Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

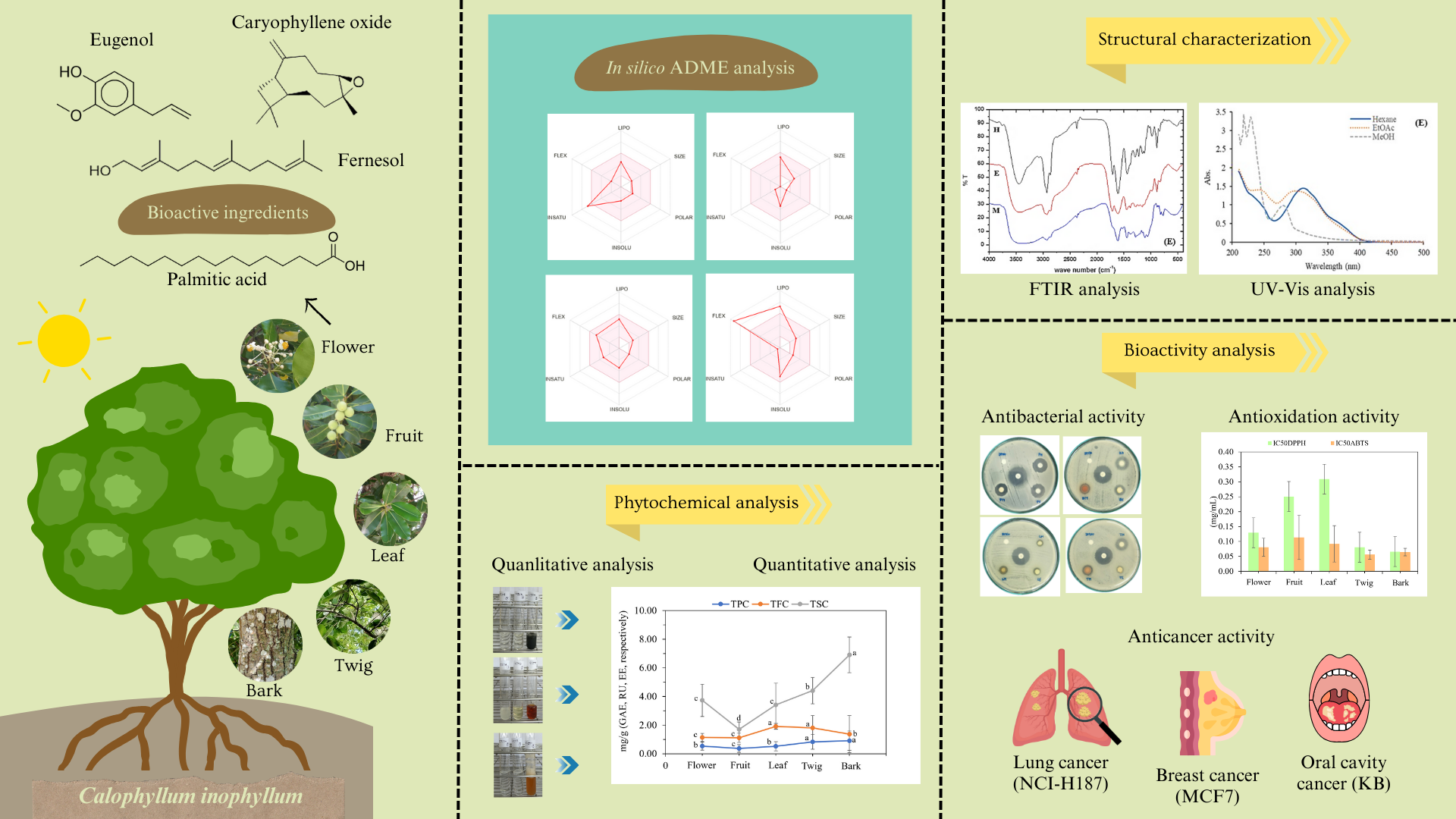

Bioactive Potential of Calophyllum inophyllum: Phytochemical Profiles, Biological Activities, and In Silico Pharmacokinetic Predictions

1 Department of General Education, Faculty of Science and Fisheries Technology, Rajamangala University of Technology Srivijaya, Sikao, Trang, 92150, Thailand

2 Department of Marine Sciences and Environment, Faculty of Science and Fisheries Technology, Rajamangala University of Technology Srivijaya, Sikao, Trang, 92150, Thailand

3 Division of Physical Science and Center of Excellence for Innovation in Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Prince of Songkla University, Hat-Yai, Songkhla, 90110, Thailand

* Corresponding Authors: Luksamee Vittaya. Email: ,

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(12), 4091-4115. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.074891

Received 20 October 2025; Accepted 28 November 2025; Issue published 29 December 2025

Abstract

Calophyllum inophyllum is a tropical plant that could have useful medicinal properties for pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications. The present study extracted the flower, fruit, leaf, twig, and bark of the plant by maceration in different organic solvents. The correlation between bioactive compounds and their biological activities was investigated, with emphasis on their therapeutic relevance through in silico pharmacokinetic predictions using SwissADME. Qualitative and quantitative analyses were conducted to determine the total phenolic, flavonoid, and saponin contents of the extracts. Spectral analysis of the extracts revealed –OH, C=O, C=C, and C–H functional groups. The antioxidant activity of the extracts was evaluated by colorimetric DPPH and ABTS assays. Antibacterial activity was also determined, along with cytotoxicity and anticancer potential. The plant part and solvent used for extraction affected the active compounds collected. Methanolic bark extract presented the highest phenolic and flavonoid contents, whereas hexane bark extract presented the highest saponin content. These results correlated with the antioxidant and antibacterial activities of the extracts. The strong correlation between antioxidant activity and total phenolic contents indicated that phenolic compounds were the dominant contributors to antioxidant activity. Methanolic bark extract showed significant DPPH scavenging activity (IC50 = 0.004 mg/mL) while hexane bark extract produced the largest zone of inhibition against Staphylococcus aureus (17.96 ± 0.00 mm). The lowest minimum inhibitory concentration (<0.098 mg/mL) was shown against Bacillus cereus by 11 out of the 15 extracts. Selective cytotoxicity was observed against cancer cells, especially lung cancer cells. In silico ADME analysis of a previously reported flower extract showed favorable pharmacokinetic properties for compounds such as eugenol and caryophyllene oxide. High gastrointestinal absorption and blood-brain barrier permeability suggested good oral bioavailability and central nervous system potential. Most extracted compounds met Lipinski’s Rule with minimal cytochrome P450 inhibition, indicating good drug-likeness. These findings highlight the promise of C. inophyllum as a source of natural antioxidants and antibacterial agents with therapeutic potential.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileThe uncertain climatic conditions that are affecting human settlement and food supplies are also contributing to the emergence of new diseases [1]. Currently, synthetic antibiotics are widely used to manage diseases [2], but the adoption of natural products into disease management might be a more promising approach to the prevention of emerging diseases. Medicinal plants and herbs have attracted significant attention as potential alternatives to synthetic antibiotics, and recent research has focused on identifying plants that thrive in fluctuating environmental conditions, such as those found in mangrove or coastal forests. These plants not only survive but thrive, adapting to harsh conditions by producing bioactive compounds to protect themselves from harmful environmental factors. Compounds from the mangrove plant Acanthus ebracteatus were shown to exhibit antioxidant and biological activities [3], compounds from Pluchea indica have shown pharmacological properties [4], and Calophyllum inophyllum has been widely studied for its potential to contribute to pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications [5]. In addition, mangrove plants such as Rhizophora mucronata and Rhizophora apiculata are cooked and eaten for their medicinal properties [6,7]. Therefore, the discovery of bioactive substances from these plants supports local traditional wisdom and extends the application and utilization of plants and herbs in medicine.

C. inophyllum is a mangrove plant and consequently endures constantly changing environmental conditions. Researchers have extracted various parts of this plant, isolating and investigating several significant bioactive compounds from the seed, fruit, leaf, and bark [5,8,9]. However, the isolation and purification processes are time-consuming and require substantial quantities of solvent and advanced analytical tools. Preliminary phytochemical screening provides a more efficient and rapid method of classifying bioactive substances, enabling quantitative studies to identify potential applications. Understanding the biological activities of different parts of C. inophyllum can assist in the identification of phytochemicals that can provide pharmaceutical or medical alternatives to synthetic chemicals and antibiotics. Moreover, this approach would accelerate the use of extracts by shortening the lengthy process of isolating specific compounds.

Recently, our research group conducted a rare study of the flower of C. inophyllum. The results showed that macerated extracts of C. inophyllum flower [10] yielded a broader range of active ingredients than distilled extracts [11,12]. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry revealed various important bioactive compounds in the flower extracts. The chemical composition of the extracts was found to depend on the solvent used for extraction [10]. The polarity of the solvent and solute interactions may explain the greater antibacterial activity of the hexane extract of C. inophyllum flower compared to the ethyl acetate and methanol extracts. The bioactive compounds detected in these extracts included α-copaene, α-muurolene, β-muurolene, γ-cadinene, δ-cadinene, caryophyllene oxide, eugenol, palmitic acid, and phytol, each exhibiting different biological activities. To further explore the pharmaceutical potential of these compounds, an in silico evaluation of their molecular properties was undertaken in the present study. Absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) were studied to predict the physicochemical properties of the compounds, their lipophilicity, water solubility, drug-likeness, pharmacokinetics, and medicinal chemistry suitability. This analysis was expected to facilitate the assessment of their potential as therapeutic agents [13]. The ADME computational approach is particularly valuable for determining the oral bioavailability, solubility, and potential drug interactions of bioactive compounds, thereby streamlining the identification of promising drug candidates from natural sources.

This research aims to determine the contents of phenolics, flavonoids, and saponins in C. inophyllum fruit, leaf, twig, and bark extracts for comparison with the contents of the previously investigated flower extracts. The ethnomedicinal properties of the plant were examined using both qualitative and quantitative analyses, and the plant parts were screened for pharmaceutically important bioactive substances. Each plant part was extracted using three solvents of varying polarity: hexane, ethyl acetate, and methanol. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy were employed to identify the functional groups and chromophores present in the bioactive compounds. To the best of our knowledge, based on a thorough literature review, this correlation-based study is the first to quantify and compare the phytochemicals and the antioxidant and antibacterial activities of extracts obtained from various parts of C. inophyllum with different solvents. The cytotoxicity and anticancer potential of the extracts were also evaluated. This study combines solvent–part interaction analysis with in silico ADME prediction to provide a clearer understanding of the influence of extraction conditions on the bioactive composition and pharmacological potential of C. inophyllum. The findings will be valuable for practical applications and for identifying the key factors influencing biological activity across different plant parts. Overall, the results highlight the potential of C. inophyllum as a natural source of bioactive ingredients for food, cosmetic, and medicinal applications.

The extracting solvents used in this study (hexane, ethyl acetate, and methanol) were of analytical grade, obtained from RCI Labscan (Bangkok, Thaliand) and used without further purification. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was from Merck (Darmstadt, Germany). Folin-Ciocalteu reagent and aluminum chloride were from Loba Chemie (Mumbai, India). Gallic acid, rutin, escin, DPPH, ABTS+, and p-iodonitrotetrazolium chloride were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (MO, USA). Mueller Hinton broth (MHB) was from Difco, Becton Dickinson (MD, USA). Petroleum ether was supplied by Fisher Scientific (Leicester, UK), and vanillin solution was obtained from Himedia (Mumbai, India).

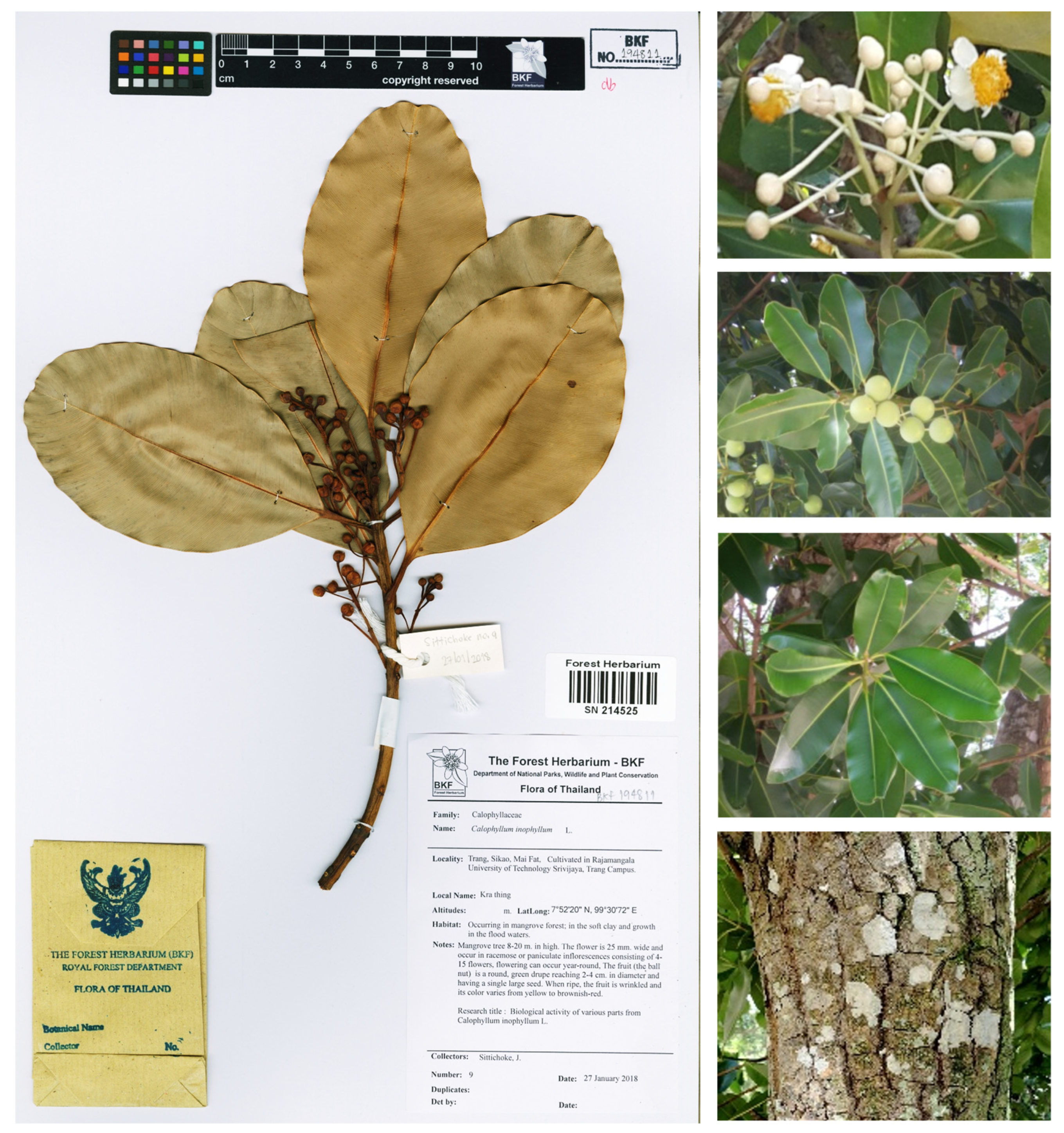

Plants were collected from Trang Province, Thailand, at the coordinates 7°52′20″ N, 99°30′72″ E. A voucher specimen (BKF 194811) was deposited at the Forest Herbarium, Bangkok, Department of National Parks, Wildlife and Plant Conservation, Thailand (Fig. 1). Fresh flowers, fruits, leaves, and twigs were collected in September, and bark samples were collected in October from mature plants. All plant materials were properly cleaned to remove debris and shade-dried at room temperature for further experiments.

Figure 1: The flower, fruit, leaf, twig, and bark of Calophyllum inophyllum.

Each dried plant part (1000 g) was extracted by maceration using hexane, ethyl acetate, and methanol sequentially at a ratio of 1:7 (plant dry weight–solvent volume) for one week. The obtained extracts were evaporated to dryness, using a rotary evaporator at 45°C. The concentrated extracts were stored in amber glass bottles at 4°C in a refrigerator until further analysis. The yields of flower, fruit, leaf, twig, and bark extracts were reported. All extracts were refrigerated prior to the quantitative analysis of phytochemical contents and antioxidant and antibacterial activities.

The preliminary phytochemical screening of C. inophyllum extracts was carried out according to the method described by Vittaya et al. [10]. To test for anthraquinone, the crude extract was shaken with a 10% solution of sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and heated for 5 min. The filtered extract was then extracted three times with 5 mL of chloroform. The extract was then introduced into a 3% ammonia solution (NH3 dilution). The appearance of a pink color in the ammonia layer indicated the presence of anthraquinone. To test for terpenoids, the crude extract was dissolved a few times in 3 mL of petroleum ether and collected by filtration. Slowly, 2 mL of chloroform and concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4) were added to the filtrate. A brown-ring between two layers indicated the presence of terpenoids. To test for flavonoids, the crude extract was mixed with 95% ethanol, and 2–3 small pieces of magnesium were introduced. The mixture was then filtered, and a few drops of concentrated hydrochloric acid (HCl) were added. The formation of a yellowish-orange precipitate indicated the presence of flavonoids. To test for saponins, 5 mL of water was added to the crude extract. The mixture was warmed, and filtered. Subsequently, 2–3 mL of water was added to the filtrate that was then shaken vigorously for 10 min. The appearance of foam indicated the presence of saponins. To test for phenolics, a few drops of 1% ferric chloride (FeCl3) solution were added to the crude extract, which was shaken with water. A dark brown or blackish-green color indicated the presence of phenolics. To test for alkaloids, the crude extract was shaken in 15 mL of 2% sulfuric acid (H2SO4) and warmed. Dragendorff’s reagent was then added to the mixture. The formation of an orange-brown precipitate indicated the presence of alkaloids.

Determination of Phenolic Content. The total phenolic content (TPC) of the extracts was determined spectroscopically using the Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method [14] with gallic acid as a standard. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was recorded at 765 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (U-1800 spectrophotometer, Hitachi High-Tech Science Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The TPC for each sample was calculated using the standard curve of gallic acid at concentrations from 100–600 μg/mL, and expressed in terms of gallic acid equivalents (mg gallic acid/g crude extract). The data were calculated according to the equation y = 0.0040x − 0.0086, R2 = 0.9977.

Determination of Flavonoid Content. The total flavonoid content (TFC) of the extracts was determined using the aluminium chloride method [14] with rutin as a standard. The absorbance was recorded at 510 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer, with measurements taken against a blank sample. TFC was calculated from a standard calibration curve prepared with rutin solutions (100–600 μg/mL) and expressed in terms of rutin equivalents (mg rutin/g crude extract). The data were calculated according to the equation y = 0.0016x + 0.0002, R2 = 0.9992.

Determination of Saponin Content. The total saponin content (TSC) of the extracts was determined according to the method described by Vittaya et al. [10] and Senguttuvan et al. [15], with a modification involving a reduced extract volume. In this method, 0.2 mL of the extract was mixed with 0.5 mL of a 0.8% (w/v) vanillin solution, followed by the addition of 5 mL of 72% (v/v) sulphuric acid. The mixture was allowed to stand for 1 min, then incubated at 70°C for 10 min. After incubation, the solution was rapidly cooled in an ice-water bath to room temperature. The absorbance was measured at 560 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer. Methanol was used as the control, while escin served as the reference standard for comparison. The TSC was expressed in terms of escin equivalent (mg escin/g crude extract) through the calculation curve of escin (y = 0.0007x + 0.0254), which was calibrated alongside the standard curve of escin at concentrations of 100–1000 μg/mL. The experiment was performed in triplicate, and the data were expressed as means ± standard deviation with a linearity R2 equal to 0.9918.

2.5 Structural Characterization

2.5.1 UV-Visible Absorption Spectroscopy

UV-Visible spectral analysis by Hitachi UV-Visible spectrophotometer (U-5100) with UV solutions 4.2 program (Tokyo, Japan) was done in the range of 200–800 nm with a resolution of 1 nm. One milliliter of sample was pipetted into a test tube and analyzed at room temperature. The solvent used to extract each plant part was utilized as a blank.

2.5.2 Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) Analysis

FTIR spectra were recorded with the PerkinElmer BX FTIR spectrophotometer (CT, USA). All samples were prepared by mixing approximately 1 mg of C. inophyllum extract with 3 mg of dry potassium bromide (KBr), using a mortar and pestle. The resulting homogeneous mixture was then pressed into a disc for analysis. The analysis covered a wavelength range of 4000–400 cm−1 at a temperature of 25°C. The spectra were recorded in transmittance mode, with the absorbance of each sample expressed as a percentage of transmittance (%T).

2.6 Antioxidant Activity Assays

DPPH radical scavenging activity was determined using spectroscopy, based on the modified method described by Vittaya et al. [6]. Briefly, a stock solution of extract or standard was prepared at a concentration of 1 mg/mL, and then 0.5 mL of this solution was mixed with 0.5 mL of 0.15 M DPPH solution. The reaction mixture was left to incubate in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance of the reaction was measured at 517 nm against the blank. The percentage of free radical scavenging activity of sample was calculated using Eq. (1): % Free radical scavenging activity = [1 − (Asample − Asampleblank)/Acontrol] × 100(1) where Asample is the absorbance of the test sample with DPPH solution, Asample blank is the absorbance of the test sample only and Acontrol is the absorbance of the DPPH solution.

ABTS radical scavenging activity was determined following the modified method described by Vittaya et al. [6]. In brief, the ABTS+ working solution was diluted to achieve an absorbance of 0.700 ± 0.025 unit at 734 nm. In a centrifuge tube, 0.9 mL of diluted ABTS+ working solution was added to 0.1 mL of standard or sample extract. The reaction mixture was incubated at room temperature for 6 min. After incubation, absorbance was recorded at 734 nm. The percentage of free radical scavenging activity for each sample was determined using Eq. (2): % Free radical scavenging activity = [(Acontrol − Asample)/Acontrol] × 100(2) where Acontrol is the absorbance of the extract without ABTS+ solution and Asample is the absorbance of the extract with ABTS+ solution.

2.7 Biological Activity Analysis

The antibacterial activity of all extracts was preliminarily assessed in triplicate using the paper disc diffusion method [16]. Seven bacterial species were tested: Bacillus cereus TISTR 687, Staphylococcus aureus TISTR 1466, Staphylococcus epidermidis TISTR 518, Escherichia coli TISTR 780, Salmonella typhi TISTR 292, Klebsiella pneumoniae TISTR 1843, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa TISTR 781. These strains were obtained from the National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (BIOTEC), Pathumthani, Thailand. For the disc diffusion assay, the bacterial cultures were incubated in tryptic soy broth at 35°C for 24 h, and their turbidity was measured against 0.5 McFarland standards (1 × 108 colony forming units/mL). With a sterile cotton swab, the bacteria were swabbed over the surface of the media (tryptic soy agar) and allowed to solidify. After incubation at 35°C for 24 h, the inhibition zones were measured in millimetres. To provide negative controls, the fifteen extracts were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to prepare stock solutions of 100 mg/mL. Ten microliters of the solutions were placed on sterile filter paper discs (6 mm in diameter, Whatman No. 1 filter paper). Gentamicin was the positive control.

2.7.2 Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

Stock solutions of the seven model pathogenic bacteria were prepared, and all tested inoculums were produced as 1 × 106 CFU/mL in Mueller Hinton broth (MHB) using a modified method [17]. All extracts and control stock solutions were prepared at an initial concentration of 100 mg/mL and serially diluted two-fold with MHB to obtain a concentration range from 0.01–50,000 μg/mL. In 96-well plates, 50 μL of each diluted concentration was mixed with 50 μL of MHB. The standardized inoculums at 1 × 106 CFU/mL were then introduced into each well and gently mixed by multichannel auto-pipette to produce a final concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL. The plates were then covered with sterile plate sealers. After incubation at 35°C for 24 h, the turbidity of the solutions was measured. Bacterial growth was confirmed by the color change from yellow to pink of p-iodonitrotetrazolium chloride (INT) dye added to the wells. The MIC was defined as the lowest extract concentration that completely inhibited bacterial growth by preventing the color change. The quadruplicate tests included a negative growth control of DMSO (CLSI, 2019). After the broth microdilution tests, the MBC was determined by the drop plate technique. Briefly, a volume of 10 μL was removed from the microtiter plate wells where no growth was observed, and then inoculated onto the surface of HMA plates. The plates were incubated at 35°C for 24 h, and the MBC was taken to be the lowest concentration of the substance at which no colonies formed under these conditions.

2.7.3 Cytotoxicity and Anticancer Assays

The anticancer activity of C. inophyllum extracts was assessed using the resazurin microplate assay (REMA) against three cancer cell lines: oral cavity cancer (KB), breast cancer (MCF7), and small cell lung cancer (NCI-H187). The cytotoxicity of the extracts was also evaluated against African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells as a normal cell line control. The positive controls used for comparison were Ellipticine, Doxorubicin, and Tamoxifen in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). For the anticancer screening, the extracts were tested at various concentrations to determine the percentage of cytotoxicity and the IC50 values. The screening was performed at the National Center for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology (BIOTEC), National Science and Technology Development Agency (NSTDA), Pathumthani, Thailand. The threshold for cytotoxicity was set at 50%, with values below 50% indicating non-cytotoxicity and values above 50% indicating cytotoxicity. IC50 values were calculated for extracts that demonstrated cytotoxicity against the cancer cell lines [18].

The primary physicochemical, lipophilicity, water solubility, pharmacokinetic, drug-likeness, and medicinal chemistry properties of phytochemical compounds identified from the extracts of C. inophyllum flower were evaluated for ADME (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) prediction. The initial step involved accessing the PubChem database (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) to obtain canonical SMILE (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry) system representations of each compound. Subsequently, these SMILEs were used for ADME prediction using the SwissADME online server (http://www.swissadme.ch/) [13].

The data were analysed using IBM SPSS software version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and expressed as means ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate determinations (n = 3). The p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Statistical analysis was carried out using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Duncan’s new multiple range test. Two-way ANOVA was used to investigate the interaction between plant parts (flower, fruit, leaf, twig, and bark) and the three organic solvents (hexane, ethyl acetate, and methanol). Pearson correlation was performed to evaluate the correlation between phytochemical compositions (TPC, TFC, and TSC) and antioxidant activity, as well as antibacterial activities against the seven model pathogenic bacteria. Principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted using a correlation matrix to evaluate the contribution of variables (assay) and factors (plant part and solvent) to the characteristics of C. inophyllum extracts.

3.1 Plant Extraction and Phytochemical Screening

Plants produce primary and secondary metabolites. Secondary metabolites play an important role in the growth of plants that survive changing terrain and climate. They include phenolics, flavonoids, alkaloids, and terpenoids. These compounds are produced as part of defense mechanisms and exhibit complex structures which depend on diverse polarities and vary across species [19]. The polarity of organic solvents used to extract these bioactive compounds has a significant impact on extraction efficiency. In this study, C. inophyllum flower, leaf, fruit, twig, and bark were extracted by maceration in hexane, ethyl acetate, and methanol. Fifteen extracts were obtained from the different plant parts. The data were presented in Table 1, and these extracts were investigated in phytochemical and biological analyses.

Table 1: Yields of various extracts of C. inophyllum.

| Plant | Parts | Solvents | Yield (g) | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. inophyllum | Flower* | Hexane | 6.73 | 1.64 |

| Ethyl acetate | 23.30 | 5.68 | ||

| MeOH | 241.46 | 58.89 | ||

| Fruit | Hexane | 221.64 | 11.31 | |

| Ethyl acetate | 126.02 | 6.43 | ||

| MeOH | 378.37 | 19.30 | ||

| Leaf | Hexane | 47.33 | 2.37 | |

| Ethyl acetate | 96.59 | 4.83 | ||

| MeOH | 234.56 | 11.73 | ||

| Twig | Hexane | 42.77 | 2.04 | |

| Ethyl acetate | 68.73 | 3.27 | ||

| MeOH | 164.53 | 7.83 | ||

| Bark | Hexane | 87.62 | 6.44 | |

| Ethyl acetate | 138.17 | 10.16 | ||

| MeOH | 320.55 | 23.57 |

Methanol extracted the highest yields from all plant parts, followed by ethyl acetate then hexane, except in the case of fruit. This result indicated that most of the compounds extracted from the various plant parts were highly polar, as methanol is a highly polar solvent and, according to the principle of ‘like dissolves like,’ polar solvents tend to dissolve polar compounds. The solubility of organic compounds is influenced by factors such as the number of hydroxyl groups present, molecular weight, and carbon chain length [20,21]. Methanol contains hydrogen bonds, which increase the solubility of both primary and secondary metabolites. The type of phytochemicals extracted also depends on the plant material. The compounds present in plant metabolites can vary from simple to highly polymerized substances such as phenolic acid, flavonoids, alkaloids, saponins, terpenoids, and anthraquinones [6,22]. Primary metabolites, such as carbohydrates and proteins, and secondary metabolites, such as phenolic compounds and flavonoids, are more soluble in methanol. While ethyl acetate is a medium-polar solvent, it can extract compounds in the same polar group but less effectively than methanol. In contrast, hexane is a non-polar solvent, and can extract compounds such as hydrocarbons, lipids, steroids, and fats [20,22]. The different yields obtained with these organic solvents (Table 1) reflect their different polarities.

The results presented in Table 2 revealed that hexane extracts of all the plant parts contained only terpenoids. In contrast, ethyl acetate extracts exhibited the presence of terpenoids, flavonoids, and phenolics, while methanol extracts showed the most diverse range of metabolites, including terpenoids, flavonoids, saponins, phenolics, alkaloids, and anthraquinones. All the extracted phytochemicals were found to some degree among the leaf, twig, and bark extracts. Anthraquinones are structurally aromatic organic compounds which consist of three benzene rings bonded to each other, and they are found in traditional medicines mainly used as laxatives [23]. Terpenoids are small secondary metabolites found in many plants, and are known for their diverse biological activities that include antioxidant and antimicrobial properties [24]. Flavonoids, a chemically distinct group of polyphenols with conjugated aromatic systems, exhibit antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antiallergic activities [25]. Certain flavonoids, including quercetin and rutin, play medicinal roles in human health, showing anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and anticancer activities [26,27]. Saponins are glycosides that have amphiphile properties and are soluble in both water and lipids. Previous studies have identified saponins in Moringa oleifera leaves, where they demonstrated cholesterol-lowering properties [28]. In addition, saponins have been shown to inhibit the growth of human gastric cancer cells [29]. Phenolics, a group of phytochemicals with one or more aromatic rings and hydroxyl groups, include phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannins, and coumarins, and are recognized for their antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anticancer activities [30]. Finally, alkaloids are organic compounds that contain nitrogen within the molecule. The functions of alkaloids in plants are assumed to be as a source of nitrogen for protein production, control of growth or germination of seeds, and protection from insects [31].

Table 2: Qualitative phytochemical analysis of various extracts of C. inophyllum.

| Plant Constituent | Verification Method | Observations | C. inophyllum | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flower | Fruit | Leaf | Twig | Bark | |||||||||||||

| H | E | M | H | E | M | H | E | M | H | E | M | H | E | M | |||

| Anthraquinone | Borntrager’s test | Formation of a rose-pink color | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | |

| Terpenoid | Salkowski’s test | Reddish brown ring | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| Flavonoid | Reduction of metal | Formation of a cherry color | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| Saponin | Forth test | Formation of a stable form | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Phenolic | Ferric chloride test | Green-bluish, dark green | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Alkaloid | Dragendorff’s test | Formation of an orange-yellow precipitate | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

3.2 Structural Characterization

3.2.1 UV-Visible Absorption Spectroscopy

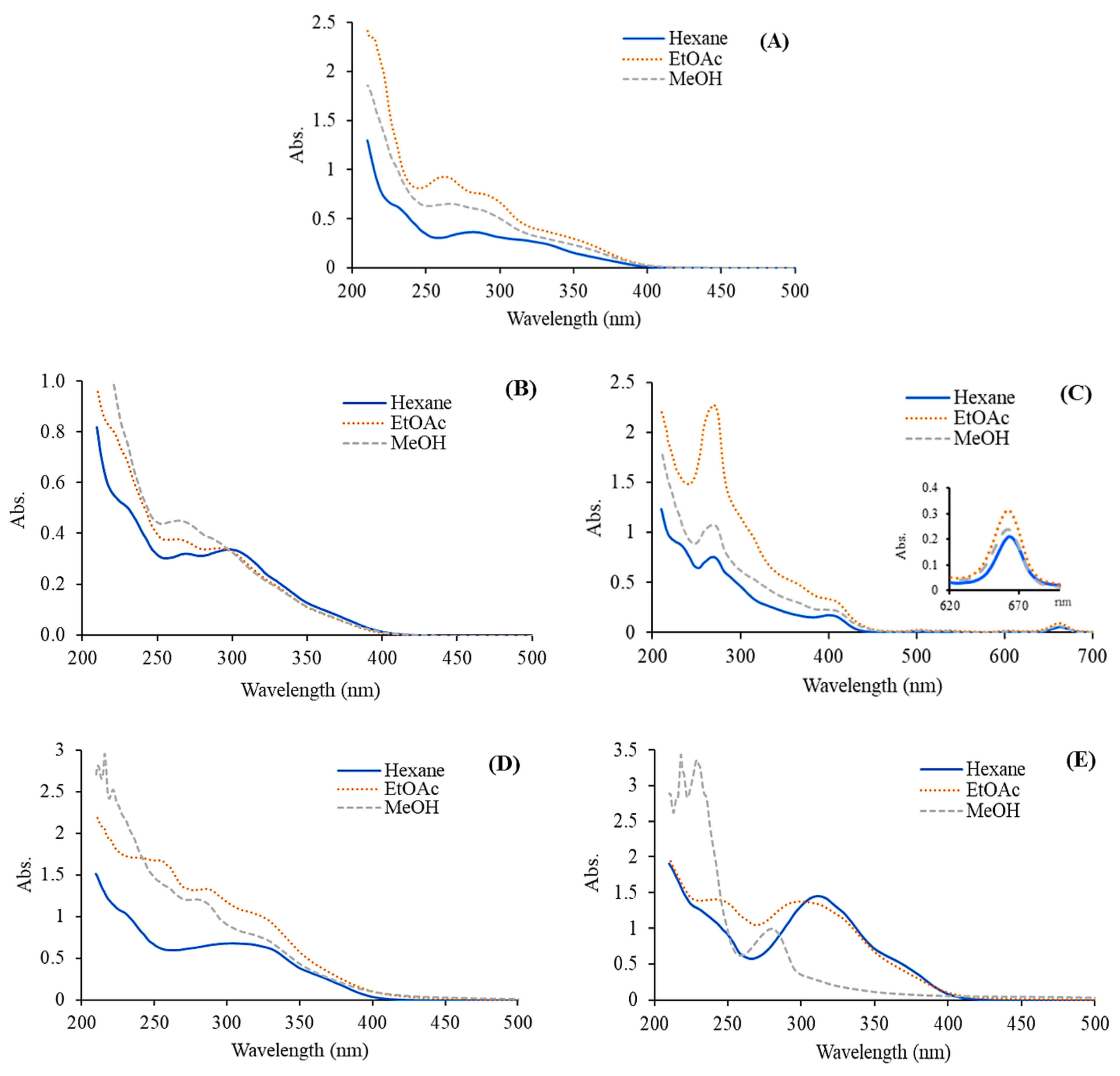

UV-vis spectra of flower, leaf, fruit, twig, and bark extracts of C. inophyllum exhibited absorbance bands in the 200–400 nm range (Fig. 2). The leaf extracts also produced an absorption band in the 600–700 nm range, which corresponds to the absorbance of chlorophyll [32]. The first photoabsorption band of phenolic compounds, around 265–315 nm, is typically attributed to their aromatic structure. Kumar and Goel [30] reported that phenolic compounds absorb in the UV region of 225–330 nm. The solvent used for extraction had a greater effect on absorption than the plant part extracted. The absorption peaks shifted due to the varying polarity of the solvents, which affects the solubility and extraction efficiency of phenolic compounds. The twig and bark extracts showed stronger absorbance in the UV region compared to the leaf extracts. This suggests that the twig and bark parts of C. inophyllum contained a higher concentration of bioactive compounds, especially phenolics, which contribute significantly to UV absorption. These results are consistent with the observed total phenolic contents (TPC) (Table 3). The lower TPC observed in hexane extracts can be attributed to the non-polar nature of hexane. However, ethyl acetate and methanol extracts demonstrated higher TPC, indicating a greater presence of hydroxyl (–OH) groups, which are known for their strong hydrogen bonding and intermolecular interactions, which enhance the stability and activity of various phytochemicals [30]. The UV absorption spectra for the flower and fruit extracts of C. inophyllum displayed solvent-dependent variations, with methanol and ethyl acetate extracts showing stronger absorption than hexane extracts. These results indicated that the polar solvents extracted these bioactive compounds more efficiently from C. inophyllum.

Figure 2: Absorption spectra of C. inophyllum extracts from different plant parts: flower (A), fruit (B), leaf (C), twig (D), and bark (E), extracted with hexane, ethyl acetate (EtOAc), and methanol (MeOH).

Table 3: Total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), total saponin content (TSC), and radical scavenging activity of C. inophyllum extracts. Two-way analysis of variance showed the effects of plant parts (PP), solvent (S), and their interaction.

| Parts | Solvents | TPC (mg GAE/g CE) | TFC (mg RU/g CE) | TSC (mg EE/g CE) | IC50 DPPH (mg/L) | IC50 ABTS (mg/L) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flower* | Hexane | 0.19 ± 0.02ij | 0.91 ± 0.18gh | 5.05 ± 0.79bc | 0.343 ± 0.003i | 0.117 ± 0.001g | ||||||

| Ethyl acetate | 0.84 ± 0.07c | 1.48 ± 0.11ef | 3.14 ± 0.55d–f | 0.014 ± 0.000a–c | 0.077 ± 0.004ef | |||||||

| Methanol | 0.57 ± 0.05e–g | 1.03 ± 0.07g | 2.99 ± 0.41ef | 0.030 ± 0.001b–d | 0.047 ± 0.003c | |||||||

| Fruit | Hexane | 0.18 ± 0.02ij | 1.34 ± 0.07f | 1.31 ± 0.35h | 0.502 ± 0.002j | 0.211 ± 0.010i | ||||||

| Ethyl acetate | 0.72 ± 0.06c–e | 1.30 ± 0.13f | 1.76 ± 0.45gh | 0.141 ± 0.002g | 0.071 ± 0.000e | |||||||

| Methanol | 0.20 ± 0.02ij | 0.70 ± 0.06h | 2.06 ± 0.51f–h | 0.109 ± 0.001f | 0.058 ± 0.002d | |||||||

| Leaf | Hexane | 0.15 ± 0.02j | 1.96 ± 0.19bc | 5.35 ± 0.63bc | 0.852 ± 0.045k | 0.172 ± 0.003h | ||||||

| Ethyl acetate | 0.65 ± 0.28d–f | 2.03 ± 0.19b | 2.30 ± 0.32f–h | 0.042 ± 0.001d | 0.059 ± 0.004d | |||||||

| Methanol | 0.77 ± 0.06cd | 1.75 ± 0.14cd | 2.60 ± 0.37fg | 0.032 ± 0.000cd | 0.045 ± 0.003c | |||||||

| Twig | Hexane | 0.33 ± 0.03hi | 0.89 ± 0.06gh | 5.19 ± 0.89bc | 0.188 ± 0.005h | 0.076 ± 0.003ef | ||||||

| Ethyl acetate | 0.69 ± 0.06c–e | 1.68 ± 0.17de | 3.80 ± 0.71de | 0.027 ± 0.000b–d | 0.045 ± 0.001c | |||||||

| Methanol | 1.48 ± 0.13b | 2.86 ± 0.12a | 4.24 ± 0.76cd | 0.027 ± 0.000b–d | 0.048 ± 0.005c | |||||||

| Bark | Hexane | 0.42 ± 0.02gh | 0.24 ± 0.01i | 7.89 ± 1.01a | 0.132 ± 0.005g | 0.080 ± 0.000f | ||||||

| Ethyl acetate | 0.51 ± 0.03fg | 0.81 ± 0.06gh | 5.66 ± 0.89b | 0.062 ± 0.002e | 0.051 ± 0.002c | |||||||

| Methanol | 1.81 ± 0.14a | 3.07 ± 0.11a | 7.17 ± 0.72a | 0.004 ± 0.000a | 0.063 ± 0.001d | |||||||

| BHT | 0.011 ± 0.000ab | 0.017 ± 0.001b | ||||||||||

| Vit C | 0.004 ± 0.000a | 0.002 ± 0.000a | ||||||||||

| Two-Way ANOVA | ||||||||||||

| Variable | df | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | |

| PP | 4 | 51.830 | <0.001 | 80.876 | <0.001 | 73.781 | <0.001 | 753.272 | <0.001 | 342.580 | <0.001 | |

| S | 2 | 209.899 | <0.001 | 160.703 | <0.001 | 24.045 | <0.001 | 4559.042 | <0.001 | 2071.829 | <0.001 | |

| PP × S | 8 | 50.424 | <0.001 | 126.575 | <0.001 | 4.484 | 0.001 | 577.928 | <0.001 | 241.216 | <0.001 | |

| Error | 30 | |||||||||||

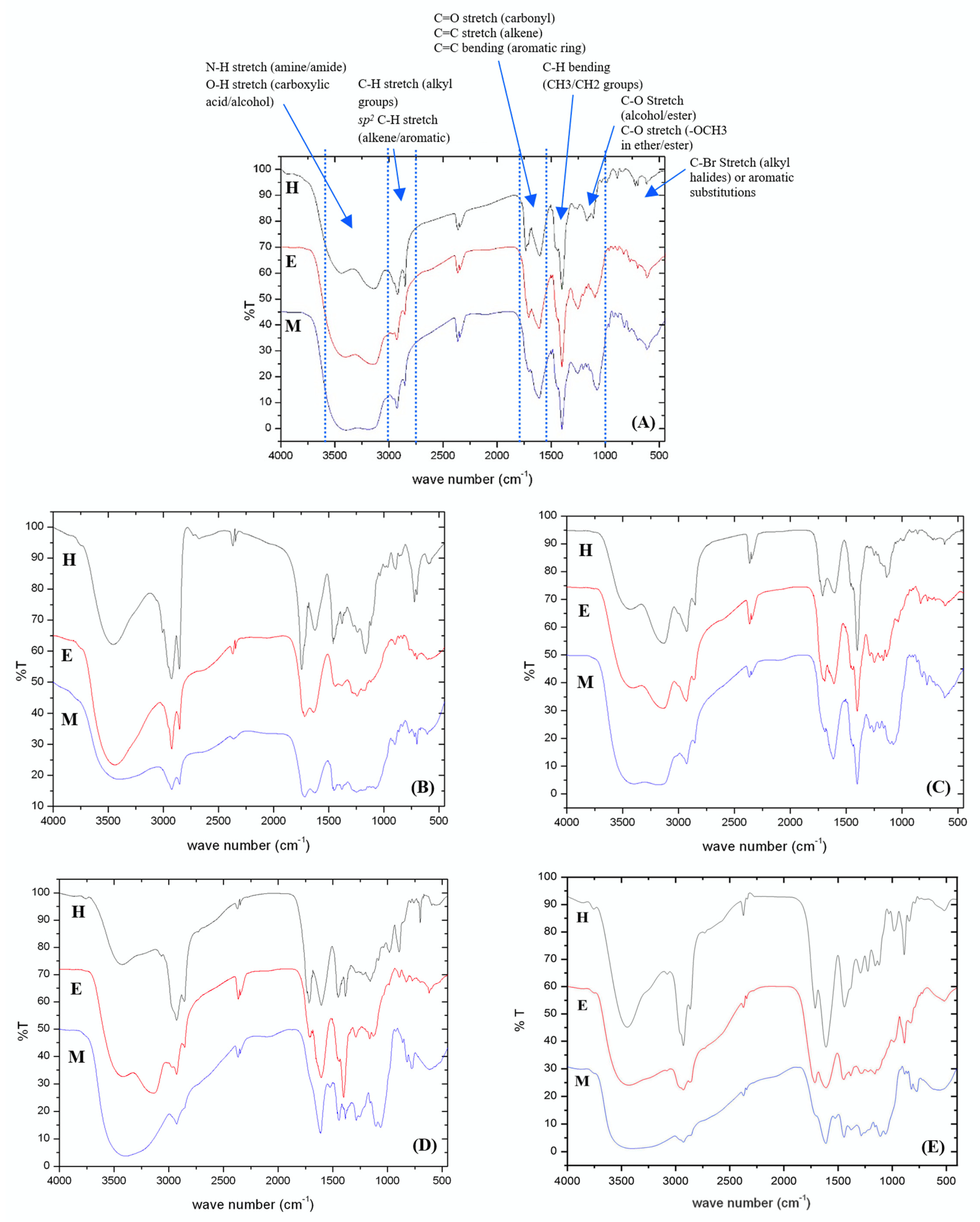

The FTIR spectra of the extracts of C. inophyllum flower are presented with peak assignments (Fig. 3). The O–H stretching peaks at 3000–3500 cm−1, 2700–3000 cm−1, and 500–1000 cm−1 correspond to the stretching oscillations of alcohol or carboxylic acid groups which overlap the stretching vibration attributed to water. The elongation bands of C–H on the aromatic ring are present at 3500–4000 cm−1. Additionally, the band at 2700–3000 cm−1 corresponds to C–H stretching in aliphatic hydrocarbons, which indicates the presence of fatty acids, lipids, and possibly essential oils [33]. The sp2 C–H stretching band in this range is associated with aromatic compounds, which may include flavonoids and phenolic acids. Moreover, the flexion band around 1500–1800 cm−1 corresponds to C=C bending in aromatic rings, C=C stretching in alkenes, or C=O stretching in carboxylic acid derivatives, suggesting the presence of carbonyl compounds such as terpenoids or aldehydes [34]. The oscillation of amine stretching and C–N bending vibrations were detected at 1000–1500 cm−1 [35]. The peak at 1000–1200 cm−1 is the elongation band of C–O stretching of methoxy (–OCH3) in alkyl aryl ether or ester compounds. It is possible that the absorption peak at 500–580 cm−1 may correspond to the stretching of C–Br in alkyl halide or the presence of substitution groups on the benzene ring [36]. The observed peaks confirmed the presence of the functional groups –OH, C=O, C–H, C=C, C–O, and N–H, and support the findings of previous studies on mangrove plants and their phytochemicals [37]. These results also support the findings of previous reports which demonstrated that C. inophyllum extracts contained phenolic and flavonoid components with potential biological activities [5,10].

Figure 3: FTIR spectra of C. inophyllum extracts from various plant parts: flower (A), fruit (B), leaf (C), twig (D), and bark (E), extracted using hexane (H), ethyl acetate (E), and methanol (M).

3.3 Phytochemical Study of C. inophyllum

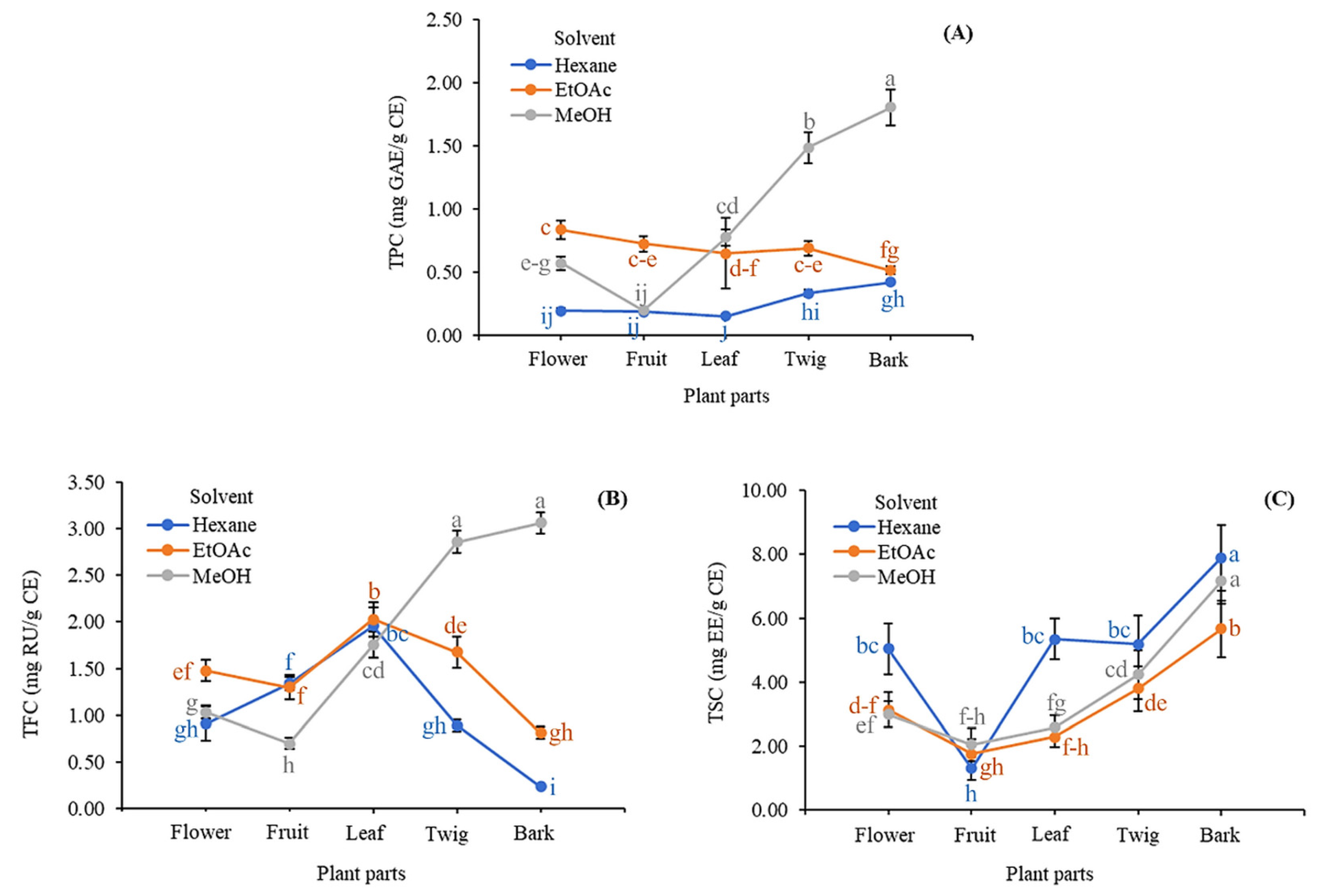

The TPC, TFC, and TSC of C. inophyllum extracts ranged from 0.19 to 1.81 mg GAE/g crude extract, 0.24 to 3.07 mg RU/g crude extract, and 1.31 to 7.89 mg EE/g crude extract, respectively (Table 3). The bark methanolic extract contained the highest TPC and TFC, and the second highest TSC (p < 0.05) (Fig. 4). A two-way ANOVA revealed a significant effect of plant parts and solvents on TPC (F = 51.830, p < 0.001 for plant parts; F = 209.899, p < 0.001 for solvents) and TFC (F = 80.876, p < 0.001 for plant parts; F = 160.703, p < 0.001 for solvents). Notably, the interaction between plant parts and solvents also had a significant effect (F = 50.424, p < 0.001) on TPC (Fig. 4A) and TFC (F = 126.575, p < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). The analysis showed similar effects on TSC of plant parts (F = 73.781, p < 0.001) and solvents (F = 24.045, p < 0.001) and their interactions (F = 4.484, p = 0.001) but the effects were less significant (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4: Interaction effects of plant parts and solvents on (A) total phenolic content (TPC), (B) total flavonoid content (TFC), and (C) total saponin content (TSC) in C. inophyllum extracts. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05) among means, n = 3; error bars represent ± SD. EtOAc: ethyl acetate, MeOH: methanol.

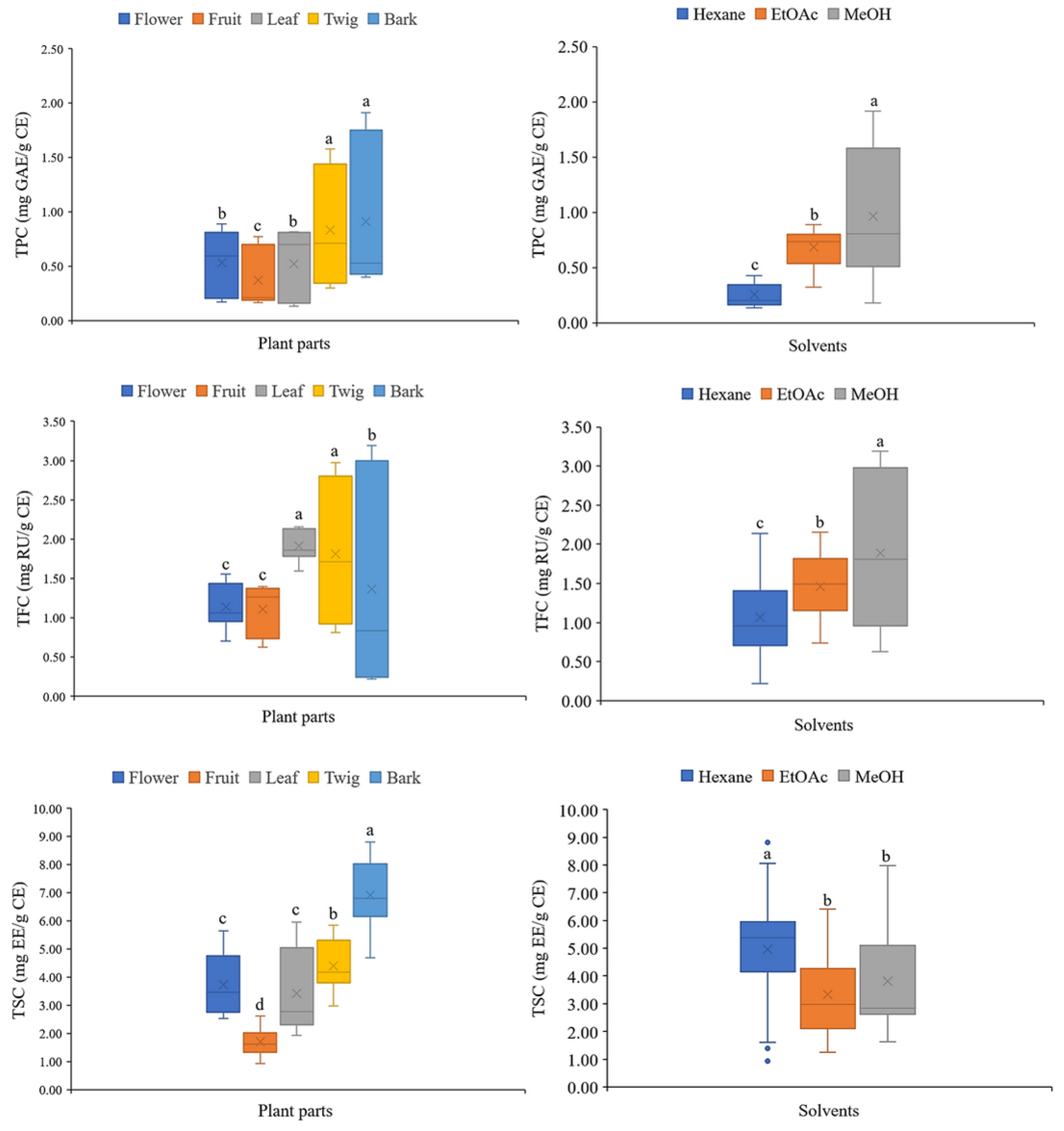

The differences in TPC, TFC, and TSC across the extracts could be influenced by environmental factors, the chemical composition of the plant material, soil conditions, harvest maturity, and post-harvest storage practices [38,39]. In the present study, the effects of the different solvents were explored. The methanolic extracts yielded the highest overall TPC and TFC, whereas the hexane extracts yielded the highest TSC (Fig. 5). When averaged across solvents, the twig and bark extracts contained the highest TPCs among the plant parts (0.83 ± 0.52 mg GAE/g CE for twig and 0.91 ± 0.68 mg GAE/g CE for bark). The leaf and twig extracts yielded the highest TFCs (1.91 ± 0.20 mg RU/g CE for leaf and 1.81 ± 0.86 mg RU/g CE for twig). The bark extract yielded the highest TSC (6.91 ± 1.25 mg EE/g CE). Among solvents (averaged across plant parts), the TPC and TFC were highest in the methanolic extracts (0.97 ± 0.62 mg GAE/g CE for TPC and 1.88 ± 0.98 mg RU/g CE for TFC), whereas TSC was highest in hexane extracts (4.96 ± 2.27 mg EE/g CE) (Fig. 5, Tables S1 and S2).

Figure 5: Total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and total saponin content (TSC) were averaged across solvents and across plant parts in C. inophyllum extracts. Different lowercase letters denote significant differences (p < 0.05) among means; error bars represent ± SD. n = 15 for solvents n = 9 for plant part EtOAc: ethyl acetate, MeOH: methanol.

The results indicated that the solvent used determined whether phenolics, flavonoids, or saponins were the major phytochemicals extracted. This finding is consistent with prior research that highlighted the influence of solvent polarity on the solubility of bioactive compounds [19]. Methanol is a polar solvent that is particularly effective in extracting phenolics and flavonoids, while hexane, a non-polar solvent, is more effective in extracting saponins. These results were consistent with the principles of solvent extraction, where the choice of solvent is crucial for optimizing yield based on the chemical nature of target compounds [40]. An understanding of the distribution of bioactive compounds among the various plant parts is also crucial. Twig and bark material yield the highest phenolic contents, while leaf and twig yield the highest flavonoid contents. This differential distribution could be attributed to the adaptive mechanisms of plants and the different roles different tissues play in protecting against environmental stressors such as UV radiation [41] and pathogens [42].

3.4 Determination of Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant activity of C. inophyllum extracts was evaluated using the DPPH and ABTS methods. Bioactive compounds such as phenolics, saponins, terpenoids, and anthraquinones, particularly those containing hydroxyl groups (–OH), act as scavengers, neutralizing lone-pair electrons in the reaction systems, causing visible color changes. DPPH changes from purple to colorless, while ABTS changes from light blue to yellow. Table 3 shows the antioxidant activities of C. inophyllum extracts from flower, fruit, leaf, twig, and bark extracted using different solvents. The methanolic bark extract demonstrated the highest antioxidant activity (0.004 ± 0.000 mg/L), which was comparable to the antioxidant activity of Vitamin C, but better than that of the synthetic antioxidant BHT (0.011 ± 0.000 mg/L). This strong antioxidant activity was likely due to the high content of natural phenolic and flavonoid compounds in the methanolic extract. The presence of hydroxyl groups in phenolic compounds plays a crucial role in trapping and neutralizing free radicals [7,43]. Therefore, this effectiveness is likely related to the high polarity of compounds extracted with methanol [9].

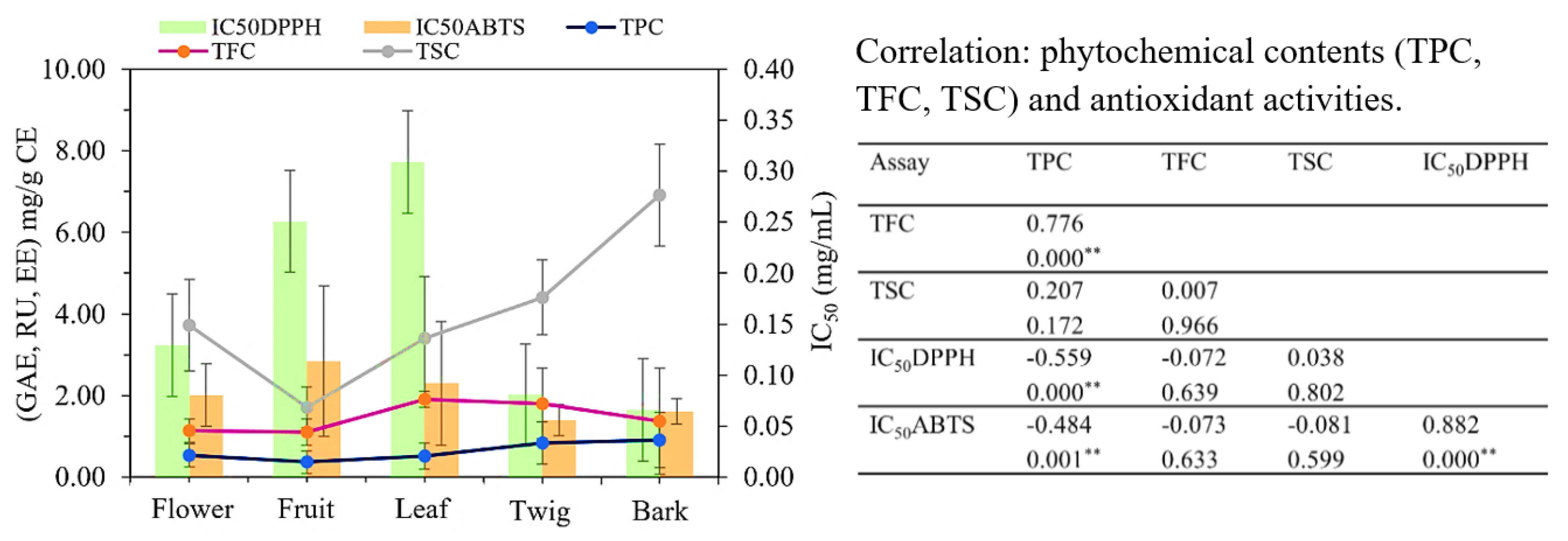

The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to study the relationship between phytochemical contents in C. inophyllum extracts and antioxidant activities (Fig. 6). A strong positive correlation was observed between TPC and TFC (r = 0.776, p < 0.001). However, antioxidant activity was significantly correlated only with TPC (r = −0.559, p < 0.001 for DPPH; r = −0.484, p = 0.001 for ABTS), and not with TFC (r = −0.072, p = 0.639 for DPPH; r = −0.073, p = 0.633 for ABTS) or TSC (r = 0.038, p = 0.802 for DPPH; r = −0.081, p = 0.599 for ABTS). The differences in antioxidant activity could be attributed to the specific types of phenolic, flavonoid, and saponin compounds present in each extract or to the presence of other primary metabolites, such as sugars, carbohydrates, proteins, and amino acids [19,44]. Similarly, Vittaya et al. [14] reported a positive correlation (r = 0.876, p = 0.002) between phenolic and flavonoid contents and antioxidant activity in Ampelocissus martini extracts.

Figure 6: Total phenolic content (TPC), total flavonoid content (TFC), and total saponin content (TSC) in each plant part were averaged across solvents. TPC and TFC were positively correlated with each other but negatively correlated with antioxidant activity [2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 2,2′-azinobis-3-ethylbenzothiazo line-6-sulfonic acid (ABTS)] of flower, fruit, leaf, twig, and bark of C. inophyllum. The data are presented as means ± SD. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) between each pair of plant parts and phytochemical contents (n = 9), ** p < 0.001.

3.5 Determination of Antibacterial Activity

All extracts of C. inophyllum showed antibacterial activity against the seven tested bacterial strains, which included three Gram positive and four Gram negative species. The diameters of the inhibition zones for Gram positive bacteria ranged from 10.57–17.16 mm against B. cereus, 8.28–17.96 mm against S. aureus, and 8.11–9.61 mm against S. epidermidis. For Gram negative bacteria, the diameters of the inhibition zones ranged from 7.57–9.08 mm against E. coli, 8.27–17.15 mm against S. typhi, 6.32–8.44 mm against K. pneu, and 8.53–18.78 mm against P. aeruginosa (Table 4). Moreover, the antibacterial effects varied depending on the plant parts, the solvents used for extraction, and their combinations. For B. cereus, S. aureus, and S. typhi, plant parts, solvents, and the interaction between plant parts and solvents were highly significant (p < 0.001). The best antibacterial activities were found in the hexane extracts from bark and twig. For S. epidermidis, plant parts and solvents were significant (p = 0.01), though the interaction between plant parts and solvents was not as strong. The methanolic bark extract demonstrated the strongest antibacterial activity against this bacterium. For E. coli and K. pneumoniae, plant parts were significant (p = 0.002 and p < 0.001, respectively), and the interaction between plant parts and solvents was also significant (p = 0.007 and p < 0.001). The methanolic extracts of twig and bark showed the highest activity against E. coli, while the hexane flower extract was most effective against K. pneumoniae. In the case of P. aeruginosa, both plant parts and solvents were significant (p < 0.001), along with their interaction (p = 0.01). The best antibacterial activities were found in the hexane extract of fruit. Overall, these results demonstrated that the hexane and methanolic extracts from bark were more effective against Gram positive bacteria than Gram negative bacteria. However, hexane extracts from twig, flower, and fruit were notably more effective against Gram negative bacteria.

Table 4: Zones of inhibition from methanolic extracts of C. inophyllum against seven pathogenic bacteria. Two-way analysis of variance showed the effects of plant parts (PP), solvent used (S), and their interaction.

| Parts | Solvents | Zone of Inhibition Diameter (mm) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram Positive | Gram Negative | ||||||||||||||

| B. cereus | S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | S. typhi | K. pneu | P. aeruginosa | |||||||||

| Flower* | H | 15.07 ± 1.03c–e,AB | 14.95 ± 0.29de,AB | 8.48 ± 0.51b–d,C | 8.54 ± 0.51bc,C | 16.63 ± 0.79c,A | 8.44 ± 0.31b,C | 13.92 ± 3.18d–f,B | |||||||

| E | 14.46 ± 0.21de,A | 14.81 ± 0.85de,A | 8.61 ± 0.58b–d,C | 8.25 ± 0.60c–f,C | 14.35 ± 0.94ef,A | 7.70 ± 0.39cd,C | 12.01 ± 2.74f,B | ||||||||

| M | 14.09 ± 0.75de,B | 13.66 ± 0.22ef,B | 8.58 ± 0.30b–d,C | 7.68 ± 0.65d–f,CD | 16.62 ± 0.35c,A | 6.85 ± 0.25e–g,D | 12.55 ± 2.18ef,B | ||||||||

| Fruit | H | 15.32 ± 1.55b–d,B | 15.71 ± 1.53cd,B | 9.10 ± 1.40b–d,C | 8.12 ± 0.10c–f,C | 17.04 ± 1.23bc,AB | 8.11 ± 0.07bc,C | 18.78 ± 0.27b,A | |||||||

| E | 14.27 ± 1.52de,B | 14.15 ± 0.60ef,B | 8.60 ± 0.52b–d,C | 7.45 ± 0.25f,C | 17.03 ± 0.80bc,A | 7.89 ± 0.47b–d,C | 17.07 ± 0.99bc,A | ||||||||

| M | 13.30 ± 0.64d–f,B | 14.11 ± 0.77ef,B | 8.93 ± 0.83b–d,C | 8.37 ± 0.22b–e,CD | 16.73 ± 1.22c,A | 7.33 ± 0.46d–f,D | 15.86 ± 1.05cd,A | ||||||||

| Leaf | H | 10.57 ± 0.06h,A | 8.28 ± 0.34h,BC | 8.11 ± 0.22de,BC | 8.04 ± 0.36c–f,BC | 8.50 ± 0.46h,B | 7.80 ± 0.23b–d,C | 8.53 ± 0.39g,B | |||||||

| E | 11.11 ± 1.02gh,A | 8.61 ± 0.39h,BC | 7.31 ± 0.54e,D | 7.74 ± 0.61c–f,CD | 8.27 ± 0.32h,BCD | 7.63 ± 0.59cd,CD | 9.03 ± 0.60g,B | ||||||||

| M | 11.73 ± 2.47f–h,A | 8.92 ± 0.48gh,BC | 8.17 ± 0.38de,BC | 7.57 ± 0.51ef,C | 8.72 ± 0.81h,CD | 7.66 ± 0.57cd,C | 9.69 ± 0.37g,B | ||||||||

| Twig | H | 17.04 ± 1.40bc,A | 16.77 ± 1.05bc,A | 8.79 ± 1.06b–d,C | 8.13 ± 0.49c–f,C | 18.47 ± 1.46b,A | 6.32 ± 0.07g,D | 14.90 ± 0.67c–e,B | |||||||

| E | 10.57 ± 0.85h,AB | 10.19 ± 1.47g,B | 8.01 ± 0.39de,C | 8.42 ± 0.65b–e,C | 11.78 ± 0.51g,A | 6.32 ± 0.12g,D | 9.26 ± 0.23g,BC | ||||||||

| M | 13.05 ± 1.70e–g,B | 12.92 ± 0.31f,B | 9.37 ± 0.27bc,C | 9.08 ± 0.23b,C | 15.88 ± 0.54cd,A | 7.44 ± 0.57c–e,D | 13.07 ± 0.65ef,B | ||||||||

| Bark | H | 17.16 ± 0.96b,AB | 17.96 ± 0.71b,A | 8.31 ± 0.45c–e,C | 8.18 ± 0.02cb–d,C | 17.15 ± 0.49bc,AB | 6.88 ± 0.30e–g,D | 16.42 ± 0.63c,B | |||||||

| E | 13.77 ± 0.47d–f,C | 15.95 ± 0.56cd,A | 8.44 ± 0.06c–e,D | 8.24 ± 0.20c–f,D | 14.91 ± 1.03de,B | 6.70 ± 0.31fg,E | 13.63 ± 0.30d–f,C | ||||||||

| M | 13.15 ± 0.43d–g,A | 13.84 ± 0.97ef,A | 9.61 ± 0.28b,B | 9.08 ± 0.23b,B | 13.22 ± 1.35fg,A | 7.27 ± 0.16d–f,C | 13.29 ± 0.68ef,A | ||||||||

| Gentamycin | 23.15 ± 0.12a,C | 23.91 ± 0.06a,B | 22.01 ± 10.34a,D | 20.74 ± 0.04a,E | 26.14 ± 0.04a,A | 18.69 ± 0.15a,F | 23.41 ± 0.17a,C | ||||||||

| Two-Way ANOVA | |||||||||||||||

| Variable | df | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P | F | P |

| PP | 4 | 13.960 | <0.001 | 110.964 | <0.001 | 3.944 | 0.011 | 5.260 | 0.002 | 125.538 | <0.001 | 16.490 | <0.001 | 44.441 | <0.001 |

| S | 2 | 15.732 | <0.001 | 31.289 | <0.001 | 5.328 | 0.010 | 2.300 | 0.118 | 24.618 | <0.001 | 2.106 | 0.139 | 11.691 | <0.001 |

| PP × S | 8 | 5.198 | <0.001 | 11.319 | <0.001 | 1.173 | 0.347 | 3.389 | 0.007 | 9.759 | <0.001 | 6.724 | <0.001 | 3.1192 | 0.010 |

| Error | 30 | ||||||||||||||

The stronger activity demonstrated by flower and twig extracts against S. typhi compared to other bacteria was consistent with the findings of previous research [10]. Also, the fruit extract was active against both S. typhi and P. aeruginosa. The leaf extract exhibited the highest activity against B. cereus compared to other plant parts, while the bark extract was most effective against S. aureus. Moreover, the chemical compositions in the flower extracts were rich in sesquiterpenoids, triterpenoids, fatty acids, and fatty acid derivatives, therefore they could inhibit the growth of Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria, especially S. typhi [10].

The Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of the C. inophyllum extracts ranged from 0.098 to >50 μg/mL against Gram positive bacteria and from 0.19 to >100 μg/mL against Gram negative bacteria (Table 5). All extracts showed strong activity against B. cereus with low MIC values between 0.098 μg/mL to 0.78 μg/mL and decreasing activity against S. typhi, S. aureus, P. aeruginosa, S. epidermidis, and E. coli, and the least activity against K. pneumoniae. The antibacterial mechanism is impacted by the molecular weight of compounds, which influences their diffusion through agar, and therefore the chemical composition of the extracts contributed to the variations in sensitivity observed between Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria [45,46].

Table 5: Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) and minimum bactericidal concentrations (MBC) of C. inophyllum extracts.

| Parts | Solvents | MIC/MBC (μg/mL) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gram Positive | Gram Negative | ||||||||||||||

| B. cereus | S. aureus | S. epidermidis | E. coli | S. typhi | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | |||||||||

| MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | MIC | MBC | ||

| Flower* | H | <0.098 | 3.12 | 12.5 | 50 | 12.5 | 25 | 25 | >50 | 12.5 | >100 | 50 | >100 | 25 | >100 |

| E | 0.39 | 25 | 6.25 | >50 | 6.25 | 25 | 6.25 | 50 | 12.5 | >100 | 12.5 | 100 | 6.25 | 100 | |

| M | 0.098 | 3.12 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 50 | 12.5 | >50 | 12.5 | >100 | 25 | >100 | 12.5 | >100 | |

| Fruit | H | <0.098 | 1.51 | 25 | 50 | 12.5 | >50 | 12.5 | >50 | 12.5 | >100 | 25 | 100 | 12.5 | >100 |

| E | <0.098 | 1.51 | 3.12 | 25 | 12.5 | >50 | 25 | >50 | 12.5 | >100 | 25 | 100 | 12.5 | 100 | |

| M | <0.098 | 1.51 | 12.5 | 25 | 12.5 | >50 | 12.5 | >50 | 6.25 | >100 | 25 | 100 | 6.25 | >100 | |

| Leaf | H | 0.39 | 50 | 6.25 | 50 | 12.5 | >50 | 25 | >50 | 6.25 | >100 | 50 | >100 | 25 | >100 |

| E | 0.78 | 50 | 3.12 | >50 | 12.5 | >50 | 12.5 | >50 | 3.12 | >100 | 25 | >100 | 12.5 | >100 | |

| M | 0.39 | 50 | 3.12 | 50 | 12.5 | >50 | 6.25 | >50 | 1.51 | 100 | 25 | >100 | 3.12 | 100 | |

| Twig | H | <0.098 | 1.51 | 50 | 50 | 12.5 | >50 | 25 | 50 | 0.19 | 50 | 50 | >100 | 12.5 | >100 |

| E | 0.098 | 25 | 6.25 | 50 | 12.5 | >50 | 12.5 | >50 | 1.51 | 100 | 25 | >100 | 6.25 | >100 | |

| M | 0.098 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 12.5 | 6.25 | >50 | 12.5 | >50 | 0.78 | 50 | 12.5 | >100 | 1.51 | 100 | |

| Bark | H | <0.098 | 0.78 | 25 | 50 | 12.5 | >50 | 25 | >50 | 12.5 | >100 | 50 | >100 | 12.5 | >100 |

| E | <0.098 | 0.19 | 12.5 | 50 | 12.5 | >50 | 12.5 | >50 | 6.25 | >100 | 25 | >100 | 12.5 | >100 | |

| M | 0.098 | 0.19 | 6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | >50 | 12.5 | 50 | 1.51 | 100 | 12.5 | 100 | 0.39 | 50 | |

Fig. 7 presents the heatmap of Pearson correlations between TPC, TPC, and TSC and antibacterial activity. The color gradient indicates the strength of the correlation (ranging from −1 to 1). Negative correlations are blue and positive correlations red. The results show that TPC was significantly positively correlated with antibacterial activity against S. epidermidis and E. coli. However, TFC displayed a highly significant negative correlation with antibacterial activity against B. cereus, S. aureus, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, and P. aeruginosa. Additionally, TFC showed a significant positive correlation with activity against E. coli but a significant negative correlation with activity against S. typhi. As mentioned above, these variations in sensitivity were associated with the chemical composition of the extracts.

Figure 7: Correlation heatmap showing the relationship between phytochemical contents and antibacterial activities of C. inophyllum extracts. Asterisks (*, **) indicate significance at p < 0.05 and p < 0.001, respectively.

3.6 Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Phytochemicals and Biological Activities in C. inophyllum Extracts

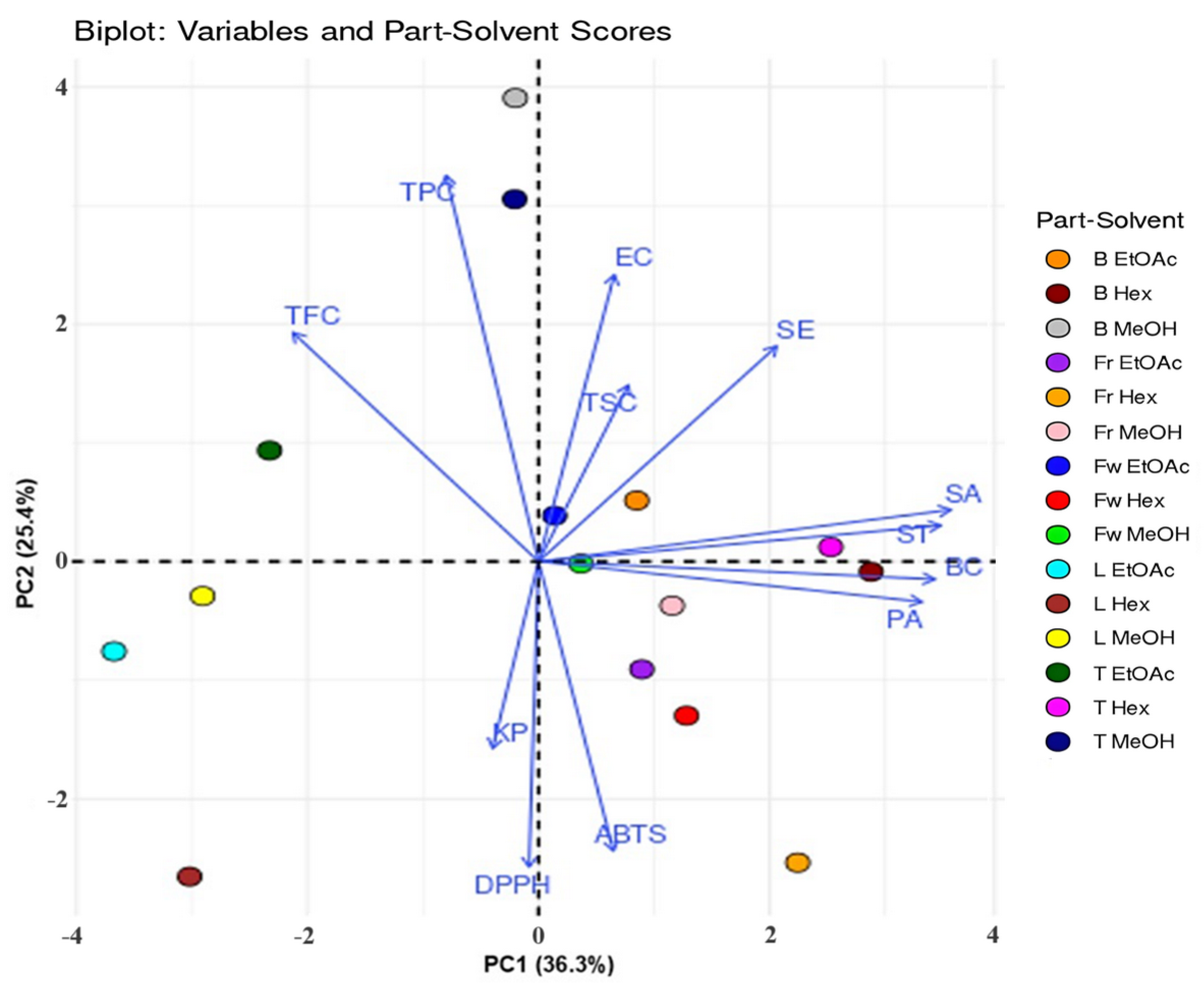

The first two principal components, PC1 and PC2, accounted for 36.3% and 25.4% of the total variance, respectively, and together explained most of the variation observed in the dataset. The loadings of variables on PC1 and PC2, along with the scores for each plant part-solvent combination, are presented in a PCA biplot (Fig. 8). The arrows indicate the direction and strength of correlation for each variable, with longer arrows representing higher contributions to the principal components. Samples located close to a particular variable arrow represent extracts with higher values for that attribute.

Figure 8: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) biplot illustrating the relationships between phytochemical contents (TPC, TFC, and TSC), antioxidant activities (DPPH and ABTS), antibacterial activities against various bacterial strains, and the different solvents used for extracting aerial parts of C. inophyllum. B: bark, Fr: fruit, Fw: flower, L: leaf, T: twig. Hex: hexane, EtOAc: ethyl acetate, MeOH: methanol. BC: B. cereus, SA: S. aureus, SE: S. epidermidis, EC: E. coli, ST: S. typhi, KP: K. pneumoniae.

The first component PC1, showed that positive scores were correlated with higher antibacterial activity against B. cereus, S. aureus, S. epidermidis, S. typhi, and P. aeruginosa. This finding indicated that hexane extracts of bark and twig possessed strong antibacterial activity. The stronger antibacterial efficacy observed in non-polar hexane extracts could be attributed to the presence of lipophilic compounds, such as terpenoids and fatty acids, which are known to disrupt bacterial cell membranes and interfere with lipid-dependent metabolic processes [22,46]. In contrast, negative PC1 scores were associated with lower antibacterial activity and the findings suggested that leaf extracts, which were particularly flavonoid-rich, did not exhibit strong antibacterial activity against the tested bacterial strains. This observation was consistent with previous studies, which have shown that the antibacterial efficacy of specific flavonoid structures can vary depending on the bacterial species and extraction methods [43]. The second component PC2, indicated that positive scores were associated with higher TPC, TFC, and antibacterial activity against E. coli and S. epidermidis. Methanol extracts of bark and twigs exhibited these properties. Conversely, negative PC2 scores corresponded to lower IC50 values for DPPH and ABTS assays, indicating higher antioxidant activities, which were observed in ethyl acetate and methanolic leaf extracts, and lower antibacterial activity, especially against K. pneumoniae, notably in fruit and leaf hexane extracts. The inverse relationship between antioxidant and antibacterial activities could be attributed to the different roles that bioactive compounds serve in each function. Antioxidants, such as phenolic acids and flavonoids, are primarily involved in neutralizing free radicals and protecting cells from oxidative damage [47,48]. Their mechanism of action is based on electron donation or radical scavenging, which may not directly impact bacterial cell walls or metabolic pathways [49,50].

3.7 Cytotoxicity and Anticancer Activity

The anticancer activities of C. inophyllum extracts are shown in Table 6. The most significant anticancer activity was observed in the leaf and bark extracts, especially those extracted with ethyl acetate and hexane. The ethyl acetate leaf extract exhibited the strongest effect against NCI-H187, with an IC50 value of 10.09 μg/mL, followed by the hexane extract, with an IC50 value of 17.45 μg/mL. These results suggest that solvents with intermediate polarity (ethyl acetate) and non-polar solvents (hexane) effectively extract the bioactive compounds responsible for anticancer activity, particularly from the leaf of C. inophyllum, which produced high TPC and TFC (Table 3). The anticancer activities of phenolics and flavonoids are well known, and the high TPC and TFC of ethyl acetate and hexane leaf extracts correlate with the strong anticancer activity observed in these extracts [51]. The ethyl acetate and hexane bark extracts showed anticancer activity, with IC50 values of 19.80 μg/mL and 18.03 μg/mL, respectively, further supporting the presence of active bioingredients and also significant saponin content in comparison to other parts. Saponins may have contributed to the observed anticancer effects, as they are known to inhibit cancer cell proliferation and induce apoptosis [29].

Table 6: Cytotoxicity of C. inophyllum extracts against three cancer cell lines: oral cavity cancer (KB), breast cancer (MCF7), small cell lung cancer (NCI-H187), along with IC50, and cytotoxicity against African green monkey kidney (Vero) cells.

| Parts | Solvents | KB | MCF7 | NCl-H187 | IC50 (μg/mL) | Vero Cell (% Cytotoxicity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flower | H | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | - | Non-cytotoxic |

| E | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | - | Non-cytotoxic | |

| M | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | - | Non-cytotoxic | |

| Fruit | H | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | - | Non-cytotoxic |

| E | Inactive | Inactive | 56.89% | 48.51 ± 0.28 | 81.60% | |

| M | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | - | Non-cytotoxic | |

| Leaf | H | Inactive | Inactive | 99.11% | 17.45 ± 1.51 | 65.58% |

| E | Inactive | Inactive | 93.29% | 10.09 ± 1.43 | 84.88% | |

| M | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | - | Non-cytotoxic | |

| Twig | H | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | - | Non-cytotoxic |

| E | Inactive | Inactive | 91.12% | 18.70 ± 0.27 | 91.98% | |

| M | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | - | Non-cytotoxic | |

| Bark | H | Inactive | Inactive | 82.42% | 18.03 ± 0.09 | 92.08% |

| E | Inactive | Inactive | 83.96% | 19.80 ± 0.92 | 87.05% | |

| M | Inactive | Inactive | Inactive | - | Non-cytotoxic | |

| Doxorubicin | 0.90 ± 0.12 | 9.38 ± 0.23 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | - | - | |

| Ellipticine | 2.49 ± 0.20 | - | 2.15 ± 0.72 | - | - | |

| Tamoxifen | - | 7.95 ± 0.84 | - | - | - |

Furthermore, certain extracts demonstrated selective cytotoxicity against cancer cells, while also showing moderate cytotoxicity against Vero cells. For instance, the leaf and bark extracts exhibited moderate toxicity (65.58% for hexane leaf extract and 84.88% for ethyl acetate leaf extract). The cytotoxicity of fruit, twig, and bark extracts also exceeded the 50% threshold for cytotoxicity. While the flower extracts were non-cytotoxic to both cancerous and normal cells, their phytochemical composition (particularly their lower TPC and TFC) likely accounts for the lack of anticancer activity. Previous studies have reported that ethanolic extracts of C. inophyllum contained high phenolic and flavonoid contents [8], and other anticancer-related compounds such as curcumin, resveratrol, epigallocatechin gallate, and thymoquinone [52,53,54,55]. Further support for the anticancer potential of this plant was recently provided by Ruangsuriya et al. [56], who found the three most abundant phytochemicals in C. inophyllum extracts to be 5-hydroxy methylfurfural (5-HMF), antiarol, and syringol, which are classified as furans and phenols. However, despite the significant activity observed in the present study against NCI-H187, no notable effects were observed against the KB and MCF7 cancer cell lines across all extracts. This lack of activity suggests that the bioactive compounds in C. inophyllum may not specifically target the pathways relevant to these cancer types, or that higher concentrations may be required to observe activity. These findings highlight the potential of this plant in the use of traditional medicine for cancer therapy. Nonetheless, the higher cytotoxicity observed in some extracts, particularly those from bark and twig, warrants caution and highlights the need for further investigation to balance anticancer efficacy with safety.

3.8 In Silico ADME Analysis of Selected Phytochemical Compounds from C. inophyllum Extract

The bioactive compounds found by Vittaya et al. [10] in a flower extract of C. inophyllum (Fig. 9) were studied by in silico ADME analysis. Selected phytochemical compounds from C. inophyllum flower extract revealed diverse pharmacokinetic profiles, highlighting their potential as drug candidates (Table 7 and Table S3). The analysis revealed that eugenol, caryophyllene oxide, farnesol, and palmitic acid demonstrated good gastrointestinal absorption, supporting their potential bioavailability if taken orally [57,58,59,60]. Other compounds, including α-copaene and β-amyrin, displayed lower GI absorption and may require formulation optimization to enhance their bioavailability. Additionally, blood-brain barrier permeability was predicted for eugenol and caryophyllene oxide, indicating potential for treating central nervous system disorders. These compounds have demonstrated neuroprotective and biological activities in previous studies [61,62,63]. Further analysis identified various cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, with compounds like α-copaene and palmitic acid identified as inhibitors of CYP1A2 and CYP2C9, emphasizing the importance of considering the potential risks of drug–drug interactions [64,65]. Most compounds adhered to Lipinski’s Rule of Five, indicating favorable drug-likeness and suitability for further development [66]. Collectively, these results indicated that C. inophyllum extracts possess significant antioxidant and antibacterial activities for potential applications in food and cosmetics, while ADME analysis supports the therapeutic potential of selected phytochemicals as candidates for further exploration in pharmaceutical development.

Figure 9: Selected phytochemical compounds identified in a C. inophyllum flower extract.

Table 7: In Silico ADME analysis of physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of selected phytochemical compounds identified in a C. inophyllum flower extract.

| Compounds | Formula | Mol. Weight (g/mol) | Num. Heavy Atoms | Num. Rotatable Bonds | TPSA (Å2) | Consensus LogP o/w | Water Solubility Class | GI Absorption | BBB Permeation | P-gp Substrate | CYP Inhibitors | Druglikeness Lipinski | Bioavailability Score | PAINS | Synthetic Accessibility Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eugenol | C10H12O2 | 164.20 | 12 | 3 | 29.46 | 2.25 | Soluble | High | Yes | No | CYP1A2 | Yes (0 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 1.58 |

| α-Copaene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 15 | 1 | 0.00 | 4.30 | Soluble | Low | Yes | No | CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2C9 | Yes (1 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 4.62 |

| β-Caryophyllene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 15 | 0 | 0.00 | 4.24 | Soluble | Low | No | No | CYP2C19, CYP2C9 | Yes (1 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 4.51 |

| α-Muurolene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 15 | 1 | 0.00 | 4.08 | Soluble | Low | No | No | CYP2C19, CYP2C9 | Yes (1 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 4.35 |

| γ-Cadinene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 15 | 1 | 0.00 | 4.18 | Soluble | Low | No | No | CYP2C19, CYP2C9 | Yes (1 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 4.35 |

| δ-Cadinene | C15H24 | 204.35 | 15 | 1 | 0.00 | 4.12 | Soluble | Low | No | No | CYP2C19, CYP2C9 | Yes (1 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 4.14 |

| Caryophyllene Oxide | C15H24O | 220.35 | 16 | 0 | 12.53 | 3.68 | Soluble | High | Yes | No | CYP2C19, CYP2C9 | Yes (0 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 4.35 |

| Farnesol | C15H26O | 222.37 | 16 | 7 | 20.23 | 3.68 | Soluble | High | Yes | No | CYP2C19, CYP2C9 | Yes (0 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 4.35 |

| Palmitic Acid | C16H32O2 | 256.42 | 18 | 14 | 37.30 | 5.20 | Moderately soluble | High | Yes | No | CYP1A2, CYP2C9 | Yes (1 violation) | 0.85 | 0 | 2.31 |

| Phytol | C20H40O | 296.53 | 21 | 13 | 20.23 | 6.25 | Moderately soluble | Low | No | Yes | CYP2C9 | Yes (1 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 4.30 |

| α-Linolenic Acid | C18H30O2 | 278.43 | 20 | 13 | 37.30 | 6.25 | Moderately soluble | Low | No | Yes | CYP2C9 | Yes (1 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 4.30 |

| 2-cis-Geranylgeraniol | C20H34O | 290.48 | 21 | 10 | 20.23 | 6.25 | Moderately soluble | Low | No | Yes | CYP2C9 | Yes (1 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 4.30 |

| β-Amyrin | C30H50O | 426.72 | 31 | 0 | 20.23 | 7.18 | Poorly soluble | Low | No | No | None | Yes (1 violation) | 0.55 | 0 | 6.04 |

C. inophyllum flower, fruit, leaf, twig, and bark were extracted by maceration in hexane, ethyl acetate, and methanol. The effects of the different plant parts and solvents on the phytochemical profiles of the extracts were investigated, including the effects of interactions between plant parts and solvents on biological activities. The extraction yield of C. inophyllum varied based on the solvent used, with methanol yielding the most extract, followed by ethyl acetate and hexane. Total phenolic and flavonoid contents were significantly correlated. The highest total phenolic and flavonoid contents were observed in ethyl acetate and methanolic extracts, which exhibited the highest antioxidant activity. The highest total saponin content was found in hexane extracts, except for the fruit extract. All extracts demonstrated inhibitory effects against Gram-positive and negative bacteria, with a particularly strong effect against S. typhi. Additionally, the leaf and bark extracts showed promising anticancer activity, especially against the NCI-H187 lung cancer cell line, suggesting potential for therapeutic application. However, further research is needed to assess its broader anticancer efficacy and safety profile. SwissADME screening identified eugenol and caryophyllene oxide as promising bioactive candidates with good gastrointestinal absorption, blood–brain barrier permeability, favorable topological polar surface areas, and minimal cytochrome P450 enzyme interactions. These characteristics suggest potential suitability for both systemic and central nervous system applications. Farnesol and palmitic acid also showed good oral bioavailability potential. Although the pharmacokinetic predictions were limited to compounds identified in the flower extracts, these findings provide a valuable foundation for further investigation. A more comprehensive identification and pharmacokinetic evaluation of compounds from other plant parts is needed to fully explore their therapeutic potential. Further studies incorporating complete ADMET profiling will also be essential to better clarify the safety and therapeutic relevance of C. inophyllum metabolites. Overall, these results highlight the potential of C. inophyllum extracts for applications in the food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical industries.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Luksamee Vittaya; Formal analysis, Luksamee Vittaya; Investigation, Luksamee Vittaya, Chakhriya Chalad and Sittichoke Janyong; Methodology, Luksamee Vittaya and Chakhriya Chalad; Supervision, Luksamee Vittaya; Validation, Luksamee Vittaya and Sittichoke Janyong; Visualization, Luksamee Vittaya and Nararak Leesakul; Writing—original draft, Luksamee Vittaya; Writing—review & editing, Nararak Leesakul. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.074891/s1.

References

1. Watts N , Amann M , Arnell N , Ayeb-Karlsson S , Beagley J , Belesova K , et al. The 2020 report of the Lancet countdown on health and climate change: responding to converging crises. Lancet. 2021; 397( 10269): 129– 70. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32290-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Guzmán-Trampe S , Ceapa CD , Manzo-Ruiz M , Sánchez S . Synthetic biology era: improving antibiotic’s world. Biochem Pharmacol. 2017; 134: 99– 113. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2017.01.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Olatunji OJ , Olatunde OO , Jayeoye TJ , Singh S , Nalinbenjapun S , Sripetthong S , et al. New insights on Acanthus ebracteatus Vahl: UPLC-ESI-QTOF-MS profile, antioxidant, antimicrobial and anticancer activities. Molecules. 2022; 27( 6): 1981. doi:10.3390/molecules27061981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chan EWC , Ng YK , Wong SK , Chan HT . Pluchea indica: an updated review of its botany, uses, bioactive compounds and pharmacological properties. Pharm Sci Asia. 2022; 49( 1): 77– 85. doi:10.29090/psa.2022.01.21.113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ferdosh S . The extraction of bioactive agents from Calophyllum inophyllum L., and their pharmacological properties. Sci Pharm. 2024; 92( 1): 6. doi:10.3390/scipharm92010006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Vittaya L , Charoendat U , Janyong S , Ui-eng J , Leesakul N . Comparative analyses of saponin, phenolic, and flavonoid contents in various parts of Rhizophora mucronata and Rhizophora apiculata and their growth inhibition of aquatic pathogenic bacteria. J App Pharm Sci. 2022; 12( 11): 111– 21. doi:10.7324/JAPS.2022.121113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Audah KA , Ettin J , Darmadi J , Azizah NN , Anisa AS , Hermawan TDF , et al. Indonesian mangrove Sonneratia caseolaris leaves ethanol extract is a potential super antioxidant and anti methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus drug. Molecules. 2022; 27( 23): 8369. doi:10.3390/molecules27238369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Cassien M , Mercier A , Thétiot-Laurent S , Culcasi M , Ricquebourg E , Asteian A , et al. Improving the antioxidant properties of Calophyllum inophyllum seed oil from French Polynesia: development and biological applications of resinous ethanol-soluble extracts. Antioxidants. 2021; 10( 2): 199. doi:10.3390/antiox10020199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hapsari S , Yohed I , Kristianita RA , Jadid N , Aparamarta HW , Gunawan S . Phenolic and flavonoid compounds extraction from Calophyllum inophyllum leaves. Arab J Chem. 2022; 15( 3): 103666. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2021.103666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Vittaya L , Chalad C , Ratsameepakai W , Leesakul N . Phytochemical characterization of bioactive compounds extracted with different solvents from Calophyllum inophyllum flowers and activity against pathogenic bacteria. S Afr N J Bot. 2023; 154: 346– 55. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2023.01.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Ojah EO , Moronkola DO , Petrelli R , Nzekoue FK , Cappellacci L , Giordani C , et al. Chemical composition of ten essential oils from Calophyllum inophyllum Linn and their toxicity against Artemia Salina. Eur J Pharm Med Res. 2019; 6( 12): 185– 94. [Google Scholar]

12. Ojah EO , Moronkola DO , Osamudiamen PM . Antioxidant assessment of characterised essential oils from Calophyllum inophyllum Linn using 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl and hydrogen peroxide methods. J Med Plants Econ Dev. 2020; 4( 1): a83. doi:10.4102/jomped.v4i1.83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Daina A , Michielin O , Zoete V . SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep. 2017; 7: 42717. doi:10.1038/srep42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Vittaya L , Aiamyang S , Ui-eng J , Knongsai S , Leesakul N . Effect of solvent extraction on phytochemical component and antioxidant activity of vine and rhizome Ampelocissus martini. Sci Technol Asia. 2019; 24( 3): 17– 26. doi:10.14456/scitechasia.2019.17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Senguttuvan J , Paulsamy S , Karthika K . Phytochemical analysis and evaluation of leaf and root parts of the medicinal herb, Hypochaeris radicata L. for in vitro antioxidant activities. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2014; 4: S359– 67. doi:10.12980/APJTB.4.2014C1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. M02–A11. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests. Wayne, PA, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2012. [Google Scholar]

17. M100-S29. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Wayne, PA, USA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2019. [Google Scholar]

18. Campoccia D , Ravaioli S , Santi S , Mariani V , Santarcangelo C , De Filippis A , et al. Exploring the anticancer effects of standardized extracts of poplar-type Propolis: in vitro cytotoxicity toward cancer and normal cell lines. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021; 141: 111895. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2021.111895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Dai J , Mumper RJ . Plant phenolics: extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules. 2010; 15( 10): 7313– 52. doi:10.3390/molecules15107313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhang QW , Lin LG , Ye WC . Techniques for extraction and isolation of natural products: a comprehensive review. Chin Med. 2018; 13: 20. doi:10.1186/s13020-018-0177-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Henkel S , Misuraca MC , Troselj P , Davidson J , Hunter CA . Polarisation effects on the solvation properties of alcohols. Chem Sci. 2017; 9( 1): 88– 99. doi:10.1039/c7sc04890d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Nabeelah Bibi S , Fawzi MM , Gokhan Z , Rajesh J , Nadeem N , Rengasamy Kannan RR , et al. Ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry, and global distribution of Mangroves—a comprehensive review. Mar Drugs. 2019; 17( 4): 231. doi:10.3390/md17040231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Malik EM , Müller CE . Anthraquinones as pharmacological tools and drugs. Med Res Rev. 2016; 36( 4): 705– 48. doi:10.1002/med.21391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Amala Dev AR , Sonia Mol J . Volatile chemical profiling and distinction of Citrus essential oils by GC analyses with correlation matrix; evaluation of its in vitro radical scavenging and microbicidal efficacy. Results Chem. 2024; 7: 101460. doi:10.1016/j.rechem.2024.101460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ullah A , Munir S , Badshah SL , Khan N , Ghani L , Poulson BG , et al. Important flavonoids and their role as a therapeutic agent. Molecules. 2020; 25( 22): 5243. doi:10.3390/molecules25225243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Mlcek J , Jurikova T , Skrovankova S , Sochor J . Quercetin and its anti-allergic immune response. Molecules. 2016; 21( 5): 623. doi:10.3390/molecules21050623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ganeshpurkar A , Saluja AK . The pharmacological potential of rutin. Saudi Pharm J. 2017; 25( 2): 149– 64. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2016.04.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Vergara-Jimenez M , Almatrafi MM , Fernandez ML . Bioactive components in Moringa oleifera leaves protect against chronic disease. Antioxidants. 2017; 6( 4): 91. doi:10.3390/antiox6040091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang Z , Xu J , Wang Y , Xiang L , He X . Total saponins from Tupistra chinensis baker inhibits growth of human gastric cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. J Ethnopharmacol. 2021; 278: 114323. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2021.114323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Kumar N , Goel N . Phenolic acids: natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnol Rep. 2019; 24: e00370. doi:10.1016/j.btre.2019.e00370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Divekar PA , Narayana S , Divekar BA , Kumar R , Gadratagi BG , Ray A , et al. Plant secondary metabolites as defense tools against herbivores for sustainable crop protection. Int J Mol Sci. 2022; 23( 5): 2690. doi:10.3390/ijms23052690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lichtenthaler HK , Buschmann C . Chlorophylls and carotenoids: measurement and characterization by UV-VIS spectroscopy. Curr Protoc Food Anal Chem. 2001; 1( 1): F4.3.1– 8. doi:10.1002/0471142913.faf0403s01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Schulz H , Baranska M . Identification and quantification of valuable plant substances by IR and Raman spectroscopy. Vib Spectrosc. 2007; 43( 1): 13– 25. doi:10.1016/j.vibspec.2006.06.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Tella JO , Oseni SO . Comparative profiling of solvent-mediated phytochemical expressions in Ocimum gratissimum and Vernonia amygdalina leaf tissues via FTIR spectroscopy and colorimetric assays. J Adv Med Pharm Sci. 2019: 1– 25. doi:10.9734/jamps/2018/v19i430095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Silverstein RM , Webster FX , Kiemle DJ . Spectrometric identification of organic compounds. 7th ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2005. [Google Scholar]

36. Smith BC . Infrared spectral interpretation: a systematic approach. 1st ed. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 1999. 288 p. [Google Scholar]

37. Bandaranayake WM . Bioactivities, bioactive compounds and chemical constituents of mangrove plants. Wetl Ecol Manag. 2002; 10( 6): 421– 52. doi:10.1023/A:1021397624349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Verma N , Shukla S . Impact of various factors responsible for fluctuation in plant secondary metabolites. J Appl Res Med Aromat Plants. 2015; 2( 4): 105– 13. doi:10.1016/j.jarmap.2015.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Bento JAC , Ribeiro PRV , Bassinello PZ , de Brito ES , Zocollo GJ , Caliari M , et al. Phenolic and saponin profile in grains of carioca beans during storage. LWT. 2021; 139: 110599. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2020.110599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Stalikas CD . Extraction, separation, and detection methods for phenolic acids and flavonoids. J Sep Sci. 2007; 30( 18): 3268– 95. doi:10.1002/jssc.200700261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lavola A , Aphalo PJ , Lahti M , Julkunen-Tiitto R . Nutrient availability and the effect of increasing UV-B radiation on secondary plant compounds in Scots pine. Environ Exp Bot. 2003; 49( 1): 49– 60. doi:10.1016/S0098-8472(02)00057-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Ramakrishna A , Ravishankar GA . Influence of abiotic stress signals on secondary metabolites in plants. Plant Signal Behav. 2011; 6( 11): 1720– 31. doi:10.4161/psb.6.11.17613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]