Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

GC-MS Analysis, Antimicrobial Activity, and Genotoxicity of Pimpinella anisum Essential oil: In Vitro, ADMET and Molecular Docking Investigations

Laboratory Medicine Department, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, Umm Al-Qura University, Makkah, 21955, Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Author: Ahmed Qasem. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Approaches in Experimental Botany: Essential Oils as Natural Therapeutics)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(3), 809-824. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.062683

Received 24 December 2024; Accepted 19 February 2025; Issue published 31 March 2025

Abstract

Pimpinella anisum, commonly known as anise, is generally used in both folk medicine and the culinary world. In traditional medicine, it is valued for its digestive, respiratory, and antispasmodic properties. This study aims to examine the volatile compounds and antibacterial effect of P. anisum essential oil (PAEO) as well as for the first time its genotoxicity employing both in vitro and computational approaches. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis identified anethole as the principal compound, which comprises 92.47% of PAEO. PAEO was tested for its potential antibacterial properties against Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Listeria innocua ATCC 33090, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Klebsiella aerogenes ATCC 13048, and a clinical strain of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi. PAEO displayed noteworthy antibacterial action toward all tested bacteria, especially Staphylococcus aureus, with an inhibition zone of 21.43 ± 0.87 mm, as determined by the disc-diffusion test. Varied between 0.0625% and 2% v/v, while the MBC values ranged from 0.125% to 8% v/v, reflecting the strength of the tested EO. The MBC/MIC ratios indicated the bactericidal nature of PAEO. The results of molecular docking revealed strong binding interactions between key PAEO molecules and microbial target proteins. ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) analysis confirmed favorable pharmacokinetic properties, indicating its potential as a safe therapeutic agent. Additionally, genotoxicity was assessed using the comet assay, which demonstrated minimal genotoxic risk, affirming the oil’s safety. These results highlight the promising antimicrobial properties of PAEO and its possible use as an active agent in the pharmacy, food, and cosmetic sectors.Keywords

On Earth, there are around 374,000 known plant species, including 295,383 flowering plants and the number of plant species continues to grow periodically [1]. The exact number of plants used in medicine is unknown, but it’s roughly estimated that around 50,000 to 80,000 flowering plants are used for medicinal purposes worldwide [2]. Plants have been the foundation of advanced traditional medicine systems in every human society around the world since ancient times [3]. Archaeological investigations evidenced that people living in Mesopotamia, now Iraq, around 60,000 years ago used a medicinal plant called Hollyhock (Alcea rosea), which implies that plants were one of the first resources utilized by ancient humans for treating diseases [4]. Even today, higher plants contribute to at least 25% of all the drugs used in clinical practice worldwide [5–8]. Considering the popularity of medicinal plants today, 70% to 80% of the world’s population relies on them for health care needs and treating or managing various diseases [9–11]. These medicinal plants are abundant in bioactive phytochemical compounds like flavonoids, alkaloids, tannins, terpenoids, steroids, saponins, cardiac glycosides, coumarins, and anthraquinones [12].

Spices have been widely used for centuries to add flavor to food, and aid in preservation, and some are also used in traditional medicine to treat various ailments [13]. Several spices have been scientifically recognized for their therapeutic properties. For instance, turmeric (Curcuma longa) is well-documented for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects, mainly ascribed to curcumin [14]. Ginger (Zingiber officinale) is frequently used to alleviate digestive discomfort and possesses anti-nausea properties [15,16]. Additionally, cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.) has been investigated for its potential role in glycemic control and metabolic health [17].

Pimpinella anisum L., commonly referred to as ‘anise’ or ‘aniseed,’ is a flowering plant that belongs to the Apiaceae family, also known as the parsley family. The seeds of this plant are famous for their aromatic odor, anise-like taste, and are extensively used to enhance the flavor and fragrance of many culinary preparations, beverages, and confections [18,19]. Anise seeds, commonly used in traditional medicine, have a long history of relieving headache pain, improving digestion, acting as a diuretic by increasing urine production for detoxification, and even helping to alleviate nightmares [20]. However, its use should be moderate, and in some cases, it should be avoided by individuals with allergies to the Apiaceae family. Recent studies have highlighted that anise seeds also possess antioxidant properties, may be beneficial in managing diabetes, and show promise in treating epilepsy and seizure disorders [21,22].

The present study aims to report the volatile composition of P. anisum essential oil (PAEO) using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) and evaluate its antimicrobial properties through in vitro assays, molecular docking, and ADMET profiling. Additionally, the study assesses the genotoxicity of PAEO using the comet test to ensure its safety for potential therapeutic applications. This comprehensive investigation not only uncovers the bioactivity of PAEO but also provides critical insights into its safety, positioning it as a promising natural antimicrobial agent for future pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

2.1 Plant Material and EO Extraction

Anise seeds were purchased in March 2023 from a local herbalist (Taza region, Morocco). The botanical name was validated by a botanist from the Department of Biology, University Mohamed V, Morocco, under ID RAB 114387. The oil isolation was carried out as follows: a total of 100 g of dried seeds was subjected to hydro-distillation for 3 h using a Clevenger-type device. The extracted oils were then collected and dehydrated using anhydrous sodium sulfate to remove any remaining moisture. Afterward, the oils were filtered and stored at 4°C until further testing.

The phytochemical profile of anise oil was analyzed using GC-MS as described in previous works [23].

Five bacterial strains were used in the current study, representing common pathogenic bacteria of significant interest in food science and medicine. These strains included three Gram-positive bacteria: Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, Listeria innocua ATCC 33090, and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, as well as two Gram-negative bacteria: Klebsiella aerogenes ATCC 13048 and a clinical strain of Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi. These bacteria are maintained in our laboratories, well-identified, and preserved as pure cultures in Tryptic Soy Broth (TSB) medium with glycerol at −70°C, and they are regularly used in our scientific research. Before the experiments, the bacteria were revitalized by sub-culturing on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar. A single colony from each revitalized strain was morphologically checked using Gram staining. Another single colony from the same pure culture was suspended in sterile normal saline (0.9%), adjusted to a density of 106 CFU/mL using a spectrophotometer at 625 nm, and used as the working solution for the antibacterial tests.

2.4 Kirby-Bauer Disk Diffusion Test

The antibacterial efficacy of P. anisum EO (PAEO) was assessed using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion test as previously described [24]. The bacterial strains, which were preconditioned and adjusted to 106 CFU/mL, were used to swab the surface of standard Petri dishes containing 25 mL of Luria-Bertani agar (LB agar) using sterile cotton swabs. Blank filter paper discs (6 mm diameter) were autoclaved and, after cooling, saturated with 10 μL of pure PAEO. The saturated discs were then placed on the inoculated Petri dishes. The positive control used was Erythromycin discs (15 μg/disc), with one disc loaded onto each plate. After that, the Petri dishes were incubated at 35°C–37°C for up to 24 h. After incubation, the widths of the zones of inhibition around each disc were measured in millimeters, and the mean was taken from three repetitions.

To determine the lowest concentration of the PAEO that may prevent the growth of microorganisms, we carried out the minimum inhibitory concentration test (MIC) using the micro-broth dilution technique as cited in Benkhaira et al. [25] with minor modifications. Under aseptic conditions and laminar flow, two-fold serial dilutions of PAEO (diluted in 10% DMSO) were made in sterile 96-well microplates (volume 250 μL per well) to achieve a final volume of 100 μL in each well, starting from 8.0% to 0.0625% (v/v) in 10% DMSO. This concentration of DMSO does not affect bacterial growth [26,27]. For the positive control, serially diluted erythromycin concentrations were also prepared and loaded into a separate row of wells. A well filled with 100 μL of 10% DMSO served as a negative control. To all wells, 100 μL of double-strength LB broth medium and 10 μL of the adjusted bacterium were added to each microplate. The incubation process was carried out at a temperature of 37°C for 24 h. To identify the growth of microorganisms, a solution of 40 μL of 0.2 μg/mL 2,3,5-triphenyl tetrazolium chloride (TTC) was used. TTC is initially colorless but changes to red when it is reduced by microbes.

The minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) was determined following the methodology published elsewhere [28] with some modifications. The test was performed by taking 20 μL from each well of the MIC test microplate, transferring it to Petri dishes containing LB agar, and incubating them at 35°C–37°C for 18 h. The MBC value is identified as the lowest concentration that revealed no bacterial growth on the petri dish. After the MBC values were obtained, the MBC/MIC ratios were calculated. The experiment was performed in triplicate.

2.7.1 Collection of Blood Samples and Cell Treatment

Before blood sample collection from the retroorbital veins of the rats, the animals were subjected to pentobarbital anesthesia to induce sedation. Subsequently, fresh blood was removed from a male Wistar rat and diluted with 2 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) devoid of Ca2+ and Mg2+ ions, characterized by a pH of 7.4 and comprising the following constituents: 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 10 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.76 mM KH2PO4. The dissolved samples in PBS were then exposed to blood cells at different concentrations. Following a 1-h exposure duration at 37°C, 10 µL of blood cells were examined. The negative control received PBS, whereas hydrogen peroxide at a concentration of 0.25 mmol/L served as the positive control.

Before conducting the alkaline comet assay, modifications were introduced to the methodology outlined in the literature [29]. Upon completion of the treatment regimen, the solution underwent centrifugation at 4500 rpm for 10 min, leading to the formation of a pellet comprising leukocytes, which was resuspended in 1 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) following removal of the supernatant. After three sequential washes, the pellet was affixed onto slides coated with 1.5% w/v NMP agarose post-dissolution in 0.5% w/v low melting point (LMP) agarose in PBS. Incubation of the slides in darkness at 4°C ensued for one hour after exposure to a lysis solution (comprising 2.5 M NaCl, 100 mM Na₂-EDTA, 20 mM Tris (tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane), 300 mM NaOH, 1% N-lauroylsarcosine sodium, 10% DMSO, and 1% Triton X-100) for five minutes. Horizontal gel electrophoresis was then conducted, utilizing an electrophoresis solution (comprising 300 mM NaOH and 1 mM Na2EDTA, with a pH of 13) for 20 min, under constant conditions (300 mA and 25 V), after rinsing with double-distilled water. Following this, the slides underwent three consecutive rounds of neutralization in a 400 mM Trizma solution adjusted to a pH of 7.5 using HCl. To visualize the comets, the ethidium bromide method, as delineated by Singh et al. [30], was employed. Each slide received a fresh cover slip following the application of 25 µL of ethidium bromide stain. Before observation, any surplus stain adhering to the backs and edges of the slides was meticulously removed.

A fluorescent microscope, specifically the ZOE Cell Imager, was employed for the examination and documentation of ethidium bromide-stained slides. The red channel was utilized for observation, with emission wavelengths set at 615/61 nm and excitation wavelengths at 556/20 nm. Subsequently, an image analyzer along with Comet Assay IV image analysis software facilitated a quantitative assessment of DNA lesions. This software enables the measurement of various metrics about DNA lesions [31]. In this analysis, fifty cells were randomly selected from each of the two replicates for every sample, ensuring robust statistical representation.

The ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) profiling of PAEO components was predicted using the ADMETlab 3.0 web server [32]. The Smiles notation of investigated components was subjected to the webserver for the appraisal of pharmacokinetic and physiochemical properties.

To investigate the plausible mechanism of observed antibacterial activity, a molecular docking simulation was performed. In this connection, PAEO components were sketched in MOE v.2019.01 software [33]. Subsequently, the geometry of the compounds was corrected followed by protonation. The energy minimization was done using the MMFF94x force filed. Moreover, the DNA Gyrase B from Proteus mirabilis was chosen as a target protein and this selection was based on the critical role of the protein in DNA replication and transcription processes [7]. Since the Protein DataBank holds no evidence of the crystal structure of the target protein, the predicted structure from the Alphafold database was retrieved for molecular docking. The structure was subjected to correction and protonation followed by minimization using the Amber10:EHT force field. Afterward, the blind docking was performed using the Triangular Matcher as a placement method with London dG and WSA/GBVI dG as scoring and rescoring functions. Thirty poses were generated for each compound while five best were retained for analysis. The protein-ligand complexes were visually analyzed to interpret the binding interactions using Chimera software.

Data of the current exploration were organized and analyzed statistically by adopted ANOVA-one way (Tukey test) using SPSS software. Except the analysis of chemical compounds, all other tests were performed in triplicate. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

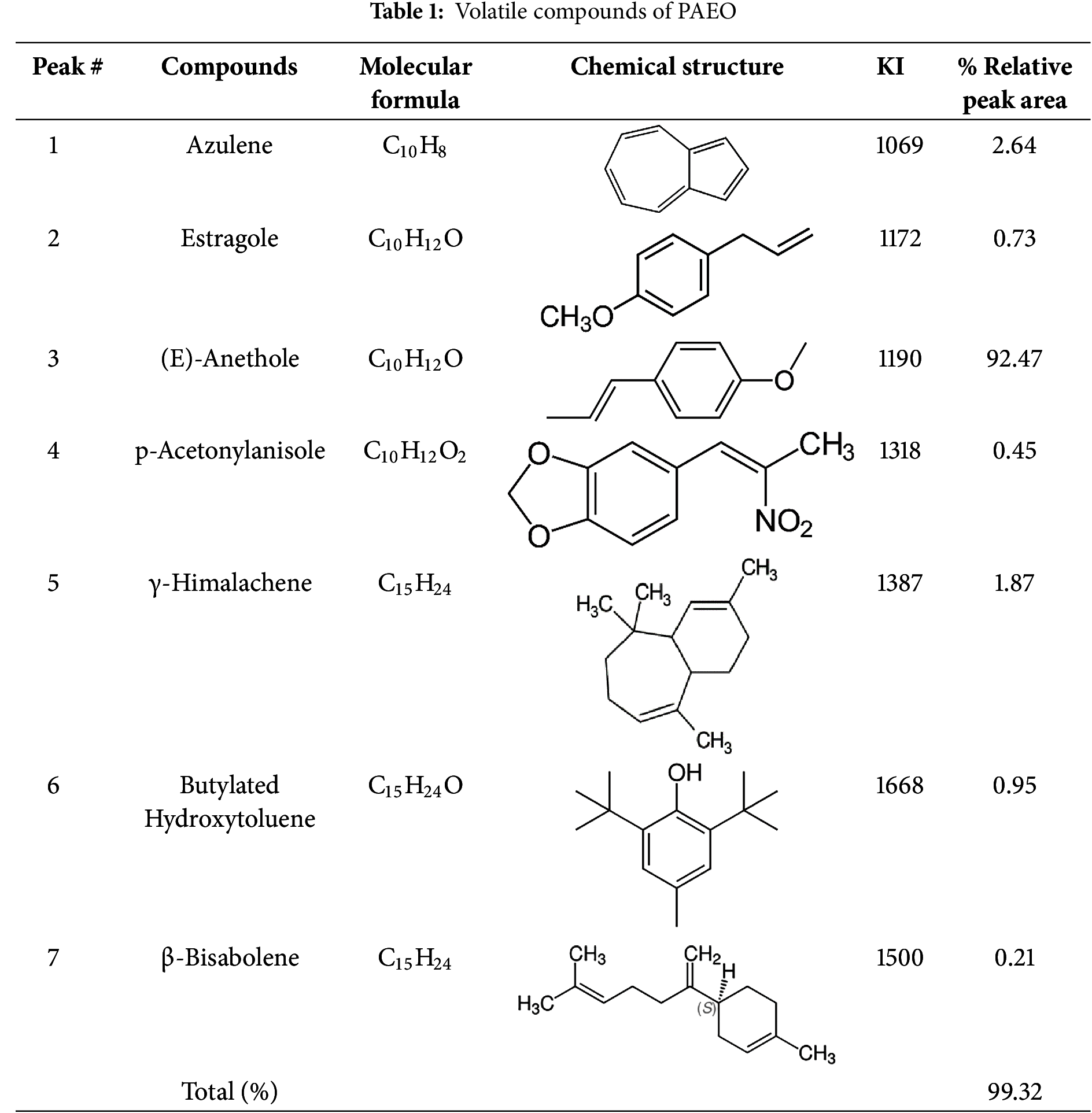

The chemical composition of anis oil (PAEO), extracted from seeds, was analyzed using GC-MS apparatus. Table 1 provides a summary of the relative peak areas of each compound, along with molecular formula, kovats index (KI).

As indicated, 7 chemical constituents were detected accounting for 99.32% of total PAEO, with anethole as the principal compound, which makes 92.47% of this oil. This bioactive component is the main contributor to the sweet, licorice-like fragrance of PAEO and is frequently associated with its biological properties. Anethole has been extensively investigated for its therapeutic effects, including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities. Other molecules, such as azulene (2.64%), γ-himalachene (1.87%), and butylated hydroxytoluene (0.95%) were detected in significant amounts.

In the literature, it has been shown that there are typically significant differences in the key components of PAEO. Rodrigues and his colleagues [34] reported anethole (more than 90%), γ-himachalene (2%−4%), cis-pseudoisoeugenyl 2-methylbutyrate (3%) as key constituents in PAEO obtained by supercritical fluid extraction (SFE). Interestingly, a comparative study carried out on PAEO collected at two different development stages of fruits, namely at the waxy (unripe) and ripe stages [35]. The results revealed eight components in the PAEO from waxy fruits, while eleven components were found in the PAEO from ripe fruits. The primary constituents of the PAEO at the waxy stage were (E)-anethole (90.3%) and estragole (3.6%). In contrast, the major chemicals of the PAEO from ripe fruits were (E)-anethole (80.7%) and eugenyl acetate (3.9%) [35].

Askari [36] found (E)-anethole (90%), eugenyl acetate (2%), and γ-gurjunene (1.85%) as predominant components. Overall, the chemical composition of the PAEO can vary depending on factors, among geographic origin, environmental conditions, and extraction methods. Among environmental factors, geographic location and soil composition play a crucial role, as calcareous and well-drained soils tend to enhance thymol levels [37]. Climate and seasonal variation also impact composition, with high temperatures and intense sunlight favoring monoterpene biosynthesis [38]. Regarding extraction methods, hydrodistillation (HD) and steam distillation (SD) are commonly used, but HD may lead to hydrolysis or degradation of thermolabile compounds, whereas SD is preferred for preserving volatile constituents [39]. Microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) enhances yield while protecting heat-sensitive compounds, and supercritical CO₂ extraction allows selective extraction at lower temperatures, preserving bioactive monoterpenes [40].

These variations primarily affect the concentrations of key components such as anethole, estragole, and azulene, which impact the oil’s aroma, therapeutic properties, and safety. For instance, PAEO with higher anethole levels are known for their sweeter fragrance and stronger antibacterial potential, while variations in estragole content may raise concerns about toxicity [19,41]. Understanding these chemical variations is critical for confirming the consistency and quality of anise oil in medicinal, cosmetic, and culinary applications.

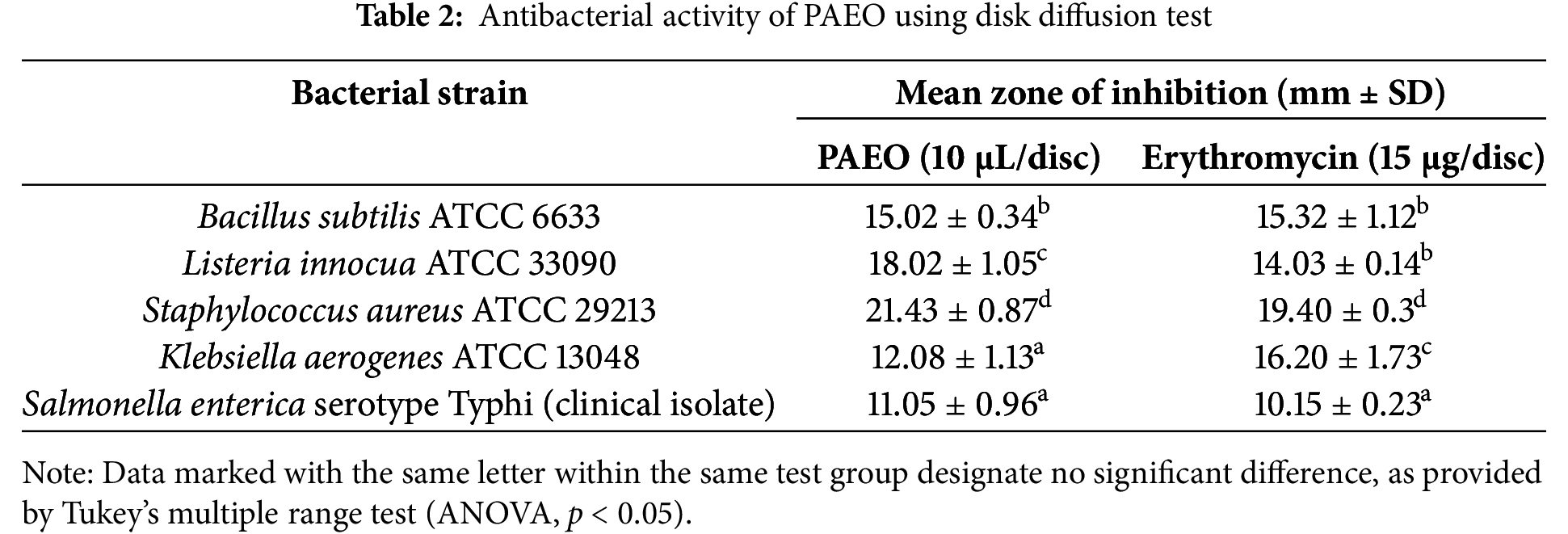

The antibacterial activity of PAEO was evaluated against five bacterial strains using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion test, with erythromycin as a positive control as shown in Table 2. For Bacillus subtilis ATCC 6633, PAEO and erythromycin showed approximately similar inhibition zones (15.02 and 15.32 mm, respectively), the statistical analysis indicating no significant difference in effectiveness. Listeria innocua ATCC 33090 exhibited a larger and statistically significant inhibition zone for PAEO (18.02 mm) compared to erythromycin (14.03 mm), suggesting the better antibacterial efficacy of the EO. Similarly, for Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, the EO demonstrated a larger inhibition zone (21.43 mm) than erythromycin (19.40 mm), highlighting its stronger antibacterial properties. Conversely, Klebsiella aerogenes ATCC 13048 was more susceptible to erythromycin (16.20 mm) than to the EO (12.08 mm), indicating the EO’s lower efficacy against this strain. For Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi, the inhibition zones for P. anisum EO and erythromycin were comparable (11.05 and 10.15 mm, respectively).

Overall, these results suggest that PAEO exhibits significant antibacterial activity, comparable or superior to erythromycin for certain strains, supporting its potential use in traditional medicine and recommending further studies to benefit from it as a potent antibacterial agent in the food and pharmaceutical industries. Our observations are consistent with previous works; The EO of Pimpinella anisum (synonym Pimpinella anisetum) from Turkey has been reported to exert remarkable antimicrobial action against various bacterial and fungal strains. Using the disc diffusion test, inhibition zones were found to range between 9.00 ± 1.33 mm and 18.00 ± 1.42 mm [42]. PAEO demonstrated inhibitory zones of 17 mm against Salmonella typhi and 16 mm against Enterococcus faecalis, effectively comparable to streptomycin [43]. A very high level of antibacterial activity in PAEO has been published by researchers from Iran, as determined by a disc-diffusion test. The average diameter of the growth inhibition zones was found to be 39 mm for Enterococcus faecalis, followed by Lactobacillus casei (40 mm), Actinomyces naeslundii (42 mm), and for Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans (18.5 mm) [44]. Accordingly, we recommend conducting comprehensive research across various geographical regions to understand how environmental factors influence the active compounds in this plant. Also, aqueous and alcoholic extracts of P. anisum have been cited to exhibit moderate antibacterial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria using the disc diffusion test [45], indicating that the bioactive compounds are concentrated in the aromatic portion. According to Rehman et al. [46], EOs are considered superior biological agents, exhibiting better antimicrobial and other bioactivities compared to other extracts. This is due to their significant content of aromatic and secondary metabolites.

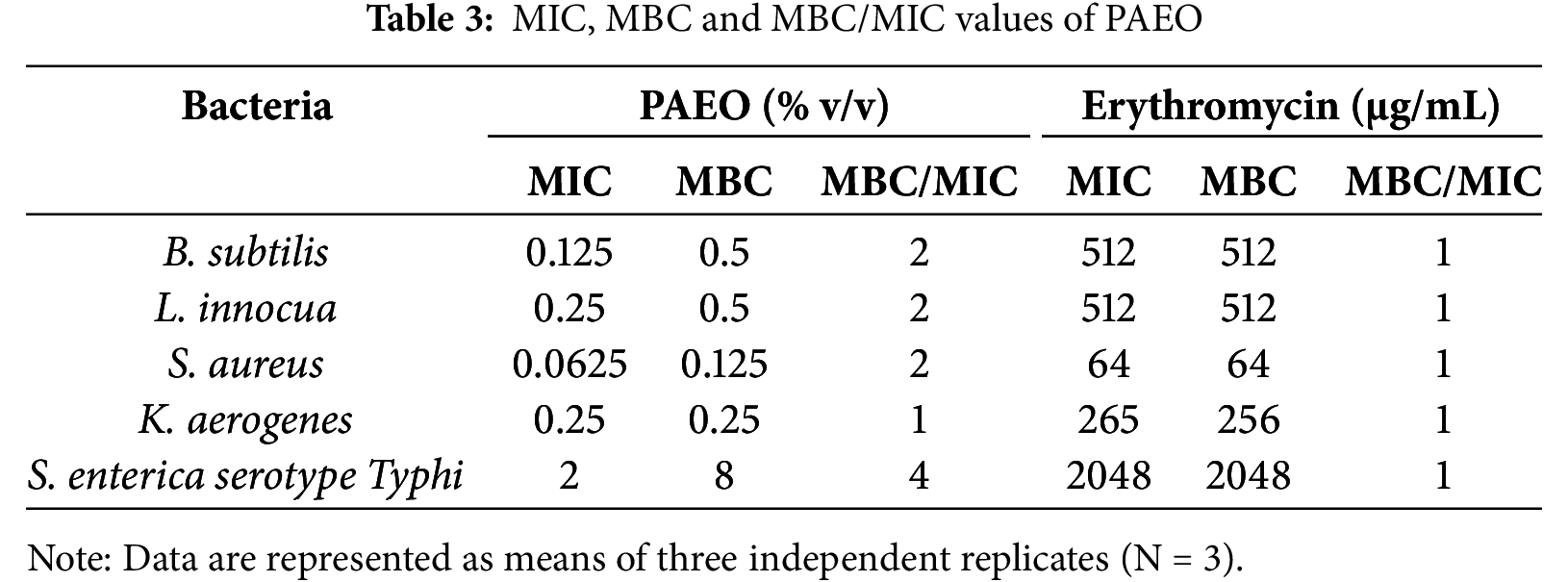

The results of the micro-dilution tests (MIC and MBC tests) are represented in Table 3. The findings revealed that PAEO demonstrated varying levels of antibacterial activity against different bacterial strains and confirmed the results of the disc-diffusion test. MIC values for PAEO ranged from 0.0625% to 2% v/v, while MBC values ranged from 0.125% to 8% v/v. The MBC/MIC ratios for PAEO were found to be between 1 and 4, indicating its bactericidal properties. In antibacterial testing, it’s better to perform the MIC test after the disc diffusion test because disc diffusion data can be imprecise [47]. In comparison, erythromycin exhibited different degrees but consistent MIC and MBC values for bacterial strains, with an MBC/MIC ratio of 1, reflecting its stable bactericidal activity. The rates of resistance to erythromycin are increasing dramatically worldwide due to bacterial mutations or the acquisition of resistance genes from other bacteria [48]. This reflects the need for alternatives such as EOs. Moreover, MBC testing is considered a valuable and relatively inexpensive method for the simultaneous evaluation of multiple antibacterial agents’ potency. Antibacterial agents are typically regarded as bactericidal if the MBC does not exceed four times the MIC, if more than 4 it is considered bacteriostatic [49]. In our study, higher MIC and MBC values were observed for erythromycin compared to PAEO, suggesting that the EO might be more effective at lower concentrations for some bacteria.

Interestingly, it has been reported that some EOs exhibit stronger antibacterial effects than antibiotics and are effective against resistant bacterial strains, suggesting a promising future for essential oils in antibacterial therapy [50]. Notably, PAEO showed strong activity against B. subtilis and L. innocua with low MIC and MBC values (0.125% and 0.5% v/v, respectively), while S. enterica exhibited the highest values (2% and 8% v/v, respectively), indicating lower susceptibility. S. enterica, a Gram-negative bacterium, remains a major global concern in food chains due to its high antibiotic resistance and its ability to cause life-threatening diseases in humans [51]. Gram-negative bacteria are generally less sensitive to essential oils due to their unique outer membrane structures, which consist of two distinct lipid membranes—the cytoplasmic cell membrane and the outer membrane—with a thin layer of peptidoglycan in between [52]. Also, our study revealed that the MBC/MIC ratio varied, being 1 for K. aerogenes and 4 for S. enterica, suggesting differences in bactericidal efficiency between strains. These results suggest that PAEO has the potential as an effective antibacterial agent at low concentrations, but further research on the mode of action is needed to fully understand its activity spectrum and applications. Furthermore, the findings are consistent with previous studies. Its effectiveness was reported against all tested microorganisms, including Lister monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 29213, Escherichia coli ATCC 35218, Pseudomonas fluorescens DSM 4358, and Candida albicans ATCC 10231, with MIC and MBC ranging from 1.25% to 2.5% and 2.5% to greater than 5%, respectively, and for most microbes, the mechanism (MBC/MIC) was bactericidal [53]. Bactericidal activity was also reported by PAEO against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and E. coli, with an MBC/MIC ratio of 2 [54]. It was noted that PAEO exhibited high MIC and MBC values mostly at 100% v/v when tested against 35 pathogenic and spoilage bacteria and yeasts [55], which is not consistent with our results, and various previous findings. Taking into account the diverse findings of the antibacterial efficacy of PAEO and its wide uses around the world, this study is of great importance to potential users, namely the food industry, food supplements, and pharmaceutical formulations. Therefore, further studies on the mechanism and accurate separation of the antibacterial compounds are necessary.

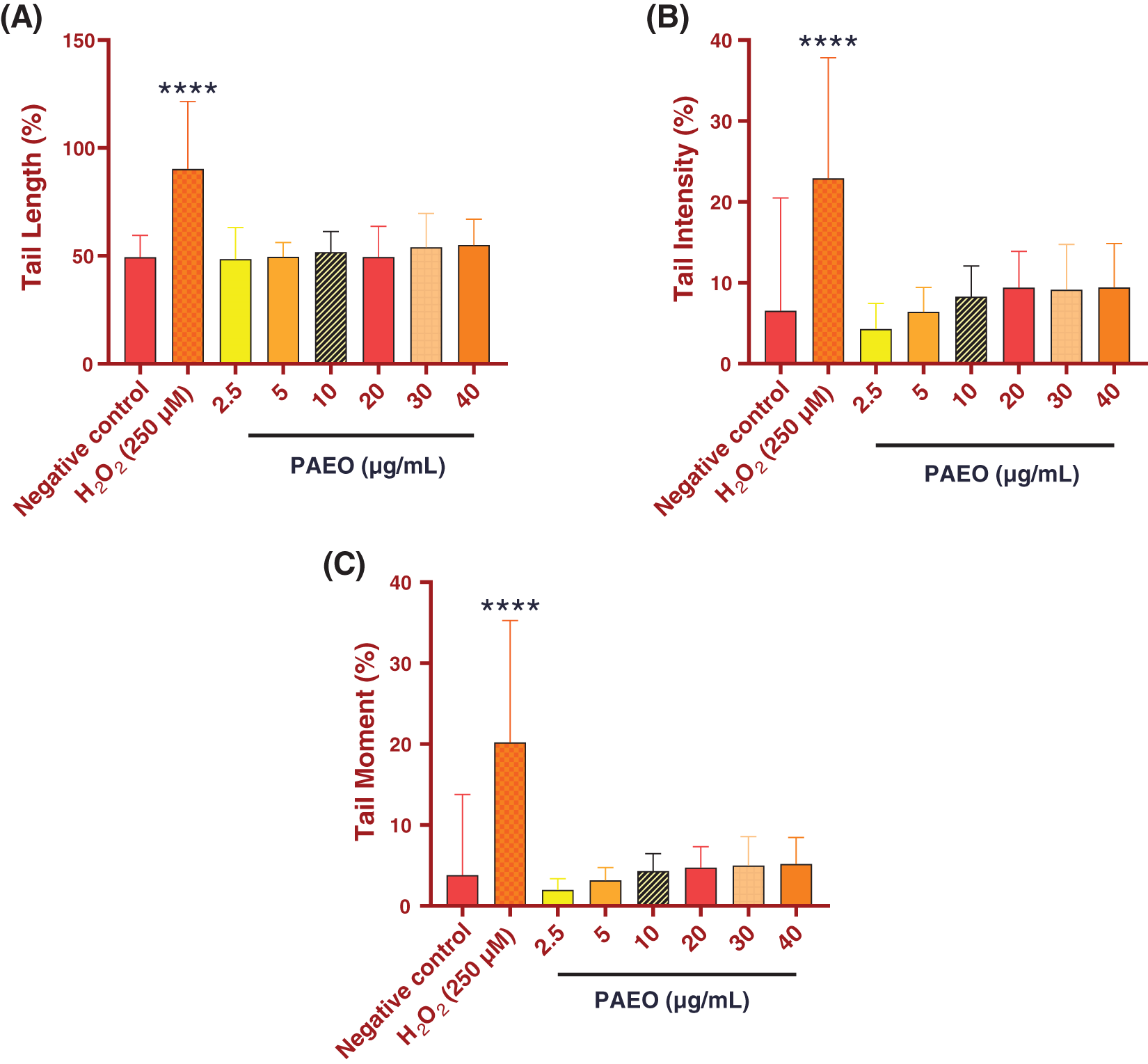

Genotoxicity refers to a phenomenon wherein substances or agents have the potential to induce damage to the DNA of cells, leading to genetic and/or chromosomal mutations. This property is considered a crucial indicator of toxicity concerning human health and the environment. Genotoxic substances can originate from various sources, including natural compounds, industrial pollutants, pesticides, pharmaceuticals, consumer chemicals, and even ionizing radiation [56,57]. To this end, it is crucial to determine the genotoxicity of natural compounds before their probable application to therapeutic agents. The comet assay, alternatively referred to as Single Cell Gel Electrophoresis (SCGE), utilizes agarose microgel electrophoresis [58,59]. Specifically, the alkaline version of the comet assay was devised for the specific detection of single-strand breaks and alkali-labile sites [30]. The objective of this examination was to provide the genotoxic impact of PAEO on rat leukocytes. Our results revealed that exposure to PAEO concentrations ranging from 2.5 to 40 µg/mL did not induce DNA damage (Fig. 1). This conclusion is drawn from the lack of significant changes in both the percentage of DNA in the comet tail and the DNA tail moment when compared to the negative control group. Therefore, it is reasonable to deduce that PAEO is not genotoxic at tested concentrations.

Figure 1: Effect of different concentrations of PAEO on (A) DNA tail length, (B) the percentage of tail intensity, and (C) DNA tail moment of rat leukocytes. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM (50 cells × 2). ****p < 0.0001 comparison with negative control group

Furthermore, at higher concentrations, essential oils can cause genetic damage through several mechanisms. These mechanisms include intercalation into DNA, inhibition of essential enzymes such as topoisomerase II, blockage of key enzymes, which display a pivotal role in hormonal metabolism, and other hand, modification of the behavior of other significant enzymes.

These interactions can lead to clastogenic effects [60,61], such as chromosomal breaks or rearrangements, which are indicators of severe genetic damage [62–66]. The molecules present in PAEO, such as sesquiterpenes like azulene and phenylpropanoids like anethole and estragole, have been extensively studied for their biological effects. Although these compounds are well known for their antioxidant properties, studies show that they have not demonstrated significant genotoxicity at appropriate concentrations [67–69]. This suggests that, when used in a controlled manner, these essential oils can be safe and effective without causing genetics.

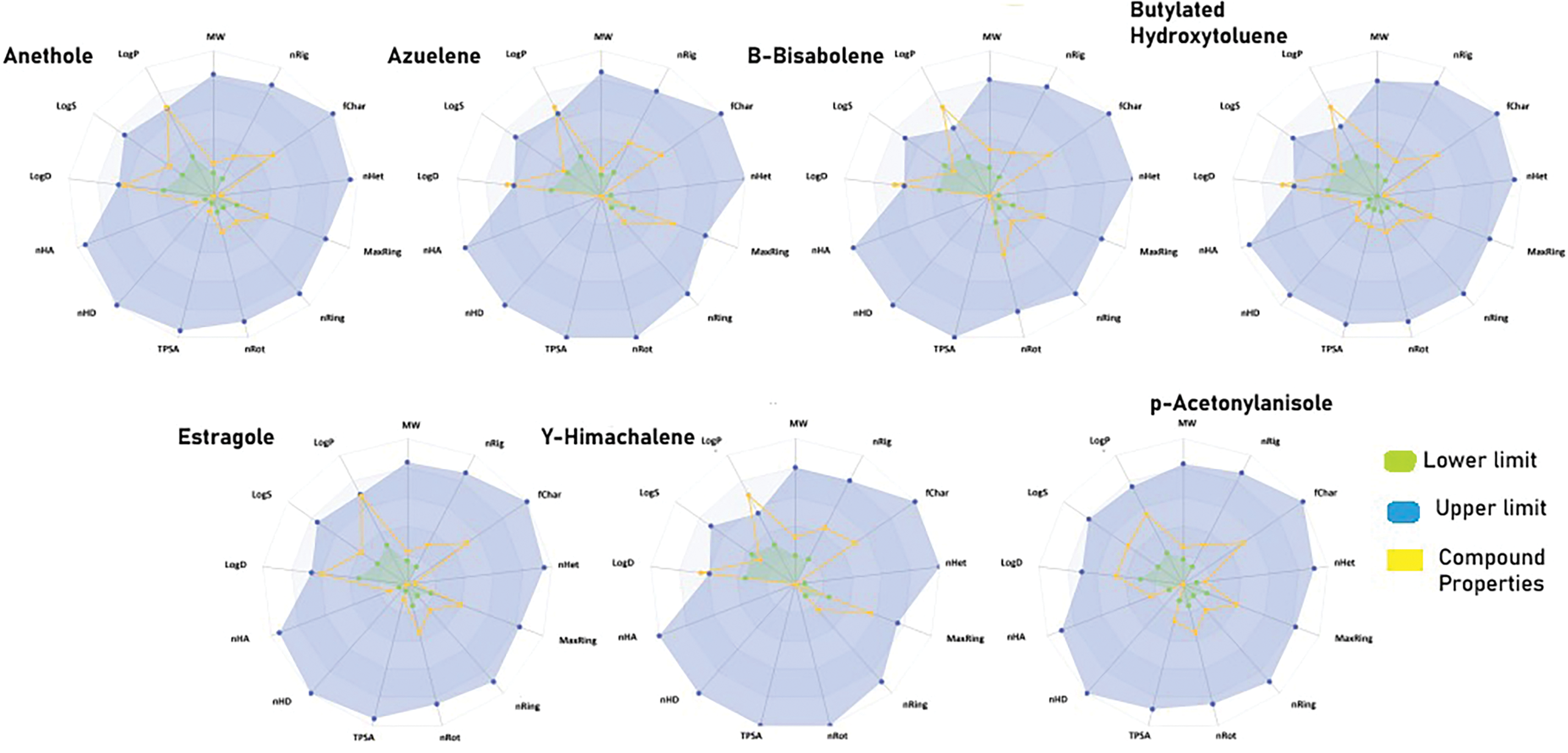

Predicting the pharmacokinetic profile of drug candidates is invaluable, especially during pre-clinical stages, to reduce late-stage failures. Therefore, the ADMET profiling of Pimpinella anisum components was predicted using the ADMETlab 3.0 webserver. The physiochemical properties were predicted as a radar having a lower and upper limit for thirteen properties. As shown in Fig. 2, most compounds fell within the optimal range for each property. However, exceptions were noted for azulene, β-bisabolene, butylated hydroxytoluene, and γ-himachalene, where both logD (distribution coefficient) and logP (partition coefficient) values were outside the optimal range. The absorption of all the compounds was evaluated by predicting the caco-2 permeability, p-glycoprotein substrate and inhibitor, and human intestinal absorption. LogP measures the lipophilicity of a compound, representing its partitioning between octanol and water in the absence of ionization. It is essential for predicting membrane permeability and hydrophobic interactions.

Figure 2: Radar chart illustrating the thirteen physicochemical properties of the studied compounds. Each property is represented by a separate axis. The lower limits of the optimal range for each property are indicated by green lines, while the upper limits are shown in blue. The yellow lines represent the measured values of the compound’s properties

LogD considers the effect of pH-dependent ionization, making it more relevant for biological systems, particularly at physiological pH (7.4).

It was observed that all the compounds exhibited excellent to moderate absorption for the properties mentioned. However, β-bisabolene, butylated hydroxytoluene, estragole, and γ-himachalene were not found to be inhibitors of P-glycoprotein. Similarly, the distribution was evaluated by predicting plasma protein binding and blood-brain barrier penetration. Azulene, β-bisabolene, and γ-himachalene were found to have poor plasma protein binding and blood-brain barrier penetration, whereas the rest of the compounds demonstrated good plasma protein binding and effective blood-brain barrier penetration. Similarly, to evaluate metabolism, the compounds were assessed for their potential as inhibitors of cytochrome P450 (CYP) family members including CYP1A2, CYP2C19, and CYP2C9. It was observed that most of the compounds were inhibitors of the aforementioned CYPs, with a few exceptions noted for β-bisabolene, γ-himachalene, and p-acetonylanisole. Similarly, excretion was evaluated by predicting plasma clearance, and all the compounds demonstrated moderate clearance rates. Toxicity was assessed by predicting AMES toxicity, carcinogenicity, rat oral acute toxicity, hematotoxicity, and hepatotoxicity. AMES toxicity refers to the mutagenic potential of a compound, which is a critical factor in evaluating its safety and toxicity. All the compounds were found to be non-toxic except for azulene, which was identified as carcinogenic. Taken together, the studied compounds exhibited a favorable ADMET profile, suggesting potential for further optimization.

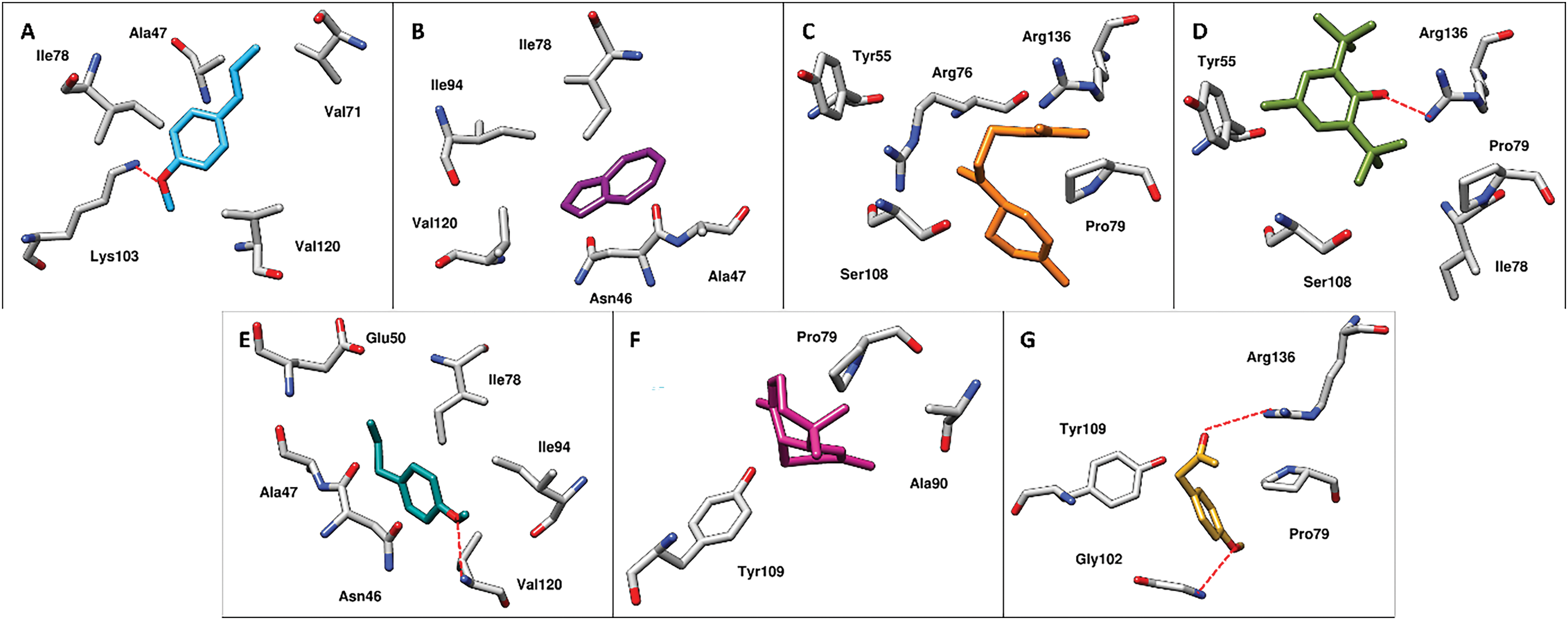

To explore the binding interactions between PAEO components and the DNA Gyrase B of Proteus mirabilis, a molecular docking simulation was performed. Since there is no crystallized structure of the ligand-bound complex available, blind docking was performed. The molecular docking simulation indicated that all PAEO components bind firmly to the binding site of the DNA Gyrase B enzyme by arbitrating significant interactions (Fig. 3). The closure examination of the docked pose of anethole into the binding site of the target protein demonstrated significant hydrophobic interactions with the docked score of −4.8 kcal/mol (Fig. 3). The phenyl ring of the compound is stacked between the Ile78 and Val120 while the terminal methyl group mediates interactions with the Ala47 and Val71. In addition, a hydrogen bond was also observed between the oxygen of the methoxy group and Lys103 at a distance of 3.1 Å. Whereas, in the case of azulene, only hydrophobic interactions were observed (Fig. 3B). The aromatic rings of azulene stacked between the Asn46, Ala47, Ile78, Ile94, and Val120 with the docked score of −4.3 kcal/mol. Similarly, the β-bisabolene resides well into the binding site of the target protein by mediating significant hydrophobic interactions with the docked score of −5.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 3C). The residues surrounding the compound include Tyr55, Arg76, Pro79, Ser108, and Arg136. Similarly, in the case of butylated-hydroxytoluene, hydrophobic interactions, and hydrogen bond contact were observed with the docked score of −5.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 3D). The substituted methyl group and the butyl group of the component mediate hydrophobic interactions with Tyr55, Arg78, Pro79, and Ser108 while a hydrogen bond was observed with the Arg136 at a distance of 2.3 Å. Similarly, the estragole also established a network of hydrophobic interactions and a hydrogen bond into the binding site of the target protein with a docked score of −4.8 kcal/mol (Fig. 3E).

Figure 3: The intermolecular interactions between the DNA gyrase B of Proteus mirabilis and A) anethole, B) azulene, C) β-bisabolene, D) butylated-hydroxytoluene, E) estragole, F) γ-himachalene and G) p-acetonylanisole present in Pimpinella anisum. The residues of enzyme surrounded by PAEO molecules are presented in grey sticks while the molecules are revealed in different color sticks. The red dotted lines represent the hydrogen bond contacts

The residues Asn46, Ala47, Glu50, Ile78, and Ile94 of DNA Gyrase B were observed to form hydrophobic interactions while Val120 of the target protein was observed to mediate a hydrogen bond at a distance of 2.4 Å. In the case of γ-himachalene, very few hydrophobic interactions were observed with the lowest docked score of −4.5 kcal/mol among all the studied compounds (Fig. 3F). The Pro79, Ala90, and Tyr109 were observed to mediate interactions with the compound. Similarly, insight into the docked pose of p-acetonylanisole into the binding site of DNA Gyrase B, hydrophobic interactions as well as hydrogen bond contacts were observed with the docked score of −5.0 kcal/mol (Fig. 3G). The Pro79 and Tyr109 were observed to form hydrophobic interactions while Gly102 and Arg136 were involved in hydrogen bond contacts at a distance of 3.1 and 3.4 Å with the oxygen of the compound. The docking results inferred that the studied compounds demonstrate favorable binding interactions with DNA gyrase B, highlighting their potential as promising candidates for further optimization as antibacterial agents.

Here, the phytochemical profile of PAEO determined with GC-MS, revealed a complex mixture of bioactive components, with anethole being the predominant component. The antimicrobial activity of the oil was thoroughly assessed through a combination of in vitro assays, ADMET profiling, and molecular docking simulation. The in vitro results demonstrated significant antibacterial and antifungal activity, particularly against resistant pathogens, aligning with the oil’s traditional medicinal uses. Molecular docking further supported these findings by emphasizing solid interactions between the PAEO key components and bacterial target proteins (Proteus mirabilis). ADMET analysis confirmed favorable pharmacokinetic properties for potential therapeutic applications, while genotoxicity assays indicated a safe profile, reinforcing the PAEO suitability for further development. This investigation opens avenues for further research on the in vivo effect of PAEO to validate its beneficial potential noticed in vitro and silico. Furthermore, exploring synergistic effects with conventional antimicrobials could enhance its efficacy. The safety profile of PAEO and multi-functional bioactivities provide evidence for its application in pharmaceuticals, food preservation, and cosmetics.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Christenhusz MJ, Byng JW. The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase. Phytotaxa. 2016;261(3):201–17. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.261.3.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Chen SL, Yu H, Luo HM, Wu Q, Li CF, Steinmetz A. Conservation and sustainable use of medicinal plants: problems, progress, and prospects. Chin Med. 2016 Dec;11(1):37. doi:10.1186/s13020-016-0108-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Shakya AK. Medicinal plants: future source of new drugs. Int J Herb Med. 2016;4(4):59–64. [Google Scholar]

4. Sofowora A, Ogunbodede E, Onayade A. The role and place of medicinal plants in the strategies for disease prevention. Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. 2013;10(5):210–29. doi:10.4314/ajtcam.v10i5.2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Chebbac K, Moussaoui AE, Bourhia M, Salamatullah AM, Alzahrani A, Guemmouh R. Chemical analysis and antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from Artemisia negrei L. against drug-resistant microbes. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2021 Sep 7;2021:5902851. doi:10.1155/2021/5902851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Bouyahya A, Omari NE, Bakrim S, Hachlafi NE, Balahbib A, Wilairatana P, et al. Advances in dietary phenolic compounds to improve chemosensitivity of anticancer drugs. Cancers. 2022;14(19):4573. doi:10.3390/cancers14194573. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Jeddi M, El Hachlafi N, El Fadili M, Benkhaira N, Al-Mijalli SH, Kandsi F, et al. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibitory activities of a chemically characterized essential oil from Lavandula angustifolia Mill.: in vitro and in silico investigations. Biochem Syst Ecol. 2023;111:104731. doi:10.1016/j.bse.2023.104731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Benkhaira N, El Hachlafi N, Jeddi M, Abdnim R, Bnouham M, Koraichi SI, et al. Unveiling the phytochemical profile, in vitro bioactivities evaluation, in silico molecular docking and ADMET study of essential oil from Clinopodium nepeta grown in Middle Atlas of Morocco. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2023;54:102923. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2023.102923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chopra B, Dhingra AK. Natural products: a lead for drug discovery and development. Phytother Res. 2021 Sep;35(9):4660–702. doi:10.1002/ptr.7099. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. El Hachlafi N, Benkhaira N, Ferioun M, Kandsi F, Jeddi M, Chebat A, et al. Moroccan medicinal plants used to treat cancer: ethnomedicinal study and insights into pharmacological evidence. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022 Oct 25;2022:1645265. doi:10.1155/2022/1645265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Najmi A, Javed SA, Al Bratty M, Alhazmi HA. Modern approaches in the discovery and development of plant-based natural products and their analogues as potential therapeutic agents. Molecules. 2022;27(2):349. doi:10.3390/molecules27020349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Morsy N. Phytochemical analysis of biologically active constituents of medicinal plants. Main Group Chem. 2014;13(1):7–21. doi:10.3233/MGC-130117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Sulieman AME, Alanaizy E, Alanaizy NA, Abdallah EM, Idriss H, Salih ZA, et al. Unveiling chemical, antioxidant and antibacterial properties of Fagonia indica grown in the Hail mountains, Saudi Arabia. Plants. 2023;12(6):1354. doi:10.3390/plants12061354. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Hamidpour R, Hamidpour S, Hamidpour M, Sohraby M, Hamidpour M. Turmeric (Curcuma longafrom a variety of traditional medicinal applications to its novel roles as active antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and anti-diabetes. Int J Pharmacol Phytochem Ethnomed. 2015;1(1):37–45. doi:10.18052/www.scipress.com/IJPPE.1.37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yang Z, Guo Z, Yan J, Xie J. Nutritional components, phytochemical compositions, biological properties, and potential food applications of ginger (Zingiber officinalea comprehensive review. J Food Compos Anal. 2024;128:106057. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2024.106057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ayustaningwarno F, Anjani G, Ayu AM, Fogliano V. A critical review of Ginger’s (Zingiber officinale) antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory activities. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1364836. doi:10.3389/fnut.2024.1364836. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Medagama AB. The glycaemic outcomes of Cinnamon, a review of the experimental evidence and clinical trials. Nutr J. 2015 Dec;14(1):108. doi:10.1186/s12937-015-0098-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Andallu B, Rajeshwari CU. Aniseeds (Pimpinella anisum L.) in health and disease. In: Nuts and seeds in health and disease prevention. USA: Academic Press; 2011. p. 175–81. [Google Scholar]

19. Soussi M, El Yaagoubi W, Nekhla H, El Hanafi L, Squalli W, Benjelloun M, et al. A multidimensional review of pimpinella anisum and recommendation for future research to face adverse climatic conditions. Chem Afr. 2023 Aug;6(4):1727–46. doi:10.1007/s42250-023-00633-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shojaii A, Abdollahi Fard M. Review of pharmacological properties and chemical constituents of Pimpinella anisum. ISRN Pharm. 2012 Jul 16;2012:1–8. doi:10.5402/2012/510795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Sun W, Shahrajabian MH, Cheng Q. Anise (Pimpinella anisum L.a dominant spice and traditional medicinal herb for both food and medicinal purposes. Cogent Biol. 2019 Jan 1;5(1):1673688. doi:10.1080/23312025.2019.1673688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mohammed FS, Uysal I, Sevindik E, Doğan M, Sevindik M. Pimpinella species (Anisetraditional use, mineral, nutrient and chemical contents, biological activities. Int J Tradit Complement Med Res. 2023;4(2):97–105. doi:10.53811/ijtcmr.1306831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Assaggaf H, Jeddi M, Mrabti HN, Ez-Zoubi A, Qasem A, Attar A, et al. Design of three-component essential oil extract mixture from Cymbopogon flexuosus, Carum carvi, and Acorus calamus with enhanced antioxidant activity. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):9195. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-59708-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Jeannot K, Gaillot S, Triponney P, Portets S, Pourchet V, Fournier D, et al. Performance of the disc diffusion method, MTS gradient tests and two commercially available microdilution tests for the determination of cefiderocol susceptibility in Acinetobacter spp. Microorganisms. 2023;11(8):1971. doi:10.3390/microorganisms11081971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Benkhaira N, Zouine N, Fadil M, Koraichi SI, El Hachlafi N, Jeddi M, et al. Application of mixture design for the optimum antibacterial action of chemically-analyzed essential oils and investigation of the antiadhesion ability of their optimal mixtures on 3D printing material. Bioprinting. 2023;34:e00299. doi:10.1016/j.bprint.2023.e00299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Ferreira S, Santos J, Duarte A, Duarte AP, Queiroz JA, Domingues FC. Screening of antimicrobial activity of Cistus ladanifer and Arbutus unedo extracts. Nat Prod Res. 2012 Aug;26(16):1558–60. doi:10.1080/14786419.2011.569504. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Nikolić M, Glamočlija J, Ferreira IC, Calhelha RC, Fernandes Â, Marković T, et al. Chemical composition, antimicrobial, antioxidant and antitumor activity of Thymus serpyllum L., Thymus algeriensis Boiss. and Reut and Thymus vulgaris L. essential oils. Ind Crops Prod. 2014;52:183–90. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.10.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Reshetnikov DV, Burova LG, Rybalova TV, Bondareva EA, Patrushev SS, Evstropov AN, et al. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of caffeine derivatives containing amino-acid fragments. Chem Nat Compd. 2022 Sep;58(5):908–15. doi:10.1007/s10600-022-03826-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Collins A, Møller P, Gajski G, Vodenková S, Abdulwahed A, Anderson D, et al. Measuring DNA modifications with the comet assay: a compendium of protocols. Nat Protoc. 2023;18(3):929–89. doi:10.1038/s41596-022-00754-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Singh NP, McCoy MT, Tice RR, Schneider EL. A simple technique for quantitation of low levels of DNA damage in individual cells. Exp Cell Res. 1988;175(1):184–91. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(88)90265-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Strubbia S, Lyons BP, Lee RJ. Spatial and temporal variation of three biomarkers in Mytilus edulis. Mar Pollut Bull. 2019;138:322–7. doi:10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.09.055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Fu Q, Cao D, Sun J, Liu X, Li H, Liu R. Prediction and bioactivity of small-molecule antimicrobial peptides from Protaetia brevitarsis Lewis larvae. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1124672. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1124672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Scholz C, Knorr S, Hamacher K, Schmidt B. DOCKTITE—a highly versatile step-by-step workflow for covalent docking and virtual screening in the molecular operating environment. J Chem Inf Model. 2015;55(2):398–406. doi:10.1021/ci500681r. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Rodrigues VM, Rosa PTV, Marques MOM, Petenate AJ, Meireles MAA. Supercritical extraction of essential oil from Aniseed (Pimpinella anisum L) using CO2: solubility, kinetics, and composition data. J Agric Food Chem. 2003 Mar 1;51(6):1518–23. doi:10.1021/jf0257493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Omidbaigi R, Hadjiakhoondi A, Saharkhiz M. Changes in content and chemical composition of Pimpinella anisum oil at various harvest time. J Essent Oil Bear Plants. 2003 Jan;6(1):46–50. doi:10.1080/0972-060X.2003.10643328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Askari F. Essential oils of pimpinella species in Iran. Germany: Universitätsverlag Göttingen; 2008. [Google Scholar]

37. Hassiotis CN, Ntana F, Lazari DM, Poulios S, Vlachonasios KE. Environmental and developmental factors affect essential oil production and quality of Lavandula angustifolia during flowering period. Ind Crops Prod. 2014;62:359–66. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.08.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Figueiredo AC, Barroso JG, Pedro LG, Scheffer JJC. Factors affecting secondary metabolite production in plants: volatile components and essential oils. Flavour Fragr J. 2008 Jul;23(4):213–26. doi:10.1002/ffj.1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Moghaddam M, Mehdizadeh L. Chemistry of essential oils and factors influencing their constituents. In: Soft chemistry and food fermentation. USA: Academic Press; 2017. p. 379–419. [Google Scholar]

40. Reyes-Jurado F, Franco-Vega A, Ramírez-Corona N, Palou E, López-Malo A. Essential oils: antimicrobial activities, extraction methods, and their modeling. Food Eng Rev. 2015 Sep;7(3):275–97. doi:10.1007/s12393-014-9099-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Mahboubi M, Mahboubi M. Pimpinella anisum and female disorders: a review. Phytomedicine Plus. 2021;1(3):100063. doi:10.1016/j.phyplu.2021.100063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Tepe B, Akpulat HA, Sokmen M, Daferera D, Yumrutas O, Aydin E, et al. Screening of the antioxidative and antimicrobial properties of the essential oils of Pimpinella anisetum and Pimpinella flabellifolia from Turkey. Food Chem. 2006;97(4):719–24. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.05.045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Abdel-Reheem MA, Oraby MM. Anti-microbial, cytotoxicity, and necrotic ripostes. Ann Agricult Sci. 2015;60(2):335–40. doi:10.1016/j.aoas.2015.10.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Bakhshi M, Kamalinejad M, Shokri M, Forouzani G, Heidari F, Tofangchiha M. In vitro antibacterial effect of Pimpinella anisum essential oil on Enterococcus faecalis, Lactobacillus casei, Actinomyces naeslundii, and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Folia Med. 2022;64(5):799–806. doi:10.3897/folmed.64.e64714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Akhtar A, Deshmukh AA, Bhonsle AV, Kshirsagar PM, Kolekar MA. In vitro antibacterial activity of Pimpinella anisum fruit extracts against some pathogenic bacteria. Vet World. 2008;1(9):272. [Google Scholar]

46. Rafia Rehman RR, Hanif MA, Zahid Mushtaq ZM, Al-Sadi AM. Biosynthesis of essential oils in aromatic plants: a review. Food Rev Int. 2016;32(2):117–60. doi:10.1080/87559129.2015.1057841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Smith P, Finnegan W, Ngo T, Kronvall G. Influence of incubation temperature and time on the precision of MIC and disc diffusion antimicrobial susceptibility test data. Aquaculture. 2018;490:19–24. doi:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.02.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Betriu C, Culebras E, Gómez M, Rodríguez-Avial I, Sánchez BA, Ágreda MC, et al. Erythromycin and clindamycin resistance and telithromycin susceptibility in Streptococcus agalactiae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003 Mar;47(3):1112–4. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.3.1112-1114.2003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Sweeney D, Shinabarger DL, Arhin FF, Belley A, Moeck G, Pillar CM. Comparative in vitro activity of oritavancin and other agents against methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;87(2):121–8. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2016.11.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Mayaud L, Carricajo A, Zhiri A, Aubert G. Comparison of bacteriostatic and bactericidal activity of 13 essential oils against strains with varying sensitivity to antibiotics. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2008;47(3):167–73. doi:10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02406.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Monte DF, Lincopan N, Fedorka-Cray PJ, Landgraf M. Current insights on high priority antibiotic-resistant Salmonella enterica in food and foodstuffs: a review. Curr Opin Food Sci. 2019;26:35–46. doi:10.1016/j.cofs.2019.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Tavares TD, Antunes JC, Padrão J, Ribeiro AI, Zille A, Amorim MTP, et al. Activity of specialized biomolecules against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. Antibiotics. 2020;9(6):314. doi:10.3390/antibiotics9060314. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Campana R, Tiboni M, Maggi F, Cappellacci L, Cianfaglione K, Morshedloo MR, et al. Comparative analysis of the antimicrobial activity of essential oils and their formulated microemulsions against foodborne pathogens and spoilage bacteria. Antibiotics. 2022;11(4):447. doi:10.3390/antibiotics11040447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Ouis N, Hariri A. Chemical analysis, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Aniseeds essential oil. Agric Conspec Sci. 2021;86(4):337–48. [Google Scholar]

55. Carvalho M, Albano H, Teixeira P. In vitro antimicrobial activities of various essential oils against pathogenic and spoilage microorganisms. J Food Qual Hazards Control. 2018;5(2):41–8. doi:10.29252/jfqhc.5.2.3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. de Diana DF, Abreu JS, Serafini DC, Ortíz JF, Samaniego MJ, Aranda AC, et al. Increased genetic damage found in waste picker women in a landfill in Paraguay measured by comet assay and the micronucleus test. Mutat Res Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 2018;836:19–23. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2018.06.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Matzenbacher CA, Garcia ALH, Dos Santos MS, Nicolau CC, Premoli S, Corrêa DS, et al. DNA damage induced by coal dust, fly and bottom ash from coal combustion evaluated using the micronucleus test and comet assay in vitro. J Hazard Mater. 2017;324:781–8. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.11.062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Hosseinzadeh H, Sadeghnia HR. Effect of safranal, a constituent of Crocus sativus (Saffronon methyl methanesulfonate (MMS)–induced DNA damage in mouse organs: an alkaline single-cell gel electrophoresis (Comet) assay. DNA Cell Biol. 2007;26(12):841–6. doi:10.1089/dna.2007.0631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Cotelle S, Férard JF. Comet assay in genetic ecotoxicology: a review. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1999;34(4):246–55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

60. Sharma NK. Modulation of radiation-induced and mitomycin C-induced chromosome damage by apigenin in human lymphocytes in vitro. J Radiat Res. 2013;54(5):789–97. doi:10.1093/jrr/rrs117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Noel S, Kasinathan M, Rath SK. Evaluation of apigenin using in vitro cytochalasin blocked micronucleus assay. Toxicol in Vitro. 2006;20(7):1168–72. doi:10.1016/j.tiv.2006.03.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Yetiştirme DH, Erdem MG, Cinkılıç N, Vatan Ö, Yılmaz D, Bağdaş D, et al. Genotoxic and anti-genotoxic effects of vanillic acid against mitomycin C-induced genomic damage in human lymphocytes in vitro. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(10):4993–8. doi:10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.10.4993. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Bhat SH, Azmi AS, Hadi SM. Prooxidant DNA breakage induced by caffeic acid in human peripheral lymphocytes: involvement of endogenous copper and a putative mechanism for anticancer properties. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2007;218(3):249–55. doi:10.1016/j.taap.2006.11.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Czeczot H, Tudek B, Kusztelak J, Szymczyk T, Dobrowolska B, Glinkowska G, et al. Isolation and studies of the mutagenic activity in the Ames test of flavonoids naturally occurring in medical herbs. Mutat Res Toxicol. 1990;240(3):209–16. doi:10.1016/0165-1218(90)90060-f. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Duthie SJ, Johnson W, Dobson VL. The effect of dietary flavonoids on DNA damage (strand breaks and oxidised pyrimdines) and growth in human cells. Mutat Res Toxicol Environ Mutagen. 1997;390(1–2):141–51. doi:10.1016/s0165-1218(97)00010-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Stanisgaw J, Rosochacki ZEF. In vitro evaluation of biological activity of cinnamic, caffeic, ferulic and chlorogenic acids with use of Escherichia coli K-12 RECA::GFP biosensor strain. Drugs. 2017;2(4):6–13. [Google Scholar]

67. Villarini M, Pagiotti R, Dominici L, Fatigoni C, Vannini S, Levorato S, et al. Investigation of the cytotoxic, genotoxic, and apoptosis-inducing effects of estragole isolated from fennel (Foeniculum vulgare). J Nat Prod. 2014;77(4):773–8. doi:10.1021/np400653p. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Gorelick NJ. Genotoxicity of trans-anethole in vitro. Mutat Res Mol Mech Mutagen. 1995;326(2):199–209. doi:10.1016/0027-5107(94)00173-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Abraham SK. Anti-genotoxicity of trans-anethole and eugenol in mice. Food Chem Toxicol. 2001;39(5):493–8. doi:10.1016/s0278-6915(00)00156-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools