Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Phytochemicals as Multi-Target Therapeutic Agents for Oxidative Stress-Driven Pathologies: Mechanisms, Synergies, and Clinical Prospects

1 Key Laboratory of Edible Fungi Resources Innovation Utilization and Cultivation, College of Agronomy and Life Sciences, Zhaotong University, Zhaotong, 657000, China

2 School of Food and Biological Engineering, Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, 212013, China

3 Department of Biotechnology, Faculty of Biological Sciences, Lahore University of Biological and Applied Sciences, Lahore, 53400, Pakistan

4 Department of Plant Pathology, Faculty of Agricultural Sciences and Technology, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, 60800, Pakistan

5 Institute of Horticulture, Lithuanian Research Centre for Agriculture and Forestry, Kaunas, Babtai, 54333, Lithuania

6 Department of Pharmaceutics, Faculty of Pharmacy, Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, 60800, Pakistan

7 Department of Plant Pathology, Muhammad Nawaz Sharif University of Agriculture, Multan, 60000, Pakistan

8 Department of Biology, College of Science, King Khalid University, Abha, 61421, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

* Corresponding Authors: Ammarah Hasnain. Email: ; Mingzheng Duan. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Molecular Insights of Plant Secondary Metabolites: Biosynthesis, Regulation, and Applications)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(7), 1941-1971. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.064056

Received 03 February 2025; Accepted 23 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Plants have long served as a cornerstone for drug discovery, offering a vast repertoire of bioactive compounds with proven efficacy in combating oxidative stress, a pivotal driver of chronic diseases such as cancer, diabetes, cardiovascular disorders, and neurodegenerative conditions. This review synthesizes current knowledge on plant-derived antioxidants, emphasizing their mechanisms, therapeutic potential, and quantitative efficacy validated through standardized assays. Key phytochemicals, including polyphenols, carotenoids, flavonoids, and terpenoids, neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) through radical scavenging, enzyme modulation, and gene regulation. For instance, lutein, a carotenoid found in leafy greens, demonstrates potent antioxidant activity with IC50 values of 1.75 μg/mL against hydroxyl radicals and 2.2 μg/mL in lipid peroxidation inhibition, underscoring its role in mitigating cardiovascular and ocular diseases. Similarly, quercetin, a ubiquitous flavonoid in onions and berries, exhibits remarkable ROS-scavenging capacity, with IC50 values of 0.55 μg/mL, 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and 1.17 μg/mL, 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (ABTS), supporting its use in reducing inflammation and neurodegeneration. The therapeutic promise of these compounds extends to disease-specific applications. Limonoids from citrus fruits, such as limonin (IC50: 15–31 μg/mL), enhance Phase II detoxification enzymes, offering protection against chemical carcinogens. Sulforaphane, a glucosinolate derived from cruciferous vegetables, shows potent anticancer activity with an IC50 of 85.66 mg in DPPH radical scavenging, while β-sitosterol (IC50: 1.43–2.42 mM) inhibits tumor proliferation and cholesterol synthesis. Synergistic interactions further amplify their efficacy: phytoestrogens like genistein (IC50: 13.00 ppm) and terpenoids such as α-pinene (IC50: 12.57 mg/mL) collectively enhance anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial responses, illustrating the multi-targeted nature of plant-based therapies. Beyond disease prevention, these compounds address age-related decline. Ascorbic acid (vitamin C), with an IC50 of 11.81 μg/mL for antioxidant activity, mitigates skin aging and accelerates wound healing, while selenium nanoparticles (IC50: 0.437 μg/mL) bolster immune function and reduce chemotherapy-induced toxicity. Dietary fibers, exemplified by sugar beet fibers (IC50: 52.32 μg/mL for DPPH scavenging), further contribute to cardiovascular health by lowering Low-Density Lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol. This review not only catalogs the antioxidant prowess of phytochemicals but also highlights their translational potential. Advances in nanotechnology, such as nano-formulated curcumin, have overcome bioavailability challenges, enhancing clinical applicability. By integrating quantitative metrics (e.g., IC50, radical scavenging rates) with mechanistic insights, this work bridges the gap between traditional knowledge and modern pharmacology.Keywords

The use of pharmacologically important plants is transitioning from the periphery to the mainstream, due to their potential therapeutic properties with fewer side effects compared to synthetic medicines. Natural chemicals derived from higher plants and microbes have long been used to create novel, clinically useful drugs [1,2]. Recently, there has been increased interest in using biologically derived and environmentally friendly plant-based medicines for the prevention and treatment of various human illnesses. Even the Western world is now seeking safe and effective natural treatments. Through in vitro research on numerous plant species, many photo-active chemicals have been identified. These substances are often classified in terms of their structure or composition, with different scientists using various schemes [1]. In ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology, a “medicinal plant” refers to any species utilized in traditional medicine containing bioactive components beneficial for treating illnesses in humans and/or animals. Ethnopharmacology aims to develop medications that validate the use of medicinal plants in traditional practices [3]. Over the course of human medication development, previously undiscovered natural substances have led to the establishment of new medical compounds and innovative therapeutics [4]. The pharmaceutical industry focuses heavily on phytochemicals as a source of novel compounds for drug development [5]. For instance, over 60% of the anti-cancer drugs in use today have been derived from plants in the field of oncology. Additionally, nearly 50% of current drugs treating various diseases are made using natural phytoactive compounds [6]. While primary metabolites perform basic life functions common to all living cells, secondary metabolites are specific to certain organisms. These secondary metabolites are derived from primary metabolites through modified synthetic pathways or using the same substrates as carbohydrates, lipids, and amino acids. The secondary metabolites from plants are the primary source of bioactive compounds for treating human ailments [7]. The increasing toxicity and bacterial resistance to synthetic medicines have driven the focus on ethnopharmacology. Numerous photo-active compounds from medicinal plants have been shown by researchers to offer safe, effective replacements with minimal harm. Many significant pharmacological qualities such as antioxidants, antibacterial, anticancer, and analgesic properties have been identified in plant-based compounds. Communities claim various plant-based products offer benefits in different contexts, though in vitro and in vivo studies are still needed to substantiate these claims. Rigorous scientific evaluations are necessary to assess the pharmacokinetics, effectiveness, safety, bioavailability, and medical interactions of recently identified phytoactive compounds and their extracts. Such investigations are crucial before administering plant-based compounds to patients to ensure their safety and efficacy, addressing both immediate and long-term side effects [8].

Phytoactive compounds are recognized for their diverse functions, including effects on gene expression, signal transmission, and microbial development. These compounds can also act as chemotherapeutic or chemopreventive agents to treat cancer by inhibiting or delaying tumorigenesis [9]. For instance, herbal extracts and essential oils have demonstrated a range of antibacterial activities, including disruption of the cell’s phospholipid bilayer, increasing cell permeability, and causing cellular damage. The cytoplasmic membrane disruption, interference with the proton motive force, and impairment of active transport mechanisms are typically used to measure the effects of these compounds [10]. Plants possess a wide variety of chemicals with antioxidant properties, including flavonoids, vitamins, phenols, and terpenoids. These antioxidants play a crucial role in scavenging free radicals, and plants like leafy vegetables and citrus fruits provide significant amounts of vitamin E, ascorbic acid, phenolics, carotenoids, and flavonols, which can help reduce oxidative stress in the human body. Recent studies have shown that these phytoactive compounds significantly contribute to the reduction of the prevalence of various diseases through their antioxidant properties [11]. The extraction of plant metabolites is critical for unlocking nature’s therapeutic potential. This process involves isolating bioactive compounds responsible for the medicinal properties of plants. By employing various techniques such as maceration, solvent extraction, steam distillation, and supercritical fluid extraction, researchers aim to optimize the yield and quality of these compounds. As science advances, innovative extraction methods continue to evolve, improving efficiency and sustainability, which contributes to the development of new natural remedies and pharmaceuticals [12]. Recent studies have shown that compounds like curcumin from turmeric, resveratrol from grapes, and Epigallocatechin Gallate (EGCG) from green tea continue to show promise in cancer treatment, particularly in chemoprevention. These compounds have demonstrated significant efficacy in inhibiting cancer cell proliferation and inducing apoptosis in various cancers. Meta-analysis in antioxidants examined the antioxidant effects of flavonoids and polyphenols, concluding that regular consumption can reduce oxidative stress and lower the incidence of chronic diseases such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Furthermore, advancements in nanotechnology have enhanced the bioavailability of compounds like curcumin and resveratrol, making them more effective in clinical settings [12].

2 Oxidative Damage and Role of Free Radicals

Oxidative stress arises from an imbalance between the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and the biological system’s intrinsic detoxification capacity. Maintaining a balance of ROS production and their intracellular levels is critical for various cellular processes, such as protein phosphorylation, immunity, apoptosis, activation of transcription factors, and cellular differentiation. ROS are byproducts of oxygen metabolism and play crucial roles in cellular signaling and physiological functions [13]. However, factors like xenobiotics, including anticancer drugs, and environmental stressors such as pollution, ultraviolet (UV) radiation, ionizing radiation, and heavy metals contribute to an increase in ROS production. These elevated ROS levels disrupt the balance, leading to oxidative stress and damage to cellular structures and tissues [14]. Oxidative stress has been implicated in the development and progression of several diseases, including cancer, diabetes, metabolic disorders, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular diseases [15,16]. Research on antioxidants such as flavonoids, vitamin E, and polyphenols has explored their protective roles in mitigating oxidative stress [17,18]. Interestingly, while oxidative stress is generally harmful, it can also be leveraged therapeutically, particularly in cancer treatment, where it shows varying degrees of clinical efficacy [13,19]. Free radicals can be generated both endogenously and exogenously. Non-enzymatic processes, such as the reaction of oxygen with organic substances or exposure to ionizing radiation, contribute to free radical generation. Mitochondrial respiration during cellular metabolism is another major source of non-enzymatic free radicals. Endogenous sources of free radicals include ischemia, immune responses, infection, inflammation, excessive exercise, cancer, mental stress, and aging [13]. Exogenous free radical production occurs when substances like heavy metals enter the body, where they break down or metabolize, generating free radicals as byproducts. This external production of free radicals further contributes to the oxidative burden and potential damage to cellular components and biological systems [13].

Mitochondria are a primary source of ROS, playing an essential role in both normal physiological functions and pathological conditions. ROS, particularly superoxide (O2•), are generated during cellular respiration. Additionally, enzymes such as lipoxygenases (LOX) and cyclooxygenases (COX), along with certain cells like endothelial and inflammatory cells, also contribute to ROS production through arachidonic acid metabolism [20]. While mitochondria have mechanisms to scavenge ROS, their capacity is insufficient to handle the large quantities of ROS generated during cellular respiration [20,21]. To protect against cellular damage caused by ROS, cells rely on an antioxidant defense system, including enzymes such as peroxidase (POD), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT), and glutathione peroxidase (GPx). These enzymes help neutralize ROS and mitigate potential cellular damage [22,23]. Enzymatic and non-enzymatic processes are both integral to ROS generation in biological systems [24,25]. Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide Phosphate (Hydrogen) (NADPH) oxidase, peroxidases, and xanthine oxidase are key players in superoxide radical (O2•) formation. These radicals participate in cellular activities and ultimately lead to the production of reactive species like peroxynitrites (ONOO), hydrogen peroxide, hypochlorous acids (HOCl), and hydroxyl radicals (OH•), which have diverse effects on cellular signaling and contribute to oxidative stress-induced damage [26,27]. The Fenton reaction, which involves iron (Fe2+) or copper (Cu+) as catalysts, reacts oxygen (O2) with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to generate highly reactive hydroxyl radicals (OH•). Of the various free radicals in vivo, the hydroxyl radical is particularly reactive. Additionally, nitric oxide synthase converts arginine into citrulline, producing nitric oxide (NO•), which plays significant physiological roles [28,29].

2.1 Detrimental Effects of Free Radicals on Human Health

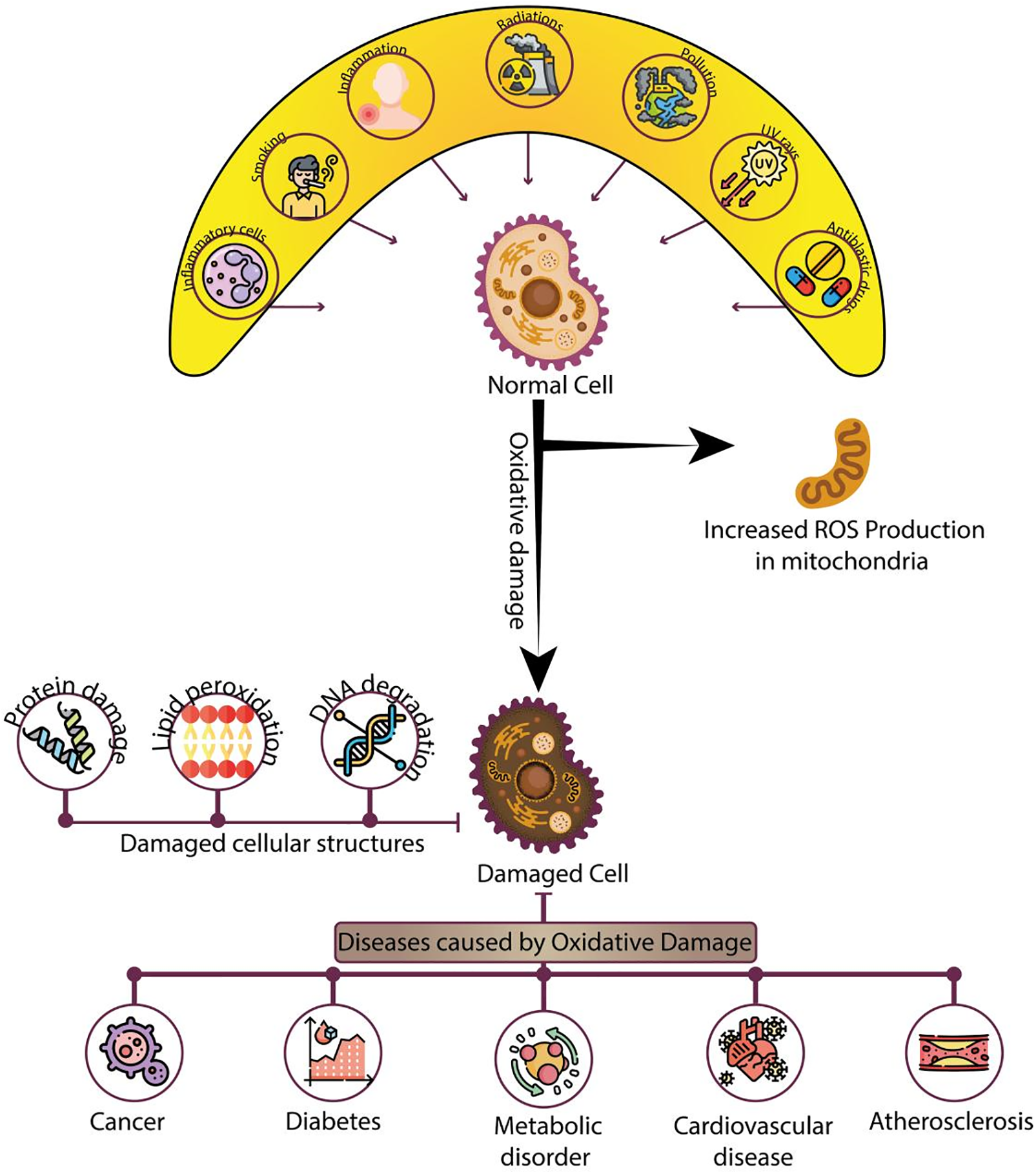

Excessive accumulation of free radicals and oxidants can lead to oxidative stress, resulting in the impairment of various cellular components, including membranes, lipoproteins, proteins, lipids, and Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). This oxidative stress occurs due to an imbalance between the production of free radicals and the cellular ability to effectively eliminate them. For example, an excess of peroxynitrite and hydroxyl radicals can initiate lipid peroxidation, causing damage to cell membranes and lipoproteins. Consequently, cytotoxic and mutagenic compounds such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and conjugated dienes are formed [30]. Lipid peroxidation, characterized by a radical chain reaction, exhibits rapid propagation and affects a wide array of lipid molecules. Oxidative stress-induced damage extends beyond lipids, as proteins undergo structural alterations that can result in diminished or complete loss of enzymatic activity. Moreover, DNA is also vulnerable to lesions caused by oxidative stress, with the notable example of 8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) production [31,32]. It is important to remember that the measurement of 8-OHdG levels in tissue has been proposed by the authors of the reference [33] as a biomarker for assessing oxidative stress. Several chronic and degenerative diseases, as well as the body’s accelerated ageing process and acute pathologies, can be brought on by oxidative stress if it is not rigorously controlled (i.e., trauma and stroke) [34]. Alcoholism, smoking, excessive exercise, overeating, exposure to UV radiation, and other dietary practices and environmental factors all have an impact on oxidative stress, including those that cause DNA, protein, lipid, and sugar lesions [35,36] (Fig. 1).

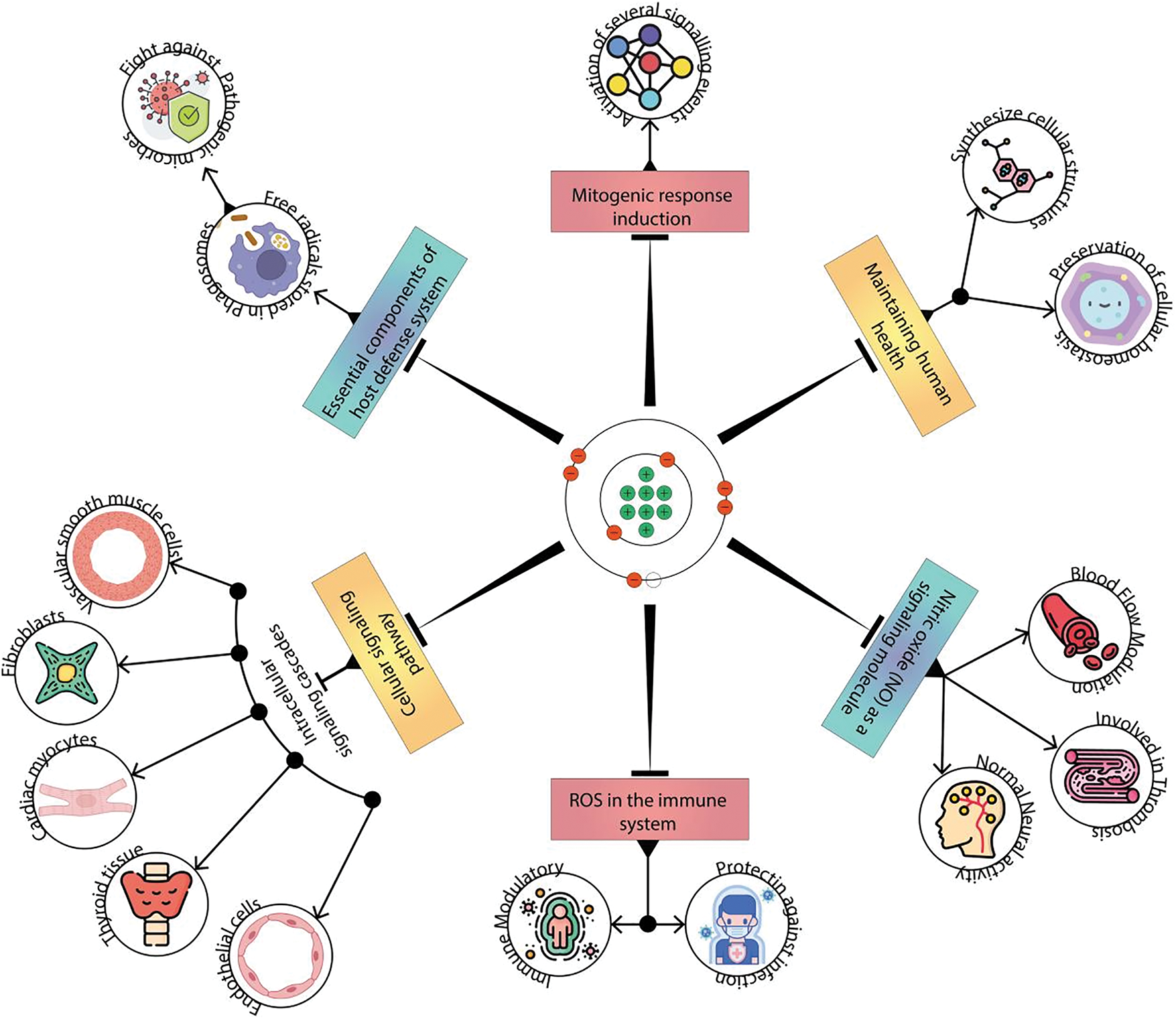

Figure 1: Role of free radicals. Role of free radicals and ROS in immune systems in maintaining human health. In moderate levels, ROS act as signaling molecules, aiding immune cell communication and activation in response to threats such as pathogens. This controlled oxidative burst is essential for effective pathogen clearance and immune defense. However, excessive ROS production, often triggered by chronic inflammation or environmental factors, can lead to oxidative stress, causing cellular damage and impairing immune function. Striking the delicate balance between ROS-mediated immune responses and potential harm is essential for a resilient immune system

3 Classes of Phytochemicals Possessing Antioxidative Properties

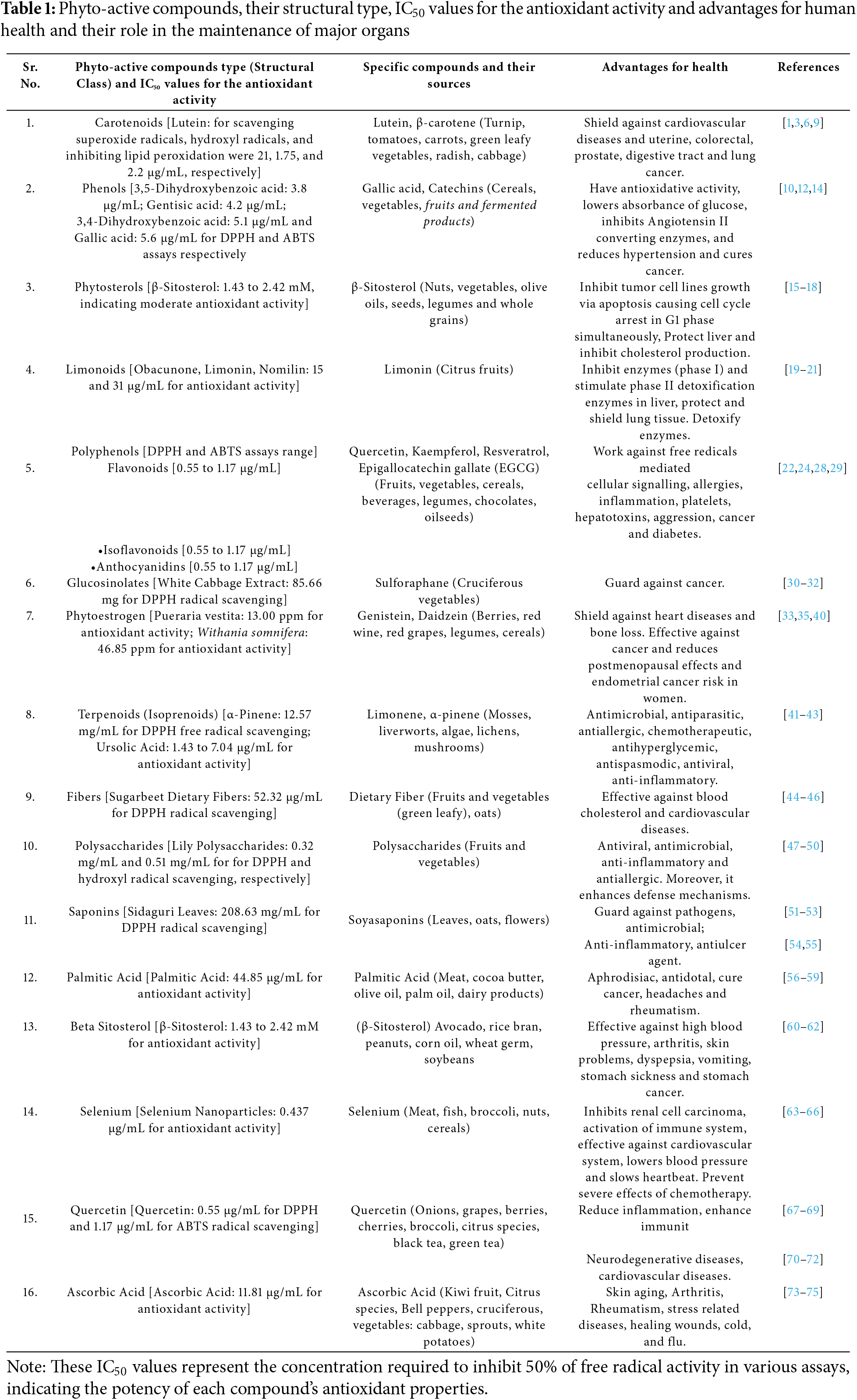

Natural phytoactive antioxidants have been identified as essential contributors to the prevention of chronic and degenerative diseases, encompassing conditions like atherosclerosis, cardiac and cerebral ischemia, cancer, neurological disorders, diabetes, pregnancy-related complications, rheumatoid arthritis, DNA damage, and the aging process [37–39]. The human body’s own natural antioxidant defense system, which includes glutathione peroxidase and catalases, can neutralize free radicals that are created inside the body [40]. Thus, to compensate for any deficiency, exogenous plant-based natural antioxidants such as vitamin C, flavones, vitamin E, and beta-carotene should be used [41,42] (Table 1).

4 Preventive and Therapeutic Effects of Antioxidants against Chronic Diseases and Health Related Conditions

Large macromolecules including lipids, DNA, and proteins can suffer oxidative damage because of an excess of oxidants in the body. Numerous human diseases, including certain forms of cancer and cardiovascular disease (CVD), are caused by this damage [76]. Antioxidant phytochemicals may therefore have a significant impact on both the prevention and management of chronic illnesses. Studies on humans and in vitro have shown that phytochemicals have antioxidant properties [77–80]. It has been reported that 19 of the 25 anthocyanins contained in blueberries could be found in human serum, it is possible that an increase in polyphenols can account for the enhanced total antioxidant capacity. The serum’s antioxidant capacity rose because of the presence of total anthocyanins. Additionally, by adhering to red blood cells, polyphenols may improve the total oxidant-scavenging capacities of human blood [81]. Fruit and vegetables possess strong antioxidant properties, which may be due to the synergistic and additive effects of the phytochemicals present in them [82]. Another crucial element, chronic inflammation, may contribute to the etiology of numerous chronic illnesses, such as CVD, cancer, and type 2 diabetes (T2D) [83]. It has been discovered that most antioxidant phytochemicals have anti-inflammatory properties. Phytochemicals such as anthocyanins, resveratrol, and curcumin have been shown to possess anti-inflammatory properties by inhibiting nuclear factor-B activity and prostaglandin formation. They can also inhibit enzymes and enhance cytokine production [84,85].

When cells proliferate and differentiate uncontrollably, it is referred to as cancer [86]. Cancer can damage any organ or tissue and is influenced by several environmental factors, including food, water, air pollution, and radiation such as X-rays, UV, and ionizing radiation [87]. Phytochemicals influence the metabolism of carcinogens through two primary processes. Phase I metabolism, involving oxidation, reduction, and dehydrogenation, constitutes the first stage of biotransformation [88]. The second stage, Phase II metabolism, involves methylation or acetylation, combining these compounds with endogenous ones or facilitating their excretion [89,90]. In addition to affecting carcinogen metabolism, phytochemicals can inhibit carcinogenesis by preventing and slowing the growth of cancer cells. These compounds can separate active carcinogens, preventing them from reaching the targeted tissues or cells [91]. When cancer cells are exposed to carcinogens, suppressing agents prevent their growth and metastasis [92]. Phenolic acids, flavonoids, and indoles are particularly effective at inducing Phase I enzymes such as microsomal mixed-function oxidase [93]. Although phytochemicals cannot directly eliminate cancer cells, controlling their growth remains essential for cancer treatment. As a result, phytochemicals are crucial in developing new drugs with various applications in cancer therapy [94–96]. Current research also points to polyamine metabolism as a potential target for treating inflammatory diseases [97–99]. Polyamines, aliphatic compounds found in living organisms, play critical roles in cellular processes, including growth and differentiation [100]. Excessive polyamine catabolism produces reactive oxygen species (ROS), raising oxidative stress and exacerbating inflammation. This makes polyamine metabolism an intriguing target for natural anticancer therapies [101]. Several natural compounds, particularly polyphenols from plants and foods, show promise in combating cancer. A high-polyphenol diet has been found to reduce oxidative stress and alleviate cancer-related anorexia/cachexia syndrome. Flavonoid quercetin, a well-known antioxidant with established anticancer properties, inhibits ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) production, disrupting polyamine formation, which promotes cell growth [102]. Studies show that an increased intake of flavonoids, particularly quercetin and kaempferol, significantly lowers serum IL-6 levels, a cytokine associated with inflammation. Additionally, curcumin, known for its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, has shown potential in treating cancer [103–105]. It has been tested on several cancer cell lines, including those from colorectal, breast, and cervical cancer. Despite promising results, the clinical use of curcumin is limited by its low oral bioavailability, poor solubility, and degradation [106–109].

Resveratrol, another potent compound, exhibits strong cytotoxic effects on cancer cells. Recent studies have shown that it inhibits Transglutaminase type 2 in cholangiocarcinoma and gallbladder cancer cell lines, although some contradictory findings remain. Nonetheless, resveratrol is still considered a promising candidate for chemo-preventive therapy [110]. Genistein, an isoflavone from soybeans, has demonstrated anti-tumor properties in numerous cancer types, including neuroblastoma, chronic lymphatic leukemia, and cancers of the ovary, breast, prostate, colon, bladder, liver, and stomach [111,112]. Genistein’s structure resembles estradiol, earning it the classification of a phytoestrogen. While its efficacy as a chemoprevention drug is still debated, studies show that adding soy to the diet may reduce the inflammatory processes linked to prostate carcinogenesis [113–115]. Lycopene, known for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant characteristics, has therapeutic effects on various malignancies, especially prostate cancer. Lycopene consumption has been shown to lower the risk of prostate cancer [116]. The discovery of natural substances has revolutionized cancer treatments, and many of these compounds are currently in clinical use. To fully understand their chemo-preventive and anticancer properties, further research and preclinical studies are needed [117,118] (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Impact of oxidative damage on cellular structures and associated diseases: This infographic depicts the sequence of events leading to oxidative damage in cells. The top section illustrates various factors such as smoking, inflammation, radiation, pollution, UV exposure, and harmful chemicals that contribute to the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and increase oxidative stress in normal cells. These factors lead to an elevation in ROS production within mitochondria, initiating oxidative damage. The center section shows the consequences of oxidative damage, including protein damage, lipid peroxidation, and DNA degradation, resulting in the deterioration of cellular structures. The damaged cell, shown in the lower part of the diagram, is associated with various diseases, including cancer, diabetes, metabolic disorders, cardiovascular diseases, and atherosclerosis. This diagram highlights the significant role of oxidative damage in the onset of these health conditions

Diabetes is a serious health issue that affects people all over the world. It is defined by chronic hyperglycemia, which can cause both microvascular and macrovascular consequences (e.g., atherosclerosis and endothelial dysfunction). Diabetes comes in two forms: type 1 diabetes (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D). Because of hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia, diabetes is frequently accompanied by an increase in free radical production or oxidative stress [119,120]. Additionally, it was shown that plasma antioxidants and tocopherol, -carotene, lycopene, -cryptoxanthin, lutein, zeaxanthin, retinol, and ascorbic acid significantly decreased with the progression of diabetes and associated complications [121–123]. The frequent use of wholegrain foods enhanced metabolic balance and delayed or avoided the onset of T2D and associated consequences, according to cohort studies [124]. Major Lactuca sativa polyphenolic components have been linked to anti-diabetic effects in mice [125]. According to a different study, Chrysobalanus icaco’s aqueous extract significantly reduced rats’ blood sugar levels and exhibited potent antioxidant activity [126,127].

Insulin resistance caused by obesity is significantly influenced by subclinical-grade inflammation as well. To avoid metabolic disorders, polyphenols in grape products lowered chronic inflammation caused by obesity. To exhibit their anti-diabetic effect, they function as an antioxidant, inhibiting endotoxin-mediated kinases and transcription factors as well as pro-inflammatory cytokines [128]. Due to its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, curcumin was also thought to be effective in the treatment and prevention of diabetes [129]. Additionally, the antioxidant polyphenol butein suppressed the production of nitric oxide in vitro, safeguarding pancreatic beta-cells from cytokine-induced damage and offering a potential treatment for T1D progression. Resveratrol may affect the expression of genes related to the onset of T2D by, for example, increasing the expression of several-cell genes and insulin in pancreatic cells [130]. A different study found that ferulic acid had synergistic effects with hypoglycemia medications and had hypoglycemic activity in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats [131]. In addition, it was discovered that kaempferol enhanced insulin secretory function, improved cell survival, and reduced hyperglycemia, while daidzein enhanced glucose absorption and glucose homeostasis in T2D model mice [132]. Additionally, it was discovered that naringenin functions as an antioxidant and improves diabetes-related memory loss in T2D rats by inhibiting increased cholinesterase activity [133], and genistein can stop diabetes [134,135]. Pycnogenol (PYC), a complex mixture of procyanidins consisting of catechin and epicatechin subunits with varying chain lengths, has demonstrated the ability to reduce glucose levels. This observation suggests a potential anti-diabetic action in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) [136]. Phytochemicals exhibit potential in diabetes prevention through various mechanisms including modulation of α-glucosidase and lipase activities, reduction of postprandial glycemic levels, anti-inflammatory properties, promotion of pancreatic function, and synergistic effects with hypoglycemic medications [137].

In streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats, cinnamon aldehyde, a phytocompound, has been shown to have significant antihyperglycemic characteristics that result in a reduction in total cholesterol and triglyceride intensity and, concurrently, an increase in high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [138]. This study highlights the potential of cinnamaldehyde, a common oral medication with hypolipidemic and hypoglycaemic qualities. According to recent research, 3T3-L1 adipocytes can exhibit increased levels of insulin resistance, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and glucose transporter-4 when exposed to polyphenols and cinnamon derivatives including procyanidin type-A polymers. The method of cinnamon’s insulin-like action was suggested to be partially explained by an increase in the levels of insulin resistance, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, cinnamon polyphenols, and glucose transporter-4 may also have anti-angiogenesis and anti-inflammatory effects [139].

4.3 Anti-Inflammatory Properties

ROS are linked to inflammatory response and autoimmune disorders because they function as an intracellular signaling component. Therefore, a fascinating approach for potential clinical applications is the utilization of natural compounds with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory action. It has been demonstrated that these organic substances block several proinflammatory mediators [140,141]. Herbal remedies, nutraceuticals (nutrient-rich compounds derived from food or plants), and functional foods possessing anti-inflammatory properties have shown potential as adjunct therapies to reduce the dosage and mitigate the adverse effects of anti-inflammatory medications [142]. Systematic reviews have assessed the anti-inflammatory properties of phytochemicals, revealing a diverse range of flavonoids that exhibit such effects through different mechanistic actions [143]. Among the widely distributed flavones, apigenin and luteolin glycosides have garnered considerable attention [144]. Flavones are prominently found in food sources such as celery, parsley, and rosemary, thereby offering natural dietary options for incorporating flavones into one’s daily intake [145,146]. Through the suppression of COX-2 and iNOS, respectively, apigenin reduces the generation of prostaglandins and nitric oxide (NO) [147]. Quercetin, a flavonol that can be found in a variety of fruits and vegetables, including apples, is one of the most researched flavanols. Flavonoids from apples have been linked to anti-inflammatory effects [148]. On sarcoidosis patients as well as in vivo models of allergic airway inflammation and arthritis, quercetin and its glycosides are powerful anti-inflammatory drugs [149]. Another class of isoflavones, namely genistein, daidzein, and glycitein, are predominantly present in leguminous plants such as soy (Glycine max) [150,151]. Genkwanin is a flavone with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, inhibits ROS production and carcinogenesis, modulates enzymes involved in neurological function, and contributes to anti-aging actions [152]. Flavanols, also known as proanthocyanins or condensed tannins, can be found in plants as monomers (such as catechin and epicatechin) as well as oligomers or polymers. These include inhibiting the production of eicosanoids, reducing platelet activation, modulating nitric oxide (NO)-dependent mechanisms, and regulating the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [153]. Catechins exhibit inhibitory effects on the inflammatory pathways implicated in the development and progression of atherosclerosis [154,155]. Anthocyanins primarily work through the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway to reduce inflammation. According to mechanistic research, the glycosides of delphinidin, malvidin, cyanidin, peonidin, and petunidin inhibit IL-1’s ability to activate NF-B in vitro in a dose-dependent manner [156]. Diterpenes from the leaves of Stevia rebaudiana, a plant utilized as a natural sweetener in the food business, have also been demonstrated to reduce the production of proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-, IL-1, and IL-6) via altering the I-B/NF-B pathway [157]. Glycyrrhizin and glycyrrhetinic acid, two triterpenes derived from licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra), have several effects, including gastric protection and blood pressure modulation through their mineralocorticoid activity [158]. An intriguing area of investigation is the potential use of secure and reliable natural items to lessen the dosage and negative effects of prescription medications [159,160]. Luteolin and quercetin were the flavonoids with the highest TNF-inhibitor potencies. In clinical trials including women with RA, quercetin’s anti-inflammatory properties were found to significantly reduce clinical symptoms and inflammation [161]. Recent clinical trials have demonstrated the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties of green tea extract in autoimmune diseases, independent of its impact on TNF generation [162]. Therefore, even while natural products are unlikely to be able to replace anti-inflammatory medications like DMARDs, they may greatly aid in dosage reduction for an affordable and secure method of treating autoimmune and many other inflammation-related diseases [163].

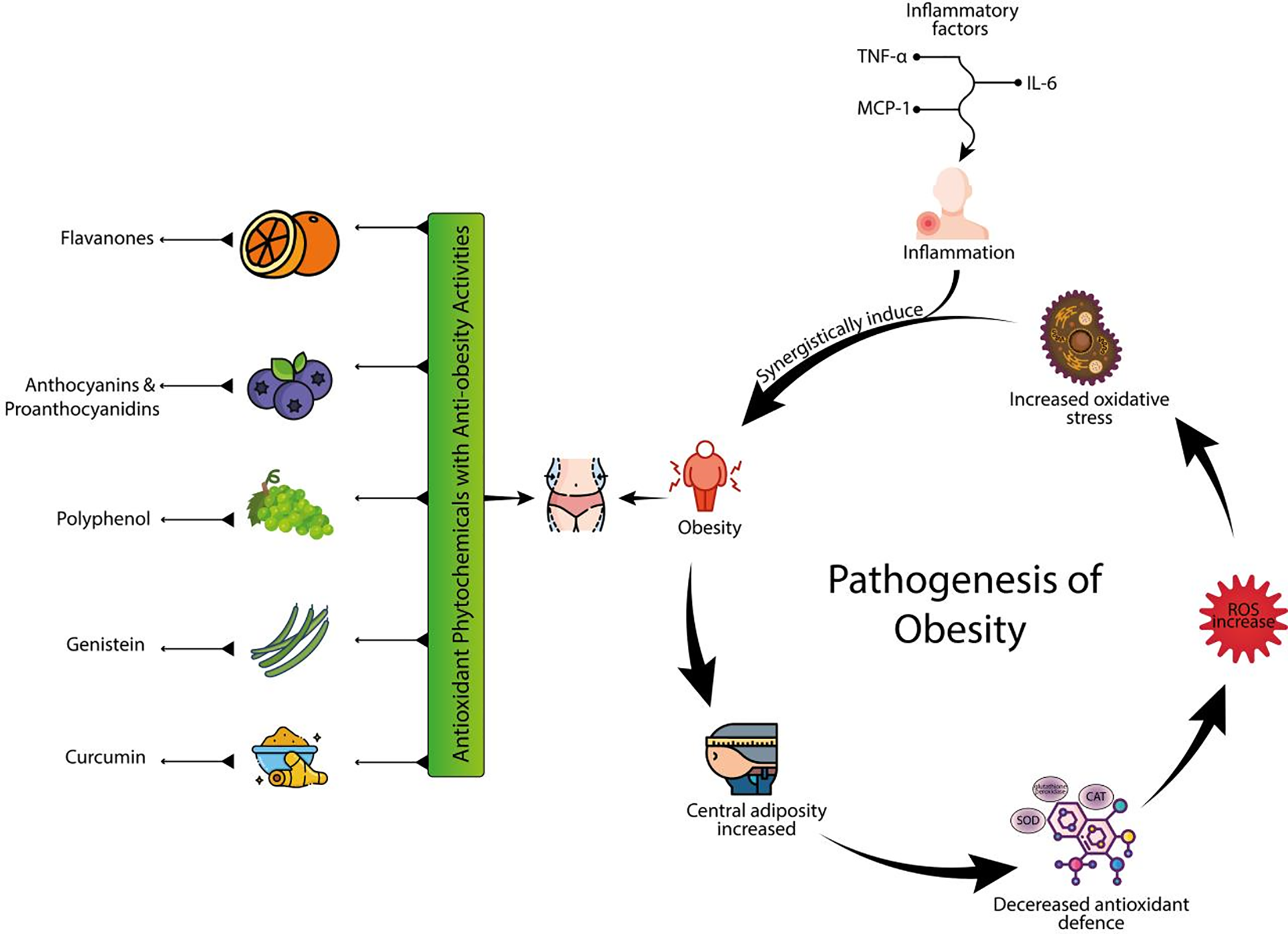

The term “obesity” refers to an abnormal or excessive accumulation of fat. The primary determinant for metabolic disorders is the excessive accumulation of visceral adipose tissue [164,165]. Type 2 diabetes is predominantly influenced by a combination of genetic factors and obesity, exacerbated by a sedentary lifestyle and imbalanced dietary habits [166]. The escalating global prevalence of obesity presents a pressing public health concern, imposing substantial social and economic burdens [167]. In the pathophysiology of obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2D), a state of chronic inflammation is initiated within the white adipose tissue, and subsequently, it exhibits a progressive systemic dissemination [168]. Fruits and plant extracts rich in antioxidant phytochemicals possess notable anti-obesity properties, as demonstrated through vitro and in vivo studies [169]. Notably, citrus fruits have been shown to exhibit inhibitory effects on α-glucosidase and pancreatic lipase in vitro, attributed to their high concentration of antioxidant phytochemicals, including flavanones [170]. This extract was employed for the treatment of a diet-induced obesity model, yielding promising results [171]. Antioxidant phytochemicals are therefore crucial for preventing obesity, especially those that have anti-inflammatory properties. In vitro and in vivo studies on several flavonoids extracted from fruits and plant extracts showed strong anti-obesity action [172]. For instance, genistein has been shown to control the life cycle of adipocytes and reduce oxidative stress and low-grade inflammation associated with obesity [173,174]. Moreover, quercetin supplementation exhibited beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity and glucose intolerance in mice, while also mitigating the increase in body weight induced by high-fat diets [175,176]. Additionally, kaempferol, luteolin, and naringenin all show anti-adipogenesis properties [177]. There are several other phytochemicals with anti-obesity properties, e.g., resveratrol has been shown to suppress adipogenesis in vitro, helping to combat obesity [178]. In addition, as compared to the control group, high fat-induced-obese mice with caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid dramatically reduced body weight, visceral fat mass, plasma leptin levels, and insulin levels. Chlorogenic acid was more effective than caffeic acid [179]. Additionally, allicin had anti-adipogenesis actions and curbed the negative health impacts of obesity in addition to reducing obesity. Antioxidant phytochemicals exhibit efficacy in both the prevention and treatment of obesity due to their direct inhibitory effects on adipogenesis, anti-inflammatory properties, and antioxidant activities [179] (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Pathogenesis of obesity and the role of antioxidant phytochemicals: This image demonstrates the role of antioxidant phytochemicals in combating obesity through their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. The central part of the image highlights several key phytochemicals, including flavones, anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins, polyphenols, genistein, and curcumin, which are shown to have anti-obesity activities. These compounds are linked to reduced obesity through their ability to counteract inflammation, with inflammatory factors such as TNF-α, MCP-1, and IL-6 triggering an inflammatory response. The image then illustrates the subsequent chain of events: obesity leads to increased central adiposity, which in turn increases oxidative stress and reactive oxygen species (ROS). This increase in ROS exacerbates the cycle, causing decreased antioxidant defense. The overall process highlights the synergistic relationship between inflammation, oxidative stress, and obesity, emphasizing the protective role of antioxidant-rich compounds in mitigating these effects

Natural remedies have long been advocated as a technique to increase an organism’s lifetime. According to epidemiological and experimental research, natural products are potent antioxidants that can treat disorders brought on by stress [180,181]. Scientific literature also points to natural products’ potential for reducing metabolic syndrome and slowing down aging [182,183]. Therefore, thorough preclinical analysis of the bioactivities and underlying mechanisms of action of natural substances may offer a strong scientific basis for clinical applications. Numerous age-related diseases are protected against by polyphenols, particularly flavonoids. Numerous studies have shown that dietary polyphenol supplements like curcumin and epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG) can lessen age-related cellular damage by lowering the production of ROS. Flavonoids and resveratrol, on the other hand, have been proven to alleviate aging mostly through regulating metabolic syndrome. They are both great natural anti-aging chemicals that can affect inflammation, oxidative damage, and cell senescence [184]. Hesperidin, Hesperetin, Naringin, and Naringenin are a few of the frequently mentioned flavonoids that can combat one or more aspects of aging or metabolic syndrome [185,186]. It is noteworthy that the body research on the preclinical use of phytochemicals to treat a variety of aging-related disorders is constantly growing. However, numerous phytochemicals have successfully undergone clinical trials to treat age-related conditions. It is important to note that some pre-clinical study limitations may have an impact on their translational significance. These include (1) choosing experimental models that lack clinical relevance, (2) employing poorly characterized mechanisms of action, and (3) using dosing and time points for data interpretation that are not clinically relevant [187]. Aged rats’ motor and cognitive deficiencies were alleviated by coffee, which has significant quantities of antioxidant phytochemicals [188]. Elaeis guineensis leaf extract in methanol also demonstrated possible anti-aging properties [189]. Antioxidant phytochemicals also demonstrated anti-aging properties through several pathways. An illustrative example involves tetrahydroxy stilbene glucoside, which demonstrated a protective effect against the aging process induced by D-galactose in mice. This effect was achieved through the regulation of the Klotho gene [190]. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) decreased liver and kidney damage and improved age-associated inflammation and oxidative stress by inhibiting NF-B signaling [191]. Through the enhancement of nuclear factor-like 2 antioxidant signaling pathways, a different study discovered that allicin might considerably improve cognitive impairment in old mice [192]. Phytoactive chemicals have the potential to increase lifespan, reduce cognitive impairment, and reduce oxidative stress and inflammation brought on by aging [193].

4.6 Anti-Neurodegenerative (Alzheimer’s Disease) Activity

A diverse collection of chronic and incurable disorders known as neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) are characterized by the increasing functional degradation of the nervous system [194]. The pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease is characterized by the deposition of β-amyloid, the formation of neurofibrillary tangles resulting from proteolytic cleavage of amyloid precursor protein (APP), and an elevation in acetylcholinesterase levels mediated by microglia activation [195]. ROS are decreased, possible carcinogenic metabolism is neutralized, and neurological illnesses are subsequently prevented by antioxidants found in phytochemicals [196,197]. Resveratrol, a terpenoid in polyphenols, helps prevent amyloid b buildup. It also possesses anti-neurotoxicity and anti-oxidative stress properties under in vitro conditions [198]. The potential risk reduction for Alzheimer’s disease can be attributed to the anti-amyloid formation properties of specific compounds present in curry, ginger, tea, and pomegranate juice [199]. Both rat research and human investigations have provided evidence of the neuroprotective effects of chlorogenic acid, which is abundantly found in fruits, vegetables, and coffee [200]. These studies suggest that chlorogenic acid possesses preventive properties against cognitive impairment and supports brain health [201]. Furthermore, red onions provide the highest amounts of dietary quercetin, which fights oxidative stress and controls cytokine signaling to prevent cognitive decline [202]. Cruciferous vegetables include sulforaphane, which inhibits microglia, lessens neuro-inflammation and improves cognitive function [203]. Because of the high levels of α-linolenic acid and polyphenols in seeds and seed oils like rapeseed, walnut, and olive, the nervous system is protected against oxidative stress [204]. The consumption of walnuts (walnut kernels) relates to a lower prevalence of neurodegenerative illnesses because they are high in healthy fatty acids, vitamins, and polyphenols, particularly ellagic acid [205].

Both in vitro and in vivo, resveratrol exhibits significant neuroprotective action, in addition, curcumin exerts neuroprotective effects in both in vitro and in vivo models of Parkinson’s disease (PD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) through regulating pathogenetic oxidative and inflammatory pathways (PD) [206]. Curcumin increases cell survival in Japanese encephalitis virus-infected Neuro2a mouse neuroblastoma cells by reducing ROS and suppressing proapoptotic signals [207]. Additionally, curcumin exhibits neuroprotective effects by safeguarding SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells against cytotoxicity induced by α-synuclein [208]. These effects are achieved through a reduction in aggregated α-synuclein cytotoxicity, suppression of intracellular ROS levels, and inhibition of caspase-3 activation. Furthermore, curcumin significantly enhances cholinergic neuronal function in vivo and effectively mitigates spatial memory deficits in the APP/PS1 animal model of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [209]. Additionally, curcumin suppressed the NF-B signaling pathway, decreased microglia and astrocyte activation, and decreased cytokine production [210]. The data obtained from this study indicates that the protective effects of curcumin on mice with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) can be attributed to their ability to reduce neuroinflammation [211]. Curcumin exhibits neuroprotective properties by inhibiting glutathione depletion and lipid peroxidation induced by the neurotoxic compound MPTP in the animal model of Parkinson’s disease (PD) [212]. More recently, in rats with Parkinson’s disease caused by rotenone, curcumin reversed motor impairments and improved the activity of antioxidant enzymes [210]. All these data support the therapeutic potential of curcumin in the treatment of neurodegenerative disease and point to its neuroprotective properties (NDDs) [212].

4.7 Protective Action against Cardiovascular Diseases

Antioxidant phytochemicals can serve as antioxidants, anti-inflammatories, and inhibitors of platelet adhesion and aggregation, which may help prevent and treat cardiovascular disease [53]. Diabetes and associated endocrine and hemorheological disorders and diseases commonly result in issues with the neurological, heart, and kidney systems [213]. Plant sterol-rich oils like flaxseed and sunflower can successfully lower blood pressure and lipid peroxidation. Thus, a diet high in grains and vegetable oils serves as a support diet for preventing cardiovascular disease. Anthocyanins give fruits their color, and the more anthocyanins there are in each amount of fruit, the darker the fruit will be [214]. Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) oxidation is inhibited by quercetin, which also lessens atherosclerotic plaque development [215]. Quercetin has been shown to have antihypertensive effects in both animal and human trials, and these effects are unaffected by dose, duration, or illness states. These experimental results imply that, even though cardiovascular disorders cannot be healed, they can be supported by food and medication to enhance the body’s health [216,217]. The development and severity of CVD are linked to platelet aggregation and adhesion, which can result in thrombosis and coronary artery obstruction under pathophysiological conditions. Antioxidant polyphenols may alter molecular processes to prevent platelet aggregation [218]. Stilbenoids, which were extracted from Gnetum macrostachyum and have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties, inhibited the adhesion and aggregation of human platelets [219]. Phlorizin, which is present in apples, also has potent antioxidant properties and protects diabetic mice from macrovascular problems. Phlorizin might be helpful because diabetic macrovascular problems are one of the main causes of CVD [57]. Additionally, anthocyanins have been shown to protect against several cardiovascular risk factors [220]. Additionally, lycopene has been shown to improve endothelial function in people with cardiovascular disease, which is why multiple studies found that people who follow a Mediterranean diet rich in tomato products have a lower risk of developing the condition [221,222]. Furthermore, an intriguing finding elucidated the cardiovascular protective effects of allicin, an antioxidant organosulfur compound found in garlic. Allicin demonstrated significant contributions to the cardiovascular system through mechanisms such as vasorelaxation promotion and reduction of cardiac hypertrophy, platelet aggregation, angiogenesis, hyperglycemia, and hyperlipidemia [223]. Consequently, the efficacy of antioxidant phytochemicals in the treatment and prevention of CVD stems from their direct antioxidant activity as well as other notable bioactivities, including anti-inflammatory effects and prevention of platelet aggregation and adhesion [224].

4.8 Protective Action against Respiratory Disease

Pulmonary oxidative stress is known to play a significant pathogenetic role in various conditions, including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), acute lung injury/adult respiratory distress syndrome (ALI/ARDS), hyperoxia, ischemia-reperfusion injury, sepsis, radiation injury, lung transplantation, and inflammation [225]. Leukocytes, activated macrophages, pulmonary epithelium, and endothelial cells all produce ROS, which damage the lungs and trigger pro-inflammatory cascades that lead to systemic and pulmonary stress [226]. Many molecules, including minuscule organic compounds like glutathione, tocopherol (vitamin E), and flavonoids, function as natural antioxidants by reducing oxidized cellular components, eradicating ROS, and detoxifying toxic oxidation products. Peroxidases, which use glutathione as a reducing agent, are examples of antioxidant enzymes that can either promote these antioxidant reactions or directly breakdown ROS e.g., superoxide dismutase [SOD] and catalase) [227]. For the treatment of pulmonary oxidative stress, numerous antioxidant medications are being explored. In trials on both animals and humans, the administration of antioxidants via various routes, such as oral, intratracheal, and vascular, for the treatment of short-term and long-term oxidative stress demonstrated rather modest protective effects. Antioxidant enzymes are now being studied for the treatment of acute oxidative stress intravenously and intratracheally [228]. Although epidemiological research has identified diets low in antioxidants as risk factors for the development of COPD and poor lung function, the effectiveness of antioxidant vitamins in individuals with established COPD has not been conclusively proven [229]. Vitamins E (-tocopherol), C (ascorbic acid), resveratrol (present in red wine and red-skinned fruits), and flavonoids. However, evidence suggests that these dietary antioxidants do not have a significant impact on improving lung function or alleviating clinical symptoms in individuals with COPD [230]. Due to resveratrol’s low oral bioavailability, sirtuin-activating chemicals, which are more effective and bioavailable counterparts, have been created [231,232]. In vitro and in vivo studies using human airway epithelial cells and rats exposed to cigarette smoke both show that (-)-epigallocatechin decreases oxidative stress and neutrophil inflammation [233–235] (Fig. 4).

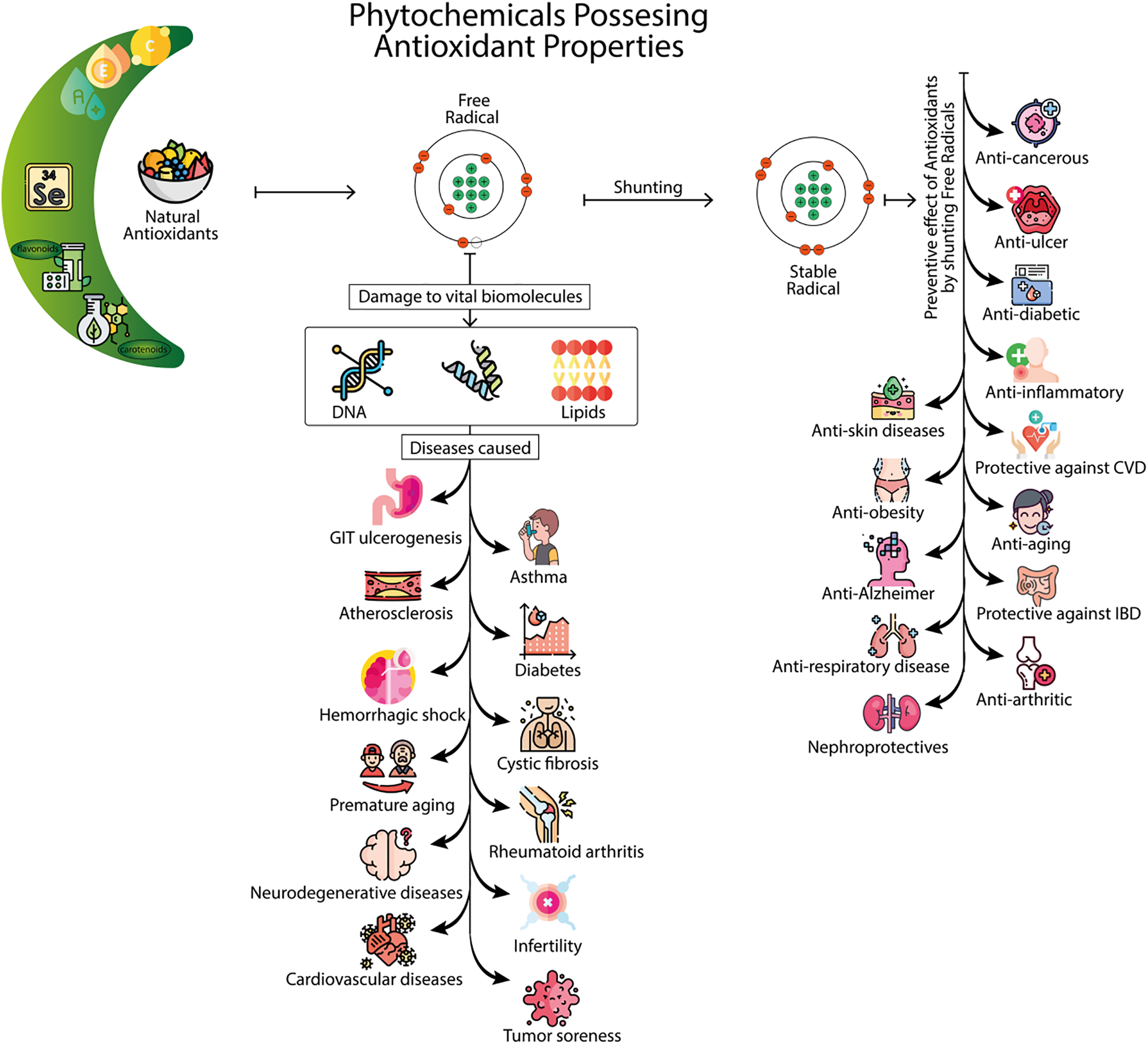

Figure 4: Phytochemicals possessing antioxidant properties: This infographic illustrates the role of natural antioxidants in protecting cells from damage caused by free radicals. On the left, various natural antioxidants, including flavonoids, carotenoids, selenium, and vitamins A, C, and E, are shown as key components that help neutralize free radicals. The central section highlights how free radicals cause damage to vital biomolecules, such as DNA and lipids, leading to various diseases. The image then demonstrates the diseases caused by oxidative stress, including GIT ulcerogenesis, atherosclerosis, asthma, diabetes, hemorrhagic shock, premature aging, neurodegenerative diseases, and cardiovascular diseases. On the right, the preventive effects of antioxidants by shunting free radicals are shown, illustrating their role in mitigating several health conditions. These include anti-cancerous, anti-inflammatory, anti-obesity, anti-aging, anti-Alzheimer’s, and nephroprotective effects. The infographic emphasizes the broad therapeutic potential of phytochemicals in combating diseases related to oxidative stress and promoting overall health

4.9 Protective Action against Skin Diseases

As the body’s largest organ, the skin regulates temperature, facilitates metabolic waste excretion, and provides critical protection against environmental biological, and physical threats. The skin is particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress due to reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated both externally and internally. While ROS are natural byproducts of cellular metabolism and typically harmless due to intracellular defense mechanisms, excessive accumulation can disrupt collagen fibers and impair skin cell function, leading to collagen fragmentation [236]. Antioxidants play a vital role in mitigating these effects by preventing, slowing, or even reversing oxidative damage associated with epidermal toxicity and disease. Traditionally classified as oils or herbal formulations based on their historical use in topical applications, these antioxidant compounds present challenges for precise phytochemical categorization [237,238].

Their inclusion in therapeutic regimens is supported by demonstrated efficacy in various clinical contexts. Melaleuca alternifolia essential oil exhibits antioxidant, antibacterial, and anti-inflammatory properties with potential applications in dermatitis and skin cancer treatment [239]. Melaleuca quinquenervia extracts show cosmetic potential through melanin inhibition in mouse melanoma cells. Vitis vinifera (grape seed) proanthocyanidins demonstrate clinical value in atopic dermatitis management and exhibit promising oncostatin effects, including mitigation of radiotherapy-induced dermatitis and suppression of melanoma/non-melanoma proliferation via autophagy and apoptosis induction [240]. However, these botanicals may cause adverse effects. Melaleuca oils can provoke contact dermatitis, with reported cases of stinging, erythema, and pruritus. Mentha-derived oils, while effective against pruritus, may trigger allergic reactions [241]. Vitis vinifera has been associated with rare hypersensitivity responses. The literature further identifies numerous phytochemicals with dermatological potential, including anti-aging, photoprotective, wound-healing, and antimicrobial agents [242].

4.10 Protective Action against Inflammatory Bowel Disease

The chronic inflammatory disorder known as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), which encompasses the two complicated disorders ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease, is brought on by dysregulated immune responses in a genetically susceptible person [243]. It was established that at the time of diagnosis, many UC patients had antioxidant nutritional deficits [244]. Since several antioxidant phytochemicals were discovered to have anti-inflammatory activities, IBD was strongly connected with them [245]. Hymenaea stigonocarpa’s antidiarrheal, gastroprotective, and cicatrizing properties may also be linked to its antioxidant impact [246]. Curcumin has demonstrated potential benefits in patients with ulcerative colitis. These studies demonstrated that anti-inflammatory antioxidant phytochemicals may have protective effects for IBD [247].

One of the global causes of death that is increasing the quickest is chronic kidney disease (CKD). Acute kidney damage (AKI) is favored by CKD progression and is predisposed to CKD [248]. Oxidative stress, a common pathophysiological hallmark of both AKI and CKD, accelerates the course of renal disorders, including CKD and AKI [249]. Phytochemicals are therefore anticipated to act as nephroprotective agents. Although these plants and their extracts are sometimes used on their own to treat renal illness, they are also commonly found in polyherbal remedies [249]. Based on pre-clinical and clinical studies, the subsequent section presents a summary of selected plants and their extracts utilized in the treatment of chronic kidney disease (CKD). This summary encompasses their respective mechanisms of action and specific beneficial effects observed about CKD [175]. The Polygonaceae family includes rhubarb, which is derived from the root of an Asian native plant called Rheum spp. It is known for its ability to treat CKD [250]. Various substances, including saponins, volatile oils, flavonoids, polysaccharides, tannins, stilbene glycosides (resveratrol and piceatannol), and anthraquinone glycosides, are present in rhubarb (physcion, chrysophanol, aloe emodin, emodin, and rhein) [251]. A nephroprotective extract can be obtained by eliminating anthraquinone glycosides, which may possess inherent toxicities. Rheum rhabarbarum extracts have consistently demonstrated their ability to reduce serum creatinine levels and ameliorate various metabolic abnormalities associated with renal failure in multiple pre-clinical and clinical investigations [252]. More than 60 bioactive substances are found in Astragalus (Astragalus membranaceus) [253]. Astragalus extract has powerful anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, according to in vitro and in vivo pre-clinical studies. Inhibiting the synthesis of TNF- and nitric oxide synthase, as well as upregulating angiotensin receptors, vascular endothelial growth factor, and the immune system, are some other methods [254].

In conclusion, this comprehensive review highlights the crucial role of plant-derived bioactive compounds in combating oxidative stress and its associated diseases. The extensive array of phyto-active compounds, including polyphenols, flavonoids, carotenoids, and other antioxidants, demonstrates remarkable potential in neutralizing harmful ROS and RNS in the human body. These natural compounds not only serve as powerful antioxidants but also exhibit promising anti-inflammatory and immune-modulating properties, making them valuable candidates for therapeutic interventions. The synergistic effects of these compounds offer a holistic approach to treating various chronic diseases while potentially slowing the aging process. As we continue to uncover the intricate mechanisms of these photoactive compounds, their application in developing novel therapeutic strategies holds immense promise for advancing medical treatments and improving human health outcomes.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Haider Ali (University of Birmingham, UK) for his valuable support in providing English editing services, which greatly enhanced the quality and clarity of this work.

Funding Statement: This work was jointly funded by the project of Scientific Research Start-up Funds for Doctoral Talents of Zhaotong University—Mingzheng Duan, Grant number: 202406; Young Talent Project of Talent Support Program for the Development of Yunnan, Grant number: 210604199008271015. And the authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Research and Graduate Studies at King Khalid University for funding this work through Large Research Project under grant number RGP2/162/46.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Ammarah Hasnain, Bismillah Mubeen, Syed Atif Hasan Naqvi; data collection: Ammarah Hasnain, Bismillah Mubeen, Syed Atif Hasan Naqvi, Fahad Hakim; analysis and interpretation of results: Syed Atif Hasan Naqvi, Fahad Hakim, Ammarah Hasanain, Bismillah Mubeen, Muhammad Umer Iqbal; draft manuscript preparation: Bismillah Mubeen, Ammarah Hasnain, Syed Atif Hasan Naqvi, Fahad Hakim, Mahmoud Moustafa, Mohammed O. Alshaharni, Muhammad Zeeshan Hassan, Syed Sheharyar Hassan Naqvi; review and editing: Mingzheng Duan, Ammarah Hasnain, Syed Atif Hasan Naqvi, Muhammad Umer Iqbal. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Shahid M, Shahzad A, Malik A, Sahai A. Phytoactive compounds from in vitro derived tissues. In: Recent trends in biotechnology and therapeutic applications of medicinal plants. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer; 2013. [cited 2025 Jun 18]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-94-007-6603-7. [Google Scholar]

2. Alharbi KS, Nadeem MS, Afzal O, Alzarea SI, Altamimi AS, Almalki WH, et al. Gingerol, a natural antioxidant, attenuates hyperglycemia and downstream complications. Metabolites. 2022;12(12):1274. doi:10.3390/metabo12121274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Anand U, Jacobo-Herrera N, Altemimi A, Lakhssassi N. A comprehensive review on medicinal plants as antimicrobial therapeutics: potential avenues of biocompatible drug discovery. Metabolites. 2019;9(11):258. doi:10.3390/metabo9110258. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Pye CR, Bertin MJ, Lokey RS, Gerwick WH, Linington RG. Retrospective analysis of natural products provides insights for future discovery trends. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(22):5601–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

5. Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs from 1981 to 2014. J Nat Prod. 2016;79(3):629–61. doi:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b01055. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Boucher HW, Ambrose PG, Chambers HF, Ebright RH, Jezek A, Murray BE, et al. White paper: developing antimicrobial drugs for resistant pathogens, narrow-spectrum indications, and unmet needs. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(2):228–36. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Pott DM, Osorio S, Vallarino JG. From central to specialized metabolism: an overview of some secondary compounds derived from the primary metabolism for their role in conferring nutritional and organoleptic characteristics to fruit. Front Plant Sci. 2019;10:835. doi:10.3389/fpls.2019.00835. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Radu A, Tit DM, Endres LM, Radu AF, Vesa CM, Bungau SG. Naturally derived bioactive compounds as precision modulators of immune and inflammatory mechanisms in psoriatic conditions. Inflammopharmacology. 2025;33(2):527–49. doi:10.1007/s10787-024-01602-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sarkar FH, Li Y. Using chemopreventive agents to enhance the efficacy of cancer therapy. Cancer Res. 2006;66(7):3347–50. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-05-4526. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Yang B, Tong Z, Shi J, Wang Z, Liu Y. Bacterial proton motive force as an unprecedented target to control antimicrobial resistance. Med Res Rev. 2023;43(4):1068–90. doi:10.1002/med.21946. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Cai Y, Sun M, Corke H. Antioxidant activity of betalains from plants of the Amaranthaceae. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(8):2288–94. doi:10.1021/jf030045u. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Anderson KJ, Teuber SS, Gobeille A, Cremin P, Waterhouse AL, Steinberg FM. Biochemical and molecular action of nutrients. J Nutr. 2001;131:2837–42. [Google Scholar]

13. Pizzino G, Irrera N, Cucinotta M, Pallio G, Mannino F, Arcoraci V, et al. Oxidative stress: harms and benefits for human health. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1–13. doi:10.1155/2017/8416763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Brewer MS. Natural antioxidants: sources, compounds, mechanisms of action, and potential applications. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2011;10(4):221–47. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2011.00156.x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Giustarini D, Dalle-Donne I, Tsikas D, Rossi R. Oxidative stress and human diseases: origin, link, measurement, mechanisms, and biomarkers. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2009;46(5–6):241–81. doi:10.3109/10408360903142326. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Rotariu D, Babes EE, Tit DM, Moisi M, Bustea C, Stoicescu M, et al. Oxidative stress—Complex pathological issues concerning the hallmark of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;152:113238. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2022.113238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Ozcan A, Ogun M. Biochemistry of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Basic Princ Clin Signif Oxid Stress. 2015;3:37–58. doi:10.5772/61193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Meitha K, Pramesti Y, Suhandono S. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in postharvest vegetables and fruits. Int J Food Sci. 2020;2020(1):8817778. doi:10.1155/2020/8817778. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. de Almeida AJPO, de Oliveira JCPL, da Silva Pontes LV, de Souza Júnior JF, Gonçalves TAF, Dantas SH, et al. ROS: basic concepts, sources, cellular signaling, and its implications in aging pathways. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022(1):1225578. doi:10.1155/2022/1225578. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Aon MA, Cortassa S, Akar FG, O’Rourke B. Mitochondrial criticality: a new concept at the turning point of life or death. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2006;1762(2):232–40. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2005.06.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Wei F, Karges J, Shen J, Xie L, Xiong K, Zhang X, et al. A mitochondria-localized oxygen self-sufficient two-photon nano-photosensitizer for ferroptosis-boosted photodynamic therapy under hypoxia. Nano Today. 2022;44:101509. doi:10.1016/j.nantod.2022.101509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Aslani BA, Ghobadi S. Studies on oxidants and antioxidants with a brief glance at their relevance to the immune system. Life Sci. 2016;146:163–73. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2016.01.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Pham-Huy LA, He H, Pham-Huy C. Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. Int J Biomed Sci. 2008;4(2):89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

24. Hrycay EG, Bandiera SM. Involvement of cytochrome P450 in reactive oxygen species formation and cancer. Adv Pharmacol. 2015;74:35–84. doi:10.1016/bs.apha.2015.03.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Bhattacharya S. Reactive oxygen species and cellular defense system. Free Radic Hum Health Dis. 2015;17–29. [Google Scholar]

26. Hassan W, Noreen H, Rehman S, Gul S, Amjad Kamal M, Paul Kamdem J, et al. Oxidative stress and antioxidant potential of one hundred medicinal plants. Curr Top Med Chem. 2017;17(12):1336–70. doi:10.2174/1568026617666170102125648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Almalki WH, Alroqib HM, Alotaibi MK, Alshareef AA, Babour EA, Alotaibi MM. Human diseases caused by oxidative stress: targeting free radicals. Nveo-Nat Volatiles Essent Oils J. 2021;8(6):4375–83. [Google Scholar]

28. Sierra-Vargas MP, Montero-Vargas JM, Debray-García Y, Vizuet-de-Rueda JC, Loaeza-Román A, Terán LM. Oxidative stress and air pollution: its impact on chronic respiratory diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(1):853. doi:10.3390/ijms24010853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Sharifi-Rad M, Anil Kumar NV, Zucca P, Varoni EM, Dini L, Panzarini E, et al. Lifestyle, oxidative stress, and antioxidants: back and forth in the pathophysiology of chronic diseases. Front Physiol. 2020;11:694. doi:10.3389/fphys.2020.00694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ayala A, Muñoz MF, Argüelles S. Lipid peroxidation: production, metabolism, and signaling mechanisms of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2014;2014(1):360438. doi:10.1155/2014/360438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Nishida N, Kudo M. Oxidative stress and epigenetic instability in human hepatocarcinogenesis. Dig Dis. 2013;31(5–6):447–53. doi:10.1159/000355243. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Valavanidis A, Vlachogianni T, Fiotakis C. 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine (8-OHdGa critical biomarker of oxidative stress and carcinogenesis. J Environ Sci Health C. 2009;27(2):120–39. doi:10.1080/10590500902885684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Melis JP, van Steeg H, Luijten M. Oxidative DNA damage and nucleotide excision repair. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2013;18(18):2409–19. doi:10.1089/ars.2012.5036. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Das SK, Vasudevan DM. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress. Life Sci. 2007;81(3):177–87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

35. Albano E. Alcohol, oxidative stress and free radical damage. Proc Nutr Soc. 2006;65(3):278–90. doi:10.1079/pns2006496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Mattson MP, Cheng A. Neurohormetic phytochemicals: low-dose toxins that induce adaptive neuronal stress responses. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29(11):632–9. doi:10.1016/j.tins.2006.09.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Jayasri MA, Mathews L, Radha A. A report on the antioxidant activity of leaves and rhizomes of Costus pictus. Int J Integr Biol. 2009;5(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

38. Altaf MM, Khan MSA, Ahmad I. Diversity of bioactive compounds and their therapeutic potential. In: Khan MSA, Ahmad I, Chattopadhyay D, editors. New look to phytomedicine. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2019. p. 15–34. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-814619-4.00002-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Doughari JH. Phytochemicals: extraction methods, basic structures and mode of action as potential chemotherapeutic agents. Rijeka, Croatia: INTECH Open Access; 2012 [cited 2025 Jun 19]. Available from: https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/32936/InTech-Phytochemicals_extraction_methods_basic_structures_and_mode_of_action_as_potential_chemotherapeutic_agents.pdf. [Google Scholar]

40. Sundaram Sanjay S, Shukla AK. Potential therapeutic applications of nano-antioxidants. In: Free radicals versus antioxidants. Singapore: Springer; 2021 [cited 2025 Jun 19]. p. 1–17. Available from: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-16-1143-8_1. [Google Scholar]

41. Atta EM, Mohamed NH, Silaev AAA. Antioxidants: an overview on the natural and synthetic types. Eur Chem Bull. 2017;6(8):365–75. [Google Scholar]

42. Goyal S, Thirumal D, Singh S, Kumar D, Singh I, Kumar G, et al. Basics of antioxidants and their importance. In: Sindhu RK, Singh I, Babu MA, editors. Antioxidants: nature’s defense against disease. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Scrivener Publishing LLC; 2025. p. 1–20. doi:10.1002/9781394270576.ch1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Mordi RC, Ademosun OT, Ajanaku CO, Olanrewaju IO, Walton JC. Free radical mediated oxidative degradation of carotenes and xanthophylls. Molecules. 2020;25(5):1038. doi:10.3390/molecules25051038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Szabo K, Cătoi AF, Vodnar DC. Bioactive compounds extracted from tomato processing by-products as a source of valuable nutrients. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2018;73:268–77. doi:10.1007/s11130-018-0691-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Carluccio E, Biagioli P, Zuchi C, Bardelli G, Murrone A, Lauciello R, et al. Fibrosis assessment by integrated backscatter and its relationship with longitudinal deformation and diastolic function in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;32:1071–80. doi:10.1007/s10554-016-0881-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Miazek K, Beton K, Śliwińska A, Brożek-Płuska B. The effect of β-carotene, tocopherols and ascorbic acid as anti-oxidant molecules on human and animal in vitro/in vivo studies: a review of research design and analytical techniques used. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1087. doi:10.3390/biom12081087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Khedkar S, Ahmad Khan M. Aqueous extract of cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.role in cancer and inflammation. Evid-Based Complement Altern Med. 2023;2023(1):5467342. doi:10.1155/2023/5467342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Pagliari S, Forcella M, Lonati E, Sacco G, Romaniello F, Rovellini P, et al. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effect of cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum J. Presl) bark extract after in vitro digestion simulation. Foods. 2023;12(3):452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

49. Banu AT, Lunghar J. Cinnamon as a potential nutraceutical and functional food ingredient. In: Amalraj A, Kuttappan S, A.C. KV, Matharu A, editors. Herbs, spices and their roles in nutraceuticals and functional foods. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023. p. 257–78. doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-90794-1.00021-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Atasoy N, Yücel UM. Antioxidants from plant sources and free radicals. In: Ahmad R, editor. Reactive oxygen species. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2021. [Google Scholar]

51. Xu DP, Li Y, Meng X, Zhou T, Zhou Y, Zheng J, et al. Natural antioxidants in foods and medicinal plants: extraction, assessment and resources. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(1):96. doi:10.3390/ijms18010096. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Chanu NR, Gogoi P, Barbhuiya PA, Dutta PP, Pathak MP, Sen S. Natural flavonoids as potential therapeutics in the management of diabetic wound: a review. Curr Top Med Chem. 2023;23(8):690–710. doi:10.2174/1568026623666230419102140. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Zhao Q, Zhong XL, Zhu SH, Wang K, Tan GF, Meng PH, et al. Research advances in Toona sinensis, a traditional Chinese medicinal plant and popular vegetable in China. Diversity. 2022;14(7):572. doi:10.3390/d14070572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Song FL, Gan RY, Zhang Y, Xiao Q, Kuang L, Li HB. Total phenolic contents and antioxidant capacities of selected Chinese medicinal plants. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11(6):2362–72. doi:10.3390/ijms11062362. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Tariq L, Bhat BA, Hamdani SS, Mir RA. Phytochemistry, pharmacology and toxicity of medicinal plants. In: Aftab T, Hakeem KR, editors. Medicinal and aromatic plants. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 217–40. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-58975-2_8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Shahrajabian MH, Sun W. The power of the underutilized and neglected medicinal plants and herbs of the middle east. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2024;19(3):159–75. doi:10.2174/0115748871276544240212105612. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Barbosa PO, Pala D, Silva CT, de Souza MO, do Amaral JF, Vieira RAL, et al. Açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) pulp dietary intake improves cellular antioxidant enzymes and biomarkers of serum in healthy women. Nutrition. 2016;32(6):674–80. doi:10.1016/j.nut.2015.12.030. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Gulcin İ. Antioxidants and antioxidant methods: an updated overview. Arch Toxicol. 2020;94(3):651–715. doi:10.1007/s00204-020-02689-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Silva AS, Reboredo-Rodríguez P, Süntar I, Sureda A, Belwal T, Loizzo MR, et al. Evaluation of the status quo of polyphenols analysis: part I—phytochemistry, bioactivity, interactions, and industrial uses. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19(6):3191–218. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Di Lorenzo C, Colombo F, Biella S, Stockley C, Restani P. Polyphenols and human health: the role of bioavailability. Nutrients. 2021;13(1):273. doi:10.3390/nu13010273. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Mokrani A, Madani K. Effect of solvent, time and temperature on the extraction of phenolic compounds and antioxidant capacity of peach (Prunus persica L.) fruit. Sep Purif Technol. 2016;162:68–76. doi:10.1016/j.seppur.2016.01.043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Dabetic NM, Todorovic VM, Djuricic ID, Antic Stankovic JA, Basic ZN, Vujovic DS, et al. Grape seed oil characterization: a novel approach for oil quality assessment. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2020;122(6):1900447. doi:10.1002/ejlt.201900447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Nagraj GS, Jaiswal S, Harper N, Jaiswal AK. Chapter 20: carrot. In: Jaiswal AK, editor. Nutritional composition and antioxidant properties of fruits and vegetables. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2020. p. 323–37. [Google Scholar]

64. Bakan E, Akbulut ZT, İnanç AL. Carotenoids in foods and their effects on human health. Akad Gıda. 2014;12(2):61–8. [Google Scholar]

65. Viskelis P, Radzevicius A, Urbonaviciene D, Viskelis J, Karkleliene R, Bobinas C. Biochemical parameters in tomato fruits from different cultivars as functional foods for agricultural, industrial, and pharmaceutical uses. Rijeka, Croacia: InTech Open; 2015. [Google Scholar]

66. Domínguez R, Gullón P, Pateiro M, Munekata PE, Zhang W, Lorenzo JM. Tomato as potential source of natural additives for meat industry. A review. Antioxidants. 2020;9(1):73. doi:10.3390/antiox9010073. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Sadiq M, Akram NA, Ashraf M, Al-Qurainy F, Ahmad P. Alpha-tocopherol-induced regulation of growth and metabolism in plants under non-stress and stress conditions. J Plant Growth Regul. 2019;38:1325–40. doi:10.1007/s00344-019-09936-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Gülcin I. Antioxidant activity of food constituents: an overview. Arch Toxicol. 2012;86:345–91. [Google Scholar]

69. Isabelle M, Lee BL, Lim MT, Koh WP, Huang D, Ong CN. Antioxidant activity and profiles of common vegetables in Singapore. Food Chem. 2010;120(4):993–1003. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.11.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Spínola VAR. Nutraceuticals and functional foods for diabetes and obesity control [dissertation]. Funchal, Portugal: Universidade da Madeira. 2018 [cited 2025 Jun 19]. Available from: https://digituma.uma.pt/entities/publication/5e27ca4c-76c7-4e39-98f6-cf10d63cde53. [Google Scholar]

71. Chaudhari SK, Arshad S, Amjad MS, Akhtar MS. Natural compounds extracted from medicinal plants and their applications. In: Akhtar M, Swamy M, Sinniah U, editors. Natural bio-active compounds. Singapore: Springer; 2019. p. 193–207. doi:10.1007/978-981-13-7154-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Pratyusha S. Phenolic compounds in the plant development and defense: an overview. In: Plant stress physiology: perspectives in agriculture. London, UK: IntechOpen; 2022. p. 125–34. doi:10.5772/intechopen.102873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Mansinhos I, Gonçalves S, Rodríguez-Solana R, Ordóñez-Díaz JL, Moreno-Rojas JM, Romano A. Impact of temperature on phenolic and osmolyte contents in in vitro cultures and micropropagated plants of two mediterranean plant species, Lavandula viridis and Thymus lotocephalus. Plants. 2022;11(24):3516. doi:10.3390/plants11243516. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Shahidi F, Ambigaipalan P. Phenolics and polyphenolics in foods, beverages and spices: antioxidant activity and health effects—a review. J Funct Foods. 2015;18:820–97. doi:10.1016/j.jff.2015.06.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Mucha P, Skoczyńska A, Malecka M, Hikisz P, Budzisz E. Overview of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of selected plant compounds and their metal ions complexes. Molecules. 2021;26(16):4886. doi:10.3390/molecules26164886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Dias MC, Pinto DC, Silva AM. Plant flavonoids: chemical characteristics and biological activity. Molecules. 2021;26(17):5377. doi:10.3390/molecules26175377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

77. Salehi B, Sharifi-Rad J, Cappellini F, Reiner Ž, Zorzan D, Imran M, et al. The therapeutic potential of anthocyanins: current approaches based on their molecular mechanism of action. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1300. doi:10.3389/fphar.2020.01300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Perron NR, Brumaghim JL. A review of the antioxidant mechanisms of polyphenol compounds related to iron binding. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2009;53:75–100. doi:10.1007/s12013-009-9043-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

79. Forester SC, Lambert JD. The role of antioxidant versus pro-oxidant effects of green tea polyphenols in cancer prevention. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2011;55(6):844–54. doi:10.1002/mnfr.201000641. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Briguglio G, Costa C, Pollicino M, Giambo F, Catania S, Fenga C. Polyphenols in cancer prevention: new insights. Int J Funct Nutr. 2020;1(2):1. [Google Scholar]

81. Stephane FFY, Jules BKJ. Terpenoids as important bioactive constituents of essential oils. In: Essential oils-bioactive compounds, new perspectives and applications. London, UK: IntechOpen. 2020 [cited 2025 Jun 18]. Available from: https://cdn.intechopen.com/pdfs/72167.pdf. [Google Scholar]

82. Pham HNT, Vuong QV, Bowyer MC, Scarlett CJ. Phytochemicals derived from Catharanthus roseus and their health benefits. Technologies. 2020;8(4):80. doi:10.3390/technologies8040080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Gawade M, Zaware M, Gaikwad C, Kumbhar R, Chavan T. Catharanthus roseus L. (Periwinklean herb with impressive health benefits & pharmacological therapeutic effects. Int Res J Plant Sci. 2023;14(2):1–6. doi:10.14303/irjps.2023.07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Alam S, Sarker MMR, Sultana TN, Chowdhury MNR, Rashid MA, Chaity NI, et al. Antidiabetic phytochemicals from medicinal plants: prospective candidates for new drug discovery and development. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:800714. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.800714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]