Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

First Occurrence of Coffee (Coffea arabica L.) Wilt Disease Caused by Neocosmospora falciformis in Saudi Arabia as Corroborated by Molecular Characterization and Pathogenicity Test

1 Department of Arid Land Agriculture, College of Agricultural and Food Sciences, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, 31982, Saudi Arabia

2 Pests and Plant Diseases Unit, College of Agricultural and Food Sciences, King Faisal University, Al-Ahsa, 31982, Saudi Arabia

3 Department of Soil, Plant and Food Sciences, University of Bari Aldo Moro, Bari, 70126, Italy

4 Institute of Sciences of Food Production (ISPA), National Research Council (CNR), Bari, 70126, Italy

* Corresponding Author: Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Plants Abiotic and Biotic Stresses: from Characterization to Development of Sustainable Control Strategies)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(3), 679-693. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.062196

Received 12 December 2024; Accepted 02 February 2025; Issue published 31 March 2025

Abstract

Coffee wilt represents one of the most devastating diseases of Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica L.) plantations in the primary coffee-producing regions. In this study, coffee trees manifesting wilt symptoms accompanied by the defoliation and drying of the whole tree were observed in the Jazan, El Baha, Najran, and Asir regions. The purpose of this investigation was to isolate and identify the Fusarium species recovered from symptomatic coffee trees. The developed fungi were initially characterized based on their morphological features followed by molecular phylogenetic multi-locus analysis of the combined sequences of ITS, TEF1-α, RPB2, and CaM. Twenty-five isolates were recovered from 28 samples. All fungal isolates were categorized morphologically under the genus Fusarium. Phylogenetic analysis positioned all the representative 15 isolates into one cluster grouping together with Neocosmospora falciformis (formerly F. falciforme) confirming their taxonomic position. Pathogenicity tests of the N. falciformis isolates were subsequently conducted on coffee seedlings, and the results revealed that all isolates induced wilt symptoms resembling those recorded in the field, and the incidence was 100%. The fungicide sensitivity test of seven investigated fungicides revealed that Maxim XL® followed by Moncut® exhibited the highest inhibitory effect against N. falciformis KSA 24-14, reaching 93.33% and 91.67%, respectively. To our knowledge, N. falciformis is a new causal pathogen of coffee wilt in Saudi Arabia. Remarkably, these results offer important insights for devising effective approaches to monitor and control such diseases.Keywords

The two primary species Coffea canephora (Robusta coffee) and Coffea arabica L. (Arabica coffee) produce coffee accounting for 70% and 30% of the world’s total commercial output of coffee, respectively. For the past four or five centuries, Yemen and Saudi Arabia have grown Arabica coffee on slender valleys and terraced mountain slopes at elevations reaching from 1200 to 1800 m [1]. In the southwestern regions of Saudi Arabia, including Al-Baha, Asir, and Jazan there are historic coffee plantations where some trees are more than 100 years old. In the southwestern area of Saudi Arabia, coffee plays a major role in the economy and is the primary cash crop grown by smallholder farmers, with social, and economic advantages for farmers in the mountainous areas. To increase interest in coffee production, research on coffee cultivation in the region has intensified [2]. Saudi Vision 2030 emphasizes transformative progress across various economic sectors, with the coffee industry being a key focus. In 2021, the coffee market was valued at USD 1.58 billion and is projected to grow to USD 2.22 billion by 2028 [3]. By 2026, Saudi Arabia aims to cultivate 1.2 million coffee trees as part of its agricultural goals. To support this initiative, the Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture has introduced multiple programs, such as the Sustainable Agricultural Rural Development Program (REF), designed to promote and enhance coffee farming across the Kingdom [4]. The Saudi Coffee Company plans to invest approximately $320 million over the next decade to boost the coffee industry. This initiative aims to elevate annual coffee production from 300 to 2500 tonnes, which is expected to create numerous employment opportunities and drive sectoral growth [5].

Coffee farmers face numerous obstacles in their agricultural yields throughout tropical regions [6]. Climate change has affected coffee production both directly, through reduced crop yields and quality, and indirectly, by fostering the spread of fungal diseases and invasive pests [6–9]. The three main diseases that affect coffee trees are Coffee Leaf Rust (CLR) [10], Coffee Wilt Disease (CWD) [11,12], and Coffee Berry Disease (CBD) [7], which are triggered by Gibberella xylarioides, Colletotrichum spp., and Hemileia vastatrix, respectively. CWD has been mainly caused by Fusarium xylarioides, a soilborne fungus that induces vascular wilt and kills coffee plants [12]. However, Neocosmospora falciformis (formerly known as; Fusarium falciforme) and other species, for example, F. solani, F. lateritium, F. xylarioides, F. stilboides have been documented to cause wilt and dry rot to coffee worldwide [11–15]. Neocosmospora (Hypocreales, Nectriaceae), which was recently separated from the F. solani species complex (FSSC), is a genus of ubiquitous fungi with a global distribution that can be found in soil, water, air, living plant material, and plant detritus [16]. Neocosmospora is recognized as an emerging threat to coffee crops, particularly in Saudi Arabia and potentially on a global scale. However, there is limited understanding regarding the fungus’s distribution, its ability to cause disease, or the frequency of associated outbreaks.

Significant advancements in the taxonomy and phylogeny of F. oxysporum have been achieved through the application of DNA-based methods, including AFLPs, RFLPs, and RAPDs [17]. AFLPs, RFLPs, and RAPDs are also affected by significant homoplasy, fail to identify alleles, and the resulting groups are influenced by the quantity and variety of restriction enzymes, probes, and primers employed. RAPD is also characterized by low reproducibility [17]. Consequently, DNA markers are recognized as a reliable solution for addressing challenges related to the taxonomy and phylogenetic classification of Fusarium species [18–20]. DNA markers that have been used for delineating Fusarium and Neocosmospora species are the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) areas, such as the 5.8S gene, both the large (LSU; 28S) and small (SSU, 18S) subunits of the nuclear ribosomal RNA genes, along with protein-encoding genes, like the largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB1), the second largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2), cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 (COX1, COI), β-tubulin (TUB2), translational elongation factor 1-α (TEF1-α), γ-actin and calmodulin (CaM) [20]. Unfortunately, none of the ribosomal markers have been proven to distinguish Fusarium and Neocosmospora at the species level. The reported markers that have a great species identification are TEF1-α and RPB2 [21]. EF-1α is frequently utilized as the primary identification marker due to its exceptional resolution capabilities for the majority of species, whereas RPB2 provides improved differentiation among closely related species [21]. Therefore, the implementation of multi-locus phylogenetic analyses is essential to support the separation of F. solani and its closely related species from Fusarium to the genus Neocosmospora [18].

The occurrence of coffee plant death due to a lack of necessary agricultural practices and phytosanitary measures is alarming, especially in the context of fungal diseases, indicating that CWD poses a significant obstacle for smallholder coffee farmers. The recent rise in CDW infections underscores the necessity for investigating Neocosmospora wilt as a developing economically significant disease of coffee based on field observations. Considering the recently reported coffee pathogens in Saudi Arabia [7–9,22], very little information regarding phytopathogens, insects, and other pathogenic agents has been documented in Saudi Arabia’s coffee. In light of this, the existing investigation represents the first attempt to characterize the possible fungal species related to wilt and decline diseases that may lead to probable losses of coffee in Saudi Arabia. The purpose of the existing investigation was to identify the fungi related to wilt-like symptoms in coffee based on phylogenetic, morphological, and pathogenicity assessment throughout in vitro and in vivo experiments.

Samplings were conducted from severely wilted coffee trees during August and September 2023 in different geographical regions in Saudi Arabia namely; Jazan, El Baha, Najran, and Asir regions. A total of 28 root samples from different trees manifesting wilt symptoms were collected. Isolation was done on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) medium amended with Ampicillin sulfate (0.1 g/L−1). The infected roots were surface-sterilized by immersing them for 5 min in a solution of 2% sodium hypochlorite, afterward washed three consecutive times with sterilized distilled water. They were then blotted using sterilized filter paper. The sterilized roots were sectioned into small pieces, each about with a diameter of 0.5 cm, and transferred onto a medium of Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA). Four fragments were positioned on every plate and maintained at 25°C for a span of 5 to 7 days. Colonies similar to Fusarium were sub-cultured and distinguished by molecular and morphological methods. The colonies growing on PDA were preliminarily identified as Fusarium, based on their depressed beige mycelia, concentric ring growth, and lack of sporodochia [23]. The primary evaluated characteristics encompassed microscopic features (including the existence of macro- and microconidia, along with chlamydospores) and macroscopic traits (including the presence of aerial mycelium, as well as the color and appearance of the colony). As noted by Stefańczyk and Sobkowiak [24], conidia were germinated for 1–2 days at 16°C on a water agar medium to obtain single-spored subcultures from the colony margin.

2.2 Molecular Characterization

2.2.1 DNA Extraction, PCR Amplification and Sequencing

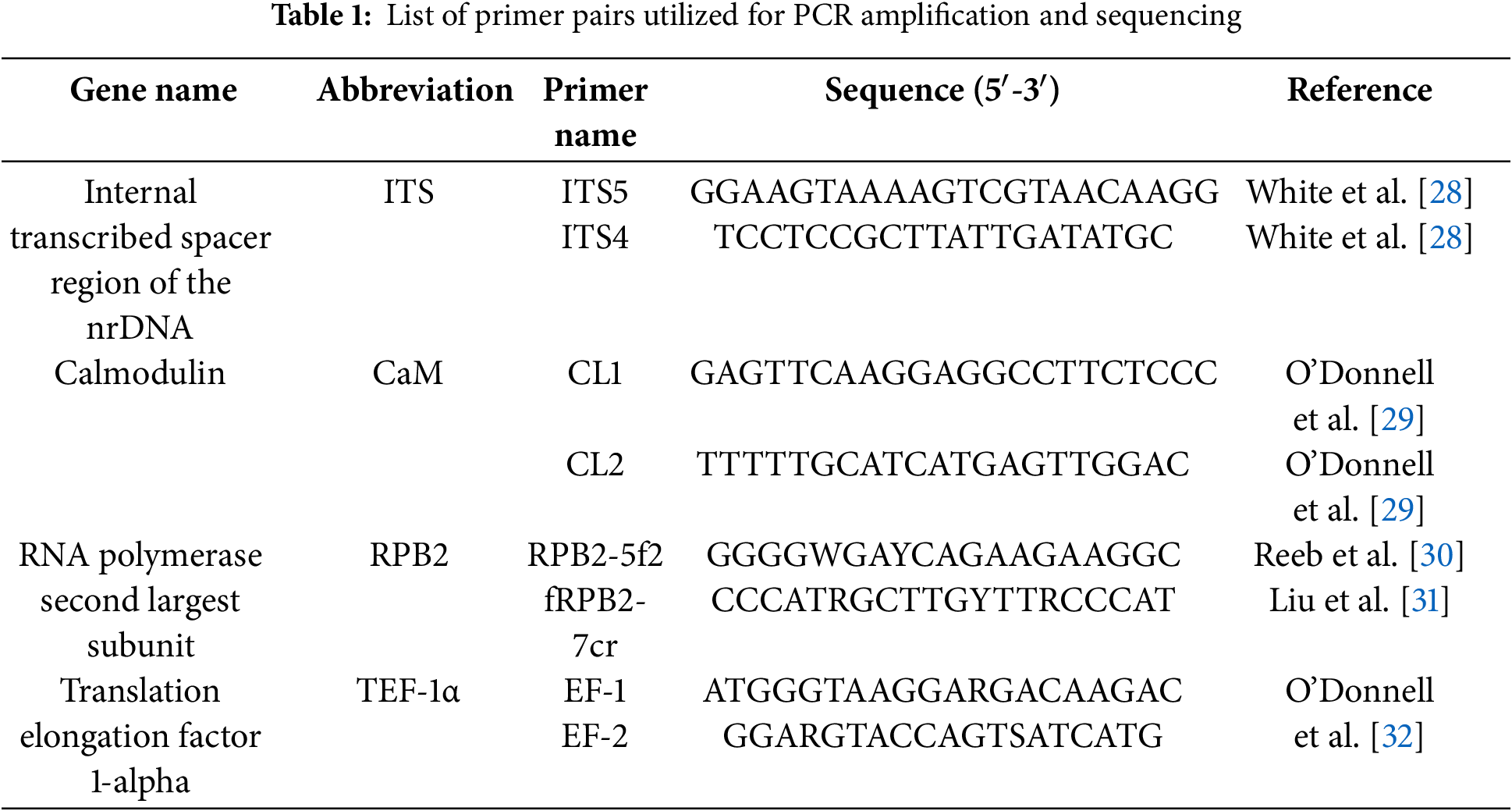

From fresh mycelium of 7-day-old fusarioid isolates, the total genomic DNA was extracted employing the Dellaporta procedure [25]. DNA markers, including translational elongation factor 1-α (TEF1-α), the second-largest subunit of RNA polymerase II (RPB2), calmodulin (CaM), and the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, were employed. The primer pairs enumerated in Table 1 were employed for the amplification and sequencing of the respective gene areas. The PCR mixtures, as detailed by Alhudaib et al. [7], were prepared in a total volume of 25 μL. PCR was done utilizing a 2720 Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and the amplification conditions for TEF1-α, CaM, and RPB2 were carried out according to the program of Khuna et al. [26], and for ITS by the procedure of Alhudaib et al. [7]. Sequencing and purification of the PCR products were done in forward and reverse directions at Macrogene Inc. (Seoul, Korea), following the manufacturer’s protocol. Utilizing MEGA v.7, the generated sequences were assembled and manually edited [27]. The sequence homology was assessed utilizing BLAST® vs. the sequence database of NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information, GenBank) (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank) (accessed on 01 February 2024).

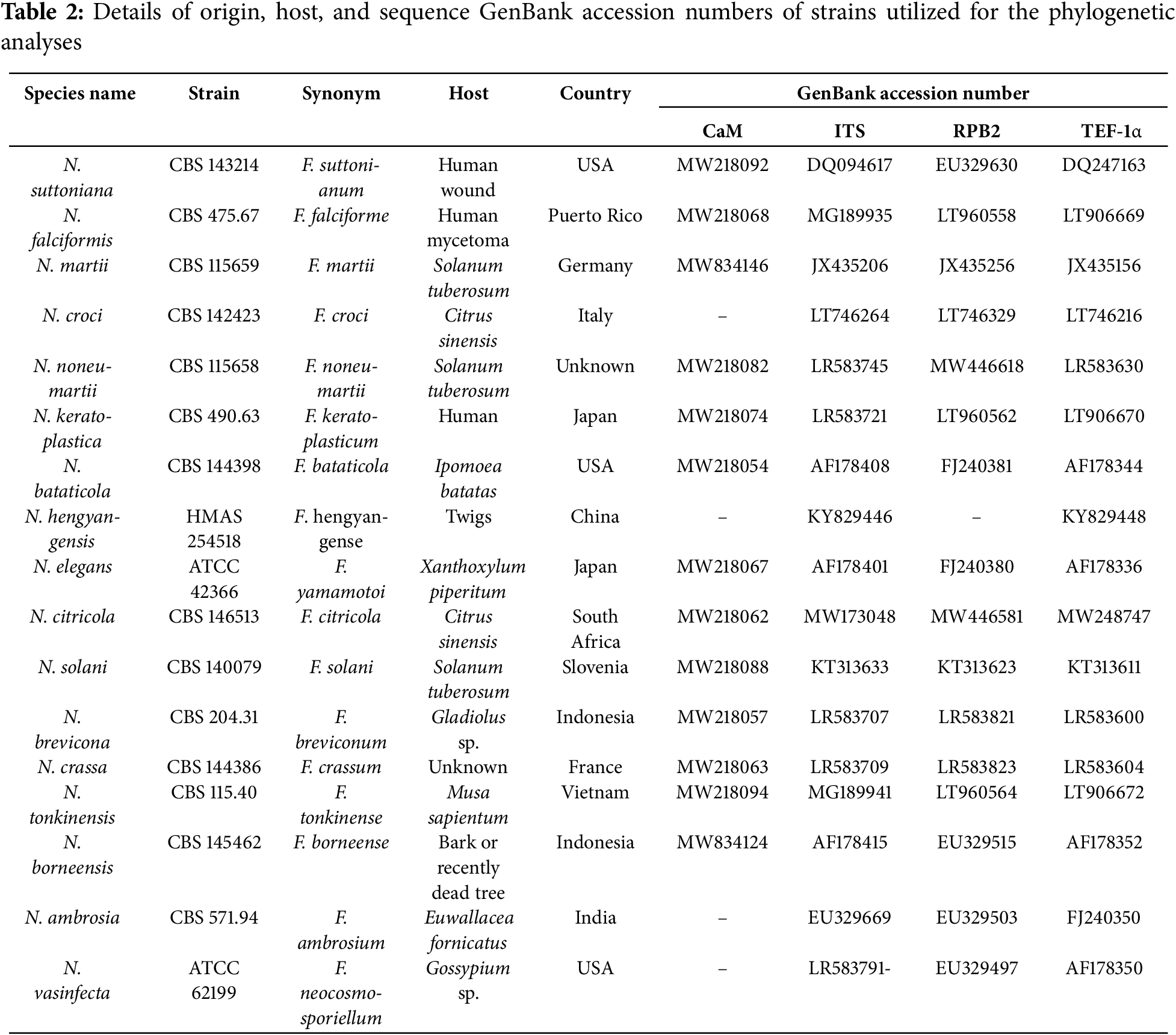

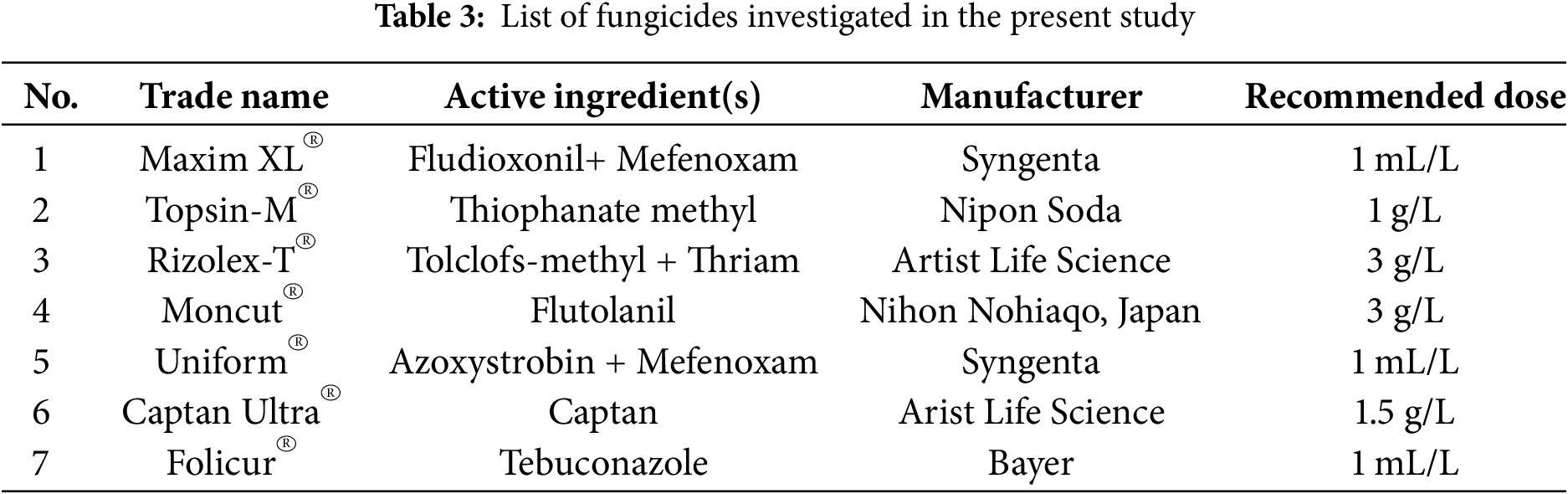

The phylogenetic position of the Saudi Arabian collection was determined by combining and analyzing concatenated sequences of CaM, ITS, RPB2, and TEF1 with the reference sequences obtained from GenBank (Table 2). MAFFT [33] was employed to compute the multi-alignment of the sequences. MEGA XI v.11.0.8 [34] was employed for concatenating and trimming the multi-sequence alignment. The UFBoot [35] ML analysis was done with IQ-Tree 2.2.2.6 [36], employing the optimal model selected through ModelFinder [37], for each partitioned locus [38].

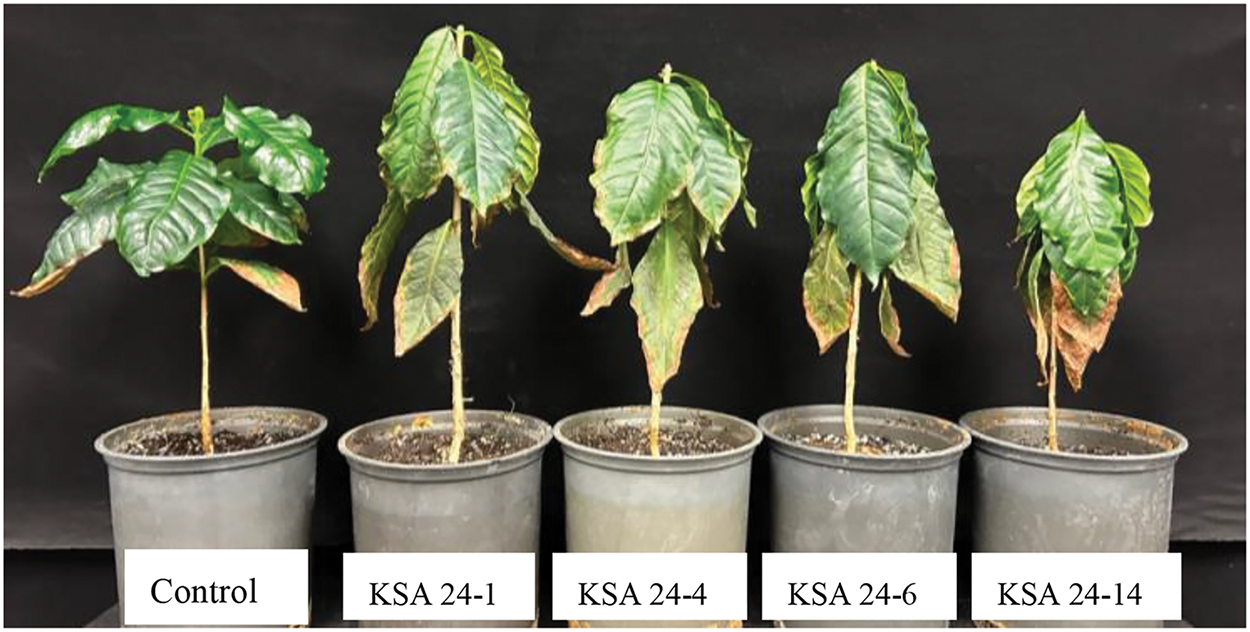

Pathogenicity test was carried out on six-month-old coffee (Coffea arabica) seedlings following the previously published method [39]. Representative isolates (KSA 24-1, KSA 24-4, KSA 24-6, and KSA 24-14) of N. falciformis were selected and cultivated in 250-mL flasks with potato dextrose broth for 5 days at 25°C in darkness with continuous agitation. After filtration and washing in sterilized water, spore suspension was adjusted to (1 × 106 spores/mL) using a hemocytometer slide under a light microscope [15]. Each pot was inoculated with 100 mL of (1 × 106 spores/mL) [39]. Coffee plants that received treatment with sterile water acted as control. The plants were maintained in a controlled growth chamber set to 25°C, with a 12-h light period alternating with 12 h of darkness. Three replicates were used in a completely randomized design. Re-isolation was carried out from diseased seedlings and the recovered fungi were compared with the original fungal cultures used.

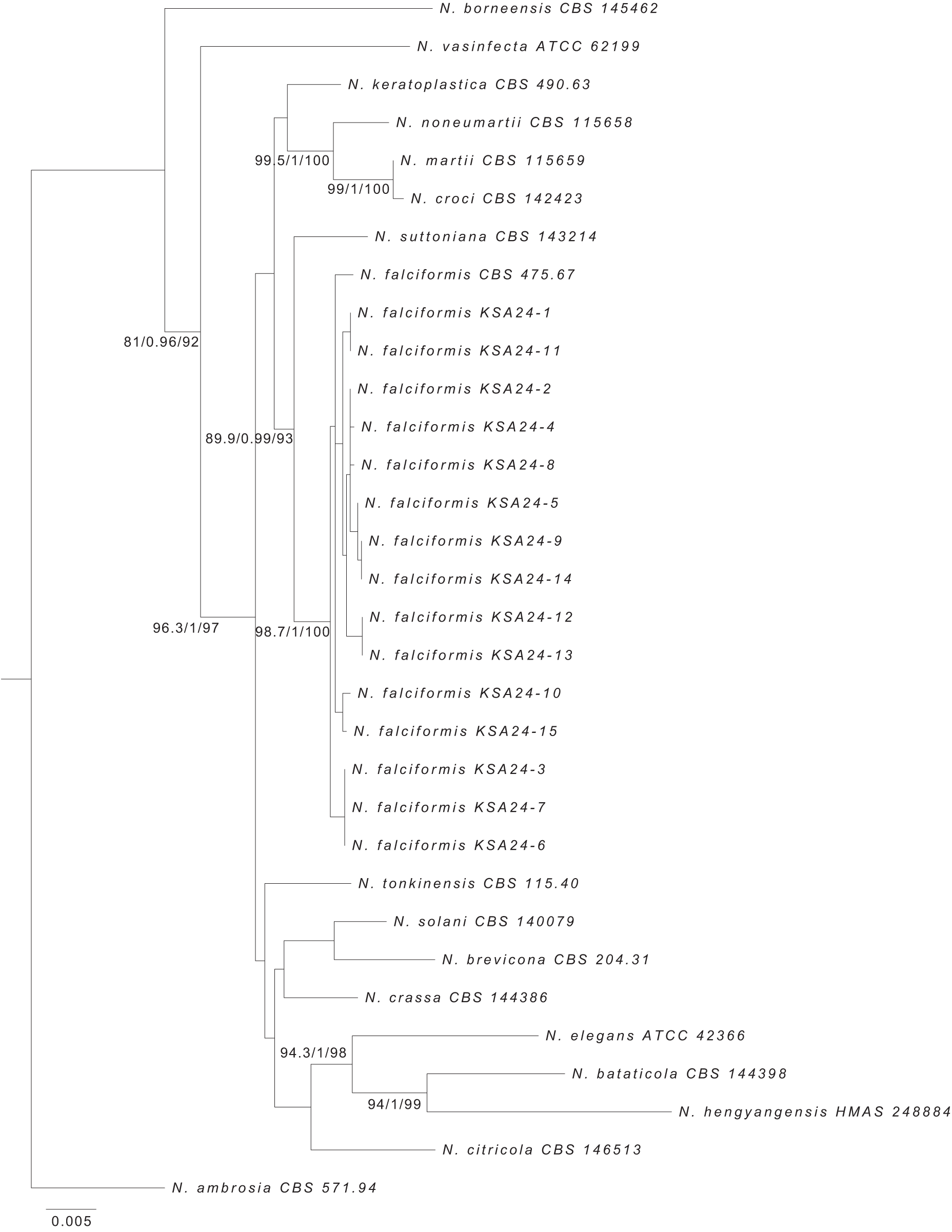

2.4 Fungicide Sensitivity Test

The comparative efficacy of seven fungicides (Table 3) was examined against N. falciformis utilizing the poison medium approach. The tested fungicides were used at a given dose as stated on the fungicide label. The PDA medium was autoclaved, and fungicides were added after cooling to 45°C–50°C and then dispensed into 90-mm Petri plates at a volume of 12 mL for each plate. Control PDA plates were left untreated with fungicides. After the media solidified, using a sterile cork borer, 5-mm discs from the outer edge of an actively growing fungal culture were introduced onto the plates and incubated at 24°C for 2 to 3 days. Every treatment was evaluated on three plates as replicates. Following incubation, the diameter of every fungal colony was assessed in two orthogonal directions. The growth inhibition percentage for each isolate and fungicide combination was computed utilizing the following equation:

The obtained data were evaluated employing analysis of variance one-way ANOVA. The CoStat software, version 2.6 [40], was utilized to separate means through Fisher’s protected least significant difference (LSD) test at a significance level of p ≤ 0.05. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) was used to express the data.

3.1 Symptoms and Morphological Characterization of Neocosmospora Isolates

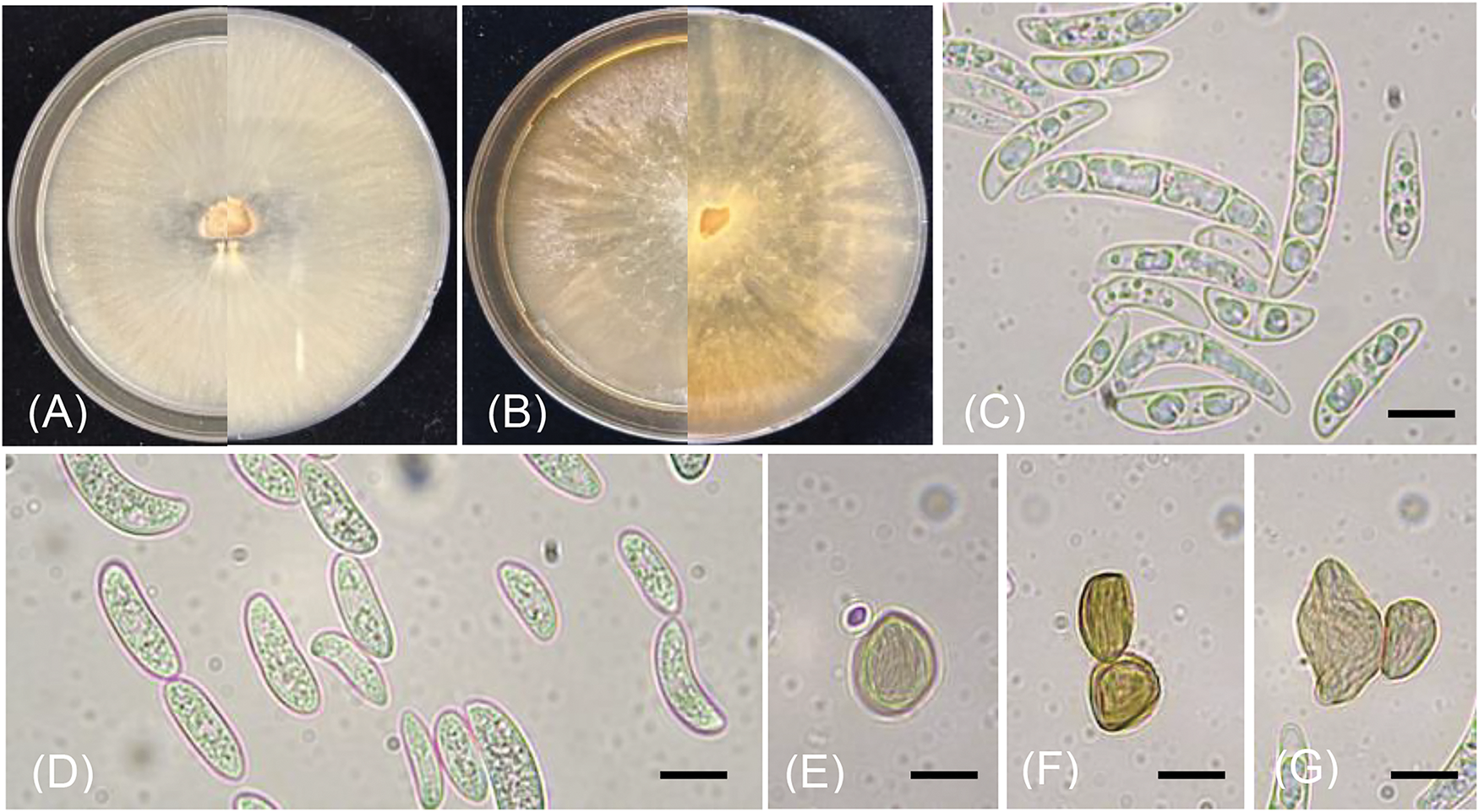

Overall, 12 coffee plantations were surveyed in the four screened regions. The symptoms were categorized into two main types: wilt and dry rot. Sever wilt symptoms were the most prevalent on coffee trees (Fig. 1A,B), while dry rot was less observed (Fig. 1C). Cross sections in the roots of wilted trees exhibited light to dark brown discoloration of vessels (Fig. 1D–F). Various patterns of coffee wilt symptoms attributed to different Fusarium species were reported in different literature confirming our observations [11–15]. Twenty-five fusariosis isolates were collected from plants exhibiting symptoms, and only 15 representative isolates were employed in the molecular and morphological identification. The isolates were initially classified as part of the Fusarium solani species complex. The colonies morphology on PDA were pale-cream to white-greyish, rapidly proliferating, exhibiting flat mycelium heavier near the colony’s center, and displaying a diffuse pale-yellow pigmentation that darkened with age (Fig. 2A,B). Such morphological criteria have been noted by various researchers [39,41,42]. Moreover, macroconidia conidia of N. falciformis were straight to curved, exhibiting moderate curvature and a slender form, occasionally exhibiting strong curvature (Fig. 2C). These conidia were one- to four-septate, measuring in width from 2.5 to 6.5 μm and in length from 17.5 to 35 μm. Microconidia were elongated oval and obovoid with a truncated base, predominantly non-septate, and infrequently one-septate (Fig. 2D). Spherical in shape, smooth, and thick-walled, chlamydospores were sometimes found as single entities or in pairs (Fig. 2E–G). The morphological characteristics of macro and microconidia were comparable to those recorded in earlier research [13,39,41]. Furthermore, no sporodochia was observed, which coincided with the finding of González et al. [41].

Figure 1: Sever wilt symptoms observed on the young and old coffee trees (A, B); root system of wilted trees showing rot of feeder roots and white mycelial growth of fungi (C); cross and longitudinal sections in infected roots showing internal browning with various degrees indicating the presence of N. falciformis fungi (D–F)

Figure 2: Colonies of N. falciformis incubated for one week at 25°C on PDA (A, B), macroconidia (C), microconidia (D), chlamydospores (E, F, G) Scale bars = 10 µm

The fifteen isolates obtained in this study were preliminarily classified as N. falciformis and were then chosen for the analysis of the phylogenetic. The alignment of RPB2, ITS, TEF-1α, and CaM included a total of 32 strains, which encompassed type species, representing all of the species belonging to the Neocosmospora solani clade and others from nearby clades. Fig. 3 displays the resulting ML tree. The findings revealed that isolates acquired in this study were grouped with N. falciformis CBS 475.67 with high statistical support values (a Bayes/ultrafast bootstrap% = 1.0/100%), which confirmed their taxonomic positions. The multi-locus dataset validated the formation of six sub-clades (Fig. 3). The clades 1, 4, and 5 contained two isolates, while, clades 2, 3, and 6 were made up of three isolates. This indicates a significant level of genetic variation in N. falciformis from Saudi Arabia. The reasons behind genetic diversity could be particular ecological and agricultural conditions that offer favorable conditions for the pathogen’s evolution, and the capacity of the pathogen for horizontal gene transfer [43,44]. Furthermore, the genetic diversity of these isolates may be attributed also to the fact that the genes are subject to a variety of selective pressures, which may have resulted in varying mutation rates. This may be one of the reasons for the presence of numerous clades or groups. Molecular diagnosis confidently validated the identification relying on morphological traits. Crous et al. [21] indicate that the primary genes employed for identification are TEF-1α and RPB2, which offer excellent resolution for most species across all genera. Additionally, RPB2 enhances the ability to distinguish between closely related species. This was evident from our data, employing TEF-1α, RPB2 offered high discriminatory power along with the employed markers ITS and CaM in resolving N. falciformis from other species. Such data produce well-supported phylogenetic relationships between isolates, which are in agreement with previous studies [18–21,44].

Figure 3: Maximum likelihood tree produced by phylogenetic analysis of TEF-1α, ITS, RPB2, and CaM datasets of the Neocosmospora solani clade. Numbers at the nodes signify SH-aLRT support (%)/a Bayes support/ultrafast bootstrap support (%), in that order. N. ambrosia CBS 571.94 was utilized as the outgroup. The expected nucleotide changes per site are represented by the scale bar. Sequences of N. falciformis obtained in this study are indicated with KSA letters followed by several isolates

All coffee seedlings inoculated with the conidial suspension of N. falciformis showed symptoms of wilt resembling those noted in the field (Fig. 4). There was no difference in the final occurrence of wilt, which was consistent across all inoculated coffee plants, with a uniform occurrence rate of 100%. Likewise, Chen et al. [45] demonstrated also that Neocosmospora silvicola caused 100% mortality in artificially inoculated detached Pinus armandii branches. Also, López-Moral et al. [46], indicated that the inoculated Prunus dulcis plants with Fusarium oxysporum under irrigation demonstrated significantly highest incidence (100%) of wilt symptoms. In this study, the initial signs manifested as either wilting or browning of leaves, leading to desiccation, loss, and finally plant death. The observed symptoms were also previously reported [15]. The isolate KSA 24-14 showed first wilt symptoms after 28 days post-inoculation, which coincided with the finding reported by Tshilenge-Djim et al. [11]. While, the other isolates (KSA 24-1, KSA 24-4, and KSA 24-6) caused first wilt symptoms after 35 days. This variation in symptom development was also noticed among Fusarium species [11,14]. There were no premature defoliated leaves observed, even after 60 days of inoculation and all leaves remained attached to infected plants. However, previous studies revealed that coffee plants treated with F. solani, F. xylarioides, F. falciforme, and F. stilboides exhibited severe defoliation [11,15]. The control plants remained symptomless (Fig. 4). The fungus was successfully recovered after the re-isolation from the wilted plants and its identification was validated by contrasting it to the original isolate, thus fulfilling Koch’s postulates. The current findings align with previously reported data suggesting that Fusarium/Neocosmospora species can induce varied degrees of wilt symptoms in inoculated coffee plants. The geographic origin and age of strains appear to be related to this variability in pathogenicity [15]. Neocosmospora falciformis is not only a plant pathogen but also an important fungus that can trigger diseases in animals and humans, mostly as an opportunistic pathogen [19]. It also encompasses aggressive plant pathogens, including the previously classified F. paranaense, a species implicated in root rot of Glycine max in Brazil that has been synonymized with N. falciformis following the phylogenetic reassessment of the genus Fusarium [19,47]. Additionally, N. falciformis, formerly known as F. falciforme, has been recognized as a pathogen affecting Phaseolus lunatus and has been linked with Fusarium wilt in Cannabis sativa, as well as causing bud and wilt rot in A. tequilana [48–50].

Figure 4: Symptoms induced by artificial inoculation of representative isolates (KSA 24-1, KSA 24-4, KSA 24-6, and KSA 24-14) of N. falciformis revealed wilt symptoms on six-month-old coffee seedlings after 35 days post-inoculation

3.4 Fungicide Sensitivity Test

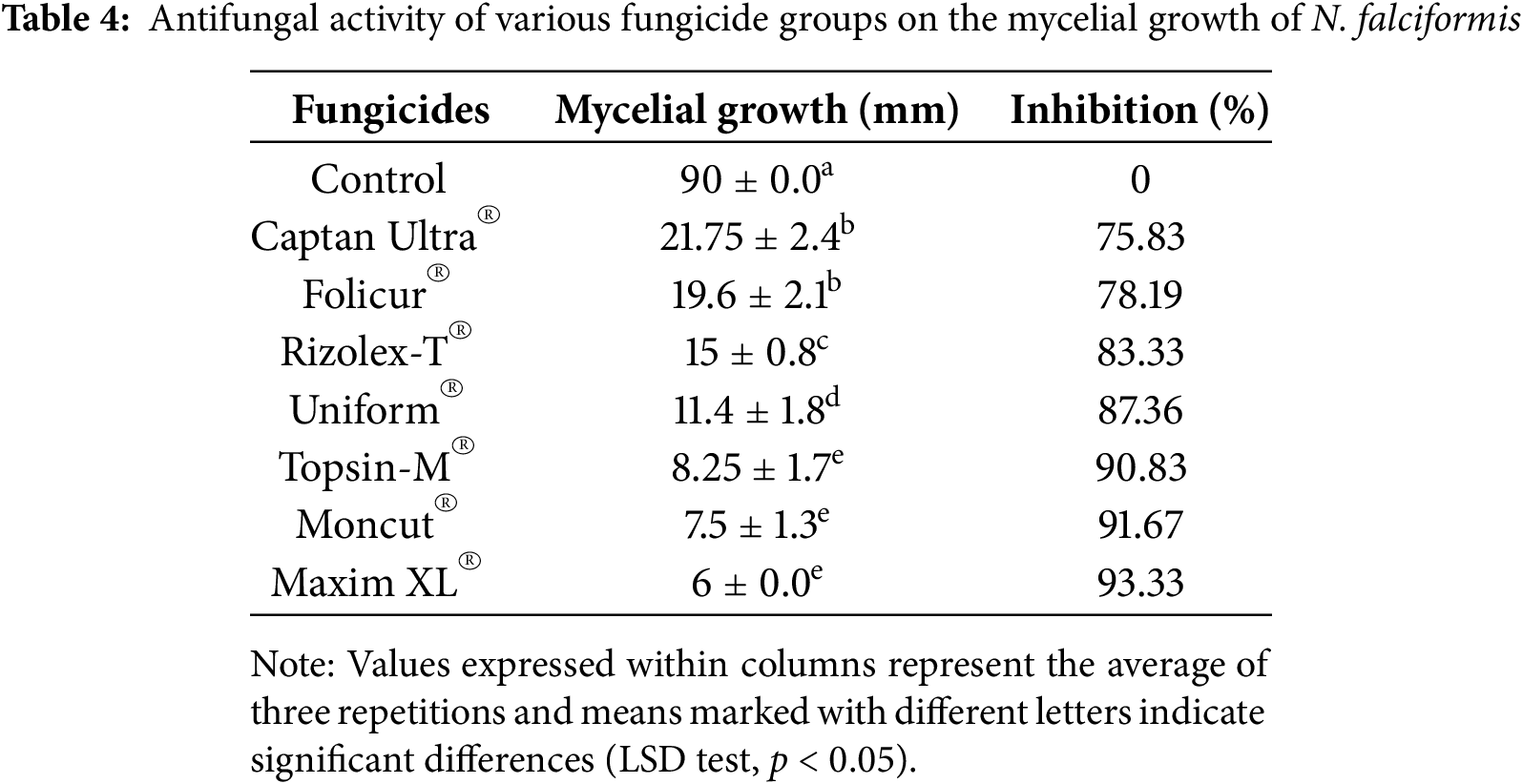

Data in Table 4 reveals that the all-tested fungicides suppressed the mycelial growth of N. falciformis KSA 24-14, regardless of fungicide concentration and displaying significant variation. Only Maxim XL® exhibited the highest inhibitory action among the tested fungicides against N. falciformis KSA 24-14, reducing the mycelial growth up to 6 mm with 93.33% inhibition, followed by Moncut® which suppressed mycelial growth to 7.5 mm with inhibitory percentage of 91.67%. The high efficacy of fludioxonil toward Fusarium oxysporum was previously documented in several researches [51,52]. Nevertheless, the excessive use and improper utilization of fludioxonil has led to the emergence of resistance to this fungicide in Fusarium [53]. Our results indicated that Thiophanate-methyl was shown to be efficient also against N. falciformis, which coincided with those published in the literature [54,55]. Nevertheless, the research of Petkar et al. [56], demonstrated for the first time that F. oxysporum is resistant to thiophanate-methyl. Also, Uniform® and Rizolex-T® were moderately effective in reducing mycelial growth of N. falciformis KSA 24-14 to values of 11.4 and 15 mm, with inhibitory percentages reaching 87.36% and 83.33%, respectively.

By contrast, Captan Ultra® and Folicur® were the least efficient fungicides for inhibiting the mycelial growth of N. falciformis, with an inhibition value of 75.83% and 78.19%, respectively. This could explain why the level of pre-existing resistance to tebuconazole is high and should, thus, be regarded as intrinsic resistance. However, earlier studies reported that tebuconazole the active ingredient of Folicur® had a great inhibitory effect against F. oxysporum [57,58]. This was also reported in an earlier study that demonstrated the development of tebuconazole resistance in F. graminearum [59]. The molecular processes underlying intrinsic resistance in Fusarium remain unexplored. Nevertheless, there is limited data regarding the activity and potential resistance risks of tebuconazole and fludioxonil in N. falciformis. Thus, in this study, the sensitivity test offers initial data to assess the resistance levels in field populations, thereby guiding the strategic selection of suitable fungicides.

This study marks the initial effort to elucidate the etiology and pathogenicity of Neocosmospora species related to the wilt and deterioration of coffee trees, aiming to manage this economically significant disease and ensure the financial success of the industry of coffee in Saudi Arabia. Identifying the causal agents may facilitate the development of an appropriate management scheme predicated on their susceptibility to fungicides. We report for the first time in Saudi Arabia the potential of N. falciformis to cause decline and wilt on coffee. Our study revealed that TEF-1α and RPB2, in combination with the markers ITS and CaM, provided significant discriminatory power in distinguishing N. falciformis from other species. It is vital to monitor the emergence of fungicide resistance, as the inconsistency observed in vitro sensitivity tests underscores the importance of adapting recommendations. This approach helps prevent the continued use of ineffective fungicides. Further investigation is required to examine the differences in sensitivity to various fungicides among isolates of the same fungal species. The validation of the tested fungicides under field conditions could also be investigated in future work.

Acknowledgement: The authors express their sincere appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research and the Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research at King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, for their financial support of this research through grant number KFU242134.

Funding Statement: This research and APC were funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research, Vice Presidency for Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, King Faisal University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work for work through grant number KFU242134.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail, Khalid Alhudaib; data collection: Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail, Khalid Alhudaib; analysis and interpretation of results: Donato Magistà; draft manuscript preparation: Ahmed Mahmoud Ismail, Donato Magistà. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The findings and datasets analyzed throughout this study are accessible within the published article. Additionally, they can be made available upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Tounekti T, Mosbah M, Al-Turki T, Khemira H. Genetic diversity analysis of coffee (Coffea arabica L.) germplasm accessions growing in the southwestern Saudi Arabia using quantitative traits. Nat Resour. 2017;8:321–36. doi:10.4236/nr.2017.85020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tounekti T, Mahdhi M, Al-Turki TA, Khemira H. Water relations and photo-protection mechanisms during drought stress in four coffee (Coffea arabica) cultivars from southwestern Saudi Arabia. South African J Bot. 2018;117:17–25. doi:10.1016/j.sajb.2018.04.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wood L. ResearchAndMarkets.com. 2022. Business wires. Business wire: Saudi Arabia Coffee Market Report 2022: rising number of initiatives to increase coffee production in Saudi Arabia presents opportunities—ResearchAndMarkets.com; 2022. [cited 2025 Feb 01]. Available from: https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/. [Google Scholar]

4. Environment MO. Initiatives and programs to develop coffee cultivation in Saudi Arabia. Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture. 2023 [cited 2025 Feb 01]. Available from: https://www.mewa.gov.sa/en/MediaCenter/News/Pages/engnews2226.aspx#:~:text=The%20Kingdom%E2%80%99s%20target%20is%20to. [Google Scholar]

5. Salian N, Gulf Business: from bean to brew: how Saudi coffee company is powering the kingdom’s coffee industry. 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 10]. Available from: https://gulfbusiness.com/saudi-coffee-company-to-support-vision-2030-goals/. [Google Scholar]

6. Bracken P, Burgess PJ, Girkin NT. Opportunities for enhancing the climate resilience of coffee production through improved crop, soil and water management. Agroecol Sustain Food Syst. 2023;47(8):1125–57. doi:10.1080/21683565.2023.2225438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Alhudaib K, Ismail AM, Magistà D. Multi-locus phylogenetic analysis revealed the association of six Colletotrichum species with anthracnose disease of coffee (Coffea arabica L.) in Saudi Arabia. J Fungi. 2023;9(7):705. doi:10.3390/jof9070705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Alhudaib K, Ismail AM. First occurrence of coffee leaf rust caused by Hemileia Vastatrix on coffee in Saudi Arabia. Microbiol Res. 2024;15(1):164–73. doi:10.3390/microbiolres15010011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Crous PW, Costa MM, Kandemir H, Vermaas M, Vu D, Zhao L, et al. Fungal planet description sheets: 1550–1613. Persoonia Mol Phylogeny Evol Fungi. 2023;51:280–417. [Google Scholar]

10. Salazar-Navarro A, Ruiz-Valdiviezo V, Joya-Dávila J, Gonzalez-Mendoza D. Coffee leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix) disease in coffee plants and perspectives by the disease control. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2024;93(5):923–49. doi:10.32604/phyton.2024.049612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Tshilenge-Djim P, Muengula-Manyi M, Kingunza-Mawanga K, Ngombo-Nzokwani A, Tshilenge-Lukanda L, Kalonji-Mbuyi A. Field assessment of the potential role of Fusarium species in the pathogenesis of coffee wilt disease in Democratic Republic of Congo. Asian Res J Agric. 2016;2(3):1–7. doi:10.9734/arja/2016/31052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Peck LD, Boa E. Coffee wilt disease: the forgotten threat to coffee. Plant Pathol. 2024;73(3):506–21. doi:10.1111/ppa.13833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tshilenge L, Kalonji A, Tshilenge P. Determination of cultural and biometrical characters of Fusarium species isolated from plant material harvested from coffee (Coffea canephora Pierre.) infected with CWD in the Democratic Republic of Congo. African J Agric Res. 2010;5(22):3145–50. [Google Scholar]

14. Serani S, Taligoola HK, Hakiza GJ. An investigation into Fusarium spp. associated with coffee and banana plants as potential pathogens of robusta coffee. Afr J Ecol. 2007;45(s1):91–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2007.00744.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Djim P. Variability of pathogenicity in Fusarium xylarioides steyaert: the causal agent of coffee wilt disease. Am J Exp Agric. 2011;1(4):306–19. doi:10.9734/ajea/2011/213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kamali-Sarvestani S, Mostowfizadeh-Ghalamfarsa R, Salmaninezhad F, Cacciola SO. Fusarium and Neocosmospora species associated with rot of cactaceae and other succulent plants. J Fungi. 2022;8(4):364. doi:10.3390/jof8040364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Bogale MA. Molecular characterization of Fusarium isolates from Ethiopia [Ph.D. thesis]. South Africa: University of Pretoria; 2006. [Google Scholar]

18. Sandoval-Denis M, Guarnaccia V, Polizzi G, Crous PW. Symptomatic citrus trees reveal a new pathogenic lineage in Fusarium and two new Neocosmospora species. Persoonia Mol Phylogeny Evol Fungi. 2017/07/01. 2018;40:1–25. doi:10.3767/persoonia.2018.40.01. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Sandoval-Denis M, Lombard L, Crous PW. Back to the roots: a reappraisal of Neocosmospora. Persoonia Mol Phylogeny Evol Fungi. 2019;43:90–185. doi:10.3767/persoonia.2019.43.04. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Tekpinar AD, Kalmer A. Utility of various molecular markers in fungal identification and phylogeny. Nov Hedwigia. 2019;109(1):187–224. doi:10.1127/nova_hedwigia/2019/0528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Crous PW, Lombard L, Sandoval-Denis M, Seifert KA, Schroers HJ, Chaverri P, et al. Fusarium: more than a node or a foot-shaped basal cell. Stud Mycol. 2021;98:100116. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

22. Al-Faifi Z, Alsolami W, Abada E, Khemira H, Almalki G, Modafer Y. Fusarium oxysporum and Colletotrichum musae associated with wilt disease of Coffea arabica in coffee gardens in Saudi Arabia. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2022;2022:3050495. doi:10.1155/2022/3050495. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Leslie JF, Summerell BA. Fusarium Laboratory Manual. Hoboken, NJ: Blackwell Publishing, John Wiley & Sons; 2007. p. 1–388. doi:10.1002/9780470278376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Stefańczyk E, Sobkowiak S. Isolation, identification and preservation of Fusarium spp. causing dry rot of potato tubers. Plant Breed Seed Sci. 2017;76(1):45–51. doi:10.1515/plass-2017-0020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Dellaporta SL, Wood J, Hicks JB. A plant DNA minipreparation: version II. Plant Mol Biol Report. 1983;1(4):19–21. doi:10.1007/bf02712670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Khuna S, Kumla J, Thitla T, Nuangmek W, Lumyong S, Suwannarach N. Morphology, Molecular identification, and pathogenicity of two novel Fusarium species associated with postharvest fruit rot of cucurbits in Northern Thailand. J Fungi. 2022;8(11):1135. doi:10.3390/jof8111135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–4. doi:10.1093/molbev/msw054. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. White TJ, Bruns T, Lee S, Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. PCR Protoc. 1990;18(1):315–22. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-372180-8.50042-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. O’Donnell K, Nirenberg HI, Aoki T, Cigelnik E. A Multigene phylogeny of the Gibberella fujikuroi species complex: detection of additional phylogenetically distinct species. Mycoscience. 2000;41(1):61–78. doi:10.1007/BF02464387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Reeb V, Lutzoni F, Roux C. Contribution of RPB2 to multilocus phylogenetic studies of the Euascomycetes (Pezizomycotina, Fungi) with special emphasis on the lichen-forming Acarosporaceae and evolution of polyspory. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;32(3):1036–60. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2004.04.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Liu YJ, Whelen S, Hall BD. Phylogenetic relationships among ascomycetes: evidence from an RNA polymerse II subunit. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16(12):1799–808. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. O’Donnell K, Kistlerr HC, Cigelnik E, Ploetz RC. Multiple evolutionary origins of the fungus causing panama disease of banana: concordant evidence from nuclear and mitochondrial gene genealogies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(5):2044–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.5.2044. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Katoh K, Rozewicki J, Yamada KD. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform. 2018;20(4):1160–6. doi:10.1093/bib/bbx108. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Tamura K, Stecher G, Kumar S. MEGA11: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(7):3022–7. doi:10.1093/molbev/msab120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Hoang DT, Chernomor O, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(2):518–22. doi:10.1093/molbev/msx281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Minh BQ, Schmidt HA, Chernomor O, Schrempf D, Woodhams MD, von Haeseler A, et al. IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol Biol Evol. 2020;37(8):2461. doi:10.1093/molbev/msaa131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, Von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods. 2017;14(6):587–9. doi:10.1038/nmeth.4285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Chernomor O, Von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. Terrace aware data structure for phylogenomic inference from supermatrices. Syst Biol. 2016;65(6):997–1008. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syw037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Thao LD, Anh PT, Trang TTT, Khanh TN, Hien LT, Binh VTP, et al. Fusarium falciforme, a pathogen causing wilt disease of chrysanthemum in Vietnam. New Dis Reports. 2021;43(2). doi:10.1002/ndr2.12013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Costat program. Statistical CoHort Software program. Monterey, CA, USA; 2002. [Google Scholar]

41. González V, García-Martínez S, Ruiz JJ, Flores-León A, Picó B, Garcés-Claver A. First report of Neocosmospora falciformis causing wilt and root rot of muskmelon in Spain. Plant Dis. 2020;104(4):1256. doi:10.1094/PDIS-09-19-2013-PDN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Patsa R, Jash S, Sarkar A, Dutta S, Poduval M. Identification and characterization of Fusarium falciforme, incitant of wilt disease in cashew seedlings and its management. Arch Phytopathol Plant Prot. 2023;56(19):1521–39. doi:10.1080/03235408.2024.2307522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ma LJ, Van Der Does HC, Borkovich KA, Coleman JJ, Daboussi MJ, Di Pietro A, et al. Comparative genomics reveals mobile pathogenicity chromosomes in Fusarium. Nature. 2010;464(7287):367–73. doi:10.1038/nature08850. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Achari SR, Kaur J, Dinh Q, Mann R, Sawbridge T, Summerell BA, et al. Phylogenetic relationship between Australian Fusarium oxysporum isolates and resolving the species complex using the multispecies coalescent model. BMC Genomics. 2020;21(1):248. doi:10.1186/s12864-020-6640-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Chen W, Fan X, Tian C, Li F, Chou G. Identification and characterization of Neocosmospora silvicola causing canker disease on Pinus armandii in China. Plant Dis. 2023;107(10):3026–36. doi:10.1094/PDIS-12-22-2982-RE. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. López-Moral A, Antón-Domínguez BI, Lovera M, Arquero O, Trapero A, Agustí-Brisach C. Identification and pathogenicity of Fusarium species associated with wilting and crown rot in almond (Prunus dulcis). Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):5720. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-56350-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Costa SS, Matos KS, Tessmann DJ, Seixas CDS, Pfenning LH. Fusarium paranaense sp. nov., a member of the Fusarium solani species complex causes root rot on soybean in Brazil. Fungal Biol. 2016;120(1):51–60. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2015.09.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Sousa ES, Melo MP, Mota JM, Sousa EMJ, Beserra JEA, Matos KS. First report of Fusarium falciforme (FSSC 3 + 4) causing root rot in lima bean (Phaseolus lunatus L.) in Brazil. Plant Dis. 2017;101(11):1954. doi:10.1094/PDIS-05-17-0657-PDN. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. López-Bautista V, Mora-Aguilera G, Gutiérrez-Espinosa MA, Mendoza-Ramos C, Martínez-Bustamante VI, Coria-Contreras JJ, et al. Morphological and molecular characterization of Fusarium spp. associated to the regional occurrence of wilt and dry bud rot in Agave tequilana. Rev Mex Fitopatol Mex J Phytopathol. 2019;38(1). doi:10.18781/r.mex.fit.1911-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Gwinn KD, Hansen Z, Kelly H, Ownley BH. Diseases of Cannabis Sativa caused by diverse Fusarium species. Front Agron. 2022;3:627240. doi:10.3389/fagro.2021.796062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang N, Xu Y, Zhang Q, Zhao L, Zhu Y, Wu Y, et al. Detection of fungicide resistance to fludioxonil and tebuconazole in Fusarium pseudograminearum, the causal agent of Fusarium crown rot in wheat. PeerJ. 2023;11:e14705. doi:10.7717/peerj.14705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Wang YF, Hao FM, Zhou HH, Chen JB, Su HC, Yang F, et al. Exploring potential mechanisms of fludioxonil resistance in Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. Melonis. J Fungi. 2022;8(8):839. doi:10.3390/jof8080839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Peters RD, Macdonald IK, MacIsaac KA, Woodworth S. First report of thiabendazole-resistant isolates of Fusarium sambucinum infecting stored potatoes in Nova Scotia, Canada. Plant Dis. 2001;85(9):1030. doi:10.1094/pdis.2001.85.9.1030a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. El-Aswad AF, Aly MI, Alsahaty SA, Basyony ABA. Efficacy evaluation of some fumigants against Fusarium oxysporum and enhancement of tomato growth as elicitor-induced defense responses. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):2479. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-29033-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Everts KL, Egel DS, Langston D, Zhou XG. Chemical management of Fusarium wilt of watermelon. Crop Prot. 2014;66:114–9. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2014.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Petkar A, Langston DB, Buck JW, Stevenson KL, Ji P. Sensitivity of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. niveum to prothioconazole and thiophanate-methyl and gene mutation conferring resistance to thiophanate-methyl. Plant Dis. 2017;101(2):366–71. doi:10.1094/PDIS-09-16-1236-RE. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Mondani L, Chiusa G, Battilani P. Chemical and biological control of Fusarium species involved in garlic dry rot at early crop stages. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2021;160(3):575–87. doi:10.1007/s10658-021-02265-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Ponnusamy R, Pasuvaraji A, Suppaiah R, Sundaresan S. Molecular characterization of Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. dianthi and evaluation of fungicides against Fusarium wilt of carnation under protected cultivation. Indian J Exp Biol. 2022;59(11):770–5. doi:10.56042/ijeb.v59i11.56830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Becher R, Weihmann F, Deising HB, Wirsel SGR. Development of a novel multiplex DNA microarray for Fusarium graminearum and analysis of azole fungicide responses. BMC Genomics. 2011;12:52. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-12-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools