Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Chemical Composition and Antifungal Efficacy of Mentha rotundifolia Essential Oil against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis in Date Palm: Valorisation of Plant Biomass for Natural Antifungal Agents

1 Division of Biotechnology and Plant Improvement, National Institute of Agronomic Research of Algeria (INRA), El Harrach, PB 200, Algiers, 16200, Algeria

2 National Institute of Agronomic Research of Algeria, Touggourt, 30200, Algeria

3 Center of Research in Physical and Chemical Analysis (CRAPC), Bou-Ismail PB 384, Tipazan, 42004, Algeria

4 National Institute of Agronomic Research of Algeria, BP 229, Adrar, 01000, Algeria

5 Faculty of Exact Sciences, Chemistry Department, University of El Oued, P.O. Box 789, El Oued, 39000, Algeria

6 Laboratory of Integrative Improvement of Plant Productions (AIVP; Code C2711100), National Higher School of Agronomy, Algiers, 16200, Algeria

* Corresponding Author: Salah Neghmouche Nacer. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Fungal and Bacterial Disease Management in Agricultural Crops Through Biological Control, Disease Resistance, and Transcriptomics Approaches)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 3975-3989. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073210

Received 12 September 2025; Accepted 19 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

Essential oils (EOs) derived from medicinal plants are gaining recognition as sustainable alternatives to synthetic fungicides in the management of plant pathogens. This study investigates the chemical composition, chromatographic profile, and antifungal of Mentha rotundifolia essential oil against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis (Foa), the pathogen responsible for Bayoud disease in date palm. The oil was extracted through hydrodistillation and characterized using thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC-MS), revealing multiple fractions corresponding to terpenoid constituents and 23 chemical constituents, predominantly oxygenated monoterpenes (68.51%), with piperitenone oxide as the major component (62.53%). The antifungal efficacy was evaluated against ten (10) isolates of F.o.a across seven (07) concentrations different concentrations. (0; 0.25; 0.5; 0.75; 1; 1.25; 1.5μL/mL). The results obtained show a progressive decrease in the diameters of the colonies of F.o.a isolates by increasing the doses of EOMR. The percentage of inhibition varies from 7.82 to 83.41%; However, the dose of 1.75μL/mL showed 100% inhibition for all F.o.a isolates tested. These outcomes demonstrate the potential of M. rotundifolia essential oil as a natural, environmentally friendly antifungal agent, supporting its application in sustainable management strategies for Bayoud disease in date palm.Keywords

The date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.) is a vital crop in arid and semi-arid regions, particularly in North Africa, where it supports both agricultural productivity and local economies. It represents not only a cornerstone of food security but also a crucial source of livelihood, employment, and cultural heritage for millions of people living in desert and oasis ecosystems. Its ability to thrive under extreme environmental conditions makes it indispensable for food security and income generation, especially in Algeria [1]. From an ecological perspective, the date palm plays a key role in stabilizing fragile soils, creating favorable microclimates that sustain biodiversity, and mitigating the processes of desertification and land degradation. Socially, it supports rural communities by providing multiple ecosystem services and raw materials for handicrafts, housing, and traditional medicine, reinforcing its multifunctional and sustainable importance in arid landscapes. Beyond its economic value, the date palm contributes to ecological balance by creating microclimates that foster the growth of understory crops, promote biodiversity, and combat desertification [2,3]. Additionally, it provides raw materials for construction, handicrafts, and traditional uses, further enhancing its socio-economic importance [1]. However, date palm cultivation is increasingly threatened by pests and diseases, which severely impact yield and plantation longevity [4,5]. Among these challenges, Bayoud disease caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Albedinis is the most devastating fungal disease affecting date palm plantations. This vascular wilt has decimated millions of trees across North Africa, particularly in Algeria and Morocco, leading to the loss of entire oases, severe reductions in date production, and irreversible genetic erosion of valuable cultivars. Its persistence in the soil and capacity for rapid dissemination make it extremely difficult to control. Beyond the economic losses, Bayoud disease contributes to ecological degradation by accelerating desertification and disrupting oasis ecosystems, posing a long-term threat to the environmental balance and socio-economic stability of affected regions. The disease has wiped out millions of palm trees across Morocco and Algeria, leading to significant genetic erosion, ecosystem degradation, and socio-economic hardship in affected regions [6]. The rapid spread of Bayoud disease has also triggered rural displacement and accelerated desertification, posing an ongoing risk to remaining healthy plantations [7]. This situation highlights the urgent need for effective, sustainable control measures.

Current management strategies rely on preventative measures, replanting resistant cultivars, and chemical treatments. However, the use of synthetic fungicides presents several major limitations. Despite their initial effectiveness, many chemical fungicides such as chloropicrin and methyl bromide are associated with serious toxicity, high application costs, and the emergence of resistant fungal strains. Their persistence in soil and water contributes to long-term environmental contamination, negatively affecting non-target organisms, including beneficial soil microbes, insects, and aquatic life. Furthermore, chronic exposure to these compounds poses potential risks to human health, ranging from respiratory and neurological disorders to carcinogenic effects. Consequently, the search for safer, eco-friendly alternatives has become a global priority.

In recent years, there has been a growing scientific and industrial interest in essential oils (EOs) as natural, renewable, and environmentally friendly alternatives to synthetic fungicides. Their complex mixtures of bioactive compounds—primarily terpenes, phenolics, and aldehydes—exhibit broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, biodegradability, and low toxicity to humans and the environment. Essential oils not only inhibit pathogen growth but can also act synergistically with existing fungicides, reducing chemical usage and resistance development. This has positioned essential oils as promising candidates for the formulation of sustainable biopesticides within integrated pest management (IPM) systems [8,9]. Essential oils derived from aromatic plants have demonstrated broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity, making them strong candidates for biopesticide development [10].

The Mentha genus (Lamiaceae family) is particularly notable for its rich diversity of bioactive compounds, many of which exhibit strong antifungal properties even at low concentrations [11]. With over 30 species cultivated globally, Mentha is widely recognized for its therapeutic and antimicrobial potential [12]. One species of growing scientific interest is Mentha rotundifolia, a perennial herb traditionally used for its medicinal properties [13,14]. Its essential oil has shown strong antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal activities, positioning it as a natural alternative to synthetic fungicides [15]. Despite this potential, the specific mechanisms behind its antifungal effects remain poorly understood, leaving a gap in current research.

Although M. rotundifolia essential oil has been previously reported to exhibit antifungal activity against some Fusarium spp. [16], the present study is, to our knowledge, the first to characterize the volatile profile of an Algerian M. rotundifolia population and to evaluate its antifungal efficacy specifically against multiple field isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis, the causal agent of Bayoud disease in date palm.

2.1 Plant Material and Extraction

Fresh leaves and stems of M. rotundifolia (L.) Huds. were collected during the flowering stage in June 2024 from the experimental station of the National Institute of Agronomic Research of Algeria (INRAA), Touggourt region, Southeast Algeria (Latitude: 33°06′18″ N; Longitude: 6°03′28″ E). Approximately 0.5 kg of fresh aerial parts were harvested for the extraction process. The plant material was taxonomically authenticated by a botanist from INRAA, and a voucher specimen was deposited in the institute’s herbarium for future reference.

Immediately after collection, the plant material was carefully cleaned to remove dust and impurities, then air-dried in the shade under controlled ambient conditions (25 ± 2°C; relative humidity 45–50%) for 10 days to prevent photodegradation and preserve volatile constituents. The dried leaves and stems were then finely ground using a mechanical grinder to obtain a uniform powder. The powdered material was preserved in airtight, light-protected glass containers at 4°C to minimize oxidation and maintain chemical stability until essential oil extraction [17,18].

The essential oil (EO) of M. rotundifolia was obtained by hydrodistillation using a Clevenger-type apparatus. For the extraction, 300 g of the dried and homogenized plant material were mixed with 3 L of distilled water in a round-bottom flask. The mixture was subjected to gentle heating for 3 h at approximately 100°C using a temperature-regulated heating mantle to ensure the optimal release of volatile constituents. Upon completion, the oil layer was carefully separated from the aqueous phase, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and stored in amber glass vials at 4°C to prevent oxidation and photodegradation prior to GC–MS and biological analyses [19]. The extraction yield was calculated according to the formula: Yield (%) = (volume of essential oil (mL)/weight of dry plant material (g)) × 100. The hydrodistillation process lasted for 3 h at approximately 100°C.

The volatile constituents of M. rotundifolia essential oil (MREO) were characterized using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) to achieve comprehensive identification and quantification of its components. Analyses were carried out on an Agilent 5973 GC–MS system operating with an electron ionization energy of 70 eV. A fused-silica capillary column HP-5MS (30 m × 0.25 mm i.d., 0.25 μm film thickness; 5% phenyl-methylpolysiloxane stationary phase, Agilent Technologies, USA) was employed. To ensure an accurate and representative metabolite profile, three chromatographic runs were performed using capillary columns with different stationary phases, enabling enhanced resolution of complex volatiles.

The temperature program began at 60°C (held for 5 min), followed by a 10°C/min ramp up to 300°C, where it was held isothermally for 10 min. The injector temperature was maintained at 250°C (splitless mode), and the detector at 280°C. Helium served as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 1.0 mL/min.

Compound identification was achieved by comparing the obtained mass spectra with those in the NIST 14 and Wiley 9 spectral libraries, as well as by comparing experimental retention indices (RIexp) with literature or theoretical RIs (RIlit) from published compilations and NIST/Wiley databases [19]. Quantification of each compound was expressed as relative peak area percentage using the following equation: Yi% = [Pi/(P1 + P2 +…+ Pn)] × 100 where Y represents the percentage abundance and P represents the individual peak area [20].

Retention indices (RI) were experimentally determined using the Kovats linear retention index method, calculated relative to an n-alkane series (C8–C40) analyzed under identical chromatographic conditions. The integration of spectral matching and retention index comparison ensured robust compound confirmation and reduced misidentification risk.

2.3 Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) Analysis

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was employed as a preliminary qualitative method to assess the chemical composition and homogeneity of M. rotundifolia essential oil prior to GC–MS analysis.

Separations were performed on silica gel G plates (20 × 10 cm) as the stationary phase, using a n-hexane:ethyl acetate solvent system (90:10, v/v) as the mobile phase. For each analysis, 10 μL of the essential oil was precisely spotted on the plate using a calibrated glass capillary. The plates were developed in a saturated chromatographic chamber until the solvent front reached approximately 1 cm from the upper edge, and duplicate plates were prepared for each sample to ensure reproducibility.

After development, the separated compounds were visualized under UV light at 254 nm and 365 nm. Chemical detection reagents including vanillin, sulfuric acid, aluminum chloride (AlCl3), and Dragendorff reagent were applied to selectively visualize distinct chemical classes, terpenoids, phenolics, and alkaloids, respectively—following standard phytochemical protocols [20].

TLC served as a rapid, cost-effective tool to visualize major chemical classes, assess inter-batch consistency, and guide the optimization of GC parameters. The subsequent GC–MS analysis provided definitive identification and quantification of individual volatile constituents, ensuring comprehensive chemical characterization of the essential oil.

2.4 Fungal Material and Isolation

Ten isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis were obtained from diseased date palm tissues exhibiting typical symptoms of Bayoud disease. The isolates were preserved in the mycological collection of the Biotechnology and Plant Improvement Division at INRAA. The fungal isolates were cultured on 90-mm Petri dishes containing Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) and incubated in darkness at 25 ± 2°C for seven days to ensure optimal growth.

Fungal isolates were obtained from symptomatic date palm tissues and identified at the INRAA mycology unit using classical morphological criteria (macroscopic colony characters, microscopic morphology of macro- and micro-conidia and chlamydospores) following standard keys [21]. Pathogenicity of representative isolates was confirmed on susceptible date-palm material.

The antifungal potential of M. rotundifolia essential oil (MREO) against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis (Foa), the causal agent of Bayoud disease, was evaluated using the poisoned food technique as previously described by Grover and Moore [20], with slight modifications.

A stock solution of the essential oil was first prepared by dissolving the required volume of MREO in 5% (v/v) Tween 20 aqueous solution, used as an emulsifying agent to enhance oil dispersion in the medium. Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium was prepared and autoclaved at 121°C for 20 min, then cooled to approximately 45°C before adding the essential oil at the desired concentrations.

The final concentrations tested were 0 (control), 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, and 1.5 μL/mL of essential oil. An additional concentration of 1.75 μL/mL was also included to verify total growth inhibition. The essential oil–medium mixture was stirred for 1–2 min to ensure complete homogeneity, and 20 mL of the treated medium was poured into 90-mm sterile Petri dishes.

After solidification, a 5-mm agar disc containing actively growing mycelium of F. oxysporum f. sp. albedinis (from a 7-day-old pure PDA culture) was aseptically placed at the center of each plate. Control plates were prepared with PDA containing 5% Tween 20 but no essential oil.

All treatments were performed in triplicate, and the plates were incubated at 25 ± 2°C in complete darkness for seven (7) days. Following incubation, colony diameters were measured along two perpendicular axes, and the mean values were used to calculate mycelial growth inhibition (MGI) using the formula:

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the results are presented as mean values ± standard deviations (SD). To determine the statistical significance of differences among treatments, data were subjected to one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison test to assess pairwise differences between means. A p-value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 25.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Prior to analysis, data were tested for normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test) to validate the assumptions of ANOVA.

Equations and mathematical expressions must be inserted into the main text. Please use MathType editor or the equation editor of MS Word to edit the equations. Consistently use one of the equation editors (MathType or equation editor of MS Word) for an article. Formulas should not be presented as images and can be formatted in either in-line or display style.

3.1 Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) Analysis

The selection of an appropriate solvent system is crucial in thin-layer chromatography (TLC) as it significantly influences the separation and resolution of sample components. In this study, a solvent system comprising hexane (90%) and ethyl acetate (10%) was employed to optimize the separation of various chemical constituents.

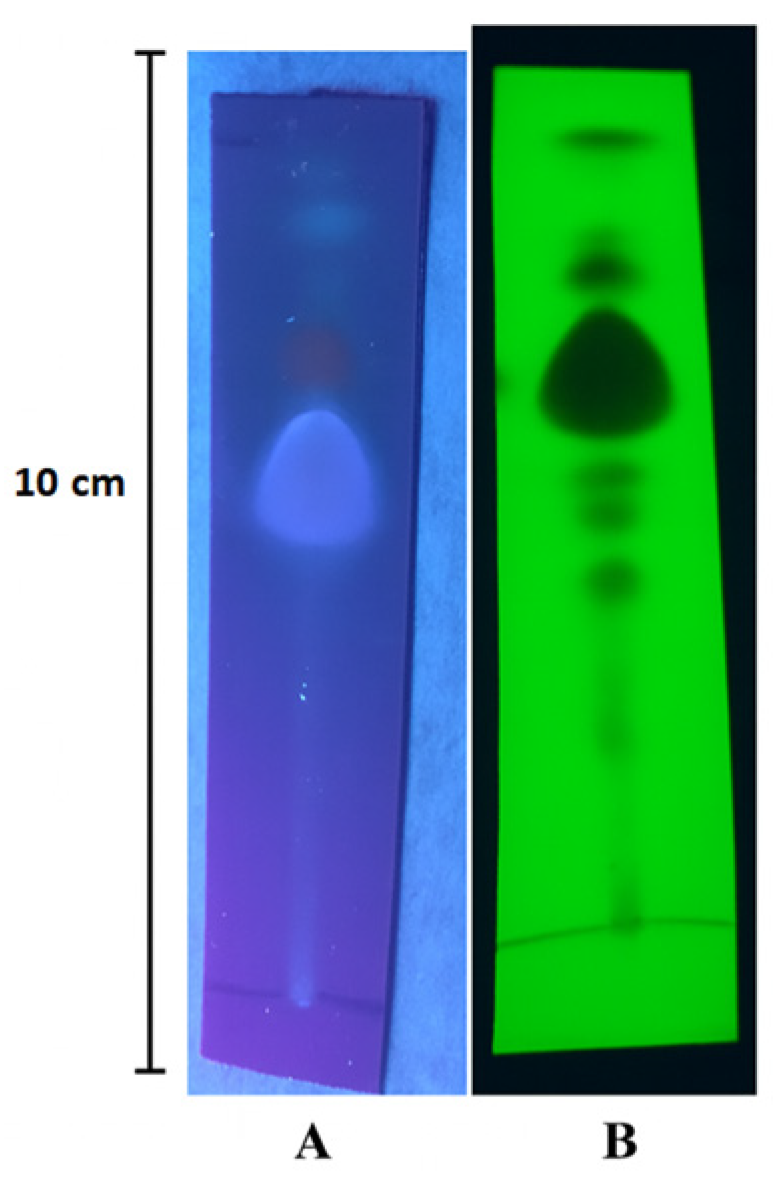

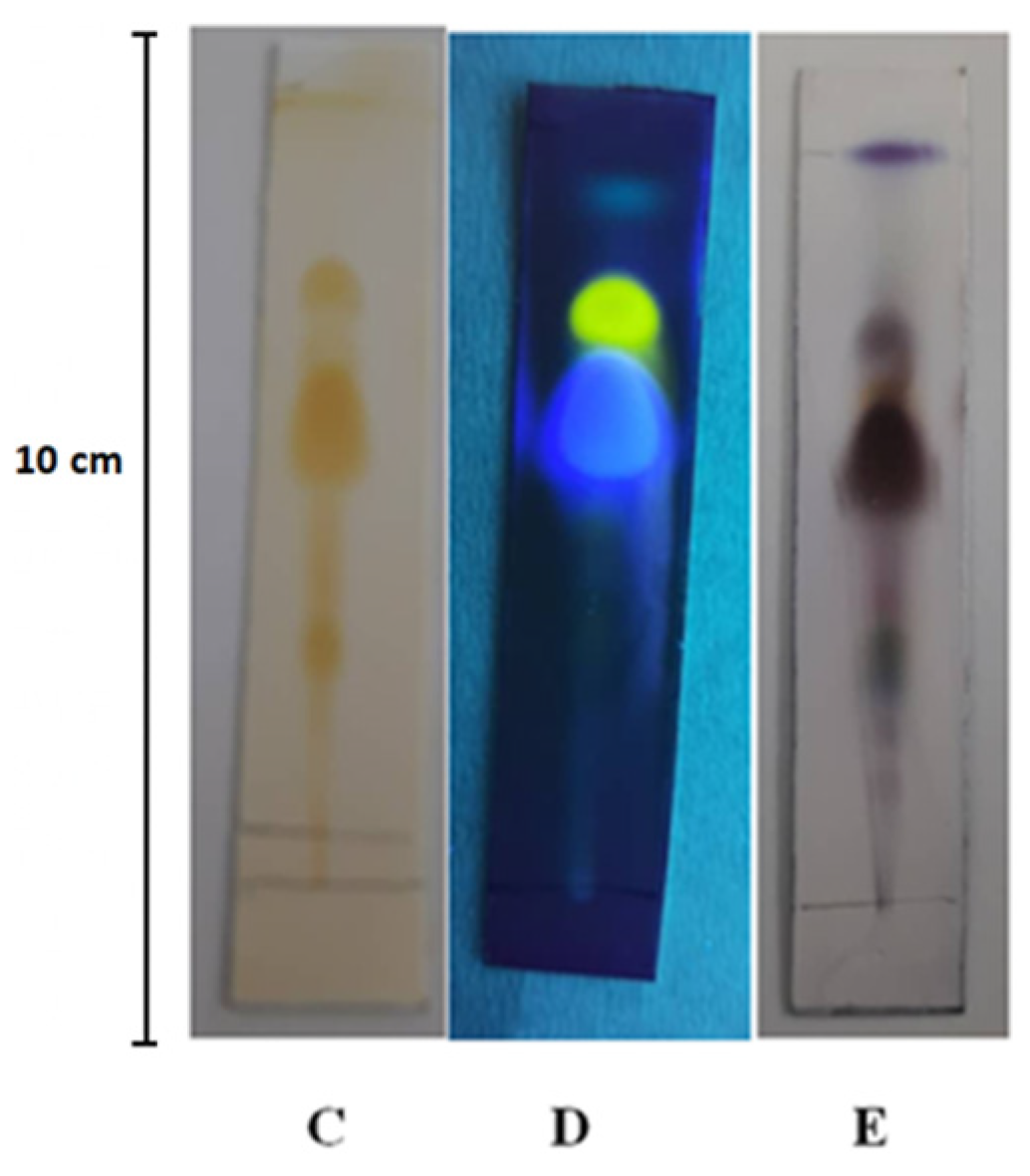

The TLC analysis revealed the presence of nine fractions under UV light at 245 nm with retention factor (Rf) values of 0.085, 0.136, 0.203, 0.288, 0.356, 0.424, 0.593, 0.746, and 0.779. Under UV light at 365 nm, only three fractions were detected with Rf values of 0.593, 0.746, and 0.932, as shown in Fig. 1. Following the application of Vanillin/Sulfuric acid reagent, nine distinct spots were observed, corresponding to Rf values of 0.153 (grey-violet), 0.203 (red-violet), 0.271 (blue-violet), 0.322 (green), 0.373 (blue-violet), 0.441 (brown), 0.593 (brown), 0.661 (yellow), and 0.745 (brown). Additionally, the application of AlCl3 reagent resulted in the formation of three spots with Rf values of 0.625 (blue), 0.786 (yellow), and 0.893 (green), These visualizations are presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 1: Chromatogram of Mentha rotundifolia essential oil under (A) UV 254 nm; (B) UV 365 nm.

Figure 2: Chromatogram of Mentha rotundifolia essential oil using certain spraying reagents. (C) Iodine Reagent; (D) Aluminum AlCl3 Reagent; (E) Vanillin/Sulfuric Acid Reagent.

TLC serves as a reliable and time-efficient analytical tool for the preliminary identification of compounds in complex mixtures. In our study, we utilised this method as a preliminary analysis tool for examining the essential oil [24]. The utilisation of a specific mixture of solvents, comprising 90% Hexane and 10% Ethyl acetate, proved to be effective in achieving improved separation of various chemicals in the given sample. Moreover, the introduction of several reagents such as iodine, sulfuvaniline, Dragendorff, and AlCl3 during the TLC (thin-layer chromatography) process significantly enhanced the differentiation between the separated compounds, enabling more precise identification and analysis. The presence of monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes were detected through the appearance of blue-violet, red-violet, grey-blue, or blue spots [25].

3.2 Yield and Chemical Profile Overview

The hydrodistillation of Mentha rotundifolia leaves and stems produced a pale-yellow essential oil with a characteristic aromatic odor and an extraction yield of 1.25% (v/w, based on dry weight). This yield is comparable to previously reported values for M. rotundifolia essential oils, which generally range from 0.47% to 4.33%, depending on origin, environmental conditions, and extraction parameters [26,27].

Variations in extraction yield among studies can be attributed to several factors, including geographical location, climatic conditions, harvest season, soil type, plant maturity, and extraction duration or temperature [28]. For instance, Soilhi et al., (2019) reported a yield of (1.1-2.5%) for Tunisian M. rotundifolia, while Hassani, (2020) obtained a higher yield of 3.85% from Moroccan samples, underscoring the influence of regional and environmental variations on essential oil productivity [29,30]. The yield obtained in this study (1.25%) therefore lies within the normal range observed in the literature, confirming that the hydrodistillation conditions employed (3 h at 100°C) were appropriate for efficient volatile oil recovery without degradation of thermolabile constituents.

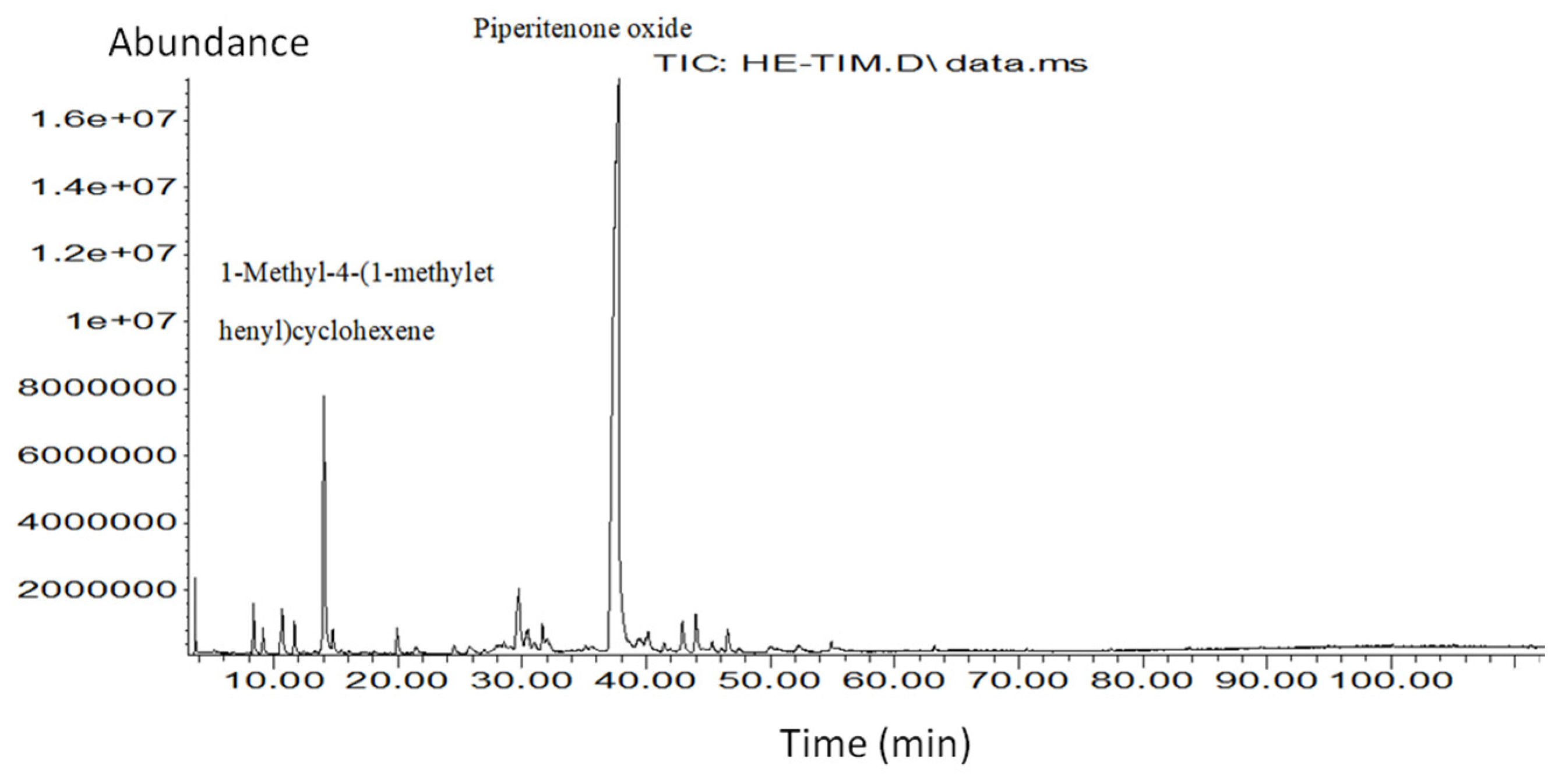

GC–MS analysis identified 23 volatile compounds (Table 1; Fig. 3), representing more than 99.8% of the total composition. The oil was dominated by piperitenoneoxide (62.53%), followed by trans-piperitone epoxide (9.84%), carvone (4.12%), and 1,8-cineole (3.76%), confirming a chemotype rich in oxygenated monoterpenes characteristic of the Mentha genus [31]. Minor compounds included α-pinene, β-pinene, terpinen-4-ol, and carvone oxide, which, although present in lower concentrations, play important roles in enhancing the bioactivity and antifungal efficacy of the oil.

Oxygenated monoterpenes such as α-pinene, β-pinene, terpinen-4-ol, and carvone oxide are well-documented for their strong antimicrobial and antioxidant properties, acting through cell membrane disruption, enzyme inhibition, and oxidative stress modulation in pathogenic microorganisms. Their synergistic interaction with major compounds like piperitenone oxide likely contributes to the potent antifungal effect of M. rotundifolia essential oil against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis.

Table 1: Chemical constituents detected in MREO.

| No. | Compound | Molecular Formula | RI (exp) | Relative Peak Area (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Toluene | C7H8 | 3672 | 0.96 |

| 2 | α-Pinene | C10H16 | 8375 | 1.31 |

| 3 | Camphene | C10H16 | 9128 | 0.72 |

| 4 | β-Pinene | C10H16 | 22,341 | 1.85 |

| 5 | 1-Methyl-4-(1-methylethenyl)cyclohexene | C10H16 | 14,037 | 9.73 |

| 6 | (E)-3,7-Dimethyl-1,3,6-octatriene | C10H16 | 14,755 | 0.84 |

| 7 | 1-Octen-3-yl acetate butanal propylhydrazone | C10H16N2O2 | 19,935 | 0.91 |

| 8 | Terpinen-4-ol | C10H18O | 24,509 | 0.51 |

| 9 | n-Valeric acid, cis-3-hexenyl ester | C11H20O2 | 28,541 | 1.71 |

| 10 | cis-Carvone oxide | C10H14O2 | 29,730 | 4.40 |

| 11 | α-Pinene | C10H16 | 8375 | 1.31 |

| 12 | 2,4-Dimethylfuran | C6H8O | 30,454 | 1.70 |

| 13 | Isophorone | C9H14O | 30,972 | 0.77 |

| 14 | 4-Acetyl-1-methyl-1-cyclohexene | C9H14O | 32,031 | 1.04 |

| 15 | Piperitenone oxide | C10H14O2 | 37,729 | 62.53 |

| 16 | (Z)-3-Methyl-2-(pentenyl)cyclopenten-1-one | C11H17O | 39,418 | 1.43 |

| 17 | (E)-Caryophyllene | C15H24 | 40,160 | 1.63 |

| 18 | cis-1,2,6-Trimethylpiperidine | C8H17N | 41,437 | 0.39 |

| 19 | (+)-Epi-bicyclosesquiphellandrene | C15H24 | 42,921 | 1.55 |

| 20 | β-Cubebene | C15H24 | 44,004 | 1.80 |

| 21 | Cycloheptasiloxane, tetradecamethyl- | C14H42O7Si7 | 45,322 | 0.66 |

| 22 | cis-Calamenene | C15H22 | 46,564 | 1.09 |

| 23 | Silane, [[4-[1,2-bis[(trimethylsilyl)oxy]ethyl]-1,2-phenylene]bis(oxy)]bis[trimethyl- | C20H42O4Si4 | 54,905 | 0.44 |

RIexp = experimentally measured retention index (this work, C8–C40 n-alkane series); RIlit= literature/library retention index used for confirmation.

Figure 3: Chromatogram of Mentha rotundifolia essential oil.

The exceptional abundance of piperitenone oxide (62.53%) in Mentha rotundifolia essential oil (MREO) aligns with previous reports describing this compound as a chemical marker of M. rotundifolia chemotypes, particularly those from Algeria, the Mediterranean Basin, and South America [32,33]. Piperitenone oxide is a key oxygenated monoterpene known for its strong antimicrobial and antifungal activity, especially against plant-pathogenic fungi, including several Fusarium species [34]. Its predominance in the present study strongly correlates with the high antifungal efficiency observed against F. oxysporum f. sp. albedinis, the causal agent of Bayoud disease.

The dose-dependent inhibition (7.82–83.41%) and complete suppression (100%) of fungal growth at 1.75 μL/mL confirm that piperitenone oxide plays a dominant role in MREO’s fungicidal activity. This compound’s biological action is primarily attributed to its lipophilic structure, which facilitates penetration into fungal membranes, leading to altered membrane integrity, ion leakage, and inhibition of key metabolic enzymes involved in respiration and cell wall synthesis. These effects collectively impair spore germination and mycelial development, resulting in the observed growth inhibition.

In addition to piperitenone oxide, the presence of other bioactive oxygenated monoterpenes, including α-pinene (1.31%), β-pinene (1.85%), terpinen-4-ol (0.51%), and carvone oxide (4.40%)—significantly enhances the oil’s overall antifungal potential. These minor constituents act synergistically with major compounds, amplifying antimicrobial efficacy through multi-target interactions that disrupt cellular structures, denature fungal proteins, and induce oxidative stress. Such synergy is well documented in complex natural matrices, where the combined effect of several terpenoids exceeds that of individual components.

This synergistic phenomenon has also been observed in other essential oils rich in oxygenated monoterpenes, such as those from Origanum vulgare, Thymus vulgaris, and Lavandula angustifolia, which exhibit potent antifungal activity against Fusarium, Aspergillus, and Candida species [35,36]. Like MREO, these oils contain compounds such as carvacrol, thymol, linalool, and 1,8-cineole, which share similar hydrophobic and reactive oxygen species (ROS)-modulating properties, further supporting the hypothesis that antifungal potency in essential oils is driven by the collective and complementary action of oxygenated monoterpenes.

The correlation between chemical composition and antifungal activity in this study underscores the chemotype-specific efficacy of MREO. The dominance of piperitenone oxide, supported by a suite of synergistic minor constituents, explains the observed differences in sensitivity among F. oxysporum isolates (DL50 values ranging from 0.95 to 1.58 μL/mL). Isolates with lower DL50 values may be more susceptible to oxidative or structural stress induced by the oil’s active terpenoids.

Environmental factors play a crucial role in determining MREO’s chemical composition and biological activity. Variations in climate, soil composition, altitude, and sunlight exposure influence the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in Mentha species [37]. For instance, samples from coastal or humid regions tend to accumulate higher proportions of oxygenated monoterpenes, whereas plants grown in arid or high-altitude environments often display increased sesquiterpene and ketone contents. Previous studies in Algeria reported piperitenone oxide contents ranging from 23.5% (Miliana) to 38.6% (Rouina) [36], illustrating the strong effect of ecological and edaphic conditions on essential oil profiles.

The detection of sesquiterpenes such as trans-caryophyllene (1.63%), β-cubebene (1.80%), and (+)-epi-bicyclosesquiphellandrene (1.55%) further supports the bioactivity of MREO. These compounds contribute anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, with trans-caryophyllene notably acting as a CB2receptor agonist comparable to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [38]. Ketones such as carvone oxide (4.40%) and isophorone (0.77%) also reinforce MREO’s antimicrobial potential by interfering with fungal enzymatic systems and membrane-bound processes [39,40,41,42].

Finally, the mode of antifungal action of MREO can be attributed to membrane disruption and enzyme inhibition mechanisms, as supported by its chemical composition. Oxygenated monoterpenes readily integrate into fungal lipid bilayers, altering permeability and causing leakage of cellular contents, while also inhibiting key enzymatic pathways responsible for ergosterol biosynthesis and cell wall maintenance. This multi-targeted mechanism reduces the likelihood of resistance development and supports the use of MREO as a natural, eco-friendly alternative to synthetic fungicides for managing Bayoud disease.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that the chemical richness and compositional balance of MREO dominated by piperitenone oxide and supported by synergistic oxygenated monoterpenes—are directly responsible for its potent antifungal, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory properties. This work thus reinforces M. rotundifolia essential oil as a promising biocontrol agent in sustainable agriculture and as a natural ingredient for pharmaceutical and food preservation applications.

3.3 Antifungal Activity: Mycelial Growth Inhibition

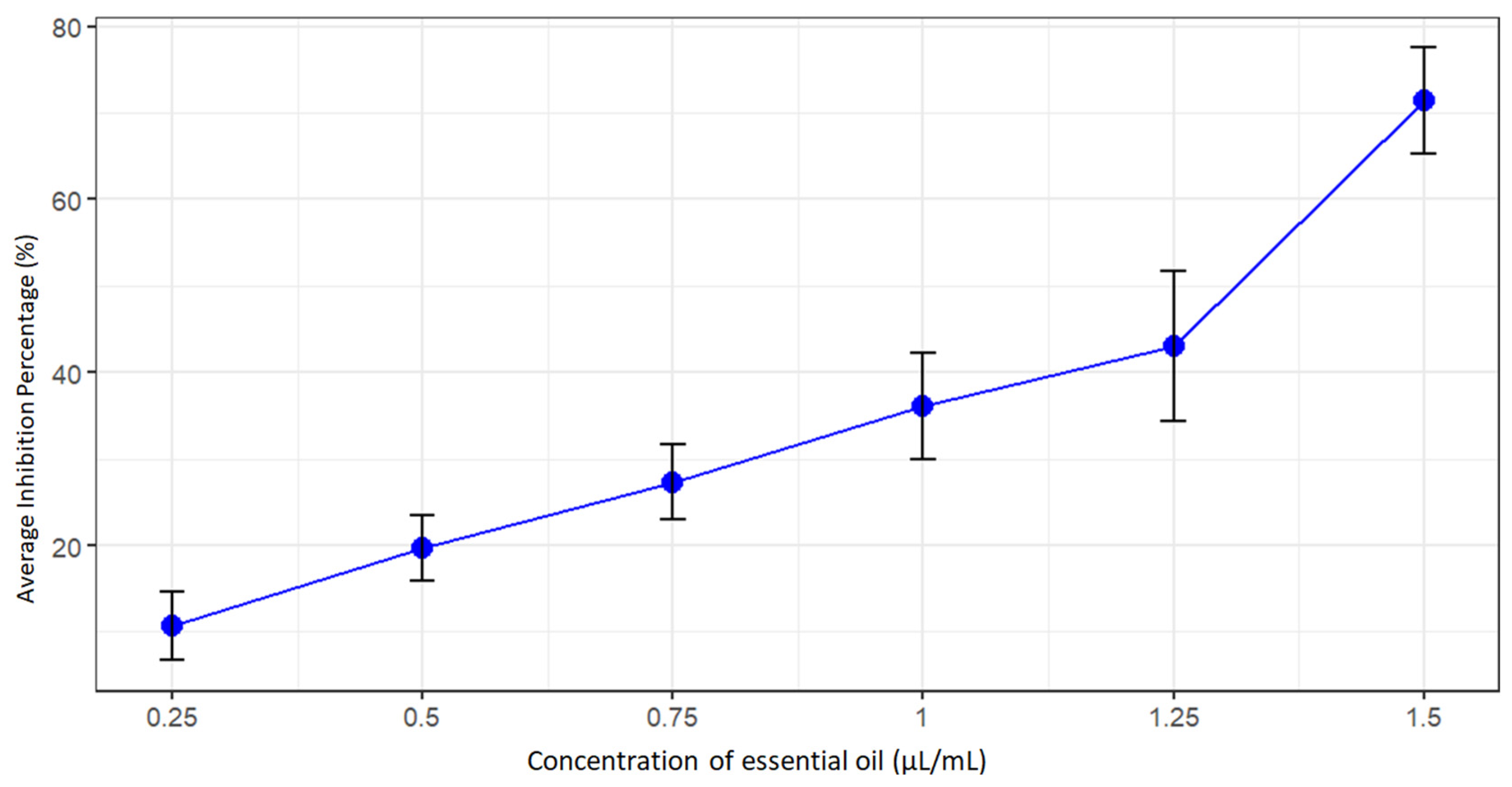

The antifungal activity of Mentha rotundifolia essential oil (MREO) was assessed against ten field isolates of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis (Foa) using the poisoned food technique at seven concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, and 1.5 μL/mL).

The results revealed a strong and dose-dependent inhibition of mycelial growth across all isolates, with inhibition percentages ranging from 7.82% to 83.41% after seven days of incubation (Fig. 4). The antifungal effect intensified progressively with increasing concentrations of the essential oil. At 1.75 μL/mL, complete inhibition (100%) of mycelial growth was achieved in all isolates, confirming the potent fungicidal activity of MREO.

Figure 4: Visualization of the inhibition rate of the essential oil as a function of the Concentration applied for all isolates.

These findings demonstrate that M. rotundifolia essential oil exhibits broad-spectrum antifungal efficacy against F. oxysporum f. sp. albedinis, likely attributed to its high content of bioactive oxygenate monoterpenes such as piperitenone oxide, terpinen-4-ol, α-pinene, and β-pinene, which are known to disrupt fungal cell membranes and interfere with metabolic processes.

Statistical analysis (one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test, p < 0.05) confirmed significant differences in antifungal responses among isolates. The calculated DL50 values (concentration required to inhibit 50% of mycelial growth) ranged from 0.95 to 1.58 μL/mL (Table 2), highlighting variability in isolate sensitivity to the essential oil.

Isolate S20/17 exhibited the lowest DL50 value (0.95 μL/mL), indicating the highest susceptibility, while isolates S24/18, S30/18, and S40 showed higher DL50 values (up to 1.58 μL/mL), reflecting relatively lower sensitivity. These inter-isolate differences may be attributed to genetic variability among F. oxysporum populations, physiological adaptation mechanisms, or differences in cell wall composition and permeability to lipophilic essential oil components.

Overall, the results confirm that M. rotundifolia essential oil exerts strong antifungal activity against F. oxysporum f. sp. albedinis at low concentrations, with complete inhibition achieved at 1.75 μL/mL, demonstrating its potential as a natural, eco-friendly alternative to synthetic fungicides for managing Bayoud disease in date palms.

Table 2: DL50 Values for Different Isolates.

| Isolate | Rep 1 | Rep 2 | Rep 3 | Mean ± SD (DL50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1/17 | 1.281 | 1.262 | 1.259 | 1.268 ± 0.012 |

| S20/17 | 1.009 | 0.899 | 0.963 | 0.957 ± 0.056 |

| S20/18 | 1.329 | 1.366 | 1.497 | 1.397 ± 0.088 |

| S21/17 | 1.244 | 1.334 | 1.319 | 1.299 ± 0.046 |

| S24/18 | 1.767 | 1.405 | 1.591 | 1.587 ± 0.147 |

| S27/18 | 1.380 | 1.337 | 1.236 | 1.318 ± 0.075 |

| S28/17 | 1.180 | 1.214 | 1.342 | 1.246 ± 0.068 |

| S30/18 | 1.513 | 1.509 | 1.579 | 1.533 ± 0.040 |

| S40 | 1.212 | 1.466 | 1.556 | 1.411 ± 0.145 |

| S8/18 | 1.225 | 1.138 | 1.218 | 1.193 ± 0.046 |

Numerous studies have investigated the antifungal activity of natural products such as microbial metabolites, plant extracts, and essential oils against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis (F.o.a), the causative agent of Bayoud disease in date palms. Despite these efforts, effective biological control strategies remain limited. Essential oils, known for their broad-spectrum antimicrobial properties, present promising alternatives to synthetic fungicides. Previous research has demonstrated varying degrees of inhibitory activity among different essential oils. For instance, essential oils derived from Origanum compactum, Myrtus communis, Thymus satureioides, Lavandula dentata, and Rosmarinus officinalis have shown differential efficacy against F.o.a. Notably, O. compactum exhibited the highest antifungal activity with a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of 2.5 μL/mL, while the other oils had MICs ranging from 10 to 40 μL/mL [43]. Lakhdari et al. reported significant antifungal activity of Cladanthus eriolepis essential oil against F.o.a, with inhibition rates ranging from 35.80% to 86.20% at concentrations of 2000 and 4000 ppm, respectively, suggesting its potential as a natural agent for managing Bayoud disease [44]. Similarly, Tanacetum annuum (Blue Tansy) essential oil demonstrated strong antifungal effects at low concentrations, with an MIC of 3.33 μL/mL [45]. Essential oils from Artemisia herba-alba, Foeniculum vulgare, and Citrus sinensis were also evaluated, with A. herba-alba showing the most potent antifungal activity, having the lowest LC50 value (0.1 μL/mL), although all three oils presented MIC and CMF values above 50 μL/mL [46]. Hassan et al. reported MIC values for Rosmarinus officinalis (0.2 g/L), Salvia officinalis (2.5 g/L), Lavandula dentata (0.6 g/L), and Cymbopogon citratus (0.5 g/L). The lethal concentrations (MLC) for L. dentata and C. citratus were 1.75 g/L and 0.95 g/L, respectively, indicating their strong antifungal potential [47]. These results collectively highlight the inhibitory effects of various essential oils on the mycelial growth of F.o.a. Consistent with these findings, our study confirms the pronounced antifungal activity of Mentha rotundifolia essential oil (OEMR), achieving 100% inhibition at a concentration of just 1.75 μL/mL—a lower dose compared to those reported in other studies. Several authors have examined the antimicrobial properties of essential oils from different Mentha species. MacNair et al. demonstrated that Mentha spicata essential oil exhibits a dose-dependent inhibitory effect, with inhibition rates reaching 90% against Fusarium solani and F. oxysporum, and 100% against Alternaria citri at 20 μL/mL. The IC50 values ranged between 8 and 15 μL/mL [48]. Jeldi et al. also noted antifungal effects of Mentha pulegium extracts against Alternaria alternata, Botrytis cinerea, Penicillium expansum, and Fusarium culmorum [49]. Similarly, Akotowanou et al. evaluated the essential oils of Pimenta racemosa and Mentha piperita against F. oxysporum in tomato, reporting minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimum fungicidal concentration (MFC) values of 0.75 μL/mL and 1.25 μL/mL for P. racemosa, and 3.75 μL/mL and 5 μL/mL for M. piperita, respectively [50]. The notable antifungal activity of Mentha rotundifolia essential oil is likely attributed to its chemical composition, particularly its richness in oxygenated monoterpenes. These compounds, along with sesquiterpenes containing aromatic rings and phenolic hydroxyl groups, are capable of forming hydrogen bonds with fungal enzymes, thereby interfering with essential biological functions [51,52,53]. Chibane et al. further supported these findings by demonstrating the inhibitory effects of various monoterpenes on mycelial growth in multiple phytopathogenic fungi [54]. Our study shows that M. rotundifolia essential oil exhibits potent antifungal activity against F.o.a isolates, with a notably low DL50 value. GC-MS analysis revealed that this efficacy is largely due to the presence of highly fungitoxic compounds, especially Piperitenone oxide, which was identified as the major constituent. This result is in agreement with previous studies that also identified Piperitenone oxide as a dominant compound in Mentha species [50,55]. Piperitenone oxide is recognized for its strong antimicrobial, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities [56]. The high abundance of this compound in M. rotundifolia essential oil likely plays a crucial role in its therapeutic efficacy, particularly in countering microbial resistance and oxidative stress. Similar findings have been reported for Mentha longifolia and Mentha spicata, reinforcing the important role of Piperitenone oxide across the Mentha genus [57].

This study confirms that M. rotundifolia essential oil (MREO) possesses strong natural antifungal potential against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis, the causative agent of Bayoud disease in date palms. GC–MS analysis revealed a complex and bioactive chemical composition, dominated by oxygenated monoterpenes such as piperitenone oxide, carvone oxide, α-pinene, and β-pinene, alongside sesquiterpenes like trans-caryophyllene. These constituents are well known for their broad-spectrum antimicrobial, antifungal, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities, which likely act synergistically to enhance the overall antifungal efficacy of the oil.

The antifungal bioassays demonstrated dose-dependent inhibition of mycelial growth, with complete inhibition (100%) achieved at 1.75 μL/mL, confirming MREO’s potent fungicidal action. Variations in isolate sensitivity (DL50 = 0.95–1.58 μL/mL) suggest that chemical composition and synergistic interactions among both major and minor constituents play a crucial role in determining antifungal performance.

Given these results, MREO can be proposed as a promising natural biofungicide for the sustainable management of Bayoud disease in date palm cultivation. Its effectiveness, combined with its renewable and eco-friendly nature, supports its integration into environmentally safe agricultural practices as an alternative to conventional synthetic fungicides.

However, the chemical variability of MREO—influenced by geographical origin, climate, soil composition, harvest time, and post-harvest processing—highlights the importance of standardizing extraction and formulation methods. Such standardization is essential to ensure reproducibility, chemical stability, and consistent biological efficacy in future applications.

Overall, this study provides a scientific foundation for the development of MREO-based antifungal formulations, encouraging further pharmacological, toxicological, and field evaluations to validate its safety, effectiveness, and potential scalability for use in both agricultural biocontrol and phytopharmaceutical products.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Hafida Khelafi conceived and designed the study. Hafida Khelafi and Mustapha Mounir Bouhenna performed the methodology. Hafida Khelafi validated the results. Hayet Meamiche carried out the formal analysis. Hafida Khelafi, Said Boudeffeur and Wassima Lakhdari performed the investigation. Hafida Khelafi and Wassima Lakhdari provided resources. Hafida Khelafi, Mustapha Mounir Bouhenna and Wassima Lakhdari curated the data. Hafida Khelafi and Salah Neghmouche Nacer drafted the original manuscript. Meriam Laouar and Wassima Lakhdari reviewed and edited the manuscript. Hafida Khelafi and Wassima Lakhdari prepared the visualizations. Hafida Khelafi supervised the work. Hafida Khelafi and Said Boudeffeur administered the project. Hafida Khelafi acquired funding for resources. Hafida Khelafi, Mustapha Mounir Bouhenna and Wassima Lakhdari contributed to the data search. Meriam Laouar carried out the critical revision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Alotaibi KD , Alharbi HA , Yaish MW , Ahmed I , Alharbi SA , Alotaibi F , et al. Date palm cultivation: a review of soil and environmental conditions and future challenges. Land Degrad Dev. 2023; 34( 9): 2431– 44. doi:10.1002/ldr.4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Mihu I , Deuri M , Borah D , Wangpan T , Kushwaha S , Tangjang S . Beyond harvest: unlocking economic value through value addition in wild edible plants for sustainable livelihood in Arunachal Himalayas. Genet Resour Crop Evol. 2025; 72( 2): 1521– 39. doi:10.1007/s10722-024-02010-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Kotagama HB , Al-Alawi AJT , Boughanmi H , Zekri S , Mbaga M , Jayasuriya H . Economic analysis determining the optimal replanting age of date palm. J Agric Mar Sci. 2014; 19( 1): 51– 61. doi:10.24200/jams.vol19iss0pp51-61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hessane A , El Youssefi A , Farhaoui Y , Aghoutane B . Artificial intelligence-empowered date palm disease and pest management. In: Internet of Things and big data analytics for a green environment. Boca Raton, FL, USA: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2024. p. 273– 89. doi:10.1201/9781032656830-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Mendel Z , Voet H , Nazarian I , Dobrinin S , Ment D . Comprehensive analysis of management strategies for red palm weevil in date palm settings, emphasizing sensor-based infestation detection. Agriculture. 2024; 14( 2): 260. doi:10.3390/agriculture14020260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Rivers M , Newton AC , Oldfield S , Global Tree Assessment Contributors . Scientists’ warning to humanity on tree extinctions. Plants People Planet. 2023; 5( 4): 466– 82. doi:10.1002/ppp3.10314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Kavvadias V , Le Guyader E , El Mazlouzi M , Gommeaux M , Boumaraf B , Moussa M , et al. Using date palm residues to improve soil properties: the case of compost and biochar. Soil Syst. 2024; 8( 3): 69. doi:10.3390/soilsystems8030069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Song B , Yang H , Wang W , Yang Y , Qin M , Li F , et al. Disinfection byproducts formed from oxidation of pesticide micropollutants in water: precursor sources, reaction kinetics, formation, influencing factors, and toxicity. Chem Eng J. 2023; 475: 146310. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.146310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Romani M , Warscheid T , Nicole L , Marcon L , Di Martino P , Suzuki MT , et al. Current and future chemical treatments to fight biodeterioration of outdoor building materials and associated biofilms: moving away from ecotoxic and towards efficient, sustainable solutions. Sci Total Environ. 2022; 802: 149846. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.149846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gupta I , Singh R , Muthusamy S , Sharma M , Grewal K , Singh HP , et al. Plant essential oils as biopesticides: applications, mechanisms, innovations, and constraints. Plants. 2023; 12( 16): 2916. doi:10.3390/plants12162916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Fazal H , Akram M , Ahmad N , Qaisar M , Kanwal F , Rehman G , et al. Nutritionally rich biochemical profile in essential oil of various Mentha species and their antimicrobial activities. Protoplasma. 2023; 260( 2): 557– 70. doi:10.1007/s00709-022-01799-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Gupta S , Kumar A , Gupta AK , Jnanesha AC , Talha M , Srivastava A , et al. Industrial mint crop revolution, new opportunities, and novel cultivation ambitions: a review. Ecol Genet Genom. 2023; 27: 100174. doi:10.1016/j.egg.2023.100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Deshmukh VP . Biomolecules and therapeutics of Mentha rotundifolia (L.) Huds. In: Bioactives and pharmacology of lamiaceae. Palm Bay, FL, USA: Apple Academic Press; 2023. p. 111– 27. [Google Scholar]

14. Chatterjee D , Mitra A . Unveiling physiological responses and modulated accumulation patterns of specialized metabolites in Mentha rotundifolia acclimated to sub-tropical environment. Physiol Mol Biol Plants. 2024; 30( 8): 1363– 81. doi:10.1007/s12298-024-01489-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Tafrihi M , Imran M , Tufail T , Gondal TA , Caruso G , Sharma S , et al. The wonderful activities of the genus Mentha: not only antioxidant properties. Molecules. 2021; 26( 4): 1118. doi:10.3390/molecules26041118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yakhlef G , Hambaba L , Pinto DCGA , Silva AMS . Chemical composition and insecticidal, repellent and antifungal activities of essential oil of Mentha rotundifolia (L.) from Algeria. Ind Crops Prod. 2020; 158: 112988. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2020.112988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Nacer SN , Zobeidi A , Bensouici C , Ben Amor ML , Haouat A , Louafi F , et al. In vitro antioxidant and antibacterial activities of ethanolic extracts from the leaves and stems of Oudneya Africana R. growing in the El Oued (Algeria). Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024; 14( 23): 29911– 22. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-04856-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Wassima L , Neghmouche Nacer S , Abderrezzak A , Bachir H , Dehliz A , Hammi H , et al. Unveiling the therapeutic potential of Haloxylon articulatum extract: a comprehensive study on its phytochemical composition, antioxidant, antifungal, and antibacterial activities. Int J Food Prop. 2024; 27( 1): 1290– 301. doi:10.1080/10942912.2024.2389297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Lakhdari W , Mounir Bouhenna M , Salah Neghmouche N , Dehliz A , Benyahia I , Bendif H , et al. Chemical composition and insecticidal activity of Artemisia absinthium L. essential oil against adults of Tenebrio molitor L. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2024; 116: 104881. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2024.104881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Nacer SN , Wassima L , Boussebaa W , Abadi A , Benyahia I , Mouhoubi D , et al. Phytochemical screening, antioxidant, antibacterial, and antifungal properties of the Cymbopogon citratus methanolic extract. Pharmacol Res Nat Prod. 2024; 5: 100094. doi:10.1016/j.prenap.2024.100094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jiang H , Zhong S , Schwarz P , Chen B , Rao J . Antifungal activity, mycotoxin inhibitory efficacy, and mode of action of hop essential oil nanoemulsion against Fusarium graminearum. Food Chem. 2023; 400: 134016. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.134016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Naima B , Abdelkrim R , Ouarda B , Salah NN , Larbi BAM . Chemical composition, antimicrobial, antioxidant and anticancer activities of essential oil from Ammodaucus leucotrichus Cosson & Durieu (Apiaceae) growing in South Algeria. Bull Chem Soc Ethiop. 2019; 33( 3): 541– 9. doi:10.4314/bcse.v33i3.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. El Aanachi S , Gali L , Nacer SN , Bensouici C , Dari K , Aassila H . Phenolic contents and in vitro investigation of the antioxidant, enzyme inhibitory, photoprotective, and antimicrobial effects of the organic extracts of Pelargonium graveolens growing in Morocco. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2020; 29: 101819. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Alamgir ANM . Methods of qualitative and quantitative analysis of plant constituents. In: Therapeutic use of medicinal plants and their extracts. Vol.2. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2018. p. 721– 804. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92387-1_9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Pyka A . Detection progress of selected drugs in TLC. BioMed Res Int. 2014; 2014( 1): 732078. doi:10.1155/2014/732078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mesquita K , Feitosa B , Cruz J , Ferreira O , Franco C , Cascaes M , et al. Chemical composition and preliminary toxicity evaluation of the essential oil from Peperomia circinnata link var. circinnata. (Piperaceae) in Artemia salina leach. Molecules. 2021; 26( 23): 7359. doi:10.3390/molecules26237359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Riahi L , Elferchichi M , Ghazghazi H , Jebali J , Ziadi S , Aouadhi C , et al. Phytochemistry, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of the essential oils of Mentha rotundifolia L. in Tunisia. Ind Crops Prod. 2013; 49: 883– 9. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.06.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Brahmi F , Lounis N , Mebarakou S , Guendouze N , Yalaoui-Guellal D , Madani K , et al. Impact of growth sites on the phenolic contents and antioxidant activities of three Algerian Mentha species (M. pulegium L., M. rotundifolia (L.) Huds., and M. spicata L.). Front Pharmacol. 2022; 13: 886337. doi:10.3389/fphar.2022.886337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Soilhi Z , Rhimi A , Heuskin S , Fauconnier ML , Mekki M . Essential oil chemical diversity of Tunisian Mentha spp. collection. Ind Crops Prod. 2019; 131: 330– 40. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2019.01.041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hassani FZE . Characterization, activities, and ethnobotanical uses of Mentha species in Morocco. Heliyon. 2020; 6( 11): e05480. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Retta DS , González SB , Guerra PE , van Baren CM , Di Leo Lira P , Bandoni AL . Essential oils of native and naturalized Lamiaceae species growing in the Patagonia region (Argentina). J Essent Oil Res. 2017; 29( 1): 64– 75. doi:10.1080/10412905.2016.1185471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Fatiha B , Khodir M , Nabila D , Sabrina I , Fatma H , Mohmed C , et al. Assessment of the chemical composition and in vitro antioxidant activity of Mentha rotundifolia (L.) Huds essential oil from Algeria. J Essent Oil Bear Plants. 2016; 19( 5): 1251– 60. doi:10.1080/0972060X.2015.1108878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Aouadi G , Haouel S , Soltani A , Ben Abada M , Boushih E , Elkahoui S , et al. Screening for insecticidal efficacy of two Algerian essential oils with special concern to their impact on biological parameters of Ephestia kuehniella (Zeller) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). J Plant Dis Prot. 2020; 127( 4): 471– 82. doi:10.1007/s41348-020-00340-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Božović M , Pirolli A , Ragno R . Mentha suaveolens ehrh. (Lamiaceae) essential oil and its main constituent piperitenone oxide: biological activities and chemistry. Molecules. 2015; 20( 5): 8605– 33. doi:10.3390/molecules20058605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Bouhlali EDT , Derouich M , Ben-Amar H , Meziani R , Essarioui A . Exploring the potential of using bioactive plant products in the management of Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. albedinis: the causal agent of Bayoud disease on date palm (Phoenix dactylifera L.). Beni Suef Univ J Basic Appl Sci. 2020; 9( 1): 46. doi:10.1186/s43088-020-00071-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Brada M , Bezzina M , Marlier M , Lognay GC . Chemical composition of the leaf oil of Mentha rotundifolia (L.) from Algeria. J Essent Oil Res. 2006; 18( 6): 663– 5. doi:10.1080/10412905.2006.9699198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Singh AK , Kumar P , Rajput VD , Mishra SK , Tiwari KN , Singh AK , et al. Phytochemicals, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory studies, and identification of bioactive compounds using GC-MS of ethanolic novel polyherbal extract. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2023; 195( 7): 4447– 68. doi:10.1007/s12010-023-04363-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Deen JI , Zawad ANMS , Uddin M , Chowdhury MAH , Al Araby SQ , Rahman MA . Terpinen-4-ol, a volatile terpene molecule, extensively electrifies the biological systems against the oxidative stress-linked pathogenesis. Adv Redox Res. 2023; 9: 100082. doi:10.1016/j.arres.2023.100082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Baradaran Rahimi V , Askari VR . A mechanistic review on immunomodulatory effects of selective type two cannabinoid receptor β-caryophyllene. Biofactors. 2022; 48( 4): 857– 82. doi:10.1002/biof.1869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Houti H , Ghanmi M , Satrani B , El Mansouri F , Cacciola F , Sadiki M , et al. Moroccan endemic Artemisia herba-alba essential oil: GC-MS analysis and antibacterial and antifungal investigation. Separations. 2023; 10( 1): 59. doi:10.3390/separations10010059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lechhab T , Lechhab W , Cacciola F , Salmoun F . Sets of internal and external factors influencing olive oil (Olea europaea L.) composition: a review. Eur Food Res Technol. 2022; 248( 4): 1069– 88. doi:10.1007/s00217-021-03947-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Hou T , Sana SS , Li H , Xing Y , Nanda A , Netala VR , et al. Essential oils and its antibacterial, antifungal and anti-oxidant activity applications: a review. Food Biosci. 2022; 47: 101716. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2022.101716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Miguel CB , Vilela GP , Almeida LM , Moreira MA , Silva GP , Miguel-Neto J , et al. Adaptative divergence of Cryptococcus neoformans: phenetic and metabolomic profiles reveal distinct pathways of virulence and resistance in clinical vs. environmental isolates. J Fungi. 2025; 11( 3): 215. doi:10.3390/jof11030215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Lakhdari W , Neghmouche Nacer S , Benyahia I , Hammi H , Bachir H , Mouhoubi D , et al. Characterization and optimization of L-asparaginase production by endophytic Fusarium sp3 isolated from Malcolmia aegyptiaca of southeast Algeria: potential for acrylamide mitigation in food processing. Food Sci Nutr. 2025; 13( 8): e70792. doi:10.1002/fsn3.70792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Goyal M , Singh I , Chauhan SB . Beyond traditional remedies: blue tansy oil’s progressive approach to acne. Curr Funct Foods. 2025; 4: e26668629333758. doi:10.2174/0126668629333758241213073022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Abu-Darwish MS , Cabral C , Gonçalves MJ , Cavaleiro C , Cruz MT , Efferth T , et al. Artemisia herba-alba essential oil from Buseirah (South Jordan): chemical characterization and assessment of safe antifungal and anti-inflammatory doses. J Ethnopharmacol. 2015; 174: 153– 60. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2015.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Hassan B , Zouheir C , Redouane B , Mohammed C , Mustapha EM , Elbachir H . Antifungal activity of the essential oils of Rosmarinus officinalis, Salvia officinalis, Lavandula dentata and Cymbopogon citratus against the mycelial growth of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis. Arab J Med Aromat Plants. 2022; 8( 1): 108– 33. [Google Scholar]

48. MacNair CR , Rutherford ST , Tan MW . Alternative therapeutic strategies to treat antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2024; 22( 5): 262– 75. doi:10.1038/s41579-023-00993-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Jeldi L , Taarabt KO , Mazri MA , Ouahmane L , Alfeddy MN . Chemical composition, antifungal and antioxidant activities of wild and cultivated Origanum compactum essential oils from the municipality of Chaoun, Morocco. South Afr J Bot. 2022; 147: 852– 8. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2022.03.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Akotowanou OCA , Adjou ES , Sessou P , Kougblenou SD , Olubi AB , Michels F , et al. Antifungal properties of Pimenta racemosa (Mill.) and Mentha × piperita (L.) essential oils against Fusarium oxysporum causing tomato fruit rot. J Adv Biol Biotechnol. 2023; 26( 11): 50– 9. doi:10.9734/jabb/2023/v26i11666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Ettakifi H , Abbassi K , Maouni S , Erbiai EH , Rahmouni A , Legssyer M , et al. Chemical characterization and antifungal activity of blue tansy (Tanacetum annuum) essential oil and crude extracts against Fusarium oxysporum f.sp. albedinis, an agent causing Bayoud disease of date palm. Antibiotics. 2023; 12( 9): 1451. doi:10.3390/antibiotics12091451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Perestrelo R , Sousa P , Hontman N , Câmara JS . Composition of different species of Lamiaceae plant family: a potential biosource of terpenoids and antifungal agents. In: Advances in antifungal drug development. Singapore: Springer Nature Singapore; 2024. p. 41– 63. doi:10.1007/978-981-97-5165-5_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Ramos da Silva LR , Ferreira OO , Cruz JN , de Jesus Pereira Franco C , Oliveira dos Anjos T , Cascaes MM , et al. Lamiaceae essential oils, phytochemical profile, antioxidant, and biological activities. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021; 2021( 1): 6748052. doi:10.1155/2021/6748052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Chibane E , Essarioui A , Ouknin M , Boumezzourh A , Bouyanzer A , Majidi L . Antifungal activity of Asteriscus graveolens (Forssk.) Less essential oil against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. albedinis, the causal agent of “Bayoud” disease on date palm. Moroc J Chem. 2020; 8( 2): 2456– 65. [Google Scholar]

55. Mokhtari N , El Farissi H , Essalmani H , Ouazzani Tayebi ET , El Idrissi El Berkani M , Mdarhri Y , et al. Chemical profiling and synergistic antifungal activity of essential oils from Moroccan aromatic plants against peanut-associated fungi. Pharmacol Res Nat Prod. 2025; 7: 100277. doi:10.1016/j.prenap.2025.100277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Wang L , Yun H , Liu Y , Zhang W . Antifungal activity and mechanism of grape seed polyphenol-copper complex. Food Biosci. 2025; 72: 107521. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2025.107521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Djekoun M , Boughendjioua H , Boubekeur MS , Djekoun M , Benaliouche F . Antifungal potential of essential oil of Mentha spicata (L.) in the biological control against phytopathogenic fungi. Glob Nest J. 2024; 26( 6): 1– 10. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools