–methyl 70% WP | / | / | / |

3.6 Investigation of the Biological Characteristics of N. clavispora

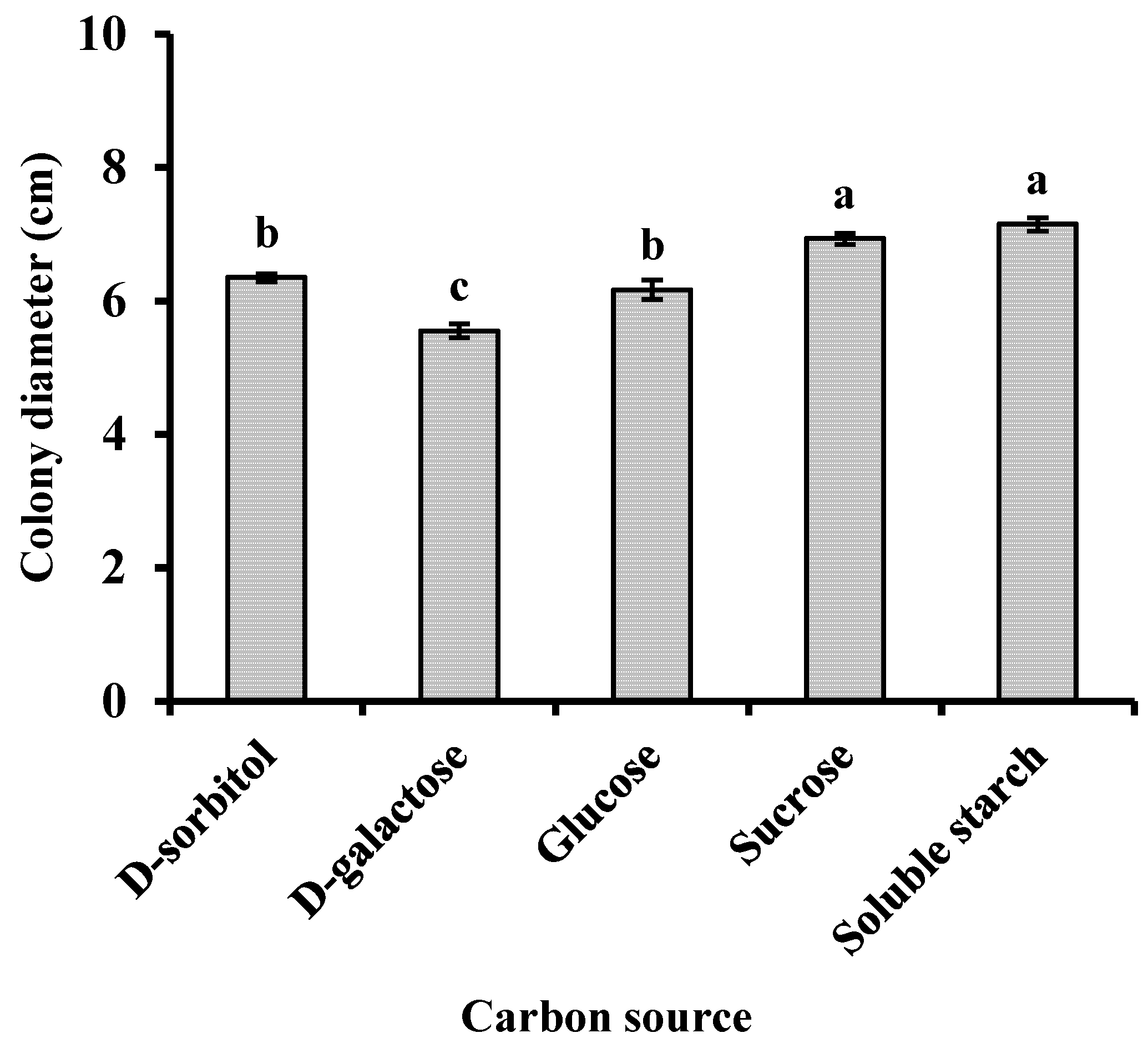

3.6.1 Effect of Carbon Source on the Mycelial Growth of N. clavispora

Using sodium nitrate as the nitrogen source, the pathogen-inoculated media were incubated at 25°C for 7 days under various carbon source conditions, and mycelial growth was measured. The pathogen was capable of growing under all tested carbon sources. Specifically, it exhibited relatively rapid growth with dense mycelia in media containing sucrose and soluble starch (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Effects of carbon source on the mycelial growth of Neopestalotiopsis clavispora. Note: Significant differences were analysed using one-way ANOVA. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

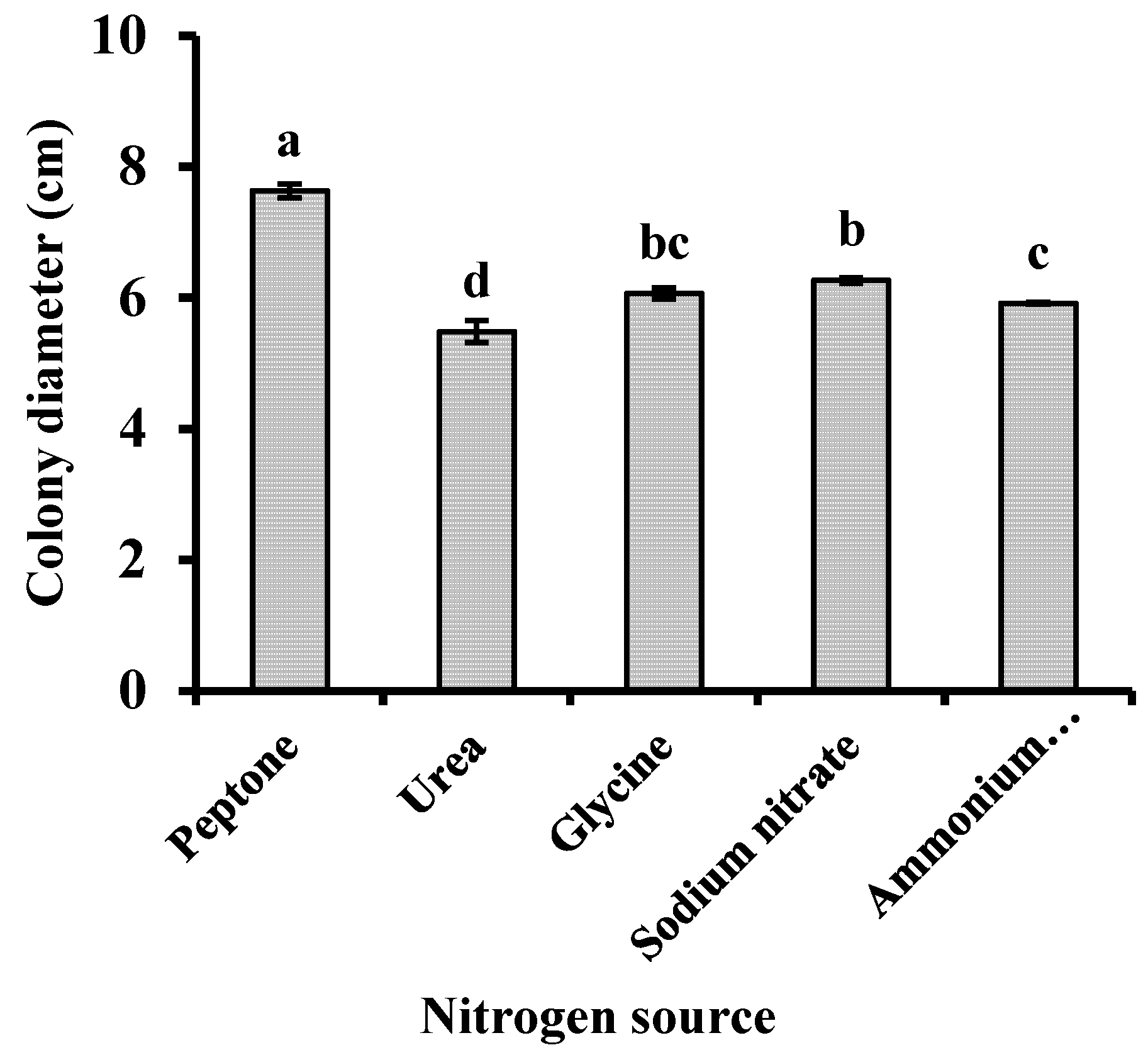

3.6.2 Effect of Nitrogen Source on the Mycelial Growth of N. clavispora

Using sucrose as the carbon source, the inoculated media were incubated at 25°C for 7 days with different nitrogen sources. Subsequently, the extent of mycelial growth was determined. The pathogen grew under all nitrogen sources tested but exhibited the fastest growth and densest mycelia when peptone was used as the nitrogen source (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Effects of nitrogen source on the mycelial growth of Neopestalotiopsis clavispora. Note: Significant differences were analysed using one-way ANOVA. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

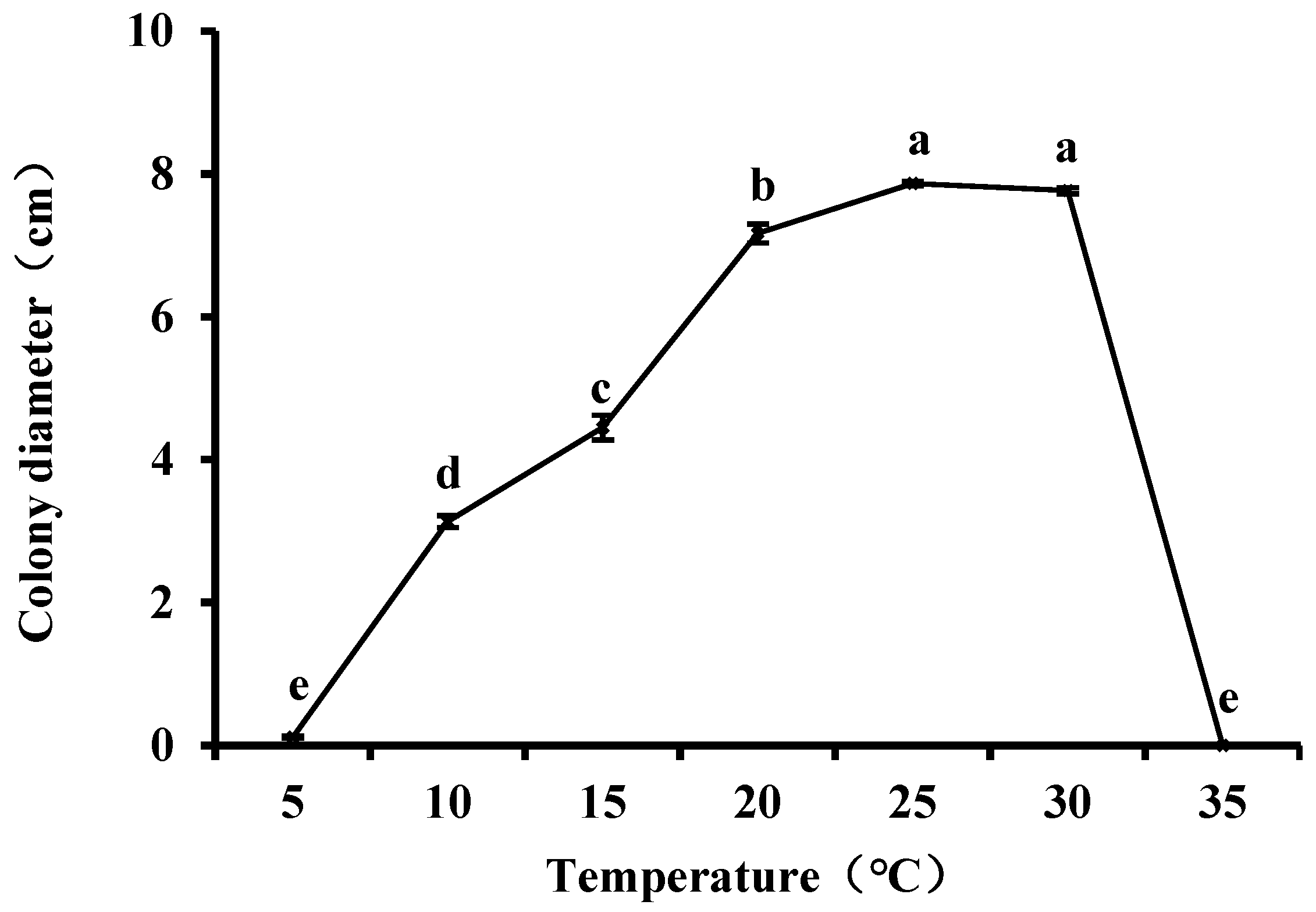

3.6.3 Effects of Temperature on the Mycelial Growth of N. clavispora

Media inoculated with N. clavispora were cultured at 5°C, 10°C, 15°C, 20°C, 25°C, 30°C and 35°C. N. clavispora mycelia grew between 10°C and 30°C, with optimal growth observed at 25°C–30°C. Mycelial growth was significantly inhibited at 5°C and completely stopped at 35°C (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Effects of incubation temperature on the mycelial growth of Neopestalotiopsis clavispora. Note: Significant differences were analysed using one-way ANOVA. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

3.6.4 Effect of pH on the Mycelial Growth of N. clavispora

Media inoculated with pathogen samples of consistent size were incubated at 20°C and 25°C. Effects of different pH values (ranging from 2.0 to 11.0) on the mycelial growth of N. clavispora were then assessed. The results indicated that the pH range for the optimal growth of the pathogen was 4–8 (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: Effects of pH on the mycelial growth of Neopestalotiopsis clavispora. Note: Significant differences were analysed using one-way ANOVA. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05).

The isolation, purification, morphological identification, molecular analysis, and pathogenicity testing of R. roxburghii Tratt. fruit rot specimens collected in Guiding County, Guizhou Province, China, identified N. clavispora as the causative pathogen. Indoor fungicide screening results indicated that thiophanate–methyl 70% WP exhibited the strongest inhibitory effect on N. clavispora. Difenoconazole–azoxystrobin 48% SC, ethylicin 80% EC, and trifloxystrobin–aebuconazole 75%WG also showed significant inhibitory effects. Additionally, 80% ethylicin emulsified oil can be considered an effective option for environmentally friendly pest control.

Diseases affecting R. roxburghii Tratt. severely affect fruit yield and quality. Therefore, isolating and identifying the causative pathogens are crucial for disease control and prevention. Colletotrichum fructicola was isolated and identified as the pathogen causing top rot disease in R. roxburghii Tratt. by Li et al. [17], whereas Paraphaeosphaeria sp. was identified as the pathogen causing leaf spot disease in R. roxburghii Tratt. by Yang [18]. Pestalotiopsis microspora, Neofusicoccum parvum, and Alternaria alternata were identified as pathogens causing leaf spot disease in R. roxburghii Tratt. by Liu et al. [19]. However, Pestalotiopsis was found to be the dominant genus of culturable epiphytic fungi in the phyllosphere of healthy and diseased R. roxburghii Tratt. In this study, N. clavispora was confirmed as the causative pathogen of fruit rot disease in R. roxburghii Tratt. The fruit rot pathogen was isolated and identified, confirming it as N. clavispora. This is the first report of this pathogen causing infection on the R. roxburghii Tratt.

N. clavispora is a fungus with an extensive host range. It can induce leaf spot, leaf blight, and rotting in various fruits. Solarte et al. [20] found that the pathogen caused the black star disease in guava, and Rajashekara et al. [21] reported that it was the causative cashew leaf blight disease in India. Diseases caused by N. clavispora have increased in recent years. It has been identified as the pathogen for grey blight disease of tea in Malaysia [22], foliar disease of rubber in the Philippines [23], and leaf spot disease in apples in Shandong [24]. Furthermore, N. clavispora thrives across a broad range of habitats and can cause extensive damage.

The growth characteristics of N. clavispora were analysed by modifying external environmental factors and using different carbon and nitrogen sources in the culture medium. The pathogen exhibited strong adaptability to adverse temperatures and pH values, remaining highly viable between 10°C and 30°C or pH 3 and 10, indicating a relatively wide range of survival. Mycelial growth was vigorous and dense at 25°C–30°C. Furthermore, the optimal temperature for growth and development closely aligns with the air temperatures during the fruit’s harvesting period (25°C–28°C). These findings on the pathogen’s growth characteristics provide a theoretical basis for the early prevention and management of disease in the field.

The indoor toxicity test of fungicides against pathogenic fungi is an important indicator for evaluating the inhibitory effect of the agents on the pathogenic fungi [25]. The toxicity analysis assessed the inhibitory effect of six fungicides on N. clavispora, with thiophanate–methyl 70% WP exhibiting the strongest inhibitory effect on mycelial growth. Amrutha et al. [26] reported that 12% carbendazim + 63% mancozeb exhibited the most significant inhibitory effect on the leaf blight of strawberry, and Liu et al. [27] reported its optimal inhibitory effect against P. podocarpi in Podocarpus macrophyllus, with thiophanate–methyl 70% WP ranking second. These findings are consistent with the results of this study. However, the long-term use of chemical pesticides often leads to the development of resistance in pathogens. Moreover, the R. roxburghii Tratt. industry in Guiding County has consistently adhered to the principles of organic and environmentally friendly development. Therefore, the selection of biological agents for the prevention and control of R. roxburghii Tratt. diseases are of particular importance. In this study, carvacrol 5% AS, tetramycin 0.3% AS, and ethylicin 80% EC showed inhibitory effects, with ethylicin 80% EC exhibiting the best performance. Thus, the findings of this study provide theoretical guidance and technical support for the development of environmentally friendly and organic strategies to control N. clavispora in the field. This study conducted only in vitro virulence tests of the pathogen, and the field efficacy of the chemical agents still requires verification and optimisation through more extensive field trials.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the Science and Technology Support Plan of Guizhou Province (Guizhou Family Combination Support 2022, No. 116).

Author Contributions: Conceptualisation, Di Wu and Wenwen Su; methodology, Chunguang Ren; software, Di Wu and Wenwen Su; validation, Wenwen Su; investigation, Di Wu and Chongpei Zheng; data curation, Liangliang Li; writing—original draft preparation, Di Wu; writing—review and editing, Wenwen Su; funding acquisition, Di Wu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Wenwen Su.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| Aqueous solution | |

| Emulsifiable concentrate | |

| Polymerase chain reaction | |

| Potato dextrose agar | |

| Suspension concentrate | |

| Water-dispersible granules | |

| Wettable powder |

References

1. Li B , Ren T , Yang M , Lu G , Tan S . Assessment of quality differences between wild and cultivated fruits of Rosa roxburghii Tratt. LWT. 2024; 202: 116300. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2024.116300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sheng X , Li X , Lu X , Liu X , Tang W , Yu Z , et al. Characterization and perceptual interaction of key aroma compounds in Rosa roxburghii Tratt by sensomics approach. Food Chem X. 2024; 24: 101892. doi:10.1016/j.fochx.2024.101892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Jiang L , Lu M , Rao T , Liu Z , Wu X , An H . Comparative analysis of fruit metabolome using widely targeted metabolomics reveals nutritional characteristics of different Rosa roxburghii genotypes. Foods. 2022; 11( 6): 850. doi:10.3390/foods11060850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Xu F , Zhu Y , Lu M , Zhao D , Qin L , Ren T . Exploring the mechanism of browning of Rosa roxburghii juice based on nontargeted metabolomics. J Food Sci. 2023; 88( 5): 1835– 48. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.16534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liu W , Li N , Hou J , Cao R , Jia L , Guo Y , et al. Structure and antitumor activity of a polysaccharide from Rosa roxburghii. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024; 273: 132807. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.132807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Ge YM , Xue Y , Zhao XF , Liu JZ , Xing WC , Hu SW , et al. Antibacterial and antioxidant activities of a novel biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles using Rosa roxburghii extract and chitosan: preparation, characterization, properties, and mechanisms. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024; 254: 127971. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.127971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wu Y , He X , Chen H , Lin Y , Zheng C , Zheng B . Extraction and characterization of hepatoprotective polysaccharides from Anoectochilus roxburghii against CCl4-induced liver injury via regulating lipid metabolism and the gut microbiota. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024; 277( Pt 3): 134305. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Fu YY , Liu JM , Lu XL , Peng QR , Xie YC , Yang M . Research progress on main active components and pharmacological effects of Rosa roxburghii Tratt. Sci Technol Food Ind. 2020; 41( 13): 328– 35. (In Chinese). doi:10.13386/j.issn1002-0306.2020.13.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li X , Wang X , Yan K , Weng G , Zhu M . Effect of Rosa roxburghii fruit on blood lipid levels: a systematic review based on human and animal studies. Int J Food Prop. 2022; 25( 1): 549– 59. doi:10.1080/10942912.2022.2053710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Liu C , Chan LP , Liang CH . The anti-aging activities against oxidative damages of Rosa roxburghii and multi-fruit concentrate drink. J Food Nutr Res. 2019; 7( 12): 845– 50. doi:10.12691/jfnr-7-12-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Karabagias VK , Karabagias IK , Prodromiti M , Gatzias I , Badeka A . Bio-functional alcoholic beverage preparation using prickly pear juice and its pulp in combination with sugar and blossom honey. Food Biosci. 2020; 35: 100591. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2020.100591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Brinker F . Prickly pear as food and medicine. J Diet Suppl. 2009; 6( 4): 362– 76. doi:10.3109/19390210903280280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang L , Wei T , Zheng L , Jiang F , Ma W , Lu M , et al. Recent advances on main active ingredients, pharmacological activities of Rosa roxbughii and its development and utilization. Foods. 2023; 12( 5): 1051. doi:10.3390/foods12051051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Liu J , Zheng X , Potter D , Hu C , Teng Y . Genetic diversity and population structure of Pyrus calleryana (Rosaceae) in Zhejiang Province, China. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2012; 45: 69– 78. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2012.06.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Huang WY , Li XQ , Han L , Liu XD , An HM , Wu XM . Advances in the researches on the occurrence and control of Rosa roxburghii disease and insect pests. China Plant Prot. 2020; 40( 5): 24– 30. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

16. Zhang C , Li J , Su Y , Wu X . Association of physcion and chitosan can efficiently control powdery mildew in Rosa roxburghii. Antibiotics. 2022; 11( 11): 1661. doi:10.3390/antibiotics11111661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li J , Luo Y , Lu M , Wu X , An H . The pathogen of top rot disease in Rosa roxburghii and its effective control fungicides. Horticulturae. 2022; 8( 11): 1036. doi:10.3390/horticulturae8111036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yang YQ . Fungal identification and systematic analysis of major fungal diseases of fruit trees in Guizhou province [ dissertation]. Guiyang, China: Guizhou University; 2023. (In Chinese). doi:10.27047/d.cnki.ggudu.2023.002035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Liu Y , Ge W , Dong C , Shao Q , Zhang Z , Zou X , et al. The analysis of microbial community characteristics revealed that the pathogens of leaf spot of Rosa roxburghii originated from the phyllosphere. Indian J Microbiol. 2023; 63( 3): 324– 36. doi:10.1007/s12088-023-01093-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Solarte F , Muñoz CG , Maharachchikumbura SSN , Álvarez E . Diversity of Neopestalotiopsis and Pestalotiopsis spp., causal agents of guava scab in Colombia. Plant Dis. 2018; 102( 1): 49– 59. doi:10.1094/pdis-01-17-0068-re. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Rajashekara H , Pandian RTP , Mahadevakumar S , Raviprasad TN , Vanitha K , Siddanna S , et al. First report of Neopestalotiopsis clavispora causing cashew leaf blight disease in India. Plant Dis. 2023; 107( 9): 2864. doi:10.1094/pdis-03-23-0545-pdn. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Shahriar SA , Nur-Shakirah AO , Mohd MH . Neopestalotiopsis clavispora and Pseudopestalotiopsis camelliae-sinensis causing grey blight disease of tea (Camellia sinensis) in Malaysia. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2022; 162( 3): 709– 24. doi:10.1007/s10658-021-02433-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Solpot TC , Villanueva JD , Abello MP , Zuñiga JBM . First report of Neopestalotiopsis clavispora causing foliar disease of rubber (Hevea brasiliensis) in the Philippines. J Phytopathol. 2024; 172( 1): e13238. doi:10.1111/jph.13238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Shi J , Li B , Wang S , Zhang W , Shang M , Wang Y , et al. Occurrence of Neopestalotiopsis clavispora causing apple leaf spot in China. Agronomy. 2024; 14( 8): 1658. doi:10.3390/agronomy14081658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Luo LL , Zhao XL , Zhou LN , He SL , Liu SR , Zhang X , et al. Identification of a pathogen causing soft rot on Amorphophallus albus and laboratory screening for bactericide. J South Agric. 2022; 53( 11): 3137– 46. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

26. Amrutha P , Vijayaraghavan R . Evaluation of fungicides and biocontrol agents against Neopestalotiopsis clavispora causing leaf blight of strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa Duch.). Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2018; 7( 8): 622– 8. doi:10.20546/ijcmas.2018.708.067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Liu YQ , Tan JJ , Zhao MT , Ding Q , Dai HZ . Biological characteristics of Phomopsis podocarpi (pathogen of Podocarpus macrophyllus leaf blight) and screening of inhibitory pesticides. J Nanjing For Univ. 2025; 2025: 1– 7. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools