Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

New Findings on the Volatilome of Persea americana Miller

1 Facultad de Agrobiología “Presidente Juárez”, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Uruapan, 60170, Michoacán, Mexico

2 Instituto de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas y Sustentabilidad, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Morelia, 58190, Michoacán, Mexico

3 Instituto Nacional de Investigaciones Forestales, Agrícolas y Pecuarias, Etla, 68200, Oaxaca, Mexico

4 Facultad de Biología, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Morelia, 58030, Michoacán, Mexico

5 Facultad de Ciencias Agropecuarias, Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo, Apatzingán, 60660, Michoacán, Mexico

* Corresponding Author: Héctor Guillén-Andrade. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Molecular Insights of Plant Secondary Metabolites: Biosynthesis, Regulation, and Applications)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 4155-4171. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.073438

Received 18 September 2025; Accepted 01 December 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) play an important role in plant survival and adaptation. They contribute to defense against pests and pathogens, tolerance to abiotic stress, and the mediation of essential ecological interactions such as pollination and attraction of dispersal agents. The complex mixture of VOCs produced by an organism, known as volatilome, varies across species, populations, and individuals, making VOCs a major factor in crop diversification and adaptation. In this context, characterizing the volatilome of crop genotypes can provide insight into their ecological associations and potential relationships with agronomic traits. In this study, the volatilome of 15 closely related ‘Hass’-type avocado variant genotypes was analyzed using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS). These genotypes had been previously characterized by agromorphological attributes such as early bearing, dwarf growth habit, and/or high productivity according to IPGRI descriptors. A total of 65 volatile compounds were identified, 18 of which—four in leaves and 14 in flowers—had not been previously reported in Persea americana. Chemical profiling allowed classification of the genotypes into eight foliar and floral chemotypes. Most dwarf genotypes, except for F4A7, exhibited distinct chemical profiles compared to the ‘Hass’ cultivar and the other variants. Correlation analyses indicated that certain compounds, including phytol (r = 0.6112) and decane (r = 0.6822), were positively associated with yield. Phytol, 2-[(8z,11z)-heptadeca-8,11-dienyl]furan, tricosane, 2,4-dimethyl-1-heptene, and decane also showed moderate associations with fruit quality traits such as size and weight, with r values ranging from 0.6585 to 0.5799. In contrast, palmitic acid, β-caryophyllene, humulene, and α-farnesene exhibited negative correlations with yield, with an average r-value of –0.5960. Furthermore, the results indicated the presence of tissue-specific compounds, with 36 volatiles detected exclusively in the floral tissue of the analyzed genotypes. These findings advance our understanding of the avocado volatilome and suggest that volatilome profiles could be used as an additional selection criterion for identifying high-performing genotypes.Keywords

Plants, through their constant interaction with biotic and abiotic factors, have developed physiological and biochemical mechanisms that constitute the basis of their vital functions and enable the synthesis of a wide diversity of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) known as volatilome [1]. This volatilome results from the interaction of ecological, evolutionary, and environmental factors [2,3]. Within this chemical diversity, primary metabolites are essential for plant growth and development [4], whereas secondary metabolites perform specialized functions including pollinator attraction, defense against pests and pathogens, recruitment of natural enemies, and mediation of intra- and interspecific interactions [2,5]. The composition and concentration of VOCs vary substantially among species, populations, and individuals [6,7]; however, domestication processes have contributed to a significant reduction in the phytochemical diversity among species [8].

In Persea americana, phytochemical studies have focused primarily on leaves and fruits, whereas other organs, particularly flowers, remain understudied [9,10]. Across the Persea genus, 363 VOCs and other metabolites have been reported in 22 species. In P. americana, 258 compounds have been identified, including 125 in pericarp, 17 in seed, 109 in foliar tissue, two in floral tissue, three in periderm, and two in roots. In foliar tissue, monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes are the most abundant compounds, with multiple functions in defense and attraction of natural enemies and pollinators. These are followed by flavonoids, which show insecticidal, repellent, and parasitoid-attracting activities. In periderm, diterpenes predominate, functioning as antifeedant compounds. Phenolics are the main components of the exocarp and seed, with antimicrobial, antifungal, insecticidal, antioxidant, and allelopathic activities, whereas terpenes dominate in the mesocarp [11,12].

In the foliar tissue of the drymifolia race, estragole accounts for up to 80% of the total concentration of the VOCs composition, regardless of genotype origin [7,13,14]. This compound is responsible for the characteristic anise-like aroma of the leaves [13] and functions as a defense mechanism, since trees with higher concentrations of this metabolite exhibit reduced incidence of galls caused by Trioza anceps [15].

In the ‘Hass’ cultivar, several VOCs have been identified across different plant organs. In the fruit, 254 compounds have been reported [10,16,17,18,19,20,21], with their distribution varying according to the tissue analyzed: in the exocarp and seed, phenolic compounds predominate, with epicatechin standing out due to its frequent occurrence and high concentrations [22]. In contrast, in the mesocarp, hexanal is the most prominent compound, associated with the fruit’s herbal aroma [17]. In foliar tissue, 113 compounds have been reported, with terpenes as the predominant group and β-caryophyllene as the most abundant, showing insecticidal activity [10,23,24]. In floral tissue, 52 compounds have been identified, with (E)-β-ocimene being both the main attractant of pollinators and the compound with the highest concentration [10]; in periderm, 36 compounds have been reported, mainly sesquiterpenes, whereas in roots, two sugars have been identified [25]. Taken together, the heterogeneous distribution of VOCs in avocado, in both presence and concentration, suggests that these compounds play specific roles in each organ [26]. Their variability may be influenced by the genetic diversity of the plant materials analyzed, the environmental conditions under which they grow [7], and the interaction between these factors [27]. Some of these compounds, in certain phenotypic combinations, have been suggested as genetic markers for beneficial agricultural traits, such as disease and pest resistance, that impact crop yield [23].

In this context, although the ‘Hass’ cultivar is globally recognized for its high productivity, broad commercial acceptance and remarkable phenotypic plasticity that has enabled its cultivation across diverse environments, current knowledge of its volatilome remains limited to individual organs and does not include its agronomically relevant variants. Furthermore, it is unknown whether ‘Hass’-type genotypes displaying contrasting phenotypic traits produce distinct VOCs profiles associated with adaptation, defense responses or agronomic value. This question is particularly relevant in Michoacán, Mexico—the world’s leading avocado-producing region—where climate variability and the increasing incidence and geographic expansion of pests and diseases driven by climate change are challenging the long-term stability of production systems. Under these conditions, reliance on a single cultivar such as ‘Hass’, despite its plasticity, becomes a potential risk.

Therefore, the identification and evaluation of ‘Hass’-type variants naturally adapted to specific microclimates within Michoacán is biologically and agronomically strategic. This region comprises ten homogeneous avocado production zones that differ in altitude, temperature, humidity, and disease pressure [28], and the genotypes analyzed in this study originate from several of these zones. These materials exhibit agronomically desirable traits—such as dwarf growth habit, early bearing, and high yield—and have undergone natural or farmer-driven selection under local environmental conditions, suggesting a degree of adaptive advantage. Although these genotypes have been morphologically characterized (unpublished data), their volatilome and metabolomic profiles remain unexplored. Determining whether their VOCs composition diverges from that of the standard ‘Hass’ cultivar is essential to understand potential links between chemical phenotype, genetic background and adaptive or productive traits. This knowledge may also support the development of selection and breeding strategies that integrate both morphological and chemical profiles, ensuring greater resilience and stability of avocado production systems.

Accordingly, the objective of the present study was to characterize the foliar and floral volatilome of 15 ‘Hass’-type avocado variant genotypes that exhibit competitive agromorphological traits relative to the ‘Hass’ cultivar.

The experiments were conducted at the Unidad de Investigaciones Avanzadas in Agrobiotecnología of the Facultad de Agrobiología “Presidente Juárez” (FAPJ)–UMSNH, in Uruapan, Michoacán, México, while the VOCs analyses were performed at the Instituto de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas y Sustentabilidad-UNAM, campus Morelia, Michoacán, México. The genetic material consisted of 15 ‘Hass’-type avocado variant genotypes and a typical ‘Hass’ genotype used as a reference (Table 1), all established in the orchard located at the FAPJ facilities, at coordinates 19°22′35.4′′ N and 102°01′39.2′′ W. It is important to emphasize that only one individual was sampled per genotype. Although this approach is commonly employed in exploratory studies focused on identifying variability among genotypes, it constitutes a notable limitation, particularly considering the allogamous nature of the species. The use of a single tree per genotype does not allow assessment of intra-genotypic variability and reduces the statistical robustness required to generalize the findings. Therefore, the results should be interpreted with caution, and future studies are strongly recommended to include multiple biological replicates per genotype to validate and extend these preliminary observations.

Table 1: Outstanding morphological and productive characteristics of 15 avocado genotypes and the ‘Hass’ cultivar established in Uruapan, Michoacán, México.

| Variant | Tree Height (m) | Flowering Type | Average Fruit Weight (g) | Yield Average (kg Tree−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F2A3 | 3.18 | B | 204.48 | 94 |

| F2A5 | 2.86 | B | 159.28 | 92 |

| F3A2 | 3.24 | A | 181.33 | 82 |

| F3A4 | 2.81 | B | 154.60 | 72 |

| F3A5 | 2.11 | B | 153.33 | 42 |

| F4A7 | 2.86 | B | 188.58 | 116 |

| F7A4 | 3.69 | B | 290.55 | 137 |

| F11A3 | 3.89 | B | 202.13 | 124 |

| F11A8 | 3.38 | B | 212.98 | 184 |

| F12A8 | 3.87 | B | 174.75 | 92 |

| F12A11 | 3.93 | B | 177.63 | 110 |

| F12A13 | 4.9 | B | 205.30 | 134 |

| F13A9 | 4.15 | B | 151.75 | 111 |

| F14A4 | 4.21 | B | 185.18 | 117 |

| F14A7 | 4.66 | B | 160.65 | 80 |

| ‘Hass’ | 6.41 | A | 226.68 | 111 |

For the VOCs analysis, mature leaves and floral buds from inflorescences at the pre-anthesis developmental stage were collected from each genotype, with only one individual sampled per avocado variant. A total of 20 leaves were collected per individual, sampled randomly from each canopy quadrant (five leaves per quadrant), and three inflorescences were collected per quadrant, resulting in 12 inflorescences per individual. The grams of leaves and floral buds used for the analyses were randomly subsampled from the composite sample of each tissue. The procedures for obtaining foliar extracts followed the method described by Torres-Gurrola et al. [29]. Floral volatile extraction was performed using a dynamic headspace method. VOCs were trapped in a commercial cartridge (ORBO™ 1103 Porapak™-Q (50/80), 150/75 mg; Supelco, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) by placing 3.0 g of floral buds in a Kitasato flask and exposing them to a nitrogen flow at 60 mL min−1 for 18 h. The adsorbent polymer was later recovered into a microcentrifuge tube containing 1.0 mL of internal standard solution (tetradecane) dissolved in hexane (0.125 mg mL−1), mixed for 1 min, and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and stored in amber vials at –4°C until further processing.

2.1 Identification and Quantification of Foliar and Floral VOCs

Chromatographic peak determination for each compound was performed following the procedure described by Torres-Gurrola et al. [29] using a gas chromatograph (Agilent HP6890®; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) coupled to a mass spectrometer (Agilent 5973, GC-MS; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Compound identification was based on two complementary approaches: (i) calculation of Kovats retention indices (RI) using homologous series of pure alkanes (C8-C20) analyzed under the same chromatographic conditions, and subsequent comparison with RI values reported in the literature, and (ii) comparison of the mass spectra of the detected compounds with those available in the NIST Mass Spectral Library (NIST11). Only compounds with spectral similarity values above 90% and consistent RI values were considered positively identified.

For foliar volatiles, the chromatograph was operated with helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1, using a split injection (60:1) of 3 μL at 250°C into an Agilent HP 5MS capillary column (30 m × 25 mm × 25 μM; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The initial oven temperature was set at 50°C, followed by a ramp of 20°C min−1 up to 200°C, and then a second ramp of 15°C min−1 to a final temperature of 300°C. The program for floral volatile analysis consisted of a splitless injection of 4.0 μL at 250°C into an Agilent HP 5MS capillary column (30 m × 25 mm × 25 μM). The initial oven temperature was set at 40°C for 3 min, followed by a ramp of 10°C min−1 up to 250°C and then maintained for 5 min.

For both analyses, the mass spectrometer was operated at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1, with an ionization voltage of 70 eV, an interface temperature of 250°C, in SCAN mode, and with a mass range of 50–500 m/z. The concentration of the identified compounds (µg g−1 dry weight) was determined using tetradecane as the internal standard: 0.5 mg mL−1 for foliar volatiles and 0.125 mg mL−1 for floral volatiles.

Concentration and proportion matrices were generated from identified VOCs, considering only pure compounds with a proportion greater than 1% ± standard error. Based on the concentration matrix, Pearson’s correlation analysis was applied to determine associations with morphological and productive characteristics. Additionally, a Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed. For VOCs with the highest descriptive values, a multiple correlation analysis was conducted to reduce the number of associations and facilitate interpretation.

To evaluate the consistency of the PCA-derived groupings, a hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using the full set of VOCs identified. Foliar and floral chemotypes were classified using Ward’s agglomerative method combined with Gower distances. This approach was selected because Gower’s metric allows the integration of variables with different scales and variances [30], such as VOCs abundances and presence/absence data, while Ward’s method minimizes intra-cluster variance [31], generating compact and homogeneous groups, which is particularly suitable for metabolomic datasets. A total of 65 VOCs were used to define clusters in both tissues, applying a minimum similarity threshold of 75% for shared compounds among genotypes. The robustness and optimal number of clusters were assessed using the pseudo-F statistic, which evaluates the balance between intra- and intergroup variability. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® Studio Release 3.82 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) [32].

The chemical analysis of the genotypes allowed the identification of 65 VOCs: 29 from foliar and 42 from floral tissue (Table 2). Only six were common to both tissues: α-pinene, β-pinene, β-caryophyllene, humulene, eucalyptol, and palmitic acid. A key contribution of this study was the identification of 18 VOCs not previously reported in the genus Persea: four in foliar and 14 in floral tissue (Table 3).

The presence of these previously unreported compounds may be attributed to biochemical and/or environmental factors. From a biogenic perspective, these VOCs could originate from modifications in key enzymatic pathways, such as lipoxygenase, terpene synthases, or phenylpropanoid metabolism, resulting from mutations or regulatory variations in genes associated with secondary metabolism. Likewise, factors such as alterations in gene expression within the fatty acid-, shikimate-, and Mevalonate/Methylerythritol Phosphate-derived pathways may lead to the synthesis of unusual intermediates or by-products not described in other species of the genus Persea [33,34]. In this context, exogenous origin cannot be entirely ruled out, since agroecological or environmental conditions, exposure to agrochemicals, or the adsorption of volatile compounds present in the atmosphere may contribute to the detection of these VOCs in the foliar and floral tissues of the genotypes analyzed [35,36]. Additionally, microbial communities associated with plant tissues may biotransform exogenous precursors into VOCs, adding further complexity to the plant volatilome [37]. Beyond their origin, these compounds may play ecological or adaptive roles, acting as mediators of direct or indirect defense by enhancing resistance through herbivore deterrence or by attracting predators and parasitoids, as documented in other plant species with local adaptations [2,5,38].

Among the floral VOCs identified, ethylbenzene, isocumene, pseudocumene, and 1,3-diphenyl-1-butene have been frequently documented as products of anthropogenic emissions, mainly originating from styrene, gasoline, and other organic solvents released by vehicles, refineries, and petrochemical activities [39]. Nevertheless, ethylbenzene, isocumene, and pseudocumene have also been reported in several plant species and within their essential oils [36]. The adsorption of these compounds from the environment by floral tissues [35] could account for their detection in some genotypes. However, this possibility also implies that biogenic origin cannot be excluded. Further research is required to elucidate the biosynthetic pathways involved and to determine whether these compounds originate from physiological processes or from exogenous environmental sources in different avocado genotypes.

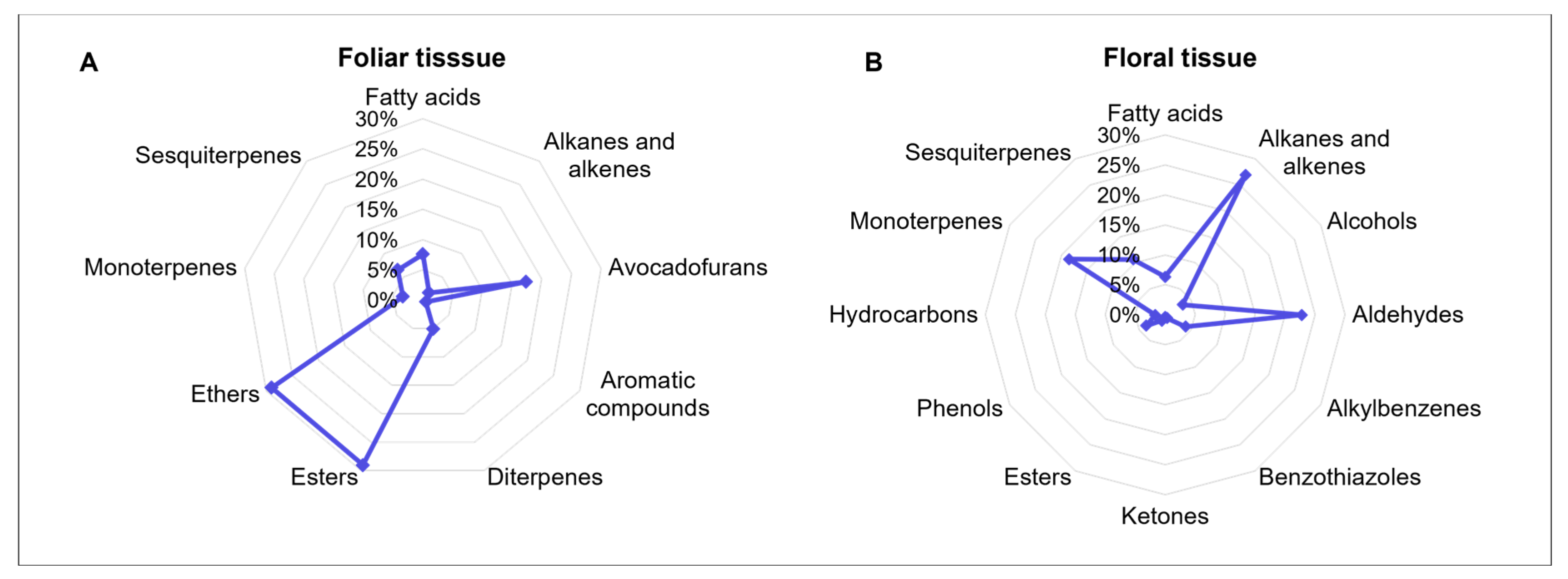

A comparative analysis of the identified volatile groups revealed apparent differences in chemical composition between tissues (Fig. 1A,B), consistent with their distinct physiological roles. In foliar tissue (Fig. 1A), ethers, esters, and avocadofurans predominated, associated with defensive functions and regulation of oxidative stress [7]. In contrast, flowers (Fig. 1B) showed higher concentrations of alkanes, alkenes, and aldehydes, which, in addition to defense, actively contribute to the attraction of pollinators and natural enemies [40]. These results show the functional specialization of the volatilome in avocados, where the leaf acts as a protective barrier, and the flower as a chemical signal emitter, essential for the reproductive success of the crop [9,26,40].

Although the total concentration of VOCs was lower in floral tissue compared to foliar tissue, the flowers exhibited a higher chemical diversity. This suggests a more complex and diversified biosynthetic activity, potentially regulated by metabolic pathways specific to floral development [9,10]. Such chemical diversity is likely to enhance ecological interactions during key stages of the reproductive cycle, as variations in floral scent play a critical role in attracting pollinators and entomophagous insects [40], as well as in guiding them to food sources and oviposition sites [9,15,17].

Figure 1: Relative concentration (0%–30%) of groups of VOCs in foliar (A) and floral (B) tissue of 15 avocado genotypes and the ‘Hass’ cultivar.

In the floral profile, terpenes accounted for 29.19% of the total VOCs, whereas in foliar tissue, they represented 14.94%. This difference in concentration may be influenced by tissue maturity, as terpenes tend to accumulate in higher amounts in young leaves [41]. Therefore, evaluating leaves at different maturity stages could provide valuable insights into variations in the volatile profile. The presence and concentration of terpenes have also been suggested to be primarily determined by genetic factors and modulated by environmental conditions [3,34]. Moreover, these compounds have been used as reliable chemical markers for discriminating avocado races, varieties, and chemotypes [42].

Typical foliar profiles reported for the ‘Hass’ cultivar [25], indicate the predominance of estragol (10%), β-caryophyllene (25%), and germacrene D (25%), together with the occurrence of α-cubebene and eugenol [42]. In contrast, the avocado genotypes analyzed in this study showed high concentrations of 2-[(8Z,11Z)-heptadeca-8,11-dienyl]furan (HDF), 2H-pyran, 2-(7-heptadecynyloxy)tetrahydro (PHT), ethyl linoleate, and methyl linoleate. These findings differ from previous reports [25] and underscore the substantial variation in foliar chemical composition, even within the same cultivar. Such variation has been attributed to differential expression of genes associated with VOCs biosynthetic pathways, which may account for differences in compound concentration as well as the presence or absence of specific metabolites among individuals of the same species [8,33]. Therefore, the phytochemical diversity observed in this study is most likely driven by the genetic variability of the variants [7,26], given that their establishment under homogeneous cultivation conditions minimizes the influence of environmental factors on the chemical profile.

In foliar tissue, HTP (28.97%) was the most abundant volatile, followed by HDF (17.34%), the latter being consistently detected in all analyzed genotypes, including the ‘Hass’ cultivar. Notably, both compounds have so far only been reported in studies conducted in Michoacán: HTP in the Mexican race P. americana var. drymifolia [14] and HDF in the ‘Hass’ cultivar [23,42]. This recurring pattern suggests that these VOCs may be linked to the specific agroecological conditions of the region and may have an ecological or adaptive significance. These compounds could contribute to local adaptation by enhancing defense against region-specific herbivores or pathogens, as has been proposed for other specialized VOCs involved in plant defense signaling [43]. Additionally, their constant presence across genotypes may indicate a conserved metabolic response to environmental stressors characteristic of this region [34,38]. In contrast, studies from other avocado-producing regions have not reported these VOCs, which supports the hypothesis that their biosynthesis could be environmentally induced or favored by genetic–environment interactions unique to Michoacán [9,10,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,24].

Table 2: Retention time, Kovats index, and concentration (%) of foliar and floral VOCs identified in 15 avocado genotypes and the ’Hass’ cultivar.

| Tissue | Volatile Compound | RT1 | KI2 | [%]3 | Volatile Compound | RT1 | KI2 | [%]3 | Volatile Compound | RT1 | KI2 | [%]3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foliar | α-Pinenea | 5.16 | 942 | 0.44 | Estragoled | 7.53 | 1208 | 0.02 | Methyl linoleateg | 13.44 | 2100 | 9.51 |

| β-Pinenea | 5.60 | 984 | 0.07 | Anetholed | 8.20 | 1299 | 0.54 | Phytolc | 13.65 | 2146 | 5.03 | |

| β-Myrcenea | 5.69 | 993 | 0.73 | EHM4g | 8.72 | 1373 | 0.07 | Linoleic acidf | 13.72 | 2162 | 6.10 | |

| α-Phellandrenea | 5.85 | 1010 | 0.32 | β-Caryophylleneb | 9.22 | 1448 | 3.68 | Ethyl linoleateg | 13.79 | 2175 | 12.46 | |

| β-Phellandrenea | 6.10 | 1038 | 0.07 | Humuleneb | 9.44 | 1483 | 0.59 | HDF5e | 14.08 | 2238 | 17.34 | |

| Eucalyptola | 6.13 | 1041 | 1.64 | Germacrene Db | 9.61 | 1509 | 1.89 | Tricosaneh | 14.38 | 2302 | 1.17 | |

| Fenchonea | 6.65 | 1099 | 0.03 | γ-Selineneb | 9.66 | 1516 | 0.10 | PHT6i | 15.30 | 2472 | 28.97 | |

| Linaloola | 6.69 | 1104 | 0.04 | Calameneneb | 9.87 | 1547 | 0.27 | DAME7g | 15.51 | 2506 | 7.00 | |

| Myrcenola | 7.30 | 1179 | 0.02 | Myristic acidf | 11.40 | 1759 | 1.22 | Hexacosaneh | 16.10 | 2599 | 0.39 | |

| α-Terpineola | 7.49 | 1203 | 0.02 | Palmitic acidf | 12.72 | 1959 | 0.27 | |||||

| Floral | Hexanaln | 5.30 | 804 | 16.08 | Eucalyptola | 9.75 | 1036 | 2.42 | α-Copaeneb | 15.06 | 1388 | 0.55 |

| 2,4-Dimethyl-1-hepteneh | 6.12 | 844 | 2.44 | Indeneo | 9.99 | 1049 | 0.22 | β-Caryophylleneb | 15.67 | 1436 | 3.87 | |

| 2-Hexenaln | 6.34 | 855 | 1.95 | 7-Octen-2-ol, 2,6-dimethyl-k | 10.41 | 1074 | 1.47 | Humuleneb | 16.11 | 1470 | 0.28 | |

| Ethylbenzenem | 6.54 | 865 | 1.59 | Undeceneh | 10.59 | 1085 | 1.07 | 4αH-Eudesmaneb | 16.19 | 1476 | 1.91 | |

| α-Pinenea | 7.96 | 937 | 3.61 | Undecaneh | 10.85 | 1100 | 0.26 | Pentadecaneh | 16.48 | 1499 | 3.76 | |

| Isocumenem | 8.33 | 957 | 0.08 | Nonanaln | 10.94 | 1105 | 3.67 | α-Farneseneb | 16.63 | 1512 | 0.87 | |

| Benzene, 1-ethyl-4-methyl-m | 8.48 | 965 | 0.93 | Isophoronel | 11.28 | 1127 | 0.36 | 2,4-di-t-Butylphenolj | 16.68 | 1516 | 3.63 | |

| β-Pinenea | 8.77 | 980 | 1.07 | Naphthaleneo | 12.30 | 1192 | 1.46 | HEBI10a | 17.38 | 1574 | 1.74 | |

| HPM8h | 8.98 | 991 | 1.28 | Dodecaneh | 12.41 | 1199 | 0.39 | Hexadecaneh | 17.68 | 1599 | 5.00 | |

| Pseudocumolm | 9.07 | 996 | 1.35 | Decanaln | 12.52 | 1207 | 1.11 | Heptadecaneh | 18.82 | 1700 | 5.54 | |

| Decaneh | 9.15 | 1000 | 0.17 | Benzothiazolep | 12.93 | 1235 | 0.62 | 2(Z),6(Z)-Farnesolb | 18.89 | 1706 | 3.17 | |

| 1-Heptanol, 2,4-dimethylk | 9.39 | 1014 | 1.92 | Tridecaneh | 13.86 | 1300 | 1.02 | 1,3-Diphenyl-1-buteneh | 19.82 | 1792 | 3.82 | |

| p-Cymenea | 9.61 | 1027 | 2.21 | PAMDPE9g | 14.70 | 1362 | 1.10 | Octadecaneh | 19.90 | 1799 | 2.19 | |

| Limonenea | 9.69 | 1032 | 7.49 | 2-Methylpropanoic acidf | 14.96 | 1381 | 1.22 | Palmitic acidf | 21.53 | 1960 | 5.11 |

Table 3: VOCs identified in foliar and floral tissue of 15 avocado genotypes reported for the first time in the genus Persea.

| Tissue | Volatile Compound | Biological Function | Species Where It Has Been Identified | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foliar tissue | Myrcenol1 | Bactericide | Thymus vulgaris | [44] |

| Calamenene1 | Phytotoxic and antioxidant | Myrcia hatschbachii | [45] | |

| Fenchone1 | Aromatic and antimicrobial | Hyptis suaveolens | [46] | |

| 6,9,12,15-docosatetraenoic acid, methyl ester1 | Pharmacological properties | Malva sylvestris | [47] | |

| Floral tissue | Ethylbenzene* | Pollutant | Poceae spp. | [39] |

| Isocumene* | Pollutant | Gossypium hirsutum | [36] | |

| Heptane, 2,2,4,6,6-pentamethyl- | Allelopathic | Eucalyptus grandis | [48] | |

| Pseudocumol* | Pollutant | Artemisia herba-alba | [36] | |

| 1-Heptanol, 2,4-dimethyl | Vitis spp. | [49] | ||

| 7-Octen-2-ol, 2,6-dimethyl- | Chenopodium murale | [50] | ||

| Isophorone | Allelochemical and oviposition deterrence | Ceratophyllum demersum L. y Vallisneria spiralis | [51,52] | |

| Benzothiazole | Antifungal | Prunella vulgaris | [53] | |

| Propanoic acid, 2-methyl-, 2,2-dimethyl-1-(2-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)propyl ester | Ceratophyllum demersum L. y Vallisneria spiralis | [51] | ||

| 2-Methylpropanoic acid | Antifungal | Humulus lupulus | [54,55] | |

| 2,4-di-t-Butylphenol | Antioxidant, antimicrobial, antifungal, and allelopathic | Osmunda regalis | [56,57] | |

| 3-Hydroxy-5,6-epoxy-β-ionone | Phlomis samia | [58] | ||

| 2(Z),6(Z)-Farnesol | Cytotoxic and antimicrobial | Citrus trifoliata y Diospyros discolor | [59,60] | |

| 1,3-Diphenyl-1-butene* | Pollutant | [61] |

Information on VOCs in avocado floral tissue remains limited. Previous reports identified (E)-β-ocimene and perillene as the predominant compounds in avocado flowers [9,10]; however, these volatiles were not detected in the present study. Instead, the VOCs with the highest relative abundance across the analyzed genotypes were hexanal (16.08%), which has been associated with defense responses as well as attraction of pollinators and natural enemies [11], and limonene (7.49%), with multiple defensive roles and recognized function in the detection of floral stages by pollinating insects [62]. The elevated concentrations of these volatiles in inflorescences underscore their ecological relevance, reinforcing the role of flowers as organs that emit specific chemical cues contributing to plant reproduction and protection [40]. These findings emphasized the importance of considering genetic, phenological, and environmental factors when comparing chemical profiles and highlighted the need to further investigate the metabolome of the genus Persea.

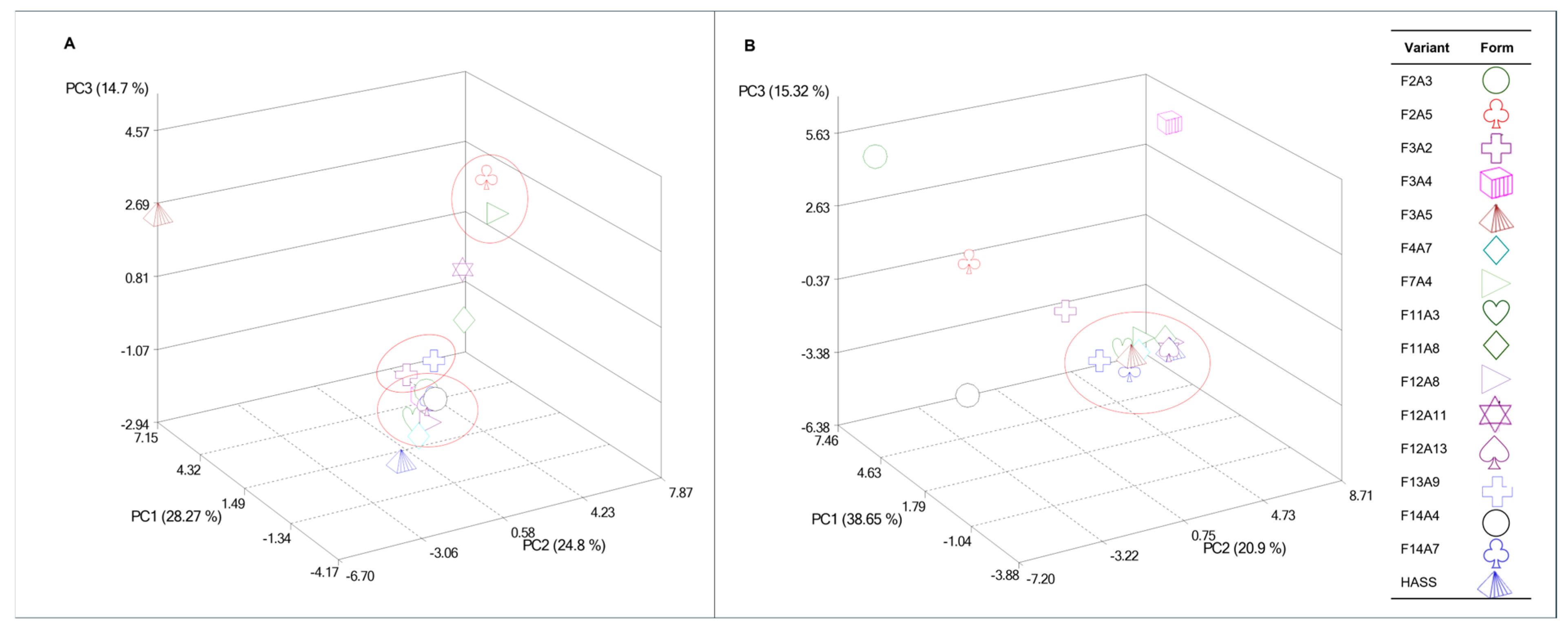

3.2 VOCs, Yield, and Fruit Characteristics

The combined analysis of Pearson’s correlation and PCA reinforced the identification of key VOCs for distinguishing among the evaluated genotypes. Significant correlations (α ≤ 0.01), primarily among terpenes, corresponded to VOCs with the highest eigenvalues in the first three principal components (Table 4), which accounted for 67.77% and 74.87% of the total variance in foliar and floral tissues, respectively. In the foliar tissue, three clusters were observed: one comprising eight genotypes and two smaller clusters with two genotypes each, while the ‘Hass’ cultivar remained distinct from all groups (Fig. 2A). In contrast, floral tissue formed a single cluster that included ten genotypes, together with the ‘Hass’ cultivar (Fig. 2B).

Table 4: Eigenvalues and variance explained by foliar tissue1 and floral tissue2 in the first three principal components based on 65 VOCs identified in 15 avocado genotypes and the ‘Hass’ cultivar.

| Tissue | Volatile Compound | Principal Components | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 (28.27%)1 | PC2 (24.8%)1 | PC3 (14.7%)1 | ||

| Foliar | α-Pinene | 0.2837 | 0.1744 | 0.1429 |

| β-Pinene | 0.1904 | 0.2917 | 0.1281 | |

| α-Phellandrene | 0.1906 | 0.2923 | 0.1219 | |

| β-Phellandrene | 0.1904 | 0.2917 | 0.1281 | |

| Fenchone | 0.1904 | 0.2917 | 0.1281 | |

| Estragole | 0.1904 | 0.2917 | 0.1281 | |

| Anethole | 0.1904 | 0.2917 | 0.1281 | |

| Humulene | −0.1497 | −0.0110 | 0.3033 | |

| Methyl linoleate | −0.2136 | 0.0169 | 0.3112 | |

| Linoleic acid | −0.1577 | 0.0459 | 0.3252 | |

| 2-[(8Z,11Z)-Heptadeca-8,11-dienyl]furan | −0.2102 | 0.0337 | 0.2928 | |

| PC1 (38.65%)2 | PC2 (20.9%)2 | PC3 (15.32%)2 | ||

| Floral | Isocumene | 0.0820 | −0.2186 | 0.2334 |

| Decane | 0.0989 | 0.2644 | 0.1702 | |

| Undecane | 0.0842 | −0.0043 | −0.2550 | |

| Nonanal | 0.2364 | −0.0487 | 0.0290 | |

| Isophorone | 0.1329 | 0.0568 | 0.2917 | |

| Naphthalene | 0.1625 | −0.1419 | 0.2341 | |

| Decanal | 0.2314 | 0.0198 | 0.0824 | |

| Benzothiazole | 0.1717 | 0.0957 | 0.2580 | |

| β-Caryophyllene | 0.1240 | 0.2579 | 0.1129 | |

| Humulene | 0.0989 | 0.2644 | 0.1702 | |

| Pentadecane | 0.0871 | −0.0347 | −0.3389 | |

| α-Farnesene | 0.0989 | 0.2644 | 0.1702 | |

Figure 2: Principal component analysis (PCA) scatter plots showing the distribution of 15 avocado genotypes and the ‘Hass’ cultivar based on 11 foliar (A) and 12 floral (B) volatile organic compounds (VOCs). Each form represents one genotype; proximity among forms indicates greater similarity in volatile composition.

Correlation analysis revealed significant negative associations (α ≤ 0.05) between yield and palmitic acid in foliar tissue, as well as with β-caryophyllene, humulene, and α-farnesene in floral tissue, with values ranging from r = −0.5808 to r = −0.6202. In contrast, phytol showed a positive correlation with yield (r = 0.6112) and has been reported to possess antimicrobial and allelopathic properties [11]. Among the associations identified between VOCs and fruit characteristics (Table 5), phytol was particularly relevant, as it correlated with four variables, whereas β-caryophyllene was associated with storage duration. The latter result is especially noteworthy, given the extensive evidence supporting its multifunctional role in plant defense [5].

Table 5: Pearson correlation coefficients (r ≤ 0.5) determined between foliar and floral VOCs with fruit characteristics of 15 avocado genotypes and the ‘Hass’ cultivar.

| Tissue | Volatile Compound | Fruit Characteristic | r | Pr > |r| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foliar | β-Caryophyllene | Days of storage | 0.6127 | 0.0116 |

| Phytol | Length | 0.6468 | 0.0068 | |

| Weight | 0.6585 | 0.0055 | ||

| Peduncle diameter | 0.5940 | 0.0152 | ||

| Peduncle length | 0.6502 | 0.0064 | ||

| 2-[(8z,11z)-Heptadeca-8,11-dienyl]furan | Diameter | 0.5972 | 0.0146 | |

| Weight | 0.5845 | 0.0174 | ||

| Peduncle diameter | 0.6484 | 0.0066 | ||

| Tricosane | Diameter | 0.6182 | 0.0107 | |

| Weight | 0.5799 | 0.0185 | ||

| Peduncle diameter | 0.6165 | 0.0110 | ||

| Floral | 2,4-Dimethyl-1-heptene | Length | 0.6045 | 0.0131 |

| β-Pinene | Peduncle length | −0.6178 | 0.0108 | |

| Decane | Skin thickness | 0.6027 | 0.0135 |

It is important to emphasize that the relationships identified in this study are correlational and do not imply causation. The negative association between palmitic acid and yield may be related to stress-associated signaling processes, as saturated fatty acids participate in stress responses that could indirectly reduce productivity [63]. Meanwhile, elevated phytol concentrations in foliar tissue may indicate higher chlorophyll content or genotype-specific differences in lipid metabolism, rather than a direct effect of phytol on yield [64]. For β-caryophyllene and other sesquiterpenes, extensive evidence supports their involvement in plant defense mechanisms [5,11,34]. Therefore, the correlation between β-caryophyllene and longer fruit storage duration does not demonstrate a direct protective effect; instead, higher levels of this compound may reflect the activation of defense pathways that influence water loss and postharvest physiology.

Significant associations between VOCs and agronomic traits may reflect direct physiological effects of these compounds; however, they could also indicate that VOCs function as markers of underlying metabolic, physiological, or genetic processes that influence these traits [34]. Therefore, functional interpretations must be made with caution until validated through targeted experimental approaches.

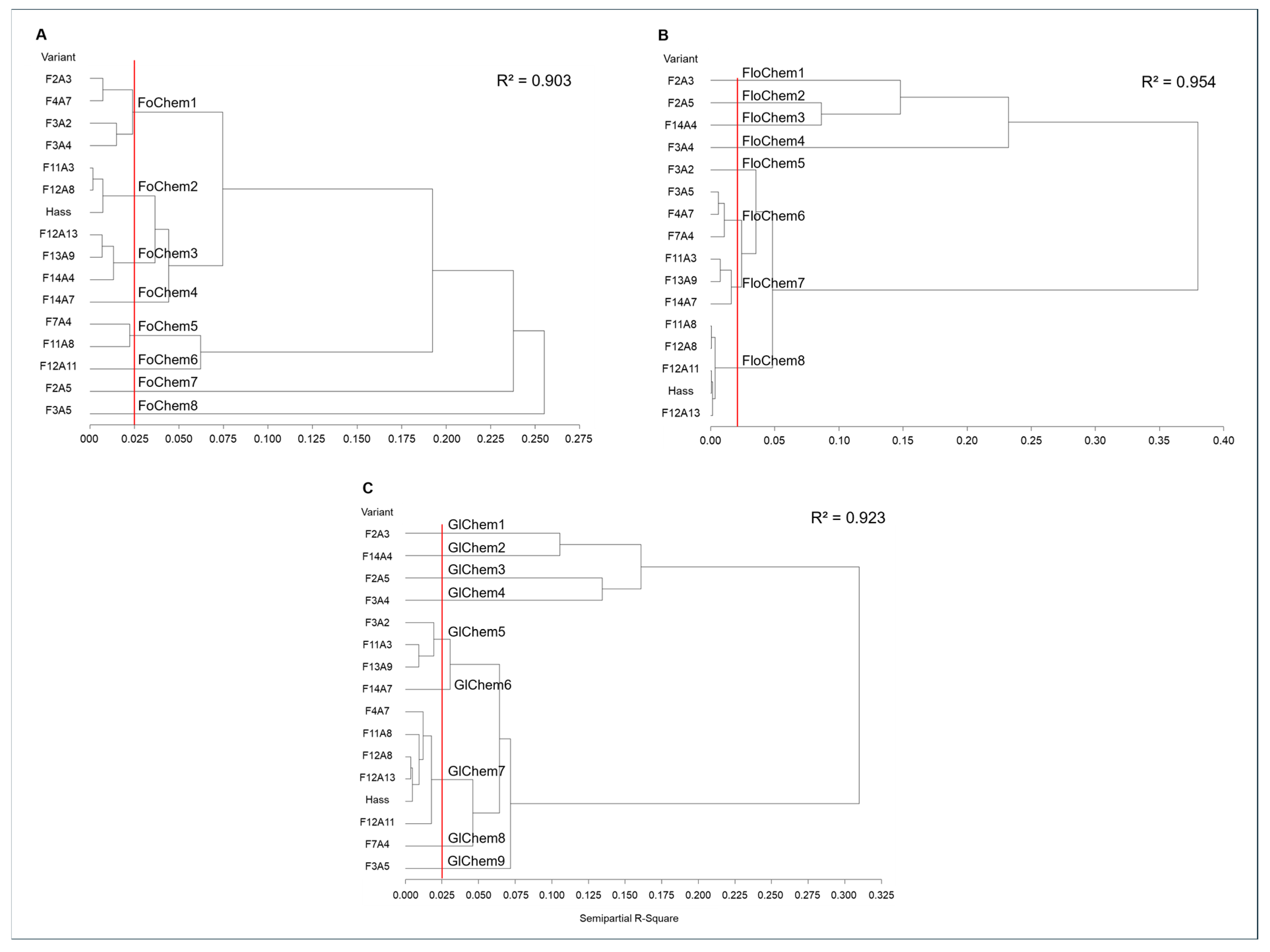

3.3 Identification of Chemotypes

The comparison of the 65 VOCs among avocado genotypes enabled the identification of eight foliar chemotypes (FoChem) and eight floral chemotypes (FloChem), shown in Fig. 3A,B, respectively. In foliar tissue, chemotype differentiation was driven by the presence of distinctive compounds, whereas in floral tissue it was determined by volatile concentration. Among the FoChem, FoChem1 was notable for comprising four dwarf growth habit genotypes (F2A3, F3A2, F3A4, and F4A7). FoChem5, consisting of F7A4 and F11A8, was characterized by large fruits (mean weight of 251 g) and high yields (160.5 kg tree−1). This last chemotype was distinguished by the presence of β-caryophyllene, phytol, HDF, and tricosane, compounds that support the associations previously observed between VOCs, fruit characteristics (Table 5), and yield in the correlation analysis.

Of the 15 genotypes evaluated, only two (F11A3 and F12A8) cluster with the ‘Hass’ cultivar, forming FoChem2. In contrast, F2A5, F3A5, F12A11, and F14A7 were distinguished by the presence of VOCs absent in the other genotypes. Within this group, FoChem7 (F2A5) was characterized by β-pinene, β-phellandrene, fenchone, estragol, and anethole, VOCs with reported roles in plant defense [11]. FoChem8 (F3A5) was defined by the presence of linalool, myrcenol, α-terpineol, and γ-selinene, together with elevated eucalyptol levels, a compound with insecticidal activity and parasitoid-attracting properties [33]. The occurrence of these terpenes has been widely associated with biotic stress responses and allelopathic activity in several species [34] positioning these genotypes as candidates for further studies on the defensive functions of their chemical profiles. FoChem4 (F14A7) was characterized by 2-Ethyl-3-hydroxyhexyl 2-methylpropanoate (EHM), a β-carotene degradation product [65] with limited information on its biological role in plants, whereas FoChem6 (F12A11) showed a high overall concentration of VOCs.

In floral tissue, FloChem6 comprised three dwarf growth habit genotypes: F3A5, F4A7, and F7A4, with VOCs concentrations ranging from 43.25 to 45.72 μg g−1. FloChem8 included the ‘Hass’ cultivar together with F11A8, F12A8, F12A11, and F12A13, and was characterized by elevated levels of hexanal, with an average concentration of 57.72 μg g−1, a compound involved in defense mechanisms and as an attractant and deterrent to oviposition [11]. Overall, this group exhibited the lowest diversity and concentration of VOCs. Similar to foliar tissue, five genotypes displayed distinctive floral chemotypes. FloChem1 (F2A3) was defined by the highest limonene concentration (9.81 µg g−1), a compound with multiple defense functions [5]. FloChem5 (F3A2), notable for its high palmitic acid content (20.89 µg g−1), was the only one with a flowering type similar to ‘Hass’, although differing in both chemical profile and fruit morphology [9,10]. FloChem4 (F3A4) stood out for the exclusive presence of decane, humulene, and α-farnesene, along with high β-caryophyllene levels (26.82 µg g−1). This last chemotype is of particular interest, as it exhibited the lowest average yield and included VOCs negatively correlated with yield; however, further evaluations across production cycles and phytopathological studies are required to confirm this association. Finally, FloChem2 (F2A5) and FloChem3 (F14A4) were differentiated from the other genotypes by the highest number and concentration of VOCs.

The distinctive VOCs identified in foliar and floral tissue may serve as chemical markers for differentiating closely related genotypes, as they were absent in the ‘Hass’ cultivar. Because all genotypes were evaluated under homogeneous cultivation conditions, the presence of these compounds can be attributed to genetic factors, reinforcing this interpretation.

Figure 3: Hierarchical clustering dendrograms, using Ward’s method with Gower distances, of avocado genotypes and the ‘Hass’ cultivar, based on 29 foliar (A), 42 floral (B), and combined (C) volatile organic compounds.

The integrated analysis of foliar and floral volatiles (Fig. 3C) confirmed the separation of genotypes with distinctive chemotypes, supporting the existence of differentiated volatile profiles at a whole-plant level. This supports the importance of further evaluating these genotypes to determine their potential as alternative or complementary cultivars to ‘Hass’, combining competitive morphological characteristics with distinctive phytochemical profiles. However, the presence of different chemotypes does not necessarily confer greater resistance [23]. Therefore, additional studies are required to establish whether differences in metabolomic profiles are associated with pests and disease susceptibility or with productive traits. Moreover, since VOCs synthesis and emission are tissue-and stage-specific processes [26], the integrated characterization of foliar and floral profiles provides valuable information to advance the understanding of the volatile metabolome in Persea.

Finally, the groupings identified through cluster analysis of FloChem were consistent with those generated by PCA, in contrast to FoChem. This discrepancy may be explained by the lower percentage of variance captured by PCA in foliar tissue (67.77%) and the broader range of VOCs concentration detected in this tissue. Overall, the results demonstrate the utility of metabolomic approaches for differentiating closely related genotypes, such as those analyzed in this study.

This study revealed distinct foliar and floral volatilome profiles among 15 ‘Hass’-type avocado variant genotypes, including 18 VOCs reported for the first time in the genus Persea. Based on these profiles, eight foliar and eight floral chemotypes were identified, demonstrating clear chemical differentiation from the ‘Hass’ cultivar. Some VOCs were unique to genotypes with a dwarf growth habit, while others showed statistically significant correlations with yield and fruit quality traits, suggesting their potential as biomarkers in breeding and selection programs. The presence of uncommon VOCs in these genotypes may be influenced by the agroecological conditions of Michoacán; however, this interpretation remains tentative and requires further validation.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Coordinación de la Investigación Científica (UMSNH), with financial support number 18199, and by the SECIHTI grant number 832390.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, validation, supervision, and project administration, Ana K. Escalera-Ordaz and Héctor Guillén-Andrade; methodology and software, Francisco J. Espinosa-García and Yolanda M. García-Rodríguez; formal analysis, investigation and validation, Elizabeth Martinez; resources and funding acquisition, Héctor Guillén-Andrade; data curation, Ana K. Escalera-Ordaz and Yolanda M. García-Rodríguez; writing—original draft preparation and visualization, Elizabeth Martinez, Ana K. Escalera-Ordaz and Héctor Guillén-Andrade; writing—review and editing, Rafael Ariza-Flores, Javier Ponce-Saavedra, and Patricio Apáez-Barrios. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Corresponding Author (HGA) upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Abbreviations

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

| UMSNH | Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo |

| UNAM | Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México |

| EHM | 2-Ethyl-3-hydroxyhexyl 2-methylpropanoate |

| HDF | 2-[(8z,11z)-Heptadeca-8,11-dienyl]furan |

| PHT | 2H-Pyran, 2-(7-heptadecynyloxy)tetrahydro |

| DAME | 6,9,12,15-Docosatetraenoic acid, methyl ester |

| HPM | Heptane, 2,2,4,6,6-pentamethyl- |

| PAMDPE | Propanoic acid, 2-methyl-, 2,2-dimethyl-1-(2-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)propyl ester |

| HEBI | 3-Hydroxy-5,6-epoxy-β-ionone |

| FoChem | Foliar chemotype |

| FloChem | Floral chemotype |

| SECIHTI | Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación |

References

1. Kasote D , Lee J , Sreenivasulu N . Editorial: volatilomics in plant and agricultural research: recent trends. Front Plant Sci. 2023; 14: 1289998. doi:10.3389/fpls.2023.1289998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Maurya AK . Application of plant volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in agriculture. In: New frontiers in stress management for durable agriculture. Singapore: Springer; 2020. p. 369– 88. doi:10.1007/978-981-15-1322-0_21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Chen L , Liao P . Current insights into plant volatile organic compound biosynthesis. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2025; 85: 102708. doi:10.1016/j.pbi.2025.102708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Salam U , Ullah S , Tang ZH , Elateeq AA , Khan Y , Khan J , et al. Plant metabolomics: an overview of the role of primary and secondary metabolites against different environmental stress factors. Life. 2023; 13( 3): 706. doi:10.3390/life13030706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Razo-Belman R , Ozuna C . Volatile organic compounds: a review of their current applications as pest biocontrol and disease management. Horticulturae. 2023; 9( 4): 441. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9040441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Bakhtiari M , Glauser G , Defossez E , Rasmann S . Ecological convergence of secondary phytochemicals along elevational gradients. New Phytol. 2021; 229( 3): 1755– 67. doi:10.1111/nph.16966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Lara-García CT , Jiménez-Islas H , Miranda-López R . Perfil de compuestos orgánicos volátiles y ácidos grasos del aguacate (Persea americana) y sus beneficios a la salud. CienciaUAT. 2021; 16( 1): 162– 77. doi:10.29059/cienciauat.v16i1.1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Espinosa-García FJ . The role of phytochemical diversity in the management of agroecosystems. Bot Sci. 2022; 100: S245– 62. doi:10.17129/botsci.3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Campuzano-Granados ÁJ , Cruz-López L . Comparative analysis of floral volatiles between the ‘Hass’ variety and Antillean race avocado. Rchsh. 2021; 27( 1): 19– 26. doi:10.5154/r.rchsh.2020.05.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Cruz-López L , Rojas JC . Behavioural and electrophysiological responses of the small avocado seed borer, Conotrachelus perseae to avocado leaf, flower and fruit volatile extracts. Bull Insectology. 2022; 75( 2): 161. [Google Scholar]

11. Torres-Gurrola G , García-Rodríguez YM , Lara-Chávez MBN , Guillén-Andrade H , Delgado-Lamas G , Espinosa-García FJ . Análisis de la riqueza de metabolitos secundarios de Persea spp. In: Lang ALA , García FJE , Manuel J , editors. Ecología Química y Alelopatía: avances y perspectivas. México: Plaza y Valdés Editores; 2016 [cited 2025 Nov 29]. p. 195– 292. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360687955_RA11_Ecologia_Quimica_y_Alelopatia_17X23_CS6_RA11. [Google Scholar]

12. Totini CH , Umehara E , Reis IMA , Lago JHG , Branco A . Chemistry and bioactivity of the genus Persea—a review. Chem Biodivers. 2023; 20( 9): e202300947. doi:10.1002/cbdv.202300947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. King JR , Knight RJ . Volatile components of the leaves of various avocado cultivars. J Agric Food Chem. 1992; 40( 7): 1182– 5. doi:10.1021/jf00019a020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Guillén-Andrade H , Escalera-Ordaz AK , Torres-Gurrola G , García-Rodríguez YM , Espinosa García FJ , Tapia-Vargas LM . Identificación de nuevos metabolitos secundarios en Persea americana Miller variedad Drymifolia. Remexca. 2019; 10( SPE23): 253– 65. doi:10.29312/remexca.v0i23.2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Torres-Gurrola G , Delgado-Lamas G , Espinosa-García FJ . The foliar chemical profile of criollo avocado, Persea americana var. drymifolia (Lauraceae), and its relationship with the incidence of a gall-forming insect, Trioza anceps (Triozidae). Biochem Syst Ecol. 2011; 39( 2): 102– 11. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2011.01.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kosińska A , Karamać M , Estrella I , Hernández T , Bartolomé B , Dykes GA . Phenolic compound profiles and antioxidant capacity of Persea americana Mill. peels and seeds of two varieties. J Agric Food Chem. 2012; 60( 18): 4613– 9. doi:10.1021/jf300090p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. García-Rojas M , Morgan A , Gudenschwager O , Zamudio S , Campos-Vargas R , González-Agüero M , et al. Biosynthesis of fatty acids-derived volatiles in ‘Hass’ avocado is modulated by ethylene and storage conditions during ripening. Sci Hortic. 2016; 202: 91– 8. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2016.02.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Liu Y , Bu M , Gong X , He J , Zhan Y . Characterization of the volatile organic compounds produced from avocado during ripening by gas chromatography ion mobility spectrometry. J Sci Food Agric. 2021; 101( 2): 666– 72. doi:10.1002/jsfa.10679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Obenland D , Collin S , Sievert J , Negm F , Arpaia ML . Influence of maturity and ripening on aroma volatiles and flavor in ‘Hass’ avocado. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2012; 71: 41– 50. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.03.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Pacheco A , Rodríguez-Sánchez DG , Villarreal-Lara R , Navarro-Silva JM , Senés-Guerrero C , Hernández-Brenes C . Stability of the antimicrobial activity of acetogenins from avocado seed, under common food processing conditions, against Clostridium sporogenes vegetative cell growth and endospore germination. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2017; 52( 11): 2311– 23. doi:10.1111/ijfs.13513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ramos-Aguilar AL , Ornelas-Paz J , Tapia-Vargas LM , Gardea-Béjar AA , Yahia EM , de Jesús Ornelas-Paz J , et al. Effect of cultivar on the content of selected phytochemicals in avocado peels. Food Res Int. 2021; 140: 110024. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.110024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Bowen J , Billing D , Connolly P , Smith W , Cooney J , Burdon J . Maturity, storage and ripening effects on anti-fungal compounds in the skin of ‘Hass’ avocado fruit. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2018; 146: 43– 50. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2018.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Espinosa-García FJ , García-Rodríguez YM , Bravo-Monzón AE , Vega-Peña EV , Delgado-Lamas G . Implications of the foliar phytochemical diversity of the avocado crop Persea americana cv. Hass in its susceptibility to pests and pathogens. PeerJ. 2021; 9: e11796. doi:10.7717/peerj.11796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Guzmán-Rodríguez LF , Cortés-Cruz MA , Rodríguez-Carpena JG , Coria-Ávalos VM , Muñoz-Flores HG . Biochemical profile of avocado (Persea americana Mill) foliar tissue and its relationship with susceptibility to mistletoe (Family Loranthaceae). Biociencias. 2019; 7( e492): 1– 16. doi:10.15741/revbio.07.e492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Meléndez-González C , Espinosa-García FJ . Metabolic profiling of Persea americana cv. Hass branch volatiles reveal seasonal chemical changes associated to the avocado branch borer, Copturus aguacatae. Sci Hortic. 2018; 240: 116– 24. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2018.06.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Arango JPB , Ospina AP , Ladino JAF , Ocampo GT . Volatilomic analysis in peel, pulp and seed of hass avocado (Persea americana Mill.) from the northern subregion of caldas by gas chromatography with mass spectrometry. Food Sci Nutr. 2025; 13( 7): e70489. doi:10.1002/fsn3.70489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Whitehead SR , Bass E , Corrigan A , Kessler A , Poveda K . Interaction diversity explains the maintenance of phytochemical diversity. Ecol Lett. 2021; 24( 6): 1205– 14. doi:10.1111/ele.13736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Gutiérrez M , Lara MB , Guillén H , Chávez A . Agroecología de la franja aguacatera en Michoacán, México. Interciencia. 2010; 35( 9): 647– 53. [Google Scholar]

29. Torres-Gurrola G , Montes-Hernández S , Espinosa-García FJ . Patrones de variación y distribución geográfica en fenotipos químicos foliares de Persea americana var. drymifolia. RevFitotecMex. 2009; 32( 1): 19– 30. doi:10.35196/rfm.2009.1.19-30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu P , Yuan H , Ning Y , Chakraborty B , Liu N , Peres MA . A modified and weighted Gower distance-based clustering analysis for mixed type data: a simulation and empirical analyses. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2024; 24( 1): 305. doi:10.1186/s12874-024-02427-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Murtagh F , Legendre P . Ward’s hierarchical agglomerative clustering method: which algorithms implement ward’s criterion? J Classif. 2014; 31( 3): 274– 95. doi:10.1007/s00357-014-9161-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. SAS Institute Inc . SAS on demand for academics. Cary, NC, USA: SAS Institute Inc.; 2025 [cited 2025 Nov 29]. Available from: https://welcome.oda.sas.com/. [Google Scholar]

33. Boncan DAT , Tsang SSK , Li C , Lee IHT , Lam HM , Chan TF , et al. Terpenes and terpenoids in plants: interactions with environment and insects. Int J Mol Sci. 2020; 21( 19): 7382. doi:10.3390/ijms21197382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Abbas F , O’Neill Rothenberg D , Zhou Y , Ke Y , Wang HC . Volatile organic compounds as mediators of plant communication and adaptation to climate change. Physiol Plant. 2022; 174( 6): e13840. doi:10.1111/ppl.13840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Araya M , Vera J , Préndez M . Urban tree species capturing anthropogenic volatile organic compounds—impact on air quality. Atmosphere. 2025; 16( 4): 356. doi:10.3390/atmos16040356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Rutz A , Sorokina M , Galgonek J , Mietchen D , Willighagen E , Gaudry A , et al. The LOTUS initiative for open knowledge management in natural products research. Elife. 2022; 11: e70780. doi:10.7554/eLife.70780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Raza W , Shen Q . Volatile organic compounds mediated plant-microbe interactions in soil. In: Sharma V , Salwan R , Al-Ani LKT , editors. Molecular aspects of plant beneficial microbes in agriculture. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2020. p. 209– 19. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-818469-1.00018-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ali S , Plotto A , Scully BT , Wood D , Stover E , Owens N , et al. Fatty acid and volatile organic compound profiling of avocado germplasm grown under East-Central Florida conditions. Sci Hortic. 2020; 261: 109008. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2019.109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Sriprapat W , Suksabye P , Areephak S , Klantup P , Waraha A , Sawattan A , et al. Uptake of toluene and ethylbenzene by plants: removal of volatile indoor air contaminants. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2014; 102: 147– 51. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2014.01.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lo MM , Benfodda Z , Molinié R , Meffre P . Volatile organic compounds emitted by flowers: ecological roles, production by plants, extraction, and identification. Plants. 2024; 13( 3): 417. doi:10.3390/plants13030417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Bellumori M , Innocenti M , Congiu F , Cencetti G , Raio A , Menicucci F , et al. Within-plant variation in Rosmarinus officinalis L. terpenes and phenols and their antimicrobial activity against the rosemary phytopathogens Alternaria alternata and Pseudomonas viridiflava. Molecules. 2021; 26( 11): 3425. doi:10.3390/molecules26113425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. García-Rodríguez YM , Torres-Gurrola G , Meléndez-González C , Espinosa-García FJ . Phenotypic variations in the foliar chemical profile of Persea americana mill. cv. hass. Chem Biodivers. 2016; 13( 12): 1767– 75. doi:10.1002/cbdv.201600169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Avesani S , Castiello U , Ravazzolo L , Bonato B . Volatile organic compounds in pea plants: a comprehensive review. Front Plant Sci. 2025; 16: 1591829. doi:10.3389/fpls.2025.1591829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Proto MR , Biondi E , Baldo D , Levoni M , Filippini G , Modesto M , et al. Essential oils and hydrolates: potential tools for defense against bacterial plant pathogens. Microorganisms. 2022; 10( 4): 702. doi:10.3390/microorganisms10040702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Gatto LJ , Fabri NT , de Souza AM , da Fonseca NST , dos Santos Furusho A , Miguel OG , et al. Chemical composition, phytotoxic potential, biological activities and antioxidant properties of Myrcia hatschbachii D. Legrand essential oil. Braz J Pharm Sci. 2020; 56: e18402. doi:10.1590/s2175-97902019000318402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Tine Y , Thiam K , Diallo A , Gaye C , Ndiaye B , Ndoye I , et al. Chemical composition of the essential oil of Hyptis suaveolens (L.) poit leaves from Senegal. World J Org Chem 2023; 10( 1): 1– 3. doi:10.12691/wjoc-10-1-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Fathi M , Ghane M , Pishkar L . Phytochemical composition, antibacterial, and antibiofilm activity of Malva sylvestris against human pathogenic bacteria. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2021; 17( 1): 114164. doi:10.5812/jjnpp.114164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Zhiqun T , Jian Z , Junli Y , Chunzi W , Danju Z . Allelopathic effects of volatile organic compounds from Eucalyptus grandis rhizosphere soil on Eisenia fetida assessed using avoidance bioassays, enzyme activity, and comet assays. Chemosphere. 2017; 173: 307– 17. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.01.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Campos-Arguedas F , Sarrailhé G , Nicolle P , Dorais M , Brereton NJB , Pitre FE , et al. Different temperature and UV patterns modulate berry maturation and volatile compounds accumulation in Vitis sp. Front Plant Sci. 2022; 13: 862259. doi:10.3389/fpls.2022.862259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Polatoğlu K , Demirci B , Çalış İ , Hüsnü K , Başer C . Difference in volatile composition of Chenopodium murale from two different locations of cyprus. Rec. Nat. Prod. 2017; 11( 1): 88– 91. [Google Scholar]

51. Qiming X , Haidong C , Huixian Z , Daqiang Y . Chemical composition of essential oils of two submerged macrophytes, Ceratophyllum demersum L. and Vallisneria spiralis L. Flavour Fragr J. 2006; 21( 3): 524– 6. doi:10.1002/ffj.1588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Cloonan K , Bedoukian RH , Leal W . Quasi-double-blind screening of semiochemicals for reducing navel orangeworm oviposition on almonds. PLoS One. 2013; 8( 11): e80182. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0080182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Golembiovska O , Tsurkan A , Vynogradov B . Components of Prunella vulgaris L. grown in Ukraine. J Pharmacogn Phytochem. 2014; 2( 6): 140– 6. [Google Scholar]

54. Strobel GA , Spang S , Kluck K , Hess WM , Sears J , Livinghouse T . Synergism among volatile organic compounds resulting in increased antibiosis in Oidium sp. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008; 283( 2): 140– 5. doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01137.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Liu Z , Wang L , Liu Y . Rapid differentiation of Chinese hop varieties (Humulus lupulus) using volatile fingerprinting by HS-SPME-GC-MS combined with multivariate statistical analysis. J Sci Food Agric. 2018; 98( 10): 3758– 66. doi:10.1002/jsfa.8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Bouazzi S , Jmii H , El Mokni R , Faidi K , Falconieri D , Piras A , et al. Cytotoxic and antiviral activities of the essential oils from Tunisian Fern, Osmunda regalis. S Afr N J Bot. 2018; 118: 52– 7. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2018.06.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Zhao F , Wang P , Lucardi RD , Su Z , Li S . Natural sources and bioactivities of 2, 4-di-tert-butylphenol and its analogs. Toxins. 2020; 12( 1): 35. doi:10.3390/toxins12010035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Yalçin FN , Ersöz T , Akbay P , Çaliş I , Dönmez AA , Sticher O . Phenolic, megastigmane, nucleotide, acetophenon and monoterpene glycosides from Phlomis samia and P. carica. Turk J Chem. 2003; 27( 6): 703– 11. [Google Scholar]

59. Andrade M , Ribeiro L , Borgoni P , Silva M , Forim M , Fernandes J , et al. Essential oil variation from twenty two genotypes of Citrus in Brazil—chemometric approach and repellency against Diaphorina citri Kuwayama. Molecules. 2016; 21( 6): 814. doi:10.3390/molecules21060814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Su YC , Hsu KP , Wang EI , Ho CL . Composition, in vitro cytotoxic, and antimicrobial activities of the flower essential oil of Diospyros discolor from Taiwan. Nat Prod Commun. 2015; 10( 7): 1311– 4. doi:10.1177/1934578X1501000744 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Myagmarsuren G , Tkach VS , Shmidt FK , Mohamad M , Suslov DS . Selective dimerization of styrene to 1, 3-diphenyl-1-butene with bis(β-diketonato)palladium/boron trifluoride etherate catalyst system. J Mol Catal A Chem. 2005; 235( 1–2): 154– 60. doi:10.1016/j.molcata.2005.03.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Chen C , Song Q . Responses of the pollinating wasp Ceratosolen solmsi marchali to odor variation between two floral stages of Ficus hispida. J Chem Ecol. 2008; 34( 12): 1536– 44. doi:10.1007/s10886-008-9558-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Maryam A , Khan RI , Abbas M , Hussain K , Muhammad S , Sabir MA , et al. Beyond the membrane: the pivotal role of lipids in plants abiotic stress adaptation. Plant Growth Regul. 2025: 1– 19. doi:10.1007/s10725-025-01363-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Gutbrod P , Yang W , Grujicic GV , Peisker H , Gutbrod K , Du LF , et al. Phytol derived from chlorophyll hydrolysis in plants is metabolized via phytenal. J Biol Chem. 2021; 296: 100530. doi:10.1016/j.jbc.2021.100530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. do Monte DS , Bezerra Tenório JA , Bastos IVGA , de S Mendonça F , Neto JE , da Silva TG , et al. Chemical and biological studies of β-carotene after exposure to Cannabis sativa smoke. Toxicol Rep. 2016; 3: 516– 22. doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2016.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools