Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Combining Ammonium Molybdate with Antagonistic Bacteria for Effective Control of Brown Rot Disease

1 Phytopathology Unit, Department of Plant Protection, Ecole Nationale d'Agriculture de Meknes, Meknes, 50001, Morocco

2 Laboratory of Biotechnology, Conservation and Valorisation of Natural Resources (LBCVNR), Faculty of Sciences Dhar El Mehraz, Sidi Mohamed Ben Abdallah University, Fez, 30000, Morocco

* Corresponding Author: Rachid Lahlali. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovations in Post-Harvest Disease Control and Quality Preservation of Horticultural Crops)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(5), 1565-1586. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.063517

Received 16 January 2025; Accepted 16 April 2025; Issue published 29 May 2025

Abstract

This study investigates the compatibility and efficacy of combining ammonium molybdate (AM) with antagonistic bacteria Bacillus amyloliquefaciens B10W10 and Pseudomonas sp. B11W11 for brown rot control (Monilinia laxa). In vitro experiments reveal variable mycelial growth inhibition rates compared to untreated controls, with B11W11 + 0.5% AM and B10W10 + 2% AM displaying the highest inhibition rates after 5 days. After 10 days, the 2% AM + B10W10 combination exhibits the highest inhibition rate. Microscopic observations show structural alterations in mycelium within inhibition zones, marked by vacuolization. The antagonistic bacteria, alone or with different ammonium molybdate concentrations, significantly impact M. laxa spore germination, with the B10W10 cell filtrate + 2% ammonium molybdate combination achieving the most substantial inhibition. Conversely, the 0.5% ammonium molybdate treatment has the lowest inhibition rate while the combination of AM and bacteria is giving better results compared to the use of bacteria alone. Fruits treated with various antagonistic bacteria and ammonium molybdate combinations demonstrate a significant reduction in disease severity. The 0.5% AM + B10W10 combination exhibits the lowest severity. FT-IR spectra analysis identifies shifts in fungal biomass functional groups, with reduced lignin-related bands and increased phenols, lipids, polysaccharides, and carbohydrates. This highlights the structural modifications caused by the biological treatments. The study also evaluates the effects on fruit quality parameters. The 2% ammonium molybdate treatment yields the lowest weight loss. TSS levels are affected by salt concentration, while acid content remains consistent across treatments. All treatments influence fruit firmness compared to controls. These findings emphasize the potential of combining ammonium molybdate and antagonistic bacteria for effective brown rot control, highlighting their compatibility and effects on disease severity, fungal biomass, spore germination, and fruit quality.Keywords

Nectarines (Prunus persica L.) and peaches (Prunus persica L.) stand among the most economically significant fruit crops, trailing closely behind apples and oranges [1,2]. With a global production exceeding 25 million tons, spread across an approximate area of 1.5 million hectares, China, Spain, and Italy emerge as the primary producers of peaches and nectarines [3,4]. Over the past years, peach and nectarine production in Morocco has witnessed significant increase, rising from 138,560 t in 2017 to 168,974 t in 2021, and reaching 247,869 t in 2022 This surge has earned Morocco recognition as one of the leading countries in the production of these stone fruits, securing the 18th position globally, according to data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations [3].

Regrettably, nectarines and peaches often face rapid deterioration both before and after harvest, particularly when storage conditions are not adequately maintained. This degradation is primarily attributed to spoilage fungi, with Monilinia spp. being a significant culprit [5]. Monilinia, the causative agent of brown rot, predominantly triggered by three species within the Monilinia genus (M. laxa, M. fructicola, and M. fructigena), stands out as a major economic concern [6]. The economic impact is substantial, with estimated annual losses amounting to 2.1 million euros [7]. When environmental conditions are conducive to disease initiation and growth in orchards, the post-harvest fruit loss can soar to as high as 80% [8].

Brown rot not only results in the withering of flowers and fruit decay in orchards but also triggers latent infections in fruits, leading to rot after harvest. These latent infections, originating in the fields, can swiftly transition into visible rot, often near or after harvest, and easily propagate through contact in refrigerated warehouses [9,10]. The ability of brown rot to rapidly develop at temperatures between 5°C–10°C can contribute to fruit rot post-harvest. Disease management heavily relies on fungicide application, especially pre- and post-harvest [11]. Despite synthetic fungicides like benzimidazole and dicarboximide still being available on the market and effective against brown rot, their usage is diminishing due to the emergence of resistant fungal strains [12]. The extensive use of synthetic fungicides has led to the proliferation of resistant strains among these phytopathogens, undermining the efficacy of chemical treatments [13,14].

The frequent application of necessary fungicides to combat brown rot remains a major obstacle to sustainable production. Therefore, genetic resistance to brown rot is highly desirable and a priority for various selection programs worldwide. However, there are currently no commercially available cultivars of nectarines or peaches that are resistant or immune to brown rot [15]. Additionally, public concerns regarding the potential harmful effects of fungicide residues on the environment and their accumulation in food, resulting in adverse effects on human health, are significant [16,17]. This situation has led to increased research on alternative management methods, such as biological control [18]. Biological control involves the use of formulations of living organisms (biofungicides) to regulate the activity of pathogenic fungi and bacteria [19]. Many bacteria have shown good potential for biocontrol against brown rot, for example, Pantoea agglomerans, a Gram-negative bacterium effective in preventive treatments [20], Bacillus subtilis [21], and B. amyloliquefaciens [22]. However, although these biological control agents have significantly reduced the incidence of the disease but they have not been able to fully control the disease [23]. In this regard, researchers have recently selected two antagonistic bacteria, B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10)/Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11), for their greater efficiency in reducing brown rot on apple fruits [24]. To address this shortfall, these bacteria have been attempted in combination with other salts, additives, and low-dose fungicides [25].

Ammonium molybdate (AM), a tetrahydrate molybdenum salt, is used as a controlled-release biological fertilizer, foliar spray, and insecticide. It is also employed to prevent and treat diseases related to parasites. It has shown superior effects in combating post-harvest root in cherries, peaches, apples, and citrus fruits. However, information on its mechanisms of action remains limited [26].

As of now, there is no existing research on the use of a combination involving either B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10) or Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11) along with ammonium molybdate to suppress M. laxa-triggered brown rot, and the associated mechanisms are yet to be explored. Thus, this research proposes an innovative biological strategy to combat one of the main post-harvest diseases affecting nectarines. It aims to: (i) evaluate the efficacy of controlling brown rot induced by M. laxa by combining B. amyloliquefaciens and Pseudomonas sp. with ammonium molybdate at different concentrations, (ii) assess the impact of these biological treatments on nectarine quality after storage, considering parameters such as firmness, titratable acidity, weight loss, and total soluble solids content.

Furthermore, the study investigates the effect of biological treatments on the organic composition of the fruit using ATR-FTIR analysis. Additionally, the inhibition of M. laxa mycelial growth is examined through optical microscopy to elucidate the underlying mechanisms.

2.1 Fingal Pathogen and Culture Conditions

The fungal pathogen Monilinia laxa (VPJR strain), responsible for brown rot disease affecting numerous rosaceous fruit trees, was used in this study. This isolate was originally obtained in Serbia in 2010 from symptomatic sweet cherry (Prunus avium) fruits. The corresponding GenBank accession number is KC544802 [27]. To maintain its long-term preservation, it was stored in a 25% glycerol solution at a temperature of −80°C. Before each experiment, M. Laxa had to be grown freshly in PDA medium at 25°C in the dark for 7–10 days.

After this, Spore suspensions were prepared by gently scraping ten-day-old fungal colonies using the tip of a sterile Pasteur pipette into 10 mL of sterile distilled water (SDW) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (v/v). The resulting mixture was then filtered through Whatman filter paper to remove mycelial fragments and agar debris, allowing for the recovery of spores. The concentration was then adjusted to 104 spores mL−1 using a hemocytometer (Malassez cell, Roche, Meylan, France).

2.2 Antagonistic Bacteria and Their Growth Conditions

Two antagonistic bacteria, namely Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11) and B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10), sourced from the culture collection at the ENA-MEKNES (National School of Agriculture, Meknes), were employed. These bacteria were chosen due to their proven ability to act as antagonists against apple brown rot throughout the post-harvest storage period [24]. Both bacteria were kept at the Plant Protection Unit in (LB) liquid medium, which contains 20% glycerol and is stored at −20°C for later use. These strains were reanimated prior to the experiment and grown in the dark at 28°C on LB medium. A bacterial suspension for each strain was produced by grinding 24-h cultures in LB medium. Then, for each bacterium, 10 mL of SDW was added to the Petri dish containing the streaked bacterial colonies. Colonies were carefully scraped with a sterile loop, then collected in a 15 mL Falcon tube and homogenized with a vortex. The concentration of each bacterial antagonist was set at approximately (1 × 108 CFU/mL) at 420 nm with a spectrophotometer (Rochester, NY, USA). To investigate the indirect impact of these antagonistic bacteria on pathogen growth inhibition, cell-free bacterial filtrates were produced using a modified protocol based on [28]. Bacterial colonies were transferred to nutrient broth and placed in a rotary shaker at 130 rpm for three days at 28°C. Following incubation, the supernatant was collected after centrifuging the suspension for half an hour at a gravity force of 5500. It was then filtered using a Millipore filter with a fineness of 0.22 µm.

The filtrates collected were kept at −20°C until use. To examine the antifungal efficacy of the bacterial metabolites, Petri dishes filled with PDA enriched with 10% cell-free bacterial filtrate were inoculated with 5 mm mycelial plugs and placed at 28°C for incubation. Each fungal pathogen was inoculated into control dishes without bacterial filtration.

2.3 Ammonium Molybdate Treatments

Concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, and 2% (w/v) ammonium molybdate (NH4)6Mo7O24, Fisher Scientific S.A. (reference A4730051), were measured alone and in combination with the two antagonistic bacteria. The fungicide BELLIS WG, containing Boscalide (25.2%) and Pyraclostrobin (12.8%) is supplied by BASF SE, Ludwigshafen, Germany and registered under the homologation number E12-9-016 in Morocco (BASF MAROC), has emerged as an optimal solution for combating various fungal diseases, including scab, powdery mildew, leaf curl, and brown rot affecting fruit-bearing trees. Its efficacy in addressing brown rot on nectarines has been confirmed at a dosage of 50 g/hL.

The nectarines chosen for this study were in good health, harvested at uniform sizes, and belonged to the Honey Blaze variety sourced from the Green Providence estate (LOUATA). Before being employed in different vivo experiments, all fruits underwent surface disinfection. This involved immersing them in a 2% sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 min, followed by two rinses with SDW, and then air-drying for 1 h under a laminar flow hood.

2.5 Compatibility between Antagonist’s Bacteria’s and AM

Before testing the combined effects of the antagonistic bacteria B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10)/Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11) and ammonium molybdate on the fungal pathogen, following the protocol of Lyousfi et al. 2022 with minor adjustments, it is crucial to assess the compatibility of the bacteria with salt. One milliliter of each q bacterial suspension of the strain (1 × 108 CFU/mL) was mixed with 100 mL of ammonium molybdate solution at different concentrations (0.5%, 1%, and 2% w/v). Distilled water was used as a negative control in place of salt. The mixture was then incubated at 28°C for 1 h under constant shaking at 150 revolutions per minute for each bacteria-fungi combination. The PDA culture was then re-implanted with the formation of mycelial plugs. A potato dextrose broth (PDB) culture was grown by adding one milliliter of each bacteria and salt solution (100 mL). This experiment was repeated three times with five replicates. A spectrophotometer was used to measure optical density (OD) to assess bacterial growth [29].

2.6 Impact of Biological Treatments on the Growth of Fungal Mycelium In Vitro

2.6.1 Effect of Treatments on Fungal Growth

Effect of Ammonium Molybdate on Fungal Growth

The various salt concentrations were prepared in SDW and added to potato dextrose agar (PDA), and the medium was poured into Petri dishes. Two 5-mm-diameter mycelium plugs of M. laxa, each originating from a culture that was 7–12 days old, were placed on the edges of a Pétri dish filled with PDA medium that included varying amounts of sel. For the control, which contained only PDA, the Petri dish received mycelial disks at the end without any treatment. Following five and ten days of dark incubation at 25°C, the colonies’ diameter was measured to evaluate growth. The experiment was conducted twice over time, with 5 replications each.

Effect of Antagonist’s Bacteria on Fungal Growth

To evaluate the impact of each antagonist on inhibiting the growth of the pathogen, bacterial cultures aged 24 h and mycelial cultures aged 7 to 12 d were employed. In each Petri dish, two mycelial disks, were positioned at the ends of the Petri dish that contained PDA media, each measuring 5 mm in diameter and originating from a 7–12 days M. laxa culture. The bacteria were inoculated in the middle of the dish between the two mycelial disks. For the control group, the Petri dish received mycelial disks at the end without any additional treatments. Subsequently, the dishes were incubated in darkness at 25°C, and growth was evaluated after 5 and 10 d by measuring the colony diameter. The experiment was performed twice over a period of time, with five replications for each trial.

Effect of the Combination of Salt and Antagonistic Bacteria on Fungal Growth

Various salt concentrations were prepared in a potato dextrose agar (PDA) medium, and the medium was poured into Petri dishes. Two mycelial disks, At the ends of the Petri plate with PDA media adjusted with salt at varying concentrations, each 5 mm in diameter and originating from a 7–12 days culture of M. laxa were inserted. The bacterium was inoculated in the middle of the dish between the two mycelial disks. For control, the Petri dish received mycelial disks at the end without any additional treatments. The dishes were then incubated in the dark at 25°C, and growth was assessed after 5 and 10 days by measuring the colony diameter. The experiment was conducted three times over time, with 5 replications each [30].

Bio-Control Assessment

Mycelial growth was assessed by measuring the diameter in two distinct stages: firstly, after 5 days of incubation at 25°C, and secondly, after 10 days of incubation, corresponding to the complete invasion of the petri dish by the fungus. Colony diameters were measured using the cross method, and the surface was calculated using the ellipse surface formula. The average surface area of the colonies on 3 plates for each treatment was obtained, and the inhibition rate was calculated using the following equation [30].

IR: Percentage inhibition of mycelial growth compared to the control (%)

Dt: Mean diameter of the control on an untreated culture medium (mm)

DC: Mean diameter of the fungus on culture medium with treatment (mm)

DO: Diameter of the mycelial disc (5 mm)

Microscopic Observation of Mycelial Growth

Microscopic observations were conducted on the Petri dishes from the confrontation test after 10 days of incubation to assess the effects of treatments on the structure and form of the pathogen’s mycelium. To achieve this, a section of the mycelium was taken at the edge of the fungal growth zone and placed between a slide and a cover slip for microscopic examination. Alterations and degradations caused by the treatments are characterized in comparison to the control under an optical microscope at a magnification of 40×.

2.6.2 Effect of Salt on the Germination of M. laxa Spores

Microtubes filled with 5 mL of potato dextrose broth (PDB) were filled with pathogen spore suspensions (1 mL; 1 × 104 spores/mL), either with or without added (depending on treatment or control). Sterile distilled water was used to generate salt concentrations of 0.5%, 1%, and 2%, which were then combined in a 1:1 (v/v) ratio with M. laxa spore suspensions. After that, the mixtures were incubated in Eppendorf tubes set on a rotating shaker at 25°C. Spore germination was seen under a microscope following a 24-h incubation period. When the germination tube’s length surpasses its lowest diameter, the spore is said to have germinated. At least 100 M. laxa spores per treatment were counted in order to determine the germination rate.

Each experimental condition is performed in triplicate, and the whole experiment is reproduced three times independently in time to ensure robustness and reproducibility of results [31]. The inhibition rate of spore germination compared to the controlwas calculated using the following formula [32]:

ISG: Percentage of spore germination compared to the control (%)

Nt: Number of germinated spores (control) in SDW without treatment

NCR: Number of germinated spores in SDW with treatment

The germination rate was determined by counting at least 100 M. laxa spores per treatment, and the entire experiment was conducted three times to ensure the validity of the results. A spore is considered germinated when the length of its germination tube surpasses its smallest diameter.

2.6.3 Effect of Antagonistic Bacteria on the Germination of M. laxa Spores

Conidia are recovered by gently scraping the surface of the culture medium with a sterile scalpel, thus detaching any spores present, and are used to prepare a spore suspension of the pathogenic fungus by inundating them into 5 mL sterile distilled water containing tween 20 (0.05%) to guarantee a quality suspension, and filtering through a sterile filter to remove residues of mycelium and culture medium. Conidial concentration (1 × 104 (ten to the power of four) spores/mL) is estimated using a Malassez cell and adjusted to the desired concentration by adding SDW. M. laxa spore suspensions are mixed with bacterial suspensions in a volume ratio of 1:1 (V/V), then incubated at 25°C in Eppendorf tubes placed on a rotary shaker. After 24 h of incubation, spore germination is assessed by microscopic observation, analyzing a minimum of 100 M. laxa spores per treatment. The inhibition rate of spore germination (ISG%) was calculated using the same formula described in Section 2.6.2, to maintain methodological consistency across the experiments

2.6.4 ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy for Fungal Biomass of M. laxa

With a few adjustments, the Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) technique of fungal biomass analysis was performed following the method of Shankar et al. 2024 with some modifications [33]. After a 10-day incubation period in PDA, the biomass was extracted from the growth medium by centrifugation and SDW washing. For further homogenization, about 50 mg of fresh and cleaned biomass was added to a 2-mL polypropylene tube along with 250 ± 30 mg of glass beads that had been acid-washed and 0.5 mL of distilled water. To eliminate any leftover water, the remaining cleaned biomass was stored at 40°C for seven days. The following setup of tissue homogenizer was used to homogenize the fungal biomass: 6 × 20 s cycle at 5500 rpm. Two hours were spent air-drying the 15 mg samples. For every biomass sample, three technical duplicates were examined. A Vertex 70 FTIR spectrometer (Bruker Optik GmbH, Ettlingen, Germany) was connected to a high-throughput screening extension unit (HTS-XT) to record FTIR spectra in transmission mode. The range in which the spectra were captured was 4000–500 cm−1 [34].

2.7 In Vivo Effect on the Development of the Fungus

The aim of the in vivo experiment was to examine the antagonistic effect of the bacteria B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10) and Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11) independently, as well as that of ammonium molybdate at three different dosages (0.5%, 1% and 2%) taken separately and in mixture, on the progression of brown rot on nectarines (M. laxa). The efficacy of these approaches was compared with the positive control, exposed only to the pathogen, and the negative control exposed to the fungicide (500 ppm). The nectarines were sanitized by immersing them in a 10% sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 min, then rinsing them twice with distilled water. They were then air-dried for one hour at room temperature under a laminar flow cabinet. The fruits were then prepared for inoculation. Each wound received 50 μL of a treatment (salts at different concentrations, bacteria alone, or combinations). After 4 h, each wound was inoculated with a spore suspension of M. laxa containing 50 μL (1 × 104 (ten to the power of four) spores/mL). The fruit was then placed in plastic containers and incubated at a temperature of 22°C in a culture chamber with high humidity (95%) [35]. After 4 h, each wound was inoculated with 50 μL of M. laxa spore suspension (1 × 104 spores/mL).

The fruit was then placed in plastic containers and kept at a temperature of 22°C with low humidity (95%) in the growth room. After incubation for 5 and 10 days, the diameter of the wounds and the severity of the disease were assessed using a caliper. Each trial included four nectarines treated simultaneously, and the experiment was carried out twice. For each treatment (4 fruits, 8 lesions), severity was assessed after 5 and 10 days of incubation using the equation below:

with:

Dt: average diameter (mm) of wounds treated with treatments/fungicides.

Dc: mean diameter (mm) of lesions in the untreated control group (inoculated solely with the pathogenic fungus).

For the evaluation procedure, nectarines were disinfected by soaking them in a 10% sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 min, followed by two washes with SDW. Then, they were air-dried for 1 h at room temperature under the laminar flow hood, making the fruits ready for inoculation. Four artificial wounds per fruit, with a diameter of 4 mm and a depth of 3 mm, were made on two sides of the equatorial zone of the fruit. Each wound was inoculated with 20 µL of bacterial suspension (1 × 108 CFU/mL/wound) of B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10) or Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11) and incubated at 22°C in light. Bacterial growth at the wound site was monitored throughout the incubation period. Tissue samples encompassing the entire wound were taken at various intervals (24, 48, 72, and 96 h) following inoculation, weighed, and placed in tubes containing a proportional amount of buffered peptone water. A series of dilutions of each sample was plated on PDA, and bacterial colonies were counted to obtain mean colony counts (log10 CFU). Each treatment was tested using three replicates, each comprising three nectarines [36].

2.8 Effects of Biological Treatments on Fruit Quality Parameters

Fruits were initially inspected, and those exhibiting visible injuries were excluded, and only fruits of nearly uniform size were selected. The selected fruits were then randomly allocated into treatment groups, with each treatment replicated twice and comprising five fruits per replicate (2 × 5 fruits per treatment). Before treatment, the initial weight of each fruit was recorded using an MP2000-2 analytical balance (±0.001 g), and the mean initial weight was calculated for each treatment group. After applying the biological treatments under controlled laboratory conditions, the fruits were incubated at 22°C for 10 days. At the end of the incubation period, the final weight of each fruit was measured using the same balance, and weight loss was calculated using the formula provided in reference [37]:

Weight Loss =

a: Average mass of fruit before treatment

b: Mass of fruit after treatment.

Brix (TSS)

The index of refractive of the fruit was measured to quantify the total soluble solids (TSS) after ten days of incubation at 22C post treatment. First, the handheld refractometer was calibrated with distilled water to ensure accurate measurements. Fruit juice was then extracted from each treatment, and a drop of the filtered juice was placed on the refractometer prism to record the refractive index. The TSS values, expressed as a percentage (1 g per 100 g of fruit), were recorded according to the protocol outlined in reference [38].

Titration consisted of gently adding 0.001 M NaOH solution (adjusted to pH 8.1) and 50 mL SDW with phenolphthalein as indicator, to 10 mL of the fruit juice sample obtained after a 10-day incubation period. For each treatment was initially diluted with sterile distilled water. The volume of NaOH used was then employed to calculate the titratable acidity (TA), It was first given as grams of malic acid per liter of juice. Subsequently, the TA was recalculated and. represented as a percentage of citric acid anhydride per liter of juice, in line with the standardized AOAC method 942.15 [39].

Following a 10-day incubation at 22°C, fruit firmness was assessed for each treatment. A Digital Firmness Instrument penetrometer was used to measure firmness as penetration force (N). The penetrometer was applied at two equidistant points along the fruit’s circumference [40].

In vivo and in vitro trials were conducted to evaluate the effect of biological treatments, with two repetitions per condition and multiple replicates to ensure the reliability of the results. The identification of significant treatment effects was performed through an analysis of variance (ANOVA) using the R software, based on statistical data analysis. If a significant difference (p < 0.05) was detected, mean comparisons were carried out using the least significant difference (LSD) test to distinguish distinct groups. Furthermore, to conduct an in-depth analysis of chemical variations, the integrated regions of the FT-IR spectra were examined using Duncan’s multiple range test (p < 0.05), providing a better understanding of changes in composition.

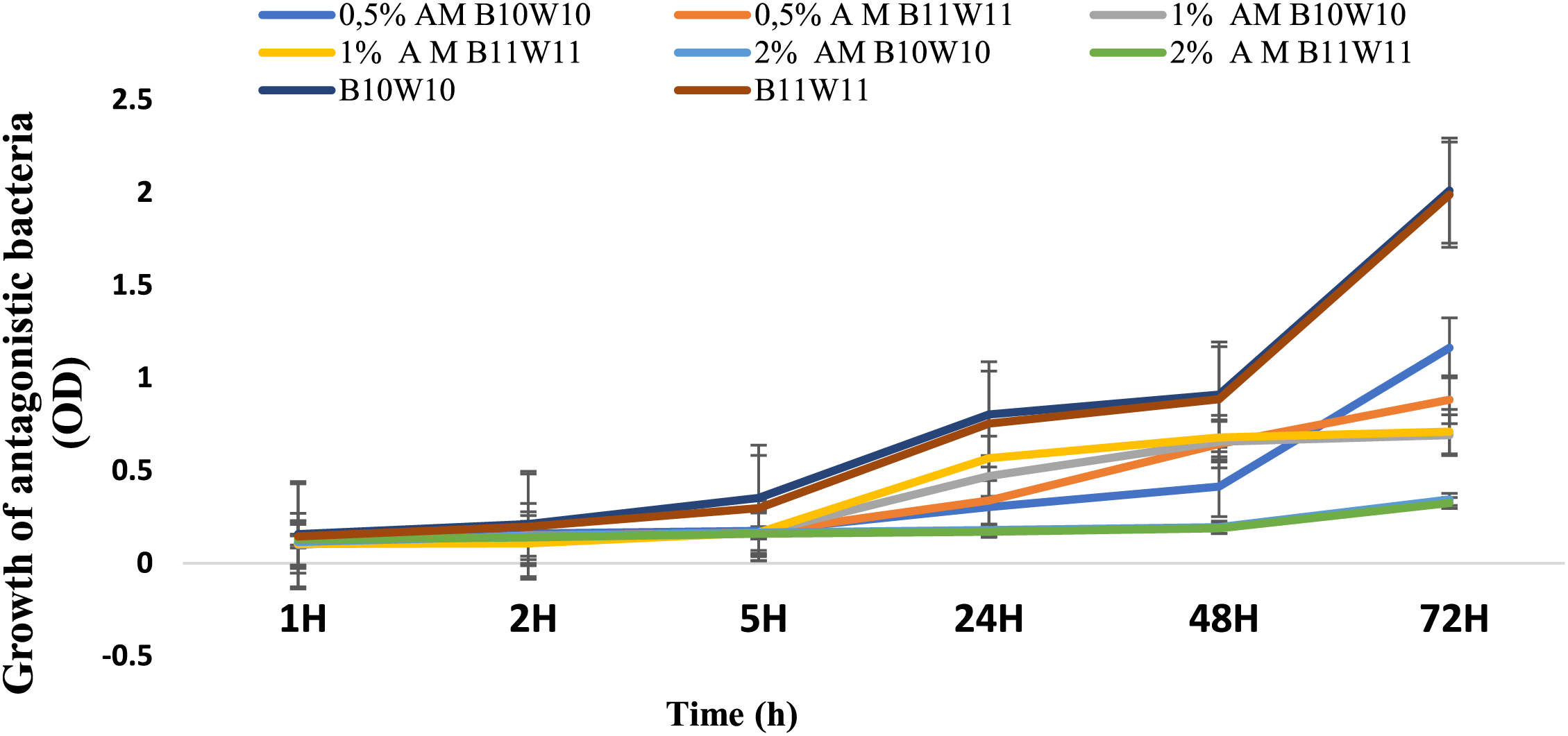

The compatibility was assessed between the two antagonistic bacteria, B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10) and Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11), with ammonium molybdate at different concentrations. For the first 2 h, the treatment trends are not significantly different (Fig. 1). The difference begins to emerge after 5 h, with a gradual progression for both individual bacteria, B10W10 and B11W11. This becomes more apparent after 24 h, where the highest optical densities are recorded for the individual bacteria, followed by the combination of 1% Ammonium molybdate and B11W11, with an optical density exceeding 0.5. However, a low optical density, below 0.5, was observed for the combinations 2% Ammonium molybdate and B11W11, 2% Ammonium molybdate and B10W10. This may be attributed to the presence of interaction or incompatibility among bacteria and the high concentration of the salt.

Figure 1: The growth of antagonistic bacteria (optical density) in a culture medium (PDB), enriched with ammonium molybdate (AM) at various concentrations, over time (up to 48 h). Treatments with the same letter are not significant

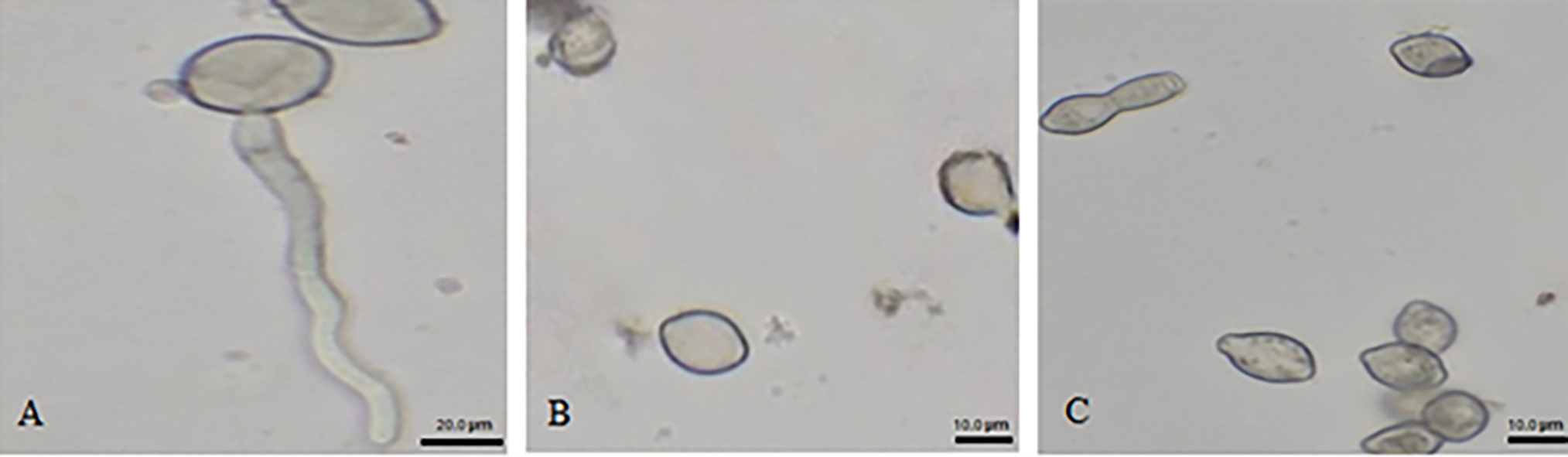

4.2 Effect of In Vitro Treatments on Mycelial Growth

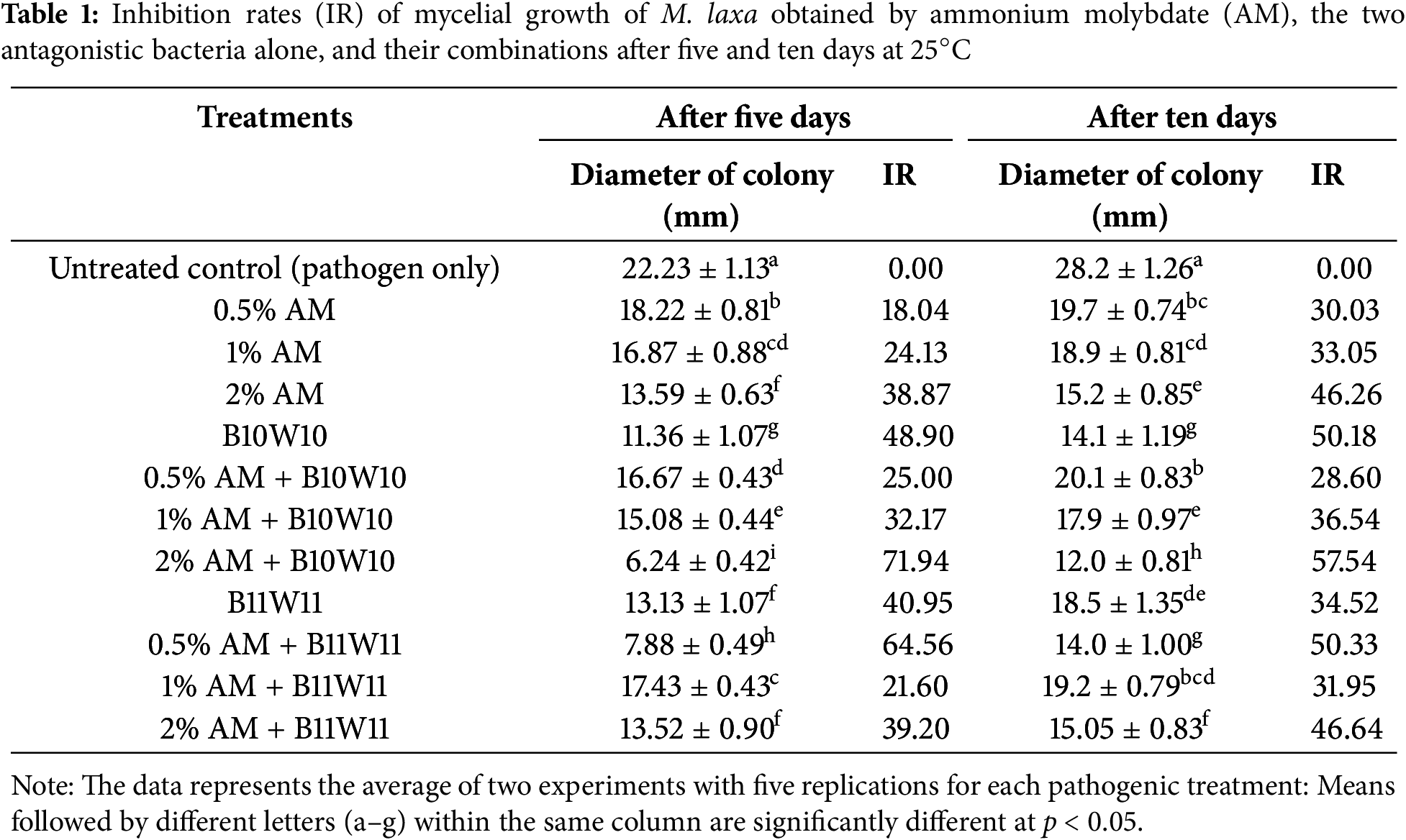

The results of the different treatments (salt, antagonistic bacteria, and bacteria/salt combination) in vitro are reflected in varying percentages of inhibition of mycelial growth compared to the untreated control (Table 1) based on incubation periods (5 and 10 days) and treatments. After five days of treatment, the highest inhibition rates were observed with the combinations B11W11 + 0.5% AM and B10W10 + 2% AM, which achieved inhibition rates of 64.56% and 71.94%, respectively, indicating a strong antifungal effect of these formulations (Table 1 and Fig. 2). After ten days, although a general decrease in inhibition rates was noted, the most effective treatment remained the combination of 2% AM + B10W10, which maintained an inhibition rate of 57.54%, suggesting its prolonged efficacy over time (Table 1).

Figure 2: Colonies morphology in vitro based on treatments with the two antagonistic bacteria and ammonium molybdate at different concentrations, as well as the fungicide against M. laxa, after 10 days of incubation at 25°C. (A) Control (M. laxa), (B) 2% AM + B10W10, (C) 0.5% AM + B11W11, (D) fungicide

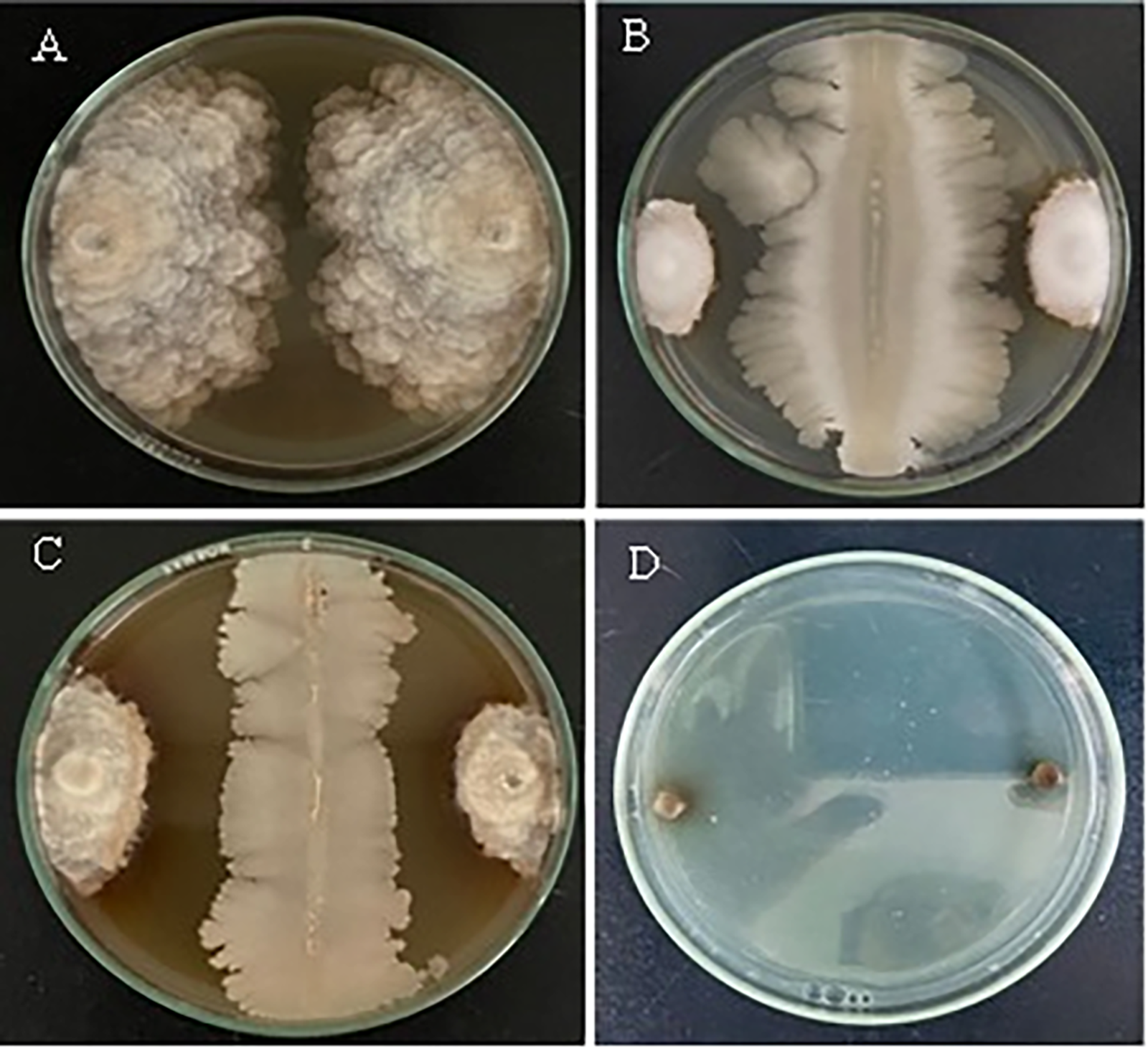

The results highlight that the inhibition rates obtained using ammonium molybdate were enhanced by increasing the concentration for bacteria B10W10, but for the second bacteria (B11W11), a low concentration of 0.5% shows more significant effectiveness than the other doses of 1% and 2%. In addition, microscopic observation of the mycelium in the inhibition zones revealed significant structural alterations, characterized by disorganization of the mycelial network and pronounced vacuolization compared with the untreated control, suggesting a disruption of fungal cellular processes. Furthermore, treatments applied to M. laxa with the two antagonistic bacteria, alone or in combination with salt at different concentrations, showed a noticeable effect on spore germination rates after one day’s incubation. This impact could be attributed to direct inhibition of spore development, or to changes in spore viability under the effect of biocontrol agents and salt (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: The morphology of the spores observed in vitro based on treatments with both antagonistic bacteria and ammonium molybdate at different concentrations, and the fungicide against M. laxa after 24 h of incubation at 25°C, (A) Control (M. laxa), (B) 2% Ammonium molybdate altered spore with the appearance of a germ tube in the 0.5% ammonium molybdate treatment (C) scale bar indicates 20 µm for (A) and 10 µm for (B) and (C)

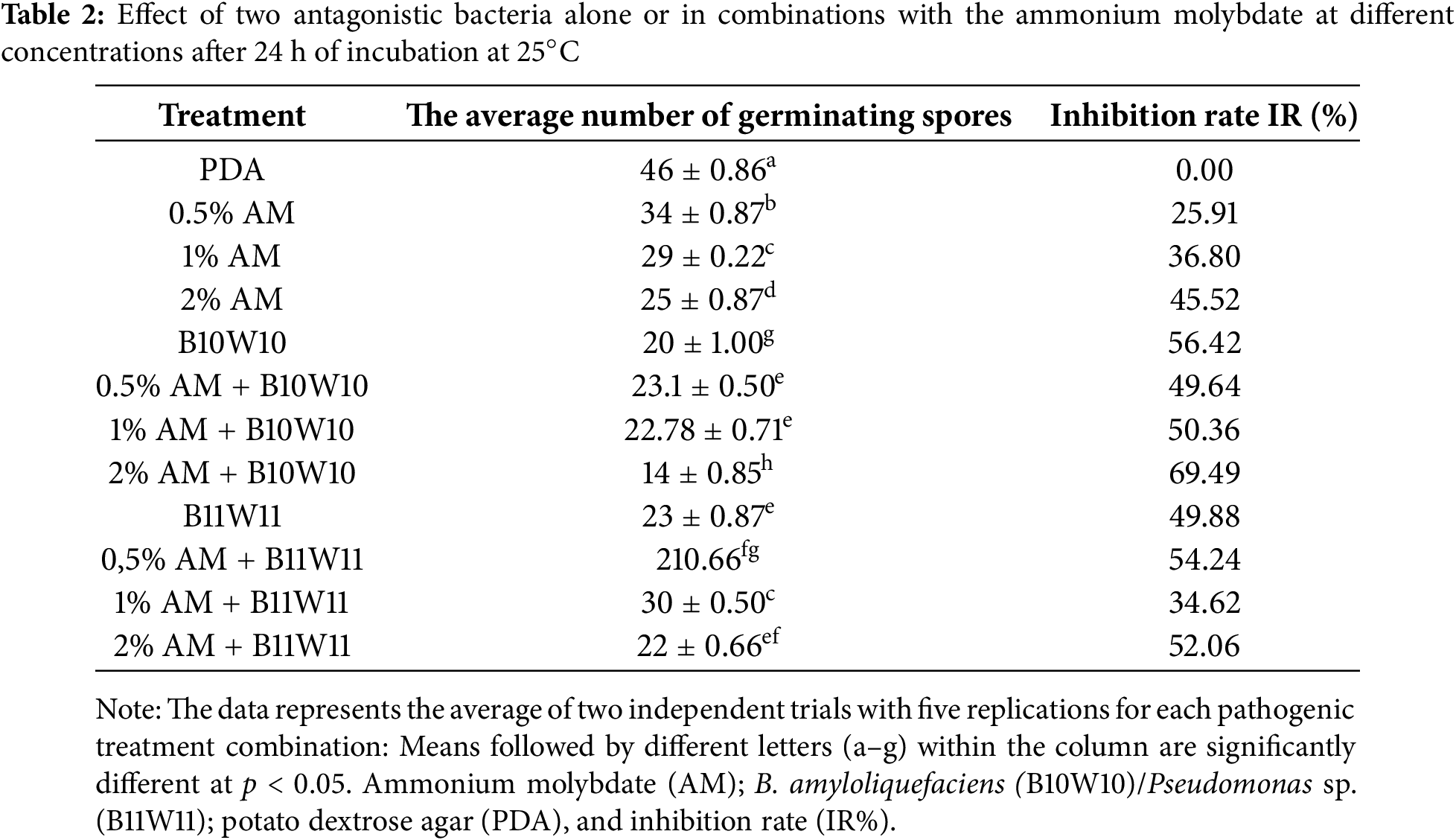

The highest inhibition rates of M. laxa spore germination reached 69.49%, coming from the combination of the cell filtrate of bacteria B10W10 with 2% ammonium molybdate. In the control group, spore germination was not inhibited (Table 2). However, the treatment with 0.5% ammonium molybdate had the least impact on the spore germination of M. laxa, with an inhibition rate of 25.91%.

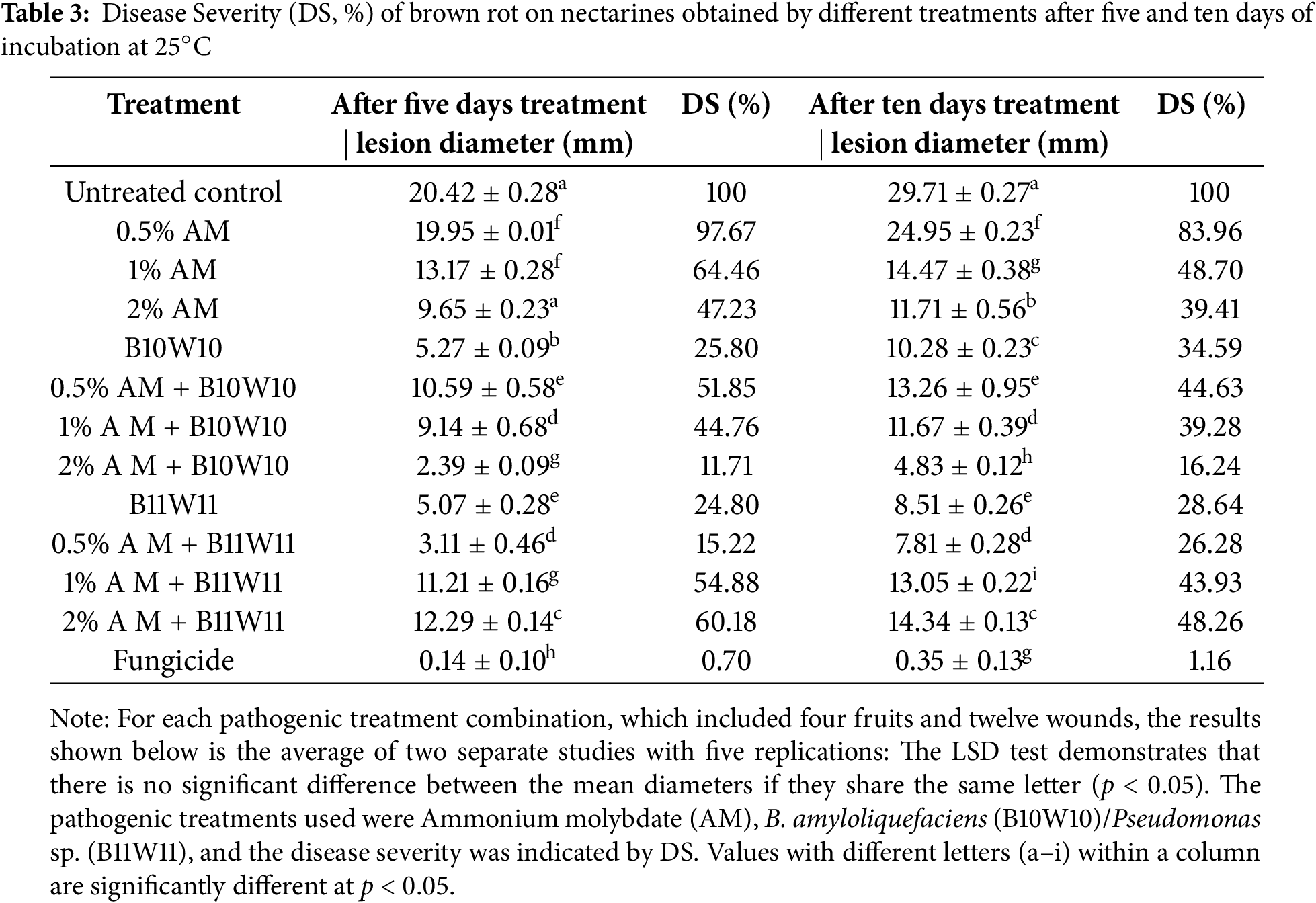

4.3 Effects of In Vivo Treatments on the Brown Rot

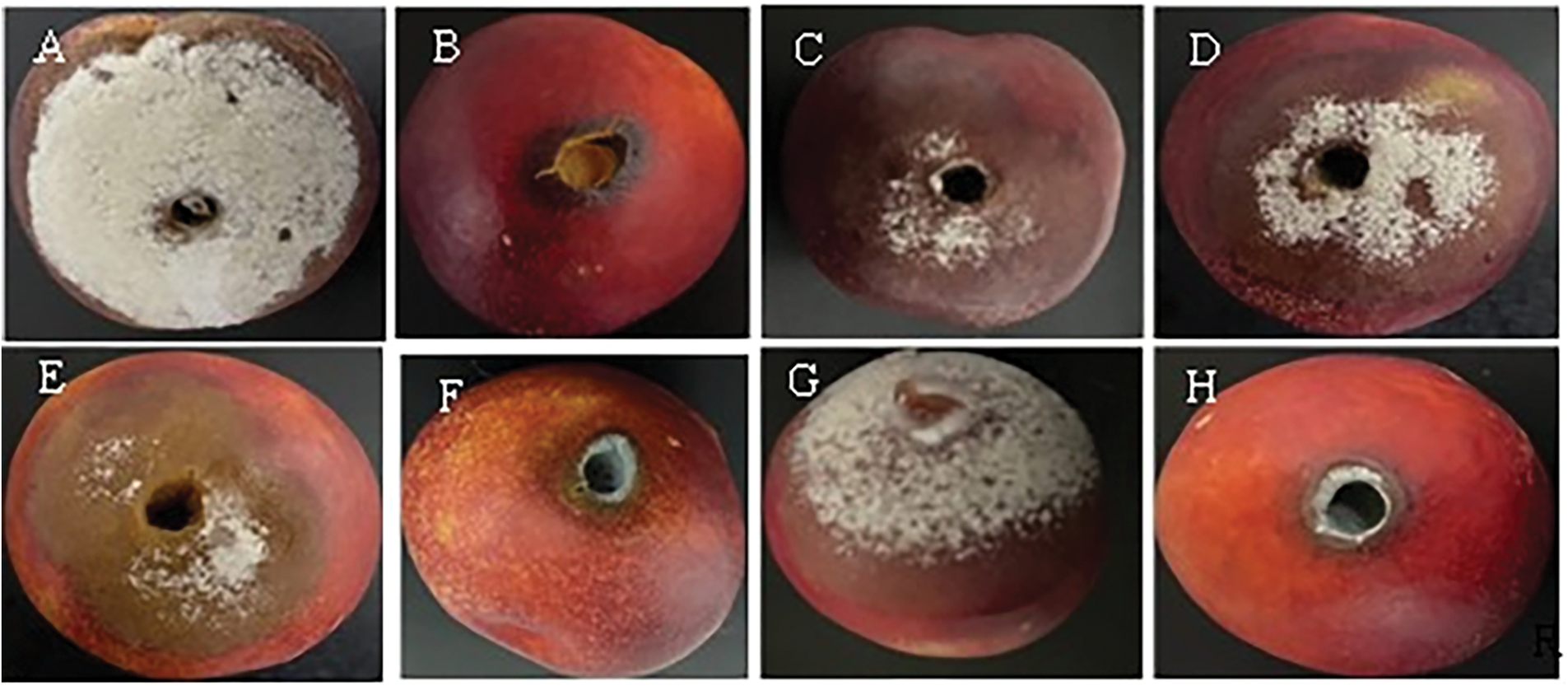

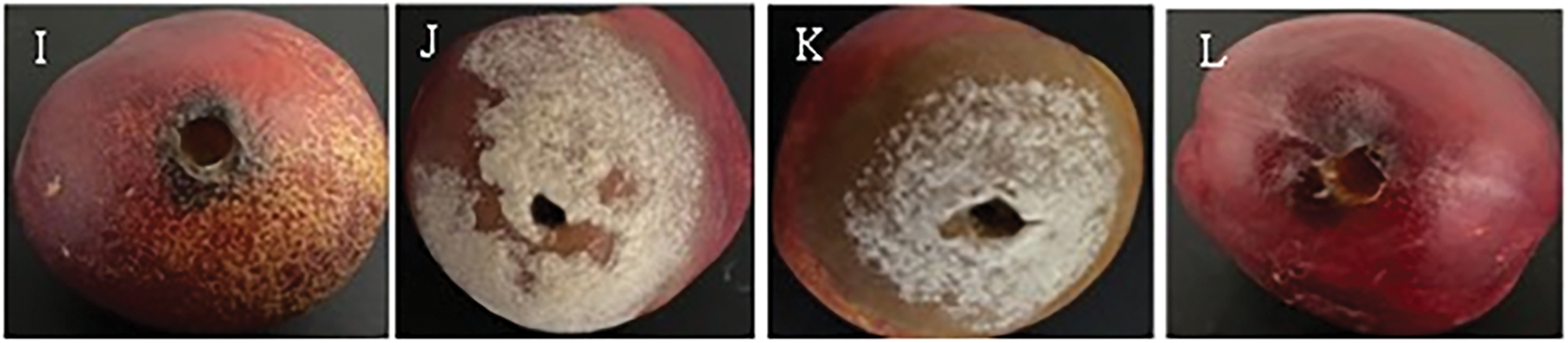

A marked difference was observed between the untreated control group and the biological treatments, highlighting the variable effectiveness of the latter in suppressing M. laxa. Fungal colony diameters under each treatment, and the resulting levels of disease severity, are shown in Table 3 and Fig. 4. Of all the treatments evaluated, the application of 0.5% AM resulted in the highest severity, reaching 97.67% five days after incubation, while the lowest disease severity was recorded for B10W10 with 2% AM and B11W11 with 0.5% AM with 11.71% and 15.22%, respectively. Therefore, the concentration of 0.5% AM combined with B10W10 yielded the lowest disease severity. Other concentrations (1% and 2%) of ammonium molybdate did not reduce severity (64.46% and 47.23%, respectively). Overall, the severity of brown rot disease increased as the incubation periods increased from 5 to 10 d. The results demonstrate that disease severity significantly decreased for all incubation periods (5 or 10 d) in fruits treated compared to the control.

Figure 4: In vivo test on nectarines of the two antagonistic bacteria B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10) and pseudomonas sp. (B11W11) with ammonium molybdate at different concentrations against M. laxa at 5 days incubation, (A): Control (M.laxa), (B): B10W10, (C): B11W11, (D): 0.5% AM, (E): 1% AM, (F): 2% AM, (G): 0.5% AM B10W10, (H): 1% AM B10W10, (I): 2% AM B10W10, (J): 0.5% AM B11W11, (K): 1% AM B11W11, (L): 2% AM B11W11

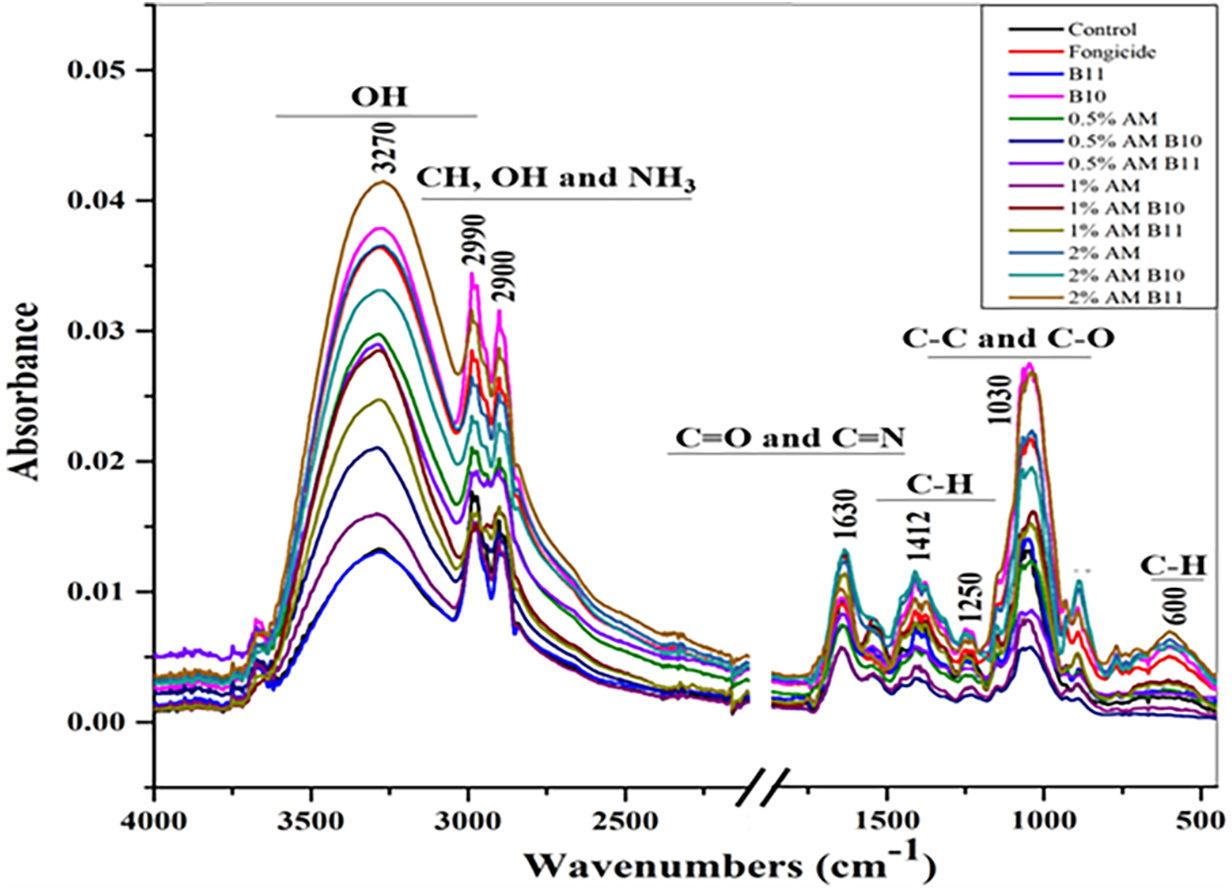

Fig. 5 shows the spectral absorbance profiles of M. laxa fungal biomass generated by FTIR analysis in response to different treatments combining ammonium molybdate (AM) and antagonistic bacteria (B10W10 and B11W11). The main absorption bands appeared at characteristic values, enabling the identification of changes in the fungal biomass compounds. The band around 3270 cm−1 corresponds to O-H bonds, which may originate from hydroxyl groups or proteins. Intensity variations in this region suggest changes in these compounds in the fungal biomass. Peaks at around 2900 and 2909 cm−1 are linked to the C-H tension vibrations of methyl and methylene groups associated with lipids. Differences in absorption could indicate changes in lipid compounds in the biomass as a function of the treatment. The band around 1630 cm−1, linked to C=O and C=N bonds, could indicate alterations in fungal proteins, perhaps caused by the treatments. The bands around 1412 and 1250 cm−1, associated with the C-H and C-O groups of cell wall polysaccharides, also showed variations in intensity, which could reflect changes in the structure of this wall under the effect of treatments. The band around 1030 cm−1, linked to the C-C and C-O vibrations of the polysaccharides, could indicate a change in the concentration or structure of the polysaccharides present in the biomass. Finally, the peak at approximately 600 cm−1 was associated with the C-H deformation vibrations of the complex organic structures. In general, treatments combining ammonium molybdate with bacteria (e.g., 0.5% AM B10W10, 1% AM B10W10) appeared to induce more pronounced changes in certain absorbance bands, notably in the 3270 cm−1 (O-H) and 1630 cm−1 (C=O) regions, which could indicate synergy between bacteria and ammonium molybdate to further alter the cellular structures of M. laxa. Treatments with bacteria alone showed less pronounced variations in absorbance, suggesting an effect on certain fungal structures but potentially with less efficacy. Different concentrations of ammonium molybdate showed a dose-dependent effect on M. laxa biomass, with increased cell disruption observed at higher concentrations. Thus, the FTIR spectrum suggests that combined treatments involving bacteria and ammonium molybdate induce greater changes in fungal biomass than treatments applied individually, which may indicate the greater effectiveness of the combinations in disrupting M. laxa cell structures.

Figure 5: Spectral bands of the fungal biomass of the fungus M. laxa based on treatments with both bacteria alone and in combination with ammonium molybdate at different concentrations

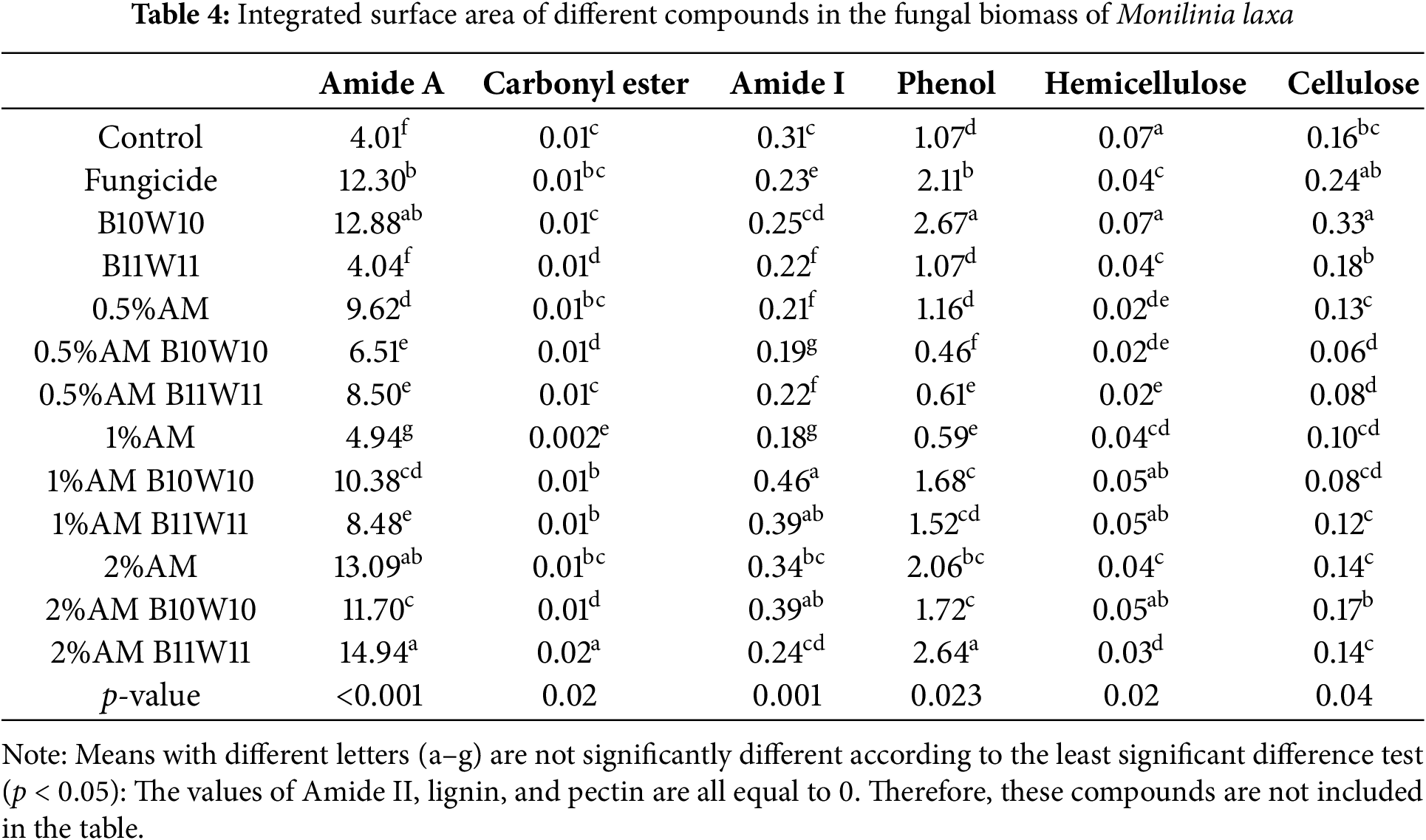

Table 4 shows the specific absorbance surface of different compounds in the fungal biomass of M. laxa in response to various treatments (control, fungicide, bacteria B10W10 and B11W11, ammonium molybdate at several concentrations, and combinations). For Amide A significant differences (p < 0.001) between the treatments. The “2% AM B11W11” combination has the highest value (14.93), while the control and “1% AM” have the lowest values, suggesting that treatments, particularly combinations with a high concentration of ammonium molybdate, have a greater effect on proteins. The absorbance surface of carbonyl esters also varied significantly (p = 0.02), although the values were low. The “2% AM B11W11” has the highest value, while the “1% AM” shows the lowest, indicating a limited effect of the treatments on this compound. The absorbance of Amide I also shows significant differences (p = 0.001), with the highest value observed for “1% AM B10W10” (0.457), indicating a strong disruption of peptide bonds in proteins.

In contrast, no absorbance was detected for Amide II in any of the treatments, suggesting an absence of any effect on this specific region. For phenols, the absorbance surface is significantly different (p = 0.023), with high values for the “B10W10” treatment and the “2% AM B11W11”, suggesting that phenols are more sensitive to treatments involving bacteria and a high concentration of ammonium molybdate. No absorbance was detected for lignin, indicating the low presence or absence of lignin in M. laxa biomass. For hemicellulose, significant variations (p = 0.02) were observed, with the highest values for the control and the “B10W10” treatment, while AM combinations with bacteria showed lower values, suggesting potential hemicellulose degradation in the presence of certain treatments. The absorbance of cellulose varied significantly (p = 0.04), with high values for the “B10W10” treatment and fungicide, whereas AM combinations with bacteria showed lower values, which may indicate cellulose alterations. No absorbance was detected for pectin in any of the treatments, indicating either the absence of pectin or levels too low to be detected in this biomass. The treatments, especially those combining 2% ammonium molybdate with bacteria, appeared to induce more marked changes in certain compounds such as amides, phenols, and hemicellulose, suggesting greater disruption of the structure of the fungal biomass.

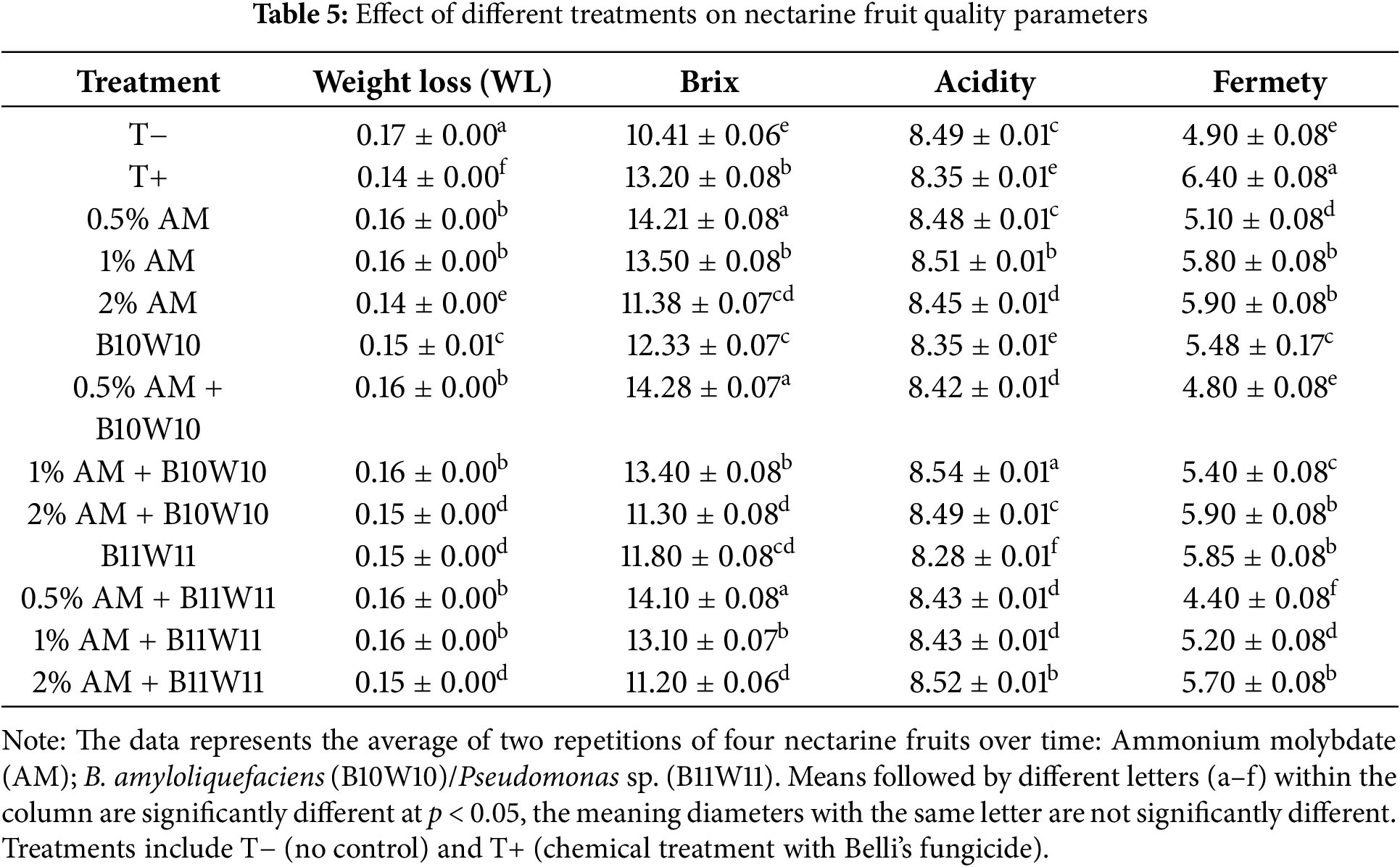

To evaluate the potential effect of antagonistic bacteria and ammonium molybdate on fruit quality indicators, measurements were taken for weight loss (WL), citric acid content (TA), fruit firmness, and total soluble solids (TSS), which are presented in Table 4. The lowest weight loss recorded after the fungicide was with the 2% Ammonium Molybdate treatment. In contrast, high weight loss was observed after the control, particularly for the 0.5% Ammonium Molybdate, 0.5% Ammonium Molybdate B10W10, and 1% Ammonium Molybdate treatments. However, TSS was significantly different among all treatments, with the 0.5% AM treatment showing statistically higher TSS than the chemical control (Table 5). On the other hand, all AM treatments, either alone or in combination with antagonists, showed statistically decreased TSS with increasing salt concentrations. The acid content of the tested treatment was found to be similar to that of the chemical control, indicating that the tested treatment had the same effect on both TA and acid content as chemical treatments. Moreover, all treatments tested showed an influence on fruit firmness compared to the untreated control and water control (pathogen only).

Brown rot, caused by M. laxa, is a prevalent disease afflicting fruits within the rosacea family. This disease results in significant losses, impacting both the quality of fruits during storage and their overall yield in the orchard [41]. The application of fungicides in the management of postharvest fruit decay is being reduced, and the transition to biological control is an ongoing process [42]. However, it’s important to mention that using only biological control has several limitations and sometimes shows low effectiveness [43]. Hence, there is a growing interest in the integration of biological agents with additional parameters, such as heat treatment [44], the application of safe chemical compounds [45], and the use of salts and food additives, enhancing their effectiveness in combating postharvest pathogens. Various salt additives, including ammonium molybdate, sodium bicarbonate, sodium carbonate, calcium chloride, calcium propionate, and potassium metabisulfite, have been investigated for their potential to promote the performance of microbial antagonists. The success of this interaction relies on several factors, namely the concentration of the antagonist population and the salt additive, their compatibility with each other, and the timing and duration of their application [46].

To this regard, the present study evaluated, the efficacy of two microbial antagonists (B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10)/Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11)), alone and in combination with ammonium molybdate to advance a strategy to achieve effective control of M. laxa, on nectarine. To the best of our knowledge, there is no existing research on the utilization of a combination of B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10) and Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11), along with ammonium molybdate, to suppress M. laxa triggered brown rot. However, species of Pseudomonas and Bacillus genera have been researched as effective BCAs to control postharvest diseases and in particular M. laxa, for their production of anti-fungal components [47,48].

Concerning the in vitro experiments, treatments of M. laxa based on the two antagonistic bacteria combined with the salt at different concentrations showed more efficiency on mycelial growth and on spore germination rate than when the antagonist was used alone. Accordingly, the highest inhibition rates were noted for treatments B11W11 + 0.5% AM and B10W10 + 2% AM with inhibition rates of 64.56% and 71.94%, respectively. Also, the highest inhibition rates of spore germination reached 69.49%, coming from the combination of the cell filtrate of bacteria B10W10 with 2% ammonium molybdate. Our results revealed that the two tested bacteria exhibited an antagonistic activity in combination with different concentrations of AM, however the best association was shown between (B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10) and 2% of ammonium molybdate. Previously, ammonium molybdate has been evaluated to many extents for its impact on enhancing the antagonistic potential of multiple BCAs such as Pseudomonas fluorescens, Cryptococcus laurentii, and Candida sake [45,49,50]. This result was in accordance with [51], who demonstrated that the potency of R. glutinis at 107 CFU mL−1 was highly devloped by adding 1 mmol L−1 of molybdate ammonium to control postharvest diseases of pear. In addition, it was proved that the incorporation of 0.1 mmol L−1 AM significantly improved the biological performance of R. paludigenum against green mold, leading to an 89.3% reduction in disease incidence [26].

In vivo experiment, it provided verification that the most effective combination for the lowest disease severity, involved the use of B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10) with 2% ammonium molybdate by reaching 11.71 (Table 3). Overall, it was revealed that fruits treated with B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10) or Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11), combined with AM showed less disease severity than fruits treated with antagonists alone. Identical results have been found by Qin et al. (2006) [52], exanimating antagonistic yeast combined with AM against Monilinia fructicola in sweet cherry. However, the compatibility test showed a low optical density for the combinations 2% Ammonium molybdate and B11W11/B10W10. Similar, in a study by Qin et al. (2006) [52], it was observed that AM lessen the population of Cryptococcus laurentii at 20°C. As a result, it was seen that the low concentration of population did not affect the induction of biocontrol potential. This outcome aligns with prior findings by [50], who underscored that the addition of AM enhanced the effectiveness of BCAs, even when the population of antagonists diminished due to the introduction of a chemical. Therefore, the improvement in biocontrol activity could be attributed to a synergistic effect [45]. In previous study, a synergistic effect has been observed between SA and B. amyloliquefaciens to control Botrytis cinerea [53].

Furthermore, other salts were tested for their capacity to enhance the activity of biocontrol antagonists, such as sodium bicarbonate which was used in combination with Cryptococcus laurentii, Hanseniaspora uvarum and Pichia guillermondii and showed efficacy against the major postharvest pathogens M. laxa, Botrytis cinerea, and Aspergillus niger [54]. Also, several studies have shown that biological control is enhanced when biological agents are combined with natural components such as SA and chitosan [55,56].

The specific mechanism through which AM promotes the antagonistic potential of microbial agents remains currently unknown. It’s possible that the presence of AM could enhance the activity of specific enzymes in antagonistic agents. These enzymes may have a role in the biocontrol mechanism by affecting the ability of BCA to compete with or inhibit the growth of pathogenic micro-organisms [57]. Molybdate ammonium has been shown to be a potent inhibitor of acid phosphatase [49]. Following the results of Wiyono et al. (2008), the effectiveness of AM varies for one organism to another, which explains that the low concentration of this salt in the presence of bacteria, did not impact the growth of phytopathogens. However, this quantity was adequate to influence the antagonistic activity exhibited by the bacteria [58]. In contrast, a study by Palou et al. (2002) suggested that AM at low concentration showed efficacy in controlling grey mold, while this low concentration of this salt may be phytotoxic [59].

In order to better understand the effects of AM and the microbial antagonists (B. amyloliquefaciens (B10W10)/Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11)), on nectarine fruits, we used FT-IR spectroscopy to examine fruits with all the treatments tested. Our results help to elucidate the potential role of this biological control method in the development of M. laxa. This method allowed us to analyze the composition of treated and untreated fruits in the presence of AM, antagonistic bacteria, and their combined application. FTIR analysis revealed that the integrated area shows clear differences among the treatments, suggesting that the presence of the above-mentioned treatments, especially those with bacterial antagonists, altered the structure and composition of the pathogen. Indeed, the content of certain bands in the cell walls of pathogenic fungi decreased in the presence of biological treatments, especially those representing lignin. On the contrary, an increase in various constituents such as phenols, lipids, nucleic acids, polysaccharides, and carbohydrates was observed in most biocontrol treatments. This suggests considerable degradation and alteration in the composition of the cell wall of the pathogenic fungus.

With regard to fruit peels, the results highlight the impact of these treatments on the composition of treated nectarine peels. The results highlight a reduction in cell wall composition, particularly lignin, following fungal infection. There are significant changes in the content of the bands illustrating phenolic components, aromatic nuclei, cellulose and pectin. A disparity was generally observed between these mixed treatments and the impact of the microbe on the constitution of the fruit skin, which appeared negligible in the combined treatments compared with the others. In addition, previous research analyzing the efficacy of B. amyloliquefaciens combined with SA in combating post-harvest green mold on citrus fruit revealed that FTIR analysis of the citrus coating revealed notable changes in the bands associated with phenolic and aromatic compounds, indicating potentiation of resistance to the fungal pest [55].

All of the tested treatments significantly affect the weight loss of nectarine fruits in comparison to the control, according to the in vivo results on the impact of the aforementioned treatments on fruit quality measures. The treatments that used AM alone at 2% and in conjunction with B10W10 at the same concentration showed the least amount of weight reduction. Also, all AM treatments, either alone or in combination with antagonists significantly decreased TSS with high salt concentrations. Furthermore, the acid content showed no significant statistical difference between chemical control and all other treatments. This suggests that the treatment being tested had a similar effect on both total acidity (TA) and acid content as the chemical treatments. When compared to the water control and the untreated control (pathogen only), all the tested treatments affected fruit firmness. Overall, it seems that all the treatments examined in this study may alter with different degrees some fruit parameters such as weight loss and firmness. Also, it’s important to note that these combinations may slow down the ripening of nectarine fruits and decrease the amount of weight lost. Our results were in line with those obtained by Lyousfi et al. (2021) [60], who demonstrate that the use of SA with bacterial antagonist significantly minimized weight loss while preserving the appearance of the fruit, acidity and TSS content.

This study evaluated the efficacy of combining ammonium molybdate with Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (B10W10) and Pseudomonas sp. (B11W11) for the control of M laxa. In vitro, the combinations B11W11 + 0.5% AM and B10W10 + 2% AM showed the highest inhibition rates after 5 days, with mycelial vacuolation observed under the microscope. The addition of 2% AM to the B10W10 cell filtrate resulted in the most marked inhibition of spores.

In vivo, these treatments significantly reduced the severity of the disease, with the 0.5% AM + B10W10 combination being the most effective. FT-IR analysis revealed structural changes in the fungal biomass, with a decrease in lignin bands and an increase in phenols and polysaccharides, indicating fungal degradation. In addition, treatment with 2% AM limited weight loss in the fruit, although firmness and TSS levels were influenced by salt concentration.

These results confirm the potential of this approach as an alternative to conventional fungicides, providing effective control of brown rot while preserving fruit quality. Further research is needed to optimize its application and improve its efficacy.

Acknowledgement: This work was financially supported by the Phytopathology Unit of the Department of Plant Protection (ENA-Meknes, Morocco).

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contributions to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Kenza Bouzoubaa, Rachid Lahlali; data collection: Kenza Bouzoubaa, Rachid Ezzouggari; analysis and interpretation of results: Kenza Bouzoubaa, Rachid Ezzouggari, Abdellatif Boutagayout; draft manuscript preparation: Kenza Bouzoubaa, Rachid Ezzouggari, Abdellatif Boutagayout, Rachid Lahlali; review and editing: Rachid Lahlali; project administrator: Rachid Lahlali. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data are contained within the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Manganaris GA, Minas I, Cirilli M, Torres R, Bassi D, Costa G. Peach for the future: a specialty crop revisited. Sci Hortic Amst. 2022;305(5):111390. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2022.111390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Obi VI, Barriuso JJ, Gogorcena Y. Peach brown rot: still in search of an ideal management option. Agriculture. 2018;8(8):125. doi:10.3390/agriculture8080125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Food and Agriculture Organization Statistics. Crops and livestock products [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 10]. 2024 Jun 10. Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL. [Google Scholar]

4. Protzman E. Peaches and nectarines: global growth in production slowing while exports plateau [Internet]. [cited 2024 Jun 12]. Available from: https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/peaches-and-nectarines-global-growth-production-slowing-while-exports-plateau. [Google Scholar]

5. Ortega SF, del Pilar Bustos López M, Nari L, Boonham N, Gullino ML, Spadaro D. Rapid detection of Monilinia fructicola and Monilinia laxa on peach and nectarine using loop-mediated isothermal amplification. Plant Dis. 2019;103(9):2305–14. doi:10.1094/PDIS-01-19-0035-RE. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Iqbal S, Abbas A, Mubeen I, Sathish M, Razaq Z, Mubeen M, et al. Taxonomy, distribution, epidemiology, disease cycle and management of brown rot disease of peach (Monilinia spp.). Not Bot Horti Agrobot Cluj-Napoca. 2022;50(1):12630. doi:10.15835/nbha50112630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Martini C, Mari M. Chapter 7-Monilinia fructicola, Monilinia laxa (Monilinia rot, brown rot). In: Bautista-Baños S, editor. Postharvest decay. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2014. p. 233–65. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-411552-1.00007-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Egüen B, Melgarejo P, de Cal A. Sensitivity of Monilinia fructicola from Spanish peach orchards to thiophanate-methyl, iprodione, and cyproconazole: fitness analysis and competitiveness. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2015;141(4):789–801. doi:10.1007/s10658-014-0579-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Garcia-Benitez C, Casals C, Usall J, Sánchez-Ramos I, Melgarejo P, De Cal A. Impact of postharvest handling on preharvest latent infections caused by Monilinia spp. in nectarines. J Fungi. 2020;6(4):266. doi:10.3390/jof6040266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Larena I, Villarino M, Melgarejo P, Cal AD. Epidemiological studies of brown rot in Spanish cherry orchards in the Jerte valley. J Fungi. 2021;7(3):203. doi:10.3390/jof7030203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Crowley-Gall A, Trouillas FP, Niño EL, Schaeffer RN, Nouri MT, Crespo M, et al. Floral microbes suppress growth of Monilinia laxa with minimal effects on honey bee feeding. Plant Dis. 2022;106(2):432–8. doi:10.1094/PDIS-03-21-0549-RE. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Saha S. Fungicides: the uncharted domain. J Mycopathol Res. 2023;61(2):149–55. doi:10.57023/JMycR.61.2.2023.149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Corkley I, Fraaije B, Hawkins N. Fungicide resistance management: maximizing the effective life of plant protection products. Plant Pathol. 2022;71(1):150–69. doi:10.1111/ppa.13467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Corrêa-Junior D, Parente CET, Frases S. Hazards associated with the combined application of fungicides and poultry litter in agricultural areas. J Xenobiotics. 2024;14(1):110–34. doi:10.3390/jox14010007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Fresnedo-Ramírez J, Famula TR, Gradziel TM. Application of a Bayesian ordinal animal model for the estimation of breeding values for the resistance to Monilinia fruticola (G. Winter) honey in progenies of peach [Prunus persica (L.) Batsch]. Breed Sci. 2017;67(2):110–22. doi:10.1270/jsbbs.16027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Ezzouggari R, Bahhou J, Taoussi M, Kallali NS, Aberkani K. Yeast warriors: exploring the potential of yeasts for sustainable citrus post-harvest disease management. Agronomy. 2024;14(2):288. doi:10.3390/agronomy14020288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Chen C, Cai N, Chen J, Wan C. UHPLC-Q-TOF/MS-based metabolomics approach reveals the antifungal potential of pinocembroside against citrus green mold phytopathogen. Plants. 2019;9(1):17. doi:10.3390/plants9010017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Stenberg JA, Sundh I, Becher PG, Björkman C, Dubey M, Egan PA, et al. When is it biological control? A framework of definitions, mechanisms, and classifications. J Pest Sci. 2021;94(3):665–76. doi:10.1007/s10340-021-01354-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Dicklow M. Biofungicides: commercial horticulture [Internet]. Amherst, MA, USA: University of Massachusetts Amherst; 2023 [cited 2025 Jan 10]. Available from: https://ag.umass.edu/greenhouse-floriculture/fact-sheets/biofungicides. [Google Scholar]

20. Bonaterra A, Mari M, Casalini L, Montesinos E. Biological control of Monilinia laxa and Rhizopus stolonifer in postharvest of stone fruit by Pantoea agglomerans EPS125 and putative mechanisms of antagonism. Int J Food Microbiol. 2003;84(1):93–104. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(02)00403-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Hussain T, Khan AA, Mohamed HI. Metabolites composition of Bacillus subtilis HussainT-AMU determined by LC-MS and their effect on fusarium dry rot of potato seed tuber. Phyton-Int J Exp Bot. 2023;92(3):783–99. doi:10.32604/phyton.2022.026045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gotor-Vila A, Teixidó N, Casals C, Torres R, De Cal A, Guijarro B, et al. Biological control of brown rot in stone fruit using Bacillus amyloliquefaciens CPA-8 under field conditions. Crop Prot. 2017;102(4):72–80. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2017.08.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ait Bahadou S, Ouijja A, Karfach A, Tahiri A, Lahlali R. New potential bacterial antagonists for the biocontrol of fire blight disease (Erwinia amylovora) in Morocco. Microb Pathog. 2018;117(2):7–15. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2018.02.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Lahlali R, Aksissou W, Lyousfi N, Ezrari S, Blenzar A, Tahiri A, et al. Biocontrol activity and putative mechanism of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (SF14 and SP10Alcaligenes faecalis ACBC1, and Pantoea agglomerans ACBP1 against brown rot disease of fruit. Microb Pathog. 2020;139:103914. doi:10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Moraes Bazioli J, Belinato JR, Costa JH, Akiyama DY, de Moraes Pontes JG, Kupper KC, et al. Biological control of citrus postharvest phytopathogens. Toxins. 2019;11(8):460. doi:10.3390/toxins11080460. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Lu L, Ji L, Qiao L, Zhang Y, Chen M, Wang C, et al. Combined treatment with Rhodosporidium paludigenum and ammonium molybdate for the management of green mold in satsuma mandarin (Citrus unshiu Marc.). Postharvest Biol Technol. 2018;140:93–9. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2018.01.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Hrustić J, Delibašić G, Stanković I, Grahovac M, Krstić B, Bulajić A, et al. Monilinia spp. causing brown rot of stone fruit in Serbia. Plant Dis. 2015;99(5):709–17. doi:10.1094/PDIS-07-14-0732-RE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Sultana F, Hossain MM. Assessing the potentials of bacterial antagonists for plant growth promotion, nutrient acquisition, and biological control of southern blight disease in tomato. PLoS One. 2022;17(6):e0267253. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0267253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Lyousfi N, Letrib C, Legrifi I, Blenzar A, El Khetabi A, El Hamss H, et al. Combination of sodium bicarbonate (SBC) with bacterial antagonists for the control of brown rot disease of fruit. J Fungi. 2022;8(6):636. doi:10.3390/jof8060636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Xu Y, Wang L, Liang W, Liu M. Biocontrol potential of endophytic Bacillus velezensis strain QSE-21 against postharvest grey mould of fruit. Biol Control. 2021;161(2):104711. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2021.104711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. El Khetabi A, Ezrari S, El Ghadraoui L, Tahiri A, Ait Haddou L, Belabess Z, et al. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of nine commercial essential oils against brown rot in apples. Horticulturae. 2021;7(12):545. doi:10.3390/horticulturae7120545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Li Z, Guo B, Wan K, Cong M, Huang H, Ge Y. Effects of bacteria-free filtrate from Bacillus megaterium strain L2 on the mycelium growth and spore germination of Alternaria alternata. Biotechnol Biotechnol Equip. 2015;29(6):1062–8. doi:10.1080/13102818.2015.1068135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Shankar A, Saini S, Sharma KK. Fungal-integrated second-generation lignocellulosic biorefinery: utilization of agricultural biomass for co-production of lignocellulolytic enzymes, mushroom, fungal polysaccharides, and bioethanol. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(1):1117–31. doi:10.1007/s13399-022-02969-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Dzurendova S, Zimmermann B, Kohler A, Tafintseva V, Slany O, Certik M, et al. Microcultivation and FTIR spectroscopy-based screening revealed a nutrient-induced co-production of high-value metabolites in oleaginous Mucoromycota fungi. PLoS One. 2020;15(6):e0234870. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234870. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Beger G, Maia JN, Linhares JC, Peres NA, Nesi CN, May De Mio LL, et al. Comparing fungicides and biologicals for grey mould control in semi-hydroponic strawberry cultivation. J Phytopathol. 2024;172(4):e13356. doi:10.1111/jph.13356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Navajas-Preciado B, Rocha-Pimienta J, Martillanes S, Galván A, Izaguirre-Pérez N, Delgado-Adámez J. Application of microbial antagonists in combination with sodium bicarbonate to control post-harvest diseases of sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.) and plums (Prunus salicina Lindl.). Appl Sci. 2024;14(23):10978. doi:10.3390/app142310978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Xiong B, Han L, Ou Y, Wu W, Wang J, Yao J, et al. Effects of different postharvest treatments on fruit quality, sucrose metabolism, and antioxidant capacity of ‘newhall’ navel oranges during storage. Plants. 2025;14(5):802. doi:10.3390/plants14050802. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Al-Gaadi KA, Zeyada AM, Tola E, Alhamdan AM, Ahmed KAM, Madugundu R, et al. Impact of storage conditions on fruit color, firmness and total soluble solids of hydroponic tomatoes grown at different salinity levels. Appl Sci. 2024;14(14):6315. doi:10.3390/app14146315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Banyal S, Kumari A, Sharma SP, Dhaliwal YS. Effect of varieties and storage on the quality parameters of nectarine (Prunus persica)-based intermediate moisture food (IMF) products. J Appl Nat Sci. 2022;14(1):216–24. doi:10.31018/jans.v14i1.3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Luo X, Zhao Y, Tian S, Yu Y, Rao X, Xu W, et al. Characterize firmness changes of nectarine and peach fruit associated with harvest maturity and storage duration using parameters of force-displacement curves. J Texture Stud. 2025;56(1). doi:10.1111/jtxs.70003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Rodríguez-Pires S, Garcia-Companys M, Espeso EA, Melgarejo P, de Cal A. Influence of light on the Monilinia laxa-stone fruit interaction. Plant Pathol. 2021;70(2):326–35. doi:10.1111/ppa.13294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Janisiewicz WJ, Korsten L. Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruits. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2002;40(1):411–41. doi:10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.120401.130158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Spadaro D, Gullino ML. State of the art and future prospects of the biological control of postharvest fruit diseases. Int J Food Microbiol. 2004;91(2):185–94. doi:10.1016/S0168-1605(03)00380-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Obagwu J, Korsten L. Integrated control of citrus green and blue molds using Bacillus subtilis in combination with sodium bicarbonate or hot water. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2003;28(1):187–94. doi:10.1016/S0925-5214(02)00145-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Nunes C, Usall J, Teixidó N, Vinas I. Improvement of Candida sake biocontrol activity against post-harvest decay by the addition of ammonium molybdate. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92(5):927–35. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2002.01602.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Sharma RR, Singh D, Singh R. Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruits and vegetables by microbial antagonists: a review. Biol Control. 2009;50(3):205–21. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Janakiev T, Dimkić I, Unković N, Ljaljević Grbić M, Opsenica D, Gašić U, et al. Phyllosphere fungal communities of plum and antifungal activity of indigenous phenazine-producing Pseudomonas synxantha against Monilinia laxa. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2287. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.02287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Calvo H, Oria R, Blanco D, Venturini ME. Potential of a new strain of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens BUZ-14 to control Monilinia fructicola and M. laxa in peaches: preliminary studies. In: Proceedings of the VIII International Postharvest Symposium: Enhancing Supply Chain and Consumer Benefits-Ethical and Technological Issues; 2016 Jun 21–24; Cartagena, Spain. [Google Scholar]

49. Hamid M, Siddiqui IA, Shahid Shaukat S. Improvement of Pseudomonas fluorescens CHA0 biocontrol activity against root-knot nematode by the addition of ammonium molybdate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003;36(4):239–44. doi:10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01299.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Wan YK, Tian SP, Qin GZ. Enhancement of biocontrol activity of yeasts by adding sodium bicarbonate or ammonium molybdate to control postharvest disease of jujube fruits. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2003;37(3):249–53. doi:10.1046/j.1472-765X.2003.01385.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Liu HM, Guo JH, Luo L, Liu P, Wang BQ, Cheng YJ, et al. Improvement of Hanseniaspora uvarum biocontrol activity against gray mold by the addition of ammonium molybdate and the possible mechanisms involved. Crop Prot. 2010;29(3):277–82. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2009.10.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Qin GZ, Tian SP, Xu Y, Chan ZL, Li BQ. Combination of antagonistic yeasts with two food additives for control of brown rot caused by Monilinia fructicola on sweet cherry fruit. J Appl Microbiol. 2006;100(3):508–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02821.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Wu G, Liu Y, Xu Y, Zhang G, Shen Q, Zhang R. Exploring elicitors of the beneficial rhizobacterium Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 to induce plant systemic resistance and their interactions with plant signaling pathways. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 2018;31(5):560–7. doi:10.1094/MPMI-11-17-0273-R. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Delgado-Adámez J, Fuentes-Pérez G, Velardo-Micharet B, González-Gómez D. Application of microbial antagonists in combination with sodium bicarbonate to control postharvest diseases of sweet cherries. Acta Hortic. 2017;1161:529–33. doi:10.17660/ActaHortic.2017.1161.84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. El Hamss H, Kajad N, Belabess Z, Lahlali R. Enhancing bioefficacy of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SF14 with salicylic acid for the control of the postharvest citrus green mould. Plant Stress. 2023;7:100144. doi:10.1016/j.stress.2023.100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Carmona-Hernandez S, Reyes-Pérez JJ, Chiquito-Contreras RG, Rincon-Enriquez G, Cerdan-Cabrera CR, Hernandez-Montiel LG. Biocontrol of postharvest fruit fungal diseases by bacterial antagonists: a review. Agronomy. 2019;9(3):121. doi:10.3390/agronomy9030121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Nadjara M, Aline K, Katia S, Kupper C. Bacillus subtilis based-formulation for the control of postbloom fruit drop of citrus. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;32(12):205. doi:10.1007/s11274-016-2157-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Wiyono S, Schulz DF, Wolf GA. Improvement of the formulation and antagonistic activity of Pseudomonas fluorescens B5 through selective additives in the pelleting process. Biol Control. 2008;46(3):348–57. doi:10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.04.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Palou L, Usall J, Smilanick JL, Aguilar MJ, Viñas I. Evaluation of food additives and low-toxicity compounds as alternative chemicals for the control of Penicillium digitatum and Penicillium italicum on citrus fruit. Pest Manag Sci. 2002;58(5):459–66. doi:10.1002/ps.477. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Lyousfi N, Lahlali R, Letrib C, Belabess Z, Ouaabou R, Ennahli S, et al. Improving the biocontrol potential of bacterial antagonists with salicylic acid against brown rot disease and impact on nectarine fruits quality. Agronomy. 2021;11(2):209. doi:10.3390/agronomy11020209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools