Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Sandalwood Essential Oil (SEO) Readily Inhibits Colletotrichum gloeosporioides-Mediated Anthracnose in Post-Harvest Stored Mango (Mangifera indica L. cv. ‘Keitt’)

1 Tropical Crops Genetic Resources Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences; Key Laboratory of Crop Gene Resources and Germplasm Enhancement in Southern China, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Haikou, 571101, China

2 School of Tropical Agriculture and Forestry, Hainan University, Danzhou, 571737, China

3 College of Horticulture, China Agricultural University, Beijing, 100193, China

4 Department of Horticulture, Faculty of Agriculture, Ataturk University, Erzurum, 25240, Turkey

5 Department of Plant Production, College of Food and Agriculture Sciences, King Saud University, P.O. Box 2460, Riyadh, 11451, Saudi Arabia

6 Sanya Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences, Sanya, 572024, China

7 Department of Plant Breeding and Genetics, University of Agriculture Faisalabad, Faisalabad, 38000, Pakistan

* Corresponding Authors: Muhammad Mubashar Zafar. Email: ; Fei Qiao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovations in Post-Harvest Disease Control and Quality Preservation of Horticultural Crops)

Phyton-International Journal of Experimental Botany 2025, 94(7), 2167-2181. https://doi.org/10.32604/phyton.2025.065068

Received 03 March 2025; Accepted 25 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

Mango (Mangifera indica L. cv. ‘Keitt’) is one of the core fruit delicacies produced by China. During the post-harvest storage span, the fungal pathogen colletotrichum gloeosporioides readily invades the fruits and leads to a significant overall yield loss. In recent years of development, the exploitation of naturally occurring fungitoxic compounds such as Sandalwood Essential Oil (SEO) has been useful in tackling various fungal species. This study demonstrates the potential of SEO as part of a storage protection strategy against C. gloeosporioides-induced post-harvest anthracnose. SEO displayed a relatively higher mycelial growth inhibition rate when compared to various other essential oils. Furthermore, the Minimal Inhibitory Concentration (MIC), Minimum Fungicidal Concentration (MFC), and EC50 (Half maximal effective concentration) of SEO were determined to be 2000, 2500, and 610.38 µL/L, respectively. Moreover, the chitosan glutamate-SEO emulsion controlled the anthracnose spread for several days by multiple folds at ½ MIC, MIC, and 2 MIC concentrations. These results strongly support the potential for large-scale production and application of SEO emulsions by agrochemical firms and post-harvest storage facilities handling Keitt mangoes.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileChina is the titan of the global fruit production sector, and it’s no surprise that it is also the 2nd largest mango (Mangifera indica L.) producer in the world as well [1]. According to the latest statistics, China produces around 2.4 million metric tons of mangoes yearly on average, and that number is projected to rise thanks to modern advancements in fruit production research [2]. In this research field, one of the main vertices deals with safe prolonged storage, especially tropical fruits such as mangoes. It is estimated that due to a lack of precise post-harvest handling practices and robust storage, 20%–30% of the total fruit becomes spoiled [3]. Microbial and fungal activity is considered the primary cause of such extensive post-harvest fruit loss [4]. Among the primary fungal pathogens responsible for mango spoilage is C. gloeosporioides. The post-harvest anthracnose (fruit rot) mediated by this particular species is the leading cause of storage decay losses in more than 100 plant species [5]. Quiescent infection is characterized as the most damaging phase of the C. gloeosporioides post-harvest attack, especially when the fruit just starts to ripen up [pre-climacteric phase]. When the ripening processes start, the fungus also starts to gradually resume its growth [6]. In mango cultivation, disease management has traditionally relied on synthetic chemical fungicides, but their repeated use often drives pathogen resistance [7–9]. Moreover, these chemicals pose considerable risks to human health and the environment: many are acutely toxic, teratogenic, or carcinogenic, persist as pollutants, and degrade only very slowly [10–13]. Due to these apparent negative effects of synthetic fungicides, alternate approaches in controlling C. gloeosporioides infections are needed.

Recent field developments reflect a growing trend in the fruit-research community toward applying naturally derived products such as essential oil extracts to postharvest fruit preservation [14,15]. The use of these extracts has proven to be very useful in tackling these devastating infections in multiple fruit species through enhanced decay control and improved storage span [16–18]. Recent investigations into essential oils have shown superior results [19–22]. These findings were evident in both in vitro and in vivo tests for anti-fungal activity [23–26]. This specific fungal-inhibition property makes them more desirable for their applications in the safe storage of post-harvest fruit crops. One of these well-researched, naturally-occurring products is SEO. SEO has demonstrated consistently strong anti-fungal activity across diverse studies, both through direct application on post-harvest fruit crops and in controlled laboratory experiments [27–31]. Essential oils like SEO primarily inhibit fungal growth by sequentially damaging proliferating fungal cells. This progressive assault irreversibly denatures critical cellular components, yielding a sustained and elevated rate of mycelial growth inhibition [32–35]. The vapor-phase bioactivity of essential oils such as SEO is another property that makes them excellent fumigants for stored fruit stocks [36]. Moreover, a growing body of research demonstrates that essential-oil extracts can substantially fortify the intrinsic defense systems of the plant, markedly improving resistance against phytopathogenic microorganisms [37–39].

This study builds upon the existing body of research on SEO and post-harvest fungal control. Presently, we have methodically demonstrated the in vivo anti-fungal efficacy of chitosan-based SEO coatings in suppressing the C. gloeosporioides-mediated anthracnose infection of the stored mango fruits. The findings serve as a valuable technical reference for future investigations into SEO-based antifungal coatings aimed at preventing anthracnose and enhancing the storage longevity of post-harvest fruit crops.

2.1 Preparation of Essential Oil Dilutions

All essential oils under testing, including wormwood, pine needle, rose essential oil, lemon, sandalwood essential oil, citronella, lavender, and perilla essential oil, were purchased from Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd. (Pudong, Shanghai, China). Each essential oil was diluted to 200 µL/L using a precisely measured volume of Tween-80 as the emulsifying agent [40]. The emulsification after the subsequent dilution process was performed using the Sonics Materials™ Ultrasonic Processor VCX130 (Newtown, CT, USA) [41].

2.2 Formulation of Coating Films

To make the SEO coating films, chitosan glutamate was used as the film base by dissolving it in 0.1% concentration of acetic acid (CH3COOH) up to the final concentration of 1% on the whole [42]. Subsequently, the Tween-80–emulsified SEO was incorporated in accurately measured volumes and stirred for 20 min to prepare a range of concentrations for application on the fruit samples.

2.3 Culturing of Fungal Samples

The potent C. gloeosporioides samples were kindly gifted to us by Dr. He Zhang (Environment and Plant Protection Institute, Chinese Academy of Tropical Agricultural Sciences). The isolates were cultured on Potato Dextrose Agar (PDA) or in Potato Dextrose Broth (PDB) at 28°C using a horizontal shaker set to 200 rpm [43]. After 4 days, the fungal conidia were collected from the subsequent suspension cultures, followed by filtration and centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 5 min. The acquired pellets were then thoroughly washed twice and resuspended at a final concentration of 1 × 106 spores/mL [44].

2.4 Calculation of Mycelial Growth Inhibition Rate

To assess the mycelial growth inhibition rate, the PDA-containing 90 mm Petri dishes were inoculated with 2.5 µL of spores each in the dead center [45]. The inoculated Petri dishes were then incubated in darkness at 28°C for 7 days. After incubation, the colony diameter (cd) was calculated, and the final percentage of the mycelial growth inhibition rate was calculated following the upcoming equation [46].

2.5 Observation of Mycelial Morphology

The mycelial proliferative morphology was keenly observed using the ZEISS Smartzoom 5 Automated Digital Microscope (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, LLC—White Plains, New York, NY, USA) [47].

2.6 Inoculation of Fruit Subjects

The fresh indigenous fruits of Mangifera indica cv. ‘Keitt’ at the mature green stage was collected from the natively occurring marketplaces. The collected fruits were then subjected to disinfection soaping using the 1% Sodium hypochlorite (NaClO) solution for 2 min before further treatment [48]. Fruits were inoculated by piercing to a 3 mm depth using a sterilized 1 mm needle, followed by the injection of 4 µL of spore suspension into each wound [49]. The post-harvest plant defense response and other crucial fruit analyses, i.e., weight loss, respiratory rate, hardness, total soluble solids, total acids, Vitamin C (Ascorbic Acid—C6H8O6) content, Catalase activity [CAT], Malondialdehyde content [MDA], Superoxide dismutase activity [SOD], and Polyphenol oxidase activity [PPO] were also performed using the standard protocols [50,51].

All experiments were biologically replicated three times using groups of 6–8 fruits each to ensure statistical robustness. Furthermore, all the statistical tests and analyses viz. one-way ANOVA, linear regression, Goodness-of-Fit (R2), and p-value were executed by feeding all data into Minitab 22.1.0 (State College, PA, USA) [52].

3.1 SEO Inhibits the Mycelial Growth of C. gloeosporioides

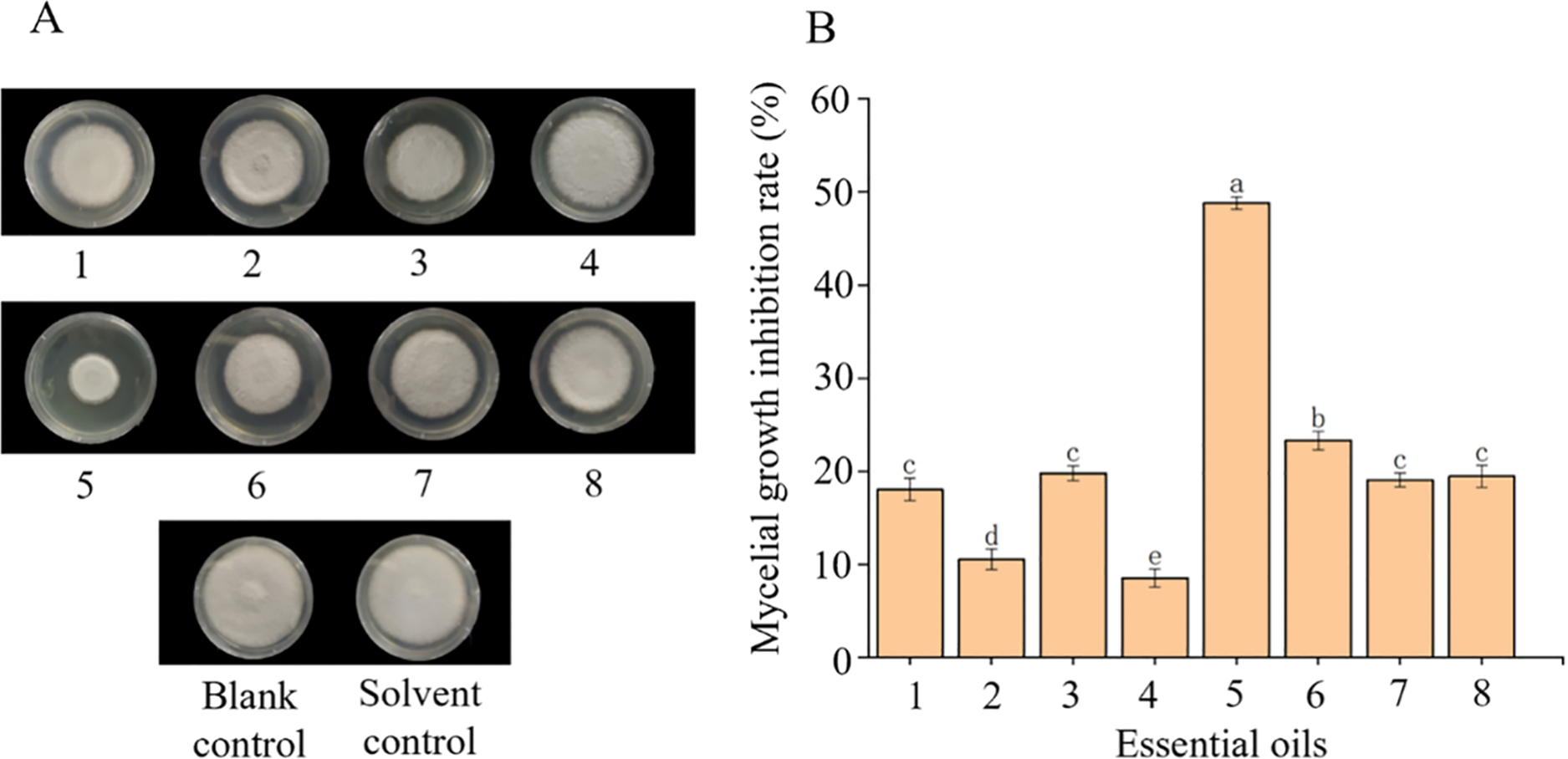

A series of naturally extracted essential oils were evaluated for their relative mycelial growth inhibition against inoculated C. gloeosporioides spores on standard 90 mm Petri dishes (oil concentration: 500 µL/L; medium: standard PDA). The essential oils under testing include wormwood, pine needles, rose essential oil, lemon, sandalwood essential oil, citronella, lavender, and perilla essential oil. Blank and the standard Tween-80 served as the control groups for subsequent testing. As far as visual observation goes, the SEO outperformed all other essential oils under testing considerations by extreme comparative margins. On statistical scales, a significant relative difference was observed between different essential oil treatments in terms of mycelial growth inhibition of C. gloeosporioides spores, see Fig. 1 below. Notably, SEO exhibited a mycelial growth inhibition rate approaching 50%. On the other hand, the next contender viz. citronella oil, showed a rate reaching just above the 20% mark. This says a lot about the relative efficacy of SEO in inhibiting proliferative mycelial growth. The other essential oils that did not differ significantly in results include wormwood, rose essential oil, lavender, and perilla essential oil, with an inhibition rate barely reaching 20% individually. This means that these two oils in particular just performed marginally better when compared to the blank and solvent controls. Interestingly, the pine needle and lemon oil did not perform any better than the four aforementioned oils with an inhibition rate hardly approaching 10%. This testing procedure highlights the potential applications of SEO as a potent anthracnose inhibitor.

Figure 1: The effect of different essential oils on inhibition of mycelial growth of C. gloeosporioides. (A) Spores of C. gloeosporioides were inoculated on the standard PDA medium and 90 mm Petri dishes each with 500 µL/L of essential oil respectively. (B) Mycelial growth inhibition rates (%) of different essential oils. Different lower-case letters (a–e) on the top of the bars indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05). Note: 1 = wormwood oil, 2 = pine needle oil, 3 = rose essential oil, 4 = lemon oil, 5 = sandalwood essential oil, 6 = citronella oil, 7 = lavender oil, and 8 = perilla essential oil. Controls = blank and solvent (Tween-80)

3.2 SEO Inhibits Mycelial Growth at Multiple Concentrations and Periods

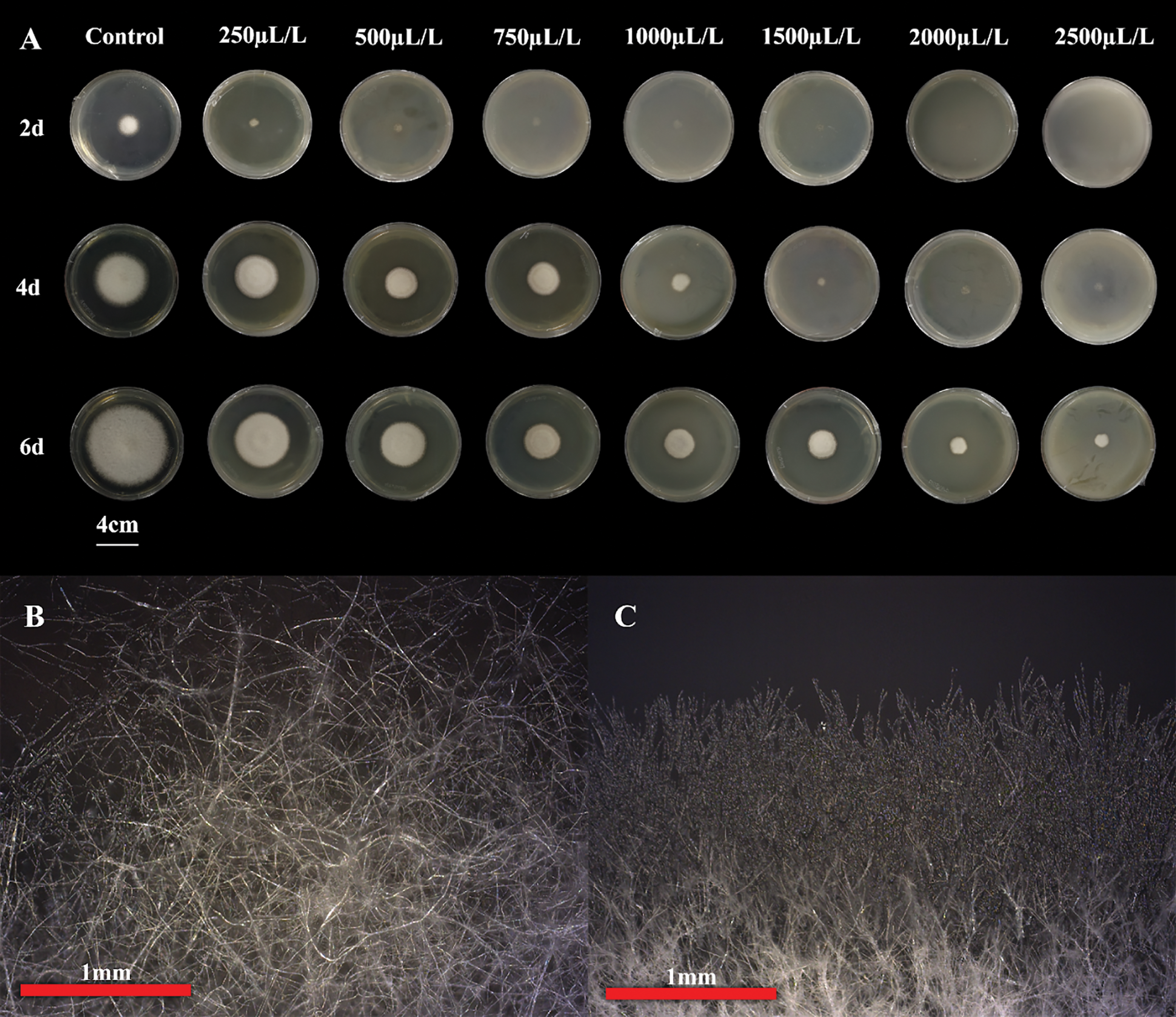

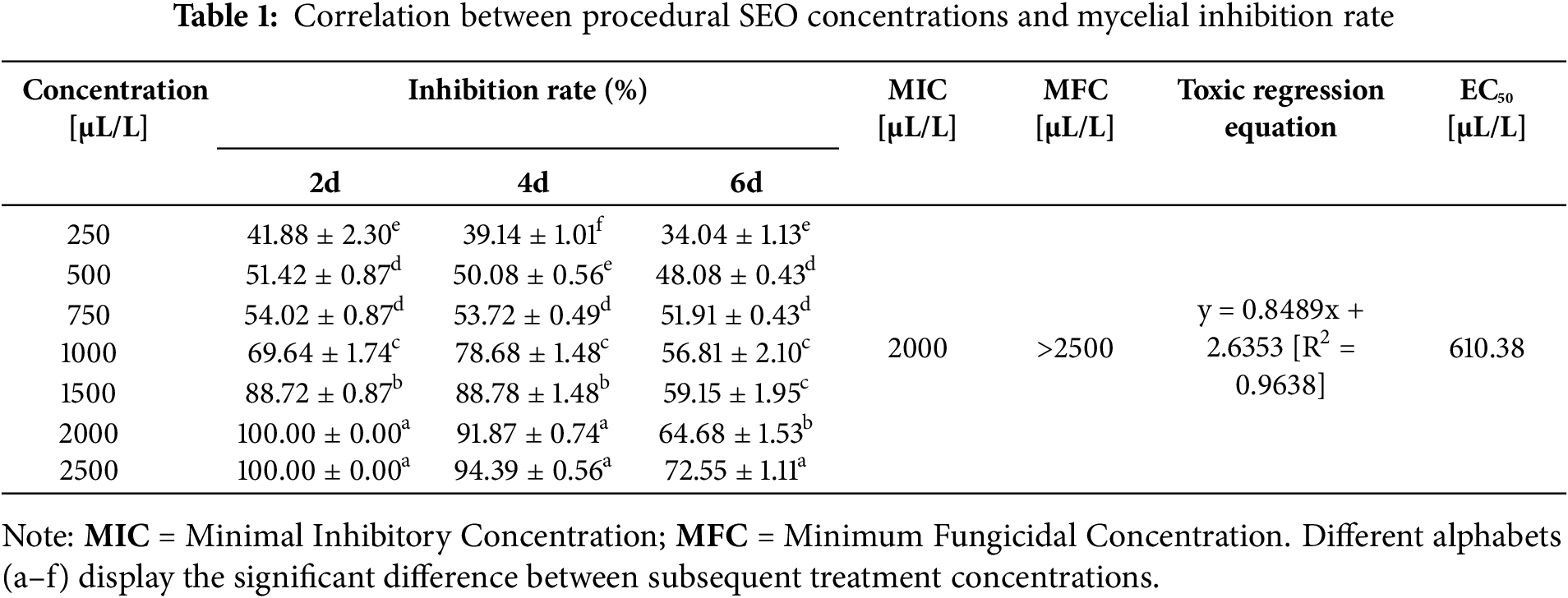

In another series of experimental iterations, the effect of different concentrations of SEO was quantified using the colonial morphology of C. gloeosporioides inoculated PDA plates, see Fig. 2A below. The mycelial growth inhibition rate was measured at fixed 2-day intervals following treatment with each concentration. At an emulsion concentration of 250 µL/L, the inhibition effect was constantly significant relative to the control group, see Table 1 below. At 500 and 750 µL/L concentrations, the inhibition rate was significant and comparatively the same, statistically. Furthermore, the inhibition rate spurts greatly over the course at concentrations of 1000 and 1500 µL/L. The two aforementioned concentrations have a 2-fold statistical difference among their subsequent rates of inhibition. Following this, when the concentrations of 2000 and 2500 µL/L were approached, a completely significant inhibition [100.00 ± 0.00] was achieved during the 2 days. Thus, 2000 µL/L served as the MIC while the Minimum Fungicidal Concentration MFC viz. Total Inhibitory Concentration was statistically plotted to be greater than the baseline of 2500 µL/L to achieve maximum efficacy. However, when the two aforementioned concentrations were coursed through the 4 days, a slightly significant decrease in the inhibition rate was also observed with it becoming more and more significant as the period reached 6 days. Moreover, the relationship between the concentration of SEO [x] and the logarithm of the fungal growth inhibition rate [y] was described using the linear regression equation. The EC50 value for mycelial growth inhibition was calculated to be approximately 610.38 µL/L, representing the concentration at which SEO inhibits 50% of mycelial growth, see Fig. 2B,C below.

Figure 2: Mycelial growth inhibition effect of SEO emulsion on C. gloeosporioides. (A) Colonial morphology of C. gloeosporioides on PDA plates at different concentrations. (B) Blank control (Red bar = 1 mm). (C) Mycelial morphology with 610.38 µL/L [EC50] emulsion (Red bar = 1 mm)

3.3 SEO Hinders the Germination of C. gloeosporioides Spores

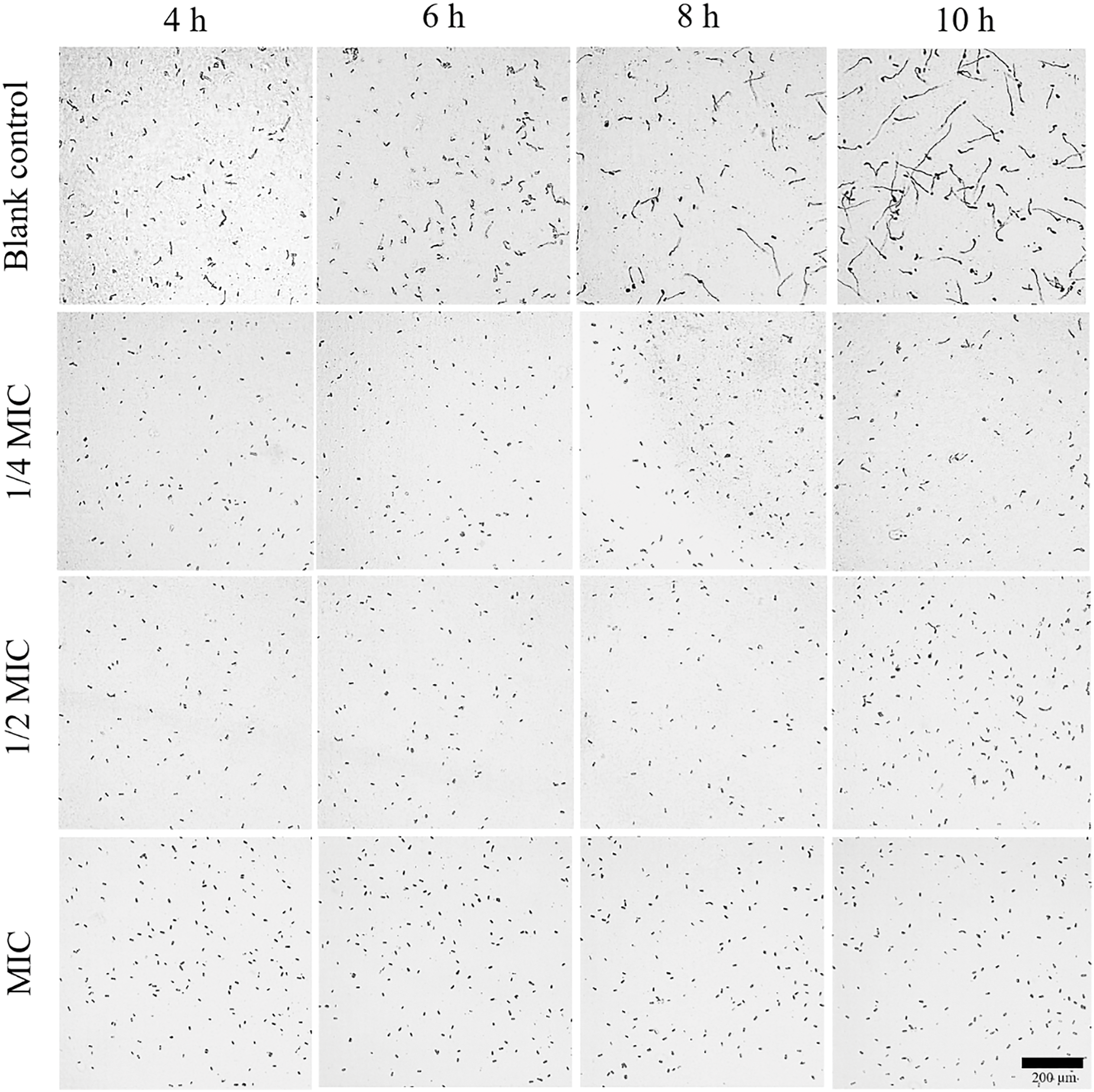

To further solidify the direct inhibition effect of SEO, inoculation of C. gloeosporioides spores was treated with ¼ MIC, ½ MIC, and MIC iterations throughout 4-, 6-, 8-, and 10-h standard to be observed for germination progression, see Fig. 3 below. In about 4 h, the blank water control showed the most germination out of all treatments. The same conditions were also observed when the time mark reached 6 h with the blank water control still leading the pack in terms of germination. However, when 8 h passed, the ¼ MIC began presenting with significant signs of germination of spores. In the same period, ½ MIC and MIC groups also presented with min spore germination. At the time point of 10 h, the blank water control group displayed the most spore germination of all followed by ¼ MIC and ½ MIC group. At this stage, the absolute MIC was the only iteration with the significant and least amount of spore germination. A clear negative correlation between increasing SEO concentration and decreasing spore germination was observed, indicating a substantial inhibitory effect.

Figure 3: Effects of SEO on the C. gloeosporioides spore germination [MIC = 2000 µL/L]. The extent of germination was observed over the time intervals of 4-, 6-, 8-, and 10-h standard with blank water control, ¼ MIC, ½ MIC, and MIC sets each simultaneously (Black bar = 1 mm)

3.4 SEO Maintains Fruit Morphology and Resists Anthracnose Progression

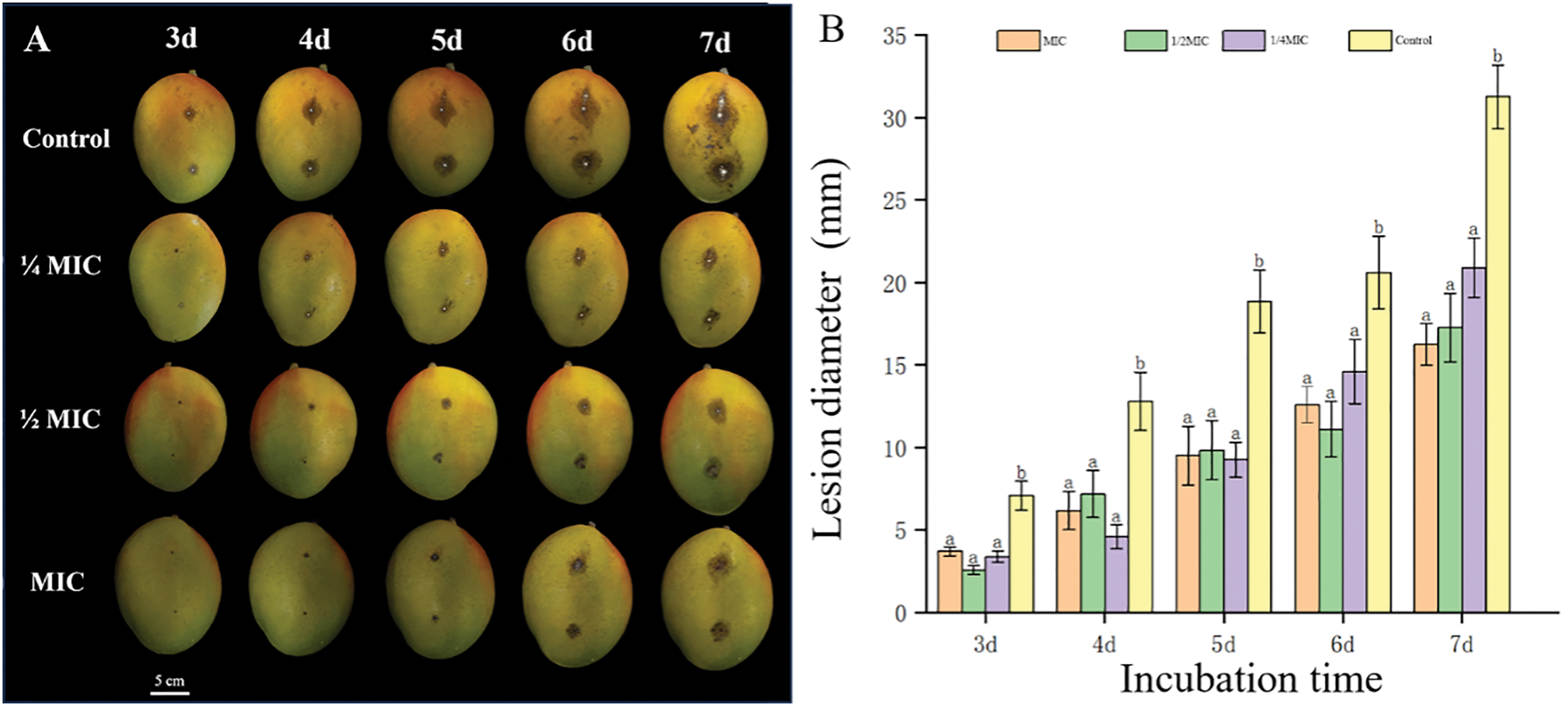

The subsequent phases of fruit morphology under active C. gloeosporioides infection were also observed under ¼ MIC, ½ MIC, and MIC sets with water as a control group, see Fig. 4A below. Each fruit was soaked in the treatment solution for 2 min immediately after inoculation and prior to incubation. The diameter of the spots of active infection were penned down during time intervals of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 days, respectively, under the aforementioned treatment sets, see Fig. 4B below. As expected, the infection progressed rapidly in the control group with visible hyphae from the spots of infection starting to appear after just 3 days post-inoculation. The ¼ MIC and ½ MIC sets resisted the proliferation of infection up to 4 and 6 days respectively, with hyphae just starting to appear only in ¼ MIC iteration after 4 days post-inoculation. The iteration with the absolute MIC concentration resisted infection proliferation the most with almost no visible hyphae during the whole course of experimentation. On the whole, the results were critically significant relative to the disease progression in the control group with statistically similar resistance potential in all other treatment groups, i.e., ¼ MIC, ½ MIC, and MIC, respectively. This experiment demonstrates that brief exposure to SEO, through a 2-min soaking, effectively enhances anthracnose resistance in mango fruits.

Figure 4: Fruit morphology and anthracnose progression under different iterations of MIC. (A) Mango fruit morphological phases under the infection of the inoculated C. gloeosporioides and different subsequent treatment concentrations (¼ MIC, ½ MIC, and MIC sets and water as control group with a 2-min soaking period each) (White bar = 5 cm). (B) Graph of the diameter of infection spots on fruit surface during incubation periods (3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 days respectively). Different lower-case letters (a, b) on the top of the bars indicate significant differences among treatments (p < 0.05)

3.5 SEO Coating Films Halt Anthracnose Progression During Storage and Maintain Post-Harvest Fruit Quality

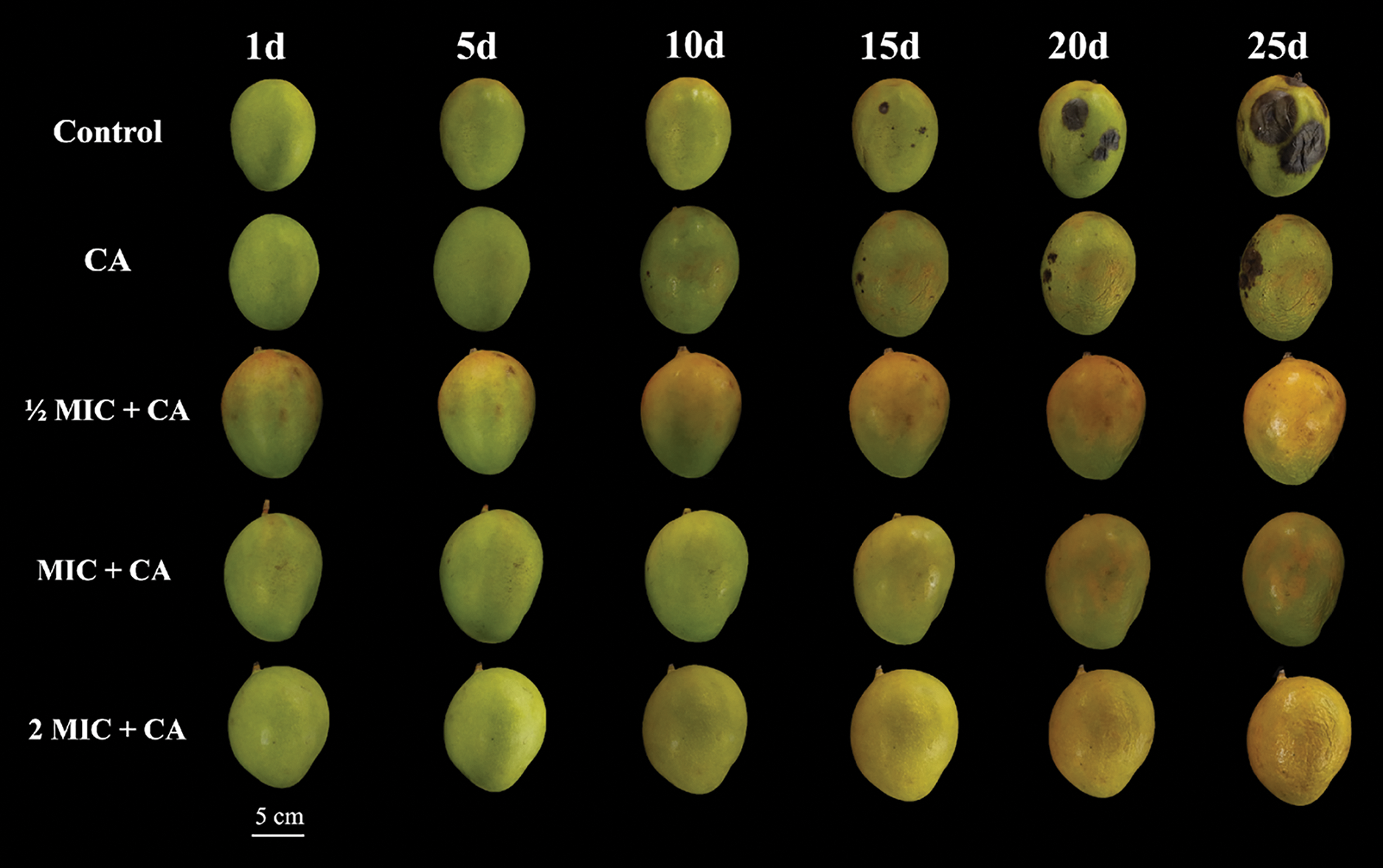

To evaluate SEO-mediated resistance during active storage, mango fruits were treated with chitosan glutamate (CA), ½ MIC + CA, MIC + CA, and 2 MIC + CA, alongside a blank control group, see Fig. 5 below. The morphology of the mango fruit in all test groups was closely observed over the constant-interval periods of 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 days. The initial observations after 1 day were more or less the same in all test groups with no significantly detectable change in fruit morphology whatsoever. When the 5-day mark was reached, the subjects in the control group began displaying yellow surface signs from the top edge of the fruit while all other test groups remained the same in terms of morphology. After 10 days, the yellowish surface of the control group started to proliferate to the rest of the fruit while the coating agent CA group began showing min signs of anthracnose on one side of the fruit. All other test groups remained the same in morphological assessment. After the 15-day mark, the control group now also had visible anthracnose spots rapidly spreading in all directions. After 20 days, both the blank control and coating agent CA group were visibly infested with anthracnose but the former had a more rapid proliferation rate relative to the latter one. There are still no signs of anthracnose in any of the remaining test groups at this point. After the final 25-day mark, the test subjects in the control group now had more than half of their surface covered with rotting disease spots while the coating agent CA group had just 1/5th of its surface covered comparatively. At this stage, all other test groups were still anthracnose-free with relatively insignificant variations in the fruit color and appearance on a whole. Significant findings from additional post-harvest analyses included weight loss, respiratory rate, firmness, total soluble solids, total acids, Vitamin C content, CAT, MDA, SOD, PPO activities, decay rate, and disease index [Supplementary Tables S0–S12].

Figure 5: Differences in mango fruit appearance during storage. The treatment conditions include a blank control, coating agent CA (Chitosan glutamate), ½ MIC + CA, MIC + CA, and 2 MIC + CA sets over an observation time interval of 1, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 days each simultaneously. All fruits were subjected to an overall 2-min soaking period (White bar = 5 cm)

Post-harvest quality assessments revealed that SEO significantly mitigated fruit weight loss compared to the blank control, even after 25 days. The respiratory rates of the fruit in all the iterations, i.e., after 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 days remained substantial with SEO. The fruit hardness was retained partially significantly up to 3.44 N/cm2 at CA + ½ MIC after the same period. Similarly, the content of total soluble solids and total acids also remained moderately substantial when compared to the control group with sequential percentage increase and decline, respectively. On the other hand, the Vitamin C content faced a steep decline in the blank control relative to the SEO iteration of CA + 2 MIC. Also, the level of the enzymes of the antioxidant defense system, i.e., CAT, MDA, SOD, and PPO also remained relatively and consistently higher in the SEO-treated groups in almost all iterations after the 25 days. Moreover, both the percentage of decay rate and the disease index number were found to be highly correlated with the concentrations of SEO used under subsequent MIC groups at the same periods. The combination of all the aforementioned factors displays the efficacy of SEO in mediating and maintaining the quality parameters of the post-harvest mango fruit. Furthermore, the SEO-enhanced antioxidant enzyme system employs complex mechanisms that help maintain mango freshness and protect against C. gloeosporioides-induced anthracnose, thereby extending storage life.

Decades of research have consistently demonstrated that essential oils effectively protect various plant species from diverse types of fruit rot, especially during post-harvest storage [53–57]. These aforementioned researches consistently show that essential oils exhibit potent antifungal, antibacterial, and antioxidant activities, which together extend fruit shelf life. By suppressing pathogen proliferation and mitigating oxidative stress, these natural compounds preserve both the quality and safety of stored produce [58–61]. The integration of essential oils in post-harvest treatment protocols offers a sustainable and eco-friendly alternative to synthetic chemicals, aligning with the growing demand for natural and organic solutions in agricultural practices. In the present research, SEO has come forward as one of the distinguished and potent members of the essential oil family in terms of resistance against C. gloeosporioides-mediated anthracnose in post-harvest stored mango. Our findings highlight the remarkable efficacy of SEO in curbing the incidence and severity of anthracnose, a prevalent and destructive fungal disease in mangoes in controlled trials, SEO exhibited robust antifungal activity, markedly reducing anthracnose symptoms compared with untreated controls. This not only underscores SEO’s potential to enhance post-harvest mango quality but also highlights its promise for managing fruit-rot diseases in a wide range of susceptible crops. Indeed, its powerful antifungal effects have been extensively documented in earlier studies across multiple plant species [62–64]. These investigations have proven crucial in establishing the efficacy of SEO as a fungitoxic agent. These kinds of research provide essential insights for scaling up the production of essential oil emulsions by large agrochemical firms, ensuring optimal physicochemical formulation values. Such strategic formulation improves the stability and efficacy of SEO-based treatments, while emphasizing the critical role of scientific validation for their successful commercial deployment against fungal diseases in agriculture.

Several factors are sequentially involved in determining the quality of the essential oil emulsions being produced such as acid number, refractive index, thermostability, specific gravity, phenolic content, saponification value, optical rotation, ester value, and organic solvent solubility [65]. Generally, essential oils emulsions such as chitosan-based SEO nano-coatings are composed of multiple fungicidal components working in a synergistic combination to provide maximum efficacy against fungal infection [66,67]. Synergistic effects are amplified when two or more essential oils are combined into a single emulsion, significantly boosting antifungal efficacy [68,69]. Since a single fungicidal compound acts on a specific biochemical pathway, fungal populations can develop resistance over time. Combining multiple fungicidal essential-oil constituents not only mitigates resistance development but also enhances economic feasibility. Moreover, in MIC assays, SEO exhibited partially significant yet stochastic effects on fruit hardness, total soluble solids, and titratable acidity. These quality parameters may improve further when broad-spectrum blends of essential oils or multiple potent fungicidal components are applied simultaneously.

Comparative analyses demonstrate that SEO significantly surpasses commonly used essential oils including wormwood, pine needle, rose, lemon, sandalwood, citronella, lavender, and perilla in antifungal efficacy. However, broader investigation into synergistic blends of multiple potent essential oils is warranted to inform the formulation of multi-component emulsions that optimize efficacy while minimizing any off-target effects. Moreover, EC50 was calculated and tested to a concentration of 610.38 µL/L while the MIC is far much higher at 2000 µL/L, therefore the MFC must be greater than 2500 µL/L for the formation of an effective emulsion. The multiple variations of MIC value were also effective to a statistically significant and correlative extent. However, anything less than the MFC concentration of 2500 µL/L might not be as effective as intended while using more concentrated emulsions might not be as economically feasible at a large scale. When specifically dealing with C. gloeosporioides-mediated anthracnose at this level, the MIC of 2000 µL/L and MFC of 2500 µL/L might also not yield expected exponentially upscaled results. Consequently, comprehensive and rigorous calculations must be performed in advance, explicitly accounting for all potential error sources that could derail the intended outcomes. The emulsion concentrations tested in this study were carefully optimized to maintain antifungal effectiveness for up to one month after harvest. However, it’s important to recognize that results observed under controlled laboratory conditions may differ when scaled up to real-world applications. Moreover, the effects might also not be fully duplicated in other fruit plant species affected by C. gloeosporioides-mediated anthracnose with the same MIC and MFC values due to a large number of unknown variables to account for the equation. The protective storage efficacy and fungitoxic potential of SEO can also be a topic of research for future studies to come.

This study underscores the significant potential of essential oils recognized for their efficacy against fruit rot in a wide range of plant species. Decades of research have documented their potent antifungal, antibacterial, and antioxidant properties, which are vital for prolonging shelf life and safeguarding both the quality and safety of fresh produce. SEO, highlighted in this research, emerges as a potent agent against C. gloeosporioides-mediated anthracnose in mangoes, demonstrating substantial efficacy in reducing disease severity. The effectiveness of SEO demonstrated in this study, positions it as a promising tool for sustainable post-harvest management in agriculture, aligning with the shift towards eco-friendly practices. Moreover, the research emphasizes the synergistic potential of essential oil combinations, enhancing their fungicidal effectiveness while minimizing the risk of resistance development. Challenges related to formulation optimization and economic viability highlight the necessity for ongoing research into scalable production methods and practical application techniques. Although our controlled experiments yielded encouraging antifungal outcomes, real-world applications may produce variable results. Therefore, additional studies are essential to assess efficacy of SEO and adaptability across diverse fruit species afflicted by anthracnose under practical post-harvest conditions.

The findings endorse SEO as a viable natural alternative to synthetic treatments in post-harvest protocols, offering promising prospects for enhancing agricultural sustainability and securing food supply chains. Future research should focus on refining formulation strategies, assessing broader applicability, and addressing practical challenges to maximize its protective benefits in agricultural settings. To meet the demands and production criteria of large-scale agrochemical firms such as in China, expansive-scale trials of SEO efficacy against C. gloeosporioides-mediated anthracnose in post-harvest stored mango fruit should be conducted. Large-scale trials will comprehensively evaluate legality, safety, and cost-effectiveness, ensuring the approach meets regulatory standards and economic viability. Expectantly, then SEO can be used commercially in mango fruit storage facilities with maximal effectiveness both in efficacy and economically.

Acknowledgement: Ongoing Research Funding Program, (ORF-2025-751), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding Statement: This research work was funded by the Hainan Province Science and Technology Special Fund [grant number ZDKJ2021012] and the National Key R&D Program of China [grant number 2023YFD2300801] received by Fei Qiao. We are also thankful to the Ongoing Research Funding Program (ORF-2025-751), King Saud University, Riyadh, Saud Arabia.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xuefei Jiang, Fei Qiao; methodology: Shenzhen Wang, Rongxiang Wang, Xuefei Jiang, Fei Qiao; data curation: Shenzhen Wang, Xiaona Fu, Muhammad Mubashar Zafar, Yuandi Zhu, Fei Qiao; investigation: Muhammad Shahzaib, Shenzhen Wang, Rundong Yao, Rongxiang Wang, Xiaona Fu, Muhammad Mubashar Zafar, Hanqing Cong, Pingyin Guan, Xuefei Jiang, Yuandi Zhu; formal analysis: Shenzhen Wang, Rundong Yao, Rongxiang Wang, Xiaona Fu, Muhammad Mubashar Zafar, Hanqing Cong, Pingyin Guan, Yuandi Zhu, Fei Qiao; software: Muhammad Shahzaib; validation: Muhammad Shahzaib, Shenzhen Wang, Rundong Yao, Hanqing Cong, Xuefei Jiang, Yuandi Zhu; resources: Muhammad Shahzaib, Fei Qiao; visualization: Muhammad Shahzaib, Mahmoud F. Seleiman, Sezai Ercisli; writing—original draft: Muhammad Shahzaib; writing—review and editing: Muhammad Shahzaib, Mahmoud F. Seleiman, Sezai Ercisli, Fei Qiao; project administration and supervision: Fei Qiao; funding acquisition: Fei Qiao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Materials.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/phyton.2025.065065/s1. Complementary methodology and tentative generated data on fruit post-harvest weight loss, respiratory rate, hardness, total soluble solids, total acids, Vitamin C content, Catalase [CAT] activity, Malondialdehyde [MDA] content, Superoxide dismutase [SOD] activity, Polyphenol oxidase [PPO] activity, decay rate, and the disease index.

References

1. Rajan S. Mango: the king of fruits. In: Mango genome. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2021. p. 1–11 doi:10.1007/978-3-030-47829-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Shahbandeh M. Global mango production 2000-2022 Statista.com: statista [Internet]; 2024 [cited 2025 Jun 16]. Available from: www.statista.com. [Google Scholar]

3. Gupta N, Jain SK. Storage behavior of mango as affected by post harvest application of plant extracts and storage conditions. J Food Sci Technol. 2014;51(10):2499–507. doi:10.1007/s13197-012-0774-0; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Vicente AR, Civello PM, Martínez GA, Powell ALT, Labavitch JM, Chaves AR. Control of postharvest spoilage in soft fruit. Stewart Postharvest Rev. 2005;1(4):1–11. doi:10.2212/spr.2005.4.1; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Phoulivong S, Cai L, Chen H, McKenzie EHC, Abdelsalam K, Chukeatirote E, et al. Colletotrichum gloeosporioides is not a common pathogen on tropical fruits. Fungal Divers. 2010;44(1):33–43. doi:10.1007/s13225-010-0046-0; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Siddiqui Y, Ali A. Chapter 11—colletotrichum gloeosporioides (Anthracnose). In: Bautista-Baños S, editor. Postharvest decay. San Diego, CA, USA: Academic Press; 2014. p. 337–71. [Google Scholar]

7. Khaskheli MI. Mango diseases: impact of fungicides. Hortic Crops. 2020:143. doi:10.5772/intechopen.87081; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Dofuor AK, Quartey NK, Osabutey AF, Antwi-Agyakwa AK, Asante K, Boateng BO, et al. Mango anthracnose disease: the current situation and direction for future research. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1168203. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1168203; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Alemu K. Dynamics and management of major postharvest fungal diseases of mango fruits. J Bio Agric Healthc. 2014;4(27):13–21; [Google Scholar]

10. Bernardes MFF, Pazin M, Pereira LC, Dorta DJ. Impact of pesticides on environmental and human health. In: Toxicology studies—cells, drugs and environment. Houston TX, USA: InTech; 2015. p. 195–233. doi:10.5772/59710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Pathak VM, Verma VK, Rawat BS, Kaur B, Babu N, Sharma A, et al. Current status of pesticide effects on environment, human health and it’s eco-friendly management as bioremediation: a comprehensive review. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:962619. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.962619; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Sharma A, Shukla A, Attri K, Kumar M, Kumar P, Suttee A, et al. Global trends in pesticides: a looming threat and viable alternatives. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2020;201(5):110812. doi:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.110812; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lushchak VI, Matviishyn TM, Storey JM, Storey KB. Pesticide toxicity: a mechanistic approach. EXCLI J. 2018;17:1101; [Google Scholar]

14. Maqbool M, Ali A, Alderson PG, Mohamed MTM, Siddiqui Y, Zahid N. Postharvest application of gum arabic and essential oils for controlling anthracnose and quality of banana and papaya during cold storage. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2011;62(1):71–6. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2011.04.002; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sivakumar D, Bautista-Baños S. A review on the use of essential oils for postharvest decay control and maintenance of fruit quality during storage. Crop Prot. 2014;64:27–37. doi:10.1016/j.cropro.2014.05.012; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shehata SA, Abdeldaym EA, Ali MR, Mohamed RM, Bob RI, Abdelgawad KF. Effect of some citrus essential oils on post-harvest shelf life and physicochemical quality of strawberries during cold storage. Agronomy. 2020;10(10):1466. doi:10.3390/agronomy10101466; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Saleh MA, Zaied NS, Maksoud MA, Hafez OM. Application of Arabic gum and essential oils as the postharvest treatments of Le Conte pear fruits during cold storage. Asian J Agric Hortic Res. 2019;3(3):1–11. doi:10.9734/ajahr/2019/v3i329999; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Perumal AB, Huang L, Nambiar RB, He Y, Li X, Sellamuthu PS. Application of essential oils in packaging films for the preservation of fruits and vegetables: a review. Food Chem. 2022;375(7):131810. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131810; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Pattnaik S, Subramanyam VR, Kole C. Antibacterial and antifungal activity of ten essential oils in vitro. Microbios. 1996;86(349):237–46; [Google Scholar]

20. Combrinck S, Regnier T, Kamatou GPP. In vitro activity of eighteen essential oils and some major components against common postharvest fungal pathogens of fruit. Ind Crops Prod. 2011;33(2):344–9. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2010.11.011; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Hu F, Tu XF, Thakur K, Hu F, Li XL, Zhang YS, et al. Comparison of antifungal activity of essential oils from different plants against three fungi. Food Chem Toxicol. 2019;134(3):110821. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2019.110821; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Stević T, Berić T, Šavikin K, Soković M, Gođevac D, Dimkić I, et al. Antifungal activity of selected essential oils against fungi isolated from medicinal plant. Ind Crops Prod. 2014;55(3):116–22. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.02.011; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Aminifard MH, Mohammadi S. Essential oils to control Botrytis cinerea in vitro and in vivo on plum fruits. J Sci Food Agric. 2013;93(2):348–53. doi:10.1002/jsfa.5765; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Al-Reza SM, Rahman A, Ahmed Y, Kang SC. Inhibition of plant pathogens in vitro and in vivo with essential oil and organic extracts of Cestrum nocturnum L. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2010;96(2):86–92. doi:10.1016/j.pestbp.2009.09.005; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Soylu EM, Kurt Ş, Soylu S. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of the essential oils of various plants against tomato grey mould disease agent Botrytis cinerea. Int J Food Microbiol. 2010;143(3):183–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.08.015; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang D, Zhang J, Jia X, Xin L, Zhai H. Antifungal effects and potential mechanism of essential oils on Collelotrichum gloeosporioides in vitro and in vivo. Molecules. 2019;24(18):3386. doi:10.3390/molecules24183386; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Das K. Sandalwood (Santalum album) oils. In: Essential oils in food preservation, flavor and safety. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2016. p. 723–30. [Google Scholar]

28. Nautiyal OH. Sandalwood (Santalum album) oil. In: Fruit Oils: Chemistry and Functionality; 2019. p. 711–40. [Google Scholar]

29. Wardana AA, Koga A, Tanaka F, Tanaka F. Antifungal features and properties of chitosan/sandalwood oil Pickering emulsion coating stabilized by appropriate cellulose nanofiber dosage for fresh fruit application. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):18412. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-643894/v1; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Boruah T, Parashar P, Ujir C, Dey SK, Nayik GA, Ansari MJ, et al. Sandalwood essential oil. In: Essential oils. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2023. p. 121–45. [Google Scholar]

31. Wardana AA, Kingwascharapong P, Wigati LP, Tanaka F, Tanaka F. The antifungal effect against Penicillium italicum and characterization of fruit coating from chitosan/ZnO nanoparticle/Indonesian sandalwood essential oil composites. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2022;32(1–2):100849. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100849; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Khan ZA, Saleem A, Imtiaz H, Ahmad R, Sajjad Y, Bilal M, et al. Azacytidine induced epigenetic variations improve fruit quality and yield in tomato grown under soil conditions. Pak J Agric Sci. 2024;61(4):1053–65. doi:10.21162/PAKJAS/24.325; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Mejhed B, Kzaiber F, Terouzi W. Effect of the combination of freezing and packaging in an acid solution on the stability of Arbutus Unedo L. Fruits. Int J Agric Biosci. 2023;12(4):292–8. doi:10.47278/journal.ijab/2023.080; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Prompreing K, Saikamwong N, Aekram S. Enhancing agricultural productivity and innovation: deep learning for citrus disease classification in Thai orchards. Int J Agric Biosci. 2025;14(2):283–8; [Google Scholar]

35. Rashid MHU, Mehwish WH, Ahmad S, Ali L, Ahmad N, Ali M, et al. Unraveling the combinational approach for the antibacterial efficacy against infectious pathogens using the herbal extracts of the leaves of Dodonaea viscosa and fruits of Rubus fruticosus. Agrobiol Rec. 2024;16:57–66; [Google Scholar]

36. Mani-López E, Cortés-Zavaleta O, López-Malo A. A review of the methods used to determine the target site or the mechanism of action of essential oils and their components against fungi. SN Appl Sci. 2021;3(1):44. doi:10.1007/s42452-020-04102-1; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Isman MB. Plant essential oils for pest and disease management. Crop Prot. 2000;19(8–10):603–8. doi:10.1016/s0261-2194(00)00079-x; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Werrie P-Y, Durenne B, Delaplace P, Fauconnier ML. Phytotoxicity of essential oils: opportunities and constraints for the development of biopesticides. A review. Foods. 2020;9(9):1291. doi:10.3390/foods9091291; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Kesraoui S, Andrés MF, Berrocal-Lobo M, Soudani S, Gonzalez-Coloma A. Direct and indirect effects of essential oils for sustainable crop protection. Plants. 2022;11(16):2144. doi:10.3390/plants11162144; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Rizvi SAH, Ling S, Tian F, Xie F, Zeng X. Toxicity and enzyme inhibition activities of the essential oil and dominant constituents derived from Artemisia absinthium L. against adult Asian citrus psyllid Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: psyllidae). Ind Crops Prod. 2018;121:468–75. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2018.05.031; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Martínez-Velasco A, Lobato-Calleros C, Hernández-Rodríguez BE, Román-Guerrero A, Alvarez-Ramirez J, Vernon-Carter EJ. High intensity ultrasound treatment of faba bean (Vicia faba L.) protein: effect on surface properties, foaming ability and structural changes. Ultrason Sonochemistry. 2018;44(2):97–105. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.02.007; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Melro E, Antunes FE, da Silva GJ, Cruz I, Ramos PE, Carvalho F, et al. Chitosan films in food applications. Tuning film properties by changing acidic dissolution conditions. Polymers. 2020;13(1):1. doi:10.3390/polym13010001; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Su Y-Y, Qi Y-L, Cai L. Induction of sporulation in plant pathogenic fungi. Mycology. 2012;3(3):195–200. doi:10.1080/21501203.2012.719042; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Prapagdee B, Kuekulvong C, Mongkolsuk S. Antifungal potential of extracellular metabolites produced by Streptomyces hygroscopicus against phytopathogenic fungi. Int J Biol Sci. 2008;4(5):330. doi:10.7150/ijbs.4.330; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mohammed S, Zeitar E, Eskov I. Inhibition of mycelial growth of rhizoctonia solani by chitosan in vitro and in vivo. Open Agric J. 2019;13(1):156–61. doi:10.2174/1874331501913010156; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Krutmuang P, Rajula J, Pittarate S, Chatima C, Thungrabeab M, Mekchay S, et al. The inhibitory action of plant extracts on the mycelial growth of Ascosphaera apis, the causative agent of chalkbrood disease in Honey bee. Toxicol Rep. 2022;9(3):713–9. doi:10.1016/j.toxrep.2022.03.036; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Shu L, Wang M, Wang S, Li Y, Xu H, Qiu Z, et al. Excessive oxalic acid secreted by Sparassis latifolia inhibits the growth of mycelia during its saprophytic process. Cells. 2022;11(15):2423. doi:10.3390/cells11152423; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Mishra V, Abrol GS, Dubey N. Chapter 14—sodium and calcium hypochlorite as postharvest disinfectants for fruits and vegetables. In: Siddiqui MW, editor. Postharvest disinfection of fruits and vegetables. Cambridge, MA, USA: Academic Press; 2018. p. 253–72. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-812698-1.00014-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Mercier J, Jiménez JI. Control of fungal decay of apples and peaches by the biofumigant fungus Muscodor albus. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2004;31(1):1–8. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2003.08.004; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Yang F, Liu S, Tian Z, Du Y, Zhang D, Long CA. Calcium disodium edetate controls citrus green mold by chelating Mn2+ and targeting pyruvate synthesis in the pathogen. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2023;206:112529. doi:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2023.112529; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Zhang Z, Yang D, Yang B, Gao Z, Li M, Jiang Y, et al. β-Aminobutyric acid induces resistance of mango fruit to postharvest anthracnose caused by Colletotrichum gloeosporioides and enhances activity of fruit defense mechanisms. Sci Hortic. 2013;160:78–84. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2013.05.023; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Mathews PG. Design of experiments with MINITAB. Milwaukee, WI, USA: Quality press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

53. Lopez-Reyes JG, Spadaro D, Gullino ML, Garibaldi A. Efficacy of plant essential oils on postharvest control of rot caused by fungi on four cultivars of apples in vivo. Flavour Fragr J. 2010;25(3):171–7. doi:10.1002/ffj.1989; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Antunes MDC, Cavaco AM. The use of essential oils for postharvest decay control. A review. Flavour Fragr J. 2010;25(5):351–66. doi:10.1002/ffj.1986; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Elshafie HS, Mancini E, Camele I, De Martino L, De Feo V. In vivo antifungal activity of two essential oils from Mediterranean plants against postharvest brown rot disease of peach fruit. Ind Crops Prod. 2015;66(1):11–5. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.12.031; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Lopez-Reyes JG, Spadaro D, Prelle A, Garibaldi A, Gullino ML. Efficacy of plant essential oils on postharvest control of rots caused by fungi on different stone fruits in vivo. J Food Prot. 2013;76(4):631–9. doi:10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-12-342; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Camele I, Altieri L, De Martino L, De Feo V, Mancini E, Rana GL. In vitro control of post-harvest fruit rot fungi by some plant essential oil components. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13(2):2290–300. doi:10.3390/ijms13022290; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Rashid S, Ali L, Saleem A, Ummer K, Nisar I, Ahmed F, et al. Studies on the seasonal variation of major elements during fruit development stages and evaluation of post-harvest changes in mango germplasm. Agrobiol Rec. 2024;15:75–90. doi:10.47278/journal.abr/2024.002; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Shahid A, Faizan M, Raza MA. Potential role of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) and zinc nanoparticles (ZnNPs) for plant disease management [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://agrobiologicalrecords.com/articles/14-0-Vol-14-59-69-2023-ABR-23-152.pdf. [Google Scholar]

60. Yessenbayeva G, Kenenbayev S, Dutbayev Y, Salykova A. Organic farming practices and crops impact chemical elements in the soil of southeastern Kazakhstan. Int J Agric Biosci. 2024;13(2):222–7. doi:10.47278/journal.ijab/2024.106; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Tahir F, Fatima F, Fatima R, Ali E. Fruit peel extracted polyphenols through ultrasonic assisted extraction: a review. Agrobiol Rec. 2023;15:1–12. doi:10.47278/journal.abr/2023.043; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Abd Algaffar SO, Seegers S, Satyal P, Setzer WN, Schmidt TJ, Khalid SA. Sandalwood oils of different origins are active in vitro against Madurella mycetomatis, the major fungal pathogen responsible for Eumycetoma. Molecules. 2024;29(8):1846. doi:10.3390/molecules29081846; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Chao SC, Young DG, Oberg CJ. Screening for inhibitory activity of essential oils on selected bacteria, fungi and viruses. J Essent Oil Res. 2000;12(5):639–49. doi:10.1080/10412905.2000.9712177; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Powers CN, Osier JL, McFeeters RL, Brazell CB, Olsen EL, Moriarity DM, et al. Antifungal and cytotoxic activities of sixty commercially-available essential oils. Molecules. 2018;23(7):1549. doi:10.3390/molecules23071549; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Endo Y. Analytical methods to evaluate the quality of edible fats and oils: the JOCS standard methods for analysis of fats, oils and related materials (2013) and advanced methods. J Oleo Sci. 2018;67(1):1–10. doi:10.5650/jos.ess17130; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Yang VW, Clausen CA. Antifungal effect of essential oils on southern yellow pine. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 2007;59(4):302–6. doi:10.1016/j.ibiod.2006.09.004; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Noori SMA, Hossaeini Marashi SM. Chitosan-based coatings and films incorporated with essential oils: applications in food models. J Food Meas Charact. 2023;17(4):4060–72. doi:10.1007/s11694-023-01931-7; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Fu Y, Zu Y, Chen L, Shi X, Wang Z, Sun S, et al. Antimicrobial activity of clove and rosemary essential oils alone and in combination. Phytother Res. 2007;21(10):989–94. doi:10.1002/ptr.2179; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Bassolé IHN, Juliani HR. Essential oils in combination and their antimicrobial properties. Molecules. 2012;17(4):3989–4006. doi:10.3390/molecules17043989; [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools