Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Correlation between Floral Color Attributes and Volatile Components among 10 Fragrant Phalaenopsis Cultivars

1 Shanghai Vocational College of Agriculture and Forestry, Shanghai, 201699, China

2 Yantai Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Yantai, 265500, China

3 College of Life Sciences, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai, 200234, China

* Corresponding Authors: Minxiao Liu. Email: ; Yingjie Zhang. Email:

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(2), 379-391. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.060726

Received 08 November 2024; Accepted 08 January 2025; Issue published 06 March 2025

Abstract

To study the main aroma components of Phalaenopsis orchid and their relationship with colors, 10 fragrant cultivars with different colors, like pink, rose, yellow, and purple, were used as samples in this experiment. Headspace-gas chromatography-mass spectrometry was used to determine the main components of floral fragrance and analyze the correlation between floral color and fragrance. The results showed that the main aroma components of the 10 fragrant cultivars of Phalaenopsis were alcohols, alkenes, esters, and benzene ring compounds, and the main aroma components of different cultivars were diverse. The main aroma components of yellow fragrant flowers were esters, alcohols, and alkenes. The purple and pink series were alcohols and phenyl rings. There was a certain correlation between flower color and floral fragrance. There was a significant positive correlation between esters and flower color C* value, and a significant negative correlation between alkenes and flower color h value. There was a significant negative correlation between alcohol and flower color C* value, and a significant positive correlation between alcohol and L* value. The content of benzene compounds was negatively correlated with L* and positively correlated with h value. This may be related to the synthesizing of anthocyanins and benzene ring compounds through the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway. In this paper, the correlation between Phalaenopsis floral color and fragrance was studied, and the synthetic pathway of floral color and fragrance components was analyzed. The proposed method and research data can provide a theoretical basis for floral color breeding and fragrance synthesis.Keywords

Phalaenopsis is the general term for plants of Phalaenopsis genus within the Orchidaceae family. These plants are admired for their elegant flower shapes and rich colors, making them important potted flowers both domestically and internationally. The flowers display a wide range of colors, such as white, yellow, orange, pink, rose-red, and purple, and the color patterns include solid and variegated colors with striped petals [1]. However, one significant drawback of Phalaenopsis is its lack of fragrance. Even though a few fragrant cultivars have been cultivated [2,3], they still suffer from weak fragrance, fewer flowers, smaller flower sizes, and poor reproductive traits. The floral fragrance of plants is primarily composed of terpenes, phenylpropanoids/benzenoids, and aliphatic compounds [4–7]. The dominant fragrance components of different fragrant Phalaenopsis cultivars vary. Current research on scent compounds of Phalaenopsis mainly focuses on terpenes, such as myrcene, sabinene, ocimene, eucalyptol, linalool, geraniol, and 1,8-cineole [8–11]. For instance, the primary aromatic compounds family of P. bellina are monoterpenes, benzenoids, and phenylpropanoids, and the geraniol; linalool [11], and their derivatives being the key contributors to its fragrance. In contrast, there are no detectable releases of monoterpene derivatives in P. equestris, however, its volatile compounds are mainly fatty acid derivatives and phenylpropanoids, these fragrant compounds are barely detectable by the human nose [12]. The main scent compounds of P. violacea are monoterpenes and sesquiterpenes, including elemicin, santol, and linalool [10]. A study by Tong et al. on eight newly hybridized fragrant Phalaenopsis cultivars found that terpenes such as 1,8-cineole, α-pinene, and linalool were the primary scent components [13]. Despite these findings, the relationship between different fragrance components and the flower colors or fragrance pattern of Phalaenopsis has not yet been reported. In Paeonia delavayi [14], the main volatile components of the green cultivar ‘Gesang Lv’ were linalool, caryophyllene, oxidized linalool, and pinene. The main volatile components of the red cultivar ‘Gesang Hong’ were macrophyllene D, methyl decanoate, hexol, and pinene. The main volatile components of the yellow cultivar ‘Gesang Huang’ were linalool, caryophyllene, methyl decanoate, and germacrene. In roses [15], three groups of ten cultivars were divided in the coordinate system of a* and b* hue, including red, yellow-white, and purplish red. A significant positive correlation between the total emission of floral volatile compounds in the aromatic hydrocarbon metabolic pathway and the b* value of petals (p < 0.01) was found, which indicated that the more yellow the flower was, the higher contents of volatile compounds in the aromatic hydrocarbons metabolic pathway were released. In this paper, the correlation between Phalaenopsis flower color and floral fragrance was analyzed for the first time.

Phalaenopsis breeding at fragrant traits poses technical challenges, such as hybrid incompatibility and poor reproductive capacity. Traditional hybridization remains the most common method for breeding new orchid varieties. This study aims to measure the fragrance components of ten fragrant Phalaenopsis cultivars and analyze the correlation between flower color and fragrance, providing a theoretical foundation for hybrid breeding, laws of inheritance of Phalaenopsis, and the synthesis of Phalaenopsis fragrances.

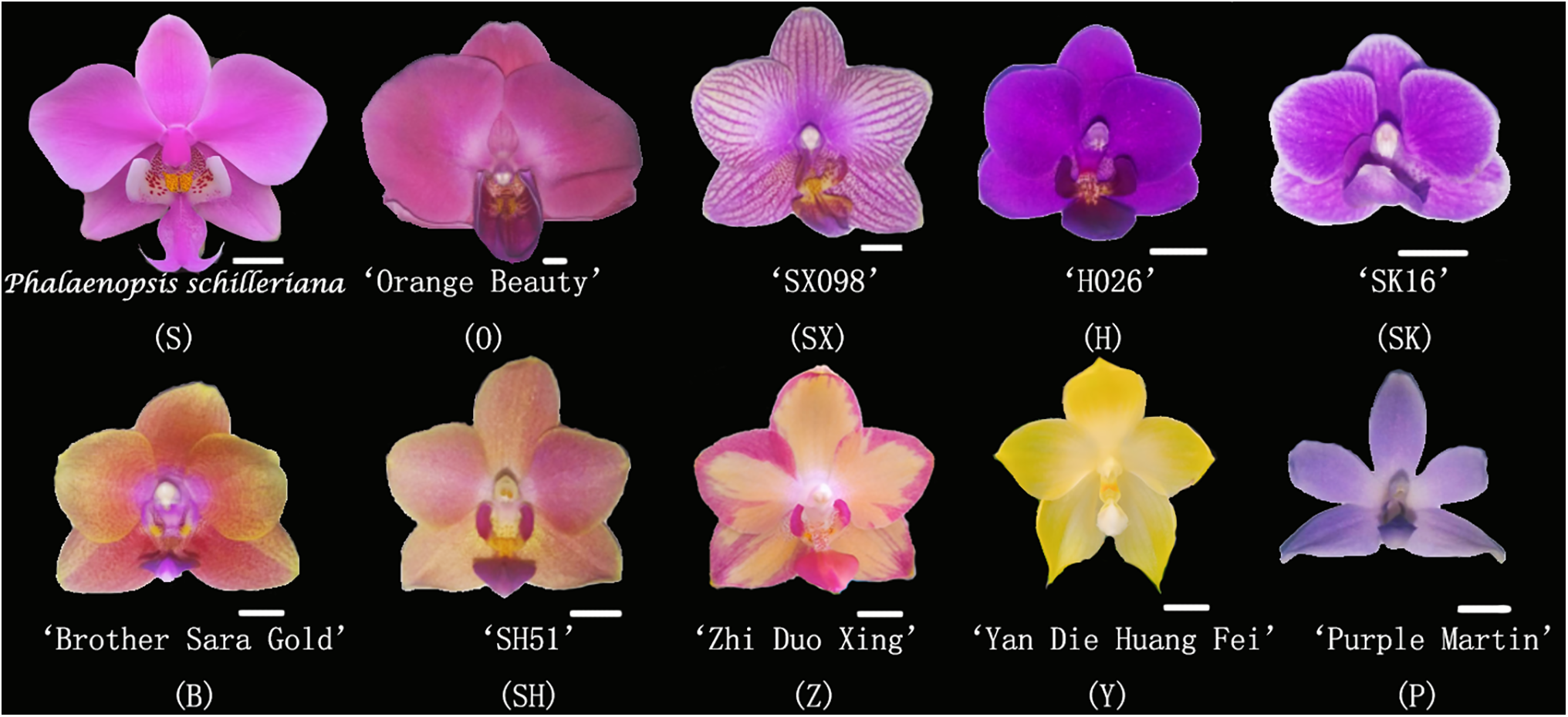

The study focused on ten fragrant Phalaenopsis orchids (see Fig. 1) selected from about 500 most popular Phalaenopsis varieties in the Chinese flower market, including three pink varieties: Phalaenopsis schilleriana (S), ‘Orange Beauty’ (O), and ‘SX098’ (SX); two rose-red varieties: ‘H026’ (H) and ‘SK16’ (SK); two orange varieties: ‘Brother Sara Gold’ (B) and ‘SH51’ (SH); two yellow varieties: ‘Zhi Duo Xing’ (Z) and ‘Yan Die Huang Fei’ (Y); and one purple variety: ‘Purple Martin’ (P). All were sourced from Xiamen HEMING Flower Technology Co., Ltd. (China) and cultivated for two years in a greenhouse equipped with a fan water curtain cooling system, internal and external sunshade system, and heating system at the Yantai Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Shandong Province, China). The temperature was 25°C–30°C, the light intensity was 10,000 lx, and the humidity was 70%~85%. The growing medium was Chilean-imported sphagnum moss, with fertilizer for 2000 to 3000 times the concentration of N, P, and K content of 20-20-20. Watering was carried out on sunny days to ensure that the leaves did not collect water at night. Yellow and blue armyworm boards were used to control pests. 4-leaves\1-heart 2a newly matured seedlings with healthy, pest-free, and similar growing conditions were selected for the experiment.

Figure 1: Experiment materials. Abbreviations: Phalaenopsis schilleriana (S), ‘Orange Beauty’ (O), ‘SX098’ (SX), ‘H026’ (H), ‘SK16’ (SK), ‘Brother Sara Gold’ (B), ‘SH51’ (SH), ‘Zhi Duo Xing’ (Z), ‘Yan Die Huang Fei’ (Y), ‘Purple Martin’ (P)

2.2 Flower Color Parameters Measurement

Flowers were collected on the second day in full opening and placed against a white background under the same lighting conditions. The color parameters of the flowers were then measured using a colorimeter (NF555, Nippon Denshoku Industries Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) to obtain the values for L* (lightness, ranging from black to white, 0–100), C* (saturation, calculated as C* = (a*2 + b*2)1/2) and h (hue angle, calculated as h = tan−1(b*/a*)) were also determined [15].

2.3 Olfactory Sensory Evaluation of Fragrance

After the experimental materials bloomed, ten plants were sampled and placed in a room with the same environmental conditions (room temperature at 25°C). The flower colors were measured using the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) color chart, and the floral fragrance was assessed through olfactory sensory evaluation. The Phalaenopsis flowers were selected on the second after they bloomed. A group of 20 people (10 males and 10 females) evaluated and scored the fragrance of each cultivar. Scoring ranges from 0 for no fragrance, 1 for a light scent, 2 for a moderate fragrance, and 3 for a strong scent. The average score was calculated, and the fragrance characteristics were described after scoring [16,17].

2.4 Analysis of Fragrance Components

Flower samples, including sepals, petals, and one gynandrium, were taken for analysis. A 2 g samples were weighed and placed in a sampling vial, then sealed and allowed to equilibrate for 10 min. The solid-phase microextraction method was employed, placing the sampling vial on a ceramic heating plate at 45°C (Corning PC-4200, Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA) for extraction by using a 100 μm polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) extraction fiber (Beijing Huayi Instrument Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 30 min. The fragrance components were measured using Headspace Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) [18]. A Shimadzu GCMS-QP2010 plus gas chromatography-mass spectrometry system (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan) was used. The chromatographic conditions were as follows: the chromatography column was Rtx-5MS (60 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 mm); the injection volume was 1 μL; helium was used as the carrier gas, pressure at 112.0 kPa; the total flow rate was 8.0 mL/min, with a column flow rate of 1 mL/min and a split ratio of 5:1. The temperature program was as follows: the injector temperature was set to 250°C, the initial column temperature was 40°C (held for 2 min), then increased to 180°C at a speed of 8°C/min, followed by a further increase to 250°C at a rate of 15°C/min, held for 5 min. The mass spectrometry conditions include an interface temperature of 230°C; the ionization method was electron ionization (EI) source; the ion source temperature was set to 200°C; and the detector voltage was 0.8 kV. The fiber head was inserted into the injector for analysis over 2 min. Each experiment was repeated three times parallelly. The sampled mass spectra were analyzed using the NIST library and WILEY library in series for compound identification, combined with manual spectral analysis to confirm the chemical constituents of the volatiles. The relative percentage of each component in the sample gas was calculated by using normalized peak area, with the formula: Content (%) = (the peak area of the specific substance/sum of all gas peak areas in the sample) × 100 [19]. By referring to the characteristics of chemical compounds and relevant literature, the volatile components of each cultivar were analyzed, allowing for the selection of non-fragrant and fragrant gas components, ultimately identifying the main fragrant components responsible for the Phalaenopsis floral scent.

The data was analyzed, and charts were created using Microsoft Excel 2016, while the correlation coefficients between flower color and fragrance were calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics 24 software.

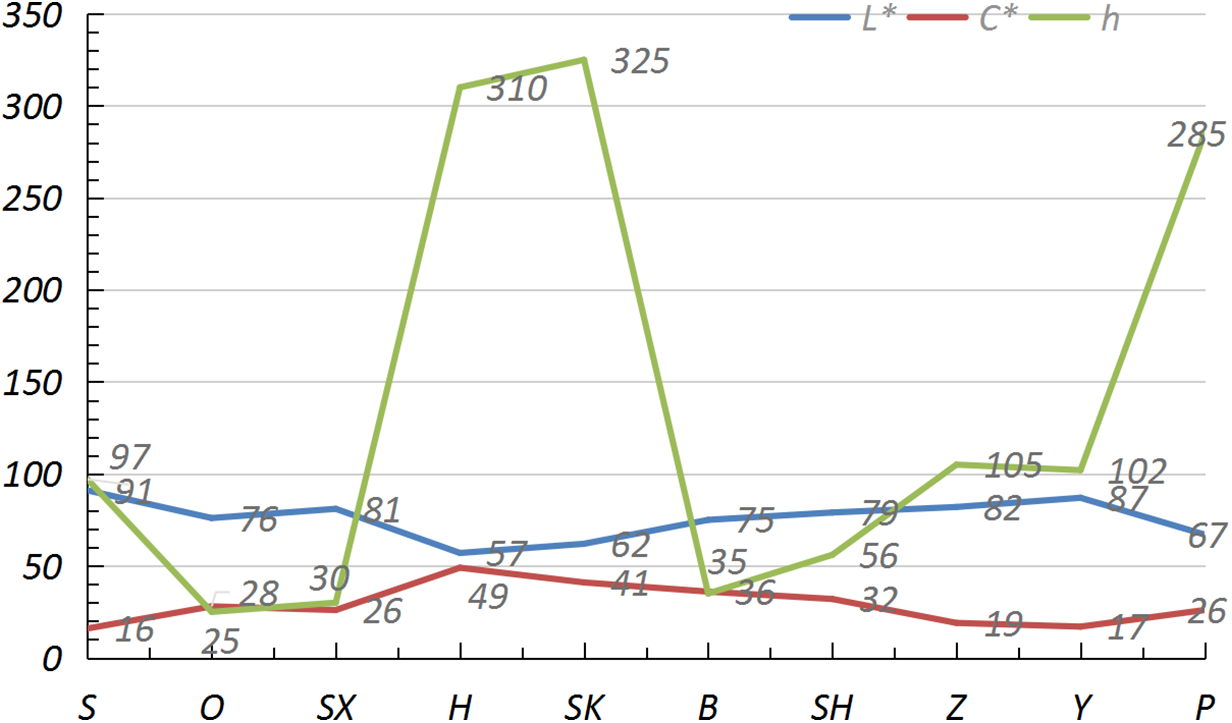

The petal colors of 10 Phalaenopsis orchids were measured (lightness L*, chroma C*, and hue angle h), as shown in Fig. 2. L* indicates the brightness and the value range is 0 to 100. The higher the value is, the lighter the color is. The C* value represents the saturation of the color. The higher the value is, the brighter the color is. h is the hue angle and the way colors are positioned in the color system, ranging from 0 to 360°. The closer the h value is to 0° (360°), the redder the color is; Closer to 90°, the more yellow the color is; Closer to 180°, the greener the color is; Closer to 270 degrees, the bluer the color is. The results indicated that pink and yellow Phalaenopsis series had higher L* values, lower C* values, and lower h values, while magenta and purple Phalaenopsis cultivars had lower L* values, higher C* values, and higher h values. The L* value of flower color was negatively correlated with C* and h values. The color distribution of these 10 Phalaenopsis cultivars is quite broad, with h values ranging from 25° to 325°. The flower colors are diverse but lack blue-green hues class. In China, red represents festivity and is used for festivals, and white and yellow represent grief and are used for funerals, so the magenta and orange cultivars with higher C* and h values are much more popular than other colors in the market.

Figure 2: Color comparison of 10 fragrant Phalaenopsis petals. Abbreviations: L* (lightness), C*(saturation), h (Hue Angle, the unit is degree)

The red color in plant petals primarily originates from anthocyanins, while yellow is mainly synthesized by carotenoids; The mix of these two pigments creates an orange color. Phalaenopsis orchids exhibits a rich variety of flower colors, encompassing nearly all color spectra except for blue-green, and the flower color pattern exhibit multiple complex models such as spots-shape, stripes-shape, and halo-shape. Wang et al. used the ISCC-NBS color nomenclature system to categorize the flower colors of Phalaenopsis orchids into seven major color groups: yellow, brown, red, violet, pink, purple, and white [20]. A negative correlation between the brightness and chroma of flower colors they observed. The results of our experiment were confirmed and consistent with those of previous studies [21], indicating that the brightness (L* value) of Phalaenopsis orchid flower colors is significantly negatively correlated with chroma (C* value) and hue angle (h). Specifically, as the depth of flower color increases, the L* value decreases, while the C* value increases.

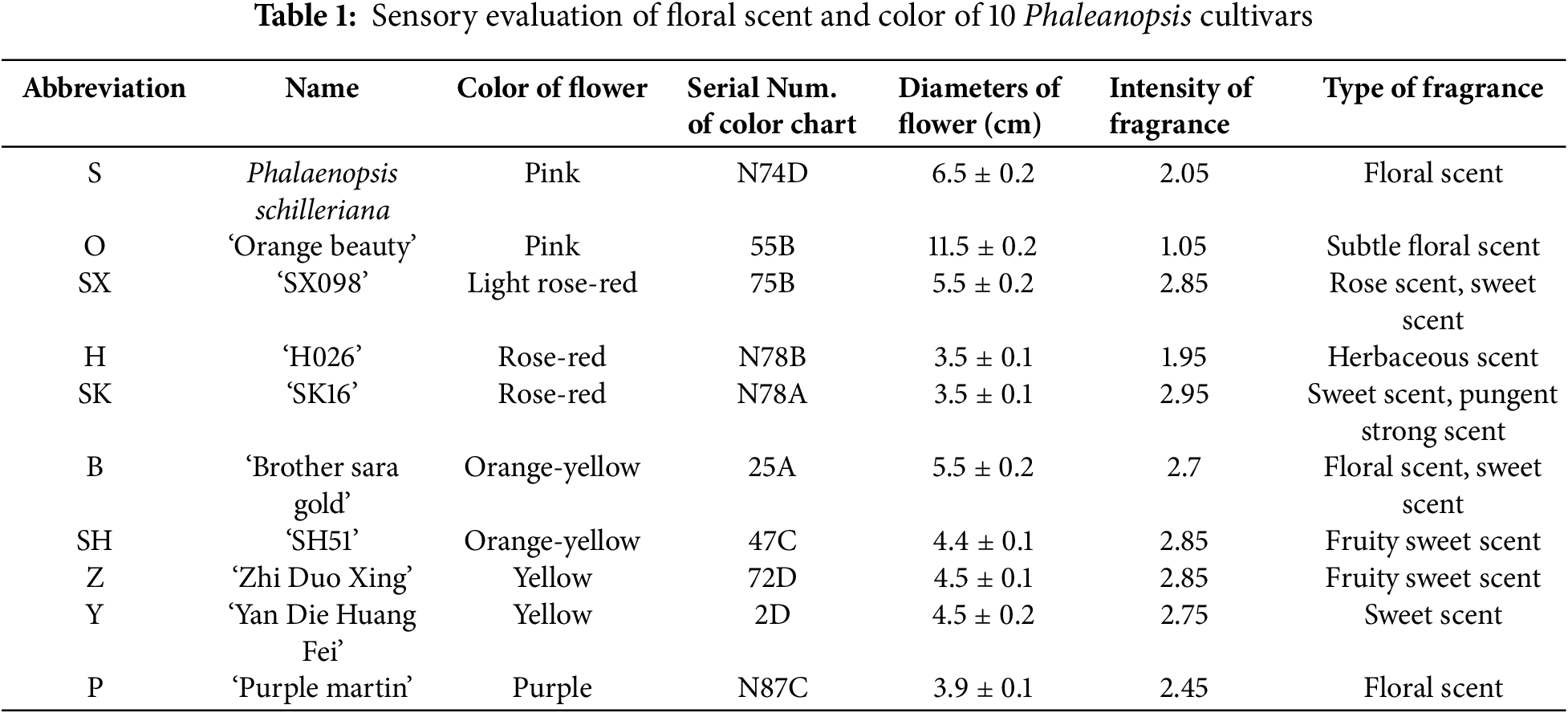

3.2 Measurement of Phalaenopsis Fragrance

The sensory evaluation was conducted on the fragrance of 10 Phalaenopsis orchid cultivars, and the results are shown in Table 1. The cultivars ‘Sara Golden’, ‘Purple Martin’, ‘SK16’, ‘SX098’, ‘SH51’, ‘Zhiduoxing’, and ‘Yandie Huangfei’ had relatively strong fragrances. Among them, ‘SH16’ had the strongest and most pungent smell. The yellow and orange cultivars, including ‘Sara Golden’, ‘SH51’, ‘Zhiduoxing’, and ‘Yandie Huangfei’, were characterized by a fruity sweet fragrance.

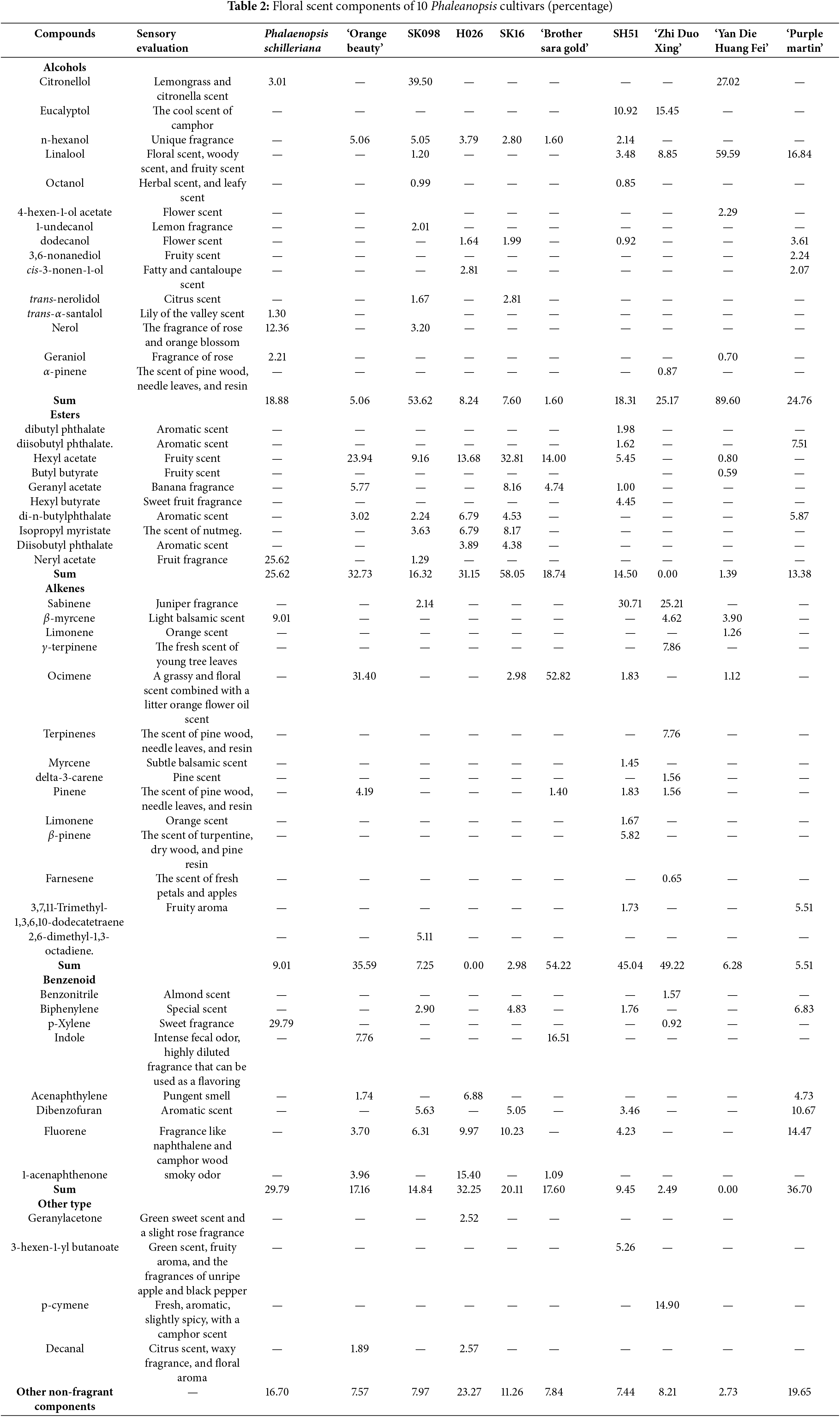

In total, over 60 gas components were identified in 10 fragrant Phalaenopsis orchids, which were mainly classified by their chemical structure into alcohols, esters, alkenes, and benzenoid compounds. Among them, ‘SK098’ and ‘Yandi Huangfei’ were primarily composed of alcohol, reaching 53.62% and 89.60%, respectively. ‘SK16’ and ‘Zhidaoxing’ had the highest proportions of ester components, at 58.05% and 49.22%. ‘Sara Huangjin’ and ‘SH51’ were dominated by alkenes, at 54.22% and 45.04%, respectively. ‘H026’ was primarily composed of esters and alkenes, accounting for 31.15% and 32.25%. ‘Zima Ding’ had 36.70% aromatic compounds and 24.76% alcohols, while the Tiger-striped Phalaenopsis orchid was mainly comprised of aromatic compounds, esters, and alcohols, accounting for 29.79%, 25.62%, and 18.88%, respectively. ‘Xiang Cheng Mei Ren’ was primarily made up of esters and alkenes, at 32.73% and 35.59%.

According to Table 2, the volatile components of 10 fragrant Phalaenopsis orchids were classified and analyzed. The results, categorized in descending order, showed that the components ranked as follows: alcohols, alkenes, esters, and aromatic compounds. Within each category, the contribution rates of components, ordered from highest to lowest, are as follows. Alcohols: linalool, citronellol, eucalyptol, n-hexanol, nerol, dodecanol. Alkenes: ocimene, cedrene, β-laurolene, α-pinene, γ-terpinene, pinene. Esters: hexyl acetate, neryl acetate, di-n-butylphthalate, geranyl acetate, isopropyl myristate, diisobutyl phthalate. Benzenoid: fluorenes, 1,4-dimethylbenzene, dibenzofuran, indole.

From the perspective of flower color classification, the main fragrance components of yellow Phalaenopsis orchids are dominated by esters (hexyl acetate), alcohols (linalool and eucalyptol), and alkenes (cedrene and basilene). In contrast, the purple-red and pink orchids primarily contain alcohols (geraniol, n-hexanol, and nerol) and aromatic compounds (1,4-dimethylbenzene and fluorenes).

Different fragrant types of Phalaenopsis orchid cultivars have distinct dominant floral scent components. Current research indicates that the fragrance components of fragrant Phalaenopsis orchids are mainly terpenes, such as linalool in P. ‘Tsuei You Beauty’ [9]. P. bellina contains nerolidol, geraniol, and linalool [11,12], while P. violacea has elaeagnol, agarol, and linalool [10]. Other flower species also exhibit different dominant aromatic components among various cultivars. For instance, the fragrance components of peonies, such as Paeonia ostii and Pa. rockii, have the highest terpenes content, whereas Pa. delavayi and Pa.lutea have a relatively higher content of benzenoid compounds [22]. The results of these experiments indicate that the main determined components of floral scent in different Phalaenopsis orchid varieties differ, and the primary compounds are alcohols, alkenes, esters, and benzenoids.

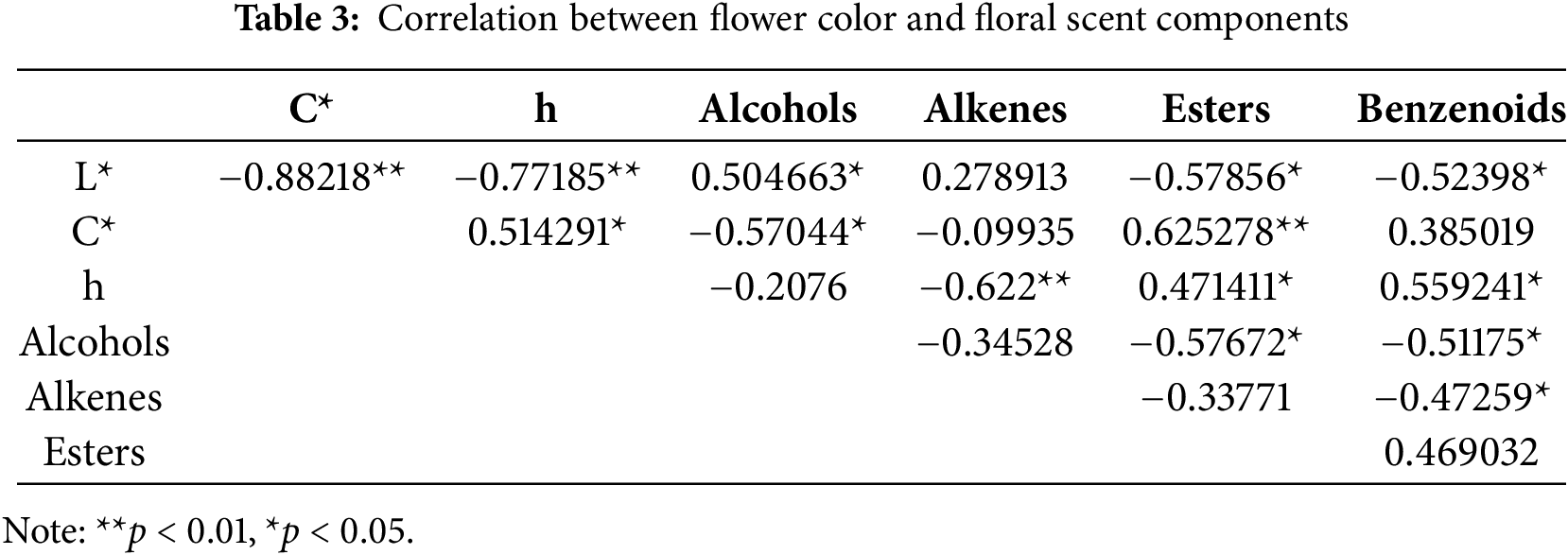

3.3 Correlation between Color and Fragrance of Phalaenopsis Orchids

A two-factor correlation analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between flower color parameters (L*, C*, h) and the contents of alcohols, alkenes, esters, and benzenoid compounds in the fragrances of 10 fragrant Phalaenopsis orchids. The Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for each value (Table 3). The results showed that the ester content in the fragrance components depicted a highly significant positive correlation with the C* value of flower color, while the alkene content displayed a highly significant negative correlation with the h value of flower color. The saturation of flower color increased, and the content of esters in the fragrance also increased. Furthermore, a greater inclination towards the yellow color spectrum correlates with a higher content of alkenes in the fragrance.

Additionally, the alcohol content in the fragrance had a significant negative correlation with the C* value of flower color and a significant positive correlation with the L* value. This indicates that as the saturation of flower color decreases and brightness increases, the content of alcohol in the fragrance rises.

Moreover, the content of benzenoid compounds was significantly negatively correlated with L* and positively correlated with h, which meant that the darker the flower colors were, the more it leaned towards the blue-purple spectrum, the higher levels of benzenoid compounds in the fragrance were. Therefore, it is likely that there exists some correlation between the color and fragrance of Phalaenopsis orchids.

The fragrance of Phalaenopsis orchids has some correlation with their color. The main fragment components of yellow-fragrant Phalaenopsis orchids are primarily alcohols, alkenes, and esters, while the purple and pink cultivars mainly contain alcohols and benzenoid compounds. As the saturation of the flower color increases, the content of esters in the fragrance also increases synergistically. Additionally, the more the flower color leans towards the yellow spectrum, the higher the content of alkenes in the fragrance. Conversely, lower saturation and higher brightness correspond to an increased content of alcohol in the floral scent. Furthermore, darker flower colors that lean towards the blue-purple spectrum are associated with higher levels of benzenoid compounds in the fragrance.

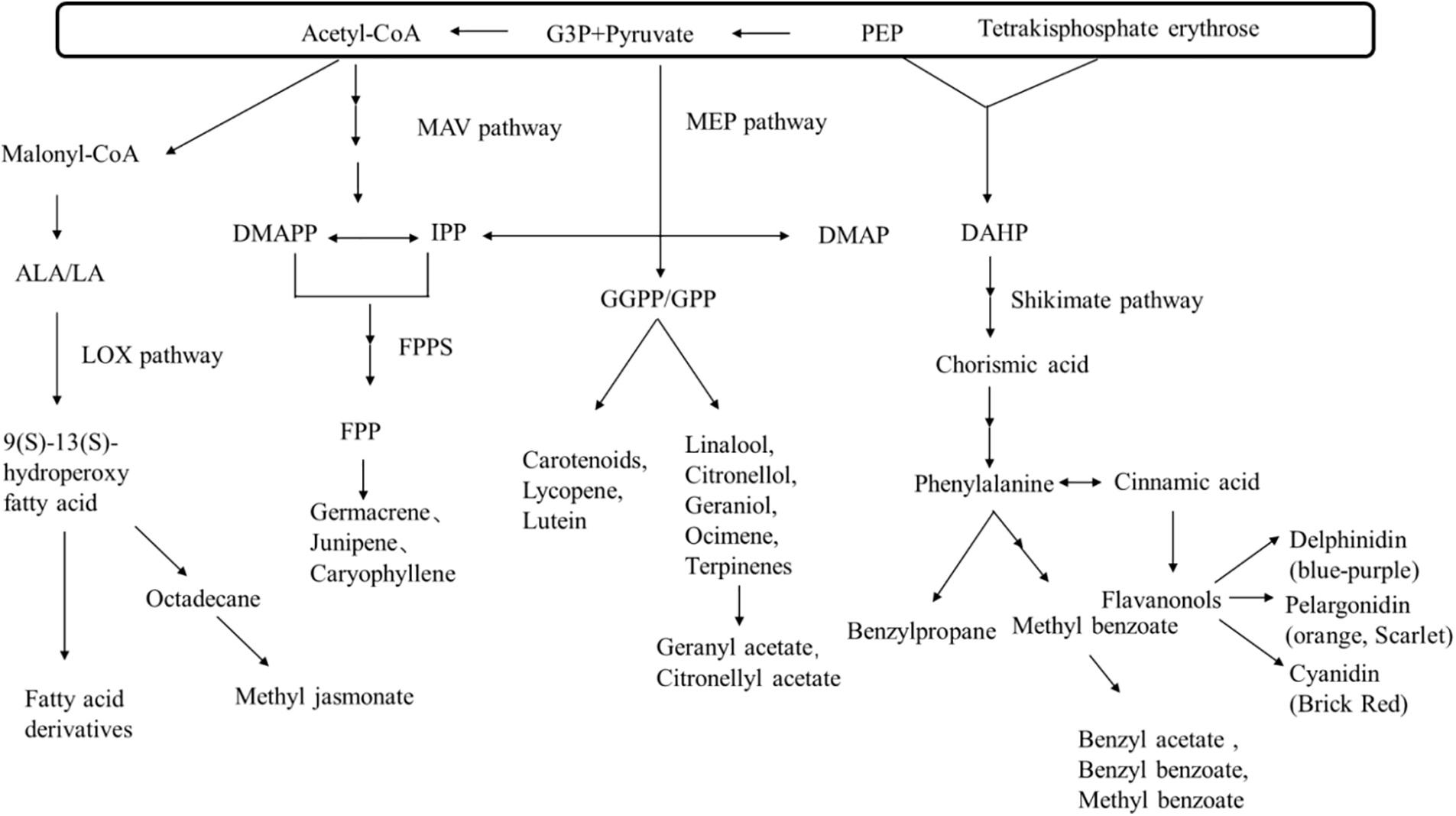

These relationships may be linked to the synthesis of anthocyanins and benzenoid compounds in the red cultivars of Phalaenopsis orchids, both of which are produced via the phenylpropanoid metabolic pathway. The synthesis pathways of floral fragrance components (such as terpenes and phenyl/phenylpropanoids) are somewhat related to the pathways of secondary metabolites, such as pigments (anthocyanins, carotenoids, etc.) [23,24]. The mevalonate pathway is an upstream pathway for the synthesis of benzenoid compounds and anthocyanins, while phenylpropanoids serve as precursors for the synthesis of benzenoid compounds and anthocyanins. The floral fragrance and color can be regulated through the mevalonate pathway simultaneously [23,25].

The flower color and fragrance are complex traits controlled by multiple genes. Based on previous studies [5,26,27], the synthesis pathways diagram for flower color and flower fragrance were depicted (Fig. 3). The diagram illustrates that the synthesis of flower color and fragrance components is closely related. For example, the synthesis of pigments such as carotenoids, and lycopene shares the methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathway with fragment molecules such as alcohols like linalool, citronellol, and geraniol and alkenes such as ocimene. The synthesis of blue-purple pigments from delphinidin and cornflower blue shares the Shikimate pathway with benzenoid compounds. These reveal the reasons behind the differences in the main aromatic components between yellow and purple Phalaenopsis orchids.

Figure 3: Synthetic pathways of floral color and aroma. ALA: alpha-linolenic acid; LA: linoleic acid; DMAPP: Dimethylallyl pyrophosphate; IPP: Isopentenyl pyrophosphate; FPPS: Farnesyl pyrophosphate synthase; FPP: Farnesyl pyrophosphate; PEP: Phosphoenolpyruvate; DMAP: Dimethylallyl phosphate; GGPP: Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate; GPP: Geranyl pyrophosphate; DAHP: 3-Deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonic acid 7-phosphate

Phalaenopsis orchids had varied phenotypic diversity, particularly in the variation of flower color [28]. Previous research has indicated that purple-red coloration in Phalaenopsis flowers may be controlled by a single gene [29], and floral fragrance is a heritable trait. Tong et al. conducted experiments on the fragrance components in eight newly hybridized fragrant Phalaenopsis cultivars, categorizing the scents into woody, minty, and fruity types, and identified fragrance compounds as candidate marker traits to distinguish between different fragrant flower groups [13].

The main components of the fragrance of Phalaenopsis are diverse in different color types. The fragrance of Phalaenopsis flowers has some correlation with their color. There was a significant positive correlation between esters and flower color C* value, and also between alcohol and L* value, and a significant negative correlation between alkenes and flower color h value, and also between alcohol and flower color C* value. This study measured both the flower color and fragrance components of Phalaenopsis orchids and analyzed the correlation between them, suggesting that flower color and flower fragrance may follow a pattern of genetic linkage. Phalaenopsis cultivars Phalaenopsis schilleriana, ‘SK16’, ‘Brother Sara Gold’, ‘SH51’, ‘Zhi Duo Xing’, ‘Yan Die Huang Fei’ and ‘Purple Martin’ with high C* and h values and strong aroma were selected as important parents for future cross-breeding. In the Phalaenopsis breeding study, if the mother was pure yellow, and the father was magenta, the base color of the first cross-generation was yellow 57.7% and purple 42.3%. At the same time, 87.2% of the first cross-generation inherited paternal magenta stripes [30]. Moreover, floral scents tend to be inherited maternally. Therefore, according to the breeding goal, the color and fragrance type of the parents should be analyzed and the combination of parents should be precisely designed in advance. In this study, the proposed methods and research data presented provide a theoretical foundation for future breeding on flower color and fragrance. The future study will focus on developing a flower evaluation system including a comprehensive index synthesizing C*, L*, and h, and identifying the necessary volatile compounds, to provide a more reliable framework for assessing Phalaenopsis quality.

Acknowledgement: The authors sincerely appreciate the support of Shandong Agricultural University and Shanghai Chenshan Botanical Garden in the aroma component determination test.

Funding Statement: This work was also supported by the Shandong Province Key Research and Development Plan Project (ID Numbers 2024LZGC026 and 2021LZGC019) and Shanghai Science and Technology Agriculture Project (ID Number 2020-02-08-00-12-F01463).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xiuyun Liu and Yingjie Zhang; analysis and interpretation of results: Jixia Sun, Feng Ming, Minxiao Liu and Xinyu Wang; draft manuscript preparation: Xiuyun Liu and Yingjie Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhao YA, Wang SY, Zhang G, Wang RH, Jiang SL, Yang SC. Comprehensive evaluation of biological characters of Phalaenopsis germplasm resources.North Hortic. 2024(1):54–9 (In Chinese). doi:10.11937/bfyy.20232537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. An HR, Kwon OK, Lee SY, Park PH, Park PM, Choi I, et al. Breeding of yellow small-type Phalaenopsis ‘yellow scent’ with fragrance. Hortic Sci Technol. 2019;37(2):304–10. doi:10.12972/kjhst.20190029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wei XL, Hong SB, Zhang JX, Zeng BD, Zhang XS, Guo YD, et al. Hybridization and breeding of superior individuals of Phalaenopsis with fragrance and multiple flowers. Guangdong Agric Sci. 2020;47(4):39–46 (In Chinese). doi:10.16768/j.issn.1004-874X.2020.04.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ding L. The relative expression and the analysis of key genes associated with the formation of floral color and scent in Phalaenopsis type Dendrobium [Ph.D. thesis]. Haikou, China: University of Hainan; 2016. [Google Scholar]

5. Kong L, Fan RH, Lin RY, Ye XX, Zhong HQ. Transcriptome analysis of pigment biosynthesis and floral scent biosynthesis in Cymbidium hybrid. Acta Bot Boreali Occidentalia Sin. 2021;41(1):86–95 (In Chinese). doi:10.7606/j.issn.1000-4025.2021.01.0086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Dunkel M, Schmidt U, Struck S, Berger L, Gruening B, Hossbach J, et al. SuperScent—a database of flavors and scents. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D291–4. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Knudsen JT, Eriksson R, Gershenzon J, Ståhl B. Diversity and distribution of floral scent. Bot Rev. 2006;72:1. doi:10.1663/0006-8101(2006)72[1:DADOFS]2.0.CO;2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Been CG, Kang SB, Kim DG, Cha YJ. Analysis of fragrant compounds and gene expression in fragrant Phalaenopsis. Flower Res J. 2014;22(4):255–63. doi:10.11623/frj.2014.22.4.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yang SZ, Fan YP. Analysis on the volatile components in two cultivars of Phalaenopsis. J South China Agric Univ. 2008;29(1):114–6+119 (In Chinese) doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-411X.2008.01.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xiao WF, Li Z, Chen HM, Hong SB, Jiang XN, Lv F. Determination of volatile components in flowers of Phalaenopsis violacea. Chin J Trop Agric. 2020;40(4):82–7. doi:10.12008/j.issn.1009-2196.2020.04.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yu D, Qin H. Monoterpenoids and sesquiterpenoids. Berlin, German: De Gruyter; 2021. doi:10.1515/9783110631593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hsiao YY, Tsai WC, Kuoh CS, Huang TH, Wang HC, Wu TS, et al. Comparison of transcripts in Phalaenopsis bellina and Phalaenopsis equestris (Orchidaceae) flowers to deduce monoterpene biosynthesis pathway. BMC Plant Biol. 2006;6(1):14. doi:10.1186/1471-2229-6-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Tong Y, Zhang YP, Hu MJ, Cao YH, Zhang YT, Tong EH, et al. Volatile component analysis of new hybrid varieties of Phalaenopsis. Guihaia. 2023;43:1016–26 (In Chinese). doi:10.11931/guihaia.gxzw202204020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ding XW, Wang ZZ, Wang QG, Jian HY, Chen M, Li SF. Analysis of floral volatile components of in Paeonia delavayi with differrent colors. South Hortic. 2022;33(3):25–30 (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-5868.2022.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhou LJ, Yu C, Cheng BX, Luo (L/YPan HT, Zhang QX. Correlation analysis of floral fragrance and flower color change in Rosa Section Chinensis. J Yunnan Univ Nat Sci Ed. 2021;43(5):1044–50 (In Chinese) doi:10.7540/j.ynu.20200375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Li DM, Liang XQ, Zhu GF, Sun YB, Xu YC, Jiang MD, et al. Identification of cool-night temperature induced reproductive transition related genes from Phalaenopsis hybrida by suppression subtractive hybridization. J Agric Biotechnol. 2013;21(8):883–95 (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1674-7968.2013.08.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Forero DP, Orrego CE, Peterson DG, Osorio C. Chemical and sensory comparison of fresh and dried lulo (Solanum quitoense Lam.) fruit aroma. Food Chem. 2015;169:85–91. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Huang XL, Zheng BQ, Wang Y. Study of aroma compounds in flowers of Dendrobium chrysotoxum in different florescence stages and diurnal variation of full blooming stage. For Res. 2018;31(4):142–9 (In Chinese). doi:10.13275/j.cnki.lykxyj.2018.04.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Yang HJ. Analysis on the volatile components of Chinese orchids [master thesis]. 2011. Hohhot, China: Inner Mongolia Agricultural University; 2011 (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

20. Wang SY, Zhang G, Yang SC, Jiang SL, Wang RH, Wang J. Numerical classification of Phalaenopsis flower colour based on phenotype. Chin J Trop Crops. 2023;44(11):2227–35 (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-2561.2023.11.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yu ZC, He XJ, Lin XX, Chen ZD, Zou LY. Analysis of anthocyanin composition and color factors in five species of Melastoma. J Trop Subtrop Bot. 2022;30(5):687–96 (In Chinese). doi:10.11926/jtsb.4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang Y, Li C, Wang S, Yuan M, Li B, Niu L, et al. Transcriptome and volatile compounds profiling analyses provide insights into the molecular mechanism underlying the floral fragrance of tree peony. Ind Crops Prod. 2021;162:113286. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Li J, Li TG, Wang TX, Wang J. Review of the mutually exclusive mechanism between the anthocyanins and betalains pigments in plants. J Plant Genet Resour. 2023;24(6):1515–26 (In Chinese). doi:10.13430/j.cnki.jpgr.20230505002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Carretero-Paulet L, Cairó A, Botella-Pavía P, Besumbes O, Campos N, Boronat A, et al. Enhanced flux through the methylerythritol 4-phosphate pathway in Arabidopsis plants overexpressing deoxyxylulose 5-phosphate reductoisomerase. Plant Mol Biol. 2006;62(4–5):683–95. doi:10.1007/s11103-006-9051-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. LI XH. Study on technique of molecular marker-assisted flower color selection and identification of flower colour and fragrance gene in Cymbidium [Ph.D. thesis]. Guangzhou, China: South China Agricultural University; 2020. [Google Scholar]

26. Li ZA. Research of terpenoids biosynthesis genes based on transcriptome analysis of tree peony floral fragrance [Ph.D. thesis]. Taian, China: Shandong Agricultural University; 2022. [Google Scholar]

27. JiangLP. Analysis of volatile terpenoids in Chrysanthemum nankingense and identification and functional verification of genes encoding terpene synthases [Ph.D. thesis]. Wuhan, China: Hubei University of Chinese Medicine; 2022. [Google Scholar]

28. Wang SY, Yang SC, Jiang SL, Zhang G, Zhao YA, Wang RH, et al. Phenotypic diversity analysis and evaluation on 57 Phalaenopsis germplasm resources. Seed. 2023;42(10):70–6+2 (In Chinese). doi:10.16590/j.cnki.1001-4705.2023.10.070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Wang J, Feng J, Yang SC, Jiang SL, Yang LJ, Zhang G, et al. Genetic analysis on floral traits in the F1 generation of Phalaenopsis hybrid. Seed. 2023;42(5):46–54 (In Chinese). doi:10.16590/j.cnki.1001-4705.2023.05.046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zhu J, Lü XH, Wang JF, Ma L, Lan CY, Miao J, et al. Study on character segregation of F1Hybrids from yellow wax variety Phalaenopsis ‘C27’ and purplish red papery variety Phalaenopsis ‘31’. Shandong Agric Sci. 2019;51(1):22 – 7 (In Chinese). doi:10.14083/j.issn.1001-4942.2019.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools