Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Nano Silver Particles Applications on Rooting of Grapevine Cuttings

1 Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Selcuk University, Konya, 42031, Türkiye

2 Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Kahramanmaraş Sutcu Imam University, Kahramanmaras, 46040, Türkiye

* Corresponding Author: Turhan Yilmaz. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Integrative Approaches to Mitigating Abiotic and Biotic Stresses in Fruit and Vine Crops: Emerging Technologies and Sustainable Solutions)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(6), 1827-1840. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.065702

Received 20 March 2025; Accepted 29 May 2025; Issue published 27 June 2025

Abstract

The reproduction of grapevine genotypes, one of the most important species in the world, while preserving their genetic characteristics, is practically done by rooting cuttings. Adventive rooting of cutting studies for seedling production in nursery conditions often remain below the expected productivity level due to biotic and abiotic stress-related reasons. Studies to increase nursery yields are still on the agenda of grapevine researchers. In this study, the effects of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) produced by the green synthesis method using grape seed extract and AgNO3 on rooting and vegetative growth of the standard (TS 4027) cuttings taken during the dormancy period of Vitis vinifera L. cvs Ekşi Kara and Gök Üzüm were investigated under greenhouse conditions. Cuttings treated by keeping in 0.1, 0.2 g·L−1 AgNPs, 0.1, 0.2 g·L−1 IBA aqueous solutions for 24 h were planted in black, 1 L volume seedling bags filled with 1:1 peat: perlite in the greenhouse, while the control was kept in pure water for 24 h and planted. Changes in sprouting rate, plant transformation rate, shoot length, shoot diameter, number of nodes, stomatal conductance, leaf temperature, photosynthetic efficiency, leaf fresh and dry weight, SPAD, root number, root length, root fresh and root weight were examined in developing seedlings. In evaluating the effects of AgNPs and Indole-3-butyric acid (IBA) treatments on cutting rooting and vegetative development, ANOVA, post hoc analysis with the Tukey test, and Principal Component Analyses (PCAs) were used to better understand and depict the correlations between the examined variables. This analysis method was performed using ggplot2 in the R Studio program. The heatmap generated by the pheatmap package was used to visualize the correlation and variation. As a result of this study, AgNPs applications were found to be more effective than IBA treatments in the rooting of grapevine cuttings and the vegetative development of young plants. In conclusion, 0.1 g·L−1 AgNPs can be tested as a support and/or economical alternative to IBA for the promotion of rooting of cuttings and vegetative development of young plants for subsequent clonal propagation.Keywords

Since grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) is one of the most important species in the world in terms of vineyard area and the economic and nutritional value of grapes [1], for fresh consumption or as an industrial product [2], the propagation of grapevine genotypes is essential. Viticulture has historically been dependent on clonal propagation of grape and grapevine rootstock varieties. Consumers’ preference for traditional varieties necessitates the preservation of varieties with known characteristics. This is achieved through clonal propagation. Adventitious root formation (ARF) is the key component of clonal propagation success [3]. Cuttings are used as a traditional material in ARF research. However, the phenotypic heterogeneity caused by the complex background has affected its use in investigating the molecular mechanism of ARF in grapevine [4]. Although propagation by cuttings is widely used in production practice as an important technique of asexual reproduction, the low ARF rate of some superior plants still restricts the rapid development of propagation by cuttings technology, and the key to improving the cutting rooting rate of plants is to find the regulation mechanism [5]. ARF is the postembryonic formation of new roots from non-root tissue cells. ARF plays an important role in clonal propagation and maintenance of elite germplasm [6,7]. However, successful clonal propagation remains a challenge in many cases where ARF is either very weak or completely unsuccessful [8]. ARF occurs in three consecutive and interconnected phases, namely induction, initiation, and expression phases. The rhizogenic effect of auxin begins in the induction phase [9]. Enzyme peroxidases catalyze the lignification process of the cell wall in the induction phase [10]. A higher auxin is required at this stage. However, phytohormones become inhibitory at the formation stage. In the late stimulation phase, ethylene and cytokinin showed inhibitory effects [11]. During the induction phase, dedifferentiation also occurs. In this step, the cell acquires the competence for proliferation and organ differentiation. Previously activated cells become committed to the formation of root primordia by the rhizomic action of auxins during the induction phase process. The first step in the cutting propagation process is the establishment of a new viable root connection through the initiation and growth of the ARF [12]. Auxin is the main stimulatory hormone for initiating ARF. Natural IAA supports ARF, maintains homeostasis, and is associated with various developmental stages of the rooting process [13,14]. In different plant species, increased auxin levels are substantially higher for ARF in the early developmental stages than in the later stages. Generally, IBA and NAA are recommended to promote ARF in the propagation of many species by shoot cuttings [15]. Clonal propagation by cuttings guarantees the characteristics of the species or new varieties. In asexual propagation, ARF is the precursor to successful propagation [16]. However, ARF is difficult in many important grapevine genotypes [3,17–20]. In studies on ARF in grapevines, generally, dormant hardwood cuttings with buds and cuttings with fresh leaves are used [21–24]. However, cuttings are a rather complex system where endogenous hormone levels, transport, dormancy, storage, inhibitory compounds, bud burst, and the time of taking the cuttings affect the ARF and the growth of the developing plants, all of which depend on pretreatment and can affect rooting [3,25]. These factors make it difficult to investigate the function and molecular regulatory mechanism of factors affecting ARF in grapevine cuttings [4]. Auxin is one of the most important hormones used in shoot cuttings to accelerate the development of adventitious roots [26]. Auxin affects root development and increases the rooting percentage of cuttings [27]. Young shoots and leaves on plants produce natural auxin, but successful rooting of cuttings requires the application of synthetic auxins [28]. Young shoots and leaves on plants produce natural auxin, but successful rooting of cuttings requires the application of synthetic auxins [29]. Despite the apparent difficulties associated with the use of auxins, there are numerous reports that auxins improve the rooting of grapevine cuttings, as evidenced by their successful use in in vitro rooting of non-dormant material [14,19,28], but in some cases, no effects of IBA have been reported [30], and there are enough inconsistencies to make these reports questionable. Finally, several rootstocks and their hybrids show improved rooting when treated with IBA [30–32]. It should be kept in mind that IBA is rapidly converted to IAA in grapevines [33] and other woody taxa [34]. Nanoparticles (NPs) are matrix systems prepared with natural or synthetic polymers, with dimensions ranging from 1 to 100 nm, called nanospheres or nanocapsules depending on the preparation method, and in which the active substance is dissolved, trapped, and/or absorbed or bound to the surface within the particle. The green method of NPs synthesis is an alternative to chemical and physical methods as it provides an environmentally friendly way of synthesizing NPs. Also, green synthesis does not require expensive, harmful, and toxic chemicals. Metallic NPs with various shapes, sizes, contents, and physicochemical properties can be synthesized. In recent years, green synthesis has been done using biological organisms such as fungi, bacteria, actinobacteria, yeasts, molds, and algae, as well as plants and their products. Molecules and pigments in plants or microorganisms, such as proteins, enzymes, phenolic compounds, amines, and alkaloids, are used as reducing agents in NPs synthesis [35]. AgNPs were synthesized using various non-toxic and biodegradable plant extracts [36–38], and AgNO3 as green reductants, and their activities were tested. Filippi et al. [39] showed that silver could induce programmed cell death in grapevine suspension cell cultures mediated by caspase-3-like activity and oxidative stress. In sustainable agriculture, NPs provide a safeguard for better management and protection of crop production inputs. The potential of NPs promotes a new green revolution that reduces agricultural risks. However, there are still large gaps in our knowledge about the various activities, allowable limits, and ecotoxicity of different NPs [40,41]. AgNPs are easy to synthesize and environmentally friendly. Therefore, there is a need to determine the production, behavior, and interactions of nano agricultural inputs, especially those produced by green synthesis, in living systems and environments. AgNPs (size range 10–20 nm) consist of silver ions as their major components. These particles have high activity and effectiveness in living systems [42]. These can be produced by various methods such as physical, chemical, and biological methods etc. The areas of use of AgNPs include breaking seed dormancy, increasing seed viability index, improving seedling fresh weight [43,44], and cutting rooting [37]. AgNPs of various sizes and shapes are being developed. They have a core-shell structure consisting of a metallic silver core and typically a coating that helps control the size of the AgNPs during synthesis and provides a surface charge to stabilize the AgNPs in solution [45]. AgNPs improved the vegetative growth and yield in (Borago officinalis) plants [46] and basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) [47], maximized the number of shoots in vitro propagation of node explants of African and French marigolds Pusa Basanti garuda and Pusa Arpita [48], accelerated root growth in Asian rice (Oryza sativa) [49], seed germination [50], promoted crop productivity [51], significantly stimulated plant metabolism, gene expression, and antioxidant enzyme activity [52]. It improved growth in cowpea, tuber development, and shoot growth in Brassica [53] and growth in Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum) [54]. Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra L.) in vitro culture provided a significant increase in shoot growth and a decrease in the number of stomata and hairy structures, its effects on the anatomical structures of organs, increased cell division in root and shoot tips and increased intercellular spaces in the mesophyll, decreased vascular tissues and sclerenchyma fiber (lignified cell walls), increased Casparian strip thickness and cell walls of the endodermis, and decreased thickness of the epidermis were detected. These effects were attributed to the inhibitory effect of AgNO3 on ethylene production and function and increased tolerance to silver metal [55]. By applying AgNPs to explants, microbial contaminants were successfully controlled, callus formation, organogenesis, and shoot growth in vitro olive (Olea europaea) culture [56], and their positive role in somatic embryogenesis, somaclonal variation, genetic transformation, and secondary metabolite production was proven [57].

In this study, the effects of AgNPs produced by the green synthesis method using grape seed extract and AgNO3 on the rooting and vegetative development of standard cuttings taken during the dormancy period of Vitis vinifera L. cvs Ekşi Kara and Gök Üzüm were investigated under greenhouse conditions.

2.1.1 Plant Resources and Research Location

Two grape varieties (Vitis vinifera L. cv; Ekşi Kara, variety number VIVC; 3852 and cv Gök Üzüm, variety number VIVC; 4847) were used in the study conducted in the 2022–2023 period. Dormant cuttings were taken from the clone vineyard of Selcuk University, Konya, at an altitude of 1200 m above sea level. The cuttings taken for this experiment were 8-year-old vines planted with 2.0 m within the row and 3.0 m between the rows, with a density of approximately 1600 vines per hectare. Viticulture procedures, including fertilization, pruning management, agricultural pesticides for control of grapevine diseases and pests, and irrigation, were routinely applied to both selected varieties. Fertilization was applied to the vineyards according to the soil analysis results, and each vineyard’s soil was plowed four times, and weed growth was suppressed by tillage. The common feature of the two grape varieties selected in the study is that they are well adapted to vineyard areas at the highest altitude (1000–1700 m above sea level), where climate extremes are experienced very frequently.

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) were produced from Ekşi Kara grape seeds extract and AgNO3 (Sigma, CAS No. 7761-88-8) by the Green synthesis method and used in the experiment at doses of 1 g·L−1 AgNPs and 2 g·L−1 AgNPs. In the FTIR (Fourier transforms infrared spectroscopy) analysis of AgNPs, it was confirmed that the AgNPs loaded into the solution were successfully incorporated into the nanoparticle (NP) skeletal structure with the adsorbed grape seed extracts, and that different functional groups emerged with surface interaction. In the XRD analysis (D8 Advance brand diffractometer), it was observed that the AgNPs formed crystal structures and spectra. The peaks were attributed to the tetragonal crystal structure and were evaluated as strong evidence of the complex formation between the grape seed extract component and AgNPs. The determination of the morphological structures of the nanoparticles was also characterized by TEM (Transmission electron microscopy, JEOL JEM 2100 UHR-TEM). In the TEM analysis, it was determined that the NPs were spherical or close to spherical and their sizes were in the range of 10–20 nm [58].

Indole butyric acid (IBA) used in the experiment was supplied by Merck (CAS No. 133-32-4). IBA doses were 0.1 g·L−1 and 0.2 g·L−1, and both chemicals were applied by soaking in water for 24 h.

Analytical Techniques for Evaluating the Rooting and Vegetative Development

This study was conducted in a randomized complete block design with three replications. In the study, standard dormant cuttings of two grape varieties were used in each experimental plot as 10 pieces. Two IBA (0.1 g·L−1 and 0.2 g·L−1), two AgNPs (1 g·L−1 and 2 g·L−1), and one control (soaking in distilled water for 24 h) treatments were evaluated, totaling 300 cuttings. Grapevine cuttings were prepared according to the rootstock cutting standard (TS 4027). AgNPs and IBA applications were applied to dormant cuttings approximately 5 cm from the cutting base in the form of 24-h soaking at the beginning of February 2023. Then, the cuttings were planted in a 1 L volume (25 × 12 cm) medium containing 1:1 peat perlite, and their development was followed in a heated polycarbonate greenhouse. Routine irrigation, fertilization, and pesticide applications were made for protection purposes. The trial was a randomized plot design with three replications, and each replication had ten cuttings. The effects of the applications on rooting and vegetative development of the cuttings were recorded as shoot rate, plant transformation rate, shoot diameter at the end of vegetation, shoot length, and number of nodes. Stomatal conductance and leaf temperature were measured with a leaf porometer (Meter SC-I Leaf Porometer) between 10:00 and 13:00 on healthy and sun-exposed leaves that had just reached full size. Stomatal conductance and leaf temperature values of three healthy leaves were measured on each seedling, and the average of the measurements made on 10 seedlings was recorded. Leaf area (cm2) was determined by scanning 10 leaves from each replication with a scanner connected to a computer in the WinFolia program, and the average leaf area was determined. Photosynthetic activity (PhiPSII) was measured with a LI-COR brand LI-600 fluorometer device between 09.30 and 10.30 in the morning on cloudless days, on leaves that had just reached full size. PhiPSII values were determined by taking the average of the measurements. Leaf fresh and dry weights were determined by weighing the fresh and dry weights of ten healthy and mature leaves from the middle 1/3 of the shoots developed from the cuttings at the end of vegetation with a precision scale, and the average leaf weights were determined. Leaf chlorophyll density (SPAD value) was measured in the middle 1/3 of the shoots, mature, sun-exposed, and healthy leaves (10 leaves from each replication), and the greenness index was measured with a Minolta SPAD meter (model 520). Root number and root thickness (root numbers thicker than 2 mm and longer than 10 cm were taken as a basis) were calculated as the averages of the determinations made on 10 seedlings for each replication. Total root lengths were measured with a tape measure from the root beginning of the shoots at the end of the vegetation period, and average values were determined. Root fresh and dry weights were determined (Mettler Toledo LA84) by removing the roots of the seedlings from the soil at the end of vegetation, cutting them from the root beginning, and weighing them with a precision scale. Root dry weights were recorded by weighing the roots after they were dried in the oven (Labor brand Test 420St model) at 72°C for 48 h.

In this study, statistical packages available in R Studio were used for all descriptive analyses. A comprehensive analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted using the capabilities of the statistical package in R Studio. The effects of two grape varieties (two levels) and two rooting chemical treatments (five levels) on rooting and vegetative growth traits (sixteen levels) were comprehensively evaluated at the p-value is 0.05 significance level. The effects were included in the statistical model, and then the data were checked for compliance with normality assumptions. Two separate models were carefully constructed to evaluate the main effects of rooting-promoting treatments on rooting and vegetative growth levels. When an ANOVA revealed statistical significance, post hoc analysis was performed with the Tukey test, an accepted technique for comprehensively investigating differences between various groups. Principal Component Analyses (PCAs) were used to better understand and depict correlations between different variables. This analysis method was performed using the ggplot2 package in R Studio. The pheatmap package in R Studio was used to create the heatmap, which shows the relationships and differences in the datasets under analysis [59].

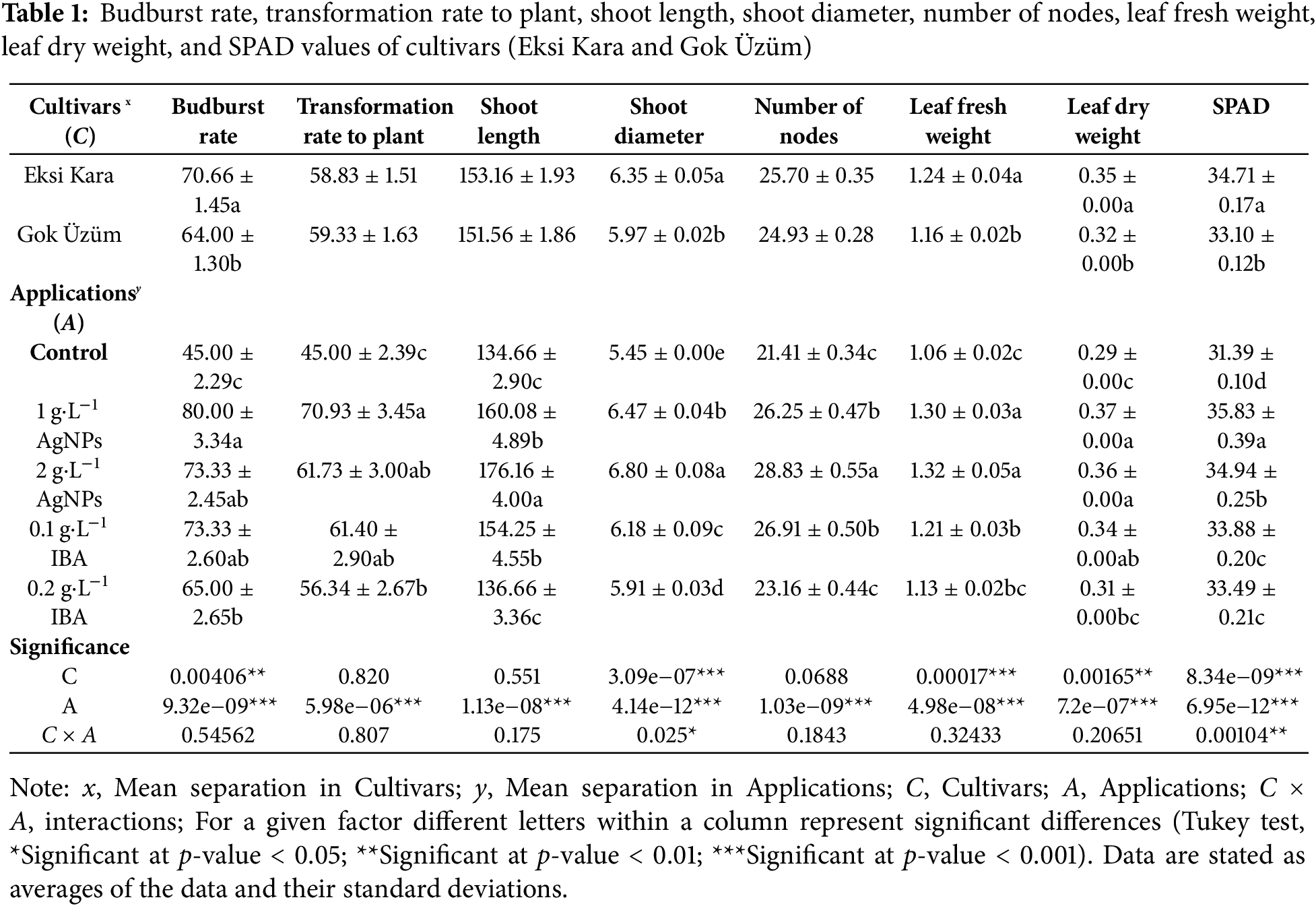

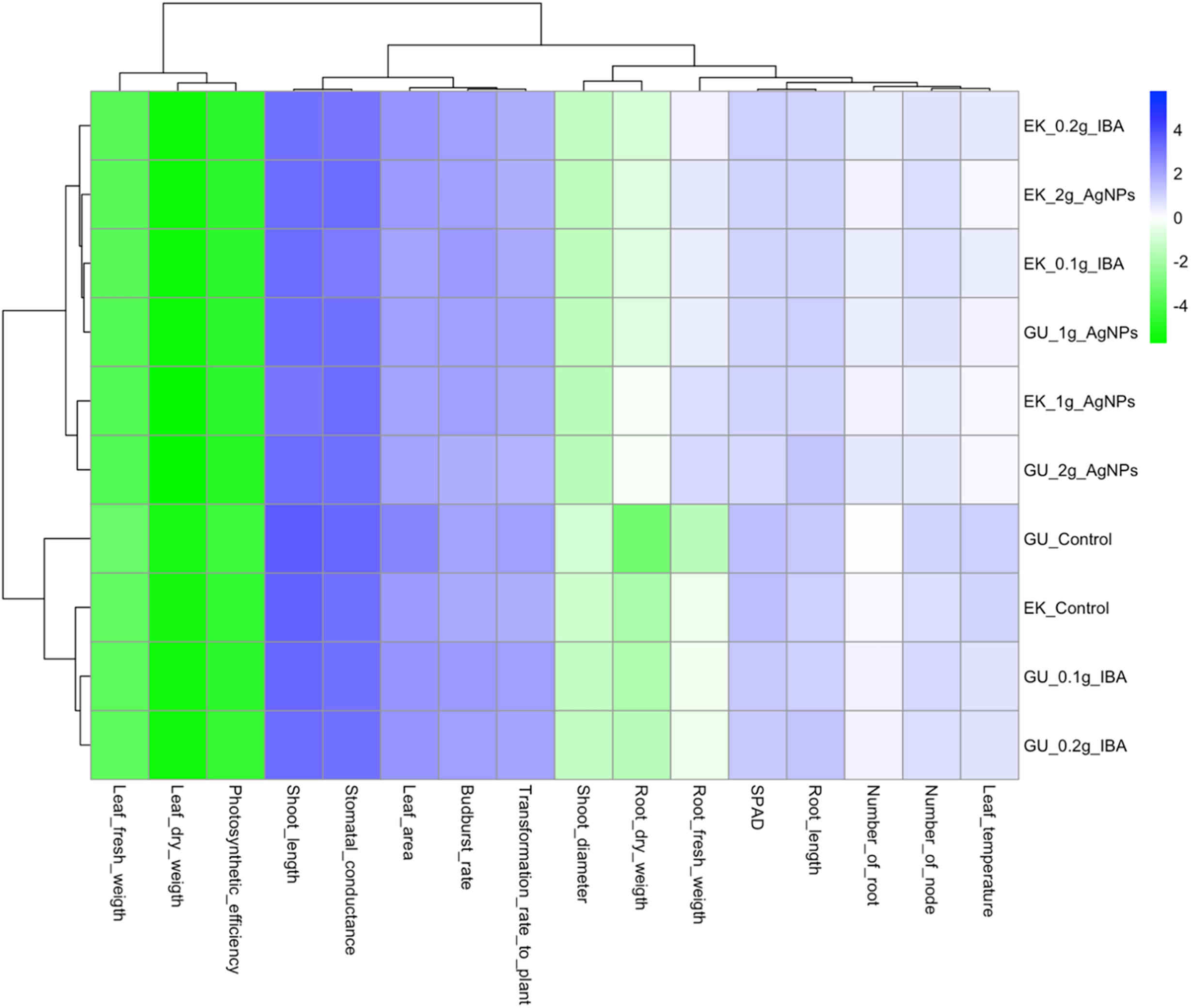

Budburst rate, shoot diameter, leaf fresh weight, leaf dry weight, and SPAD were statistically different in the two cultivars. Cv Eksi Kara cuttings had a higher bud burst rate, shoot diameter, leaf fresh weight, leaf dry weight, and SPAD than cv Gok Üzüm cuttings. However, there are no statistically significant differences in the transformation rate to plant, shoot length, and number of nodes for the cultivars Eksi Kara and Gok Üzüm. While the treatments of 1 g·L−1 AgNPs were statistically the best application on the bud burst rate, transformation rate to plant, leaf fresh weight, leaf dry weight, and SPAD values, 2 g·L−1 AgNPs treatments had great shoot length and number of nodes (Table 1). There are statistically significant differences in the number of roots, root length, root fresh weight, root dry weight, stomatal conductance, photosynthetic efficiency, and leaf area, except leaf temperature, among the cultivars. Cv Eksi Kara saplings had a greater number of roots, root fresh weight, root dry weight, stomatal conductance, photosynthetic efficiency, and leaf area values than cv Gok Üzüm saplings. While the treatments of 1 g·L−1 AgNPs were statistically the best application on the number of roots, root fresh weight, root dry weight, stomatal conductance, and photosynthetic efficiency, 2 g·L−1 AgNPs treatment had great root length. Control had a greater value than the other treatments in the leaf temperature (Table 2 and Fig. 1a–e).

Figure 1: AgNPs and IBA effects on rooting of grapevine dormant cuttings. The images in the upper row belong to cv Ekşi Kara, and those in the lower row belong to cv Gök Üzüm. (a), control, (b), 1 g·L−1 AgNPs, (c), 2 g·L−1 AgNPs, (d), 0.1 g·L−1 IBA, (e), 0.2 g·L−1 IBA applications are presented as representatives

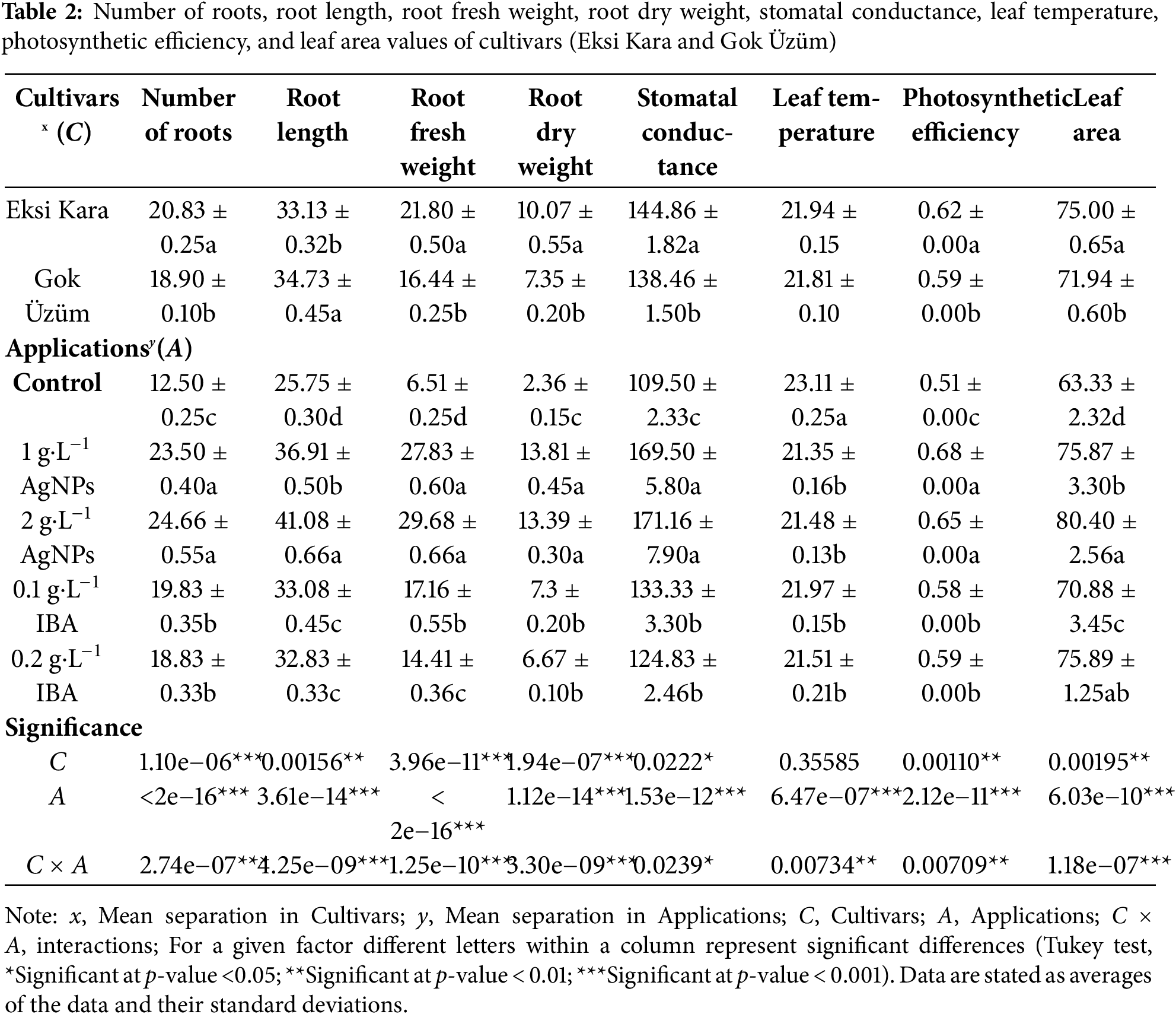

When the eigenvalues and their orders were examined, the first eigenvalue (PC1) accounted for 74.4% of the variance, and the second eigenvalue (PC2) accounted for 6.2% of the variance (Fig. 2a). Grapevine genotypes differed in their effects across treatments, with the greatest differences occurring in leaf temperature. PCA biplots were colored by grapevine genotypes (Fig. 2a) and cultivars (Fig. 2b). In the individual factor grouping map, it was separated from the control AgNPs and IBA applications. AgNPs applications were positively separated from IBA applications. In other words, AgNPs treatments significantly increased the rooting and vegetative development properties of grapevine saplings compared to IBA treatments. The coordinates of the investigated features showed accumulation in the range of −4–−7 and −4–2. IBA applications were separated depending on the dose. 0.2 g·L−1 IBA treatments were positively separated from 0.1 g·L−1 IBA treatments. In AgNPs treatments, while the effects of application doses on some features overlapped, there were also non-overlapping features (Fig. 2c). A heat map analysis was created and presented, examining the individual effect components of the treatments. The individual factors, in decreasing order, bud burst, plant transformation rate, shoot length, shoot diameter, node number, leaf fresh weight, leaf dry weight, and SPAD values, were positively correlated with the other traits studied. Again, in decreasing order, root number, root length, root fresh weight, root dry weight, stomatal conductance, leaf temperature, photosynthetic activity, and leaf area were negatively correlated (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2: PCA biplot of colored via cultivars and applications. Budburst rate, transformation rate to plant, shoot length, shoot diameter, number of nodes, leaf fresh weight, leaf dry weight, SPAD, number of roots, root length, root fresh weight, root dry weight, stomatal conductance, leaf temperature, photosynthetic efficiency, and leaf area variables (a), cultivars (b), applications (c), and correlation of all variables (d) were demonstrated

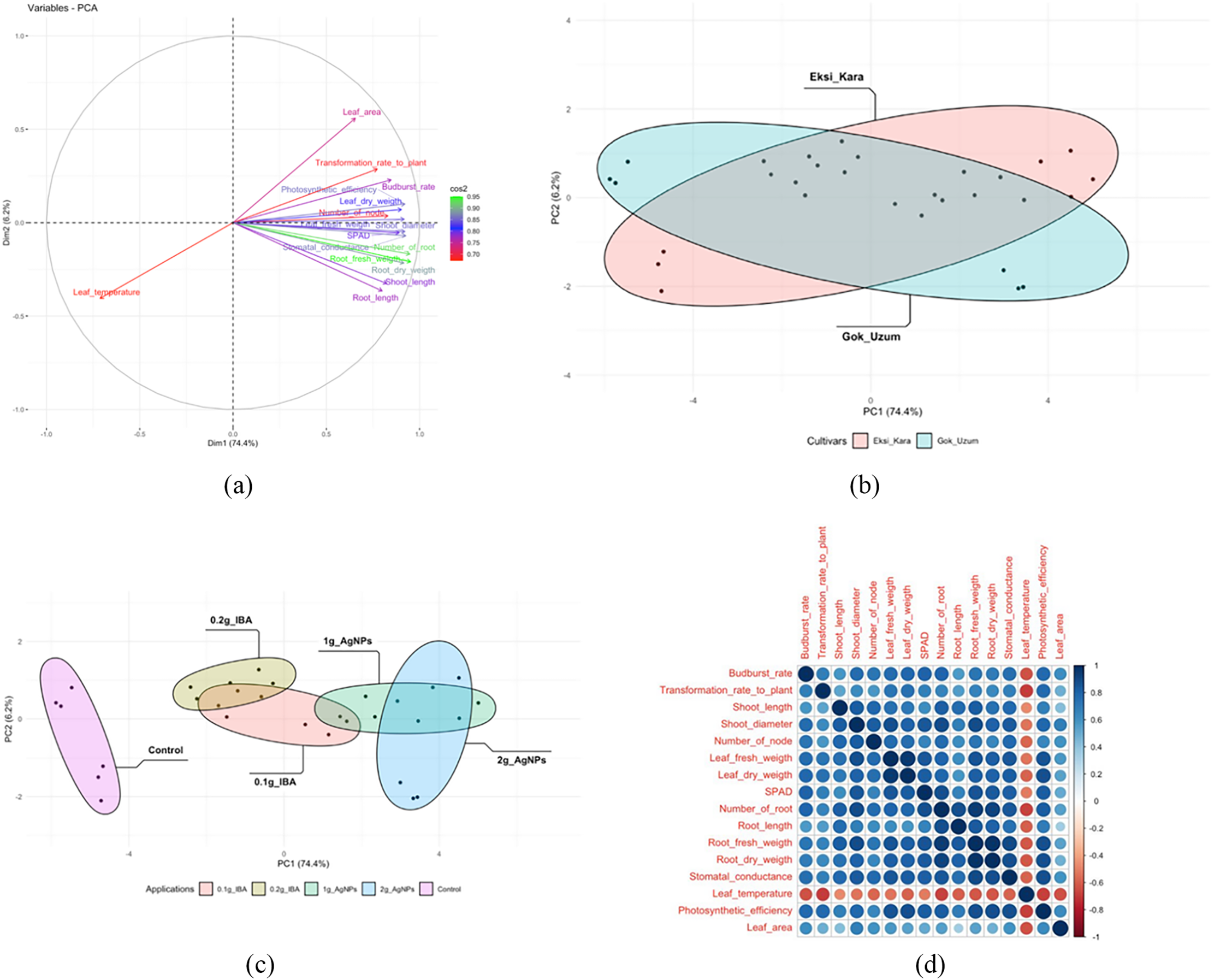

In the divisive hierarchical clustering analysis, cv Gök Üzüm 0.1 g·L−1 AgNPs and Ekşi Kara 0.1 g·L−1 IBA treatments formed a main column with leaf fresh and leaf dry weight and photosynthetic activity values, while all other characteristics were in the second column. Shoot length, stomatal conductance, leaf area, bud burst rate, and plant conversion rate were a subgroup of the traits in the second column, and other traits were also in the second sub-column. The effects of cv Gök Üzüm 0.1 g·L−1 AgNPs and cv Ekşi Kara 0.1 g·L−1 AgNPs treatments were largely similar. The results were largely similar in the cvs Gök Üzüm and Ekşi Kara control. Since rooting and vegetative development values were obtained from cv Ekşi Kara 0.1 g·L−1 and 0.2 g·L−1 IBA treatments, and cv Gök Üzüm 0.1 g·L−1 and 0.2 g·L−1 IBA treatments were quite similar, the 0.1 g·L−1 IBA treatment was prioritized in the following studies. The fact that the application results of cv Ekşi Kara 0.1 g·L−1 AgNPs and cv Gök Üzüm 0.1 g·L−1 AgNPs were in the same group limited the effect of genotypic difference at this dose to a great extent. In other words, the genotypic difference was not found to be very effective in 0.1 g·L−1 AgNPs treatments. However, the effect of grapevine genotype was very significant in 0.2 g·L−1 AgNPs treatments. It was suggested that genotype differences should be considered in subsequent studies in 0.2 g·L−1 AgNPs dose trials (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Performed a heatmap analysis of the components of budburst rate, transformation rate to plant, shoot length, shoot diameter, number of nodes, leaf fresh weight, leaf dry weight, SPAD, number of roots, root length, root fresh weight, root dry weight, stomatal conductance, leaf temperature, photosynthetic efficiency, and leaf area values of Eksi Kara and Gok Üzüm cultivars were illustrated

In a previous study, high doses of AgNPs (25 and 50 ppm) inhibited spontaneous mycorrhizal root colonization in pot-grown Scots pine seedlings, while the 5 ppm dose was recommended as a stimulant for this species, as it increased mycorrhizal colonization and root length and root dry weight [60]. In another study, it was documented that AgNPs increased root growth threefold in in vitro tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and ex vitro Hibiscus rosa sinensis cuttings compared to controls and increased their rooting ability against phytopathogens that inhibit root growth [58]. With the application of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, and 50 mg dm−3 AgNPs, the growth and development of in vitro propagated lavender (Lavandula angustifolia cv Munstead) were positively affected, shoot growth was stimulated, plant weight increased, and roots were more elongated than the control. While 11.8% of the cuttings were rooted in the control, the rooting rate in AgNPs treatments was determined between 39.1% and 88.9%, depending on the dose [61]. It was determined that AgNPs were absorbed by Arabidopsis roots, mostly located in the cell wall and intercellular spaces, and affected root growth dose-dependently. 50 mg·L−1 AgNPs increased root elongation, while 100 mg·L−1 and above concentrations decreased it. Moreover, 50 mg·L−1 AgNPs increased root apical meristem cell number and cell cycle-related gene expression (CYCB1;1), while 100 mg·L−1 and above doses decreased it. These results were shown as evidence that AgNPs regulate root growth by affecting cell division [62]. In the in vitro culture of the Picual olive variety, AgNPs (0, 5, 10, and 20 mg·L−1) gave the highest shoot growth values, and the addition of very low concentrations of AgNPs to the in vitro olive culture medium supplemented with 4 mg·L−1 Zeatin was recommended [63]. 1 mg·L−1 AgNPs treatments promoted rooting and vegetative growth in 41 B grapevine rootstock cuttings, increased shoot length, shoot diameter, number of nodes, and fresh and dry weights of roots and shoots. The highest leaf area and SPAD values were recorded in 1 g·L−1 IBA application [64]. In guava semi-hardwood cuttings, auxin-AgNPs (IBA-AgNPs and NAA-AgNPs) and double-dipping treatments increased rooting efficiency compared to auxin-only treatments, and all root parameters were found to be higher in IBA-AgNPs treatments [65]. In micropropagation of Limonium sinuatum (L.) Mill. ‘White’, rooting time was found to be 3 days shorter in 0.4 mg·L−1 AgNP supplemented medium compared to the control. AgNPs stimulated shoot proliferation and rooting by changing endogenous hormones, and the obtained seedlings were better adapted to greenhouse conditions than the control [66]. In wood cuttings of Dalbergia sissoo Roxb, 50 and 100 mg·L−1 IBA treatments increased the root length (30.53 cm and 25.50 cm, respectively) compared to the control (21.3 cm), while 30 and 60 mg·L−1 AgNPs treatments decreased it (11.5 and 11.56 cm, respectively). IBA and AgNPs treatments increased the shoot’s fresh and dry weight [67]. In adventitious root formation from Quercus robur L. shoot cuttings, the combination of 0.3 mg·L−1 6-Benzylaminopurine and 100 mg·L−1 cefotaxime was found to be the most suitable for shoot multiplication, while 0.1 mg·L−1 NAA and 1/2MS medium were found to be the most effective for root induction [68]. Thomas et al. [22] reported that VvPRP1 and VvPRP2 genes, which are induced during rooting in grapevine shoot cuttings, are rapidly induced in cuttings within 6 h after explant preparation. Furthermore, the transcripts of each gene are most concentrated in the basal part of the cuttings in the region of new root formation. The induction of these genes is not significantly increased by IAA application, and the expression of the VvPRP1 gene can be induced by wounding. VvPRP genes may play an important role in the initiation of new roots in grapevine shoot cuttings, probably by altering the mechanical properties of the cell wall to promote root formation. Grape seed extracts contain varying amounts of monomers, oligomers, and catechin polymers with a flavan-3-ol molecule. These bioactive components are reducing agents and hydrogen-donating antioxidants. Their intrinsic properties are due to the nature of the polyphenol. AgNPs produced from grape seed extract and AgNO3 by the green synthesis method stimulated the rooting of grapevine rootstock cuttings [37].

In this comprehensive study, the effects of IBA and AgNPs treatments on cuttings of cvs Ekşi Kara and Gök Üzüm were carefully monitored. Sixteen rooting and vegetative development parameters were analyzed, which helped to elucidate the complex interactions involved in promoting the rooting and vegetative development of grapevine cultivars. The study found that both grape cultivar cuttings were significantly affected by IBA and AgNPs treatments, with significant variations observed in the studied traits. In addition to IBA, which is well known for its contribution to the rooting and development value of grapevine cuttings, AgNPs treatments, tested for the first time in this study, were determined to have a more stimulating effect on the rooting and vegetative development of grapevine cuttings than IBA. Differences were determined among grapevine cultivars in terms of the effects of the treatments. It was pointed out that dose trials are necessary in grapevine genotypes for fine-tuning of AgNPs treatments. This study mainly emphasized the complex interactions between external stimulant and dose selection, rooting, and vegetative development traits to promote the rooting and vegetative development of grapevine cuttings. Although ecological conditions and the characteristics of grapevine cuttings were not considered in this study, future studies will provide more specific results for comparing both cuttings of grapevine genotypes with standard but different rooting characteristics and the ecologies in which the cuttings were produced. Researchers, grapevine nurseries, and other species cuttings rooting nursery producers can greatly benefit from these results to maximize seedling yield and quality in grapevine propagation and to deepen their understanding of the effectiveness of chemical applications for cuttings rooting, which will further advance the continuous progress of the agricultural and viticultural sectors.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Project design, research, and evaluation of the results, and writing the manuscript: Zeki Kara; Research and evaluation of the results: Dilek Koç; Lab analysis, evaluation of the results, and writing the manuscript: Osman Doğan; Evaluation of the results, and writing the manuscript: Turhan Yilmaz. Zeki Kara and Dilek Koç declare that they have contributed equally to the article. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Puri N, Mishra S, Bahadur V, Prasad V. Effect of PGR on growth and establishment of grapes (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. Thompson seedless under prayagraj agro climatic condition. Int J Plant Soil Sci. 2023;35(12):74–80. doi:10.9734/ijpss/2023/v35i122968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Kumsa F. Factors affecting in vitro cultivation of grape (Vitis vinifera L.a review. Int J Agric Res Innov Technol. 2020;10(1):1–5. doi:10.3329/ijarit.v10i1.48087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Smart DR, Kocsis L, Walker MA, Stockert C. Dormant buds and adventitious root formation by Vitis and other woody plants. J Plant Growth Regul. 2002;21(4):296–314. doi:10.1007/s00344-003-0001-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Chang X, Zhang Y, Yuan K, Ni Y, Ma P, Liu J, et al. A simple, rapid, and quantifiable system for studying adventitious root formation in grapevine. Plant Growth Regul. 2022;98(1):117–26. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-1318845/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sun X, Yang C, Hu Y, Zou X. Rooting mechanism of plant cuttings: a review. J Agric. 2021;11(10):33. [Google Scholar]

6. Bonga J. Conifer clonal propagation in tree improvement programs. In: Park YS, Bonga TM, Moon HK, editors. Vegetative propagation of forest trees. Seoul, Republic of Korea: National Institute of Forest Science; 2016. p. 3–31. [Google Scholar]

7. Díaz-Sala C. A perspective on adventitious root formation in tree species. Plants. 2020;9(12):1789. doi:10.3390/plants10030486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Pant M, Gautam A, Chaudhary S, Singh A, Husen A. Adventitious root formation in ornamental and horticulture plants. In: Husen A, editor. Environmental, physiological and chemical controls of adventitious rooting in cuttings. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 455–69. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-90636-4.00006-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Li SW. Molecular bases for the regulation of adventitious root generation in plants. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:614072. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.614072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Klerk GJD, Keppel M, Brugge JT, Meekes H. Timing of the phases in adventitous root formation in apple microcuttings. J Exp Bot. 1995;46(8):965–72. doi:10.1093/jxb/46.8.965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Agulló-Antón MÁ., Ferrández-Ayela A, Fernández-García N, Nicolás C, Albacete A, Pérez-Alfocea F, et al. Early steps of adventitious rooting: morphology, hormonal profiling and carbohydrate turnover in carnation stem cuttings. Physiol Plant. 2014;150(3):446–62. doi:10.1111/ppl.12114. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Bellini C, Pacurar DI, Perrone I. Adventitious roots and lateral roots: similarities and differences. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65(1):639–66. doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-035645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Druege U, Franken P, Hajirezaei MR. Plant hormone homeostasis, signaling, and function during adventitious root formation in cuttings. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:381. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

14. Lakehal A, Chaabouni S, Cavel E, Le Hir R, Ranjan A, Raneshan Z, et al. A molecular framework for the control of adventitious rooting by TIR1/AFB2-Aux/IAA-dependent auxin signaling in Arabidopsis. Mol Plant. 2019;12(11):1499–514. doi:10.1101/518357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Husen A, Iqbal M, Siddiqui SN, Sohrab SS, Masresha G. Effect of indole-3-butyric acid on clonal propagation of mulberry (Morus alba L.) stem cuttings: rooting and associated biochemical changes. Proc Natl Acad Sci India Sect B Biol Sci. 2017;87(1):161–6. doi:10.1007/s40011-015-0597-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Geiss G, Gutierrez L, Bellini C. Adventitious root formation: new insights and perspectives. In: Beeckman T, editor. Annual plant reviews volume 37: root development. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2009. p. 127–56. [Google Scholar]

17. Kracke H, Cristoferi G, Marangoni B. Hormonal changes during the rooting of hardwood cuttings of grapevine rootstocks. Am J Enol Vitic. 1981;32(2):135–7. doi:10.5344/ajev.1981.32.2.135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Castro PR, Melotto E, Soares F, Passos I, Pommer C. Rooting stimulation in muscadine grape cuttings. Sci Agric. 1994;51(3):436–45. doi:10.1590/s0103-90161994000300009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Keeley K, Preece JE, Taylor BH, Dami IE. Effects of high auxin concentrations, cold storage, and cane position on improved rooting of Vitis aestivalis michx. Norton Cuttings Am J Enol Vitic. 2004;55(3):265–8. doi:10.5344/ajev.2004.55.3.265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shiozaki S, Makibuchi M, Ogata T. Indole-3-acetic acid, polyamines, and phenols in hardwood cuttings of recalcitrant-to-root wild grapes native to East Asia: Vitis davidii and Vitis kiusiana. J Bot. 2013;1(2):819531. doi:10.1155/2013/819531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Kaur S, Cheema S, Chhabra B, Talwar K. Chemical induction of physiological changes during adventitious root formation and bud break in grapevine cuttings. Plant Growth Regul. 2002;37:63–8. [Google Scholar]

22. Thomas P, Lee M, Schiefelbein J. Molecular identification of proline-rich protein genes induced during root formation in grape (Vitis vinifera L.) stem cuttings. Plant Cell Environ. 2003;26(9):1497–504. doi:10.1046/j.1365-3040.2003.01071.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Thomas P, Schiefelbein JW. Roles of leaf in regulation of root and shoot growth from single node softwood cuttings of grape (Vitis vinifera). Ann Appl Biol. 2004;144(1):27–37. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.2004.tb00313.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Jaleta A, Sulaiman M. A review on the effect of rooting media on rooting and growth of cutting propagated grape (Vitis vinifera L). World J Agric Soil Sci. 2019;3(4):1–8. [Google Scholar]

25. Zhou Q, Gao B, Li WF, Mao J, Yang SJ, Li W, et al. Effects of exogenous growth regulators and bud picking on grafting of grapevine hard branches. Sci Hortic. 2020;264(6):109186. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2020.109186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Sahin S, Uysal M. Influence of IBA treatments on root development and mineral uptake of grapevine cuttings. Feb-Fresenius Environ Bull. 2018;27(2):757–64. [Google Scholar]

27. Ahmed S, Jaffar MA, Ali N, Ramzan M, Habib Q. Effect of naphthalene acetic acid on sprouting and rooting of stem cuttings of grapes. Sci Lett. 2017;5(3):225–32. [Google Scholar]

28. Galavi M, Karimian MA, Mousavi SR. Effects of different auxin (IBA) concentrations and planting-beds on rooting grape cuttings (Vitis vinifera). Annu Rev Res Biol. 2013;3(4):517–23. [Google Scholar]

29. Dunsin O, Ajiboye G, Adeyemo T. Effect of alternative hormones on the rootability of Parkia biglobosa. J Agric For Soc Sci. 2014;12(2):69–77. doi:10.4314/joafss.v12i2.8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Alley C. Grapevine propagation. XI. Rooting of cuttings: effects of indolebutyric acid (IBA) and refrigeration on rooting. Am J Enol Vitic. 1979;30(1):28–32. doi:10.5344/ajev.1979.30.1.28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Singh R, Singh P. Effect of callusing and IBA treatments on the performance of hardwood cuttings of Thompson Seedless and Himrod grapes. Punjab Hortic J. 1973;2(3)):166–70. [Google Scholar]

32. Kawai Y. Changes in endogenous IAA during rooting of hardwood cuttings of grape, ‘Muscat Bailey A’ with and without a bud. J Jpn Soc Hortic Sci. 1996;65(1):33–9. doi:10.2503/jjshs.65.33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Epstein E, Lavee S. Conversion of indole-3-butyric acid to indole-3-acetic acid by cuttings of grapevine (Vitis vinifera) and olive (Olea europea). Plant Cell Physiol. 1984;25(5):697–703. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a076762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Van der Krieken W, Kodde J, Visser M, Blaakmeer A, de Groot K, Leegstra L, et al. Increased induction of adventitious rooting by slow release auxins and elicitor. In: Altman A, Waisel Y, editors. Biology of root formation and development. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1997. p. 95–104 doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-5403-5_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Gerami Z, Mahdizadeh FF, Aliyar S, Lajayer BA, Hatami M. The mechanisms involved in the synthesis of biogenic nanoparticles. In: Ghorbanpour M, Shahid MA, editors. Nano-enabled agrochemicals in agriculture. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 63–77. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-91009-5.00029-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Hebbalalu D, Lalley J, Nadagouda MN, Varma RS. Greener techniques for the synthesis of silver nanoparticles using plant extracts, enzymes, bacteria, biodegradable polymers, and microwaves. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2013;1(7):703–12. doi:10.1021/sc4000362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kara Z, Sabır A, Koç F, Sabır FK, Avcı A, Koplay M, et al. Silver nanoparticles synthesis by grape seeds (Vitis vinifera L.) extract and rooting effect on grape cuttings. Erwerbs Obstbau. 2021;63(Suppl 1):1–8. doi:10.1007/s10341-021-00572-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Keshari A, Saxena S, Pal G, Srivashtav V, Srivastav R. Analysing the phytochemistry and anti-oxidant property of fabricated silver nanoparticles using Catharanthus roseus leaf extract. Res J Biotechnol. 2021;16:12. [Google Scholar]

39. Filippi A, Zancani M, Petrussa E, Braidot E. Caspase-3-like activity and proteasome degradation in grapevine suspension cell cultures undergoing silver-induced programmed cell death. J Plant Physiol. 2019;233(20):42–51. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2018.12.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Li M, Ahammed GJ, Li C, Bao X, Yu J, Huang C, et al. Brassinosteroid ameliorates zinc oxide nanoparticles-induced oxidative stress by improving antioxidant potential and redox homeostasis in tomato seedling. Front Plant Sci. 2016;7:615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

41. He X, Deng H, Hwang HM. The current application of nanotechnology in food and agriculture. J Food Drug Anal. 2019;27(1):1–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

42. Mishra S, Singh BR, Singh A, Keswani C, Naqvi AH, Singh H. Biofabricated silver nanoparticles act as a strong fungicide against Bipolaris sorokiniana causing spot blotch disease in wheat. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e97881. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0097881. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Hojjat SS. Impact of silver nanoparticles on germinated fenugreek seed. Int J Agric Crop Sci. 2015;8(4):627–30. [Google Scholar]

44. Yazar K, Kara Z, Avcı A, Doğan O, Ekinci H, Demir N. 41 B asma anacı çekirdeklerinde gümüş nano parçacık uygulamalarının çimlenme ve vejetatif gelişmeye etkileri. Bahçe. 2023;52(Özel Sayı 1):72–7. (In Turkish). [Google Scholar]

45. Reidy B, Haase A, Luch A, Dawson KA, Lynch I. Mechanisms of silver nanoparticle release, transformation and toxicity: a critical review of current knowledge and recommendations for future studies and applications. Materials. 2013;6(6):2295–350. doi:10.3390/ma6062295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Seif Sahandi M, Sorooshzadeh A, Rezazadeh S, Naghdibadi H. Effect of nano silver and silver nitrate on seed yield of borage. J Med Plants Res. 2011;5(2):171–5. [Google Scholar]

47. Shahraki SH, Ahmadi T, Jamali B, Rahimi M. The biochemical and growth-associated traits of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) affected by silver nanoparticles and silver. BMC Plant Biol. 2024;24(1):92. doi:10.1186/s12870-024-04770-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Kumar KR, Singh KP, Raju DVS, Panwar S, Bhatia R, Kumar S, et al. Standardization of in vitro culture establishment and proliferation of micro-shoots in African and French marigold genotypes. Int J Curr Microbiol Appl Sci. 2018;7(1):2768–81. [Google Scholar]

49. Mirzajani F, Askari H, Hamzelou S, Farzaneh M, Ghassempour A. Effect of silver nanoparticles on Oryza sativa L. and its rhizosphere bacteria. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2013;88(7):48–54. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.10.018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Parveen A, Rao S. Effect of nanosilver on seed germination and seedling growth in Pennisetum glaucum. J Clust Sci. 2015;26(3):693–701. doi:10.1007/s10876-014-0728-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Khan S, Zahoor M, Khan RS, Ikram M, Islam NU. The impact of silver nanoparticles on the growth of plants: the agriculture applications. Heliyon. 2023;9(6):e16928. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e16928. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Gupta SD, Agarwal A, Pradhan S. Phytostimulatory effect of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) on rice seedling growth: an insight from antioxidative enzyme activities and gene expression patterns. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2018;161(4):624–33. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.06.023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Pallavi MCM, Srivastava R, Arora S, Sharma AK. Impact assessment of silver nanoparticles on plant growth and soil bacterial diversity. Biotech. 2016;3(6):1–10. doi:10.1007/s13205-016-0567-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Jasim B, Thomas R, Mathew J, Radhakrishnan E. Plant growth and diosgenin enhancement effect of silver nanoparticles in Fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum L.). Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25(3):443–7. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2016.09.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Kumar V, Parvatam G, Ravishankar GA. AgNO3: a potential regulator of ethylene activity and plant growth modulator. Electron J Biotechnol. 2009;12(2):8–9. [Google Scholar]

56. Malandrakis AA, Kavroulaki N, Chrysikopoulos CV. Use of copper, silver and zinc nanoparticles against foliar and soil-borne plant pathogens. Sci Total Environ. 2019;670(2):292–9. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Tymoszuk A, Kulus D. Effect of silver nanoparticles on the in vitro regeneration, biochemical, genetic, and phenotype variation in adventitious shoots produced from leaf explants in chrysanthemum. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(13):7406. doi:10.3390/ijms23137406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Thangavelu RM, Gunasekaran D, Jesse MI, Mohammed Riyaz SU, Sundarajan D, Krishnan K. Nanobiotechnology approach using plant rooting hormone synthesized silver nanoparticle as nanobullets for the dynamic applications in horticulture—an in vitro and ex vitro study. Arab J Chem. 2018;11(1):48–61. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2016.09.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. R: a language and environment for statistical computing [Internet]. [cited 2024 Aug 8]. Available from: http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

60. Aleksandrowicz-Trzcinska M, Szaniawski A, Studnicki M, Bederska-Blaszczyk M, Olchowik J, Urban A. The effect of silver and copper nanoparticles on the growth and mycorrhizal colonisation of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) in a container nursery experiment. Forests. 2018;11(5):690. doi:10.3390/f10030269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Jadczak P, Kulpa D, Bihun M, Przewodowski W. Positive effect of AgNPs and AuNPs in in vitro cultures of Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2019;139(1):191–7. doi:10.1007/s11240-019-01656-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Wang L, Sun J, Lin L, Fu Y, Alenius H, Lindsey K, et al. Silver nanoparticles regulate Arabidopsis root growth by concentration-dependent modification of reactive oxygen species accumulation and cell division. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;190(3):110072. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2019.110072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Hegazi ESS, Yousef A, Abd Allatif AM, Mahmoud TS, Mostafa MKM. Effect of silver nanoparticles, medium composition and growth regulators on in vitro propagation of picual olive cultivar. Egypt J Chem. 2021;64(12):6961–9. doi:10.21608/ejchem.2021.78774.3853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Kara Z, Doğan O, Yazar K. Promoting rooting and vegetative growth in 41 B vine rootstock cuttings with encapsulated nano silver and IBA applications. Vitic Stud. 2023;3(2):73–80. [Google Scholar]

65. Abdallatif AM, Hmmam I, Ali MA. Impact of silver nanoparticles mixture with NAA and IBA on rooting potential of Psidium guajava L. stem cuttings. Egypt J Chem. 2022;65(132):1119–28. doi:10.21608/ejchem.2022.155986.6751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Cuong DM, Mai NTN, Tung HT, Khai HD, Luan VQ, Phong TH, et al. Positive effect of silver nanoparticles in micropropagation of Limonium sinuatum (L.) Mill. ‘White’. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2023;155(2):417–32. doi:10.1007/s11240-023-02488-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Albarzinji IM, Swara BJ. Effects of nano silver and indole butyric acid application on growth and some physiological characteristics on hardwood cutting of Dalbergia sissoo Roxb. UHD J Sci Technol. 2024;8(2):31–7. doi:10.21928/uhdjst.v8n2y2024.pp31-37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Wang T, Li H, Zhao J, Huang J, Zhong Y, Xu Z, et al. Exploration of suitable conditions for shoot proliferation and rooting of Quercus robur L. in plant tissue culture technology. Life. 2025;15(3):348. doi:10.3390/life15030348. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools